User login

Managing Chronic, Nonmalignant Pain in Patients with a Substance Use Disorder

Reducing the legal risks of labor induction and augmentation

- 18 common allegations in oxytocin-related litigation

- 6 risk-reducing strategies

Martin L. Gimovsky, MD

WHAT’S YOUR VERDICT?

Does this patient have grounds for a lawsuit?

At 41 weeks’ estimated gestation, Elena, a 32-year-old primipara with an uneventful antepartum course, is scheduled for induction of labor for postdates. On admission she is 1 cm dilated and 70% effaced, with the fetal vertex at –3 station. Fetal heart rate monitoring shows a normal baseline, moderate variability, and accelerations. No decelerations are observed.

After the membranes are ruptured artificially, labor progresses slowly, and chorioamnionitis is suspected.

Fetal tachycardia with minimal variability and variable decelerations develops. Oxytocin is titrated to achieve uterine contractions every 2 minutes. Elena eventually becomes completely dilated and pushes for 95 minutes. During this time, the fetal variable decelerations increase in duration, with loss of variability and continued tachycardia.

Because of these findings, delivery is expedited with a vacuum extractor. The newborn is depressed, admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit for respiratory support to “rule out sepsis,” and is later found to have neurologic injury.

In your opinion, does Elena have grounds for a lawsuit?

If such a case spurs a lawsuit, as it often will, the plaintiff’s attorney is likely to declare any or all of these allegations:

- failure to discontinue oxytocin in light of nonreassuring fetal heart rate

- failure to identify and respond to uterine hyperstimulation

- failure to identify and respond to fetal distress

- failure to react in a timely manner to fetal distress

- inappropriate delivery method

- failure to use a fetal scalp electrode

- failure to recognize and act upon arrest of dilatation in a timely manner

These allegations are only the most probable ones in circumstances such as Elena’s. When unanticipated morbidity or death occurs after oxytocin is used, physicians and nurses may find themselves facing any of the 18 allegations listed in the TABLE—or even others.

In court, these allegations will be based on the opinions of independent physicians, certified nurse-midwives, and registered nurses with the education, experience, and credentials to qualify as “experts.” Courts usually allow experts when the substance of the allegations is beyond the public’s general knowledge.

Although allegations often include inaccuracies, erroneous assumptions, and conclusions based on “information and belief” rather than scientific evidence, they remain part of the claim until disproved over the course of the legal proceedings.

TABLE

18 common allegations in oxytocin-related litigation

| 1. Unnecessary induction due to lack of medical indication |

| 2. Failure to establish fetal well-being prior to initiating oxytocin |

| 3. Failure to adequately monitor fetal heart rate during oxytocin infusion |

| 4. Failure to adequately monitor uterine contractions |

| 5. Failure to place a spiral electrode and/or intrauterine pressure catheter |

| 6. Failure to discontinue oxytocin in light of nonreassuring fetal heart rate |

| 7. Failure to identify and respond to fetal distress |

| 8. Delay in identifying and responding to nonreassuring fetal heart rate |

| 9. Failure to notify provider of nonreassuring fetal heart rate |

| 10. Failure to identify and respond to uterine hyperstimulation and/or elevated resting tone |

| 11. Inappropriate titration of oxytocin not based on accepted protocols |

| 12. Administration of oxytocin without a physician’s order |

| 13. Failure to follow physician’s order |

| 14. Failure to order a cesarean section when fetal heart rate became nonreassuring |

| 15. Delay in cesarean section after being ordered by the physician |

| 16. Failure to follow hospital policies and procedures |

| 17. Inadequate policies and procedures governing oxytocin administration |

| 18. Failure to initiate chain of command |

Elective inductions can spell trouble

Although the rate of induction has more than doubled since 1989, to 20.6% of births or more than 840,000 pregnancies in 2003,1 still no consensus exists for patient selection. In some centers, inductions are reserved for women with medical indications only, whereas in others, more than half are elective.2

Because of this divergence, when there is a negative outcome after an elective induction, the obstetrician can anticipate an allegation of unnecessary induction due to lack of a medical indication.

Fetal monitoring

Proven or not, it’s the norm

Although we lack overwhelming proof of its superiority to intermittent auscultation,3 electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) is used in most labor and delivery settings during oxytocin administration for induction or augmentation of labor—and fetal heart rate and uterine activity typically guide initiation and titration of oxytocin.

Nevertheless, because EFM is the unofficial standard, an obstetrician who chooses to use intermittent auscultation of fetal heart rate during oxytocin infusion can anticipate strong criticism if the delivery results in a compromised neonate.

A 2005 Cochrane review4 of 18,561 births compared EFM with intermittent auscultation in labor and delivery and found fewer neonatal seizures in the EFM group but no differences in Apgar scores of less than 4 and 7, NICU admissions, perinatal deaths, or cerebral palsy.

“Default” intervals

Not only is the type of fetal monitoring important, but also how closely and how often the strip is evaluated. However, no studies have determined the optimal frequency of EFM interpretation during normal labors, let alone those induced or augmented with oxytocin. Furthermore, no single best methodology has been identified. Rather, the “default” timing of EFM interpretation has been loosely based on the historical practice of evaluating and documenting intermittent auscultation at 30-minute intervals during active labor and 15-minute intervals during the second stage for low-risk patients. For high-risk patients, the intervals have been every 15 minutes during the active phase and every 5 minutes during the second stage.

What will expert witnesses look for?

After adverse outcomes, the EFM tracing will be examined closely by “experts” looking for evidence that it contained abnormalities demonstrating fetal compromise or predicting the infant’s injury or death.

These experts also scrutinize the actions of physicians and nurses for appropriateness, timeliness, and effectiveness; the timing of the decision for expedited delivery; and the events occurring between that decision and the time of delivery or abdominal skin incision.

The monitor’s shortcomings

Many courts now require experts to base their opinions on reliable scientific studies; however, in malpractice claims involving EFM, expert interpretation often is based on the expert’s own personal or institutional experience or common practices rather than scientific evidence.

One of the most pervasive public misconceptions is that fetal monitoring can reliably detect when a fetus lacks sufficient oxygen, is experiencing a physiologically stressful labor that is depleting oxygen reserves, or is becoming asphyxiated. In reality, the positive predictive value (ability of the technology to identify the compromised fetus without including healthy fetuses) is very low: 0.14%. Thus, of 1,000 fetuses with nonreassuring tracings, only 1 or 2 are actually compromised.5 This may explain why providers and nurses are reluctant to deem all nonreassuring recordings as accurate.

The only thing EFM reliably identifies with a high degree of specificity is the oxygenated fetus that is not experiencing metabolic acidemia. Recordings with “nonreassuring” features are statistically unlikely to imply a diagnosis of fetal metabolic acidosis, hypoxemia, or stress or distress.

Should EFM precede oxytocin?

No minimal duration of monitoring prior to oxytocin administration has been consistently determined. Researchers do not even agree that initial monitoring of the fetus scheduled for induction has benefit.

This does not mean that oxytocin can be started without knowledge of the maternal and fetal condition—only that the best timing and methods of assessment prior to induction of labor are unknown.

What is “nonreassuring”?

Starting oxytocin in a woman with a “non-reassuring” tracing opens the OB to criticism. This is the most contentious aspect of medical and nursing management because we lack standardized definitions of “reassuring” and “nonreassuring.”

Nurses typically label a tracing nonreassuring based solely on decelerations or other variant patterns such as tachycardia. However, while a tracing’s individual characteristics may reflect a variety of etiologies (one of which is decreased uteroplacental perfusion), variability and/or accelerations signify an overall reassuring status, or fetal tolerance of labor.

Physicians generally examine the tracing in light of other clinical factors, such as labor progress, historical data, or parity—and also in light of any specific actions that have been taken and the expected time of their peak effect.

