User login

COVID-19 and the precipitous dismantlement of societal norms

As the life-altering coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic gradually ebbs, we are all its survivors. Now, we are experiencing COVID-19 fatigue, trying to emerge from its dense fog that pervaded every facet of our lives. We are fully cognizant that there will not be a return to the previous “normal.” The pernicious virus had a transformative effect that did not spare any component of our society. Full recovery will not be easy.

As the uncertainty lingers about another devastating return of the pandemic later this year, we can see the reverberation of this invisible assault on human existence. Although a relatively small fraction of the population lost their lives, the rest of us are valiantly trying to readjust to the multiple ways our world has changed. Consider the following abrupt and sweeping burdens inflicted by the pandemic within a few short weeks:

Mental health. The acute stress of thanatophobia generated a triad of anxiety, depression, and nosophobia on a large scale. The demand for psychiatric care rapidly escalated. Suicide rate increased not only because of the stress of being locked down at home (alien to most people’s lifestyle) but because of the coincidental timing of the pandemic during April and May, the peak time of year for suicide. Animal researchers use immobilization as a paradigm to stress a rat or mouse. Many humans immobilized during the pandemic have developed exquisite empathy towards those rodents! The impact on children may also have long-term effects because playing and socializing with friends is a vital part of their lives. Parents have noticed dysphoria and acting out among their children, and an intense compensatory preoccupation with video games and electronic communications with friends.

Physical health. Medical care focused heavily on COVID-19 victims, to the detriment of all other medical conditions. Non-COVID-19 hospital admissions plummeted, and all elective surgeries and procedures were put on hold, depriving many people of medical care they badly needed. Emergency department (ED) visits also declined dramatically, including the usual flow of heart attacks, stroke, pulmonary embolus, asthma attacks, etc. The minimization of driving greatly reduced the admission of accident victims to EDs. Colonoscopies, cardiac stents, hip replacements, MRIs, mammography, and other procedures that are vital to maintain health and quality of life were halted. Dentists shuttered their practices due to the high risk of infection from exposure to oral secretions and breathing. One can only imagine the suffering of having a toothache with no dental help available, and how that might lead to narcotic abuse.

Social health. The imperative of social distancing disrupted most ordinary human activities, such as dining out, sitting in an auditorium for Grand Rounds or a lecture, visiting friends at their homes, the cherished interactions between grandparents and grandchildren (the lack of which I painfully experienced), and even seeing each other’s smiles behind the ubiquitous masks. And forget about hugging or kissing. The aversion to being near anyone who is coughing or sneezing led to an adaptive social paranoia and the social shunning of anyone who appeared to have an upper respiratory infection, even if it was unrelated to COVID-19.

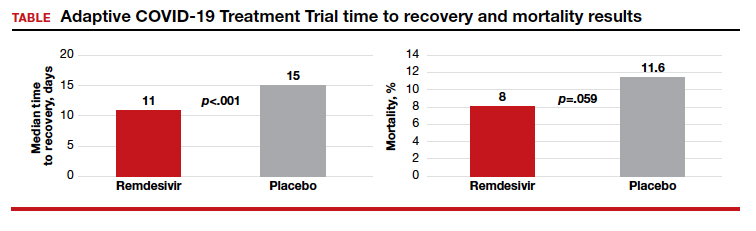

Redemption for the pharmaceutical industry. The deadly pandemic intensified the public’s awareness of the importance of developing treatments and vaccines for COVID-19. The often-demonized pharmaceutical companies, with their extensive R&D infrastructure, emerged as a major source of hope for discovering an effective treatment for the coronavirus infection, or—better still—one or more vaccines that will enable society to return to its normal functions. It was quite impressive how many pharmaceutical companies “came to the rescue” with clinical trials to repurpose existing medications or to develop new ones. It was very encouraging to see multiple vaccine candidates being developed and expedited for testing around the world. A process that usually takes years was reduced to a few months, thanks to the existing technical infrastructure and thousands of scientists who enable rapid drug development. It is possible that the public may gradually modify its perception of the pharmaceutical industry from a “corporate villain” to an “indispensable health industry” for urgent medical crises such as a pandemic, and also for hundreds of medical diseases that are still in need of safe, effective therapies.

Economic burden. The unimaginable nightmare scenario of a total shutdown of all businesses led to the unprecedented loss of millions of jobs and livelihoods, reflected in miles-long lines of families at food banks. Overnight, the government switched from worrying about its $20-trillion deficit to printing several more trillion dollars to rescue the economy from collapse. The huge magnitude of a trillion can be appreciated if one is aware that it takes roughly 32 years to count to 1 billion, and 32,000 years to count to 1 trillion. Stimulating the economy while the gross domestic product threatens to sink by terrifying percentages (20% to 30%) was urgently needed, even though it meant mortgaging the future, especially when interest rates, and servicing the debt, will inevitably rise from the current zero to much higher levels in the future. The collapse of the once-thriving airline industry (bookings were down an estimated 98%) is an example of why desperate measures were needed to salvage an economy paralyzed by a viral pandemic.

Continue to: Political repercussions

Political repercussions. In our already hyperpartisan country, the COVID-19 crisis created more fissures across party lines. The blame game escalated as each side tried to exploit the crisis for political gain during a presidential election year. None of the leaders, from mayors to governors to the president, had any notion of how to wisely manage an unforeseen catastrophic pandemic. Thus, a political cacophony has developed, further exacerbating the public’s anxiety and uncertainty, especially about how and when the pandemic will end.

Education disruption. Never before have all schools and colleges around the country abruptly closed and sent students of all ages to shelter at home. Massive havoc ensued, with a wholesale switch to solitary online learning, the loss of the unique school and college social experience in the classroom and on campus, and the loss of experiencing commencement to receive a diploma (an important milestone for every graduate). Even medical students were not allowed to complete their clinical rotations and were sent home to attend online classes. A complete paradigm shift emerged about entrance exams: the SAT and ACT were eliminated for college applicants, and the MCAT for medical school applicants. This was unthinkable before the pandemic descended upon us, but benchmarks suddenly evaporated to adjust to the new reality. Then there followed disastrous financial losses by institutions of higher learning as well as academic medical centers and teaching hospitals, all slashing their budgets, furloughing employees, cutting salaries, and eliminating programs. Even the “sacred” tenure of senior faculty became a casualty of the financial “exigency.” Children’s nutrition suffered, especially among those in lower socioeconomic groups for whom the main meal of the day was the school lunch, and was made worse by their parents’ loss of income. For millions of people, the emotional toll was inevitable following the draconian measure of closing all educational institutions to contain the spread of the pandemic.

Family burden. Sheltering at home might have been fun for a few days, but after many weeks, it festered into a major stress, especially for those living in a small house, condominium, or apartment. The resilience of many families was tested as the exercise of freedoms collided with the fear of getting infected. Families were deprived of celebrating birthdays, weddings, funerals, graduation parties, retirement parties, Mother’s Day, Father’s Day, and various religious holidays, including Easter, Passover, and Eid al-Fitr.

Sexual burden. Intimacy and sexual contact between consenting adults living apart were sacrificed on the altar of the pernicious viral pandemic. Mandatory social distancing of 6 feet or more to avoid each other’s droplets emanating from simple speech, not just sneezing or coughing, makes intimacy practically impossible. Thus, physical closeness became taboo, and avoiding another person’s saliva or body secretions became a must to avoid contracting the virus. Being single was quite a lonely experience during this pandemic!

Entertainment deprivation. Americans are known to thrive on an extensive diet of spectator sports. Going to football, basketball, baseball, or hockey games to root for one’s team is intrinsically American. The pursuit of happiness extends to attending concerts, movies, Broadway shows, theme parks, and cruises with thousands of others. The pandemic ripped all those pleasurable leisure activities from our daily lives, leaving a big hole in people’s lives at the precise time fun activities were needed as a useful diversion from the dismal stress of a pandemic. To make things worse, it is uncertain when (if ever) such group activities will be restored, especially if the pandemic returns with another wave. But optimists would hurry to remind us that the “Roaring 20s” blossomed in the decade following the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic.

Continue to: Legal system

Legal system. Astounding changes were instigated by the pandemic, such as the release of thousands of inmates, including felons, to avoid the spread of the virus in crowded prisons. For us psychiatrists, the silver lining in that unexpected action is that many of those released were patients with mental illness who were incarcerated because of the lack of hospitals that would take them. The police started issuing citations instead of arresting and jailing violators. Enforcement of the law was welcome when it targeted those who gouged the public for personal profit during the scarcity of masks, sanitizers, or even toilet paper and soap.

