User login

Doctors of Virtue and Vice: The Best and Worst of Federal Practice in 2023

Regular readers of Federal Practitioner may recall that I have had a tradition of dedicating the last column of the year to an ethics rendition of the popular trope of the annual best and worst. This year we will examine the stories of 2 military physicians through the lens of virtue ethics. Aristotle (384-322

Virtue ethics is among the oldest of ethical theories, and Aristotle articulates this school of thought in his work Nicomachean Ethics.2 It is a good fit for Federal Practitioner as it has been constructively applied to the moral development of both military3 and medical professionals.4

Here is a Reader’s Digest version of virtue theory with apologizes to all the real philosophers out there. There are different ways to categorize ethical theories. One approach is to distinguish them based on the aspects of primary interest. Consequentialist ethics theories are concerned with the outcomes of actions. Deontologic theories emphasize the intention of the moral agent. In contrast, virtue ethics theories focus on the character of a person. The virtuous individual is one who has practiced the habits of moral excellence and embodies the good life. They are honored as heroes and revered as saints; they are the exemplars we imitate in our aspirations.3

The epigraph sums up one of Aristotle’s central philosophical doctrines: the close relationship of ethics and politics.1 Personal virtue is intelligible only in the context of community and aim, and the goal of virtue is to contribute to human happiness.5 War, whether in ancient Greece or modern Europe, is among the forces most inimical to human flourishing. The current war in Ukraine that has united much of the Western world in opposition to tyranny has divided the 2 physicians in our story along the normative lines of virtue ethics.

The doctor of virtue: Michael Siclari, MD. A 71-year-old US Department of Veterans Affairs physician, Siclari had previously served in the military as a National Guard physician during Operation Enduring Freedom (2001-2014) in Afghanistan. He decided to serve again in Ukraine. Siclari expressed his reasons for going to Ukraine in the language of what Aristotle thought was among the highest virtues: justice. “In retrospect, as I think about why I wanted to go to Ukraine, I think it’s more of a sense that I thought an injustice was happening.”7

Echoing the great Rabbi Hillel, Siclari saw the Russian invasion of Ukraine as a personal call to use his experience and training as a trauma and emergency medicine physician to help the Ukrainian people. “If not me, then who?” Siclari demonstrated another virtue: generosity in taking 10 days of personal leave in August 2022 to make the trip to Ukraine, hoping to work in a combat zone tending to wounded soldiers as he had in Afghanistan. When due to logistics he instead was assigned to care for refugees and assist with evacuations from the battlefield, he humbly and compassionately cared for those in his charge. Even now, back home, he speaks to audiences of health care professionals encouraging them to consider similar acts of altruism.5

Virtue for Aristotle is technically defined as the mean between 2 extremes of disposition or temperament. The virtue of courage is found in the moral middle ground between the deficiency of bravery that is cowardice and the vice of excess of reckless abandon. The former person fears too much and the latter too little and both thus exhibit vicious behavior.

The doctor of vice: James Lee Henry. Henry is a major and internal medicine physician in the United States Army stationed at Fort Bragg, headquarters of the US Army Special Operations Command. Along with his wife Anna Gabrielian, a civilian anesthesiologist, he was charged in September with conspiring to divulge the protected health information of American military and government employees to the Russian government.8 According to the Grand Jury indictment, Henry delivered into the hands of an undercover Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) agent, the medical records of a US Army officer, Department of Defense employee, and the spouses of 3 Army veterans, 2 of whom were deceased.9 In a gross twisting of virtue language, Gabrielian explained her motivation for the couple’s espionage in terms of sacrifice and loyalty. In an antipode of Siclari’s service, Henry purportedly wanted to join the Russian army but did not have the requisite combat experience. For his part, Henry’s abysmal defense of his betrayal of his country and his oath speaks for itself, if the United States were to declare war on Russia, Henry told the FBI agent, “at that point, I’ll have some ethical issues I have to work through.”8

We become virtuous people through imitating the example of those who have perfected the habits of moral excellence. During 2022, 2 federal practitioners responded to the challenge of war: one displayed the zenith of virtue, the other exhibited the nadir of vice. Seldom does a single year present us with such clear choices of who and how we want to be in 2023. American culture has so trivialized New Year’s resolutions that they are no longer substantive enough for the weight of the profound question of what constitutes the good life. Rather let us make a commitment in keeping with such morally serious matters. All of us live as mixed creatures, drawn to virtue and prone to vice. May we all strive this coming year to help each other meet the high bar another great man of virtue Abraham Lincoln set in his first inaugural address, to be the “better angels of our natures.”10

1. Aristotle. Politics. Book I, 1253.a31.

2. The Ethics of Aristotle. Aristotle. The Nicomachean Ethics. Thompson JAK, trans. Penguin Books; 1953.

3. Schonfeld TL, Hester DM. Brief introduction to ethics and ethical theory. In: Schonfeld TL, Hester DM, eds. Guidance for Healthcare Ethics Committees. 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press; 2022:11-19.

4. Olsthoorn P. Military Ethics and Virtues: An Interdisciplinary Approach for the 21st Century. Routledge; 2010.

5. Pellegrino ED, Thomasma DC. The Virtues in Medical Practice. Oxford University Press; 1993.

6. Edward Clayton. Aristotle Politics. In: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Accessed November 28, 2022. https://iep.utm.edu/aristotle-politics

7. Tippets R. A VA doctor’s calling to help in Ukraine. VA News. October 23, 2022. Accessed November 28, 2022. https://news.va.gov/109957/a-va-doctors-calling-to-help-in-ukraine

8. Lybrand H. US Army doctor and anesthesiologist charged with conspiring to US military records to the Russian government. CNN Politics, September 29, 2022. Accessed November 28, 2022 https://www.cnn.com/2022/09/29/politics/us-army-doctor-anesthesiologist-russian-government-medical-records

9. United States v Anna Gabrielian and James Lee Henry, (SD Md 2022). Accessed November 28, 2022. https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/23106067-gabrielian-and-henry-indictment

10. Lincoln A. First Inaugural Address of Abraham Lincoln. Accessed November 28, 2022. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/lincoln1.asp

Regular readers of Federal Practitioner may recall that I have had a tradition of dedicating the last column of the year to an ethics rendition of the popular trope of the annual best and worst. This year we will examine the stories of 2 military physicians through the lens of virtue ethics. Aristotle (384-322

Virtue ethics is among the oldest of ethical theories, and Aristotle articulates this school of thought in his work Nicomachean Ethics.2 It is a good fit for Federal Practitioner as it has been constructively applied to the moral development of both military3 and medical professionals.4

Here is a Reader’s Digest version of virtue theory with apologizes to all the real philosophers out there. There are different ways to categorize ethical theories. One approach is to distinguish them based on the aspects of primary interest. Consequentialist ethics theories are concerned with the outcomes of actions. Deontologic theories emphasize the intention of the moral agent. In contrast, virtue ethics theories focus on the character of a person. The virtuous individual is one who has practiced the habits of moral excellence and embodies the good life. They are honored as heroes and revered as saints; they are the exemplars we imitate in our aspirations.3

The epigraph sums up one of Aristotle’s central philosophical doctrines: the close relationship of ethics and politics.1 Personal virtue is intelligible only in the context of community and aim, and the goal of virtue is to contribute to human happiness.5 War, whether in ancient Greece or modern Europe, is among the forces most inimical to human flourishing. The current war in Ukraine that has united much of the Western world in opposition to tyranny has divided the 2 physicians in our story along the normative lines of virtue ethics.

