User login

Ectopic pregnancy: A 5-step plan for medical management

- In properly selected cases, medical therapy and surgery produce similar outcomes, but medicine is less expensive.

- Surgery is still the first choice for hemorrhage, medical failure, rupture or near-rupture, and when medical therapy is contraindicated.

- Systemic methotrexate and laparoscopic salpingostomy produce similar success rates and long-term fertility.

- Single-dose methotrexate is associated with a higher risk of rupture than multiple doses.

Although ectopic pregnancy remains a leading cause of life-threatening first-trimester morbidity, accounting for about 9% of maternal deaths annually,1 we now are able to diagnose and treat most cases well before rupture occurs—in some cases, as early as 5 weeks’ gestation. As a result, medical therapy with systemic methotrexate has become the first-line treatment, with surgery reserved for hemorrhage, medical failures, neglected cases, and circumstances in which medical therapy is contraindicated.

Early diagnosis not only makes medical therapy possible, it also is cheaper, since it avoids rupture, blood loss, and surgery; preserves fertility; and minimizes lost productivity. This is important because ectopic pregnancy is an expensive condition, with an annual health-care bill exceeding $1 billion.2

Despite this progress, serious challenges remain. Medical management is not for everyone. Success is inversely related to initial serum human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) levels3 and diminishes substantially when embryonic cardiac activity is observed during ultrasound imaging.4

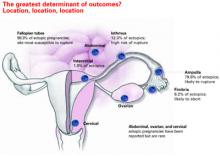

In addition, because medical therapy has made outpatient treatment the norm in most cases, it has become virtually impossible to chart the prevalence of ectopic pregnancy. In past years, when hospital records were used, ectopic pregnancy rates were increasing relentlessly, from 4.5 per 1,000 pregnancies in 1970 to 16.8 in 1989 and 19.7 (108,000 cases) in 1992.1,5

Reasons for increasing rates

Today the prevalence of ectopic pregnancy is probably still rising, for several reasons:

- a greater incidence of risk factors such as sexually transmitted and tubal disease,6

- improved diagnostic methods, and

- the use of assisted reproductive technology (ART) to treat infertility (roughly 2% of ART pregnancies are ectopic).7

This article describes a 5-step approach to diagnosis and medical management with multiple-dose methotrexate, as well as fine points of treatment and basic surgical technique. It includes a protocol for multiple-dose methotrexate, a table summarizing treatment outcomes, and several case histories.

Likelihood of ectopic pregnancy

If 100 women present with a positive pregnancy test and pain and bleeding, approximately 60 will have a normal pregnancy, 30 are experiencing spontaneous abortion, and 9 have an ectopic pregnancy.8

STEP 1Assess risk factors and symptoms

The first step in early diagnosis is being vigilant for risk factors and symptoms associated with ectopic pregnancy, most of which are well known9:

Tubal disease carries a 3.5-fold common adjusted odds ratio (OR) for ectopic pregnancy. In addition, women with a previous ectopic pregnancy are 6 to 8 times more likely to experience another, while a history of tubal surgery raises that likelihood to 21. A history of pelvic infection, including gonorrhea, serologically confirmed chlamydia, and pelvic inflammatory disease, increases the risk of ectopic pregnancy 2 to 4 times.9

Contraception. Intrauterine devices (IUDs) are associated with an increased OR of 6.4.10 This does not mean that IUDs cause ectopic pregnancy. Rather, when a woman with an IUD becomes pregnant, an ectopic gestation should be high on the list of possibilities. A similar relationship exists between ectopic pregnancy and tubal ligation, which carries an OR of 9.3.9 Oral contraceptives are associated with a reduced risk of ectopic pregnancy unless they are used as emergency contraception (ie, after fertilization), in which case they are associated with an increased risk (TABLE 1).

Diethylstilbestrol exposure in utero alters fallopian tube morphology and can lead to absent or minimal fimbrial tissue, a small tubal os, and decreased length and caliber of the tube.11 Abnormal tubal anatomy caused by this exposure multiplies the risk of ectopic pregnancy by a factor of 5.9

In vitro fertilization. When blocked tubes are treated, the embryos can migrate retrograde into the oviduct, implant, and eventually rupture. The OR for ectopic pregnancy with assisted reproduction is 4.0.8

Although a patient’s ß-hCG levels, symptoms, or imaging may suggest ectopic pregnancy, missed diagnoses abound, especially when the physician omits 1 element of the triad: ß-hCG levels, ultrasound imaging, and curettage.

CASE 1: Pain and bleeding, with a high hCG

Mrs. Jones presents with pain and bleeding and a ß-hCG level of 6,000 mIU/mL. Ultrasound imaging reveals no intrauterine pregnancy. Should you presume the diagnosis is ectopic pregnancy and start methotrexate therapy? Or should you play it safe and perform curettage?

To explore these questions, Barnhart and colleagues22 performed a retrospective cohort analysis involving women with ß-hCG levels above 2,000 mIU/mL and no ultrasound evidence of an intrauterine pregnancy. They found that, when the physician presumed a diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy on the basis of ultrasound and ß-hCG levels alone, the diagnosis was wrong in almost 40% of cases.

Where’s the harm in presumptive treatment?

Some practitioners argue that proceeding with methotrexate therapy under these circumstances causes no harm. However, presumptive treatment unnecessarily exposes women to the side effects of chemotherapy and artificially inflates methotrexate success rates. Presumptive treatment does not decrease overall side effects or save money. It also falsely labels a woman as having an ectopic pregnancy, which directly affects future diagnosis and prognosis.

For these reasons, always perform uterine curettage when ultrasound imaging is inconclusive and ß-hCG levels are below normal.

CASE 2: Pregnant and in pain, with an adnexal mass

A pregnant patient complaining of moderate pain has a 4-cm adnexal mass identified at ultrasound, with no evidence of an intrauterine gestational sac. What is her diagnosis?

It’s impossible to know based on the ultrasound alone—even though the ultrasonographer may diagnose ectopic pregnancy. Unless you interpret these findings in light of her ß-hCG levels, you have no way of knowing whether she is experiencing a normal gestation, spontaneous abortion, or ectopic pregnancy. In this case, the adnexal mass turned out to be a corpus luteum with hydrosalpinx, and the woman had a viable intrauterine pregnancy.

CASE 3: Intrauterine pregnancy and pain

A 28-year-old gravida 1 para 0 at 8 weeks’ gestation has a fetal heart rate of 160 following in vitro fertilization. She has a history of tubal disease and complains of severe left lower quadrant pain of sudden onset. Repeat ultrasound shows multiple bilateral ovarian cysts with a gestational sac and fetal heart rate of 144 in the left adnexa. How do you proceed?

Heterotopic pregnancy sometimes complicates in vitro fertilization and can be a difficult diagnosis when multiple cysts from superovulation obscure visualization of the adnexal implantation.

The best treatment is laparoscopic removal of the ectopic implantation. Methotrexate is contraindicated because of the possibility of injuring the viable intrauterine pregnancy.

Cigarette smoking increases the likelihood of ectopic pregnancy 2.5 times,12 probably by affecting ciliary action within the fallopian tubes.

Salpingitis isthmic nodosa is anatomic thickening of the proximal portion of the fallopian tubes with multiple lumen diverticula. It increases the risk of ectopic pregnancy 1.5 times, compared with age- and race-matched controls.13

Don’t depend solely on risk factors. Many ectopic pregnancies present without them.

Symptoms. Many ectopic pregnancies never produce symptoms; rather, they resolve spontaneously or are timely diagnosed and treated medically. Risk factors should therefore be examined in any woman in early pregnancy and investigated further if ectopic pregnancy is likely.

When symptoms do occur, they usually involve 1 or all of the classic triad: amenorrhea, irregular bleeding, and lower abdominal pain. In addition, syncope, shock, and pain radiating to the patient’s shoulder can result from hemoperitoneum.

TABLE 1

High, moderate, and low levels of risk factors for ectopic pregnancy

| RISK FACTOR | ODDS RATIO* |

|---|---|

| High risk | |

| Tubal surgery | 21.0 |

| Tubal ligation | 9.3 |

| Previous ectopic pregnancy | 8.3 |

| In utero exposure to diethylstilbestrol | 5.6 |

| Use of intrauterine device | 4.2–45.0 |

| Documented tubal pathology | 3.8–21.0 |

| Assisted reproduction | 4.0 |

| Emergency contraception | High |

| Moderate risk | |

| Infertility | 2.5–21.0 |

| Previous genital infections | 2.5–3.7 |

| Multiple sexual partners | 2.1 |

| Salpingitis (isthmic) | 1.5 |

| Slight risk | |

| Previous pelvic, abdominal surgery | 0.9–3.8 |

| Cigarette smoking | 2.3–2.5 |

| Vaginal douching | 1.1–3.1 |

| Early age at first intercourse (<18 years) | 1.6 |

| Reprinted with permission from Elsevier (The Lancet, 1998, vol 351, 1115–1120). | |

| * Single values = common odds ratio from homogeneous studies; point estimates = range of values from heterogeneous studies | |

STEP 2Document the pregnancy and measure ß-hCG

Once you identify the high-risk patient, or a woman comes in complaining of pain and spotting or bleeding, run a pregnancy test to confirm that she is pregnant and, if it is positive, obtain a quantitative ß-hCG.

