User login

How useful is random biopsy when no colposcopic lesions are seen?

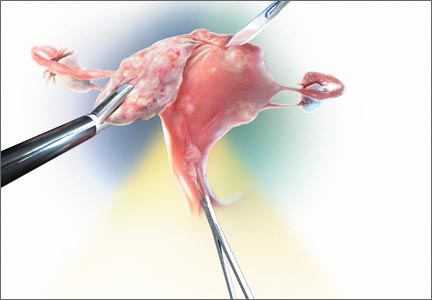

When performing colposcopy for abnormal cytology results or high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV), clinicians often are faced with an absence of visible lesions. This situation raises the following question in his or her mind: “Should I perform a random biopsy?”

Details of the study

In a multicenter US study of more than 47,000 women, performed to assess HPV diagnostics between May 2008 and August 2009, colposcopy was performed in nonpregnant women aged 25 or older with an intact uterus due to atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance or greater cytology results or high-risk HPV. The study participants and the colposcopists were blinded to the test results. In women with satisfactory colposcopy results but in whom no colposcopic lesions were noted, one random biopsy of the squamocolumnar junction was performed.

Among 2,796 women (mean age, 39.5 years) with a random biopsy performed, the findings were: normal, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN)−1, CIN2, and CIN3 in 90.0%, 5.7%, 1.3%, and 1.4%, respectively. Among all participants aged 25 and older, random biopsies accounted for 20.9% and 18.9% of the CIN2 or worse and CIN3 or worse cases, respectively. Among women positive for HPV 16 or 18, the likelihood of the random biopsy detecting CIN2 or worse was 24.7% and 8.6% for those with abnormal cytology or normal cytology, respectively.

What this evidence means for your practice

Consistent with other reports, the results of this post hoc analysis underscore the limitations of colposcopy. Just as results of a prior study indicated that taking two or more biopsies increases diagnostic yield,1 this large study points out the substantial benefit gained from performing a random biopsy of the squamocolumnar junction when no colposcopic lesions are identified.

—Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Reference

- Gage JC, Hanson VW, Abbey K, et al; SCUS LSIL Triage Study (ALTS) Group. Number of cervical biopsies and sensitivity of colposcopy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(2):264–272.

When performing colposcopy for abnormal cytology results or high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV), clinicians often are faced with an absence of visible lesions. This situation raises the following question in his or her mind: “Should I perform a random biopsy?”

Details of the study

In a multicenter US study of more than 47,000 women, performed to assess HPV diagnostics between May 2008 and August 2009, colposcopy was performed in nonpregnant women aged 25 or older with an intact uterus due to atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance or greater cytology results or high-risk HPV. The study participants and the colposcopists were blinded to the test results. In women with satisfactory colposcopy results but in whom no colposcopic lesions were noted, one random biopsy of the squamocolumnar junction was performed.

Among 2,796 women (mean age, 39.5 years) with a random biopsy performed, the findings were: normal, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN)−1, CIN2, and CIN3 in 90.0%, 5.7%, 1.3%, and 1.4%, respectively. Among all participants aged 25 and older, random biopsies accounted for 20.9% and 18.9% of the CIN2 or worse and CIN3 or worse cases, respectively. Among women positive for HPV 16 or 18, the likelihood of the random biopsy detecting CIN2 or worse was 24.7% and 8.6% for those with abnormal cytology or normal cytology, respectively.

What this evidence means for your practice

Consistent with other reports, the results of this post hoc analysis underscore the limitations of colposcopy. Just as results of a prior study indicated that taking two or more biopsies increases diagnostic yield,1 this large study points out the substantial benefit gained from performing a random biopsy of the squamocolumnar junction when no colposcopic lesions are identified.

—Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

When performing colposcopy for abnormal cytology results or high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV), clinicians often are faced with an absence of visible lesions. This situation raises the following question in his or her mind: “Should I perform a random biopsy?”

Details of the study

In a multicenter US study of more than 47,000 women, performed to assess HPV diagnostics between May 2008 and August 2009, colposcopy was performed in nonpregnant women aged 25 or older with an intact uterus due to atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance or greater cytology results or high-risk HPV. The study participants and the colposcopists were blinded to the test results. In women with satisfactory colposcopy results but in whom no colposcopic lesions were noted, one random biopsy of the squamocolumnar junction was performed.

Among 2,796 women (mean age, 39.5 years) with a random biopsy performed, the findings were: normal, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN)−1, CIN2, and CIN3 in 90.0%, 5.7%, 1.3%, and 1.4%, respectively. Among all participants aged 25 and older, random biopsies accounted for 20.9% and 18.9% of the CIN2 or worse and CIN3 or worse cases, respectively. Among women positive for HPV 16 or 18, the likelihood of the random biopsy detecting CIN2 or worse was 24.7% and 8.6% for those with abnormal cytology or normal cytology, respectively.

What this evidence means for your practice

Consistent with other reports, the results of this post hoc analysis underscore the limitations of colposcopy. Just as results of a prior study indicated that taking two or more biopsies increases diagnostic yield,1 this large study points out the substantial benefit gained from performing a random biopsy of the squamocolumnar junction when no colposcopic lesions are identified.

—Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Reference

- Gage JC, Hanson VW, Abbey K, et al; SCUS LSIL Triage Study (ALTS) Group. Number of cervical biopsies and sensitivity of colposcopy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(2):264–272.

Reference

- Gage JC, Hanson VW, Abbey K, et al; SCUS LSIL Triage Study (ALTS) Group. Number of cervical biopsies and sensitivity of colposcopy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(2):264–272.

VIDEO: Emory’s medical director offers advice on managing an Ebola patient

PHILADELPHIA – How would your hospital handle an Ebola patient? Ask Dr. Bruce Ribner.

At ID Week 2014 in Philadelphia, Dr. Ribner, medical director of Emory University Hospital’s serious communicable diseases unit in Atlanta, gave a detailed account of his hospital’s management of the first two American patients treated at Emory after contracting the disease while working in Africa.

PHILADELPHIA – How would your hospital handle an Ebola patient? Ask Dr. Bruce Ribner.

At ID Week 2014 in Philadelphia, Dr. Ribner, medical director of Emory University Hospital’s serious communicable diseases unit in Atlanta, gave a detailed account of his hospital’s management of the first two American patients treated at Emory after contracting the disease while working in Africa.

PHILADELPHIA – How would your hospital handle an Ebola patient? Ask Dr. Bruce Ribner.

At ID Week 2014 in Philadelphia, Dr. Ribner, medical director of Emory University Hospital’s serious communicable diseases unit in Atlanta, gave a detailed account of his hospital’s management of the first two American patients treated at Emory after contracting the disease while working in Africa.

AT ID WEEK 2014

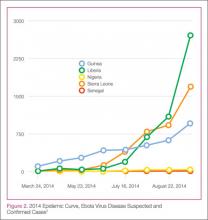

Global Ebola—Are We Prepared?

In this age of globalization, just a few hours of air travel separates even the most remote places in our world. Given this reality, the recent epidemic of Ebola virus disease (EVD) in West Africa (Figure 1) has arrived on the doorstep of Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas. Ill and potentially infected US healthcare workers and missionaries brought home for treatment and quarantine, plus the travel of the general population through the affected countries of Sierra Leone, Liberia, Guinea, and Nigeria, require all acute-care providers to be cognizant that this deadly disease may present in any community ED in the United States. Awareness and knowledge of the appropriate steps to manage care safely and effectively, while mindfully preventing the potential for viral transmission, is paramount.

Hemorrhagic Fevers

Viral hemorrhagic fevers are manifestations of four distinct families of RNA viruses: arenaviruses, bunyaviruses, flaviviruses, and filoviruses. All of these families of viruses depend on a natural insect or animal (nonhuman) host and are thus restricted geographically to the regions where the endemic hosts reside. The viruses can only infect a human when one comes into direct contact with an infected host; this human becomes an infectious host when symptoms of disease develop and subsequently, the possibility of transmission to other close direct human contacts exists.