The doctor of virtue: Michael Siclari, MD. A 71-year-old US Department of Veterans Affairs physician, Siclari had previously served in the military as a National Guard physician during Operation Enduring Freedom (2001-2014) in Afghanistan. He decided to serve again in Ukraine. Siclari expressed his reasons for going to Ukraine in the language of what Aristotle thought was among the highest virtues: justice. “In retrospect, as I think about why I wanted to go to Ukraine, I think it’s more of a sense that I thought an injustice was happening.”7

Echoing the great Rabbi Hillel, Siclari saw the Russian invasion of Ukraine as a personal call to use his experience and training as a trauma and emergency medicine physician to help the Ukrainian people. “If not me, then who?” Siclari demonstrated another virtue: generosity in taking 10 days of personal leave in August 2022 to make the trip to Ukraine, hoping to work in a combat zone tending to wounded soldiers as he had in Afghanistan. When due to logistics he instead was assigned to care for refugees and assist with evacuations from the battlefield, he humbly and compassionately cared for those in his charge. Even now, back home, he speaks to audiences of health care professionals encouraging them to consider similar acts of altruism.5

Virtue for Aristotle is technically defined as the mean between 2 extremes of disposition or temperament. The virtue of courage is found in the moral middle ground between the deficiency of bravery that is cowardice and the vice of excess of reckless abandon. The former person fears too much and the latter too little and both thus exhibit vicious behavior.

The doctor of vice: James Lee Henry. Henry is a major and internal medicine physician in the United States Army stationed at Fort Bragg, headquarters of the US Army Special Operations Command. Along with his wife Anna Gabrielian, a civilian anesthesiologist, he was charged in September with conspiring to divulge the protected health information of American military and government employees to the Russian government.8 According to the Grand Jury indictment, Henry delivered into the hands of an undercover Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) agent, the medical records of a US Army officer, Department of Defense employee, and the spouses of 3 Army veterans, 2 of whom were deceased.9 In a gross twisting of virtue language, Gabrielian explained her motivation for the couple’s espionage in terms of sacrifice and loyalty. In an antipode of Siclari’s service, Henry purportedly wanted to join the Russian army but did not have the requisite combat experience. For his part, Henry’s abysmal defense of his betrayal of his country and his oath speaks for itself, if the United States were to declare war on Russia, Henry told the FBI agent, “at that point, I’ll have some ethical issues I have to work through.”8

We become virtuous people through imitating the example of those who have perfected the habits of moral excellence. During 2022, 2 federal practitioners responded to the challenge of war: one displayed the zenith of virtue, the other exhibited the nadir of vice. Seldom does a single year present us with such clear choices of who and how we want to be in 2023. American culture has so trivialized New Year’s resolutions that they are no longer substantive enough for the weight of the profound question of what constitutes the good life. Rather let us make a commitment in keeping with such morally serious matters. All of us live as mixed creatures, drawn to virtue and prone to vice. May we all strive this coming year to help each other meet the high bar another great man of virtue Abraham Lincoln set in his first inaugural address, to be the “better angels of our natures.”10

Regular readers of Federal Practitioner may recall that I have had a tradition of dedicating the last column of the year to an ethics rendition of the popular trope of the annual best and worst. This year we will examine the stories of 2 military physicians through the lens of virtue ethics. Aristotle (384-322

Virtue ethics is among the oldest of ethical theories, and Aristotle articulates this school of thought in his work Nicomachean Ethics.2 It is a good fit for Federal Practitioner as it has been constructively applied to the moral development of both military3 and medical professionals.4

Here is a Reader’s Digest version of virtue theory with apologizes to all the real philosophers out there. There are different ways to categorize ethical theories. One approach is to distinguish them based on the aspects of primary interest. Consequentialist ethics theories are concerned with the outcomes of actions. Deontologic theories emphasize the intention of the moral agent. In contrast, virtue ethics theories focus on the character of a person. The virtuous individual is one who has practiced the habits of moral excellence and embodies the good life. They are honored as heroes and revered as saints; they are the exemplars we imitate in our aspirations.3

The epigraph sums up one of Aristotle’s central philosophical doctrines: the close relationship of ethics and politics.1 Personal virtue is intelligible only in the context of community and aim, and the goal of virtue is to contribute to human happiness.5 War, whether in ancient Greece or modern Europe, is among the forces most inimical to human flourishing. The current war in Ukraine that has united much of the Western world in opposition to tyranny has divided the 2 physicians in our story along the normative lines of virtue ethics.

The doctor of virtue: Michael Siclari, MD. A 71-year-old US Department of Veterans Affairs physician, Siclari had previously served in the military as a National Guard physician during Operation Enduring Freedom (2001-2014) in Afghanistan. He decided to serve again in Ukraine. Siclari expressed his reasons for going to Ukraine in the language of what Aristotle thought was among the highest virtues: justice. “In retrospect, as I think about why I wanted to go to Ukraine, I think it’s more of a sense that I thought an injustice was happening.”7

Echoing the great Rabbi Hillel, Siclari saw the Russian invasion of Ukraine as a personal call to use his experience and training as a trauma and emergency medicine physician to help the Ukrainian people. “If not me, then who?” Siclari demonstrated another virtue: generosity in taking 10 days of personal leave in August 2022 to make the trip to Ukraine, hoping to work in a combat zone tending to wounded soldiers as he had in Afghanistan. When due to logistics he instead was assigned to care for refugees and assist with evacuations from the battlefield, he humbly and compassionately cared for those in his charge. Even now, back home, he speaks to audiences of health care professionals encouraging them to consider similar acts of altruism.5

Virtue for Aristotle is technically defined as the mean between 2 extremes of disposition or temperament. The virtue of courage is found in the moral middle ground between the deficiency of bravery that is cowardice and the vice of excess of reckless abandon. The former person fears too much and the latter too little and both thus exhibit vicious behavior.

The doctor of vice: James Lee Henry. Henry is a major and internal medicine physician in the United States Army stationed at Fort Bragg, headquarters of the US Army Special Operations Command. Along with his wife Anna Gabrielian, a civilian anesthesiologist, he was charged in September with conspiring to divulge the protected health information of American military and government employees to the Russian government.8 According to the Grand Jury indictment, Henry delivered into the hands of an undercover Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) agent, the medical records of a US Army officer, Department of Defense employee, and the spouses of 3 Army veterans, 2 of whom were deceased.9 In a gross twisting of virtue language, Gabrielian explained her motivation for the couple’s espionage in terms of sacrifice and loyalty. In an antipode of Siclari’s service, Henry purportedly wanted to join the Russian army but did not have the requisite combat experience. For his part, Henry’s abysmal defense of his betrayal of his country and his oath speaks for itself, if the United States were to declare war on Russia, Henry told the FBI agent, “at that point, I’ll have some ethical issues I have to work through.”8

We become virtuous people through imitating the example of those who have perfected the habits of moral excellence. During 2022, 2 federal practitioners responded to the challenge of war: one displayed the zenith of virtue, the other exhibited the nadir of vice. Seldom does a single year present us with such clear choices of who and how we want to be in 2023. American culture has so trivialized New Year’s resolutions that they are no longer substantive enough for the weight of the profound question of what constitutes the good life. Rather let us make a commitment in keeping with such morally serious matters. All of us live as mixed creatures, drawn to virtue and prone to vice. May we all strive this coming year to help each other meet the high bar another great man of virtue Abraham Lincoln set in his first inaugural address, to be the “better angels of our natures.”10

1. Aristotle. Politics. Book I, 1253.a31.

2. The Ethics of Aristotle. Aristotle. The Nicomachean Ethics. Thompson JAK, trans. Penguin Books; 1953.

3. Schonfeld TL, Hester DM. Brief introduction to ethics and ethical theory. In: Schonfeld TL, Hester DM, eds. Guidance for Healthcare Ethics Committees. 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press; 2022:11-19.

4. Olsthoorn P. Military Ethics and Virtues: An Interdisciplinary Approach for the 21st Century. Routledge; 2010.

5. Pellegrino ED, Thomasma DC. The Virtues in Medical Practice. Oxford University Press; 1993.

6. Edward Clayton. Aristotle Politics. In: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Accessed November 28, 2022. https://iep.utm.edu/aristotle-politics

7. Tippets R. A VA doctor’s calling to help in Ukraine. VA News. October 23, 2022. Accessed November 28, 2022. https://news.va.gov/109957/a-va-doctors-calling-to-help-in-ukraine

8. Lybrand H. US Army doctor and anesthesiologist charged with conspiring to US military records to the Russian government. CNN Politics, September 29, 2022. Accessed November 28, 2022 https://www.cnn.com/2022/09/29/politics/us-army-doctor-anesthesiologist-russian-government-medical-records

9. United States v Anna Gabrielian and James Lee Henry, (SD Md 2022). Accessed November 28, 2022. https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/23106067-gabrielian-and-henry-indictment

10. Lincoln A. First Inaugural Address of Abraham Lincoln. Accessed November 28, 2022. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/lincoln1.asp

1. Aristotle. Politics. Book I, 1253.a31.

2. The Ethics of Aristotle. Aristotle. The Nicomachean Ethics. Thompson JAK, trans. Penguin Books; 1953.

3. Schonfeld TL, Hester DM. Brief introduction to ethics and ethical theory. In: Schonfeld TL, Hester DM, eds. Guidance for Healthcare Ethics Committees. 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press; 2022:11-19.

