User login

Brittle Diabetes: Drilling Down to the Cause

How to Evaluate Vaginal Bleeding and Discharge

Four Steps to Diagnosing Drug Overdose

Misconceptions About Opioid Dosing

Cardiac Assessment in Acute Stroke

UPDATE: MINIMALLY INVASIVE SURGERY

Cervical stenosis and difficult uterine and vaginal anatomy pose a challenge for the gynecologist who needs access to the cervix and uterus to evaluate pathology. Overcoming this hurdle requires a careful, considered approach to avoid the complications of dilation, such as laceration, creation of a false passage, uterine perforation, and failed procedures. Care and consideration also ensure a successful and comfortable procedure; save the patient a great deal of time and the higher expense of the operating room (OR); and avert the need for general anesthesia.

In this first Update on Minimally Invasive Surgery, I will:

- describe the continuing shift from the OR to office for many gynecologic procedures

- review recent data on cervical softening

- outline the components of mechanical dilation

- offer tips on pain relief.

Need for cervical access should not prohibit office-based procedures

Cervical access is critical to increase the percentage of procedures performed in the office setting. The office has long been the ideal environment for minor procedures such as endometrial biopsy, dilation and curettage, diagnostic hysteroscopy, hysterosonography, and insertion of an intrauterine device—but difficulty traversing the cervix has relegated many of these procedures to the OR.

Minor procedures such as tubal sterilization and endometrial ablation have begun to move from the outpatient environment into the office as well, upping the number of office procedures that require safe access to the endometrial cavity.

For example, hysteroscopic tubal occlusion (Essure) is performed transcervically, thereby eliminating all incisions and the need for general anesthesia. Approximately 50% of all Essure sterilization procedures performed in the United States today are done in an office, and that percentage is expected to rise to 60% in 2009.1

The smallest operative hysteroscopes that allow for placement of Essure coils have an outer-sheath diameter between 5 and 6 mm. Even with such small diameters, cervical dilation is sometimes needed.

Endometrial ablation offers women who have menorrhagia a minimally invasive option for treatment. Several FDA-approved devices are used safely in the office.2-5 Cervical dilation requirements for these devices range from 5 to 7.8 mm, making cervical access paramount (TABLE).

A number of measures, such as cervical softening and mechanical dilation, can ease dilation in an office setting so that a stenotic cervix no longer requires an OR for the procedure to be completed. Successful in-office cervical dilation also greatly reduces cost.

TABLE

Size of the instrument varies across endometrial ablation systems

| Instrument | Diameter | Instrument | Diameter |

|---|---|---|---|

| ThermaChoice (uterine balloon therapy) | 5 mm | NovaSure | 7.2 mm |

| Her Option (cryoablation therapy) | 5 mm | Hydro ThermAblator | 7.8 mm |

New data back efficacy of vaginal misoprostol for cervical softening

da Costa AR, Pinto-Neto AM, Amorim M, Paiva LH, Scavuzzi A, Schettini J. Use of misoprostol prior to hysteroscopy in postmenopausal women: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:67–73.

Waddell G, Desindes S, Takser L, Bequchemin M, Bessett P. Cervical ripening using vaginal misoprostol before hysteroscopy: a double-blind randomized trial. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:739–744.

Uckuyu A, Ozcimen E, Sevinc FC, Zeyneloglu HB. Efficacy of vaginal misoprostol before hysteroscopy for cervical priming in patients who have undergone cesarean section and no vaginal deliveries. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:472–475.

Valente EP, Amorim MM, da Costa AR, de Miranda VD. Vaginal misoprostol prior to diagnostic hysteroscopy in patients of reproductive age: a randomized clinical trial. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:452–458.

A synthetic analog of prostaglandin E1, misoprostol is thought to act on the extracellular matrix of the cervix, leading to water absorption, neutrophil collagenase release, and cervical softening. Smooth muscle is activated by the drug, especially in the uterus.

Pharmacokinetic studies suggest that the oral route of misoprostol has the shortest interval to peak serum concentration (within 30 minutes of ingestion), but that concentration declines within 1 hour. The vaginal route, on the other hand, has fewer side effects, with longer duration and approximately three times the bioavailability.6,7 Peak values are equal to those of orally administered misoprostol. They are attained at 60 minutes, then decline slowly, reaching 50% of peak values by 240 minutes. Serum concentration remains elevated, improving efficacy.

I recommend an interval of 4 to 12 hours between vaginal placement and the start of the procedure.

Vaginal route is clearly effective in premenopausal women

In premenopausal women, several recent randomized clinical trials show that vaginal misoprostol, administered before hysteroscopy, not only decreases pain and the force and amount of dilation needed, but also reduces complications of cervical dilation.8 As Uckuyu and colleagues observe, these findings are consistent in nulliparous women who have a history of cesarean delivery and who receive 400 μg of vaginal misoprostol 6 to 12 hours before hysteroscopy.

Several studies found no improvement in ease of dilation or operative time in menopausal women who received misoprostol before hysteroscopy.9,10 However, in their randomized, placebo-controlled trial, da Costa and colleagues found that women who received 200 μg of vaginal misoprostol 8 hours before hysteroscopy had a significant decrease in intraprocedural pain associated with cervical dilation.

Recommended protocol

For women at significant risk of cervical stenosis, give 400 μg of intravaginal misoprostol approximately 12 hours before the scheduled procedure. The patient should begin round-the-clock use of a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) an hour before insertion of the misoprostol tablets.

Side effects of vaginal and oral misoprostol include occasional diarrhea, abdominal cramping, uterine bleeding, and pyrexia. These effects are usually mild and limited.8 Concomitant administration of NSAIDs reduces or eliminates these side effects.

Although you may sometimes find an incompletely dissolved tablet within the vagina, active medication usually has been absorbed, leaving the less soluble vehicle behind.

Frequent causes of stenosis include:

- Loop electrosurgical excision procedure, conization, and laser vaporization—In one series, 43% of cases of cervical stenosis resulted from one of these procedures, with a recurrence rate of 14%.11

- Scarring of the external os—Common in the parous cervix. Usually, only minimal dilation is needed; the remainder of the cervix is traversed easily.

- Narrow or closed external os—Common in menopausal women and increasingly common in nulligravid and nulliparous women as the rate of elective cesarean delivery rises. In these cases, both the endocervical canal and internal os are narrow, necessitating dilation through the entire length of the cervix.

- Genital atrophy—In postmenopausal women, cervical stenosis as a result of genital atrophy is associated with pain upon cervical dilation. The situation generally necessitates local anesthesia.12

When mechanical dilation is necessary, a few prerequisites can make a difference

By assessing each patient carefully, the gynecologist can customize the intervention. Accordingly, it is wise to have multiple types of dilators accessible to accommodate varying clinical needs and anatomic scenarios.

Begin by stabilizing the cervix. Use of a single-toothed tenaculum, placed on the anterior lip of the cervix, has several advantages. Countertraction against the dilating instrument can facilitate more controlled placement of the dilator, preventing perforation of the uterus. This maneuver is especially useful when the cervical canal and internal os are tight or resistant.

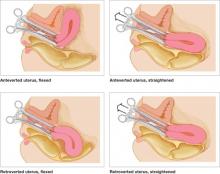

Use of a tenaculum when placing a hysteroscope produces a similar result and can add an element of safety to uterine access, especially when the uterus is significantly flexed (FIGURE 1).

FIGURE 1 Straighten a flexed uterus before dilating the cervix

When the uterus is flexed, creating acute angulation at the cervicouterine junction, it can be difficult to move the dilator through the internal os. By placing a tenaculum at the 12 o’clock position on the cervix of an anteverted uterus, or 6 o’clock on a retroverted uterus, and applying outward traction, you can straighten the distorted canal.

A local anesthetic can help

It is helpful to administer a local anesthetic before placing a penetrating instrument such as the tenaculum. Patients are usually grateful for the extra few minutes taken to ensure their comfort.

