User login

ColCORONA: Colchicine reduces complications in outpatient COVID-19

The oral, anti-inflammatory drug colchicine can prevent complications and hospitalizations in nonhospitalized patients newly diagnosed with COVID-19, according to a press release from the ColCORONA trial investigators.

After 1 month of therapy, there was a 21% risk reduction in the primary composite endpoint of death or hospitalizations that missed statistical significance, compared with placebo among 4,488 outpatients enrolled in the global, phase 3 trial.

After excluding 329 patients without a confirmatory polymerase chain reaction test, however, the use of colchicine was reported to significantly reduce hospitalizations by 25%, the need for mechanical ventilation by 50%, and deaths by 44%.

“We believe that this is a medical breakthrough. There’s no approved therapy to prevent complications of COVID-19 in outpatients, to prevent them from reaching the hospital,” lead investigator Jean-Claude Tardif, MD, from the Montreal Heart Institute, said in an interview.

“I know that several countries will be reviewing the data very rapidly and that Greece approved it today,” he said. “So this is providing hope for patients.”

Having been burned by hydroxychloroquine and other treatments brought forth without peer review, the response to the announcement was tempered by a desire for more details.

Asked for comment, Steven E. Nissen, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic Foundation, was cautious. “The press release about the trial is vague and lacks details such as hazard ratios, confidence intervals, and P values,” he said in an interview.

“It is impossible to evaluate the results of this trial without these details. It is also uncertain how rigorously data were collected,” he added. “We’ll need to see the manuscript to adequately interpret the results.”

The evidence in the press release is hard to interpret, but early intervention with anti-inflammatory therapy has considerable biologic appeal in COVID, said Paul Ridker, MD, MPH, who led the pivotal CANTOS trial of the anti-inflammatory drug canakinumab in the post-MI setting, and is also chair of the ACTIV-4B trial currently investigating anticoagulants and antithrombotics in outpatient COVID-19.

“Colchicine is both inexpensive and generally well tolerated, and the apparent benefits so far reported are substantial,” Dr. Ridker, from Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said in an interview. “We are eager to see the full data as rapidly as possible.”

The commonly used gout and rheumatic disease agent costs about 26 cents in Canada and between $4 and $6 in the United States. As previously reported, it reduced the time to clinical deterioration and hospital stay but not mortality in the 105-patient Greek Study in the Effects of Colchicine in COVID-19 Complications Prevention (GRECCO-19) study.

Dr. Tardif said he’s looking forward to having the data in the public domain and that they acted swiftly because the evidence was “clinically persuasive” and “the health system is congested now.”

“We received the results Friday, Jan. 22 at 5 p.m., an hour later we were in meetings with our data safety monitoring board [DSMB], 2 hours later we issued a press release, and a day later we’re submitting a full manuscript to a major scientific journal, so I don’t know if anyone has done this at this speed,” he said. “So we are actually very proud of what we did.”

ColCORONA was designed to enroll 6,000 outpatients, at least 40 years of age, who were diagnosed with COVID-19 infection within the previous 24 hours, and had a least one high-risk criterion, including age at least 70 years, body mass index of at least 30 kg/m2, diabetes mellitus, uncontrolled hypertension, known respiratory disease, heart failure or coronary disease, fever of at least 38.4° C within the last 48 hours, dyspnea at presentation, bicytopenia, pancytopenia, or the combination of high neutrophil count and low lymphocyte count.

Participants were randomly assigned to receive either placebo or colchicine 0.5 mg twice daily for 3 days and then once daily for another 27 days.

The number needed to prevent one COVID-19 complication is about 60 patients, Dr. Tardif said.

Colchicine was well tolerated and resulted in fewer serious adverse events than with placebo, he said. Diarrhea occurred more often with colchicine, but there was no increase in pneumonia. Caution should be used, however, in treating patients with severe renal disease.

Dr. Tardif said he would not prescribe colchicine to an 18-year-old COVID outpatient who doesn’t have any concomitant diseases, but would for those meeting the study protocol.

“As long as a patient appears to me to be at risk of a complication, I would prescribe it, without a doubt,” he said. “I can tell you that when we held the meeting with the DSMB Friday evening, I actually put each member on the spot and asked them: ‘If it were you – not even treating a patient, but if you had COVID today, would you take it based on the data you’ve seen?’ and all of the DSMB members said they would.

“So we’ll have that debate in the public domain when the paper is out, but I believe most physicians will use it to treat their patients.”

The trial was coordinated by the Montreal Heart Institute and funded by the government of Quebec; the U.S. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Montreal philanthropist Sophie Desmarais; and the COVID-19 Therapeutics Accelerator launched by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Wellcome, and Mastercard. CGI, Dacima, and Pharmascience of Montreal were also collaborators.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The oral, anti-inflammatory drug colchicine can prevent complications and hospitalizations in nonhospitalized patients newly diagnosed with COVID-19, according to a press release from the ColCORONA trial investigators.

After 1 month of therapy, there was a 21% risk reduction in the primary composite endpoint of death or hospitalizations that missed statistical significance, compared with placebo among 4,488 outpatients enrolled in the global, phase 3 trial.

After excluding 329 patients without a confirmatory polymerase chain reaction test, however, the use of colchicine was reported to significantly reduce hospitalizations by 25%, the need for mechanical ventilation by 50%, and deaths by 44%.

“We believe that this is a medical breakthrough. There’s no approved therapy to prevent complications of COVID-19 in outpatients, to prevent them from reaching the hospital,” lead investigator Jean-Claude Tardif, MD, from the Montreal Heart Institute, said in an interview.

“I know that several countries will be reviewing the data very rapidly and that Greece approved it today,” he said. “So this is providing hope for patients.”

Having been burned by hydroxychloroquine and other treatments brought forth without peer review, the response to the announcement was tempered by a desire for more details.

Asked for comment, Steven E. Nissen, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic Foundation, was cautious. “The press release about the trial is vague and lacks details such as hazard ratios, confidence intervals, and P values,” he said in an interview.

“It is impossible to evaluate the results of this trial without these details. It is also uncertain how rigorously data were collected,” he added. “We’ll need to see the manuscript to adequately interpret the results.”

The evidence in the press release is hard to interpret, but early intervention with anti-inflammatory therapy has considerable biologic appeal in COVID, said Paul Ridker, MD, MPH, who led the pivotal CANTOS trial of the anti-inflammatory drug canakinumab in the post-MI setting, and is also chair of the ACTIV-4B trial currently investigating anticoagulants and antithrombotics in outpatient COVID-19.

“Colchicine is both inexpensive and generally well tolerated, and the apparent benefits so far reported are substantial,” Dr. Ridker, from Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said in an interview. “We are eager to see the full data as rapidly as possible.”

The commonly used gout and rheumatic disease agent costs about 26 cents in Canada and between $4 and $6 in the United States. As previously reported, it reduced the time to clinical deterioration and hospital stay but not mortality in the 105-patient Greek Study in the Effects of Colchicine in COVID-19 Complications Prevention (GRECCO-19) study.

Dr. Tardif said he’s looking forward to having the data in the public domain and that they acted swiftly because the evidence was “clinically persuasive” and “the health system is congested now.”

“We received the results Friday, Jan. 22 at 5 p.m., an hour later we were in meetings with our data safety monitoring board [DSMB], 2 hours later we issued a press release, and a day later we’re submitting a full manuscript to a major scientific journal, so I don’t know if anyone has done this at this speed,” he said. “So we are actually very proud of what we did.”

ColCORONA was designed to enroll 6,000 outpatients, at least 40 years of age, who were diagnosed with COVID-19 infection within the previous 24 hours, and had a least one high-risk criterion, including age at least 70 years, body mass index of at least 30 kg/m2, diabetes mellitus, uncontrolled hypertension, known respiratory disease, heart failure or coronary disease, fever of at least 38.4° C within the last 48 hours, dyspnea at presentation, bicytopenia, pancytopenia, or the combination of high neutrophil count and low lymphocyte count.

Participants were randomly assigned to receive either placebo or colchicine 0.5 mg twice daily for 3 days and then once daily for another 27 days.

The number needed to prevent one COVID-19 complication is about 60 patients, Dr. Tardif said.

Colchicine was well tolerated and resulted in fewer serious adverse events than with placebo, he said. Diarrhea occurred more often with colchicine, but there was no increase in pneumonia. Caution should be used, however, in treating patients with severe renal disease.

