User login

How Should Acute Alcoholic Hepatitis be Treated?

Case

A 53-year-old man with a history of daily alcohol use presents with one week of jaundice. His blood pressure is 95/60 mmHg, pulse 105/minute, and temperature 38.0°C. Examination discloses icterus, ascites, and an enlarged, tender liver. His bilirubin is 9 mg/dl, AST 250 IU/dL, ALT 115 IU/dL, prothromin time 22 seconds, INR 2.7, creatinine 0.9 mg/dL, and leukocyte count 15,000/cu mm with 70% neutrophils. He is admitted with a diagnosis of acute alcoholic hepatitis. How should he be treated?

Background

Hospitalists frequently encounter patients who use alcohol and have abnormal liver tests. Regular, heavy alcohol consumption is associated with a variety of forms of liver disease, including fatty liver, inflammation, hepatic fibrosis, and cirrhosis. The term “alcoholic hepatitis” describes a more severe form of alcohol-related liver disease associated with significant short-term mortality.

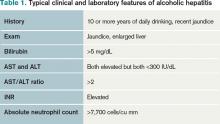

Alcoholic hepatitis typically occurs after more than 10 years of regular heavy alcohol use; average consumption in one study was 100 g/day (the equivalent of 10 drinks per day).1 The typical patient presents with recent onset of jaundice, ascites, and proximal muscle loss. Fever and leukocytosis also are common but should prompt an evaluation for infection, especially spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Liver biopsy in these patients shows steatosis, swollen hepatocytes containing eosinophilic inclusion (Mallory) bodies, and a prominent neutrophilic inflammatory cell infiltrate. Because of the accuracy of clinical diagnosis, biopsy is rarely required, relying instead on clinical and laboratory features for diagnosis (see Table 1, below).

Prognosis can be determined with prediction models. The most common are Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) and Maddrey’s discriminate score (see Table 2). Several websites allow quick calculation of these scores and provide estimated 30-day or 90-day mortality. These scores can be used to guide therapy.

Review of the Data

How should hospitalists treat this serious illness? The evidence-based literature supporting the efficacy of treatments for alcoholic hepatitis is limited, and expert opinions sometimes conflict.

Abstinence has been shown to improve survival in all stages of alcohol-related liver disease.2 This can be accomplished by admitting this patient population to the hospital. A number of interventions and therapies are available to increase the chance of continued abstinence following discharge (see Table 3).

Nutritional support. Protein-calorie malnutrition is seen in up to 90% of patients with cirrhosis.3 The cause of malnutrition in these patients includes decreased caloric intake, metabolic derangements that accompany liver disease, and micronutrient and vitamin deficiencies. Many of these patients rely almost solely on alcohol for caloric intake; this contributes to potassium depletion, which is frequently seen. After admission, these patients are often evaluated for other conditions (such as gastrointestinal bleeding and altered mental status) that require them to be NPO overnight, thus further confounding their malnutrition. Enteral nutritional support was shown in a multicenter study to be associated with reduced infectious complications and improved one-year mortality.4

Little clinical data support specific recommendations for the amount of nutritional support. The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) recommends 35 calories/kg to 40 calories/kg of body weight per day and a protein intake of 1.2 g/kg to 1.5g/kg per day.5 In an average, 70-kg patient, this is 2,450 to 2,800 calories a day. For patients who are not able to meet these nutritional needs by mouth, enteral feeding with a small-bore (Dobhoff) feeding tube can be used, even in patients with known esophageal varices.

Most of these patients have anorexia and nausea and do not meet these caloric recommendations by eating. Nutritional support is a low-risk intervention that can be provided on almost all inpatient medical care areas. Hospitalists should be attentive to nutritional support early in the hospitalization of these patients.

Corticosteroid therapy is recommended by the ACG for patients with alcoholic hepatitis and a Maddrey’s discriminant function greater than 32.5 There is much debate about this recommendation, as conflicting data about efficacy exist.

A 2008 Cochrane review included clinical trials published before July 2007 that examined corticosteroid use in patients with alcoholic hepatitis. A total of 15 trials with 721 randomized patients were included. The review concluded that corticosteroids did not statistically reduce mortality compared with placebo or no intervention; however, mortality was reduced in the subgroup of patients with Maddrey’s scores greater than 32 and hepatic encephalopathy.6 The review concluded that current evidence does not support the use of corticosteroids in alcoholic hepatitis, and more randomized trials were needed.

Another meta-analysis demonstrated a mortality benefit when the largest studies, which included 221 patients with high Maddrey’s scores, were analyzed separately.7 Contraindications to corticosteroid treatment include active infection, gastrointestinal bleeding, acute pancreatitis, and renal failure. Other concerns about corticosteroids include potential adverse reactions (hyperglycemia) and increased risk of infection. Prednisolone is preferred over prednisone because it is the active drug. The recommended dosage is 40 mg/day for 28 days followed by a taper (20 mg/day for one week, then 10 mg/day for one week).

Some data suggest that if patients on corticosteroid therapy do not demonstrate a decrease in their bilirubin levels by Day 7, they are at higher risk of developing infections, have a poorer prognosis, and that corticosteroid therapy should be stopped.8 Some experts use the Lille model to decide whether to continue corticosteroids. In one study, patients who did not respond to prednisolone did not improve when switched to pentoxifyline.9

Patients discharged on corticosteroids require very careful coordination with outpatient providers as prolonged corticosteroid treatment courses can lead to serious complications and death. Critics of corticosteroid therapy in these patients often cite problems related to prolonged steroid use, especially in patients who do not respond to therapy.10

Pentoxifylline, an oral phosphodiesterase inhibitor, is recommended by the ACG, especially if corticosteroids are contraindicated.5 In 2008, 101 patients with alcoholic hepatitis were enrolled in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial comparing pentoxifylline and placebo. This study demonstrated that patients who received pentoxifylline had decreased 28-day mortality (24.6% versus 46% receiving placebo). Of those patients who died during the study, only 50% (versus 91% in the placebo group) developed hepatorenal syndrome.11 However, a Cochrane review of all studies with pentoxifylline concluded that no firm conclusions could be drawn.12

One small, randomized trial comparing pentoxifylline with prednisolone demonstrated that pentoxifylline was superior.13 Pentoxifylline can be prescribed to patients who have contraindications to corticosteroid use (infection or gastrointestinal bleeding). The recommended dose is 400 mg orally three times daily (TID) for four weeks. Common side effects are nausea and vomiting. Pentoxifylline cannot be administered by nasogastric tubes and should not be used in patients with recent cerebral or retinal hemorrhage.

Other therapies. Several studies have examined vitamin E, N-acetylcystine, and other antioxidants as treatment for alcoholic hepatitis. No clear benefit has been demonstrated for any of these drugs. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha inhibitors (e.g. infliximab) have been studied, but increased mortality was demonstrated and these studies were discontinued. Patients are not usually considered for liver transplantation until they have at least six months of abstinence from alcohol as recommended by the American Society of Transplantation.14

Discharge considerations. No clinical trials have studied optimal timing of discharge. Expert opinion based on clinical experience recommends that patients be kept in the hospital until they are eating, signs of alcohol withdrawal and encephalopathy are absent, and bilirubin is less than 10 mg/dL.14 These patients often are quite sick and hospitalization frequently exceeds 10 days. Careful outpatient follow-up and assistance with continued abstinence is very important.

Back to the Case

The patient fits the typical clinical picture of alcoholic hepatitis. Cessation of alcohol consumption is the most important treatment and is accomplished by admission to the hospital. Because of his daily alcohol consumption, folate, thiamine, multivitamins, and oral vitamin K are ordered. Though he has no symptoms of alcohol withdrawal, a note is added about potential withdrawal to the handoff report.

An infectious workup is completed by ordering blood and urine cultures, a chest X-ray, and performing paracentesis to exclude spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. A dietary consult with calorie count is given, along with a plan to discuss with the patient the importance of consuming at least 2,500 calories a day is made. Tube feedings will be considered if the patient does not meet this goal in 48 hours. Clinical calculators determine his Maddrey’s and MELD scores (50 and 25, respectively). If he is actively bleeding or infected, pentoxifylline (400 mg TID for 28 days) is favored due to its lower-side-effect profile.

