User login

Pink Ulcerated Nodule on the Forearm

Pink Ulcerated Nodule on the Forearm

THE DIAGNOSIS: Cutaneous Cryptococcosis

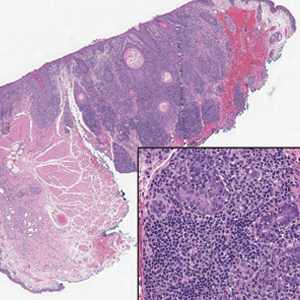

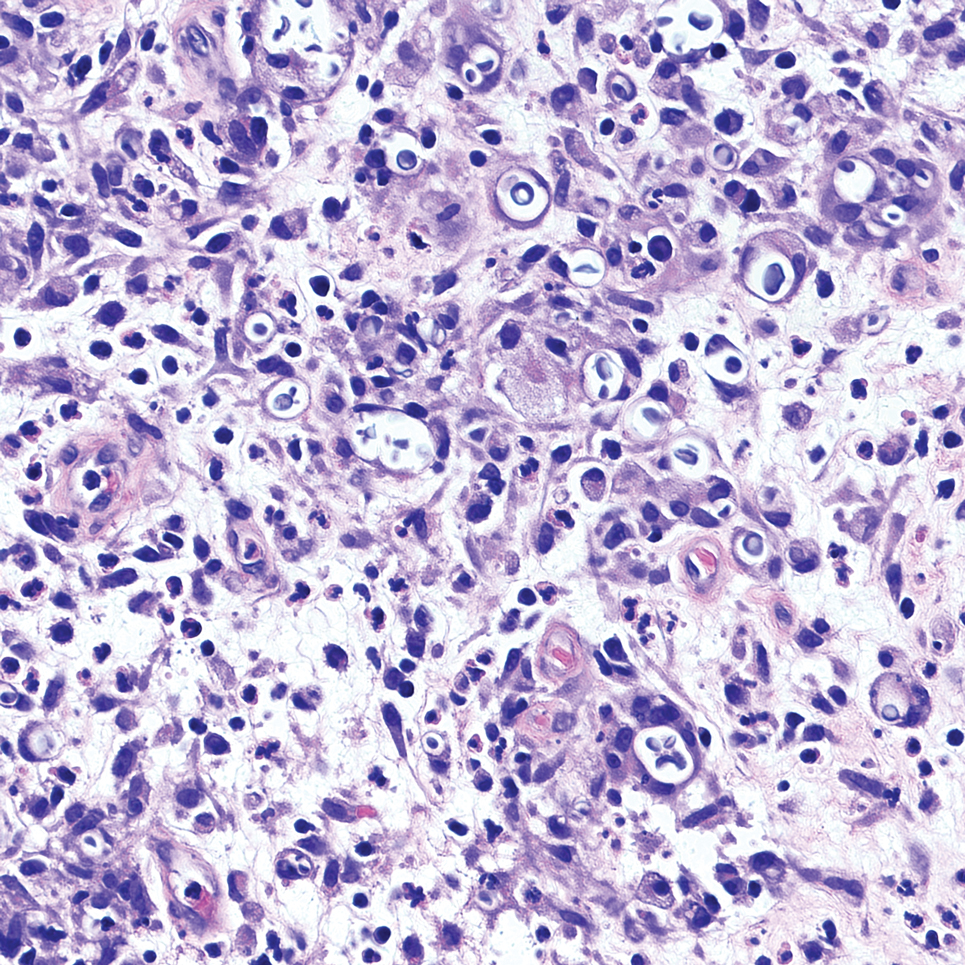

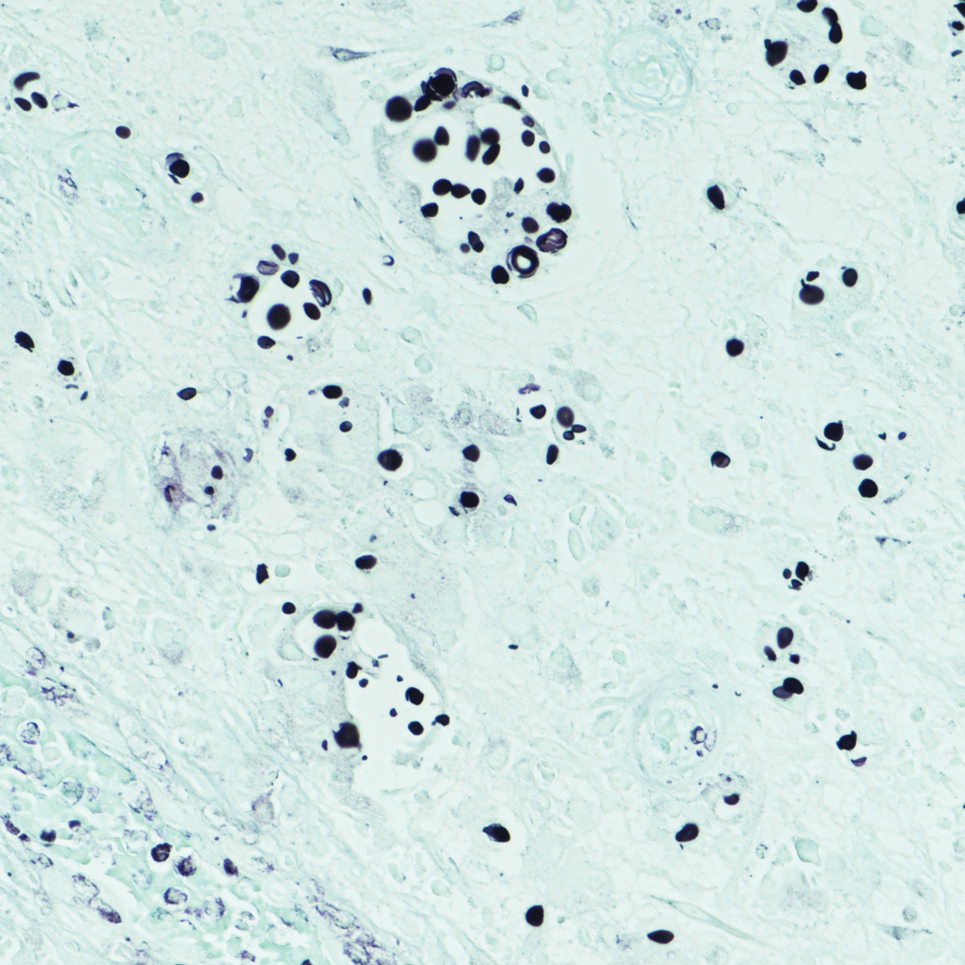

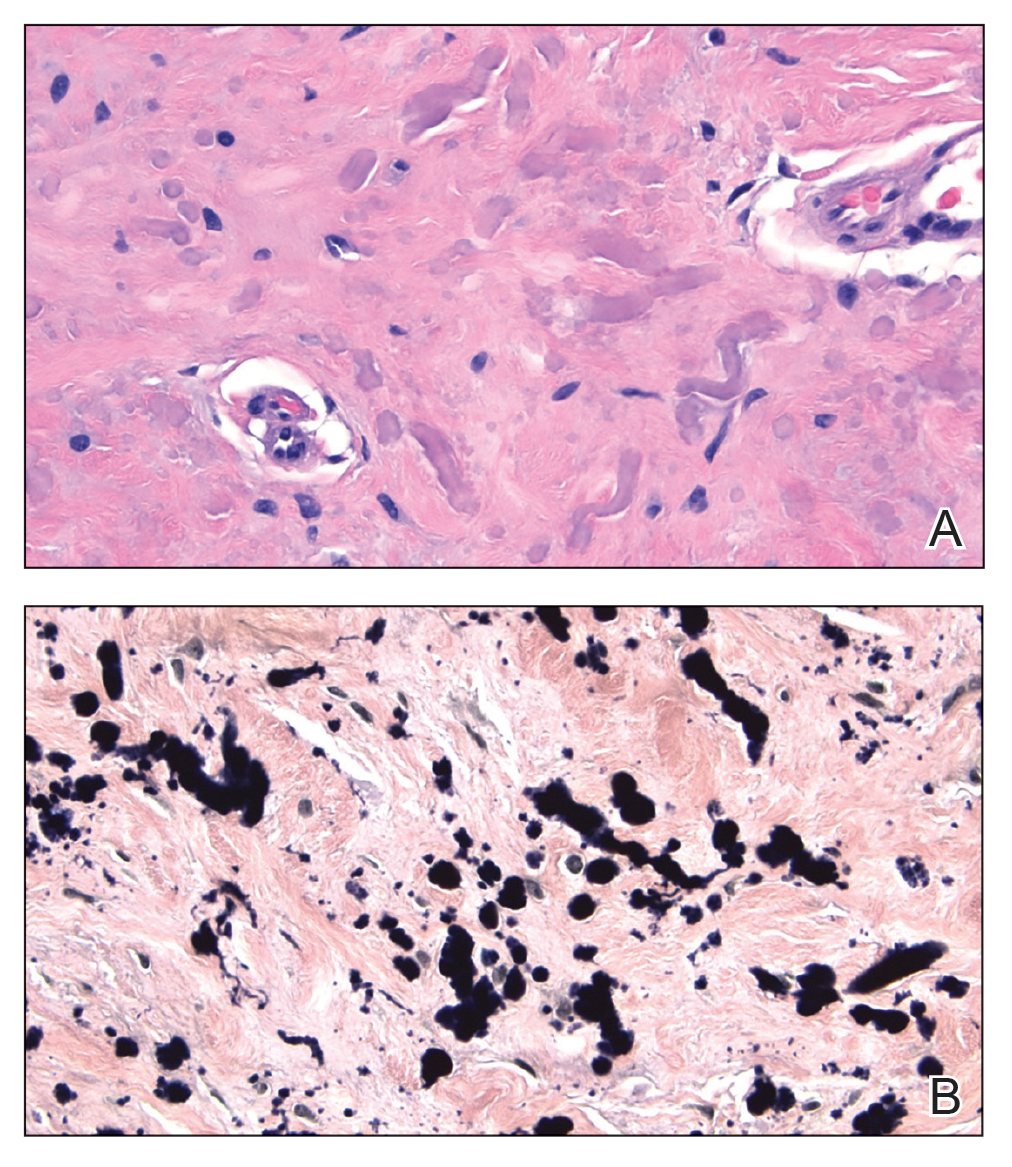

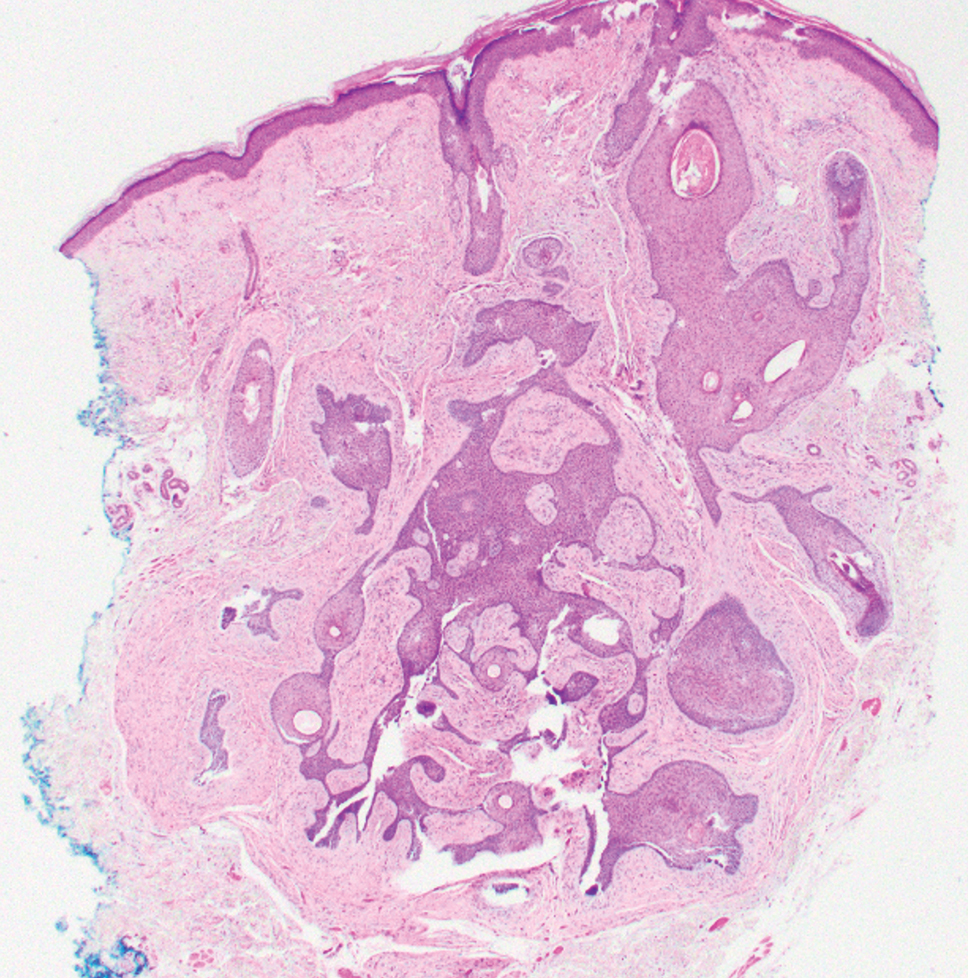

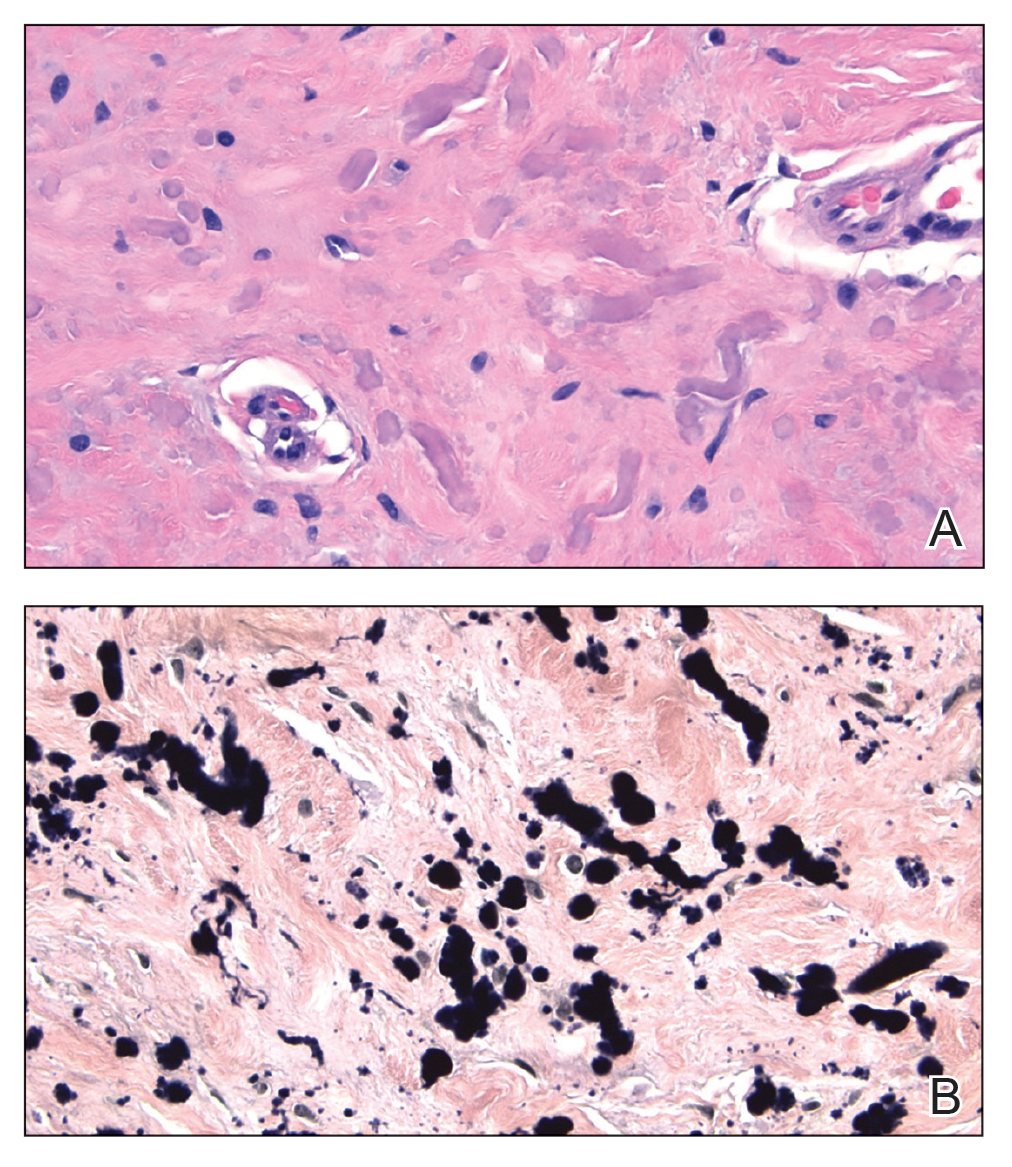

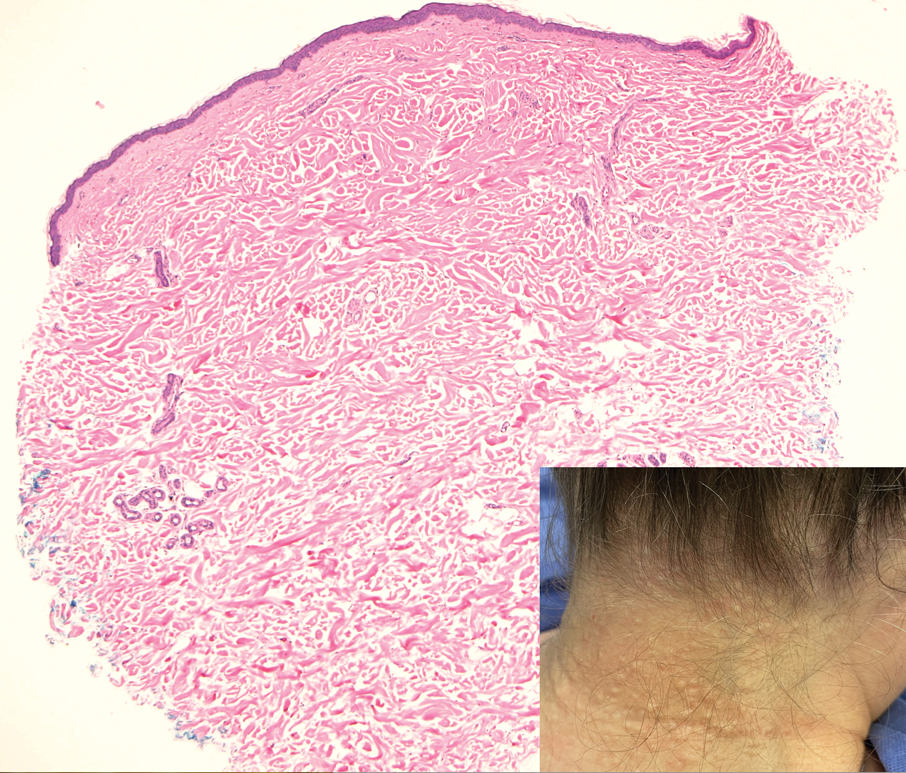

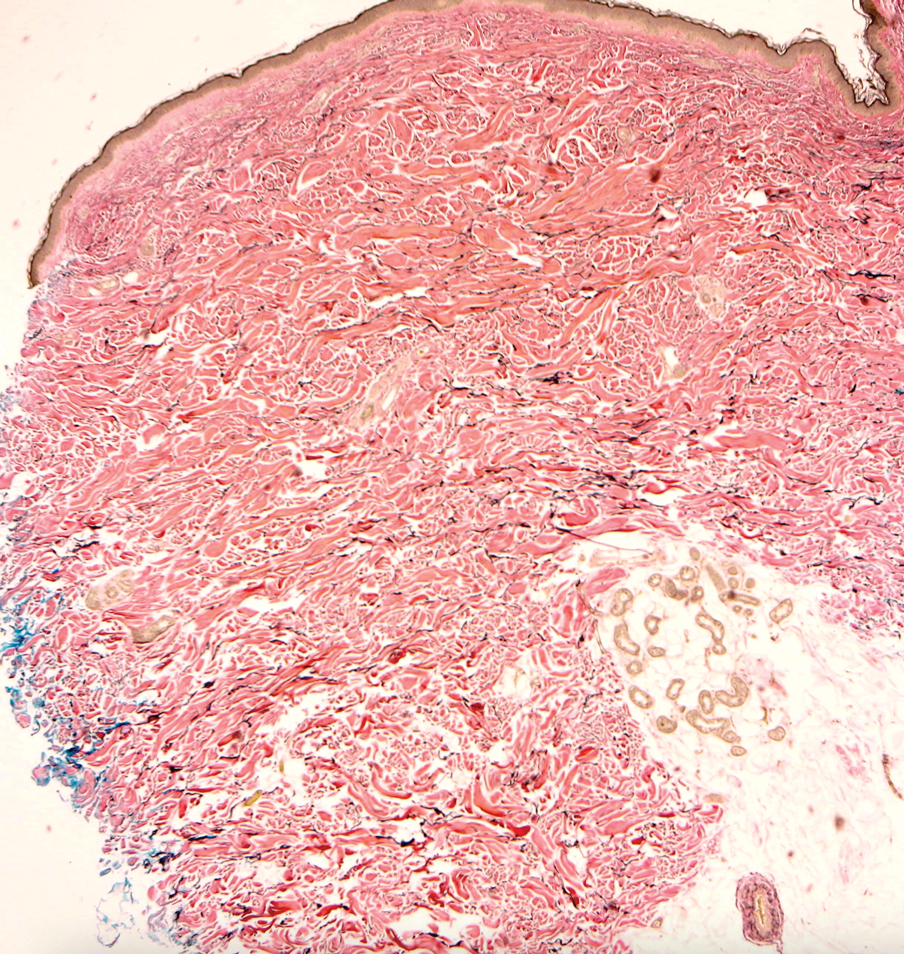

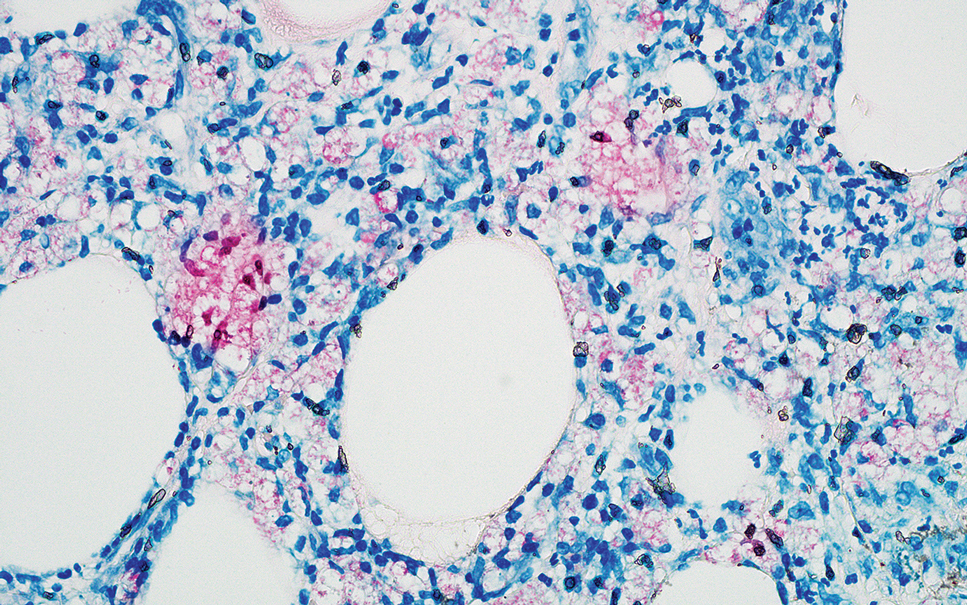

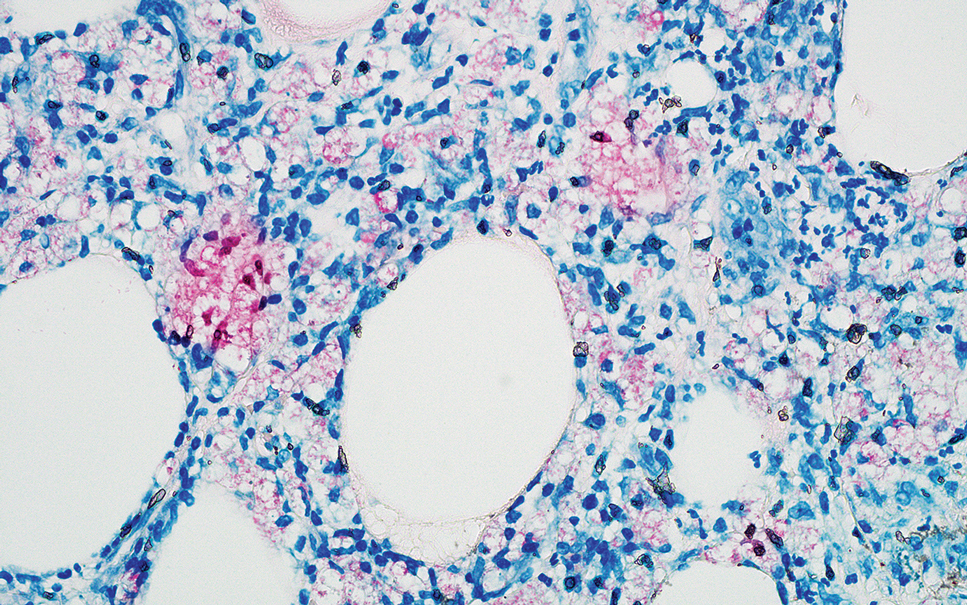

Biopsy of the ulcerated nodule showed numerous yeastlike organisms within clear mucinous capsules and with some surrounding inflammation. On Grocott methenamine silver staining, the organisms stained black. Workup for disseminated cryptococcus was negative, leading to a diagnosis of primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in the setting of immunosuppression. Notably, cryptococcosis infection has been reported in patients taking fingolimod (a sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor) for multiple sclerosis, which was the case for our patient.1

The genus Cryptococcus comprises more than 30 species of encapsulated basidiomycetous fungi distributed ubiquitously in nature. Currently, only 2 species are known to cause infectious disease in humans: Cryptococcus neoformans, which affects both immunocompromised and immunocompetent patients and frequently is isolated from pigeon droppings, as well as Cryptococcus gatti, which primarily affects immunocompetent patients and is more commonly isolated from soil and decaying wood.2

Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis (PCC), characterized by direct inoculation of C neoformans or C gatti via skin injury, is rare and typically is seen in patients with decreased cell-mediated immunity, such as those on chronic corticosteroid therapy, solid-organ transplant recipients, and those with HIV.3 Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis typically manifests as a solitary or confined lesion on exposed areas of the skin and often is accompanied by regional lymphadenopathy.4,5 The most common cutaneous findings associated with PCC include ulceration, cellulitis, and whitlow.5 In immunocompetent hosts, frequently affected sites include the arms, fingers, and face, while the trunk and lower extremities are more commonly affected in immunocompromised hosts.3 Secondary cutaneous cryptococcosis occurs through hematologic spread in patients with disseminated cryptococcosis after inhalation of Cryptococcosis spores and differs from PCC in that it typically manifests as multiple lesions scattered on both exposed and covered areas of the skin. Patients also may have signs and symptoms of disseminated cryptococcosis such as pneumonia and/or meningitis at presentation.5

Despite the difference between PCC and secondary cutaneous cryptococcosis, almost every type of skin lesion has been observed in cryptococcosis, including pustules, nodules, vesicles, acneform lesions, purpura, ulcers, abscesses, molluscumlike lesions, granulomas, draining sinuses, and cellulitis.6,7

Cutaneous cryptococcosis generally is associated with 2 types of histologic reactions: gelatinous and granulomatous. The gelatinous reaction shows numerous yeastlike organisms ranging from 4 μm to 12 μm in diameter with large mucinous polysaccharide capsules and scant inflammation. Organisms may be seen in mucoid sheets.8 The granulomatous type shows a more pronounced reaction with fewer organisms ranging from 2 μm to 4 μm in diameter found within giant cells, histiocytes, and lymphocytes.6,9 Areas of necrosis occasionally can be observed.8

