User login

Key ways to differentiate a benign from a malignant adnexal mass

Click here to register for PAGS 2014 December 4 to 6 at the Bellagio in Las Vegas

More from PAGS 2013:

Lichen sclerosis: My approach to treatment

Michael Baggish, MD

Click here to register for PAGS 2014 December 4 to 6 at the Bellagio in Las Vegas

More from PAGS 2013:

Lichen sclerosis: My approach to treatment

Michael Baggish, MD

Click here to register for PAGS 2014 December 4 to 6 at the Bellagio in Las Vegas

More from PAGS 2013:

Lichen sclerosis: My approach to treatment

Michael Baggish, MD

Why FDA hearing on morcellation safety could drive innovation

As a member of the Obstetrics & Gynecology Devices Panel FDA Advisory Committee, Dr. Iglesia digested the information presented at the hearing on July 10 and 11 and made her recommendations, along with her fellow panel members, for the fate of laparoscopic power morcellators to the FDA. Tune in to this special audiocast to hear Dr. Iglesia discuss the specific issues the panel weighed when making their final recommendations.

Dr. Iglesia is Director, Section of Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery, MedStar Washington Hospital Center, and Associate Professor, Departments of ObGyn and Urology, Georgetown University School of Medicine, Washington, DC. She also serves on the OBG Management Board of Editors.

TRANSCRIPT

Janelle Yates: OBG Management Editorial Board Member Dr. Cheryl Iglesia attended the July 10th and 11th FDA hearing on microscopic power morcellation as a member of the Obstetrics and Gynecology Devices Panel Advisory Committee. In this audiocast, she describes the hearing and the panel’s recommendations as well as many of the fine points considered in weighing the risks and benefits of power morcellation. Dr. Iglesia is Director of the Section of Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery at MedStar Washington Hospital Center, and Associate Professor in the Departments of Ob/Gyn and Neurology at Georgetown University’s School of Medicine in Washington, DC.

Dr. Iglesia, could you describe your role on the FDA’s Obstetrics and Gynecology Device Panel Advisory Committee?

Cheryl B. Iglesia, MD: I’m considered a special government employee and I have a 5-year term on the ObGyn Devices Panel. I was a member of the panel that reviewed vaginal mesh, and this is my second ObGyn devices panel as a consultant on power morcellation for laparoscopy. After the hearing, which was July 10th and 11th, we make recommendations as a panel but no final decisions are made until everything has been reviewed by officials at the FDA, and the FDA will come up with final decisions based in part on some of the recommendations that the panel has made. Therefore I can’t give you an official view, and what I’ll be talking about right now mostly represents my own opinion.

Ms. Yates: Just to review: What was the goal of the 2-day hearing, and whose points of view were represented to the panel?

Dr. Iglesia: The goal was to discuss the risk of disseminating unsuspected uterine malignancy with power morcellation. We talked on the panel about what the risk is of occult leiomyosarcoma in women with uterine fibroids. We talked about the preoperative screening evaluation process, talked about options for interoperative strategies to minimize or mitigate intraperitoneal fragmentation or dissemination of the tissue. They talked about various types of morcellators and, moving forward, if leiomyosarcoma was diagnosed, whether or not power morcellation upgraded an occult malignancy. And what the benchmarks should be for future devices, and whether or not future devices— not just for the power morcellators with containment, like containment bags—how they should be evaluated and tested moving forward. There was also some discussion about the role of registries.

Ms. Yates: What final recommendations did the panel make to the FDA?

Dr. Iglesia: Overall, there was a very long discussion about the risk of having an unsuspected sarcoma and the rates ranged from one in 350 to one in 7,450. What we as a panel realized is that while there are some indicators that could be suspicious for leiomyosarcoma, particularly on an MRI, that one cannot be 100% certain, particularly when you have a fibroid that’s degenerating, that it’s not just leiomyosarcoma but other occult malignancies.

The bottom line is the patients must be adequately worked up, particularly if there is abnormal bleeding. An evaluation would include normal cervical cytology, normal endometrial sampling, either sonograms or MRIs if indicated, and we talked about patient selection. In particular of being very worried about using morcellation in the postmenopausal woman who’s bleeding. We talked a lot about other options for morcellation. In general, if you can remove a uterus through the vagina or intact, that’s ideal because there’s a lot of data about the pros and cons from the vaginal approach to hysterectomy. But we’re not 100% certain that containment bags are going to be the “be-all and end-all.” In that, particularly if you’re doing subtotal hysterectomies, you still might be cutting through cancers and occult malignancies and the containment bags are very thin so that there’s a possibility that there could be leakage and/or breakage or unintended injury to other interperitoneal organs like bowels and vessels, etc. So we can’t be complacent about being 100% certain that things will go right even with the use of a bag.

Ms. Yates: Were there any final recommendations about informed consent?

Dr. Iglesia: A lot of discussion, particularly on the second day, was in the area of labeling special controls and it would be labeling for a patient and practitioners or physician surgeons who are using the morcellator. To the extent that—and there have been some precedents I think in silicon breast and other devices—where both the patient and the physician have to sign off that they’re aware that morcellators may be used, that there’s a potential for dissemination of an occult malignancy or even dissemination of benign disease like leiomyomatosis and incomplete removal. There are risks of using the morcellator in terms of injury, just a whole checklist. But it’s interesting for the labeling, both the patient and the physician in this: One of the recommendations for special controls would be included.

Ms. Yates: And would that involve a black box warning?

Dr. Iglesia: I think there were several discussions about the black box warning; I’m not sure what the final discussion is. Some people believe that with the black box on an administrative level, it sends a signal and a reminder to everyone about the labeling. But labeling can be done without a black box and it can be done with a black box. I’m not 100% certain how that will ultimately be decided upon by the FDA.

Ms. Yates: What were your reactions to the hearing, apart from your role on the panel? Did you feel that adequate testimony was heard from all the parties that have a stake in the immediate and long-term fate of laparoscopic power morcellation?

Dr. Iglesia: I think that the FDA did an excellent job in convening all the players, anybody who has interests in the stake I feel was represented--from industry and companies that make morcellators, companies that make containment bags, medical societies, ACOG, and AAGL gave testimony. AAGL’s testimony was very powerful, particularly by Dr. Jubilee Brown in mentioning that without the morcellator more women may be subjected to abdominal procedure, which in and of itself has some morbidity and mortality associated with that type of operation, and it was a nice study analysis. In terms of a decision tree what the potential harms would be without available morcellators to use, and I thought the MRI imaging that was done by the radiologist was also very interesting and discussed the limits of our ability to detect.

I also found some of the testimony to be extremely powerful from the patients, including that of Dr. Amy Reed and her family and the other women who presented. In some of the cases, we and several people on the panel, including myself, did wonder about the selection or the choice to use the morcellator in the first place in some cases, particularly in women who had uterine fibroids and they were postmenopausal. I think that that would be a particular case where you know go ahead and make an incision because there’s a potential higher index of suspicion for cancer in those kinds of cases.

Ms. Yates: Do you care to predict whether gynecologic surgeons will continue to use power morcellators after this controversy?

Dr. Iglesia: You know, and this was also discussed by Dr. Fisher and some of the officials from the FDA, that if anything this would be a call for innovation and improving products that could morcellate and contain at the same time. I know that we have some hysteroscopic morcellators that you can insert and there’s a vacuum and so things get kind of vacuumed up and whether or not we can develop something that has very little spill—obviously none at all would be key—and I do believe that at some point there will be some ingenuity and some improvements made to the current devices that will allow us to continue this is in our armamentarium.

