User login

Telehealth models of care for pediatric hospital medicine

PHM 2021 session

Let’s Go Virtual! Developing, Implementing, and Evaluating Telehealth Models of Care for Pediatric Hospital Medicine

Presenters

Brooke Geyer, DO; Christina Olson, MD; and Amy Willis, MD, FAAP

Session summary

Dr. Geyer, Dr. Olson, and Dr. Willis of the University of Colorado presented and facilitated a workshop discussing the role of telehealth in pediatric hospital medicine. Participants were given a brief introduction to the basics of telehealth practices before breaking up into small groups to explore the process of developing, implementing, and evaluating a telehealth model in a pediatric hospital. For each of these topics, the presenters led the breakout groups through a discussion of Colorado’s successful telehealth models, including virtual nocturnists, health system resource optimization, and virtual transitions of care, as well as addressed the participants’ questions unique to their telehealth experiences. The session emphasized the emerging role of telehealth in pediatric hospital medicine and that “telehealth is here to stay, and we have an opportunity to redesign health care forever.”

Key takeaways

- Telehealth is more than just synchronous virtual patient care, it encompasses asynchronous care, remote patient monitoring, education, policy, and more.

- Telehealth standards of care are the same as in-person care.

- Development and implementation of a telehealth model in pediatric hospital medicine is feasible with appropriate planning and conversations with key stakeholders.

- Evaluation and refinement of telehealth models is an iterative process that will take time, much like Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles in quality improvement work.

Dr. Scott is a second-year pediatric hospital medicine fellow at New York–Presbyterian Columbia/Cornell. Her academic interests are in curriculum development and evaluation in medical education with a focus on telemedicine.

PHM 2021 session

Let’s Go Virtual! Developing, Implementing, and Evaluating Telehealth Models of Care for Pediatric Hospital Medicine

Presenters

Brooke Geyer, DO; Christina Olson, MD; and Amy Willis, MD, FAAP

Session summary

Dr. Geyer, Dr. Olson, and Dr. Willis of the University of Colorado presented and facilitated a workshop discussing the role of telehealth in pediatric hospital medicine. Participants were given a brief introduction to the basics of telehealth practices before breaking up into small groups to explore the process of developing, implementing, and evaluating a telehealth model in a pediatric hospital. For each of these topics, the presenters led the breakout groups through a discussion of Colorado’s successful telehealth models, including virtual nocturnists, health system resource optimization, and virtual transitions of care, as well as addressed the participants’ questions unique to their telehealth experiences. The session emphasized the emerging role of telehealth in pediatric hospital medicine and that “telehealth is here to stay, and we have an opportunity to redesign health care forever.”

Key takeaways

- Telehealth is more than just synchronous virtual patient care, it encompasses asynchronous care, remote patient monitoring, education, policy, and more.

- Telehealth standards of care are the same as in-person care.

- Development and implementation of a telehealth model in pediatric hospital medicine is feasible with appropriate planning and conversations with key stakeholders.

- Evaluation and refinement of telehealth models is an iterative process that will take time, much like Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles in quality improvement work.

Dr. Scott is a second-year pediatric hospital medicine fellow at New York–Presbyterian Columbia/Cornell. Her academic interests are in curriculum development and evaluation in medical education with a focus on telemedicine.

PHM 2021 session

Let’s Go Virtual! Developing, Implementing, and Evaluating Telehealth Models of Care for Pediatric Hospital Medicine

Presenters

Brooke Geyer, DO; Christina Olson, MD; and Amy Willis, MD, FAAP

Session summary

Dr. Geyer, Dr. Olson, and Dr. Willis of the University of Colorado presented and facilitated a workshop discussing the role of telehealth in pediatric hospital medicine. Participants were given a brief introduction to the basics of telehealth practices before breaking up into small groups to explore the process of developing, implementing, and evaluating a telehealth model in a pediatric hospital. For each of these topics, the presenters led the breakout groups through a discussion of Colorado’s successful telehealth models, including virtual nocturnists, health system resource optimization, and virtual transitions of care, as well as addressed the participants’ questions unique to their telehealth experiences. The session emphasized the emerging role of telehealth in pediatric hospital medicine and that “telehealth is here to stay, and we have an opportunity to redesign health care forever.”

Key takeaways

- Telehealth is more than just synchronous virtual patient care, it encompasses asynchronous care, remote patient monitoring, education, policy, and more.

- Telehealth standards of care are the same as in-person care.

- Development and implementation of a telehealth model in pediatric hospital medicine is feasible with appropriate planning and conversations with key stakeholders.

- Evaluation and refinement of telehealth models is an iterative process that will take time, much like Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles in quality improvement work.

Dr. Scott is a second-year pediatric hospital medicine fellow at New York–Presbyterian Columbia/Cornell. Her academic interests are in curriculum development and evaluation in medical education with a focus on telemedicine.

Hospitalist movers and shakers – September 2021

Chi-Cheng Huang, MD, SFHM, was recently was named one of the Notable Asian/Pacific American Physicians in U.S. History by the American Board of Internal Medicine. May was Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month. Dr. Huang is the executive medical director and service line director of general medicine and hospital medicine within the Wake Forest Baptist Health System (Winston-Salem, N.C.) and associate professor at Wake Forest School of Medicine.

Dr. Huang is a board-certified hospitalist and pediatrician, and he is the founder of the Bolivian Children Project, a non-profit organization that focuses on sheltering street children in La Paz and other areas of Bolivia. Dr. Huang was inspired to start the project during a year sabbatical from medical school. He worked at an orphanage and cared for children who were victims of physical abuse. The Bolivian Children Project supports those children, and Dr. Huang’s book, When Invisible Children Sing, tells their story.

Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, SFHM, has been elected president of the Florida Medical Association. It is the first time in its history that the FMA will have a DO as its president. Dr. Lenchus is a hospitalist and chief medical officer at the Broward Health Medical Center in Fort Lauderdale, Fla.

Mark V. Williams, MD, MHM, will join Washington University School of Medicine and BJC HealthCare, both in St. Louis, as professor and chief for the Division of Hospital Medicine in October 2021. Dr. Williams is currently professor and director of the Center for Health Services Research at the University of Kentucky and chief quality officer at UK HealthCare, both in Lexington.

Dr. Williams was a founding member of the Society of Hospital Medicine, one of the first two elected members of the Board of SHM, its former president, founding editor of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, and principal investigator for Project BOOST. He established the first hospitalist program at a public hospital (Grady Memorial in Atlanta) in 1998, and later became the founding chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine in 2007 at Northwestern University School of Medicine in Chicago. At the University of Kentucky, he established the Center for Health Services Research and the Division of Hospital Medicine in 2014.

At Washington University, Dr. Williams will be tasked with translating the division of hospital medicine’s scholarly work, innovation, and research into practice improvement, focusing on developing new systems of health care delivery that are patient-centered, cost effective, and provide outstanding value.

Jordan Messler, MD, SFHM, has been named the new chief medical officer at Glytec (Waltham, Mass.), where he has worked as executive director of clinical practice since 2018. Dr. Messler will be tasked with leading strategy and product development while also supporting efforts in quality care, customer relations, and delivery of products.

Glytec provides insulin management software across the care continuum and is touted as the only cloud-based software provider of its kind. Dr. Messler’s background includes expertise in glycemic management. In addition, he still works as a hospitalist at Morton Plant Hospitalist Group (Clearwater, Fla.).

Dr. Messler is a senior fellow with SHM and is physician editor of SHM’s official blog The Hospital Leader.

Tiffani Maycock, DO, recently was named to the Board of Directors for the American Board of Family Medicine. Dr. Maycock is director of the Selma Family Medicine Residency Program at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, where she is an assistant professor in the department of family medicine.

Dr. Maycock helped create hospitalist services at Vaughan Regional Medical Center (Selma, Ala.) – Selma Family Medicine’s primary teaching site – and currently serves as its hospitalist director and on its Medical Executive Committee. She has worked at the facility since 2017.

Preetham Talari, MD, SFHM, has been named associate chief of quality safety for the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of Kentucky’s UK HealthCare (Lexington, Ky.). Dr. Talari is an associate professor of internal medicine in the Division of Hospital Medicine at the UK College of Medicine.

Over the last decade, Dr. Talari’s work in quality, safety, and health care leadership has positioned him as a leader in several UK Healthcare committees and transformation projects. In his role as associate chief, Dr. Talari collaborates with hospital medicine directors, enterprise leadership, and medical education leadership to improve the system’s quality of care.

Dr. Talari is the president of the Kentucky chapter of SHM and is a member of SHM’s Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Committee.

Adrian Paraschiv, MD, FHM, is being recognized by Continental Who’s Who as a Trusted Internist and Hospitalist in the field of Medicine in acknowledgment of his commitment to providing quality health care services.

Dr. Paraschiv is a board-certified Internist at Garnet Health Medical Center in Middletown, N.Y. He also serves in an administrative capacity as the Garnet Health Doctors Hospitalist Division’s Associate Program Director. He is also the Director of Clinical Informatics. Dr. Paraschiv is certified as the Epic physician builder in analytics, information technology, and improved documentation.