ß-hCG levels are normally measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA), which detect ß-hCG in urine and serum at levels as low as 20 mIU/mL and 10 mIU/mL, respectively.14 ß-hCG is produced by trophoblastic cells in normal pregnancy, and approximately doubles every 2 days when titers are below 10,000 mIU/mL15—although in some normal pregnancies, ß-hCG may increase as slowly as 53% or as rapidly as 230% over 2 days.16 Eighty-five percent of abnormal pregnancies—whether intrauterine or ectopic—have impaired ß-hCG production with prolonged doubling time. Thus, in failing pregnancies, ß-hCG levels will plateau or fail to rise normally.

A single ß-hCG level fails to predict the risk of rupture, since ectopic pregnancies can rupture at ß-hCG levels as low as 10 mIU/mL or far exceeding 10,000 mIU/mL, or at any level in between.

STEP 3Obtain an ultrasound scan

Transvaginal ultrasound reliably detects normal intrauterine gestations when ß-hCG passes somewhere between 1,000 mIU/mL and 2,000 mIU/mL (First International Reference Preparation), depending on the expertise of the ultrasonographer and the particular equipment used.8,17 This is known as the “discriminatory zone.” ß-hCG levels reach this zone as early as 1 week after missed menses.18

The discriminatory zone is not the lowest ß-hCG concentration at which an intrauterine pregnancy can be visualized via ultrasound. Rather, it is the value at which any intrauterine pregnancy will be apparent. At that value, the absence of an intrauterine pregnancy confirms—by negative conclusion—that the patient has a nonviable gestation.

When intrauterine pregnancy is visualized. The diagnosis is definitive and the woman’s symptoms can be explained as “threatened abortion.” No further investigation is necessary aside from routine prenatal care if the pregnancy continues.

When an extrauterine gestation is observed, such as a gestational sac with a detectable fetal heart rate, ectopic pregnancy can be diagnosed with 100% specificity but low sensitivity (15% to 20%). A complex adnexal mass without an intrauterine pregnancy improves sensitivity from 21% to 84% at the expense of lower specificity (93% to 99.5%).19

Even when an adnexal mass is visualized, cardiac activity is not usually present. If cardiac activity is apparent, proceed to surgery, since methotrexate usually will not resolve these gestations.

Be aware that some adnexal masses suspicious for ectopic pregnancy may turn out to be other entities, such as a corpus luteum, hydrosalpinx, ovarian neoplasm, or endometrioma. Unless a fetal heart rate is detected by ultrasound, the diagnosis is uncertain and curettage is needed to establish a definitive diagnosis.

No intrauterine pregnancy, no extrauterine mass. Despite the high resolution of transvaginal ultrasound, many patients with ectopic pregnancy have no apparent adnexal mass,20 particularly when diagnosis is early. In these cases, proceed to curettage (step 4).

Don’t interpret ultrasound findings in a vacuum

This is especially unwise when ß-hCG levels are low—even when the ultrasound report points to intrauterine pregnancy. At ß-hCG levels below 1,500 mIU/mL, the sensitivity of ultrasound in diagnosing intrauterine pregnancy drops from 98% to 33% and predictive value is substantially lower. Interpret ultrasound and ß-hCG levels together for greater accuracy.

How size influences management

Ultrasound can detect ectopic pregnancies as small as 2 cm. In general, an ectopic sac size larger than 4 cm should be treated surgically.

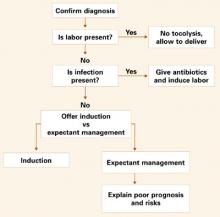

STEP 4Perform uterine curettage

If ultrasound imaging is inconclusive and ß-hCG levels are plateauing or rising subnormally, perform uterine curettage. If ß-hCG levels decrease 15% or more 8 to 12 hours after the procedure, a complete abortion can be strongly suspected.21 If ß-hCG levels plateau or rise, the trophoblasts were not removed by curettage, and ectopic pregnancy is diagnosed.21

Keep in mind these important points:

- Without uterine curettage, roughly 40% of ectopic pregnancy diagnoses are incorrect.22

- Because curettage will result in termination of pregnancy, it is vital that it be limited to cases involving abnormal ß-hCG levels, not normally rising values.

STEP 5Administer methotrexate

Medical management is indicated when the following circumstances are present:

- No viable intrauterine pregnancy is present.

- No rupture has occurred.

- Any adnexal mass is 4 cm in size or smaller.

- ß-hCG levels are below 10,000 mIU/mL.

If there is a positive fetal heart beat, surgery is preferred.

Firm diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy is essential prior to methotrexate administration. If the drug is given to a woman carrying a viable pregnancy, it may result in loss of the pregnancy or methotrexate embryopathy.23

How methotrexate resolves ectopic pregnancy

Systemic methotrexate has been used successfully in the treatment of ectopic pregnancy for more than 20 years. A folic acid antagonist, it inhibits de novo synthesis of purines and pyrimidines. It thus interferes with DNA synthesis and cell multiplication.24 Actively proliferating trophoblasts are particularly vulnerable.25

When methotrexate is administered to normally pregnant women, it blunts the normal ß-hCG increment over the next 7 days. Circulating progesterone and 17-a-hydroxyprogesterone concentrations also decline, and abortion occurs.26

Methotrexate directly impairs trophoblastic production of hCG; the decrement in corpus luteum progesterone is a secondary event.

Side effects include abdominal distress, chills and fever, dizziness, immunosuppression, leukopenia, malaise, nausea, ulcerative stomatitis, photosensitivity, and undue fatigue.

Breastfeeding is an absolute contraindication to methotrexate, while relative contraindications include abnormal liver function tests, blood dyscrasias, excessive alcohol consumption, HIV/AIDS, psoriasis, ongoing radiotherapy, rheumatoid arthritis, and significant pulmonary disease.

Multiple-dose methotrexate is superior

In a recent meta-analysis comparing single-and multiple-dose regimens of methotrexate, Barnhart and colleagues4 found the latter to be more effective, although the single dose was more commonly given. The single-dose regimen was associated with a significantly greater chance of failure in both crude (OR 1.71; 1.04, 2.82) and adjusted (OR 4.74; 1.77, 12.62) analyses. Consequently, we advocate the multiple-dose regimen detailed in TABLE 2: 1 mg of methotrexate per kilogram of body weight on day 1, alternating with 0.1 mg of leucovorin per kilogram on succeeding days. Continue this regimen until ß-hCG levels decline in 2 consecutive daily titers, or 4 doses of methotrexate are given, whichever comes first.

If treatment is unsuccessful after 4 doses, additional methotrexate is unlikely to be effective and will involve significant additional cost and morbidity. If ß-hCG levels plateau or continue to rise, surgery is indicated.

Although multiple-dose therapy is more effective than a single dose, the optimal number of doses probably falls somewhere between 1 and 4.4 A 2-dose protocol currently under investigation may provide an optimal compromise.

Artificially high efficacy rates with “single-dose” therapy. Unusually high success rates in initial studies of the single-dose regimen may have been due to the inclusion of spontaneously aborting intrauterine pregnancies.27 Although 6 subsequent studies—1 cohort and 5 case-control studies involving 304 patients—found an overall success rate (no surgical intervention) of 87.2%, 11.5% of participants required more than 1 dose.9

Still the standard. Despite its lower efficacy rates, single-dose methotrexate remains the “standard” in the United States, as recommended in an American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists practice bulletin.28 The usual intramuscular dose is 50 mg per square meter of body surface area, with ß-hCG titers on days 4 and 7 and an additional dose if ß-hCG levels fail to resolve.

What the evidence shows

Multidose methotrexate. Twelve studies measured the success of multiple-dose systemic methotrexate (TABLE 3); they included 1 randomized, controlled trial, 1 cohort study, and 10 case series. Between 1982 and 1997, 325 cases were treated with multiple-dose methotrexate. Of these, 93.8% had successful resolution with no subsequent therapy, and 78.9% of the 161 women tested had patent oviducts. In addition, of 95 women hoping to conceive, 57.9% had a subsequent intrauterine pregnancy and 7.4% developed a recurrent ectopic pregnancy. These rates compared favorably with numerous laparoscopic surgery series published during the same years.9

Methotrexate versus laparoscopic salpingostomy. In 1 randomized clinical comparison,29 100 women with laparoscopy-confirmed ectopic pregnancy were randomized to methotrexate or laparoscopic salpingostomy. Of the 51 patients treated medically, 7 (14%) required surgical intervention for active bleeding and/or tubal rupture. An additional course of methotrexate was required in 2 patients (4%) for persistent trophoblasts.

Of the 49 patients in the salpingostomy group, 4 women (8%) failed therapy and required salpingectomies, and 10 patients (20%) were treated with methotrexate for persistent trophoblasts.

Tubal patency was present in 23 of 42 women (55%) in the methotrexate group, compared with 23 of 39 (59%) in the salpingostomy group.

Overall, this randomized study29 and previous meta-analysis demonstrate that systemic multiple-dose methotrexate is comparable in efficacy to laparoscopic salpingostomy.

