User login

Pitted Depressions on the Hands and Elbows

The Diagnosis: Bazex‐Dupré‐Christol Syndrome

Bazex‐Dupré‐Christol syndrome (BDCS) is a rare X-linked dominant genodermatosis characterized by a triad of hypotrichosis, follicular atrophoderma, and multiple basal cell carcinomas (BCCs). Since first being described in 1964,1 there have been fewer than 200 reported cases of BDCS.2 Although a causative gene has not yet been identified, the mutation has been mapped to an 11.4-Mb interval in the Xq25-27.1 region of the X chromosome.3

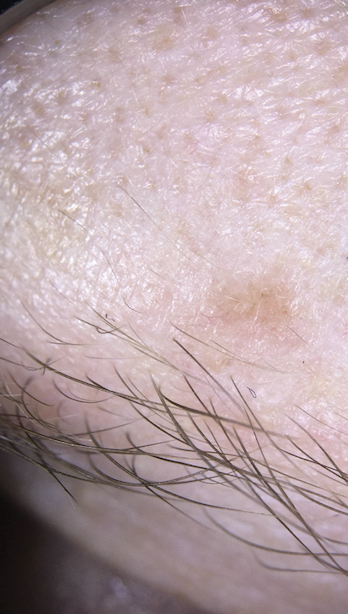

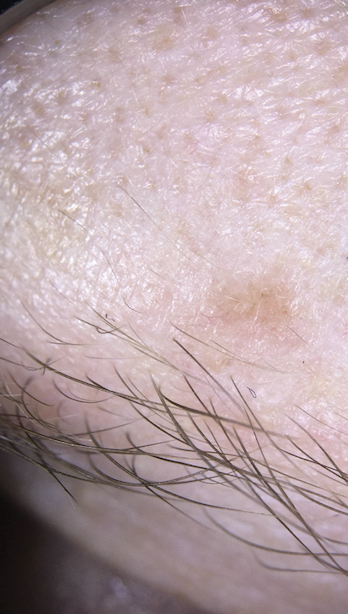

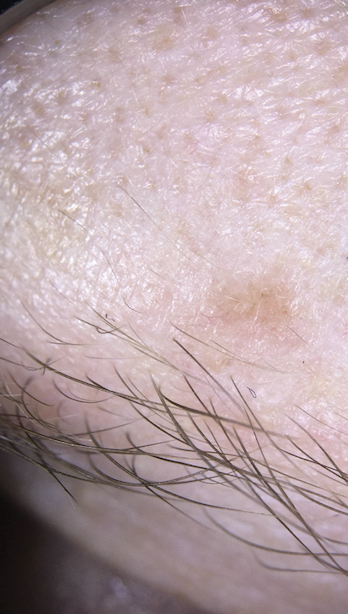

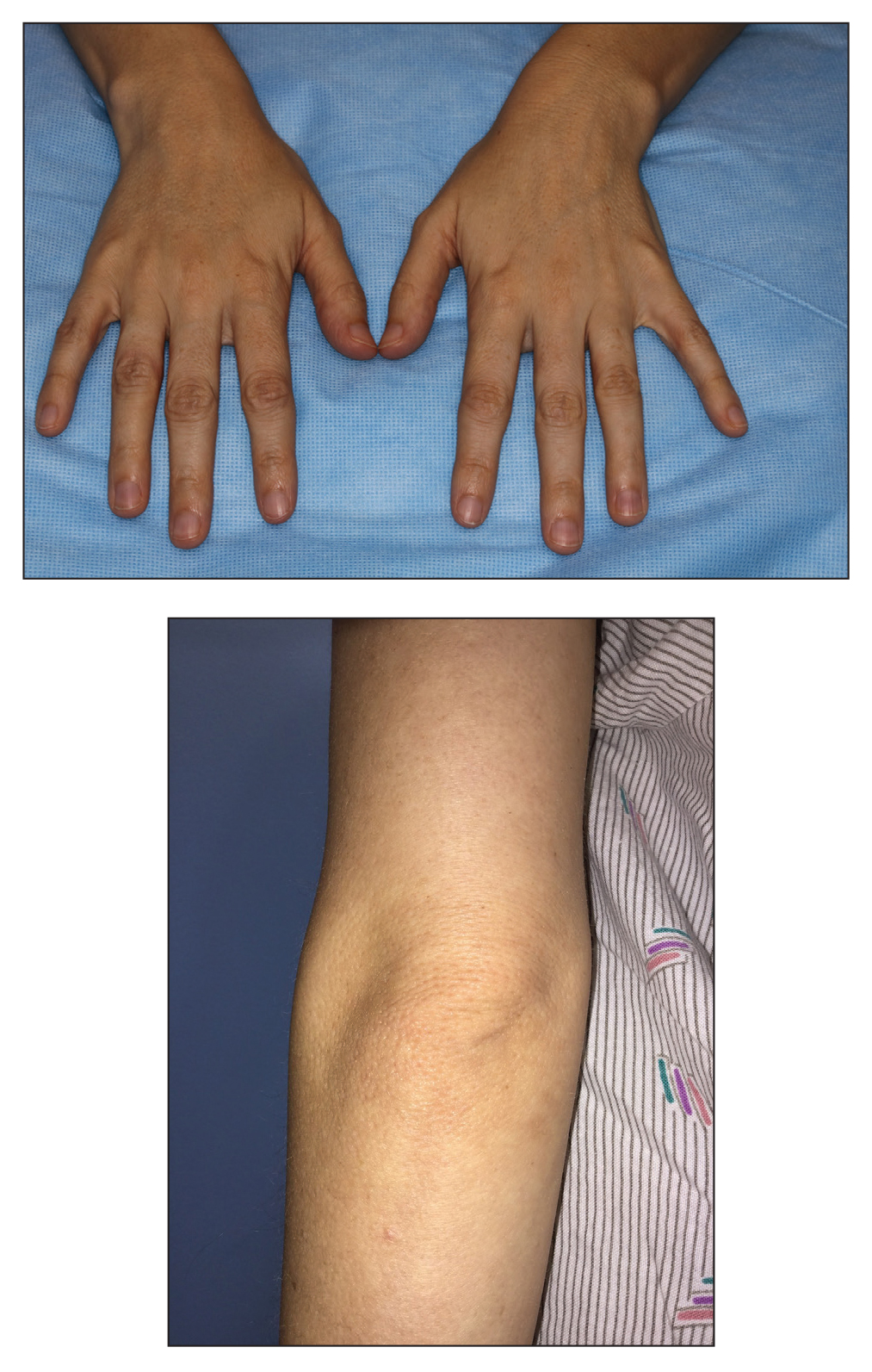

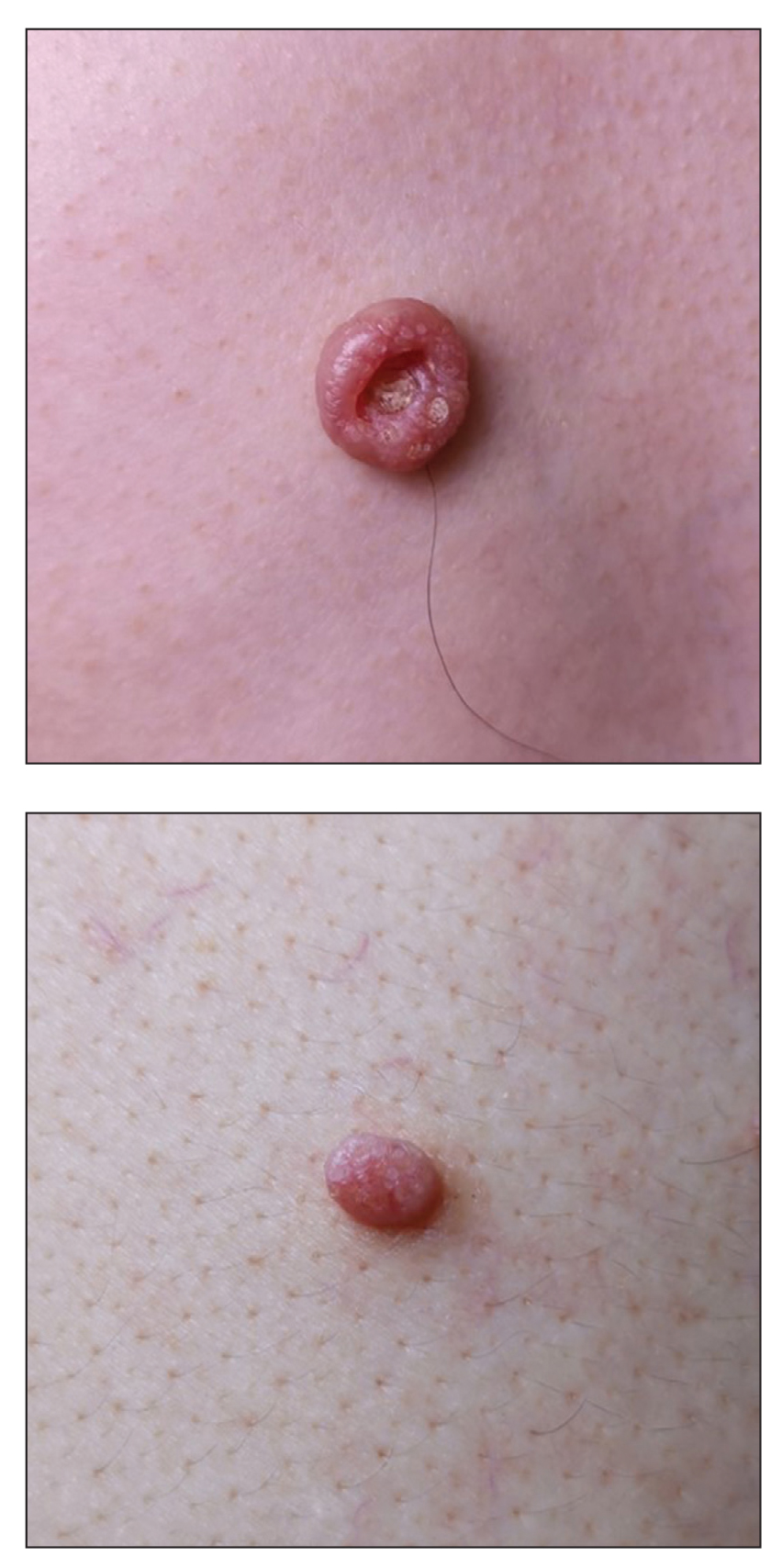

Classically, congenital hypotrichosis is the first observed symptom and can present shortly after birth.4 It typically is widespread, though sometimes it may be confined to the eyebrows, eyelashes, and scalp. Follicular atrophoderma, which occurs due to a laxation and deepening of the follicular ostia, is seen in 80% of cases and typically presents in early childhood as depressions lacking hair.2 It commonly is found on the face, extensor surfaces of the elbows and knees, and dorsal aspects of the hands and feet. Physical examination of our patient revealed follicular atrophoderma on both the dorsal surfaces of the hands and the extensor surfaces of the elbows. Hair shaft anomalies including pili torti, pili bifurcati, and trichorrhexis nodosa are infrequently observed symptoms of BDCS.2