Dr. Tardif said he would not prescribe colchicine to an 18-year-old COVID outpatient who doesn’t have any concomitant diseases, but would for those meeting the study protocol.

“As long as a patient appears to me to be at risk of a complication, I would prescribe it, without a doubt,” he said. “I can tell you that when we held the meeting with the DSMB Friday evening, I actually put each member on the spot and asked them: ‘If it were you – not even treating a patient, but if you had COVID today, would you take it based on the data you’ve seen?’ and all of the DSMB members said they would.

“So we’ll have that debate in the public domain when the paper is out, but I believe most physicians will use it to treat their patients.”

The trial was coordinated by the Montreal Heart Institute and funded by the government of Quebec; the U.S. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Montreal philanthropist Sophie Desmarais; and the COVID-19 Therapeutics Accelerator launched by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Wellcome, and Mastercard. CGI, Dacima, and Pharmascience of Montreal were also collaborators.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The oral, anti-inflammatory drug colchicine can prevent complications and hospitalizations in nonhospitalized patients newly diagnosed with COVID-19, according to a press release from the ColCORONA trial investigators.

After 1 month of therapy, there was a 21% risk reduction in the primary composite endpoint of death or hospitalizations that missed statistical significance, compared with placebo among 4,488 outpatients enrolled in the global, phase 3 trial.

After excluding 329 patients without a confirmatory polymerase chain reaction test, however, the use of colchicine was reported to significantly reduce hospitalizations by 25%, the need for mechanical ventilation by 50%, and deaths by 44%.

“We believe that this is a medical breakthrough. There’s no approved therapy to prevent complications of COVID-19 in outpatients, to prevent them from reaching the hospital,” lead investigator Jean-Claude Tardif, MD, from the Montreal Heart Institute, said in an interview.

“I know that several countries will be reviewing the data very rapidly and that Greece approved it today,” he said. “So this is providing hope for patients.”

Having been burned by hydroxychloroquine and other treatments brought forth without peer review, the response to the announcement was tempered by a desire for more details.

Asked for comment, Steven E. Nissen, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic Foundation, was cautious. “The press release about the trial is vague and lacks details such as hazard ratios, confidence intervals, and P values,” he said in an interview.

“It is impossible to evaluate the results of this trial without these details. It is also uncertain how rigorously data were collected,” he added. “We’ll need to see the manuscript to adequately interpret the results.”

The evidence in the press release is hard to interpret, but early intervention with anti-inflammatory therapy has considerable biologic appeal in COVID, said Paul Ridker, MD, MPH, who led the pivotal CANTOS trial of the anti-inflammatory drug canakinumab in the post-MI setting, and is also chair of the ACTIV-4B trial currently investigating anticoagulants and antithrombotics in outpatient COVID-19.

“Colchicine is both inexpensive and generally well tolerated, and the apparent benefits so far reported are substantial,” Dr. Ridker, from Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said in an interview. “We are eager to see the full data as rapidly as possible.”

The commonly used gout and rheumatic disease agent costs about 26 cents in Canada and between $4 and $6 in the United States. As previously reported, it reduced the time to clinical deterioration and hospital stay but not mortality in the 105-patient Greek Study in the Effects of Colchicine in COVID-19 Complications Prevention (GRECCO-19) study.

Dr. Tardif said he’s looking forward to having the data in the public domain and that they acted swiftly because the evidence was “clinically persuasive” and “the health system is congested now.”

“We received the results Friday, Jan. 22 at 5 p.m., an hour later we were in meetings with our data safety monitoring board [DSMB], 2 hours later we issued a press release, and a day later we’re submitting a full manuscript to a major scientific journal, so I don’t know if anyone has done this at this speed,” he said. “So we are actually very proud of what we did.”

ColCORONA was designed to enroll 6,000 outpatients, at least 40 years of age, who were diagnosed with COVID-19 infection within the previous 24 hours, and had a least one high-risk criterion, including age at least 70 years, body mass index of at least 30 kg/m2, diabetes mellitus, uncontrolled hypertension, known respiratory disease, heart failure or coronary disease, fever of at least 38.4° C within the last 48 hours, dyspnea at presentation, bicytopenia, pancytopenia, or the combination of high neutrophil count and low lymphocyte count.

Participants were randomly assigned to receive either placebo or colchicine 0.5 mg twice daily for 3 days and then once daily for another 27 days.

The number needed to prevent one COVID-19 complication is about 60 patients, Dr. Tardif said.

Colchicine was well tolerated and resulted in fewer serious adverse events than with placebo, he said. Diarrhea occurred more often with colchicine, but there was no increase in pneumonia. Caution should be used, however, in treating patients with severe renal disease.

Dr. Tardif said he would not prescribe colchicine to an 18-year-old COVID outpatient who doesn’t have any concomitant diseases, but would for those meeting the study protocol.

“As long as a patient appears to me to be at risk of a complication, I would prescribe it, without a doubt,” he said. “I can tell you that when we held the meeting with the DSMB Friday evening, I actually put each member on the spot and asked them: ‘If it were you – not even treating a patient, but if you had COVID today, would you take it based on the data you’ve seen?’ and all of the DSMB members said they would.

“So we’ll have that debate in the public domain when the paper is out, but I believe most physicians will use it to treat their patients.”

The trial was coordinated by the Montreal Heart Institute and funded by the government of Quebec; the U.S. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Montreal philanthropist Sophie Desmarais; and the COVID-19 Therapeutics Accelerator launched by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Wellcome, and Mastercard. CGI, Dacima, and Pharmascience of Montreal were also collaborators.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Full-dose anticoagulation reduces need for life support in COVID-19

Full-dose anticoagulation was superior to low, prophylactic doses in reducing the need for vital organ support such as ventilation in moderately ill patients hospitalized for COVID-19, according to a report released Jan. 22 by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

“This is a major advance for patients hospitalized with COVID. Full dose of anticoagulation in these non-ICU patients improved outcomes and there’s a trend toward a reduction in mortality,” Judith Hochman, MD, director of the Cardiovascular Clinical Research Center at NYU Langone Medical Center, New York, said in an interview.

“We have treatments that are improving outcomes but not as many that reduce mortality, so we’re hopeful when the full dataset comes in that will be confirmed,” she said.

The observation of increased rates of blood clots and inflammation among COVID-19 patients, which can lead to complications such as lung failure, heart attack, and stroke, has given rise to various anticoagulant treatment protocols and a need for randomized data on routinely administering increased doses of anticoagulation to hospitalized patients.

Today’s top-line findings come from three linked clinical trials – REMAP-CAP, ACTIV-4, and ATTACC – examining the safety and efficacy of full-dose anticoagulation to treat moderately ill or critically ill adults hospitalized with COVID-19 compared with a lower dose typically used to prevent blood clots in hospitalized patients.

In December 2020, all three trials paused enrollment of the critically ill subgroup after results showed that full-dose anticoagulation started in the intensive care unit (ICU) was not beneficial and may have been harmful in some patients.

Moderately ill patients with COVID-19, defined as those who did not require ICU care or organ support, made up 80% of participants at enrollment in the three trials, Dr. Hochman said.

Among more than 1,000 moderately ill patients reviewed as of the data cut with the data safety monitoring board, full doses of low molecular weight or unfractionated heparin were superior to low prophylactic doses for the primary endpoint of need for ventilation or other organ supportive interventions at 21 days after randomization.

This met the predefined threshold for 99% probability of superiority and recruitment was stopped, Dr. Hochman reported. “Obviously safety figured into this decision. The risk/benefit ratio was very clear.”

The results do not pertain to patients with a previous indication for anticoagulation, who were excluded from the trials.

Data from an additional 1,000 patients will be reviewed and the data published sometime in the next 2-3 months, she said.

With large numbers of COVID-19 patients requiring hospitalization, the outcomes could help reduce the overload on intensive care units around the world, the NIH noted.

The results also highlight the critical role of timing in the course of COVID-19.

“We believe that full anticoagulation is effective early in the disease course,” Dr. Hochman said. “Based on the results so far from these three platform trials, those that were very, very sick at the time of enrollment really didn’t benefit and we needed to have caught them at an earlier stage.

“It’s possible that the people in the ICU are just different and the minute they get sick they need the ICU; so we haven’t clearly demonstrated this time course and when to intervene, but that’s the implication of the findings.”

