User login

Informed Consent Substitutes: A Decision Making Flow Chart

Reducing Wait Times for Cardiac Consultation

Milk-Alkali Syndrome [published correction appears in: Fed Pract. 2005;22(3):66.]

Frozen eggs and other marvels take “hi-tech” up a notch or 2

Be prepared for questions when the marketing starts

We can expect younger patients wishing to preserve reproductive capacity to ask our advice on freezing their eggs. (This technology is of limited applicability to the average reproductive-aged woman). The official position of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine is that, until outcome data are available, it is too early to incorporate this practice into general use.

However, a growing number of assisted reproductive technology (ART) centers will be offering—and marketing—the procedure.

Related to the growing interest in preserving female fertility so that women can delay childbearing: a momentous discovery reported in 2004 suggests that our time-honored dogma on growth of new human oocytes may be wrong.

In addition, 2 laboratory studies suggest a future for assisted reproductive technologies, when every embryo is assessed for its likelihood to result in a healthy infant.

These reports demonstrate the excitement of translational research in bringing basic discoveries into the clinical arena. They highlight the incredible development of both stem cell biology and nanotechnology, and suggest how such fields are rapidly becoming relevant in the modern practice of infertility. While it is difficult to predict an accurate timeline, or certainty, of the application of these discoveries to a modern infertility practice, it is safe to say that these and similar discoveries will influence our usual practice in the foreseeable future.

Oocytes unlimited after all?

Johnson J, Canning J, Kaneko T, Pru J, Tilly J. Germline stem cells and follicular renewal in the postnatal mammalian ovary. Nature. 2004;428:145–150.

Along-held belief is that women reach their peak oocyte number at midgestation, and that number continuously declines until oocytes are depleted, sometime after menopause. This study from Jonathan Tilly’s group at Harvard Medical School presents evidence for germline stem cells in the ovaries of mice capable of replenishing oocytes into adult life. Removal of these germline stem cells caused a rapid depletion of primordial follicles, suggesting that the primordial follicle reserve was continuously replenished from germline stem cells.

While it is quite a leap to assume that human ovaries contain similar germline stem cells, the possibility that reproductive age woman may be able to develop new oocytes is truly exciting. If such oogonial stem cells exist in women—and could be harvested and cryopreserved, as mature oocytes are now being harvested and preserved—it opens the possibility that a renewable supply of oocytes may be available for women who wish to preserve the capacity to reproduce.

Practical implications

Whether for personal use following cancer therapy or oophorectomy, or as a source of oocytes for donation to women who have lost ovarian function, the potential holds great promise. However, extensive further work is required, not the least of which is independent verification of Dr. Tilly’s findings and the extension of that discovery to women.

For the practicing obstetrician/gynecologist fielding a question about “growing new eggs” from a savvy patient surfing the Net, know that the concept has a scientific basis but is definitely not ready for prime time.

New standard ahead for embryo assessment

In vivo assessment without injury

Kulkarni RN, Roper MG, Dahlgren G, Shih DQ, Kauri LM, Peters JL, Stoffel M, Kennedy RT. Islet secretory defect in insulin receptor substrate 1 null mice is linked with reduced calcium signaling and expression of sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SECA)-2b and -3. Diabetes. 2004;53:1517–1525.

The assessment of human embryos for their viability and the likelihood of implanting and developing into a healthy baby has been a challenge for in vitro fertilization programs worldwide. Recent interest has focused on removing single cells from embryos and performing genetic studies. However, this is expensive, time consuming, and runs the risk of damaging embryos in the process of removing single blastomeres.

This study by Kennedy and colleagues, while not immediately applicable to human ART programs, demonstrates a technique for monitoring the secretion products from individual pancreatic beta cells. Using microelectrodes placed adjacent to individually cultured beta cells, insulin secretion from each cell was estimated by measuring the number of exocytotic events in normal and IRS-1 knock-out mice. The in vivo measurement of specific secretion products from individual cells without injuring them is an exciting example of the miniaturization of clinical science.

Practical implications

The extension of this technique to the safe assessment of human embryos in vivo while they are in culture is logical and opens up an entire area of both investigation and potential clinical practice. If the metabolic activity of the individual embryos indicates the likelihood of implantation and development, then this could become a new standard in the assessment of every embryo resulting from an ART cycle.

Much work will be required to translate this exciting new technique to human embryos, but it does offer a logical approach to the longstanding problem of embryo assessment.

Real-time assessment

Schuster TG, Cho B, Keller LM, Takayama S, Smith GD. Isolation of motile spermatozoa from semen samples using microfluidics. Reproductive Biomedicine Online. 2004;1(Jul-Aug):75–81.

One of the challenges of assessing individual human embryos in vivo is the dilution effect on any secretion products secreted from an embryo into the relatively vast amount of media in a traditional ART Petri dish. This report describes the first of a series of microfluidic devices designed to separate motile from nonmotile spermatozoa in very small volumes. Such devices can be used to isolate motile sperm from nonmotile sperm and debris for ART procedures when numbers are exceptionally low.

However, similar microfluidic devices are being developed to include tiny chambers that could be used to contain individual human embryos receiving a constant stream of nutrient media with a constant output of spent media and secretory products. In conjunction with the capacity to analyze such tiny amounts of secretory products in vivo from individual cells, this suggests a system for evaluating all human embryos in modern microchambers and continually monitoring for appropriate secretion and subsequent selection for optimal reproductive capacity.

Practical implications

The promise of real-time embryo assessment is certainly upon us, though much work needs to be done to develop these microfluidic incubation chambers before they will be clinically applicable.

For the practicing Ob/Gyn, it is useful to know that the era of preimplantation evaluation of all embryos is not far off. Whether that will translate into fewer fetal/neonatal defects remains to be seen.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Be prepared for questions when the marketing starts

We can expect younger patients wishing to preserve reproductive capacity to ask our advice on freezing their eggs. (This technology is of limited applicability to the average reproductive-aged woman). The official position of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine is that, until outcome data are available, it is too early to incorporate this practice into general use.

However, a growing number of assisted reproductive technology (ART) centers will be offering—and marketing—the procedure.

Related to the growing interest in preserving female fertility so that women can delay childbearing: a momentous discovery reported in 2004 suggests that our time-honored dogma on growth of new human oocytes may be wrong.

In addition, 2 laboratory studies suggest a future for assisted reproductive technologies, when every embryo is assessed for its likelihood to result in a healthy infant.

These reports demonstrate the excitement of translational research in bringing basic discoveries into the clinical arena. They highlight the incredible development of both stem cell biology and nanotechnology, and suggest how such fields are rapidly becoming relevant in the modern practice of infertility. While it is difficult to predict an accurate timeline, or certainty, of the application of these discoveries to a modern infertility practice, it is safe to say that these and similar discoveries will influence our usual practice in the foreseeable future.

Oocytes unlimited after all?

Johnson J, Canning J, Kaneko T, Pru J, Tilly J. Germline stem cells and follicular renewal in the postnatal mammalian ovary. Nature. 2004;428:145–150.

Along-held belief is that women reach their peak oocyte number at midgestation, and that number continuously declines until oocytes are depleted, sometime after menopause. This study from Jonathan Tilly’s group at Harvard Medical School presents evidence for germline stem cells in the ovaries of mice capable of replenishing oocytes into adult life. Removal of these germline stem cells caused a rapid depletion of primordial follicles, suggesting that the primordial follicle reserve was continuously replenished from germline stem cells.

While it is quite a leap to assume that human ovaries contain similar germline stem cells, the possibility that reproductive age woman may be able to develop new oocytes is truly exciting. If such oogonial stem cells exist in women—and could be harvested and cryopreserved, as mature oocytes are now being harvested and preserved—it opens the possibility that a renewable supply of oocytes may be available for women who wish to preserve the capacity to reproduce.

Practical implications

Whether for personal use following cancer therapy or oophorectomy, or as a source of oocytes for donation to women who have lost ovarian function, the potential holds great promise. However, extensive further work is required, not the least of which is independent verification of Dr. Tilly’s findings and the extension of that discovery to women.

For the practicing obstetrician/gynecologist fielding a question about “growing new eggs” from a savvy patient surfing the Net, know that the concept has a scientific basis but is definitely not ready for prime time.