TABLE 2

Multiple-dose methotrexate protocol

Discontinue treatment when there is a decline in 2 consecutive ß-hCG titers or after 4 doses, whichever comes first.

| DAY | INTERVENTION | DOSE (MG) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Baseline studies ß-hCG titer, CBC, and platelets Methotrexate | 1.0 |

| 2 | Leucovori | 0.1 |

| 3 | Methotrexate | 1.0 |

| 4 | Leucovorin ß-hCG titer | 0.1 |

| 5 | Methotrexate ß-hCG titer | 1.0 |

| 6 | Leucovorin ß-hCG titer | 0.1 |

| 7 | Methotrexate ß-hCG titer | 1.0 |

| 8 | Leucovorin ß-hCG titer CBC and platelets Renal and liver function tests | 0.1 |

| Weekly | ß-hCG titer until negative |

TABLE 3

Treatment outcomes for ectopic pregnancy

| METHOD | NUMBER OF STUDIES | NUMBER OF PATIENTS | NUMBER WITH SUCCESSFUL RESOLUTION | TUBAL PATENCY RATE | SUBSEQUENT FERTILITY RATE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INTRAUTERINE PREGNANCY | ECTOPIC PREGNANCY | |||||

| Conservative laparoscopic surgery | 32 | 1,626 | 1,516 (93%) | 170/223 (76%) | 366/647 (57%) | 87/647 (13%) |

| Variable-dose methotrexate | 12 | 338 | 314 (93%) | 136/182 (75%) | 55/95 (58%) | 7/95 (7%) |

| Single-dose methotrexate | 7 | 393 | 340 (87%) | 61/75 (81%) | 39/64 (61%) | 5/64 (8%) |

| Direct-injection methotrexate | 21 | 660 | 502 (76%) | 130/162 (80%) | 87/152 (57%) | 9/152 (6%) |

| Expectant management | 14 | 628 | 425 (68%) | 60/79 (76%) | 12/14 (86%) | 1/14 (7%) |

| Reprinted with permission from Elsevier (The Lancet, 1998, vol 351, 1115–1120). | ||||||

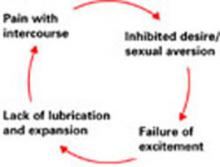

Fine points of treatment

During methotrexate therapy, examine the patient only once to avoid triggering a rupture, and counsel her to avoid intercourse for the same reason.30 Do not perform repeat vaginal ultrasound examination. Also inform her that transient pain (“separation pain”) from tubal abortion frequently occurs 3 to 7 days after the start of therapy, lasts 4 to 12 hours, and then resolves.31 This is perhaps the most difficult aspect of methotrexate therapy, as it is not always easy to differentiate the pain of tubal abortion from the pain of rupture.

If ß-hCG titers continue to rise rapidly between methotrexate doses, rupture is more likely and surgery should proceed.32

Overall, isthmic ectopic pregnancies (12.3% of ectopics) appear to be at a particularly high risk for rupture and comprise nearly half of methotrexate failures.32 Unfortunately, there is no way to identify isthmic pregnancies without surgery.

Avoid NSAIDs and GI-“unfriendly” foods. Counsel the patient to avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) because they may impair natural hemostasis. Gasforming foods such as leeks, corn, and cabbage can cause distension, which may be mistaken for rupture.

Also instruct the patient to avoid folic acid, which impairs the efficacy of methotrexate.

Ultrasound surveillance is unnecessary. If an adnexal mass was identified at initial imaging, there is no need to view it again, since these masses tend to enlarge and form hematomas and can cause undue anxiety in both physician and patient. In properly selected patients, multidose methotrexate with monitoring of ß-hCG levels should suffice.

When surgery is indicated

Surgical intervention is necessary when pain is severe, persists beyond 12 hours, and is associated with orthostatic hypotension, falling hematocrit, or persistently elevated ß-hCG levels after methotrexate therapy.

Laparoscopy is the preferred approach. Advantages include less blood loss and analgesia,33 shortened postoperative recovery, and lower costs.

Technique. For unruptured ampullary ectopic pregnancy, salpingostomy is preferred. Make a linear incision over the bulging antimesenteric border of the fallopian tube using electrocautery, scissors, or laser. Remove the products of conception using forceps or suction, and leave the incision to heal by secondary intention.

For isthmic pregnancies, use segmental excision followed by delayed microsurgical anastomosis.34 The isthmic tubal lumen is narrower and the muscularis thicker than in the ampulla. Thus, the isthmus is predisposed to greater damage after salpingostomy and greater rates of proximal obstruction.33

An increased risk of persistent ectopic pregnancy has been a criticism of salpingostomy. However, when 1 dose of systemic methotrexate is combined with salpingostomy, the risk of persistent pregnancy is virtually eliminated.35

When rupture occurs, salpingectomy is the first choice for treatment, as it arrests hemorrhage and shortens the procedure. Either laparoscopy or laparotomy is appropriate.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ectopic Pregnancy - United States, 1990-1992. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1995;44:46-48.

2. Washington AE, Katz P. Ectopic pregnancy in the United States: economic consequences and payment source trends. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;81:287-292.

3. Lipscomb GH, McCord ML, Stovall TG, Huff G, Portera SG, Ling FW. Predictors of success of methotrexate treatment in women with tubal ectopic pregnancies. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1974-1978.

4. Barnhart K, Esposito M, Coutifaris C. An update on the medical treatment of ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2000;27:653-667.

5. Goldner TE, Lawson HW, Xia Z, et al. Surveillance for ectopic pregnancy—United States, 1970-1989. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ. 1993;42:73-85.

6. Ankum WM, Mol BW, Van der Veen F, et al. Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy: a meta analysis. Fertil Steril. 1996;65:1093-1099.

7. 2001 Assisted Reproductive Technology Success Rates: National Summary and Fertility Clinical Reports; December 2003

8. Barnhart K, Mennuti MT, Benjamin I, et al. Prompt diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy in an emergency department setting. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84:1010-1015.

9. Pisarska MD, Carson SA, Buster JE. Ectopic pregnancy. Lancet. 1998;351:1115-1120.

10. A multinational case-control study of ectopic pregnancy. The World Health Organization’s Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction: Task Force on Intrauterine Devices for Fertility Regulation. Clin Reprod Fertil. 1985;3:131-143.

11. Russell JB. The etiology of ectopic pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1987;30:181-190.

12. Chow WH, Daling JR, Cates W, Jr, et al. Epidemiology of ectopic pregnancy. Epidemiol Rev. 1987;9:70-94.

13. Majmudar B, Henderson PH, III, Semple E. Salpingitis isthmica nodosa: a high-risk factor for tubal pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1983;62:73-78.

14. Christensen H, Thyssen HH, Schebye O, et al. Three highly sensitive “bedside” serum and urine tests for pregnancy compared. Clin Chem. 1990;36:1686-1688.

15. Kadar N, Romero R. Further observations on serial human chorionic gonadotropin patterns in ectopic pregnancies and spontaneous abortions. Fertil Steril. 1988;50:367-370.

16. Barnhart KT, Sammel MD, Rinaudo PF, et al. Symptomatic patients with an early viable intrauterine pregnancy: HCG curves redefined. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:50-55.

17. Bateman BG, Nunley WC, Jr, Kolp LA, et al. Vaginal sonography findings and hCG dynamics of early intrauterine and tubal pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:421-427.

18. Kadar N, DeVore G, Romero R. Discriminatory hCG zone: its use in the sonographic evaluation for ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1981;58:156-161.

19. Brown DL, Doubilet PM. Transvaginal sonography for diagnosing ectopic pregnancy: positivity criteria and performance characteristics. J Ultrasound Med. 1994;13:259-266.

20. Russell SA, Filly RA, Damato N. Sonographic diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy with endovaginal probes: what really has changed? J Ultrasound Med. 1993;12:145-151.

21. Stovall TG, Ling FW, Carson SA, et al. Serum progesterone and uterine curettage in differential diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 1992;57:456-457.

22. Barnhart KT, Katz I, Hummel A, Gracia CR. Presumed diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:505-510.

23. Adam MP, Manning MA, Beck AE, et al. Methotrexate/misoprostol embryopathy: report of four cases resulting from failed medical abortion. Am J Med Genet. 2003;123A:72-78.

24. DeLoia JA, Stewart-Akers AM, Creinin MD. Effects of methotrexate on trophoblast proliferation and local immune responses. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:1063-1069.

25. Sand PK, Stubblefield PA, Ory SJ. Methotrexate inhibition of normal trophoblasts in vitro. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1986;155:324-329.

26. Creinin MD, Stewart-Akers AM, DeLoia JA. Methotrexate effects on trophoblast and the corpus luteum in early pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:604-609.

27. Stovall TG, Ling FW, Gray LA. Single-dose methotrexate for treatment of ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77:754-757.

28. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin #3: Medical Management of Tubal Pregnancy. Washington, DC: ACOG; 1998.

29. Hajenius PJ, Engelsbel S, Mol BW, et al. Randomised trial of systemic methotrexate versus laparoscopic salpingostomy in tubal pregnancy. Lancet. 1997;350:774-779.

30. Stovall TG, Ling FW, Gray LA. Single-dose methotrexate for treatment of ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77:754-757.

31. Lipscomb GH, Puckett KJ, Bran D, et al. Management of separation pain after single-dose methotrexate therapy for ectopic pregnancy. Prim Care Update Ob Gyns. 1998;5:175.-

32. Dudley P, et al. Characterizing ectopic pregnancies that rupture despite treatment with methotrexate. Fertil Steril [in press].

