User login

Cutting the medicolegal risk of shoulder dystocia

Clip-and-save shoulder dystocia documentation form

Practice recommendations

Among the intrapartum events that constitute bona fide emergencies, shoulder dystocia stands out. This obstetric emergency is the focus of an increasing number of medical liability cases. Most lawsuits involving shoulder dystocia allege negligence as the cause of the brachial plexus injury, fractured clavicle or humerus, or other injury. The defendant physicians named in these suits are often accused of inappropriately managing the prenatal or intrapartum course or the dystocia itself—or of inadequately documenting the steps taken to resolve the emergency.

To glean insights into the litigation process as it involves shoulder dystocia, we retrospectively reviewed all cases closed by the Boston-based ProMutual Group, a major liability insurance carrier, over a 7-year period. We wanted to learn more about the plaintiffs themselves, as well as the clinical and medicolegal factors that led to jury awards or indemnity payments. We also wanted data that could serve as the foundation for guidelines on how to proceed in the event of shoulder dystocia, as well as a documentation tool.

This shoulder dystocia case from an insurer’s closed claim file illustrates a problem often linked to litigation. Minor changes were made to conceal the identities of the involved parties.

Nurse and physician document different times

A 31-year-old woman in her 10th week of pregnancy had one prior uncomplicated vaginal delivery of a 9 lb 7 oz infant. Her prenatal course proceeds unremarkably, with a normal glucose tolerance test and total weight gain of 36 lb. At 41 weeks and 2 days, the estimated fetal weight is documented as 4,120 g. Labor is induced with oxytocin. Because of maternal fatigue, vacuum delivery is attempted.

Notes of the physician and the nurse differ regarding the time of the first of 3 vacuum applications.

After delivery of the head, shoulder dystocia is encountered. In a note handwritten immediately after delivery, the physician states that the head was “reconstituted as right occiput anterior with the left shoulder anterior.”

In a note dictated later, however, the same physician states the right shoulder was anterior.

Help is summoned and arrives 20 minutes after the dystocia is first encountered. The time that help was summoned is in question since there is an 18-minute discrepancy between the times the physician and the nurse note that assistance was called.

Despite the use of suprapubic pressure and maneuvers including McRoberts and Wood’s corkscrew, shoulder dystocia persists for 24 minutes. Apgars of the 11 lb 3 oz infant are 0, 1, and 3. The child is resuscitated but dies within 2 days of birth.

Outcome

Settled with a 7-figure indemnity payment.

What the defense experts said

The key issues involve documentation and summoning assistance. Discrepancies in documentation almost always cast doubt upon the credibility of a defendant. Ideally, there should be no discrepancies between nurse and physician notes and, certainly, no discrepancies between 2 notes on the same case by the same physician. If, in this case, the physician realized after writing the first note that the anterior shoulder had been incorrectly identified, a correction should have been written as a separate note.

Use of the shoulder dystocia documentation tool (see) helps create a chronology of events, which may prove vital to a successful defense.

The call for help might not have been delayed if the labor and delivery unit had had a shoulder dystocia protocol including “drills” for all team members. Help should be called as soon as a shoulder dystocia is encountered so that, when needed, it is available. Under no circumstances should it take 20 minutes for assistance to arrive.

Brachial plexus injury not always caused by shoulder dystocia

Between 21% and 42% of shoulder dystocias involve an injury1—usually brachial plexus injury. Plaintiff attorneys have manipulated this fact to attribute many cases of neonatal brachial plexus injury to mismanagement of shoulder dystocia by the obstetrician.

They fault the physician for failing to estimate fetal weight, perform a timely cesarean, use appropriate maneuvers correctly, or have a pediatrician present. They criticize nothing more resoundingly than use of “inappropriate” or “excessive” lateral traction to the fetal head.2

Nontraction injuries. The reality can be strikingly different, however. Some cases of brachial plexus injury involve no traction at all.

- Brachial plexus injuries have been reported in infants who had precipitate vaginal deliveries without any physical intervention by the obstetrician.2

- These injuries also have occurred in infants delivered via cesarean section.1,3,4

- In some cases, brachial plexus injuries have affected the posterior arm of neonates whose anterior arm was involved in shoulder dystocia.1,2,5-7

A retrospective study4 found that, of 39 cases of brachial plexus injury, only 17 were associated with shoulder dystocia. Similar findings have emerged from other studies.2,3,8

Other causes. It is unclear how brachial plexus injuries occur in the absence of shoulder dystocia. Some think they arise in response to infectious agents such as toxoplasmosis, coxsackievirus, mumps, pertussis, or mycoplasma pneumonia.2 Some assume a mechanical cause, such as fetal response to longstanding abnormal intrauterine pressure exerted by maternal conditions such as bicornate uterus and uterine fibroids, especially in the lower segment.1,2

When brachial plexus injuries occur in the absence of shoulder dystocia, they likely originated before labor and delivery.4 Some experts suggest serial electromyelograms within the first 7 days of life to establish a prenatal rather than intrapartum etiology. A positive electromyelogram within 1 week of birth would suggest antepartum causation.2,9

Recognizing risk factors for shoulder dystocia best way to reduce injury

Most brachial plexus injuries or impairments are associated with shoulder dystocia,9 and shoulder dystocia is the most common way brachial plexus injuries are introduced into litigation.

Decreasing the number of brachial plexusrelated liability cases, therefore, depends on decreasing the incidence of shoulder dystocia. Unfortunately, a failsafe method continues to elude both clinicians and researchers.10-12

Retrospective studies have identified certain factors that may—but do not necessarily—increase the risk of shoulder dystocia.

Prenatal risk factors include high maternal or paternal birth weight, maternal obesity, excessive weight gain during pregnancy, advanced age, short stature, multiparity, postdates, prior shoulder dystocia, small pelvis, prior delivery of a macrosomic infant, gestational diabetes in an earlier pregnancy, abnormal blood sugars in the current pregnancy, or fetal macrosomia.13,14-16

Intrapartum risk factors include a rapid or prolonged second stage, failure or arrest of descent, presence of considerable molding, and need for a midpelvic delivery.10,15

Predictability. Prospective studies have not established the predictability of shoulder dystocia. A 2000 study17 showed that 55% of cases with 1 or more risk factors experienced shoulder dystocia. Predictability increases somewhat when both maternal diabetes and fetal macrosomia complicate pregnancy, since the rate of shoulder dystocia in women with diabetes is consistently higher than in nondiabetic gravidas. This becomes a significant issue when the infant weighs more than 4,000 g.

Indications for prophylactic cesarean in women with diabetes

In 1999, Wagner et al9 found that 70% of shoulder dystocias in women with diabetes occurred when the fetal weight exceeded 4,000 g. They concluded that cesarean delivery for infants with an estimated weight over 4,250 g would reduce the rate of shoulder dystocia by 75% and increase the cesarean delivery rate by 1%.

Others are more conservative. Gross and colleagues11 suggested that, for every additional 26 cesarean deliveries, only 1 case of shoulder dystocia would be prevented.

Macrosomia. Most obstetricians and researchers still do not advocate prophylactic cesarean delivery for macrosomia alone because, by some estimates, 98% of macrosomic infants are delivered without difficulty.18 However, they do suggest that obstetricians at least consider the possibility of cesarean delivery for a macrosomic fetus when the woman has diabetes.

In a study completed in 2000, Skolbekken19 suggested a cutoff of 4,250 g for women with diabetes. Dildy20 suggested limits of more than 4,500 g for diabetic women and more than 5,000 g for nondiabetic gravidas. However, Conway and Langer21 assert that a cutoff of 4,500 g is too liberal for women with diabetes and maintain that, at this cutoff, 40% of shoulder dystocias would not be prevented.

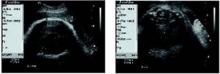

• Ultrasound measurements. Since estimates of fetal weight have a margin of error approaching 40%,9 others have chosen different parameters for determining fetal macrosomia in women with diabetes. In a retrospective study involving 31 women with gestational diabetes, Cohen et al22 found that subtracting the fetal biparietal diameter from the abdominal diameter—with both measurements obtained via ultrasound—yields a predictability score higher than estimated fetal weight. Specifically, if the difference between the 2 measurements is 2.6 cm or more, the rate of shoulder dystocia is high enough to warrant elective cesarean (FIGURE ).

FIGURE Using ultrasound measurements to predict macrosomia

A simple way to predict fetal macrosomia in women with diabetes is to subtract the fetal biparietal diameter (9.3 cm in the scan at left) from the abdominal diameter (average of 12.44 cm in the scan at right). If the difference exceeds 2.6 cm, elective cesarean is warranted. In this case it is 3.14 cm, indicating elective cesarean is warranted.