What was interesting was that one of the questions that was addressed to the panel was, “When do you see that the benefits may outweigh the risks, in what population?” And leiomyosarcoma, which is just one of the occult malignancies—and there’s different types of sarcomas including endometrial stromal sarcomas and other endometrial cancer and malignancies. What’s interesting is that when you look at fibroids and even when you do a myomectomy it’s not necessarily just the power of morcellation, it’s just cutting through cancer or morcellating either vaginally or open. You’re doing an open myomectomy, just removal of the fibroid, and it turns out that that’s cancer. You know that is not a good prognosis to start with, but to spread it clearly is not good for the patient and makes a bad condition even worse.

But it really means that we need to do a better job in pretty accurately identifying patients. And while we’re there, we did mention on the panel that maybe we can develop risk calculators or ways to stratify based on the MRI imaging, patient age, patient race, and whether or not something has a higher index of suspicion for being cancerous. What I meant to say is the two benefits outweigh the risk.

One other case was the young 20-something-year-old fertility patient with the fibroids that clearly have an impact. I mean you don’t want to do a hysterectomy and you still want to remove the fibroid in as noninvasive a way as possible and morcellation may be the best in terms of creating less adhesions. The other case was something that I had mentioned in patients who have prolapse who you’re thinking about placing mesh. Some people do subtotal hysterectomies and then attach the mesh to the cervix as opposed to the vaginal cuff to decrease the risk of cuff erosion and that’s another technique where benefits might outweigh the risk, particularly in older postmenopausal women with not particularly enlarged uteri. So, more to come.

As a member of the Obstetrics & Gynecology Devices Panel FDA Advisory Committee, Dr. Iglesia digested the information presented at the hearing on July 10 and 11 and made her recommendations, along with her fellow panel members, for the fate of laparoscopic power morcellators to the FDA. Tune in to this special audiocast to hear Dr. Iglesia discuss the specific issues the panel weighed when making their final recommendations.

Dr. Iglesia is Director, Section of Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery, MedStar Washington Hospital Center, and Associate Professor, Departments of ObGyn and Urology, Georgetown University School of Medicine, Washington, DC. She also serves on the OBG Management Board of Editors.

TRANSCRIPT

Janelle Yates: OBG Management Editorial Board Member Dr. Cheryl Iglesia attended the July 10th and 11th FDA hearing on microscopic power morcellation as a member of the Obstetrics and Gynecology Devices Panel Advisory Committee. In this audiocast, she describes the hearing and the panel’s recommendations as well as many of the fine points considered in weighing the risks and benefits of power morcellation. Dr. Iglesia is Director of the Section of Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery at MedStar Washington Hospital Center, and Associate Professor in the Departments of Ob/Gyn and Neurology at Georgetown University’s School of Medicine in Washington, DC.

Dr. Iglesia, could you describe your role on the FDA’s Obstetrics and Gynecology Device Panel Advisory Committee?

Cheryl B. Iglesia, MD: I’m considered a special government employee and I have a 5-year term on the ObGyn Devices Panel. I was a member of the panel that reviewed vaginal mesh, and this is my second ObGyn devices panel as a consultant on power morcellation for laparoscopy. After the hearing, which was July 10th and 11th, we make recommendations as a panel but no final decisions are made until everything has been reviewed by officials at the FDA, and the FDA will come up with final decisions based in part on some of the recommendations that the panel has made. Therefore I can’t give you an official view, and what I’ll be talking about right now mostly represents my own opinion.

Ms. Yates: Just to review: What was the goal of the 2-day hearing, and whose points of view were represented to the panel?

Dr. Iglesia: The goal was to discuss the risk of disseminating unsuspected uterine malignancy with power morcellation. We talked on the panel about what the risk is of occult leiomyosarcoma in women with uterine fibroids. We talked about the preoperative screening evaluation process, talked about options for interoperative strategies to minimize or mitigate intraperitoneal fragmentation or dissemination of the tissue. They talked about various types of morcellators and, moving forward, if leiomyosarcoma was diagnosed, whether or not power morcellation upgraded an occult malignancy. And what the benchmarks should be for future devices, and whether or not future devices— not just for the power morcellators with containment, like containment bags—how they should be evaluated and tested moving forward. There was also some discussion about the role of registries.

Ms. Yates: What final recommendations did the panel make to the FDA?

Dr. Iglesia: Overall, there was a very long discussion about the risk of having an unsuspected sarcoma and the rates ranged from one in 350 to one in 7,450. What we as a panel realized is that while there are some indicators that could be suspicious for leiomyosarcoma, particularly on an MRI, that one cannot be 100% certain, particularly when you have a fibroid that’s degenerating, that it’s not just leiomyosarcoma but other occult malignancies.

The bottom line is the patients must be adequately worked up, particularly if there is abnormal bleeding. An evaluation would include normal cervical cytology, normal endometrial sampling, either sonograms or MRIs if indicated, and we talked about patient selection. In particular of being very worried about using morcellation in the postmenopausal woman who’s bleeding. We talked a lot about other options for morcellation. In general, if you can remove a uterus through the vagina or intact, that’s ideal because there’s a lot of data about the pros and cons from the vaginal approach to hysterectomy. But we’re not 100% certain that containment bags are going to be the “be-all and end-all.” In that, particularly if you’re doing subtotal hysterectomies, you still might be cutting through cancers and occult malignancies and the containment bags are very thin so that there’s a possibility that there could be leakage and/or breakage or unintended injury to other interperitoneal organs like bowels and vessels, etc. So we can’t be complacent about being 100% certain that things will go right even with the use of a bag.

Ms. Yates: Were there any final recommendations about informed consent?

Dr. Iglesia: A lot of discussion, particularly on the second day, was in the area of labeling special controls and it would be labeling for a patient and practitioners or physician surgeons who are using the morcellator. To the extent that—and there have been some precedents I think in silicon breast and other devices—where both the patient and the physician have to sign off that they’re aware that morcellators may be used, that there’s a potential for dissemination of an occult malignancy or even dissemination of benign disease like leiomyomatosis and incomplete removal. There are risks of using the morcellator in terms of injury, just a whole checklist. But it’s interesting for the labeling, both the patient and the physician in this: One of the recommendations for special controls would be included.

Ms. Yates: And would that involve a black box warning?

Dr. Iglesia: I think there were several discussions about the black box warning; I’m not sure what the final discussion is. Some people believe that with the black box on an administrative level, it sends a signal and a reminder to everyone about the labeling. But labeling can be done without a black box and it can be done with a black box. I’m not 100% certain how that will ultimately be decided upon by the FDA.

Ms. Yates: What were your reactions to the hearing, apart from your role on the panel? Did you feel that adequate testimony was heard from all the parties that have a stake in the immediate and long-term fate of laparoscopic power morcellation?

Dr. Iglesia: I think that the FDA did an excellent job in convening all the players, anybody who has interests in the stake I feel was represented--from industry and companies that make morcellators, companies that make containment bags, medical societies, ACOG, and AAGL gave testimony. AAGL’s testimony was very powerful, particularly by Dr. Jubilee Brown in mentioning that without the morcellator more women may be subjected to abdominal procedure, which in and of itself has some morbidity and mortality associated with that type of operation, and it was a nice study analysis. In terms of a decision tree what the potential harms would be without available morcellators to use, and I thought the MRI imaging that was done by the radiologist was also very interesting and discussed the limits of our ability to detect.

I also found some of the testimony to be extremely powerful from the patients, including that of Dr. Amy Reed and her family and the other women who presented. In some of the cases, we and several people on the panel, including myself, did wonder about the selection or the choice to use the morcellator in the first place in some cases, particularly in women who had uterine fibroids and they were postmenopausal. I think that that would be a particular case where you know go ahead and make an incision because there’s a potential higher index of suspicion for cancer in those kinds of cases.

Ms. Yates: Do you care to predict whether gynecologic surgeons will continue to use power morcellators after this controversy?