4. Olsthoorn P. Military Ethics and Virtues: An Interdisciplinary Approach for the 21st Century. Routledge; 2010.

5. Pellegrino ED, Thomasma DC. The Virtues in Medical Practice. Oxford University Press; 1993.

6. Edward Clayton. Aristotle Politics. In: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Accessed November 28, 2022. https://iep.utm.edu/aristotle-politics

7. Tippets R. A VA doctor’s calling to help in Ukraine. VA News. October 23, 2022. Accessed November 28, 2022. https://news.va.gov/109957/a-va-doctors-calling-to-help-in-ukraine

8. Lybrand H. US Army doctor and anesthesiologist charged with conspiring to US military records to the Russian government. CNN Politics, September 29, 2022. Accessed November 28, 2022 https://www.cnn.com/2022/09/29/politics/us-army-doctor-anesthesiologist-russian-government-medical-records

9. United States v Anna Gabrielian and James Lee Henry, (SD Md 2022). Accessed November 28, 2022. https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/23106067-gabrielian-and-henry-indictment

10. Lincoln A. First Inaugural Address of Abraham Lincoln. Accessed November 28, 2022. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/lincoln1.asp

The Long Arc of Justice for Veteran Benefits

This Veterans Day we honor the passing of the largest expansion of veterans benefits and services in history. On August 10, 2022, President Biden signed the Sergeant First Class Heath Robinson Honoring our Promise to Address Comprehensive Toxics (PACT) Act. This act was named for a combat medic who died of a rare form of lung cancer believed to be the result of a toxic military exposure. His widow was present during the President's State of the Union address that urged Congress to pass the legislation.2

Like all other congressional bills and government regulations, the PACT Act is complex in its details and still a work in progress. Simply put, the PACT Act expands and/or extends enrollment for a group of previously ineligible veterans. Eligibility will no longer require that veterans demonstrate a service-connected disability due to toxic exposure, including those from burn pits. This has long been a barrier for many veterans seeking benefits and not just related to toxic exposures. Logistical barriers and documentary losses have prevented many service members from establishing a clean chain of evidence for the injuries or illnesses they sustained while in uniform.

The new process is a massive step forward by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to establish high standards of procedural justice for settling beneficiary claims. The PACT Act removes the burden from the shoulders of the veteran and places it squarely on the VA to demonstrate that > 20 different medical conditions--primarily cancers and respiratory illnesses--are linked to toxic exposure. The VA must establish that exposure occurred to cohorts of service members in specific theaters and time frames. A veteran who served in that area and period and has one of the indexed illnesses is presumed to have been exposed in the line of duty.3,4

As a result, the VA instituted a new screening process to determine that toxic military exposures (a) led to illness; and (b) both exposure and illness are connected to service. According to the VA, the new process is evidence based, transparent, and allows the VA to fast-track policy decisions related to exposures. The PACT Act includes a provision intended to promote sustained implementation and prevent the program from succumbing as so many new initiatives have to inadequate adoption. VA is required to deploy its considerable internal research capacity to collaborate with external partners in and outside government to study military members with toxic exposures.4

Congress had initially proposed that the provisions of the PACT ACT would take effect in 2026, providing time to ramp up the process. The White House and VA telescoped that time line so veterans can begin now to apply for benefits that they could foreseeably receive in 2023. However, a long-standing problem for the VA has been unfunded agency or congressional mandates. These have often end in undermining the legislative intention or policy purpose of the program undermining their legislative intention or policy purpose through staffing shortages, leading to lack of or delayed access. The PACT Act promises to eschew the infamous Phoenix problem by providing increased personnel, training infrastructure, and technology resources for both the Veterans Benefit Administration and the Veterans Health Administration. Ironically, many seasoned VA observers expect the PACT expansion will lead to even larger backlogs of claims as hundreds of newly eligible veterans are added to the extant rolls of those seeking benefits.5

An estimated 1 in 5 veterans may be entitled to PACT benefits. The PACT Act is the latest of a long uneven movement toward distributive justice for veteran benefits and services. It is fitting in the month of Veterans Day 2022 to trace that trajectory. Congress first passed veteran benefits legislation in 1917, focused on soldiers with disabilities. This resulted in a massive investment in building hospitals. Ironically, part of the impetus for VA health care was an earlier toxic military exposure. World War I service members suffered from the detrimental effects of mustard gas among other chemical byproducts. In 1924, VA benefits and services underwent a momentous opening to include individuals with non-service-connected disabilities. Four years later, the VA tent became even bigger, welcoming women, National Guard, and militia members to receive care under its auspices.6

The PACT Act is a fitting memorial for Veterans Day as an increasingly divided country presents a unified response to veterans and their survivors exposed to a variety of toxins across multiple wars. The PACT Act was hard won with veterans and their advocates having to fight years of political bickering, government abdication of accountability, and scientific sparring before this bipartisan legislation passed.7 It covers Vietnam War veterans with several conditions due to Agent Orange exposure; Gulf War and post-9/11 veterans with cancer and respiratory conditions; and the service members deployed to Afghanistan and Iraq afflicted with illnesses due to the smoke of burn pits and other toxins.

As many areas of the country roll back LGBTQ+ rights to health care and social services, the VA has emerged as a leader in the movement for diversity and inclusion. VA Secretary McDonough provided a pathway to VA eligibility for other than honorably discharged veterans, including those LGBTQ+ persons discharged under Don't Ask, Don't Tell.8 Lest we take this new inclusivity for granted, we should never forget that this journey toward equity for the military and VA has been long, slow, and uneven. There are many difficult miles yet to travel if we are to achieve liberty and justice for veteran members of racial minorities, women, and other marginalized populations. Even the PACT Act does not cover all putative exposures to toxins.9 Yet it is a significant step closer to fulfilling the motto of the VA LGBTQ+ program: to serve all who served.10

- Parker T. Of justice and the conscience. In: Ten Sermons of Religion. Crosby, Nichols and Company; 1853:66-85.

- The White House. Fact sheet: President Biden signs the PACT Act and delivers on his promise to America's veterans. August 9, 2022. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/08/10/fact-sheet-president-biden-signs-the-pact-act-and-delivers-on-his-promise-to-americas-veterans

- Shane L. Vets can apply for all PACT benefits now after VA speeds up law. Military Times. September 1, 2022. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.militarytimes.com/news/burn-pits/2022/09/01/vets-can-apply-for-all-pact-act-benefits-now-after-va-speeds-up-law

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. The PACT Act and your VA benefits. Updated September 28, 2022. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.va.gov/resources/the-pact-act-and-your-va-benefits

- Wentling N. Discharged LGBTQ+ veterans now eligible for benefits under new guidance issued by VA. Stars & Stripes. September 20, 2021. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.stripes.com/veterans/2021-09-20/veterans-affairs-dont-ask-dont-tell-benefits-lgbt-discharges-2956761.html

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, VA History Office. History--Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). Updated May 27, 2021. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.va.gov/HISTORY/VA_History/Overview.asp

- Atkins D, Kilbourne A, Lipson L. Health equity research in the Veterans Health Administration: we've come far but aren't there yet. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(suppl 4):S525-S526. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.302216

- Stack MK. The soldiers came home sick. The government denied it was responsible. New York Times. Updated January 16, 2022. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/11/magazine/military-burn-pits.html

- Namaz A, Sagalyn D. VA secretary discusses health care overhaul helping veterans exposed to toxic burn pits. PBS NewsHour. September 1, 2022. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/va-secretary-discusses-health-care-overhaul-helping-veterans-exposed-to-toxic-burn-pits

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Patient Care Services. VHA LGBTQ+ health program. Updated September 13, 2022. Accessed October 31, 2022. https://www.patientcare.va.gov/lgbt

This Veterans Day we honor the passing of the largest expansion of veterans benefits and services in history. On August 10, 2022, President Biden signed the Sergeant First Class Heath Robinson Honoring our Promise to Address Comprehensive Toxics (PACT) Act. This act was named for a combat medic who died of a rare form of lung cancer believed to be the result of a toxic military exposure. His widow was present during the President's State of the Union address that urged Congress to pass the legislation.2

Like all other congressional bills and government regulations, the PACT Act is complex in its details and still a work in progress. Simply put, the PACT Act expands and/or extends enrollment for a group of previously ineligible veterans. Eligibility will no longer require that veterans demonstrate a service-connected disability due to toxic exposure, including those from burn pits. This has long been a barrier for many veterans seeking benefits and not just related to toxic exposures. Logistical barriers and documentary losses have prevented many service members from establishing a clean chain of evidence for the injuries or illnesses they sustained while in uniform.