When dystocia occurs, have a plan and stick to it

Shoulder dystocia immediately places both mother and neonate at risk for temporary or permanent injury. Thus, it is imperative that all obstetricians and other health-care providers who deliver infants have a well developed plan of action for this emergency. They should immediately ask for obstetric assistance and instruct the mother to discontinue any pushing.

Attempts at vigorous downward traction should be avoided, and no fundal pressure should be applied, as these are known to increase the potential for brachial plexus injury. Gentle downward traction is considered the standard of care.17

The obstetrician’s goal is to free the impacted shoulder as quickly as possible, since a fetus can endure only 8 to 10 minutes of asphyxia before permanent neurologic damage occurs.17 The standard of care requires the obstetrician to know and use certain maneuvers to relieve shoulder dystocia. These maneuvers are designed to facilitate vaginal delivery and reduce the risk of permanent brachial plexus injury. The McRoberts maneuver, with flexion and slight rotation of the maternal hips onto the maternal abdomen, is the standard for initial relief of shoulder dystocia.17,23

This shoulder dystocia case from an insurer’s closed claim file illustrates a problem often linked to litigation. Minor changes were made to conceal the identities of the involved parties.

Prompt maneuvers, good outcome

A 28-year-old gravida weighing 214 lb has had 2 previous spontaneous deliveries of infants weighing 8 lb 5 oz and 9 lb 3 oz. Except for a weight gain of more than 60 lb, the pregnancy progressed without complications, and a 3-hour glucose tolerance test was normal. At 40 weeks, the obstetrician notes “concern” about an estimated fetal weight of 10 lb. Induction is planned, but spontaneous labor begins before oxytocin can be given. After 5 hours, the head is delivered without difficulty, but shoulder dystocia follows. The obstetrician extends the episiotomy and performs McRoberts and Wood’s corkscrew maneuvers, but the dystocia persists. Upon noting cyanosis, the obstetrician fractures the infant’s clavicle and quickly delivers a 10 lb 9 oz infant with Apgar scores of 8 and 10. Pediatricians examine the child immediately and diagnose Erb’s palsy, which subsequently resolves. X-rays confirm an undisplaced fracture of the right clavicle. Although the child recovers completely, the family sues, alleging a failure to perform cesarean delivery.

Outcome

Case closed with no payment.

What the defense experts said

Key issues are documentation and informed consent. The overriding opinion of 3 experts who reviewed the case for the defense was that cesarean delivery was not indicated and that in fracturing the clavicle, the physician acted responsibly, quickly, and within the standard of care. One defense expert said failure to document exact maneuvers used to relieve shoulder dystocia deviated from the standard of care. Another defense expert said the physician should have obtained informed consent from this at-risk patient, and explained the risks of shoulder dystocia, including neonatal injury, so that the she might have been better able to appreciate the fact that the obstetrician’s fast action may have saved her child from brain damage or death.

Factors that lead to litigation

In a review article, Hickson24 cited factors that prompted families to file medical liability claims following perinatal injury. Some families observed that, in their search for the cause of an injury, they found 1 or more aspects of care to be inappropriate.

The desire for information, perception of being misled, anger with the medical profession, desire to prevent injuries to others, recognition of long-term sequelae, and advice by knowledgeable acquaintances, as well as the need for money, all appeared to contribute to the decision to file medical liability claims.

Convey the risks, and listen carefully. Communication problems between physicians and patients are a contributing factor. Even when physicians provide technically adequate care, families expect answers to their questions and want to feel as though they have been consulted about important medical decisions.24 If these expectations are not met, even patients who have not experienced an adverse outcome may become angry and express dissatisfaction with care.24

The need for communication is critical when shoulder dystocia results in neonatal injury. Empathizing with the family, helping them understand that most brachial plexus injuries are not long-term, and offering to answer their questions both at the moment and later, may help prevent litigation.

This type of communication can be difficult. It helps to realize that an acknowledgment of distress and concern is not an admission of guilt, and an explanation is not an apology.15 However, an absence of communication or an attempt by the physician to place blame may be perceived as an admission of guilt that gives rise to a lawsuit.

Action plan is what counts in court. A review by Gross et al11 concluded that obstetricians should have a shoulder dystocia plan that enables an instant and orderly response. Also recommended is a protocol to help anticipate clinical problems and prevent medicolegal problems.

Gross and colleagues11 found that the Ob/Gyns with the most defensible cases paid close attention to the patient’s history and prenatal course and, upon encountering dystocia, implemented at least 2 maneuvers (if necessary) and thoroughly documented their actions immediately after delivery.

Fetterman15 agreed, asserting that what counts in court is not so much whether the obstetrician employed the McRoberts maneuver before or after the Wood’s corkscrew maneuver but whether he or she had an action plan in mind, implemented that plan properly, and thoroughly documented the actions taken and the reasons underlying them.

Dissecting legal cases for clues to reduced risk

In the review of medicolegal cases for this article, we limited our search to cases closed between Jan 1, 1995, and Dec 31, 2002, using a computer to search for codes specific to shoulder dystocia as well as the phrases “shoulder dystocia,” “Erb’s palsy,” and “brachial plexus injury.” We identified 61 cases involving 117 defendants and created a data sheet to gather information on patient and physician demographics, medical and obstetric history, description of the incident, analysis rendered by defense and plaintiff experts, and legal and financial outcomes.

Of 117 defendants, 76 were obstetricians. There also were 16 hospitals, 15 corporations, 5 certified nurse-midwives, 1 family physician, 1 emergency physician, and 3 persons categorized as “other.” Age, race, and parity of the 61 plaintiffs are given in TABLE 1.

Twenty-six of the 61 cases, involving 74 defendants, closed with no payment. That is, they were either dismissed or closed with a jury verdict for the defense. The remaining 35 cases involved 43 defendants and were closed with an aggregate indemnity payment of $19.2 million. The mean payment was $445,000 per defendant.

These guidelines are recommended to help prevent, predict, and manage shoulder dystocia and brachial plexus injury.

Obtain a prenatal history that includes the birth weights of both parents and any history of prior shoulder dystocia or cesarean delivery performed for “failure to progress.”

Estimate the fetal weight and take into account the risk for shoulder dystocia when the fetus is determined by ultrasound to be macrosomic.

Perform glucose testing on all patients, and follow up on even a single abnormal glucose reading. Discuss the possibility of shoulder dystocia and the accompanying risk of neonatal injury with “at risk” patients.

Consider obtaining informed consent for vaginal delivery of a patient with risk factors for shoulder dystocia.

Consider cesarean delivery for :

- nondiabetic women when the estimated fetal weight (EFW) exceeds 4,500 g,

- diabetic gravidas when the EFW exceeds 4,000 g,

- women with a prior delivery complicated by shoulder dystocia or brachial plexus palsy,

- gravidas with a prolonged second stage and nonprogression of labor, and

- patients who express fear and doubt about vaginal delivery.

Be sparing with the use of oxytocin when the fetus is known or suspected to be macrosomic, taking special care not to be aggressive with induction.

Use forceps or vacuum extraction with caution, and limit the number of attempts with each.

Minimize traction on the fetal head. Traction that is deemed to be “excessive” may be used against the physician in a liability suit. Gentle traction is acceptable.

Do not use or order fundal pressure. It will almost invariably be used against you in a lawsuit.

Be able to define and correctly describe maneuvers generally accepted as the standard for shoulder dystocia and, when necessary, use and document them appropriately. These include the McRoberts, Wood’s corkscrew, Rubin, and Zavanelli maneuvers; extended episiotomy; suprapubic pressure; and fracture of the anterior clavicle.

Be alert to the possibility of brachial plexus injury in the absence of shoulder dystocia. Obstetricians have been erroneously accused of causing brachial plexus injury by plaintiff attorneys who do not understand that this injury is not always the result of dystocia. Thorough contemporaneous documentation is key in these instances.

Request immediate pediatric assessment of a newborn involved in shoulder dystocia. Have the placenta sent for examination, and request cord blood gases.

Communicate openly and honestly with the parents of a child who has suffered a brachial plexus injury. This may be the single greatest tool for reducing the risk of liability litigation.

Consider serial electromyelograms during the first 7 days of life for a neonate with a brachial plexus palsy. These studies can help determine the etiology of the injury.

Use a shoulder dystocia documentation tool such as the one on page 91. Thorough documentation of all relevant prenatal and intrapartum events is critical to a successful defense. A 12-point detailed delivery note as recommended by Fetterman will also prevent or reduce legal risk.15

Schedule shoulder dystocia “drills” in the labor and delivery unit to familiarize obstetric team members with their roles.

