User login

Vesicles and Bullae on the Leg

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous B-cell Lymphoma

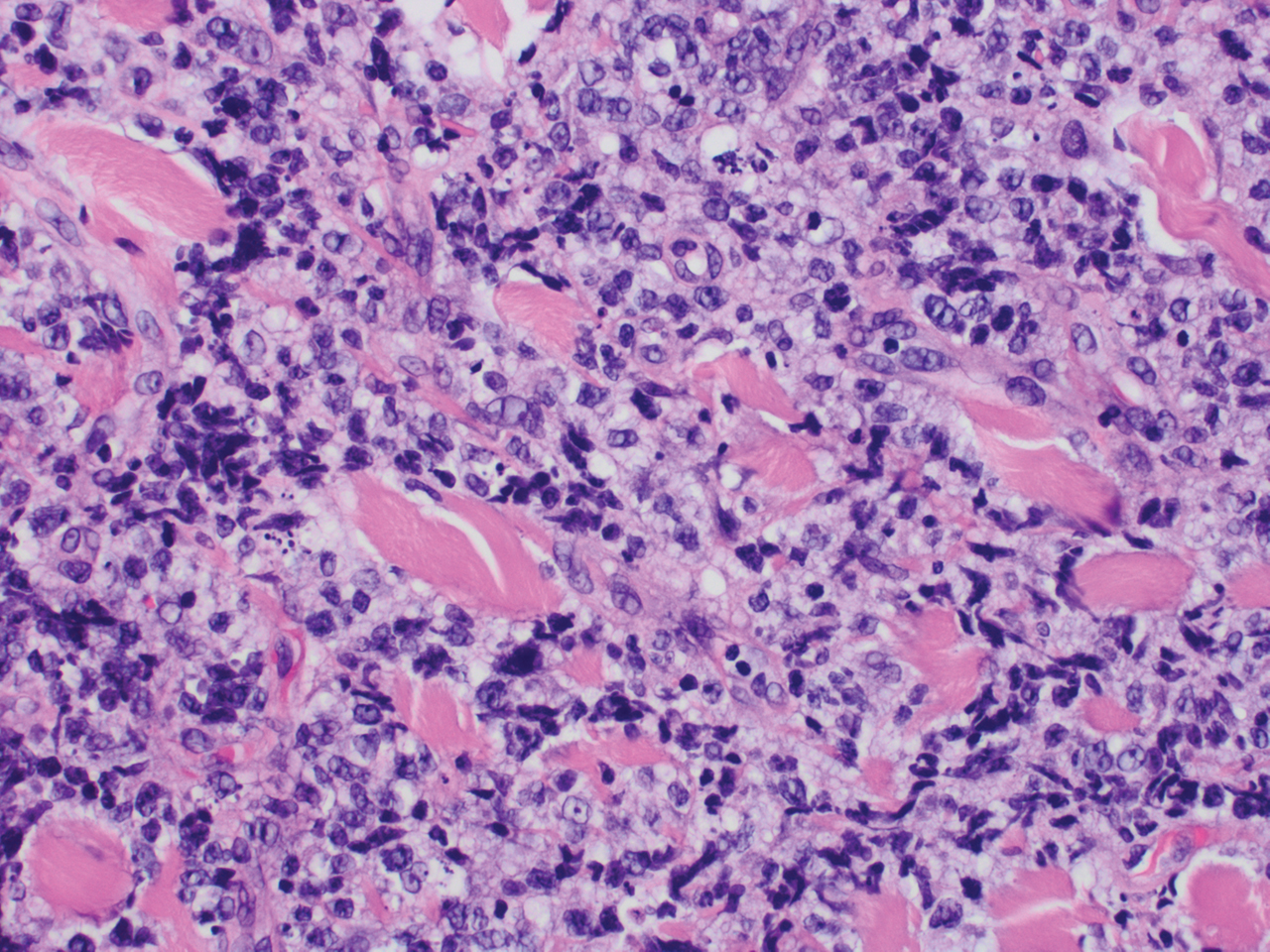

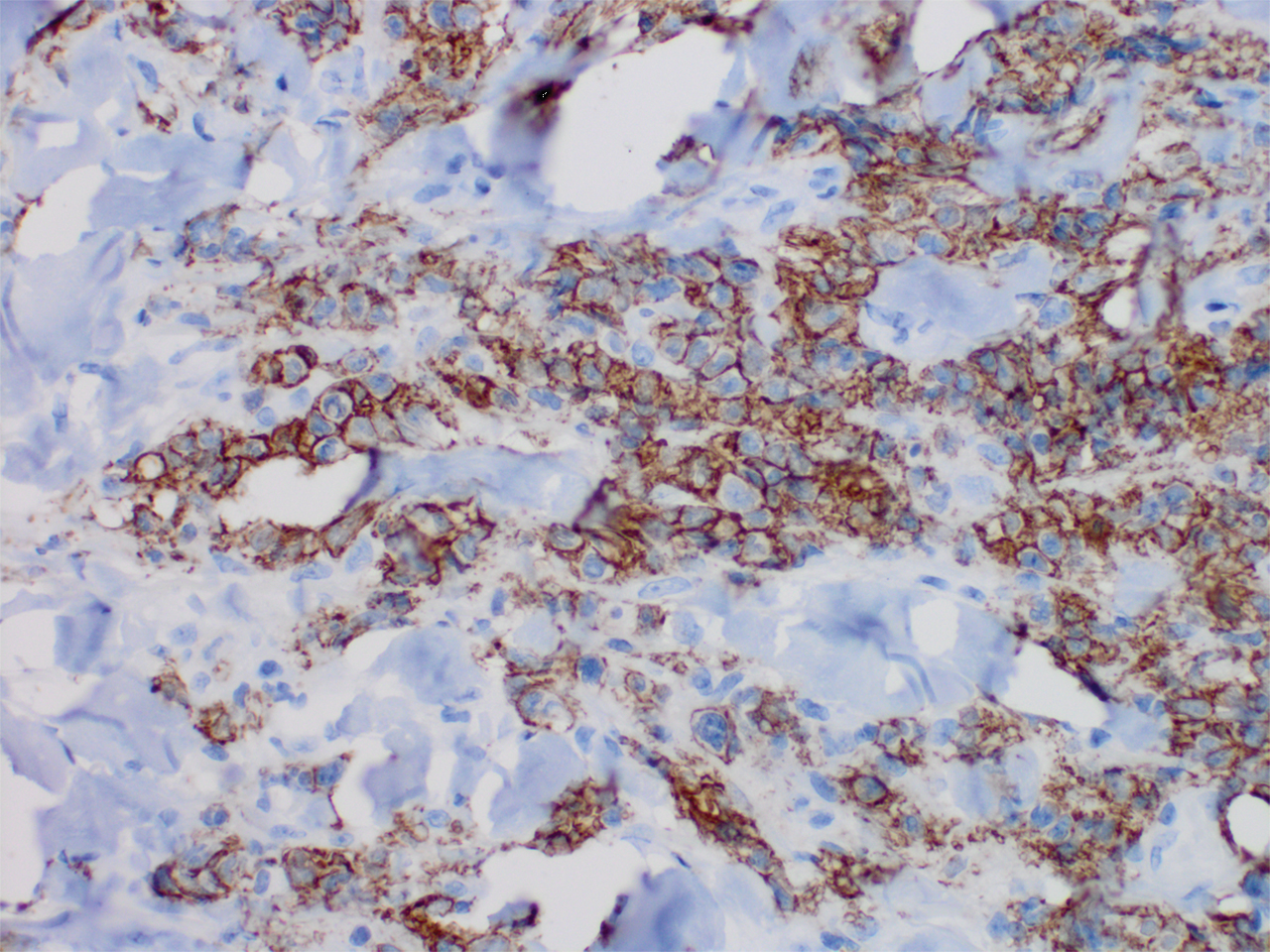

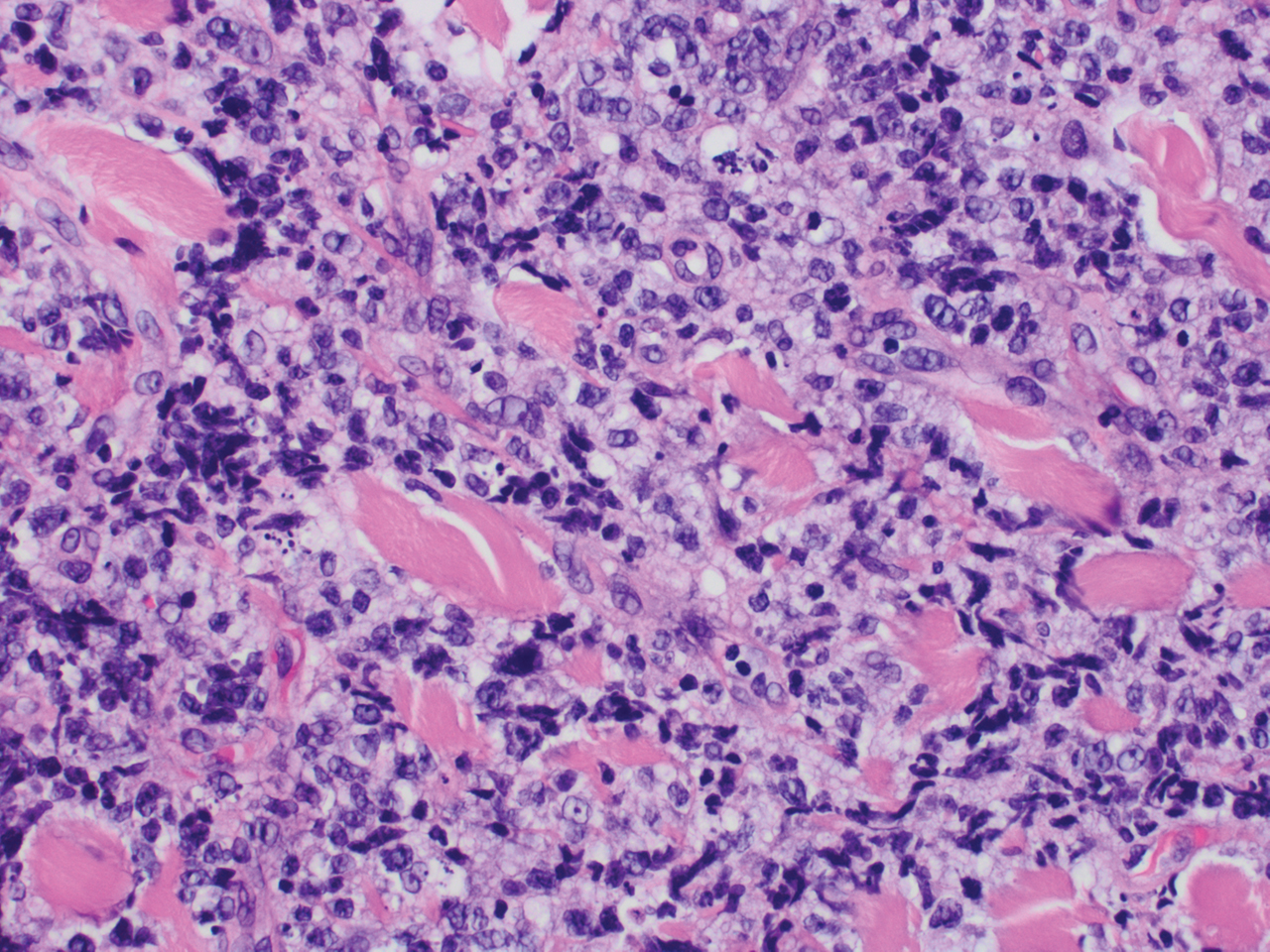

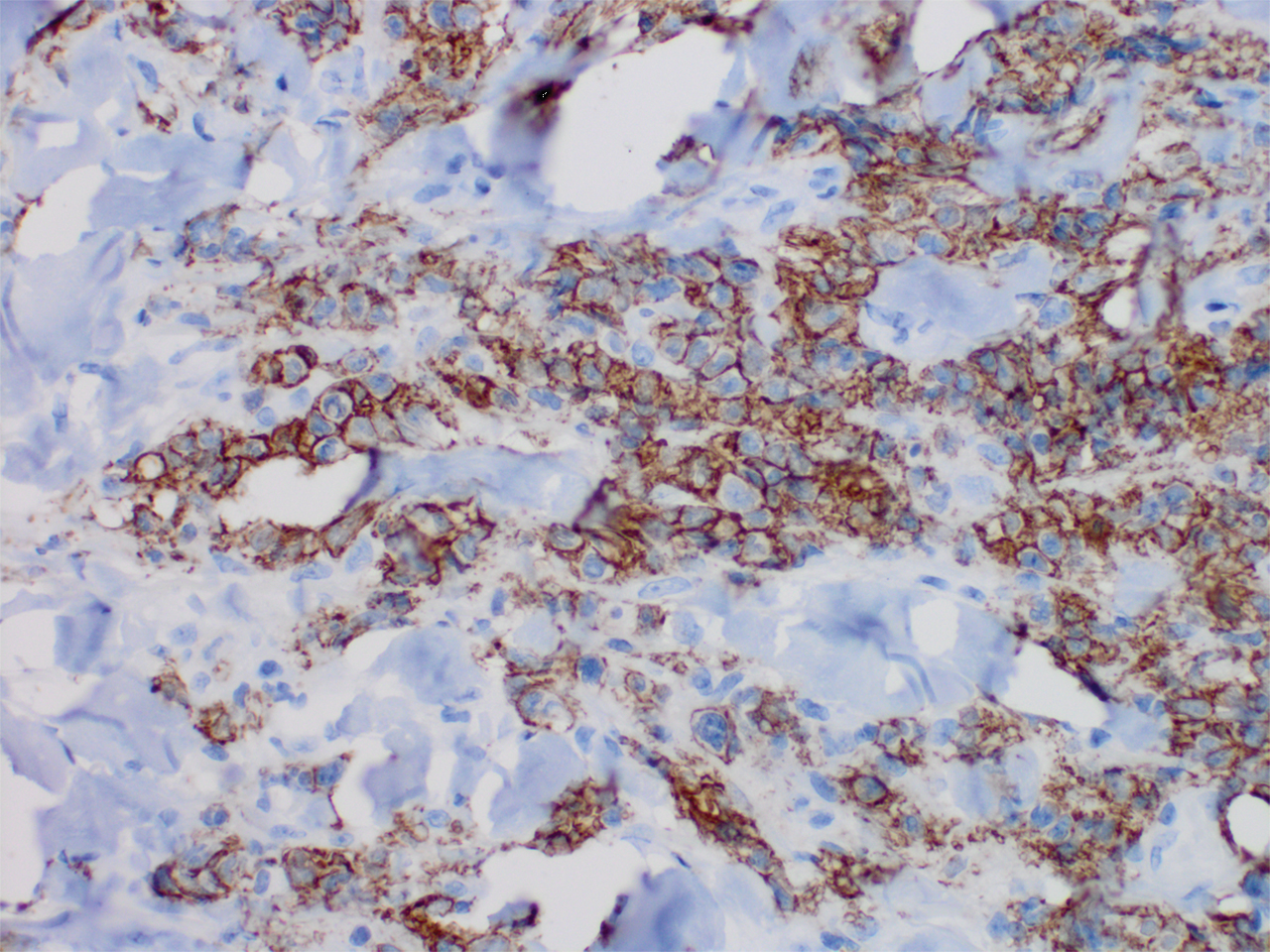

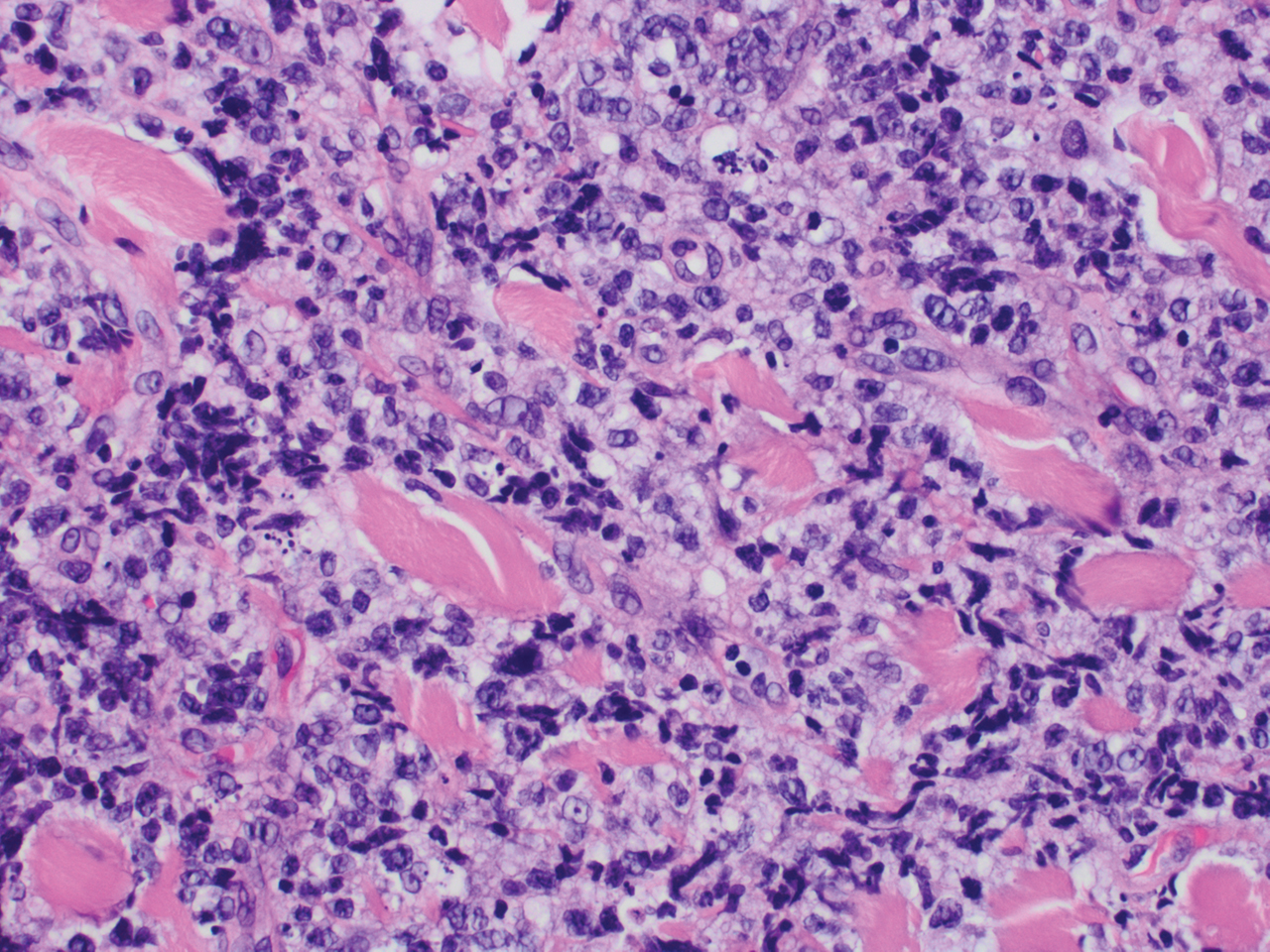

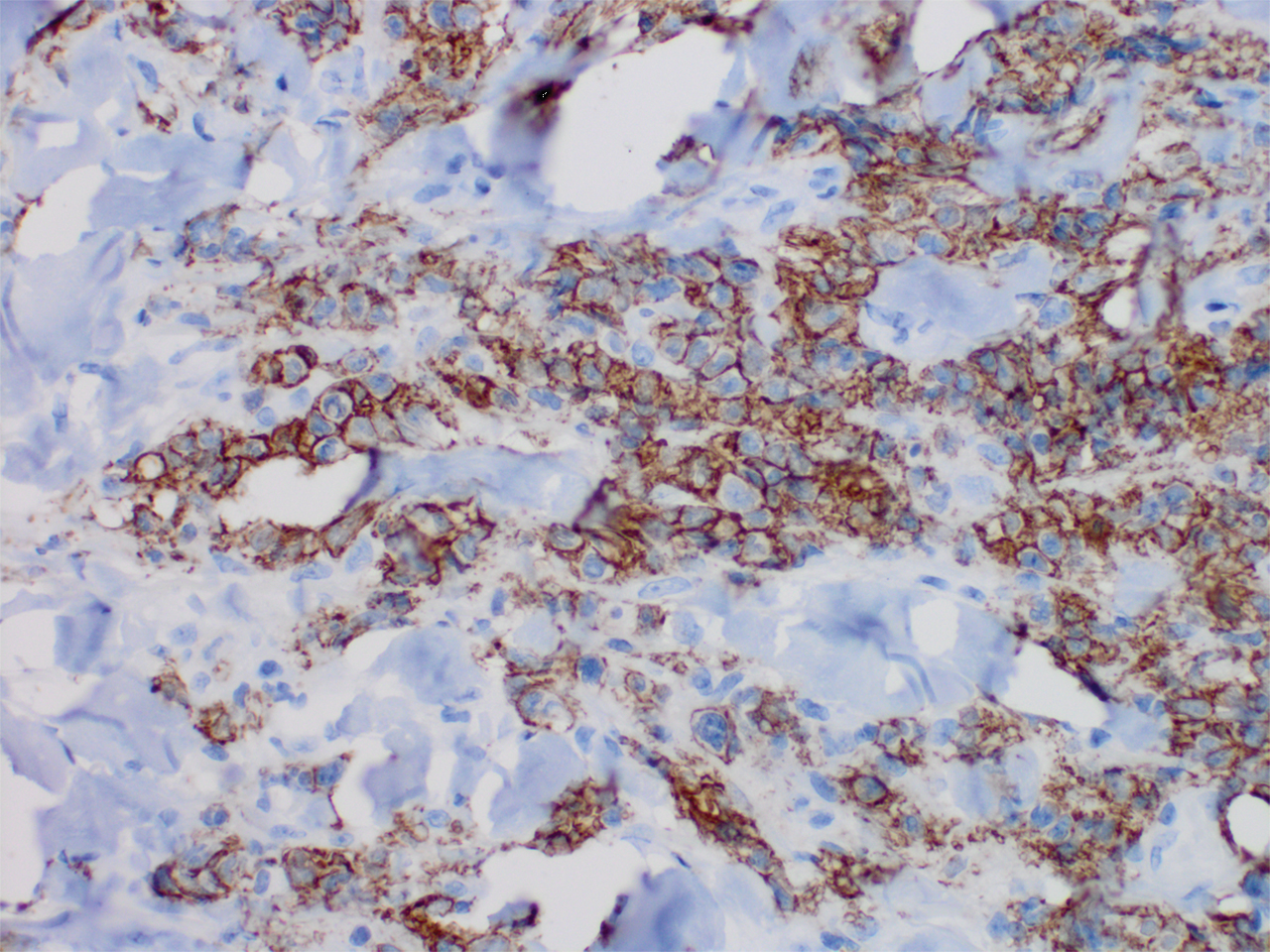

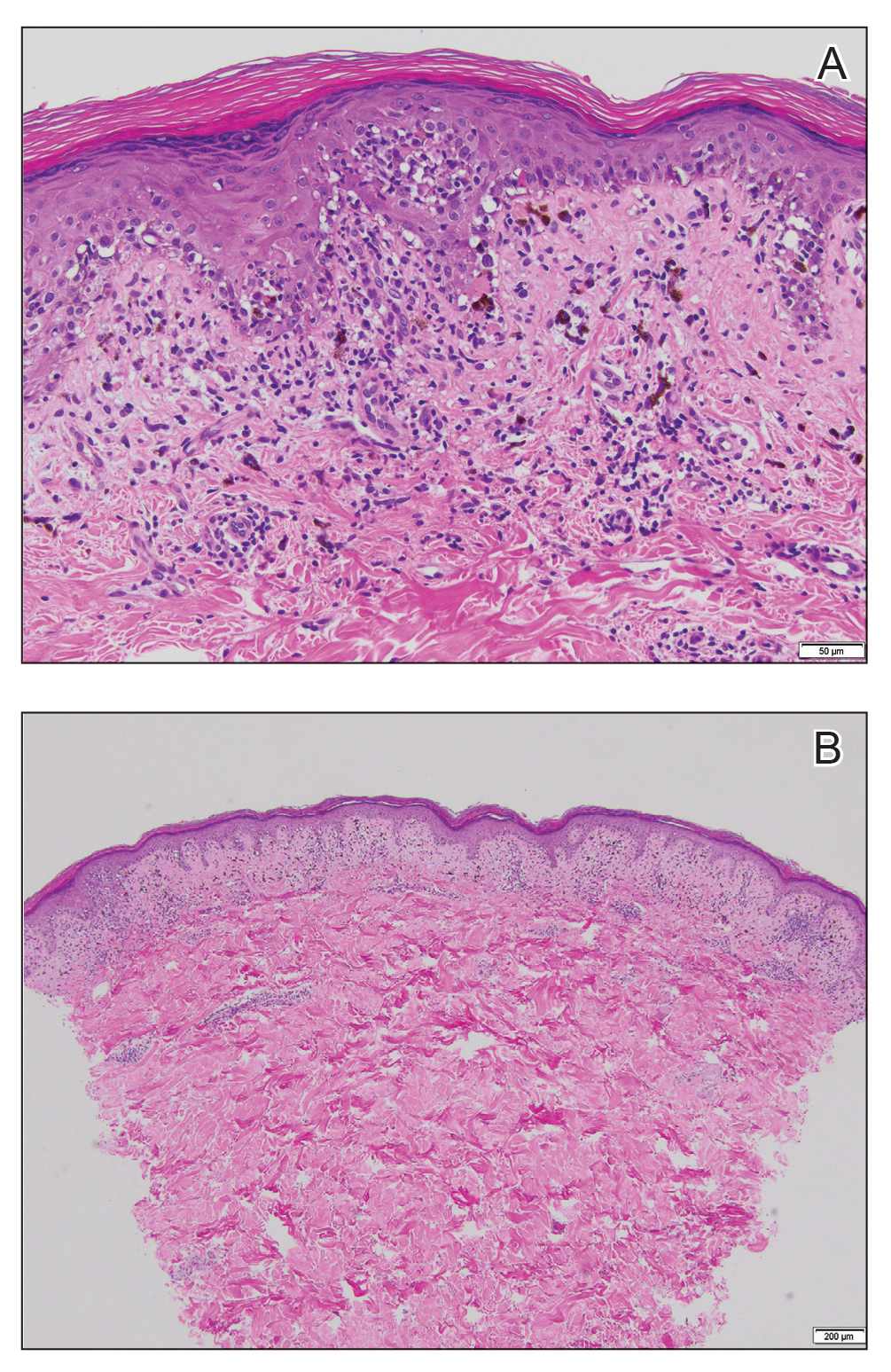

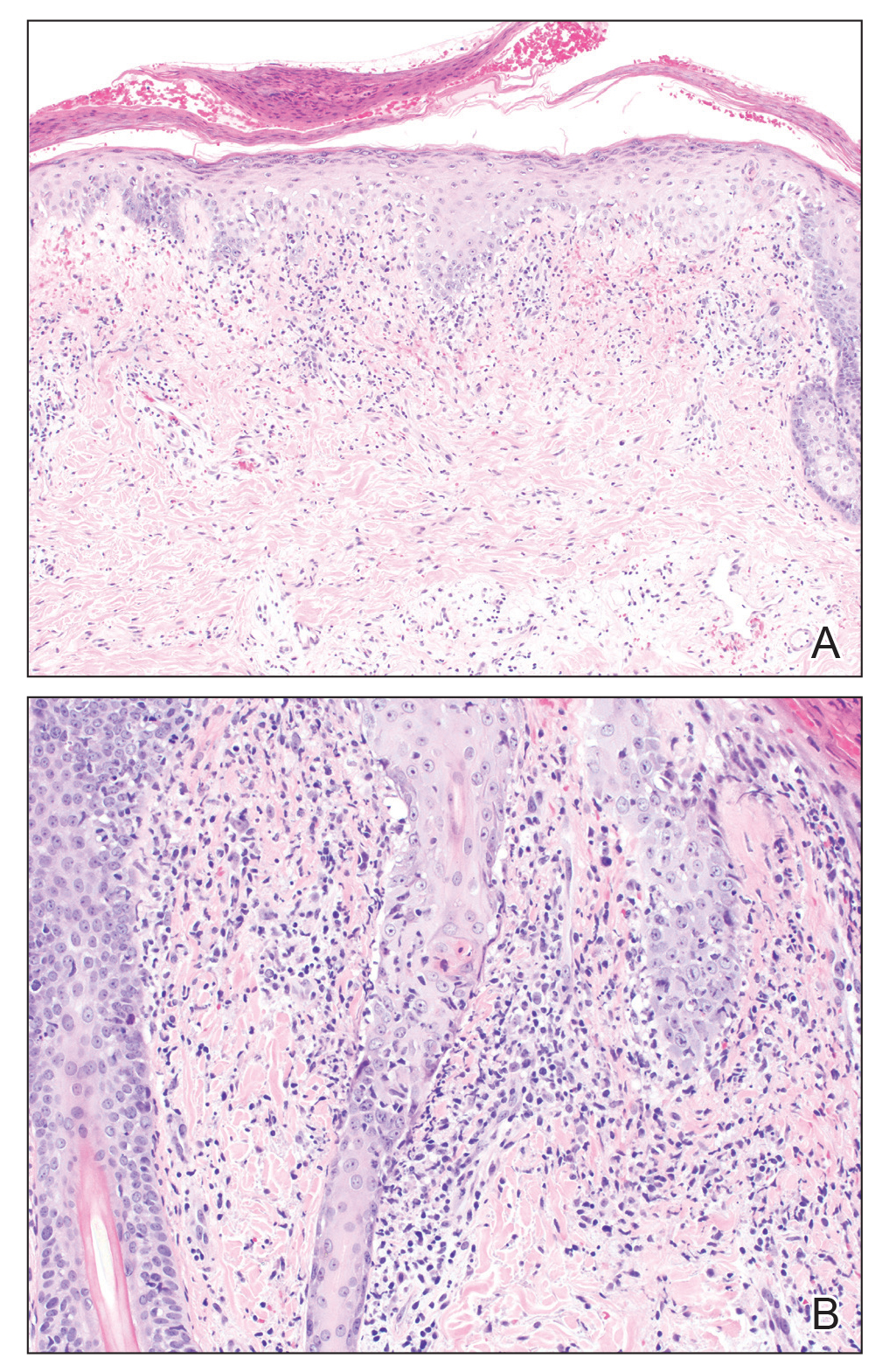

Histopathology revealed a dense and diffuse lymphocytic infiltrate throughout the dermis with occasional individual cell necrosis. On closer inspection, the infiltrate consisted of intermediate-sized lymphocytes, some with a vesiculated nucleus and ample amount of cytoplasm, while others contained hyperchromatic nuclei (Figure 1). These cells stained strongly positive for B-cell marker (CD20), while only a few mature lymphocytes demonstrated T-cell phenotype (CD3)(Figure 2).

Although the patient recounted a 3-month history of lower leg edema, he also reported that the rash began a few weeks after his diagnosis of systemic B-cell follicular lymphoma. Throughout this time, he was seen by various physicians who attributed the edema and skin changes to chronic stasis, peripheral venous insufficiency, and diabetic peripheral neuropathy. His primary care physician prescribed an antifungal lotion, which he discontinued on his own due to lack of improvement. Upon arrival to the emergency department, he was started on intravenous cefazolin and subcutaneous heparin. Doppler ultrasonography of the legs was ordered to rule out a deep venous thrombosis. Dermatology was consulted and proceeded with a punch biopsy to investigate for cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (BCL) with a plan to follow up as an outpatient for results upon discharge. He also was prescribed triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily for symptomatic relief.

The patient's left axillary lymph node was biopsied for pathologic evaluation. Immunohistochemical staining revealed expression of B-cell markers CD20, CD79a, and PAX5, along with the antiapoptotic markers BCL-2 and BCL-6. Fluorescence in situ hybridization displayed gene rearrangements of BCL-2, BCL-6, and t(14;18)/IgH-BCL2 in the majority of cells. CD3 and CD5 immunostains were negative, indicating that T cells were not involved in this process. Flow cytometry identified a monoclonal κ B-cell population in 40% to 50% of the total cells, which co-expressed CD10, CD19, CD22, and CD38; the cells were negative for CD5, CD20, and CD23. Cell size was variably enlarged and CD71 positive, otherwise known as transferrin receptor 1, indicating the mediation of iron transport into cells of erythroid lineage that is necessary for proliferation.1 Bone marrow core biopsy did not identify features of bone marrow involvement by the lymphoma. Based on these results, the patient was diagnosed with systemic B-cell follicular lymphoma grade 3b stage IIIA. Oncology initiated a systemic chemotherapy regimen with obinutuzumab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride (hydroxydaunorubicin), vincristine sulfate, and prednisone.

Skin involvement in B-cell follicular lymphoma can be primary or secondary. Although all subtypes of BCL can have secondary cutaneous involvement, it is most common in advanced-stage disease (stages III or IV).2 Cutaneous manifestations of primary cutaneous follicle-center lymphoma (PCFCL) and systemic/nodal follicular lymphoma secondarily involving the skin can be difficult to distinguish clinically and histopathologically; both appear as solitary or grouped plaques and nodules most commonly on the head, neck, or trunk, and rarely on the legs.3 Although the pathologic features of these two diagnoses can seem almost identical, it is important to differentiate them due to their differing prognosis and management. Patients with follicular lymphoma involving the skin are more likely than those with PCFCL to develop lymphadenopathy and B symptoms.3 Primary cutaneous follicle-center lymphoma also generally runs an indolent course and requires local therapy, while secondary involvement of the skin due to systemic/nodal follicular lymphoma has a worse prognosis and requires systemic chemotherapy treatment.4

Immunohistochemical markers are the most helpful tool used to distinguish PCFCL from systemic/nodal follicular lymphoma involving the skin. Tumors of B-cell origin are expected to express associated B-cell markers such as CD20, CD79a, and PAX52; BCL-6, a marker of germinal center cells, also is expected to stain positive.2 CD10 is positive in a majority of cases with a follicular growth pattern, while those with a diffuse pattern of growth may have a negative stain.2 The most valuable histopathologic indicator differentiating primary and secondary skin involvement is the intensity of BCL-2 expression.5 The prognostic significance of the t(14;18)/IgH-BCL2 rearrangement is controversial, with rearrangement identified in more than 75% of systemic/nodal follicular lymphoma cases and less commonly found in PCFCL, with one report arguing an incidence ranging from 1% to 40%.5

A comprehensive history and physical examination are necessary to develop a differential diagnosis. Our patient's lower leg edema and extensive medical history made the diagnosis more complicated. Pitting edema was present on physical examination, making elephantiasis nostras verrucosa less likely, as it would instead present with nonpitting edema and a woody feel.6 Our patient did not have epidemiologic exposure to filariasis through foreign travel and did not present with any classic signs or symptoms of lymphatic filariasis, such as fever, eosinophilia, chyluria, or hydrocele.7 Although a negative history of HIV makes Kaposi sarcoma and bacillary angiomatosis less likely diagnoses, a biopsy would be useful to rule out these conditions. Positive inguinal lymphadenopathy present on physical examination may have contributed to lymphatic flow obstruction leading to the leg lymphedema in our patient.

- Marsee DK, Pinkus GS, Yu H. CD71 (transferrin receptor): an effective marker for erythroid precursors in bone marrow biopsy specimens. Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;134:429-435.

- Jaffe ES. Navigating the cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: avoiding the rocky shoals. Mod Pathol. 2020;33(suppl 1):96-106.

- Skala SL, Hristov B, Hristov AC. Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142:1313-1321.

- Suárez AL, Pulitzer M, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: part I. clinical features, diagnosis, and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:329.e1-13; quiz 341-342.

- Servitje O, Climent F, Colomo L, et al. Primary cutaneous vs secondary cutaneous follicular lymphomas: a comparative study focused on BCL2, CD10, and t(14;18) expression. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;46:182-189.

- Fredman R, Tenenhaus M. Elephantiasis nostras verrucose [published online October 12, 2012]. Eplasty. 2012;12:ic14.

- Lourens GB, Ferrell DK. Lymphatic filariasis. Nurs Clin of North Am. 2019;54:181-192.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous B-cell Lymphoma

Histopathology revealed a dense and diffuse lymphocytic infiltrate throughout the dermis with occasional individual cell necrosis. On closer inspection, the infiltrate consisted of intermediate-sized lymphocytes, some with a vesiculated nucleus and ample amount of cytoplasm, while others contained hyperchromatic nuclei (Figure 1). These cells stained strongly positive for B-cell marker (CD20), while only a few mature lymphocytes demonstrated T-cell phenotype (CD3)(Figure 2).