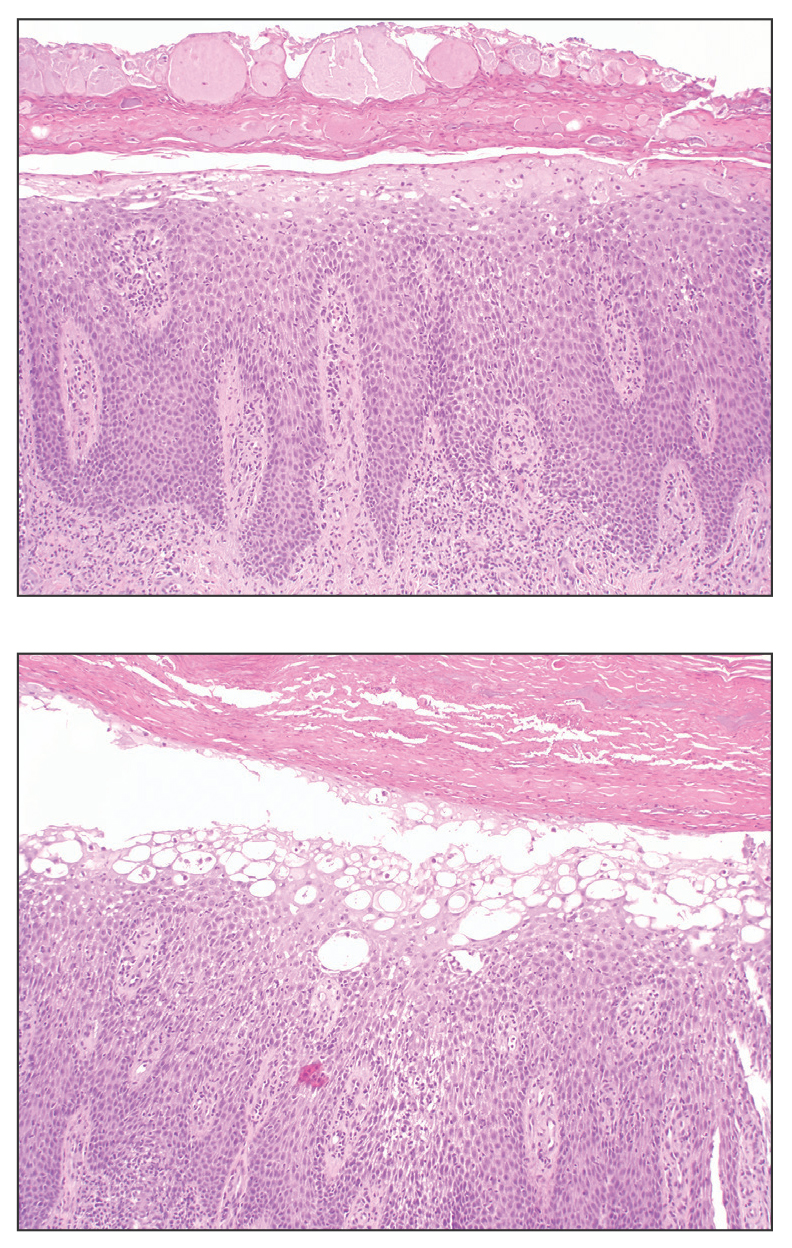

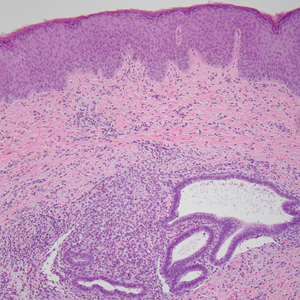

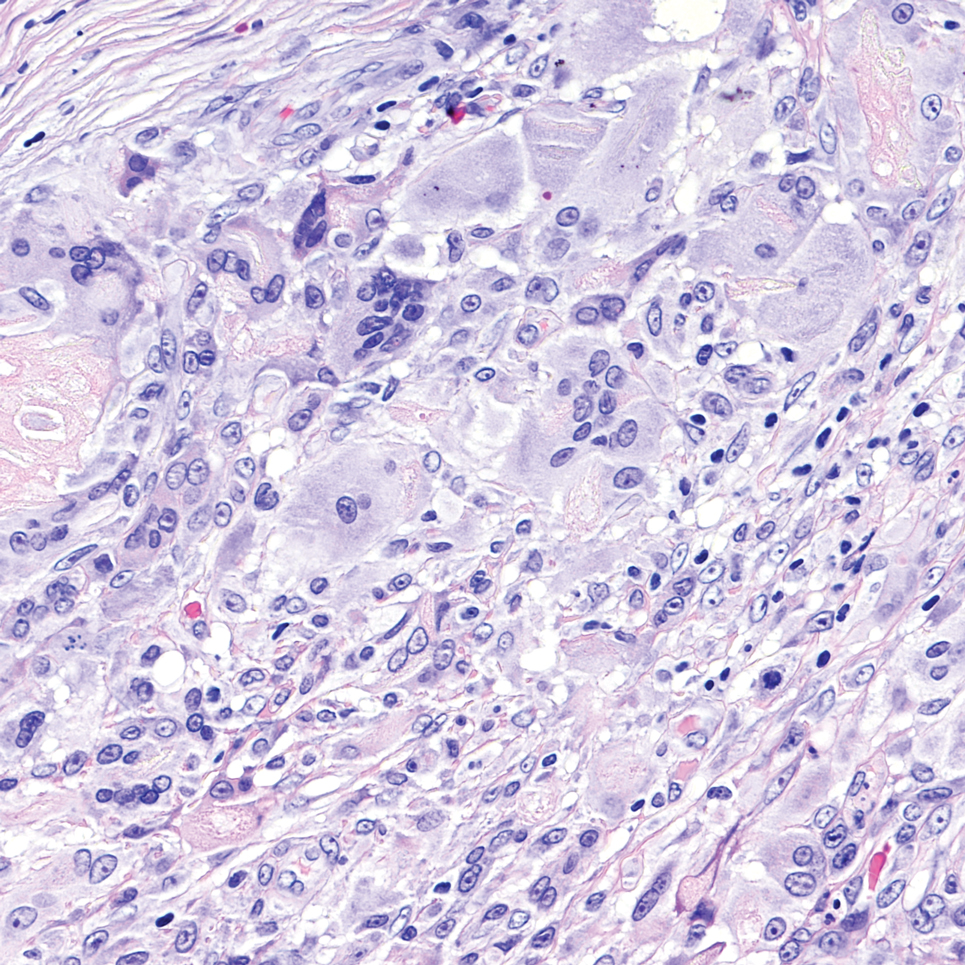

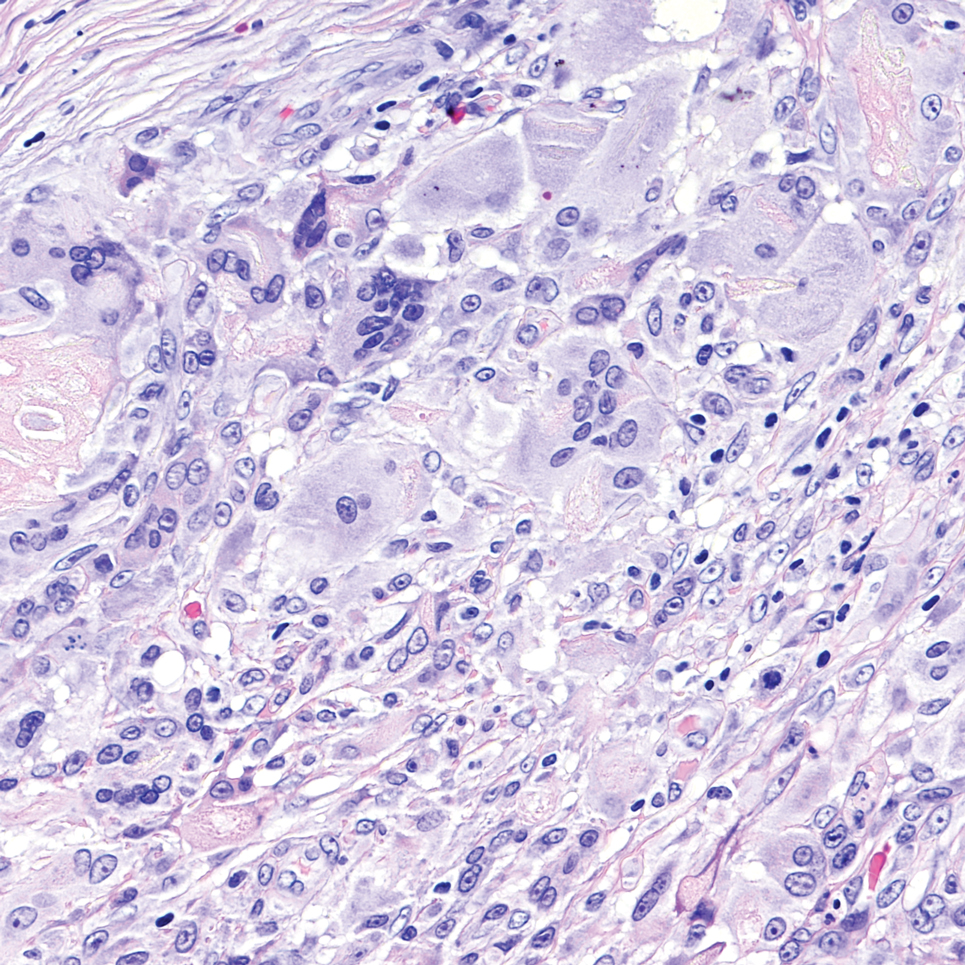

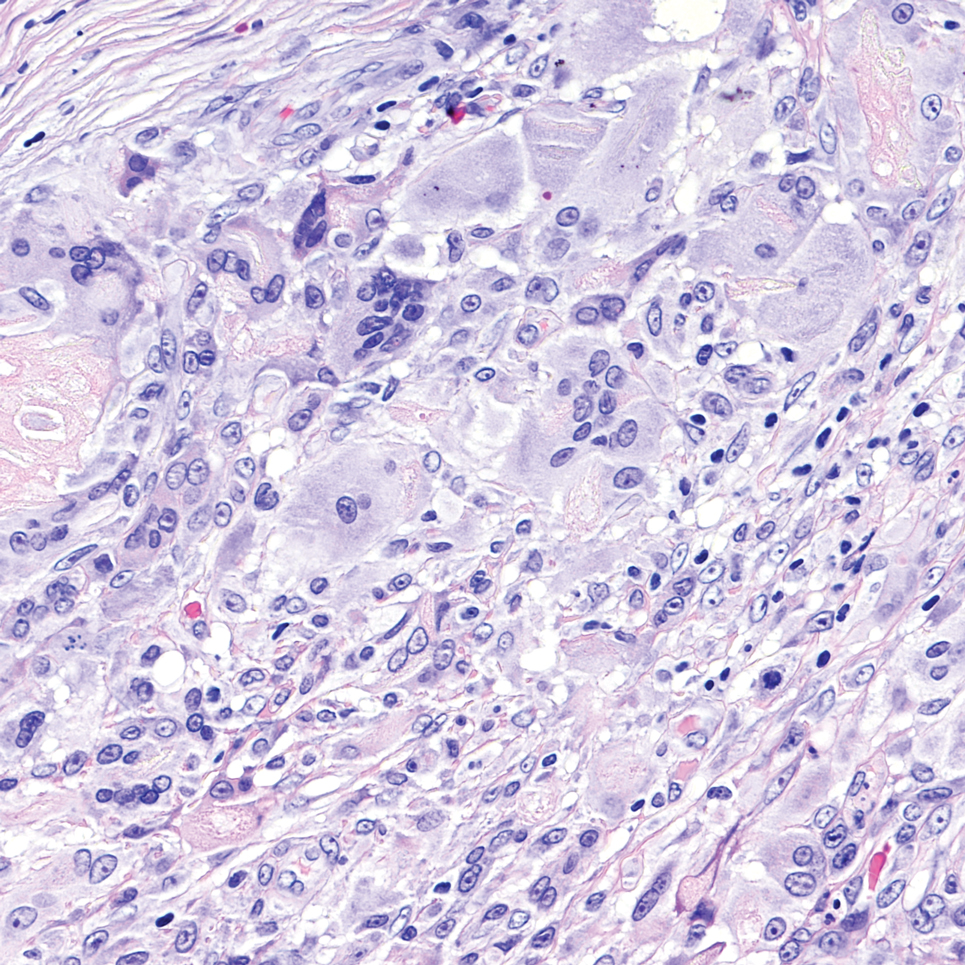

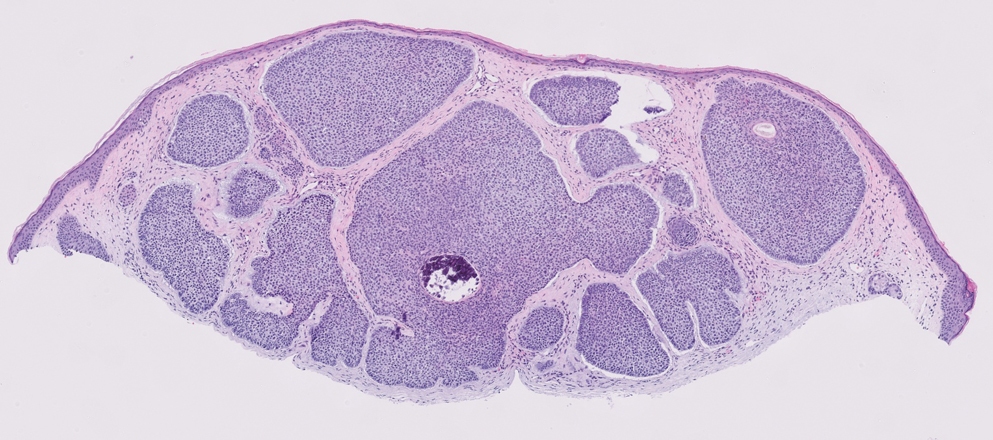

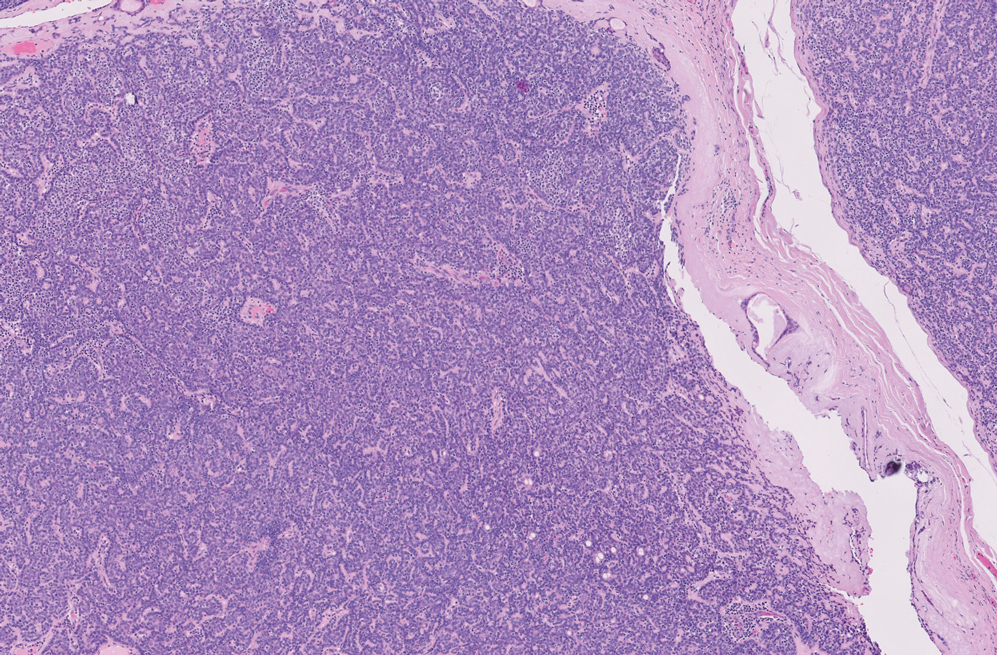

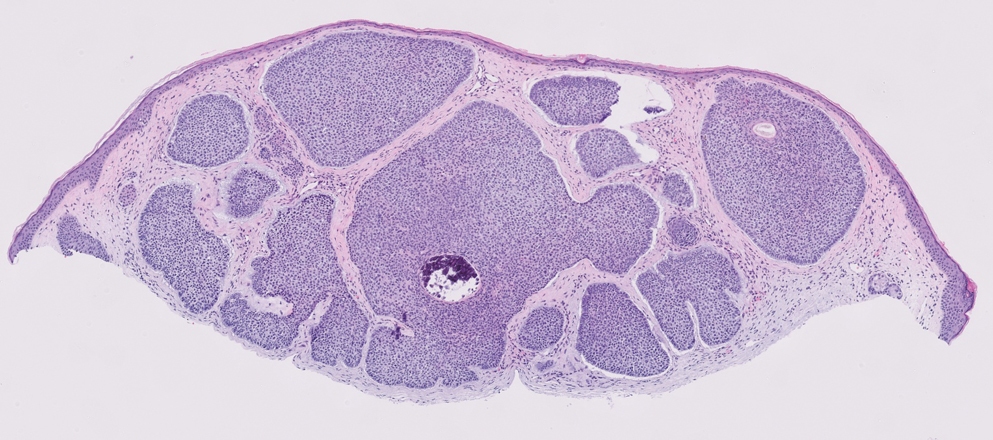

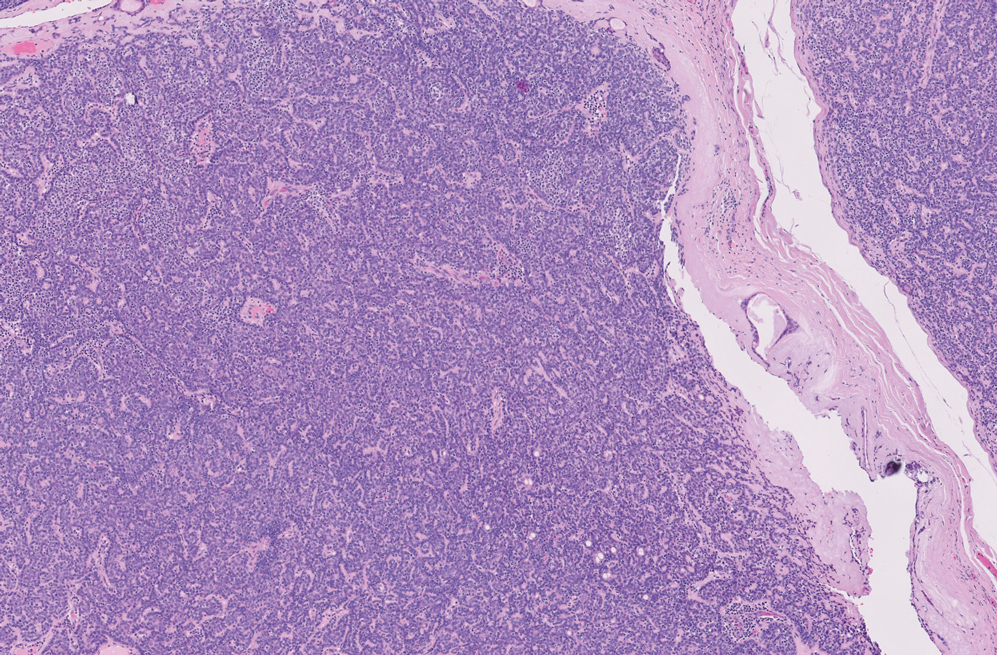

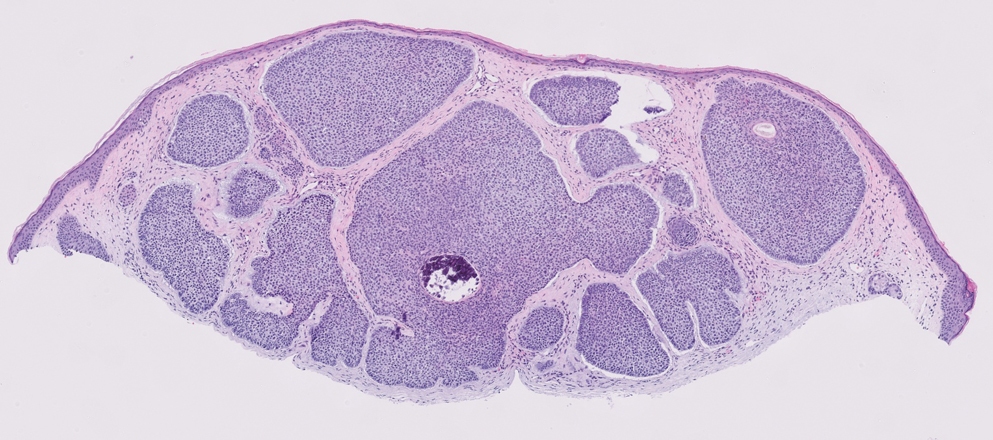

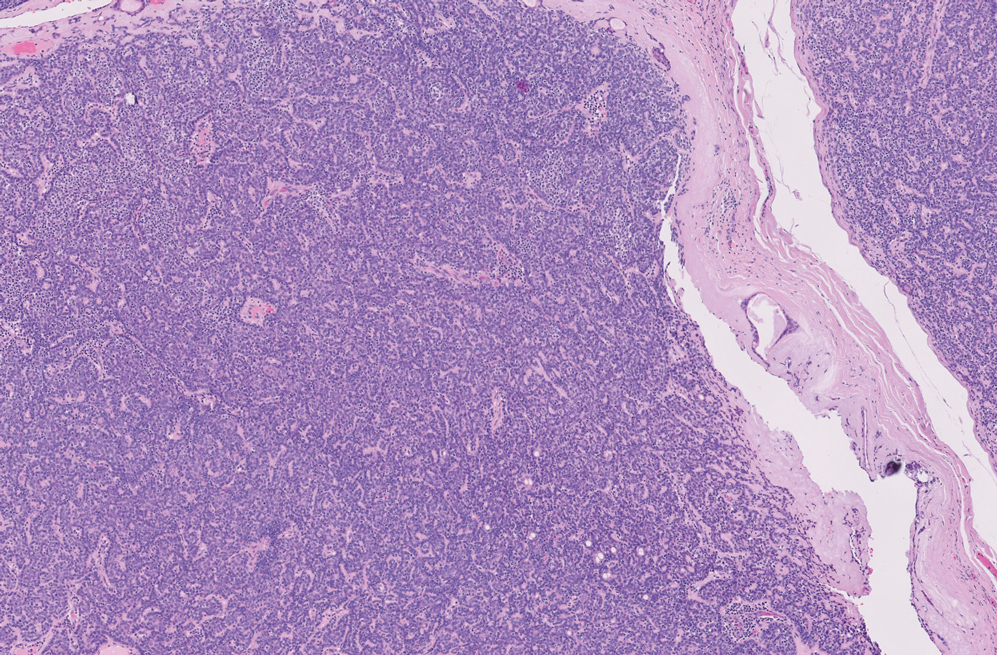

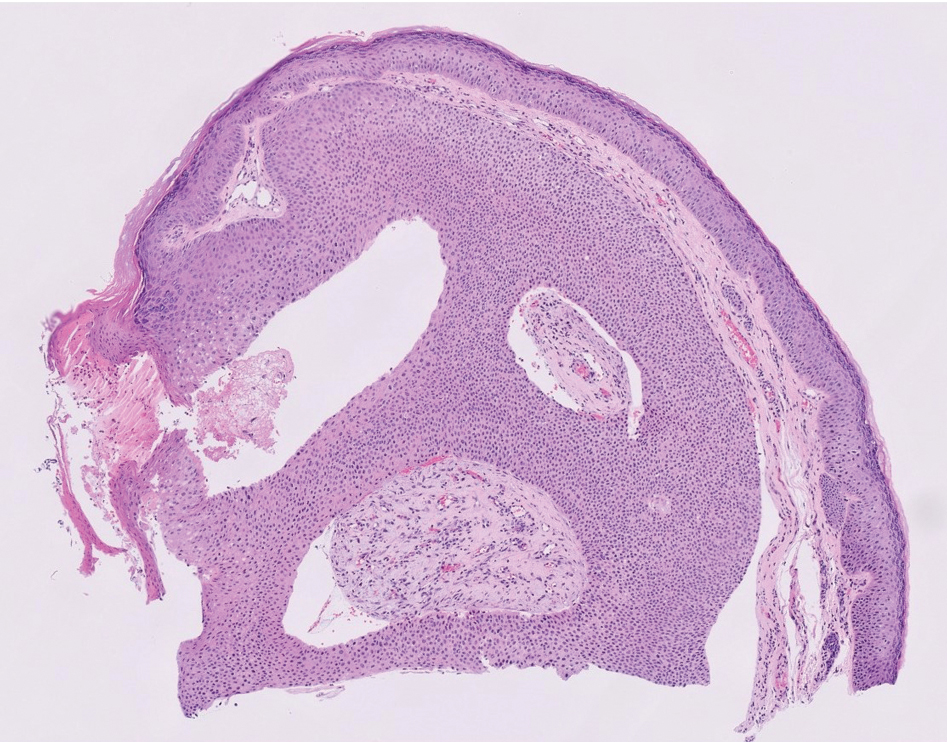

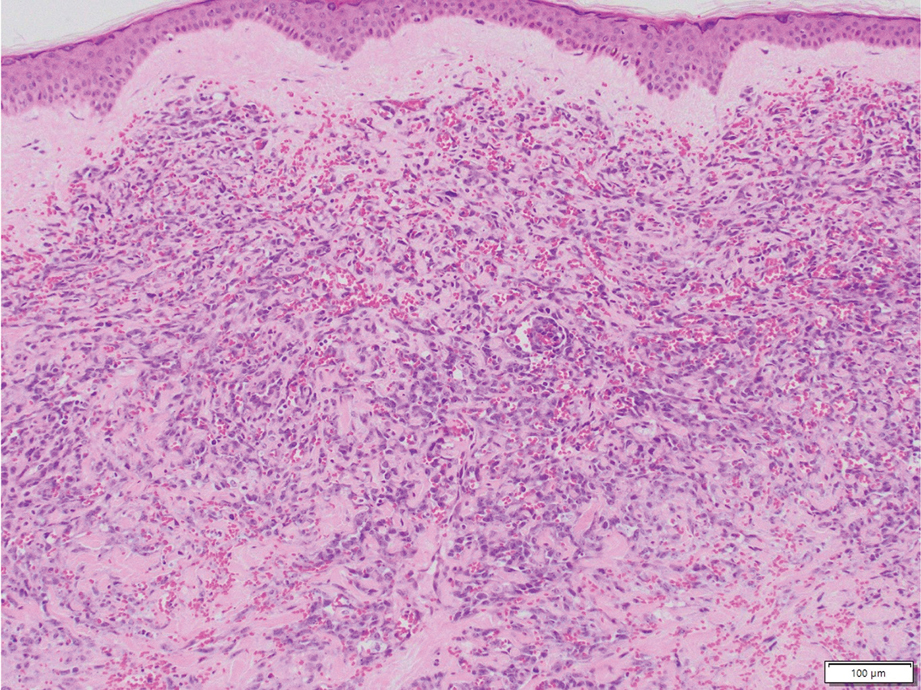

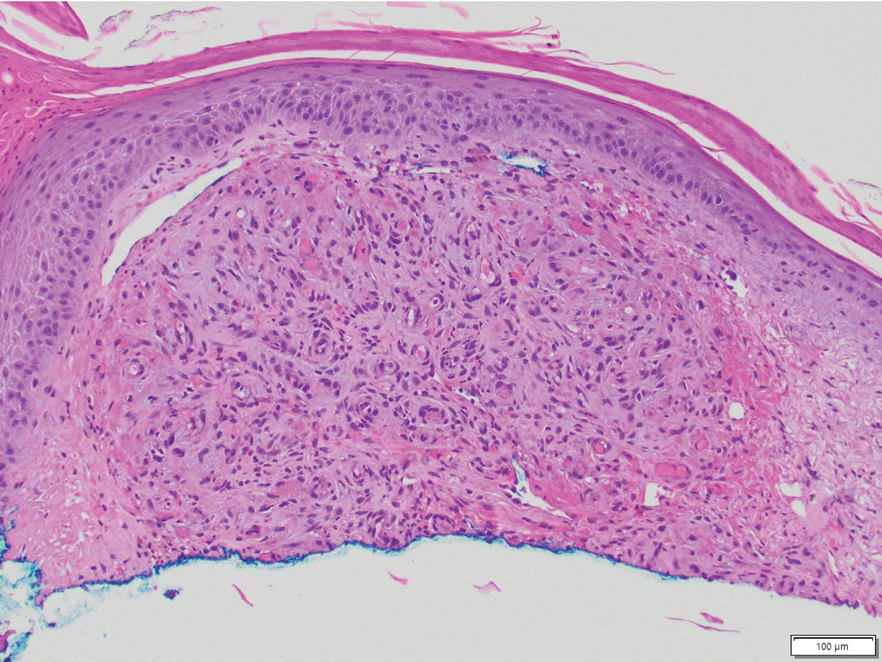

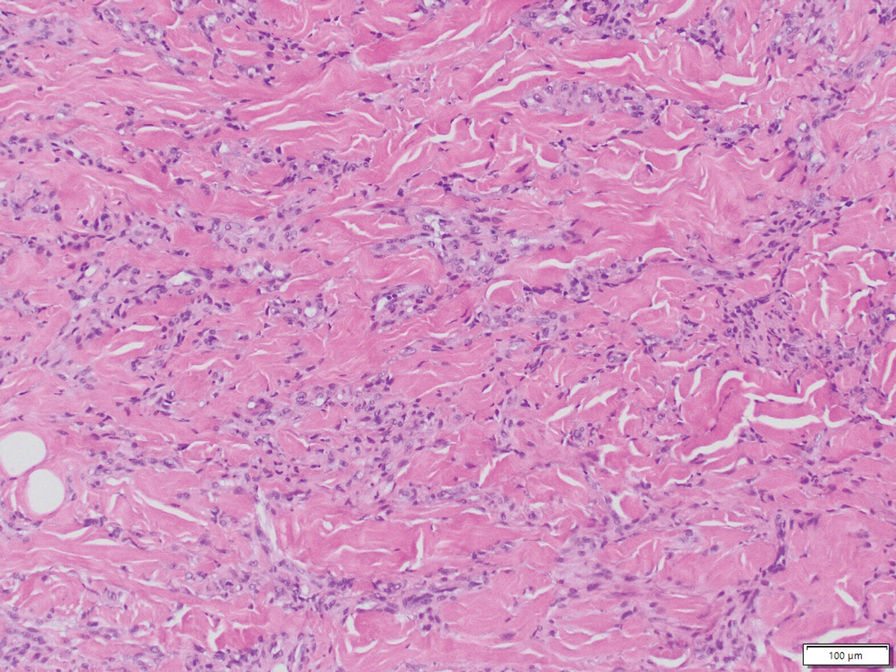

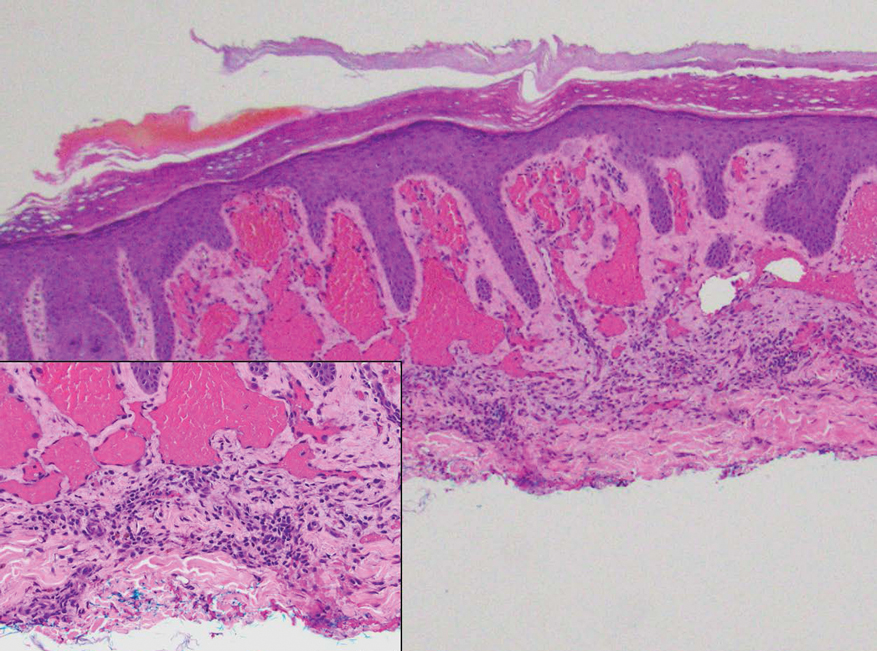

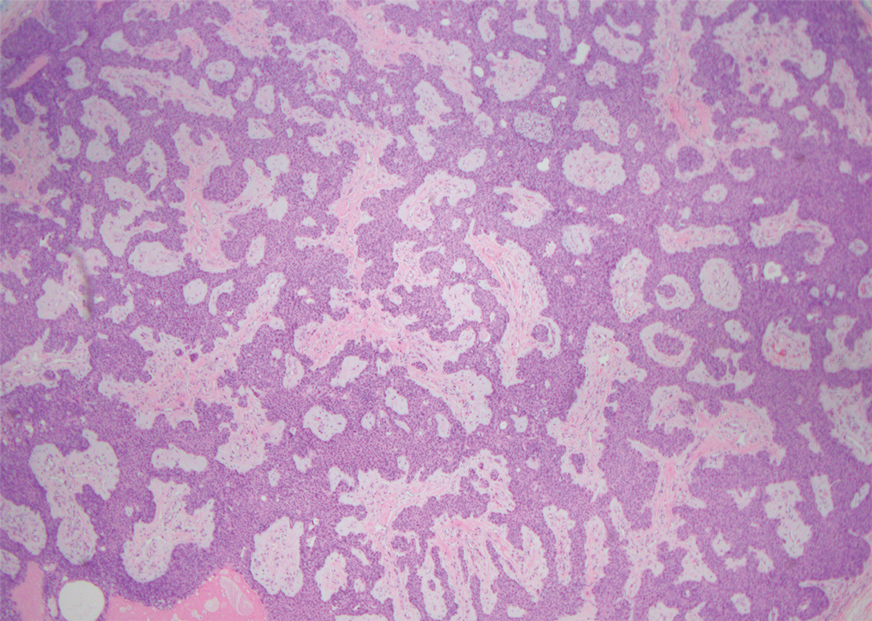

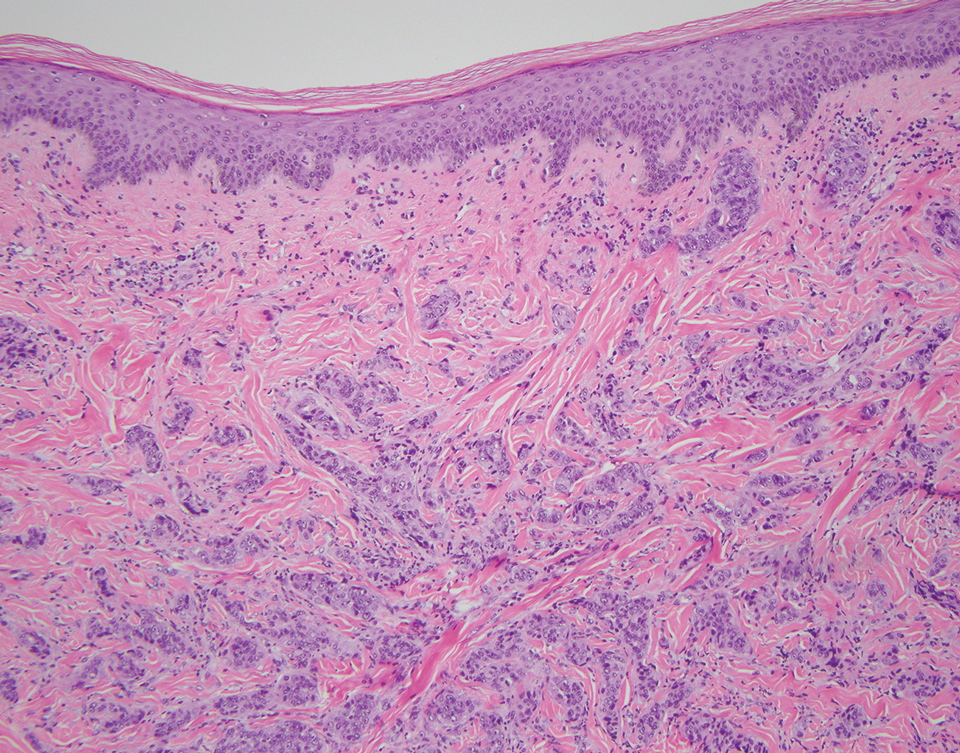

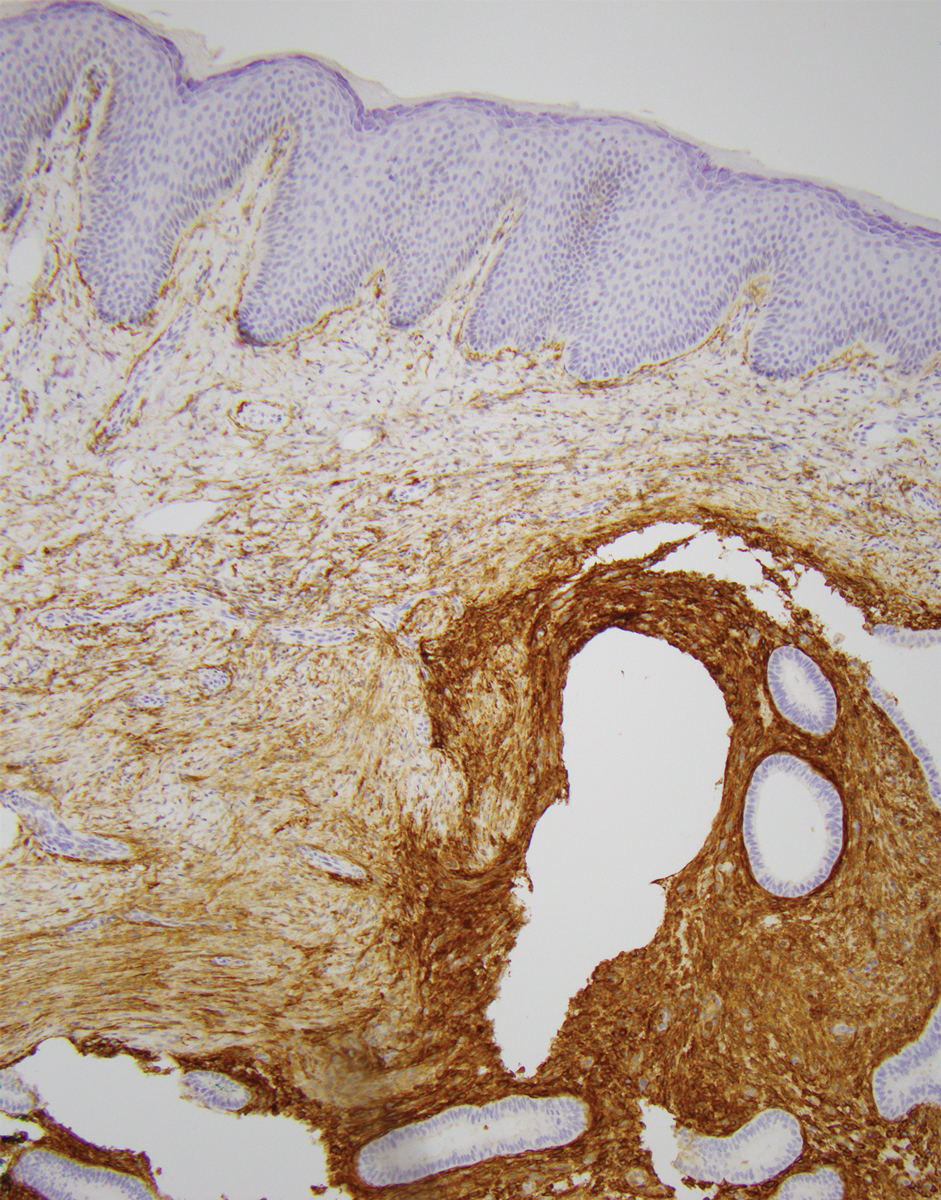

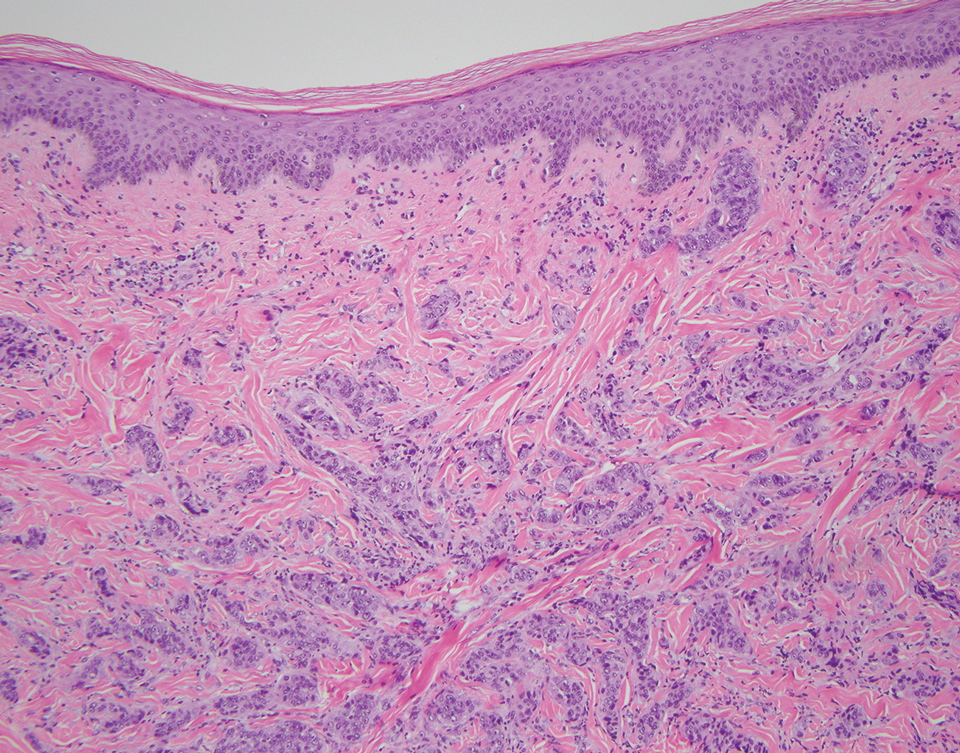

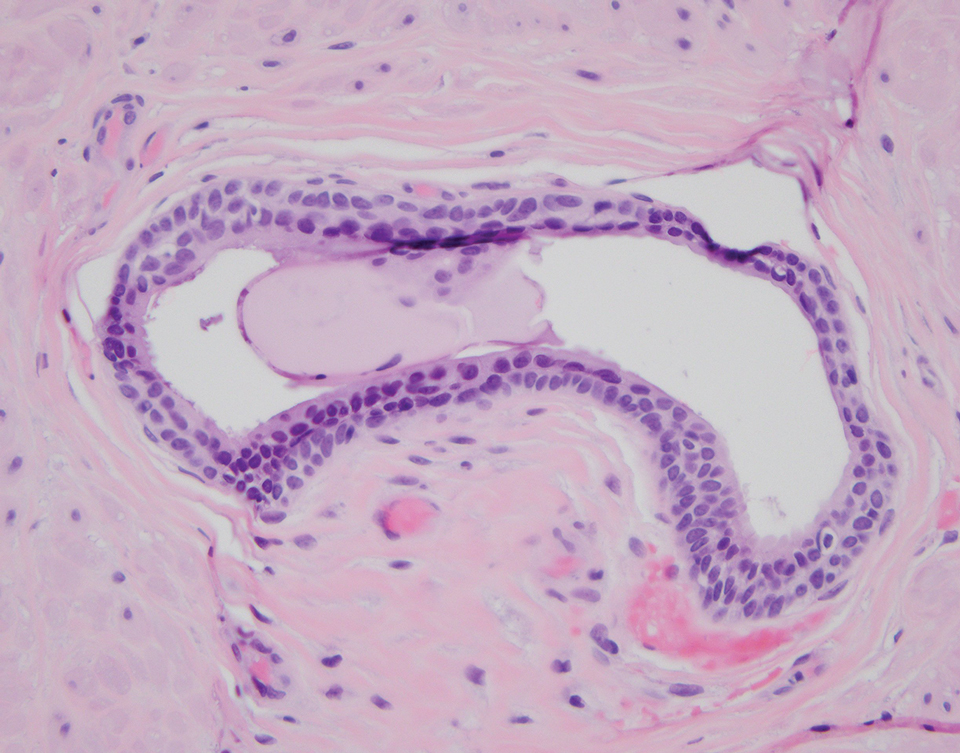

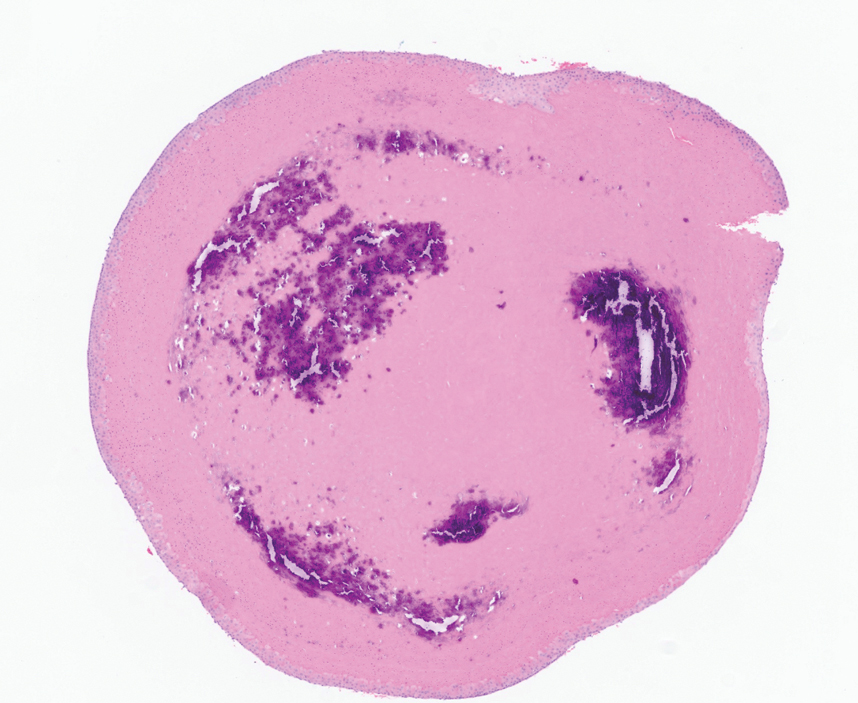

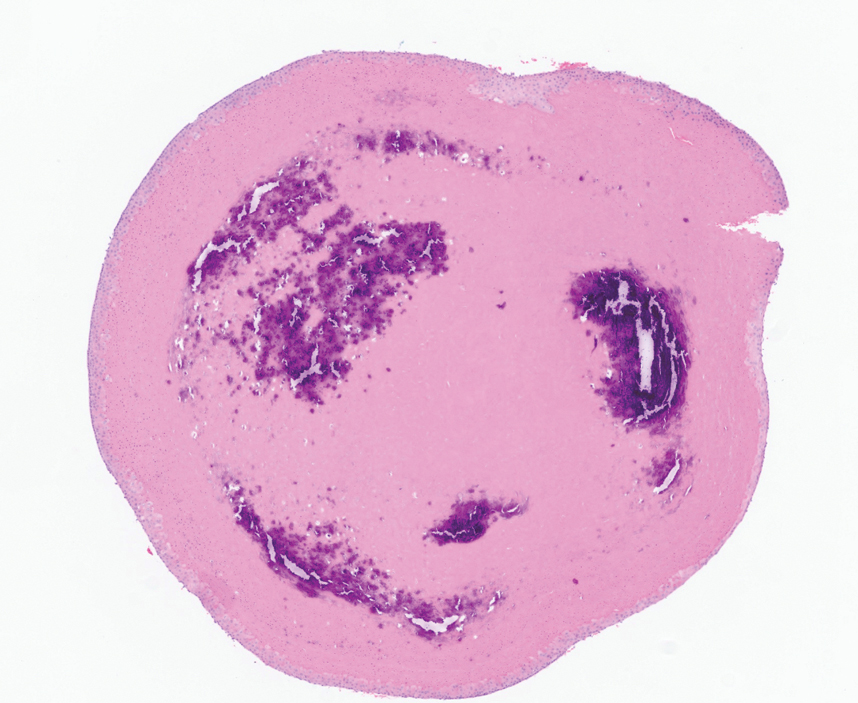

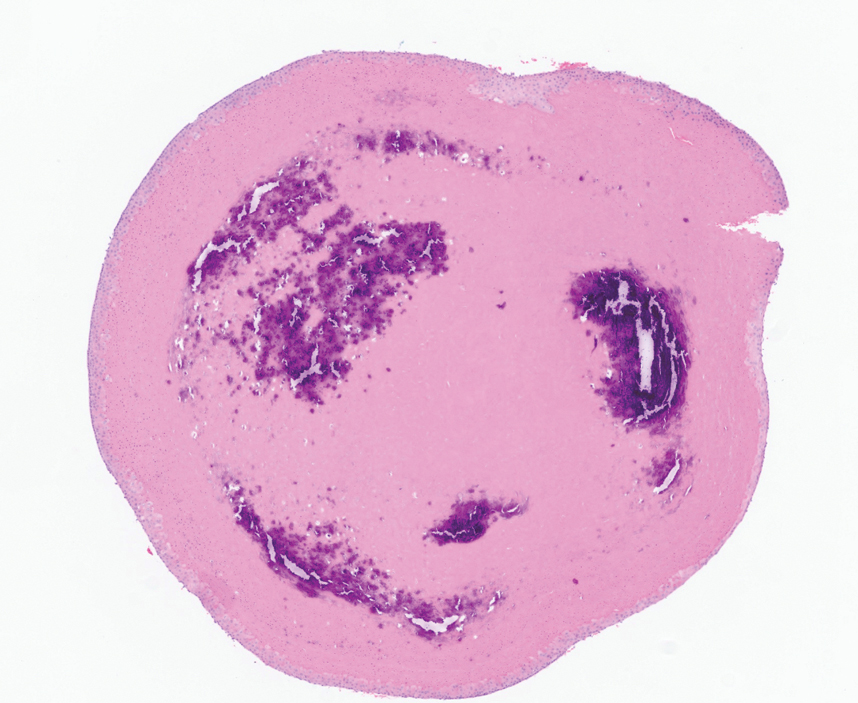

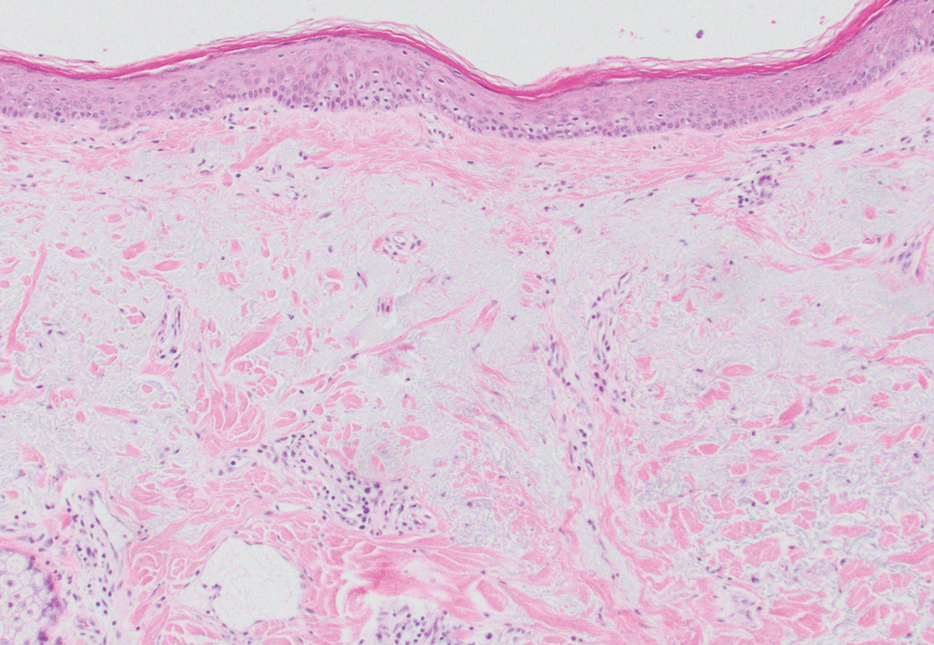

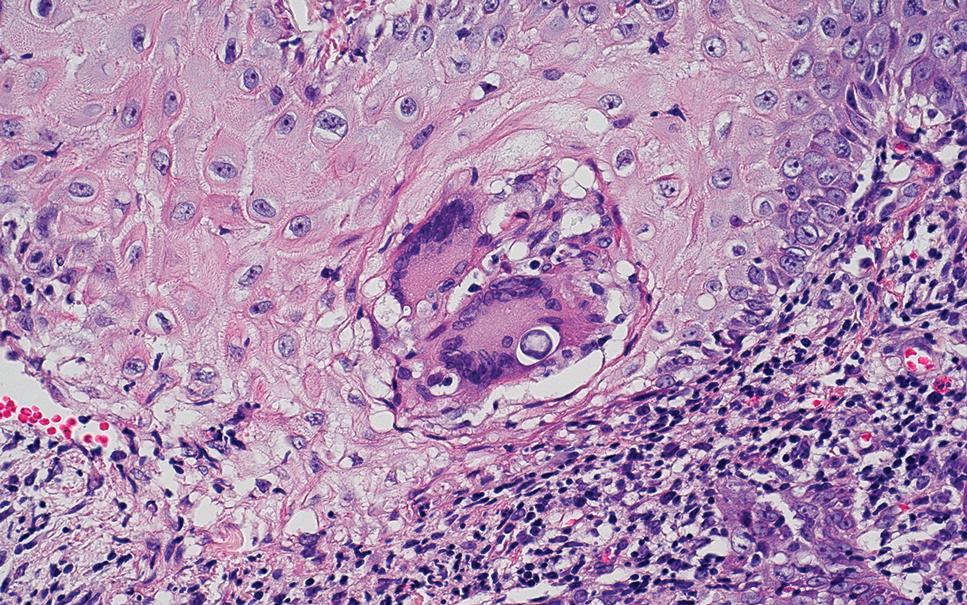

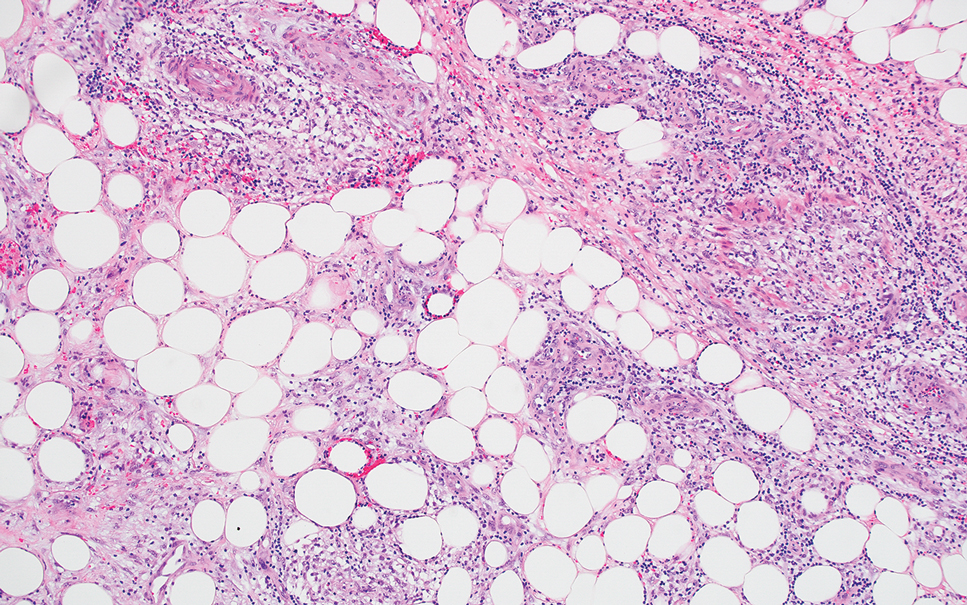

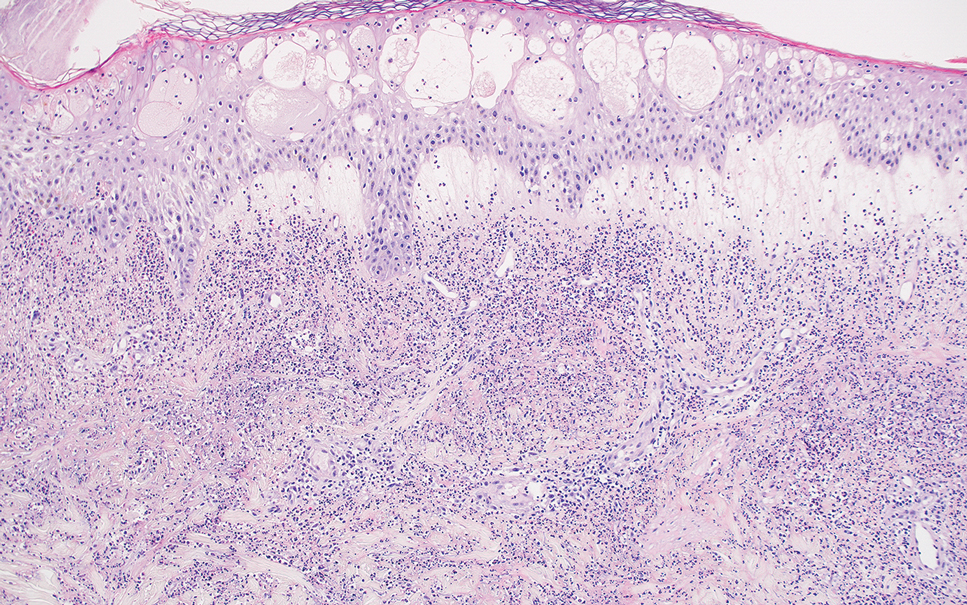

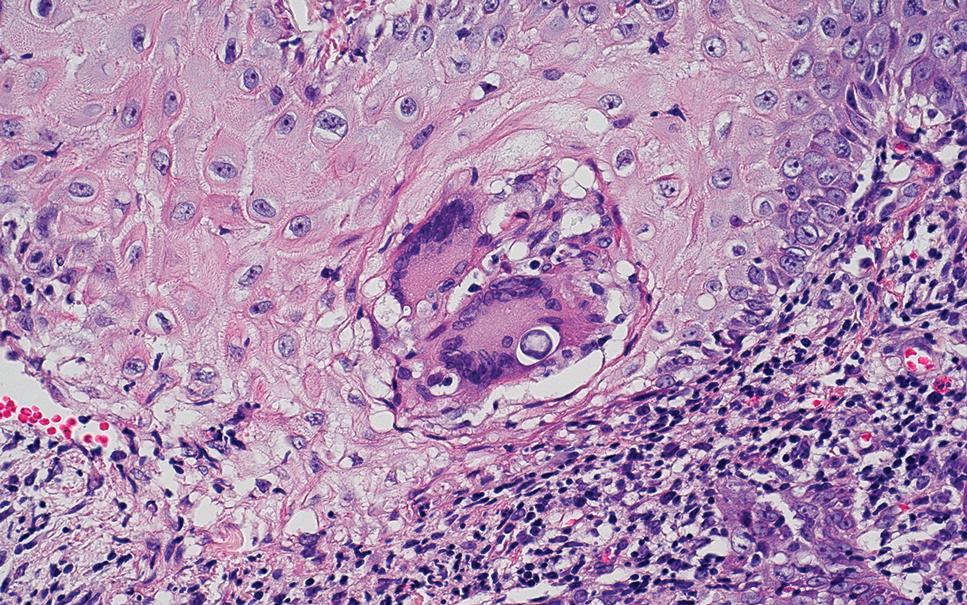

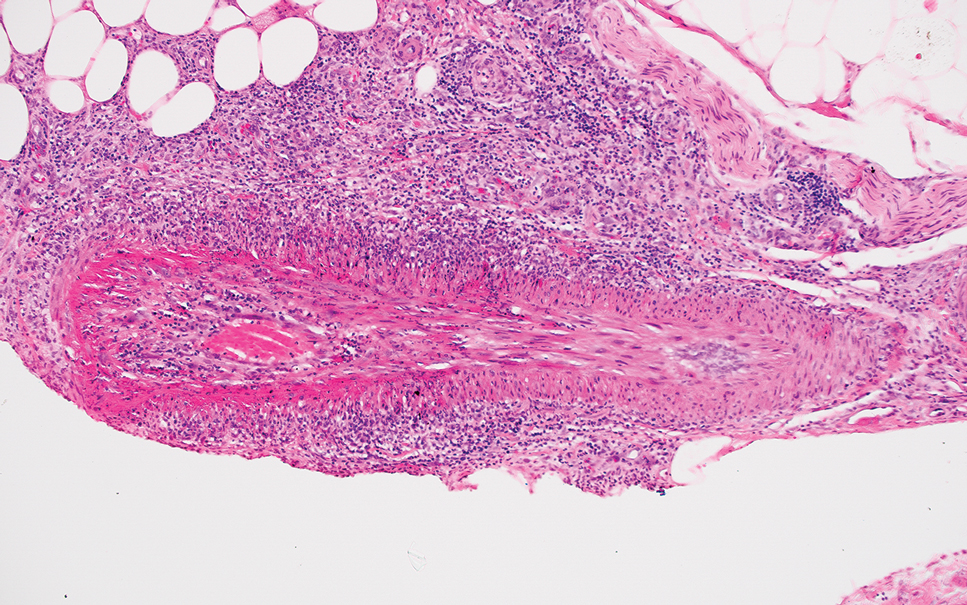

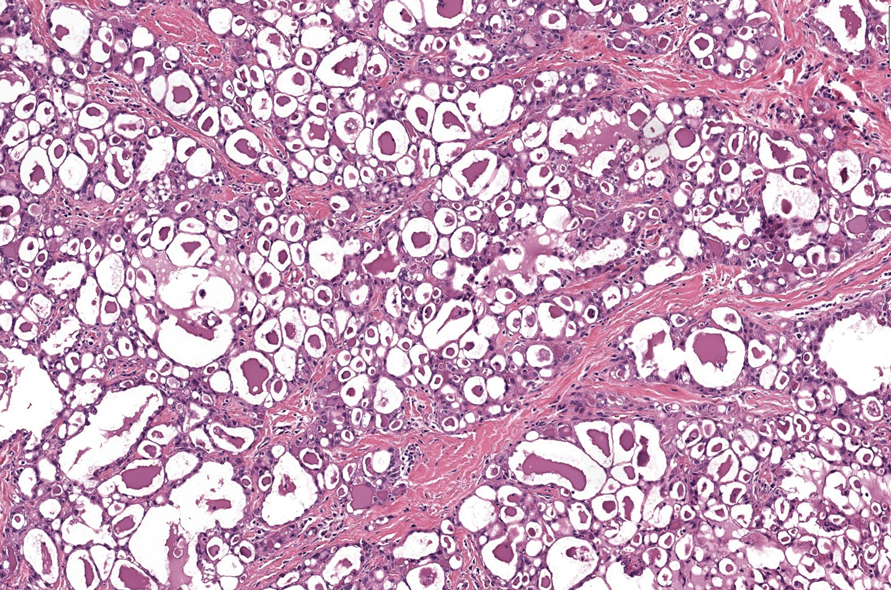

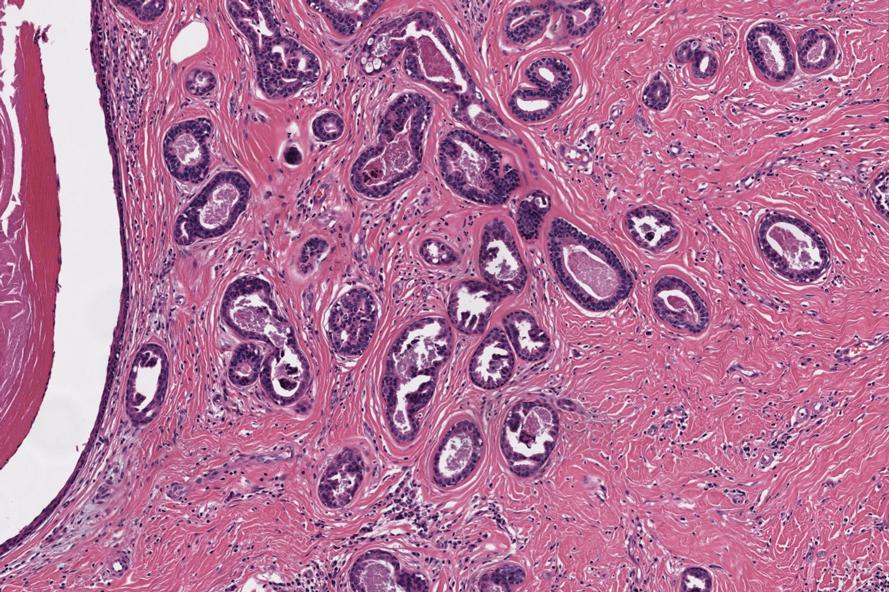

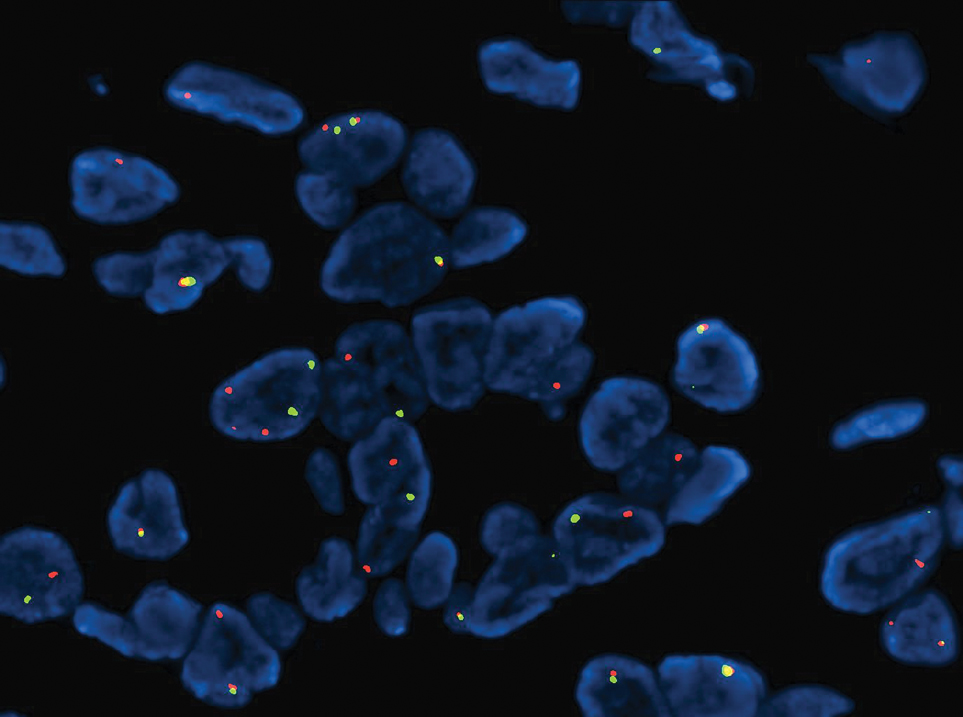

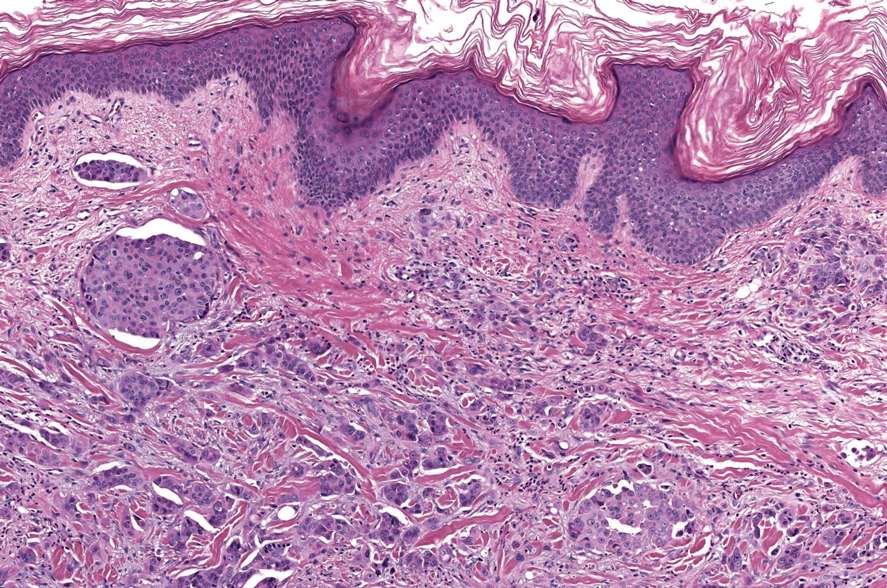

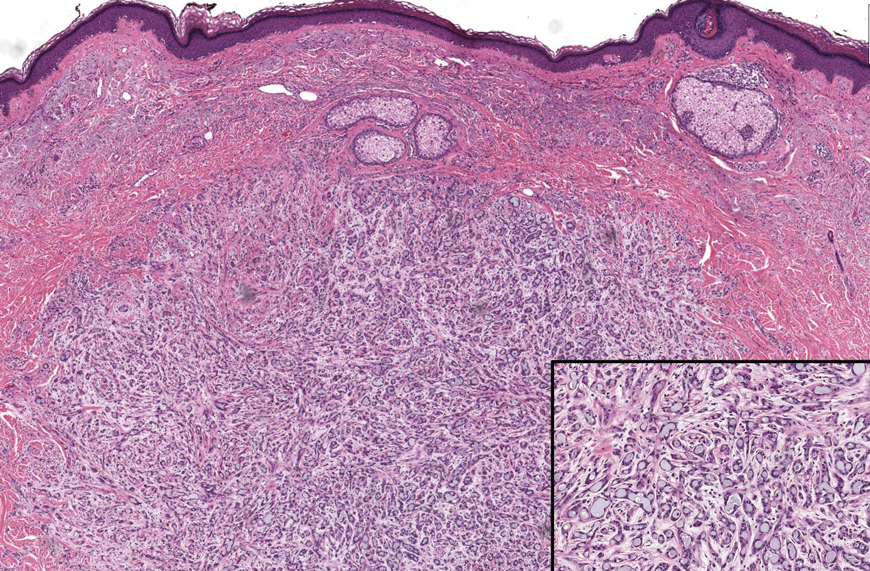

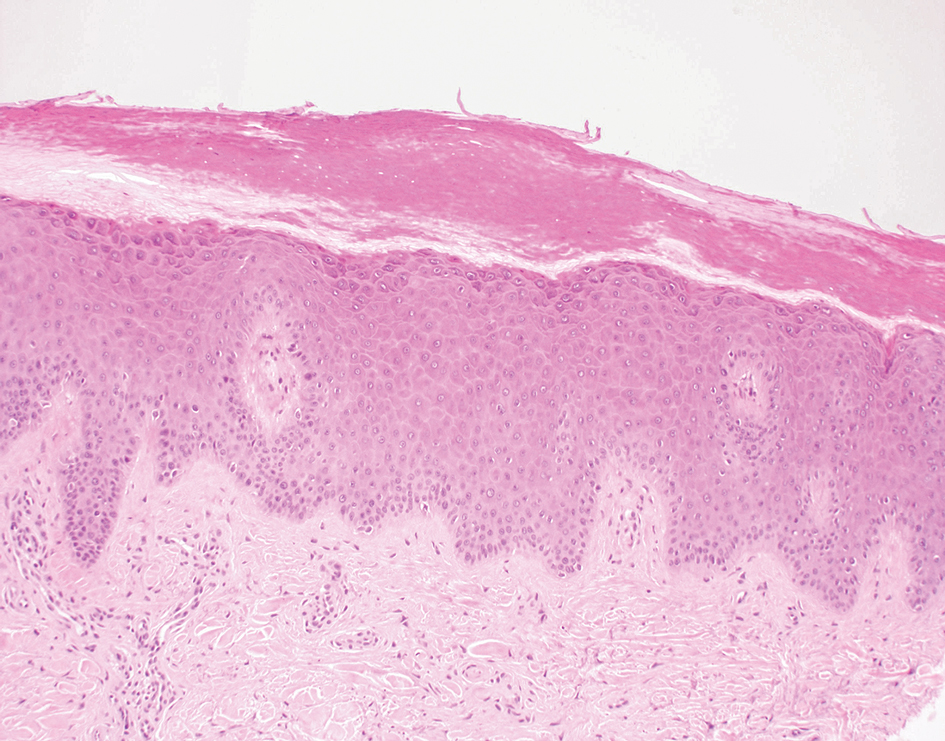

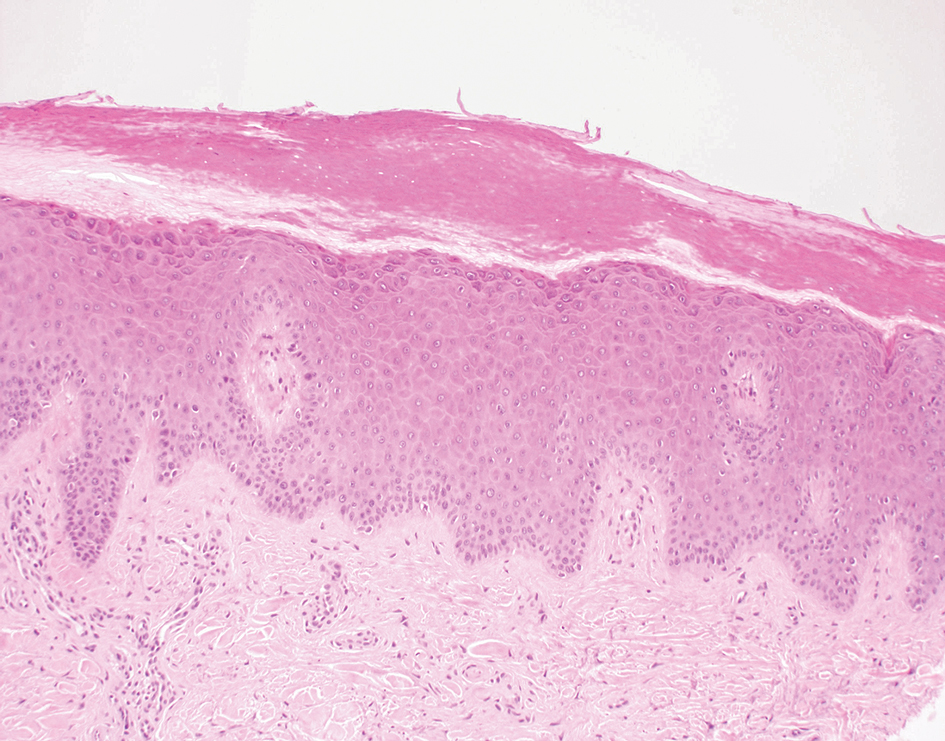

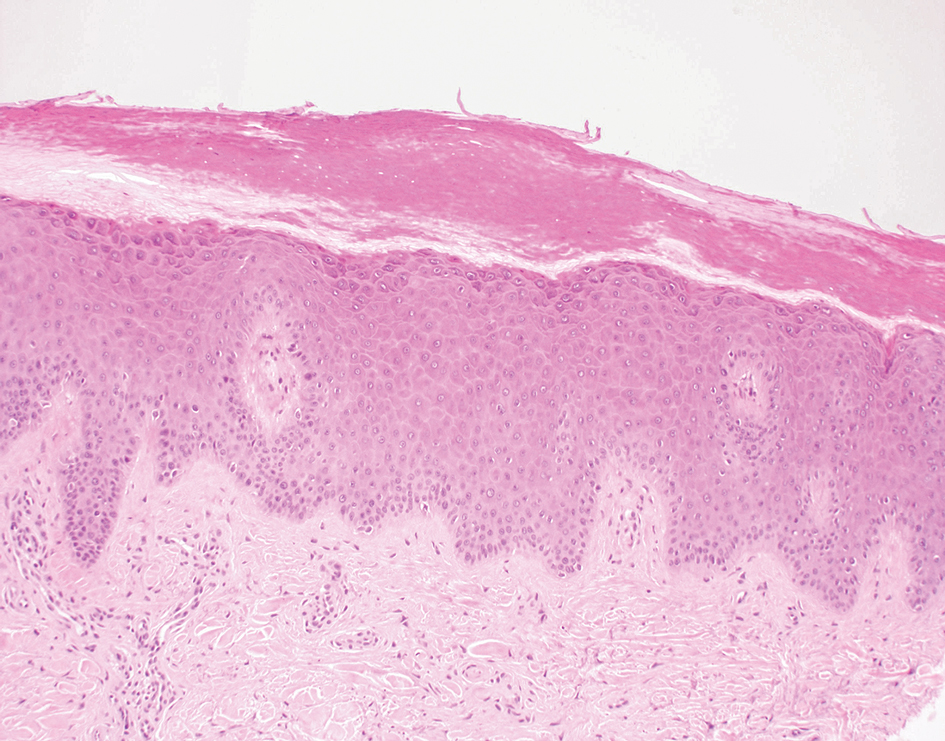

It is important to consider infection with Blastomyces dermatitidis and Histoplasma capsulatum in the differential Both entities can manifest as necrotizing granulomas on histology (Figures 1 and 2).10 Microscopic morphology can help differentiate these pathogenic fungi from Cryptococcus diagnosis of cryptococcosis. species which show pleomorphic, narrow-based budding yeast with wide capsules. In contrast, H capsulatum is characterized by small, intracellular, yeastlike cells with microconidia and macroconidia, while B dermatitidis is distinguished by spherical, thick-walled cells with broad-based budding.11 