User login

Rapid recovery pathway for pediatric PSF/AIS patients

An important alternative amidst the opioid crisis

Clinical question

In pediatric postoperative spinal fusion/adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients, do alternatives to traditional opioid-based analgesic pain regimens lead to improved clinical outcomes?

Background

Traditional care for pediatric postoperative spinal fusion (PSF) patients has included late mobilization most often because of significant pain that requires significant opioid administration. This has led to side effects of heavy opioid use, primarily nausea/vomiting and sleepiness.

In the United States, prescribers have become more aware of the pitfalls of opioid use given that more people now die of opioid misuse than breast cancer. An approach of multimodal analgesia with early mobilization has been shown to have decreased length of stay (LOS) and improve patient satisfaction, but data on clinical outcomes have been lacking.

Study design

Single-center quality improvement (QI) project.

Setting

Urban, 527-bed, quaternary care, free-standing children’s hospital.

Synopsis

Based on the recognition that multiple “standards” of care were utilized in the postoperative management of PSF patients, a QI project was undertaken. The primary outcome measured was functional recovery, as measured by average LOS and pain scores at the first 6:00 am after surgery then on postoperative days 1, 2, and 3.

Process measures were: use of multimodal agents (gabapentin and ketorolac) and discontinuation of patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) before postoperative day 3. Balancing measures were 30-day readmissions or ED revisit. Patients were divided into three groups by analyzing outcomes in three consecutive time periods: conventional management (n = 134), transition period (n = 104), and rapid recovery pathway (n = 84). In the conventional management time period, patients received intraoperative methadone and postoperative morphine/hydromorphone PCA. During the transition period, plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles with ketorolac and gabapentin pilots were instituted and assessed. Finally, a rapid recovery pathway (RRP) was designed and published as a web-based algorithm. Standardized entry order sets were developed to maintain compliance and consistency among health care professionals, and a transition period was allowed to reach the highest possible percentage of patients adhering to multimodal analgesia regimen.

Adherence to the multimodal regimen led to 90% of patients receiving ketorolac on postoperative day 1, 100% receiving gabapentin on night of surgery, 86% off of IV PCA by postoperative day 3, and 100% order set adherence after full implementation of the RRP. LOS decreased from 5.7 to 4 days after RRP implementation. Pain scores also showed significant improvement on postoperative day 0 (average pain score, 3.8 vs. 4.9) and postoperative day 1 (3.8 vs. 5). Balancing measures of 30-day readmissions or ED visits after discharge was 2.9% and rose to 3.6% after full implementation.

Bottom line

Multimodal analgesia – including preoperative gabapentin and acetaminophen, intraoperative methadone and acetaminophen, and postoperative PCA diazepam, gabapentin, acetaminophen, and ketorolac – results in decreased length of stay and improved self-reported daily pain scores.

Citation

Muhly WT et al. Rapid recovery pathway after spinal fusion for idiopathic scoliosis. Pediatrics. 2016 Apr;137(4):e20151568.

Dr. Giordano is a pediatric neurosurgery hospitalist and assistant professor in pediatrics at Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York.

An important alternative amidst the opioid crisis

An important alternative amidst the opioid crisis

Clinical question

In pediatric postoperative spinal fusion/adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients, do alternatives to traditional opioid-based analgesic pain regimens lead to improved clinical outcomes?

Background

Traditional care for pediatric postoperative spinal fusion (PSF) patients has included late mobilization most often because of significant pain that requires significant opioid administration. This has led to side effects of heavy opioid use, primarily nausea/vomiting and sleepiness.

In the United States, prescribers have become more aware of the pitfalls of opioid use given that more people now die of opioid misuse than breast cancer. An approach of multimodal analgesia with early mobilization has been shown to have decreased length of stay (LOS) and improve patient satisfaction, but data on clinical outcomes have been lacking.

Study design

Single-center quality improvement (QI) project.

Setting

Urban, 527-bed, quaternary care, free-standing children’s hospital.

Synopsis

Based on the recognition that multiple “standards” of care were utilized in the postoperative management of PSF patients, a QI project was undertaken. The primary outcome measured was functional recovery, as measured by average LOS and pain scores at the first 6:00 am after surgery then on postoperative days 1, 2, and 3.

Process measures were: use of multimodal agents (gabapentin and ketorolac) and discontinuation of patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) before postoperative day 3. Balancing measures were 30-day readmissions or ED revisit. Patients were divided into three groups by analyzing outcomes in three consecutive time periods: conventional management (n = 134), transition period (n = 104), and rapid recovery pathway (n = 84). In the conventional management time period, patients received intraoperative methadone and postoperative morphine/hydromorphone PCA. During the transition period, plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles with ketorolac and gabapentin pilots were instituted and assessed. Finally, a rapid recovery pathway (RRP) was designed and published as a web-based algorithm. Standardized entry order sets were developed to maintain compliance and consistency among health care professionals, and a transition period was allowed to reach the highest possible percentage of patients adhering to multimodal analgesia regimen.

Adherence to the multimodal regimen led to 90% of patients receiving ketorolac on postoperative day 1, 100% receiving gabapentin on night of surgery, 86% off of IV PCA by postoperative day 3, and 100% order set adherence after full implementation of the RRP. LOS decreased from 5.7 to 4 days after RRP implementation. Pain scores also showed significant improvement on postoperative day 0 (average pain score, 3.8 vs. 4.9) and postoperative day 1 (3.8 vs. 5). Balancing measures of 30-day readmissions or ED visits after discharge was 2.9% and rose to 3.6% after full implementation.

Bottom line

Multimodal analgesia – including preoperative gabapentin and acetaminophen, intraoperative methadone and acetaminophen, and postoperative PCA diazepam, gabapentin, acetaminophen, and ketorolac – results in decreased length of stay and improved self-reported daily pain scores.

Citation

Muhly WT et al. Rapid recovery pathway after spinal fusion for idiopathic scoliosis. Pediatrics. 2016 Apr;137(4):e20151568.

Dr. Giordano is a pediatric neurosurgery hospitalist and assistant professor in pediatrics at Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York.

Clinical question

In pediatric postoperative spinal fusion/adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients, do alternatives to traditional opioid-based analgesic pain regimens lead to improved clinical outcomes?

Background

Traditional care for pediatric postoperative spinal fusion (PSF) patients has included late mobilization most often because of significant pain that requires significant opioid administration. This has led to side effects of heavy opioid use, primarily nausea/vomiting and sleepiness.

In the United States, prescribers have become more aware of the pitfalls of opioid use given that more people now die of opioid misuse than breast cancer. An approach of multimodal analgesia with early mobilization has been shown to have decreased length of stay (LOS) and improve patient satisfaction, but data on clinical outcomes have been lacking.

Study design

Single-center quality improvement (QI) project.

Setting

Urban, 527-bed, quaternary care, free-standing children’s hospital.

Synopsis

Based on the recognition that multiple “standards” of care were utilized in the postoperative management of PSF patients, a QI project was undertaken. The primary outcome measured was functional recovery, as measured by average LOS and pain scores at the first 6:00 am after surgery then on postoperative days 1, 2, and 3.

Process measures were: use of multimodal agents (gabapentin and ketorolac) and discontinuation of patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) before postoperative day 3. Balancing measures were 30-day readmissions or ED revisit. Patients were divided into three groups by analyzing outcomes in three consecutive time periods: conventional management (n = 134), transition period (n = 104), and rapid recovery pathway (n = 84). In the conventional management time period, patients received intraoperative methadone and postoperative morphine/hydromorphone PCA. During the transition period, plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles with ketorolac and gabapentin pilots were instituted and assessed. Finally, a rapid recovery pathway (RRP) was designed and published as a web-based algorithm. Standardized entry order sets were developed to maintain compliance and consistency among health care professionals, and a transition period was allowed to reach the highest possible percentage of patients adhering to multimodal analgesia regimen.

Adherence to the multimodal regimen led to 90% of patients receiving ketorolac on postoperative day 1, 100% receiving gabapentin on night of surgery, 86% off of IV PCA by postoperative day 3, and 100% order set adherence after full implementation of the RRP. LOS decreased from 5.7 to 4 days after RRP implementation. Pain scores also showed significant improvement on postoperative day 0 (average pain score, 3.8 vs. 4.9) and postoperative day 1 (3.8 vs. 5). Balancing measures of 30-day readmissions or ED visits after discharge was 2.9% and rose to 3.6% after full implementation.

Bottom line

Multimodal analgesia – including preoperative gabapentin and acetaminophen, intraoperative methadone and acetaminophen, and postoperative PCA diazepam, gabapentin, acetaminophen, and ketorolac – results in decreased length of stay and improved self-reported daily pain scores.