If the cervix is resistant, or the patient is uncomfortable, after initial attempts to dilate the cervix, consider placing a paracervical or intracervical stromal local anesthetic. Lidocaine 1% has a rapid onset of action, reaching peak effectiveness in just a few minutes, with a duration of approximately 60 minutes. Bupivacaine 0.25% has a slightly slower onset of action (8–10 minutes), but offers long duration—about 240 minutes.

Place 5 to 10 cc of local anesthetic paracervically at the 4 and 8 o’clock positions. The choice of anesthetic depends on the procedure. For example, a nulligravid patient may benefit from bupivacaine because cervical dilation can cause significant and prolonged cramping. Bupivacaine is more potent than lidocaine and, therefore, potentially more cardiotoxic, so caution is advised.

Used correctly, local anesthetic facilitates cervical dilation.

Types of dilators

Many instruments are available. Be familiar with the benefits and shortcomings of each to achieve successful cervical dilation in the office.

Lacrimal-duct dilators. These instruments have long been used by gynecologists for cervical access when the closed external os is no more than a tiny dimple. These ophthalmologic instruments come in diameters smaller than 1 mm and allow the closed menopausal cervix to be dilated enough to allow placement of more traditional instruments (FIGURE 2).

Traditional dilators. Tapered metal or plastic dilators facilitate access to a tightly stenotic external os (FIGURE 3). These instruments have a more symmetrical segment proximal to the tip to allow gentle, gradual dilation of the canal. However, when dilation is needed for the entire length of the cervix, as it frequently is in nulliparous women, the tapered end will not dilate the internal os unless it is passed far enough into the canal—but passing the instrument too far increases the risk of uterine perforation. In this scenario, a symmetric dilator may be a better option to achieve uniform diameter of the endocervical canal from external to internal os. Be cautious: These symmetric dilators sometimes require additional force.

When the entire length of the cervix needs to be dilated, it may be wise to use a symmetric dilator that is the same size as the tapered dilator before increasing the diameter, to reduce the risk of perforation.

FIGURE 2 A borrowed tool to unlock the external os

From the world of ophthalmology, a lacrimal-duct dilator facilitates dilation of the extremely stenotic cervix.

FIGURE 3 Tapered instruments allow gradual dilation

Tapered cervical dilators, like this disposable set, have a more symmetrical segment proximal to the tip.

When every dilator is too large

Occasionally, the external os is so completely closed that even a lacrimal-duct dilator cannot be placed. In this situation, administer 2 cc of local anesthetic in the region of the external os, then gently penetrate the os using the tip of a #11 scalpel blade. This technique generally allows quick and easy access to the endocervical canal. (Typically, the entire canal will not be stenotic and, once the external opening is created, easy dilation can be accomplished.)

Navigating a crooked cervical canal

When the cervical canal is distorted, sometimes even the most carefully selected dilator will fail.

Why?

Because the diameter of the cervix is not the obstacle.

When a straight—or even partially curved—dilator cannot traverse the tortuous path of a distorted canal, the small flexible hysteroscope may offer a solution, allowing identification of the anatomic obstruction and visualization of the course of the cervical canal. Prior visualization of the canal enhances proprioception with the dilating instrument and improves the likelihood of safe uterine access.

The use of concomitant ultrasonography may also be helpful.11

From the standpoint of a payer, obtaining surgical access to the site of a procedure is included in the procedure payment. This is generally the rule for surgical access on the day of the procedure. Some payers reimburse separately, however, when access (specifically, dilation of the cervix) is performed a day, or few days, before the procedure because of an anatomic problem—such as the cervical stenosis discussed in the main “Update” article.

What are your options?

You have several coding options available for dilation of the cervix, depending on the approach you take:

- When you’ve given oral misoprostol, bill the visit at which you prescribed the drug.

- When you’ve inserted misoprostol vaginally, report code 59200 [insertion of cervical dilator (e.g., laminaria, prostaglandin) (separate procedure)].

The fact that 59200 is found in the “Maternity Care and Delivery” chapter of the CPT does not limit its use to obstetric cases. Because this code has a zero-day global period, you are not considered to be in the postoperative period of the first procedure when the surgical procedure is performed the next day (or even longer afterward), and the two procedures will not be bundled.

Another method of cervical dilation is represented by code 57800 [Dilation of cervical canal, instrumental (separate procedure)], which also has a zero-day global period.

The diagnosis code must support the service

That’s true whichever technique you choose. In this case, the diagnosis code will be either:

- 622.4 (Stricture and stenosis of cervix) or

- 752.49 (Other anomalies of cervix, vagina, and external female genitalia)—when the stenosis is the result of a congenital condition.—

MELANIE WITT, RN, CPC, COBGC, MA

1. Essure Earnings Report Fourth Quarter 2008. Mountain View, Calif: Conceptus Inc.

2. Farrugia M, Hussain S. Hysteroscopic endometrial ablation using the Hydro ThermAblator in an outpatient hysteroscopy clinic: feasibility and acceptability. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2006;13:178-182.

3. Fernandez H, Capella S, Audiebert F. Uterine thermal balloon therapy under local anesthesia for the treatment of menorrhagia: a pilot study. Hum Reprod. 1997;12:2511-2514.

4. Bertrand J. Use of NovaSure endometrial ablation system in an office setting environment. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12(5 Suppl):14.-

5. Roy K, Whiteside D, Manjon J, et al. Assessment of procedure tolerability during Her Option endometrial cryoablation in an outpatient setting. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12(5 Suppl):87.-

6. Khan RU, El-Rafeay H, Sharma S, Sooranna D, Stafford M. Oral, rectal, and vaginal pharmacokinetics of misoprostol. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:866-869.

7. Zieman M, Fong S, Benowitz N, Bankster D, Darney P. Absorption kinetics of misoprostol with oral or vaginal administration. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:88-92.

8. Preutthipan S, Herabutya Y. A randomized controlled trial of vaginal misoprostol for cervical priming before hysteroscopy. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:427-430.

9. Fung TM, Lam MW, Wong SF, Ho LC. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of vaginal misoprostol for cervical priming before hysteroscopy in postmenopausal women. BJOG. 2002;119:561-565.

10. Ngai SW, Chan YM, Ho PC. The use of misoprostol prior to hysteroscopy in postmenopausal women. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:1486-1488.

11. Valle RF, Sankpal R, Marlow J, Cohen L. Cervical stenosis: a challenging clinical entity. J Gynecol Surg. 2002;18:129-143.

12. Perez-Medina T, Bajo MJ, Martinez-Cortes L, Castellanos P, Perez de Avila I. Six thousand office diagnostic-operative hysteroscopies. Int J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;71:33-38.

Cervical stenosis and difficult uterine and vaginal anatomy pose a challenge for the gynecologist who needs access to the cervix and uterus to evaluate pathology. Overcoming this hurdle requires a careful, considered approach to avoid the complications of dilation, such as laceration, creation of a false passage, uterine perforation, and failed procedures. Care and consideration also ensure a successful and comfortable procedure; save the patient a great deal of time and the higher expense of the operating room (OR); and avert the need for general anesthesia.

In this first Update on Minimally Invasive Surgery, I will:

- describe the continuing shift from the OR to office for many gynecologic procedures

- review recent data on cervical softening

- outline the components of mechanical dilation

- offer tips on pain relief.

Need for cervical access should not prohibit office-based procedures

Cervical access is critical to increase the percentage of procedures performed in the office setting. The office has long been the ideal environment for minor procedures such as endometrial biopsy, dilation and curettage, diagnostic hysteroscopy, hysterosonography, and insertion of an intrauterine device—but difficulty traversing the cervix has relegated many of these procedures to the OR.

Minor procedures such as tubal sterilization and endometrial ablation have begun to move from the outpatient environment into the office as well, upping the number of office procedures that require safe access to the endometrial cavity.

For example, hysteroscopic tubal occlusion (Essure) is performed transcervically, thereby eliminating all incisions and the need for general anesthesia. Approximately 50% of all Essure sterilization procedures performed in the United States today are done in an office, and that percentage is expected to rise to 60% in 2009.1

The smallest operative hysteroscopes that allow for placement of Essure coils have an outer-sheath diameter between 5 and 6 mm. Even with such small diameters, cervical dilation is sometimes needed.