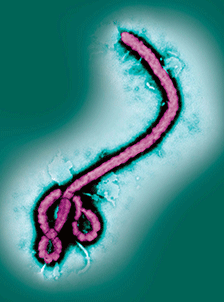

Ebola Virus Species

The family within which the Ebola virus species are classified is the filoviruses. Five species of Ebola filovirus have been isolated to date: Ebola virus (Zaire ebolavirus), Sudan virus (Sudan ebolavirus), Taï Forest virus (Taï Forest ebolavirus, formerly Côte d’Ivoire ebolavirus), and Bundibugyo virus (Bundibugyo ebolavirus). The fifth, Reston virus (Reston ebolavirus), has caused disease in nonhuman primates, but not in humans. This epidemic has been attributed to a variant of the Zaire species.2 Transmission through direct contact with body fluids of febrile live infected patients and the postmortem period continues in communities and healthcare sites, as lack of adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) and meticulous environmental hygiene remains a challenge in many of these settings.

Clinical Presentation

In EVD, the onset of symptoms typically occurs abruptly at an average of 8 to 10 days postexposure and includes fever, headache, myalgia, and malaise; in some patients, an erythematous maculopapular rash involving the face, neck, trunk, and arms erupts by days 5 to 7.1 The nonspecific nature of these early signs and symptoms warrants caution in any patient known to have traveled in an endemic country with potential exposure to body fluids of infected patients—underscoring the importance of both obtaining a complete travel history to determine the potential for disease exposure in patients presenting with infectious-disease symptoms and effectively communicating this information to all ED staff.

In addition, such caution includes healthcare mission workers caring for Ebola patients, those involved in butchering infected animals for meat, and persons participating in traditional funeral rituals for those deceased from Ebola without the use of adequate PPE and/or environmental hygiene. Other more common infectious diseases with shared features of EVD must also be considered at this stage and include malaria, meningococcemia, measles, and typhoid fever, among others.

After the first 5 days of exposure, progression of symptoms may include severe watery diarrhea, nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, shortness of breath, chest pain, headache, and/or confusion. Conjunctival injection may also develop. Not all patients will have signs of hemorrhagic fever with bleeding from the mouth, eyes, ears, in stool, or from internal organs, but petechiae, ecchymosis, and oozing from venipuncture sites may develop. Those at the highest risk of death show signs of sepsis, such as shock and multiorgan system failure, which may include hemorrhagic manifestations, early in the course of their illness. Patients with these complications typically expire between days 6 to16.1 Survivors of the disease tend to have fever with less severe symptoms for a period of several more days, and then begin to improve clinically between days 6 to 11 after onset of symptoms1 (Figure 3).

Ecology

A zoonotic filovirus transmissible from animal populations to humans causes EVD. Research strongly suggests that fruit bats are the reservoir and hosts for this filovirus. Direct human contact with bats or with wild animals that have been infected by bats initiates the human-to-human transmission of EVD.3

Pathogenesis

Through direct contact with mucous membranes, a break in the skin, or parenterally, Ebola enters and infects multiple cell types. Incubation periods appear shorter in infections acquired through direct injection (6 days) than for contact transmission (10 days).1 Emesis, urine, stool, sweat, semen, cerebrospinal fluid, breast milk, and saliva are actively capable of viral transmission. From point of entry, the virus migrates to the lymph nodes, then to liver, spleen, and adrenal glands. Hepatocellular necrosis leads to clotting-factor derangement and dysfunction resulting in coagulopathy and bleeding and potential liver failure. Necrosis of adrenal tissue may be present and results in impaired steroid synthesis and hypotension. The presence of the virus appears to incite a cytokine inflammatory storm causing microvascular leakage, with the end effect of multiorgan system failure, shock, coagulopathy, and lymphocytopenia from cellular apoptosis.1 With cellular death, immune system function is further disabled, more viral particles are released into the infected host, and body fluids remain infectious postmortem.

Laboratory Findings

Laboratory findings in viral hemorrhagic fevers can vary depending on the exact viral cause and the stage in the disease process. Leukocyte counts in early stages can reveal leukopenia and specifically lymphopenia, while in later stages leukocytosis with a left shift of neutrophils can predominate. Hemoglobin and hematocrit can show relative hemoconcentration, especially if renal manifestations of the disease occur. Thrombocytopenia also develops with viral hemorrhagic fevers, although in late stages thrombocytosis has been seen. Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine (Cr) levels will rise with the occurrence of acute renal failure in late stages of the disease. Liver function studies, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) in particular, and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) have been found to rise in severe disease and in late stages due to multifocal hepatic necrosis, with AST typically greater than ALT. An association between elevated AST (~900 IU/L), BUN, Cr, albumin levels, and mortality has been statistically confirmed by McElroy et al4 in the Ebola outbreak in Uganda in 2000 to 2001; findings previously confirmed in the same geographic and temporal outbreak by Rollin et al.5 Survivors did not have nearly the same degree of elevation in liver enzymes, with AST levels averaging ~150 IU/L.5 The authors suggested that normalizing AST levels was perhaps indicative of acute recovery, but some patients still succumbed to complications of the illness.5

Coagulation studies, including prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, d-dimer, and fibrin split products will reflect disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) in those patients who develop hemorrhagic manifestations, which is common in late stages of the disease. Direct infection of vascular endothelial cells with damage to these cells has been shown to occur in the course of infection, yet nonhuman primate experimental studies and pathology examinations of Ebola victims have implied that DIC plays an important part in the hemorrhagic disease leading to the fatal shock syndrome seen in the most severe cases.6 Observed in 2000 during the care of Sudan species EVD patients in Uganda reported by Rollin et al,5 a distinct difference has been noted in quantitative d-dimer levels between survivors and fatal cases. Case fatalities showed a 4-fold increase in quantitative d-dimer levels (140,000 ng/mL) compared with survivors (44,000 ng/mL) during the acute phase of infection 6 to 8 days postsymptom onset.5

Acute phase reactants, high nitric oxide levels, cytokines, and higher viral loads have also been associated with fatal outcomes.4 McElroy et al4 measured the common acute phase reactant biomarker ferritin in patients of the 2000 Uganda outbreak and found levels to be higher in samples from patients who died and from patients with hemorrhagic complications and higher viral loads. Thus, these authors postulate ferritin is a potential marker for EVD severity.4

Commercially available assays for detection of viral particles are still in development and no point-of-care rapid detection testing is available. No test can reliably be used to diagnose viral hemorrhagic fever prior to symptom onset.7 Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) of viral particles or tissue cell cultures are available only through the CDC, and are the current most reliable methods to confirm the diagnosis of viral hemorrhagic fevers, including Ebola.