Citation

Muhly WT et al. Rapid recovery pathway after spinal fusion for idiopathic scoliosis. Pediatrics. 2016 Apr;137(4):e20151568.

Dr. Giordano is a pediatric neurosurgery hospitalist and assistant professor in pediatrics at Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York.

Clopidogrel and aspirin in acute ischemic stroke and high-risk TIA

Clinical question: Is the combination of aspirin and clopidogrel effective in reducing stroke recurrence?

Background: The risk of recurrent stroke varies from 3% to 15% in the 3 months after a minor ischemic stroke (NIH Stroke Scale score of 3 or less) or high-risk transient ischemic attack (ABCD2 score of 4 or less). Dual-antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel reduces recurrent coronary syndrome; therefore, this strategy can prevent recurrent stroke.

Study design: Prospective, randomized, double-blind, multicenter, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: 269 sites in 10 countries, mostly in the United States, from May 28, 2010, to Dec. 19, 2017.

Synopsis: The POINT (Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New TIA and Minor Ischemic Stroke) trial enrolled 4,881 patients older than 18 years of age randomized to a loading dose of 600 mg of clopidogrel followed by 75 mg per day or placebo, and aspirin 162 mg daily for 5 days followed by 81 mg daily. The primary outcome was the risk of major ischemic events, including ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, or death from ischemic vascular causes. Major ischemic events were observed in 5.0% receiving dual therapy and in 6.5% of those receiving aspirin alone (hazard ratio, 0.75; 95% confidence interval, 0.59-0.95; P = .02) with most occurring within a week after the initial stroke. Major hemorrhage occurred in only 23 patients (0.9%), most of which were extracranial and nonfatal. One of the main limitations is the difficulty in objectively diagnosing TIAs, accounting for 43% of the patients in the study.

Bottom line: Dual-antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel is beneficial, mainly in the first week after a minor stroke or high-risk TIA with low risk of major bleeding.

Citation: Johnston SC et al. Clopidogrel and aspirin in acute ischemic stroke and high-risk TIA. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:215-25.

Dr. Vela-Duarte is assistant professor of neurology at the University of Colorado, Denver.

Clinical question: Is the combination of aspirin and clopidogrel effective in reducing stroke recurrence?

Background: The risk of recurrent stroke varies from 3% to 15% in the 3 months after a minor ischemic stroke (NIH Stroke Scale score of 3 or less) or high-risk transient ischemic attack (ABCD2 score of 4 or less). Dual-antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel reduces recurrent coronary syndrome; therefore, this strategy can prevent recurrent stroke.

Study design: Prospective, randomized, double-blind, multicenter, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: 269 sites in 10 countries, mostly in the United States, from May 28, 2010, to Dec. 19, 2017.

Synopsis: The POINT (Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New TIA and Minor Ischemic Stroke) trial enrolled 4,881 patients older than 18 years of age randomized to a loading dose of 600 mg of clopidogrel followed by 75 mg per day or placebo, and aspirin 162 mg daily for 5 days followed by 81 mg daily. The primary outcome was the risk of major ischemic events, including ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, or death from ischemic vascular causes. Major ischemic events were observed in 5.0% receiving dual therapy and in 6.5% of those receiving aspirin alone (hazard ratio, 0.75; 95% confidence interval, 0.59-0.95; P = .02) with most occurring within a week after the initial stroke. Major hemorrhage occurred in only 23 patients (0.9%), most of which were extracranial and nonfatal. One of the main limitations is the difficulty in objectively diagnosing TIAs, accounting for 43% of the patients in the study.

Bottom line: Dual-antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel is beneficial, mainly in the first week after a minor stroke or high-risk TIA with low risk of major bleeding.

Citation: Johnston SC et al. Clopidogrel and aspirin in acute ischemic stroke and high-risk TIA. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:215-25.

Dr. Vela-Duarte is assistant professor of neurology at the University of Colorado, Denver.

Clinical question: Is the combination of aspirin and clopidogrel effective in reducing stroke recurrence?

Background: The risk of recurrent stroke varies from 3% to 15% in the 3 months after a minor ischemic stroke (NIH Stroke Scale score of 3 or less) or high-risk transient ischemic attack (ABCD2 score of 4 or less). Dual-antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel reduces recurrent coronary syndrome; therefore, this strategy can prevent recurrent stroke.

Study design: Prospective, randomized, double-blind, multicenter, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: 269 sites in 10 countries, mostly in the United States, from May 28, 2010, to Dec. 19, 2017.

Synopsis: The POINT (Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New TIA and Minor Ischemic Stroke) trial enrolled 4,881 patients older than 18 years of age randomized to a loading dose of 600 mg of clopidogrel followed by 75 mg per day or placebo, and aspirin 162 mg daily for 5 days followed by 81 mg daily. The primary outcome was the risk of major ischemic events, including ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, or death from ischemic vascular causes. Major ischemic events were observed in 5.0% receiving dual therapy and in 6.5% of those receiving aspirin alone (hazard ratio, 0.75; 95% confidence interval, 0.59-0.95; P = .02) with most occurring within a week after the initial stroke. Major hemorrhage occurred in only 23 patients (0.9%), most of which were extracranial and nonfatal. One of the main limitations is the difficulty in objectively diagnosing TIAs, accounting for 43% of the patients in the study.

Bottom line: Dual-antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel is beneficial, mainly in the first week after a minor stroke or high-risk TIA with low risk of major bleeding.

Citation: Johnston SC et al. Clopidogrel and aspirin in acute ischemic stroke and high-risk TIA. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:215-25.

Dr. Vela-Duarte is assistant professor of neurology at the University of Colorado, Denver.

Rivaroxaban for stroke prevention after embolic stroke

Clinical question: Does rivaroxaban prevent recurrent ischemic stroke in patients with embolic stroke from undetermined source?

Background: Embolic stroke of undetermined source (ESUS) represents approximately 20% of ischemic strokes. Rivaroxaban inhibits factor Xa and is shown to be effective for secondary stroke prevention in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Strategies to prevent cryptogenic stroke caused by mechanisms other than cardioembolic sources are lacking.

Study design: International, double-blind, event-driven, randomized, phase III trial.

Setting: 459 hospitals in 31 countries, during 2014-2017.

Synopsis: 7,213 patients with ESUS were randomized to receive either 15 mg of rivaroxaban once daily or aspirin 100 mg once daily. The primary outcome was established as the first recurrent stroke of any type or systemic embolism. The primary safety endpoint was major bleeding.

Recurrent stroke was observed in 158 in the rivaroxaban group and 156 in the aspirin group, mostly ischemic. The trial was terminated early because of a higher incidence of intracranial hemorrhage and major bleeding among patients assigned to rivaroxaban at an annual rate of 1.8%, compared with 0.7% (hazard ratio, 2.72; 95% confidence interval, 1.68-4.39; P less than .001). Although the study utilized strict criteria to define ESUS, it is feasible that the lack of benefit may be due to heterogeneous arterial, cardiogenic, and paradoxical emboli with diverse composition and poor response to rivaroxaban.

Bottom line: Rivaroxaban does not confer protection from recurrent stroke in patients with embolic stroke of unknown origin and increases risk for intracranial hemorrhage and major bleeding.

Citation: Hart RG et al. Rivaroxaban for stroke prevention after embolic stroke of undetermined source. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(23):2191-201.

Dr. Vela-Duarte is assistant professor of neurology at the University of Colorado, Denver

Clinical question: Does rivaroxaban prevent recurrent ischemic stroke in patients with embolic stroke from undetermined source?

Background: Embolic stroke of undetermined source (ESUS) represents approximately 20% of ischemic strokes. Rivaroxaban inhibits factor Xa and is shown to be effective for secondary stroke prevention in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Strategies to prevent cryptogenic stroke caused by mechanisms other than cardioembolic sources are lacking.

Study design: International, double-blind, event-driven, randomized, phase III trial.

Setting: 459 hospitals in 31 countries, during 2014-2017.

Synopsis: 7,213 patients with ESUS were randomized to receive either 15 mg of rivaroxaban once daily or aspirin 100 mg once daily. The primary outcome was established as the first recurrent stroke of any type or systemic embolism. The primary safety endpoint was major bleeding.

