User login

Joining forces

Tough economic times and the unpredictable consequences of health care reform are making a growing number of solo practitioners and small private groups very nervous. I’ve been receiving many inquiries about protective options, such as joining a multispecialty group, or merging two or more small practices into larger entities.

If becoming an employee of a large corporation does not appeal to you, a merger can offer significant advantages in stabilization of income and expenses; but careful planning – and a written agreement – is essential.

If you are considering this option, here are some things to think about.

• What is the compensation formula? Will everyone be paid only for what they do individually, or will revenue be shared equally? I favor a combination, so productivity is rewarded but your income doesn’t drop to zero when you take time off.

• Who will be in charge, and what percentage vote will be needed to approve important decisions? Typically, the majority rules; but you may wish to create a list of pivotal moves that will require unanimous approval, such as purchasing expensive equipment, borrowing money, or adding new partners.

• Will you keep your retirement plans separate, or combine them? If the latter, you will have to agree on the terms of the new plan, which can be the same as or different from any of the existing plans. You’ll probably need some legal guidance to ensure that assets from existing plans can be transferred into a new plan without tax issues.

If both practices are incorporated, there are two basic options for combining them. Corporation A can simply absorb corporation B; the latter ceases to exist, and corporation A, the so-called "surviving entity," assumes all assets and liabilities of both old corporations. Corporation B shareholders exchange shares of its stock for shares of corporation A, with adjustments for any inequalities in stock value.

The second option is to start a completely new corporation, which I’ll call corporation C. Corporations A and B dissolve, and distribute their equipment and charts to their shareholders, who then transfer the assets to corporation C.

Option 2 is popular, but I am not a fan. It is billed as an opportunity to start fresh, shielding everyone from exposure to malpractice suits and other liabilities, but the reality is, anyone looking to sue either old corporation will simply sue corporation C as the so-called "successor" corporation, on the grounds that it has assumed responsibility for its predecessors’ liabilities. You also will need new provider numbers, which may impede cash flow for months. Plus, the IRS treats corporate liquidations, even for merger purposes, as sales of assets, and taxes them.

In general, most experts that I’ve talked with favor the outright merger of corporations; it is tax neutral, and while it may theoretically be less satisfactory liability-wise, you can minimize risk by examining financial and legal records, and by identifying any glaring flaws in charting or coding. Your lawyers can add "hold harmless" clauses to the merger agreement, indemnifying each party against the others’ liabilities. This area, especially, is where you need experienced, competent legal advice.

Another common sticking point is known as "equalization." Ideally, each party brings an equal amount of assets to the table, but in the real world that is hardly ever the case. One party may contribute more equipment, for example, and the others are often asked to make up the difference ("equalize") with something else, usually cash.

An alternative is to agree that any inequalities will be compensated at the other end, in the form of buyout value; that is, physicians contributing more assets will receive larger buyouts when they leave or retire than those contributing less.

Non-compete provisions are always a difficult issue, mostly because they are so hard (and expensive) to enforce. An increasingly popular alternative is, once again, to deal with it at the other end, with a buyout penalty. An unhappy partner can leave, and compete, but at the cost of a substantially reduced buyout. This permits competition, but discourages it; and it compensates the remaining partners.

These are only some of the pivotal business and legal issues that must be settled in advance. A little planning and negotiation can prevent a lot of grief, regret, and legal expenses in the future.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J.

Tough economic times and the unpredictable consequences of health care reform are making a growing number of solo practitioners and small private groups very nervous. I’ve been receiving many inquiries about protective options, such as joining a multispecialty group, or merging two or more small practices into larger entities.

If becoming an employee of a large corporation does not appeal to you, a merger can offer significant advantages in stabilization of income and expenses; but careful planning – and a written agreement – is essential.

If you are considering this option, here are some things to think about.

• What is the compensation formula? Will everyone be paid only for what they do individually, or will revenue be shared equally? I favor a combination, so productivity is rewarded but your income doesn’t drop to zero when you take time off.

• Who will be in charge, and what percentage vote will be needed to approve important decisions? Typically, the majority rules; but you may wish to create a list of pivotal moves that will require unanimous approval, such as purchasing expensive equipment, borrowing money, or adding new partners.

• Will you keep your retirement plans separate, or combine them? If the latter, you will have to agree on the terms of the new plan, which can be the same as or different from any of the existing plans. You’ll probably need some legal guidance to ensure that assets from existing plans can be transferred into a new plan without tax issues.

If both practices are incorporated, there are two basic options for combining them. Corporation A can simply absorb corporation B; the latter ceases to exist, and corporation A, the so-called "surviving entity," assumes all assets and liabilities of both old corporations. Corporation B shareholders exchange shares of its stock for shares of corporation A, with adjustments for any inequalities in stock value.

The second option is to start a completely new corporation, which I’ll call corporation C. Corporations A and B dissolve, and distribute their equipment and charts to their shareholders, who then transfer the assets to corporation C.

Option 2 is popular, but I am not a fan. It is billed as an opportunity to start fresh, shielding everyone from exposure to malpractice suits and other liabilities, but the reality is, anyone looking to sue either old corporation will simply sue corporation C as the so-called "successor" corporation, on the grounds that it has assumed responsibility for its predecessors’ liabilities. You also will need new provider numbers, which may impede cash flow for months. Plus, the IRS treats corporate liquidations, even for merger purposes, as sales of assets, and taxes them.

In general, most experts that I’ve talked with favor the outright merger of corporations; it is tax neutral, and while it may theoretically be less satisfactory liability-wise, you can minimize risk by examining financial and legal records, and by identifying any glaring flaws in charting or coding. Your lawyers can add "hold harmless" clauses to the merger agreement, indemnifying each party against the others’ liabilities. This area, especially, is where you need experienced, competent legal advice.

Another common sticking point is known as "equalization." Ideally, each party brings an equal amount of assets to the table, but in the real world that is hardly ever the case. One party may contribute more equipment, for example, and the others are often asked to make up the difference ("equalize") with something else, usually cash.

An alternative is to agree that any inequalities will be compensated at the other end, in the form of buyout value; that is, physicians contributing more assets will receive larger buyouts when they leave or retire than those contributing less.

Non-compete provisions are always a difficult issue, mostly because they are so hard (and expensive) to enforce. An increasingly popular alternative is, once again, to deal with it at the other end, with a buyout penalty. An unhappy partner can leave, and compete, but at the cost of a substantially reduced buyout. This permits competition, but discourages it; and it compensates the remaining partners.

These are only some of the pivotal business and legal issues that must be settled in advance. A little planning and negotiation can prevent a lot of grief, regret, and legal expenses in the future.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J.

Tough economic times and the unpredictable consequences of health care reform are making a growing number of solo practitioners and small private groups very nervous. I’ve been receiving many inquiries about protective options, such as joining a multispecialty group, or merging two or more small practices into larger entities.

If becoming an employee of a large corporation does not appeal to you, a merger can offer significant advantages in stabilization of income and expenses; but careful planning – and a written agreement – is essential.

If you are considering this option, here are some things to think about.

• What is the compensation formula? Will everyone be paid only for what they do individually, or will revenue be shared equally? I favor a combination, so productivity is rewarded but your income doesn’t drop to zero when you take time off.

• Who will be in charge, and what percentage vote will be needed to approve important decisions? Typically, the majority rules; but you may wish to create a list of pivotal moves that will require unanimous approval, such as purchasing expensive equipment, borrowing money, or adding new partners.

• Will you keep your retirement plans separate, or combine them? If the latter, you will have to agree on the terms of the new plan, which can be the same as or different from any of the existing plans. You’ll probably need some legal guidance to ensure that assets from existing plans can be transferred into a new plan without tax issues.

If both practices are incorporated, there are two basic options for combining them. Corporation A can simply absorb corporation B; the latter ceases to exist, and corporation A, the so-called "surviving entity," assumes all assets and liabilities of both old corporations. Corporation B shareholders exchange shares of its stock for shares of corporation A, with adjustments for any inequalities in stock value.

The second option is to start a completely new corporation, which I’ll call corporation C. Corporations A and B dissolve, and distribute their equipment and charts to their shareholders, who then transfer the assets to corporation C.

Option 2 is popular, but I am not a fan. It is billed as an opportunity to start fresh, shielding everyone from exposure to malpractice suits and other liabilities, but the reality is, anyone looking to sue either old corporation will simply sue corporation C as the so-called "successor" corporation, on the grounds that it has assumed responsibility for its predecessors’ liabilities. You also will need new provider numbers, which may impede cash flow for months. Plus, the IRS treats corporate liquidations, even for merger purposes, as sales of assets, and taxes them.

In general, most experts that I’ve talked with favor the outright merger of corporations; it is tax neutral, and while it may theoretically be less satisfactory liability-wise, you can minimize risk by examining financial and legal records, and by identifying any glaring flaws in charting or coding. Your lawyers can add "hold harmless" clauses to the merger agreement, indemnifying each party against the others’ liabilities. This area, especially, is where you need experienced, competent legal advice.

Another common sticking point is known as "equalization." Ideally, each party brings an equal amount of assets to the table, but in the real world that is hardly ever the case. One party may contribute more equipment, for example, and the others are often asked to make up the difference ("equalize") with something else, usually cash.

An alternative is to agree that any inequalities will be compensated at the other end, in the form of buyout value; that is, physicians contributing more assets will receive larger buyouts when they leave or retire than those contributing less.

Non-compete provisions are always a difficult issue, mostly because they are so hard (and expensive) to enforce. An increasingly popular alternative is, once again, to deal with it at the other end, with a buyout penalty. An unhappy partner can leave, and compete, but at the cost of a substantially reduced buyout. This permits competition, but discourages it; and it compensates the remaining partners.

These are only some of the pivotal business and legal issues that must be settled in advance. A little planning and negotiation can prevent a lot of grief, regret, and legal expenses in the future.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J.

Listen to Project BOOST lead analyst Luke Hansen, MD, MPH, discuss the outcomes study published in JHM

Click here to listen to our interview with Dr. Hansen

Click here to listen to our interview with Dr. Hansen

Click here to listen to our interview with Dr. Hansen

11 Things Neurologists Think Hospitalists Need To Know

11 Things: At a Glance

- You might be overdiagnosing transient ischemic attacks (TIA).

- Early mobilization after a stroke might be better for some patients.

- MRI is the best tool to evaluate TIA patients.

- Consider focal seizure or complex partial seizure as one of the possible causes of confusion or speech disturbance, or both.

- Tracking the time a hospitalized patient was last seen to be normal is crucial.

- Consider neuromuscular disorders when a patient presents with weakness.

- Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are not the only cause of altered mental status.

- Take care in distinguishing aphasia from general confusion.

- A simple checklist might eliminate the need to consult the neurologist.

- Calling a neurologist earlier is way better than calling later.

- Hire a neurohospitalist if your institution doesn’t have one already.

When a patient is admitted to the hospital with neurological symptoms, such as altered mental status, he or she might not be the only one who is confused. Hospitalists might be a little confused, too.

Of all the subspecialties to which hospitalists are exposed, none might make them more uncomfortable than neurology. Because of what often is a dearth of training in this area, and because of the vexing and sometimes fleeting nature of symptoms, hospitalists might be inclined to lean on neurologists more than other specialists.

The Hospitalist spoke with a half-dozen experts, gathering their words of guidance and clinical tips. Here’s hoping they give you a little extra confidence the next time you see a patient with altered mental status.

You might be overdiagnosing transient ischemic attacks (TIA).

Ira Chang, MD, a neurohospitalist with Blue Sky Neurology in Englewood, Colo., and assistant clinical professor at the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center in Denver, says TIA is all too commonly a go-to diagnosis, frequently when there’s another cause.

“I think that hospitalists, and maybe medical internists in general, are very quick to diagnose anything that has a neurologic symptom that comes and goes as a TIA,” she says. “Patients have to have specific neurologic symptoms that we think are due to arterial blood flow or ischemia problems.”

Near-fainting spells and dizzy spells involving confusion commonly are diagnosed as TIA when these symptoms could be due to “a number of other causes,” Dr. Chang adds.

Kevin Barrett, MD, assistant professor of neurology and a neurohospitalist at Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla., says the suspicion of a TIA should be greater if the patient is older or has traditional cardiovascular risk factors, such as hyptertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, or tobacco use.

A TIA typically causes symptoms referable to common arterial distributions. Carotid-distribution TIA often causes ipsilateral loss of vision and contralateral weakness or numbness. Posterior-circulation TIAs bring on symptoms such as ataxia, unilateral or bilateral limb weakness, diplopia, and slurred or slow speech.

TIA diagnoses can be tricky even for those trained in neurology, Dr. Barrett says.

“Even among fellowship-trained vascular neurologists, TIA can be a challenging diagnosis, often with poor inter-observer agreement,” he notes.

Early mobilization after a stroke might be better for some patients.

After receiving tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) therapy for stroke, patients historically were kept on bed rest for 24 hours to reduce the risk of hemorrhage. Evidence now is coming to light that some patients might benefit from getting out of bed sooner, Dr. Barrett says.1

“We’re learning that in selected patients, they can actually be mobilized at 12 hours,” he says. “In some cases, that would not only reduce the risk of complications related to immobilization like DVT but shorten length of stay. These are all important metrics for anybody who practices primarily within an inpatient setting.”

Early mobilization generally is more suitable for patients with less severe deficits and who are hemodynamically stable.

MRI is the best tool to evaluate TIA patients.

TIA patients who have transient symptoms and normal diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) abnormalities on an MRI are at a very low risk. “Less than 1% of those patients have a stroke within the subsequent seven days,” Dr. Barrett says.2 “But those patients who do have a DWI abnormality, they’re at very high risk: 7.1% at seven days.

“The utility of MRI following TIA is becoming very much apparent. It is something that hospitalists should be aware of.”

Consider focal seizure or complex partial seizure as one of the possible causes of confusion or speech disturbance, or both.

Patients experiencing confusion or speech disturbance or altered mentation—particularly if they’re elderly or have dementia—could be having a partial seizure, Dr. Chang says. Dementia patients have a 10% to 15% incidence of complex partial seizures, she says.

“I see that underdiagnosed a lot,” she says. “They keep coming back, and everybody diagnoses them with TIAs. So they keep getting put on aspirin, and they get switched to Aggrenox [to prevent clotting]. They keep coming back with the same symptoms.”

Tracking the time a hospitalized patient was last seen to be normal is crucial.

About 10% to 15% of strokes occur in patients who are in the hospital.

“While a lot of those strokes are perioperative, there also are patients who are going to be on hospitalist services,” says Eric Adelman, MD, assistant professor of neurology at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

Hospitalists should note that patients suffering strokes are found not just in the ED but also on the floor, where all the tools for treatment might not be as readily available. That makes those cases a challenge and makes forethought that much more important, Dr. Adelman says.

“It’s a matter of trying to track down last normal times,” he says. “If they’re eligible for tPA and they’re within the therapeutic window, we should be able to do that within a hospital.”

Establishing a neurological baseline is particularly important for patients who are at higher stroke risk, like those with atrial fibrillation and other cardiovascular risk factors.

“In case something does happen,” Dr. Adelman says, “at least you have a baseline so you can [know that] at time X, we knew they had full strength in their right arm, and now they don’t.”

Consider neuromuscular disorders when a patient presents with weakness.

It’s safe to say some hospitalists might miss a neuromuscular disorder, Dr. Chang says.

“A lot of disorders that are harder for hospitalists to diagnose and that tend to take longer to call a neurologist [on] are things that are due to myasthenia gravis [a breakdown between nerves and muscles leading to muscle fatigue], myopathy, or ALS,” she says. “Many patients present with weakness. I think a lot of times there will be a lot of tests on and a lot of treatment for general medical conditions that can cause weakness.”

And that might be a case of misdirected attention. Patients with weakness accompanied by persistent swallowing problems, slurred speech with no other obvious cause, or the inability to lift their head off the bed without an obvious cause may end up with a neuromuscular diagnosis, she says.

It would be helpful to have a neurologist’s input in these cases, she says, where “nothing’s getting better, and three, four, five days later, the patient’s still weak.

“I think a neurologist would be more in tune with something like that,” she adds.

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are not the only cause of altered mental status.

That might seem obvious, but too often, a UTI can be pegged as the source of altered mental status when it should not be, Dr. Chang says.

“We get a lot of people who come in with confusion and they have a slightly abnormal urinalysis and they diagnose them with UTI,” Dr. Chang says. “And it turns out that they actually had a stroke or they had a seizure.”

Significantly altered mentation should show a significantly abnormal urine with a positive culture, she says. “They ought to have significant laboratory support for a urinary tract infection.”

Dr. Barrett says a neurologic review of systems, or at least a neurologic exam, should be the physician’s guide.

“Those are key parts of a hospitalist’s practice,” he says, “because that’s what’s truly going to guide them to consider primary neurological causes of altered mental status.”

Take care in distinguishing aphasia from general confusion.

If a patient is still talking and is fairly fluent, that doesn’t mean they aren’t suffering from certain types of aphasia, a disorder caused by damage to parts of the brain that control language, Dr. Adelman says.

“Oftentimes, when you’re dealing with a patient with confusion, you want to make sure that it’s confusion, or encephalopathy, rather than a focal neurologic problem like aphasia,” he says. “Frequently patients with aphasia will have other symptoms such as a facial drop or weakness in the arm, but stroke can present as isolated aphasia.”

A good habit to get into is to determine whether the patient can repeat a phrase, follow a command, or name objects, he says. If they can, they probably do not have aphasia.

“The thing that you worry about with aphasia, particularly acute onset aphasia, is an ischemic stroke,” Dr. Adelman says.

A simple checklist might eliminate the need to consult the neurologist.

When Edgar Kenton, MD, now director of the stroke program at Geisinger Health System in Danville, Pa., was at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta, he found he was getting snowed under with consults from hospitalists. There were about 15 hospitalists for just one or two neurologists.

“There was no way I was able to see these patients, particularly in follow-up, because you might get five consults every day,” he says. “By the middle of the week, that’s 15 consults. You don’t get a chance to go back and see the patients because you’re just going from one consult to the other.”

The situation improved with a checklist of things to consider when a patient presents with altered mental status. Before seeking a consult, neurologists suggested the hospitalists check the electrolytes, blood pressure, and urine, and use CT scans as a screening test. That might uncover the root of the patient’s problems. If those are clear, by all means get the neurologist involved, he says.

“We were able to educate the hospitalists so they knew when to call; they knew when it was beyond their expertise to take care of the patient, so we weren’t getting called for every patient with altered mental status when all they needed to do was to check the electrolytes,” Dr. Kenton says.

Calling a neurologist earlier is way better than calling later.

Once the decision is made to consult with a neurologist, the consult should be done right away, Dr. Kenton says, not after a few days when symptoms don’t appear to be improving.

“We’ll get the call on a Friday afternoon because they thought, finally, ‘Well, you know, we need to get neurology involved because we a) haven’t solved the problem and b) there may be some other tests we should be getting,’” he says of common situations. “That has been a problem. If you don’t have a neurohospitalist involved day by day, working with the patient and the general hospitalist, neurology becomes an afterthought.”

He says accurate and early diagnosis is paramount to the patient.

“If the diagnosis is delayed, obviously there’s more insult to the patients, more persistent insult,” he says, noting the timing is particularly important in neurological conditions “because things can get bad in a hurry.”

He strongly urges hospitalists to consult with a neurologist before ordering an entire battery of tests.

At Geisinger, neurologists are encouraging hospitalists to chat informally with neurosurgeons about cases for guidance at the outset rather than after several days.

Hire a neurohospitalist if your institution doesn’t have one already.

At the top of the list of Dr. Kenton’s suggestions on caring for hospitalized neurology patients is this declaration: “Get a neurohospitalist.”

“It’s important to have the neurologist involved from the time the patient’s admitted,” he says. “That’s the value of connecting the general hospitalist with neurologists.”

S. Andrew Josephson, MD, director of the neurohospitalist program at the University of California at San Francisco, says his colleagues are team players and improve patient care.

“Neurology consultations can be called very quickly, and a nice partnership can develop between internal medicine hospitalists and neurohospitalists to care for those patients who have those medical and neurologic problems,” he says.

He also says having a neurohospitalist on board can ease some of the tension.

“No longer if there’s a neurologic condition does a hospitalist have to think about, ‘Well, does this rise to the level of something that I need to get the neurologist to drive across the city to come see?’” he explains. “‘Or is this something we should try to manage ourselves?’”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

References

- Bernhardt J, Dewey H, Thrift A, Collier J, Donnan G. A very early rehabilitation trial for stroke (AVERT): phase II safety and feasibility. Stroke. 2008;39;390-396.

- Giles MF, Albers GW, Amarenco P, et al. Early stroke risk and ABCD2 score performance in tissue- vs. time-defined TIA: a multicenter study. Neurology. 2011;77(13):1222-1228.

- Zinchuk AV, Flanagan EP, Tubridy NJ, Miller WA, McCullough LD. Attitudes of US medical trainees towards neurology education: “Neurophobia”—a global issue. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10:49.

11 Things: At a Glance

- You might be overdiagnosing transient ischemic attacks (TIA).

- Early mobilization after a stroke might be better for some patients.

- MRI is the best tool to evaluate TIA patients.

- Consider focal seizure or complex partial seizure as one of the possible causes of confusion or speech disturbance, or both.

- Tracking the time a hospitalized patient was last seen to be normal is crucial.

- Consider neuromuscular disorders when a patient presents with weakness.

- Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are not the only cause of altered mental status.

- Take care in distinguishing aphasia from general confusion.

- A simple checklist might eliminate the need to consult the neurologist.

- Calling a neurologist earlier is way better than calling later.

- Hire a neurohospitalist if your institution doesn’t have one already.

When a patient is admitted to the hospital with neurological symptoms, such as altered mental status, he or she might not be the only one who is confused. Hospitalists might be a little confused, too.

Of all the subspecialties to which hospitalists are exposed, none might make them more uncomfortable than neurology. Because of what often is a dearth of training in this area, and because of the vexing and sometimes fleeting nature of symptoms, hospitalists might be inclined to lean on neurologists more than other specialists.

The Hospitalist spoke with a half-dozen experts, gathering their words of guidance and clinical tips. Here’s hoping they give you a little extra confidence the next time you see a patient with altered mental status.

You might be overdiagnosing transient ischemic attacks (TIA).

Ira Chang, MD, a neurohospitalist with Blue Sky Neurology in Englewood, Colo., and assistant clinical professor at the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center in Denver, says TIA is all too commonly a go-to diagnosis, frequently when there’s another cause.

“I think that hospitalists, and maybe medical internists in general, are very quick to diagnose anything that has a neurologic symptom that comes and goes as a TIA,” she says. “Patients have to have specific neurologic symptoms that we think are due to arterial blood flow or ischemia problems.”

Near-fainting spells and dizzy spells involving confusion commonly are diagnosed as TIA when these symptoms could be due to “a number of other causes,” Dr. Chang adds.

Kevin Barrett, MD, assistant professor of neurology and a neurohospitalist at Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla., says the suspicion of a TIA should be greater if the patient is older or has traditional cardiovascular risk factors, such as hyptertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, or tobacco use.

A TIA typically causes symptoms referable to common arterial distributions. Carotid-distribution TIA often causes ipsilateral loss of vision and contralateral weakness or numbness. Posterior-circulation TIAs bring on symptoms such as ataxia, unilateral or bilateral limb weakness, diplopia, and slurred or slow speech.

TIA diagnoses can be tricky even for those trained in neurology, Dr. Barrett says.

“Even among fellowship-trained vascular neurologists, TIA can be a challenging diagnosis, often with poor inter-observer agreement,” he notes.

Early mobilization after a stroke might be better for some patients.

After receiving tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) therapy for stroke, patients historically were kept on bed rest for 24 hours to reduce the risk of hemorrhage. Evidence now is coming to light that some patients might benefit from getting out of bed sooner, Dr. Barrett says.1

“We’re learning that in selected patients, they can actually be mobilized at 12 hours,” he says. “In some cases, that would not only reduce the risk of complications related to immobilization like DVT but shorten length of stay. These are all important metrics for anybody who practices primarily within an inpatient setting.”

Early mobilization generally is more suitable for patients with less severe deficits and who are hemodynamically stable.

MRI is the best tool to evaluate TIA patients.

TIA patients who have transient symptoms and normal diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) abnormalities on an MRI are at a very low risk. “Less than 1% of those patients have a stroke within the subsequent seven days,” Dr. Barrett says.2 “But those patients who do have a DWI abnormality, they’re at very high risk: 7.1% at seven days.

“The utility of MRI following TIA is becoming very much apparent. It is something that hospitalists should be aware of.”

Consider focal seizure or complex partial seizure as one of the possible causes of confusion or speech disturbance, or both.

Patients experiencing confusion or speech disturbance or altered mentation—particularly if they’re elderly or have dementia—could be having a partial seizure, Dr. Chang says. Dementia patients have a 10% to 15% incidence of complex partial seizures, she says.

“I see that underdiagnosed a lot,” she says. “They keep coming back, and everybody diagnoses them with TIAs. So they keep getting put on aspirin, and they get switched to Aggrenox [to prevent clotting]. They keep coming back with the same symptoms.”

Tracking the time a hospitalized patient was last seen to be normal is crucial.

About 10% to 15% of strokes occur in patients who are in the hospital.

“While a lot of those strokes are perioperative, there also are patients who are going to be on hospitalist services,” says Eric Adelman, MD, assistant professor of neurology at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

Hospitalists should note that patients suffering strokes are found not just in the ED but also on the floor, where all the tools for treatment might not be as readily available. That makes those cases a challenge and makes forethought that much more important, Dr. Adelman says.

“It’s a matter of trying to track down last normal times,” he says. “If they’re eligible for tPA and they’re within the therapeutic window, we should be able to do that within a hospital.”

Establishing a neurological baseline is particularly important for patients who are at higher stroke risk, like those with atrial fibrillation and other cardiovascular risk factors.

“In case something does happen,” Dr. Adelman says, “at least you have a baseline so you can [know that] at time X, we knew they had full strength in their right arm, and now they don’t.”

Consider neuromuscular disorders when a patient presents with weakness.

It’s safe to say some hospitalists might miss a neuromuscular disorder, Dr. Chang says.

“A lot of disorders that are harder for hospitalists to diagnose and that tend to take longer to call a neurologist [on] are things that are due to myasthenia gravis [a breakdown between nerves and muscles leading to muscle fatigue], myopathy, or ALS,” she says. “Many patients present with weakness. I think a lot of times there will be a lot of tests on and a lot of treatment for general medical conditions that can cause weakness.”

And that might be a case of misdirected attention. Patients with weakness accompanied by persistent swallowing problems, slurred speech with no other obvious cause, or the inability to lift their head off the bed without an obvious cause may end up with a neuromuscular diagnosis, she says.

It would be helpful to have a neurologist’s input in these cases, she says, where “nothing’s getting better, and three, four, five days later, the patient’s still weak.

“I think a neurologist would be more in tune with something like that,” she adds.

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are not the only cause of altered mental status.

That might seem obvious, but too often, a UTI can be pegged as the source of altered mental status when it should not be, Dr. Chang says.

“We get a lot of people who come in with confusion and they have a slightly abnormal urinalysis and they diagnose them with UTI,” Dr. Chang says. “And it turns out that they actually had a stroke or they had a seizure.”

Significantly altered mentation should show a significantly abnormal urine with a positive culture, she says. “They ought to have significant laboratory support for a urinary tract infection.”

Dr. Barrett says a neurologic review of systems, or at least a neurologic exam, should be the physician’s guide.

“Those are key parts of a hospitalist’s practice,” he says, “because that’s what’s truly going to guide them to consider primary neurological causes of altered mental status.”

Take care in distinguishing aphasia from general confusion.

If a patient is still talking and is fairly fluent, that doesn’t mean they aren’t suffering from certain types of aphasia, a disorder caused by damage to parts of the brain that control language, Dr. Adelman says.

“Oftentimes, when you’re dealing with a patient with confusion, you want to make sure that it’s confusion, or encephalopathy, rather than a focal neurologic problem like aphasia,” he says. “Frequently patients with aphasia will have other symptoms such as a facial drop or weakness in the arm, but stroke can present as isolated aphasia.”

A good habit to get into is to determine whether the patient can repeat a phrase, follow a command, or name objects, he says. If they can, they probably do not have aphasia.

“The thing that you worry about with aphasia, particularly acute onset aphasia, is an ischemic stroke,” Dr. Adelman says.

A simple checklist might eliminate the need to consult the neurologist.

When Edgar Kenton, MD, now director of the stroke program at Geisinger Health System in Danville, Pa., was at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta, he found he was getting snowed under with consults from hospitalists. There were about 15 hospitalists for just one or two neurologists.

“There was no way I was able to see these patients, particularly in follow-up, because you might get five consults every day,” he says. “By the middle of the week, that’s 15 consults. You don’t get a chance to go back and see the patients because you’re just going from one consult to the other.”

The situation improved with a checklist of things to consider when a patient presents with altered mental status. Before seeking a consult, neurologists suggested the hospitalists check the electrolytes, blood pressure, and urine, and use CT scans as a screening test. That might uncover the root of the patient’s problems. If those are clear, by all means get the neurologist involved, he says.

“We were able to educate the hospitalists so they knew when to call; they knew when it was beyond their expertise to take care of the patient, so we weren’t getting called for every patient with altered mental status when all they needed to do was to check the electrolytes,” Dr. Kenton says.

Calling a neurologist earlier is way better than calling later.

Once the decision is made to consult with a neurologist, the consult should be done right away, Dr. Kenton says, not after a few days when symptoms don’t appear to be improving.

“We’ll get the call on a Friday afternoon because they thought, finally, ‘Well, you know, we need to get neurology involved because we a) haven’t solved the problem and b) there may be some other tests we should be getting,’” he says of common situations. “That has been a problem. If you don’t have a neurohospitalist involved day by day, working with the patient and the general hospitalist, neurology becomes an afterthought.”

He says accurate and early diagnosis is paramount to the patient.

“If the diagnosis is delayed, obviously there’s more insult to the patients, more persistent insult,” he says, noting the timing is particularly important in neurological conditions “because things can get bad in a hurry.”

He strongly urges hospitalists to consult with a neurologist before ordering an entire battery of tests.

At Geisinger, neurologists are encouraging hospitalists to chat informally with neurosurgeons about cases for guidance at the outset rather than after several days.

Hire a neurohospitalist if your institution doesn’t have one already.

At the top of the list of Dr. Kenton’s suggestions on caring for hospitalized neurology patients is this declaration: “Get a neurohospitalist.”

“It’s important to have the neurologist involved from the time the patient’s admitted,” he says. “That’s the value of connecting the general hospitalist with neurologists.”

S. Andrew Josephson, MD, director of the neurohospitalist program at the University of California at San Francisco, says his colleagues are team players and improve patient care.

“Neurology consultations can be called very quickly, and a nice partnership can develop between internal medicine hospitalists and neurohospitalists to care for those patients who have those medical and neurologic problems,” he says.

He also says having a neurohospitalist on board can ease some of the tension.

“No longer if there’s a neurologic condition does a hospitalist have to think about, ‘Well, does this rise to the level of something that I need to get the neurologist to drive across the city to come see?’” he explains. “‘Or is this something we should try to manage ourselves?’”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

References

- Bernhardt J, Dewey H, Thrift A, Collier J, Donnan G. A very early rehabilitation trial for stroke (AVERT): phase II safety and feasibility. Stroke. 2008;39;390-396.

- Giles MF, Albers GW, Amarenco P, et al. Early stroke risk and ABCD2 score performance in tissue- vs. time-defined TIA: a multicenter study. Neurology. 2011;77(13):1222-1228.

- Zinchuk AV, Flanagan EP, Tubridy NJ, Miller WA, McCullough LD. Attitudes of US medical trainees towards neurology education: “Neurophobia”—a global issue. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10:49.

11 Things: At a Glance

- You might be overdiagnosing transient ischemic attacks (TIA).

- Early mobilization after a stroke might be better for some patients.

- MRI is the best tool to evaluate TIA patients.

- Consider focal seizure or complex partial seizure as one of the possible causes of confusion or speech disturbance, or both.

- Tracking the time a hospitalized patient was last seen to be normal is crucial.

- Consider neuromuscular disorders when a patient presents with weakness.

- Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are not the only cause of altered mental status.

- Take care in distinguishing aphasia from general confusion.

- A simple checklist might eliminate the need to consult the neurologist.

- Calling a neurologist earlier is way better than calling later.

- Hire a neurohospitalist if your institution doesn’t have one already.

When a patient is admitted to the hospital with neurological symptoms, such as altered mental status, he or she might not be the only one who is confused. Hospitalists might be a little confused, too.

Of all the subspecialties to which hospitalists are exposed, none might make them more uncomfortable than neurology. Because of what often is a dearth of training in this area, and because of the vexing and sometimes fleeting nature of symptoms, hospitalists might be inclined to lean on neurologists more than other specialists.

The Hospitalist spoke with a half-dozen experts, gathering their words of guidance and clinical tips. Here’s hoping they give you a little extra confidence the next time you see a patient with altered mental status.

You might be overdiagnosing transient ischemic attacks (TIA).

Ira Chang, MD, a neurohospitalist with Blue Sky Neurology in Englewood, Colo., and assistant clinical professor at the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center in Denver, says TIA is all too commonly a go-to diagnosis, frequently when there’s another cause.

“I think that hospitalists, and maybe medical internists in general, are very quick to diagnose anything that has a neurologic symptom that comes and goes as a TIA,” she says. “Patients have to have specific neurologic symptoms that we think are due to arterial blood flow or ischemia problems.”

Near-fainting spells and dizzy spells involving confusion commonly are diagnosed as TIA when these symptoms could be due to “a number of other causes,” Dr. Chang adds.

Kevin Barrett, MD, assistant professor of neurology and a neurohospitalist at Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla., says the suspicion of a TIA should be greater if the patient is older or has traditional cardiovascular risk factors, such as hyptertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, or tobacco use.

A TIA typically causes symptoms referable to common arterial distributions. Carotid-distribution TIA often causes ipsilateral loss of vision and contralateral weakness or numbness. Posterior-circulation TIAs bring on symptoms such as ataxia, unilateral or bilateral limb weakness, diplopia, and slurred or slow speech.

TIA diagnoses can be tricky even for those trained in neurology, Dr. Barrett says.

“Even among fellowship-trained vascular neurologists, TIA can be a challenging diagnosis, often with poor inter-observer agreement,” he notes.

Early mobilization after a stroke might be better for some patients.

After receiving tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) therapy for stroke, patients historically were kept on bed rest for 24 hours to reduce the risk of hemorrhage. Evidence now is coming to light that some patients might benefit from getting out of bed sooner, Dr. Barrett says.1

“We’re learning that in selected patients, they can actually be mobilized at 12 hours,” he says. “In some cases, that would not only reduce the risk of complications related to immobilization like DVT but shorten length of stay. These are all important metrics for anybody who practices primarily within an inpatient setting.”

Early mobilization generally is more suitable for patients with less severe deficits and who are hemodynamically stable.

MRI is the best tool to evaluate TIA patients.

TIA patients who have transient symptoms and normal diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) abnormalities on an MRI are at a very low risk. “Less than 1% of those patients have a stroke within the subsequent seven days,” Dr. Barrett says.2 “But those patients who do have a DWI abnormality, they’re at very high risk: 7.1% at seven days.

“The utility of MRI following TIA is becoming very much apparent. It is something that hospitalists should be aware of.”

Consider focal seizure or complex partial seizure as one of the possible causes of confusion or speech disturbance, or both.

Patients experiencing confusion or speech disturbance or altered mentation—particularly if they’re elderly or have dementia—could be having a partial seizure, Dr. Chang says. Dementia patients have a 10% to 15% incidence of complex partial seizures, she says.

“I see that underdiagnosed a lot,” she says. “They keep coming back, and everybody diagnoses them with TIAs. So they keep getting put on aspirin, and they get switched to Aggrenox [to prevent clotting]. They keep coming back with the same symptoms.”

Tracking the time a hospitalized patient was last seen to be normal is crucial.

About 10% to 15% of strokes occur in patients who are in the hospital.

“While a lot of those strokes are perioperative, there also are patients who are going to be on hospitalist services,” says Eric Adelman, MD, assistant professor of neurology at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

Hospitalists should note that patients suffering strokes are found not just in the ED but also on the floor, where all the tools for treatment might not be as readily available. That makes those cases a challenge and makes forethought that much more important, Dr. Adelman says.

“It’s a matter of trying to track down last normal times,” he says. “If they’re eligible for tPA and they’re within the therapeutic window, we should be able to do that within a hospital.”

Establishing a neurological baseline is particularly important for patients who are at higher stroke risk, like those with atrial fibrillation and other cardiovascular risk factors.

“In case something does happen,” Dr. Adelman says, “at least you have a baseline so you can [know that] at time X, we knew they had full strength in their right arm, and now they don’t.”

Consider neuromuscular disorders when a patient presents with weakness.

It’s safe to say some hospitalists might miss a neuromuscular disorder, Dr. Chang says.

“A lot of disorders that are harder for hospitalists to diagnose and that tend to take longer to call a neurologist [on] are things that are due to myasthenia gravis [a breakdown between nerves and muscles leading to muscle fatigue], myopathy, or ALS,” she says. “Many patients present with weakness. I think a lot of times there will be a lot of tests on and a lot of treatment for general medical conditions that can cause weakness.”

And that might be a case of misdirected attention. Patients with weakness accompanied by persistent swallowing problems, slurred speech with no other obvious cause, or the inability to lift their head off the bed without an obvious cause may end up with a neuromuscular diagnosis, she says.

It would be helpful to have a neurologist’s input in these cases, she says, where “nothing’s getting better, and three, four, five days later, the patient’s still weak.

“I think a neurologist would be more in tune with something like that,” she adds.

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are not the only cause of altered mental status.

That might seem obvious, but too often, a UTI can be pegged as the source of altered mental status when it should not be, Dr. Chang says.

“We get a lot of people who come in with confusion and they have a slightly abnormal urinalysis and they diagnose them with UTI,” Dr. Chang says. “And it turns out that they actually had a stroke or they had a seizure.”

Significantly altered mentation should show a significantly abnormal urine with a positive culture, she says. “They ought to have significant laboratory support for a urinary tract infection.”

Dr. Barrett says a neurologic review of systems, or at least a neurologic exam, should be the physician’s guide.

“Those are key parts of a hospitalist’s practice,” he says, “because that’s what’s truly going to guide them to consider primary neurological causes of altered mental status.”

Take care in distinguishing aphasia from general confusion.

If a patient is still talking and is fairly fluent, that doesn’t mean they aren’t suffering from certain types of aphasia, a disorder caused by damage to parts of the brain that control language, Dr. Adelman says.

“Oftentimes, when you’re dealing with a patient with confusion, you want to make sure that it’s confusion, or encephalopathy, rather than a focal neurologic problem like aphasia,” he says. “Frequently patients with aphasia will have other symptoms such as a facial drop or weakness in the arm, but stroke can present as isolated aphasia.”

A good habit to get into is to determine whether the patient can repeat a phrase, follow a command, or name objects, he says. If they can, they probably do not have aphasia.

“The thing that you worry about with aphasia, particularly acute onset aphasia, is an ischemic stroke,” Dr. Adelman says.

A simple checklist might eliminate the need to consult the neurologist.

When Edgar Kenton, MD, now director of the stroke program at Geisinger Health System in Danville, Pa., was at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta, he found he was getting snowed under with consults from hospitalists. There were about 15 hospitalists for just one or two neurologists.

“There was no way I was able to see these patients, particularly in follow-up, because you might get five consults every day,” he says. “By the middle of the week, that’s 15 consults. You don’t get a chance to go back and see the patients because you’re just going from one consult to the other.”

The situation improved with a checklist of things to consider when a patient presents with altered mental status. Before seeking a consult, neurologists suggested the hospitalists check the electrolytes, blood pressure, and urine, and use CT scans as a screening test. That might uncover the root of the patient’s problems. If those are clear, by all means get the neurologist involved, he says.

“We were able to educate the hospitalists so they knew when to call; they knew when it was beyond their expertise to take care of the patient, so we weren’t getting called for every patient with altered mental status when all they needed to do was to check the electrolytes,” Dr. Kenton says.

Calling a neurologist earlier is way better than calling later.

Once the decision is made to consult with a neurologist, the consult should be done right away, Dr. Kenton says, not after a few days when symptoms don’t appear to be improving.

“We’ll get the call on a Friday afternoon because they thought, finally, ‘Well, you know, we need to get neurology involved because we a) haven’t solved the problem and b) there may be some other tests we should be getting,’” he says of common situations. “That has been a problem. If you don’t have a neurohospitalist involved day by day, working with the patient and the general hospitalist, neurology becomes an afterthought.”

He says accurate and early diagnosis is paramount to the patient.

“If the diagnosis is delayed, obviously there’s more insult to the patients, more persistent insult,” he says, noting the timing is particularly important in neurological conditions “because things can get bad in a hurry.”

He strongly urges hospitalists to consult with a neurologist before ordering an entire battery of tests.

At Geisinger, neurologists are encouraging hospitalists to chat informally with neurosurgeons about cases for guidance at the outset rather than after several days.

Hire a neurohospitalist if your institution doesn’t have one already.

At the top of the list of Dr. Kenton’s suggestions on caring for hospitalized neurology patients is this declaration: “Get a neurohospitalist.”

“It’s important to have the neurologist involved from the time the patient’s admitted,” he says. “That’s the value of connecting the general hospitalist with neurologists.”

S. Andrew Josephson, MD, director of the neurohospitalist program at the University of California at San Francisco, says his colleagues are team players and improve patient care.

“Neurology consultations can be called very quickly, and a nice partnership can develop between internal medicine hospitalists and neurohospitalists to care for those patients who have those medical and neurologic problems,” he says.

He also says having a neurohospitalist on board can ease some of the tension.

“No longer if there’s a neurologic condition does a hospitalist have to think about, ‘Well, does this rise to the level of something that I need to get the neurologist to drive across the city to come see?’” he explains. “‘Or is this something we should try to manage ourselves?’”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

References

- Bernhardt J, Dewey H, Thrift A, Collier J, Donnan G. A very early rehabilitation trial for stroke (AVERT): phase II safety and feasibility. Stroke. 2008;39;390-396.

- Giles MF, Albers GW, Amarenco P, et al. Early stroke risk and ABCD2 score performance in tissue- vs. time-defined TIA: a multicenter study. Neurology. 2011;77(13):1222-1228.

- Zinchuk AV, Flanagan EP, Tubridy NJ, Miller WA, McCullough LD. Attitudes of US medical trainees towards neurology education: “Neurophobia”—a global issue. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10:49.

Nonphysician Practice Administrators More Common as Hospital Medicine Groups Expand

I can remember a time not so long ago when it was rare for me to encounter a dedicated nonphysician practice manager when visiting a hospital medicine group (HMG). Most groups had no nonphysician management support at all, or maybe just a part-time clerical person to help sort mail and post charges. In some cases, a single person supported the hospitalists and also worked with several other physician groups; this person spent only a small portion of their time with the hospitalist practice.

We all can acknowledge that most HMGs have grown much larger and more complex in recent years. SHM’s 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report suggests that one outcome of this growth is the increasing presence of nonphysician practice administrators: Fully 75% of all respondent HMGs serving adults only reported having a nonphysician administrator.

Interestingly, group size appears to have little impact on HMG administration. HMGs with four or fewer FTEs were just as likely to have an administrator as groups with 30 or more FTEs. The prevalence of administrators was highest in the South region (87%) and lowest in the West (48%). And it was highest among multistate hospitalist companies (84%) and lowest among private multispecialty or primary-care medical groups (45%).

The median time allocation for practice administrators was 1.0 FTE (the mean was 0.79 FTE). Again, very small groups are just as likely to have a full-time administrator as very large groups.

In my experience, extremely wide variation exists in nonphysician practice administrators’ roles, backgrounds, and qualifications. The survey attempted to categorize administrator roles in a meaningful way that might correlate with level of responsibility and compensation by asking about the incumbent’s management level:

- Senior management (e.g. CEO, president, executive director);

- Middle management (e.g. director, administrator, manager); or

- First-line management (e.g. supervisor or coordinator).

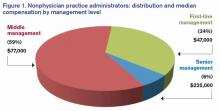

The majority of practice administrators were classified as middle management, as shown in Figure 1.

The survey collected information about compensation for practice administrators by management level. Senior management positions earned a median of $225,000 annually per FTE (though the sample size, n=10, was very small). Middle managers earned a median of $77,000, and first-line managers earned a median of $47,000.

SHM has worked diligently to reach out to nonphysician practice administrators and support them with a wide variety of tools and resources. SHM currently counts about 450 administrators as members and offers membership discounts for nonphysicians.

SHM’s Administrators’ Committee offers a series of quarterly roundtables via webinar; last year, it developed the white paper Core Competencies for a Hospitalist Practice Administrator, which can be downloaded at www.hospitalmedicine.org/Graphics/Administrators_White_Paper.pdf. And this year, for the first time, administrators became eligible for induction as Fellows in Hospital Medicine.

If you are a nonphysician practice administrator working for an HMG, or if you have one in your practice, I encourage you to get involved. Take advantage of the resources available to administrators through SHM. And please be sure that information about your administrator job gets included in the next State of Hospital Medicine survey, which will be conducted in early 2014.

Leslie Flores is a partner in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants and a member of SHM's Practice Analysis Committee.

I can remember a time not so long ago when it was rare for me to encounter a dedicated nonphysician practice manager when visiting a hospital medicine group (HMG). Most groups had no nonphysician management support at all, or maybe just a part-time clerical person to help sort mail and post charges. In some cases, a single person supported the hospitalists and also worked with several other physician groups; this person spent only a small portion of their time with the hospitalist practice.

We all can acknowledge that most HMGs have grown much larger and more complex in recent years. SHM’s 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report suggests that one outcome of this growth is the increasing presence of nonphysician practice administrators: Fully 75% of all respondent HMGs serving adults only reported having a nonphysician administrator.

Interestingly, group size appears to have little impact on HMG administration. HMGs with four or fewer FTEs were just as likely to have an administrator as groups with 30 or more FTEs. The prevalence of administrators was highest in the South region (87%) and lowest in the West (48%). And it was highest among multistate hospitalist companies (84%) and lowest among private multispecialty or primary-care medical groups (45%).

The median time allocation for practice administrators was 1.0 FTE (the mean was 0.79 FTE). Again, very small groups are just as likely to have a full-time administrator as very large groups.

In my experience, extremely wide variation exists in nonphysician practice administrators’ roles, backgrounds, and qualifications. The survey attempted to categorize administrator roles in a meaningful way that might correlate with level of responsibility and compensation by asking about the incumbent’s management level:

- Senior management (e.g. CEO, president, executive director);

- Middle management (e.g. director, administrator, manager); or

- First-line management (e.g. supervisor or coordinator).

The majority of practice administrators were classified as middle management, as shown in Figure 1.

The survey collected information about compensation for practice administrators by management level. Senior management positions earned a median of $225,000 annually per FTE (though the sample size, n=10, was very small). Middle managers earned a median of $77,000, and first-line managers earned a median of $47,000.

SHM has worked diligently to reach out to nonphysician practice administrators and support them with a wide variety of tools and resources. SHM currently counts about 450 administrators as members and offers membership discounts for nonphysicians.

SHM’s Administrators’ Committee offers a series of quarterly roundtables via webinar; last year, it developed the white paper Core Competencies for a Hospitalist Practice Administrator, which can be downloaded at www.hospitalmedicine.org/Graphics/Administrators_White_Paper.pdf. And this year, for the first time, administrators became eligible for induction as Fellows in Hospital Medicine.

If you are a nonphysician practice administrator working for an HMG, or if you have one in your practice, I encourage you to get involved. Take advantage of the resources available to administrators through SHM. And please be sure that information about your administrator job gets included in the next State of Hospital Medicine survey, which will be conducted in early 2014.

Leslie Flores is a partner in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants and a member of SHM's Practice Analysis Committee.

I can remember a time not so long ago when it was rare for me to encounter a dedicated nonphysician practice manager when visiting a hospital medicine group (HMG). Most groups had no nonphysician management support at all, or maybe just a part-time clerical person to help sort mail and post charges. In some cases, a single person supported the hospitalists and also worked with several other physician groups; this person spent only a small portion of their time with the hospitalist practice.

We all can acknowledge that most HMGs have grown much larger and more complex in recent years. SHM’s 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report suggests that one outcome of this growth is the increasing presence of nonphysician practice administrators: Fully 75% of all respondent HMGs serving adults only reported having a nonphysician administrator.

Interestingly, group size appears to have little impact on HMG administration. HMGs with four or fewer FTEs were just as likely to have an administrator as groups with 30 or more FTEs. The prevalence of administrators was highest in the South region (87%) and lowest in the West (48%). And it was highest among multistate hospitalist companies (84%) and lowest among private multispecialty or primary-care medical groups (45%).

The median time allocation for practice administrators was 1.0 FTE (the mean was 0.79 FTE). Again, very small groups are just as likely to have a full-time administrator as very large groups.

In my experience, extremely wide variation exists in nonphysician practice administrators’ roles, backgrounds, and qualifications. The survey attempted to categorize administrator roles in a meaningful way that might correlate with level of responsibility and compensation by asking about the incumbent’s management level:

- Senior management (e.g. CEO, president, executive director);

- Middle management (e.g. director, administrator, manager); or

- First-line management (e.g. supervisor or coordinator).

The majority of practice administrators were classified as middle management, as shown in Figure 1.

The survey collected information about compensation for practice administrators by management level. Senior management positions earned a median of $225,000 annually per FTE (though the sample size, n=10, was very small). Middle managers earned a median of $77,000, and first-line managers earned a median of $47,000.

SHM has worked diligently to reach out to nonphysician practice administrators and support them with a wide variety of tools and resources. SHM currently counts about 450 administrators as members and offers membership discounts for nonphysicians.

SHM’s Administrators’ Committee offers a series of quarterly roundtables via webinar; last year, it developed the white paper Core Competencies for a Hospitalist Practice Administrator, which can be downloaded at www.hospitalmedicine.org/Graphics/Administrators_White_Paper.pdf. And this year, for the first time, administrators became eligible for induction as Fellows in Hospital Medicine.

If you are a nonphysician practice administrator working for an HMG, or if you have one in your practice, I encourage you to get involved. Take advantage of the resources available to administrators through SHM. And please be sure that information about your administrator job gets included in the next State of Hospital Medicine survey, which will be conducted in early 2014.

Leslie Flores is a partner in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants and a member of SHM's Practice Analysis Committee.

Can Medicare Pay for Value?

Can quality measurement and comparisons serve as the backbone for a major shift in the Medicare payment system to reward value instead of volume? That is the question being explored over the next few years as the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) and, by extension, the physician value-based payment modifier (VBPM) come fully into effect for all physicians.

There seems to be a consensus in the policy community that the fee-for-service model of payment is past its prime and needs to be replaced with a more dynamic and responsive payment system. Medicare hopes that PQRS and the VBPM will enable adjustments to physician payments to reward high-quality and low-cost care. Although these programs currently are add-ons to the fee-for-service system, they likely will serve as stepping stones to more radical departures from the existing payment system.

SHM advocates refinements to policies for PQRS and similar programs to make them more meaningful and productive for both hospitalists and the broader health-care system. Each year, SHM submits comments on the Physician Fee Schedule Rule, which creates and updates the regulatory framework for PQRS and the VBPM. SHM also provided feedback on Quality and Resource Use Reports (QRURs), the report cards for the modifier that were being tested over the past year.

From a practical standpoint, SHM engages with measure development and endorsement processes to ensure there are reportable quality measures in PQRS that fit hospitalist practice. In addition, SHM is helping to increase accessibility to PQRS reporting by offering members reduced fare access to registry reporting through the PQRI Wizard.

The comments range from the technical aspects of individual quality measures in PQRS to how hospitalists appear to be performing in these programs. SHM firmly believes that the unique positioning of hospitalists within the health-care system presents challenges for their identification and evaluation in Medicare programs. In some sense, hospitalists exist on the line between the inpatient and outpatient worlds, a location not adequately captured in pay-for-performance programs.

It’s imperative that pay-for-performance programs have reasonable and actionable outcomes for providers. If quality measures are not clinically meaningful and do not capture a plurality of the care provided by an individual hospitalist, it is difficult for the program to meet its stated aims. If payment is to be influenced by performance on quality measures, it follows that those measures should be relevant to the care provided.

There is a long way to go toward creating quality measurement and evaluation programs that are relevant and actionable for clinical quality improvement (QI). By becoming involved in SHM’s policy efforts, members are able to share their experiences and impressions of programs with SHM and lawmakers. This partnership helps create more responsive and intuitive programs, which in turn leads to greater participation and, hopefully, improved patient outcomes. As these programs continue to evolve and more health professionals are required to participate, SHM will be looking to its membership for their perspectives.

Join the grassroots network to stay involved and up to date by registering at www.hospitalmedicine.org/grassroots.

Joshua Lapps is SHM’s government relations specialist.

Can quality measurement and comparisons serve as the backbone for a major shift in the Medicare payment system to reward value instead of volume? That is the question being explored over the next few years as the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) and, by extension, the physician value-based payment modifier (VBPM) come fully into effect for all physicians.

There seems to be a consensus in the policy community that the fee-for-service model of payment is past its prime and needs to be replaced with a more dynamic and responsive payment system. Medicare hopes that PQRS and the VBPM will enable adjustments to physician payments to reward high-quality and low-cost care. Although these programs currently are add-ons to the fee-for-service system, they likely will serve as stepping stones to more radical departures from the existing payment system.

SHM advocates refinements to policies for PQRS and similar programs to make them more meaningful and productive for both hospitalists and the broader health-care system. Each year, SHM submits comments on the Physician Fee Schedule Rule, which creates and updates the regulatory framework for PQRS and the VBPM. SHM also provided feedback on Quality and Resource Use Reports (QRURs), the report cards for the modifier that were being tested over the past year.

From a practical standpoint, SHM engages with measure development and endorsement processes to ensure there are reportable quality measures in PQRS that fit hospitalist practice. In addition, SHM is helping to increase accessibility to PQRS reporting by offering members reduced fare access to registry reporting through the PQRI Wizard.

The comments range from the technical aspects of individual quality measures in PQRS to how hospitalists appear to be performing in these programs. SHM firmly believes that the unique positioning of hospitalists within the health-care system presents challenges for their identification and evaluation in Medicare programs. In some sense, hospitalists exist on the line between the inpatient and outpatient worlds, a location not adequately captured in pay-for-performance programs.

It’s imperative that pay-for-performance programs have reasonable and actionable outcomes for providers. If quality measures are not clinically meaningful and do not capture a plurality of the care provided by an individual hospitalist, it is difficult for the program to meet its stated aims. If payment is to be influenced by performance on quality measures, it follows that those measures should be relevant to the care provided.

There is a long way to go toward creating quality measurement and evaluation programs that are relevant and actionable for clinical quality improvement (QI). By becoming involved in SHM’s policy efforts, members are able to share their experiences and impressions of programs with SHM and lawmakers. This partnership helps create more responsive and intuitive programs, which in turn leads to greater participation and, hopefully, improved patient outcomes. As these programs continue to evolve and more health professionals are required to participate, SHM will be looking to its membership for their perspectives.

Join the grassroots network to stay involved and up to date by registering at www.hospitalmedicine.org/grassroots.

Joshua Lapps is SHM’s government relations specialist.

Can quality measurement and comparisons serve as the backbone for a major shift in the Medicare payment system to reward value instead of volume? That is the question being explored over the next few years as the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) and, by extension, the physician value-based payment modifier (VBPM) come fully into effect for all physicians.

There seems to be a consensus in the policy community that the fee-for-service model of payment is past its prime and needs to be replaced with a more dynamic and responsive payment system. Medicare hopes that PQRS and the VBPM will enable adjustments to physician payments to reward high-quality and low-cost care. Although these programs currently are add-ons to the fee-for-service system, they likely will serve as stepping stones to more radical departures from the existing payment system.

SHM advocates refinements to policies for PQRS and similar programs to make them more meaningful and productive for both hospitalists and the broader health-care system. Each year, SHM submits comments on the Physician Fee Schedule Rule, which creates and updates the regulatory framework for PQRS and the VBPM. SHM also provided feedback on Quality and Resource Use Reports (QRURs), the report cards for the modifier that were being tested over the past year.

From a practical standpoint, SHM engages with measure development and endorsement processes to ensure there are reportable quality measures in PQRS that fit hospitalist practice. In addition, SHM is helping to increase accessibility to PQRS reporting by offering members reduced fare access to registry reporting through the PQRI Wizard.

The comments range from the technical aspects of individual quality measures in PQRS to how hospitalists appear to be performing in these programs. SHM firmly believes that the unique positioning of hospitalists within the health-care system presents challenges for their identification and evaluation in Medicare programs. In some sense, hospitalists exist on the line between the inpatient and outpatient worlds, a location not adequately captured in pay-for-performance programs.

It’s imperative that pay-for-performance programs have reasonable and actionable outcomes for providers. If quality measures are not clinically meaningful and do not capture a plurality of the care provided by an individual hospitalist, it is difficult for the program to meet its stated aims. If payment is to be influenced by performance on quality measures, it follows that those measures should be relevant to the care provided.

There is a long way to go toward creating quality measurement and evaluation programs that are relevant and actionable for clinical quality improvement (QI). By becoming involved in SHM’s policy efforts, members are able to share their experiences and impressions of programs with SHM and lawmakers. This partnership helps create more responsive and intuitive programs, which in turn leads to greater participation and, hopefully, improved patient outcomes. As these programs continue to evolve and more health professionals are required to participate, SHM will be looking to its membership for their perspectives.

Join the grassroots network to stay involved and up to date by registering at www.hospitalmedicine.org/grassroots.

Joshua Lapps is SHM’s government relations specialist.

Three Easy Ways to Get Ahead in Hospital Medicine

Getting involved—and getting ahead—in hospital medicine has never been easier, with just some planning and preparation. Here are three ways to move your hospital—and your career—forward this month.

1. Add “award-winning” to your CV: SHM’s Awards of Excellence deadline is Sept. 16.

Although 2013’s award-winners are still fresh in hospitalists’ minds, now is the time to put together award applications for the 2014 Awards of Excellence.

Each year, SHM presents six different awards that recognize individuals and one award to a team that is transforming health care and revolutionizing patient care for hospitalized patients:

- Excellence in Research Award;

- Excellence in Hospital Medicine for Non-Physicians;

- Award for Excellence in Teaching;

- Award for Outstanding Service in Hospital Medicine;

- Award for Clinical Excellence; and

- Excellence in Teamwork in Quality Improvement.

Last year, SHM received award nominations from a diverse group of hospitalists and looks forward to receiving even more this year. Each winner receives an all-expenses-paid trip to HM14 in Las Vegas, including complimentary meeting registration.

The deadline for applications for SHM’s five individual awards is Sept. 16. The deadline for the Excellence in Teamwork in Quality Improvement is Oct. 15. All SHM members are eligible, and nominees can be self-nominated.

For more information, visit www.hospital medicine.org/awards.

2. Bring the experts in reducing readmissions to your hospital: Apply now for Project BOOST.

There is still time to apply for SHM’s Project BOOST, which helps hospitals design discharge programs to reduce readmissions. SHM will accept applications for Project BOOST until the end of August.

Project BOOST is based on SHM’s award-winning mentored implementation model that brings individualized attention from national experts in reducing readmissions to hospitals across the country. Each Project BOOST site receives:

- A comprehensive intervention developed by a panel of nationally recognized experts based on the best available evidence.