DCH Health System (Tuscaloosa, Ala.) recently selected Capstone Health Services Foundation (Tuscaloosa) and IN Compass Health Inc. (Alpharetta, Ga.) as its joint hospitalist service provider for facilities in Northport and Tuscaloosa. Capstone will provide the physicians, while IN Compass will handle staffing management of the hospitalists, as well as day-to-day operations and calculating quality care metrics. The agreement is slated to begin on Oct. 1, 2021, at Northport Medical Center, and on Nov. 1, 2021, at DCH Regional Medical Center.

Capstone is an affiliate of the University of Alabama and oversees University Hospitalist Group, which currently provides hospitalists at DCH Regional Medical Center. Its partnership with IN Compass includes working together in recruiting and hiring physicians for both facilities.

UPMC Kane Medical Center (Kane, Pa.) recently announced the creation of a virtual telemedicine hospitalist program. UPMC Kane is partnering with the UPMC Center for Community Hospitalist Medicine to create this new mode of care.

Telehospitalists will care for UPMC Kane patients using advanced diagnostic technique and high-definition cameras. The physicians will bring expert service to Kane 24 hours per day utilizing physicians and specialists based in Pittsburgh. Those hospitalists will work with local nurse practitioners and support staff and deliver care to Kane patients.

Wake Forest Baptist Health (Winston-Salem, N.C.) has launched a Hospitalist at Home program with hopes of keeping patients safe while also reducing time they spend in the hospital. The telehealth initiative kicked into gear at the start of 2021 and considered the first of its kind in the region.

Patients who qualify for the program establish a plan before they leave the hospital. Wake Forest Baptist Health paramedics makes home visits and conducts care with a hospitalist reviewing the visit virtually. Those appointments continue until the patient does not require monitoring.

The impetus of creating the program was the COVID-19 pandemic, however, Wake Forest said it expects to care for between 75-100 patients through Hospitalist at Home at any one time.

Chi-Cheng Huang, MD, SFHM, was recently was named one of the Notable Asian/Pacific American Physicians in U.S. History by the American Board of Internal Medicine. May was Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month. Dr. Huang is the executive medical director and service line director of general medicine and hospital medicine within the Wake Forest Baptist Health System (Winston-Salem, N.C.) and associate professor at Wake Forest School of Medicine.

Dr. Huang is a board-certified hospitalist and pediatrician, and he is the founder of the Bolivian Children Project, a non-profit organization that focuses on sheltering street children in La Paz and other areas of Bolivia. Dr. Huang was inspired to start the project during a year sabbatical from medical school. He worked at an orphanage and cared for children who were victims of physical abuse. The Bolivian Children Project supports those children, and Dr. Huang’s book, When Invisible Children Sing, tells their story.

Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, SFHM, has been elected president of the Florida Medical Association. It is the first time in its history that the FMA will have a DO as its president. Dr. Lenchus is a hospitalist and chief medical officer at the Broward Health Medical Center in Fort Lauderdale, Fla.

Mark V. Williams, MD, MHM, will join Washington University School of Medicine and BJC HealthCare, both in St. Louis, as professor and chief for the Division of Hospital Medicine in October 2021. Dr. Williams is currently professor and director of the Center for Health Services Research at the University of Kentucky and chief quality officer at UK HealthCare, both in Lexington.

Dr. Williams was a founding member of the Society of Hospital Medicine, one of the first two elected members of the Board of SHM, its former president, founding editor of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, and principal investigator for Project BOOST. He established the first hospitalist program at a public hospital (Grady Memorial in Atlanta) in 1998, and later became the founding chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine in 2007 at Northwestern University School of Medicine in Chicago. At the University of Kentucky, he established the Center for Health Services Research and the Division of Hospital Medicine in 2014.

At Washington University, Dr. Williams will be tasked with translating the division of hospital medicine’s scholarly work, innovation, and research into practice improvement, focusing on developing new systems of health care delivery that are patient-centered, cost effective, and provide outstanding value.

Jordan Messler, MD, SFHM, has been named the new chief medical officer at Glytec (Waltham, Mass.), where he has worked as executive director of clinical practice since 2018. Dr. Messler will be tasked with leading strategy and product development while also supporting efforts in quality care, customer relations, and delivery of products.

Glytec provides insulin management software across the care continuum and is touted as the only cloud-based software provider of its kind. Dr. Messler’s background includes expertise in glycemic management. In addition, he still works as a hospitalist at Morton Plant Hospitalist Group (Clearwater, Fla.).

Dr. Messler is a senior fellow with SHM and is physician editor of SHM’s official blog The Hospital Leader.

Tiffani Maycock, DO, recently was named to the Board of Directors for the American Board of Family Medicine. Dr. Maycock is director of the Selma Family Medicine Residency Program at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, where she is an assistant professor in the department of family medicine.

Dr. Maycock helped create hospitalist services at Vaughan Regional Medical Center (Selma, Ala.) – Selma Family Medicine’s primary teaching site – and currently serves as its hospitalist director and on its Medical Executive Committee. She has worked at the facility since 2017.

Preetham Talari, MD, SFHM, has been named associate chief of quality safety for the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of Kentucky’s UK HealthCare (Lexington, Ky.). Dr. Talari is an associate professor of internal medicine in the Division of Hospital Medicine at the UK College of Medicine.

Over the last decade, Dr. Talari’s work in quality, safety, and health care leadership has positioned him as a leader in several UK Healthcare committees and transformation projects. In his role as associate chief, Dr. Talari collaborates with hospital medicine directors, enterprise leadership, and medical education leadership to improve the system’s quality of care.

Dr. Talari is the president of the Kentucky chapter of SHM and is a member of SHM’s Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Committee.

Adrian Paraschiv, MD, FHM, is being recognized by Continental Who’s Who as a Trusted Internist and Hospitalist in the field of Medicine in acknowledgment of his commitment to providing quality health care services.

Dr. Paraschiv is a board-certified Internist at Garnet Health Medical Center in Middletown, N.Y. He also serves in an administrative capacity as the Garnet Health Doctors Hospitalist Division’s Associate Program Director. He is also the Director of Clinical Informatics. Dr. Paraschiv is certified as the Epic physician builder in analytics, information technology, and improved documentation.

DCH Health System (Tuscaloosa, Ala.) recently selected Capstone Health Services Foundation (Tuscaloosa) and IN Compass Health Inc. (Alpharetta, Ga.) as its joint hospitalist service provider for facilities in Northport and Tuscaloosa. Capstone will provide the physicians, while IN Compass will handle staffing management of the hospitalists, as well as day-to-day operations and calculating quality care metrics. The agreement is slated to begin on Oct. 1, 2021, at Northport Medical Center, and on Nov. 1, 2021, at DCH Regional Medical Center.

Capstone is an affiliate of the University of Alabama and oversees University Hospitalist Group, which currently provides hospitalists at DCH Regional Medical Center. Its partnership with IN Compass includes working together in recruiting and hiring physicians for both facilities.

UPMC Kane Medical Center (Kane, Pa.) recently announced the creation of a virtual telemedicine hospitalist program. UPMC Kane is partnering with the UPMC Center for Community Hospitalist Medicine to create this new mode of care.

Telehospitalists will care for UPMC Kane patients using advanced diagnostic technique and high-definition cameras. The physicians will bring expert service to Kane 24 hours per day utilizing physicians and specialists based in Pittsburgh. Those hospitalists will work with local nurse practitioners and support staff and deliver care to Kane patients.

Wake Forest Baptist Health (Winston-Salem, N.C.) has launched a Hospitalist at Home program with hopes of keeping patients safe while also reducing time they spend in the hospital. The telehealth initiative kicked into gear at the start of 2021 and considered the first of its kind in the region.

Patients who qualify for the program establish a plan before they leave the hospital. Wake Forest Baptist Health paramedics makes home visits and conducts care with a hospitalist reviewing the visit virtually. Those appointments continue until the patient does not require monitoring.

The impetus of creating the program was the COVID-19 pandemic, however, Wake Forest said it expects to care for between 75-100 patients through Hospitalist at Home at any one time.

Chi-Cheng Huang, MD, SFHM, was recently was named one of the Notable Asian/Pacific American Physicians in U.S. History by the American Board of Internal Medicine. May was Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month. Dr. Huang is the executive medical director and service line director of general medicine and hospital medicine within the Wake Forest Baptist Health System (Winston-Salem, N.C.) and associate professor at Wake Forest School of Medicine.

Dr. Huang is a board-certified hospitalist and pediatrician, and he is the founder of the Bolivian Children Project, a non-profit organization that focuses on sheltering street children in La Paz and other areas of Bolivia. Dr. Huang was inspired to start the project during a year sabbatical from medical school. He worked at an orphanage and cared for children who were victims of physical abuse. The Bolivian Children Project supports those children, and Dr. Huang’s book, When Invisible Children Sing, tells their story.

Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, SFHM, has been elected president of the Florida Medical Association. It is the first time in its history that the FMA will have a DO as its president. Dr. Lenchus is a hospitalist and chief medical officer at the Broward Health Medical Center in Fort Lauderdale, Fla.

Mark V. Williams, MD, MHM, will join Washington University School of Medicine and BJC HealthCare, both in St. Louis, as professor and chief for the Division of Hospital Medicine in October 2021. Dr. Williams is currently professor and director of the Center for Health Services Research at the University of Kentucky and chief quality officer at UK HealthCare, both in Lexington.

Dr. Williams was a founding member of the Society of Hospital Medicine, one of the first two elected members of the Board of SHM, its former president, founding editor of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, and principal investigator for Project BOOST. He established the first hospitalist program at a public hospital (Grady Memorial in Atlanta) in 1998, and later became the founding chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine in 2007 at Northwestern University School of Medicine in Chicago. At the University of Kentucky, he established the Center for Health Services Research and the Division of Hospital Medicine in 2014.

At Washington University, Dr. Williams will be tasked with translating the division of hospital medicine’s scholarly work, innovation, and research into practice improvement, focusing on developing new systems of health care delivery that are patient-centered, cost effective, and provide outstanding value.

Jordan Messler, MD, SFHM, has been named the new chief medical officer at Glytec (Waltham, Mass.), where he has worked as executive director of clinical practice since 2018. Dr. Messler will be tasked with leading strategy and product development while also supporting efforts in quality care, customer relations, and delivery of products.

Glytec provides insulin management software across the care continuum and is touted as the only cloud-based software provider of its kind. Dr. Messler’s background includes expertise in glycemic management. In addition, he still works as a hospitalist at Morton Plant Hospitalist Group (Clearwater, Fla.).

Dr. Messler is a senior fellow with SHM and is physician editor of SHM’s official blog The Hospital Leader.

Tiffani Maycock, DO, recently was named to the Board of Directors for the American Board of Family Medicine. Dr. Maycock is director of the Selma Family Medicine Residency Program at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, where she is an assistant professor in the department of family medicine.

Dr. Maycock helped create hospitalist services at Vaughan Regional Medical Center (Selma, Ala.) – Selma Family Medicine’s primary teaching site – and currently serves as its hospitalist director and on its Medical Executive Committee. She has worked at the facility since 2017.

Preetham Talari, MD, SFHM, has been named associate chief of quality safety for the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of Kentucky’s UK HealthCare (Lexington, Ky.). Dr. Talari is an associate professor of internal medicine in the Division of Hospital Medicine at the UK College of Medicine.

Over the last decade, Dr. Talari’s work in quality, safety, and health care leadership has positioned him as a leader in several UK Healthcare committees and transformation projects. In his role as associate chief, Dr. Talari collaborates with hospital medicine directors, enterprise leadership, and medical education leadership to improve the system’s quality of care.

Dr. Talari is the president of the Kentucky chapter of SHM and is a member of SHM’s Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Committee.

Adrian Paraschiv, MD, FHM, is being recognized by Continental Who’s Who as a Trusted Internist and Hospitalist in the field of Medicine in acknowledgment of his commitment to providing quality health care services.

Dr. Paraschiv is a board-certified Internist at Garnet Health Medical Center in Middletown, N.Y. He also serves in an administrative capacity as the Garnet Health Doctors Hospitalist Division’s Associate Program Director. He is also the Director of Clinical Informatics. Dr. Paraschiv is certified as the Epic physician builder in analytics, information technology, and improved documentation.

DCH Health System (Tuscaloosa, Ala.) recently selected Capstone Health Services Foundation (Tuscaloosa) and IN Compass Health Inc. (Alpharetta, Ga.) as its joint hospitalist service provider for facilities in Northport and Tuscaloosa. Capstone will provide the physicians, while IN Compass will handle staffing management of the hospitalists, as well as day-to-day operations and calculating quality care metrics. The agreement is slated to begin on Oct. 1, 2021, at Northport Medical Center, and on Nov. 1, 2021, at DCH Regional Medical Center.

Capstone is an affiliate of the University of Alabama and oversees University Hospitalist Group, which currently provides hospitalists at DCH Regional Medical Center. Its partnership with IN Compass includes working together in recruiting and hiring physicians for both facilities.

UPMC Kane Medical Center (Kane, Pa.) recently announced the creation of a virtual telemedicine hospitalist program. UPMC Kane is partnering with the UPMC Center for Community Hospitalist Medicine to create this new mode of care.

Telehospitalists will care for UPMC Kane patients using advanced diagnostic technique and high-definition cameras. The physicians will bring expert service to Kane 24 hours per day utilizing physicians and specialists based in Pittsburgh. Those hospitalists will work with local nurse practitioners and support staff and deliver care to Kane patients.

Wake Forest Baptist Health (Winston-Salem, N.C.) has launched a Hospitalist at Home program with hopes of keeping patients safe while also reducing time they spend in the hospital. The telehealth initiative kicked into gear at the start of 2021 and considered the first of its kind in the region.

Patients who qualify for the program establish a plan before they leave the hospital. Wake Forest Baptist Health paramedics makes home visits and conducts care with a hospitalist reviewing the visit virtually. Those appointments continue until the patient does not require monitoring.

The impetus of creating the program was the COVID-19 pandemic, however, Wake Forest said it expects to care for between 75-100 patients through Hospitalist at Home at any one time.

POCUS in hospital pediatrics

PHM 2021 Session

Safe and (Ultra)sound: Why you should use POCUS in your Pediatric Practice

Presenter

Ria Dancel, MD, FAAP, FACP

Session summary

Dr. Ria Dancel and her colleagues from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill presented a broad overview of point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) applications in the field of pediatric hospital medicine. They discussed its advantages and potential uses, ranging from common scenarios to critical care to procedural guidance. Using illustrative scenarios and interactive cases, she discussed the bedside applications to improve care of hospitalized children. The benefits and risks of radiography and POCUS were reviewed.

The session highlighted the use of POCUS in SSTI (skin and soft tissue infection) to help with differentiating cellulitis from abscesses. Use of POCUS for safer incision and drainages and making day-to-day changes in management was discussed. The ease and benefits of performing real-time lung ultrasound in different pathologies (like pneumonia, effusion, COVID-19) was presented. The speakers discussed the use of POCUS in emergency situations like hypotension and different types of shock. The use of ultrasound in common bedside procedures (bladder catheterization, lumbar ultrasound, peripheral IV placement) were also highlighted. Current literature and evidence were reviewed.

Key takeaways

- Pediatric POCUS is an extremely valuable bedside tool in pediatric hospital medicine.

- It can be used to guide clinical care for many conditions including SSTI, pneumonia, and shock.

- It can be used for procedural guidance for bladder catheterization, lumbar puncture, and intravenous access.

Dr. Patra is a pediatric hospitalist at West Virginia University Children’s Hospital, Morgantown, and associate professor at West Virginia University School of Medicine. He is interested in medical education, quality improvement and clinical research. He is a member of the Executive Council of the Pediatric Special Interest Group of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

PHM 2021 Session

Safe and (Ultra)sound: Why you should use POCUS in your Pediatric Practice

Presenter

Ria Dancel, MD, FAAP, FACP

Session summary

Dr. Ria Dancel and her colleagues from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill presented a broad overview of point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) applications in the field of pediatric hospital medicine. They discussed its advantages and potential uses, ranging from common scenarios to critical care to procedural guidance. Using illustrative scenarios and interactive cases, she discussed the bedside applications to improve care of hospitalized children. The benefits and risks of radiography and POCUS were reviewed.

The session highlighted the use of POCUS in SSTI (skin and soft tissue infection) to help with differentiating cellulitis from abscesses. Use of POCUS for safer incision and drainages and making day-to-day changes in management was discussed. The ease and benefits of performing real-time lung ultrasound in different pathologies (like pneumonia, effusion, COVID-19) was presented. The speakers discussed the use of POCUS in emergency situations like hypotension and different types of shock. The use of ultrasound in common bedside procedures (bladder catheterization, lumbar ultrasound, peripheral IV placement) were also highlighted. Current literature and evidence were reviewed.

Key takeaways

- Pediatric POCUS is an extremely valuable bedside tool in pediatric hospital medicine.

- It can be used to guide clinical care for many conditions including SSTI, pneumonia, and shock.

- It can be used for procedural guidance for bladder catheterization, lumbar puncture, and intravenous access.

Dr. Patra is a pediatric hospitalist at West Virginia University Children’s Hospital, Morgantown, and associate professor at West Virginia University School of Medicine. He is interested in medical education, quality improvement and clinical research. He is a member of the Executive Council of the Pediatric Special Interest Group of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

PHM 2021 Session

Safe and (Ultra)sound: Why you should use POCUS in your Pediatric Practice

Presenter

Ria Dancel, MD, FAAP, FACP

Session summary

Dr. Ria Dancel and her colleagues from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill presented a broad overview of point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) applications in the field of pediatric hospital medicine. They discussed its advantages and potential uses, ranging from common scenarios to critical care to procedural guidance. Using illustrative scenarios and interactive cases, she discussed the bedside applications to improve care of hospitalized children. The benefits and risks of radiography and POCUS were reviewed.