Patient Management in the ED

Standard infection-control procedures in place in US hospitals, when meticulously practiced, should be adequate to prevent transmission of EVD. As Ebola virus is only transmitted through direct contact with infected body fluids and secretions, PPE including mask, gloves, gown, shoe covers, and eye protection (goggles or face shield), should be appropriate. In donning PPE, remember that gloves should be the last item to pull in place and to pull off, turning the gown and gloves inside out. One’s hands should be washed before removing the mask and face shield/goggles, and they should be rewashed after completion of PPE removal. A tight fit of the glove over the elastic wristband of the gown is preferable and can ensure a better barrier to any biohazard. Meticulous hand hygiene after removal and proper disposal of PPE is paramount to successful contact protection. Diligent care should be taken in any procedure that might expose a healthcare provider to body fluids, such as blood draws, central line insertion, lumbar puncture and other invasive procedures. Standard contact isolation methods with the patient in a single room with the door closed is sufficient. Appropriate use of standard hospital disinfectants, including bleach solutions or hospital grade ammonium cleaners are already standard practice and easily implemented. It is recommended that procedures that produce aerosol particles should be avoided in patients with suspected infection; yet in some circumstances, the course of care may require such procedures. In this case, to minimize potential airborne spread, airborne and droplet precautions should also be initiated by placing the patient in a negative pressure room and implementing the use of properly fitted N-95 respirators for all present in the room.8

The mainstay of treatment for viral hemorrhagic fevers in the ED begins with initiation of contact isolation of the patient to prevent spread to the healthy. Supportive care involving aggressive intravenous fluid resuscitation to maintain blood pressure, oxygen support as needed, blood products as indicated for DIC, correction of electrolyte abnormalities, including dialysis for renal failure, is the only treatment widely available at this time. In patients who exhibit generalized edema as a result of hypoproteinemia from liver damage and third spacing, serum protein monitoring and replacement is indicated.9

An experimental treatment, ZMapp, which is a monoclonal antibody that is derived from mice and blocks Ebola from entering cells, has recently been used in combination with supportive treatment in six individuals infected with Ebola. However, ZMapp is still in early stages of development and testing is not widely available. No clinical trials have begun, but are planned. Two individuals treated with ZMapp have recovered in the United States; three healthcare workers are recovering in West Africa10,11; and one patient has died. It is not clear whether this medication is responsible wholly or in part for their recovery.

According to Dr Bruce Ribner, Director of Emory University Hospital’s Infectious Disease unit in an interview with Scientific American’s Dina Fine Maron on August 27, 2014, the two patients cared for at Emory have developed immunity to Zaire Ebolavirus.11 Continued outpatient monitoring is allowing study to help understand immunity to Ebola, and may lead to further treatment and vaccination development. Thus far, cross-protection against other Ebola viral strains for these recovered individuals is not as robust, indicating that this family of viruses are different enough that recovery from infection with one species may not be enough to confer immunity to a different species exposure. Blood transfusions from recovered patients have been described, but there is no clinical evidence to support any benefit from this therapy at this time.9

Personal protective equipment is a mainstay in the collection of specimens for viral-specific testing by the CDC, including full-face shield or goggles, masks to cover nose and mouth, gowns, and gloves. For routine laboratory testing and patient care, all of the above PPE is recommended, along with use of a biosafety cabinet or plexiglass splash guard, which is in accordance with Occupational Safety and Health Administration bloodborne pathogens standards.12

Specimens should be collected for Ebola testing only after the onset of symptoms, such as fever (see Table for supplemental information). In patients suspected of having viral exposure, it may take up to 3 days for the virus to reach detectable levels with RT-PCR. Consultation per hospital procedure with the local and/or state health department prior to specimen transport for testing to the CDC is mandatory. Public health officials will help ensure appropriate patient selection and proper procedures for specimen collection, and make arrangements for testing, which is only available through the CDC. The CDC will not accept any specimen without appropriate local/state health department consultation.

Ideally, preferred specimens for Ebola testing include 4 mL of whole blood properly preserved with EDTA, clot activator, sodium polyanethol sulfonate, or citrate in plastic collection tubes stored at 4˚C or frozen.12 Specimens should be placed in a durable, leak-proof container for transport within a facility; pneumatic tube systems should be avoided due to concerns for glass breakage or leaks. Hospitals should follow state or local health department policies and procedures for Ebola testing prior to notifying the CDC and initiating sample transportation.

The Dallas Index Case

Deplaning a flight from Liberia in Dallas, Texas on September 20, this index patient had no outward signs of illness, and thus no reason to cause any health concern. Joining in the community with friends and family, it was not until 4 days later that he reportedly developed a fever. Yet 2 more days passed before this patient initially sought ambulatory care at Dallas Health Presbyterian Hospital Emergency Department, during which time additional close contacts were exposed to infection. After evaluation, antibiotics were prescribed and the patient was released. Though this case is under investigation, according to a CNN report,13 the patient did inform a member of the ED nursing staff of his travel history, but this information was not communicated to the rest of the healthcare team. The presence and recognition of this patient’s travel history with disease symptoms heightens the level of suspicion for the possibility of EVD, and is the cornerstone of patient selection for Ebola testing.14

After the patient was discharged, another 2 days passed, during which time his condition deteriorated at home. Emergency medical services (EMS) transport was summoned to take the patient back to the hospital, expanding exposure to first responders, who appropriately utilized masks and gloves during transport. During this ED visit, his travel history was obtained and communicated, and he was appropriately isolated, supported, and admitted. These are early reported details of the case, and local public health officials continue to work with a team from the CDC to trace, isolate, and monitor all contacts with this patient (including the transporting emergency medical technicians) for evidence of further cases.15

This index case illustrates valuable lessons for all emergency care workers going forward. Ebola virus disease is now global, in the sense that it has proven its ability to present in a community far from its endemic home. Infectious diseases in their early stages present in nonspecific constellations of symptoms, and the key to rapid identification of EVD lies in careful attention to the recent travel history and exposure potential. Since patients may not offer this information for various reasons (eg, degree of symptoms, language barriers, fear, denial), it must be sought out lest more index patients be released into the public. As CDC Director Thomas Frieden related to CNN, “If someone’s been in West Africa within 21 days and they’ve got a fever, immediately isolate them and get them tested for Ebola.”13

Concerning the EMS transport of this patient, the ambulance used was disinfected per standard local protocols and remained in service for 2 days after this patient was transported. Though local officials are confident in the disinfection technique, it was pulled from service after the diagnosis was confirmed to ensure its full sterilization from Ebola virus16 before returning to full service. The rapid and robust public health response in progress will undoubtedly reveal further information over the coming days to weeks. To quote Michael Osterholm, PhD, MPH, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, “We are going to see more cases show up around the world.”15

In addition to the index patient, it is important to keep in mind that secondary cases may present. If this occurs, the travel question must be altered to reflect the possibility that a secondary patient may not have been the traveler but rather one who was in close contact with an ill person who was in contact with him or her. Such a scenario would have a huge impact if that traveler did not seek treatment and would in turn require ED personnel to seek-out the information and report it to local public health officials.

Quelling the Panic

Even though Ebola is only spread through direct contact with infected bodily secretions, there is still significant public fear of the disease due to the high mortality rate and the graphic nature of symptoms in late stages of the disease. Daily monitoring of contacts of symptomatic Ebola patients for evidence of disease development—mainly fever—is sensible. Asymptomatic persons need not be confined or hospitalized unless fever develops, in which case contact isolation should occur until formal Ebola testing can rule-out the disease. Personal protective equipment, standardized hospital cleaning protocols with meticulous adherence, as well as quickly burying the deceased with adequate contact precautions, can all limit potential exposure and spread of the disease. Public health discussion and education about the virus and methods of transmission are needed so that individuals are not denied proper treatment or scared away from medical centers.

Importantly, communication by public health and medical experts on local and national levels should be with news media that embrace honest and careful reporting to avoid sensationalism and foster appropriate concern—ensuring that content is fundamental to curtailing panic and undue public fear.

For Internationally Traveling Clinicians

At present, the area endemic for Ebola remains confined to sub-Saharan Africa and West Africa. Clinicians should remain alert when traveling or treating patients in these areas. However, with the ease of international air travel, the potential for the spread of disease is recognized with many bordering nations now screening passengers from affected countries and some closing their borders to travelers from endemic areas. If a clinician encounters febrile patients in endemic areas, the differential diagnosis for any febrile illness must include Ebola, as well as malaria and other more common infectious agents. A thorough history about recent travel, ill contacts, and possible exposures should be sufficient in categorizing the risk of Ebola, but a high index of suspicion is necessary for prompt and proper treatment of those affected and to curtail spread of disease.