33. Murphy AA, Nager CW, Wujek JJ, et al. Operative laparoscopy versus laparotomy for the management of ectopic pregnancy: a prospective trial. Fertil Steril. 1992;57:1180-1185.

34. Balasch J, Barri PN. Treatment of ectopic pregnancy: the new gynaecological dilemma. Hum Reprod. 1994;9:547-558.

35. Gracia CR, Bron HA, Barnhart KT. Prophylactic methotrexate after linear salpingostomy: a decision analysis. Fertil Steril. 2001;76:1191-1195.

36. Breen JL. A 21-year survey of 654 ectopic pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1970;106:1004-1019.

- In properly selected cases, medical therapy and surgery produce similar outcomes, but medicine is less expensive.

- Surgery is still the first choice for hemorrhage, medical failure, rupture or near-rupture, and when medical therapy is contraindicated.

- Systemic methotrexate and laparoscopic salpingostomy produce similar success rates and long-term fertility.

- Single-dose methotrexate is associated with a higher risk of rupture than multiple doses.

Although ectopic pregnancy remains a leading cause of life-threatening first-trimester morbidity, accounting for about 9% of maternal deaths annually,1 we now are able to diagnose and treat most cases well before rupture occurs—in some cases, as early as 5 weeks’ gestation. As a result, medical therapy with systemic methotrexate has become the first-line treatment, with surgery reserved for hemorrhage, medical failures, neglected cases, and circumstances in which medical therapy is contraindicated.

Early diagnosis not only makes medical therapy possible, it also is cheaper, since it avoids rupture, blood loss, and surgery; preserves fertility; and minimizes lost productivity. This is important because ectopic pregnancy is an expensive condition, with an annual health-care bill exceeding $1 billion.2

Despite this progress, serious challenges remain. Medical management is not for everyone. Success is inversely related to initial serum human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) levels3 and diminishes substantially when embryonic cardiac activity is observed during ultrasound imaging.4

In addition, because medical therapy has made outpatient treatment the norm in most cases, it has become virtually impossible to chart the prevalence of ectopic pregnancy. In past years, when hospital records were used, ectopic pregnancy rates were increasing relentlessly, from 4.5 per 1,000 pregnancies in 1970 to 16.8 in 1989 and 19.7 (108,000 cases) in 1992.1,5

Reasons for increasing rates

Today the prevalence of ectopic pregnancy is probably still rising, for several reasons:

- a greater incidence of risk factors such as sexually transmitted and tubal disease,6

- improved diagnostic methods, and

- the use of assisted reproductive technology (ART) to treat infertility (roughly 2% of ART pregnancies are ectopic).7

This article describes a 5-step approach to diagnosis and medical management with multiple-dose methotrexate, as well as fine points of treatment and basic surgical technique. It includes a protocol for multiple-dose methotrexate, a table summarizing treatment outcomes, and several case histories.

Likelihood of ectopic pregnancy

If 100 women present with a positive pregnancy test and pain and bleeding, approximately 60 will have a normal pregnancy, 30 are experiencing spontaneous abortion, and 9 have an ectopic pregnancy.8

STEP 1Assess risk factors and symptoms

The first step in early diagnosis is being vigilant for risk factors and symptoms associated with ectopic pregnancy, most of which are well known9:

Tubal disease carries a 3.5-fold common adjusted odds ratio (OR) for ectopic pregnancy. In addition, women with a previous ectopic pregnancy are 6 to 8 times more likely to experience another, while a history of tubal surgery raises that likelihood to 21. A history of pelvic infection, including gonorrhea, serologically confirmed chlamydia, and pelvic inflammatory disease, increases the risk of ectopic pregnancy 2 to 4 times.9

Contraception. Intrauterine devices (IUDs) are associated with an increased OR of 6.4.10 This does not mean that IUDs cause ectopic pregnancy. Rather, when a woman with an IUD becomes pregnant, an ectopic gestation should be high on the list of possibilities. A similar relationship exists between ectopic pregnancy and tubal ligation, which carries an OR of 9.3.9 Oral contraceptives are associated with a reduced risk of ectopic pregnancy unless they are used as emergency contraception (ie, after fertilization), in which case they are associated with an increased risk (TABLE 1).

Diethylstilbestrol exposure in utero alters fallopian tube morphology and can lead to absent or minimal fimbrial tissue, a small tubal os, and decreased length and caliber of the tube.11 Abnormal tubal anatomy caused by this exposure multiplies the risk of ectopic pregnancy by a factor of 5.9

In vitro fertilization. When blocked tubes are treated, the embryos can migrate retrograde into the oviduct, implant, and eventually rupture. The OR for ectopic pregnancy with assisted reproduction is 4.0.8

Although a patient’s ß-hCG levels, symptoms, or imaging may suggest ectopic pregnancy, missed diagnoses abound, especially when the physician omits 1 element of the triad: ß-hCG levels, ultrasound imaging, and curettage.

CASE 1: Pain and bleeding, with a high hCG

Mrs. Jones presents with pain and bleeding and a ß-hCG level of 6,000 mIU/mL. Ultrasound imaging reveals no intrauterine pregnancy. Should you presume the diagnosis is ectopic pregnancy and start methotrexate therapy? Or should you play it safe and perform curettage?

To explore these questions, Barnhart and colleagues22 performed a retrospective cohort analysis involving women with ß-hCG levels above 2,000 mIU/mL and no ultrasound evidence of an intrauterine pregnancy. They found that, when the physician presumed a diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy on the basis of ultrasound and ß-hCG levels alone, the diagnosis was wrong in almost 40% of cases.

Where’s the harm in presumptive treatment?

Some practitioners argue that proceeding with methotrexate therapy under these circumstances causes no harm. However, presumptive treatment unnecessarily exposes women to the side effects of chemotherapy and artificially inflates methotrexate success rates. Presumptive treatment does not decrease overall side effects or save money. It also falsely labels a woman as having an ectopic pregnancy, which directly affects future diagnosis and prognosis.

For these reasons, always perform uterine curettage when ultrasound imaging is inconclusive and ß-hCG levels are below normal.

CASE 2: Pregnant and in pain, with an adnexal mass

A pregnant patient complaining of moderate pain has a 4-cm adnexal mass identified at ultrasound, with no evidence of an intrauterine gestational sac. What is her diagnosis?

It’s impossible to know based on the ultrasound alone—even though the ultrasonographer may diagnose ectopic pregnancy. Unless you interpret these findings in light of her ß-hCG levels, you have no way of knowing whether she is experiencing a normal gestation, spontaneous abortion, or ectopic pregnancy. In this case, the adnexal mass turned out to be a corpus luteum with hydrosalpinx, and the woman had a viable intrauterine pregnancy.

CASE 3: Intrauterine pregnancy and pain

A 28-year-old gravida 1 para 0 at 8 weeks’ gestation has a fetal heart rate of 160 following in vitro fertilization. She has a history of tubal disease and complains of severe left lower quadrant pain of sudden onset. Repeat ultrasound shows multiple bilateral ovarian cysts with a gestational sac and fetal heart rate of 144 in the left adnexa. How do you proceed?

Heterotopic pregnancy sometimes complicates in vitro fertilization and can be a difficult diagnosis when multiple cysts from superovulation obscure visualization of the adnexal implantation.

The best treatment is laparoscopic removal of the ectopic implantation. Methotrexate is contraindicated because of the possibility of injuring the viable intrauterine pregnancy.

Cigarette smoking increases the likelihood of ectopic pregnancy 2.5 times,12 probably by affecting ciliary action within the fallopian tubes.

Salpingitis isthmic nodosa is anatomic thickening of the proximal portion of the fallopian tubes with multiple lumen diverticula. It increases the risk of ectopic pregnancy 1.5 times, compared with age- and race-matched controls.13

Don’t depend solely on risk factors. Many ectopic pregnancies present without them.

Symptoms. Many ectopic pregnancies never produce symptoms; rather, they resolve spontaneously or are timely diagnosed and treated medically. Risk factors should therefore be examined in any woman in early pregnancy and investigated further if ectopic pregnancy is likely.

When symptoms do occur, they usually involve 1 or all of the classic triad: amenorrhea, irregular bleeding, and lower abdominal pain. In addition, syncope, shock, and pain radiating to the patient’s shoulder can result from hemoperitoneum.

TABLE 1

High, moderate, and low levels of risk factors for ectopic pregnancy

| RISK FACTOR | ODDS RATIO* |

|---|---|

| High risk | |

| Tubal surgery | 21.0 |

| Tubal ligation | 9.3 |

| Previous ectopic pregnancy | 8.3 |

| In utero exposure to diethylstilbestrol | 5.6 |

| Use of intrauterine device | 4.2–45.0 |

| Documented tubal pathology | 3.8–21.0 |

| Assisted reproduction | 4.0 |

| Emergency contraception | High |

| Moderate risk | |

| Infertility | 2.5–21.0 |

| Previous genital infections | 2.5–3.7 |

| Multiple sexual partners | 2.1 |

| Salpingitis (isthmic) | 1.5 |

| Slight risk | |

| Previous pelvic, abdominal surgery | 0.9–3.8 |

| Cigarette smoking | 2.3–2.5 |

| Vaginal douching | 1.1–3.1 |

| Early age at first intercourse (<18 years) | 1.6 |

| Reprinted with permission from Elsevier (The Lancet, 1998, vol 351, 1115–1120). | |

| * Single values = common odds ratio from homogeneous studies; point estimates = range of values from heterogeneous studies | |

STEP 2Document the pregnancy and measure ß-hCG

Once you identify the high-risk patient, or a woman comes in complaining of pain and spotting or bleeding, run a pregnancy test to confirm that she is pregnant and, if it is positive, obtain a quantitative ß-hCG.

