User login

What’s the best VTE treatment for patients with cancer?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

No head-to-head studies or umbrella meta-analyses assess all the main treatments for VTE against each other.

Long-term LMWH decreases VTE recurrence compared with VKA

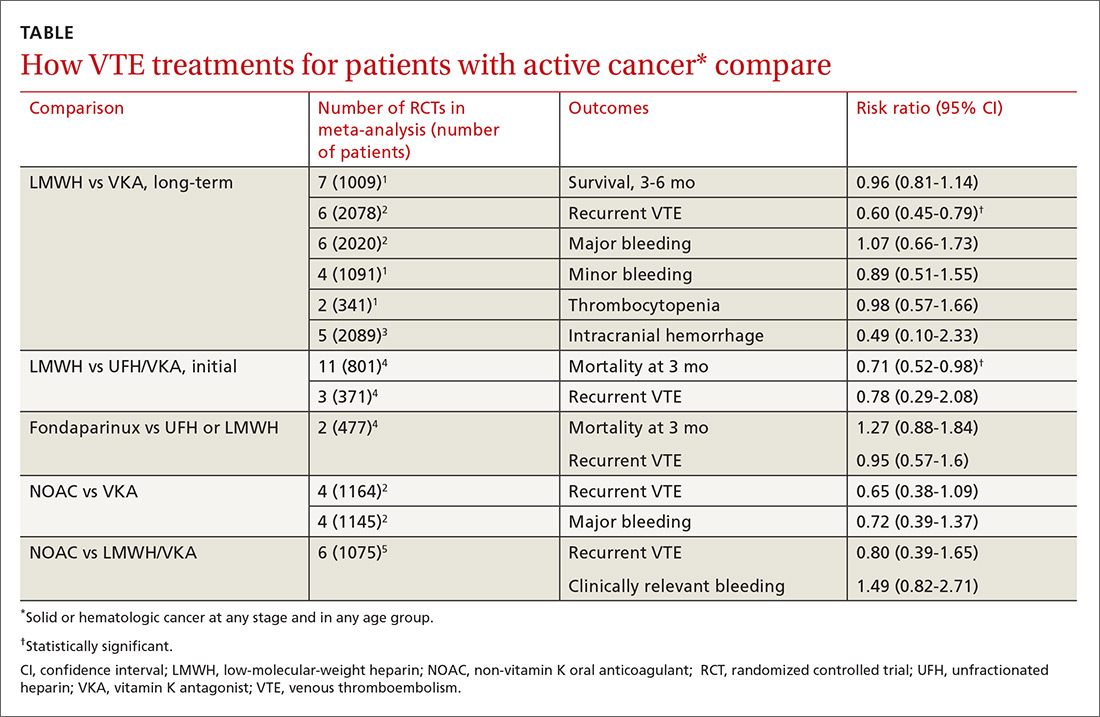

Two meta-analyses of RCTs evaluating LMWH and VKA for long-term treatment (3-12 months) of confirmed VTE in patients with cancer found that LMWH didn’t change mortality, but reduced the rate of VTE recurrence compared with VKA (40% relative reduction).1,2 The comparison showed no differences in major or minor bleeding or thrombocytopenia between LMWH and VKA (TABLE1-5).

The studies included patients with any solid or hematologic cancer at any stage and from any age group, including children. Overall, the mean age of patients was in the mid 60s; approximately 50% were male when specified. Investigators rated the evidence quality as moderate for VTE, but low for the other outcomes.1

The most recent meta-analysis of the same RCTs comparing LMWH with VKA evaluated intracranial hemorrhage rates and found no difference.3

Initial therapy with LMWH: A look at mortality

A meta-analysis of RCTs that compared LMWH with UFH/VKA for initial treatment of confirmed VTE in adult cancer patients (any type or stage of cancer, mean ages not specified) found that LMWH reduced mortality by 30%, but didn’t affect VTE recurrence or major bleeding.4

The control groups received UFH for 5 to 10 days and then continued with VKA, whereas the experimental groups received different types of LMWH (reviparin, nadroparin, tinzaparin, enoxaparin) initially and for 3 months thereafter. Investigators rated all studies low quality because of imprecision and publication bias favoring LMWH.

Fondaparinux shows no advantage for initial therapy

The same meta-analysis compared initial treatment with fondaparinux and initial therapy with enoxaparin or UFH transitioning to warfarin.4 It found no differences in any outcomes at 3 months. Investigators rated both studies as low quality for recurrent VTE and moderate for mortality and bleeding.

Continue to: Non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants vs LMWH/VKA or VKA

Non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants vs LMWH/VKA or VKA: No differences

A meta-analysis of RCTs comparing NOACs (dabigatran, edoxaban, apixaban, rivaroxaban) with VKA for 6 months found no differences in recurrent VTE or major bleeding.2

A second meta-analysis of RCTs that compared NOACs (rivaroxaban, dabigatran, apixaban) with control (LMWH followed by VKA) in adult cancer patients (mean ages, 54-66 years; 50%-60% men) reported no difference in the composite outcome of recurrent VTE or VTE-related death nor clinically significant bleeding over 1 to 36 months (most RCTs ran 3-12 months).5 Separate comparisons for rivaroxaban and dabigatran found no difference in the composite outcome, and rivaroxaban also produced no difference in clinically-significant bleeding.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The 2016 CHEST guidelines recommend LMWH as first-line treatment for VTE in patients with cancer and indicate no preference between NOACs and VKA for second-line treatment.6

1. Akl EA, Kahale L, Barba M, et al. Anticoagulation for the long-term treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(7):CD006650.

2. Posch F, Königsbrügge O, Zielinski C, et al. Treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer: A network meta-analysis comparing efficacy and safety of anticoagulants. Thromb Res. 2015;136:582-589.

3. Rojas-Hernandez CM, Oo TH, García-Perdomo HA. Risk of intracranial hemorrhage associated with therapeutic anticoagulation for venous thromboembolism in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2017;43:233-240.

4. Akl EA, Kahale L, Neumann I, et al. Anticoagulation for the initial treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(6):CD006649.

5. Sardar P, Chatterjee S, Herzog E, et al. New oral anticoagulants in patients with cancer: current state of evidence. Am J Ther. 2015;22:460-468.

6. Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;149:315-352.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

No head-to-head studies or umbrella meta-analyses assess all the main treatments for VTE against each other.

Long-term LMWH decreases VTE recurrence compared with VKA

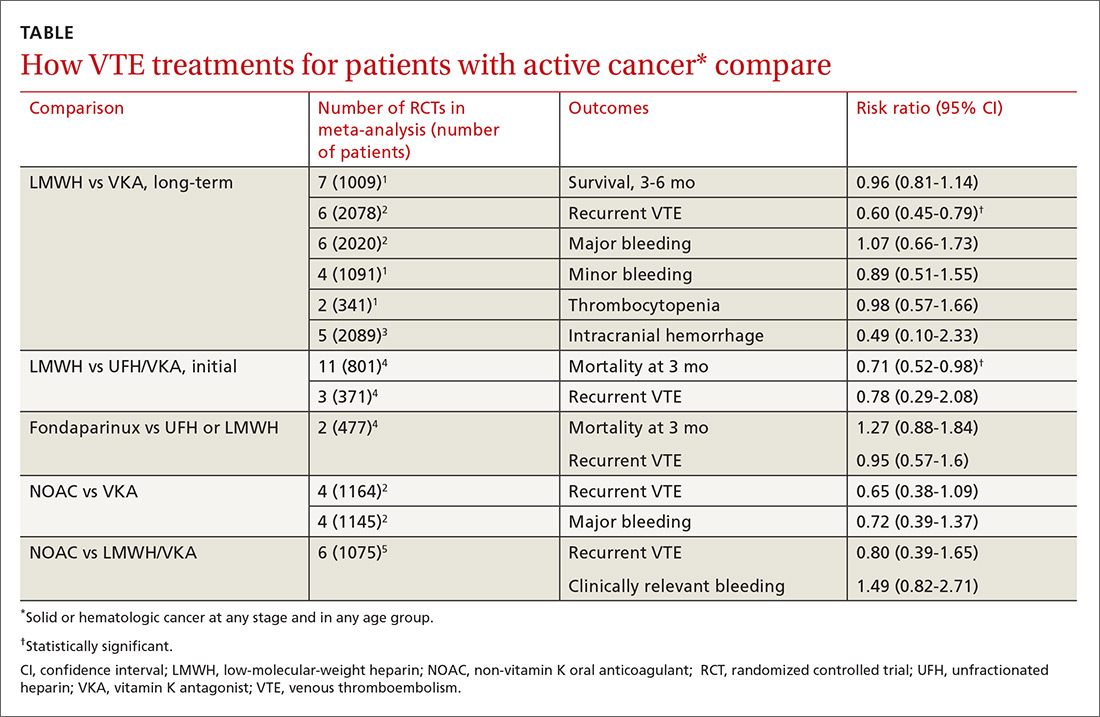

Two meta-analyses of RCTs evaluating LMWH and VKA for long-term treatment (3-12 months) of confirmed VTE in patients with cancer found that LMWH didn’t change mortality, but reduced the rate of VTE recurrence compared with VKA (40% relative reduction).1,2 The comparison showed no differences in major or minor bleeding or thrombocytopenia between LMWH and VKA (TABLE1-5).

The studies included patients with any solid or hematologic cancer at any stage and from any age group, including children. Overall, the mean age of patients was in the mid 60s; approximately 50% were male when specified. Investigators rated the evidence quality as moderate for VTE, but low for the other outcomes.1

The most recent meta-analysis of the same RCTs comparing LMWH with VKA evaluated intracranial hemorrhage rates and found no difference.3

Initial therapy with LMWH: A look at mortality

A meta-analysis of RCTs that compared LMWH with UFH/VKA for initial treatment of confirmed VTE in adult cancer patients (any type or stage of cancer, mean ages not specified) found that LMWH reduced mortality by 30%, but didn’t affect VTE recurrence or major bleeding.4

The control groups received UFH for 5 to 10 days and then continued with VKA, whereas the experimental groups received different types of LMWH (reviparin, nadroparin, tinzaparin, enoxaparin) initially and for 3 months thereafter. Investigators rated all studies low quality because of imprecision and publication bias favoring LMWH.

Fondaparinux shows no advantage for initial therapy

The same meta-analysis compared initial treatment with fondaparinux and initial therapy with enoxaparin or UFH transitioning to warfarin.4 It found no differences in any outcomes at 3 months. Investigators rated both studies as low quality for recurrent VTE and moderate for mortality and bleeding.

Continue to: Non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants vs LMWH/VKA or VKA

Non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants vs LMWH/VKA or VKA: No differences

A meta-analysis of RCTs comparing NOACs (dabigatran, edoxaban, apixaban, rivaroxaban) with VKA for 6 months found no differences in recurrent VTE or major bleeding.2

A second meta-analysis of RCTs that compared NOACs (rivaroxaban, dabigatran, apixaban) with control (LMWH followed by VKA) in adult cancer patients (mean ages, 54-66 years; 50%-60% men) reported no difference in the composite outcome of recurrent VTE or VTE-related death nor clinically significant bleeding over 1 to 36 months (most RCTs ran 3-12 months).5 Separate comparisons for rivaroxaban and dabigatran found no difference in the composite outcome, and rivaroxaban also produced no difference in clinically-significant bleeding.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The 2016 CHEST guidelines recommend LMWH as first-line treatment for VTE in patients with cancer and indicate no preference between NOACs and VKA for second-line treatment.6

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

No head-to-head studies or umbrella meta-analyses assess all the main treatments for VTE against each other.