Despite the efforts of the national and local health systems and many nongovernmental organizations, including the World Health Organization, this epidemic continues to hold strong in the affected West African countries. Methods of containment of the virus are seemingly simple by modern standards, yet tragically beyond access for many on the ground. Lack of clean water sources in affected communities is a significant barrier to basic personal and environmental hygiene. Inadequate safe food sources and poaching encourages the hunt for primate bushmeat and thus presents a formidable local challenge.17 Lack of adequate PPE for healthcare workers, for those responsible for facility environmental hygiene, and for family members participating in traditional funeral rites for Ebola victims compounds the problem. Illness and deaths among exposed healthcare workers have led to the loss of significant numbers of nurses and doctors. This has caused legitimate fear in qualified individuals who subsequently decline to accept jobs caring for Ebola patients, which in turn increases the burden on those who remain. Additionally, some nongovernmental organizations have canceled scheduled aid trips to West Africa in response to the epidemic out of concern for the health of their workers. Meticulous management of environmental hygiene including sharps, surfaces, soiled linens, reusable medical equipment, waste products, and the preparations for burial of the deceased pose definite challenges to containment and prevention of transmission. Strict adherence to the use of PPE and hand hygiene is essential for all in contact with Ebola patients, pre- and postmortem. The lack of layperson comprehension and community understanding of the illness itself and the mechanism of viral transmission along with fear and mistrust for healthcare providers and nongovernmental medical missionaries are all serious barriers to the containment of disease spread. In fact, rumors that the virus does not truly exist, and that the illness is a result of biological warfare, cannibalistic rituals, or witchcraft add to the complexity of the situation.11

For these reasons, it is essential that efforts to control this epidemic in endemic healthcare facilities include effective health surveillance, infection-control programs, and community outreach fostering mutual trust-building, honest communication, and education. Success will require a multifaceted approach, and a global response will be needed to quiet this global threat. On September 16, the United States announced a robust response to deploy military engineers and medical personnel to assist in training healthcare workers and building care centers in Liberia. The United Nations, France, and the United Kingdom are also supporting this important effort to build stronger healthcare infrastructures in these vulnerable countries.16

Conclusion

This 2014 epidemic of EVD raises justifiable concerns regarding the impact of globalization. Though unlikely to pose a direct threat of epidemic proportion on US soil, the unanticipated occurrence of an index case may trigger a terrifying outbreak in any community, as it already has in the city of Dallas. Given that the early stages of EVD are indistinguishable from most other viral syndromes, the importance of reflection on individual and general healthcare facility adherence to standard infection control precautions and procedures warrant merit. Eliciting accurate travel histories and possible exposures are germane to narrowing the scope of possible etiologies of all infectious diseases. As an opportunity for improvement, this epidemic should incite elevated caution in the everyday handling of all patients with febrile illnesses and contact-transmissible infections including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Clostridium difficile, which affect a great number of US patients on a daily basis. Not only could this strategy prevent additional local outbreaks of EVD, but it would promote the safety of healthcare workers and the community served through attention to better infection preventive measures at the point of care, every time.

Dr McCammon is an assistant professor, department of emergency medicine, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk. Dr Chidester is an instructor, department of emergency medicine, and a fellow in international wilderness medicine, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk.

- Ebola virus disease information for clinicians in U.S. Healthcare Settings. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/hcp/clinician-information-us-healthcare-settings.html. Updated September 5, 2014. Accessed September 23, 2014.

- 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/outbreaks/guinea/. Updated September 18, 2014. Accessed September 23, 2014.

- Virus ecology graphic. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/resources/virus-ecology.html. Updated August 1, 2014. Accessed September 23, 2014.

- McElroy AK, Erickson BR, Flietstra TD, et al. Ebola hemorrhagic fever: novel biomarker correlates of clinical outcome. J Infect Dis. 2014;210(4):558-566.

- Rollin PE, Bausch DG, Sanchez A. Blood chemistry measurements and D-Dimer levels associated with fatal and nonfatal outcomes in humans infected with Sudan Ebola virus. J Infect Dis. 2007;196(Suppl 2):S364-S371.

- Geisbert TW, Young HA, Jahrling PB, et al. Pathogenesis of Ebola hemorrhagic fever in primate models: evidence that hemorrhage is not a direct effect of virus-induced cytolysis of endothelial cells. Am J Pathol. 2003;163(6): 2371-2382.

- Blumberg L, Enria D, Bausch DG. Viral haemorrhagic fevers. In: Farrar J, Hotez, PJ, Junghanss T, Kang G, Lalloo D, White N, eds. Manson’s Tropical Diseases: Expert Consult. 23rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014:171-194.

- Safe management of patients with Ebola virus disease (EVD) in U.S. hospitals. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/hcp/patient-management-us-hospitals.html. Updated September 5, 2014. Accessed September 23, 2014.

- Maron DF. Ebola doctor reveals how infected Americans were cured. Scientific American. http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/ebola-doctor-revealshow-infected-americans-were-cured/.

- Tribune wire reports. American Ebola patients treated with ZMapp experimental drug. Chicago Tribune. August 21, 2014. http://www.chicagotribune.com/lifestyles/health/chi-ebola-zmapp-20140821-story.html. Accessed September 23, 2014.

- Ebola crisis: doctors in Liberia ‘recovering after taking ZMapp’ [transcript]. BBC News. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-28860204. August 19, 2014. Accessed September 23, 2014.

- Interim guidance for specimen collection, transport, testing, and submission for persons under investigation for Ebola virus disease in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/hcp/interim-guidance-specimen-collection-submission-patients-suspected-infection-ebola.html. Updated September 8, 2014. Accessed September 23, 2014.

- Catherine E. Shoichet CE, Fantz A, Yan H. Hospital ‘dropped the ball’ with Ebola patient’s travel history, NIH official says. CNN News. http://www.cnn.com/2014/10/01/health/ebola-us/index.html. Accessed October 2, 2014.

- Ebola (Ebola Virus Disease): Diagnosis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web Site. http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/diagnosis/. Updated September 19, 2014. Accessed October 1, 2014.

- Gilblom K, Langreth R. Dallas hospital initially let Ebola patient go with drugs. Bloomberg News Web Site. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2014-09-30/first-ebola-case-is-diagnosed-in-the-u-s-cdc-reports.html. Accessed October 1, 2014.

- Bates D, Szathmary Z and Boyle L. Up to twelve Americans could have Ebola: Fears grow in Dallas after first victim of deadly virus to reach U.S. remained at large for a week. September 30, 2014. Mail Online. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2775608/CDC-confirms-Dallas-patient-isolation-testing-returning-region-plagued-Ebola-HAS-deadly-virus.html. Updated October 1, 2014. Accessed October 1, 2014.

- International affairs: bushmeat. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Web site. http://www.fws.gov/international/wildlife-without-borders/global-program/bushmeat.html. Accessed September 23, 2014.

In this age of globalization, just a few hours of air travel separates even the most remote places in our world. Given this reality, the recent epidemic of Ebola virus disease (EVD) in West Africa (Figure 1) has arrived on the doorstep of Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas. Ill and potentially infected US healthcare workers and missionaries brought home for treatment and quarantine, plus the travel of the general population through the affected countries of Sierra Leone, Liberia, Guinea, and Nigeria, require all acute-care providers to be cognizant that this deadly disease may present in any community ED in the United States. Awareness and knowledge of the appropriate steps to manage care safely and effectively, while mindfully preventing the potential for viral transmission, is paramount.

Hemorrhagic Fevers

Viral hemorrhagic fevers are manifestations of four distinct families of RNA viruses: arenaviruses, bunyaviruses, flaviviruses, and filoviruses. All of these families of viruses depend on a natural insect or animal (nonhuman) host and are thus restricted geographically to the regions where the endemic hosts reside. The viruses can only infect a human when one comes into direct contact with an infected host; this human becomes an infectious host when symptoms of disease develop and subsequently, the possibility of transmission to other close direct human contacts exists.

