User login

The new SoHM report is here, and it’s the best yet!

Survey content more wide-ranging than ever

On behalf of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee, I’m thrilled to introduce the 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report (SoHM) and the resumption of this monthly Survey Insights column written by committee members.

It’s a bit like giving birth. A 9-month–long process that started last January with the excitement of launching the survey and encouraging hospital medicine groups (HMGs) to participate. Then the long, drawn-out process of validating and analyzing data, and organizing it into tables and charts, watching our baby grow and take shape before our eyes, with a few small hiccups along the way. Then graphic design and the agonizing process of copy editing – over and over until our eyes crossed – and printing.

Like all expectant parents, by August we were saying, “Enough already; when will this ever end?”

But we finally have a baby, and what proud parents we are! Here are a couple of key things you should know about the 2018 SoHM:

- The total number of HMGs participating in this year’s survey was marginally lower than in 2016 (569 this year vs. 595 in 2016), but the respondent groups are much more diverse. While more than half of respondent HMGs (52%) are employed by hospitals or health systems, multistate management companies employ 25%, and universities or their affiliates employ 12%. More pediatric hospitalist groups (38) and HMGs that serve both adults and children (31) participated this year, compared with 2016, and almost twice as many academic HMGs participated as in the previous survey (96 this year vs. 59 in 2016).

- The survey content is more wide-ranging than ever. As usual, SHM licensed hospitalist compensation and productivity data from the Medical Group Management Association for inclusion in this report, and the SoHM also covers just about every other aspect of hospitalist group structure and operations imaginable. In addition to traditional questions regarding scope of services, staffing and scheduling models, leadership configuration, and financial support, this year’s report includes new information on:

- Hospitalist comanagement roles with surgical and medical subspecialties.

- Information about unfilled positions and how they are covered (including locum tenens use).

- Utilization of dedicated daytime admitters.

- Prevalence of geographic or unit-based assignment models.

- Responsibility for CPT code selection.

- Amount of financial support per wRVU.

The report has retained its colorful, easy-to-read report layout and the user-friendly interface of the digital version. And because we have more diversity this year with regard to HMG employment models, we have been able to reintroduce findings by employment model.

The 2018 SoHM report is now available for purchase at www.hospitalmedicine.org/sohm. I encourage you to obtain the SoHM report for yourself; you’ll almost certainly find more than one interesting and useful tidbit of information. Use the report to assess how your practice compares to your peers, but always keep in mind that surveys don’t tell you what should be – they tell you only what currently is.

New best practices not reflected in survey data are emerging all the time, and the ways others do things won’t always be right for your group’s unique situation and needs. Whether you are partners or employees, you and your colleagues “own” the success of your practice and are the best judges of what is right for you.

Leslie Flores, MHA, SFHM, is a partner with Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants, and a member of the SHM Practice Analysis Committee.

Survey content more wide-ranging than ever

Survey content more wide-ranging than ever

On behalf of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee, I’m thrilled to introduce the 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report (SoHM) and the resumption of this monthly Survey Insights column written by committee members.

It’s a bit like giving birth. A 9-month–long process that started last January with the excitement of launching the survey and encouraging hospital medicine groups (HMGs) to participate. Then the long, drawn-out process of validating and analyzing data, and organizing it into tables and charts, watching our baby grow and take shape before our eyes, with a few small hiccups along the way. Then graphic design and the agonizing process of copy editing – over and over until our eyes crossed – and printing.

Like all expectant parents, by August we were saying, “Enough already; when will this ever end?”

But we finally have a baby, and what proud parents we are! Here are a couple of key things you should know about the 2018 SoHM:

- The total number of HMGs participating in this year’s survey was marginally lower than in 2016 (569 this year vs. 595 in 2016), but the respondent groups are much more diverse. While more than half of respondent HMGs (52%) are employed by hospitals or health systems, multistate management companies employ 25%, and universities or their affiliates employ 12%. More pediatric hospitalist groups (38) and HMGs that serve both adults and children (31) participated this year, compared with 2016, and almost twice as many academic HMGs participated as in the previous survey (96 this year vs. 59 in 2016).

- The survey content is more wide-ranging than ever. As usual, SHM licensed hospitalist compensation and productivity data from the Medical Group Management Association for inclusion in this report, and the SoHM also covers just about every other aspect of hospitalist group structure and operations imaginable. In addition to traditional questions regarding scope of services, staffing and scheduling models, leadership configuration, and financial support, this year’s report includes new information on:

- Hospitalist comanagement roles with surgical and medical subspecialties.

- Information about unfilled positions and how they are covered (including locum tenens use).

- Utilization of dedicated daytime admitters.

- Prevalence of geographic or unit-based assignment models.

- Responsibility for CPT code selection.

- Amount of financial support per wRVU.

The report has retained its colorful, easy-to-read report layout and the user-friendly interface of the digital version. And because we have more diversity this year with regard to HMG employment models, we have been able to reintroduce findings by employment model.

The 2018 SoHM report is now available for purchase at www.hospitalmedicine.org/sohm. I encourage you to obtain the SoHM report for yourself; you’ll almost certainly find more than one interesting and useful tidbit of information. Use the report to assess how your practice compares to your peers, but always keep in mind that surveys don’t tell you what should be – they tell you only what currently is.

New best practices not reflected in survey data are emerging all the time, and the ways others do things won’t always be right for your group’s unique situation and needs. Whether you are partners or employees, you and your colleagues “own” the success of your practice and are the best judges of what is right for you.

Leslie Flores, MHA, SFHM, is a partner with Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants, and a member of the SHM Practice Analysis Committee.

On behalf of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee, I’m thrilled to introduce the 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report (SoHM) and the resumption of this monthly Survey Insights column written by committee members.

It’s a bit like giving birth. A 9-month–long process that started last January with the excitement of launching the survey and encouraging hospital medicine groups (HMGs) to participate. Then the long, drawn-out process of validating and analyzing data, and organizing it into tables and charts, watching our baby grow and take shape before our eyes, with a few small hiccups along the way. Then graphic design and the agonizing process of copy editing – over and over until our eyes crossed – and printing.

Like all expectant parents, by August we were saying, “Enough already; when will this ever end?”

But we finally have a baby, and what proud parents we are! Here are a couple of key things you should know about the 2018 SoHM:

- The total number of HMGs participating in this year’s survey was marginally lower than in 2016 (569 this year vs. 595 in 2016), but the respondent groups are much more diverse. While more than half of respondent HMGs (52%) are employed by hospitals or health systems, multistate management companies employ 25%, and universities or their affiliates employ 12%. More pediatric hospitalist groups (38) and HMGs that serve both adults and children (31) participated this year, compared with 2016, and almost twice as many academic HMGs participated as in the previous survey (96 this year vs. 59 in 2016).

- The survey content is more wide-ranging than ever. As usual, SHM licensed hospitalist compensation and productivity data from the Medical Group Management Association for inclusion in this report, and the SoHM also covers just about every other aspect of hospitalist group structure and operations imaginable. In addition to traditional questions regarding scope of services, staffing and scheduling models, leadership configuration, and financial support, this year’s report includes new information on:

- Hospitalist comanagement roles with surgical and medical subspecialties.

- Information about unfilled positions and how they are covered (including locum tenens use).

- Utilization of dedicated daytime admitters.

- Prevalence of geographic or unit-based assignment models.

- Responsibility for CPT code selection.

- Amount of financial support per wRVU.

The report has retained its colorful, easy-to-read report layout and the user-friendly interface of the digital version. And because we have more diversity this year with regard to HMG employment models, we have been able to reintroduce findings by employment model.

The 2018 SoHM report is now available for purchase at www.hospitalmedicine.org/sohm. I encourage you to obtain the SoHM report for yourself; you’ll almost certainly find more than one interesting and useful tidbit of information. Use the report to assess how your practice compares to your peers, but always keep in mind that surveys don’t tell you what should be – they tell you only what currently is.

New best practices not reflected in survey data are emerging all the time, and the ways others do things won’t always be right for your group’s unique situation and needs. Whether you are partners or employees, you and your colleagues “own” the success of your practice and are the best judges of what is right for you.

Leslie Flores, MHA, SFHM, is a partner with Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants, and a member of the SHM Practice Analysis Committee.

Procalcitonin not helpful in critically ill COPD

Clinical question: Can a procalcitonin (PCT)–guided strategy safely reduce antibiotic exposure in patients admitted to the ICU with severe acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) with or without pneumonia?

