User login

Nigerian-Born Hospitalist Steers Career Down Path of Administrative Challenges

In some ways, Femi Adewunmi, MD, MBA, CPE, SFHM, seemed destined to become a physician. He grew up in a medical family—his mother is an orthodontist; his father is an obstetrician/gynecologist. As a child, he often spent holidays visiting patients at the hospital where his dad worked. He grew to appreciate medicine as a noble profession, and when he reached his teens, he never seriously considered another career path.

“There were times when I was in medical school, dreading having to study for the numerous tests and exams, when I wished I had someone I could have blamed my decision to go to medical school on,” says Dr. Adewunmi, a native of Nigeria who has practiced as a hospitalist in the U.S. since 2003. “But no one pushed me to do it. It was something I always looked forward to doing, and I’m very glad I stuck with it.”

Dr. Adewunmi has only become more passionate about his work since then. His experience as a front-line hospitalist laid the foundation for a series of leadership roles, first directing the HM program at Johnston Memorial Hospital in Smithfield, N.C., and now as regional chief medical officer for Sound Physicians, which provides inpatient services to more than 70 hospitals nationally.

“I really want to be a good physician executive,” he says. “It’s definitely a case of ‘The more you learn, the more you realize how little you know.’ I still have a lot to learn, but I’m looking forward to the challenge.”

When did you decide to go into HM?

During residency, I realized I loved taking care of patients in the hospital, both along the wards and in the ICU. I enjoyed my outpatient clinics but found myself looking for any reason I could to stay in the hospital caring for patients. I was interested in patient safety and I was doing a little bit of utilization review, so I also felt it would give me a great overall perspective of the healthcare system.

What about leading the hospitalist program at Johnston Memorial appealed to you?

I enjoyed clinical medicine, and I still do, but I was looking to do more. I wanted to make an impact at a systems level, and I knew, to do that, I eventually had to gain some leadership experience.

What is the most valuable lesson you learned in that role?

Understanding that change doesn’t happen instantaneously. For instance, as a clinician, you sometimes admit patients with congestive heart failure. You diagnose correctly, treat appropriately, and in a few days, the patients do better and go home. You get pretty swift gratification. Administration is much different. You put processes in place and it could take weeks or several quarters before you start to see the effects of the changes you implement.

What appealed to you about moving from a single-site leadership position at Johnston to a regional position with Sound?

I wanted to continue evolving. I wanted more of a challenge and was seeking opportunities where I would have operational responsibility—overseeing performance improvement in quality, satisfaction, and financial performance for several programs. In addition, I wanted to be accountable for physician development, recruiting, negotiations, and the whole gamut of business development. It was the next logical step in my career.

Why did you pursue an MBA?

I’d made that decision just before I got into medical school. I recall first thinking about it after a conversation I had with my father as a teenager. When I told him that I had made up my mind to study medicine, he said, “You should consider getting an MBA as well. Your generation is going to need to have business experience and expertise, and be better in that area than our generation was.” It’s been invaluable for me in terms of preparing me for handling the business side of medicine, including ways to make operations more efficient and to reduce costs without compromising the quality of care provided.

You have worked in both hospital-employed and privately contracted HM programs. Do you prefer one model?

In general, the larger organizations tend to have an advantage in that they have established protocols and processes that work and have been refined over time. Couple that with the economies of scale they enjoy, as we move into an era of value-based purchasing, it’s becoming harder for the smaller community-based hospital to do that as well. That said, I have seen local hospital-run programs that function really well and have administrative support, so there is definitely enough room for both models.

You were in the inaugural FHM class. What did that recognition mean to you?

I saw it as validation of how we were starting to mature as a specialty and as recognition of a commitment to being a hospitalist, not just an internist. I never practiced outpatient medicine. I went straight from residency to hospitalist medicine. That’s how I identify myself, and I was happy to see that physicians specializing in hospital medicine were starting to get recognized.

What is your biggest professional reward?

The satisfaction from knowing you’re making a difference—not just by the care you provide one-on-one to your patients, but also knowing you’re contributing at a systems level or a population level because you’re making decisions and trying to redefine processes that actually could impact a much larger cohort.

What is your biggest professional challenge?

Trying to find enough hours in the day to do all that needs to be done.

What is next for you professionally?

I enjoy having varied opportunities and being involved in many different aspects of operations. That’s what attracted me to a larger company such as Sound Physicians, and I see myself staying in that type of role. Down the road, I’d love to be able to take some of my knowledge to Nigeria and find a way to help develop and shape the healthcare sector back home.

Why would that mean so much to you?

It would be a chance to give back. We still have people dying from largely preventable diseases, and our healthcare system is not what it should be. We don’t have enough physicians for the population, and most of the physicians are in urban areas.

Close to half of the members of my graduating medical school class are either in the U.S., Europe, Asia, or South Africa.

That type of brain drain has a tremendous effect over several decades. That’s a lot of talent outside the country, and we need that back home.

Mark Leiser is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

In some ways, Femi Adewunmi, MD, MBA, CPE, SFHM, seemed destined to become a physician. He grew up in a medical family—his mother is an orthodontist; his father is an obstetrician/gynecologist. As a child, he often spent holidays visiting patients at the hospital where his dad worked. He grew to appreciate medicine as a noble profession, and when he reached his teens, he never seriously considered another career path.

“There were times when I was in medical school, dreading having to study for the numerous tests and exams, when I wished I had someone I could have blamed my decision to go to medical school on,” says Dr. Adewunmi, a native of Nigeria who has practiced as a hospitalist in the U.S. since 2003. “But no one pushed me to do it. It was something I always looked forward to doing, and I’m very glad I stuck with it.”

Dr. Adewunmi has only become more passionate about his work since then. His experience as a front-line hospitalist laid the foundation for a series of leadership roles, first directing the HM program at Johnston Memorial Hospital in Smithfield, N.C., and now as regional chief medical officer for Sound Physicians, which provides inpatient services to more than 70 hospitals nationally.

“I really want to be a good physician executive,” he says. “It’s definitely a case of ‘The more you learn, the more you realize how little you know.’ I still have a lot to learn, but I’m looking forward to the challenge.”

When did you decide to go into HM?

During residency, I realized I loved taking care of patients in the hospital, both along the wards and in the ICU. I enjoyed my outpatient clinics but found myself looking for any reason I could to stay in the hospital caring for patients. I was interested in patient safety and I was doing a little bit of utilization review, so I also felt it would give me a great overall perspective of the healthcare system.

What about leading the hospitalist program at Johnston Memorial appealed to you?

I enjoyed clinical medicine, and I still do, but I was looking to do more. I wanted to make an impact at a systems level, and I knew, to do that, I eventually had to gain some leadership experience.

What is the most valuable lesson you learned in that role?

Understanding that change doesn’t happen instantaneously. For instance, as a clinician, you sometimes admit patients with congestive heart failure. You diagnose correctly, treat appropriately, and in a few days, the patients do better and go home. You get pretty swift gratification. Administration is much different. You put processes in place and it could take weeks or several quarters before you start to see the effects of the changes you implement.

What appealed to you about moving from a single-site leadership position at Johnston to a regional position with Sound?