Ebola Virus Species

The family within which the Ebola virus species are classified is the filoviruses. Five species of Ebola filovirus have been isolated to date: Ebola virus (Zaire ebolavirus), Sudan virus (Sudan ebolavirus), Taï Forest virus (Taï Forest ebolavirus, formerly Côte d’Ivoire ebolavirus), and Bundibugyo virus (Bundibugyo ebolavirus). The fifth, Reston virus (Reston ebolavirus), has caused disease in nonhuman primates, but not in humans. This epidemic has been attributed to a variant of the Zaire species.2 Transmission through direct contact with body fluids of febrile live infected patients and the postmortem period continues in communities and healthcare sites, as lack of adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) and meticulous environmental hygiene remains a challenge in many of these settings.

Clinical Presentation

In EVD, the onset of symptoms typically occurs abruptly at an average of 8 to 10 days postexposure and includes fever, headache, myalgia, and malaise; in some patients, an erythematous maculopapular rash involving the face, neck, trunk, and arms erupts by days 5 to 7.1 The nonspecific nature of these early signs and symptoms warrants caution in any patient known to have traveled in an endemic country with potential exposure to body fluids of infected patients—underscoring the importance of both obtaining a complete travel history to determine the potential for disease exposure in patients presenting with infectious-disease symptoms and effectively communicating this information to all ED staff.

In addition, such caution includes healthcare mission workers caring for Ebola patients, those involved in butchering infected animals for meat, and persons participating in traditional funeral rituals for those deceased from Ebola without the use of adequate PPE and/or environmental hygiene. Other more common infectious diseases with shared features of EVD must also be considered at this stage and include malaria, meningococcemia, measles, and typhoid fever, among others.

After the first 5 days of exposure, progression of symptoms may include severe watery diarrhea, nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, shortness of breath, chest pain, headache, and/or confusion. Conjunctival injection may also develop. Not all patients will have signs of hemorrhagic fever with bleeding from the mouth, eyes, ears, in stool, or from internal organs, but petechiae, ecchymosis, and oozing from venipuncture sites may develop. Those at the highest risk of death show signs of sepsis, such as shock and multiorgan system failure, which may include hemorrhagic manifestations, early in the course of their illness. Patients with these complications typically expire between days 6 to16.1 Survivors of the disease tend to have fever with less severe symptoms for a period of several more days, and then begin to improve clinically between days 6 to 11 after onset of symptoms1 (Figure 3).

Ecology

A zoonotic filovirus transmissible from animal populations to humans causes EVD. Research strongly suggests that fruit bats are the reservoir and hosts for this filovirus. Direct human contact with bats or with wild animals that have been infected by bats initiates the human-to-human transmission of EVD.3

Pathogenesis

Through direct contact with mucous membranes, a break in the skin, or parenterally, Ebola enters and infects multiple cell types. Incubation periods appear shorter in infections acquired through direct injection (6 days) than for contact transmission (10 days).1 Emesis, urine, stool, sweat, semen, cerebrospinal fluid, breast milk, and saliva are actively capable of viral transmission. From point of entry, the virus migrates to the lymph nodes, then to liver, spleen, and adrenal glands. Hepatocellular necrosis leads to clotting-factor derangement and dysfunction resulting in coagulopathy and bleeding and potential liver failure. Necrosis of adrenal tissue may be present and results in impaired steroid synthesis and hypotension. The presence of the virus appears to incite a cytokine inflammatory storm causing microvascular leakage, with the end effect of multiorgan system failure, shock, coagulopathy, and lymphocytopenia from cellular apoptosis.1 With cellular death, immune system function is further disabled, more viral particles are released into the infected host, and body fluids remain infectious postmortem.

Laboratory Findings

Laboratory findings in viral hemorrhagic fevers can vary depending on the exact viral cause and the stage in the disease process. Leukocyte counts in early stages can reveal leukopenia and specifically lymphopenia, while in later stages leukocytosis with a left shift of neutrophils can predominate. Hemoglobin and hematocrit can show relative hemoconcentration, especially if renal manifestations of the disease occur. Thrombocytopenia also develops with viral hemorrhagic fevers, although in late stages thrombocytosis has been seen. Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine (Cr) levels will rise with the occurrence of acute renal failure in late stages of the disease. Liver function studies, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) in particular, and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) have been found to rise in severe disease and in late stages due to multifocal hepatic necrosis, with AST typically greater than ALT. An association between elevated AST (~900 IU/L), BUN, Cr, albumin levels, and mortality has been statistically confirmed by McElroy et al4 in the Ebola outbreak in Uganda in 2000 to 2001; findings previously confirmed in the same geographic and temporal outbreak by Rollin et al.5 Survivors did not have nearly the same degree of elevation in liver enzymes, with AST levels averaging ~150 IU/L.5 The authors suggested that normalizing AST levels was perhaps indicative of acute recovery, but some patients still succumbed to complications of the illness.5

Coagulation studies, including prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, d-dimer, and fibrin split products will reflect disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) in those patients who develop hemorrhagic manifestations, which is common in late stages of the disease. Direct infection of vascular endothelial cells with damage to these cells has been shown to occur in the course of infection, yet nonhuman primate experimental studies and pathology examinations of Ebola victims have implied that DIC plays an important part in the hemorrhagic disease leading to the fatal shock syndrome seen in the most severe cases.6 Observed in 2000 during the care of Sudan species EVD patients in Uganda reported by Rollin et al,5 a distinct difference has been noted in quantitative d-dimer levels between survivors and fatal cases. Case fatalities showed a 4-fold increase in quantitative d-dimer levels (140,000 ng/mL) compared with survivors (44,000 ng/mL) during the acute phase of infection 6 to 8 days postsymptom onset.5

Acute phase reactants, high nitric oxide levels, cytokines, and higher viral loads have also been associated with fatal outcomes.4 McElroy et al4 measured the common acute phase reactant biomarker ferritin in patients of the 2000 Uganda outbreak and found levels to be higher in samples from patients who died and from patients with hemorrhagic complications and higher viral loads. Thus, these authors postulate ferritin is a potential marker for EVD severity.4

Commercially available assays for detection of viral particles are still in development and no point-of-care rapid detection testing is available. No test can reliably be used to diagnose viral hemorrhagic fever prior to symptom onset.7 Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) of viral particles or tissue cell cultures are available only through the CDC, and are the current most reliable methods to confirm the diagnosis of viral hemorrhagic fevers, including Ebola.

Patient Management in the ED

Standard infection-control procedures in place in US hospitals, when meticulously practiced, should be adequate to prevent transmission of EVD. As Ebola virus is only transmitted through direct contact with infected body fluids and secretions, PPE including mask, gloves, gown, shoe covers, and eye protection (goggles or face shield), should be appropriate. In donning PPE, remember that gloves should be the last item to pull in place and to pull off, turning the gown and gloves inside out. One’s hands should be washed before removing the mask and face shield/goggles, and they should be rewashed after completion of PPE removal. A tight fit of the glove over the elastic wristband of the gown is preferable and can ensure a better barrier to any biohazard. Meticulous hand hygiene after removal and proper disposal of PPE is paramount to successful contact protection. Diligent care should be taken in any procedure that might expose a healthcare provider to body fluids, such as blood draws, central line insertion, lumbar puncture and other invasive procedures. Standard contact isolation methods with the patient in a single room with the door closed is sufficient. Appropriate use of standard hospital disinfectants, including bleach solutions or hospital grade ammonium cleaners are already standard practice and easily implemented. It is recommended that procedures that produce aerosol particles should be avoided in patients with suspected infection; yet in some circumstances, the course of care may require such procedures. In this case, to minimize potential airborne spread, airborne and droplet precautions should also be initiated by placing the patient in a negative pressure room and implementing the use of properly fitted N-95 respirators for all present in the room.8

The mainstay of treatment for viral hemorrhagic fevers in the ED begins with initiation of contact isolation of the patient to prevent spread to the healthy. Supportive care involving aggressive intravenous fluid resuscitation to maintain blood pressure, oxygen support as needed, blood products as indicated for DIC, correction of electrolyte abnormalities, including dialysis for renal failure, is the only treatment widely available at this time. In patients who exhibit generalized edema as a result of hypoproteinemia from liver damage and third spacing, serum protein monitoring and replacement is indicated.9

An experimental treatment, ZMapp, which is a monoclonal antibody that is derived from mice and blocks Ebola from entering cells, has recently been used in combination with supportive treatment in six individuals infected with Ebola. However, ZMapp is still in early stages of development and testing is not widely available. No clinical trials have begun, but are planned. Two individuals treated with ZMapp have recovered in the United States; three healthcare workers are recovering in West Africa10,11; and one patient has died. It is not clear whether this medication is responsible wholly or in part for their recovery.