Endometrial ablation offers women who have menorrhagia a minimally invasive option for treatment. Several FDA-approved devices are used safely in the office.2-5 Cervical dilation requirements for these devices range from 5 to 7.8 mm, making cervical access paramount (TABLE).

A number of measures, such as cervical softening and mechanical dilation, can ease dilation in an office setting so that a stenotic cervix no longer requires an OR for the procedure to be completed. Successful in-office cervical dilation also greatly reduces cost.

TABLE

Size of the instrument varies across endometrial ablation systems

| Instrument | Diameter | Instrument | Diameter |

|---|---|---|---|

| ThermaChoice (uterine balloon therapy) | 5 mm | NovaSure | 7.2 mm |

| Her Option (cryoablation therapy) | 5 mm | Hydro ThermAblator | 7.8 mm |

New data back efficacy of vaginal misoprostol for cervical softening

da Costa AR, Pinto-Neto AM, Amorim M, Paiva LH, Scavuzzi A, Schettini J. Use of misoprostol prior to hysteroscopy in postmenopausal women: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:67–73.

Waddell G, Desindes S, Takser L, Bequchemin M, Bessett P. Cervical ripening using vaginal misoprostol before hysteroscopy: a double-blind randomized trial. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:739–744.

Uckuyu A, Ozcimen E, Sevinc FC, Zeyneloglu HB. Efficacy of vaginal misoprostol before hysteroscopy for cervical priming in patients who have undergone cesarean section and no vaginal deliveries. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:472–475.

Valente EP, Amorim MM, da Costa AR, de Miranda VD. Vaginal misoprostol prior to diagnostic hysteroscopy in patients of reproductive age: a randomized clinical trial. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:452–458.

A synthetic analog of prostaglandin E1, misoprostol is thought to act on the extracellular matrix of the cervix, leading to water absorption, neutrophil collagenase release, and cervical softening. Smooth muscle is activated by the drug, especially in the uterus.

Pharmacokinetic studies suggest that the oral route of misoprostol has the shortest interval to peak serum concentration (within 30 minutes of ingestion), but that concentration declines within 1 hour. The vaginal route, on the other hand, has fewer side effects, with longer duration and approximately three times the bioavailability.6,7 Peak values are equal to those of orally administered misoprostol. They are attained at 60 minutes, then decline slowly, reaching 50% of peak values by 240 minutes. Serum concentration remains elevated, improving efficacy.

I recommend an interval of 4 to 12 hours between vaginal placement and the start of the procedure.

Vaginal route is clearly effective in premenopausal women

In premenopausal women, several recent randomized clinical trials show that vaginal misoprostol, administered before hysteroscopy, not only decreases pain and the force and amount of dilation needed, but also reduces complications of cervical dilation.8 As Uckuyu and colleagues observe, these findings are consistent in nulliparous women who have a history of cesarean delivery and who receive 400 μg of vaginal misoprostol 6 to 12 hours before hysteroscopy.

Several studies found no improvement in ease of dilation or operative time in menopausal women who received misoprostol before hysteroscopy.9,10 However, in their randomized, placebo-controlled trial, da Costa and colleagues found that women who received 200 μg of vaginal misoprostol 8 hours before hysteroscopy had a significant decrease in intraprocedural pain associated with cervical dilation.

Recommended protocol

For women at significant risk of cervical stenosis, give 400 μg of intravaginal misoprostol approximately 12 hours before the scheduled procedure. The patient should begin round-the-clock use of a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) an hour before insertion of the misoprostol tablets.

Side effects of vaginal and oral misoprostol include occasional diarrhea, abdominal cramping, uterine bleeding, and pyrexia. These effects are usually mild and limited.8 Concomitant administration of NSAIDs reduces or eliminates these side effects.

Although you may sometimes find an incompletely dissolved tablet within the vagina, active medication usually has been absorbed, leaving the less soluble vehicle behind.

Frequent causes of stenosis include:

- Loop electrosurgical excision procedure, conization, and laser vaporization—In one series, 43% of cases of cervical stenosis resulted from one of these procedures, with a recurrence rate of 14%.11

- Scarring of the external os—Common in the parous cervix. Usually, only minimal dilation is needed; the remainder of the cervix is traversed easily.

- Narrow or closed external os—Common in menopausal women and increasingly common in nulligravid and nulliparous women as the rate of elective cesarean delivery rises. In these cases, both the endocervical canal and internal os are narrow, necessitating dilation through the entire length of the cervix.

- Genital atrophy—In postmenopausal women, cervical stenosis as a result of genital atrophy is associated with pain upon cervical dilation. The situation generally necessitates local anesthesia.12

When mechanical dilation is necessary, a few prerequisites can make a difference

By assessing each patient carefully, the gynecologist can customize the intervention. Accordingly, it is wise to have multiple types of dilators accessible to accommodate varying clinical needs and anatomic scenarios.

Begin by stabilizing the cervix. Use of a single-toothed tenaculum, placed on the anterior lip of the cervix, has several advantages. Countertraction against the dilating instrument can facilitate more controlled placement of the dilator, preventing perforation of the uterus. This maneuver is especially useful when the cervical canal and internal os are tight or resistant.

Use of a tenaculum when placing a hysteroscope produces a similar result and can add an element of safety to uterine access, especially when the uterus is significantly flexed (FIGURE 1).

FIGURE 1 Straighten a flexed uterus before dilating the cervix

When the uterus is flexed, creating acute angulation at the cervicouterine junction, it can be difficult to move the dilator through the internal os. By placing a tenaculum at the 12 o’clock position on the cervix of an anteverted uterus, or 6 o’clock on a retroverted uterus, and applying outward traction, you can straighten the distorted canal.

A local anesthetic can help

It is helpful to administer a local anesthetic before placing a penetrating instrument such as the tenaculum. Patients are usually grateful for the extra few minutes taken to ensure their comfort.

If the cervix is resistant, or the patient is uncomfortable, after initial attempts to dilate the cervix, consider placing a paracervical or intracervical stromal local anesthetic. Lidocaine 1% has a rapid onset of action, reaching peak effectiveness in just a few minutes, with a duration of approximately 60 minutes. Bupivacaine 0.25% has a slightly slower onset of action (8–10 minutes), but offers long duration—about 240 minutes.

Place 5 to 10 cc of local anesthetic paracervically at the 4 and 8 o’clock positions. The choice of anesthetic depends on the procedure. For example, a nulligravid patient may benefit from bupivacaine because cervical dilation can cause significant and prolonged cramping. Bupivacaine is more potent than lidocaine and, therefore, potentially more cardiotoxic, so caution is advised.

Used correctly, local anesthetic facilitates cervical dilation.

Types of dilators

Many instruments are available. Be familiar with the benefits and shortcomings of each to achieve successful cervical dilation in the office.

Lacrimal-duct dilators. These instruments have long been used by gynecologists for cervical access when the closed external os is no more than a tiny dimple. These ophthalmologic instruments come in diameters smaller than 1 mm and allow the closed menopausal cervix to be dilated enough to allow placement of more traditional instruments (FIGURE 2).

Traditional dilators. Tapered metal or plastic dilators facilitate access to a tightly stenotic external os (FIGURE 3). These instruments have a more symmetrical segment proximal to the tip to allow gentle, gradual dilation of the canal. However, when dilation is needed for the entire length of the cervix, as it frequently is in nulliparous women, the tapered end will not dilate the internal os unless it is passed far enough into the canal—but passing the instrument too far increases the risk of uterine perforation. In this scenario, a symmetric dilator may be a better option to achieve uniform diameter of the endocervical canal from external to internal os. Be cautious: These symmetric dilators sometimes require additional force.

When the entire length of the cervix needs to be dilated, it may be wise to use a symmetric dilator that is the same size as the tapered dilator before increasing the diameter, to reduce the risk of perforation.

FIGURE 2 A borrowed tool to unlock the external os

From the world of ophthalmology, a lacrimal-duct dilator facilitates dilation of the extremely stenotic cervix.

FIGURE 3 Tapered instruments allow gradual dilation

Tapered cervical dilators, like this disposable set, have a more symmetrical segment proximal to the tip.

