User login

The state of inpatient COVID-19 care

A brief evidence-based review of everything we have learned

Evidence on emerging treatments for COVID-19 has been incomplete, often disappointing, and rapidly changing. The concept of a practice-changing press release is as novel as the coronavirus. The pandemic has created an interdependent set of inpatient challenges: keeping up with evolving science and operationalizing clinical workflows, technology, and therapeutics to adapt what we are learning.

At Dell Medical School, we have created a Therapeutics and Informatics Committee to put evidence into practice in real-time, and below is a brief framework of what we have learned to date:

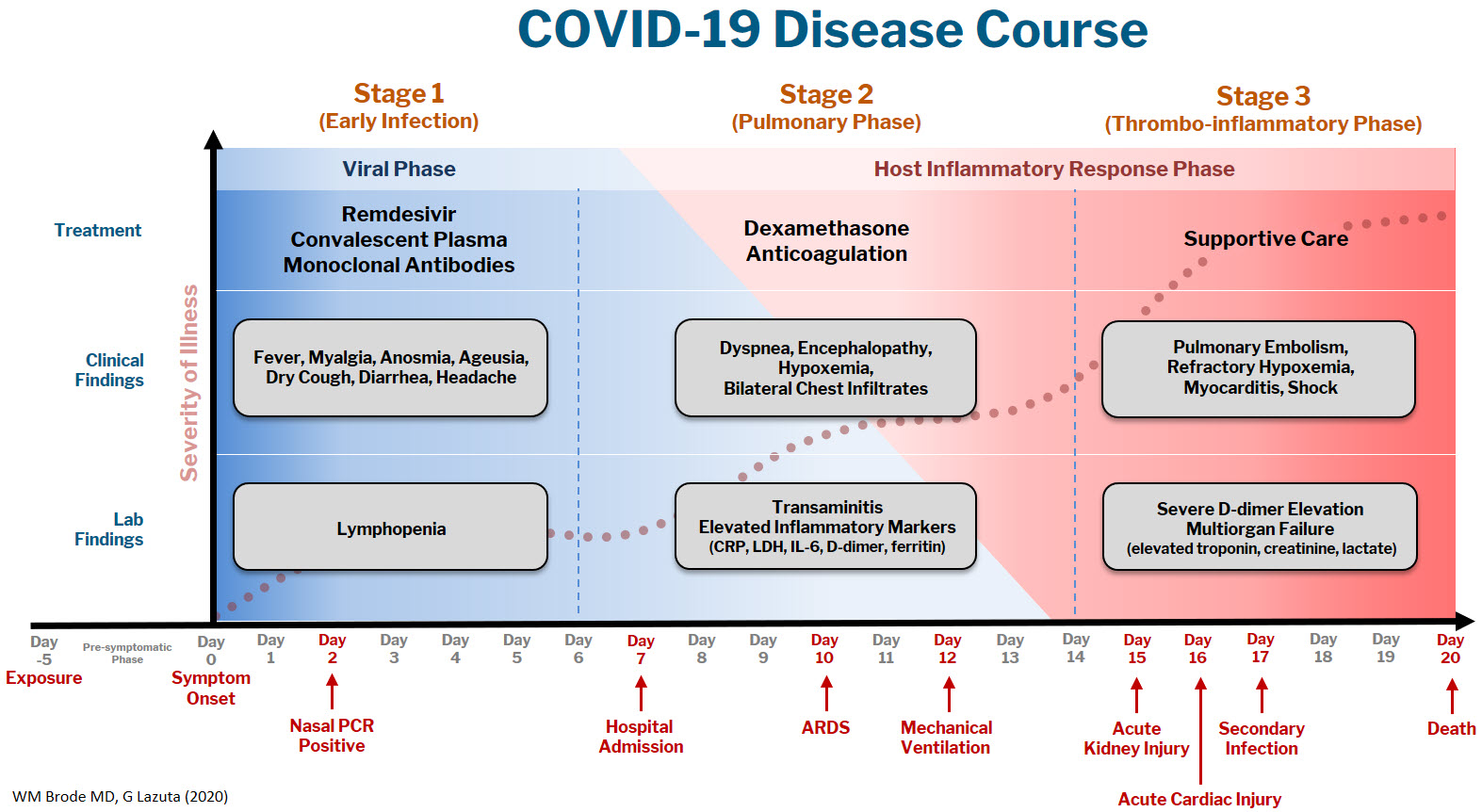

The COVID-19 disease course can be broken down into 3 stages, and workup and interventions should be targeted to those stages.1–3

Stage 1 is the viral phase following a median 5-day pre-symptomatic phase from exposure; this is indistinguishable from an influenza-like illness with the typical fever, cough, GI symptoms, and the more specific anosmia, ageusia, and orthostasis.

Stage 2 is the pulmonary phase where patients develop COVID-19 pneumonia and will have diffuse chest infiltrates on imaging. This stage usually represents the tail end of the viral phase prior to recovery, but for the ~15% of patients who present to the hospital needing admission because of hypoxemia (the definition of severe COVID-19, typically 5-7 days from symptom onset) this phase is characterized by elevated inflammatory markers and an exuberant host-immune response.

Stage 3 is the dreaded thrombo-inflammatory phase, which is a late manifestation usually >10 days from symptom onset and appears to be independent of viral replication. The morbidity and mortality associated with COVID-19 is likely a result of diffuse microthrombosis, and critical disease should no longer be thought of as a “cytokine storm,” but as life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection. Unlike sepsis, the predominant pathology is not vasodilation and shock, but a hypercoagulable state with diffuse endothelial damage.4,5

Workup on presentation to the hospital should focus on identifying which phase of illness the patient is in, based on timing of symptom onset, inflammatory markers, and end-organ damage. CBC, CMP, D-dimer, troponin, and CRP are likely sufficient baseline labs in addition to a chest X-ray. There are many risk stratification tools, but to date, the 4C Mortality 4C Deterioration Scores are recommended due to their large derivation cohort and reliance on only 8 practical variables.6

Remdesivir and convalescent plasma (CVP) disrupt viral replication in stages 1 and 2 of the illness. Remdesivir has shown efficacy reducing hospital length of stay and a small trend towards decreasing mortality, especially if given within 10 days of symptom onset, although its effectiveness in general use is very small, if it exists at all.7,8 CVP efficacy has been disappointing and should not be the standard of care: multiple RCTs do not show any clinical benefit, although the Mayo Clinic registry data suggests that high-titer CVP given within 3 days from diagnosis decreases mortality compared to low-titer plasma.9-11 Monoclonal antibodies are theoretically “supercharged” high-titer CVP, but are approved for outpatient use only. Trials for hospitalized patients requiring oxygen were stopped due to futility. By the time the patient is hospitalized, it is probably too late in the disease course for CVP or monoclonal antibodies to be effective.

Dexamethasone is the only treatment with a proven mortality benefit. The RECOVERY trial showed the greatest mortality benefit (number needed to treat [NNT] of 8) in mechanically ventilated patients > 7 days from symptom onset. While there is a benefit to patients requiring any oxygen (NNT of 35), early administration to patients in the viral phase is associated with higher mortality as corticosteroids can reduce viral clearance.12 Corticosteroids should therefore be targeted to a therapeutic window to reduce the dysregulated host immune response and treat ARDS in phases 2 and 3; earlier is not necessarily better.

Incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) increases linearly with disease severity (one metanalysis showing a rate of 24% in the ICU13) and autopsy studies demonstrate diffuse microthrombosis even when VTE was not suspected5. Observational studies have shown VTE pharmacoprophylaxis reduces mortality, but the optimal agent, timing, and intensity of regimens is not yet clear.14-15 A recent press release from the NIH reported that full dose prophylactic anticoagulation in moderately ill patients reduced disease progression and trended toward lower mortality. Interestingly, for critically ill patients requiring high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) or mechanical ventilation, intensified anticoagulation regiments had potential harm, and enrollment was stopped in this cohort.16 This announcement is a hopeful sign that intensified anticoagulation regimens can prevent thrombo-inflammation, but until the data of multiple ongoing trials is published it remains expert opinion only.

The most important treatment remains delivering oxygen with fidelity, correcting the much-observed “silent” or “happy hypoxemic.”17 Given the high mortality associated with mechanical ventilation and that hypoxemia can be out of proportion to respiratory distress, arbitrary thresholds should not be used to decide when to intubate and instead should evaluate work of breathing, hypercapnia, mentation, or progression of end-organ damage rather than a single cutoff.18 High-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) can correct severe hypoxemia in addition to self-proning, and while there is scant outcomes data for this strategy, it has been adopted widely as ICU capacity is strained nationally. A ventilator can add PEEP for alveolar recruitment or perform the work of breathing for a patient, but a patient will receive 100% FiO2 whether it is delivered through the nares on HFNC or 10 inches lower by an endotracheal tube.

In the absence of a single therapeutic cure or breakthrough, caring for a COVID-19 patient requires the hospital system to instead do a thousand things conscientiously and consistently. This is supportive care: most patients will get better with time and attentive evaluation for end-organ complications like myocarditis, encephalopathy, or pressure ulcers. It requires nursing to patient ratios that allows for this type of vigilance, with shared protocols, order sets, and close communication among team members that provides this support. The treatment of COVID-19 continues to evolve, but as we confront rising hospital volumes nationally, it is important to standardize care for patients throughout each of the 3 stages of illness until we find that single breakthrough.

Dr. Brode is a practicing internal medicine physician at Dell Seton Medical Center and assistant professor in the Department of Internal Medicine at Dell Medical School, both in Austin, Texas. He is a clinician educator who emphasizes knowing the patient as a person first, evidence-based diagnosis, and comprehensive care for the patients who are most vulnerable. This article is part of a series originally published in The Hospital Leader, the official blog of SHM.