I wanted to continue evolving. I wanted more of a challenge and was seeking opportunities where I would have operational responsibility—overseeing performance improvement in quality, satisfaction, and financial performance for several programs. In addition, I wanted to be accountable for physician development, recruiting, negotiations, and the whole gamut of business development. It was the next logical step in my career.

Why did you pursue an MBA?

I’d made that decision just before I got into medical school. I recall first thinking about it after a conversation I had with my father as a teenager. When I told him that I had made up my mind to study medicine, he said, “You should consider getting an MBA as well. Your generation is going to need to have business experience and expertise, and be better in that area than our generation was.” It’s been invaluable for me in terms of preparing me for handling the business side of medicine, including ways to make operations more efficient and to reduce costs without compromising the quality of care provided.

You have worked in both hospital-employed and privately contracted HM programs. Do you prefer one model?

In general, the larger organizations tend to have an advantage in that they have established protocols and processes that work and have been refined over time. Couple that with the economies of scale they enjoy, as we move into an era of value-based purchasing, it’s becoming harder for the smaller community-based hospital to do that as well. That said, I have seen local hospital-run programs that function really well and have administrative support, so there is definitely enough room for both models.

You were in the inaugural FHM class. What did that recognition mean to you?

I saw it as validation of how we were starting to mature as a specialty and as recognition of a commitment to being a hospitalist, not just an internist. I never practiced outpatient medicine. I went straight from residency to hospitalist medicine. That’s how I identify myself, and I was happy to see that physicians specializing in hospital medicine were starting to get recognized.

What is your biggest professional reward?

The satisfaction from knowing you’re making a difference—not just by the care you provide one-on-one to your patients, but also knowing you’re contributing at a systems level or a population level because you’re making decisions and trying to redefine processes that actually could impact a much larger cohort.

What is your biggest professional challenge?

Trying to find enough hours in the day to do all that needs to be done.

What is next for you professionally?

I enjoy having varied opportunities and being involved in many different aspects of operations. That’s what attracted me to a larger company such as Sound Physicians, and I see myself staying in that type of role. Down the road, I’d love to be able to take some of my knowledge to Nigeria and find a way to help develop and shape the healthcare sector back home.

Why would that mean so much to you?

It would be a chance to give back. We still have people dying from largely preventable diseases, and our healthcare system is not what it should be. We don’t have enough physicians for the population, and most of the physicians are in urban areas.

Close to half of the members of my graduating medical school class are either in the U.S., Europe, Asia, or South Africa.

That type of brain drain has a tremendous effect over several decades. That’s a lot of talent outside the country, and we need that back home.

Mark Leiser is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

In some ways, Femi Adewunmi, MD, MBA, CPE, SFHM, seemed destined to become a physician. He grew up in a medical family—his mother is an orthodontist; his father is an obstetrician/gynecologist. As a child, he often spent holidays visiting patients at the hospital where his dad worked. He grew to appreciate medicine as a noble profession, and when he reached his teens, he never seriously considered another career path.

“There were times when I was in medical school, dreading having to study for the numerous tests and exams, when I wished I had someone I could have blamed my decision to go to medical school on,” says Dr. Adewunmi, a native of Nigeria who has practiced as a hospitalist in the U.S. since 2003. “But no one pushed me to do it. It was something I always looked forward to doing, and I’m very glad I stuck with it.”

Dr. Adewunmi has only become more passionate about his work since then. His experience as a front-line hospitalist laid the foundation for a series of leadership roles, first directing the HM program at Johnston Memorial Hospital in Smithfield, N.C., and now as regional chief medical officer for Sound Physicians, which provides inpatient services to more than 70 hospitals nationally.

“I really want to be a good physician executive,” he says. “It’s definitely a case of ‘The more you learn, the more you realize how little you know.’ I still have a lot to learn, but I’m looking forward to the challenge.”

When did you decide to go into HM?

During residency, I realized I loved taking care of patients in the hospital, both along the wards and in the ICU. I enjoyed my outpatient clinics but found myself looking for any reason I could to stay in the hospital caring for patients. I was interested in patient safety and I was doing a little bit of utilization review, so I also felt it would give me a great overall perspective of the healthcare system.

What about leading the hospitalist program at Johnston Memorial appealed to you?

I enjoyed clinical medicine, and I still do, but I was looking to do more. I wanted to make an impact at a systems level, and I knew, to do that, I eventually had to gain some leadership experience.

What is the most valuable lesson you learned in that role?

Understanding that change doesn’t happen instantaneously. For instance, as a clinician, you sometimes admit patients with congestive heart failure. You diagnose correctly, treat appropriately, and in a few days, the patients do better and go home. You get pretty swift gratification. Administration is much different. You put processes in place and it could take weeks or several quarters before you start to see the effects of the changes you implement.

What appealed to you about moving from a single-site leadership position at Johnston to a regional position with Sound?

I wanted to continue evolving. I wanted more of a challenge and was seeking opportunities where I would have operational responsibility—overseeing performance improvement in quality, satisfaction, and financial performance for several programs. In addition, I wanted to be accountable for physician development, recruiting, negotiations, and the whole gamut of business development. It was the next logical step in my career.

Why did you pursue an MBA?

I’d made that decision just before I got into medical school. I recall first thinking about it after a conversation I had with my father as a teenager. When I told him that I had made up my mind to study medicine, he said, “You should consider getting an MBA as well. Your generation is going to need to have business experience and expertise, and be better in that area than our generation was.” It’s been invaluable for me in terms of preparing me for handling the business side of medicine, including ways to make operations more efficient and to reduce costs without compromising the quality of care provided.

You have worked in both hospital-employed and privately contracted HM programs. Do you prefer one model?

In general, the larger organizations tend to have an advantage in that they have established protocols and processes that work and have been refined over time. Couple that with the economies of scale they enjoy, as we move into an era of value-based purchasing, it’s becoming harder for the smaller community-based hospital to do that as well. That said, I have seen local hospital-run programs that function really well and have administrative support, so there is definitely enough room for both models.

You were in the inaugural FHM class. What did that recognition mean to you?

I saw it as validation of how we were starting to mature as a specialty and as recognition of a commitment to being a hospitalist, not just an internist. I never practiced outpatient medicine. I went straight from residency to hospitalist medicine. That’s how I identify myself, and I was happy to see that physicians specializing in hospital medicine were starting to get recognized.

What is your biggest professional reward?

The satisfaction from knowing you’re making a difference—not just by the care you provide one-on-one to your patients, but also knowing you’re contributing at a systems level or a population level because you’re making decisions and trying to redefine processes that actually could impact a much larger cohort.

What is your biggest professional challenge?

Trying to find enough hours in the day to do all that needs to be done.

What is next for you professionally?

I enjoy having varied opportunities and being involved in many different aspects of operations. That’s what attracted me to a larger company such as Sound Physicians, and I see myself staying in that type of role. Down the road, I’d love to be able to take some of my knowledge to Nigeria and find a way to help develop and shape the healthcare sector back home.

Why would that mean so much to you?