According to Dr Bruce Ribner, Director of Emory University Hospital’s Infectious Disease unit in an interview with Scientific American’s Dina Fine Maron on August 27, 2014, the two patients cared for at Emory have developed immunity to Zaire Ebolavirus.11 Continued outpatient monitoring is allowing study to help understand immunity to Ebola, and may lead to further treatment and vaccination development. Thus far, cross-protection against other Ebola viral strains for these recovered individuals is not as robust, indicating that this family of viruses are different enough that recovery from infection with one species may not be enough to confer immunity to a different species exposure. Blood transfusions from recovered patients have been described, but there is no clinical evidence to support any benefit from this therapy at this time.9

Personal protective equipment is a mainstay in the collection of specimens for viral-specific testing by the CDC, including full-face shield or goggles, masks to cover nose and mouth, gowns, and gloves. For routine laboratory testing and patient care, all of the above PPE is recommended, along with use of a biosafety cabinet or plexiglass splash guard, which is in accordance with Occupational Safety and Health Administration bloodborne pathogens standards.12

Specimens should be collected for Ebola testing only after the onset of symptoms, such as fever (see Table for supplemental information). In patients suspected of having viral exposure, it may take up to 3 days for the virus to reach detectable levels with RT-PCR. Consultation per hospital procedure with the local and/or state health department prior to specimen transport for testing to the CDC is mandatory. Public health officials will help ensure appropriate patient selection and proper procedures for specimen collection, and make arrangements for testing, which is only available through the CDC. The CDC will not accept any specimen without appropriate local/state health department consultation.

Ideally, preferred specimens for Ebola testing include 4 mL of whole blood properly preserved with EDTA, clot activator, sodium polyanethol sulfonate, or citrate in plastic collection tubes stored at 4˚C or frozen.12 Specimens should be placed in a durable, leak-proof container for transport within a facility; pneumatic tube systems should be avoided due to concerns for glass breakage or leaks. Hospitals should follow state or local health department policies and procedures for Ebola testing prior to notifying the CDC and initiating sample transportation.

The Dallas Index Case

Deplaning a flight from Liberia in Dallas, Texas on September 20, this index patient had no outward signs of illness, and thus no reason to cause any health concern. Joining in the community with friends and family, it was not until 4 days later that he reportedly developed a fever. Yet 2 more days passed before this patient initially sought ambulatory care at Dallas Health Presbyterian Hospital Emergency Department, during which time additional close contacts were exposed to infection. After evaluation, antibiotics were prescribed and the patient was released. Though this case is under investigation, according to a CNN report,13 the patient did inform a member of the ED nursing staff of his travel history, but this information was not communicated to the rest of the healthcare team. The presence and recognition of this patient’s travel history with disease symptoms heightens the level of suspicion for the possibility of EVD, and is the cornerstone of patient selection for Ebola testing.14

After the patient was discharged, another 2 days passed, during which time his condition deteriorated at home. Emergency medical services (EMS) transport was summoned to take the patient back to the hospital, expanding exposure to first responders, who appropriately utilized masks and gloves during transport. During this ED visit, his travel history was obtained and communicated, and he was appropriately isolated, supported, and admitted. These are early reported details of the case, and local public health officials continue to work with a team from the CDC to trace, isolate, and monitor all contacts with this patient (including the transporting emergency medical technicians) for evidence of further cases.15

This index case illustrates valuable lessons for all emergency care workers going forward. Ebola virus disease is now global, in the sense that it has proven its ability to present in a community far from its endemic home. Infectious diseases in their early stages present in nonspecific constellations of symptoms, and the key to rapid identification of EVD lies in careful attention to the recent travel history and exposure potential. Since patients may not offer this information for various reasons (eg, degree of symptoms, language barriers, fear, denial), it must be sought out lest more index patients be released into the public. As CDC Director Thomas Frieden related to CNN, “If someone’s been in West Africa within 21 days and they’ve got a fever, immediately isolate them and get them tested for Ebola.”13

Concerning the EMS transport of this patient, the ambulance used was disinfected per standard local protocols and remained in service for 2 days after this patient was transported. Though local officials are confident in the disinfection technique, it was pulled from service after the diagnosis was confirmed to ensure its full sterilization from Ebola virus16 before returning to full service. The rapid and robust public health response in progress will undoubtedly reveal further information over the coming days to weeks. To quote Michael Osterholm, PhD, MPH, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, “We are going to see more cases show up around the world.”15

In addition to the index patient, it is important to keep in mind that secondary cases may present. If this occurs, the travel question must be altered to reflect the possibility that a secondary patient may not have been the traveler but rather one who was in close contact with an ill person who was in contact with him or her. Such a scenario would have a huge impact if that traveler did not seek treatment and would in turn require ED personnel to seek-out the information and report it to local public health officials.

Quelling the Panic

Even though Ebola is only spread through direct contact with infected bodily secretions, there is still significant public fear of the disease due to the high mortality rate and the graphic nature of symptoms in late stages of the disease. Daily monitoring of contacts of symptomatic Ebola patients for evidence of disease development—mainly fever—is sensible. Asymptomatic persons need not be confined or hospitalized unless fever develops, in which case contact isolation should occur until formal Ebola testing can rule-out the disease. Personal protective equipment, standardized hospital cleaning protocols with meticulous adherence, as well as quickly burying the deceased with adequate contact precautions, can all limit potential exposure and spread of the disease. Public health discussion and education about the virus and methods of transmission are needed so that individuals are not denied proper treatment or scared away from medical centers.

Importantly, communication by public health and medical experts on local and national levels should be with news media that embrace honest and careful reporting to avoid sensationalism and foster appropriate concern—ensuring that content is fundamental to curtailing panic and undue public fear.

For Internationally Traveling Clinicians

At present, the area endemic for Ebola remains confined to sub-Saharan Africa and West Africa. Clinicians should remain alert when traveling or treating patients in these areas. However, with the ease of international air travel, the potential for the spread of disease is recognized with many bordering nations now screening passengers from affected countries and some closing their borders to travelers from endemic areas. If a clinician encounters febrile patients in endemic areas, the differential diagnosis for any febrile illness must include Ebola, as well as malaria and other more common infectious agents. A thorough history about recent travel, ill contacts, and possible exposures should be sufficient in categorizing the risk of Ebola, but a high index of suspicion is necessary for prompt and proper treatment of those affected and to curtail spread of disease.

