User login

Increasing racial diversity in hospital medicine’s leadership ranks

Have you ever done something where you’re not quite sure why you did it at the time, but later on you realize it was part of some larger cosmic purpose, and you go, “Ahhh, now I understand…that’s why!”? Call it a fortuitous coincidence. Or a subconscious act of anticipation. Maybe a little push from God.

Last summer, as SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee was planning the State of Hospital Medicine survey for 2020, we received a request from SHM’s Diversity, Equity & Inclusion (DEI) Special Interest Group (SIG) to include a series of questions related to hospitalist gender, race and ethnic distribution in the new survey. We’ve generally resisted doing things like this because the SoHM is designed to capture data at the group level, not the individual level – and honestly, it’s as much as a lot of groups can do to tell us reliably how many FTEs they have, much less provide details about individual providers. In addition, the survey is already really long, and we are always looking for ways to make it shorter and easier for participants while still collecting the information report users care most about.

But we wanted to take the asks from the DEI SIG seriously, and as we considered their request, we realized that though it wasn’t practical to collect this information for individual hospital medicine group (HMG) members, we could collect it for group leaders. Little did we know last summer that issues of gender and racial diversity and equity would be so front-and-center right now, as we prepare to release the 2020 SoHM Report in early September. Ahhh, now I understand…that’s why – with the prompting of the DEI SIG – we so fortuitously chose to include those questions this year!

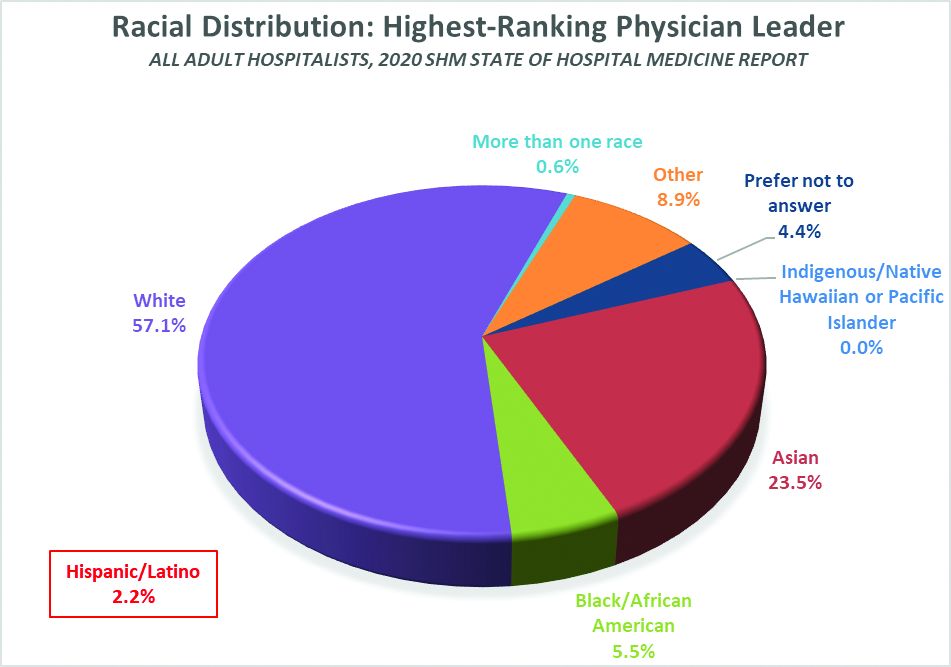

Here’s a sneak preview of what we learned. Among SoHM respondents, 57.1% reported that the highest-ranking leader in their HMG is White, and 23.5% of highest-ranking leaders are Asian. Only 5.5% of HMG leaders were Black/African American. Ethnicity was a separate question, and only 2.2% of HMG leaders were reported as Hispanic/Latino.

I have been profoundly moved by the wretched deaths of George Floyd and other people of color at the hands of police in recent months, and by the subsequent protests and our growing national reckoning over issues of racial equity and justice. In my efforts to understand more about race in America, I have been challenged by my friend Ryan Brown, MD, specialty medical director for hospital medicine with Atrium Health in Charlotte, N.C., and others to go beyond just learning about these issues. I want to use my voice to advocate for change, and my actions to participate in effecting change, within the context of my sphere of influence.

So, what does that have to do with the SoHM data on HMG leader demographics? Well, it’s clear that Black and brown people are woefully underrepresented in the ranks of hospital medicine leadership.

Unfortunately, we don’t have good information on racial diversity for hospitalists as a specialty, though I understand that SHM is working on plans to update membership profiles to begin collecting this information. In searching the Internet, I found a 2018 paper from the Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved that studied racial and ethnic distribution of U.S. primary care physicians (doi: 10.1353/hpu.2018.0036). It reported that, in 2012, 7.8% of general internists were Black, along with 5.8% of family medicine/general practice physicians and 6.8% of pediatricians. A separate data set issued by the Association of American Medical Colleges reported that, in 2019, 6.4% of all actively practicing general internal medicine doctors were Black (5.5% of male IM physicians and 7.9% of female IM physicians). While this doesn’t mean hospitalists have the same racial and ethnic distribution, this is probably the best proxy we can come up with.

At first glance, having 5.5% of HMG leaders who are Black doesn’t seem terribly out of line with the reported range of 6.4 to 7.8% in the general population of internal medicine physicians (apologies to the family medicine and pediatric hospitalists reading this, but I’ll confine my discussion to internists for ease and brevity, since they represent the vast majority of the nation’s hospitalists). But do the math. It means Black hospitalists are likely underrepresented in HMG leadership ranks by something like 14% to 29% compared to their likely presence among hospitalists in general.

The real problem, of course, is that according the U.S. Census Bureau, 13.4% of the U.S. population is Black. So even if the racial distribution of HMG leaders catches up to the general hospitalist population, hospital medicine is still woefully underrepresenting the racial and ethnic distribution of our patient population.

The disconnect between the ethnic distribution of HMG leaders vs. hospitalists (based on general internal medicine distribution) is even more pronounced for Latinos. The JHCPU paper reported that, in 2012, 5.6% of general internists were Hispanic. The AAMC data set reported 5.8% of IM doctors were Hispanic/Latino. But only 2.2% of SoHM respondent HMGs reported a Hispanic/Latino leader, which means Latinos are underrepresented by somewhere around 61% or so relative to the likely hospitalist population, and by a whole lot more considering the fact that Latinos make up about 18.5% of the U.S. population.

I’m not saying that a White or Asian doctor can’t provide skilled, compassionate care to a Black or Latino patient, or vice-versa. It happens every day. I guess what I am saying is that we as a country and in the medical profession need to do a better job of creating pathways and promoting careers in medicine for people of color. A JAMA paper from 2019 reported that while the numbers and proportions of minority medical school matriculants has slowly been increasing from 2002 to 2017, the rate of increase was “slower than their age-matched counterparts in the U.S. population, resulting in increased underrepresentation” (doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.10490). This means we’re falling behind, not catching up.

We need to make sure that people like Dr. Ryan Brown aren’t discouraged from pursuing medicine by teachers or school counselors because of their skin color or accent, or their gender or sexual orientation. And among those who become doctors, we need to promote hospital medicine as a desirable specialty for people of color and actively invite them in.

In my view, much of this starts with creating more and better paths to leadership within hospital medicine for people of color. Hospital medicine group leaders wield enormous – and increasing – influence, not only within their HMGs and within SHM, but within their institutions and health care systems. We need their voices and their influence to promote diversity within their groups, their institutions, within hospital medicine, and within medicine and the U.S. health care system more broadly.

The Society of Hospital Medicine is already taking steps to promote diversity, equity and inclusion. These include issuing a formal Diversity and Inclusion Statement, creating the DEI SIG, and the recent formation of a Board-designated DEI task force charged with making recommendations to promote DEI within SHM and in hospital medicine more broadly. But I want to challenge SHM to do more, particularly with regard to promoting diversity in leadership. Here are a few ideas to consider:

- Create and sponsor a mentoring program in which hospitalists volunteer to mentor minority junior high and high school students and help them prepare to pursue a career in medicine.

- Develop a formal, structured advocacy or collaboration effort with organizations like AAMC and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education designed to promote meaningful increases in the proportion of medical school students and residents who are people of color, and in the proportion who choose primary care – and ultimately, hospital medicine.