It would be a chance to give back. We still have people dying from largely preventable diseases, and our healthcare system is not what it should be. We don’t have enough physicians for the population, and most of the physicians are in urban areas.

Close to half of the members of my graduating medical school class are either in the U.S., Europe, Asia, or South Africa.

That type of brain drain has a tremendous effect over several decades. That’s a lot of talent outside the country, and we need that back home.

Mark Leiser is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Time-based billing allows hospitalists to avoid

Providers typically rely on the “key components” (history, exam, medical decision-making) when documenting in the medical record. However, there are instances when the majority of the encounter constitutes counseling/coordination of care (C/CC). Physicians might only document a brief history and exam, or nothing at all. Utilizing time-based billing principles allows a physician to disregard the “key component” requirements and select a visit level reflective of this effort.

For example, a 64-year-old female is hospitalized with newly diagnosed diabetes and requires extensive counseling regarding disease management, lifestyle modification, and medication regime, as well as coordination of care for outpatient programs and services. The hospitalist reviews some of the pertinent information with the patient and leaves the room to coordinate the patient’s ongoing care (25 minutes). The hospitalist then asks a resident to assist with the remaining counseling efforts (20 minutes). Code 99232 (inpatient visit, 25 minutes total visit time) would be appropriate to report.

Counseling, Coordination of Care

Time may be used as the determining factor for the visit level, if more than 50% of the total visit time involves C/CC.1 Time is not used for visit-level selection if C/CC is minimal or absent from the patient encounter. Total visit time is acknowledged as the physician’s face-to-face (i.e. bedside) time combined with time spent on the unit/floor reviewing data, obtaining relevant patient information, and discussing the individual case with other involved healthcare providers.

Time associated with activities performed outside of the patient’s unit/floor is not considered when calculating total visit time. Time associated with teaching students/interns also is excluded; only the attending physician’s time counts.

When the requirements have been met, the physician selects the visit level that corresponds with the documented total visit time (see Table 1). In the scenario above, the visit level is chosen based on the attending physician’s documented time (25 minutes). The resident’s time cannot be included.

Documentation Requirements

Physicians must document the interaction during the patient encounter: history and exam, if updated or performed; discussion points; and patient response, if applicable. The medical record entry must contain both the C/CC time and the total visit time.2 “Total visit time=35 minutes; >50% spent counseling/coordinating care” or “20 of 35 minutes spent counseling/coordinating care.”

A payor may prefer one documentation style over another. It is always best to ask about the payor’s policy and review local documentation standards to ensure compliance.

Family Discussions

Physicians are always involved in family discussions. It is appropriate to count this as C/CC time. In the event that the family discussion takes place without the patient present, only count this as C/CC time if:

- The patient is unable or clinically incompetent to participate in discussions;

- The time is spent on the unit/floor with the family members or surrogate decision-makers obtaining a medical history, reviewing the patient’s condition or prognosis, or discussing treatment or limitation(s) of treatment; and

- The conversation bears directly on the management of the patient.4

The medical record should reflect these criteria. Do not consider the time if the discussion takes place in an area outside of the patient’s unit/floor, or if the time is spent counseling family members through their grieving process.

It is not uncommon for the family discussion to take place later in the day, after the physician has made earlier rounds. If the earlier encounter involved C/CC, the physician would report the cumulative time spent for that service date. If the earlier encounter was a typical patient evaluation (i.e. history update and physical) and management service (i.e. care plan review/revision), this second encounter might be regarded as a prolonged care service.

Prolonged Care

Prolonged care codes exist for both outpatient and inpatient services. A hospitalists’ focus involves the inpatient code series:

99356: Prolonged service in the inpatient or observation setting, requiring unit/floor time beyond the usual service, first hour; and

99357: Prolonged service in the inpatient or observation setting, requiring unit/floor time beyond the usual service, each additional 30 minutes.

Code 99356 is reported during the first hour of prolonged services, after the initial 30 minutes is reached; code 99357 is reported for each additional 30 minutes of prolonged care beyond the first hour, after the first 15 minutes of each additional segment. Both are “add on” codes and cannot be reported alone on a claim form; a “primary” code must be reported. Similarly, 99357 cannot be reported without 99356, and 99356 must be reported with one of the following inpatient service (primary) codes: 99218-99220, 99221-99223, 99231-99233, 99251-99255, 99304-99310. Only one unit of 99356 may be reported per patient per physician group per day, whereas multiple units of 99357 may be reported in a single day.

The CPT definition of prolonged care varies from that of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Since 2009, CPT recognizes the total duration spent by a physician on a given date, even if the time spent by the physician on that date is not continuous; the time involves both face-to-face time and unit/floor time.5 CMS only attributes direct face-to-face time between the physician and the patient toward prolonged care billing. Time spent reviewing charts or discussion of a patient with house medical staff, waiting for test results, waiting for changes in the patient’s condition, waiting for end of a therapy session, or waiting for use of facilities cannot be billed as prolonged services.5 This is in direct opposition to its policy for C/CC services, and makes prolonged care services inefficient.

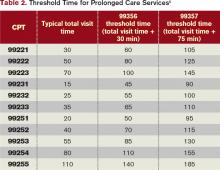

Medicare also identifies “threshold” time (see Table 2). The total physician visit time must exceed the time requirements associated with the “primary” codes by a 30-minute threshold (e.g. 99221+99356=30 minutes+30 minutes=60 minutes threshold time). The physician must document the total face-to-face time spent in separate notes throughout the day or, more realistically, in one cumulative note.

When two providers from the same group and same specialty perform services on the same date (e.g. physician A saw the patient during morning rounds, and physician B spoke with the patient/family in the afternoon), only one physician can report the cumulative service.6 As always, query payors for coverage, because some non-Medicare insurers do not recognize these codes.

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.1B. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2012.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.1C. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2012.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicare National Coverage Determinations Manual: Chapter 1, Section 70.1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/ncd103c1_Part1.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2012.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.15.1C. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2012.

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Anderson C, Boudreau A, Connelly J. Current Procedural Terminology 2012 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2011:7-21.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.5. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2012.

Providers typically rely on the “key components” (history, exam, medical decision-making) when documenting in the medical record. However, there are instances when the majority of the encounter constitutes counseling/coordination of care (C/CC). Physicians might only document a brief history and exam, or nothing at all. Utilizing time-based billing principles allows a physician to disregard the “key component” requirements and select a visit level reflective of this effort.

For example, a 64-year-old female is hospitalized with newly diagnosed diabetes and requires extensive counseling regarding disease management, lifestyle modification, and medication regime, as well as coordination of care for outpatient programs and services. The hospitalist reviews some of the pertinent information with the patient and leaves the room to coordinate the patient’s ongoing care (25 minutes). The hospitalist then asks a resident to assist with the remaining counseling efforts (20 minutes). Code 99232 (inpatient visit, 25 minutes total visit time) would be appropriate to report.

Counseling, Coordination of Care

Time may be used as the determining factor for the visit level, if more than 50% of the total visit time involves C/CC.1 Time is not used for visit-level selection if C/CC is minimal or absent from the patient encounter. Total visit time is acknowledged as the physician’s face-to-face (i.e. bedside) time combined with time spent on the unit/floor reviewing data, obtaining relevant patient information, and discussing the individual case with other involved healthcare providers.