References

1. Cummings MJ, et al. Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. The Lancet. 2020 June 6;395(10239):1763-1770. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31189-2.

2. Oudkerk M, et al. Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of thromboembolic complications in COVID-19: Report of the National Institute for Public Health of the Netherlands. Radiology. 2020;297(1):E216-E222. doi:10.1148/radiol.2020201629.

3. Siddiqi HK, and Mehra MR. COVID-19 illness in native and immunosuppressed states: A clinical–therapeutic staging proposal. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020;39:405-407.

4. Connors JM, and Levy JH. COVID-19 and its implications for thrombosis and anticoagulation. Blood. 2020;135:2033-2040.

5. Ackermann M, et al. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 July 9;383:120-128. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2015432.

6. Knight SR, et al. Risk stratification of patients admitted to hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: Development and validation of the 4C Mortality Score. BMJ. 2020;370:m3339. doi:10.1136/bmj.m3339.

7. Beigel JH, et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19 – Final report. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1813-1826. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2007764.

8. Repurposed antiviral drugs for COVID-19: Interim WHO SOLIDARITY trial results. medRxiv. 2020;10.15.20209817. doi:10.1101/2020.10.15.20209817.

9. Agarwal A, et al. Convalescent plasma in the management of moderate covid-19 in adults in India: open label phase II multicentre randomised controlled trial (PLACID Trial). BMJ. 2020;371:m3939.

10. Simonovich VA, et al. A randomized trial of convalescent plasma in Covid-19 severe pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020 Nov 24. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2031304.

11. Joyner MJ, et al. Convalescent Plasma Antibody Levels and the Risk of Death from Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2021; 384:1015-1027. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2031893.

12. The RECOVERY Collaborative Group: Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19 – Preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2020 July 17. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2021436.

13. Porfidia A, et al. Venous thromboembolism in patients with COVID-19: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Res. 2020 Dec;196:67-74.

14. Nadkarni GN, et al. Anticoagulation, mortality, bleeding and pathology among patients hospitalized with COVID-19: A single health system study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Oct 20;76(16):1815-1826. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.08.041.

15. Paranjpe I, et al. Association of treatment dose anticoagulation with in-hospital survival among hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Jul 7;76(1):122-124. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.001.

16. Full-dose blood thinners decreased need for life support and improved outcome in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. National Institutes of Health. Available at https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/full-dose-blood-thinners-decreased-need-life-support-improved-outcome-hospitalized-covid-19-patients.

17. Tobin MJ, et al. Why COVID-19 silent hypoxemia is baffling to physicians. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020 Aug 1;202(3):356-360. doi:10.1164/rccm.202006-2157CP.

18. Berlin DA, et al. Severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2451-2460. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp2009575.

A brief evidence-based review of everything we have learned

A brief evidence-based review of everything we have learned

Evidence on emerging treatments for COVID-19 has been incomplete, often disappointing, and rapidly changing. The concept of a practice-changing press release is as novel as the coronavirus. The pandemic has created an interdependent set of inpatient challenges: keeping up with evolving science and operationalizing clinical workflows, technology, and therapeutics to adapt what we are learning.

At Dell Medical School, we have created a Therapeutics and Informatics Committee to put evidence into practice in real-time, and below is a brief framework of what we have learned to date:

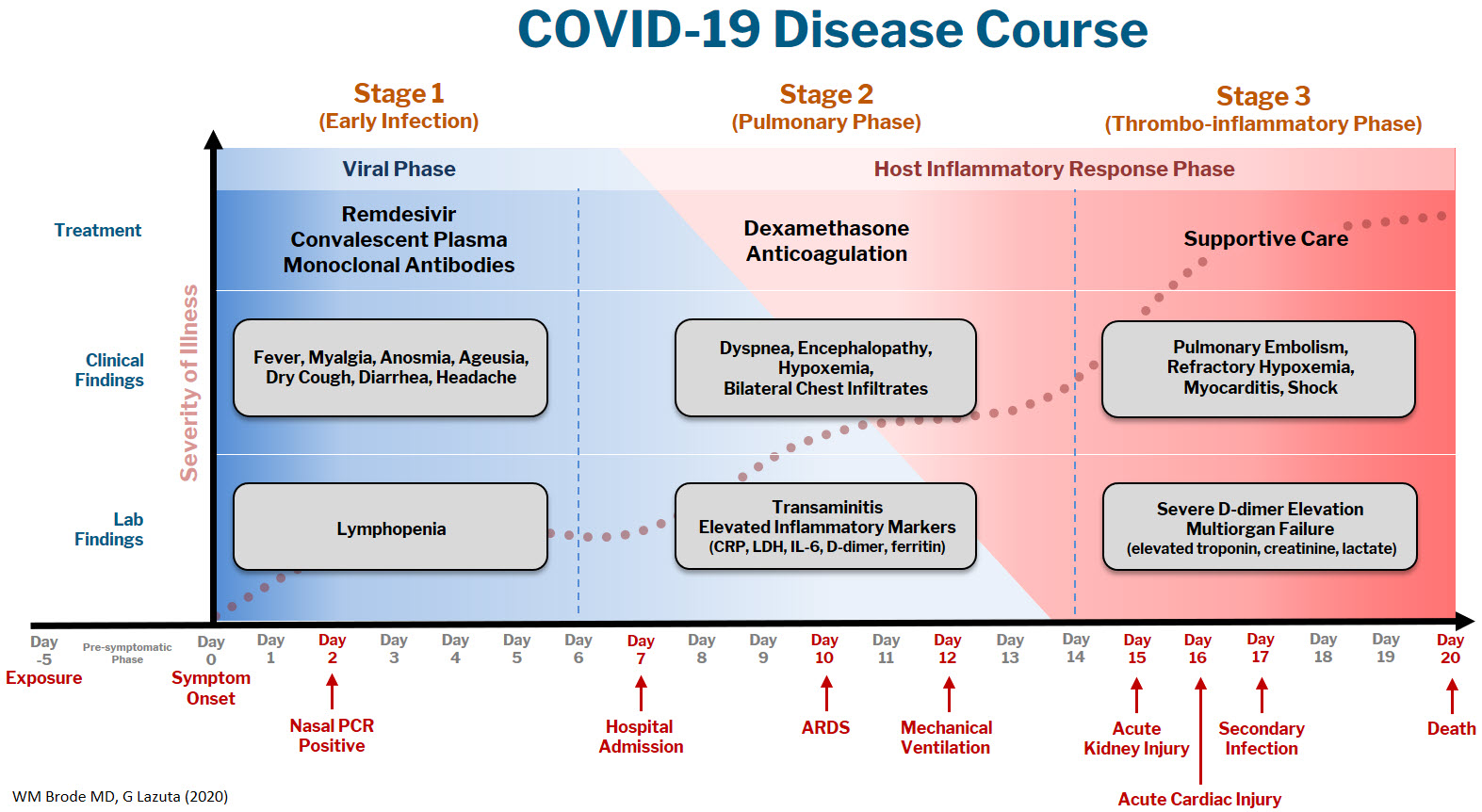

The COVID-19 disease course can be broken down into 3 stages, and workup and interventions should be targeted to those stages.1–3

Stage 1 is the viral phase following a median 5-day pre-symptomatic phase from exposure; this is indistinguishable from an influenza-like illness with the typical fever, cough, GI symptoms, and the more specific anosmia, ageusia, and orthostasis.

Stage 2 is the pulmonary phase where patients develop COVID-19 pneumonia and will have diffuse chest infiltrates on imaging. This stage usually represents the tail end of the viral phase prior to recovery, but for the ~15% of patients who present to the hospital needing admission because of hypoxemia (the definition of severe COVID-19, typically 5-7 days from symptom onset) this phase is characterized by elevated inflammatory markers and an exuberant host-immune response.

Stage 3 is the dreaded thrombo-inflammatory phase, which is a late manifestation usually >10 days from symptom onset and appears to be independent of viral replication. The morbidity and mortality associated with COVID-19 is likely a result of diffuse microthrombosis, and critical disease should no longer be thought of as a “cytokine storm,” but as life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection. Unlike sepsis, the predominant pathology is not vasodilation and shock, but a hypercoagulable state with diffuse endothelial damage.4,5

Workup on presentation to the hospital should focus on identifying which phase of illness the patient is in, based on timing of symptom onset, inflammatory markers, and end-organ damage. CBC, CMP, D-dimer, troponin, and CRP are likely sufficient baseline labs in addition to a chest X-ray. There are many risk stratification tools, but to date, the 4C Mortality 4C Deterioration Scores are recommended due to their large derivation cohort and reliance on only 8 practical variables.6

Remdesivir and convalescent plasma (CVP) disrupt viral replication in stages 1 and 2 of the illness. Remdesivir has shown efficacy reducing hospital length of stay and a small trend towards decreasing mortality, especially if given within 10 days of symptom onset, although its effectiveness in general use is very small, if it exists at all.7,8 CVP efficacy has been disappointing and should not be the standard of care: multiple RCTs do not show any clinical benefit, although the Mayo Clinic registry data suggests that high-titer CVP given within 3 days from diagnosis decreases mortality compared to low-titer plasma.9-11 Monoclonal antibodies are theoretically “supercharged” high-titer CVP, but are approved for outpatient use only. Trials for hospitalized patients requiring oxygen were stopped due to futility. By the time the patient is hospitalized, it is probably too late in the disease course for CVP or monoclonal antibodies to be effective.