- Work hard to collect reliable racial, ethnic and gender information about SHM members and consider collaborating with MGMA to incorporate demographic questions into its survey tool for individual hospitalist compensation and productivity data. Challenge us on the Practice Analysis Committee who are responsible for the SoHM survey to continue surveying leadership demographics, and to consider how we can expand our collection of DEI information in 2022.

- Undertake a public relations campaign to highlight to health systems and other employers the under-representation of Black and Latino hospitalists in leadership positions, and to promote conscious efforts to increase those ranks.

- Create scholarships for hospitalists from underrepresented racial and ethnic groups to attend SHM-sponsored leadership development programs such as Leadership Academy, Academic Hospitalist Academy, and Quality and Safety Educators Academy, with the goal of increasing their ranks in positions of influence throughout healthcare. A scholarship program might even include raising funds to help minority hospitalists pursue Master’s-level programs such as an MBA, MHA, or MMM.

- Develop an educational track, mentoring program, or other support initiative for early-career hospitalist leaders and those interested in developing leadership skills, and ensure it gives specific attention to strategies for increasing the proportion of hospitalists of color in leadership positions.

- Review and revise existing SHM documents such as The Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group, the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine, and various white papers and position statements to ensure they address diversity, equity and inclusion – both with regard to the hospital medicine workforce and leadership, and with regard to patient care and eliminating health disparities.

I’m sure there are plenty of other similar actions we can take that I haven’t thought of. But we need to start the conversation about concrete steps our Society, and the medical specialty we represent, can take to foster real change. And then, we need to follow our words up with actions.

Ms. Flores is a partner at Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants in La Quinta, Calif. She serves on SHM’s Practice Analysis and Annual Conference Committees and helps to coordinate SHM’s biannual State of Hospital Medicine survey.

Have you ever done something where you’re not quite sure why you did it at the time, but later on you realize it was part of some larger cosmic purpose, and you go, “Ahhh, now I understand…that’s why!”? Call it a fortuitous coincidence. Or a subconscious act of anticipation. Maybe a little push from God.

Last summer, as SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee was planning the State of Hospital Medicine survey for 2020, we received a request from SHM’s Diversity, Equity & Inclusion (DEI) Special Interest Group (SIG) to include a series of questions related to hospitalist gender, race and ethnic distribution in the new survey. We’ve generally resisted doing things like this because the SoHM is designed to capture data at the group level, not the individual level – and honestly, it’s as much as a lot of groups can do to tell us reliably how many FTEs they have, much less provide details about individual providers. In addition, the survey is already really long, and we are always looking for ways to make it shorter and easier for participants while still collecting the information report users care most about.

But we wanted to take the asks from the DEI SIG seriously, and as we considered their request, we realized that though it wasn’t practical to collect this information for individual hospital medicine group (HMG) members, we could collect it for group leaders. Little did we know last summer that issues of gender and racial diversity and equity would be so front-and-center right now, as we prepare to release the 2020 SoHM Report in early September. Ahhh, now I understand…that’s why – with the prompting of the DEI SIG – we so fortuitously chose to include those questions this year!

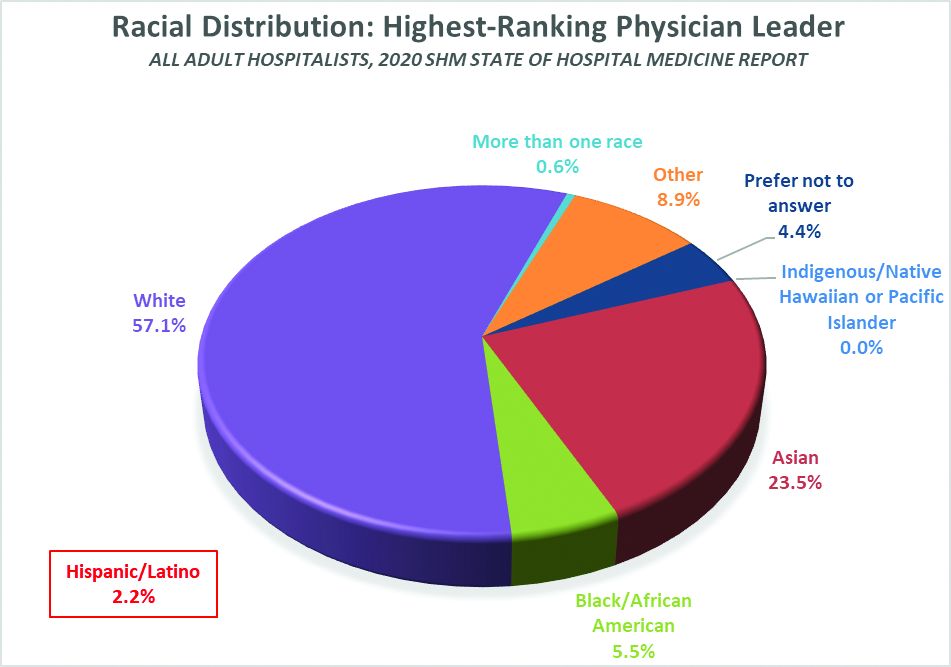

Here’s a sneak preview of what we learned. Among SoHM respondents, 57.1% reported that the highest-ranking leader in their HMG is White, and 23.5% of highest-ranking leaders are Asian. Only 5.5% of HMG leaders were Black/African American. Ethnicity was a separate question, and only 2.2% of HMG leaders were reported as Hispanic/Latino.

I have been profoundly moved by the wretched deaths of George Floyd and other people of color at the hands of police in recent months, and by the subsequent protests and our growing national reckoning over issues of racial equity and justice. In my efforts to understand more about race in America, I have been challenged by my friend Ryan Brown, MD, specialty medical director for hospital medicine with Atrium Health in Charlotte, N.C., and others to go beyond just learning about these issues. I want to use my voice to advocate for change, and my actions to participate in effecting change, within the context of my sphere of influence.

So, what does that have to do with the SoHM data on HMG leader demographics? Well, it’s clear that Black and brown people are woefully underrepresented in the ranks of hospital medicine leadership.

Unfortunately, we don’t have good information on racial diversity for hospitalists as a specialty, though I understand that SHM is working on plans to update membership profiles to begin collecting this information. In searching the Internet, I found a 2018 paper from the Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved that studied racial and ethnic distribution of U.S. primary care physicians (doi: 10.1353/hpu.2018.0036). It reported that, in 2012, 7.8% of general internists were Black, along with 5.8% of family medicine/general practice physicians and 6.8% of pediatricians. A separate data set issued by the Association of American Medical Colleges reported that, in 2019, 6.4% of all actively practicing general internal medicine doctors were Black (5.5% of male IM physicians and 7.9% of female IM physicians). While this doesn’t mean hospitalists have the same racial and ethnic distribution, this is probably the best proxy we can come up with.

At first glance, having 5.5% of HMG leaders who are Black doesn’t seem terribly out of line with the reported range of 6.4 to 7.8% in the general population of internal medicine physicians (apologies to the family medicine and pediatric hospitalists reading this, but I’ll confine my discussion to internists for ease and brevity, since they represent the vast majority of the nation’s hospitalists). But do the math. It means Black hospitalists are likely underrepresented in HMG leadership ranks by something like 14% to 29% compared to their likely presence among hospitalists in general.

The real problem, of course, is that according the U.S. Census Bureau, 13.4% of the U.S. population is Black. So even if the racial distribution of HMG leaders catches up to the general hospitalist population, hospital medicine is still woefully underrepresenting the racial and ethnic distribution of our patient population.

The disconnect between the ethnic distribution of HMG leaders vs. hospitalists (based on general internal medicine distribution) is even more pronounced for Latinos. The JHCPU paper reported that, in 2012, 5.6% of general internists were Hispanic. The AAMC data set reported 5.8% of IM doctors were Hispanic/Latino. But only 2.2% of SoHM respondent HMGs reported a Hispanic/Latino leader, which means Latinos are underrepresented by somewhere around 61% or so relative to the likely hospitalist population, and by a whole lot more considering the fact that Latinos make up about 18.5% of the U.S. population.