Background: Studies have demonstrated PCT-based strategies can safely reduce antibiotic use in patients without severe lower respiratory tract infections, community-acquired pneumonia, or acute exacerbations of COPD. The data on safety of PCT-based strategies in critically ill patients is limited.

Study design: Prospective, multicenter, randomized, controlled trial.

Setting: ICUs of 11 hospitals in France, including 7 tertiary care hospitals.

Synopsis: In this study 302 patients admitted to the ICU with severe exacerbations of COPD with or without pneumonia were randomly assigned to groups with antibiotic therapy guided by a PCT protocol or standard guidelines. Overall, the study failed to demonstrate noninferiority of a PCT-based strategy to reduce exposure to antibiotics. Specifically, the adjusted difference in mortality was 6.6% higher (90% confidence interval, 0.3%-13.5%) in the intervention group with no significant reduction in antibiotic exposure.

One limitation of this study was that it was an open trial in which clinicians were aware that their management was being observed.

Bottom line: A PCT-based algorithm was not effective in safely reducing antibiotic exposure in patients with acute exacerbations of COPD admitted to the ICU.

Citation: Daubin C et al. Procalcitonin algorithm to guide initial antibiotic therapy in acute exacerbations of COPD admitted to the ICU: A randomized multicenter study. Intensive Care Med. 2018 Apr;44(4):428-37.

Dr. Agith is a hospitalist in the division of hospital medicine in the department of medicine at Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Ill.

Clinical question: Can a procalcitonin (PCT)–guided strategy safely reduce antibiotic exposure in patients admitted to the ICU with severe acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) with or without pneumonia?

Background: Studies have demonstrated PCT-based strategies can safely reduce antibiotic use in patients without severe lower respiratory tract infections, community-acquired pneumonia, or acute exacerbations of COPD. The data on safety of PCT-based strategies in critically ill patients is limited.

Study design: Prospective, multicenter, randomized, controlled trial.

Setting: ICUs of 11 hospitals in France, including 7 tertiary care hospitals.

Synopsis: In this study 302 patients admitted to the ICU with severe exacerbations of COPD with or without pneumonia were randomly assigned to groups with antibiotic therapy guided by a PCT protocol or standard guidelines. Overall, the study failed to demonstrate noninferiority of a PCT-based strategy to reduce exposure to antibiotics. Specifically, the adjusted difference in mortality was 6.6% higher (90% confidence interval, 0.3%-13.5%) in the intervention group with no significant reduction in antibiotic exposure.

One limitation of this study was that it was an open trial in which clinicians were aware that their management was being observed.

Bottom line: A PCT-based algorithm was not effective in safely reducing antibiotic exposure in patients with acute exacerbations of COPD admitted to the ICU.

Citation: Daubin C et al. Procalcitonin algorithm to guide initial antibiotic therapy in acute exacerbations of COPD admitted to the ICU: A randomized multicenter study. Intensive Care Med. 2018 Apr;44(4):428-37.

Dr. Agith is a hospitalist in the division of hospital medicine in the department of medicine at Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Ill.

Clinical question: Can a procalcitonin (PCT)–guided strategy safely reduce antibiotic exposure in patients admitted to the ICU with severe acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) with or without pneumonia?

Background: Studies have demonstrated PCT-based strategies can safely reduce antibiotic use in patients without severe lower respiratory tract infections, community-acquired pneumonia, or acute exacerbations of COPD. The data on safety of PCT-based strategies in critically ill patients is limited.

Study design: Prospective, multicenter, randomized, controlled trial.

Setting: ICUs of 11 hospitals in France, including 7 tertiary care hospitals.

Synopsis: In this study 302 patients admitted to the ICU with severe exacerbations of COPD with or without pneumonia were randomly assigned to groups with antibiotic therapy guided by a PCT protocol or standard guidelines. Overall, the study failed to demonstrate noninferiority of a PCT-based strategy to reduce exposure to antibiotics. Specifically, the adjusted difference in mortality was 6.6% higher (90% confidence interval, 0.3%-13.5%) in the intervention group with no significant reduction in antibiotic exposure.

One limitation of this study was that it was an open trial in which clinicians were aware that their management was being observed.

Bottom line: A PCT-based algorithm was not effective in safely reducing antibiotic exposure in patients with acute exacerbations of COPD admitted to the ICU.

Citation: Daubin C et al. Procalcitonin algorithm to guide initial antibiotic therapy in acute exacerbations of COPD admitted to the ICU: A randomized multicenter study. Intensive Care Med. 2018 Apr;44(4):428-37.

Dr. Agith is a hospitalist in the division of hospital medicine in the department of medicine at Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Ill.

Perioperative diabetes and HbA1c in mortality

Clinical question: Do preoperative hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) and perioperative glucose predict outcomes in patients undergoing noncardiac and cardiac surgeries?

Background: Hyperglycemia in the perioperative period has been associated with infection, delayed wound healing, and postoperative mortality. Studies have investigated the effects of HbA1c or hyperglycemia on postoperative outcomes, but none have been performed to assess the effect of one while controlling for the other.

Study design: Retrospective analysis.

Setting: Single-center, Duke University Health System.

Synopsis: Using a database of electronic health records at Duke University Health System, Durham, N.C., investigators reviewed 13,077 surgeries (6,684 noncardiac and 6,393 cardiac) to determine the association of preoperative HbA1c with perioperative glucose and 30-day mortality. For noncardiac surgery, increased average perioperative glucose was associated with increased mortality (P = .04). In cardiac surgery both low and high average glucose was associated with increased mortality (P = .001). By contrast, HbA1c was not a significant predictor of postoperative mortality in cardiac surgery (P = .08), and in noncardiac surgery, HbA1C was negatively associated with 30-day mortality (P = .01). Overall, perioperative glucose was predictive of 30-day mortality, but HbA1c was not associated with 30-day mortality after researchers controlled for glucose.

Because the study is retrospective, no causal relationship can be established. Hospitalists involved in perioperative care should aim for optimization of glucose control regardless of preoperative HbA1c.

Bottom line: Perioperative glucose is related to surgical outcomes, but HbA1c is a less useful indicator of 30-day postoperative mortality.

Citation: Van den Boom W et al. Effect of A1C and glucose on postoperative mortality in noncardiac and cardiac surgeries. Diabetes Care. 2018 Feb;41:782-8.

Clinical question: Do preoperative hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) and perioperative glucose predict outcomes in patients undergoing noncardiac and cardiac surgeries?

Background: Hyperglycemia in the perioperative period has been associated with infection, delayed wound healing, and postoperative mortality. Studies have investigated the effects of HbA1c or hyperglycemia on postoperative outcomes, but none have been performed to assess the effect of one while controlling for the other.

Study design: Retrospective analysis.

Setting: Single-center, Duke University Health System.

Synopsis: Using a database of electronic health records at Duke University Health System, Durham, N.C., investigators reviewed 13,077 surgeries (6,684 noncardiac and 6,393 cardiac) to determine the association of preoperative HbA1c with perioperative glucose and 30-day mortality. For noncardiac surgery, increased average perioperative glucose was associated with increased mortality (P = .04). In cardiac surgery both low and high average glucose was associated with increased mortality (P = .001). By contrast, HbA1c was not a significant predictor of postoperative mortality in cardiac surgery (P = .08), and in noncardiac surgery, HbA1C was negatively associated with 30-day mortality (P = .01). Overall, perioperative glucose was predictive of 30-day mortality, but HbA1c was not associated with 30-day mortality after researchers controlled for glucose.

Because the study is retrospective, no causal relationship can be established. Hospitalists involved in perioperative care should aim for optimization of glucose control regardless of preoperative HbA1c.

Bottom line: Perioperative glucose is related to surgical outcomes, but HbA1c is a less useful indicator of 30-day postoperative mortality.

Citation: Van den Boom W et al. Effect of A1C and glucose on postoperative mortality in noncardiac and cardiac surgeries. Diabetes Care. 2018 Feb;41:782-8.

Clinical question: Do preoperative hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) and perioperative glucose predict outcomes in patients undergoing noncardiac and cardiac surgeries?

Background: Hyperglycemia in the perioperative period has been associated with infection, delayed wound healing, and postoperative mortality. Studies have investigated the effects of HbA1c or hyperglycemia on postoperative outcomes, but none have been performed to assess the effect of one while controlling for the other.

Study design: Retrospective analysis.

Setting: Single-center, Duke University Health System.