His MELD score predicts a 90-day mortality of 43%; a meeting is planned to discuss code status and end-of-life issues with the patient and his family. Due to the severity of his illness, a gastroenterology consultation is recommended.

Bottom Line

Alcoholic hepatitis is a serious disease with significant short-term mortality. Treatment options are limited but include abstinence from alcohol, supplemental nutrition, and, for select patients, pentoxifylline or corticosteroids. Because most transplant centers require six months of abstinence, these patients usually are not eligible for urgent liver transplantation.

Dr. Parada is a clinical instructor and chief medical resident in the Department of Internal Medicine at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine and the University of New Mexico Hospital, Albuquerque. Dr. Pierce is associate professor in the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine and the University of New Mexico Hospital.

References

- Naveau S, Giraud V, Borotto E, Aubert A, Capron F, Chaput JC. Excess weight risk factor for alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 1997;25:108-111.

- Pessione F, Ramond MJ, Peters L, et al. Five-year survival predictive factors in patients with excessive alcohol intake and cirrhosis. Effect of alcoholic hepatitis, smoking and abstinence. Liver Int. 2003;23:45-53.

- Mendenhall CL, Anderson S, Weesner RE, Goldberg SJ, Crolic KA. Protein-calorie malnutrition associated with alcoholic hepatitis. Veterans Administration Cooperative Study Group on alcoholic hepatitis. Am J Med. 1984;76:211-222.

- Cabre E, Rodriguez-Iglesias P, Caballeria J, et al. Short- and long-term outcome of severe alcohol-induced hepatitis treated with steroids or enteral nutrition: a multicenter randomized trial. Hepatology. 2000;32:36-42.

- O’Shea RS, Dasarathy S, McCullough AJ, Practice Guideline Committee of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;51:307-328.

- Rambaldi A, Saconato HH, Christensen E, Thorlund K, Wetterslev J, Gluud C. Systematic review: Glucocorticosteroids for alcoholic hepatitis—a Cochrane hepato-biliary group systematic review with meta-analyses and trial sequential analyses of randomized clinical trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:1167-1178.

- Mathurin P, Mendenhall CL, Carithers RL Jr., et al. Corticosteroids improve short-term survival in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis (AH): individual data analysis of the last three randomized placebo controlled double blind trials of corticosteroids in severe AH. J Hepatol. 2002;36:480-487.

- Louvet A, Naveau S, Abdelnour M, et al. The Lille model: A new tool for therapeutic strategy in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis treated with steroids. Hepatology. 2007;45:1348-1354.

- Louvet A, Diaz E, Dharancy S, et al. Early switch topentoxifylline in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis is inefficient in non-responders to corticosteroids. J Hepatol. 2008;48:465-470.

- Amini M, Runyon BA. Alcoholic hepatitis 2010: A clinician’s guide to diagnosis and therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4905-4912.

- Akriviadis E, Botla R, Briggs W, Han S, Reynolds T, Shakil O. Pentoxifylline improves short-term survival in severe acute alcoholic hepatitis: A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1637-1648.

- Whitfield K, Rambaldi A, Wetterslev J, Gluud C. Pentoxifylline for alcoholic hepatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(4):CD007339.

- De BK, Gangopadhyay S, Dutta D, Baksi SD, Pani A, Ghosh P. Pentoxifylline versus prednisolone for severe alcoholic hepatitis: A randomized controlled trial. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1613-1619.

- Lucey MR, Brown KA, Everson GT, et al. Minimal criteria for placement of adults on the liver transplant waiting list: a report of a national conference organized by the American Society of Transplant Physicians and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Liver Transpl Surg. 1997;3:628-637.

Case

A 53-year-old man with a history of daily alcohol use presents with one week of jaundice. His blood pressure is 95/60 mmHg, pulse 105/minute, and temperature 38.0°C. Examination discloses icterus, ascites, and an enlarged, tender liver. His bilirubin is 9 mg/dl, AST 250 IU/dL, ALT 115 IU/dL, prothromin time 22 seconds, INR 2.7, creatinine 0.9 mg/dL, and leukocyte count 15,000/cu mm with 70% neutrophils. He is admitted with a diagnosis of acute alcoholic hepatitis. How should he be treated?

Background

Hospitalists frequently encounter patients who use alcohol and have abnormal liver tests. Regular, heavy alcohol consumption is associated with a variety of forms of liver disease, including fatty liver, inflammation, hepatic fibrosis, and cirrhosis. The term “alcoholic hepatitis” describes a more severe form of alcohol-related liver disease associated with significant short-term mortality.

Alcoholic hepatitis typically occurs after more than 10 years of regular heavy alcohol use; average consumption in one study was 100 g/day (the equivalent of 10 drinks per day).1 The typical patient presents with recent onset of jaundice, ascites, and proximal muscle loss. Fever and leukocytosis also are common but should prompt an evaluation for infection, especially spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Liver biopsy in these patients shows steatosis, swollen hepatocytes containing eosinophilic inclusion (Mallory) bodies, and a prominent neutrophilic inflammatory cell infiltrate. Because of the accuracy of clinical diagnosis, biopsy is rarely required, relying instead on clinical and laboratory features for diagnosis (see Table 1, below).

Prognosis can be determined with prediction models. The most common are Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) and Maddrey’s discriminate score (see Table 2). Several websites allow quick calculation of these scores and provide estimated 30-day or 90-day mortality. These scores can be used to guide therapy.

Review of the Data

How should hospitalists treat this serious illness? The evidence-based literature supporting the efficacy of treatments for alcoholic hepatitis is limited, and expert opinions sometimes conflict.

Abstinence has been shown to improve survival in all stages of alcohol-related liver disease.2 This can be accomplished by admitting this patient population to the hospital. A number of interventions and therapies are available to increase the chance of continued abstinence following discharge (see Table 3).

Nutritional support. Protein-calorie malnutrition is seen in up to 90% of patients with cirrhosis.3 The cause of malnutrition in these patients includes decreased caloric intake, metabolic derangements that accompany liver disease, and micronutrient and vitamin deficiencies. Many of these patients rely almost solely on alcohol for caloric intake; this contributes to potassium depletion, which is frequently seen. After admission, these patients are often evaluated for other conditions (such as gastrointestinal bleeding and altered mental status) that require them to be NPO overnight, thus further confounding their malnutrition. Enteral nutritional support was shown in a multicenter study to be associated with reduced infectious complications and improved one-year mortality.4

Little clinical data support specific recommendations for the amount of nutritional support. The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) recommends 35 calories/kg to 40 calories/kg of body weight per day and a protein intake of 1.2 g/kg to 1.5g/kg per day.5 In an average, 70-kg patient, this is 2,450 to 2,800 calories a day. For patients who are not able to meet these nutritional needs by mouth, enteral feeding with a small-bore (Dobhoff) feeding tube can be used, even in patients with known esophageal varices.

Most of these patients have anorexia and nausea and do not meet these caloric recommendations by eating. Nutritional support is a low-risk intervention that can be provided on almost all inpatient medical care areas. Hospitalists should be attentive to nutritional support early in the hospitalization of these patients.

Corticosteroid therapy is recommended by the ACG for patients with alcoholic hepatitis and a Maddrey’s discriminant function greater than 32.5 There is much debate about this recommendation, as conflicting data about efficacy exist.

A 2008 Cochrane review included clinical trials published before July 2007 that examined corticosteroid use in patients with alcoholic hepatitis. A total of 15 trials with 721 randomized patients were included. The review concluded that corticosteroids did not statistically reduce mortality compared with placebo or no intervention; however, mortality was reduced in the subgroup of patients with Maddrey’s scores greater than 32 and hepatic encephalopathy.6 The review concluded that current evidence does not support the use of corticosteroids in alcoholic hepatitis, and more randomized trials were needed.