Although the patient recounted a 3-month history of lower leg edema, he also reported that the rash began a few weeks after his diagnosis of systemic B-cell follicular lymphoma. Throughout this time, he was seen by various physicians who attributed the edema and skin changes to chronic stasis, peripheral venous insufficiency, and diabetic peripheral neuropathy. His primary care physician prescribed an antifungal lotion, which he discontinued on his own due to lack of improvement. Upon arrival to the emergency department, he was started on intravenous cefazolin and subcutaneous heparin. Doppler ultrasonography of the legs was ordered to rule out a deep venous thrombosis. Dermatology was consulted and proceeded with a punch biopsy to investigate for cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (BCL) with a plan to follow up as an outpatient for results upon discharge. He also was prescribed triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily for symptomatic relief.

The patient's left axillary lymph node was biopsied for pathologic evaluation. Immunohistochemical staining revealed expression of B-cell markers CD20, CD79a, and PAX5, along with the antiapoptotic markers BCL-2 and BCL-6. Fluorescence in situ hybridization displayed gene rearrangements of BCL-2, BCL-6, and t(14;18)/IgH-BCL2 in the majority of cells. CD3 and CD5 immunostains were negative, indicating that T cells were not involved in this process. Flow cytometry identified a monoclonal κ B-cell population in 40% to 50% of the total cells, which co-expressed CD10, CD19, CD22, and CD38; the cells were negative for CD5, CD20, and CD23. Cell size was variably enlarged and CD71 positive, otherwise known as transferrin receptor 1, indicating the mediation of iron transport into cells of erythroid lineage that is necessary for proliferation.1 Bone marrow core biopsy did not identify features of bone marrow involvement by the lymphoma. Based on these results, the patient was diagnosed with systemic B-cell follicular lymphoma grade 3b stage IIIA. Oncology initiated a systemic chemotherapy regimen with obinutuzumab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride (hydroxydaunorubicin), vincristine sulfate, and prednisone.

Skin involvement in B-cell follicular lymphoma can be primary or secondary. Although all subtypes of BCL can have secondary cutaneous involvement, it is most common in advanced-stage disease (stages III or IV).2 Cutaneous manifestations of primary cutaneous follicle-center lymphoma (PCFCL) and systemic/nodal follicular lymphoma secondarily involving the skin can be difficult to distinguish clinically and histopathologically; both appear as solitary or grouped plaques and nodules most commonly on the head, neck, or trunk, and rarely on the legs.3 Although the pathologic features of these two diagnoses can seem almost identical, it is important to differentiate them due to their differing prognosis and management. Patients with follicular lymphoma involving the skin are more likely than those with PCFCL to develop lymphadenopathy and B symptoms.3 Primary cutaneous follicle-center lymphoma also generally runs an indolent course and requires local therapy, while secondary involvement of the skin due to systemic/nodal follicular lymphoma has a worse prognosis and requires systemic chemotherapy treatment.4

Immunohistochemical markers are the most helpful tool used to distinguish PCFCL from systemic/nodal follicular lymphoma involving the skin. Tumors of B-cell origin are expected to express associated B-cell markers such as CD20, CD79a, and PAX52; BCL-6, a marker of germinal center cells, also is expected to stain positive.2 CD10 is positive in a majority of cases with a follicular growth pattern, while those with a diffuse pattern of growth may have a negative stain.2 The most valuable histopathologic indicator differentiating primary and secondary skin involvement is the intensity of BCL-2 expression.5 The prognostic significance of the t(14;18)/IgH-BCL2 rearrangement is controversial, with rearrangement identified in more than 75% of systemic/nodal follicular lymphoma cases and less commonly found in PCFCL, with one report arguing an incidence ranging from 1% to 40%.5

A comprehensive history and physical examination are necessary to develop a differential diagnosis. Our patient's lower leg edema and extensive medical history made the diagnosis more complicated. Pitting edema was present on physical examination, making elephantiasis nostras verrucosa less likely, as it would instead present with nonpitting edema and a woody feel.6 Our patient did not have epidemiologic exposure to filariasis through foreign travel and did not present with any classic signs or symptoms of lymphatic filariasis, such as fever, eosinophilia, chyluria, or hydrocele.7 Although a negative history of HIV makes Kaposi sarcoma and bacillary angiomatosis less likely diagnoses, a biopsy would be useful to rule out these conditions. Positive inguinal lymphadenopathy present on physical examination may have contributed to lymphatic flow obstruction leading to the leg lymphedema in our patient.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous B-cell Lymphoma

Histopathology revealed a dense and diffuse lymphocytic infiltrate throughout the dermis with occasional individual cell necrosis. On closer inspection, the infiltrate consisted of intermediate-sized lymphocytes, some with a vesiculated nucleus and ample amount of cytoplasm, while others contained hyperchromatic nuclei (Figure 1). These cells stained strongly positive for B-cell marker (CD20), while only a few mature lymphocytes demonstrated T-cell phenotype (CD3)(Figure 2).

Although the patient recounted a 3-month history of lower leg edema, he also reported that the rash began a few weeks after his diagnosis of systemic B-cell follicular lymphoma. Throughout this time, he was seen by various physicians who attributed the edema and skin changes to chronic stasis, peripheral venous insufficiency, and diabetic peripheral neuropathy. His primary care physician prescribed an antifungal lotion, which he discontinued on his own due to lack of improvement. Upon arrival to the emergency department, he was started on intravenous cefazolin and subcutaneous heparin. Doppler ultrasonography of the legs was ordered to rule out a deep venous thrombosis. Dermatology was consulted and proceeded with a punch biopsy to investigate for cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (BCL) with a plan to follow up as an outpatient for results upon discharge. He also was prescribed triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily for symptomatic relief.

The patient's left axillary lymph node was biopsied for pathologic evaluation. Immunohistochemical staining revealed expression of B-cell markers CD20, CD79a, and PAX5, along with the antiapoptotic markers BCL-2 and BCL-6. Fluorescence in situ hybridization displayed gene rearrangements of BCL-2, BCL-6, and t(14;18)/IgH-BCL2 in the majority of cells. CD3 and CD5 immunostains were negative, indicating that T cells were not involved in this process. Flow cytometry identified a monoclonal κ B-cell population in 40% to 50% of the total cells, which co-expressed CD10, CD19, CD22, and CD38; the cells were negative for CD5, CD20, and CD23. Cell size was variably enlarged and CD71 positive, otherwise known as transferrin receptor 1, indicating the mediation of iron transport into cells of erythroid lineage that is necessary for proliferation.1 Bone marrow core biopsy did not identify features of bone marrow involvement by the lymphoma. Based on these results, the patient was diagnosed with systemic B-cell follicular lymphoma grade 3b stage IIIA. Oncology initiated a systemic chemotherapy regimen with obinutuzumab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride (hydroxydaunorubicin), vincristine sulfate, and prednisone.