The question of even earlier treatment is being examined in the partner ACTIV-4B trial, which is enrolling patients with COVID-19 illness not requiring hospitalization and randomizing them to the direct oral anticoagulant apixaban or aspirin or placebo.

“It’s a very important trial and we really want to get the message out that patients should volunteer for it,” said Dr. Hochman, principal investigator of the ACTIV-4 trial.

In the United States, the ACTIV-4 trial is being led by a collaborative effort involving a number of universities, including the University of Pittsburgh and New York University.

The REMAP-CAP, ACTIV-4, and ATTACC study platforms span five continents in more than 300 hospitals and are supported by multiple international funding organizations including the National Institutes of Health, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the National Institute for Health Research (United Kingdom), the National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia), and the PREPARE and RECOVER consortia (European Union).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Full-dose anticoagulation was superior to low, prophylactic doses in reducing the need for vital organ support such as ventilation in moderately ill patients hospitalized for COVID-19, according to a report released Jan. 22 by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

“This is a major advance for patients hospitalized with COVID. Full dose of anticoagulation in these non-ICU patients improved outcomes and there’s a trend toward a reduction in mortality,” Judith Hochman, MD, director of the Cardiovascular Clinical Research Center at NYU Langone Medical Center, New York, said in an interview.

“We have treatments that are improving outcomes but not as many that reduce mortality, so we’re hopeful when the full dataset comes in that will be confirmed,” she said.

The observation of increased rates of blood clots and inflammation among COVID-19 patients, which can lead to complications such as lung failure, heart attack, and stroke, has given rise to various anticoagulant treatment protocols and a need for randomized data on routinely administering increased doses of anticoagulation to hospitalized patients.

Today’s top-line findings come from three linked clinical trials – REMAP-CAP, ACTIV-4, and ATTACC – examining the safety and efficacy of full-dose anticoagulation to treat moderately ill or critically ill adults hospitalized with COVID-19 compared with a lower dose typically used to prevent blood clots in hospitalized patients.

In December 2020, all three trials paused enrollment of the critically ill subgroup after results showed that full-dose anticoagulation started in the intensive care unit (ICU) was not beneficial and may have been harmful in some patients.

Moderately ill patients with COVID-19, defined as those who did not require ICU care or organ support, made up 80% of participants at enrollment in the three trials, Dr. Hochman said.

Among more than 1,000 moderately ill patients reviewed as of the data cut with the data safety monitoring board, full doses of low molecular weight or unfractionated heparin were superior to low prophylactic doses for the primary endpoint of need for ventilation or other organ supportive interventions at 21 days after randomization.

This met the predefined threshold for 99% probability of superiority and recruitment was stopped, Dr. Hochman reported. “Obviously safety figured into this decision. The risk/benefit ratio was very clear.”

The results do not pertain to patients with a previous indication for anticoagulation, who were excluded from the trials.

Data from an additional 1,000 patients will be reviewed and the data published sometime in the next 2-3 months, she said.

With large numbers of COVID-19 patients requiring hospitalization, the outcomes could help reduce the overload on intensive care units around the world, the NIH noted.

The results also highlight the critical role of timing in the course of COVID-19.

“We believe that full anticoagulation is effective early in the disease course,” Dr. Hochman said. “Based on the results so far from these three platform trials, those that were very, very sick at the time of enrollment really didn’t benefit and we needed to have caught them at an earlier stage.

“It’s possible that the people in the ICU are just different and the minute they get sick they need the ICU; so we haven’t clearly demonstrated this time course and when to intervene, but that’s the implication of the findings.”

The question of even earlier treatment is being examined in the partner ACTIV-4B trial, which is enrolling patients with COVID-19 illness not requiring hospitalization and randomizing them to the direct oral anticoagulant apixaban or aspirin or placebo.

“It’s a very important trial and we really want to get the message out that patients should volunteer for it,” said Dr. Hochman, principal investigator of the ACTIV-4 trial.

In the United States, the ACTIV-4 trial is being led by a collaborative effort involving a number of universities, including the University of Pittsburgh and New York University.

The REMAP-CAP, ACTIV-4, and ATTACC study platforms span five continents in more than 300 hospitals and are supported by multiple international funding organizations including the National Institutes of Health, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the National Institute for Health Research (United Kingdom), the National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia), and the PREPARE and RECOVER consortia (European Union).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Full-dose anticoagulation was superior to low, prophylactic doses in reducing the need for vital organ support such as ventilation in moderately ill patients hospitalized for COVID-19, according to a report released Jan. 22 by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

“This is a major advance for patients hospitalized with COVID. Full dose of anticoagulation in these non-ICU patients improved outcomes and there’s a trend toward a reduction in mortality,” Judith Hochman, MD, director of the Cardiovascular Clinical Research Center at NYU Langone Medical Center, New York, said in an interview.

“We have treatments that are improving outcomes but not as many that reduce mortality, so we’re hopeful when the full dataset comes in that will be confirmed,” she said.

The observation of increased rates of blood clots and inflammation among COVID-19 patients, which can lead to complications such as lung failure, heart attack, and stroke, has given rise to various anticoagulant treatment protocols and a need for randomized data on routinely administering increased doses of anticoagulation to hospitalized patients.

Today’s top-line findings come from three linked clinical trials – REMAP-CAP, ACTIV-4, and ATTACC – examining the safety and efficacy of full-dose anticoagulation to treat moderately ill or critically ill adults hospitalized with COVID-19 compared with a lower dose typically used to prevent blood clots in hospitalized patients.

In December 2020, all three trials paused enrollment of the critically ill subgroup after results showed that full-dose anticoagulation started in the intensive care unit (ICU) was not beneficial and may have been harmful in some patients.

Moderately ill patients with COVID-19, defined as those who did not require ICU care or organ support, made up 80% of participants at enrollment in the three trials, Dr. Hochman said.

Among more than 1,000 moderately ill patients reviewed as of the data cut with the data safety monitoring board, full doses of low molecular weight or unfractionated heparin were superior to low prophylactic doses for the primary endpoint of need for ventilation or other organ supportive interventions at 21 days after randomization.

This met the predefined threshold for 99% probability of superiority and recruitment was stopped, Dr. Hochman reported. “Obviously safety figured into this decision. The risk/benefit ratio was very clear.”

The results do not pertain to patients with a previous indication for anticoagulation, who were excluded from the trials.

Data from an additional 1,000 patients will be reviewed and the data published sometime in the next 2-3 months, she said.

With large numbers of COVID-19 patients requiring hospitalization, the outcomes could help reduce the overload on intensive care units around the world, the NIH noted.

The results also highlight the critical role of timing in the course of COVID-19.

“We believe that full anticoagulation is effective early in the disease course,” Dr. Hochman said. “Based on the results so far from these three platform trials, those that were very, very sick at the time of enrollment really didn’t benefit and we needed to have caught them at an earlier stage.

“It’s possible that the people in the ICU are just different and the minute they get sick they need the ICU; so we haven’t clearly demonstrated this time course and when to intervene, but that’s the implication of the findings.”

The question of even earlier treatment is being examined in the partner ACTIV-4B trial, which is enrolling patients with COVID-19 illness not requiring hospitalization and randomizing them to the direct oral anticoagulant apixaban or aspirin or placebo.

“It’s a very important trial and we really want to get the message out that patients should volunteer for it,” said Dr. Hochman, principal investigator of the ACTIV-4 trial.

In the United States, the ACTIV-4 trial is being led by a collaborative effort involving a number of universities, including the University of Pittsburgh and New York University.

The REMAP-CAP, ACTIV-4, and ATTACC study platforms span five continents in more than 300 hospitals and are supported by multiple international funding organizations including the National Institutes of Health, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the National Institute for Health Research (United Kingdom), the National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia), and the PREPARE and RECOVER consortia (European Union).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Income inequality plus race drive COVID incidence, death rates in U.S.

according to an analysis of U.S. county-level data.

The study, published in JAMA Network Open (2021 Jan 20. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.34578), was led by Tim F. Liao, PhD, of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and Fernando de Maio, of DePaul University, Chicago. They wrote: “This analysis confirms the association between racial/ethnic composition and COVID-19 incidence and mortality. A higher level of Black or Hispanic composition in a county is associated with a higher COVID-19 incidence and mortality; a higher level of economic inequality is also associated with a higher level of incidence and mortality.”

