User login

Foot “Sprain” Hiding Virulent Infection

On returning from a trip to the beach, a 65-year-old Rhode Island woman had worsening foot pain for a day before presenting to a hospital emergency department (ED). The PA who examined her diagnosed a foot sprain, and she was discharged. The PA’s supervising emergency physician, though not consulted, later signed off on the patient’s chart.

In actuality, the woman had a virulent strain of group A streptococcus, which was diagnosed when she returned to the ED two days later. Her condition did not improve, and she died after two days in the hospital.

The plaintiff alleged negligence in the defendant PA’s failure to make a correct diagnosis at the first ED visit. The plaintiff claimed that a blood test should have been performed, as well as a re-check of the decedent’s vital signs. The plaintiff also faulted the PA’s failure to communicate with the defendant emergency physician.

The defendants claimed that the diagnosis of foot sprain was reasonable, and that the PA was qualified to make that diagnosis.

Outcome

A defense verdict was returned.

Comment

When an advanced practice clinician provides care that involves a malpractice claim, it is almost a given that a claim will be made against the supervising physician as well. It is these circumstances that highlight the importance of good communication and support between the two. The facts in this case indicate that the supervising physician signed off on the medical record but did not examine the patient. This is frequently the case in a busy ED, especially when the injury appears to be minor and no complicating factors are evident. The relationship between the two professionals allows the supervising physician to have confidence that the PA is able to make an appropriate diagnostic decision.

There is little in the history presented that would support a finding of malpractice. Pain alone would not likely lead to an alternative diagnosis of virulent strep A infection. Only when the patient returned were symptoms apparently present that led to the alternate diagnosis of a virulent strep A infection. Unfortunately, despite immediate and appropriate treatment, the patient died.

Every defense lawyer knows that defendants who blame each other hand the plaintiff a win. Fortunately, in this case the supervising physician supported the PA’s decision making. Wouldn’t it be better if each professional were considered individually responsible for his or her actions? I believe both patients and physicians would be better served in a system that recognized individual responsibility without reliance on the theory of supervisory liability. —JP

Cases reprinted with permission fromMedical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements and Experts, Lewis Laska, Editor, (800) 298-6288.

On returning from a trip to the beach, a 65-year-old Rhode Island woman had worsening foot pain for a day before presenting to a hospital emergency department (ED). The PA who examined her diagnosed a foot sprain, and she was discharged. The PA’s supervising emergency physician, though not consulted, later signed off on the patient’s chart.

In actuality, the woman had a virulent strain of group A streptococcus, which was diagnosed when she returned to the ED two days later. Her condition did not improve, and she died after two days in the hospital.

The plaintiff alleged negligence in the defendant PA’s failure to make a correct diagnosis at the first ED visit. The plaintiff claimed that a blood test should have been performed, as well as a re-check of the decedent’s vital signs. The plaintiff also faulted the PA’s failure to communicate with the defendant emergency physician.

The defendants claimed that the diagnosis of foot sprain was reasonable, and that the PA was qualified to make that diagnosis.

Outcome

A defense verdict was returned.

Comment

When an advanced practice clinician provides care that involves a malpractice claim, it is almost a given that a claim will be made against the supervising physician as well. It is these circumstances that highlight the importance of good communication and support between the two. The facts in this case indicate that the supervising physician signed off on the medical record but did not examine the patient. This is frequently the case in a busy ED, especially when the injury appears to be minor and no complicating factors are evident. The relationship between the two professionals allows the supervising physician to have confidence that the PA is able to make an appropriate diagnostic decision.

There is little in the history presented that would support a finding of malpractice. Pain alone would not likely lead to an alternative diagnosis of virulent strep A infection. Only when the patient returned were symptoms apparently present that led to the alternate diagnosis of a virulent strep A infection. Unfortunately, despite immediate and appropriate treatment, the patient died.

Every defense lawyer knows that defendants who blame each other hand the plaintiff a win. Fortunately, in this case the supervising physician supported the PA’s decision making. Wouldn’t it be better if each professional were considered individually responsible for his or her actions? I believe both patients and physicians would be better served in a system that recognized individual responsibility without reliance on the theory of supervisory liability. —JP

Cases reprinted with permission fromMedical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements and Experts, Lewis Laska, Editor, (800) 298-6288.

On returning from a trip to the beach, a 65-year-old Rhode Island woman had worsening foot pain for a day before presenting to a hospital emergency department (ED). The PA who examined her diagnosed a foot sprain, and she was discharged. The PA’s supervising emergency physician, though not consulted, later signed off on the patient’s chart.

In actuality, the woman had a virulent strain of group A streptococcus, which was diagnosed when she returned to the ED two days later. Her condition did not improve, and she died after two days in the hospital.

The plaintiff alleged negligence in the defendant PA’s failure to make a correct diagnosis at the first ED visit. The plaintiff claimed that a blood test should have been performed, as well as a re-check of the decedent’s vital signs. The plaintiff also faulted the PA’s failure to communicate with the defendant emergency physician.

The defendants claimed that the diagnosis of foot sprain was reasonable, and that the PA was qualified to make that diagnosis.

Outcome

A defense verdict was returned.

Comment

When an advanced practice clinician provides care that involves a malpractice claim, it is almost a given that a claim will be made against the supervising physician as well. It is these circumstances that highlight the importance of good communication and support between the two. The facts in this case indicate that the supervising physician signed off on the medical record but did not examine the patient. This is frequently the case in a busy ED, especially when the injury appears to be minor and no complicating factors are evident. The relationship between the two professionals allows the supervising physician to have confidence that the PA is able to make an appropriate diagnostic decision.

There is little in the history presented that would support a finding of malpractice. Pain alone would not likely lead to an alternative diagnosis of virulent strep A infection. Only when the patient returned were symptoms apparently present that led to the alternate diagnosis of a virulent strep A infection. Unfortunately, despite immediate and appropriate treatment, the patient died.

Every defense lawyer knows that defendants who blame each other hand the plaintiff a win. Fortunately, in this case the supervising physician supported the PA’s decision making. Wouldn’t it be better if each professional were considered individually responsible for his or her actions? I believe both patients and physicians would be better served in a system that recognized individual responsibility without reliance on the theory of supervisory liability. —JP

Cases reprinted with permission fromMedical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements and Experts, Lewis Laska, Editor, (800) 298-6288.

Hospitalist Explains Benefits of Bundling, Other Integration Strategies

Click here to listen to excerpts of Dr. Duke's interview with The Hospitalist

Click here to listen to excerpts of Dr. Duke's interview with The Hospitalist

Click here to listen to excerpts of Dr. Duke's interview with The Hospitalist

Hospitalist Outlines Importance of Nutrition in Patient Care

Click here to listen to excerpts of Dr. Parkhurst's interview with The Hospitalist

Click here to listen to excerpts of Dr. Parkhurst's interview with The Hospitalist

Click here to listen to excerpts of Dr. Parkhurst's interview with The Hospitalist

Why It's Important to Have Supportive Colleagues

Commemorating Round-the-Clock Hospital Medicine Programs

The steam engine. The telephone. Television. ATMs. The Internet. Smartphones. The 24/7 hospitalist program.

Perhaps the single most important innovation along the road to where we are now in HM has been the development of the hospital-sponsored, 24/7, on-site hospitalist program. And the father of this invention may be the most significant figure in HM you’ve never heard of: John Holbrook, MD, FACEP. An emergency-medicine physician since the mid-1970s, Dr. Holbrook did something in July 1993 that was considered off the wall, yet proved to be revolutionary: From nothing, he launched a 24/7 hospitalist program staffed with board-eligible and board-certified internists at Mercy Hospital in Springfield, Mass. The inpatient physicians (this was before the word “hospitalist” came to be) were employed by a subsidiary of the hospital and worked in place of community primary-care physicians (PCPs), taking care of hospitalized patients who did not have a PCP, or whose PCP chose not to come to the hospital.

Of great significance, from the beginning, and perhaps by unintentional design, these physicians were agents of change and improvement for the hospital itself.

To be sure, in places like Southern California, 24/7, on-site hospitalist programs were in place in the late 1980s. Some claim those programs may have been the birthplace of the hospitalist model. However, such programs came to be in order to help medical groups manage full capitated risk delegated to them from HMOs on a population of patients, and were not supported by the hospital, per se. This is distinct from hospitalist programs—such as Mercy’s—sponsored by hospitals (whether employed or contracted) in predominantly fee-for-service markets, which then comprised the lion’s share of the U.S. market.

I had the extraordinary good fortune to happen along in July 1994, get hired by Dr. Holbrook, and soon after begin serving as medical director for the Mercy program, which I would do for the next decade. To this day, Dr. Holbrook is a mentor and trusted advisor to me. I caught up with him in recognition of the 20th anniversary of the Mercy Inpatient Medicine Service.

Question: What gave you the idea to launch what was, at the time, considered such an unconventional program?

Answer: Before the specialty of emergency medicine, a patient’s private physician would be called in most cases when a patient present in the ED: 25 or 50 doctors might be called over 24 hours, each to see one patient each. The inefficiency and disruption caused by this system was a natural and logical stimulus to develop the specialty of emergency medicine. I saw hospitalist medicine as an exact analogy.

Q: What were you observing in the healthcare environment that drove you to create the Mercy Inpatient Medicine Service?

A: Working for many years in the emergency department of a community hospital without a house staff, the ED docs would admit a patient at night or on the weekend and the attending physician would often plan to see the patient “in the morning.” When the patient would decompensate in the middle of the night, the ED doc would get a call to run to the floor to “Band-Aid” the situation.

Q: How did you convince the board of trustees to fund it?

A: The reasons were primarily economic. No. 1, the hospital was losing market share because local physicians would prefer to admit to the teaching hospital [a nearby competitor], where they were not required to come in during the middle of the night. No. 2, the cost of a hospitalization managed by a hospitalist was less expensive than either a hospital stay managed by house staff or managed over the telephone by a private attending at home.

Q: What was the most difficult operational challenge for the program?

A: Effective and timely communication with the community physicians was the most difficult operational challenge. Access to outpatient medical treatment immediately prior to a hospitalization and timely communication to the community physician were both challenges that we never adequately solved in the early days. I understand that these issues can still be problematic.

Q: How was it received by patients?

A: Overall, patients were very happy with the system. In the old system, with a typical four-physician practice, a patient had only a 1 in 4 chance of being admitted by the doctor who was familiar with the case. The fact that the hospitalist was available in the hospital made the improvement in quality apparent to most patients.

Q: How did you get the medical staff to buy into the program?

A: I personally visited every private physician who participated. Physicians were given the option of not participating, or of part-time participation—for example, on weekends or holidays only. The word spread. Physicians came up to me and told me that the program enabled them to continue practicing for another five years. Physicians’ spouses thanked me.

Q: Are you surprised HM as a field has grown so quickly?

A: I am not really that surprised. It is a better way to organize health care. I am surprised that it did not occur sooner. We talked about instituting this system for 10 years before 1993.

Q: What big challenges remain for hospital medicine? What are some solutions?

A: I believe that the biggest global challenge for hospital medicine remains communication with community-based providers, both before the hospitalization as well as during hospitalization and immediately after discharge. In the era of the EMR, the Internet, and the iPhone and Android, this should be easier. HIPAA has not helped.

The other growing challenge will become apparent as hospitalists age in the profession: Disruption of the diurnal sleep cycle becomes increasingly problematic for many physicians after the age of 50 and can easily lead to burnout. The early hospitalists were all in their 30s. The attractive lifestyle choice for the 30-year-old can lead to burnout for the 55-year-old. The emergency-medicine literature has noted a similar problem of shift work/sleep fragmentation.

Final Thoughts

I believe Dr. Holbrook’s assessments on the future of our specialty are on target. As HM continues to mature, we need to continue to focus on how we communicate with providers outside the four walls of the hospital and how to address barriers to making HM a sustainable career.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

(Editor's note: Updated July 12, 2013.)

The steam engine. The telephone. Television. ATMs. The Internet. Smartphones. The 24/7 hospitalist program.

Perhaps the single most important innovation along the road to where we are now in HM has been the development of the hospital-sponsored, 24/7, on-site hospitalist program. And the father of this invention may be the most significant figure in HM you’ve never heard of: John Holbrook, MD, FACEP. An emergency-medicine physician since the mid-1970s, Dr. Holbrook did something in July 1993 that was considered off the wall, yet proved to be revolutionary: From nothing, he launched a 24/7 hospitalist program staffed with board-eligible and board-certified internists at Mercy Hospital in Springfield, Mass. The inpatient physicians (this was before the word “hospitalist” came to be) were employed by a subsidiary of the hospital and worked in place of community primary-care physicians (PCPs), taking care of hospitalized patients who did not have a PCP, or whose PCP chose not to come to the hospital.

Of great significance, from the beginning, and perhaps by unintentional design, these physicians were agents of change and improvement for the hospital itself.

To be sure, in places like Southern California, 24/7, on-site hospitalist programs were in place in the late 1980s. Some claim those programs may have been the birthplace of the hospitalist model. However, such programs came to be in order to help medical groups manage full capitated risk delegated to them from HMOs on a population of patients, and were not supported by the hospital, per se. This is distinct from hospitalist programs—such as Mercy’s—sponsored by hospitals (whether employed or contracted) in predominantly fee-for-service markets, which then comprised the lion’s share of the U.S. market.

I had the extraordinary good fortune to happen along in July 1994, get hired by Dr. Holbrook, and soon after begin serving as medical director for the Mercy program, which I would do for the next decade. To this day, Dr. Holbrook is a mentor and trusted advisor to me. I caught up with him in recognition of the 20th anniversary of the Mercy Inpatient Medicine Service.

Question: What gave you the idea to launch what was, at the time, considered such an unconventional program?

Answer: Before the specialty of emergency medicine, a patient’s private physician would be called in most cases when a patient present in the ED: 25 or 50 doctors might be called over 24 hours, each to see one patient each. The inefficiency and disruption caused by this system was a natural and logical stimulus to develop the specialty of emergency medicine. I saw hospitalist medicine as an exact analogy.

Q: What were you observing in the healthcare environment that drove you to create the Mercy Inpatient Medicine Service?

A: Working for many years in the emergency department of a community hospital without a house staff, the ED docs would admit a patient at night or on the weekend and the attending physician would often plan to see the patient “in the morning.” When the patient would decompensate in the middle of the night, the ED doc would get a call to run to the floor to “Band-Aid” the situation.

Q: How did you convince the board of trustees to fund it?

A: The reasons were primarily economic. No. 1, the hospital was losing market share because local physicians would prefer to admit to the teaching hospital [a nearby competitor], where they were not required to come in during the middle of the night. No. 2, the cost of a hospitalization managed by a hospitalist was less expensive than either a hospital stay managed by house staff or managed over the telephone by a private attending at home.

Q: What was the most difficult operational challenge for the program?

A: Effective and timely communication with the community physicians was the most difficult operational challenge. Access to outpatient medical treatment immediately prior to a hospitalization and timely communication to the community physician were both challenges that we never adequately solved in the early days. I understand that these issues can still be problematic.

Q: How was it received by patients?

A: Overall, patients were very happy with the system. In the old system, with a typical four-physician practice, a patient had only a 1 in 4 chance of being admitted by the doctor who was familiar with the case. The fact that the hospitalist was available in the hospital made the improvement in quality apparent to most patients.

Q: How did you get the medical staff to buy into the program?

A: I personally visited every private physician who participated. Physicians were given the option of not participating, or of part-time participation—for example, on weekends or holidays only. The word spread. Physicians came up to me and told me that the program enabled them to continue practicing for another five years. Physicians’ spouses thanked me.

Q: Are you surprised HM as a field has grown so quickly?

A: I am not really that surprised. It is a better way to organize health care. I am surprised that it did not occur sooner. We talked about instituting this system for 10 years before 1993.

Q: What big challenges remain for hospital medicine? What are some solutions?

A: I believe that the biggest global challenge for hospital medicine remains communication with community-based providers, both before the hospitalization as well as during hospitalization and immediately after discharge. In the era of the EMR, the Internet, and the iPhone and Android, this should be easier. HIPAA has not helped.

The other growing challenge will become apparent as hospitalists age in the profession: Disruption of the diurnal sleep cycle becomes increasingly problematic for many physicians after the age of 50 and can easily lead to burnout. The early hospitalists were all in their 30s. The attractive lifestyle choice for the 30-year-old can lead to burnout for the 55-year-old. The emergency-medicine literature has noted a similar problem of shift work/sleep fragmentation.

Final Thoughts

I believe Dr. Holbrook’s assessments on the future of our specialty are on target. As HM continues to mature, we need to continue to focus on how we communicate with providers outside the four walls of the hospital and how to address barriers to making HM a sustainable career.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

(Editor's note: Updated July 12, 2013.)

The steam engine. The telephone. Television. ATMs. The Internet. Smartphones. The 24/7 hospitalist program.

Perhaps the single most important innovation along the road to where we are now in HM has been the development of the hospital-sponsored, 24/7, on-site hospitalist program. And the father of this invention may be the most significant figure in HM you’ve never heard of: John Holbrook, MD, FACEP. An emergency-medicine physician since the mid-1970s, Dr. Holbrook did something in July 1993 that was considered off the wall, yet proved to be revolutionary: From nothing, he launched a 24/7 hospitalist program staffed with board-eligible and board-certified internists at Mercy Hospital in Springfield, Mass. The inpatient physicians (this was before the word “hospitalist” came to be) were employed by a subsidiary of the hospital and worked in place of community primary-care physicians (PCPs), taking care of hospitalized patients who did not have a PCP, or whose PCP chose not to come to the hospital.

Of great significance, from the beginning, and perhaps by unintentional design, these physicians were agents of change and improvement for the hospital itself.

To be sure, in places like Southern California, 24/7, on-site hospitalist programs were in place in the late 1980s. Some claim those programs may have been the birthplace of the hospitalist model. However, such programs came to be in order to help medical groups manage full capitated risk delegated to them from HMOs on a population of patients, and were not supported by the hospital, per se. This is distinct from hospitalist programs—such as Mercy’s—sponsored by hospitals (whether employed or contracted) in predominantly fee-for-service markets, which then comprised the lion’s share of the U.S. market.

I had the extraordinary good fortune to happen along in July 1994, get hired by Dr. Holbrook, and soon after begin serving as medical director for the Mercy program, which I would do for the next decade. To this day, Dr. Holbrook is a mentor and trusted advisor to me. I caught up with him in recognition of the 20th anniversary of the Mercy Inpatient Medicine Service.

Question: What gave you the idea to launch what was, at the time, considered such an unconventional program?

Answer: Before the specialty of emergency medicine, a patient’s private physician would be called in most cases when a patient present in the ED: 25 or 50 doctors might be called over 24 hours, each to see one patient each. The inefficiency and disruption caused by this system was a natural and logical stimulus to develop the specialty of emergency medicine. I saw hospitalist medicine as an exact analogy.

Q: What were you observing in the healthcare environment that drove you to create the Mercy Inpatient Medicine Service?

A: Working for many years in the emergency department of a community hospital without a house staff, the ED docs would admit a patient at night or on the weekend and the attending physician would often plan to see the patient “in the morning.” When the patient would decompensate in the middle of the night, the ED doc would get a call to run to the floor to “Band-Aid” the situation.

Q: How did you convince the board of trustees to fund it?

A: The reasons were primarily economic. No. 1, the hospital was losing market share because local physicians would prefer to admit to the teaching hospital [a nearby competitor], where they were not required to come in during the middle of the night. No. 2, the cost of a hospitalization managed by a hospitalist was less expensive than either a hospital stay managed by house staff or managed over the telephone by a private attending at home.

Q: What was the most difficult operational challenge for the program?

A: Effective and timely communication with the community physicians was the most difficult operational challenge. Access to outpatient medical treatment immediately prior to a hospitalization and timely communication to the community physician were both challenges that we never adequately solved in the early days. I understand that these issues can still be problematic.

Q: How was it received by patients?

A: Overall, patients were very happy with the system. In the old system, with a typical four-physician practice, a patient had only a 1 in 4 chance of being admitted by the doctor who was familiar with the case. The fact that the hospitalist was available in the hospital made the improvement in quality apparent to most patients.

Q: How did you get the medical staff to buy into the program?

A: I personally visited every private physician who participated. Physicians were given the option of not participating, or of part-time participation—for example, on weekends or holidays only. The word spread. Physicians came up to me and told me that the program enabled them to continue practicing for another five years. Physicians’ spouses thanked me.

Q: Are you surprised HM as a field has grown so quickly?

A: I am not really that surprised. It is a better way to organize health care. I am surprised that it did not occur sooner. We talked about instituting this system for 10 years before 1993.

Q: What big challenges remain for hospital medicine? What are some solutions?

A: I believe that the biggest global challenge for hospital medicine remains communication with community-based providers, both before the hospitalization as well as during hospitalization and immediately after discharge. In the era of the EMR, the Internet, and the iPhone and Android, this should be easier. HIPAA has not helped.

The other growing challenge will become apparent as hospitalists age in the profession: Disruption of the diurnal sleep cycle becomes increasingly problematic for many physicians after the age of 50 and can easily lead to burnout. The early hospitalists were all in their 30s. The attractive lifestyle choice for the 30-year-old can lead to burnout for the 55-year-old. The emergency-medicine literature has noted a similar problem of shift work/sleep fragmentation.

Final Thoughts

I believe Dr. Holbrook’s assessments on the future of our specialty are on target. As HM continues to mature, we need to continue to focus on how we communicate with providers outside the four walls of the hospital and how to address barriers to making HM a sustainable career.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

(Editor's note: Updated July 12, 2013.)

Four Factors Physicians Should Consider Before Job Termination

Leaving a job is never an easy decision, whether it is made voluntarily or not. A physician terminating a relationship with an employer may face emotionally charged conversations, difficult financial considerations, and long-term legal consequences. As you plan your exit strategy, it is critical for you to be aware of these issues and address them proactively with your employer. This can minimize hard feelings and surprises down the road for you, your former employer, and your colleagues.

In today’s competitive climate, a physician might work for several employers during the length of his or her career. With the tighter financial medical market and pressures from managed care mounting, employers are less likely to tolerate a nonproductive employee. Interoffice or personality conflicts may become intolerable for an unhappy or stressed physician. Physician turnover is a more common occurrence, and if not handled properly, it can be disruptive for all parties involved.

The following steps are meant for physicians contemplating leaving their place of employment or who may be asked to leave in the near future.

Step 1: Consider the Employment Agreement

Ideally, physician-separation matters are addressed preemptively when the physician enters the employer-employee relationship and signs an employment agreement. Thus, before contemplating a move, you should always start by reviewing the terms of your current employment agreement. A well-drafted employment agreement should specify the grounds for termination, both for cause (i.e. a specific set of reasons for immediate termination) and without cause (i.e. either party may terminate voluntarily). The agreement should specify the parties’ rights and obligations following a termination. These rights and obligations likely will vary depending on the basis for termination.

Typically, an employer will provide malpractice insurance for its physicians during the term of employment. However, physicians may be responsible for the cost of “tail coverage” upon the termination of employment. This is designed to protect the departing physician’s professional acts after leaving the employ of an employer with claims-made coverage. Because the coverage can be quite costly, a well-drafted employment agreement often will set forth which party is responsible for the procurement and payment of tail coverage. It is prudent for a departing physician to review the employment agreement to identify who has the affirmative obligation to provide the tail coverage, as it can be a costly surprise at termination.

The employment agreement also must be reviewed to determine the proper method to provide notice of termination (such as first-class mail, overnight courier, or hand delivery). Often, employment agreements will include a clause titled “Notice” that outlines the delivery method for proper notice to the employer.

Step 2: Consider a Termination/Separation Agreement

Entering into a termination agreement (sometimes referred to as a separation agreement) between the departing physician and the employer may address and resolve many of the outstanding issues that are not otherwise addressed in the employment agreement. A termination agreement may avoid unnecessary problems down the road and potentially acrimonious and costly litigation.

The termination agreement can fill in the gaps where the employment agreement is silent (or if an employment agreement does not exist). The key elements of a termination agreement often include:

- The effective date of the separation as well as what exactly is ending (e.g. employment, co-ownership, board membership, medical staff privileges);

- Payment and buyout terms;

- The physician’s removal from any management or administrative position (e.g. member of the governing board);

- Deferred compensation payments or severance pay that may need to be calculated and distributed;

- Employer obligations (if any) to provide the departing physician’s fringe benefits and business expenses, including retirement-plan contributions, health insurance, life insurance, medical dues, etc.; and

- Unused vacation days, bonuses, or expenses due.

If previously addressed in the employment agreement, the parties should reaffirm their respective rights and obligations regarding medical records, confidential information, noncompetition and nonsolicitation provisions. Otherwise, the termination agreement should identify the physician’s competitive and solicitation activities post-termination.

A noncompetition provision should include the geographic territory in which and the time period during which the departing physician cannot compete with the former employer. It is important to remember courts will render these provisions as unenforceable and invalid if improperly drafted or overly broad. It is common to see nondisparagement provisions, whereby each party agrees to refrain from making any negative or false statements regarding the other. Nondisclosure provisions are common as well with regards to what may be disclosed to third parties.

The separation agreement also should address the return of company property, including office key, credit card, computer, cell phone, and beeper. Patient records and charts should be completed and returned to the employer. Often, the departing physician will still be allowed reasonable access to patient records post-termination for certain authorized purposes (e.g. defending disciplinary actions, malpractice claims, and billing/payer claims and audits), usually at the physician’s own expense.

The termination agreement may also outline how patients will be notified about the physician’s departure. If a patient wishes to continue treatment with the departing physician, the former employer must be ready to transition the patient.

A well-written termination agreement will provide for mutual releases. However, there are often exclusions from the mutual releases, such as pre-termination date liabilities; medical malpractice claims resulting from the physician’s misconduct; or taxes, interests, and penalties covering the pre-termination date.

Step 3: Severance Pay

Depending on the circumstances surrounding the termination and employment agreements, a physician may be entitled to severance payments beginning on the date of termination and/or for a period of time post-termination. The departing physician should determine whether severance is appropriate and whether he or she is willing to forego severance payments in exchange for other benefits. Depending on the dollar amount and the physician’s career objectives, it may be worthwhile to sacrifice severance payments for a less onerous noncompete provision, for example.

Step 4: Take the High Road

Because you never know when your paths might cross with former coworkers or employers, it is always sensible to remain discreet and level-headed during this trying period. Although it is natural to discuss an impending move with others, a prudent physician will avoid water-cooler gossip.

In the event conflicts arise, limit the public disclosure of these disputes. Neither side wins the public relations battle, and often, both sides lose. This is a circumstance where experienced legal counsel can be invaluable as you navigate these potentially rocky waters. You would be well served to seek legal advice to discuss your intentions before making an actual move.

As always, remember conversations you have with counsel are typically protected by attorney-client privilege. It is always advisable to secure legal counsel to review the terms of an employment agreement, negotiate a fair termination/separation agreement, and serve as an advocate during this challenging career move.

Steven M. Harris, Esq., is a nationally recognized healthcare attorney and a member of the law firm McDonald Hopkins LLC in Chicago. Write to him at [email protected].

Leaving a job is never an easy decision, whether it is made voluntarily or not. A physician terminating a relationship with an employer may face emotionally charged conversations, difficult financial considerations, and long-term legal consequences. As you plan your exit strategy, it is critical for you to be aware of these issues and address them proactively with your employer. This can minimize hard feelings and surprises down the road for you, your former employer, and your colleagues.

In today’s competitive climate, a physician might work for several employers during the length of his or her career. With the tighter financial medical market and pressures from managed care mounting, employers are less likely to tolerate a nonproductive employee. Interoffice or personality conflicts may become intolerable for an unhappy or stressed physician. Physician turnover is a more common occurrence, and if not handled properly, it can be disruptive for all parties involved.

The following steps are meant for physicians contemplating leaving their place of employment or who may be asked to leave in the near future.

Step 1: Consider the Employment Agreement

Ideally, physician-separation matters are addressed preemptively when the physician enters the employer-employee relationship and signs an employment agreement. Thus, before contemplating a move, you should always start by reviewing the terms of your current employment agreement. A well-drafted employment agreement should specify the grounds for termination, both for cause (i.e. a specific set of reasons for immediate termination) and without cause (i.e. either party may terminate voluntarily). The agreement should specify the parties’ rights and obligations following a termination. These rights and obligations likely will vary depending on the basis for termination.

Typically, an employer will provide malpractice insurance for its physicians during the term of employment. However, physicians may be responsible for the cost of “tail coverage” upon the termination of employment. This is designed to protect the departing physician’s professional acts after leaving the employ of an employer with claims-made coverage. Because the coverage can be quite costly, a well-drafted employment agreement often will set forth which party is responsible for the procurement and payment of tail coverage. It is prudent for a departing physician to review the employment agreement to identify who has the affirmative obligation to provide the tail coverage, as it can be a costly surprise at termination.

The employment agreement also must be reviewed to determine the proper method to provide notice of termination (such as first-class mail, overnight courier, or hand delivery). Often, employment agreements will include a clause titled “Notice” that outlines the delivery method for proper notice to the employer.

Step 2: Consider a Termination/Separation Agreement

Entering into a termination agreement (sometimes referred to as a separation agreement) between the departing physician and the employer may address and resolve many of the outstanding issues that are not otherwise addressed in the employment agreement. A termination agreement may avoid unnecessary problems down the road and potentially acrimonious and costly litigation.

The termination agreement can fill in the gaps where the employment agreement is silent (or if an employment agreement does not exist). The key elements of a termination agreement often include:

- The effective date of the separation as well as what exactly is ending (e.g. employment, co-ownership, board membership, medical staff privileges);

- Payment and buyout terms;

- The physician’s removal from any management or administrative position (e.g. member of the governing board);

- Deferred compensation payments or severance pay that may need to be calculated and distributed;

- Employer obligations (if any) to provide the departing physician’s fringe benefits and business expenses, including retirement-plan contributions, health insurance, life insurance, medical dues, etc.; and

- Unused vacation days, bonuses, or expenses due.

If previously addressed in the employment agreement, the parties should reaffirm their respective rights and obligations regarding medical records, confidential information, noncompetition and nonsolicitation provisions. Otherwise, the termination agreement should identify the physician’s competitive and solicitation activities post-termination.

A noncompetition provision should include the geographic territory in which and the time period during which the departing physician cannot compete with the former employer. It is important to remember courts will render these provisions as unenforceable and invalid if improperly drafted or overly broad. It is common to see nondisparagement provisions, whereby each party agrees to refrain from making any negative or false statements regarding the other. Nondisclosure provisions are common as well with regards to what may be disclosed to third parties.

The separation agreement also should address the return of company property, including office key, credit card, computer, cell phone, and beeper. Patient records and charts should be completed and returned to the employer. Often, the departing physician will still be allowed reasonable access to patient records post-termination for certain authorized purposes (e.g. defending disciplinary actions, malpractice claims, and billing/payer claims and audits), usually at the physician’s own expense.

The termination agreement may also outline how patients will be notified about the physician’s departure. If a patient wishes to continue treatment with the departing physician, the former employer must be ready to transition the patient.

A well-written termination agreement will provide for mutual releases. However, there are often exclusions from the mutual releases, such as pre-termination date liabilities; medical malpractice claims resulting from the physician’s misconduct; or taxes, interests, and penalties covering the pre-termination date.

Step 3: Severance Pay

Depending on the circumstances surrounding the termination and employment agreements, a physician may be entitled to severance payments beginning on the date of termination and/or for a period of time post-termination. The departing physician should determine whether severance is appropriate and whether he or she is willing to forego severance payments in exchange for other benefits. Depending on the dollar amount and the physician’s career objectives, it may be worthwhile to sacrifice severance payments for a less onerous noncompete provision, for example.

Step 4: Take the High Road

Because you never know when your paths might cross with former coworkers or employers, it is always sensible to remain discreet and level-headed during this trying period. Although it is natural to discuss an impending move with others, a prudent physician will avoid water-cooler gossip.

In the event conflicts arise, limit the public disclosure of these disputes. Neither side wins the public relations battle, and often, both sides lose. This is a circumstance where experienced legal counsel can be invaluable as you navigate these potentially rocky waters. You would be well served to seek legal advice to discuss your intentions before making an actual move.

As always, remember conversations you have with counsel are typically protected by attorney-client privilege. It is always advisable to secure legal counsel to review the terms of an employment agreement, negotiate a fair termination/separation agreement, and serve as an advocate during this challenging career move.

Steven M. Harris, Esq., is a nationally recognized healthcare attorney and a member of the law firm McDonald Hopkins LLC in Chicago. Write to him at [email protected].

Leaving a job is never an easy decision, whether it is made voluntarily or not. A physician terminating a relationship with an employer may face emotionally charged conversations, difficult financial considerations, and long-term legal consequences. As you plan your exit strategy, it is critical for you to be aware of these issues and address them proactively with your employer. This can minimize hard feelings and surprises down the road for you, your former employer, and your colleagues.

In today’s competitive climate, a physician might work for several employers during the length of his or her career. With the tighter financial medical market and pressures from managed care mounting, employers are less likely to tolerate a nonproductive employee. Interoffice or personality conflicts may become intolerable for an unhappy or stressed physician. Physician turnover is a more common occurrence, and if not handled properly, it can be disruptive for all parties involved.

The following steps are meant for physicians contemplating leaving their place of employment or who may be asked to leave in the near future.

Step 1: Consider the Employment Agreement

Ideally, physician-separation matters are addressed preemptively when the physician enters the employer-employee relationship and signs an employment agreement. Thus, before contemplating a move, you should always start by reviewing the terms of your current employment agreement. A well-drafted employment agreement should specify the grounds for termination, both for cause (i.e. a specific set of reasons for immediate termination) and without cause (i.e. either party may terminate voluntarily). The agreement should specify the parties’ rights and obligations following a termination. These rights and obligations likely will vary depending on the basis for termination.

Typically, an employer will provide malpractice insurance for its physicians during the term of employment. However, physicians may be responsible for the cost of “tail coverage” upon the termination of employment. This is designed to protect the departing physician’s professional acts after leaving the employ of an employer with claims-made coverage. Because the coverage can be quite costly, a well-drafted employment agreement often will set forth which party is responsible for the procurement and payment of tail coverage. It is prudent for a departing physician to review the employment agreement to identify who has the affirmative obligation to provide the tail coverage, as it can be a costly surprise at termination.

The employment agreement also must be reviewed to determine the proper method to provide notice of termination (such as first-class mail, overnight courier, or hand delivery). Often, employment agreements will include a clause titled “Notice” that outlines the delivery method for proper notice to the employer.

Step 2: Consider a Termination/Separation Agreement

Entering into a termination agreement (sometimes referred to as a separation agreement) between the departing physician and the employer may address and resolve many of the outstanding issues that are not otherwise addressed in the employment agreement. A termination agreement may avoid unnecessary problems down the road and potentially acrimonious and costly litigation.

The termination agreement can fill in the gaps where the employment agreement is silent (or if an employment agreement does not exist). The key elements of a termination agreement often include:

- The effective date of the separation as well as what exactly is ending (e.g. employment, co-ownership, board membership, medical staff privileges);

- Payment and buyout terms;

- The physician’s removal from any management or administrative position (e.g. member of the governing board);

- Deferred compensation payments or severance pay that may need to be calculated and distributed;

- Employer obligations (if any) to provide the departing physician’s fringe benefits and business expenses, including retirement-plan contributions, health insurance, life insurance, medical dues, etc.; and

- Unused vacation days, bonuses, or expenses due.

If previously addressed in the employment agreement, the parties should reaffirm their respective rights and obligations regarding medical records, confidential information, noncompetition and nonsolicitation provisions. Otherwise, the termination agreement should identify the physician’s competitive and solicitation activities post-termination.

A noncompetition provision should include the geographic territory in which and the time period during which the departing physician cannot compete with the former employer. It is important to remember courts will render these provisions as unenforceable and invalid if improperly drafted or overly broad. It is common to see nondisparagement provisions, whereby each party agrees to refrain from making any negative or false statements regarding the other. Nondisclosure provisions are common as well with regards to what may be disclosed to third parties.

The separation agreement also should address the return of company property, including office key, credit card, computer, cell phone, and beeper. Patient records and charts should be completed and returned to the employer. Often, the departing physician will still be allowed reasonable access to patient records post-termination for certain authorized purposes (e.g. defending disciplinary actions, malpractice claims, and billing/payer claims and audits), usually at the physician’s own expense.

The termination agreement may also outline how patients will be notified about the physician’s departure. If a patient wishes to continue treatment with the departing physician, the former employer must be ready to transition the patient.

A well-written termination agreement will provide for mutual releases. However, there are often exclusions from the mutual releases, such as pre-termination date liabilities; medical malpractice claims resulting from the physician’s misconduct; or taxes, interests, and penalties covering the pre-termination date.

Step 3: Severance Pay

Depending on the circumstances surrounding the termination and employment agreements, a physician may be entitled to severance payments beginning on the date of termination and/or for a period of time post-termination. The departing physician should determine whether severance is appropriate and whether he or she is willing to forego severance payments in exchange for other benefits. Depending on the dollar amount and the physician’s career objectives, it may be worthwhile to sacrifice severance payments for a less onerous noncompete provision, for example.

Step 4: Take the High Road

Because you never know when your paths might cross with former coworkers or employers, it is always sensible to remain discreet and level-headed during this trying period. Although it is natural to discuss an impending move with others, a prudent physician will avoid water-cooler gossip.

In the event conflicts arise, limit the public disclosure of these disputes. Neither side wins the public relations battle, and often, both sides lose. This is a circumstance where experienced legal counsel can be invaluable as you navigate these potentially rocky waters. You would be well served to seek legal advice to discuss your intentions before making an actual move.

As always, remember conversations you have with counsel are typically protected by attorney-client privilege. It is always advisable to secure legal counsel to review the terms of an employment agreement, negotiate a fair termination/separation agreement, and serve as an advocate during this challenging career move.

Steven M. Harris, Esq., is a nationally recognized healthcare attorney and a member of the law firm McDonald Hopkins LLC in Chicago. Write to him at [email protected].

Not One Ovary but Both Removed

In Illinois, a 36-year-old woman underwent a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, performed by the defendant gynecologist.

The plaintiff claimed that the defendant removed both of her ovaries although she had consented to the removal of only the left ovary. The plaintiff also claimed that her colon was perforated during the surgery, necessitating multiple subsequent hospitalizations.

Outcome

According to a published report, a $1.2 million verdict was returned against both defendants (the gynecologist and the medical facility where the surgery took place).

Comment

Setting aside the issue of the bowel damage for a moment, it is important to consider the matter of patient consent for medical procedures.

A patient who has not given consent for a procedure can recover for damages under the tort of battery, whether or not harm was suffered—even if the procedure was helpful.

Tortious battery is an offensive contact occurring without a person’s consent. The question of “offensiveness” is decided by an objective “reasonable person standard.” In the classic example, a person bumped by other passengers on a crowded subway cannot recover for battery because a reasonable person expects this type of contact on crowded subways. Yet a person groped on that same subway has a case of battery because a reasonable person does not expect this contact, as it is offensive.

Here, the patient presumably consented to a unilateral, not a bilateral, oophorectomy. In any instance where the patient has given consent for surgery, it is important to not exceed the scope of that consent. However, the extent of surgery will commonly depend on intraoperative findings, with decisions often made on the spot. In such cases, the possibility of the contingent procedure must be addressed in the surgical consent, as well as specific circumstances under which the more extensive procedure will occur.

Bowel perforation is a risk inherent in many intraoperative procedures, both intraluminal and extraluminal. While this risk may be unavoidable, the jury in this case likely concluded that the surgeon was careless with regard to the patient’s wishes and must have been careless in his technique as well.

In sum, make sure the patient fully understands any procedure and has signed a proper consent for that procedure. Risks inherent in a procedure must be discussed fully with the patient and included on the consent form. Lastly, the consent form should address the anticipated scope of the procedure, as well as any conditions that might require the scope to be broadened.

In Illinois, a 36-year-old woman underwent a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, performed by the defendant gynecologist.

The plaintiff claimed that the defendant removed both of her ovaries although she had consented to the removal of only the left ovary. The plaintiff also claimed that her colon was perforated during the surgery, necessitating multiple subsequent hospitalizations.

Outcome

According to a published report, a $1.2 million verdict was returned against both defendants (the gynecologist and the medical facility where the surgery took place).

Comment

Setting aside the issue of the bowel damage for a moment, it is important to consider the matter of patient consent for medical procedures.

A patient who has not given consent for a procedure can recover for damages under the tort of battery, whether or not harm was suffered—even if the procedure was helpful.

Tortious battery is an offensive contact occurring without a person’s consent. The question of “offensiveness” is decided by an objective “reasonable person standard.” In the classic example, a person bumped by other passengers on a crowded subway cannot recover for battery because a reasonable person expects this type of contact on crowded subways. Yet a person groped on that same subway has a case of battery because a reasonable person does not expect this contact, as it is offensive.

Here, the patient presumably consented to a unilateral, not a bilateral, oophorectomy. In any instance where the patient has given consent for surgery, it is important to not exceed the scope of that consent. However, the extent of surgery will commonly depend on intraoperative findings, with decisions often made on the spot. In such cases, the possibility of the contingent procedure must be addressed in the surgical consent, as well as specific circumstances under which the more extensive procedure will occur.

Bowel perforation is a risk inherent in many intraoperative procedures, both intraluminal and extraluminal. While this risk may be unavoidable, the jury in this case likely concluded that the surgeon was careless with regard to the patient’s wishes and must have been careless in his technique as well.

In sum, make sure the patient fully understands any procedure and has signed a proper consent for that procedure. Risks inherent in a procedure must be discussed fully with the patient and included on the consent form. Lastly, the consent form should address the anticipated scope of the procedure, as well as any conditions that might require the scope to be broadened.

In Illinois, a 36-year-old woman underwent a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, performed by the defendant gynecologist.

The plaintiff claimed that the defendant removed both of her ovaries although she had consented to the removal of only the left ovary. The plaintiff also claimed that her colon was perforated during the surgery, necessitating multiple subsequent hospitalizations.

Outcome

According to a published report, a $1.2 million verdict was returned against both defendants (the gynecologist and the medical facility where the surgery took place).

Comment

Setting aside the issue of the bowel damage for a moment, it is important to consider the matter of patient consent for medical procedures.

A patient who has not given consent for a procedure can recover for damages under the tort of battery, whether or not harm was suffered—even if the procedure was helpful.

Tortious battery is an offensive contact occurring without a person’s consent. The question of “offensiveness” is decided by an objective “reasonable person standard.” In the classic example, a person bumped by other passengers on a crowded subway cannot recover for battery because a reasonable person expects this type of contact on crowded subways. Yet a person groped on that same subway has a case of battery because a reasonable person does not expect this contact, as it is offensive.

Here, the patient presumably consented to a unilateral, not a bilateral, oophorectomy. In any instance where the patient has given consent for surgery, it is important to not exceed the scope of that consent. However, the extent of surgery will commonly depend on intraoperative findings, with decisions often made on the spot. In such cases, the possibility of the contingent procedure must be addressed in the surgical consent, as well as specific circumstances under which the more extensive procedure will occur.

Bowel perforation is a risk inherent in many intraoperative procedures, both intraluminal and extraluminal. While this risk may be unavoidable, the jury in this case likely concluded that the surgeon was careless with regard to the patient’s wishes and must have been careless in his technique as well.

In sum, make sure the patient fully understands any procedure and has signed a proper consent for that procedure. Risks inherent in a procedure must be discussed fully with the patient and included on the consent form. Lastly, the consent form should address the anticipated scope of the procedure, as well as any conditions that might require the scope to be broadened.

Respondeat superior: What are your responsibilities?

Dear Dr. Mossman:

In my residency program, we cover the psychiatric emergency room (ER) overnight, and we admit, discharge, and make treatment recommendations without calling the attending psychiatrists about every decision. But if something goes wrong—eg, a discharged patient later commits suicide—I’ve heard that the faculty psychiatrist may be held liable despite never having met the patient. Should we awaken our attendings to discuss every major treatment decision?

Submitted by “Dr. R”

Postgraduate medical training programs in all specialties let interns and residents make judgments and decisions outside the direct supervision of board-certified faculty members. Medical education cannot occur unless doctors learn to take independent responsibility for patients. But if poor decisions by physicians-in-training lead to bad outcomes, might their teachers and training institutions share the blame—and the legal liability for damages?

The answer is “yes.” To understand why, and to learn about how Dr. R’s residency program should address this possibility, we’ll cover:

• the theory of respondeat superior

• factors affecting potential vicarious liability

• how postgraduate training balances supervision needs with letting residents get real-world treatment experience.

Vicarious liability

In general, if Person A injures Person B, Person B may initiate a tort action against Person A to seek monetary compensation. If the injury occurred while Person A was working for Person C, then under a legal doctrine called respondeat superior (Latin for “let the master answer”), courts may allow Person B to sue Person C, too, even if Person C wasn’t present when the injury occurred and did nothing that harmed Person B directly.

Respondeat superior imposes vicarious liability on an employer for negligent acts by employees who are “performing work assigned by the employer or engaging in a course of conduct subject to the employer’s control.”1 The doctrine extends back to 17th-century English courts and originated under the theory that, during a servant’s employment, one may presume that the servant acted by his master’s authority.2

Modern authors state that the justification for imposing vicarious liability “is largely one of public or social policy under which it has been determined that, irrespective of fault, a party should be held to respond for the acts of another.”3 Employers usually have more resources to pay damages than their employees do,4 and “in hard fact, the reason for the employers’ liability is the damages are taken from a deep pocket.”5

Determining potential responsibility

In Dr. R’s scenario, an adverse event follows the actions of a psychiatry resident who is performing a training activity at a hospital ER. Whether an attorney acting on behalf of an injured client can bring a claim of respondeat superior against the hospital, the resident’s academic institution, or the attending psychiatrist will depend on the nature of the relationships among these parties. This often becomes a complex legal matter that involves examining the residency program’s educational arrangements, official training documents (eg, affiliation agreements between a university and a hospital), employment contracts, and supervisory policies. In addition, statutes and legal precedents governing vicarious liability vary from state to state. Although an initial malpractice filing may name several individuals and institutions as defendants, courts eventually must apply their jurisdictions’ rules governing vicarious liability to determine which parties can lawfully bear potential liability.

Some courts have held that a private hospital generally is not responsible for negligent actions by attending physicians because the hospital does not control patient care decisions and physicians are not the hospital’s employees.6-8 Physicians in training, however, usually are employees of hospitals or their training institutions. Residents and attending physicians in many psychiatry training programs work at hospitals where patients reasonably believe that the doctors function as part of the hospital’s larger service enterprise. In some jurisdictions, this makes the hospitals potentially liable for their doctors’ acts,9 even when the doctors, as public employees, may have statutory immunity from being sued as individuals.10

Reuter11 has suggested that other agency theories may allow a resident’s error to create liability for an attending physician or medical school. The resident may be viewed as a “borrowed servant” such that, although a hospital was the resident’s general employer, the attending physician still exercised sufficient control with respect to the faulty act in question. A medical school faculty physician also may be liable along with the hospital under a joint employment theory based upon the faculty member’s “right to control” how the resident cares for the attending’s patient.11

Taking into account recent cases and trends in public expectations, Kachalia and Studdert12 suggest that potential liability of attending physicians rests on 2 factors: whether the treatment context and structure of supervisory obligations establishes a patient-physician relationship between the attending physician and the injured patient, and whether the attending physician has provided adequate supervision. Details of these 2 factors appear in Table 1.12-14

Independence vs oversight

Potential malpractice liability is one of many factors that postgraduate psychiatry programs consider when titrating the amount and intensity of supervision against letting residents make independent decisions and take on clinical responsibility for patients. Patients deserve good care and protection from mistakes that inexperienced physicians may make. At the same time, society recognizes that educating future physicians requires allowing residents to get real-world experiences in evaluating and treating patients.

These ideas are expressed in the “Program Requirements” for psychiatry residencies promulgated by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME).15 According to the ACGME, the “essential learning activity” that teaches physicians how to provide medical care is “interaction with patients under the guidance and supervision of faculty members” who let residents “exercise those skills with greater independence.”15

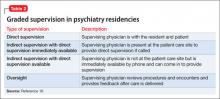

Psychiatry residencies must fashion learning experiences and supervisory schemes that give residents “graded and progressive responsibility” for providing care. Although each patient should have “an identifiable, appropriately-credentialed and privileged attending physician,” residents may provide substantial services under various levels of supervision described in Table 2.16

Deciding when and what kinds of patient care may be delegated to residents is the responsibility of residency program directors, who should base their judgments on explicit, prespecified criteria using information provided by supervising faculty members. Before letting first-year residents see patients on their own, psychiatry programs must determine that the residents can:

• take a history accurately

• do emergency psychiatric assessments

• present findings and data accurately to supervisors.

Physicians at all levels need to recognize when they should ask for help. The most important ACGME criterion for allowing a psychiatry resident to work under less stringent supervision is that the resident has demonstrated an “ability and willingness to ask for help when indicated.”16

Getting specifics

One way to respond Dr. R’s questions is to ask, “Do you know when you need help, and will you ask for it?” But her concerns deserve a more detailed (and more thoughtful) response that inquires about details of her training program and its specific educational experiences. Although it would be impossible to list everything to consider, some possible topics include:

• At what level of experience and training do residents assume this coverage responsibility?

• What kind of preparation do residents receive?

• What range of problems and conditions do the patients present?

• What level of clinical support is available on site—eg, experienced psychiatric nurses, other mental health staff, or other medical specialists?

• What has the program’s experience shown about residents’ actual readiness to handle these coverage duties?

• What guidelines have faculty members provided about when to call an attending physician or request a faculty member’s presence? Do these guidelines seem sound, given the above considerations?

Bottom Line

Psychiatry residents have supervisee relationships that create potential vicarious liability for institutions and faculty members. Residency training programs address these concerns by implementing adequate preparation for advanced responsibility, developing evaluative criteria and supervisory guidelines, and making sure that residents will ask for help when they need it.

Related Resources

- Regan JJ, Regan WM. Medical malpractice and respondeat superior. South Med J. 2002;95(5):545-548.

- Winrow B, Winrow AR. Personal protection: vicarious liability as applied to the various business structures. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2008;53(2):146-149.

- Pozgar GD. Legal aspects of health care administration. 11th edition. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC; 2012.

Disclosure

Dr. Mossman reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

References

1. Restatement of the law of agency. 3rd ed. §7.07(2). Philadelphia, PA: American Law Institute; 2006.

2. Baty T. Vicarious liability: a short history of the liability of employers, principals, partners, associations and trade-union members. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press; 1916.

3. Dessauer v Memorial General Hosp, 628 P.2d 337 (N.M. 1981).

4. Firestone MH. Agency. In: Sandbar SS, Firestone MH, eds. Legal medicine. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2007:43-47.

5. Dobbs D, Keeton RE, Owen DG. Prosser and Keaton on torts. 5th ed. St. Paul, MN: West Publishing Co; 1984.

6. Austin v Litvak, 682 P.2d 41 (Colo. 1984).

7. Kirk v Michael Reese Hospital and Medical Center, 513 N.E.2d 387 (Ill. 1987).

8. Gregg v National Medical Health Care Services, Inc., 499 P.2d 925 (Ariz. App. 1985).

9. Adamski v Tacoma General Hospital, 579 P.2d 970 (Wash. App. 1978).

10. Johnson v LeBonheur Children’s Medical Center, 74 S.W.3d 338 (Tenn. 2002).

11. Reuter SR. Professional liability in postgraduate medical education. Who is liable for resident negligence? J Leg Med. 1994;15(4):485-531.

12. Kachalia A, Studdert DM. Professional liability issues in graduate medical education. JAMA. 2004;292(9):1051-1056.

13. Lownsbury v VanBuren, 762 N.E.2d 354 (Ohio 2002).

14. Sterling v Johns Hopkins Hospital, 802 A.2d 440 (Md Ct Spec App 2002).

15. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Program and institutional guidelines. https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/tabid/147/ProgramandInstitutional Guidelines/MedicalAccreditation/Psychiatry.aspx. Accessed April 8, 2013.

16. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME program requirements for graduate medical education in psychiatry. https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/400_psychiatry_07012007_u04122008.pdf. Published July 1, 2007. Accessed April 8, 2013.

Dear Dr. Mossman:

In my residency program, we cover the psychiatric emergency room (ER) overnight, and we admit, discharge, and make treatment recommendations without calling the attending psychiatrists about every decision. But if something goes wrong—eg, a discharged patient later commits suicide—I’ve heard that the faculty psychiatrist may be held liable despite never having met the patient. Should we awaken our attendings to discuss every major treatment decision?

Submitted by “Dr. R”

Postgraduate medical training programs in all specialties let interns and residents make judgments and decisions outside the direct supervision of board-certified faculty members. Medical education cannot occur unless doctors learn to take independent responsibility for patients. But if poor decisions by physicians-in-training lead to bad outcomes, might their teachers and training institutions share the blame—and the legal liability for damages?

The answer is “yes.” To understand why, and to learn about how Dr. R’s residency program should address this possibility, we’ll cover:

• the theory of respondeat superior

• factors affecting potential vicarious liability

• how postgraduate training balances supervision needs with letting residents get real-world treatment experience.

Vicarious liability

In general, if Person A injures Person B, Person B may initiate a tort action against Person A to seek monetary compensation. If the injury occurred while Person A was working for Person C, then under a legal doctrine called respondeat superior (Latin for “let the master answer”), courts may allow Person B to sue Person C, too, even if Person C wasn’t present when the injury occurred and did nothing that harmed Person B directly.

Respondeat superior imposes vicarious liability on an employer for negligent acts by employees who are “performing work assigned by the employer or engaging in a course of conduct subject to the employer’s control.”1 The doctrine extends back to 17th-century English courts and originated under the theory that, during a servant’s employment, one may presume that the servant acted by his master’s authority.2

Modern authors state that the justification for imposing vicarious liability “is largely one of public or social policy under which it has been determined that, irrespective of fault, a party should be held to respond for the acts of another.”3 Employers usually have more resources to pay damages than their employees do,4 and “in hard fact, the reason for the employers’ liability is the damages are taken from a deep pocket.”5

Determining potential responsibility

In Dr. R’s scenario, an adverse event follows the actions of a psychiatry resident who is performing a training activity at a hospital ER. Whether an attorney acting on behalf of an injured client can bring a claim of respondeat superior against the hospital, the resident’s academic institution, or the attending psychiatrist will depend on the nature of the relationships among these parties. This often becomes a complex legal matter that involves examining the residency program’s educational arrangements, official training documents (eg, affiliation agreements between a university and a hospital), employment contracts, and supervisory policies. In addition, statutes and legal precedents governing vicarious liability vary from state to state. Although an initial malpractice filing may name several individuals and institutions as defendants, courts eventually must apply their jurisdictions’ rules governing vicarious liability to determine which parties can lawfully bear potential liability.

Some courts have held that a private hospital generally is not responsible for negligent actions by attending physicians because the hospital does not control patient care decisions and physicians are not the hospital’s employees.6-8 Physicians in training, however, usually are employees of hospitals or their training institutions. Residents and attending physicians in many psychiatry training programs work at hospitals where patients reasonably believe that the doctors function as part of the hospital’s larger service enterprise. In some jurisdictions, this makes the hospitals potentially liable for their doctors’ acts,9 even when the doctors, as public employees, may have statutory immunity from being sued as individuals.10

Reuter11 has suggested that other agency theories may allow a resident’s error to create liability for an attending physician or medical school. The resident may be viewed as a “borrowed servant” such that, although a hospital was the resident’s general employer, the attending physician still exercised sufficient control with respect to the faulty act in question. A medical school faculty physician also may be liable along with the hospital under a joint employment theory based upon the faculty member’s “right to control” how the resident cares for the attending’s patient.11

Taking into account recent cases and trends in public expectations, Kachalia and Studdert12 suggest that potential liability of attending physicians rests on 2 factors: whether the treatment context and structure of supervisory obligations establishes a patient-physician relationship between the attending physician and the injured patient, and whether the attending physician has provided adequate supervision. Details of these 2 factors appear in Table 1.12-14

Independence vs oversight

Potential malpractice liability is one of many factors that postgraduate psychiatry programs consider when titrating the amount and intensity of supervision against letting residents make independent decisions and take on clinical responsibility for patients. Patients deserve good care and protection from mistakes that inexperienced physicians may make. At the same time, society recognizes that educating future physicians requires allowing residents to get real-world experiences in evaluating and treating patients.

These ideas are expressed in the “Program Requirements” for psychiatry residencies promulgated by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME).15 According to the ACGME, the “essential learning activity” that teaches physicians how to provide medical care is “interaction with patients under the guidance and supervision of faculty members” who let residents “exercise those skills with greater independence.”15