New standard ahead for embryo assessment

In vivo assessment without injury

Kulkarni RN, Roper MG, Dahlgren G, Shih DQ, Kauri LM, Peters JL, Stoffel M, Kennedy RT. Islet secretory defect in insulin receptor substrate 1 null mice is linked with reduced calcium signaling and expression of sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SECA)-2b and -3. Diabetes. 2004;53:1517–1525.

The assessment of human embryos for their viability and the likelihood of implanting and developing into a healthy baby has been a challenge for in vitro fertilization programs worldwide. Recent interest has focused on removing single cells from embryos and performing genetic studies. However, this is expensive, time consuming, and runs the risk of damaging embryos in the process of removing single blastomeres.

This study by Kennedy and colleagues, while not immediately applicable to human ART programs, demonstrates a technique for monitoring the secretion products from individual pancreatic beta cells. Using microelectrodes placed adjacent to individually cultured beta cells, insulin secretion from each cell was estimated by measuring the number of exocytotic events in normal and IRS-1 knock-out mice. The in vivo measurement of specific secretion products from individual cells without injuring them is an exciting example of the miniaturization of clinical science.

Practical implications

The extension of this technique to the safe assessment of human embryos in vivo while they are in culture is logical and opens up an entire area of both investigation and potential clinical practice. If the metabolic activity of the individual embryos indicates the likelihood of implantation and development, then this could become a new standard in the assessment of every embryo resulting from an ART cycle.

Much work will be required to translate this exciting new technique to human embryos, but it does offer a logical approach to the longstanding problem of embryo assessment.

Real-time assessment

Schuster TG, Cho B, Keller LM, Takayama S, Smith GD. Isolation of motile spermatozoa from semen samples using microfluidics. Reproductive Biomedicine Online. 2004;1(Jul-Aug):75–81.

One of the challenges of assessing individual human embryos in vivo is the dilution effect on any secretion products secreted from an embryo into the relatively vast amount of media in a traditional ART Petri dish. This report describes the first of a series of microfluidic devices designed to separate motile from nonmotile spermatozoa in very small volumes. Such devices can be used to isolate motile sperm from nonmotile sperm and debris for ART procedures when numbers are exceptionally low.

However, similar microfluidic devices are being developed to include tiny chambers that could be used to contain individual human embryos receiving a constant stream of nutrient media with a constant output of spent media and secretory products. In conjunction with the capacity to analyze such tiny amounts of secretory products in vivo from individual cells, this suggests a system for evaluating all human embryos in modern microchambers and continually monitoring for appropriate secretion and subsequent selection for optimal reproductive capacity.

Practical implications

The promise of real-time embryo assessment is certainly upon us, though much work needs to be done to develop these microfluidic incubation chambers before they will be clinically applicable.

For the practicing Ob/Gyn, it is useful to know that the era of preimplantation evaluation of all embryos is not far off. Whether that will translate into fewer fetal/neonatal defects remains to be seen.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Be prepared for questions when the marketing starts

We can expect younger patients wishing to preserve reproductive capacity to ask our advice on freezing their eggs. (This technology is of limited applicability to the average reproductive-aged woman). The official position of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine is that, until outcome data are available, it is too early to incorporate this practice into general use.

However, a growing number of assisted reproductive technology (ART) centers will be offering—and marketing—the procedure.

Related to the growing interest in preserving female fertility so that women can delay childbearing: a momentous discovery reported in 2004 suggests that our time-honored dogma on growth of new human oocytes may be wrong.

In addition, 2 laboratory studies suggest a future for assisted reproductive technologies, when every embryo is assessed for its likelihood to result in a healthy infant.

These reports demonstrate the excitement of translational research in bringing basic discoveries into the clinical arena. They highlight the incredible development of both stem cell biology and nanotechnology, and suggest how such fields are rapidly becoming relevant in the modern practice of infertility. While it is difficult to predict an accurate timeline, or certainty, of the application of these discoveries to a modern infertility practice, it is safe to say that these and similar discoveries will influence our usual practice in the foreseeable future.

Oocytes unlimited after all?

Johnson J, Canning J, Kaneko T, Pru J, Tilly J. Germline stem cells and follicular renewal in the postnatal mammalian ovary. Nature. 2004;428:145–150.

Along-held belief is that women reach their peak oocyte number at midgestation, and that number continuously declines until oocytes are depleted, sometime after menopause. This study from Jonathan Tilly’s group at Harvard Medical School presents evidence for germline stem cells in the ovaries of mice capable of replenishing oocytes into adult life. Removal of these germline stem cells caused a rapid depletion of primordial follicles, suggesting that the primordial follicle reserve was continuously replenished from germline stem cells.

While it is quite a leap to assume that human ovaries contain similar germline stem cells, the possibility that reproductive age woman may be able to develop new oocytes is truly exciting. If such oogonial stem cells exist in women—and could be harvested and cryopreserved, as mature oocytes are now being harvested and preserved—it opens the possibility that a renewable supply of oocytes may be available for women who wish to preserve the capacity to reproduce.

Practical implications

Whether for personal use following cancer therapy or oophorectomy, or as a source of oocytes for donation to women who have lost ovarian function, the potential holds great promise. However, extensive further work is required, not the least of which is independent verification of Dr. Tilly’s findings and the extension of that discovery to women.

For the practicing obstetrician/gynecologist fielding a question about “growing new eggs” from a savvy patient surfing the Net, know that the concept has a scientific basis but is definitely not ready for prime time.

New standard ahead for embryo assessment

In vivo assessment without injury

Kulkarni RN, Roper MG, Dahlgren G, Shih DQ, Kauri LM, Peters JL, Stoffel M, Kennedy RT. Islet secretory defect in insulin receptor substrate 1 null mice is linked with reduced calcium signaling and expression of sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SECA)-2b and -3. Diabetes. 2004;53:1517–1525.

The assessment of human embryos for their viability and the likelihood of implanting and developing into a healthy baby has been a challenge for in vitro fertilization programs worldwide. Recent interest has focused on removing single cells from embryos and performing genetic studies. However, this is expensive, time consuming, and runs the risk of damaging embryos in the process of removing single blastomeres.

This study by Kennedy and colleagues, while not immediately applicable to human ART programs, demonstrates a technique for monitoring the secretion products from individual pancreatic beta cells. Using microelectrodes placed adjacent to individually cultured beta cells, insulin secretion from each cell was estimated by measuring the number of exocytotic events in normal and IRS-1 knock-out mice. The in vivo measurement of specific secretion products from individual cells without injuring them is an exciting example of the miniaturization of clinical science.

Practical implications

The extension of this technique to the safe assessment of human embryos in vivo while they are in culture is logical and opens up an entire area of both investigation and potential clinical practice. If the metabolic activity of the individual embryos indicates the likelihood of implantation and development, then this could become a new standard in the assessment of every embryo resulting from an ART cycle.

Much work will be required to translate this exciting new technique to human embryos, but it does offer a logical approach to the longstanding problem of embryo assessment.

Real-time assessment

Schuster TG, Cho B, Keller LM, Takayama S, Smith GD. Isolation of motile spermatozoa from semen samples using microfluidics. Reproductive Biomedicine Online. 2004;1(Jul-Aug):75–81.

One of the challenges of assessing individual human embryos in vivo is the dilution effect on any secretion products secreted from an embryo into the relatively vast amount of media in a traditional ART Petri dish. This report describes the first of a series of microfluidic devices designed to separate motile from nonmotile spermatozoa in very small volumes. Such devices can be used to isolate motile sperm from nonmotile sperm and debris for ART procedures when numbers are exceptionally low.

However, similar microfluidic devices are being developed to include tiny chambers that could be used to contain individual human embryos receiving a constant stream of nutrient media with a constant output of spent media and secretory products. In conjunction with the capacity to analyze such tiny amounts of secretory products in vivo from individual cells, this suggests a system for evaluating all human embryos in modern microchambers and continually monitoring for appropriate secretion and subsequent selection for optimal reproductive capacity.

Practical implications

The promise of real-time embryo assessment is certainly upon us, though much work needs to be done to develop these microfluidic incubation chambers before they will be clinically applicable.

