User login

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: How to take the fear out of expanding a hospitalist group

Click here to listen to Brian Hazen, MD, medical director of Inova Fairfax Hospital Group in Fairfax, Va.

Click here to listen to Brian Hazen, MD, medical director of Inova Fairfax Hospital Group in Fairfax, Va.

Click here to listen to Brian Hazen, MD, medical director of Inova Fairfax Hospital Group in Fairfax, Va.

Local Factors Play Major Role in Determining Compensation Rates for Pediatric Hospitalists

Although pediatricians make up less than 6% of the hospitalists surveyed by the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA), they represent a very different data profile from other specialties reported in SHM’s 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report.

The nonpediatric HM specialties (internal medicine, family medicine, and med/peds) have similar data profiles with regard to productivity and compensation statistics. They are all within 2% of the $233,855 “all adult hospitalists” median compensation. Although there is a bit more variability in the productivity data, all three groups are clustered within 10% of each other. The key to understanding their similarity is that they all serve mostly adult inpatients. While some of these physicians may also care for hospitalized children, I suspect this population is a small proportion of their daily workload.

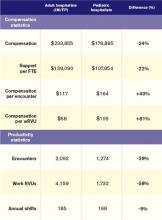

Pediatric hospitalists only treat pediatric patients and differ significantly from adult hospitalists, as summarized in Table 1.

Pediatricians remain among the lowest-earning specialties nationally, whether in the office or on children’s wards. The key to understanding the differences between adult and pediatric hospitalists is that they derive their compensation and productivity expectations from two separate and distinct physician marketplaces. Adult hospitalists benefit from more than a decade of rapidly growing demand for their services, as well as higher compensation for their office-based counterparts. Meanwhile, the market for pediatric hospitalists remains smaller and more segmented, allowing local factors to drive compensation more than a national demand for their services would.

Pediatric hospitalists appear to earn about a quarter less than their adult counterparts while receiving a similarly lower amount of hospital financial support per provider. Pediatric hospitalists also appear to work less than adult hospitalists, reflected in fewer shifts annually and fewer hours per shift; 75% of adult hospitalist groups report shift lengths of 12 hours or more, compared with 48% of pediatric hospitalist groups. This may stem from the frequent lulls in census common to a community hospital pediatrics service, in contrast to more consistent demand posed by geriatric populations. Although pediatric hospitalists receive more compensation per encounter or wRVU, they cannot generate those encounters or work RVUs at the same clip as adult hospitalists. Pediatricians must hold a family meeting for every single patient, and even something as seemingly simple as obtaining intravenous access might consume 45 minutes of a hospitalist’s time.

Thus, pediatric hospitalists find themselves caught in the same market as other pediatric specialists. These providers remain undervalued compared to virtually all other physicians. Those who seek to improve their financial prospects likely need to work more shifts or generate more workload relative to the expectations of their pediatrician peers.

Personally, I can’t help but wonder what attention pediatric care might enjoy if kids had a vote, a pension, an entitlement program, and a lobby on K Street like their grandparents do.

Dr. Ahlstrom is clinical director of Hospitalists of Northern Michigan and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Although pediatricians make up less than 6% of the hospitalists surveyed by the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA), they represent a very different data profile from other specialties reported in SHM’s 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report.

The nonpediatric HM specialties (internal medicine, family medicine, and med/peds) have similar data profiles with regard to productivity and compensation statistics. They are all within 2% of the $233,855 “all adult hospitalists” median compensation. Although there is a bit more variability in the productivity data, all three groups are clustered within 10% of each other. The key to understanding their similarity is that they all serve mostly adult inpatients. While some of these physicians may also care for hospitalized children, I suspect this population is a small proportion of their daily workload.

Pediatric hospitalists only treat pediatric patients and differ significantly from adult hospitalists, as summarized in Table 1.

Pediatricians remain among the lowest-earning specialties nationally, whether in the office or on children’s wards. The key to understanding the differences between adult and pediatric hospitalists is that they derive their compensation and productivity expectations from two separate and distinct physician marketplaces. Adult hospitalists benefit from more than a decade of rapidly growing demand for their services, as well as higher compensation for their office-based counterparts. Meanwhile, the market for pediatric hospitalists remains smaller and more segmented, allowing local factors to drive compensation more than a national demand for their services would.

Pediatric hospitalists appear to earn about a quarter less than their adult counterparts while receiving a similarly lower amount of hospital financial support per provider. Pediatric hospitalists also appear to work less than adult hospitalists, reflected in fewer shifts annually and fewer hours per shift; 75% of adult hospitalist groups report shift lengths of 12 hours or more, compared with 48% of pediatric hospitalist groups. This may stem from the frequent lulls in census common to a community hospital pediatrics service, in contrast to more consistent demand posed by geriatric populations. Although pediatric hospitalists receive more compensation per encounter or wRVU, they cannot generate those encounters or work RVUs at the same clip as adult hospitalists. Pediatricians must hold a family meeting for every single patient, and even something as seemingly simple as obtaining intravenous access might consume 45 minutes of a hospitalist’s time.

Thus, pediatric hospitalists find themselves caught in the same market as other pediatric specialists. These providers remain undervalued compared to virtually all other physicians. Those who seek to improve their financial prospects likely need to work more shifts or generate more workload relative to the expectations of their pediatrician peers.

Personally, I can’t help but wonder what attention pediatric care might enjoy if kids had a vote, a pension, an entitlement program, and a lobby on K Street like their grandparents do.

Dr. Ahlstrom is clinical director of Hospitalists of Northern Michigan and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Although pediatricians make up less than 6% of the hospitalists surveyed by the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA), they represent a very different data profile from other specialties reported in SHM’s 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report.

The nonpediatric HM specialties (internal medicine, family medicine, and med/peds) have similar data profiles with regard to productivity and compensation statistics. They are all within 2% of the $233,855 “all adult hospitalists” median compensation. Although there is a bit more variability in the productivity data, all three groups are clustered within 10% of each other. The key to understanding their similarity is that they all serve mostly adult inpatients. While some of these physicians may also care for hospitalized children, I suspect this population is a small proportion of their daily workload.

Pediatric hospitalists only treat pediatric patients and differ significantly from adult hospitalists, as summarized in Table 1.

Pediatricians remain among the lowest-earning specialties nationally, whether in the office or on children’s wards. The key to understanding the differences between adult and pediatric hospitalists is that they derive their compensation and productivity expectations from two separate and distinct physician marketplaces. Adult hospitalists benefit from more than a decade of rapidly growing demand for their services, as well as higher compensation for their office-based counterparts. Meanwhile, the market for pediatric hospitalists remains smaller and more segmented, allowing local factors to drive compensation more than a national demand for their services would.

Pediatric hospitalists appear to earn about a quarter less than their adult counterparts while receiving a similarly lower amount of hospital financial support per provider. Pediatric hospitalists also appear to work less than adult hospitalists, reflected in fewer shifts annually and fewer hours per shift; 75% of adult hospitalist groups report shift lengths of 12 hours or more, compared with 48% of pediatric hospitalist groups. This may stem from the frequent lulls in census common to a community hospital pediatrics service, in contrast to more consistent demand posed by geriatric populations. Although pediatric hospitalists receive more compensation per encounter or wRVU, they cannot generate those encounters or work RVUs at the same clip as adult hospitalists. Pediatricians must hold a family meeting for every single patient, and even something as seemingly simple as obtaining intravenous access might consume 45 minutes of a hospitalist’s time.

Thus, pediatric hospitalists find themselves caught in the same market as other pediatric specialists. These providers remain undervalued compared to virtually all other physicians. Those who seek to improve their financial prospects likely need to work more shifts or generate more workload relative to the expectations of their pediatrician peers.

Personally, I can’t help but wonder what attention pediatric care might enjoy if kids had a vote, a pension, an entitlement program, and a lobby on K Street like their grandparents do.

Dr. Ahlstrom is clinical director of Hospitalists of Northern Michigan and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Hospitalists to Unveil Patient Care Recommendations As Part of Choosing Wisely Campaign

This month, hospitalists will be a vital part of Choosing Wisely, an important public initiative from the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Foundation that identifies treatments and procedures that might be overused by caregivers.

On Feb. 21 in Washington, D.C., the ABIM Foundation, SHM, and more than a dozen other medical specialties will announce recommendations that, in the ABIM Foundation’s words, “represent specific, evidence-based recommendations physicians and patients should discuss to help make wise decisions about the most appropriate care based on their individual situation.” Hospitalists who helped SHM develop its recommendations will be in attendance to help field questions about SHM’s work with Choosing Wisely and its lists.

SHM has developed two lists of recommendations: one for adult HM and another for pediatric HM. SHM will make a special announcement Feb. 21 in The Hospitalist eWire with both lists and commentary for how hospitalists can have informed conversations with their patients about the lists. The Hospitalist will follow up with a feature story and other information about Choosing Wisely in its March issue.

As part of the campaign, the ABIM Foundation, SHM, and consumer magazine Consumer Reports have teamed up to develop material specifically designed to educate patients about the Choosing Wisely recommendations. Materials will be available on the ABIM Foundation and SHM websites.

SHM will continue the conversation about high-value care and working with patients to make wise decisions well beyond February and March. At HM13, SHM’s annual meeting in Washington, D.C., SHM will offer a pre-course on Choosing Wisely and its philosophy. The pre-course is May 16, the day before the official start of HM13.

For more information about Choosing Wisely, visit www.choosingwisely.org. To register for the Choosing Wisely pre-course at HM13, visit www.hospitalmedicine2013.org.

This month, hospitalists will be a vital part of Choosing Wisely, an important public initiative from the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Foundation that identifies treatments and procedures that might be overused by caregivers.

On Feb. 21 in Washington, D.C., the ABIM Foundation, SHM, and more than a dozen other medical specialties will announce recommendations that, in the ABIM Foundation’s words, “represent specific, evidence-based recommendations physicians and patients should discuss to help make wise decisions about the most appropriate care based on their individual situation.” Hospitalists who helped SHM develop its recommendations will be in attendance to help field questions about SHM’s work with Choosing Wisely and its lists.

SHM has developed two lists of recommendations: one for adult HM and another for pediatric HM. SHM will make a special announcement Feb. 21 in The Hospitalist eWire with both lists and commentary for how hospitalists can have informed conversations with their patients about the lists. The Hospitalist will follow up with a feature story and other information about Choosing Wisely in its March issue.

As part of the campaign, the ABIM Foundation, SHM, and consumer magazine Consumer Reports have teamed up to develop material specifically designed to educate patients about the Choosing Wisely recommendations. Materials will be available on the ABIM Foundation and SHM websites.

SHM will continue the conversation about high-value care and working with patients to make wise decisions well beyond February and March. At HM13, SHM’s annual meeting in Washington, D.C., SHM will offer a pre-course on Choosing Wisely and its philosophy. The pre-course is May 16, the day before the official start of HM13.

For more information about Choosing Wisely, visit www.choosingwisely.org. To register for the Choosing Wisely pre-course at HM13, visit www.hospitalmedicine2013.org.

This month, hospitalists will be a vital part of Choosing Wisely, an important public initiative from the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Foundation that identifies treatments and procedures that might be overused by caregivers.

On Feb. 21 in Washington, D.C., the ABIM Foundation, SHM, and more than a dozen other medical specialties will announce recommendations that, in the ABIM Foundation’s words, “represent specific, evidence-based recommendations physicians and patients should discuss to help make wise decisions about the most appropriate care based on their individual situation.” Hospitalists who helped SHM develop its recommendations will be in attendance to help field questions about SHM’s work with Choosing Wisely and its lists.

SHM has developed two lists of recommendations: one for adult HM and another for pediatric HM. SHM will make a special announcement Feb. 21 in The Hospitalist eWire with both lists and commentary for how hospitalists can have informed conversations with their patients about the lists. The Hospitalist will follow up with a feature story and other information about Choosing Wisely in its March issue.

As part of the campaign, the ABIM Foundation, SHM, and consumer magazine Consumer Reports have teamed up to develop material specifically designed to educate patients about the Choosing Wisely recommendations. Materials will be available on the ABIM Foundation and SHM websites.

SHM will continue the conversation about high-value care and working with patients to make wise decisions well beyond February and March. At HM13, SHM’s annual meeting in Washington, D.C., SHM will offer a pre-course on Choosing Wisely and its philosophy. The pre-course is May 16, the day before the official start of HM13.

For more information about Choosing Wisely, visit www.choosingwisely.org. To register for the Choosing Wisely pre-course at HM13, visit www.hospitalmedicine2013.org.

Pharmacist-Hospitalist Collaboration Can Improve Care, Save Money

A healthy collaboration between hospitalists and pharmacists can generate cost savings and promote positive outcomes, such as preventing adverse drug events and improving care transitions, says Jonathan Edwards, PharmD, BCPS, a clinical pharmacy specialist at Huntsville Hospital in Alabama.

At the 2012 national conference of the American College of Clinical Pharmacy in Hollywood, Fla., Edwards presented a poster that detailed the effectiveness of such interdisciplinary collaboration at Huntsville Hospital, where pharmacists and physicians developed six order sets, a collaborative practice, and a patient interaction program from November 2011 to February 2012. During the study period, researchers documented a total cost savings of $9,825 resulting from 156 patient interventions.

Edwards’ collaborative study at Huntsville started with two physicians who had launched a service teaching hospitalists what pharmacists do, and how they could help in their efforts.

“We got together and developed an order set for treating acute alcohol withdrawal. That went well, so we did five more order sets,” Edwards says. “Then we thought: What if pharmacists got more involved by meeting directly with patients in the hospital to optimize their medication management and help them reach their goals for treatment? We now evaluate patients on the hospitalist service in three units.”

For Edwards, key factors that make the hospitalist-pharmacist relationship work include communicating the pharmacist’s availability to help with the hospitalist’s patients, identifying the physician’s openness to help, and clarifying how the physician prefers to be contacted.

Last October, the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) and the American Pharmacists Association (APhA) recognized eight care-transitions programs for best practices that improved patient outcomes and reduced hospital readmissions as part of the Medication Management in Care Transitions (MMCT) Project.

“The MMCT project highlights the valuable role pharmacists can play in addressing medication-related problems that can lead to hospital readmissions,” APhA chief executive officer Thomas E. Menighan, BSPharm, MBA, ScD (Hon), FAPhA, said in a news release. “By putting together these best practices, our goal is to provide a model for better coordination of care and better connectivity between pharmacists and healthcare providers in different practice settings that leads to improved patient health.”

Visit our website for more information about maximizing patient care through pharmacist-hospitalist collaboration.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

Articles first published in the Jan. 16, 2013, edition of The Hospitalist eWire.

A healthy collaboration between hospitalists and pharmacists can generate cost savings and promote positive outcomes, such as preventing adverse drug events and improving care transitions, says Jonathan Edwards, PharmD, BCPS, a clinical pharmacy specialist at Huntsville Hospital in Alabama.

At the 2012 national conference of the American College of Clinical Pharmacy in Hollywood, Fla., Edwards presented a poster that detailed the effectiveness of such interdisciplinary collaboration at Huntsville Hospital, where pharmacists and physicians developed six order sets, a collaborative practice, and a patient interaction program from November 2011 to February 2012. During the study period, researchers documented a total cost savings of $9,825 resulting from 156 patient interventions.

Edwards’ collaborative study at Huntsville started with two physicians who had launched a service teaching hospitalists what pharmacists do, and how they could help in their efforts.

“We got together and developed an order set for treating acute alcohol withdrawal. That went well, so we did five more order sets,” Edwards says. “Then we thought: What if pharmacists got more involved by meeting directly with patients in the hospital to optimize their medication management and help them reach their goals for treatment? We now evaluate patients on the hospitalist service in three units.”

For Edwards, key factors that make the hospitalist-pharmacist relationship work include communicating the pharmacist’s availability to help with the hospitalist’s patients, identifying the physician’s openness to help, and clarifying how the physician prefers to be contacted.

Last October, the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) and the American Pharmacists Association (APhA) recognized eight care-transitions programs for best practices that improved patient outcomes and reduced hospital readmissions as part of the Medication Management in Care Transitions (MMCT) Project.

“The MMCT project highlights the valuable role pharmacists can play in addressing medication-related problems that can lead to hospital readmissions,” APhA chief executive officer Thomas E. Menighan, BSPharm, MBA, ScD (Hon), FAPhA, said in a news release. “By putting together these best practices, our goal is to provide a model for better coordination of care and better connectivity between pharmacists and healthcare providers in different practice settings that leads to improved patient health.”

Visit our website for more information about maximizing patient care through pharmacist-hospitalist collaboration.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

Articles first published in the Jan. 16, 2013, edition of The Hospitalist eWire.

A healthy collaboration between hospitalists and pharmacists can generate cost savings and promote positive outcomes, such as preventing adverse drug events and improving care transitions, says Jonathan Edwards, PharmD, BCPS, a clinical pharmacy specialist at Huntsville Hospital in Alabama.

At the 2012 national conference of the American College of Clinical Pharmacy in Hollywood, Fla., Edwards presented a poster that detailed the effectiveness of such interdisciplinary collaboration at Huntsville Hospital, where pharmacists and physicians developed six order sets, a collaborative practice, and a patient interaction program from November 2011 to February 2012. During the study period, researchers documented a total cost savings of $9,825 resulting from 156 patient interventions.

Edwards’ collaborative study at Huntsville started with two physicians who had launched a service teaching hospitalists what pharmacists do, and how they could help in their efforts.

“We got together and developed an order set for treating acute alcohol withdrawal. That went well, so we did five more order sets,” Edwards says. “Then we thought: What if pharmacists got more involved by meeting directly with patients in the hospital to optimize their medication management and help them reach their goals for treatment? We now evaluate patients on the hospitalist service in three units.”

For Edwards, key factors that make the hospitalist-pharmacist relationship work include communicating the pharmacist’s availability to help with the hospitalist’s patients, identifying the physician’s openness to help, and clarifying how the physician prefers to be contacted.

Last October, the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) and the American Pharmacists Association (APhA) recognized eight care-transitions programs for best practices that improved patient outcomes and reduced hospital readmissions as part of the Medication Management in Care Transitions (MMCT) Project.

“The MMCT project highlights the valuable role pharmacists can play in addressing medication-related problems that can lead to hospital readmissions,” APhA chief executive officer Thomas E. Menighan, BSPharm, MBA, ScD (Hon), FAPhA, said in a news release. “By putting together these best practices, our goal is to provide a model for better coordination of care and better connectivity between pharmacists and healthcare providers in different practice settings that leads to improved patient health.”

Visit our website for more information about maximizing patient care through pharmacist-hospitalist collaboration.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

Articles first published in the Jan. 16, 2013, edition of The Hospitalist eWire.

Hospitalist Rajan Gurunathan, MD, Stresses Commitment and Community

Rajan Gurunathan, MD, was an undergraduate student at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore in the early 1990s weighing his career options.

“I went through a lot of permutations, actually,” he says. “Scientist, clinical researcher, doctor, physician/scientist—all of those things entered my mind at some point.”

He applied to dual-track MD and PhD programs, but ultimately decided that interacting with people—patients in particular—was the goal for him. He earned his medical degree from UMDNJ-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in Camden, N.J., and completed his internship in the department of medicine at St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital Center in New York City, not far from where he grew up as a child in northern New Jersey.

And he never left.

—Anthony Back, MD, professor of medicine, University of Washington, Seattle

Dr. Gurunathan has risen through the ranks at St. Luke’s-Roosevelt, from resident to chief resident to chief of the section of hospital medicine. He is a faculty member for the Clinical Quality Fellowship Program at the Great New York Hospital Association and an assistant clinical professor of medicine at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York.

His long tenure at St. Luke’s-Roosevelt has been “an incredible experience because I really get a sense and feeling of commitment from the community,” he adds. “I’ve seen it grow over time and see how the needs have changed and how the service the hospital has been able to provide has only grown over time.”

After several years of presenting posters at SHM’s annual meetings, Dr. Gurunathan joined Team Hospitalist in April 2012 to become an even more active member of his specialty.

QUESTION: When you started as an intern 15 years ago, did you expect that you’d still be at the same institution?

Answer: No, I wouldn’t have expected that at all. In fact, there was a time where I was briefly considering a general medicine fellowship at Johns Hopkins, and I was prepared to go there. And family circumstances, etc., made me decide not to move on and to make a commitment and join the department as faculty, first as a chief and then as faculty. And I was really lucky to have those opportunities, because while my course didn’t go exactly the way that I’d planned, I wouldn’t have changed a thing.

Q: When you now deal with the residents and younger staff members, what’s that experience like for you?

A: It’s a really neat experience, and often brings a chuckle to my face when I see that they’re frustrated about the same things, because I can certainly commiserate. But I can really also see the value of what they provide every day, and having been in their shoes, I know a little bit about what they’ve been through and the work that they do. So I have a real appreciation for that.

Q: What brought you to hospital medicine?

A: I’ve always enjoyed the collegiality of a hospital environment in terms of multiple disciplines working together in ways to help care for patients. It’s a paradox in the sense that it’s fascinating to see disease and be able to be impactful in that way, but it’s also unfortunate sometimes to see what people have to go through.

Q: Is there something specific about the setting that’s kept you in the academic world?

A: A lot of things, actually. As I mentioned, hospitals in general should have a collegial nature. Again, it’s a really nice place where people share a unique common goal of banding together and fighting a goal, and academic departments are the same. So it’s being with people with like-minded intellectual interests. And we’re fortunate enough to have a number of strong mentors within the department who have had a lot of clinical training and bring a lot of experience and a wealth of knowledge, and being able to utilize their experience and draw from their experiences only makes people better clinicians. And we’re fortunate enough to have a pretty supportive department in general where there is a lot of collegiality and camaraderie.

Q: As an administrator, what is the value of being an SHM member, to you?

A: I think what I’ve seen administratively is the changing face of healthcare and how hospitals are going to need to continue to transform with time due to things that are both regulatory- and quality-of-care-based, in terms of improving outcomes and keeping people healthy. SHM has really embraced [those changes] and taken them head-on for really important reasons, not only in terms of helping people adapt to the changing landscape, but also training them in the ways that we need to be thinking about problems now and in the future.

Q: You’ve attended multiple annual meetings and presented posters. What value have you taken out of them, and would you recommend the experience to others?

A: Absolutely. I think as people develop, it’s good to always learn new skills, and my clinical research is an area that I would actually like to build up. So I’ve had a little bit of exposure, and it’s been nice to be able to draw from the resources of SHM and be able to partake. We presented something last year, which was a really neat experience, and we’re looking to bring some new faculty this year and encourage them to get involved in the scholarship process. These are the kinds of things that can really help hone skills, and that’s a good thing.

Q: Once you’re inside the doors of a New York City hospital, is daily practice much different than anywhere else?

A: I would say yes and no. I would say no in that I think all hospitals are really neat places and really incredible places. I heard somebody say once at a talk that hospitals were places of refuge, and I really do believe that. That being said, I think there is something slightly unique about New York City in a lot of ways. Certainly the challenges that New York City hospitals face are somewhat unique in terms of patient population, difficulty in socioeconomic factors, insurance issues. I think they are really fun places to work, but they’re not for the faint of heart.

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Rajan Gurunathan, MD, was an undergraduate student at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore in the early 1990s weighing his career options.

“I went through a lot of permutations, actually,” he says. “Scientist, clinical researcher, doctor, physician/scientist—all of those things entered my mind at some point.”

He applied to dual-track MD and PhD programs, but ultimately decided that interacting with people—patients in particular—was the goal for him. He earned his medical degree from UMDNJ-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in Camden, N.J., and completed his internship in the department of medicine at St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital Center in New York City, not far from where he grew up as a child in northern New Jersey.

And he never left.

—Anthony Back, MD, professor of medicine, University of Washington, Seattle

Dr. Gurunathan has risen through the ranks at St. Luke’s-Roosevelt, from resident to chief resident to chief of the section of hospital medicine. He is a faculty member for the Clinical Quality Fellowship Program at the Great New York Hospital Association and an assistant clinical professor of medicine at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York.

His long tenure at St. Luke’s-Roosevelt has been “an incredible experience because I really get a sense and feeling of commitment from the community,” he adds. “I’ve seen it grow over time and see how the needs have changed and how the service the hospital has been able to provide has only grown over time.”

After several years of presenting posters at SHM’s annual meetings, Dr. Gurunathan joined Team Hospitalist in April 2012 to become an even more active member of his specialty.

QUESTION: When you started as an intern 15 years ago, did you expect that you’d still be at the same institution?

Answer: No, I wouldn’t have expected that at all. In fact, there was a time where I was briefly considering a general medicine fellowship at Johns Hopkins, and I was prepared to go there. And family circumstances, etc., made me decide not to move on and to make a commitment and join the department as faculty, first as a chief and then as faculty. And I was really lucky to have those opportunities, because while my course didn’t go exactly the way that I’d planned, I wouldn’t have changed a thing.

Q: When you now deal with the residents and younger staff members, what’s that experience like for you?

A: It’s a really neat experience, and often brings a chuckle to my face when I see that they’re frustrated about the same things, because I can certainly commiserate. But I can really also see the value of what they provide every day, and having been in their shoes, I know a little bit about what they’ve been through and the work that they do. So I have a real appreciation for that.

Q: What brought you to hospital medicine?

A: I’ve always enjoyed the collegiality of a hospital environment in terms of multiple disciplines working together in ways to help care for patients. It’s a paradox in the sense that it’s fascinating to see disease and be able to be impactful in that way, but it’s also unfortunate sometimes to see what people have to go through.

Q: Is there something specific about the setting that’s kept you in the academic world?

A: A lot of things, actually. As I mentioned, hospitals in general should have a collegial nature. Again, it’s a really nice place where people share a unique common goal of banding together and fighting a goal, and academic departments are the same. So it’s being with people with like-minded intellectual interests. And we’re fortunate enough to have a number of strong mentors within the department who have had a lot of clinical training and bring a lot of experience and a wealth of knowledge, and being able to utilize their experience and draw from their experiences only makes people better clinicians. And we’re fortunate enough to have a pretty supportive department in general where there is a lot of collegiality and camaraderie.

Q: As an administrator, what is the value of being an SHM member, to you?

A: I think what I’ve seen administratively is the changing face of healthcare and how hospitals are going to need to continue to transform with time due to things that are both regulatory- and quality-of-care-based, in terms of improving outcomes and keeping people healthy. SHM has really embraced [those changes] and taken them head-on for really important reasons, not only in terms of helping people adapt to the changing landscape, but also training them in the ways that we need to be thinking about problems now and in the future.

Q: You’ve attended multiple annual meetings and presented posters. What value have you taken out of them, and would you recommend the experience to others?

A: Absolutely. I think as people develop, it’s good to always learn new skills, and my clinical research is an area that I would actually like to build up. So I’ve had a little bit of exposure, and it’s been nice to be able to draw from the resources of SHM and be able to partake. We presented something last year, which was a really neat experience, and we’re looking to bring some new faculty this year and encourage them to get involved in the scholarship process. These are the kinds of things that can really help hone skills, and that’s a good thing.

Q: Once you’re inside the doors of a New York City hospital, is daily practice much different than anywhere else?

A: I would say yes and no. I would say no in that I think all hospitals are really neat places and really incredible places. I heard somebody say once at a talk that hospitals were places of refuge, and I really do believe that. That being said, I think there is something slightly unique about New York City in a lot of ways. Certainly the challenges that New York City hospitals face are somewhat unique in terms of patient population, difficulty in socioeconomic factors, insurance issues. I think they are really fun places to work, but they’re not for the faint of heart.

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Rajan Gurunathan, MD, was an undergraduate student at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore in the early 1990s weighing his career options.

“I went through a lot of permutations, actually,” he says. “Scientist, clinical researcher, doctor, physician/scientist—all of those things entered my mind at some point.”

He applied to dual-track MD and PhD programs, but ultimately decided that interacting with people—patients in particular—was the goal for him. He earned his medical degree from UMDNJ-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in Camden, N.J., and completed his internship in the department of medicine at St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital Center in New York City, not far from where he grew up as a child in northern New Jersey.

And he never left.

—Anthony Back, MD, professor of medicine, University of Washington, Seattle

Dr. Gurunathan has risen through the ranks at St. Luke’s-Roosevelt, from resident to chief resident to chief of the section of hospital medicine. He is a faculty member for the Clinical Quality Fellowship Program at the Great New York Hospital Association and an assistant clinical professor of medicine at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York.

His long tenure at St. Luke’s-Roosevelt has been “an incredible experience because I really get a sense and feeling of commitment from the community,” he adds. “I’ve seen it grow over time and see how the needs have changed and how the service the hospital has been able to provide has only grown over time.”

After several years of presenting posters at SHM’s annual meetings, Dr. Gurunathan joined Team Hospitalist in April 2012 to become an even more active member of his specialty.

QUESTION: When you started as an intern 15 years ago, did you expect that you’d still be at the same institution?

Answer: No, I wouldn’t have expected that at all. In fact, there was a time where I was briefly considering a general medicine fellowship at Johns Hopkins, and I was prepared to go there. And family circumstances, etc., made me decide not to move on and to make a commitment and join the department as faculty, first as a chief and then as faculty. And I was really lucky to have those opportunities, because while my course didn’t go exactly the way that I’d planned, I wouldn’t have changed a thing.

Q: When you now deal with the residents and younger staff members, what’s that experience like for you?

A: It’s a really neat experience, and often brings a chuckle to my face when I see that they’re frustrated about the same things, because I can certainly commiserate. But I can really also see the value of what they provide every day, and having been in their shoes, I know a little bit about what they’ve been through and the work that they do. So I have a real appreciation for that.

Q: What brought you to hospital medicine?

A: I’ve always enjoyed the collegiality of a hospital environment in terms of multiple disciplines working together in ways to help care for patients. It’s a paradox in the sense that it’s fascinating to see disease and be able to be impactful in that way, but it’s also unfortunate sometimes to see what people have to go through.

Q: Is there something specific about the setting that’s kept you in the academic world?

A: A lot of things, actually. As I mentioned, hospitals in general should have a collegial nature. Again, it’s a really nice place where people share a unique common goal of banding together and fighting a goal, and academic departments are the same. So it’s being with people with like-minded intellectual interests. And we’re fortunate enough to have a number of strong mentors within the department who have had a lot of clinical training and bring a lot of experience and a wealth of knowledge, and being able to utilize their experience and draw from their experiences only makes people better clinicians. And we’re fortunate enough to have a pretty supportive department in general where there is a lot of collegiality and camaraderie.

Q: As an administrator, what is the value of being an SHM member, to you?

A: I think what I’ve seen administratively is the changing face of healthcare and how hospitals are going to need to continue to transform with time due to things that are both regulatory- and quality-of-care-based, in terms of improving outcomes and keeping people healthy. SHM has really embraced [those changes] and taken them head-on for really important reasons, not only in terms of helping people adapt to the changing landscape, but also training them in the ways that we need to be thinking about problems now and in the future.

Q: You’ve attended multiple annual meetings and presented posters. What value have you taken out of them, and would you recommend the experience to others?

A: Absolutely. I think as people develop, it’s good to always learn new skills, and my clinical research is an area that I would actually like to build up. So I’ve had a little bit of exposure, and it’s been nice to be able to draw from the resources of SHM and be able to partake. We presented something last year, which was a really neat experience, and we’re looking to bring some new faculty this year and encourage them to get involved in the scholarship process. These are the kinds of things that can really help hone skills, and that’s a good thing.

Q: Once you’re inside the doors of a New York City hospital, is daily practice much different than anywhere else?

A: I would say yes and no. I would say no in that I think all hospitals are really neat places and really incredible places. I heard somebody say once at a talk that hospitals were places of refuge, and I really do believe that. That being said, I think there is something slightly unique about New York City in a lot of ways. Certainly the challenges that New York City hospitals face are somewhat unique in terms of patient population, difficulty in socioeconomic factors, insurance issues. I think they are really fun places to work, but they’re not for the faint of heart.

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

The economics of surgical gynecology: How we can not only survive, but thrive, in the 21st Century

Barbara S. Levy, MD, spent 29 years in private practice before accepting an appointment as vice president of health policy at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Those 29 years in private practice weren’t her only window onto the health-care arena, however. She has served as chair of the Resource Based Relative Value Scale Update Committee for the American Medical Association for 3 years; as medical director of Women’s and Children’s Services at Franciscan Health System in Tacoma, Washington; and as a long-time member of the OBG Management Board of Editors. As a result, she offers an informed and well-rounded perspective on the economics of surgical gynecology—the subject of a keynote address she delivered at the 2012 Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery (PAGS) symposium in December.

We sat down with Dr. Levy after her talk to explore some of the issues she raised—the focus of this Q&A. Dr. Levy also summarizes the high points of her talk in a video presentation available at obgmanagement.com.

OBG Management: What prompted you to leave private practice, move across country, and accept the post at ACOG?

Dr. Levy: I had spent the better part of 29 years complaining and feeling reasonably unhappy with what organized medicine was doing—or not doing—for ObGyns and our patients. I felt that the specialty was not really out there in front of the curve, driving the bus, so to speak, but was a victim of broader forces. So when I was given an opportunity to influence the way we approach health-care policy, to enable us to drive our own bus, I decided to take the challenge. I’m not sure I can make a difference, but I’m going to do everything possible to put us in control of our destiny. There are a lot of pitfalls out there, but I think that, given a commitment to doing what is right, we may be able to change the way we deliver health care in this country.

OBG Management: So what’s wrong with the way we deliver health care in the United States?

Dr. Levy: We are spending an inordinate amount of money. I’ve heard it referred to as an “investment,” but I’m not sure that word is accurate. It’s really an expenditure of trillions of dollars—as much as 17% of gross domestic product—but what are we getting in return? We’re not getting what we want or need. There is a lot of innovation out there, but what is it bringing us? Do we have better health care in this country, based on our per capita expenditure, than other developed nations have? The answer is “No.”

OBG Management: Why do you think that is?

Dr. Levy: If you look at the growth in Part B Medicare, and focus on where we’re spending the money, the culprits are pharmaceuticals, a huge increase in testing and imaging, and a sharp rise in office-based procedures. The complexity of services has also increased dramatically. Our population is aging, and obesity is epidemic and driving costs for management of diabetes, hypertension, and chronic heart disease, as well as joint replacements and back surgery. About 85% of Medicare dollars go to the care of 15% to 20% of the Medicare population. Yes, we’re reducing death rates from cardiovascular disease and cancer, but now we have a larger population of patients who have chronic, active disease.

OBG Management: Who’s responsible for this problem?

Dr. Levy: Our health-care systems have created this mess in many ways. We spend $98 billion annually on hospitalization for pregnancy and childbirth, but our mortality rate is increasing. We rank 50th in the world in maternal mortality despite a cesarean delivery rate over 30%, despite all the money that we’re spending—with maternal mortality higher here than in almost every European country, as well as several nations in Asia and the Middle East.1

OBG Management: Why are we spending so much money?

Dr. Levy: We have become so fearful—of poor outcomes, of litigation, and our patients are coming to us with demands for tests and treatment that cost them little or nothing—that we intervene with tests and procedures that increase the cost of care without providing any true benefit in terms of outcome.

We’ve also made some poor choices. We’ve allowed ourselves to be the victims of legislation, of rule-making, because we don’t sit down and read the 1,300 or so pages in the Federal Register from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) on proposed rule-making every year. Things happen to us that we aren’t aware of. We have allowed ourselves to be drawn in by innovation, by testing, and by fear until we have begun to do things that may not have any real benefit for our patients.

Both physicians and hospitals have driven volume to increase reimbursement. And industry has been drawn into the mix because the medical field is the only one that’s expanding. We have become our own worst enemies. We have not stepped up to the plate to define quality and value, so now others are doing it—and they don’t necessarily use the same definitions we do. We have allowed our fears of liability and misperceptions about the value of procedures to drive our decisions. For example, when we perform robotic hysterectomy in a woman who is a great candidate for the vaginal approach, we quadruple the cost of the surgery. Consider that we perform roughly 500,000 hysterectomies every year, and you can see how costs mount rapidly.

Flaws in the US health-care system

OBG Management: What are some of the other problems afflicting the US health-care system?

Dr. Levy: There are tremendous disparities in quality and cost across the country. Why? How we spend money in health care is cultural. It’s influenced by what we become accustomed to, what our particular environment calls “standard.” Here’s an example: A man who is experiencing knee pain tries to make an appointment with an orthopedic surgeon, but when he telephones the physician’s office, he is told that he can’t make an appointment until he has an MRI. That’s cultural, not medically justified.

Patients also play a role. When the patient comes in with a ream of paper from the Internet, and she wants a CA 125 test because she thinks it’s somehow going to prevent ovarian cancer, we need to explain to her, in a way she can understand, that adding that testing is of no benefit and may actually cause harm. We need quick statements that can help defuse the demand for increased testing.

Role of the government

OBG Management: What role does the government play?

Dr. Levy: The Medicare Resource-Based Relative Value Scale (RBRVS) was enacted into law in 1992. Most payers now follow this scale to determine reimbursement, based on how many resources it requires to perform a service. Resources are defined in the law—we can’t change them. But the American Medical Association did convene the RBRVS Update Committee (RUC), of which I am the chair, to do the best we can to define for the federal government exactly how many of those resources are necessary for a particular intervention. For example, how much time does it really take to perform laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy—and how does that compare with reading a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis or with performing a five-vessel bypass? How many office visits for hypertension does it take to equal an open-heart surgery and 90 days of care? That’s not an easy set of relative intensities to work through, but the RUC does do that and makes recommendations to CMS for the relative value units (RVUs) for the services we provide.

OBG Management: Is it time alone that determines the value of a service?

Dr. Levy: Physician work is defined as the time it takes to perform a procedure—but also as the intensity of that service as compared with other physician services.

There are also practice-expense RVUs, intended to address the cost of clinical staff, medical supplies, and equipment. Right now approximately 52% of reimbursement goes toward the practice-expense component, and less than 50% for the physician’s work.

In 1992, when the RBRVS was enacted, women’s health services were significantly undervalued because ObGyns did not form a large part of the Medicare fee schedule. Over the past 20 years, ACOG and the RUC have worked diligently to correct those initial inequities.

On the RUC, we believe that no physicians are paid at a level that is fair and appropriate, compared with a plumber or electrician. So the shift to a value-based system and away from the volume-based system may be beneficial to us.

Challenges ahead

OBG Management: What challenges do ObGyns face in attempting to overcome these problems?

Dr. Levy: The primary challenge is to face reality as it is—not as it was in the “good old days” or as we wish it to be. We need to become advocates for ourselves and our patients. Advocacy would support and promote our patients’ health-care rights and enhance community health. It would also foster policy initiatives that focus on availability, safety, and quality of care.

In our advocacy, we need to focus first on quality. If we don’t define quality ourselves, others are going to decide that quality is a constant and that the only thing that matters is cost, and they will shift all services to the lowest-cost providers. That is not the way we want things to go.

Some changes are already in play:

- Out-of-pocket costs for patients are increasing, motivating patients to become more discriminating

- Payment models will soon focus on “episodes of care,” with incentives for systems to reduce surgical volumes while preserving the patient’s quality of life

- Surgery will shift from low-volume surgeons to high-volume physicians who have demonstrated excellent outcomes. This is otherwise known as “value-based purchasing,” based on a model from Harvard Business School.2

Bundled payments will become the norm

OBG Management: Can you elaborate a bit on episodes of care?

Dr. Levy: By episode of care, I mean bundled payments. For example, pregnancy services where prenatal care, delivery, and postpartum care are bundled, or management of fibroids where the diagnosis, imaging, medical, and, potentially, surgical management could all be included in a single payment. All interventions in these periods would be grouped together and reimbursed at a set rate. As a result, the clinicians caring for the patient during these episodes have more of an incentive to reduce unnecessary costs. Are a first-trimester ultrasound scan and two second-trimester scans really necessary? Or might there be a less expensive way to ensure the same optimal outcome? Are the fibroids symptomatic or might observation be a more appropriate option for the patient?

OBG Management: Some people might assume you are prescribing “cookbook medicine” by urging a reduction in variations in care.

Dr. Levy: Not at all. I’m talking about reducing significant variations in outcomes, not processes. Physicians should remain free to treat the patient, using whatever approach they deem to be in her best interest. However, cost pressures mean that we will need to become more creative in keeping costs down without impairing outcomes.

OBG Management: What will happen if physicians don’t keep these cost pressures in mind?

Dr. Levy: People are already keeping score. CMS and payers are using ICD-9 diagnoses, married to the CPT code—the intervention, as well as the episode—and including the costs of things we may have no idea are being spent, such as pharmaceuticals, a return to the emergency room, and so on. We need to be aware of what other people are measuring. We need to understand what we are being measured on: patient satisfaction, quality of life, morbidity and mortality, and cost.

What can gynecologic surgeons do?

OBG Management: Here’s the million dollar question: What can gynecologic surgeons do about this problem?

Dr. Levy: We need to step up to the plate. We need to read the literature critically to focus on clinically meaningful outcomes. Although small differences in blood loss, analgesic use, or operating times may be statistically significant, they do not produce outcomes that are apparent and meaningful to our patients.

We also need to encourage comparative effectiveness research, which is essential to ensure the most clinically meaningful and cost-effective care.

Now that “DSH” payments—disproportional share, or the incremental amount of money that hospitals collected to reimburse them for care of the uninsured—are going away, hospitals are going to need to cut expenses 20% to 25% over the next 3 years to survive. You can bet they are going to change the way they look at you. Be prepared for them to limit the “toys” you are allowed to have, and other cuts.

OBG Management: Can you recommend specific steps?

Dr. Levy: Yes, we need to:

- think creatively to contain costs. A good book on this subject is Unaccountable: What Hospitals Won’t Tell You and How Transparency Can Revolutionize Health Care, by Marty Makary, MD.3

- track our own outcomes. Although it is irritating and time-consuming to enter data, it’s a little easier with electronic medical records. We need to document our own long-term outcomes. In fact, ACOG is working with the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology to look at ways we can create a structure for us to track our own outcomes as part of the maintenance of certification (MOC) process. When you track data, the Hawthorne effect comes into play: You get better at the activity you’re tracking, simply by writing it down.

- collaborate with others in our communities to improve public health issues such as obesity, smoking, and teenage access to contraception

- question and challenge preconceived notions and beliefs. We have a lot of them in surgery. For example, we tell patients not to lift after hysterectomy, not to have sex after hysteroscopic resection—but we have absolutely no data suggesting that these admonitions are helpful. Bowel prep is another example. Data have demonstrated that it not only does not benefit the patient, mechanical prep causes harm—but the randomized, controlled trials documenting this fact appear in the surgical literature, not the gynecologic literature. And guess how long it takes for us to incorporate definitive data like that into gynecologic practice? 17 years.

- get a seat at every table to participate in data definitions, acquisition, and dissemination to inform our daily clinical decisions

- participate in efforts to define and improve quality of care.

OBG Management: Any last comments?

Dr. Levy: I just want to emphasize how important it is that we take control of our destiny. If we are not at the table, we may be on the menu! But if we step up to the plate and approach these challenges the right way, we can become the premier surgical specialty.

- Why (and how) we must repeal the sustainable growth rate

Lucia DiVenere, MA (December 2012) - Women’s health under the Affordable Care Act: What is covered?

Lucia DiVenere, MA (September 2012) - How state budget crises are putting the squeeze on Medicaid

(and you)

Lucia DiVenere, MA (February 2012)

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. World Health Organization. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2008 estimates developed by WHO UNICEF, UNFPA and The World Bank. World Health Organization 2010, Annex 1. 2010. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241500265_eng.pdf. Accessed January 18, 2013.

2. Porter ME, Teisberg EO. Redefining health care: creating value-based competition on results. Boston MA: Harvard Business Review Press; 2006.

3. Makary M. Unaccountable: What Hospitalists Won’t Tell You and How Transparency Can Revolutionize Health Care. New York NY: Bloomsbury Press; 2012

Barbara S. Levy, MD, spent 29 years in private practice before accepting an appointment as vice president of health policy at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Those 29 years in private practice weren’t her only window onto the health-care arena, however. She has served as chair of the Resource Based Relative Value Scale Update Committee for the American Medical Association for 3 years; as medical director of Women’s and Children’s Services at Franciscan Health System in Tacoma, Washington; and as a long-time member of the OBG Management Board of Editors. As a result, she offers an informed and well-rounded perspective on the economics of surgical gynecology—the subject of a keynote address she delivered at the 2012 Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery (PAGS) symposium in December.

We sat down with Dr. Levy after her talk to explore some of the issues she raised—the focus of this Q&A. Dr. Levy also summarizes the high points of her talk in a video presentation available at obgmanagement.com.

OBG Management: What prompted you to leave private practice, move across country, and accept the post at ACOG?

Dr. Levy: I had spent the better part of 29 years complaining and feeling reasonably unhappy with what organized medicine was doing—or not doing—for ObGyns and our patients. I felt that the specialty was not really out there in front of the curve, driving the bus, so to speak, but was a victim of broader forces. So when I was given an opportunity to influence the way we approach health-care policy, to enable us to drive our own bus, I decided to take the challenge. I’m not sure I can make a difference, but I’m going to do everything possible to put us in control of our destiny. There are a lot of pitfalls out there, but I think that, given a commitment to doing what is right, we may be able to change the way we deliver health care in this country.

OBG Management: So what’s wrong with the way we deliver health care in the United States?

Dr. Levy: We are spending an inordinate amount of money. I’ve heard it referred to as an “investment,” but I’m not sure that word is accurate. It’s really an expenditure of trillions of dollars—as much as 17% of gross domestic product—but what are we getting in return? We’re not getting what we want or need. There is a lot of innovation out there, but what is it bringing us? Do we have better health care in this country, based on our per capita expenditure, than other developed nations have? The answer is “No.”

OBG Management: Why do you think that is?

Dr. Levy: If you look at the growth in Part B Medicare, and focus on where we’re spending the money, the culprits are pharmaceuticals, a huge increase in testing and imaging, and a sharp rise in office-based procedures. The complexity of services has also increased dramatically. Our population is aging, and obesity is epidemic and driving costs for management of diabetes, hypertension, and chronic heart disease, as well as joint replacements and back surgery. About 85% of Medicare dollars go to the care of 15% to 20% of the Medicare population. Yes, we’re reducing death rates from cardiovascular disease and cancer, but now we have a larger population of patients who have chronic, active disease.

OBG Management: Who’s responsible for this problem?

Dr. Levy: Our health-care systems have created this mess in many ways. We spend $98 billion annually on hospitalization for pregnancy and childbirth, but our mortality rate is increasing. We rank 50th in the world in maternal mortality despite a cesarean delivery rate over 30%, despite all the money that we’re spending—with maternal mortality higher here than in almost every European country, as well as several nations in Asia and the Middle East.1

OBG Management: Why are we spending so much money?

Dr. Levy: We have become so fearful—of poor outcomes, of litigation, and our patients are coming to us with demands for tests and treatment that cost them little or nothing—that we intervene with tests and procedures that increase the cost of care without providing any true benefit in terms of outcome.

We’ve also made some poor choices. We’ve allowed ourselves to be the victims of legislation, of rule-making, because we don’t sit down and read the 1,300 or so pages in the Federal Register from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) on proposed rule-making every year. Things happen to us that we aren’t aware of. We have allowed ourselves to be drawn in by innovation, by testing, and by fear until we have begun to do things that may not have any real benefit for our patients.

Both physicians and hospitals have driven volume to increase reimbursement. And industry has been drawn into the mix because the medical field is the only one that’s expanding. We have become our own worst enemies. We have not stepped up to the plate to define quality and value, so now others are doing it—and they don’t necessarily use the same definitions we do. We have allowed our fears of liability and misperceptions about the value of procedures to drive our decisions. For example, when we perform robotic hysterectomy in a woman who is a great candidate for the vaginal approach, we quadruple the cost of the surgery. Consider that we perform roughly 500,000 hysterectomies every year, and you can see how costs mount rapidly.

Flaws in the US health-care system

OBG Management: What are some of the other problems afflicting the US health-care system?

Dr. Levy: There are tremendous disparities in quality and cost across the country. Why? How we spend money in health care is cultural. It’s influenced by what we become accustomed to, what our particular environment calls “standard.” Here’s an example: A man who is experiencing knee pain tries to make an appointment with an orthopedic surgeon, but when he telephones the physician’s office, he is told that he can’t make an appointment until he has an MRI. That’s cultural, not medically justified.

Patients also play a role. When the patient comes in with a ream of paper from the Internet, and she wants a CA 125 test because she thinks it’s somehow going to prevent ovarian cancer, we need to explain to her, in a way she can understand, that adding that testing is of no benefit and may actually cause harm. We need quick statements that can help defuse the demand for increased testing.

Role of the government

OBG Management: What role does the government play?

Dr. Levy: The Medicare Resource-Based Relative Value Scale (RBRVS) was enacted into law in 1992. Most payers now follow this scale to determine reimbursement, based on how many resources it requires to perform a service. Resources are defined in the law—we can’t change them. But the American Medical Association did convene the RBRVS Update Committee (RUC), of which I am the chair, to do the best we can to define for the federal government exactly how many of those resources are necessary for a particular intervention. For example, how much time does it really take to perform laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy—and how does that compare with reading a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis or with performing a five-vessel bypass? How many office visits for hypertension does it take to equal an open-heart surgery and 90 days of care? That’s not an easy set of relative intensities to work through, but the RUC does do that and makes recommendations to CMS for the relative value units (RVUs) for the services we provide.

OBG Management: Is it time alone that determines the value of a service?

Dr. Levy: Physician work is defined as the time it takes to perform a procedure—but also as the intensity of that service as compared with other physician services.

There are also practice-expense RVUs, intended to address the cost of clinical staff, medical supplies, and equipment. Right now approximately 52% of reimbursement goes toward the practice-expense component, and less than 50% for the physician’s work.

In 1992, when the RBRVS was enacted, women’s health services were significantly undervalued because ObGyns did not form a large part of the Medicare fee schedule. Over the past 20 years, ACOG and the RUC have worked diligently to correct those initial inequities.

On the RUC, we believe that no physicians are paid at a level that is fair and appropriate, compared with a plumber or electrician. So the shift to a value-based system and away from the volume-based system may be beneficial to us.

Challenges ahead

OBG Management: What challenges do ObGyns face in attempting to overcome these problems?

Dr. Levy: The primary challenge is to face reality as it is—not as it was in the “good old days” or as we wish it to be. We need to become advocates for ourselves and our patients. Advocacy would support and promote our patients’ health-care rights and enhance community health. It would also foster policy initiatives that focus on availability, safety, and quality of care.

In our advocacy, we need to focus first on quality. If we don’t define quality ourselves, others are going to decide that quality is a constant and that the only thing that matters is cost, and they will shift all services to the lowest-cost providers. That is not the way we want things to go.

Some changes are already in play:

- Out-of-pocket costs for patients are increasing, motivating patients to become more discriminating

- Payment models will soon focus on “episodes of care,” with incentives for systems to reduce surgical volumes while preserving the patient’s quality of life

- Surgery will shift from low-volume surgeons to high-volume physicians who have demonstrated excellent outcomes. This is otherwise known as “value-based purchasing,” based on a model from Harvard Business School.2

Bundled payments will become the norm

OBG Management: Can you elaborate a bit on episodes of care?

Dr. Levy: By episode of care, I mean bundled payments. For example, pregnancy services where prenatal care, delivery, and postpartum care are bundled, or management of fibroids where the diagnosis, imaging, medical, and, potentially, surgical management could all be included in a single payment. All interventions in these periods would be grouped together and reimbursed at a set rate. As a result, the clinicians caring for the patient during these episodes have more of an incentive to reduce unnecessary costs. Are a first-trimester ultrasound scan and two second-trimester scans really necessary? Or might there be a less expensive way to ensure the same optimal outcome? Are the fibroids symptomatic or might observation be a more appropriate option for the patient?

OBG Management: Some people might assume you are prescribing “cookbook medicine” by urging a reduction in variations in care.

Dr. Levy: Not at all. I’m talking about reducing significant variations in outcomes, not processes. Physicians should remain free to treat the patient, using whatever approach they deem to be in her best interest. However, cost pressures mean that we will need to become more creative in keeping costs down without impairing outcomes.

OBG Management: What will happen if physicians don’t keep these cost pressures in mind?

Dr. Levy: People are already keeping score. CMS and payers are using ICD-9 diagnoses, married to the CPT code—the intervention, as well as the episode—and including the costs of things we may have no idea are being spent, such as pharmaceuticals, a return to the emergency room, and so on. We need to be aware of what other people are measuring. We need to understand what we are being measured on: patient satisfaction, quality of life, morbidity and mortality, and cost.

What can gynecologic surgeons do?

OBG Management: Here’s the million dollar question: What can gynecologic surgeons do about this problem?

Dr. Levy: We need to step up to the plate. We need to read the literature critically to focus on clinically meaningful outcomes. Although small differences in blood loss, analgesic use, or operating times may be statistically significant, they do not produce outcomes that are apparent and meaningful to our patients.

We also need to encourage comparative effectiveness research, which is essential to ensure the most clinically meaningful and cost-effective care.

Now that “DSH” payments—disproportional share, or the incremental amount of money that hospitals collected to reimburse them for care of the uninsured—are going away, hospitals are going to need to cut expenses 20% to 25% over the next 3 years to survive. You can bet they are going to change the way they look at you. Be prepared for them to limit the “toys” you are allowed to have, and other cuts.

OBG Management: Can you recommend specific steps?

Dr. Levy: Yes, we need to:

- think creatively to contain costs. A good book on this subject is Unaccountable: What Hospitals Won’t Tell You and How Transparency Can Revolutionize Health Care, by Marty Makary, MD.3

- track our own outcomes. Although it is irritating and time-consuming to enter data, it’s a little easier with electronic medical records. We need to document our own long-term outcomes. In fact, ACOG is working with the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology to look at ways we can create a structure for us to track our own outcomes as part of the maintenance of certification (MOC) process. When you track data, the Hawthorne effect comes into play: You get better at the activity you’re tracking, simply by writing it down.

- collaborate with others in our communities to improve public health issues such as obesity, smoking, and teenage access to contraception

- question and challenge preconceived notions and beliefs. We have a lot of them in surgery. For example, we tell patients not to lift after hysterectomy, not to have sex after hysteroscopic resection—but we have absolutely no data suggesting that these admonitions are helpful. Bowel prep is another example. Data have demonstrated that it not only does not benefit the patient, mechanical prep causes harm—but the randomized, controlled trials documenting this fact appear in the surgical literature, not the gynecologic literature. And guess how long it takes for us to incorporate definitive data like that into gynecologic practice? 17 years.

- get a seat at every table to participate in data definitions, acquisition, and dissemination to inform our daily clinical decisions

- participate in efforts to define and improve quality of care.

OBG Management: Any last comments?

Dr. Levy: I just want to emphasize how important it is that we take control of our destiny. If we are not at the table, we may be on the menu! But if we step up to the plate and approach these challenges the right way, we can become the premier surgical specialty.

- Why (and how) we must repeal the sustainable growth rate

Lucia DiVenere, MA (December 2012) - Women’s health under the Affordable Care Act: What is covered?

Lucia DiVenere, MA (September 2012) - How state budget crises are putting the squeeze on Medicaid

(and you)

Lucia DiVenere, MA (February 2012)

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Barbara S. Levy, MD, spent 29 years in private practice before accepting an appointment as vice president of health policy at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Those 29 years in private practice weren’t her only window onto the health-care arena, however. She has served as chair of the Resource Based Relative Value Scale Update Committee for the American Medical Association for 3 years; as medical director of Women’s and Children’s Services at Franciscan Health System in Tacoma, Washington; and as a long-time member of the OBG Management Board of Editors. As a result, she offers an informed and well-rounded perspective on the economics of surgical gynecology—the subject of a keynote address she delivered at the 2012 Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery (PAGS) symposium in December.

We sat down with Dr. Levy after her talk to explore some of the issues she raised—the focus of this Q&A. Dr. Levy also summarizes the high points of her talk in a video presentation available at obgmanagement.com.

OBG Management: What prompted you to leave private practice, move across country, and accept the post at ACOG?

Dr. Levy: I had spent the better part of 29 years complaining and feeling reasonably unhappy with what organized medicine was doing—or not doing—for ObGyns and our patients. I felt that the specialty was not really out there in front of the curve, driving the bus, so to speak, but was a victim of broader forces. So when I was given an opportunity to influence the way we approach health-care policy, to enable us to drive our own bus, I decided to take the challenge. I’m not sure I can make a difference, but I’m going to do everything possible to put us in control of our destiny. There are a lot of pitfalls out there, but I think that, given a commitment to doing what is right, we may be able to change the way we deliver health care in this country.

OBG Management: So what’s wrong with the way we deliver health care in the United States?

Dr. Levy: We are spending an inordinate amount of money. I’ve heard it referred to as an “investment,” but I’m not sure that word is accurate. It’s really an expenditure of trillions of dollars—as much as 17% of gross domestic product—but what are we getting in return? We’re not getting what we want or need. There is a lot of innovation out there, but what is it bringing us? Do we have better health care in this country, based on our per capita expenditure, than other developed nations have? The answer is “No.”

OBG Management: Why do you think that is?

Dr. Levy: If you look at the growth in Part B Medicare, and focus on where we’re spending the money, the culprits are pharmaceuticals, a huge increase in testing and imaging, and a sharp rise in office-based procedures. The complexity of services has also increased dramatically. Our population is aging, and obesity is epidemic and driving costs for management of diabetes, hypertension, and chronic heart disease, as well as joint replacements and back surgery. About 85% of Medicare dollars go to the care of 15% to 20% of the Medicare population. Yes, we’re reducing death rates from cardiovascular disease and cancer, but now we have a larger population of patients who have chronic, active disease.

OBG Management: Who’s responsible for this problem?

Dr. Levy: Our health-care systems have created this mess in many ways. We spend $98 billion annually on hospitalization for pregnancy and childbirth, but our mortality rate is increasing. We rank 50th in the world in maternal mortality despite a cesarean delivery rate over 30%, despite all the money that we’re spending—with maternal mortality higher here than in almost every European country, as well as several nations in Asia and the Middle East.1

OBG Management: Why are we spending so much money?

Dr. Levy: We have become so fearful—of poor outcomes, of litigation, and our patients are coming to us with demands for tests and treatment that cost them little or nothing—that we intervene with tests and procedures that increase the cost of care without providing any true benefit in terms of outcome.

We’ve also made some poor choices. We’ve allowed ourselves to be the victims of legislation, of rule-making, because we don’t sit down and read the 1,300 or so pages in the Federal Register from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) on proposed rule-making every year. Things happen to us that we aren’t aware of. We have allowed ourselves to be drawn in by innovation, by testing, and by fear until we have begun to do things that may not have any real benefit for our patients.