Another meta-analysis demonstrated a mortality benefit when the largest studies, which included 221 patients with high Maddrey’s scores, were analyzed separately.7 Contraindications to corticosteroid treatment include active infection, gastrointestinal bleeding, acute pancreatitis, and renal failure. Other concerns about corticosteroids include potential adverse reactions (hyperglycemia) and increased risk of infection. Prednisolone is preferred over prednisone because it is the active drug. The recommended dosage is 40 mg/day for 28 days followed by a taper (20 mg/day for one week, then 10 mg/day for one week).

Some data suggest that if patients on corticosteroid therapy do not demonstrate a decrease in their bilirubin levels by Day 7, they are at higher risk of developing infections, have a poorer prognosis, and that corticosteroid therapy should be stopped.8 Some experts use the Lille model to decide whether to continue corticosteroids. In one study, patients who did not respond to prednisolone did not improve when switched to pentoxifyline.9

Patients discharged on corticosteroids require very careful coordination with outpatient providers as prolonged corticosteroid treatment courses can lead to serious complications and death. Critics of corticosteroid therapy in these patients often cite problems related to prolonged steroid use, especially in patients who do not respond to therapy.10

Pentoxifylline, an oral phosphodiesterase inhibitor, is recommended by the ACG, especially if corticosteroids are contraindicated.5 In 2008, 101 patients with alcoholic hepatitis were enrolled in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial comparing pentoxifylline and placebo. This study demonstrated that patients who received pentoxifylline had decreased 28-day mortality (24.6% versus 46% receiving placebo). Of those patients who died during the study, only 50% (versus 91% in the placebo group) developed hepatorenal syndrome.11 However, a Cochrane review of all studies with pentoxifylline concluded that no firm conclusions could be drawn.12

One small, randomized trial comparing pentoxifylline with prednisolone demonstrated that pentoxifylline was superior.13 Pentoxifylline can be prescribed to patients who have contraindications to corticosteroid use (infection or gastrointestinal bleeding). The recommended dose is 400 mg orally three times daily (TID) for four weeks. Common side effects are nausea and vomiting. Pentoxifylline cannot be administered by nasogastric tubes and should not be used in patients with recent cerebral or retinal hemorrhage.

Other therapies. Several studies have examined vitamin E, N-acetylcystine, and other antioxidants as treatment for alcoholic hepatitis. No clear benefit has been demonstrated for any of these drugs. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha inhibitors (e.g. infliximab) have been studied, but increased mortality was demonstrated and these studies were discontinued. Patients are not usually considered for liver transplantation until they have at least six months of abstinence from alcohol as recommended by the American Society of Transplantation.14

Discharge considerations. No clinical trials have studied optimal timing of discharge. Expert opinion based on clinical experience recommends that patients be kept in the hospital until they are eating, signs of alcohol withdrawal and encephalopathy are absent, and bilirubin is less than 10 mg/dL.14 These patients often are quite sick and hospitalization frequently exceeds 10 days. Careful outpatient follow-up and assistance with continued abstinence is very important.

Back to the Case

The patient fits the typical clinical picture of alcoholic hepatitis. Cessation of alcohol consumption is the most important treatment and is accomplished by admission to the hospital. Because of his daily alcohol consumption, folate, thiamine, multivitamins, and oral vitamin K are ordered. Though he has no symptoms of alcohol withdrawal, a note is added about potential withdrawal to the handoff report.

An infectious workup is completed by ordering blood and urine cultures, a chest X-ray, and performing paracentesis to exclude spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. A dietary consult with calorie count is given, along with a plan to discuss with the patient the importance of consuming at least 2,500 calories a day is made. Tube feedings will be considered if the patient does not meet this goal in 48 hours. Clinical calculators determine his Maddrey’s and MELD scores (50 and 25, respectively). If he is actively bleeding or infected, pentoxifylline (400 mg TID for 28 days) is favored due to its lower-side-effect profile.

His MELD score predicts a 90-day mortality of 43%; a meeting is planned to discuss code status and end-of-life issues with the patient and his family. Due to the severity of his illness, a gastroenterology consultation is recommended.

Bottom Line

Alcoholic hepatitis is a serious disease with significant short-term mortality. Treatment options are limited but include abstinence from alcohol, supplemental nutrition, and, for select patients, pentoxifylline or corticosteroids. Because most transplant centers require six months of abstinence, these patients usually are not eligible for urgent liver transplantation.

Dr. Parada is a clinical instructor and chief medical resident in the Department of Internal Medicine at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine and the University of New Mexico Hospital, Albuquerque. Dr. Pierce is associate professor in the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine and the University of New Mexico Hospital.

References

- Naveau S, Giraud V, Borotto E, Aubert A, Capron F, Chaput JC. Excess weight risk factor for alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 1997;25:108-111.

- Pessione F, Ramond MJ, Peters L, et al. Five-year survival predictive factors in patients with excessive alcohol intake and cirrhosis. Effect of alcoholic hepatitis, smoking and abstinence. Liver Int. 2003;23:45-53.

- Mendenhall CL, Anderson S, Weesner RE, Goldberg SJ, Crolic KA. Protein-calorie malnutrition associated with alcoholic hepatitis. Veterans Administration Cooperative Study Group on alcoholic hepatitis. Am J Med. 1984;76:211-222.

- Cabre E, Rodriguez-Iglesias P, Caballeria J, et al. Short- and long-term outcome of severe alcohol-induced hepatitis treated with steroids or enteral nutrition: a multicenter randomized trial. Hepatology. 2000;32:36-42.

- O’Shea RS, Dasarathy S, McCullough AJ, Practice Guideline Committee of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;51:307-328.

- Rambaldi A, Saconato HH, Christensen E, Thorlund K, Wetterslev J, Gluud C. Systematic review: Glucocorticosteroids for alcoholic hepatitis—a Cochrane hepato-biliary group systematic review with meta-analyses and trial sequential analyses of randomized clinical trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:1167-1178.

- Mathurin P, Mendenhall CL, Carithers RL Jr., et al. Corticosteroids improve short-term survival in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis (AH): individual data analysis of the last three randomized placebo controlled double blind trials of corticosteroids in severe AH. J Hepatol. 2002;36:480-487.

- Louvet A, Naveau S, Abdelnour M, et al. The Lille model: A new tool for therapeutic strategy in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis treated with steroids. Hepatology. 2007;45:1348-1354.

- Louvet A, Diaz E, Dharancy S, et al. Early switch topentoxifylline in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis is inefficient in non-responders to corticosteroids. J Hepatol. 2008;48:465-470.

- Amini M, Runyon BA. Alcoholic hepatitis 2010: A clinician’s guide to diagnosis and therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4905-4912.

- Akriviadis E, Botla R, Briggs W, Han S, Reynolds T, Shakil O. Pentoxifylline improves short-term survival in severe acute alcoholic hepatitis: A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1637-1648.

- Whitfield K, Rambaldi A, Wetterslev J, Gluud C. Pentoxifylline for alcoholic hepatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(4):CD007339.

- De BK, Gangopadhyay S, Dutta D, Baksi SD, Pani A, Ghosh P. Pentoxifylline versus prednisolone for severe alcoholic hepatitis: A randomized controlled trial. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1613-1619.

- Lucey MR, Brown KA, Everson GT, et al. Minimal criteria for placement of adults on the liver transplant waiting list: a report of a national conference organized by the American Society of Transplant Physicians and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Liver Transpl Surg. 1997;3:628-637.

Case

A 53-year-old man with a history of daily alcohol use presents with one week of jaundice. His blood pressure is 95/60 mmHg, pulse 105/minute, and temperature 38.0°C. Examination discloses icterus, ascites, and an enlarged, tender liver. His bilirubin is 9 mg/dl, AST 250 IU/dL, ALT 115 IU/dL, prothromin time 22 seconds, INR 2.7, creatinine 0.9 mg/dL, and leukocyte count 15,000/cu mm with 70% neutrophils. He is admitted with a diagnosis of acute alcoholic hepatitis. How should he be treated?

Background

Hospitalists frequently encounter patients who use alcohol and have abnormal liver tests. Regular, heavy alcohol consumption is associated with a variety of forms of liver disease, including fatty liver, inflammation, hepatic fibrosis, and cirrhosis. The term “alcoholic hepatitis” describes a more severe form of alcohol-related liver disease associated with significant short-term mortality.