Recurrent stroke was observed in 158 in the rivaroxaban group and 156 in the aspirin group, mostly ischemic. The trial was terminated early because of a higher incidence of intracranial hemorrhage and major bleeding among patients assigned to rivaroxaban at an annual rate of 1.8%, compared with 0.7% (hazard ratio, 2.72; 95% confidence interval, 1.68-4.39; P less than .001). Although the study utilized strict criteria to define ESUS, it is feasible that the lack of benefit may be due to heterogeneous arterial, cardiogenic, and paradoxical emboli with diverse composition and poor response to rivaroxaban.

Bottom line: Rivaroxaban does not confer protection from recurrent stroke in patients with embolic stroke of unknown origin and increases risk for intracranial hemorrhage and major bleeding.

Citation: Hart RG et al. Rivaroxaban for stroke prevention after embolic stroke of undetermined source. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(23):2191-201.

Dr. Vela-Duarte is assistant professor of neurology at the University of Colorado, Denver

Clinical question: Does rivaroxaban prevent recurrent ischemic stroke in patients with embolic stroke from undetermined source?

Background: Embolic stroke of undetermined source (ESUS) represents approximately 20% of ischemic strokes. Rivaroxaban inhibits factor Xa and is shown to be effective for secondary stroke prevention in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Strategies to prevent cryptogenic stroke caused by mechanisms other than cardioembolic sources are lacking.

Study design: International, double-blind, event-driven, randomized, phase III trial.

Setting: 459 hospitals in 31 countries, during 2014-2017.

Synopsis: 7,213 patients with ESUS were randomized to receive either 15 mg of rivaroxaban once daily or aspirin 100 mg once daily. The primary outcome was established as the first recurrent stroke of any type or systemic embolism. The primary safety endpoint was major bleeding.

Recurrent stroke was observed in 158 in the rivaroxaban group and 156 in the aspirin group, mostly ischemic. The trial was terminated early because of a higher incidence of intracranial hemorrhage and major bleeding among patients assigned to rivaroxaban at an annual rate of 1.8%, compared with 0.7% (hazard ratio, 2.72; 95% confidence interval, 1.68-4.39; P less than .001). Although the study utilized strict criteria to define ESUS, it is feasible that the lack of benefit may be due to heterogeneous arterial, cardiogenic, and paradoxical emboli with diverse composition and poor response to rivaroxaban.

Bottom line: Rivaroxaban does not confer protection from recurrent stroke in patients with embolic stroke of unknown origin and increases risk for intracranial hemorrhage and major bleeding.

Citation: Hart RG et al. Rivaroxaban for stroke prevention after embolic stroke of undetermined source. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(23):2191-201.

Dr. Vela-Duarte is assistant professor of neurology at the University of Colorado, Denver

Transforming glycemic control at Norwalk Hospital

SHM eQUIPS program yields new protocols, guidelines

The Hospitalist recently sat down with Nancy J. Rennert, MD, FACE, FACP, CPHQ, chief of endocrinology and diabetes at Norwalk (Conn.) Hospital, Western Connecticut Health Network, to discuss her institution’s glycemic control initiatives.

Tell us a bit about your program:

Norwalk Hospital is a 366-bed community teaching hospital founded 125 years ago, now part of the growing Western Connecticut Health Network. Our residency and fellowship training programs are affiliated with Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and we are a branch campus of the University of Vermont, Burlington.

With leadership support, we created our Glycemic Care Team (GCT) 4 years ago to focus on improving the quality of care for persons with diabetes who were admitted to our hospital (often for another primary medical reason). Our hospitalists – 8 on the teaching service and 11 on the nonteaching service – are key players in our efforts as they care for the majority of medical inpatients. GCT is interdisciplinary and includes stakeholders at all levels, including quality, pharmacy, nutrition, hospital medicine, diabetes education, administrative leadership, endocrinology, information technology, point-of-care testing/pathology, surgery and more. We meet monthly with an agenda that includes safety events, glucometrics, and discussion of policies and protocols. Subgroups complete tasks in between the monthly meetings, and we bring in other clinical specialties as indicated based on the issues at hand.

What prior challenges did you encounter that led you to enroll in the Glycemic Control (GC) eQUIPS Program?

In order to know if our GCT was making a positive difference, we needed to first measure our baseline metrics and then identify our goals and develop our processes. We wanted actionable data analysis and the ability to differentiate areas of our hospital such as individual clinical units. After researching the options, we chose SHM’s GC eQUIPS Program, which we found to be user friendly. The national benchmarking was an important aspect for us as well. As a kick-off event, I invited Greg Maynard, MD, MHM, a hospitalist and the chief quality officer, UC Davis Medical Center, to speak on inpatient diabetes and was thrilled when he accepted my invitation. This provided an exciting start to our journey with SHM’s eQUIPS data management program.

As we began to obtain baseline measurements of glucose control, we needed a standardized, validated tool. The point-of-care glucose meters generated an enormous amount of data, but we were unable to sort this and analyze it in a meaningful and potentially actionable way. We were especially concerned about hypoglycemia. Our first task was to develop a prescriber ordered and nurse driven hypoglycemia protocol. How would we measure the overall effectiveness and success of the stepwise components of the protocol? The eQUIPS hypoglycemia management report was ideal in that it detailed metrics in stepwise fashion as it related to our protocol. For example, we were able to see the time from detection of hypoglycemia to the next point-of-care glucose check and to resolution of the event.

In addition, we wanted some comparative benchmarking data. The GC eQUIPS Program has a robust database of U.S. hospitals, which helped us define our ultimate goal – to be in the upper quartile of all measures. And we did it! Because of the amazing teamwork and leadership support, we were able to achieve national distinction from SHM as a “Top Performer” hospital for glycemic care.

How did the program help you and the team design your initiatives?

Data are powerful and convincing. We post and report our eQUIPS Glucometrics to our clinical staff monthly by unit, and through this process, we obtain the necessary “buy-ins” as well as participation to design clinical protocols and order sets. For example, we noted that many patients would be placed on “sliding scale”/coverage insulin alone at the time of hospital admission. This often would not be adjusted during the hospital stay. Our data showed that this practice was associated with more glucose fluctuations and hypoglycemia. When we reviewed this with our hospitalists, we achieved consensus and developed basal/bolus correction insulin protocols, which are embedded in the admission care sets. Following use of these order sets, we noted less hypoglycemia (decreased from 5.9% and remains less than 3.6%) and lower glucose variability. With the help of the eQUIPS metrics and benchmarking, we now have more than 20 protocols and safety rules built into our EHR system.

What were the key benefits that the GC eQUIPS Program provided that you were unable to find elsewhere?

The unique features we found most useful are the national benchmarking and “real-world” data presentation. National benchmarking allows us to compare ourselves with other hospitals (we can sort for like hospitals or all hospitals) and to periodically evaluate our processes and reexamine our goals. As part of this program, we can communicate with leaders of other high-performing hospitals and share strategies and challenges as well as discuss successes and failures. The quarterly benchmark webinar is another opportunity to be part of this professional community and we often pick up helpful information.

We particularly like the hyperglycemia/hypoglycemia scatter plots, which demonstrate the practical and important impact of glycemic control. Often there is a see-saw effect in which, if one parameter goes up, the other goes down; finding the sweet spot between hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia is key and clinically important.

Do you have any other comments to share related to your institution’s participation in the program?

We are fortunate to have many successes driven by our participation with the GC eQUIPS Program:

- Coordination of capillary blood glucose (CBG) testing, insulin administration and meal delivery: Use of rapid-acting insulin premeal is standard of care and requires that CBG testing, insulin, and meal delivery be precisely coordinated for optimal insulin action. We developed a process in which the catering associate calls the nurse using a voice-activated pager when the meal tray leaves the kitchen. Then, the nurse checks the CBG and gives insulin when the tray arrives. The tray contains a card to empower the patient to wait for the nurse to administer insulin prior to eating. This also provides an opportunity for nutritional education and carbohydrate awareness. Implementation of this process increased the percentage of patients who had a CBG and insulin administration within 15 minutes before a meal from less than 10% to more than 60%.

- Patient education regarding insulin use: In many cases, hospital patients may be started on insulin and their oral agents may be discontinued. This can be confusing and frightening to patients who often do not know if they will need to be on insulin long term. Our GCT created a script for the staff nurse to inform and reassure patients that this is standard practice and does not mean that they will need to remain on insulin after hospital discharge. The clinical team will communicate with the patient and together they will review treatment options. We have received many positive reviews from patients and staff for improving communication around this aspect of insulin therapy.

- Clinician and leader education: When our data revealed an uptick in hypoglycemia in our critical care units, we engaged the physicians, nurses, and staff and reviewed patient charts to identify potential process changes. To keep hypoglycemia in the spotlight, our director of critical care added hypoglycemia to the ICU checklist, which is discussed on all team clinical rounds. We are also developing an electronic metric (24-hour glucose maximum and minimum values) that can be quickly reviewed by the clinical team daily.