Require comanagement of any midwifery patient at increased risk for shoulder dystocia.

Neonatal injury occurred in all 61 cases. Erb’s palsy was the overwhelming pediatric outcome (57 of 61 cases, or 93.4%), with an aggregate indemnity payment of $17.6 million. Fractured humerus was the outcome in 1 case, and 3 cases involved neonatal deaths.

Reasons for indemnity payments included:

- probable liability (18 defendants),

- plaintiff was sympathetic, likely to evoke an emotional response from the jury (8 defendants),

- clear liability (7 defendants),

- defendant would not have made a strong witness in his or her own defense (5 defendants),

- defendant had died or was too ill to stand trial (3 defendants),

- medical record had been altered (2 defendants),

- case was considered too inflammatory to risk a jury award (2 defendants), and

- policy limits were too low to risk a potentially high jury award (1 defendant).

Five defendants were involved in cases with multiple medicolegal issues that argued for settlement.

The effect of birth weight. Notably, 74% of infants involved in these cases were macrosomic (birth weight over 4,000 g). Except for neonatal injury (100%), no single maternal or fetal variable appears with greater frequency.

The mean indemnity in closed cases increased in direct proportion to fetal weight, ranging from $500,000 in cases involving infants whose birth weight was less than 4,000 g to $950,000 when the birth weight was 5,000 g or more.

Maternal factors seen with greatest frequency included obesity, excessive weight gain in pregnancy, and gestational diabetes. Analysis of prepregnant body mass index found that 19 women had a weight within the “obese” category, 18 of whom gave birth to macrosomic infants. Eight of these cases closed without indemnity payment and 10 closed with an aggregate indemnity payment of $6.5 million.

Forty-eight of the 61 plaintiffs (78.8%) exceeded the normal weight gain in pregnancy based on height and prepregnant weight. Twenty-nine of these cases closed with an aggregate indemnity payment of $16.6 million.

Influence of diabetes. Fifty-two of 61 plaintiffs underwent a glucose screening test. Of these, 23 went on to have a glucose tolerance test, with 12 testing positive for gestational diabetes. Further analysis revealed borderline screening glucose values in an additional 16 cases. These women were not considered diabetic by their obstetricians, were not retested for diabetes, and did not receive nutritional counseling. Macrosomic infants were born to 9 of the 12 patients with gestational diabetes and to 13 of the 16 borderline cases.

Of 28 cases with confirmed or suspected gestational diabetes, 14 women delivered infants weighing over 4,250 g; 11 of the 14 weighed more than 4,500 g.

In a comparison of cases involving diabetic and nondiabetic women who delivered infants weighing more than 4,250 g, 82% of the cases involving nondiabetic women closed without payment. Among cases involving diabetes (actual or borderline), the corresponding figure was 27.3%.

Labor and delivery interventions were cited in all cases. Oxytocin was used in 42 of the 61 cases (68.9%), forceps in 9 (14.8%), and vacuum extraction in 7 (11.5%). Suprapubic pressure was used in 37 cases (60.7%), fundal pressure in 9 (14.8%), and traction on the fetal head in 16 cases (26.2%).

In addition, defense experts determined that the McRoberts maneuver was used in 41 cases (67.2%) and the Wood’s corkscrew maneuver in 28 (45.9%).

Seven cases involved a second stage of labor exceeding 2.5 hours. The ratio of wins to losses decreased substantially with the use of oxytocin, forceps, fundal pressure, or a prolonged second stage.

Data were analyzed using selected variables thought to have an association with winning or losing cases and with indemnity (TABLE 2). No statistically significant models emerged. This is likely due to inadequate power (low number of cases) and the large number of interactions between variables relative to the outcomes evaluated.

TABLE 1

Plaintiff demographics

| CHARACTERISTIC | ALL CASES (n = 61) | CASES WITH INDEMNITY (n = 35) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age, in years (range) | 28 (17–40) | 29 (18–38) |

| Race (%) | ||

| White | 35 (57) | 21 (60) |

| Black | 12 (20) | 7 (20) |

| Hispanic | 11 (18) | 6 (17) |

| Asian | 1 (2) | — |

| Unknown | 2 (3) | 1 (3) |

| Parity (%) | ||

| 0 | 19 (31) | 11 (31) |

| 1 | 26 (43) | 16 (46) |

| 2 | 11 (18) | 7 (20) |

| 3 | 2 (3) | 1 (3) |

| 4 | 2 (3) | — |

| 5 | 1 (2) | — |

TABLE 2

Litigation outcomes for selected prenatal and intrapartum variables

| CHARACTERISTIC | CLOSED WITHOUT INDEMNITY | CLOSED WITHOUT INDEMNITY PAYMENT | MEAN INDEMNITY ($) | TOTAL INDEMNITY ($) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prenatal factors | ||||

| Gestational diabetes | 5 | 7 | 413,300 | 2,893,000 |

| Adjusted diabetes | 10 | 18 | 521,400 | 9,386,000 |

| Obesity | 8 | 13 | 651,300 | 8,466,000 |

| Intrapartum factors | ||||

| Prolonged second stage | 1 | 6 | 707,700 | 4,247,000 |

| Oxytocin induction | 2 | 10 | 406,500 | 4,065,300 |

| Oxytocin augmentation | 15 | 15 | 737,000 | 11,100,000 |

| Forceps delivery | 1 | 8 | 552,100 | 4,416,800 |

| Vacuum extraction | 3 | 4 | 531,300 | 2,125,000 |

| Episiotomy | 20 | 30 | 579,400 | 17,382,100 |

| McRoberts maneuver | 20 | 21 | 542,900 | 11,400,300 |

| Wood’s corkscrew maneuver | 12 | 16 | 652,300 | 10,436,200 |

| Suprapubic pressure | 17 | 20 | 629,000 | 12,579,400 |

| Traction to fetal head | 7 | 9 | 665,500 | 5,989,500 |

| Fundal pressure | 4 | 7 | 660,700 | 4,625,000 |

4 factors raise risk of litigation

After reviewing the literature and analyzing the ProMutual data, we concluded that shoulder dystocia remains largely unpredictable. However, certain clinical factors are clearly associated with an increased risk for litigation:

- prenatal factors,

- labor and delivery interventions,

- maneuvers performed at the time of the dystocia, and

- fetal outcomes.

Prenatal factors. The most significant prenatal factors were maternal obesity, excessive weight gain in pregnancy, and, especially, diabetes and fetal macrosomia.

• Fetal macrosomia. Although most macrosomic infants deliver without complication, fetal macrosomia was involved in more than 72% of the cases reviewed. Because macrosomia represents a risk not only for shoulder dystocia but also for the litigation that may arise from it, it is important to:

- know and document the estimated fetal weight (EFW);

- discuss the risk of dystocia and its sequelae with the mother and her partner; and

- consider cesarean delivery for estimated fetal weights that suggest macrosomia (see the recommendations on page 82 for specifics).

It also is advisable to mobilize a team for the possibility of shoulder dystocia if vaginal delivery is attempted.

Preparing for the increased risk of a macrosomic fetus can be successful only if macrosomia is both diagnosed and anticipated.

Because macrosomia often is accompanied by maternal diabetes, serum glucose testing is recommended for all gravidas, with follow-up of both abnormal and borderline values.

Labor and delivery interventions were cited in all cases, with data indicating a decreasing ratio of wins to losses with the use of oxytocin, forceps, or fundal pressure, and prolonged second stage.

- Use of oxytocin to augment an already established labor carried less risk than oxytocin for labor induction. Ten of the 12 cases (83.3%) in which oxytocin was used for induction closed with an indemnity payment. However, of the 30 cases in which oxytocin was used for labor augmentation, 50% closed with payment.

- • Forceps and a prolonged second stage. Eight of 9 cases (88.9%) involving forceps and 6 of 7 cases (85.7%) involving a prolonged second stage closed with indemnity payment.

Consider cesarean delivery when the second stage is prolonged or labor fails to progress. Be cautious using forceps and vacuum extraction in these circumstances, and limit the number of attempts with either.

Maneuvers performed at the time of dystocia. The most common maneuverswere McRoberts, suprapubic pressure, and Wood’s corkscrew. The ratio of wins to losses decreased with traction of the fetal head and use of fundal pressure.

Part of the risk-management protocol for obstetricians should be appropriate use of McRoberts maneuver, suprapubic pressure, and Wood’s corkscrew, and cutting a large episiotomy. In addition, be careful not to push, pull, rotate the head, or apply fundal pressure.

Fetal outcomes. All cases involved neonatal injury (Erb’s palsy, fractured humerus) or death.