Synopsis: Using a database of electronic health records at Duke University Health System, Durham, N.C., investigators reviewed 13,077 surgeries (6,684 noncardiac and 6,393 cardiac) to determine the association of preoperative HbA1c with perioperative glucose and 30-day mortality. For noncardiac surgery, increased average perioperative glucose was associated with increased mortality (P = .04). In cardiac surgery both low and high average glucose was associated with increased mortality (P = .001). By contrast, HbA1c was not a significant predictor of postoperative mortality in cardiac surgery (P = .08), and in noncardiac surgery, HbA1C was negatively associated with 30-day mortality (P = .01). Overall, perioperative glucose was predictive of 30-day mortality, but HbA1c was not associated with 30-day mortality after researchers controlled for glucose.

Because the study is retrospective, no causal relationship can be established. Hospitalists involved in perioperative care should aim for optimization of glucose control regardless of preoperative HbA1c.

Bottom line: Perioperative glucose is related to surgical outcomes, but HbA1c is a less useful indicator of 30-day postoperative mortality.

Citation: Van den Boom W et al. Effect of A1C and glucose on postoperative mortality in noncardiac and cardiac surgeries. Diabetes Care. 2018 Feb;41:782-8.

Predicting failure of nonoperative management of spinal epidural abscess

Clinical question: Can one predict whether nonoperative management of spinal epidural abscesses will fail?

Background: Even though spinal epidural abscesses have a low incidence and nonspecific presentation, a delay in treatment can lead to significant morbidity. Previously, operative management was the preferred treatment; however, improvements in imaging and timing of diagnosis have led to an increased interest in nonoperative management. Few studies have identified possible predictors of failure for nonoperative management, and no algorithm exists for weighing the different possible predictors with the outcome of nonoperative management failure.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: A Massachusetts hospital system with two tertiary academic medical centers and three regional community hospitals.

Synopsis: The study evaluated 1,053 patients admitted with a spinal epidural abscess during 1993-2016. Of these, 432 patients were managed nonoperatively, and 367 were included in the analysis. Failure of nonoperative management occurred in 99 patients (27%). These patients were compared with 266 patients with successful nonoperative management with more than 60 days of follow-up. Six independent factors were associated with failure of nonoperative management including motor deficit at presentation (odds ratio, 7.85), pathological or compression fractures (OR, 6.12), active malignancy (OR, 3.32), diabetes (OR, 2.92), sensory changes at presentation (3.48), and location of the abscess dorsal to the thecal sac (OR, 0.29). Subsequently, a clinical algorithm was created to predict the likelihood of failure of nonoperative management.

Because of its retrospective design, the study was unable to assess the efficacy of surgery versus nonoperative management.

Bottom line: Specific measures of general health, neurologic status at presentation, and anatomical data of a patient with a spinal epidural abscess have led to the development of a clinical algorithm to determine the risk of failure in nonoperative management of spinal epidural abscesses.

Citation: Shah AA et al. Nonoperative management of spinal epidural abscess: Development of a predictive algorithm for failure. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100(7):546-55.

Dr. Tsien is a hospitalist in the division of hospital medicine in the department of medicine at Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Ill.

Clinical question: Can one predict whether nonoperative management of spinal epidural abscesses will fail?

Background: Even though spinal epidural abscesses have a low incidence and nonspecific presentation, a delay in treatment can lead to significant morbidity. Previously, operative management was the preferred treatment; however, improvements in imaging and timing of diagnosis have led to an increased interest in nonoperative management. Few studies have identified possible predictors of failure for nonoperative management, and no algorithm exists for weighing the different possible predictors with the outcome of nonoperative management failure.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: A Massachusetts hospital system with two tertiary academic medical centers and three regional community hospitals.

Synopsis: The study evaluated 1,053 patients admitted with a spinal epidural abscess during 1993-2016. Of these, 432 patients were managed nonoperatively, and 367 were included in the analysis. Failure of nonoperative management occurred in 99 patients (27%). These patients were compared with 266 patients with successful nonoperative management with more than 60 days of follow-up. Six independent factors were associated with failure of nonoperative management including motor deficit at presentation (odds ratio, 7.85), pathological or compression fractures (OR, 6.12), active malignancy (OR, 3.32), diabetes (OR, 2.92), sensory changes at presentation (3.48), and location of the abscess dorsal to the thecal sac (OR, 0.29). Subsequently, a clinical algorithm was created to predict the likelihood of failure of nonoperative management.

Because of its retrospective design, the study was unable to assess the efficacy of surgery versus nonoperative management.

Bottom line: Specific measures of general health, neurologic status at presentation, and anatomical data of a patient with a spinal epidural abscess have led to the development of a clinical algorithm to determine the risk of failure in nonoperative management of spinal epidural abscesses.

Citation: Shah AA et al. Nonoperative management of spinal epidural abscess: Development of a predictive algorithm for failure. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100(7):546-55.

Dr. Tsien is a hospitalist in the division of hospital medicine in the department of medicine at Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Ill.

Clinical question: Can one predict whether nonoperative management of spinal epidural abscesses will fail?

Background: Even though spinal epidural abscesses have a low incidence and nonspecific presentation, a delay in treatment can lead to significant morbidity. Previously, operative management was the preferred treatment; however, improvements in imaging and timing of diagnosis have led to an increased interest in nonoperative management. Few studies have identified possible predictors of failure for nonoperative management, and no algorithm exists for weighing the different possible predictors with the outcome of nonoperative management failure.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: A Massachusetts hospital system with two tertiary academic medical centers and three regional community hospitals.

Synopsis: The study evaluated 1,053 patients admitted with a spinal epidural abscess during 1993-2016. Of these, 432 patients were managed nonoperatively, and 367 were included in the analysis. Failure of nonoperative management occurred in 99 patients (27%). These patients were compared with 266 patients with successful nonoperative management with more than 60 days of follow-up. Six independent factors were associated with failure of nonoperative management including motor deficit at presentation (odds ratio, 7.85), pathological or compression fractures (OR, 6.12), active malignancy (OR, 3.32), diabetes (OR, 2.92), sensory changes at presentation (3.48), and location of the abscess dorsal to the thecal sac (OR, 0.29). Subsequently, a clinical algorithm was created to predict the likelihood of failure of nonoperative management.

Because of its retrospective design, the study was unable to assess the efficacy of surgery versus nonoperative management.

Bottom line: Specific measures of general health, neurologic status at presentation, and anatomical data of a patient with a spinal epidural abscess have led to the development of a clinical algorithm to determine the risk of failure in nonoperative management of spinal epidural abscesses.

Citation: Shah AA et al. Nonoperative management of spinal epidural abscess: Development of a predictive algorithm for failure. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100(7):546-55.

Dr. Tsien is a hospitalist in the division of hospital medicine in the department of medicine at Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Ill.

Hospital-level care coordination strategies and the patient experience

Clinical question: Does patient experience correlate with specific hospital care coordination and transition strategies, and if so, which strategies most strongly correlate with higher patient experience scores?

Background: Patient experience is an increasingly important measure in value-based payment programs. However, progress has been slow in improving patient experience, and little empirical data exist regarding which strategies are effective. Care transitions are critical times during a hospitalization, with many hospitals already implementing measures to improve the discharge process and prevent readmission of patients. It is not known whether those measures also influence patient experience scores, and if they do improve scores, which measures are most effective at doing so.

Study design: An analytic observational survey design.

Setting: Hospitals eligible for the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) between June 2013 and December 2014.

Synopsis: A survey was developed and given to chief medical officers at 1,600 hospitals between June 2013 and December 2014; the survey assessed care coordination strategies employed by these institutions. 992 hospitals (62% response rate) were subsequently categorized as “low-strategy,” “mid-strategy,” or “high-strategy” hospitals. Patient satisfaction scores from the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey in 2014 were correlated to the number of strategies and the specific strategies each hospital employed. In general, the higher-strategy hospitals had significantly higher HCAHPS survey scores than did low-strategy hospitals (+2.23 points; P less than .001). Specifically, creating and sharing a discharge summary prior to discharge (+1.43 points; P less than .001), using a discharge planner (+1.71 points; P less than .001), and calling patients 48 hours post discharge (+1.64 points; P less than .001) all resulted in overall higher hospital ratings by patients.

One limitation of this study is that no causal inference can be made between the specific strategies associated with higher HCAHPS scores and care coordination strategies.

Bottom line: Hospital-led care transition strategies with direct patient interactions led to higher patient satisfaction scores.

Citation: Figueroa JF et al. Hospital-level care coordination strategies associated with better patient experience. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018 Apr 4. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007597.