When to notify the OB

Another contentious issue in labor induction is exactly when nurses should notify the physician of a nonreassuring fetal heart rate. Unfortunately, there is no consensus about this question, either; again, most EFM tracings requiring nursing intervention exhibit an overall reassuring status.

Because evaluation of nonreassuring findings may take several minutes, nurses usually notify the physician when their assessment is complete. If the worrisome tracing resolves after intervention, a nurse may appropriately postpone notification until the next opportunity for communication with the physician.

Uterine monitoring

Can monitoring predict rupture?

In cases involving uterine rupture and/or placental abruption, experts may allege that the event could have been predicted with an intrauterine pressure catheter. However, in a study of “controlled” uterine rupture (recording of intrauterine pressure before and during uterine incision at the time of cesarean section), Devoe et al6 found no real differences in contraction frequency or duration, peak contraction pressures, or uterine resting tone prior to and after uterine “rupture” (incision).

We also lack prospective studies demonstrating that intrauterine pressure catheterization can predict placental abruption. Placement of the device purely for this reason is not indicated.

Titration of oxytocin

No consensus on frequency or intensity of contractions

Criticism of the method of oxytocin titration is common in malpractice claims because no data satisfactorily define adequate frequency or intensity of contractions.

Nor do we have widely accepted terminology to describe uterine activity. For example, hyperstimulation is sometimes defined as increased frequency of contractions with an abnormal fetal heart rate tracing, and sometimes as increased frequency of contractions without a nonreassuring fetal heart rate. The same inconsistencies hold true for the terms “hypertonus,” “tetany,” “tachysystole,” and others.

“Adequate labor pattern” has been defined as 3 to 5 contractions in 10 minutes or 7 contractions in 15 minutes,7 even though these criteria are based on limited data. Although clinically adequate labor is defined by cervical dilatation and effacement with fetal descent, this definition frequently leaves us titrating oxytocin by “trial and error.” Fortunately, the half-life of oxytocin is short, and we can use fetal and uterine response to guide titration.

No definitive predictors of rupture, abruption, asphyxiation

When uterine rupture, placental abruption, and/or variant fetal heart patterns occur with hyperstimulation or elevated resting tone, the possibility of a cause-and-effect will be explored in legal claims. Although uterine rupture has been attributed to oxytocin in older, nonprospective, uncontrolled studies, more recent investigations8 failed to confirm this link.

The effect of uterine hyperstimulation on fetal oxygenation is even less well established. Contractions increase placental vascular resistance, which in turn decreases uteroplacental blood flow. This phenomenon has been demonstrated in studies utilizing Doppler velocimetry,9 radioangiography,10 and fetal pulse oximetry.11 However, none have been able to quantify, in millimeters of mercury, the intensity of uterine contractions or baseline tonus required to compromise fetal oxygenation.

Risk-reducing tactics

These strategies12 do not represent the standard of care, but may help reduce liability:

- Routinely assess fetal heart rate during examination of the laboring patient.

- Document EFM interpretation comprehensively. Include baseline, variability, accelerations, decelerations, and uterine activity, as well as overall impression.

- Date and time every entry.

- When notified of a finding, detail the notification, as well as the orders and plan of care communicated to the nurse.

- Develop a mechanism for documentation when you are located outside the hospital (eg, progress notes that are later posted in the chart).

- Use digital storage and retrieval with central monitoring of displays to allow physicians to observe EFM tracings via remote access.

- Use handheld PDA-type displays.

- Go to the bedside to evaluate a patient when nurses ask you to do so. Document date and time, and the fetal heart rate interpretation.

- Decrease or discontinue oxytocin when variant fetal heart rate patterns suggest decreased uteroplacental perfusion (FIGURE 1).

- Avoid further increases in oxytocin once adequate labor (progressive cervical change) is established.

- Consider decreasing oxytocin—or avoid further increases—when uterine contractions are more frequent than 5 in 10 minutes or 7 in 15 minutes (FIGURE 2).

- Use National Institute of Child Health and Human Development terminology in verbal communications with nurses and physicians (see the Web version of this article for a downloadable PDF file of this terminology).

Martin L. Gimovsky, MD

Program Director, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Newark Beth Israel Medical Center, Newark, NJ

Clinical Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York City

As obstetricians, we are fortunate to participate in the most basic aspect of the human condition: the need to reproduce. Sometimes it is easy to overlook this fact, given the routine nature of many of our practices.

A case in point: oxytocin administration to induce or augment labor, an everyday occurrence in virtually all labor and delivery suites. Oxytocin is so ubiquitous, it can be easy to use it less than meticulously. Although the risks associated with its use are largely recognized, and the appropriate responses well known, a few points bear repeating.

Twin challenges: Protect and document

Safe and judicious use of oxytocin involves 2 challenges: minimizing medical risks to mother and fetus, and creating a supportive medical record. As in all aspects of medical care, we are required to know how to handle the clinical situation, and to document our skill, knowledge, and experience. Nowhere is this of greater concern than in the management of labor and delivery.

Here are 6 additional strategies for reducing legal risks of oxytocin use in labor.

1. Start with a written note

I suggest entering a written note into the record prior to administering oxytocin, outlining the reasoning behind the decision to proceed. Taking this pretreatment pause or “time out”—as the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations calls it—provides an opportunity to consider the risks, benefits, and alternatives of oxytocin use. This note should include the medical indication.

2. Conduct a comprehensive consent process

A passive signature on a general consent form is a minimalist way of demonstrating patient consent. By beginning the charting at the time of the consent discussion, you can demonstrate your consideration of the patient’s understanding and desires, not to mention your adherence to the highest standards of care.

Was an alternative approach possible? The patient should have the benefit of your opinion as well as a discussion of other reasonable strategies. Involving her in an active discussion is a fundamental component of informed consent—especially since improper consent is a frequent allegation in malpractice actions.

3. Describe both uterine and fetal responses

Because oxytocin directly affects uterine activity and indirectly affects placental perfusion, any chart notation needs to include references to both. For example, the comment that “contractions are every 2 minutes” requires the additional observation that the fetal heart rate tracing “is reassuring,”…“unchanged from earlier,”…or “demonstrates changes that are being evaluated.”

Whether a notation is made at the time of a routine labor check or when the physician is called to the bedside, comments on both uterine activity and fetal response are needed.

4. Discontinue oxytocin when the uterus overreacts

On occasion, excessive uterine activity may occur when oxytocin is first administered. Excessive uterine activity on a continuing basis can lead to fetal asphyxia. Although reducing the oxytocin dose will ultimately diminish uterine activity, I teach residents to discontinue oxytocin completely as soon as excessive uterine activity occurs.

Because this is a clinically important intervention, the medical record should be notated.

5. Adjust oxytocin to reflect changes in labor patterns

It makes good sense to avoid further oxytocin increases once the patient is in active labor (ie, progressive cervical change) and to decrease doses when contractions occur more frequently than every 2 minutes, even in the face of a reassuring fetal heart rate. This is not a situation in which, “if a little is good, a lot is better.”

6. Consider including a labor curve

Adding a labor curve or partograph to the chart can be a further safeguard, as it makes it easy to identify prolonged labors and potential complications in a timely manner.

All 6 strategies help demonstrate and preserve your hard work and concern for the patient. As always, adherence to principles of sound care and communication is the bedrock of successful obstetrics. There is no substitute.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

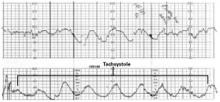

FIGURE 1 Tachysystole with decelerations signifies uterine hyperstimulation

Decrease or discontinue oxytocin when variant fetal heart rate patterns suggest decreased uteroplacental perfusion. This tracing shows uterine hyperstimulation (tachysystole with decelerations).

FIGURE 2 Titrate oxytocin to “normalize” contractions

Consider decreasing oxytocin—or avoid further increases—when uterine contractions are more frequent than 5 in 10 minutes or 7 in 15 minutes. This tracing shows 6 uterine contractions in 10 minutes. The fetal heart rate channel demonstrates moderate variability and, therefore, fetal tolerance of a frequent contraction pattern.