The session highlighted the use of POCUS in SSTI (skin and soft tissue infection) to help with differentiating cellulitis from abscesses. Use of POCUS for safer incision and drainages and making day-to-day changes in management was discussed. The ease and benefits of performing real-time lung ultrasound in different pathologies (like pneumonia, effusion, COVID-19) was presented. The speakers discussed the use of POCUS in emergency situations like hypotension and different types of shock. The use of ultrasound in common bedside procedures (bladder catheterization, lumbar ultrasound, peripheral IV placement) were also highlighted. Current literature and evidence were reviewed.

Key takeaways

- Pediatric POCUS is an extremely valuable bedside tool in pediatric hospital medicine.

- It can be used to guide clinical care for many conditions including SSTI, pneumonia, and shock.

- It can be used for procedural guidance for bladder catheterization, lumbar puncture, and intravenous access.

Dr. Patra is a pediatric hospitalist at West Virginia University Children’s Hospital, Morgantown, and associate professor at West Virginia University School of Medicine. He is interested in medical education, quality improvement and clinical research. He is a member of the Executive Council of the Pediatric Special Interest Group of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

New fellowship, no problem

Using growth mindset to tackle fellowship in a new program

Growth mindset is a well-established phenomenon in childhood education that is now starting to appear in health care education literature.1 This concept emphasizes the capacity of individuals to change and grow through experience and that an individual’s basic qualities can be cultivated through hard work, open-mindedness, and help from others.2

Growth mindset opposes the concept of fixed mindset, which implies intelligence or other personal traits are set in stone, unable to be fundamentally changed.2 Individuals with fixed mindsets are less adept at coping with perceived failures and critical feedback because they view these as attacks on their own abilities.2 This oftentimes leads these individuals to avoid potential challenges and feedback because of fear of being exposed as incompetent or feeling inadequate. Conversely, individuals with a growth mindset embrace challenges and failures as learning opportunities and identify feedback as a critical element of growth.2 These individuals maintain a sense of resilience in the face of adversity and strive to become lifelong learners.

As the field of pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) continues to rapidly evolve, so too does the landscape of PHM fellowships. New programs are opening at a torrid pace to accommodate the increasing demand of residents looking to enter the field with new subspecialty accreditation. Most first-year PHM fellows in established programs enter with a clear precedent to follow, set forth by fellows who have come before them. For PHM fellows in new programs, however, there is often no beaten path to follow.

Entering fellowship as a first-year PHM fellow in a new program and blazing one’s own trail can be intriguing and exhilarating given the unique opportunities available. However, the potential challenges for both fellows and program directors during this transition cannot be understated. The role of new PHM fellows within the institutional framework may initially be unclear to others, which can lead to ambiguous expectations and disruptions to normal workflows. Furthermore, assessing and evaluating new fellows may prove difficult as a result of these unclear expectations and general uncertainties. Using the growth mindset can help both PHM fellows and program directors take a deliberate approach to the challenges and uncertainty that may accompany the creation of a new fellowship program.

One of the challenges new PHM fellows may encounter lies within the structure of the care team. Resident and medical student learners may express consternation that the new fellow role may limit their own autonomy. In addition, finding the right balance of autonomy and supervision between the attending-fellow dyad may prove to be difficult. However, using the growth mindset may allow fellows to see the inherent benefits of this new role.

Fellows should seize the opportunity to discuss the nuances and differing approaches to difficult clinical questions, managing a team and interpersonal dynamics, and balancing clinical and nonclinical responsibilities with an experienced supervising clinician; issues that are often less pressing as a resident. The fellow role also affords the opportunity to more carefully observe different clinical styles of practice to subsequently shape one’s own preferred style.

Finally, fellows should employ a growth mindset to optimize clinical time by discussing expectations with involved stakeholders prior to rotations and explicitly identifying goals for feedback and improvement. Program directors can also help stakeholders including faculty, residency programs, medical schools, and other health care professionals on the clinical teams prepare for this transition by providing expectations for the fellow role and by soliciting questions and feedback before and after fellows begin.

One of the key tenets of the growth mindset is actively seeking out constructive feedback and learning from failures to grow and improve. This can be a particularly useful practice for fellows during the course of their scholarly pursuits in clinical research, quality improvement, and medical education. From initial stages of idea development through the final steps of manuscript submission and peer review, fellows will undoubtedly navigate a plethora of challenges and setbacks along the way. Program directors and other core faculty members can promote a growth mindset culture by honestly discussing their own challenges and failures in career endeavors in addition to giving thoughtful constructive feedback.

Fellows should routinely practice explicitly identifying knowledge and skills gaps that represent areas for potential improvement. But perhaps most importantly, fellows must strive to see all feedback and perceived failures not as personal affronts or as commentaries on personal abilities, but rather as opportunities to strengthen their scholarly products and gain valuable experience for future endeavors.

Not all learners will come equipped with a growth mindset. So, what can fellows and program directors in new programs do to develop this practice and mitigate some of the inevitable uncertainty? To begin, program directors should think about how to create cultures of growth and development as the fixed and growth mindsets are not just limited to individuals.3 Program directors can strive to augment this process by committing to solicit feedback for themselves and acknowledging their own vulnerabilities and perceived weaknesses.

Fellows must have early, honest discussions with program directors and other stakeholders about expectations and goals. Program directors should consider creating lists of “must meet” individuals within the institution that can help fellows begin to carve out their roles in the clinical, educational, and research realms. Deliberately crafting a mentorship team that will encourage a commitment to growth and improvement is critical. Seeking out growth feedback, particularly in areas that prove challenging, should become common practice for fellows from the onset.

Most importantly, fellows should reframe uncertainty as opportunity for growth and progression. Seeing oneself as a work in progress provides a new perspective that prioritizes learning and emphasizes improvement potential.

Embodying this approach requires patience and practice. Being part of a newly created fellowship represents an opportunity to learn from personal challenges rather than leaning on the precedent set by previous fellows. And although fellows will often face uncertainty as a part of the novelty within a new program, they can ultimately succeed by practicing the principles of Dweck’s Growth Mindset: embracing challenges and failure as learning experiences, seeking out feedback, and pursuing the opportunities among ambiguity.

Dr. Herchline is a pediatric hospitalist at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and recent fellow graduate of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. During fellowship, he completed a master’s degree in medical education at the University of Pennsylvania. His academic interests include graduate medical education, interprofessional collaboration and teamwork, and quality improvement.

References

1. Klein J et al. A growth mindset approach to preparing trainees for medical error. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017 Sep;26(9):771-4. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-006416.

2. Dweck C. Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York: Ballantine Books; 2006.

3. Murphy MC, Dweck CS. A culture of genius: How an organization’s lay theory shapes people’s cognition, affect, and behavior. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2010 Mar;36(3):283-96. doi: 10.1177/0146167209347380.

Using growth mindset to tackle fellowship in a new program

Using growth mindset to tackle fellowship in a new program

Growth mindset is a well-established phenomenon in childhood education that is now starting to appear in health care education literature.1 This concept emphasizes the capacity of individuals to change and grow through experience and that an individual’s basic qualities can be cultivated through hard work, open-mindedness, and help from others.2

Growth mindset opposes the concept of fixed mindset, which implies intelligence or other personal traits are set in stone, unable to be fundamentally changed.2 Individuals with fixed mindsets are less adept at coping with perceived failures and critical feedback because they view these as attacks on their own abilities.2 This oftentimes leads these individuals to avoid potential challenges and feedback because of fear of being exposed as incompetent or feeling inadequate. Conversely, individuals with a growth mindset embrace challenges and failures as learning opportunities and identify feedback as a critical element of growth.2 These individuals maintain a sense of resilience in the face of adversity and strive to become lifelong learners.

As the field of pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) continues to rapidly evolve, so too does the landscape of PHM fellowships. New programs are opening at a torrid pace to accommodate the increasing demand of residents looking to enter the field with new subspecialty accreditation. Most first-year PHM fellows in established programs enter with a clear precedent to follow, set forth by fellows who have come before them. For PHM fellows in new programs, however, there is often no beaten path to follow.

Entering fellowship as a first-year PHM fellow in a new program and blazing one’s own trail can be intriguing and exhilarating given the unique opportunities available. However, the potential challenges for both fellows and program directors during this transition cannot be understated. The role of new PHM fellows within the institutional framework may initially be unclear to others, which can lead to ambiguous expectations and disruptions to normal workflows. Furthermore, assessing and evaluating new fellows may prove difficult as a result of these unclear expectations and general uncertainties. Using the growth mindset can help both PHM fellows and program directors take a deliberate approach to the challenges and uncertainty that may accompany the creation of a new fellowship program.