Dexamethasone is the only treatment with a proven mortality benefit. The RECOVERY trial showed the greatest mortality benefit (number needed to treat [NNT] of 8) in mechanically ventilated patients > 7 days from symptom onset. While there is a benefit to patients requiring any oxygen (NNT of 35), early administration to patients in the viral phase is associated with higher mortality as corticosteroids can reduce viral clearance.12 Corticosteroids should therefore be targeted to a therapeutic window to reduce the dysregulated host immune response and treat ARDS in phases 2 and 3; earlier is not necessarily better.

Incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) increases linearly with disease severity (one metanalysis showing a rate of 24% in the ICU13) and autopsy studies demonstrate diffuse microthrombosis even when VTE was not suspected5. Observational studies have shown VTE pharmacoprophylaxis reduces mortality, but the optimal agent, timing, and intensity of regimens is not yet clear.14-15 A recent press release from the NIH reported that full dose prophylactic anticoagulation in moderately ill patients reduced disease progression and trended toward lower mortality. Interestingly, for critically ill patients requiring high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) or mechanical ventilation, intensified anticoagulation regiments had potential harm, and enrollment was stopped in this cohort.16 This announcement is a hopeful sign that intensified anticoagulation regimens can prevent thrombo-inflammation, but until the data of multiple ongoing trials is published it remains expert opinion only.

The most important treatment remains delivering oxygen with fidelity, correcting the much-observed “silent” or “happy hypoxemic.”17 Given the high mortality associated with mechanical ventilation and that hypoxemia can be out of proportion to respiratory distress, arbitrary thresholds should not be used to decide when to intubate and instead should evaluate work of breathing, hypercapnia, mentation, or progression of end-organ damage rather than a single cutoff.18 High-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) can correct severe hypoxemia in addition to self-proning, and while there is scant outcomes data for this strategy, it has been adopted widely as ICU capacity is strained nationally. A ventilator can add PEEP for alveolar recruitment or perform the work of breathing for a patient, but a patient will receive 100% FiO2 whether it is delivered through the nares on HFNC or 10 inches lower by an endotracheal tube.

In the absence of a single therapeutic cure or breakthrough, caring for a COVID-19 patient requires the hospital system to instead do a thousand things conscientiously and consistently. This is supportive care: most patients will get better with time and attentive evaluation for end-organ complications like myocarditis, encephalopathy, or pressure ulcers. It requires nursing to patient ratios that allows for this type of vigilance, with shared protocols, order sets, and close communication among team members that provides this support. The treatment of COVID-19 continues to evolve, but as we confront rising hospital volumes nationally, it is important to standardize care for patients throughout each of the 3 stages of illness until we find that single breakthrough.

Dr. Brode is a practicing internal medicine physician at Dell Seton Medical Center and assistant professor in the Department of Internal Medicine at Dell Medical School, both in Austin, Texas. He is a clinician educator who emphasizes knowing the patient as a person first, evidence-based diagnosis, and comprehensive care for the patients who are most vulnerable. This article is part of a series originally published in The Hospital Leader, the official blog of SHM.

References

1. Cummings MJ, et al. Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. The Lancet. 2020 June 6;395(10239):1763-1770. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31189-2.

2. Oudkerk M, et al. Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of thromboembolic complications in COVID-19: Report of the National Institute for Public Health of the Netherlands. Radiology. 2020;297(1):E216-E222. doi:10.1148/radiol.2020201629.

3. Siddiqi HK, and Mehra MR. COVID-19 illness in native and immunosuppressed states: A clinical–therapeutic staging proposal. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020;39:405-407.

4. Connors JM, and Levy JH. COVID-19 and its implications for thrombosis and anticoagulation. Blood. 2020;135:2033-2040.

5. Ackermann M, et al. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 July 9;383:120-128. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2015432.

6. Knight SR, et al. Risk stratification of patients admitted to hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: Development and validation of the 4C Mortality Score. BMJ. 2020;370:m3339. doi:10.1136/bmj.m3339.

7. Beigel JH, et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19 – Final report. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1813-1826. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2007764.

8. Repurposed antiviral drugs for COVID-19: Interim WHO SOLIDARITY trial results. medRxiv. 2020;10.15.20209817. doi:10.1101/2020.10.15.20209817.

9. Agarwal A, et al. Convalescent plasma in the management of moderate covid-19 in adults in India: open label phase II multicentre randomised controlled trial (PLACID Trial). BMJ. 2020;371:m3939.

10. Simonovich VA, et al. A randomized trial of convalescent plasma in Covid-19 severe pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020 Nov 24. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2031304.

11. Joyner MJ, et al. Convalescent Plasma Antibody Levels and the Risk of Death from Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2021; 384:1015-1027. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2031893.

12. The RECOVERY Collaborative Group: Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19 – Preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2020 July 17. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2021436.

13. Porfidia A, et al. Venous thromboembolism in patients with COVID-19: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Res. 2020 Dec;196:67-74.

14. Nadkarni GN, et al. Anticoagulation, mortality, bleeding and pathology among patients hospitalized with COVID-19: A single health system study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Oct 20;76(16):1815-1826. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.08.041.

15. Paranjpe I, et al. Association of treatment dose anticoagulation with in-hospital survival among hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Jul 7;76(1):122-124. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.001.

16. Full-dose blood thinners decreased need for life support and improved outcome in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. National Institutes of Health. Available at https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/full-dose-blood-thinners-decreased-need-life-support-improved-outcome-hospitalized-covid-19-patients.

17. Tobin MJ, et al. Why COVID-19 silent hypoxemia is baffling to physicians. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020 Aug 1;202(3):356-360. doi:10.1164/rccm.202006-2157CP.

18. Berlin DA, et al. Severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2451-2460. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp2009575.

Evidence on emerging treatments for COVID-19 has been incomplete, often disappointing, and rapidly changing. The concept of a practice-changing press release is as novel as the coronavirus. The pandemic has created an interdependent set of inpatient challenges: keeping up with evolving science and operationalizing clinical workflows, technology, and therapeutics to adapt what we are learning.

At Dell Medical School, we have created a Therapeutics and Informatics Committee to put evidence into practice in real-time, and below is a brief framework of what we have learned to date:

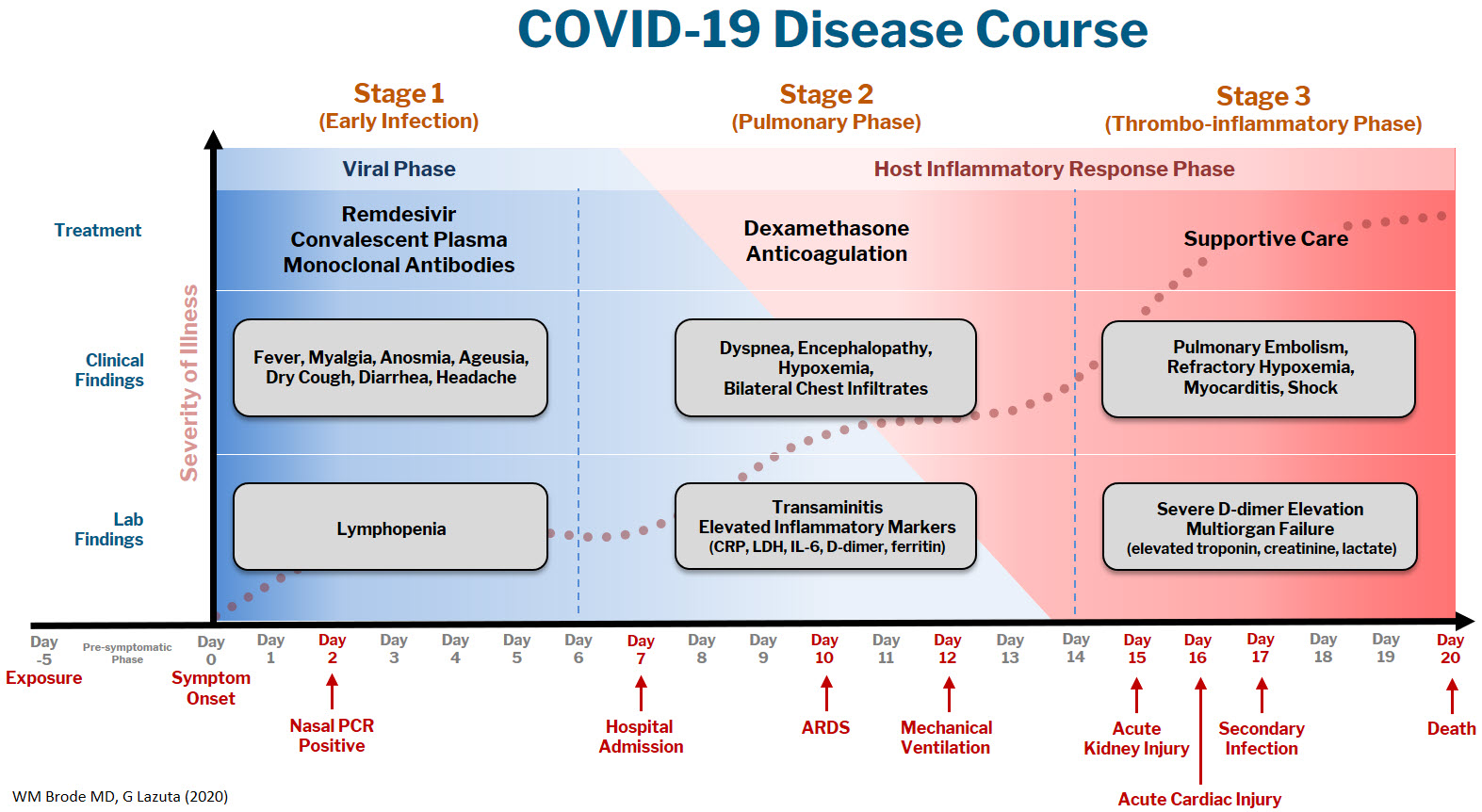

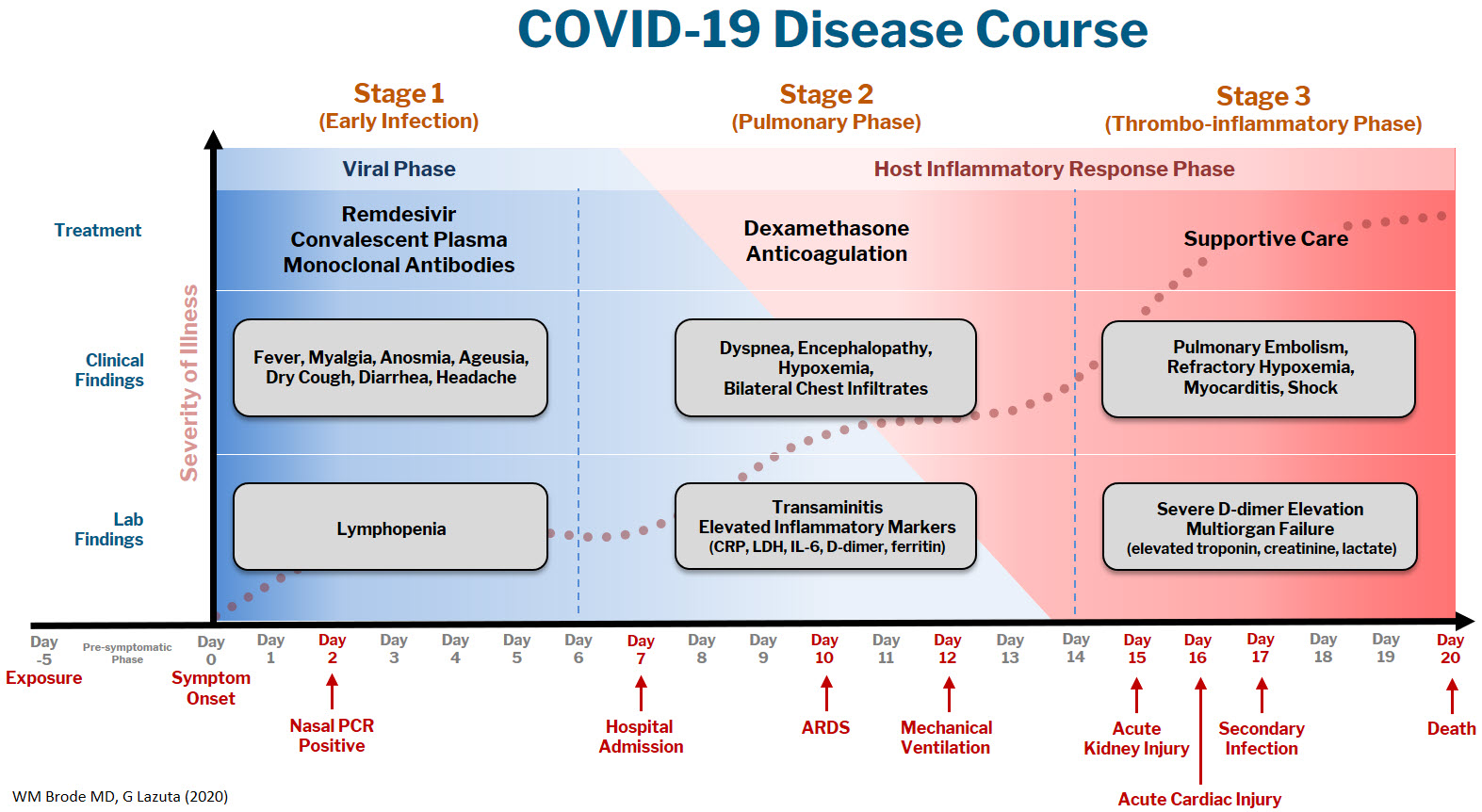

The COVID-19 disease course can be broken down into 3 stages, and workup and interventions should be targeted to those stages.1–3

Stage 1 is the viral phase following a median 5-day pre-symptomatic phase from exposure; this is indistinguishable from an influenza-like illness with the typical fever, cough, GI symptoms, and the more specific anosmia, ageusia, and orthostasis.

Stage 2 is the pulmonary phase where patients develop COVID-19 pneumonia and will have diffuse chest infiltrates on imaging. This stage usually represents the tail end of the viral phase prior to recovery, but for the ~15% of patients who present to the hospital needing admission because of hypoxemia (the definition of severe COVID-19, typically 5-7 days from symptom onset) this phase is characterized by elevated inflammatory markers and an exuberant host-immune response.

Stage 3 is the dreaded thrombo-inflammatory phase, which is a late manifestation usually >10 days from symptom onset and appears to be independent of viral replication. The morbidity and mortality associated with COVID-19 is likely a result of diffuse microthrombosis, and critical disease should no longer be thought of as a “cytokine storm,” but as life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection. Unlike sepsis, the predominant pathology is not vasodilation and shock, but a hypercoagulable state with diffuse endothelial damage.4,5

Workup on presentation to the hospital should focus on identifying which phase of illness the patient is in, based on timing of symptom onset, inflammatory markers, and end-organ damage. CBC, CMP, D-dimer, troponin, and CRP are likely sufficient baseline labs in addition to a chest X-ray. There are many risk stratification tools, but to date, the 4C Mortality 4C Deterioration Scores are recommended due to their large derivation cohort and reliance on only 8 practical variables.6

Remdesivir and convalescent plasma (CVP) disrupt viral replication in stages 1 and 2 of the illness. Remdesivir has shown efficacy reducing hospital length of stay and a small trend towards decreasing mortality, especially if given within 10 days of symptom onset, although its effectiveness in general use is very small, if it exists at all.7,8 CVP efficacy has been disappointing and should not be the standard of care: multiple RCTs do not show any clinical benefit, although the Mayo Clinic registry data suggests that high-titer CVP given within 3 days from diagnosis decreases mortality compared to low-titer plasma.9-11 Monoclonal antibodies are theoretically “supercharged” high-titer CVP, but are approved for outpatient use only. Trials for hospitalized patients requiring oxygen were stopped due to futility. By the time the patient is hospitalized, it is probably too late in the disease course for CVP or monoclonal antibodies to be effective.

Dexamethasone is the only treatment with a proven mortality benefit. The RECOVERY trial showed the greatest mortality benefit (number needed to treat [NNT] of 8) in mechanically ventilated patients > 7 days from symptom onset. While there is a benefit to patients requiring any oxygen (NNT of 35), early administration to patients in the viral phase is associated with higher mortality as corticosteroids can reduce viral clearance.12 Corticosteroids should therefore be targeted to a therapeutic window to reduce the dysregulated host immune response and treat ARDS in phases 2 and 3; earlier is not necessarily better.

Incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) increases linearly with disease severity (one metanalysis showing a rate of 24% in the ICU13) and autopsy studies demonstrate diffuse microthrombosis even when VTE was not suspected5. Observational studies have shown VTE pharmacoprophylaxis reduces mortality, but the optimal agent, timing, and intensity of regimens is not yet clear.14-15 A recent press release from the NIH reported that full dose prophylactic anticoagulation in moderately ill patients reduced disease progression and trended toward lower mortality. Interestingly, for critically ill patients requiring high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) or mechanical ventilation, intensified anticoagulation regiments had potential harm, and enrollment was stopped in this cohort.16 This announcement is a hopeful sign that intensified anticoagulation regimens can prevent thrombo-inflammation, but until the data of multiple ongoing trials is published it remains expert opinion only.

The most important treatment remains delivering oxygen with fidelity, correcting the much-observed “silent” or “happy hypoxemic.”17 Given the high mortality associated with mechanical ventilation and that hypoxemia can be out of proportion to respiratory distress, arbitrary thresholds should not be used to decide when to intubate and instead should evaluate work of breathing, hypercapnia, mentation, or progression of end-organ damage rather than a single cutoff.18 High-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) can correct severe hypoxemia in addition to self-proning, and while there is scant outcomes data for this strategy, it has been adopted widely as ICU capacity is strained nationally. A ventilator can add PEEP for alveolar recruitment or perform the work of breathing for a patient, but a patient will receive 100% FiO2 whether it is delivered through the nares on HFNC or 10 inches lower by an endotracheal tube.

In the absence of a single therapeutic cure or breakthrough, caring for a COVID-19 patient requires the hospital system to instead do a thousand things conscientiously and consistently. This is supportive care: most patients will get better with time and attentive evaluation for end-organ complications like myocarditis, encephalopathy, or pressure ulcers. It requires nursing to patient ratios that allows for this type of vigilance, with shared protocols, order sets, and close communication among team members that provides this support. The treatment of COVID-19 continues to evolve, but as we confront rising hospital volumes nationally, it is important to standardize care for patients throughout each of the 3 stages of illness until we find that single breakthrough.

Dr. Brode is a practicing internal medicine physician at Dell Seton Medical Center and assistant professor in the Department of Internal Medicine at Dell Medical School, both in Austin, Texas. He is a clinician educator who emphasizes knowing the patient as a person first, evidence-based diagnosis, and comprehensive care for the patients who are most vulnerable. This article is part of a series originally published in The Hospital Leader, the official blog of SHM.

References

1. Cummings MJ, et al. Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. The Lancet. 2020 June 6;395(10239):1763-1770. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31189-2.

2. Oudkerk M, et al. Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of thromboembolic complications in COVID-19: Report of the National Institute for Public Health of the Netherlands. Radiology. 2020;297(1):E216-E222. doi:10.1148/radiol.2020201629.