The analysis, which examined data from the first 200 days of the pandemic from January to August 2020, examined the joint associations between income inequality and racial and ethnic composition. Researchers mined data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Census Bureau, the Kaiser Family Foundation, and other sources for 3,142 U.S. counties.

Income inequality was measured with the Gini index, on a 0-100 scale, with zero meaning perfect income equality (everyone has the same income) and 100 meaning perfect inequality (only one person or group has all of the income). The average Gini score across all the counties was 44.5, with a range of 25.6-66.5.

Researchers found that, for every 1.0% increase in a county’s Black population, there was a 1.9% increase in COVID-19 incidence (risk ratio, 1.019; 95% confidence interval, 1.016-1.022) and a 2.6% increase in COVID-19 mortality (RR, 1.026; 95% CI, 1.020-1.033). For every 1.0% increase in a county’s Hispanic population, there was a 2.4% increase in incidence (RR, 1.024; 95% CI, 1.012-1.025) and a 1.9% increase in mortality (RR, 1.019; 95% CI, 1.012-1.025).

Income inequality had an even greater effect on COVID-19 incidence and mortality. For each 1.0% rise in a county’s income inequality, there was a 2.0% rise in incidence (RR, 1.020; 95% CI, 1.012-1.027), and a 3.0% rise in mortality (RR, 1.030; 95% CI, 1.012-1.047).

In counties with lower percentages of Black and Hispanic population – up to about 50% for blacks and about 20%-30% for Hispanics – greater income inequality was correlated with higher COVID-19 incidence and mortality. But as the proportion of the Black and Hispanic population increased, race and ethnic population became the much more dominant predictive factor. In other words, the researchers said, income inequality seems to become less of a factor in COVID-related health as the minority population number grows in a given county.

“This finding implies that counties with relatively low proportions of Black or Hispanic residents may experience health effects of income inequality associated with the neomaterial pathway, which connects income inequality to population health through the breakdown of public infrastructure,” such as education, transportation and health care, the researchers said.

The study also examined the interaction between these factors and political attributes of a county, such as whether a governor faced a term limit, was Republican, or was male, and these were found to have no effect on COVID-19 incidence and mortality. Counties in states participating in Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act had a 32% lower COVID-19 incidence rate, researchers found, but there was no correlation with mortality rates.

“This analysis found racial/ethnic composition, while important, does not reveal the full complexity of the story,” the researchers wrote. “Income inequality – a measure not typically included in public health county-level surveillance – also needs to be considered as a driver of the disproportionate burden borne by minoritized communities across the United States.”

The findings, they said, support using composite variables that “measure both income inequality and racial/ethnic composition simultaneously.”

The investigators had no disclosures.

according to an analysis of U.S. county-level data.

The study, published in JAMA Network Open (2021 Jan 20. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.34578), was led by Tim F. Liao, PhD, of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and Fernando de Maio, of DePaul University, Chicago. They wrote: “This analysis confirms the association between racial/ethnic composition and COVID-19 incidence and mortality. A higher level of Black or Hispanic composition in a county is associated with a higher COVID-19 incidence and mortality; a higher level of economic inequality is also associated with a higher level of incidence and mortality.”

The analysis, which examined data from the first 200 days of the pandemic from January to August 2020, examined the joint associations between income inequality and racial and ethnic composition. Researchers mined data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Census Bureau, the Kaiser Family Foundation, and other sources for 3,142 U.S. counties.

Income inequality was measured with the Gini index, on a 0-100 scale, with zero meaning perfect income equality (everyone has the same income) and 100 meaning perfect inequality (only one person or group has all of the income). The average Gini score across all the counties was 44.5, with a range of 25.6-66.5.

Researchers found that, for every 1.0% increase in a county’s Black population, there was a 1.9% increase in COVID-19 incidence (risk ratio, 1.019; 95% confidence interval, 1.016-1.022) and a 2.6% increase in COVID-19 mortality (RR, 1.026; 95% CI, 1.020-1.033). For every 1.0% increase in a county’s Hispanic population, there was a 2.4% increase in incidence (RR, 1.024; 95% CI, 1.012-1.025) and a 1.9% increase in mortality (RR, 1.019; 95% CI, 1.012-1.025).

Income inequality had an even greater effect on COVID-19 incidence and mortality. For each 1.0% rise in a county’s income inequality, there was a 2.0% rise in incidence (RR, 1.020; 95% CI, 1.012-1.027), and a 3.0% rise in mortality (RR, 1.030; 95% CI, 1.012-1.047).

In counties with lower percentages of Black and Hispanic population – up to about 50% for blacks and about 20%-30% for Hispanics – greater income inequality was correlated with higher COVID-19 incidence and mortality. But as the proportion of the Black and Hispanic population increased, race and ethnic population became the much more dominant predictive factor. In other words, the researchers said, income inequality seems to become less of a factor in COVID-related health as the minority population number grows in a given county.

“This finding implies that counties with relatively low proportions of Black or Hispanic residents may experience health effects of income inequality associated with the neomaterial pathway, which connects income inequality to population health through the breakdown of public infrastructure,” such as education, transportation and health care, the researchers said.

The study also examined the interaction between these factors and political attributes of a county, such as whether a governor faced a term limit, was Republican, or was male, and these were found to have no effect on COVID-19 incidence and mortality. Counties in states participating in Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act had a 32% lower COVID-19 incidence rate, researchers found, but there was no correlation with mortality rates.

“This analysis found racial/ethnic composition, while important, does not reveal the full complexity of the story,” the researchers wrote. “Income inequality – a measure not typically included in public health county-level surveillance – also needs to be considered as a driver of the disproportionate burden borne by minoritized communities across the United States.”

The findings, they said, support using composite variables that “measure both income inequality and racial/ethnic composition simultaneously.”

The investigators had no disclosures.

according to an analysis of U.S. county-level data.

The study, published in JAMA Network Open (2021 Jan 20. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.34578), was led by Tim F. Liao, PhD, of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and Fernando de Maio, of DePaul University, Chicago. They wrote: “This analysis confirms the association between racial/ethnic composition and COVID-19 incidence and mortality. A higher level of Black or Hispanic composition in a county is associated with a higher COVID-19 incidence and mortality; a higher level of economic inequality is also associated with a higher level of incidence and mortality.”

The analysis, which examined data from the first 200 days of the pandemic from January to August 2020, examined the joint associations between income inequality and racial and ethnic composition. Researchers mined data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Census Bureau, the Kaiser Family Foundation, and other sources for 3,142 U.S. counties.

Income inequality was measured with the Gini index, on a 0-100 scale, with zero meaning perfect income equality (everyone has the same income) and 100 meaning perfect inequality (only one person or group has all of the income). The average Gini score across all the counties was 44.5, with a range of 25.6-66.5.

Researchers found that, for every 1.0% increase in a county’s Black population, there was a 1.9% increase in COVID-19 incidence (risk ratio, 1.019; 95% confidence interval, 1.016-1.022) and a 2.6% increase in COVID-19 mortality (RR, 1.026; 95% CI, 1.020-1.033). For every 1.0% increase in a county’s Hispanic population, there was a 2.4% increase in incidence (RR, 1.024; 95% CI, 1.012-1.025) and a 1.9% increase in mortality (RR, 1.019; 95% CI, 1.012-1.025).

Income inequality had an even greater effect on COVID-19 incidence and mortality. For each 1.0% rise in a county’s income inequality, there was a 2.0% rise in incidence (RR, 1.020; 95% CI, 1.012-1.027), and a 3.0% rise in mortality (RR, 1.030; 95% CI, 1.012-1.047).

In counties with lower percentages of Black and Hispanic population – up to about 50% for blacks and about 20%-30% for Hispanics – greater income inequality was correlated with higher COVID-19 incidence and mortality. But as the proportion of the Black and Hispanic population increased, race and ethnic population became the much more dominant predictive factor. In other words, the researchers said, income inequality seems to become less of a factor in COVID-related health as the minority population number grows in a given county.

“This finding implies that counties with relatively low proportions of Black or Hispanic residents may experience health effects of income inequality associated with the neomaterial pathway, which connects income inequality to population health through the breakdown of public infrastructure,” such as education, transportation and health care, the researchers said.