Medical practice. In addition to delaying medical care for patients, the freeze on so-called elective surgeries or procedures (many of which were actually necessary) was financially ruinous for physicians. Another regrettable consequence of the pandemic is a drop in pediatric vaccinations because parents were reluctant to take their children to the pediatrician. On a more positive note, the massive switch to telehealth was advantageous for both patients and psychiatrists because this technology is well-suited for psychiatric care. Fortunately, regulations that hampered telepsychiatry practice were substantially loosened or eliminated, and even the usually sacrosanct HIPAA regulations were temporarily sidelined.

Medical research. Both human and animal research came to a screeching halt, and many research assistants were furloughed. Data collection was disrupted, and a generation of scientific and medical discoveries became a casualty of the pandemic.

Medical literature. It was stunning to see how quickly COVID-19 occupied most of the pages of prominent journals. The scholarly articles were frankly quite useful, covering topics ranging from risk factors to early symptoms to treatment and pathophysiology across multiple organs. As with other paradigm shifts, there was an accelerated publication push, sometimes with expedited peer reviews to inform health care workers and the public while the pandemic was still raging. However, a couple of very prominent journals had to retract flawed articles that were hastily published without the usual due diligence and rigorous peer review. The pandemic clearly disrupted the science publishing process.

Travel effects. The steep reduction of flights (by 98%) was financially catastrophic, not only for airline companies but to business travel across the country. However, fewer cars on the road resulted in fewer accidents and deaths, and also reduced pollution. Paradoxically, to prevent crowding in subways, trains, and buses, officials reversed their traditional instructions and advised the public to drive their own cars instead of using public transportation!

Continue to: Heroism of front-line medical personnel

Heroism of front-line medical personnel. Everyone saluted and prayed for the health care professionals working at the bedside of highly infectious patients who needed 24/7 intensive care. Many have died while carrying out the noble but hazardous medical duties. Those heroes deserve our lasting respect and admiration.