Time associated with activities performed outside of the patient’s unit/floor is not considered when calculating total visit time. Time associated with teaching students/interns also is excluded; only the attending physician’s time counts.

When the requirements have been met, the physician selects the visit level that corresponds with the documented total visit time (see Table 1). In the scenario above, the visit level is chosen based on the attending physician’s documented time (25 minutes). The resident’s time cannot be included.

Documentation Requirements

Physicians must document the interaction during the patient encounter: history and exam, if updated or performed; discussion points; and patient response, if applicable. The medical record entry must contain both the C/CC time and the total visit time.2 “Total visit time=35 minutes; >50% spent counseling/coordinating care” or “20 of 35 minutes spent counseling/coordinating care.”

A payor may prefer one documentation style over another. It is always best to ask about the payor’s policy and review local documentation standards to ensure compliance.

Family Discussions

Physicians are always involved in family discussions. It is appropriate to count this as C/CC time. In the event that the family discussion takes place without the patient present, only count this as C/CC time if:

- The patient is unable or clinically incompetent to participate in discussions;

- The time is spent on the unit/floor with the family members or surrogate decision-makers obtaining a medical history, reviewing the patient’s condition or prognosis, or discussing treatment or limitation(s) of treatment; and

- The conversation bears directly on the management of the patient.4

The medical record should reflect these criteria. Do not consider the time if the discussion takes place in an area outside of the patient’s unit/floor, or if the time is spent counseling family members through their grieving process.

It is not uncommon for the family discussion to take place later in the day, after the physician has made earlier rounds. If the earlier encounter involved C/CC, the physician would report the cumulative time spent for that service date. If the earlier encounter was a typical patient evaluation (i.e. history update and physical) and management service (i.e. care plan review/revision), this second encounter might be regarded as a prolonged care service.

Prolonged Care

Prolonged care codes exist for both outpatient and inpatient services. A hospitalists’ focus involves the inpatient code series:

99356: Prolonged service in the inpatient or observation setting, requiring unit/floor time beyond the usual service, first hour; and

99357: Prolonged service in the inpatient or observation setting, requiring unit/floor time beyond the usual service, each additional 30 minutes.

Code 99356 is reported during the first hour of prolonged services, after the initial 30 minutes is reached; code 99357 is reported for each additional 30 minutes of prolonged care beyond the first hour, after the first 15 minutes of each additional segment. Both are “add on” codes and cannot be reported alone on a claim form; a “primary” code must be reported. Similarly, 99357 cannot be reported without 99356, and 99356 must be reported with one of the following inpatient service (primary) codes: 99218-99220, 99221-99223, 99231-99233, 99251-99255, 99304-99310. Only one unit of 99356 may be reported per patient per physician group per day, whereas multiple units of 99357 may be reported in a single day.

The CPT definition of prolonged care varies from that of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Since 2009, CPT recognizes the total duration spent by a physician on a given date, even if the time spent by the physician on that date is not continuous; the time involves both face-to-face time and unit/floor time.5 CMS only attributes direct face-to-face time between the physician and the patient toward prolonged care billing. Time spent reviewing charts or discussion of a patient with house medical staff, waiting for test results, waiting for changes in the patient’s condition, waiting for end of a therapy session, or waiting for use of facilities cannot be billed as prolonged services.5 This is in direct opposition to its policy for C/CC services, and makes prolonged care services inefficient.

Medicare also identifies “threshold” time (see Table 2). The total physician visit time must exceed the time requirements associated with the “primary” codes by a 30-minute threshold (e.g. 99221+99356=30 minutes+30 minutes=60 minutes threshold time). The physician must document the total face-to-face time spent in separate notes throughout the day or, more realistically, in one cumulative note.

When two providers from the same group and same specialty perform services on the same date (e.g. physician A saw the patient during morning rounds, and physician B spoke with the patient/family in the afternoon), only one physician can report the cumulative service.6 As always, query payors for coverage, because some non-Medicare insurers do not recognize these codes.

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.1B. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2012.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.1C. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2012.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicare National Coverage Determinations Manual: Chapter 1, Section 70.1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/ncd103c1_Part1.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2012.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.15.1C. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2012.

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Anderson C, Boudreau A, Connelly J. Current Procedural Terminology 2012 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2011:7-21.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.5. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2012.

Providers typically rely on the “key components” (history, exam, medical decision-making) when documenting in the medical record. However, there are instances when the majority of the encounter constitutes counseling/coordination of care (C/CC). Physicians might only document a brief history and exam, or nothing at all. Utilizing time-based billing principles allows a physician to disregard the “key component” requirements and select a visit level reflective of this effort.

For example, a 64-year-old female is hospitalized with newly diagnosed diabetes and requires extensive counseling regarding disease management, lifestyle modification, and medication regime, as well as coordination of care for outpatient programs and services. The hospitalist reviews some of the pertinent information with the patient and leaves the room to coordinate the patient’s ongoing care (25 minutes). The hospitalist then asks a resident to assist with the remaining counseling efforts (20 minutes). Code 99232 (inpatient visit, 25 minutes total visit time) would be appropriate to report.

Counseling, Coordination of Care

Time may be used as the determining factor for the visit level, if more than 50% of the total visit time involves C/CC.1 Time is not used for visit-level selection if C/CC is minimal or absent from the patient encounter. Total visit time is acknowledged as the physician’s face-to-face (i.e. bedside) time combined with time spent on the unit/floor reviewing data, obtaining relevant patient information, and discussing the individual case with other involved healthcare providers.

Time associated with activities performed outside of the patient’s unit/floor is not considered when calculating total visit time. Time associated with teaching students/interns also is excluded; only the attending physician’s time counts.

When the requirements have been met, the physician selects the visit level that corresponds with the documented total visit time (see Table 1). In the scenario above, the visit level is chosen based on the attending physician’s documented time (25 minutes). The resident’s time cannot be included.

Documentation Requirements

Physicians must document the interaction during the patient encounter: history and exam, if updated or performed; discussion points; and patient response, if applicable. The medical record entry must contain both the C/CC time and the total visit time.2 “Total visit time=35 minutes; >50% spent counseling/coordinating care” or “20 of 35 minutes spent counseling/coordinating care.”

A payor may prefer one documentation style over another. It is always best to ask about the payor’s policy and review local documentation standards to ensure compliance.

Family Discussions

Physicians are always involved in family discussions. It is appropriate to count this as C/CC time. In the event that the family discussion takes place without the patient present, only count this as C/CC time if:

- The patient is unable or clinically incompetent to participate in discussions;

- The time is spent on the unit/floor with the family members or surrogate decision-makers obtaining a medical history, reviewing the patient’s condition or prognosis, or discussing treatment or limitation(s) of treatment; and

- The conversation bears directly on the management of the patient.4

The medical record should reflect these criteria. Do not consider the time if the discussion takes place in an area outside of the patient’s unit/floor, or if the time is spent counseling family members through their grieving process.