The new process is a massive step forward by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to establish high standards of procedural justice for settling beneficiary claims. The PACT Act removes the burden from the shoulders of the veteran and places it squarely on the VA to demonstrate that > 20 different medical conditions--primarily cancers and respiratory illnesses--are linked to toxic exposure. The VA must establish that exposure occurred to cohorts of service members in specific theaters and time frames. A veteran who served in that area and period and has one of the indexed illnesses is presumed to have been exposed in the line of duty.3,4

As a result, the VA instituted a new screening process to determine that toxic military exposures (a) led to illness; and (b) both exposure and illness are connected to service. According to the VA, the new process is evidence based, transparent, and allows the VA to fast-track policy decisions related to exposures. The PACT Act includes a provision intended to promote sustained implementation and prevent the program from succumbing as so many new initiatives have to inadequate adoption. VA is required to deploy its considerable internal research capacity to collaborate with external partners in and outside government to study military members with toxic exposures.4

Congress had initially proposed that the provisions of the PACT ACT would take effect in 2026, providing time to ramp up the process. The White House and VA telescoped that time line so veterans can begin now to apply for benefits that they could foreseeably receive in 2023. However, a long-standing problem for the VA has been unfunded agency or congressional mandates. These have often end in undermining the legislative intention or policy purpose of the program undermining their legislative intention or policy purpose through staffing shortages, leading to lack of or delayed access. The PACT Act promises to eschew the infamous Phoenix problem by providing increased personnel, training infrastructure, and technology resources for both the Veterans Benefit Administration and the Veterans Health Administration. Ironically, many seasoned VA observers expect the PACT expansion will lead to even larger backlogs of claims as hundreds of newly eligible veterans are added to the extant rolls of those seeking benefits.5

An estimated 1 in 5 veterans may be entitled to PACT benefits. The PACT Act is the latest of a long uneven movement toward distributive justice for veteran benefits and services. It is fitting in the month of Veterans Day 2022 to trace that trajectory. Congress first passed veteran benefits legislation in 1917, focused on soldiers with disabilities. This resulted in a massive investment in building hospitals. Ironically, part of the impetus for VA health care was an earlier toxic military exposure. World War I service members suffered from the detrimental effects of mustard gas among other chemical byproducts. In 1924, VA benefits and services underwent a momentous opening to include individuals with non-service-connected disabilities. Four years later, the VA tent became even bigger, welcoming women, National Guard, and militia members to receive care under its auspices.6

The PACT Act is a fitting memorial for Veterans Day as an increasingly divided country presents a unified response to veterans and their survivors exposed to a variety of toxins across multiple wars. The PACT Act was hard won with veterans and their advocates having to fight years of political bickering, government abdication of accountability, and scientific sparring before this bipartisan legislation passed.7 It covers Vietnam War veterans with several conditions due to Agent Orange exposure; Gulf War and post-9/11 veterans with cancer and respiratory conditions; and the service members deployed to Afghanistan and Iraq afflicted with illnesses due to the smoke of burn pits and other toxins.

As many areas of the country roll back LGBTQ+ rights to health care and social services, the VA has emerged as a leader in the movement for diversity and inclusion. VA Secretary McDonough provided a pathway to VA eligibility for other than honorably discharged veterans, including those LGBTQ+ persons discharged under Don't Ask, Don't Tell.8 Lest we take this new inclusivity for granted, we should never forget that this journey toward equity for the military and VA has been long, slow, and uneven. There are many difficult miles yet to travel if we are to achieve liberty and justice for veteran members of racial minorities, women, and other marginalized populations. Even the PACT Act does not cover all putative exposures to toxins.9 Yet it is a significant step closer to fulfilling the motto of the VA LGBTQ+ program: to serve all who served.10

This Veterans Day we honor the passing of the largest expansion of veterans benefits and services in history. On August 10, 2022, President Biden signed the Sergeant First Class Heath Robinson Honoring our Promise to Address Comprehensive Toxics (PACT) Act. This act was named for a combat medic who died of a rare form of lung cancer believed to be the result of a toxic military exposure. His widow was present during the President's State of the Union address that urged Congress to pass the legislation.2

Like all other congressional bills and government regulations, the PACT Act is complex in its details and still a work in progress. Simply put, the PACT Act expands and/or extends enrollment for a group of previously ineligible veterans. Eligibility will no longer require that veterans demonstrate a service-connected disability due to toxic exposure, including those from burn pits. This has long been a barrier for many veterans seeking benefits and not just related to toxic exposures. Logistical barriers and documentary losses have prevented many service members from establishing a clean chain of evidence for the injuries or illnesses they sustained while in uniform.

The new process is a massive step forward by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to establish high standards of procedural justice for settling beneficiary claims. The PACT Act removes the burden from the shoulders of the veteran and places it squarely on the VA to demonstrate that > 20 different medical conditions--primarily cancers and respiratory illnesses--are linked to toxic exposure. The VA must establish that exposure occurred to cohorts of service members in specific theaters and time frames. A veteran who served in that area and period and has one of the indexed illnesses is presumed to have been exposed in the line of duty.3,4

As a result, the VA instituted a new screening process to determine that toxic military exposures (a) led to illness; and (b) both exposure and illness are connected to service. According to the VA, the new process is evidence based, transparent, and allows the VA to fast-track policy decisions related to exposures. The PACT Act includes a provision intended to promote sustained implementation and prevent the program from succumbing as so many new initiatives have to inadequate adoption. VA is required to deploy its considerable internal research capacity to collaborate with external partners in and outside government to study military members with toxic exposures.4

Congress had initially proposed that the provisions of the PACT ACT would take effect in 2026, providing time to ramp up the process. The White House and VA telescoped that time line so veterans can begin now to apply for benefits that they could foreseeably receive in 2023. However, a long-standing problem for the VA has been unfunded agency or congressional mandates. These have often end in undermining the legislative intention or policy purpose of the program undermining their legislative intention or policy purpose through staffing shortages, leading to lack of or delayed access. The PACT Act promises to eschew the infamous Phoenix problem by providing increased personnel, training infrastructure, and technology resources for both the Veterans Benefit Administration and the Veterans Health Administration. Ironically, many seasoned VA observers expect the PACT expansion will lead to even larger backlogs of claims as hundreds of newly eligible veterans are added to the extant rolls of those seeking benefits.5

An estimated 1 in 5 veterans may be entitled to PACT benefits. The PACT Act is the latest of a long uneven movement toward distributive justice for veteran benefits and services. It is fitting in the month of Veterans Day 2022 to trace that trajectory. Congress first passed veteran benefits legislation in 1917, focused on soldiers with disabilities. This resulted in a massive investment in building hospitals. Ironically, part of the impetus for VA health care was an earlier toxic military exposure. World War I service members suffered from the detrimental effects of mustard gas among other chemical byproducts. In 1924, VA benefits and services underwent a momentous opening to include individuals with non-service-connected disabilities. Four years later, the VA tent became even bigger, welcoming women, National Guard, and militia members to receive care under its auspices.6

The PACT Act is a fitting memorial for Veterans Day as an increasingly divided country presents a unified response to veterans and their survivors exposed to a variety of toxins across multiple wars. The PACT Act was hard won with veterans and their advocates having to fight years of political bickering, government abdication of accountability, and scientific sparring before this bipartisan legislation passed.7 It covers Vietnam War veterans with several conditions due to Agent Orange exposure; Gulf War and post-9/11 veterans with cancer and respiratory conditions; and the service members deployed to Afghanistan and Iraq afflicted with illnesses due to the smoke of burn pits and other toxins.