Why policies and procedures are a double-edged sword

Although policies and procedures are intended to help guide health care assessments and interventions, they are routinely subpoenaed and entered as evidence in an attempt to define the standard of care. Failure to follow these policies and procedures may be viewed by expert witnesses as a breach in that standard.

Use of oxytocin requires a medical or nursing professional to make judgments based on training, experience, and knowledge. Although policies and procedures cannot address every possible scenario or replace informed judgment, physicians and nurses are routinely criticized for failing to administer oxytocin or otherwise proceed exactly as outlined.

Some reasons policies and procedures should not be viewed as standard of care:

- They are typically written by a person in an administrative position who does not actually provide the care outlined.

- They are usually not routinely updated as new literature is published.

- Since they do not provide guidelines for unanticipated or unusual situations, deviation from policy is reasonable and even necessary in many scenarios.

- They are rarely written to reflect “reasonable” care; instead, they suggest an “ideal” level of care.

Reasonable protocols. Every physician and health care provider should be familiar with the hospital’s policies and procedures and help hospital personnel revise those that appear to limit the physician’s ability to easily adjust care or exercise judgment. Among the suggestions:

- Make all recommendations practical. This means they can be followed most of the time in most situations.

- Avoid terms such as “mandatory,” “always,” “never,” “should,” or “must.”

- Limit recommendations that can be considered “endpoints” for increasing oxytocin, such as: “Increase oxytocin until contractions are 2 to 3 minutes apart and 60 seconds in duration.” Recommendations written in this fashion are difficult to follow clinically; although the criteria may be met, labor may not progress, warranting an increase in oxytocin beyond the endpoints in the guidelines. Guidelines that discuss considerations for decreasing or discontinuing the drug would be better.

It also is important to foster understanding among medical and nursing staff that policies and procedures are guidelines and that medical and nursing judgment supersedes policy recommendations.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

1. Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, Ventura SJ, Menacker F, Munson ML. Birth: final data for 2003. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2005;54(2):1-116.

2. Rayburn WF, Zhang J. Rising rates of labor induction: present concerns and future strategies. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:164-167.

3. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin Number 49, December 2003: Dystocia and augmentation of labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:1445-1454.

4. Thacker SB, et al. Continuous electronic heart rate monitoring for fetal assessment during labor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(3):ISSN 1464-780X.

5. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin Number 62, May 2005: Intrapartum fetal heart rate monitoring. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1161-1169.

6. Devoe LD, Croom CS, et al. The prediction of “controlled” uterine rupture by the use of intrauterine pressure catheters. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80:626-629.

7. Norwitz ER, Robinson JN, Repke JT. Labor and delivery. In: Gabbe SG, Niebyl JR, Simpson JL, eds. Obstetrics. Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 4th ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2002;355.-

8. Phelan JP, Korst LM, Settles DK. Uterine activity patterns in uterine rupture: a case-control study. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:394-397.

9. Bower S, Campbell S, Vyas S, McGirr C. Braxton-Hicks contractions can alter uteroplacental perfusion. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1991;1:46-49.

10. Borell U, Fernstroem I, Ohlson L, Wiqvist N. Influence of uterine contractions on the uteroplacental blood flow at term. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1965;93:44-57.

11. Johnson N, van Oudgaarden E, Montague I, McNamara H. The effect of oxytocin-induced hyperstimulation on fetal oxygen. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994;101:805-807.

12. Lucidi RS, Chez RA, et al. The clinical use of intrauterine pressure catheters. J Matern Fetal Med. 2001;10:420-422.

- 18 common allegations in oxytocin-related litigation

- 6 risk-reducing strategies

Martin L. Gimovsky, MD

WHAT’S YOUR VERDICT?

Does this patient have grounds for a lawsuit?

At 41 weeks’ estimated gestation, Elena, a 32-year-old primipara with an uneventful antepartum course, is scheduled for induction of labor for postdates. On admission she is 1 cm dilated and 70% effaced, with the fetal vertex at –3 station. Fetal heart rate monitoring shows a normal baseline, moderate variability, and accelerations. No decelerations are observed.

After the membranes are ruptured artificially, labor progresses slowly, and chorioamnionitis is suspected.

Fetal tachycardia with minimal variability and variable decelerations develops. Oxytocin is titrated to achieve uterine contractions every 2 minutes. Elena eventually becomes completely dilated and pushes for 95 minutes. During this time, the fetal variable decelerations increase in duration, with loss of variability and continued tachycardia.

Because of these findings, delivery is expedited with a vacuum extractor. The newborn is depressed, admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit for respiratory support to “rule out sepsis,” and is later found to have neurologic injury.

In your opinion, does Elena have grounds for a lawsuit?

If such a case spurs a lawsuit, as it often will, the plaintiff’s attorney is likely to declare any or all of these allegations:

- failure to discontinue oxytocin in light of nonreassuring fetal heart rate

- failure to identify and respond to uterine hyperstimulation

- failure to identify and respond to fetal distress

- failure to react in a timely manner to fetal distress

- inappropriate delivery method

- failure to use a fetal scalp electrode

- failure to recognize and act upon arrest of dilatation in a timely manner

These allegations are only the most probable ones in circumstances such as Elena’s. When unanticipated morbidity or death occurs after oxytocin is used, physicians and nurses may find themselves facing any of the 18 allegations listed in the TABLE—or even others.

In court, these allegations will be based on the opinions of independent physicians, certified nurse-midwives, and registered nurses with the education, experience, and credentials to qualify as “experts.” Courts usually allow experts when the substance of the allegations is beyond the public’s general knowledge.

Although allegations often include inaccuracies, erroneous assumptions, and conclusions based on “information and belief” rather than scientific evidence, they remain part of the claim until disproved over the course of the legal proceedings.

TABLE

18 common allegations in oxytocin-related litigation

| 1. Unnecessary induction due to lack of medical indication |

| 2. Failure to establish fetal well-being prior to initiating oxytocin |

| 3. Failure to adequately monitor fetal heart rate during oxytocin infusion |

| 4. Failure to adequately monitor uterine contractions |

| 5. Failure to place a spiral electrode and/or intrauterine pressure catheter |

| 6. Failure to discontinue oxytocin in light of nonreassuring fetal heart rate |

| 7. Failure to identify and respond to fetal distress |

| 8. Delay in identifying and responding to nonreassuring fetal heart rate |

| 9. Failure to notify provider of nonreassuring fetal heart rate |

| 10. Failure to identify and respond to uterine hyperstimulation and/or elevated resting tone |

| 11. Inappropriate titration of oxytocin not based on accepted protocols |

| 12. Administration of oxytocin without a physician’s order |

| 13. Failure to follow physician’s order |

| 14. Failure to order a cesarean section when fetal heart rate became nonreassuring |

| 15. Delay in cesarean section after being ordered by the physician |

| 16. Failure to follow hospital policies and procedures |

| 17. Inadequate policies and procedures governing oxytocin administration |

| 18. Failure to initiate chain of command |

Elective inductions can spell trouble

Although the rate of induction has more than doubled since 1989, to 20.6% of births or more than 840,000 pregnancies in 2003,1 still no consensus exists for patient selection. In some centers, inductions are reserved for women with medical indications only, whereas in others, more than half are elective.2

Because of this divergence, when there is a negative outcome after an elective induction, the obstetrician can anticipate an allegation of unnecessary induction due to lack of a medical indication.

Fetal monitoring

Proven or not, it’s the norm

Although we lack overwhelming proof of its superiority to intermittent auscultation,3 electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) is used in most labor and delivery settings during oxytocin administration for induction or augmentation of labor—and fetal heart rate and uterine activity typically guide initiation and titration of oxytocin.