Alcoholic hepatitis typically occurs after more than 10 years of regular heavy alcohol use; average consumption in one study was 100 g/day (the equivalent of 10 drinks per day).1 The typical patient presents with recent onset of jaundice, ascites, and proximal muscle loss. Fever and leukocytosis also are common but should prompt an evaluation for infection, especially spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Liver biopsy in these patients shows steatosis, swollen hepatocytes containing eosinophilic inclusion (Mallory) bodies, and a prominent neutrophilic inflammatory cell infiltrate. Because of the accuracy of clinical diagnosis, biopsy is rarely required, relying instead on clinical and laboratory features for diagnosis (see Table 1, below).

Prognosis can be determined with prediction models. The most common are Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) and Maddrey’s discriminate score (see Table 2). Several websites allow quick calculation of these scores and provide estimated 30-day or 90-day mortality. These scores can be used to guide therapy.

Review of the Data

How should hospitalists treat this serious illness? The evidence-based literature supporting the efficacy of treatments for alcoholic hepatitis is limited, and expert opinions sometimes conflict.

Abstinence has been shown to improve survival in all stages of alcohol-related liver disease.2 This can be accomplished by admitting this patient population to the hospital. A number of interventions and therapies are available to increase the chance of continued abstinence following discharge (see Table 3).

Nutritional support. Protein-calorie malnutrition is seen in up to 90% of patients with cirrhosis.3 The cause of malnutrition in these patients includes decreased caloric intake, metabolic derangements that accompany liver disease, and micronutrient and vitamin deficiencies. Many of these patients rely almost solely on alcohol for caloric intake; this contributes to potassium depletion, which is frequently seen. After admission, these patients are often evaluated for other conditions (such as gastrointestinal bleeding and altered mental status) that require them to be NPO overnight, thus further confounding their malnutrition. Enteral nutritional support was shown in a multicenter study to be associated with reduced infectious complications and improved one-year mortality.4

Little clinical data support specific recommendations for the amount of nutritional support. The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) recommends 35 calories/kg to 40 calories/kg of body weight per day and a protein intake of 1.2 g/kg to 1.5g/kg per day.5 In an average, 70-kg patient, this is 2,450 to 2,800 calories a day. For patients who are not able to meet these nutritional needs by mouth, enteral feeding with a small-bore (Dobhoff) feeding tube can be used, even in patients with known esophageal varices.

Most of these patients have anorexia and nausea and do not meet these caloric recommendations by eating. Nutritional support is a low-risk intervention that can be provided on almost all inpatient medical care areas. Hospitalists should be attentive to nutritional support early in the hospitalization of these patients.

Corticosteroid therapy is recommended by the ACG for patients with alcoholic hepatitis and a Maddrey’s discriminant function greater than 32.5 There is much debate about this recommendation, as conflicting data about efficacy exist.

A 2008 Cochrane review included clinical trials published before July 2007 that examined corticosteroid use in patients with alcoholic hepatitis. A total of 15 trials with 721 randomized patients were included. The review concluded that corticosteroids did not statistically reduce mortality compared with placebo or no intervention; however, mortality was reduced in the subgroup of patients with Maddrey’s scores greater than 32 and hepatic encephalopathy.6 The review concluded that current evidence does not support the use of corticosteroids in alcoholic hepatitis, and more randomized trials were needed.

Another meta-analysis demonstrated a mortality benefit when the largest studies, which included 221 patients with high Maddrey’s scores, were analyzed separately.7 Contraindications to corticosteroid treatment include active infection, gastrointestinal bleeding, acute pancreatitis, and renal failure. Other concerns about corticosteroids include potential adverse reactions (hyperglycemia) and increased risk of infection. Prednisolone is preferred over prednisone because it is the active drug. The recommended dosage is 40 mg/day for 28 days followed by a taper (20 mg/day for one week, then 10 mg/day for one week).

Some data suggest that if patients on corticosteroid therapy do not demonstrate a decrease in their bilirubin levels by Day 7, they are at higher risk of developing infections, have a poorer prognosis, and that corticosteroid therapy should be stopped.8 Some experts use the Lille model to decide whether to continue corticosteroids. In one study, patients who did not respond to prednisolone did not improve when switched to pentoxifyline.9

Patients discharged on corticosteroids require very careful coordination with outpatient providers as prolonged corticosteroid treatment courses can lead to serious complications and death. Critics of corticosteroid therapy in these patients often cite problems related to prolonged steroid use, especially in patients who do not respond to therapy.10

Pentoxifylline, an oral phosphodiesterase inhibitor, is recommended by the ACG, especially if corticosteroids are contraindicated.5 In 2008, 101 patients with alcoholic hepatitis were enrolled in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial comparing pentoxifylline and placebo. This study demonstrated that patients who received pentoxifylline had decreased 28-day mortality (24.6% versus 46% receiving placebo). Of those patients who died during the study, only 50% (versus 91% in the placebo group) developed hepatorenal syndrome.11 However, a Cochrane review of all studies with pentoxifylline concluded that no firm conclusions could be drawn.12

One small, randomized trial comparing pentoxifylline with prednisolone demonstrated that pentoxifylline was superior.13 Pentoxifylline can be prescribed to patients who have contraindications to corticosteroid use (infection or gastrointestinal bleeding). The recommended dose is 400 mg orally three times daily (TID) for four weeks. Common side effects are nausea and vomiting. Pentoxifylline cannot be administered by nasogastric tubes and should not be used in patients with recent cerebral or retinal hemorrhage.

Other therapies. Several studies have examined vitamin E, N-acetylcystine, and other antioxidants as treatment for alcoholic hepatitis. No clear benefit has been demonstrated for any of these drugs. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha inhibitors (e.g. infliximab) have been studied, but increased mortality was demonstrated and these studies were discontinued. Patients are not usually considered for liver transplantation until they have at least six months of abstinence from alcohol as recommended by the American Society of Transplantation.14

Discharge considerations. No clinical trials have studied optimal timing of discharge. Expert opinion based on clinical experience recommends that patients be kept in the hospital until they are eating, signs of alcohol withdrawal and encephalopathy are absent, and bilirubin is less than 10 mg/dL.14 These patients often are quite sick and hospitalization frequently exceeds 10 days. Careful outpatient follow-up and assistance with continued abstinence is very important.

Back to the Case

The patient fits the typical clinical picture of alcoholic hepatitis. Cessation of alcohol consumption is the most important treatment and is accomplished by admission to the hospital. Because of his daily alcohol consumption, folate, thiamine, multivitamins, and oral vitamin K are ordered. Though he has no symptoms of alcohol withdrawal, a note is added about potential withdrawal to the handoff report.

An infectious workup is completed by ordering blood and urine cultures, a chest X-ray, and performing paracentesis to exclude spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. A dietary consult with calorie count is given, along with a plan to discuss with the patient the importance of consuming at least 2,500 calories a day is made. Tube feedings will be considered if the patient does not meet this goal in 48 hours. Clinical calculators determine his Maddrey’s and MELD scores (50 and 25, respectively). If he is actively bleeding or infected, pentoxifylline (400 mg TID for 28 days) is favored due to its lower-side-effect profile.

His MELD score predicts a 90-day mortality of 43%; a meeting is planned to discuss code status and end-of-life issues with the patient and his family. Due to the severity of his illness, a gastroenterology consultation is recommended.

Bottom Line

Alcoholic hepatitis is a serious disease with significant short-term mortality. Treatment options are limited but include abstinence from alcohol, supplemental nutrition, and, for select patients, pentoxifylline or corticosteroids. Because most transplant centers require six months of abstinence, these patients usually are not eligible for urgent liver transplantation.

Dr. Parada is a clinical instructor and chief medical resident in the Department of Internal Medicine at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine and the University of New Mexico Hospital, Albuquerque. Dr. Pierce is associate professor in the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine and the University of New Mexico Hospital.

References

- Naveau S, Giraud V, Borotto E, Aubert A, Capron F, Chaput JC. Excess weight risk factor for alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 1997;25:108-111.