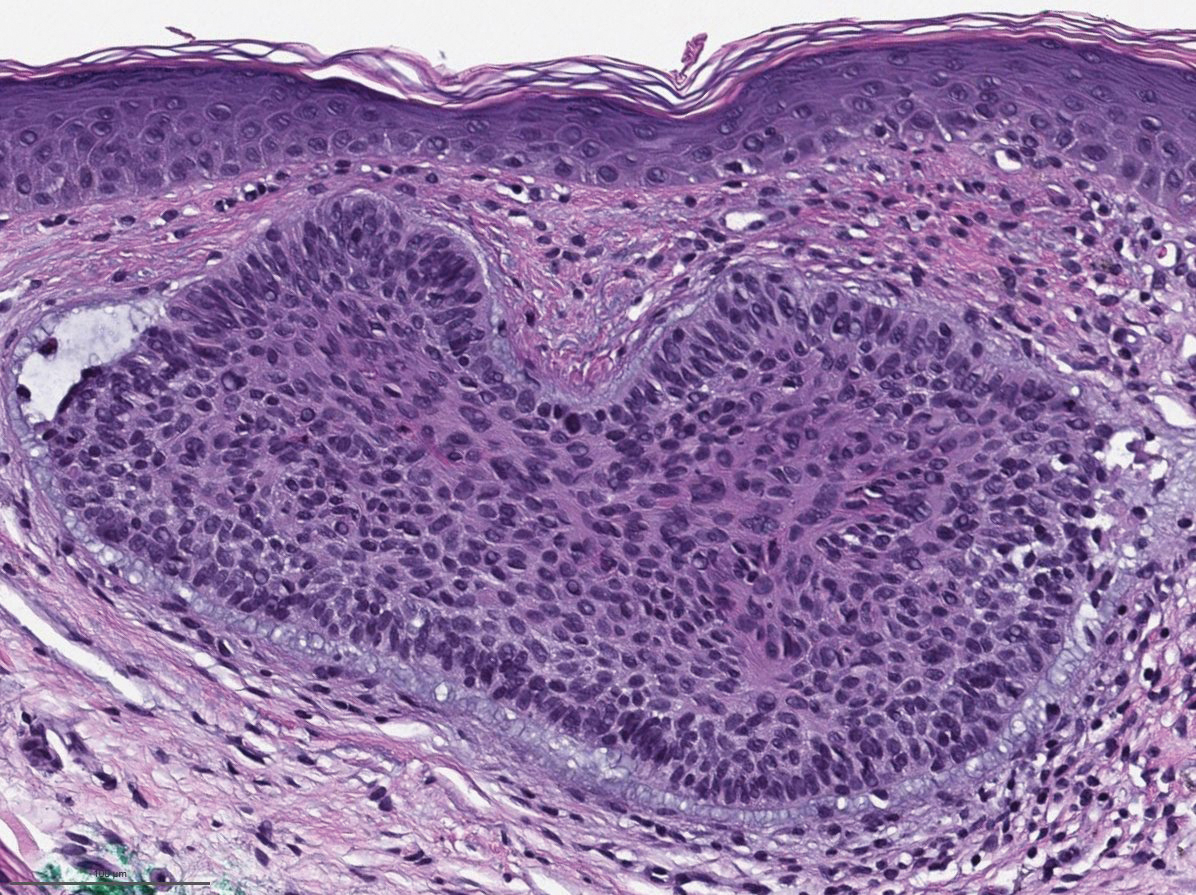

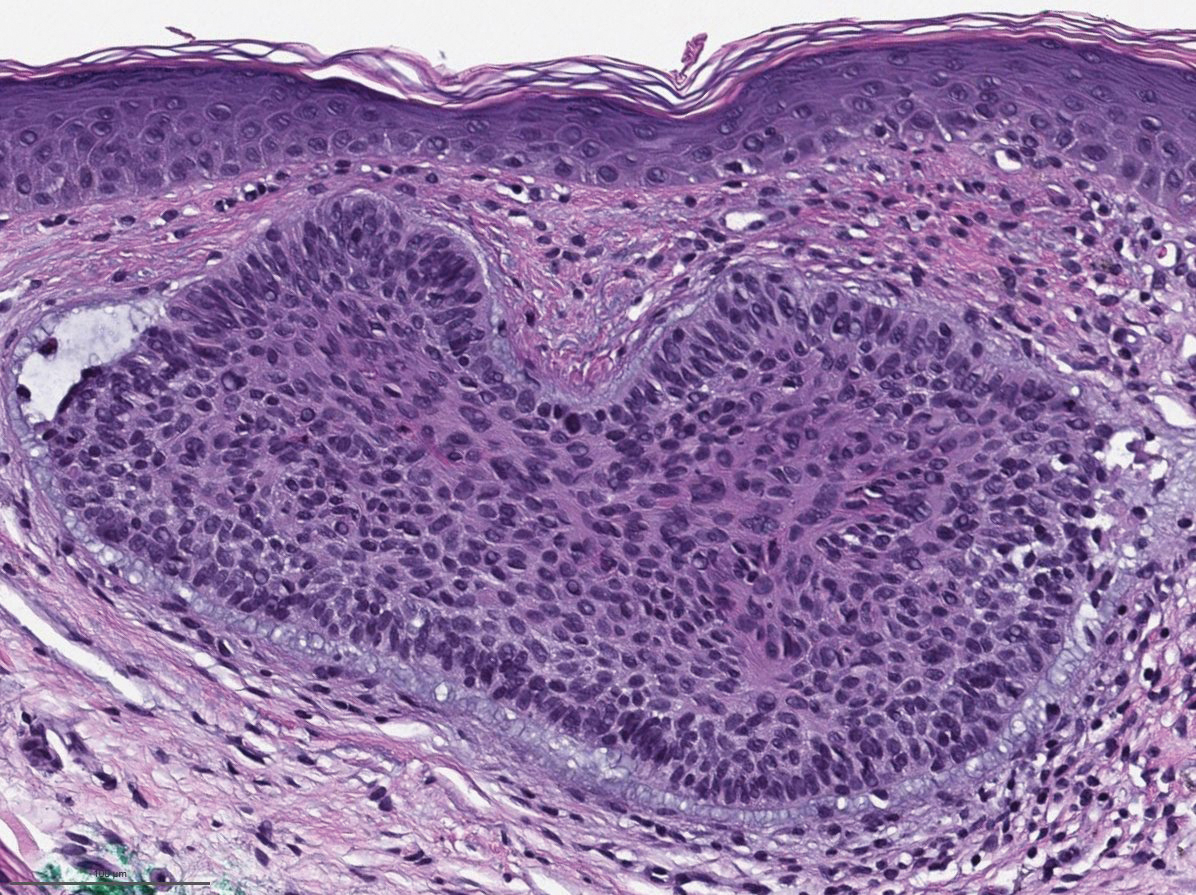

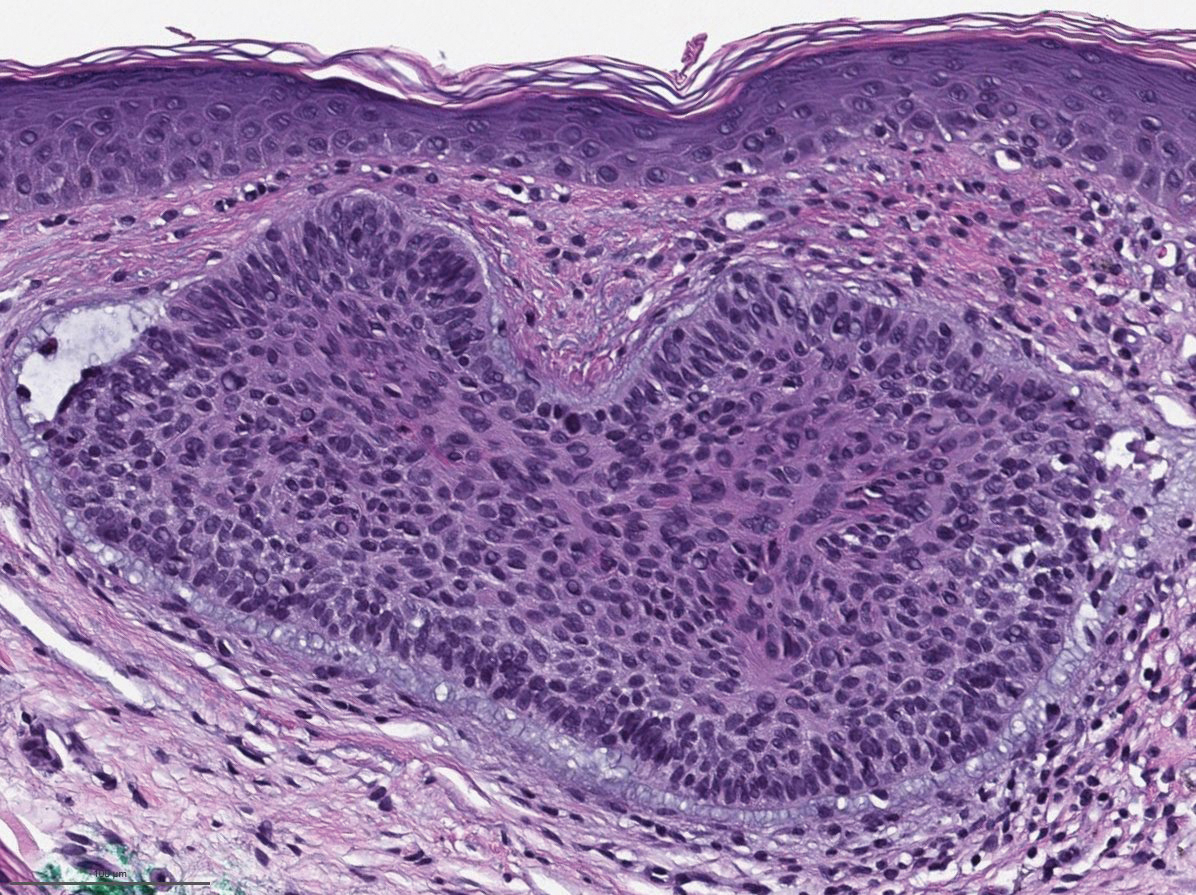

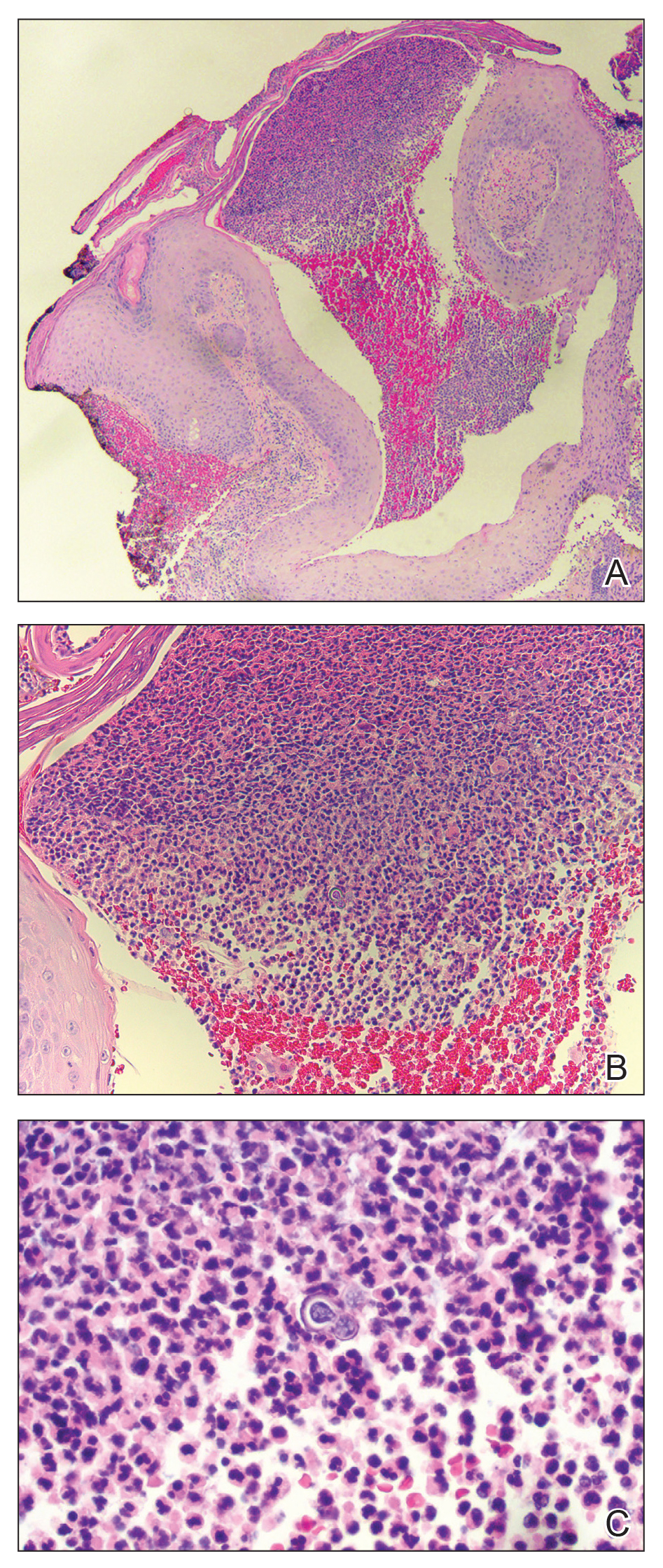

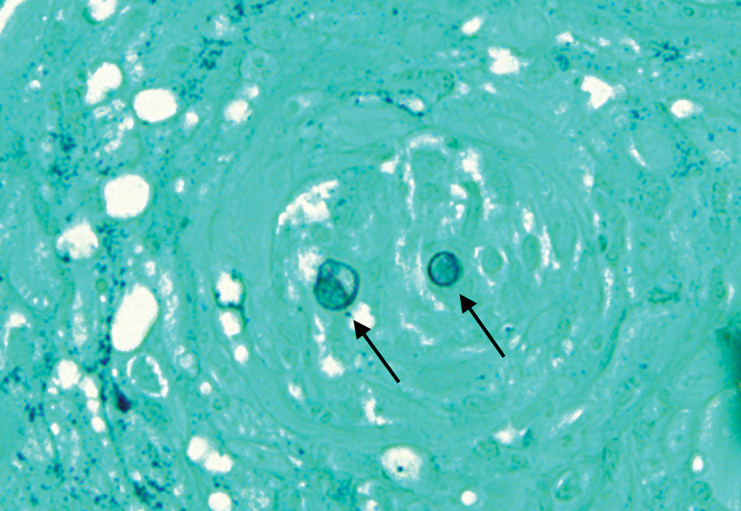

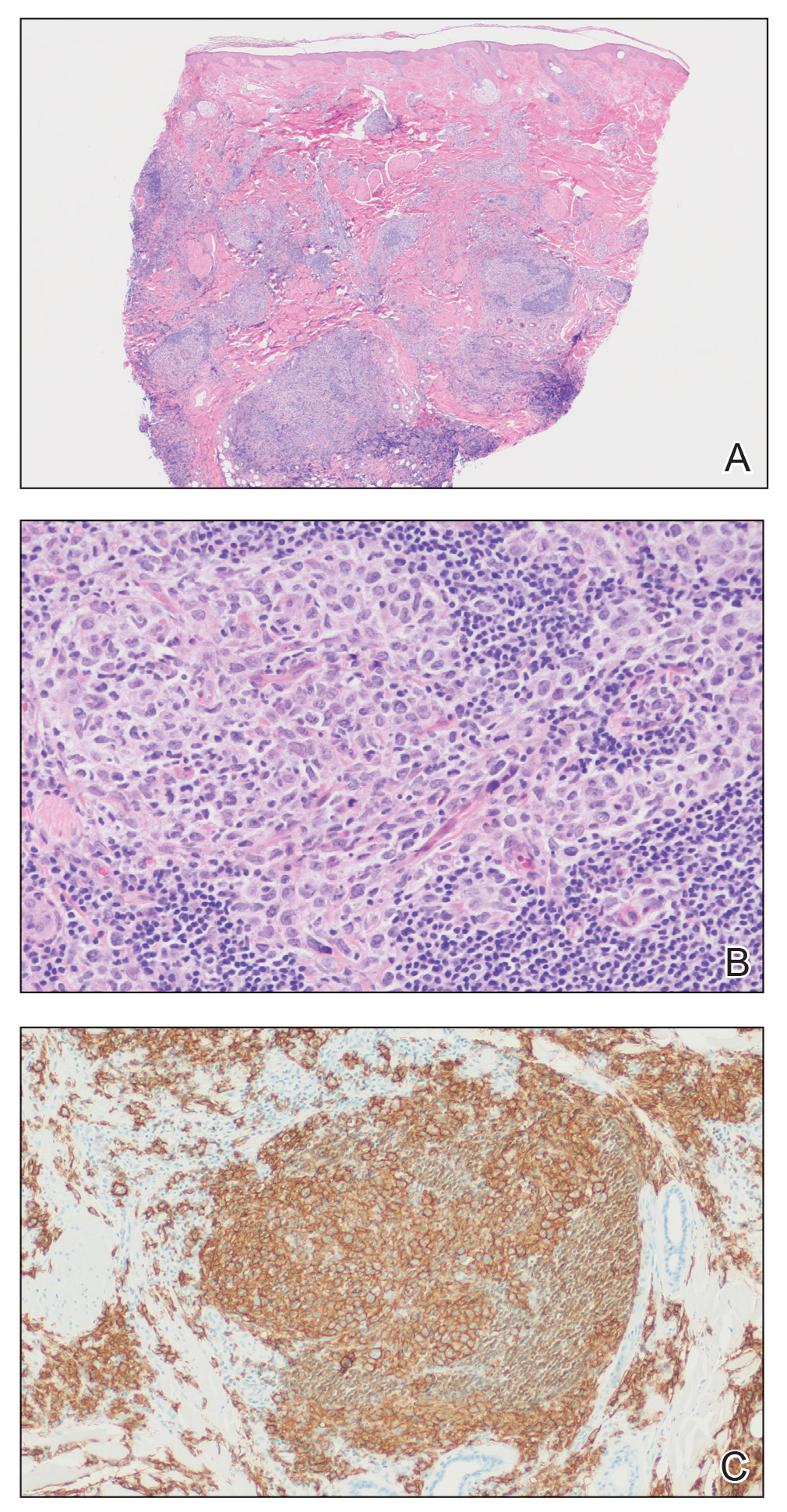

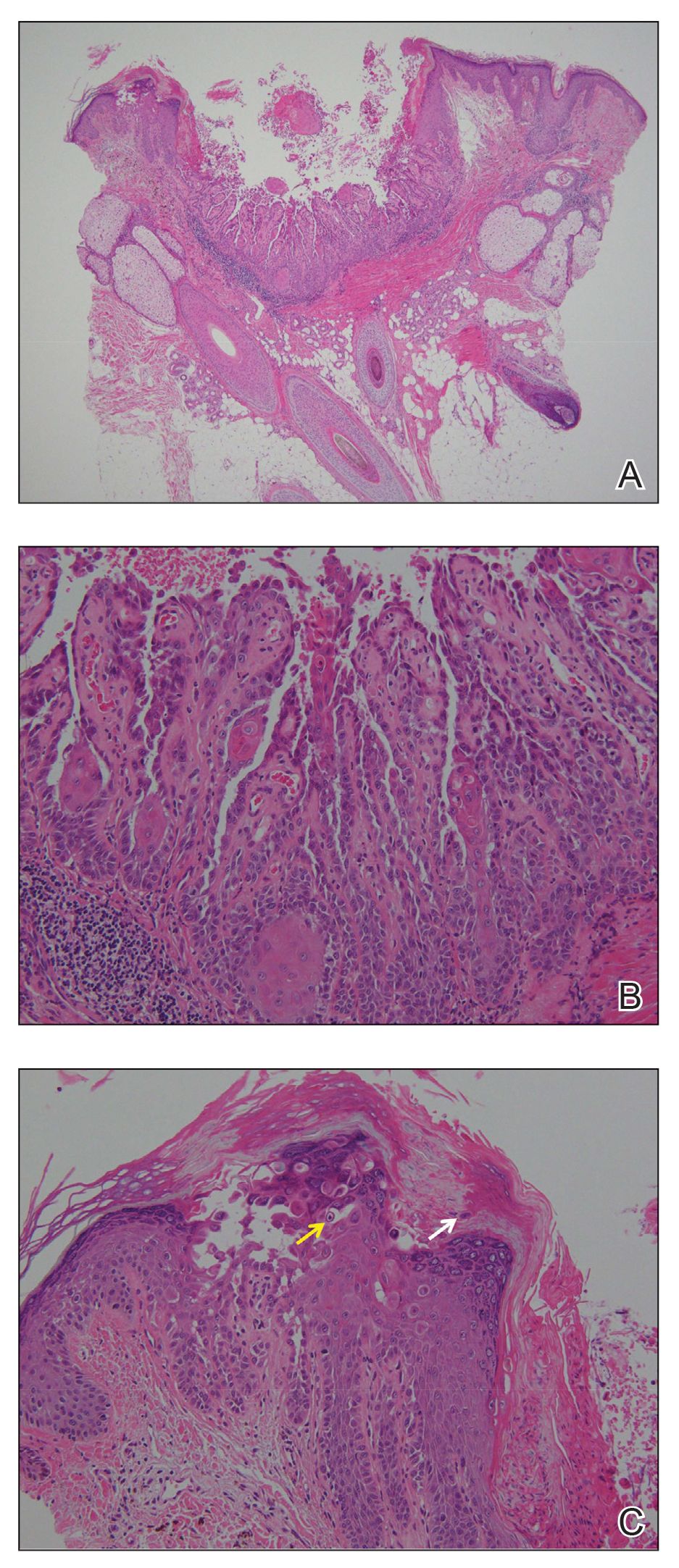

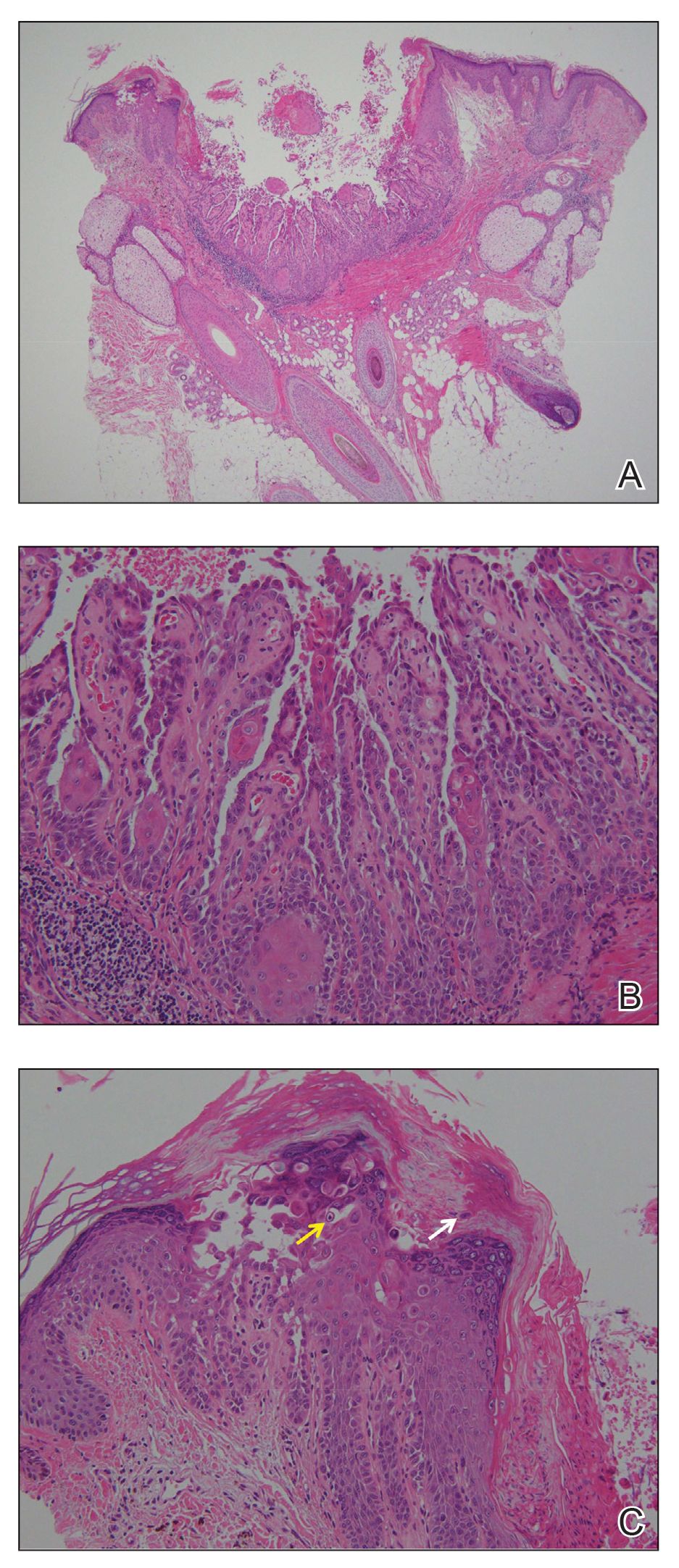

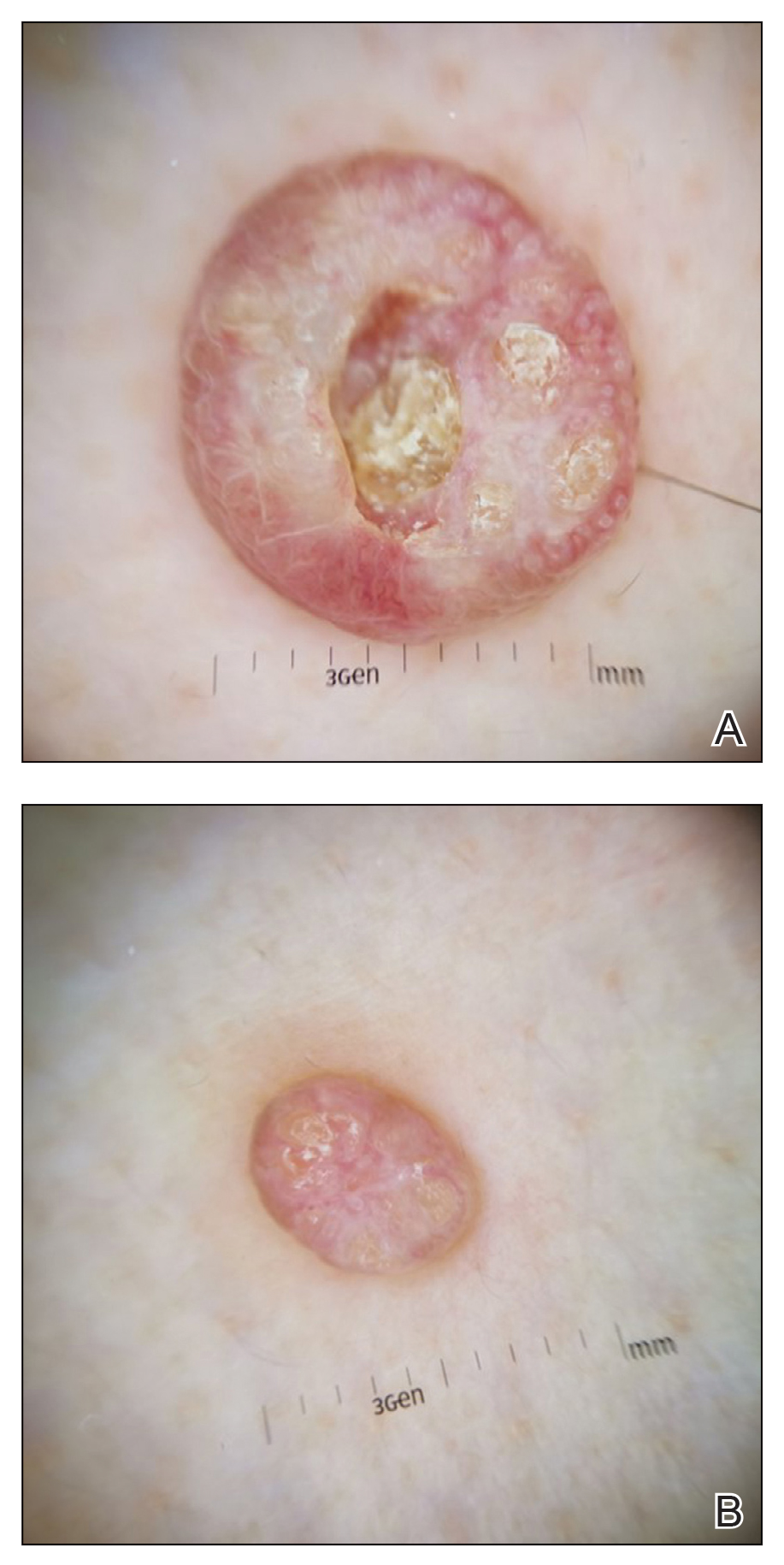

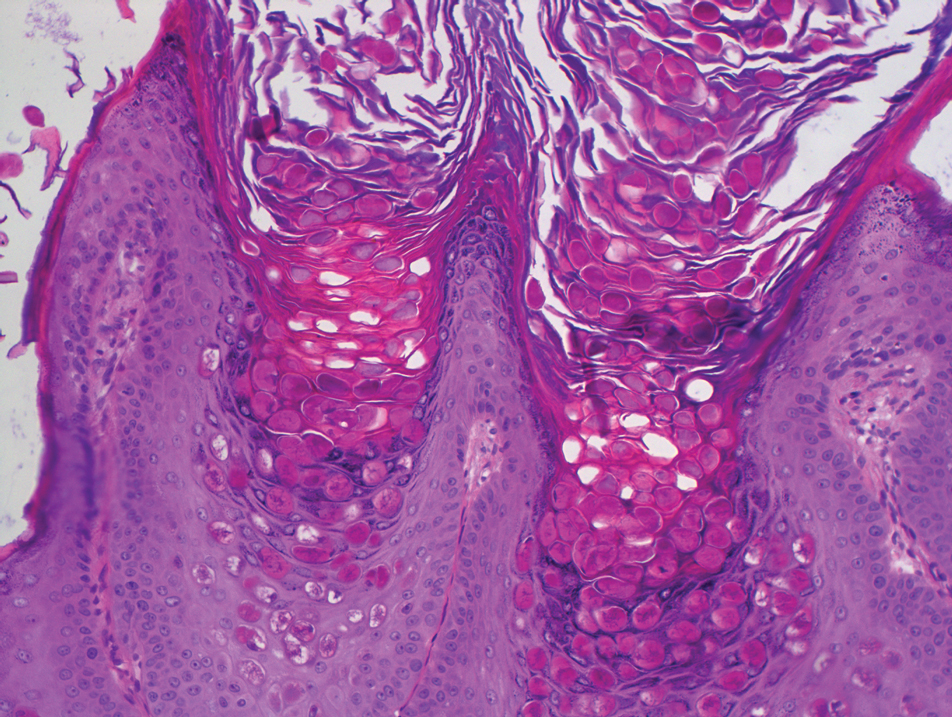

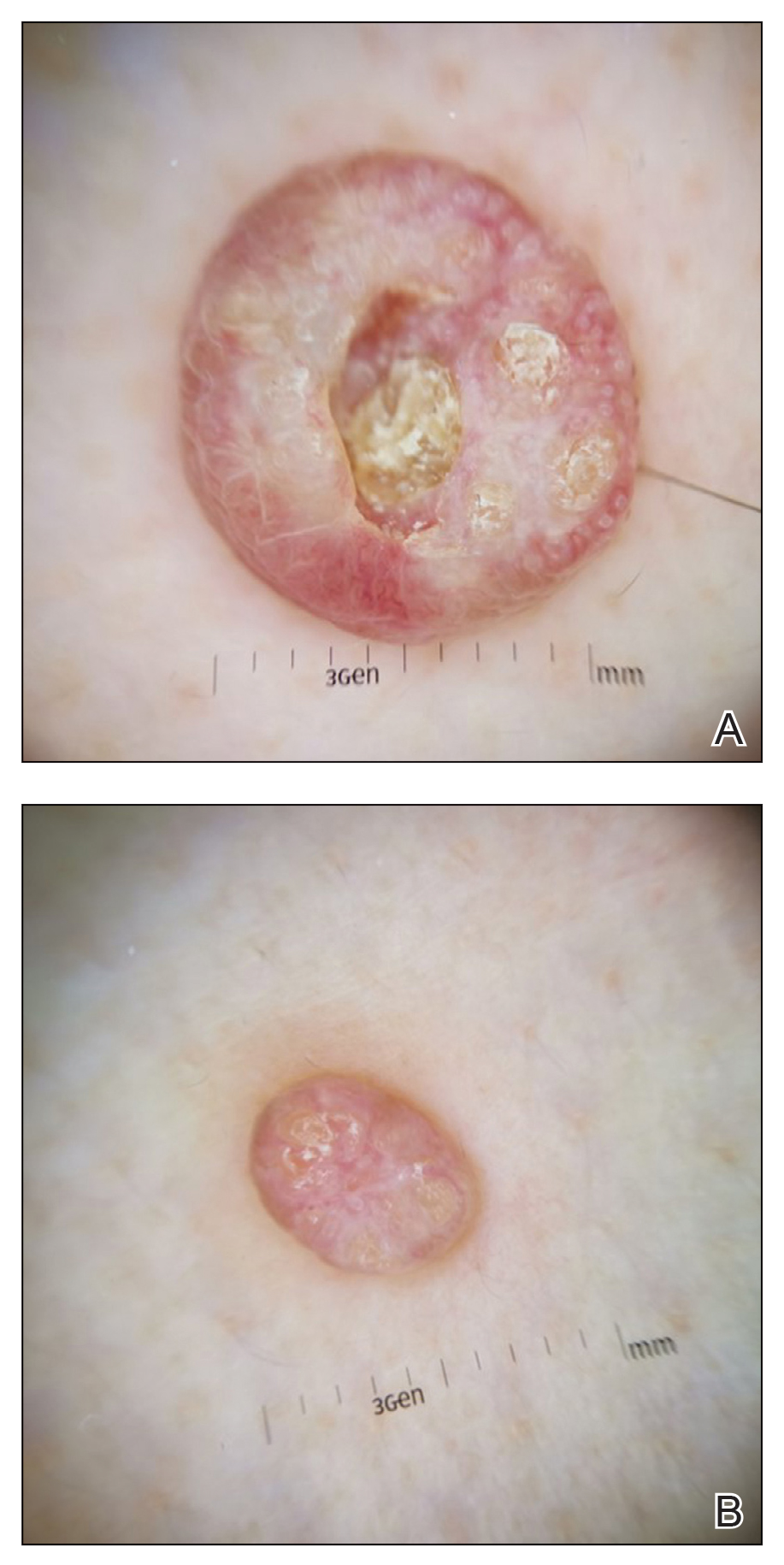

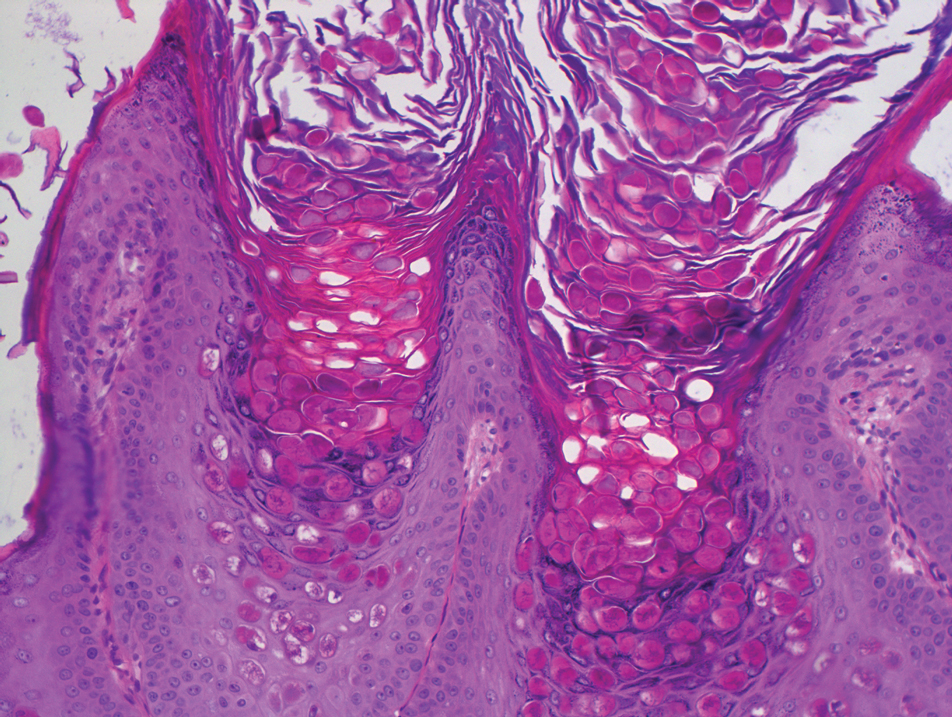

Basal cell carcinoma often manifests in the second or third decades of life, though there are reports of BCC developing in BDCS patients as young as 3 years. Basal cell carcinoma typically arises on sun-exposed areas, especially the face, neck, and chest. These lesions can be pigmented or nonpigmented and range from 2 to 20 mm in diameter.4 Our patient presented with a BCC on the forehead (Figure 1). Histopathologic evaluation showed a proliferation of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading (Figure 2), confirming the diagnosis of BCC.