I’m not saying that a White or Asian doctor can’t provide skilled, compassionate care to a Black or Latino patient, or vice-versa. It happens every day. I guess what I am saying is that we as a country and in the medical profession need to do a better job of creating pathways and promoting careers in medicine for people of color. A JAMA paper from 2019 reported that while the numbers and proportions of minority medical school matriculants has slowly been increasing from 2002 to 2017, the rate of increase was “slower than their age-matched counterparts in the U.S. population, resulting in increased underrepresentation” (doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.10490). This means we’re falling behind, not catching up.

We need to make sure that people like Dr. Ryan Brown aren’t discouraged from pursuing medicine by teachers or school counselors because of their skin color or accent, or their gender or sexual orientation. And among those who become doctors, we need to promote hospital medicine as a desirable specialty for people of color and actively invite them in.

In my view, much of this starts with creating more and better paths to leadership within hospital medicine for people of color. Hospital medicine group leaders wield enormous – and increasing – influence, not only within their HMGs and within SHM, but within their institutions and health care systems. We need their voices and their influence to promote diversity within their groups, their institutions, within hospital medicine, and within medicine and the U.S. health care system more broadly.

The Society of Hospital Medicine is already taking steps to promote diversity, equity and inclusion. These include issuing a formal Diversity and Inclusion Statement, creating the DEI SIG, and the recent formation of a Board-designated DEI task force charged with making recommendations to promote DEI within SHM and in hospital medicine more broadly. But I want to challenge SHM to do more, particularly with regard to promoting diversity in leadership. Here are a few ideas to consider:

- Create and sponsor a mentoring program in which hospitalists volunteer to mentor minority junior high and high school students and help them prepare to pursue a career in medicine.

- Develop a formal, structured advocacy or collaboration effort with organizations like AAMC and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education designed to promote meaningful increases in the proportion of medical school students and residents who are people of color, and in the proportion who choose primary care – and ultimately, hospital medicine.

- Work hard to collect reliable racial, ethnic and gender information about SHM members and consider collaborating with MGMA to incorporate demographic questions into its survey tool for individual hospitalist compensation and productivity data. Challenge us on the Practice Analysis Committee who are responsible for the SoHM survey to continue surveying leadership demographics, and to consider how we can expand our collection of DEI information in 2022.

- Undertake a public relations campaign to highlight to health systems and other employers the under-representation of Black and Latino hospitalists in leadership positions, and to promote conscious efforts to increase those ranks.

- Create scholarships for hospitalists from underrepresented racial and ethnic groups to attend SHM-sponsored leadership development programs such as Leadership Academy, Academic Hospitalist Academy, and Quality and Safety Educators Academy, with the goal of increasing their ranks in positions of influence throughout healthcare. A scholarship program might even include raising funds to help minority hospitalists pursue Master’s-level programs such as an MBA, MHA, or MMM.

- Develop an educational track, mentoring program, or other support initiative for early-career hospitalist leaders and those interested in developing leadership skills, and ensure it gives specific attention to strategies for increasing the proportion of hospitalists of color in leadership positions.

- Review and revise existing SHM documents such as The Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group, the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine, and various white papers and position statements to ensure they address diversity, equity and inclusion – both with regard to the hospital medicine workforce and leadership, and with regard to patient care and eliminating health disparities.

I’m sure there are plenty of other similar actions we can take that I haven’t thought of. But we need to start the conversation about concrete steps our Society, and the medical specialty we represent, can take to foster real change. And then, we need to follow our words up with actions.

Ms. Flores is a partner at Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants in La Quinta, Calif. She serves on SHM’s Practice Analysis and Annual Conference Committees and helps to coordinate SHM’s biannual State of Hospital Medicine survey.

Have you ever done something where you’re not quite sure why you did it at the time, but later on you realize it was part of some larger cosmic purpose, and you go, “Ahhh, now I understand…that’s why!”? Call it a fortuitous coincidence. Or a subconscious act of anticipation. Maybe a little push from God.

Last summer, as SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee was planning the State of Hospital Medicine survey for 2020, we received a request from SHM’s Diversity, Equity & Inclusion (DEI) Special Interest Group (SIG) to include a series of questions related to hospitalist gender, race and ethnic distribution in the new survey. We’ve generally resisted doing things like this because the SoHM is designed to capture data at the group level, not the individual level – and honestly, it’s as much as a lot of groups can do to tell us reliably how many FTEs they have, much less provide details about individual providers. In addition, the survey is already really long, and we are always looking for ways to make it shorter and easier for participants while still collecting the information report users care most about.

But we wanted to take the asks from the DEI SIG seriously, and as we considered their request, we realized that though it wasn’t practical to collect this information for individual hospital medicine group (HMG) members, we could collect it for group leaders. Little did we know last summer that issues of gender and racial diversity and equity would be so front-and-center right now, as we prepare to release the 2020 SoHM Report in early September. Ahhh, now I understand…that’s why – with the prompting of the DEI SIG – we so fortuitously chose to include those questions this year!

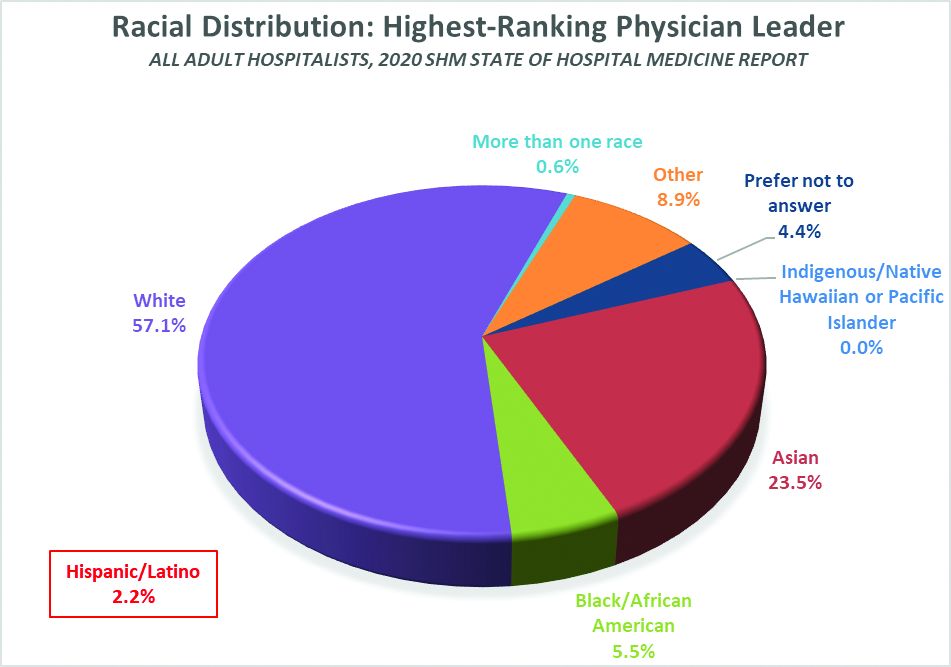

Here’s a sneak preview of what we learned. Among SoHM respondents, 57.1% reported that the highest-ranking leader in their HMG is White, and 23.5% of highest-ranking leaders are Asian. Only 5.5% of HMG leaders were Black/African American. Ethnicity was a separate question, and only 2.2% of HMG leaders were reported as Hispanic/Latino.

I have been profoundly moved by the wretched deaths of George Floyd and other people of color at the hands of police in recent months, and by the subsequent protests and our growing national reckoning over issues of racial equity and justice. In my efforts to understand more about race in America, I have been challenged by my friend Ryan Brown, MD, specialty medical director for hospital medicine with Atrium Health in Charlotte, N.C., and others to go beyond just learning about these issues. I want to use my voice to advocate for change, and my actions to participate in effecting change, within the context of my sphere of influence.

So, what does that have to do with the SoHM data on HMG leader demographics? Well, it’s clear that Black and brown people are woefully underrepresented in the ranks of hospital medicine leadership.

Unfortunately, we don’t have good information on racial diversity for hospitalists as a specialty, though I understand that SHM is working on plans to update membership profiles to begin collecting this information. In searching the Internet, I found a 2018 paper from the Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved that studied racial and ethnic distribution of U.S. primary care physicians (doi: 10.1353/hpu.2018.0036). It reported that, in 2012, 7.8% of general internists were Black, along with 5.8% of family medicine/general practice physicians and 6.8% of pediatricians. A separate data set issued by the Association of American Medical Colleges reported that, in 2019, 6.4% of all actively practicing general internal medicine doctors were Black (5.5% of male IM physicians and 7.9% of female IM physicians). While this doesn’t mean hospitalists have the same racial and ethnic distribution, this is probably the best proxy we can come up with.