For the practicing Ob/Gyn, it is useful to know that the era of preimplantation evaluation of all embryos is not far off. Whether that will translate into fewer fetal/neonatal defects remains to be seen.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

OBG Management ©2005 Dowden Health Media

Preeclampsia: 3 preemptive tactics

We routinely use every means possible to overcome the complications of hypertensive disorders and related preterm births. Yet our best opportunity to reduce morbidity and mortality could be before preeclampsia develops.

Preemptive tactics can be effective in preventing or reducing severity of preeclampsia. The patient’s active cooperation is a must, but the effort to recruit her cooperation can mean a better outcome.

If a diabetic or hypertensive woman doesn’t take her medications properly or if an obese woman postpones weight loss until after preeclampsia develops, it is too late to reduce the level of risk.

At-risk patients can benefit from being informed of any other ways to reduce risk as well; for example, by controlling the number of fetuses transferred via assisted reproductive techniques.

Trends that are driving up the prevalence of risk factors will only increase the number of preconception and obstetric cases with high-risk potential:

- The increased proportion of births among nulliparous women and women older than 35 years.

- The increased proportion of multifetal gestation as a result of assisted reproductive therapy.

- The increased prevalence of obesity in women, which is likely to lead to greater frequency of gestational diabetes, insulin resistance, and chronic hypertension.

Step 1Start risk-reducing tactics as early as possible

Retrospective studies have identified factors that multiply the risk of preeclampsia. Some are identifiable—and modifiable—before conception or beginning at the first prenatal visit (TABLE 1).

- Identify risk factors and recruit the patient’s efforts to reduce risks—before conception whenever possible.

- Set up prenatal care to watch closely for signal findings and make a prompt diagnosis.

- Develop a delivery plan that balances maternal and fetal needs. Identify indications for delivery.

Preconception risk factors

Obesity carries a 10 to 15% risk for preeclampsia. Prevention or effective treatment can greatly reduce risk.

Hypertension.Women with uncontrolled hypertension should have their blood pressure controlled prior to conception and as early as possible in the first trimester. In these women, the risk of preeclampsia may be reduced to below the 10 to 40% rate, depending on severity.

Renal disease. Risk for an adverse pregnancy outcome depends on maternal renal function at time of conception. Women should be encouraged to conceive while serum creatinine is less than 1.2 mg/dl.

Pregestational diabetes mellitus. Risk for preeclampsia and adverse outcomes depends on duration of diabetes, as well as vascular complications and blood sugar control prior to conception and early in pregnancy. Encourage these women to complete childbearing as early as possible and before vascular complications develop, and to aggressively control their diabetes and hypertension (if present) at least a few months prior to conception and throughout pregnancy.

Maternal age older than 35 years increases risk depending on associated medical conditions, nulliparity, and need for assisted reproductive therapy. These women are more likely to be nulliparous, overweight, chronically hypertensive, and to require assisted reproductive therapy. ART may involve multifetal gestation and donor insemination or oocyte donation—both of which increase risk and severity of preeclampsia. Therefore, these patients need to be made aware of their risks and helped to take steps to minimize risks.

TABLE 1

Preconception risk factors for preeclampsia

| 20 to 30% | Previous preeclampsia |

| 50% | Previous preeclampsia at 28 weeks |

| 15 to 25% | Chronic hypertension |

| 40% | Severe hypertension |

| 25% | Renal disease |

| 20% | Pregestational diabetes mellitus |

| 10 to 15% | Class B/C diabetes |

| 35% | Class F/R diabetes |

| 10 to 40% | Thrombophilia |

| 10 to 15% | Obesity/insulin resistance |

| 10 to 20% | Age >35 years |

| 10 to 15% | Family history of preeclampsia |

| 6 to 7% | Nulliparity/primipaternity |

Pregnancy-related risk factors

Many risk factors may be identified for the first time during pregnancy (TABLE 2). It is important to realize that the magnitude of risk depends on number of risk factors.

Nulliparity and primipaternity. Over the past decade, several epidemiologic studies suggested that immune maladaptation plays an important pathogenetic role in development of preeclampsia.

Generally, preeclampsia is considered a disease of first pregnancy. Indeed, a previous miscarriage of a previous normotensive pregnancy with the same partner is has a lowered frequency of preeclampsia. This protective effect is lost, however, with change of partner, suggesting that primipaternity increases the rate of preeclampsia.

A large prospective study on the relation between duration of sperm exposure with a partner and the rate of preeclampsia showed that women who conceive after a cohabitation period of 0 to 4 months have a 10-fold rate of preeclampsia, compared to those who conceive after a cohabitation period of at least 12 months. A similar study confirmed these findings.

The protective effects of long-term sperm exposure could explain the high frequency of preeclampsia in teenage pregnancy. (These women tend to have limited sperm exposure with a partner, or multiple partners). Thus, it is important to teach these women about their risks and the need for regular prenatal care.

Multifetal gestation increases the rate as well as the severity of preeclampsia, and the rate increases with the number of fetuses. Lowering the number of embryos transferred will substantially reduce the risk of preeclampsia and adverse outcomes.

There is no therapy to prevent preeclampsia in these women; however, we should acknowledge the increased risk and develop antenatal-care programs that allow close observation and early detection of preeclampsia in these women.

Hydropic degeneration of placenta. It is well-established that pregnancies complicated by fetal hydrops or hydropic degeneration of the placenta (with or without a coexisting fetus) are at very high risk for preeclampsia. In these cases, preeclampsia usually develops in the second trimester and is usually severe, and therefore causes substantial maternal and perinatal morbidities. Development of preeclampsia in such pregnancies requires immediate hospitalization and consideration for prompt delivery.

Unexplained elevated serum markers in the second trimester. Maternal serum screening with alpha fetoprotein (AFP), human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) and inhibin A is commonly used to identify those at risk for aneuploidy or neural tube defects.

Unexplained elevations in AFP, HCG or inhibin A have been associated with increased adverse pregnancy outcome such as fetal death, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), preterm delivery, and preeclampsia. However, the data on the association between abnormalities in these biomarkers and preeclampsia have been inconsistent. Nevertheless, retrospective studies suggest that elevation in these serum markers during the second trimester increases the risk of preeclampsia by at least twofold. The risk is probably higher in those who have abnormalities in more than 1 of these markers. Since unexplained abnormalities of these serum markers may reflect early placental pathology, it is suggested that these pregnancies may benefit from close obstetric surveillance.

Serum and urinary markers of abnormal angiogenesis and subsequent preeclampsia were strongly associate, in newly published studies reported by Levine and colleagues. For example, circulating soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase (sFLt1) is elevated in pregnant women prior to onset of preeclampsia, whereas urinary placental growth factor is reduced several weeks prior to clinical onset of preeclampsia. Both of these markers appear to hold some promise.

Unexplained proteinuria or hematuria. Generally, proteinuria is considered a late manifestation of preeclampsia. However, recent retrospective studies suggest that some women with preeclampsia, particularly those with HELLP syndrome, might not have hypertension (>140 mm Hg systolic or >90 mm Hg diastolic). In some women, persistent proteinuria (3+ on dipstick) or >300 mg/24 hour may be the first sign of preeclampsia or could be a marker of silent renal disease.

No prospective studies have evaluated the risk of preeclampsia in asymptomatic women with persistent proteinuria. I suggest, however, that women with this finding will benefit from intensified obstetric surveillance (more frequent prenatal visits) and/or biochemical evaluation (platelet count, liver enzymes), particularly if they have headaches, visual changes, epigastric or right upper quadrant pain, nausea or vomiting, or respiratory symptoms (chest pain or shortness of breath)—likewise, for pregnant women with persistent hematuria of unknown origin.

Unexplained fetal growth restriction. Impaired trophoblast invasion is a key features of pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia or unexplained IUGR. Preeclampsia can manifest either as a maternal syndrome (hypertension and proteinuria with or without symptoms) or a fetal abnormal growth syndrome.

In clinical practice, most cases of unexplained IUGR are probably delivered before the maternal syndrome develops. In some cases, unexplained IUGR may be the first manifestation of preeclampsia, particularly those with IUGR before 34 weeks’ gestation. The absolute risk of clinical preeclampsia in such women is unknown because of lack of prospective data. Nevertheless, a woman with idiopathic IUGR prior to 34 weeks’ gestation whose pregnancy is managed expectantly is at increased risk for future preeclampsia. These women should receive intensive maternal surveillance for preeclampsia, and a diagnosis of preeclampsia should be considered in those who develop maternal symptoms or abnormal blood tests.