Skin involvement in B-cell follicular lymphoma can be primary or secondary. Although all subtypes of BCL can have secondary cutaneous involvement, it is most common in advanced-stage disease (stages III or IV).2 Cutaneous manifestations of primary cutaneous follicle-center lymphoma (PCFCL) and systemic/nodal follicular lymphoma secondarily involving the skin can be difficult to distinguish clinically and histopathologically; both appear as solitary or grouped plaques and nodules most commonly on the head, neck, or trunk, and rarely on the legs.3 Although the pathologic features of these two diagnoses can seem almost identical, it is important to differentiate them due to their differing prognosis and management. Patients with follicular lymphoma involving the skin are more likely than those with PCFCL to develop lymphadenopathy and B symptoms.3 Primary cutaneous follicle-center lymphoma also generally runs an indolent course and requires local therapy, while secondary involvement of the skin due to systemic/nodal follicular lymphoma has a worse prognosis and requires systemic chemotherapy treatment.4

Immunohistochemical markers are the most helpful tool used to distinguish PCFCL from systemic/nodal follicular lymphoma involving the skin. Tumors of B-cell origin are expected to express associated B-cell markers such as CD20, CD79a, and PAX52; BCL-6, a marker of germinal center cells, also is expected to stain positive.2 CD10 is positive in a majority of cases with a follicular growth pattern, while those with a diffuse pattern of growth may have a negative stain.2 The most valuable histopathologic indicator differentiating primary and secondary skin involvement is the intensity of BCL-2 expression.5 The prognostic significance of the t(14;18)/IgH-BCL2 rearrangement is controversial, with rearrangement identified in more than 75% of systemic/nodal follicular lymphoma cases and less commonly found in PCFCL, with one report arguing an incidence ranging from 1% to 40%.5

A comprehensive history and physical examination are necessary to develop a differential diagnosis. Our patient's lower leg edema and extensive medical history made the diagnosis more complicated. Pitting edema was present on physical examination, making elephantiasis nostras verrucosa less likely, as it would instead present with nonpitting edema and a woody feel.6 Our patient did not have epidemiologic exposure to filariasis through foreign travel and did not present with any classic signs or symptoms of lymphatic filariasis, such as fever, eosinophilia, chyluria, or hydrocele.7 Although a negative history of HIV makes Kaposi sarcoma and bacillary angiomatosis less likely diagnoses, a biopsy would be useful to rule out these conditions. Positive inguinal lymphadenopathy present on physical examination may have contributed to lymphatic flow obstruction leading to the leg lymphedema in our patient.

- Marsee DK, Pinkus GS, Yu H. CD71 (transferrin receptor): an effective marker for erythroid precursors in bone marrow biopsy specimens. Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;134:429-435.

- Jaffe ES. Navigating the cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: avoiding the rocky shoals. Mod Pathol. 2020;33(suppl 1):96-106.

- Skala SL, Hristov B, Hristov AC. Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142:1313-1321.

- Suárez AL, Pulitzer M, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: part I. clinical features, diagnosis, and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:329.e1-13; quiz 341-342.

- Servitje O, Climent F, Colomo L, et al. Primary cutaneous vs secondary cutaneous follicular lymphomas: a comparative study focused on BCL2, CD10, and t(14;18) expression. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;46:182-189.

- Fredman R, Tenenhaus M. Elephantiasis nostras verrucose [published online October 12, 2012]. Eplasty. 2012;12:ic14.

- Lourens GB, Ferrell DK. Lymphatic filariasis. Nurs Clin of North Am. 2019;54:181-192.

- Marsee DK, Pinkus GS, Yu H. CD71 (transferrin receptor): an effective marker for erythroid precursors in bone marrow biopsy specimens. Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;134:429-435.

- Jaffe ES. Navigating the cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: avoiding the rocky shoals. Mod Pathol. 2020;33(suppl 1):96-106.

- Skala SL, Hristov B, Hristov AC. Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142:1313-1321.

- Suárez AL, Pulitzer M, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: part I. clinical features, diagnosis, and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:329.e1-13; quiz 341-342.

- Servitje O, Climent F, Colomo L, et al. Primary cutaneous vs secondary cutaneous follicular lymphomas: a comparative study focused on BCL2, CD10, and t(14;18) expression. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;46:182-189.

- Fredman R, Tenenhaus M. Elephantiasis nostras verrucose [published online October 12, 2012]. Eplasty. 2012;12:ic14.

- Lourens GB, Ferrell DK. Lymphatic filariasis. Nurs Clin of North Am. 2019;54:181-192.

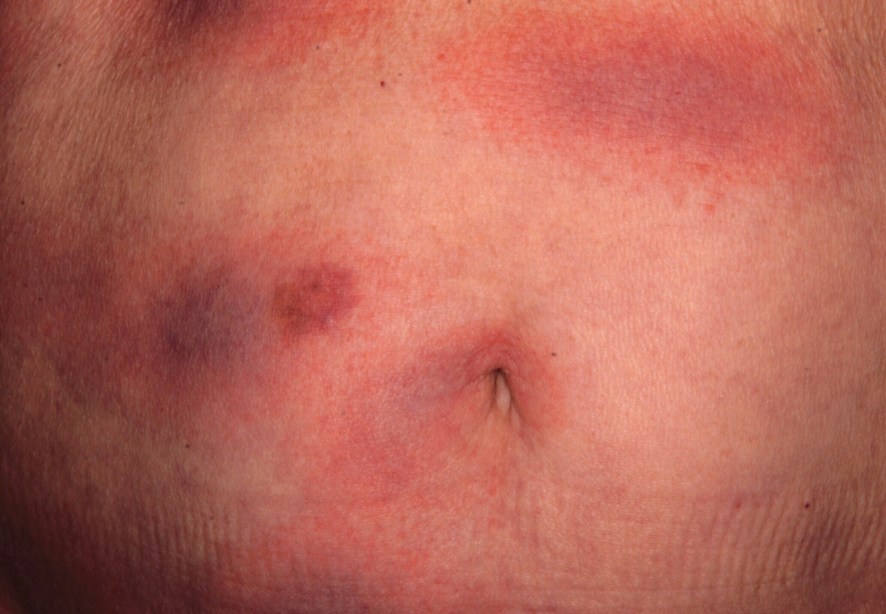

A 60-year-old man presented to the emergency department with slowly progressing edema of the lower legs of 3 months’ duration. In the week prior to presentation to the emergency department, he noticed a sudden eruption of vesicles and bullae on the right leg that drained clear fluid and healed with brown crust. The lesions were associated with mild burning, pruritus, and pain. He denied fever, chills, recent travel, or injury. His medical history was notable for poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, hyperlipidemia, and chronic anemia. Physical examination revealed multiple scattered erythematous vesicles and bullae on the right leg on a background of hyperpigmentation. Bilateral 2+ pitting edema of the legs also was present. A punch biopsy of a lesion was performed.

