User login

A Cross-sectional Analysis of Regional Trends in Medicare Reimbursement for Phototherapy Services From 2010 to 2023

To the Editor:

Phototherapy regularly is utilized in the outpatient setting to address various skin pathologies, including atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, pruritus, vitiligo, and mycosis fungoides.1,2 Phototherapy is broadly defined by the measured administration of nonionizing radiation within the UV range including wavelengths within the UVA (eg, psoralen sensitizer plus UVA-1) and UVB (eg, broadband UVB, narrowband UVB) spectrums.1,3 Generally, the mechanism of action is derived from effects on inflammatory components of cutaneous disorders and the induction of apoptosis, both precipitating numerous downstream events.4

From 2015 to 2018, there were more than 1.3 million outpatient phototherapy visits in the United States, with the most common procedural indications being dermatitis not otherwise specified, atopic dermatitis, and pruritus.5 From 2000 to 2015, the quantity of phototherapy services billed to Medicare trended upwards by an average of 5% per year, increasing from 334,670 in the year 2000 to 692,093 in 2015.6 Therefore, an illustration of associated costs would be beneficial. Additionally, because total cost and physician reimbursement fluctuate from year to year, studies demonstrating overall trends can inform both US policymakers and physicians. There is a paucity of research on geographical trends for procedural reimbursements in dermatology for phototherapy. Understanding geographic trends of reimbursement could duly serve to optimize dermatologist practice patterns involving access to viable and quality care for patients seeking treatment as well as draw health policymakers’ attention to striking adjustments in physician fees. Therefore, in this study we aimed to illustrate the most recent regional payment trends in phototherapy procedures for Medicare B patients.

We queried the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS) database (https://www.cms.gov/medicare/payment/fee-schedules/physician/lookup-tool) for the years 2010 to 2023 for Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes common to phototherapy procedures: actinotherapy (96900); photochemotherapy by Goeckerman treatment or using petrolatum and UVB (96910); photochemotherapy using psoralen plus UVA (96912); and photochemotherapy of severe dermatoses requiring a minimum of 4 hours of care under direct physician supervision (96913). Nonfacility prices for these procedures were analyzed. For 2010, due to midyear alterations to Medicare reimbursement (owed to bills HR 3962 and HR 4872), the mean price data of MPFS files 2010A and 2010B were used. All dollar values were converted to January 2023 US dollars using corresponding consumer price index inflation data. The Medicare Administrative Contractors were used to group state pricing information by region in accordance with established US Census Bureau subdivisions (https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/economic-census/guidance-geographies/levels.html). Weighted percentage change in reimbursement rate was calculated using physician (MD or DO) utilization (procedure volume) data available in the 2020 Physician and Other Practitioners Public Use File (https://data.cms.gov/provider-summary-by-type-of-service/medicare-physician-other-practitioners/medicare-physician-other-practitioners-by-provider-and-service). All descriptive statistics and visualization were generated using R software (v4.2.2)(R Development Core Team).

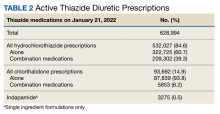

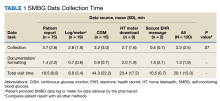

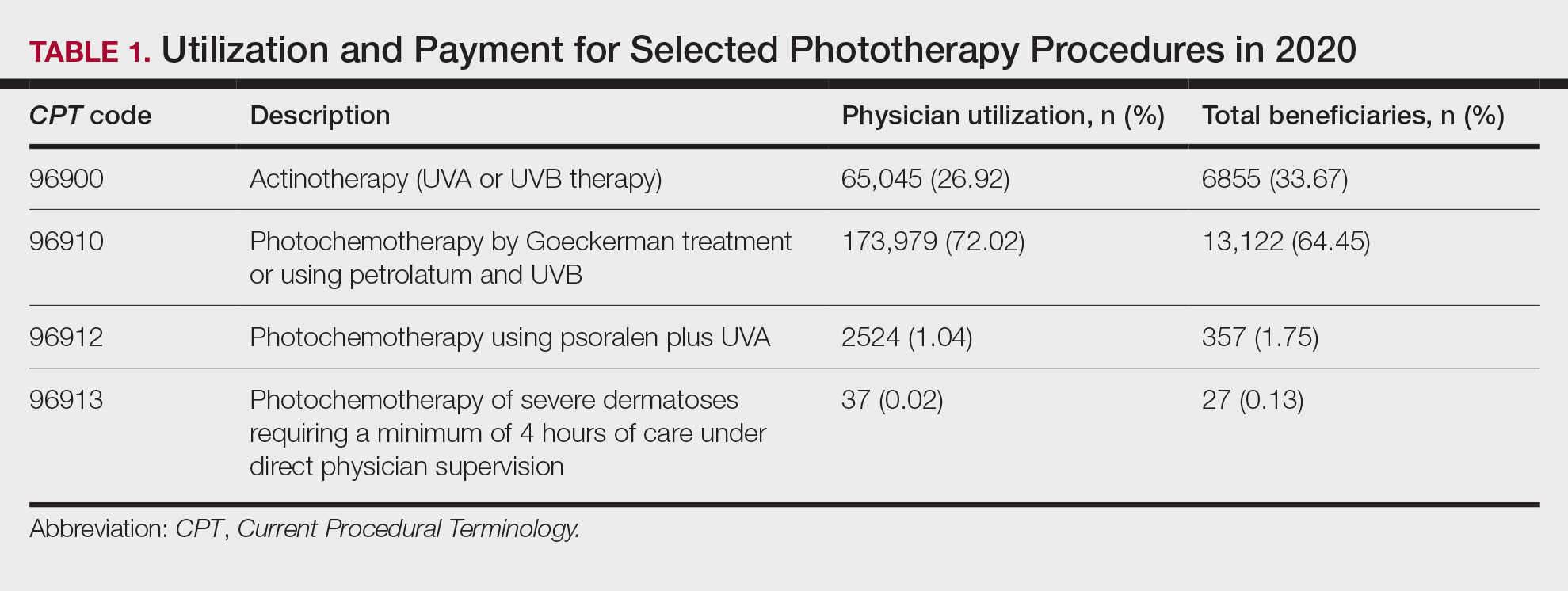

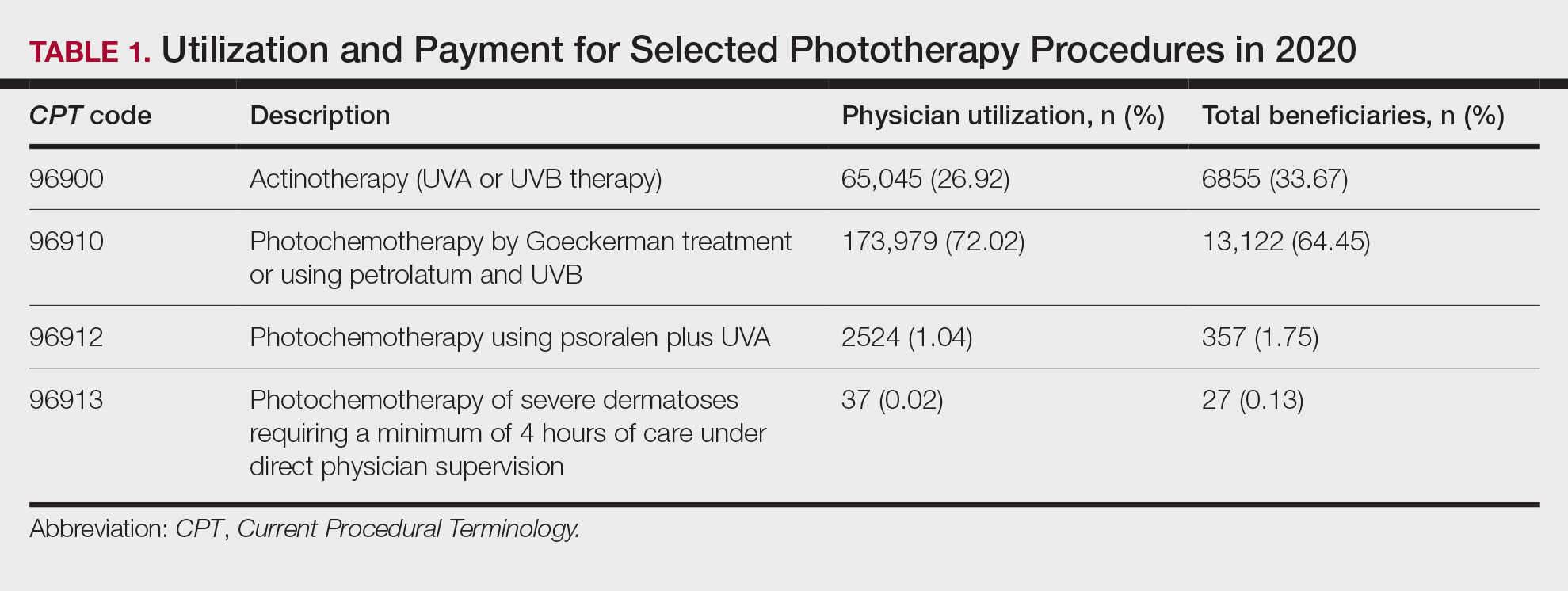

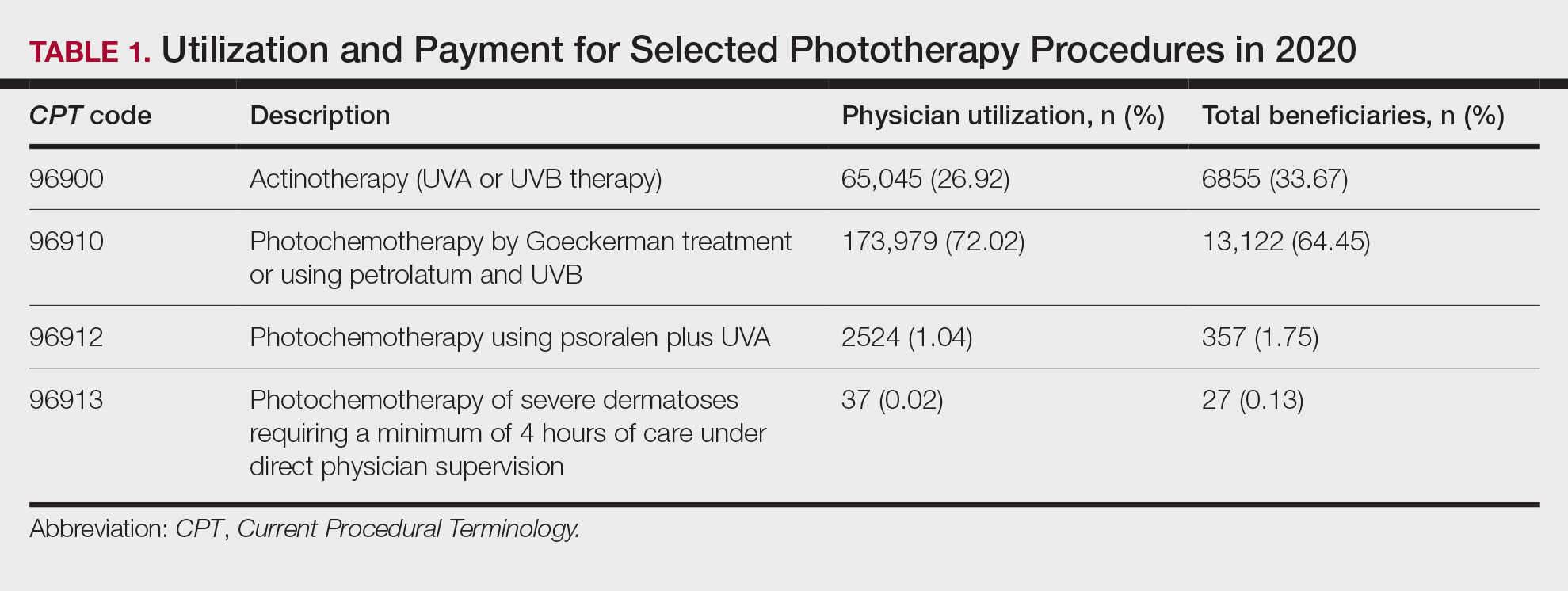

Table 1 provides physician utilization data and the corresponding number of Part B beneficiaries for phototherapy procedures in 2020. There were 65,045 services of actinotherapy provided to a total of 6855 unique Part B beneficiaries, 173,979 services of photochemotherapy by Goeckerman treatment or using petrolatum and UVB provided to 13,122 unique Part B beneficiaries, 2524 services of photochemotherapy using psoralen plus UVA provided to a total of 357 unique Part B beneficiaries, and 37 services of photochemotherapy of severe dermatoses requiring a minimum of 4 hours of care under direct physician supervision provided to a total of 27 unique Part B beneficiaries.