One of the challenges new PHM fellows may encounter lies within the structure of the care team. Resident and medical student learners may express consternation that the new fellow role may limit their own autonomy. In addition, finding the right balance of autonomy and supervision between the attending-fellow dyad may prove to be difficult. However, using the growth mindset may allow fellows to see the inherent benefits of this new role.

Fellows should seize the opportunity to discuss the nuances and differing approaches to difficult clinical questions, managing a team and interpersonal dynamics, and balancing clinical and nonclinical responsibilities with an experienced supervising clinician; issues that are often less pressing as a resident. The fellow role also affords the opportunity to more carefully observe different clinical styles of practice to subsequently shape one’s own preferred style.

Finally, fellows should employ a growth mindset to optimize clinical time by discussing expectations with involved stakeholders prior to rotations and explicitly identifying goals for feedback and improvement. Program directors can also help stakeholders including faculty, residency programs, medical schools, and other health care professionals on the clinical teams prepare for this transition by providing expectations for the fellow role and by soliciting questions and feedback before and after fellows begin.

One of the key tenets of the growth mindset is actively seeking out constructive feedback and learning from failures to grow and improve. This can be a particularly useful practice for fellows during the course of their scholarly pursuits in clinical research, quality improvement, and medical education. From initial stages of idea development through the final steps of manuscript submission and peer review, fellows will undoubtedly navigate a plethora of challenges and setbacks along the way. Program directors and other core faculty members can promote a growth mindset culture by honestly discussing their own challenges and failures in career endeavors in addition to giving thoughtful constructive feedback.

Fellows should routinely practice explicitly identifying knowledge and skills gaps that represent areas for potential improvement. But perhaps most importantly, fellows must strive to see all feedback and perceived failures not as personal affronts or as commentaries on personal abilities, but rather as opportunities to strengthen their scholarly products and gain valuable experience for future endeavors.

Not all learners will come equipped with a growth mindset. So, what can fellows and program directors in new programs do to develop this practice and mitigate some of the inevitable uncertainty? To begin, program directors should think about how to create cultures of growth and development as the fixed and growth mindsets are not just limited to individuals.3 Program directors can strive to augment this process by committing to solicit feedback for themselves and acknowledging their own vulnerabilities and perceived weaknesses.

Fellows must have early, honest discussions with program directors and other stakeholders about expectations and goals. Program directors should consider creating lists of “must meet” individuals within the institution that can help fellows begin to carve out their roles in the clinical, educational, and research realms. Deliberately crafting a mentorship team that will encourage a commitment to growth and improvement is critical. Seeking out growth feedback, particularly in areas that prove challenging, should become common practice for fellows from the onset.

Most importantly, fellows should reframe uncertainty as opportunity for growth and progression. Seeing oneself as a work in progress provides a new perspective that prioritizes learning and emphasizes improvement potential.

Embodying this approach requires patience and practice. Being part of a newly created fellowship represents an opportunity to learn from personal challenges rather than leaning on the precedent set by previous fellows. And although fellows will often face uncertainty as a part of the novelty within a new program, they can ultimately succeed by practicing the principles of Dweck’s Growth Mindset: embracing challenges and failure as learning experiences, seeking out feedback, and pursuing the opportunities among ambiguity.

Dr. Herchline is a pediatric hospitalist at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and recent fellow graduate of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. During fellowship, he completed a master’s degree in medical education at the University of Pennsylvania. His academic interests include graduate medical education, interprofessional collaboration and teamwork, and quality improvement.

References

1. Klein J et al. A growth mindset approach to preparing trainees for medical error. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017 Sep;26(9):771-4. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-006416.

2. Dweck C. Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York: Ballantine Books; 2006.

3. Murphy MC, Dweck CS. A culture of genius: How an organization’s lay theory shapes people’s cognition, affect, and behavior. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2010 Mar;36(3):283-96. doi: 10.1177/0146167209347380.

Growth mindset is a well-established phenomenon in childhood education that is now starting to appear in health care education literature.1 This concept emphasizes the capacity of individuals to change and grow through experience and that an individual’s basic qualities can be cultivated through hard work, open-mindedness, and help from others.2

Growth mindset opposes the concept of fixed mindset, which implies intelligence or other personal traits are set in stone, unable to be fundamentally changed.2 Individuals with fixed mindsets are less adept at coping with perceived failures and critical feedback because they view these as attacks on their own abilities.2 This oftentimes leads these individuals to avoid potential challenges and feedback because of fear of being exposed as incompetent or feeling inadequate. Conversely, individuals with a growth mindset embrace challenges and failures as learning opportunities and identify feedback as a critical element of growth.2 These individuals maintain a sense of resilience in the face of adversity and strive to become lifelong learners.

As the field of pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) continues to rapidly evolve, so too does the landscape of PHM fellowships. New programs are opening at a torrid pace to accommodate the increasing demand of residents looking to enter the field with new subspecialty accreditation. Most first-year PHM fellows in established programs enter with a clear precedent to follow, set forth by fellows who have come before them. For PHM fellows in new programs, however, there is often no beaten path to follow.

Entering fellowship as a first-year PHM fellow in a new program and blazing one’s own trail can be intriguing and exhilarating given the unique opportunities available. However, the potential challenges for both fellows and program directors during this transition cannot be understated. The role of new PHM fellows within the institutional framework may initially be unclear to others, which can lead to ambiguous expectations and disruptions to normal workflows. Furthermore, assessing and evaluating new fellows may prove difficult as a result of these unclear expectations and general uncertainties. Using the growth mindset can help both PHM fellows and program directors take a deliberate approach to the challenges and uncertainty that may accompany the creation of a new fellowship program.

One of the challenges new PHM fellows may encounter lies within the structure of the care team. Resident and medical student learners may express consternation that the new fellow role may limit their own autonomy. In addition, finding the right balance of autonomy and supervision between the attending-fellow dyad may prove to be difficult. However, using the growth mindset may allow fellows to see the inherent benefits of this new role.

Fellows should seize the opportunity to discuss the nuances and differing approaches to difficult clinical questions, managing a team and interpersonal dynamics, and balancing clinical and nonclinical responsibilities with an experienced supervising clinician; issues that are often less pressing as a resident. The fellow role also affords the opportunity to more carefully observe different clinical styles of practice to subsequently shape one’s own preferred style.

Finally, fellows should employ a growth mindset to optimize clinical time by discussing expectations with involved stakeholders prior to rotations and explicitly identifying goals for feedback and improvement. Program directors can also help stakeholders including faculty, residency programs, medical schools, and other health care professionals on the clinical teams prepare for this transition by providing expectations for the fellow role and by soliciting questions and feedback before and after fellows begin.

One of the key tenets of the growth mindset is actively seeking out constructive feedback and learning from failures to grow and improve. This can be a particularly useful practice for fellows during the course of their scholarly pursuits in clinical research, quality improvement, and medical education. From initial stages of idea development through the final steps of manuscript submission and peer review, fellows will undoubtedly navigate a plethora of challenges and setbacks along the way. Program directors and other core faculty members can promote a growth mindset culture by honestly discussing their own challenges and failures in career endeavors in addition to giving thoughtful constructive feedback.

Fellows should routinely practice explicitly identifying knowledge and skills gaps that represent areas for potential improvement. But perhaps most importantly, fellows must strive to see all feedback and perceived failures not as personal affronts or as commentaries on personal abilities, but rather as opportunities to strengthen their scholarly products and gain valuable experience for future endeavors.

Not all learners will come equipped with a growth mindset. So, what can fellows and program directors in new programs do to develop this practice and mitigate some of the inevitable uncertainty? To begin, program directors should think about how to create cultures of growth and development as the fixed and growth mindsets are not just limited to individuals.3 Program directors can strive to augment this process by committing to solicit feedback for themselves and acknowledging their own vulnerabilities and perceived weaknesses.

Fellows must have early, honest discussions with program directors and other stakeholders about expectations and goals. Program directors should consider creating lists of “must meet” individuals within the institution that can help fellows begin to carve out their roles in the clinical, educational, and research realms. Deliberately crafting a mentorship team that will encourage a commitment to growth and improvement is critical. Seeking out growth feedback, particularly in areas that prove challenging, should become common practice for fellows from the onset.

Most importantly, fellows should reframe uncertainty as opportunity for growth and progression. Seeing oneself as a work in progress provides a new perspective that prioritizes learning and emphasizes improvement potential.

Embodying this approach requires patience and practice. Being part of a newly created fellowship represents an opportunity to learn from personal challenges rather than leaning on the precedent set by previous fellows. And although fellows will often face uncertainty as a part of the novelty within a new program, they can ultimately succeed by practicing the principles of Dweck’s Growth Mindset: embracing challenges and failure as learning experiences, seeking out feedback, and pursuing the opportunities among ambiguity.

Dr. Herchline is a pediatric hospitalist at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and recent fellow graduate of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. During fellowship, he completed a master’s degree in medical education at the University of Pennsylvania. His academic interests include graduate medical education, interprofessional collaboration and teamwork, and quality improvement.

References

1. Klein J et al. A growth mindset approach to preparing trainees for medical error. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017 Sep;26(9):771-4. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-006416.

