User login

Never prouder to be a hospitalist

I have been a proud hospitalist for more than 20 years, and yet I have never been prouder to be a hospitalist than now. The pandemic has been brutal, killing more than 600,000 Americans as of this writing. It has stretched the health care system, its doctors, nurses, and other providers to the limit. Yet we will get through it, we are getting through it, and hospitalists deserve a huge portion of the credit.

According to the CDC, there have been over 2.3 million COVID-19 hospitalizations. In my home state of Maryland, between two-thirds and three-quarters of hospitalized COVID patients are cared for on general medical floors, the domain of hospitalists. When hospitals needed COVID units, hospitalists stepped up to design and staff them. When our ICU colleagues needed support, especially in those early dark days, hospitalists stepped in. When our outpatient colleagues were called into the hospital, hospitalists were there to help them on board. When the House of Medicine was in chaos due to COVID-19, hospitalists ran towards that fire. Our previous 20+ years of collective experience made us the ideal specialty to manage the inpatient challenges over the last 18 months.

Need a new clinical schedule by Sunday? Check.

Need help with new clinical protocols? Check.

Need to help other colleagues? Check.

Need to reprogram the EMR? Check.

Need a new way to teach residents and students on the wards? Check.

Need a whole new unit – no, wait – a new hospital wing? No, scratch that – a whole new COVID hospital in a few weeks? Check. (I personally did that last one at the Baltimore Convention Center!)

For me and many hospitalists like me, it is as if the last 20 years were prep work for the pandemic.

Here at SHM, we know the pandemic is hard work – exhausting, even. SHM has been actively focused on supporting hospitalists during this crisis so that hospitalists can focus on patients. Early in the pandemic, SHM quickly pivoted to supply hospitalists with COVID-19 resources in their fight against the coronavirus. Numerous COVID-19 webinars, a COVID addendum to the State of Hospital Medicine Report, and a dedicated COVID issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine were early and successful information dissemination strategies.

As the world – and hospitalists – dug in for a multi-year pandemic, SHM continued to advance the care of patients by opening our library of educational content for free to anyone. Our Public Policy Committee was active around both COVID-19- and hospitalist-related topics: immigration, telehealth, wellbeing, and financial impacts, to name a few.

As the pandemic slogged on, our Wellbeing Task Force came up with innovative support measures, including a check-in guide for hospitalists and fellow health care workers and dedicated wellness sessions complete with a licensed therapist for members. All the while, despite the restrictions and hurdles the pandemic has thrown our way, SHM members keep meeting and collaborating through virtual chapter events, committee work, special interest groups, and our annual conference, SHM Converge. Thank you to the countless members who donated their time to SHM, so that SHM could support hospitalists and their patients.

Now, we are transitioning into a new phase of the pandemic. The medical miracles that are the COVID-19 vaccines have made that possible. Fully vaccinated, I no longer worry that every time someone sneezes, or when I care for patients with a fever, that I am playing a high stakes poker game with my life. Don’t get me wrong; as I write, the Delta variant has a hold on the nation, and I know it’s not over yet. But it does appear as if the medical war on COVID is shifting from national to regional (or even local) responses.

During this new phase, we must rebuild our personal and professional lives. If you haven’t read Retired Lieutenant General Mark Hertling’s perspective piece in the August issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, I strongly encourage you to do so. He shares profound lessons on transitioning from active combat that are directly applicable to hospitalists who have been “deployed” battling COVID-19.

SHM will continue to pivot to meet our members’ needs too. We are already gearing up for more in-person education and networking. Chapters are starting to meet in person, and SHM is happy to provide visiting faculty. I will visit members from Florida to Maine and places in between starting this fall! Our Board of Directors and other SHM leaders are also starting to meet with members in person. Our own Leadership Academy will take place at Amelia Island in Florida in October, where we can learn, network, and even decompress. We also can’t wait for SHM Converge 2022 in Nashville, where we hope to reunite with many of you after 2 years of virtual conferences.

Our response to the pandemic, a once in a century crisis where our own safety was at risk, where doing the right thing might mean death or harming loved ones, our response of running into the fire to save lives is truly inspiring. The power of care – for our patients, for our family and friends, and for our hospital medicine community and the community at large – is evident more now than ever.

There have always been good reasons to be proud of being a hospitalist: taking care of the acutely ill, helping hospitals improve, teaching young doctors, and watching my specialty grow by leaps and bounds, to name just a few. But I’ve never been prouder than I am now.

Dr. Howell is the CEO of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

I have been a proud hospitalist for more than 20 years, and yet I have never been prouder to be a hospitalist than now. The pandemic has been brutal, killing more than 600,000 Americans as of this writing. It has stretched the health care system, its doctors, nurses, and other providers to the limit. Yet we will get through it, we are getting through it, and hospitalists deserve a huge portion of the credit.

According to the CDC, there have been over 2.3 million COVID-19 hospitalizations. In my home state of Maryland, between two-thirds and three-quarters of hospitalized COVID patients are cared for on general medical floors, the domain of hospitalists. When hospitals needed COVID units, hospitalists stepped up to design and staff them. When our ICU colleagues needed support, especially in those early dark days, hospitalists stepped in. When our outpatient colleagues were called into the hospital, hospitalists were there to help them on board. When the House of Medicine was in chaos due to COVID-19, hospitalists ran towards that fire. Our previous 20+ years of collective experience made us the ideal specialty to manage the inpatient challenges over the last 18 months.

Need a new clinical schedule by Sunday? Check.

Need help with new clinical protocols? Check.

Need to help other colleagues? Check.

Need to reprogram the EMR? Check.

Need a new way to teach residents and students on the wards? Check.

Need a whole new unit – no, wait – a new hospital wing? No, scratch that – a whole new COVID hospital in a few weeks? Check. (I personally did that last one at the Baltimore Convention Center!)

For me and many hospitalists like me, it is as if the last 20 years were prep work for the pandemic.

Here at SHM, we know the pandemic is hard work – exhausting, even. SHM has been actively focused on supporting hospitalists during this crisis so that hospitalists can focus on patients. Early in the pandemic, SHM quickly pivoted to supply hospitalists with COVID-19 resources in their fight against the coronavirus. Numerous COVID-19 webinars, a COVID addendum to the State of Hospital Medicine Report, and a dedicated COVID issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine were early and successful information dissemination strategies.

As the world – and hospitalists – dug in for a multi-year pandemic, SHM continued to advance the care of patients by opening our library of educational content for free to anyone. Our Public Policy Committee was active around both COVID-19- and hospitalist-related topics: immigration, telehealth, wellbeing, and financial impacts, to name a few.

As the pandemic slogged on, our Wellbeing Task Force came up with innovative support measures, including a check-in guide for hospitalists and fellow health care workers and dedicated wellness sessions complete with a licensed therapist for members. All the while, despite the restrictions and hurdles the pandemic has thrown our way, SHM members keep meeting and collaborating through virtual chapter events, committee work, special interest groups, and our annual conference, SHM Converge. Thank you to the countless members who donated their time to SHM, so that SHM could support hospitalists and their patients.

Now, we are transitioning into a new phase of the pandemic. The medical miracles that are the COVID-19 vaccines have made that possible. Fully vaccinated, I no longer worry that every time someone sneezes, or when I care for patients with a fever, that I am playing a high stakes poker game with my life. Don’t get me wrong; as I write, the Delta variant has a hold on the nation, and I know it’s not over yet. But it does appear as if the medical war on COVID is shifting from national to regional (or even local) responses.

During this new phase, we must rebuild our personal and professional lives. If you haven’t read Retired Lieutenant General Mark Hertling’s perspective piece in the August issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, I strongly encourage you to do so. He shares profound lessons on transitioning from active combat that are directly applicable to hospitalists who have been “deployed” battling COVID-19.

SHM will continue to pivot to meet our members’ needs too. We are already gearing up for more in-person education and networking. Chapters are starting to meet in person, and SHM is happy to provide visiting faculty. I will visit members from Florida to Maine and places in between starting this fall! Our Board of Directors and other SHM leaders are also starting to meet with members in person. Our own Leadership Academy will take place at Amelia Island in Florida in October, where we can learn, network, and even decompress. We also can’t wait for SHM Converge 2022 in Nashville, where we hope to reunite with many of you after 2 years of virtual conferences.