Nevertheless, because EFM is the unofficial standard, an obstetrician who chooses to use intermittent auscultation of fetal heart rate during oxytocin infusion can anticipate strong criticism if the delivery results in a compromised neonate.

A 2005 Cochrane review4 of 18,561 births compared EFM with intermittent auscultation in labor and delivery and found fewer neonatal seizures in the EFM group but no differences in Apgar scores of less than 4 and 7, NICU admissions, perinatal deaths, or cerebral palsy.

“Default” intervals

Not only is the type of fetal monitoring important, but also how closely and how often the strip is evaluated. However, no studies have determined the optimal frequency of EFM interpretation during normal labors, let alone those induced or augmented with oxytocin. Furthermore, no single best methodology has been identified. Rather, the “default” timing of EFM interpretation has been loosely based on the historical practice of evaluating and documenting intermittent auscultation at 30-minute intervals during active labor and 15-minute intervals during the second stage for low-risk patients. For high-risk patients, the intervals have been every 15 minutes during the active phase and every 5 minutes during the second stage.

What will expert witnesses look for?

After adverse outcomes, the EFM tracing will be examined closely by “experts” looking for evidence that it contained abnormalities demonstrating fetal compromise or predicting the infant’s injury or death.

These experts also scrutinize the actions of physicians and nurses for appropriateness, timeliness, and effectiveness; the timing of the decision for expedited delivery; and the events occurring between that decision and the time of delivery or abdominal skin incision.

The monitor’s shortcomings

Many courts now require experts to base their opinions on reliable scientific studies; however, in malpractice claims involving EFM, expert interpretation often is based on the expert’s own personal or institutional experience or common practices rather than scientific evidence.

One of the most pervasive public misconceptions is that fetal monitoring can reliably detect when a fetus lacks sufficient oxygen, is experiencing a physiologically stressful labor that is depleting oxygen reserves, or is becoming asphyxiated. In reality, the positive predictive value (ability of the technology to identify the compromised fetus without including healthy fetuses) is very low: 0.14%. Thus, of 1,000 fetuses with nonreassuring tracings, only 1 or 2 are actually compromised.5 This may explain why providers and nurses are reluctant to deem all nonreassuring recordings as accurate.

The only thing EFM reliably identifies with a high degree of specificity is the oxygenated fetus that is not experiencing metabolic acidemia. Recordings with “nonreassuring” features are statistically unlikely to imply a diagnosis of fetal metabolic acidosis, hypoxemia, or stress or distress.

Should EFM precede oxytocin?

No minimal duration of monitoring prior to oxytocin administration has been consistently determined. Researchers do not even agree that initial monitoring of the fetus scheduled for induction has benefit.

This does not mean that oxytocin can be started without knowledge of the maternal and fetal condition—only that the best timing and methods of assessment prior to induction of labor are unknown.

What is “nonreassuring”?

Starting oxytocin in a woman with a “non-reassuring” tracing opens the OB to criticism. This is the most contentious aspect of medical and nursing management because we lack standardized definitions of “reassuring” and “nonreassuring.”

Nurses typically label a tracing nonreassuring based solely on decelerations or other variant patterns such as tachycardia. However, while a tracing’s individual characteristics may reflect a variety of etiologies (one of which is decreased uteroplacental perfusion), variability and/or accelerations signify an overall reassuring status, or fetal tolerance of labor.

Physicians generally examine the tracing in light of other clinical factors, such as labor progress, historical data, or parity—and also in light of any specific actions that have been taken and the expected time of their peak effect.

When to notify the OB

Another contentious issue in labor induction is exactly when nurses should notify the physician of a nonreassuring fetal heart rate. Unfortunately, there is no consensus about this question, either; again, most EFM tracings requiring nursing intervention exhibit an overall reassuring status.

Because evaluation of nonreassuring findings may take several minutes, nurses usually notify the physician when their assessment is complete. If the worrisome tracing resolves after intervention, a nurse may appropriately postpone notification until the next opportunity for communication with the physician.

Uterine monitoring

Can monitoring predict rupture?

In cases involving uterine rupture and/or placental abruption, experts may allege that the event could have been predicted with an intrauterine pressure catheter. However, in a study of “controlled” uterine rupture (recording of intrauterine pressure before and during uterine incision at the time of cesarean section), Devoe et al6 found no real differences in contraction frequency or duration, peak contraction pressures, or uterine resting tone prior to and after uterine “rupture” (incision).

We also lack prospective studies demonstrating that intrauterine pressure catheterization can predict placental abruption. Placement of the device purely for this reason is not indicated.

Titration of oxytocin

No consensus on frequency or intensity of contractions

Criticism of the method of oxytocin titration is common in malpractice claims because no data satisfactorily define adequate frequency or intensity of contractions.

Nor do we have widely accepted terminology to describe uterine activity. For example, hyperstimulation is sometimes defined as increased frequency of contractions with an abnormal fetal heart rate tracing, and sometimes as increased frequency of contractions without a nonreassuring fetal heart rate. The same inconsistencies hold true for the terms “hypertonus,” “tetany,” “tachysystole,” and others.

“Adequate labor pattern” has been defined as 3 to 5 contractions in 10 minutes or 7 contractions in 15 minutes,7 even though these criteria are based on limited data. Although clinically adequate labor is defined by cervical dilatation and effacement with fetal descent, this definition frequently leaves us titrating oxytocin by “trial and error.” Fortunately, the half-life of oxytocin is short, and we can use fetal and uterine response to guide titration.

No definitive predictors of rupture, abruption, asphyxiation

When uterine rupture, placental abruption, and/or variant fetal heart patterns occur with hyperstimulation or elevated resting tone, the possibility of a cause-and-effect will be explored in legal claims. Although uterine rupture has been attributed to oxytocin in older, nonprospective, uncontrolled studies, more recent investigations8 failed to confirm this link.

The effect of uterine hyperstimulation on fetal oxygenation is even less well established. Contractions increase placental vascular resistance, which in turn decreases uteroplacental blood flow. This phenomenon has been demonstrated in studies utilizing Doppler velocimetry,9 radioangiography,10 and fetal pulse oximetry.11 However, none have been able to quantify, in millimeters of mercury, the intensity of uterine contractions or baseline tonus required to compromise fetal oxygenation.

Risk-reducing tactics

These strategies12 do not represent the standard of care, but may help reduce liability:

- Routinely assess fetal heart rate during examination of the laboring patient.

- Document EFM interpretation comprehensively. Include baseline, variability, accelerations, decelerations, and uterine activity, as well as overall impression.

- Date and time every entry.

- When notified of a finding, detail the notification, as well as the orders and plan of care communicated to the nurse.

- Develop a mechanism for documentation when you are located outside the hospital (eg, progress notes that are later posted in the chart).

- Use digital storage and retrieval with central monitoring of displays to allow physicians to observe EFM tracings via remote access.

- Use handheld PDA-type displays.

- Go to the bedside to evaluate a patient when nurses ask you to do so. Document date and time, and the fetal heart rate interpretation.

- Decrease or discontinue oxytocin when variant fetal heart rate patterns suggest decreased uteroplacental perfusion (FIGURE 1).

- Avoid further increases in oxytocin once adequate labor (progressive cervical change) is established.

- Consider decreasing oxytocin—or avoid further increases—when uterine contractions are more frequent than 5 in 10 minutes or 7 in 15 minutes (FIGURE 2).

- Use National Institute of Child Health and Human Development terminology in verbal communications with nurses and physicians (see the Web version of this article for a downloadable PDF file of this terminology).

Martin L. Gimovsky, MD

Program Director, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Newark Beth Israel Medical Center, Newark, NJ

Clinical Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York City

As obstetricians, we are fortunate to participate in the most basic aspect of the human condition: the need to reproduce. Sometimes it is easy to overlook this fact, given the routine nature of many of our practices.