2. Dweck C. Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York: Ballantine Books; 2006.

3. Murphy MC, Dweck CS. A culture of genius: How an organization’s lay theory shapes people’s cognition, affect, and behavior. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2010 Mar;36(3):283-96. doi: 10.1177/0146167209347380.

Mean leadership

The differences between the mean and median of leadership data

Let me apologize for misleading all of you; this is not an article about malignant physician leaders; instead, it goes over the numbers and trends uncovered by the 2020 State of Hospital Medicine report (SoHM).1 The hospital medicine leader ends up doing many tasks like planning, growth, collaboration, finance, recruiting, scheduling, onboarding, coaching, and most near and dear to our hearts, putting out the fires and conflict resolution.

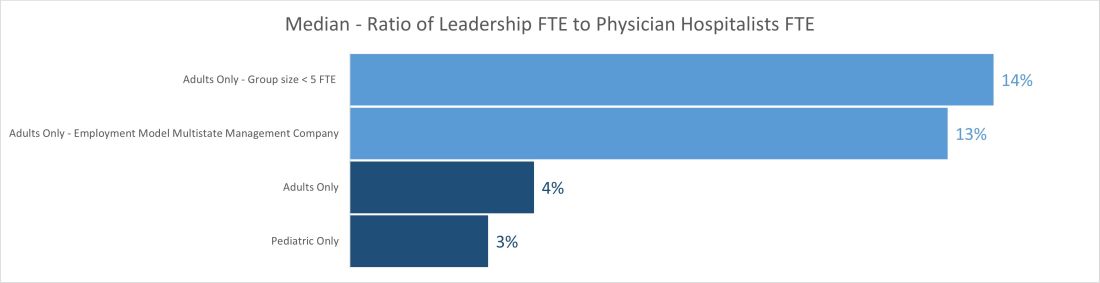

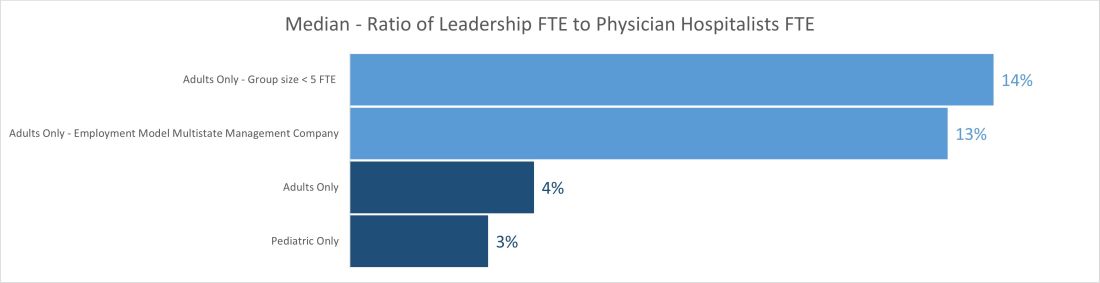

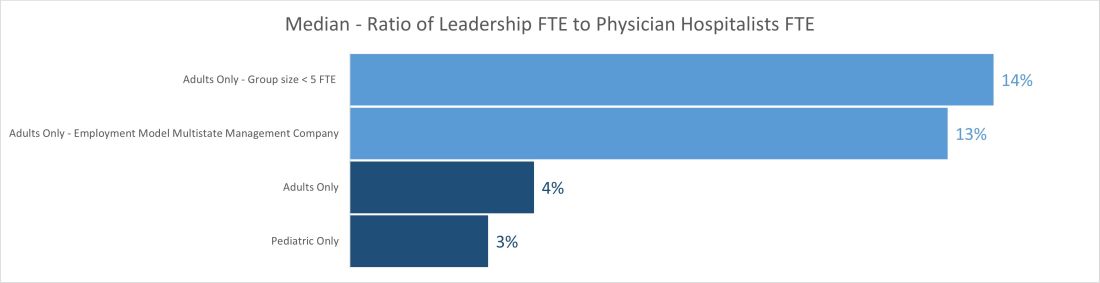

Ratio of leadership FTE to physician hospitalists FTE

If my pun has already put you off, you can avoid reading the rest of the piece and go to the 2020 SoHM to look at pages 52 (Table 3.7c), 121 (Table 4.7c), and 166 (Table 5.7c). It has a newly added table (3.7c), and it is phenomenal; it is the ratio of leadership FTE to physician hospitalists FTE. As an avid user of SoHM, I always ended up doing a makeshift calculation to “guesstimate” this number. Now that we have it calculated for us and the ultimate revelation lies in its narrow range across all groups. We might differ in the region, employment type, academics, teaching, or size, but this range is relatively narrow.

The median ratio of leadership FTE to total FTE lies between 2% and 5% in pediatric groups and between 3% and 6% for most adult groups. The only two outliers are on the adult side, with less than 5 FTE and multistate management companies. The higher median for the less than 5 FTE group size is understandable because of the small number of hospitalist FTEs that the leader’s time must be spread over. Even a small amount of dedicated leadership time will result in a high ratio of leader time to hospitalist clinical time if the group is very small. The multistate management company is probably a result of multiple layers of physician leadership (for example, regional medical directors) and travel-related time adjustments. Still, it raises the question of why the local leadership is not developed to decrease the leadership cost and better access.

Another helpful pattern is the decrease in standard deviation with the increase in group size. The hospital medicine leaders and CEOs of the hospital need to watch this number closely; any extremes on high or low side would be indicators for a deep dive in leadership structure and health.

Total number and total dedicated FTE for all physician leaders

Once we start seeing the differences between the mean and median of leadership data, we can see the median is relatively static while the mean has increased year after year and took a big jump in the 2020 SoHM. The chart below shows trends for the number of individuals in leadership positions (“Total No” and total FTEs allocated to leadership (“Total FTE”) over the last several surveys. The data is heavily skewed toward the right (positive); so, it makes sense to use the median in this case rather than mean. A few factors could explain the right skew of data.

- Large groups of 30 or more hospitalists are increasing, and so is their leadership need.

- There is more recognition of the need for dedicated leadership individuals and FTE.

- The leadership is getting less concentrated among just one or a few leaders.

- Outliers on the high side.

- Lower bounds of 0 or 0.1 FTE.