For this reason, we recommend an action plan that includes immediate pediatric or neonatal assessment of neuromuscular function of the infant’s anterior shoulder. Assess the Moro reflex and the possibility of brachial plexus injury and fractures of the clavicle and humerus. Also examine the placenta, send it to pathology, and perform a cord blood gas analysis.

Last words

Shoulder dystocia is the unfortunate complication of a small number of deliveries, but the focus of an increasing number of lawsuits. Because the neonatal injuries that so often accompany shoulder dystocia often lead to litigation, obstetricians should prepare to identify risk and help patients make informed choices. We should be prepared to manage this emergency whenever it occurs and thoroughly document actions.

Dr. Zylstra reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

1. Gherman RB, Goodwin TM, Ouzounian JG, Miller DA, Paul RH. Brachial plexus palsy associated with cesarean section: an in utero injury? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177:1162-1164.

2. Gherman RB, Ouzounian JG, Goodwin TM. Brachial plexus palsy: an in utero injury? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:1303-1307.

3. Gilbert WM, Nesbitt TS, Danielsen B. Associated factors in 1611 cases of brachial plexus injury. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:536-540.

4. Jennett RJ, Tarby TJ, Kreinick CJ. Brachial plexus palsy: an old problem revisited. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166:1673-1677.

5. Hankins GDV, Clark SL. Brachial plexus palsy involving the posterior shoulder at spontaneous vaginal delivery. Am J Perinatol. 1995;12:44-45.

6. Gherman RB, Ouzounian JG, Miller DA, Kwok L, Goodwin TM. Spontaneous vaginal delivery: a risk factor for Erb’s palsy? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:423-427.

7. Dodds SD, Wolfe SW. Perinatal brachial plexus palsy. Curr Opin Pediatrics. 2000;23:40-47.

8. Wade DM. A Comment on the Trial of Brachial Plexus/Erb’s Palsy Medical Malpractice Cases. Evidence Technologies, Inc. 1994.

9. Wagner RK, Nielsen PE, Gonik B. Controversies in labor management: shoulder dystocia. Obstet Gynecol Clin. 1999;26(2):371-382.

10. McFarland M, Hod M, Piper JM, Xenakis EM-J, Langer O. Are labor abnormalities more common in shoulder dystocia? Am J ObstetGynecol. 1995;173:1211-1214.

11. Gross TL, Sokol RJ, Williams T, Thompson K. Shoulder dystocia: A fetal-physician risk. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;156:1408-1418.

12. Acker DB, Sachs BP, Friedman EA. Risk factors for shoulder dystocia. Obstet Gynecol. 1985;66:762-768.

13. Shoulder dystocia and Erb’s palsy. The Keenan Law Firm. 2002. Available at www.shoulderdystociaattorney.com. Accessed July 23, 2004.

14. Acker DB, Gregory KD, Sachs BP, Friedman EA. Risk factors for Erb-Duchenne palsy. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;71(Part l):390-392.

15. Fetterman HH. Cutting the legal risks of shoulder dystocia. OBG Management. March 1995;41-51.

16. Iffy L, Varadi V, Jakobovits A. Common intrapartum denominators of shoulder dystocia related birth injuries. Zentralbl Gynakol. 1994;116(1):33-37.

17. Calhoun BC, Hume RR, Walters JL. Shoulder Dystocia as a risk for obstetric liability. Legal Medicine. 2000;12-15.

18. Jennett RJ, Tarby TJ. Brachial plexus palsy: an old problem revisited again. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:1354-1357.

19. Skolbekken JA. Shoulder dystocia—malpractice or acceptable risk? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79:750-756.

20. Dildy GA. Fetal macrosomia [slide presentation]. Presented at the 18th Annual Conference on Obstetrics, Gynecology, Perinatal Medicine, and the Law, Boston University School of Medicine and the Center for Human Genetics, January 2002, Kauai, Hawaii.

21. Conway D, Langer O. Elective delivery of infants with macrosomia in diabetic women: reduced shoulder dystocia versus increased cesarean deliveries. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178(5):922-925.

22. Cohen B, Penning S, Major C, Ansley D, Porto M, Garite T. Sonographic prediction of shoulder dystocia in infants of diabetic mothers. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;88:10-13.

23. Gherman RB, Goodwin TM, Souter I, Neumann K, Ouzounian JG, Paul RH. The McRoberts’ maneuver for the alleviation of shoulder dystocia: how successful is it? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:656-661.

24. Hickson GB, Clayton DW, Githens PB, Sloan FA. Factors that prompted families to file medical malpractice claims following perinatal injuries. JAMA. 1992;267:1359-1363.

Clip-and-save shoulder dystocia documentation form

Practice recommendations

Among the intrapartum events that constitute bona fide emergencies, shoulder dystocia stands out. This obstetric emergency is the focus of an increasing number of medical liability cases. Most lawsuits involving shoulder dystocia allege negligence as the cause of the brachial plexus injury, fractured clavicle or humerus, or other injury. The defendant physicians named in these suits are often accused of inappropriately managing the prenatal or intrapartum course or the dystocia itself—or of inadequately documenting the steps taken to resolve the emergency.

To glean insights into the litigation process as it involves shoulder dystocia, we retrospectively reviewed all cases closed by the Boston-based ProMutual Group, a major liability insurance carrier, over a 7-year period. We wanted to learn more about the plaintiffs themselves, as well as the clinical and medicolegal factors that led to jury awards or indemnity payments. We also wanted data that could serve as the foundation for guidelines on how to proceed in the event of shoulder dystocia, as well as a documentation tool.

This shoulder dystocia case from an insurer’s closed claim file illustrates a problem often linked to litigation. Minor changes were made to conceal the identities of the involved parties.

Nurse and physician document different times

A 31-year-old woman in her 10th week of pregnancy had one prior uncomplicated vaginal delivery of a 9 lb 7 oz infant. Her prenatal course proceeds unremarkably, with a normal glucose tolerance test and total weight gain of 36 lb. At 41 weeks and 2 days, the estimated fetal weight is documented as 4,120 g. Labor is induced with oxytocin. Because of maternal fatigue, vacuum delivery is attempted.

Notes of the physician and the nurse differ regarding the time of the first of 3 vacuum applications.

After delivery of the head, shoulder dystocia is encountered. In a note handwritten immediately after delivery, the physician states that the head was “reconstituted as right occiput anterior with the left shoulder anterior.”

In a note dictated later, however, the same physician states the right shoulder was anterior.

Help is summoned and arrives 20 minutes after the dystocia is first encountered. The time that help was summoned is in question since there is an 18-minute discrepancy between the times the physician and the nurse note that assistance was called.

Despite the use of suprapubic pressure and maneuvers including McRoberts and Wood’s corkscrew, shoulder dystocia persists for 24 minutes. Apgars of the 11 lb 3 oz infant are 0, 1, and 3. The child is resuscitated but dies within 2 days of birth.

Outcome

Settled with a 7-figure indemnity payment.

What the defense experts said

The key issues involve documentation and summoning assistance. Discrepancies in documentation almost always cast doubt upon the credibility of a defendant. Ideally, there should be no discrepancies between nurse and physician notes and, certainly, no discrepancies between 2 notes on the same case by the same physician. If, in this case, the physician realized after writing the first note that the anterior shoulder had been incorrectly identified, a correction should have been written as a separate note.

Use of the shoulder dystocia documentation tool (see) helps create a chronology of events, which may prove vital to a successful defense.

The call for help might not have been delayed if the labor and delivery unit had had a shoulder dystocia protocol including “drills” for all team members. Help should be called as soon as a shoulder dystocia is encountered so that, when needed, it is available. Under no circumstances should it take 20 minutes for assistance to arrive.

Brachial plexus injury not always caused by shoulder dystocia

Between 21% and 42% of shoulder dystocias involve an injury1—usually brachial plexus injury. Plaintiff attorneys have manipulated this fact to attribute many cases of neonatal brachial plexus injury to mismanagement of shoulder dystocia by the obstetrician.

They fault the physician for failing to estimate fetal weight, perform a timely cesarean, use appropriate maneuvers correctly, or have a pediatrician present. They criticize nothing more resoundingly than use of “inappropriate” or “excessive” lateral traction to the fetal head.2

Nontraction injuries. The reality can be strikingly different, however. Some cases of brachial plexus injury involve no traction at all.