3. Siddiqi HK, and Mehra MR. COVID-19 illness in native and immunosuppressed states: A clinical–therapeutic staging proposal. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020;39:405-407.

4. Connors JM, and Levy JH. COVID-19 and its implications for thrombosis and anticoagulation. Blood. 2020;135:2033-2040.

5. Ackermann M, et al. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 July 9;383:120-128. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2015432.

6. Knight SR, et al. Risk stratification of patients admitted to hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: Development and validation of the 4C Mortality Score. BMJ. 2020;370:m3339. doi:10.1136/bmj.m3339.

7. Beigel JH, et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19 – Final report. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1813-1826. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2007764.

8. Repurposed antiviral drugs for COVID-19: Interim WHO SOLIDARITY trial results. medRxiv. 2020;10.15.20209817. doi:10.1101/2020.10.15.20209817.

9. Agarwal A, et al. Convalescent plasma in the management of moderate covid-19 in adults in India: open label phase II multicentre randomised controlled trial (PLACID Trial). BMJ. 2020;371:m3939.

10. Simonovich VA, et al. A randomized trial of convalescent plasma in Covid-19 severe pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020 Nov 24. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2031304.

11. Joyner MJ, et al. Convalescent Plasma Antibody Levels and the Risk of Death from Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2021; 384:1015-1027. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2031893.

12. The RECOVERY Collaborative Group: Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19 – Preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2020 July 17. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2021436.

13. Porfidia A, et al. Venous thromboembolism in patients with COVID-19: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Res. 2020 Dec;196:67-74.

14. Nadkarni GN, et al. Anticoagulation, mortality, bleeding and pathology among patients hospitalized with COVID-19: A single health system study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Oct 20;76(16):1815-1826. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.08.041.

15. Paranjpe I, et al. Association of treatment dose anticoagulation with in-hospital survival among hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Jul 7;76(1):122-124. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.001.

16. Full-dose blood thinners decreased need for life support and improved outcome in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. National Institutes of Health. Available at https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/full-dose-blood-thinners-decreased-need-life-support-improved-outcome-hospitalized-covid-19-patients.

17. Tobin MJ, et al. Why COVID-19 silent hypoxemia is baffling to physicians. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020 Aug 1;202(3):356-360. doi:10.1164/rccm.202006-2157CP.

18. Berlin DA, et al. Severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2451-2460. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp2009575.

COVID-19 may damage blood vessels in the brain

Until now, the neurological manifestations of COVID-19 have been believed to be a result of direct damage to nerve cells. However, a new study suggests that the virus might actually damage the brain’s small blood vessels rather than nerve cells themselves.

The findings add further weight to previous research into neurological complications from COVID-19, according to Anna Cervantes, MD. Dr. Cervantes is assistant professor of neurology at the Boston University and has been studying the neurological effects of COVID-19, though she was not involved in this study. “I can tell from my personal experience, and things we’ve published on and the literature that’s out there – there are patients that are having complications like stroke that aren’t even critically ill from COVID. We’re seeing that not in just the acute setting, but also in a delayed fashion. Even though most of the coagulopathy is largely venous and probably microvascular, this does affect the brain through a myriad of ways,” Dr. Cervantes said.

The research was published online Jan. 12 in the New England Journal of Medicine. Myoung‑Hwa Lee, PhD, was the lead author.

The study included high resolution magnetic resonance imaging and histopathological examination of 13 individuals with a median age of 50 years. Among 10 patients with brain alterations, the researchers conducted further studies in 5 individuals using multiplex fluorescence imaging and chromogenic immunostaining in all 10.

The team conducted conventional histopathology on the brains of 18 individuals. Fourteen had a history of chronic illness, including diabetes, and hypertension, and 11 had died unexpectedly or been found dead. Magnetic resonance microscopy revealed punctuate hypo-intensities in nine subjects, indicating microvascular injury and fibrinogen leakage. Histopathology using fluorescence imaging showed the same features. Collagen IV immunostaining showed thinning of the basal lamina of the endothelial cells in five patients. Ten patients had congested blood vessels and surrounding fibrinogen leakage, but comparatively intact vasculature. The researchers interpreted linear hypo-intensities as micro-hemorrhages.

The researchers found little perivascular inflammation, and no vascular occlusion. Thirteen subjects had perivascular-activated microglia, macrophage infiltrates, and hypertrophic astrocytes. Eight had CD3+ and CD8+ T cells in the perivascular spaces and in lumens next to endothelial cells, which could help explain vascular injury.

The researchers found no evidence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus itself, despite efforts using polymerase chain reaction with multiple primer sets, RNA sequencing within the brain, or RNA in situ hybridization and immunostaining. Subjects may have cleared the virus by the time they died, or viral copy numbers could have been below the detection limit of the assays.

The researchers also obtained a convenience sample of subjects who had died from COVID-19. Magnetic resonance microscopy, histopathology, and immunohistochemical analysis of sections revealed microvascular injury in the brain and olfactory bulb, despite no evidence of viral infection. The authors stressed that they could not draw conclusions about the neurological features of COVID-19 because of a lack of clinical information.

Dr. Cervantes noted that limitation: “We’re seeing a lot of patients with encephalopathy or alterations in their mental status. A lot of things can cause that, and some are common in patients who are critically ill, like medications and metabolic derangement.”

Still, the findings could help to inform future medical management. “There’s going to be a large number of patients who don’t have really bad pulmonary disease but still may have encephalopathy. So if there is small vessel involvement because of inflammation that we might not necessarily catch in a lumbar puncture or routine imaging, there’s still somebody we can make better (using) steroids. Having more information on what’s happening on a pathophysiologic level and on pathology is really helpful.”

The study was supported by internal funds from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Dr. Cervantes has no relevant financial disclosures.

Until now, the neurological manifestations of COVID-19 have been believed to be a result of direct damage to nerve cells. However, a new study suggests that the virus might actually damage the brain’s small blood vessels rather than nerve cells themselves.

The findings add further weight to previous research into neurological complications from COVID-19, according to Anna Cervantes, MD. Dr. Cervantes is assistant professor of neurology at the Boston University and has been studying the neurological effects of COVID-19, though she was not involved in this study. “I can tell from my personal experience, and things we’ve published on and the literature that’s out there – there are patients that are having complications like stroke that aren’t even critically ill from COVID. We’re seeing that not in just the acute setting, but also in a delayed fashion. Even though most of the coagulopathy is largely venous and probably microvascular, this does affect the brain through a myriad of ways,” Dr. Cervantes said.

The research was published online Jan. 12 in the New England Journal of Medicine. Myoung‑Hwa Lee, PhD, was the lead author.

The study included high resolution magnetic resonance imaging and histopathological examination of 13 individuals with a median age of 50 years. Among 10 patients with brain alterations, the researchers conducted further studies in 5 individuals using multiplex fluorescence imaging and chromogenic immunostaining in all 10.

The team conducted conventional histopathology on the brains of 18 individuals. Fourteen had a history of chronic illness, including diabetes, and hypertension, and 11 had died unexpectedly or been found dead. Magnetic resonance microscopy revealed punctuate hypo-intensities in nine subjects, indicating microvascular injury and fibrinogen leakage. Histopathology using fluorescence imaging showed the same features. Collagen IV immunostaining showed thinning of the basal lamina of the endothelial cells in five patients. Ten patients had congested blood vessels and surrounding fibrinogen leakage, but comparatively intact vasculature. The researchers interpreted linear hypo-intensities as micro-hemorrhages.

The researchers found little perivascular inflammation, and no vascular occlusion. Thirteen subjects had perivascular-activated microglia, macrophage infiltrates, and hypertrophic astrocytes. Eight had CD3+ and CD8+ T cells in the perivascular spaces and in lumens next to endothelial cells, which could help explain vascular injury.

The researchers found no evidence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus itself, despite efforts using polymerase chain reaction with multiple primer sets, RNA sequencing within the brain, or RNA in situ hybridization and immunostaining. Subjects may have cleared the virus by the time they died, or viral copy numbers could have been below the detection limit of the assays.

The researchers also obtained a convenience sample of subjects who had died from COVID-19. Magnetic resonance microscopy, histopathology, and immunohistochemical analysis of sections revealed microvascular injury in the brain and olfactory bulb, despite no evidence of viral infection. The authors stressed that they could not draw conclusions about the neurological features of COVID-19 because of a lack of clinical information.

Dr. Cervantes noted that limitation: “We’re seeing a lot of patients with encephalopathy or alterations in their mental status. A lot of things can cause that, and some are common in patients who are critically ill, like medications and metabolic derangement.”

Still, the findings could help to inform future medical management. “There’s going to be a large number of patients who don’t have really bad pulmonary disease but still may have encephalopathy. So if there is small vessel involvement because of inflammation that we might not necessarily catch in a lumbar puncture or routine imaging, there’s still somebody we can make better (using) steroids. Having more information on what’s happening on a pathophysiologic level and on pathology is really helpful.”

The study was supported by internal funds from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Dr. Cervantes has no relevant financial disclosures.

Until now, the neurological manifestations of COVID-19 have been believed to be a result of direct damage to nerve cells. However, a new study suggests that the virus might actually damage the brain’s small blood vessels rather than nerve cells themselves.

The findings add further weight to previous research into neurological complications from COVID-19, according to Anna Cervantes, MD. Dr. Cervantes is assistant professor of neurology at the Boston University and has been studying the neurological effects of COVID-19, though she was not involved in this study. “I can tell from my personal experience, and things we’ve published on and the literature that’s out there – there are patients that are having complications like stroke that aren’t even critically ill from COVID. We’re seeing that not in just the acute setting, but also in a delayed fashion. Even though most of the coagulopathy is largely venous and probably microvascular, this does affect the brain through a myriad of ways,” Dr. Cervantes said.