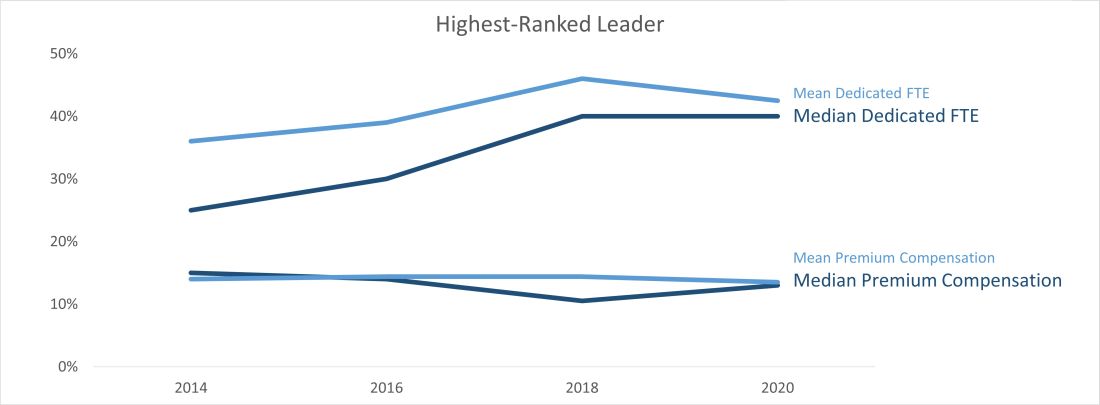

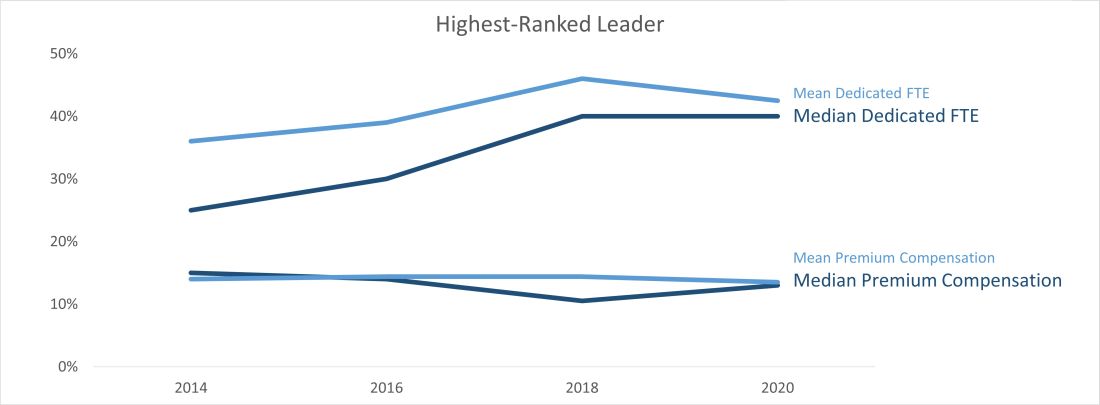

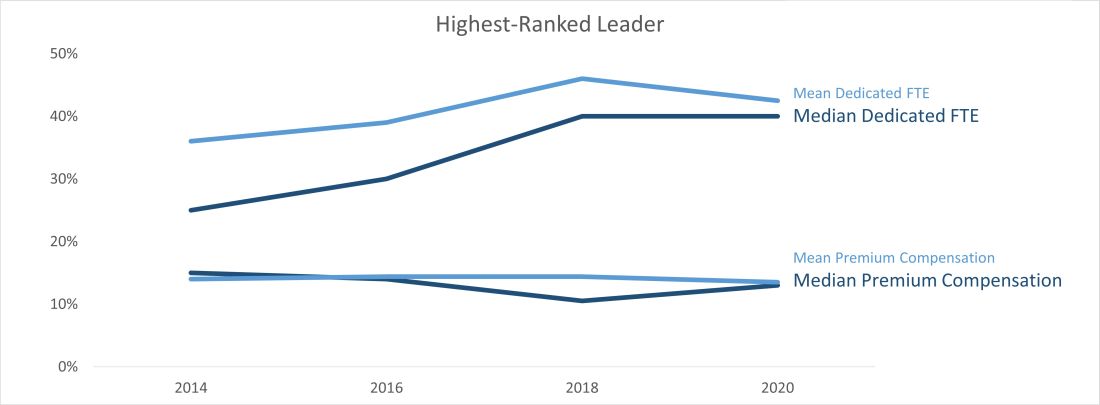

Highest-ranked leader dedicated FTE and premium compensation

Another pleasing trend is an increase in dedicated FTE for the highest-paid leader. Like any skill-set development, leadership requires the investment of deliberate practice, financial acumen, negotiation skills, and increased vulnerability. Time helps way more in developing these skill sets than money. SoHM trends show increase in dedicated FTE for the highest physician leader over the years and static premium compensation.

At last, we can say median leadership is always better than “mean” leadership in skewed data. Pun apart, every group needs leadership, and SoHM offers a nice window to the trends in leadership amongst many practice groups. It is a valuable resource for every group.

Dr. Chadha is chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky Healthcare, Lexington. He actively leads efforts of recruiting, practice analysis, and operation of the group. He is finishing his first tenure in the Practice Analysis Committee. He is often found spending a lot more than required time with spreadsheets and graphs.

Reference

1. 2020 State of Hospital Medicine. www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/

The differences between the mean and median of leadership data

The differences between the mean and median of leadership data

Let me apologize for misleading all of you; this is not an article about malignant physician leaders; instead, it goes over the numbers and trends uncovered by the 2020 State of Hospital Medicine report (SoHM).1 The hospital medicine leader ends up doing many tasks like planning, growth, collaboration, finance, recruiting, scheduling, onboarding, coaching, and most near and dear to our hearts, putting out the fires and conflict resolution.

Ratio of leadership FTE to physician hospitalists FTE

If my pun has already put you off, you can avoid reading the rest of the piece and go to the 2020 SoHM to look at pages 52 (Table 3.7c), 121 (Table 4.7c), and 166 (Table 5.7c). It has a newly added table (3.7c), and it is phenomenal; it is the ratio of leadership FTE to physician hospitalists FTE. As an avid user of SoHM, I always ended up doing a makeshift calculation to “guesstimate” this number. Now that we have it calculated for us and the ultimate revelation lies in its narrow range across all groups. We might differ in the region, employment type, academics, teaching, or size, but this range is relatively narrow.

The median ratio of leadership FTE to total FTE lies between 2% and 5% in pediatric groups and between 3% and 6% for most adult groups. The only two outliers are on the adult side, with less than 5 FTE and multistate management companies. The higher median for the less than 5 FTE group size is understandable because of the small number of hospitalist FTEs that the leader’s time must be spread over. Even a small amount of dedicated leadership time will result in a high ratio of leader time to hospitalist clinical time if the group is very small. The multistate management company is probably a result of multiple layers of physician leadership (for example, regional medical directors) and travel-related time adjustments. Still, it raises the question of why the local leadership is not developed to decrease the leadership cost and better access.

Another helpful pattern is the decrease in standard deviation with the increase in group size. The hospital medicine leaders and CEOs of the hospital need to watch this number closely; any extremes on high or low side would be indicators for a deep dive in leadership structure and health.

Total number and total dedicated FTE for all physician leaders

Once we start seeing the differences between the mean and median of leadership data, we can see the median is relatively static while the mean has increased year after year and took a big jump in the 2020 SoHM. The chart below shows trends for the number of individuals in leadership positions (“Total No” and total FTEs allocated to leadership (“Total FTE”) over the last several surveys. The data is heavily skewed toward the right (positive); so, it makes sense to use the median in this case rather than mean. A few factors could explain the right skew of data.

- Large groups of 30 or more hospitalists are increasing, and so is their leadership need.

- There is more recognition of the need for dedicated leadership individuals and FTE.

- The leadership is getting less concentrated among just one or a few leaders.

- Outliers on the high side.

- Lower bounds of 0 or 0.1 FTE.

Highest-ranked leader dedicated FTE and premium compensation

Another pleasing trend is an increase in dedicated FTE for the highest-paid leader. Like any skill-set development, leadership requires the investment of deliberate practice, financial acumen, negotiation skills, and increased vulnerability. Time helps way more in developing these skill sets than money. SoHM trends show increase in dedicated FTE for the highest physician leader over the years and static premium compensation.

At last, we can say median leadership is always better than “mean” leadership in skewed data. Pun apart, every group needs leadership, and SoHM offers a nice window to the trends in leadership amongst many practice groups. It is a valuable resource for every group.

Dr. Chadha is chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky Healthcare, Lexington. He actively leads efforts of recruiting, practice analysis, and operation of the group. He is finishing his first tenure in the Practice Analysis Committee. He is often found spending a lot more than required time with spreadsheets and graphs.

Reference

1. 2020 State of Hospital Medicine. www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/

Let me apologize for misleading all of you; this is not an article about malignant physician leaders; instead, it goes over the numbers and trends uncovered by the 2020 State of Hospital Medicine report (SoHM).1 The hospital medicine leader ends up doing many tasks like planning, growth, collaboration, finance, recruiting, scheduling, onboarding, coaching, and most near and dear to our hearts, putting out the fires and conflict resolution.

Ratio of leadership FTE to physician hospitalists FTE

If my pun has already put you off, you can avoid reading the rest of the piece and go to the 2020 SoHM to look at pages 52 (Table 3.7c), 121 (Table 4.7c), and 166 (Table 5.7c). It has a newly added table (3.7c), and it is phenomenal; it is the ratio of leadership FTE to physician hospitalists FTE. As an avid user of SoHM, I always ended up doing a makeshift calculation to “guesstimate” this number. Now that we have it calculated for us and the ultimate revelation lies in its narrow range across all groups. We might differ in the region, employment type, academics, teaching, or size, but this range is relatively narrow.

The median ratio of leadership FTE to total FTE lies between 2% and 5% in pediatric groups and between 3% and 6% for most adult groups. The only two outliers are on the adult side, with less than 5 FTE and multistate management companies. The higher median for the less than 5 FTE group size is understandable because of the small number of hospitalist FTEs that the leader’s time must be spread over. Even a small amount of dedicated leadership time will result in a high ratio of leader time to hospitalist clinical time if the group is very small. The multistate management company is probably a result of multiple layers of physician leadership (for example, regional medical directors) and travel-related time adjustments. Still, it raises the question of why the local leadership is not developed to decrease the leadership cost and better access.

Another helpful pattern is the decrease in standard deviation with the increase in group size. The hospital medicine leaders and CEOs of the hospital need to watch this number closely; any extremes on high or low side would be indicators for a deep dive in leadership structure and health.

Total number and total dedicated FTE for all physician leaders

Once we start seeing the differences between the mean and median of leadership data, we can see the median is relatively static while the mean has increased year after year and took a big jump in the 2020 SoHM. The chart below shows trends for the number of individuals in leadership positions (“Total No” and total FTEs allocated to leadership (“Total FTE”) over the last several surveys. The data is heavily skewed toward the right (positive); so, it makes sense to use the median in this case rather than mean. A few factors could explain the right skew of data.

- Large groups of 30 or more hospitalists are increasing, and so is their leadership need.

- There is more recognition of the need for dedicated leadership individuals and FTE.

- The leadership is getting less concentrated among just one or a few leaders.

- Outliers on the high side.

- Lower bounds of 0 or 0.1 FTE.

Highest-ranked leader dedicated FTE and premium compensation

Another pleasing trend is an increase in dedicated FTE for the highest-paid leader. Like any skill-set development, leadership requires the investment of deliberate practice, financial acumen, negotiation skills, and increased vulnerability. Time helps way more in developing these skill sets than money. SoHM trends show increase in dedicated FTE for the highest physician leader over the years and static premium compensation.