A case in point: oxytocin administration to induce or augment labor, an everyday occurrence in virtually all labor and delivery suites. Oxytocin is so ubiquitous, it can be easy to use it less than meticulously. Although the risks associated with its use are largely recognized, and the appropriate responses well known, a few points bear repeating.

Twin challenges: Protect and document

Safe and judicious use of oxytocin involves 2 challenges: minimizing medical risks to mother and fetus, and creating a supportive medical record. As in all aspects of medical care, we are required to know how to handle the clinical situation, and to document our skill, knowledge, and experience. Nowhere is this of greater concern than in the management of labor and delivery.

Here are 6 additional strategies for reducing legal risks of oxytocin use in labor.

1. Start with a written note

I suggest entering a written note into the record prior to administering oxytocin, outlining the reasoning behind the decision to proceed. Taking this pretreatment pause or “time out”—as the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations calls it—provides an opportunity to consider the risks, benefits, and alternatives of oxytocin use. This note should include the medical indication.

2. Conduct a comprehensive consent process

A passive signature on a general consent form is a minimalist way of demonstrating patient consent. By beginning the charting at the time of the consent discussion, you can demonstrate your consideration of the patient’s understanding and desires, not to mention your adherence to the highest standards of care.

Was an alternative approach possible? The patient should have the benefit of your opinion as well as a discussion of other reasonable strategies. Involving her in an active discussion is a fundamental component of informed consent—especially since improper consent is a frequent allegation in malpractice actions.

3. Describe both uterine and fetal responses

Because oxytocin directly affects uterine activity and indirectly affects placental perfusion, any chart notation needs to include references to both. For example, the comment that “contractions are every 2 minutes” requires the additional observation that the fetal heart rate tracing “is reassuring,”…“unchanged from earlier,”…or “demonstrates changes that are being evaluated.”

Whether a notation is made at the time of a routine labor check or when the physician is called to the bedside, comments on both uterine activity and fetal response are needed.

4. Discontinue oxytocin when the uterus overreacts

On occasion, excessive uterine activity may occur when oxytocin is first administered. Excessive uterine activity on a continuing basis can lead to fetal asphyxia. Although reducing the oxytocin dose will ultimately diminish uterine activity, I teach residents to discontinue oxytocin completely as soon as excessive uterine activity occurs.

Because this is a clinically important intervention, the medical record should be notated.

5. Adjust oxytocin to reflect changes in labor patterns

It makes good sense to avoid further oxytocin increases once the patient is in active labor (ie, progressive cervical change) and to decrease doses when contractions occur more frequently than every 2 minutes, even in the face of a reassuring fetal heart rate. This is not a situation in which, “if a little is good, a lot is better.”

6. Consider including a labor curve

Adding a labor curve or partograph to the chart can be a further safeguard, as it makes it easy to identify prolonged labors and potential complications in a timely manner.

All 6 strategies help demonstrate and preserve your hard work and concern for the patient. As always, adherence to principles of sound care and communication is the bedrock of successful obstetrics. There is no substitute.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

FIGURE 1 Tachysystole with decelerations signifies uterine hyperstimulation

Decrease or discontinue oxytocin when variant fetal heart rate patterns suggest decreased uteroplacental perfusion. This tracing shows uterine hyperstimulation (tachysystole with decelerations).

FIGURE 2 Titrate oxytocin to “normalize” contractions

Consider decreasing oxytocin—or avoid further increases—when uterine contractions are more frequent than 5 in 10 minutes or 7 in 15 minutes. This tracing shows 6 uterine contractions in 10 minutes. The fetal heart rate channel demonstrates moderate variability and, therefore, fetal tolerance of a frequent contraction pattern.

Why policies and procedures are a double-edged sword

Although policies and procedures are intended to help guide health care assessments and interventions, they are routinely subpoenaed and entered as evidence in an attempt to define the standard of care. Failure to follow these policies and procedures may be viewed by expert witnesses as a breach in that standard.

Use of oxytocin requires a medical or nursing professional to make judgments based on training, experience, and knowledge. Although policies and procedures cannot address every possible scenario or replace informed judgment, physicians and nurses are routinely criticized for failing to administer oxytocin or otherwise proceed exactly as outlined.

Some reasons policies and procedures should not be viewed as standard of care:

- They are typically written by a person in an administrative position who does not actually provide the care outlined.

- They are usually not routinely updated as new literature is published.

- Since they do not provide guidelines for unanticipated or unusual situations, deviation from policy is reasonable and even necessary in many scenarios.

- They are rarely written to reflect “reasonable” care; instead, they suggest an “ideal” level of care.

Reasonable protocols. Every physician and health care provider should be familiar with the hospital’s policies and procedures and help hospital personnel revise those that appear to limit the physician’s ability to easily adjust care or exercise judgment. Among the suggestions:

- Make all recommendations practical. This means they can be followed most of the time in most situations.

- Avoid terms such as “mandatory,” “always,” “never,” “should,” or “must.”

- Limit recommendations that can be considered “endpoints” for increasing oxytocin, such as: “Increase oxytocin until contractions are 2 to 3 minutes apart and 60 seconds in duration.” Recommendations written in this fashion are difficult to follow clinically; although the criteria may be met, labor may not progress, warranting an increase in oxytocin beyond the endpoints in the guidelines. Guidelines that discuss considerations for decreasing or discontinuing the drug would be better.

It also is important to foster understanding among medical and nursing staff that policies and procedures are guidelines and that medical and nursing judgment supersedes policy recommendations.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

- 18 common allegations in oxytocin-related litigation

- 6 risk-reducing strategies

Martin L. Gimovsky, MD

WHAT’S YOUR VERDICT?

Does this patient have grounds for a lawsuit?

At 41 weeks’ estimated gestation, Elena, a 32-year-old primipara with an uneventful antepartum course, is scheduled for induction of labor for postdates. On admission she is 1 cm dilated and 70% effaced, with the fetal vertex at –3 station. Fetal heart rate monitoring shows a normal baseline, moderate variability, and accelerations. No decelerations are observed.

After the membranes are ruptured artificially, labor progresses slowly, and chorioamnionitis is suspected.

Fetal tachycardia with minimal variability and variable decelerations develops. Oxytocin is titrated to achieve uterine contractions every 2 minutes. Elena eventually becomes completely dilated and pushes for 95 minutes. During this time, the fetal variable decelerations increase in duration, with loss of variability and continued tachycardia.

Because of these findings, delivery is expedited with a vacuum extractor. The newborn is depressed, admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit for respiratory support to “rule out sepsis,” and is later found to have neurologic injury.

In your opinion, does Elena have grounds for a lawsuit?

If such a case spurs a lawsuit, as it often will, the plaintiff’s attorney is likely to declare any or all of these allegations:

- failure to discontinue oxytocin in light of nonreassuring fetal heart rate

- failure to identify and respond to uterine hyperstimulation

- failure to identify and respond to fetal distress

- failure to react in a timely manner to fetal distress

- inappropriate delivery method

- failure to use a fetal scalp electrode

- failure to recognize and act upon arrest of dilatation in a timely manner

These allegations are only the most probable ones in circumstances such as Elena’s. When unanticipated morbidity or death occurs after oxytocin is used, physicians and nurses may find themselves facing any of the 18 allegations listed in the TABLE—or even others.

In court, these allegations will be based on the opinions of independent physicians, certified nurse-midwives, and registered nurses with the education, experience, and credentials to qualify as “experts.” Courts usually allow experts when the substance of the allegations is beyond the public’s general knowledge.

Although allegations often include inaccuracies, erroneous assumptions, and conclusions based on “information and belief” rather than scientific evidence, they remain part of the claim until disproved over the course of the legal proceedings.