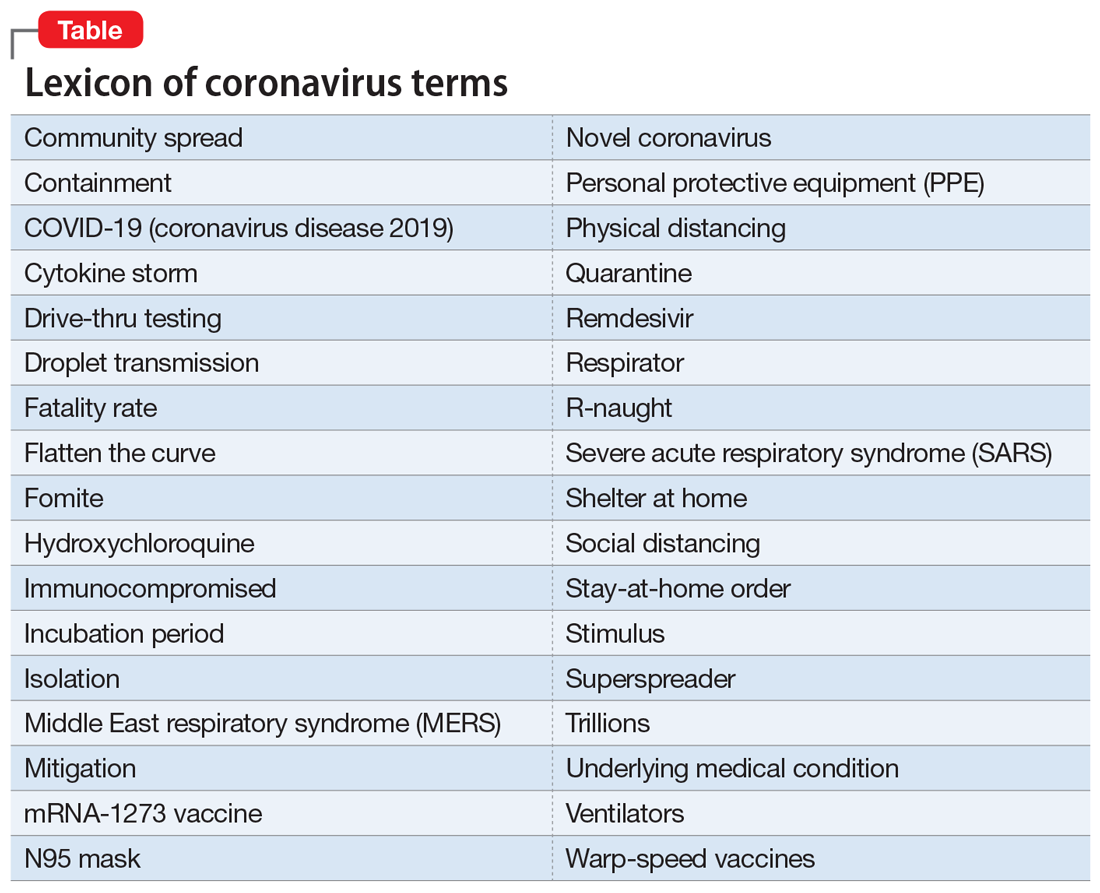

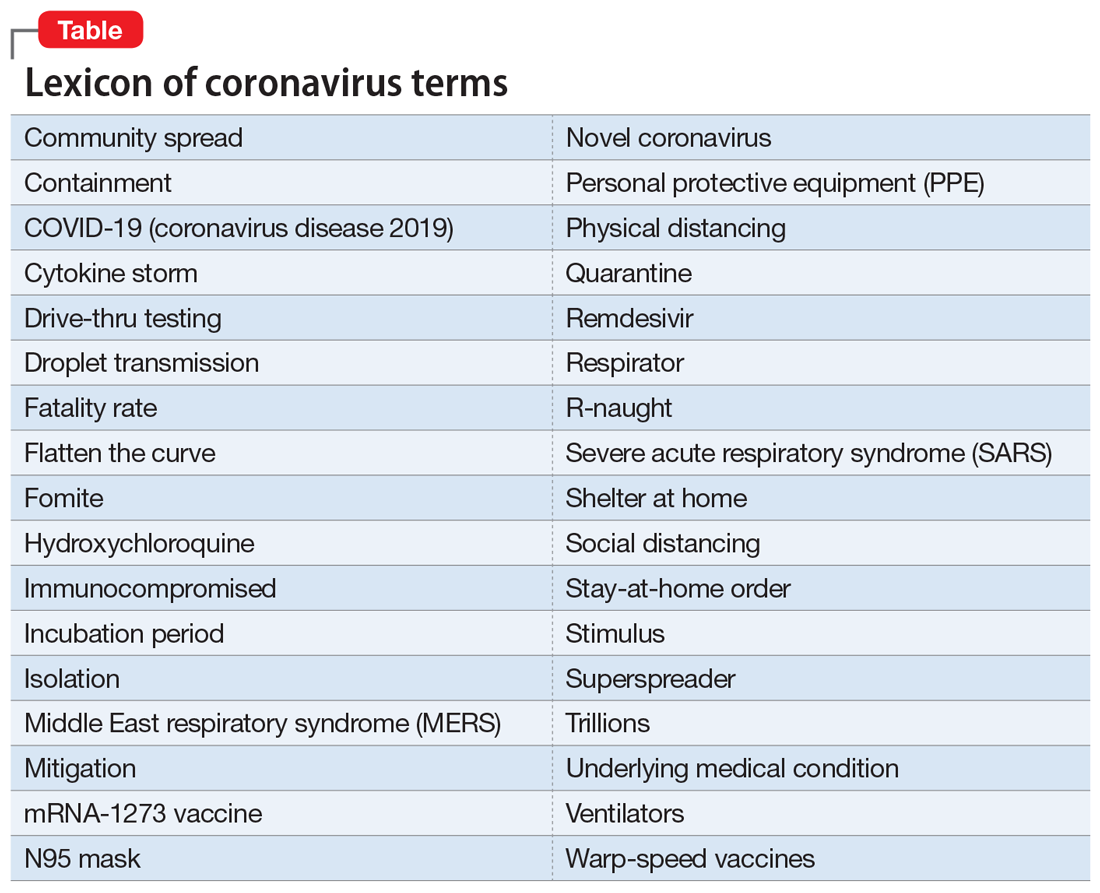

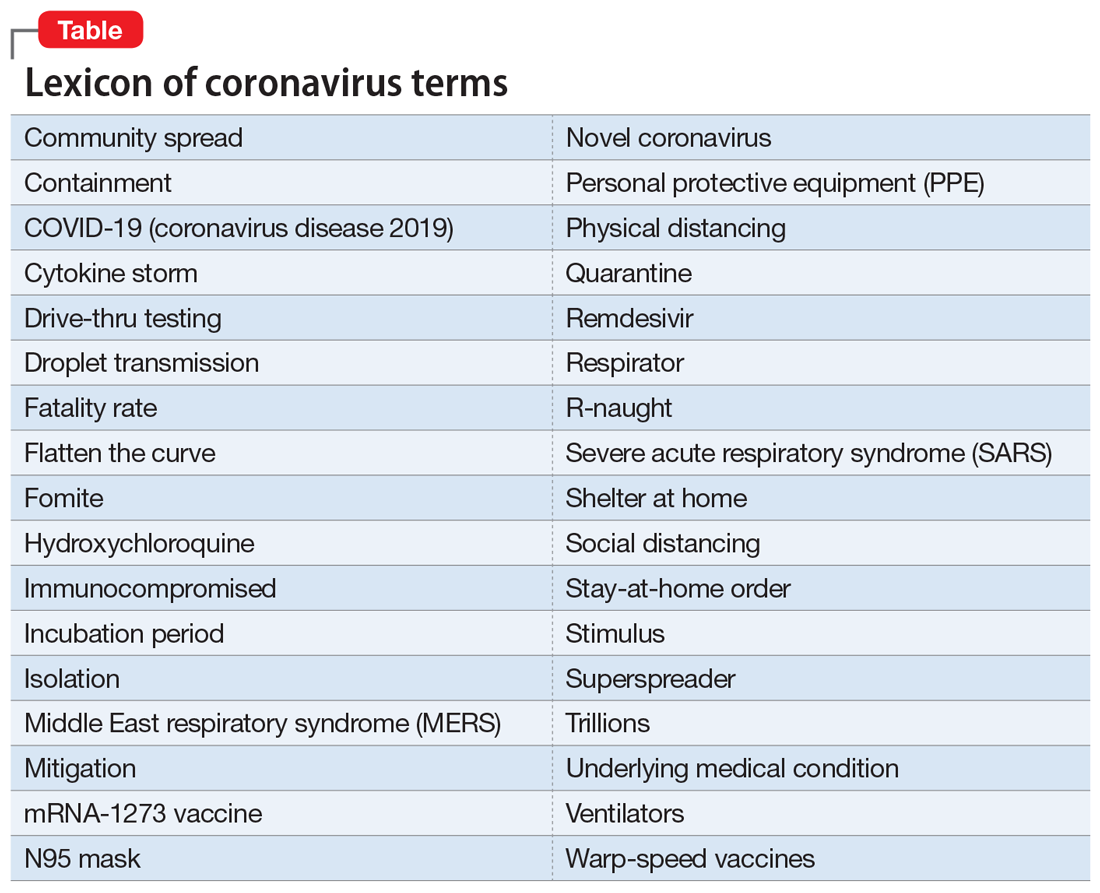

The COVID-19 pandemic insidiously permeated and altered every aspect of our complex society and revealed how fragile our “normal lifestyle” really is. It is possible that nothing will ever be the same again, and an uneasy sense of vulnerability will engulf us as we cautiously return to a “new normal.” Even our language has expanded with the lexicon of pandemic terminology (Table). We all pray and hope that this plague never returns. And let’s hope one or more vaccines are developed soon so we can manage future recurrences like the annual flu season. In the meantime, keep your masks and sanitizers close by…

Postscript: Shortly after I completed this editorial, the ongoing COVID-19 plague was overshadowed by the scourge of racism, with massive protests, at times laced by violence, triggered by the death of a black man in custody of the police, under condemnable circumstances. The COVID-19 pandemic and the necessary social distancing it requires were temporarily ignored during the ensuing protests. The combined effect of those overlapping scourges are jarring to the country’s psyche, complicating and perhaps sabotaging the social recovery from the pandemic.

As the life-altering coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic gradually ebbs, we are all its survivors. Now, we are experiencing COVID-19 fatigue, trying to emerge from its dense fog that pervaded every facet of our lives. We are fully cognizant that there will not be a return to the previous “normal.” The pernicious virus had a transformative effect that did not spare any component of our society. Full recovery will not be easy.

As the uncertainty lingers about another devastating return of the pandemic later this year, we can see the reverberation of this invisible assault on human existence. Although a relatively small fraction of the population lost their lives, the rest of us are valiantly trying to readjust to the multiple ways our world has changed. Consider the following abrupt and sweeping burdens inflicted by the pandemic within a few short weeks:

Mental health. The acute stress of thanatophobia generated a triad of anxiety, depression, and nosophobia on a large scale. The demand for psychiatric care rapidly escalated. Suicide rate increased not only because of the stress of being locked down at home (alien to most people’s lifestyle) but because of the coincidental timing of the pandemic during April and May, the peak time of year for suicide. Animal researchers use immobilization as a paradigm to stress a rat or mouse. Many humans immobilized during the pandemic have developed exquisite empathy towards those rodents! The impact on children may also have long-term effects because playing and socializing with friends is a vital part of their lives. Parents have noticed dysphoria and acting out among their children, and an intense compensatory preoccupation with video games and electronic communications with friends.

Physical health. Medical care focused heavily on COVID-19 victims, to the detriment of all other medical conditions. Non-COVID-19 hospital admissions plummeted, and all elective surgeries and procedures were put on hold, depriving many people of medical care they badly needed. Emergency department (ED) visits also declined dramatically, including the usual flow of heart attacks, stroke, pulmonary embolus, asthma attacks, etc. The minimization of driving greatly reduced the admission of accident victims to EDs. Colonoscopies, cardiac stents, hip replacements, MRIs, mammography, and other procedures that are vital to maintain health and quality of life were halted. Dentists shuttered their practices due to the high risk of infection from exposure to oral secretions and breathing. One can only imagine the suffering of having a toothache with no dental help available, and how that might lead to narcotic abuse.

Social health. The imperative of social distancing disrupted most ordinary human activities, such as dining out, sitting in an auditorium for Grand Rounds or a lecture, visiting friends at their homes, the cherished interactions between grandparents and grandchildren (the lack of which I painfully experienced), and even seeing each other’s smiles behind the ubiquitous masks. And forget about hugging or kissing. The aversion to being near anyone who is coughing or sneezing led to an adaptive social paranoia and the social shunning of anyone who appeared to have an upper respiratory infection, even if it was unrelated to COVID-19.

Redemption for the pharmaceutical industry. The deadly pandemic intensified the public’s awareness of the importance of developing treatments and vaccines for COVID-19. The often-demonized pharmaceutical companies, with their extensive R&D infrastructure, emerged as a major source of hope for discovering an effective treatment for the coronavirus infection, or—better still—one or more vaccines that will enable society to return to its normal functions. It was quite impressive how many pharmaceutical companies “came to the rescue” with clinical trials to repurpose existing medications or to develop new ones. It was very encouraging to see multiple vaccine candidates being developed and expedited for testing around the world. A process that usually takes years was reduced to a few months, thanks to the existing technical infrastructure and thousands of scientists who enable rapid drug development. It is possible that the public may gradually modify its perception of the pharmaceutical industry from a “corporate villain” to an “indispensable health industry” for urgent medical crises such as a pandemic, and also for hundreds of medical diseases that are still in need of safe, effective therapies.

Economic burden. The unimaginable nightmare scenario of a total shutdown of all businesses led to the unprecedented loss of millions of jobs and livelihoods, reflected in miles-long lines of families at food banks. Overnight, the government switched from worrying about its $20-trillion deficit to printing several more trillion dollars to rescue the economy from collapse. The huge magnitude of a trillion can be appreciated if one is aware that it takes roughly 32 years to count to 1 billion, and 32,000 years to count to 1 trillion. Stimulating the economy while the gross domestic product threatens to sink by terrifying percentages (20% to 30%) was urgently needed, even though it meant mortgaging the future, especially when interest rates, and servicing the debt, will inevitably rise from the current zero to much higher levels in the future. The collapse of the once-thriving airline industry (bookings were down an estimated 98%) is an example of why desperate measures were needed to salvage an economy paralyzed by a viral pandemic.

Continue to: Political repercussions

Political repercussions. In our already hyperpartisan country, the COVID-19 crisis created more fissures across party lines. The blame game escalated as each side tried to exploit the crisis for political gain during a presidential election year. None of the leaders, from mayors to governors to the president, had any notion of how to wisely manage an unforeseen catastrophic pandemic. Thus, a political cacophony has developed, further exacerbating the public’s anxiety and uncertainty, especially about how and when the pandemic will end.