The research was published online Jan. 12 in the New England Journal of Medicine. Myoung‑Hwa Lee, PhD, was the lead author.

The study included high resolution magnetic resonance imaging and histopathological examination of 13 individuals with a median age of 50 years. Among 10 patients with brain alterations, the researchers conducted further studies in 5 individuals using multiplex fluorescence imaging and chromogenic immunostaining in all 10.

The team conducted conventional histopathology on the brains of 18 individuals. Fourteen had a history of chronic illness, including diabetes, and hypertension, and 11 had died unexpectedly or been found dead. Magnetic resonance microscopy revealed punctuate hypo-intensities in nine subjects, indicating microvascular injury and fibrinogen leakage. Histopathology using fluorescence imaging showed the same features. Collagen IV immunostaining showed thinning of the basal lamina of the endothelial cells in five patients. Ten patients had congested blood vessels and surrounding fibrinogen leakage, but comparatively intact vasculature. The researchers interpreted linear hypo-intensities as micro-hemorrhages.

The researchers found little perivascular inflammation, and no vascular occlusion. Thirteen subjects had perivascular-activated microglia, macrophage infiltrates, and hypertrophic astrocytes. Eight had CD3+ and CD8+ T cells in the perivascular spaces and in lumens next to endothelial cells, which could help explain vascular injury.

The researchers found no evidence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus itself, despite efforts using polymerase chain reaction with multiple primer sets, RNA sequencing within the brain, or RNA in situ hybridization and immunostaining. Subjects may have cleared the virus by the time they died, or viral copy numbers could have been below the detection limit of the assays.

The researchers also obtained a convenience sample of subjects who had died from COVID-19. Magnetic resonance microscopy, histopathology, and immunohistochemical analysis of sections revealed microvascular injury in the brain and olfactory bulb, despite no evidence of viral infection. The authors stressed that they could not draw conclusions about the neurological features of COVID-19 because of a lack of clinical information.

Dr. Cervantes noted that limitation: “We’re seeing a lot of patients with encephalopathy or alterations in their mental status. A lot of things can cause that, and some are common in patients who are critically ill, like medications and metabolic derangement.”

Still, the findings could help to inform future medical management. “There’s going to be a large number of patients who don’t have really bad pulmonary disease but still may have encephalopathy. So if there is small vessel involvement because of inflammation that we might not necessarily catch in a lumbar puncture or routine imaging, there’s still somebody we can make better (using) steroids. Having more information on what’s happening on a pathophysiologic level and on pathology is really helpful.”

The study was supported by internal funds from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Dr. Cervantes has no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Patients fend for themselves to access highly touted COVID antibody treatments

By the time he tested positive for COVID-19 on Jan. 12, Gary Herritz was feeling pretty sick. He suspects he was infected a week earlier, during a medical appointment in which he saw health workers who were wearing masks beneath their noses or who had removed them entirely.

His scratchy throat had turned to a dry cough, headache, joint pain, and fever – all warning signs to Mr. Herritz, who underwent liver transplant surgery in 2012, followed by a rejection scare in 2018. He knew his compromised immune system left him especially vulnerable to a potentially deadly case of COVID.

“The thing with transplant patients is we can crash in a heartbeat,” said Mr. Herritz, 39. “The outcome for transplant patients [with COVID] is not good.”

On Twitter, Mr. Herritz had read about monoclonal antibody therapy, the treatment famously given to President Donald Trump and other high-profile politicians and authorized by the Food and Drug Administration for emergency use in high-risk COVID patients. But as his symptoms worsened, Mr. Herritz found himself very much on his own as he scrambled for access.

His primary care doctor wasn’t sure he qualified for treatment. His transplant team in Wisconsin, where he’d had the liver surgery, wasn’t calling back. No one was sure exactly where he should go to get it. From bed in Pascagoula, Miss., he spent 2 days punching in phone numbers, reaching out to health officials in four states, before he finally landed an appointment to receive a treatment aimed at keeping patients like him out of the hospital – and, perhaps, the morgue.

“I am not rich, I am not special, I am not a political figure,” Mr. Herritz, a former community service officer, wrote on Twitter. “I just called until someone would listen.”

Months after Mr. Trump emphatically credited an experimental antibody therapy for his quick recovery from covid and even as drugmakers ramp up supplies, only a trickle of the product has found its way into regular people. While hundreds of thousands of vials sit unused, sick patients who, research indicates, could benefit from early treatment – available for free – have largely been fending for themselves.

Federal officials have allocated more than 785,000 doses of two antibody treatments authorized for emergency use during the pandemic, and more than 550,000 doses have been delivered to sites across the nation. The federal government has contracted for nearly 2.5 million doses of the products from drugmakers Eli Lilly and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals at a cost of more than $4.4 billion.

So far, however, only about 30% of the available doses have been administered to patients, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services officials said.

Scores of high-risk COVID patients who are eligible remain unaware or have not been offered the option. Research has shown the therapy is most effective if given early in the illness, within 10 days of a positive COVID test. But many would-be recipients have missed this crucial window because of a patchwork system in the United States that can delay testing and diagnosis.

“The bottleneck here in the funnel is administration, not availability of the product,” said Dr. Janet Woodcock, a veteran FDA official in charge of therapeutics for the federal Operation Warp Speed effort.

Among the daunting hurdles: Until this week, there has been no nationwide system to tell people where they could obtain the drugs, which are delivered through IV infusions that require hours to administer and monitor. Finding space to keep COVID-infected patients separate from others has been difficult in some health centers slammed by the pandemic.

“The health care system is crashing,” Dr. Woodcock told reporters. “What we’ve heard around the country is the No. 1 barrier is staffing.”

At the same time, many hospitals have refused to offer the therapy because doctors were unimpressed with the research federal officials used to justify its use.

Monoclonal antibodies are lab-produced molecules that act as substitutes for the body’s own antibodies that fight infection. The COVID treatments are designed to block the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes infection from attaching to and entering human cells. Such treatments are usually prohibitively expensive, but for the time being the federal government is footing the bulk of the bill, though patients likely will be charged administrative fees.

Nationwide, nearly 4,000 sites offer the infusion therapies. But for patients and families of people most at risk – those 65 and older or with underlying health conditions – finding the sites and gaining access has been almost impossible, said Brian Nyquist, chief executive officer of the National Infusion Center Association, which is tracking supplies of the antibody products. Like Mr. Herritz, many seeking information about monoclonals find themselves on a lone crusade.

“If they’re not hammering the phones and advocating for access for their loved ones, others often won’t,” he said. “Tenacity is critical.”

Regeneron officials said they’re fielding calls about COVID treatments daily to the company’s medical information line. More than 3,500 people have flooded Eli Lilly’s COVID hotline with questions about access.

As of this week, all states are required to list on a federal locator map sites that have received the monoclonal antibody products, HHS officials said. The updated map shows wide distribution, but a listing doesn’t guarantee availability or access; patients still need to check. It’s best to confer with a primary care provider before reaching out to the centers. For best results, treatment should occur as soon as possible after a positive COVID test.

Some health systems have refused to offer the monoclonal antibody therapies because of doubts about the data used to authorize them. Early studies suggested that Lilly’s therapy, bamlanivimab, reduced the need for hospitalization or emergency treatment in outpatient COVID cases by about 70%, while Regeneron’s antibody cocktail of casirivimab plus imdevimab reduced the need by about 50%.

But those studies were small, just a few hundred subjects, and the results were limited. “A lot of doctors, actually, they’re not impressed with the data,” said Dr. Daniel Griffin, an infectious disease expert at Columbia University who cohosts the podcast “This Week in Virology.” “There really is still that question of, ‘Does this stuff really work?’ ”

As more patients are treated, however, there’s growing evidence that the therapies can keep high-risk patients out of the hospital, not only easing their recovery but also decreasing the burden on health systems struggling with record numbers of patients.

Dr. Raymund Razonable, an infectious disease expert at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, said he has treated more than 2,500 COVID patients with monoclonal antibody therapy with promising results. “It’s looking good,” he said, declining to provide details because they’re embargoed for publication. “We are seeing reductions in hospitalizations; we’re seeing reductions in ICU care; we’re also seeing reductions in mortality.”

Banking on observations from Mayo experts and others, federal officials have been pushing for wider use of antibody therapies. HHS officials have partnered with hospitals in three hard-hit states – California, Arizona, and Nevada – to set up infusion centers that are treating dozens of COVID patients each day.

One of those sites went up in late December at El Centro Regional Medical Center in California’s Imperial County, an impoverished farming region on the state’s southern border that has recorded among the highest COVID infection rates in the state. For months, the medical center strained to absorb the overwhelming influx of patients, but chief executive Dr. Adolphe Edward said a new walk-up infusion site has already put a dent in the COVID load.

More than 130 people have been treated, all patients who were able to get the 2-hour infusions and then recuperate at home. “If those folks would not have had the treatment, they would have come through the emergency department and we would have had to admit the lion’s share of them,” he said.

It’s important to make sure people in high-risk groups know to seek out the therapy and to get it early, Dr. Edward said. He and his staff have been working with area doctors’ offices and nonprofit groups and relying on word of mouth.

“On multiple levels, we’re saying, ‘If you’ve tested positive for the virus, come and let us see if you are eligible,’ ” Dr. Edward said.

Greater awareness is a goal of the HHS effort, said Dr. John Redd, chief medical officer for the assistant secretary for preparedness and response. “These antibodies are meant for everyone,” he said. “Everyone across the country should have equal access to these products.”