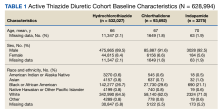

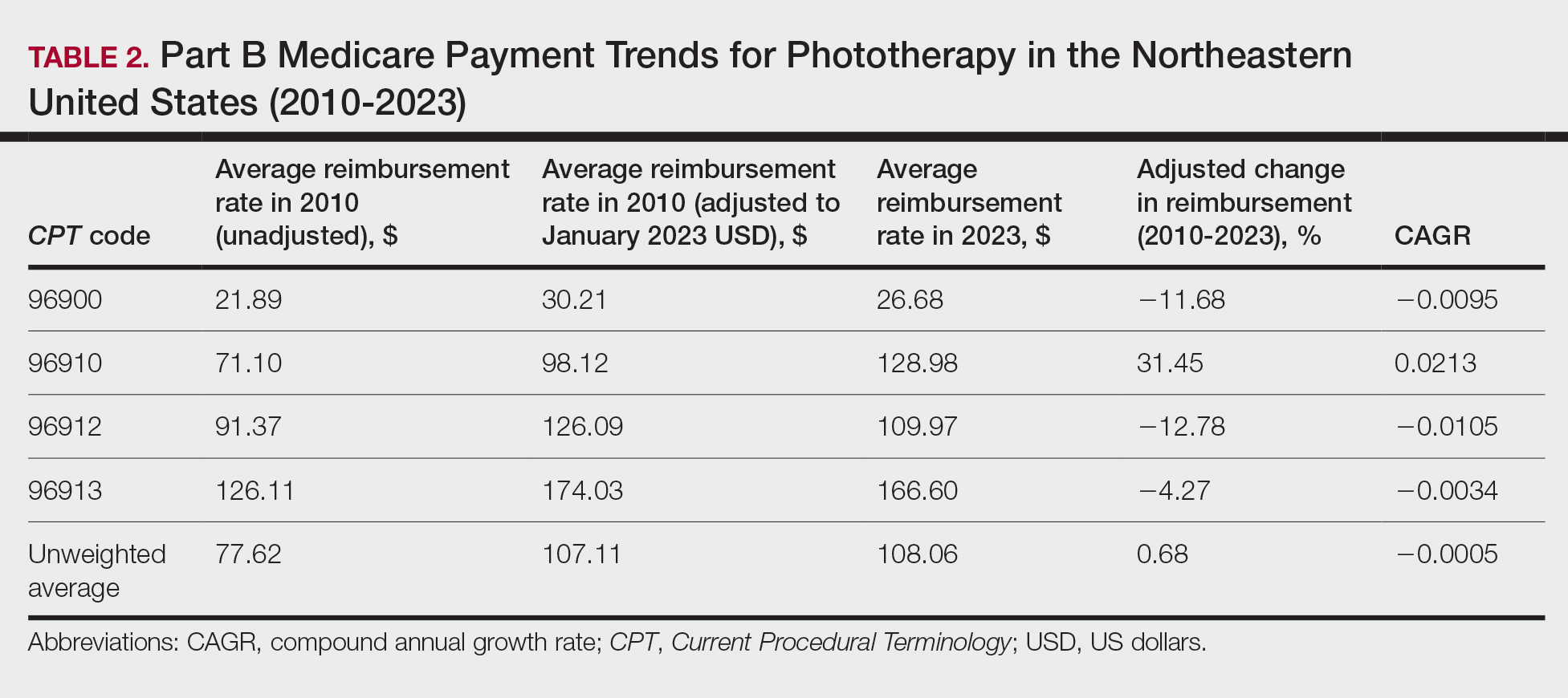

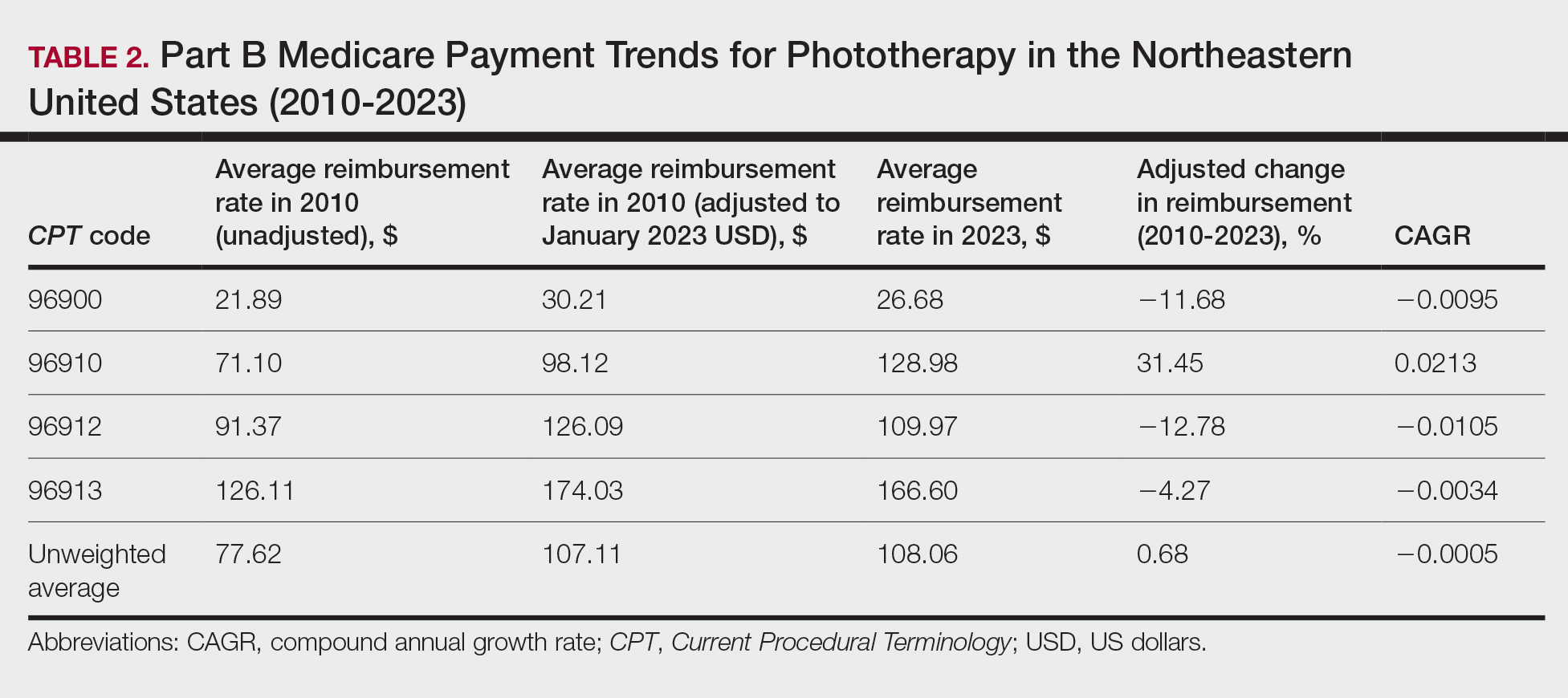

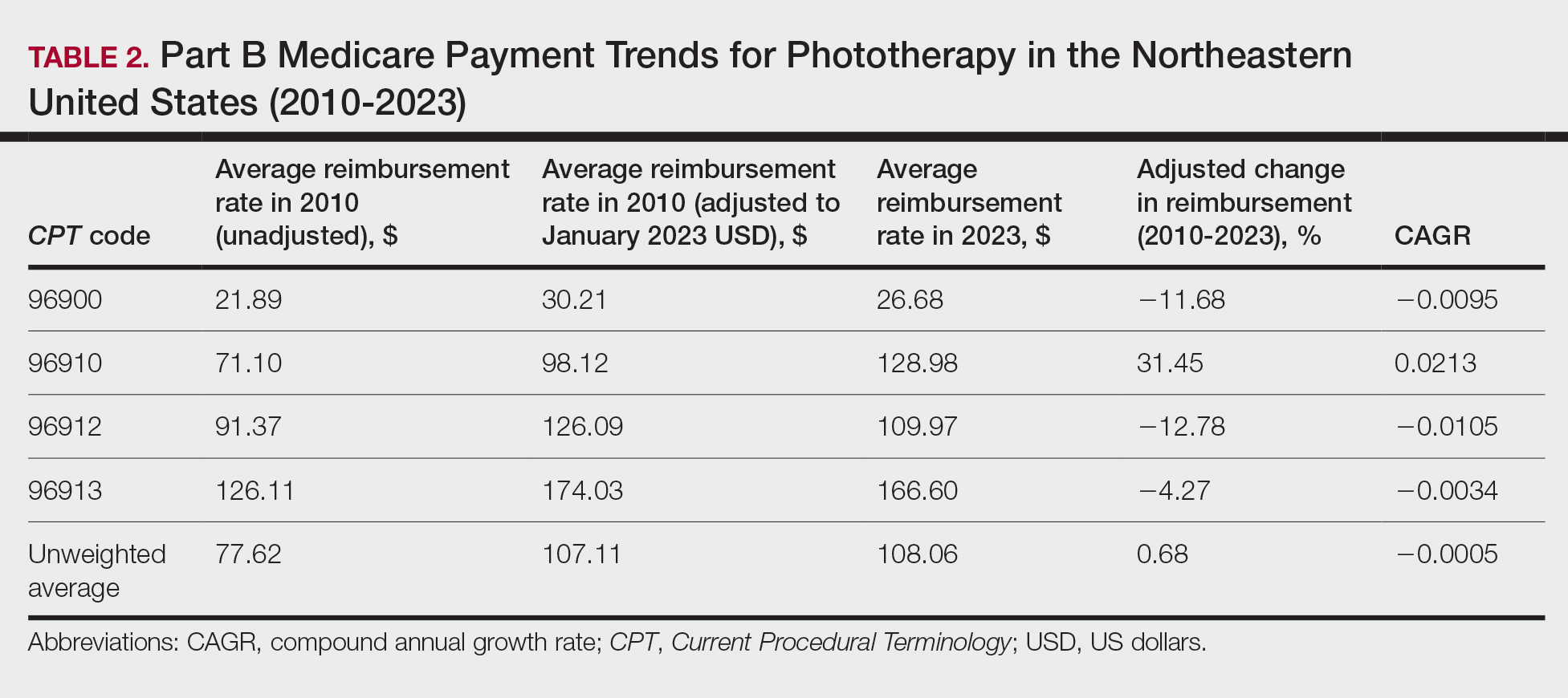

On average (unweighted), phototherapy reimbursement rates in the North increased by 0.68% between 2010 and 2023 (Table 2). After weighting for 2020 physician utilization, the average change in reimbursement rate was +19.37%. During this time period, CPT code 96910 reported the greatest adjusted increase in reimbursement (+31.45%)($98.12 to $128.98; compound annual growth rate [CAGR], +0.0213), and CPT code 96912 reported the greatest adjusted decrease in reimbursement (−12.76%)($126.09 to $109.97; CAGR, −0.0105). For CPT code 96900, the reported adjusted decrease in reimbursement was −11.68% ($30.21 to $26.68; CAGR, −0.0095), and for CPT code 96913, the reported adjusted decrease in reimbursement was −4.27% ($174.03 to $166.60; CAGR, −0.0034).