Education disruption. Never before have all schools and colleges around the country abruptly closed and sent students of all ages to shelter at home. Massive havoc ensued, with a wholesale switch to solitary online learning, the loss of the unique school and college social experience in the classroom and on campus, and the loss of experiencing commencement to receive a diploma (an important milestone for every graduate). Even medical students were not allowed to complete their clinical rotations and were sent home to attend online classes. A complete paradigm shift emerged about entrance exams: the SAT and ACT were eliminated for college applicants, and the MCAT for medical school applicants. This was unthinkable before the pandemic descended upon us, but benchmarks suddenly evaporated to adjust to the new reality. Then there followed disastrous financial losses by institutions of higher learning as well as academic medical centers and teaching hospitals, all slashing their budgets, furloughing employees, cutting salaries, and eliminating programs. Even the “sacred” tenure of senior faculty became a casualty of the financial “exigency.” Children’s nutrition suffered, especially among those in lower socioeconomic groups for whom the main meal of the day was the school lunch, and was made worse by their parents’ loss of income. For millions of people, the emotional toll was inevitable following the draconian measure of closing all educational institutions to contain the spread of the pandemic.

Family burden. Sheltering at home might have been fun for a few days, but after many weeks, it festered into a major stress, especially for those living in a small house, condominium, or apartment. The resilience of many families was tested as the exercise of freedoms collided with the fear of getting infected. Families were deprived of celebrating birthdays, weddings, funerals, graduation parties, retirement parties, Mother’s Day, Father’s Day, and various religious holidays, including Easter, Passover, and Eid al-Fitr.

Sexual burden. Intimacy and sexual contact between consenting adults living apart were sacrificed on the altar of the pernicious viral pandemic. Mandatory social distancing of 6 feet or more to avoid each other’s droplets emanating from simple speech, not just sneezing or coughing, makes intimacy practically impossible. Thus, physical closeness became taboo, and avoiding another person’s saliva or body secretions became a must to avoid contracting the virus. Being single was quite a lonely experience during this pandemic!

Entertainment deprivation. Americans are known to thrive on an extensive diet of spectator sports. Going to football, basketball, baseball, or hockey games to root for one’s team is intrinsically American. The pursuit of happiness extends to attending concerts, movies, Broadway shows, theme parks, and cruises with thousands of others. The pandemic ripped all those pleasurable leisure activities from our daily lives, leaving a big hole in people’s lives at the precise time fun activities were needed as a useful diversion from the dismal stress of a pandemic. To make things worse, it is uncertain when (if ever) such group activities will be restored, especially if the pandemic returns with another wave. But optimists would hurry to remind us that the “Roaring 20s” blossomed in the decade following the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic.

Continue to: Legal system

Legal system. Astounding changes were instigated by the pandemic, such as the release of thousands of inmates, including felons, to avoid the spread of the virus in crowded prisons. For us psychiatrists, the silver lining in that unexpected action is that many of those released were patients with mental illness who were incarcerated because of the lack of hospitals that would take them. The police started issuing citations instead of arresting and jailing violators. Enforcement of the law was welcome when it targeted those who gouged the public for personal profit during the scarcity of masks, sanitizers, or even toilet paper and soap.

Medical practice. In addition to delaying medical care for patients, the freeze on so-called elective surgeries or procedures (many of which were actually necessary) was financially ruinous for physicians. Another regrettable consequence of the pandemic is a drop in pediatric vaccinations because parents were reluctant to take their children to the pediatrician. On a more positive note, the massive switch to telehealth was advantageous for both patients and psychiatrists because this technology is well-suited for psychiatric care. Fortunately, regulations that hampered telepsychiatry practice were substantially loosened or eliminated, and even the usually sacrosanct HIPAA regulations were temporarily sidelined.

Medical research. Both human and animal research came to a screeching halt, and many research assistants were furloughed. Data collection was disrupted, and a generation of scientific and medical discoveries became a casualty of the pandemic.

Medical literature. It was stunning to see how quickly COVID-19 occupied most of the pages of prominent journals. The scholarly articles were frankly quite useful, covering topics ranging from risk factors to early symptoms to treatment and pathophysiology across multiple organs. As with other paradigm shifts, there was an accelerated publication push, sometimes with expedited peer reviews to inform health care workers and the public while the pandemic was still raging. However, a couple of very prominent journals had to retract flawed articles that were hastily published without the usual due diligence and rigorous peer review. The pandemic clearly disrupted the science publishing process.

Travel effects. The steep reduction of flights (by 98%) was financially catastrophic, not only for airline companies but to business travel across the country. However, fewer cars on the road resulted in fewer accidents and deaths, and also reduced pollution. Paradoxically, to prevent crowding in subways, trains, and buses, officials reversed their traditional instructions and advised the public to drive their own cars instead of using public transportation!

Continue to: Heroism of front-line medical personnel

Heroism of front-line medical personnel. Everyone saluted and prayed for the health care professionals working at the bedside of highly infectious patients who needed 24/7 intensive care. Many have died while carrying out the noble but hazardous medical duties. Those heroes deserve our lasting respect and admiration.

The COVID-19 pandemic insidiously permeated and altered every aspect of our complex society and revealed how fragile our “normal lifestyle” really is. It is possible that nothing will ever be the same again, and an uneasy sense of vulnerability will engulf us as we cautiously return to a “new normal.” Even our language has expanded with the lexicon of pandemic terminology (Table). We all pray and hope that this plague never returns. And let’s hope one or more vaccines are developed soon so we can manage future recurrences like the annual flu season. In the meantime, keep your masks and sanitizers close by…

Postscript: Shortly after I completed this editorial, the ongoing COVID-19 plague was overshadowed by the scourge of racism, with massive protests, at times laced by violence, triggered by the death of a black man in custody of the police, under condemnable circumstances. The COVID-19 pandemic and the necessary social distancing it requires were temporarily ignored during the ensuing protests. The combined effect of those overlapping scourges are jarring to the country’s psyche, complicating and perhaps sabotaging the social recovery from the pandemic.

As the life-altering coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic gradually ebbs, we are all its survivors. Now, we are experiencing COVID-19 fatigue, trying to emerge from its dense fog that pervaded every facet of our lives. We are fully cognizant that there will not be a return to the previous “normal.” The pernicious virus had a transformative effect that did not spare any component of our society. Full recovery will not be easy.

As the uncertainty lingers about another devastating return of the pandemic later this year, we can see the reverberation of this invisible assault on human existence. Although a relatively small fraction of the population lost their lives, the rest of us are valiantly trying to readjust to the multiple ways our world has changed. Consider the following abrupt and sweeping burdens inflicted by the pandemic within a few short weeks:

Mental health. The acute stress of thanatophobia generated a triad of anxiety, depression, and nosophobia on a large scale. The demand for psychiatric care rapidly escalated. Suicide rate increased not only because of the stress of being locked down at home (alien to most people’s lifestyle) but because of the coincidental timing of the pandemic during April and May, the peak time of year for suicide. Animal researchers use immobilization as a paradigm to stress a rat or mouse. Many humans immobilized during the pandemic have developed exquisite empathy towards those rodents! The impact on children may also have long-term effects because playing and socializing with friends is a vital part of their lives. Parents have noticed dysphoria and acting out among their children, and an intense compensatory preoccupation with video games and electronic communications with friends.

Physical health. Medical care focused heavily on COVID-19 victims, to the detriment of all other medical conditions. Non-COVID-19 hospital admissions plummeted, and all elective surgeries and procedures were put on hold, depriving many people of medical care they badly needed. Emergency department (ED) visits also declined dramatically, including the usual flow of heart attacks, stroke, pulmonary embolus, asthma attacks, etc. The minimization of driving greatly reduced the admission of accident victims to EDs. Colonoscopies, cardiac stents, hip replacements, MRIs, mammography, and other procedures that are vital to maintain health and quality of life were halted. Dentists shuttered their practices due to the high risk of infection from exposure to oral secretions and breathing. One can only imagine the suffering of having a toothache with no dental help available, and how that might lead to narcotic abuse.

Social health. The imperative of social distancing disrupted most ordinary human activities, such as dining out, sitting in an auditorium for Grand Rounds or a lecture, visiting friends at their homes, the cherished interactions between grandparents and grandchildren (the lack of which I painfully experienced), and even seeing each other’s smiles behind the ubiquitous masks. And forget about hugging or kissing. The aversion to being near anyone who is coughing or sneezing led to an adaptive social paranoia and the social shunning of anyone who appeared to have an upper respiratory infection, even if it was unrelated to COVID-19.

Redemption for the pharmaceutical industry. The deadly pandemic intensified the public’s awareness of the importance of developing treatments and vaccines for COVID-19. The often-demonized pharmaceutical companies, with their extensive R&D infrastructure, emerged as a major source of hope for discovering an effective treatment for the coronavirus infection, or—better still—one or more vaccines that will enable society to return to its normal functions. It was quite impressive how many pharmaceutical companies “came to the rescue” with clinical trials to repurpose existing medications or to develop new ones. It was very encouraging to see multiple vaccine candidates being developed and expedited for testing around the world. A process that usually takes years was reduced to a few months, thanks to the existing technical infrastructure and thousands of scientists who enable rapid drug development. It is possible that the public may gradually modify its perception of the pharmaceutical industry from a “corporate villain” to an “indispensable health industry” for urgent medical crises such as a pandemic, and also for hundreds of medical diseases that are still in need of safe, effective therapies.