Our response to the pandemic, a once in a century crisis where our own safety was at risk, where doing the right thing might mean death or harming loved ones, our response of running into the fire to save lives is truly inspiring. The power of care – for our patients, for our family and friends, and for our hospital medicine community and the community at large – is evident more now than ever.

There have always been good reasons to be proud of being a hospitalist: taking care of the acutely ill, helping hospitals improve, teaching young doctors, and watching my specialty grow by leaps and bounds, to name just a few. But I’ve never been prouder than I am now.

Dr. Howell is the CEO of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

I have been a proud hospitalist for more than 20 years, and yet I have never been prouder to be a hospitalist than now. The pandemic has been brutal, killing more than 600,000 Americans as of this writing. It has stretched the health care system, its doctors, nurses, and other providers to the limit. Yet we will get through it, we are getting through it, and hospitalists deserve a huge portion of the credit.

According to the CDC, there have been over 2.3 million COVID-19 hospitalizations. In my home state of Maryland, between two-thirds and three-quarters of hospitalized COVID patients are cared for on general medical floors, the domain of hospitalists. When hospitals needed COVID units, hospitalists stepped up to design and staff them. When our ICU colleagues needed support, especially in those early dark days, hospitalists stepped in. When our outpatient colleagues were called into the hospital, hospitalists were there to help them on board. When the House of Medicine was in chaos due to COVID-19, hospitalists ran towards that fire. Our previous 20+ years of collective experience made us the ideal specialty to manage the inpatient challenges over the last 18 months.

Need a new clinical schedule by Sunday? Check.

Need help with new clinical protocols? Check.

Need to help other colleagues? Check.

Need to reprogram the EMR? Check.

Need a new way to teach residents and students on the wards? Check.

Need a whole new unit – no, wait – a new hospital wing? No, scratch that – a whole new COVID hospital in a few weeks? Check. (I personally did that last one at the Baltimore Convention Center!)

For me and many hospitalists like me, it is as if the last 20 years were prep work for the pandemic.

Here at SHM, we know the pandemic is hard work – exhausting, even. SHM has been actively focused on supporting hospitalists during this crisis so that hospitalists can focus on patients. Early in the pandemic, SHM quickly pivoted to supply hospitalists with COVID-19 resources in their fight against the coronavirus. Numerous COVID-19 webinars, a COVID addendum to the State of Hospital Medicine Report, and a dedicated COVID issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine were early and successful information dissemination strategies.

As the world – and hospitalists – dug in for a multi-year pandemic, SHM continued to advance the care of patients by opening our library of educational content for free to anyone. Our Public Policy Committee was active around both COVID-19- and hospitalist-related topics: immigration, telehealth, wellbeing, and financial impacts, to name a few.

As the pandemic slogged on, our Wellbeing Task Force came up with innovative support measures, including a check-in guide for hospitalists and fellow health care workers and dedicated wellness sessions complete with a licensed therapist for members. All the while, despite the restrictions and hurdles the pandemic has thrown our way, SHM members keep meeting and collaborating through virtual chapter events, committee work, special interest groups, and our annual conference, SHM Converge. Thank you to the countless members who donated their time to SHM, so that SHM could support hospitalists and their patients.

Now, we are transitioning into a new phase of the pandemic. The medical miracles that are the COVID-19 vaccines have made that possible. Fully vaccinated, I no longer worry that every time someone sneezes, or when I care for patients with a fever, that I am playing a high stakes poker game with my life. Don’t get me wrong; as I write, the Delta variant has a hold on the nation, and I know it’s not over yet. But it does appear as if the medical war on COVID is shifting from national to regional (or even local) responses.

During this new phase, we must rebuild our personal and professional lives. If you haven’t read Retired Lieutenant General Mark Hertling’s perspective piece in the August issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, I strongly encourage you to do so. He shares profound lessons on transitioning from active combat that are directly applicable to hospitalists who have been “deployed” battling COVID-19.

SHM will continue to pivot to meet our members’ needs too. We are already gearing up for more in-person education and networking. Chapters are starting to meet in person, and SHM is happy to provide visiting faculty. I will visit members from Florida to Maine and places in between starting this fall! Our Board of Directors and other SHM leaders are also starting to meet with members in person. Our own Leadership Academy will take place at Amelia Island in Florida in October, where we can learn, network, and even decompress. We also can’t wait for SHM Converge 2022 in Nashville, where we hope to reunite with many of you after 2 years of virtual conferences.

Our response to the pandemic, a once in a century crisis where our own safety was at risk, where doing the right thing might mean death or harming loved ones, our response of running into the fire to save lives is truly inspiring. The power of care – for our patients, for our family and friends, and for our hospital medicine community and the community at large – is evident more now than ever.

There have always been good reasons to be proud of being a hospitalist: taking care of the acutely ill, helping hospitals improve, teaching young doctors, and watching my specialty grow by leaps and bounds, to name just a few. But I’ve never been prouder than I am now.

Dr. Howell is the CEO of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Hospital disaster preparation confronts COVID

Hospitalist groups should have disaster response plans

Jason Persoff, MD, SFHM, now a hospitalist at University of Colorado Hospital in Aurora and an amateur storm chaser, got a close look at how natural disasters can impact hospital care when a tornado destroyed St. John’s Regional Medical Center in Joplin, Mo., on May 22, 2011.

He and a colleague who had been following the storm responded to injuries on the highway before reporting for a long day’s service at the other hospital in Joplin, Freeman Hospital West, caring for patients transferred from St. John’s on an impromptu unit without access to their medical records.

“During my medical training, I had done emergency medicine as an EMT, so I was interested in how the system responds to emergencies,” he explained. “At Joplin I learned how it feels when the boots on the ground in a crisis are not connected to an incident command structure.” Another thing he learned was the essential role for hospitalists in a hospital’s response to a crisis – and thus the need to involve them well in advance in the hospital’s planning for future emergencies.

“Disaster preparation – when done right – helps you ‘herd cats’ in a crisis situation,” he said. “The tornado and its wake served as defining moments for me. I used them as the impetus to improve health care’s response to disasters.” Part of that commitment was to help hospitalists understand their part in emergency preparation.1

Dr. Persoff is now the assistant medical director of emergency preparedness at University of Colorado Hospital. He also helped to create a position called physician support supervisor, which is filled by physicians who have held leadership positions in a hospital to help coordinate the disparate needs of all clinicians in a crisis and facilitate rapid response.2

But then along came the COVID pandemic – which in many locales around the world was unprecedented in scope. Dr. Persoff said his hospital was fairly well prepared, after a decade of engagement with emergency planning. It drew on experience with H1N1, also known as swine flu, and the Ebola virus, which killed 11,323 people, primarily in West Africa, from 2013 to 2016, as models. In a matter of days, the CU division of hospital medicine was able to modify and deploy its existing disaster plans to quickly respond to an influx of COVID patients.3

“Basically, what we set out to do was to treat COVID patients as if they were Ebola patients, cordoning them off in a small area of the hospital. That was naive of us,” he said. “We weren’t able to grasp the scale at the outset. It does defy the imagination – how the hospital could fill up with just one type of patient.”

What is disaster planning?

Emergency preparation for hospitals emerged as a recognized medical specialization in the 1970s. Initially it was largely considered the realm of emergency physicians, trauma services, or critical care doctors. Resources such as the World Health Organization, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, and similar groups recommend an all-hazards approach, a broad and flexible strategy for managing emergencies that could include natural disasters – earthquakes, storms, tornadoes, or wildfires – or human-caused events, such as mass shootings or terrorist attacks. The Joint Commission requires accredited hospitals to conduct several disaster drills annually.

The U.S. Hospital Preparedness Program was created in 2002 to enhance the ability of hospitals and health systems to prepare for and respond to bioterrorism attacks on civilians and other public health emergencies, including natural disasters and pandemics. It offers a foundation for national preparedness and a primary source of federal funding for health care system preparedness. The hospital, at the heart of the health care system, is expected to receive the injured and infected, because patients know they can obtain care there.