Milia, which are not considered part of the classic BDCS triad, are seen in 70% of cases.2 They commonly are found on the face and often diminish with age. Milia may precede the formation of follicular atrophoderma and BCC. Hypohidrosis most commonly occurs on the forehead but can be widespread.2 Other less commonly observed features include epidermal cysts, hyperpigmentation of the face, and trichoepitheliomas.4 The management of BDCS involves frequent clinical examinations, BCC treatment, genetic counseling, and photoprotection.2,4

Nevoid BCC syndrome (NBCCS), also known as Gorlin-Goltz syndrome, is an autosomal-dominant disease characterized by multiple nevoid BCCs, macrocephaly with a large forehead, cleft lip or palate, jaw keratocysts, palmar and plantar pits, and calcification of the falx cerebri.5 Nevoid BCC syndrome is caused by a mutation in the PTCH1 gene in the hedgehog signaling pathway.6 The absence of common symptoms of NBCCS including macrocephaly, palmar or plantar pits, and cleft lip or palate, as well as negative genetic testing, suggested that our patient did not have NBCCS.

Rombo syndrome shares features with BDCS. Similar to BDCS, symptoms of Rombo syndrome include follicular atrophy, milialike papules, and BCC. Patients with Rombo syndrome typically present with atrophoderma vermiculatum on the cheeks and forehead in childhood.7 This atrophoderma presents with a pitted atrophic appearance in a reticular pattern on sun-exposed areas. Other distinguishing features from BDCS include cyanotic redness of sun-exposed skin and telangiectatic vessels.8

Multiple hereditary infundibulocystic BCC is another rare genodermatosis that is characterized by the presence of multiple infundibulocystic BCCs on the face and genitals. Infundibulocystic BCC is a well-differentiated subtype of BCC characterized by buds and cords of basaloid cells with scant stroma. Multiple hereditary infundibulocystic BCC is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion and has been linked to SUFU mutation in the sonic hedgehog pathway.9

Rothmund-Thomson syndrome is an autosomalrecessive disorder characterized by sparse hair, skeletal and dental abnormalities, and a high risk for developing keratinocyte carcinomas. It is differentiated from BDCS clinically by the presence of erythema, edema, and blistering, resulting in poikiloderma, plantar hyperkeratotic lesions, and bone defects.10

- Bazex A. Génodermatose complexe de type indéterminé associant une hypotrichose, un état atrophodermique généralisé et des dégénérescences cutanées multiples (épitheliomas baso-cellulaires). Bull Soc Fr Derm Syphiligr. 1964;71:206.

- Al Sabbagh MM, Baqi MA. Bazex-Dupre-Christol syndrome: review of clinical and molecular aspects. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1102-1106.

- Parren LJ, Abuzahra F, Wagenvoort T, et al. Linkage refinement of Bazex-Dupre-Christol syndrome to an 11.4-Mb interval on chromosome Xq25-27.1. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:201-203.

- Abuzahra F, Parren LJ, Frank J. Multiple familial and pigmented basal cell carcinomas in early childhood--Bazex-Dupre-Christol syndrome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:117-121.

- Shevchenko A, Durkin JR, Moon AT. Generalized basaloid follicular hamartoma syndrome versus Gorlin syndrome: a diagnostic challenge. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E396-E397.

- Fujii K, Miyashita T. Gorlin syndrome (nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome): update and literature review. Pediatr Int. 2014;56:667-674.

- van Steensel MA, Jaspers NG, Steijlen PM. A case of Rombo syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:1215-1218.

- Lee YC, Son SJ, Han TY, et al. A case of atrophoderma vermiculatum showing a good response to topical tretinoin. Ann Dermatol. 2018;30:116-118.

- Schulman JM, Oh DH, Sanborn JZ, et al. Multiple hereditary infundibulocystic basal cell carcinoma syndrome associated with a germline SUFU mutation. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:323-327.

- Larizza L, Roversi G, Volpi L. Rothmund-Thomson syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5:2.

The Diagnosis: Bazex‐Dupré‐Christol Syndrome

Bazex‐Dupré‐Christol syndrome (BDCS) is a rare X-linked dominant genodermatosis characterized by a triad of hypotrichosis, follicular atrophoderma, and multiple basal cell carcinomas (BCCs). Since first being described in 1964,1 there have been fewer than 200 reported cases of BDCS.2 Although a causative gene has not yet been identified, the mutation has been mapped to an 11.4-Mb interval in the Xq25-27.1 region of the X chromosome.3

Classically, congenital hypotrichosis is the first observed symptom and can present shortly after birth.4 It typically is widespread, though sometimes it may be confined to the eyebrows, eyelashes, and scalp. Follicular atrophoderma, which occurs due to a laxation and deepening of the follicular ostia, is seen in 80% of cases and typically presents in early childhood as depressions lacking hair.2 It commonly is found on the face, extensor surfaces of the elbows and knees, and dorsal aspects of the hands and feet. Physical examination of our patient revealed follicular atrophoderma on both the dorsal surfaces of the hands and the extensor surfaces of the elbows. Hair shaft anomalies including pili torti, pili bifurcati, and trichorrhexis nodosa are infrequently observed symptoms of BDCS.2

Basal cell carcinoma often manifests in the second or third decades of life, though there are reports of BCC developing in BDCS patients as young as 3 years. Basal cell carcinoma typically arises on sun-exposed areas, especially the face, neck, and chest. These lesions can be pigmented or nonpigmented and range from 2 to 20 mm in diameter.4 Our patient presented with a BCC on the forehead (Figure 1). Histopathologic evaluation showed a proliferation of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading (Figure 2), confirming the diagnosis of BCC.

Milia, which are not considered part of the classic BDCS triad, are seen in 70% of cases.2 They commonly are found on the face and often diminish with age. Milia may precede the formation of follicular atrophoderma and BCC. Hypohidrosis most commonly occurs on the forehead but can be widespread.2 Other less commonly observed features include epidermal cysts, hyperpigmentation of the face, and trichoepitheliomas.4 The management of BDCS involves frequent clinical examinations, BCC treatment, genetic counseling, and photoprotection.2,4

Nevoid BCC syndrome (NBCCS), also known as Gorlin-Goltz syndrome, is an autosomal-dominant disease characterized by multiple nevoid BCCs, macrocephaly with a large forehead, cleft lip or palate, jaw keratocysts, palmar and plantar pits, and calcification of the falx cerebri.5 Nevoid BCC syndrome is caused by a mutation in the PTCH1 gene in the hedgehog signaling pathway.6 The absence of common symptoms of NBCCS including macrocephaly, palmar or plantar pits, and cleft lip or palate, as well as negative genetic testing, suggested that our patient did not have NBCCS.

Rombo syndrome shares features with BDCS. Similar to BDCS, symptoms of Rombo syndrome include follicular atrophy, milialike papules, and BCC. Patients with Rombo syndrome typically present with atrophoderma vermiculatum on the cheeks and forehead in childhood.7 This atrophoderma presents with a pitted atrophic appearance in a reticular pattern on sun-exposed areas. Other distinguishing features from BDCS include cyanotic redness of sun-exposed skin and telangiectatic vessels.8

Multiple hereditary infundibulocystic BCC is another rare genodermatosis that is characterized by the presence of multiple infundibulocystic BCCs on the face and genitals. Infundibulocystic BCC is a well-differentiated subtype of BCC characterized by buds and cords of basaloid cells with scant stroma. Multiple hereditary infundibulocystic BCC is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion and has been linked to SUFU mutation in the sonic hedgehog pathway.9

Rothmund-Thomson syndrome is an autosomalrecessive disorder characterized by sparse hair, skeletal and dental abnormalities, and a high risk for developing keratinocyte carcinomas. It is differentiated from BDCS clinically by the presence of erythema, edema, and blistering, resulting in poikiloderma, plantar hyperkeratotic lesions, and bone defects.10

The Diagnosis: Bazex‐Dupré‐Christol Syndrome

Bazex‐Dupré‐Christol syndrome (BDCS) is a rare X-linked dominant genodermatosis characterized by a triad of hypotrichosis, follicular atrophoderma, and multiple basal cell carcinomas (BCCs). Since first being described in 1964,1 there have been fewer than 200 reported cases of BDCS.2 Although a causative gene has not yet been identified, the mutation has been mapped to an 11.4-Mb interval in the Xq25-27.1 region of the X chromosome.3

Classically, congenital hypotrichosis is the first observed symptom and can present shortly after birth.4 It typically is widespread, though sometimes it may be confined to the eyebrows, eyelashes, and scalp. Follicular atrophoderma, which occurs due to a laxation and deepening of the follicular ostia, is seen in 80% of cases and typically presents in early childhood as depressions lacking hair.2 It commonly is found on the face, extensor surfaces of the elbows and knees, and dorsal aspects of the hands and feet. Physical examination of our patient revealed follicular atrophoderma on both the dorsal surfaces of the hands and the extensor surfaces of the elbows. Hair shaft anomalies including pili torti, pili bifurcati, and trichorrhexis nodosa are infrequently observed symptoms of BDCS.2

Basal cell carcinoma often manifests in the second or third decades of life, though there are reports of BCC developing in BDCS patients as young as 3 years. Basal cell carcinoma typically arises on sun-exposed areas, especially the face, neck, and chest. These lesions can be pigmented or nonpigmented and range from 2 to 20 mm in diameter.4 Our patient presented with a BCC on the forehead (Figure 1). Histopathologic evaluation showed a proliferation of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading (Figure 2), confirming the diagnosis of BCC.

Milia, which are not considered part of the classic BDCS triad, are seen in 70% of cases.2 They commonly are found on the face and often diminish with age. Milia may precede the formation of follicular atrophoderma and BCC. Hypohidrosis most commonly occurs on the forehead but can be widespread.2 Other less commonly observed features include epidermal cysts, hyperpigmentation of the face, and trichoepitheliomas.4 The management of BDCS involves frequent clinical examinations, BCC treatment, genetic counseling, and photoprotection.2,4

Nevoid BCC syndrome (NBCCS), also known as Gorlin-Goltz syndrome, is an autosomal-dominant disease characterized by multiple nevoid BCCs, macrocephaly with a large forehead, cleft lip or palate, jaw keratocysts, palmar and plantar pits, and calcification of the falx cerebri.5 Nevoid BCC syndrome is caused by a mutation in the PTCH1 gene in the hedgehog signaling pathway.6 The absence of common symptoms of NBCCS including macrocephaly, palmar or plantar pits, and cleft lip or palate, as well as negative genetic testing, suggested that our patient did not have NBCCS.

Rombo syndrome shares features with BDCS. Similar to BDCS, symptoms of Rombo syndrome include follicular atrophy, milialike papules, and BCC. Patients with Rombo syndrome typically present with atrophoderma vermiculatum on the cheeks and forehead in childhood.7 This atrophoderma presents with a pitted atrophic appearance in a reticular pattern on sun-exposed areas. Other distinguishing features from BDCS include cyanotic redness of sun-exposed skin and telangiectatic vessels.8

Multiple hereditary infundibulocystic BCC is another rare genodermatosis that is characterized by the presence of multiple infundibulocystic BCCs on the face and genitals. Infundibulocystic BCC is a well-differentiated subtype of BCC characterized by buds and cords of basaloid cells with scant stroma. Multiple hereditary infundibulocystic BCC is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion and has been linked to SUFU mutation in the sonic hedgehog pathway.9

Rothmund-Thomson syndrome is an autosomalrecessive disorder characterized by sparse hair, skeletal and dental abnormalities, and a high risk for developing keratinocyte carcinomas. It is differentiated from BDCS clinically by the presence of erythema, edema, and blistering, resulting in poikiloderma, plantar hyperkeratotic lesions, and bone defects.10

- Bazex A. Génodermatose complexe de type indéterminé associant une hypotrichose, un état atrophodermique généralisé et des dégénérescences cutanées multiples (épitheliomas baso-cellulaires). Bull Soc Fr Derm Syphiligr. 1964;71:206.

- Al Sabbagh MM, Baqi MA. Bazex-Dupre-Christol syndrome: review of clinical and molecular aspects. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1102-1106.

- Parren LJ, Abuzahra F, Wagenvoort T, et al. Linkage refinement of Bazex-Dupre-Christol syndrome to an 11.4-Mb interval on chromosome Xq25-27.1. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:201-203.

- Abuzahra F, Parren LJ, Frank J. Multiple familial and pigmented basal cell carcinomas in early childhood--Bazex-Dupre-Christol syndrome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:117-121.

- Shevchenko A, Durkin JR, Moon AT. Generalized basaloid follicular hamartoma syndrome versus Gorlin syndrome: a diagnostic challenge. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E396-E397.

- Fujii K, Miyashita T. Gorlin syndrome (nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome): update and literature review. Pediatr Int. 2014;56:667-674.

- van Steensel MA, Jaspers NG, Steijlen PM. A case of Rombo syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:1215-1218.

- Lee YC, Son SJ, Han TY, et al. A case of atrophoderma vermiculatum showing a good response to topical tretinoin. Ann Dermatol. 2018;30:116-118.

- Schulman JM, Oh DH, Sanborn JZ, et al. Multiple hereditary infundibulocystic basal cell carcinoma syndrome associated with a germline SUFU mutation. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:323-327.

- Larizza L, Roversi G, Volpi L. Rothmund-Thomson syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5:2.

- Bazex A. Génodermatose complexe de type indéterminé associant une hypotrichose, un état atrophodermique généralisé et des dégénérescences cutanées multiples (épitheliomas baso-cellulaires). Bull Soc Fr Derm Syphiligr. 1964;71:206.

- Al Sabbagh MM, Baqi MA. Bazex-Dupre-Christol syndrome: review of clinical and molecular aspects. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1102-1106.

- Parren LJ, Abuzahra F, Wagenvoort T, et al. Linkage refinement of Bazex-Dupre-Christol syndrome to an 11.4-Mb interval on chromosome Xq25-27.1. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:201-203.

- Abuzahra F, Parren LJ, Frank J. Multiple familial and pigmented basal cell carcinomas in early childhood--Bazex-Dupre-Christol syndrome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:117-121.

- Shevchenko A, Durkin JR, Moon AT. Generalized basaloid follicular hamartoma syndrome versus Gorlin syndrome: a diagnostic challenge. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E396-E397.