Economic burden. The unimaginable nightmare scenario of a total shutdown of all businesses led to the unprecedented loss of millions of jobs and livelihoods, reflected in miles-long lines of families at food banks. Overnight, the government switched from worrying about its $20-trillion deficit to printing several more trillion dollars to rescue the economy from collapse. The huge magnitude of a trillion can be appreciated if one is aware that it takes roughly 32 years to count to 1 billion, and 32,000 years to count to 1 trillion. Stimulating the economy while the gross domestic product threatens to sink by terrifying percentages (20% to 30%) was urgently needed, even though it meant mortgaging the future, especially when interest rates, and servicing the debt, will inevitably rise from the current zero to much higher levels in the future. The collapse of the once-thriving airline industry (bookings were down an estimated 98%) is an example of why desperate measures were needed to salvage an economy paralyzed by a viral pandemic.

Continue to: Political repercussions

Political repercussions. In our already hyperpartisan country, the COVID-19 crisis created more fissures across party lines. The blame game escalated as each side tried to exploit the crisis for political gain during a presidential election year. None of the leaders, from mayors to governors to the president, had any notion of how to wisely manage an unforeseen catastrophic pandemic. Thus, a political cacophony has developed, further exacerbating the public’s anxiety and uncertainty, especially about how and when the pandemic will end.

Education disruption. Never before have all schools and colleges around the country abruptly closed and sent students of all ages to shelter at home. Massive havoc ensued, with a wholesale switch to solitary online learning, the loss of the unique school and college social experience in the classroom and on campus, and the loss of experiencing commencement to receive a diploma (an important milestone for every graduate). Even medical students were not allowed to complete their clinical rotations and were sent home to attend online classes. A complete paradigm shift emerged about entrance exams: the SAT and ACT were eliminated for college applicants, and the MCAT for medical school applicants. This was unthinkable before the pandemic descended upon us, but benchmarks suddenly evaporated to adjust to the new reality. Then there followed disastrous financial losses by institutions of higher learning as well as academic medical centers and teaching hospitals, all slashing their budgets, furloughing employees, cutting salaries, and eliminating programs. Even the “sacred” tenure of senior faculty became a casualty of the financial “exigency.” Children’s nutrition suffered, especially among those in lower socioeconomic groups for whom the main meal of the day was the school lunch, and was made worse by their parents’ loss of income. For millions of people, the emotional toll was inevitable following the draconian measure of closing all educational institutions to contain the spread of the pandemic.

Family burden. Sheltering at home might have been fun for a few days, but after many weeks, it festered into a major stress, especially for those living in a small house, condominium, or apartment. The resilience of many families was tested as the exercise of freedoms collided with the fear of getting infected. Families were deprived of celebrating birthdays, weddings, funerals, graduation parties, retirement parties, Mother’s Day, Father’s Day, and various religious holidays, including Easter, Passover, and Eid al-Fitr.

Sexual burden. Intimacy and sexual contact between consenting adults living apart were sacrificed on the altar of the pernicious viral pandemic. Mandatory social distancing of 6 feet or more to avoid each other’s droplets emanating from simple speech, not just sneezing or coughing, makes intimacy practically impossible. Thus, physical closeness became taboo, and avoiding another person’s saliva or body secretions became a must to avoid contracting the virus. Being single was quite a lonely experience during this pandemic!

Entertainment deprivation. Americans are known to thrive on an extensive diet of spectator sports. Going to football, basketball, baseball, or hockey games to root for one’s team is intrinsically American. The pursuit of happiness extends to attending concerts, movies, Broadway shows, theme parks, and cruises with thousands of others. The pandemic ripped all those pleasurable leisure activities from our daily lives, leaving a big hole in people’s lives at the precise time fun activities were needed as a useful diversion from the dismal stress of a pandemic. To make things worse, it is uncertain when (if ever) such group activities will be restored, especially if the pandemic returns with another wave. But optimists would hurry to remind us that the “Roaring 20s” blossomed in the decade following the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic.

Continue to: Legal system

Legal system. Astounding changes were instigated by the pandemic, such as the release of thousands of inmates, including felons, to avoid the spread of the virus in crowded prisons. For us psychiatrists, the silver lining in that unexpected action is that many of those released were patients with mental illness who were incarcerated because of the lack of hospitals that would take them. The police started issuing citations instead of arresting and jailing violators. Enforcement of the law was welcome when it targeted those who gouged the public for personal profit during the scarcity of masks, sanitizers, or even toilet paper and soap.

Medical practice. In addition to delaying medical care for patients, the freeze on so-called elective surgeries or procedures (many of which were actually necessary) was financially ruinous for physicians. Another regrettable consequence of the pandemic is a drop in pediatric vaccinations because parents were reluctant to take their children to the pediatrician. On a more positive note, the massive switch to telehealth was advantageous for both patients and psychiatrists because this technology is well-suited for psychiatric care. Fortunately, regulations that hampered telepsychiatry practice were substantially loosened or eliminated, and even the usually sacrosanct HIPAA regulations were temporarily sidelined.

Medical research. Both human and animal research came to a screeching halt, and many research assistants were furloughed. Data collection was disrupted, and a generation of scientific and medical discoveries became a casualty of the pandemic.

Medical literature. It was stunning to see how quickly COVID-19 occupied most of the pages of prominent journals. The scholarly articles were frankly quite useful, covering topics ranging from risk factors to early symptoms to treatment and pathophysiology across multiple organs. As with other paradigm shifts, there was an accelerated publication push, sometimes with expedited peer reviews to inform health care workers and the public while the pandemic was still raging. However, a couple of very prominent journals had to retract flawed articles that were hastily published without the usual due diligence and rigorous peer review. The pandemic clearly disrupted the science publishing process.

Travel effects. The steep reduction of flights (by 98%) was financially catastrophic, not only for airline companies but to business travel across the country. However, fewer cars on the road resulted in fewer accidents and deaths, and also reduced pollution. Paradoxically, to prevent crowding in subways, trains, and buses, officials reversed their traditional instructions and advised the public to drive their own cars instead of using public transportation!

Continue to: Heroism of front-line medical personnel

Heroism of front-line medical personnel. Everyone saluted and prayed for the health care professionals working at the bedside of highly infectious patients who needed 24/7 intensive care. Many have died while carrying out the noble but hazardous medical duties. Those heroes deserve our lasting respect and admiration.

The COVID-19 pandemic insidiously permeated and altered every aspect of our complex society and revealed how fragile our “normal lifestyle” really is. It is possible that nothing will ever be the same again, and an uneasy sense of vulnerability will engulf us as we cautiously return to a “new normal.” Even our language has expanded with the lexicon of pandemic terminology (Table). We all pray and hope that this plague never returns. And let’s hope one or more vaccines are developed soon so we can manage future recurrences like the annual flu season. In the meantime, keep your masks and sanitizers close by…

Postscript: Shortly after I completed this editorial, the ongoing COVID-19 plague was overshadowed by the scourge of racism, with massive protests, at times laced by violence, triggered by the death of a black man in custody of the police, under condemnable circumstances. The COVID-19 pandemic and the necessary social distancing it requires were temporarily ignored during the ensuing protests. The combined effect of those overlapping scourges are jarring to the country’s psyche, complicating and perhaps sabotaging the social recovery from the pandemic.

In your practice, are you planning to have a chaperone present for all intimate examinations?

Although pelvic examinations may only last a few minutes, the examination is scary and uncomfortable for many patients. To help minimize fear and discomfort, the exam should take place in a comfortable and professional environment. The clinician should provide appropriate gowns, private facilities for undressing, sensitively use draping, and clearly explain the components of the examination. Trained professional chaperones play an important role in intimate physical examinations, including:

- providing reassurance to the patient of the professional integrity of the intimate examination

- supporting and educating the patient during the examination

- increasing the efficiency of the clinician during a procedure

- acting as a witness should a misunderstanding with the patient arise.

Major medical professional societies have issued guidance to clinicians on the use of a chaperone during intimate physical examinations. Professional society guidance ranges from endorsing joint decision-making between physician and patient on the presence of a chaperone to more proscriptive guidance that emphasizes the importance of a chaperone at every intimate physical examination.