One of the fundamental tools for crisis response is the incident command system (ICS), which spells out how to quickly establish a command structure and assign responsibility for key tasks as well as overall leadership. The National Incident Management System organizes emergency management across all government levels and the private sector to ensure that the most pressing needs are met and precious resources are used without duplication. ICS is a standardized approach to command, control, and coordination of emergency response using a common hierarchy recognized across organizations, with advance training in how it should be deployed.

A crisis like never before

Nearly every hospital or health system goes through drills for an emergency, said Hassan Khouli, MD, chair of the department of critical care medicine at the Cleveland Clinic, and coauthor of an article in the journal Chest last year outlining 10 principles of emergency preparedness derived from its experience with the COVID pandemic.4 Some of these include: don’t wait; engage a variety of stakeholders; identify sources of truth; and prioritize hospital employees’ safety and well-being.

Part of the preparation is doing table-top exercises, with case scenarios or actual situations presented, working with clinicians on brainstorming and identifying opportunities for improvement, Dr. Khouli said. “These drills are so important, regardless of what the disaster turns out to be. We’ve done that over the years. We are a large health system, very process and detail oriented. Our emergency incident command structure was activated before we saw our first COVID patient,” he said.

“This was a crisis like never before, with huge amounts of uncertainty,” he noted. “But I believe the Cleveland Clinic system did very well, measured by outcomes such as surveys of health care teams across the system, which gave us reassuring results, and clinical outcomes with lower ICU and hospital mortality rates.”

Christopher Whinney, MD, SFHM, department chair of hospital medicine at Cleveland Clinic, said hospitalists worked hand in hand with the health system’s incident command structure and took responsibility for managing non-ICU COVID patients at six hospitals in the system.

“Hospitalists had a place at the table, and we collaborated well with incident command, enterprise redeployment committees, and emergency and critical care colleagues,” he noted. Hospitalists were on the leadership team for a number of planning meetings, and key stakeholders for bringing information back to their groups.

“First thing we did was to look at our workforce. The challenge was how to respond to up to a hundred COVID admissions per day – how to mobilize providers and build surge teams that incorporated primary care providers and medical trainees. We onboarded 200 providers to do hospital care within 60 days,” he said.

“We realized that communication with patients and families was a big part of the challenge, so we assigned people with good communication skills to fill this role. While we were fortunate not to get the terrible surges they had in other places, we felt we were prepared for the worst.”

Challenges of surge capacity

Every disaster is different, said Srikant Polepalli, MD, associate hospitalist medical director for Staten Island University Hospital in New York, part of the Northwell Health system. He brought the experience of being part of the response to Superstorm Sandy in October 2012 to the COVID pandemic.

“Specifically for hospitalists, the biggest challenge is working on surge capacity for a sudden influx of patients,” he said. “But with Northwell as our umbrella, we can triage and load-balance to move patients from hospital to hospital as needed. With the pandemic, we started with one COVID unit and then expanded to fill the entire hospital.”

Dr. Polepalli was appointed medical director for a temporary field hospital installed at South Beach Psychiatric Center, also in Staten Island. “We were able to acquire help and bring in people ranging from hospitalists to ER physicians, travel nurses, operation managers and the National Guard. Our command center did a phenomenal job of allocating and obtaining resources. It helped to have a structure that was already established and to rely on the resources of the health system,” Dr. Polepalli said. Not every hospital has a structure like Northwell’s.

“We’re not out of the pandemic yet, but we’ll continue with disaster drills and planning,” he said. “We must continue to adapt and have converted our temporary facilities to COVID testing centers, antibody infusion centers, and vaccination centers.”

For Alfred Burger, MD, SFHM, a hospitalist at Mount Sinai’s Beth Israel campus in New York, hospital medicine, now in its maturing phase, is still feeling its way through hospital and health care system transformation.

“My group is an academic, multicampus hospitalist group employed by the hospital system. When I meet other hospitalists at SHM conferences, whether they come from privately owned, corporately owned, or contracted models, they vary widely in terms of how involved the hospitalists are in crisis planning and their ability to respond to crises. At large academic medical centers like ours, one or more doctors is tasked with being involved in preparing for the next disaster,” he said.

“I think we responded the best we could, although it was difficult as we lost many patients to COVID. We were trying to save lives using the tools we knew from treating pneumonias and other forms of acute inflammatory lung injuries. We used every bit of our training in situations where no one had the right answers. But disasters teach us how to be flexible and pivot on the fly, and what to do when things don’t go our way.”

What is disaster response?

Medical response to a disaster essentially boils down to three main things: stuff, staff, and space, Dr. Persoff said. Those are the cornerstones of an emergency plan.

“There is not a hazard that exists that you can’t take an all-hazards approach to dealing with fundamental realities on the ground. No plan can be comprehensive enough to deal with all the intricacies of an emergency. But many plans can have the bones of a response that will allow you to face adverse circumstances,” he said.

“We actually became quite efficient early on in the pandemic, able to adapt in the moment. We were able to build an effective bridge between workers on the ground and our incident command structure, which seemed to reduce a lot of stress and create situational awareness. We implemented ICS as soon as we heard that China was building a COVID hospital, back in February of 2020.”

When one thinks about mass trauma, such as a 747 crash, Dr. Persoff said, the need is to treat burn victims and trauma victims in large numbers. At that point, the ED downstairs is filled with medical patients. Hospital medicine can rapidly admit those patients to clear out room in the ED. Surgeons are also dedicated to rapidly treating those patients, but what about patients who are on the floor following their surgeries? Hospitalists can offer consultations or primary management so the surgeons can stay in the OR, and the same in the ICU, while safely discharging hospitalized patients in a timely manner to make room for incoming patients.

“The lessons of COVID have been hard-taught and hard-earned. No good plan survives contact with the enemy,” he said. “But I think we’ll be better prepared for the next pandemic.”

Maria Frank, MD, FACP, SFHM, a hospitalist at Denver Health who chairs SHM’s Disaster Management Special Interest Group, says she got the bug for disaster preparation during postresidency training as an internist in emergency medicine. “I’m also the medical director for our biocontainment unit, created for infections like Ebola.” SHM’s SIG, which has 150 members, is now writing a review article on disaster planning for the field.

“I got a call on Dec. 27, 2019, about this new pneumonia, and they said, ‘We don’t know what it is, but it’s a coronavirus,’” she recalled. “When I got off the phone, I said, ‘Let’s make sure our response plan works and we have enough of everything on hand.’” Dr. Frank said she was expecting something more like SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome). “When they called the public health emergency of international concern for COVID, I was at a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention meeting in Atlanta. It really wasn’t a surprise for us.”

All hospitals plan for disasters, although they use different names and have different levels of commitment, Dr. Frank said. What’s not consistent is the participation of hospitalists. “Even when a disaster is 100% trauma related, consider a hospital like mine that has at least four times as many hospitalists as surgeons at any given time. The hospitalists need to take overall management for the patients who aren’t actually in the operating room.”

Time to debrief

Dr. Frank recommends debriefing on the hospital’s and the hospitalist group’s experience with COVID. “Look at the biggest challenges your group faced. Was it staffing, or time off, or the need for day care? Was it burnout, lack of knowledge, lack of [personal protective equipment]?” Each hospital could use its own COVID experience to work on identifying the challenges and the problems, she said. “I’d encourage each department and division to do this exercise individually. Then come together to find common ground with other departments in the hospital.”

This debriefing exercise isn’t just for doctors – it’s also for nurses, environmental services, security, and many other departments, she said. “COVID showed us how crisis response is a group effort. What will bring us together is to learn the challenges each of us faced. It was amazing to see hospitalists doing what they do best.” Post pandemic, hospitalists should also consider getting involved in research and publications, in order to share their lessons.