It is not uncommon for the family discussion to take place later in the day, after the physician has made earlier rounds. If the earlier encounter involved C/CC, the physician would report the cumulative time spent for that service date. If the earlier encounter was a typical patient evaluation (i.e. history update and physical) and management service (i.e. care plan review/revision), this second encounter might be regarded as a prolonged care service.

Prolonged Care

Prolonged care codes exist for both outpatient and inpatient services. A hospitalists’ focus involves the inpatient code series:

99356: Prolonged service in the inpatient or observation setting, requiring unit/floor time beyond the usual service, first hour; and

99357: Prolonged service in the inpatient or observation setting, requiring unit/floor time beyond the usual service, each additional 30 minutes.

Code 99356 is reported during the first hour of prolonged services, after the initial 30 minutes is reached; code 99357 is reported for each additional 30 minutes of prolonged care beyond the first hour, after the first 15 minutes of each additional segment. Both are “add on” codes and cannot be reported alone on a claim form; a “primary” code must be reported. Similarly, 99357 cannot be reported without 99356, and 99356 must be reported with one of the following inpatient service (primary) codes: 99218-99220, 99221-99223, 99231-99233, 99251-99255, 99304-99310. Only one unit of 99356 may be reported per patient per physician group per day, whereas multiple units of 99357 may be reported in a single day.

The CPT definition of prolonged care varies from that of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Since 2009, CPT recognizes the total duration spent by a physician on a given date, even if the time spent by the physician on that date is not continuous; the time involves both face-to-face time and unit/floor time.5 CMS only attributes direct face-to-face time between the physician and the patient toward prolonged care billing. Time spent reviewing charts or discussion of a patient with house medical staff, waiting for test results, waiting for changes in the patient’s condition, waiting for end of a therapy session, or waiting for use of facilities cannot be billed as prolonged services.5 This is in direct opposition to its policy for C/CC services, and makes prolonged care services inefficient.

Medicare also identifies “threshold” time (see Table 2). The total physician visit time must exceed the time requirements associated with the “primary” codes by a 30-minute threshold (e.g. 99221+99356=30 minutes+30 minutes=60 minutes threshold time). The physician must document the total face-to-face time spent in separate notes throughout the day or, more realistically, in one cumulative note.

When two providers from the same group and same specialty perform services on the same date (e.g. physician A saw the patient during morning rounds, and physician B spoke with the patient/family in the afternoon), only one physician can report the cumulative service.6 As always, query payors for coverage, because some non-Medicare insurers do not recognize these codes.

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.1B. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2012.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.1C. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2012.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicare National Coverage Determinations Manual: Chapter 1, Section 70.1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/ncd103c1_Part1.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2012.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.15.1C. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2012.

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Anderson C, Boudreau A, Connelly J. Current Procedural Terminology 2012 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2011:7-21.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.5. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2012.

Hospitalists Provide Leadership as Unit Medical Directors

A project to formalize “local leadership models”—partnering leadership teams comprising a hospitalist and a nurse manager on each participating unit—at the University of Michigan Health System helped to redefine the role of unit medical director and led to allocating sufficient time (15% to 20% of an FTE) for hospitalists to fill that role. The process also led to a joint role description for the physician and nurse leaders.

“In our organization, we had the medical director concept in place previously, but things were missing, with no direct accountability, no dedicated effort, and lack of clarity on reporting,” explains hospitalist Christopher Kim, MD, MBA, lead author of an article about the project published in the American Journal of Medical Quality.1 “We learned from other organizations, and one of the first things we learned was to make sure we hired the right person as medical director. We need an energetic, enthusiastic physician who can reach out to nurses and bridge gaps in communication and coordination of care.”

The clinical partnership model was piloted on five units—four adult and one pediatric—and has since been adopted by eight others. The physician/nurse leaders work on such issues as improving care transitions, reducing pressure ulcers and catheter-related urinary tract infections, developing multi-disciplinary rounding on the units, and sharing quality data with staff.

“Take UTIs or pressure ulcers; we’re all familiar with recommended practice, but how it gets played out on the units varies. If team leaders understand this, they can champion the processes and

create an educational push for them,” Dr. Kim says. “Those organizations that have done this well cite higher staff satisfaction as a result.”

Study results show that the initial five units were “among the highest-performing units in our facility on satisfaction,” he adds. “It’s an exciting opportunity to bring change processes necessary to build a local clinical care environment that will improve the overall experience of the patient.”

Reference

A project to formalize “local leadership models”—partnering leadership teams comprising a hospitalist and a nurse manager on each participating unit—at the University of Michigan Health System helped to redefine the role of unit medical director and led to allocating sufficient time (15% to 20% of an FTE) for hospitalists to fill that role. The process also led to a joint role description for the physician and nurse leaders.

“In our organization, we had the medical director concept in place previously, but things were missing, with no direct accountability, no dedicated effort, and lack of clarity on reporting,” explains hospitalist Christopher Kim, MD, MBA, lead author of an article about the project published in the American Journal of Medical Quality.1 “We learned from other organizations, and one of the first things we learned was to make sure we hired the right person as medical director. We need an energetic, enthusiastic physician who can reach out to nurses and bridge gaps in communication and coordination of care.”

The clinical partnership model was piloted on five units—four adult and one pediatric—and has since been adopted by eight others. The physician/nurse leaders work on such issues as improving care transitions, reducing pressure ulcers and catheter-related urinary tract infections, developing multi-disciplinary rounding on the units, and sharing quality data with staff.

“Take UTIs or pressure ulcers; we’re all familiar with recommended practice, but how it gets played out on the units varies. If team leaders understand this, they can champion the processes and

create an educational push for them,” Dr. Kim says. “Those organizations that have done this well cite higher staff satisfaction as a result.”

Study results show that the initial five units were “among the highest-performing units in our facility on satisfaction,” he adds. “It’s an exciting opportunity to bring change processes necessary to build a local clinical care environment that will improve the overall experience of the patient.”

Reference

A project to formalize “local leadership models”—partnering leadership teams comprising a hospitalist and a nurse manager on each participating unit—at the University of Michigan Health System helped to redefine the role of unit medical director and led to allocating sufficient time (15% to 20% of an FTE) for hospitalists to fill that role. The process also led to a joint role description for the physician and nurse leaders.

“In our organization, we had the medical director concept in place previously, but things were missing, with no direct accountability, no dedicated effort, and lack of clarity on reporting,” explains hospitalist Christopher Kim, MD, MBA, lead author of an article about the project published in the American Journal of Medical Quality.1 “We learned from other organizations, and one of the first things we learned was to make sure we hired the right person as medical director. We need an energetic, enthusiastic physician who can reach out to nurses and bridge gaps in communication and coordination of care.”

The clinical partnership model was piloted on five units—four adult and one pediatric—and has since been adopted by eight others. The physician/nurse leaders work on such issues as improving care transitions, reducing pressure ulcers and catheter-related urinary tract infections, developing multi-disciplinary rounding on the units, and sharing quality data with staff.

“Take UTIs or pressure ulcers; we’re all familiar with recommended practice, but how it gets played out on the units varies. If team leaders understand this, they can champion the processes and

create an educational push for them,” Dr. Kim says. “Those organizations that have done this well cite higher staff satisfaction as a result.”