Examples of professional societies’ guidance that supports joint decision-making between physician and patient about the presence of a chaperone include:

- American Medical Association: “Adopt a policy that patients are free to request a chaperone and ensure that the policy is communicated to patients. Always honor a patient’s request to have a chaperone.”1

- Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada: “It is a reasonable and acceptable practice to perform a physical examination, including breast and pelvic examination without the presence of a third person in the room unless the woman or health care provider indicates a desire for a third party to be present.” “If the health care provider chooses to have a third person present during all examinations, the health care provider should explain this policy to the woman.”2

- American College of Physicians: “Care and respect should guide the performance of the physical examination. The location and degree of privacy should be appropriate for the examination being performed, with chaperone services as an option. An appropriate setting and sufficient time should be allocated to encourage exploration of aspects of the patient’s life pertinent to health, including habits, relationships, sexuality, vocation, culture, religion, and spirituality.”3

By contrast, the following professional society guidance strongly recommends the presence of a chaperone for every intimate physical examination:

- United States Veterans Administration: “A female chaperone must be in the examination room during breast and pelvic exams…this includes procedures such as urodynamic testing or treatments such as pelvic floor physical therapy.”4

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists: “The presence of a chaperone is considered essential for every pelvic examination. Verbal consent should be obtained in the presence of the chaperone who is to be present during the examination and recorded in the notes. If the patient declines the presence of a chaperone, the doctor should explain that a chaperone is also required to help in many cases and then attempt to arrange for the chaperone to be standing nearby within earshot. The reasons for declining a chaperone and alternative arrangements offered should be documented. Consent should also be specific to whether the intended examination is vaginal, rectal or both. Communication skills are essential in conducting intimate examinations.”5

- American College Health Association (ACHA): “It is ACHA’s recommendation that, as part of institutional policy, a chaperone be provided for every sensitive medical examination and procedure.”6

Continue to: New guidance from ACOG on trained chaperones...

New guidance from ACOG on trained chaperones

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recently issued a committee opinion recommending “that a chaperone be present for all breast, genital, and rectal examinations. The need for a chaperone is irrespective of the sex or gender of the person performing the examination and applies to examinations performed in the outpatient and inpatient settings, including labor and delivery, as well as during diagnostic studies such as transvaginal ultrasonography and urodynamic testing.”7

This new proscriptive guidance will significantly change practice for the many obstetrician-gynecologists who do not routinely have a chaperone present during intimate examinations. The policy provides exceptions to the presence of a chaperone in cases of medical emergencies and if the patient declines a chaperone. ACOG recommends that when a patient declines a chaperone the clinician should educate the patient that a “chaperone is an integral part of the clinical team whose role includes assisting with the examination and protecting the patient and the physician. Any concerns the patient has regarding the presence of a chaperone should be elicited and addressed if feasible. If, after counseling, the patient refuses the chaperone, this decision should be respected and documented in the medical record.”7 ACOG discourages the use of family members, medical students, and residents as chaperones.

Sexual trauma is common and may cause lasting adverse effects, including poor health.1 When sexual trauma is reported, the experience may not be believed or taken seriously, compounding the injury. Sometimes sexual trauma contributes to risky behaviors including smoking cigarettes, excessive alcohol consumption, drug misuse, and risky sex as a means to cope with the mental distress of the trauma.

Trauma-informed medical care has four pillars:

1. Recognize that many people have experienced significant trauma(s), which adversely impacts their health.

2. Be aware of the signs and symptoms of trauma.

3. Integrate knowledge about trauma into medical encounters.

4. Avoid re-traumatizing the person.

Symptoms of psychological distress caused by past trauma include anxiety, fear, anger, irritability, mood swings, feeling disconnected, numbness, sadness, or hopelessness. Clinical actions that help to reduce distress among trauma survivors include:

• sensitively ask patients to share their traumatic experiences

• empower the patient by explicitly giving her control over all aspects of the examination, indicating that the exam will stop if the patient feels uncomfortable

• explain the steps in the exam and educate about the purpose of each step

• keep the patient’s body covered as much as possible

• use the smallest speculum that permits an adequate exam

• utilize a chaperone to help support the patient.

Clinicians can strengthen their empathic skills by reflecting on how their own personal experiences, traumas, cultural-biases, and gender influence their ap-proach to the care of patients.

Reference

1. Hall KS, Moreau C, Trussell J. Young women’s perceived health and lifetime sexual experience: results from the national survey of family growth. J Sex Med. 2012;9:1382-1391. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02686.x.

Training of chaperones

Chaperones are health care professionals who should be trained for their specific role. Chaperones need to protect patient privacy and the confidentiality of health information. Chaperones should be trained to recognize the components of a professional intimate examination and to identify variances from standard practice. In many ambulatory practices, medical assistants perform the role of chaperone. The American Association of Medical Assistants (AAMA) offers national certification for medical assistants through an examination developed by the National Board of Medical Examiners. To be eligible for AAMA certification an individual must complete at least two semesters of medical assisting education that includes courses in anatomy, physiology, pharmacology, and relevant mathematics.

Reporting variances that occur during an intimate examination

Best practices are evolving on how to deal with the rare event of a chaperone witnessing a physician perform an intimate examination that is outside of standard professional practice. Chaperones may be reluctant to report a variance because physicians are in a powerful position, and the accuracy of their report will be challenged, threatening the chaperone’s employment. Processes for encouraging all team members to report concerns must be clearly explained to the chaperone and other members of the health care team. Clinicians should be aware that deviations from standard practice will be reported and investigated. Medical practices must develop a reporting system that ensures the reporting individual will be protected from retaliation.

In addition, the chaperone needs to know to whom they should report a variance. In large multispecialty medical practices, chaperones often can report concerns to nursing leaders or human resources. In small ambulatory practices, chaperones may be advised to report concerns about a physician to the practice manager or medical director. Regardless, every practice should have the best process for reporting a concern. In turn, the practice leaders who are responsible for investigating reports of concerning behavior should have a defined process for confidentially interviewing the chaperone, clinician, and patient.

Even when a chaperone is present for intimate examinations, problems can arise if the chaperone is not trained to recognize variances from standard practice or does not have a clear means for reporting variances and when the practice does not have a process for investigating reported variances.

Sadly, misconduct has been documented among priests, ministers, sports coaches, professors, scout masters, and clinicians. Trusted professionals are in positions of power in relation to their clients, patients, and students. Physicians and nurses are held in high esteem and trust by patients. To preserve the trust of the public we must treat all people with dignity and respect their autonomy. The presence of a chaperone during intimate examinations may help us fulfill Hippocrates’ edict, “First, do no harm.” ●

Ronee A. Skornik, MSW, MD

As a female obstetrician-gynecologist trained in psychiatric social work, I have found that some of my patients who have known me over a long period of time find the presence of a chaperone not only unnecessary but also uncomfortable both in terms of physical exposure and in what they may want to tell me during the examination. Personally, I strongly favor a chaperone for all intimate examinations, to safeguard both the patient and the clinician. However, I do understand why some patients prefer to see me without the presence of a chaperone, and I want to honor their wishes. If a chaperone is responsive to the patient’s requests, including where the chaperone stands and his or her role during the exam, the reluctant patient may be more willing to have a chaperone. A chaperone who develops a relationship with the patient and honors the patient’s preferences is a valuable member of the care team.

- American Medical Association. Code of Medical Ethics Opinion 1.2.4. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/ethics/use-chaperones. Accessed May 26, 2020.

- Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada. No. 266—The presence of a third party during breast and pelvic examinations. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2017;39:e496-e497. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2017.09.005.

- American College of Physicians. ACP Policy Com-pendium Summer 2016. https://www.acponline.org/system/files/documents/advocacy/acp_policy_compendium_summer_2016.pdf. Accessed May 26, 2020.

- Department of Veterans Affairs. VHA Directive 1330.01(2). Healthcare Services for Women Veterans. February 15, 2017. Amended July 24, 2018. http://www.va.gov/ vhapublications/ viewpublication.asp?pub_id=5332. Accessed May 26, 2020.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Obtaining valid consent: clinical governance advice no. 6. January 2015. https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/clinical-governance-advice/cga6.pdf. Accessed May 26, 2020.

- American College Health Association Guidelines. Best practices for sensitive exams. October 2019. https://www.acha.org/documents/resources/guidelines/ACHA_Best_Practices_for_Sensitive_Exams_October2019.pdf. Accessed May 26, 2020.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Ethics. Sexual misconduct: ACOG Committee Opinion No. 796. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:e43-e50

Although pelvic examinations may only last a few minutes, the examination is scary and uncomfortable for many patients. To help minimize fear and discomfort, the exam should take place in a comfortable and professional environment. The clinician should provide appropriate gowns, private facilities for undressing, sensitively use draping, and clearly explain the components of the examination. Trained professional chaperones play an important role in intimate physical examinations, including:

- providing reassurance to the patient of the professional integrity of the intimate examination

- supporting and educating the patient during the examination

- increasing the efficiency of the clinician during a procedure

- acting as a witness should a misunderstanding with the patient arise.