- Fujii K, Miyashita T. Gorlin syndrome (nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome): update and literature review. Pediatr Int. 2014;56:667-674.

- van Steensel MA, Jaspers NG, Steijlen PM. A case of Rombo syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:1215-1218.

- Lee YC, Son SJ, Han TY, et al. A case of atrophoderma vermiculatum showing a good response to topical tretinoin. Ann Dermatol. 2018;30:116-118.

- Schulman JM, Oh DH, Sanborn JZ, et al. Multiple hereditary infundibulocystic basal cell carcinoma syndrome associated with a germline SUFU mutation. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:323-327.

- Larizza L, Roversi G, Volpi L. Rothmund-Thomson syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5:2.

A 28-year-old woman presented for evaluation of a pearly papule on the forehead of several months’ duration that was concerning for basal cell carcinoma (BCC). She had a history of numerous BCCs starting at the age of 17 years. She denied radiation or other carcinogenic exposures and had no other notable medical history. The patient’s mother and grandmother also had numerous BCCs. Physical examination revealed hypotrichosis; numerous 3- to 5-mm white cystic papules on the face, chest, and upper arms; and 1- to 5-mm pitted depressions on the dorsal aspects of the hands (top) and extensor surfaces of the elbows (bottom). A proliferation of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading was seen on histopathologic evaluation. Genetic testing revealed no protein patched homolog 1, PTCH1, or suppressor of fused homolog, SUFU, gene mutations.