Study results show that the initial five units were “among the highest-performing units in our facility on satisfaction,” he adds. “It’s an exciting opportunity to bring change processes necessary to build a local clinical care environment that will improve the overall experience of the patient.”

Reference

First Set of CMS Advisors Includes Hospitalists

In January, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) selected 73 professionals as the initial set of advisors for its Innovation Center (http://innovations.cms.gov/). The advisors include 37 physicians, as well as some nurses and health administrators. Each advisor will receive six months of intensive training in quality-improvement (QI) methods and health systems research in order to deepen skills that could help drive improvements in patient care across the system.

Each of the 920 applicants named a project they wanted to pursue at their home institution; many already are involved in quality activities, says Fran Griffin, the program coordinator. CMS hopes that advisors will become “change agents” and mentors to others within their organizations and communities, she adds. “But we are clear that we are not funding research. We want people to come and be educated, and we want to know if they are learning these skills and applying what they learn in real time,” Griffin says.

Advisors will participate in four in-person meetings, the first of which was held in January, as well as four conference calls or webinars each month. The Innovation Center aims to eventually bring 200 advisors on board, with a second cycle of applications and selections expected later this spring.Funded by the Affordable Care Act, the program provides a stipend of up to $20,000 to the advisor’s institution to free up 10 hours a week for training and to complete their projects. Of the initial set of advisors, at least two are hospitalists: Stephen Liu, MD, MPH, FACPM, of Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Hanover, N.H., and Jason Stein, MD, SFHM, director of the clinical research program at Emory School of Medicine in Atlanta. Topics pursued by the advisors include unnecessary hospital readmissions, improving care transitions, chronic disease management, and the development of medical homes outside the hospital.

Dr. Liu’s proposed project is to re-engineer and improve geriatric inpatient stays to help preserve patients’ functional status. “Overall, I had a great experience at the first meeting of the advisors,” Dr. Liu says. “It was great to discuss the challenges and opportunities for improvement at each of the different settings represented, and to learn that many of the challenges are similar to those we face in the inpatient setting, such as communication with primary-care providers, transitions of care, and avoiding complications from hospitalizations.”

For more information or to receive email updates, visit www.innovations.cms.gov/initiatives.

In January, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) selected 73 professionals as the initial set of advisors for its Innovation Center (http://innovations.cms.gov/). The advisors include 37 physicians, as well as some nurses and health administrators. Each advisor will receive six months of intensive training in quality-improvement (QI) methods and health systems research in order to deepen skills that could help drive improvements in patient care across the system.

Each of the 920 applicants named a project they wanted to pursue at their home institution; many already are involved in quality activities, says Fran Griffin, the program coordinator. CMS hopes that advisors will become “change agents” and mentors to others within their organizations and communities, she adds. “But we are clear that we are not funding research. We want people to come and be educated, and we want to know if they are learning these skills and applying what they learn in real time,” Griffin says.

Advisors will participate in four in-person meetings, the first of which was held in January, as well as four conference calls or webinars each month. The Innovation Center aims to eventually bring 200 advisors on board, with a second cycle of applications and selections expected later this spring.Funded by the Affordable Care Act, the program provides a stipend of up to $20,000 to the advisor’s institution to free up 10 hours a week for training and to complete their projects. Of the initial set of advisors, at least two are hospitalists: Stephen Liu, MD, MPH, FACPM, of Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Hanover, N.H., and Jason Stein, MD, SFHM, director of the clinical research program at Emory School of Medicine in Atlanta. Topics pursued by the advisors include unnecessary hospital readmissions, improving care transitions, chronic disease management, and the development of medical homes outside the hospital.

Dr. Liu’s proposed project is to re-engineer and improve geriatric inpatient stays to help preserve patients’ functional status. “Overall, I had a great experience at the first meeting of the advisors,” Dr. Liu says. “It was great to discuss the challenges and opportunities for improvement at each of the different settings represented, and to learn that many of the challenges are similar to those we face in the inpatient setting, such as communication with primary-care providers, transitions of care, and avoiding complications from hospitalizations.”

For more information or to receive email updates, visit www.innovations.cms.gov/initiatives.

In January, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) selected 73 professionals as the initial set of advisors for its Innovation Center (http://innovations.cms.gov/). The advisors include 37 physicians, as well as some nurses and health administrators. Each advisor will receive six months of intensive training in quality-improvement (QI) methods and health systems research in order to deepen skills that could help drive improvements in patient care across the system.

Each of the 920 applicants named a project they wanted to pursue at their home institution; many already are involved in quality activities, says Fran Griffin, the program coordinator. CMS hopes that advisors will become “change agents” and mentors to others within their organizations and communities, she adds. “But we are clear that we are not funding research. We want people to come and be educated, and we want to know if they are learning these skills and applying what they learn in real time,” Griffin says.

Advisors will participate in four in-person meetings, the first of which was held in January, as well as four conference calls or webinars each month. The Innovation Center aims to eventually bring 200 advisors on board, with a second cycle of applications and selections expected later this spring.Funded by the Affordable Care Act, the program provides a stipend of up to $20,000 to the advisor’s institution to free up 10 hours a week for training and to complete their projects. Of the initial set of advisors, at least two are hospitalists: Stephen Liu, MD, MPH, FACPM, of Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Hanover, N.H., and Jason Stein, MD, SFHM, director of the clinical research program at Emory School of Medicine in Atlanta. Topics pursued by the advisors include unnecessary hospital readmissions, improving care transitions, chronic disease management, and the development of medical homes outside the hospital.

Dr. Liu’s proposed project is to re-engineer and improve geriatric inpatient stays to help preserve patients’ functional status. “Overall, I had a great experience at the first meeting of the advisors,” Dr. Liu says. “It was great to discuss the challenges and opportunities for improvement at each of the different settings represented, and to learn that many of the challenges are similar to those we face in the inpatient setting, such as communication with primary-care providers, transitions of care, and avoiding complications from hospitalizations.”

For more information or to receive email updates, visit www.innovations.cms.gov/initiatives.

Understanding Physicians’ Attitudes toward Safety Culture

Results from a survey to assess physicians’ and medical trainees’ perceptions and attitudes about the culture of patient safety at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) Medical Center were reported at HM11 in Dallas by Patrick Kneeland, MD, who has since moved to Providence Regional Medical Center’s Everett Clinic in Seattle, where he co-chairs the Medical Quality Review Committee.

“We were interested in perceptions about what most determines a safety culture within a hospital,” and about differences and similarities between faculty, fellows, and residents, Dr. Kneeland explains. A positive safety culture is essential to enhancing patient safety, and it requires support and commitment at multiple levels.

Dr. Kneeland and colleagues used an established, validated instrument, the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s “Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture,” which is used by hospitals to assess their staffs’ attitudes toward safety. But the UCSF team

modified the instrument to include additional survey dimensions, such as trainee supervision, event disclosure to patients, and physician-to-physician handoffs.1 Of 290 physicians surveyed in UCSF’s Department of Medicine, 53% completed the survey.