- Hypoglycemia and hyperkalemia: Analysis of our hypoglycemia data revealed a higher-than-expected rate in the ED in patients who did not have a diabetes diagnosis. Further review showed that this was associated with insulin treatment of hyperkalemia. Subsequently, we engaged our resident trainees and other team members in a study to characterize this hypoglycemia-hyperkalemia, and we have recently submitted a manuscript for publication detailing our findings and recommendations for glucose monitoring in these patients.

- Guideline for medical consultation on nonmedical services: Based on review of glucometrics on the nonmedical units and discussions with our hospitalist teams, we designed a guideline that includes recommendations for Medical Consultation in Nonmedical Admissions. Comanagement by a medical consultant will be requested earlier, and we will monitor if this influences glucometrics, patient and hospitalist satisfaction, etc.

- Medical student and house staff education: Two of our GCT hospitalists organize a monthly patient safety conference. After the students and trainees are asked to propose actionable solutions, the hospitalists discuss proposals generated at our GCT meetings. The students and trainees have the opportunity to participate in quality improvement, and we get great ideas from them as well.

Perhaps our biggest success is our Glycemic Care Team itself. We now receive questions and items to review from all departments and are seen as the hospital’s expert team on diabetes and hyperglycemia. It is truly a pleasure to lead this group of extremely high functioning and dedicated professionals. It is said that “team work makes the dream work.” Moving forward, I hope to expand our Glycemic Care Team to all the hospitals in our network.

SHM eQUIPS program yields new protocols, guidelines

SHM eQUIPS program yields new protocols, guidelines

The Hospitalist recently sat down with Nancy J. Rennert, MD, FACE, FACP, CPHQ, chief of endocrinology and diabetes at Norwalk (Conn.) Hospital, Western Connecticut Health Network, to discuss her institution’s glycemic control initiatives.

Tell us a bit about your program:

Norwalk Hospital is a 366-bed community teaching hospital founded 125 years ago, now part of the growing Western Connecticut Health Network. Our residency and fellowship training programs are affiliated with Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and we are a branch campus of the University of Vermont, Burlington.

With leadership support, we created our Glycemic Care Team (GCT) 4 years ago to focus on improving the quality of care for persons with diabetes who were admitted to our hospital (often for another primary medical reason). Our hospitalists – 8 on the teaching service and 11 on the nonteaching service – are key players in our efforts as they care for the majority of medical inpatients. GCT is interdisciplinary and includes stakeholders at all levels, including quality, pharmacy, nutrition, hospital medicine, diabetes education, administrative leadership, endocrinology, information technology, point-of-care testing/pathology, surgery and more. We meet monthly with an agenda that includes safety events, glucometrics, and discussion of policies and protocols. Subgroups complete tasks in between the monthly meetings, and we bring in other clinical specialties as indicated based on the issues at hand.

What prior challenges did you encounter that led you to enroll in the Glycemic Control (GC) eQUIPS Program?

In order to know if our GCT was making a positive difference, we needed to first measure our baseline metrics and then identify our goals and develop our processes. We wanted actionable data analysis and the ability to differentiate areas of our hospital such as individual clinical units. After researching the options, we chose SHM’s GC eQUIPS Program, which we found to be user friendly. The national benchmarking was an important aspect for us as well. As a kick-off event, I invited Greg Maynard, MD, MHM, a hospitalist and the chief quality officer, UC Davis Medical Center, to speak on inpatient diabetes and was thrilled when he accepted my invitation. This provided an exciting start to our journey with SHM’s eQUIPS data management program.

As we began to obtain baseline measurements of glucose control, we needed a standardized, validated tool. The point-of-care glucose meters generated an enormous amount of data, but we were unable to sort this and analyze it in a meaningful and potentially actionable way. We were especially concerned about hypoglycemia. Our first task was to develop a prescriber ordered and nurse driven hypoglycemia protocol. How would we measure the overall effectiveness and success of the stepwise components of the protocol? The eQUIPS hypoglycemia management report was ideal in that it detailed metrics in stepwise fashion as it related to our protocol. For example, we were able to see the time from detection of hypoglycemia to the next point-of-care glucose check and to resolution of the event.

In addition, we wanted some comparative benchmarking data. The GC eQUIPS Program has a robust database of U.S. hospitals, which helped us define our ultimate goal – to be in the upper quartile of all measures. And we did it! Because of the amazing teamwork and leadership support, we were able to achieve national distinction from SHM as a “Top Performer” hospital for glycemic care.

How did the program help you and the team design your initiatives?

Data are powerful and convincing. We post and report our eQUIPS Glucometrics to our clinical staff monthly by unit, and through this process, we obtain the necessary “buy-ins” as well as participation to design clinical protocols and order sets. For example, we noted that many patients would be placed on “sliding scale”/coverage insulin alone at the time of hospital admission. This often would not be adjusted during the hospital stay. Our data showed that this practice was associated with more glucose fluctuations and hypoglycemia. When we reviewed this with our hospitalists, we achieved consensus and developed basal/bolus correction insulin protocols, which are embedded in the admission care sets. Following use of these order sets, we noted less hypoglycemia (decreased from 5.9% and remains less than 3.6%) and lower glucose variability. With the help of the eQUIPS metrics and benchmarking, we now have more than 20 protocols and safety rules built into our EHR system.

What were the key benefits that the GC eQUIPS Program provided that you were unable to find elsewhere?

The unique features we found most useful are the national benchmarking and “real-world” data presentation. National benchmarking allows us to compare ourselves with other hospitals (we can sort for like hospitals or all hospitals) and to periodically evaluate our processes and reexamine our goals. As part of this program, we can communicate with leaders of other high-performing hospitals and share strategies and challenges as well as discuss successes and failures. The quarterly benchmark webinar is another opportunity to be part of this professional community and we often pick up helpful information.

We particularly like the hyperglycemia/hypoglycemia scatter plots, which demonstrate the practical and important impact of glycemic control. Often there is a see-saw effect in which, if one parameter goes up, the other goes down; finding the sweet spot between hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia is key and clinically important.

Do you have any other comments to share related to your institution’s participation in the program?

We are fortunate to have many successes driven by our participation with the GC eQUIPS Program:

- Coordination of capillary blood glucose (CBG) testing, insulin administration and meal delivery: Use of rapid-acting insulin premeal is standard of care and requires that CBG testing, insulin, and meal delivery be precisely coordinated for optimal insulin action. We developed a process in which the catering associate calls the nurse using a voice-activated pager when the meal tray leaves the kitchen. Then, the nurse checks the CBG and gives insulin when the tray arrives. The tray contains a card to empower the patient to wait for the nurse to administer insulin prior to eating. This also provides an opportunity for nutritional education and carbohydrate awareness. Implementation of this process increased the percentage of patients who had a CBG and insulin administration within 15 minutes before a meal from less than 10% to more than 60%.

- Patient education regarding insulin use: In many cases, hospital patients may be started on insulin and their oral agents may be discontinued. This can be confusing and frightening to patients who often do not know if they will need to be on insulin long term. Our GCT created a script for the staff nurse to inform and reassure patients that this is standard practice and does not mean that they will need to remain on insulin after hospital discharge. The clinical team will communicate with the patient and together they will review treatment options. We have received many positive reviews from patients and staff for improving communication around this aspect of insulin therapy.

- Clinician and leader education: When our data revealed an uptick in hypoglycemia in our critical care units, we engaged the physicians, nurses, and staff and reviewed patient charts to identify potential process changes. To keep hypoglycemia in the spotlight, our director of critical care added hypoglycemia to the ICU checklist, which is discussed on all team clinical rounds. We are also developing an electronic metric (24-hour glucose maximum and minimum values) that can be quickly reviewed by the clinical team daily.

- Hypoglycemia and hyperkalemia: Analysis of our hypoglycemia data revealed a higher-than-expected rate in the ED in patients who did not have a diabetes diagnosis. Further review showed that this was associated with insulin treatment of hyperkalemia. Subsequently, we engaged our resident trainees and other team members in a study to characterize this hypoglycemia-hyperkalemia, and we have recently submitted a manuscript for publication detailing our findings and recommendations for glucose monitoring in these patients.

- Guideline for medical consultation on nonmedical services: Based on review of glucometrics on the nonmedical units and discussions with our hospitalist teams, we designed a guideline that includes recommendations for Medical Consultation in Nonmedical Admissions. Comanagement by a medical consultant will be requested earlier, and we will monitor if this influences glucometrics, patient and hospitalist satisfaction, etc.