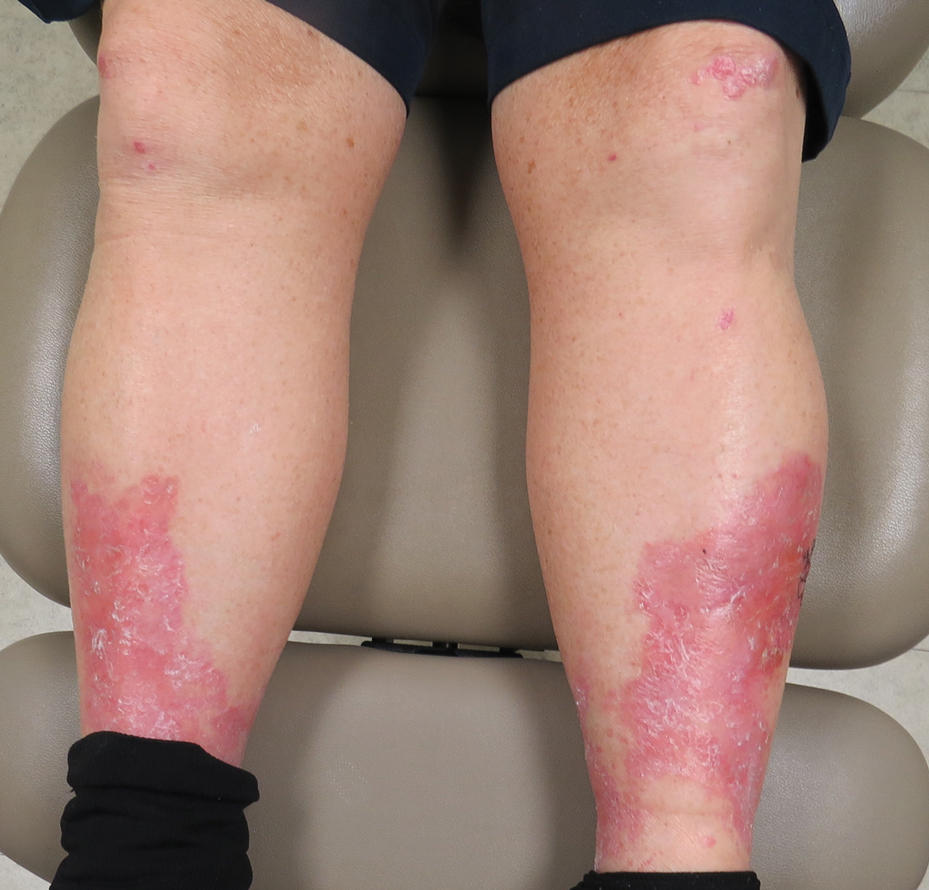

Erythema, Blisters, and Scars on the Elbows, Knees, and Legs

The Diagnosis: Epidermolysis Bullosa Acquisita

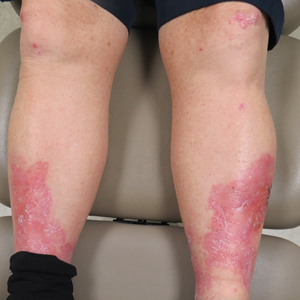

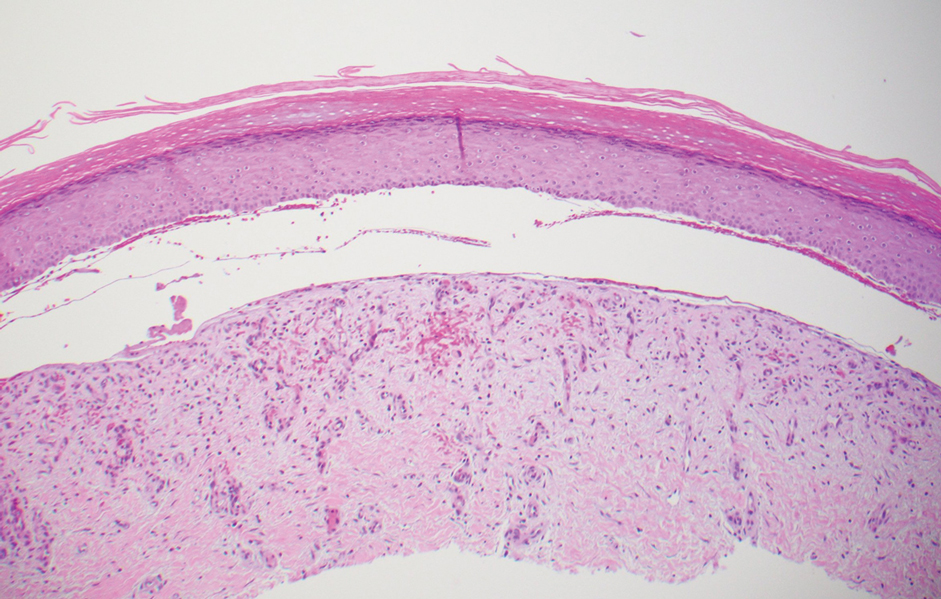

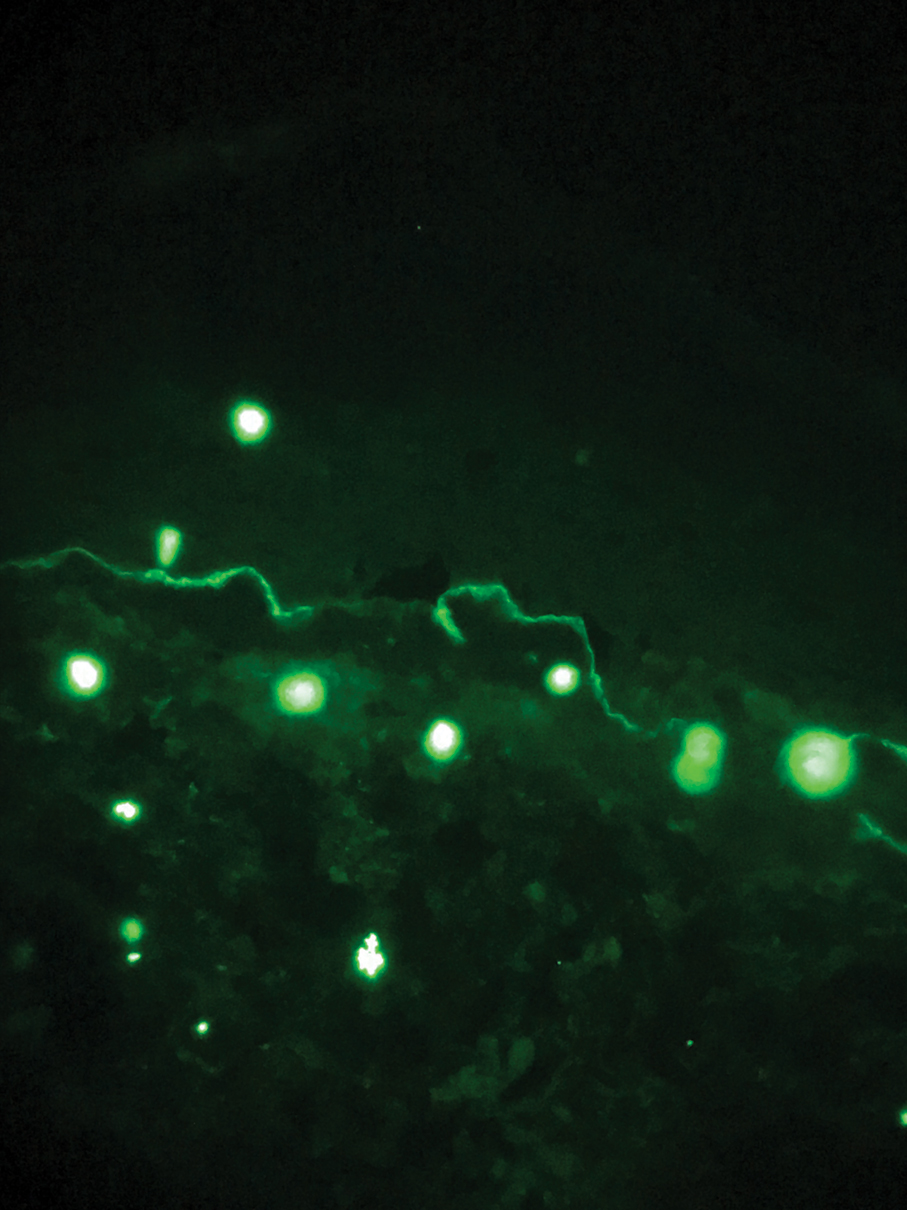

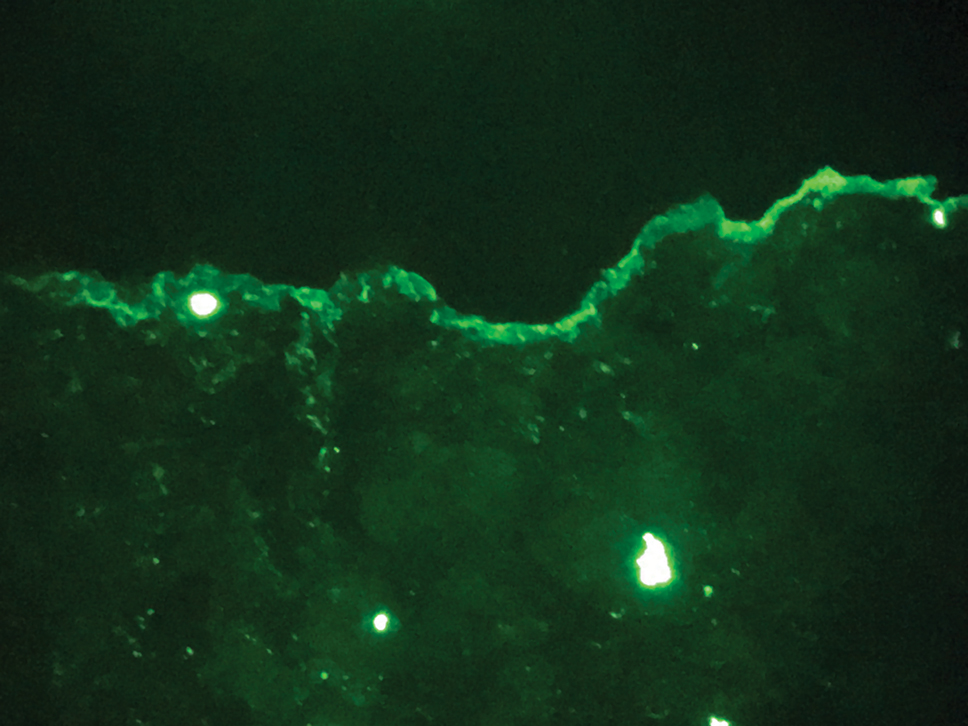

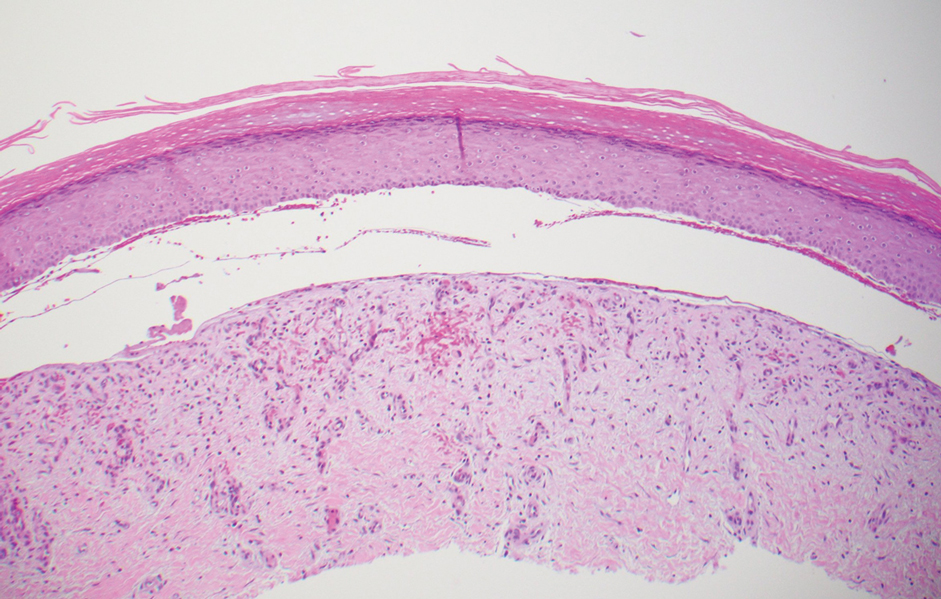

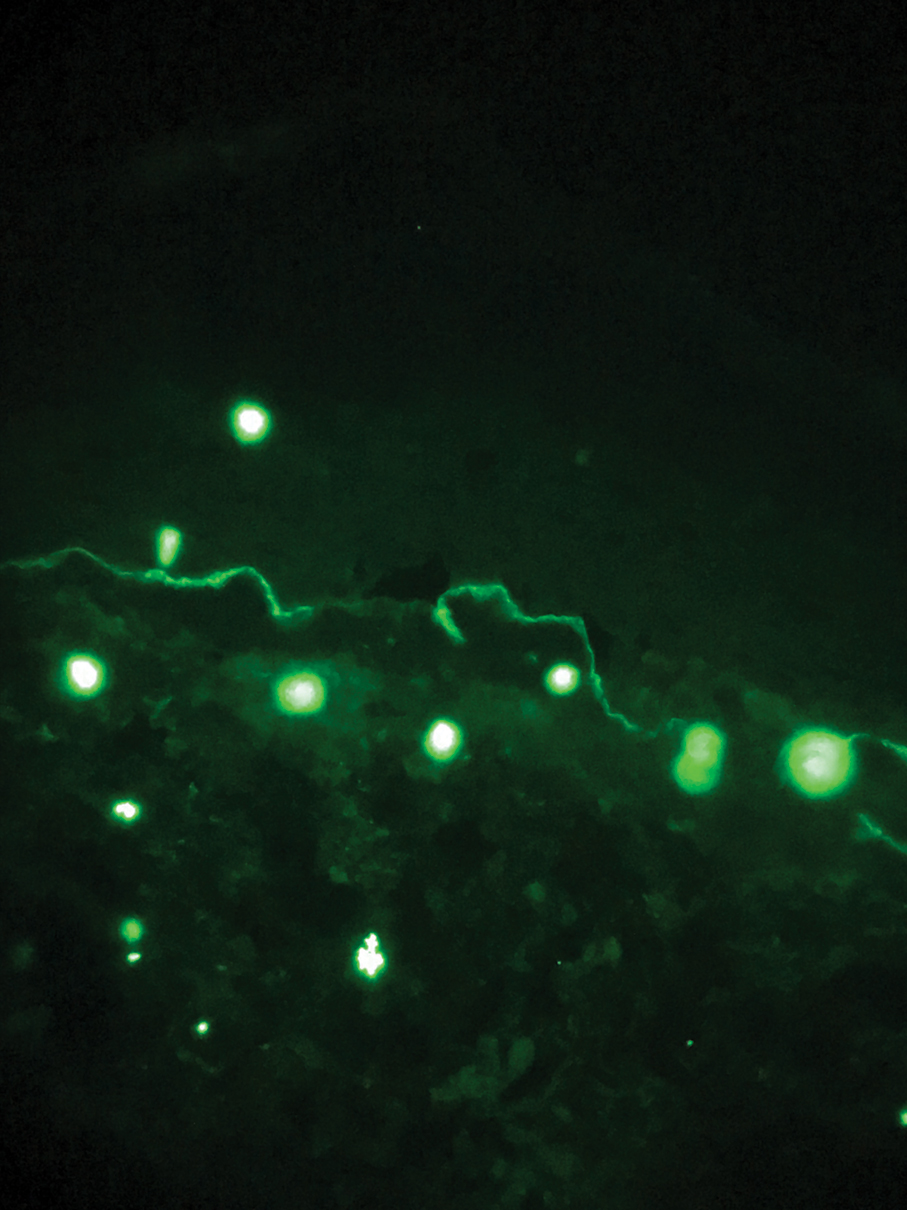

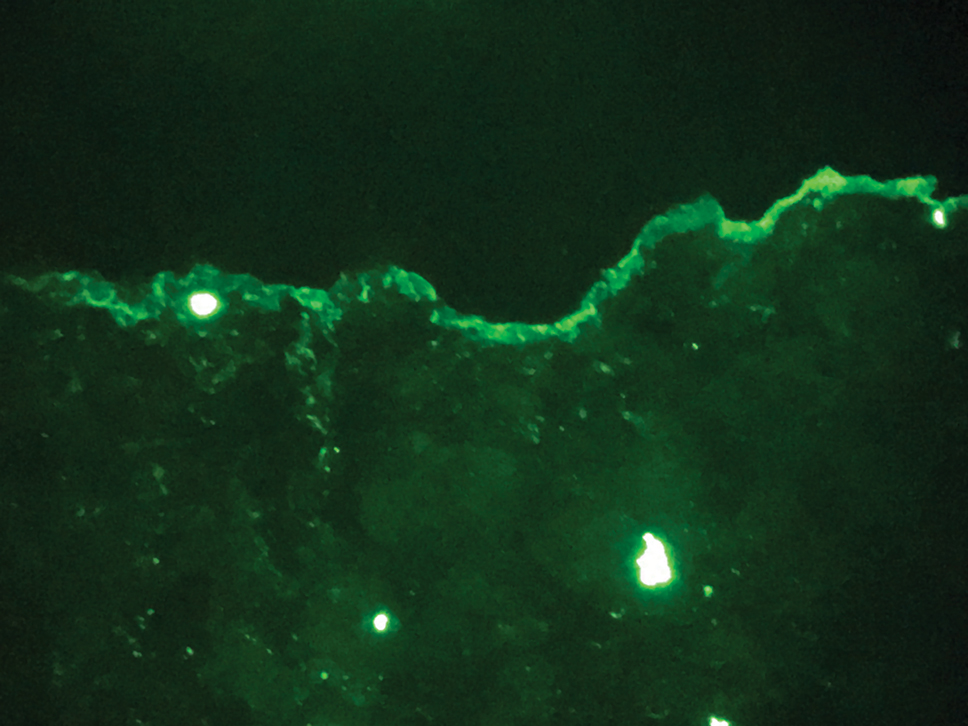

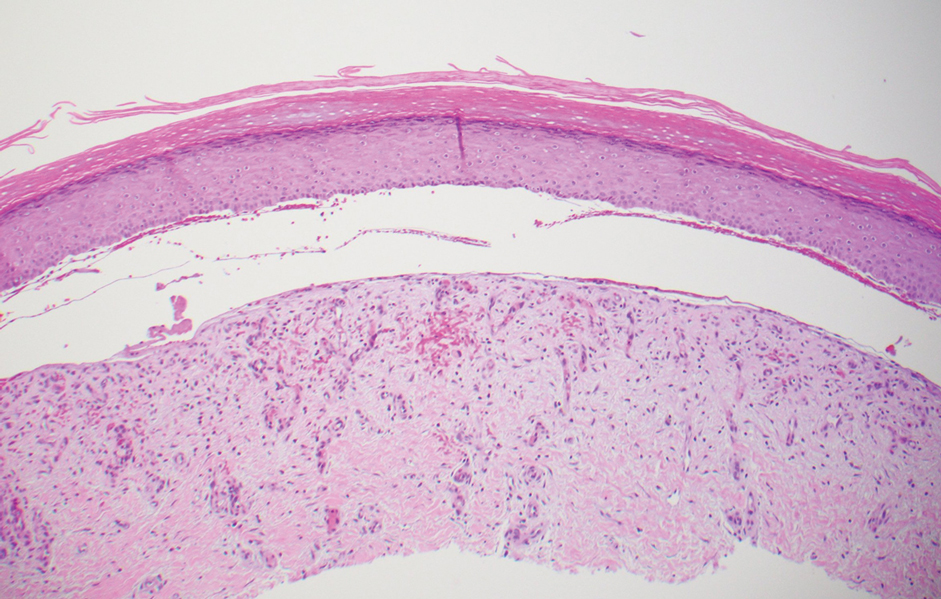

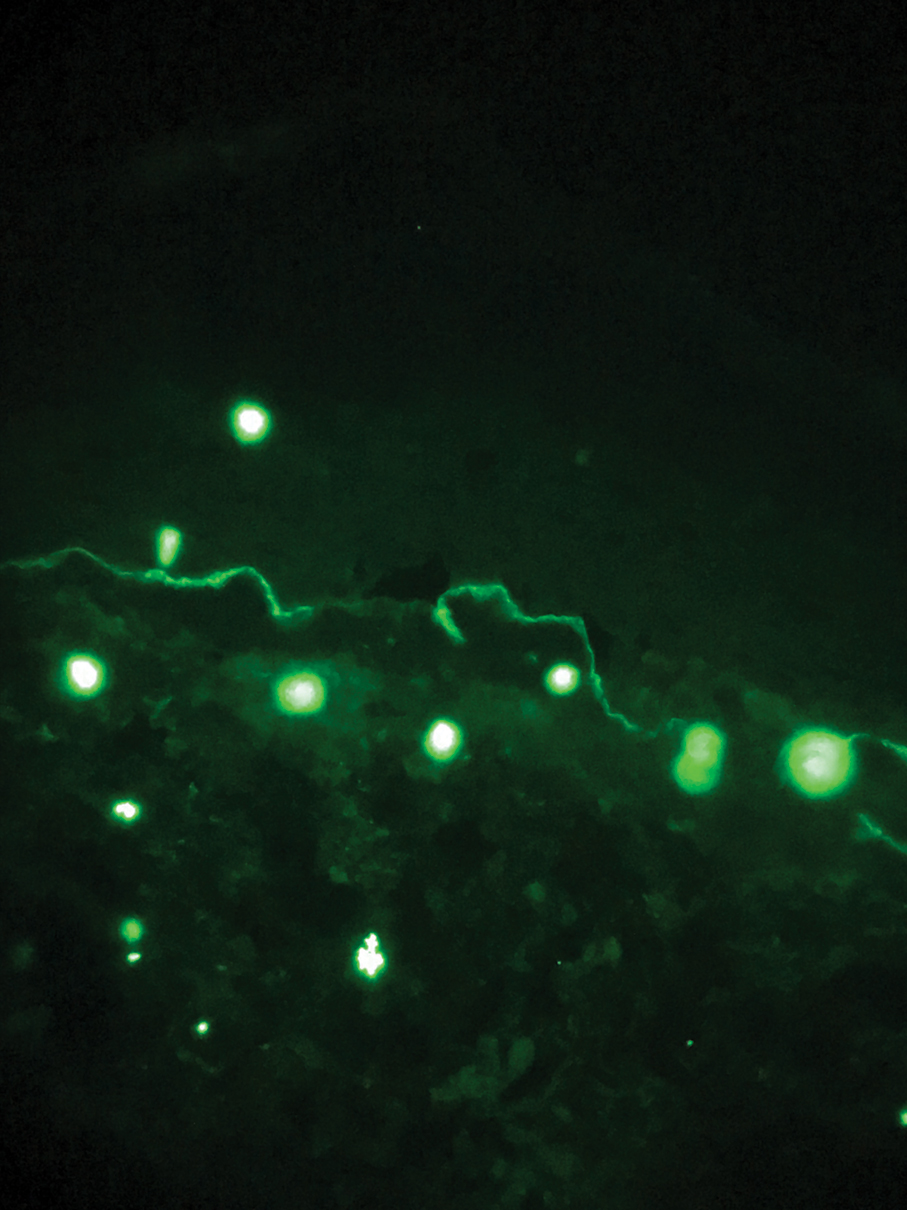

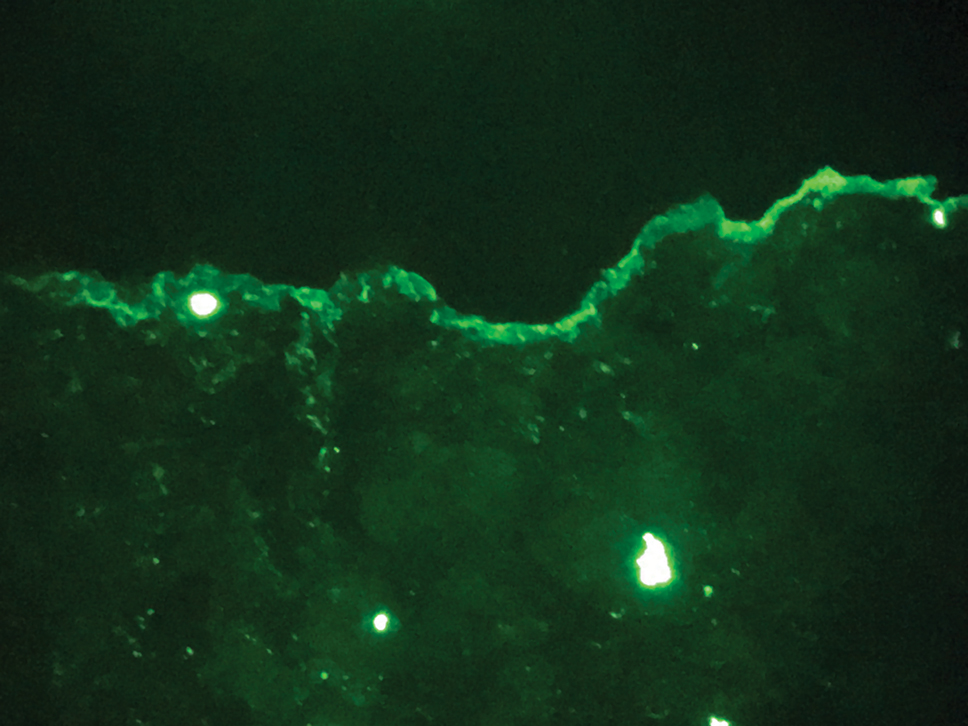

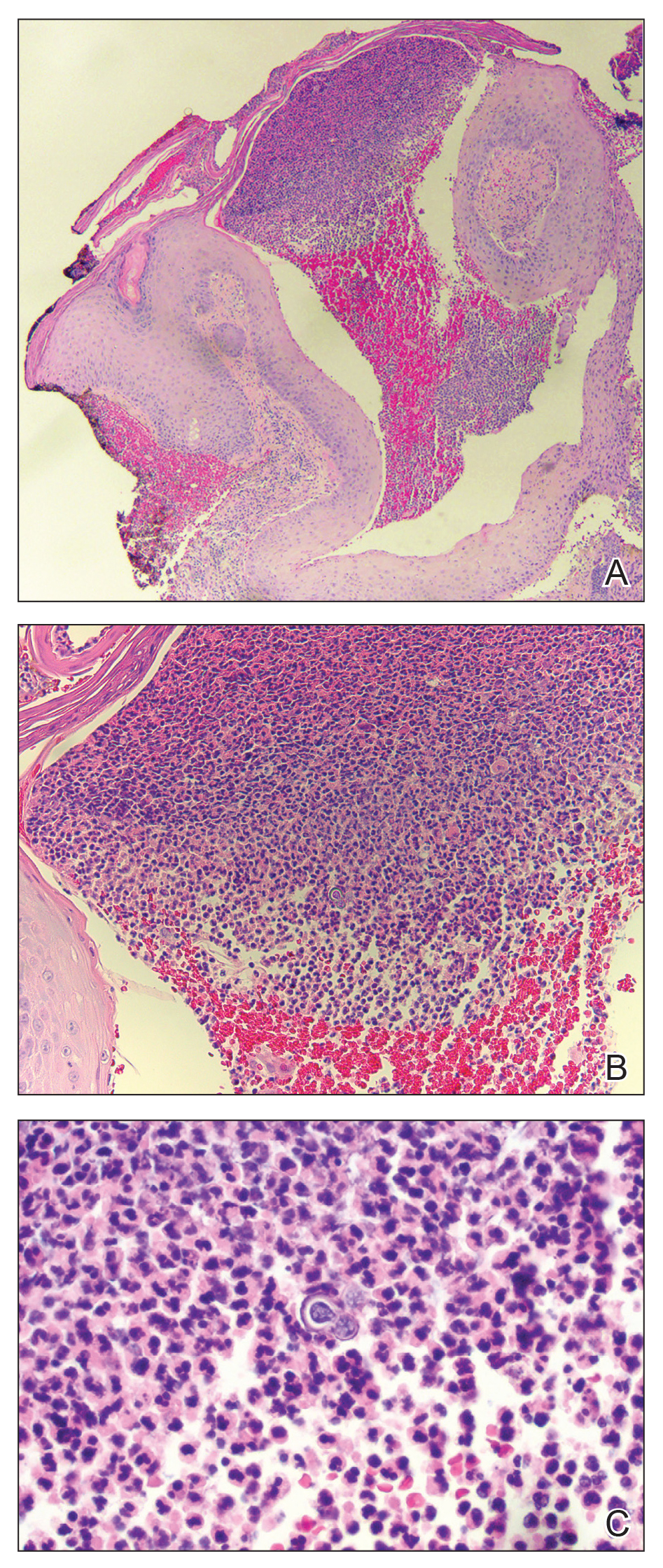

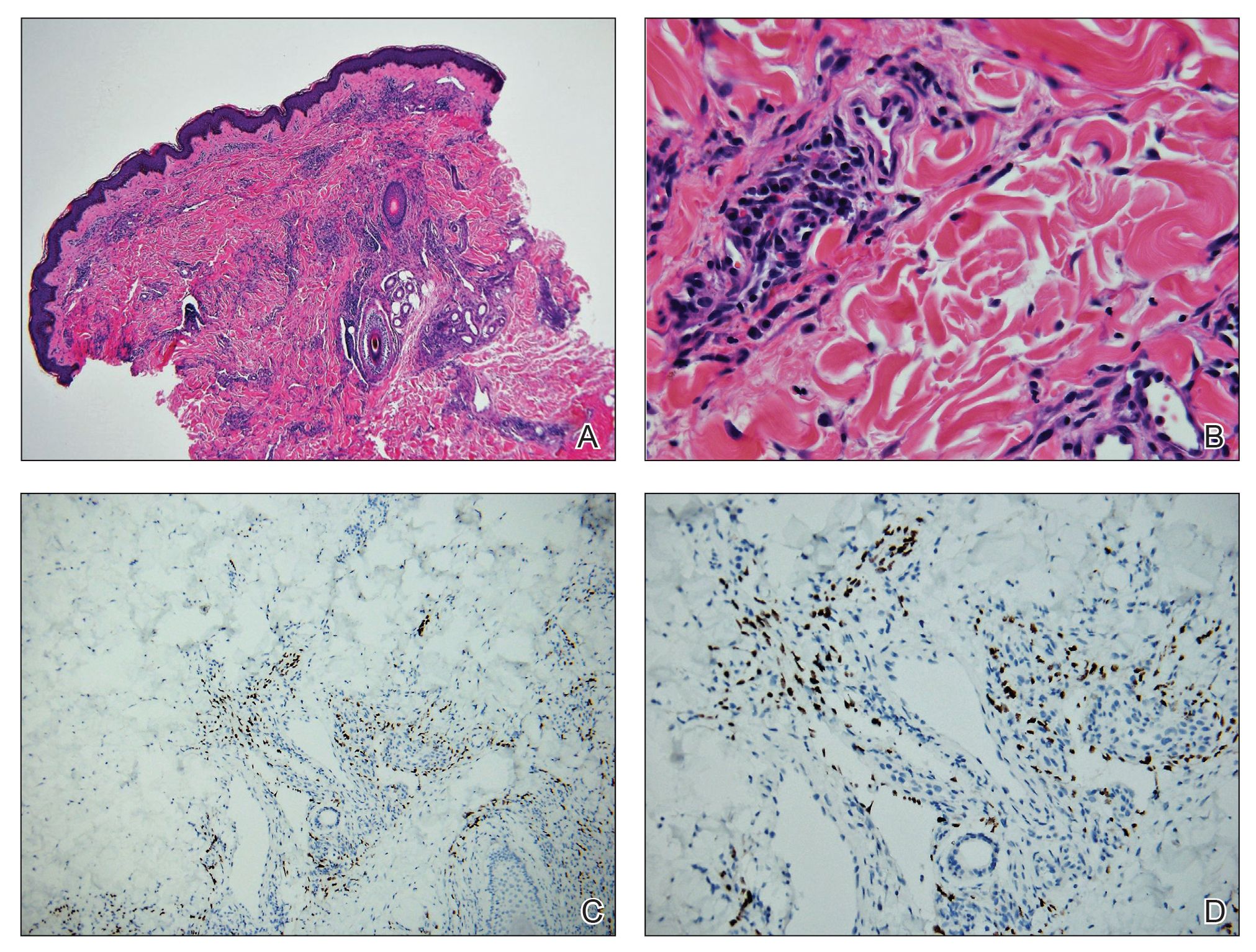

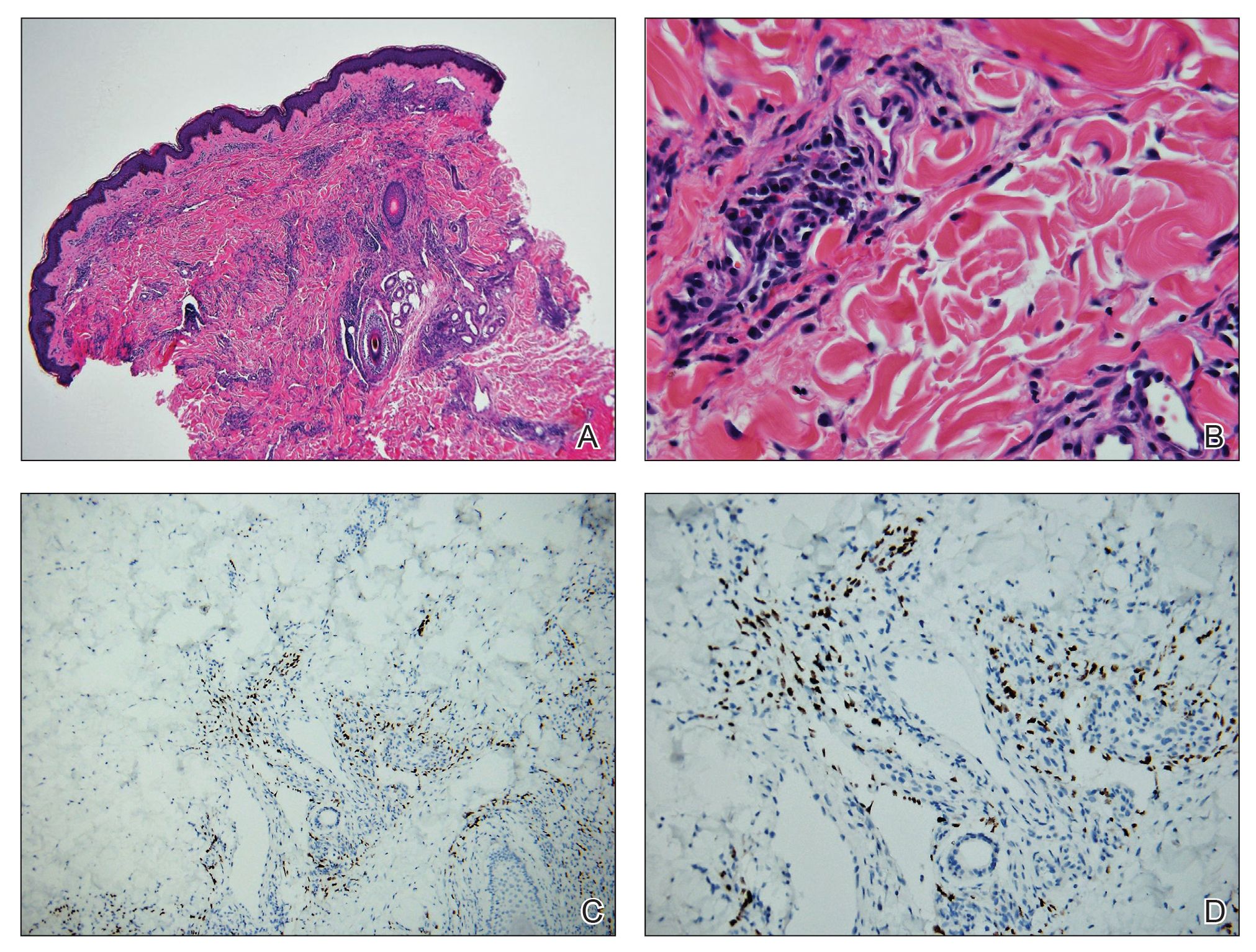

The diagnosis of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA) was made based on the clinical and pathologic findings. A blistering disorder that resolves with milia is characteristic of EBA. Hematoxylin and eosin staining demonstrated a pauci-inflammatory separation between the epidermis and dermis (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence studies showed linear IgG deposition along the basement membrane zone while C3 was negative (Figure 2). Salt-split skin was essential, as it revealed IgG deposition to the floor of the split (Figure 3), a pattern seen in EBA and not bullous pemphigoid (BP).1

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita is an acquired autoimmune bullous disorder that results from antibodies to type VII collagen, an anchoring fibril that attaches the lamina densa to the dermis. The epidemiology and etiology of the trigger that leads to antibody production are not well known, but an association between EBA and inflammatory bowel disease has been described.2 Although this disease may present in childhood, EBA most commonly is a disorder seen in adults and the elderly. A classic noninflammatory mechanobullous form as well as an inflammatory BP-like form are the most commonly encountered presentations. Light microscopy demonstrates subepidermal cleavage without acantholysis. In the inflammatory BP-like subtype, an inflammatory infiltrate may be present. Direct immunofluorescence is remarkable for a linear band of IgG deposits along the basement membrane zone, with or without C3 deposition in a similar pattern.1

Bullous pemphigoid is within the differential of EBA. It can be difficult to differentiate clinically, especially when a patient has the BP-like variant of EBA because, as the name implies, it mimics BP. Patients with BP often will report a pruritic patch that will then develop into an urticarial plaque. Scarring and milia rarely are seen in BP but can be observed in the multiple presentations of EBA. Hematoxylin and eosin staining and direct immunofluorescence may be almost identical, and differentiating between the 2 disorders can be a challenge. Immunodeposition in EBA occurs in a U-shaped, serrated pattern, while the pattern in BP is N-shaped and serrated.3 Although the U-shaped, serrated pattern is relatively specific, it is not always easy to interpret and requires a high-quality biopsy specimen, which can be difficult to discern with certainty in suboptimal preparations. Another way to differentiate between the 2 entities is to utilize the salt-split skin technique, as performed in our patient. With salt-split skin, the biopsy is placed into a solution of 1 mol/L sodium chloride and incubated at 4 °C (39 °F) for 18 to 24 hours. A blister is then produced at the level of the lamina lucida, which allows for the staining of immunoreactants to occur either above or below that split (commonly referred to as staining on the roof or floor of the blister cavity). With EBA, there is immunoreactant deposition on the floor of the blister, while the opposite occurs in BP.4

Epidermolysis bullosa simplex is the most common type of epidermolysis bullosa, with keratin genes KRT5 and KRT14 as frequent mutations. Patients develop blisters, vesicles, bullae, and milia on traumatized areas of the body such as the hands, elbows, knees, and feet. This disease presents early in childhood. Histology exhibits a cell-poor subepidermal blister.5 With porphyria cutanea tarda, reduced activity of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase, a major enzyme in the heme synthesis pathway, leads to blisters with erosions and milia on sun-exposed areas of the body. Histologic evaluation reveals a subepidermal pauci-inflammatory vesicle with festooning of the dermal papillae and amphophilic basement membrane within the epidermis. Direct immunofluorescence of porphyria cutanea tarda demonstrates IgM and C3 in the vessels.6 Sweet syndrome is a neutrophilic dermatosis that presents as erythematous, edematous, hot, and tender plaques along with fever and leukocytosis. It is associated with myeloproliferative disorders. Biopsy demonstrates papillary dermal edema along with diffuse neutrophilic infiltrate.7

Numerous medications have been recommended for the treatment of EBA, ranging from steroids to steroid-sparing drugs such as colchicine and dapsone.8,9 Our patient was educated on physical precautions and was started on dapsone alone due to comorbid diabetes mellitus and renal disease. Within a few weeks of initiating dapsone, he observed a reduction in erythema, and within months he experienced a decrease in blister eruption frequency.

- Vorobyev A, Ludwig RJ, Schmidt E. Clinical features and diagnosis of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2017;13:157-169.

- Reddy H, Shipman AR, Wojnarowska F. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita and inflammatory bowel disease: a review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:225-230.