For now, patients like Mr. Herritz, the Mississippi liver transplant recipient, say reality is falling well short of that goal. If he hadn’t continued to call in search of a referral, he wouldn’t have been treated. And without the therapy, Mr. Herritz believes, he was just days away from hospitalization.

“I think it’s horrible that if I didn’t have Twitter, I wouldn’t know anything about this,” he said. “I think about all the people who have died not knowing this was an option for high-risk individuals.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

By the time he tested positive for COVID-19 on Jan. 12, Gary Herritz was feeling pretty sick. He suspects he was infected a week earlier, during a medical appointment in which he saw health workers who were wearing masks beneath their noses or who had removed them entirely.

His scratchy throat had turned to a dry cough, headache, joint pain, and fever – all warning signs to Mr. Herritz, who underwent liver transplant surgery in 2012, followed by a rejection scare in 2018. He knew his compromised immune system left him especially vulnerable to a potentially deadly case of COVID.

“The thing with transplant patients is we can crash in a heartbeat,” said Mr. Herritz, 39. “The outcome for transplant patients [with COVID] is not good.”

On Twitter, Mr. Herritz had read about monoclonal antibody therapy, the treatment famously given to President Donald Trump and other high-profile politicians and authorized by the Food and Drug Administration for emergency use in high-risk COVID patients. But as his symptoms worsened, Mr. Herritz found himself very much on his own as he scrambled for access.

His primary care doctor wasn’t sure he qualified for treatment. His transplant team in Wisconsin, where he’d had the liver surgery, wasn’t calling back. No one was sure exactly where he should go to get it. From bed in Pascagoula, Miss., he spent 2 days punching in phone numbers, reaching out to health officials in four states, before he finally landed an appointment to receive a treatment aimed at keeping patients like him out of the hospital – and, perhaps, the morgue.

“I am not rich, I am not special, I am not a political figure,” Mr. Herritz, a former community service officer, wrote on Twitter. “I just called until someone would listen.”

Months after Mr. Trump emphatically credited an experimental antibody therapy for his quick recovery from covid and even as drugmakers ramp up supplies, only a trickle of the product has found its way into regular people. While hundreds of thousands of vials sit unused, sick patients who, research indicates, could benefit from early treatment – available for free – have largely been fending for themselves.

Federal officials have allocated more than 785,000 doses of two antibody treatments authorized for emergency use during the pandemic, and more than 550,000 doses have been delivered to sites across the nation. The federal government has contracted for nearly 2.5 million doses of the products from drugmakers Eli Lilly and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals at a cost of more than $4.4 billion.

So far, however, only about 30% of the available doses have been administered to patients, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services officials said.

Scores of high-risk COVID patients who are eligible remain unaware or have not been offered the option. Research has shown the therapy is most effective if given early in the illness, within 10 days of a positive COVID test. But many would-be recipients have missed this crucial window because of a patchwork system in the United States that can delay testing and diagnosis.

“The bottleneck here in the funnel is administration, not availability of the product,” said Dr. Janet Woodcock, a veteran FDA official in charge of therapeutics for the federal Operation Warp Speed effort.

Among the daunting hurdles: Until this week, there has been no nationwide system to tell people where they could obtain the drugs, which are delivered through IV infusions that require hours to administer and monitor. Finding space to keep COVID-infected patients separate from others has been difficult in some health centers slammed by the pandemic.

“The health care system is crashing,” Dr. Woodcock told reporters. “What we’ve heard around the country is the No. 1 barrier is staffing.”

At the same time, many hospitals have refused to offer the therapy because doctors were unimpressed with the research federal officials used to justify its use.

Monoclonal antibodies are lab-produced molecules that act as substitutes for the body’s own antibodies that fight infection. The COVID treatments are designed to block the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes infection from attaching to and entering human cells. Such treatments are usually prohibitively expensive, but for the time being the federal government is footing the bulk of the bill, though patients likely will be charged administrative fees.

Nationwide, nearly 4,000 sites offer the infusion therapies. But for patients and families of people most at risk – those 65 and older or with underlying health conditions – finding the sites and gaining access has been almost impossible, said Brian Nyquist, chief executive officer of the National Infusion Center Association, which is tracking supplies of the antibody products. Like Mr. Herritz, many seeking information about monoclonals find themselves on a lone crusade.

“If they’re not hammering the phones and advocating for access for their loved ones, others often won’t,” he said. “Tenacity is critical.”

Regeneron officials said they’re fielding calls about COVID treatments daily to the company’s medical information line. More than 3,500 people have flooded Eli Lilly’s COVID hotline with questions about access.

As of this week, all states are required to list on a federal locator map sites that have received the monoclonal antibody products, HHS officials said. The updated map shows wide distribution, but a listing doesn’t guarantee availability or access; patients still need to check. It’s best to confer with a primary care provider before reaching out to the centers. For best results, treatment should occur as soon as possible after a positive COVID test.

Some health systems have refused to offer the monoclonal antibody therapies because of doubts about the data used to authorize them. Early studies suggested that Lilly’s therapy, bamlanivimab, reduced the need for hospitalization or emergency treatment in outpatient COVID cases by about 70%, while Regeneron’s antibody cocktail of casirivimab plus imdevimab reduced the need by about 50%.

But those studies were small, just a few hundred subjects, and the results were limited. “A lot of doctors, actually, they’re not impressed with the data,” said Dr. Daniel Griffin, an infectious disease expert at Columbia University who cohosts the podcast “This Week in Virology.” “There really is still that question of, ‘Does this stuff really work?’ ”

As more patients are treated, however, there’s growing evidence that the therapies can keep high-risk patients out of the hospital, not only easing their recovery but also decreasing the burden on health systems struggling with record numbers of patients.

Dr. Raymund Razonable, an infectious disease expert at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, said he has treated more than 2,500 COVID patients with monoclonal antibody therapy with promising results. “It’s looking good,” he said, declining to provide details because they’re embargoed for publication. “We are seeing reductions in hospitalizations; we’re seeing reductions in ICU care; we’re also seeing reductions in mortality.”

Banking on observations from Mayo experts and others, federal officials have been pushing for wider use of antibody therapies. HHS officials have partnered with hospitals in three hard-hit states – California, Arizona, and Nevada – to set up infusion centers that are treating dozens of COVID patients each day.

One of those sites went up in late December at El Centro Regional Medical Center in California’s Imperial County, an impoverished farming region on the state’s southern border that has recorded among the highest COVID infection rates in the state. For months, the medical center strained to absorb the overwhelming influx of patients, but chief executive Dr. Adolphe Edward said a new walk-up infusion site has already put a dent in the COVID load.

More than 130 people have been treated, all patients who were able to get the 2-hour infusions and then recuperate at home. “If those folks would not have had the treatment, they would have come through the emergency department and we would have had to admit the lion’s share of them,” he said.

It’s important to make sure people in high-risk groups know to seek out the therapy and to get it early, Dr. Edward said. He and his staff have been working with area doctors’ offices and nonprofit groups and relying on word of mouth.

“On multiple levels, we’re saying, ‘If you’ve tested positive for the virus, come and let us see if you are eligible,’ ” Dr. Edward said.

Greater awareness is a goal of the HHS effort, said Dr. John Redd, chief medical officer for the assistant secretary for preparedness and response. “These antibodies are meant for everyone,” he said. “Everyone across the country should have equal access to these products.”

For now, patients like Mr. Herritz, the Mississippi liver transplant recipient, say reality is falling well short of that goal. If he hadn’t continued to call in search of a referral, he wouldn’t have been treated. And without the therapy, Mr. Herritz believes, he was just days away from hospitalization.

“I think it’s horrible that if I didn’t have Twitter, I wouldn’t know anything about this,” he said. “I think about all the people who have died not knowing this was an option for high-risk individuals.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

By the time he tested positive for COVID-19 on Jan. 12, Gary Herritz was feeling pretty sick. He suspects he was infected a week earlier, during a medical appointment in which he saw health workers who were wearing masks beneath their noses or who had removed them entirely.

His scratchy throat had turned to a dry cough, headache, joint pain, and fever – all warning signs to Mr. Herritz, who underwent liver transplant surgery in 2012, followed by a rejection scare in 2018. He knew his compromised immune system left him especially vulnerable to a potentially deadly case of COVID.

“The thing with transplant patients is we can crash in a heartbeat,” said Mr. Herritz, 39. “The outcome for transplant patients [with COVID] is not good.”

On Twitter, Mr. Herritz had read about monoclonal antibody therapy, the treatment famously given to President Donald Trump and other high-profile politicians and authorized by the Food and Drug Administration for emergency use in high-risk COVID patients. But as his symptoms worsened, Mr. Herritz found himself very much on his own as he scrambled for access.

His primary care doctor wasn’t sure he qualified for treatment. His transplant team in Wisconsin, where he’d had the liver surgery, wasn’t calling back. No one was sure exactly where he should go to get it. From bed in Pascagoula, Miss., he spent 2 days punching in phone numbers, reaching out to health officials in four states, before he finally landed an appointment to receive a treatment aimed at keeping patients like him out of the hospital – and, perhaps, the morgue.

“I am not rich, I am not special, I am not a political figure,” Mr. Herritz, a former community service officer, wrote on Twitter. “I just called until someone would listen.”

Months after Mr. Trump emphatically credited an experimental antibody therapy for his quick recovery from covid and even as drugmakers ramp up supplies, only a trickle of the product has found its way into regular people. While hundreds of thousands of vials sit unused, sick patients who, research indicates, could benefit from early treatment – available for free – have largely been fending for themselves.