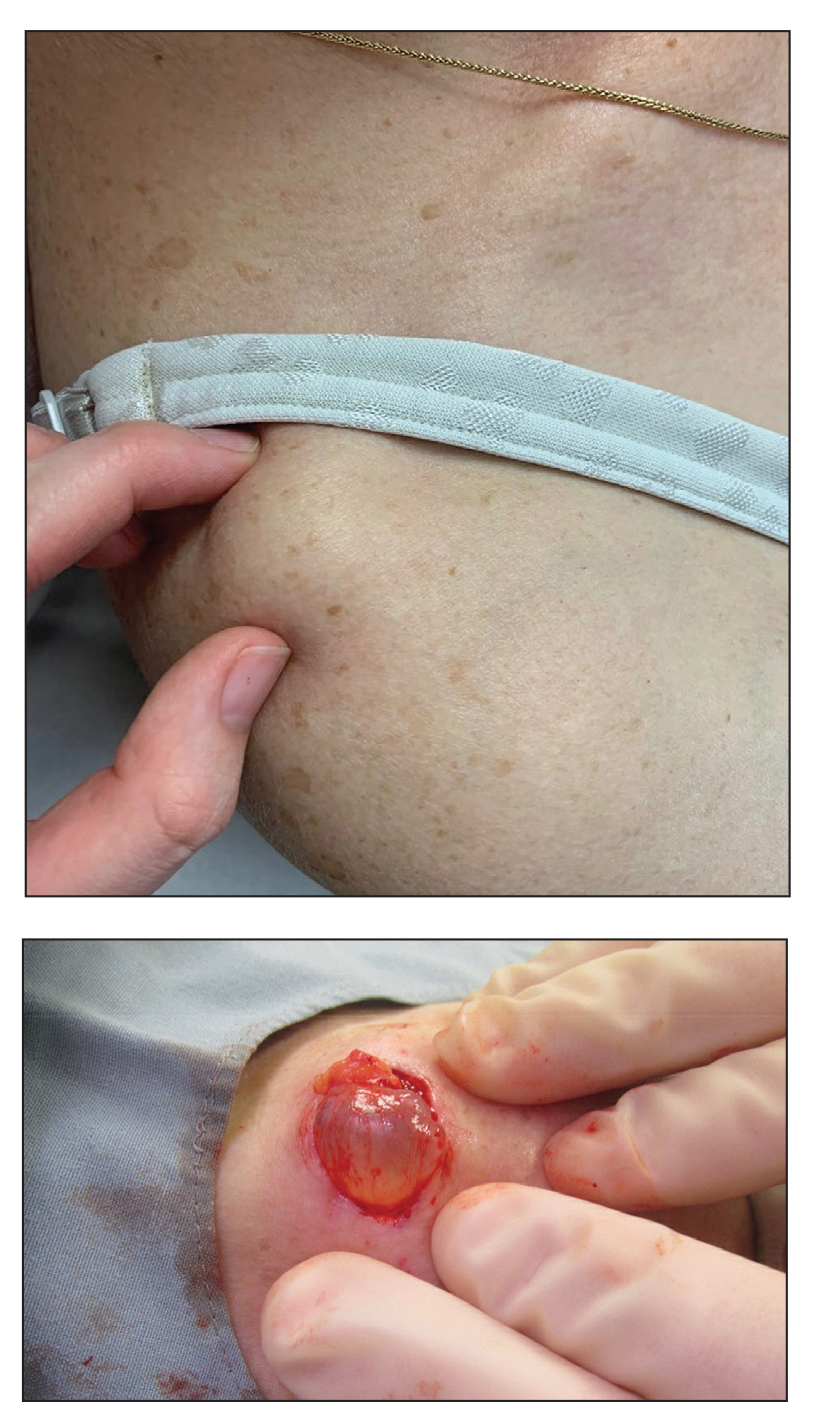

Asymptomatic Discolored Lesions on the Groin

The Diagnosis: Lichen Planus Pigmentosus-Inversus

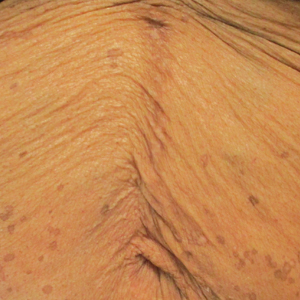

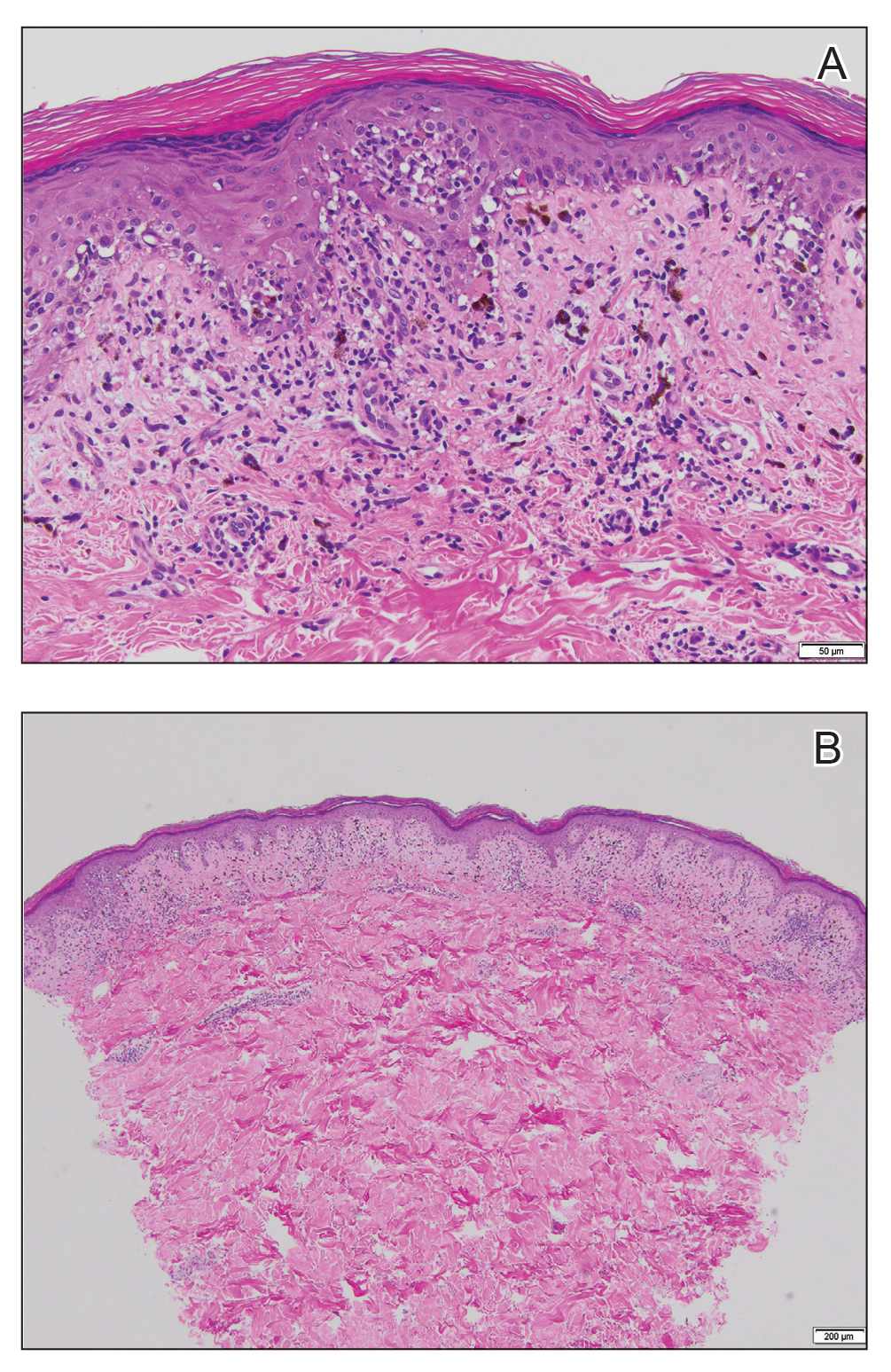

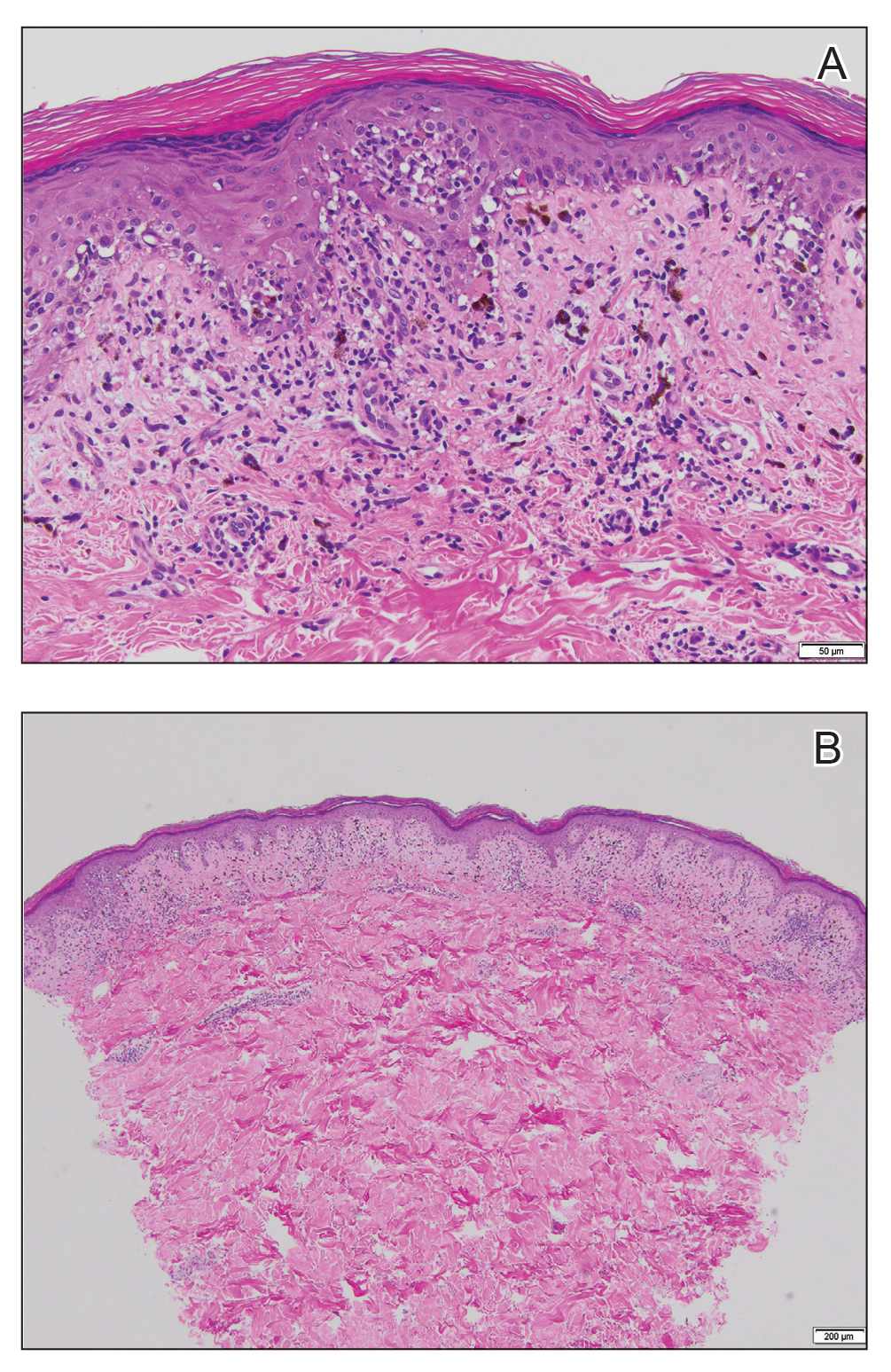

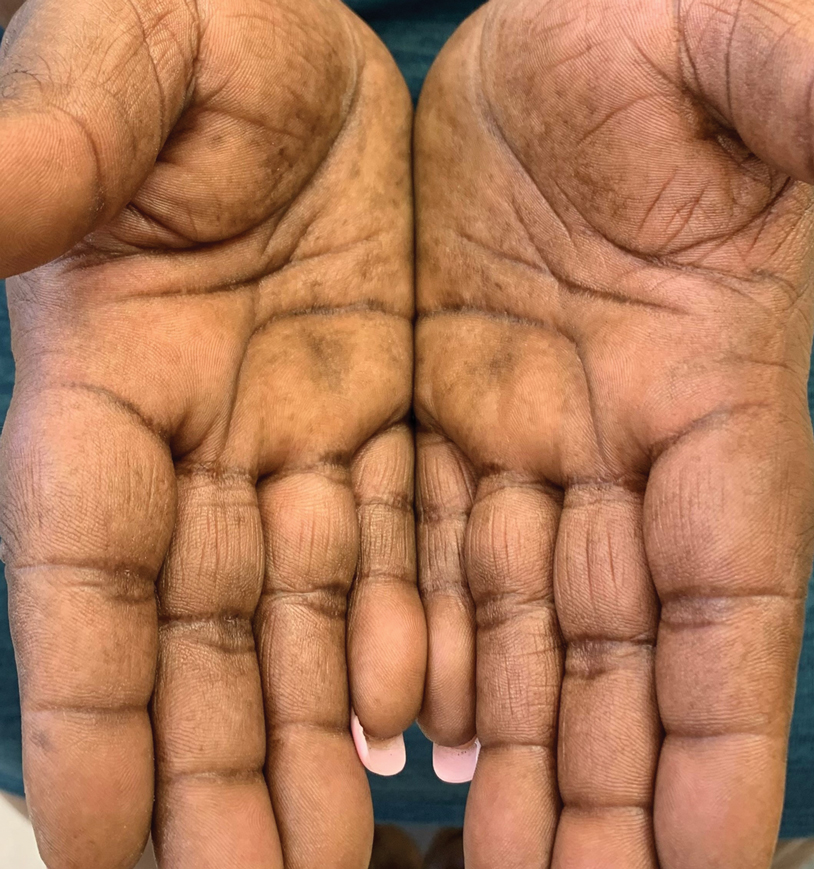

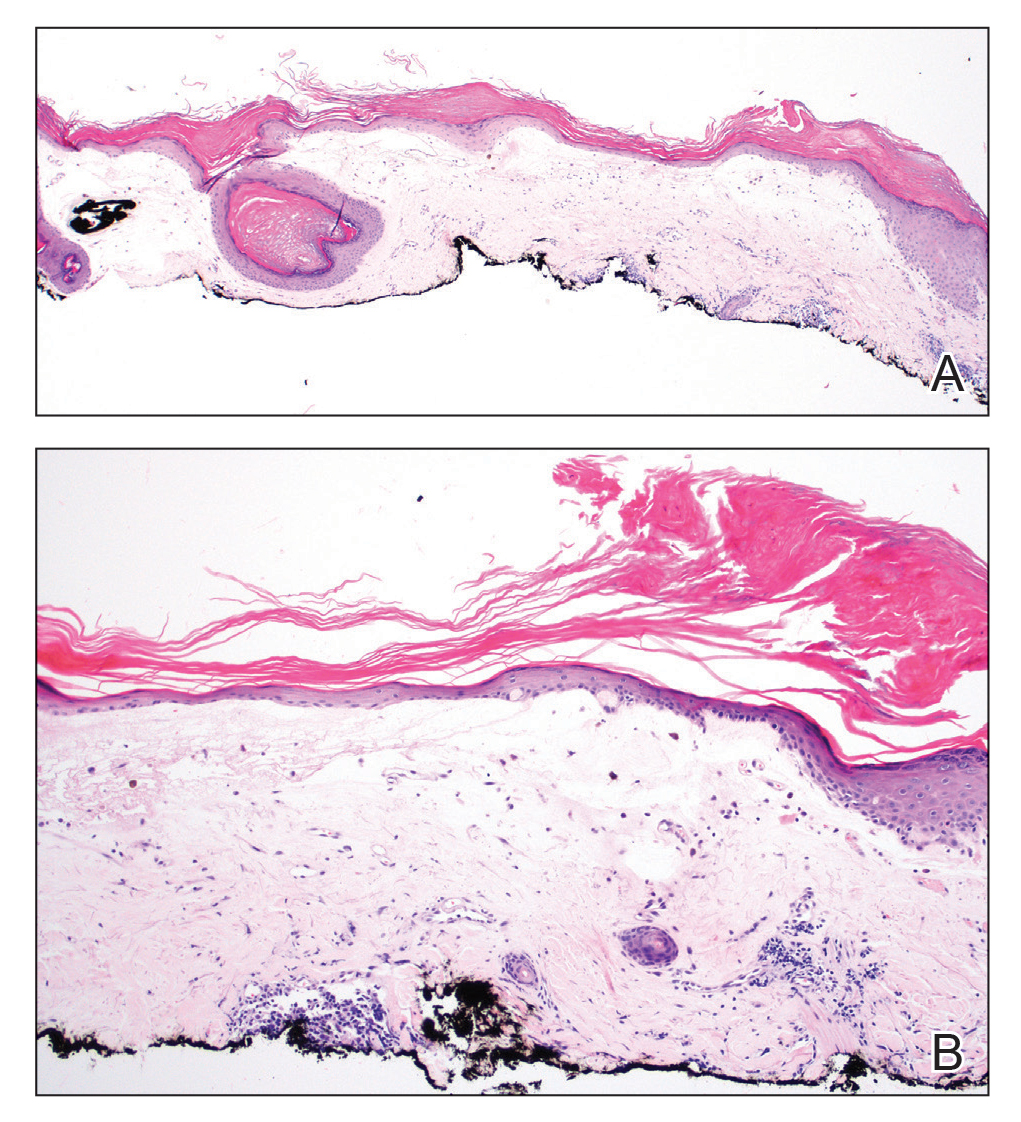

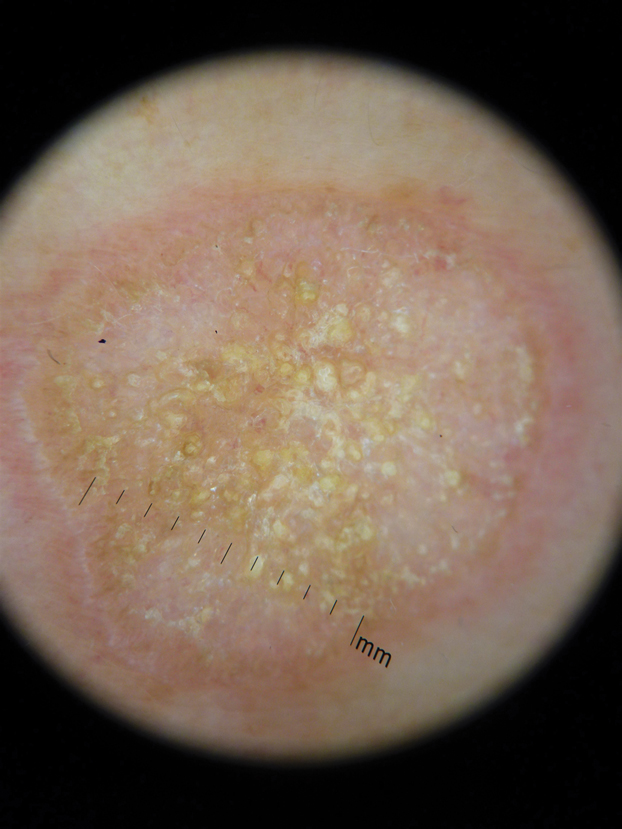

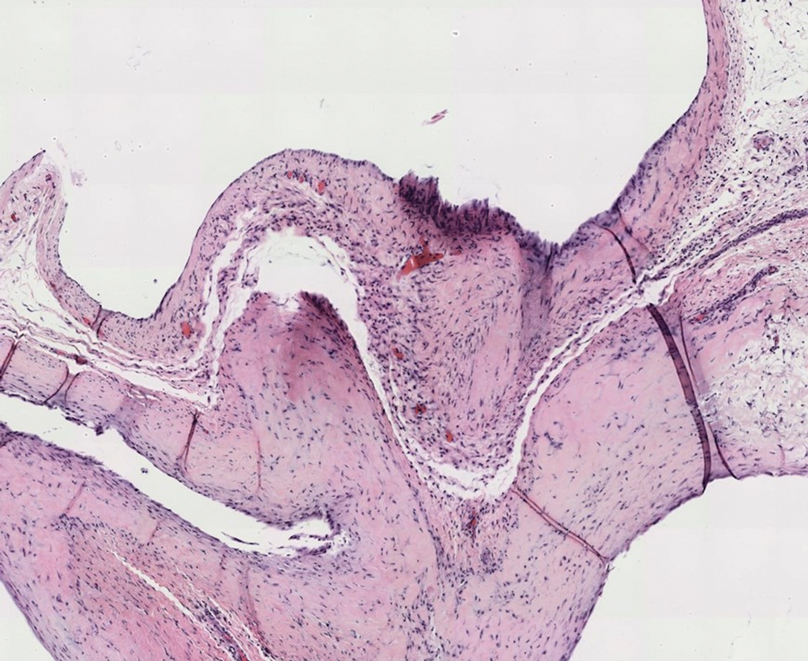

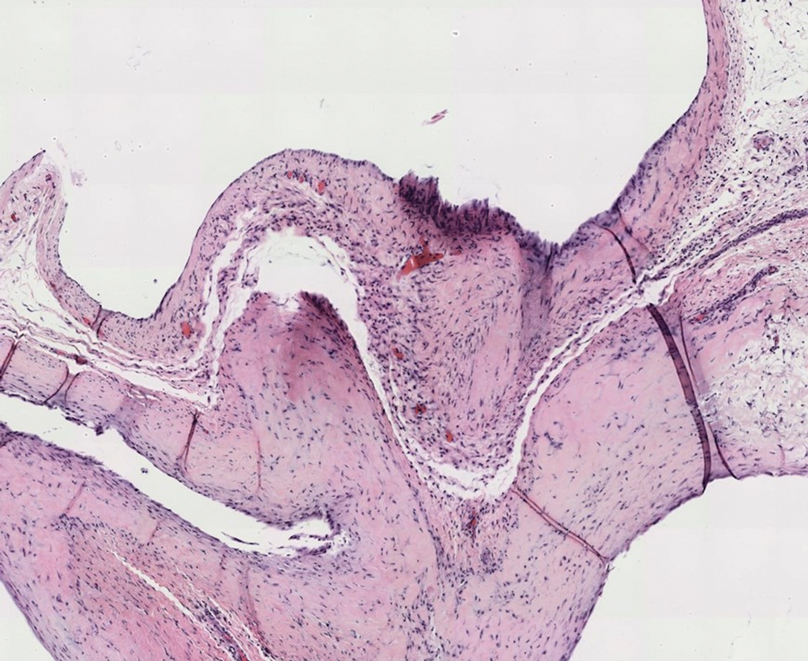

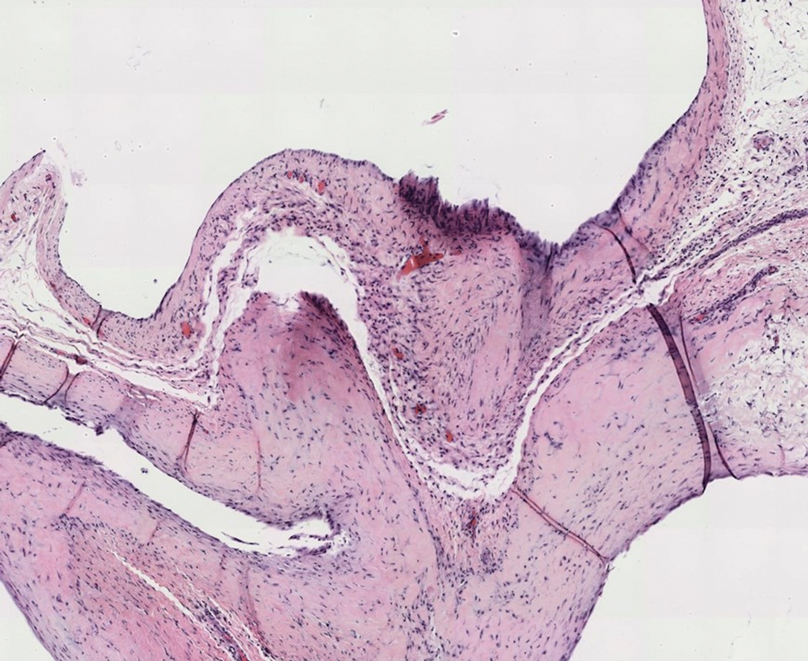

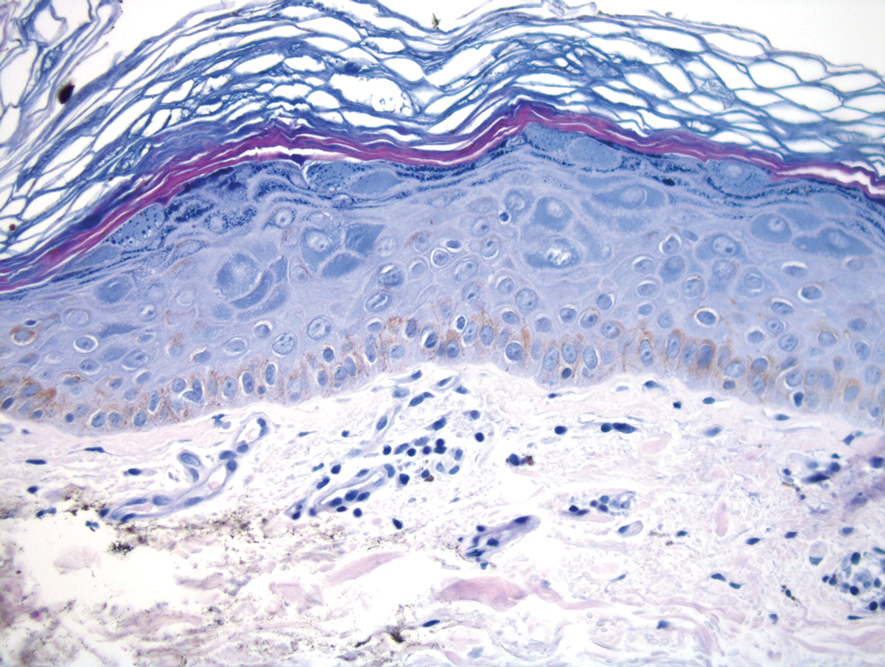

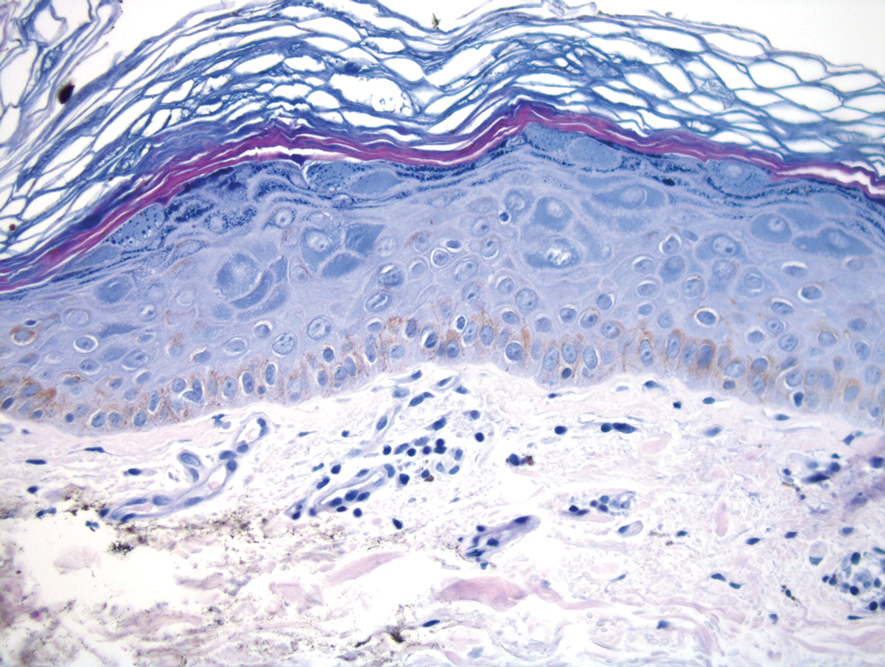

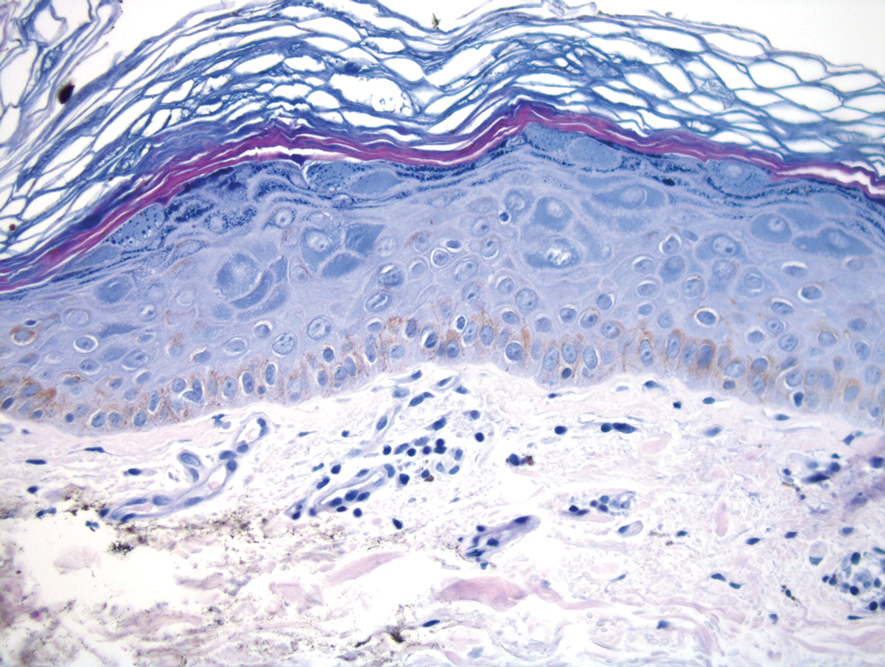

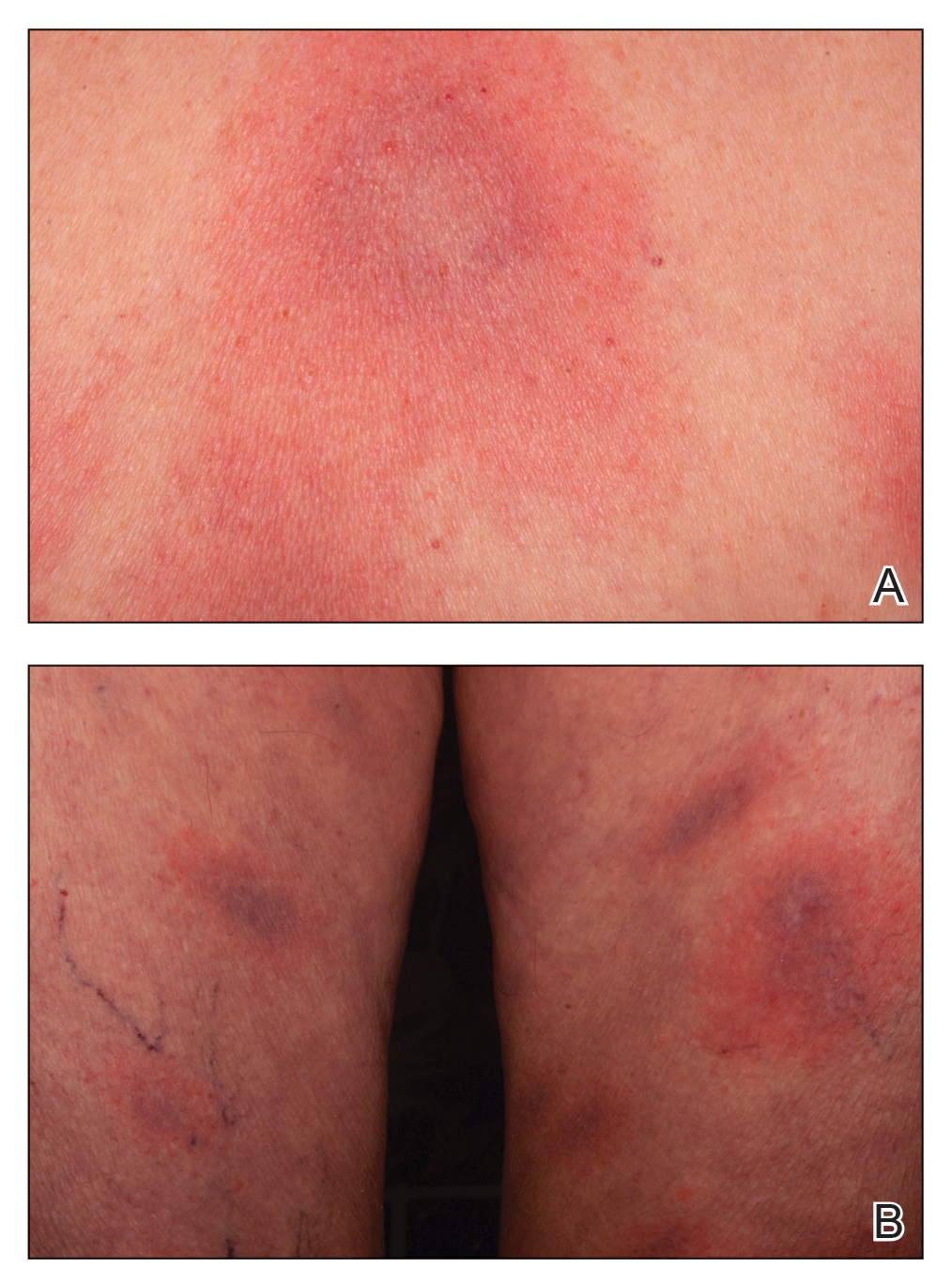

Histopathologic examination revealed hyperkeratosis with dense, bandlike, lymphocytic inflammation at the dermoepidermal junction with associated melanin-containing macrophages in the papillary dermis (Figure 1). The physical examination and histopathology were consistent with a diagnosis of lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus (LPPI). Treatment was discussed with the patient, with options including phototherapy, tacrolimus, or a high-dose steroid. Given that the lesions were asymptomatic and not bothersome, the patient denied treatment and agreed to routine follow-up.

The first case of LPPI was reported in 20011; since then, approximately 100 cases have been reported in the literature.2 A rare variant of lichen planus, LPPI predominantly occurs in middle-aged women.2,3 Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus is characterized by well-circumscribed, brown macules confined to non-sun-exposed intertriginous areas such as the axillae and groin.2 Although the rash remains localized, multiple lesions could arise in the same area, such as the groin as seen in our patient (Figure 2). Unlike in lichen planus, the oral mucosa, nails, and scalp are not affected. Furthermore, pruritus typically is absent in most cases of LPPI.2,4 Histopathologic findings include an atrophic epidermis with lichenoid infiltrates of lymphocytes and histocytes as well as substantial pigmentary incontinence with melanin-containing macrophages in the papillary dermis.4,5

Given the gender, age, and clinical features of our patient, this case represents a classic scenario of LPPI. It currently is unknown if ethnicity plays a role in the disorder. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus initially was thought to be more prevalent in White patients; however, studies have been reported in individuals with darker skin.1,2

The main differential diagnosis includes erythema dyschromicum perstans, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, and lichen planus. Although erythema dyschromicum perstans develops in individuals with darker skin, lesions are restricted to the upper torso and limbs.2-4 In both lichen planus and lichen actinicus, skin findings primarily develop in sun-exposed areas, such as the face, neck, and hands.4,6 Given the negative history of trauma, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation was unlikely in our patient. Furthermore, a distinguishing characteristic of LPPI is the deposition of melanin deep within the dermal layer.3

Lesions developing in nonexposed intertriginous skin makes LPPI unique and distinguishes it from other more common conditions. The lesions commonly are hyperpigmented and are not as pruritic as other lichen-associated conditions. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus often persists for months, and the rash generally is resistant to treatment.2,5 Topical tacrolimus and high-dose steroids may improve symptoms, though results have varied substantially. In addition, some cases have resolved spontaneously.1,4,6,7 Because LPPI is asymptomatic and benign, spontaneous resolution and routine care is a reasonable treatment strategy. Some cases have supported this strategy as safe and high-value care.2

- Mohamed M, Korbi M, Hammedi F, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus inversus: a series of 10 Tunisian patients. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:1088-1091.

- Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus: a rare variant of lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(suppl 1):AB239. https://doi.org /10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.959

- Chen S, Sun W, Zhou G, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus: report of three Chinese cases and review of the published work. J Dermatol. 2015;42:77-80.

- Tabanlıoǧlu-Onan D, Íncel-Uysal P, Öktem A, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus: a peculiar variant of lichen planus. Dermatologica Sinica. 2017;35:210-212.

- Barros HR, Almeida JR, Mattos e Dinato SL, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus inversus. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):146-149.

- Bennàssar A, Mas A, Julià M, et al. Annular plaques in the skin folds: 4 cases of lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:602-605.

- Ghorbel HH, Badri T, Ben Brahim E, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus inversus. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:580.

The Diagnosis: Lichen Planus Pigmentosus-Inversus

Histopathologic examination revealed hyperkeratosis with dense, bandlike, lymphocytic inflammation at the dermoepidermal junction with associated melanin-containing macrophages in the papillary dermis (Figure 1). The physical examination and histopathology were consistent with a diagnosis of lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus (LPPI). Treatment was discussed with the patient, with options including phototherapy, tacrolimus, or a high-dose steroid. Given that the lesions were asymptomatic and not bothersome, the patient denied treatment and agreed to routine follow-up.