- Brachial plexus injuries have been reported in infants who had precipitate vaginal deliveries without any physical intervention by the obstetrician.2

- These injuries also have occurred in infants delivered via cesarean section.1,3,4

- In some cases, brachial plexus injuries have affected the posterior arm of neonates whose anterior arm was involved in shoulder dystocia.1,2,5-7

A retrospective study4 found that, of 39 cases of brachial plexus injury, only 17 were associated with shoulder dystocia. Similar findings have emerged from other studies.2,3,8

Other causes. It is unclear how brachial plexus injuries occur in the absence of shoulder dystocia. Some think they arise in response to infectious agents such as toxoplasmosis, coxsackievirus, mumps, pertussis, or mycoplasma pneumonia.2 Some assume a mechanical cause, such as fetal response to longstanding abnormal intrauterine pressure exerted by maternal conditions such as bicornate uterus and uterine fibroids, especially in the lower segment.1,2

When brachial plexus injuries occur in the absence of shoulder dystocia, they likely originated before labor and delivery.4 Some experts suggest serial electromyelograms within the first 7 days of life to establish a prenatal rather than intrapartum etiology. A positive electromyelogram within 1 week of birth would suggest antepartum causation.2,9

Recognizing risk factors for shoulder dystocia best way to reduce injury

Most brachial plexus injuries or impairments are associated with shoulder dystocia,9 and shoulder dystocia is the most common way brachial plexus injuries are introduced into litigation.

Decreasing the number of brachial plexusrelated liability cases, therefore, depends on decreasing the incidence of shoulder dystocia. Unfortunately, a failsafe method continues to elude both clinicians and researchers.10-12

Retrospective studies have identified certain factors that may—but do not necessarily—increase the risk of shoulder dystocia.

Prenatal risk factors include high maternal or paternal birth weight, maternal obesity, excessive weight gain during pregnancy, advanced age, short stature, multiparity, postdates, prior shoulder dystocia, small pelvis, prior delivery of a macrosomic infant, gestational diabetes in an earlier pregnancy, abnormal blood sugars in the current pregnancy, or fetal macrosomia.13,14-16

Intrapartum risk factors include a rapid or prolonged second stage, failure or arrest of descent, presence of considerable molding, and need for a midpelvic delivery.10,15

Predictability. Prospective studies have not established the predictability of shoulder dystocia. A 2000 study17 showed that 55% of cases with 1 or more risk factors experienced shoulder dystocia. Predictability increases somewhat when both maternal diabetes and fetal macrosomia complicate pregnancy, since the rate of shoulder dystocia in women with diabetes is consistently higher than in nondiabetic gravidas. This becomes a significant issue when the infant weighs more than 4,000 g.

Indications for prophylactic cesarean in women with diabetes

In 1999, Wagner et al9 found that 70% of shoulder dystocias in women with diabetes occurred when the fetal weight exceeded 4,000 g. They concluded that cesarean delivery for infants with an estimated weight over 4,250 g would reduce the rate of shoulder dystocia by 75% and increase the cesarean delivery rate by 1%.

Others are more conservative. Gross and colleagues11 suggested that, for every additional 26 cesarean deliveries, only 1 case of shoulder dystocia would be prevented.

Macrosomia. Most obstetricians and researchers still do not advocate prophylactic cesarean delivery for macrosomia alone because, by some estimates, 98% of macrosomic infants are delivered without difficulty.18 However, they do suggest that obstetricians at least consider the possibility of cesarean delivery for a macrosomic fetus when the woman has diabetes.

In a study completed in 2000, Skolbekken19 suggested a cutoff of 4,250 g for women with diabetes. Dildy20 suggested limits of more than 4,500 g for diabetic women and more than 5,000 g for nondiabetic gravidas. However, Conway and Langer21 assert that a cutoff of 4,500 g is too liberal for women with diabetes and maintain that, at this cutoff, 40% of shoulder dystocias would not be prevented.

• Ultrasound measurements. Since estimates of fetal weight have a margin of error approaching 40%,9 others have chosen different parameters for determining fetal macrosomia in women with diabetes. In a retrospective study involving 31 women with gestational diabetes, Cohen et al22 found that subtracting the fetal biparietal diameter from the abdominal diameter—with both measurements obtained via ultrasound—yields a predictability score higher than estimated fetal weight. Specifically, if the difference between the 2 measurements is 2.6 cm or more, the rate of shoulder dystocia is high enough to warrant elective cesarean (FIGURE ).

FIGURE Using ultrasound measurements to predict macrosomia

A simple way to predict fetal macrosomia in women with diabetes is to subtract the fetal biparietal diameter (9.3 cm in the scan at left) from the abdominal diameter (average of 12.44 cm in the scan at right). If the difference exceeds 2.6 cm, elective cesarean is warranted. In this case it is 3.14 cm, indicating elective cesarean is warranted.

When dystocia occurs, have a plan and stick to it

Shoulder dystocia immediately places both mother and neonate at risk for temporary or permanent injury. Thus, it is imperative that all obstetricians and other health-care providers who deliver infants have a well developed plan of action for this emergency. They should immediately ask for obstetric assistance and instruct the mother to discontinue any pushing.

Attempts at vigorous downward traction should be avoided, and no fundal pressure should be applied, as these are known to increase the potential for brachial plexus injury. Gentle downward traction is considered the standard of care.17

The obstetrician’s goal is to free the impacted shoulder as quickly as possible, since a fetus can endure only 8 to 10 minutes of asphyxia before permanent neurologic damage occurs.17 The standard of care requires the obstetrician to know and use certain maneuvers to relieve shoulder dystocia. These maneuvers are designed to facilitate vaginal delivery and reduce the risk of permanent brachial plexus injury. The McRoberts maneuver, with flexion and slight rotation of the maternal hips onto the maternal abdomen, is the standard for initial relief of shoulder dystocia.17,23

This shoulder dystocia case from an insurer’s closed claim file illustrates a problem often linked to litigation. Minor changes were made to conceal the identities of the involved parties.

Prompt maneuvers, good outcome

A 28-year-old gravida weighing 214 lb has had 2 previous spontaneous deliveries of infants weighing 8 lb 5 oz and 9 lb 3 oz. Except for a weight gain of more than 60 lb, the pregnancy progressed without complications, and a 3-hour glucose tolerance test was normal. At 40 weeks, the obstetrician notes “concern” about an estimated fetal weight of 10 lb. Induction is planned, but spontaneous labor begins before oxytocin can be given. After 5 hours, the head is delivered without difficulty, but shoulder dystocia follows. The obstetrician extends the episiotomy and performs McRoberts and Wood’s corkscrew maneuvers, but the dystocia persists. Upon noting cyanosis, the obstetrician fractures the infant’s clavicle and quickly delivers a 10 lb 9 oz infant with Apgar scores of 8 and 10. Pediatricians examine the child immediately and diagnose Erb’s palsy, which subsequently resolves. X-rays confirm an undisplaced fracture of the right clavicle. Although the child recovers completely, the family sues, alleging a failure to perform cesarean delivery.

Outcome

Case closed with no payment.

What the defense experts said

Key issues are documentation and informed consent. The overriding opinion of 3 experts who reviewed the case for the defense was that cesarean delivery was not indicated and that in fracturing the clavicle, the physician acted responsibly, quickly, and within the standard of care. One defense expert said failure to document exact maneuvers used to relieve shoulder dystocia deviated from the standard of care. Another defense expert said the physician should have obtained informed consent from this at-risk patient, and explained the risks of shoulder dystocia, including neonatal injury, so that the she might have been better able to appreciate the fact that the obstetrician’s fast action may have saved her child from brain damage or death.

Factors that lead to litigation

In a review article, Hickson24 cited factors that prompted families to file medical liability claims following perinatal injury. Some families observed that, in their search for the cause of an injury, they found 1 or more aspects of care to be inappropriate.

The desire for information, perception of being misled, anger with the medical profession, desire to prevent injuries to others, recognition of long-term sequelae, and advice by knowledgeable acquaintances, as well as the need for money, all appeared to contribute to the decision to file medical liability claims.

Convey the risks, and listen carefully. Communication problems between physicians and patients are a contributing factor. Even when physicians provide technically adequate care, families expect answers to their questions and want to feel as though they have been consulted about important medical decisions.24 If these expectations are not met, even patients who have not experienced an adverse outcome may become angry and express dissatisfaction with care.24

The need for communication is critical when shoulder dystocia results in neonatal injury. Empathizing with the family, helping them understand that most brachial plexus injuries are not long-term, and offering to answer their questions both at the moment and later, may help prevent litigation.

This type of communication can be difficult. It helps to realize that an acknowledgment of distress and concern is not an admission of guilt, and an explanation is not an apology.15 However, an absence of communication or an attempt by the physician to place blame may be perceived as an admission of guilt that gives rise to a lawsuit.

Action plan is what counts in court. A review by Gross et al11 concluded that obstetricians should have a shoulder dystocia plan that enables an instant and orderly response. Also recommended is a protocol to help anticipate clinical problems and prevent medicolegal problems.