As many areas of the country roll back LGBTQ+ rights to health care and social services, the VA has emerged as a leader in the movement for diversity and inclusion. VA Secretary McDonough provided a pathway to VA eligibility for other than honorably discharged veterans, including those LGBTQ+ persons discharged under Don't Ask, Don't Tell.8 Lest we take this new inclusivity for granted, we should never forget that this journey toward equity for the military and VA has been long, slow, and uneven. There are many difficult miles yet to travel if we are to achieve liberty and justice for veteran members of racial minorities, women, and other marginalized populations. Even the PACT Act does not cover all putative exposures to toxins.9 Yet it is a significant step closer to fulfilling the motto of the VA LGBTQ+ program: to serve all who served.10

- Parker T. Of justice and the conscience. In: Ten Sermons of Religion. Crosby, Nichols and Company; 1853:66-85.

- The White House. Fact sheet: President Biden signs the PACT Act and delivers on his promise to America's veterans. August 9, 2022. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/08/10/fact-sheet-president-biden-signs-the-pact-act-and-delivers-on-his-promise-to-americas-veterans

- Shane L. Vets can apply for all PACT benefits now after VA speeds up law. Military Times. September 1, 2022. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.militarytimes.com/news/burn-pits/2022/09/01/vets-can-apply-for-all-pact-act-benefits-now-after-va-speeds-up-law

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. The PACT Act and your VA benefits. Updated September 28, 2022. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.va.gov/resources/the-pact-act-and-your-va-benefits

- Wentling N. Discharged LGBTQ+ veterans now eligible for benefits under new guidance issued by VA. Stars & Stripes. September 20, 2021. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.stripes.com/veterans/2021-09-20/veterans-affairs-dont-ask-dont-tell-benefits-lgbt-discharges-2956761.html

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, VA History Office. History--Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). Updated May 27, 2021. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.va.gov/HISTORY/VA_History/Overview.asp

- Atkins D, Kilbourne A, Lipson L. Health equity research in the Veterans Health Administration: we've come far but aren't there yet. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(suppl 4):S525-S526. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.302216

- Stack MK. The soldiers came home sick. The government denied it was responsible. New York Times. Updated January 16, 2022. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/11/magazine/military-burn-pits.html

- Namaz A, Sagalyn D. VA secretary discusses health care overhaul helping veterans exposed to toxic burn pits. PBS NewsHour. September 1, 2022. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/va-secretary-discusses-health-care-overhaul-helping-veterans-exposed-to-toxic-burn-pits

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Patient Care Services. VHA LGBTQ+ health program. Updated September 13, 2022. Accessed October 31, 2022. https://www.patientcare.va.gov/lgbt

- Parker T. Of justice and the conscience. In: Ten Sermons of Religion. Crosby, Nichols and Company; 1853:66-85.

- The White House. Fact sheet: President Biden signs the PACT Act and delivers on his promise to America's veterans. August 9, 2022. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/08/10/fact-sheet-president-biden-signs-the-pact-act-and-delivers-on-his-promise-to-americas-veterans

- Shane L. Vets can apply for all PACT benefits now after VA speeds up law. Military Times. September 1, 2022. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.militarytimes.com/news/burn-pits/2022/09/01/vets-can-apply-for-all-pact-act-benefits-now-after-va-speeds-up-law

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. The PACT Act and your VA benefits. Updated September 28, 2022. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.va.gov/resources/the-pact-act-and-your-va-benefits

- Wentling N. Discharged LGBTQ+ veterans now eligible for benefits under new guidance issued by VA. Stars & Stripes. September 20, 2021. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.stripes.com/veterans/2021-09-20/veterans-affairs-dont-ask-dont-tell-benefits-lgbt-discharges-2956761.html

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, VA History Office. History--Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). Updated May 27, 2021. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.va.gov/HISTORY/VA_History/Overview.asp

- Atkins D, Kilbourne A, Lipson L. Health equity research in the Veterans Health Administration: we've come far but aren't there yet. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(suppl 4):S525-S526. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.302216

- Stack MK. The soldiers came home sick. The government denied it was responsible. New York Times. Updated January 16, 2022. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/11/magazine/military-burn-pits.html

- Namaz A, Sagalyn D. VA secretary discusses health care overhaul helping veterans exposed to toxic burn pits. PBS NewsHour. September 1, 2022. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/va-secretary-discusses-health-care-overhaul-helping-veterans-exposed-to-toxic-burn-pits

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Patient Care Services. VHA LGBTQ+ health program. Updated September 13, 2022. Accessed October 31, 2022. https://www.patientcare.va.gov/lgbt

Medicaid Expansion and Veterans’ Reliance on the VA for Depression Care

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is the largest integrated health care system in the United States, providing care for more than 9 million veterans.1 With veterans experiencing mental health conditions like posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), substance use disorders, and other serious mental illnesses (SMI) at higher rates compared with the general population, the VA plays an important role in the provision of mental health services.2-5 Since the implementation of its Mental Health Strategic Plan in 2004, the VA has overseen the development of a wide array of mental health programs geared toward the complex needs of veterans. Research has demonstrated VA care outperforming Medicaid-reimbursed services in terms of the percentage of veterans filling antidepressants for at least 12 weeks after initiation of treatment for major depressive disorder (MDD), as well as posthospitalization follow-up.6

Eligible veterans enrolled in the VA often also seek non-VA care. Medicaid covers nearly 10% of all nonelderly veterans, and of these veterans, 39% rely solely on Medicaid for health care access.7 Today, Medicaid is the largest payer for mental health services in the US, providing coverage for approximately 27% of Americans who have SMI and helping fulfill unmet mental health needs.8,9 Understanding which of these systems veterans choose to use, and under which circumstances, is essential in guiding the allocation of limited health care resources.10

Beyond Medicaid, alternatives to VA care may include TRICARE, Medicare, Indian Health Services, and employer-based or self-purchased private insurance. While these options potentially increase convenience, choice, and access to health care practitioners (HCPs) and services not available at local VA systems, cross-system utilization with poor integration may cause care coordination and continuity problems, such as medication mismanagement and opioid overdose, unnecessary duplicate utilization, and possible increased mortality.11-15 As recent national legislative changes, such as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), Veterans Access, Choice and Accountability Act, and the VA MISSION Act, continue to shift the health care landscape for veterans, questions surrounding how veterans are changing their health care use become significant.16,17

Here, we approach the impacts of Medicaid expansion on veterans’ reliance on the VA for mental health services with a unique lens. We leverage a difference-in-difference design to study 2 historical Medicaid expansions in Arizona (AZ) and New York (NY), which extended eligibility to childless adults in 2001. Prior Medicaid dual-eligible mental health research investigated reliance shifts during the immediate postenrollment year in a subset of veterans newly enrolled in Medicaid.18 However, this study took place in a period of relative policy stability. In contrast, we investigate the potential effects of a broad policy shift by analyzing state-level changes in veterans’ reliance over 6 years after a statewide Medicaid expansion. We match expansion states with demographically similar nonexpansion states to account for unobserved trends and confounding effects. Prior studies have used this method to evaluate post-Medicaid expansion mortality changes and changes in veteran dual enrollment and hospitalizations.10,19 While a study of ACA Medicaid expansion states would be ideal, Medicaid data from most states were only available through 2014 at the time of this analysis. Our study offers a quasi-experimental framework leveraging longitudinal data that can be applied as more post-ACA data become available.