Capsular material also can help distinguish Cryptococcus from other pathogenic fungi. Special stains highlighting the polysaccharide capsule of Cryptococcus can best identify the yeast. The capsule stains red with periodic acid–Schiff, blue with Alcian blue, and black with Grocott methenamine silver. Mucicarmine is especially useful as it can stain the mucinous capsule pinkish red and typically does not stain other pathogenic fungi.12 Capsule-deficient organisms can lead to considerable difficulties in diagnosis given the organisms can vary in size and may mimic H capsulatum or B dermatitidis. The Fontana-Masson stain is a valuable tool in identifying capsule-deficient organisms, as melanin is found in Cryptococcus cell walls; thus, positive staining excludes H capsulatum and B dermatitidis.13

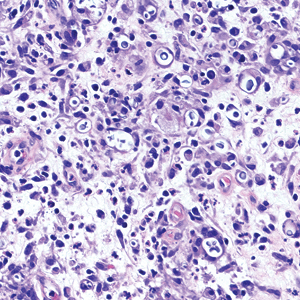

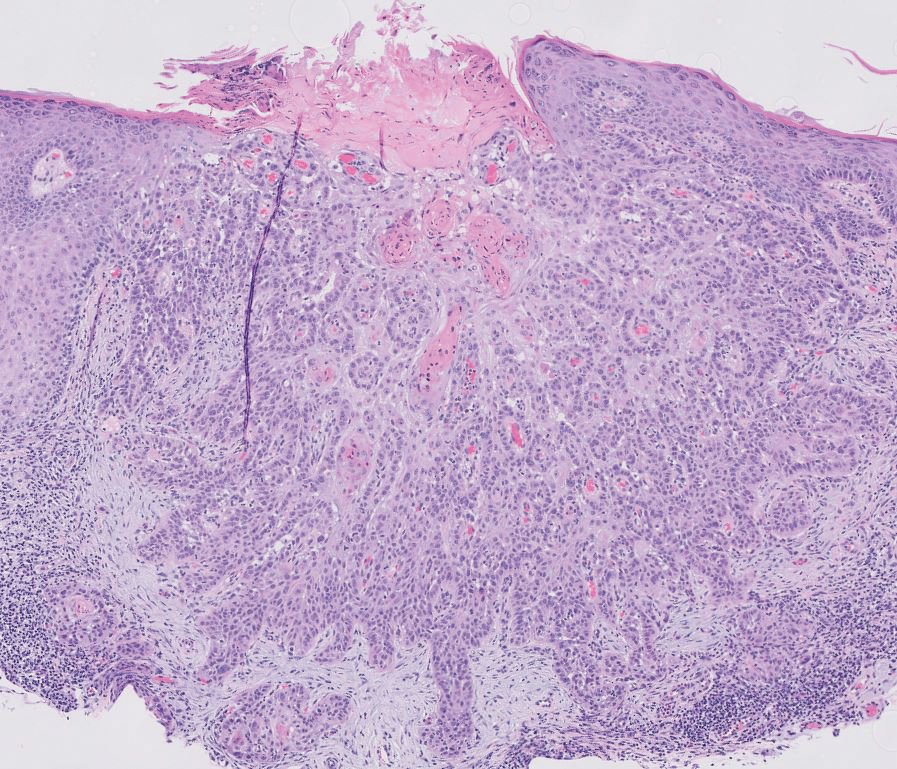

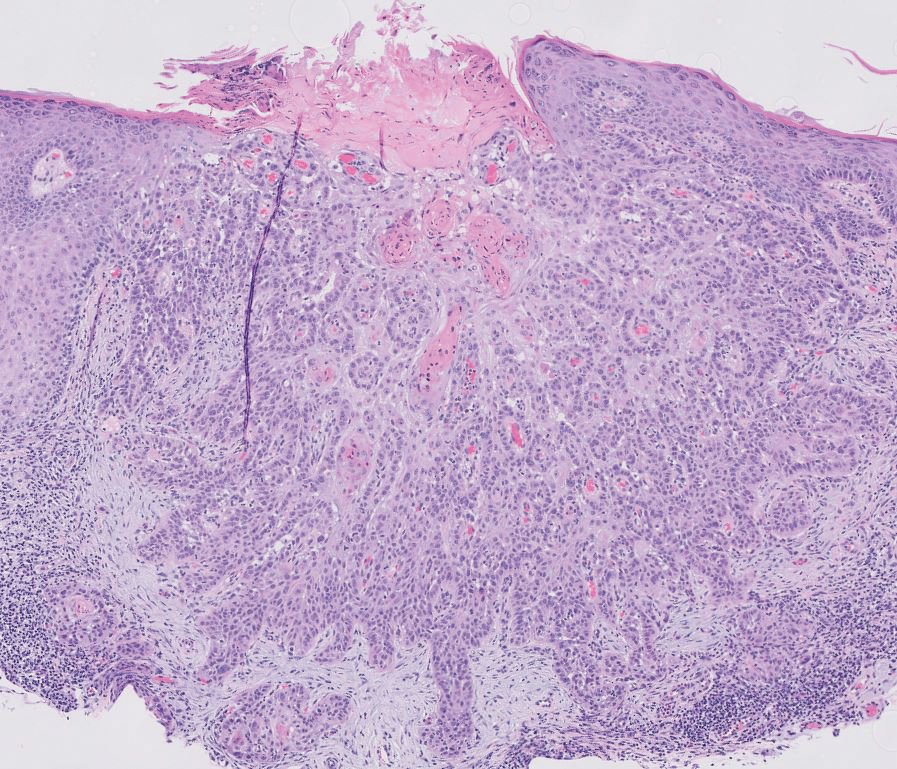

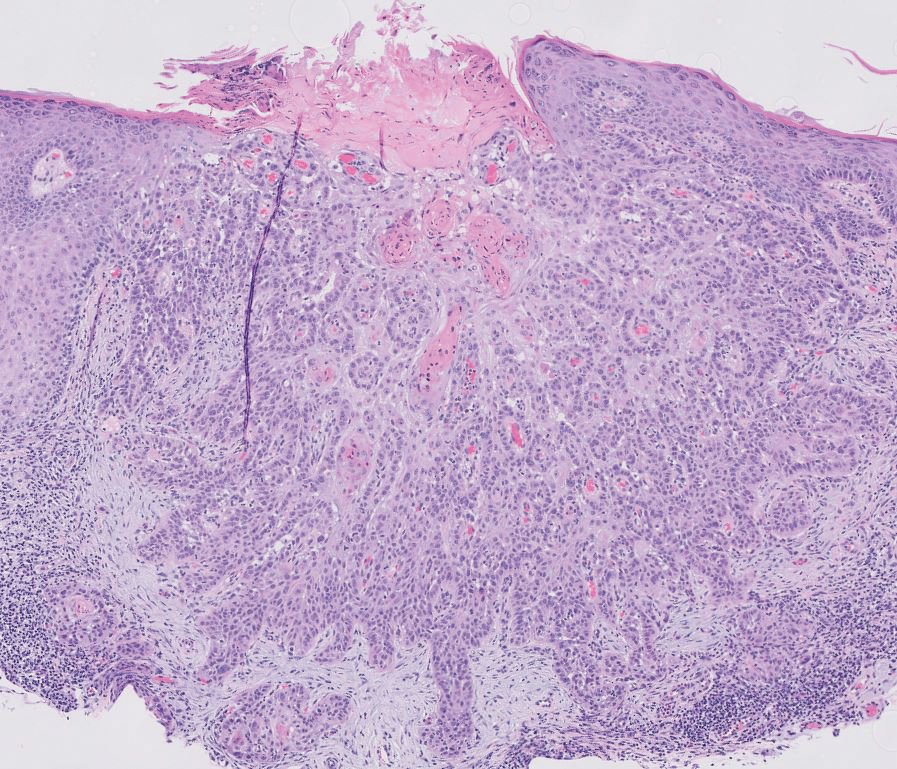

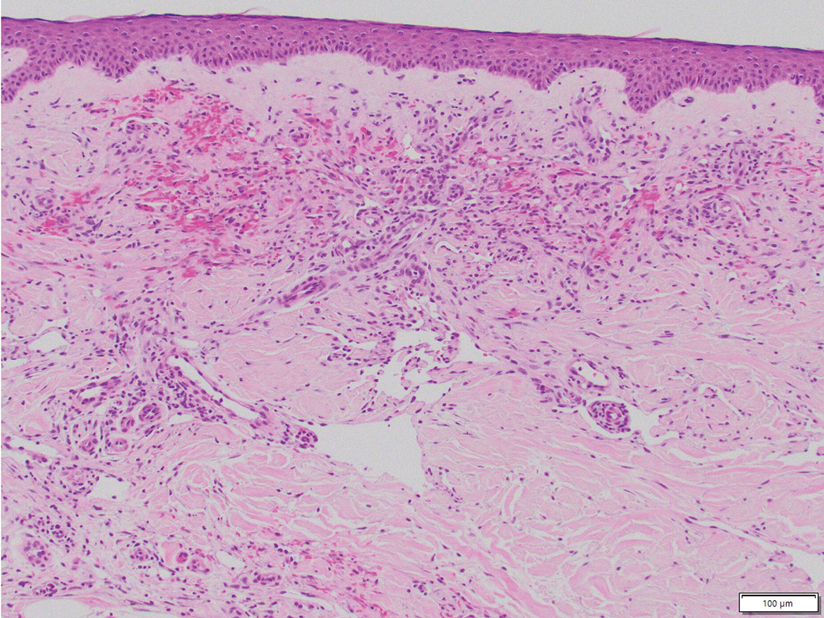

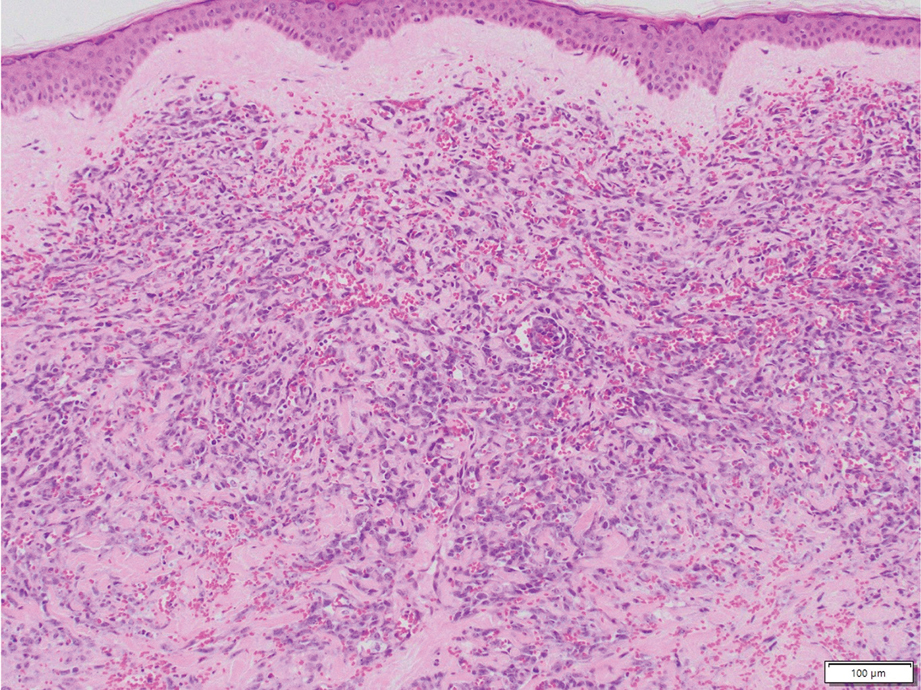

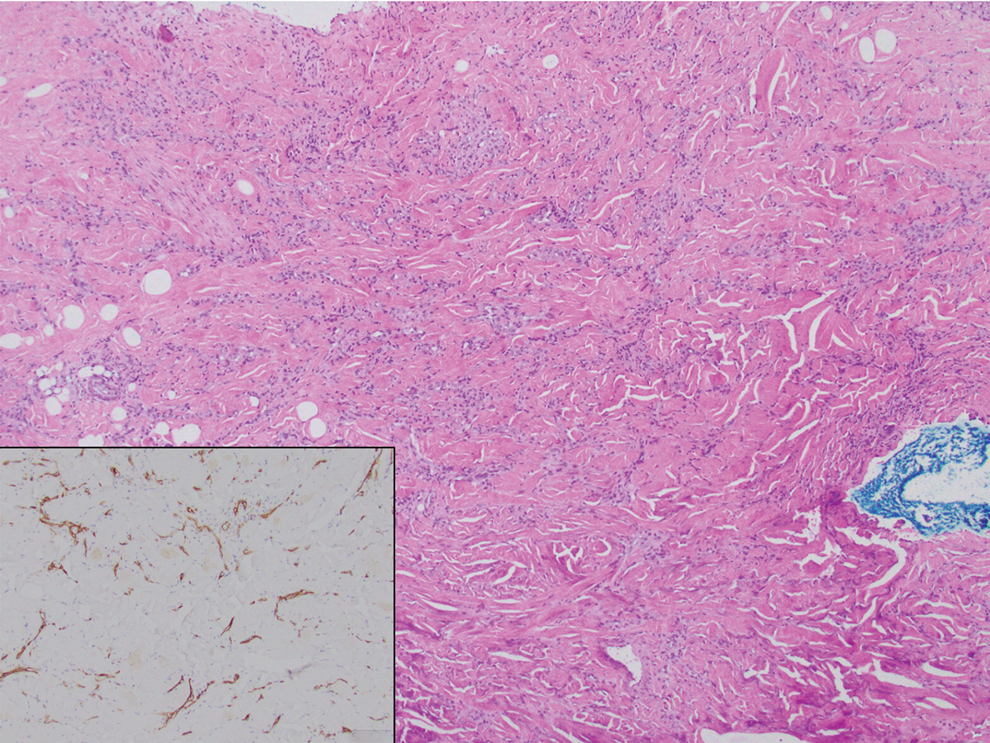

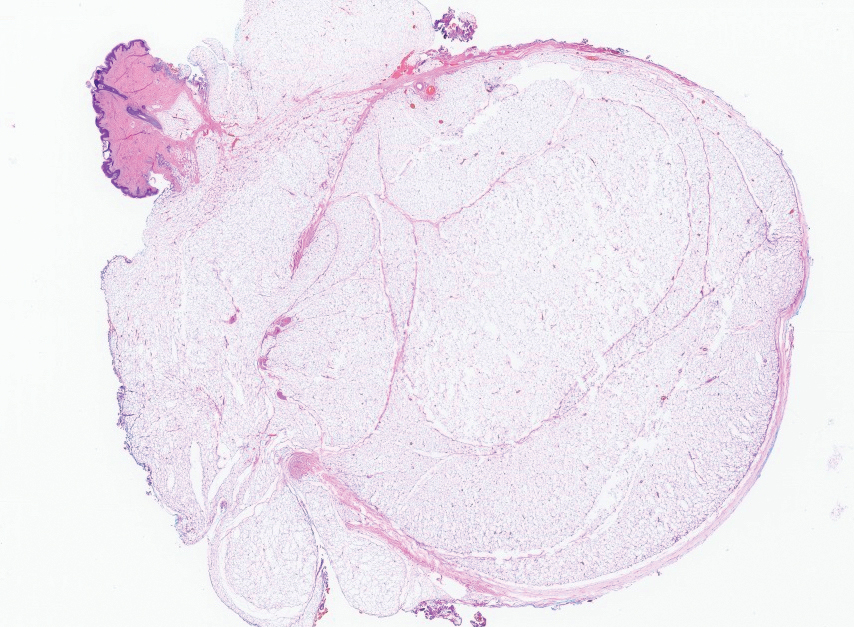

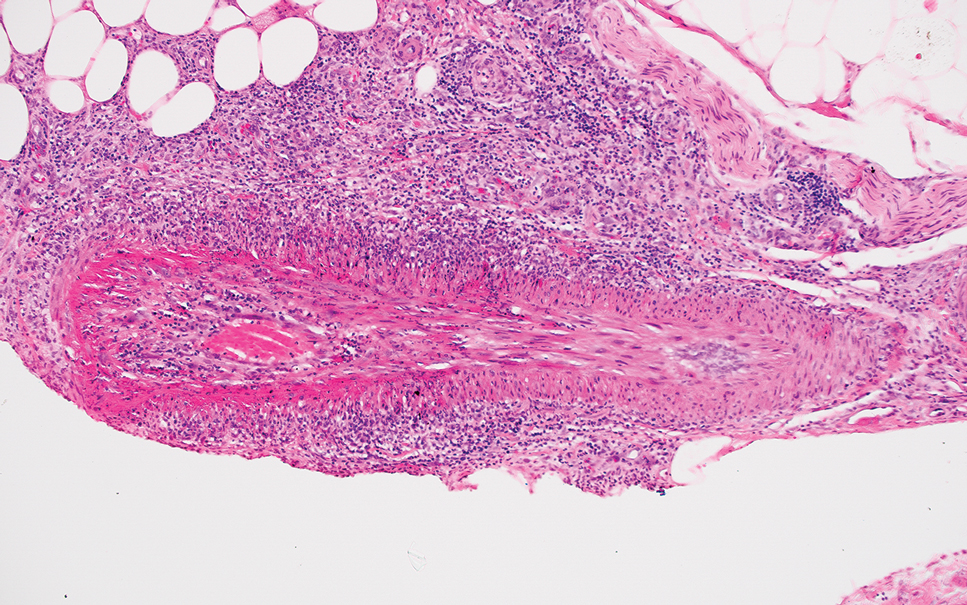

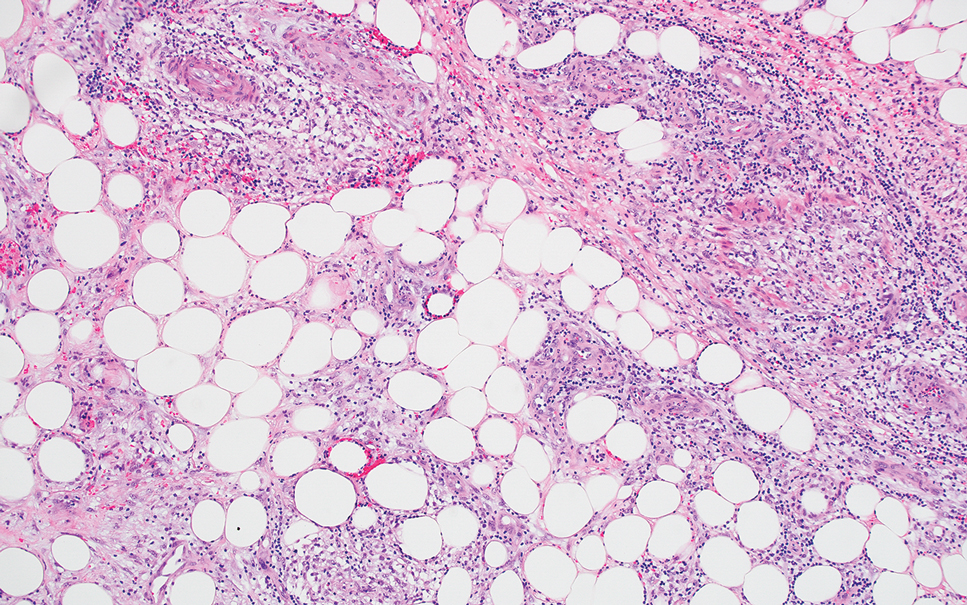

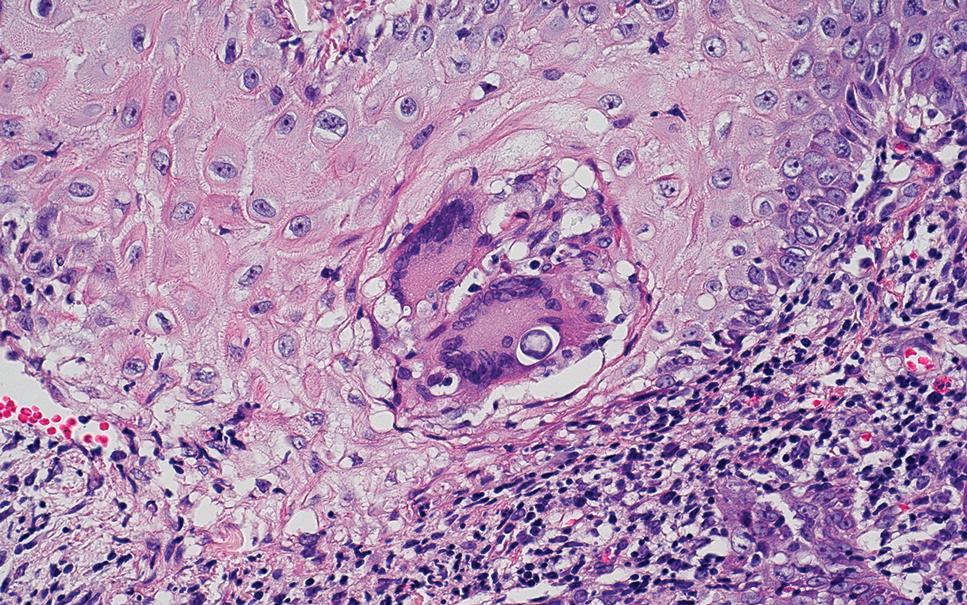

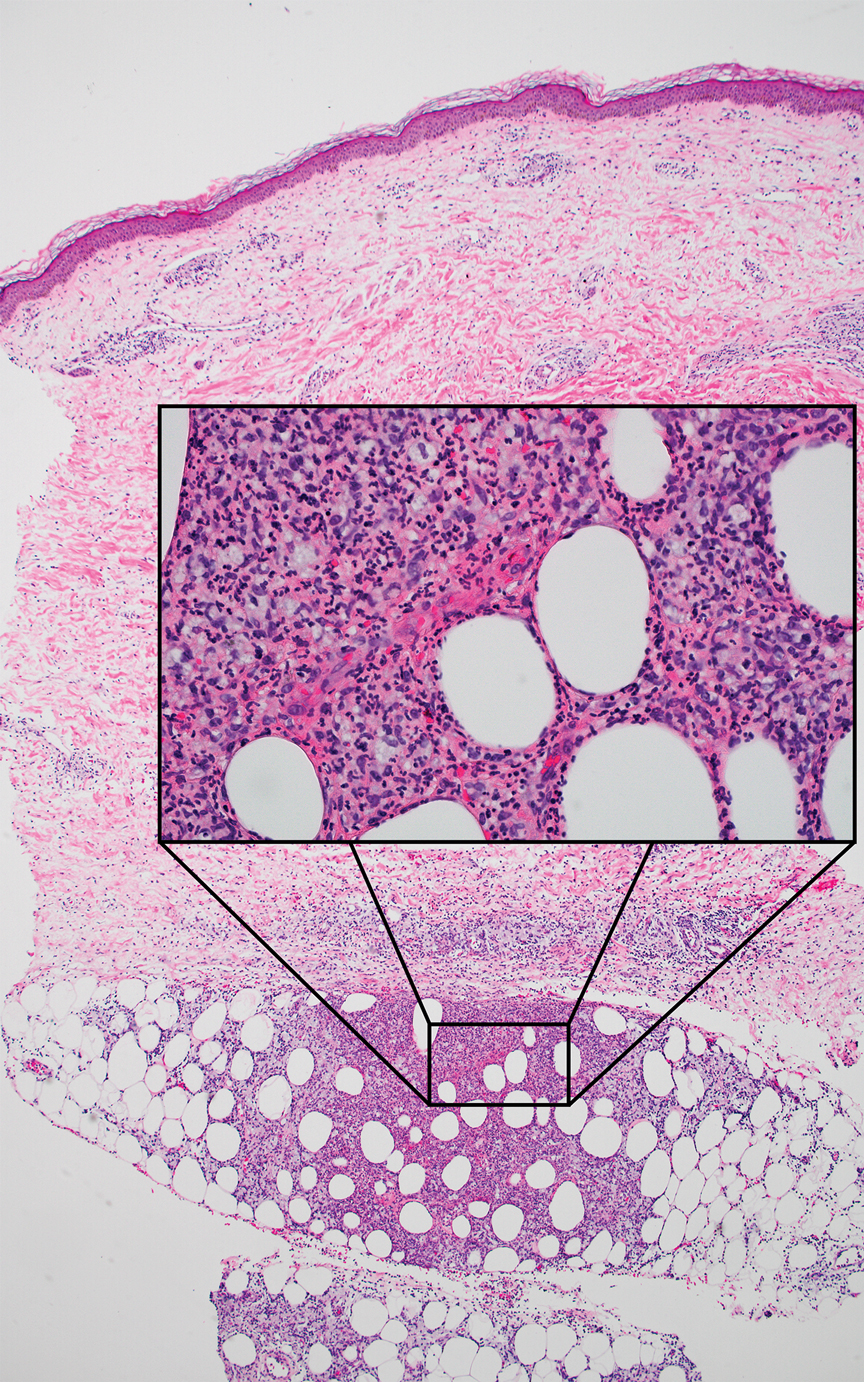

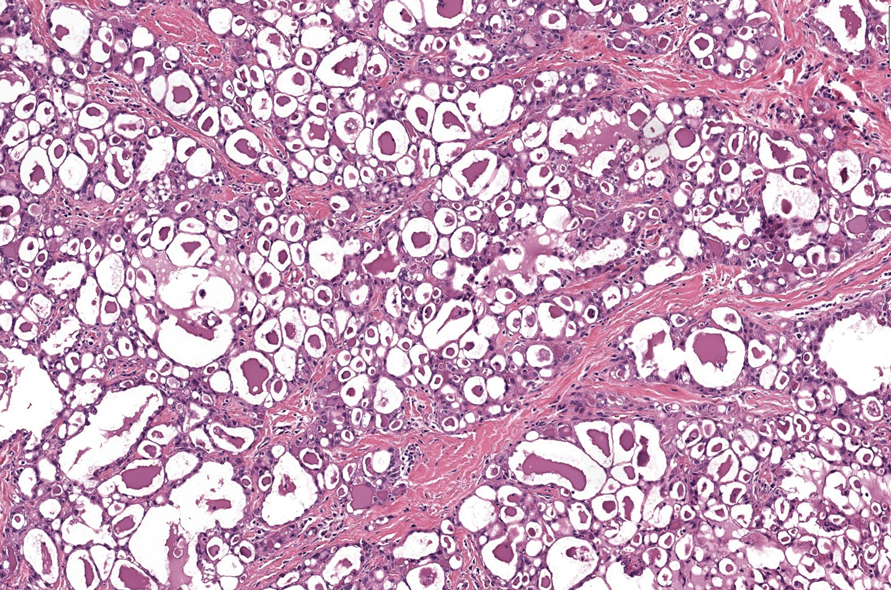

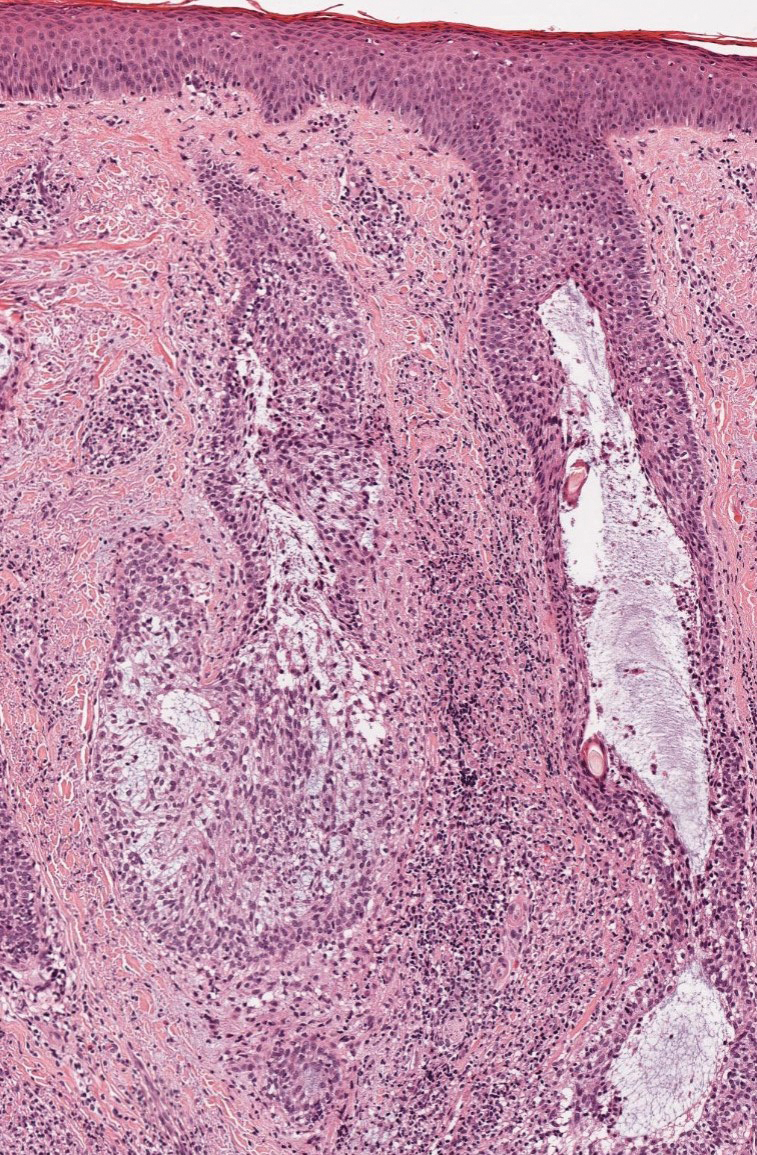

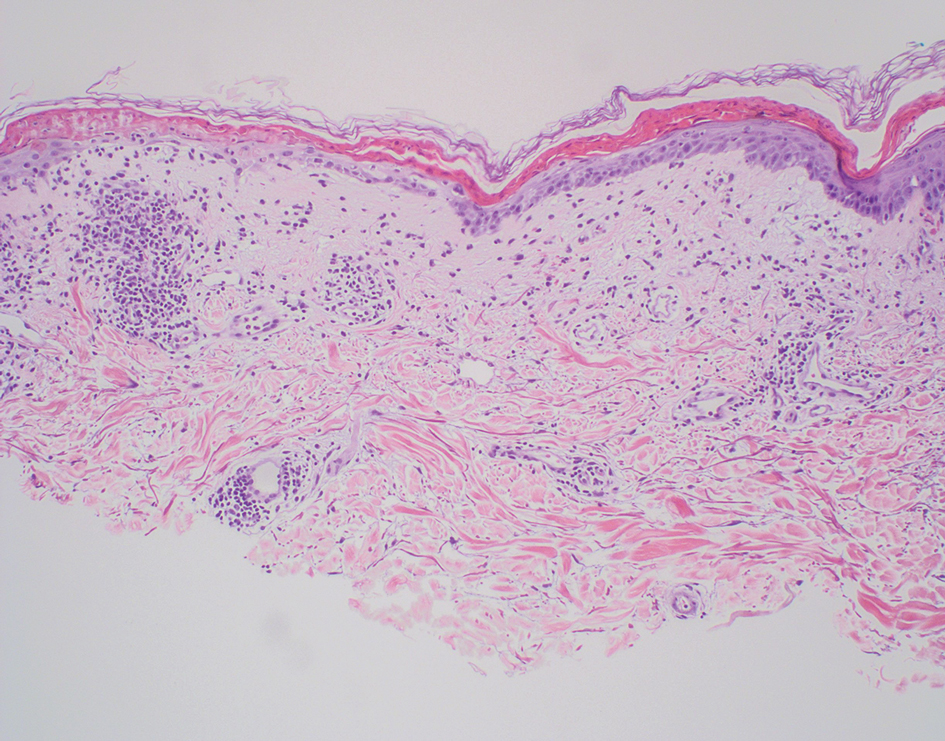

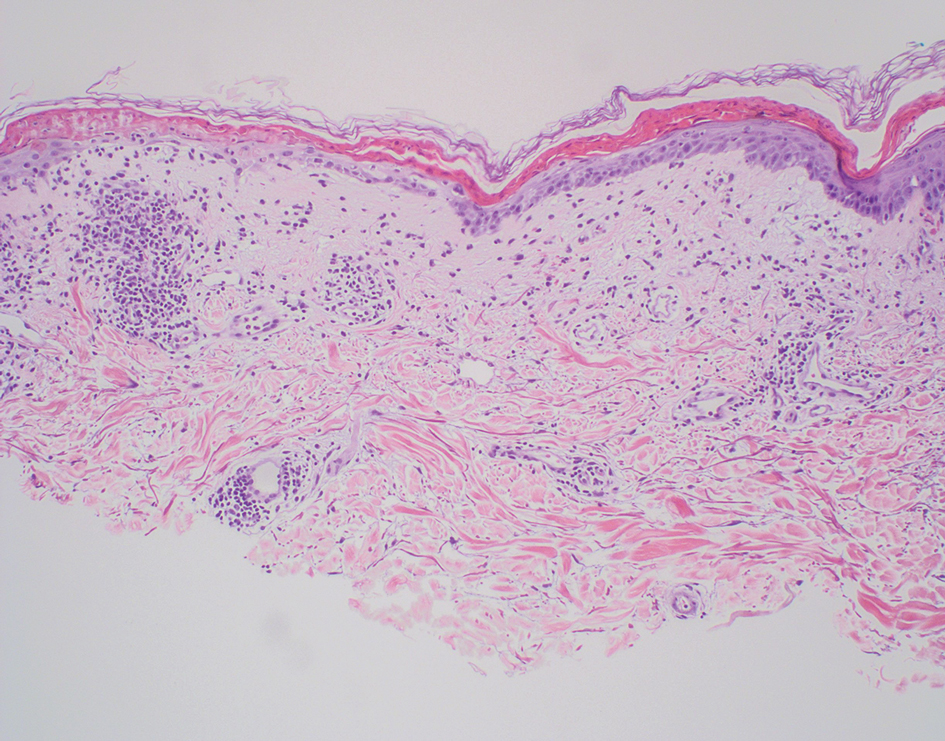

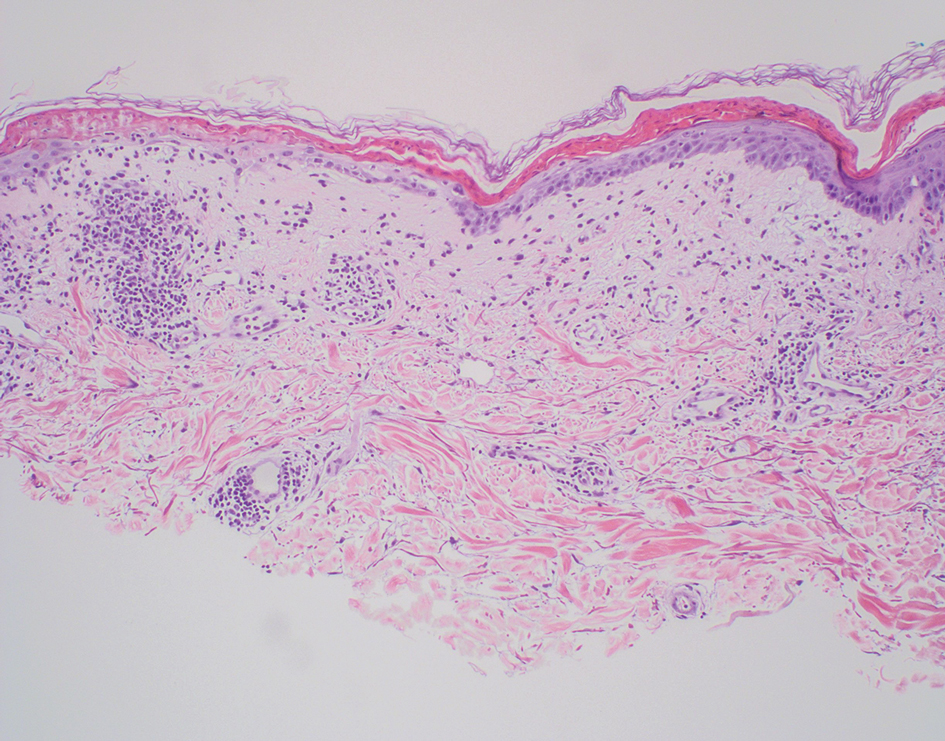

Cutaneous foreign body granuloma, which refers to a granulomatous inflammatory reaction to a foreign body in the skin, is another differential diagnosis that is important to distinguish from cutaneous cryptococcosis. On histology, a collection of histiocytes surround the inert material, forming giant cells without an immune response (Figure 3).10 In contrast, granulomas caused by infectious etiologies (eg, Cryptococcus species) have an associated adaptive immune response and can be further classified as necrotizing or non-necrotizing. Necrotizing granulomas have a distinct central necrosis with a surrounding lymphohistiocytic reaction with peripheral chronic inflammation.10