“One of the things we learned is that hospitalists are very versatile,” Dr. Frank added. But it’s also good for the group to have members specialize, for example, in biocontainment. “We are experts in discharging patients, in patient flow and operations, in coordinating complex medical care. So we would naturally take the lead in, for example, opening a geographic unit or collaborating with other specialists to create innovative models. That’s our job. It’s essential that we’re involved well in advance.”

COVID may be a once-in-a-lifetime experience, but there will be other disasters to come, she said. “If your hospital doesn’t have a disaster plan for hospitalists, get involved in establishing one. Each hospitalist group should have its own response plan. Talk to your peers at other hospitals, and get involved at the institutional level. I’m happy to share our plan; just contact me.” Readers can contact Dr. Frank at [email protected].

References

1. Persoff J et al. The role of hospital medicine in emergency preparedness: A framework for hospitalist leadership in disaster preparedness, response and recovery. J Hosp Med. 2018 Oct;13(10):713-7. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3073.

2. Persoff J et al. Expanding the hospital incident command system with a physician-centric role during a pandemic: The role of the physician clinical support supervisor. J Hosp Adm. 2020;9(3):7-10. doi: 10.5430/jha.v9n3p7.

3. Bowden K et al. Harnessing the power of hospitalists in operational disaster planning: COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2020 Sep;35(9):273-7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05952-6.

4. Orsini E et al. Lessons on outbreak preparedness from the Cleveland Clinic. Chest. 2020;158(5):2090-6. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.06.009.

Hospitalist groups should have disaster response plans

Hospitalist groups should have disaster response plans

Jason Persoff, MD, SFHM, now a hospitalist at University of Colorado Hospital in Aurora and an amateur storm chaser, got a close look at how natural disasters can impact hospital care when a tornado destroyed St. John’s Regional Medical Center in Joplin, Mo., on May 22, 2011.

He and a colleague who had been following the storm responded to injuries on the highway before reporting for a long day’s service at the other hospital in Joplin, Freeman Hospital West, caring for patients transferred from St. John’s on an impromptu unit without access to their medical records.

“During my medical training, I had done emergency medicine as an EMT, so I was interested in how the system responds to emergencies,” he explained. “At Joplin I learned how it feels when the boots on the ground in a crisis are not connected to an incident command structure.” Another thing he learned was the essential role for hospitalists in a hospital’s response to a crisis – and thus the need to involve them well in advance in the hospital’s planning for future emergencies.

“Disaster preparation – when done right – helps you ‘herd cats’ in a crisis situation,” he said. “The tornado and its wake served as defining moments for me. I used them as the impetus to improve health care’s response to disasters.” Part of that commitment was to help hospitalists understand their part in emergency preparation.1

Dr. Persoff is now the assistant medical director of emergency preparedness at University of Colorado Hospital. He also helped to create a position called physician support supervisor, which is filled by physicians who have held leadership positions in a hospital to help coordinate the disparate needs of all clinicians in a crisis and facilitate rapid response.2

But then along came the COVID pandemic – which in many locales around the world was unprecedented in scope. Dr. Persoff said his hospital was fairly well prepared, after a decade of engagement with emergency planning. It drew on experience with H1N1, also known as swine flu, and the Ebola virus, which killed 11,323 people, primarily in West Africa, from 2013 to 2016, as models. In a matter of days, the CU division of hospital medicine was able to modify and deploy its existing disaster plans to quickly respond to an influx of COVID patients.3

“Basically, what we set out to do was to treat COVID patients as if they were Ebola patients, cordoning them off in a small area of the hospital. That was naive of us,” he said. “We weren’t able to grasp the scale at the outset. It does defy the imagination – how the hospital could fill up with just one type of patient.”

What is disaster planning?

Emergency preparation for hospitals emerged as a recognized medical specialization in the 1970s. Initially it was largely considered the realm of emergency physicians, trauma services, or critical care doctors. Resources such as the World Health Organization, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, and similar groups recommend an all-hazards approach, a broad and flexible strategy for managing emergencies that could include natural disasters – earthquakes, storms, tornadoes, or wildfires – or human-caused events, such as mass shootings or terrorist attacks. The Joint Commission requires accredited hospitals to conduct several disaster drills annually.

The U.S. Hospital Preparedness Program was created in 2002 to enhance the ability of hospitals and health systems to prepare for and respond to bioterrorism attacks on civilians and other public health emergencies, including natural disasters and pandemics. It offers a foundation for national preparedness and a primary source of federal funding for health care system preparedness. The hospital, at the heart of the health care system, is expected to receive the injured and infected, because patients know they can obtain care there.

One of the fundamental tools for crisis response is the incident command system (ICS), which spells out how to quickly establish a command structure and assign responsibility for key tasks as well as overall leadership. The National Incident Management System organizes emergency management across all government levels and the private sector to ensure that the most pressing needs are met and precious resources are used without duplication. ICS is a standardized approach to command, control, and coordination of emergency response using a common hierarchy recognized across organizations, with advance training in how it should be deployed.

A crisis like never before

Nearly every hospital or health system goes through drills for an emergency, said Hassan Khouli, MD, chair of the department of critical care medicine at the Cleveland Clinic, and coauthor of an article in the journal Chest last year outlining 10 principles of emergency preparedness derived from its experience with the COVID pandemic.4 Some of these include: don’t wait; engage a variety of stakeholders; identify sources of truth; and prioritize hospital employees’ safety and well-being.

Part of the preparation is doing table-top exercises, with case scenarios or actual situations presented, working with clinicians on brainstorming and identifying opportunities for improvement, Dr. Khouli said. “These drills are so important, regardless of what the disaster turns out to be. We’ve done that over the years. We are a large health system, very process and detail oriented. Our emergency incident command structure was activated before we saw our first COVID patient,” he said.

“This was a crisis like never before, with huge amounts of uncertainty,” he noted. “But I believe the Cleveland Clinic system did very well, measured by outcomes such as surveys of health care teams across the system, which gave us reassuring results, and clinical outcomes with lower ICU and hospital mortality rates.”

Christopher Whinney, MD, SFHM, department chair of hospital medicine at Cleveland Clinic, said hospitalists worked hand in hand with the health system’s incident command structure and took responsibility for managing non-ICU COVID patients at six hospitals in the system.

“Hospitalists had a place at the table, and we collaborated well with incident command, enterprise redeployment committees, and emergency and critical care colleagues,” he noted. Hospitalists were on the leadership team for a number of planning meetings, and key stakeholders for bringing information back to their groups.

“First thing we did was to look at our workforce. The challenge was how to respond to up to a hundred COVID admissions per day – how to mobilize providers and build surge teams that incorporated primary care providers and medical trainees. We onboarded 200 providers to do hospital care within 60 days,” he said.

“We realized that communication with patients and families was a big part of the challenge, so we assigned people with good communication skills to fill this role. While we were fortunate not to get the terrible surges they had in other places, we felt we were prepared for the worst.”

Challenges of surge capacity

Every disaster is different, said Srikant Polepalli, MD, associate hospitalist medical director for Staten Island University Hospital in New York, part of the Northwell Health system. He brought the experience of being part of the response to Superstorm Sandy in October 2012 to the COVID pandemic.

“Specifically for hospitalists, the biggest challenge is working on surge capacity for a sudden influx of patients,” he said. “But with Northwell as our umbrella, we can triage and load-balance to move patients from hospital to hospital as needed. With the pandemic, we started with one COVID unit and then expanded to fill the entire hospital.”

Dr. Polepalli was appointed medical director for a temporary field hospital installed at South Beach Psychiatric Center, also in Staten Island. “We were able to acquire help and bring in people ranging from hospitalists to ER physicians, travel nurses, operation managers and the National Guard. Our command center did a phenomenal job of allocating and obtaining resources. It helped to have a structure that was already established and to rely on the resources of the health system,” Dr. Polepalli said. Not every hospital has a structure like Northwell’s.

“We’re not out of the pandemic yet, but we’ll continue with disaster drills and planning,” he said. “We must continue to adapt and have converted our temporary facilities to COVID testing centers, antibody infusion centers, and vaccination centers.”