Long-term LMWH decreases VTE recurrence compared with VKA

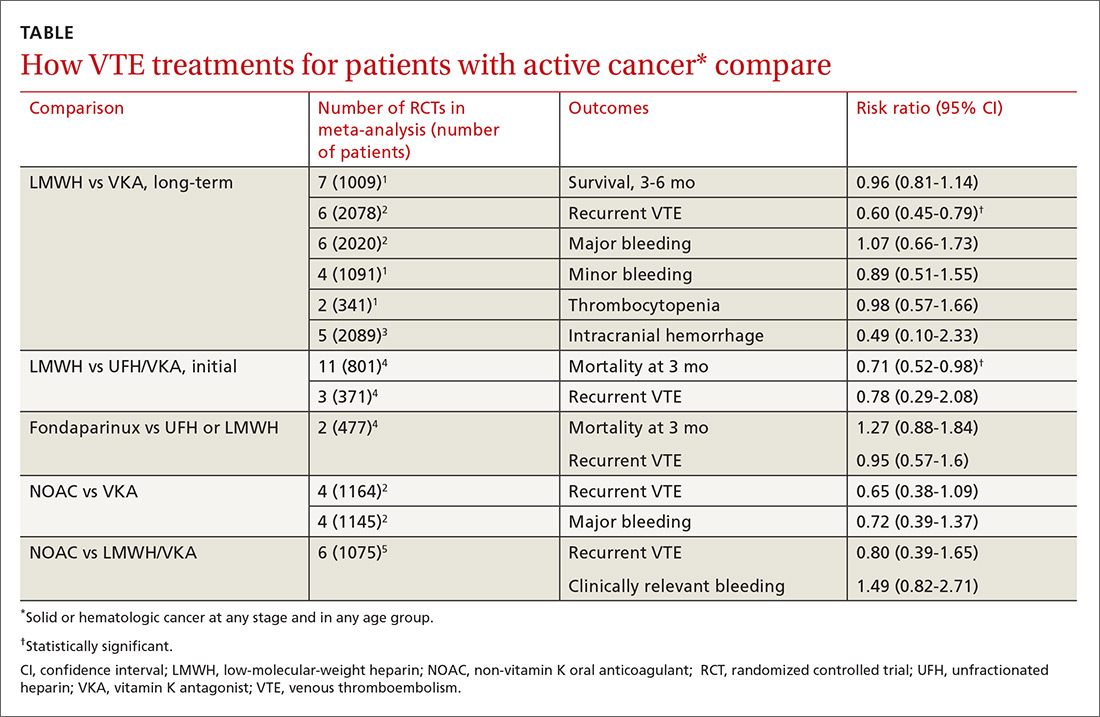

Two meta-analyses of RCTs evaluating LMWH and VKA for long-term treatment (3-12 months) of confirmed VTE in patients with cancer found that LMWH didn’t change mortality, but reduced the rate of VTE recurrence compared with VKA (40% relative reduction).1,2 The comparison showed no differences in major or minor bleeding or thrombocytopenia between LMWH and VKA (TABLE1-5).

The studies included patients with any solid or hematologic cancer at any stage and from any age group, including children. Overall, the mean age of patients was in the mid 60s; approximately 50% were male when specified. Investigators rated the evidence quality as moderate for VTE, but low for the other outcomes.1

The most recent meta-analysis of the same RCTs comparing LMWH with VKA evaluated intracranial hemorrhage rates and found no difference.3

Initial therapy with LMWH: A look at mortality

A meta-analysis of RCTs that compared LMWH with UFH/VKA for initial treatment of confirmed VTE in adult cancer patients (any type or stage of cancer, mean ages not specified) found that LMWH reduced mortality by 30%, but didn’t affect VTE recurrence or major bleeding.4

The control groups received UFH for 5 to 10 days and then continued with VKA, whereas the experimental groups received different types of LMWH (reviparin, nadroparin, tinzaparin, enoxaparin) initially and for 3 months thereafter. Investigators rated all studies low quality because of imprecision and publication bias favoring LMWH.

Fondaparinux shows no advantage for initial therapy

The same meta-analysis compared initial treatment with fondaparinux and initial therapy with enoxaparin or UFH transitioning to warfarin.4 It found no differences in any outcomes at 3 months. Investigators rated both studies as low quality for recurrent VTE and moderate for mortality and bleeding.

Continue to: Non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants vs LMWH/VKA or VKA

Non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants vs LMWH/VKA or VKA: No differences

A meta-analysis of RCTs comparing NOACs (dabigatran, edoxaban, apixaban, rivaroxaban) with VKA for 6 months found no differences in recurrent VTE or major bleeding.2

A second meta-analysis of RCTs that compared NOACs (rivaroxaban, dabigatran, apixaban) with control (LMWH followed by VKA) in adult cancer patients (mean ages, 54-66 years; 50%-60% men) reported no difference in the composite outcome of recurrent VTE or VTE-related death nor clinically significant bleeding over 1 to 36 months (most RCTs ran 3-12 months).5 Separate comparisons for rivaroxaban and dabigatran found no difference in the composite outcome, and rivaroxaban also produced no difference in clinically-significant bleeding.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The 2016 CHEST guidelines recommend LMWH as first-line treatment for VTE in patients with cancer and indicate no preference between NOACs and VKA for second-line treatment.6

1. Akl EA, Kahale L, Barba M, et al. Anticoagulation for the long-term treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(7):CD006650.

2. Posch F, Königsbrügge O, Zielinski C, et al. Treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer: A network meta-analysis comparing efficacy and safety of anticoagulants. Thromb Res. 2015;136:582-589.

3. Rojas-Hernandez CM, Oo TH, García-Perdomo HA. Risk of intracranial hemorrhage associated with therapeutic anticoagulation for venous thromboembolism in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2017;43:233-240.

4. Akl EA, Kahale L, Neumann I, et al. Anticoagulation for the initial treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(6):CD006649.

5. Sardar P, Chatterjee S, Herzog E, et al. New oral anticoagulants in patients with cancer: current state of evidence. Am J Ther. 2015;22:460-468.

6. Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;149:315-352.

1. Akl EA, Kahale L, Barba M, et al. Anticoagulation for the long-term treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(7):CD006650.

2. Posch F, Königsbrügge O, Zielinski C, et al. Treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer: A network meta-analysis comparing efficacy and safety of anticoagulants. Thromb Res. 2015;136:582-589.

3. Rojas-Hernandez CM, Oo TH, García-Perdomo HA. Risk of intracranial hemorrhage associated with therapeutic anticoagulation for venous thromboembolism in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2017;43:233-240.

4. Akl EA, Kahale L, Neumann I, et al. Anticoagulation for the initial treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(6):CD006649.

5. Sardar P, Chatterjee S, Herzog E, et al. New oral anticoagulants in patients with cancer: current state of evidence. Am J Ther. 2015;22:460-468.

6. Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;149:315-352.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

No head-to-head studies directly compare all the main treatments for venous thromboembolism (VTE) in cancer patients. Long-term treatment (3-12 months) with low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) reduces recurrence of VTE by 40% compared with vitamin K antagonists (VKA), but doesn’t change rates of mortality, major or minor bleeding, or intracranial hemorrhage in patients with solid or hematologic cancer at any stage or in any age group. Initial treatment with LMWH reduces mortality by 30% compared with unfractionated heparin (UFH) for 5 to 10 days followed by warfarin, but doesn’t alter recurrent VTE or bleeding. Non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants (NOACs) have risks of recurrent VTE or VTE-related death (composite outcome) and clinically significant bleeding comparable to VKA or LMWH/VKA (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials [RCTs], mostly of low quality).

How effectively do ACE inhibitors and ARBs prevent migraines?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