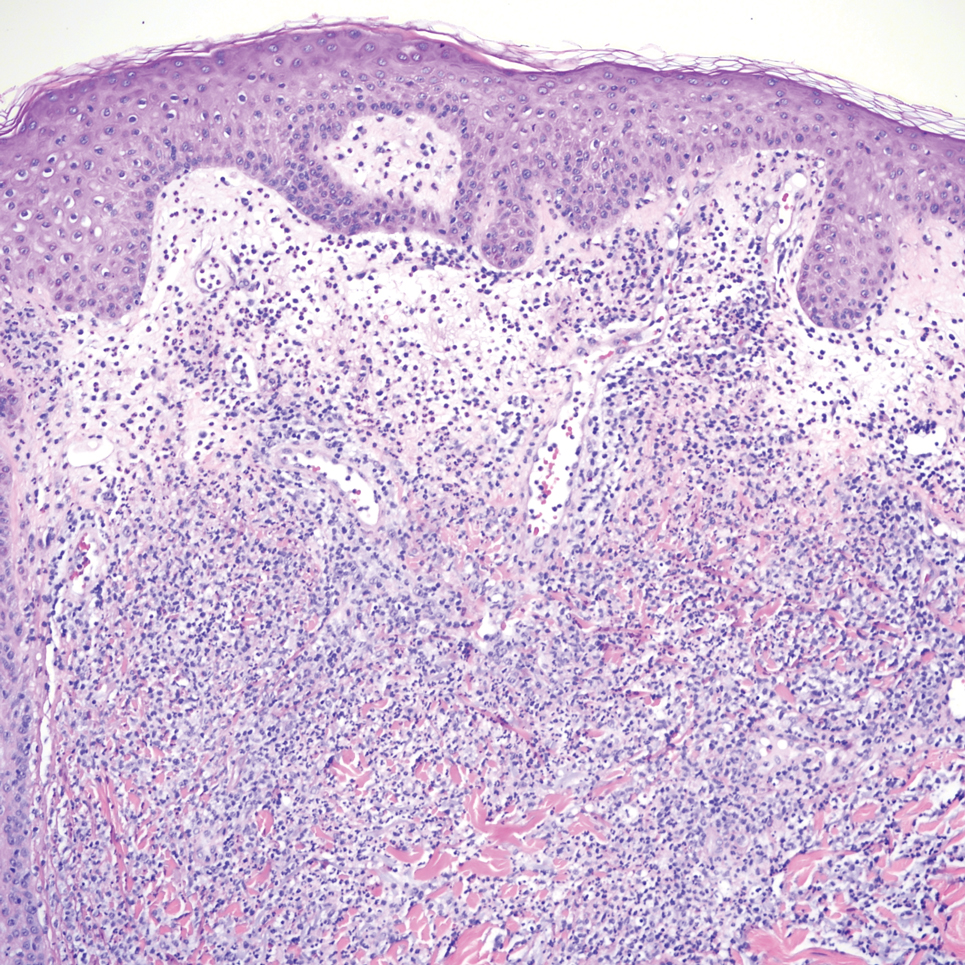

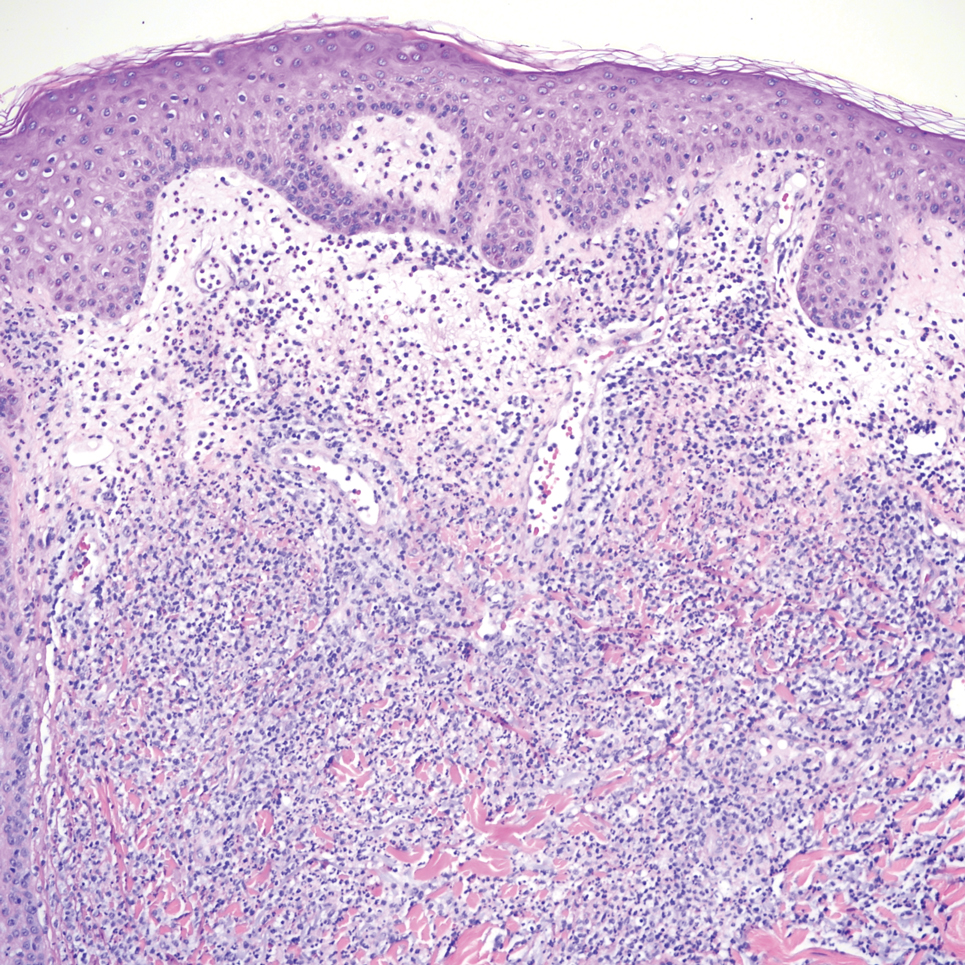

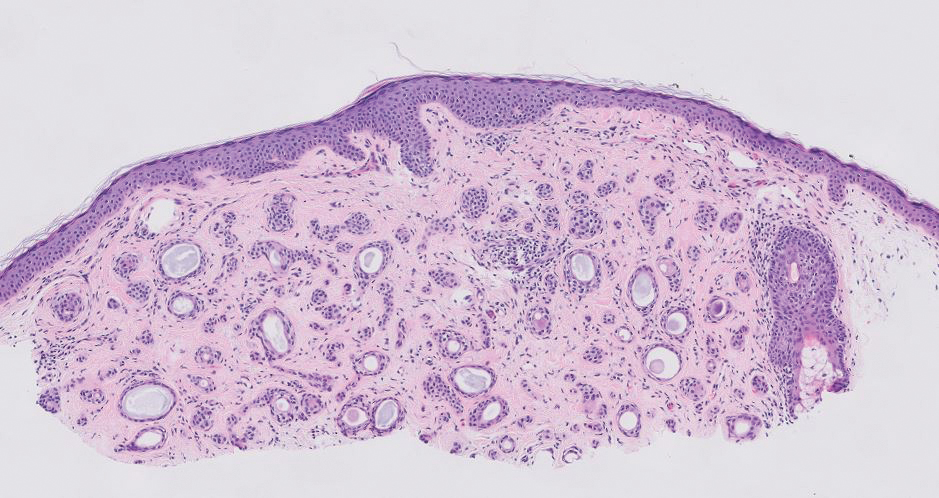

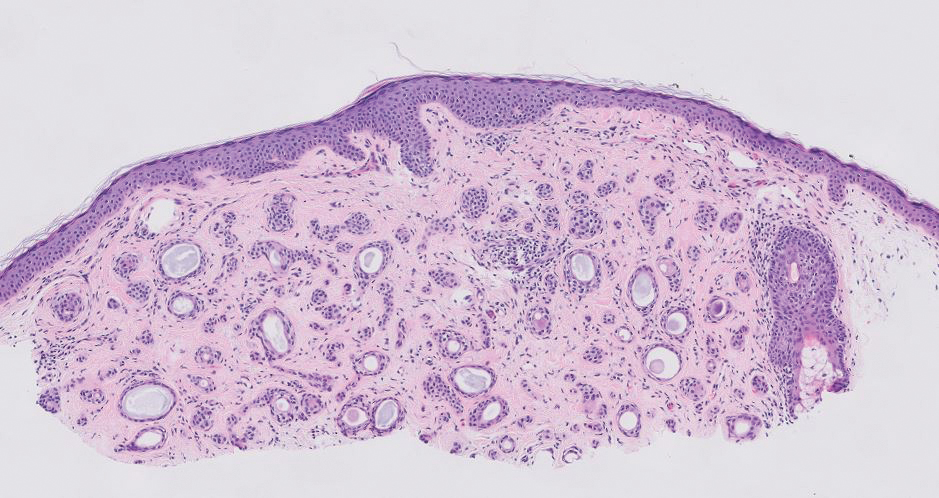

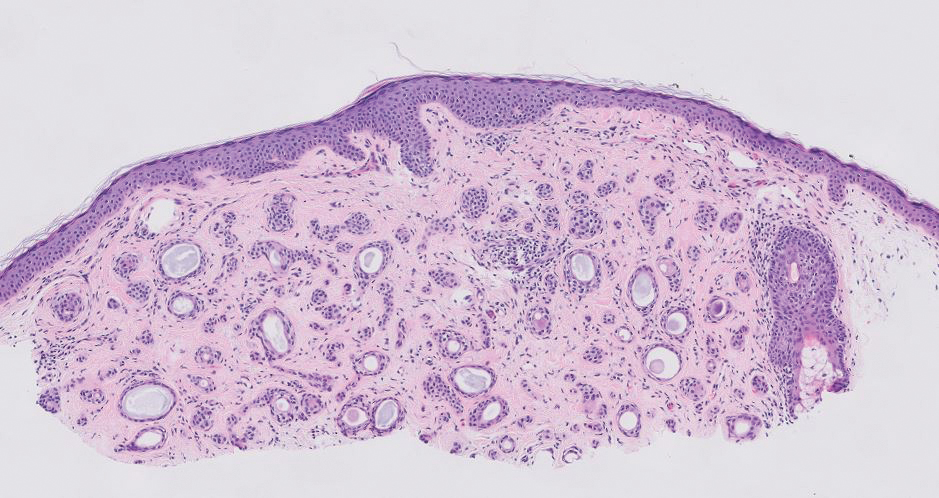

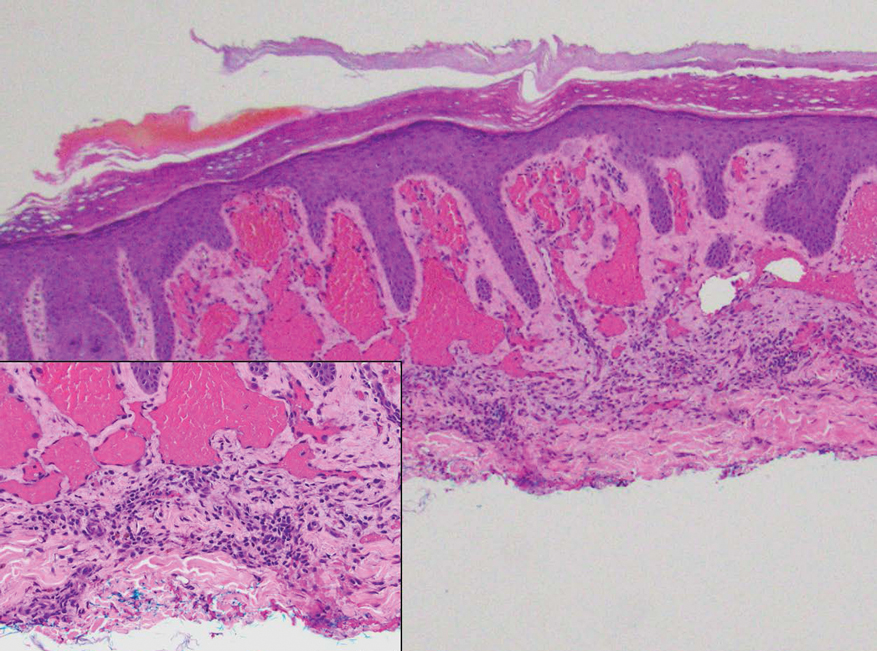

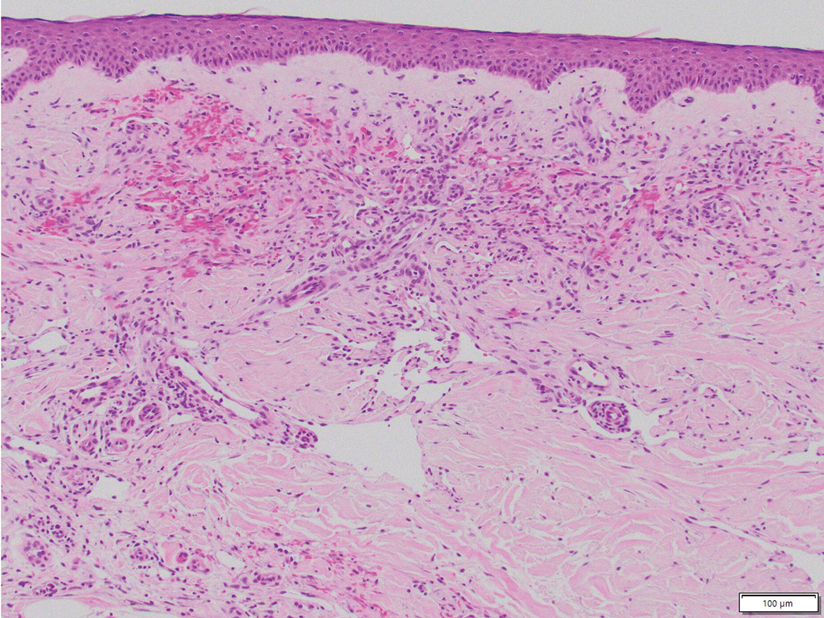

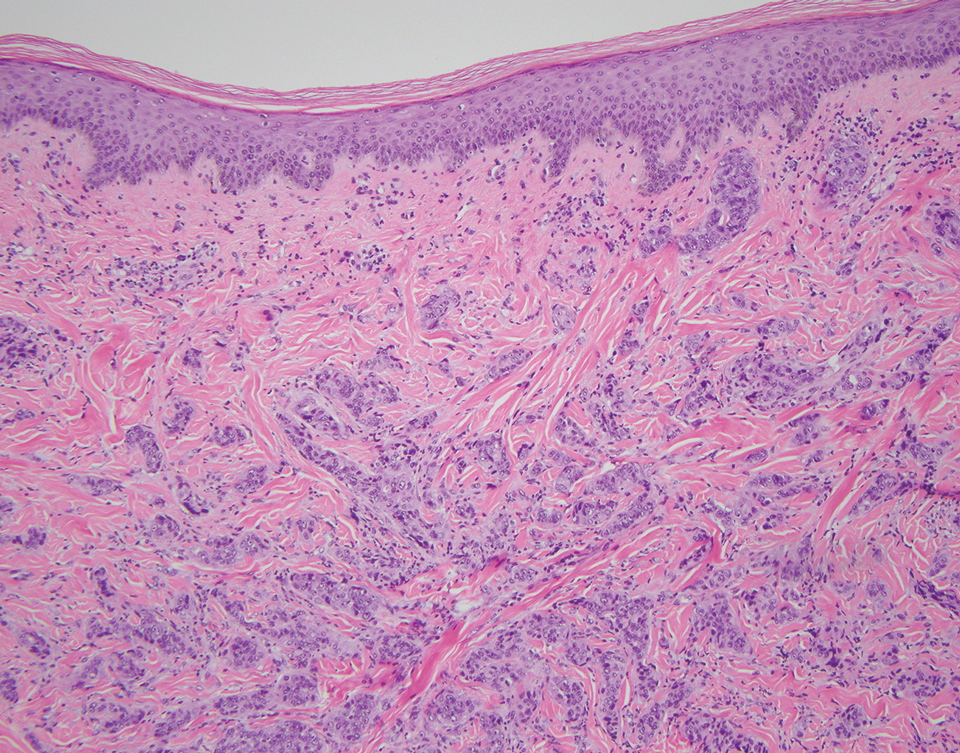

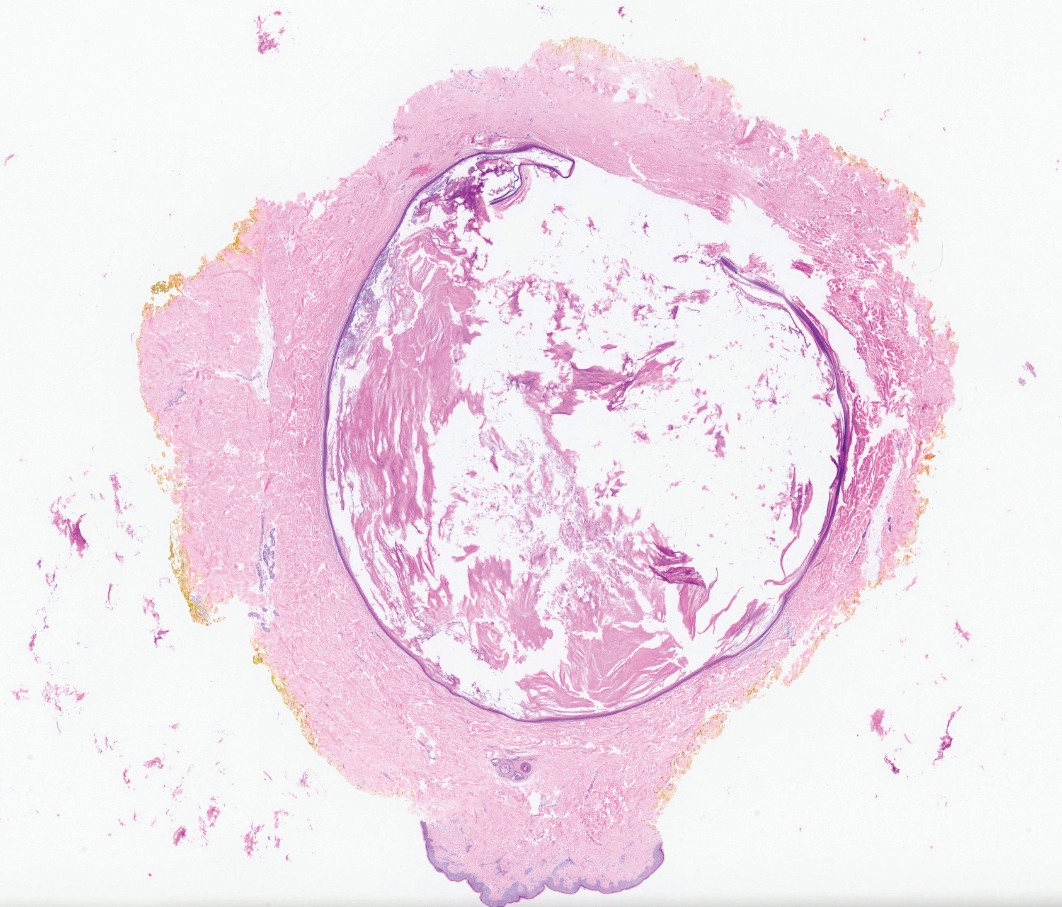

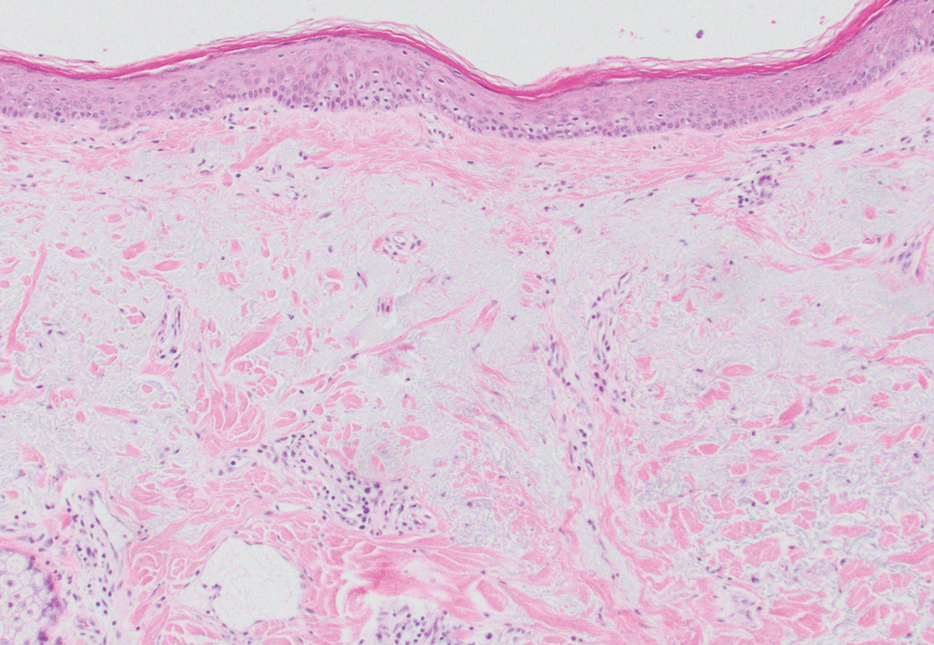

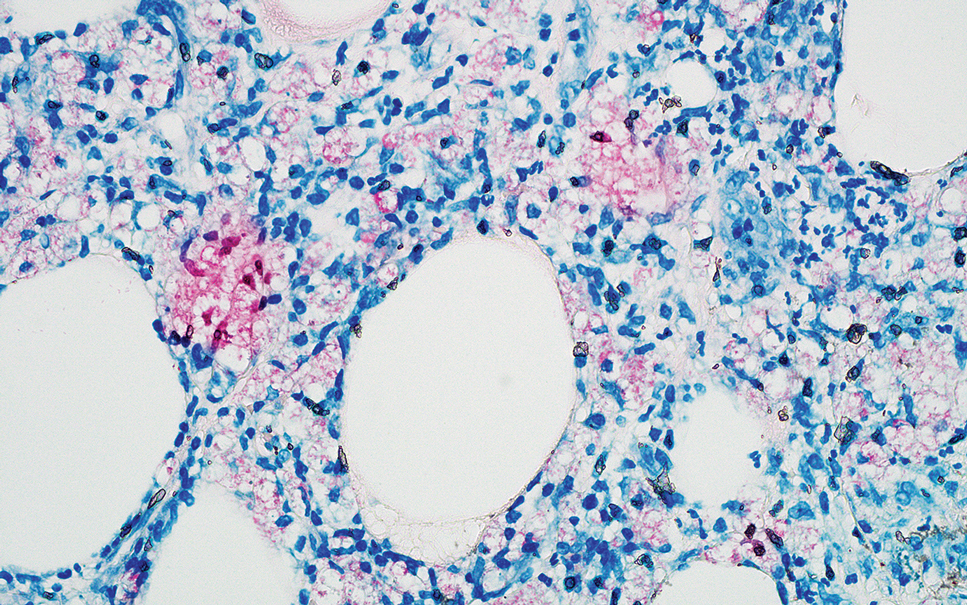

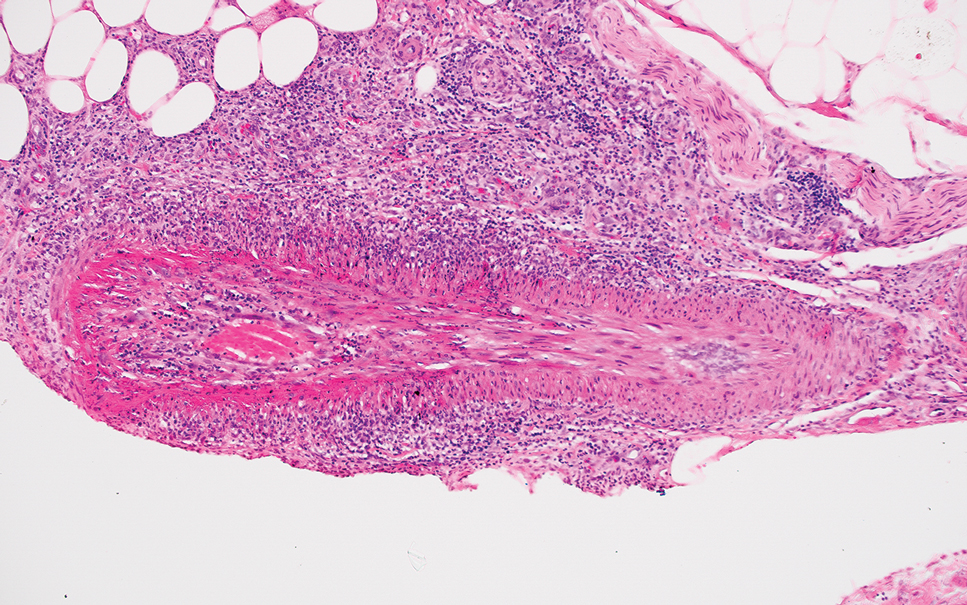

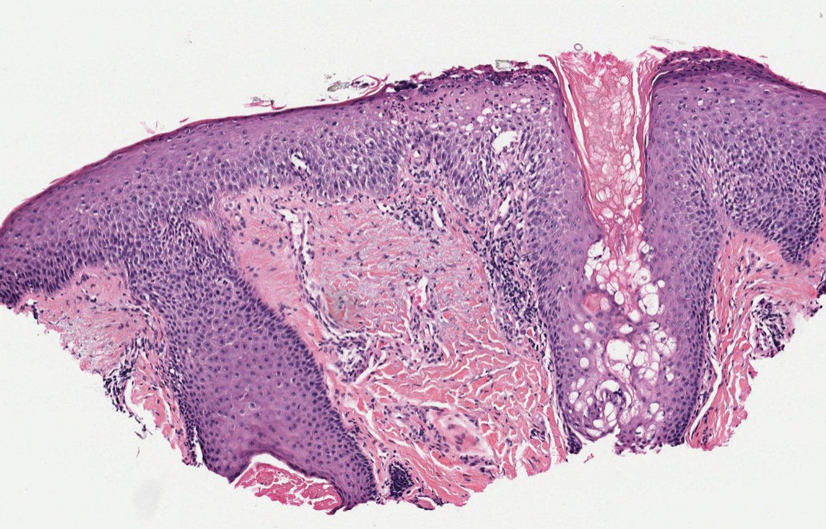

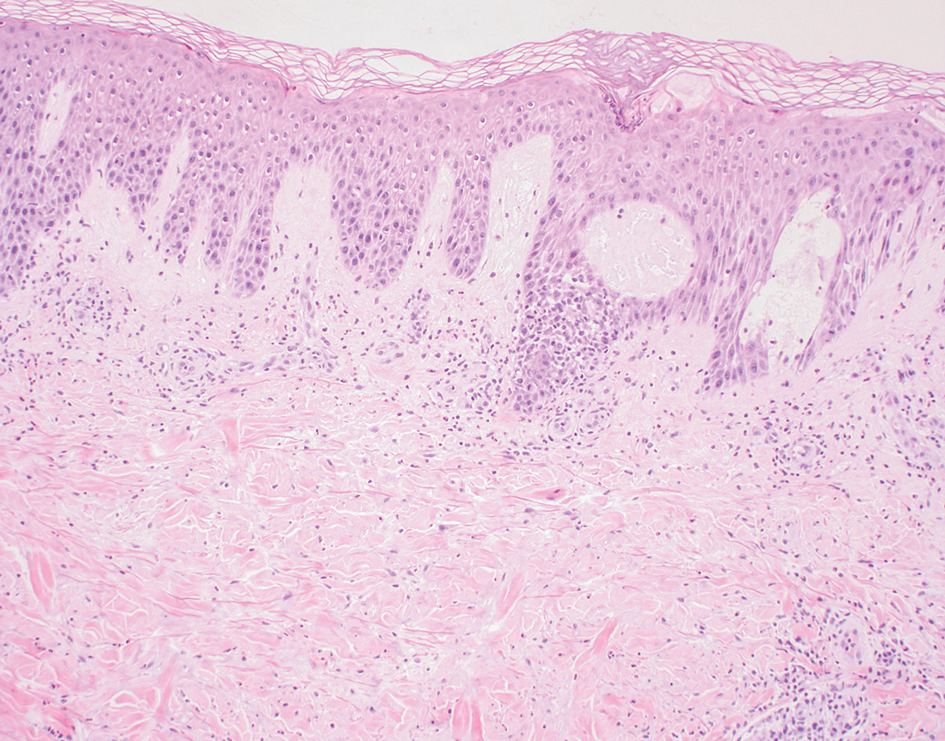

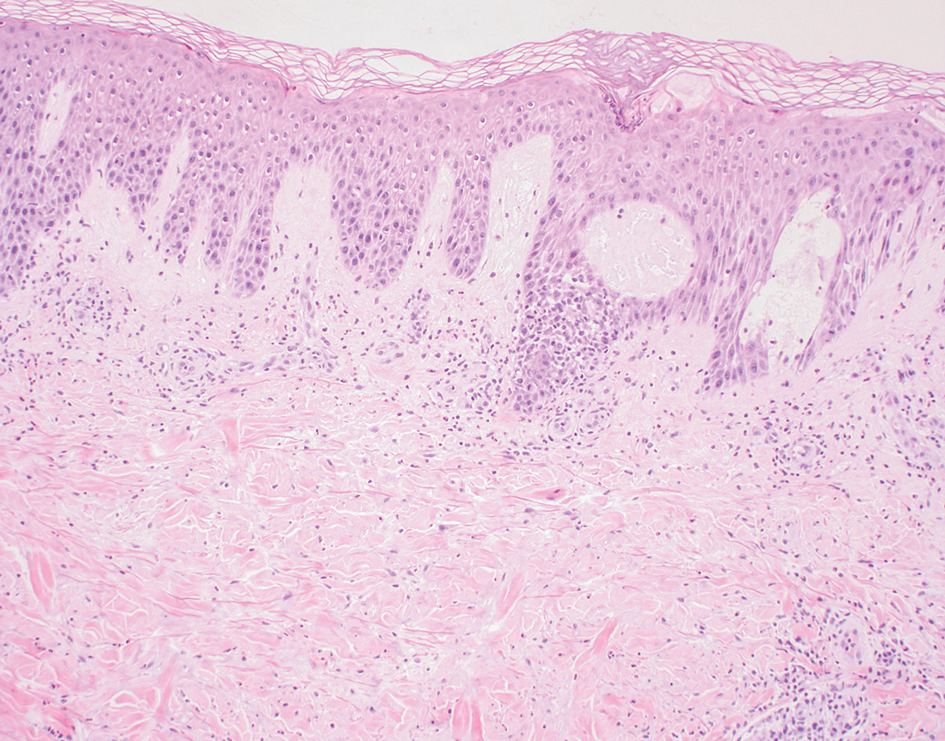

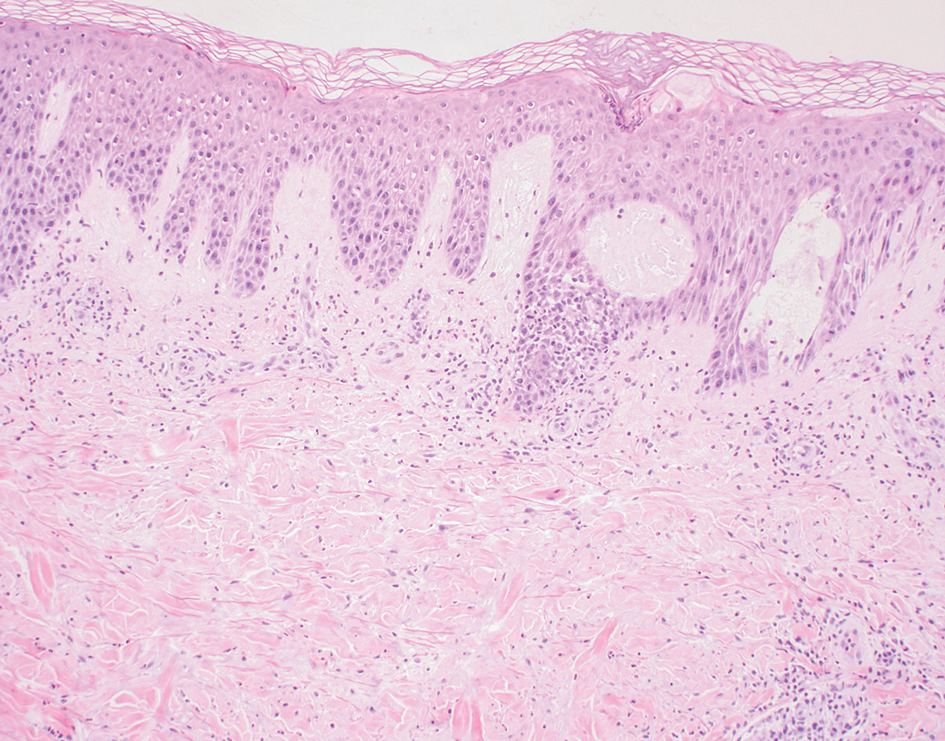

Sweet syndrome is another mimicker of cutaneous cryptococcosis. A histologic variant of Sweet syndrome has been reported that has characteristic cutaneous lesions clinically but shows basophilic bodies with a surrounding halo on pathology that can be mistaken for Cryptococcus yeast. Classic histopathology of Sweet syndrome features papillary dermal edema with neutrophil or histiocytelike inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 4). Identification of Sweet syndrome can be aided by positive myeloperoxidase staining and negative periodic acid–Schiff staining.14,15

- Lehmann NM, Kammeyer JA. Cerebral venous thrombosis due to Cryptococcus in a multiple sclerosis patient on fingolimod. Case Rep Neurol. 2022; 14:286-290. doi:10.1159/000524359

- Maziarz EK, Perfect JR. Cryptococcosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016;30:179-206. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2015.10.006.

- Christianson JC, Engber W, Andes D. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts. Med Mycol. 2003;41:177-188. doi:10.1080/1369378031000137224

- Tilak R, Prakash P, Nigam C, et al. Cryptococcal meningitis with an antecedent cutaneous Cryptococcal lesion. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:12.

- Neuville S, Dromer F, Morin O, et al. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis: a distinct clinical entity. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:337-347. doi:10.1086/345956

- Dimino-Emme L, Gurevitch AW. Cutaneous manifestations of disseminated cryptococcosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:844-850.

- Anderson DJ, Schmidt C, Goodman J, Pomeroy C. Cryptococcal disease presenting as cellulitis. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14:666-672. doi:10.1093/clinids/14.3.666

- Moore M. Cryptococcosis with cutaneous manifestations: four cases with a review of published reports. J Invest Dermatol. 1957;28(2):159-182. doi: 10.1038/jid.1957.17

- Phan NQ, Tirado M, Moeckel SMC, et al. Cutaneous and pulmonary cryptococcosis in an immunocompetent patient. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2019;17:1283-1286. doi:10.1111/ddg.13997.

- Shah KK, Pritt BS, Alexander MP. Histopathologic review of granulomatous inflammation. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2017;7:1-12. doi: 10.1016/j.jctube.2017.02.001

- Fridlington E, Colome-Grimmer M, Kelly E, et al. Tzanck smear as a rapid diagnostic tool for disseminated cryptococcal infection. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:25-27. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.1.25

- Hernandez AD. Cutaneous Cryptococcosis. Dermatol Clin. 1989; 7:269-274.

- Ro JY, Lee SS, Ayala AG. Advantage of Fontana-Masson stain in capsule-deficient cryptococcal infection. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1987;111:53-57.

- Jordan AA, Graciaa DS, Gopalsamy SN, et al. Sweet syndrome imitating cutaneous cryptococcal disease. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022;9:ofac608. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofac608

- Ko JS, Fernandez AP, Anderson KA, et al. Morphologic mimickers of Cryptococcus occurring within inflammatory infiltrates in the setting of neutrophilic dermatitis: a series of three cases highlighting clinical dilemmas associated with a novel histopathologic pitfall. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:38-45. doi: 10.1111/cup.12019

THE DIAGNOSIS: Cutaneous Cryptococcosis

Biopsy of the ulcerated nodule showed numerous yeastlike organisms within clear mucinous capsules and with some surrounding inflammation. On Grocott methenamine silver staining, the organisms stained black. Workup for disseminated cryptococcus was negative, leading to a diagnosis of primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in the setting of immunosuppression. Notably, cryptococcosis infection has been reported in patients taking fingolimod (a sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor) for multiple sclerosis, which was the case for our patient.1

The genus Cryptococcus comprises more than 30 species of encapsulated basidiomycetous fungi distributed ubiquitously in nature. Currently, only 2 species are known to cause infectious disease in humans: Cryptococcus neoformans, which affects both immunocompromised and immunocompetent patients and frequently is isolated from pigeon droppings, as well as Cryptococcus gatti, which primarily affects immunocompetent patients and is more commonly isolated from soil and decaying wood.2

Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis (PCC), characterized by direct inoculation of C neoformans or C gatti via skin injury, is rare and typically is seen in patients with decreased cell-mediated immunity, such as those on chronic corticosteroid therapy, solid-organ transplant recipients, and those with HIV.3 Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis typically manifests as a solitary or confined lesion on exposed areas of the skin and often is accompanied by regional lymphadenopathy.4,5 The most common cutaneous findings associated with PCC include ulceration, cellulitis, and whitlow.5 In immunocompetent hosts, frequently affected sites include the arms, fingers, and face, while the trunk and lower extremities are more commonly affected in immunocompromised hosts.3 Secondary cutaneous cryptococcosis occurs through hematologic spread in patients with disseminated cryptococcosis after inhalation of Cryptococcosis spores and differs from PCC in that it typically manifests as multiple lesions scattered on both exposed and covered areas of the skin. Patients also may have signs and symptoms of disseminated cryptococcosis such as pneumonia and/or meningitis at presentation.5

Despite the difference between PCC and secondary cutaneous cryptococcosis, almost every type of skin lesion has been observed in cryptococcosis, including pustules, nodules, vesicles, acneform lesions, purpura, ulcers, abscesses, molluscumlike lesions, granulomas, draining sinuses, and cellulitis.6,7

Cutaneous cryptococcosis generally is associated with 2 types of histologic reactions: gelatinous and granulomatous. The gelatinous reaction shows numerous yeastlike organisms ranging from 4 μm to 12 μm in diameter with large mucinous polysaccharide capsules and scant inflammation. Organisms may be seen in mucoid sheets.8 The granulomatous type shows a more pronounced reaction with fewer organisms ranging from 2 μm to 4 μm in diameter found within giant cells, histiocytes, and lymphocytes.6,9 Areas of necrosis occasionally can be observed.8

It is important to consider infection with Blastomyces dermatitidis and Histoplasma capsulatum in the differential Both entities can manifest as necrotizing granulomas on histology (Figures 1 and 2).10 Microscopic morphology can help differentiate these pathogenic fungi from Cryptococcus diagnosis of cryptococcosis. species which show pleomorphic, narrow-based budding yeast with wide capsules. In contrast, H capsulatum is characterized by small, intracellular, yeastlike cells with microconidia and macroconidia, while B dermatitidis is distinguished by spherical, thick-walled cells with broad-based budding.11 Capsular material also can help distinguish Cryptococcus from other pathogenic fungi. Special stains highlighting the polysaccharide capsule of Cryptococcus can best identify the yeast. The capsule stains red with periodic acid–Schiff, blue with Alcian blue, and black with Grocott methenamine silver. Mucicarmine is especially useful as it can stain the mucinous capsule pinkish red and typically does not stain other pathogenic fungi.12 Capsule-deficient organisms can lead to considerable difficulties in diagnosis given the organisms can vary in size and may mimic H capsulatum or B dermatitidis. The Fontana-Masson stain is a valuable tool in identifying capsule-deficient organisms, as melanin is found in Cryptococcus cell walls; thus, positive staining excludes H capsulatum and B dermatitidis.13

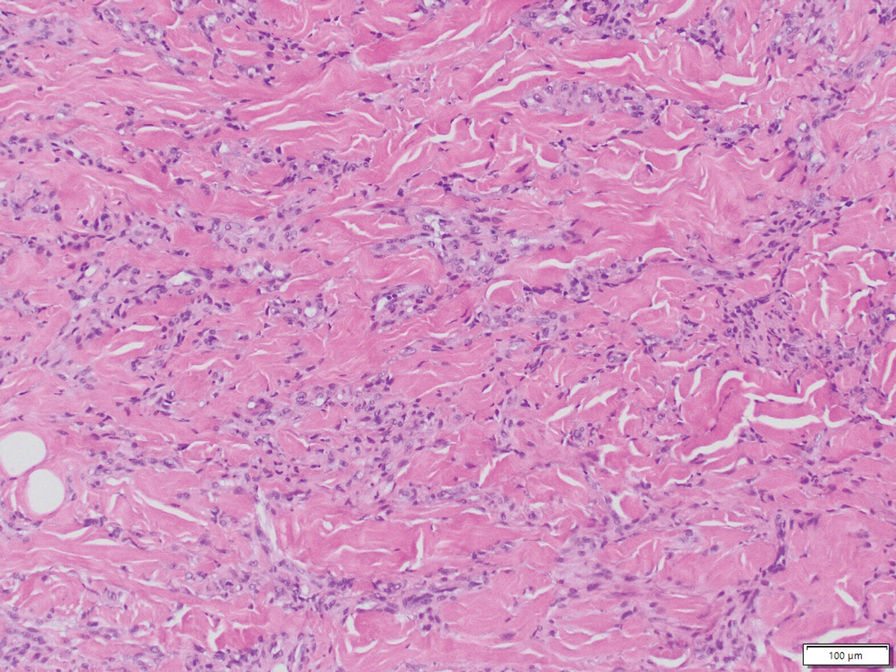

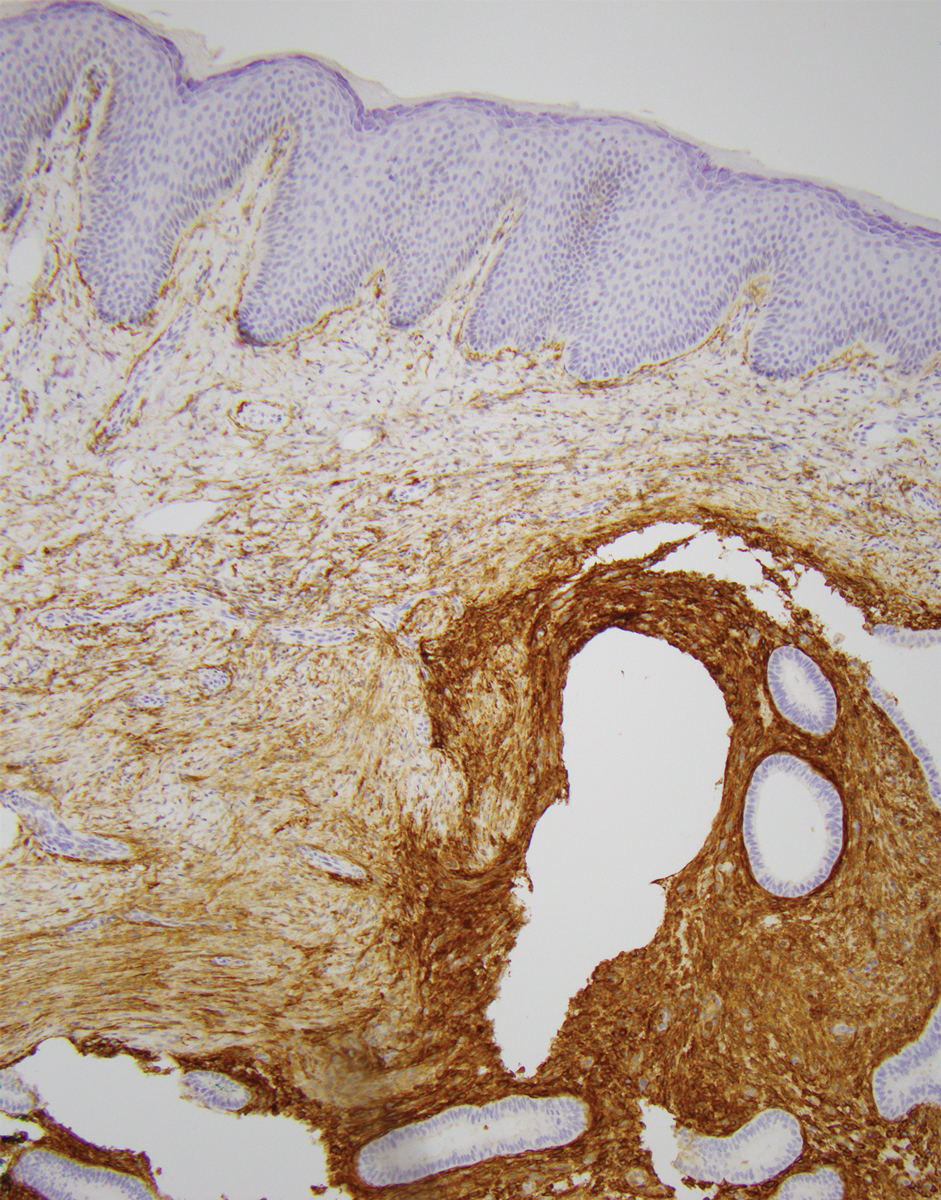

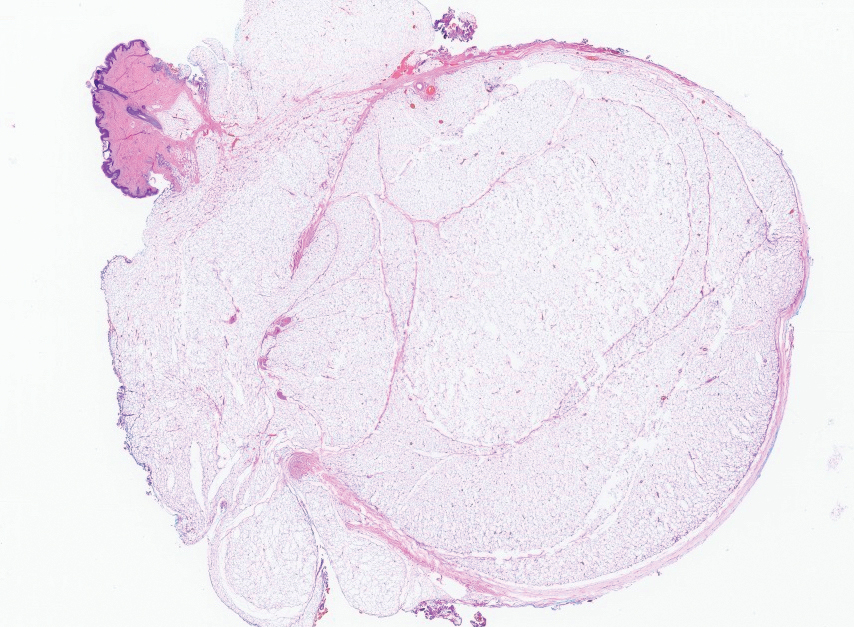

Cutaneous foreign body granuloma, which refers to a granulomatous inflammatory reaction to a foreign body in the skin, is another differential diagnosis that is important to distinguish from cutaneous cryptococcosis. On histology, a collection of histiocytes surround the inert material, forming giant cells without an immune response (Figure 3).10 In contrast, granulomas caused by infectious etiologies (eg, Cryptococcus species) have an associated adaptive immune response and can be further classified as necrotizing or non-necrotizing. Necrotizing granulomas have a distinct central necrosis with a surrounding lymphohistiocytic reaction with peripheral chronic inflammation.10