Dr. Tsien is a hospitalist in the division of hospital medicine in the department of medicine at Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Ill.

Clinical question: Does patient experience correlate with specific hospital care coordination and transition strategies, and if so, which strategies most strongly correlate with higher patient experience scores?

Background: Patient experience is an increasingly important measure in value-based payment programs. However, progress has been slow in improving patient experience, and little empirical data exist regarding which strategies are effective. Care transitions are critical times during a hospitalization, with many hospitals already implementing measures to improve the discharge process and prevent readmission of patients. It is not known whether those measures also influence patient experience scores, and if they do improve scores, which measures are most effective at doing so.

Study design: An analytic observational survey design.

Setting: Hospitals eligible for the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) between June 2013 and December 2014.

Synopsis: A survey was developed and given to chief medical officers at 1,600 hospitals between June 2013 and December 2014; the survey assessed care coordination strategies employed by these institutions. 992 hospitals (62% response rate) were subsequently categorized as “low-strategy,” “mid-strategy,” or “high-strategy” hospitals. Patient satisfaction scores from the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey in 2014 were correlated to the number of strategies and the specific strategies each hospital employed. In general, the higher-strategy hospitals had significantly higher HCAHPS survey scores than did low-strategy hospitals (+2.23 points; P less than .001). Specifically, creating and sharing a discharge summary prior to discharge (+1.43 points; P less than .001), using a discharge planner (+1.71 points; P less than .001), and calling patients 48 hours post discharge (+1.64 points; P less than .001) all resulted in overall higher hospital ratings by patients.

One limitation of this study is that no causal inference can be made between the specific strategies associated with higher HCAHPS scores and care coordination strategies.

Bottom line: Hospital-led care transition strategies with direct patient interactions led to higher patient satisfaction scores.

Citation: Figueroa JF et al. Hospital-level care coordination strategies associated with better patient experience. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018 Apr 4. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007597.

Dr. Tsien is a hospitalist in the division of hospital medicine in the department of medicine at Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Ill.

Clinical question: Does patient experience correlate with specific hospital care coordination and transition strategies, and if so, which strategies most strongly correlate with higher patient experience scores?

Background: Patient experience is an increasingly important measure in value-based payment programs. However, progress has been slow in improving patient experience, and little empirical data exist regarding which strategies are effective. Care transitions are critical times during a hospitalization, with many hospitals already implementing measures to improve the discharge process and prevent readmission of patients. It is not known whether those measures also influence patient experience scores, and if they do improve scores, which measures are most effective at doing so.

Study design: An analytic observational survey design.

Setting: Hospitals eligible for the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) between June 2013 and December 2014.

Synopsis: A survey was developed and given to chief medical officers at 1,600 hospitals between June 2013 and December 2014; the survey assessed care coordination strategies employed by these institutions. 992 hospitals (62% response rate) were subsequently categorized as “low-strategy,” “mid-strategy,” or “high-strategy” hospitals. Patient satisfaction scores from the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey in 2014 were correlated to the number of strategies and the specific strategies each hospital employed. In general, the higher-strategy hospitals had significantly higher HCAHPS survey scores than did low-strategy hospitals (+2.23 points; P less than .001). Specifically, creating and sharing a discharge summary prior to discharge (+1.43 points; P less than .001), using a discharge planner (+1.71 points; P less than .001), and calling patients 48 hours post discharge (+1.64 points; P less than .001) all resulted in overall higher hospital ratings by patients.

One limitation of this study is that no causal inference can be made between the specific strategies associated with higher HCAHPS scores and care coordination strategies.

Bottom line: Hospital-led care transition strategies with direct patient interactions led to higher patient satisfaction scores.

Citation: Figueroa JF et al. Hospital-level care coordination strategies associated with better patient experience. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018 Apr 4. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007597.

Dr. Tsien is a hospitalist in the division of hospital medicine in the department of medicine at Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Ill.

Palliative care consultations reduce hospital costs

Background: Health care costs are on the rise, and previous studies have found that PCC can reduce hospital costs. Timing of consultation and allocation of palliative care intervention to a certain population of patients may reveal a more significant cost reduction.

Study design: Meta-analysis.

Setting: English peer reviewed articles.

Synopsis: A systematic search was performed for articles that provided economic evaluation of PCC for adult inpatients in acute care hospitals. Patients were included if they had least one of seven conditions: cancer, heart failure, liver failure, kidney failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, AIDS/HIV, or neurodegenerative conditions. Six data sets were reviewed, which included 133,118 patients altogether. There was a significant reduction in costs with PCC within 3 days of admission, regardless of the diagnosis (–$3,237; 95% confidence interval, –$3,581 to –$2,893). In the stratified analysis, the pooled meta-analysis suggested a statistically significant reduction in costs for both cancer (–$4,251; 95% CI, –$4,664 to –$3,837; P less than .001) and noncancer (–$2,105; 95% CI, –$2,698 to –$1,511; P less than .001) subsamples. In patients with cancer, the treatment effect was greater for patients with four or more comorbidities than it was for those with two or fewer.

Only six samples were evaluated, and causation could not be established because all samples had observational designs. There also was potential interpretation bias because the private investigator for each of the samples contributed to interpretation of the data and participated as an author. Overall evaluation of the economic value of PCC in this study was limited because analysis was focused to a single index hospital admission rather than including additional hospitalizations and outpatient costs.

Bottom line: Acute care hospitals might reduce hospital costs by increasing resources to allow palliative care consultations in patients with serious illnesses.

Citation: May P et al. Economics of palliative care for hospitalized adults with serious illness. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(6):820-9.

Dr. Libot is a hospitalist in the division of hospital medicine in the department of medicine at Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Ill.

Background: Health care costs are on the rise, and previous studies have found that PCC can reduce hospital costs. Timing of consultation and allocation of palliative care intervention to a certain population of patients may reveal a more significant cost reduction.

Study design: Meta-analysis.

Setting: English peer reviewed articles.

Synopsis: A systematic search was performed for articles that provided economic evaluation of PCC for adult inpatients in acute care hospitals. Patients were included if they had least one of seven conditions: cancer, heart failure, liver failure, kidney failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, AIDS/HIV, or neurodegenerative conditions. Six data sets were reviewed, which included 133,118 patients altogether. There was a significant reduction in costs with PCC within 3 days of admission, regardless of the diagnosis (–$3,237; 95% confidence interval, –$3,581 to –$2,893). In the stratified analysis, the pooled meta-analysis suggested a statistically significant reduction in costs for both cancer (–$4,251; 95% CI, –$4,664 to –$3,837; P less than .001) and noncancer (–$2,105; 95% CI, –$2,698 to –$1,511; P less than .001) subsamples. In patients with cancer, the treatment effect was greater for patients with four or more comorbidities than it was for those with two or fewer.

Only six samples were evaluated, and causation could not be established because all samples had observational designs. There also was potential interpretation bias because the private investigator for each of the samples contributed to interpretation of the data and participated as an author. Overall evaluation of the economic value of PCC in this study was limited because analysis was focused to a single index hospital admission rather than including additional hospitalizations and outpatient costs.

Bottom line: Acute care hospitals might reduce hospital costs by increasing resources to allow palliative care consultations in patients with serious illnesses.

Citation: May P et al. Economics of palliative care for hospitalized adults with serious illness. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(6):820-9.

Dr. Libot is a hospitalist in the division of hospital medicine in the department of medicine at Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Ill.

Background: Health care costs are on the rise, and previous studies have found that PCC can reduce hospital costs. Timing of consultation and allocation of palliative care intervention to a certain population of patients may reveal a more significant cost reduction.

Study design: Meta-analysis.

Setting: English peer reviewed articles.

Synopsis: A systematic search was performed for articles that provided economic evaluation of PCC for adult inpatients in acute care hospitals. Patients were included if they had least one of seven conditions: cancer, heart failure, liver failure, kidney failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, AIDS/HIV, or neurodegenerative conditions. Six data sets were reviewed, which included 133,118 patients altogether. There was a significant reduction in costs with PCC within 3 days of admission, regardless of the diagnosis (–$3,237; 95% confidence interval, –$3,581 to –$2,893). In the stratified analysis, the pooled meta-analysis suggested a statistically significant reduction in costs for both cancer (–$4,251; 95% CI, –$4,664 to –$3,837; P less than .001) and noncancer (–$2,105; 95% CI, –$2,698 to –$1,511; P less than .001) subsamples. In patients with cancer, the treatment effect was greater for patients with four or more comorbidities than it was for those with two or fewer.