- Medical student and house staff education: Two of our GCT hospitalists organize a monthly patient safety conference. After the students and trainees are asked to propose actionable solutions, the hospitalists discuss proposals generated at our GCT meetings. The students and trainees have the opportunity to participate in quality improvement, and we get great ideas from them as well.

Perhaps our biggest success is our Glycemic Care Team itself. We now receive questions and items to review from all departments and are seen as the hospital’s expert team on diabetes and hyperglycemia. It is truly a pleasure to lead this group of extremely high functioning and dedicated professionals. It is said that “team work makes the dream work.” Moving forward, I hope to expand our Glycemic Care Team to all the hospitals in our network.

The Hospitalist recently sat down with Nancy J. Rennert, MD, FACE, FACP, CPHQ, chief of endocrinology and diabetes at Norwalk (Conn.) Hospital, Western Connecticut Health Network, to discuss her institution’s glycemic control initiatives.

Tell us a bit about your program:

Norwalk Hospital is a 366-bed community teaching hospital founded 125 years ago, now part of the growing Western Connecticut Health Network. Our residency and fellowship training programs are affiliated with Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and we are a branch campus of the University of Vermont, Burlington.

With leadership support, we created our Glycemic Care Team (GCT) 4 years ago to focus on improving the quality of care for persons with diabetes who were admitted to our hospital (often for another primary medical reason). Our hospitalists – 8 on the teaching service and 11 on the nonteaching service – are key players in our efforts as they care for the majority of medical inpatients. GCT is interdisciplinary and includes stakeholders at all levels, including quality, pharmacy, nutrition, hospital medicine, diabetes education, administrative leadership, endocrinology, information technology, point-of-care testing/pathology, surgery and more. We meet monthly with an agenda that includes safety events, glucometrics, and discussion of policies and protocols. Subgroups complete tasks in between the monthly meetings, and we bring in other clinical specialties as indicated based on the issues at hand.

What prior challenges did you encounter that led you to enroll in the Glycemic Control (GC) eQUIPS Program?

In order to know if our GCT was making a positive difference, we needed to first measure our baseline metrics and then identify our goals and develop our processes. We wanted actionable data analysis and the ability to differentiate areas of our hospital such as individual clinical units. After researching the options, we chose SHM’s GC eQUIPS Program, which we found to be user friendly. The national benchmarking was an important aspect for us as well. As a kick-off event, I invited Greg Maynard, MD, MHM, a hospitalist and the chief quality officer, UC Davis Medical Center, to speak on inpatient diabetes and was thrilled when he accepted my invitation. This provided an exciting start to our journey with SHM’s eQUIPS data management program.

As we began to obtain baseline measurements of glucose control, we needed a standardized, validated tool. The point-of-care glucose meters generated an enormous amount of data, but we were unable to sort this and analyze it in a meaningful and potentially actionable way. We were especially concerned about hypoglycemia. Our first task was to develop a prescriber ordered and nurse driven hypoglycemia protocol. How would we measure the overall effectiveness and success of the stepwise components of the protocol? The eQUIPS hypoglycemia management report was ideal in that it detailed metrics in stepwise fashion as it related to our protocol. For example, we were able to see the time from detection of hypoglycemia to the next point-of-care glucose check and to resolution of the event.

In addition, we wanted some comparative benchmarking data. The GC eQUIPS Program has a robust database of U.S. hospitals, which helped us define our ultimate goal – to be in the upper quartile of all measures. And we did it! Because of the amazing teamwork and leadership support, we were able to achieve national distinction from SHM as a “Top Performer” hospital for glycemic care.

How did the program help you and the team design your initiatives?

Data are powerful and convincing. We post and report our eQUIPS Glucometrics to our clinical staff monthly by unit, and through this process, we obtain the necessary “buy-ins” as well as participation to design clinical protocols and order sets. For example, we noted that many patients would be placed on “sliding scale”/coverage insulin alone at the time of hospital admission. This often would not be adjusted during the hospital stay. Our data showed that this practice was associated with more glucose fluctuations and hypoglycemia. When we reviewed this with our hospitalists, we achieved consensus and developed basal/bolus correction insulin protocols, which are embedded in the admission care sets. Following use of these order sets, we noted less hypoglycemia (decreased from 5.9% and remains less than 3.6%) and lower glucose variability. With the help of the eQUIPS metrics and benchmarking, we now have more than 20 protocols and safety rules built into our EHR system.

What were the key benefits that the GC eQUIPS Program provided that you were unable to find elsewhere?

The unique features we found most useful are the national benchmarking and “real-world” data presentation. National benchmarking allows us to compare ourselves with other hospitals (we can sort for like hospitals or all hospitals) and to periodically evaluate our processes and reexamine our goals. As part of this program, we can communicate with leaders of other high-performing hospitals and share strategies and challenges as well as discuss successes and failures. The quarterly benchmark webinar is another opportunity to be part of this professional community and we often pick up helpful information.

We particularly like the hyperglycemia/hypoglycemia scatter plots, which demonstrate the practical and important impact of glycemic control. Often there is a see-saw effect in which, if one parameter goes up, the other goes down; finding the sweet spot between hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia is key and clinically important.

Do you have any other comments to share related to your institution’s participation in the program?

We are fortunate to have many successes driven by our participation with the GC eQUIPS Program:

- Coordination of capillary blood glucose (CBG) testing, insulin administration and meal delivery: Use of rapid-acting insulin premeal is standard of care and requires that CBG testing, insulin, and meal delivery be precisely coordinated for optimal insulin action. We developed a process in which the catering associate calls the nurse using a voice-activated pager when the meal tray leaves the kitchen. Then, the nurse checks the CBG and gives insulin when the tray arrives. The tray contains a card to empower the patient to wait for the nurse to administer insulin prior to eating. This also provides an opportunity for nutritional education and carbohydrate awareness. Implementation of this process increased the percentage of patients who had a CBG and insulin administration within 15 minutes before a meal from less than 10% to more than 60%.

- Patient education regarding insulin use: In many cases, hospital patients may be started on insulin and their oral agents may be discontinued. This can be confusing and frightening to patients who often do not know if they will need to be on insulin long term. Our GCT created a script for the staff nurse to inform and reassure patients that this is standard practice and does not mean that they will need to remain on insulin after hospital discharge. The clinical team will communicate with the patient and together they will review treatment options. We have received many positive reviews from patients and staff for improving communication around this aspect of insulin therapy.

- Clinician and leader education: When our data revealed an uptick in hypoglycemia in our critical care units, we engaged the physicians, nurses, and staff and reviewed patient charts to identify potential process changes. To keep hypoglycemia in the spotlight, our director of critical care added hypoglycemia to the ICU checklist, which is discussed on all team clinical rounds. We are also developing an electronic metric (24-hour glucose maximum and minimum values) that can be quickly reviewed by the clinical team daily.

- Hypoglycemia and hyperkalemia: Analysis of our hypoglycemia data revealed a higher-than-expected rate in the ED in patients who did not have a diabetes diagnosis. Further review showed that this was associated with insulin treatment of hyperkalemia. Subsequently, we engaged our resident trainees and other team members in a study to characterize this hypoglycemia-hyperkalemia, and we have recently submitted a manuscript for publication detailing our findings and recommendations for glucose monitoring in these patients.

- Guideline for medical consultation on nonmedical services: Based on review of glucometrics on the nonmedical units and discussions with our hospitalist teams, we designed a guideline that includes recommendations for Medical Consultation in Nonmedical Admissions. Comanagement by a medical consultant will be requested earlier, and we will monitor if this influences glucometrics, patient and hospitalist satisfaction, etc.

- Medical student and house staff education: Two of our GCT hospitalists organize a monthly patient safety conference. After the students and trainees are asked to propose actionable solutions, the hospitalists discuss proposals generated at our GCT meetings. The students and trainees have the opportunity to participate in quality improvement, and we get great ideas from them as well.

Perhaps our biggest success is our Glycemic Care Team itself. We now receive questions and items to review from all departments and are seen as the hospital’s expert team on diabetes and hyperglycemia. It is truly a pleasure to lead this group of extremely high functioning and dedicated professionals. It is said that “team work makes the dream work.” Moving forward, I hope to expand our Glycemic Care Team to all the hospitals in our network.

Beware bacteremia suspicious of colon cancer

Clinical question: Is bacteremia from certain microbes associated with colorectal cancer?

Background: Streptococcus bovis bacteremia is classically associated with colorectal cancer. A number of other bacterial species have been found in colorectal cancer microbiota and may even exert oncogenic effects. However, it is not known whether bacteremia from these microbes is associated with colorectal cancer.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Public hospitals in Hong Kong.