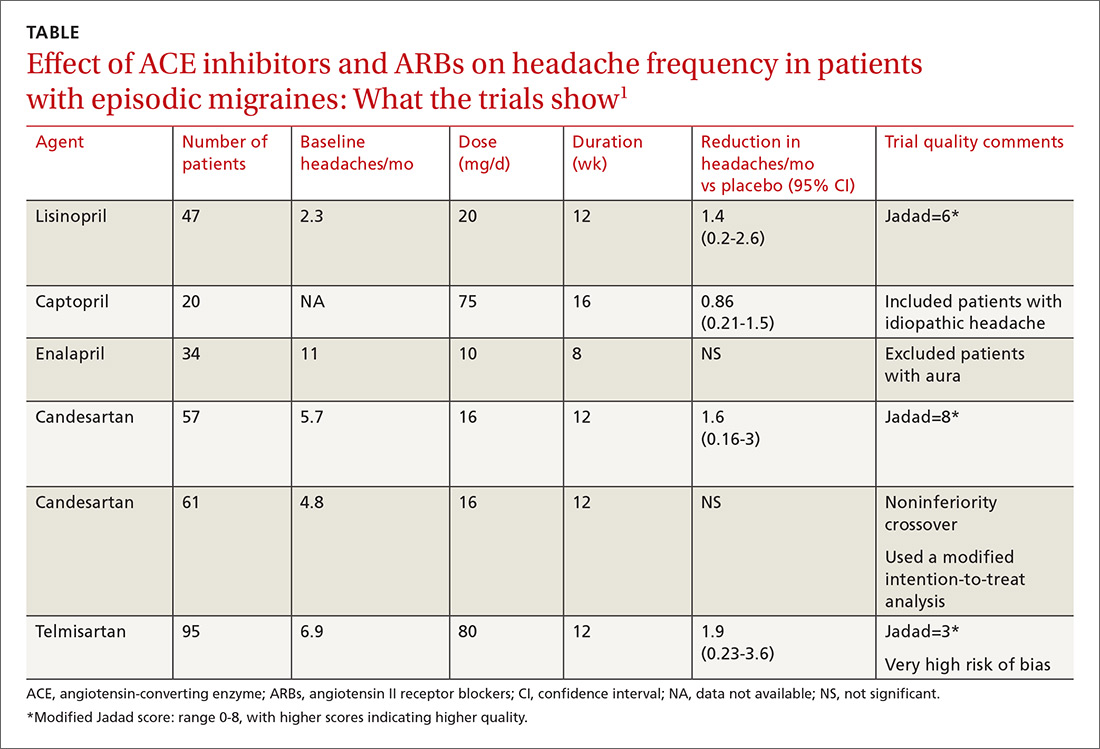

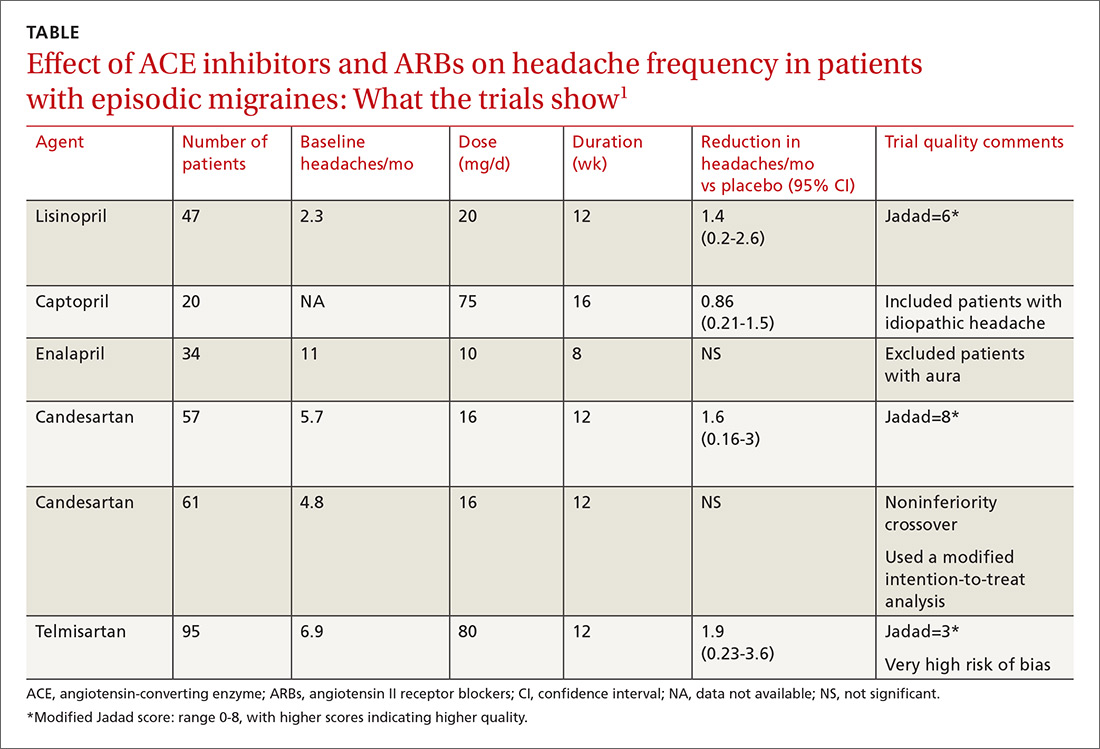

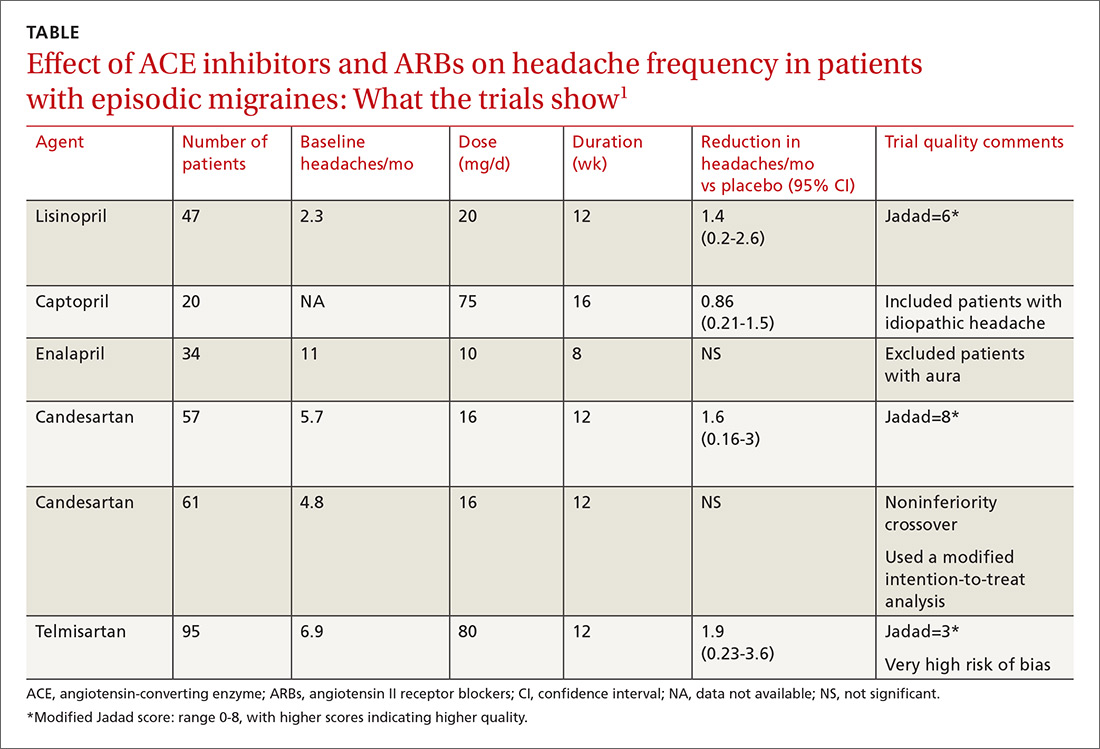

A network meta-analysis of 179 placebo-controlled trials of medications to treat migraine1 headache identified 3 trials involving ACE inhibitors and 3 involving ARBs (TABLE1). The authors of the meta-analysis gave 2 trials (one of lisinopril and one of candesartan) relatively high scores for methodologic quality.

Lisinopril reduces hours, days with headache and days with migraine

The first, a placebo-controlled lisinopril crossover trial, included 60 patients, 19 to 59 years of age, who experienced migraines with or without auras 2 to 6 times per month.2 Thirty patients received lisinopril 10 mg once daily for 1 week followed by 20 mg once daily (using 10-mg tablets) for 11 weeks. The other 30 patients received a similarly titrated placebo for 12 weeks. After a 2-week washout period, the groups were given the other therapy. Patients took triptan medications and analgesics as needed. Primary outcomes, extracted from headache diaries, included the number of hours and days with headache (of any type) and number of days with migraine specifically.

Out of the initial 60 participants, 47 completed the study. Using intention-to-treat analysis, lisinopril therapy resulted in fewer hours with headache (162 vs 138, a 15% difference; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0-30), fewer days with headache (25 vs 21, a 16% difference; 95% CI, 5-27), and fewer days with migraine (19 vs 15, a 22% change; 95% CI, 11-33), compared with placebo. Three patients discontinued lisinopril because of adverse events. Mean blood pressure reduction with lisinopril was 7 mm Hg systolic and 5 mm Hg diastolic more than placebo (P<.0001 for both comparisons).

Candesartan also decreases headaches and migraine

The other study given a high methodologic quality score by the network-meta-analysis authors was a placebo-controlled candesartan crossover trial.3 It enrolled 60 patients, 18 to 65 years of age, who experienced migraines with or without auras 2 to 6 times per month.

Thirty patients received 16 mg candesartan daily for 12 weeks, followed by a 4-week washout period before taking a placebo tablet daily for 12 weeks. The other 30 received placebo followed by candesartan. Patients took triptan medications and analgesics as needed. The primary outcome measure was days with headache, recorded by patients using daily diaries. Three patients didn’t complete the study.

Using intention-to-treat analysis, the mean number of days with headache was 18.5 with placebo and 13.6 with candesartan (P=.001). Secondary end points that also favored candesartan were hours with migraine (92 vs 59; P<.001), hours with headache (139 vs 95; P<.001), days with migraine (13 vs 9; P<.001), and days of sick leave (3.9 vs 1.4; P=.01). Adverse events, including dizziness, were similar with candesartan and placebo. Mean blood pressure reduction with candesartan was 11 mm Hg systolic and 7 mm Hg diastolic over placebo (P<.001 for both comparisons).

Continue to: Overall both drugs have a significant effect on number of headaches

Overall both drugs have a significant effect on number of headaches

Among all ACE inhibitor and ARB trials in the review, a network meta-analysis (designed to compare interventions never studied head-to-head) could be performed only on candesartan, which had a small effect size on headache frequency relative to placebo (2 trials, 118 patients; standardized mean difference [SMD]= −0.33; 95% CI, −0.59 to −0.7).1 (An SMD of 0.2 is considered small, 0.6 moderate, and 1.2 large). Combining data from all ACE inhibitor and ARB trials together in a standard meta-analysis yielded a large effect size on number of headaches per month compared with placebo (6 trials, 351 patients; SMD= −1.12; 95% CI, −1.97 to −0.27).1

RECOMMENDATIONS

In 2012, the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society published guidelines on pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults.4 The guidelines stated that lisinopril and candesartan were “possibly effective” for migraine prevention (level C recommendation based on a single lower-quality randomized clinical trial). They further advised clinicians to be “mindful of comorbid and coexistent conditions in patients with migraine to maximize potential treatment efficacy.”

1. Jackson JL, Cogbil E, Santana-Davila R, et al. A comparative effectiveness meta-analysis of drugs for the prophylaxis of migraine headache. PloS One. 2015;10:e0130733.

2. Schrader H, Stovner LJ, Helde G, et al. Prophylactic treatment of migraine with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (lisinopril): randomized, placebo controlled, crossover study. BMJ. 2001;322:19-22.

3. Tronvik E, Stovner LJ, Helde G, et al. Prophylactic treatment of migraine with an angiotensin II receptor blocker: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289:65-69.

4. Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, et al. Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology. 2012;78:1337-1345.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A network meta-analysis of 179 placebo-controlled trials of medications to treat migraine1 headache identified 3 trials involving ACE inhibitors and 3 involving ARBs (TABLE1). The authors of the meta-analysis gave 2 trials (one of lisinopril and one of candesartan) relatively high scores for methodologic quality.

Lisinopril reduces hours, days with headache and days with migraine

The first, a placebo-controlled lisinopril crossover trial, included 60 patients, 19 to 59 years of age, who experienced migraines with or without auras 2 to 6 times per month.2 Thirty patients received lisinopril 10 mg once daily for 1 week followed by 20 mg once daily (using 10-mg tablets) for 11 weeks. The other 30 patients received a similarly titrated placebo for 12 weeks. After a 2-week washout period, the groups were given the other therapy. Patients took triptan medications and analgesics as needed. Primary outcomes, extracted from headache diaries, included the number of hours and days with headache (of any type) and number of days with migraine specifically.

Out of the initial 60 participants, 47 completed the study. Using intention-to-treat analysis, lisinopril therapy resulted in fewer hours with headache (162 vs 138, a 15% difference; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0-30), fewer days with headache (25 vs 21, a 16% difference; 95% CI, 5-27), and fewer days with migraine (19 vs 15, a 22% change; 95% CI, 11-33), compared with placebo. Three patients discontinued lisinopril because of adverse events. Mean blood pressure reduction with lisinopril was 7 mm Hg systolic and 5 mm Hg diastolic more than placebo (P<.0001 for both comparisons).

Candesartan also decreases headaches and migraine

The other study given a high methodologic quality score by the network-meta-analysis authors was a placebo-controlled candesartan crossover trial.3 It enrolled 60 patients, 18 to 65 years of age, who experienced migraines with or without auras 2 to 6 times per month.

Thirty patients received 16 mg candesartan daily for 12 weeks, followed by a 4-week washout period before taking a placebo tablet daily for 12 weeks. The other 30 received placebo followed by candesartan. Patients took triptan medications and analgesics as needed. The primary outcome measure was days with headache, recorded by patients using daily diaries. Three patients didn’t complete the study.