The study also examined the interaction between these factors and political attributes of a county, such as whether a governor faced a term limit, was Republican, or was male, and these were found to have no effect on COVID-19 incidence and mortality. Counties in states participating in Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act had a 32% lower COVID-19 incidence rate, researchers found, but there was no correlation with mortality rates.

“This analysis found racial/ethnic composition, while important, does not reveal the full complexity of the story,” the researchers wrote. “Income inequality – a measure not typically included in public health county-level surveillance – also needs to be considered as a driver of the disproportionate burden borne by minoritized communities across the United States.”

The findings, they said, support using composite variables that “measure both income inequality and racial/ethnic composition simultaneously.”

The investigators had no disclosures.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

What we know and don’t know about virus variants and vaccines

About 20 states across the country have detected the more transmissible B.1.1.7 SARS-CoV-2 variant to date. Given the unknowns of the emerging situation, experts with the Infectious Diseases Society of America addressed vaccine effectiveness, how well equipped the United States is to track new mutations, and shared their impressions of President Joe Biden’s COVID-19 executive orders.

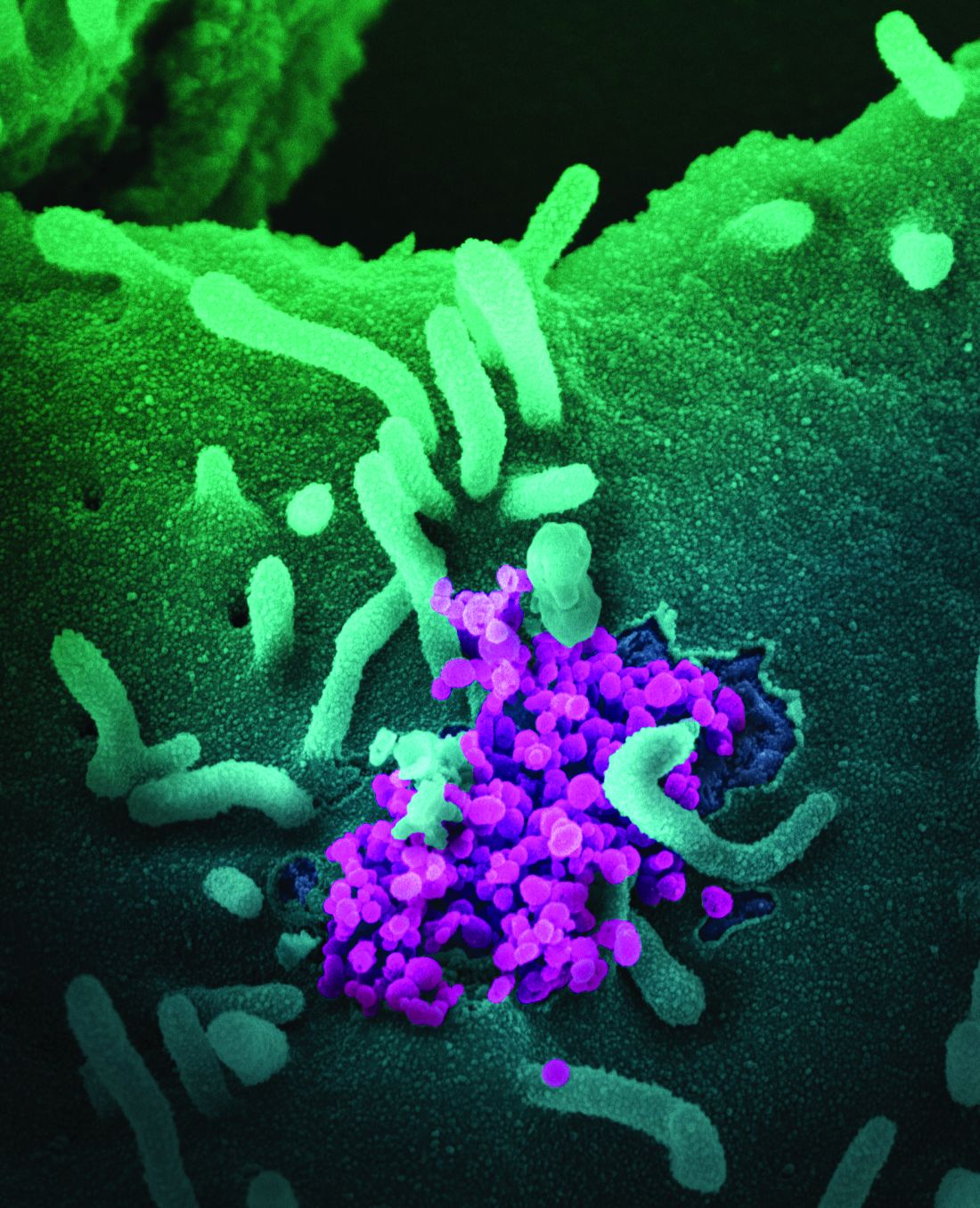

One of the major concerns remains the ability of COVID-19 vaccines to work on new strains. “All of our vaccines target the spike protein and try to elicit neutralizing antibodies that bind to that protein,” Mirella Salvatore, MD, assistant professor of medicine and population health sciences at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, said during an IDSA press briefing on Thursday.

The B.1.1.7 mutation occurs in the “very important” spike protein, a component of the SARS-CoV-2 virus necessary for binding, which allows the virus to enter cells, added Dr. Salvatore, an IDSA fellow.

The evidence suggests that SARS-CoV-2 should be capable of producing one or two mutations per month. However, the B.1.1.7 variant surprised investigators in the United Kingdom when they first discovered the strain had 17 mutations, Dr. Salvatore said.

It’s still unknown why this particular strain is more transmissible, but Dr. Salvatore speculated that the mutation gives the virus an advantage and increases binding, allowing it to enter cells more easily. She added that the mutations might have arisen among immunocompromised people infected with SARS-CoV-2, but “that is just a hypothesis.”

On a positive note, Kathryn M. Edwards, MD, another IDSA fellow, explained at the briefing that the existing vaccines target more than one location on the virus’ spike protein. Therefore, “if there is a mutation that changes one structure of the spike protein, there will be other areas where the binding can occur.”

This polyclonal response “is why the vaccine can still be effective against this virus,” added Dr. Edwards, scientific director of the Vanderbilt Vaccine Research Program and professor of pediatrics at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

Dr. Salvatore emphasized that, although the new variant is more transmissible, it doesn’t appear to be more lethal. “This might affect overall mortality but not for the individual who gets the infection.”

Staying one step ahead

When asked for assurance that COVID-19 vaccines will work against emerging variants, Dr. Edwards said, “It may be we will have to change the vaccine so it is more responsive to new variants, but at this point that does not seem to be the case.”

Should the vaccines require an update, the messenger RNA vaccines have an advantage – researchers can rapidly revise them. “All you need to do is put all the little nucleotides together,” Dr. Edwards said.

“A number of us are looking at how this will work, and we look to influenza,” she added. Dr. Edwards drew an analogy to choosing – and sometimes updating – the influenza strains each year for the annual flu vaccine. With appropriate funding, the same system could be replicated to address any evolving changes to SARS-CoV-2.

On funding, Dr. Salvatore said more money would be required to optimize the surveillance system for emerging strains in the United States.

“We actually have this system – there is a wonderful network that sequences the influenza strains,” she said. “The structure exists, we just need the funding.”

“The CDC is getting the system tooled up to get more viruses to be sequenced,” Dr. Edwards said.

Both experts praised the CDC for its website with up-to-date surveillance information on emerging strains of SARS-CoV-2.

President Biden’s backing of science

A reporter asked each infectious disease expert to share their impression of President Biden’s newly signed COVID-19 executive orders.

“The biggest takeaway is the role of science and the lessons we’ve learned from masks, handwashing, and distancing,” Dr. Edwards said. “We need to heed the advice ... [especially] with a variant that is more contagious.

“It is encouraging that science will be listened to – that is the overall message,” she added.

Dr. Salvatore agreed, saying that the orders give “the feeling that we can now act by following science.”

“We have plenty of papers that show the effectiveness of masking,” for example, she said. Dr. Salvatore acknowledged that there are “a lot of contrasting ideas about masking” across the United States but stressed their importance.

“We should follow measures that we know work,” she said.

Both experts said more research is needed to stay ahead of this evolving scenario. “We still need a lot of basic science showing how this virus replicates in the cell,” Dr. Salvatore said. “We need to really characterize all these mutations and their functions.”