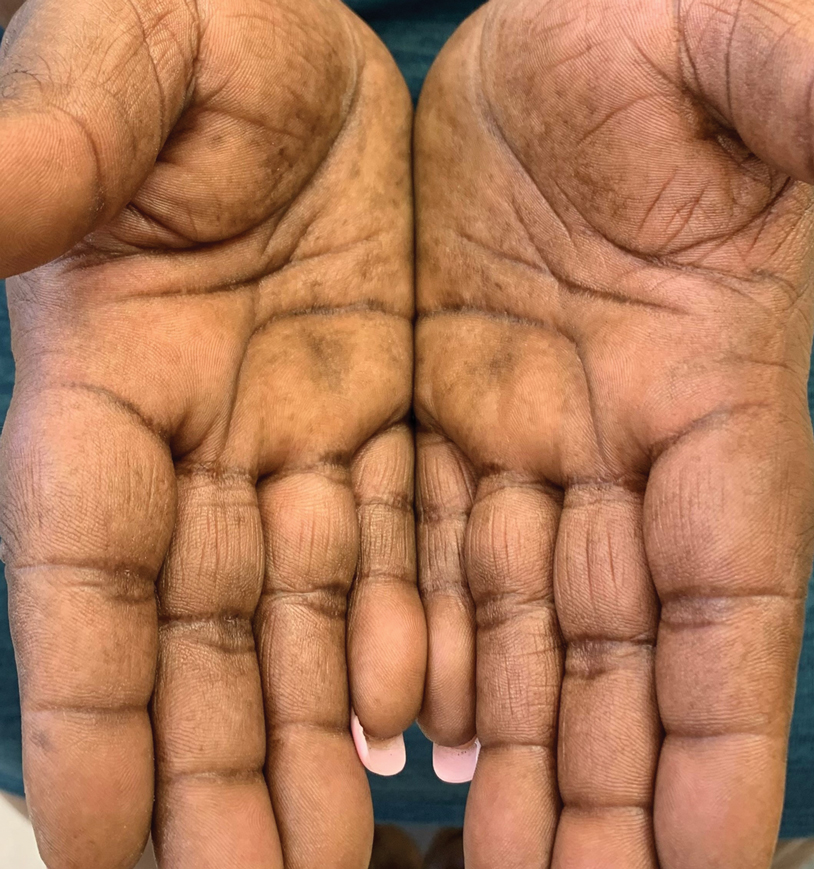

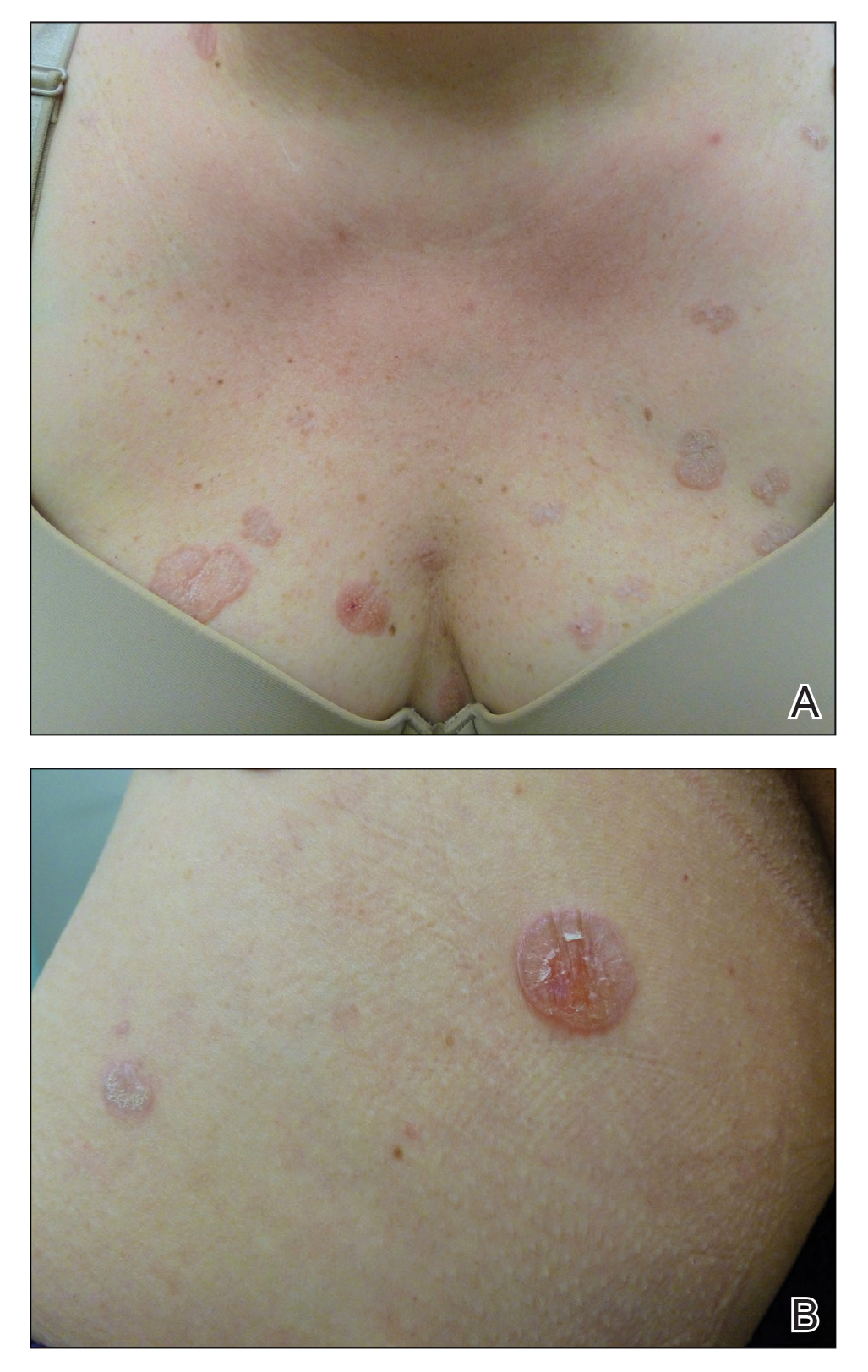

The first case of LPPI was reported in 20011; since then, approximately 100 cases have been reported in the literature.2 A rare variant of lichen planus, LPPI predominantly occurs in middle-aged women.2,3 Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus is characterized by well-circumscribed, brown macules confined to non-sun-exposed intertriginous areas such as the axillae and groin.2 Although the rash remains localized, multiple lesions could arise in the same area, such as the groin as seen in our patient (Figure 2). Unlike in lichen planus, the oral mucosa, nails, and scalp are not affected. Furthermore, pruritus typically is absent in most cases of LPPI.2,4 Histopathologic findings include an atrophic epidermis with lichenoid infiltrates of lymphocytes and histocytes as well as substantial pigmentary incontinence with melanin-containing macrophages in the papillary dermis.4,5

Given the gender, age, and clinical features of our patient, this case represents a classic scenario of LPPI. It currently is unknown if ethnicity plays a role in the disorder. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus initially was thought to be more prevalent in White patients; however, studies have been reported in individuals with darker skin.1,2

The main differential diagnosis includes erythema dyschromicum perstans, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, and lichen planus. Although erythema dyschromicum perstans develops in individuals with darker skin, lesions are restricted to the upper torso and limbs.2-4 In both lichen planus and lichen actinicus, skin findings primarily develop in sun-exposed areas, such as the face, neck, and hands.4,6 Given the negative history of trauma, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation was unlikely in our patient. Furthermore, a distinguishing characteristic of LPPI is the deposition of melanin deep within the dermal layer.3

Lesions developing in nonexposed intertriginous skin makes LPPI unique and distinguishes it from other more common conditions. The lesions commonly are hyperpigmented and are not as pruritic as other lichen-associated conditions. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus often persists for months, and the rash generally is resistant to treatment.2,5 Topical tacrolimus and high-dose steroids may improve symptoms, though results have varied substantially. In addition, some cases have resolved spontaneously.1,4,6,7 Because LPPI is asymptomatic and benign, spontaneous resolution and routine care is a reasonable treatment strategy. Some cases have supported this strategy as safe and high-value care.2

The Diagnosis: Lichen Planus Pigmentosus-Inversus

Histopathologic examination revealed hyperkeratosis with dense, bandlike, lymphocytic inflammation at the dermoepidermal junction with associated melanin-containing macrophages in the papillary dermis (Figure 1). The physical examination and histopathology were consistent with a diagnosis of lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus (LPPI). Treatment was discussed with the patient, with options including phototherapy, tacrolimus, or a high-dose steroid. Given that the lesions were asymptomatic and not bothersome, the patient denied treatment and agreed to routine follow-up.

The first case of LPPI was reported in 20011; since then, approximately 100 cases have been reported in the literature.2 A rare variant of lichen planus, LPPI predominantly occurs in middle-aged women.2,3 Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus is characterized by well-circumscribed, brown macules confined to non-sun-exposed intertriginous areas such as the axillae and groin.2 Although the rash remains localized, multiple lesions could arise in the same area, such as the groin as seen in our patient (Figure 2). Unlike in lichen planus, the oral mucosa, nails, and scalp are not affected. Furthermore, pruritus typically is absent in most cases of LPPI.2,4 Histopathologic findings include an atrophic epidermis with lichenoid infiltrates of lymphocytes and histocytes as well as substantial pigmentary incontinence with melanin-containing macrophages in the papillary dermis.4,5

Given the gender, age, and clinical features of our patient, this case represents a classic scenario of LPPI. It currently is unknown if ethnicity plays a role in the disorder. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus initially was thought to be more prevalent in White patients; however, studies have been reported in individuals with darker skin.1,2

The main differential diagnosis includes erythema dyschromicum perstans, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, and lichen planus. Although erythema dyschromicum perstans develops in individuals with darker skin, lesions are restricted to the upper torso and limbs.2-4 In both lichen planus and lichen actinicus, skin findings primarily develop in sun-exposed areas, such as the face, neck, and hands.4,6 Given the negative history of trauma, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation was unlikely in our patient. Furthermore, a distinguishing characteristic of LPPI is the deposition of melanin deep within the dermal layer.3

Lesions developing in nonexposed intertriginous skin makes LPPI unique and distinguishes it from other more common conditions. The lesions commonly are hyperpigmented and are not as pruritic as other lichen-associated conditions. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus often persists for months, and the rash generally is resistant to treatment.2,5 Topical tacrolimus and high-dose steroids may improve symptoms, though results have varied substantially. In addition, some cases have resolved spontaneously.1,4,6,7 Because LPPI is asymptomatic and benign, spontaneous resolution and routine care is a reasonable treatment strategy. Some cases have supported this strategy as safe and high-value care.2

- Mohamed M, Korbi M, Hammedi F, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus inversus: a series of 10 Tunisian patients. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:1088-1091.

- Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus: a rare variant of lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(suppl 1):AB239. https://doi.org /10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.959

- Chen S, Sun W, Zhou G, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus: report of three Chinese cases and review of the published work. J Dermatol. 2015;42:77-80.

- Tabanlıoǧlu-Onan D, Íncel-Uysal P, Öktem A, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus: a peculiar variant of lichen planus. Dermatologica Sinica. 2017;35:210-212.

- Barros HR, Almeida JR, Mattos e Dinato SL, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus inversus. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):146-149.

- Bennàssar A, Mas A, Julià M, et al. Annular plaques in the skin folds: 4 cases of lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:602-605.

- Ghorbel HH, Badri T, Ben Brahim E, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus inversus. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:580.

- Mohamed M, Korbi M, Hammedi F, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus inversus: a series of 10 Tunisian patients. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:1088-1091.

- Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus: a rare variant of lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(suppl 1):AB239. https://doi.org /10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.959

- Chen S, Sun W, Zhou G, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus: report of three Chinese cases and review of the published work. J Dermatol. 2015;42:77-80.

- Tabanlıoǧlu-Onan D, Íncel-Uysal P, Öktem A, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus: a peculiar variant of lichen planus. Dermatologica Sinica. 2017;35:210-212.

- Barros HR, Almeida JR, Mattos e Dinato SL, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus inversus. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):146-149.

- Bennàssar A, Mas A, Julià M, et al. Annular plaques in the skin folds: 4 cases of lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:602-605.

- Ghorbel HH, Badri T, Ben Brahim E, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus inversus. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:580.

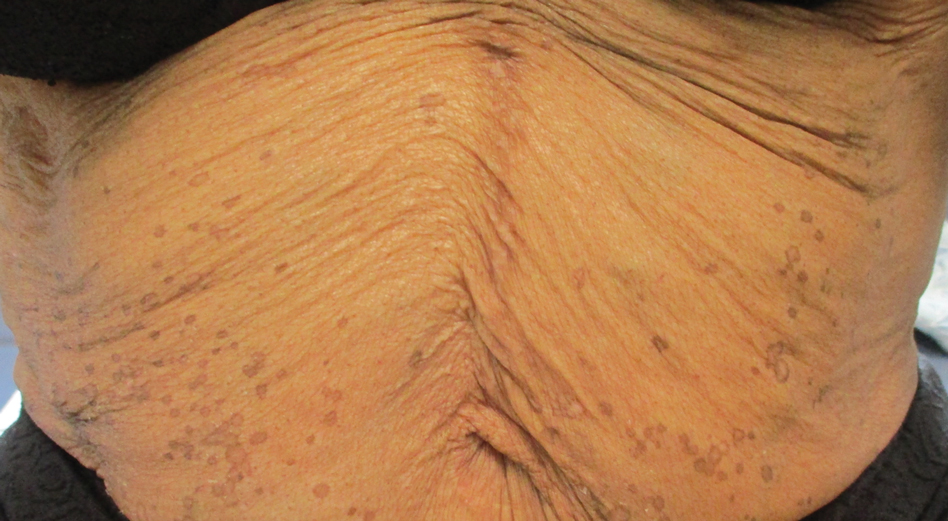

A 45-year-old African American woman presented with an asymptomatic rash that had worsened over the month prior to presentation. It initially began on the upper thighs and then spread to the abdomen, groin, and buttocks. The rash was mildly pruritic and had grown both in size and number of lesions. She had not tried any new over-the-counter medications. Her medical history was notable for late-stage breast cancer diagnosed 4 years prior that was treated with radiation and neoadjuvant NeoPACT—carboplatin, docetaxel, and pembrolizumab. One year prior to presentation, she underwent a lumpectomy that was complicated by gas gangrene of the finger. She has been in remission since the surgery. Physical examination at the current presentation was remarkable for multiple well-circumscribed, hyperpigmented macules on the medial thighs, lower abdomen, and buttocks. Syphilis antibody screening was negative.

Crusted Papules on the Bilateral Helices and Lobules

The Diagnosis: Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease

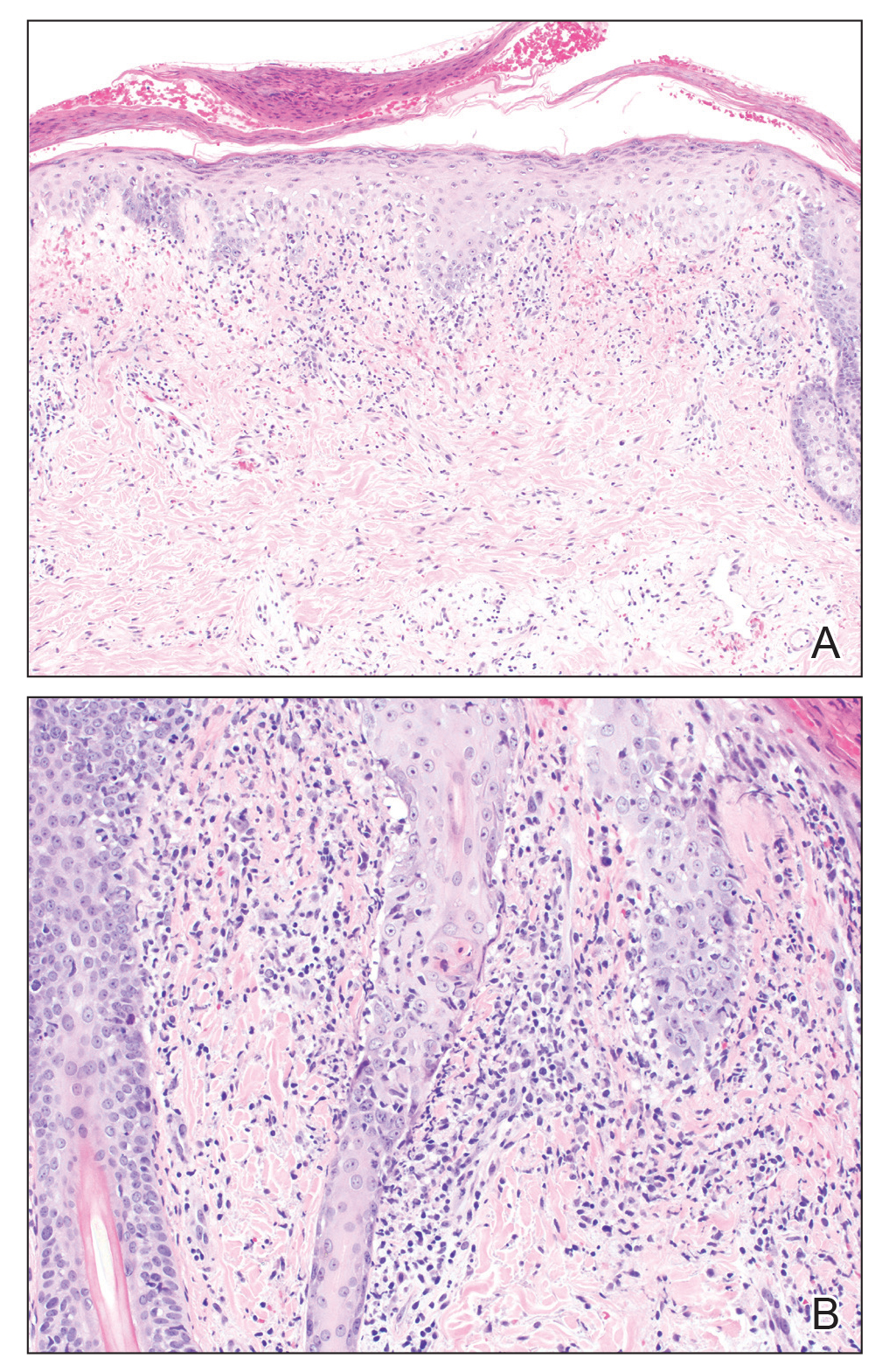

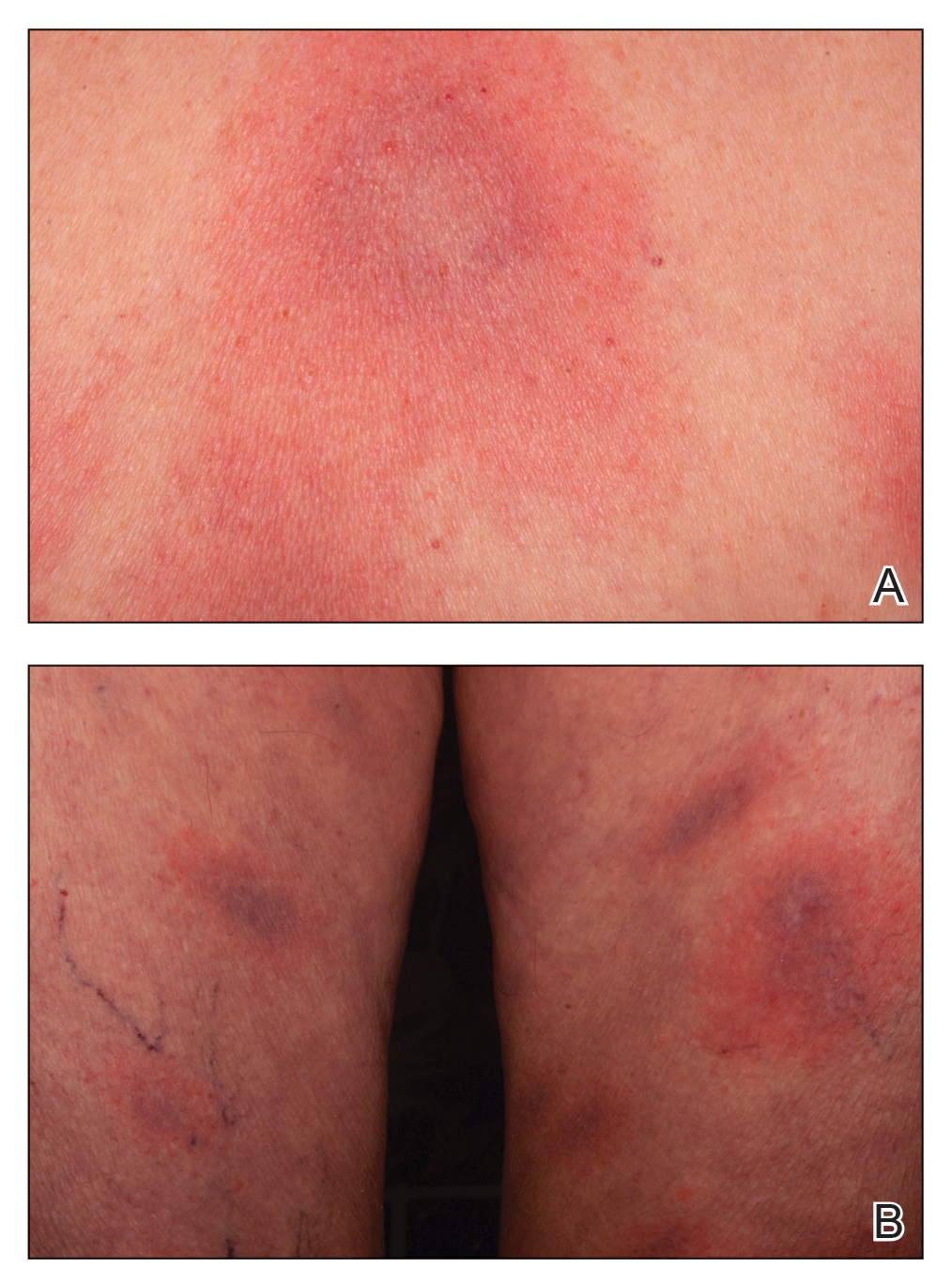

A skin biopsy from the left helix was obtained. Histopathologic examination revealed a vacuolar interface reaction with marked papillary dermal edema and a patchy perijunctional lymphocytic infiltrate. The dermis was free of increased mucin (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical staining for CD56 and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–encoded small nuclear RNA chromogenic in situ hybridization were negative. Laboratory workup was remarkable for elevated transaminases and inflammatory markers (eg, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate) but negative for rheumatologic markers (eg, antinuclear antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, myeloperoxidase antibodies, serine protease IgG). An extensive infectious workup was unrevealing. Computed tomography highlighted prominent lymphadenopathy throughout the cervical and supraclavicular chains and a large necrotic lymph node in the porta hepatis (Figure 2). Right neck lymph node aspiration revealed necrotizing lymphadenitis in a background of histiocytes and mixed lymphocytes. Coupling the clinical presentation and histomorphology with imaging, a diagnosis of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease (KD) was rendered.

Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease is a rare illness of unknown etiology characterized by cervical lymphadenopathy and fever. Originally described in Japan, KD affects all racial and ethnic groups1,2 but more commonly is seen in women and patients younger than 40 years.3 It can be associated with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and other autoimmune diseases (eg, relapsing polychondritis, adult-onset Still disease),3 and lymphoma.4 Multiple infections have been implicated in the pathogenesis of KD, including EBV and other human herpesviruses; HIV; human T-cell leukemia virus type 1; dengue virus; parvovirus B19; and Yersinia enterocolitica, Bartonella, Brucella, and Toxoplasma infections.3,5,6

Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease classically presents with fever and cervical lymphadenopathy. In a retrospective review of 244 patients with KD, the 3 most common manifestations included lymphadenopathy, fever, and rash.7 A diagnosis of KD is rendered based on clinical presentation and lymph node histopathologic findings of paracortical necrosis and florid histiocytic infiltrate.1

The cutaneous manifestations of KD are heterogeneous yet mostly transient. Cutaneous involvement is reported in 16.6% to 40% of patients.3,5,6 Common cutaneous manifestations include erythematous macules, papules, patches, and plaques; erosions, nodules, and bullae less commonly can occur.6 A variety of cutaneous manifestations have been reported in KD, including lesions mimicking pigmented purpuric dermatoses, vasculitis, Sweet syndrome, drug eruptions, and viral exanthems.6 Signs and symptoms of KD usually resolve within 1 to 4 months. Although there are no established treatments for this disease, patients with severe or persistent symptoms can be treated with steroids or hydroxychloroquine. Recurrences after treatment have been reported.8

Systemic lupus erythematosus is a multiorgan disease with protean manifestations. Cutaneous manifestations of SLE include malar erythema and discoid, annular, and papulosquamous lesions. Histopathologic patterns frequently observed in cutaneous lesions associated with SLE include interface dermatitis with perivascular infiltrates, dermal mucin, and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (marked by CD123 staining); these findings were notably absent in our case.6

Lupus vulgaris is a form of cutaneous tuberculosis that results from reactivation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in tubercles formed during preceding hematogenous dissemination. The head and neck region is the most common location, particularly the nose, cheeks, and earlobes. Small, brown-red, soft papules coalesce into gelatinous plaques, demonstrating a characteristic apple jelly appearance on diascopy. Other clinical manifestations include the plaque/plane, hypertrophic/tumorlike, and ulcerative/scarring forms.9 Delayed-type hypersensitivity testing by tuberculin skin test, interferon-gamma release assay, or polymerase chain reaction–based assays can detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Histopathology shows well-formed granulomas surrounded by chronic inflammatory cells and central necrosis.

Hydroa vacciniforme–like (HV-like) eruption is a rare photosensitive disorder characterized by vesiculopapules on sun-exposed areas. Hydroa vacciniforme–like eruptions rarely have been reported to progress to EBVassociated malignant lymphoma.10 Unlike typical hydroa vacciniforme, which resolves by early adulthood, HV-like eruptions can become more severe with age and are associated with systemic manifestations, including fevers, lymphadenopathy, and liver damage. Histopathologic examination reveals a dense infiltrate of atypical T lymphocytes or natural killer cells (CD56+), which stain positive for EBV-encoded small nuclear RNA,10 in contrast to the patchy perijunctional lymphocytic infiltrate seen in KD.

This case highlights the protean cutaneous manifestations of a rare rheumatologic entity. It demonstrates the importance of a full systemic workup when considering an enigmatic disease. Our patient was started on prednisone 20 mg and hydroxychloroquine 200 mg daily. Within 24 hours, the fevers and rash both improved.

- Turner RR, Martin J, Dorfman RF. Necrotizing lymphadenitis. a study of 30 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1983;7:115-123.

- Dorfman RF, Berry GJ. Kikuchi’s histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis: an analysis of 108 cases with emphasis on differential diagnosis. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1988;5:329-345.

- Atwater AR, Longley BJ, Aughenbaugh WD. Kikuchi’s disease: case report and systematic review of cutaneous and histopathologic presentations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:130-136.

- Yoshino T, Mannami T, Ichimura K, et al. Two cases of histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis (Kikuchi-Fujimoto’s disease) following diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:1328-1331.

- Yen A, Fearneyhough P, Raimer SS, et al. EBV-associated Kikuchi’s histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis with cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:342-346.

- Kim JH, Kim YB, In SI, et al. The cutaneous lesions of Kikuchi’s disease: a comprehensive analysis of 16 cases based on the clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and immunofluorescence studies with an emphasis on the differential diagnosis. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:1245-1254.

- Kucukardali Y, Solmazgul E, Kunter E, et al. Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease: analysis of 244 cases. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:50-54.

- Smith KG, Becker GJ, Busmanis I. Recurrent Kikuchi’s disease. Lancet. 1992;340:124.

- Macgregor R. Cutaneous tuberculosis. Clin Dermatol. 1995;13:245-255.

- Iwatsuki K, Ohtsuka M, Harada H, et al. Clinicopathologic manifestations of Epstein-Barr virus–associated cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1081-1086.

The Diagnosis: Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease

A skin biopsy from the left helix was obtained. Histopathologic examination revealed a vacuolar interface reaction with marked papillary dermal edema and a patchy perijunctional lymphocytic infiltrate. The dermis was free of increased mucin (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical staining for CD56 and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–encoded small nuclear RNA chromogenic in situ hybridization were negative. Laboratory workup was remarkable for elevated transaminases and inflammatory markers (eg, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate) but negative for rheumatologic markers (eg, antinuclear antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, myeloperoxidase antibodies, serine protease IgG). An extensive infectious workup was unrevealing. Computed tomography highlighted prominent lymphadenopathy throughout the cervical and supraclavicular chains and a large necrotic lymph node in the porta hepatis (Figure 2). Right neck lymph node aspiration revealed necrotizing lymphadenitis in a background of histiocytes and mixed lymphocytes. Coupling the clinical presentation and histomorphology with imaging, a diagnosis of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease (KD) was rendered.

Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease is a rare illness of unknown etiology characterized by cervical lymphadenopathy and fever. Originally described in Japan, KD affects all racial and ethnic groups1,2 but more commonly is seen in women and patients younger than 40 years.3 It can be associated with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and other autoimmune diseases (eg, relapsing polychondritis, adult-onset Still disease),3 and lymphoma.4 Multiple infections have been implicated in the pathogenesis of KD, including EBV and other human herpesviruses; HIV; human T-cell leukemia virus type 1; dengue virus; parvovirus B19; and Yersinia enterocolitica, Bartonella, Brucella, and Toxoplasma infections.3,5,6

Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease classically presents with fever and cervical lymphadenopathy. In a retrospective review of 244 patients with KD, the 3 most common manifestations included lymphadenopathy, fever, and rash.7 A diagnosis of KD is rendered based on clinical presentation and lymph node histopathologic findings of paracortical necrosis and florid histiocytic infiltrate.1

The cutaneous manifestations of KD are heterogeneous yet mostly transient. Cutaneous involvement is reported in 16.6% to 40% of patients.3,5,6 Common cutaneous manifestations include erythematous macules, papules, patches, and plaques; erosions, nodules, and bullae less commonly can occur.6 A variety of cutaneous manifestations have been reported in KD, including lesions mimicking pigmented purpuric dermatoses, vasculitis, Sweet syndrome, drug eruptions, and viral exanthems.6 Signs and symptoms of KD usually resolve within 1 to 4 months. Although there are no established treatments for this disease, patients with severe or persistent symptoms can be treated with steroids or hydroxychloroquine. Recurrences after treatment have been reported.8

Systemic lupus erythematosus is a multiorgan disease with protean manifestations. Cutaneous manifestations of SLE include malar erythema and discoid, annular, and papulosquamous lesions. Histopathologic patterns frequently observed in cutaneous lesions associated with SLE include interface dermatitis with perivascular infiltrates, dermal mucin, and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (marked by CD123 staining); these findings were notably absent in our case.6

Lupus vulgaris is a form of cutaneous tuberculosis that results from reactivation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in tubercles formed during preceding hematogenous dissemination. The head and neck region is the most common location, particularly the nose, cheeks, and earlobes. Small, brown-red, soft papules coalesce into gelatinous plaques, demonstrating a characteristic apple jelly appearance on diascopy. Other clinical manifestations include the plaque/plane, hypertrophic/tumorlike, and ulcerative/scarring forms.9 Delayed-type hypersensitivity testing by tuberculin skin test, interferon-gamma release assay, or polymerase chain reaction–based assays can detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Histopathology shows well-formed granulomas surrounded by chronic inflammatory cells and central necrosis.

Hydroa vacciniforme–like (HV-like) eruption is a rare photosensitive disorder characterized by vesiculopapules on sun-exposed areas. Hydroa vacciniforme–like eruptions rarely have been reported to progress to EBVassociated malignant lymphoma.10 Unlike typical hydroa vacciniforme, which resolves by early adulthood, HV-like eruptions can become more severe with age and are associated with systemic manifestations, including fevers, lymphadenopathy, and liver damage. Histopathologic examination reveals a dense infiltrate of atypical T lymphocytes or natural killer cells (CD56+), which stain positive for EBV-encoded small nuclear RNA,10 in contrast to the patchy perijunctional lymphocytic infiltrate seen in KD.

This case highlights the protean cutaneous manifestations of a rare rheumatologic entity. It demonstrates the importance of a full systemic workup when considering an enigmatic disease. Our patient was started on prednisone 20 mg and hydroxychloroquine 200 mg daily. Within 24 hours, the fevers and rash both improved.

The Diagnosis: Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease

A skin biopsy from the left helix was obtained. Histopathologic examination revealed a vacuolar interface reaction with marked papillary dermal edema and a patchy perijunctional lymphocytic infiltrate. The dermis was free of increased mucin (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical staining for CD56 and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–encoded small nuclear RNA chromogenic in situ hybridization were negative. Laboratory workup was remarkable for elevated transaminases and inflammatory markers (eg, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate) but negative for rheumatologic markers (eg, antinuclear antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, myeloperoxidase antibodies, serine protease IgG). An extensive infectious workup was unrevealing. Computed tomography highlighted prominent lymphadenopathy throughout the cervical and supraclavicular chains and a large necrotic lymph node in the porta hepatis (Figure 2). Right neck lymph node aspiration revealed necrotizing lymphadenitis in a background of histiocytes and mixed lymphocytes. Coupling the clinical presentation and histomorphology with imaging, a diagnosis of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease (KD) was rendered.

Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease is a rare illness of unknown etiology characterized by cervical lymphadenopathy and fever. Originally described in Japan, KD affects all racial and ethnic groups1,2 but more commonly is seen in women and patients younger than 40 years.3 It can be associated with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and other autoimmune diseases (eg, relapsing polychondritis, adult-onset Still disease),3 and lymphoma.4 Multiple infections have been implicated in the pathogenesis of KD, including EBV and other human herpesviruses; HIV; human T-cell leukemia virus type 1; dengue virus; parvovirus B19; and Yersinia enterocolitica, Bartonella, Brucella, and Toxoplasma infections.3,5,6

Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease classically presents with fever and cervical lymphadenopathy. In a retrospective review of 244 patients with KD, the 3 most common manifestations included lymphadenopathy, fever, and rash.7 A diagnosis of KD is rendered based on clinical presentation and lymph node histopathologic findings of paracortical necrosis and florid histiocytic infiltrate.1

The cutaneous manifestations of KD are heterogeneous yet mostly transient. Cutaneous involvement is reported in 16.6% to 40% of patients.3,5,6 Common cutaneous manifestations include erythematous macules, papules, patches, and plaques; erosions, nodules, and bullae less commonly can occur.6 A variety of cutaneous manifestations have been reported in KD, including lesions mimicking pigmented purpuric dermatoses, vasculitis, Sweet syndrome, drug eruptions, and viral exanthems.6 Signs and symptoms of KD usually resolve within 1 to 4 months. Although there are no established treatments for this disease, patients with severe or persistent symptoms can be treated with steroids or hydroxychloroquine. Recurrences after treatment have been reported.8

Systemic lupus erythematosus is a multiorgan disease with protean manifestations. Cutaneous manifestations of SLE include malar erythema and discoid, annular, and papulosquamous lesions. Histopathologic patterns frequently observed in cutaneous lesions associated with SLE include interface dermatitis with perivascular infiltrates, dermal mucin, and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (marked by CD123 staining); these findings were notably absent in our case.6

Lupus vulgaris is a form of cutaneous tuberculosis that results from reactivation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in tubercles formed during preceding hematogenous dissemination. The head and neck region is the most common location, particularly the nose, cheeks, and earlobes. Small, brown-red, soft papules coalesce into gelatinous plaques, demonstrating a characteristic apple jelly appearance on diascopy. Other clinical manifestations include the plaque/plane, hypertrophic/tumorlike, and ulcerative/scarring forms.9 Delayed-type hypersensitivity testing by tuberculin skin test, interferon-gamma release assay, or polymerase chain reaction–based assays can detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Histopathology shows well-formed granulomas surrounded by chronic inflammatory cells and central necrosis.

Hydroa vacciniforme–like (HV-like) eruption is a rare photosensitive disorder characterized by vesiculopapules on sun-exposed areas. Hydroa vacciniforme–like eruptions rarely have been reported to progress to EBVassociated malignant lymphoma.10 Unlike typical hydroa vacciniforme, which resolves by early adulthood, HV-like eruptions can become more severe with age and are associated with systemic manifestations, including fevers, lymphadenopathy, and liver damage. Histopathologic examination reveals a dense infiltrate of atypical T lymphocytes or natural killer cells (CD56+), which stain positive for EBV-encoded small nuclear RNA,10 in contrast to the patchy perijunctional lymphocytic infiltrate seen in KD.

This case highlights the protean cutaneous manifestations of a rare rheumatologic entity. It demonstrates the importance of a full systemic workup when considering an enigmatic disease. Our patient was started on prednisone 20 mg and hydroxychloroquine 200 mg daily. Within 24 hours, the fevers and rash both improved.

- Turner RR, Martin J, Dorfman RF. Necrotizing lymphadenitis. a study of 30 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1983;7:115-123.

- Dorfman RF, Berry GJ. Kikuchi’s histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis: an analysis of 108 cases with emphasis on differential diagnosis. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1988;5:329-345.

- Atwater AR, Longley BJ, Aughenbaugh WD. Kikuchi’s disease: case report and systematic review of cutaneous and histopathologic presentations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:130-136.

- Yoshino T, Mannami T, Ichimura K, et al. Two cases of histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis (Kikuchi-Fujimoto’s disease) following diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:1328-1331.

- Yen A, Fearneyhough P, Raimer SS, et al. EBV-associated Kikuchi’s histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis with cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:342-346.

- Kim JH, Kim YB, In SI, et al. The cutaneous lesions of Kikuchi’s disease: a comprehensive analysis of 16 cases based on the clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and immunofluorescence studies with an emphasis on the differential diagnosis. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:1245-1254.

- Kucukardali Y, Solmazgul E, Kunter E, et al. Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease: analysis of 244 cases. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:50-54.

- Smith KG, Becker GJ, Busmanis I. Recurrent Kikuchi’s disease. Lancet. 1992;340:124.

- Macgregor R. Cutaneous tuberculosis. Clin Dermatol. 1995;13:245-255.

- Iwatsuki K, Ohtsuka M, Harada H, et al. Clinicopathologic manifestations of Epstein-Barr virus–associated cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1081-1086.

- Turner RR, Martin J, Dorfman RF. Necrotizing lymphadenitis. a study of 30 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1983;7:115-123.

- Dorfman RF, Berry GJ. Kikuchi’s histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis: an analysis of 108 cases with emphasis on differential diagnosis. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1988;5:329-345.

- Atwater AR, Longley BJ, Aughenbaugh WD. Kikuchi’s disease: case report and systematic review of cutaneous and histopathologic presentations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:130-136.

- Yoshino T, Mannami T, Ichimura K, et al. Two cases of histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis (Kikuchi-Fujimoto’s disease) following diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:1328-1331.

- Yen A, Fearneyhough P, Raimer SS, et al. EBV-associated Kikuchi’s histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis with cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:342-346.

- Kim JH, Kim YB, In SI, et al. The cutaneous lesions of Kikuchi’s disease: a comprehensive analysis of 16 cases based on the clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and immunofluorescence studies with an emphasis on the differential diagnosis. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:1245-1254.

- Kucukardali Y, Solmazgul E, Kunter E, et al. Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease: analysis of 244 cases. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:50-54.

- Smith KG, Becker GJ, Busmanis I. Recurrent Kikuchi’s disease. Lancet. 1992;340:124.

- Macgregor R. Cutaneous tuberculosis. Clin Dermatol. 1995;13:245-255.

- Iwatsuki K, Ohtsuka M, Harada H, et al. Clinicopathologic manifestations of Epstein-Barr virus–associated cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1081-1086.

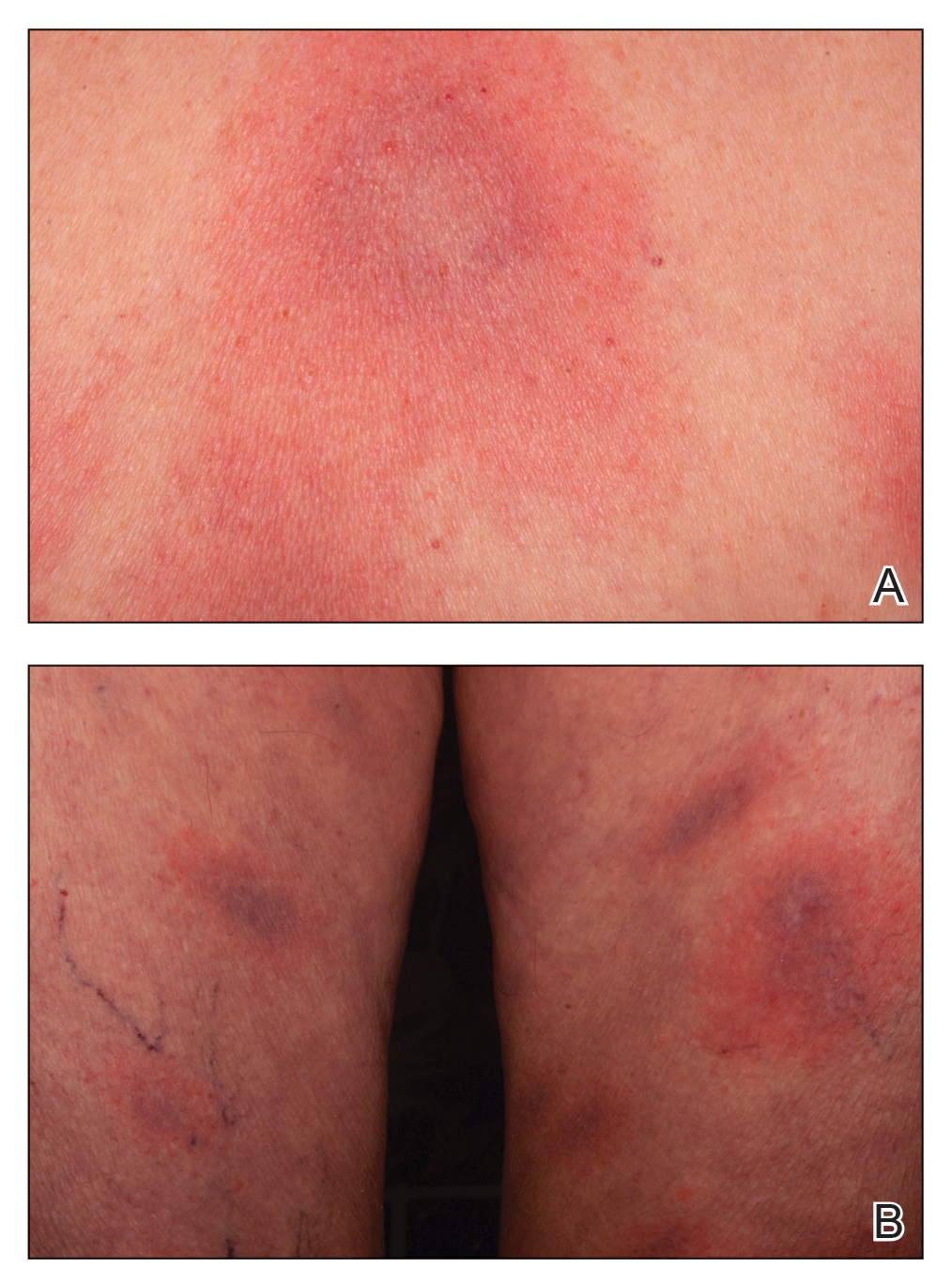

A healthy 42-year-old Japanese man presented with painful lymphadenopathy and fevers of 1 month’s duration as well as a pruritic rash and bilateral ear redness and crusting of 1 week’s duration. He initially was seen at an outside facility and was treated with antibiotics and supportive care for cervical adenitis. During clinical evaluation, he denied joint pain, photosensitivity, and oral lesions. His medical and family history were noncontributory. Although he reported recent travel to multiple countries, he denied exposure to animals, ticks, or sick individuals. Physical examination revealed erythematous blanching papules on the nose and cheeks (top) as well as crusted papules coalescing into plaques on the bilateral helices and lobules (bottom).