Using intention-to-treat analysis, the mean number of days with headache was 18.5 with placebo and 13.6 with candesartan (P=.001). Secondary end points that also favored candesartan were hours with migraine (92 vs 59; P<.001), hours with headache (139 vs 95; P<.001), days with migraine (13 vs 9; P<.001), and days of sick leave (3.9 vs 1.4; P=.01). Adverse events, including dizziness, were similar with candesartan and placebo. Mean blood pressure reduction with candesartan was 11 mm Hg systolic and 7 mm Hg diastolic over placebo (P<.001 for both comparisons).

Continue to: Overall both drugs have a significant effect on number of headaches

Overall both drugs have a significant effect on number of headaches

Among all ACE inhibitor and ARB trials in the review, a network meta-analysis (designed to compare interventions never studied head-to-head) could be performed only on candesartan, which had a small effect size on headache frequency relative to placebo (2 trials, 118 patients; standardized mean difference [SMD]= −0.33; 95% CI, −0.59 to −0.7).1 (An SMD of 0.2 is considered small, 0.6 moderate, and 1.2 large). Combining data from all ACE inhibitor and ARB trials together in a standard meta-analysis yielded a large effect size on number of headaches per month compared with placebo (6 trials, 351 patients; SMD= −1.12; 95% CI, −1.97 to −0.27).1

RECOMMENDATIONS

In 2012, the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society published guidelines on pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults.4 The guidelines stated that lisinopril and candesartan were “possibly effective” for migraine prevention (level C recommendation based on a single lower-quality randomized clinical trial). They further advised clinicians to be “mindful of comorbid and coexistent conditions in patients with migraine to maximize potential treatment efficacy.”

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A network meta-analysis of 179 placebo-controlled trials of medications to treat migraine1 headache identified 3 trials involving ACE inhibitors and 3 involving ARBs (TABLE1). The authors of the meta-analysis gave 2 trials (one of lisinopril and one of candesartan) relatively high scores for methodologic quality.

Lisinopril reduces hours, days with headache and days with migraine

The first, a placebo-controlled lisinopril crossover trial, included 60 patients, 19 to 59 years of age, who experienced migraines with or without auras 2 to 6 times per month.2 Thirty patients received lisinopril 10 mg once daily for 1 week followed by 20 mg once daily (using 10-mg tablets) for 11 weeks. The other 30 patients received a similarly titrated placebo for 12 weeks. After a 2-week washout period, the groups were given the other therapy. Patients took triptan medications and analgesics as needed. Primary outcomes, extracted from headache diaries, included the number of hours and days with headache (of any type) and number of days with migraine specifically.

Out of the initial 60 participants, 47 completed the study. Using intention-to-treat analysis, lisinopril therapy resulted in fewer hours with headache (162 vs 138, a 15% difference; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0-30), fewer days with headache (25 vs 21, a 16% difference; 95% CI, 5-27), and fewer days with migraine (19 vs 15, a 22% change; 95% CI, 11-33), compared with placebo. Three patients discontinued lisinopril because of adverse events. Mean blood pressure reduction with lisinopril was 7 mm Hg systolic and 5 mm Hg diastolic more than placebo (P<.0001 for both comparisons).

Candesartan also decreases headaches and migraine

The other study given a high methodologic quality score by the network-meta-analysis authors was a placebo-controlled candesartan crossover trial.3 It enrolled 60 patients, 18 to 65 years of age, who experienced migraines with or without auras 2 to 6 times per month.

Thirty patients received 16 mg candesartan daily for 12 weeks, followed by a 4-week washout period before taking a placebo tablet daily for 12 weeks. The other 30 received placebo followed by candesartan. Patients took triptan medications and analgesics as needed. The primary outcome measure was days with headache, recorded by patients using daily diaries. Three patients didn’t complete the study.

Using intention-to-treat analysis, the mean number of days with headache was 18.5 with placebo and 13.6 with candesartan (P=.001). Secondary end points that also favored candesartan were hours with migraine (92 vs 59; P<.001), hours with headache (139 vs 95; P<.001), days with migraine (13 vs 9; P<.001), and days of sick leave (3.9 vs 1.4; P=.01). Adverse events, including dizziness, were similar with candesartan and placebo. Mean blood pressure reduction with candesartan was 11 mm Hg systolic and 7 mm Hg diastolic over placebo (P<.001 for both comparisons).

Continue to: Overall both drugs have a significant effect on number of headaches

Overall both drugs have a significant effect on number of headaches

Among all ACE inhibitor and ARB trials in the review, a network meta-analysis (designed to compare interventions never studied head-to-head) could be performed only on candesartan, which had a small effect size on headache frequency relative to placebo (2 trials, 118 patients; standardized mean difference [SMD]= −0.33; 95% CI, −0.59 to −0.7).1 (An SMD of 0.2 is considered small, 0.6 moderate, and 1.2 large). Combining data from all ACE inhibitor and ARB trials together in a standard meta-analysis yielded a large effect size on number of headaches per month compared with placebo (6 trials, 351 patients; SMD= −1.12; 95% CI, −1.97 to −0.27).1

RECOMMENDATIONS

In 2012, the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society published guidelines on pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults.4 The guidelines stated that lisinopril and candesartan were “possibly effective” for migraine prevention (level C recommendation based on a single lower-quality randomized clinical trial). They further advised clinicians to be “mindful of comorbid and coexistent conditions in patients with migraine to maximize potential treatment efficacy.”

1. Jackson JL, Cogbil E, Santana-Davila R, et al. A comparative effectiveness meta-analysis of drugs for the prophylaxis of migraine headache. PloS One. 2015;10:e0130733.

2. Schrader H, Stovner LJ, Helde G, et al. Prophylactic treatment of migraine with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (lisinopril): randomized, placebo controlled, crossover study. BMJ. 2001;322:19-22.

3. Tronvik E, Stovner LJ, Helde G, et al. Prophylactic treatment of migraine with an angiotensin II receptor blocker: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289:65-69.

4. Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, et al. Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology. 2012;78:1337-1345.

1. Jackson JL, Cogbil E, Santana-Davila R, et al. A comparative effectiveness meta-analysis of drugs for the prophylaxis of migraine headache. PloS One. 2015;10:e0130733.

2. Schrader H, Stovner LJ, Helde G, et al. Prophylactic treatment of migraine with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (lisinopril): randomized, placebo controlled, crossover study. BMJ. 2001;322:19-22.

3. Tronvik E, Stovner LJ, Helde G, et al. Prophylactic treatment of migraine with an angiotensin II receptor blocker: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289:65-69.

4. Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, et al. Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology. 2012;78:1337-1345.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

The angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor lisinopril reduces the number of migraines by about 1.5 per month in patients experiencing 2 to 6 migraines monthly (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, small crossover trial); the angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) candesartan may produce a similar reduction (SOR: C, conflicting crossover trials).

Considered as a group, ACE inhibitors and ARBs have a moderate to large effect on the frequency of migraine headaches (SOR: B, meta-analysis of small clinical trials), although only lisinopril and candesartan show fair to good evidence of efficacy.

Providers may consider lisinopril or candesartan for migraine prevention, taking into account their effect on other medical conditions (SOR: C, expert opinion).

Do statins alter the risk or progression of dementia?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2016 Cochrane systematic review identified 2 double-blind RCTs that evaluated statins for preventing cognitive decline and dementia in patients with either risk factors or a history of vascular disease.1 The authors couldn’t perform a meta-analysis because of heterogeneity.

Statins don’t prevent dementia

The first RCT found that 5804 patients (70-82 years old with pre-existing vascular disease or increased risk because of smoking, hypertension, or diabetes) manifested equivalent cognitive decline at 3.5 years after random assignment to pravastatin 40 mg/d or placebo.2 Investigators measured cognition with the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE), which scores cognitive function on a scale of 0 to 30, with higher numbers indicating better function (mean difference [MD] at follow-up=0.06 points; 95% confidence interval [CI], −0.04 to 0.16).

A second RCT evaluated simvastatin 40 mg/d or placebo for as long as 5 years in 20,536 patients 40 to 80 years of age with a history of coronary artery disease or diabetes.3 The study excluded patients with dementia at baseline. The odds of developing dementia didn’t differ between groups (odds ratio=1.0; 95% CI, 0.61-1.65).

Both studies were originally designed to measure cardiovascular outcomes. The authors rated both as high quality with a low risk of bias.

A contrast to earlier, lower-quality studies

These results contrast with an earlier meta-analysis based on one of the previously described RCTs and lower-quality evidence (16 cohort studies and 3 case-control studies) that found using statins to be associated with lower relative risk (RR) of dementia than not using a statin (all-type dementia RR=0.82; 95% CI, 0.69-0.97; Alzheimer’s disease RR=0.70; 95% CI, 0.60-0.83).3,4

The total patient population was more than 2 million and varied widely. Duration of statin use and type of statin (simvastatin, atorvastatin, fluvastatin, pravastatin, rosuvastatin) also varied. The authors noted potential bias in results for 2 reasons: Cross-sectional studies included patients with impaired cognition who were less likely to be prescribed statins, and statin use was determined by patient self-report.

Statins don’t treat dementia

A Cochrane review that included 4 RCTs with 1154 patients, 50 to 90 years old, assessed the effect of ≥6 months of statin therapy (atorvastatin 80 mg/d or simvastatin 40-80 mg/d) on the course of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia.5 Most patients had mild to moderate dementia and most were also taking an anticholinesterase inhibitor.

Continue to: All studies reported...

All studies reported outcomes using the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-Cog), scored 0 to 70, with lower numbers indicating better function, and the MMSE. Results of statin use were equivalent to placebo (ADAS-Cog MD= −0.26; 95% CI, −1.05 to 0.52; MMSE MD= −0.32; 95% CI, −0.71 to 0.06).

But do they slow its progression?

In contrast, a case-control study of 6431 patients with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease concluded that statin use was associated with slower progression of AD.6 Using cholinesterase inhibitor discontinuation as a proxy for worsening dementia, researchers noted that patients with early statin exposure (719 patients) had a lower rate of cholinesterase discontinuation than patients who didn’t receive early statin therapy (RR=0.85; 95% CI, 0.76-0.95).

A 2016 systematic review attempted to identify randomized clinical trials evaluating the effects of statin withdrawal in dementia.7 None were found.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Based primarily on post-marketing surveillance data, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has warned that memory loss and confusion are occasionally associated with statin use from within one day to several years of initiation.8 The FDA indicated that such symptoms are rare, not associated with dementia or clinically significant cognitive decline, and resolve with discontinuation of the medication.

1. McGuinness B, Craig D, Bullock R, et al. Statins for the prevention of dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(1):CD003160.

2. Trompet S, van Vliet P, de Craen AJ, et al. Pravastatin and cognitive function in the elderly. Results of the PROSPER study. J Neurol. 2010;257:85-90.

3. Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20,536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:7-22.

4. Wong WB, Lin VW, Boudreau D, et al. Statins in the prevention of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis of observational studies and an assessment of confounding. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22:345-358.

5. McGuinness B, Craig D, Bullock R, et al. Statins for the treatment of dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(7):CD007514.

6. Lin FC, Chuang YS, Hsieh HM, et al. Early statin use and the progression of Alzheimer disease: a total population-based case-control study. Medicine. 2015;94:e2143.