When every dilator is too large

Occasionally, the external os is so completely closed that even a lacrimal-duct dilator cannot be placed. In this situation, administer 2 cc of local anesthetic in the region of the external os, then gently penetrate the os using the tip of a #11 scalpel blade. This technique generally allows quick and easy access to the endocervical canal. (Typically, the entire canal will not be stenotic and, once the external opening is created, easy dilation can be accomplished.)

Navigating a crooked cervical canal

When the cervical canal is distorted, sometimes even the most carefully selected dilator will fail.

Why?

Because the diameter of the cervix is not the obstacle.

When a straight—or even partially curved—dilator cannot traverse the tortuous path of a distorted canal, the small flexible hysteroscope may offer a solution, allowing identification of the anatomic obstruction and visualization of the course of the cervical canal. Prior visualization of the canal enhances proprioception with the dilating instrument and improves the likelihood of safe uterine access.

The use of concomitant ultrasonography may also be helpful.11

From the standpoint of a payer, obtaining surgical access to the site of a procedure is included in the procedure payment. This is generally the rule for surgical access on the day of the procedure. Some payers reimburse separately, however, when access (specifically, dilation of the cervix) is performed a day, or few days, before the procedure because of an anatomic problem—such as the cervical stenosis discussed in the main “Update” article.

What are your options?

You have several coding options available for dilation of the cervix, depending on the approach you take:

- When you’ve given oral misoprostol, bill the visit at which you prescribed the drug.

- When you’ve inserted misoprostol vaginally, report code 59200 [insertion of cervical dilator (e.g., laminaria, prostaglandin) (separate procedure)].

The fact that 59200 is found in the “Maternity Care and Delivery” chapter of the CPT does not limit its use to obstetric cases. Because this code has a zero-day global period, you are not considered to be in the postoperative period of the first procedure when the surgical procedure is performed the next day (or even longer afterward), and the two procedures will not be bundled.

Another method of cervical dilation is represented by code 57800 [Dilation of cervical canal, instrumental (separate procedure)], which also has a zero-day global period.

The diagnosis code must support the service

That’s true whichever technique you choose. In this case, the diagnosis code will be either:

- 622.4 (Stricture and stenosis of cervix) or

- 752.49 (Other anomalies of cervix, vagina, and external female genitalia)—when the stenosis is the result of a congenital condition.—

MELANIE WITT, RN, CPC, COBGC, MA

Cervical stenosis and difficult uterine and vaginal anatomy pose a challenge for the gynecologist who needs access to the cervix and uterus to evaluate pathology. Overcoming this hurdle requires a careful, considered approach to avoid the complications of dilation, such as laceration, creation of a false passage, uterine perforation, and failed procedures. Care and consideration also ensure a successful and comfortable procedure; save the patient a great deal of time and the higher expense of the operating room (OR); and avert the need for general anesthesia.

In this first Update on Minimally Invasive Surgery, I will:

- describe the continuing shift from the OR to office for many gynecologic procedures

- review recent data on cervical softening

- outline the components of mechanical dilation

- offer tips on pain relief.

Need for cervical access should not prohibit office-based procedures

Cervical access is critical to increase the percentage of procedures performed in the office setting. The office has long been the ideal environment for minor procedures such as endometrial biopsy, dilation and curettage, diagnostic hysteroscopy, hysterosonography, and insertion of an intrauterine device—but difficulty traversing the cervix has relegated many of these procedures to the OR.

Minor procedures such as tubal sterilization and endometrial ablation have begun to move from the outpatient environment into the office as well, upping the number of office procedures that require safe access to the endometrial cavity.

For example, hysteroscopic tubal occlusion (Essure) is performed transcervically, thereby eliminating all incisions and the need for general anesthesia. Approximately 50% of all Essure sterilization procedures performed in the United States today are done in an office, and that percentage is expected to rise to 60% in 2009.1

The smallest operative hysteroscopes that allow for placement of Essure coils have an outer-sheath diameter between 5 and 6 mm. Even with such small diameters, cervical dilation is sometimes needed.

Endometrial ablation offers women who have menorrhagia a minimally invasive option for treatment. Several FDA-approved devices are used safely in the office.2-5 Cervical dilation requirements for these devices range from 5 to 7.8 mm, making cervical access paramount (TABLE).

A number of measures, such as cervical softening and mechanical dilation, can ease dilation in an office setting so that a stenotic cervix no longer requires an OR for the procedure to be completed. Successful in-office cervical dilation also greatly reduces cost.

TABLE

Size of the instrument varies across endometrial ablation systems

| Instrument | Diameter | Instrument | Diameter |

|---|---|---|---|

| ThermaChoice (uterine balloon therapy) | 5 mm | NovaSure | 7.2 mm |

| Her Option (cryoablation therapy) | 5 mm | Hydro ThermAblator | 7.8 mm |

New data back efficacy of vaginal misoprostol for cervical softening

da Costa AR, Pinto-Neto AM, Amorim M, Paiva LH, Scavuzzi A, Schettini J. Use of misoprostol prior to hysteroscopy in postmenopausal women: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:67–73.

Waddell G, Desindes S, Takser L, Bequchemin M, Bessett P. Cervical ripening using vaginal misoprostol before hysteroscopy: a double-blind randomized trial. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:739–744.

Uckuyu A, Ozcimen E, Sevinc FC, Zeyneloglu HB. Efficacy of vaginal misoprostol before hysteroscopy for cervical priming in patients who have undergone cesarean section and no vaginal deliveries. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:472–475.

Valente EP, Amorim MM, da Costa AR, de Miranda VD. Vaginal misoprostol prior to diagnostic hysteroscopy in patients of reproductive age: a randomized clinical trial. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:452–458.

A synthetic analog of prostaglandin E1, misoprostol is thought to act on the extracellular matrix of the cervix, leading to water absorption, neutrophil collagenase release, and cervical softening. Smooth muscle is activated by the drug, especially in the uterus.

Pharmacokinetic studies suggest that the oral route of misoprostol has the shortest interval to peak serum concentration (within 30 minutes of ingestion), but that concentration declines within 1 hour. The vaginal route, on the other hand, has fewer side effects, with longer duration and approximately three times the bioavailability.6,7 Peak values are equal to those of orally administered misoprostol. They are attained at 60 minutes, then decline slowly, reaching 50% of peak values by 240 minutes. Serum concentration remains elevated, improving efficacy.

I recommend an interval of 4 to 12 hours between vaginal placement and the start of the procedure.

Vaginal route is clearly effective in premenopausal women

In premenopausal women, several recent randomized clinical trials show that vaginal misoprostol, administered before hysteroscopy, not only decreases pain and the force and amount of dilation needed, but also reduces complications of cervical dilation.8 As Uckuyu and colleagues observe, these findings are consistent in nulliparous women who have a history of cesarean delivery and who receive 400 μg of vaginal misoprostol 6 to 12 hours before hysteroscopy.

Several studies found no improvement in ease of dilation or operative time in menopausal women who received misoprostol before hysteroscopy.9,10 However, in their randomized, placebo-controlled trial, da Costa and colleagues found that women who received 200 μg of vaginal misoprostol 8 hours before hysteroscopy had a significant decrease in intraprocedural pain associated with cervical dilation.

Recommended protocol

For women at significant risk of cervical stenosis, give 400 μg of intravaginal misoprostol approximately 12 hours before the scheduled procedure. The patient should begin round-the-clock use of a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) an hour before insertion of the misoprostol tablets.

Side effects of vaginal and oral misoprostol include occasional diarrhea, abdominal cramping, uterine bleeding, and pyrexia. These effects are usually mild and limited.8 Concomitant administration of NSAIDs reduces or eliminates these side effects.

Although you may sometimes find an incompletely dissolved tablet within the vagina, active medication usually has been absorbed, leaving the less soluble vehicle behind.

Frequent causes of stenosis include:

- Loop electrosurgical excision procedure, conization, and laser vaporization—In one series, 43% of cases of cervical stenosis resulted from one of these procedures, with a recurrence rate of 14%.11

- Scarring of the external os—Common in the parous cervix. Usually, only minimal dilation is needed; the remainder of the cervix is traversed easily.