“What was surprising from our survey was the overall high degree of agreement, but with some interesting differences,” Dr. Kneeland explains. In terms of the overall rating of safety culture, on a 1-to-5 scale with five being the highest, fellows rated the safety culture the highest, followed by faculty, and then residents. “Even though, across the board, 70 percent or more said adverse events should be disclosed to patients, only half of the trainees felt encouraged to do so, and half felt there is some danger in doing so,” he says.

Findings led to a major educational initiative around error disclosure, and to having the chief residents openly discuss overnight adverse patient events at morning rounds. The goal is to make event reporting part of customary practice. UCSF plans to repeat the survey in five years, using the initial results as a benchmark, Dr. Kneeland adds.

For more information or to request a copy of the modified survey, email Dr. Kneeland at [email protected].

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

Reference

Results from a survey to assess physicians’ and medical trainees’ perceptions and attitudes about the culture of patient safety at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) Medical Center were reported at HM11 in Dallas by Patrick Kneeland, MD, who has since moved to Providence Regional Medical Center’s Everett Clinic in Seattle, where he co-chairs the Medical Quality Review Committee.

“We were interested in perceptions about what most determines a safety culture within a hospital,” and about differences and similarities between faculty, fellows, and residents, Dr. Kneeland explains. A positive safety culture is essential to enhancing patient safety, and it requires support and commitment at multiple levels.

Dr. Kneeland and colleagues used an established, validated instrument, the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s “Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture,” which is used by hospitals to assess their staffs’ attitudes toward safety. But the UCSF team

modified the instrument to include additional survey dimensions, such as trainee supervision, event disclosure to patients, and physician-to-physician handoffs.1 Of 290 physicians surveyed in UCSF’s Department of Medicine, 53% completed the survey.

“What was surprising from our survey was the overall high degree of agreement, but with some interesting differences,” Dr. Kneeland explains. In terms of the overall rating of safety culture, on a 1-to-5 scale with five being the highest, fellows rated the safety culture the highest, followed by faculty, and then residents. “Even though, across the board, 70 percent or more said adverse events should be disclosed to patients, only half of the trainees felt encouraged to do so, and half felt there is some danger in doing so,” he says.

Findings led to a major educational initiative around error disclosure, and to having the chief residents openly discuss overnight adverse patient events at morning rounds. The goal is to make event reporting part of customary practice. UCSF plans to repeat the survey in five years, using the initial results as a benchmark, Dr. Kneeland adds.

For more information or to request a copy of the modified survey, email Dr. Kneeland at [email protected].

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

Reference

Results from a survey to assess physicians’ and medical trainees’ perceptions and attitudes about the culture of patient safety at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) Medical Center were reported at HM11 in Dallas by Patrick Kneeland, MD, who has since moved to Providence Regional Medical Center’s Everett Clinic in Seattle, where he co-chairs the Medical Quality Review Committee.

“We were interested in perceptions about what most determines a safety culture within a hospital,” and about differences and similarities between faculty, fellows, and residents, Dr. Kneeland explains. A positive safety culture is essential to enhancing patient safety, and it requires support and commitment at multiple levels.

Dr. Kneeland and colleagues used an established, validated instrument, the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s “Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture,” which is used by hospitals to assess their staffs’ attitudes toward safety. But the UCSF team

modified the instrument to include additional survey dimensions, such as trainee supervision, event disclosure to patients, and physician-to-physician handoffs.1 Of 290 physicians surveyed in UCSF’s Department of Medicine, 53% completed the survey.

“What was surprising from our survey was the overall high degree of agreement, but with some interesting differences,” Dr. Kneeland explains. In terms of the overall rating of safety culture, on a 1-to-5 scale with five being the highest, fellows rated the safety culture the highest, followed by faculty, and then residents. “Even though, across the board, 70 percent or more said adverse events should be disclosed to patients, only half of the trainees felt encouraged to do so, and half felt there is some danger in doing so,” he says.

Findings led to a major educational initiative around error disclosure, and to having the chief residents openly discuss overnight adverse patient events at morning rounds. The goal is to make event reporting part of customary practice. UCSF plans to repeat the survey in five years, using the initial results as a benchmark, Dr. Kneeland adds.

For more information or to request a copy of the modified survey, email Dr. Kneeland at [email protected].

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

Reference

By the Numbers: 8.3%

8.3%1 in 12 adults ages 21 and older Discharged from the hospital to the community were readmitted within 30 days, according to the National Institute for Health Care Reform. One in 3 (32.9%) were readmitted within one year, suggesting that a significant number of patients remain at risk for readmission far beyond the typically measured 30-day window.

8.3%1 in 12 adults ages 21 and older Discharged from the hospital to the community were readmitted within 30 days, according to the National Institute for Health Care Reform. One in 3 (32.9%) were readmitted within one year, suggesting that a significant number of patients remain at risk for readmission far beyond the typically measured 30-day window.

8.3%1 in 12 adults ages 21 and older Discharged from the hospital to the community were readmitted within 30 days, according to the National Institute for Health Care Reform. One in 3 (32.9%) were readmitted within one year, suggesting that a significant number of patients remain at risk for readmission far beyond the typically measured 30-day window.

Presenting Complaint Overshadows More Serious Problem

Cases reprinted with permission from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements and Experts, Lewis Laska, Editor, (800) 298-6288.

Presenting Complaint Overshadows More Serious Problem

A Florida woman who presented to a walk-in clinic for a respiratory condition had also sustained a puncture wound on her finger from an air-powered paint gun. The defendant physician prescribed an antibiotic but did not order an x-ray.

The patient returned to the clinic two days later with increased pain, swelling, and blackening of the finger. The defendant prescribed two pain medications but did not order an x-ray; nor did he mention follow-up treatment.

Later that day, the woman presented to a hospital emergency department (ED) and subsequently underwent amputation of the distal end of her index finger.

The plaintiff alleged negligence on the physician’s failure to send her to the ED or to provide proper care for her finger injury. The defendants claimed that the plaintiff presented to the clinic for evaluation of a respiratory condition and was prescribed an antibiotic. When the plaintiff had a problem with the first antibiotic, the defendant substituted another. The defendant denied that the plaintiff ever complained of a finger injury.

OUTCOME

According to a published account, a verdict of $241,275 was returned. This included $2,000 to be awarded to the plaintiff’s husband for loss of services.

COMMENT

High-pressure injection injuries are often underestimated, legally risky, and potentially devastating to the patient.

As expected, the hands are most likely to be involved, and grease and paint are the substances most commonly injected. The most common injury sites are the index finger or palm of the nondominant hand, which is injected when the user attempts to clean the gun’s nozzle or to steady the gun with a free hand.

These cases can be catastrophic. Outwardly, the injury appears to be an innocuous puncture wound, but the internal injury is severe. Clinicians unfamiliar with high-pressure injection injuries often treat them as a typical puncture wound, as was done in this case. High-pressure injection injuries require immediate surgical consultation and operative management. Even when competent, prompt surgical management takes place, amputation rates are high.