At first glance, having 5.5% of HMG leaders who are Black doesn’t seem terribly out of line with the reported range of 6.4 to 7.8% in the general population of internal medicine physicians (apologies to the family medicine and pediatric hospitalists reading this, but I’ll confine my discussion to internists for ease and brevity, since they represent the vast majority of the nation’s hospitalists). But do the math. It means Black hospitalists are likely underrepresented in HMG leadership ranks by something like 14% to 29% compared to their likely presence among hospitalists in general.

The real problem, of course, is that according the U.S. Census Bureau, 13.4% of the U.S. population is Black. So even if the racial distribution of HMG leaders catches up to the general hospitalist population, hospital medicine is still woefully underrepresenting the racial and ethnic distribution of our patient population.

The disconnect between the ethnic distribution of HMG leaders vs. hospitalists (based on general internal medicine distribution) is even more pronounced for Latinos. The JHCPU paper reported that, in 2012, 5.6% of general internists were Hispanic. The AAMC data set reported 5.8% of IM doctors were Hispanic/Latino. But only 2.2% of SoHM respondent HMGs reported a Hispanic/Latino leader, which means Latinos are underrepresented by somewhere around 61% or so relative to the likely hospitalist population, and by a whole lot more considering the fact that Latinos make up about 18.5% of the U.S. population.

I’m not saying that a White or Asian doctor can’t provide skilled, compassionate care to a Black or Latino patient, or vice-versa. It happens every day. I guess what I am saying is that we as a country and in the medical profession need to do a better job of creating pathways and promoting careers in medicine for people of color. A JAMA paper from 2019 reported that while the numbers and proportions of minority medical school matriculants has slowly been increasing from 2002 to 2017, the rate of increase was “slower than their age-matched counterparts in the U.S. population, resulting in increased underrepresentation” (doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.10490). This means we’re falling behind, not catching up.

We need to make sure that people like Dr. Ryan Brown aren’t discouraged from pursuing medicine by teachers or school counselors because of their skin color or accent, or their gender or sexual orientation. And among those who become doctors, we need to promote hospital medicine as a desirable specialty for people of color and actively invite them in.

In my view, much of this starts with creating more and better paths to leadership within hospital medicine for people of color. Hospital medicine group leaders wield enormous – and increasing – influence, not only within their HMGs and within SHM, but within their institutions and health care systems. We need their voices and their influence to promote diversity within their groups, their institutions, within hospital medicine, and within medicine and the U.S. health care system more broadly.

The Society of Hospital Medicine is already taking steps to promote diversity, equity and inclusion. These include issuing a formal Diversity and Inclusion Statement, creating the DEI SIG, and the recent formation of a Board-designated DEI task force charged with making recommendations to promote DEI within SHM and in hospital medicine more broadly. But I want to challenge SHM to do more, particularly with regard to promoting diversity in leadership. Here are a few ideas to consider:

- Create and sponsor a mentoring program in which hospitalists volunteer to mentor minority junior high and high school students and help them prepare to pursue a career in medicine.

- Develop a formal, structured advocacy or collaboration effort with organizations like AAMC and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education designed to promote meaningful increases in the proportion of medical school students and residents who are people of color, and in the proportion who choose primary care – and ultimately, hospital medicine.

- Work hard to collect reliable racial, ethnic and gender information about SHM members and consider collaborating with MGMA to incorporate demographic questions into its survey tool for individual hospitalist compensation and productivity data. Challenge us on the Practice Analysis Committee who are responsible for the SoHM survey to continue surveying leadership demographics, and to consider how we can expand our collection of DEI information in 2022.

- Undertake a public relations campaign to highlight to health systems and other employers the under-representation of Black and Latino hospitalists in leadership positions, and to promote conscious efforts to increase those ranks.

- Create scholarships for hospitalists from underrepresented racial and ethnic groups to attend SHM-sponsored leadership development programs such as Leadership Academy, Academic Hospitalist Academy, and Quality and Safety Educators Academy, with the goal of increasing their ranks in positions of influence throughout healthcare. A scholarship program might even include raising funds to help minority hospitalists pursue Master’s-level programs such as an MBA, MHA, or MMM.

- Develop an educational track, mentoring program, or other support initiative for early-career hospitalist leaders and those interested in developing leadership skills, and ensure it gives specific attention to strategies for increasing the proportion of hospitalists of color in leadership positions.

- Review and revise existing SHM documents such as The Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group, the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine, and various white papers and position statements to ensure they address diversity, equity and inclusion – both with regard to the hospital medicine workforce and leadership, and with regard to patient care and eliminating health disparities.

I’m sure there are plenty of other similar actions we can take that I haven’t thought of. But we need to start the conversation about concrete steps our Society, and the medical specialty we represent, can take to foster real change. And then, we need to follow our words up with actions.

Ms. Flores is a partner at Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants in La Quinta, Calif. She serves on SHM’s Practice Analysis and Annual Conference Committees and helps to coordinate SHM’s biannual State of Hospital Medicine survey.

Hospitalists and unit-based assignments

What seems like a usual day to a seasoned hospitalist can be a daunting task for a new hospitalist. A routine day as a hospitalist begins with prerounding, organizing, familiarizing, and gathering data on the list of patients, and most importantly prioritizing the tasks for the day. I have experienced both traditional and unit-based rounding models, and the geographic (unit-based) rounding model stands out for me.

The push for geographic rounding comes from the need to achieve excellence in patient care, coordination with nursing staff, higher HCAHPS (Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) scores, better provider satisfaction, and efficiency in work flow and in documentation. The goal is typically to use this well-established tool to provide quality care to acutely ill patients admitted to the hospital, creating an environment of improved communication with the staff. It’s a “patient-centered care” model – if the patient wants to see a physician, it’s quicker to get to the patient and provides more visibility for the physician. These encounters result in improved patient-provider relationships, which in turn influences HCAHPS scores. Proximity encourages empathy, better work flow, and productivity.

The American health care system is intense and complex, and effective hospital medicine groups (HMGs) strive to provide quality care. Performance of an effective HMG is often scored on a “balanced score card.” The “balanced score” evaluates performance on domains such as clinical quality and safety, financial stability, HCAHPS, and operational effectiveness (length of stay and readmission rates). In my experience, effective unit-based rounding positively influences all the measures of the balanced score card.

Multidisciplinary roundings (MDRs) provide a platform where “the team” meets every morning to discuss the daily plan of care, everyone gets on the same page, and unit-based assignments facilitate hospitalist participation in MDRs. MDRs typically are a collaborative effort between care team members, such as a case manager, nurse, and hospitalist, physical therapist, and pharmacist. Each team member provides a precise input. Team members feel accountable and are better prepared for the day. It’s easier to develop a rapport with your patient when the same organized, comprehensive plan of care gets communicated to the patient.

It is important that each team member is prepared prior to the rounds. The total time for the rounds is often tightly controlled, as a fundamental concern is that MDRs can take up too much time. Use of a checklist or whiteboard during the unit-based rounds can improve efficiency. Midday MDRs are another gem in patient care, where the team proactively addresses early barriers in patient care and discharge plans for the next day.

The 2020 State of Hospital Medicine report highlights utilization of unit-based rounding, including breakdowns based on employment model. In groups serving adults patients only, 43% of university/medical school practices utilized unit-based assignments versus 48% for hospital-employed HMGs and only 32% for HMGs employed by multistate management companies. In HMGs that served pediatric patients only, 27% utilized unit-based assignments.

Undoubtedly geographic rounding has its own challenges. The pros and cons and the feasibility needs to be determined by each HMG. It’s often best to conduct the unit-based rounds on a few units and then roll it out to all the floors.

An important prerequisite to establishing a unit-based model for rounding is a detailed data analysis of total number of patients in various units to ensure there is adequate staffing. It must be practical to localize providers to different units, and complexity of various units can differ. At Lahey Hospital and Medical Center in Burlington, Mass., an efficient unit-based model has been achieved with complex units typically assigned two providers. Units including oncology and the progressive care unit can be a challenge, because of higher intensity and patient turnover.