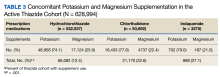

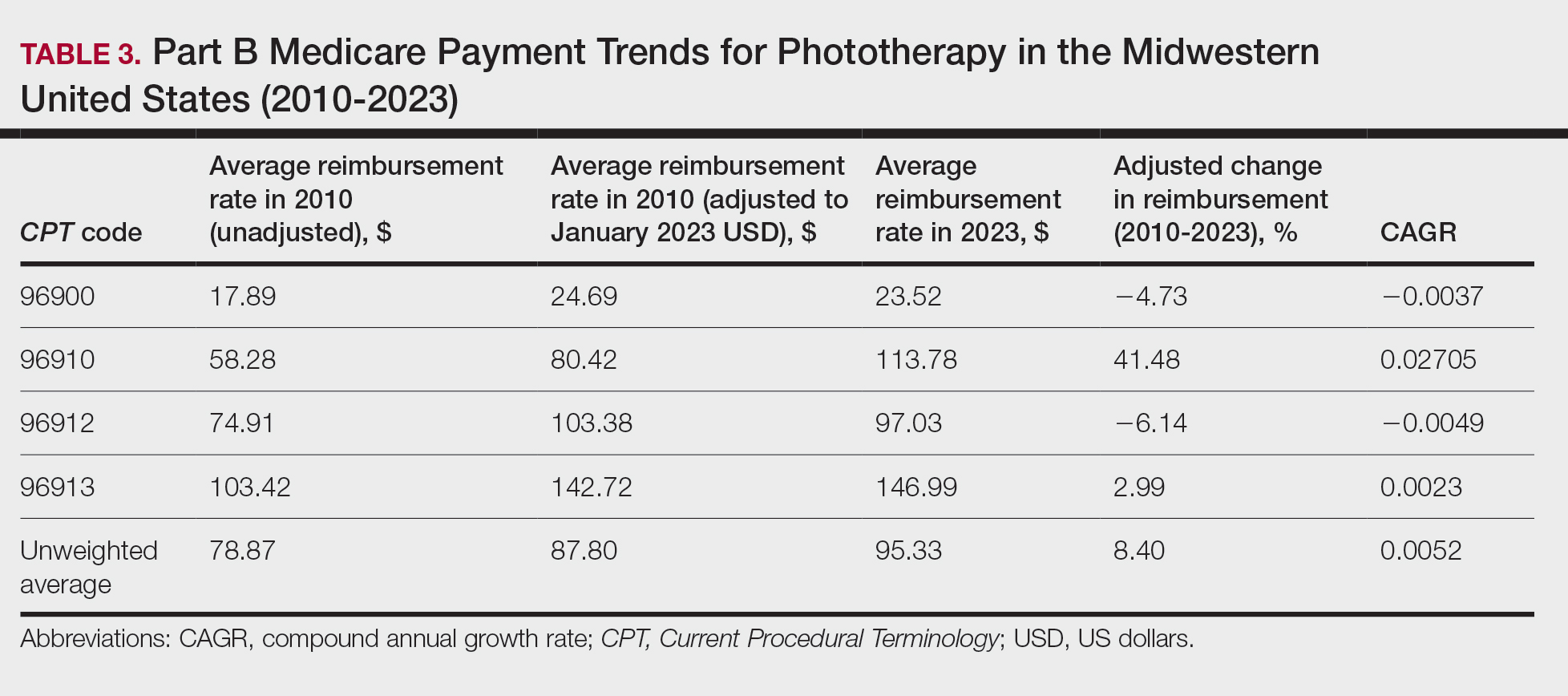

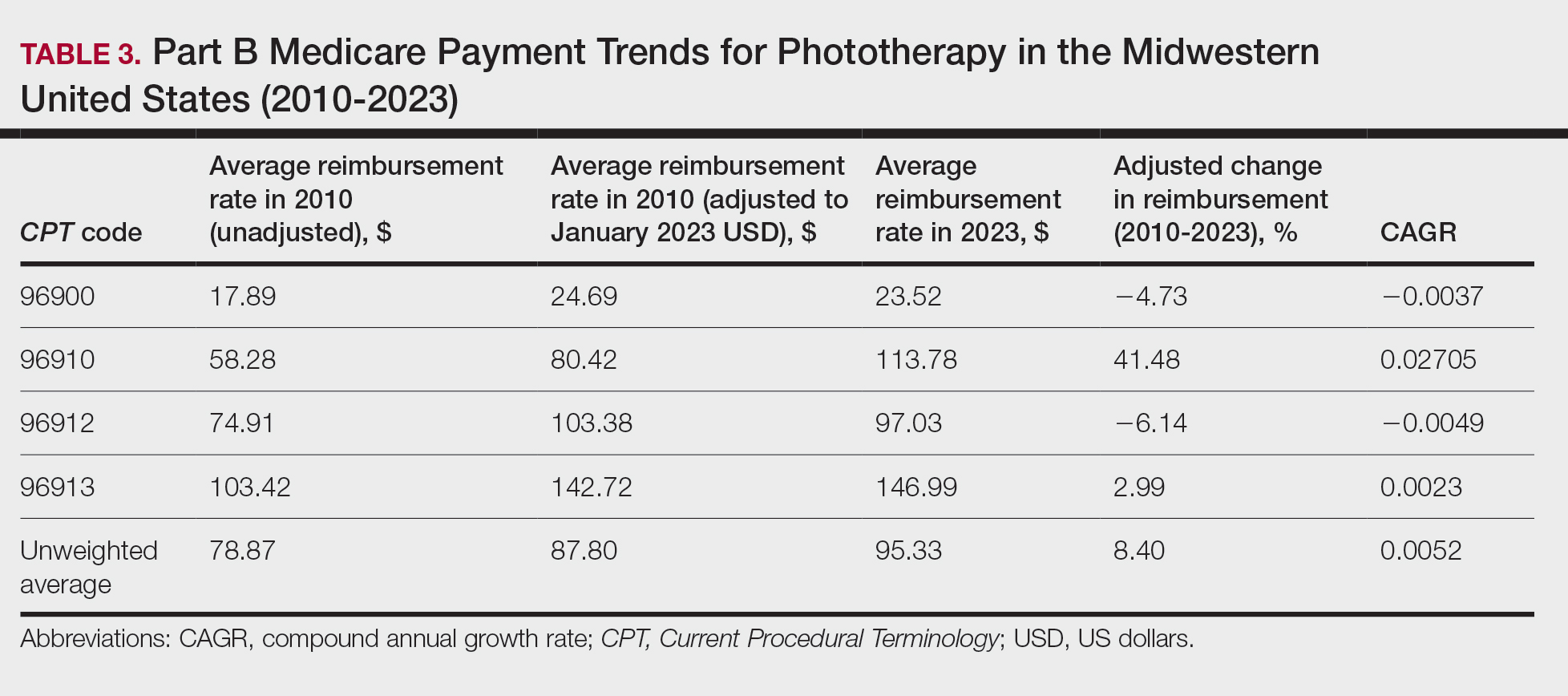

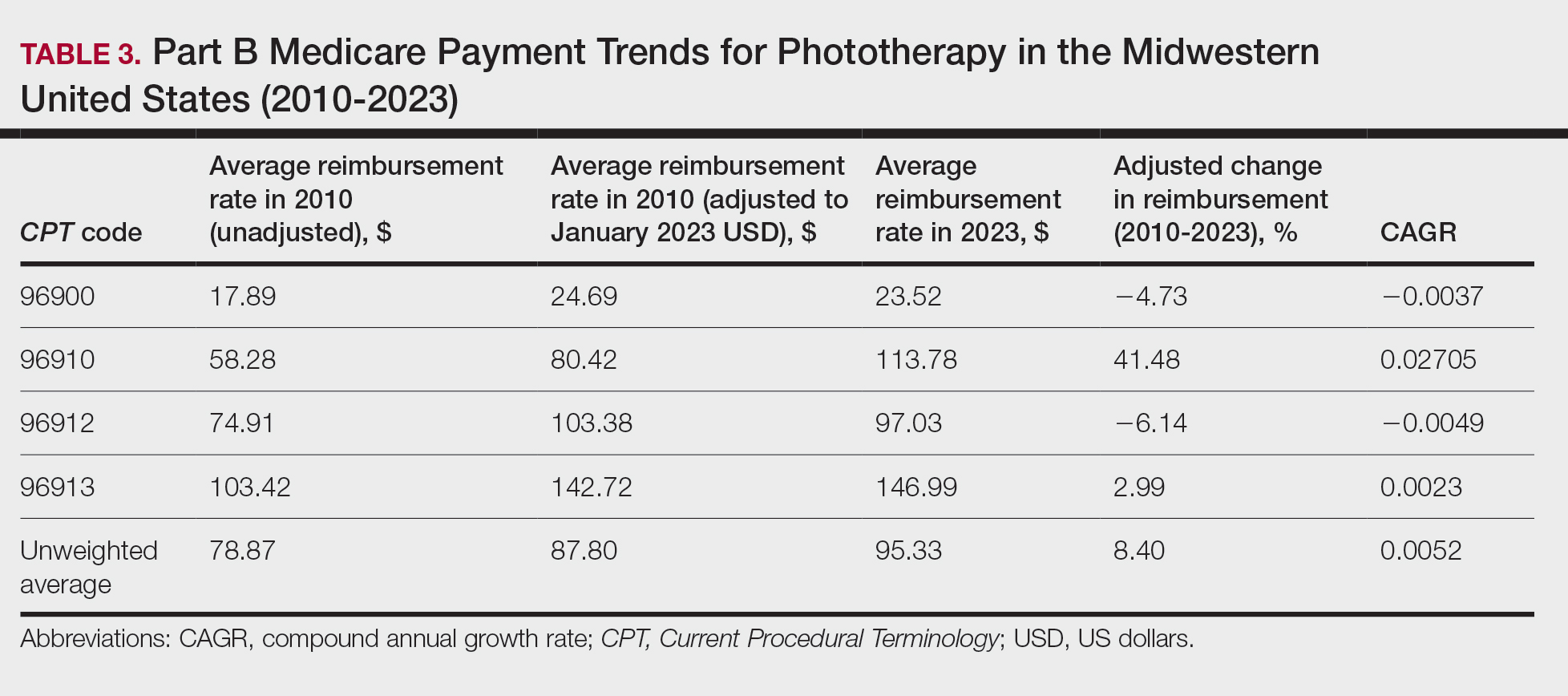

On average (unweighted), phototherapy reimbursement rates in the Midwest increased by 8.40% between 2010 and 2023 (Table 3). After weighting for 2020 physician utilization, the average change in reimbursement rate was +28.53%. During this time period, CPT code 96910 reported the greatest adjusted change in reimbursement (+41.48%)($80.42 to $113.78; CAGR, +0.0270), and CPT code 96912 reported the greatest adjusted decrease in reimbursement (−6.14%)($103.28 to $97.03; CAGR, −0.0049). For CPT code 96900, the reported adjusted decrease in reimbursement was −4.73% ($24.69 to $23.52; CAGR, −0.0037), and for CPT code 96913, the reported adjusted increase in reimbursement was +2.99% ($142.72 to $146.99; CAGR, +0.0023).

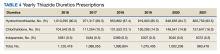

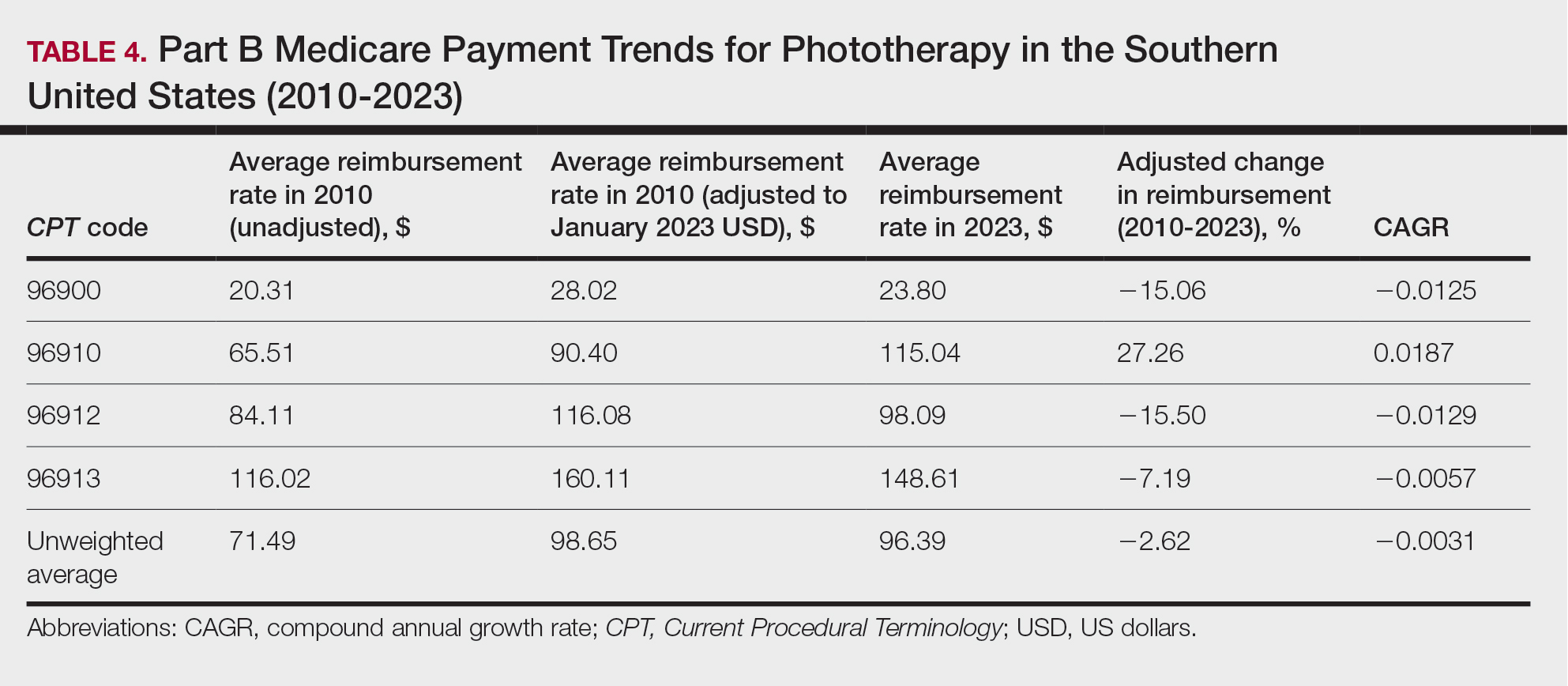

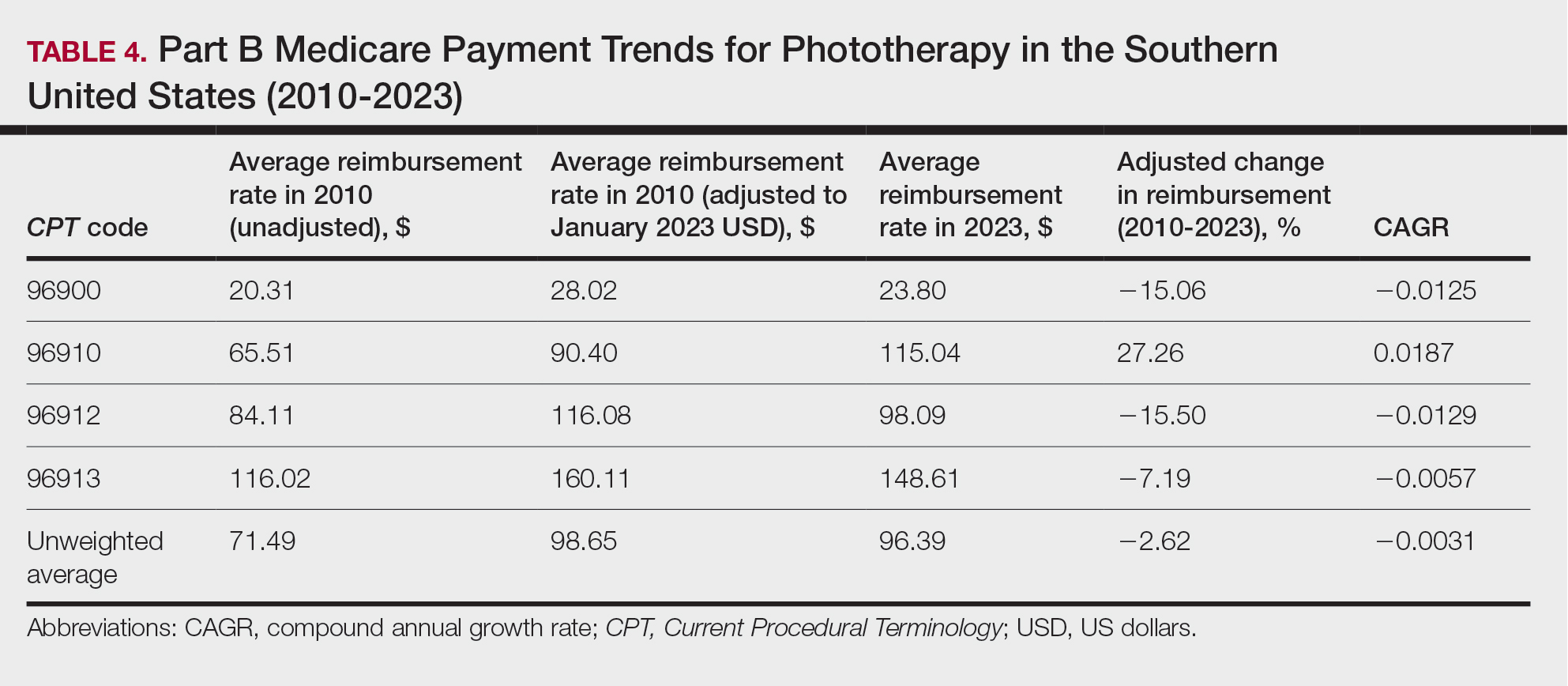

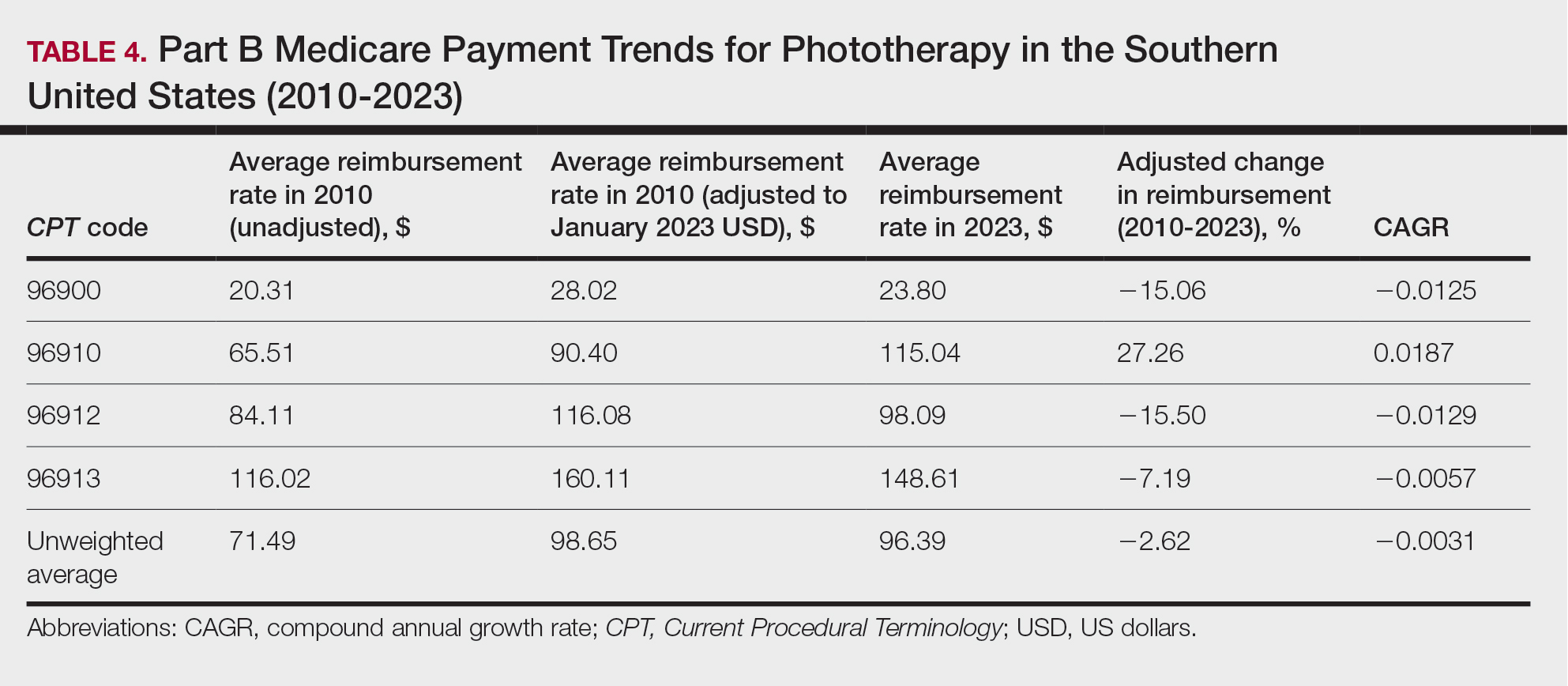

On average (unweighted), phototherapy reimbursement rates in the South decreased by 2.62% between 2010 and 2023 (Table 4). After weighting for 2020 physician utilization, the average change in reimbursement rate was +15.41%. During this time period, CPT code 96910 reported the greatest adjusted change in reimbursement (+27.26%)($90.40 to $115.04 USD; CAGR, +0.0187), and CPT code 96912 reported the greatest adjusted decrease in reimbursement (−15.50%)($116.08 to $98.09; CAGR, −0.0129). For CPT code 96900, the reported adjusted decrease in reimbursement was −15.06% ($28.02 to $23.80; CAGR, −0.0125), and for CPT code 96913, the reported adjusted decrease in reimbursement was −7.19% ($160.11 to $148.61; CAGR, −0.0057).