For Alfred Burger, MD, SFHM, a hospitalist at Mount Sinai’s Beth Israel campus in New York, hospital medicine, now in its maturing phase, is still feeling its way through hospital and health care system transformation.

“My group is an academic, multicampus hospitalist group employed by the hospital system. When I meet other hospitalists at SHM conferences, whether they come from privately owned, corporately owned, or contracted models, they vary widely in terms of how involved the hospitalists are in crisis planning and their ability to respond to crises. At large academic medical centers like ours, one or more doctors is tasked with being involved in preparing for the next disaster,” he said.

“I think we responded the best we could, although it was difficult as we lost many patients to COVID. We were trying to save lives using the tools we knew from treating pneumonias and other forms of acute inflammatory lung injuries. We used every bit of our training in situations where no one had the right answers. But disasters teach us how to be flexible and pivot on the fly, and what to do when things don’t go our way.”

What is disaster response?

Medical response to a disaster essentially boils down to three main things: stuff, staff, and space, Dr. Persoff said. Those are the cornerstones of an emergency plan.

“There is not a hazard that exists that you can’t take an all-hazards approach to dealing with fundamental realities on the ground. No plan can be comprehensive enough to deal with all the intricacies of an emergency. But many plans can have the bones of a response that will allow you to face adverse circumstances,” he said.

“We actually became quite efficient early on in the pandemic, able to adapt in the moment. We were able to build an effective bridge between workers on the ground and our incident command structure, which seemed to reduce a lot of stress and create situational awareness. We implemented ICS as soon as we heard that China was building a COVID hospital, back in February of 2020.”

When one thinks about mass trauma, such as a 747 crash, Dr. Persoff said, the need is to treat burn victims and trauma victims in large numbers. At that point, the ED downstairs is filled with medical patients. Hospital medicine can rapidly admit those patients to clear out room in the ED. Surgeons are also dedicated to rapidly treating those patients, but what about patients who are on the floor following their surgeries? Hospitalists can offer consultations or primary management so the surgeons can stay in the OR, and the same in the ICU, while safely discharging hospitalized patients in a timely manner to make room for incoming patients.

“The lessons of COVID have been hard-taught and hard-earned. No good plan survives contact with the enemy,” he said. “But I think we’ll be better prepared for the next pandemic.”

Maria Frank, MD, FACP, SFHM, a hospitalist at Denver Health who chairs SHM’s Disaster Management Special Interest Group, says she got the bug for disaster preparation during postresidency training as an internist in emergency medicine. “I’m also the medical director for our biocontainment unit, created for infections like Ebola.” SHM’s SIG, which has 150 members, is now writing a review article on disaster planning for the field.

“I got a call on Dec. 27, 2019, about this new pneumonia, and they said, ‘We don’t know what it is, but it’s a coronavirus,’” she recalled. “When I got off the phone, I said, ‘Let’s make sure our response plan works and we have enough of everything on hand.’” Dr. Frank said she was expecting something more like SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome). “When they called the public health emergency of international concern for COVID, I was at a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention meeting in Atlanta. It really wasn’t a surprise for us.”

All hospitals plan for disasters, although they use different names and have different levels of commitment, Dr. Frank said. What’s not consistent is the participation of hospitalists. “Even when a disaster is 100% trauma related, consider a hospital like mine that has at least four times as many hospitalists as surgeons at any given time. The hospitalists need to take overall management for the patients who aren’t actually in the operating room.”

Time to debrief

Dr. Frank recommends debriefing on the hospital’s and the hospitalist group’s experience with COVID. “Look at the biggest challenges your group faced. Was it staffing, or time off, or the need for day care? Was it burnout, lack of knowledge, lack of [personal protective equipment]?” Each hospital could use its own COVID experience to work on identifying the challenges and the problems, she said. “I’d encourage each department and division to do this exercise individually. Then come together to find common ground with other departments in the hospital.”

This debriefing exercise isn’t just for doctors – it’s also for nurses, environmental services, security, and many other departments, she said. “COVID showed us how crisis response is a group effort. What will bring us together is to learn the challenges each of us faced. It was amazing to see hospitalists doing what they do best.” Post pandemic, hospitalists should also consider getting involved in research and publications, in order to share their lessons.

“One of the things we learned is that hospitalists are very versatile,” Dr. Frank added. But it’s also good for the group to have members specialize, for example, in biocontainment. “We are experts in discharging patients, in patient flow and operations, in coordinating complex medical care. So we would naturally take the lead in, for example, opening a geographic unit or collaborating with other specialists to create innovative models. That’s our job. It’s essential that we’re involved well in advance.”

COVID may be a once-in-a-lifetime experience, but there will be other disasters to come, she said. “If your hospital doesn’t have a disaster plan for hospitalists, get involved in establishing one. Each hospitalist group should have its own response plan. Talk to your peers at other hospitals, and get involved at the institutional level. I’m happy to share our plan; just contact me.” Readers can contact Dr. Frank at [email protected].

References

1. Persoff J et al. The role of hospital medicine in emergency preparedness: A framework for hospitalist leadership in disaster preparedness, response and recovery. J Hosp Med. 2018 Oct;13(10):713-7. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3073.

2. Persoff J et al. Expanding the hospital incident command system with a physician-centric role during a pandemic: The role of the physician clinical support supervisor. J Hosp Adm. 2020;9(3):7-10. doi: 10.5430/jha.v9n3p7.

3. Bowden K et al. Harnessing the power of hospitalists in operational disaster planning: COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2020 Sep;35(9):273-7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05952-6.

4. Orsini E et al. Lessons on outbreak preparedness from the Cleveland Clinic. Chest. 2020;158(5):2090-6. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.06.009.

Jason Persoff, MD, SFHM, now a hospitalist at University of Colorado Hospital in Aurora and an amateur storm chaser, got a close look at how natural disasters can impact hospital care when a tornado destroyed St. John’s Regional Medical Center in Joplin, Mo., on May 22, 2011.

He and a colleague who had been following the storm responded to injuries on the highway before reporting for a long day’s service at the other hospital in Joplin, Freeman Hospital West, caring for patients transferred from St. John’s on an impromptu unit without access to their medical records.

“During my medical training, I had done emergency medicine as an EMT, so I was interested in how the system responds to emergencies,” he explained. “At Joplin I learned how it feels when the boots on the ground in a crisis are not connected to an incident command structure.” Another thing he learned was the essential role for hospitalists in a hospital’s response to a crisis – and thus the need to involve them well in advance in the hospital’s planning for future emergencies.

“Disaster preparation – when done right – helps you ‘herd cats’ in a crisis situation,” he said. “The tornado and its wake served as defining moments for me. I used them as the impetus to improve health care’s response to disasters.” Part of that commitment was to help hospitalists understand their part in emergency preparation.1

Dr. Persoff is now the assistant medical director of emergency preparedness at University of Colorado Hospital. He also helped to create a position called physician support supervisor, which is filled by physicians who have held leadership positions in a hospital to help coordinate the disparate needs of all clinicians in a crisis and facilitate rapid response.2

But then along came the COVID pandemic – which in many locales around the world was unprecedented in scope. Dr. Persoff said his hospital was fairly well prepared, after a decade of engagement with emergency planning. It drew on experience with H1N1, also known as swine flu, and the Ebola virus, which killed 11,323 people, primarily in West Africa, from 2013 to 2016, as models. In a matter of days, the CU division of hospital medicine was able to modify and deploy its existing disaster plans to quickly respond to an influx of COVID patients.3

“Basically, what we set out to do was to treat COVID patients as if they were Ebola patients, cordoning them off in a small area of the hospital. That was naive of us,” he said. “We weren’t able to grasp the scale at the outset. It does defy the imagination – how the hospital could fill up with just one type of patient.”

What is disaster planning?

Emergency preparation for hospitals emerged as a recognized medical specialization in the 1970s. Initially it was largely considered the realm of emergency physicians, trauma services, or critical care doctors. Resources such as the World Health Organization, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, and similar groups recommend an all-hazards approach, a broad and flexible strategy for managing emergencies that could include natural disasters – earthquakes, storms, tornadoes, or wildfires – or human-caused events, such as mass shootings or terrorist attacks. The Joint Commission requires accredited hospitals to conduct several disaster drills annually.