Gross and colleagues11 found that the Ob/Gyns with the most defensible cases paid close attention to the patient’s history and prenatal course and, upon encountering dystocia, implemented at least 2 maneuvers (if necessary) and thoroughly documented their actions immediately after delivery.

Fetterman15 agreed, asserting that what counts in court is not so much whether the obstetrician employed the McRoberts maneuver before or after the Wood’s corkscrew maneuver but whether he or she had an action plan in mind, implemented that plan properly, and thoroughly documented the actions taken and the reasons underlying them.

Dissecting legal cases for clues to reduced risk

In the review of medicolegal cases for this article, we limited our search to cases closed between Jan 1, 1995, and Dec 31, 2002, using a computer to search for codes specific to shoulder dystocia as well as the phrases “shoulder dystocia,” “Erb’s palsy,” and “brachial plexus injury.” We identified 61 cases involving 117 defendants and created a data sheet to gather information on patient and physician demographics, medical and obstetric history, description of the incident, analysis rendered by defense and plaintiff experts, and legal and financial outcomes.

Of 117 defendants, 76 were obstetricians. There also were 16 hospitals, 15 corporations, 5 certified nurse-midwives, 1 family physician, 1 emergency physician, and 3 persons categorized as “other.” Age, race, and parity of the 61 plaintiffs are given in TABLE 1.

Twenty-six of the 61 cases, involving 74 defendants, closed with no payment. That is, they were either dismissed or closed with a jury verdict for the defense. The remaining 35 cases involved 43 defendants and were closed with an aggregate indemnity payment of $19.2 million. The mean payment was $445,000 per defendant.

These guidelines are recommended to help prevent, predict, and manage shoulder dystocia and brachial plexus injury.

Obtain a prenatal history that includes the birth weights of both parents and any history of prior shoulder dystocia or cesarean delivery performed for “failure to progress.”

Estimate the fetal weight and take into account the risk for shoulder dystocia when the fetus is determined by ultrasound to be macrosomic.

Perform glucose testing on all patients, and follow up on even a single abnormal glucose reading. Discuss the possibility of shoulder dystocia and the accompanying risk of neonatal injury with “at risk” patients.

Consider obtaining informed consent for vaginal delivery of a patient with risk factors for shoulder dystocia.

Consider cesarean delivery for :

- nondiabetic women when the estimated fetal weight (EFW) exceeds 4,500 g,

- diabetic gravidas when the EFW exceeds 4,000 g,

- women with a prior delivery complicated by shoulder dystocia or brachial plexus palsy,

- gravidas with a prolonged second stage and nonprogression of labor, and

- patients who express fear and doubt about vaginal delivery.

Be sparing with the use of oxytocin when the fetus is known or suspected to be macrosomic, taking special care not to be aggressive with induction.

Use forceps or vacuum extraction with caution, and limit the number of attempts with each.

Minimize traction on the fetal head. Traction that is deemed to be “excessive” may be used against the physician in a liability suit. Gentle traction is acceptable.

Do not use or order fundal pressure. It will almost invariably be used against you in a lawsuit.

Be able to define and correctly describe maneuvers generally accepted as the standard for shoulder dystocia and, when necessary, use and document them appropriately. These include the McRoberts, Wood’s corkscrew, Rubin, and Zavanelli maneuvers; extended episiotomy; suprapubic pressure; and fracture of the anterior clavicle.

Be alert to the possibility of brachial plexus injury in the absence of shoulder dystocia. Obstetricians have been erroneously accused of causing brachial plexus injury by plaintiff attorneys who do not understand that this injury is not always the result of dystocia. Thorough contemporaneous documentation is key in these instances.

Request immediate pediatric assessment of a newborn involved in shoulder dystocia. Have the placenta sent for examination, and request cord blood gases.

Communicate openly and honestly with the parents of a child who has suffered a brachial plexus injury. This may be the single greatest tool for reducing the risk of liability litigation.

Consider serial electromyelograms during the first 7 days of life for a neonate with a brachial plexus palsy. These studies can help determine the etiology of the injury.

Use a shoulder dystocia documentation tool such as the one on page 91. Thorough documentation of all relevant prenatal and intrapartum events is critical to a successful defense. A 12-point detailed delivery note as recommended by Fetterman will also prevent or reduce legal risk.15

Schedule shoulder dystocia “drills” in the labor and delivery unit to familiarize obstetric team members with their roles.

Require comanagement of any midwifery patient at increased risk for shoulder dystocia.

Neonatal injury occurred in all 61 cases. Erb’s palsy was the overwhelming pediatric outcome (57 of 61 cases, or 93.4%), with an aggregate indemnity payment of $17.6 million. Fractured humerus was the outcome in 1 case, and 3 cases involved neonatal deaths.

Reasons for indemnity payments included:

- probable liability (18 defendants),

- plaintiff was sympathetic, likely to evoke an emotional response from the jury (8 defendants),

- clear liability (7 defendants),

- defendant would not have made a strong witness in his or her own defense (5 defendants),

- defendant had died or was too ill to stand trial (3 defendants),

- medical record had been altered (2 defendants),

- case was considered too inflammatory to risk a jury award (2 defendants), and

- policy limits were too low to risk a potentially high jury award (1 defendant).

Five defendants were involved in cases with multiple medicolegal issues that argued for settlement.

The effect of birth weight. Notably, 74% of infants involved in these cases were macrosomic (birth weight over 4,000 g). Except for neonatal injury (100%), no single maternal or fetal variable appears with greater frequency.

The mean indemnity in closed cases increased in direct proportion to fetal weight, ranging from $500,000 in cases involving infants whose birth weight was less than 4,000 g to $950,000 when the birth weight was 5,000 g or more.

Maternal factors seen with greatest frequency included obesity, excessive weight gain in pregnancy, and gestational diabetes. Analysis of prepregnant body mass index found that 19 women had a weight within the “obese” category, 18 of whom gave birth to macrosomic infants. Eight of these cases closed without indemnity payment and 10 closed with an aggregate indemnity payment of $6.5 million.

Forty-eight of the 61 plaintiffs (78.8%) exceeded the normal weight gain in pregnancy based on height and prepregnant weight. Twenty-nine of these cases closed with an aggregate indemnity payment of $16.6 million.

Influence of diabetes. Fifty-two of 61 plaintiffs underwent a glucose screening test. Of these, 23 went on to have a glucose tolerance test, with 12 testing positive for gestational diabetes. Further analysis revealed borderline screening glucose values in an additional 16 cases. These women were not considered diabetic by their obstetricians, were not retested for diabetes, and did not receive nutritional counseling. Macrosomic infants were born to 9 of the 12 patients with gestational diabetes and to 13 of the 16 borderline cases.

Of 28 cases with confirmed or suspected gestational diabetes, 14 women delivered infants weighing over 4,250 g; 11 of the 14 weighed more than 4,500 g.

In a comparison of cases involving diabetic and nondiabetic women who delivered infants weighing more than 4,250 g, 82% of the cases involving nondiabetic women closed without payment. Among cases involving diabetes (actual or borderline), the corresponding figure was 27.3%.

Labor and delivery interventions were cited in all cases. Oxytocin was used in 42 of the 61 cases (68.9%), forceps in 9 (14.8%), and vacuum extraction in 7 (11.5%). Suprapubic pressure was used in 37 cases (60.7%), fundal pressure in 9 (14.8%), and traction on the fetal head in 16 cases (26.2%).

In addition, defense experts determined that the McRoberts maneuver was used in 41 cases (67.2%) and the Wood’s corkscrew maneuver in 28 (45.9%).

Seven cases involved a second stage of labor exceeding 2.5 hours. The ratio of wins to losses decreased substantially with the use of oxytocin, forceps, fundal pressure, or a prolonged second stage.

Data were analyzed using selected variables thought to have an association with winning or losing cases and with indemnity (TABLE 2). No statistically significant models emerged. This is likely due to inadequate power (low number of cases) and the large number of interactions between variables relative to the outcomes evaluated.