ß-hCG levels are normally measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA), which detect ß-hCG in urine and serum at levels as low as 20 mIU/mL and 10 mIU/mL, respectively.14 ß-hCG is produced by trophoblastic cells in normal pregnancy, and approximately doubles every 2 days when titers are below 10,000 mIU/mL15—although in some normal pregnancies, ß-hCG may increase as slowly as 53% or as rapidly as 230% over 2 days.16 Eighty-five percent of abnormal pregnancies—whether intrauterine or ectopic—have impaired ß-hCG production with prolonged doubling time. Thus, in failing pregnancies, ß-hCG levels will plateau or fail to rise normally.

A single ß-hCG level fails to predict the risk of rupture, since ectopic pregnancies can rupture at ß-hCG levels as low as 10 mIU/mL or far exceeding 10,000 mIU/mL, or at any level in between.

STEP 3Obtain an ultrasound scan

Transvaginal ultrasound reliably detects normal intrauterine gestations when ß-hCG passes somewhere between 1,000 mIU/mL and 2,000 mIU/mL (First International Reference Preparation), depending on the expertise of the ultrasonographer and the particular equipment used.8,17 This is known as the “discriminatory zone.” ß-hCG levels reach this zone as early as 1 week after missed menses.18

The discriminatory zone is not the lowest ß-hCG concentration at which an intrauterine pregnancy can be visualized via ultrasound. Rather, it is the value at which any intrauterine pregnancy will be apparent. At that value, the absence of an intrauterine pregnancy confirms—by negative conclusion—that the patient has a nonviable gestation.

When intrauterine pregnancy is visualized. The diagnosis is definitive and the woman’s symptoms can be explained as “threatened abortion.” No further investigation is necessary aside from routine prenatal care if the pregnancy continues.

When an extrauterine gestation is observed, such as a gestational sac with a detectable fetal heart rate, ectopic pregnancy can be diagnosed with 100% specificity but low sensitivity (15% to 20%). A complex adnexal mass without an intrauterine pregnancy improves sensitivity from 21% to 84% at the expense of lower specificity (93% to 99.5%).19

Even when an adnexal mass is visualized, cardiac activity is not usually present. If cardiac activity is apparent, proceed to surgery, since methotrexate usually will not resolve these gestations.

Be aware that some adnexal masses suspicious for ectopic pregnancy may turn out to be other entities, such as a corpus luteum, hydrosalpinx, ovarian neoplasm, or endometrioma. Unless a fetal heart rate is detected by ultrasound, the diagnosis is uncertain and curettage is needed to establish a definitive diagnosis.

No intrauterine pregnancy, no extrauterine mass. Despite the high resolution of transvaginal ultrasound, many patients with ectopic pregnancy have no apparent adnexal mass,20 particularly when diagnosis is early. In these cases, proceed to curettage (step 4).

Don’t interpret ultrasound findings in a vacuum

This is especially unwise when ß-hCG levels are low—even when the ultrasound report points to intrauterine pregnancy. At ß-hCG levels below 1,500 mIU/mL, the sensitivity of ultrasound in diagnosing intrauterine pregnancy drops from 98% to 33% and predictive value is substantially lower. Interpret ultrasound and ß-hCG levels together for greater accuracy.

How size influences management

Ultrasound can detect ectopic pregnancies as small as 2 cm. In general, an ectopic sac size larger than 4 cm should be treated surgically.

STEP 4Perform uterine curettage

If ultrasound imaging is inconclusive and ß-hCG levels are plateauing or rising subnormally, perform uterine curettage. If ß-hCG levels decrease 15% or more 8 to 12 hours after the procedure, a complete abortion can be strongly suspected.21 If ß-hCG levels plateau or rise, the trophoblasts were not removed by curettage, and ectopic pregnancy is diagnosed.21

Keep in mind these important points:

- Without uterine curettage, roughly 40% of ectopic pregnancy diagnoses are incorrect.22

- Because curettage will result in termination of pregnancy, it is vital that it be limited to cases involving abnormal ß-hCG levels, not normally rising values.

STEP 5Administer methotrexate

Medical management is indicated when the following circumstances are present:

- No viable intrauterine pregnancy is present.

- No rupture has occurred.

- Any adnexal mass is 4 cm in size or smaller.

- ß-hCG levels are below 10,000 mIU/mL.

If there is a positive fetal heart beat, surgery is preferred.

Firm diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy is essential prior to methotrexate administration. If the drug is given to a woman carrying a viable pregnancy, it may result in loss of the pregnancy or methotrexate embryopathy.23

How methotrexate resolves ectopic pregnancy

Systemic methotrexate has been used successfully in the treatment of ectopic pregnancy for more than 20 years. A folic acid antagonist, it inhibits de novo synthesis of purines and pyrimidines. It thus interferes with DNA synthesis and cell multiplication.24 Actively proliferating trophoblasts are particularly vulnerable.25

When methotrexate is administered to normally pregnant women, it blunts the normal ß-hCG increment over the next 7 days. Circulating progesterone and 17-a-hydroxyprogesterone concentrations also decline, and abortion occurs.26

Methotrexate directly impairs trophoblastic production of hCG; the decrement in corpus luteum progesterone is a secondary event.

Side effects include abdominal distress, chills and fever, dizziness, immunosuppression, leukopenia, malaise, nausea, ulcerative stomatitis, photosensitivity, and undue fatigue.

Breastfeeding is an absolute contraindication to methotrexate, while relative contraindications include abnormal liver function tests, blood dyscrasias, excessive alcohol consumption, HIV/AIDS, psoriasis, ongoing radiotherapy, rheumatoid arthritis, and significant pulmonary disease.

Multiple-dose methotrexate is superior

In a recent meta-analysis comparing single-and multiple-dose regimens of methotrexate, Barnhart and colleagues4 found the latter to be more effective, although the single dose was more commonly given. The single-dose regimen was associated with a significantly greater chance of failure in both crude (OR 1.71; 1.04, 2.82) and adjusted (OR 4.74; 1.77, 12.62) analyses. Consequently, we advocate the multiple-dose regimen detailed in TABLE 2: 1 mg of methotrexate per kilogram of body weight on day 1, alternating with 0.1 mg of leucovorin per kilogram on succeeding days. Continue this regimen until ß-hCG levels decline in 2 consecutive daily titers, or 4 doses of methotrexate are given, whichever comes first.

If treatment is unsuccessful after 4 doses, additional methotrexate is unlikely to be effective and will involve significant additional cost and morbidity. If ß-hCG levels plateau or continue to rise, surgery is indicated.

Although multiple-dose therapy is more effective than a single dose, the optimal number of doses probably falls somewhere between 1 and 4.4 A 2-dose protocol currently under investigation may provide an optimal compromise.

Artificially high efficacy rates with “single-dose” therapy. Unusually high success rates in initial studies of the single-dose regimen may have been due to the inclusion of spontaneously aborting intrauterine pregnancies.27 Although 6 subsequent studies—1 cohort and 5 case-control studies involving 304 patients—found an overall success rate (no surgical intervention) of 87.2%, 11.5% of participants required more than 1 dose.9

Still the standard. Despite its lower efficacy rates, single-dose methotrexate remains the “standard” in the United States, as recommended in an American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists practice bulletin.28 The usual intramuscular dose is 50 mg per square meter of body surface area, with ß-hCG titers on days 4 and 7 and an additional dose if ß-hCG levels fail to resolve.

What the evidence shows

Multidose methotrexate. Twelve studies measured the success of multiple-dose systemic methotrexate (TABLE 3); they included 1 randomized, controlled trial, 1 cohort study, and 10 case series. Between 1982 and 1997, 325 cases were treated with multiple-dose methotrexate. Of these, 93.8% had successful resolution with no subsequent therapy, and 78.9% of the 161 women tested had patent oviducts. In addition, of 95 women hoping to conceive, 57.9% had a subsequent intrauterine pregnancy and 7.4% developed a recurrent ectopic pregnancy. These rates compared favorably with numerous laparoscopic surgery series published during the same years.9

Methotrexate versus laparoscopic salpingostomy. In 1 randomized clinical comparison,29 100 women with laparoscopy-confirmed ectopic pregnancy were randomized to methotrexate or laparoscopic salpingostomy. Of the 51 patients treated medically, 7 (14%) required surgical intervention for active bleeding and/or tubal rupture. An additional course of methotrexate was required in 2 patients (4%) for persistent trophoblasts.

Of the 49 patients in the salpingostomy group, 4 women (8%) failed therapy and required salpingectomies, and 10 patients (20%) were treated with methotrexate for persistent trophoblasts.