TABLE

18 common allegations in oxytocin-related litigation

| 1. Unnecessary induction due to lack of medical indication |

| 2. Failure to establish fetal well-being prior to initiating oxytocin |

| 3. Failure to adequately monitor fetal heart rate during oxytocin infusion |

| 4. Failure to adequately monitor uterine contractions |

| 5. Failure to place a spiral electrode and/or intrauterine pressure catheter |

| 6. Failure to discontinue oxytocin in light of nonreassuring fetal heart rate |

| 7. Failure to identify and respond to fetal distress |

| 8. Delay in identifying and responding to nonreassuring fetal heart rate |

| 9. Failure to notify provider of nonreassuring fetal heart rate |

| 10. Failure to identify and respond to uterine hyperstimulation and/or elevated resting tone |

| 11. Inappropriate titration of oxytocin not based on accepted protocols |

| 12. Administration of oxytocin without a physician’s order |

| 13. Failure to follow physician’s order |

| 14. Failure to order a cesarean section when fetal heart rate became nonreassuring |

| 15. Delay in cesarean section after being ordered by the physician |

| 16. Failure to follow hospital policies and procedures |

| 17. Inadequate policies and procedures governing oxytocin administration |

| 18. Failure to initiate chain of command |

Elective inductions can spell trouble

Although the rate of induction has more than doubled since 1989, to 20.6% of births or more than 840,000 pregnancies in 2003,1 still no consensus exists for patient selection. In some centers, inductions are reserved for women with medical indications only, whereas in others, more than half are elective.2

Because of this divergence, when there is a negative outcome after an elective induction, the obstetrician can anticipate an allegation of unnecessary induction due to lack of a medical indication.

Fetal monitoring

Proven or not, it’s the norm

Although we lack overwhelming proof of its superiority to intermittent auscultation,3 electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) is used in most labor and delivery settings during oxytocin administration for induction or augmentation of labor—and fetal heart rate and uterine activity typically guide initiation and titration of oxytocin.

Nevertheless, because EFM is the unofficial standard, an obstetrician who chooses to use intermittent auscultation of fetal heart rate during oxytocin infusion can anticipate strong criticism if the delivery results in a compromised neonate.

A 2005 Cochrane review4 of 18,561 births compared EFM with intermittent auscultation in labor and delivery and found fewer neonatal seizures in the EFM group but no differences in Apgar scores of less than 4 and 7, NICU admissions, perinatal deaths, or cerebral palsy.

“Default” intervals

Not only is the type of fetal monitoring important, but also how closely and how often the strip is evaluated. However, no studies have determined the optimal frequency of EFM interpretation during normal labors, let alone those induced or augmented with oxytocin. Furthermore, no single best methodology has been identified. Rather, the “default” timing of EFM interpretation has been loosely based on the historical practice of evaluating and documenting intermittent auscultation at 30-minute intervals during active labor and 15-minute intervals during the second stage for low-risk patients. For high-risk patients, the intervals have been every 15 minutes during the active phase and every 5 minutes during the second stage.

What will expert witnesses look for?

After adverse outcomes, the EFM tracing will be examined closely by “experts” looking for evidence that it contained abnormalities demonstrating fetal compromise or predicting the infant’s injury or death.

These experts also scrutinize the actions of physicians and nurses for appropriateness, timeliness, and effectiveness; the timing of the decision for expedited delivery; and the events occurring between that decision and the time of delivery or abdominal skin incision.

The monitor’s shortcomings

Many courts now require experts to base their opinions on reliable scientific studies; however, in malpractice claims involving EFM, expert interpretation often is based on the expert’s own personal or institutional experience or common practices rather than scientific evidence.

One of the most pervasive public misconceptions is that fetal monitoring can reliably detect when a fetus lacks sufficient oxygen, is experiencing a physiologically stressful labor that is depleting oxygen reserves, or is becoming asphyxiated. In reality, the positive predictive value (ability of the technology to identify the compromised fetus without including healthy fetuses) is very low: 0.14%. Thus, of 1,000 fetuses with nonreassuring tracings, only 1 or 2 are actually compromised.5 This may explain why providers and nurses are reluctant to deem all nonreassuring recordings as accurate.

The only thing EFM reliably identifies with a high degree of specificity is the oxygenated fetus that is not experiencing metabolic acidemia. Recordings with “nonreassuring” features are statistically unlikely to imply a diagnosis of fetal metabolic acidosis, hypoxemia, or stress or distress.

Should EFM precede oxytocin?

No minimal duration of monitoring prior to oxytocin administration has been consistently determined. Researchers do not even agree that initial monitoring of the fetus scheduled for induction has benefit.

This does not mean that oxytocin can be started without knowledge of the maternal and fetal condition—only that the best timing and methods of assessment prior to induction of labor are unknown.

What is “nonreassuring”?

Starting oxytocin in a woman with a “non-reassuring” tracing opens the OB to criticism. This is the most contentious aspect of medical and nursing management because we lack standardized definitions of “reassuring” and “nonreassuring.”

Nurses typically label a tracing nonreassuring based solely on decelerations or other variant patterns such as tachycardia. However, while a tracing’s individual characteristics may reflect a variety of etiologies (one of which is decreased uteroplacental perfusion), variability and/or accelerations signify an overall reassuring status, or fetal tolerance of labor.

Physicians generally examine the tracing in light of other clinical factors, such as labor progress, historical data, or parity—and also in light of any specific actions that have been taken and the expected time of their peak effect.

When to notify the OB

Another contentious issue in labor induction is exactly when nurses should notify the physician of a nonreassuring fetal heart rate. Unfortunately, there is no consensus about this question, either; again, most EFM tracings requiring nursing intervention exhibit an overall reassuring status.

Because evaluation of nonreassuring findings may take several minutes, nurses usually notify the physician when their assessment is complete. If the worrisome tracing resolves after intervention, a nurse may appropriately postpone notification until the next opportunity for communication with the physician.

Uterine monitoring

Can monitoring predict rupture?

In cases involving uterine rupture and/or placental abruption, experts may allege that the event could have been predicted with an intrauterine pressure catheter. However, in a study of “controlled” uterine rupture (recording of intrauterine pressure before and during uterine incision at the time of cesarean section), Devoe et al6 found no real differences in contraction frequency or duration, peak contraction pressures, or uterine resting tone prior to and after uterine “rupture” (incision).

We also lack prospective studies demonstrating that intrauterine pressure catheterization can predict placental abruption. Placement of the device purely for this reason is not indicated.

Titration of oxytocin

No consensus on frequency or intensity of contractions

Criticism of the method of oxytocin titration is common in malpractice claims because no data satisfactorily define adequate frequency or intensity of contractions.

Nor do we have widely accepted terminology to describe uterine activity. For example, hyperstimulation is sometimes defined as increased frequency of contractions with an abnormal fetal heart rate tracing, and sometimes as increased frequency of contractions without a nonreassuring fetal heart rate. The same inconsistencies hold true for the terms “hypertonus,” “tetany,” “tachysystole,” and others.

“Adequate labor pattern” has been defined as 3 to 5 contractions in 10 minutes or 7 contractions in 15 minutes,7 even though these criteria are based on limited data. Although clinically adequate labor is defined by cervical dilatation and effacement with fetal descent, this definition frequently leaves us titrating oxytocin by “trial and error.” Fortunately, the half-life of oxytocin is short, and we can use fetal and uterine response to guide titration.

No definitive predictors of rupture, abruption, asphyxiation

When uterine rupture, placental abruption, and/or variant fetal heart patterns occur with hyperstimulation or elevated resting tone, the possibility of a cause-and-effect will be explored in legal claims. Although uterine rupture has been attributed to oxytocin in older, nonprospective, uncontrolled studies, more recent investigations8 failed to confirm this link.

The effect of uterine hyperstimulation on fetal oxygenation is even less well established. Contractions increase placental vascular resistance, which in turn decreases uteroplacental blood flow. This phenomenon has been demonstrated in studies utilizing Doppler velocimetry,9 radioangiography,10 and fetal pulse oximetry.11 However, none have been able to quantify, in millimeters of mercury, the intensity of uterine contractions or baseline tonus required to compromise fetal oxygenation.