Given the rising incidence of suicide among veterans, understanding care-seeking behaviors for depression among veterans is important as it is the most common psychiatric condition found in those who died by suicide.20,21 Furthermore, depression may be useful as a clinical proxy for mental health policy impacts, given that the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) screening tool is well validated and increasingly research accessible, and it is a chronic condition responsive to both well-managed pharmacologic treatment and psychotherapeutic interventions.22,23

In this study, we quantify the change in care-seeking behavior for depression among veterans after Medicaid expansion, using a quasi-experimental design. We hypothesize that new access to Medicaid would be associated with a shift away from using VA services for depression. Given the income-dependent eligibility requirements of Medicaid, we also hypothesize that veterans who qualified for VA coverage due to low income, determined by a regional means test (Priority group 5, “income-eligible”), would be more likely to shift care compared with those whose serviced-connected conditions related to their military service (Priority groups 1-4, “service-connected”) provide VA access.

Methods

To investigate the relative changes in veterans’ reliance on the VA for depression care after the 2001 NY and AZ Medicaid expansions We used a retrospective, difference-in-difference analysis. Our comparison pairings, based on prior demographic analyses were as follows: NY with Pennsylvania(PA); AZ with New Mexico and Nevada (NM/NV).19 The time frame of our analysis was 1999 to 2006, with pre- and postexpansion periods defined as 1999 to 2000 and 2001 to 2006, respectively.

Data

We included veterans aged 18 to 64 years, seeking care for depression from 1999 to 2006, who were also VA-enrolled and residing in our states of interest. We counted veterans as enrolled in Medicaid if they were enrolled at least 1 month in a given year.

Using similar methods like those used in prior studies, we selected patients with encounters documenting depression as the primary outpatient or inpatient diagnosis using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes: 296.2x for a single episode of major depressive disorder, 296.3x for a recurrent episode of MDD, 300.4 for dysthymia, and 311.0 for depression not otherwise specified.18,24 We used data from the Medicaid Analytic eXtract files (MAX) for Medicaid data and the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) for VA data. We chose 1999 as the first study year because it was the earliest year MAX data were available.

Our final sample included 1833 person-years pre-expansion and 7157 postexpansion in our inpatient analysis, as well as 31,767 person-years pre-expansion and 130,382 postexpansion in our outpatient analysis.

Outcomes and Variables

Our primary outcomes were comparative shifts in VA reliance between expansion and nonexpansion states after Medicaid expansion for both inpatient and outpatient depression care. For each year of study, we calculated a veteran’s VA reliance by aggregating the number of days with depression-related encounters at the VA and dividing by the total number of days with a VA or Medicaid depression-related encounters for the year. To provide context to these shifts in VA reliance, we further analyzed the changes in the proportion of annual VA-Medicaid dual users and annual per capita utilization of depression care across the VA and Medicaid.

We conducted subanalyses by income-eligible and service-connected veterans and adjusted our models for age, non-White race, sex, distances to the nearest inpatient and outpatient VA facilities, and VA Relative Risk Score, which is a measure of disease burden and clinical complexity validated specifically for veterans.25

Statistical Analysis

We used fractional logistic regression to model the adjusted effect of Medicaid expansion on VA reliance for depression care. In parallel, we leveraged ordered logit regression and negative binomial regression models to examine the proportion of VA-Medicaid dual users and the per capita utilization of Medicaid and VA depression care, respectively. To estimate the difference-in-difference effects, we used the interaction term of 2 categorical variables—expansion vs nonexpansion states and pre- vs postexpansion status—as the independent variable. We then calculated the average marginal effects with 95% CIs to estimate the differences in outcomes between expansion and nonexpansion states from pre- to postexpansion periods, as well as year-by-year shifts as a robustness check. We conducted these analyses using Stata MP, version 15.

Results

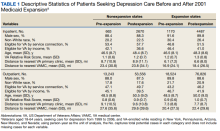

Baseline and postexpansion characteristics

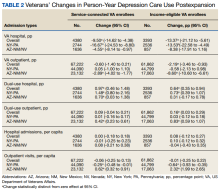

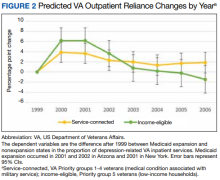

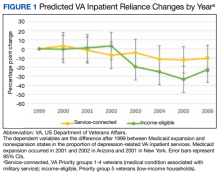

VA Reliance

Overall, we observed postexpansion decreases in VA reliance for depression care

At the state level, reliance on the VA for inpatient depression care in NY decreased by 13.53 pp (95% CI, -22.58 to -4.49) for income-eligible veterans and 16.67 pp (95% CI, -24.53 to -8.80) for service-connected veterans. No relative differences were observed in the outpatient comparisons for both income-eligible (-0.58 pp; 95% CI, -2.13 to 0.98) and service-connected (0.05 pp; 95% CI, -1.00 to 1.10) veterans. In AZ, Medicaid expansion was associated with decreased VA reliance for outpatient depression care among income-eligible veterans (-8.60 pp; 95% CI, -10.60 to -6.61), greater than that for service-connected veterans (-2.89 pp; 95% CI, -4.02 to -1.77). This decrease in VA reliance was significant in the inpatient context only for service-connected veterans (-4.55 pp; 95% CI, -8.14 to -0.97), not income-eligible veterans (-8.38 pp; 95% CI, -17.91 to 1.16).

By applying the aggregate pp changes toward the postexpansion number of visits across both expansion and nonexpansion states, we found that expansion of Medicaid across all our study states would have resulted in 996 fewer hospitalizations and 10,109 fewer outpatient visits for depression at VA in the postexpansion period vs if no states had chosen to expand Medicaid.

Dual Use/Per Capita Utilization

Overall, Medicaid expansion was associated with greater dual use for inpatient depression care—a 0.97-pp (95% CI, 0.46 to 1.48) increase among service-connected veterans and a 0.64-pp (95% CI, 0.35 to 0.94) increase among income-eligible veterans.

At the state level, NY similarly showed increases in dual use among both service-connected (1.48 pp; 95% CI, 0.80 to 2.16) and income-eligible veterans (0.73 pp; 95% CI, 0.39 to 1.07) after Medicaid expansion. However, dual use in AZ increased significantly only among service-connected veterans (0.70 pp; 95% CI, 0.03 to 1.38), not income-eligible veterans (0.31 pp; 95% CI, -0.17 to 0.78).

Among outpatient visits, Medicaid expansion was associated with increased dual use only for income-eligible veterans (0.16 pp; 95% CI, 0.03-0.29), and not service-connected veterans (0.09 pp; 95% CI, -0.04 to 0.21). State-level analyses showed that Medicaid expansion in NY was not associated with changes in dual use for either service-connected (0.01 pp; 95% CI, -0.16 to 0.17) or income-eligible veterans (0.03 pp; 95% CI, -0.12 to 0.18), while expansion in AZ was associated with increases in dual use among both service-connected (0.42 pp; 95% CI, 0.23 to 0.61) and income-eligible veterans (0.83 pp; 95% CI, 0.59 to 1.07).

Concerning per capita utilization of depression care after Medicaid expansion, analyses showed no detectable changes for either inpatient or outpatient services, among both service-connected and income-eligible veterans. However, while this pattern held at the state level among hospitalizations, outpatient visit results showed divergent trends between AZ and NY. In NY, Medicaid expansion was associated with decreased per capita utilization of outpatient depression care among both service-connected (-0.25 visits annually; 95% CI, -0.48 to -0.01) and income-eligible veterans (-0.64 visits annually; 95% CI, -0.93 to -0.35). In AZ, Medicaid expansion was associated with increased per capita utilization of outpatient depression care among both service-connected (0.62 visits annually; 95% CI, 0.32-0.91) and income-eligible veterans (2.32 visits annually; 95% CI, 1.99-2.65).

Discussion

Our study quantified changes in depression-related health care utilization after Medicaid expansions in NY and AZ in 2001. Overall, the balance of evidence indicated that Medicaid expansion was associated with decreased reliance on the VA for depression-related services. There was an exception: income-eligible veterans in AZ did not shift their hospital care away from the VA in a statistically discernible way, although the point estimate was lower. More broadly, these findings concerning veterans’ reliance varied not only in inpatient vs outpatient services and income- vs service-connected eligibility, but also in the state-level contexts of veteran dual users and per capita utilization.