7. McGuinness B, Cardwell CR, Passmore P. Statin withdrawal in people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(9):CD012050.

8. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: Important safety label changes to cholesterol-lowering statin drugs. Available at: www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm293101.htm. Accessed August 24, 2018.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2016 Cochrane systematic review identified 2 double-blind RCTs that evaluated statins for preventing cognitive decline and dementia in patients with either risk factors or a history of vascular disease.1 The authors couldn’t perform a meta-analysis because of heterogeneity.

Statins don’t prevent dementia

The first RCT found that 5804 patients (70-82 years old with pre-existing vascular disease or increased risk because of smoking, hypertension, or diabetes) manifested equivalent cognitive decline at 3.5 years after random assignment to pravastatin 40 mg/d or placebo.2 Investigators measured cognition with the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE), which scores cognitive function on a scale of 0 to 30, with higher numbers indicating better function (mean difference [MD] at follow-up=0.06 points; 95% confidence interval [CI], −0.04 to 0.16).

A second RCT evaluated simvastatin 40 mg/d or placebo for as long as 5 years in 20,536 patients 40 to 80 years of age with a history of coronary artery disease or diabetes.3 The study excluded patients with dementia at baseline. The odds of developing dementia didn’t differ between groups (odds ratio=1.0; 95% CI, 0.61-1.65).

Both studies were originally designed to measure cardiovascular outcomes. The authors rated both as high quality with a low risk of bias.

A contrast to earlier, lower-quality studies

These results contrast with an earlier meta-analysis based on one of the previously described RCTs and lower-quality evidence (16 cohort studies and 3 case-control studies) that found using statins to be associated with lower relative risk (RR) of dementia than not using a statin (all-type dementia RR=0.82; 95% CI, 0.69-0.97; Alzheimer’s disease RR=0.70; 95% CI, 0.60-0.83).3,4

The total patient population was more than 2 million and varied widely. Duration of statin use and type of statin (simvastatin, atorvastatin, fluvastatin, pravastatin, rosuvastatin) also varied. The authors noted potential bias in results for 2 reasons: Cross-sectional studies included patients with impaired cognition who were less likely to be prescribed statins, and statin use was determined by patient self-report.

Statins don’t treat dementia

A Cochrane review that included 4 RCTs with 1154 patients, 50 to 90 years old, assessed the effect of ≥6 months of statin therapy (atorvastatin 80 mg/d or simvastatin 40-80 mg/d) on the course of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia.5 Most patients had mild to moderate dementia and most were also taking an anticholinesterase inhibitor.

Continue to: All studies reported...

All studies reported outcomes using the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-Cog), scored 0 to 70, with lower numbers indicating better function, and the MMSE. Results of statin use were equivalent to placebo (ADAS-Cog MD= −0.26; 95% CI, −1.05 to 0.52; MMSE MD= −0.32; 95% CI, −0.71 to 0.06).

But do they slow its progression?

In contrast, a case-control study of 6431 patients with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease concluded that statin use was associated with slower progression of AD.6 Using cholinesterase inhibitor discontinuation as a proxy for worsening dementia, researchers noted that patients with early statin exposure (719 patients) had a lower rate of cholinesterase discontinuation than patients who didn’t receive early statin therapy (RR=0.85; 95% CI, 0.76-0.95).

A 2016 systematic review attempted to identify randomized clinical trials evaluating the effects of statin withdrawal in dementia.7 None were found.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Based primarily on post-marketing surveillance data, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has warned that memory loss and confusion are occasionally associated with statin use from within one day to several years of initiation.8 The FDA indicated that such symptoms are rare, not associated with dementia or clinically significant cognitive decline, and resolve with discontinuation of the medication.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2016 Cochrane systematic review identified 2 double-blind RCTs that evaluated statins for preventing cognitive decline and dementia in patients with either risk factors or a history of vascular disease.1 The authors couldn’t perform a meta-analysis because of heterogeneity.

Statins don’t prevent dementia

The first RCT found that 5804 patients (70-82 years old with pre-existing vascular disease or increased risk because of smoking, hypertension, or diabetes) manifested equivalent cognitive decline at 3.5 years after random assignment to pravastatin 40 mg/d or placebo.2 Investigators measured cognition with the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE), which scores cognitive function on a scale of 0 to 30, with higher numbers indicating better function (mean difference [MD] at follow-up=0.06 points; 95% confidence interval [CI], −0.04 to 0.16).

A second RCT evaluated simvastatin 40 mg/d or placebo for as long as 5 years in 20,536 patients 40 to 80 years of age with a history of coronary artery disease or diabetes.3 The study excluded patients with dementia at baseline. The odds of developing dementia didn’t differ between groups (odds ratio=1.0; 95% CI, 0.61-1.65).

Both studies were originally designed to measure cardiovascular outcomes. The authors rated both as high quality with a low risk of bias.

A contrast to earlier, lower-quality studies

These results contrast with an earlier meta-analysis based on one of the previously described RCTs and lower-quality evidence (16 cohort studies and 3 case-control studies) that found using statins to be associated with lower relative risk (RR) of dementia than not using a statin (all-type dementia RR=0.82; 95% CI, 0.69-0.97; Alzheimer’s disease RR=0.70; 95% CI, 0.60-0.83).3,4

The total patient population was more than 2 million and varied widely. Duration of statin use and type of statin (simvastatin, atorvastatin, fluvastatin, pravastatin, rosuvastatin) also varied. The authors noted potential bias in results for 2 reasons: Cross-sectional studies included patients with impaired cognition who were less likely to be prescribed statins, and statin use was determined by patient self-report.

Statins don’t treat dementia

A Cochrane review that included 4 RCTs with 1154 patients, 50 to 90 years old, assessed the effect of ≥6 months of statin therapy (atorvastatin 80 mg/d or simvastatin 40-80 mg/d) on the course of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia.5 Most patients had mild to moderate dementia and most were also taking an anticholinesterase inhibitor.

Continue to: All studies reported...

All studies reported outcomes using the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-Cog), scored 0 to 70, with lower numbers indicating better function, and the MMSE. Results of statin use were equivalent to placebo (ADAS-Cog MD= −0.26; 95% CI, −1.05 to 0.52; MMSE MD= −0.32; 95% CI, −0.71 to 0.06).

But do they slow its progression?

In contrast, a case-control study of 6431 patients with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease concluded that statin use was associated with slower progression of AD.6 Using cholinesterase inhibitor discontinuation as a proxy for worsening dementia, researchers noted that patients with early statin exposure (719 patients) had a lower rate of cholinesterase discontinuation than patients who didn’t receive early statin therapy (RR=0.85; 95% CI, 0.76-0.95).

A 2016 systematic review attempted to identify randomized clinical trials evaluating the effects of statin withdrawal in dementia.7 None were found.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Based primarily on post-marketing surveillance data, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has warned that memory loss and confusion are occasionally associated with statin use from within one day to several years of initiation.8 The FDA indicated that such symptoms are rare, not associated with dementia or clinically significant cognitive decline, and resolve with discontinuation of the medication.

1. McGuinness B, Craig D, Bullock R, et al. Statins for the prevention of dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(1):CD003160.

2. Trompet S, van Vliet P, de Craen AJ, et al. Pravastatin and cognitive function in the elderly. Results of the PROSPER study. J Neurol. 2010;257:85-90.

3. Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20,536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:7-22.

4. Wong WB, Lin VW, Boudreau D, et al. Statins in the prevention of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis of observational studies and an assessment of confounding. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22:345-358.

5. McGuinness B, Craig D, Bullock R, et al. Statins for the treatment of dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(7):CD007514.

6. Lin FC, Chuang YS, Hsieh HM, et al. Early statin use and the progression of Alzheimer disease: a total population-based case-control study. Medicine. 2015;94:e2143.

7. McGuinness B, Cardwell CR, Passmore P. Statin withdrawal in people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(9):CD012050.

8. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: Important safety label changes to cholesterol-lowering statin drugs. Available at: www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm293101.htm. Accessed August 24, 2018.

1. McGuinness B, Craig D, Bullock R, et al. Statins for the prevention of dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(1):CD003160.

2. Trompet S, van Vliet P, de Craen AJ, et al. Pravastatin and cognitive function in the elderly. Results of the PROSPER study. J Neurol. 2010;257:85-90.

3. Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20,536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:7-22.

4. Wong WB, Lin VW, Boudreau D, et al. Statins in the prevention of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis of observational studies and an assessment of confounding. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22:345-358.

5. McGuinness B, Craig D, Bullock R, et al. Statins for the treatment of dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(7):CD007514.

6. Lin FC, Chuang YS, Hsieh HM, et al. Early statin use and the progression of Alzheimer disease: a total population-based case-control study. Medicine. 2015;94:e2143.

7. McGuinness B, Cardwell CR, Passmore P. Statin withdrawal in people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(9):CD012050.

8. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: Important safety label changes to cholesterol-lowering statin drugs. Available at: www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm293101.htm. Accessed August 24, 2018.

EVIDENCE-BASED SUMMARY:

Neither moderate- nor high-intensity statin therapy (with simvastatin or atorvastatin, respectively) improves existing mild to moderately severe Alzheimer’s or vascular dementia (SOR: A, RCTs).

Although statin use is associated with a mild, rare, reversible delirium, it isn’t linked to permanent cognitive decline (SOR: C, expert opinion).

How often does long-term PPI therapy cause clinically significant hypomagnesemia?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies examined the risk of hypomagnesemia, defined in various studies as serum magnesium levels of 1.6, 1.7, or 1.8 mg/dL.1 Two cohort studies, one case-control study, and 6 cross-sectional studies met inclusion criteria; 115,455 patients were enrolled. The studies were significantly heterogeneous (I2=89.1%), because of varying study designs, population sizes, and population characteristics.

PPI use increased the risk of hypomagnesemia (pooled odds ratio [OR]=1.5; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1-2.0) after adjustment for possible confounders such as use of diuretics.

Risk rises with long-term use, but severe hypomagnesemia is rare

Two more recent cohort studies produced conflicting results. Of 414 patients in a managed care cohort who received long-term PPIs, only 8 had mild hypomagnesemia (1.2-1.5 mg/dL) on nearly 14% of their combined 289 measurements. At final measurement, all patients had normal serum magnesium levels.2

A cross-sectional analysis of data from a retrospective cohort analysis of 9818 patients in the Netherlands found that any PPI use during the previous year was associated with an increased risk of hypomagnesemia (serum magnesium <1.73 mg/dL) compared with no use (adjusted OR=2; 95% CI, 1.4-2.9).3 The risk was greatest with use longer than 182 days (OR=3.0; 95% CI, 1.7-5.2). As with studies included in the meta-analysis, this study examined laboratory values exclusively. Only 3 of 724 PPI users had a serum magnesium level below 1.2 mg/dL, the point at which symptoms usually occur.

Case-control studies produce conflicting results

Two recent case-control studies also produced conflicting results. The first compared 154 outpatients who used PPIs for at least 6 months (mean, 27.5 months) with 84 nonusers.4 No association was found with hypomagnesemia (2.17 mg/dL vs 2.19 mg/dL), and none of the patients had a serum magnesium level below 1.7 mg/dL. The control group was poorly defined, however, and the study excluded patients taking diuretics.