- Vodegel RM, Jonkman MF, Pas HH, et al. U-serrated immunodeposition pattern differentiates type VII collagen targeting bullous diseases from other subepidermal bullous autoimmune diseases. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:112-118.

- Gardner KM, Crawford RI. Distinguishing epidermolysis bullosa acquisita from bullous pemphigoid without direct immunofluorescence. J Cutan Med Surg. 2018;22:22-24.

- Sprecher E. Epidermolysis bullosa simplex. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:23-32.

- Maynard B, Peters MS. Histologic and immunofluorescence study of cutaneous porphyrias. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:40-47.

- Nelson CA, Stephen S, Ashchyan HJ, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses: pathogenesis, Sweet syndrome, neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, and Behçet disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018:79:987-1006.

- Kirtschig G, Murrell D, Wojnarowska F, et al. Interventions for mucous membrane pemphigoid and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;1:CD004056

- Gürcan HM, Ahmed AR. Current concepts in the treatment of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2011;12:1259-1268.

The Diagnosis: Epidermolysis Bullosa Acquisita

The diagnosis of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA) was made based on the clinical and pathologic findings. A blistering disorder that resolves with milia is characteristic of EBA. Hematoxylin and eosin staining demonstrated a pauci-inflammatory separation between the epidermis and dermis (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence studies showed linear IgG deposition along the basement membrane zone while C3 was negative (Figure 2). Salt-split skin was essential, as it revealed IgG deposition to the floor of the split (Figure 3), a pattern seen in EBA and not bullous pemphigoid (BP).1

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita is an acquired autoimmune bullous disorder that results from antibodies to type VII collagen, an anchoring fibril that attaches the lamina densa to the dermis. The epidemiology and etiology of the trigger that leads to antibody production are not well known, but an association between EBA and inflammatory bowel disease has been described.2 Although this disease may present in childhood, EBA most commonly is a disorder seen in adults and the elderly. A classic noninflammatory mechanobullous form as well as an inflammatory BP-like form are the most commonly encountered presentations. Light microscopy demonstrates subepidermal cleavage without acantholysis. In the inflammatory BP-like subtype, an inflammatory infiltrate may be present. Direct immunofluorescence is remarkable for a linear band of IgG deposits along the basement membrane zone, with or without C3 deposition in a similar pattern.1

Bullous pemphigoid is within the differential of EBA. It can be difficult to differentiate clinically, especially when a patient has the BP-like variant of EBA because, as the name implies, it mimics BP. Patients with BP often will report a pruritic patch that will then develop into an urticarial plaque. Scarring and milia rarely are seen in BP but can be observed in the multiple presentations of EBA. Hematoxylin and eosin staining and direct immunofluorescence may be almost identical, and differentiating between the 2 disorders can be a challenge. Immunodeposition in EBA occurs in a U-shaped, serrated pattern, while the pattern in BP is N-shaped and serrated.3 Although the U-shaped, serrated pattern is relatively specific, it is not always easy to interpret and requires a high-quality biopsy specimen, which can be difficult to discern with certainty in suboptimal preparations. Another way to differentiate between the 2 entities is to utilize the salt-split skin technique, as performed in our patient. With salt-split skin, the biopsy is placed into a solution of 1 mol/L sodium chloride and incubated at 4 °C (39 °F) for 18 to 24 hours. A blister is then produced at the level of the lamina lucida, which allows for the staining of immunoreactants to occur either above or below that split (commonly referred to as staining on the roof or floor of the blister cavity). With EBA, there is immunoreactant deposition on the floor of the blister, while the opposite occurs in BP.4

Epidermolysis bullosa simplex is the most common type of epidermolysis bullosa, with keratin genes KRT5 and KRT14 as frequent mutations. Patients develop blisters, vesicles, bullae, and milia on traumatized areas of the body such as the hands, elbows, knees, and feet. This disease presents early in childhood. Histology exhibits a cell-poor subepidermal blister.5 With porphyria cutanea tarda, reduced activity of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase, a major enzyme in the heme synthesis pathway, leads to blisters with erosions and milia on sun-exposed areas of the body. Histologic evaluation reveals a subepidermal pauci-inflammatory vesicle with festooning of the dermal papillae and amphophilic basement membrane within the epidermis. Direct immunofluorescence of porphyria cutanea tarda demonstrates IgM and C3 in the vessels.6 Sweet syndrome is a neutrophilic dermatosis that presents as erythematous, edematous, hot, and tender plaques along with fever and leukocytosis. It is associated with myeloproliferative disorders. Biopsy demonstrates papillary dermal edema along with diffuse neutrophilic infiltrate.7

Numerous medications have been recommended for the treatment of EBA, ranging from steroids to steroid-sparing drugs such as colchicine and dapsone.8,9 Our patient was educated on physical precautions and was started on dapsone alone due to comorbid diabetes mellitus and renal disease. Within a few weeks of initiating dapsone, he observed a reduction in erythema, and within months he experienced a decrease in blister eruption frequency.