Given that the overall per capita utilization of depression care was unchanged from pre- to postexpansion periods, one might interpret the decreases in VA reliance and increases in Medicaid-VA dual users as a substitution effect from VA care to non-VA care. This could be plausible for hospitalizations where state-level analyses showed similarly stable levels of per capita utilization. However, state-level trends in our outpatient utilization analysis, especially with a substantial 2.32 pp increase in annual per capita visits among income-eligible veterans in AZ, leave open the possibility that in some cases veterans may be complementing VA care with Medicaid-reimbursed services.

The causes underlying these differences in reliance shifts between NY and AZ are likely also influenced by the policy contexts of their respective Medicaid expansions. For example, in 1999, NY passed Kendra’s Law, which established a procedure for obtaining court orders for assisted outpatient mental health treatment for individuals deemed unlikely to survive safely in the community.26 A reasonable inference is that there was less unfulfilled outpatient mental health need in NY under the existing accessibility provisioned by Kendra’s Law. In addition, while both states extended coverage to childless adults under 100% of the Federal Poverty level (FPL), the AZ Medicaid expansion was via a voters’ initiative and extended family coverage to 200% FPL vs 150% FPL for families in NY. Given that the AZ Medicaid expansion enjoyed both broader public participation and generosity in terms of eligibility, its uptake and therefore effect size may have been larger than in NY for nonacute outpatient care.

Our findings contribute to the growing body of literature surrounding the changes in health care utilization after Medicaid expansion, specifically for a newly dual-eligible population of veterans seeking mental health services for depression. While prior research concerning Medicare dual-enrolled veterans has shown high reliance on the VA for both mental health diagnoses and services, scholars have established the association of Medicaid enrollment with decreased VA reliance.27-29 Our analysis is the first to investigate state-level effects of Medicaid expansion on VA reliance for a single mental health condition using a natural experimental framework. We focus on a population that includes a large portion of veterans who are newly Medicaid-eligible due to a sweeping policy change and use demographically matched nonexpansion states to draw comparisons in VA reliance for depression care. Our findings of Medicaid expansion–associated decreases in VA reliance for depression care complement prior literature that describe Medicaid enrollment–associated decreases in VA reliance for overall mental health care.

Implications

From a systems-level perspective, the implications of shifting services away from the VA are complex and incompletely understood. The VA lacks interoperability with the electronic health records (EHRs) used by Medicaid clinicians. Consequently, significant issues of service duplication and incomplete clinical data exist for veterans seeking treatment outside of the VA system, posing health care quality and safety concerns.30 On one hand, Medicaid access is associated with increased health care utilization attributed to filling unmet needs for Medicare dual enrollees, as well as increased prescription filling for psychiatric medications.31,32 Furthermore, the only randomized control trial of Medicaid expansion to date was associated with a 9-pp decrease in positive screening rates for depression among those who received access at around 2 years postexpansion.33 On the other hand, the VA has developed a mental health system tailored to the particular needs of veterans, and health care practitioners at the VA have significantly greater rates of military cultural competency compared to those in nonmilitary settings (70% vs 24% in the TRICARE network and 8% among those with no military or TRICARE affiliation).34 Compared to individuals seeking mental health services with private insurance plans, veterans were about twice as likely to receive appropriate treatment for schizophrenia and depression at the VA.35 These documented strengths of VA mental health care may together help explain the small absolute number of visits that were associated with shifts away from VA overall after Medicaid expansion.

Finally, it is worth considering extrinsic factors that influence utilization among newly dual-eligible veterans. For example, hospitalizations are less likely to be planned than outpatient services, translating to a greater importance of proximity to a nearby medical facility than a veteran’s preference of where to seek care. In the same vein, major VA medical centers are fewer and more distant on average than VA outpatient clinics, therefore reducing the advantage of a Medicaid-reimbursed outpatient clinic in terms of distance.36 These realities may partially explain the proportionally larger shifts away from the VA for hospitalizations compared to outpatient care for depression.

Limitations and Future Directions

Our results should be interpreted within methodological and data limitations. With only 2 states in our sample, NY demonstrably skewed overall results, contributing 1.7 to 3 times more observations than AZ across subanalyses—a challenge also cited by Sommers and colleagues.19 Our veteran groupings were also unable to distinguish those veterans classified as service-connected who may also have qualified by income-eligible criteria (which would tend to understate the size of results) and those veterans who gained and then lost Medicaid coverage in a given year. Our study also faces limitations in generalizability and establishing causality. First, we included only 2 historical state Medicaid expansions, compared with the 38 states and Washington, DC, that have now expanded Medicaid to date under the ACA. Just in the 2 states from our study, we noted significant heterogeneity in the shifts associated with Medicaid expansion, which makes extrapolating specific trends difficult. Differences in underlying health care resources, legislation, and other external factors may limit the applicability of Medicaid expansion in the era of the ACA, as well as the Veterans Choice and MISSION acts. Second, while we leveraged a difference-in-difference analysis using demographically matched, neighboring comparison states, our findings are nevertheless drawn from observational data obviating causality. VA data for other sources of coverage such as private insurance are limited and not included in our study, and MAX datasets vary by quality across states, translating to potential gaps in our study cohort.28

Moving forward, our study demonstrates the potential for applying a natural experimental approach to studying dual-eligible veterans at the interface of Medicaid expansion. We focused on changes in VA reliance for the specific condition of depression and, in doing so, invite further inquiry into the impact of state mental health policy on outcomes more proximate to veterans’ outcomes. Clinical indicators, such as rates of antidepressant filling, utilization and duration of psychotherapy, and PHQ-9 scores, can similarly be investigated by natural experimental design. While current limits of administrative data and the siloing of EHRs may pose barriers to some of these avenues of research, multidisciplinary methodologies and data querying innovations such as natural language processing algorithms for clinical notes hold exciting opportunities to bridge the gap between policy and clinical efficacy.

Conclusions

This study applied a difference-in-difference analysis and found that Medicaid expansion is associated with decreases in VA reliance for both inpatient and outpatient services for depression. As additional data are generated from the Medicaid expansions of the ACA, similarly robust methods should be applied to further explore the impacts associated with such policy shifts and open the door to a better understanding of implications at the clinical level.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the efforts of Janine Wong, who proofread and formatted the manuscript.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. About VA. 2019. Updated September 27, 2022. Accessed September 29, 2022. https://www.va.gov/health/

2. Richardson LK, Frueh BC, Acierno R. Prevalence estimates of combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder: critical review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010;44(1):4-19. doi:10.3109/00048670903393597

3. Lan CW, Fiellin DA, Barry DT, et al. The epidemiology of substance use disorders in US veterans: a systematic review and analysis of assessment methods. Am J Addict. 2016;25(1):7-24. doi:10.1111/ajad.12319

4. Grant BF, Saha TD, June Ruan W, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 drug use disorder results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions-III. JAMA Psychiat. 2016;73(1):39-47. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.015.2132

5. Pemberton MR, Forman-Hoffman VL, Lipari RN, Ashley OS, Heller DC, Williams MR. Prevalence of past year substance use and mental illness by veteran status in a nationally representative sample. CBHSQ Data Review. Published November 9, 2016. Accessed October 6, 2022. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/prevalence-past-year-substance-use-and-mental-illness-veteran-status-nationally

6. Watkins KE, Pincus HA, Smith B, et al. Veterans Health Administration Mental Health Program Evaluation: Capstone Report. 2011. Accessed September 29, 2022. https://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/TR956.html

7. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicaid’s role in covering veterans. June 29, 2017. Accessed September 29, 2022. https://www.kff.org/infographic/medicaids-role-in-covering-veterans

8. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: detailed tables. September 7, 2017. Accessed September 29, 2022. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs-2016/NSDUH-DetTabs-2016.pdf

9. Wen H, Druss BG, Cummings JR. Effect of Medicaid expansions on health insurance coverage and access to care among low-income adults with behavioral health conditions. Health Serv Res. 2015;50:1787-1809. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12411

10. O’Mahen PN, Petersen LA. Effects of state-level Medicaid expansion on Veterans Health Administration dual enrollment and utilization: potential implications for future coverage expansions. Med Care. 2020;58(6):526-533. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001327

11. Ono SS, Dziak KM, Wittrock SM, et al. Treating dual-use patients across two health care systems: a qualitative study. Fed Pract. 2015;32(8):32-37.