Despite the efforts of the national and local health systems and many nongovernmental organizations, including the World Health Organization, this epidemic continues to hold strong in the affected West African countries. Methods of containment of the virus are seemingly simple by modern standards, yet tragically beyond access for many on the ground. Lack of clean water sources in affected communities is a significant barrier to basic personal and environmental hygiene. Inadequate safe food sources and poaching encourages the hunt for primate bushmeat and thus presents a formidable local challenge.17 Lack of adequate PPE for healthcare workers, for those responsible for facility environmental hygiene, and for family members participating in traditional funeral rites for Ebola victims compounds the problem. Illness and deaths among exposed healthcare workers have led to the loss of significant numbers of nurses and doctors. This has caused legitimate fear in qualified individuals who subsequently decline to accept jobs caring for Ebola patients, which in turn increases the burden on those who remain. Additionally, some nongovernmental organizations have canceled scheduled aid trips to West Africa in response to the epidemic out of concern for the health of their workers. Meticulous management of environmental hygiene including sharps, surfaces, soiled linens, reusable medical equipment, waste products, and the preparations for burial of the deceased pose definite challenges to containment and prevention of transmission. Strict adherence to the use of PPE and hand hygiene is essential for all in contact with Ebola patients, pre- and postmortem. The lack of layperson comprehension and community understanding of the illness itself and the mechanism of viral transmission along with fear and mistrust for healthcare providers and nongovernmental medical missionaries are all serious barriers to the containment of disease spread. In fact, rumors that the virus does not truly exist, and that the illness is a result of biological warfare, cannibalistic rituals, or witchcraft add to the complexity of the situation.11

For these reasons, it is essential that efforts to control this epidemic in endemic healthcare facilities include effective health surveillance, infection-control programs, and community outreach fostering mutual trust-building, honest communication, and education. Success will require a multifaceted approach, and a global response will be needed to quiet this global threat. On September 16, the United States announced a robust response to deploy military engineers and medical personnel to assist in training healthcare workers and building care centers in Liberia. The United Nations, France, and the United Kingdom are also supporting this important effort to build stronger healthcare infrastructures in these vulnerable countries.16

Conclusion

This 2014 epidemic of EVD raises justifiable concerns regarding the impact of globalization. Though unlikely to pose a direct threat of epidemic proportion on US soil, the unanticipated occurrence of an index case may trigger a terrifying outbreak in any community, as it already has in the city of Dallas. Given that the early stages of EVD are indistinguishable from most other viral syndromes, the importance of reflection on individual and general healthcare facility adherence to standard infection control precautions and procedures warrant merit. Eliciting accurate travel histories and possible exposures are germane to narrowing the scope of possible etiologies of all infectious diseases. As an opportunity for improvement, this epidemic should incite elevated caution in the everyday handling of all patients with febrile illnesses and contact-transmissible infections including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Clostridium difficile, which affect a great number of US patients on a daily basis. Not only could this strategy prevent additional local outbreaks of EVD, but it would promote the safety of healthcare workers and the community served through attention to better infection preventive measures at the point of care, every time.

Dr McCammon is an assistant professor, department of emergency medicine, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk. Dr Chidester is an instructor, department of emergency medicine, and a fellow in international wilderness medicine, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk.

In this age of globalization, just a few hours of air travel separates even the most remote places in our world. Given this reality, the recent epidemic of Ebola virus disease (EVD) in West Africa (Figure 1) has arrived on the doorstep of Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas. Ill and potentially infected US healthcare workers and missionaries brought home for treatment and quarantine, plus the travel of the general population through the affected countries of Sierra Leone, Liberia, Guinea, and Nigeria, require all acute-care providers to be cognizant that this deadly disease may present in any community ED in the United States. Awareness and knowledge of the appropriate steps to manage care safely and effectively, while mindfully preventing the potential for viral transmission, is paramount.

Hemorrhagic Fevers

Viral hemorrhagic fevers are manifestations of four distinct families of RNA viruses: arenaviruses, bunyaviruses, flaviviruses, and filoviruses. All of these families of viruses depend on a natural insect or animal (nonhuman) host and are thus restricted geographically to the regions where the endemic hosts reside. The viruses can only infect a human when one comes into direct contact with an infected host; this human becomes an infectious host when symptoms of disease develop and subsequently, the possibility of transmission to other close direct human contacts exists.

Ebola Virus Species

The family within which the Ebola virus species are classified is the filoviruses. Five species of Ebola filovirus have been isolated to date: Ebola virus (Zaire ebolavirus), Sudan virus (Sudan ebolavirus), Taï Forest virus (Taï Forest ebolavirus, formerly Côte d’Ivoire ebolavirus), and Bundibugyo virus (Bundibugyo ebolavirus). The fifth, Reston virus (Reston ebolavirus), has caused disease in nonhuman primates, but not in humans. This epidemic has been attributed to a variant of the Zaire species.2 Transmission through direct contact with body fluids of febrile live infected patients and the postmortem period continues in communities and healthcare sites, as lack of adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) and meticulous environmental hygiene remains a challenge in many of these settings.

Clinical Presentation

In EVD, the onset of symptoms typically occurs abruptly at an average of 8 to 10 days postexposure and includes fever, headache, myalgia, and malaise; in some patients, an erythematous maculopapular rash involving the face, neck, trunk, and arms erupts by days 5 to 7.1 The nonspecific nature of these early signs and symptoms warrants caution in any patient known to have traveled in an endemic country with potential exposure to body fluids of infected patients—underscoring the importance of both obtaining a complete travel history to determine the potential for disease exposure in patients presenting with infectious-disease symptoms and effectively communicating this information to all ED staff.

In addition, such caution includes healthcare mission workers caring for Ebola patients, those involved in butchering infected animals for meat, and persons participating in traditional funeral rituals for those deceased from Ebola without the use of adequate PPE and/or environmental hygiene. Other more common infectious diseases with shared features of EVD must also be considered at this stage and include malaria, meningococcemia, measles, and typhoid fever, among others.

After the first 5 days of exposure, progression of symptoms may include severe watery diarrhea, nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, shortness of breath, chest pain, headache, and/or confusion. Conjunctival injection may also develop. Not all patients will have signs of hemorrhagic fever with bleeding from the mouth, eyes, ears, in stool, or from internal organs, but petechiae, ecchymosis, and oozing from venipuncture sites may develop. Those at the highest risk of death show signs of sepsis, such as shock and multiorgan system failure, which may include hemorrhagic manifestations, early in the course of their illness. Patients with these complications typically expire between days 6 to16.1 Survivors of the disease tend to have fever with less severe symptoms for a period of several more days, and then begin to improve clinically between days 6 to 11 after onset of symptoms1 (Figure 3).

Ecology

A zoonotic filovirus transmissible from animal populations to humans causes EVD. Research strongly suggests that fruit bats are the reservoir and hosts for this filovirus. Direct human contact with bats or with wild animals that have been infected by bats initiates the human-to-human transmission of EVD.3

Pathogenesis

Through direct contact with mucous membranes, a break in the skin, or parenterally, Ebola enters and infects multiple cell types. Incubation periods appear shorter in infections acquired through direct injection (6 days) than for contact transmission (10 days).1 Emesis, urine, stool, sweat, semen, cerebrospinal fluid, breast milk, and saliva are actively capable of viral transmission. From point of entry, the virus migrates to the lymph nodes, then to liver, spleen, and adrenal glands. Hepatocellular necrosis leads to clotting-factor derangement and dysfunction resulting in coagulopathy and bleeding and potential liver failure. Necrosis of adrenal tissue may be present and results in impaired steroid synthesis and hypotension. The presence of the virus appears to incite a cytokine inflammatory storm causing microvascular leakage, with the end effect of multiorgan system failure, shock, coagulopathy, and lymphocytopenia from cellular apoptosis.1 With cellular death, immune system function is further disabled, more viral particles are released into the infected host, and body fluids remain infectious postmortem.