“We need to be concerned, do follow-up studies,” she added, “but we don’t need to panic.”

This article was based on an Infectious Diseases Society of America Media Briefing on Jan. 21, 2021. Dr. Salvatore disclosed that she is a site principal investigator on a study from Verily Life Sciences/Brin Foundation on Predictors of Severe COVID-19 Outcomes and principal investigator for an investigator-initiated study sponsored by Genentech on combination therapy in influenza. Dr. Edwards disclosed National Institutes of Health and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention grants; consulting for Bionet and IBM; and being a member of data safety and monitoring committees for Sanofi, X-4 Pharma, Seqirus, Moderna, Pfizer, and Merck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

About 20 states across the country have detected the more transmissible B.1.1.7 SARS-CoV-2 variant to date. Given the unknowns of the emerging situation, experts with the Infectious Diseases Society of America addressed vaccine effectiveness, how well equipped the United States is to track new mutations, and shared their impressions of President Joe Biden’s COVID-19 executive orders.

One of the major concerns remains the ability of COVID-19 vaccines to work on new strains. “All of our vaccines target the spike protein and try to elicit neutralizing antibodies that bind to that protein,” Mirella Salvatore, MD, assistant professor of medicine and population health sciences at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, said during an IDSA press briefing on Thursday.

The B.1.1.7 mutation occurs in the “very important” spike protein, a component of the SARS-CoV-2 virus necessary for binding, which allows the virus to enter cells, added Dr. Salvatore, an IDSA fellow.

The evidence suggests that SARS-CoV-2 should be capable of producing one or two mutations per month. However, the B.1.1.7 variant surprised investigators in the United Kingdom when they first discovered the strain had 17 mutations, Dr. Salvatore said.

It’s still unknown why this particular strain is more transmissible, but Dr. Salvatore speculated that the mutation gives the virus an advantage and increases binding, allowing it to enter cells more easily. She added that the mutations might have arisen among immunocompromised people infected with SARS-CoV-2, but “that is just a hypothesis.”

On a positive note, Kathryn M. Edwards, MD, another IDSA fellow, explained at the briefing that the existing vaccines target more than one location on the virus’ spike protein. Therefore, “if there is a mutation that changes one structure of the spike protein, there will be other areas where the binding can occur.”

This polyclonal response “is why the vaccine can still be effective against this virus,” added Dr. Edwards, scientific director of the Vanderbilt Vaccine Research Program and professor of pediatrics at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

Dr. Salvatore emphasized that, although the new variant is more transmissible, it doesn’t appear to be more lethal. “This might affect overall mortality but not for the individual who gets the infection.”

Staying one step ahead

When asked for assurance that COVID-19 vaccines will work against emerging variants, Dr. Edwards said, “It may be we will have to change the vaccine so it is more responsive to new variants, but at this point that does not seem to be the case.”

Should the vaccines require an update, the messenger RNA vaccines have an advantage – researchers can rapidly revise them. “All you need to do is put all the little nucleotides together,” Dr. Edwards said.

“A number of us are looking at how this will work, and we look to influenza,” she added. Dr. Edwards drew an analogy to choosing – and sometimes updating – the influenza strains each year for the annual flu vaccine. With appropriate funding, the same system could be replicated to address any evolving changes to SARS-CoV-2.

On funding, Dr. Salvatore said more money would be required to optimize the surveillance system for emerging strains in the United States.

“We actually have this system – there is a wonderful network that sequences the influenza strains,” she said. “The structure exists, we just need the funding.”

“The CDC is getting the system tooled up to get more viruses to be sequenced,” Dr. Edwards said.

Both experts praised the CDC for its website with up-to-date surveillance information on emerging strains of SARS-CoV-2.

President Biden’s backing of science

A reporter asked each infectious disease expert to share their impression of President Biden’s newly signed COVID-19 executive orders.

“The biggest takeaway is the role of science and the lessons we’ve learned from masks, handwashing, and distancing,” Dr. Edwards said. “We need to heed the advice ... [especially] with a variant that is more contagious.

“It is encouraging that science will be listened to – that is the overall message,” she added.

Dr. Salvatore agreed, saying that the orders give “the feeling that we can now act by following science.”

“We have plenty of papers that show the effectiveness of masking,” for example, she said. Dr. Salvatore acknowledged that there are “a lot of contrasting ideas about masking” across the United States but stressed their importance.

“We should follow measures that we know work,” she said.

Both experts said more research is needed to stay ahead of this evolving scenario. “We still need a lot of basic science showing how this virus replicates in the cell,” Dr. Salvatore said. “We need to really characterize all these mutations and their functions.”

“We need to be concerned, do follow-up studies,” she added, “but we don’t need to panic.”

This article was based on an Infectious Diseases Society of America Media Briefing on Jan. 21, 2021. Dr. Salvatore disclosed that she is a site principal investigator on a study from Verily Life Sciences/Brin Foundation on Predictors of Severe COVID-19 Outcomes and principal investigator for an investigator-initiated study sponsored by Genentech on combination therapy in influenza. Dr. Edwards disclosed National Institutes of Health and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention grants; consulting for Bionet and IBM; and being a member of data safety and monitoring committees for Sanofi, X-4 Pharma, Seqirus, Moderna, Pfizer, and Merck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

About 20 states across the country have detected the more transmissible B.1.1.7 SARS-CoV-2 variant to date. Given the unknowns of the emerging situation, experts with the Infectious Diseases Society of America addressed vaccine effectiveness, how well equipped the United States is to track new mutations, and shared their impressions of President Joe Biden’s COVID-19 executive orders.

One of the major concerns remains the ability of COVID-19 vaccines to work on new strains. “All of our vaccines target the spike protein and try to elicit neutralizing antibodies that bind to that protein,” Mirella Salvatore, MD, assistant professor of medicine and population health sciences at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, said during an IDSA press briefing on Thursday.

The B.1.1.7 mutation occurs in the “very important” spike protein, a component of the SARS-CoV-2 virus necessary for binding, which allows the virus to enter cells, added Dr. Salvatore, an IDSA fellow.

The evidence suggests that SARS-CoV-2 should be capable of producing one or two mutations per month. However, the B.1.1.7 variant surprised investigators in the United Kingdom when they first discovered the strain had 17 mutations, Dr. Salvatore said.

It’s still unknown why this particular strain is more transmissible, but Dr. Salvatore speculated that the mutation gives the virus an advantage and increases binding, allowing it to enter cells more easily. She added that the mutations might have arisen among immunocompromised people infected with SARS-CoV-2, but “that is just a hypothesis.”

On a positive note, Kathryn M. Edwards, MD, another IDSA fellow, explained at the briefing that the existing vaccines target more than one location on the virus’ spike protein. Therefore, “if there is a mutation that changes one structure of the spike protein, there will be other areas where the binding can occur.”

This polyclonal response “is why the vaccine can still be effective against this virus,” added Dr. Edwards, scientific director of the Vanderbilt Vaccine Research Program and professor of pediatrics at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

Dr. Salvatore emphasized that, although the new variant is more transmissible, it doesn’t appear to be more lethal. “This might affect overall mortality but not for the individual who gets the infection.”

Staying one step ahead

When asked for assurance that COVID-19 vaccines will work against emerging variants, Dr. Edwards said, “It may be we will have to change the vaccine so it is more responsive to new variants, but at this point that does not seem to be the case.”

Should the vaccines require an update, the messenger RNA vaccines have an advantage – researchers can rapidly revise them. “All you need to do is put all the little nucleotides together,” Dr. Edwards said.

“A number of us are looking at how this will work, and we look to influenza,” she added. Dr. Edwards drew an analogy to choosing – and sometimes updating – the influenza strains each year for the annual flu vaccine. With appropriate funding, the same system could be replicated to address any evolving changes to SARS-CoV-2.

On funding, Dr. Salvatore said more money would be required to optimize the surveillance system for emerging strains in the United States.

“We actually have this system – there is a wonderful network that sequences the influenza strains,” she said. “The structure exists, we just need the funding.”

“The CDC is getting the system tooled up to get more viruses to be sequenced,” Dr. Edwards said.

Both experts praised the CDC for its website with up-to-date surveillance information on emerging strains of SARS-CoV-2.

