User login

Does nurse-physician rounding matter?

Advancing the Quadruple Aim

Inadequate and fragmented communication between physicians and nurses can lead to unwelcome events for the hospitalized patient and clinicians. Missing orders, medication errors, patient misidentification, and lack of physician awareness of significant changes in patient status are just some examples of how deficits in formal communication can affect health outcomes during acute stays.

A 2000 Institute of Medicine report showed that bad systems, not bad people, account for the majority of errors and injuries caused by complexity, professional fragmentation, and barriers in communication. Their recommendation was to train physicians, nurses, and other professionals in teamwork.1,2 However, as Milisa Manojlovich, PhD, RN, found, there are significant differences in how physicians and nurses perceive collaboration and communication.3

Nurse-physician rounding was historically standard for patient care during hospitalization. When physicians split time between inpatient and outpatient care, nurses had to maximize their time to collaborate and communicate with physicians whenever the physicians left their outpatient offices to come and round on their patients. Today most inpatient care is delivered by hospitalists on a 24-hour basis. This continuous availability of physicians reduces the perceived need to have joint rounds.

However, health care teams in acute care facilities now face higher and sicker patient volumes, different productivity models and demands, new compliance standards, changing work flows, and increased complexity of treatment and management of patients. This has led to gaps in timely communication and partnership.4-6 Erosion of the traditional nurse-physician relationships affects the quality of patient care, the patient’s experience, and patient safety.8-10 Poor communication among health care team members is one of the most common causes of patient care errors.4 Poor nurse-physician communication can also lead to medical errors, poor outcomes caused by lack of coordination within the treatment team, increased use of unnecessary resources with inefficiency, and increases in the complexity of communication among team members, and time wastage.5,7,11 All these lead to poor work flows and directly affect patient safety.7

At Lee Health System in Lee County, Fla., we saw an opportunity in this changing health care environment to promote nurse-physician rounding. We created a structured, standardized process for morning rounding and engaged unit clerks, nursing leadership, and hospitalist service line leaders. We envisioned improvement of the patient experience, nurse-physician relationship, quality of care, the discharge planning process, and efficiency, as well as decreasing length of stay, improving communication, and bringing the patient and the treatment team closer, as demonstrated by Bradley Monash, MD, et al.12

Some data suggest that patient-centered bedside rounds on hospitalized patients have no effect on patient perceptions or their satisfaction with care.13 However, we felt that collaboration among a multidisciplinary team would help us achieve better outcomes. For example, our patients would perceive the care team (MD-RN) as a cohesive unit, and in turn gain trust in the members of the treatment team, as found by Nathalie McIntosh, PhD, et al and by Jason Ramirez, MD.7,16 Our vision was to empower nurses to be advocates for patients and their family members as they navigated their acute care admission. Nurses could also support physicians by communicating the physicians’ care plans to families and patients. After rounding with the physician, the nurse would be part of the decision-making process and care planning.17

Every rounding session had discharge planning and hospital stay expectations that were shared with the patient and nurse, who could then partner with case managers and social workers, which would streamline and reduce length of stay.14 We hoped rounding would also decrease the number of nurse pages to clarify or question orders. This would, in turn, improve daily work flow for the physicians and the nursing team with improvements in employee satisfaction scores.15 A study also has demonstrated a reduction in readmission rates from nurse-physician rounding.19

A disconnect in communication and trust between physicians and the nursing staff was reflected in low patient experience scores and perceived quality of care received during in-hospital stay. Gwendolyn Lancaster, EdD, MSN, RN, CCRN, et al, as well as a Joint Commission report, demonstrated how a lack of communication and poor team dynamics can translate to poor patient experience and be a major cause for sentinel events.6,20 Artificial, forced hierarchies and role perception among health care team members led to frustration, hostility, and distrust, which compromises quality and patient safety.1

One of our biggest challenges when we started this project was explaining the “Why” to the hospitalist group and nursing staff. Physicians were used to being the dominant partner in the team. Partnering with and engaging nurses in shared decision making and care planning was a seismic shift in culture and work flow within the care team. Early gains helped skeptical team members begin to understand the value in nurse-physician rounding. Near universal adoption of the rounding process at Lee Health has caused improvements in the working relationship and trust among the health care professionals. We have seen improvements in utilization management, as well as appropriateness and timeliness of resource use, because of better communication and understanding of care plans by nursing and physicians. Collaboration with specialists and alignment in care planning are other gains. Hospitalists and nurses are both very satisfied with the decrease in the number of pages during the day, and this has lowered stressors on health care teams.

How we did it

Nurse-physician rounding is a proven method to improve collaboration, communication, and relationships among health care team members in acute care facilities. In the complex health care challenges faced today, this improved work flow for taking care of patients can help advance the Quadruple Aim of high quality, low cost, improved patient experience, physician, and staff satisfaction.21

Lee Health System includes four facilities in Lee County, with a total of 1,216 licensed adult acute care beds. The pilot project was started in 2014.

Initially the vice president of nursing and the hospitalist medical director met to create an education plan for nurses and physicians. We chose one adult medicine unit to pilot the project because there already existed a closely knit nursing and hospitalist team. In our facility there is no strict geographical rounding; each hospitalist carries between three and six patients in the unit. As a first step, a nurse floor assignment sheet was faxed in the morning to the hospitalist office with the direct phone numbers of the nurses. The unit clerk, using physician assignments in the EHR, teamed up the physician and nurses for rounding. Once the physician arrived at the unit, he or she checked in with the unit clerk, who alerted nurses that the hospitalist was available on the floor to commence rounding. If the primary nurse was unavailable because of other duties or breaks, the charge nurse rounded with the physician.

Once in the room with the patient, the duo introduced themselves as members of the treatment team and acknowledged the patient’s needs. During the visit, care plans and treatment were reviewed, the patient’s questions were answered, a physical exam was completed, and lab and imaging results were discussed; the nurse also helped raise questions he or she had received from family members so answers could be communicated to the family later. Patients appreciated knowing that their physicians and nurses were working together as a team for their safety and recovery. During the visit, care was taken to focus specially on the course of hospitalization and discharge planning.

We tracked the rounding with a manual paper process maintained by the charge nurse. Our initial rounding rates were 30%-40%, and we continued to promote this initiative to the team, and eventually the importance and value of these rounds caught on with both nurses and physicians, and now our current average rounding rate is 90%. We then decided to scale this to all units in the hospital.

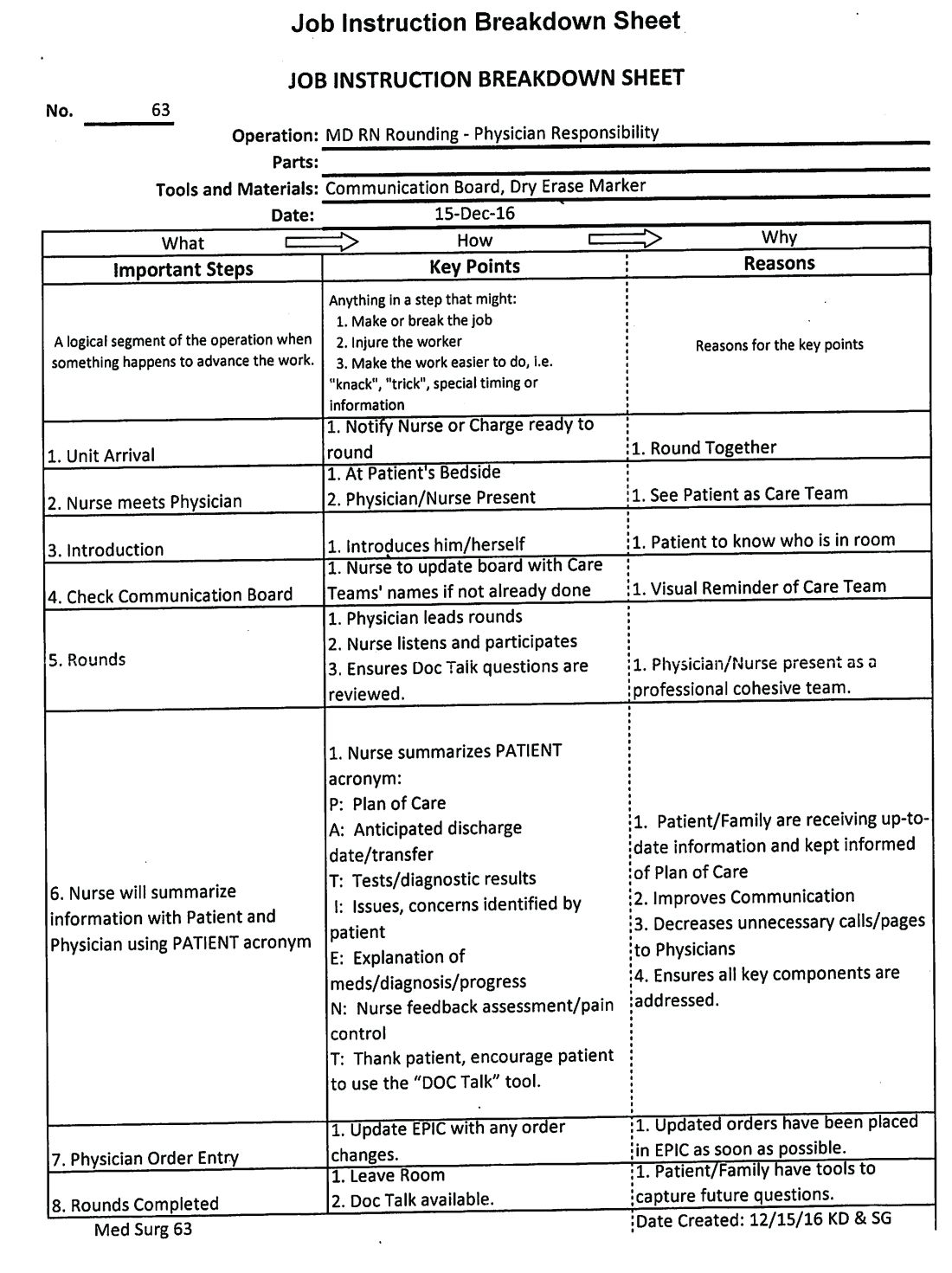

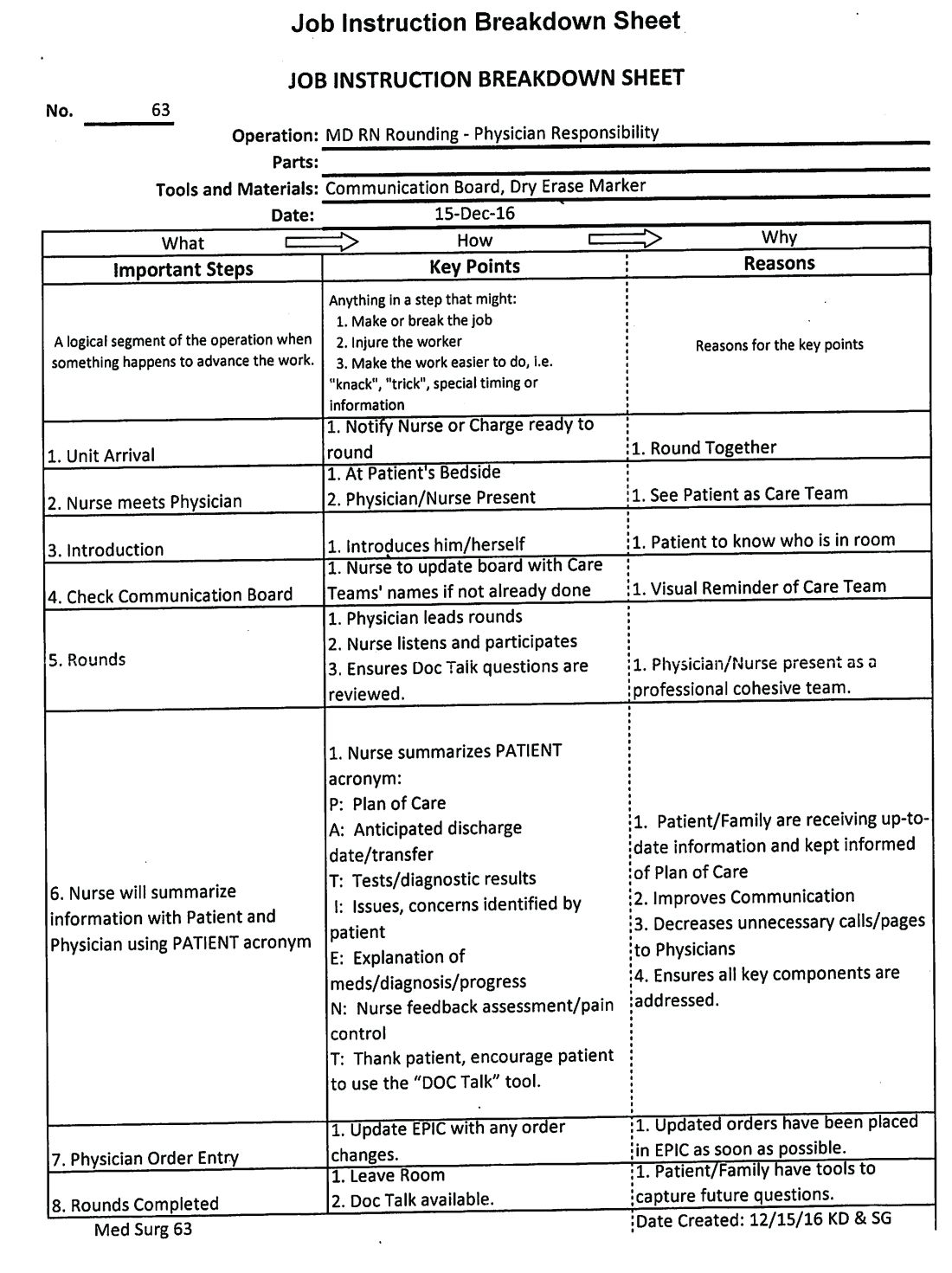

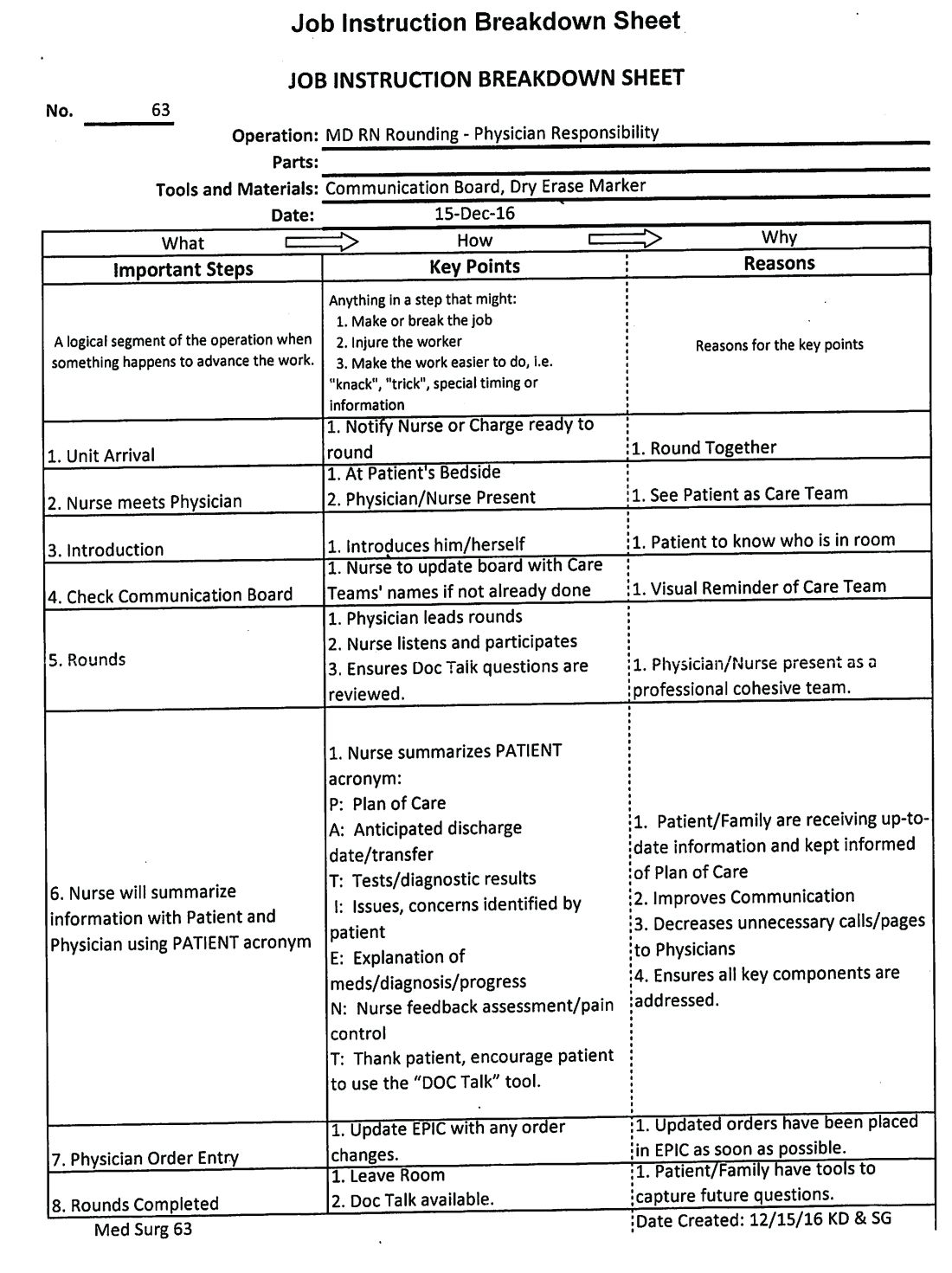

This process was repeated at other hospitals in the system once a standardized work flow was created (See Image 1). This initiative was next presented to the health system board of directors, who agreed that nurse-physician rounding should be the standard of care across our health system. Through partnership and collaboration with the IT department, we developed a tool to track nurse-physician rounding through our EHR system, which gave accountability to both physicians and nurses.

In conclusion, improved communication by timely nurse-physician rounding can lead to better outcomes for patients and also reduce costs and improve patient and staff experience, advancing the Quadruple Aim. Moving forward to build and sustain this work flow, we plan to continue nurse-physician collaboration across the health system consistently and for all areas of acute care operations.

Explaining the “Why,” sharing data on the benefits of the model, and reinforcing documentation of the rounding in our EHR are some steps we have put into action at leadership and staff meetings to sustain the activity. We are soliciting feedback, as well as monitoring and identifying any unaddressed barriers during rounding. Addition of this process measure to our quality improvement bonus opportunity also has helped to sustain performance from our teams.

Dr. Laufer is system medical director of hospital medicine and transitional care at Lee Health in Ft. Myers, Fla. Dr. Prasad is chief medical officer of Lee Physician Group, Ft. Myers, Fla.

References

1. Leape LL et al. Five years after to err is human: What we have learned? JAMA. 2005;293(19):2384-90.

2. Sutcliffe KM et al. Communication failures: An insidious contributor to medical mishaps. Acad Med. 2004;79(2):186-94.

3. Manojlovich M. Reframing communication with physicians as sensemaking. J Nurs Care Qual. 2013 Oct-Dec;28(4):295-303.

4. Siegele P. Enhancing outcomes in a surgical intensive care unit by implementing daily goals. Crit Care Nurse. 2009 Dec;29(6):58-69.

5. Asthon J et al. Qualitative evaluation of regular morning meeting aimed at improving interdisciplinary communication and patient outcomes. Int J Nurs Pract. 2005 Oct;11(5):206-13.

6. Lancaster G et al. Interdisciplinary Communication and collaboration among physicians, nurses, and unlicensed assistive personnel. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2015 May;47(3):275-84.

7. McIntosh N et al. Impact of provider coordination on nurse and physician perception of patient care quality. J Nurs Care Qual. 2014 Jul-Sep;29(3):269-79.

8. Jo M et al. An organizational assessment of disruptive clinical behavior. J Nurs Care Qual. 2013 Apr-Jun;28(2):110-21.

9. World Health Organization. Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. Geneva, 2010.

10. O’Connor P et al. A mixed-methods study of the causes and impact of poor teamwork between junior doctors and nurses. Int J Qual Health Care. 2016 Jun;28(3):339-45.

11. Manojlovich M. Nurse/Physician communication through a sense making lens. Med Care. 2010 Nov;48(11):941-6.

12. Monash B et al. Standardized attending rounds to improve the patient experience: A pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial. J Hosp Med. 2017 Mar;12(3):143-9.

13. O’Leary KJ et al. Effect of patient-centered bedside rounds on hospitalized patients decision control, activation and satisfaction with care. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016 Dec;25(12):921-8.

14. Dutton RP et al. Daily multidisciplinary rounds shorten length of stay for trauma patients. J Trauma. 2003 Nov;55(5):913-9.

15. Manojlovich M et al. Healthy work environments, nurse-physician communication, and patients’ outcomes. Am J Crit Care. 2007 Nov;16(6):536-43.

16. Ramirez J et al. Patient satisfaction with bedside teaching rounds compared with nonbedside rounds. South Med J. 2016 Feb;109(2):112-5.

17. Sollami A et al. Nurse-Physician collaboration: A meta-analytical investigation of survey scores. J Interprof Care. 2015 May;29(3):223-9.

18. House S et al. Nurses and physicians perceptions of nurse-physician collaboration. J Nurs Adm. 2017 Mar;47(3):165-71.

19. Townsend-Gervis M et al. Interdisciplinary rounds and structured communications reduce re-admissions and improve some patients’ outcomes. West J Nurs Res. 2014 Aug;36(7):917-28.

20. The Joint Commission. Sentinel Events. http://www.jointcommission.org/sentinel_event.aspx. Accessed Oct 2017.

21. Bodenheimer T et al. From Triple to Quadruple Aim: Care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014 Nov-Dec;12(6):573-6.

Advancing the Quadruple Aim

Advancing the Quadruple Aim

Inadequate and fragmented communication between physicians and nurses can lead to unwelcome events for the hospitalized patient and clinicians. Missing orders, medication errors, patient misidentification, and lack of physician awareness of significant changes in patient status are just some examples of how deficits in formal communication can affect health outcomes during acute stays.

A 2000 Institute of Medicine report showed that bad systems, not bad people, account for the majority of errors and injuries caused by complexity, professional fragmentation, and barriers in communication. Their recommendation was to train physicians, nurses, and other professionals in teamwork.1,2 However, as Milisa Manojlovich, PhD, RN, found, there are significant differences in how physicians and nurses perceive collaboration and communication.3

Nurse-physician rounding was historically standard for patient care during hospitalization. When physicians split time between inpatient and outpatient care, nurses had to maximize their time to collaborate and communicate with physicians whenever the physicians left their outpatient offices to come and round on their patients. Today most inpatient care is delivered by hospitalists on a 24-hour basis. This continuous availability of physicians reduces the perceived need to have joint rounds.

However, health care teams in acute care facilities now face higher and sicker patient volumes, different productivity models and demands, new compliance standards, changing work flows, and increased complexity of treatment and management of patients. This has led to gaps in timely communication and partnership.4-6 Erosion of the traditional nurse-physician relationships affects the quality of patient care, the patient’s experience, and patient safety.8-10 Poor communication among health care team members is one of the most common causes of patient care errors.4 Poor nurse-physician communication can also lead to medical errors, poor outcomes caused by lack of coordination within the treatment team, increased use of unnecessary resources with inefficiency, and increases in the complexity of communication among team members, and time wastage.5,7,11 All these lead to poor work flows and directly affect patient safety.7

At Lee Health System in Lee County, Fla., we saw an opportunity in this changing health care environment to promote nurse-physician rounding. We created a structured, standardized process for morning rounding and engaged unit clerks, nursing leadership, and hospitalist service line leaders. We envisioned improvement of the patient experience, nurse-physician relationship, quality of care, the discharge planning process, and efficiency, as well as decreasing length of stay, improving communication, and bringing the patient and the treatment team closer, as demonstrated by Bradley Monash, MD, et al.12

Some data suggest that patient-centered bedside rounds on hospitalized patients have no effect on patient perceptions or their satisfaction with care.13 However, we felt that collaboration among a multidisciplinary team would help us achieve better outcomes. For example, our patients would perceive the care team (MD-RN) as a cohesive unit, and in turn gain trust in the members of the treatment team, as found by Nathalie McIntosh, PhD, et al and by Jason Ramirez, MD.7,16 Our vision was to empower nurses to be advocates for patients and their family members as they navigated their acute care admission. Nurses could also support physicians by communicating the physicians’ care plans to families and patients. After rounding with the physician, the nurse would be part of the decision-making process and care planning.17

Every rounding session had discharge planning and hospital stay expectations that were shared with the patient and nurse, who could then partner with case managers and social workers, which would streamline and reduce length of stay.14 We hoped rounding would also decrease the number of nurse pages to clarify or question orders. This would, in turn, improve daily work flow for the physicians and the nursing team with improvements in employee satisfaction scores.15 A study also has demonstrated a reduction in readmission rates from nurse-physician rounding.19

A disconnect in communication and trust between physicians and the nursing staff was reflected in low patient experience scores and perceived quality of care received during in-hospital stay. Gwendolyn Lancaster, EdD, MSN, RN, CCRN, et al, as well as a Joint Commission report, demonstrated how a lack of communication and poor team dynamics can translate to poor patient experience and be a major cause for sentinel events.6,20 Artificial, forced hierarchies and role perception among health care team members led to frustration, hostility, and distrust, which compromises quality and patient safety.1

One of our biggest challenges when we started this project was explaining the “Why” to the hospitalist group and nursing staff. Physicians were used to being the dominant partner in the team. Partnering with and engaging nurses in shared decision making and care planning was a seismic shift in culture and work flow within the care team. Early gains helped skeptical team members begin to understand the value in nurse-physician rounding. Near universal adoption of the rounding process at Lee Health has caused improvements in the working relationship and trust among the health care professionals. We have seen improvements in utilization management, as well as appropriateness and timeliness of resource use, because of better communication and understanding of care plans by nursing and physicians. Collaboration with specialists and alignment in care planning are other gains. Hospitalists and nurses are both very satisfied with the decrease in the number of pages during the day, and this has lowered stressors on health care teams.

How we did it

Nurse-physician rounding is a proven method to improve collaboration, communication, and relationships among health care team members in acute care facilities. In the complex health care challenges faced today, this improved work flow for taking care of patients can help advance the Quadruple Aim of high quality, low cost, improved patient experience, physician, and staff satisfaction.21

Lee Health System includes four facilities in Lee County, with a total of 1,216 licensed adult acute care beds. The pilot project was started in 2014.

Initially the vice president of nursing and the hospitalist medical director met to create an education plan for nurses and physicians. We chose one adult medicine unit to pilot the project because there already existed a closely knit nursing and hospitalist team. In our facility there is no strict geographical rounding; each hospitalist carries between three and six patients in the unit. As a first step, a nurse floor assignment sheet was faxed in the morning to the hospitalist office with the direct phone numbers of the nurses. The unit clerk, using physician assignments in the EHR, teamed up the physician and nurses for rounding. Once the physician arrived at the unit, he or she checked in with the unit clerk, who alerted nurses that the hospitalist was available on the floor to commence rounding. If the primary nurse was unavailable because of other duties or breaks, the charge nurse rounded with the physician.

Once in the room with the patient, the duo introduced themselves as members of the treatment team and acknowledged the patient’s needs. During the visit, care plans and treatment were reviewed, the patient’s questions were answered, a physical exam was completed, and lab and imaging results were discussed; the nurse also helped raise questions he or she had received from family members so answers could be communicated to the family later. Patients appreciated knowing that their physicians and nurses were working together as a team for their safety and recovery. During the visit, care was taken to focus specially on the course of hospitalization and discharge planning.

We tracked the rounding with a manual paper process maintained by the charge nurse. Our initial rounding rates were 30%-40%, and we continued to promote this initiative to the team, and eventually the importance and value of these rounds caught on with both nurses and physicians, and now our current average rounding rate is 90%. We then decided to scale this to all units in the hospital.

This process was repeated at other hospitals in the system once a standardized work flow was created (See Image 1). This initiative was next presented to the health system board of directors, who agreed that nurse-physician rounding should be the standard of care across our health system. Through partnership and collaboration with the IT department, we developed a tool to track nurse-physician rounding through our EHR system, which gave accountability to both physicians and nurses.

In conclusion, improved communication by timely nurse-physician rounding can lead to better outcomes for patients and also reduce costs and improve patient and staff experience, advancing the Quadruple Aim. Moving forward to build and sustain this work flow, we plan to continue nurse-physician collaboration across the health system consistently and for all areas of acute care operations.

Explaining the “Why,” sharing data on the benefits of the model, and reinforcing documentation of the rounding in our EHR are some steps we have put into action at leadership and staff meetings to sustain the activity. We are soliciting feedback, as well as monitoring and identifying any unaddressed barriers during rounding. Addition of this process measure to our quality improvement bonus opportunity also has helped to sustain performance from our teams.

Dr. Laufer is system medical director of hospital medicine and transitional care at Lee Health in Ft. Myers, Fla. Dr. Prasad is chief medical officer of Lee Physician Group, Ft. Myers, Fla.

References

1. Leape LL et al. Five years after to err is human: What we have learned? JAMA. 2005;293(19):2384-90.

2. Sutcliffe KM et al. Communication failures: An insidious contributor to medical mishaps. Acad Med. 2004;79(2):186-94.

3. Manojlovich M. Reframing communication with physicians as sensemaking. J Nurs Care Qual. 2013 Oct-Dec;28(4):295-303.

4. Siegele P. Enhancing outcomes in a surgical intensive care unit by implementing daily goals. Crit Care Nurse. 2009 Dec;29(6):58-69.

5. Asthon J et al. Qualitative evaluation of regular morning meeting aimed at improving interdisciplinary communication and patient outcomes. Int J Nurs Pract. 2005 Oct;11(5):206-13.

6. Lancaster G et al. Interdisciplinary Communication and collaboration among physicians, nurses, and unlicensed assistive personnel. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2015 May;47(3):275-84.

7. McIntosh N et al. Impact of provider coordination on nurse and physician perception of patient care quality. J Nurs Care Qual. 2014 Jul-Sep;29(3):269-79.

8. Jo M et al. An organizational assessment of disruptive clinical behavior. J Nurs Care Qual. 2013 Apr-Jun;28(2):110-21.

9. World Health Organization. Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. Geneva, 2010.

10. O’Connor P et al. A mixed-methods study of the causes and impact of poor teamwork between junior doctors and nurses. Int J Qual Health Care. 2016 Jun;28(3):339-45.

11. Manojlovich M. Nurse/Physician communication through a sense making lens. Med Care. 2010 Nov;48(11):941-6.

12. Monash B et al. Standardized attending rounds to improve the patient experience: A pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial. J Hosp Med. 2017 Mar;12(3):143-9.

13. O’Leary KJ et al. Effect of patient-centered bedside rounds on hospitalized patients decision control, activation and satisfaction with care. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016 Dec;25(12):921-8.

14. Dutton RP et al. Daily multidisciplinary rounds shorten length of stay for trauma patients. J Trauma. 2003 Nov;55(5):913-9.

15. Manojlovich M et al. Healthy work environments, nurse-physician communication, and patients’ outcomes. Am J Crit Care. 2007 Nov;16(6):536-43.

16. Ramirez J et al. Patient satisfaction with bedside teaching rounds compared with nonbedside rounds. South Med J. 2016 Feb;109(2):112-5.

17. Sollami A et al. Nurse-Physician collaboration: A meta-analytical investigation of survey scores. J Interprof Care. 2015 May;29(3):223-9.

18. House S et al. Nurses and physicians perceptions of nurse-physician collaboration. J Nurs Adm. 2017 Mar;47(3):165-71.

19. Townsend-Gervis M et al. Interdisciplinary rounds and structured communications reduce re-admissions and improve some patients’ outcomes. West J Nurs Res. 2014 Aug;36(7):917-28.

20. The Joint Commission. Sentinel Events. http://www.jointcommission.org/sentinel_event.aspx. Accessed Oct 2017.

21. Bodenheimer T et al. From Triple to Quadruple Aim: Care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014 Nov-Dec;12(6):573-6.

Inadequate and fragmented communication between physicians and nurses can lead to unwelcome events for the hospitalized patient and clinicians. Missing orders, medication errors, patient misidentification, and lack of physician awareness of significant changes in patient status are just some examples of how deficits in formal communication can affect health outcomes during acute stays.

A 2000 Institute of Medicine report showed that bad systems, not bad people, account for the majority of errors and injuries caused by complexity, professional fragmentation, and barriers in communication. Their recommendation was to train physicians, nurses, and other professionals in teamwork.1,2 However, as Milisa Manojlovich, PhD, RN, found, there are significant differences in how physicians and nurses perceive collaboration and communication.3

Nurse-physician rounding was historically standard for patient care during hospitalization. When physicians split time between inpatient and outpatient care, nurses had to maximize their time to collaborate and communicate with physicians whenever the physicians left their outpatient offices to come and round on their patients. Today most inpatient care is delivered by hospitalists on a 24-hour basis. This continuous availability of physicians reduces the perceived need to have joint rounds.

However, health care teams in acute care facilities now face higher and sicker patient volumes, different productivity models and demands, new compliance standards, changing work flows, and increased complexity of treatment and management of patients. This has led to gaps in timely communication and partnership.4-6 Erosion of the traditional nurse-physician relationships affects the quality of patient care, the patient’s experience, and patient safety.8-10 Poor communication among health care team members is one of the most common causes of patient care errors.4 Poor nurse-physician communication can also lead to medical errors, poor outcomes caused by lack of coordination within the treatment team, increased use of unnecessary resources with inefficiency, and increases in the complexity of communication among team members, and time wastage.5,7,11 All these lead to poor work flows and directly affect patient safety.7

At Lee Health System in Lee County, Fla., we saw an opportunity in this changing health care environment to promote nurse-physician rounding. We created a structured, standardized process for morning rounding and engaged unit clerks, nursing leadership, and hospitalist service line leaders. We envisioned improvement of the patient experience, nurse-physician relationship, quality of care, the discharge planning process, and efficiency, as well as decreasing length of stay, improving communication, and bringing the patient and the treatment team closer, as demonstrated by Bradley Monash, MD, et al.12

Some data suggest that patient-centered bedside rounds on hospitalized patients have no effect on patient perceptions or their satisfaction with care.13 However, we felt that collaboration among a multidisciplinary team would help us achieve better outcomes. For example, our patients would perceive the care team (MD-RN) as a cohesive unit, and in turn gain trust in the members of the treatment team, as found by Nathalie McIntosh, PhD, et al and by Jason Ramirez, MD.7,16 Our vision was to empower nurses to be advocates for patients and their family members as they navigated their acute care admission. Nurses could also support physicians by communicating the physicians’ care plans to families and patients. After rounding with the physician, the nurse would be part of the decision-making process and care planning.17

Every rounding session had discharge planning and hospital stay expectations that were shared with the patient and nurse, who could then partner with case managers and social workers, which would streamline and reduce length of stay.14 We hoped rounding would also decrease the number of nurse pages to clarify or question orders. This would, in turn, improve daily work flow for the physicians and the nursing team with improvements in employee satisfaction scores.15 A study also has demonstrated a reduction in readmission rates from nurse-physician rounding.19

A disconnect in communication and trust between physicians and the nursing staff was reflected in low patient experience scores and perceived quality of care received during in-hospital stay. Gwendolyn Lancaster, EdD, MSN, RN, CCRN, et al, as well as a Joint Commission report, demonstrated how a lack of communication and poor team dynamics can translate to poor patient experience and be a major cause for sentinel events.6,20 Artificial, forced hierarchies and role perception among health care team members led to frustration, hostility, and distrust, which compromises quality and patient safety.1

One of our biggest challenges when we started this project was explaining the “Why” to the hospitalist group and nursing staff. Physicians were used to being the dominant partner in the team. Partnering with and engaging nurses in shared decision making and care planning was a seismic shift in culture and work flow within the care team. Early gains helped skeptical team members begin to understand the value in nurse-physician rounding. Near universal adoption of the rounding process at Lee Health has caused improvements in the working relationship and trust among the health care professionals. We have seen improvements in utilization management, as well as appropriateness and timeliness of resource use, because of better communication and understanding of care plans by nursing and physicians. Collaboration with specialists and alignment in care planning are other gains. Hospitalists and nurses are both very satisfied with the decrease in the number of pages during the day, and this has lowered stressors on health care teams.

How we did it

Nurse-physician rounding is a proven method to improve collaboration, communication, and relationships among health care team members in acute care facilities. In the complex health care challenges faced today, this improved work flow for taking care of patients can help advance the Quadruple Aim of high quality, low cost, improved patient experience, physician, and staff satisfaction.21

Lee Health System includes four facilities in Lee County, with a total of 1,216 licensed adult acute care beds. The pilot project was started in 2014.

Initially the vice president of nursing and the hospitalist medical director met to create an education plan for nurses and physicians. We chose one adult medicine unit to pilot the project because there already existed a closely knit nursing and hospitalist team. In our facility there is no strict geographical rounding; each hospitalist carries between three and six patients in the unit. As a first step, a nurse floor assignment sheet was faxed in the morning to the hospitalist office with the direct phone numbers of the nurses. The unit clerk, using physician assignments in the EHR, teamed up the physician and nurses for rounding. Once the physician arrived at the unit, he or she checked in with the unit clerk, who alerted nurses that the hospitalist was available on the floor to commence rounding. If the primary nurse was unavailable because of other duties or breaks, the charge nurse rounded with the physician.

Once in the room with the patient, the duo introduced themselves as members of the treatment team and acknowledged the patient’s needs. During the visit, care plans and treatment were reviewed, the patient’s questions were answered, a physical exam was completed, and lab and imaging results were discussed; the nurse also helped raise questions he or she had received from family members so answers could be communicated to the family later. Patients appreciated knowing that their physicians and nurses were working together as a team for their safety and recovery. During the visit, care was taken to focus specially on the course of hospitalization and discharge planning.

We tracked the rounding with a manual paper process maintained by the charge nurse. Our initial rounding rates were 30%-40%, and we continued to promote this initiative to the team, and eventually the importance and value of these rounds caught on with both nurses and physicians, and now our current average rounding rate is 90%. We then decided to scale this to all units in the hospital.

This process was repeated at other hospitals in the system once a standardized work flow was created (See Image 1). This initiative was next presented to the health system board of directors, who agreed that nurse-physician rounding should be the standard of care across our health system. Through partnership and collaboration with the IT department, we developed a tool to track nurse-physician rounding through our EHR system, which gave accountability to both physicians and nurses.

In conclusion, improved communication by timely nurse-physician rounding can lead to better outcomes for patients and also reduce costs and improve patient and staff experience, advancing the Quadruple Aim. Moving forward to build and sustain this work flow, we plan to continue nurse-physician collaboration across the health system consistently and for all areas of acute care operations.

Explaining the “Why,” sharing data on the benefits of the model, and reinforcing documentation of the rounding in our EHR are some steps we have put into action at leadership and staff meetings to sustain the activity. We are soliciting feedback, as well as monitoring and identifying any unaddressed barriers during rounding. Addition of this process measure to our quality improvement bonus opportunity also has helped to sustain performance from our teams.

Dr. Laufer is system medical director of hospital medicine and transitional care at Lee Health in Ft. Myers, Fla. Dr. Prasad is chief medical officer of Lee Physician Group, Ft. Myers, Fla.

References

1. Leape LL et al. Five years after to err is human: What we have learned? JAMA. 2005;293(19):2384-90.

2. Sutcliffe KM et al. Communication failures: An insidious contributor to medical mishaps. Acad Med. 2004;79(2):186-94.

3. Manojlovich M. Reframing communication with physicians as sensemaking. J Nurs Care Qual. 2013 Oct-Dec;28(4):295-303.

4. Siegele P. Enhancing outcomes in a surgical intensive care unit by implementing daily goals. Crit Care Nurse. 2009 Dec;29(6):58-69.

5. Asthon J et al. Qualitative evaluation of regular morning meeting aimed at improving interdisciplinary communication and patient outcomes. Int J Nurs Pract. 2005 Oct;11(5):206-13.

6. Lancaster G et al. Interdisciplinary Communication and collaboration among physicians, nurses, and unlicensed assistive personnel. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2015 May;47(3):275-84.

7. McIntosh N et al. Impact of provider coordination on nurse and physician perception of patient care quality. J Nurs Care Qual. 2014 Jul-Sep;29(3):269-79.

8. Jo M et al. An organizational assessment of disruptive clinical behavior. J Nurs Care Qual. 2013 Apr-Jun;28(2):110-21.

9. World Health Organization. Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. Geneva, 2010.

10. O’Connor P et al. A mixed-methods study of the causes and impact of poor teamwork between junior doctors and nurses. Int J Qual Health Care. 2016 Jun;28(3):339-45.

11. Manojlovich M. Nurse/Physician communication through a sense making lens. Med Care. 2010 Nov;48(11):941-6.

12. Monash B et al. Standardized attending rounds to improve the patient experience: A pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial. J Hosp Med. 2017 Mar;12(3):143-9.

13. O’Leary KJ et al. Effect of patient-centered bedside rounds on hospitalized patients decision control, activation and satisfaction with care. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016 Dec;25(12):921-8.

14. Dutton RP et al. Daily multidisciplinary rounds shorten length of stay for trauma patients. J Trauma. 2003 Nov;55(5):913-9.

15. Manojlovich M et al. Healthy work environments, nurse-physician communication, and patients’ outcomes. Am J Crit Care. 2007 Nov;16(6):536-43.

16. Ramirez J et al. Patient satisfaction with bedside teaching rounds compared with nonbedside rounds. South Med J. 2016 Feb;109(2):112-5.

17. Sollami A et al. Nurse-Physician collaboration: A meta-analytical investigation of survey scores. J Interprof Care. 2015 May;29(3):223-9.

18. House S et al. Nurses and physicians perceptions of nurse-physician collaboration. J Nurs Adm. 2017 Mar;47(3):165-71.

19. Townsend-Gervis M et al. Interdisciplinary rounds and structured communications reduce re-admissions and improve some patients’ outcomes. West J Nurs Res. 2014 Aug;36(7):917-28.

20. The Joint Commission. Sentinel Events. http://www.jointcommission.org/sentinel_event.aspx. Accessed Oct 2017.

21. Bodenheimer T et al. From Triple to Quadruple Aim: Care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014 Nov-Dec;12(6):573-6.

Burnout may jeopardize patient care

because of depersonalization of care, according to recent research published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“The primary conclusion of this review is that physician burnout might jeopardize patient care,” Maria Panagioti, PhD, from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Primary Care Research and the NIHR Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre at the University of Manchester (United Kingdom) and her colleagues wrote in their study. “Physician wellness and quality of patient care are critical [as are] complementary dimensions of health care organization efficiency.”

Dr. Panagioti and her colleagues performed a search of the MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, and PsycInfo databases and found 47 eligible studies on the topics of physician burnout and patient care, which altogether included data from a pooled cohort of 42,473 physicians. The physicians were median 38 years old, with 44.7% of studies looking at physicians in residency or early career (up to 5 years post residency) and 55.3% of studies examining experienced physicians. The meta-analysis also evaluated physicians in a hospital setting (63.8%), primary care (13.8%), and across various different health care settings (8.5%).

The researchers found physicians with burnout were significantly associated with higher rates of patient safety issues (odds ratio, 1.96; 95% confidence interval, 1.59-2.40), reduced patient satisfaction (OR, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.42-3.68), and lower quality of care (OR, 2.31; 95% CI, 1.87-2.85). System-reported instances of patient safety issues and low professionalism were not statistically significant, but the subgroup differences did reach statistical significance (Cohen Q, 8.14; P = .007). Among residents and physicians in their early career, there was a greater association between burnout and low professionalism (OR, 3.39; 95% CI, 2.38-4.40), compared with physicians in the middle or later in their career (OR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.46-2.01; Cohen Q, 7.27; P = .003).

“Investments in organizational strategies to jointly monitor and improve physician wellness and patient care outcomes are needed,” Dr. Panagioti and her colleagues wrote in the study. “Interventions aimed at improving the culture of health care organizations, as well as interventions focused on individual physicians but supported and funded by health care organizations, are beneficial.”

Researchers noted the study quality was low to moderate. Variation in outcomes across studies, heterogeneity among studies, potential selection bias by excluding gray literature, and the inability to establish causal links from findings because of the cross-sectional nature of the studies analyzed were potential limitations in the study, they reported.

The study was funded by the United Kingdom NIHR School for Primary Care Research and the NIHR Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre. The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Panagioti M et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Sept 4. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3713.

Because of a lack of funding for research into burnout and the immediate need for change based on the effect it has on patient care seen in Pangioti et al., the question of how to address physician burnout should be answered with quality improvement programs aimed at making immediate changes in health care settings, Mark Linzer, MD, wrote in a related editorial.

“Resonating with these concepts, I propose that, for the burnout prevention and wellness field, we encourage quality improvement projects of high standards: multiple sites, concurrent control groups, longitudinal design, and blinding when feasible, with assessment of outcomes and costs,” he wrote. “These studies can point us toward what we will evaluate in larger trials and allow a place for the rapidly developing information base to be viewed and thus become part of the developing science of work conditions, burnout reduction, and the anticipated result on quality and safety.”

There are research questions that have yet to be answered on this topic, he added, such as to what extent do factors like workflow redesign, use and upkeep of electronic medical records, and chaotic workplaces affect burnout. Further, regulatory environments may play a role, and it is still not known whether reducing burnout among physicians will also reduce burnout among staff. Future studies should also look at how burnout affects trainees and female physicians, he suggested.

“The link between burnout and adverse patient outcomes is stronger, thanks to the work of Panagioti and colleagues,” Dr. Linzer said. “With close to half of U.S. physicians experiencing symptoms of burnout, more work is needed to understand how to reduce it and what we can expect from doing so.”

Dr. Linzer is from the Hennepin Healthcare Systems in Minneapolis. These comments summarize his editorial regarding the findings of Pangioti et al. He reported support for Wellness Champion training by the American College of Physicians and the Association of Chiefs and Leaders in General Internal Medicine and that he has received support for American Medical Association research projects.

Because of a lack of funding for research into burnout and the immediate need for change based on the effect it has on patient care seen in Pangioti et al., the question of how to address physician burnout should be answered with quality improvement programs aimed at making immediate changes in health care settings, Mark Linzer, MD, wrote in a related editorial.

“Resonating with these concepts, I propose that, for the burnout prevention and wellness field, we encourage quality improvement projects of high standards: multiple sites, concurrent control groups, longitudinal design, and blinding when feasible, with assessment of outcomes and costs,” he wrote. “These studies can point us toward what we will evaluate in larger trials and allow a place for the rapidly developing information base to be viewed and thus become part of the developing science of work conditions, burnout reduction, and the anticipated result on quality and safety.”

There are research questions that have yet to be answered on this topic, he added, such as to what extent do factors like workflow redesign, use and upkeep of electronic medical records, and chaotic workplaces affect burnout. Further, regulatory environments may play a role, and it is still not known whether reducing burnout among physicians will also reduce burnout among staff. Future studies should also look at how burnout affects trainees and female physicians, he suggested.

“The link between burnout and adverse patient outcomes is stronger, thanks to the work of Panagioti and colleagues,” Dr. Linzer said. “With close to half of U.S. physicians experiencing symptoms of burnout, more work is needed to understand how to reduce it and what we can expect from doing so.”

Dr. Linzer is from the Hennepin Healthcare Systems in Minneapolis. These comments summarize his editorial regarding the findings of Pangioti et al. He reported support for Wellness Champion training by the American College of Physicians and the Association of Chiefs and Leaders in General Internal Medicine and that he has received support for American Medical Association research projects.

Because of a lack of funding for research into burnout and the immediate need for change based on the effect it has on patient care seen in Pangioti et al., the question of how to address physician burnout should be answered with quality improvement programs aimed at making immediate changes in health care settings, Mark Linzer, MD, wrote in a related editorial.

“Resonating with these concepts, I propose that, for the burnout prevention and wellness field, we encourage quality improvement projects of high standards: multiple sites, concurrent control groups, longitudinal design, and blinding when feasible, with assessment of outcomes and costs,” he wrote. “These studies can point us toward what we will evaluate in larger trials and allow a place for the rapidly developing information base to be viewed and thus become part of the developing science of work conditions, burnout reduction, and the anticipated result on quality and safety.”

There are research questions that have yet to be answered on this topic, he added, such as to what extent do factors like workflow redesign, use and upkeep of electronic medical records, and chaotic workplaces affect burnout. Further, regulatory environments may play a role, and it is still not known whether reducing burnout among physicians will also reduce burnout among staff. Future studies should also look at how burnout affects trainees and female physicians, he suggested.

“The link between burnout and adverse patient outcomes is stronger, thanks to the work of Panagioti and colleagues,” Dr. Linzer said. “With close to half of U.S. physicians experiencing symptoms of burnout, more work is needed to understand how to reduce it and what we can expect from doing so.”

Dr. Linzer is from the Hennepin Healthcare Systems in Minneapolis. These comments summarize his editorial regarding the findings of Pangioti et al. He reported support for Wellness Champion training by the American College of Physicians and the Association of Chiefs and Leaders in General Internal Medicine and that he has received support for American Medical Association research projects.

because of depersonalization of care, according to recent research published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“The primary conclusion of this review is that physician burnout might jeopardize patient care,” Maria Panagioti, PhD, from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Primary Care Research and the NIHR Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre at the University of Manchester (United Kingdom) and her colleagues wrote in their study. “Physician wellness and quality of patient care are critical [as are] complementary dimensions of health care organization efficiency.”

Dr. Panagioti and her colleagues performed a search of the MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, and PsycInfo databases and found 47 eligible studies on the topics of physician burnout and patient care, which altogether included data from a pooled cohort of 42,473 physicians. The physicians were median 38 years old, with 44.7% of studies looking at physicians in residency or early career (up to 5 years post residency) and 55.3% of studies examining experienced physicians. The meta-analysis also evaluated physicians in a hospital setting (63.8%), primary care (13.8%), and across various different health care settings (8.5%).

The researchers found physicians with burnout were significantly associated with higher rates of patient safety issues (odds ratio, 1.96; 95% confidence interval, 1.59-2.40), reduced patient satisfaction (OR, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.42-3.68), and lower quality of care (OR, 2.31; 95% CI, 1.87-2.85). System-reported instances of patient safety issues and low professionalism were not statistically significant, but the subgroup differences did reach statistical significance (Cohen Q, 8.14; P = .007). Among residents and physicians in their early career, there was a greater association between burnout and low professionalism (OR, 3.39; 95% CI, 2.38-4.40), compared with physicians in the middle or later in their career (OR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.46-2.01; Cohen Q, 7.27; P = .003).

“Investments in organizational strategies to jointly monitor and improve physician wellness and patient care outcomes are needed,” Dr. Panagioti and her colleagues wrote in the study. “Interventions aimed at improving the culture of health care organizations, as well as interventions focused on individual physicians but supported and funded by health care organizations, are beneficial.”

Researchers noted the study quality was low to moderate. Variation in outcomes across studies, heterogeneity among studies, potential selection bias by excluding gray literature, and the inability to establish causal links from findings because of the cross-sectional nature of the studies analyzed were potential limitations in the study, they reported.

The study was funded by the United Kingdom NIHR School for Primary Care Research and the NIHR Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre. The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Panagioti M et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Sept 4. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3713.

because of depersonalization of care, according to recent research published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“The primary conclusion of this review is that physician burnout might jeopardize patient care,” Maria Panagioti, PhD, from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Primary Care Research and the NIHR Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre at the University of Manchester (United Kingdom) and her colleagues wrote in their study. “Physician wellness and quality of patient care are critical [as are] complementary dimensions of health care organization efficiency.”

Dr. Panagioti and her colleagues performed a search of the MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, and PsycInfo databases and found 47 eligible studies on the topics of physician burnout and patient care, which altogether included data from a pooled cohort of 42,473 physicians. The physicians were median 38 years old, with 44.7% of studies looking at physicians in residency or early career (up to 5 years post residency) and 55.3% of studies examining experienced physicians. The meta-analysis also evaluated physicians in a hospital setting (63.8%), primary care (13.8%), and across various different health care settings (8.5%).

The researchers found physicians with burnout were significantly associated with higher rates of patient safety issues (odds ratio, 1.96; 95% confidence interval, 1.59-2.40), reduced patient satisfaction (OR, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.42-3.68), and lower quality of care (OR, 2.31; 95% CI, 1.87-2.85). System-reported instances of patient safety issues and low professionalism were not statistically significant, but the subgroup differences did reach statistical significance (Cohen Q, 8.14; P = .007). Among residents and physicians in their early career, there was a greater association between burnout and low professionalism (OR, 3.39; 95% CI, 2.38-4.40), compared with physicians in the middle or later in their career (OR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.46-2.01; Cohen Q, 7.27; P = .003).

“Investments in organizational strategies to jointly monitor and improve physician wellness and patient care outcomes are needed,” Dr. Panagioti and her colleagues wrote in the study. “Interventions aimed at improving the culture of health care organizations, as well as interventions focused on individual physicians but supported and funded by health care organizations, are beneficial.”

Researchers noted the study quality was low to moderate. Variation in outcomes across studies, heterogeneity among studies, potential selection bias by excluding gray literature, and the inability to establish causal links from findings because of the cross-sectional nature of the studies analyzed were potential limitations in the study, they reported.

The study was funded by the United Kingdom NIHR School for Primary Care Research and the NIHR Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre. The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Panagioti M et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Sept 4. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3713.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Burnout among physicians was associated with lower quality of care because of unprofessionalism, reduced patient satisfaction, and an increased risk of patient safety issues.

Major finding: Physicians with burnout were significantly associated with higher rates of patient safety issues (odds ratio, 1.96; 95% confidence interval, 1.59-2.40), reduced patient satisfaction (OR, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.42-3.68), and lower quality of care (OR, 2.31; 95% CI, 1.87-2.85).

Study details: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 42,473 physicians from 47 different studies.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the United Kingdom National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) School for Primary Care Research and the NIHR Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Source: Panagioti M et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Sept 4. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3713.

Factor Xa inhibitors versus vitamin K antagonists for preventing embolism in AF patients

Clinical question: Do factor Xa inhibitors reduce the incidence of strokes and systemic embolic events, compared with warfarin, in people with atrial fibrillation?

Background: Factor Xa inhibitors, called DOACs or direct-acting anticoagulants, and vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) are part of treatment guidelines for preventing stroke and systemic embolic events in people with atrial fibrillation (AF). This study assessed the effectiveness and safety of treatment with factor Xa inhibitors versus VKAs for preventing cerebral or systemic embolic events in AF.

Study design: Cochrane Review update.

Setting: Data obtained from trial registers of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (August 2017), the Cochrane Heart Group and the Cochrane Stroke Group (September 2016), Embase (1980 to April 2017), and MEDLINE (1950 to April 2017). Authors also screened reference lists and contacted pharmaceutical companies, authors, and sponsors of relevant published trials.

Synopsis: The study included 42,084 participants from 10 trials with a diagnosis of AF who were eligible for long-term anticoagulation with warfarin (target INR 2-3).

The trials directly compared dose-adjusted warfarin with factor Xa inhibitors. Median follow-up ranged from 12 weeks to 1.9 years, and composite primary endpoint was all strokes (both ischemic and hemorrhagic) and non–central nervous systemic embolic events. Factor Xa inhibitor significantly decreased the number of strokes and systemic embolic events, compared with dose-adjusted warfarin (odds ratio, 0.81; 95% confidence interval, 0.72-0.91), reduced the number of major bleeding events (OR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.63-1.34), and significantly reduced the risk of intracranial hemorrhage (OR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.45-0.70). They also significantly reduced the number of all-cause deaths (OR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.81-0.97). One limitation of this study is the heterogeneity and hence lower quality of evidence. This study shows a small net clinical benefit of using factor Xa inhibitors in AF because of a reduction in strokes and systemic embolic events and also a lower risk of bleeding (including intracranial hemorrhages), compared with using warfarin.

Bottom line: Patients with AF have a lower incidence of strokes and systemic embolic events when treated with factor Xa inhibitors, compared with those treated with warfarin.

Citation: Bruins Slot KM et al. Factor Xa inhibitors versus vitamin K antagonists for preventing cerebral or systemic embolism in patients with atrial fibrillation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Mar 6. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008980.pub3.

Dr. Veedu is a hospitalist and instructor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky, Lexington.

Clinical question: Do factor Xa inhibitors reduce the incidence of strokes and systemic embolic events, compared with warfarin, in people with atrial fibrillation?

Background: Factor Xa inhibitors, called DOACs or direct-acting anticoagulants, and vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) are part of treatment guidelines for preventing stroke and systemic embolic events in people with atrial fibrillation (AF). This study assessed the effectiveness and safety of treatment with factor Xa inhibitors versus VKAs for preventing cerebral or systemic embolic events in AF.

Study design: Cochrane Review update.

Setting: Data obtained from trial registers of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (August 2017), the Cochrane Heart Group and the Cochrane Stroke Group (September 2016), Embase (1980 to April 2017), and MEDLINE (1950 to April 2017). Authors also screened reference lists and contacted pharmaceutical companies, authors, and sponsors of relevant published trials.

Synopsis: The study included 42,084 participants from 10 trials with a diagnosis of AF who were eligible for long-term anticoagulation with warfarin (target INR 2-3).

The trials directly compared dose-adjusted warfarin with factor Xa inhibitors. Median follow-up ranged from 12 weeks to 1.9 years, and composite primary endpoint was all strokes (both ischemic and hemorrhagic) and non–central nervous systemic embolic events. Factor Xa inhibitor significantly decreased the number of strokes and systemic embolic events, compared with dose-adjusted warfarin (odds ratio, 0.81; 95% confidence interval, 0.72-0.91), reduced the number of major bleeding events (OR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.63-1.34), and significantly reduced the risk of intracranial hemorrhage (OR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.45-0.70). They also significantly reduced the number of all-cause deaths (OR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.81-0.97). One limitation of this study is the heterogeneity and hence lower quality of evidence. This study shows a small net clinical benefit of using factor Xa inhibitors in AF because of a reduction in strokes and systemic embolic events and also a lower risk of bleeding (including intracranial hemorrhages), compared with using warfarin.

Bottom line: Patients with AF have a lower incidence of strokes and systemic embolic events when treated with factor Xa inhibitors, compared with those treated with warfarin.

Citation: Bruins Slot KM et al. Factor Xa inhibitors versus vitamin K antagonists for preventing cerebral or systemic embolism in patients with atrial fibrillation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Mar 6. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008980.pub3.

Dr. Veedu is a hospitalist and instructor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky, Lexington.

Clinical question: Do factor Xa inhibitors reduce the incidence of strokes and systemic embolic events, compared with warfarin, in people with atrial fibrillation?

Background: Factor Xa inhibitors, called DOACs or direct-acting anticoagulants, and vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) are part of treatment guidelines for preventing stroke and systemic embolic events in people with atrial fibrillation (AF). This study assessed the effectiveness and safety of treatment with factor Xa inhibitors versus VKAs for preventing cerebral or systemic embolic events in AF.

Study design: Cochrane Review update.

Setting: Data obtained from trial registers of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (August 2017), the Cochrane Heart Group and the Cochrane Stroke Group (September 2016), Embase (1980 to April 2017), and MEDLINE (1950 to April 2017). Authors also screened reference lists and contacted pharmaceutical companies, authors, and sponsors of relevant published trials.

Synopsis: The study included 42,084 participants from 10 trials with a diagnosis of AF who were eligible for long-term anticoagulation with warfarin (target INR 2-3).

The trials directly compared dose-adjusted warfarin with factor Xa inhibitors. Median follow-up ranged from 12 weeks to 1.9 years, and composite primary endpoint was all strokes (both ischemic and hemorrhagic) and non–central nervous systemic embolic events. Factor Xa inhibitor significantly decreased the number of strokes and systemic embolic events, compared with dose-adjusted warfarin (odds ratio, 0.81; 95% confidence interval, 0.72-0.91), reduced the number of major bleeding events (OR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.63-1.34), and significantly reduced the risk of intracranial hemorrhage (OR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.45-0.70). They also significantly reduced the number of all-cause deaths (OR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.81-0.97). One limitation of this study is the heterogeneity and hence lower quality of evidence. This study shows a small net clinical benefit of using factor Xa inhibitors in AF because of a reduction in strokes and systemic embolic events and also a lower risk of bleeding (including intracranial hemorrhages), compared with using warfarin.

Bottom line: Patients with AF have a lower incidence of strokes and systemic embolic events when treated with factor Xa inhibitors, compared with those treated with warfarin.

Citation: Bruins Slot KM et al. Factor Xa inhibitors versus vitamin K antagonists for preventing cerebral or systemic embolism in patients with atrial fibrillation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Mar 6. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008980.pub3.

Dr. Veedu is a hospitalist and instructor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky, Lexington.

How to handle anorexia in community hospitals

Food is nonnegotiable

ATLANTA – Everyone has to be on the same page when it comes to anorexia nervosa in a community hospital, according to pediatric hospitalists at Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital in Greensboro, N.C.

Anorexia cases used to be rare there. When one came in, “everyone was anxious because we just didn’t know quite what to do,” said Suresh Nagappan, MD, a pediatrician and member of the teaching faculty at the hospital. Parents would hear one thing from one provider, something else from the next, and leave angry and confused. “Basically, it was a mess. We needed to standardize it,” he added.

So Dr. Nagappan and his colleagues created guidelines for treating patients with eating disorders about 3 years ago. “It was meeting after meeting for months, but well worth it,” he said at Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

Word of the hospital’s newfound expertise in anorexia has spread since then, and now it’s not unusual for Moses H. Cone to handle a few cases a week.

The pediatric hospitalist team has come to realize that, first and foremost, patients and families need to know why they are there; it’s about medical stabilization, not treating the eating disorder. That comes after discharge. Families need help sometimes to understand that it’s not a quick fix.

To make things clear, there’s strict criteria now for admission, based on American Academy of Pediatrics guidance. The main trigger is being under 75% of ideal body weight, but patients must also have systolic blood pressure below 90 mm Hg and other worrisome signs. “Sometimes, it feels like we’re splitting hairs” on who gets admitted, “but if we don’t have strict criteria on admission, we don’t have an end goal for discharge,” said pediatrician Maggie S. Hall, MD, also on the Moses H. Cone teaching faculty.

As for treatment, “food is medicine, and it’s not negotiable. We make that clear to everyone on day 1. If patients don’t eat their actual meal, they have 20 minutes to drink a supplement. If they can’t do that, they get a nasogastric tube,” Dr. Nagappan said. The tube is pulled after each meal, so that it remains an incentive to eat.

The team start patients with 1,600 calories a day and increase the intake by 200-250 calories a day. The goal is for a patient to gain 100-200 grams per day. Patients pick out what they want to eat with the help of a dietitian. When meals set off overwhelming anxiety, the Moses H. Cone team has learned that benzodiazepines can help.

Ironically, the initiation of regular meals is the most dangerous time for patients. As anorexic bodies switch from catabolic to anabolic metabolism, electrolytes can drop to dangerously low levels, causing arrhythmias, heart failure, and death. In general, “the reason these kids die is cardiac,” Dr. Nagappan said at the meeting, sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the AAP, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Refeeding syndrome, as it’s known, is clinically significant in perhaps 6% of patients. The risk goes up if they are below 70% of their ideal body weight; have a prolonged QTc interval; or begin treatment with low phosphorous, magnesium, or potassium.

To counter the threat, electrolytes are measured twice a day at Moses H. Cone during the first week of treatment, and ECGs are taken daily for the first few days. “One thing to be really careful about is when you notice their heart rate beginning to creep up during rest. That can be a sign of developing cardiomyopathy; it’s an indication for us to get echocardiograms,” Dr. Hall said.

The Moses H. Cone team like to include families in meal times – it’s been shown to help – but family members need to be coached beforehand. They can’t be punitive. Mealtime talk has to be positive, and can’t focus on eating. Parents often need help handling their own anger and guilt before trying to eat with their child. Progress has to be monitored, but Dr. Nagappan cautioned that “you have to be really careful about how you get weights”; it should always be in the morning after the first void. Urine needs to be checked to make sure patients aren’t water loading.

Staff should be neutral about weight results, and keep them to themselves. Even something as benign as “good job” can be a problem. “You don’t want these patients focused on their weight. You want them focused on getting better and eating and taking it step by step,” he said.

The presenters had no disclosures to report.

Food is nonnegotiable

Food is nonnegotiable

ATLANTA – Everyone has to be on the same page when it comes to anorexia nervosa in a community hospital, according to pediatric hospitalists at Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital in Greensboro, N.C.

Anorexia cases used to be rare there. When one came in, “everyone was anxious because we just didn’t know quite what to do,” said Suresh Nagappan, MD, a pediatrician and member of the teaching faculty at the hospital. Parents would hear one thing from one provider, something else from the next, and leave angry and confused. “Basically, it was a mess. We needed to standardize it,” he added.

So Dr. Nagappan and his colleagues created guidelines for treating patients with eating disorders about 3 years ago. “It was meeting after meeting for months, but well worth it,” he said at Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

Word of the hospital’s newfound expertise in anorexia has spread since then, and now it’s not unusual for Moses H. Cone to handle a few cases a week.

The pediatric hospitalist team has come to realize that, first and foremost, patients and families need to know why they are there; it’s about medical stabilization, not treating the eating disorder. That comes after discharge. Families need help sometimes to understand that it’s not a quick fix.

To make things clear, there’s strict criteria now for admission, based on American Academy of Pediatrics guidance. The main trigger is being under 75% of ideal body weight, but patients must also have systolic blood pressure below 90 mm Hg and other worrisome signs. “Sometimes, it feels like we’re splitting hairs” on who gets admitted, “but if we don’t have strict criteria on admission, we don’t have an end goal for discharge,” said pediatrician Maggie S. Hall, MD, also on the Moses H. Cone teaching faculty.

As for treatment, “food is medicine, and it’s not negotiable. We make that clear to everyone on day 1. If patients don’t eat their actual meal, they have 20 minutes to drink a supplement. If they can’t do that, they get a nasogastric tube,” Dr. Nagappan said. The tube is pulled after each meal, so that it remains an incentive to eat.

The team start patients with 1,600 calories a day and increase the intake by 200-250 calories a day. The goal is for a patient to gain 100-200 grams per day. Patients pick out what they want to eat with the help of a dietitian. When meals set off overwhelming anxiety, the Moses H. Cone team has learned that benzodiazepines can help.

Ironically, the initiation of regular meals is the most dangerous time for patients. As anorexic bodies switch from catabolic to anabolic metabolism, electrolytes can drop to dangerously low levels, causing arrhythmias, heart failure, and death. In general, “the reason these kids die is cardiac,” Dr. Nagappan said at the meeting, sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the AAP, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Refeeding syndrome, as it’s known, is clinically significant in perhaps 6% of patients. The risk goes up if they are below 70% of their ideal body weight; have a prolonged QTc interval; or begin treatment with low phosphorous, magnesium, or potassium.

To counter the threat, electrolytes are measured twice a day at Moses H. Cone during the first week of treatment, and ECGs are taken daily for the first few days. “One thing to be really careful about is when you notice their heart rate beginning to creep up during rest. That can be a sign of developing cardiomyopathy; it’s an indication for us to get echocardiograms,” Dr. Hall said.

The Moses H. Cone team like to include families in meal times – it’s been shown to help – but family members need to be coached beforehand. They can’t be punitive. Mealtime talk has to be positive, and can’t focus on eating. Parents often need help handling their own anger and guilt before trying to eat with their child. Progress has to be monitored, but Dr. Nagappan cautioned that “you have to be really careful about how you get weights”; it should always be in the morning after the first void. Urine needs to be checked to make sure patients aren’t water loading.

Staff should be neutral about weight results, and keep them to themselves. Even something as benign as “good job” can be a problem. “You don’t want these patients focused on their weight. You want them focused on getting better and eating and taking it step by step,” he said.

The presenters had no disclosures to report.

ATLANTA – Everyone has to be on the same page when it comes to anorexia nervosa in a community hospital, according to pediatric hospitalists at Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital in Greensboro, N.C.

Anorexia cases used to be rare there. When one came in, “everyone was anxious because we just didn’t know quite what to do,” said Suresh Nagappan, MD, a pediatrician and member of the teaching faculty at the hospital. Parents would hear one thing from one provider, something else from the next, and leave angry and confused. “Basically, it was a mess. We needed to standardize it,” he added.

So Dr. Nagappan and his colleagues created guidelines for treating patients with eating disorders about 3 years ago. “It was meeting after meeting for months, but well worth it,” he said at Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

Word of the hospital’s newfound expertise in anorexia has spread since then, and now it’s not unusual for Moses H. Cone to handle a few cases a week.

The pediatric hospitalist team has come to realize that, first and foremost, patients and families need to know why they are there; it’s about medical stabilization, not treating the eating disorder. That comes after discharge. Families need help sometimes to understand that it’s not a quick fix.

To make things clear, there’s strict criteria now for admission, based on American Academy of Pediatrics guidance. The main trigger is being under 75% of ideal body weight, but patients must also have systolic blood pressure below 90 mm Hg and other worrisome signs. “Sometimes, it feels like we’re splitting hairs” on who gets admitted, “but if we don’t have strict criteria on admission, we don’t have an end goal for discharge,” said pediatrician Maggie S. Hall, MD, also on the Moses H. Cone teaching faculty.

As for treatment, “food is medicine, and it’s not negotiable. We make that clear to everyone on day 1. If patients don’t eat their actual meal, they have 20 minutes to drink a supplement. If they can’t do that, they get a nasogastric tube,” Dr. Nagappan said. The tube is pulled after each meal, so that it remains an incentive to eat.

The team start patients with 1,600 calories a day and increase the intake by 200-250 calories a day. The goal is for a patient to gain 100-200 grams per day. Patients pick out what they want to eat with the help of a dietitian. When meals set off overwhelming anxiety, the Moses H. Cone team has learned that benzodiazepines can help.

Ironically, the initiation of regular meals is the most dangerous time for patients. As anorexic bodies switch from catabolic to anabolic metabolism, electrolytes can drop to dangerously low levels, causing arrhythmias, heart failure, and death. In general, “the reason these kids die is cardiac,” Dr. Nagappan said at the meeting, sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the AAP, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Refeeding syndrome, as it’s known, is clinically significant in perhaps 6% of patients. The risk goes up if they are below 70% of their ideal body weight; have a prolonged QTc interval; or begin treatment with low phosphorous, magnesium, or potassium.

To counter the threat, electrolytes are measured twice a day at Moses H. Cone during the first week of treatment, and ECGs are taken daily for the first few days. “One thing to be really careful about is when you notice their heart rate beginning to creep up during rest. That can be a sign of developing cardiomyopathy; it’s an indication for us to get echocardiograms,” Dr. Hall said.

The Moses H. Cone team like to include families in meal times – it’s been shown to help – but family members need to be coached beforehand. They can’t be punitive. Mealtime talk has to be positive, and can’t focus on eating. Parents often need help handling their own anger and guilt before trying to eat with their child. Progress has to be monitored, but Dr. Nagappan cautioned that “you have to be really careful about how you get weights”; it should always be in the morning after the first void. Urine needs to be checked to make sure patients aren’t water loading.

Staff should be neutral about weight results, and keep them to themselves. Even something as benign as “good job” can be a problem. “You don’t want these patients focused on their weight. You want them focused on getting better and eating and taking it step by step,” he said.

The presenters had no disclosures to report.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM PHM 2018

Short Takes

Digoxin and mortality in atrial fibrillation

Using propensity score-matched controls, post hoc subgroup analysis of the ARISTOTLE trial showed an independent dose-dependent association between serum digoxin levels and mortality in those receiving digoxin, with a 19% higher adjusted hazard of death for each increase of 0.5 ng/mL (P = .001). For those initiating digoxin there was an independent association with higher mortality, regardless of heart failure (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.78; 95% confidence interval, 1.37-2.31; P less than .0001).

Citation: Lopes RD et al. Digoxin and mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Mar 13;71(10):1063-74.

ED opioid overdoses

Prior studies have shown a recent increase in opioid overdose-related deaths, and this analysis of 136 million ED visits in 45 states showed a continued upward trend from July 2016 to September 2017 with average increases of 5.6% per quarter in all regions and across all demographic groups, but this increase was especially pronounced in urban areas. The authors of this analysis called for the medical community to use these data to educate providers and organize resources for the rapidly evolving opioid epidemic.