Abnormal uterine artery Doppler velocimetry at 18 to 24 weeks’ gestation. Several observational studies reported an association between elevated uterine artery resistance as measured by Doppler (with or without presence of a notch) in the second trimester and subsequent preeclampsia and/or IUGR. The reported rates of preeclampsia among women with abnormal Doppler results range from 6% to 40%. The risk varies depending on the site measured, gestational age at time of measurement, normal indices used, abnormality on repeat measurement, and population studied.

A systemic review of 27 studies, which included approximately 13,000 women, revealed that an abnormal uterine artery Doppler waveform increases the risk of preeclampsia by 4- to 6-fold, compared to normal Doppler results. The review concluded that uterine artery Doppler evaluation has a limited value as a screening test to predict preeclampsia.

What should the physician do when faced with an ultrasound report indicating an abnormal uterine artery Doppler finding?

Is low-dose aspirin helpful? Several randomized trials evaluated the potential role of low-dose aspirin in reducing the risk of preeclampsia in women with abnormal uterine artery Doppler indices. A meta-analysis suggested that low-dose aspirin significantly reduced the rate of preeclampsia (16% in placebo versus 10% with aspirin, odds ratio of 0.55). This analysis included a total of 498 subjects.

In contrast, a recent randomized trial in 560 women with abnormal uterine artery Doppler at 23 weeks’, who were assigned to aspirin 150 mg or placebo, found no differences in rates of preeclampsia (18% versus 19%) or in preeclampsia requiring delivery before 34 weeks’ (6% versus 8%). A similar randomized trial using 100 mg aspirin daily in 237 women with abnormal uterine artery Doppler at 22 to 24 weeks revealed no reduction in rate of preeclampsia compared to placebo.

Consequently, low-dose aspirin is not recommended for prevention of preeclamp-sia in these women.

Close surveillance is warranted. Although there is no available proven therapy to reduce the risk of preeclampsia in these women, they should be closely observed because of the increased rate of adverse outcomes, including preeclampsia.

TABLE 2

Pregnancy-related risk factors for preeclampsia

| Magnitude of risk depends on the number of factors | |

|---|---|

| 2-fold normal | Unexplained midtrimester elevations of serum AFP, HCG, inhibin-A |

| 10 to 30% | Abnormal uterine artery Doppler velocimetry |

| 0 to 30% | Hydrops/hydropic degeneration of placenta |

| 10 to 20% | Multifetal gestation (depends on number of fetuses and maternal age) |

| 10% | Partner who fathered preeclampsia in another woman |

| 8 to 10% | Gestational diabetes mellitus |

| 8 to 10% | Limited sperm exposure (teenage pregnancy) |

| 6 to 7% | Nulliparity/primipaternity |

| Limited data | Donor insemination, oocyte donation |

| Limited data | Unexplained persistent proteinuria or hematuria |

| Unknown | Unexplained fetal growth restriction |

Step 2Watch for signal findings, diagnose preeclampsia early

Signs and symptoms may call for close surveillance at any time. Early detection of preeclampsia is the best way to reduce adverse outcomes.

Prenatal care does not prevent preeclampsia, of course. All pregnant women are at risk, some more than others. Still, adequate and proper prenatal care is the best strategy to detect preeclampsia early.

We may need to modify the frequency and type of maternal and fetal surveillance at any time. Thus, patients with multiple risk factors or risk exceeding 10% should have more frequent visits, especially beyond 24 weeks. Maternal blood pressure (both systolic and diastolic), urine protein values, abrupt and excessive weight gain, maternal symptoms, and fetal growth warrant particular attention.

Diagnostic criteria vary with risk

The diagnosis of preeclampsia is different in patients with different risk factors. In healthy nulliparous women, the diagnosis requires persistent hypertension and proteinuria (new onset after 20 weeks’ gestation). However, in some patients the diagnosis should be made based on new onset hypertension and maternal symptoms or abnormal blood tests (low platelets or elevated liver enzymes).

Urine dipstick is a reliable screening test in women who remain normotensive.

24-hour urine measurement is the best test to confirm proteinuria if hypertension develops. Several studies found that urine dipstick values less than (1+) and random urine protein to creatinine ratio measurements are not accurate to predict proteinuria in women with gestational hypertension.

When is it gestational hypertension? The term applies only women with all of these findings:

- mild hypertension <160/<110 mm Hg

- proteinuria <300 mg/24-hour urine

- normal platelet count

- normal liver enzymes

- normal fetal growth

- no maternal symptoms

Once gestational hypertension is diagnosed, obtain blood tests and ultrasound evaluation to document fetal growth and amniotic fluid status.

Women with severe gestational hypertension and those with abnormal tests should be diagnosed as having preeclampsia and managed as such.

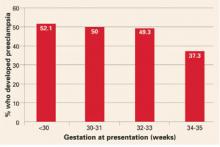

Women with gestational hypertension are at high risk for preeclampsia, and risk of progression depends on gestational age at time of diagnosis. Women who develop gestational hypertension at 24 to 35 weeks have a 46% chance of developing preeclampsia with a high rate of preterm delivery (32% <36 weeks and 12.5% <34 weeks) (FIGURE). These women require very close surveillance. In contrast, maternal and perinatal outcome is usually favorable when only mild gestational hypertension develops at or beyond 36 weeks.

When hypertension, proteinuria occur before 20 weeks

The traditional diagnostic criteria for preeclampsia in healthy women are not reliable in women who have either hypertension or proteinuria prior to 20 weeks’ gestation, particularly in those taking antihypertensive medications and in those who have class F diabetes mellitus. Because of the physiologic changes during pregnancy, women with diabetes and renal disease will have serial increases in blood pressure as well as protein excretion with advanced gestational age, particularly in the third trimester. Diagnostic criteria (TABLE 3) should be individualized based on medical conditions and current therapy. Antihypertensive drugs and preexisting proteinuria make it more difficult to classify preeclampsia as mild or severe.

TABLE 3

Diagnostic criteria

| GESTATIONAL HYPERTENSION IN HEALTHY WOMEN | |

| Blood pressure <160 mm Hg diastolic and <110 mm Hg systolic | |

| Proteinuria <300 mg/24-hour collection | |

| Platelet count >100,000/mm3 | |

| Normal liver enzymes | |

| No maternal symptoms | |

| No intrauterine growth restriction or oligohydraminos by ultrasound | |

| PREECLAMPSIA IN WOMEN WITH PREEXISTING MEDICAL CONDITIONS | |

| Condition | Criteria |

| Hypertension only | Proteinuria >500 mg/24-hours or thrombocytopenia |

| Proteinuria only | New onset hypertension plus symptoms or thrombocytopenia or elevated liver enzymes |

| Hypertension plus proteinuria (renal disease or class F diabetes) | Worsening severe hypertension and/or new onset of symptoms, thrombocytopenia, elevated liver enzymes |

FIGURE Whether preeclampsia will develop depends on when gestational hypertension begins

Adapted from Barton JR, et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:979-983.

Step 3Consider how to balance risk to mother and fetus

Once a diagnosis is made, promptly evaluate mother and fetus, continue close surveillance, select those who will benefit from hospitalization, and identify indications for delivery (TABLE 4).

Delivery will always reduce the risks for the mother, but in certain situations, it might not be the best option for an extremely premature fetus. Sometimes delivery is best for both mother and fetus.

The best strategy takes into consideration:

- maternal and fetal status at initial evaluation,

- preexisting medical conditions that could affect pregnancy outcome,

- fetal gestational age at time of diagnosis,

- labor or rupture of fetal membranes (both could affect management), and

- maternal choice of available options.

Women who remain undelivered require close maternal and fetal evaluation. In otherwise healthy women, management depends on whether the preeclampsia is mild or severe, and, if there are other medical conditions, on the status of those conditions, as well.