TABLE 1

Plaintiff demographics

| CHARACTERISTIC | ALL CASES (n = 61) | CASES WITH INDEMNITY (n = 35) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age, in years (range) | 28 (17–40) | 29 (18–38) |

| Race (%) | ||

| White | 35 (57) | 21 (60) |

| Black | 12 (20) | 7 (20) |

| Hispanic | 11 (18) | 6 (17) |

| Asian | 1 (2) | — |

| Unknown | 2 (3) | 1 (3) |

| Parity (%) | ||

| 0 | 19 (31) | 11 (31) |

| 1 | 26 (43) | 16 (46) |

| 2 | 11 (18) | 7 (20) |

| 3 | 2 (3) | 1 (3) |

| 4 | 2 (3) | — |

| 5 | 1 (2) | — |

TABLE 2

Litigation outcomes for selected prenatal and intrapartum variables

| CHARACTERISTIC | CLOSED WITHOUT INDEMNITY | CLOSED WITHOUT INDEMNITY PAYMENT | MEAN INDEMNITY ($) | TOTAL INDEMNITY ($) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prenatal factors | ||||

| Gestational diabetes | 5 | 7 | 413,300 | 2,893,000 |

| Adjusted diabetes | 10 | 18 | 521,400 | 9,386,000 |

| Obesity | 8 | 13 | 651,300 | 8,466,000 |

| Intrapartum factors | ||||

| Prolonged second stage | 1 | 6 | 707,700 | 4,247,000 |

| Oxytocin induction | 2 | 10 | 406,500 | 4,065,300 |

| Oxytocin augmentation | 15 | 15 | 737,000 | 11,100,000 |

| Forceps delivery | 1 | 8 | 552,100 | 4,416,800 |

| Vacuum extraction | 3 | 4 | 531,300 | 2,125,000 |

| Episiotomy | 20 | 30 | 579,400 | 17,382,100 |

| McRoberts maneuver | 20 | 21 | 542,900 | 11,400,300 |

| Wood’s corkscrew maneuver | 12 | 16 | 652,300 | 10,436,200 |

| Suprapubic pressure | 17 | 20 | 629,000 | 12,579,400 |

| Traction to fetal head | 7 | 9 | 665,500 | 5,989,500 |

| Fundal pressure | 4 | 7 | 660,700 | 4,625,000 |

4 factors raise risk of litigation

After reviewing the literature and analyzing the ProMutual data, we concluded that shoulder dystocia remains largely unpredictable. However, certain clinical factors are clearly associated with an increased risk for litigation:

- prenatal factors,

- labor and delivery interventions,

- maneuvers performed at the time of the dystocia, and

- fetal outcomes.

Prenatal factors. The most significant prenatal factors were maternal obesity, excessive weight gain in pregnancy, and, especially, diabetes and fetal macrosomia.

• Fetal macrosomia. Although most macrosomic infants deliver without complication, fetal macrosomia was involved in more than 72% of the cases reviewed. Because macrosomia represents a risk not only for shoulder dystocia but also for the litigation that may arise from it, it is important to:

- know and document the estimated fetal weight (EFW);

- discuss the risk of dystocia and its sequelae with the mother and her partner; and

- consider cesarean delivery for estimated fetal weights that suggest macrosomia (see the recommendations on page 82 for specifics).

It also is advisable to mobilize a team for the possibility of shoulder dystocia if vaginal delivery is attempted.

Preparing for the increased risk of a macrosomic fetus can be successful only if macrosomia is both diagnosed and anticipated.

Because macrosomia often is accompanied by maternal diabetes, serum glucose testing is recommended for all gravidas, with follow-up of both abnormal and borderline values.

Labor and delivery interventions were cited in all cases, with data indicating a decreasing ratio of wins to losses with the use of oxytocin, forceps, or fundal pressure, and prolonged second stage.

- Use of oxytocin to augment an already established labor carried less risk than oxytocin for labor induction. Ten of the 12 cases (83.3%) in which oxytocin was used for induction closed with an indemnity payment. However, of the 30 cases in which oxytocin was used for labor augmentation, 50% closed with payment.

- • Forceps and a prolonged second stage. Eight of 9 cases (88.9%) involving forceps and 6 of 7 cases (85.7%) involving a prolonged second stage closed with indemnity payment.

Consider cesarean delivery when the second stage is prolonged or labor fails to progress. Be cautious using forceps and vacuum extraction in these circumstances, and limit the number of attempts with either.

Maneuvers performed at the time of dystocia. The most common maneuverswere McRoberts, suprapubic pressure, and Wood’s corkscrew. The ratio of wins to losses decreased with traction of the fetal head and use of fundal pressure.

Part of the risk-management protocol for obstetricians should be appropriate use of McRoberts maneuver, suprapubic pressure, and Wood’s corkscrew, and cutting a large episiotomy. In addition, be careful not to push, pull, rotate the head, or apply fundal pressure.

Fetal outcomes. All cases involved neonatal injury (Erb’s palsy, fractured humerus) or death.

For this reason, we recommend an action plan that includes immediate pediatric or neonatal assessment of neuromuscular function of the infant’s anterior shoulder. Assess the Moro reflex and the possibility of brachial plexus injury and fractures of the clavicle and humerus. Also examine the placenta, send it to pathology, and perform a cord blood gas analysis.

Last words

Shoulder dystocia is the unfortunate complication of a small number of deliveries, but the focus of an increasing number of lawsuits. Because the neonatal injuries that so often accompany shoulder dystocia often lead to litigation, obstetricians should prepare to identify risk and help patients make informed choices. We should be prepared to manage this emergency whenever it occurs and thoroughly document actions.

Dr. Zylstra reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Clip-and-save shoulder dystocia documentation form

Practice recommendations

Among the intrapartum events that constitute bona fide emergencies, shoulder dystocia stands out. This obstetric emergency is the focus of an increasing number of medical liability cases. Most lawsuits involving shoulder dystocia allege negligence as the cause of the brachial plexus injury, fractured clavicle or humerus, or other injury. The defendant physicians named in these suits are often accused of inappropriately managing the prenatal or intrapartum course or the dystocia itself—or of inadequately documenting the steps taken to resolve the emergency.

To glean insights into the litigation process as it involves shoulder dystocia, we retrospectively reviewed all cases closed by the Boston-based ProMutual Group, a major liability insurance carrier, over a 7-year period. We wanted to learn more about the plaintiffs themselves, as well as the clinical and medicolegal factors that led to jury awards or indemnity payments. We also wanted data that could serve as the foundation for guidelines on how to proceed in the event of shoulder dystocia, as well as a documentation tool.

This shoulder dystocia case from an insurer’s closed claim file illustrates a problem often linked to litigation. Minor changes were made to conceal the identities of the involved parties.

Nurse and physician document different times

A 31-year-old woman in her 10th week of pregnancy had one prior uncomplicated vaginal delivery of a 9 lb 7 oz infant. Her prenatal course proceeds unremarkably, with a normal glucose tolerance test and total weight gain of 36 lb. At 41 weeks and 2 days, the estimated fetal weight is documented as 4,120 g. Labor is induced with oxytocin. Because of maternal fatigue, vacuum delivery is attempted.

Notes of the physician and the nurse differ regarding the time of the first of 3 vacuum applications.

After delivery of the head, shoulder dystocia is encountered. In a note handwritten immediately after delivery, the physician states that the head was “reconstituted as right occiput anterior with the left shoulder anterior.”

In a note dictated later, however, the same physician states the right shoulder was anterior.

Help is summoned and arrives 20 minutes after the dystocia is first encountered. The time that help was summoned is in question since there is an 18-minute discrepancy between the times the physician and the nurse note that assistance was called.

Despite the use of suprapubic pressure and maneuvers including McRoberts and Wood’s corkscrew, shoulder dystocia persists for 24 minutes. Apgars of the 11 lb 3 oz infant are 0, 1, and 3. The child is resuscitated but dies within 2 days of birth.

Outcome

Settled with a 7-figure indemnity payment.

What the defense experts said

The key issues involve documentation and summoning assistance. Discrepancies in documentation almost always cast doubt upon the credibility of a defendant. Ideally, there should be no discrepancies between nurse and physician notes and, certainly, no discrepancies between 2 notes on the same case by the same physician. If, in this case, the physician realized after writing the first note that the anterior shoulder had been incorrectly identified, a correction should have been written as a separate note.

Use of the shoulder dystocia documentation tool (see) helps create a chronology of events, which may prove vital to a successful defense.

The call for help might not have been delayed if the labor and delivery unit had had a shoulder dystocia protocol including “drills” for all team members. Help should be called as soon as a shoulder dystocia is encountered so that, when needed, it is available. Under no circumstances should it take 20 minutes for assistance to arrive.

Brachial plexus injury not always caused by shoulder dystocia

Between 21% and 42% of shoulder dystocias involve an injury1—usually brachial plexus injury. Plaintiff attorneys have manipulated this fact to attribute many cases of neonatal brachial plexus injury to mismanagement of shoulder dystocia by the obstetrician.

They fault the physician for failing to estimate fetal weight, perform a timely cesarean, use appropriate maneuvers correctly, or have a pediatrician present. They criticize nothing more resoundingly than use of “inappropriate” or “excessive” lateral traction to the fetal head.2

Nontraction injuries. The reality can be strikingly different, however. Some cases of brachial plexus injury involve no traction at all.