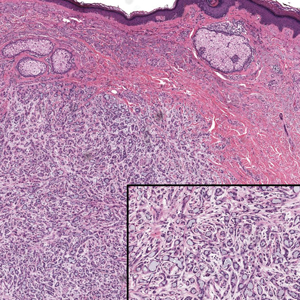

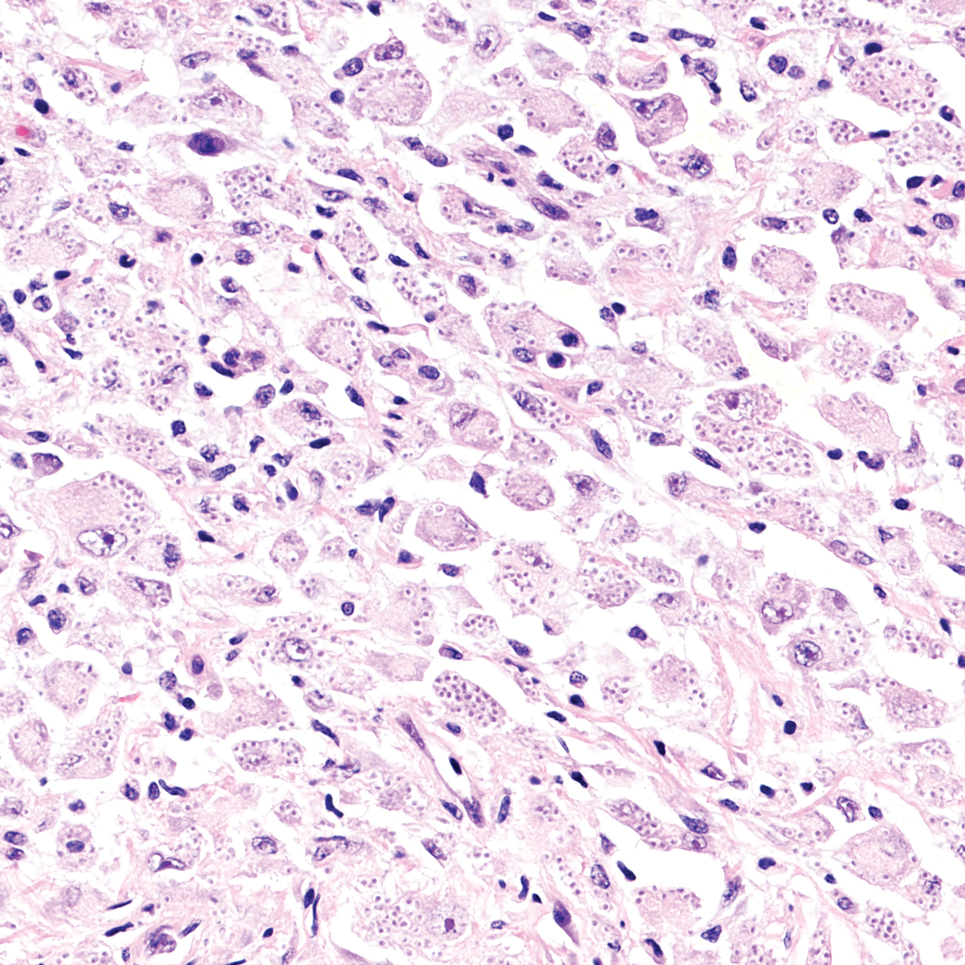

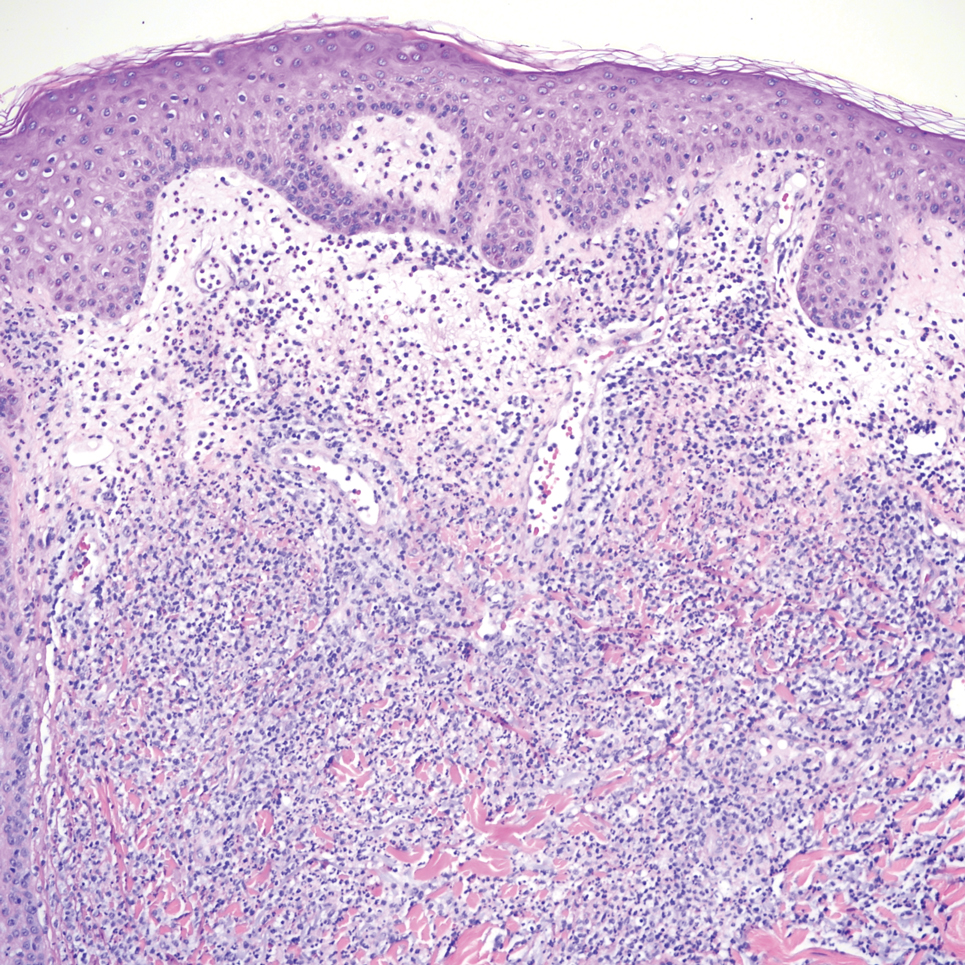

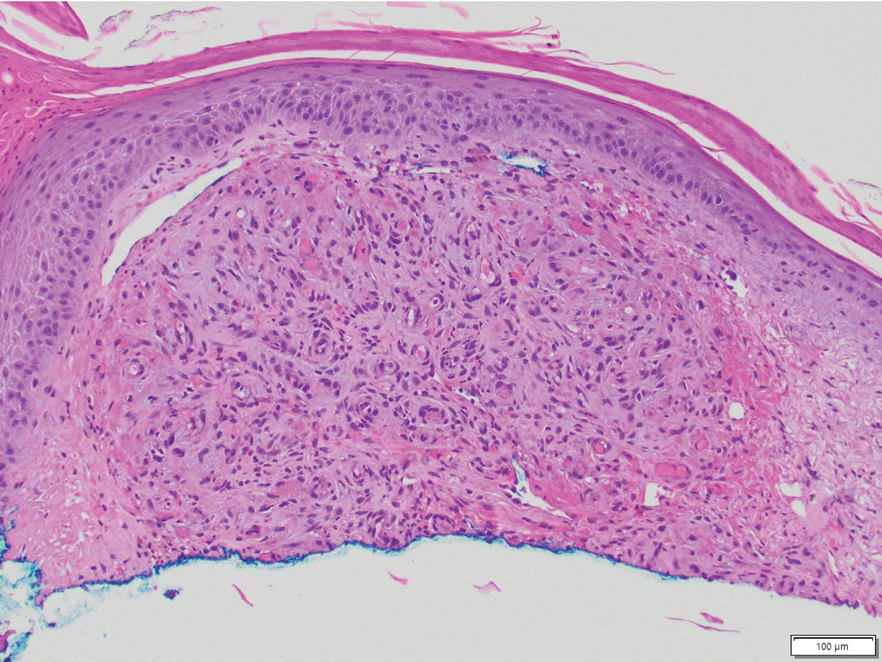

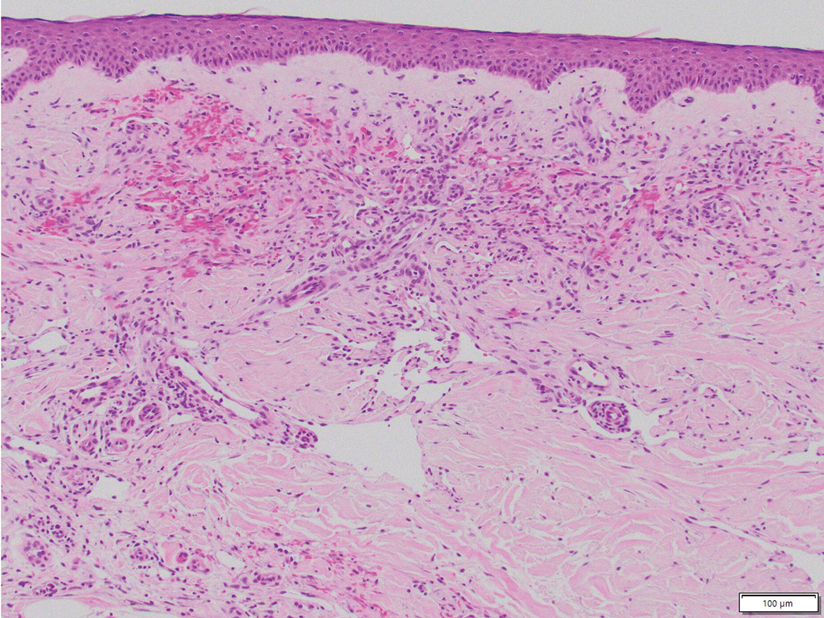

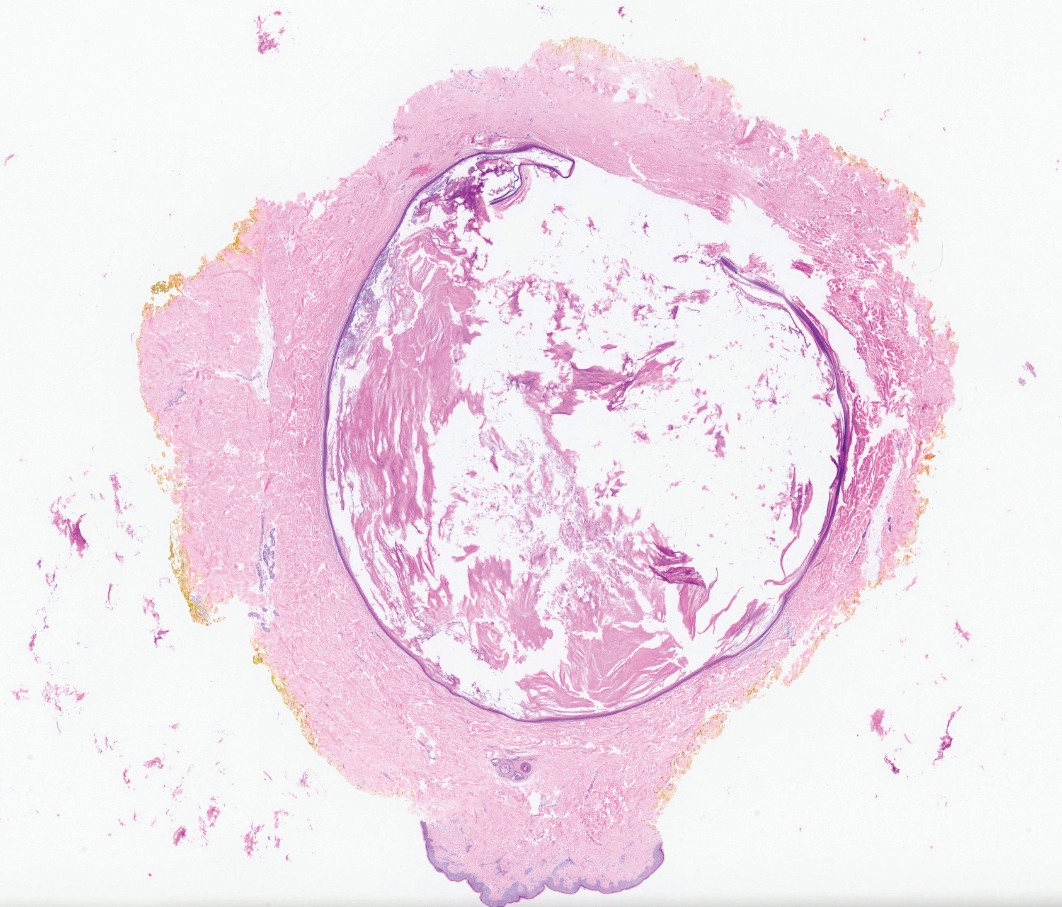

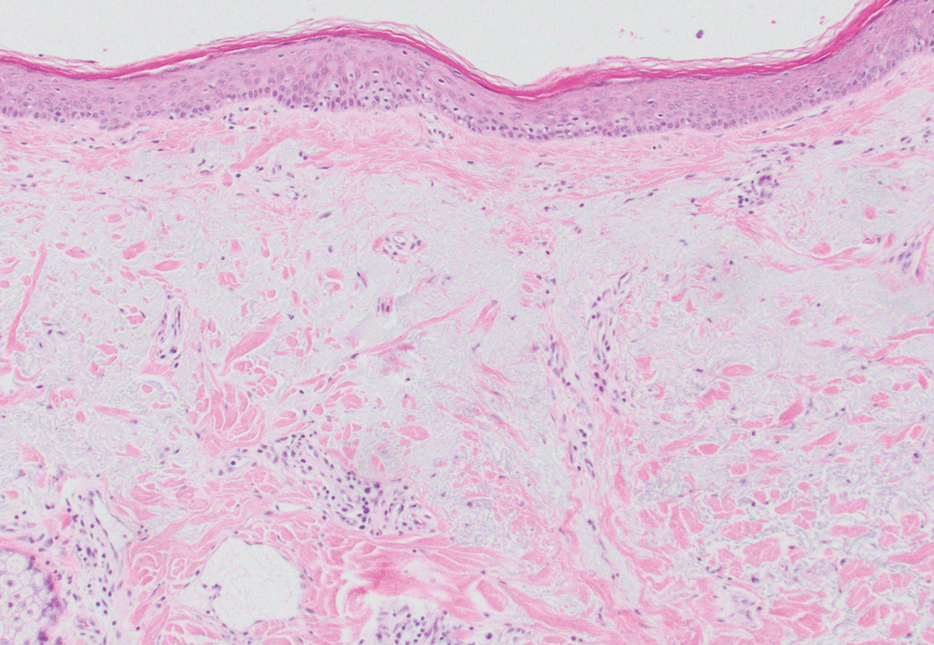

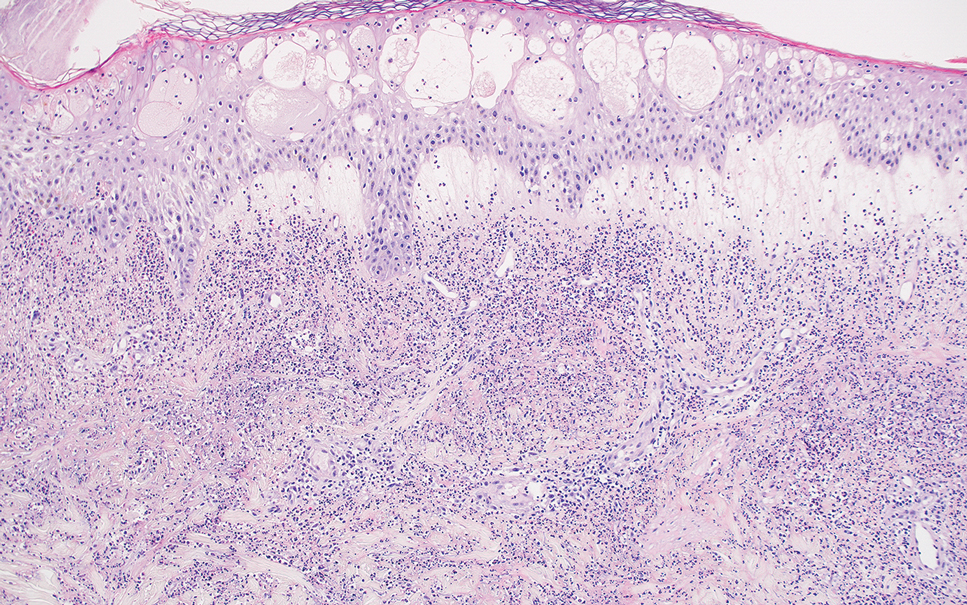

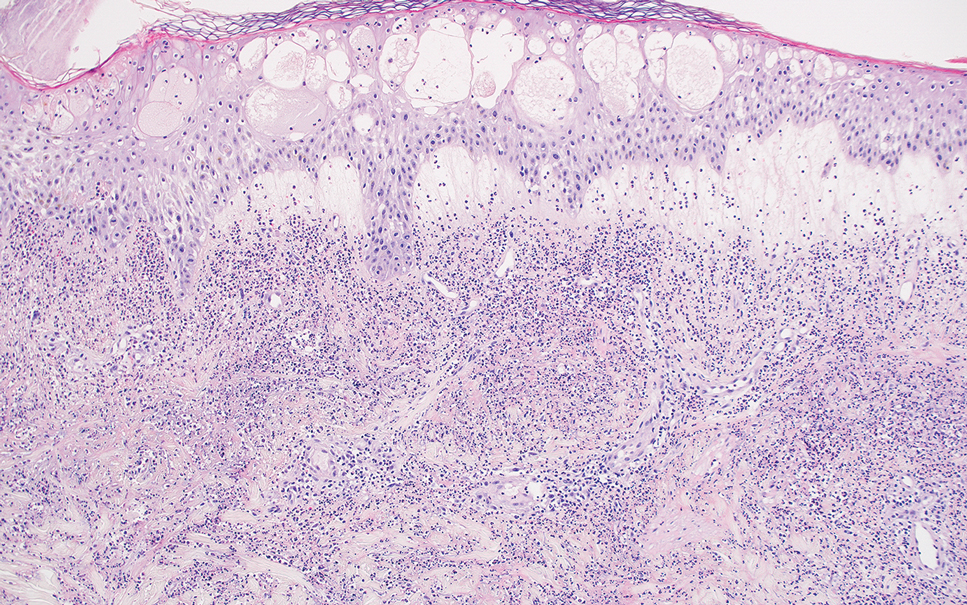

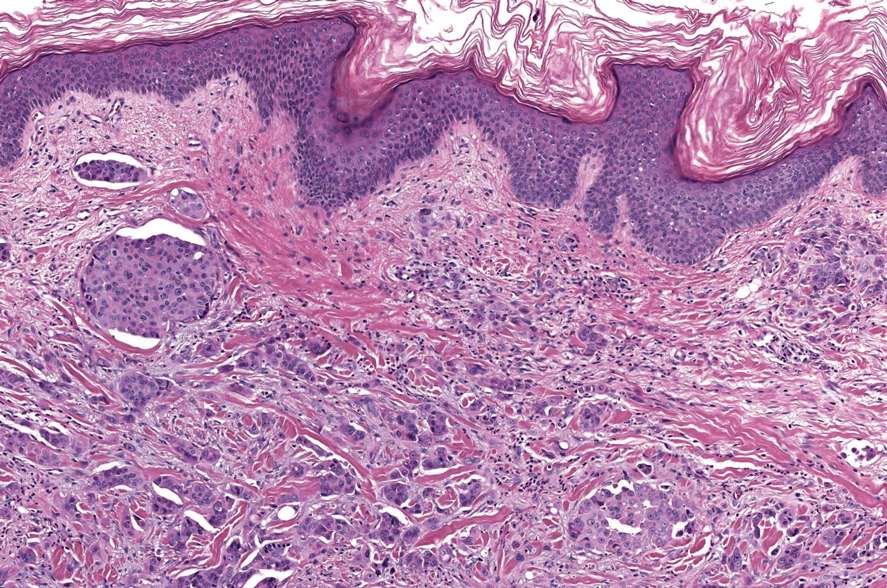

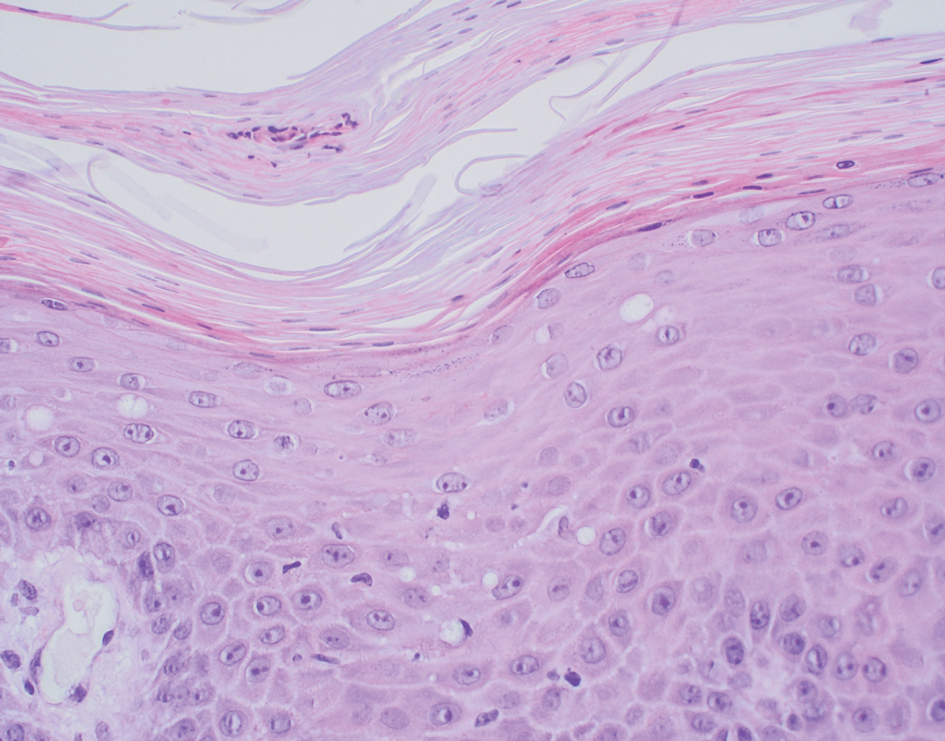

Sweet syndrome is another mimicker of cutaneous cryptococcosis. A histologic variant of Sweet syndrome has been reported that has characteristic cutaneous lesions clinically but shows basophilic bodies with a surrounding halo on pathology that can be mistaken for Cryptococcus yeast. Classic histopathology of Sweet syndrome features papillary dermal edema with neutrophil or histiocytelike inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 4). Identification of Sweet syndrome can be aided by positive myeloperoxidase staining and negative periodic acid–Schiff staining.14,15

THE DIAGNOSIS: Cutaneous Cryptococcosis

Biopsy of the ulcerated nodule showed numerous yeastlike organisms within clear mucinous capsules and with some surrounding inflammation. On Grocott methenamine silver staining, the organisms stained black. Workup for disseminated cryptococcus was negative, leading to a diagnosis of primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in the setting of immunosuppression. Notably, cryptococcosis infection has been reported in patients taking fingolimod (a sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor) for multiple sclerosis, which was the case for our patient.1

The genus Cryptococcus comprises more than 30 species of encapsulated basidiomycetous fungi distributed ubiquitously in nature. Currently, only 2 species are known to cause infectious disease in humans: Cryptococcus neoformans, which affects both immunocompromised and immunocompetent patients and frequently is isolated from pigeon droppings, as well as Cryptococcus gatti, which primarily affects immunocompetent patients and is more commonly isolated from soil and decaying wood.2

Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis (PCC), characterized by direct inoculation of C neoformans or C gatti via skin injury, is rare and typically is seen in patients with decreased cell-mediated immunity, such as those on chronic corticosteroid therapy, solid-organ transplant recipients, and those with HIV.3 Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis typically manifests as a solitary or confined lesion on exposed areas of the skin and often is accompanied by regional lymphadenopathy.4,5 The most common cutaneous findings associated with PCC include ulceration, cellulitis, and whitlow.5 In immunocompetent hosts, frequently affected sites include the arms, fingers, and face, while the trunk and lower extremities are more commonly affected in immunocompromised hosts.3 Secondary cutaneous cryptococcosis occurs through hematologic spread in patients with disseminated cryptococcosis after inhalation of Cryptococcosis spores and differs from PCC in that it typically manifests as multiple lesions scattered on both exposed and covered areas of the skin. Patients also may have signs and symptoms of disseminated cryptococcosis such as pneumonia and/or meningitis at presentation.5

Despite the difference between PCC and secondary cutaneous cryptococcosis, almost every type of skin lesion has been observed in cryptococcosis, including pustules, nodules, vesicles, acneform lesions, purpura, ulcers, abscesses, molluscumlike lesions, granulomas, draining sinuses, and cellulitis.6,7

Cutaneous cryptococcosis generally is associated with 2 types of histologic reactions: gelatinous and granulomatous. The gelatinous reaction shows numerous yeastlike organisms ranging from 4 μm to 12 μm in diameter with large mucinous polysaccharide capsules and scant inflammation. Organisms may be seen in mucoid sheets.8 The granulomatous type shows a more pronounced reaction with fewer organisms ranging from 2 μm to 4 μm in diameter found within giant cells, histiocytes, and lymphocytes.6,9 Areas of necrosis occasionally can be observed.8

It is important to consider infection with Blastomyces dermatitidis and Histoplasma capsulatum in the differential Both entities can manifest as necrotizing granulomas on histology (Figures 1 and 2).10 Microscopic morphology can help differentiate these pathogenic fungi from Cryptococcus diagnosis of cryptococcosis. species which show pleomorphic, narrow-based budding yeast with wide capsules. In contrast, H capsulatum is characterized by small, intracellular, yeastlike cells with microconidia and macroconidia, while B dermatitidis is distinguished by spherical, thick-walled cells with broad-based budding.11 Capsular material also can help distinguish Cryptococcus from other pathogenic fungi. Special stains highlighting the polysaccharide capsule of Cryptococcus can best identify the yeast. The capsule stains red with periodic acid–Schiff, blue with Alcian blue, and black with Grocott methenamine silver. Mucicarmine is especially useful as it can stain the mucinous capsule pinkish red and typically does not stain other pathogenic fungi.12 Capsule-deficient organisms can lead to considerable difficulties in diagnosis given the organisms can vary in size and may mimic H capsulatum or B dermatitidis. The Fontana-Masson stain is a valuable tool in identifying capsule-deficient organisms, as melanin is found in Cryptococcus cell walls; thus, positive staining excludes H capsulatum and B dermatitidis.13

Cutaneous foreign body granuloma, which refers to a granulomatous inflammatory reaction to a foreign body in the skin, is another differential diagnosis that is important to distinguish from cutaneous cryptococcosis. On histology, a collection of histiocytes surround the inert material, forming giant cells without an immune response (Figure 3).10 In contrast, granulomas caused by infectious etiologies (eg, Cryptococcus species) have an associated adaptive immune response and can be further classified as necrotizing or non-necrotizing. Necrotizing granulomas have a distinct central necrosis with a surrounding lymphohistiocytic reaction with peripheral chronic inflammation.10

Sweet syndrome is another mimicker of cutaneous cryptococcosis. A histologic variant of Sweet syndrome has been reported that has characteristic cutaneous lesions clinically but shows basophilic bodies with a surrounding halo on pathology that can be mistaken for Cryptococcus yeast. Classic histopathology of Sweet syndrome features papillary dermal edema with neutrophil or histiocytelike inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 4). Identification of Sweet syndrome can be aided by positive myeloperoxidase staining and negative periodic acid–Schiff staining.14,15

- Lehmann NM, Kammeyer JA. Cerebral venous thrombosis due to Cryptococcus in a multiple sclerosis patient on fingolimod. Case Rep Neurol. 2022; 14:286-290. doi:10.1159/000524359

- Maziarz EK, Perfect JR. Cryptococcosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016;30:179-206. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2015.10.006.

- Christianson JC, Engber W, Andes D. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts. Med Mycol. 2003;41:177-188. doi:10.1080/1369378031000137224

- Tilak R, Prakash P, Nigam C, et al. Cryptococcal meningitis with an antecedent cutaneous Cryptococcal lesion. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:12.

- Neuville S, Dromer F, Morin O, et al. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis: a distinct clinical entity. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:337-347. doi:10.1086/345956

- Dimino-Emme L, Gurevitch AW. Cutaneous manifestations of disseminated cryptococcosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:844-850.

- Anderson DJ, Schmidt C, Goodman J, Pomeroy C. Cryptococcal disease presenting as cellulitis. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14:666-672. doi:10.1093/clinids/14.3.666

- Moore M. Cryptococcosis with cutaneous manifestations: four cases with a review of published reports. J Invest Dermatol. 1957;28(2):159-182. doi: 10.1038/jid.1957.17

- Phan NQ, Tirado M, Moeckel SMC, et al. Cutaneous and pulmonary cryptococcosis in an immunocompetent patient. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2019;17:1283-1286. doi:10.1111/ddg.13997.

- Shah KK, Pritt BS, Alexander MP. Histopathologic review of granulomatous inflammation. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2017;7:1-12. doi: 10.1016/j.jctube.2017.02.001

- Fridlington E, Colome-Grimmer M, Kelly E, et al. Tzanck smear as a rapid diagnostic tool for disseminated cryptococcal infection. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:25-27. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.1.25

- Hernandez AD. Cutaneous Cryptococcosis. Dermatol Clin. 1989; 7:269-274.

- Ro JY, Lee SS, Ayala AG. Advantage of Fontana-Masson stain in capsule-deficient cryptococcal infection. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1987;111:53-57.

- Jordan AA, Graciaa DS, Gopalsamy SN, et al. Sweet syndrome imitating cutaneous cryptococcal disease. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022;9:ofac608. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofac608

- Ko JS, Fernandez AP, Anderson KA, et al. Morphologic mimickers of Cryptococcus occurring within inflammatory infiltrates in the setting of neutrophilic dermatitis: a series of three cases highlighting clinical dilemmas associated with a novel histopathologic pitfall. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:38-45. doi: 10.1111/cup.12019

- Lehmann NM, Kammeyer JA. Cerebral venous thrombosis due to Cryptococcus in a multiple sclerosis patient on fingolimod. Case Rep Neurol. 2022; 14:286-290. doi:10.1159/000524359

- Maziarz EK, Perfect JR. Cryptococcosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016;30:179-206. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2015.10.006.

- Christianson JC, Engber W, Andes D. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts. Med Mycol. 2003;41:177-188. doi:10.1080/1369378031000137224

- Tilak R, Prakash P, Nigam C, et al. Cryptococcal meningitis with an antecedent cutaneous Cryptococcal lesion. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:12.

- Neuville S, Dromer F, Morin O, et al. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis: a distinct clinical entity. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:337-347. doi:10.1086/345956

- Dimino-Emme L, Gurevitch AW. Cutaneous manifestations of disseminated cryptococcosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:844-850.

- Anderson DJ, Schmidt C, Goodman J, Pomeroy C. Cryptococcal disease presenting as cellulitis. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14:666-672. doi:10.1093/clinids/14.3.666

- Moore M. Cryptococcosis with cutaneous manifestations: four cases with a review of published reports. J Invest Dermatol. 1957;28(2):159-182. doi: 10.1038/jid.1957.17

- Phan NQ, Tirado M, Moeckel SMC, et al. Cutaneous and pulmonary cryptococcosis in an immunocompetent patient. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2019;17:1283-1286. doi:10.1111/ddg.13997.

- Shah KK, Pritt BS, Alexander MP. Histopathologic review of granulomatous inflammation. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2017;7:1-12. doi: 10.1016/j.jctube.2017.02.001

- Fridlington E, Colome-Grimmer M, Kelly E, et al. Tzanck smear as a rapid diagnostic tool for disseminated cryptococcal infection. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:25-27. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.1.25

- Hernandez AD. Cutaneous Cryptococcosis. Dermatol Clin. 1989; 7:269-274.

- Ro JY, Lee SS, Ayala AG. Advantage of Fontana-Masson stain in capsule-deficient cryptococcal infection. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1987;111:53-57.

- Jordan AA, Graciaa DS, Gopalsamy SN, et al. Sweet syndrome imitating cutaneous cryptococcal disease. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022;9:ofac608. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofac608

- Ko JS, Fernandez AP, Anderson KA, et al. Morphologic mimickers of Cryptococcus occurring within inflammatory infiltrates in the setting of neutrophilic dermatitis: a series of three cases highlighting clinical dilemmas associated with a novel histopathologic pitfall. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:38-45. doi: 10.1111/cup.12019

Pink Ulcerated Nodule on the Forearm

Pink Ulcerated Nodule on the Forearm

A 51-year-old man with a history of multiple sclerosis treated with fingolimod presented to the dermatology department with an ulcerated lesion on the left forearm of 2 to 3 months’ duration. The patient reported that he recently presented to the emergency department for drainage of the lesion, which was unsuccessful. Shortly after, he traumatized the lesion at his construction job. At the current presentation, physical examination revealed a 1-cm, flesh-colored to faintly pink, ulcerated nodule on the left forearm. A biopsy was performed.

Pink Papule on the Lower Eyelid

Pink Papule on the Lower Eyelid

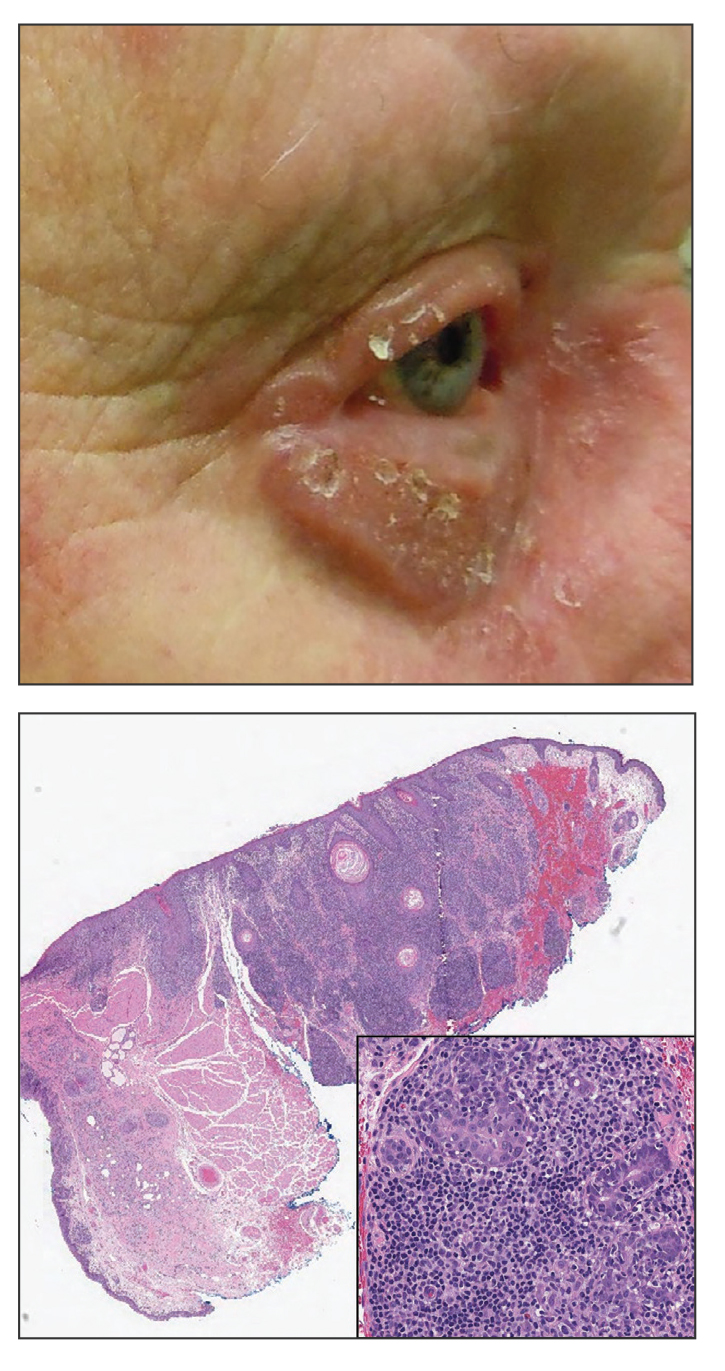

THE DIAGNOSIS: Poroma

Poromas are benign adnexal neoplasms that often are classified into the broader category of acrospiromas. They most commonly affect areas with a high density of eccrine sweat glands, such as the palms and soles, but also can appear in any area of the body with sweat glands.1 Poromas may have cuboidal eccrine cells with ovoid nuclei and a delicate vascularized stroma on histology or may show apocrinelike features with sebaceous cells.2,3 Immunohistochemically, poromas stain positively for carcinoembryonic antigen, epithelial membrane antigen, and periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) with diastase sensitivity.1,4 Cytokeratin (CK) 1 and CK-10 are expressed in the tumor nests.1

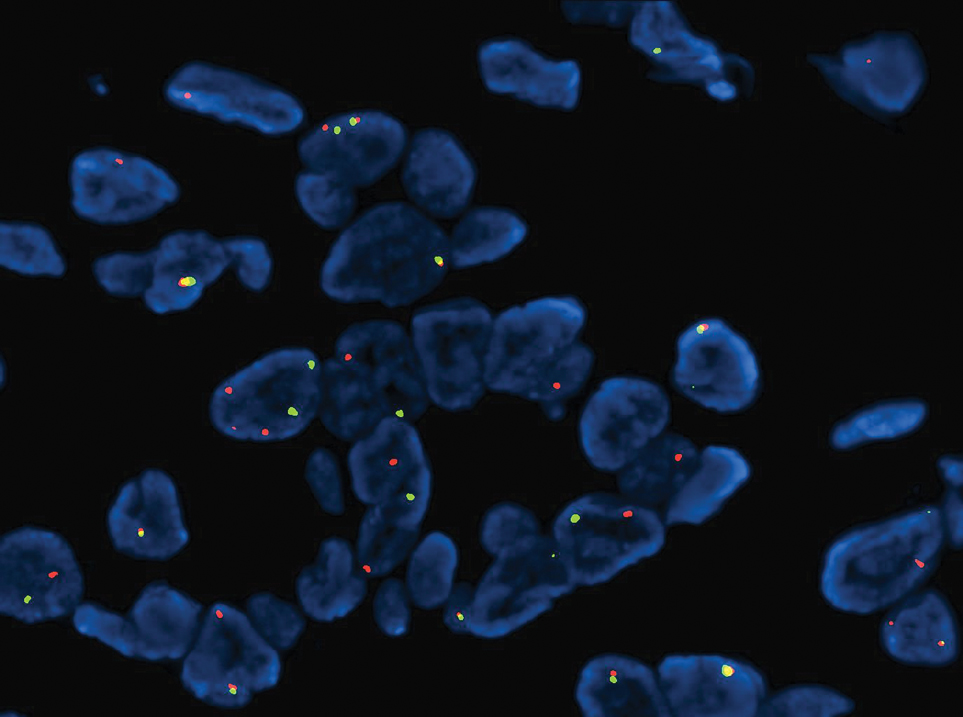

Poromas are the benign counterpart of porocarcinomas, which can recur and may become invasive and metastasize. Porocarcinomas have been shown to undergo malignant transformation from poromas as well as develop de novo.5 Histologic differentiation between the 2 conditions is key in determining excisional margins for treatment and follow-up. Poromas are histologically similar to porocarcinomas, but the latter show invasion into the dermis, nuclear and cytoplasmic pleomorphism, nuclear hyperchromatism, and increased mitotic activity.6 S-100 protein can be positive in porocarcinoma.7 Both poromas and porocarcinomas are associated with Yes-associated protein 1 (YAP1), Mastermind-like protein 2 (MAML2), and NUT midline carcinoma family member 1 (NUTM1) gene fusions.5

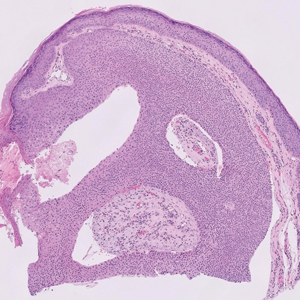

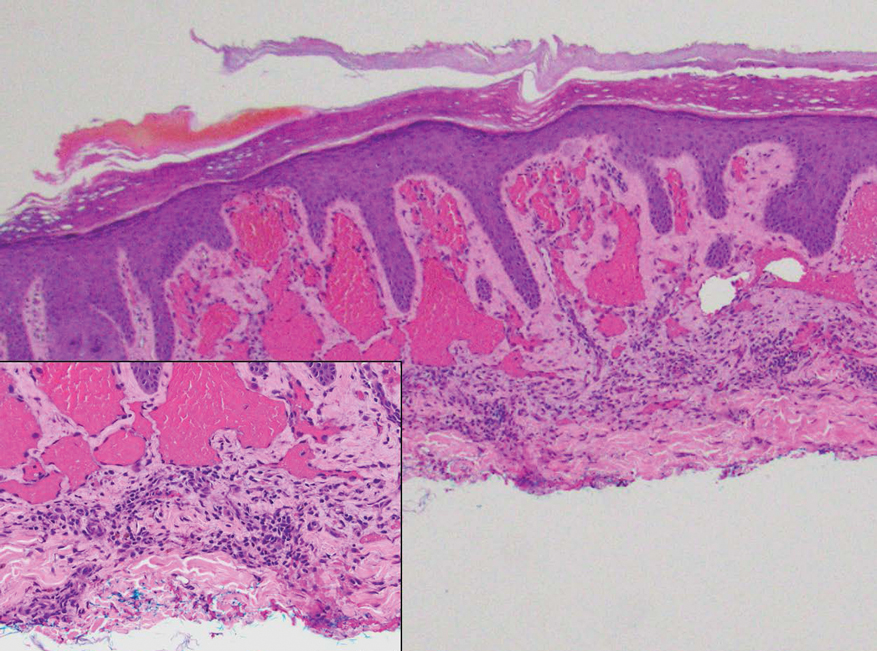

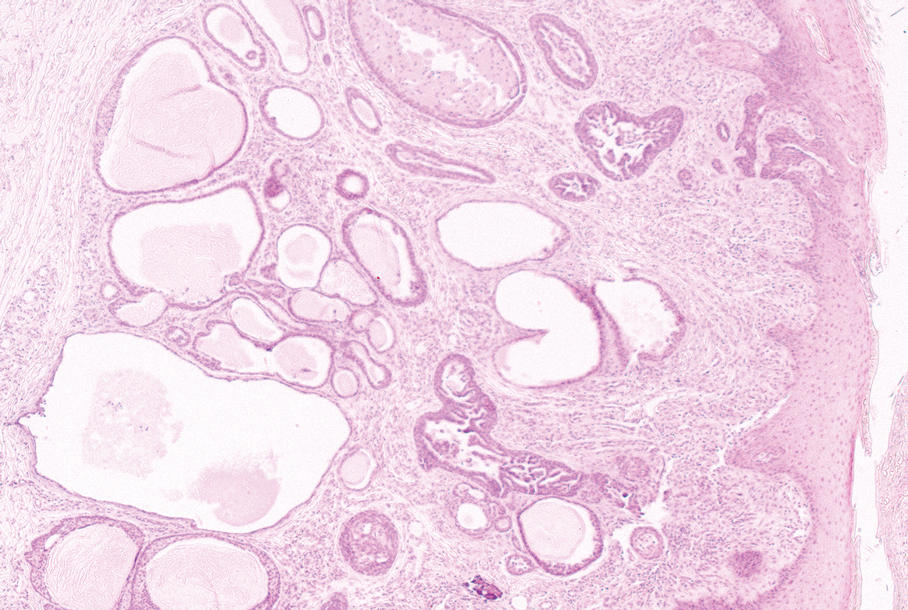

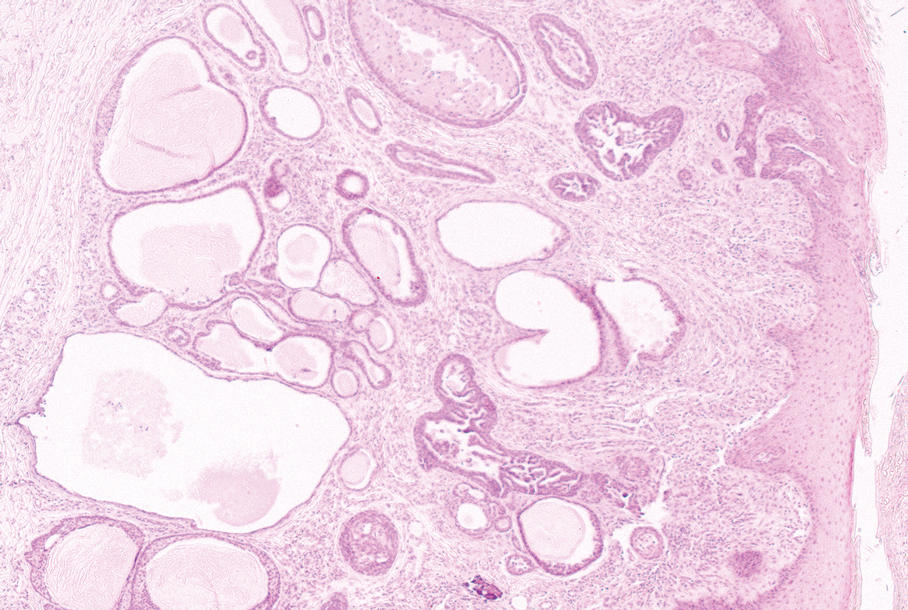

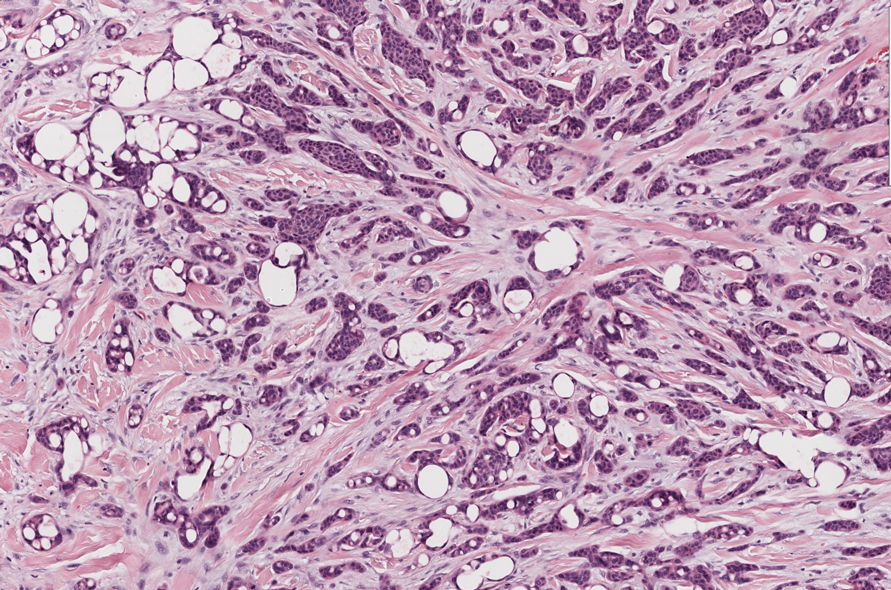

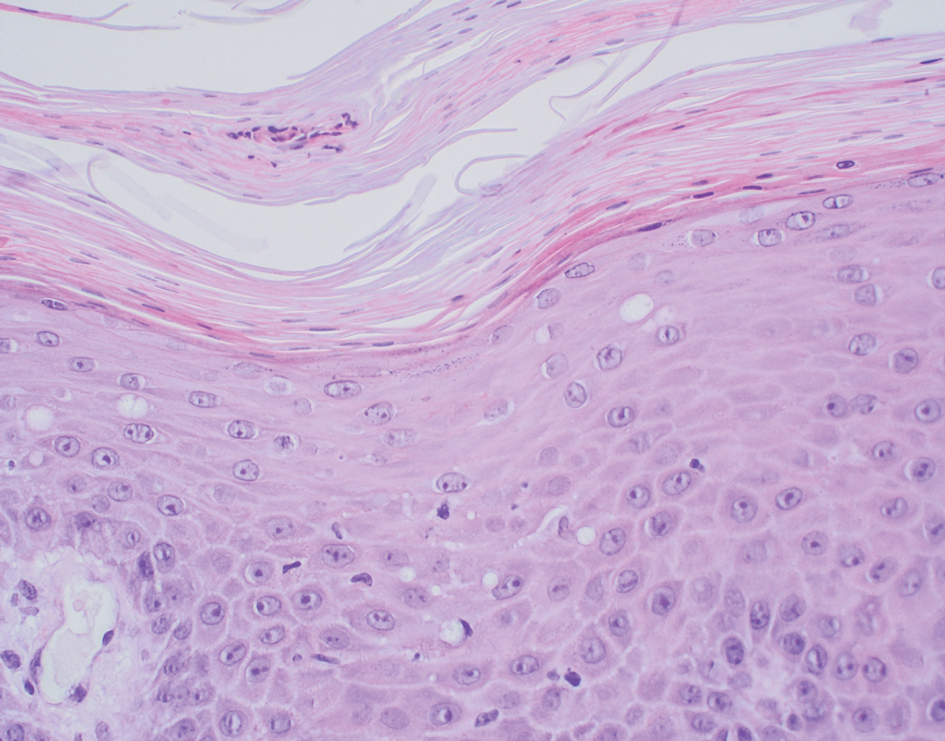

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common cutaneous malignancy. It rarely metastasizes but can be locally destructive.8 Basal cell carcinomas typically occur on sun-exposed skin in middle-aged and elderly patients and classically manifest as pink or flesh-colored pearly papules with rolled borders and overlying telangiectasia.9 Risk factors for BCC include a chronic sun exposure, lighter skin phenotypes, immunosuppression, and a family history of skin cancer. The 2 most common subtypes of BCC are nodular and superficial, which comprise around 85% of BCCs.10 Histologically, nodular BCCs demonstrate nests of malignant basaloid cells with central disorganization, peripheral palisading, tumor-stroma clefting, and a mucoid stroma with spindle cells (Figure 1). Superficial BCC manifests with small islands of malignant basaloid cells with peripheral palisading that connect with the epidermis, often with a lichenoid inflammatory infiltrate.9 Basal cell carcinomas stain positively for Ber-EP4 and are associated with patched 1 (PTCH1), patched 2 (PTCH2), and tumor protein 53 (TP53) gene mutations.9,11

