User login

A White female presented with pruritic, reticulated, erythematous plaques on the abdomen

It is characterized by pruritic, erythematous papules, papulovesicles, and vesicles that appear in a reticular pattern, most commonly on the trunk. The lesions are typically followed by postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH).

Although PP has been described in people of all races, ages, and sexes, it is predominantly observed in Japan, often in female young adults. Triggers may include a ketogenic diet, diabetes mellitus, and pregnancy. Friction and contact allergic reactions to chrome or nickel have been proposed as exogenous trigger factors. Individual cases of Sjögren’s syndrome, Helicobacter pylori infections, and adult Still syndrome have also been associated with recurrent eruptions.

The diagnosis of PP is made both clinically and by biopsy. The histological features vary according to the stage of the disease. In early-stage disease, superficial and perivascular infiltration of neutrophils are prominent. Later stages are characterized by spongiosis and necrotic keratinocytes.

The first-line therapy for prurigo pigmentosa is oral minocycline. However, for some patients, doxycycline, macrolide antibiotics, or dapsone may be indicated. Adding carbohydrates to a keto diet may be helpful. In this patient, a punch biopsy was performed, which revealed an interface dermatitis with eosinophils and neutrophils, consistent with prurigo pigmentosa. The cause of her PP remains idiopathic. She was treated with 100 mg doxycycline twice a day, which resulted in a resolution of active lesions. The patient did have postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

This case and photo were submitted by Brooke Resh Sateesh, MD, of San Diego Family Dermatology, San Diego, California, and Mina Zulal, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (UKE), Hamburg, Germany. Dr. Bilu Martin edited the column.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

1. Beutler et al. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015 Dec;16(6):533-43.

2. Kim et al. J Dermatol. 2012 Nov;39(11):891-7.

3. Mufti et al. JAAD Int. 2021 Apr 10;3:79-87.

It is characterized by pruritic, erythematous papules, papulovesicles, and vesicles that appear in a reticular pattern, most commonly on the trunk. The lesions are typically followed by postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH).

Although PP has been described in people of all races, ages, and sexes, it is predominantly observed in Japan, often in female young adults. Triggers may include a ketogenic diet, diabetes mellitus, and pregnancy. Friction and contact allergic reactions to chrome or nickel have been proposed as exogenous trigger factors. Individual cases of Sjögren’s syndrome, Helicobacter pylori infections, and adult Still syndrome have also been associated with recurrent eruptions.

The diagnosis of PP is made both clinically and by biopsy. The histological features vary according to the stage of the disease. In early-stage disease, superficial and perivascular infiltration of neutrophils are prominent. Later stages are characterized by spongiosis and necrotic keratinocytes.

The first-line therapy for prurigo pigmentosa is oral minocycline. However, for some patients, doxycycline, macrolide antibiotics, or dapsone may be indicated. Adding carbohydrates to a keto diet may be helpful. In this patient, a punch biopsy was performed, which revealed an interface dermatitis with eosinophils and neutrophils, consistent with prurigo pigmentosa. The cause of her PP remains idiopathic. She was treated with 100 mg doxycycline twice a day, which resulted in a resolution of active lesions. The patient did have postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

This case and photo were submitted by Brooke Resh Sateesh, MD, of San Diego Family Dermatology, San Diego, California, and Mina Zulal, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (UKE), Hamburg, Germany. Dr. Bilu Martin edited the column.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

1. Beutler et al. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015 Dec;16(6):533-43.

2. Kim et al. J Dermatol. 2012 Nov;39(11):891-7.

3. Mufti et al. JAAD Int. 2021 Apr 10;3:79-87.

It is characterized by pruritic, erythematous papules, papulovesicles, and vesicles that appear in a reticular pattern, most commonly on the trunk. The lesions are typically followed by postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH).

Although PP has been described in people of all races, ages, and sexes, it is predominantly observed in Japan, often in female young adults. Triggers may include a ketogenic diet, diabetes mellitus, and pregnancy. Friction and contact allergic reactions to chrome or nickel have been proposed as exogenous trigger factors. Individual cases of Sjögren’s syndrome, Helicobacter pylori infections, and adult Still syndrome have also been associated with recurrent eruptions.

The diagnosis of PP is made both clinically and by biopsy. The histological features vary according to the stage of the disease. In early-stage disease, superficial and perivascular infiltration of neutrophils are prominent. Later stages are characterized by spongiosis and necrotic keratinocytes.

The first-line therapy for prurigo pigmentosa is oral minocycline. However, for some patients, doxycycline, macrolide antibiotics, or dapsone may be indicated. Adding carbohydrates to a keto diet may be helpful. In this patient, a punch biopsy was performed, which revealed an interface dermatitis with eosinophils and neutrophils, consistent with prurigo pigmentosa. The cause of her PP remains idiopathic. She was treated with 100 mg doxycycline twice a day, which resulted in a resolution of active lesions. The patient did have postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

This case and photo were submitted by Brooke Resh Sateesh, MD, of San Diego Family Dermatology, San Diego, California, and Mina Zulal, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (UKE), Hamburg, Germany. Dr. Bilu Martin edited the column.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

1. Beutler et al. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015 Dec;16(6):533-43.

2. Kim et al. J Dermatol. 2012 Nov;39(11):891-7.

3. Mufti et al. JAAD Int. 2021 Apr 10;3:79-87.

A healthy White male presented with a rash consisting of erythematous to purpuric macules

Vasculitis is a process in which blood vessels become inflamed and necrotic. Classic small vessel vasculitis reveals a leukocytoclastic vasculitis and most commonly presents as palpable purpura. .” A form of EIV has been described in the literature as “Disney dermatitis.” It is often seen in healthy adults after a long day of walking at the parks. Other forms of exercise, such as jogging, hiking, or swimming, may also cause the condition.

Clinically, EIV affects the lower legs and presents as purpuric macules. Edema may be present. Lesions may be asymptomatic or may present with pruritus or burning. Diagnosis is often made clinically. Skin biopsies for H&E and DIF (direct immunofluorescence) can help distinguish the type of vasculitis that is present. Laboratory tests may be needed to exclude other causes of vasculitis. Episodes may be recurrent.

Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP), also called anaphylactoid purpura, is a subtype of small-vessel vasculitis where IgA immunoglobulin is deposited in the vessel walls. It is the most common form of vasculitis is children (usually ages 4-8). In addition to skin, organs such as joints, kidneys, and intestines can be involved. Schamberg’s disease, or capillaritis, is also called pigmented purpura. In this benign condition, leakage from capillaries results in erythematous to brown patches on the lower extremities. A true vasculitis is not seen. The brown discoloration is due to hemosiderin deposition. Cryoglobulinemia is a rare condition in which abnormal immunoglobulin complexes deposit in tissues and vessels. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis is present in small vessels. Palpable purpura and livedo may be seen clinically, and systemic symptoms may be present.

Treatment of EIV is largely supportive as lesions will resolve on their own over 3-4 weeks. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may result. Temporary cessation of exercise and compression stockings can help speed up the resolution of lesions. Systemic medications used in the treatment of severe vasculitis, such as systemic steroids, dapsone, and colchicine, are not needed in EIV.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Vasculitis is a process in which blood vessels become inflamed and necrotic. Classic small vessel vasculitis reveals a leukocytoclastic vasculitis and most commonly presents as palpable purpura. .” A form of EIV has been described in the literature as “Disney dermatitis.” It is often seen in healthy adults after a long day of walking at the parks. Other forms of exercise, such as jogging, hiking, or swimming, may also cause the condition.

Clinically, EIV affects the lower legs and presents as purpuric macules. Edema may be present. Lesions may be asymptomatic or may present with pruritus or burning. Diagnosis is often made clinically. Skin biopsies for H&E and DIF (direct immunofluorescence) can help distinguish the type of vasculitis that is present. Laboratory tests may be needed to exclude other causes of vasculitis. Episodes may be recurrent.

Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP), also called anaphylactoid purpura, is a subtype of small-vessel vasculitis where IgA immunoglobulin is deposited in the vessel walls. It is the most common form of vasculitis is children (usually ages 4-8). In addition to skin, organs such as joints, kidneys, and intestines can be involved. Schamberg’s disease, or capillaritis, is also called pigmented purpura. In this benign condition, leakage from capillaries results in erythematous to brown patches on the lower extremities. A true vasculitis is not seen. The brown discoloration is due to hemosiderin deposition. Cryoglobulinemia is a rare condition in which abnormal immunoglobulin complexes deposit in tissues and vessels. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis is present in small vessels. Palpable purpura and livedo may be seen clinically, and systemic symptoms may be present.

Treatment of EIV is largely supportive as lesions will resolve on their own over 3-4 weeks. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may result. Temporary cessation of exercise and compression stockings can help speed up the resolution of lesions. Systemic medications used in the treatment of severe vasculitis, such as systemic steroids, dapsone, and colchicine, are not needed in EIV.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Vasculitis is a process in which blood vessels become inflamed and necrotic. Classic small vessel vasculitis reveals a leukocytoclastic vasculitis and most commonly presents as palpable purpura. .” A form of EIV has been described in the literature as “Disney dermatitis.” It is often seen in healthy adults after a long day of walking at the parks. Other forms of exercise, such as jogging, hiking, or swimming, may also cause the condition.

Clinically, EIV affects the lower legs and presents as purpuric macules. Edema may be present. Lesions may be asymptomatic or may present with pruritus or burning. Diagnosis is often made clinically. Skin biopsies for H&E and DIF (direct immunofluorescence) can help distinguish the type of vasculitis that is present. Laboratory tests may be needed to exclude other causes of vasculitis. Episodes may be recurrent.

Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP), also called anaphylactoid purpura, is a subtype of small-vessel vasculitis where IgA immunoglobulin is deposited in the vessel walls. It is the most common form of vasculitis is children (usually ages 4-8). In addition to skin, organs such as joints, kidneys, and intestines can be involved. Schamberg’s disease, or capillaritis, is also called pigmented purpura. In this benign condition, leakage from capillaries results in erythematous to brown patches on the lower extremities. A true vasculitis is not seen. The brown discoloration is due to hemosiderin deposition. Cryoglobulinemia is a rare condition in which abnormal immunoglobulin complexes deposit in tissues and vessels. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis is present in small vessels. Palpable purpura and livedo may be seen clinically, and systemic symptoms may be present.

Treatment of EIV is largely supportive as lesions will resolve on their own over 3-4 weeks. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may result. Temporary cessation of exercise and compression stockings can help speed up the resolution of lesions. Systemic medications used in the treatment of severe vasculitis, such as systemic steroids, dapsone, and colchicine, are not needed in EIV.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

A Hispanic male presented with a 3-month history of a spreading, itchy rash

, more often on exposed skin. In the United States, Trichophyton rubrum, T. mentagrophytes, and Microsporum canis are the most common causal organisms. People can become infected from contact with other people, animals, or soil. Variants of tinea corporis include tinea imbricata (caused by T. concentricum), bullous tinea corporis, tinea gladiatorum (seen in wrestlers), tinea incognito (atypical tinea resulting from topical steroid use), and Majocchi’s granuloma. Widespread tinea may be secondary to underlying immunodeficiency such as HIV/AIDS or treatment with topical or oral steroids.

The typical presentation of tinea corporis is scaly erythematous or hypopigmented annular patches with a raised border and central clearing. In tinea imbricata, which is more commonly seen in southeast Asia, India, and Central America, concentric circles and serpiginous plaques are present. Majocchi’s granuloma has a deeper involvement of fungus in the hair follicles, presenting with papules and pustules at the periphery of the patches. Lesions of tinea incognito may lack a scaly border and can be more widespread.

Diagnosis can be confirmed with a skin scraping and potassium hydroxide (KOH) staining, which will reveal septate and branching hyphae. Biopsy is often helpful, especially in tinea incognito. Classically, a “sandwich sign” is seen: hyphae between orthokeratosis and compact hyperkeratosis or parakeratosis. In this patient, a biopsy from the left hip revealed dermatophytosis, with PAS positive for organisms.

Localized lesions respond to topical antifungal creams such as azoles or topical terbinafine. More extensive tinea will often require a systemic antifungal with griseofulvin, terbinafine, itraconazole, or fluconazole. This patient responded to topical ketoconazole cream and oral terbinafine. A workup for underlying immunodeficiency was negative.

Dr. Bilu Martin provided this case and photo.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at MDedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

, more often on exposed skin. In the United States, Trichophyton rubrum, T. mentagrophytes, and Microsporum canis are the most common causal organisms. People can become infected from contact with other people, animals, or soil. Variants of tinea corporis include tinea imbricata (caused by T. concentricum), bullous tinea corporis, tinea gladiatorum (seen in wrestlers), tinea incognito (atypical tinea resulting from topical steroid use), and Majocchi’s granuloma. Widespread tinea may be secondary to underlying immunodeficiency such as HIV/AIDS or treatment with topical or oral steroids.

The typical presentation of tinea corporis is scaly erythematous or hypopigmented annular patches with a raised border and central clearing. In tinea imbricata, which is more commonly seen in southeast Asia, India, and Central America, concentric circles and serpiginous plaques are present. Majocchi’s granuloma has a deeper involvement of fungus in the hair follicles, presenting with papules and pustules at the periphery of the patches. Lesions of tinea incognito may lack a scaly border and can be more widespread.

Diagnosis can be confirmed with a skin scraping and potassium hydroxide (KOH) staining, which will reveal septate and branching hyphae. Biopsy is often helpful, especially in tinea incognito. Classically, a “sandwich sign” is seen: hyphae between orthokeratosis and compact hyperkeratosis or parakeratosis. In this patient, a biopsy from the left hip revealed dermatophytosis, with PAS positive for organisms.

Localized lesions respond to topical antifungal creams such as azoles or topical terbinafine. More extensive tinea will often require a systemic antifungal with griseofulvin, terbinafine, itraconazole, or fluconazole. This patient responded to topical ketoconazole cream and oral terbinafine. A workup for underlying immunodeficiency was negative.

Dr. Bilu Martin provided this case and photo.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at MDedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

, more often on exposed skin. In the United States, Trichophyton rubrum, T. mentagrophytes, and Microsporum canis are the most common causal organisms. People can become infected from contact with other people, animals, or soil. Variants of tinea corporis include tinea imbricata (caused by T. concentricum), bullous tinea corporis, tinea gladiatorum (seen in wrestlers), tinea incognito (atypical tinea resulting from topical steroid use), and Majocchi’s granuloma. Widespread tinea may be secondary to underlying immunodeficiency such as HIV/AIDS or treatment with topical or oral steroids.

The typical presentation of tinea corporis is scaly erythematous or hypopigmented annular patches with a raised border and central clearing. In tinea imbricata, which is more commonly seen in southeast Asia, India, and Central America, concentric circles and serpiginous plaques are present. Majocchi’s granuloma has a deeper involvement of fungus in the hair follicles, presenting with papules and pustules at the periphery of the patches. Lesions of tinea incognito may lack a scaly border and can be more widespread.

Diagnosis can be confirmed with a skin scraping and potassium hydroxide (KOH) staining, which will reveal septate and branching hyphae. Biopsy is often helpful, especially in tinea incognito. Classically, a “sandwich sign” is seen: hyphae between orthokeratosis and compact hyperkeratosis or parakeratosis. In this patient, a biopsy from the left hip revealed dermatophytosis, with PAS positive for organisms.

Localized lesions respond to topical antifungal creams such as azoles or topical terbinafine. More extensive tinea will often require a systemic antifungal with griseofulvin, terbinafine, itraconazole, or fluconazole. This patient responded to topical ketoconazole cream and oral terbinafine. A workup for underlying immunodeficiency was negative.

Dr. Bilu Martin provided this case and photo.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at MDedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

A 64-year-old woman presents with a history of asymptomatic erythematous grouped papules on the right breast

. Recurrences may occur. Rarely, lymph nodes, the gastrointestinal system, lung, bone and bone marrow may be involved as extracutaneous sites.

Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas account for approximately 25% of all cutaneous lymphomas. Clinically, patients present with either solitary or multiple papules or plaques, typically on the upper extremities or trunk.

Histopathology is vital for the correct diagnosis. In this patient, the histologic report was written as follows: “The findings are those of a well-differentiated but atypical diffuse mixed small lymphocytic infiltrate representing a mixture of T-cells and B-cells. The minor component of the infiltrate is of T-cell lineage, whereby the cells do not show any phenotypic abnormalities. The background cell population is interpreted as reactive. However, the dominant cell population is in fact of B-cell lineage. It is extensively highlighted by CD20. Only a minor component of the B cell infiltrate appeared to be in the context of representing germinal centers as characterized by small foci of centrocytic and centroblastic infiltration highlighted by BCL6 and CD10. The overwhelming B-cell component is a non–germinal center small B cell that does demonstrate BCL2 positivity and significant immunoreactivity for CD23. This small lymphocytic infiltrate obscures the germinal centers. There are only a few plasma cells; they do not show light chain restriction.”

The pathologist remarked that “this type of morphology of a diffuse small B-cell lymphocytic infiltrate that is without any evidence of light chain restriction amidst plasma cells, whereby the B cell component is dominant over the T-cell component would in fact be consistent with a unique variant of marginal zone lymphoma derived from a naive mantle zone.”

PCMZL has an excellent prognosis. When limited to the skin, local radiation or excision are effective treatments. Intravenous rituximab has been used to treat multifocal PCMZL. This patient was found to have no extracutaneous involvement and was treated with radiation.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

Virmani P et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2017 Jun 14;3(4):269-72.

Magro CM and Olson LC. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2018 Jun;34:116-21.

. Recurrences may occur. Rarely, lymph nodes, the gastrointestinal system, lung, bone and bone marrow may be involved as extracutaneous sites.

Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas account for approximately 25% of all cutaneous lymphomas. Clinically, patients present with either solitary or multiple papules or plaques, typically on the upper extremities or trunk.

Histopathology is vital for the correct diagnosis. In this patient, the histologic report was written as follows: “The findings are those of a well-differentiated but atypical diffuse mixed small lymphocytic infiltrate representing a mixture of T-cells and B-cells. The minor component of the infiltrate is of T-cell lineage, whereby the cells do not show any phenotypic abnormalities. The background cell population is interpreted as reactive. However, the dominant cell population is in fact of B-cell lineage. It is extensively highlighted by CD20. Only a minor component of the B cell infiltrate appeared to be in the context of representing germinal centers as characterized by small foci of centrocytic and centroblastic infiltration highlighted by BCL6 and CD10. The overwhelming B-cell component is a non–germinal center small B cell that does demonstrate BCL2 positivity and significant immunoreactivity for CD23. This small lymphocytic infiltrate obscures the germinal centers. There are only a few plasma cells; they do not show light chain restriction.”

The pathologist remarked that “this type of morphology of a diffuse small B-cell lymphocytic infiltrate that is without any evidence of light chain restriction amidst plasma cells, whereby the B cell component is dominant over the T-cell component would in fact be consistent with a unique variant of marginal zone lymphoma derived from a naive mantle zone.”

PCMZL has an excellent prognosis. When limited to the skin, local radiation or excision are effective treatments. Intravenous rituximab has been used to treat multifocal PCMZL. This patient was found to have no extracutaneous involvement and was treated with radiation.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

Virmani P et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2017 Jun 14;3(4):269-72.

Magro CM and Olson LC. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2018 Jun;34:116-21.

. Recurrences may occur. Rarely, lymph nodes, the gastrointestinal system, lung, bone and bone marrow may be involved as extracutaneous sites.

Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas account for approximately 25% of all cutaneous lymphomas. Clinically, patients present with either solitary or multiple papules or plaques, typically on the upper extremities or trunk.

Histopathology is vital for the correct diagnosis. In this patient, the histologic report was written as follows: “The findings are those of a well-differentiated but atypical diffuse mixed small lymphocytic infiltrate representing a mixture of T-cells and B-cells. The minor component of the infiltrate is of T-cell lineage, whereby the cells do not show any phenotypic abnormalities. The background cell population is interpreted as reactive. However, the dominant cell population is in fact of B-cell lineage. It is extensively highlighted by CD20. Only a minor component of the B cell infiltrate appeared to be in the context of representing germinal centers as characterized by small foci of centrocytic and centroblastic infiltration highlighted by BCL6 and CD10. The overwhelming B-cell component is a non–germinal center small B cell that does demonstrate BCL2 positivity and significant immunoreactivity for CD23. This small lymphocytic infiltrate obscures the germinal centers. There are only a few plasma cells; they do not show light chain restriction.”

The pathologist remarked that “this type of morphology of a diffuse small B-cell lymphocytic infiltrate that is without any evidence of light chain restriction amidst plasma cells, whereby the B cell component is dominant over the T-cell component would in fact be consistent with a unique variant of marginal zone lymphoma derived from a naive mantle zone.”

PCMZL has an excellent prognosis. When limited to the skin, local radiation or excision are effective treatments. Intravenous rituximab has been used to treat multifocal PCMZL. This patient was found to have no extracutaneous involvement and was treated with radiation.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

Virmani P et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2017 Jun 14;3(4):269-72.

Magro CM and Olson LC. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2018 Jun;34:116-21.

24-year-old female presents with a 3-month history of nonpruritic rash

, typically characterized by symmetrical, nonblanching, purpuric, telangiectatic, and atrophic patches with a predilection for the lower extremities and buttocks.

Plaques are usually 1-3 cm in diameter and annular with punctate telangiectasias and cayenne pepper petechiae in the border. The annular patches may form concentric rings. It is most commonly seen in children and young females.

The etiology of Majocchi’s disease is largely unknown and idiopathic.

Triggers are not always detected but may be associated with viral infections, chronic comorbidities, and medications. Levofloxacin and isotretinoin have been described in as reports as causing PATM. Other medications reported to cause PPD include sedatives, stimulants, antibiotics, NSAIDS, and cardiovascular drugs.

Diagnosis of PATM is clinical and histopathologic. Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) may show fibrinogen, IgM, and/or C3 deposition in superficial dermal vessels. Histopathologic findings show lymphocytic infiltrate involving the superficial small vessels, extravasated red blood cells, and hemosiderin-laden macrophages.

There is no consensus regarding treatment with variable responses to proposed treatment based on reports and case studies. The first line of treatment is topical corticosteroids and compression hose. Additional treatments, including narrowband UVB phototherapy (NBUVB), griseofulvin, pentoxifylline, cyclosporine, colchicine, rutoside with ascorbic acid, and methotrexate, have been used with varying success.

In this patient, a punch biopsy was performed, which revealed lymphocytes and extravasated erythrocytes and siderophages in the dermis. She was treated with topical steroids with improvement. She started NBUVB, a short course of griseofulvin, and vitamin C supplements.

This case and the photos were photo submitted by Ms. Xu, of the University of California, San Diego, and Dr. Sateesh, of San Diego Family Dermatology. Dr. Donna Bilu Martin edited the column.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

1. Garcez A et al. An Bras Dermatol. Sep-Oct 2020;95(5):664-6. doi: 10.1016/j.abd.2020.02.007.

2. Asadbeigi S, Momtahen S. Pigmented purpuric dermatosis. PathologyOutlines.com website.

3. Martínez P et al. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 2020 Apr;111(3):196-204. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2019.02.013.

4. Hoesly FJ et al. Int J Dermatol. 2009 Oct;48(10):1129-33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04160.x.

, typically characterized by symmetrical, nonblanching, purpuric, telangiectatic, and atrophic patches with a predilection for the lower extremities and buttocks.

Plaques are usually 1-3 cm in diameter and annular with punctate telangiectasias and cayenne pepper petechiae in the border. The annular patches may form concentric rings. It is most commonly seen in children and young females.

The etiology of Majocchi’s disease is largely unknown and idiopathic.

Triggers are not always detected but may be associated with viral infections, chronic comorbidities, and medications. Levofloxacin and isotretinoin have been described in as reports as causing PATM. Other medications reported to cause PPD include sedatives, stimulants, antibiotics, NSAIDS, and cardiovascular drugs.

Diagnosis of PATM is clinical and histopathologic. Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) may show fibrinogen, IgM, and/or C3 deposition in superficial dermal vessels. Histopathologic findings show lymphocytic infiltrate involving the superficial small vessels, extravasated red blood cells, and hemosiderin-laden macrophages.

There is no consensus regarding treatment with variable responses to proposed treatment based on reports and case studies. The first line of treatment is topical corticosteroids and compression hose. Additional treatments, including narrowband UVB phototherapy (NBUVB), griseofulvin, pentoxifylline, cyclosporine, colchicine, rutoside with ascorbic acid, and methotrexate, have been used with varying success.

In this patient, a punch biopsy was performed, which revealed lymphocytes and extravasated erythrocytes and siderophages in the dermis. She was treated with topical steroids with improvement. She started NBUVB, a short course of griseofulvin, and vitamin C supplements.

This case and the photos were photo submitted by Ms. Xu, of the University of California, San Diego, and Dr. Sateesh, of San Diego Family Dermatology. Dr. Donna Bilu Martin edited the column.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

1. Garcez A et al. An Bras Dermatol. Sep-Oct 2020;95(5):664-6. doi: 10.1016/j.abd.2020.02.007.

2. Asadbeigi S, Momtahen S. Pigmented purpuric dermatosis. PathologyOutlines.com website.

3. Martínez P et al. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 2020 Apr;111(3):196-204. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2019.02.013.

4. Hoesly FJ et al. Int J Dermatol. 2009 Oct;48(10):1129-33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04160.x.

, typically characterized by symmetrical, nonblanching, purpuric, telangiectatic, and atrophic patches with a predilection for the lower extremities and buttocks.

Plaques are usually 1-3 cm in diameter and annular with punctate telangiectasias and cayenne pepper petechiae in the border. The annular patches may form concentric rings. It is most commonly seen in children and young females.

The etiology of Majocchi’s disease is largely unknown and idiopathic.

Triggers are not always detected but may be associated with viral infections, chronic comorbidities, and medications. Levofloxacin and isotretinoin have been described in as reports as causing PATM. Other medications reported to cause PPD include sedatives, stimulants, antibiotics, NSAIDS, and cardiovascular drugs.

Diagnosis of PATM is clinical and histopathologic. Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) may show fibrinogen, IgM, and/or C3 deposition in superficial dermal vessels. Histopathologic findings show lymphocytic infiltrate involving the superficial small vessels, extravasated red blood cells, and hemosiderin-laden macrophages.

There is no consensus regarding treatment with variable responses to proposed treatment based on reports and case studies. The first line of treatment is topical corticosteroids and compression hose. Additional treatments, including narrowband UVB phototherapy (NBUVB), griseofulvin, pentoxifylline, cyclosporine, colchicine, rutoside with ascorbic acid, and methotrexate, have been used with varying success.

In this patient, a punch biopsy was performed, which revealed lymphocytes and extravasated erythrocytes and siderophages in the dermis. She was treated with topical steroids with improvement. She started NBUVB, a short course of griseofulvin, and vitamin C supplements.

This case and the photos were photo submitted by Ms. Xu, of the University of California, San Diego, and Dr. Sateesh, of San Diego Family Dermatology. Dr. Donna Bilu Martin edited the column.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

1. Garcez A et al. An Bras Dermatol. Sep-Oct 2020;95(5):664-6. doi: 10.1016/j.abd.2020.02.007.

2. Asadbeigi S, Momtahen S. Pigmented purpuric dermatosis. PathologyOutlines.com website.

3. Martínez P et al. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 2020 Apr;111(3):196-204. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2019.02.013.

4. Hoesly FJ et al. Int J Dermatol. 2009 Oct;48(10):1129-33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04160.x.

A 31-year-old female presented with a burning rash on upper arms, groin, and axillae

The exact cause is unknown, but possible causes include medications, dental amalgam fillings, or an autoimmune reaction. Drugs implicated in causing LP include beta-blockers, methyldopa, penicillamine, quinidine, and quinine. A meta-analysis of case-control studies show a statistically significant association between hepatitis C infection and LP patients; thus, all patients presenting with LP should be screened for hepatitis.1 Individuals of all age groups and races can be affected by LP, but it is predominantly observed in middle-aged adults. Women are also twice as likely to get oral lichen planus.2

Atrophic lichen planus, the least common form of LP, presents as flat, violaceous papules with an atrophic, pale center. Although these papules can be found anywhere on the body, they most commonly affect the trunk and/or legs on areas of the skin previously affected by classical lichen planus.3 In most cases, LP is diagnosed by observing its clinical features. A biopsy is recommended to confirm the diagnosis for more atypical cases.

Histopathology reveals thinning of the epidermis with flattening of the rete ridges, vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer, and a lichenoid mononuclear infiltrate in the papillary dermis.

If the patient is diagnosed with LP but experiences no symptoms, treatment is not needed as LP may resolve spontaneously within 1-2 years. Recurrences are common, however. Lesions may heal with hyperpigmentation. Possible treatments that can help relieve symptoms of pruritus are high potency topical corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, and antihistamines. In more severe and widespread cases, lesions may respond well to systemic corticosteroids or intralesional steroid injections.4 Phototherapy is reported to be effective as well. Acitretin, isotretinoin, methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, and mycophenolate mofetil are all described in the literature. It is important to note that LP on mucous membranes may be more persistent and resistant to treatment.1

In this patient, a punch biopsy was performed, confirming the diagnosis. The patient was treated with topical and intralesional steroids, as well as a course of prednisone, and her lesions improved with treatment. Hepatitis serologies were negative.

This case and photo were submitted by Ms. Erras of the University of California, San Diego, and Dr. Sateesh, of San Diego Family Dermatology, and edited by Donna Bilu Martin, MD.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

1. Usatine R, Tinitigan M. Am Fam Physician. 2011 Jul 1;84(1):53-602.

2. Lichen planus, Johns Hopkins Medicine. [Cited 2022 Mar 13.]

3. Atrophic lichen planus, Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program. [Cited 2022 Mar 13.]

4. ”Atrophic lichen planus,” Medscape, 2004 Feb 1. [Cited 2022 Mar 13.]

The exact cause is unknown, but possible causes include medications, dental amalgam fillings, or an autoimmune reaction. Drugs implicated in causing LP include beta-blockers, methyldopa, penicillamine, quinidine, and quinine. A meta-analysis of case-control studies show a statistically significant association between hepatitis C infection and LP patients; thus, all patients presenting with LP should be screened for hepatitis.1 Individuals of all age groups and races can be affected by LP, but it is predominantly observed in middle-aged adults. Women are also twice as likely to get oral lichen planus.2

Atrophic lichen planus, the least common form of LP, presents as flat, violaceous papules with an atrophic, pale center. Although these papules can be found anywhere on the body, they most commonly affect the trunk and/or legs on areas of the skin previously affected by classical lichen planus.3 In most cases, LP is diagnosed by observing its clinical features. A biopsy is recommended to confirm the diagnosis for more atypical cases.

Histopathology reveals thinning of the epidermis with flattening of the rete ridges, vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer, and a lichenoid mononuclear infiltrate in the papillary dermis.

If the patient is diagnosed with LP but experiences no symptoms, treatment is not needed as LP may resolve spontaneously within 1-2 years. Recurrences are common, however. Lesions may heal with hyperpigmentation. Possible treatments that can help relieve symptoms of pruritus are high potency topical corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, and antihistamines. In more severe and widespread cases, lesions may respond well to systemic corticosteroids or intralesional steroid injections.4 Phototherapy is reported to be effective as well. Acitretin, isotretinoin, methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, and mycophenolate mofetil are all described in the literature. It is important to note that LP on mucous membranes may be more persistent and resistant to treatment.1

In this patient, a punch biopsy was performed, confirming the diagnosis. The patient was treated with topical and intralesional steroids, as well as a course of prednisone, and her lesions improved with treatment. Hepatitis serologies were negative.

This case and photo were submitted by Ms. Erras of the University of California, San Diego, and Dr. Sateesh, of San Diego Family Dermatology, and edited by Donna Bilu Martin, MD.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

1. Usatine R, Tinitigan M. Am Fam Physician. 2011 Jul 1;84(1):53-602.

2. Lichen planus, Johns Hopkins Medicine. [Cited 2022 Mar 13.]

3. Atrophic lichen planus, Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program. [Cited 2022 Mar 13.]

4. ”Atrophic lichen planus,” Medscape, 2004 Feb 1. [Cited 2022 Mar 13.]

The exact cause is unknown, but possible causes include medications, dental amalgam fillings, or an autoimmune reaction. Drugs implicated in causing LP include beta-blockers, methyldopa, penicillamine, quinidine, and quinine. A meta-analysis of case-control studies show a statistically significant association between hepatitis C infection and LP patients; thus, all patients presenting with LP should be screened for hepatitis.1 Individuals of all age groups and races can be affected by LP, but it is predominantly observed in middle-aged adults. Women are also twice as likely to get oral lichen planus.2

Atrophic lichen planus, the least common form of LP, presents as flat, violaceous papules with an atrophic, pale center. Although these papules can be found anywhere on the body, they most commonly affect the trunk and/or legs on areas of the skin previously affected by classical lichen planus.3 In most cases, LP is diagnosed by observing its clinical features. A biopsy is recommended to confirm the diagnosis for more atypical cases.

Histopathology reveals thinning of the epidermis with flattening of the rete ridges, vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer, and a lichenoid mononuclear infiltrate in the papillary dermis.

If the patient is diagnosed with LP but experiences no symptoms, treatment is not needed as LP may resolve spontaneously within 1-2 years. Recurrences are common, however. Lesions may heal with hyperpigmentation. Possible treatments that can help relieve symptoms of pruritus are high potency topical corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, and antihistamines. In more severe and widespread cases, lesions may respond well to systemic corticosteroids or intralesional steroid injections.4 Phototherapy is reported to be effective as well. Acitretin, isotretinoin, methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, and mycophenolate mofetil are all described in the literature. It is important to note that LP on mucous membranes may be more persistent and resistant to treatment.1

In this patient, a punch biopsy was performed, confirming the diagnosis. The patient was treated with topical and intralesional steroids, as well as a course of prednisone, and her lesions improved with treatment. Hepatitis serologies were negative.

This case and photo were submitted by Ms. Erras of the University of California, San Diego, and Dr. Sateesh, of San Diego Family Dermatology, and edited by Donna Bilu Martin, MD.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

1. Usatine R, Tinitigan M. Am Fam Physician. 2011 Jul 1;84(1):53-602.

2. Lichen planus, Johns Hopkins Medicine. [Cited 2022 Mar 13.]

3. Atrophic lichen planus, Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program. [Cited 2022 Mar 13.]

4. ”Atrophic lichen planus,” Medscape, 2004 Feb 1. [Cited 2022 Mar 13.]

Betamethasone cream did not alleviate symptoms.

A 34-year-old male presented with 10 days of a pruritic rash

Less frequently observable infectious agents associated with EM are Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Histoplasma capsulatum, and parapoxvirus (orf). Rarely, EM is triggered by drug eruption or systemic disease. Individuals of all age groups and races can be affected by EM. However, it is predominantly observed in young adult patients (20-40 years of age), and there is a male predominance.

Patients typically present with the abrupt onset of symmetrical red papules that evolve into typical and atypical targetoid lesions. Lesions evolve in 48-72 hours, favoring acrofacial sites that then spread down towards the trunk. Systemic symptoms such as fever and arthralgia may accompany the skin lesions.1-3

Erythema multiforme is recognized in two forms: EM minor and EM major. Both forms share the same characteristic of target lesions. However, the presence of mucosal involvement distinguishes the two. Mucosal involvement is absent or mild in EM minor, while mucosal involvement in EM major is often severe.2,3 Painful bullous lesions are commonly present in the mouth, genital, and ocular mucous membranes. Severe symptoms can often result in difficulty eating and drinking.

Diagnosis is largely clinical. Further histologic study may accompany diagnoses to exclude differential diagnosis. In EM, direct immunofluorescence (DIF) is negative. Histopathology reveals apoptosis of individual keratinocytes.1,2

Therapeutic treatment for painful bullous lesions in the mouth involve antiseptic rinses and anesthetic solutions. Preventive treatment for patients with HSV-associated EM recurrence includes oral acyclovir or valacyclovir.2

In this patient, a punch biopsy was performed, confirming the diagnosis. A DIF was negative, and a chest x-ray was negative. Treatment was initiated with oral acyclovir, doxycycline, and a prednisone taper. In addition, topical clobetasol propionate and magic mouthwash (Maalox/lidocaine/nystatin) was prescribed. The patient was placed on daily suppressive valacyclovir to prevent frequent recurrence of EM.

This case and photo were submitted by Ms. Pham, the University of California, Los Angeles, and Dr. Sateesh, San Diego Family Dermatology. Dr. Bilu-Martin edited the column.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

1. Hafsi W and Badri T. Erythema Multiforme, in “StatPearls [Internet].” Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, 2022 Jan.

2. Bolognia J et al. Dermatology. St. Louis: Mosby/Elsevier, 2008.

3. Oakley A. Erythema Multiforme. DermNet NZ. 2015 Oct.

Less frequently observable infectious agents associated with EM are Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Histoplasma capsulatum, and parapoxvirus (orf). Rarely, EM is triggered by drug eruption or systemic disease. Individuals of all age groups and races can be affected by EM. However, it is predominantly observed in young adult patients (20-40 years of age), and there is a male predominance.

Patients typically present with the abrupt onset of symmetrical red papules that evolve into typical and atypical targetoid lesions. Lesions evolve in 48-72 hours, favoring acrofacial sites that then spread down towards the trunk. Systemic symptoms such as fever and arthralgia may accompany the skin lesions.1-3

Erythema multiforme is recognized in two forms: EM minor and EM major. Both forms share the same characteristic of target lesions. However, the presence of mucosal involvement distinguishes the two. Mucosal involvement is absent or mild in EM minor, while mucosal involvement in EM major is often severe.2,3 Painful bullous lesions are commonly present in the mouth, genital, and ocular mucous membranes. Severe symptoms can often result in difficulty eating and drinking.

Diagnosis is largely clinical. Further histologic study may accompany diagnoses to exclude differential diagnosis. In EM, direct immunofluorescence (DIF) is negative. Histopathology reveals apoptosis of individual keratinocytes.1,2

Therapeutic treatment for painful bullous lesions in the mouth involve antiseptic rinses and anesthetic solutions. Preventive treatment for patients with HSV-associated EM recurrence includes oral acyclovir or valacyclovir.2

In this patient, a punch biopsy was performed, confirming the diagnosis. A DIF was negative, and a chest x-ray was negative. Treatment was initiated with oral acyclovir, doxycycline, and a prednisone taper. In addition, topical clobetasol propionate and magic mouthwash (Maalox/lidocaine/nystatin) was prescribed. The patient was placed on daily suppressive valacyclovir to prevent frequent recurrence of EM.

This case and photo were submitted by Ms. Pham, the University of California, Los Angeles, and Dr. Sateesh, San Diego Family Dermatology. Dr. Bilu-Martin edited the column.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

1. Hafsi W and Badri T. Erythema Multiforme, in “StatPearls [Internet].” Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, 2022 Jan.

2. Bolognia J et al. Dermatology. St. Louis: Mosby/Elsevier, 2008.

3. Oakley A. Erythema Multiforme. DermNet NZ. 2015 Oct.

Less frequently observable infectious agents associated with EM are Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Histoplasma capsulatum, and parapoxvirus (orf). Rarely, EM is triggered by drug eruption or systemic disease. Individuals of all age groups and races can be affected by EM. However, it is predominantly observed in young adult patients (20-40 years of age), and there is a male predominance.

Patients typically present with the abrupt onset of symmetrical red papules that evolve into typical and atypical targetoid lesions. Lesions evolve in 48-72 hours, favoring acrofacial sites that then spread down towards the trunk. Systemic symptoms such as fever and arthralgia may accompany the skin lesions.1-3

Erythema multiforme is recognized in two forms: EM minor and EM major. Both forms share the same characteristic of target lesions. However, the presence of mucosal involvement distinguishes the two. Mucosal involvement is absent or mild in EM minor, while mucosal involvement in EM major is often severe.2,3 Painful bullous lesions are commonly present in the mouth, genital, and ocular mucous membranes. Severe symptoms can often result in difficulty eating and drinking.

Diagnosis is largely clinical. Further histologic study may accompany diagnoses to exclude differential diagnosis. In EM, direct immunofluorescence (DIF) is negative. Histopathology reveals apoptosis of individual keratinocytes.1,2

Therapeutic treatment for painful bullous lesions in the mouth involve antiseptic rinses and anesthetic solutions. Preventive treatment for patients with HSV-associated EM recurrence includes oral acyclovir or valacyclovir.2

In this patient, a punch biopsy was performed, confirming the diagnosis. A DIF was negative, and a chest x-ray was negative. Treatment was initiated with oral acyclovir, doxycycline, and a prednisone taper. In addition, topical clobetasol propionate and magic mouthwash (Maalox/lidocaine/nystatin) was prescribed. The patient was placed on daily suppressive valacyclovir to prevent frequent recurrence of EM.

This case and photo were submitted by Ms. Pham, the University of California, Los Angeles, and Dr. Sateesh, San Diego Family Dermatology. Dr. Bilu-Martin edited the column.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

1. Hafsi W and Badri T. Erythema Multiforme, in “StatPearls [Internet].” Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, 2022 Jan.

2. Bolognia J et al. Dermatology. St. Louis: Mosby/Elsevier, 2008.

3. Oakley A. Erythema Multiforme. DermNet NZ. 2015 Oct.

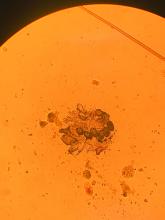

75-year-old White male presenting with progressive pruritus and a worsening rash

, although it can also be contracted through contaminated bedding and clothing. It can affect all races and ages.

Patients typically present with extremely pruritic, symmetric papules and excoriations. In nodular scabies, nodules and large papules are seen on exam. Thin lines in the skin called burrows may be present, especially in the webs between fingers. Female mites create burrows as they tunnel through the epidermis and lay eggs. The wrists, areola, waistline, and groin may all be involved, creating an imaginary circle between the areas described as the “circle of Hebra.” Penile and scrotal lesions are common in men.

Patients usually experience worse pruritus at night, which disturbs sleep. Crusted scabies is a severe form of scabies more often seen in those with immunocompromised immune systems. Clinically, thick crusted and scaly patches are present that are teeming with mites.

Diagnosis can be confirmed by performing a scabies prep, during which a burrow is scraped with a surgical blade. A drop of mineral oil is placed on the skin cells. The mite, ova, and feces can be visualized under the microscope. Wrists and hands usually have the highest yield for finding the parasites.

Topical treatments include permethrin 5% cream, lindane, benzyl benzoate, and crotamiton, and should be applied as two treatments a week apart. In the United States, permethrin is most commonly used. Ivermectin pills are used off label and are very effective and may be repeated for 1-2 weeks. All household contacts should be treated. Patients may still have pruritus for 2-4 weeks following treatment.

In this patient, a scabies prep was performed prior to performing repeat skin biopsies. Microscopic examination revealed ova, one mite, and feces. Treatment was initiated with ivermectin and permethrin.

Photos and case were submitted by Susannah Berke, MD, and Damon McClain, MD, Three Rivers Dermatology, Coraopolis, Pa.; and Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

, although it can also be contracted through contaminated bedding and clothing. It can affect all races and ages.

Patients typically present with extremely pruritic, symmetric papules and excoriations. In nodular scabies, nodules and large papules are seen on exam. Thin lines in the skin called burrows may be present, especially in the webs between fingers. Female mites create burrows as they tunnel through the epidermis and lay eggs. The wrists, areola, waistline, and groin may all be involved, creating an imaginary circle between the areas described as the “circle of Hebra.” Penile and scrotal lesions are common in men.

Patients usually experience worse pruritus at night, which disturbs sleep. Crusted scabies is a severe form of scabies more often seen in those with immunocompromised immune systems. Clinically, thick crusted and scaly patches are present that are teeming with mites.

Diagnosis can be confirmed by performing a scabies prep, during which a burrow is scraped with a surgical blade. A drop of mineral oil is placed on the skin cells. The mite, ova, and feces can be visualized under the microscope. Wrists and hands usually have the highest yield for finding the parasites.

Topical treatments include permethrin 5% cream, lindane, benzyl benzoate, and crotamiton, and should be applied as two treatments a week apart. In the United States, permethrin is most commonly used. Ivermectin pills are used off label and are very effective and may be repeated for 1-2 weeks. All household contacts should be treated. Patients may still have pruritus for 2-4 weeks following treatment.

In this patient, a scabies prep was performed prior to performing repeat skin biopsies. Microscopic examination revealed ova, one mite, and feces. Treatment was initiated with ivermectin and permethrin.

Photos and case were submitted by Susannah Berke, MD, and Damon McClain, MD, Three Rivers Dermatology, Coraopolis, Pa.; and Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

, although it can also be contracted through contaminated bedding and clothing. It can affect all races and ages.

Patients typically present with extremely pruritic, symmetric papules and excoriations. In nodular scabies, nodules and large papules are seen on exam. Thin lines in the skin called burrows may be present, especially in the webs between fingers. Female mites create burrows as they tunnel through the epidermis and lay eggs. The wrists, areola, waistline, and groin may all be involved, creating an imaginary circle between the areas described as the “circle of Hebra.” Penile and scrotal lesions are common in men.

Patients usually experience worse pruritus at night, which disturbs sleep. Crusted scabies is a severe form of scabies more often seen in those with immunocompromised immune systems. Clinically, thick crusted and scaly patches are present that are teeming with mites.

Diagnosis can be confirmed by performing a scabies prep, during which a burrow is scraped with a surgical blade. A drop of mineral oil is placed on the skin cells. The mite, ova, and feces can be visualized under the microscope. Wrists and hands usually have the highest yield for finding the parasites.

Topical treatments include permethrin 5% cream, lindane, benzyl benzoate, and crotamiton, and should be applied as two treatments a week apart. In the United States, permethrin is most commonly used. Ivermectin pills are used off label and are very effective and may be repeated for 1-2 weeks. All household contacts should be treated. Patients may still have pruritus for 2-4 weeks following treatment.

In this patient, a scabies prep was performed prior to performing repeat skin biopsies. Microscopic examination revealed ova, one mite, and feces. Treatment was initiated with ivermectin and permethrin.

Photos and case were submitted by Susannah Berke, MD, and Damon McClain, MD, Three Rivers Dermatology, Coraopolis, Pa.; and Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

A 22-year-old presented with erythematous papules on her fingers and toes

than men. Clinically, distal extremities such as toes, fingertips and heels, as well as the rims of the ears or nose develop erythematous to purple plaques. Lesions may be painful or pruritic. Over time, lesions may develop atrophy and resemble those of discoid lupus. While the pathogenesis is unknown, exposure to cold or wet environments can precipitate lesions.

Histopathology reveals a deep and superficial lymphocytic infiltrate with perieccrine involvement and fibrin deposition in vessels. Dermal edema is often present. Direct immunofluorescence shows an interface dermatitis positive for IgM, IgA, and C3.

The Mayo Clinic developed diagnostic criteria for diagnosing chilblains lupus. Two major criteria are acral skin lesions induced by cold exposure and evidence of lupus erythematosus in skin lesions (histopathologically or by direct immunofluorescence). Three minor criteria are the coexistence of systemic lupus erythematosus or discoid lupus erythematosus, response to antilupus treatment, and negative cryoglobulin and cold agglutinin studies.

Chilblains, or perniosis, has a similar clinical presentation to chilblain lupus erythematosus. However, serologic evidence of lupus, such as a positive antinuclear antibody (ANA), will be absent. Lupus pernio (Besnier-Tenneson syndrome) is a form of sarcoidosis that tends to favor the nose. These lesions are not precipitated by cold. It can be differentiated on histology. “COVID toes” is an entity described during the coronavirus pandemic, during which dermatologists noted pernio-like lesions in patients testing positive for coronavirus.

The patient’s labs revealed a positive ANA at 1:320 in a nucleolar speckled pattern, elevated double-stranded DNA, low C3 and C4 levels, elevated cardiolipin IgM Ab, and elevated sedimentation rate. COVID-19 antigen testing and COVID-19 antibodies were negative. A serum protein electrophoresis was negative. Cryoglobulins were negative.

Treatment includes protection from cold. Smoking cessation should be discussed. Topical steroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors are first-line treatments for mild disease. Antimalarials, such as hydroxychloroquine can be helpful. Systemic calcium channel blockers, systemic steroids, mycophenolate mofetil, and tacrolimus have all been reported as treatments. This patient responded well to hydroxychloroquine and topical steroids with full resolution of lesions.

This case was submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

Su WP et al. Cutis. 1994 Dec;54(6):395-9.

Werth V and Newman S. Chilblain lupus (SLE pernio). Dermatology Advisor. 2017.

than men. Clinically, distal extremities such as toes, fingertips and heels, as well as the rims of the ears or nose develop erythematous to purple plaques. Lesions may be painful or pruritic. Over time, lesions may develop atrophy and resemble those of discoid lupus. While the pathogenesis is unknown, exposure to cold or wet environments can precipitate lesions.

Histopathology reveals a deep and superficial lymphocytic infiltrate with perieccrine involvement and fibrin deposition in vessels. Dermal edema is often present. Direct immunofluorescence shows an interface dermatitis positive for IgM, IgA, and C3.

The Mayo Clinic developed diagnostic criteria for diagnosing chilblains lupus. Two major criteria are acral skin lesions induced by cold exposure and evidence of lupus erythematosus in skin lesions (histopathologically or by direct immunofluorescence). Three minor criteria are the coexistence of systemic lupus erythematosus or discoid lupus erythematosus, response to antilupus treatment, and negative cryoglobulin and cold agglutinin studies.

Chilblains, or perniosis, has a similar clinical presentation to chilblain lupus erythematosus. However, serologic evidence of lupus, such as a positive antinuclear antibody (ANA), will be absent. Lupus pernio (Besnier-Tenneson syndrome) is a form of sarcoidosis that tends to favor the nose. These lesions are not precipitated by cold. It can be differentiated on histology. “COVID toes” is an entity described during the coronavirus pandemic, during which dermatologists noted pernio-like lesions in patients testing positive for coronavirus.

The patient’s labs revealed a positive ANA at 1:320 in a nucleolar speckled pattern, elevated double-stranded DNA, low C3 and C4 levels, elevated cardiolipin IgM Ab, and elevated sedimentation rate. COVID-19 antigen testing and COVID-19 antibodies were negative. A serum protein electrophoresis was negative. Cryoglobulins were negative.

Treatment includes protection from cold. Smoking cessation should be discussed. Topical steroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors are first-line treatments for mild disease. Antimalarials, such as hydroxychloroquine can be helpful. Systemic calcium channel blockers, systemic steroids, mycophenolate mofetil, and tacrolimus have all been reported as treatments. This patient responded well to hydroxychloroquine and topical steroids with full resolution of lesions.

This case was submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

Su WP et al. Cutis. 1994 Dec;54(6):395-9.

Werth V and Newman S. Chilblain lupus (SLE pernio). Dermatology Advisor. 2017.

than men. Clinically, distal extremities such as toes, fingertips and heels, as well as the rims of the ears or nose develop erythematous to purple plaques. Lesions may be painful or pruritic. Over time, lesions may develop atrophy and resemble those of discoid lupus. While the pathogenesis is unknown, exposure to cold or wet environments can precipitate lesions.

Histopathology reveals a deep and superficial lymphocytic infiltrate with perieccrine involvement and fibrin deposition in vessels. Dermal edema is often present. Direct immunofluorescence shows an interface dermatitis positive for IgM, IgA, and C3.

The Mayo Clinic developed diagnostic criteria for diagnosing chilblains lupus. Two major criteria are acral skin lesions induced by cold exposure and evidence of lupus erythematosus in skin lesions (histopathologically or by direct immunofluorescence). Three minor criteria are the coexistence of systemic lupus erythematosus or discoid lupus erythematosus, response to antilupus treatment, and negative cryoglobulin and cold agglutinin studies.

Chilblains, or perniosis, has a similar clinical presentation to chilblain lupus erythematosus. However, serologic evidence of lupus, such as a positive antinuclear antibody (ANA), will be absent. Lupus pernio (Besnier-Tenneson syndrome) is a form of sarcoidosis that tends to favor the nose. These lesions are not precipitated by cold. It can be differentiated on histology. “COVID toes” is an entity described during the coronavirus pandemic, during which dermatologists noted pernio-like lesions in patients testing positive for coronavirus.

The patient’s labs revealed a positive ANA at 1:320 in a nucleolar speckled pattern, elevated double-stranded DNA, low C3 and C4 levels, elevated cardiolipin IgM Ab, and elevated sedimentation rate. COVID-19 antigen testing and COVID-19 antibodies were negative. A serum protein electrophoresis was negative. Cryoglobulins were negative.

Treatment includes protection from cold. Smoking cessation should be discussed. Topical steroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors are first-line treatments for mild disease. Antimalarials, such as hydroxychloroquine can be helpful. Systemic calcium channel blockers, systemic steroids, mycophenolate mofetil, and tacrolimus have all been reported as treatments. This patient responded well to hydroxychloroquine and topical steroids with full resolution of lesions.

This case was submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

Su WP et al. Cutis. 1994 Dec;54(6):395-9.

Werth V and Newman S. Chilblain lupus (SLE pernio). Dermatology Advisor. 2017.

A 73-year-old White male presented with 2 days of a very pruritic rash

Reactions can occur anytime from within the first 2 weeks of treatment up to 10 days after the treatment has been discontinued. If a drug is rechallenged, eruptions may occur sooner. Pruritus is commonly seen. Clinically, erythematous papules and macules present symmetrically on the trunk and upper extremities and then become more generalized. A low-grade fever may be present.

Antibiotics are the most common causes of exanthematous drug eruptions. Penicillins and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole are common offenders. Cephalosporins, anticonvulsants, and allopurinol may also induce a reaction. As this condition is diagnosed clinically, skin biopsy is often not necessary. Histology is nonspecific and shows a mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and few epidermal necrotic keratinocytes.

In drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), symptoms present 2-6 weeks after the offending medication has been started. The cutaneous rash appears similar to an exanthematous drug eruption; however, lesions will also present on the face, and facial edema may occur. Fever is often present. Laboratory findings include a marked peripheral blood hypereosinophilia. Elevated liver function tests may be seen. Viruses such as Epstein-Barr virus, enteroviruses, adenovirus, early HIV, human herpesvirus 6, and parvovirus B19 have a similar clinical appearance to an exanthematous drug eruption. A mild eosinophilia, as seen in a drug eruption, helps to distinguish between a drug eruption and viral exanthem. In Stevens-Johnson Syndrome, mucosal membranes are involved and skin is often painful or appears dusky.

Treatment of exanthematous drug eruptions is largely supportive. Discontinuing the drug will help speed resolution and topical steroids may alleviate pruritus.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

1. Bolognia J et al. “Dermatology” (St. Louis: Mosby/Elsevier, 2008).

2. James W et al. “Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin,” 13th ed. (Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier, 2006).

Reactions can occur anytime from within the first 2 weeks of treatment up to 10 days after the treatment has been discontinued. If a drug is rechallenged, eruptions may occur sooner. Pruritus is commonly seen. Clinically, erythematous papules and macules present symmetrically on the trunk and upper extremities and then become more generalized. A low-grade fever may be present.

Antibiotics are the most common causes of exanthematous drug eruptions. Penicillins and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole are common offenders. Cephalosporins, anticonvulsants, and allopurinol may also induce a reaction. As this condition is diagnosed clinically, skin biopsy is often not necessary. Histology is nonspecific and shows a mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and few epidermal necrotic keratinocytes.

In drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), symptoms present 2-6 weeks after the offending medication has been started. The cutaneous rash appears similar to an exanthematous drug eruption; however, lesions will also present on the face, and facial edema may occur. Fever is often present. Laboratory findings include a marked peripheral blood hypereosinophilia. Elevated liver function tests may be seen. Viruses such as Epstein-Barr virus, enteroviruses, adenovirus, early HIV, human herpesvirus 6, and parvovirus B19 have a similar clinical appearance to an exanthematous drug eruption. A mild eosinophilia, as seen in a drug eruption, helps to distinguish between a drug eruption and viral exanthem. In Stevens-Johnson Syndrome, mucosal membranes are involved and skin is often painful or appears dusky.

Treatment of exanthematous drug eruptions is largely supportive. Discontinuing the drug will help speed resolution and topical steroids may alleviate pruritus.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

1. Bolognia J et al. “Dermatology” (St. Louis: Mosby/Elsevier, 2008).

2. James W et al. “Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin,” 13th ed. (Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier, 2006).

Reactions can occur anytime from within the first 2 weeks of treatment up to 10 days after the treatment has been discontinued. If a drug is rechallenged, eruptions may occur sooner. Pruritus is commonly seen. Clinically, erythematous papules and macules present symmetrically on the trunk and upper extremities and then become more generalized. A low-grade fever may be present.

Antibiotics are the most common causes of exanthematous drug eruptions. Penicillins and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole are common offenders. Cephalosporins, anticonvulsants, and allopurinol may also induce a reaction. As this condition is diagnosed clinically, skin biopsy is often not necessary. Histology is nonspecific and shows a mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and few epidermal necrotic keratinocytes.

In drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), symptoms present 2-6 weeks after the offending medication has been started. The cutaneous rash appears similar to an exanthematous drug eruption; however, lesions will also present on the face, and facial edema may occur. Fever is often present. Laboratory findings include a marked peripheral blood hypereosinophilia. Elevated liver function tests may be seen. Viruses such as Epstein-Barr virus, enteroviruses, adenovirus, early HIV, human herpesvirus 6, and parvovirus B19 have a similar clinical appearance to an exanthematous drug eruption. A mild eosinophilia, as seen in a drug eruption, helps to distinguish between a drug eruption and viral exanthem. In Stevens-Johnson Syndrome, mucosal membranes are involved and skin is often painful or appears dusky.

Treatment of exanthematous drug eruptions is largely supportive. Discontinuing the drug will help speed resolution and topical steroids may alleviate pruritus.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

1. Bolognia J et al. “Dermatology” (St. Louis: Mosby/Elsevier, 2008).

2. James W et al. “Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin,” 13th ed. (Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier, 2006).