The U.S. Hospital Preparedness Program was created in 2002 to enhance the ability of hospitals and health systems to prepare for and respond to bioterrorism attacks on civilians and other public health emergencies, including natural disasters and pandemics. It offers a foundation for national preparedness and a primary source of federal funding for health care system preparedness. The hospital, at the heart of the health care system, is expected to receive the injured and infected, because patients know they can obtain care there.

One of the fundamental tools for crisis response is the incident command system (ICS), which spells out how to quickly establish a command structure and assign responsibility for key tasks as well as overall leadership. The National Incident Management System organizes emergency management across all government levels and the private sector to ensure that the most pressing needs are met and precious resources are used without duplication. ICS is a standardized approach to command, control, and coordination of emergency response using a common hierarchy recognized across organizations, with advance training in how it should be deployed.

A crisis like never before

Nearly every hospital or health system goes through drills for an emergency, said Hassan Khouli, MD, chair of the department of critical care medicine at the Cleveland Clinic, and coauthor of an article in the journal Chest last year outlining 10 principles of emergency preparedness derived from its experience with the COVID pandemic.4 Some of these include: don’t wait; engage a variety of stakeholders; identify sources of truth; and prioritize hospital employees’ safety and well-being.

Part of the preparation is doing table-top exercises, with case scenarios or actual situations presented, working with clinicians on brainstorming and identifying opportunities for improvement, Dr. Khouli said. “These drills are so important, regardless of what the disaster turns out to be. We’ve done that over the years. We are a large health system, very process and detail oriented. Our emergency incident command structure was activated before we saw our first COVID patient,” he said.

“This was a crisis like never before, with huge amounts of uncertainty,” he noted. “But I believe the Cleveland Clinic system did very well, measured by outcomes such as surveys of health care teams across the system, which gave us reassuring results, and clinical outcomes with lower ICU and hospital mortality rates.”

Christopher Whinney, MD, SFHM, department chair of hospital medicine at Cleveland Clinic, said hospitalists worked hand in hand with the health system’s incident command structure and took responsibility for managing non-ICU COVID patients at six hospitals in the system.

“Hospitalists had a place at the table, and we collaborated well with incident command, enterprise redeployment committees, and emergency and critical care colleagues,” he noted. Hospitalists were on the leadership team for a number of planning meetings, and key stakeholders for bringing information back to their groups.

“First thing we did was to look at our workforce. The challenge was how to respond to up to a hundred COVID admissions per day – how to mobilize providers and build surge teams that incorporated primary care providers and medical trainees. We onboarded 200 providers to do hospital care within 60 days,” he said.

“We realized that communication with patients and families was a big part of the challenge, so we assigned people with good communication skills to fill this role. While we were fortunate not to get the terrible surges they had in other places, we felt we were prepared for the worst.”

Challenges of surge capacity

Every disaster is different, said Srikant Polepalli, MD, associate hospitalist medical director for Staten Island University Hospital in New York, part of the Northwell Health system. He brought the experience of being part of the response to Superstorm Sandy in October 2012 to the COVID pandemic.

“Specifically for hospitalists, the biggest challenge is working on surge capacity for a sudden influx of patients,” he said. “But with Northwell as our umbrella, we can triage and load-balance to move patients from hospital to hospital as needed. With the pandemic, we started with one COVID unit and then expanded to fill the entire hospital.”

Dr. Polepalli was appointed medical director for a temporary field hospital installed at South Beach Psychiatric Center, also in Staten Island. “We were able to acquire help and bring in people ranging from hospitalists to ER physicians, travel nurses, operation managers and the National Guard. Our command center did a phenomenal job of allocating and obtaining resources. It helped to have a structure that was already established and to rely on the resources of the health system,” Dr. Polepalli said. Not every hospital has a structure like Northwell’s.

“We’re not out of the pandemic yet, but we’ll continue with disaster drills and planning,” he said. “We must continue to adapt and have converted our temporary facilities to COVID testing centers, antibody infusion centers, and vaccination centers.”

For Alfred Burger, MD, SFHM, a hospitalist at Mount Sinai’s Beth Israel campus in New York, hospital medicine, now in its maturing phase, is still feeling its way through hospital and health care system transformation.

“My group is an academic, multicampus hospitalist group employed by the hospital system. When I meet other hospitalists at SHM conferences, whether they come from privately owned, corporately owned, or contracted models, they vary widely in terms of how involved the hospitalists are in crisis planning and their ability to respond to crises. At large academic medical centers like ours, one or more doctors is tasked with being involved in preparing for the next disaster,” he said.

“I think we responded the best we could, although it was difficult as we lost many patients to COVID. We were trying to save lives using the tools we knew from treating pneumonias and other forms of acute inflammatory lung injuries. We used every bit of our training in situations where no one had the right answers. But disasters teach us how to be flexible and pivot on the fly, and what to do when things don’t go our way.”

What is disaster response?

Medical response to a disaster essentially boils down to three main things: stuff, staff, and space, Dr. Persoff said. Those are the cornerstones of an emergency plan.

“There is not a hazard that exists that you can’t take an all-hazards approach to dealing with fundamental realities on the ground. No plan can be comprehensive enough to deal with all the intricacies of an emergency. But many plans can have the bones of a response that will allow you to face adverse circumstances,” he said.

“We actually became quite efficient early on in the pandemic, able to adapt in the moment. We were able to build an effective bridge between workers on the ground and our incident command structure, which seemed to reduce a lot of stress and create situational awareness. We implemented ICS as soon as we heard that China was building a COVID hospital, back in February of 2020.”

When one thinks about mass trauma, such as a 747 crash, Dr. Persoff said, the need is to treat burn victims and trauma victims in large numbers. At that point, the ED downstairs is filled with medical patients. Hospital medicine can rapidly admit those patients to clear out room in the ED. Surgeons are also dedicated to rapidly treating those patients, but what about patients who are on the floor following their surgeries? Hospitalists can offer consultations or primary management so the surgeons can stay in the OR, and the same in the ICU, while safely discharging hospitalized patients in a timely manner to make room for incoming patients.

“The lessons of COVID have been hard-taught and hard-earned. No good plan survives contact with the enemy,” he said. “But I think we’ll be better prepared for the next pandemic.”

Maria Frank, MD, FACP, SFHM, a hospitalist at Denver Health who chairs SHM’s Disaster Management Special Interest Group, says she got the bug for disaster preparation during postresidency training as an internist in emergency medicine. “I’m also the medical director for our biocontainment unit, created for infections like Ebola.” SHM’s SIG, which has 150 members, is now writing a review article on disaster planning for the field.

“I got a call on Dec. 27, 2019, about this new pneumonia, and they said, ‘We don’t know what it is, but it’s a coronavirus,’” she recalled. “When I got off the phone, I said, ‘Let’s make sure our response plan works and we have enough of everything on hand.’” Dr. Frank said she was expecting something more like SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome). “When they called the public health emergency of international concern for COVID, I was at a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention meeting in Atlanta. It really wasn’t a surprise for us.”

All hospitals plan for disasters, although they use different names and have different levels of commitment, Dr. Frank said. What’s not consistent is the participation of hospitalists. “Even when a disaster is 100% trauma related, consider a hospital like mine that has at least four times as many hospitalists as surgeons at any given time. The hospitalists need to take overall management for the patients who aren’t actually in the operating room.”

Time to debrief

Dr. Frank recommends debriefing on the hospital’s and the hospitalist group’s experience with COVID. “Look at the biggest challenges your group faced. Was it staffing, or time off, or the need for day care? Was it burnout, lack of knowledge, lack of [personal protective equipment]?” Each hospital could use its own COVID experience to work on identifying the challenges and the problems, she said. “I’d encourage each department and division to do this exercise individually. Then come together to find common ground with other departments in the hospital.”

This debriefing exercise isn’t just for doctors – it’s also for nurses, environmental services, security, and many other departments, she said. “COVID showed us how crisis response is a group effort. What will bring us together is to learn the challenges each of us faced. It was amazing to see hospitalists doing what they do best.” Post pandemic, hospitalists should also consider getting involved in research and publications, in order to share their lessons.