TABLE 4

Indications for delivery

| Consider delivery in gravidas with 1 or more indications |

|---|

| Gestational age ≥38 weeks for mild disease |

| Gestational age ≥34 weeks for severe disease |

| 33-34 weeks with severe disease after steroids |

| Onset of labor and/or membrane rupture ≥34 weeks |

| Eclampsia or pulmonary edema (any gestational age) |

| HELLP syndrome (any gestational age) |

| Severe cerebral symptoms or epigastric pain |

| Acute renal insufficiency (serum creatinine >1.2 mg/dl) |

| Persistent thrombocytopenia (platelet count <100,000) |

| Maternal desire for delivery |

| Severe oligohydraminos or IUGR < 5th percentile |

| Nonreassuring fetal testing |

Chronic hypertension

- Underlies 30% of cases of hypertension during pregnancy.

- Begins before pregnancy or before 20 weeks’ gestation.

Gestational hypertension

- The most common form of hypertension during pregnancy.

- Acute onset beyond 20 weeks’ gestation in a woman known to be normotensive before pregnancy or prior to 20 weeks’ gestation.

Preeclampsia

- Can superimpose upon chronic hypertension, renal disease, or connective tissue disease, or develop in women with gestational hypertension.

- Preeclampsia in healthy nulliparous women: hypertension and proteinuria after 20 weeks’ gestation.

- Preeclampsia in women with preexisting chronic hypertension and absent proteinuria: an exacerbation of hypertension and new onset proteinuria.

Eclampsia

- Development of convulsions in women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

“HELLP syndrome”

- Hemolysis,

- Elevated liver enzymes, and

- Low platelet count

Suspected or confirmed preeclampsia in a woman who has documented evidence of hemolysis (abnormal peripheral smear, or elevated bilirubin, or anemia, or low heptoglobin levels), plus elevated liver enzymes (AST or ALT), and thrombocytopenia (platelet count below 100,000).

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barton JR, O’Brien JM, Bergauer NK, Jacques DL, Sibai BM. Mild gestational hypertension remote from term: Progression and outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:979-983.

Boggess KA, Lief S, Martha AP, Moos K, Beck J, Offenbacher S. Maternal periodontal disease is associated with an increased risk for preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:227-231.

Buchbinder A, Sibai BM, Caritis S, MacPherson C, Hauth J, Lindheimer MD. Adverse perinatal outcomes are significantly higher in severe gestational hypertension than in mild preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:66-71.

Caritis S, Sibai B, Hauth J, Lindheimer MD, Klebanoff M, Thom E. Low-dose aspirin to prevent preeclampsia in women at high risk. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:701-705.

Cedergren MI. Maternal morbid obesity and the risk of adverse pregnancy outcome. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:219-224.

Chien PE, Arnott N, Gordon A, Owen P, Khan KS. How useful is uterine artery Doppler flow velocimetry in the prediction of pre-eclampsia, intrauterine growth retardation and perinatal death? An Overview. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;107:196-208.

Coomarasamy A, Papaioannou S, Gee H, Khan KS. Aspirin for the prevention of preeclampsia in women with abnormal uterine artery Doppler: A meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:861-866.

Curet LB. Pregnancy outcomes in healthy nulliparous women who subsequently developed hypertension. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:24-28.

Dekker G, Robillard PY. The birth interval hypothesis - Does it really indicate the end of the primipaternity hypothesis? J Reprod Immunol. 2003;59:245-251.

Dekker G, Sibai B. Primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention of pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2001;357:209-215.

Durnwald C, Mercer B. A prospective comparison of total protein/creatinine ratio versus 24-hour urine protein in women with suspected preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:848-52.

Einarsson JI, Sangi-Haghpeykar H, Gardner NO. Sperm exposure and development of preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:1241-1243.

Hauth JC, Ewell MG, Levine RL, Esterlitz JR, Sibai BM, Curet LB. Pregnancy outcomes in healthy nulliparous women who subsequently developed hypertension. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:24-28.

Hnat MD, Sibai BM, Caritis S, Hiouth J, Lindheimer MD, MacPherson C. Perinatal outcome in women with recurrent preeclampsia compared with women who develop preeclampsia as nulliparous. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:422-426.

Kupferminc MJ. Thrombophilia and pregnancy. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2003;1:111-166.

Levine RG, Thadhani R, Qian C, et al. Urinary placental growth factor and risk of preeclampsia. JAMA. 2005;293:77-85.

Levine RJ, Maynard SE, Qian C, et al. Circulating angiogenic factors and the risk of preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:672-683.

Nilsson E, Salonen Ros H, Cnattingius S, Lichtenstein P. The importance of genetic and environmental effects for preeclampsia and gestational hypertension: a family study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;111:200-206.

O’Brien TE, Ray JG, Chan WS. Maternal body mass index and the risk of preeclampsia: a systematic overview. Epidemiology. 2003;14:368-374.

Ragip A Al, Baykal C, Karacay O, Geyik PO, Altun S, Dolen I. Random urine protein-creatinine ratio to predict proteinuria in new-onset mild hypertension in late pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:367-371.

Saftlas AF, Levine RJ, Klebanoff MA, Martz KL, Ewell MG, Morris CD, Sibai BM. Abortion, changed paternity, and risk of preeclampsia in nulliparous women. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:1108-1114.

Sibai BM, Caritis S, Hauth J, Lilndheimer MD, MacPherson C, Klebanoff M, et al. Hypertensive disorders in twin versus singleton gestations. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:938-942.

Sibai BM. Chronic hypertension in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:369-33377.

Sibai BM. Diagnosis and management of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:181-192.

Subtil D, Goeusse P, Houfflin-Debarge V, Puech F, Lequien P, Breart G, Uzan S, Quandalle F, Delcourt YM, Malek YM. Essai Regional Aspirine Mere-Enfant (ERASME) Collaborative Group. Randomised comparison of uterine artery Doppler and aspirin (100 mg) with placebo in nulliparous women: the Essai Regional Aspirine Mere-Enfant study (Part 2). Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;110:485-491.

Wen SW, Demissie K, Yang Q, Walker MC. Maternal morbidity and obstetric complications in triplet pregnancies and quadruplet and higher-order multiple pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:254-258.

Yu CKH, Papageorghiou AT, Parra M, Dias RP, Nicolaides KH. Randomized controlled trial using low-dose aspirin in the prevention of pre-eclampsia in women with abnormal uterine artery Doppler at 23 weeks’ gestation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003;22:233-239.

We routinely use every means possible to overcome the complications of hypertensive disorders and related preterm births. Yet our best opportunity to reduce morbidity and mortality could be before preeclampsia develops.

Preemptive tactics can be effective in preventing or reducing severity of preeclampsia. The patient’s active cooperation is a must, but the effort to recruit her cooperation can mean a better outcome.

If a diabetic or hypertensive woman doesn’t take her medications properly or if an obese woman postpones weight loss until after preeclampsia develops, it is too late to reduce the level of risk.

At-risk patients can benefit from being informed of any other ways to reduce risk as well; for example, by controlling the number of fetuses transferred via assisted reproductive techniques.

Trends that are driving up the prevalence of risk factors will only increase the number of preconception and obstetric cases with high-risk potential:

- The increased proportion of births among nulliparous women and women older than 35 years.

- The increased proportion of multifetal gestation as a result of assisted reproductive therapy.

- The increased prevalence of obesity in women, which is likely to lead to greater frequency of gestational diabetes, insulin resistance, and chronic hypertension.

Step 1Start risk-reducing tactics as early as possible

Retrospective studies have identified factors that multiply the risk of preeclampsia. Some are identifiable—and modifiable—before conception or beginning at the first prenatal visit (TABLE 1).

- Identify risk factors and recruit the patient’s efforts to reduce risks—before conception whenever possible.

- Set up prenatal care to watch closely for signal findings and make a prompt diagnosis.

- Develop a delivery plan that balances maternal and fetal needs. Identify indications for delivery.

Preconception risk factors

Obesity carries a 10 to 15% risk for preeclampsia. Prevention or effective treatment can greatly reduce risk.

Hypertension.Women with uncontrolled hypertension should have their blood pressure controlled prior to conception and as early as possible in the first trimester. In these women, the risk of preeclampsia may be reduced to below the 10 to 40% rate, depending on severity.