Conversely, a study that compared 366 patients hospitalized with a primary or secondary diagnosis of hypomagnesemia (determined from an insurance claims database and defined as the presence of ICD-10 codes for hypomagnesemia or magnesium deficiency) with 1464 matched controls found that hospitalized patients with hypomagnesemia were more likely than controls to be current PPI users (adjusted OR=1.4; 95% CI, 1.1-1.9).5 Whether hypomagnesemia was the cause of the hospitalizations or an incidental finding wasn’t clear.

Concurrent use of diuretics and loop diuretics can increase risk

In a subgroup analysis of the second case-control study, PPI users who also used diuretics had an increased risk of hypomagnesemia (adjusted OR=1.7; 95% CI, 1.1-2.7) compared with patients who weren’t taking diuretics (adjusted OR=1.3; 95% CI, 0.8-1.9).5

Continue to: A comparison of the use of loop diuretics and...

A comparison of the use of loop diuretics and thiazides by patients taking PPIs found that concurrent use of loop diuretics increased serum magnesium reduction (−0.08 mg/dL; 95% CI, −0.14 to −0.02), but thiazides didn’t. Numbers were small: Of the 45 participants taking both a PPI and a loop diuretic, only 5 had hypomagnesemia (OR=7.2; 95% CI, 1.7-30.8).3

RECOMMENDATIONS

In 2011, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) warned of a possible increased risk of hypomagnesemia in patients taking PPIs long-term. The FDA advisory panel recommended evaluating serum magnesium before beginning long-term PPI therapy and in patients concurrently taking diuretics, digoxin, or other medications associated with hypomagnesemia.6

1. Park CH, Kim EH, Roh YH, et al. The association between the use of proton pump inhibitors and the risk of hypomagnesemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e112558.

2. Sharara AI, Chalhoub JM, Hammoud N, et al. Low prevalence of hypomagnesemia in long-term recipients of proton pump inhibitors in a managed care cohort. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:317-321.

3. Kieboom BC, Kiefte-de Jong JC, Eijgelsheim M, et al. Proton pump inhibitors and hypomagnesemia in the general population: a population-based cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:775-782.

4. Biyik M, Solak Y, Ucar R, et al. Hypomagnesemia among outpatient long-term proton pump inhibitor users. Am J Ther. 2014;24:e52-e55.

5. Zipursky J, Macdonald EM, Hollands S, et al. Proton pump inhibitors and hospitalization with hypomagnesemia: a population-based case-control study. PLoS Med. 2014;11:e1001736.

6. United States Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: Low magnesium levels can be associated with long-term use of Proton Pump Inhibitor drugs (PPIs). 03/02/2011. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm245011.htm. Accessed August 24, 2018.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies examined the risk of hypomagnesemia, defined in various studies as serum magnesium levels of 1.6, 1.7, or 1.8 mg/dL.1 Two cohort studies, one case-control study, and 6 cross-sectional studies met inclusion criteria; 115,455 patients were enrolled. The studies were significantly heterogeneous (I2=89.1%), because of varying study designs, population sizes, and population characteristics.

PPI use increased the risk of hypomagnesemia (pooled odds ratio [OR]=1.5; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1-2.0) after adjustment for possible confounders such as use of diuretics.

Risk rises with long-term use, but severe hypomagnesemia is rare

Two more recent cohort studies produced conflicting results. Of 414 patients in a managed care cohort who received long-term PPIs, only 8 had mild hypomagnesemia (1.2-1.5 mg/dL) on nearly 14% of their combined 289 measurements. At final measurement, all patients had normal serum magnesium levels.2

A cross-sectional analysis of data from a retrospective cohort analysis of 9818 patients in the Netherlands found that any PPI use during the previous year was associated with an increased risk of hypomagnesemia (serum magnesium <1.73 mg/dL) compared with no use (adjusted OR=2; 95% CI, 1.4-2.9).3 The risk was greatest with use longer than 182 days (OR=3.0; 95% CI, 1.7-5.2). As with studies included in the meta-analysis, this study examined laboratory values exclusively. Only 3 of 724 PPI users had a serum magnesium level below 1.2 mg/dL, the point at which symptoms usually occur.

Case-control studies produce conflicting results

Two recent case-control studies also produced conflicting results. The first compared 154 outpatients who used PPIs for at least 6 months (mean, 27.5 months) with 84 nonusers.4 No association was found with hypomagnesemia (2.17 mg/dL vs 2.19 mg/dL), and none of the patients had a serum magnesium level below 1.7 mg/dL. The control group was poorly defined, however, and the study excluded patients taking diuretics.

Conversely, a study that compared 366 patients hospitalized with a primary or secondary diagnosis of hypomagnesemia (determined from an insurance claims database and defined as the presence of ICD-10 codes for hypomagnesemia or magnesium deficiency) with 1464 matched controls found that hospitalized patients with hypomagnesemia were more likely than controls to be current PPI users (adjusted OR=1.4; 95% CI, 1.1-1.9).5 Whether hypomagnesemia was the cause of the hospitalizations or an incidental finding wasn’t clear.

Concurrent use of diuretics and loop diuretics can increase risk

In a subgroup analysis of the second case-control study, PPI users who also used diuretics had an increased risk of hypomagnesemia (adjusted OR=1.7; 95% CI, 1.1-2.7) compared with patients who weren’t taking diuretics (adjusted OR=1.3; 95% CI, 0.8-1.9).5

Continue to: A comparison of the use of loop diuretics and...

A comparison of the use of loop diuretics and thiazides by patients taking PPIs found that concurrent use of loop diuretics increased serum magnesium reduction (−0.08 mg/dL; 95% CI, −0.14 to −0.02), but thiazides didn’t. Numbers were small: Of the 45 participants taking both a PPI and a loop diuretic, only 5 had hypomagnesemia (OR=7.2; 95% CI, 1.7-30.8).3

RECOMMENDATIONS

In 2011, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) warned of a possible increased risk of hypomagnesemia in patients taking PPIs long-term. The FDA advisory panel recommended evaluating serum magnesium before beginning long-term PPI therapy and in patients concurrently taking diuretics, digoxin, or other medications associated with hypomagnesemia.6

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies examined the risk of hypomagnesemia, defined in various studies as serum magnesium levels of 1.6, 1.7, or 1.8 mg/dL.1 Two cohort studies, one case-control study, and 6 cross-sectional studies met inclusion criteria; 115,455 patients were enrolled. The studies were significantly heterogeneous (I2=89.1%), because of varying study designs, population sizes, and population characteristics.

PPI use increased the risk of hypomagnesemia (pooled odds ratio [OR]=1.5; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1-2.0) after adjustment for possible confounders such as use of diuretics.

Risk rises with long-term use, but severe hypomagnesemia is rare

Two more recent cohort studies produced conflicting results. Of 414 patients in a managed care cohort who received long-term PPIs, only 8 had mild hypomagnesemia (1.2-1.5 mg/dL) on nearly 14% of their combined 289 measurements. At final measurement, all patients had normal serum magnesium levels.2

A cross-sectional analysis of data from a retrospective cohort analysis of 9818 patients in the Netherlands found that any PPI use during the previous year was associated with an increased risk of hypomagnesemia (serum magnesium <1.73 mg/dL) compared with no use (adjusted OR=2; 95% CI, 1.4-2.9).3 The risk was greatest with use longer than 182 days (OR=3.0; 95% CI, 1.7-5.2). As with studies included in the meta-analysis, this study examined laboratory values exclusively. Only 3 of 724 PPI users had a serum magnesium level below 1.2 mg/dL, the point at which symptoms usually occur.

Case-control studies produce conflicting results

Two recent case-control studies also produced conflicting results. The first compared 154 outpatients who used PPIs for at least 6 months (mean, 27.5 months) with 84 nonusers.4 No association was found with hypomagnesemia (2.17 mg/dL vs 2.19 mg/dL), and none of the patients had a serum magnesium level below 1.7 mg/dL. The control group was poorly defined, however, and the study excluded patients taking diuretics.

Conversely, a study that compared 366 patients hospitalized with a primary or secondary diagnosis of hypomagnesemia (determined from an insurance claims database and defined as the presence of ICD-10 codes for hypomagnesemia or magnesium deficiency) with 1464 matched controls found that hospitalized patients with hypomagnesemia were more likely than controls to be current PPI users (adjusted OR=1.4; 95% CI, 1.1-1.9).5 Whether hypomagnesemia was the cause of the hospitalizations or an incidental finding wasn’t clear.

Concurrent use of diuretics and loop diuretics can increase risk

In a subgroup analysis of the second case-control study, PPI users who also used diuretics had an increased risk of hypomagnesemia (adjusted OR=1.7; 95% CI, 1.1-2.7) compared with patients who weren’t taking diuretics (adjusted OR=1.3; 95% CI, 0.8-1.9).5

Continue to: A comparison of the use of loop diuretics and...

A comparison of the use of loop diuretics and thiazides by patients taking PPIs found that concurrent use of loop diuretics increased serum magnesium reduction (−0.08 mg/dL; 95% CI, −0.14 to −0.02), but thiazides didn’t. Numbers were small: Of the 45 participants taking both a PPI and a loop diuretic, only 5 had hypomagnesemia (OR=7.2; 95% CI, 1.7-30.8).3

RECOMMENDATIONS

In 2011, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) warned of a possible increased risk of hypomagnesemia in patients taking PPIs long-term. The FDA advisory panel recommended evaluating serum magnesium before beginning long-term PPI therapy and in patients concurrently taking diuretics, digoxin, or other medications associated with hypomagnesemia.6

1. Park CH, Kim EH, Roh YH, et al. The association between the use of proton pump inhibitors and the risk of hypomagnesemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e112558.

2. Sharara AI, Chalhoub JM, Hammoud N, et al. Low prevalence of hypomagnesemia in long-term recipients of proton pump inhibitors in a managed care cohort. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:317-321.

3. Kieboom BC, Kiefte-de Jong JC, Eijgelsheim M, et al. Proton pump inhibitors and hypomagnesemia in the general population: a population-based cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:775-782.

4. Biyik M, Solak Y, Ucar R, et al. Hypomagnesemia among outpatient long-term proton pump inhibitor users. Am J Ther. 2014;24:e52-e55.

5. Zipursky J, Macdonald EM, Hollands S, et al. Proton pump inhibitors and hospitalization with hypomagnesemia: a population-based case-control study. PLoS Med. 2014;11:e1001736.

6. United States Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: Low magnesium levels can be associated with long-term use of Proton Pump Inhibitor drugs (PPIs). 03/02/2011. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm245011.htm. Accessed August 24, 2018.

1. Park CH, Kim EH, Roh YH, et al. The association between the use of proton pump inhibitors and the risk of hypomagnesemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e112558.

2. Sharara AI, Chalhoub JM, Hammoud N, et al. Low prevalence of hypomagnesemia in long-term recipients of proton pump inhibitors in a managed care cohort. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:317-321.

3. Kieboom BC, Kiefte-de Jong JC, Eijgelsheim M, et al. Proton pump inhibitors and hypomagnesemia in the general population: a population-based cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:775-782.