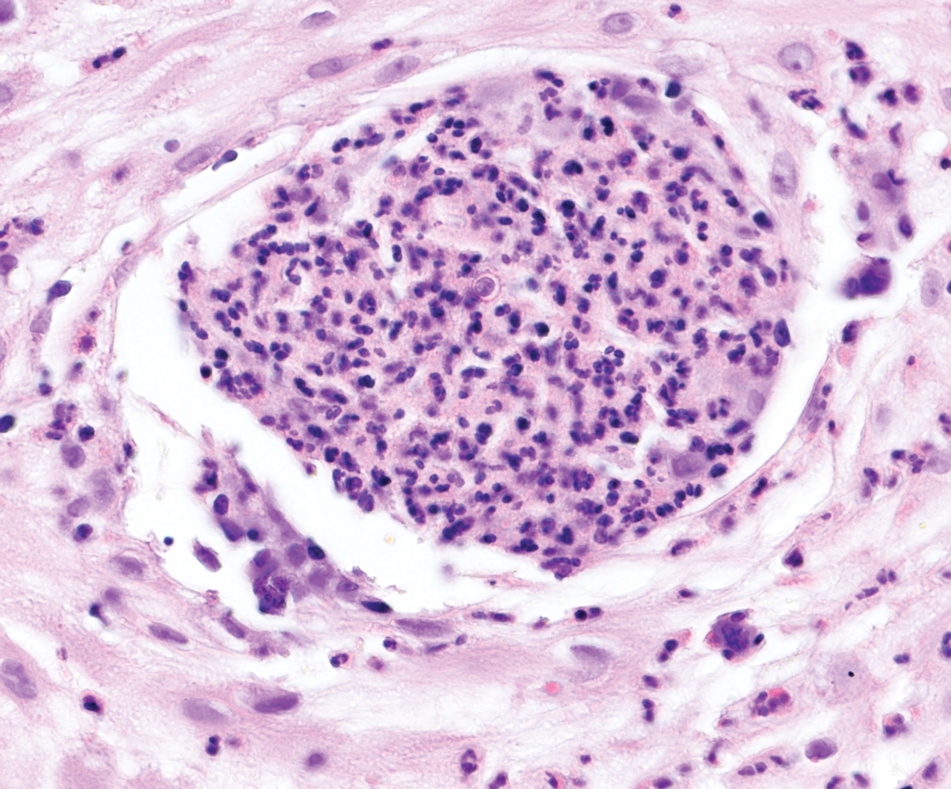

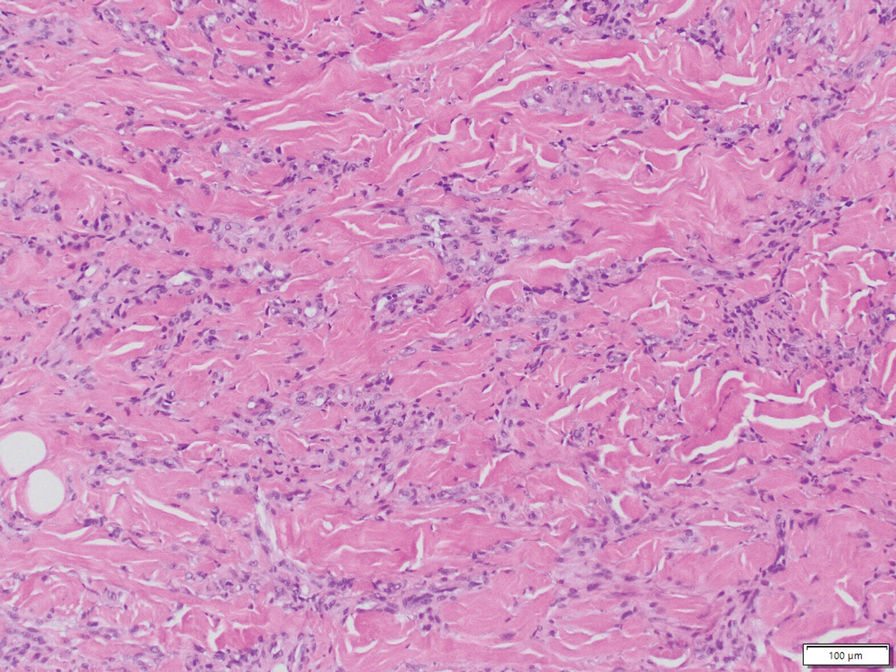

Spiradenomas are benign adnexal tumors manifesting as painful, usually singular, 1- to 3-cm nodules in younger adults.12 Histologically, spiradenomas have large clusters of small irregularly shaped aggregations of small basaloid and large polygonal cells with surrounding hyalinized basement membrane material and intratumoral lymphocytes (Figure 2).4 Spiradenomas stain positive for p63, D2-40, and CK7 and are associated with cylindromatosis lysine 63 deubiquitinase (CYLD) and alpha-protein kinase 1 (ALPK1) gene mutations.5

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the second most common nonmelanoma skin cancer worldwide.13 Lesions typically develop on sun-exposed skin and manifest as red, hyperkeratotic, and sometimes ulcerated plaques or nodules.14 Risk factors for SCC include chronic sun exposure, lighter skin phenotypes, increased age, and immunosuppression. Histologically, there are several variants of SCC: low-risk variants include keratoacanthomas, verrucous carcinomas, and clear cell SCC, and high-risk variants include acantholytic SCC, spindle cell SCC, and adenosquamous carcinoma.14 Generally, low-grade SCC will have well-differentiated or moderately differentiated intercellular bridges or keratin pearls with tumor cells in a solid or sheetlike pattern (Figure 3). High-grade SCC will be poorly differentiated with the presence of infiltrating individual tumor cells.15 Immunohistochemically, SCC stains positive for p63, p40, AE1/AE3, CK5/6, and MNF116 while Ber-Ep4 is negative.14,15 Poorly differentiated SCCs have high rates of mutation, commonly in the tumor protein 53 (TP53), Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A), Ras pathway, and notch receptor 1 (NOTCH-1) genes.13

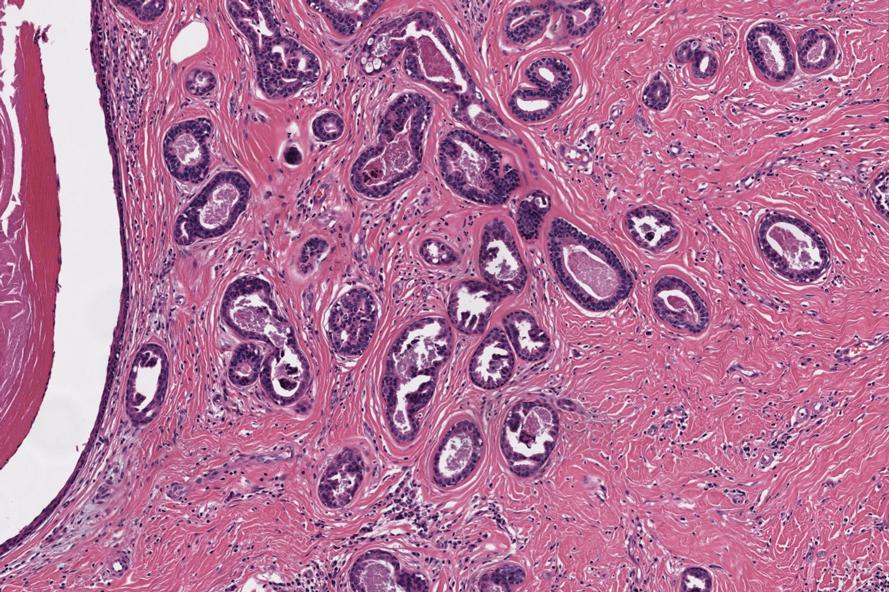

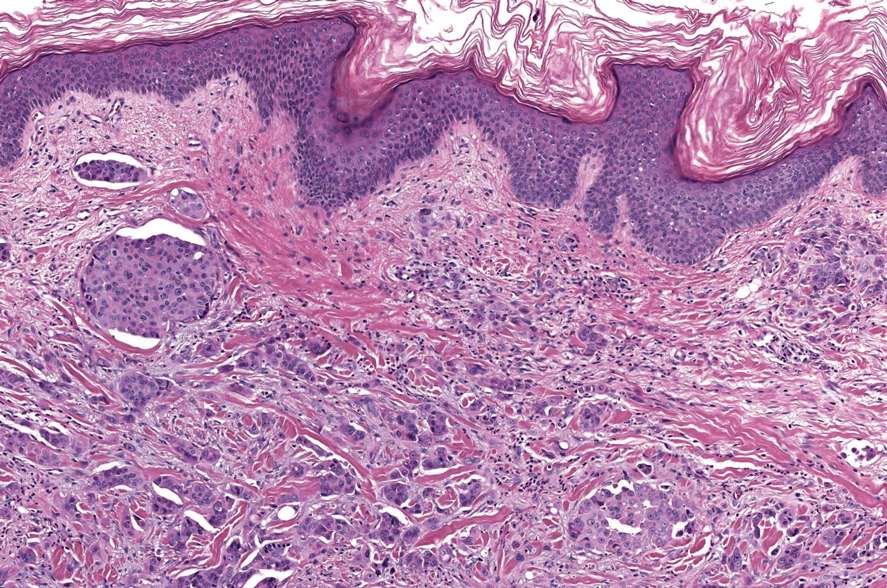

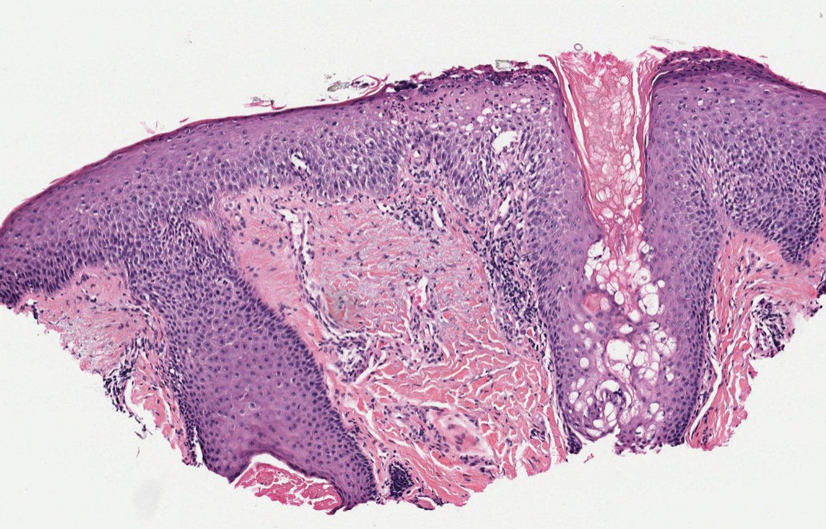

Syringomas are benign adnexal tumors that manifest as multiple soft, yellow to flesh-colored, 1- to 2-mm papules typically located on the lower eyelids, most commonly in women of reproductive age.16 Syringomas are described on histology as small comma-shaped nests with cords of eosinophilic to clear cells with central ducts surrounded by a sclerotic stroma (Figure 4). They stain positively for carcinoembryonic antigen, epithelial membrane antigen, and CK-5 and are associated with genetic mutations in phosphatidylinositol-4, 5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha (PIK3CA) and AKT serine/threonine kinase 1 (ATK1).4

Due to its regular exposure to sunlight, the eyelid accounts for 5% to 10% of all skin malignancies. Common eyelid lesions include squamous papilloma, seborrheic keratosis, epidermal inclusion cyst, hidrocystoma, intradermal nevus, BCC, SCC, and sebaceous carcinoma.17 Aside from syringomas, benign sweat gland tumors like poromas, hidradenomas, and spiradenomas usually do not manifest on the eyelids but should be included in the differential diagnosis of an unidentifiable lesion due to the small risk for malignant transformation. Eyelid poromas manifest polymorphically, most commonly being clinically diagnosed as BCC, making the histologic examination key for proper diagnosis and management.18

- Patterson J. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 5th ed. Elsevier Limited; 2021.

- Aoki K, Baba S, Nohara T, et al. Eccrine poroma. J Dermatol. 1980; 7:263-269. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.1980.tb01967.x

- Harvell JD, Kerschmann RL, LeBoit PE. Eccrine or apocrine poroma? six poromas with divergent adnexal differentiation. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:1-9. doi:10.1097/00000372-199602000-00001

- Miller AC, Adjei S, Temiz LA, et al. Dermal duct tumor: a diagnostic dilemma. Dermatopathology. 2022;9:36-47. doi:10.3390

- Macagno N, Sohier P, Kervarrec T, et al. Recent advances on immunohistochemistry and molecular biology for the diagnosis of adnexal sweat gland tumors. Cancers. 2022;14:476. doi:10.3390/cancers14030476

- Robson A, Greene J, Ansari N, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma (malignant eccrine poroma): a clinicopathologic study of 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:710-720. doi:10.1097/00000478-200106000-00002 /dermatopathology9010007

- Kurisu Y, Tsuji M, Yasuda E, et al. A case of eccrine porocarcinoma: usefulness of immunostain for S-100 protein in the diagnoses of recurrent and metastatic dedifferentiated lesions. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:348-351. doi:10.5021/ad.2013.25.3.348

- Stanoszek LM, Wang GY, Harms PW. Histologic mimics of basal cell carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017;141:1490-1502. doi:10.5858 /arpa.2017-0222-RA

- Niculet E, Craescu M, Rebegea L, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: comprehensive clinical and histopathological aspects, novel imaging tools and therapeutic approaches (review). Exp Ther Med. 2022;23:60. doi:10.3892/etm.2021.10982

- Pelucchi C, Di Landro A, Naldi L, et al. Risk factors for histological types and anatomic sites of cutaneous basal-cell carcinoma: an Italian case-control study. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:935-944. doi:10.1038/sj.jid.5700598

- Sunjaya AP, Sunjaya AF, Tan ST. The use of BEREP4 immunohistochemistry staining for detection of basal cell carcinoma. J Skin Cancer. 2017;2017:2692604. doi:10.1155/2017/2692604

- Kim J, Yang HJ, Pyo JS. Eccrine spiradenoma of the scalp. Arch Craniofacial Surg. 2017;18:211-213. doi:10.7181/acfs.2017.18.3.211

- Que SKT, Zwald FO, Schmults CD. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: incidence, risk factors, diagnosis, and staging. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:237-247. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.059

- Waldman A, Schmults C. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:1-12. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2018.08.001

- Yanofsky VR, Mercer SE, Phelps RG. Histopathological variants of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a review. J Skin Cancer. 2011;2011:210813. doi:10.1155/2011/210813

- Lee JH, Chang JY, Lee KH. Syringoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistologic study and results of treatment. Yonsei Med J. 2007;48:35-40. doi:10.3349/ymj.2007.48.1.35

- Adamski WZ, Maciejewski J, Adamska K, et al. The prevalence of various eyelid skin lesions in a single-centre observation study. Adv Dermatol Allergol Dermatol Alergol. 2021;38:804-807. doi:10.5114 /ada.2020.95652

- Mencía-Gutiérrez E, Navarro-Perea C, Gutiérrez-Díaz E, et al. Eyelid eccrine poroma: a case report and review of literature. Cureus. 202:12:E8906. doi:10.7759/cureus.8906

THE DIAGNOSIS: Poroma

Poromas are benign adnexal neoplasms that often are classified into the broader category of acrospiromas. They most commonly affect areas with a high density of eccrine sweat glands, such as the palms and soles, but also can appear in any area of the body with sweat glands.1 Poromas may have cuboidal eccrine cells with ovoid nuclei and a delicate vascularized stroma on histology or may show apocrinelike features with sebaceous cells.2,3 Immunohistochemically, poromas stain positively for carcinoembryonic antigen, epithelial membrane antigen, and periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) with diastase sensitivity.1,4 Cytokeratin (CK) 1 and CK-10 are expressed in the tumor nests.1

Poromas are the benign counterpart of porocarcinomas, which can recur and may become invasive and metastasize. Porocarcinomas have been shown to undergo malignant transformation from poromas as well as develop de novo.5 Histologic differentiation between the 2 conditions is key in determining excisional margins for treatment and follow-up. Poromas are histologically similar to porocarcinomas, but the latter show invasion into the dermis, nuclear and cytoplasmic pleomorphism, nuclear hyperchromatism, and increased mitotic activity.6 S-100 protein can be positive in porocarcinoma.7 Both poromas and porocarcinomas are associated with Yes-associated protein 1 (YAP1), Mastermind-like protein 2 (MAML2), and NUT midline carcinoma family member 1 (NUTM1) gene fusions.5

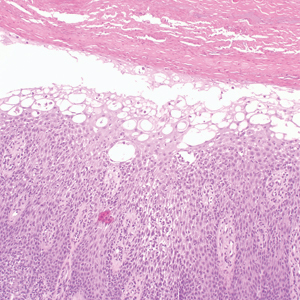

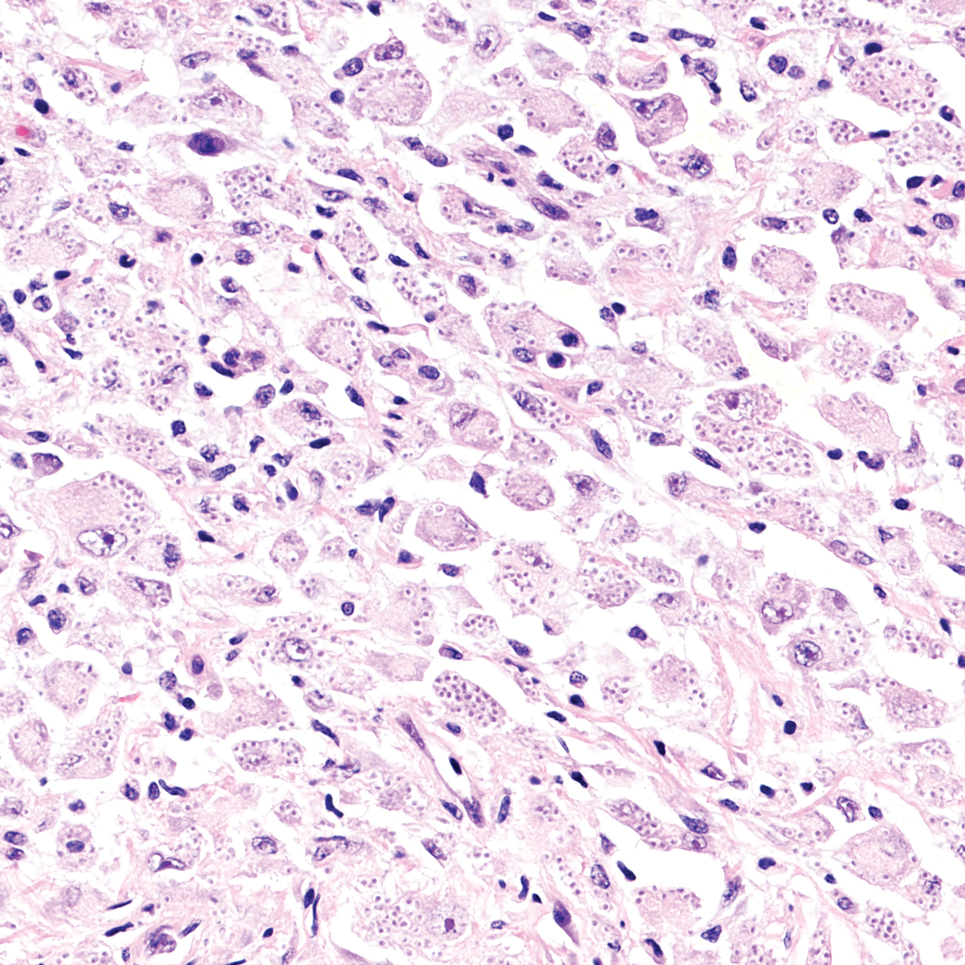

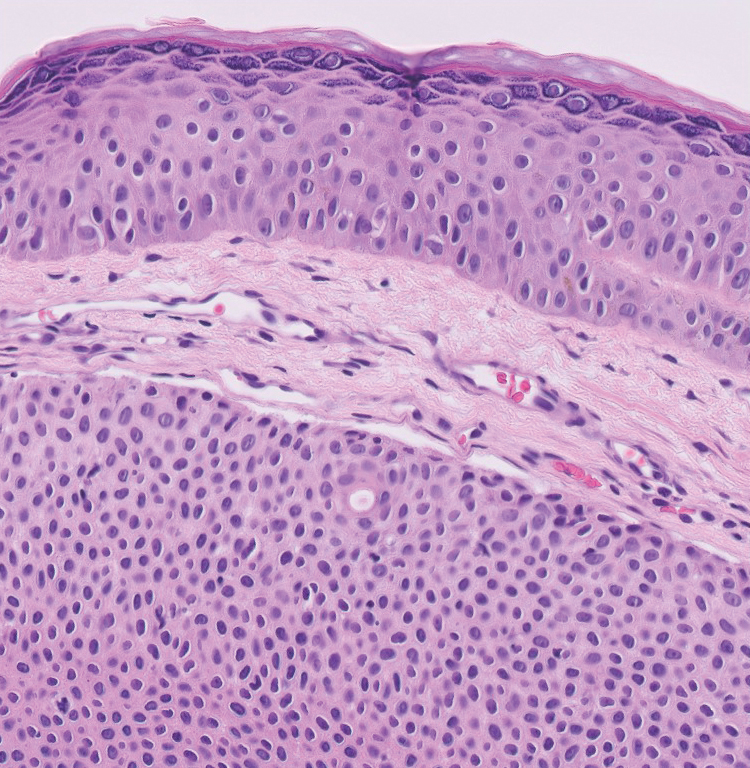

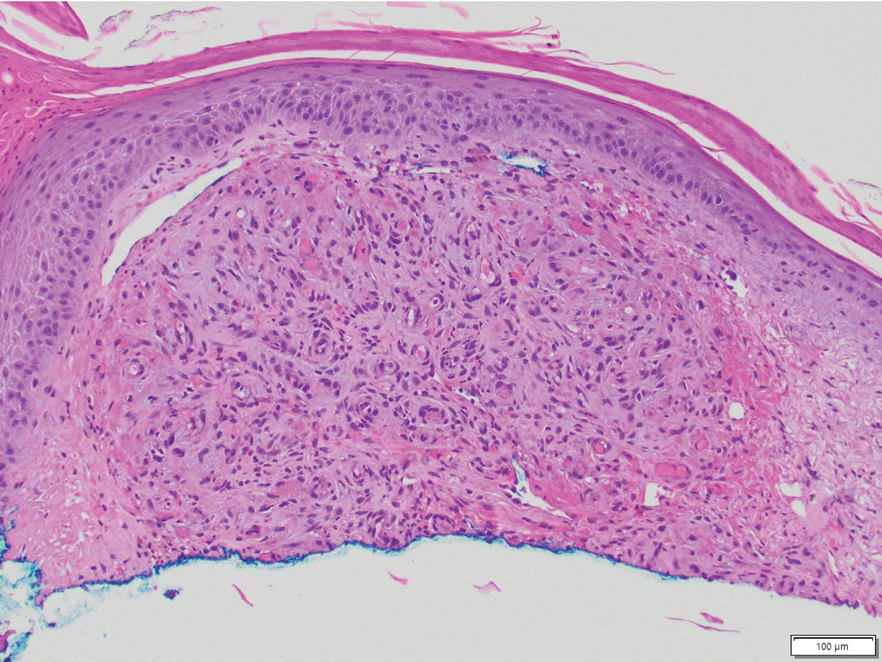

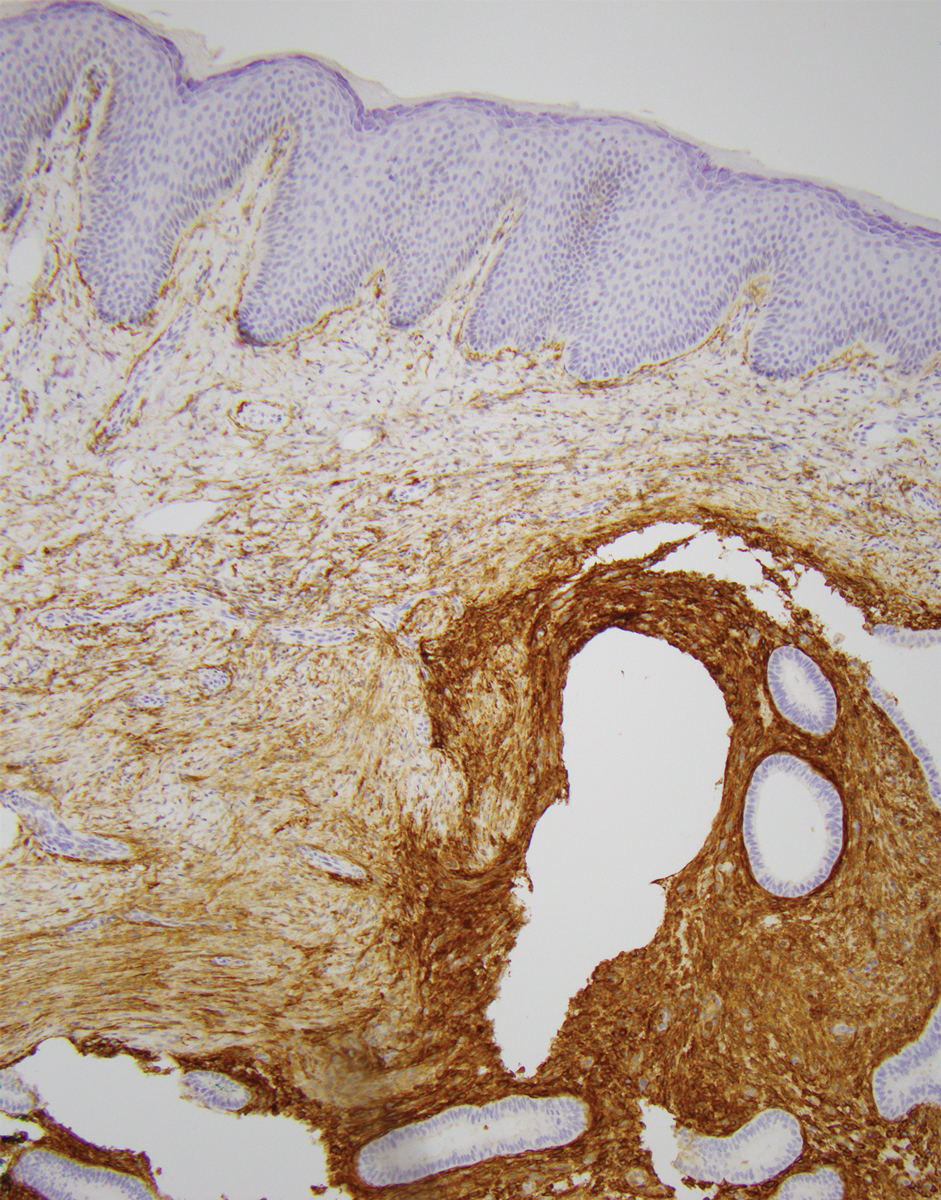

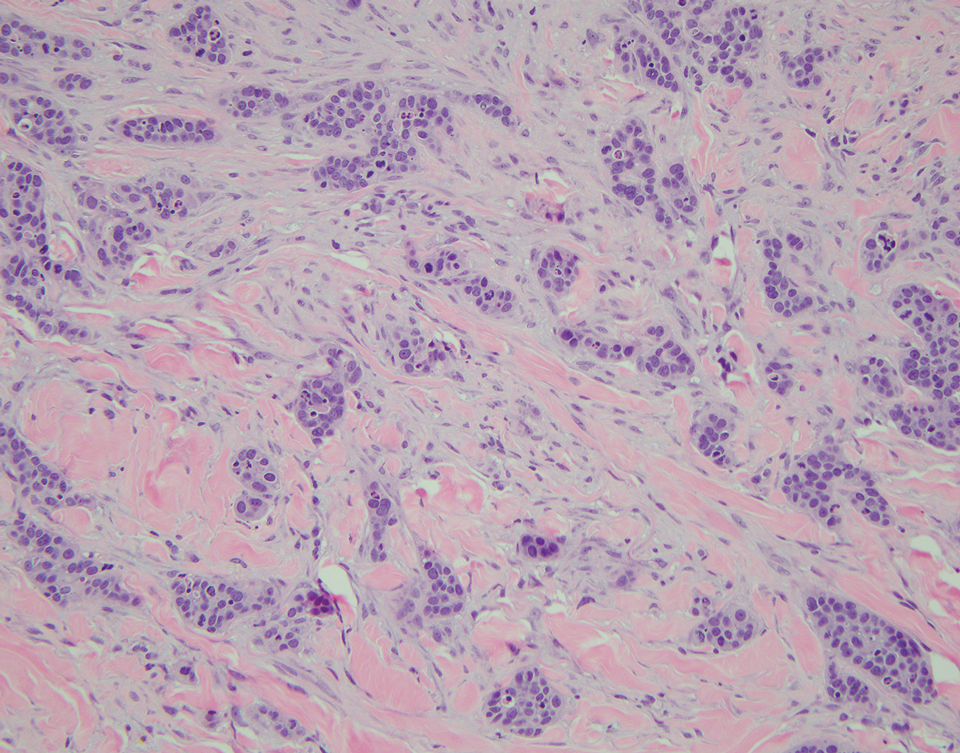

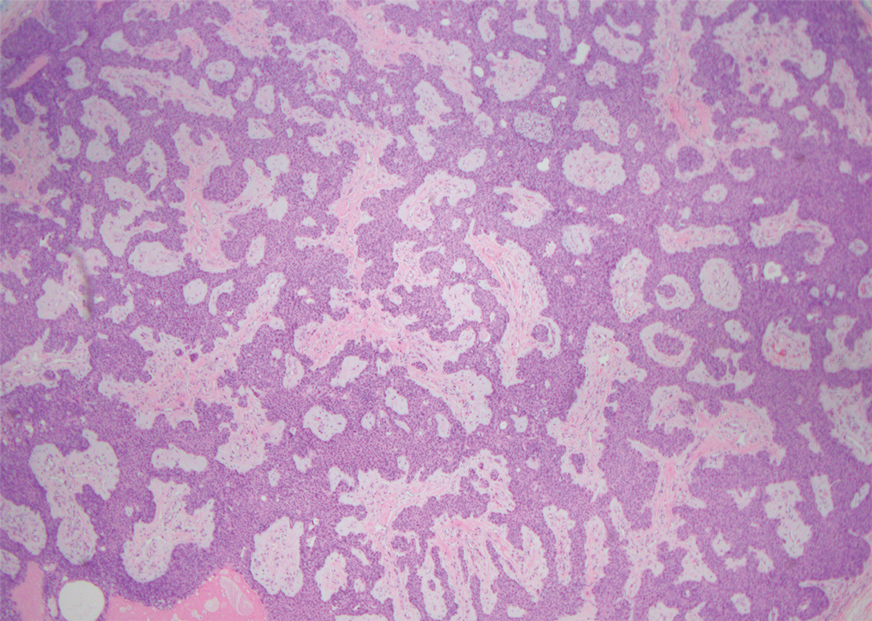

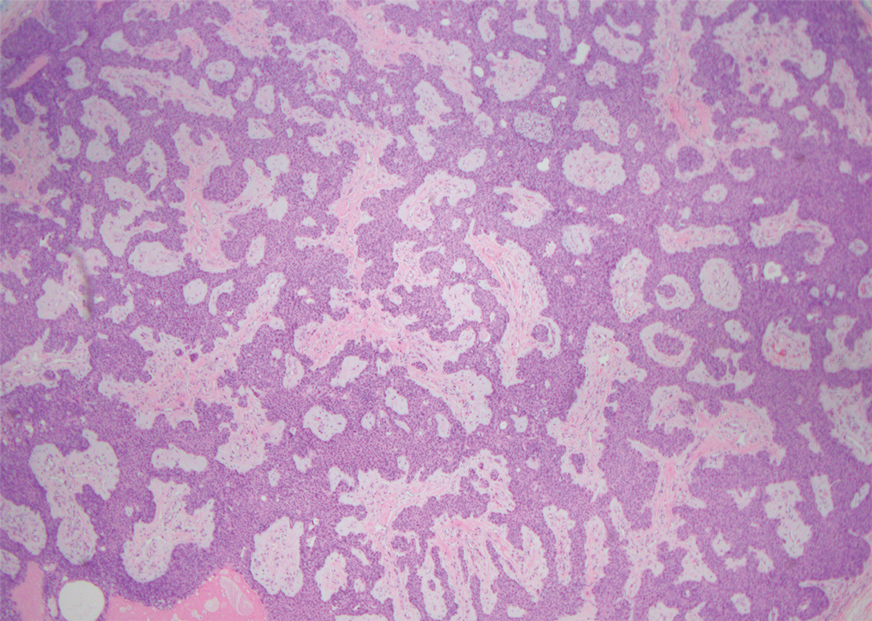

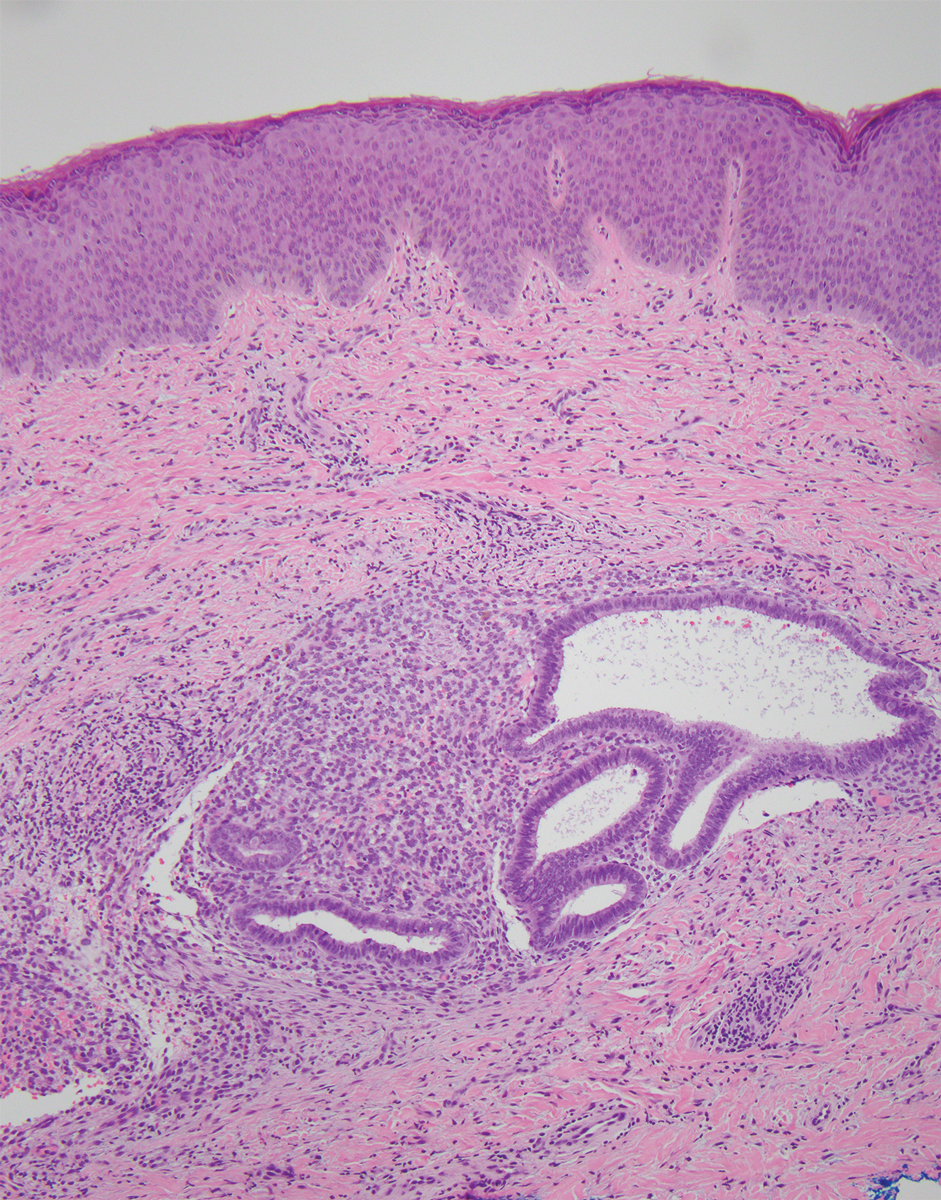

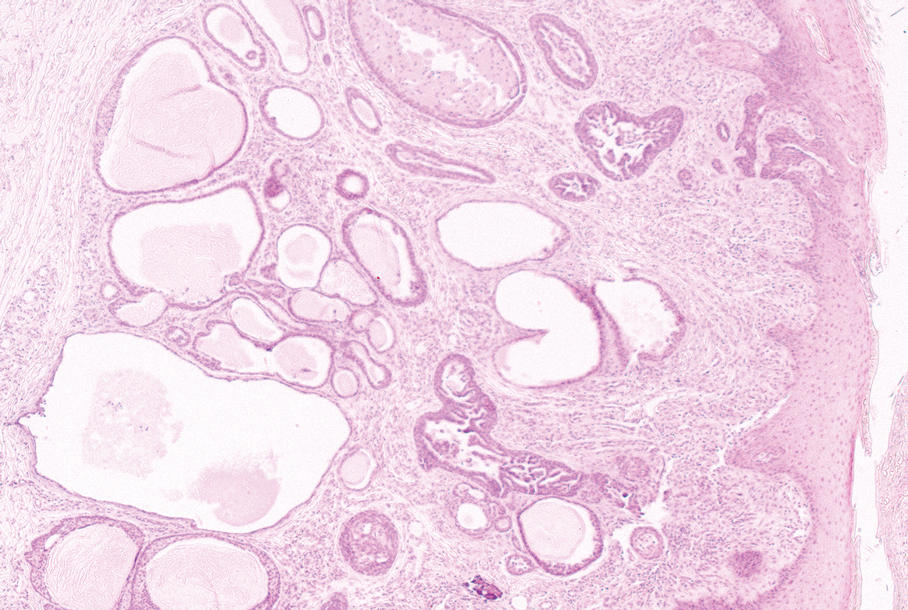

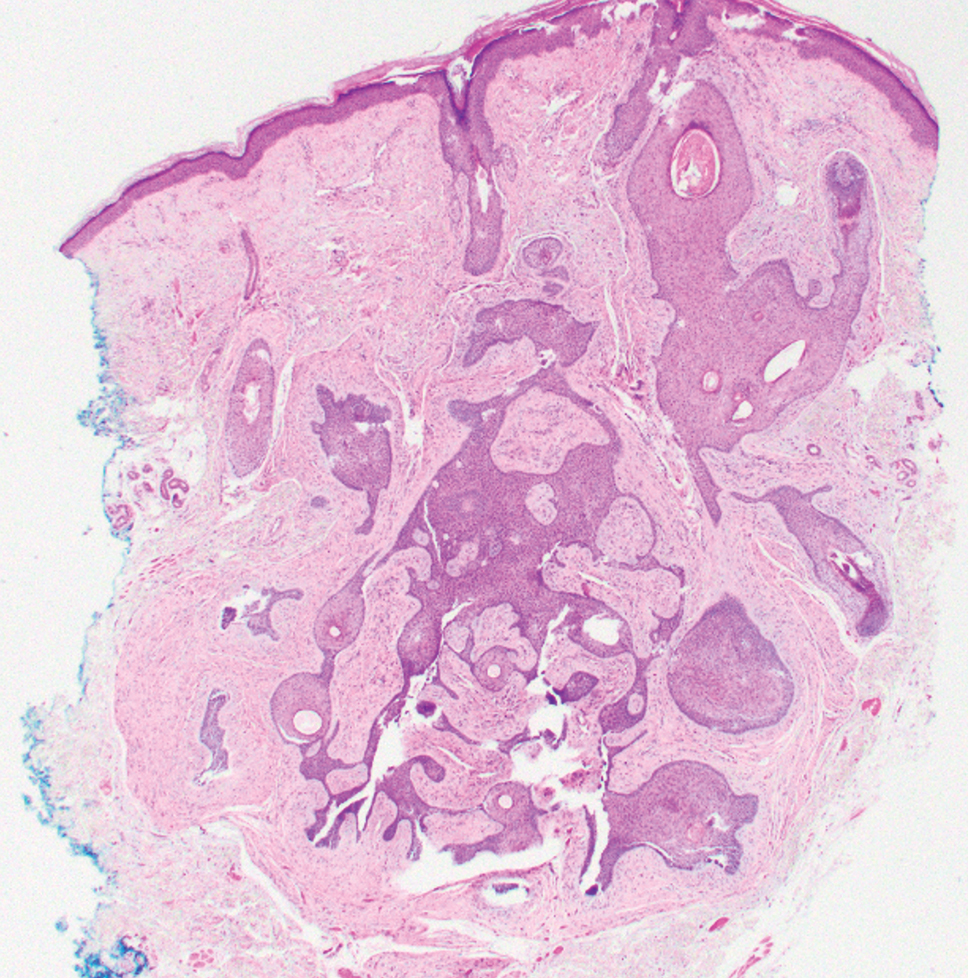

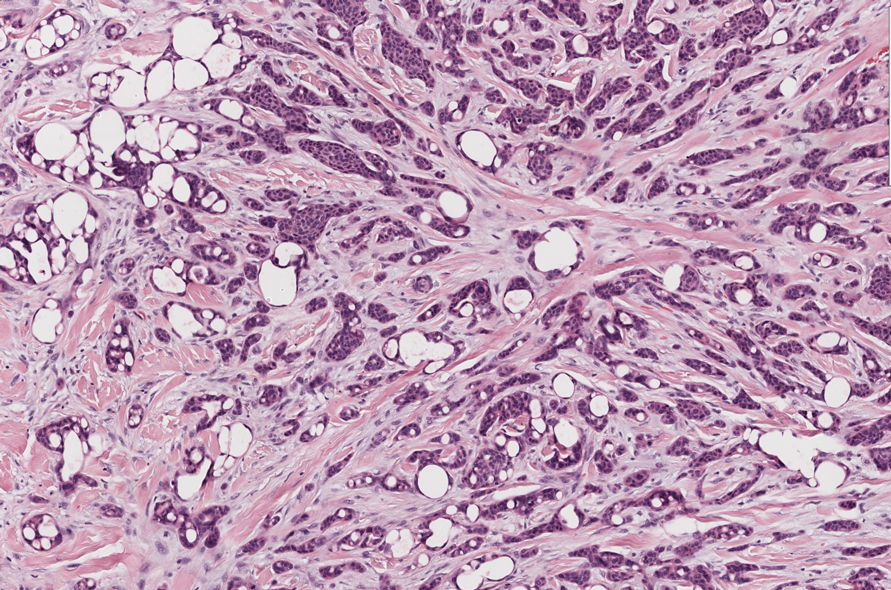

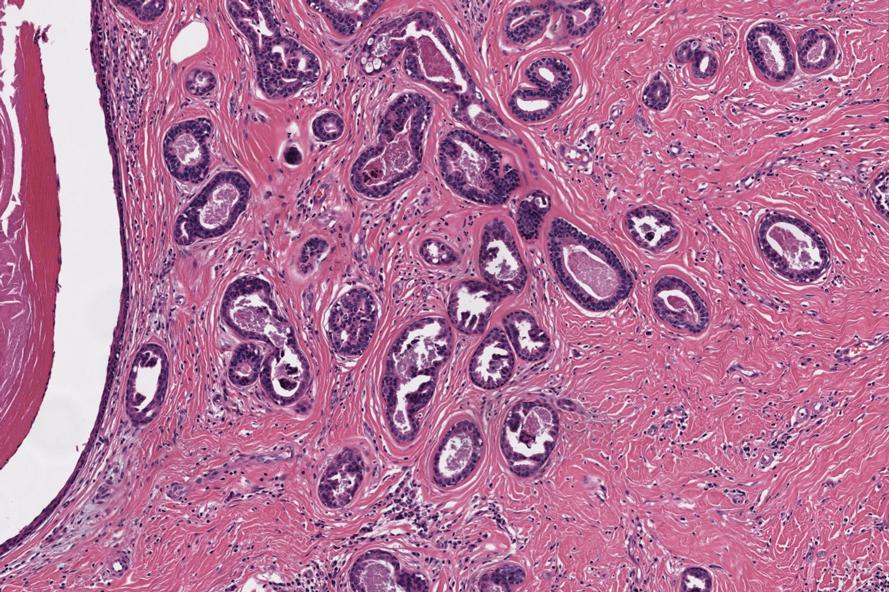

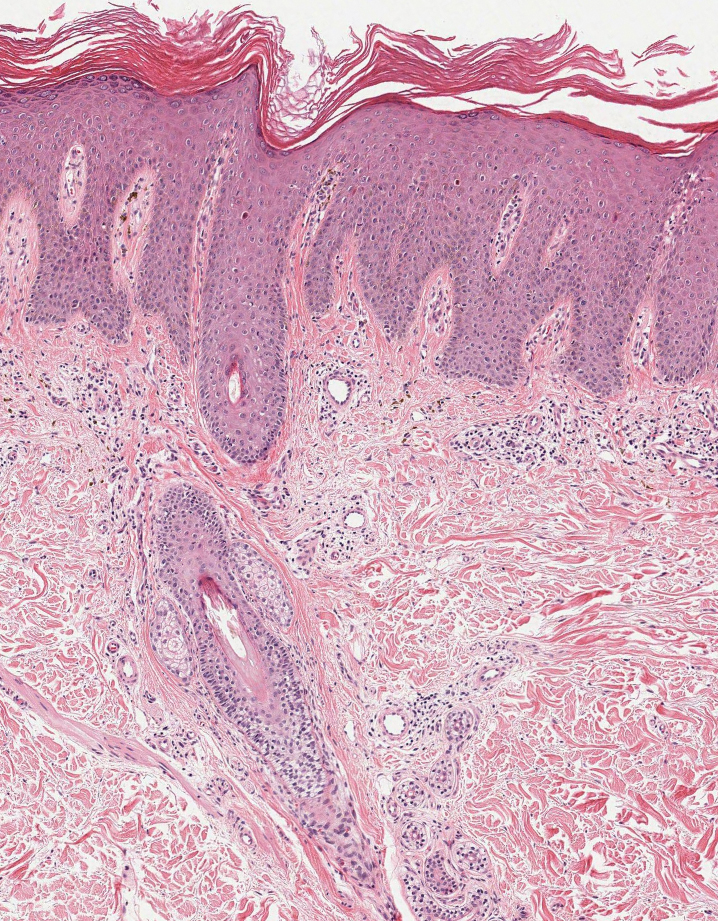

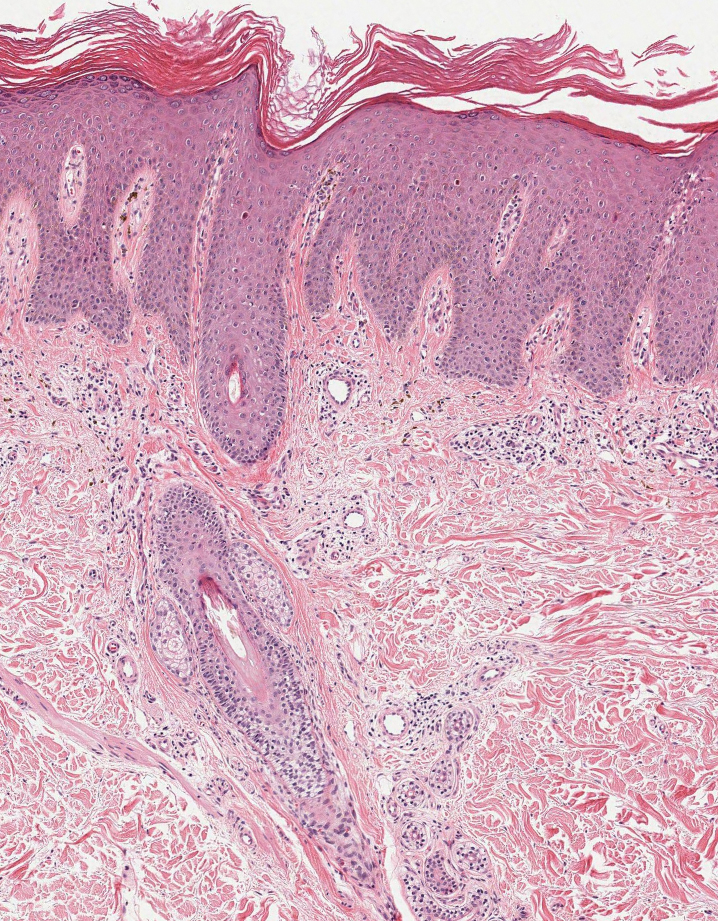

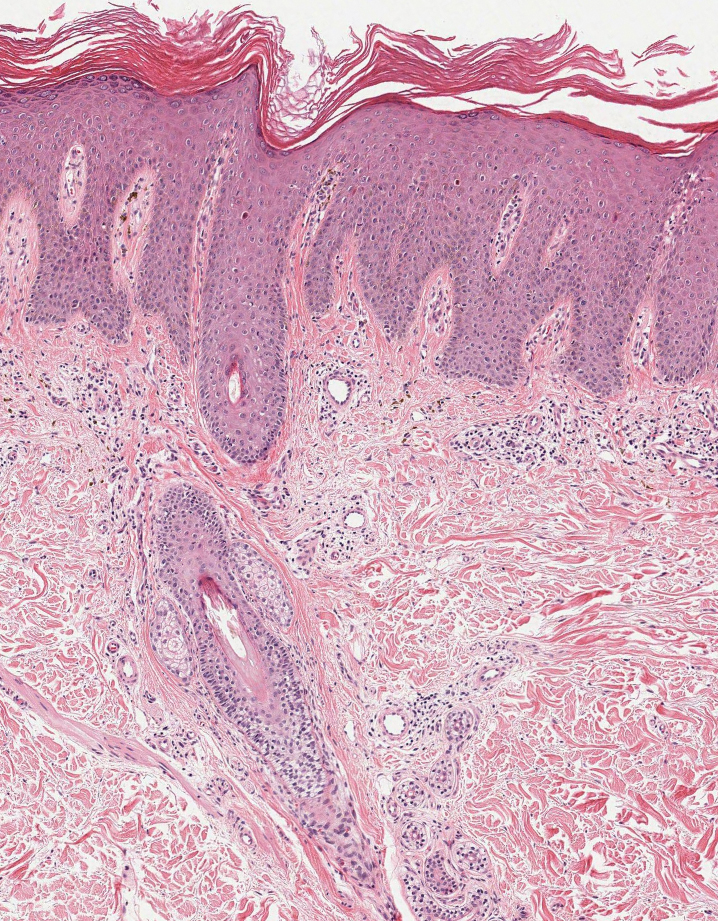

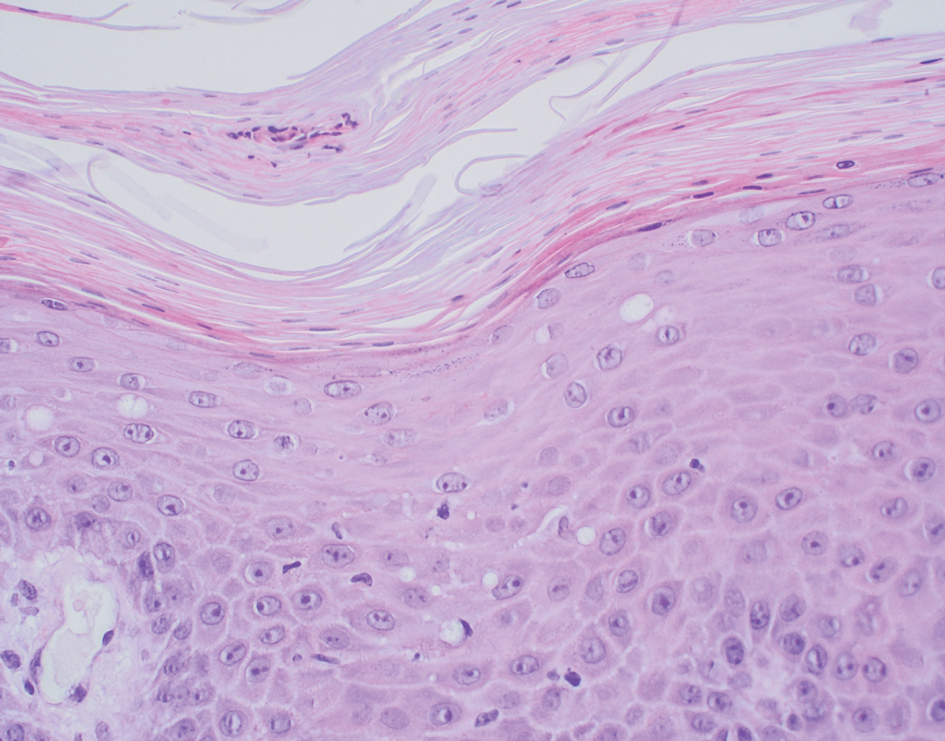

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common cutaneous malignancy. It rarely metastasizes but can be locally destructive.8 Basal cell carcinomas typically occur on sun-exposed skin in middle-aged and elderly patients and classically manifest as pink or flesh-colored pearly papules with rolled borders and overlying telangiectasia.9 Risk factors for BCC include a chronic sun exposure, lighter skin phenotypes, immunosuppression, and a family history of skin cancer. The 2 most common subtypes of BCC are nodular and superficial, which comprise around 85% of BCCs.10 Histologically, nodular BCCs demonstrate nests of malignant basaloid cells with central disorganization, peripheral palisading, tumor-stroma clefting, and a mucoid stroma with spindle cells (Figure 1). Superficial BCC manifests with small islands of malignant basaloid cells with peripheral palisading that connect with the epidermis, often with a lichenoid inflammatory infiltrate.9 Basal cell carcinomas stain positively for Ber-EP4 and are associated with patched 1 (PTCH1), patched 2 (PTCH2), and tumor protein 53 (TP53) gene mutations.9,11