- Narrow or closed external os—Common in menopausal women and increasingly common in nulligravid and nulliparous women as the rate of elective cesarean delivery rises. In these cases, both the endocervical canal and internal os are narrow, necessitating dilation through the entire length of the cervix.

- Genital atrophy—In postmenopausal women, cervical stenosis as a result of genital atrophy is associated with pain upon cervical dilation. The situation generally necessitates local anesthesia.12

When mechanical dilation is necessary, a few prerequisites can make a difference

By assessing each patient carefully, the gynecologist can customize the intervention. Accordingly, it is wise to have multiple types of dilators accessible to accommodate varying clinical needs and anatomic scenarios.

Begin by stabilizing the cervix. Use of a single-toothed tenaculum, placed on the anterior lip of the cervix, has several advantages. Countertraction against the dilating instrument can facilitate more controlled placement of the dilator, preventing perforation of the uterus. This maneuver is especially useful when the cervical canal and internal os are tight or resistant.

Use of a tenaculum when placing a hysteroscope produces a similar result and can add an element of safety to uterine access, especially when the uterus is significantly flexed (FIGURE 1).

FIGURE 1 Straighten a flexed uterus before dilating the cervix

When the uterus is flexed, creating acute angulation at the cervicouterine junction, it can be difficult to move the dilator through the internal os. By placing a tenaculum at the 12 o’clock position on the cervix of an anteverted uterus, or 6 o’clock on a retroverted uterus, and applying outward traction, you can straighten the distorted canal.

A local anesthetic can help

It is helpful to administer a local anesthetic before placing a penetrating instrument such as the tenaculum. Patients are usually grateful for the extra few minutes taken to ensure their comfort.

If the cervix is resistant, or the patient is uncomfortable, after initial attempts to dilate the cervix, consider placing a paracervical or intracervical stromal local anesthetic. Lidocaine 1% has a rapid onset of action, reaching peak effectiveness in just a few minutes, with a duration of approximately 60 minutes. Bupivacaine 0.25% has a slightly slower onset of action (8–10 minutes), but offers long duration—about 240 minutes.

Place 5 to 10 cc of local anesthetic paracervically at the 4 and 8 o’clock positions. The choice of anesthetic depends on the procedure. For example, a nulligravid patient may benefit from bupivacaine because cervical dilation can cause significant and prolonged cramping. Bupivacaine is more potent than lidocaine and, therefore, potentially more cardiotoxic, so caution is advised.

Used correctly, local anesthetic facilitates cervical dilation.

Types of dilators

Many instruments are available. Be familiar with the benefits and shortcomings of each to achieve successful cervical dilation in the office.

Lacrimal-duct dilators. These instruments have long been used by gynecologists for cervical access when the closed external os is no more than a tiny dimple. These ophthalmologic instruments come in diameters smaller than 1 mm and allow the closed menopausal cervix to be dilated enough to allow placement of more traditional instruments (FIGURE 2).

Traditional dilators. Tapered metal or plastic dilators facilitate access to a tightly stenotic external os (FIGURE 3). These instruments have a more symmetrical segment proximal to the tip to allow gentle, gradual dilation of the canal. However, when dilation is needed for the entire length of the cervix, as it frequently is in nulliparous women, the tapered end will not dilate the internal os unless it is passed far enough into the canal—but passing the instrument too far increases the risk of uterine perforation. In this scenario, a symmetric dilator may be a better option to achieve uniform diameter of the endocervical canal from external to internal os. Be cautious: These symmetric dilators sometimes require additional force.

When the entire length of the cervix needs to be dilated, it may be wise to use a symmetric dilator that is the same size as the tapered dilator before increasing the diameter, to reduce the risk of perforation.

FIGURE 2 A borrowed tool to unlock the external os

From the world of ophthalmology, a lacrimal-duct dilator facilitates dilation of the extremely stenotic cervix.

FIGURE 3 Tapered instruments allow gradual dilation

Tapered cervical dilators, like this disposable set, have a more symmetrical segment proximal to the tip.

When every dilator is too large

Occasionally, the external os is so completely closed that even a lacrimal-duct dilator cannot be placed. In this situation, administer 2 cc of local anesthetic in the region of the external os, then gently penetrate the os using the tip of a #11 scalpel blade. This technique generally allows quick and easy access to the endocervical canal. (Typically, the entire canal will not be stenotic and, once the external opening is created, easy dilation can be accomplished.)

Navigating a crooked cervical canal

When the cervical canal is distorted, sometimes even the most carefully selected dilator will fail.

Why?

Because the diameter of the cervix is not the obstacle.

When a straight—or even partially curved—dilator cannot traverse the tortuous path of a distorted canal, the small flexible hysteroscope may offer a solution, allowing identification of the anatomic obstruction and visualization of the course of the cervical canal. Prior visualization of the canal enhances proprioception with the dilating instrument and improves the likelihood of safe uterine access.

The use of concomitant ultrasonography may also be helpful.11

From the standpoint of a payer, obtaining surgical access to the site of a procedure is included in the procedure payment. This is generally the rule for surgical access on the day of the procedure. Some payers reimburse separately, however, when access (specifically, dilation of the cervix) is performed a day, or few days, before the procedure because of an anatomic problem—such as the cervical stenosis discussed in the main “Update” article.

What are your options?

You have several coding options available for dilation of the cervix, depending on the approach you take:

- When you’ve given oral misoprostol, bill the visit at which you prescribed the drug.

- When you’ve inserted misoprostol vaginally, report code 59200 [insertion of cervical dilator (e.g., laminaria, prostaglandin) (separate procedure)].

The fact that 59200 is found in the “Maternity Care and Delivery” chapter of the CPT does not limit its use to obstetric cases. Because this code has a zero-day global period, you are not considered to be in the postoperative period of the first procedure when the surgical procedure is performed the next day (or even longer afterward), and the two procedures will not be bundled.

Another method of cervical dilation is represented by code 57800 [Dilation of cervical canal, instrumental (separate procedure)], which also has a zero-day global period.

The diagnosis code must support the service

That’s true whichever technique you choose. In this case, the diagnosis code will be either:

- 622.4 (Stricture and stenosis of cervix) or

- 752.49 (Other anomalies of cervix, vagina, and external female genitalia)—when the stenosis is the result of a congenital condition.—

MELANIE WITT, RN, CPC, COBGC, MA

1. Essure Earnings Report Fourth Quarter 2008. Mountain View, Calif: Conceptus Inc.

2. Farrugia M, Hussain S. Hysteroscopic endometrial ablation using the Hydro ThermAblator in an outpatient hysteroscopy clinic: feasibility and acceptability. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2006;13:178-182.

3. Fernandez H, Capella S, Audiebert F. Uterine thermal balloon therapy under local anesthesia for the treatment of menorrhagia: a pilot study. Hum Reprod. 1997;12:2511-2514.

4. Bertrand J. Use of NovaSure endometrial ablation system in an office setting environment. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12(5 Suppl):14.-

5. Roy K, Whiteside D, Manjon J, et al. Assessment of procedure tolerability during Her Option endometrial cryoablation in an outpatient setting. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12(5 Suppl):87.-

6. Khan RU, El-Rafeay H, Sharma S, Sooranna D, Stafford M. Oral, rectal, and vaginal pharmacokinetics of misoprostol. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:866-869.

7. Zieman M, Fong S, Benowitz N, Bankster D, Darney P. Absorption kinetics of misoprostol with oral or vaginal administration. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:88-92.

8. Preutthipan S, Herabutya Y. A randomized controlled trial of vaginal misoprostol for cervical priming before hysteroscopy. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:427-430.

9. Fung TM, Lam MW, Wong SF, Ho LC. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of vaginal misoprostol for cervical priming before hysteroscopy in postmenopausal women. BJOG. 2002;119:561-565.

10. Ngai SW, Chan YM, Ho PC. The use of misoprostol prior to hysteroscopy in postmenopausal women. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:1486-1488.