Dr. Iglesia: You know, and this was also discussed by Dr. Fisher and some of the officials from the FDA, that if anything this would be a call for innovation and improving products that could morcellate and contain at the same time. I know that we have some hysteroscopic morcellators that you can insert and there’s a vacuum and so things get kind of vacuumed up and whether or not we can develop something that has very little spill—obviously none at all would be key—and I do believe that at some point there will be some ingenuity and some improvements made to the current devices that will allow us to continue this is in our armamentarium.

What was interesting was that one of the questions that was addressed to the panel was, “When do you see that the benefits may outweigh the risks, in what population?” And leiomyosarcoma, which is just one of the occult malignancies—and there’s different types of sarcomas including endometrial stromal sarcomas and other endometrial cancer and malignancies. What’s interesting is that when you look at fibroids and even when you do a myomectomy it’s not necessarily just the power of morcellation, it’s just cutting through cancer or morcellating either vaginally or open. You’re doing an open myomectomy, just removal of the fibroid, and it turns out that that’s cancer. You know that is not a good prognosis to start with, but to spread it clearly is not good for the patient and makes a bad condition even worse.

But it really means that we need to do a better job in pretty accurately identifying patients. And while we’re there, we did mention on the panel that maybe we can develop risk calculators or ways to stratify based on the MRI imaging, patient age, patient race, and whether or not something has a higher index of suspicion for being cancerous. What I meant to say is the two benefits outweigh the risk.

One other case was the young 20-something-year-old fertility patient with the fibroids that clearly have an impact. I mean you don’t want to do a hysterectomy and you still want to remove the fibroid in as noninvasive a way as possible and morcellation may be the best in terms of creating less adhesions. The other case was something that I had mentioned in patients who have prolapse who you’re thinking about placing mesh. Some people do subtotal hysterectomies and then attach the mesh to the cervix as opposed to the vaginal cuff to decrease the risk of cuff erosion and that’s another technique where benefits might outweigh the risk, particularly in older postmenopausal women with not particularly enlarged uteri. So, more to come.

As a member of the Obstetrics & Gynecology Devices Panel FDA Advisory Committee, Dr. Iglesia digested the information presented at the hearing on July 10 and 11 and made her recommendations, along with her fellow panel members, for the fate of laparoscopic power morcellators to the FDA. Tune in to this special audiocast to hear Dr. Iglesia discuss the specific issues the panel weighed when making their final recommendations.

Dr. Iglesia is Director, Section of Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery, MedStar Washington Hospital Center, and Associate Professor, Departments of ObGyn and Urology, Georgetown University School of Medicine, Washington, DC. She also serves on the OBG Management Board of Editors.

TRANSCRIPT

Janelle Yates: OBG Management Editorial Board Member Dr. Cheryl Iglesia attended the July 10th and 11th FDA hearing on microscopic power morcellation as a member of the Obstetrics and Gynecology Devices Panel Advisory Committee. In this audiocast, she describes the hearing and the panel’s recommendations as well as many of the fine points considered in weighing the risks and benefits of power morcellation. Dr. Iglesia is Director of the Section of Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery at MedStar Washington Hospital Center, and Associate Professor in the Departments of Ob/Gyn and Neurology at Georgetown University’s School of Medicine in Washington, DC.

Dr. Iglesia, could you describe your role on the FDA’s Obstetrics and Gynecology Device Panel Advisory Committee?

Cheryl B. Iglesia, MD: I’m considered a special government employee and I have a 5-year term on the ObGyn Devices Panel. I was a member of the panel that reviewed vaginal mesh, and this is my second ObGyn devices panel as a consultant on power morcellation for laparoscopy. After the hearing, which was July 10th and 11th, we make recommendations as a panel but no final decisions are made until everything has been reviewed by officials at the FDA, and the FDA will come up with final decisions based in part on some of the recommendations that the panel has made. Therefore I can’t give you an official view, and what I’ll be talking about right now mostly represents my own opinion.

Ms. Yates: Just to review: What was the goal of the 2-day hearing, and whose points of view were represented to the panel?

Dr. Iglesia: The goal was to discuss the risk of disseminating unsuspected uterine malignancy with power morcellation. We talked on the panel about what the risk is of occult leiomyosarcoma in women with uterine fibroids. We talked about the preoperative screening evaluation process, talked about options for interoperative strategies to minimize or mitigate intraperitoneal fragmentation or dissemination of the tissue. They talked about various types of morcellators and, moving forward, if leiomyosarcoma was diagnosed, whether or not power morcellation upgraded an occult malignancy. And what the benchmarks should be for future devices, and whether or not future devices— not just for the power morcellators with containment, like containment bags—how they should be evaluated and tested moving forward. There was also some discussion about the role of registries.

Ms. Yates: What final recommendations did the panel make to the FDA?

Dr. Iglesia: Overall, there was a very long discussion about the risk of having an unsuspected sarcoma and the rates ranged from one in 350 to one in 7,450. What we as a panel realized is that while there are some indicators that could be suspicious for leiomyosarcoma, particularly on an MRI, that one cannot be 100% certain, particularly when you have a fibroid that’s degenerating, that it’s not just leiomyosarcoma but other occult malignancies.

The bottom line is the patients must be adequately worked up, particularly if there is abnormal bleeding. An evaluation would include normal cervical cytology, normal endometrial sampling, either sonograms or MRIs if indicated, and we talked about patient selection. In particular of being very worried about using morcellation in the postmenopausal woman who’s bleeding. We talked a lot about other options for morcellation. In general, if you can remove a uterus through the vagina or intact, that’s ideal because there’s a lot of data about the pros and cons from the vaginal approach to hysterectomy. But we’re not 100% certain that containment bags are going to be the “be-all and end-all.” In that, particularly if you’re doing subtotal hysterectomies, you still might be cutting through cancers and occult malignancies and the containment bags are very thin so that there’s a possibility that there could be leakage and/or breakage or unintended injury to other interperitoneal organs like bowels and vessels, etc. So we can’t be complacent about being 100% certain that things will go right even with the use of a bag.

Ms. Yates: Were there any final recommendations about informed consent?

Dr. Iglesia: A lot of discussion, particularly on the second day, was in the area of labeling special controls and it would be labeling for a patient and practitioners or physician surgeons who are using the morcellator. To the extent that—and there have been some precedents I think in silicon breast and other devices—where both the patient and the physician have to sign off that they’re aware that morcellators may be used, that there’s a potential for dissemination of an occult malignancy or even dissemination of benign disease like leiomyomatosis and incomplete removal. There are risks of using the morcellator in terms of injury, just a whole checklist. But it’s interesting for the labeling, both the patient and the physician in this: One of the recommendations for special controls would be included.

Ms. Yates: And would that involve a black box warning?

Dr. Iglesia: I think there were several discussions about the black box warning; I’m not sure what the final discussion is. Some people believe that with the black box on an administrative level, it sends a signal and a reminder to everyone about the labeling. But labeling can be done without a black box and it can be done with a black box. I’m not 100% certain how that will ultimately be decided upon by the FDA.

Ms. Yates: What were your reactions to the hearing, apart from your role on the panel? Did you feel that adequate testimony was heard from all the parties that have a stake in the immediate and long-term fate of laparoscopic power morcellation?

Dr. Iglesia: I think that the FDA did an excellent job in convening all the players, anybody who has interests in the stake I feel was represented--from industry and companies that make morcellators, companies that make containment bags, medical societies, ACOG, and AAGL gave testimony. AAGL’s testimony was very powerful, particularly by Dr. Jubilee Brown in mentioning that without the morcellator more women may be subjected to abdominal procedure, which in and of itself has some morbidity and mortality associated with that type of operation, and it was a nice study analysis. In terms of a decision tree what the potential harms would be without available morcellators to use, and I thought the MRI imaging that was done by the radiologist was also very interesting and discussed the limits of our ability to detect.