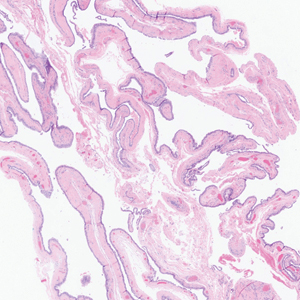

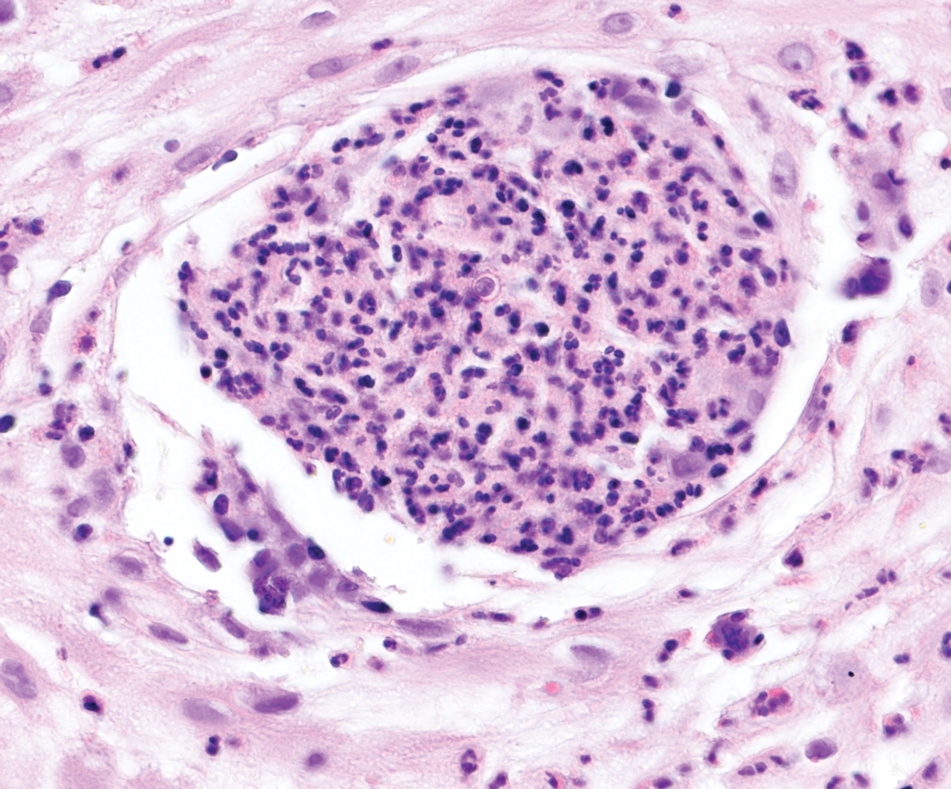

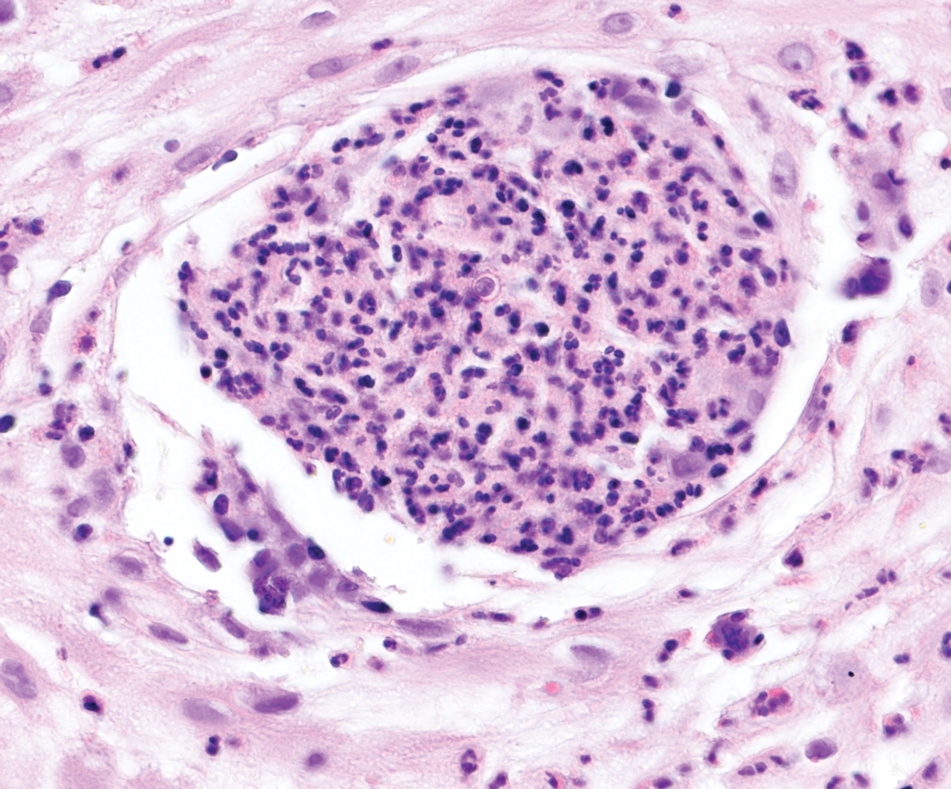

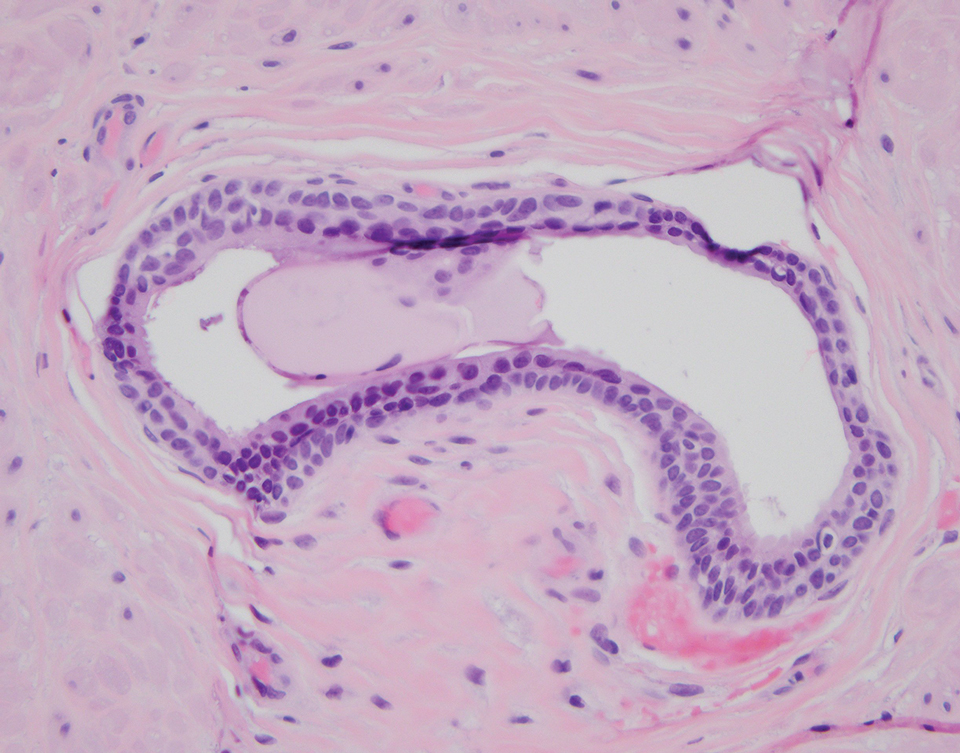

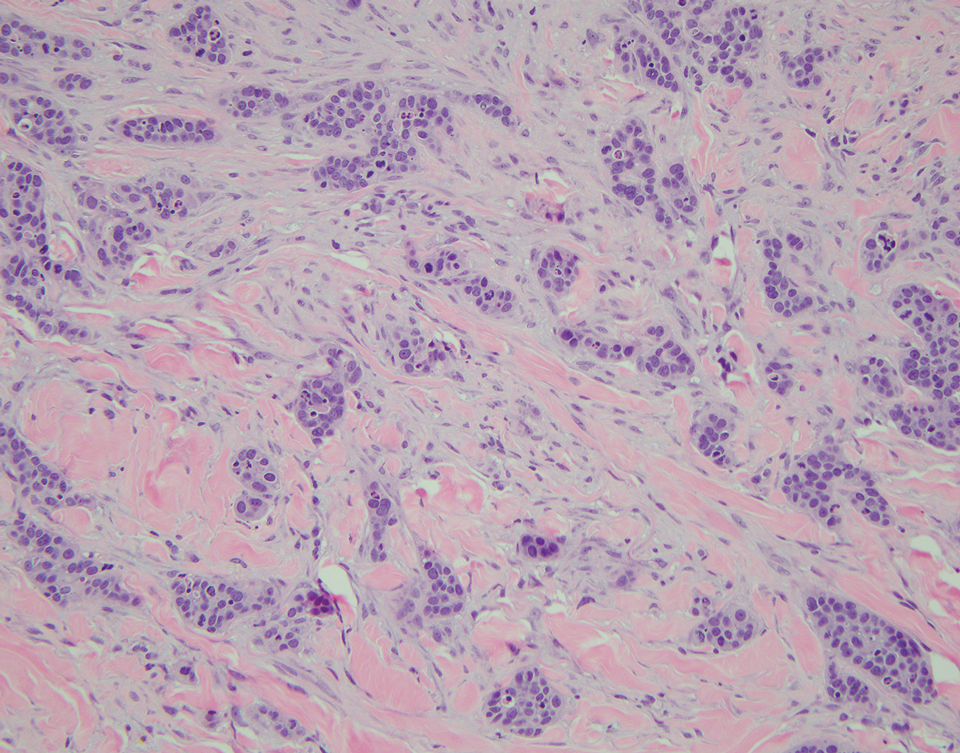

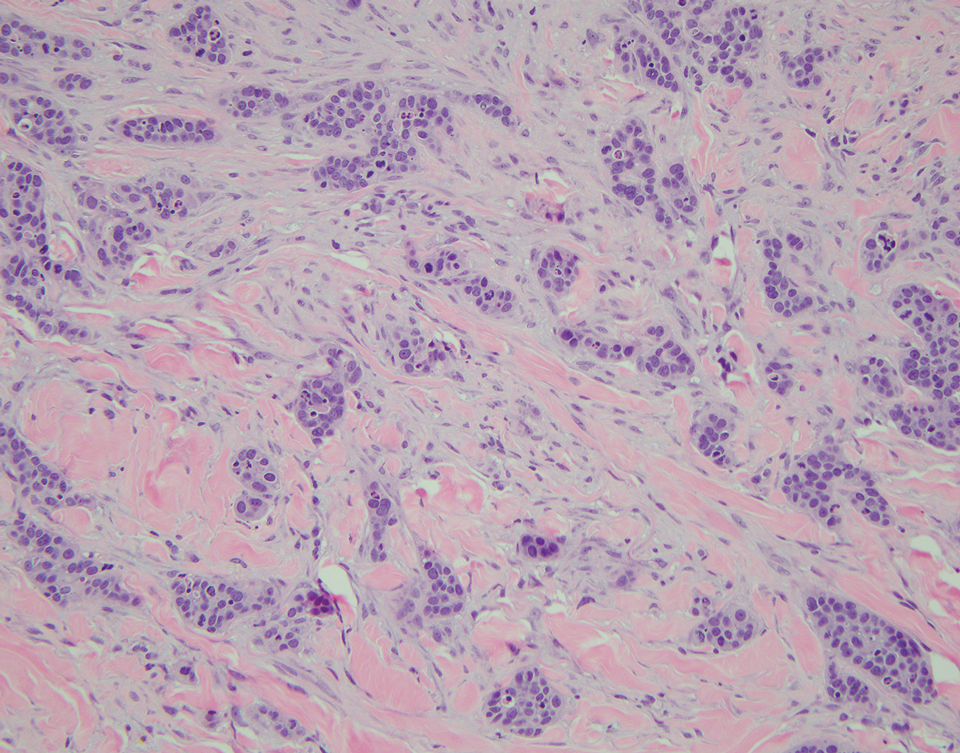

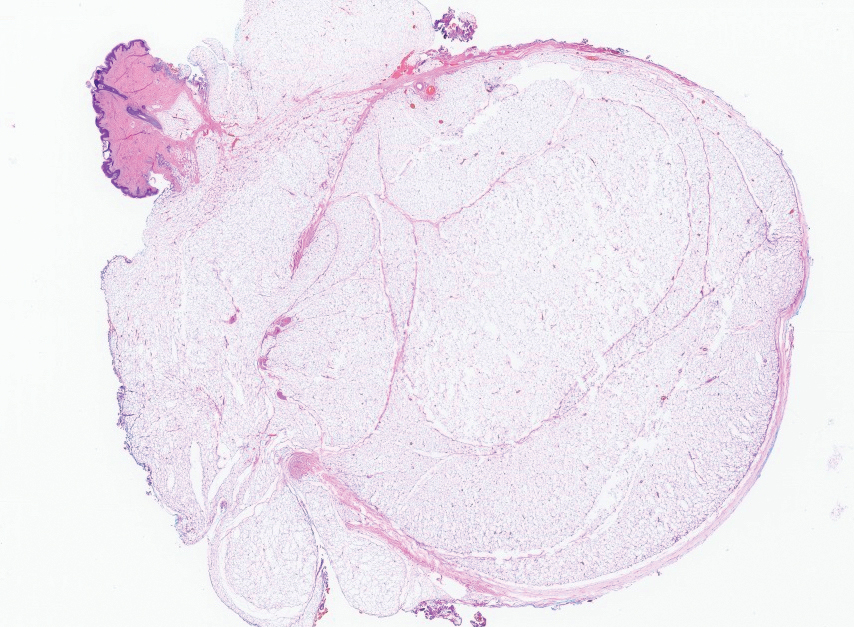

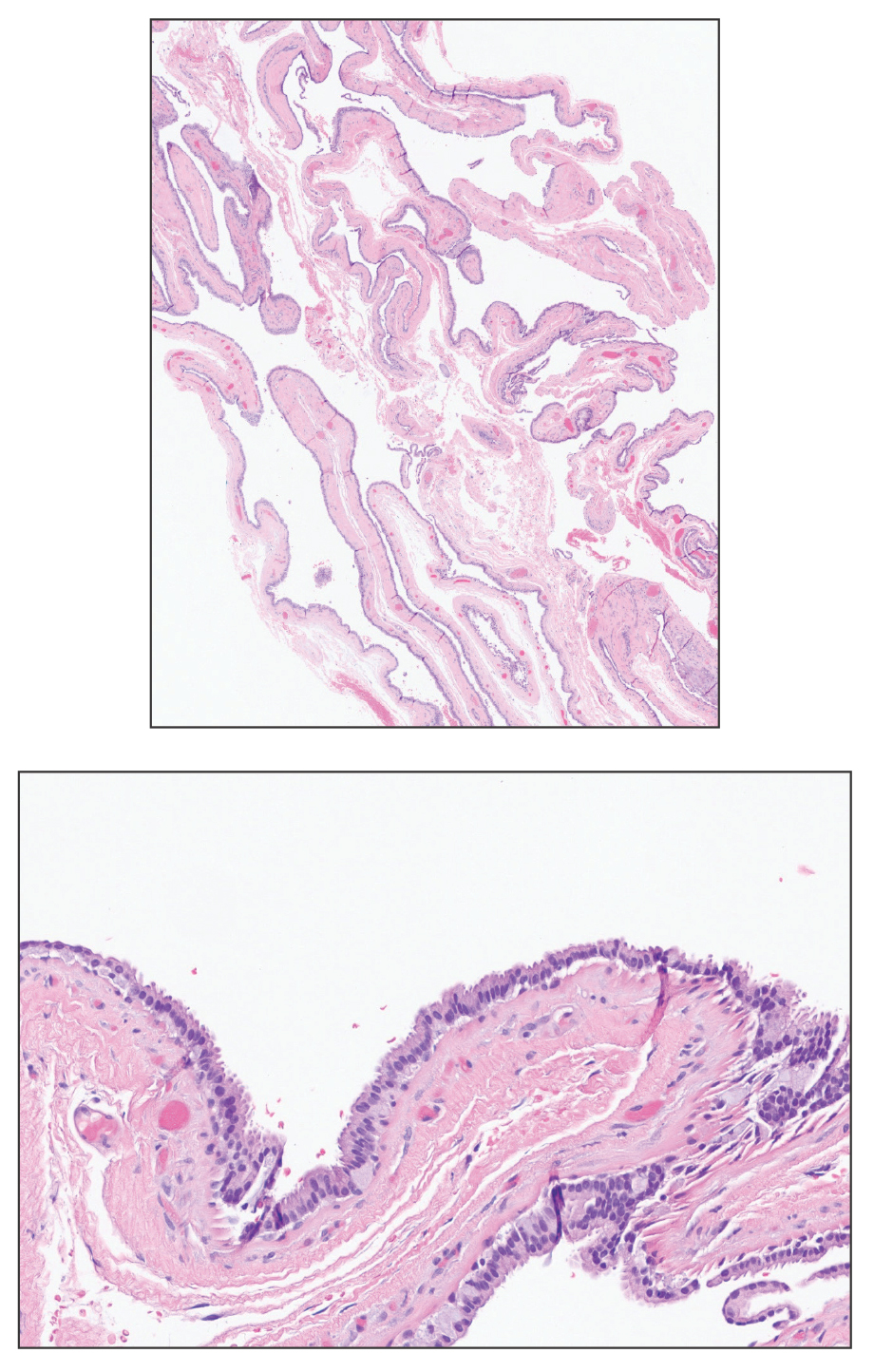

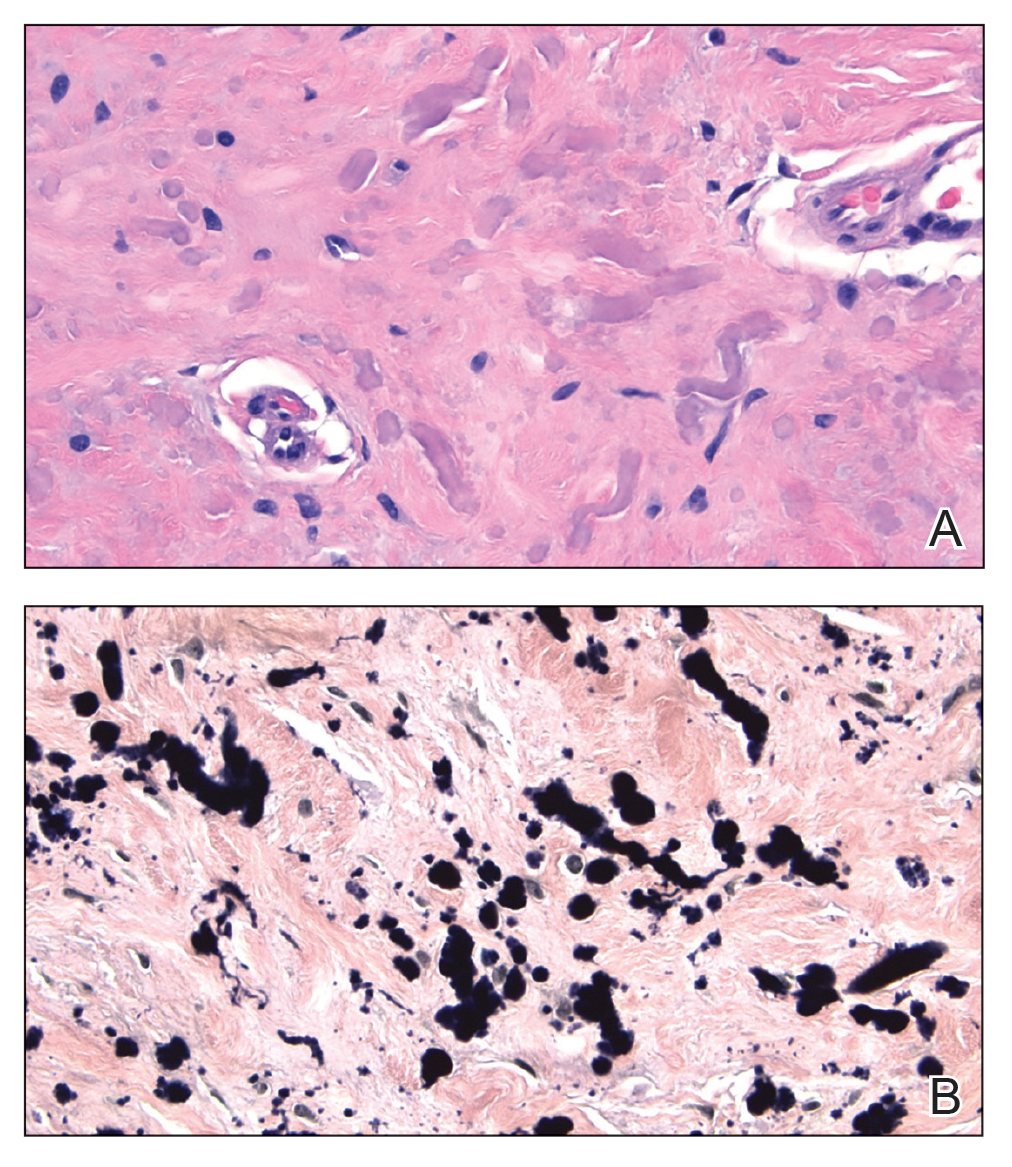

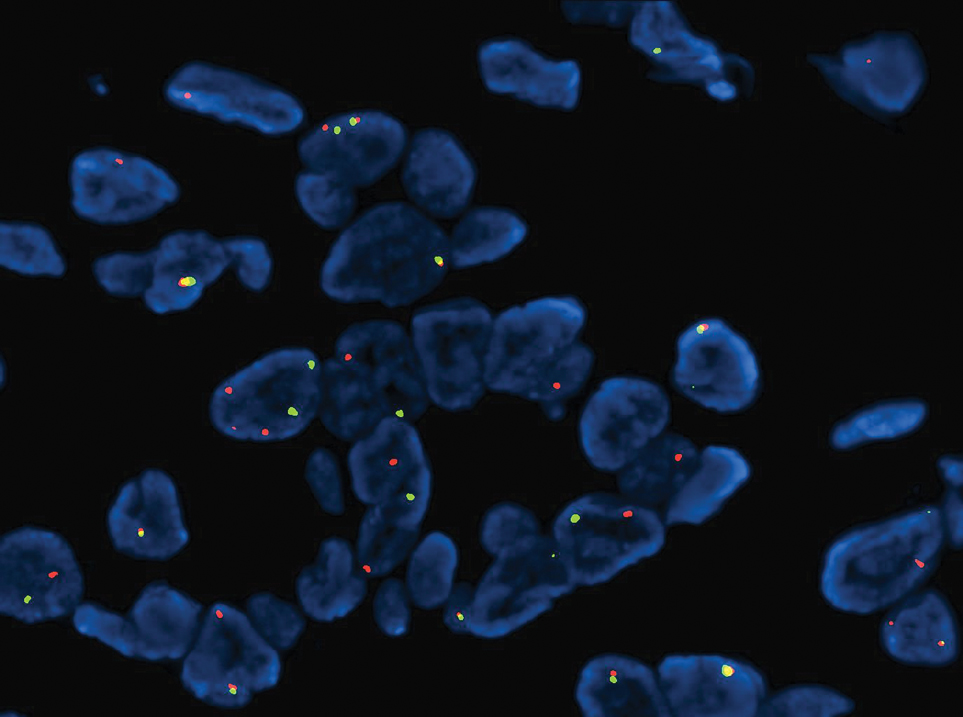

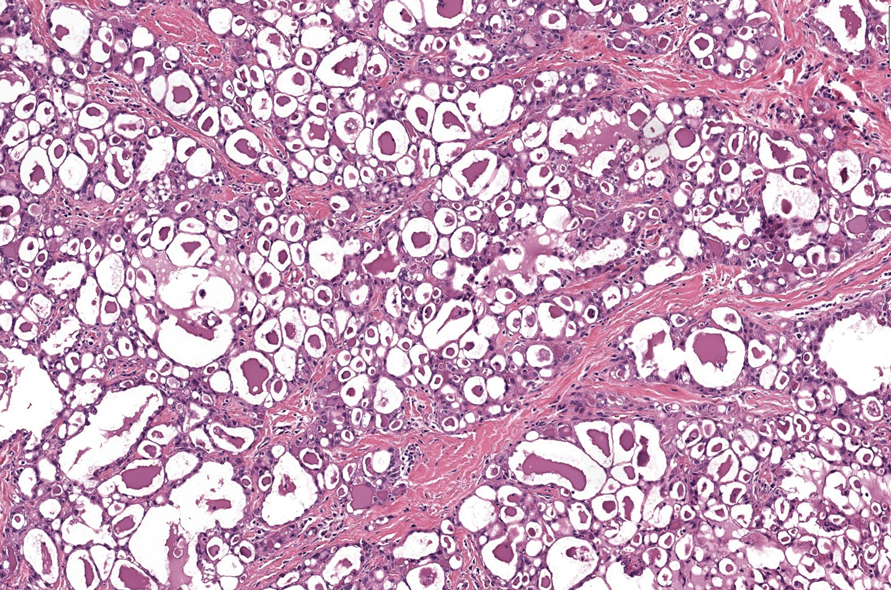

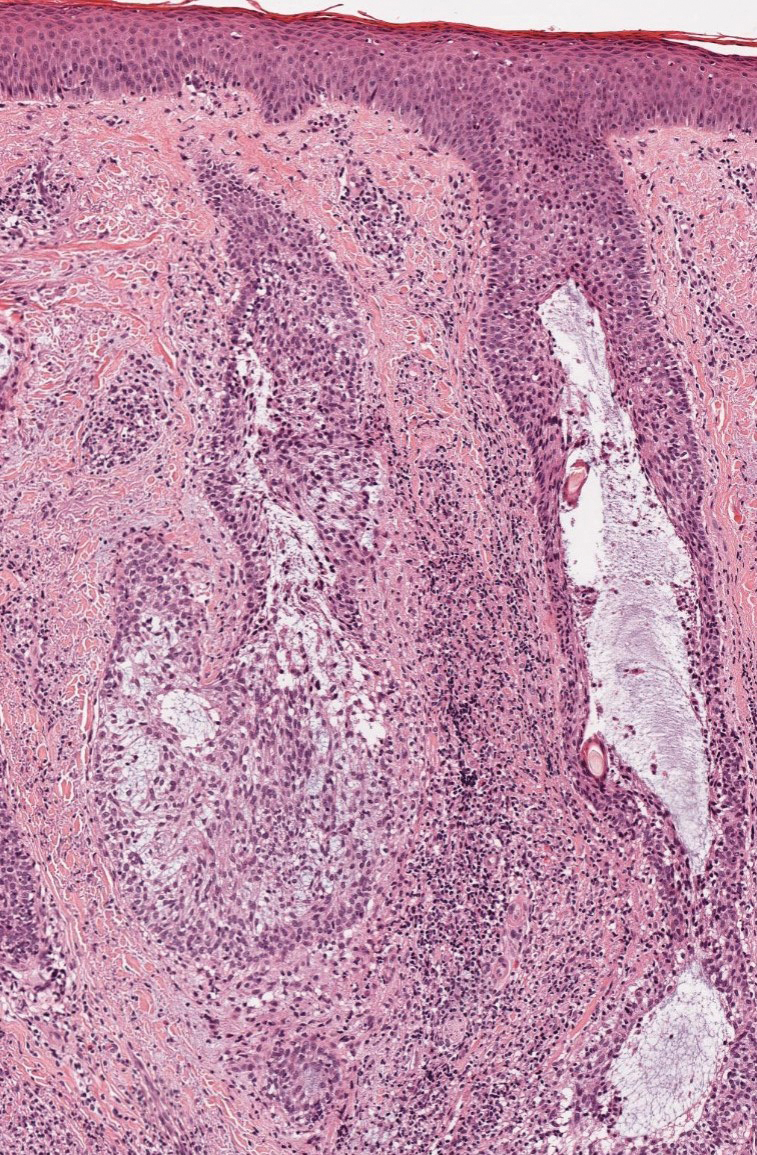

Spiradenomas are benign adnexal tumors manifesting as painful, usually singular, 1- to 3-cm nodules in younger adults.12 Histologically, spiradenomas have large clusters of small irregularly shaped aggregations of small basaloid and large polygonal cells with surrounding hyalinized basement membrane material and intratumoral lymphocytes (Figure 2).4 Spiradenomas stain positive for p63, D2-40, and CK7 and are associated with cylindromatosis lysine 63 deubiquitinase (CYLD) and alpha-protein kinase 1 (ALPK1) gene mutations.5

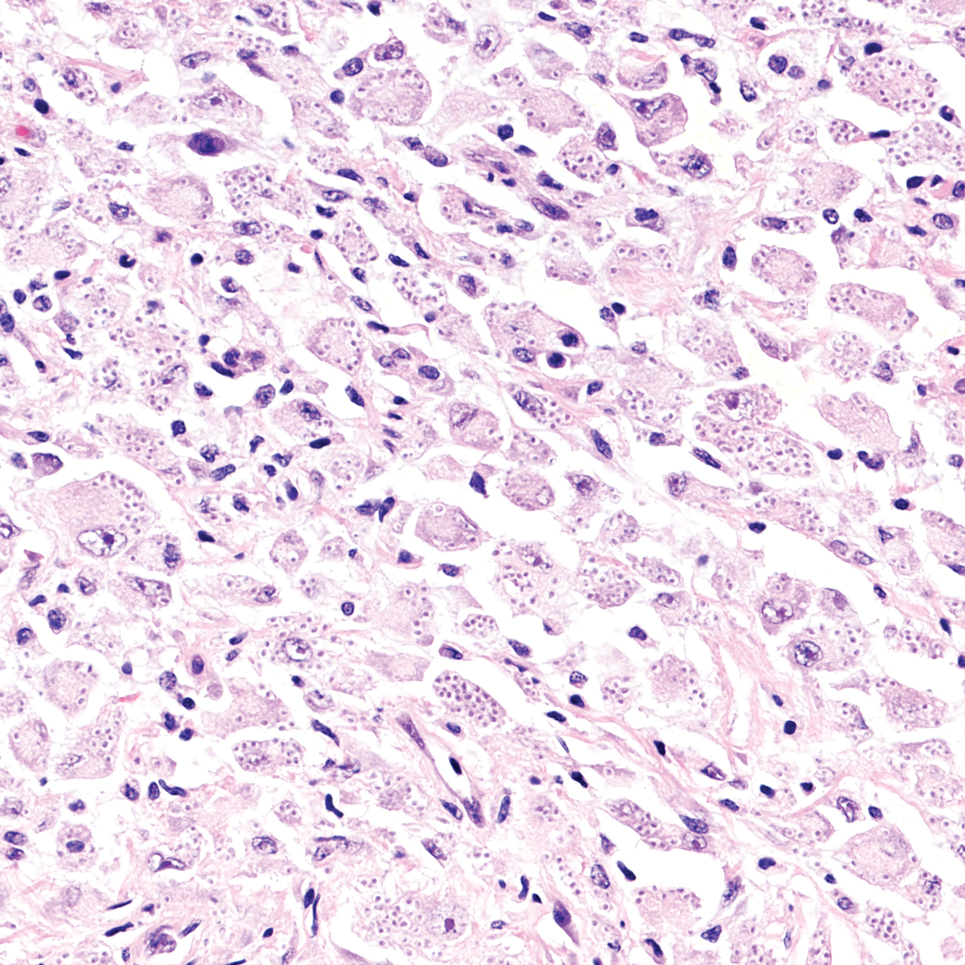

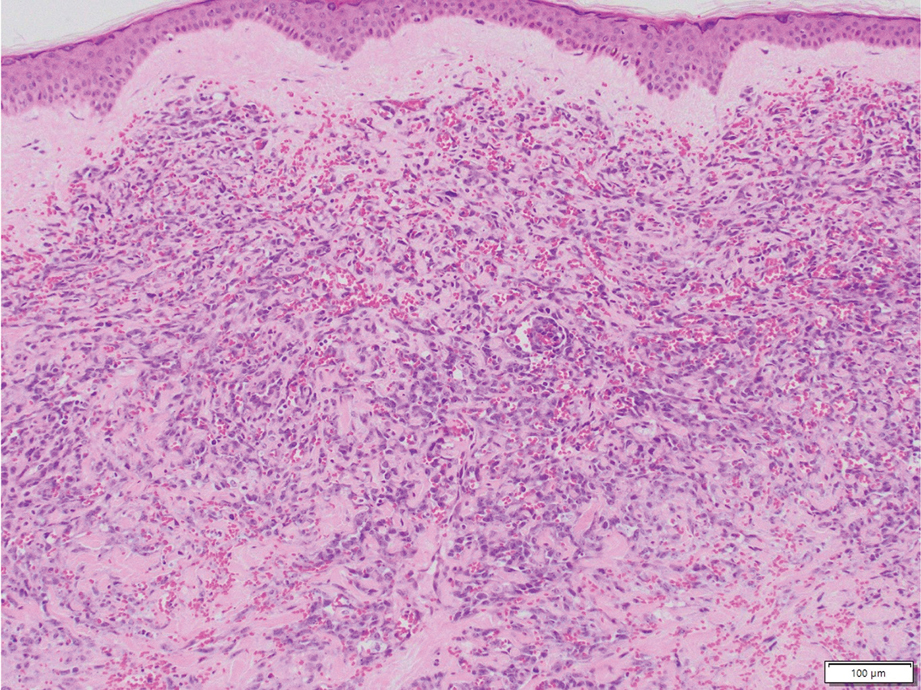

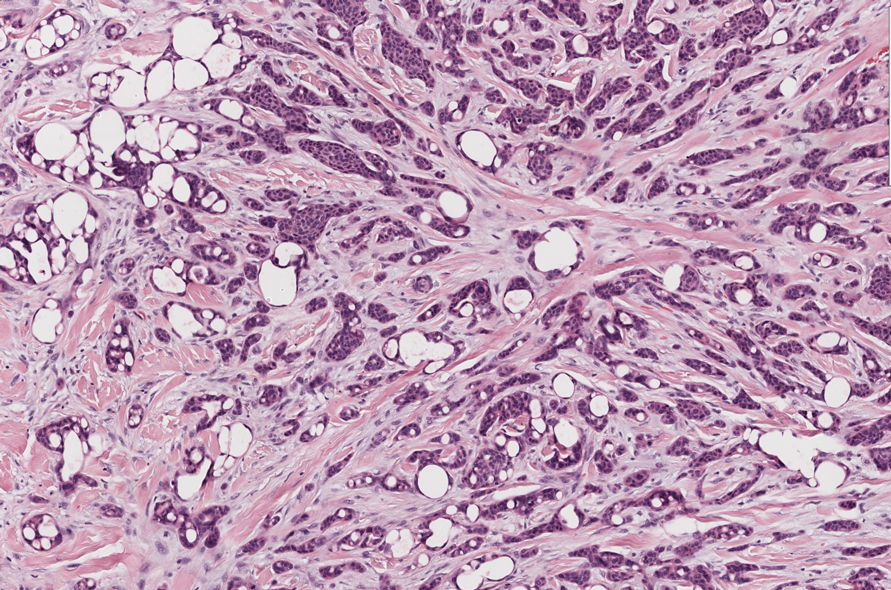

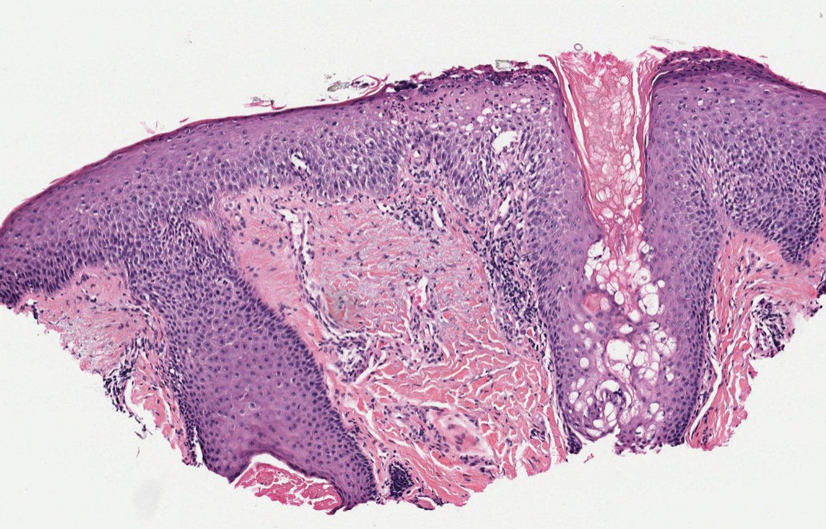

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the second most common nonmelanoma skin cancer worldwide.13 Lesions typically develop on sun-exposed skin and manifest as red, hyperkeratotic, and sometimes ulcerated plaques or nodules.14 Risk factors for SCC include chronic sun exposure, lighter skin phenotypes, increased age, and immunosuppression. Histologically, there are several variants of SCC: low-risk variants include keratoacanthomas, verrucous carcinomas, and clear cell SCC, and high-risk variants include acantholytic SCC, spindle cell SCC, and adenosquamous carcinoma.14 Generally, low-grade SCC will have well-differentiated or moderately differentiated intercellular bridges or keratin pearls with tumor cells in a solid or sheetlike pattern (Figure 3). High-grade SCC will be poorly differentiated with the presence of infiltrating individual tumor cells.15 Immunohistochemically, SCC stains positive for p63, p40, AE1/AE3, CK5/6, and MNF116 while Ber-Ep4 is negative.14,15 Poorly differentiated SCCs have high rates of mutation, commonly in the tumor protein 53 (TP53), Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A), Ras pathway, and notch receptor 1 (NOTCH-1) genes.13

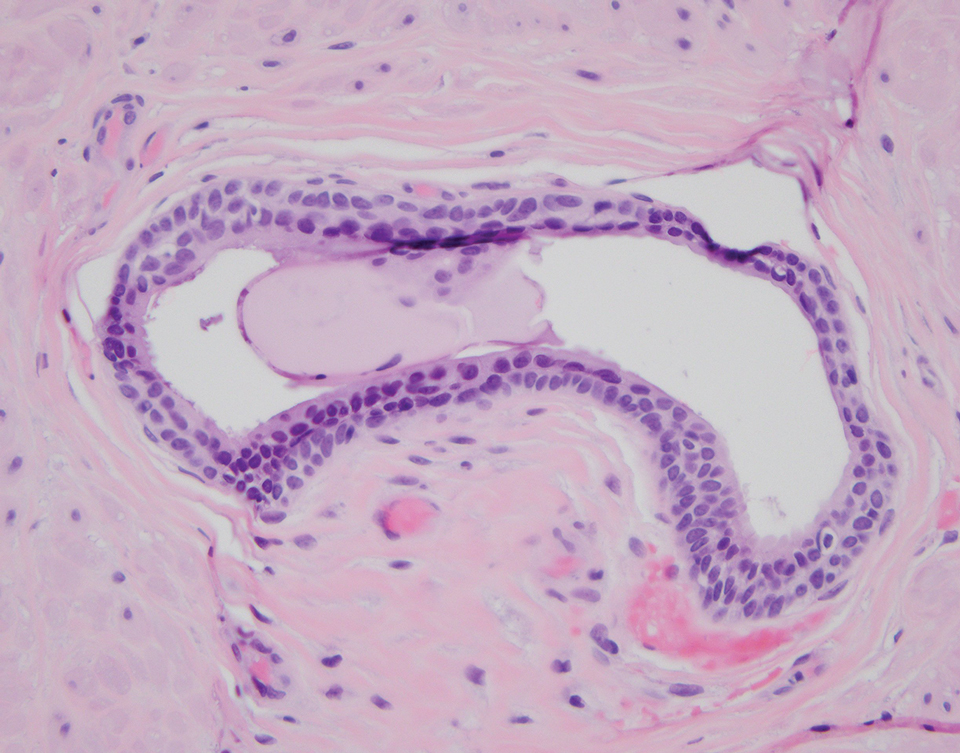

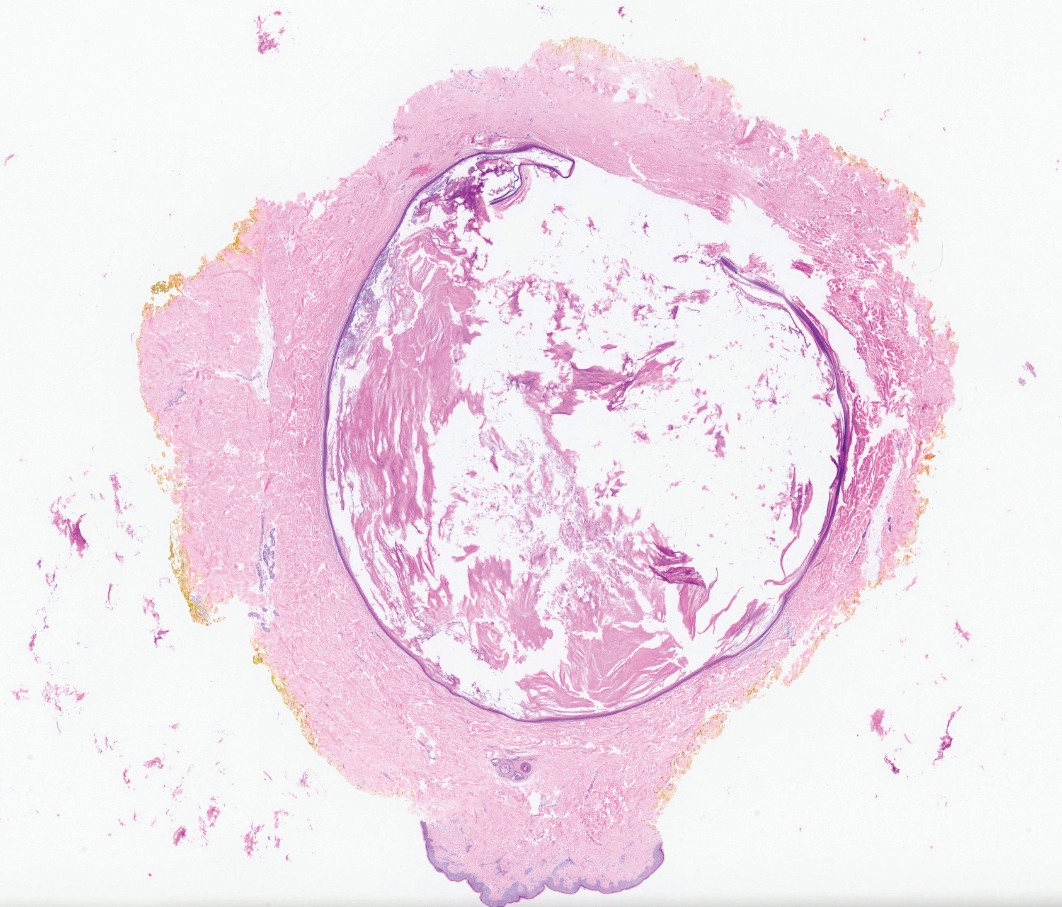

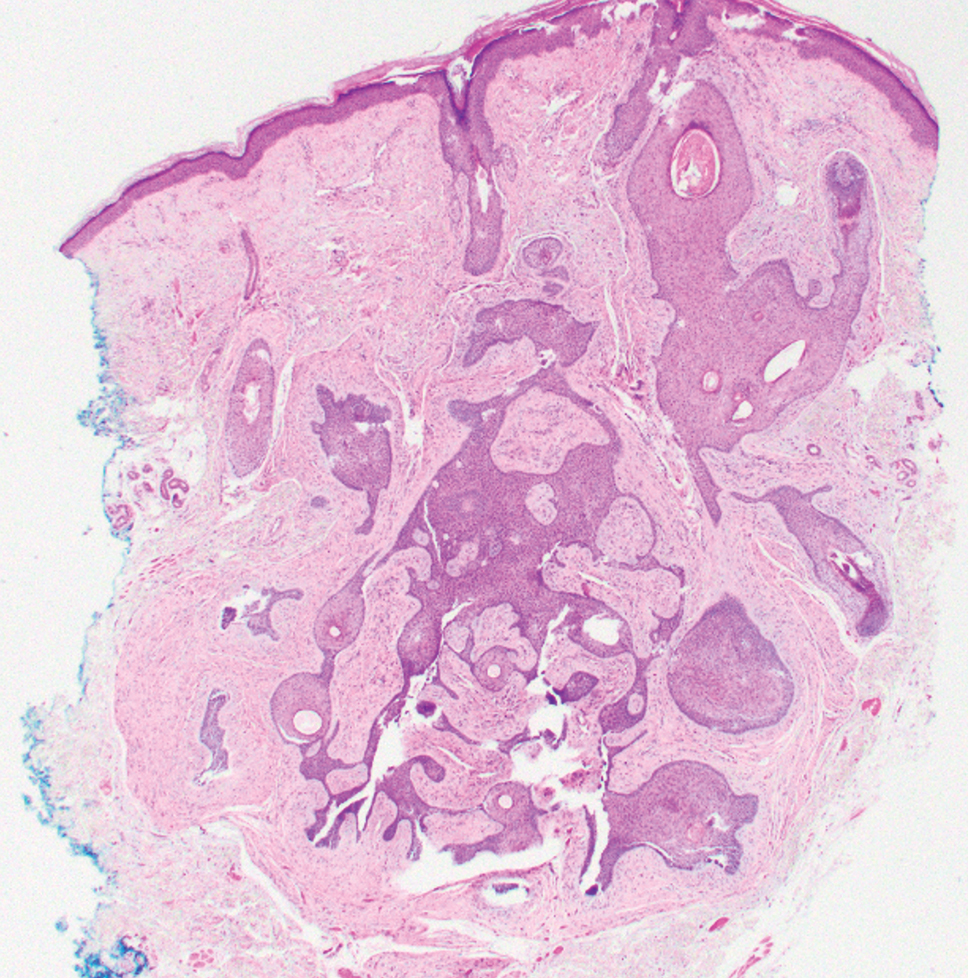

Syringomas are benign adnexal tumors that manifest as multiple soft, yellow to flesh-colored, 1- to 2-mm papules typically located on the lower eyelids, most commonly in women of reproductive age.16 Syringomas are described on histology as small comma-shaped nests with cords of eosinophilic to clear cells with central ducts surrounded by a sclerotic stroma (Figure 4). They stain positively for carcinoembryonic antigen, epithelial membrane antigen, and CK-5 and are associated with genetic mutations in phosphatidylinositol-4, 5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha (PIK3CA) and AKT serine/threonine kinase 1 (ATK1).4

Due to its regular exposure to sunlight, the eyelid accounts for 5% to 10% of all skin malignancies. Common eyelid lesions include squamous papilloma, seborrheic keratosis, epidermal inclusion cyst, hidrocystoma, intradermal nevus, BCC, SCC, and sebaceous carcinoma.17 Aside from syringomas, benign sweat gland tumors like poromas, hidradenomas, and spiradenomas usually do not manifest on the eyelids but should be included in the differential diagnosis of an unidentifiable lesion due to the small risk for malignant transformation. Eyelid poromas manifest polymorphically, most commonly being clinically diagnosed as BCC, making the histologic examination key for proper diagnosis and management.18

THE DIAGNOSIS: Poroma

Poromas are benign adnexal neoplasms that often are classified into the broader category of acrospiromas. They most commonly affect areas with a high density of eccrine sweat glands, such as the palms and soles, but also can appear in any area of the body with sweat glands.1 Poromas may have cuboidal eccrine cells with ovoid nuclei and a delicate vascularized stroma on histology or may show apocrinelike features with sebaceous cells.2,3 Immunohistochemically, poromas stain positively for carcinoembryonic antigen, epithelial membrane antigen, and periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) with diastase sensitivity.1,4 Cytokeratin (CK) 1 and CK-10 are expressed in the tumor nests.1

Poromas are the benign counterpart of porocarcinomas, which can recur and may become invasive and metastasize. Porocarcinomas have been shown to undergo malignant transformation from poromas as well as develop de novo.5 Histologic differentiation between the 2 conditions is key in determining excisional margins for treatment and follow-up. Poromas are histologically similar to porocarcinomas, but the latter show invasion into the dermis, nuclear and cytoplasmic pleomorphism, nuclear hyperchromatism, and increased mitotic activity.6 S-100 protein can be positive in porocarcinoma.7 Both poromas and porocarcinomas are associated with Yes-associated protein 1 (YAP1), Mastermind-like protein 2 (MAML2), and NUT midline carcinoma family member 1 (NUTM1) gene fusions.5

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common cutaneous malignancy. It rarely metastasizes but can be locally destructive.8 Basal cell carcinomas typically occur on sun-exposed skin in middle-aged and elderly patients and classically manifest as pink or flesh-colored pearly papules with rolled borders and overlying telangiectasia.9 Risk factors for BCC include a chronic sun exposure, lighter skin phenotypes, immunosuppression, and a family history of skin cancer. The 2 most common subtypes of BCC are nodular and superficial, which comprise around 85% of BCCs.10 Histologically, nodular BCCs demonstrate nests of malignant basaloid cells with central disorganization, peripheral palisading, tumor-stroma clefting, and a mucoid stroma with spindle cells (Figure 1). Superficial BCC manifests with small islands of malignant basaloid cells with peripheral palisading that connect with the epidermis, often with a lichenoid inflammatory infiltrate.9 Basal cell carcinomas stain positively for Ber-EP4 and are associated with patched 1 (PTCH1), patched 2 (PTCH2), and tumor protein 53 (TP53) gene mutations.9,11

Spiradenomas are benign adnexal tumors manifesting as painful, usually singular, 1- to 3-cm nodules in younger adults.12 Histologically, spiradenomas have large clusters of small irregularly shaped aggregations of small basaloid and large polygonal cells with surrounding hyalinized basement membrane material and intratumoral lymphocytes (Figure 2).4 Spiradenomas stain positive for p63, D2-40, and CK7 and are associated with cylindromatosis lysine 63 deubiquitinase (CYLD) and alpha-protein kinase 1 (ALPK1) gene mutations.5

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the second most common nonmelanoma skin cancer worldwide.13 Lesions typically develop on sun-exposed skin and manifest as red, hyperkeratotic, and sometimes ulcerated plaques or nodules.14 Risk factors for SCC include chronic sun exposure, lighter skin phenotypes, increased age, and immunosuppression. Histologically, there are several variants of SCC: low-risk variants include keratoacanthomas, verrucous carcinomas, and clear cell SCC, and high-risk variants include acantholytic SCC, spindle cell SCC, and adenosquamous carcinoma.14 Generally, low-grade SCC will have well-differentiated or moderately differentiated intercellular bridges or keratin pearls with tumor cells in a solid or sheetlike pattern (Figure 3). High-grade SCC will be poorly differentiated with the presence of infiltrating individual tumor cells.15 Immunohistochemically, SCC stains positive for p63, p40, AE1/AE3, CK5/6, and MNF116 while Ber-Ep4 is negative.14,15 Poorly differentiated SCCs have high rates of mutation, commonly in the tumor protein 53 (TP53), Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A), Ras pathway, and notch receptor 1 (NOTCH-1) genes.13

Syringomas are benign adnexal tumors that manifest as multiple soft, yellow to flesh-colored, 1- to 2-mm papules typically located on the lower eyelids, most commonly in women of reproductive age.16 Syringomas are described on histology as small comma-shaped nests with cords of eosinophilic to clear cells with central ducts surrounded by a sclerotic stroma (Figure 4). They stain positively for carcinoembryonic antigen, epithelial membrane antigen, and CK-5 and are associated with genetic mutations in phosphatidylinositol-4, 5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha (PIK3CA) and AKT serine/threonine kinase 1 (ATK1).4

Due to its regular exposure to sunlight, the eyelid accounts for 5% to 10% of all skin malignancies. Common eyelid lesions include squamous papilloma, seborrheic keratosis, epidermal inclusion cyst, hidrocystoma, intradermal nevus, BCC, SCC, and sebaceous carcinoma.17 Aside from syringomas, benign sweat gland tumors like poromas, hidradenomas, and spiradenomas usually do not manifest on the eyelids but should be included in the differential diagnosis of an unidentifiable lesion due to the small risk for malignant transformation. Eyelid poromas manifest polymorphically, most commonly being clinically diagnosed as BCC, making the histologic examination key for proper diagnosis and management.18

- Patterson J. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 5th ed. Elsevier Limited; 2021.