- Pessione F, Ramond MJ, Peters L, et al. Five-year survival predictive factors in patients with excessive alcohol intake and cirrhosis. Effect of alcoholic hepatitis, smoking and abstinence. Liver Int. 2003;23:45-53.

- Mendenhall CL, Anderson S, Weesner RE, Goldberg SJ, Crolic KA. Protein-calorie malnutrition associated with alcoholic hepatitis. Veterans Administration Cooperative Study Group on alcoholic hepatitis. Am J Med. 1984;76:211-222.

- Cabre E, Rodriguez-Iglesias P, Caballeria J, et al. Short- and long-term outcome of severe alcohol-induced hepatitis treated with steroids or enteral nutrition: a multicenter randomized trial. Hepatology. 2000;32:36-42.

- O’Shea RS, Dasarathy S, McCullough AJ, Practice Guideline Committee of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;51:307-328.

- Rambaldi A, Saconato HH, Christensen E, Thorlund K, Wetterslev J, Gluud C. Systematic review: Glucocorticosteroids for alcoholic hepatitis—a Cochrane hepato-biliary group systematic review with meta-analyses and trial sequential analyses of randomized clinical trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:1167-1178.

- Mathurin P, Mendenhall CL, Carithers RL Jr., et al. Corticosteroids improve short-term survival in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis (AH): individual data analysis of the last three randomized placebo controlled double blind trials of corticosteroids in severe AH. J Hepatol. 2002;36:480-487.

- Louvet A, Naveau S, Abdelnour M, et al. The Lille model: A new tool for therapeutic strategy in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis treated with steroids. Hepatology. 2007;45:1348-1354.

- Louvet A, Diaz E, Dharancy S, et al. Early switch topentoxifylline in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis is inefficient in non-responders to corticosteroids. J Hepatol. 2008;48:465-470.

- Amini M, Runyon BA. Alcoholic hepatitis 2010: A clinician’s guide to diagnosis and therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4905-4912.

- Akriviadis E, Botla R, Briggs W, Han S, Reynolds T, Shakil O. Pentoxifylline improves short-term survival in severe acute alcoholic hepatitis: A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1637-1648.

- Whitfield K, Rambaldi A, Wetterslev J, Gluud C. Pentoxifylline for alcoholic hepatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(4):CD007339.

- De BK, Gangopadhyay S, Dutta D, Baksi SD, Pani A, Ghosh P. Pentoxifylline versus prednisolone for severe alcoholic hepatitis: A randomized controlled trial. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1613-1619.

- Lucey MR, Brown KA, Everson GT, et al. Minimal criteria for placement of adults on the liver transplant waiting list: a report of a national conference organized by the American Society of Transplant Physicians and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Liver Transpl Surg. 1997;3:628-637.

Guidelines for VTE Prophylaxis in Medical Patient Populations, Including Stroke

Review: VTE prophylaxis guidelines

Background: Pharmacologic interventions with heparin or related drugs and mechanical interventions have become the standard of care in the prevention of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in hospitalized patients. The studies evaluating the efficacy of these therapies in relation to each other have become more robust over the last decade. Despite these advances, however, there remains controversy over meaningful outcomes and how the results should be applied to different patient populations.

Many studies address the issue of VTE prophylaxis using surrogate outcomes, such as asymptomatic deep venous thromboembolism (DVT), given the low incidence of significant clinical outcomes, e.g., symptomatic DVT, pulmonary embolus (PE), or mortality. There have been few large, prospective, randomized trials that show a statistically significant benefit of pharmacologic or mechanical VTE prophylaxis in a purely medical population when looking for these meaningful outcomes.

Significant bleeding and thrombocytopenia are the most common risks identified in pharmacologic intervention studies against which the benefits have to be weighed. Stroke patients are one medical population in which bleeding risk has been of particular concern.

Guideline update: In November 2011, the American College of Physicians (ACP) published new guidelines for medical patients regarding VTE prophylaxis.1 These evidence-based guidelines were not based on new trial data, but rather a review of previous studies looking at only medical patients; they did not consider asymptomatic DVT as a significant outcome.

The new guidelines recommend that all hospitalized medical patients, including stroke patients, be evaluated for risk of VTE and bleeding, which is not a change from any previous standard. Routine use of VTE prophylaxis is not recommended, and prophylactic pharmacologic therapy with heparin or related drugs should only be instituted if the benefit in a decreased incidence of VTE outweighs the risk of bleeding in an individual patient. The use of mechanical prophylaxis with graduated compression stockings is not recommended, given the risk of lower extremity skin damage and a lack of clear benefit.

Last month, the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) followed suit in their 9th edition of clinical practice guidelines regarding VTE prevention in non-surgical patients.2 The ACC recommends the use of heparin or related drugs for VTE prophylaxis for medical patients at increased risk of thrombosis, but recommends against pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis in patients at low risk. Patients at high risk of bleeding with a concomitant high risk of VTE are recommended to use mechanical prophylaxis until the bleeding risk diminishes. These guidelines go a step further and provide parameters defining both high risk of VTE and high risk of bleeding, making them a very clinically useful tool. Neither guideline indicates a prefererence for pharmacologic prophylaxis.

Analysis: The most comprehensive and broadly accepted guidelines for VTE prevention before these updates were put forth by ACCP and published in the June 2008 issue of Chest.3

This review-based guideline, which included asymptomatic DVT as an appropriate outcome, recommended the routine use of heparin or related drugs for prophylaxis of VTE in medical patients confined to bed who have at least one risk factor for VTE. For patients with a contraindication to anticoagulant prophylaxis, they recommend mechanical thromboprophylaxis.

Most national organizations have established their standards and measures based on these clinical practice guidelines. The Joint Commission’s VTE-1 Core Measure evaluates the percentage of inpatients who received VTE prophylaxis or who had documentation as to why no prophylaxis was given.4 The measure states that “appropriately used thromboprophylaxis has a desirable risk-benefit ratio and is cost-effective,” but it does not define appropriate use and lists limited exclusion criteria. The Joint Commission has responded in a statement to the new ACP guidelines, but it has not changed its guidelines based on the 2008 Chest guidelines.5

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), through the Inpatient Prospective Payment System 2009, determined that VTE during a hospitalization for total knee or hip replacement was a hospital-acquired condition that will not be reimbursable.6 This is not the case in general medical inpatients. Also of interest, observational studies suggest that 50% of patients who develop a VTE in hospital will do so despite appropriate prophylaxis.

Surgical patient populations are not addressed in the ACP update but are covered in the 2012 Chest updated guidelines. The recommendations for surgical patients have no major changes since 2008 except for choice of anticoagulant for specific patient populations and new categories of intermediate and high risk, the specifics of which are beyond the scope of this review.

Surgical patients with risk factors for VTE undergoing major procedures should receive pharmacologic prophylaxis with the addition of mechanical prophylaxis. For patients with a high risk of bleeding, mechanical prophylaxis can be used alone until bleeding risk diminishes.

Caution is recommended for any patient undergoing neuraxial analgesia or anesthesia when considering pharmacologic prophylaxis. Routine use of pharmacologic prophylaxis is recommended in patients undergoing bariatric surgery, elective hip replacement, hip fracture surgery, major thoracic surgery, or major open urologic procedures regardless of VTE risk factors, and should be extended in patients with additional VTE risks. All other surgical populations should be evaluated for bleeding risk and VTE risk factors prior to decision for pharmacologic and/or mechanical prophylaxis.

HM takeaways: In medical populations including stroke, routine use of VTE prophylaxis is not recommended, and should only be instituted if they are at high risk of VTE and the benefit in a decreased incidence of VTE outweighs the risk of bleeding.

Dr. Pell is a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine.

Review: VTE prophylaxis guidelines

Background: Pharmacologic interventions with heparin or related drugs and mechanical interventions have become the standard of care in the prevention of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in hospitalized patients. The studies evaluating the efficacy of these therapies in relation to each other have become more robust over the last decade. Despite these advances, however, there remains controversy over meaningful outcomes and how the results should be applied to different patient populations.