11. Valle RF, Sankpal R, Marlow J, Cohen L. Cervical stenosis: a challenging clinical entity. J Gynecol Surg. 2002;18:129-143.

12. Perez-Medina T, Bajo MJ, Martinez-Cortes L, Castellanos P, Perez de Avila I. Six thousand office diagnostic-operative hysteroscopies. Int J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;71:33-38.

1. Essure Earnings Report Fourth Quarter 2008. Mountain View, Calif: Conceptus Inc.

2. Farrugia M, Hussain S. Hysteroscopic endometrial ablation using the Hydro ThermAblator in an outpatient hysteroscopy clinic: feasibility and acceptability. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2006;13:178-182.

3. Fernandez H, Capella S, Audiebert F. Uterine thermal balloon therapy under local anesthesia for the treatment of menorrhagia: a pilot study. Hum Reprod. 1997;12:2511-2514.

4. Bertrand J. Use of NovaSure endometrial ablation system in an office setting environment. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12(5 Suppl):14.-

5. Roy K, Whiteside D, Manjon J, et al. Assessment of procedure tolerability during Her Option endometrial cryoablation in an outpatient setting. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12(5 Suppl):87.-

6. Khan RU, El-Rafeay H, Sharma S, Sooranna D, Stafford M. Oral, rectal, and vaginal pharmacokinetics of misoprostol. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:866-869.

7. Zieman M, Fong S, Benowitz N, Bankster D, Darney P. Absorption kinetics of misoprostol with oral or vaginal administration. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:88-92.

8. Preutthipan S, Herabutya Y. A randomized controlled trial of vaginal misoprostol for cervical priming before hysteroscopy. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:427-430.

9. Fung TM, Lam MW, Wong SF, Ho LC. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of vaginal misoprostol for cervical priming before hysteroscopy in postmenopausal women. BJOG. 2002;119:561-565.

10. Ngai SW, Chan YM, Ho PC. The use of misoprostol prior to hysteroscopy in postmenopausal women. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:1486-1488.

11. Valle RF, Sankpal R, Marlow J, Cohen L. Cervical stenosis: a challenging clinical entity. J Gynecol Surg. 2002;18:129-143.

12. Perez-Medina T, Bajo MJ, Martinez-Cortes L, Castellanos P, Perez de Avila I. Six thousand office diagnostic-operative hysteroscopies. Int J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;71:33-38.

Best practices for call—to make for a sustainable career

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Call is a fact of life for most obstetricians; there’s no alternative to having obstetric care available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Although we recognize call as part of the job we’ve accepted, many of us have a love–hate relationship with the call schedule.

One of the most fulfilling experiences in our career is following a patient through her pregnancy and then safely placing a baby in her arms. And call is the time during which many of us earn a significant part of our income. But it is also a time when we can never fully relax—particularly as we become more aware of the potential safety issues and medicolegal concerns inherent in traditional call practices.

We studied the matter with the goal of making call more palatable

In 2004 and 2005, we surveyed 66 obstetricians, attempting to talk to one person from every large or medium-sized group practice in the state of Wisconsin.

Our aim? To identify patterns in call practice that might be beneficial to our groups and other obstetricians.

Some of our findings were published in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology.1 We have since formulated suggestions for groups to consider when they design or modify their call practices.

Those suggestions form the bulk of this article. Please read on—you may find that they apply to your work.

A shortage of physicians?

Residencies in obstetrics and gynecology are increasingly hard to fill. The medical malpractice climate is often cited as a major reason, but studies demonstrate that “lifestyle” is as much or more of a concern for medical students who are deciding on a specialty.2-4

At the other end of the career trajectory, obstetricians are retiring from the specialty earlier than in the past, and research shows that obstetric call is one of the most important variables driving retirement.5 The combined effect of these two realities will likely challenge our ability to maintain sufficient numbers of obstetricians.

Although the restriction of resident work hours has drawn attention of late, the work-life demands of practicing obstetricians have been largely ignored. (For an exception, see “The unbearable unhappiness of the ObGyn: A crisis looms,” by Louis Weinstein, MD, in the December 2008 issue of OBG Management at www.obgmanagement.com.)

We found significant differences between residents’ call and the typical private-practice call (TABLE).

TABLE

Residency versus private practice: Which call pattern is more onerous?

| Residency | Private practice |

|---|---|

| More intense | Less intense |

| Focused (often on only one area) | Multiple responsibilities and sometimes multiple hospitals |

| More likely to go without sleep | Less likely to go without sleep |

| Shorter duration | Longer duration |

Dangers of call

Although 56% of respondents to our survey indicated that they go without sleep for 24 hours most or some of the time, only 13% reported being concerned that fatigue limits their ability to safely deliver care.1 This finding runs contrary to many studies that demonstrate that prolonged periods of wakefulness are associated with a high risk of error and potential compromise of patient safety.

The need to be in several places at once

“A bigger concern than fatigue is the risk inherent in handling multiple simultaneous responsibilities”Perhaps a bigger concern than fatigue—and largely unexplored in scientific study—is the risk inherent in handling multiple simultaneous responsibilities. It is not uncommon for a doctor to be seeing one patient in the clinic while another patient is being prepped in the operating room and a third patient is in labor.

“I can be two places at the same time on a good day with a tailwind, but never three,” one OB joked.

Even when the OB’s activity is limited to the labor and delivery unit, it is not unusual for two patients to be delivering at once, sometimes in different hospitals.

In our study, 26% of obstetricians delivered in more than one hospital, with the maximum being five hospitals.1 One OB proudly described having five patients in five different hospitals and being fortunate enough to deliver them all.

Is it possible, or wise, to attempt to please every patient?

It can sometimes be difficult to balance patient satisfaction and patient safety. Most women in labor prefer to have their own doctor provide their care. At one time, they seemed to have accepted the fact that the physician might be late for an office visit because of a simultaneous delivery.6 Now, however, they seem less accepting of even this inconvenience.

There is no “standard” call pattern

Overall, we found no standard pattern of call. Each system seems to have evolved, or been designed, to meet the needs required to provide care.

Our perception is that call arrangements must balance two main concerns: safety and sustainability. Someone must be available and able to function, but the call pattern cannot be so onerous that the doctors sharing it find it unlivable. Each group of obstetricians who provide care needs to identify rules that ensure safety—but also care that can be delivered over years of a career.

Best practices

We have several suggestions for best practices, though we recognize that some of them may not be practical for every practice. However, we believe that these generalizations may be useful to a broad range of obstetric call groups.

Deliver in one hospital only

The obstetricians we surveyed who were delivering at multiple hospitals indicated that the decision to do so was patient-driven; many physicians were dissatisfied with this practice.

Groups that had restricted themselves to one hospital felt that this decision had made their call easier and more sustainable.

Develop a formal backup policy

Many survey respondents indicated that, even without a formal policy, they can call a partner or other obstetrician in the community when the volume of work becomes too much to handle. We found that there is a true brotherhood and sisterhood of obstetricians who will drop everything to help when called upon.

Certainly, the volume of deliveries and other responsibilities will determine how frequently you need to call your backup. Unless a formal backup system is in place, however, there is no certainty that you will be able to reach another obstetrician and that he or she will be able to help. When you need assistance, it’s a terrible distraction to spend 30 minutes going down the list of your partners, trying to figure out who is in town and who isn’t. What if you call one of your partners late Saturday night and find him or her to be in no condition to perform?

If your call is busy enough, make sure a designated backup is carrying a beeper and understands his or her call responsibilities.

Restrict your responsibilities while on call

In a large practice, where it is not unusual for at least one or two patients to be in labor at any given time, consider assigning the call person solely to labor and delivery to ensure adequate availability for emergencies.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that a provider be “immediately available” when a patient is attempting vaginal birth after cesarean or when oxytocin is being utilized.7 Although the definition of “immediately available” is not codified, it probably means that the obstetrician should not be doing a major surgical procedure or seeing a full schedule of patients in an office 10 miles from the hospital.