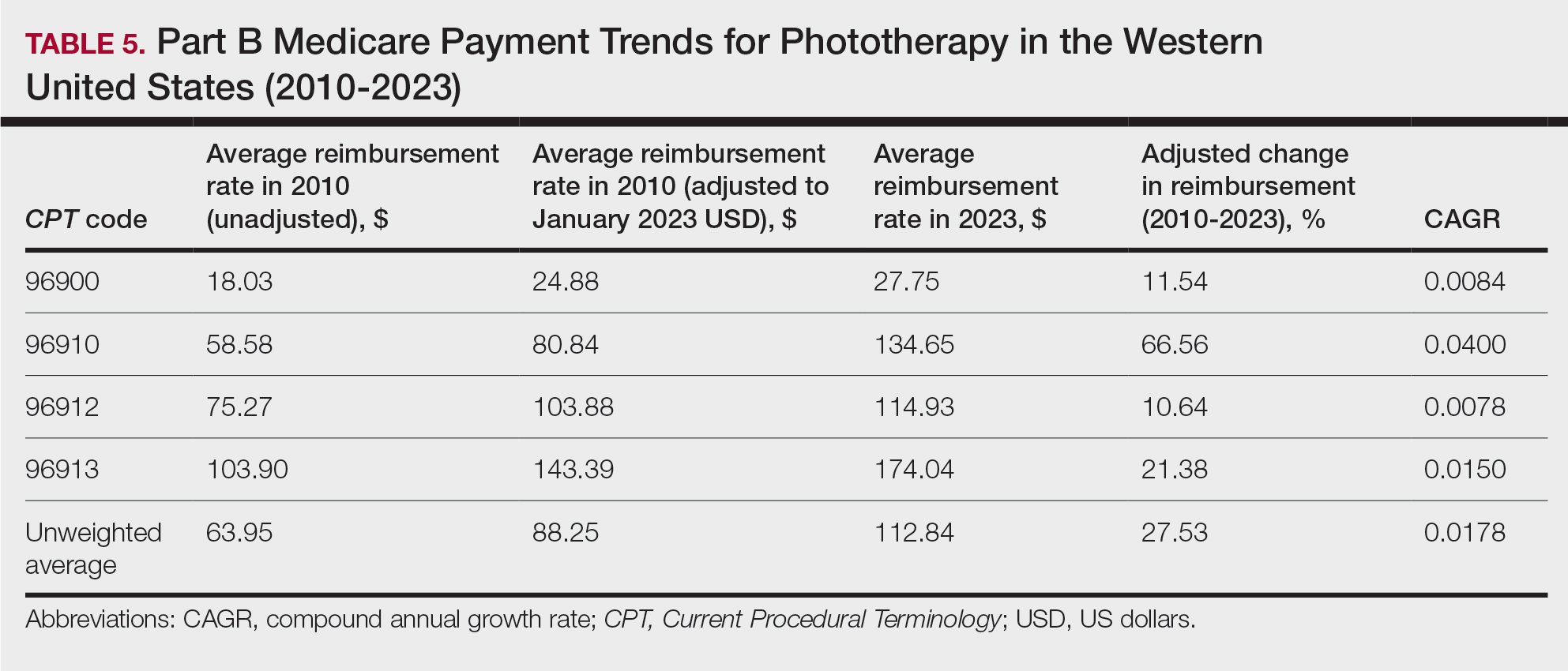

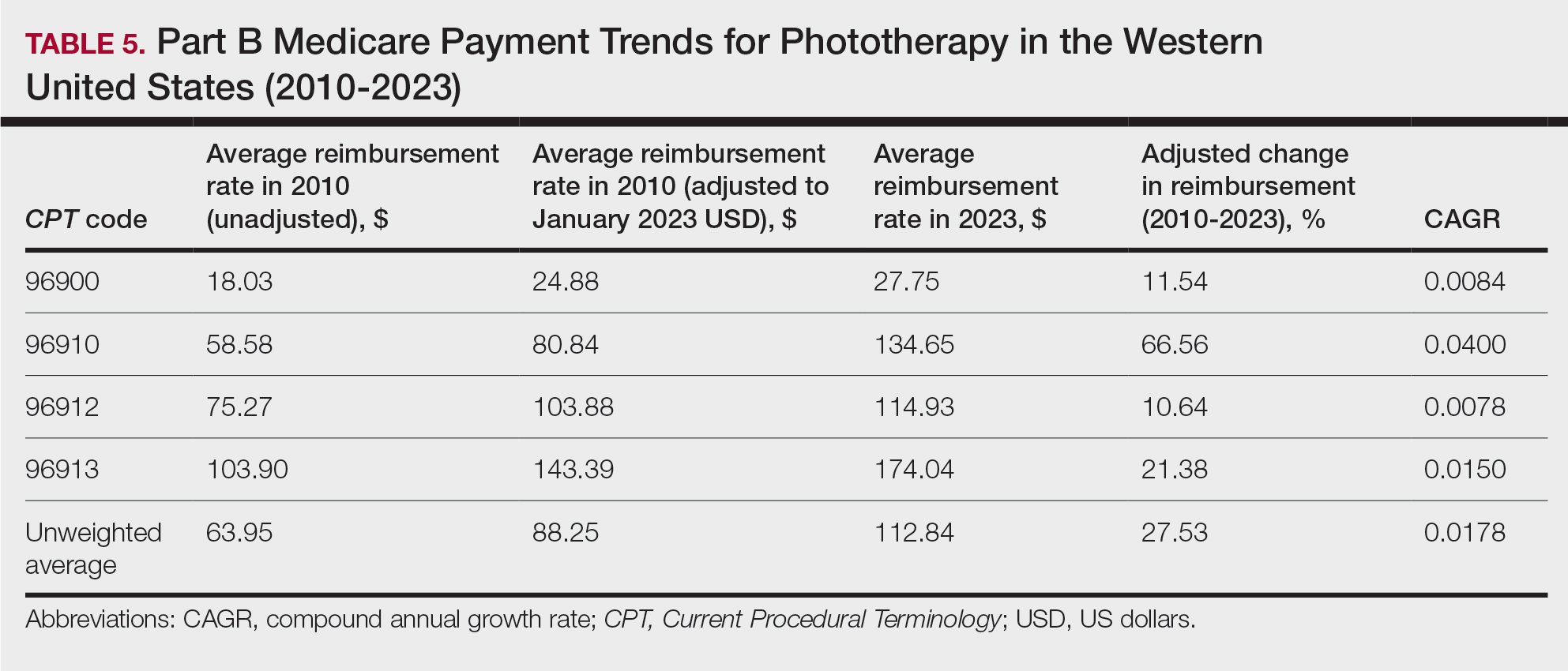

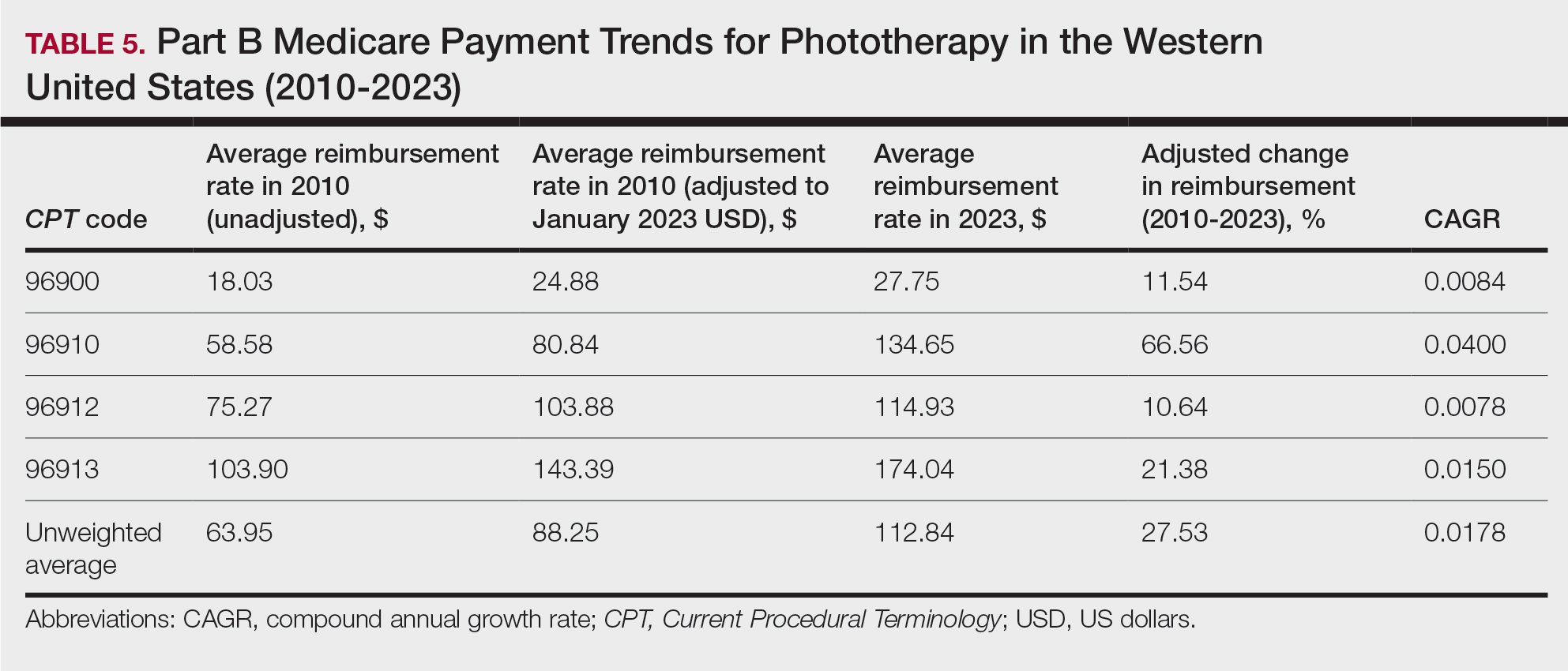

On average (unweighted), phototherapy reimbursement rates in the West increased by 27.53% between 2010 and 2023 (Table 5). After weighting for 2020 physician utilization, the average change in reimbursement rate was +51.16%. Reimbursement for all analyzed procedures increased in the western United States. During this time period, CPT code 96910 reported the greatest adjusted increase in reimbursement (+66.56%)($80.84 to $134.65; CAGR, +0.0400), and CPT code 96912 reported the lowest adjusted increase in reimbursement (+10.64%)($103.88 to $114.93; CAGR, +0.0078). For CPT code 96900, the reported adjusted increase in reimbursement was 11.54% ($24.88 to $27.75; CAGR, +0.0084), and for CPT code 96913, the reported adjusted increase in reimbursement was 21.38% ($143.39 to $174.04; CAGR, +0.0150).

In this study evaluating geographical payment trends for phototherapy from 2010 to 2023, we demonstrated regional inconsistency in mean inflation-adjusted Medicare reimbursement rates. We found that all phototherapy procedures had increased reimbursement in the western United States, whereas all other regions reported cuts in reimbursement rates for at least half of the analyzed procedures. After adjusting for procedure utilization by physicians, weighted mean reimbursement for phototherapy increased in all US regions.

In a cross-sectional study that explored trends in the geographic distribution of dermatologists from 2012 to 2017, dermatologists in the northeastern and western United States were more likely to be located in higher-income zip codes, whereas dermatologists in the southern United States were more likely to be located in lower-income zip codes,7 suggesting that payment rate changes are not concordant with cost of living. Additionally, Lauck and colleagues8 observed that 75% of the top 20 most common procedures performed by dermatologists had decreased reimbursement (mean change, −10.8%) from 2011 to 2021. Other studies on Medicare reimbursement trends over the last 2 decades have reported major decreases within other specialties, suggesting that declining Medicare reimbursements are not unique to dermatology.9,10 It is critical to monitor these developments, as the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services emphasized health care policy changes aimed at increasing reimbursements for evaluation and management services with compensatory payment cuts in billing for procedural services.11

Mazmudar et al12 previously reported a mean reimbursement decrease of −6.6% for laser/phototherapy procedures between 2007 and 2021, but these data did not include the heavily utilized Goeckerman treatment. Changes in reimbursement pose major ramifications for dermatologists—for practice size, scope, and longevity—as rates influence changes in commercial insurance reimbursements.13 Medicare plays a major role in the US health care system as the second largest expenditure14; indeed, between 2000 and 2015, Part B billing volume for phototherapy procedures increased 5% annually. However, phototherapy remains inaccessible in many locations due to unequal regional distribution of phototherapy clinics.6 Moreover, home phototherapy units are not yet widely utilized because of safety and efficacy concerns, lack of physician oversight, and difficulty obtaining insurance coverage.15 Acknowledgment and consideration of these geographical trends may persuasively allow policymakers, hospitals, and physicians to facilitate cost-effective phototherapy reimbursements that ensure continued access to quality and sustainable dermatologic care in the United States that tailor to regional needs.