Only six samples were evaluated, and causation could not be established because all samples had observational designs. There also was potential interpretation bias because the private investigator for each of the samples contributed to interpretation of the data and participated as an author. Overall evaluation of the economic value of PCC in this study was limited because analysis was focused to a single index hospital admission rather than including additional hospitalizations and outpatient costs.

Bottom line: Acute care hospitals might reduce hospital costs by increasing resources to allow palliative care consultations in patients with serious illnesses.

Citation: May P et al. Economics of palliative care for hospitalized adults with serious illness. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(6):820-9.

Dr. Libot is a hospitalist in the division of hospital medicine in the department of medicine at Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Ill.

Treating cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome

Incidence may increase as marijuana use rises

Case

WS is a 54-year-old African American male with a medical history of diabetes mellitus type 2, hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, and gastroparesis. He has multiple admissions for intractable nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain believed to be from diabetic gastroparesis despite a normal gastric-emptying study. Endoscopy done in prior admission showed duodenitis, gastritis, and esophagitis, and colonoscopy revealed diverticulosis. He had a negative gastric-emptying study of 6% retention at 4 hrs. His last hemoglobin A1c was 5 and his glucose has been well controlled. He is hospitalized again for intractable abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. His examination was unremarkable except for dry mucosa and epigastric tenderness. His labs were also insignificant except for prerenal azotemia. Upon further questioning he admitted to significant marijuana use, and his symptoms transiently improved with a hot shower in the hospital. He was diagnosed with cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) and admitted for further management.

Background

In the United States, 9 states and the District of Columbia have legalized recreational marijuana use, and 29 states and DC have legalized medical marijuana. Marijuana use is likely to rise, and with it may arise an increasing incidence of CHS.

The exact prevalence of CHS is not known. Diagnosis is often delayed as there is no reliable diagnostic test. A high index of suspicion is needed for prompt diagnosis.

CHS was first described in 2004 in South Australia and since then many case reports have been published. Marijuana has both proemetic and antiemetic effects. Unlike its antiemetic effect, the pathophysiology of the proemetic effect of marijuana is not well understood.

Key clinical features

CHS typically has three phases. Initially patients present with prodromal symptoms of abdominal discomfort and nausea. There is no emesis at this early phase. Patients are still able to tolerate a liquid diet in this prodromal phase.

This is followed by a more active phase of intractable vomiting, which is relieved by hot showers or baths. Most patients take compulsively long hot showers or baths many times a day. Also, they develop diaphoresis, restlessness, agitation, and weight loss.

The active phase is followed by a recovery phase when symptoms resolve and patients return to baseline, only to have it recur if marijuana use continues.

Diagnostic approach and management

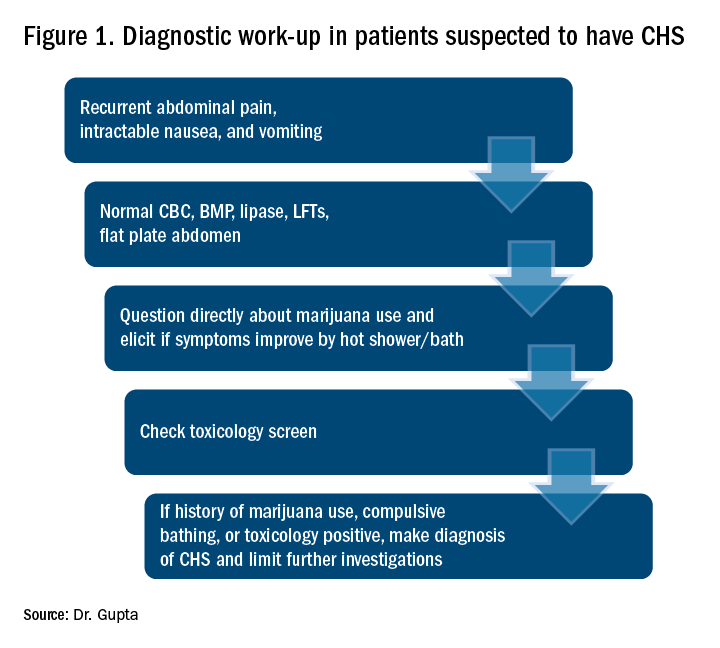

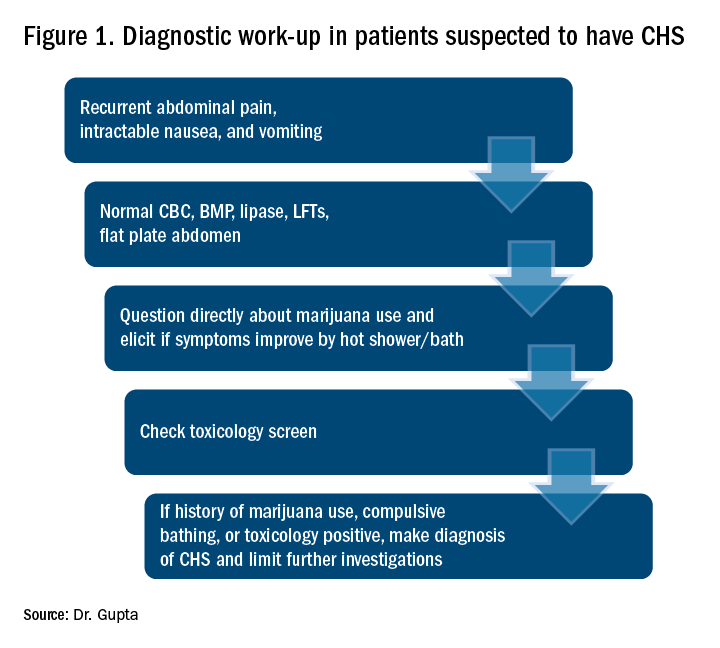

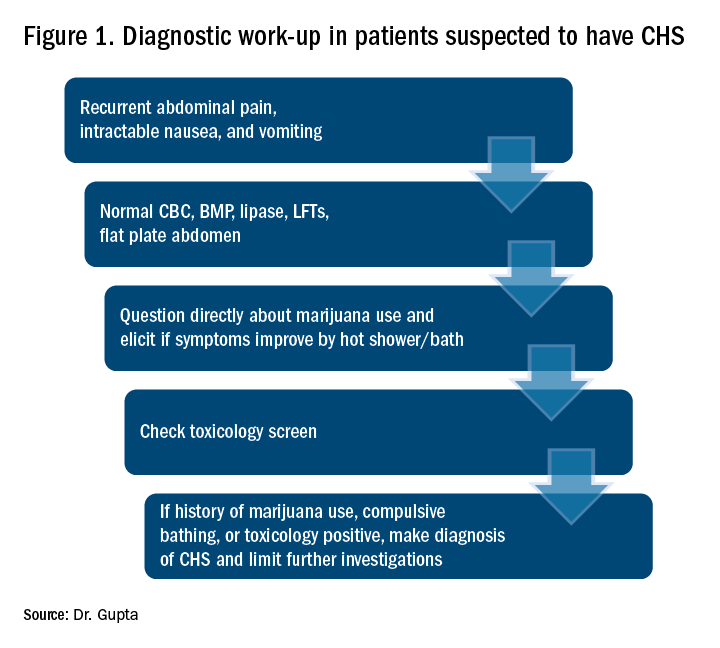

CHS should be suspected in patients coming in with recurrent symptoms of abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, and who have normal CBC, basic metabolic panel, lipase, and liver function tests. Patients should be directly questioned about marijuana use and whether symptoms are relieved with hot showers. A toxicology screen should be done. For patients with marijuana use and compulsive hot showers, further work up of their symptoms (e.g., upper endoscopy, abdominal ultrasound, and/or nuclear medicine emptying study) should be avoided. Figure 1 shows the suggested work-up.

The differential diagnosis for recurrent abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting is chronic pancreatitis, gastroparesis, severe gastritis, medication adverse effects (especially GLP1 receptor agonists), cyclic vomiting syndrome, psychogenic vomiting, and (with the rise of narcotic abuse) narcotic bowel syndrome.

Our patient had a history of diabetes with an HbA1c at goal and a normal nuclear medicine gastric-emptying study (6% retention at 4 hours). He was also on liraglutide, but his symptoms predated this medicine use.