Each unit is tagged to another unit in the same geographical area; these units are designated “sister pods.” The intention of these units is to strike a balance and level off patient load when needed. This process helps with standardization of the work between the providers. A big challenge of the unit-based model is to understand that it’s not always feasible to maintain consistency in patient assignments. Some patients can get transferred to a different unit due to limited telemetry and specialty units. At Lahey the provider manages their own patient as “patient drift” happens, in an attempt to maintain continuity of care.

The ultimate goal of unit-based assignments is to improve quality, financial, and operational metrics for the organization and take a deeper dive into provider and staff satisfaction. The simplest benefit for a hospitalist is to reduce travel time while rounding.

Education and teaching opportunities during the daily MDRs are still debatable. Another big step in this area may be a “resident-centered MDR” with the dual goals of improving both quality of care and resident education by focusing on evidence-based medicine.

Dr. Puri is a hospitalist at Lahey Hospital and Medical Center in Burlington, Mass.

What seems like a usual day to a seasoned hospitalist can be a daunting task for a new hospitalist. A routine day as a hospitalist begins with prerounding, organizing, familiarizing, and gathering data on the list of patients, and most importantly prioritizing the tasks for the day. I have experienced both traditional and unit-based rounding models, and the geographic (unit-based) rounding model stands out for me.

The push for geographic rounding comes from the need to achieve excellence in patient care, coordination with nursing staff, higher HCAHPS (Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) scores, better provider satisfaction, and efficiency in work flow and in documentation. The goal is typically to use this well-established tool to provide quality care to acutely ill patients admitted to the hospital, creating an environment of improved communication with the staff. It’s a “patient-centered care” model – if the patient wants to see a physician, it’s quicker to get to the patient and provides more visibility for the physician. These encounters result in improved patient-provider relationships, which in turn influences HCAHPS scores. Proximity encourages empathy, better work flow, and productivity.

The American health care system is intense and complex, and effective hospital medicine groups (HMGs) strive to provide quality care. Performance of an effective HMG is often scored on a “balanced score card.” The “balanced score” evaluates performance on domains such as clinical quality and safety, financial stability, HCAHPS, and operational effectiveness (length of stay and readmission rates). In my experience, effective unit-based rounding positively influences all the measures of the balanced score card.

Multidisciplinary roundings (MDRs) provide a platform where “the team” meets every morning to discuss the daily plan of care, everyone gets on the same page, and unit-based assignments facilitate hospitalist participation in MDRs. MDRs typically are a collaborative effort between care team members, such as a case manager, nurse, and hospitalist, physical therapist, and pharmacist. Each team member provides a precise input. Team members feel accountable and are better prepared for the day. It’s easier to develop a rapport with your patient when the same organized, comprehensive plan of care gets communicated to the patient.

It is important that each team member is prepared prior to the rounds. The total time for the rounds is often tightly controlled, as a fundamental concern is that MDRs can take up too much time. Use of a checklist or whiteboard during the unit-based rounds can improve efficiency. Midday MDRs are another gem in patient care, where the team proactively addresses early barriers in patient care and discharge plans for the next day.

The 2020 State of Hospital Medicine report highlights utilization of unit-based rounding, including breakdowns based on employment model. In groups serving adults patients only, 43% of university/medical school practices utilized unit-based assignments versus 48% for hospital-employed HMGs and only 32% for HMGs employed by multistate management companies. In HMGs that served pediatric patients only, 27% utilized unit-based assignments.

Undoubtedly geographic rounding has its own challenges. The pros and cons and the feasibility needs to be determined by each HMG. It’s often best to conduct the unit-based rounds on a few units and then roll it out to all the floors.

An important prerequisite to establishing a unit-based model for rounding is a detailed data analysis of total number of patients in various units to ensure there is adequate staffing. It must be practical to localize providers to different units, and complexity of various units can differ. At Lahey Hospital and Medical Center in Burlington, Mass., an efficient unit-based model has been achieved with complex units typically assigned two providers. Units including oncology and the progressive care unit can be a challenge, because of higher intensity and patient turnover.

Each unit is tagged to another unit in the same geographical area; these units are designated “sister pods.” The intention of these units is to strike a balance and level off patient load when needed. This process helps with standardization of the work between the providers. A big challenge of the unit-based model is to understand that it’s not always feasible to maintain consistency in patient assignments. Some patients can get transferred to a different unit due to limited telemetry and specialty units. At Lahey the provider manages their own patient as “patient drift” happens, in an attempt to maintain continuity of care.

The ultimate goal of unit-based assignments is to improve quality, financial, and operational metrics for the organization and take a deeper dive into provider and staff satisfaction. The simplest benefit for a hospitalist is to reduce travel time while rounding.

Education and teaching opportunities during the daily MDRs are still debatable. Another big step in this area may be a “resident-centered MDR” with the dual goals of improving both quality of care and resident education by focusing on evidence-based medicine.

Dr. Puri is a hospitalist at Lahey Hospital and Medical Center in Burlington, Mass.

What seems like a usual day to a seasoned hospitalist can be a daunting task for a new hospitalist. A routine day as a hospitalist begins with prerounding, organizing, familiarizing, and gathering data on the list of patients, and most importantly prioritizing the tasks for the day. I have experienced both traditional and unit-based rounding models, and the geographic (unit-based) rounding model stands out for me.

The push for geographic rounding comes from the need to achieve excellence in patient care, coordination with nursing staff, higher HCAHPS (Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) scores, better provider satisfaction, and efficiency in work flow and in documentation. The goal is typically to use this well-established tool to provide quality care to acutely ill patients admitted to the hospital, creating an environment of improved communication with the staff. It’s a “patient-centered care” model – if the patient wants to see a physician, it’s quicker to get to the patient and provides more visibility for the physician. These encounters result in improved patient-provider relationships, which in turn influences HCAHPS scores. Proximity encourages empathy, better work flow, and productivity.

The American health care system is intense and complex, and effective hospital medicine groups (HMGs) strive to provide quality care. Performance of an effective HMG is often scored on a “balanced score card.” The “balanced score” evaluates performance on domains such as clinical quality and safety, financial stability, HCAHPS, and operational effectiveness (length of stay and readmission rates). In my experience, effective unit-based rounding positively influences all the measures of the balanced score card.

Multidisciplinary roundings (MDRs) provide a platform where “the team” meets every morning to discuss the daily plan of care, everyone gets on the same page, and unit-based assignments facilitate hospitalist participation in MDRs. MDRs typically are a collaborative effort between care team members, such as a case manager, nurse, and hospitalist, physical therapist, and pharmacist. Each team member provides a precise input. Team members feel accountable and are better prepared for the day. It’s easier to develop a rapport with your patient when the same organized, comprehensive plan of care gets communicated to the patient.

It is important that each team member is prepared prior to the rounds. The total time for the rounds is often tightly controlled, as a fundamental concern is that MDRs can take up too much time. Use of a checklist or whiteboard during the unit-based rounds can improve efficiency. Midday MDRs are another gem in patient care, where the team proactively addresses early barriers in patient care and discharge plans for the next day.

The 2020 State of Hospital Medicine report highlights utilization of unit-based rounding, including breakdowns based on employment model. In groups serving adults patients only, 43% of university/medical school practices utilized unit-based assignments versus 48% for hospital-employed HMGs and only 32% for HMGs employed by multistate management companies. In HMGs that served pediatric patients only, 27% utilized unit-based assignments.

Undoubtedly geographic rounding has its own challenges. The pros and cons and the feasibility needs to be determined by each HMG. It’s often best to conduct the unit-based rounds on a few units and then roll it out to all the floors.

An important prerequisite to establishing a unit-based model for rounding is a detailed data analysis of total number of patients in various units to ensure there is adequate staffing. It must be practical to localize providers to different units, and complexity of various units can differ. At Lahey Hospital and Medical Center in Burlington, Mass., an efficient unit-based model has been achieved with complex units typically assigned two providers. Units including oncology and the progressive care unit can be a challenge, because of higher intensity and patient turnover.