- Brachial plexus injuries have been reported in infants who had precipitate vaginal deliveries without any physical intervention by the obstetrician.2

- These injuries also have occurred in infants delivered via cesarean section.1,3,4

- In some cases, brachial plexus injuries have affected the posterior arm of neonates whose anterior arm was involved in shoulder dystocia.1,2,5-7

A retrospective study4 found that, of 39 cases of brachial plexus injury, only 17 were associated with shoulder dystocia. Similar findings have emerged from other studies.2,3,8

Other causes. It is unclear how brachial plexus injuries occur in the absence of shoulder dystocia. Some think they arise in response to infectious agents such as toxoplasmosis, coxsackievirus, mumps, pertussis, or mycoplasma pneumonia.2 Some assume a mechanical cause, such as fetal response to longstanding abnormal intrauterine pressure exerted by maternal conditions such as bicornate uterus and uterine fibroids, especially in the lower segment.1,2

When brachial plexus injuries occur in the absence of shoulder dystocia, they likely originated before labor and delivery.4 Some experts suggest serial electromyelograms within the first 7 days of life to establish a prenatal rather than intrapartum etiology. A positive electromyelogram within 1 week of birth would suggest antepartum causation.2,9

Recognizing risk factors for shoulder dystocia best way to reduce injury

Most brachial plexus injuries or impairments are associated with shoulder dystocia,9 and shoulder dystocia is the most common way brachial plexus injuries are introduced into litigation.

Decreasing the number of brachial plexusrelated liability cases, therefore, depends on decreasing the incidence of shoulder dystocia. Unfortunately, a failsafe method continues to elude both clinicians and researchers.10-12

Retrospective studies have identified certain factors that may—but do not necessarily—increase the risk of shoulder dystocia.

Prenatal risk factors include high maternal or paternal birth weight, maternal obesity, excessive weight gain during pregnancy, advanced age, short stature, multiparity, postdates, prior shoulder dystocia, small pelvis, prior delivery of a macrosomic infant, gestational diabetes in an earlier pregnancy, abnormal blood sugars in the current pregnancy, or fetal macrosomia.13,14-16

Intrapartum risk factors include a rapid or prolonged second stage, failure or arrest of descent, presence of considerable molding, and need for a midpelvic delivery.10,15

Predictability. Prospective studies have not established the predictability of shoulder dystocia. A 2000 study17 showed that 55% of cases with 1 or more risk factors experienced shoulder dystocia. Predictability increases somewhat when both maternal diabetes and fetal macrosomia complicate pregnancy, since the rate of shoulder dystocia in women with diabetes is consistently higher than in nondiabetic gravidas. This becomes a significant issue when the infant weighs more than 4,000 g.

Indications for prophylactic cesarean in women with diabetes

In 1999, Wagner et al9 found that 70% of shoulder dystocias in women with diabetes occurred when the fetal weight exceeded 4,000 g. They concluded that cesarean delivery for infants with an estimated weight over 4,250 g would reduce the rate of shoulder dystocia by 75% and increase the cesarean delivery rate by 1%.

Others are more conservative. Gross and colleagues11 suggested that, for every additional 26 cesarean deliveries, only 1 case of shoulder dystocia would be prevented.

Macrosomia. Most obstetricians and researchers still do not advocate prophylactic cesarean delivery for macrosomia alone because, by some estimates, 98% of macrosomic infants are delivered without difficulty.18 However, they do suggest that obstetricians at least consider the possibility of cesarean delivery for a macrosomic fetus when the woman has diabetes.

In a study completed in 2000, Skolbekken19 suggested a cutoff of 4,250 g for women with diabetes. Dildy20 suggested limits of more than 4,500 g for diabetic women and more than 5,000 g for nondiabetic gravidas. However, Conway and Langer21 assert that a cutoff of 4,500 g is too liberal for women with diabetes and maintain that, at this cutoff, 40% of shoulder dystocias would not be prevented.

• Ultrasound measurements. Since estimates of fetal weight have a margin of error approaching 40%,9 others have chosen different parameters for determining fetal macrosomia in women with diabetes. In a retrospective study involving 31 women with gestational diabetes, Cohen et al22 found that subtracting the fetal biparietal diameter from the abdominal diameter—with both measurements obtained via ultrasound—yields a predictability score higher than estimated fetal weight. Specifically, if the difference between the 2 measurements is 2.6 cm or more, the rate of shoulder dystocia is high enough to warrant elective cesarean (FIGURE ).

FIGURE Using ultrasound measurements to predict macrosomia

A simple way to predict fetal macrosomia in women with diabetes is to subtract the fetal biparietal diameter (9.3 cm in the scan at left) from the abdominal diameter (average of 12.44 cm in the scan at right). If the difference exceeds 2.6 cm, elective cesarean is warranted. In this case it is 3.14 cm, indicating elective cesarean is warranted.

When dystocia occurs, have a plan and stick to it

Shoulder dystocia immediately places both mother and neonate at risk for temporary or permanent injury. Thus, it is imperative that all obstetricians and other health-care providers who deliver infants have a well developed plan of action for this emergency. They should immediately ask for obstetric assistance and instruct the mother to discontinue any pushing.

Attempts at vigorous downward traction should be avoided, and no fundal pressure should be applied, as these are known to increase the potential for brachial plexus injury. Gentle downward traction is considered the standard of care.17

The obstetrician’s goal is to free the impacted shoulder as quickly as possible, since a fetus can endure only 8 to 10 minutes of asphyxia before permanent neurologic damage occurs.17 The standard of care requires the obstetrician to know and use certain maneuvers to relieve shoulder dystocia. These maneuvers are designed to facilitate vaginal delivery and reduce the risk of permanent brachial plexus injury. The McRoberts maneuver, with flexion and slight rotation of the maternal hips onto the maternal abdomen, is the standard for initial relief of shoulder dystocia.17,23

This shoulder dystocia case from an insurer’s closed claim file illustrates a problem often linked to litigation. Minor changes were made to conceal the identities of the involved parties.

Prompt maneuvers, good outcome

A 28-year-old gravida weighing 214 lb has had 2 previous spontaneous deliveries of infants weighing 8 lb 5 oz and 9 lb 3 oz. Except for a weight gain of more than 60 lb, the pregnancy progressed without complications, and a 3-hour glucose tolerance test was normal. At 40 weeks, the obstetrician notes “concern” about an estimated fetal weight of 10 lb. Induction is planned, but spontaneous labor begins before oxytocin can be given. After 5 hours, the head is delivered without difficulty, but shoulder dystocia follows. The obstetrician extends the episiotomy and performs McRoberts and Wood’s corkscrew maneuvers, but the dystocia persists. Upon noting cyanosis, the obstetrician fractures the infant’s clavicle and quickly delivers a 10 lb 9 oz infant with Apgar scores of 8 and 10. Pediatricians examine the child immediately and diagnose Erb’s palsy, which subsequently resolves. X-rays confirm an undisplaced fracture of the right clavicle. Although the child recovers completely, the family sues, alleging a failure to perform cesarean delivery.

Outcome

Case closed with no payment.

What the defense experts said

Key issues are documentation and informed consent. The overriding opinion of 3 experts who reviewed the case for the defense was that cesarean delivery was not indicated and that in fracturing the clavicle, the physician acted responsibly, quickly, and within the standard of care. One defense expert said failure to document exact maneuvers used to relieve shoulder dystocia deviated from the standard of care. Another defense expert said the physician should have obtained informed consent from this at-risk patient, and explained the risks of shoulder dystocia, including neonatal injury, so that the she might have been better able to appreciate the fact that the obstetrician’s fast action may have saved her child from brain damage or death.

Factors that lead to litigation

In a review article, Hickson24 cited factors that prompted families to file medical liability claims following perinatal injury. Some families observed that, in their search for the cause of an injury, they found 1 or more aspects of care to be inappropriate.

The desire for information, perception of being misled, anger with the medical profession, desire to prevent injuries to others, recognition of long-term sequelae, and advice by knowledgeable acquaintances, as well as the need for money, all appeared to contribute to the decision to file medical liability claims.

Convey the risks, and listen carefully. Communication problems between physicians and patients are a contributing factor. Even when physicians provide technically adequate care, families expect answers to their questions and want to feel as though they have been consulted about important medical decisions.24 If these expectations are not met, even patients who have not experienced an adverse outcome may become angry and express dissatisfaction with care.24

The need for communication is critical when shoulder dystocia results in neonatal injury. Empathizing with the family, helping them understand that most brachial plexus injuries are not long-term, and offering to answer their questions both at the moment and later, may help prevent litigation.