President Biden’s backing of science

A reporter asked each infectious disease expert to share their impression of President Biden’s newly signed COVID-19 executive orders.

“The biggest takeaway is the role of science and the lessons we’ve learned from masks, handwashing, and distancing,” Dr. Edwards said. “We need to heed the advice ... [especially] with a variant that is more contagious.

“It is encouraging that science will be listened to – that is the overall message,” she added.

Dr. Salvatore agreed, saying that the orders give “the feeling that we can now act by following science.”

“We have plenty of papers that show the effectiveness of masking,” for example, she said. Dr. Salvatore acknowledged that there are “a lot of contrasting ideas about masking” across the United States but stressed their importance.

“We should follow measures that we know work,” she said.

Both experts said more research is needed to stay ahead of this evolving scenario. “We still need a lot of basic science showing how this virus replicates in the cell,” Dr. Salvatore said. “We need to really characterize all these mutations and their functions.”

“We need to be concerned, do follow-up studies,” she added, “but we don’t need to panic.”

This article was based on an Infectious Diseases Society of America Media Briefing on Jan. 21, 2021. Dr. Salvatore disclosed that she is a site principal investigator on a study from Verily Life Sciences/Brin Foundation on Predictors of Severe COVID-19 Outcomes and principal investigator for an investigator-initiated study sponsored by Genentech on combination therapy in influenza. Dr. Edwards disclosed National Institutes of Health and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention grants; consulting for Bionet and IBM; and being a member of data safety and monitoring committees for Sanofi, X-4 Pharma, Seqirus, Moderna, Pfizer, and Merck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Controversy flares over ivermectin for COVID-19

The National Institutes of Health has dropped its recommendation against the inexpensive antiparasitic drug ivermectin for treatment of COVID-19, and the agency now advises it can’t recommend for or against its use, leaving the decision to physicians and their patients.

“Results from adequately powered, well-designed, and well-conducted clinical trials are needed to provide more specific, evidence-based guidance on the role of ivermectin for the treatment of COVID-19,” according to new NIH guidance released last week.

Passionate arguments have been waged for and against the drug’s use.

The NIH update disappointed members of the Front Line COVID-19 Critical Care Alliance (FLCCC), which outlined its case for endorsing ivermectin in a public statement Jan. 18. Point by point, the group of 10 physicians argued against each limitation that drove the NIH’s ruling.

The group’s members said that, although grateful the recommendation against the drug was dropped, a neutral approach is not acceptable as total U.S. deaths surpassed 400,000 since last spring – and currently approach 4,000 a day. Results from research are enough to support its use, and the drug will immediately save lives, they say.

“Patients do not have time to wait,” they write, “and we as health care providers in society do not have that time either.”

NIH, which in August had recommended against ivermectin’s use, invited the group to present evidence to its treatment guidance panel on Jan. 6 to detail the emerging science surrounding ivermectin. The group cited rapidly growing evidence of the drug’s effectiveness.

Pierre Kory, MD, president/cofounder of FLCCC and a pulmonary and critical care specialist at Aurora St. Luke’s Medical Center in Milwaukee, also spoke before a Senate panel on Dec. 8 in a widely shared impassioned video, touting ivermectin as a COVID-19 “miracle” drug, a term he said he doesn’t use lightly.

Dr. Kory pleaded with the NIH to consider the emerging data. “Please, I’m just asking that they review our manuscript,” he told the senators.

“We have immense amounts of data to show that ivermectin must be implemented and implemented now,” he said.

Some draw parallels to hydroxychloroquine

Critics have said there’s not enough data to institute a protocol, and some draw parallels to another repurposed drug – hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) – which was once considered a promising treatment for COVID-19, based on flawed and incomplete evidence, and now is not recommended.

Paul Sax, MD, a professor of medicine at Harvard and clinical director of the HIV program and division of infectious diseases at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, wrote in a blog post earlier this month in the New England Journal of Medicine Journal Watch that ivermectin has more robust evidence for it than HCQ ever did.

“But we’re not quite yet at the ‘practice changing’ level,” he writes. “Results from at least five randomized clinical trials are expected soon that might further inform the decision.”

He said the best argument for the drug is seen in this explanation of a meta-analysis of studies of between 100 and 500 patients by Andrew Hill, MD, with the department of pharmacology, University of Liverpool (England).

Dr. Sax advises against two biases in considering ivermectin. One is assuming that because HCQ failed, other antiparasitic drugs will too.

The second bias to avoid, he says, is discounting studies done in low- and middle-income countries because “they weren’t done in the right places.”

“That’s not just bias,” he says. “It’s also snobbery.”

Ivermectin has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treatment of onchocerciasis (river blindness) and strongyloidiasis, but is not FDA-approved for the treatment of any viral infection. It also is sometimes used to treat animals.

In dropping the recommendation against ivermectin, the NIH gave it the same neutral declaration as monoclonal antibodies and convalescent plasma.

Some physicians say they won’t prescribe it

Some physicians say they won’t be recommending it to their COVID-19 patients.

Amesh Adalja, MD, an infectious disease expert and senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security in Baltimore,said in an interview that the NIH update hasn’t changed his mind and he isn’t prescribing it for his patients.

He said although “there’s enough of a signal” that he would like to see more data, “we haven’t seen anything in terms of a really robust study.”

He noted that the Infectious Diseases Society of America has 15 recommendations for COVID-19 treatment “and not one of them has to do with ivermectin.”

He added, “It’s not enough to see if it works, but we need to see who it works in and when it works in them.”

He also acknowledged that “some prominent physicians” are recommending it.

Among them is Paul Marik, MD, endowed professor of medicine and chief of pulmonary and critical care medicine at Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk. A cofounder of FLCCC, Dr. Marik has championed ivermectin and developed a protocol for its use to prevent and treat COVID-19.

The data surrounding ivermectin have met with hope, criticism, and warnings.

Australian researchers published a study ahead of print in Antiviral Research that found ivermectin inhibited the replication of SARS-CoV-2 in a laboratory setting.

The study concluded that the drug resulted post infection in a 5,000-fold reduction in viral RNA at 48 hours. After that study, however, the FDA in April warned consumers not to self-medicate with ivermectin products intended for animals.

The NIH acknowledged that several randomized trials and retrospective studies of ivermectin use in patients with COVID-19 have now been published in peer-reviewed journals or on preprint servers.

“Some clinical studies showed no benefits or worsening of disease after ivermectin use, whereas others reported shorter time to resolution of disease manifestations attributed to COVID-19, greater reduction in inflammatory markers, shorter time to viral clearance, or lower mortality rates in patients who received ivermectin than in patients who received comparator drugs or placebo,” the NIH guidance reads.

The NIH acknowledges limitations: the studies have been small; doses of ivermectin have varied; some patients were taking other medications at the same time (including doxycycline, hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin, zinc, and corticosteroids, which may be potential confounders); and patients’ severity of COVID was not always clearly described in the studies.

Nasia Safdar, MD, medical director of infection prevention at the University of Wisconsin Hospital in Madison, told this news organization she agrees more research is needed before ivermectin is recommended by regulatory bodies for COVID-19.

That said, Dr. Safdar added, “in individual circumstances if a physician is confronted with a patient in dire straits and you’re not sure what to do, might you consider it? I think after a discussion with the patient, perhaps, but the level of evidence certainly doesn’t rise to the level of a policy.”

A downside of recommending a treatment without conclusive data, even if harm isn’t the primary concern, she said, is that supplies could dwindle for its intended use in other diseases. Also, premature approval can limit the robust research needed to see not only whether it works better for prevention or treatment, but also if it’s effective depending on patient populations and the severity of COVID-19.

Dr. Adalja and Dr. Safdar have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The National Institutes of Health has dropped its recommendation against the inexpensive antiparasitic drug ivermectin for treatment of COVID-19, and the agency now advises it can’t recommend for or against its use, leaving the decision to physicians and their patients.

“Results from adequately powered, well-designed, and well-conducted clinical trials are needed to provide more specific, evidence-based guidance on the role of ivermectin for the treatment of COVID-19,” according to new NIH guidance released last week.

Passionate arguments have been waged for and against the drug’s use.

The NIH update disappointed members of the Front Line COVID-19 Critical Care Alliance (FLCCC), which outlined its case for endorsing ivermectin in a public statement Jan. 18. Point by point, the group of 10 physicians argued against each limitation that drove the NIH’s ruling.