Leaders in one large hospital chain have defined being immediately available as being available within 5 minutes. 8

Restrict responsibilities after being on call

This recommendation, too, is volume-driven. If it is likely that you will get little or no sleep during call, the next day’s activities should not include a difficult hysterectomy for severe endometriosis or endometrial cancer. If you must schedule these cases, do so with the patient’s understanding that last-minute rescheduling may be needed.

Even seeing a full slate of clinic patients may be challenging and could have a negative impact on patient satisfaction if you do not sleep the night before. Keep your next day short, and concentrate on activities that require limited mental and physical attention.

Align reimbursement systems

It became apparent, during our discussions with obstetricians in our survey, that financial incentives were aligned in ways that could potentially cause the physicians to overextend themselves. Although none of our respondents expressed concern about this fact from a safety standpoint, it was clear that people may sometimes work when they shouldn’t because of their desire to capture the charges for the care given.

A Canadian study reported a significant drop in elective inductions, as well as increased mean duration of labor, after implementing an income-pooling remuneration system. 9

Take call intelligently

Don’t begin call with a sleep deficit. Make sure you get a good night’s rest the night before. If possible, learn how to take “combat naps.” Even 20-minute naps can be helpful.

In our survey, all respondents indicated that their hospital had dedicated call quarters. Some institutions even provided meals and exercise facilities. See “How to combat fatigue (and win) during call”

Here are more ways to improve call

Depending on the size of your call pool and volume of deliveries, you might consider the following options to improve your call system.

A few simple measures can boost mental and physical alertness during extended duty.

Physical activity—This is the best strategy to counter fatigue. Stretch often, and walk around. Bright lights help.

Talk—Active participation in a conversation helps keep you focused; passive listening does not.

Drink caffeinated beverages—This calls for moderation, of course. Caffeine isn’t, and shouldn’t be, a cure-all.

Eat well and keep hydrated—A healthy diet and lots of uncaffeinated fluids keep your body running smoothly.

Take short naps—Even 20 minutes can help.

Support your colleagues—Cover another physician long enough for him or her to take a nap, and then take your turn.

Call for help—Call in backup if you are faced with a difficult situation and sense symptoms of serious fatigue in yourself. Also, watch for those symptoms in your colleagues.

Take a shower—A change of clothes helps, too.

Source: Adapted from “Fatigue countermeasures: alertness management in flight operations.” Available at http://humanfactors.arc.nasa.gov/zteam. Accessed March 12, 2009.

If you increase the number of obstetricians in your call pool, the number of calls you take may diminish. However, the volume of activity will probably increase as a result, so that you have a greater chance of being busy while on call. Hiring a nurse-midwife may decrease the number of uncomplicated vaginal deliveries you perform, but you still need to be prepared to provide backup.

Shorten the call duration

The most common duration of call in our study was 24 hours. However, some call pools take call for a weekend or week at a time.1 This gives the physician a longer interval between calls, but the unpredictability of the patient load may make this a horrendously long period of time.

Another potential disadvantage of a shortened call, especially when it is abbreviated to less than 24 hours, is that it increases the number of handoffs in patient care and, therefore, enhances the risk that the circumstances of any given patient will be incompletely understood at this time.

In a busy OB practice, handoffs usually involve a meeting of obstetricians in labor and delivery to “run the board.” When participants attempt to make these handoffs as complete as possible, patient safety is significantly improved.

One way to ensure completeness of patient handoffs is to borrow training and skills from the world of airline pilots. There, crew resource management has introduced the concept of SBAR [Situation-Background-Assessment-Recommendation] as a specific tool to decrease risk inherent in handoffs.

Another helpful idea is attending nurses’ report sessions. These reports can provide you with useful information that you may not have recognized otherwise. By giving them your attention, you may also strengthen relationships with the nurses, your first line of defense.

Develop in-house call

Dildy and colleagues estimated that a call volume of approximately 2,400 deliveries a year would justify a hospital developing 24-hour in-house obstetric coverage.10 In our study, almost all of the hospitals that required in-house call did so because they had residencies, and in-house staff call was required.

Although Clark and colleagues found 24-hour in-house call to be safer than regular call in their review of closed perinatal claims at one large hospital chain, there has been a paucity of studies that confirm or extend our knowledge in this area.11

Hire laborists

Weinstein introduced the word “laborist” into our lexicon in a 2003 paper.12 Barbieri suggested the addition of “nocturnalist” or “weekendist” as possible terms to describe specialists assigned to work certain shifts that prove particularly onerous to practicing obstetricians.13 A number of hospitals and groups are examining and developing this call model.14 However, little research has been conducted on its effects on patient safety and obstetric practice.

For more information, visit www.oblaborist.org and http://obgynhospitalist.com.

Balance—that is the goal

For some of us, perfect balance between safety and patient satisfaction, and between work and home life, may be impossible. Nevertheless, we all need to explore ways to make call a safe and sustainable practice. For many of us, the growing recognition that we have more beautiful, sunny Sunday afternoons behind us than in front of us may be the signal to shift our focus to less demanding, and time-depleting, call schedules.

1. Schauberger CW, Gribble RK, Rooney BL. On call: a survey of Wisconsin obstetric groups. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:39.e1-39.e4.

2. Dorsey ER, Jarjoura D, Rutecki GW. Influence of controllable lifestyle on recent trends in specialty choice by US medical students. JAMA. 2003;290:1173-1178.

3. Gariti DL, Zollinger TW, Look KY. Factors detracting students from applying for an obstetrics and gynecology residency. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:289-293.

4. Deutsch A, McCarthy J, Murray K, Sayer R. Why are fewer medical students in Florida choosing obstetrics and gynecology? South Med J. 2007;100:1095-1098.

5. Bettes BA, Chalas E, Coleman VH, Schulkin J. Heavier workload, less personal control: impact of delivery on obstetrician/gynecologists’ career satisfaction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:851-857.

6. Pradhan A, Raman A, Lim C, Yoon E, Ananth C. The patient perspective. Is the hospitalist model a viable option for obstetric care [abstract]. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:40S-41S.

7. American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Guidelines for Perinatal Care. 6th ed. Elk Grove, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2007:157.

8. Clark SL, Belfort MA, Byrum SL, Meyers JA, Perlin JB. Improved outcomes, fewer cesarean deliveries, and reduced litigation: results of a new paradigm in patient safety. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:105.e1-105.e7.

9. Bland ES, Oppenheimer LW, Holmes P, Wen SW. The effect of income pooling within a call group on rates of obstetric intervention. CMAJ. 2001;164:337-339.

10. Dildy GA, Clark SL, Belfort MA, Herbst MA, Thompson J. Twenty-four hour, in-house obstetric coverage in a community-based tertiary care hospital [abstract]. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:43S.-

11. Clark SL, Belfort MA, Dildy GA. Reducing obstetric litigation through alterations in practice patterns—experience with 189 closed claims. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:S118.-

12. Weinstein L. The laborist: a new focus of practice for the obstetrician. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:310-312.

13. Barbieri RL. Will the “ists” preserve the rewards of OB practice? OBG Management. 2007;199(9):8-12.

14. Yates J. The laborists are here, but can they thrive in US hospitals? OBG Management. 2008;20(8):26-34.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Call is a fact of life for most obstetricians; there’s no alternative to having obstetric care available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Although we recognize call as part of the job we’ve accepted, many of us have a love–hate relationship with the call schedule.

One of the most fulfilling experiences in our career is following a patient through her pregnancy and then safely placing a baby in her arms. And call is the time during which many of us earn a significant part of our income. But it is also a time when we can never fully relax—particularly as we become more aware of the potential safety issues and medicolegal concerns inherent in traditional call practices.

We studied the matter with the goal of making call more palatable

In 2004 and 2005, we surveyed 66 obstetricians, attempting to talk to one person from every large or medium-sized group practice in the state of Wisconsin.

Our aim? To identify patterns in call practice that might be beneficial to our groups and other obstetricians.

Some of our findings were published in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology.1 We have since formulated suggestions for groups to consider when they design or modify their call practices.

Those suggestions form the bulk of this article. Please read on—you may find that they apply to your work.

A shortage of physicians?