“One of the things we learned is that hospitalists are very versatile,” Dr. Frank added. But it’s also good for the group to have members specialize, for example, in biocontainment. “We are experts in discharging patients, in patient flow and operations, in coordinating complex medical care. So we would naturally take the lead in, for example, opening a geographic unit or collaborating with other specialists to create innovative models. That’s our job. It’s essential that we’re involved well in advance.”

COVID may be a once-in-a-lifetime experience, but there will be other disasters to come, she said. “If your hospital doesn’t have a disaster plan for hospitalists, get involved in establishing one. Each hospitalist group should have its own response plan. Talk to your peers at other hospitals, and get involved at the institutional level. I’m happy to share our plan; just contact me.” Readers can contact Dr. Frank at [email protected].

References

1. Persoff J et al. The role of hospital medicine in emergency preparedness: A framework for hospitalist leadership in disaster preparedness, response and recovery. J Hosp Med. 2018 Oct;13(10):713-7. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3073.

2. Persoff J et al. Expanding the hospital incident command system with a physician-centric role during a pandemic: The role of the physician clinical support supervisor. J Hosp Adm. 2020;9(3):7-10. doi: 10.5430/jha.v9n3p7.

3. Bowden K et al. Harnessing the power of hospitalists in operational disaster planning: COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2020 Sep;35(9):273-7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05952-6.

4. Orsini E et al. Lessons on outbreak preparedness from the Cleveland Clinic. Chest. 2020;158(5):2090-6. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.06.009.

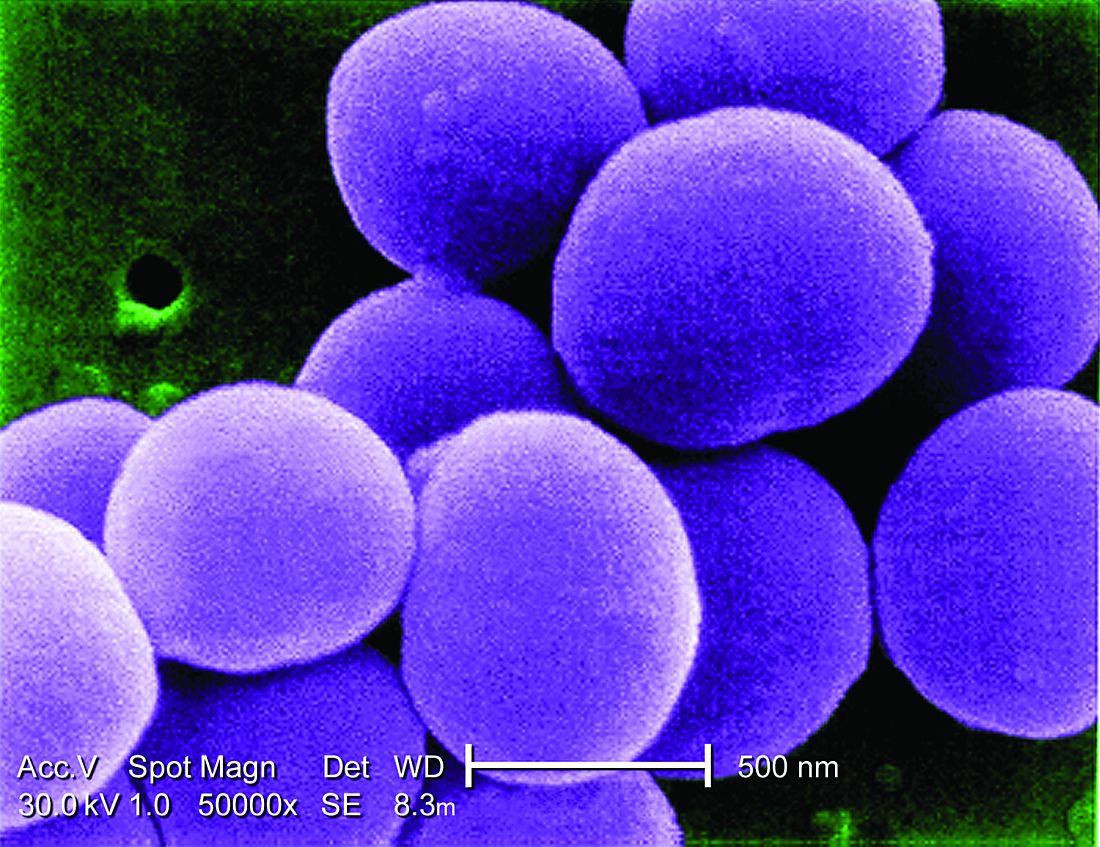

Early transition to oral beta-lactams for low-risk S. aureus bacteremia may be acceptable

Background: There is consensus that LR-SAB can be safely treated with 14 days of antibiotic therapy, but the use of and/or proportion of duration of oral antibiotics is not clear. There is evidence that oral therapy has fewer treatment complications, compared with IV treatments. Objective of this study was to assess the safety of early oral switch (EOS) prior to 14 days for LR-SAB.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Single institution tertiary care hospital in Wellington, New Zealand.

Synopsis: Study population included adults with health care–associated SAB deemed low risk (no positive blood cultures >72 hours after initial positive culture, no evidence of deep infection as determined by an infectious disease consultant, no nonremovable prosthetics). The primary outcome was occurrence of SAB-related complication (recurrence of SAB, deep-seated infection, readmission, attributable mortality) within 90 days.

Of the initial 469 episodes of SAB, 100 met inclusion, and 84 of those patients had EOS. Line infection was the source in a majority of patients (79% and 88% in EOS and IV, respectively). Only 5% of patients had MRSA. Overall, 86% of EOS patients were treated with an oral beta-lactam, within the EOS group, median duration of IV and oral antibiotics was 5 and 10 days, respectively. SAB recurrence within 90 days occurred in three (4%) and one (6%) patients in EOS vs. IV groups, respectively (P = .64). No deaths within 90 days were deemed attributable to SAB. Limitations include small size, single center, and observational, retrospective framework.

Bottom line: The study suggests that EOS with oral beta-lactams in selected patients with LR-SAB may be adequate; however, the study is too small to provide robust high-level evidence. Instead, the authors hope the data will lead to larger, more powerful prospective studies to examine if a simpler, cheaper, and in some ways safer treatment course is possible.

Citation: Bupha-Intr O et al. Efficacy of early oral switch with beta-lactams for low-risk Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020 Feb 3;AAC.02345-19. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02345-19.

Dr. Sneed is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Background: There is consensus that LR-SAB can be safely treated with 14 days of antibiotic therapy, but the use of and/or proportion of duration of oral antibiotics is not clear. There is evidence that oral therapy has fewer treatment complications, compared with IV treatments. Objective of this study was to assess the safety of early oral switch (EOS) prior to 14 days for LR-SAB.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Single institution tertiary care hospital in Wellington, New Zealand.

Synopsis: Study population included adults with health care–associated SAB deemed low risk (no positive blood cultures >72 hours after initial positive culture, no evidence of deep infection as determined by an infectious disease consultant, no nonremovable prosthetics). The primary outcome was occurrence of SAB-related complication (recurrence of SAB, deep-seated infection, readmission, attributable mortality) within 90 days.

Of the initial 469 episodes of SAB, 100 met inclusion, and 84 of those patients had EOS. Line infection was the source in a majority of patients (79% and 88% in EOS and IV, respectively). Only 5% of patients had MRSA. Overall, 86% of EOS patients were treated with an oral beta-lactam, within the EOS group, median duration of IV and oral antibiotics was 5 and 10 days, respectively. SAB recurrence within 90 days occurred in three (4%) and one (6%) patients in EOS vs. IV groups, respectively (P = .64). No deaths within 90 days were deemed attributable to SAB. Limitations include small size, single center, and observational, retrospective framework.