Synopsis: Using the Clinical Data Analysis and Reporting System (representing greater than 90% of inpatient services provided in Hong Kong), researchers identified 15,215 patients with bacteremia from 11 genera of bacteria known to be present in the colorectal cancer microbiota, including Bacteroides, Clostridium, Filifactor, Fusobacterium, Gemella, Granulicatella, Parvimonas, Peptostreptococcus, Prevotella, Solobacterium, and Streptococcus. Compared with matched controls without bacteremia, a higher proportion of exposed patients had a subsequent diagnosis of colorectal cancer (1.69% vs. 1.16%; hazard ratio, 1.72; 95% confidence interval, 1.40-2.12). Bacteremia with other organisms was not associated with colorectal cancer, and bacteremia with the preidentified organisms was not associated with other types of non–colorectal cancer or nonmalignant gastrointestinal diseases, with the exception of a few genera commonly associated with diverticulitis.

Given the observational nature of this study, no causal relationship can be established. It is not clear if these species are involved in the oncogenesis of colorectal cancer or if colorectal tumors merely serve as a site of entry for bacteria into the bloodstream.

Bottom line: Bacteremia with certain bacterial genera is associated with colon cancer and should prompt consideration of colonoscopy to evaluate for malignancy.

Citation: Kwong TNY et al. Association between bacteremia from specific microbes and subsequent diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 2018 Aug;155(2):383-90.

Dr. Scarpato is clinical instructor in the division of hospital medicine, University of Colorado, Denver.

Clinical question: Is bacteremia from certain microbes associated with colorectal cancer?

Background: Streptococcus bovis bacteremia is classically associated with colorectal cancer. A number of other bacterial species have been found in colorectal cancer microbiota and may even exert oncogenic effects. However, it is not known whether bacteremia from these microbes is associated with colorectal cancer.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Public hospitals in Hong Kong.

Synopsis: Using the Clinical Data Analysis and Reporting System (representing greater than 90% of inpatient services provided in Hong Kong), researchers identified 15,215 patients with bacteremia from 11 genera of bacteria known to be present in the colorectal cancer microbiota, including Bacteroides, Clostridium, Filifactor, Fusobacterium, Gemella, Granulicatella, Parvimonas, Peptostreptococcus, Prevotella, Solobacterium, and Streptococcus. Compared with matched controls without bacteremia, a higher proportion of exposed patients had a subsequent diagnosis of colorectal cancer (1.69% vs. 1.16%; hazard ratio, 1.72; 95% confidence interval, 1.40-2.12). Bacteremia with other organisms was not associated with colorectal cancer, and bacteremia with the preidentified organisms was not associated with other types of non–colorectal cancer or nonmalignant gastrointestinal diseases, with the exception of a few genera commonly associated with diverticulitis.

Given the observational nature of this study, no causal relationship can be established. It is not clear if these species are involved in the oncogenesis of colorectal cancer or if colorectal tumors merely serve as a site of entry for bacteria into the bloodstream.

Bottom line: Bacteremia with certain bacterial genera is associated with colon cancer and should prompt consideration of colonoscopy to evaluate for malignancy.

Citation: Kwong TNY et al. Association between bacteremia from specific microbes and subsequent diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 2018 Aug;155(2):383-90.

Dr. Scarpato is clinical instructor in the division of hospital medicine, University of Colorado, Denver.

Clinical question: Is bacteremia from certain microbes associated with colorectal cancer?

Background: Streptococcus bovis bacteremia is classically associated with colorectal cancer. A number of other bacterial species have been found in colorectal cancer microbiota and may even exert oncogenic effects. However, it is not known whether bacteremia from these microbes is associated with colorectal cancer.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Public hospitals in Hong Kong.

Synopsis: Using the Clinical Data Analysis and Reporting System (representing greater than 90% of inpatient services provided in Hong Kong), researchers identified 15,215 patients with bacteremia from 11 genera of bacteria known to be present in the colorectal cancer microbiota, including Bacteroides, Clostridium, Filifactor, Fusobacterium, Gemella, Granulicatella, Parvimonas, Peptostreptococcus, Prevotella, Solobacterium, and Streptococcus. Compared with matched controls without bacteremia, a higher proportion of exposed patients had a subsequent diagnosis of colorectal cancer (1.69% vs. 1.16%; hazard ratio, 1.72; 95% confidence interval, 1.40-2.12). Bacteremia with other organisms was not associated with colorectal cancer, and bacteremia with the preidentified organisms was not associated with other types of non–colorectal cancer or nonmalignant gastrointestinal diseases, with the exception of a few genera commonly associated with diverticulitis.

Given the observational nature of this study, no causal relationship can be established. It is not clear if these species are involved in the oncogenesis of colorectal cancer or if colorectal tumors merely serve as a site of entry for bacteria into the bloodstream.

Bottom line: Bacteremia with certain bacterial genera is associated with colon cancer and should prompt consideration of colonoscopy to evaluate for malignancy.

Citation: Kwong TNY et al. Association between bacteremia from specific microbes and subsequent diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 2018 Aug;155(2):383-90.

Dr. Scarpato is clinical instructor in the division of hospital medicine, University of Colorado, Denver.

In the Literature - Short Takes

Sepsis Campaign bundles shortened to 1 hour

In response to the 2016 Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines, the 3-hour and 6-hour bundles have been combined and shortened into a 1-hour bundle to emphasize the emergent nature of sepsis. Elements of the bundle remain to same: measuring lactate, obtaining blood cultures, administration of broad-spectrume antibiotics, administration of 30mL/kg crystalloid, and vasopressors when necessary.

Citation: Levy MM et al. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign bundle: 2018 update. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(6):997-1000

Early ED discharge for PE

This randomized trial showed that low-risk emergency department patients diagnosed with pulmonary embolism who were discharged from the ED with rivaroxaban within 24 hours of presentation had decreased length of stay and nearly $2,500 in cost savings, compared with patients treated according to standard of care (often including hospitalization) without increased risk of bleeding, recurrent venous thromboembolism, or death.

Citation: Peacock WF et al. Emergency department discharge of pulmonary embolus patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2018. doi: 10.1111/acem.13451.

Outbreak of coagulopathy associated with synthetic cannabinoids

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports a recent outbreak of life-threatening coagulopathy associated with synthetic cannabinoid use, because of contamination with vitmin K antagonist agents. All patients who report synthetic cannabinoid use should be screened with INR testing, especially prior to procedures.

Citation: Outbreak of life-threatening coagulopathy associated with synthetic cannabinoid use. CDC Health Alert Network. June 27, 2018.

Lumbar puncture safe when performed on patients on dual-antiplatelet therapy

In a retrospective review of 100 adult patients who underwent lumbar puncture procedures while taking dual-antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel, Mayo clinic investigators found no epidural hematomas or other serious complications with at least 3 months of follow-up. This study was nto powered to detect the risk of spinal hematoma so caution and open discussion with patients still is recommended.

Citation: Carabenciov ID et al. Safety of lumbar puncture performed on dual anti-platelet therapy. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2018;93(5):627-9.

Sepsis Campaign bundles shortened to 1 hour

In response to the 2016 Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines, the 3-hour and 6-hour bundles have been combined and shortened into a 1-hour bundle to emphasize the emergent nature of sepsis. Elements of the bundle remain to same: measuring lactate, obtaining blood cultures, administration of broad-spectrume antibiotics, administration of 30mL/kg crystalloid, and vasopressors when necessary.

Citation: Levy MM et al. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign bundle: 2018 update. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(6):997-1000

Early ED discharge for PE

This randomized trial showed that low-risk emergency department patients diagnosed with pulmonary embolism who were discharged from the ED with rivaroxaban within 24 hours of presentation had decreased length of stay and nearly $2,500 in cost savings, compared with patients treated according to standard of care (often including hospitalization) without increased risk of bleeding, recurrent venous thromboembolism, or death.

Citation: Peacock WF et al. Emergency department discharge of pulmonary embolus patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2018. doi: 10.1111/acem.13451.

Outbreak of coagulopathy associated with synthetic cannabinoids

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports a recent outbreak of life-threatening coagulopathy associated with synthetic cannabinoid use, because of contamination with vitmin K antagonist agents. All patients who report synthetic cannabinoid use should be screened with INR testing, especially prior to procedures.

Citation: Outbreak of life-threatening coagulopathy associated with synthetic cannabinoid use. CDC Health Alert Network. June 27, 2018.