Many studies address the issue of VTE prophylaxis using surrogate outcomes, such as asymptomatic deep venous thromboembolism (DVT), given the low incidence of significant clinical outcomes, e.g., symptomatic DVT, pulmonary embolus (PE), or mortality. There have been few large, prospective, randomized trials that show a statistically significant benefit of pharmacologic or mechanical VTE prophylaxis in a purely medical population when looking for these meaningful outcomes.

Significant bleeding and thrombocytopenia are the most common risks identified in pharmacologic intervention studies against which the benefits have to be weighed. Stroke patients are one medical population in which bleeding risk has been of particular concern.

Guideline update: In November 2011, the American College of Physicians (ACP) published new guidelines for medical patients regarding VTE prophylaxis.1 These evidence-based guidelines were not based on new trial data, but rather a review of previous studies looking at only medical patients; they did not consider asymptomatic DVT as a significant outcome.

The new guidelines recommend that all hospitalized medical patients, including stroke patients, be evaluated for risk of VTE and bleeding, which is not a change from any previous standard. Routine use of VTE prophylaxis is not recommended, and prophylactic pharmacologic therapy with heparin or related drugs should only be instituted if the benefit in a decreased incidence of VTE outweighs the risk of bleeding in an individual patient. The use of mechanical prophylaxis with graduated compression stockings is not recommended, given the risk of lower extremity skin damage and a lack of clear benefit.

Last month, the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) followed suit in their 9th edition of clinical practice guidelines regarding VTE prevention in non-surgical patients.2 The ACC recommends the use of heparin or related drugs for VTE prophylaxis for medical patients at increased risk of thrombosis, but recommends against pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis in patients at low risk. Patients at high risk of bleeding with a concomitant high risk of VTE are recommended to use mechanical prophylaxis until the bleeding risk diminishes. These guidelines go a step further and provide parameters defining both high risk of VTE and high risk of bleeding, making them a very clinically useful tool. Neither guideline indicates a prefererence for pharmacologic prophylaxis.

Analysis: The most comprehensive and broadly accepted guidelines for VTE prevention before these updates were put forth by ACCP and published in the June 2008 issue of Chest.3

This review-based guideline, which included asymptomatic DVT as an appropriate outcome, recommended the routine use of heparin or related drugs for prophylaxis of VTE in medical patients confined to bed who have at least one risk factor for VTE. For patients with a contraindication to anticoagulant prophylaxis, they recommend mechanical thromboprophylaxis.

Most national organizations have established their standards and measures based on these clinical practice guidelines. The Joint Commission’s VTE-1 Core Measure evaluates the percentage of inpatients who received VTE prophylaxis or who had documentation as to why no prophylaxis was given.4 The measure states that “appropriately used thromboprophylaxis has a desirable risk-benefit ratio and is cost-effective,” but it does not define appropriate use and lists limited exclusion criteria. The Joint Commission has responded in a statement to the new ACP guidelines, but it has not changed its guidelines based on the 2008 Chest guidelines.5

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), through the Inpatient Prospective Payment System 2009, determined that VTE during a hospitalization for total knee or hip replacement was a hospital-acquired condition that will not be reimbursable.6 This is not the case in general medical inpatients. Also of interest, observational studies suggest that 50% of patients who develop a VTE in hospital will do so despite appropriate prophylaxis.

Surgical patient populations are not addressed in the ACP update but are covered in the 2012 Chest updated guidelines. The recommendations for surgical patients have no major changes since 2008 except for choice of anticoagulant for specific patient populations and new categories of intermediate and high risk, the specifics of which are beyond the scope of this review.

Surgical patients with risk factors for VTE undergoing major procedures should receive pharmacologic prophylaxis with the addition of mechanical prophylaxis. For patients with a high risk of bleeding, mechanical prophylaxis can be used alone until bleeding risk diminishes.

Caution is recommended for any patient undergoing neuraxial analgesia or anesthesia when considering pharmacologic prophylaxis. Routine use of pharmacologic prophylaxis is recommended in patients undergoing bariatric surgery, elective hip replacement, hip fracture surgery, major thoracic surgery, or major open urologic procedures regardless of VTE risk factors, and should be extended in patients with additional VTE risks. All other surgical populations should be evaluated for bleeding risk and VTE risk factors prior to decision for pharmacologic and/or mechanical prophylaxis.

HM takeaways: In medical populations including stroke, routine use of VTE prophylaxis is not recommended, and should only be instituted if they are at high risk of VTE and the benefit in a decreased incidence of VTE outweighs the risk of bleeding.

Dr. Pell is a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine.

Review: VTE prophylaxis guidelines

Background: Pharmacologic interventions with heparin or related drugs and mechanical interventions have become the standard of care in the prevention of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in hospitalized patients. The studies evaluating the efficacy of these therapies in relation to each other have become more robust over the last decade. Despite these advances, however, there remains controversy over meaningful outcomes and how the results should be applied to different patient populations.

Many studies address the issue of VTE prophylaxis using surrogate outcomes, such as asymptomatic deep venous thromboembolism (DVT), given the low incidence of significant clinical outcomes, e.g., symptomatic DVT, pulmonary embolus (PE), or mortality. There have been few large, prospective, randomized trials that show a statistically significant benefit of pharmacologic or mechanical VTE prophylaxis in a purely medical population when looking for these meaningful outcomes.

Significant bleeding and thrombocytopenia are the most common risks identified in pharmacologic intervention studies against which the benefits have to be weighed. Stroke patients are one medical population in which bleeding risk has been of particular concern.

Guideline update: In November 2011, the American College of Physicians (ACP) published new guidelines for medical patients regarding VTE prophylaxis.1 These evidence-based guidelines were not based on new trial data, but rather a review of previous studies looking at only medical patients; they did not consider asymptomatic DVT as a significant outcome.

The new guidelines recommend that all hospitalized medical patients, including stroke patients, be evaluated for risk of VTE and bleeding, which is not a change from any previous standard. Routine use of VTE prophylaxis is not recommended, and prophylactic pharmacologic therapy with heparin or related drugs should only be instituted if the benefit in a decreased incidence of VTE outweighs the risk of bleeding in an individual patient. The use of mechanical prophylaxis with graduated compression stockings is not recommended, given the risk of lower extremity skin damage and a lack of clear benefit.

Last month, the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) followed suit in their 9th edition of clinical practice guidelines regarding VTE prevention in non-surgical patients.2 The ACC recommends the use of heparin or related drugs for VTE prophylaxis for medical patients at increased risk of thrombosis, but recommends against pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis in patients at low risk. Patients at high risk of bleeding with a concomitant high risk of VTE are recommended to use mechanical prophylaxis until the bleeding risk diminishes. These guidelines go a step further and provide parameters defining both high risk of VTE and high risk of bleeding, making them a very clinically useful tool. Neither guideline indicates a prefererence for pharmacologic prophylaxis.

Analysis: The most comprehensive and broadly accepted guidelines for VTE prevention before these updates were put forth by ACCP and published in the June 2008 issue of Chest.3

This review-based guideline, which included asymptomatic DVT as an appropriate outcome, recommended the routine use of heparin or related drugs for prophylaxis of VTE in medical patients confined to bed who have at least one risk factor for VTE. For patients with a contraindication to anticoagulant prophylaxis, they recommend mechanical thromboprophylaxis.

Most national organizations have established their standards and measures based on these clinical practice guidelines. The Joint Commission’s VTE-1 Core Measure evaluates the percentage of inpatients who received VTE prophylaxis or who had documentation as to why no prophylaxis was given.4 The measure states that “appropriately used thromboprophylaxis has a desirable risk-benefit ratio and is cost-effective,” but it does not define appropriate use and lists limited exclusion criteria. The Joint Commission has responded in a statement to the new ACP guidelines, but it has not changed its guidelines based on the 2008 Chest guidelines.5

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), through the Inpatient Prospective Payment System 2009, determined that VTE during a hospitalization for total knee or hip replacement was a hospital-acquired condition that will not be reimbursable.6 This is not the case in general medical inpatients. Also of interest, observational studies suggest that 50% of patients who develop a VTE in hospital will do so despite appropriate prophylaxis.