Bottom line: The study suggests that EOS with oral beta-lactams in selected patients with LR-SAB may be adequate; however, the study is too small to provide robust high-level evidence. Instead, the authors hope the data will lead to larger, more powerful prospective studies to examine if a simpler, cheaper, and in some ways safer treatment course is possible.

Citation: Bupha-Intr O et al. Efficacy of early oral switch with beta-lactams for low-risk Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020 Feb 3;AAC.02345-19. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02345-19.

Dr. Sneed is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Background: There is consensus that LR-SAB can be safely treated with 14 days of antibiotic therapy, but the use of and/or proportion of duration of oral antibiotics is not clear. There is evidence that oral therapy has fewer treatment complications, compared with IV treatments. Objective of this study was to assess the safety of early oral switch (EOS) prior to 14 days for LR-SAB.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Single institution tertiary care hospital in Wellington, New Zealand.

Synopsis: Study population included adults with health care–associated SAB deemed low risk (no positive blood cultures >72 hours after initial positive culture, no evidence of deep infection as determined by an infectious disease consultant, no nonremovable prosthetics). The primary outcome was occurrence of SAB-related complication (recurrence of SAB, deep-seated infection, readmission, attributable mortality) within 90 days.

Of the initial 469 episodes of SAB, 100 met inclusion, and 84 of those patients had EOS. Line infection was the source in a majority of patients (79% and 88% in EOS and IV, respectively). Only 5% of patients had MRSA. Overall, 86% of EOS patients were treated with an oral beta-lactam, within the EOS group, median duration of IV and oral antibiotics was 5 and 10 days, respectively. SAB recurrence within 90 days occurred in three (4%) and one (6%) patients in EOS vs. IV groups, respectively (P = .64). No deaths within 90 days were deemed attributable to SAB. Limitations include small size, single center, and observational, retrospective framework.

Bottom line: The study suggests that EOS with oral beta-lactams in selected patients with LR-SAB may be adequate; however, the study is too small to provide robust high-level evidence. Instead, the authors hope the data will lead to larger, more powerful prospective studies to examine if a simpler, cheaper, and in some ways safer treatment course is possible.

Citation: Bupha-Intr O et al. Efficacy of early oral switch with beta-lactams for low-risk Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020 Feb 3;AAC.02345-19. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02345-19.

Dr. Sneed is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Unclear benefit to home NIPPV in COPD

Background: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a prevalent condition that is associated with significant mortality, morbidity, and health care utilization. Use of noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation (NIPPV) in acute hypercapnic respiratory failure caused by COPD exacerbations is well established. However, the benefits of in-home NIPPV for COPD with chronic hypercapnia is unclear.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Multicenter catchment of 21 randomized control trials (RCTs) and 12 observational studies involving more than 51,000 patients during 1995-2019.

Synopsis: Patients included were those with COPD and hypercapnia who used NIPPV for more than 1 month. Home bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP), compared to no device use was associated with lower risk of mortality, all-cause hospital admission, and intubation, but no significant difference in quality of life. Noninvasive home mechanical ventilation, compared with no device was significantly associated with lower risk of hospital admission, but not a significant difference in mortality. Of note, there was no statistically significant difference in any outcome for either BiPAP or home mechanical ventilation if evidence was limited to RCTs. Importantly, on rigorous measure, the evidence was low to moderate quality or insufficient, and some outcomes analysis was based on small numbers of studies.

Bottom line: While there is suggestion of benefit on some measures with the use of home NIPPV, the evidence is not robust enough to clearly guide use.

Citation: Wilson et al. Association of home noninvasive positive pressure ventilation with clinical outcomes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA. 2020 Feb 4;323(5):455-65.

Dr. Sneed is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Background: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a prevalent condition that is associated with significant mortality, morbidity, and health care utilization. Use of noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation (NIPPV) in acute hypercapnic respiratory failure caused by COPD exacerbations is well established. However, the benefits of in-home NIPPV for COPD with chronic hypercapnia is unclear.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Multicenter catchment of 21 randomized control trials (RCTs) and 12 observational studies involving more than 51,000 patients during 1995-2019.

Synopsis: Patients included were those with COPD and hypercapnia who used NIPPV for more than 1 month. Home bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP), compared to no device use was associated with lower risk of mortality, all-cause hospital admission, and intubation, but no significant difference in quality of life. Noninvasive home mechanical ventilation, compared with no device was significantly associated with lower risk of hospital admission, but not a significant difference in mortality. Of note, there was no statistically significant difference in any outcome for either BiPAP or home mechanical ventilation if evidence was limited to RCTs. Importantly, on rigorous measure, the evidence was low to moderate quality or insufficient, and some outcomes analysis was based on small numbers of studies.

Bottom line: While there is suggestion of benefit on some measures with the use of home NIPPV, the evidence is not robust enough to clearly guide use.

Citation: Wilson et al. Association of home noninvasive positive pressure ventilation with clinical outcomes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA. 2020 Feb 4;323(5):455-65.

Dr. Sneed is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Background: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a prevalent condition that is associated with significant mortality, morbidity, and health care utilization. Use of noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation (NIPPV) in acute hypercapnic respiratory failure caused by COPD exacerbations is well established. However, the benefits of in-home NIPPV for COPD with chronic hypercapnia is unclear.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Multicenter catchment of 21 randomized control trials (RCTs) and 12 observational studies involving more than 51,000 patients during 1995-2019.

Synopsis: Patients included were those with COPD and hypercapnia who used NIPPV for more than 1 month. Home bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP), compared to no device use was associated with lower risk of mortality, all-cause hospital admission, and intubation, but no significant difference in quality of life. Noninvasive home mechanical ventilation, compared with no device was significantly associated with lower risk of hospital admission, but not a significant difference in mortality. Of note, there was no statistically significant difference in any outcome for either BiPAP or home mechanical ventilation if evidence was limited to RCTs. Importantly, on rigorous measure, the evidence was low to moderate quality or insufficient, and some outcomes analysis was based on small numbers of studies.

Bottom line: While there is suggestion of benefit on some measures with the use of home NIPPV, the evidence is not robust enough to clearly guide use.

Citation: Wilson et al. Association of home noninvasive positive pressure ventilation with clinical outcomes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA. 2020 Feb 4;323(5):455-65.

Dr. Sneed is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

No prehydration prior to contrast-enhanced CT in patients with stage 3 CKD

Background: Postcontrast acute kidney injury (PC-AKI) is known to have a mild, often self-limiting, clinical course. Despite this, preventative measures are advised by international guidelines in high-risk patients.

Study design: The Kompas trial was a multicenter, open-label, noninferiority randomized clinical trial in which 523 patients with stage 3 CKD were randomized to receive no hydration or prehydration with 250 mL of 1.4% sodium bicarbonate in a 1-hour infusion before undergoing elective contrast-enhanced CT. The primary endpoint was the mean relative increase in serum creatinine 2-5 days after contrast administration, compared with baseline.

Setting: Six hospitals in the Netherlands during April 2013–September 2016.

Synopsis: Of the 523 patients, (median age, 74 years), the mean relative increase in creatinine level 2-5 days after contrast administration compared with baseline was 3.0% in the no-prehydration group vs. 3.5% in the prehydration group. This demonstrates that withholding prehydration is noninferior to administrating prehydration. PC-AKI occurred in 7 of 262 patients in the no-prehydration group and 4 of 261 patients in the prehydration group and no patients required dialysis or developed heart failure. These results reassure us that prehydration with sodium bicarbonate can be safely omitted in patients with stage 3 CKD who undergo contrast-enhanced CT.

Bottom line: Prehydration with sodium bicarbonate is not needed to prevent additional renal injury in patients with CKD stage 3 undergoing contrast-enhanced CT imaging.

Citation: Timal RJ et al. Effect of no prehydration vs sodium bicarbonate prehydration prior to contrast-enhanced computed tomography in the prevention of postcontrast acute kidney injury in adults with chronic kidney disease: The Kompas Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Feb 17. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.7428.

Dr. Moulder is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Background: Postcontrast acute kidney injury (PC-AKI) is known to have a mild, often self-limiting, clinical course. Despite this, preventative measures are advised by international guidelines in high-risk patients.