In sum, this analysis reveals regional trends in Part B physician reimbursement for phototherapy procedures, with all US regions reporting a mean increase in phototherapy reimbursement after adjusting for utilization, albeit to varying degrees. Mean reimbursement for photochemotherapy by Goeckerman treatment or using petrolatum and UVB increased most among phototherapy procedures. Mean reimbursement for both actinotherapy and photochemotherapy using psoralen plus UVA decreased in all regions except the western United States.

Limitations include the restriction to Part B MPFS and the reliance on single-year (2020) physician utilization data to compute weighted changes in average reimbursement across a multiyear range, effectively restricting sweeping conclusions. Still, this study puts forth actionable insights for dermatologists and policymakers alike to appreciate and consider.

- Rathod DG, Muneer H, Masood S. Phototherapy. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2002.

- Branisteanu DE, Dirzu DS, Toader MP, et al. Phototherapy in dermatological maladies (Review). Exp Ther Med. 2022;23:259. doi:10.3892/etm.2022.11184

- Barros NM, Sbroglio LL, Buffara MO, et al. Phototherapy. An Bras Dermatol. 2021;96:397-407. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2021.03.001

- Vieyra-Garcia PA, Wolf P. A deep dive into UV-based phototherapy: mechanisms of action and emerging molecular targets in inflammation and cancer. Pharmacol Ther. 2021;222:107784. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107784

- Oulee A, Javadi SS, Martin A, et al. Phototherapy trends in dermatology 2015-2018. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33:2545-2546. doi:10.1080/09546634.2021.2019660

- Tan SY, Buzney E, Mostaghimi A. Trends in phototherapy utilization among Medicare beneficiaries in the United States, 2000 to 2015. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:672-679. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.03.018

- Benlagha I, Nguyen BM. Changes in dermatology practice characteristics in the United States from 2012 to 2017. JAAD Int. 2021;3:92-101. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2021.03.005

- Lauck K, Nguyen QB, Hebert A. Trends in Medicare reimbursement within dermatology: 2011-2021. Skin. 2022;6:122-131. doi:10.25251/skin.6.2.5

- Smith JF, Moore ML, Pollock JR, et al. National and geographic trends in Medicare reimbursement rates for orthopedic shoulder and upper extremity surgery from 2000 to 2020. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2022;31:860-867. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2021.09.001

- Haglin JM, Eltorai AEM, Richter KR, et al. Medicare reimbursement for general surgery procedures: 2000 to 2018. Ann Surg. 2020;271:17-22. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000003289

- Fleishon HB. Evaluation and management coding initiative. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17:1539-1540. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2020.09.057

- Mazmudar RS, Sheth A, Tripathi R, et al. Inflation-adjusted trends in Medicare reimbursement for common dermatologic procedures, 2007-2021. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1355-1358. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.3453

- Clemens J, Gottlieb JD. In the shadow of a giant: Medicare’s influence on private physician payments. J Polit Econ. 2017;125:1-39. doi:10.1086/689772

- Ya J, Ezaldein HH, Scott JF. Trends in Medicare utilization by dermatologists, 2012-2015. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:471-474. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4212

- Rajpara AN, O’Neill JL, Nolan BV, et al. Review of home phototherapy. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:2.

To the Editor:

Phototherapy regularly is utilized in the outpatient setting to address various skin pathologies, including atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, pruritus, vitiligo, and mycosis fungoides.1,2 Phototherapy is broadly defined by the measured administration of nonionizing radiation within the UV range including wavelengths within the UVA (eg, psoralen sensitizer plus UVA-1) and UVB (eg, broadband UVB, narrowband UVB) spectrums.1,3 Generally, the mechanism of action is derived from effects on inflammatory components of cutaneous disorders and the induction of apoptosis, both precipitating numerous downstream events.4

From 2015 to 2018, there were more than 1.3 million outpatient phototherapy visits in the United States, with the most common procedural indications being dermatitis not otherwise specified, atopic dermatitis, and pruritus.5 From 2000 to 2015, the quantity of phototherapy services billed to Medicare trended upwards by an average of 5% per year, increasing from 334,670 in the year 2000 to 692,093 in 2015.6 Therefore, an illustration of associated costs would be beneficial. Additionally, because total cost and physician reimbursement fluctuate from year to year, studies demonstrating overall trends can inform both US policymakers and physicians. There is a paucity of research on geographical trends for procedural reimbursements in dermatology for phototherapy. Understanding geographic trends of reimbursement could duly serve to optimize dermatologist practice patterns involving access to viable and quality care for patients seeking treatment as well as draw health policymakers’ attention to striking adjustments in physician fees. Therefore, in this study we aimed to illustrate the most recent regional payment trends in phototherapy procedures for Medicare B patients.

We queried the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS) database (https://www.cms.gov/medicare/payment/fee-schedules/physician/lookup-tool) for the years 2010 to 2023 for Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes common to phototherapy procedures: actinotherapy (96900); photochemotherapy by Goeckerman treatment or using petrolatum and UVB (96910); photochemotherapy using psoralen plus UVA (96912); and photochemotherapy of severe dermatoses requiring a minimum of 4 hours of care under direct physician supervision (96913). Nonfacility prices for these procedures were analyzed. For 2010, due to midyear alterations to Medicare reimbursement (owed to bills HR 3962 and HR 4872), the mean price data of MPFS files 2010A and 2010B were used. All dollar values were converted to January 2023 US dollars using corresponding consumer price index inflation data. The Medicare Administrative Contractors were used to group state pricing information by region in accordance with established US Census Bureau subdivisions (https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/economic-census/guidance-geographies/levels.html). Weighted percentage change in reimbursement rate was calculated using physician (MD or DO) utilization (procedure volume) data available in the 2020 Physician and Other Practitioners Public Use File (https://data.cms.gov/provider-summary-by-type-of-service/medicare-physician-other-practitioners/medicare-physician-other-practitioners-by-provider-and-service). All descriptive statistics and visualization were generated using R software (v4.2.2)(R Development Core Team).

Table 1 provides physician utilization data and the corresponding number of Part B beneficiaries for phototherapy procedures in 2020. There were 65,045 services of actinotherapy provided to a total of 6855 unique Part B beneficiaries, 173,979 services of photochemotherapy by Goeckerman treatment or using petrolatum and UVB provided to 13,122 unique Part B beneficiaries, 2524 services of photochemotherapy using psoralen plus UVA provided to a total of 357 unique Part B beneficiaries, and 37 services of photochemotherapy of severe dermatoses requiring a minimum of 4 hours of care under direct physician supervision provided to a total of 27 unique Part B beneficiaries.

On average (unweighted), phototherapy reimbursement rates in the North increased by 0.68% between 2010 and 2023 (Table 2). After weighting for 2020 physician utilization, the average change in reimbursement rate was +19.37%. During this time period, CPT code 96910 reported the greatest adjusted increase in reimbursement (+31.45%)($98.12 to $128.98; compound annual growth rate [CAGR], +0.0213), and CPT code 96912 reported the greatest adjusted decrease in reimbursement (−12.76%)($126.09 to $109.97; CAGR, −0.0105). For CPT code 96900, the reported adjusted decrease in reimbursement was −11.68% ($30.21 to $26.68; CAGR, −0.0095), and for CPT code 96913, the reported adjusted decrease in reimbursement was −4.27% ($174.03 to $166.60; CAGR, −0.0034).

On average (unweighted), phototherapy reimbursement rates in the Midwest increased by 8.40% between 2010 and 2023 (Table 3). After weighting for 2020 physician utilization, the average change in reimbursement rate was +28.53%. During this time period, CPT code 96910 reported the greatest adjusted change in reimbursement (+41.48%)($80.42 to $113.78; CAGR, +0.0270), and CPT code 96912 reported the greatest adjusted decrease in reimbursement (−6.14%)($103.28 to $97.03; CAGR, −0.0049). For CPT code 96900, the reported adjusted decrease in reimbursement was −4.73% ($24.69 to $23.52; CAGR, −0.0037), and for CPT code 96913, the reported adjusted increase in reimbursement was +2.99% ($142.72 to $146.99; CAGR, +0.0023).

On average (unweighted), phototherapy reimbursement rates in the South decreased by 2.62% between 2010 and 2023 (Table 4). After weighting for 2020 physician utilization, the average change in reimbursement rate was +15.41%. During this time period, CPT code 96910 reported the greatest adjusted change in reimbursement (+27.26%)($90.40 to $115.04 USD; CAGR, +0.0187), and CPT code 96912 reported the greatest adjusted decrease in reimbursement (−15.50%)($116.08 to $98.09; CAGR, −0.0129). For CPT code 96900, the reported adjusted decrease in reimbursement was −15.06% ($28.02 to $23.80; CAGR, −0.0125), and for CPT code 96913, the reported adjusted decrease in reimbursement was −7.19% ($160.11 to $148.61; CAGR, −0.0057).

On average (unweighted), phototherapy reimbursement rates in the West increased by 27.53% between 2010 and 2023 (Table 5). After weighting for 2020 physician utilization, the average change in reimbursement rate was +51.16%. Reimbursement for all analyzed procedures increased in the western United States. During this time period, CPT code 96910 reported the greatest adjusted increase in reimbursement (+66.56%)($80.84 to $134.65; CAGR, +0.0400), and CPT code 96912 reported the lowest adjusted increase in reimbursement (+10.64%)($103.88 to $114.93; CAGR, +0.0078). For CPT code 96900, the reported adjusted increase in reimbursement was 11.54% ($24.88 to $27.75; CAGR, +0.0084), and for CPT code 96913, the reported adjusted increase in reimbursement was 21.38% ($143.39 to $174.04; CAGR, +0.0150).

In this study evaluating geographical payment trends for phototherapy from 2010 to 2023, we demonstrated regional inconsistency in mean inflation-adjusted Medicare reimbursement rates. We found that all phototherapy procedures had increased reimbursement in the western United States, whereas all other regions reported cuts in reimbursement rates for at least half of the analyzed procedures. After adjusting for procedure utilization by physicians, weighted mean reimbursement for phototherapy increased in all US regions.

In a cross-sectional study that explored trends in the geographic distribution of dermatologists from 2012 to 2017, dermatologists in the northeastern and western United States were more likely to be located in higher-income zip codes, whereas dermatologists in the southern United States were more likely to be located in lower-income zip codes,7 suggesting that payment rate changes are not concordant with cost of living. Additionally, Lauck and colleagues8 observed that 75% of the top 20 most common procedures performed by dermatologists had decreased reimbursement (mean change, −10.8%) from 2011 to 2021. Other studies on Medicare reimbursement trends over the last 2 decades have reported major decreases within other specialties, suggesting that declining Medicare reimbursements are not unique to dermatology.9,10 It is critical to monitor these developments, as the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services emphasized health care policy changes aimed at increasing reimbursements for evaluation and management services with compensatory payment cuts in billing for procedural services.11

Mazmudar et al12 previously reported a mean reimbursement decrease of −6.6% for laser/phototherapy procedures between 2007 and 2021, but these data did not include the heavily utilized Goeckerman treatment. Changes in reimbursement pose major ramifications for dermatologists—for practice size, scope, and longevity—as rates influence changes in commercial insurance reimbursements.13 Medicare plays a major role in the US health care system as the second largest expenditure14; indeed, between 2000 and 2015, Part B billing volume for phototherapy procedures increased 5% annually. However, phototherapy remains inaccessible in many locations due to unequal regional distribution of phototherapy clinics.6 Moreover, home phototherapy units are not yet widely utilized because of safety and efficacy concerns, lack of physician oversight, and difficulty obtaining insurance coverage.15 Acknowledgment and consideration of these geographical trends may persuasively allow policymakers, hospitals, and physicians to facilitate cost-effective phototherapy reimbursements that ensure continued access to quality and sustainable dermatologic care in the United States that tailor to regional needs.

In sum, this analysis reveals regional trends in Part B physician reimbursement for phototherapy procedures, with all US regions reporting a mean increase in phototherapy reimbursement after adjusting for utilization, albeit to varying degrees. Mean reimbursement for photochemotherapy by Goeckerman treatment or using petrolatum and UVB increased most among phototherapy procedures. Mean reimbursement for both actinotherapy and photochemotherapy using psoralen plus UVA decreased in all regions except the western United States.

Limitations include the restriction to Part B MPFS and the reliance on single-year (2020) physician utilization data to compute weighted changes in average reimbursement across a multiyear range, effectively restricting sweeping conclusions. Still, this study puts forth actionable insights for dermatologists and policymakers alike to appreciate and consider.

To the Editor:

Phototherapy regularly is utilized in the outpatient setting to address various skin pathologies, including atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, pruritus, vitiligo, and mycosis fungoides.1,2 Phototherapy is broadly defined by the measured administration of nonionizing radiation within the UV range including wavelengths within the UVA (eg, psoralen sensitizer plus UVA-1) and UVB (eg, broadband UVB, narrowband UVB) spectrums.1,3 Generally, the mechanism of action is derived from effects on inflammatory components of cutaneous disorders and the induction of apoptosis, both precipitating numerous downstream events.4

From 2015 to 2018, there were more than 1.3 million outpatient phototherapy visits in the United States, with the most common procedural indications being dermatitis not otherwise specified, atopic dermatitis, and pruritus.5 From 2000 to 2015, the quantity of phototherapy services billed to Medicare trended upwards by an average of 5% per year, increasing from 334,670 in the year 2000 to 692,093 in 2015.6 Therefore, an illustration of associated costs would be beneficial. Additionally, because total cost and physician reimbursement fluctuate from year to year, studies demonstrating overall trends can inform both US policymakers and physicians. There is a paucity of research on geographical trends for procedural reimbursements in dermatology for phototherapy. Understanding geographic trends of reimbursement could duly serve to optimize dermatologist practice patterns involving access to viable and quality care for patients seeking treatment as well as draw health policymakers’ attention to striking adjustments in physician fees. Therefore, in this study we aimed to illustrate the most recent regional payment trends in phototherapy procedures for Medicare B patients.

We queried the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS) database (https://www.cms.gov/medicare/payment/fee-schedules/physician/lookup-tool) for the years 2010 to 2023 for Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes common to phototherapy procedures: actinotherapy (96900); photochemotherapy by Goeckerman treatment or using petrolatum and UVB (96910); photochemotherapy using psoralen plus UVA (96912); and photochemotherapy of severe dermatoses requiring a minimum of 4 hours of care under direct physician supervision (96913). Nonfacility prices for these procedures were analyzed. For 2010, due to midyear alterations to Medicare reimbursement (owed to bills HR 3962 and HR 4872), the mean price data of MPFS files 2010A and 2010B were used. All dollar values were converted to January 2023 US dollars using corresponding consumer price index inflation data. The Medicare Administrative Contractors were used to group state pricing information by region in accordance with established US Census Bureau subdivisions (https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/economic-census/guidance-geographies/levels.html). Weighted percentage change in reimbursement rate was calculated using physician (MD or DO) utilization (procedure volume) data available in the 2020 Physician and Other Practitioners Public Use File (https://data.cms.gov/provider-summary-by-type-of-service/medicare-physician-other-practitioners/medicare-physician-other-practitioners-by-provider-and-service). All descriptive statistics and visualization were generated using R software (v4.2.2)(R Development Core Team).