4. Biyik M, Solak Y, Ucar R, et al. Hypomagnesemia among outpatient long-term proton pump inhibitor users. Am J Ther. 2014;24:e52-e55.

5. Zipursky J, Macdonald EM, Hollands S, et al. Proton pump inhibitors and hospitalization with hypomagnesemia: a population-based case-control study. PLoS Med. 2014;11:e1001736.

6. United States Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: Low magnesium levels can be associated with long-term use of Proton Pump Inhibitor drugs (PPIs). 03/02/2011. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm245011.htm. Accessed August 24, 2018.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Rarely. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) may be associated with decreases in serum magnesium laboratory values to below 1.6 to 1.8 mg/dL, especially when used concurrently with diuretics and loop diuretics (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C, disease-oriented outcomes based on cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional studies). Clinically significant or symptomatic hypomagnesemia (below 1.2 mg/dL) appears to be quite rare, however.

What’s the best secondary treatment for patients who fail initial triple therapy for H pylori?

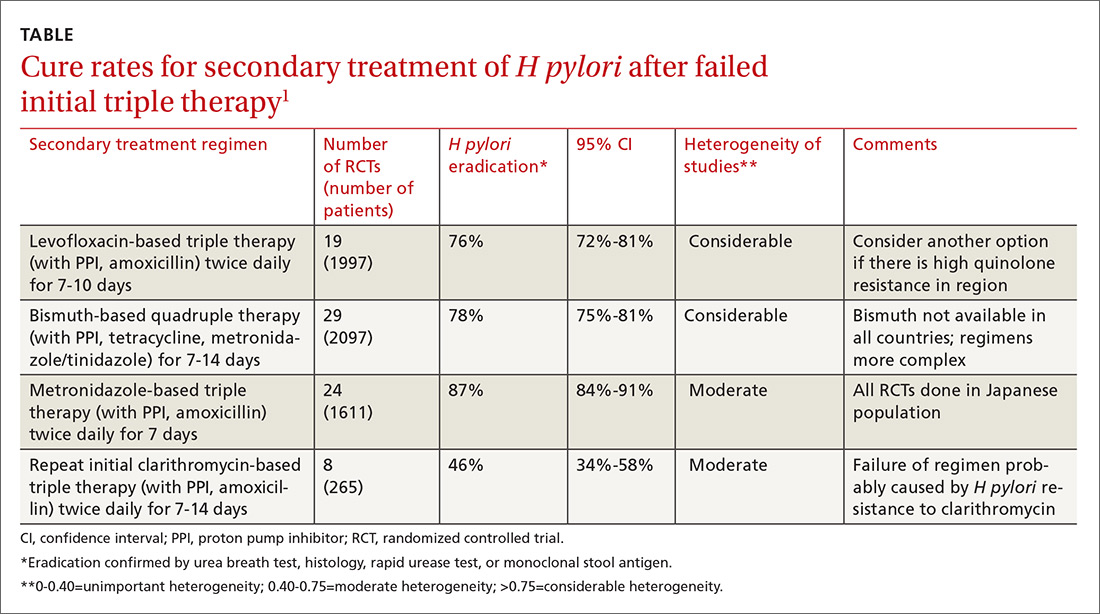

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

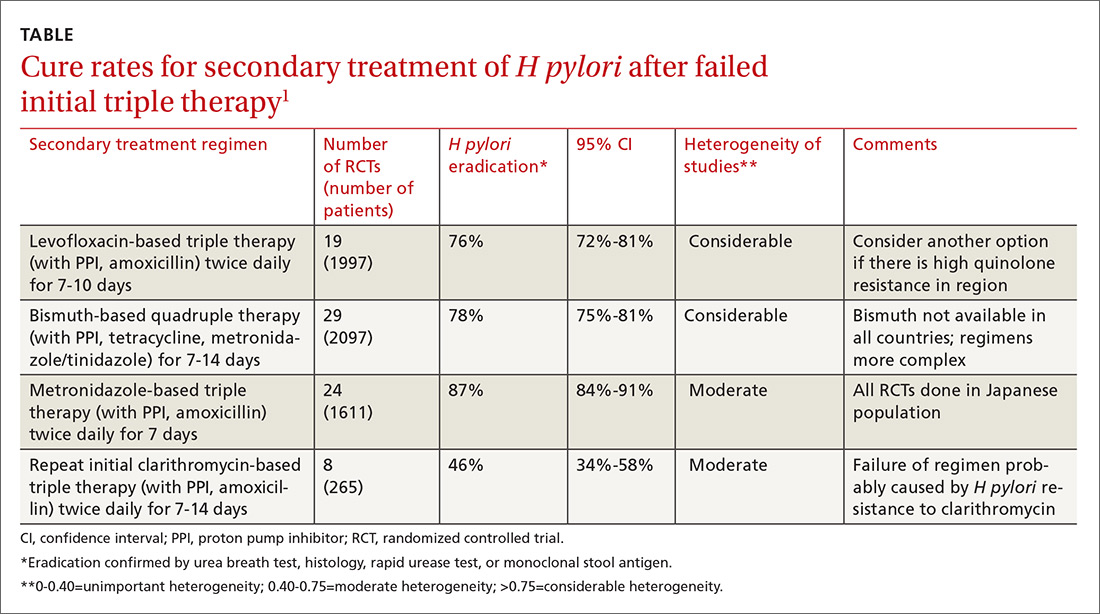

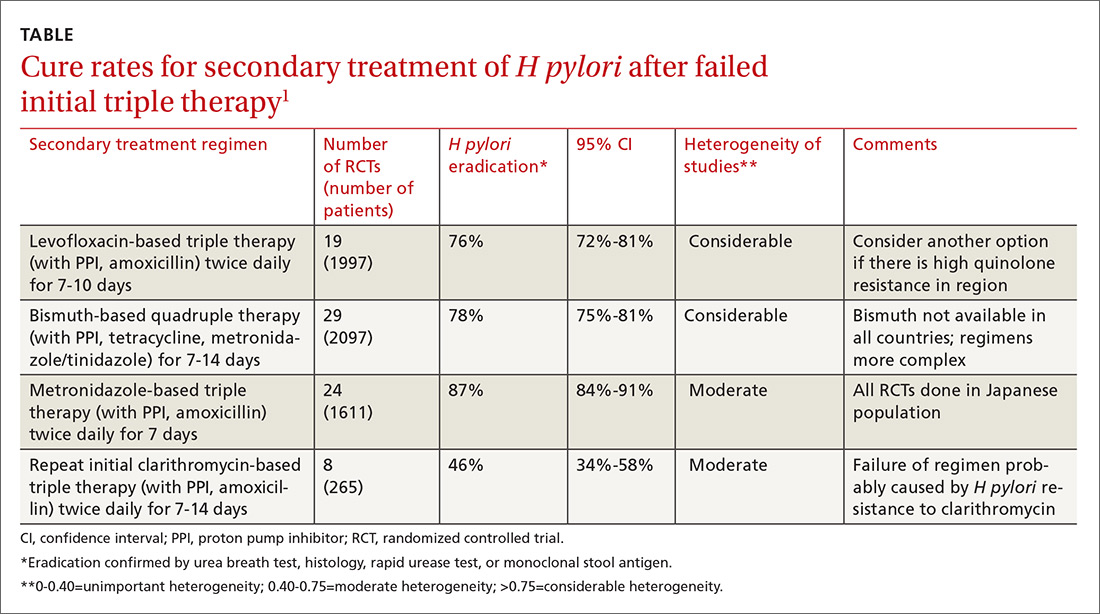

A meta-analysis of RCTs evaluating levofloxacin-based triple therapy as a secondary treatment regimen for patients with H pylori infection who had failed initial clarithromycin-based triple therapy found cure rates averaging 76% (TABLE).1 Most of the regimens comprised levofloxacin (500 mg), amoxicillin (1 g), and a PPI (40 mg), all twice daily for 7 to 10 days. Ten-day regimens produced better cure rates than 7-day regimens (84% vs 69%; comparison statistic not supplied).

The meta-analysis also included RCTs evaluating bismuth-based quadruple therapy as secondary treatment, which found cure rates averaging 78%.1 The regimens varied, comprising bismuth salts (120-600 mg, 2-4 times daily), metronidazole (250-500 mg, 2-4 times daily), tetracycline (250-500 mg, 2-4 times daily), and a PPI (40 mg twice daily). Longer duration of therapy produced higher cure rates (7 days=76%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.72-0.80 in 29 RCTs with 2097 patients; 10 days=77%; 95% CI, 0.60-0.93 in 2 RCTs with 142 patients; 14 days=82%; 95% CI, 0.76-0.88 in 12 RCTs with 831 patients).

Repeating the original clarithromycin-based triple therapy (8 RCTs, 265 patients) produced low cure rates (46%).1

Metronidazole-based therapy has high cure rate in a homogeneous population

A meta-analysis of 24 RCTs (1611 patients) that evaluated metronidazole-based triple therapy (mostly composed of amoxicillin 750 mg, metronidazole 250 mg, and any of a number of PPIs, all dosed at 40 mg) twice daily for 7 days found cure rates averaging 87% in an exclusively Japanese study population.1

Comparable cure rates for levofloxacin- and bismuth-based therapy

Six RCTs with a total of 1057 patients compared cure rates for levofloxacin-based triple therapy with bismuth-based quadruple therapy and found no difference.1

Two earlier meta-analyses not included in the previously described study, comprising 8 RCTs with a total of 613 patients, produced conflicting results. The larger study (15 RCTs, 1462 patients) found no difference in cure rates.2 The smaller study (7 RCTs, 787 patients) favored quadruple therapy.3

Continue to: Two secondary antibiotic regimens show similar cure rates

Two secondary antibiotic regimens show similar cure rates

A meta-analysis of 4 RCTs (total 460 patients) that compared susceptibility-guided antibiotic secondary treatment (SGT) with empiric antibiotic secondary treatment found no difference in cure rates, although the largest single RCT (172 patients) favored SGT.4

RECOMMENDATIONS

The Maastricht IV/Florence Consensus Report (a periodically updated European study group evaluating Helicobacter management) includes expert opinion-based guidelines for H pylori treatment that recommend using antibiotic susceptibility to select treatment regimens in the event of 2 treatment failures.5 The report also notes that bismuth-based quadruple therapy may not be available in all countries and has a more complex dosing regimen, and that local resistance to levofloxacin must be taken into account when prescribing levofloxacin-based triple therapy.

1. Marin AC, McNicholl AG, Gisbert JP. A review of rescue regimens after clarithromycin-containing triple therapy failure (for Helicobacter pylori eradication). Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2013;14:843-861.

2. Di Caro S, Fini L, Daoud Y, et al. Levofloxacin/amoxicillin-based schemes vs quadruple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication in second-line. World J Gastro. 2012;18:5669-5678.

3. Wu C, Chen X, Liu J, et al. Moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy versus bismuth-containing quadruple therapy for second-line treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection: a meta-analysis. Helicobacter. 2011;16:131-138.

4. Lopez-Gongora S, Puig I, Calvet X, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis: susceptibility-guided versus empirical antibiotic treatment for Helicobacter pylori infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:2447-2455.

5. Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection—the Maastricht IV/Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2012;61:646-664.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A meta-analysis of RCTs evaluating levofloxacin-based triple therapy as a secondary treatment regimen for patients with H pylori infection who had failed initial clarithromycin-based triple therapy found cure rates averaging 76% (TABLE).1 Most of the regimens comprised levofloxacin (500 mg), amoxicillin (1 g), and a PPI (40 mg), all twice daily for 7 to 10 days. Ten-day regimens produced better cure rates than 7-day regimens (84% vs 69%; comparison statistic not supplied).

The meta-analysis also included RCTs evaluating bismuth-based quadruple therapy as secondary treatment, which found cure rates averaging 78%.1 The regimens varied, comprising bismuth salts (120-600 mg, 2-4 times daily), metronidazole (250-500 mg, 2-4 times daily), tetracycline (250-500 mg, 2-4 times daily), and a PPI (40 mg twice daily). Longer duration of therapy produced higher cure rates (7 days=76%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.72-0.80 in 29 RCTs with 2097 patients; 10 days=77%; 95% CI, 0.60-0.93 in 2 RCTs with 142 patients; 14 days=82%; 95% CI, 0.76-0.88 in 12 RCTs with 831 patients).

Repeating the original clarithromycin-based triple therapy (8 RCTs, 265 patients) produced low cure rates (46%).1

Metronidazole-based therapy has high cure rate in a homogeneous population

A meta-analysis of 24 RCTs (1611 patients) that evaluated metronidazole-based triple therapy (mostly composed of amoxicillin 750 mg, metronidazole 250 mg, and any of a number of PPIs, all dosed at 40 mg) twice daily for 7 days found cure rates averaging 87% in an exclusively Japanese study population.1

Comparable cure rates for levofloxacin- and bismuth-based therapy

Six RCTs with a total of 1057 patients compared cure rates for levofloxacin-based triple therapy with bismuth-based quadruple therapy and found no difference.1

Two earlier meta-analyses not included in the previously described study, comprising 8 RCTs with a total of 613 patients, produced conflicting results. The larger study (15 RCTs, 1462 patients) found no difference in cure rates.2 The smaller study (7 RCTs, 787 patients) favored quadruple therapy.3

Continue to: Two secondary antibiotic regimens show similar cure rates

Two secondary antibiotic regimens show similar cure rates

A meta-analysis of 4 RCTs (total 460 patients) that compared susceptibility-guided antibiotic secondary treatment (SGT) with empiric antibiotic secondary treatment found no difference in cure rates, although the largest single RCT (172 patients) favored SGT.4

RECOMMENDATIONS

The Maastricht IV/Florence Consensus Report (a periodically updated European study group evaluating Helicobacter management) includes expert opinion-based guidelines for H pylori treatment that recommend using antibiotic susceptibility to select treatment regimens in the event of 2 treatment failures.5 The report also notes that bismuth-based quadruple therapy may not be available in all countries and has a more complex dosing regimen, and that local resistance to levofloxacin must be taken into account when prescribing levofloxacin-based triple therapy.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A meta-analysis of RCTs evaluating levofloxacin-based triple therapy as a secondary treatment regimen for patients with H pylori infection who had failed initial clarithromycin-based triple therapy found cure rates averaging 76% (TABLE).1 Most of the regimens comprised levofloxacin (500 mg), amoxicillin (1 g), and a PPI (40 mg), all twice daily for 7 to 10 days. Ten-day regimens produced better cure rates than 7-day regimens (84% vs 69%; comparison statistic not supplied).

The meta-analysis also included RCTs evaluating bismuth-based quadruple therapy as secondary treatment, which found cure rates averaging 78%.1 The regimens varied, comprising bismuth salts (120-600 mg, 2-4 times daily), metronidazole (250-500 mg, 2-4 times daily), tetracycline (250-500 mg, 2-4 times daily), and a PPI (40 mg twice daily). Longer duration of therapy produced higher cure rates (7 days=76%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.72-0.80 in 29 RCTs with 2097 patients; 10 days=77%; 95% CI, 0.60-0.93 in 2 RCTs with 142 patients; 14 days=82%; 95% CI, 0.76-0.88 in 12 RCTs with 831 patients).

Repeating the original clarithromycin-based triple therapy (8 RCTs, 265 patients) produced low cure rates (46%).1

Metronidazole-based therapy has high cure rate in a homogeneous population

A meta-analysis of 24 RCTs (1611 patients) that evaluated metronidazole-based triple therapy (mostly composed of amoxicillin 750 mg, metronidazole 250 mg, and any of a number of PPIs, all dosed at 40 mg) twice daily for 7 days found cure rates averaging 87% in an exclusively Japanese study population.1

Comparable cure rates for levofloxacin- and bismuth-based therapy

Six RCTs with a total of 1057 patients compared cure rates for levofloxacin-based triple therapy with bismuth-based quadruple therapy and found no difference.1

Two earlier meta-analyses not included in the previously described study, comprising 8 RCTs with a total of 613 patients, produced conflicting results. The larger study (15 RCTs, 1462 patients) found no difference in cure rates.2 The smaller study (7 RCTs, 787 patients) favored quadruple therapy.3

Continue to: Two secondary antibiotic regimens show similar cure rates

Two secondary antibiotic regimens show similar cure rates

A meta-analysis of 4 RCTs (total 460 patients) that compared susceptibility-guided antibiotic secondary treatment (SGT) with empiric antibiotic secondary treatment found no difference in cure rates, although the largest single RCT (172 patients) favored SGT.4

RECOMMENDATIONS

The Maastricht IV/Florence Consensus Report (a periodically updated European study group evaluating Helicobacter management) includes expert opinion-based guidelines for H pylori treatment that recommend using antibiotic susceptibility to select treatment regimens in the event of 2 treatment failures.5 The report also notes that bismuth-based quadruple therapy may not be available in all countries and has a more complex dosing regimen, and that local resistance to levofloxacin must be taken into account when prescribing levofloxacin-based triple therapy.

1. Marin AC, McNicholl AG, Gisbert JP. A review of rescue regimens after clarithromycin-containing triple therapy failure (for Helicobacter pylori eradication). Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2013;14:843-861.

2. Di Caro S, Fini L, Daoud Y, et al. Levofloxacin/amoxicillin-based schemes vs quadruple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication in second-line. World J Gastro. 2012;18:5669-5678.

3. Wu C, Chen X, Liu J, et al. Moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy versus bismuth-containing quadruple therapy for second-line treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection: a meta-analysis. Helicobacter. 2011;16:131-138.

4. Lopez-Gongora S, Puig I, Calvet X, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis: susceptibility-guided versus empirical antibiotic treatment for Helicobacter pylori infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:2447-2455.

5. Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection—the Maastricht IV/Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2012;61:646-664.

1. Marin AC, McNicholl AG, Gisbert JP. A review of rescue regimens after clarithromycin-containing triple therapy failure (for Helicobacter pylori eradication). Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2013;14:843-861.

2. Di Caro S, Fini L, Daoud Y, et al. Levofloxacin/amoxicillin-based schemes vs quadruple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication in second-line. World J Gastro. 2012;18:5669-5678.

3. Wu C, Chen X, Liu J, et al. Moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy versus bismuth-containing quadruple therapy for second-line treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection: a meta-analysis. Helicobacter. 2011;16:131-138.

4. Lopez-Gongora S, Puig I, Calvet X, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis: susceptibility-guided versus empirical antibiotic treatment for Helicobacter pylori infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:2447-2455.

5. Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection—the Maastricht IV/Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2012;61:646-664.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Treating patients with Helicobacter pylori infection who have failed clarithromycin-based triple therapy with either levofloxacin-based triple therapy (with amoxicillin and a proton pump inhibitor [PPI]) or a bismuth-based quadruple therapy produces cure rates of 75% to 81%. Ten-day regimens produce higher cure rates than 7-day regimens. Repeating the initial clarithromycin-based triple therapy cures fewer than half of patients (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Treating with a metronidazole-based triple therapy (with amoxicillin and a PPI) also produces high (87%) cure rates (SOR: A, meta-analyses of RCTs in exclusively Japanese populations).

Selecting a secondary treatment regimen based on H pylori antibiotic susceptibility testing probably doesn’t improve cure rates over empiric antibiotic treatment (SOR: B, meta-analyses of RCTs with conflicting results). However, after 2 treatment failures it may be necessary (SOR: C, expert opinion-based guidelines).

Bismuth-based quadruple therapy has a more complex dosing regimen, and bismuth isn’t available in some countries. Rising rates of H pylori resistance to levofloxacin in certain areas could make levofloxacin-based triple therapy less effective in the future (SOR: C, expert opinion-based guidelines).

What are the benefits/risks of giving betamethasone to women at risk of late preterm labor?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2016 systematic review and meta-analysis of 3 RCTs that included 3200 women with late preterm labor (between 34 weeks 0 days and 36 weeks 6 days) found that women who were given betamethasone had a significantly lower incidence of transient tachypnea of the newborn (number needed to treat [NNT]=37; relative risk [RR]=0.72; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.56-0.92), severe respiratory distress syndrome (NNT=114; RR=0.60; 95% CI, 0.33-0.94), and use of surfactant (NNT=92; RR=0.61; 95% CI, 0.38-0.99).1

A composite outcome measure also favors betamethasone

In addition to these 3 outcomes, the largest RCT in the meta-analysis evaluated a composite outcome and found that betamethasone improved it by 20%. The RCT, comparing 1427 women in the experimental arm with 1400 controls, found benefit to administering 12 mg betamethasone intramuscularly every 24 hours for 2 days for women at high risk of late preterm delivery.2 Enrollment criteria included women with 3 cm dilation or 75% effacement, preterm premature rupture of membranes, or a planned delivery scheduled in the late preterm period.

The primary outcome was a composite score based on one or more of the following within 72 hours after birth: continuous positive airway pressure or high-flow nasal cannula for at least 2 continuous hours, supplemental oxygen with a fraction of inspired oxygen of 0.30 or more for at least 4 continuous hours, mechanical ventilation, stillbirth or neonatal death, or the need for extracorporeal circulation membrane oxygenation. The betamethasone group had 165 women (11.6%) with the primary outcome compared with 202 (14.4%) in the control arm (NNT=34; RR=0.80; 95% CI, 0.66–0.97; P<.02).

Neonatal hypoglycemia may increase, but not dangerously

The same RCT explored the risks of late preterm betamethasone. There was no increase in chorioamnionitis nor neonatal sepsis in the betamethasone group.2 Although neonatal hypoglycemia increased (24% vs 15%; number needed to harm=11.1; RR=1.60; 95% CI, 1.37-1.87; P<.001), no increase was seen in intermediate care nursery or ICU stays (41.8% vs 44.9%; RR=0.93; 95% CI, 0.85-1.01; P=.09) nor length of hospital stay (7 vs 8 days; P=.20).

Three letters to the editor questioned whether hypoglycemia from late-term corticosteroids may lead to long-term neurocognitive delays.3 The authors responded that meta-analyses of RCTs haven’t found an association between antenatal steroid use and neurocognitive delay and that studies that have found an association between hypoglycemia and neurocognitive delay looked at profound and prolonged hypoglycemia, which wasn’t seen in the late preterm betamethasone study.

Continue to: RECOMMENDATIONS

RECOMMENDATIONS