Each unit is tagged to another unit in the same geographical area; these units are designated “sister pods.” The intention of these units is to strike a balance and level off patient load when needed. This process helps with standardization of the work between the providers. A big challenge of the unit-based model is to understand that it’s not always feasible to maintain consistency in patient assignments. Some patients can get transferred to a different unit due to limited telemetry and specialty units. At Lahey the provider manages their own patient as “patient drift” happens, in an attempt to maintain continuity of care.

The ultimate goal of unit-based assignments is to improve quality, financial, and operational metrics for the organization and take a deeper dive into provider and staff satisfaction. The simplest benefit for a hospitalist is to reduce travel time while rounding.

Education and teaching opportunities during the daily MDRs are still debatable. Another big step in this area may be a “resident-centered MDR” with the dual goals of improving both quality of care and resident education by focusing on evidence-based medicine.

Dr. Puri is a hospitalist at Lahey Hospital and Medical Center in Burlington, Mass.

SHM Chapter innovations: A provider exchange program

The SHM Annual Conference is more than an educational event. It also provides an opportunity to collaborate, network and create innovative ideas to improve the quality of inpatient care.

During the 2019 Annual Conference (HM19) – the last “in-person” Annual Conference before the COVID pandemic – SHM chapter leaders from the New Mexico chapter (Krystle Apodaca) and the Wiregrass chapter (Amith Skandhan), which covers the counties of Southern Alabama and the Panhandle of Florida, met during a networking event.

As we talked, we realized the unique differences and similarities our practice settings shared. We debated the role of clinician wellbeing, quality of medical education, and faculty development on individual hospital medicine group (HMG) practice styles.

Clinician well-being is the prerequisite to the Triple Aim of improving the health of populations, enhancing the patient experience, and reducing the cost of care. Engagement in local SHM chapter activities promotes the efficiency of practice, a culture of wellness, and personal resilience. Each HMG faces similar challenges but approaches to solving them vary. Professional challenges can affect the well-being of individual clinicians. During our discussion we realized that an interinstitutional exchange programs could provide a platform to exchange ideas and establish mentors.

The quality of medical education is directly linked to the quality of faculty development. Improving the quality of medical education requires a multifaceted approach by highly developed faculty. The complex factors affecting medical education and faculty development are further complicated by geographic location, patient characteristics, and professional growth opportunities.

Overcoming these obstacles requires an innovative and collaborative approach. Although faculty exchanges are common in academic medicine, they are not commonly attempted with HMGs. Hospitalists are responsible for a significant part of inpatient training for residents, medical students, and nurse practitioners/physician assistants (NPs/PAs) but their faculty training can vary based on location.

As a young specialty, hospital medicine is still evolving and incorporating NPs/PAs and physician hospitalists in varied practice models. Each HMG addresses common obstacles differently based on their culture and practice styles. As chapter leaders we determined that an exchange program would afford the opportunity for visiting faculty members to experience these differences.

We shared the idea of a chapter-level exchange with SHM’s Chapter Development Committee and obtained chapter development funds to execute the event. We also requested that an SHM national board member visit during the exchange to provide insight and feedback. We researched the characteristics of individual academic HMGs and structured a faculty exchange involving physicians and NPs/PAs. During the exchange program planning, the visiting faculty itinerary was tailored to a well-planned agenda for one week, with separate tracks for physicians and NPs/PAs, giving increased access to their individual peer practice styles. Additionally, the visiting faculty had meetings and discussions with the HMG and hospital leadership, to specifically address the visiting faculty’s institutional challenges.

The overall goal of the exchange program was to promote cross-institutional collaboration, increase engagement, improve medical education through faculty development and improve the quality of care. The focus of the exchange program was to share ideas and innovation, and learn the approaches to unique challenges at each institution. Out of this also grew collaboration and mentoring opportunities.

SHM’s New Mexico chapter is based in Albuquerque, a city in the desert Southwest with an ethnically diverse population of 545,000, The chapter leadership works at the University of New Mexico (UNM), a 553-bed medical center. UNM has a well-established internal medicine residency program, an academic hospitalist program, and an NP/PA fellowship program embedded within the hospital medicine department. At the time of the exchange, the HMG at UNM has 26 physicians and 9 NP/PA’s.

The SHM Wiregrass chapter is located in Dothan, Ala., a town of 80,000 near the Gulf of Mexico. Chapter leadership works at Southeast Health, a tertiary care facility with 420 beds, an affiliated medical school, and an internal medicine residency program. At the time of the exchange, the HMG at SEH has 28 physicians and 5 NP/PA’s.

These are two similarly sized hospital medicine programs, located in different geographic regions, and serving different populations. SHM board member Howard Epstein, MD, SFHM, vice president and chief medical officer of Presbyterian Healthcare Services in Albuquerque, participated on behalf of the Society when SEH faculty visited UNM. Kris Rehm, MD, SFHM, a pediatric hospitalist and the vice chair of outreach medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, came to Dothan during the faculty visit by UNM.

Two SEH faculty members, a physician and an NP, visited the University of New Mexico Hospital for one week. They participated as observers, rounding with the teams and meeting the UNM HMG leadership. The focus of the discussions included faculty education, a curriculum for quality improvement, and ways to address practice challenges. The SEH faculty also presented a QI project from their institution, and established collaborative relationships.

During the second part of the exchange, three UNM faculty members, including one physician and two NPs, visited SEH for one week. During the visit, they observed NP/PA hospitalist team models, discussed innovations, established mentoring relationships with leadership, and discussed QI projects at SEH. Additionally, the visiting UNM faculty participated in Women In Medicine events and participated as judges for a poster competition. They also had an opportunity to explore the rural landscape and visit the beach.

The evaluation process after the exchanges involved interviews, a survey, and the establishment of shared QI projects in mutual areas of challenge. The survey provided feedback, lessons learned from the exchange, and areas to be improved. Collaborative QI projects currently underway as a result of the exchange include paging etiquette, quality of sleep for hospitalized patients, and onboarding of NPs/PAs in HMGs.

This innovation changed our thinking as medical educators by addressing faculty development and medical education via clinician well-being. The physician and NP/PA Faculty Exchange program was an essential and meaningful innovation that resulted in increased SHM member engagement, crossinstitutional collaboration, networking, and mentorship.

This event created opportunities for faculty collaboration and expanded the professional network of participating institutions. The costs of the exchange were minimal given support from SHM. We believe that once the COVID pandemic has ended, this initiative has the potential to expand facilitated exchanges nationally and internationally, enhance faculty development, and improve medical education.

Dr. Apodaca is assistant professor and nurse practitioner hospitalist at the University of New Mexico. She serves as codirector of the UNM APP Hospital Medicine Fellowship and director of the APP Hospital Medicine Team. Dr. Skandhan is a hospitalist and member of the Core Faculty for the Internal Medicine Residency Program at Southeast Health (SEH), Dothan Ala., and an assistant professor at the Alabama College of Osteopathic Medicine. He serves as the medical director/physician liaison for the Clinical Documentation Program at SEH and also as the director for physician integration for Southeast Health Statera Network, an Accountable Care Organization.

The SHM Annual Conference is more than an educational event. It also provides an opportunity to collaborate, network and create innovative ideas to improve the quality of inpatient care.

During the 2019 Annual Conference (HM19) – the last “in-person” Annual Conference before the COVID pandemic – SHM chapter leaders from the New Mexico chapter (Krystle Apodaca) and the Wiregrass chapter (Amith Skandhan), which covers the counties of Southern Alabama and the Panhandle of Florida, met during a networking event.

As we talked, we realized the unique differences and similarities our practice settings shared. We debated the role of clinician wellbeing, quality of medical education, and faculty development on individual hospital medicine group (HMG) practice styles.

Clinician well-being is the prerequisite to the Triple Aim of improving the health of populations, enhancing the patient experience, and reducing the cost of care. Engagement in local SHM chapter activities promotes the efficiency of practice, a culture of wellness, and personal resilience. Each HMG faces similar challenges but approaches to solving them vary. Professional challenges can affect the well-being of individual clinicians. During our discussion we realized that an interinstitutional exchange programs could provide a platform to exchange ideas and establish mentors.

The quality of medical education is directly linked to the quality of faculty development. Improving the quality of medical education requires a multifaceted approach by highly developed faculty. The complex factors affecting medical education and faculty development are further complicated by geographic location, patient characteristics, and professional growth opportunities.