Lumbar puncture safe when performed on patients on dual-antiplatelet therapy

In a retrospective review of 100 adult patients who underwent lumbar puncture procedures while taking dual-antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel, Mayo clinic investigators found no epidural hematomas or other serious complications with at least 3 months of follow-up. This study was nto powered to detect the risk of spinal hematoma so caution and open discussion with patients still is recommended.

Citation: Carabenciov ID et al. Safety of lumbar puncture performed on dual anti-platelet therapy. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2018;93(5):627-9.

Sepsis Campaign bundles shortened to 1 hour

In response to the 2016 Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines, the 3-hour and 6-hour bundles have been combined and shortened into a 1-hour bundle to emphasize the emergent nature of sepsis. Elements of the bundle remain to same: measuring lactate, obtaining blood cultures, administration of broad-spectrume antibiotics, administration of 30mL/kg crystalloid, and vasopressors when necessary.

Citation: Levy MM et al. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign bundle: 2018 update. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(6):997-1000

Early ED discharge for PE

This randomized trial showed that low-risk emergency department patients diagnosed with pulmonary embolism who were discharged from the ED with rivaroxaban within 24 hours of presentation had decreased length of stay and nearly $2,500 in cost savings, compared with patients treated according to standard of care (often including hospitalization) without increased risk of bleeding, recurrent venous thromboembolism, or death.

Citation: Peacock WF et al. Emergency department discharge of pulmonary embolus patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2018. doi: 10.1111/acem.13451.

Outbreak of coagulopathy associated with synthetic cannabinoids

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports a recent outbreak of life-threatening coagulopathy associated with synthetic cannabinoid use, because of contamination with vitmin K antagonist agents. All patients who report synthetic cannabinoid use should be screened with INR testing, especially prior to procedures.

Citation: Outbreak of life-threatening coagulopathy associated with synthetic cannabinoid use. CDC Health Alert Network. June 27, 2018.

Lumbar puncture safe when performed on patients on dual-antiplatelet therapy

In a retrospective review of 100 adult patients who underwent lumbar puncture procedures while taking dual-antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel, Mayo clinic investigators found no epidural hematomas or other serious complications with at least 3 months of follow-up. This study was nto powered to detect the risk of spinal hematoma so caution and open discussion with patients still is recommended.

Citation: Carabenciov ID et al. Safety of lumbar puncture performed on dual anti-platelet therapy. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2018;93(5):627-9.

How do hospital medicine groups deal with staffing shortages?

Persistent demand for hospitalists nationally

During the last two decades, the United States health care labor market had an almost insatiable appetite for hospitalists, driving the specialty from nothing to over 50,000 members. Evidence of persistent demand for hospitalists abounds in the freshly released 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) report: rising salaries, growing responsibility for the overall hospital census, and a diversifying scope of services.

The SoHM offers fascinating and detailed insights into these trends, as well as hundreds of other aspects of the field’s growth. Unfortunately, this expanding and dynamic labor market has a challenging side for hospitals, management companies, and hospitalist group leaders – we are constantly recruiting and dealing with open positions!

As a multisite leader at an academic health system, I’m looking toward the next season of recruitment with excitement. In the fall and winter we’re fortunate to receive applications from the best and brightest graduating residents and hospitalists. I realize this is a blessing, particularly compared with programs in rural areas that may not hear from many applicants. However, even when we succeed at filling the openings, there is an inevitable trickle of talent out of our clinical labor pool during the spring and summer. One person is invited to spend 20% of their time leading a teaching program, another secures a highly coveted grant, and yet another has to move because their spouse is relocated. By then, we don’t have a packed roster of applicants and have to solve the challenge in other ways. What does the typical hospital medicine program do when faced with this circumstance?

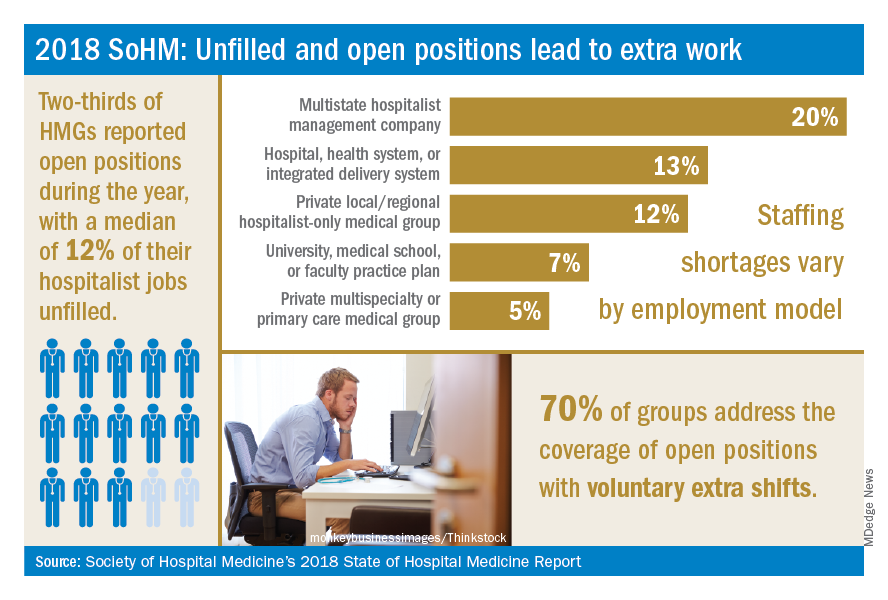

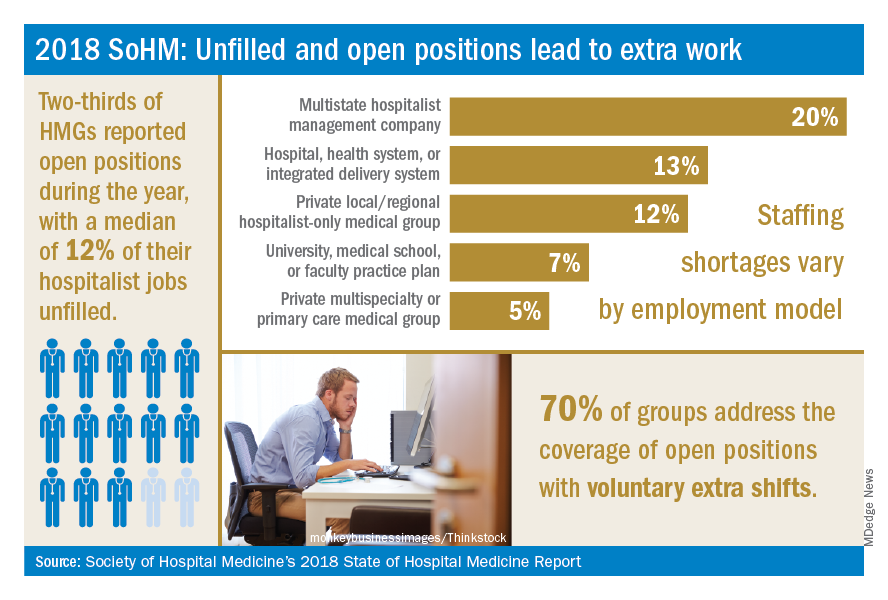

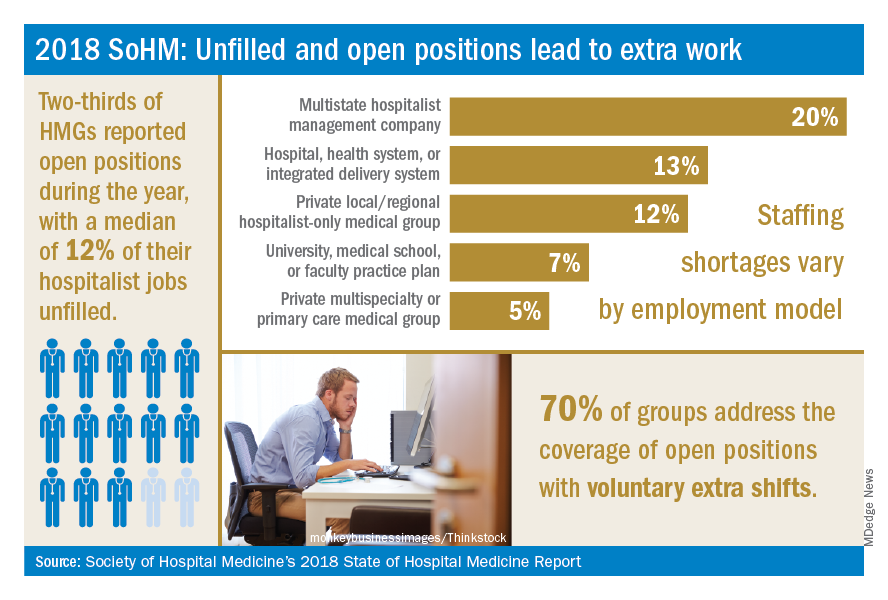

The 2018 SoHM survey first asked program leaders whether they had open and unfilled physician positions during the last year because of turnover, growth, or other factors. On average, 66% of groups serving adults and 48% of groups serving children said “yes.” For the job seekers out there, take note of some important regional differences: The regions with the highest percentage of programs dealing with unfilled positions were the East and West Coasts at 79% and 73%, respectively.