The mainstay of treatment for CHS is supportive therapy with intravenous fluids and antiemetics like 5-HT3-receptor antagonists (ondansetron); D2-receptor antagonists (metoclopramide); and H1-receptor antagonists (diphenhydramine). The effectiveness of these agents is limited, which is also a clue for the diagnosis of CHS. If traditional agents fail in controlling the symptoms, haloperidol can be tried, but it has been used with limited success. Our patient did not respond to traditional antiemetics, but responded well to a small dose of lorazepam. Even though a benzodiazepine is not the mainstay of treatment, it may be tried if other agents fail. Acid-suppression therapy with a proton pump inhibitor should be used as esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) usually reveals mild gastritis and esophagitis, as in our patient. Narcotic use should be avoided for management of abdominal pain.

Patients should be counseled against marijuana use. This may be difficult if marijuana is being used as an appetite stimulant or for treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. If willing, patients should be referred to a substance abuse rehabilitation center.

Back to the case

In this case, after a diagnosis of CHS was made, the patient was counseled against marijuana use. His abdominal pain and intractable vomiting did not improve with conservative management of n.p.o status, prochlorperazine, metoclopramide, and ondansetron. He was given a trial of low-dose lorazepam with significant improvement in his symptoms. He was counseled extensively against marijuana use and discharged. A follow-up phone call at 3 months showed continued abstinence and no recurrence of symptoms.

Dr. Gupta is a hospitalist at Yale New Haven Health and Bridgeport (Conn.) Hospital.

References

1. Bajgoric S et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: A guide for the practising clinician. BMJ Case Rep. 2015. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-210246.

2. Batke M et al. The cannabis hyperemesis syndrome characterized by persistent nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, and compulsive bathing associated with chronic marijuana use: A report of eight cases in the united states. Dig Dis Sci. 2010 Nov;55(11):3113-9.

3. Iacopetti CL et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: a case report and review of pathophysiology. Clin Med Res. 2014 Sep;12(1-2):65-7.

4. Hickey JL et al. Haloperidol for treatment of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. Am J Emerg Med. 2013 Jun. 31(6):1003.e5-6. Epub 2013 Apr 10.

Key points

Suspect CHS for patients with recurrent abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting with negative initial work-up.

- Ask directly about marijuana use.

- Ask whether symptoms are relieved with hot shower/ bath.

- Send a toxicology screen.

- Make a diagnosis of CHS if:

1. Positive marijuana use.

2. Symptom improvement with hot baths or

3. Toxicology positive for marijuana.

- Manage conservatively with hydration and antiemetics.

- Suspect CHS if traditional antiemetics are not providing relief .

- If traditional antiemetics fail, trial of haloperidol or low-dose benzodiazepines.

- Avoid narcotics.

- Avoid unnecessary investigations.

- Counsel patients against marijuana use and refer to substance abuse center if patient agrees.

Incidence may increase as marijuana use rises

Incidence may increase as marijuana use rises

Case

WS is a 54-year-old African American male with a medical history of diabetes mellitus type 2, hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, and gastroparesis. He has multiple admissions for intractable nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain believed to be from diabetic gastroparesis despite a normal gastric-emptying study. Endoscopy done in prior admission showed duodenitis, gastritis, and esophagitis, and colonoscopy revealed diverticulosis. He had a negative gastric-emptying study of 6% retention at 4 hrs. His last hemoglobin A1c was 5 and his glucose has been well controlled. He is hospitalized again for intractable abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. His examination was unremarkable except for dry mucosa and epigastric tenderness. His labs were also insignificant except for prerenal azotemia. Upon further questioning he admitted to significant marijuana use, and his symptoms transiently improved with a hot shower in the hospital. He was diagnosed with cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) and admitted for further management.

Background

In the United States, 9 states and the District of Columbia have legalized recreational marijuana use, and 29 states and DC have legalized medical marijuana. Marijuana use is likely to rise, and with it may arise an increasing incidence of CHS.

The exact prevalence of CHS is not known. Diagnosis is often delayed as there is no reliable diagnostic test. A high index of suspicion is needed for prompt diagnosis.

CHS was first described in 2004 in South Australia and since then many case reports have been published. Marijuana has both proemetic and antiemetic effects. Unlike its antiemetic effect, the pathophysiology of the proemetic effect of marijuana is not well understood.

Key clinical features

CHS typically has three phases. Initially patients present with prodromal symptoms of abdominal discomfort and nausea. There is no emesis at this early phase. Patients are still able to tolerate a liquid diet in this prodromal phase.

This is followed by a more active phase of intractable vomiting, which is relieved by hot showers or baths. Most patients take compulsively long hot showers or baths many times a day. Also, they develop diaphoresis, restlessness, agitation, and weight loss.

The active phase is followed by a recovery phase when symptoms resolve and patients return to baseline, only to have it recur if marijuana use continues.

Diagnostic approach and management

CHS should be suspected in patients coming in with recurrent symptoms of abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, and who have normal CBC, basic metabolic panel, lipase, and liver function tests. Patients should be directly questioned about marijuana use and whether symptoms are relieved with hot showers. A toxicology screen should be done. For patients with marijuana use and compulsive hot showers, further work up of their symptoms (e.g., upper endoscopy, abdominal ultrasound, and/or nuclear medicine emptying study) should be avoided. Figure 1 shows the suggested work-up.

The differential diagnosis for recurrent abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting is chronic pancreatitis, gastroparesis, severe gastritis, medication adverse effects (especially GLP1 receptor agonists), cyclic vomiting syndrome, psychogenic vomiting, and (with the rise of narcotic abuse) narcotic bowel syndrome.

Our patient had a history of diabetes with an HbA1c at goal and a normal nuclear medicine gastric-emptying study (6% retention at 4 hours). He was also on liraglutide, but his symptoms predated this medicine use.

The mainstay of treatment for CHS is supportive therapy with intravenous fluids and antiemetics like 5-HT3-receptor antagonists (ondansetron); D2-receptor antagonists (metoclopramide); and H1-receptor antagonists (diphenhydramine). The effectiveness of these agents is limited, which is also a clue for the diagnosis of CHS. If traditional agents fail in controlling the symptoms, haloperidol can be tried, but it has been used with limited success. Our patient did not respond to traditional antiemetics, but responded well to a small dose of lorazepam. Even though a benzodiazepine is not the mainstay of treatment, it may be tried if other agents fail. Acid-suppression therapy with a proton pump inhibitor should be used as esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) usually reveals mild gastritis and esophagitis, as in our patient. Narcotic use should be avoided for management of abdominal pain.

Patients should be counseled against marijuana use. This may be difficult if marijuana is being used as an appetite stimulant or for treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. If willing, patients should be referred to a substance abuse rehabilitation center.

Back to the case

In this case, after a diagnosis of CHS was made, the patient was counseled against marijuana use. His abdominal pain and intractable vomiting did not improve with conservative management of n.p.o status, prochlorperazine, metoclopramide, and ondansetron. He was given a trial of low-dose lorazepam with significant improvement in his symptoms. He was counseled extensively against marijuana use and discharged. A follow-up phone call at 3 months showed continued abstinence and no recurrence of symptoms.

Dr. Gupta is a hospitalist at Yale New Haven Health and Bridgeport (Conn.) Hospital.

References

1. Bajgoric S et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: A guide for the practising clinician. BMJ Case Rep. 2015. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-210246.

2. Batke M et al. The cannabis hyperemesis syndrome characterized by persistent nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, and compulsive bathing associated with chronic marijuana use: A report of eight cases in the united states. Dig Dis Sci. 2010 Nov;55(11):3113-9.

3. Iacopetti CL et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: a case report and review of pathophysiology. Clin Med Res. 2014 Sep;12(1-2):65-7.

4. Hickey JL et al. Haloperidol for treatment of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. Am J Emerg Med. 2013 Jun. 31(6):1003.e5-6. Epub 2013 Apr 10.

Key points

Suspect CHS for patients with recurrent abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting with negative initial work-up.

- Ask directly about marijuana use.

- Ask whether symptoms are relieved with hot shower/ bath.

- Send a toxicology screen.

- Make a diagnosis of CHS if:

1. Positive marijuana use.

2. Symptom improvement with hot baths or

3. Toxicology positive for marijuana.

- Manage conservatively with hydration and antiemetics.

- Suspect CHS if traditional antiemetics are not providing relief .

- If traditional antiemetics fail, trial of haloperidol or low-dose benzodiazepines.

- Avoid narcotics.

- Avoid unnecessary investigations.

- Counsel patients against marijuana use and refer to substance abuse center if patient agrees.