Tubal patency was present in 23 of 42 women (55%) in the methotrexate group, compared with 23 of 39 (59%) in the salpingostomy group.

Overall, this randomized study29 and previous meta-analysis demonstrate that systemic multiple-dose methotrexate is comparable in efficacy to laparoscopic salpingostomy.

TABLE 2

Multiple-dose methotrexate protocol

Discontinue treatment when there is a decline in 2 consecutive ß-hCG titers or after 4 doses, whichever comes first.

| DAY | INTERVENTION | DOSE (MG) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Baseline studies ß-hCG titer, CBC, and platelets Methotrexate | 1.0 |

| 2 | Leucovori | 0.1 |

| 3 | Methotrexate | 1.0 |

| 4 | Leucovorin ß-hCG titer | 0.1 |

| 5 | Methotrexate ß-hCG titer | 1.0 |

| 6 | Leucovorin ß-hCG titer | 0.1 |

| 7 | Methotrexate ß-hCG titer | 1.0 |

| 8 | Leucovorin ß-hCG titer CBC and platelets Renal and liver function tests | 0.1 |

| Weekly | ß-hCG titer until negative |

TABLE 3

Treatment outcomes for ectopic pregnancy

| METHOD | NUMBER OF STUDIES | NUMBER OF PATIENTS | NUMBER WITH SUCCESSFUL RESOLUTION | TUBAL PATENCY RATE | SUBSEQUENT FERTILITY RATE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INTRAUTERINE PREGNANCY | ECTOPIC PREGNANCY | |||||

| Conservative laparoscopic surgery | 32 | 1,626 | 1,516 (93%) | 170/223 (76%) | 366/647 (57%) | 87/647 (13%) |

| Variable-dose methotrexate | 12 | 338 | 314 (93%) | 136/182 (75%) | 55/95 (58%) | 7/95 (7%) |

| Single-dose methotrexate | 7 | 393 | 340 (87%) | 61/75 (81%) | 39/64 (61%) | 5/64 (8%) |

| Direct-injection methotrexate | 21 | 660 | 502 (76%) | 130/162 (80%) | 87/152 (57%) | 9/152 (6%) |

| Expectant management | 14 | 628 | 425 (68%) | 60/79 (76%) | 12/14 (86%) | 1/14 (7%) |

| Reprinted with permission from Elsevier (The Lancet, 1998, vol 351, 1115–1120). | ||||||

Fine points of treatment

During methotrexate therapy, examine the patient only once to avoid triggering a rupture, and counsel her to avoid intercourse for the same reason.30 Do not perform repeat vaginal ultrasound examination. Also inform her that transient pain (“separation pain”) from tubal abortion frequently occurs 3 to 7 days after the start of therapy, lasts 4 to 12 hours, and then resolves.31 This is perhaps the most difficult aspect of methotrexate therapy, as it is not always easy to differentiate the pain of tubal abortion from the pain of rupture.

If ß-hCG titers continue to rise rapidly between methotrexate doses, rupture is more likely and surgery should proceed.32

Overall, isthmic ectopic pregnancies (12.3% of ectopics) appear to be at a particularly high risk for rupture and comprise nearly half of methotrexate failures.32 Unfortunately, there is no way to identify isthmic pregnancies without surgery.

Avoid NSAIDs and GI-“unfriendly” foods. Counsel the patient to avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) because they may impair natural hemostasis. Gasforming foods such as leeks, corn, and cabbage can cause distension, which may be mistaken for rupture.

Also instruct the patient to avoid folic acid, which impairs the efficacy of methotrexate.

Ultrasound surveillance is unnecessary. If an adnexal mass was identified at initial imaging, there is no need to view it again, since these masses tend to enlarge and form hematomas and can cause undue anxiety in both physician and patient. In properly selected patients, multidose methotrexate with monitoring of ß-hCG levels should suffice.

When surgery is indicated

Surgical intervention is necessary when pain is severe, persists beyond 12 hours, and is associated with orthostatic hypotension, falling hematocrit, or persistently elevated ß-hCG levels after methotrexate therapy.

Laparoscopy is the preferred approach. Advantages include less blood loss and analgesia,33 shortened postoperative recovery, and lower costs.

Technique. For unruptured ampullary ectopic pregnancy, salpingostomy is preferred. Make a linear incision over the bulging antimesenteric border of the fallopian tube using electrocautery, scissors, or laser. Remove the products of conception using forceps or suction, and leave the incision to heal by secondary intention.

For isthmic pregnancies, use segmental excision followed by delayed microsurgical anastomosis.34 The isthmic tubal lumen is narrower and the muscularis thicker than in the ampulla. Thus, the isthmus is predisposed to greater damage after salpingostomy and greater rates of proximal obstruction.33

An increased risk of persistent ectopic pregnancy has been a criticism of salpingostomy. However, when 1 dose of systemic methotrexate is combined with salpingostomy, the risk of persistent pregnancy is virtually eliminated.35

When rupture occurs, salpingectomy is the first choice for treatment, as it arrests hemorrhage and shortens the procedure. Either laparoscopy or laparotomy is appropriate.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

- In properly selected cases, medical therapy and surgery produce similar outcomes, but medicine is less expensive.

- Surgery is still the first choice for hemorrhage, medical failure, rupture or near-rupture, and when medical therapy is contraindicated.

- Systemic methotrexate and laparoscopic salpingostomy produce similar success rates and long-term fertility.

- Single-dose methotrexate is associated with a higher risk of rupture than multiple doses.

Although ectopic pregnancy remains a leading cause of life-threatening first-trimester morbidity, accounting for about 9% of maternal deaths annually,1 we now are able to diagnose and treat most cases well before rupture occurs—in some cases, as early as 5 weeks’ gestation. As a result, medical therapy with systemic methotrexate has become the first-line treatment, with surgery reserved for hemorrhage, medical failures, neglected cases, and circumstances in which medical therapy is contraindicated.

Early diagnosis not only makes medical therapy possible, it also is cheaper, since it avoids rupture, blood loss, and surgery; preserves fertility; and minimizes lost productivity. This is important because ectopic pregnancy is an expensive condition, with an annual health-care bill exceeding $1 billion.2

Despite this progress, serious challenges remain. Medical management is not for everyone. Success is inversely related to initial serum human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) levels3 and diminishes substantially when embryonic cardiac activity is observed during ultrasound imaging.4

In addition, because medical therapy has made outpatient treatment the norm in most cases, it has become virtually impossible to chart the prevalence of ectopic pregnancy. In past years, when hospital records were used, ectopic pregnancy rates were increasing relentlessly, from 4.5 per 1,000 pregnancies in 1970 to 16.8 in 1989 and 19.7 (108,000 cases) in 1992.1,5

Reasons for increasing rates

Today the prevalence of ectopic pregnancy is probably still rising, for several reasons:

- a greater incidence of risk factors such as sexually transmitted and tubal disease,6

- improved diagnostic methods, and

- the use of assisted reproductive technology (ART) to treat infertility (roughly 2% of ART pregnancies are ectopic).7

This article describes a 5-step approach to diagnosis and medical management with multiple-dose methotrexate, as well as fine points of treatment and basic surgical technique. It includes a protocol for multiple-dose methotrexate, a table summarizing treatment outcomes, and several case histories.

Likelihood of ectopic pregnancy

If 100 women present with a positive pregnancy test and pain and bleeding, approximately 60 will have a normal pregnancy, 30 are experiencing spontaneous abortion, and 9 have an ectopic pregnancy.8

STEP 1Assess risk factors and symptoms

The first step in early diagnosis is being vigilant for risk factors and symptoms associated with ectopic pregnancy, most of which are well known9:

Tubal disease carries a 3.5-fold common adjusted odds ratio (OR) for ectopic pregnancy. In addition, women with a previous ectopic pregnancy are 6 to 8 times more likely to experience another, while a history of tubal surgery raises that likelihood to 21. A history of pelvic infection, including gonorrhea, serologically confirmed chlamydia, and pelvic inflammatory disease, increases the risk of ectopic pregnancy 2 to 4 times.9

Contraception. Intrauterine devices (IUDs) are associated with an increased OR of 6.4.10 This does not mean that IUDs cause ectopic pregnancy. Rather, when a woman with an IUD becomes pregnant, an ectopic gestation should be high on the list of possibilities. A similar relationship exists between ectopic pregnancy and tubal ligation, which carries an OR of 9.3.9 Oral contraceptives are associated with a reduced risk of ectopic pregnancy unless they are used as emergency contraception (ie, after fertilization), in which case they are associated with an increased risk (TABLE 1).

Diethylstilbestrol exposure in utero alters fallopian tube morphology and can lead to absent or minimal fimbrial tissue, a small tubal os, and decreased length and caliber of the tube.11 Abnormal tubal anatomy caused by this exposure multiplies the risk of ectopic pregnancy by a factor of 5.9

In vitro fertilization. When blocked tubes are treated, the embryos can migrate retrograde into the oviduct, implant, and eventually rupture. The OR for ectopic pregnancy with assisted reproduction is 4.0.8

Although a patient’s ß-hCG levels, symptoms, or imaging may suggest ectopic pregnancy, missed diagnoses abound, especially when the physician omits 1 element of the triad: ß-hCG levels, ultrasound imaging, and curettage.