Table 1 provides physician utilization data and the corresponding number of Part B beneficiaries for phototherapy procedures in 2020. There were 65,045 services of actinotherapy provided to a total of 6855 unique Part B beneficiaries, 173,979 services of photochemotherapy by Goeckerman treatment or using petrolatum and UVB provided to 13,122 unique Part B beneficiaries, 2524 services of photochemotherapy using psoralen plus UVA provided to a total of 357 unique Part B beneficiaries, and 37 services of photochemotherapy of severe dermatoses requiring a minimum of 4 hours of care under direct physician supervision provided to a total of 27 unique Part B beneficiaries.

On average (unweighted), phototherapy reimbursement rates in the North increased by 0.68% between 2010 and 2023 (Table 2). After weighting for 2020 physician utilization, the average change in reimbursement rate was +19.37%. During this time period, CPT code 96910 reported the greatest adjusted increase in reimbursement (+31.45%)($98.12 to $128.98; compound annual growth rate [CAGR], +0.0213), and CPT code 96912 reported the greatest adjusted decrease in reimbursement (−12.76%)($126.09 to $109.97; CAGR, −0.0105). For CPT code 96900, the reported adjusted decrease in reimbursement was −11.68% ($30.21 to $26.68; CAGR, −0.0095), and for CPT code 96913, the reported adjusted decrease in reimbursement was −4.27% ($174.03 to $166.60; CAGR, −0.0034).

On average (unweighted), phototherapy reimbursement rates in the Midwest increased by 8.40% between 2010 and 2023 (Table 3). After weighting for 2020 physician utilization, the average change in reimbursement rate was +28.53%. During this time period, CPT code 96910 reported the greatest adjusted change in reimbursement (+41.48%)($80.42 to $113.78; CAGR, +0.0270), and CPT code 96912 reported the greatest adjusted decrease in reimbursement (−6.14%)($103.28 to $97.03; CAGR, −0.0049). For CPT code 96900, the reported adjusted decrease in reimbursement was −4.73% ($24.69 to $23.52; CAGR, −0.0037), and for CPT code 96913, the reported adjusted increase in reimbursement was +2.99% ($142.72 to $146.99; CAGR, +0.0023).

On average (unweighted), phototherapy reimbursement rates in the South decreased by 2.62% between 2010 and 2023 (Table 4). After weighting for 2020 physician utilization, the average change in reimbursement rate was +15.41%. During this time period, CPT code 96910 reported the greatest adjusted change in reimbursement (+27.26%)($90.40 to $115.04 USD; CAGR, +0.0187), and CPT code 96912 reported the greatest adjusted decrease in reimbursement (−15.50%)($116.08 to $98.09; CAGR, −0.0129). For CPT code 96900, the reported adjusted decrease in reimbursement was −15.06% ($28.02 to $23.80; CAGR, −0.0125), and for CPT code 96913, the reported adjusted decrease in reimbursement was −7.19% ($160.11 to $148.61; CAGR, −0.0057).

On average (unweighted), phototherapy reimbursement rates in the West increased by 27.53% between 2010 and 2023 (Table 5). After weighting for 2020 physician utilization, the average change in reimbursement rate was +51.16%. Reimbursement for all analyzed procedures increased in the western United States. During this time period, CPT code 96910 reported the greatest adjusted increase in reimbursement (+66.56%)($80.84 to $134.65; CAGR, +0.0400), and CPT code 96912 reported the lowest adjusted increase in reimbursement (+10.64%)($103.88 to $114.93; CAGR, +0.0078). For CPT code 96900, the reported adjusted increase in reimbursement was 11.54% ($24.88 to $27.75; CAGR, +0.0084), and for CPT code 96913, the reported adjusted increase in reimbursement was 21.38% ($143.39 to $174.04; CAGR, +0.0150).

In this study evaluating geographical payment trends for phototherapy from 2010 to 2023, we demonstrated regional inconsistency in mean inflation-adjusted Medicare reimbursement rates. We found that all phototherapy procedures had increased reimbursement in the western United States, whereas all other regions reported cuts in reimbursement rates for at least half of the analyzed procedures. After adjusting for procedure utilization by physicians, weighted mean reimbursement for phototherapy increased in all US regions.

In a cross-sectional study that explored trends in the geographic distribution of dermatologists from 2012 to 2017, dermatologists in the northeastern and western United States were more likely to be located in higher-income zip codes, whereas dermatologists in the southern United States were more likely to be located in lower-income zip codes,7 suggesting that payment rate changes are not concordant with cost of living. Additionally, Lauck and colleagues8 observed that 75% of the top 20 most common procedures performed by dermatologists had decreased reimbursement (mean change, −10.8%) from 2011 to 2021. Other studies on Medicare reimbursement trends over the last 2 decades have reported major decreases within other specialties, suggesting that declining Medicare reimbursements are not unique to dermatology.9,10 It is critical to monitor these developments, as the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services emphasized health care policy changes aimed at increasing reimbursements for evaluation and management services with compensatory payment cuts in billing for procedural services.11

Mazmudar et al12 previously reported a mean reimbursement decrease of −6.6% for laser/phototherapy procedures between 2007 and 2021, but these data did not include the heavily utilized Goeckerman treatment. Changes in reimbursement pose major ramifications for dermatologists—for practice size, scope, and longevity—as rates influence changes in commercial insurance reimbursements.13 Medicare plays a major role in the US health care system as the second largest expenditure14; indeed, between 2000 and 2015, Part B billing volume for phototherapy procedures increased 5% annually. However, phototherapy remains inaccessible in many locations due to unequal regional distribution of phototherapy clinics.6 Moreover, home phototherapy units are not yet widely utilized because of safety and efficacy concerns, lack of physician oversight, and difficulty obtaining insurance coverage.15 Acknowledgment and consideration of these geographical trends may persuasively allow policymakers, hospitals, and physicians to facilitate cost-effective phototherapy reimbursements that ensure continued access to quality and sustainable dermatologic care in the United States that tailor to regional needs.

In sum, this analysis reveals regional trends in Part B physician reimbursement for phototherapy procedures, with all US regions reporting a mean increase in phototherapy reimbursement after adjusting for utilization, albeit to varying degrees. Mean reimbursement for photochemotherapy by Goeckerman treatment or using petrolatum and UVB increased most among phototherapy procedures. Mean reimbursement for both actinotherapy and photochemotherapy using psoralen plus UVA decreased in all regions except the western United States.

Limitations include the restriction to Part B MPFS and the reliance on single-year (2020) physician utilization data to compute weighted changes in average reimbursement across a multiyear range, effectively restricting sweeping conclusions. Still, this study puts forth actionable insights for dermatologists and policymakers alike to appreciate and consider.

- Rathod DG, Muneer H, Masood S. Phototherapy. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2002.

- Branisteanu DE, Dirzu DS, Toader MP, et al. Phototherapy in dermatological maladies (Review). Exp Ther Med. 2022;23:259. doi:10.3892/etm.2022.11184

- Barros NM, Sbroglio LL, Buffara MO, et al. Phototherapy. An Bras Dermatol. 2021;96:397-407. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2021.03.001

- Vieyra-Garcia PA, Wolf P. A deep dive into UV-based phototherapy: mechanisms of action and emerging molecular targets in inflammation and cancer. Pharmacol Ther. 2021;222:107784. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107784

- Oulee A, Javadi SS, Martin A, et al. Phototherapy trends in dermatology 2015-2018. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33:2545-2546. doi:10.1080/09546634.2021.2019660

- Tan SY, Buzney E, Mostaghimi A. Trends in phototherapy utilization among Medicare beneficiaries in the United States, 2000 to 2015. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:672-679. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.03.018

- Benlagha I, Nguyen BM. Changes in dermatology practice characteristics in the United States from 2012 to 2017. JAAD Int. 2021;3:92-101. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2021.03.005

- Lauck K, Nguyen QB, Hebert A. Trends in Medicare reimbursement within dermatology: 2011-2021. Skin. 2022;6:122-131. doi:10.25251/skin.6.2.5

- Smith JF, Moore ML, Pollock JR, et al. National and geographic trends in Medicare reimbursement rates for orthopedic shoulder and upper extremity surgery from 2000 to 2020. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2022;31:860-867. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2021.09.001

- Haglin JM, Eltorai AEM, Richter KR, et al. Medicare reimbursement for general surgery procedures: 2000 to 2018. Ann Surg. 2020;271:17-22. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000003289

- Fleishon HB. Evaluation and management coding initiative. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17:1539-1540. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2020.09.057

- Mazmudar RS, Sheth A, Tripathi R, et al. Inflation-adjusted trends in Medicare reimbursement for common dermatologic procedures, 2007-2021. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1355-1358. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.3453

- Clemens J, Gottlieb JD. In the shadow of a giant: Medicare’s influence on private physician payments. J Polit Econ. 2017;125:1-39. doi:10.1086/689772

- Ya J, Ezaldein HH, Scott JF. Trends in Medicare utilization by dermatologists, 2012-2015. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:471-474. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4212

- Rajpara AN, O’Neill JL, Nolan BV, et al. Review of home phototherapy. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:2.

- Rathod DG, Muneer H, Masood S. Phototherapy. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2002.

- Branisteanu DE, Dirzu DS, Toader MP, et al. Phototherapy in dermatological maladies (Review). Exp Ther Med. 2022;23:259. doi:10.3892/etm.2022.11184

- Barros NM, Sbroglio LL, Buffara MO, et al. Phototherapy. An Bras Dermatol. 2021;96:397-407. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2021.03.001

- Vieyra-Garcia PA, Wolf P. A deep dive into UV-based phototherapy: mechanisms of action and emerging molecular targets in inflammation and cancer. Pharmacol Ther. 2021;222:107784. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107784

- Oulee A, Javadi SS, Martin A, et al. Phototherapy trends in dermatology 2015-2018. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33:2545-2546. doi:10.1080/09546634.2021.2019660

- Tan SY, Buzney E, Mostaghimi A. Trends in phototherapy utilization among Medicare beneficiaries in the United States, 2000 to 2015. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:672-679. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.03.018

- Benlagha I, Nguyen BM. Changes in dermatology practice characteristics in the United States from 2012 to 2017. JAAD Int. 2021;3:92-101. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2021.03.005

- Lauck K, Nguyen QB, Hebert A. Trends in Medicare reimbursement within dermatology: 2011-2021. Skin. 2022;6:122-131. doi:10.25251/skin.6.2.5

- Smith JF, Moore ML, Pollock JR, et al. National and geographic trends in Medicare reimbursement rates for orthopedic shoulder and upper extremity surgery from 2000 to 2020. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2022;31:860-867. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2021.09.001

- Haglin JM, Eltorai AEM, Richter KR, et al. Medicare reimbursement for general surgery procedures: 2000 to 2018. Ann Surg. 2020;271:17-22. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000003289

- Fleishon HB. Evaluation and management coding initiative. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17:1539-1540. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2020.09.057

- Mazmudar RS, Sheth A, Tripathi R, et al. Inflation-adjusted trends in Medicare reimbursement for common dermatologic procedures, 2007-2021. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1355-1358. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.3453

- Clemens J, Gottlieb JD. In the shadow of a giant: Medicare’s influence on private physician payments. J Polit Econ. 2017;125:1-39. doi:10.1086/689772

- Ya J, Ezaldein HH, Scott JF. Trends in Medicare utilization by dermatologists, 2012-2015. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:471-474. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4212

- Rajpara AN, O’Neill JL, Nolan BV, et al. Review of home phototherapy. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:2.

Practice Points

- After weighting for procedure utilization, mean reimbursement for phototherapy increased across all US regions from 2010 to 2023 (mean change, +28.62%), yet with marked regional diversity.

- The southern United States reported the least growth in weighted mean reimbursement (+15.41%), and the western United States reported the greatest growth in weighted mean reimbursement (+51.16%).

- Region- and procedure-specific payment changes are especially valuable to dermatologists and policymakers alike, potentially reinvigorating payment reform discussions.

The Impact of a Paracentesis Clinic on Internal Medicine Resident Procedural Competency

Competency in paracentesis is an important procedural skill for medical practitioners caring for patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis. Paracentesis is performed to drain ascitic fluid for both diagnosis and/or therapeutic purposes.1 While this procedure can be performed without the use of ultrasound, it is preferable to use ultrasound to identify an area of fluid that is away from dangerous anatomy including bowel loops, the liver, and spleen. After prepping the area, lidocaine is administered locally. A catheter is then inserted until fluid begins flowing freely. The catheter is connected to a suction canister or collection kit, and the patient is monitored until the flow ceases. Samples can be sent for analysis to determine the etiology of ascites, identify concerns for infection, and more.

Paracentesis is a very common procedure. Barsuk and colleagues noted that between 2010 and 2012, 97,577 procedures were performed across 120 academic medical centers and 290 affiliated hospitals.2 Patients undergo paracentesis in a variety of settings including the emergency department, inpatient hospitalizations, and clinics. Some patients may require only 1 paracentesis procedure while others may require it regularly.

Due to the rising need for paracentesis in the Central Texas Veterans Affairs Hospital (CTVAH) in Temple, a paracentesis clinic was started in February 2018. The goal of the paracentesis clinic was multifocal—to reduce hospital admissions, improve access to regularly scheduled procedures, decrease wait times, and increase patient satisfaction.3 Through the CTVAH affiliation with the Texas A&M internal medicine residency program, the paracentesis clinic started involving and training residents on this procedure. Up to 3 residents are on weekly rotation and can perform up to 6 paracentesis procedures in a week. The purpose of this article was to evaluate resident competency in paracentesis after completion of the paracentesis clinic.

Methods

The paracentesis clinic schedules up to 3 patients on Tuesdays and Thursdays between 8

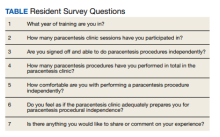

A survey was sent via email to all categorical internal medicine residents across all 3 program years at the time of data collection. Competency for paracentesis sign-off was defined as completing and logging 5 procedures supervised by a competent physician who confirmed that all portions of the procedure were performed correctly. Residents were also asked to answer questions on a scale from 1 to 10, with 1 representing no confidence and 10 representing strong confidence to practice independently (Table).

We also evaluated the number of procedures performed by internal medicine residents 3 years before the clinic was started in 2015 up to the completion of 2022. The numbers were obtained by examining procedural log data for each year for all internal medicine residents.