Thick Hyperkeratotic Plaques on the Palms and Soles

The Diagnosis: Keratoderma Climactericum

Keratoderma climactericum was first reported in 1934 by Haxthausen1 as nonpruritic circumscribed hyperkeratosis located mainly on the palms and soles. The initial eruption was described as discrete lesions with an oval or round shape that progressed to less-defined, confluent, hyperkeratotic patches with fissures.1 Keratoderma climactericum also may be referred to as Haxthausen disease and is considered an acquired palmoplantar keratoderma.2

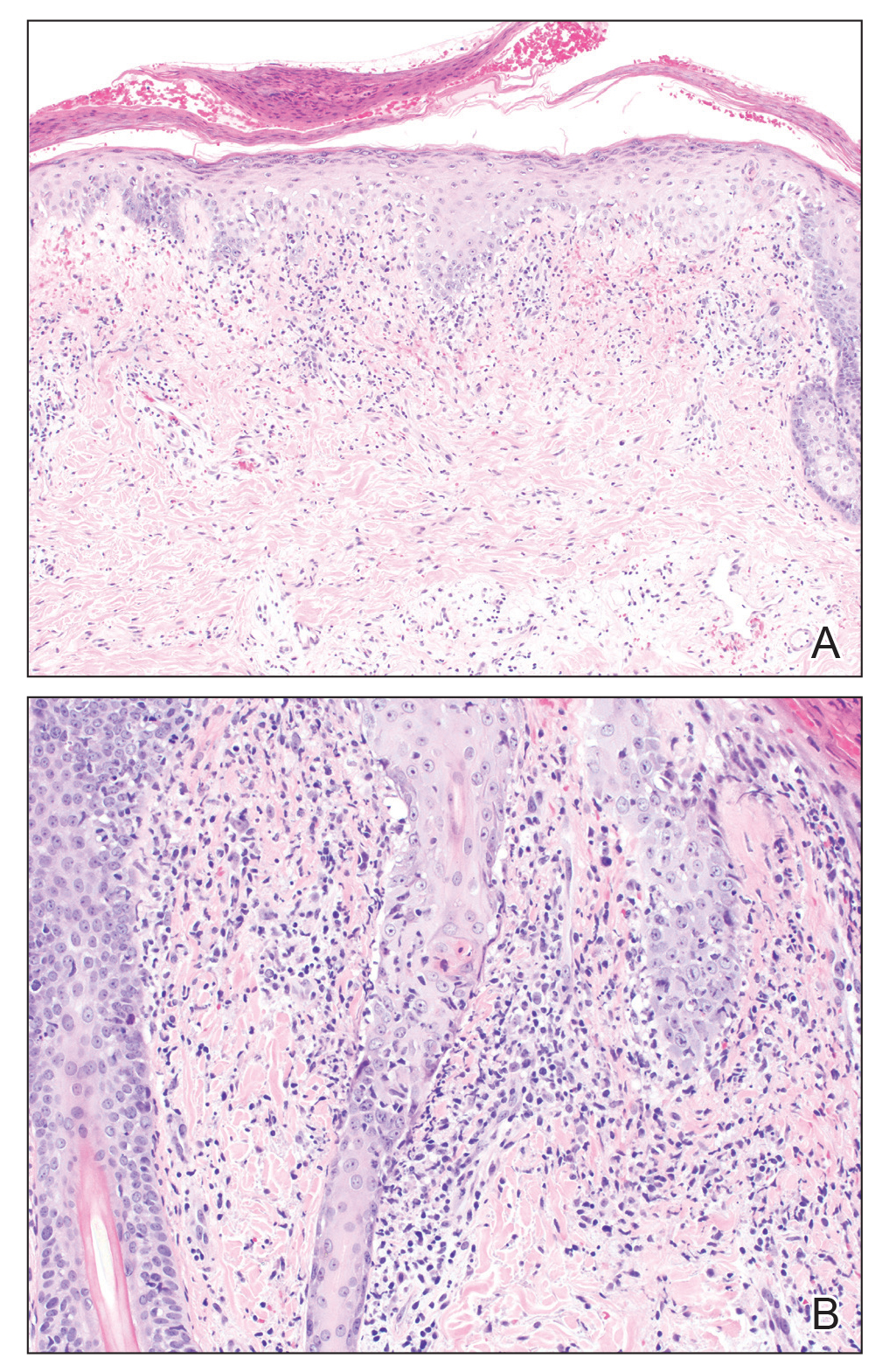

Keratoderma climactericum is a rare dermatologic disorder that presents in women of menopausal age who have no family or personal history of skin disease. Keratoderma climactericum is associated with hypertension and obesity.2 Keratotic lesions usually first occur on the plantar surfaces with eventual development of fissuring and hyperkeratosis that causes painful walking. The keratotic lesions on the plantar surfaces often are nonpruritic and gradually become confluent over time. As the disease progresses, keratotic lesions appear on the central palms, which can lead to confluent hyperkeratosis on the palmar surfaces (Figure 1).2 The exact mechanism of keratoderma climactericum has not been described but is believed to be due to hormonal dysregulation.2

In 1986, Deschamps et al3 presented 10 cases of keratoderma climactericum occurring in menopausal women with an average age of 57 years. The lesions began on the soles at areas of greatest pressure. Histopathology for each patient showed orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis, irregular hyperplasia, interpapillary ridges, and exocytosis of lymphocytes in the epidermis. Seven patients were treated with etretinate, which first led to the removal of palmar lesions, followed by improvement in plantar lesions and pain when walking. There was no association of keratoderma climactericum and sex hormones, as hormone levels were negative or normal for each patient.3

Three cases of keratoderma climactericum following bilateral oophorectomy in young women were reported by Wachtel4 in 1981. Unlike in women of menopausal age, there was no association of keratoderma climactericum with hypertension or obesity. Additionally, the lesions on the palms and soles were more diffusely distributed than in women of menopausal age. Estrogen administration completely reversed each patient's hyperkeratotic palms and soles.4 A definitive pathogenic role of estrogens in the development of keratoderma climactericum has yet to be determined.2

Histopathology is not specific for keratoderma climactericum, making the disease a clinical diagnosis. However, a biopsy may be useful to rule out palmoplantar psoriasis.2 Clinical information such as the age and sex of the patient, distribution of disease, presence of fissuring, and progression of disease from soles to palms should be considered when making a diagnosis of keratoderma climactericum. The differential diagnosis of keratoderma climactericum should include fungal infections, contact dermatitis, irritant dermatitis, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, underlying malignancy, and pityriasis rubra pilaris.

Treatment options for keratoderma climactericum include salicylic acid, emollients, oral retinoids, urea ointments, estriol cream, and topical steroids.5,6 Our patient was prescribed acitretin 25 mg daily and ammonium lactate to apply topically as needed for dry skin. Five months after the initial presentation, fissures and dry skin on the bilateral soles were still present. Ammonium lactate was discontinued, and the patient was prescribed urea cream 40%. Fifteen months after the initial presentation, the patient reported substantial improvement on the hands and feet and noted that she no longer needed the urea cream. Physical examination revealed no presence of hyperkeratosis or fissuring on the palms (Figure 2), and mild hyperkeratosis was present on the plantar surfaces of the feet (Figure 3). The patient continued to use acitretin to prevent disease relapse.

Keratoderma climactericum is an unusual and debilitating condition that occurs in women of menopausal age. It is diagnosed by its specific clinical presentation. More common diagnoses such as tinea and dermatitis should be ruled out before considering keratoderma climactericum.

- Haxthausen H. Keratoderma climactericum. Br J Dermatol. 1934;46:161-167.

- Patel S, Zirwas M, English JC. Acquired palmoplantar keratoderma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2007;8:1-11.

- Deschamps P, Leroy D, Pedailles S, et al. Keratoderma climactericum (Haxthausen's disease): clinical signs, laboratory findings and etretinate treatment in 10 patients. Dermatologica. 1986;172:258-262.

- Wachtel TJ. Plantar and palmar hyperkeratosis in young castrated women. Int J Dermatol. 1981;20:270-271.

- Bristow I. The management of heel fissures using a steroid impregnated tape (Haelan) in a patient with Keratoderma climactericum. Podiatry Now. 2008;11:22-23.

- Mendes-Bastos P. Plantar keratoderma climactericum: successful improvement with a topical estriol cream. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;17:811-813.

The Diagnosis: Keratoderma Climactericum

Keratoderma climactericum was first reported in 1934 by Haxthausen1 as nonpruritic circumscribed hyperkeratosis located mainly on the palms and soles. The initial eruption was described as discrete lesions with an oval or round shape that progressed to less-defined, confluent, hyperkeratotic patches with fissures.1 Keratoderma climactericum also may be referred to as Haxthausen disease and is considered an acquired palmoplantar keratoderma.2

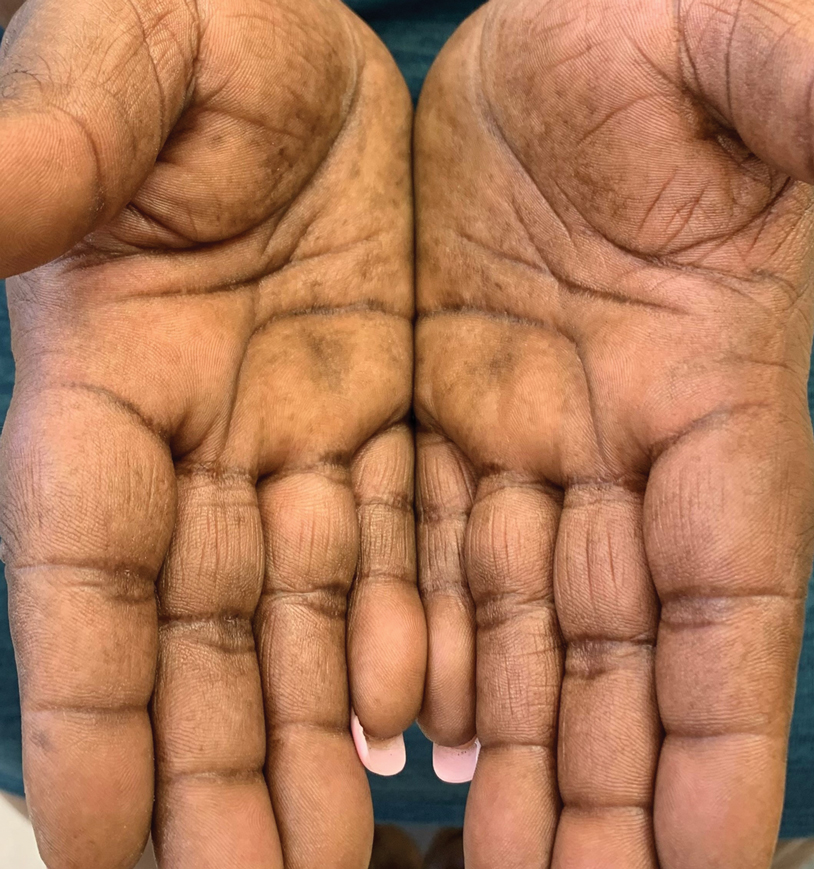

Keratoderma climactericum is a rare dermatologic disorder that presents in women of menopausal age who have no family or personal history of skin disease. Keratoderma climactericum is associated with hypertension and obesity.2 Keratotic lesions usually first occur on the plantar surfaces with eventual development of fissuring and hyperkeratosis that causes painful walking. The keratotic lesions on the plantar surfaces often are nonpruritic and gradually become confluent over time. As the disease progresses, keratotic lesions appear on the central palms, which can lead to confluent hyperkeratosis on the palmar surfaces (Figure 1).2 The exact mechanism of keratoderma climactericum has not been described but is believed to be due to hormonal dysregulation.2

In 1986, Deschamps et al3 presented 10 cases of keratoderma climactericum occurring in menopausal women with an average age of 57 years. The lesions began on the soles at areas of greatest pressure. Histopathology for each patient showed orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis, irregular hyperplasia, interpapillary ridges, and exocytosis of lymphocytes in the epidermis. Seven patients were treated with etretinate, which first led to the removal of palmar lesions, followed by improvement in plantar lesions and pain when walking. There was no association of keratoderma climactericum and sex hormones, as hormone levels were negative or normal for each patient.3

Three cases of keratoderma climactericum following bilateral oophorectomy in young women were reported by Wachtel4 in 1981. Unlike in women of menopausal age, there was no association of keratoderma climactericum with hypertension or obesity. Additionally, the lesions on the palms and soles were more diffusely distributed than in women of menopausal age. Estrogen administration completely reversed each patient's hyperkeratotic palms and soles.4 A definitive pathogenic role of estrogens in the development of keratoderma climactericum has yet to be determined.2

Histopathology is not specific for keratoderma climactericum, making the disease a clinical diagnosis. However, a biopsy may be useful to rule out palmoplantar psoriasis.2 Clinical information such as the age and sex of the patient, distribution of disease, presence of fissuring, and progression of disease from soles to palms should be considered when making a diagnosis of keratoderma climactericum. The differential diagnosis of keratoderma climactericum should include fungal infections, contact dermatitis, irritant dermatitis, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, underlying malignancy, and pityriasis rubra pilaris.

Treatment options for keratoderma climactericum include salicylic acid, emollients, oral retinoids, urea ointments, estriol cream, and topical steroids.5,6 Our patient was prescribed acitretin 25 mg daily and ammonium lactate to apply topically as needed for dry skin. Five months after the initial presentation, fissures and dry skin on the bilateral soles were still present. Ammonium lactate was discontinued, and the patient was prescribed urea cream 40%. Fifteen months after the initial presentation, the patient reported substantial improvement on the hands and feet and noted that she no longer needed the urea cream. Physical examination revealed no presence of hyperkeratosis or fissuring on the palms (Figure 2), and mild hyperkeratosis was present on the plantar surfaces of the feet (Figure 3). The patient continued to use acitretin to prevent disease relapse.

Keratoderma climactericum is an unusual and debilitating condition that occurs in women of menopausal age. It is diagnosed by its specific clinical presentation. More common diagnoses such as tinea and dermatitis should be ruled out before considering keratoderma climactericum.

The Diagnosis: Keratoderma Climactericum

Keratoderma climactericum was first reported in 1934 by Haxthausen1 as nonpruritic circumscribed hyperkeratosis located mainly on the palms and soles. The initial eruption was described as discrete lesions with an oval or round shape that progressed to less-defined, confluent, hyperkeratotic patches with fissures.1 Keratoderma climactericum also may be referred to as Haxthausen disease and is considered an acquired palmoplantar keratoderma.2

Keratoderma climactericum is a rare dermatologic disorder that presents in women of menopausal age who have no family or personal history of skin disease. Keratoderma climactericum is associated with hypertension and obesity.2 Keratotic lesions usually first occur on the plantar surfaces with eventual development of fissuring and hyperkeratosis that causes painful walking. The keratotic lesions on the plantar surfaces often are nonpruritic and gradually become confluent over time. As the disease progresses, keratotic lesions appear on the central palms, which can lead to confluent hyperkeratosis on the palmar surfaces (Figure 1).2 The exact mechanism of keratoderma climactericum has not been described but is believed to be due to hormonal dysregulation.2

In 1986, Deschamps et al3 presented 10 cases of keratoderma climactericum occurring in menopausal women with an average age of 57 years. The lesions began on the soles at areas of greatest pressure. Histopathology for each patient showed orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis, irregular hyperplasia, interpapillary ridges, and exocytosis of lymphocytes in the epidermis. Seven patients were treated with etretinate, which first led to the removal of palmar lesions, followed by improvement in plantar lesions and pain when walking. There was no association of keratoderma climactericum and sex hormones, as hormone levels were negative or normal for each patient.3

Three cases of keratoderma climactericum following bilateral oophorectomy in young women were reported by Wachtel4 in 1981. Unlike in women of menopausal age, there was no association of keratoderma climactericum with hypertension or obesity. Additionally, the lesions on the palms and soles were more diffusely distributed than in women of menopausal age. Estrogen administration completely reversed each patient's hyperkeratotic palms and soles.4 A definitive pathogenic role of estrogens in the development of keratoderma climactericum has yet to be determined.2

Histopathology is not specific for keratoderma climactericum, making the disease a clinical diagnosis. However, a biopsy may be useful to rule out palmoplantar psoriasis.2 Clinical information such as the age and sex of the patient, distribution of disease, presence of fissuring, and progression of disease from soles to palms should be considered when making a diagnosis of keratoderma climactericum. The differential diagnosis of keratoderma climactericum should include fungal infections, contact dermatitis, irritant dermatitis, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, underlying malignancy, and pityriasis rubra pilaris.

Treatment options for keratoderma climactericum include salicylic acid, emollients, oral retinoids, urea ointments, estriol cream, and topical steroids.5,6 Our patient was prescribed acitretin 25 mg daily and ammonium lactate to apply topically as needed for dry skin. Five months after the initial presentation, fissures and dry skin on the bilateral soles were still present. Ammonium lactate was discontinued, and the patient was prescribed urea cream 40%. Fifteen months after the initial presentation, the patient reported substantial improvement on the hands and feet and noted that she no longer needed the urea cream. Physical examination revealed no presence of hyperkeratosis or fissuring on the palms (Figure 2), and mild hyperkeratosis was present on the plantar surfaces of the feet (Figure 3). The patient continued to use acitretin to prevent disease relapse.

Keratoderma climactericum is an unusual and debilitating condition that occurs in women of menopausal age. It is diagnosed by its specific clinical presentation. More common diagnoses such as tinea and dermatitis should be ruled out before considering keratoderma climactericum.

- Haxthausen H. Keratoderma climactericum. Br J Dermatol. 1934;46:161-167.

- Patel S, Zirwas M, English JC. Acquired palmoplantar keratoderma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2007;8:1-11.

- Deschamps P, Leroy D, Pedailles S, et al. Keratoderma climactericum (Haxthausen's disease): clinical signs, laboratory findings and etretinate treatment in 10 patients. Dermatologica. 1986;172:258-262.

- Wachtel TJ. Plantar and palmar hyperkeratosis in young castrated women. Int J Dermatol. 1981;20:270-271.

- Bristow I. The management of heel fissures using a steroid impregnated tape (Haelan) in a patient with Keratoderma climactericum. Podiatry Now. 2008;11:22-23.

- Mendes-Bastos P. Plantar keratoderma climactericum: successful improvement with a topical estriol cream. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;17:811-813.

- Haxthausen H. Keratoderma climactericum. Br J Dermatol. 1934;46:161-167.

- Patel S, Zirwas M, English JC. Acquired palmoplantar keratoderma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2007;8:1-11.

- Deschamps P, Leroy D, Pedailles S, et al. Keratoderma climactericum (Haxthausen's disease): clinical signs, laboratory findings and etretinate treatment in 10 patients. Dermatologica. 1986;172:258-262.

- Wachtel TJ. Plantar and palmar hyperkeratosis in young castrated women. Int J Dermatol. 1981;20:270-271.

- Bristow I. The management of heel fissures using a steroid impregnated tape (Haelan) in a patient with Keratoderma climactericum. Podiatry Now. 2008;11:22-23.

- Mendes-Bastos P. Plantar keratoderma climactericum: successful improvement with a topical estriol cream. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;17:811-813.

A 52-year-old woman with a history of rheumatoid arthritis presented with a rash on the palms and soles of 7 years' duration that started around the onset of menopause. Physical examination revealed thick hyperkeratotic plaques with multiple deep fissures on the palms and soles. The patient's current medications included methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis. She previously had been prescribed adalimumab by an outside physician for the rash, which provided no relief, and currently was using urea ointment, which caused a burning sensation on the palms and soles. The patient denied a personal or family history of psoriasis.