Surgical patient populations are not addressed in the ACP update but are covered in the 2012 Chest updated guidelines. The recommendations for surgical patients have no major changes since 2008 except for choice of anticoagulant for specific patient populations and new categories of intermediate and high risk, the specifics of which are beyond the scope of this review.

Surgical patients with risk factors for VTE undergoing major procedures should receive pharmacologic prophylaxis with the addition of mechanical prophylaxis. For patients with a high risk of bleeding, mechanical prophylaxis can be used alone until bleeding risk diminishes.

Caution is recommended for any patient undergoing neuraxial analgesia or anesthesia when considering pharmacologic prophylaxis. Routine use of pharmacologic prophylaxis is recommended in patients undergoing bariatric surgery, elective hip replacement, hip fracture surgery, major thoracic surgery, or major open urologic procedures regardless of VTE risk factors, and should be extended in patients with additional VTE risks. All other surgical populations should be evaluated for bleeding risk and VTE risk factors prior to decision for pharmacologic and/or mechanical prophylaxis.

HM takeaways: In medical populations including stroke, routine use of VTE prophylaxis is not recommended, and should only be instituted if they are at high risk of VTE and the benefit in a decreased incidence of VTE outweighs the risk of bleeding.

Dr. Pell is a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine.

In the Literature: Physician Reviews of HM-Relevant Research

In This Edition

Literature At A Glance

A guide to this month’s studies

- Higher loading dose of clopidogrel in STEMI

- Early vs. late surgery following hip fracture

- Beta-blockers in chronic kidney disease

- Long-term azithromycin in COPD

- CT screening for lung cancer

- Timing of parenteral nutrition in the ICU

- Intrapleural management of empyema with DNase and t-PA

- Effect of weekend elective admissions on hospital flow

- Expectations and outcomes of medical comanagement

Higher-Dose Clopidogrel Improves Outcomes at 30 Days in STEMI Patients

Clinical question: Does a 600-mg loading dose of clopidogrel given before percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in patients with an ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) provide more protection from thrombotic complications at 30 days than a 300-mg dose?

Background: Clopidogrel at 600 mg is active more quickly (two hours versus 12 hours) and inhibits platelets more completely than does a 300-mg dose, but it has never been tested prospectively in patients undergoing percutaneous intervention with a STEMI.

Study design: Prospective, multicenter, randomized controlled trial.

Setting: Five hospitals in Italy, Belgium, Serbia, and Hungary.

Synopsis: Two-hundred-one patients with STEMI were randomized to either 600 mg or 300 mg of clopidogrel, given an average of 30 minutes before initial PCI, as well as other standard treatment for STEMI. The primary outcome was “infarct size,” judged as the area under the curve (AUC) of serial creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB) and troponin measurements. At 30 days, patients who received the 600-mg dose of clopidogrel had lower AUCs of cardiac biomarkers, statistically significant (though clinically small) improvement in left ventricle ejection fraction at discharge, lower incidence of severely impaired post-PCI thrombolitis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) flow, and fewer “major cardiovascular events,” driven mainly by a reduction in revascularizations. Measurement of biomarkers to calculate infarct size can be confounded by hypertrophy, and the trial was underpowered for cardiovascular events. However, there was no increase in bleeding events.

Bottom line: In patients with STEMI, treatment with a higher loading dose of clopidogrel before PCI reduces revascularizations and might decrease infarct size without an increase in adverse events.

Citation: Patti G, Bárczi G, Orlic D, et al. Outcome comparison of 600- and 300-mg loading doses of clopidogrel in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: results from the ARMYDA-6 MI (Antiplatelet therapy for Reduction of MYocardial Damage during Angioplasty-Myocardial Infarction) randomized study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:1592-1599.

Medical Comorbidities Explain Most of Excess Risk Seen in Patients with Delayed Hip Fracture Repair

Clinical question: Could the increased mortality found with delays in hip fracture surgery be confounded by the premorbid functional status and medical comorbidities of patients whose surgery is more likely to be delayed?

Background: Guidelines recommend operating on patients with hip fracture within 24 hours, but the supporting evidence has not adjusted for underlying medical comorbidities, which could delay surgery and contribute to poor outcomes, making delays look harmful.

Study design: Prospective cohort, single-center design.

Setting: University hospital in Spain.

Synopsis: The study included 2,250 consecutive elderly patients admitted to the hospital for hip fracture who had their functional status and medical comorbidities assessed at enrollment. If their surgery was delayed beyond 24 hours, the reason was sought. Medical outcomes assessed daily while in hospital were delirium, pneumonia, heart failure, urinary tract infection, and new pressure sores, while the dose of pain medication, surgical complications, and in-hospital mortality were also compiled. No post-discharge data were available.

The median time to surgery was 72 hours. Patients with more medical comorbidities and poorer preoperative functional status had longer delays to operation, most commonly due to interrupting antiplatelet treatment or need for preoperative “echocardiography or other examinations.” When these medical factors were included in logistic regression analysis, the increased mortality seen with delays of surgery in the cohort was no longer statistically significant, suggesting the underlying comorbidities of these patients, rather than the delay to surgery itself, explained the increased mortality.

Bottom line: Delaying hip fracture surgery is less important than preoperative functional status and medical comorbidity in contributing to poor outcomes.

Citation: Vidán MT, Sánchez E, Gracia Y, Marañón E, Vaquero J, Serra JA. Causes and effects of surgical delay in patients with hip fracture: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:226-233.

Beta-Blockers Decrease All-Cause and Cardiovascular Mortality in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease

Clinical question: Are beta-blockers as effective in patients on dialysis and with end-stage chronic kidney disease (CKD) as they are in patients without severe renal disease?

Background: Patients with CKD have been largely excluded from trials of beta-blocker therapy even though they have high rates of cardiovascular disease and might be most likely to benefit. However, patients on dialysis might be predisposed to adverse complications of beta-blocker therapy, including hypotension.

Study design: Meta-analysis of eight trials of beta-blockade versus placebo (six heart failure trials) or ACE-I (two non-heart-failure trials) that included post-hoc analyses of CKD patients.

Setting: Varied, usually multinational RCTs.

Synopsis: The six congestive heart failure (CHF) studies were not designed to evaluate patients with CKD, and the two non-CHF studies were intended to evaluate progression of CKD, not cardiac outcomes. Thus, this is a meta-analysis of post-hoc CKD subgroups included in these trials. Compared with placebo, beta-blockers reduced all-cause and cardiovascular mortality without significant heterogeneity between trials. The magnitude of the effect was similar in CKD and non-CKD patients. Patients with CKD treated with beta-blockers were at increased risk of bradycardia and hypotension, but this did not lead to increased discontinuation of the drug. Only 114 dialysis patients were included in one of the eight trials (7,000 patients overall) and no outcomes were assessed.

Bottom line: Beta-blockers lower all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with CKD similarly to patients without kidney disease but are associated with an increased risk for hypotension and bradycardia. Their effect in dialysis patients is unknown.

Citation: Badve SV, Roberts MA, Hawley CM, et al. Effects of beta-adrenergic antagonists in patients with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:1152-1161.

Daily Long-Term Azithromycin in COPD Patients Decreases Frequency of Exacerbations

Clinical question: Does long-term treatment with azithromycin decrease COPD exacerbations and improve quality of life with an acceptable risk profile?

Background: Patients with acute exacerbations of COPD have increased risks of death and more rapid decline in lung function. Macrolide antibiotics might decrease exacerbations via antibacterial and anti-inflammatory effects. Small studies of long-term treatment with macrolides in COPD have had conflicting results.

Study design: Prospective, multicenter, parallel-group, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: Twelve U.S. academic health centers.

Synopsis: Eligible patients were those older than 40 with pulmonary function test-proven obstructive disease, a significant smoking history, a use of supplemental oxygen, or an oral glucocorticoid treatment in the previous year, and those who had previously come to healthcare attention for a COPD exacerbation. They were randomized to daily azithromycin (250 mg) or placebo. The primary outcome was time to first COPD exacerbation at one year. The investigators used deep nasopharyngeal swabs to evaluate the development of microbial resistance, and all patients were regularly screened for hearing loss. Time to first exacerbation and frequency of exacerbations decreased significantly with azithromycin treatment; the number needed to treat to prevent a COPD exacerbation was 2.86. More than half of nasopharyngeal samples had evidence of macrolide resistance at enrollment, and this increased to more than 80% at one year. Audiometric testing did show a decrease in hearing in those treated with azithromycin, but even those who did not stop their medication had recovery on subsequent testing.