CASE 1: Pain and bleeding, with a high hCG

Mrs. Jones presents with pain and bleeding and a ß-hCG level of 6,000 mIU/mL. Ultrasound imaging reveals no intrauterine pregnancy. Should you presume the diagnosis is ectopic pregnancy and start methotrexate therapy? Or should you play it safe and perform curettage?

To explore these questions, Barnhart and colleagues22 performed a retrospective cohort analysis involving women with ß-hCG levels above 2,000 mIU/mL and no ultrasound evidence of an intrauterine pregnancy. They found that, when the physician presumed a diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy on the basis of ultrasound and ß-hCG levels alone, the diagnosis was wrong in almost 40% of cases.

Where’s the harm in presumptive treatment?

Some practitioners argue that proceeding with methotrexate therapy under these circumstances causes no harm. However, presumptive treatment unnecessarily exposes women to the side effects of chemotherapy and artificially inflates methotrexate success rates. Presumptive treatment does not decrease overall side effects or save money. It also falsely labels a woman as having an ectopic pregnancy, which directly affects future diagnosis and prognosis.

For these reasons, always perform uterine curettage when ultrasound imaging is inconclusive and ß-hCG levels are below normal.

CASE 2: Pregnant and in pain, with an adnexal mass

A pregnant patient complaining of moderate pain has a 4-cm adnexal mass identified at ultrasound, with no evidence of an intrauterine gestational sac. What is her diagnosis?

It’s impossible to know based on the ultrasound alone—even though the ultrasonographer may diagnose ectopic pregnancy. Unless you interpret these findings in light of her ß-hCG levels, you have no way of knowing whether she is experiencing a normal gestation, spontaneous abortion, or ectopic pregnancy. In this case, the adnexal mass turned out to be a corpus luteum with hydrosalpinx, and the woman had a viable intrauterine pregnancy.

CASE 3: Intrauterine pregnancy and pain

A 28-year-old gravida 1 para 0 at 8 weeks’ gestation has a fetal heart rate of 160 following in vitro fertilization. She has a history of tubal disease and complains of severe left lower quadrant pain of sudden onset. Repeat ultrasound shows multiple bilateral ovarian cysts with a gestational sac and fetal heart rate of 144 in the left adnexa. How do you proceed?

Heterotopic pregnancy sometimes complicates in vitro fertilization and can be a difficult diagnosis when multiple cysts from superovulation obscure visualization of the adnexal implantation.

The best treatment is laparoscopic removal of the ectopic implantation. Methotrexate is contraindicated because of the possibility of injuring the viable intrauterine pregnancy.

Cigarette smoking increases the likelihood of ectopic pregnancy 2.5 times,12 probably by affecting ciliary action within the fallopian tubes.

Salpingitis isthmic nodosa is anatomic thickening of the proximal portion of the fallopian tubes with multiple lumen diverticula. It increases the risk of ectopic pregnancy 1.5 times, compared with age- and race-matched controls.13

Don’t depend solely on risk factors. Many ectopic pregnancies present without them.

Symptoms. Many ectopic pregnancies never produce symptoms; rather, they resolve spontaneously or are timely diagnosed and treated medically. Risk factors should therefore be examined in any woman in early pregnancy and investigated further if ectopic pregnancy is likely.

When symptoms do occur, they usually involve 1 or all of the classic triad: amenorrhea, irregular bleeding, and lower abdominal pain. In addition, syncope, shock, and pain radiating to the patient’s shoulder can result from hemoperitoneum.

TABLE 1

High, moderate, and low levels of risk factors for ectopic pregnancy

| RISK FACTOR | ODDS RATIO* |

|---|---|

| High risk | |

| Tubal surgery | 21.0 |

| Tubal ligation | 9.3 |

| Previous ectopic pregnancy | 8.3 |

| In utero exposure to diethylstilbestrol | 5.6 |

| Use of intrauterine device | 4.2–45.0 |

| Documented tubal pathology | 3.8–21.0 |

| Assisted reproduction | 4.0 |

| Emergency contraception | High |

| Moderate risk | |

| Infertility | 2.5–21.0 |

| Previous genital infections | 2.5–3.7 |

| Multiple sexual partners | 2.1 |

| Salpingitis (isthmic) | 1.5 |

| Slight risk | |

| Previous pelvic, abdominal surgery | 0.9–3.8 |

| Cigarette smoking | 2.3–2.5 |

| Vaginal douching | 1.1–3.1 |

| Early age at first intercourse (<18 years) | 1.6 |

| Reprinted with permission from Elsevier (The Lancet, 1998, vol 351, 1115–1120). | |

| * Single values = common odds ratio from homogeneous studies; point estimates = range of values from heterogeneous studies | |

STEP 2Document the pregnancy and measure ß-hCG

Once you identify the high-risk patient, or a woman comes in complaining of pain and spotting or bleeding, run a pregnancy test to confirm that she is pregnant and, if it is positive, obtain a quantitative ß-hCG.

ß-hCG levels are normally measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA), which detect ß-hCG in urine and serum at levels as low as 20 mIU/mL and 10 mIU/mL, respectively.14 ß-hCG is produced by trophoblastic cells in normal pregnancy, and approximately doubles every 2 days when titers are below 10,000 mIU/mL15—although in some normal pregnancies, ß-hCG may increase as slowly as 53% or as rapidly as 230% over 2 days.16 Eighty-five percent of abnormal pregnancies—whether intrauterine or ectopic—have impaired ß-hCG production with prolonged doubling time. Thus, in failing pregnancies, ß-hCG levels will plateau or fail to rise normally.

A single ß-hCG level fails to predict the risk of rupture, since ectopic pregnancies can rupture at ß-hCG levels as low as 10 mIU/mL or far exceeding 10,000 mIU/mL, or at any level in between.

STEP 3Obtain an ultrasound scan

Transvaginal ultrasound reliably detects normal intrauterine gestations when ß-hCG passes somewhere between 1,000 mIU/mL and 2,000 mIU/mL (First International Reference Preparation), depending on the expertise of the ultrasonographer and the particular equipment used.8,17 This is known as the “discriminatory zone.” ß-hCG levels reach this zone as early as 1 week after missed menses.18

The discriminatory zone is not the lowest ß-hCG concentration at which an intrauterine pregnancy can be visualized via ultrasound. Rather, it is the value at which any intrauterine pregnancy will be apparent. At that value, the absence of an intrauterine pregnancy confirms—by negative conclusion—that the patient has a nonviable gestation.

When intrauterine pregnancy is visualized. The diagnosis is definitive and the woman’s symptoms can be explained as “threatened abortion.” No further investigation is necessary aside from routine prenatal care if the pregnancy continues.

When an extrauterine gestation is observed, such as a gestational sac with a detectable fetal heart rate, ectopic pregnancy can be diagnosed with 100% specificity but low sensitivity (15% to 20%). A complex adnexal mass without an intrauterine pregnancy improves sensitivity from 21% to 84% at the expense of lower specificity (93% to 99.5%).19

Even when an adnexal mass is visualized, cardiac activity is not usually present. If cardiac activity is apparent, proceed to surgery, since methotrexate usually will not resolve these gestations.

Be aware that some adnexal masses suspicious for ectopic pregnancy may turn out to be other entities, such as a corpus luteum, hydrosalpinx, ovarian neoplasm, or endometrioma. Unless a fetal heart rate is detected by ultrasound, the diagnosis is uncertain and curettage is needed to establish a definitive diagnosis.

No intrauterine pregnancy, no extrauterine mass. Despite the high resolution of transvaginal ultrasound, many patients with ectopic pregnancy have no apparent adnexal mass,20 particularly when diagnosis is early. In these cases, proceed to curettage (step 4).

Don’t interpret ultrasound findings in a vacuum

This is especially unwise when ß-hCG levels are low—even when the ultrasound report points to intrauterine pregnancy. At ß-hCG levels below 1,500 mIU/mL, the sensitivity of ultrasound in diagnosing intrauterine pregnancy drops from 98% to 33% and predictive value is substantially lower. Interpret ultrasound and ß-hCG levels together for greater accuracy.

How size influences management

Ultrasound can detect ectopic pregnancies as small as 2 cm. In general, an ectopic sac size larger than 4 cm should be treated surgically.

STEP 4Perform uterine curettage

If ultrasound imaging is inconclusive and ß-hCG levels are plateauing or rising subnormally, perform uterine curettage. If ß-hCG levels decrease 15% or more 8 to 12 hours after the procedure, a complete abortion can be strongly suspected.21 If ß-hCG levels plateau or rise, the trophoblasts were not removed by curettage, and ectopic pregnancy is diagnosed.21

Keep in mind these important points:

- Without uterine curettage, roughly 40% of ectopic pregnancy diagnoses are incorrect.22

- Because curettage will result in termination of pregnancy, it is vital that it be limited to cases involving abnormal ß-hCG levels, not normally rising values.

STEP 5Administer methotrexate

Medical management is indicated when the following circumstances are present:

- No viable intrauterine pregnancy is present.

- No rupture has occurred.

- Any adnexal mass is 4 cm in size or smaller.

- ß-hCG levels are below 10,000 mIU/mL.

If there is a positive fetal heart beat, surgery is preferred.