Hyperkeratotic Nummular Plaques on the Upper Trunk

The Diagnosis: Extragenital Lichen Sclerosus Et Atrophicus

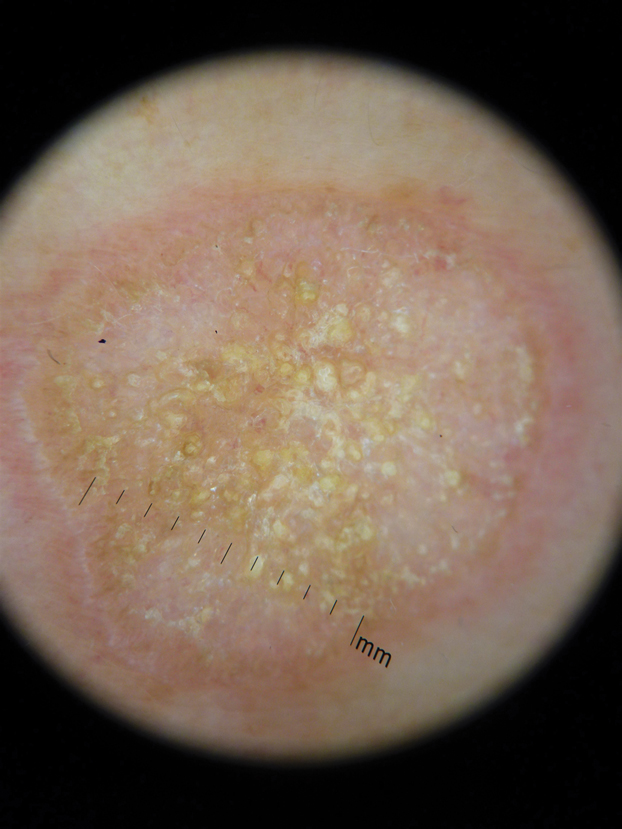

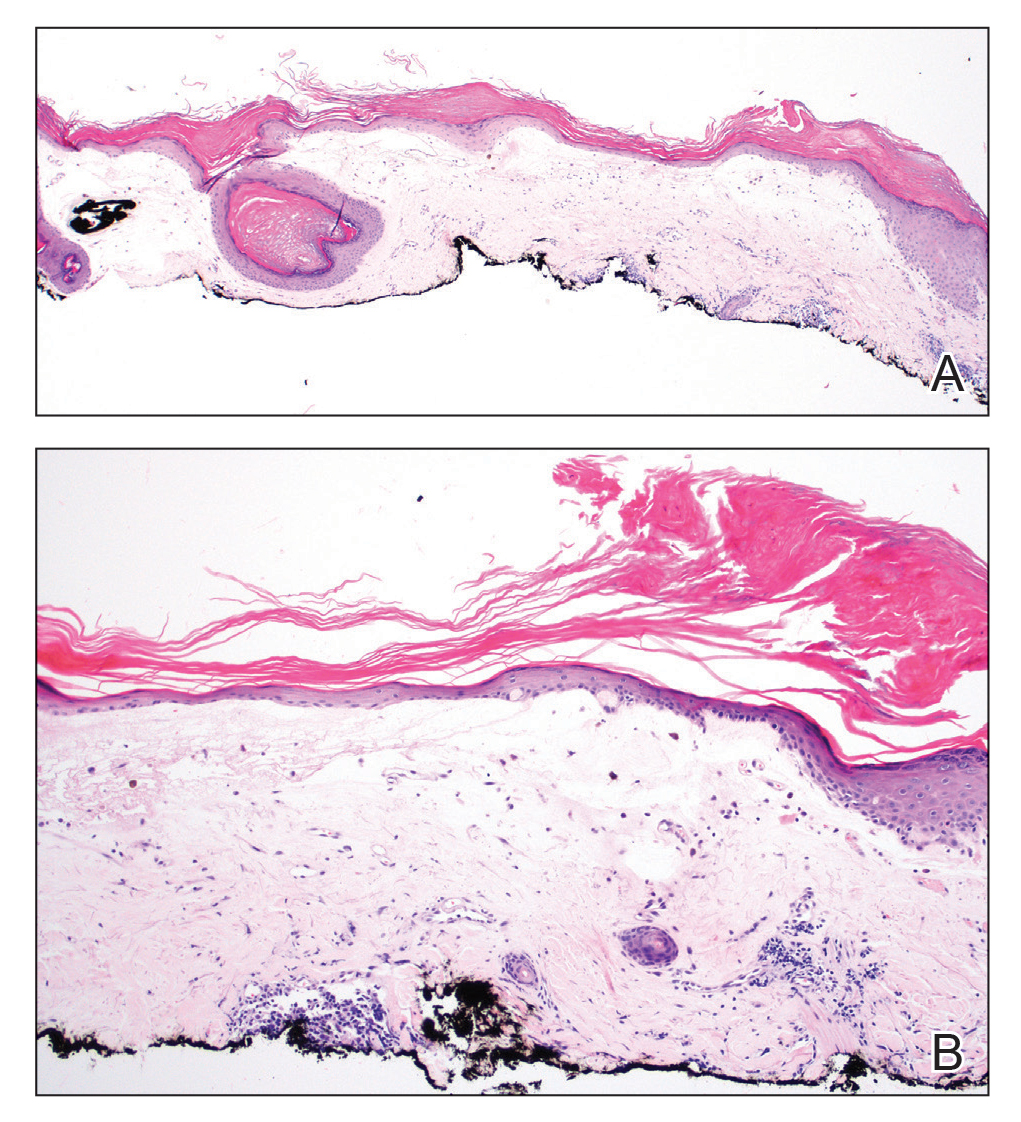

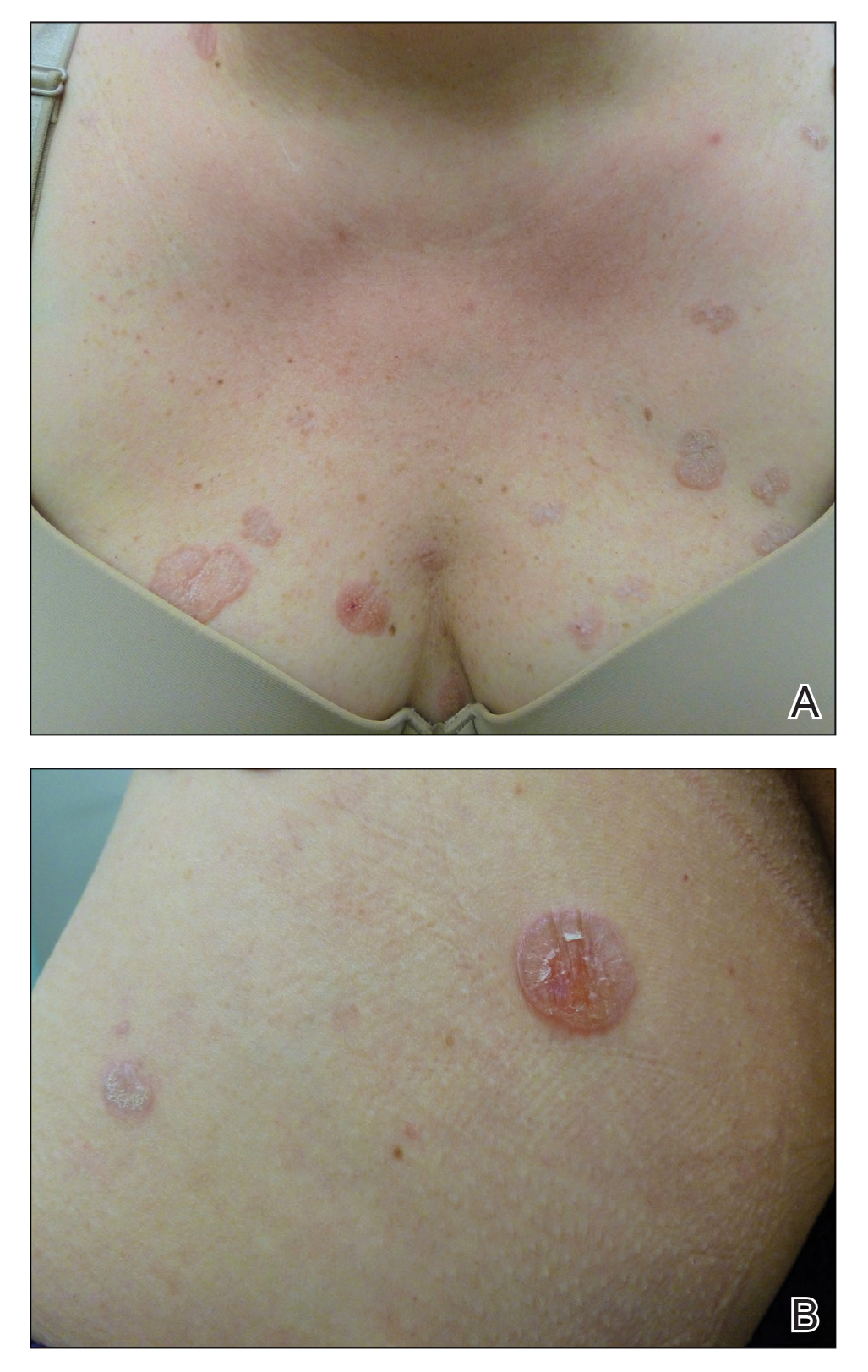

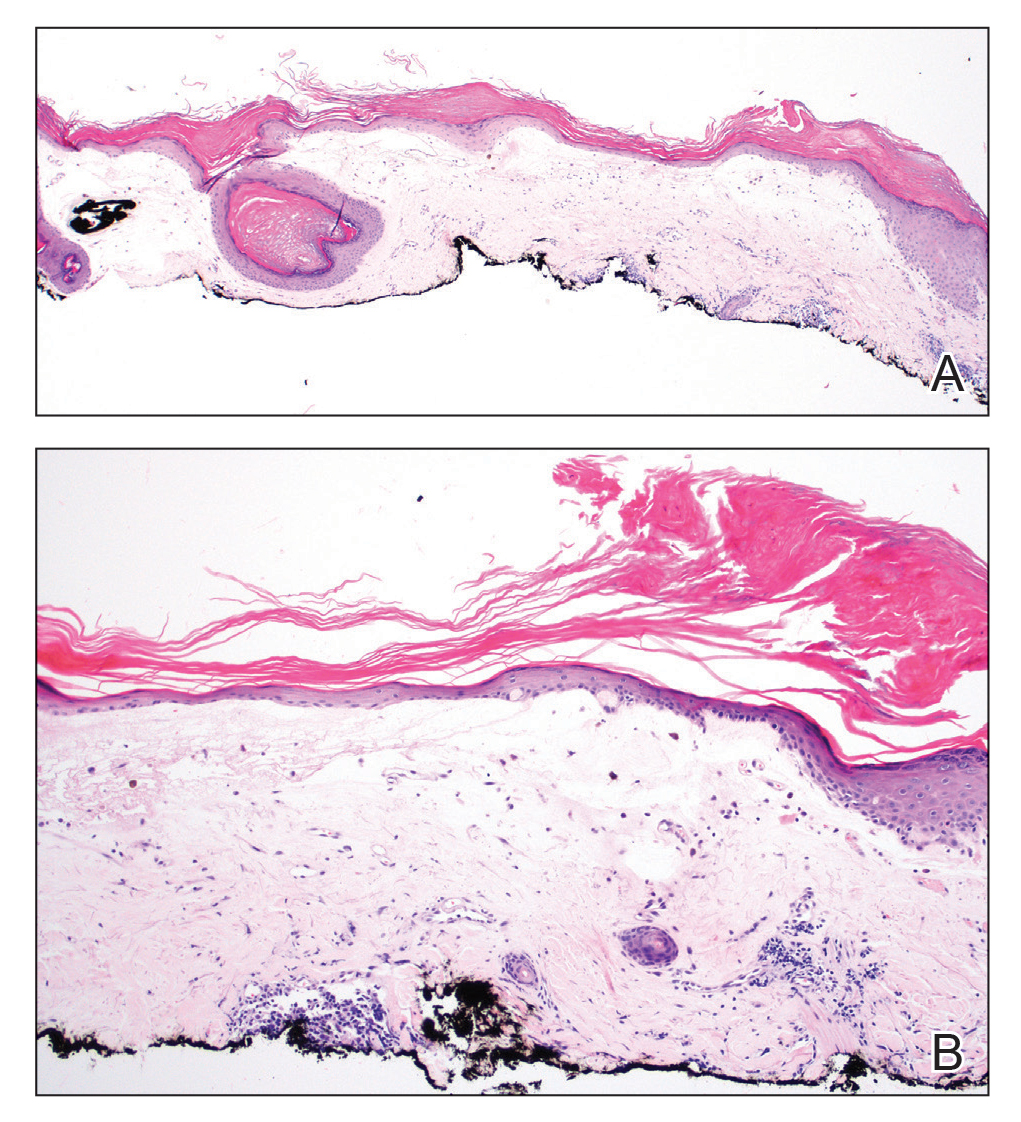

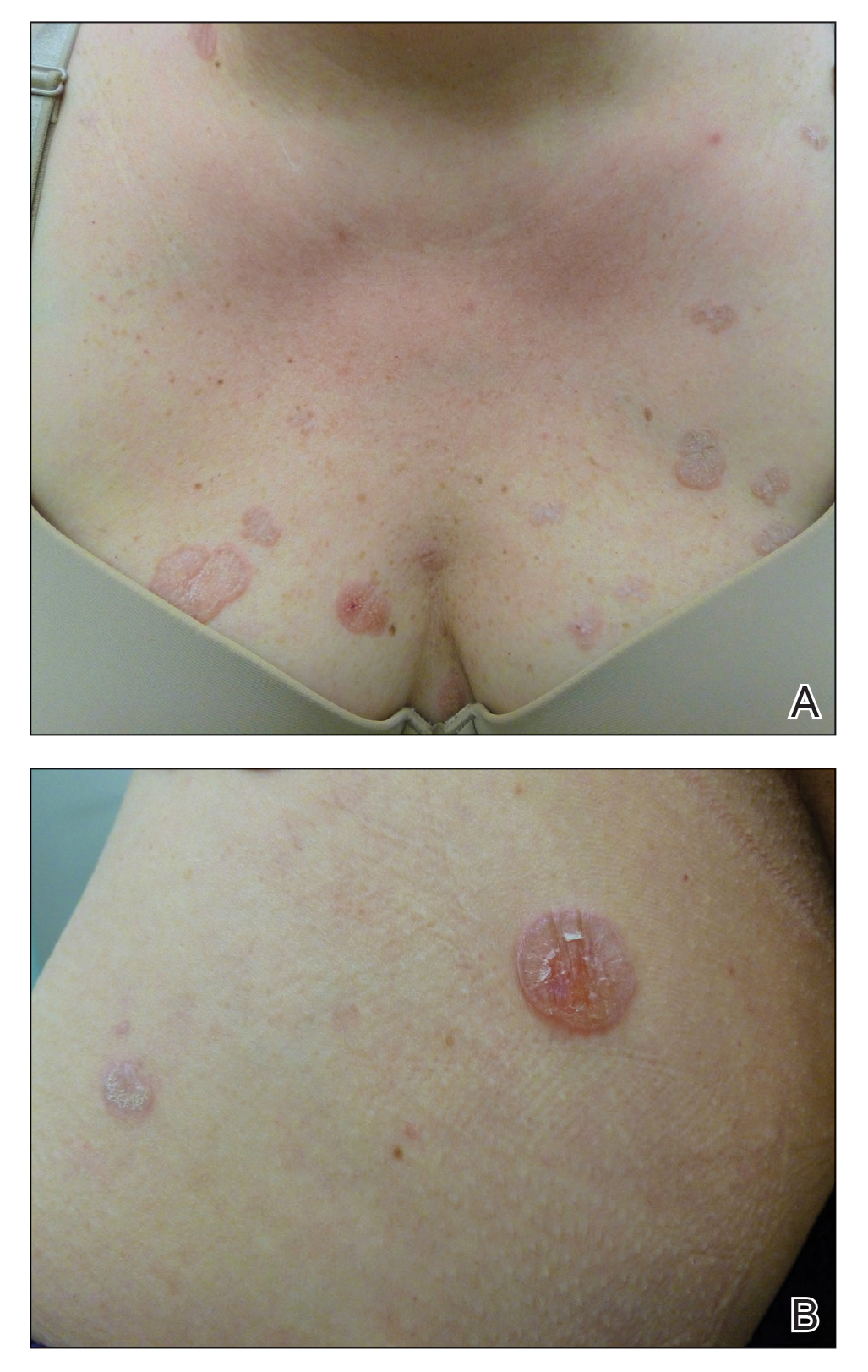

Histopathologic evaluation revealed hyperkeratosis, follicular plugging, epidermal atrophy, and homogenization of papillary dermal collagen with an underlying lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence of a plaque with a superimposed bulla was negative for deposition of C3, IgG, IgA, IgM, or fibrinogen. Accordingly, clinicopathologic correlation supported a diagnosis of extragenital lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LSA). Of note, the patient's history of genital irritation was due to genital LSA that preceded the extragenital manifestations.

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is an inflammatory dermatosis that typically presents as atrophic white papules of the anogenital area that coalesce into pruritic plaques; the exact etiology remains to be elucidated, yet various circulating autoantibodies have been identified, suggesting a role for autoimmunity.1,2 Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is more common in women than in men, with a bimodal peak in the age of onset affecting postmenopausal and prepubertal populations.1 In women, affected areas include the labia minora and majora, clitoris, perineum, and perianal skin; LSA spares the mucosal surfaces of the vagina and cervix.2 In men, uncircumscribed genital skin more commonly is affected. Involvement is localized to the foreskin and glans with occasional urethral involvement.2

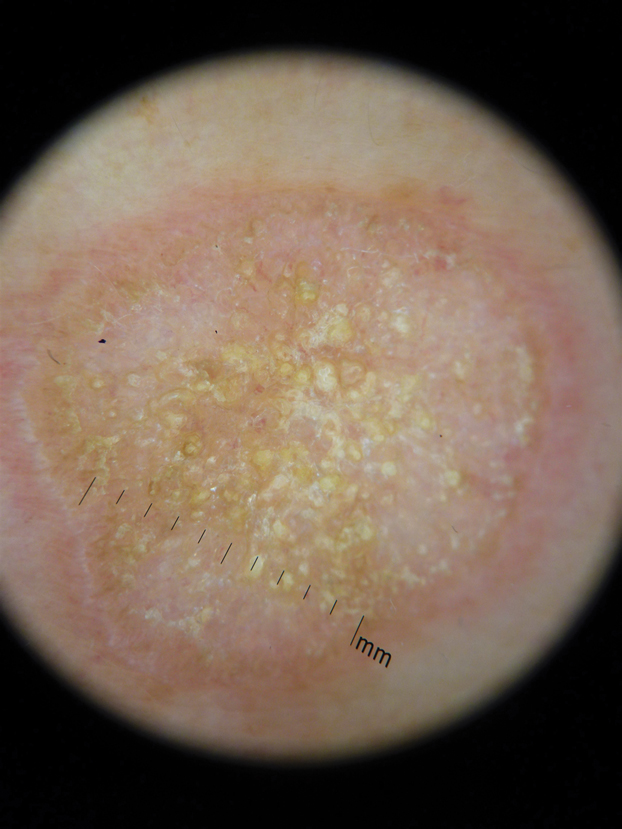

In contrast, extragenital LSA tends to present as asymptomatic papules and plaques that develop atrophy with time, involving the back, shoulders, neck, chest, thighs, axillae, and flexural wrists2,3; an erythematous rim often is present,4 and hyperkeratosis with follicular plugging may be prominent.5 Our patient's case emphasizes the predilection of plaques for the chest and intermammary skin (Figure 2A). Approximately 15% of LSA cases have extragenital involvement, and extragenital-limited disease accounts for roughly 5% of cases.6,7 Unlike genital LSA, extragenital disease has not been associated with an increased risk for squamous cell carcinoma.1 Bullae formation within plaques of genital or extragenital LSA has been reported3,8 and is exemplified in our patient (Figure 2B). Intralesional bullae formation likely is due to a combination of internal and external factors, mainly the inability to withstand shear forces due to an atrophic epidermis with basal vacuolar injury overlying an edematous papillary dermis with altered collagen.8 Dermatoscopic findings may aid in recognizing extragenital LSA9,10; our patient's plaques demonstrated the characteristic findings of comedolike openings, structureless white areas, and pink borders (Figure 3).

The clinical differential diagnosis for well-demarcated, pink, scaly plaques is broad. Nummular eczema usually presents as coin-shaped eczematous plaques on the dorsal aspects of the hands or lower extremities, and histology shows epidermal spongiosis.11 Nummular eczema may be considered due to the striking round morphology of various plaques, yet our patient's presentation was better served by a consideration of several papulosquamous disorders.

Lichen planus (LP) presents as intensely pruritic, violaceous, polygonal, flat-topped papules with overlying reticular white lines, or Wickham striae, that favor the flexural wrists, lower back, and lower extremities. Lichen planus also may have oral and genital mucosal involvement. Similar to LSA, LP is more common in women and preferentially affects the postmenopausal population.12 Additionally, hypertrophic LP may obscure Wickham striae and mimic extragenital LSA; distinguishing features of hypertrophic LP are intense pruritus and a predilection for the shins. Histology is defined by orthohyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, sawtooth acanthosis, and vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer with Civatte bodies or dyskeratotic basal keratinocytes overlying a characteristic bandlike infiltrate of lymphocytes.12

Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) is characterized by intense pruritus and presents as hyperkeratotic plaques with a predilection for accessible regions such as the posterior neck and extremities.13 The striking annular demarcation of this case makes LSC unlikely. Comparable to LSA and LP, LSC also may present with both genital and extragenital findings. Histology of LSC is characterized by irregular acanthosis or thickening of the epidermis with vertical streaking of collagen and vascular bundles of the papillary dermis.13

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) is important to consider for a new papulosquamous eruption with a predilection for the sun-exposed skin of a middle-aged woman. The presence of papules on the volar wrist and history of genital irritation, however, make this entity less likely. Similar to LSA, histologic examination of SCLE reveals epidermal atrophy, basal layer degeneration, and papillary dermal edema with lymphocytic inflammation. However, SCLE lacks the band of inflammation underlying pale homogenized papillary dermal collagen, the most distinguishing feature of LSA; instead, SCLE shows superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytes and mucin in the dermis.14

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus may be chronic and progressive in nature or cycle through remissions and relapses.2 Treatment is not curative, and management is directed to alleviating symptoms and preventing the progression of disease. First-line management of extragenital LSA is potent topical steroids.1 Adjuvant topical calcineurin inhibitors may be used as steroid-sparing agents.2 Phototherapy is a second-line therapy and even narrowband UVB phototherapy has demonstrated efficacy in managing extragenital LSA.15,16 Our patient was started on mometasone ointment and calcipotriene cream with slight improvement after a 6-month trial. Ongoing management is focused on optimizing application of topical therapies.

- Powell JJ, Wojnarowska F. Lichen sclerosus. Lancet. 1999;353:1777-1783.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:27-47.

- Meffert JJ, Davis BM, Grimwood RE. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:393-416.

- Surkan M, Hull P. A case of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus with distinct erythematous borders. J Cutan Med Surg. 2015;19:600-603.

- Kimura A, Kambe N, Satoh T, et al. Follicular keratosis and bullous formation are typical signs of extragenital lichen sclerosus. J Dermatol. 2011;38:834-836.

- Meyrick Thomas RH, Ridley CM, McGibbon DH, et al. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus and autoimmunity: a study of 350 women. Br J Dermatol. 1988;118:41-46.

- Wallace HJ. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc. 1971;57:9-30.

- Hallel-Halevy D, Grunwald MH, Yerushalmi J, et al. Bullous lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:500-501.

- Garrido-Ríos AA, Álvarez-Garrido H, Sanz-Muñoz C, et al. Dermoscopy of extragenital lichen sclerosus. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1468.