Overcoming these obstacles requires an innovative and collaborative approach. Although faculty exchanges are common in academic medicine, they are not commonly attempted with HMGs. Hospitalists are responsible for a significant part of inpatient training for residents, medical students, and nurse practitioners/physician assistants (NPs/PAs) but their faculty training can vary based on location.

As a young specialty, hospital medicine is still evolving and incorporating NPs/PAs and physician hospitalists in varied practice models. Each HMG addresses common obstacles differently based on their culture and practice styles. As chapter leaders we determined that an exchange program would afford the opportunity for visiting faculty members to experience these differences.

We shared the idea of a chapter-level exchange with SHM’s Chapter Development Committee and obtained chapter development funds to execute the event. We also requested that an SHM national board member visit during the exchange to provide insight and feedback. We researched the characteristics of individual academic HMGs and structured a faculty exchange involving physicians and NPs/PAs. During the exchange program planning, the visiting faculty itinerary was tailored to a well-planned agenda for one week, with separate tracks for physicians and NPs/PAs, giving increased access to their individual peer practice styles. Additionally, the visiting faculty had meetings and discussions with the HMG and hospital leadership, to specifically address the visiting faculty’s institutional challenges.

The overall goal of the exchange program was to promote cross-institutional collaboration, increase engagement, improve medical education through faculty development and improve the quality of care. The focus of the exchange program was to share ideas and innovation, and learn the approaches to unique challenges at each institution. Out of this also grew collaboration and mentoring opportunities.

SHM’s New Mexico chapter is based in Albuquerque, a city in the desert Southwest with an ethnically diverse population of 545,000, The chapter leadership works at the University of New Mexico (UNM), a 553-bed medical center. UNM has a well-established internal medicine residency program, an academic hospitalist program, and an NP/PA fellowship program embedded within the hospital medicine department. At the time of the exchange, the HMG at UNM has 26 physicians and 9 NP/PA’s.

The SHM Wiregrass chapter is located in Dothan, Ala., a town of 80,000 near the Gulf of Mexico. Chapter leadership works at Southeast Health, a tertiary care facility with 420 beds, an affiliated medical school, and an internal medicine residency program. At the time of the exchange, the HMG at SEH has 28 physicians and 5 NP/PA’s.

These are two similarly sized hospital medicine programs, located in different geographic regions, and serving different populations. SHM board member Howard Epstein, MD, SFHM, vice president and chief medical officer of Presbyterian Healthcare Services in Albuquerque, participated on behalf of the Society when SEH faculty visited UNM. Kris Rehm, MD, SFHM, a pediatric hospitalist and the vice chair of outreach medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, came to Dothan during the faculty visit by UNM.

Two SEH faculty members, a physician and an NP, visited the University of New Mexico Hospital for one week. They participated as observers, rounding with the teams and meeting the UNM HMG leadership. The focus of the discussions included faculty education, a curriculum for quality improvement, and ways to address practice challenges. The SEH faculty also presented a QI project from their institution, and established collaborative relationships.

During the second part of the exchange, three UNM faculty members, including one physician and two NPs, visited SEH for one week. During the visit, they observed NP/PA hospitalist team models, discussed innovations, established mentoring relationships with leadership, and discussed QI projects at SEH. Additionally, the visiting UNM faculty participated in Women In Medicine events and participated as judges for a poster competition. They also had an opportunity to explore the rural landscape and visit the beach.

The evaluation process after the exchanges involved interviews, a survey, and the establishment of shared QI projects in mutual areas of challenge. The survey provided feedback, lessons learned from the exchange, and areas to be improved. Collaborative QI projects currently underway as a result of the exchange include paging etiquette, quality of sleep for hospitalized patients, and onboarding of NPs/PAs in HMGs.

This innovation changed our thinking as medical educators by addressing faculty development and medical education via clinician well-being. The physician and NP/PA Faculty Exchange program was an essential and meaningful innovation that resulted in increased SHM member engagement, crossinstitutional collaboration, networking, and mentorship.

This event created opportunities for faculty collaboration and expanded the professional network of participating institutions. The costs of the exchange were minimal given support from SHM. We believe that once the COVID pandemic has ended, this initiative has the potential to expand facilitated exchanges nationally and internationally, enhance faculty development, and improve medical education.

Dr. Apodaca is assistant professor and nurse practitioner hospitalist at the University of New Mexico. She serves as codirector of the UNM APP Hospital Medicine Fellowship and director of the APP Hospital Medicine Team. Dr. Skandhan is a hospitalist and member of the Core Faculty for the Internal Medicine Residency Program at Southeast Health (SEH), Dothan Ala., and an assistant professor at the Alabama College of Osteopathic Medicine. He serves as the medical director/physician liaison for the Clinical Documentation Program at SEH and also as the director for physician integration for Southeast Health Statera Network, an Accountable Care Organization.

The SHM Annual Conference is more than an educational event. It also provides an opportunity to collaborate, network and create innovative ideas to improve the quality of inpatient care.

During the 2019 Annual Conference (HM19) – the last “in-person” Annual Conference before the COVID pandemic – SHM chapter leaders from the New Mexico chapter (Krystle Apodaca) and the Wiregrass chapter (Amith Skandhan), which covers the counties of Southern Alabama and the Panhandle of Florida, met during a networking event.

As we talked, we realized the unique differences and similarities our practice settings shared. We debated the role of clinician wellbeing, quality of medical education, and faculty development on individual hospital medicine group (HMG) practice styles.

Clinician well-being is the prerequisite to the Triple Aim of improving the health of populations, enhancing the patient experience, and reducing the cost of care. Engagement in local SHM chapter activities promotes the efficiency of practice, a culture of wellness, and personal resilience. Each HMG faces similar challenges but approaches to solving them vary. Professional challenges can affect the well-being of individual clinicians. During our discussion we realized that an interinstitutional exchange programs could provide a platform to exchange ideas and establish mentors.

The quality of medical education is directly linked to the quality of faculty development. Improving the quality of medical education requires a multifaceted approach by highly developed faculty. The complex factors affecting medical education and faculty development are further complicated by geographic location, patient characteristics, and professional growth opportunities.

Overcoming these obstacles requires an innovative and collaborative approach. Although faculty exchanges are common in academic medicine, they are not commonly attempted with HMGs. Hospitalists are responsible for a significant part of inpatient training for residents, medical students, and nurse practitioners/physician assistants (NPs/PAs) but their faculty training can vary based on location.

As a young specialty, hospital medicine is still evolving and incorporating NPs/PAs and physician hospitalists in varied practice models. Each HMG addresses common obstacles differently based on their culture and practice styles. As chapter leaders we determined that an exchange program would afford the opportunity for visiting faculty members to experience these differences.

We shared the idea of a chapter-level exchange with SHM’s Chapter Development Committee and obtained chapter development funds to execute the event. We also requested that an SHM national board member visit during the exchange to provide insight and feedback. We researched the characteristics of individual academic HMGs and structured a faculty exchange involving physicians and NPs/PAs. During the exchange program planning, the visiting faculty itinerary was tailored to a well-planned agenda for one week, with separate tracks for physicians and NPs/PAs, giving increased access to their individual peer practice styles. Additionally, the visiting faculty had meetings and discussions with the HMG and hospital leadership, to specifically address the visiting faculty’s institutional challenges.

The overall goal of the exchange program was to promote cross-institutional collaboration, increase engagement, improve medical education through faculty development and improve the quality of care. The focus of the exchange program was to share ideas and innovation, and learn the approaches to unique challenges at each institution. Out of this also grew collaboration and mentoring opportunities.

SHM’s New Mexico chapter is based in Albuquerque, a city in the desert Southwest with an ethnically diverse population of 545,000, The chapter leadership works at the University of New Mexico (UNM), a 553-bed medical center. UNM has a well-established internal medicine residency program, an academic hospitalist program, and an NP/PA fellowship program embedded within the hospital medicine department. At the time of the exchange, the HMG at UNM has 26 physicians and 9 NP/PA’s.

The SHM Wiregrass chapter is located in Dothan, Ala., a town of 80,000 near the Gulf of Mexico. Chapter leadership works at Southeast Health, a tertiary care facility with 420 beds, an affiliated medical school, and an internal medicine residency program. At the time of the exchange, the HMG at SEH has 28 physicians and 5 NP/PA’s.

These are two similarly sized hospital medicine programs, located in different geographic regions, and serving different populations. SHM board member Howard Epstein, MD, SFHM, vice president and chief medical officer of Presbyterian Healthcare Services in Albuquerque, participated on behalf of the Society when SEH faculty visited UNM. Kris Rehm, MD, SFHM, a pediatric hospitalist and the vice chair of outreach medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, came to Dothan during the faculty visit by UNM.

Two SEH faculty members, a physician and an NP, visited the University of New Mexico Hospital for one week. They participated as observers, rounding with the teams and meeting the UNM HMG leadership. The focus of the discussions included faculty education, a curriculum for quality improvement, and ways to address practice challenges. The SEH faculty also presented a QI project from their institution, and established collaborative relationships.

During the second part of the exchange, three UNM faculty members, including one physician and two NPs, visited SEH for one week. During the visit, they observed NP/PA hospitalist team models, discussed innovations, established mentoring relationships with leadership, and discussed QI projects at SEH. Additionally, the visiting UNM faculty participated in Women In Medicine events and participated as judges for a poster competition. They also had an opportunity to explore the rural landscape and visit the beach.

The evaluation process after the exchanges involved interviews, a survey, and the establishment of shared QI projects in mutual areas of challenge. The survey provided feedback, lessons learned from the exchange, and areas to be improved. Collaborative QI projects currently underway as a result of the exchange include paging etiquette, quality of sleep for hospitalized patients, and onboarding of NPs/PAs in HMGs.

This innovation changed our thinking as medical educators by addressing faculty development and medical education via clinician well-being. The physician and NP/PA Faculty Exchange program was an essential and meaningful innovation that resulted in increased SHM member engagement, crossinstitutional collaboration, networking, and mentorship.

This event created opportunities for faculty collaboration and expanded the professional network of participating institutions. The costs of the exchange were minimal given support from SHM. We believe that once the COVID pandemic has ended, this initiative has the potential to expand facilitated exchanges nationally and internationally, enhance faculty development, and improve medical education.

Dr. Apodaca is assistant professor and nurse practitioner hospitalist at the University of New Mexico. She serves as codirector of the UNM APP Hospital Medicine Fellowship and director of the APP Hospital Medicine Team. Dr. Skandhan is a hospitalist and member of the Core Faculty for the Internal Medicine Residency Program at Southeast Health (SEH), Dothan Ala., and an assistant professor at the Alabama College of Osteopathic Medicine. He serves as the medical director/physician liaison for the Clinical Documentation Program at SEH and also as the director for physician integration for Southeast Health Statera Network, an Accountable Care Organization.

Medicine and the meritocracy

Addressing systemic bias, gender inequity and discrimination

There are many challenges facing modern medicine today. Recent events have highlighted important issues affecting our society as a whole – systemic racism, sexism, and implicit bias. In medicine, we have seen a renewed focus on health equity, health disparities and the implicit systemic bias that affect those who work in the field. It is truly troubling that it has taken the continued loss of black lives to police brutality and a pandemic for this conversation to happen at every level in society.

Systemic bias is present throughout corporate America, and it is no different within the physician workforce. Overall, there has been gradual interest in promoting and teaching diversity. Institutions have been slowly creating policies and administrative positions focused on inclusion and diversity over the last decade. So has diversity training objectively increased representation and advancement of women and minority groups? Do traditionally marginalized groups have better access to health? And are women and people of color (POC) represented equally in leadership positions in medicine?

Clearly, the answers are not straightforward.

Diving into the data

A guilty pleasure of mine is to assess how diverse and inclusive an institution is by looking at the wall of pictures recognizing top leadership in hospitals. Despite women accounting for 47.9% of graduates from medical school in 2018-2019, I still see very few women or POC elevated to this level. Of the total women graduates, 22.6% were Asian, 8% were Black and 5.4% were Hispanic.

Being of Indian descent, I am a woman of color (albeit one who may not be as profoundly affected by racism in medicine as my less represented colleagues). It is especially rare for me to see someone I can identify with in the ranks of top leadership. I find encouragement in seeing any woman on any leadership board because to me, it means that there is hope. The literature seems to support this degree of disparity as well. For example, a recent analysis shows that presidential leadership in medical societies are predominantly held by men (82.6% male vs. 17.4% female). Other datasets demonstrate that only 15% of deans and interim deans are women and AAMC’s report shows that women account for only 18% of all department chairs.

Growing up, my parents fueled my interest to pursue medicine. They described it as a noble profession that rewarded true merit and dedication to the cause. However, those that have been traditionally elevated in medicine are men. If merit knows no gender, why does a gender gap exist? If merit is blind to race, why are minorities so poorly represented in the workforce (much less in leadership)? My view of the wall leaves me wondering about the role of both sexism and racism in medicine.

These visual representations of the medical culture reinforce the acceptable norms and values – white and masculine – in medicine. The feminist movement over the last several decades has increased awareness about the need for equality of the sexes. However, it was not until the concept of intersectionality was introduced by Black feminist Professor Kimberle Crenshaw, that feminism become a more inclusive term. Professor Crenshaw’s paper details how every individual has intersecting factors – race, gender, sexual identity, socioeconomic status – that create the sum of their experience be it privilege, oppression, or discrimination.

For example, a White woman has privileges that a woman of color does not. Among non-white women, race and sexual identity are confounding factors – a Black woman, a Black LGBTQ woman, and an Asian woman, for example, will not experience discrimination in the same way. The farther you deviate from the accepted norms and values, the harder it is for you to obtain support and achieve recognition.

Addressing the patriarchal structure and systemic bias in medicine

Why do patriarchal structures still exist in medicine? How do we resolve systemic bias? Addressing them in isolation – race or gender or sexual identity – is unlikely to create long-lasting change. For change to occur, organizations and individuals need to be intrinsically motivated. Creating awareness and challenging the status quo is the first step.

Over the last decade, implicit bias training and diversity training have become mandatory in various industries and states. Diversity training has grown to be a multi-billion-dollar industry that corporate America has embraced over the last several years. And yet, research shows that mandating such training may not be the most effective. To get results, organizations need to implement programs that “spark engagement, increase contact between different groups and draw on people’s desire to look good to others.”

Historically, the medical curriculum has not included a discourse on feminist theories and the advancement of women in medicine. Cultural competency training is typically offered on an annual basis once we are in the workforce, but in my experience, it focuses more on our interactions with patients and other health care colleagues, and less with regards to our physician peers and leadership. Is this enough to change deep rooted beliefs and traditions?

We can take our cue from non-medical organizations and consider changing this culture of no culture in medicine – introducing diversity task forces that hold departments accountable for recruiting and promoting women and minorities; employing diversity managers; voluntary training; cross-training to increase contact among different groups and mentoring programs that match senior leadership to women and POC. While some medical institutions have implemented some of these principles, changing century-old traditions will require embracing concepts of organizational change and every available effective tool.

Committing to change

Change is especially hard when the target outcome is not accurately quantifiable – even if you can measure attitudes, values, and beliefs, these are subject to reporting bias and tokenism. At the organizational level, change management involves employing a systematic approach to change organizational values, goals, policies, and processes.

Individual change, self-reflection, and personal growth are key components in changing culture. Reflexivity is being aware of your own values, norms, position, and power – an important concept to understand and apply in our everyday interactions. Believing that one’s class, gender, race and sexual orientation are irrelevant to their practice of medicine would not foster the change that we direly need in medicine. Rather, identifying how your own values and professional identity are shaped by your medical training, your organization and the broader cultural context are critically important to developing a greater empathic sense to motivate systemic change.

There has been valuable discussion on bottom-up changes to ensure women and POC have support, encouragement and a pathway to advance in an organization. Some of these include policy and process changes including providing flexible working conditions for women and sponsorship of women and minorities to help them navigate the barriers and microaggressions they encounter at work. While technical (policy) changes form the foundation for any organizational change, it is important to remember that the people side of change – the resistance that you encounter for any change effort in an organization – is equally important to address at the organizational level. A top-down approach is also vital to ensure that change is permanent in an organization and does not end when the individuals responsible for the change leave the organization.