Bottom line: Daily azithromycin decreases COPD exacerbations in those with a history of previous exacerbation at the cost of increased macrolide resistance and possible reversible decrements in hearing. The high degree of macrolide resistance at enrollment suggests non-antibacterial mechanisms might be responsible.

Citation: Albert RK, Connett J, Bailey WC, et al. Azithromycin for prevention of exacerbations of COPD. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:689-698.

Serial Low-Dose CT Scans Decrease Lung Cancer Mortality

Clinical question: Does annual screening with low-dose CT scans reduce mortality from lung cancer in current or former heavy smokers?

Background: Lung cancer is still the top cause of cancer death in the United States, and its prevalence is increasing in the developing world. Prior trials of screening chest radiography and sputum samples have not shown a decrease in lung cancer mortality, but CT scans could help identify lung cancer at an earlier, more treatable stage.

Study design: Prospective, multicenter, randomized trial of low-dose (roughly one-fifth the radiation of traditional CT) annual CT versus annual chest radiography.

Setting: Thirty-three U.S. medical institutions.

Synopsis: The study enrolled 53,454 current or prior smokers with a history of smoking more than 30 packs a year who were randomly assigned to undergo three annual CT scans or chest X-rays. Any CT scans that showed a noncalcified nodule greater than 4 mm and chest X-rays that showed a noncalcified nodule or mass of any size were classified as “positive,” but follow-up was left to the discretion of the treating physicians. Participants were followed for 6.5 years on average.

Of those screened with CT, 40% had a positive screening test at some point, more than three times the rate of chest radiography, and 96.4% of these were false-positives, which was similar to chest radiography. Adverse events as a result of workup of eventual false positives were uncommon, occurring in around 1% of those who did not have lung cancer and in 11% of those who did. Screening reduced lung cancer mortality by 20% compared with chest radiography, with a number needed to screen to prevent one lung cancer death of 320. Cost-effectiveness and effects of radiation were not assessed.

Bottom line: Serial screening with low-dose CT reduces lung cancer mortality at the cost of a high rate of false-positives. Questions remain about cost-effectiveness and radiation exposure.

Citation: National Lung Screening Trial Research Team, Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:395-409.

One-Week Delay in Starting Parenteral Nutrition in ICU Patients Is Associated with Better Outcomes

Clinical question: In patients admitted to the ICU who are at risk for malnutrition, does supplementing enteral feeding with parenteral feeding on the day of admission improve outcomes when compared with supplementation starting on Day 8?

Background: Patients with critical illness are at risk for malnutrition, which may lead to worsened outcomes. Many are unable to tolerate enteral feeding. However, adding parenteral nutrition has risks, including overfeeding and hyperglycemia.

Study design: Prospective, multicenter, randomized controlled trial. Neither patients/families nor ICU physicians were blinded.

Setting: Two university hospitals in Belgium.

Synopsis: The study included 4,640 patients admitted to the ICU who were “at risk” for malnutrition (assessed using a Nutritional Risk Score of >3). They were randomized to early initiation of parenteral nutrition on Day 1 or late initiation of parenteral nutrition on Day 8, in both cases only if needed to supplement enteral feeding. Both groups received intensive IV insulin protocols to keep blood glucose at 80 mg/dL to 110 mg/dL. The study populations were well-matched, with similar APACHE II scores. Of the total patients, 42% were emergency admissions to the ICU (more than half of which had sepsis), while scheduled cardiac surgery patients made up the majority of the rest of the study participants.

Patients with late initiation of total parenteral nutrition (TPN) were more likely to be discharged alive from the ICU within eight days despite having increased risk of hypoglycemia and more elevation of inflammatory markers. They had shorter ICU and hospital stays, fewer days on the ventilator, fewer infectious complications, were less likely to develop renal failure, and had lower overall costs. The unblinded management of these patients raises concern in interpreting infectious outcomes because study investigators could have been biased to look for infection more often in the early initiation group.

Bottom line: In ICU patients at risk for malnutrition, delaying initiation of TPN to supplement enteral feeding shortens ICU stay and reduces infectious complications when compared with early initiation of TPN.

Citation: Casaer MP, Mesotten D, Hermans G, et al. Early versus late parenteral nutrition in critically ill adults. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:506-17.

Intrapleural Instillation of Combined DNase and t-PA Improve Outcomes in Patients with Empyema

Clinical question: Does the intrapleural administration of a fibrinolytic, a recombinant DNase, or a combination of the two improve outcomes in patients with pleural infections compared with placebo?

Background: Pleural-based infections confer high morbidity and mortality, especially in the one-third of cases in which chest tube drainage fails. Observational data suggest intrapleural administration of fibrinolytics can improve drainage; however, a large randomized trial (MIST1) failed to show improvement with streptokinase.

Study design: Randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, factorial, multicenter trial.

Setting: University hospitals in the U.K.

Synopsis: A total of 193 patients with clinical evidence of an infection as well as laboratory evidence of pleural infection were randomized in factorial design to placebo, DNase alone, t-PA alone, and DNase plus t-PA as a twice-daily, hourlong instillation into the pleural space on hospital days 1 through 3. The combination group had improvements in the size of the pleural effusion compared with placebo, the primary endpoint. This group also was less likely to be referred for surgery, had shorter hospital stays, had less fever, and had lower inflammatory markers by hospital Day 7. Neither of the single-agent groups were better than placebo. The confidence intervals for all outcomes besides radiographic size of the effusion were large, as the trial had limited power for secondary endpoints.

Bottom line: In patients with empyema, the addition of twice-daily instillations of DNase and tPA can improve drainage and decrease risk of treatment failure when combined with chest tube drainage and antibiotics.

Citation: Rahman NM, Maskell NA, West A, et al. Intrapleural use of tissue plasminogen activator and DNase in pleural infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:518-526.

Smoothing Admissions over the Week Improves Patient Flow

Clinical question: What is the difference between weekday and weekend hospital occupancy, and what might the effect be of redistributing, or “smoothing,” elective admissions across the week?

Background: Efforts to improve patient flow have largely focused on reducing the average length of stay (ALOS). As the ALOS decreases, though, further reductions have limited yield in improving patient flow and could occur at the expense of patient safety. Smoothing admissions is a recognized but underutilized tool to address patient flow and hospital overcrowding.

Study design: Retrospective cohort.

Setting: Thirty-nine freestanding, tertiary-care children’s hospitals in the U.S.

Synopsis: Hospital occupancy ranged from 70.9% to 108.1% for weekdays, and from 65.7% to 94.4% on weekends. The mean difference between weekday and weekend occupancy was 8.2%. Using a mathematical model to redistribute admissions from peak days to nonpeak days (within a one-week time frame), the investigators found that percent occupancy on average dropped by 6.6%—the same number of patients over the same time interval, but with lower average occupancy. And, while not projected by these authors, the correlate of lower average occupancy would be reduced waits and delays for admission and within-hospital services. Only 2.6%, or about 7.5 admissions per week per hospital, would need to be rescheduled in order to realize this gain.

Bottom line: Where feasible, reshuffling elective admissions to “smooth” demand across the week is associated with improved hospital flow.

Citation: Fieldston ES, Hall M, Shah SS, et al. Addressing inpatient crowding by smoothing occupancy at children’s hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:466-473.

Variability in Preferences, Experiences, and Expectations for Hospitalist Roles in Comanagement

Clinical question: Do provider expectations and experiences in comanagement differ from the traditional medical consultation model?

Background: Hospitalists participate in traditional medical consultation and, increasingly, a variety of comanagement with surgical and various medical specialists. It is uncertain what preferences and expectations on either side of the comanagement relationship might be. Learning more might lead to a better conceptual understanding and working definition of inpatient comanagement.

Study design: Baseline and follow-up surveys.

Setting: Large single-site academic medical center, hospitalist-hepatologist comanagement service.