Case

WS is a 54-year-old African American male with a medical history of diabetes mellitus type 2, hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, and gastroparesis. He has multiple admissions for intractable nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain believed to be from diabetic gastroparesis despite a normal gastric-emptying study. Endoscopy done in prior admission showed duodenitis, gastritis, and esophagitis, and colonoscopy revealed diverticulosis. He had a negative gastric-emptying study of 6% retention at 4 hrs. His last hemoglobin A1c was 5 and his glucose has been well controlled. He is hospitalized again for intractable abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. His examination was unremarkable except for dry mucosa and epigastric tenderness. His labs were also insignificant except for prerenal azotemia. Upon further questioning he admitted to significant marijuana use, and his symptoms transiently improved with a hot shower in the hospital. He was diagnosed with cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) and admitted for further management.

Background

In the United States, 9 states and the District of Columbia have legalized recreational marijuana use, and 29 states and DC have legalized medical marijuana. Marijuana use is likely to rise, and with it may arise an increasing incidence of CHS.

The exact prevalence of CHS is not known. Diagnosis is often delayed as there is no reliable diagnostic test. A high index of suspicion is needed for prompt diagnosis.

CHS was first described in 2004 in South Australia and since then many case reports have been published. Marijuana has both proemetic and antiemetic effects. Unlike its antiemetic effect, the pathophysiology of the proemetic effect of marijuana is not well understood.

Key clinical features

CHS typically has three phases. Initially patients present with prodromal symptoms of abdominal discomfort and nausea. There is no emesis at this early phase. Patients are still able to tolerate a liquid diet in this prodromal phase.

This is followed by a more active phase of intractable vomiting, which is relieved by hot showers or baths. Most patients take compulsively long hot showers or baths many times a day. Also, they develop diaphoresis, restlessness, agitation, and weight loss.

The active phase is followed by a recovery phase when symptoms resolve and patients return to baseline, only to have it recur if marijuana use continues.

Diagnostic approach and management

CHS should be suspected in patients coming in with recurrent symptoms of abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, and who have normal CBC, basic metabolic panel, lipase, and liver function tests. Patients should be directly questioned about marijuana use and whether symptoms are relieved with hot showers. A toxicology screen should be done. For patients with marijuana use and compulsive hot showers, further work up of their symptoms (e.g., upper endoscopy, abdominal ultrasound, and/or nuclear medicine emptying study) should be avoided. Figure 1 shows the suggested work-up.

The differential diagnosis for recurrent abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting is chronic pancreatitis, gastroparesis, severe gastritis, medication adverse effects (especially GLP1 receptor agonists), cyclic vomiting syndrome, psychogenic vomiting, and (with the rise of narcotic abuse) narcotic bowel syndrome.

Our patient had a history of diabetes with an HbA1c at goal and a normal nuclear medicine gastric-emptying study (6% retention at 4 hours). He was also on liraglutide, but his symptoms predated this medicine use.

The mainstay of treatment for CHS is supportive therapy with intravenous fluids and antiemetics like 5-HT3-receptor antagonists (ondansetron); D2-receptor antagonists (metoclopramide); and H1-receptor antagonists (diphenhydramine). The effectiveness of these agents is limited, which is also a clue for the diagnosis of CHS. If traditional agents fail in controlling the symptoms, haloperidol can be tried, but it has been used with limited success. Our patient did not respond to traditional antiemetics, but responded well to a small dose of lorazepam. Even though a benzodiazepine is not the mainstay of treatment, it may be tried if other agents fail. Acid-suppression therapy with a proton pump inhibitor should be used as esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) usually reveals mild gastritis and esophagitis, as in our patient. Narcotic use should be avoided for management of abdominal pain.

Patients should be counseled against marijuana use. This may be difficult if marijuana is being used as an appetite stimulant or for treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. If willing, patients should be referred to a substance abuse rehabilitation center.

Back to the case

In this case, after a diagnosis of CHS was made, the patient was counseled against marijuana use. His abdominal pain and intractable vomiting did not improve with conservative management of n.p.o status, prochlorperazine, metoclopramide, and ondansetron. He was given a trial of low-dose lorazepam with significant improvement in his symptoms. He was counseled extensively against marijuana use and discharged. A follow-up phone call at 3 months showed continued abstinence and no recurrence of symptoms.

Dr. Gupta is a hospitalist at Yale New Haven Health and Bridgeport (Conn.) Hospital.

References

1. Bajgoric S et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: A guide for the practising clinician. BMJ Case Rep. 2015. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-210246.

2. Batke M et al. The cannabis hyperemesis syndrome characterized by persistent nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, and compulsive bathing associated with chronic marijuana use: A report of eight cases in the united states. Dig Dis Sci. 2010 Nov;55(11):3113-9.

3. Iacopetti CL et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: a case report and review of pathophysiology. Clin Med Res. 2014 Sep;12(1-2):65-7.

4. Hickey JL et al. Haloperidol for treatment of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. Am J Emerg Med. 2013 Jun. 31(6):1003.e5-6. Epub 2013 Apr 10.

Key points

Suspect CHS for patients with recurrent abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting with negative initial work-up.

- Ask directly about marijuana use.

- Ask whether symptoms are relieved with hot shower/ bath.

- Send a toxicology screen.

- Make a diagnosis of CHS if:

1. Positive marijuana use.

2. Symptom improvement with hot baths or

3. Toxicology positive for marijuana.

- Manage conservatively with hydration and antiemetics.

- Suspect CHS if traditional antiemetics are not providing relief .

- If traditional antiemetics fail, trial of haloperidol or low-dose benzodiazepines.

- Avoid narcotics.

- Avoid unnecessary investigations.

- Counsel patients against marijuana use and refer to substance abuse center if patient agrees.

Atrial fib guidelines may fall short on oral anticoagulation

Anticoagulation thresholds based on CHA2DS2-VASc risk score varied from population to population, researchers reported in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

After accounting for differing rates of stroke in published studies, the benefit of warfarin anticoagulation varied nearly fourfold, said Sachin J. Shah, MD, of the University of California San Francisco and his associates. They called for guidelines that “better reflect the uncertainty in current thresholds of stroke risk score for recommending anticoagulation.”

Oral anticoagulation markedly reduces risk of ischemic stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation but increases the risk of major bleeding, including intracranial hemorrhage, which often is fatal. Therefore, when deciding whether to recommend oral anticoagulation, physicians must estimate clinical net benefit by quantifying the difference between reduction in stroke risk and increase in major bleeding risk, weighted by the severity of each outcome.

Guidelines on nonvalvular atrial fibrillation from the European Society of Cardiology and joint guidelines from the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and Heart Rhythm Society (AHA/ACC/HRS) recommend oral anticoagulation when CHA2DS2-VASc (congestive heart failure, hypertension, age, diabetes, stroke, and vascular disease) risk score is 2 or greater. These guidelines implicitly assume that a particular CHA2DS2-VASc score denotes the same amount of risk across populations, even though a recent meta-analysis found otherwise, as the researchers noted.

To further test this assumption, they applied an existing Markov model to data from more than 33,000 members of the ATRIA-CVRN cohort. All patients had nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, were members of Kaiser Permanente Northern California, and were diagnosed during 1996-1997. About 81% had a CHA2DS2-VASc score of at least 2. For each patient, the researchers produced four estimates of the net clinical benefit of oral anticoagulation based on ischemic stroke rates from ATRIA, the Swedish AF cohort study, the SPORTIF study, and the Danish National Patient Registry.

Optimal anticoagulation thresholds were a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 3 or more using stroke rates from ATRIA, 2 or more based on Swedish AF rates, 1 or more based on SPORTIF rates, and 0 or more using rates from the Danish National Patient Registry. Oral anticoagulation thresholds were lower but still varied widely after accounting for the lower rates of intracranial hemorrhage associated with non–vitamin K antagonist therapy.

Therefore, current guidelines based on CHA2DS2-VASc score may need revising “in favor of more accurate, individualized assessments of risk for both ischemic stroke and major bleeding,” the investigators wrote. “Until such time, guidelines should better reflect the uncertainty of the current approach in which a patient’s CHA2DS2-VASc score is used as the primary basis for recommending oral anticoagulation.”

The study had no primary funding source. Dr. Shah reported having no conflicts of interest. Three coinvestigators disclosed research support from relevant pharmaceutical or device companies.