Major medical professional societies have issued guidance to clinicians on the use of a chaperone during intimate physical examinations. Professional society guidance ranges from endorsing joint decision-making between physician and patient on the presence of a chaperone to more proscriptive guidance that emphasizes the importance of a chaperone at every intimate physical examination.

Examples of professional societies’ guidance that supports joint decision-making between physician and patient about the presence of a chaperone include:

- American Medical Association: “Adopt a policy that patients are free to request a chaperone and ensure that the policy is communicated to patients. Always honor a patient’s request to have a chaperone.”1

- Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada: “It is a reasonable and acceptable practice to perform a physical examination, including breast and pelvic examination without the presence of a third person in the room unless the woman or health care provider indicates a desire for a third party to be present.” “If the health care provider chooses to have a third person present during all examinations, the health care provider should explain this policy to the woman.”2

- American College of Physicians: “Care and respect should guide the performance of the physical examination. The location and degree of privacy should be appropriate for the examination being performed, with chaperone services as an option. An appropriate setting and sufficient time should be allocated to encourage exploration of aspects of the patient’s life pertinent to health, including habits, relationships, sexuality, vocation, culture, religion, and spirituality.”3

By contrast, the following professional society guidance strongly recommends the presence of a chaperone for every intimate physical examination:

- United States Veterans Administration: “A female chaperone must be in the examination room during breast and pelvic exams…this includes procedures such as urodynamic testing or treatments such as pelvic floor physical therapy.”4

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists: “The presence of a chaperone is considered essential for every pelvic examination. Verbal consent should be obtained in the presence of the chaperone who is to be present during the examination and recorded in the notes. If the patient declines the presence of a chaperone, the doctor should explain that a chaperone is also required to help in many cases and then attempt to arrange for the chaperone to be standing nearby within earshot. The reasons for declining a chaperone and alternative arrangements offered should be documented. Consent should also be specific to whether the intended examination is vaginal, rectal or both. Communication skills are essential in conducting intimate examinations.”5

- American College Health Association (ACHA): “It is ACHA’s recommendation that, as part of institutional policy, a chaperone be provided for every sensitive medical examination and procedure.”6

Continue to: New guidance from ACOG on trained chaperones...

New guidance from ACOG on trained chaperones

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recently issued a committee opinion recommending “that a chaperone be present for all breast, genital, and rectal examinations. The need for a chaperone is irrespective of the sex or gender of the person performing the examination and applies to examinations performed in the outpatient and inpatient settings, including labor and delivery, as well as during diagnostic studies such as transvaginal ultrasonography and urodynamic testing.”7

This new proscriptive guidance will significantly change practice for the many obstetrician-gynecologists who do not routinely have a chaperone present during intimate examinations. The policy provides exceptions to the presence of a chaperone in cases of medical emergencies and if the patient declines a chaperone. ACOG recommends that when a patient declines a chaperone the clinician should educate the patient that a “chaperone is an integral part of the clinical team whose role includes assisting with the examination and protecting the patient and the physician. Any concerns the patient has regarding the presence of a chaperone should be elicited and addressed if feasible. If, after counseling, the patient refuses the chaperone, this decision should be respected and documented in the medical record.”7 ACOG discourages the use of family members, medical students, and residents as chaperones.

Sexual trauma is common and may cause lasting adverse effects, including poor health.1 When sexual trauma is reported, the experience may not be believed or taken seriously, compounding the injury. Sometimes sexual trauma contributes to risky behaviors including smoking cigarettes, excessive alcohol consumption, drug misuse, and risky sex as a means to cope with the mental distress of the trauma.

Trauma-informed medical care has four pillars:

1. Recognize that many people have experienced significant trauma(s), which adversely impacts their health.

2. Be aware of the signs and symptoms of trauma.

3. Integrate knowledge about trauma into medical encounters.

4. Avoid re-traumatizing the person.

Symptoms of psychological distress caused by past trauma include anxiety, fear, anger, irritability, mood swings, feeling disconnected, numbness, sadness, or hopelessness. Clinical actions that help to reduce distress among trauma survivors include:

• sensitively ask patients to share their traumatic experiences

• empower the patient by explicitly giving her control over all aspects of the examination, indicating that the exam will stop if the patient feels uncomfortable

• explain the steps in the exam and educate about the purpose of each step

• keep the patient’s body covered as much as possible

• use the smallest speculum that permits an adequate exam

• utilize a chaperone to help support the patient.

Clinicians can strengthen their empathic skills by reflecting on how their own personal experiences, traumas, cultural-biases, and gender influence their ap-proach to the care of patients.

Reference

1. Hall KS, Moreau C, Trussell J. Young women’s perceived health and lifetime sexual experience: results from the national survey of family growth. J Sex Med. 2012;9:1382-1391. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02686.x.

Training of chaperones

Chaperones are health care professionals who should be trained for their specific role. Chaperones need to protect patient privacy and the confidentiality of health information. Chaperones should be trained to recognize the components of a professional intimate examination and to identify variances from standard practice. In many ambulatory practices, medical assistants perform the role of chaperone. The American Association of Medical Assistants (AAMA) offers national certification for medical assistants through an examination developed by the National Board of Medical Examiners. To be eligible for AAMA certification an individual must complete at least two semesters of medical assisting education that includes courses in anatomy, physiology, pharmacology, and relevant mathematics.

Reporting variances that occur during an intimate examination

Best practices are evolving on how to deal with the rare event of a chaperone witnessing a physician perform an intimate examination that is outside of standard professional practice. Chaperones may be reluctant to report a variance because physicians are in a powerful position, and the accuracy of their report will be challenged, threatening the chaperone’s employment. Processes for encouraging all team members to report concerns must be clearly explained to the chaperone and other members of the health care team. Clinicians should be aware that deviations from standard practice will be reported and investigated. Medical practices must develop a reporting system that ensures the reporting individual will be protected from retaliation.

In addition, the chaperone needs to know to whom they should report a variance. In large multispecialty medical practices, chaperones often can report concerns to nursing leaders or human resources. In small ambulatory practices, chaperones may be advised to report concerns about a physician to the practice manager or medical director. Regardless, every practice should have the best process for reporting a concern. In turn, the practice leaders who are responsible for investigating reports of concerning behavior should have a defined process for confidentially interviewing the chaperone, clinician, and patient.

Even when a chaperone is present for intimate examinations, problems can arise if the chaperone is not trained to recognize variances from standard practice or does not have a clear means for reporting variances and when the practice does not have a process for investigating reported variances.

Sadly, misconduct has been documented among priests, ministers, sports coaches, professors, scout masters, and clinicians. Trusted professionals are in positions of power in relation to their clients, patients, and students. Physicians and nurses are held in high esteem and trust by patients. To preserve the trust of the public we must treat all people with dignity and respect their autonomy. The presence of a chaperone during intimate examinations may help us fulfill Hippocrates’ edict, “First, do no harm.” ●

Ronee A. Skornik, MSW, MD

As a female obstetrician-gynecologist trained in psychiatric social work, I have found that some of my patients who have known me over a long period of time find the presence of a chaperone not only unnecessary but also uncomfortable both in terms of physical exposure and in what they may want to tell me during the examination. Personally, I strongly favor a chaperone for all intimate examinations, to safeguard both the patient and the clinician. However, I do understand why some patients prefer to see me without the presence of a chaperone, and I want to honor their wishes. If a chaperone is responsive to the patient’s requests, including where the chaperone stands and his or her role during the exam, the reluctant patient may be more willing to have a chaperone. A chaperone who develops a relationship with the patient and honors the patient’s preferences is a valuable member of the care team.

Although pelvic examinations may only last a few minutes, the examination is scary and uncomfortable for many patients. To help minimize fear and discomfort, the exam should take place in a comfortable and professional environment. The clinician should provide appropriate gowns, private facilities for undressing, sensitively use draping, and clearly explain the components of the examination. Trained professional chaperones play an important role in intimate physical examinations, including:

- providing reassurance to the patient of the professional integrity of the intimate examination

- supporting and educating the patient during the examination

- increasing the efficiency of the clinician during a procedure

- acting as a witness should a misunderstanding with the patient arise.

Major medical professional societies have issued guidance to clinicians on the use of a chaperone during intimate physical examinations. Professional society guidance ranges from endorsing joint decision-making between physician and patient on the presence of a chaperone to more proscriptive guidance that emphasizes the importance of a chaperone at every intimate physical examination.