Jurors find the loss of a limb or a digit compelling and recognize the important life-long consequences of such an injury. Jurors expect clinicians to recognize that paint or grease that fills a finger under high pressure represents a threat to the limb, and they will expect the clinician to act swiftly in an effort to save the digit.

Moreover, such cases are easy for the plaintiff’s attorney to try. Unlike electrolyte disturbances or complicated metabolic derangements, high-pressure injection injuries are easy to understand and will keep the average juror’s attention. The plaintiff’s attorney will offer dramatic testimonial evidence of necrosis and inflammation as the paint is shown to move along the tendon sheath. Damaging intraoperative photographic evidence may be produced, and photographs of the resulting wound are almost certain.

High-pressure injection injuries are limb/digit-threatening. Move quickly to offer the patient the best possible result and minimize your malpractice risk. —DML

Mismanaged Infection in Man With Previous Splenectomy

In Ohio, a 27-year-old man presented to the ED with a temperature of 103°F and other signs and symptoms of infection. He had a history of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP), for which he had previously undergone removal of his spleen. At the ED, he was seen by the defendant emergency physician, Dr. A., who made a diagnosis of flu and obtained a culture.

Dr. A. also called Dr. B., the defendant oncologist/hematologist, for a consult. According to Dr. A., he asked Dr. B. whether antibiotics should be prescribed before the patient was released, and Dr. B. told him antibiotics were not necessary. The man was then discharged.

By the next morning, his symptoms had worsened. He presented to a second ED, where he died as a result of an overwhelming infection.

Plaintiff for the decedent claimed that antibiotics should have been prescribed due to his pre-existing ITP and history of splenectomy. Dr. A. claimed that he had appropriately consulted with Dr. B. and had followed the instructions he was given. Dr. B. acknowledged that he had been called and notified that the decedent was in the ED, but he maintained that he had not been asked for advice about whether to prescribe antibiotics.

OUTCOME

According to a published account, a $750,000 verdict was returned. Dr. B. was found 70% at fault, and Dr. A. was found 30% at fault.

COMMENT

This case involves failure to recognize and treat overwhelming postsplenectomy infection (OPSI). Given the patient’s young age and the lost possibility for a full recovery, the jury’s verdict is restrained and probably reflects a relatively conservative jury pool.

Asplenic patients are usually aware that they do not have a spleen, but they may not recognize their associated risk for serious infection. The fact of the matter is that asplenic patients are immunocompromised. When an asplenic patient presents with a febrile illness that is consistent with OPSI, this is a true medical emergency. These patients must undergo a vigorous workup and expeditious administration of antibiotics to offer the best chance for survival. Even with appropriate antibiotic treatment and supportive therapies, mortality associated with OPSI ranges between 50% and 80%.

In this case, the emergency physician obtained a hematology/oncology consultation. There is a dispute between the defendant physicians as to whether antibiotics were recommended or even discussed. It is unclear from the record whether or not the emergency physician’s clinical note includes such a discussion. The jury apportioned the majority of the liability to the hematologist but still found the emergency physician negligent.

Conflict between clinicians or departments can get testy in the clinical record; don’t let that happen. An otherwise defensible record of care can become a nightmare for defense counsel when an interpersonal or interdepartmental conflict is played out in the clinical record. As with personal conflict, defensive addendums to a patient’s record can be damaging. Jurors generally reward “finger pointing” between medical professionals with a verdict for the plaintiff, even when the care itself may be defensible. Regularly held peer review offers clinicians an opportunity to discuss difficult cases without fearing that those discussions will be used as evidence. A formal peer review committee is the exclusive and proper outlet to discuss challenging clinical cases.

Appropriate care for our patients is the ultimate necessity. It can be tricky for a clinician seeking a consultation to challenge the consultant’s recommendation. When confronted with a recommendation that leaves you (the referring clinician) with “heartburn,” it may be helpful for you to restate your misgivings affirmatively—for example, “My concern with that approach is ___,” then state the risks in the gravest terms the situation will allow. Make your preferred course of action apparent: “Honestly, I’d like to admit the patient because of ____.”

If you remain uneasy, seek another colleague’s opinion. Record the substance of the consultation, concerns, and responses fully, accurately but dispassionately, in the patient’s record.

Make sure to give the consultant all the clinical information available; and if you are the consultant, be sure you have received all available information. Treat the consultation formally and with your full attention. The jury will expect the consultant to be fully involved in caring for the patient.

Here, if the emergency physician did not agree with the hematologist, it would have been reasonable for him to obtain a second opinion or to admit the patient and begin empiric antibiotic treatment. —DML

Cases reprinted with permission from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements and Experts, Lewis Laska, Editor, (800) 298-6288.

Presenting Complaint Overshadows More Serious Problem

A Florida woman who presented to a walk-in clinic for a respiratory condition had also sustained a puncture wound on her finger from an air-powered paint gun. The defendant physician prescribed an antibiotic but did not order an x-ray.

The patient returned to the clinic two days later with increased pain, swelling, and blackening of the finger. The defendant prescribed two pain medications but did not order an x-ray; nor did he mention follow-up treatment.

Later that day, the woman presented to a hospital emergency department (ED) and subsequently underwent amputation of the distal end of her index finger.

The plaintiff alleged negligence on the physician’s failure to send her to the ED or to provide proper care for her finger injury. The defendants claimed that the plaintiff presented to the clinic for evaluation of a respiratory condition and was prescribed an antibiotic. When the plaintiff had a problem with the first antibiotic, the defendant substituted another. The defendant denied that the plaintiff ever complained of a finger injury.

OUTCOME

According to a published account, a verdict of $241,275 was returned. This included $2,000 to be awarded to the plaintiff’s husband for loss of services.

COMMENT

High-pressure injection injuries are often underestimated, legally risky, and potentially devastating to the patient.

As expected, the hands are most likely to be involved, and grease and paint are the substances most commonly injected. The most common injury sites are the index finger or palm of the nondominant hand, which is injected when the user attempts to clean the gun’s nozzle or to steady the gun with a free hand.

These cases can be catastrophic. Outwardly, the injury appears to be an innocuous puncture wound, but the internal injury is severe. Clinicians unfamiliar with high-pressure injection injuries often treat them as a typical puncture wound, as was done in this case. High-pressure injection injuries require immediate surgical consultation and operative management. Even when competent, prompt surgical management takes place, amputation rates are high.

Jurors find the loss of a limb or a digit compelling and recognize the important life-long consequences of such an injury. Jurors expect clinicians to recognize that paint or grease that fills a finger under high pressure represents a threat to the limb, and they will expect the clinician to act swiftly in an effort to save the digit.

Moreover, such cases are easy for the plaintiff’s attorney to try. Unlike electrolyte disturbances or complicated metabolic derangements, high-pressure injection injuries are easy to understand and will keep the average juror’s attention. The plaintiff’s attorney will offer dramatic testimonial evidence of necrosis and inflammation as the paint is shown to move along the tendon sheath. Damaging intraoperative photographic evidence may be produced, and photographs of the resulting wound are almost certain.

High-pressure injection injuries are limb/digit-threatening. Move quickly to offer the patient the best possible result and minimize your malpractice risk. —DML

Mismanaged Infection in Man With Previous Splenectomy