SOURCE: Shah SJ et al. Ann Intern Med. 2018 Sep 25. doi: 10.7326/M17-2762

Based on this study, the CHA2DS2-VASc score threshold for anticoagulation might not be a “one-size-fits all approach but rather a starting point for a more tailored assessment,” wrote Jennifer M. Wright, MD, and Craig T. January, MD, PhD, in an editorial accompanying the report.

The CHA2DS2-VASc algorithm uses fixed whole integers and therefore might lack the sensitivity and flexibility needed to accurately reflect the effects of its components, the experts wrote. “For example, female sex now seems to be a risk modifier, and its intensity depends on other risk factors.”

However, CHA2DS2-VASc remains the main way to assess net clinical benefit of oral anticoagulation for patients with anticoagulation, they conceded. “When it comes to the conversation about the risks and benefits of anticoagulation for our patients with atrial fibrillation, we must remember that each patient is an individual and has his or her own ‘score.’ ”

The editorialists are with the University of Wisconsin in Madison. They reported having no relevant conflicts of interest. These comments are based on their editorial (Ann Intern Med. 2018 Sep 25. doi: 10.7326/M18-2355).

Based on this study, the CHA2DS2-VASc score threshold for anticoagulation might not be a “one-size-fits all approach but rather a starting point for a more tailored assessment,” wrote Jennifer M. Wright, MD, and Craig T. January, MD, PhD, in an editorial accompanying the report.

The CHA2DS2-VASc algorithm uses fixed whole integers and therefore might lack the sensitivity and flexibility needed to accurately reflect the effects of its components, the experts wrote. “For example, female sex now seems to be a risk modifier, and its intensity depends on other risk factors.”

However, CHA2DS2-VASc remains the main way to assess net clinical benefit of oral anticoagulation for patients with anticoagulation, they conceded. “When it comes to the conversation about the risks and benefits of anticoagulation for our patients with atrial fibrillation, we must remember that each patient is an individual and has his or her own ‘score.’ ”

The editorialists are with the University of Wisconsin in Madison. They reported having no relevant conflicts of interest. These comments are based on their editorial (Ann Intern Med. 2018 Sep 25. doi: 10.7326/M18-2355).

Based on this study, the CHA2DS2-VASc score threshold for anticoagulation might not be a “one-size-fits all approach but rather a starting point for a more tailored assessment,” wrote Jennifer M. Wright, MD, and Craig T. January, MD, PhD, in an editorial accompanying the report.

The CHA2DS2-VASc algorithm uses fixed whole integers and therefore might lack the sensitivity and flexibility needed to accurately reflect the effects of its components, the experts wrote. “For example, female sex now seems to be a risk modifier, and its intensity depends on other risk factors.”

However, CHA2DS2-VASc remains the main way to assess net clinical benefit of oral anticoagulation for patients with anticoagulation, they conceded. “When it comes to the conversation about the risks and benefits of anticoagulation for our patients with atrial fibrillation, we must remember that each patient is an individual and has his or her own ‘score.’ ”

The editorialists are with the University of Wisconsin in Madison. They reported having no relevant conflicts of interest. These comments are based on their editorial (Ann Intern Med. 2018 Sep 25. doi: 10.7326/M18-2355).

Anticoagulation thresholds based on CHA2DS2-VASc risk score varied from population to population, researchers reported in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

After accounting for differing rates of stroke in published studies, the benefit of warfarin anticoagulation varied nearly fourfold, said Sachin J. Shah, MD, of the University of California San Francisco and his associates. They called for guidelines that “better reflect the uncertainty in current thresholds of stroke risk score for recommending anticoagulation.”

Oral anticoagulation markedly reduces risk of ischemic stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation but increases the risk of major bleeding, including intracranial hemorrhage, which often is fatal. Therefore, when deciding whether to recommend oral anticoagulation, physicians must estimate clinical net benefit by quantifying the difference between reduction in stroke risk and increase in major bleeding risk, weighted by the severity of each outcome.

Guidelines on nonvalvular atrial fibrillation from the European Society of Cardiology and joint guidelines from the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and Heart Rhythm Society (AHA/ACC/HRS) recommend oral anticoagulation when CHA2DS2-VASc (congestive heart failure, hypertension, age, diabetes, stroke, and vascular disease) risk score is 2 or greater. These guidelines implicitly assume that a particular CHA2DS2-VASc score denotes the same amount of risk across populations, even though a recent meta-analysis found otherwise, as the researchers noted.

To further test this assumption, they applied an existing Markov model to data from more than 33,000 members of the ATRIA-CVRN cohort. All patients had nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, were members of Kaiser Permanente Northern California, and were diagnosed during 1996-1997. About 81% had a CHA2DS2-VASc score of at least 2. For each patient, the researchers produced four estimates of the net clinical benefit of oral anticoagulation based on ischemic stroke rates from ATRIA, the Swedish AF cohort study, the SPORTIF study, and the Danish National Patient Registry.

Optimal anticoagulation thresholds were a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 3 or more using stroke rates from ATRIA, 2 or more based on Swedish AF rates, 1 or more based on SPORTIF rates, and 0 or more using rates from the Danish National Patient Registry. Oral anticoagulation thresholds were lower but still varied widely after accounting for the lower rates of intracranial hemorrhage associated with non–vitamin K antagonist therapy.

Therefore, current guidelines based on CHA2DS2-VASc score may need revising “in favor of more accurate, individualized assessments of risk for both ischemic stroke and major bleeding,” the investigators wrote. “Until such time, guidelines should better reflect the uncertainty of the current approach in which a patient’s CHA2DS2-VASc score is used as the primary basis for recommending oral anticoagulation.”

The study had no primary funding source. Dr. Shah reported having no conflicts of interest. Three coinvestigators disclosed research support from relevant pharmaceutical or device companies.

SOURCE: Shah SJ et al. Ann Intern Med. 2018 Sep 25. doi: 10.7326/M17-2762

Anticoagulation thresholds based on CHA2DS2-VASc risk score varied from population to population, researchers reported in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

After accounting for differing rates of stroke in published studies, the benefit of warfarin anticoagulation varied nearly fourfold, said Sachin J. Shah, MD, of the University of California San Francisco and his associates. They called for guidelines that “better reflect the uncertainty in current thresholds of stroke risk score for recommending anticoagulation.”

Oral anticoagulation markedly reduces risk of ischemic stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation but increases the risk of major bleeding, including intracranial hemorrhage, which often is fatal. Therefore, when deciding whether to recommend oral anticoagulation, physicians must estimate clinical net benefit by quantifying the difference between reduction in stroke risk and increase in major bleeding risk, weighted by the severity of each outcome.

Guidelines on nonvalvular atrial fibrillation from the European Society of Cardiology and joint guidelines from the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and Heart Rhythm Society (AHA/ACC/HRS) recommend oral anticoagulation when CHA2DS2-VASc (congestive heart failure, hypertension, age, diabetes, stroke, and vascular disease) risk score is 2 or greater. These guidelines implicitly assume that a particular CHA2DS2-VASc score denotes the same amount of risk across populations, even though a recent meta-analysis found otherwise, as the researchers noted.

To further test this assumption, they applied an existing Markov model to data from more than 33,000 members of the ATRIA-CVRN cohort. All patients had nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, were members of Kaiser Permanente Northern California, and were diagnosed during 1996-1997. About 81% had a CHA2DS2-VASc score of at least 2. For each patient, the researchers produced four estimates of the net clinical benefit of oral anticoagulation based on ischemic stroke rates from ATRIA, the Swedish AF cohort study, the SPORTIF study, and the Danish National Patient Registry.

Optimal anticoagulation thresholds were a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 3 or more using stroke rates from ATRIA, 2 or more based on Swedish AF rates, 1 or more based on SPORTIF rates, and 0 or more using rates from the Danish National Patient Registry. Oral anticoagulation thresholds were lower but still varied widely after accounting for the lower rates of intracranial hemorrhage associated with non–vitamin K antagonist therapy.

Therefore, current guidelines based on CHA2DS2-VASc score may need revising “in favor of more accurate, individualized assessments of risk for both ischemic stroke and major bleeding,” the investigators wrote. “Until such time, guidelines should better reflect the uncertainty of the current approach in which a patient’s CHA2DS2-VASc score is used as the primary basis for recommending oral anticoagulation.”

The study had no primary funding source. Dr. Shah reported having no conflicts of interest. Three coinvestigators disclosed research support from relevant pharmaceutical or device companies.

SOURCE: Shah SJ et al. Ann Intern Med. 2018 Sep 25. doi: 10.7326/M17-2762

FROM THE ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: