User login

Failure to Identify Blockage During Catheterization

A 37-year-old Virginia man experienced sudden-onset chest pain, dyspnea, diaphoresis, and jaw pain. He was transported to a community hospital, where he was admitted. The patient’s ECG was read as normal, and his troponin levels were mildly elevated. This took place in January.

The next day, he was seen by a cardiologist, who recommended a stress test. Instead, the patient requested a cardiac catheterization, based on his understanding that it was the definitive test to rule out heart disease. The cardiologist consented and had the patient transferred to a regional medical center. There, the patient was seen by Dr. A., an invasive cardiologist. Two days later, Dr. A. performed a cardiac catheterization and informed the patient that his coronary arteries were clean, normal, and free of disease. Dr. A. diagnosed the patient with pericarditis, recommended treatment with NSAIDs, and discharged him home.

Over the next two months, the patient’s chest pain and dyspnea returned. He saw a nurse practitioner at his family medicine practice four times. The NP had electronic access to Dr. A.’s catheterization report and to the patient’s discharge summary. The NP continued treatment for pericarditis.

In April, the patient experienced a massive MI. He was ultimately taken back to the regional medical center, where he received care from cardiologist Dr. B. (a partner of Dr. A.’s). Dr. B. performed an emergency cardiac catheterization and identified a complete blockage of the left anterior descending artery (LAD).

After several unsuccessful attempts, Dr. B. was able to dilate the artery and place two stents to improve blood flow. Further, Dr. B. reviewed the earlier catheterization performed by Dr. A. and noted a blockage of the LAD, which he characterized as an “eccentric 70% or so stenosis very proximally.”

Following the MI, the patient was hospitalized several times and underwent eight subsequent cardiac catheterizations. He had an internal cardiac defibrillator placed and eventually required coronary artery bypass surgery. His post-MI ejection fraction was 25% to 30%, compared with 55% to 60% noted by Dr. A. after the initial cardiac catheterization. The patient was determined to be in NYHA Class II or III heart failure and was expected to require a left ventricular assist device and ultimately a heart transplant within five to six years. The patient was assessed to have a 50% 10-year mortality.

The plaintiff claimed that Dr. A.’s interpretation of the cardiac catheterization as “normal” was negligent. The plaintiff contended that a stent should have been placed and that the plaintiff should have been told he had coronary artery disease (CAD).

The defendants admitted that Dr. A. had missed a partial blockage of the LAD but maintained that the blockage was only 20% to 30%; this, they argued, was clinically insignificant and did not warrant a stent. The defendants also claimed that the diagnosis of pericarditis was reasonable and that the plaintiff’s MI was the result of an unexpected plaque rupture.

Outcome

According to a published account, a $25 million verdict was returned. Posttrial motions regarding application of state caps were pending.

Comment

This $25 million dollar verdict is believed to be the largest medical malpractice verdict in Virginia history. For several reasons, this case warrants discussion.

Here, we have a 37-year-old patient presenting with symptoms suggestive of ischemic heart disease. His catheterization was initially read as “normal,” but a second look revealed a stenotic LAD. Dr. A. informed the patient that his coronary arteries were “clean, normal, and free of disease.” Yet during trial, Dr. A. changed his position—admitting disease but insisting that the blockage was clinically insignificant at only 25% to 30%.

The patient was diagnosed and treated for pericarditis and remained symptomatic during the next two months. The patient saw his NP four times with these symptoms and continued to be treated for pericarditis.

Three months after his first presentation, he experienced a massive MI with complete occlusion of the LAD. His left ventricular function is severely impaired, and he faces a 50% chance of mortality within 10 years, even with a successful heart transplant.

The jurors in this case seem to have found the plaintiff’s expert credible. They considered Dr. B.’s reassessment that the LAD was 70% occluded both alarming and vastly at odds with his partner’s first assessment of “normal” and second assessment of “only 25% to 30% occluded.” The jurors obviously dismissed the defense theory that a 25% to 30% “clinically insignificant” plaque suddenly and unexpectedly ruptured.

The patient’s four subsequent visits to the NP could have represented an opportunity to reconsider whether the source of his pain was related to coronary flow. Admittedly, it is tempting to view an essentially negative cath report as conclusive—and I submit many of us would. But the character, quality, and location of the pain (as well as the troponin bump during the initial presentation) could have raised suspicion that the source of the pain was related to coronary flow.

In counterargument, it would be difficult to fault the NP for relying on the faulty catheterization report if he or she had no reason to suspect that it was erroneous. Unless the patient’s presentation on those four visits had been suggestive of CAD or discordant with pericarditis, it is not likely the NP breached the standard of care.

Always consider the possibility that a study could have been misinterpreted or that it could have mistakenly described the wrong patient. Additionally, even a reassuring cath report can’t account for all clinically important coronary events, such as vasospastic causes or plaque disruption. If the patient’s story is compelling, be willing to revisit the possibility of CAD.

Further, the plaintiff’s expert likely testified that the first cath report demonstrated a significant stenosis which required stenting and that the standard of care required aspirin, b-blockers, and lipid-lowering agents. Whether or not stent placement and medical optimization would have ultimately made a difference for this patient in the next three months, we don’t know. We do know the plaintiff’s attorney was able to persuade the jury that these efforts would have spared the patient and that the missed diagnosis was causally related to the plaintiff’s subsequent severe MI and unfortunate sequelae—justifying the monumental $25 million verdict.

Virginia state law places a $2 million cap on medical malpractice damages. However, as of the date of this writing, the plaintiff’s attorney is challenging the validity of Virginia’s cap.

The defendant’s theory brings up an important issue: the adherent plaque that does not by itself cause clinically important flow disruption—but causes mayhem if ruptured. The rupture of a “vulnerable plaque” was the unfortunate case with Tim Russert, the late, great host of Meet the Press. Mr. Russert was known to have CAD and by all accounts was well optimized, but suffered an unexpected and unpredictable rupture of a “vulnerable plaque,” which proved fatal.

Consider traditional fixed stenotic lesions that cause the usual flow limitations, but also remember that a modest lesion could represent a “vulnerable plaque” capable of rupture. —DML

Cases reprinted with permission from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements and Experts, Lewis Laska, Editor, (800) 298-6288.

A 37-year-old Virginia man experienced sudden-onset chest pain, dyspnea, diaphoresis, and jaw pain. He was transported to a community hospital, where he was admitted. The patient’s ECG was read as normal, and his troponin levels were mildly elevated. This took place in January.

The next day, he was seen by a cardiologist, who recommended a stress test. Instead, the patient requested a cardiac catheterization, based on his understanding that it was the definitive test to rule out heart disease. The cardiologist consented and had the patient transferred to a regional medical center. There, the patient was seen by Dr. A., an invasive cardiologist. Two days later, Dr. A. performed a cardiac catheterization and informed the patient that his coronary arteries were clean, normal, and free of disease. Dr. A. diagnosed the patient with pericarditis, recommended treatment with NSAIDs, and discharged him home.

Over the next two months, the patient’s chest pain and dyspnea returned. He saw a nurse practitioner at his family medicine practice four times. The NP had electronic access to Dr. A.’s catheterization report and to the patient’s discharge summary. The NP continued treatment for pericarditis.

In April, the patient experienced a massive MI. He was ultimately taken back to the regional medical center, where he received care from cardiologist Dr. B. (a partner of Dr. A.’s). Dr. B. performed an emergency cardiac catheterization and identified a complete blockage of the left anterior descending artery (LAD).

After several unsuccessful attempts, Dr. B. was able to dilate the artery and place two stents to improve blood flow. Further, Dr. B. reviewed the earlier catheterization performed by Dr. A. and noted a blockage of the LAD, which he characterized as an “eccentric 70% or so stenosis very proximally.”

Following the MI, the patient was hospitalized several times and underwent eight subsequent cardiac catheterizations. He had an internal cardiac defibrillator placed and eventually required coronary artery bypass surgery. His post-MI ejection fraction was 25% to 30%, compared with 55% to 60% noted by Dr. A. after the initial cardiac catheterization. The patient was determined to be in NYHA Class II or III heart failure and was expected to require a left ventricular assist device and ultimately a heart transplant within five to six years. The patient was assessed to have a 50% 10-year mortality.

The plaintiff claimed that Dr. A.’s interpretation of the cardiac catheterization as “normal” was negligent. The plaintiff contended that a stent should have been placed and that the plaintiff should have been told he had coronary artery disease (CAD).

The defendants admitted that Dr. A. had missed a partial blockage of the LAD but maintained that the blockage was only 20% to 30%; this, they argued, was clinically insignificant and did not warrant a stent. The defendants also claimed that the diagnosis of pericarditis was reasonable and that the plaintiff’s MI was the result of an unexpected plaque rupture.

Outcome

According to a published account, a $25 million verdict was returned. Posttrial motions regarding application of state caps were pending.

Comment

This $25 million dollar verdict is believed to be the largest medical malpractice verdict in Virginia history. For several reasons, this case warrants discussion.

Here, we have a 37-year-old patient presenting with symptoms suggestive of ischemic heart disease. His catheterization was initially read as “normal,” but a second look revealed a stenotic LAD. Dr. A. informed the patient that his coronary arteries were “clean, normal, and free of disease.” Yet during trial, Dr. A. changed his position—admitting disease but insisting that the blockage was clinically insignificant at only 25% to 30%.

The patient was diagnosed and treated for pericarditis and remained symptomatic during the next two months. The patient saw his NP four times with these symptoms and continued to be treated for pericarditis.

Three months after his first presentation, he experienced a massive MI with complete occlusion of the LAD. His left ventricular function is severely impaired, and he faces a 50% chance of mortality within 10 years, even with a successful heart transplant.

The jurors in this case seem to have found the plaintiff’s expert credible. They considered Dr. B.’s reassessment that the LAD was 70% occluded both alarming and vastly at odds with his partner’s first assessment of “normal” and second assessment of “only 25% to 30% occluded.” The jurors obviously dismissed the defense theory that a 25% to 30% “clinically insignificant” plaque suddenly and unexpectedly ruptured.

The patient’s four subsequent visits to the NP could have represented an opportunity to reconsider whether the source of his pain was related to coronary flow. Admittedly, it is tempting to view an essentially negative cath report as conclusive—and I submit many of us would. But the character, quality, and location of the pain (as well as the troponin bump during the initial presentation) could have raised suspicion that the source of the pain was related to coronary flow.

In counterargument, it would be difficult to fault the NP for relying on the faulty catheterization report if he or she had no reason to suspect that it was erroneous. Unless the patient’s presentation on those four visits had been suggestive of CAD or discordant with pericarditis, it is not likely the NP breached the standard of care.

Always consider the possibility that a study could have been misinterpreted or that it could have mistakenly described the wrong patient. Additionally, even a reassuring cath report can’t account for all clinically important coronary events, such as vasospastic causes or plaque disruption. If the patient’s story is compelling, be willing to revisit the possibility of CAD.

Further, the plaintiff’s expert likely testified that the first cath report demonstrated a significant stenosis which required stenting and that the standard of care required aspirin, b-blockers, and lipid-lowering agents. Whether or not stent placement and medical optimization would have ultimately made a difference for this patient in the next three months, we don’t know. We do know the plaintiff’s attorney was able to persuade the jury that these efforts would have spared the patient and that the missed diagnosis was causally related to the plaintiff’s subsequent severe MI and unfortunate sequelae—justifying the monumental $25 million verdict.

Virginia state law places a $2 million cap on medical malpractice damages. However, as of the date of this writing, the plaintiff’s attorney is challenging the validity of Virginia’s cap.

The defendant’s theory brings up an important issue: the adherent plaque that does not by itself cause clinically important flow disruption—but causes mayhem if ruptured. The rupture of a “vulnerable plaque” was the unfortunate case with Tim Russert, the late, great host of Meet the Press. Mr. Russert was known to have CAD and by all accounts was well optimized, but suffered an unexpected and unpredictable rupture of a “vulnerable plaque,” which proved fatal.

Consider traditional fixed stenotic lesions that cause the usual flow limitations, but also remember that a modest lesion could represent a “vulnerable plaque” capable of rupture. —DML

Cases reprinted with permission from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements and Experts, Lewis Laska, Editor, (800) 298-6288.

A 37-year-old Virginia man experienced sudden-onset chest pain, dyspnea, diaphoresis, and jaw pain. He was transported to a community hospital, where he was admitted. The patient’s ECG was read as normal, and his troponin levels were mildly elevated. This took place in January.

The next day, he was seen by a cardiologist, who recommended a stress test. Instead, the patient requested a cardiac catheterization, based on his understanding that it was the definitive test to rule out heart disease. The cardiologist consented and had the patient transferred to a regional medical center. There, the patient was seen by Dr. A., an invasive cardiologist. Two days later, Dr. A. performed a cardiac catheterization and informed the patient that his coronary arteries were clean, normal, and free of disease. Dr. A. diagnosed the patient with pericarditis, recommended treatment with NSAIDs, and discharged him home.

Over the next two months, the patient’s chest pain and dyspnea returned. He saw a nurse practitioner at his family medicine practice four times. The NP had electronic access to Dr. A.’s catheterization report and to the patient’s discharge summary. The NP continued treatment for pericarditis.

In April, the patient experienced a massive MI. He was ultimately taken back to the regional medical center, where he received care from cardiologist Dr. B. (a partner of Dr. A.’s). Dr. B. performed an emergency cardiac catheterization and identified a complete blockage of the left anterior descending artery (LAD).

After several unsuccessful attempts, Dr. B. was able to dilate the artery and place two stents to improve blood flow. Further, Dr. B. reviewed the earlier catheterization performed by Dr. A. and noted a blockage of the LAD, which he characterized as an “eccentric 70% or so stenosis very proximally.”

Following the MI, the patient was hospitalized several times and underwent eight subsequent cardiac catheterizations. He had an internal cardiac defibrillator placed and eventually required coronary artery bypass surgery. His post-MI ejection fraction was 25% to 30%, compared with 55% to 60% noted by Dr. A. after the initial cardiac catheterization. The patient was determined to be in NYHA Class II or III heart failure and was expected to require a left ventricular assist device and ultimately a heart transplant within five to six years. The patient was assessed to have a 50% 10-year mortality.

The plaintiff claimed that Dr. A.’s interpretation of the cardiac catheterization as “normal” was negligent. The plaintiff contended that a stent should have been placed and that the plaintiff should have been told he had coronary artery disease (CAD).

The defendants admitted that Dr. A. had missed a partial blockage of the LAD but maintained that the blockage was only 20% to 30%; this, they argued, was clinically insignificant and did not warrant a stent. The defendants also claimed that the diagnosis of pericarditis was reasonable and that the plaintiff’s MI was the result of an unexpected plaque rupture.

Outcome

According to a published account, a $25 million verdict was returned. Posttrial motions regarding application of state caps were pending.

Comment

This $25 million dollar verdict is believed to be the largest medical malpractice verdict in Virginia history. For several reasons, this case warrants discussion.

Here, we have a 37-year-old patient presenting with symptoms suggestive of ischemic heart disease. His catheterization was initially read as “normal,” but a second look revealed a stenotic LAD. Dr. A. informed the patient that his coronary arteries were “clean, normal, and free of disease.” Yet during trial, Dr. A. changed his position—admitting disease but insisting that the blockage was clinically insignificant at only 25% to 30%.

The patient was diagnosed and treated for pericarditis and remained symptomatic during the next two months. The patient saw his NP four times with these symptoms and continued to be treated for pericarditis.

Three months after his first presentation, he experienced a massive MI with complete occlusion of the LAD. His left ventricular function is severely impaired, and he faces a 50% chance of mortality within 10 years, even with a successful heart transplant.

The jurors in this case seem to have found the plaintiff’s expert credible. They considered Dr. B.’s reassessment that the LAD was 70% occluded both alarming and vastly at odds with his partner’s first assessment of “normal” and second assessment of “only 25% to 30% occluded.” The jurors obviously dismissed the defense theory that a 25% to 30% “clinically insignificant” plaque suddenly and unexpectedly ruptured.

The patient’s four subsequent visits to the NP could have represented an opportunity to reconsider whether the source of his pain was related to coronary flow. Admittedly, it is tempting to view an essentially negative cath report as conclusive—and I submit many of us would. But the character, quality, and location of the pain (as well as the troponin bump during the initial presentation) could have raised suspicion that the source of the pain was related to coronary flow.

In counterargument, it would be difficult to fault the NP for relying on the faulty catheterization report if he or she had no reason to suspect that it was erroneous. Unless the patient’s presentation on those four visits had been suggestive of CAD or discordant with pericarditis, it is not likely the NP breached the standard of care.

Always consider the possibility that a study could have been misinterpreted or that it could have mistakenly described the wrong patient. Additionally, even a reassuring cath report can’t account for all clinically important coronary events, such as vasospastic causes or plaque disruption. If the patient’s story is compelling, be willing to revisit the possibility of CAD.

Further, the plaintiff’s expert likely testified that the first cath report demonstrated a significant stenosis which required stenting and that the standard of care required aspirin, b-blockers, and lipid-lowering agents. Whether or not stent placement and medical optimization would have ultimately made a difference for this patient in the next three months, we don’t know. We do know the plaintiff’s attorney was able to persuade the jury that these efforts would have spared the patient and that the missed diagnosis was causally related to the plaintiff’s subsequent severe MI and unfortunate sequelae—justifying the monumental $25 million verdict.

Virginia state law places a $2 million cap on medical malpractice damages. However, as of the date of this writing, the plaintiff’s attorney is challenging the validity of Virginia’s cap.

The defendant’s theory brings up an important issue: the adherent plaque that does not by itself cause clinically important flow disruption—but causes mayhem if ruptured. The rupture of a “vulnerable plaque” was the unfortunate case with Tim Russert, the late, great host of Meet the Press. Mr. Russert was known to have CAD and by all accounts was well optimized, but suffered an unexpected and unpredictable rupture of a “vulnerable plaque,” which proved fatal.

Consider traditional fixed stenotic lesions that cause the usual flow limitations, but also remember that a modest lesion could represent a “vulnerable plaque” capable of rupture. —DML

Cases reprinted with permission from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements and Experts, Lewis Laska, Editor, (800) 298-6288.

Hospitalists Should Refrain from Texting Patient Information

Refrain from Texting about Your Patients

Can I text my partners patient information?

–Stephen Henry, San Luis Obispo, Calif.

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Can you? Sure. Do you? Probably. Should you? No.

Texting any patient information falls under the category of ePHI (Electronic Protected Health Information) as part of HIPAA. Technically, such patient-specific information must be protected at all times. Once you send a text, at least three copies are known to exist: one on each of the devices, plus one copy on the network it went through, adding for each network it has to cross. Sure, your phone may be password-protected, but is your partner’s? What about the carrier? How protected is their data?

HIPAA goes into excruciating technical detail about all the safeguards that must be present. You are more than welcome to read it (www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/administrative/securityrule) to see if you meet all the standards. Or you can take my word for it: You don’t.

So you can see why most health organizations expressly prohibit the texting of patient information. If you rang up your local health-care or hospital lawyer, I’m sure they would tell you to never text patient information. Is that reasonable advice? In 2013, I doubt it.

So what’s the practical advice to follow? For starters, password-protect your phone, if you haven’t already. Nothing worse than losing your phone and having patient information on it. A lot of the OCR (Office for Civil Rights, a branch of Health and Human Services) fines for HIPAA violations stem from folks misplacing unencrypted devices with patient information on them.

Just as important, don’t text anything that you wouldn’t want to see blown up on a lawyer’s display board in court. I’ve seen some really egregious examples of communication between doctors that have no business being preserved electronically. Texting “Mr. X in Room 2101 is a meth-using, narcotic-seeking, half-naked, lunatic troll” is an absolutely stupid thing to do. For that matter, so are remarks that seem less offensive: “And his son is completely unreasonable.” Save your commentary and stick to the facts, because you just generated three copies forever.

If you receive an insensitive text, don’t reply. Simply call the sending physician to discuss any issues. Even being on a “secure” texting network won’t protect you from errors of commission.

If I were to text about a patient (purely hypothetically, mind you), I would limit the information as much as possible. Keep it simple and generic (what HIPAA likes to call “de-identified information”)—for example, “Room 428 is ready for discharge.”

Please, hold the subjective commentary. There is no good reason to have an extended text exchange about a patient; you are creating an electronic trail that has no good reason to exist and never really goes away. It’s just the same as writing in the chart, except that it has the illusion of privacy. And that’s all it is: an illusion.

At the end of the day, I’d probably worry more about the discoverable aspect of your text messages in a lawsuit than the possibility of a HIPAA fine, but neither one sounds like much fun to me.

Refrain from Texting about Your Patients

Can I text my partners patient information?

–Stephen Henry, San Luis Obispo, Calif.

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Can you? Sure. Do you? Probably. Should you? No.

Texting any patient information falls under the category of ePHI (Electronic Protected Health Information) as part of HIPAA. Technically, such patient-specific information must be protected at all times. Once you send a text, at least three copies are known to exist: one on each of the devices, plus one copy on the network it went through, adding for each network it has to cross. Sure, your phone may be password-protected, but is your partner’s? What about the carrier? How protected is their data?

HIPAA goes into excruciating technical detail about all the safeguards that must be present. You are more than welcome to read it (www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/administrative/securityrule) to see if you meet all the standards. Or you can take my word for it: You don’t.

So you can see why most health organizations expressly prohibit the texting of patient information. If you rang up your local health-care or hospital lawyer, I’m sure they would tell you to never text patient information. Is that reasonable advice? In 2013, I doubt it.

So what’s the practical advice to follow? For starters, password-protect your phone, if you haven’t already. Nothing worse than losing your phone and having patient information on it. A lot of the OCR (Office for Civil Rights, a branch of Health and Human Services) fines for HIPAA violations stem from folks misplacing unencrypted devices with patient information on them.

Just as important, don’t text anything that you wouldn’t want to see blown up on a lawyer’s display board in court. I’ve seen some really egregious examples of communication between doctors that have no business being preserved electronically. Texting “Mr. X in Room 2101 is a meth-using, narcotic-seeking, half-naked, lunatic troll” is an absolutely stupid thing to do. For that matter, so are remarks that seem less offensive: “And his son is completely unreasonable.” Save your commentary and stick to the facts, because you just generated three copies forever.

If you receive an insensitive text, don’t reply. Simply call the sending physician to discuss any issues. Even being on a “secure” texting network won’t protect you from errors of commission.

If I were to text about a patient (purely hypothetically, mind you), I would limit the information as much as possible. Keep it simple and generic (what HIPAA likes to call “de-identified information”)—for example, “Room 428 is ready for discharge.”

Please, hold the subjective commentary. There is no good reason to have an extended text exchange about a patient; you are creating an electronic trail that has no good reason to exist and never really goes away. It’s just the same as writing in the chart, except that it has the illusion of privacy. And that’s all it is: an illusion.

At the end of the day, I’d probably worry more about the discoverable aspect of your text messages in a lawsuit than the possibility of a HIPAA fine, but neither one sounds like much fun to me.

Refrain from Texting about Your Patients

Can I text my partners patient information?

–Stephen Henry, San Luis Obispo, Calif.

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Can you? Sure. Do you? Probably. Should you? No.

Texting any patient information falls under the category of ePHI (Electronic Protected Health Information) as part of HIPAA. Technically, such patient-specific information must be protected at all times. Once you send a text, at least three copies are known to exist: one on each of the devices, plus one copy on the network it went through, adding for each network it has to cross. Sure, your phone may be password-protected, but is your partner’s? What about the carrier? How protected is their data?

HIPAA goes into excruciating technical detail about all the safeguards that must be present. You are more than welcome to read it (www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/administrative/securityrule) to see if you meet all the standards. Or you can take my word for it: You don’t.

So you can see why most health organizations expressly prohibit the texting of patient information. If you rang up your local health-care or hospital lawyer, I’m sure they would tell you to never text patient information. Is that reasonable advice? In 2013, I doubt it.

So what’s the practical advice to follow? For starters, password-protect your phone, if you haven’t already. Nothing worse than losing your phone and having patient information on it. A lot of the OCR (Office for Civil Rights, a branch of Health and Human Services) fines for HIPAA violations stem from folks misplacing unencrypted devices with patient information on them.

Just as important, don’t text anything that you wouldn’t want to see blown up on a lawyer’s display board in court. I’ve seen some really egregious examples of communication between doctors that have no business being preserved electronically. Texting “Mr. X in Room 2101 is a meth-using, narcotic-seeking, half-naked, lunatic troll” is an absolutely stupid thing to do. For that matter, so are remarks that seem less offensive: “And his son is completely unreasonable.” Save your commentary and stick to the facts, because you just generated three copies forever.

If you receive an insensitive text, don’t reply. Simply call the sending physician to discuss any issues. Even being on a “secure” texting network won’t protect you from errors of commission.

If I were to text about a patient (purely hypothetically, mind you), I would limit the information as much as possible. Keep it simple and generic (what HIPAA likes to call “de-identified information”)—for example, “Room 428 is ready for discharge.”

Please, hold the subjective commentary. There is no good reason to have an extended text exchange about a patient; you are creating an electronic trail that has no good reason to exist and never really goes away. It’s just the same as writing in the chart, except that it has the illusion of privacy. And that’s all it is: an illusion.

At the end of the day, I’d probably worry more about the discoverable aspect of your text messages in a lawsuit than the possibility of a HIPAA fine, but neither one sounds like much fun to me.

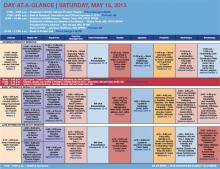

SHM To Award First Certificates of Leadership at HM13

This month, Thomas McIlraith, MD, SFHM, will be on stage at HM13 accepting one of the first SHM Certificates in Leadership. As chair of hospital medicine at Sacramento, Calif.-based Mercy Medical Group, Dr. McIlraith already is familiar with the need for leadership in our specialty and shares why SHM’s Leadership Academy and new certification have helped his hospital and his career.

Question: What made you apply for the Certificate in Leadership in the first place?

Answer: I have always felt that a young field like hospital medicine needs to have resources to develop leadership; I don’t think there is another place in the field of medicine that has more shared responsibility requiring coordinated response than hospital medicine.

I have always been impressed and grateful that SHM recognized this and put forth the considerable effort required to create and develop the Leadership Academies into the premiere institution that they have evolved into. That is why I not only got involved in the leadership academies personally, but also had my entire leadership team complete the curriculum.

Certification is the culmination of that experience for me; I am hoping it is not the end, however. I have had other leadership training course work, and while the SHM Leadership Academies and the certification process were the best experience, I have learned that you can never have too much leadership training.

There are always new challenges a leader will be called on to face, and leadership skills need to continually grow.

Q: What’s been the biggest impact on your career so far? How do you plan on using it in the future?

A: It is not enough to be successful; you have to be able to tell the story of your success. Most of us want to be humble and focus on serving our patients, but the tree that falls in the woods is applicable to successful hospital medicine programs: If nobody hears about it, are you really successful? Can you really drive change?

Lenny Marcus put it best in his SHM Leadership Academy session on meta-leadership: Learning how to communicate to your boss is leading up; communicating across the silos of your organization is meta-leadership. The academies teach you about the skills you need for leadership; certification allows you to put those skills into action.

I vividly remember the day that academy instructor Eric Rice called me up to give me feedback on the first draft of my project. I was already stressed out because in four days I knew I had to give a critical presentation to top hospital leadership and health plan medical directors about our group. We had two new hospital presidents and a new service area senior vice president that had already terminated their contract with the ED group that covered three of the four hospitals. I knew they were scrutinizing my group; the pressure was on.

Eric gave the feedback that I had been focusing on the clinical aspects of my project and said I needed to tell the economic story—to measure the economic impact of my intervention. Further, he advised me on how to get the data to tell that story. I knew that he had just given me the material I needed to blow away the upcoming presentation to the hospital presidents, but would I get the data in time? I called up the CFO of the hospital as Eric advised, told him that I needed the data for a presentation I was giving to his boss in four days.

I got the data in time and blew away the presentation. I got to inform one of the new presidents that we had improved the contribution margin in his ICU by half a million dollars and cut length of stay by 0.9 days, while dramatically improving sepsis mortality. I was then able to go on and tell the HM leaders of our entire hospital system about our intervention and encouraged them to take similar steps.

Someday I hope I get the chance to tell Lenny Marcus this story; I hope he will consider me a meta-leader.

After the dust settled from those successes, I went back to my computer to write up the final draft of my project and I was able to tell a much better story than I ever could have without that advice Eric Rice and the committee [gave me].

My new boss was at the presentation that I gave. We went to the American Medical Group Association conference recently, and he did not hesitate to walk around bragging about what we had done, often quoting the numbers I delivered in my presentation. In another coda to the story, the new service area senior vice president asked my wife and I to join him and his wife for dinner; we have struck up a very valuable friendship.

—Thomas McIlraith, MD, SFHM

Q: What would you say to others who are thinking about applying for the certificate?

A: What are you waiting for?

On a more serious note, we are all engaged with important projects to make our hospitals run better, to keep our patients safer, and give our patients better experience. In the certification process, you continue with that work while top leaders from the field of hospital medicine coach and advise you.

Not only do you come out with a better product in the short term, but also you have better skills for taking on projects in the future; you know what questions to ask and what stories to tell and to whom. That stays with you long after the certification project is over.

Q: How are the results of your project benefiting your institution?

A: My hospitalists are seeing increased productivity and my hospitals are seeing stronger contribution margin in tough economic times. Further, the successful completion of the project has elevated the reputation of my department.