I also found some of the testimony to be extremely powerful from the patients, including that of Dr. Amy Reed and her family and the other women who presented. In some of the cases, we and several people on the panel, including myself, did wonder about the selection or the choice to use the morcellator in the first place in some cases, particularly in women who had uterine fibroids and they were postmenopausal. I think that that would be a particular case where you know go ahead and make an incision because there’s a potential higher index of suspicion for cancer in those kinds of cases.

Ms. Yates: Do you care to predict whether gynecologic surgeons will continue to use power morcellators after this controversy?

Dr. Iglesia: You know, and this was also discussed by Dr. Fisher and some of the officials from the FDA, that if anything this would be a call for innovation and improving products that could morcellate and contain at the same time. I know that we have some hysteroscopic morcellators that you can insert and there’s a vacuum and so things get kind of vacuumed up and whether or not we can develop something that has very little spill—obviously none at all would be key—and I do believe that at some point there will be some ingenuity and some improvements made to the current devices that will allow us to continue this is in our armamentarium.

What was interesting was that one of the questions that was addressed to the panel was, “When do you see that the benefits may outweigh the risks, in what population?” And leiomyosarcoma, which is just one of the occult malignancies—and there’s different types of sarcomas including endometrial stromal sarcomas and other endometrial cancer and malignancies. What’s interesting is that when you look at fibroids and even when you do a myomectomy it’s not necessarily just the power of morcellation, it’s just cutting through cancer or morcellating either vaginally or open. You’re doing an open myomectomy, just removal of the fibroid, and it turns out that that’s cancer. You know that is not a good prognosis to start with, but to spread it clearly is not good for the patient and makes a bad condition even worse.

But it really means that we need to do a better job in pretty accurately identifying patients. And while we’re there, we did mention on the panel that maybe we can develop risk calculators or ways to stratify based on the MRI imaging, patient age, patient race, and whether or not something has a higher index of suspicion for being cancerous. What I meant to say is the two benefits outweigh the risk.

One other case was the young 20-something-year-old fertility patient with the fibroids that clearly have an impact. I mean you don’t want to do a hysterectomy and you still want to remove the fibroid in as noninvasive a way as possible and morcellation may be the best in terms of creating less adhesions. The other case was something that I had mentioned in patients who have prolapse who you’re thinking about placing mesh. Some people do subtotal hysterectomies and then attach the mesh to the cervix as opposed to the vaginal cuff to decrease the risk of cuff erosion and that’s another technique where benefits might outweigh the risk, particularly in older postmenopausal women with not particularly enlarged uteri. So, more to come.

Does prenatal acetaminophen exposure increase the risk of behavioral problems in the child?

In the continuing drive to determine the cause of neurobehavioral complications, particularly ADHD and HKD, a number of studies have reported associations with various substances. These include pesticides,1 hormones,2 hormone disrupters,1 and, possibly, genetics. Nevertheless, the etiology of these disorders remains a mystery. ADHD is a complex and heterogeneous disorder. Although we do not yet understand the cause, genetics (or, more accurately, pharmacogenetics) seems likely to play a role.

This study from a large Danish population appears to suggest that the prenatal use of acetaminophen may increase the risk of ADHD and HKD. It is yet another study in which the data indicate and the authors claim that use of a particular drug during pregnancy is responsible for this condition. However, despite the extremely large sample size (which increases the likelihood of positive findings), the hazard ratios were only marginally significant, suggesting that the relevance of the conclusions is questionable.

Details of the study

The 64,322 live-born children and mothers in the Danish National Birth Cohort from 1996 to 2002 were evaluated three ways:

- through parental reports of behavioral problems in children at age 7 using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

- through retrieval of HKD diagnoses from the Danish National Hospital Registry or the Danish Psychiatric Central Registry prior to 2011

- through prescriptions for ADHD (primarily methylphenidate [Ritalin]) for children from the Danish Prescription Registry.

Liew and colleagues then estimated hazard ratios for receiving a diagnosis of HKD or using a medication for ADHD, as well as risk ratios for behavioral problems in children after prenatal exposure to acetaminophen.

Stronger associations between prenatal acetaminophen use and HKD or ADHD were found when the mother used the medication in more than one trimester. Exposure-response trends increased with the frequency of acetaminophen use during pregnancy for all three outcomes (HKD diagnosis, ADHD-like behaviors, and ADHD medication use; P trend <.001). Results did not appear to be confounded by maternal inflammation, infection during pregnancy, or the mother’s mental health status.

Related articles:

• How can pregnant women safely relieve low-back pain? Roselyn Jan W. Clemente-Fuentes, MD; Heather Pickett, DO; Misty Carney, MLIS; and Paul Crawford, MD (January 2014)

• Perinatal depression: What you can do to reduce its long-term effects. Janelle Yates (February 2014)

• Low-dose aspirin and preeclampsia prevention: Ready for prime time, but as a “re-run” or as a “new series”? John T. Repke, MD (Guest Editorial; June 2014)

Why these findings are less than compelling

Acetaminophen is the most commonly used medication during pregnancy, although few investigators have analyzed neurobehavioral complications in children exposed to this drug in utero. Another recent epidemiologic study from Norway also suggests that long-term exposure (>28 days) to acetaminophen increases the risk of poor gross motor functioning, poor communication skills, and externalizing and internalizing behavior problems.3

The rationale behind an association between acetaminophen and ADHD and HKD is that the medication is an endocrine-disrupting agent. The evidence of this status comes primarily from in vitro experiments from one group of researchers, which may not represent in vivo conditions.4,5

Epidemiologic studies frequently are confounded by poor design and methodology. It also should be noted that correlation is not necessarily the same as causation. In this study, the design and methodology were appropriate considering the data available. Researchers often use large databases like this to research “hot topics” such as the association between ADHD and prenatal acetaminophen use. In this study, acetaminophen cannot be associated definitively with an increased risk of ADHD or HKD. Further research is needed, with greater attention to possible confounding factors, such as why these women consumed chronic doses and for what conditions.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

For the time being, you should probably counsel your patients to use acetaminophen sparingly during pregnancy, and certainly not on a daily basis. We also should encourage nonpharmacologic pain management, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, when appropriate, and caution patients against long-term use of analgesics, when possible, during gestation and lactation.

Thomas W. Hale, RPH, PhD; Aarienne Einarson, RN; and Teresa Baker, MD

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: [email protected]

1. Kajta M, Wojtowicz AK. Impact of endocrine-disrupting chemicals on neural development and the onset of neurological disorders. Pharmacol Rep. 2013;65(6):1632–1639.

2. de Bruin EI, Verheij F, Wiegman T, Ferdinand RF. Differences in finger length ratio between males with autism, pervasive developmental disorder–not otherwise specified, ADHD, and anxiety disorders. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2006;48(12):962–965.

3. Brandlistuen RE, Ystrom E, Nulman I, Koren G, Nordeng H. Prenatal paracetamol exposure and child neurodevelopment: A sibling-controlled cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(6):1702–1713.

4. Kristensen DM, Lesne L, Le Fol V, et al. Paracetamol (acetaminophen), aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid), and indomethacin are anti-androgenic in the rat foetal testis. Int J Androl. 2012;35(3):377–384.

5. Albert O, Desdoits-Lethimonier C, Lesne L, et al. Paracetamol, aspirin, and indomethacin display endocrine disrupting properties in the adult human testis in vitro. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(7):1890–1898.

In the continuing drive to determine the cause of neurobehavioral complications, particularly ADHD and HKD, a number of studies have reported associations with various substances. These include pesticides,1 hormones,2 hormone disrupters,1 and, possibly, genetics. Nevertheless, the etiology of these disorders remains a mystery. ADHD is a complex and heterogeneous disorder. Although we do not yet understand the cause, genetics (or, more accurately, pharmacogenetics) seems likely to play a role.

This study from a large Danish population appears to suggest that the prenatal use of acetaminophen may increase the risk of ADHD and HKD. It is yet another study in which the data indicate and the authors claim that use of a particular drug during pregnancy is responsible for this condition. However, despite the extremely large sample size (which increases the likelihood of positive findings), the hazard ratios were only marginally significant, suggesting that the relevance of the conclusions is questionable.

Details of the study

The 64,322 live-born children and mothers in the Danish National Birth Cohort from 1996 to 2002 were evaluated three ways:

- through parental reports of behavioral problems in children at age 7 using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

- through retrieval of HKD diagnoses from the Danish National Hospital Registry or the Danish Psychiatric Central Registry prior to 2011

- through prescriptions for ADHD (primarily methylphenidate [Ritalin]) for children from the Danish Prescription Registry.

Liew and colleagues then estimated hazard ratios for receiving a diagnosis of HKD or using a medication for ADHD, as well as risk ratios for behavioral problems in children after prenatal exposure to acetaminophen.

Stronger associations between prenatal acetaminophen use and HKD or ADHD were found when the mother used the medication in more than one trimester. Exposure-response trends increased with the frequency of acetaminophen use during pregnancy for all three outcomes (HKD diagnosis, ADHD-like behaviors, and ADHD medication use; P trend <.001). Results did not appear to be confounded by maternal inflammation, infection during pregnancy, or the mother’s mental health status.

Related articles:

• How can pregnant women safely relieve low-back pain? Roselyn Jan W. Clemente-Fuentes, MD; Heather Pickett, DO; Misty Carney, MLIS; and Paul Crawford, MD (January 2014)

• Perinatal depression: What you can do to reduce its long-term effects. Janelle Yates (February 2014)

• Low-dose aspirin and preeclampsia prevention: Ready for prime time, but as a “re-run” or as a “new series”? John T. Repke, MD (Guest Editorial; June 2014)

Why these findings are less than compelling

Acetaminophen is the most commonly used medication during pregnancy, although few investigators have analyzed neurobehavioral complications in children exposed to this drug in utero. Another recent epidemiologic study from Norway also suggests that long-term exposure (>28 days) to acetaminophen increases the risk of poor gross motor functioning, poor communication skills, and externalizing and internalizing behavior problems.3

The rationale behind an association between acetaminophen and ADHD and HKD is that the medication is an endocrine-disrupting agent. The evidence of this status comes primarily from in vitro experiments from one group of researchers, which may not represent in vivo conditions.4,5

Epidemiologic studies frequently are confounded by poor design and methodology. It also should be noted that correlation is not necessarily the same as causation. In this study, the design and methodology were appropriate considering the data available. Researchers often use large databases like this to research “hot topics” such as the association between ADHD and prenatal acetaminophen use. In this study, acetaminophen cannot be associated definitively with an increased risk of ADHD or HKD. Further research is needed, with greater attention to possible confounding factors, such as why these women consumed chronic doses and for what conditions.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

For the time being, you should probably counsel your patients to use acetaminophen sparingly during pregnancy, and certainly not on a daily basis. We also should encourage nonpharmacologic pain management, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, when appropriate, and caution patients against long-term use of analgesics, when possible, during gestation and lactation.

Thomas W. Hale, RPH, PhD; Aarienne Einarson, RN; and Teresa Baker, MD

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: [email protected]

In the continuing drive to determine the cause of neurobehavioral complications, particularly ADHD and HKD, a number of studies have reported associations with various substances. These include pesticides,1 hormones,2 hormone disrupters,1 and, possibly, genetics. Nevertheless, the etiology of these disorders remains a mystery. ADHD is a complex and heterogeneous disorder. Although we do not yet understand the cause, genetics (or, more accurately, pharmacogenetics) seems likely to play a role.

This study from a large Danish population appears to suggest that the prenatal use of acetaminophen may increase the risk of ADHD and HKD. It is yet another study in which the data indicate and the authors claim that use of a particular drug during pregnancy is responsible for this condition. However, despite the extremely large sample size (which increases the likelihood of positive findings), the hazard ratios were only marginally significant, suggesting that the relevance of the conclusions is questionable.

Details of the study

The 64,322 live-born children and mothers in the Danish National Birth Cohort from 1996 to 2002 were evaluated three ways:

- through parental reports of behavioral problems in children at age 7 using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

- through retrieval of HKD diagnoses from the Danish National Hospital Registry or the Danish Psychiatric Central Registry prior to 2011

- through prescriptions for ADHD (primarily methylphenidate [Ritalin]) for children from the Danish Prescription Registry.

Liew and colleagues then estimated hazard ratios for receiving a diagnosis of HKD or using a medication for ADHD, as well as risk ratios for behavioral problems in children after prenatal exposure to acetaminophen.

Stronger associations between prenatal acetaminophen use and HKD or ADHD were found when the mother used the medication in more than one trimester. Exposure-response trends increased with the frequency of acetaminophen use during pregnancy for all three outcomes (HKD diagnosis, ADHD-like behaviors, and ADHD medication use; P trend <.001). Results did not appear to be confounded by maternal inflammation, infection during pregnancy, or the mother’s mental health status.

Related articles:

• How can pregnant women safely relieve low-back pain? Roselyn Jan W. Clemente-Fuentes, MD; Heather Pickett, DO; Misty Carney, MLIS; and Paul Crawford, MD (January 2014)

• Perinatal depression: What you can do to reduce its long-term effects. Janelle Yates (February 2014)

• Low-dose aspirin and preeclampsia prevention: Ready for prime time, but as a “re-run” or as a “new series”? John T. Repke, MD (Guest Editorial; June 2014)

Why these findings are less than compelling

Acetaminophen is the most commonly used medication during pregnancy, although few investigators have analyzed neurobehavioral complications in children exposed to this drug in utero. Another recent epidemiologic study from Norway also suggests that long-term exposure (>28 days) to acetaminophen increases the risk of poor gross motor functioning, poor communication skills, and externalizing and internalizing behavior problems.3

The rationale behind an association between acetaminophen and ADHD and HKD is that the medication is an endocrine-disrupting agent. The evidence of this status comes primarily from in vitro experiments from one group of researchers, which may not represent in vivo conditions.4,5

Epidemiologic studies frequently are confounded by poor design and methodology. It also should be noted that correlation is not necessarily the same as causation. In this study, the design and methodology were appropriate considering the data available. Researchers often use large databases like this to research “hot topics” such as the association between ADHD and prenatal acetaminophen use. In this study, acetaminophen cannot be associated definitively with an increased risk of ADHD or HKD. Further research is needed, with greater attention to possible confounding factors, such as why these women consumed chronic doses and for what conditions.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

For the time being, you should probably counsel your patients to use acetaminophen sparingly during pregnancy, and certainly not on a daily basis. We also should encourage nonpharmacologic pain management, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, when appropriate, and caution patients against long-term use of analgesics, when possible, during gestation and lactation.

Thomas W. Hale, RPH, PhD; Aarienne Einarson, RN; and Teresa Baker, MD

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: [email protected]

1. Kajta M, Wojtowicz AK. Impact of endocrine-disrupting chemicals on neural development and the onset of neurological disorders. Pharmacol Rep. 2013;65(6):1632–1639.

2. de Bruin EI, Verheij F, Wiegman T, Ferdinand RF. Differences in finger length ratio between males with autism, pervasive developmental disorder–not otherwise specified, ADHD, and anxiety disorders. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2006;48(12):962–965.

3. Brandlistuen RE, Ystrom E, Nulman I, Koren G, Nordeng H. Prenatal paracetamol exposure and child neurodevelopment: A sibling-controlled cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(6):1702–1713.

4. Kristensen DM, Lesne L, Le Fol V, et al. Paracetamol (acetaminophen), aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid), and indomethacin are anti-androgenic in the rat foetal testis. Int J Androl. 2012;35(3):377–384.

5. Albert O, Desdoits-Lethimonier C, Lesne L, et al. Paracetamol, aspirin, and indomethacin display endocrine disrupting properties in the adult human testis in vitro. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(7):1890–1898.

1. Kajta M, Wojtowicz AK. Impact of endocrine-disrupting chemicals on neural development and the onset of neurological disorders. Pharmacol Rep. 2013;65(6):1632–1639.

2. de Bruin EI, Verheij F, Wiegman T, Ferdinand RF. Differences in finger length ratio between males with autism, pervasive developmental disorder–not otherwise specified, ADHD, and anxiety disorders. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2006;48(12):962–965.

3. Brandlistuen RE, Ystrom E, Nulman I, Koren G, Nordeng H. Prenatal paracetamol exposure and child neurodevelopment: A sibling-controlled cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(6):1702–1713.

4. Kristensen DM, Lesne L, Le Fol V, et al. Paracetamol (acetaminophen), aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid), and indomethacin are anti-androgenic in the rat foetal testis. Int J Androl. 2012;35(3):377–384.

5. Albert O, Desdoits-Lethimonier C, Lesne L, et al. Paracetamol, aspirin, and indomethacin display endocrine disrupting properties in the adult human testis in vitro. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(7):1890–1898.

Proper Inpatient Documentation, Coding Essential to Avoid a Medicare Audit

Several years ago we sent a CPT coding auditor 15 chart notes generated by each doctor in our group. Among each doctors’ 15 notes were at least one or two billed as initial hospital care, follow up, discharge, critical care, and so on. This coding expert returned a report showing that, out of all the notes reviewed, a significant portion were not billed at the correct level. Most of the incorrectly billed notes were judged to reflect “up-coding,” and a few were seen as “down-coded.”

This was distressing and hard to believe.

So I took the same set of notes and paid a second coding expert for an independent review. She didn’t know about the first audit but returned a report that showed a nearly identical portion of incorrectly coded notes.

Two independent audits showing nearly the same portion of notes coded incorrectly was alarming. But it was difficult for my partners and me to address, because the auditors didn’t agree on the correct code for many of the notes. In some cases, both flagged a note as incorrectly coded but didn’t agree on the correct code. For a number of the notes, one auditor said the visit was “up-coded,” while the other said it was “down-coded.” There was so little agreement between the two of them that we had a hard time coming up with any firm conclusions about what we should do to improve our performance.

If experts who think about coding all the time can’t agree on the right code for a given note, how can hospitalists be expected to code nearly all of our visits accurately?

RAC: Recovery Audit Contractor

Despite what I believe is poor inter-rater reliability among coding auditors, we need to work diligently to comply with coding guidelines. A 2003 Federal law mandated a program of Recovery Audit Contractors, or RAC for short, to find cases of “up-coding” or other overbilling and require the provider to repay any resulting loss.

A number of companies are in the business of conducting RAC audits (one of them, CGI, is the Canadian company blamed for the failed “Obamacare” exchange websites), and there is a reasonable chance one of these companies has reviewed some of your charges—or those of your hospitalist colleagues.

The RAC auditors review information about your charges, and if they determine that you up-coded or overbilled, they send a “demand letter” summarizing their findings, along with the amount of money they have determined you should pay back. (Theoretically, they could notify you of “under-coding,” so that you can be paid more for past work, but I haven’t yet come across an example of that.)

It is common to appeal the RAC findings, but that can be a long process, and many organizations decide to pay back all the money requested by the RAC as quickly as possible to avoid paying interest on a delayed payment if the appeal is unsuccessful. In the case of a successful appeal, the money previously refunded by the doctor would be returned.

Page 338 of the CMS Fiscal Year 2015 “Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees” says that “…about 50 percent of the estimated 43,000 appeals [of adverse RAC audit findings] were fully or partially overturned…” This could mean the RACs are a sort of loose cannon, accusing many providers of overbilling while knowing that some won’t bother to appeal because they don’t understand the process or because the dollar amount involved for a single provider is too small to justify the time and expense of conducting the appeal. In this way, a RAC audit is like the $15 rebate on the last electronic gadget you bought. The seller knows that many people, including me, will fail to do the work required to claim the rebate.

Accuracy Strategies

There are a number of ways to help your group ensure appropriate CPT coding and reduce the chance a RAC will ask for money back.

Education. There are many ways to help providers in your practice understand the elements of documentation and coding. Periodic training classes (e.g. during orientation and annually thereafter) are useful but may not be enough. For me, this is a little like learning a foreign language by going to a couple of classes. Instead, I think “immersion training” is more effective. That might mean a doctor spends a few minutes with a certified coder on most working days for a few weeks. For example, they could meet for 15 minutes near lunchtime and review how the doctor plans to bill visits made that morning. Lastly, consider targeted education for each doctor, based on any problems found in an audit of his/her coding.

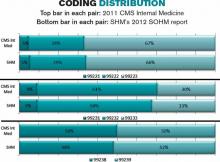

Review coding patterns. As I wrote in my August 2007 column, there is value in ensuring that each doctor in the group can see how her coding pattern differs from the group as a whole or any individual in the group. That is, what portion of follow-up visits was billed at the lowest, middle, and highest levels? What about admissions, discharges, and so on? I provided a sample report in that same column.

It also is worth taking the time to compare each doctor’s coding pattern to both the CMS Internal Medicine data and SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine report. The accompanying figure shows the most current data sets available.

Keep in mind that the goal is not to simply ensure that your coding pattern matches these external data sets; knowing where yours differs from these sets can suggest where you might want to investigate further or seek additional education.

Coding audits. Having a certified coder audit your performance at least annually is a good idea. It can help uncover areas in which you’d benefit from further review and training, and if, heaven forbid, questions are ever raised about whether you’re intentionally up-coding (fraud), showing that you’re audited regularly could help demonstrate your efforts to code correctly. In the latter case, it is probably more valuable if the audit is done independently of your employer.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Several years ago we sent a CPT coding auditor 15 chart notes generated by each doctor in our group. Among each doctors’ 15 notes were at least one or two billed as initial hospital care, follow up, discharge, critical care, and so on. This coding expert returned a report showing that, out of all the notes reviewed, a significant portion were not billed at the correct level. Most of the incorrectly billed notes were judged to reflect “up-coding,” and a few were seen as “down-coded.”

This was distressing and hard to believe.

So I took the same set of notes and paid a second coding expert for an independent review. She didn’t know about the first audit but returned a report that showed a nearly identical portion of incorrectly coded notes.

Two independent audits showing nearly the same portion of notes coded incorrectly was alarming. But it was difficult for my partners and me to address, because the auditors didn’t agree on the correct code for many of the notes. In some cases, both flagged a note as incorrectly coded but didn’t agree on the correct code. For a number of the notes, one auditor said the visit was “up-coded,” while the other said it was “down-coded.” There was so little agreement between the two of them that we had a hard time coming up with any firm conclusions about what we should do to improve our performance.

If experts who think about coding all the time can’t agree on the right code for a given note, how can hospitalists be expected to code nearly all of our visits accurately?

RAC: Recovery Audit Contractor

Despite what I believe is poor inter-rater reliability among coding auditors, we need to work diligently to comply with coding guidelines. A 2003 Federal law mandated a program of Recovery Audit Contractors, or RAC for short, to find cases of “up-coding” or other overbilling and require the provider to repay any resulting loss.

A number of companies are in the business of conducting RAC audits (one of them, CGI, is the Canadian company blamed for the failed “Obamacare” exchange websites), and there is a reasonable chance one of these companies has reviewed some of your charges—or those of your hospitalist colleagues.

The RAC auditors review information about your charges, and if they determine that you up-coded or overbilled, they send a “demand letter” summarizing their findings, along with the amount of money they have determined you should pay back. (Theoretically, they could notify you of “under-coding,” so that you can be paid more for past work, but I haven’t yet come across an example of that.)

It is common to appeal the RAC findings, but that can be a long process, and many organizations decide to pay back all the money requested by the RAC as quickly as possible to avoid paying interest on a delayed payment if the appeal is unsuccessful. In the case of a successful appeal, the money previously refunded by the doctor would be returned.

Page 338 of the CMS Fiscal Year 2015 “Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees” says that “…about 50 percent of the estimated 43,000 appeals [of adverse RAC audit findings] were fully or partially overturned…” This could mean the RACs are a sort of loose cannon, accusing many providers of overbilling while knowing that some won’t bother to appeal because they don’t understand the process or because the dollar amount involved for a single provider is too small to justify the time and expense of conducting the appeal. In this way, a RAC audit is like the $15 rebate on the last electronic gadget you bought. The seller knows that many people, including me, will fail to do the work required to claim the rebate.

Accuracy Strategies

There are a number of ways to help your group ensure appropriate CPT coding and reduce the chance a RAC will ask for money back.

Education. There are many ways to help providers in your practice understand the elements of documentation and coding. Periodic training classes (e.g. during orientation and annually thereafter) are useful but may not be enough. For me, this is a little like learning a foreign language by going to a couple of classes. Instead, I think “immersion training” is more effective. That might mean a doctor spends a few minutes with a certified coder on most working days for a few weeks. For example, they could meet for 15 minutes near lunchtime and review how the doctor plans to bill visits made that morning. Lastly, consider targeted education for each doctor, based on any problems found in an audit of his/her coding.

Review coding patterns. As I wrote in my August 2007 column, there is value in ensuring that each doctor in the group can see how her coding pattern differs from the group as a whole or any individual in the group. That is, what portion of follow-up visits was billed at the lowest, middle, and highest levels? What about admissions, discharges, and so on? I provided a sample report in that same column.

It also is worth taking the time to compare each doctor’s coding pattern to both the CMS Internal Medicine data and SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine report. The accompanying figure shows the most current data sets available.

Keep in mind that the goal is not to simply ensure that your coding pattern matches these external data sets; knowing where yours differs from these sets can suggest where you might want to investigate further or seek additional education.

Coding audits. Having a certified coder audit your performance at least annually is a good idea. It can help uncover areas in which you’d benefit from further review and training, and if, heaven forbid, questions are ever raised about whether you’re intentionally up-coding (fraud), showing that you’re audited regularly could help demonstrate your efforts to code correctly. In the latter case, it is probably more valuable if the audit is done independently of your employer.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Several years ago we sent a CPT coding auditor 15 chart notes generated by each doctor in our group. Among each doctors’ 15 notes were at least one or two billed as initial hospital care, follow up, discharge, critical care, and so on. This coding expert returned a report showing that, out of all the notes reviewed, a significant portion were not billed at the correct level. Most of the incorrectly billed notes were judged to reflect “up-coding,” and a few were seen as “down-coded.”

This was distressing and hard to believe.

So I took the same set of notes and paid a second coding expert for an independent review. She didn’t know about the first audit but returned a report that showed a nearly identical portion of incorrectly coded notes.

Two independent audits showing nearly the same portion of notes coded incorrectly was alarming. But it was difficult for my partners and me to address, because the auditors didn’t agree on the correct code for many of the notes. In some cases, both flagged a note as incorrectly coded but didn’t agree on the correct code. For a number of the notes, one auditor said the visit was “up-coded,” while the other said it was “down-coded.” There was so little agreement between the two of them that we had a hard time coming up with any firm conclusions about what we should do to improve our performance.

If experts who think about coding all the time can’t agree on the right code for a given note, how can hospitalists be expected to code nearly all of our visits accurately?

RAC: Recovery Audit Contractor

Despite what I believe is poor inter-rater reliability among coding auditors, we need to work diligently to comply with coding guidelines. A 2003 Federal law mandated a program of Recovery Audit Contractors, or RAC for short, to find cases of “up-coding” or other overbilling and require the provider to repay any resulting loss.

A number of companies are in the business of conducting RAC audits (one of them, CGI, is the Canadian company blamed for the failed “Obamacare” exchange websites), and there is a reasonable chance one of these companies has reviewed some of your charges—or those of your hospitalist colleagues.

The RAC auditors review information about your charges, and if they determine that you up-coded or overbilled, they send a “demand letter” summarizing their findings, along with the amount of money they have determined you should pay back. (Theoretically, they could notify you of “under-coding,” so that you can be paid more for past work, but I haven’t yet come across an example of that.)

It is common to appeal the RAC findings, but that can be a long process, and many organizations decide to pay back all the money requested by the RAC as quickly as possible to avoid paying interest on a delayed payment if the appeal is unsuccessful. In the case of a successful appeal, the money previously refunded by the doctor would be returned.

Page 338 of the CMS Fiscal Year 2015 “Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees” says that “…about 50 percent of the estimated 43,000 appeals [of adverse RAC audit findings] were fully or partially overturned…” This could mean the RACs are a sort of loose cannon, accusing many providers of overbilling while knowing that some won’t bother to appeal because they don’t understand the process or because the dollar amount involved for a single provider is too small to justify the time and expense of conducting the appeal. In this way, a RAC audit is like the $15 rebate on the last electronic gadget you bought. The seller knows that many people, including me, will fail to do the work required to claim the rebate.

Accuracy Strategies

There are a number of ways to help your group ensure appropriate CPT coding and reduce the chance a RAC will ask for money back.

Education. There are many ways to help providers in your practice understand the elements of documentation and coding. Periodic training classes (e.g. during orientation and annually thereafter) are useful but may not be enough. For me, this is a little like learning a foreign language by going to a couple of classes. Instead, I think “immersion training” is more effective. That might mean a doctor spends a few minutes with a certified coder on most working days for a few weeks. For example, they could meet for 15 minutes near lunchtime and review how the doctor plans to bill visits made that morning. Lastly, consider targeted education for each doctor, based on any problems found in an audit of his/her coding.

Review coding patterns. As I wrote in my August 2007 column, there is value in ensuring that each doctor in the group can see how her coding pattern differs from the group as a whole or any individual in the group. That is, what portion of follow-up visits was billed at the lowest, middle, and highest levels? What about admissions, discharges, and so on? I provided a sample report in that same column.

It also is worth taking the time to compare each doctor’s coding pattern to both the CMS Internal Medicine data and SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine report. The accompanying figure shows the most current data sets available.

Keep in mind that the goal is not to simply ensure that your coding pattern matches these external data sets; knowing where yours differs from these sets can suggest where you might want to investigate further or seek additional education.

Coding audits. Having a certified coder audit your performance at least annually is a good idea. It can help uncover areas in which you’d benefit from further review and training, and if, heaven forbid, questions are ever raised about whether you’re intentionally up-coding (fraud), showing that you’re audited regularly could help demonstrate your efforts to code correctly. In the latter case, it is probably more valuable if the audit is done independently of your employer.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Hypertension and pregnancy and preventing the first cesarean delivery

This peer to peer discussion focuses on individual takeaways from ACOG’s Hypertension in Pregnancy guidelines1 and the recent joint ACOG−Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine report on emerging clinical and scientific advances in safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery.2

In this 20-minute audiocast, listen to these experts discuss:

Changing diagnostic tools for preeclampsia

- The 24-hour urinary protein estimation: When is it necessary?

- Use of magnesium sulfate for seizure prophylaxis

Preventing the first cesarean delivery

- Redefining the stages of labor: When is the second-stage too long?

- The lost skill of forceps delivery

- Is cesarean delivery rate the optimal metric for measuring neonatal outcome?

John T. Repke, MD, is University Professor and Chairman of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Penn State University College of Medicine, and Obstetrician-Gynecologist-in-Chief at the Milton S. Hershey Medical Center in Hershey, Pennsylvania. Dr. Repke is a member of the Board of Editors of OBG Management and is author of the June 2014 Guest Editorial on hypertension and pregnancy.

Errol R. Norwitz, MD, PhD, is the Louis E. Phaneuf Professor and Chairman of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Tufts Medical Center and Tufts University School of Medicine in Boston, Massachusetts. Dr. Norwitz is a member of the Board of Editors of OBG Management and is author of the June 2014 Update on operative vaginal delivery.

The speakers report no financial relationships relevant to this audiocast.

Click here for a downloadable transcript

TRANSCRIPT

ACOG guidelines on hypertension and pregnancy raise some questions

John T. Repke, MD: So, Errol, I was impressed over the first couple of days of being at the meeting. As you know, we had a postgraduate course, and one of the items that we talked about was the new hypertension and pregnancy document that was released by the Task Force on Hypertension and Pregnancy1 charged by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. I’ve got to say that while the goal of the document was to provide some standardization and clarification, there still seems to be a lot of confusion in my audience about how to interpret some of the guidelines. Have you found that?

Errol R. Norwitz, MD, PhD: Yes, I have. I found it interesting that it was put out as an executive summary, and not as a practice bulletin, which will probably follow in months. That document, which came out in November 2013, helped to address many of the issues we’ve had over the years of preeclampsia, in terms of its definition and some of the management issues. But, it also raised a number of questions that still need to be resolved.

Dr. Repke: Yes. I think one of the things to keep in mind, and I’ve tabulated all of the recommendations, is that about 60 recommendations came out of that document and only six of the 60 were accompanied by a strong quality of evidence, or rather, a high quality of evidence, and a strong recommendation. And a lot of those things were addressing issues that I think most practitioners already did, in so far as using antenatal steroids for maturation; using magnesium sulfate for patients with preeclampsia with severe features; and using magnesium sulfate as a treatment of eclampsia. But a lot of the other recommendations really were based on either moderate- or low-quality evidence, and had qualified recommendations. And, I think that’s what has led to some of the confusion.

Changing diagnostic tools for preeclampsia

Dr. Repke: What sort of specific things are your practitioners asking you about as far as, “Is this gestational hypertension or is this preeclampsia?” The guidelines say proteinuria is not required anymore. How are you dealing with that?

Should we still do the 24-hour urinary protein estimation?

Dr. Norwitz: The biggest change, in my mind, is the statement that you no longer require significant proteinuria to make the diagnosis of preeclampsia, and, indeed, of severe preeclampsia. So, if you do have significant proteinuria, then that would confirm the diagnosis. But, you can also have preeclampsia in the presence of other endorgan injuries, such as kidney injury and liver injury in the absence of significant proteinuria.

So, one of the questions that comes up is, “Should we actually do the 24-hour urinary protein estimation?”

And, my answer is, “yes.” If you have significant proteinuria, then that would confirm the diagnosis. If you don’t, you can still make the diagnosis in the setting of low platelets, elevated liver enzymes, or abnormal renal function. So, the issue is, and I’d be curious to hear your answer, if you have someone with platelets of, let’s say, 78, a new onset of sustained elevation of blood pressure, would you do the 24-hour urine estimation or just defer it?

Dr. Repke: We wouldn’t perform the 24-hour urine test under those circumstances. And, we would consider that nuance of hypertension with a severe feature that is now preeclampsia with severe feature, and the management would be based on gestational age. With a platelet count that low, the management would be stabilization and delivery. Although, if stabilized, I think that’s the type of patient that potentially could have delivery delayed until you could get an effective antenatal steroid if she was less that 34 weeks’ gestation.

Dr. Norwitz: So, that’s one issue I think needs to be clarified. If there’s other evidence of endorgan damage, then you can defer the 24-hour urinary protein. That’s another question that comes up. I’m pleased they could resolve the issue of repeated 24-hour urinary estimations. Once you have your 300 mg suggestive of the diagnosis of preeclampsia, there’s no reason to then repeat it looking for elevation and increased leakage of protein into the urine, because it doesn’t correlate with adverse outcome for the mother or fetus. So, that issue was clarified.

Dr. Repke: I think that two questions that came up in our course, and I think they were very legitimate, are, “Do we even need to do urine protein at all?” Because if you look at the guidelines for management, the only difference between preeclampsia management without severe features and gestational hypertension is frequency of antenatal testing until you decide to begin delivery. Now, in the old days, one would say, “Well, another difference would be that the preeclamptic would get magnesium sulfate.” But the current Hypertension in Pregnancy Guidelines1 suggest that preeclampsia without severe features doesn’t necessarily have to be managed with magnesium sulfate. So, I’m still wrestling with whether, other than the fact that it might be for study purposes or for categorization or research, whether proteinuria adds anything to the equation.

And, then the second question is, “How do you resolve the issue of disagreement?” So, the example is protein:creatinine ratio allows for a more rapid diagnosis of significant proteinuria. If that patient doesn’t have to deliver immediately and a 24-hour urine sample is obtained, which do you believe if you have a protein:creatinine ratio greater than 0.3, but now your 24-hour urine is 212 mg/dL? And, I don’t have the answer to that, but that’s another area of confusion.

Dr. Norwitz: And, I think that confusion will persist. I don’t think this document is going to resolve it.

New terminology: Preeclampsia with or without severe features

Dr. Norwitz: I do like the difference in terminology between preeclampsia with severe features and preeclampsia without severe features. I think the old terminology of severe and mild preeclampsia was somewhat confusing. I certainly appreciate that alteration in terminology, although it may take a while for it to catch on. I’m still seeing the term “mild preeclampsia” used quite widely.

Use of magnesium sulfate for seizure prophylaxis

Dr. Norwitz: You did raise the issue of magnesium sulfate for seizure prophylaxis in the setting of severe preeclampsia without severe features. And I was struck by the statement. Not only is it not necessary to give it, but in the Executive Summary, as you suggest, it is not indicated and you recommended against starting it. Is that how you interpret it as the well?

Dr. Repke: Well, I might have interpreted the statement the way I wanted to interpret it. And, as you know, in our institution, because we feel we are a teaching program, people can progress very quickly intrapartum from not having severe features to having severe features, and we don’t want to miss that window of opportunity. Our practice in that regard does not follow the guidelines. We use intrapartum magnesium prophylaxis for all patients with the diagnosis of preeclampsia, and continue it for 24 hours postpartum.

Dr. Norwitz: And I would have to say we decided do the same. So, once a diagnosis of preeclampsia is made, we would give intrapartum, and then postpartum magnesium seizure prophylaxis for 24 hours, regardless of whether there’s evidence of severe features or no severe features.

Dr. Repke: And there again, I think it’s why, for you and I, it will still be important to assess the proteinuria because that diagnostic difference between preeclampsia and gestational hypertension is going to alter management. But if you follow the document word for word, if you’re not going to use magnesium without severe features, I’m not really sure what proteinuria adds. I guess, at the end of the day, you’ve got to be a good doctor. And, you’ve got to be physically assessing your patient on a very regular basis.

Preventing the first cesarean delivery. Will cesarean rates decline?

Dr. Repke: So, speaking of guidelines, the Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine (SMFM) just came out with a document trying to address this issue of the cesarean-section rate in the United States and are there things that we can be doing to lower the primary C-section rate.2 My feeling is probably disseminated from the recognition that vaginal birth after C-section never got to the levels of acceptance that anybody hoped back when Healthy People 2010 was first written. And, we could eliminate that issue or, at least significantly reduce that issue, if the first C-section never took place.