At last, we can say median leadership is always better than “mean” leadership in skewed data. Pun apart, every group needs leadership, and SoHM offers a nice window to the trends in leadership amongst many practice groups. It is a valuable resource for every group.

Dr. Chadha is chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky Healthcare, Lexington. He actively leads efforts of recruiting, practice analysis, and operation of the group. He is finishing his first tenure in the Practice Analysis Committee. He is often found spending a lot more than required time with spreadsheets and graphs.

Reference

1. 2020 State of Hospital Medicine. www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/

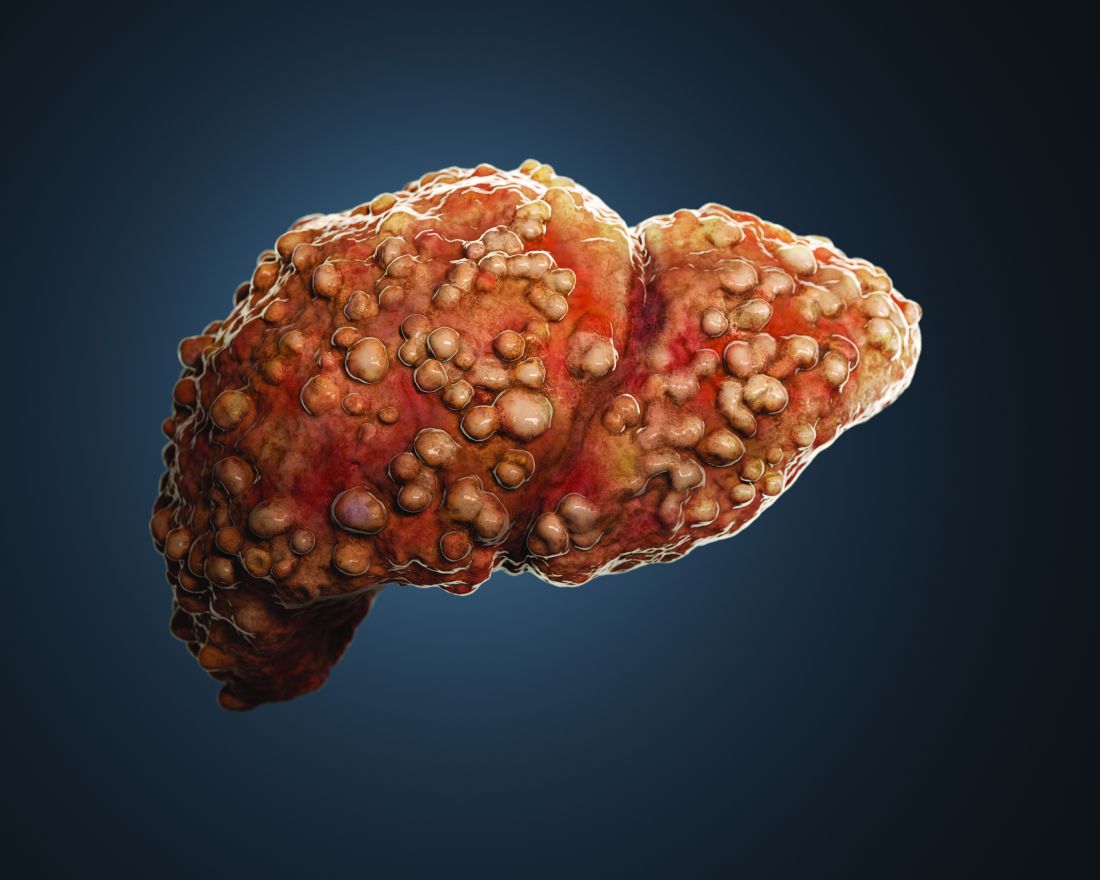

Should hospitalists use albumin to treat non-SBP infections in patients with cirrhosis?

Caution is advised in patients at risk of pulmonary edema

Case

A 56 year-old male with hypertension, alcohol use disorder, stage II chronic kidney disease, and biopsy-proven cirrhosis presents with fever and chills, pyuria, flank pain, and an acute kidney injury concerning for pyelonephritis. Is there a benefit in treating with albumin in addition to guideline-based antibiotics?

Brief overview of the issue

Albumin is a negatively charged human protein produced by the liver. Albumin comprises 50% of plasma protein and over 75% of plasma oncotic pressure.1 It was first used at Walter Reed Hospital in 1940 and subsequently for burn injuries after the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941.2

Albumin serves several important physiologic functions including maintaining oncotic pressure, endothelial support, antioxidation, nitrogen oxide scavenging, and buffering and transport of solutes and drugs, including antibiotics. In cirrhosis, albumin is diluted due to sodium and water retention. There is increased redistribution, decreased synthesis by the liver, and impaired albumin molecule binding.3

For patients with liver disease, per the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), albumin should be administered to prevent post paracentesis circulatory dysfunction after large volume paracentesis, to prevent renal failure and mortality in the setting of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), and in the diagnosis and treatment of hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) type I to potentially improve mortality.4,5 Beyond these three guideline-based indications, other uses for albumin for patients with liver disease have been proposed, including treatment of hyponatremia, posttransplant fluid resuscitation, diuretic unresponsive ascites, and long-term management of cirrhosis. There has yet to be strong evidence supporting these additional indications. However, given the known benefits of albumin in patients with SBP, there has been recent research into treatment of non-SBP infections, including urinary tract infections.

Overview of the data

There have been three randomized controlled trials (RCTs) regarding albumin administration for the treatment of non-SBP infections for hospitalized patients with cirrhosis. All three trials randomized patients to a treatment arm of albumin and antibiotics versus a control group of antibiotics alone. The treatment protocol prescribed 20% albumin with 1.5 g/kg on day 1 and 1.0 g/kg on day 3. The most common infections studied were pneumonia and urinary tract infection. These RCTs found that albumin administration was associated with improved renal and/or circulatory function, but not with a reduction in mortality.

First, there was a single center RCT by Guevara et al. in 2012 of 110 patients with cirrhosis and infection based on SIRS criteria.6 The primary outcome was 90-day survival with secondary outcomes of renal failure development, renal function at days 3,7 and 14, and circulatory function measured by plasma renin, aldosterone, and norepinephrine. Renal function and circulatory function improved in the albumin group, but not mortality. In a multivariable regression analysis, albumin was statistically predictive of survival (hazard ratio of 0.294).

Second, there was a multicenter RCT by Thévenot et al. in 2015 of 193 patients.7 The primary outcome was 90-day renal failure and the secondary outcome was 90-day survival. Renal failure was chosen as the primary endpoint because of its association with survival in this patient population. The treatment group had delayed onset of renal failure, but no difference in the development of 90-day renal failure or 90-day mortality rate. Notably, eight patients (8.3%) in the albumin group developed pulmonary edema with two deaths. This led the oversight committee to prematurely terminate the study.

Third and most recently, there was a multicenter RCT by Fernández et al. in 2019 of 118 patients.8 The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality, with secondary outcomes of circulatory dysfunction measured by plasma renin concentration, systemic inflammation measured by plasma IL-6 and biomarkers, complications including acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) and nosocomial bacterial infections, and 90-day mortality. Between the albumin and control group, there were no differences in in-hospital mortality (13.1% vs. 10.5%, P > .66), inflammation, circulatory dysfunction, or liver severity. However, a significantly higher proportion of patients in the albumin group had resolution of their ACLF (82.3% vs. 33.3%, P = .003) and a lower proportion developed nosocomial infections (6.6% vs. 24.6%, P = .007). A major weakness of this study was that patients in the albumin group had a higher combined rate of ACLF and kidney dysfunction (44.3% vs. 24.6%, P = .02).

Beyond these three randomized controlled trials, there was a study on the long-term administration of albumin for patients with cirrhosis and ascites. Patients who received twice weekly albumin infusions had a lower 2-year mortality rate and a reduction in the incidence of both SBP and non-SBP infections.9 Another long-term study of albumin administration found similar results with greater 18-month survival and fewer non-SBP infections.10 A trial looking at inflammation in patients without bacterial infections and in biobanked samples from cirrhotic patients with bacterial infections found that treatment with albumin reduced systemic inflammation.11

In summary, the three RCTs looked at comparable patients with cirrhosis and a non-SBP infection and all underwent similar treatment protocols with 20% albumin dosed at 1.5 g/kg on day 1 and 1.0 g/kg on day 3. All studies evaluated mortality in either the primary or secondary outcome, and none found significant differences in mortality between treatment and control groups. Each study also evaluated and found improvement in renal and/or circulatory function. Fernández et al. also found increased resolution of ACLF, fewer nosocomial infections, and reduction in some inflammatory markers. However, all studies had relatively small sample sizes that were underpowered to detect mortality differences. Furthermore, randomization did not lead to well-matched groups, with the treatment group patients in the Fernández study having higher rates of ACLF and kidney dysfunction.