Risk-reducing tactics

These strategies12 do not represent the standard of care, but may help reduce liability:

- Routinely assess fetal heart rate during examination of the laboring patient.

- Document EFM interpretation comprehensively. Include baseline, variability, accelerations, decelerations, and uterine activity, as well as overall impression.

- Date and time every entry.

- When notified of a finding, detail the notification, as well as the orders and plan of care communicated to the nurse.

- Develop a mechanism for documentation when you are located outside the hospital (eg, progress notes that are later posted in the chart).

- Use digital storage and retrieval with central monitoring of displays to allow physicians to observe EFM tracings via remote access.

- Use handheld PDA-type displays.

- Go to the bedside to evaluate a patient when nurses ask you to do so. Document date and time, and the fetal heart rate interpretation.

- Decrease or discontinue oxytocin when variant fetal heart rate patterns suggest decreased uteroplacental perfusion (FIGURE 1).

- Avoid further increases in oxytocin once adequate labor (progressive cervical change) is established.

- Consider decreasing oxytocin—or avoid further increases—when uterine contractions are more frequent than 5 in 10 minutes or 7 in 15 minutes (FIGURE 2).

- Use National Institute of Child Health and Human Development terminology in verbal communications with nurses and physicians (see the Web version of this article for a downloadable PDF file of this terminology).

Martin L. Gimovsky, MD

Program Director, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Newark Beth Israel Medical Center, Newark, NJ

Clinical Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York City

As obstetricians, we are fortunate to participate in the most basic aspect of the human condition: the need to reproduce. Sometimes it is easy to overlook this fact, given the routine nature of many of our practices.

A case in point: oxytocin administration to induce or augment labor, an everyday occurrence in virtually all labor and delivery suites. Oxytocin is so ubiquitous, it can be easy to use it less than meticulously. Although the risks associated with its use are largely recognized, and the appropriate responses well known, a few points bear repeating.

Twin challenges: Protect and document

Safe and judicious use of oxytocin involves 2 challenges: minimizing medical risks to mother and fetus, and creating a supportive medical record. As in all aspects of medical care, we are required to know how to handle the clinical situation, and to document our skill, knowledge, and experience. Nowhere is this of greater concern than in the management of labor and delivery.

Here are 6 additional strategies for reducing legal risks of oxytocin use in labor.

1. Start with a written note

I suggest entering a written note into the record prior to administering oxytocin, outlining the reasoning behind the decision to proceed. Taking this pretreatment pause or “time out”—as the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations calls it—provides an opportunity to consider the risks, benefits, and alternatives of oxytocin use. This note should include the medical indication.

2. Conduct a comprehensive consent process

A passive signature on a general consent form is a minimalist way of demonstrating patient consent. By beginning the charting at the time of the consent discussion, you can demonstrate your consideration of the patient’s understanding and desires, not to mention your adherence to the highest standards of care.

Was an alternative approach possible? The patient should have the benefit of your opinion as well as a discussion of other reasonable strategies. Involving her in an active discussion is a fundamental component of informed consent—especially since improper consent is a frequent allegation in malpractice actions.

3. Describe both uterine and fetal responses

Because oxytocin directly affects uterine activity and indirectly affects placental perfusion, any chart notation needs to include references to both. For example, the comment that “contractions are every 2 minutes” requires the additional observation that the fetal heart rate tracing “is reassuring,”…“unchanged from earlier,”…or “demonstrates changes that are being evaluated.”

Whether a notation is made at the time of a routine labor check or when the physician is called to the bedside, comments on both uterine activity and fetal response are needed.

4. Discontinue oxytocin when the uterus overreacts

On occasion, excessive uterine activity may occur when oxytocin is first administered. Excessive uterine activity on a continuing basis can lead to fetal asphyxia. Although reducing the oxytocin dose will ultimately diminish uterine activity, I teach residents to discontinue oxytocin completely as soon as excessive uterine activity occurs.

Because this is a clinically important intervention, the medical record should be notated.

5. Adjust oxytocin to reflect changes in labor patterns

It makes good sense to avoid further oxytocin increases once the patient is in active labor (ie, progressive cervical change) and to decrease doses when contractions occur more frequently than every 2 minutes, even in the face of a reassuring fetal heart rate. This is not a situation in which, “if a little is good, a lot is better.”

6. Consider including a labor curve

Adding a labor curve or partograph to the chart can be a further safeguard, as it makes it easy to identify prolonged labors and potential complications in a timely manner.

All 6 strategies help demonstrate and preserve your hard work and concern for the patient. As always, adherence to principles of sound care and communication is the bedrock of successful obstetrics. There is no substitute.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

FIGURE 1 Tachysystole with decelerations signifies uterine hyperstimulation

Decrease or discontinue oxytocin when variant fetal heart rate patterns suggest decreased uteroplacental perfusion. This tracing shows uterine hyperstimulation (tachysystole with decelerations).

FIGURE 2 Titrate oxytocin to “normalize” contractions

Consider decreasing oxytocin—or avoid further increases—when uterine contractions are more frequent than 5 in 10 minutes or 7 in 15 minutes. This tracing shows 6 uterine contractions in 10 minutes. The fetal heart rate channel demonstrates moderate variability and, therefore, fetal tolerance of a frequent contraction pattern.

Why policies and procedures are a double-edged sword

Although policies and procedures are intended to help guide health care assessments and interventions, they are routinely subpoenaed and entered as evidence in an attempt to define the standard of care. Failure to follow these policies and procedures may be viewed by expert witnesses as a breach in that standard.

Use of oxytocin requires a medical or nursing professional to make judgments based on training, experience, and knowledge. Although policies and procedures cannot address every possible scenario or replace informed judgment, physicians and nurses are routinely criticized for failing to administer oxytocin or otherwise proceed exactly as outlined.

Some reasons policies and procedures should not be viewed as standard of care:

- They are typically written by a person in an administrative position who does not actually provide the care outlined.

- They are usually not routinely updated as new literature is published.

- Since they do not provide guidelines for unanticipated or unusual situations, deviation from policy is reasonable and even necessary in many scenarios.

- They are rarely written to reflect “reasonable” care; instead, they suggest an “ideal” level of care.

Reasonable protocols. Every physician and health care provider should be familiar with the hospital’s policies and procedures and help hospital personnel revise those that appear to limit the physician’s ability to easily adjust care or exercise judgment. Among the suggestions:

- Make all recommendations practical. This means they can be followed most of the time in most situations.

- Avoid terms such as “mandatory,” “always,” “never,” “should,” or “must.”

- Limit recommendations that can be considered “endpoints” for increasing oxytocin, such as: “Increase oxytocin until contractions are 2 to 3 minutes apart and 60 seconds in duration.” Recommendations written in this fashion are difficult to follow clinically; although the criteria may be met, labor may not progress, warranting an increase in oxytocin beyond the endpoints in the guidelines. Guidelines that discuss considerations for decreasing or discontinuing the drug would be better.

It also is important to foster understanding among medical and nursing staff that policies and procedures are guidelines and that medical and nursing judgment supersedes policy recommendations.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

1. Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, Ventura SJ, Menacker F, Munson ML. Birth: final data for 2003. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2005;54(2):1-116.

2. Rayburn WF, Zhang J. Rising rates of labor induction: present concerns and future strategies. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:164-167.

3. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin Number 49, December 2003: Dystocia and augmentation of labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:1445-1454.

4. Thacker SB, et al. Continuous electronic heart rate monitoring for fetal assessment during labor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(3):ISSN 1464-780X.

5. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin Number 62, May 2005: Intrapartum fetal heart rate monitoring. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1161-1169.

6. Devoe LD, Croom CS, et al. The prediction of “controlled” uterine rupture by the use of intrauterine pressure catheters. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80:626-629.