The group’s members said that, although grateful the recommendation against the drug was dropped, a neutral approach is not acceptable as total U.S. deaths surpassed 400,000 since last spring – and currently approach 4,000 a day. Results from research are enough to support its use, and the drug will immediately save lives, they say.

“Patients do not have time to wait,” they write, “and we as health care providers in society do not have that time either.”

NIH, which in August had recommended against ivermectin’s use, invited the group to present evidence to its treatment guidance panel on Jan. 6 to detail the emerging science surrounding ivermectin. The group cited rapidly growing evidence of the drug’s effectiveness.

Pierre Kory, MD, president/cofounder of FLCCC and a pulmonary and critical care specialist at Aurora St. Luke’s Medical Center in Milwaukee, also spoke before a Senate panel on Dec. 8 in a widely shared impassioned video, touting ivermectin as a COVID-19 “miracle” drug, a term he said he doesn’t use lightly.

Dr. Kory pleaded with the NIH to consider the emerging data. “Please, I’m just asking that they review our manuscript,” he told the senators.

“We have immense amounts of data to show that ivermectin must be implemented and implemented now,” he said.

Some draw parallels to hydroxychloroquine

Critics have said there’s not enough data to institute a protocol, and some draw parallels to another repurposed drug – hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) – which was once considered a promising treatment for COVID-19, based on flawed and incomplete evidence, and now is not recommended.

Paul Sax, MD, a professor of medicine at Harvard and clinical director of the HIV program and division of infectious diseases at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, wrote in a blog post earlier this month in the New England Journal of Medicine Journal Watch that ivermectin has more robust evidence for it than HCQ ever did.

“But we’re not quite yet at the ‘practice changing’ level,” he writes. “Results from at least five randomized clinical trials are expected soon that might further inform the decision.”

He said the best argument for the drug is seen in this explanation of a meta-analysis of studies of between 100 and 500 patients by Andrew Hill, MD, with the department of pharmacology, University of Liverpool (England).

Dr. Sax advises against two biases in considering ivermectin. One is assuming that because HCQ failed, other antiparasitic drugs will too.

The second bias to avoid, he says, is discounting studies done in low- and middle-income countries because “they weren’t done in the right places.”

“That’s not just bias,” he says. “It’s also snobbery.”

Ivermectin has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treatment of onchocerciasis (river blindness) and strongyloidiasis, but is not FDA-approved for the treatment of any viral infection. It also is sometimes used to treat animals.

In dropping the recommendation against ivermectin, the NIH gave it the same neutral declaration as monoclonal antibodies and convalescent plasma.

Some physicians say they won’t prescribe it

Some physicians say they won’t be recommending it to their COVID-19 patients.

Amesh Adalja, MD, an infectious disease expert and senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security in Baltimore,said in an interview that the NIH update hasn’t changed his mind and he isn’t prescribing it for his patients.

He said although “there’s enough of a signal” that he would like to see more data, “we haven’t seen anything in terms of a really robust study.”

He noted that the Infectious Diseases Society of America has 15 recommendations for COVID-19 treatment “and not one of them has to do with ivermectin.”

He added, “It’s not enough to see if it works, but we need to see who it works in and when it works in them.”

He also acknowledged that “some prominent physicians” are recommending it.

Among them is Paul Marik, MD, endowed professor of medicine and chief of pulmonary and critical care medicine at Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk. A cofounder of FLCCC, Dr. Marik has championed ivermectin and developed a protocol for its use to prevent and treat COVID-19.

The data surrounding ivermectin have met with hope, criticism, and warnings.

Australian researchers published a study ahead of print in Antiviral Research that found ivermectin inhibited the replication of SARS-CoV-2 in a laboratory setting.

The study concluded that the drug resulted post infection in a 5,000-fold reduction in viral RNA at 48 hours. After that study, however, the FDA in April warned consumers not to self-medicate with ivermectin products intended for animals.

The NIH acknowledged that several randomized trials and retrospective studies of ivermectin use in patients with COVID-19 have now been published in peer-reviewed journals or on preprint servers.

“Some clinical studies showed no benefits or worsening of disease after ivermectin use, whereas others reported shorter time to resolution of disease manifestations attributed to COVID-19, greater reduction in inflammatory markers, shorter time to viral clearance, or lower mortality rates in patients who received ivermectin than in patients who received comparator drugs or placebo,” the NIH guidance reads.

The NIH acknowledges limitations: the studies have been small; doses of ivermectin have varied; some patients were taking other medications at the same time (including doxycycline, hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin, zinc, and corticosteroids, which may be potential confounders); and patients’ severity of COVID was not always clearly described in the studies.

Nasia Safdar, MD, medical director of infection prevention at the University of Wisconsin Hospital in Madison, told this news organization she agrees more research is needed before ivermectin is recommended by regulatory bodies for COVID-19.

That said, Dr. Safdar added, “in individual circumstances if a physician is confronted with a patient in dire straits and you’re not sure what to do, might you consider it? I think after a discussion with the patient, perhaps, but the level of evidence certainly doesn’t rise to the level of a policy.”

A downside of recommending a treatment without conclusive data, even if harm isn’t the primary concern, she said, is that supplies could dwindle for its intended use in other diseases. Also, premature approval can limit the robust research needed to see not only whether it works better for prevention or treatment, but also if it’s effective depending on patient populations and the severity of COVID-19.

Dr. Adalja and Dr. Safdar have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The National Institutes of Health has dropped its recommendation against the inexpensive antiparasitic drug ivermectin for treatment of COVID-19, and the agency now advises it can’t recommend for or against its use, leaving the decision to physicians and their patients.

“Results from adequately powered, well-designed, and well-conducted clinical trials are needed to provide more specific, evidence-based guidance on the role of ivermectin for the treatment of COVID-19,” according to new NIH guidance released last week.

Passionate arguments have been waged for and against the drug’s use.

The NIH update disappointed members of the Front Line COVID-19 Critical Care Alliance (FLCCC), which outlined its case for endorsing ivermectin in a public statement Jan. 18. Point by point, the group of 10 physicians argued against each limitation that drove the NIH’s ruling.

The group’s members said that, although grateful the recommendation against the drug was dropped, a neutral approach is not acceptable as total U.S. deaths surpassed 400,000 since last spring – and currently approach 4,000 a day. Results from research are enough to support its use, and the drug will immediately save lives, they say.

“Patients do not have time to wait,” they write, “and we as health care providers in society do not have that time either.”

NIH, which in August had recommended against ivermectin’s use, invited the group to present evidence to its treatment guidance panel on Jan. 6 to detail the emerging science surrounding ivermectin. The group cited rapidly growing evidence of the drug’s effectiveness.

Pierre Kory, MD, president/cofounder of FLCCC and a pulmonary and critical care specialist at Aurora St. Luke’s Medical Center in Milwaukee, also spoke before a Senate panel on Dec. 8 in a widely shared impassioned video, touting ivermectin as a COVID-19 “miracle” drug, a term he said he doesn’t use lightly.

Dr. Kory pleaded with the NIH to consider the emerging data. “Please, I’m just asking that they review our manuscript,” he told the senators.

“We have immense amounts of data to show that ivermectin must be implemented and implemented now,” he said.

Some draw parallels to hydroxychloroquine

Critics have said there’s not enough data to institute a protocol, and some draw parallels to another repurposed drug – hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) – which was once considered a promising treatment for COVID-19, based on flawed and incomplete evidence, and now is not recommended.

Paul Sax, MD, a professor of medicine at Harvard and clinical director of the HIV program and division of infectious diseases at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, wrote in a blog post earlier this month in the New England Journal of Medicine Journal Watch that ivermectin has more robust evidence for it than HCQ ever did.

“But we’re not quite yet at the ‘practice changing’ level,” he writes. “Results from at least five randomized clinical trials are expected soon that might further inform the decision.”

He said the best argument for the drug is seen in this explanation of a meta-analysis of studies of between 100 and 500 patients by Andrew Hill, MD, with the department of pharmacology, University of Liverpool (England).

Dr. Sax advises against two biases in considering ivermectin. One is assuming that because HCQ failed, other antiparasitic drugs will too.

The second bias to avoid, he says, is discounting studies done in low- and middle-income countries because “they weren’t done in the right places.”

“That’s not just bias,” he says. “It’s also snobbery.”