Federal officials have allocated more than 785,000 doses of two antibody treatments authorized for emergency use during the pandemic, and more than 550,000 doses have been delivered to sites across the nation. The federal government has contracted for nearly 2.5 million doses of the products from drugmakers Eli Lilly and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals at a cost of more than $4.4 billion.

So far, however, only about 30% of the available doses have been administered to patients, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services officials said.

Scores of high-risk COVID patients who are eligible remain unaware or have not been offered the option. Research has shown the therapy is most effective if given early in the illness, within 10 days of a positive COVID test. But many would-be recipients have missed this crucial window because of a patchwork system in the United States that can delay testing and diagnosis.

“The bottleneck here in the funnel is administration, not availability of the product,” said Dr. Janet Woodcock, a veteran FDA official in charge of therapeutics for the federal Operation Warp Speed effort.

Among the daunting hurdles: Until this week, there has been no nationwide system to tell people where they could obtain the drugs, which are delivered through IV infusions that require hours to administer and monitor. Finding space to keep COVID-infected patients separate from others has been difficult in some health centers slammed by the pandemic.

“The health care system is crashing,” Dr. Woodcock told reporters. “What we’ve heard around the country is the No. 1 barrier is staffing.”

At the same time, many hospitals have refused to offer the therapy because doctors were unimpressed with the research federal officials used to justify its use.

Monoclonal antibodies are lab-produced molecules that act as substitutes for the body’s own antibodies that fight infection. The COVID treatments are designed to block the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes infection from attaching to and entering human cells. Such treatments are usually prohibitively expensive, but for the time being the federal government is footing the bulk of the bill, though patients likely will be charged administrative fees.

Nationwide, nearly 4,000 sites offer the infusion therapies. But for patients and families of people most at risk – those 65 and older or with underlying health conditions – finding the sites and gaining access has been almost impossible, said Brian Nyquist, chief executive officer of the National Infusion Center Association, which is tracking supplies of the antibody products. Like Mr. Herritz, many seeking information about monoclonals find themselves on a lone crusade.

“If they’re not hammering the phones and advocating for access for their loved ones, others often won’t,” he said. “Tenacity is critical.”

Regeneron officials said they’re fielding calls about COVID treatments daily to the company’s medical information line. More than 3,500 people have flooded Eli Lilly’s COVID hotline with questions about access.

As of this week, all states are required to list on a federal locator map sites that have received the monoclonal antibody products, HHS officials said. The updated map shows wide distribution, but a listing doesn’t guarantee availability or access; patients still need to check. It’s best to confer with a primary care provider before reaching out to the centers. For best results, treatment should occur as soon as possible after a positive COVID test.

Some health systems have refused to offer the monoclonal antibody therapies because of doubts about the data used to authorize them. Early studies suggested that Lilly’s therapy, bamlanivimab, reduced the need for hospitalization or emergency treatment in outpatient COVID cases by about 70%, while Regeneron’s antibody cocktail of casirivimab plus imdevimab reduced the need by about 50%.

But those studies were small, just a few hundred subjects, and the results were limited. “A lot of doctors, actually, they’re not impressed with the data,” said Dr. Daniel Griffin, an infectious disease expert at Columbia University who cohosts the podcast “This Week in Virology.” “There really is still that question of, ‘Does this stuff really work?’ ”

As more patients are treated, however, there’s growing evidence that the therapies can keep high-risk patients out of the hospital, not only easing their recovery but also decreasing the burden on health systems struggling with record numbers of patients.

Dr. Raymund Razonable, an infectious disease expert at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, said he has treated more than 2,500 COVID patients with monoclonal antibody therapy with promising results. “It’s looking good,” he said, declining to provide details because they’re embargoed for publication. “We are seeing reductions in hospitalizations; we’re seeing reductions in ICU care; we’re also seeing reductions in mortality.”

Banking on observations from Mayo experts and others, federal officials have been pushing for wider use of antibody therapies. HHS officials have partnered with hospitals in three hard-hit states – California, Arizona, and Nevada – to set up infusion centers that are treating dozens of COVID patients each day.

One of those sites went up in late December at El Centro Regional Medical Center in California’s Imperial County, an impoverished farming region on the state’s southern border that has recorded among the highest COVID infection rates in the state. For months, the medical center strained to absorb the overwhelming influx of patients, but chief executive Dr. Adolphe Edward said a new walk-up infusion site has already put a dent in the COVID load.

More than 130 people have been treated, all patients who were able to get the 2-hour infusions and then recuperate at home. “If those folks would not have had the treatment, they would have come through the emergency department and we would have had to admit the lion’s share of them,” he said.

It’s important to make sure people in high-risk groups know to seek out the therapy and to get it early, Dr. Edward said. He and his staff have been working with area doctors’ offices and nonprofit groups and relying on word of mouth.

“On multiple levels, we’re saying, ‘If you’ve tested positive for the virus, come and let us see if you are eligible,’ ” Dr. Edward said.

Greater awareness is a goal of the HHS effort, said Dr. John Redd, chief medical officer for the assistant secretary for preparedness and response. “These antibodies are meant for everyone,” he said. “Everyone across the country should have equal access to these products.”

For now, patients like Mr. Herritz, the Mississippi liver transplant recipient, say reality is falling well short of that goal. If he hadn’t continued to call in search of a referral, he wouldn’t have been treated. And without the therapy, Mr. Herritz believes, he was just days away from hospitalization.

“I think it’s horrible that if I didn’t have Twitter, I wouldn’t know anything about this,” he said. “I think about all the people who have died not knowing this was an option for high-risk individuals.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Think twice before intensifying BP regimen in older hospitalized patients

Background: It is common practice for providers to intensify antihypertensive regimen during admission for noncardiac conditions even if a patient has a history of well-controlled blood pressure as an outpatient. Many providers have assumed that these changes will benefit patients; however, this outcome had never been studied.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Veterans Affairs hospitals.

Synopsis: The authors analyzed a well-matched retrospective cohort of 4,056 adults aged 65 years or older with hypertension who were admitted for noncardiac conditions including pneumonia, urinary tract infection, and venous thromboembolism. Half of the cohort was discharged with intensification of their antihypertensives, defined as a new antihypertensive medication or an increase of 20% of a prior medication.

Patients discharged with regimen intensification were more likely to be readmitted (hazard ratio, 1.23; 95% confidence interval, 1.07-1.42; number needed to harm = 27), experience a medication-related serious adverse event (HR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.06-1.88; NNH = 63), and have a cardiovascular event (HR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.13-2.4) within 30 days of discharge. At 1 year, no significant difference in mortality, cardiovascular events, or systolic BP were noted between the two groups.

A subgroup analysis of patients with poorly controlled blood pressure as outpatients (defined as systolic blood pressure greater than 140 mm Hg) who had their anti-hypertensive medications intensified did not show significant difference in 30-day readmission, severe adverse events, or cardiovascular events.

Limitations of the study include observational design and majority male sex (97.5%) of the study population.

Bottom line: Intensification of antihypertensive regimen among older adults hospitalized for noncardiac conditions with well-controlled blood pressure as an outpatient can potentially cause harm.

Citation: Anderson TS et al. Clinical outcomes after intensifying antihypertensive medication regimens among older adults at hospital discharge. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Aug 19. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.3007.

Dr. Zarookian is a hospitalist at Maine Medical Center in Portland and Stephens Memorial Hospital in Norway, Maine.

Background: It is common practice for providers to intensify antihypertensive regimen during admission for noncardiac conditions even if a patient has a history of well-controlled blood pressure as an outpatient. Many providers have assumed that these changes will benefit patients; however, this outcome had never been studied.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Veterans Affairs hospitals.

Synopsis: The authors analyzed a well-matched retrospective cohort of 4,056 adults aged 65 years or older with hypertension who were admitted for noncardiac conditions including pneumonia, urinary tract infection, and venous thromboembolism. Half of the cohort was discharged with intensification of their antihypertensives, defined as a new antihypertensive medication or an increase of 20% of a prior medication.

Patients discharged with regimen intensification were more likely to be readmitted (hazard ratio, 1.23; 95% confidence interval, 1.07-1.42; number needed to harm = 27), experience a medication-related serious adverse event (HR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.06-1.88; NNH = 63), and have a cardiovascular event (HR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.13-2.4) within 30 days of discharge. At 1 year, no significant difference in mortality, cardiovascular events, or systolic BP were noted between the two groups.

A subgroup analysis of patients with poorly controlled blood pressure as outpatients (defined as systolic blood pressure greater than 140 mm Hg) who had their anti-hypertensive medications intensified did not show significant difference in 30-day readmission, severe adverse events, or cardiovascular events.

Limitations of the study include observational design and majority male sex (97.5%) of the study population.

Bottom line: Intensification of antihypertensive regimen among older adults hospitalized for noncardiac conditions with well-controlled blood pressure as an outpatient can potentially cause harm.

Citation: Anderson TS et al. Clinical outcomes after intensifying antihypertensive medication regimens among older adults at hospital discharge. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Aug 19. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.3007.

Dr. Zarookian is a hospitalist at Maine Medical Center in Portland and Stephens Memorial Hospital in Norway, Maine.

Background: It is common practice for providers to intensify antihypertensive regimen during admission for noncardiac conditions even if a patient has a history of well-controlled blood pressure as an outpatient. Many providers have assumed that these changes will benefit patients; however, this outcome had never been studied.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Veterans Affairs hospitals.

Synopsis: The authors analyzed a well-matched retrospective cohort of 4,056 adults aged 65 years or older with hypertension who were admitted for noncardiac conditions including pneumonia, urinary tract infection, and venous thromboembolism. Half of the cohort was discharged with intensification of their antihypertensives, defined as a new antihypertensive medication or an increase of 20% of a prior medication.