Residencies in obstetrics and gynecology are increasingly hard to fill. The medical malpractice climate is often cited as a major reason, but studies demonstrate that “lifestyle” is as much or more of a concern for medical students who are deciding on a specialty.2-4

At the other end of the career trajectory, obstetricians are retiring from the specialty earlier than in the past, and research shows that obstetric call is one of the most important variables driving retirement.5 The combined effect of these two realities will likely challenge our ability to maintain sufficient numbers of obstetricians.

Although the restriction of resident work hours has drawn attention of late, the work-life demands of practicing obstetricians have been largely ignored. (For an exception, see “The unbearable unhappiness of the ObGyn: A crisis looms,” by Louis Weinstein, MD, in the December 2008 issue of OBG Management at www.obgmanagement.com.)

We found significant differences between residents’ call and the typical private-practice call (TABLE).

TABLE

Residency versus private practice: Which call pattern is more onerous?

| Residency | Private practice |

|---|---|

| More intense | Less intense |

| Focused (often on only one area) | Multiple responsibilities and sometimes multiple hospitals |

| More likely to go without sleep | Less likely to go without sleep |

| Shorter duration | Longer duration |

Dangers of call

Although 56% of respondents to our survey indicated that they go without sleep for 24 hours most or some of the time, only 13% reported being concerned that fatigue limits their ability to safely deliver care.1 This finding runs contrary to many studies that demonstrate that prolonged periods of wakefulness are associated with a high risk of error and potential compromise of patient safety.

The need to be in several places at once

“A bigger concern than fatigue is the risk inherent in handling multiple simultaneous responsibilities”Perhaps a bigger concern than fatigue—and largely unexplored in scientific study—is the risk inherent in handling multiple simultaneous responsibilities. It is not uncommon for a doctor to be seeing one patient in the clinic while another patient is being prepped in the operating room and a third patient is in labor.

“I can be two places at the same time on a good day with a tailwind, but never three,” one OB joked.

Even when the OB’s activity is limited to the labor and delivery unit, it is not unusual for two patients to be delivering at once, sometimes in different hospitals.

In our study, 26% of obstetricians delivered in more than one hospital, with the maximum being five hospitals.1 One OB proudly described having five patients in five different hospitals and being fortunate enough to deliver them all.

Is it possible, or wise, to attempt to please every patient?

It can sometimes be difficult to balance patient satisfaction and patient safety. Most women in labor prefer to have their own doctor provide their care. At one time, they seemed to have accepted the fact that the physician might be late for an office visit because of a simultaneous delivery.6 Now, however, they seem less accepting of even this inconvenience.

There is no “standard” call pattern

Overall, we found no standard pattern of call. Each system seems to have evolved, or been designed, to meet the needs required to provide care.

Our perception is that call arrangements must balance two main concerns: safety and sustainability. Someone must be available and able to function, but the call pattern cannot be so onerous that the doctors sharing it find it unlivable. Each group of obstetricians who provide care needs to identify rules that ensure safety—but also care that can be delivered over years of a career.

Best practices

We have several suggestions for best practices, though we recognize that some of them may not be practical for every practice. However, we believe that these generalizations may be useful to a broad range of obstetric call groups.

Deliver in one hospital only

The obstetricians we surveyed who were delivering at multiple hospitals indicated that the decision to do so was patient-driven; many physicians were dissatisfied with this practice.

Groups that had restricted themselves to one hospital felt that this decision had made their call easier and more sustainable.

Develop a formal backup policy

Many survey respondents indicated that, even without a formal policy, they can call a partner or other obstetrician in the community when the volume of work becomes too much to handle. We found that there is a true brotherhood and sisterhood of obstetricians who will drop everything to help when called upon.

Certainly, the volume of deliveries and other responsibilities will determine how frequently you need to call your backup. Unless a formal backup system is in place, however, there is no certainty that you will be able to reach another obstetrician and that he or she will be able to help. When you need assistance, it’s a terrible distraction to spend 30 minutes going down the list of your partners, trying to figure out who is in town and who isn’t. What if you call one of your partners late Saturday night and find him or her to be in no condition to perform?

If your call is busy enough, make sure a designated backup is carrying a beeper and understands his or her call responsibilities.

Restrict your responsibilities while on call

In a large practice, where it is not unusual for at least one or two patients to be in labor at any given time, consider assigning the call person solely to labor and delivery to ensure adequate availability for emergencies.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that a provider be “immediately available” when a patient is attempting vaginal birth after cesarean or when oxytocin is being utilized.7 Although the definition of “immediately available” is not codified, it probably means that the obstetrician should not be doing a major surgical procedure or seeing a full schedule of patients in an office 10 miles from the hospital.

Leaders in one large hospital chain have defined being immediately available as being available within 5 minutes. 8

Restrict responsibilities after being on call

This recommendation, too, is volume-driven. If it is likely that you will get little or no sleep during call, the next day’s activities should not include a difficult hysterectomy for severe endometriosis or endometrial cancer. If you must schedule these cases, do so with the patient’s understanding that last-minute rescheduling may be needed.

Even seeing a full slate of clinic patients may be challenging and could have a negative impact on patient satisfaction if you do not sleep the night before. Keep your next day short, and concentrate on activities that require limited mental and physical attention.

Align reimbursement systems

It became apparent, during our discussions with obstetricians in our survey, that financial incentives were aligned in ways that could potentially cause the physicians to overextend themselves. Although none of our respondents expressed concern about this fact from a safety standpoint, it was clear that people may sometimes work when they shouldn’t because of their desire to capture the charges for the care given.

A Canadian study reported a significant drop in elective inductions, as well as increased mean duration of labor, after implementing an income-pooling remuneration system. 9

Take call intelligently

Don’t begin call with a sleep deficit. Make sure you get a good night’s rest the night before. If possible, learn how to take “combat naps.” Even 20-minute naps can be helpful.

In our survey, all respondents indicated that their hospital had dedicated call quarters. Some institutions even provided meals and exercise facilities. See “How to combat fatigue (and win) during call”

Here are more ways to improve call

Depending on the size of your call pool and volume of deliveries, you might consider the following options to improve your call system.

A few simple measures can boost mental and physical alertness during extended duty.

Physical activity—This is the best strategy to counter fatigue. Stretch often, and walk around. Bright lights help.

Talk—Active participation in a conversation helps keep you focused; passive listening does not.

Drink caffeinated beverages—This calls for moderation, of course. Caffeine isn’t, and shouldn’t be, a cure-all.

Eat well and keep hydrated—A healthy diet and lots of uncaffeinated fluids keep your body running smoothly.

Take short naps—Even 20 minutes can help.

Support your colleagues—Cover another physician long enough for him or her to take a nap, and then take your turn.

Call for help—Call in backup if you are faced with a difficult situation and sense symptoms of serious fatigue in yourself. Also, watch for those symptoms in your colleagues.

Take a shower—A change of clothes helps, too.

Source: Adapted from “Fatigue countermeasures: alertness management in flight operations.” Available at http://humanfactors.arc.nasa.gov/zteam. Accessed March 12, 2009.

If you increase the number of obstetricians in your call pool, the number of calls you take may diminish. However, the volume of activity will probably increase as a result, so that you have a greater chance of being busy while on call. Hiring a nurse-midwife may decrease the number of uncomplicated vaginal deliveries you perform, but you still need to be prepared to provide backup.

Shorten the call duration

The most common duration of call in our study was 24 hours. However, some call pools take call for a weekend or week at a time.1 This gives the physician a longer interval between calls, but the unpredictability of the patient load may make this a horrendously long period of time.

Another potential disadvantage of a shortened call, especially when it is abbreviated to less than 24 hours, is that it increases the number of handoffs in patient care and, therefore, enhances the risk that the circumstances of any given patient will be incompletely understood at this time.

In a busy OB practice, handoffs usually involve a meeting of obstetricians in labor and delivery to “run the board.” When participants attempt to make these handoffs as complete as possible, patient safety is significantly improved.

One way to ensure completeness of patient handoffs is to borrow training and skills from the world of airline pilots. There, crew resource management has introduced the concept of SBAR [Situation-Background-Assessment-Recommendation] as a specific tool to decrease risk inherent in handoffs.