Renal disease. Risk for an adverse pregnancy outcome depends on maternal renal function at time of conception. Women should be encouraged to conceive while serum creatinine is less than 1.2 mg/dl.

Pregestational diabetes mellitus. Risk for preeclampsia and adverse outcomes depends on duration of diabetes, as well as vascular complications and blood sugar control prior to conception and early in pregnancy. Encourage these women to complete childbearing as early as possible and before vascular complications develop, and to aggressively control their diabetes and hypertension (if present) at least a few months prior to conception and throughout pregnancy.

Maternal age older than 35 years increases risk depending on associated medical conditions, nulliparity, and need for assisted reproductive therapy. These women are more likely to be nulliparous, overweight, chronically hypertensive, and to require assisted reproductive therapy. ART may involve multifetal gestation and donor insemination or oocyte donation—both of which increase risk and severity of preeclampsia. Therefore, these patients need to be made aware of their risks and helped to take steps to minimize risks.

TABLE 1

Preconception risk factors for preeclampsia

| 20 to 30% | Previous preeclampsia |

| 50% | Previous preeclampsia at 28 weeks |

| 15 to 25% | Chronic hypertension |

| 40% | Severe hypertension |

| 25% | Renal disease |

| 20% | Pregestational diabetes mellitus |

| 10 to 15% | Class B/C diabetes |

| 35% | Class F/R diabetes |

| 10 to 40% | Thrombophilia |

| 10 to 15% | Obesity/insulin resistance |

| 10 to 20% | Age >35 years |

| 10 to 15% | Family history of preeclampsia |

| 6 to 7% | Nulliparity/primipaternity |

Pregnancy-related risk factors

Many risk factors may be identified for the first time during pregnancy (TABLE 2). It is important to realize that the magnitude of risk depends on number of risk factors.

Nulliparity and primipaternity. Over the past decade, several epidemiologic studies suggested that immune maladaptation plays an important pathogenetic role in development of preeclampsia.

Generally, preeclampsia is considered a disease of first pregnancy. Indeed, a previous miscarriage of a previous normotensive pregnancy with the same partner is has a lowered frequency of preeclampsia. This protective effect is lost, however, with change of partner, suggesting that primipaternity increases the rate of preeclampsia.

A large prospective study on the relation between duration of sperm exposure with a partner and the rate of preeclampsia showed that women who conceive after a cohabitation period of 0 to 4 months have a 10-fold rate of preeclampsia, compared to those who conceive after a cohabitation period of at least 12 months. A similar study confirmed these findings.

The protective effects of long-term sperm exposure could explain the high frequency of preeclampsia in teenage pregnancy. (These women tend to have limited sperm exposure with a partner, or multiple partners). Thus, it is important to teach these women about their risks and the need for regular prenatal care.

Multifetal gestation increases the rate as well as the severity of preeclampsia, and the rate increases with the number of fetuses. Lowering the number of embryos transferred will substantially reduce the risk of preeclampsia and adverse outcomes.

There is no therapy to prevent preeclampsia in these women; however, we should acknowledge the increased risk and develop antenatal-care programs that allow close observation and early detection of preeclampsia in these women.

Hydropic degeneration of placenta. It is well-established that pregnancies complicated by fetal hydrops or hydropic degeneration of the placenta (with or without a coexisting fetus) are at very high risk for preeclampsia. In these cases, preeclampsia usually develops in the second trimester and is usually severe, and therefore causes substantial maternal and perinatal morbidities. Development of preeclampsia in such pregnancies requires immediate hospitalization and consideration for prompt delivery.

Unexplained elevated serum markers in the second trimester. Maternal serum screening with alpha fetoprotein (AFP), human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) and inhibin A is commonly used to identify those at risk for aneuploidy or neural tube defects.

Unexplained elevations in AFP, HCG or inhibin A have been associated with increased adverse pregnancy outcome such as fetal death, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), preterm delivery, and preeclampsia. However, the data on the association between abnormalities in these biomarkers and preeclampsia have been inconsistent. Nevertheless, retrospective studies suggest that elevation in these serum markers during the second trimester increases the risk of preeclampsia by at least twofold. The risk is probably higher in those who have abnormalities in more than 1 of these markers. Since unexplained abnormalities of these serum markers may reflect early placental pathology, it is suggested that these pregnancies may benefit from close obstetric surveillance.

Serum and urinary markers of abnormal angiogenesis and subsequent preeclampsia were strongly associate, in newly published studies reported by Levine and colleagues. For example, circulating soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase (sFLt1) is elevated in pregnant women prior to onset of preeclampsia, whereas urinary placental growth factor is reduced several weeks prior to clinical onset of preeclampsia. Both of these markers appear to hold some promise.

Unexplained proteinuria or hematuria. Generally, proteinuria is considered a late manifestation of preeclampsia. However, recent retrospective studies suggest that some women with preeclampsia, particularly those with HELLP syndrome, might not have hypertension (>140 mm Hg systolic or >90 mm Hg diastolic). In some women, persistent proteinuria (3+ on dipstick) or >300 mg/24 hour may be the first sign of preeclampsia or could be a marker of silent renal disease.

No prospective studies have evaluated the risk of preeclampsia in asymptomatic women with persistent proteinuria. I suggest, however, that women with this finding will benefit from intensified obstetric surveillance (more frequent prenatal visits) and/or biochemical evaluation (platelet count, liver enzymes), particularly if they have headaches, visual changes, epigastric or right upper quadrant pain, nausea or vomiting, or respiratory symptoms (chest pain or shortness of breath)—likewise, for pregnant women with persistent hematuria of unknown origin.

Unexplained fetal growth restriction. Impaired trophoblast invasion is a key features of pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia or unexplained IUGR. Preeclampsia can manifest either as a maternal syndrome (hypertension and proteinuria with or without symptoms) or a fetal abnormal growth syndrome.

In clinical practice, most cases of unexplained IUGR are probably delivered before the maternal syndrome develops. In some cases, unexplained IUGR may be the first manifestation of preeclampsia, particularly those with IUGR before 34 weeks’ gestation. The absolute risk of clinical preeclampsia in such women is unknown because of lack of prospective data. Nevertheless, a woman with idiopathic IUGR prior to 34 weeks’ gestation whose pregnancy is managed expectantly is at increased risk for future preeclampsia. These women should receive intensive maternal surveillance for preeclampsia, and a diagnosis of preeclampsia should be considered in those who develop maternal symptoms or abnormal blood tests.

Abnormal uterine artery Doppler velocimetry at 18 to 24 weeks’ gestation. Several observational studies reported an association between elevated uterine artery resistance as measured by Doppler (with or without presence of a notch) in the second trimester and subsequent preeclampsia and/or IUGR. The reported rates of preeclampsia among women with abnormal Doppler results range from 6% to 40%. The risk varies depending on the site measured, gestational age at time of measurement, normal indices used, abnormality on repeat measurement, and population studied.

A systemic review of 27 studies, which included approximately 13,000 women, revealed that an abnormal uterine artery Doppler waveform increases the risk of preeclampsia by 4- to 6-fold, compared to normal Doppler results. The review concluded that uterine artery Doppler evaluation has a limited value as a screening test to predict preeclampsia.

What should the physician do when faced with an ultrasound report indicating an abnormal uterine artery Doppler finding?

Is low-dose aspirin helpful? Several randomized trials evaluated the potential role of low-dose aspirin in reducing the risk of preeclampsia in women with abnormal uterine artery Doppler indices. A meta-analysis suggested that low-dose aspirin significantly reduced the rate of preeclampsia (16% in placebo versus 10% with aspirin, odds ratio of 0.55). This analysis included a total of 498 subjects.

In contrast, a recent randomized trial in 560 women with abnormal uterine artery Doppler at 23 weeks’, who were assigned to aspirin 150 mg or placebo, found no differences in rates of preeclampsia (18% versus 19%) or in preeclampsia requiring delivery before 34 weeks’ (6% versus 8%). A similar randomized trial using 100 mg aspirin daily in 237 women with abnormal uterine artery Doppler at 22 to 24 weeks revealed no reduction in rate of preeclampsia compared to placebo.

Consequently, low-dose aspirin is not recommended for prevention of preeclamp-sia in these women.