7. Norwitz ER, Robinson JN, Repke JT. Labor and delivery. In: Gabbe SG, Niebyl JR, Simpson JL, eds. Obstetrics. Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 4th ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2002;355.-

8. Phelan JP, Korst LM, Settles DK. Uterine activity patterns in uterine rupture: a case-control study. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:394-397.

9. Bower S, Campbell S, Vyas S, McGirr C. Braxton-Hicks contractions can alter uteroplacental perfusion. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1991;1:46-49.

10. Borell U, Fernstroem I, Ohlson L, Wiqvist N. Influence of uterine contractions on the uteroplacental blood flow at term. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1965;93:44-57.

11. Johnson N, van Oudgaarden E, Montague I, McNamara H. The effect of oxytocin-induced hyperstimulation on fetal oxygen. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994;101:805-807.

12. Lucidi RS, Chez RA, et al. The clinical use of intrauterine pressure catheters. J Matern Fetal Med. 2001;10:420-422.

1. Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, Ventura SJ, Menacker F, Munson ML. Birth: final data for 2003. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2005;54(2):1-116.

2. Rayburn WF, Zhang J. Rising rates of labor induction: present concerns and future strategies. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:164-167.

3. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin Number 49, December 2003: Dystocia and augmentation of labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:1445-1454.

4. Thacker SB, et al. Continuous electronic heart rate monitoring for fetal assessment during labor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(3):ISSN 1464-780X.

5. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin Number 62, May 2005: Intrapartum fetal heart rate monitoring. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1161-1169.

6. Devoe LD, Croom CS, et al. The prediction of “controlled” uterine rupture by the use of intrauterine pressure catheters. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80:626-629.

7. Norwitz ER, Robinson JN, Repke JT. Labor and delivery. In: Gabbe SG, Niebyl JR, Simpson JL, eds. Obstetrics. Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 4th ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2002;355.-

8. Phelan JP, Korst LM, Settles DK. Uterine activity patterns in uterine rupture: a case-control study. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:394-397.

9. Bower S, Campbell S, Vyas S, McGirr C. Braxton-Hicks contractions can alter uteroplacental perfusion. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1991;1:46-49.

10. Borell U, Fernstroem I, Ohlson L, Wiqvist N. Influence of uterine contractions on the uteroplacental blood flow at term. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1965;93:44-57.

11. Johnson N, van Oudgaarden E, Montague I, McNamara H. The effect of oxytocin-induced hyperstimulation on fetal oxygen. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994;101:805-807.

12. Lucidi RS, Chez RA, et al. The clinical use of intrauterine pressure catheters. J Matern Fetal Med. 2001;10:420-422.

Preventing fragility fractures: Effective drugs and doses

The numbers tell why. The total number of fragility fractures in American women in a single year—1 million—out-numbers all heart attacks, strokes, breast cancers, and gynecologic cancers combined. A quality-of-life study by Toteson and Hammond found that 4 out of 10 Caucasian women over 50 will fracture a hip, spine, or wrist, sooner or later. One of every 5 who fracture a hip ends up in a nursing home. The direct care cost of osteoporotic fractures was $17 billion in 2001 dollars.

Now, we have more treatment options than ever. And 2005 has been a banner year for discoveries we can put into practice immediately, in our efforts to prevent fragility fractures.

Why so confusing?

McClung MR. The relationship between bone mineral density and fracture risk. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2005;3:57–63.

- The terms osteopenia and osteoporosis are arbitrary cutoffs. Fracture risk is a continuum and involves multiple factors in addition to bone mass.

The clinically crucial part of that definition is…“increasing the risk of fragility fractures.” Certainly, low bone mass on DEXA is a risk factor. And guidelines from the World Health Organization (WHO), the National Osteoporosis Foundation, and the North American Menopause Society are based on T-scores. However, treatment that bases intervention on absolute fracture risk would be much more appropriate; in fact, the WHO is expected to shortly issue a method to calculate fracture risk. Factors are likely to include age, previous fracture, family history, body mass index, ever use of steroids, propensity for falling, eyesight, overall health, and bone mass (ie, BMD determinations).

We need to realize that WHO definitions of T-score categories are meant for postmenopausal women. Inappropriate use of DEXA scanning in a premenopausal patient may identify a woman with low bone mass, but her bone quality and risk of fragility fracture differ greatly from that of a distantly postmenopausal woman with the same T-score. It may seem counterintuitive, but a 50-year-old woman with a T-score of –3.0 has the same absolute fracture risk, going forward, as an 80-year-old woman with a T-score of –1.

Although the risk of fracture is greatest in women with osteoporosis, there are many more women with osteopenia who will have a fracture. But that doesn’t mean we should prescribe pharmacotherapy for every osteopenic woman in an attempt to prevent fractures. As the US Surgeon General’s report last October estimated, 34 million women have osteopenia and “only” 10 million have osteoporosis. Not every woman with osteopenia should be a candidate for pharmacotherapy, but these facts do underscore the need for a better way to assess absolute fracture risk.

ADDITIONAL REFERENCES

- Miller PD, Barlas S, Brenneman SK, et al. An approach to identifying osteopenic women at increased short-term risk of fracture. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1113–1120.

- Salkeld G, Cameron ID, Cumming RG, et al. Quality of life related to fear of falling and hip fracture in older women: a time trade off study. BMJ. 2000;320:341–346.

- Schuit SC, van der Klift M, Weel AE, et al. Fracture incidence and association with bone mineral density in elderly men and women: the Rotterdam Study. Bone. 2004;34:195–202.

- Tosteson AN, Hammond CS. Quality-of-life assessment in osteoporosis: health-status and preference-based measures. PharmacoEconomics. 2002;20:289–303.

Are all bisphosphonates created equal?

Rosen CJ, Hochberg MC, Bonnick SL, et al. Postmenopausal osteoporosis: a randomized double-blind study. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:141–151.

- Antifracture efficacy at the spine appears to be indistinguishable among antiresorptive agents, despite differences in BMD and bone turnover. Gastrointestinal tolerability was similar in the FACT study.

Endpoints of the FACT study. The primary endpoint was change from baseline BMD at the hip trochanter at 12 months. Secondary endpoints included BMD at multiple sites, bone turnover markers, and drug tolerability. After 12 months, BMD increased 3.4% with alendronate and 2.1% with risedronate (P.001 alendronate produced significantly greater reductions in bone markers. fracture data were collected as part of the safety monitoring: fractures group and risedronate group.>

Antiresorptives lower fracture risk even without increasing BMD

However, until a head-to-head antifracture efficacy study is done, we cannot infer whether alendronate or risedronate is more effective, based on surrogate endpoints. In fact, if one looks at observations on calcitonin and raloxifene, all 4 drugs provide a similar level of fracture protection, at least in the spine, despite marked differences in turnover markers and BMD. This similarity in antifracture efficacy is probably because antiresorptive drugs affect bone quality and microarchitecture, as well as bone mass.

Antiresorptive medications reduce fracture risk, even in the absence of substantial increases in BMD. This finding has significant implications for monitoring therapy. The misconception that efficacy depends on the amount of bone gained often prompts physicians to stop a drug or add a second drug if a patient’s bone density does not increase. The indication of treatment success, however, is absence of bone loss, not extent of bone gain.

The key to meaningful monitoring

Serial observations with DEXA scanning are fraught with error if one does not understand the concept of least specific change. Least specific change is defined as 2.77 times the precision error of the scanning machine used. Thus, in good centers, BMD measurement of the spine should vary no more than ±3%; measurement of the hip may vary as much as ±5%. For example, a patient who gains 2% over time in the hip and spine is no different statistically from a patient who loses 2% over time in the hip and spine. However, many patients and clinicians feel gratified by a modest increase—and consider an alternative or additional medication if there is a mild decrease. If we take into account the “least specific change,” it becomes evident that in both cases, the patients are in fact unchanged.

Daily pill more likely to get blamed for GI symptoms?