Firm diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy is essential prior to methotrexate administration. If the drug is given to a woman carrying a viable pregnancy, it may result in loss of the pregnancy or methotrexate embryopathy.23

How methotrexate resolves ectopic pregnancy

Systemic methotrexate has been used successfully in the treatment of ectopic pregnancy for more than 20 years. A folic acid antagonist, it inhibits de novo synthesis of purines and pyrimidines. It thus interferes with DNA synthesis and cell multiplication.24 Actively proliferating trophoblasts are particularly vulnerable.25

When methotrexate is administered to normally pregnant women, it blunts the normal ß-hCG increment over the next 7 days. Circulating progesterone and 17-a-hydroxyprogesterone concentrations also decline, and abortion occurs.26

Methotrexate directly impairs trophoblastic production of hCG; the decrement in corpus luteum progesterone is a secondary event.

Side effects include abdominal distress, chills and fever, dizziness, immunosuppression, leukopenia, malaise, nausea, ulcerative stomatitis, photosensitivity, and undue fatigue.

Breastfeeding is an absolute contraindication to methotrexate, while relative contraindications include abnormal liver function tests, blood dyscrasias, excessive alcohol consumption, HIV/AIDS, psoriasis, ongoing radiotherapy, rheumatoid arthritis, and significant pulmonary disease.

Multiple-dose methotrexate is superior

In a recent meta-analysis comparing single-and multiple-dose regimens of methotrexate, Barnhart and colleagues4 found the latter to be more effective, although the single dose was more commonly given. The single-dose regimen was associated with a significantly greater chance of failure in both crude (OR 1.71; 1.04, 2.82) and adjusted (OR 4.74; 1.77, 12.62) analyses. Consequently, we advocate the multiple-dose regimen detailed in TABLE 2: 1 mg of methotrexate per kilogram of body weight on day 1, alternating with 0.1 mg of leucovorin per kilogram on succeeding days. Continue this regimen until ß-hCG levels decline in 2 consecutive daily titers, or 4 doses of methotrexate are given, whichever comes first.

If treatment is unsuccessful after 4 doses, additional methotrexate is unlikely to be effective and will involve significant additional cost and morbidity. If ß-hCG levels plateau or continue to rise, surgery is indicated.

Although multiple-dose therapy is more effective than a single dose, the optimal number of doses probably falls somewhere between 1 and 4.4 A 2-dose protocol currently under investigation may provide an optimal compromise.

Artificially high efficacy rates with “single-dose” therapy. Unusually high success rates in initial studies of the single-dose regimen may have been due to the inclusion of spontaneously aborting intrauterine pregnancies.27 Although 6 subsequent studies—1 cohort and 5 case-control studies involving 304 patients—found an overall success rate (no surgical intervention) of 87.2%, 11.5% of participants required more than 1 dose.9

Still the standard. Despite its lower efficacy rates, single-dose methotrexate remains the “standard” in the United States, as recommended in an American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists practice bulletin.28 The usual intramuscular dose is 50 mg per square meter of body surface area, with ß-hCG titers on days 4 and 7 and an additional dose if ß-hCG levels fail to resolve.

What the evidence shows

Multidose methotrexate. Twelve studies measured the success of multiple-dose systemic methotrexate (TABLE 3); they included 1 randomized, controlled trial, 1 cohort study, and 10 case series. Between 1982 and 1997, 325 cases were treated with multiple-dose methotrexate. Of these, 93.8% had successful resolution with no subsequent therapy, and 78.9% of the 161 women tested had patent oviducts. In addition, of 95 women hoping to conceive, 57.9% had a subsequent intrauterine pregnancy and 7.4% developed a recurrent ectopic pregnancy. These rates compared favorably with numerous laparoscopic surgery series published during the same years.9

Methotrexate versus laparoscopic salpingostomy. In 1 randomized clinical comparison,29 100 women with laparoscopy-confirmed ectopic pregnancy were randomized to methotrexate or laparoscopic salpingostomy. Of the 51 patients treated medically, 7 (14%) required surgical intervention for active bleeding and/or tubal rupture. An additional course of methotrexate was required in 2 patients (4%) for persistent trophoblasts.

Of the 49 patients in the salpingostomy group, 4 women (8%) failed therapy and required salpingectomies, and 10 patients (20%) were treated with methotrexate for persistent trophoblasts.

Tubal patency was present in 23 of 42 women (55%) in the methotrexate group, compared with 23 of 39 (59%) in the salpingostomy group.

Overall, this randomized study29 and previous meta-analysis demonstrate that systemic multiple-dose methotrexate is comparable in efficacy to laparoscopic salpingostomy.

TABLE 2

Multiple-dose methotrexate protocol

Discontinue treatment when there is a decline in 2 consecutive ß-hCG titers or after 4 doses, whichever comes first.

| DAY | INTERVENTION | DOSE (MG) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Baseline studies ß-hCG titer, CBC, and platelets Methotrexate | 1.0 |

| 2 | Leucovori | 0.1 |

| 3 | Methotrexate | 1.0 |

| 4 | Leucovorin ß-hCG titer | 0.1 |

| 5 | Methotrexate ß-hCG titer | 1.0 |

| 6 | Leucovorin ß-hCG titer | 0.1 |

| 7 | Methotrexate ß-hCG titer | 1.0 |

| 8 | Leucovorin ß-hCG titer CBC and platelets Renal and liver function tests | 0.1 |

| Weekly | ß-hCG titer until negative |

TABLE 3

Treatment outcomes for ectopic pregnancy

| METHOD | NUMBER OF STUDIES | NUMBER OF PATIENTS | NUMBER WITH SUCCESSFUL RESOLUTION | TUBAL PATENCY RATE | SUBSEQUENT FERTILITY RATE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INTRAUTERINE PREGNANCY | ECTOPIC PREGNANCY | |||||

| Conservative laparoscopic surgery | 32 | 1,626 | 1,516 (93%) | 170/223 (76%) | 366/647 (57%) | 87/647 (13%) |

| Variable-dose methotrexate | 12 | 338 | 314 (93%) | 136/182 (75%) | 55/95 (58%) | 7/95 (7%) |

| Single-dose methotrexate | 7 | 393 | 340 (87%) | 61/75 (81%) | 39/64 (61%) | 5/64 (8%) |

| Direct-injection methotrexate | 21 | 660 | 502 (76%) | 130/162 (80%) | 87/152 (57%) | 9/152 (6%) |

| Expectant management | 14 | 628 | 425 (68%) | 60/79 (76%) | 12/14 (86%) | 1/14 (7%) |

| Reprinted with permission from Elsevier (The Lancet, 1998, vol 351, 1115–1120). | ||||||

Fine points of treatment

During methotrexate therapy, examine the patient only once to avoid triggering a rupture, and counsel her to avoid intercourse for the same reason.30 Do not perform repeat vaginal ultrasound examination. Also inform her that transient pain (“separation pain”) from tubal abortion frequently occurs 3 to 7 days after the start of therapy, lasts 4 to 12 hours, and then resolves.31 This is perhaps the most difficult aspect of methotrexate therapy, as it is not always easy to differentiate the pain of tubal abortion from the pain of rupture.

If ß-hCG titers continue to rise rapidly between methotrexate doses, rupture is more likely and surgery should proceed.32

Overall, isthmic ectopic pregnancies (12.3% of ectopics) appear to be at a particularly high risk for rupture and comprise nearly half of methotrexate failures.32 Unfortunately, there is no way to identify isthmic pregnancies without surgery.

Avoid NSAIDs and GI-“unfriendly” foods. Counsel the patient to avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) because they may impair natural hemostasis. Gasforming foods such as leeks, corn, and cabbage can cause distension, which may be mistaken for rupture.

Also instruct the patient to avoid folic acid, which impairs the efficacy of methotrexate.

Ultrasound surveillance is unnecessary. If an adnexal mass was identified at initial imaging, there is no need to view it again, since these masses tend to enlarge and form hematomas and can cause undue anxiety in both physician and patient. In properly selected patients, multidose methotrexate with monitoring of ß-hCG levels should suffice.

When surgery is indicated

Surgical intervention is necessary when pain is severe, persists beyond 12 hours, and is associated with orthostatic hypotension, falling hematocrit, or persistently elevated ß-hCG levels after methotrexate therapy.

Laparoscopy is the preferred approach. Advantages include less blood loss and analgesia,33 shortened postoperative recovery, and lower costs.

Technique. For unruptured ampullary ectopic pregnancy, salpingostomy is preferred. Make a linear incision over the bulging antimesenteric border of the fallopian tube using electrocautery, scissors, or laser. Remove the products of conception using forceps or suction, and leave the incision to heal by secondary intention.

For isthmic pregnancies, use segmental excision followed by delayed microsurgical anastomosis.34 The isthmic tubal lumen is narrower and the muscularis thicker than in the ampulla. Thus, the isthmus is predisposed to greater damage after salpingostomy and greater rates of proximal obstruction.33

An increased risk of persistent ectopic pregnancy has been a criticism of salpingostomy. However, when 1 dose of systemic methotrexate is combined with salpingostomy, the risk of persistent pregnancy is virtually eliminated.35

When rupture occurs, salpingectomy is the first choice for treatment, as it arrests hemorrhage and shortens the procedure. Either laparoscopy or laparotomy is appropriate.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ectopic Pregnancy - United States, 1990-1992. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1995;44:46-48.