Close surveillance is warranted. Although there is no available proven therapy to reduce the risk of preeclampsia in these women, they should be closely observed because of the increased rate of adverse outcomes, including preeclampsia.

TABLE 2

Pregnancy-related risk factors for preeclampsia

| Magnitude of risk depends on the number of factors | |

|---|---|

| 2-fold normal | Unexplained midtrimester elevations of serum AFP, HCG, inhibin-A |

| 10 to 30% | Abnormal uterine artery Doppler velocimetry |

| 0 to 30% | Hydrops/hydropic degeneration of placenta |

| 10 to 20% | Multifetal gestation (depends on number of fetuses and maternal age) |

| 10% | Partner who fathered preeclampsia in another woman |

| 8 to 10% | Gestational diabetes mellitus |

| 8 to 10% | Limited sperm exposure (teenage pregnancy) |

| 6 to 7% | Nulliparity/primipaternity |

| Limited data | Donor insemination, oocyte donation |

| Limited data | Unexplained persistent proteinuria or hematuria |

| Unknown | Unexplained fetal growth restriction |

Step 2Watch for signal findings, diagnose preeclampsia early

Signs and symptoms may call for close surveillance at any time. Early detection of preeclampsia is the best way to reduce adverse outcomes.

Prenatal care does not prevent preeclampsia, of course. All pregnant women are at risk, some more than others. Still, adequate and proper prenatal care is the best strategy to detect preeclampsia early.

We may need to modify the frequency and type of maternal and fetal surveillance at any time. Thus, patients with multiple risk factors or risk exceeding 10% should have more frequent visits, especially beyond 24 weeks. Maternal blood pressure (both systolic and diastolic), urine protein values, abrupt and excessive weight gain, maternal symptoms, and fetal growth warrant particular attention.

Diagnostic criteria vary with risk

The diagnosis of preeclampsia is different in patients with different risk factors. In healthy nulliparous women, the diagnosis requires persistent hypertension and proteinuria (new onset after 20 weeks’ gestation). However, in some patients the diagnosis should be made based on new onset hypertension and maternal symptoms or abnormal blood tests (low platelets or elevated liver enzymes).

Urine dipstick is a reliable screening test in women who remain normotensive.

24-hour urine measurement is the best test to confirm proteinuria if hypertension develops. Several studies found that urine dipstick values less than (1+) and random urine protein to creatinine ratio measurements are not accurate to predict proteinuria in women with gestational hypertension.

When is it gestational hypertension? The term applies only women with all of these findings:

- mild hypertension <160/<110 mm Hg

- proteinuria <300 mg/24-hour urine

- normal platelet count

- normal liver enzymes

- normal fetal growth

- no maternal symptoms

Once gestational hypertension is diagnosed, obtain blood tests and ultrasound evaluation to document fetal growth and amniotic fluid status.

Women with severe gestational hypertension and those with abnormal tests should be diagnosed as having preeclampsia and managed as such.

Women with gestational hypertension are at high risk for preeclampsia, and risk of progression depends on gestational age at time of diagnosis. Women who develop gestational hypertension at 24 to 35 weeks have a 46% chance of developing preeclampsia with a high rate of preterm delivery (32% <36 weeks and 12.5% <34 weeks) (FIGURE). These women require very close surveillance. In contrast, maternal and perinatal outcome is usually favorable when only mild gestational hypertension develops at or beyond 36 weeks.

When hypertension, proteinuria occur before 20 weeks

The traditional diagnostic criteria for preeclampsia in healthy women are not reliable in women who have either hypertension or proteinuria prior to 20 weeks’ gestation, particularly in those taking antihypertensive medications and in those who have class F diabetes mellitus. Because of the physiologic changes during pregnancy, women with diabetes and renal disease will have serial increases in blood pressure as well as protein excretion with advanced gestational age, particularly in the third trimester. Diagnostic criteria (TABLE 3) should be individualized based on medical conditions and current therapy. Antihypertensive drugs and preexisting proteinuria make it more difficult to classify preeclampsia as mild or severe.

TABLE 3

Diagnostic criteria

| GESTATIONAL HYPERTENSION IN HEALTHY WOMEN | |

| Blood pressure <160 mm Hg diastolic and <110 mm Hg systolic | |

| Proteinuria <300 mg/24-hour collection | |

| Platelet count >100,000/mm3 | |

| Normal liver enzymes | |

| No maternal symptoms | |

| No intrauterine growth restriction or oligohydraminos by ultrasound | |

| PREECLAMPSIA IN WOMEN WITH PREEXISTING MEDICAL CONDITIONS | |

| Condition | Criteria |

| Hypertension only | Proteinuria >500 mg/24-hours or thrombocytopenia |

| Proteinuria only | New onset hypertension plus symptoms or thrombocytopenia or elevated liver enzymes |

| Hypertension plus proteinuria (renal disease or class F diabetes) | Worsening severe hypertension and/or new onset of symptoms, thrombocytopenia, elevated liver enzymes |

FIGURE Whether preeclampsia will develop depends on when gestational hypertension begins

Adapted from Barton JR, et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:979-983.

Step 3Consider how to balance risk to mother and fetus

Once a diagnosis is made, promptly evaluate mother and fetus, continue close surveillance, select those who will benefit from hospitalization, and identify indications for delivery (TABLE 4).

Delivery will always reduce the risks for the mother, but in certain situations, it might not be the best option for an extremely premature fetus. Sometimes delivery is best for both mother and fetus.

The best strategy takes into consideration:

- maternal and fetal status at initial evaluation,

- preexisting medical conditions that could affect pregnancy outcome,

- fetal gestational age at time of diagnosis,

- labor or rupture of fetal membranes (both could affect management), and

- maternal choice of available options.

Women who remain undelivered require close maternal and fetal evaluation. In otherwise healthy women, management depends on whether the preeclampsia is mild or severe, and, if there are other medical conditions, on the status of those conditions, as well.

TABLE 4

Indications for delivery

| Consider delivery in gravidas with 1 or more indications |

|---|

| Gestational age ≥38 weeks for mild disease |

| Gestational age ≥34 weeks for severe disease |

| 33-34 weeks with severe disease after steroids |

| Onset of labor and/or membrane rupture ≥34 weeks |

| Eclampsia or pulmonary edema (any gestational age) |

| HELLP syndrome (any gestational age) |

| Severe cerebral symptoms or epigastric pain |

| Acute renal insufficiency (serum creatinine >1.2 mg/dl) |

| Persistent thrombocytopenia (platelet count <100,000) |

| Maternal desire for delivery |

| Severe oligohydraminos or IUGR < 5th percentile |

| Nonreassuring fetal testing |

Chronic hypertension

- Underlies 30% of cases of hypertension during pregnancy.

- Begins before pregnancy or before 20 weeks’ gestation.

Gestational hypertension

- The most common form of hypertension during pregnancy.

- Acute onset beyond 20 weeks’ gestation in a woman known to be normotensive before pregnancy or prior to 20 weeks’ gestation.

Preeclampsia

- Can superimpose upon chronic hypertension, renal disease, or connective tissue disease, or develop in women with gestational hypertension.

- Preeclampsia in healthy nulliparous women: hypertension and proteinuria after 20 weeks’ gestation.

- Preeclampsia in women with preexisting chronic hypertension and absent proteinuria: an exacerbation of hypertension and new onset proteinuria.

Eclampsia

- Development of convulsions in women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

“HELLP syndrome”

- Hemolysis,

- Elevated liver enzymes, and

- Low platelet count

Suspected or confirmed preeclampsia in a woman who has documented evidence of hemolysis (abnormal peripheral smear, or elevated bilirubin, or anemia, or low heptoglobin levels), plus elevated liver enzymes (AST or ALT), and thrombocytopenia (platelet count below 100,000).

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

We routinely use every means possible to overcome the complications of hypertensive disorders and related preterm births. Yet our best opportunity to reduce morbidity and mortality could be before preeclampsia develops.

Preemptive tactics can be effective in preventing or reducing severity of preeclampsia. The patient’s active cooperation is a must, but the effort to recruit her cooperation can mean a better outcome.

If a diabetic or hypertensive woman doesn’t take her medications properly or if an obese woman postpones weight loss until after preeclampsia develops, it is too late to reduce the level of risk.