12. Weeks WB, Mahar PJ, Wright SM. Utilization of VA and Medicare services by Medicare-eligible veterans: the impact of additional access points in a rural setting. J Healthc Manag. 2005;50(2):95-106.

13. Gellad WF, Thorpe JM, Zhao X, et al. Impact of dual use of Department of Veterans Affairs and Medicare part d drug benefits on potentially unsafe opioid use. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(2):248-255. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2017.304174

14. Coughlin SS, Young L. A review of dual health care system use by veterans with cardiometabolic disease. J Hosp Manag Health Policy. 2018;2:39. doi:10.21037/jhmhp.2018.07.05

15. Radomski TR, Zhao X, Thorpe CT, et al. The impact of medication-based risk adjustment on the association between veteran health outcomes and dual health system use. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(9):967-973. doi:10.1007/s11606-017-4064-4

16. Kullgren JT, Fagerlin A, Kerr EA. Completing the MISSION: a blueprint for helping veterans make the most of new choices. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(5):1567-1570. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-05404-w

17. VA MISSION Act of 2018, 38 USC §101 (2018). https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/USCODE-2018-title38/USCODE-2018-title38-partI-chap1-sec101

18. Vanneman ME, Phibbs CS, Dally SK, Trivedi AN, Yoon J. The impact of Medicaid enrollment on Veterans Health Administration enrollees’ behavioral health services use. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(suppl 3):5238-5259. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13062

19. Sommers BD, Baicker K, Epstein AM. Mortality and access to care among adults after state Medicaid expansions. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(11):1025-1034. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1202099

20. US Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Mental Health. 2019 national veteran suicide prevention annual report. 2019. Accessed September 29, 2022. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2019/2019_National_Veteran_Suicide_Prevention_Annual_Report_508.pdf

21. Hawton K, Casañas I Comabella C, Haw C, Saunders K. Risk factors for suicide in individuals with depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2013;147(1-3):17-28. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.004

22. Adekkanattu P, Sholle ET, DeFerio J, Pathak J, Johnson SB, Campion TR Jr. Ascertaining depression severity by extracting Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) scores from clinical notes. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2018;2018:147-156.

23. DeRubeis RJ, Siegle GJ, Hollon SD. Cognitive therapy versus medication for depression: treatment outcomes and neural mechanisms. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9(10):788-796. doi:10.1038/nrn2345

24. Cully JA, Zimmer M, Khan MM, Petersen LA. Quality of depression care and its impact on health service use and mortality among veterans. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(12):1399-1405. doi:10.1176/ps.2008.59.12.1399

25. Byrne MM, Kuebeler M, Pietz K, Petersen LA. Effect of using information from only one system for dually eligible health care users. Med Care. 2006;44(8):768-773. doi:10.1097/01.mlr.0000218786.44722.14

26. Watkins KE, Smith B, Akincigil A, et al. The quality of medication treatment for mental disorders in the Department of Veterans Affairs and in private-sector plans. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(4):391-396. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201400537

27. Petersen LA, Byrne MM, Daw CN, Hasche J, Reis B, Pietz K. Relationship between clinical conditions and use of Veterans Affairs health care among Medicare-enrolled veterans. Health Serv Res. 2010;45(3):762-791. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01107.x

28. Yoon J, Vanneman ME, Dally SK, Trivedi AN, Phibbs Ciaran S. Use of Veterans Affairs and Medicaid services for dually enrolled veterans. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(3):1539-1561. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12727

29. Yoon J, Vanneman ME, Dally SK, Trivedi AN, Phibbs Ciaran S. Veterans’ reliance on VA care by type of service and distance to VA for nonelderly VA-Medicaid dual enrollees. Med Care. 2019;57(3):225-229. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001066

30. Gaglioti A, Cozad A, Wittrock S, et al. Non-VA primary care providers’ perspectives on comanagement for rural veterans. Mil Med. 2014;179(11):1236-1243. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00342

31. Moon S, Shin J. Health care utilization among Medicare-Medicaid dual eligibles: a count data analysis. BMC Public Health. 2006;6(1):88. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-6-88

32. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Facilitating access to mental health services: a look at Medicaid, private insurance, and the uninsured. November 27, 2017. Accessed September 29, 2022. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/facilitating-access-to-mental-health-services-a-look-at-medicaid-private-insurance-and-the-uninsured

33. Baicker K, Taubman SL, Allen HL, et al. The Oregon experiment - effects of Medicaid on clinical outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(18):1713-1722. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1212321

34. Tanielian T, Farris C, Batka C, et al. Ready to serve: community-based provider capacity to deliver culturally competent, quality mental health care to veterans and their families. 2014. Accessed September 29, 2022. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR800/RR806/RAND_RR806.pdf

35. Kizer KW, Dudley RA. Extreme makeover: transformation of the Veterans Health Care System. Annu Rev Public Health. 2009;30(1):313-339. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090940

36. Brennan KJ. Kendra’s Law: final report on the status of assisted outpatient treatment, appendix 2. 2002. Accessed September 29, 2022. https://omh.ny.gov/omhweb/kendra_web/finalreport/appendix2.htm

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is the largest integrated health care system in the United States, providing care for more than 9 million veterans.1 With veterans experiencing mental health conditions like posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), substance use disorders, and other serious mental illnesses (SMI) at higher rates compared with the general population, the VA plays an important role in the provision of mental health services.2-5 Since the implementation of its Mental Health Strategic Plan in 2004, the VA has overseen the development of a wide array of mental health programs geared toward the complex needs of veterans. Research has demonstrated VA care outperforming Medicaid-reimbursed services in terms of the percentage of veterans filling antidepressants for at least 12 weeks after initiation of treatment for major depressive disorder (MDD), as well as posthospitalization follow-up.6

Eligible veterans enrolled in the VA often also seek non-VA care. Medicaid covers nearly 10% of all nonelderly veterans, and of these veterans, 39% rely solely on Medicaid for health care access.7 Today, Medicaid is the largest payer for mental health services in the US, providing coverage for approximately 27% of Americans who have SMI and helping fulfill unmet mental health needs.8,9 Understanding which of these systems veterans choose to use, and under which circumstances, is essential in guiding the allocation of limited health care resources.10

Beyond Medicaid, alternatives to VA care may include TRICARE, Medicare, Indian Health Services, and employer-based or self-purchased private insurance. While these options potentially increase convenience, choice, and access to health care practitioners (HCPs) and services not available at local VA systems, cross-system utilization with poor integration may cause care coordination and continuity problems, such as medication mismanagement and opioid overdose, unnecessary duplicate utilization, and possible increased mortality.11-15 As recent national legislative changes, such as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), Veterans Access, Choice and Accountability Act, and the VA MISSION Act, continue to shift the health care landscape for veterans, questions surrounding how veterans are changing their health care use become significant.16,17

Here, we approach the impacts of Medicaid expansion on veterans’ reliance on the VA for mental health services with a unique lens. We leverage a difference-in-difference design to study 2 historical Medicaid expansions in Arizona (AZ) and New York (NY), which extended eligibility to childless adults in 2001. Prior Medicaid dual-eligible mental health research investigated reliance shifts during the immediate postenrollment year in a subset of veterans newly enrolled in Medicaid.18 However, this study took place in a period of relative policy stability. In contrast, we investigate the potential effects of a broad policy shift by analyzing state-level changes in veterans’ reliance over 6 years after a statewide Medicaid expansion. We match expansion states with demographically similar nonexpansion states to account for unobserved trends and confounding effects. Prior studies have used this method to evaluate post-Medicaid expansion mortality changes and changes in veteran dual enrollment and hospitalizations.10,19 While a study of ACA Medicaid expansion states would be ideal, Medicaid data from most states were only available through 2014 at the time of this analysis. Our study offers a quasi-experimental framework leveraging longitudinal data that can be applied as more post-ACA data become available.