Laboratory Findings

Laboratory findings in viral hemorrhagic fevers can vary depending on the exact viral cause and the stage in the disease process. Leukocyte counts in early stages can reveal leukopenia and specifically lymphopenia, while in later stages leukocytosis with a left shift of neutrophils can predominate. Hemoglobin and hematocrit can show relative hemoconcentration, especially if renal manifestations of the disease occur. Thrombocytopenia also develops with viral hemorrhagic fevers, although in late stages thrombocytosis has been seen. Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine (Cr) levels will rise with the occurrence of acute renal failure in late stages of the disease. Liver function studies, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) in particular, and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) have been found to rise in severe disease and in late stages due to multifocal hepatic necrosis, with AST typically greater than ALT. An association between elevated AST (~900 IU/L), BUN, Cr, albumin levels, and mortality has been statistically confirmed by McElroy et al4 in the Ebola outbreak in Uganda in 2000 to 2001; findings previously confirmed in the same geographic and temporal outbreak by Rollin et al.5 Survivors did not have nearly the same degree of elevation in liver enzymes, with AST levels averaging ~150 IU/L.5 The authors suggested that normalizing AST levels was perhaps indicative of acute recovery, but some patients still succumbed to complications of the illness.5

Coagulation studies, including prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, d-dimer, and fibrin split products will reflect disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) in those patients who develop hemorrhagic manifestations, which is common in late stages of the disease. Direct infection of vascular endothelial cells with damage to these cells has been shown to occur in the course of infection, yet nonhuman primate experimental studies and pathology examinations of Ebola victims have implied that DIC plays an important part in the hemorrhagic disease leading to the fatal shock syndrome seen in the most severe cases.6 Observed in 2000 during the care of Sudan species EVD patients in Uganda reported by Rollin et al,5 a distinct difference has been noted in quantitative d-dimer levels between survivors and fatal cases. Case fatalities showed a 4-fold increase in quantitative d-dimer levels (140,000 ng/mL) compared with survivors (44,000 ng/mL) during the acute phase of infection 6 to 8 days postsymptom onset.5

Acute phase reactants, high nitric oxide levels, cytokines, and higher viral loads have also been associated with fatal outcomes.4 McElroy et al4 measured the common acute phase reactant biomarker ferritin in patients of the 2000 Uganda outbreak and found levels to be higher in samples from patients who died and from patients with hemorrhagic complications and higher viral loads. Thus, these authors postulate ferritin is a potential marker for EVD severity.4

Commercially available assays for detection of viral particles are still in development and no point-of-care rapid detection testing is available. No test can reliably be used to diagnose viral hemorrhagic fever prior to symptom onset.7 Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) of viral particles or tissue cell cultures are available only through the CDC, and are the current most reliable methods to confirm the diagnosis of viral hemorrhagic fevers, including Ebola.

Patient Management in the ED

Standard infection-control procedures in place in US hospitals, when meticulously practiced, should be adequate to prevent transmission of EVD. As Ebola virus is only transmitted through direct contact with infected body fluids and secretions, PPE including mask, gloves, gown, shoe covers, and eye protection (goggles or face shield), should be appropriate. In donning PPE, remember that gloves should be the last item to pull in place and to pull off, turning the gown and gloves inside out. One’s hands should be washed before removing the mask and face shield/goggles, and they should be rewashed after completion of PPE removal. A tight fit of the glove over the elastic wristband of the gown is preferable and can ensure a better barrier to any biohazard. Meticulous hand hygiene after removal and proper disposal of PPE is paramount to successful contact protection. Diligent care should be taken in any procedure that might expose a healthcare provider to body fluids, such as blood draws, central line insertion, lumbar puncture and other invasive procedures. Standard contact isolation methods with the patient in a single room with the door closed is sufficient. Appropriate use of standard hospital disinfectants, including bleach solutions or hospital grade ammonium cleaners are already standard practice and easily implemented. It is recommended that procedures that produce aerosol particles should be avoided in patients with suspected infection; yet in some circumstances, the course of care may require such procedures. In this case, to minimize potential airborne spread, airborne and droplet precautions should also be initiated by placing the patient in a negative pressure room and implementing the use of properly fitted N-95 respirators for all present in the room.8

The mainstay of treatment for viral hemorrhagic fevers in the ED begins with initiation of contact isolation of the patient to prevent spread to the healthy. Supportive care involving aggressive intravenous fluid resuscitation to maintain blood pressure, oxygen support as needed, blood products as indicated for DIC, correction of electrolyte abnormalities, including dialysis for renal failure, is the only treatment widely available at this time. In patients who exhibit generalized edema as a result of hypoproteinemia from liver damage and third spacing, serum protein monitoring and replacement is indicated.9

An experimental treatment, ZMapp, which is a monoclonal antibody that is derived from mice and blocks Ebola from entering cells, has recently been used in combination with supportive treatment in six individuals infected with Ebola. However, ZMapp is still in early stages of development and testing is not widely available. No clinical trials have begun, but are planned. Two individuals treated with ZMapp have recovered in the United States; three healthcare workers are recovering in West Africa10,11; and one patient has died. It is not clear whether this medication is responsible wholly or in part for their recovery.

According to Dr Bruce Ribner, Director of Emory University Hospital’s Infectious Disease unit in an interview with Scientific American’s Dina Fine Maron on August 27, 2014, the two patients cared for at Emory have developed immunity to Zaire Ebolavirus.11 Continued outpatient monitoring is allowing study to help understand immunity to Ebola, and may lead to further treatment and vaccination development. Thus far, cross-protection against other Ebola viral strains for these recovered individuals is not as robust, indicating that this family of viruses are different enough that recovery from infection with one species may not be enough to confer immunity to a different species exposure. Blood transfusions from recovered patients have been described, but there is no clinical evidence to support any benefit from this therapy at this time.9

Personal protective equipment is a mainstay in the collection of specimens for viral-specific testing by the CDC, including full-face shield or goggles, masks to cover nose and mouth, gowns, and gloves. For routine laboratory testing and patient care, all of the above PPE is recommended, along with use of a biosafety cabinet or plexiglass splash guard, which is in accordance with Occupational Safety and Health Administration bloodborne pathogens standards.12

Specimens should be collected for Ebola testing only after the onset of symptoms, such as fever (see Table for supplemental information). In patients suspected of having viral exposure, it may take up to 3 days for the virus to reach detectable levels with RT-PCR. Consultation per hospital procedure with the local and/or state health department prior to specimen transport for testing to the CDC is mandatory. Public health officials will help ensure appropriate patient selection and proper procedures for specimen collection, and make arrangements for testing, which is only available through the CDC. The CDC will not accept any specimen without appropriate local/state health department consultation.

Ideally, preferred specimens for Ebola testing include 4 mL of whole blood properly preserved with EDTA, clot activator, sodium polyanethol sulfonate, or citrate in plastic collection tubes stored at 4˚C or frozen.12 Specimens should be placed in a durable, leak-proof container for transport within a facility; pneumatic tube systems should be avoided due to concerns for glass breakage or leaks. Hospitals should follow state or local health department policies and procedures for Ebola testing prior to notifying the CDC and initiating sample transportation.

The Dallas Index Case

Deplaning a flight from Liberia in Dallas, Texas on September 20, this index patient had no outward signs of illness, and thus no reason to cause any health concern. Joining in the community with friends and family, it was not until 4 days later that he reportedly developed a fever. Yet 2 more days passed before this patient initially sought ambulatory care at Dallas Health Presbyterian Hospital Emergency Department, during which time additional close contacts were exposed to infection. After evaluation, antibiotics were prescribed and the patient was released. Though this case is under investigation, according to a CNN report,13 the patient did inform a member of the ED nursing staff of his travel history, but this information was not communicated to the rest of the healthcare team. The presence and recognition of this patient’s travel history with disease symptoms heightens the level of suspicion for the possibility of EVD, and is the cornerstone of patient selection for Ebola testing.14