At-risk patients can benefit from being informed of any other ways to reduce risk as well; for example, by controlling the number of fetuses transferred via assisted reproductive techniques.

Trends that are driving up the prevalence of risk factors will only increase the number of preconception and obstetric cases with high-risk potential:

- The increased proportion of births among nulliparous women and women older than 35 years.

- The increased proportion of multifetal gestation as a result of assisted reproductive therapy.

- The increased prevalence of obesity in women, which is likely to lead to greater frequency of gestational diabetes, insulin resistance, and chronic hypertension.

Step 1Start risk-reducing tactics as early as possible

Retrospective studies have identified factors that multiply the risk of preeclampsia. Some are identifiable—and modifiable—before conception or beginning at the first prenatal visit (TABLE 1).

- Identify risk factors and recruit the patient’s efforts to reduce risks—before conception whenever possible.

- Set up prenatal care to watch closely for signal findings and make a prompt diagnosis.

- Develop a delivery plan that balances maternal and fetal needs. Identify indications for delivery.

Preconception risk factors

Obesity carries a 10 to 15% risk for preeclampsia. Prevention or effective treatment can greatly reduce risk.

Hypertension.Women with uncontrolled hypertension should have their blood pressure controlled prior to conception and as early as possible in the first trimester. In these women, the risk of preeclampsia may be reduced to below the 10 to 40% rate, depending on severity.

Renal disease. Risk for an adverse pregnancy outcome depends on maternal renal function at time of conception. Women should be encouraged to conceive while serum creatinine is less than 1.2 mg/dl.

Pregestational diabetes mellitus. Risk for preeclampsia and adverse outcomes depends on duration of diabetes, as well as vascular complications and blood sugar control prior to conception and early in pregnancy. Encourage these women to complete childbearing as early as possible and before vascular complications develop, and to aggressively control their diabetes and hypertension (if present) at least a few months prior to conception and throughout pregnancy.

Maternal age older than 35 years increases risk depending on associated medical conditions, nulliparity, and need for assisted reproductive therapy. These women are more likely to be nulliparous, overweight, chronically hypertensive, and to require assisted reproductive therapy. ART may involve multifetal gestation and donor insemination or oocyte donation—both of which increase risk and severity of preeclampsia. Therefore, these patients need to be made aware of their risks and helped to take steps to minimize risks.

TABLE 1

Preconception risk factors for preeclampsia

| 20 to 30% | Previous preeclampsia |

| 50% | Previous preeclampsia at 28 weeks |

| 15 to 25% | Chronic hypertension |

| 40% | Severe hypertension |

| 25% | Renal disease |

| 20% | Pregestational diabetes mellitus |

| 10 to 15% | Class B/C diabetes |

| 35% | Class F/R diabetes |

| 10 to 40% | Thrombophilia |

| 10 to 15% | Obesity/insulin resistance |

| 10 to 20% | Age >35 years |

| 10 to 15% | Family history of preeclampsia |

| 6 to 7% | Nulliparity/primipaternity |

Pregnancy-related risk factors

Many risk factors may be identified for the first time during pregnancy (TABLE 2). It is important to realize that the magnitude of risk depends on number of risk factors.

Nulliparity and primipaternity. Over the past decade, several epidemiologic studies suggested that immune maladaptation plays an important pathogenetic role in development of preeclampsia.

Generally, preeclampsia is considered a disease of first pregnancy. Indeed, a previous miscarriage of a previous normotensive pregnancy with the same partner is has a lowered frequency of preeclampsia. This protective effect is lost, however, with change of partner, suggesting that primipaternity increases the rate of preeclampsia.

A large prospective study on the relation between duration of sperm exposure with a partner and the rate of preeclampsia showed that women who conceive after a cohabitation period of 0 to 4 months have a 10-fold rate of preeclampsia, compared to those who conceive after a cohabitation period of at least 12 months. A similar study confirmed these findings.

The protective effects of long-term sperm exposure could explain the high frequency of preeclampsia in teenage pregnancy. (These women tend to have limited sperm exposure with a partner, or multiple partners). Thus, it is important to teach these women about their risks and the need for regular prenatal care.

Multifetal gestation increases the rate as well as the severity of preeclampsia, and the rate increases with the number of fetuses. Lowering the number of embryos transferred will substantially reduce the risk of preeclampsia and adverse outcomes.

There is no therapy to prevent preeclampsia in these women; however, we should acknowledge the increased risk and develop antenatal-care programs that allow close observation and early detection of preeclampsia in these women.

Hydropic degeneration of placenta. It is well-established that pregnancies complicated by fetal hydrops or hydropic degeneration of the placenta (with or without a coexisting fetus) are at very high risk for preeclampsia. In these cases, preeclampsia usually develops in the second trimester and is usually severe, and therefore causes substantial maternal and perinatal morbidities. Development of preeclampsia in such pregnancies requires immediate hospitalization and consideration for prompt delivery.

Unexplained elevated serum markers in the second trimester. Maternal serum screening with alpha fetoprotein (AFP), human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) and inhibin A is commonly used to identify those at risk for aneuploidy or neural tube defects.

Unexplained elevations in AFP, HCG or inhibin A have been associated with increased adverse pregnancy outcome such as fetal death, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), preterm delivery, and preeclampsia. However, the data on the association between abnormalities in these biomarkers and preeclampsia have been inconsistent. Nevertheless, retrospective studies suggest that elevation in these serum markers during the second trimester increases the risk of preeclampsia by at least twofold. The risk is probably higher in those who have abnormalities in more than 1 of these markers. Since unexplained abnormalities of these serum markers may reflect early placental pathology, it is suggested that these pregnancies may benefit from close obstetric surveillance.

Serum and urinary markers of abnormal angiogenesis and subsequent preeclampsia were strongly associate, in newly published studies reported by Levine and colleagues. For example, circulating soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase (sFLt1) is elevated in pregnant women prior to onset of preeclampsia, whereas urinary placental growth factor is reduced several weeks prior to clinical onset of preeclampsia. Both of these markers appear to hold some promise.

Unexplained proteinuria or hematuria. Generally, proteinuria is considered a late manifestation of preeclampsia. However, recent retrospective studies suggest that some women with preeclampsia, particularly those with HELLP syndrome, might not have hypertension (>140 mm Hg systolic or >90 mm Hg diastolic). In some women, persistent proteinuria (3+ on dipstick) or >300 mg/24 hour may be the first sign of preeclampsia or could be a marker of silent renal disease.

No prospective studies have evaluated the risk of preeclampsia in asymptomatic women with persistent proteinuria. I suggest, however, that women with this finding will benefit from intensified obstetric surveillance (more frequent prenatal visits) and/or biochemical evaluation (platelet count, liver enzymes), particularly if they have headaches, visual changes, epigastric or right upper quadrant pain, nausea or vomiting, or respiratory symptoms (chest pain or shortness of breath)—likewise, for pregnant women with persistent hematuria of unknown origin.

Unexplained fetal growth restriction. Impaired trophoblast invasion is a key features of pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia or unexplained IUGR. Preeclampsia can manifest either as a maternal syndrome (hypertension and proteinuria with or without symptoms) or a fetal abnormal growth syndrome.

In clinical practice, most cases of unexplained IUGR are probably delivered before the maternal syndrome develops. In some cases, unexplained IUGR may be the first manifestation of preeclampsia, particularly those with IUGR before 34 weeks’ gestation. The absolute risk of clinical preeclampsia in such women is unknown because of lack of prospective data. Nevertheless, a woman with idiopathic IUGR prior to 34 weeks’ gestation whose pregnancy is managed expectantly is at increased risk for future preeclampsia. These women should receive intensive maternal surveillance for preeclampsia, and a diagnosis of preeclampsia should be considered in those who develop maternal symptoms or abnormal blood tests.

Abnormal uterine artery Doppler velocimetry at 18 to 24 weeks’ gestation. Several observational studies reported an association between elevated uterine artery resistance as measured by Doppler (with or without presence of a notch) in the second trimester and subsequent preeclampsia and/or IUGR. The reported rates of preeclampsia among women with abnormal Doppler results range from 6% to 40%. The risk varies depending on the site measured, gestational age at time of measurement, normal indices used, abnormality on repeat measurement, and population studied.