Next, the survey asked respondents to describe the percentage of total approved physician staffing that was open or unfilled during the year. On average, 12% of positions went unfilled, with important variation between different types of employers. For a typical HM group with 15 full-time equivalents, that means constantly working short two physicians!

Not only is it hard for group leaders to manage chronic understaffing, it definitely takes a toll on the group. We asked leaders to describe all of the ways their groups address coverage of the open positions. The most common tactics were for existing hospitalists to perform voluntary extra shifts (70%) and the use of moonlighters (57%). Also important were the use of locum tenens physicians (44%) and just leaving some shifts uncovered (31%).

The last option might work in a large group, where everyone can pick up an extra couple of patients, but it nonetheless degrades continuity and care progression. In a small group, leaving shifts uncovered sounds like a recipe for burnout and unsafe care – hopefully subsequent surveys will find that we can avoid that approach! Obviously, the solutions must be tailored to the group, their resources, and the alternative sources of labor available in that locality.

The SoHM report provides insight into how this is commonly handled by different employers and in different regions – we encourage anyone who is interested to purchase the report (www.hospitalmedicine.org/sohm) to dig deeper. For better or worse, the issue of unfilled positions looks likely to persist for the intermediate future. The exciting rise of hospital medicine against the backdrop of an aging population means job security, rising income, and opportunities for many to live where they choose. Until the job market saturates, though, we’ll all find ourselves looking at email inboxes with a request or two to pick up an extra shift!

Dr. White is associate professor of medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle. He is the chair of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Reference

Society of Hospital Medicine. 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report. pp. 89, 90, 181, 152.

Persistent demand for hospitalists nationally

Persistent demand for hospitalists nationally

During the last two decades, the United States health care labor market had an almost insatiable appetite for hospitalists, driving the specialty from nothing to over 50,000 members. Evidence of persistent demand for hospitalists abounds in the freshly released 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) report: rising salaries, growing responsibility for the overall hospital census, and a diversifying scope of services.

The SoHM offers fascinating and detailed insights into these trends, as well as hundreds of other aspects of the field’s growth. Unfortunately, this expanding and dynamic labor market has a challenging side for hospitals, management companies, and hospitalist group leaders – we are constantly recruiting and dealing with open positions!

As a multisite leader at an academic health system, I’m looking toward the next season of recruitment with excitement. In the fall and winter we’re fortunate to receive applications from the best and brightest graduating residents and hospitalists. I realize this is a blessing, particularly compared with programs in rural areas that may not hear from many applicants. However, even when we succeed at filling the openings, there is an inevitable trickle of talent out of our clinical labor pool during the spring and summer. One person is invited to spend 20% of their time leading a teaching program, another secures a highly coveted grant, and yet another has to move because their spouse is relocated. By then, we don’t have a packed roster of applicants and have to solve the challenge in other ways. What does the typical hospital medicine program do when faced with this circumstance?

The 2018 SoHM survey first asked program leaders whether they had open and unfilled physician positions during the last year because of turnover, growth, or other factors. On average, 66% of groups serving adults and 48% of groups serving children said “yes.” For the job seekers out there, take note of some important regional differences: The regions with the highest percentage of programs dealing with unfilled positions were the East and West Coasts at 79% and 73%, respectively.

Next, the survey asked respondents to describe the percentage of total approved physician staffing that was open or unfilled during the year. On average, 12% of positions went unfilled, with important variation between different types of employers. For a typical HM group with 15 full-time equivalents, that means constantly working short two physicians!

Not only is it hard for group leaders to manage chronic understaffing, it definitely takes a toll on the group. We asked leaders to describe all of the ways their groups address coverage of the open positions. The most common tactics were for existing hospitalists to perform voluntary extra shifts (70%) and the use of moonlighters (57%). Also important were the use of locum tenens physicians (44%) and just leaving some shifts uncovered (31%).

The last option might work in a large group, where everyone can pick up an extra couple of patients, but it nonetheless degrades continuity and care progression. In a small group, leaving shifts uncovered sounds like a recipe for burnout and unsafe care – hopefully subsequent surveys will find that we can avoid that approach! Obviously, the solutions must be tailored to the group, their resources, and the alternative sources of labor available in that locality.

The SoHM report provides insight into how this is commonly handled by different employers and in different regions – we encourage anyone who is interested to purchase the report (www.hospitalmedicine.org/sohm) to dig deeper. For better or worse, the issue of unfilled positions looks likely to persist for the intermediate future. The exciting rise of hospital medicine against the backdrop of an aging population means job security, rising income, and opportunities for many to live where they choose. Until the job market saturates, though, we’ll all find ourselves looking at email inboxes with a request or two to pick up an extra shift!

Dr. White is associate professor of medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle. He is the chair of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Reference

Society of Hospital Medicine. 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report. pp. 89, 90, 181, 152.

During the last two decades, the United States health care labor market had an almost insatiable appetite for hospitalists, driving the specialty from nothing to over 50,000 members. Evidence of persistent demand for hospitalists abounds in the freshly released 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) report: rising salaries, growing responsibility for the overall hospital census, and a diversifying scope of services.

The SoHM offers fascinating and detailed insights into these trends, as well as hundreds of other aspects of the field’s growth. Unfortunately, this expanding and dynamic labor market has a challenging side for hospitals, management companies, and hospitalist group leaders – we are constantly recruiting and dealing with open positions!

As a multisite leader at an academic health system, I’m looking toward the next season of recruitment with excitement. In the fall and winter we’re fortunate to receive applications from the best and brightest graduating residents and hospitalists. I realize this is a blessing, particularly compared with programs in rural areas that may not hear from many applicants. However, even when we succeed at filling the openings, there is an inevitable trickle of talent out of our clinical labor pool during the spring and summer. One person is invited to spend 20% of their time leading a teaching program, another secures a highly coveted grant, and yet another has to move because their spouse is relocated. By then, we don’t have a packed roster of applicants and have to solve the challenge in other ways. What does the typical hospital medicine program do when faced with this circumstance?

The 2018 SoHM survey first asked program leaders whether they had open and unfilled physician positions during the last year because of turnover, growth, or other factors. On average, 66% of groups serving adults and 48% of groups serving children said “yes.” For the job seekers out there, take note of some important regional differences: The regions with the highest percentage of programs dealing with unfilled positions were the East and West Coasts at 79% and 73%, respectively.

Next, the survey asked respondents to describe the percentage of total approved physician staffing that was open or unfilled during the year. On average, 12% of positions went unfilled, with important variation between different types of employers. For a typical HM group with 15 full-time equivalents, that means constantly working short two physicians!

Not only is it hard for group leaders to manage chronic understaffing, it definitely takes a toll on the group. We asked leaders to describe all of the ways their groups address coverage of the open positions. The most common tactics were for existing hospitalists to perform voluntary extra shifts (70%) and the use of moonlighters (57%). Also important were the use of locum tenens physicians (44%) and just leaving some shifts uncovered (31%).

The last option might work in a large group, where everyone can pick up an extra couple of patients, but it nonetheless degrades continuity and care progression. In a small group, leaving shifts uncovered sounds like a recipe for burnout and unsafe care – hopefully subsequent surveys will find that we can avoid that approach! Obviously, the solutions must be tailored to the group, their resources, and the alternative sources of labor available in that locality.

The SoHM report provides insight into how this is commonly handled by different employers and in different regions – we encourage anyone who is interested to purchase the report (www.hospitalmedicine.org/sohm) to dig deeper. For better or worse, the issue of unfilled positions looks likely to persist for the intermediate future. The exciting rise of hospital medicine against the backdrop of an aging population means job security, rising income, and opportunities for many to live where they choose. Until the job market saturates, though, we’ll all find ourselves looking at email inboxes with a request or two to pick up an extra shift!

Dr. White is associate professor of medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle. He is the chair of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Reference

Society of Hospital Medicine. 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report. pp. 89, 90, 181, 152.

Procalcitonin testing does not decrease antibiotic use for LRTIs