This month, Thomas McIlraith, MD, SFHM, will be on stage at HM13 accepting one of the first SHM Certificates in Leadership. As chair of hospital medicine at Sacramento, Calif.-based Mercy Medical Group, Dr. McIlraith already is familiar with the need for leadership in our specialty and shares why SHM’s Leadership Academy and new certification have helped his hospital and his career.

Question: What made you apply for the Certificate in Leadership in the first place?

Answer: I have always felt that a young field like hospital medicine needs to have resources to develop leadership; I don’t think there is another place in the field of medicine that has more shared responsibility requiring coordinated response than hospital medicine.

I have always been impressed and grateful that SHM recognized this and put forth the considerable effort required to create and develop the Leadership Academies into the premiere institution that they have evolved into. That is why I not only got involved in the leadership academies personally, but also had my entire leadership team complete the curriculum.

Certification is the culmination of that experience for me; I am hoping it is not the end, however. I have had other leadership training course work, and while the SHM Leadership Academies and the certification process were the best experience, I have learned that you can never have too much leadership training.

There are always new challenges a leader will be called on to face, and leadership skills need to continually grow.

Q: What’s been the biggest impact on your career so far? How do you plan on using it in the future?

A: It is not enough to be successful; you have to be able to tell the story of your success. Most of us want to be humble and focus on serving our patients, but the tree that falls in the woods is applicable to successful hospital medicine programs: If nobody hears about it, are you really successful? Can you really drive change?

Lenny Marcus put it best in his SHM Leadership Academy session on meta-leadership: Learning how to communicate to your boss is leading up; communicating across the silos of your organization is meta-leadership. The academies teach you about the skills you need for leadership; certification allows you to put those skills into action.

I vividly remember the day that academy instructor Eric Rice called me up to give me feedback on the first draft of my project. I was already stressed out because in four days I knew I had to give a critical presentation to top hospital leadership and health plan medical directors about our group. We had two new hospital presidents and a new service area senior vice president that had already terminated their contract with the ED group that covered three of the four hospitals. I knew they were scrutinizing my group; the pressure was on.

Eric gave the feedback that I had been focusing on the clinical aspects of my project and said I needed to tell the economic story—to measure the economic impact of my intervention. Further, he advised me on how to get the data to tell that story. I knew that he had just given me the material I needed to blow away the upcoming presentation to the hospital presidents, but would I get the data in time? I called up the CFO of the hospital as Eric advised, told him that I needed the data for a presentation I was giving to his boss in four days.

I got the data in time and blew away the presentation. I got to inform one of the new presidents that we had improved the contribution margin in his ICU by half a million dollars and cut length of stay by 0.9 days, while dramatically improving sepsis mortality. I was then able to go on and tell the HM leaders of our entire hospital system about our intervention and encouraged them to take similar steps.

Someday I hope I get the chance to tell Lenny Marcus this story; I hope he will consider me a meta-leader.

After the dust settled from those successes, I went back to my computer to write up the final draft of my project and I was able to tell a much better story than I ever could have without that advice Eric Rice and the committee [gave me].

My new boss was at the presentation that I gave. We went to the American Medical Group Association conference recently, and he did not hesitate to walk around bragging about what we had done, often quoting the numbers I delivered in my presentation. In another coda to the story, the new service area senior vice president asked my wife and I to join him and his wife for dinner; we have struck up a very valuable friendship.

—Thomas McIlraith, MD, SFHM

Q: What would you say to others who are thinking about applying for the certificate?

A: What are you waiting for?

On a more serious note, we are all engaged with important projects to make our hospitals run better, to keep our patients safer, and give our patients better experience. In the certification process, you continue with that work while top leaders from the field of hospital medicine coach and advise you.

Not only do you come out with a better product in the short term, but also you have better skills for taking on projects in the future; you know what questions to ask and what stories to tell and to whom. That stays with you long after the certification project is over.

Q: How are the results of your project benefiting your institution?

A: My hospitalists are seeing increased productivity and my hospitals are seeing stronger contribution margin in tough economic times. Further, the successful completion of the project has elevated the reputation of my department.

This month, Thomas McIlraith, MD, SFHM, will be on stage at HM13 accepting one of the first SHM Certificates in Leadership. As chair of hospital medicine at Sacramento, Calif.-based Mercy Medical Group, Dr. McIlraith already is familiar with the need for leadership in our specialty and shares why SHM’s Leadership Academy and new certification have helped his hospital and his career.

Question: What made you apply for the Certificate in Leadership in the first place?

Answer: I have always felt that a young field like hospital medicine needs to have resources to develop leadership; I don’t think there is another place in the field of medicine that has more shared responsibility requiring coordinated response than hospital medicine.

I have always been impressed and grateful that SHM recognized this and put forth the considerable effort required to create and develop the Leadership Academies into the premiere institution that they have evolved into. That is why I not only got involved in the leadership academies personally, but also had my entire leadership team complete the curriculum.

Certification is the culmination of that experience for me; I am hoping it is not the end, however. I have had other leadership training course work, and while the SHM Leadership Academies and the certification process were the best experience, I have learned that you can never have too much leadership training.

There are always new challenges a leader will be called on to face, and leadership skills need to continually grow.

Q: What’s been the biggest impact on your career so far? How do you plan on using it in the future?

A: It is not enough to be successful; you have to be able to tell the story of your success. Most of us want to be humble and focus on serving our patients, but the tree that falls in the woods is applicable to successful hospital medicine programs: If nobody hears about it, are you really successful? Can you really drive change?

Lenny Marcus put it best in his SHM Leadership Academy session on meta-leadership: Learning how to communicate to your boss is leading up; communicating across the silos of your organization is meta-leadership. The academies teach you about the skills you need for leadership; certification allows you to put those skills into action.

I vividly remember the day that academy instructor Eric Rice called me up to give me feedback on the first draft of my project. I was already stressed out because in four days I knew I had to give a critical presentation to top hospital leadership and health plan medical directors about our group. We had two new hospital presidents and a new service area senior vice president that had already terminated their contract with the ED group that covered three of the four hospitals. I knew they were scrutinizing my group; the pressure was on.

Eric gave the feedback that I had been focusing on the clinical aspects of my project and said I needed to tell the economic story—to measure the economic impact of my intervention. Further, he advised me on how to get the data to tell that story. I knew that he had just given me the material I needed to blow away the upcoming presentation to the hospital presidents, but would I get the data in time? I called up the CFO of the hospital as Eric advised, told him that I needed the data for a presentation I was giving to his boss in four days.

I got the data in time and blew away the presentation. I got to inform one of the new presidents that we had improved the contribution margin in his ICU by half a million dollars and cut length of stay by 0.9 days, while dramatically improving sepsis mortality. I was then able to go on and tell the HM leaders of our entire hospital system about our intervention and encouraged them to take similar steps.

Someday I hope I get the chance to tell Lenny Marcus this story; I hope he will consider me a meta-leader.

After the dust settled from those successes, I went back to my computer to write up the final draft of my project and I was able to tell a much better story than I ever could have without that advice Eric Rice and the committee [gave me].

My new boss was at the presentation that I gave. We went to the American Medical Group Association conference recently, and he did not hesitate to walk around bragging about what we had done, often quoting the numbers I delivered in my presentation. In another coda to the story, the new service area senior vice president asked my wife and I to join him and his wife for dinner; we have struck up a very valuable friendship.

—Thomas McIlraith, MD, SFHM

Q: What would you say to others who are thinking about applying for the certificate?

A: What are you waiting for?

On a more serious note, we are all engaged with important projects to make our hospitals run better, to keep our patients safer, and give our patients better experience. In the certification process, you continue with that work while top leaders from the field of hospital medicine coach and advise you.

Not only do you come out with a better product in the short term, but also you have better skills for taking on projects in the future; you know what questions to ask and what stories to tell and to whom. That stays with you long after the certification project is over.

Q: How are the results of your project benefiting your institution?

A: My hospitalists are seeing increased productivity and my hospitals are seeing stronger contribution margin in tough economic times. Further, the successful completion of the project has elevated the reputation of my department.

Sunshine Rule Requires Physicians to Report Gifts from Drug, Medical Device Companies

—Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM

Hospitalist leaders are taking a wait-and-see approach to the Physician Payment Sunshine Act, which requires reporting of payments and gifts from drug and medical device companies. But as wary as many are after publication of the Final Rule 1 in February, SHM and other groups already have claimed at least one victory in tweaking the new rules.

The Sunshine Rule, as it’s known, was included in the Affordable Care Act of 2010. The rule, created by the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services (CMS), requires manufacturers to publicly report gifts, payments, or other transfers of value to physicians from pharmaceutical and medical device manufacturers worth more than $10 (see “Dos and Don’ts,” below).1

One major change to the law sought by SHM and others was tied to the reporting of indirect payments to speakers at accredited continuing medical education (CME) classes or courses. The proposed rule required reporting of those payments even if a particular industry group did not select the speakers or pay them. SHM and three dozen other societies lobbied CMS to change the rule.2 The final rule says indirect payments don’t have to be reported if the CME program meets widely accepted accreditation standards and the industry participant is neither directly paid nor selected by the vendor.

CME Coalition, a Washington, D.C.-based advocacy group, said in a statement the caveat recognizes that CMS “is sending a strong message to commercial supporters: Underwriting accredited continuing education programs for health-care providers is to be applauded, not restricted.”

SHM Public Policy Committee member Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM, said the initial rule was too restrictive and could have reduced physician participation in important CME activities. He said the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) and other industry groups already govern the ethical issue of accepting direct payments that could imply bias to patients.

“I’m not so sure we needed the Sunshine Act as part of the ACA at all because these same things were in effect from the ACCME and other CME accrediting organizations,” said Dr. Lenchus, a Team Hospitalist member and president of the medical staff at Jackson Health System in Miami. “What this has done is impose additional administrative requirements that now take time away from our seeing patients or doing clinical activity.”

Those costs will add up quickly, according to figures from the Federal Register, Dr. Lenchus said. CMS projects the administrative costs of reviewing reports at $1.9 million for teaching hospital staff—the category Dr. Lenchus says is most applicable to hospitalists.

Dr. Lenchus says there was discussion within the Public Policy Committee about how much information needed to be publicly reported in relation to CME. Some members “wanted nothing recorded” and “some people wanted everything recorded.”

“The rule that has been implemented strikes a nice balance between the two,” he said.

Transparent Process

Industry groups and group purchasing organizations (GPOs) currently are working to put in place systems and procedures to begin collecting the data in August. Data will be collected through the end of 2013 and must be reported to CMS by March 31, 2014. CMS will then unveil a public website showcasing the information by Sept. 30, 2014.

Public Policy Committee member Jack Percelay, MD, MPH, FAAP, SFHM, said some hospitalists might feel they are “being picked on again” by having to report the added information. He instead looks at the intended push toward added transparency as “a set of obligations we have as physicians.”

“We have tremendous discretion about how health-care dollars are spent and with that comes a fiduciary responsibility, both to the patient and to the public,” he said. “This does not seem terribly burdensome to me. If I was getting nickel and dimed for every piece of candy I took through the exhibit hall during a meeting, that would be ridiculous. I’m happy to do this in a reasoned way.”

Dr. Percelay noted that the Sunshine Rule does not prevent industry payments to physicians or groups, but simply requires the public reporting and display of the remuneration. In that vein, he likened it to ethical rules that govern those who hold elected office.

“Someone should be able to Google and see that I’ve [received] funds from market research,” he said. “It’s not much different from politicians. It’s then up to the public and the media to do their due diligence.”

Dr. Lenchus said the public database has the potential to be misinterpreted by a public unfamiliar with how health care works. In particular, patients might not be able to discern the differences between the value of lunches, the payments for being on advisory boards, and industry-funded research.

“I really fear the public will look at this website, see there is any financial inducement to any physician, and erroneously conclude that any prescription of that company’s medication means that person is getting a kickback,” he says. “And we know that’s absolutely false.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare, Medicaid, Children’s Health Insurance Programs; transparency reports and reporting of physician ownership or investment interests. Federal Register website. Available at: https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2013/02/08/2013-02572/medicare-mediaid-childrens-health-insurance-programs-transparency-reports-and-reporting-of. Accessed March 24, 2013.

- Council of Medical Specialty Societies. Letter to CMS. SHM website. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Letters_to_Congress_ and_Regulatory_Agencies&Template=/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm&ContentID=30674. Accessed March 24, 2013.

—Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM

Hospitalist leaders are taking a wait-and-see approach to the Physician Payment Sunshine Act, which requires reporting of payments and gifts from drug and medical device companies. But as wary as many are after publication of the Final Rule 1 in February, SHM and other groups already have claimed at least one victory in tweaking the new rules.

The Sunshine Rule, as it’s known, was included in the Affordable Care Act of 2010. The rule, created by the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services (CMS), requires manufacturers to publicly report gifts, payments, or other transfers of value to physicians from pharmaceutical and medical device manufacturers worth more than $10 (see “Dos and Don’ts,” below).1

One major change to the law sought by SHM and others was tied to the reporting of indirect payments to speakers at accredited continuing medical education (CME) classes or courses. The proposed rule required reporting of those payments even if a particular industry group did not select the speakers or pay them. SHM and three dozen other societies lobbied CMS to change the rule.2 The final rule says indirect payments don’t have to be reported if the CME program meets widely accepted accreditation standards and the industry participant is neither directly paid nor selected by the vendor.

CME Coalition, a Washington, D.C.-based advocacy group, said in a statement the caveat recognizes that CMS “is sending a strong message to commercial supporters: Underwriting accredited continuing education programs for health-care providers is to be applauded, not restricted.”

SHM Public Policy Committee member Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM, said the initial rule was too restrictive and could have reduced physician participation in important CME activities. He said the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) and other industry groups already govern the ethical issue of accepting direct payments that could imply bias to patients.

“I’m not so sure we needed the Sunshine Act as part of the ACA at all because these same things were in effect from the ACCME and other CME accrediting organizations,” said Dr. Lenchus, a Team Hospitalist member and president of the medical staff at Jackson Health System in Miami. “What this has done is impose additional administrative requirements that now take time away from our seeing patients or doing clinical activity.”

Those costs will add up quickly, according to figures from the Federal Register, Dr. Lenchus said. CMS projects the administrative costs of reviewing reports at $1.9 million for teaching hospital staff—the category Dr. Lenchus says is most applicable to hospitalists.

Dr. Lenchus says there was discussion within the Public Policy Committee about how much information needed to be publicly reported in relation to CME. Some members “wanted nothing recorded” and “some people wanted everything recorded.”

“The rule that has been implemented strikes a nice balance between the two,” he said.

Transparent Process

Industry groups and group purchasing organizations (GPOs) currently are working to put in place systems and procedures to begin collecting the data in August. Data will be collected through the end of 2013 and must be reported to CMS by March 31, 2014. CMS will then unveil a public website showcasing the information by Sept. 30, 2014.

Public Policy Committee member Jack Percelay, MD, MPH, FAAP, SFHM, said some hospitalists might feel they are “being picked on again” by having to report the added information. He instead looks at the intended push toward added transparency as “a set of obligations we have as physicians.”

“We have tremendous discretion about how health-care dollars are spent and with that comes a fiduciary responsibility, both to the patient and to the public,” he said. “This does not seem terribly burdensome to me. If I was getting nickel and dimed for every piece of candy I took through the exhibit hall during a meeting, that would be ridiculous. I’m happy to do this in a reasoned way.”

Dr. Percelay noted that the Sunshine Rule does not prevent industry payments to physicians or groups, but simply requires the public reporting and display of the remuneration. In that vein, he likened it to ethical rules that govern those who hold elected office.

“Someone should be able to Google and see that I’ve [received] funds from market research,” he said. “It’s not much different from politicians. It’s then up to the public and the media to do their due diligence.”

Dr. Lenchus said the public database has the potential to be misinterpreted by a public unfamiliar with how health care works. In particular, patients might not be able to discern the differences between the value of lunches, the payments for being on advisory boards, and industry-funded research.

“I really fear the public will look at this website, see there is any financial inducement to any physician, and erroneously conclude that any prescription of that company’s medication means that person is getting a kickback,” he says. “And we know that’s absolutely false.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare, Medicaid, Children’s Health Insurance Programs; transparency reports and reporting of physician ownership or investment interests. Federal Register website. Available at: https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2013/02/08/2013-02572/medicare-mediaid-childrens-health-insurance-programs-transparency-reports-and-reporting-of. Accessed March 24, 2013.

- Council of Medical Specialty Societies. Letter to CMS. SHM website. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Letters_to_Congress_ and_Regulatory_Agencies&Template=/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm&ContentID=30674. Accessed March 24, 2013.

—Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM

Hospitalist leaders are taking a wait-and-see approach to the Physician Payment Sunshine Act, which requires reporting of payments and gifts from drug and medical device companies. But as wary as many are after publication of the Final Rule 1 in February, SHM and other groups already have claimed at least one victory in tweaking the new rules.

The Sunshine Rule, as it’s known, was included in the Affordable Care Act of 2010. The rule, created by the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services (CMS), requires manufacturers to publicly report gifts, payments, or other transfers of value to physicians from pharmaceutical and medical device manufacturers worth more than $10 (see “Dos and Don’ts,” below).1

One major change to the law sought by SHM and others was tied to the reporting of indirect payments to speakers at accredited continuing medical education (CME) classes or courses. The proposed rule required reporting of those payments even if a particular industry group did not select the speakers or pay them. SHM and three dozen other societies lobbied CMS to change the rule.2 The final rule says indirect payments don’t have to be reported if the CME program meets widely accepted accreditation standards and the industry participant is neither directly paid nor selected by the vendor.

CME Coalition, a Washington, D.C.-based advocacy group, said in a statement the caveat recognizes that CMS “is sending a strong message to commercial supporters: Underwriting accredited continuing education programs for health-care providers is to be applauded, not restricted.”

SHM Public Policy Committee member Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM, said the initial rule was too restrictive and could have reduced physician participation in important CME activities. He said the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) and other industry groups already govern the ethical issue of accepting direct payments that could imply bias to patients.

“I’m not so sure we needed the Sunshine Act as part of the ACA at all because these same things were in effect from the ACCME and other CME accrediting organizations,” said Dr. Lenchus, a Team Hospitalist member and president of the medical staff at Jackson Health System in Miami. “What this has done is impose additional administrative requirements that now take time away from our seeing patients or doing clinical activity.”

Those costs will add up quickly, according to figures from the Federal Register, Dr. Lenchus said. CMS projects the administrative costs of reviewing reports at $1.9 million for teaching hospital staff—the category Dr. Lenchus says is most applicable to hospitalists.

Dr. Lenchus says there was discussion within the Public Policy Committee about how much information needed to be publicly reported in relation to CME. Some members “wanted nothing recorded” and “some people wanted everything recorded.”

“The rule that has been implemented strikes a nice balance between the two,” he said.

Transparent Process

Industry groups and group purchasing organizations (GPOs) currently are working to put in place systems and procedures to begin collecting the data in August. Data will be collected through the end of 2013 and must be reported to CMS by March 31, 2014. CMS will then unveil a public website showcasing the information by Sept. 30, 2014.

Public Policy Committee member Jack Percelay, MD, MPH, FAAP, SFHM, said some hospitalists might feel they are “being picked on again” by having to report the added information. He instead looks at the intended push toward added transparency as “a set of obligations we have as physicians.”

“We have tremendous discretion about how health-care dollars are spent and with that comes a fiduciary responsibility, both to the patient and to the public,” he said. “This does not seem terribly burdensome to me. If I was getting nickel and dimed for every piece of candy I took through the exhibit hall during a meeting, that would be ridiculous. I’m happy to do this in a reasoned way.”

Dr. Percelay noted that the Sunshine Rule does not prevent industry payments to physicians or groups, but simply requires the public reporting and display of the remuneration. In that vein, he likened it to ethical rules that govern those who hold elected office.

“Someone should be able to Google and see that I’ve [received] funds from market research,” he said. “It’s not much different from politicians. It’s then up to the public and the media to do their due diligence.”

Dr. Lenchus said the public database has the potential to be misinterpreted by a public unfamiliar with how health care works. In particular, patients might not be able to discern the differences between the value of lunches, the payments for being on advisory boards, and industry-funded research.

“I really fear the public will look at this website, see there is any financial inducement to any physician, and erroneously conclude that any prescription of that company’s medication means that person is getting a kickback,” he says. “And we know that’s absolutely false.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare, Medicaid, Children’s Health Insurance Programs; transparency reports and reporting of physician ownership or investment interests. Federal Register website. Available at: https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2013/02/08/2013-02572/medicare-mediaid-childrens-health-insurance-programs-transparency-reports-and-reporting-of. Accessed March 24, 2013.

- Council of Medical Specialty Societies. Letter to CMS. SHM website. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Letters_to_Congress_ and_Regulatory_Agencies&Template=/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm&ContentID=30674. Accessed March 24, 2013.

Foot "Sprain" Hiding Virulent Infection

On returning from a trip to the beach, a 65-year-old Rhode Island woman had worsening foot pain for a day before presenting to a hospital emergency department (ED). The PA who examined her diagnosed a foot sprain, and she was discharged. The PA's supervising emergency physician, though not consulted, later signed off on the patient's chart.

In actuality, the woman had a virulent strain of group A streptococcus, which was diagnosed when she returned to the ED two days later. Her condition did not improve, and she died after two days in the hospital.

The plaintiff alleged negligence in the defendant PA's failure to make a correct diagnosis at the first ED visit. The plaintiff claimed that a blood test should have been performed, as well as a re-check of the decedent's vital signs. The plaintiff also faulted the PA's failure to communicate with the defendant emergency physician.

The defendants claimed that the diagnosis of foot sprain was reasonable, and that the PA was qualified to make that diagnosis.

Outcome

A defense verdict was returned.

Comment

When an advanced practice clinician provides care that involves a malpractice claim, it is almost a given that a claim will be made against the supervising physician as well. It is these circumstances that highlight the importance of good communication and support between the two. The facts in this case indicate that the supervising physician signed off on the medical record but did not examine the patient. This is frequently the case in a busy ED, especially when the injury appears to be minor and no complicating factors are evident. The relationship between the two professionals allows the supervising physician to have confidence that the PA is able to make an appropriate diagnostic decision.

There is little in the history presented that would support a finding of malpractice. Pain alone would not likely lead to an alternative diagnosis of virulent strep A infection. Only when the patient returned were symptoms apparently present that led to the alternate diagnosis of a virulent strep A infection. Unfortunately, despite immediate and appropriate treatment, the patient died.

Every defense lawyer knows that defendants who blame each other hand the plaintiff a win. Fortunately, in this case the supervising physician supported the PA's decision making. Wouldn't it be better if each professional were considered individually responsible for his or her actions? I believe both patients and physicians would be better served in a system that recognized individual responsibility without reliance on the theory of supervisory liability. —JP

Cases reprinted with permission fromMedical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements and Experts, Lewis Laska, Editor, (800) 298-6288.

On returning from a trip to the beach, a 65-year-old Rhode Island woman had worsening foot pain for a day before presenting to a hospital emergency department (ED). The PA who examined her diagnosed a foot sprain, and she was discharged. The PA's supervising emergency physician, though not consulted, later signed off on the patient's chart.

In actuality, the woman had a virulent strain of group A streptococcus, which was diagnosed when she returned to the ED two days later. Her condition did not improve, and she died after two days in the hospital.

The plaintiff alleged negligence in the defendant PA's failure to make a correct diagnosis at the first ED visit. The plaintiff claimed that a blood test should have been performed, as well as a re-check of the decedent's vital signs. The plaintiff also faulted the PA's failure to communicate with the defendant emergency physician.

The defendants claimed that the diagnosis of foot sprain was reasonable, and that the PA was qualified to make that diagnosis.

Outcome

A defense verdict was returned.

Comment

When an advanced practice clinician provides care that involves a malpractice claim, it is almost a given that a claim will be made against the supervising physician as well. It is these circumstances that highlight the importance of good communication and support between the two. The facts in this case indicate that the supervising physician signed off on the medical record but did not examine the patient. This is frequently the case in a busy ED, especially when the injury appears to be minor and no complicating factors are evident. The relationship between the two professionals allows the supervising physician to have confidence that the PA is able to make an appropriate diagnostic decision.

There is little in the history presented that would support a finding of malpractice. Pain alone would not likely lead to an alternative diagnosis of virulent strep A infection. Only when the patient returned were symptoms apparently present that led to the alternate diagnosis of a virulent strep A infection. Unfortunately, despite immediate and appropriate treatment, the patient died.

Every defense lawyer knows that defendants who blame each other hand the plaintiff a win. Fortunately, in this case the supervising physician supported the PA's decision making. Wouldn't it be better if each professional were considered individually responsible for his or her actions? I believe both patients and physicians would be better served in a system that recognized individual responsibility without reliance on the theory of supervisory liability. —JP

Cases reprinted with permission fromMedical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements and Experts, Lewis Laska, Editor, (800) 298-6288.

On returning from a trip to the beach, a 65-year-old Rhode Island woman had worsening foot pain for a day before presenting to a hospital emergency department (ED). The PA who examined her diagnosed a foot sprain, and she was discharged. The PA's supervising emergency physician, though not consulted, later signed off on the patient's chart.

In actuality, the woman had a virulent strain of group A streptococcus, which was diagnosed when she returned to the ED two days later. Her condition did not improve, and she died after two days in the hospital.

The plaintiff alleged negligence in the defendant PA's failure to make a correct diagnosis at the first ED visit. The plaintiff claimed that a blood test should have been performed, as well as a re-check of the decedent's vital signs. The plaintiff also faulted the PA's failure to communicate with the defendant emergency physician.

The defendants claimed that the diagnosis of foot sprain was reasonable, and that the PA was qualified to make that diagnosis.

Outcome

A defense verdict was returned.

Comment

When an advanced practice clinician provides care that involves a malpractice claim, it is almost a given that a claim will be made against the supervising physician as well. It is these circumstances that highlight the importance of good communication and support between the two. The facts in this case indicate that the supervising physician signed off on the medical record but did not examine the patient. This is frequently the case in a busy ED, especially when the injury appears to be minor and no complicating factors are evident. The relationship between the two professionals allows the supervising physician to have confidence that the PA is able to make an appropriate diagnostic decision.

There is little in the history presented that would support a finding of malpractice. Pain alone would not likely lead to an alternative diagnosis of virulent strep A infection. Only when the patient returned were symptoms apparently present that led to the alternate diagnosis of a virulent strep A infection. Unfortunately, despite immediate and appropriate treatment, the patient died.

Every defense lawyer knows that defendants who blame each other hand the plaintiff a win. Fortunately, in this case the supervising physician supported the PA's decision making. Wouldn't it be better if each professional were considered individually responsible for his or her actions? I believe both patients and physicians would be better served in a system that recognized individual responsibility without reliance on the theory of supervisory liability. —JP

Cases reprinted with permission fromMedical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements and Experts, Lewis Laska, Editor, (800) 298-6288.

Child’s brain damage blamed on late cesarean … and more

A MOTHER WANTED A HOME BIRTH with a midwife. When complications arose and labor stopped progressing, the midwife called an ambulance. The emergency department (ED) physician ordered an urgent cesarean delivery, but the procedure did not begin for another 2 hours. The child was born with brain damage, multiple physical and mental disabilities, complex seizure disorder, and cerebral palsy.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The child’s injuries occurred because cesarean delivery was delayed for 2 hours. Based on fetal heart-rate monitoring, the injuries most likely occurred in the last 18 minutes before birth, and were probably caused by compression of the umbilical cord. An earlier cesarean delivery would have avoided the injuries.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE All of the injuries occurred prior to the mother’s arrival at the hospital, while she was under the care of the midwife. Fetal distress was present for an hour before the ambulance was called. When the mother arrived at the ED, she was an unknown patient, as the midwife did not have a collaborating physician. While the ED physician determined that a cesarean delivery was required, it was not considered an emergency. The mother was taken to the OR as soon as possible. Fetal monitoring strips at the hospital were reassuring.

VERDICT A $55 million Maryland verdict was returned against the hospital, including $26 million in noneconomic damages. After the court reduced noneconomic damages and future lost wages awards, the net verdict was $28 million.

ARDS after hysterectomy

A MORBIDLY OBESE WOMAN underwent a hysterectomy. The asthmatic, 38-year-old patient vomited after surgery. A pulmonologist undertook her care and determined that she had acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). He prescribed the administration of oxygen. When she vomited again during the early morning hours of the second postsurgical day, he ordered intubation and went to the hospital immediately, but the patient quickly deteriorated. She died from cardiac arrest.

ESTATE’S CLAIM The patient’s death was due to failure to diagnose and treat ARDS in a timely manner. A bronchoscopy and frequent radiographs should have been performed. If the patient had been intubated earlier and steps had been taken to reduce the risk of vomiting, she would have had a better chance of survival. She should have been transferred to another facility when ARDS was diagnosed.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE A bronchoscopy was not necessary. ARDS was diagnosed and treated in a timely manner. She was too unstable to transfer to another hospital.

VERDICT The hospital reached a confidential settlement, and the claim against the anesthesiologist was dismissed. The trial proceeded against the pulmonologist and his group. A New York defense verdict was returned.

Mother’s HELLP syndrome missed; fetus dies

DURING HER PREGNANCY, a 23-year-old woman was monitored for hypertension by her ObGyn and nurse midwife. At her 36-week prenatal visit, she was found to have preeclampsia, including proteinuria. She was sent directly to the ED, where the baby was monitored and laboratory tests were ordered by a nurse and nurse midwife. After 2 hours, she was told she had a urinary tract infection and discharged. Three days later, she returned to the ED in critical condition; she had suffered an intrauterine fetal demise.