- Aoki K, Baba S, Nohara T, et al. Eccrine poroma. J Dermatol. 1980; 7:263-269. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.1980.tb01967.x

- Harvell JD, Kerschmann RL, LeBoit PE. Eccrine or apocrine poroma? six poromas with divergent adnexal differentiation. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:1-9. doi:10.1097/00000372-199602000-00001

- Miller AC, Adjei S, Temiz LA, et al. Dermal duct tumor: a diagnostic dilemma. Dermatopathology. 2022;9:36-47. doi:10.3390

- Macagno N, Sohier P, Kervarrec T, et al. Recent advances on immunohistochemistry and molecular biology for the diagnosis of adnexal sweat gland tumors. Cancers. 2022;14:476. doi:10.3390/cancers14030476

- Robson A, Greene J, Ansari N, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma (malignant eccrine poroma): a clinicopathologic study of 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:710-720. doi:10.1097/00000478-200106000-00002 /dermatopathology9010007

- Kurisu Y, Tsuji M, Yasuda E, et al. A case of eccrine porocarcinoma: usefulness of immunostain for S-100 protein in the diagnoses of recurrent and metastatic dedifferentiated lesions. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:348-351. doi:10.5021/ad.2013.25.3.348

- Stanoszek LM, Wang GY, Harms PW. Histologic mimics of basal cell carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017;141:1490-1502. doi:10.5858 /arpa.2017-0222-RA

- Niculet E, Craescu M, Rebegea L, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: comprehensive clinical and histopathological aspects, novel imaging tools and therapeutic approaches (review). Exp Ther Med. 2022;23:60. doi:10.3892/etm.2021.10982

- Pelucchi C, Di Landro A, Naldi L, et al. Risk factors for histological types and anatomic sites of cutaneous basal-cell carcinoma: an Italian case-control study. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:935-944. doi:10.1038/sj.jid.5700598

- Sunjaya AP, Sunjaya AF, Tan ST. The use of BEREP4 immunohistochemistry staining for detection of basal cell carcinoma. J Skin Cancer. 2017;2017:2692604. doi:10.1155/2017/2692604

- Kim J, Yang HJ, Pyo JS. Eccrine spiradenoma of the scalp. Arch Craniofacial Surg. 2017;18:211-213. doi:10.7181/acfs.2017.18.3.211

- Que SKT, Zwald FO, Schmults CD. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: incidence, risk factors, diagnosis, and staging. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:237-247. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.059

- Waldman A, Schmults C. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:1-12. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2018.08.001

- Yanofsky VR, Mercer SE, Phelps RG. Histopathological variants of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a review. J Skin Cancer. 2011;2011:210813. doi:10.1155/2011/210813

- Lee JH, Chang JY, Lee KH. Syringoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistologic study and results of treatment. Yonsei Med J. 2007;48:35-40. doi:10.3349/ymj.2007.48.1.35

- Adamski WZ, Maciejewski J, Adamska K, et al. The prevalence of various eyelid skin lesions in a single-centre observation study. Adv Dermatol Allergol Dermatol Alergol. 2021;38:804-807. doi:10.5114 /ada.2020.95652

- Mencía-Gutiérrez E, Navarro-Perea C, Gutiérrez-Díaz E, et al. Eyelid eccrine poroma: a case report and review of literature. Cureus. 202:12:E8906. doi:10.7759/cureus.8906

- Patterson J. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 5th ed. Elsevier Limited; 2021.

- Aoki K, Baba S, Nohara T, et al. Eccrine poroma. J Dermatol. 1980; 7:263-269. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.1980.tb01967.x

- Harvell JD, Kerschmann RL, LeBoit PE. Eccrine or apocrine poroma? six poromas with divergent adnexal differentiation. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:1-9. doi:10.1097/00000372-199602000-00001

- Miller AC, Adjei S, Temiz LA, et al. Dermal duct tumor: a diagnostic dilemma. Dermatopathology. 2022;9:36-47. doi:10.3390

- Macagno N, Sohier P, Kervarrec T, et al. Recent advances on immunohistochemistry and molecular biology for the diagnosis of adnexal sweat gland tumors. Cancers. 2022;14:476. doi:10.3390/cancers14030476

- Robson A, Greene J, Ansari N, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma (malignant eccrine poroma): a clinicopathologic study of 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:710-720. doi:10.1097/00000478-200106000-00002 /dermatopathology9010007

- Kurisu Y, Tsuji M, Yasuda E, et al. A case of eccrine porocarcinoma: usefulness of immunostain for S-100 protein in the diagnoses of recurrent and metastatic dedifferentiated lesions. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:348-351. doi:10.5021/ad.2013.25.3.348

- Stanoszek LM, Wang GY, Harms PW. Histologic mimics of basal cell carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017;141:1490-1502. doi:10.5858 /arpa.2017-0222-RA

- Niculet E, Craescu M, Rebegea L, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: comprehensive clinical and histopathological aspects, novel imaging tools and therapeutic approaches (review). Exp Ther Med. 2022;23:60. doi:10.3892/etm.2021.10982

- Pelucchi C, Di Landro A, Naldi L, et al. Risk factors for histological types and anatomic sites of cutaneous basal-cell carcinoma: an Italian case-control study. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:935-944. doi:10.1038/sj.jid.5700598

- Sunjaya AP, Sunjaya AF, Tan ST. The use of BEREP4 immunohistochemistry staining for detection of basal cell carcinoma. J Skin Cancer. 2017;2017:2692604. doi:10.1155/2017/2692604

- Kim J, Yang HJ, Pyo JS. Eccrine spiradenoma of the scalp. Arch Craniofacial Surg. 2017;18:211-213. doi:10.7181/acfs.2017.18.3.211

- Que SKT, Zwald FO, Schmults CD. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: incidence, risk factors, diagnosis, and staging. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:237-247. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.059

- Waldman A, Schmults C. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:1-12. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2018.08.001

- Yanofsky VR, Mercer SE, Phelps RG. Histopathological variants of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a review. J Skin Cancer. 2011;2011:210813. doi:10.1155/2011/210813

- Lee JH, Chang JY, Lee KH. Syringoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistologic study and results of treatment. Yonsei Med J. 2007;48:35-40. doi:10.3349/ymj.2007.48.1.35

- Adamski WZ, Maciejewski J, Adamska K, et al. The prevalence of various eyelid skin lesions in a single-centre observation study. Adv Dermatol Allergol Dermatol Alergol. 2021;38:804-807. doi:10.5114 /ada.2020.95652

- Mencía-Gutiérrez E, Navarro-Perea C, Gutiérrez-Díaz E, et al. Eyelid eccrine poroma: a case report and review of literature. Cureus. 202:12:E8906. doi:10.7759/cureus.8906

Pink Papule on the Lower Eyelid

Pink Papule on the Lower Eyelid

A 57-year-old man with no notable medical history presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of an asymptomatic papule on the left lower eyelid. The patient reported that the lesion seemed to wax and wane in size over time. Physical examination revealed a small, pink, verrucous papule on the left lower eyelid. A shave biopsy of the lesion revealed a well-circumscribed collection of small, monomorphic, cuboidal cells with basophilic round nuclei, inconspicuous nucleoli, and compact eosinophilic cytoplasm (top) with focal areas of duct formation (bottom) that was sharply demarcated from normal keratinocytes.

Painful Ulcers on the Elbows, Knees, and Ankles

Painful Ulcers on the Elbows, Knees, and Ankles

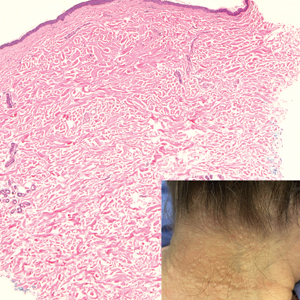

THE DIAGNOSIS: Diffuse Dermal Angiomatosis

Diffuse dermal angiomatosis (DDA) is a rare benign condition that manifests as tender, indurated, erythematous or violaceous plaques that can develop ulceration and necrosis. It typically occurs in areas susceptible to chronic hypoxia, such as the arms and legs, as was seen in our patient, as well as on large pendulous breasts in females. This condition is a distinct variant of reactive angioendotheliomatosis associated with smoking, trauma, underlying vaso-occlusion, and hypercoagulability.1,2 Risk factors include a history of smoking as well as conditions associated with chronic hypoxia, such as severe peripheral vascular disease, subclavian artery stenosis, hypercoagulable states, monoclonal gammopathy, steal syndrome from an arteriovenous fistula, end-stage renal failure, calciphylaxis, and obesity.1

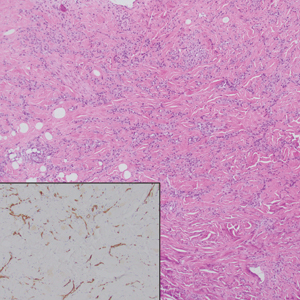

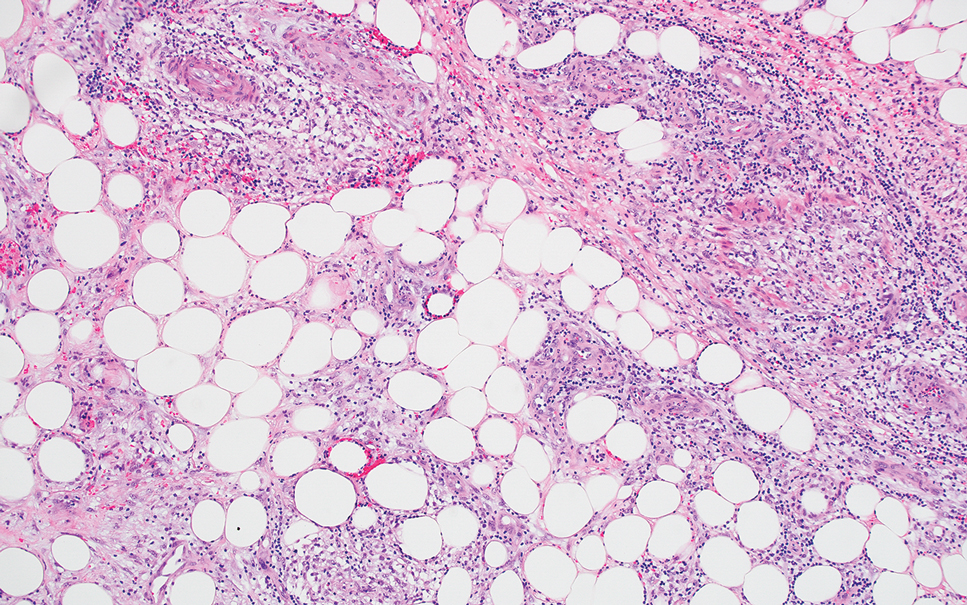

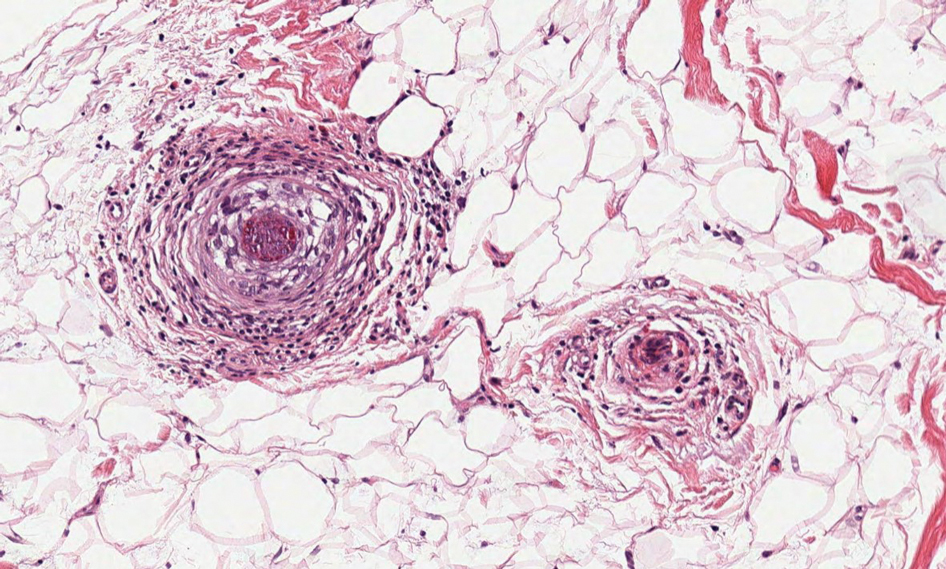

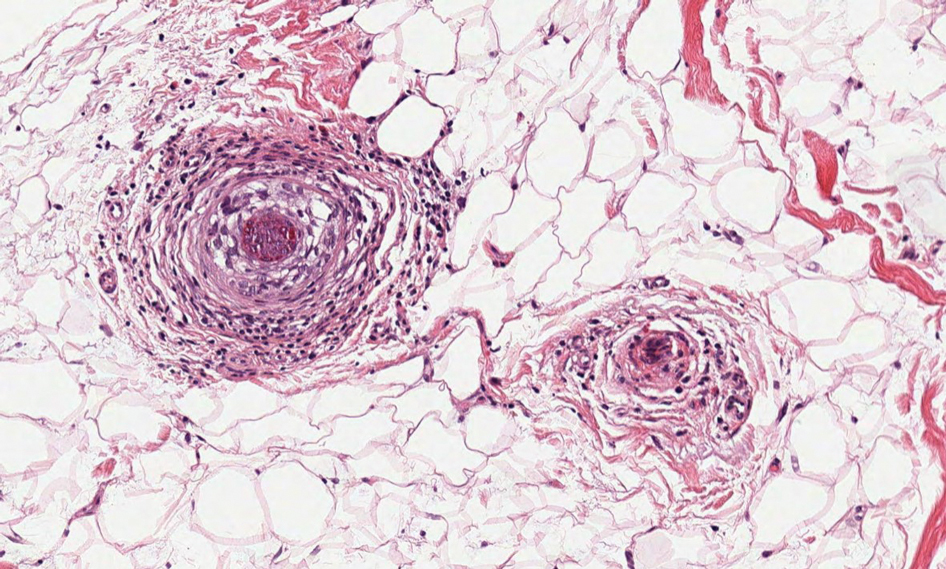

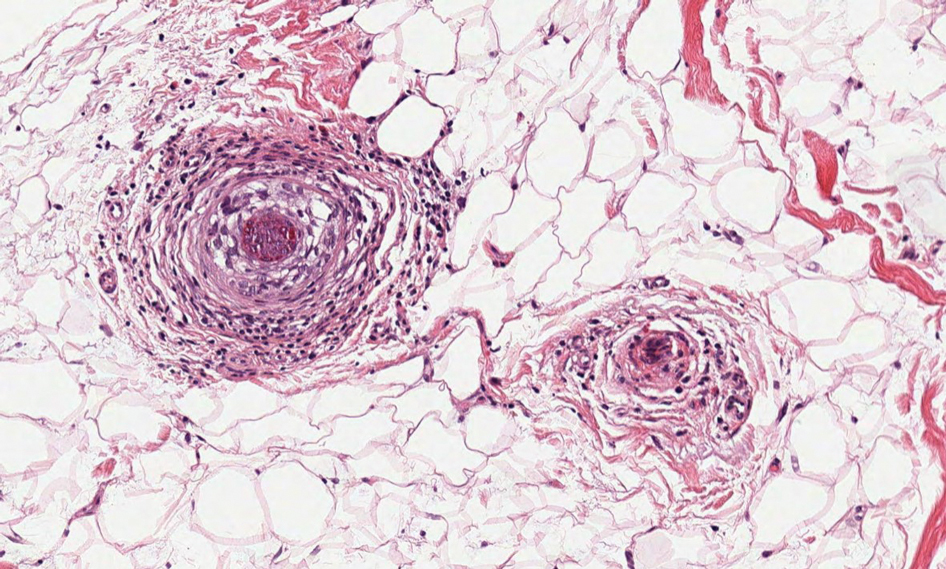

Histopathology of DDA reveals a diffuse dermal proliferation of capillaries due to upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor secondary to chronic ischemia and hypoxia.1,2 Small, well-formed capillaries surrounded by pericytes dissect through dermal collagen into the subcutis (eFigure 1). Spindle-shaped cells with vacuolated cytoplasm and scattered extravasated erythrocytes with hemosiderin may be observed.2 Cellular atypia generally is not seen.2,3 Diffuse dermal angiomatosis is characterized by positive CD31, CD34, and ERG immunostaining1 and HHV-8 and D2-40 negativity.2 In our patient, the areas suggestive of connective tissue calciumlike depositions were concerning for dystrophic calcification related to end-stage renal disease. Although Von Kossa staining failed to highlight vascular calcifications, early calciphylaxis from end-stage renal disease could not be excluded.

The main goal of DDA treatment is to target tissue hypoxia, and primary preventive measures aim to reduce risk factors associated with atherosclerosis.1 Treatment options for DDA include revascularization, reduction mammoplasty, excision, isotretinoin, oral corticosteroids, smoking cessation, pentoxifylline plus aspirin, and management of underlying calciphylaxis.1,2 Spontaneous resolution of DDA rarely has been reported.1

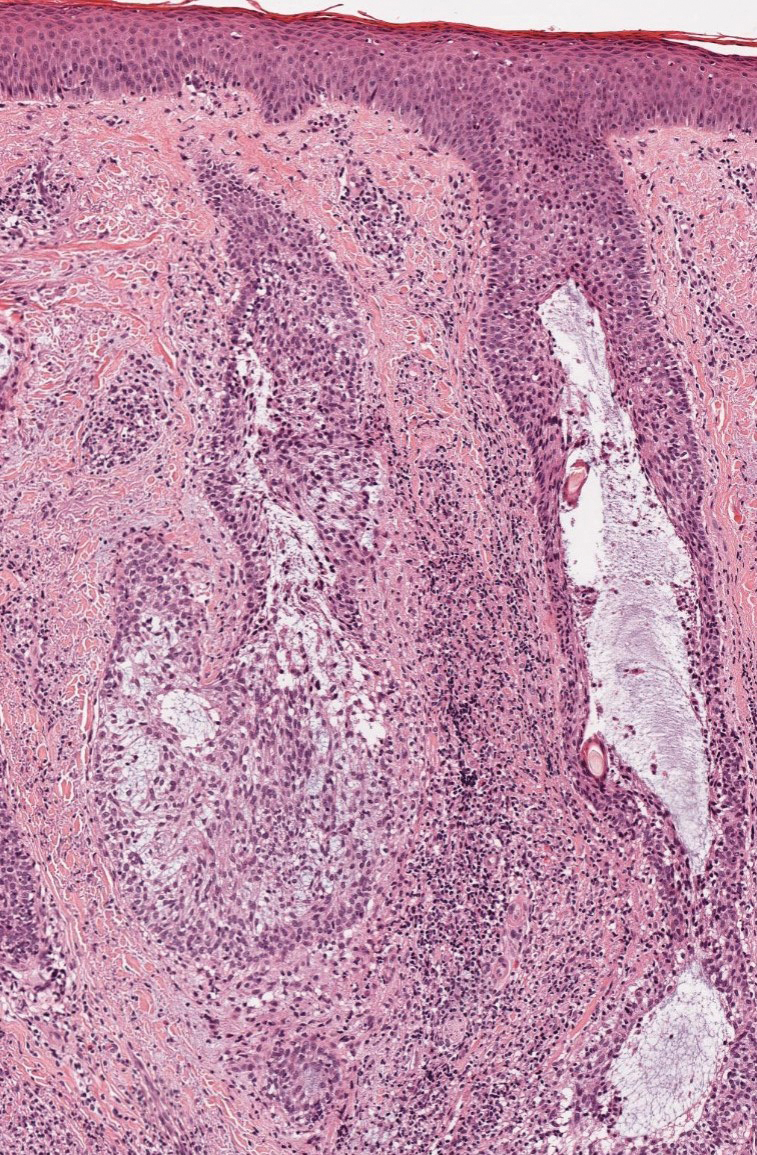

Acroangiodermatitis, also known as pseudo–Kaposi sarcoma (KS), is a rare angioproliferative disorder that often is associated with vascular anomalies.4,5 It is divided into 2 main variants: Mali type, which is associated with chronic venous insufficiency, and Stewart-Bluefarb type, associated with arteriovenous malformations.4 This condition is characterized by red to violaceous macules, papules, or plaques that may become ulcerated or coalesce to form larger confluent patches, typically arising on the lower extremities.4,6,7 Histopathology of acroangiodermatitis reveals circumscribed lobular proliferation of thick-walled dermal vessels (eFigure 2), in contrast to the diffuse dermal proliferation of endothelial cells between collagen bundles seen in DDA.2,3,6

Angiosarcoma is a rare, highly aggressive vascular tumor that originates from vascular or lymphatic endothelial cells. It typically manifests with raised, bruiselike, erythematous to violaceous papules or plaques.8,9 Histopathologically, the hallmark feature of angiosarcoma is abnormal, pleomorphic, malignant endothelial cells with pale, light, eosinophilic cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei (eFigure 3).2,9 In poorly differentiated cases, malignant endothelial cells may exhibit an epithelioid morphology with areas of hemorrhage and necrosis.9 Immunohistochemistry is positive for ERG, CD34, CD31, vascular endothelial growth factor, and D2-40.2,9

Kaposi sarcoma is a soft tissue malignancy known to occur in immunosuppressed patients such as individuals with AIDS or those undergoing immunosuppressive therapy for organ transplantation.10 There are 4 major forms of KS: classic (appearing on the lower extremities in elderly men of Mediterranean and Eastern European descent), endemic (occurring in children specifically in Africa with generalized lymph node involvement), HIV/ AIDS–related (occurring in patients not taking highly active antiretroviral therapy with diffuse involvement of the skin and internal organs), and iatrogenic (occurring in immunosuppressed patients with diffuse involvement of the skin and internal organs).10,11 Kaposi sarcoma presents as multiple reddish brown, raised or flat, painless, nonblanching mucocutaneous lesions that occasionally can ulcerate and bleed.11 Histopathologic features of KS include vascular proliferation in the dermis with diffuse slitlike lumen formation with the promontory sign, hyaline globules, hemosiderin accumulation, and an inflammatory component that often contains plasma cells (eFigure 4).2,11 Kaposi sarcoma is characterized by positive staining for CD31, CD34, D2-40, and HHV-8; the last 2 are an important distinction from DDA.2

Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma, also known as hobnail hemangioma, is a benign vascular lesion that typically manifests as a solitary, brown to violaceous papule or plaque on the trunk or extremities.12 It is sometimes surrounded by a pale area and a peripheral ecchymotic ring, giving the lesion a targetoid appearance.12,13 Histopathologic features include dilated, thin-walled vessels with prominent endothelial hobnailing in the papillary dermis, slit-shaped vascular channels between collagen bundles in the deeper dermis, and an interstitial lymphocytic infiltrate with extravasated erythrocytes and hemosiderin deposits (eFigure 5).12,14 The etiology of targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma remains unclear. Chronic inflammation, trauma, exposure to ionizing radiation, and vascular obstruction have been suggested as inciting factors, though many cases have been reported without a history of cutaneous injury.12,13 Studies suggest a lymphatic origin instead of its original classification as a hemangioma.13,15 The endothelial cells stain positive with CD31 and may stain with D2-40 and CD34.13,15

- Nguyen N, Silfvast-Kaiser AS, Frieder J, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast. Proc Bayl Univ Med Cent. 2020;33:273-275. doi:10.1080/08998280.2020.1722052

- Frikha F, Boudaya S, Abid N, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast with adjacent fat necrosis: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt1vq114n7

- Yang H, Ahmed I, Mathew V, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:343-347. doi:10.1001 /archderm.142.3.343

- Chhabra G, Verma P, Khullar G, et al. Acroangiodermatitis, Mali and Stewart-Bluefarb type: two additional cases in adolescents. Australas J Dermatol. 2021;62:E156-E157. doi:10.1111/ajd.13386

- Ramírez-Marín HA, Ruben-Castillo C, Barrera-Godínez A, et al. Acroangiodermatitis of the hand secondary to a dysfunctional a rteriovenous fistula. Ann Vasc Surg. 2021;77:350.e13-350.e17. doi:10.1016/j.avsg.2021.05.042

- Sun L, Duarte S, Soares-de-Almeida L. Acroangiodermatitis of Mali—an unusual cause of painful ulcer. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas. 2023;114:546. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2022.07.013

- Parsi K, O’Connor A, Bester L. Stewart–Bluefarb syndrome: report of five cases and a review of literature. Phlebology. 2015;30:505-514. doi:10.1177/0268355514548090

- Alharbi A, Kim YC, AlShomer F, et al. Utility of multimodal treatment protocols in the management of scalp cutaneous angiosarcoma. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2023;11:E4827. doi:10.1097 /GOX.0000000000004827

- Young RJ, Brown NJ, Reed MW, et al. Angiosarcoma. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:983-991. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70023-1

- Bishop BN, Lynch DT. Kaposi sarcoma. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Updated June 5, 2023. Accessed January 7, 2024. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534839/

- Cesarman E, Damania B, Krown SE, et al. Kaposi sarcoma. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 2019;5:1-21. doi:10.1038/s41572-019-0060-9

- AbuHilal M, Breslavet M, Ho N, et al. Hobnail hemangioma (superficial hemosiderotic lymphovascular malformation) in children: a series of 6 pediatric cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20:216-220. doi:10.1177/1203475415612421

- Kakizaki P, Valente NYS, Paiva DLM, et al. Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:956-959. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20143264

- Trindade F, Kutzner H, Tellechea Ó, et al. Hobnail hemangioma reclassified as superficial lymphatic malformation: a study of 52 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:112-115. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2011.05.019

- Hejnold M, Dyduch G, Mojsa I, et al. Hobnail hemangioma: a immunohistochemical study and literature review. Pol J Pathol. 2012;63:189-192. doi:10.5114/pjp.2012.31504

THE DIAGNOSIS: Diffuse Dermal Angiomatosis

Diffuse dermal angiomatosis (DDA) is a rare benign condition that manifests as tender, indurated, erythematous or violaceous plaques that can develop ulceration and necrosis. It typically occurs in areas susceptible to chronic hypoxia, such as the arms and legs, as was seen in our patient, as well as on large pendulous breasts in females. This condition is a distinct variant of reactive angioendotheliomatosis associated with smoking, trauma, underlying vaso-occlusion, and hypercoagulability.1,2 Risk factors include a history of smoking as well as conditions associated with chronic hypoxia, such as severe peripheral vascular disease, subclavian artery stenosis, hypercoagulable states, monoclonal gammopathy, steal syndrome from an arteriovenous fistula, end-stage renal failure, calciphylaxis, and obesity.1

Histopathology of DDA reveals a diffuse dermal proliferation of capillaries due to upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor secondary to chronic ischemia and hypoxia.1,2 Small, well-formed capillaries surrounded by pericytes dissect through dermal collagen into the subcutis (eFigure 1). Spindle-shaped cells with vacuolated cytoplasm and scattered extravasated erythrocytes with hemosiderin may be observed.2 Cellular atypia generally is not seen.2,3 Diffuse dermal angiomatosis is characterized by positive CD31, CD34, and ERG immunostaining1 and HHV-8 and D2-40 negativity.2 In our patient, the areas suggestive of connective tissue calciumlike depositions were concerning for dystrophic calcification related to end-stage renal disease. Although Von Kossa staining failed to highlight vascular calcifications, early calciphylaxis from end-stage renal disease could not be excluded.

The main goal of DDA treatment is to target tissue hypoxia, and primary preventive measures aim to reduce risk factors associated with atherosclerosis.1 Treatment options for DDA include revascularization, reduction mammoplasty, excision, isotretinoin, oral corticosteroids, smoking cessation, pentoxifylline plus aspirin, and management of underlying calciphylaxis.1,2 Spontaneous resolution of DDA rarely has been reported.1

Acroangiodermatitis, also known as pseudo–Kaposi sarcoma (KS), is a rare angioproliferative disorder that often is associated with vascular anomalies.4,5 It is divided into 2 main variants: Mali type, which is associated with chronic venous insufficiency, and Stewart-Bluefarb type, associated with arteriovenous malformations.4 This condition is characterized by red to violaceous macules, papules, or plaques that may become ulcerated or coalesce to form larger confluent patches, typically arising on the lower extremities.4,6,7 Histopathology of acroangiodermatitis reveals circumscribed lobular proliferation of thick-walled dermal vessels (eFigure 2), in contrast to the diffuse dermal proliferation of endothelial cells between collagen bundles seen in DDA.2,3,6

Angiosarcoma is a rare, highly aggressive vascular tumor that originates from vascular or lymphatic endothelial cells. It typically manifests with raised, bruiselike, erythematous to violaceous papules or plaques.8,9 Histopathologically, the hallmark feature of angiosarcoma is abnormal, pleomorphic, malignant endothelial cells with pale, light, eosinophilic cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei (eFigure 3).2,9 In poorly differentiated cases, malignant endothelial cells may exhibit an epithelioid morphology with areas of hemorrhage and necrosis.9 Immunohistochemistry is positive for ERG, CD34, CD31, vascular endothelial growth factor, and D2-40.2,9

Kaposi sarcoma is a soft tissue malignancy known to occur in immunosuppressed patients such as individuals with AIDS or those undergoing immunosuppressive therapy for organ transplantation.10 There are 4 major forms of KS: classic (appearing on the lower extremities in elderly men of Mediterranean and Eastern European descent), endemic (occurring in children specifically in Africa with generalized lymph node involvement), HIV/ AIDS–related (occurring in patients not taking highly active antiretroviral therapy with diffuse involvement of the skin and internal organs), and iatrogenic (occurring in immunosuppressed patients with diffuse involvement of the skin and internal organs).10,11 Kaposi sarcoma presents as multiple reddish brown, raised or flat, painless, nonblanching mucocutaneous lesions that occasionally can ulcerate and bleed.11 Histopathologic features of KS include vascular proliferation in the dermis with diffuse slitlike lumen formation with the promontory sign, hyaline globules, hemosiderin accumulation, and an inflammatory component that often contains plasma cells (eFigure 4).2,11 Kaposi sarcoma is characterized by positive staining for CD31, CD34, D2-40, and HHV-8; the last 2 are an important distinction from DDA.2

Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma, also known as hobnail hemangioma, is a benign vascular lesion that typically manifests as a solitary, brown to violaceous papule or plaque on the trunk or extremities.12 It is sometimes surrounded by a pale area and a peripheral ecchymotic ring, giving the lesion a targetoid appearance.12,13 Histopathologic features include dilated, thin-walled vessels with prominent endothelial hobnailing in the papillary dermis, slit-shaped vascular channels between collagen bundles in the deeper dermis, and an interstitial lymphocytic infiltrate with extravasated erythrocytes and hemosiderin deposits (eFigure 5).12,14 The etiology of targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma remains unclear. Chronic inflammation, trauma, exposure to ionizing radiation, and vascular obstruction have been suggested as inciting factors, though many cases have been reported without a history of cutaneous injury.12,13 Studies suggest a lymphatic origin instead of its original classification as a hemangioma.13,15 The endothelial cells stain positive with CD31 and may stain with D2-40 and CD34.13,15

THE DIAGNOSIS: Diffuse Dermal Angiomatosis

Diffuse dermal angiomatosis (DDA) is a rare benign condition that manifests as tender, indurated, erythematous or violaceous plaques that can develop ulceration and necrosis. It typically occurs in areas susceptible to chronic hypoxia, such as the arms and legs, as was seen in our patient, as well as on large pendulous breasts in females. This condition is a distinct variant of reactive angioendotheliomatosis associated with smoking, trauma, underlying vaso-occlusion, and hypercoagulability.1,2 Risk factors include a history of smoking as well as conditions associated with chronic hypoxia, such as severe peripheral vascular disease, subclavian artery stenosis, hypercoagulable states, monoclonal gammopathy, steal syndrome from an arteriovenous fistula, end-stage renal failure, calciphylaxis, and obesity.1

Histopathology of DDA reveals a diffuse dermal proliferation of capillaries due to upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor secondary to chronic ischemia and hypoxia.1,2 Small, well-formed capillaries surrounded by pericytes dissect through dermal collagen into the subcutis (eFigure 1). Spindle-shaped cells with vacuolated cytoplasm and scattered extravasated erythrocytes with hemosiderin may be observed.2 Cellular atypia generally is not seen.2,3 Diffuse dermal angiomatosis is characterized by positive CD31, CD34, and ERG immunostaining1 and HHV-8 and D2-40 negativity.2 In our patient, the areas suggestive of connective tissue calciumlike depositions were concerning for dystrophic calcification related to end-stage renal disease. Although Von Kossa staining failed to highlight vascular calcifications, early calciphylaxis from end-stage renal disease could not be excluded.

The main goal of DDA treatment is to target tissue hypoxia, and primary preventive measures aim to reduce risk factors associated with atherosclerosis.1 Treatment options for DDA include revascularization, reduction mammoplasty, excision, isotretinoin, oral corticosteroids, smoking cessation, pentoxifylline plus aspirin, and management of underlying calciphylaxis.1,2 Spontaneous resolution of DDA rarely has been reported.1

Acroangiodermatitis, also known as pseudo–Kaposi sarcoma (KS), is a rare angioproliferative disorder that often is associated with vascular anomalies.4,5 It is divided into 2 main variants: Mali type, which is associated with chronic venous insufficiency, and Stewart-Bluefarb type, associated with arteriovenous malformations.4 This condition is characterized by red to violaceous macules, papules, or plaques that may become ulcerated or coalesce to form larger confluent patches, typically arising on the lower extremities.4,6,7 Histopathology of acroangiodermatitis reveals circumscribed lobular proliferation of thick-walled dermal vessels (eFigure 2), in contrast to the diffuse dermal proliferation of endothelial cells between collagen bundles seen in DDA.2,3,6

Angiosarcoma is a rare, highly aggressive vascular tumor that originates from vascular or lymphatic endothelial cells. It typically manifests with raised, bruiselike, erythematous to violaceous papules or plaques.8,9 Histopathologically, the hallmark feature of angiosarcoma is abnormal, pleomorphic, malignant endothelial cells with pale, light, eosinophilic cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei (eFigure 3).2,9 In poorly differentiated cases, malignant endothelial cells may exhibit an epithelioid morphology with areas of hemorrhage and necrosis.9 Immunohistochemistry is positive for ERG, CD34, CD31, vascular endothelial growth factor, and D2-40.2,9

Kaposi sarcoma is a soft tissue malignancy known to occur in immunosuppressed patients such as individuals with AIDS or those undergoing immunosuppressive therapy for organ transplantation.10 There are 4 major forms of KS: classic (appearing on the lower extremities in elderly men of Mediterranean and Eastern European descent), endemic (occurring in children specifically in Africa with generalized lymph node involvement), HIV/ AIDS–related (occurring in patients not taking highly active antiretroviral therapy with diffuse involvement of the skin and internal organs), and iatrogenic (occurring in immunosuppressed patients with diffuse involvement of the skin and internal organs).10,11 Kaposi sarcoma presents as multiple reddish brown, raised or flat, painless, nonblanching mucocutaneous lesions that occasionally can ulcerate and bleed.11 Histopathologic features of KS include vascular proliferation in the dermis with diffuse slitlike lumen formation with the promontory sign, hyaline globules, hemosiderin accumulation, and an inflammatory component that often contains plasma cells (eFigure 4).2,11 Kaposi sarcoma is characterized by positive staining for CD31, CD34, D2-40, and HHV-8; the last 2 are an important distinction from DDA.2

Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma, also known as hobnail hemangioma, is a benign vascular lesion that typically manifests as a solitary, brown to violaceous papule or plaque on the trunk or extremities.12 It is sometimes surrounded by a pale area and a peripheral ecchymotic ring, giving the lesion a targetoid appearance.12,13 Histopathologic features include dilated, thin-walled vessels with prominent endothelial hobnailing in the papillary dermis, slit-shaped vascular channels between collagen bundles in the deeper dermis, and an interstitial lymphocytic infiltrate with extravasated erythrocytes and hemosiderin deposits (eFigure 5).12,14 The etiology of targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma remains unclear. Chronic inflammation, trauma, exposure to ionizing radiation, and vascular obstruction have been suggested as inciting factors, though many cases have been reported without a history of cutaneous injury.12,13 Studies suggest a lymphatic origin instead of its original classification as a hemangioma.13,15 The endothelial cells stain positive with CD31 and may stain with D2-40 and CD34.13,15

- Nguyen N, Silfvast-Kaiser AS, Frieder J, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast. Proc Bayl Univ Med Cent. 2020;33:273-275. doi:10.1080/08998280.2020.1722052

- Frikha F, Boudaya S, Abid N, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast with adjacent fat necrosis: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt1vq114n7

- Yang H, Ahmed I, Mathew V, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:343-347. doi:10.1001 /archderm.142.3.343

- Chhabra G, Verma P, Khullar G, et al. Acroangiodermatitis, Mali and Stewart-Bluefarb type: two additional cases in adolescents. Australas J Dermatol. 2021;62:E156-E157. doi:10.1111/ajd.13386

- Ramírez-Marín HA, Ruben-Castillo C, Barrera-Godínez A, et al. Acroangiodermatitis of the hand secondary to a dysfunctional a rteriovenous fistula. Ann Vasc Surg. 2021;77:350.e13-350.e17. doi:10.1016/j.avsg.2021.05.042

- Sun L, Duarte S, Soares-de-Almeida L. Acroangiodermatitis of Mali—an unusual cause of painful ulcer. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas. 2023;114:546. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2022.07.013

- Parsi K, O’Connor A, Bester L. Stewart–Bluefarb syndrome: report of five cases and a review of literature. Phlebology. 2015;30:505-514. doi:10.1177/0268355514548090

- Alharbi A, Kim YC, AlShomer F, et al. Utility of multimodal treatment protocols in the management of scalp cutaneous angiosarcoma. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2023;11:E4827. doi:10.1097 /GOX.0000000000004827

- Young RJ, Brown NJ, Reed MW, et al. Angiosarcoma. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:983-991. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70023-1

- Bishop BN, Lynch DT. Kaposi sarcoma. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Updated June 5, 2023. Accessed January 7, 2024. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534839/

- Cesarman E, Damania B, Krown SE, et al. Kaposi sarcoma. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 2019;5:1-21. doi:10.1038/s41572-019-0060-9

- AbuHilal M, Breslavet M, Ho N, et al. Hobnail hemangioma (superficial hemosiderotic lymphovascular malformation) in children: a series of 6 pediatric cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20:216-220. doi:10.1177/1203475415612421

- Kakizaki P, Valente NYS, Paiva DLM, et al. Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:956-959. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20143264

- Trindade F, Kutzner H, Tellechea Ó, et al. Hobnail hemangioma reclassified as superficial lymphatic malformation: a study of 52 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:112-115. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2011.05.019

- Hejnold M, Dyduch G, Mojsa I, et al. Hobnail hemangioma: a immunohistochemical study and literature review. Pol J Pathol. 2012;63:189-192. doi:10.5114/pjp.2012.31504

- Nguyen N, Silfvast-Kaiser AS, Frieder J, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast. Proc Bayl Univ Med Cent. 2020;33:273-275. doi:10.1080/08998280.2020.1722052

- Frikha F, Boudaya S, Abid N, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast with adjacent fat necrosis: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt1vq114n7

- Yang H, Ahmed I, Mathew V, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:343-347. doi:10.1001 /archderm.142.3.343

- Chhabra G, Verma P, Khullar G, et al. Acroangiodermatitis, Mali and Stewart-Bluefarb type: two additional cases in adolescents. Australas J Dermatol. 2021;62:E156-E157. doi:10.1111/ajd.13386

- Ramírez-Marín HA, Ruben-Castillo C, Barrera-Godínez A, et al. Acroangiodermatitis of the hand secondary to a dysfunctional a rteriovenous fistula. Ann Vasc Surg. 2021;77:350.e13-350.e17. doi:10.1016/j.avsg.2021.05.042

- Sun L, Duarte S, Soares-de-Almeida L. Acroangiodermatitis of Mali—an unusual cause of painful ulcer. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas. 2023;114:546. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2022.07.013

- Parsi K, O’Connor A, Bester L. Stewart–Bluefarb syndrome: report of five cases and a review of literature. Phlebology. 2015;30:505-514. doi:10.1177/0268355514548090

- Alharbi A, Kim YC, AlShomer F, et al. Utility of multimodal treatment protocols in the management of scalp cutaneous angiosarcoma. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2023;11:E4827. doi:10.1097 /GOX.0000000000004827

- Young RJ, Brown NJ, Reed MW, et al. Angiosarcoma. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:983-991. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70023-1

- Bishop BN, Lynch DT. Kaposi sarcoma. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Updated June 5, 2023. Accessed January 7, 2024. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534839/

- Cesarman E, Damania B, Krown SE, et al. Kaposi sarcoma. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 2019;5:1-21. doi:10.1038/s41572-019-0060-9

- AbuHilal M, Breslavet M, Ho N, et al. Hobnail hemangioma (superficial hemosiderotic lymphovascular malformation) in children: a series of 6 pediatric cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20:216-220. doi:10.1177/1203475415612421

- Kakizaki P, Valente NYS, Paiva DLM, et al. Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:956-959. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20143264

- Trindade F, Kutzner H, Tellechea Ó, et al. Hobnail hemangioma reclassified as superficial lymphatic malformation: a study of 52 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:112-115. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2011.05.019

- Hejnold M, Dyduch G, Mojsa I, et al. Hobnail hemangioma: a immunohistochemical study and literature review. Pol J Pathol. 2012;63:189-192. doi:10.5114/pjp.2012.31504

Painful Ulcers on the Elbows, Knees, and Ankles

Painful Ulcers on the Elbows, Knees, and Ankles