Examples of professional societies’ guidance that supports joint decision-making between physician and patient about the presence of a chaperone include:

- American Medical Association: “Adopt a policy that patients are free to request a chaperone and ensure that the policy is communicated to patients. Always honor a patient’s request to have a chaperone.”1

- Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada: “It is a reasonable and acceptable practice to perform a physical examination, including breast and pelvic examination without the presence of a third person in the room unless the woman or health care provider indicates a desire for a third party to be present.” “If the health care provider chooses to have a third person present during all examinations, the health care provider should explain this policy to the woman.”2

- American College of Physicians: “Care and respect should guide the performance of the physical examination. The location and degree of privacy should be appropriate for the examination being performed, with chaperone services as an option. An appropriate setting and sufficient time should be allocated to encourage exploration of aspects of the patient’s life pertinent to health, including habits, relationships, sexuality, vocation, culture, religion, and spirituality.”3

By contrast, the following professional society guidance strongly recommends the presence of a chaperone for every intimate physical examination:

- United States Veterans Administration: “A female chaperone must be in the examination room during breast and pelvic exams…this includes procedures such as urodynamic testing or treatments such as pelvic floor physical therapy.”4

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists: “The presence of a chaperone is considered essential for every pelvic examination. Verbal consent should be obtained in the presence of the chaperone who is to be present during the examination and recorded in the notes. If the patient declines the presence of a chaperone, the doctor should explain that a chaperone is also required to help in many cases and then attempt to arrange for the chaperone to be standing nearby within earshot. The reasons for declining a chaperone and alternative arrangements offered should be documented. Consent should also be specific to whether the intended examination is vaginal, rectal or both. Communication skills are essential in conducting intimate examinations.”5

- American College Health Association (ACHA): “It is ACHA’s recommendation that, as part of institutional policy, a chaperone be provided for every sensitive medical examination and procedure.”6

Continue to: New guidance from ACOG on trained chaperones...

New guidance from ACOG on trained chaperones

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recently issued a committee opinion recommending “that a chaperone be present for all breast, genital, and rectal examinations. The need for a chaperone is irrespective of the sex or gender of the person performing the examination and applies to examinations performed in the outpatient and inpatient settings, including labor and delivery, as well as during diagnostic studies such as transvaginal ultrasonography and urodynamic testing.”7

This new proscriptive guidance will significantly change practice for the many obstetrician-gynecologists who do not routinely have a chaperone present during intimate examinations. The policy provides exceptions to the presence of a chaperone in cases of medical emergencies and if the patient declines a chaperone. ACOG recommends that when a patient declines a chaperone the clinician should educate the patient that a “chaperone is an integral part of the clinical team whose role includes assisting with the examination and protecting the patient and the physician. Any concerns the patient has regarding the presence of a chaperone should be elicited and addressed if feasible. If, after counseling, the patient refuses the chaperone, this decision should be respected and documented in the medical record.”7 ACOG discourages the use of family members, medical students, and residents as chaperones.

Sexual trauma is common and may cause lasting adverse effects, including poor health.1 When sexual trauma is reported, the experience may not be believed or taken seriously, compounding the injury. Sometimes sexual trauma contributes to risky behaviors including smoking cigarettes, excessive alcohol consumption, drug misuse, and risky sex as a means to cope with the mental distress of the trauma.

Trauma-informed medical care has four pillars:

1. Recognize that many people have experienced significant trauma(s), which adversely impacts their health.

2. Be aware of the signs and symptoms of trauma.

3. Integrate knowledge about trauma into medical encounters.

4. Avoid re-traumatizing the person.

Symptoms of psychological distress caused by past trauma include anxiety, fear, anger, irritability, mood swings, feeling disconnected, numbness, sadness, or hopelessness. Clinical actions that help to reduce distress among trauma survivors include:

• sensitively ask patients to share their traumatic experiences

• empower the patient by explicitly giving her control over all aspects of the examination, indicating that the exam will stop if the patient feels uncomfortable

• explain the steps in the exam and educate about the purpose of each step

• keep the patient’s body covered as much as possible

• use the smallest speculum that permits an adequate exam

• utilize a chaperone to help support the patient.

Clinicians can strengthen their empathic skills by reflecting on how their own personal experiences, traumas, cultural-biases, and gender influence their ap-proach to the care of patients.

Reference

1. Hall KS, Moreau C, Trussell J. Young women’s perceived health and lifetime sexual experience: results from the national survey of family growth. J Sex Med. 2012;9:1382-1391. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02686.x.

Training of chaperones

Chaperones are health care professionals who should be trained for their specific role. Chaperones need to protect patient privacy and the confidentiality of health information. Chaperones should be trained to recognize the components of a professional intimate examination and to identify variances from standard practice. In many ambulatory practices, medical assistants perform the role of chaperone. The American Association of Medical Assistants (AAMA) offers national certification for medical assistants through an examination developed by the National Board of Medical Examiners. To be eligible for AAMA certification an individual must complete at least two semesters of medical assisting education that includes courses in anatomy, physiology, pharmacology, and relevant mathematics.

Reporting variances that occur during an intimate examination

Best practices are evolving on how to deal with the rare event of a chaperone witnessing a physician perform an intimate examination that is outside of standard professional practice. Chaperones may be reluctant to report a variance because physicians are in a powerful position, and the accuracy of their report will be challenged, threatening the chaperone’s employment. Processes for encouraging all team members to report concerns must be clearly explained to the chaperone and other members of the health care team. Clinicians should be aware that deviations from standard practice will be reported and investigated. Medical practices must develop a reporting system that ensures the reporting individual will be protected from retaliation.

In addition, the chaperone needs to know to whom they should report a variance. In large multispecialty medical practices, chaperones often can report concerns to nursing leaders or human resources. In small ambulatory practices, chaperones may be advised to report concerns about a physician to the practice manager or medical director. Regardless, every practice should have the best process for reporting a concern. In turn, the practice leaders who are responsible for investigating reports of concerning behavior should have a defined process for confidentially interviewing the chaperone, clinician, and patient.

Even when a chaperone is present for intimate examinations, problems can arise if the chaperone is not trained to recognize variances from standard practice or does not have a clear means for reporting variances and when the practice does not have a process for investigating reported variances.

Sadly, misconduct has been documented among priests, ministers, sports coaches, professors, scout masters, and clinicians. Trusted professionals are in positions of power in relation to their clients, patients, and students. Physicians and nurses are held in high esteem and trust by patients. To preserve the trust of the public we must treat all people with dignity and respect their autonomy. The presence of a chaperone during intimate examinations may help us fulfill Hippocrates’ edict, “First, do no harm.” ●

Ronee A. Skornik, MSW, MD

As a female obstetrician-gynecologist trained in psychiatric social work, I have found that some of my patients who have known me over a long period of time find the presence of a chaperone not only unnecessary but also uncomfortable both in terms of physical exposure and in what they may want to tell me during the examination. Personally, I strongly favor a chaperone for all intimate examinations, to safeguard both the patient and the clinician. However, I do understand why some patients prefer to see me without the presence of a chaperone, and I want to honor their wishes. If a chaperone is responsive to the patient’s requests, including where the chaperone stands and his or her role during the exam, the reluctant patient may be more willing to have a chaperone. A chaperone who develops a relationship with the patient and honors the patient’s preferences is a valuable member of the care team.

- American Medical Association. Code of Medical Ethics Opinion 1.2.4. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/ethics/use-chaperones. Accessed May 26, 2020.

- Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada. No. 266—The presence of a third party during breast and pelvic examinations. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2017;39:e496-e497. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2017.09.005.

- American College of Physicians. ACP Policy Com-pendium Summer 2016. https://www.acponline.org/system/files/documents/advocacy/acp_policy_compendium_summer_2016.pdf. Accessed May 26, 2020.

- Department of Veterans Affairs. VHA Directive 1330.01(2). Healthcare Services for Women Veterans. February 15, 2017. Amended July 24, 2018. http://www.va.gov/ vhapublications/ viewpublication.asp?pub_id=5332. Accessed May 26, 2020.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Obtaining valid consent: clinical governance advice no. 6. January 2015. https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/clinical-governance-advice/cga6.pdf. Accessed May 26, 2020.

- American College Health Association Guidelines. Best practices for sensitive exams. October 2019. https://www.acha.org/documents/resources/guidelines/ACHA_Best_Practices_for_Sensitive_Exams_October2019.pdf. Accessed May 26, 2020.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Ethics. Sexual misconduct: ACOG Committee Opinion No. 796. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:e43-e50

- American Medical Association. Code of Medical Ethics Opinion 1.2.4. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/ethics/use-chaperones. Accessed May 26, 2020.

- Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada. No. 266—The presence of a third party during breast and pelvic examinations. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2017;39:e496-e497. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2017.09.005.

- American College of Physicians. ACP Policy Com-pendium Summer 2016. https://www.acponline.org/system/files/documents/advocacy/acp_policy_compendium_summer_2016.pdf. Accessed May 26, 2020.