Results

Thirty-three residents completed the survey: 10 first-year internal medicine residents (PGY1), 12 second-year residents (PGY2), and 11 third-year residents (PGY3). The mean participation was 4.8 paracentesis sessions per person for the duration of the study. The range of paracentesis procedures performed varied based on PGY year: PGY1s performed 1 to > 10 procedures, PGY2s performed 2 to > 10 procedures, and PGY3s performed 5 to > 10 procedures. Thirty-six percent of residents completed > 10 procedures in the paracentesis clinic; 82% of PGY3s had completed > 10 procedures by December of their third year. Twenty-six residents (79%) were credentialed to perform paracentesis procedures independently after performing > 5 procedures, and 7 residents were not yet cleared for procedural independence.

In the survey, residents rated their comfort with performing paracentesis procedures independently at a mean of 7.9. The mean comfort reported by PGY1s was 7.2, PGY2s was 7.3, and PGY3s was 9.3. Residents also rated their opinion on whether or not the paracentesis clinic adequately prepared them for paracentesis procedural independence; the mean was 8.9 across all residents.

The total number of procedures performed by residents at CTVAH also increased. Starting in 2015, 3 years before the clinic was started, 38 procedures were performed by internal medicine residents, followed by 72 procedures in 2016; 76 in 2017; 58 in 2018; 94 in 2019; 88 in 2020; 136 in 2021; and 188 in 2022.

Discussion

Paracentesis is a simple but invasive procedure to relieve ascites, often relieving patients’ symptoms, preventing hospital admission, and increasing patient satisfaction.4 The CTVAH does not have the capacity to perform outpatient paracentesis effectively in its emergency or radiology departments. Furthermore, the use of the emergency or radiology departments for routine paracentesis may not be feasible due to the acuity of care being provided, as these procedures can be time consuming and can draw away critical resources and time from patients that need emergent care. The paracentesis clinic was then formed to provide veterans access to the procedural care they need, while also preparing residents to ably and confidently perform the procedure independently.

Based on our study, most residents were cleared to independently perform paracentesis procedures across all 3 years, with 79% of residents having completed the required 5 supervised procedures to independently practice. A study assessing unsupervised practice standards showed that paracentesis skill declines as soon as 3 months after training. However, retraining was shown to potentially interrupt this skill decline.5 Studies have shown that procedure-driven electives or services significantly improved paracentesis certification rates and total logged procedures, with minimal funding or scheduling changes required.6 Our clinic showed a significant increase in the number of procedures logged starting with the minimum of 38 procedures in 2015 and ending with 188 procedures logged at the end of 2022.

By allowing residents to routinely return to the paracentesis clinic across all 3 years, residents were more likely to feel comfortable independently performing the procedure, with residents reporting a mean comfort score of 7.9. The spaced repetition and ability to work with the clinic during elective time allows regular opportunities to undergo supervised training in a controlled environment and created scheduled retraining opportunities. Future studies should evaluate residents prior to each paracentesis clinic to ascertain if skill decline is occurring at a slower rate.

The inpatient effect of the clinic is also multifocal. Pham and colleagues showed that integrating paracentesis into timely training can reduce paracentesis delay and delays in care.7 By increasing the volume of procedures each resident performs and creating a sense of confidence amongst residents, the clinic increases the number of residents able and willing to perform inpatient procedures, thus reducing the number of unnecessary consultations and hospital resources. One of the reasons the paracentesis clinic was started was to allow patients to have scheduled times to remove fluid from their abdomen, thus cutting down on emergency department procedures and unnecessary admissions. Additionally, the benefits of early paracentesis procedural performance by residents and internal medicine physicians have been demonstrated in the literature. A study by Gaetano and colleagues noted that patients undergoing early paracentesis had reduced mortality of 5.5% vs 7.5% in those undergoing late paracentesis.8 This study also showed the in-hospital mortality rate was decreased with paracentesis (6.3%) vs without paracentesis (8.9%).8 By offering residents a chance to participate in the clinic, we have shown that regular opportunities to perform paracentesis may increase the number of physicians capable of independently practicing, improve procedural competency, and improve patient access to this procedure.

Limitations

Our study was not free of bias and has potential weaknesses. The survey was sent to all current residents who have participated in the paracentesis clinic, but not every resident filled out the survey (55% of all residents across 3 years completed the survey, 68.7% who had done clinic that year completed the survey). There is a possibility that those not signed off avoided doing the survey, but we are unable to confirm this. The survey also depended on resident recall of the number of paracenteses completed or looking at their procedure log. It is possible that some procedures were not documented, changing the true number. Additionally, rating comfortability with procedures is subjective, which may also create a source of potential weakness. Future projects should include a baseline survey for residents, followed by a repeat survey a year later to show changes from baseline competency.

Conclusions

A dedicated paracentesis clinic with internal medicine resident involvement may increase resident paracentesis procedural independence, the number of procedures available and performed, and procedural comfort level.

1. Aponte EM, O’Rourke MC, Katta S. Paracentesis. StatPearls [internet]. September 5, 2022. Accessed December 11, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK435998

2. Barsuk JH, Feinglass J, Kozmic SE, Hohmann SF, Ganger D, Wayne DB. Specialties performing paracentesis procedures at university hospitals: implications for training and certification. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):162-168. doi:10.1002/jhm.2153

3. Cheng Y-W, Sandrasegaran K, Cheng K, et al. A dedicated paracentesis clinic decreases healthcare utilization for serial paracenteses in decompensated cirrhosis. Abdominal Radiology. 2017;43(8):2190-2197. doi:10.1007/s00261-017-1406-y

4. Wang J, Khan S, Wyer P, et al. The role of ultrasound-guided therapeutic paracentesis in an outpatient transitional care program: A case series. Am J Hospice Palliat Med. 2018;35(9):1256-1260. doi:10.1177/1049909118755378

5. Sall D, Warm EJ, Kinnear B, Kelleher M, Jandarov R, O’Toole J. See one, do one, forget one: early skill decay after paracentesis training. J Gen Int Med. 2020;36(5):1346-1351. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06242-x

6. Berger M, Divilov V, Paredes H, Kesar V, Sun E. Improving resident paracentesis certification rates by using an innovative resident driven procedure service. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(suppl). doi:10.14309/00000434-201810001-00980

7. Pham C, Xu A, Suaez MG. S1250 a pilot study to improve resident paracentesis training and reduce paracentesis delay in admitted patients with cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(10S). doi:10.14309/01.ajg.0000861640.53682.93

8. Gaetano JN, Micic D, Aronsohn A, et al. The benefit of paracentesis on hospitalized adults with cirrhosis and ascites. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31(5):1025-1030. doi:10.1111/jgh.13255

Competency in paracentesis is an important procedural skill for medical practitioners caring for patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis. Paracentesis is performed to drain ascitic fluid for both diagnosis and/or therapeutic purposes.1 While this procedure can be performed without the use of ultrasound, it is preferable to use ultrasound to identify an area of fluid that is away from dangerous anatomy including bowel loops, the liver, and spleen. After prepping the area, lidocaine is administered locally. A catheter is then inserted until fluid begins flowing freely. The catheter is connected to a suction canister or collection kit, and the patient is monitored until the flow ceases. Samples can be sent for analysis to determine the etiology of ascites, identify concerns for infection, and more.

Paracentesis is a very common procedure. Barsuk and colleagues noted that between 2010 and 2012, 97,577 procedures were performed across 120 academic medical centers and 290 affiliated hospitals.2 Patients undergo paracentesis in a variety of settings including the emergency department, inpatient hospitalizations, and clinics. Some patients may require only 1 paracentesis procedure while others may require it regularly.

Due to the rising need for paracentesis in the Central Texas Veterans Affairs Hospital (CTVAH) in Temple, a paracentesis clinic was started in February 2018. The goal of the paracentesis clinic was multifocal—to reduce hospital admissions, improve access to regularly scheduled procedures, decrease wait times, and increase patient satisfaction.3 Through the CTVAH affiliation with the Texas A&M internal medicine residency program, the paracentesis clinic started involving and training residents on this procedure. Up to 3 residents are on weekly rotation and can perform up to 6 paracentesis procedures in a week. The purpose of this article was to evaluate resident competency in paracentesis after completion of the paracentesis clinic.

Methods

The paracentesis clinic schedules up to 3 patients on Tuesdays and Thursdays between 8

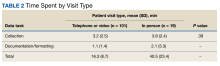

A survey was sent via email to all categorical internal medicine residents across all 3 program years at the time of data collection. Competency for paracentesis sign-off was defined as completing and logging 5 procedures supervised by a competent physician who confirmed that all portions of the procedure were performed correctly. Residents were also asked to answer questions on a scale from 1 to 10, with 1 representing no confidence and 10 representing strong confidence to practice independently (Table).

We also evaluated the number of procedures performed by internal medicine residents 3 years before the clinic was started in 2015 up to the completion of 2022. The numbers were obtained by examining procedural log data for each year for all internal medicine residents.

Results

Thirty-three residents completed the survey: 10 first-year internal medicine residents (PGY1), 12 second-year residents (PGY2), and 11 third-year residents (PGY3). The mean participation was 4.8 paracentesis sessions per person for the duration of the study. The range of paracentesis procedures performed varied based on PGY year: PGY1s performed 1 to > 10 procedures, PGY2s performed 2 to > 10 procedures, and PGY3s performed 5 to > 10 procedures. Thirty-six percent of residents completed > 10 procedures in the paracentesis clinic; 82% of PGY3s had completed > 10 procedures by December of their third year. Twenty-six residents (79%) were credentialed to perform paracentesis procedures independently after performing > 5 procedures, and 7 residents were not yet cleared for procedural independence.

In the survey, residents rated their comfort with performing paracentesis procedures independently at a mean of 7.9. The mean comfort reported by PGY1s was 7.2, PGY2s was 7.3, and PGY3s was 9.3. Residents also rated their opinion on whether or not the paracentesis clinic adequately prepared them for paracentesis procedural independence; the mean was 8.9 across all residents.

The total number of procedures performed by residents at CTVAH also increased. Starting in 2015, 3 years before the clinic was started, 38 procedures were performed by internal medicine residents, followed by 72 procedures in 2016; 76 in 2017; 58 in 2018; 94 in 2019; 88 in 2020; 136 in 2021; and 188 in 2022.

Discussion

Paracentesis is a simple but invasive procedure to relieve ascites, often relieving patients’ symptoms, preventing hospital admission, and increasing patient satisfaction.4 The CTVAH does not have the capacity to perform outpatient paracentesis effectively in its emergency or radiology departments. Furthermore, the use of the emergency or radiology departments for routine paracentesis may not be feasible due to the acuity of care being provided, as these procedures can be time consuming and can draw away critical resources and time from patients that need emergent care. The paracentesis clinic was then formed to provide veterans access to the procedural care they need, while also preparing residents to ably and confidently perform the procedure independently.

Based on our study, most residents were cleared to independently perform paracentesis procedures across all 3 years, with 79% of residents having completed the required 5 supervised procedures to independently practice. A study assessing unsupervised practice standards showed that paracentesis skill declines as soon as 3 months after training. However, retraining was shown to potentially interrupt this skill decline.5 Studies have shown that procedure-driven electives or services significantly improved paracentesis certification rates and total logged procedures, with minimal funding or scheduling changes required.6 Our clinic showed a significant increase in the number of procedures logged starting with the minimum of 38 procedures in 2015 and ending with 188 procedures logged at the end of 2022.

By allowing residents to routinely return to the paracentesis clinic across all 3 years, residents were more likely to feel comfortable independently performing the procedure, with residents reporting a mean comfort score of 7.9. The spaced repetition and ability to work with the clinic during elective time allows regular opportunities to undergo supervised training in a controlled environment and created scheduled retraining opportunities. Future studies should evaluate residents prior to each paracentesis clinic to ascertain if skill decline is occurring at a slower rate.

The inpatient effect of the clinic is also multifocal. Pham and colleagues showed that integrating paracentesis into timely training can reduce paracentesis delay and delays in care.7 By increasing the volume of procedures each resident performs and creating a sense of confidence amongst residents, the clinic increases the number of residents able and willing to perform inpatient procedures, thus reducing the number of unnecessary consultations and hospital resources. One of the reasons the paracentesis clinic was started was to allow patients to have scheduled times to remove fluid from their abdomen, thus cutting down on emergency department procedures and unnecessary admissions. Additionally, the benefits of early paracentesis procedural performance by residents and internal medicine physicians have been demonstrated in the literature. A study by Gaetano and colleagues noted that patients undergoing early paracentesis had reduced mortality of 5.5% vs 7.5% in those undergoing late paracentesis.8 This study also showed the in-hospital mortality rate was decreased with paracentesis (6.3%) vs without paracentesis (8.9%).8 By offering residents a chance to participate in the clinic, we have shown that regular opportunities to perform paracentesis may increase the number of physicians capable of independently practicing, improve procedural competency, and improve patient access to this procedure.

Limitations

Our study was not free of bias and has potential weaknesses. The survey was sent to all current residents who have participated in the paracentesis clinic, but not every resident filled out the survey (55% of all residents across 3 years completed the survey, 68.7% who had done clinic that year completed the survey). There is a possibility that those not signed off avoided doing the survey, but we are unable to confirm this. The survey also depended on resident recall of the number of paracenteses completed or looking at their procedure log. It is possible that some procedures were not documented, changing the true number. Additionally, rating comfortability with procedures is subjective, which may also create a source of potential weakness. Future projects should include a baseline survey for residents, followed by a repeat survey a year later to show changes from baseline competency.

Conclusions

A dedicated paracentesis clinic with internal medicine resident involvement may increase resident paracentesis procedural independence, the number of procedures available and performed, and procedural comfort level.

Competency in paracentesis is an important procedural skill for medical practitioners caring for patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis. Paracentesis is performed to drain ascitic fluid for both diagnosis and/or therapeutic purposes.1 While this procedure can be performed without the use of ultrasound, it is preferable to use ultrasound to identify an area of fluid that is away from dangerous anatomy including bowel loops, the liver, and spleen. After prepping the area, lidocaine is administered locally. A catheter is then inserted until fluid begins flowing freely. The catheter is connected to a suction canister or collection kit, and the patient is monitored until the flow ceases. Samples can be sent for analysis to determine the etiology of ascites, identify concerns for infection, and more.

Paracentesis is a very common procedure. Barsuk and colleagues noted that between 2010 and 2012, 97,577 procedures were performed across 120 academic medical centers and 290 affiliated hospitals.2 Patients undergo paracentesis in a variety of settings including the emergency department, inpatient hospitalizations, and clinics. Some patients may require only 1 paracentesis procedure while others may require it regularly.

Due to the rising need for paracentesis in the Central Texas Veterans Affairs Hospital (CTVAH) in Temple, a paracentesis clinic was started in February 2018. The goal of the paracentesis clinic was multifocal—to reduce hospital admissions, improve access to regularly scheduled procedures, decrease wait times, and increase patient satisfaction.3 Through the CTVAH affiliation with the Texas A&M internal medicine residency program, the paracentesis clinic started involving and training residents on this procedure. Up to 3 residents are on weekly rotation and can perform up to 6 paracentesis procedures in a week. The purpose of this article was to evaluate resident competency in paracentesis after completion of the paracentesis clinic.

Methods

The paracentesis clinic schedules up to 3 patients on Tuesdays and Thursdays between 8

A survey was sent via email to all categorical internal medicine residents across all 3 program years at the time of data collection. Competency for paracentesis sign-off was defined as completing and logging 5 procedures supervised by a competent physician who confirmed that all portions of the procedure were performed correctly. Residents were also asked to answer questions on a scale from 1 to 10, with 1 representing no confidence and 10 representing strong confidence to practice independently (Table).

We also evaluated the number of procedures performed by internal medicine residents 3 years before the clinic was started in 2015 up to the completion of 2022. The numbers were obtained by examining procedural log data for each year for all internal medicine residents.

Results

Thirty-three residents completed the survey: 10 first-year internal medicine residents (PGY1), 12 second-year residents (PGY2), and 11 third-year residents (PGY3). The mean participation was 4.8 paracentesis sessions per person for the duration of the study. The range of paracentesis procedures performed varied based on PGY year: PGY1s performed 1 to > 10 procedures, PGY2s performed 2 to > 10 procedures, and PGY3s performed 5 to > 10 procedures. Thirty-six percent of residents completed > 10 procedures in the paracentesis clinic; 82% of PGY3s had completed > 10 procedures by December of their third year. Twenty-six residents (79%) were credentialed to perform paracentesis procedures independently after performing > 5 procedures, and 7 residents were not yet cleared for procedural independence.

In the survey, residents rated their comfort with performing paracentesis procedures independently at a mean of 7.9. The mean comfort reported by PGY1s was 7.2, PGY2s was 7.3, and PGY3s was 9.3. Residents also rated their opinion on whether or not the paracentesis clinic adequately prepared them for paracentesis procedural independence; the mean was 8.9 across all residents.

The total number of procedures performed by residents at CTVAH also increased. Starting in 2015, 3 years before the clinic was started, 38 procedures were performed by internal medicine residents, followed by 72 procedures in 2016; 76 in 2017; 58 in 2018; 94 in 2019; 88 in 2020; 136 in 2021; and 188 in 2022.

Discussion

Paracentesis is a simple but invasive procedure to relieve ascites, often relieving patients’ symptoms, preventing hospital admission, and increasing patient satisfaction.4 The CTVAH does not have the capacity to perform outpatient paracentesis effectively in its emergency or radiology departments. Furthermore, the use of the emergency or radiology departments for routine paracentesis may not be feasible due to the acuity of care being provided, as these procedures can be time consuming and can draw away critical resources and time from patients that need emergent care. The paracentesis clinic was then formed to provide veterans access to the procedural care they need, while also preparing residents to ably and confidently perform the procedure independently.

Based on our study, most residents were cleared to independently perform paracentesis procedures across all 3 years, with 79% of residents having completed the required 5 supervised procedures to independently practice. A study assessing unsupervised practice standards showed that paracentesis skill declines as soon as 3 months after training. However, retraining was shown to potentially interrupt this skill decline.5 Studies have shown that procedure-driven electives or services significantly improved paracentesis certification rates and total logged procedures, with minimal funding or scheduling changes required.6 Our clinic showed a significant increase in the number of procedures logged starting with the minimum of 38 procedures in 2015 and ending with 188 procedures logged at the end of 2022.

By allowing residents to routinely return to the paracentesis clinic across all 3 years, residents were more likely to feel comfortable independently performing the procedure, with residents reporting a mean comfort score of 7.9. The spaced repetition and ability to work with the clinic during elective time allows regular opportunities to undergo supervised training in a controlled environment and created scheduled retraining opportunities. Future studies should evaluate residents prior to each paracentesis clinic to ascertain if skill decline is occurring at a slower rate.

The inpatient effect of the clinic is also multifocal. Pham and colleagues showed that integrating paracentesis into timely training can reduce paracentesis delay and delays in care.7 By increasing the volume of procedures each resident performs and creating a sense of confidence amongst residents, the clinic increases the number of residents able and willing to perform inpatient procedures, thus reducing the number of unnecessary consultations and hospital resources. One of the reasons the paracentesis clinic was started was to allow patients to have scheduled times to remove fluid from their abdomen, thus cutting down on emergency department procedures and unnecessary admissions. Additionally, the benefits of early paracentesis procedural performance by residents and internal medicine physicians have been demonstrated in the literature. A study by Gaetano and colleagues noted that patients undergoing early paracentesis had reduced mortality of 5.5% vs 7.5% in those undergoing late paracentesis.8 This study also showed the in-hospital mortality rate was decreased with paracentesis (6.3%) vs without paracentesis (8.9%).8 By offering residents a chance to participate in the clinic, we have shown that regular opportunities to perform paracentesis may increase the number of physicians capable of independently practicing, improve procedural competency, and improve patient access to this procedure.

Limitations

Our study was not free of bias and has potential weaknesses. The survey was sent to all current residents who have participated in the paracentesis clinic, but not every resident filled out the survey (55% of all residents across 3 years completed the survey, 68.7% who had done clinic that year completed the survey). There is a possibility that those not signed off avoided doing the survey, but we are unable to confirm this. The survey also depended on resident recall of the number of paracenteses completed or looking at their procedure log. It is possible that some procedures were not documented, changing the true number. Additionally, rating comfortability with procedures is subjective, which may also create a source of potential weakness. Future projects should include a baseline survey for residents, followed by a repeat survey a year later to show changes from baseline competency.

Conclusions

A dedicated paracentesis clinic with internal medicine resident involvement may increase resident paracentesis procedural independence, the number of procedures available and performed, and procedural comfort level.

1. Aponte EM, O’Rourke MC, Katta S. Paracentesis. StatPearls [internet]. September 5, 2022. Accessed December 11, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK435998

2. Barsuk JH, Feinglass J, Kozmic SE, Hohmann SF, Ganger D, Wayne DB. Specialties performing paracentesis procedures at university hospitals: implications for training and certification. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):162-168. doi:10.1002/jhm.2153

3. Cheng Y-W, Sandrasegaran K, Cheng K, et al. A dedicated paracentesis clinic decreases healthcare utilization for serial paracenteses in decompensated cirrhosis. Abdominal Radiology. 2017;43(8):2190-2197. doi:10.1007/s00261-017-1406-y

4. Wang J, Khan S, Wyer P, et al. The role of ultrasound-guided therapeutic paracentesis in an outpatient transitional care program: A case series. Am J Hospice Palliat Med. 2018;35(9):1256-1260. doi:10.1177/1049909118755378

5. Sall D, Warm EJ, Kinnear B, Kelleher M, Jandarov R, O’Toole J. See one, do one, forget one: early skill decay after paracentesis training. J Gen Int Med. 2020;36(5):1346-1351. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06242-x

6. Berger M, Divilov V, Paredes H, Kesar V, Sun E. Improving resident paracentesis certification rates by using an innovative resident driven procedure service. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(suppl). doi:10.14309/00000434-201810001-00980

7. Pham C, Xu A, Suaez MG. S1250 a pilot study to improve resident paracentesis training and reduce paracentesis delay in admitted patients with cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(10S). doi:10.14309/01.ajg.0000861640.53682.93

8. Gaetano JN, Micic D, Aronsohn A, et al. The benefit of paracentesis on hospitalized adults with cirrhosis and ascites. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31(5):1025-1030. doi:10.1111/jgh.13255

1. Aponte EM, O’Rourke MC, Katta S. Paracentesis. StatPearls [internet]. September 5, 2022. Accessed December 11, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK435998

2. Barsuk JH, Feinglass J, Kozmic SE, Hohmann SF, Ganger D, Wayne DB. Specialties performing paracentesis procedures at university hospitals: implications for training and certification. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):162-168. doi:10.1002/jhm.2153

3. Cheng Y-W, Sandrasegaran K, Cheng K, et al. A dedicated paracentesis clinic decreases healthcare utilization for serial paracenteses in decompensated cirrhosis. Abdominal Radiology. 2017;43(8):2190-2197. doi:10.1007/s00261-017-1406-y

4. Wang J, Khan S, Wyer P, et al. The role of ultrasound-guided therapeutic paracentesis in an outpatient transitional care program: A case series. Am J Hospice Palliat Med. 2018;35(9):1256-1260. doi:10.1177/1049909118755378

5. Sall D, Warm EJ, Kinnear B, Kelleher M, Jandarov R, O’Toole J. See one, do one, forget one: early skill decay after paracentesis training. J Gen Int Med. 2020;36(5):1346-1351. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06242-x

6. Berger M, Divilov V, Paredes H, Kesar V, Sun E. Improving resident paracentesis certification rates by using an innovative resident driven procedure service. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(suppl). doi:10.14309/00000434-201810001-00980

7. Pham C, Xu A, Suaez MG. S1250 a pilot study to improve resident paracentesis training and reduce paracentesis delay in admitted patients with cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(10S). doi:10.14309/01.ajg.0000861640.53682.93

8. Gaetano JN, Micic D, Aronsohn A, et al. The benefit of paracentesis on hospitalized adults with cirrhosis and ascites. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31(5):1025-1030. doi:10.1111/jgh.13255

Piperacillin/Tazobactam Use vs Cefepime May Be Associated With Acute Decompensated Heart Failure

Piperacillin/tazobactam (PTZ) is a combination IV antibiotic comprised of the semisynthetic antipseudomonal β-lactam, piperacillin sodium, and the β-lactamase inhibitor, tazobactam sodium.1 PTZ is extensively prescribed in the hospital setting for a multitude of infections including but not limited to the US Food and Drug Administration–approved indications: intra-abdominal infection, skin and skin structure infection (SSTI), urinary tract infection (UTI), and pneumonia. Given its broad spectrum of activity and relative safety profile, PTZ is a mainstay of many empiric IV antibiotic regimens. The primary elimination pathway for PTZ is renal excretion, and dosage adjustments are recommended with reduced creatinine clearance. Additionally, PTZ use has been associated with acute renal injury and delayed renal recovery.1-3

There are various mechanisms through which medications can contribute to acute decomopensated heart failure (ADHF).4 These mechanisms include direct cardiotoxicity; negative inotropic, lusitropic, or chronotropic effects; exacerbating hypertension; sodium loading; and drug-drug interactions that limit the benefits of heart failure (HF) medications. One potentially overlooked constituent of PTZ is the sodium content, with the standard formulation containing 65 mg of sodium per gram of piperacillin.1-3 Furthermore, PTZ must be diluted in 50 to 150 mL of diluent, commonly 0.9% sodium chloride, which can contribute an additional 177 to 531 mg of sodium per dose. PTZ prescribing information advises caution for use in patients with decreased renal, hepatic, and/or cardiac function and notes that geriatric patients, particularly with HF, may be at risk of impaired natriuresis in the setting of large sodium doses.

It is estimated that roughly 6.2 million adults in the United States have HF and prevalence continues to rise.5,6 Mortality rates after hospitalization due to HF are 20% to 25% at 1 year. Health care expenditures for the management of HF surpass $30 billion per year in the US, with most of this cost attributed to hospitalizations. Consequently, it is important to continue to identify and practice preventative strategies when managing patients with HF.

Methods

This single-center, retrospective, cohort study was conducted at James H. Quillen Veterans Affairs Medical Center (JHQVAMC) in Mountain Home, Tennessee, a 174-bed tertiary medical center. The purpose of this study was to compare the incidence of ADHF in patients who received PTZ vs cefepime (CFP). This project was reviewed by the JHQVAMC Institutional Review Board and deemed exempt as a clinical process improvement operations activity.

The antimicrobial stewardship team at JHQVAMC reviewed the use of PTZ in veterans between January 1, 2018, to December 31, 2019, and compared baseline demographics, history of HF, and outcomes in patients receiving analogous broad-spectrum empiric antibiotic therapy with CFP.

Statistical Analysis

Analysis was conducted with R Software. Pearson χ2 and t tests were used to compare baseline demographics, length of stay, readmission, and mortality. Significance used was α = .05.

Results

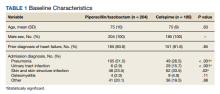

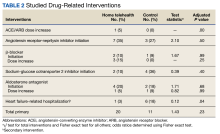

A retrospective chart review was performed on 389 veterans. Of the 389, 204 patients received at least 24 hours of PTZ, and 185 patients received CFP. The mean age in both groups was 75 years. Patients in the PTZ group were more likely to have been admitted with the diagnosis of pneumonia (105 vs 49, P < .001). However, 29 patients (15.7%) in the CFP group were admitted with a UTI diagnosis compared with 6 patients (2.9%) in the PTZ group (P < .001) and 62 patients (33.5%) in the CFP group were admitted with a SSTI diagnosis compared with 48 patients (23.5%) in the PTZ group (P = .03). Otherwise, there were no differences between other admitting diagnoses. Additionally, there was no difference in prior history of HF between groups (Table 1).

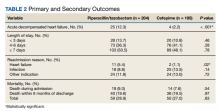

Twenty-five patients (12.3%) in the PTZ group and 4 patients (2.2%) in the CFP group were subsequently diagnosed with ADHF (P < .001). Hospital readmissions due to HF were higher in the PTZ group compared with the CFP group (11 vs 2, P = .02). Hospital readmission due to other causes was not significantly different between groups. Hospital readmission due to infection occurred in 18 patients who received PTZ and 25 who received CFP (8.8% vs 13.5%, P = .14). Hospital readmission due to any other indication occurred in 24 patients who received PTZ and 24 who received CFP (11.8% vs 13.0%, P = .72). There was no statistically significant difference in all-cause mortality during the associated admission or within 6 months of discharge between groups, with 59 total deaths in the PTZ group and 50 in the CFP group (28.9% vs 27.0%, P = .63).

There was no difference in length of stay outcomes between patients receiving PTZ compared with CFP. Twenty-eight patients in the PTZ group and 20 in the CFP group had a length of stay duration of < 3 days (13.7% vs 10.8%, P = .46). Seventy-three patients in the PTZ group and 76 in the CFP group had a length of stay duration of 4 to 6 days (36.3% vs 41.1%, P = .28). One hundred three patients in the PTZ group and 89 in the CFP group had a length of stay duration ≥ 7 days (50.5% vs 48.1%, P = .78). Table 2 includes a complete overview of primary and secondary endpoint results.

Discussion

The American Heart Association (AHA) lists PTZ as a medication that may cause or exacerbate HF, though no studies have identified a clear association between PTZ use and ADHF.4 Sodium restriction is consistently recommended as an important strategy for the prevention of ADHF. Accordingly, PTZ prescribing information and the AHA advise careful consideration with PTZ use in this patient population.1,4