The Diagnosis: Epidermolysis Bullosa Acquisita

The diagnosis of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA) was made based on the clinical and pathologic findings. A blistering disorder that resolves with milia is characteristic of EBA. Hematoxylin and eosin staining demonstrated a pauci-inflammatory separation between the epidermis and dermis (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence studies showed linear IgG deposition along the basement membrane zone while C3 was negative (Figure 2). Salt-split skin was essential, as it revealed IgG deposition to the floor of the split (Figure 3), a pattern seen in EBA and not bullous pemphigoid (BP).1

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita is an acquired autoimmune bullous disorder that results from antibodies to type VII collagen, an anchoring fibril that attaches the lamina densa to the dermis. The epidemiology and etiology of the trigger that leads to antibody production are not well known, but an association between EBA and inflammatory bowel disease has been described.2 Although this disease may present in childhood, EBA most commonly is a disorder seen in adults and the elderly. A classic noninflammatory mechanobullous form as well as an inflammatory BP-like form are the most commonly encountered presentations. Light microscopy demonstrates subepidermal cleavage without acantholysis. In the inflammatory BP-like subtype, an inflammatory infiltrate may be present. Direct immunofluorescence is remarkable for a linear band of IgG deposits along the basement membrane zone, with or without C3 deposition in a similar pattern.1

Bullous pemphigoid is within the differential of EBA. It can be difficult to differentiate clinically, especially when a patient has the BP-like variant of EBA because, as the name implies, it mimics BP. Patients with BP often will report a pruritic patch that will then develop into an urticarial plaque. Scarring and milia rarely are seen in BP but can be observed in the multiple presentations of EBA. Hematoxylin and eosin staining and direct immunofluorescence may be almost identical, and differentiating between the 2 disorders can be a challenge. Immunodeposition in EBA occurs in a U-shaped, serrated pattern, while the pattern in BP is N-shaped and serrated.3 Although the U-shaped, serrated pattern is relatively specific, it is not always easy to interpret and requires a high-quality biopsy specimen, which can be difficult to discern with certainty in suboptimal preparations. Another way to differentiate between the 2 entities is to utilize the salt-split skin technique, as performed in our patient. With salt-split skin, the biopsy is placed into a solution of 1 mol/L sodium chloride and incubated at 4 °C (39 °F) for 18 to 24 hours. A blister is then produced at the level of the lamina lucida, which allows for the staining of immunoreactants to occur either above or below that split (commonly referred to as staining on the roof or floor of the blister cavity). With EBA, there is immunoreactant deposition on the floor of the blister, while the opposite occurs in BP.4

Epidermolysis bullosa simplex is the most common type of epidermolysis bullosa, with keratin genes KRT5 and KRT14 as frequent mutations. Patients develop blisters, vesicles, bullae, and milia on traumatized areas of the body such as the hands, elbows, knees, and feet. This disease presents early in childhood. Histology exhibits a cell-poor subepidermal blister.5 With porphyria cutanea tarda, reduced activity of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase, a major enzyme in the heme synthesis pathway, leads to blisters with erosions and milia on sun-exposed areas of the body. Histologic evaluation reveals a subepidermal pauci-inflammatory vesicle with festooning of the dermal papillae and amphophilic basement membrane within the epidermis. Direct immunofluorescence of porphyria cutanea tarda demonstrates IgM and C3 in the vessels.6 Sweet syndrome is a neutrophilic dermatosis that presents as erythematous, edematous, hot, and tender plaques along with fever and leukocytosis. It is associated with myeloproliferative disorders. Biopsy demonstrates papillary dermal edema along with diffuse neutrophilic infiltrate.7

Numerous medications have been recommended for the treatment of EBA, ranging from steroids to steroid-sparing drugs such as colchicine and dapsone.8,9 Our patient was educated on physical precautions and was started on dapsone alone due to comorbid diabetes mellitus and renal disease. Within a few weeks of initiating dapsone, he observed a reduction in erythema, and within months he experienced a decrease in blister eruption frequency.

- Vorobyev A, Ludwig RJ, Schmidt E. Clinical features and diagnosis of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2017;13:157-169.

- Reddy H, Shipman AR, Wojnarowska F. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita and inflammatory bowel disease: a review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:225-230.

- Vodegel RM, Jonkman MF, Pas HH, et al. U-serrated immunodeposition pattern differentiates type VII collagen targeting bullous diseases from other subepidermal bullous autoimmune diseases. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:112-118.

- Gardner KM, Crawford RI. Distinguishing epidermolysis bullosa acquisita from bullous pemphigoid without direct immunofluorescence. J Cutan Med Surg. 2018;22:22-24.

- Sprecher E. Epidermolysis bullosa simplex. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:23-32.

- Maynard B, Peters MS. Histologic and immunofluorescence study of cutaneous porphyrias. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:40-47.

- Nelson CA, Stephen S, Ashchyan HJ, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses: pathogenesis, Sweet syndrome, neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, and Behçet disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018:79:987-1006.

- Kirtschig G, Murrell D, Wojnarowska F, et al. Interventions for mucous membrane pemphigoid and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;1:CD004056

- Gürcan HM, Ahmed AR. Current concepts in the treatment of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2011;12:1259-1268.

- Vorobyev A, Ludwig RJ, Schmidt E. Clinical features and diagnosis of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2017;13:157-169.

- Reddy H, Shipman AR, Wojnarowska F. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita and inflammatory bowel disease: a review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:225-230.

- Vodegel RM, Jonkman MF, Pas HH, et al. U-serrated immunodeposition pattern differentiates type VII collagen targeting bullous diseases from other subepidermal bullous autoimmune diseases. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:112-118.

- Gardner KM, Crawford RI. Distinguishing epidermolysis bullosa acquisita from bullous pemphigoid without direct immunofluorescence. J Cutan Med Surg. 2018;22:22-24.

- Sprecher E. Epidermolysis bullosa simplex. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:23-32.

- Maynard B, Peters MS. Histologic and immunofluorescence study of cutaneous porphyrias. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:40-47.

- Nelson CA, Stephen S, Ashchyan HJ, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses: pathogenesis, Sweet syndrome, neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, and Behçet disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018:79:987-1006.

- Kirtschig G, Murrell D, Wojnarowska F, et al. Interventions for mucous membrane pemphigoid and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;1:CD004056

- Gürcan HM, Ahmed AR. Current concepts in the treatment of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2011;12:1259-1268.

A 69-year-old man presented with an asymptomatic rash on the extensor surfaces of 2 years' duration. He reported recurrent blisters that would then scar over. The lesions did not occur in relation to any known trauma. The patient's medical history revealed dialysis-dependent end-stage renal disease secondary to type 2 diabetes mellitus. His medications were noncontributory, and there was no family history of blistering disorders. He had tried triamcinolone cream without any improvement. Physical examination was remarkable for erythematous blisters and bullae with scales and milia on the elbows, knees, and lower legs. The oral mucosa was unremarkable. Shave biopsies of the skin for direct immunofluorescence and salt-split skin studies were obtained.

Atrophic Lesion on the Abdomen

The Diagnosis: Anetoderma of Prematurity

Anetoderma is a rare benign cutaneous disorder characterized by atrophic patches of skin due to dermal thinning. The term anetoderma is derived from the Greek words anetos (relaxed) and derma (skin).1 The physical appearance of the skin is associated with a reduction or loss of elastic tissue in the dermal layer, as seen on histolopathology.2

Two forms of anetoderma have been described. Primary anetoderma is an idiopathic form with no preceding inflammatory lesions. Secondary anetoderma is a reactive process linked to a known preceding inflammatory, infectious, autoimmune, or drug-induced condition.3 On histopathology, both primary and secondary anetoderma are characterized by a loss of elastic tissue or elastin fibers in the superficial to mid dermis.2

Anetoderma of prematurity was first described in 1996 by Prizant et al4 in 9 extremely premature (24-29 weeks' gestation) infants in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs). Although the exact mechanism behind anetoderma of prematurity is still unknown, Prizant et al4 and other investigators5 postulated that application of adhesive monitoring leads in the NICU played a role in the development of the lesions.

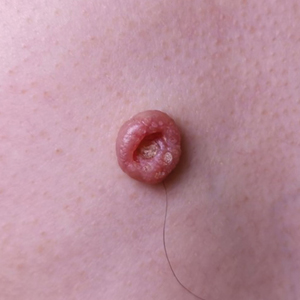

Iatrogenic anetoderma of prematurity is clinically characterized by circumscribed areas of either wrinkled macular depression or pouchlike herniations, ranging from flesh-colored to violaceous hues. Lesion size varies from a few millimeters to several centimeters in diameter, and they often are oval or round in shape.2 Although not common, it is possible for the atrophic patches to be preceded by an area of ecchymosis without necrosis or atrophy and, if present, they usually evolve within a few days to the characteristic appearance of anetoderma.3 They are found at discrete sites where monitoring leads or other medical devices are commonly placed, such as the forehead, abdomen, chest, and proximal limbs.

Lesions of anetoderma of prematurity are not present at birth, which distinguishes them from congenital anetoderma.6 It is unclear if the lesions are associated with the degree of prematurity, extremely low birth weight, or other associated factors of preterm birth. Although often clinically diagnosed, the diagnosis can be confirmed by a loss of elastic fibers on histopathology when stained with Verhoeff-van Gieson stain.1 Over time, the atrophic patches have the potential to evolve into herniated forms of anetoderma. Self-healing or improvement of the lesions often does not occur. Although the lesion is benign, it often requires surgical correction later in life for cosmesis.

Infants in the NICU are at risk for iatrogenic cutaneous injuries, which rarely may include anetoderma. Anetoderma of prematurity has been linked to the use of monitoring leads, adhesive tape, and other medical devices placed on the skin. Prizant et al4 postulated that the cause of anetoderma in these infants was irritants such as skin cleansers, urine, or sweat that may be trapped under the electrodes. Other hypotheses include local hypoxemia due to prolonged pressure from the electrodes on immature skin or excessive traction used when removing adhesive tape from the skin.7,8 Premature infants may be more susceptible to these lesions because of the reduced epidermal thickness of premature skin; immaturity of skin structure; or functional immaturity of elastin deposition regulators, such as elastase, lysyl oxidase, the complement system, and decay-accelerating factor.3 The diagnosis should be differentiated from congenital anetoderma, which also has been described in premature neonates but is characterized by lesions that are present at birth. Its origins are still unclear, despite having histopathologic features similar to iatrogenic anetoderma.9

Focal dermal hypoplasia (FDH) is the hallmark cutaneous finding in Goltz syndrome, a rare set of congenital abnormalities of the skin, oral structures, musculoskeletal system, and central nervous system. Similar to congenital anetoderma, FDH also is characterized by atrophic cutaneous lesions; however, the cutaneous lesions in FDH appear as linear, streaky atrophic lesions often with telangiectasias that follow Blaschko lines.10 The cutaneous lesions in FDH often are associated with other noncutaneous signs such as polydactyly or asymmetric limbs.10 Cutis laxa is caused by an abnormality in the elastic tissue resulting in a loose sagging appearance of the skin and frequently results in an aged facial appearance. There are both acquired and inherited forms that can be either solely cutaneous or present with extracutaneous features, such as cardiac abnormalities or emphysema.11

In contrast to the atrophic appearance of anetodermas, connective tissue nevi and nevus lipomatosus superficialis present as hamartomas that either can be present at birth or arise in infancy. Connective tissue nevi are hamartomas of dermal connective tissue that consist of excessive production of collagen, elastin, or glycosaminoglycans and appear as slightly elevated, flesh-colored to yellow nodules or plaques.12 Connective tissue nevi often are described in association with other diseases, most commonly tuberous sclerosis (shagreen patches) or familial cutaneous collagenoma. Nevus lipomatosus superficialis is an asymptomatic connective tissue hamartoma composed of mature adipocytes in the dermis. The lesions consist of clusters of flesh-colored to yellow, soft, rubbery papules or nodules with a smooth or verrucoid surface that do not cross the midline and may follow Blaschko lines.11

With advances in neonatal infant medical care, survival of extremely premature infants is increasing, and it is possible that this rare cutaneous disorder may become more prevalent. Care should be taken to avoid unnecessary pressure on surfaces where electrodes are placed and tightly applied adhesive tape. When electrodes are placed on the ventral side, the child should be placed supine; similarly, place electrodes on the dorsal side when the child is lying prone.5 A diagnosis of anetoderma of prematurity later in childhood may be difficult, so knowledge and awareness can help guide pediatricians and dermatologists to a correct diagnosis and prevent unnecessary evaluations and/or concerns.

- Misch KJ, Rhodes EL, Allen J, et al. Anetoderma of Jadassohn. J R Soc Med.1988;81:734-736.

- Venencie PY, Winkelmann RK. Histopathologic findings in anetoderma. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1040-1044.

- Maffeis L, Pugni L, Pietrasanta C, et al. Case report iatrogenic anetoderma of prematurity: a case report and review of the literature. 2014;2014:781493.

- Prizant TL, Lucky AW, Frieden IJ, et al. Spontaneous atrophic patches in extremely premature infants: anetoderma of prematurity. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:671-674.

- Goujon E, Beer F, Gay S, et al. Anetoderma of prematurity: an iatrogenic consequence of neonatal intensive care anetoderma of prematurity from NICU. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:565-567.

- Wain EM, Mellerio JE, Robson A, et al. Congenital anetoderma in a preterm infant. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:626-629.

- Colditz PB, Dunster KR, Joy GJ, et al. Anetoderma of prematurity in association with electrocardiographic electrodes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:479-481.

- Goujan E, Beer F, Gay S, et al. Study supervision. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:565-567.

- Aberer E, Weissenbacher G. Congenital anetoderma induced by intrauterine infection? Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:526-527.

- Mallory SB, Krafchik BR, Moore DJ, et al. Goltz syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 1989;6:251-253.

- Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L. Dermatology. Elsevier Saunders; 2017.

- Uitto J, Santa Cruz DJ, Eisen AZ. Connective tissue nevi of the skin. clinical, genetic, and histopathologic classification of hamartomas of the collagen, elastin, and proteoglycan type. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:441-461.

The Diagnosis: Anetoderma of Prematurity

Anetoderma is a rare benign cutaneous disorder characterized by atrophic patches of skin due to dermal thinning. The term anetoderma is derived from the Greek words anetos (relaxed) and derma (skin).1 The physical appearance of the skin is associated with a reduction or loss of elastic tissue in the dermal layer, as seen on histolopathology.2

Two forms of anetoderma have been described. Primary anetoderma is an idiopathic form with no preceding inflammatory lesions. Secondary anetoderma is a reactive process linked to a known preceding inflammatory, infectious, autoimmune, or drug-induced condition.3 On histopathology, both primary and secondary anetoderma are characterized by a loss of elastic tissue or elastin fibers in the superficial to mid dermis.2

Anetoderma of prematurity was first described in 1996 by Prizant et al4 in 9 extremely premature (24-29 weeks' gestation) infants in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs). Although the exact mechanism behind anetoderma of prematurity is still unknown, Prizant et al4 and other investigators5 postulated that application of adhesive monitoring leads in the NICU played a role in the development of the lesions.

Iatrogenic anetoderma of prematurity is clinically characterized by circumscribed areas of either wrinkled macular depression or pouchlike herniations, ranging from flesh-colored to violaceous hues. Lesion size varies from a few millimeters to several centimeters in diameter, and they often are oval or round in shape.2 Although not common, it is possible for the atrophic patches to be preceded by an area of ecchymosis without necrosis or atrophy and, if present, they usually evolve within a few days to the characteristic appearance of anetoderma.3 They are found at discrete sites where monitoring leads or other medical devices are commonly placed, such as the forehead, abdomen, chest, and proximal limbs.

Lesions of anetoderma of prematurity are not present at birth, which distinguishes them from congenital anetoderma.6 It is unclear if the lesions are associated with the degree of prematurity, extremely low birth weight, or other associated factors of preterm birth. Although often clinically diagnosed, the diagnosis can be confirmed by a loss of elastic fibers on histopathology when stained with Verhoeff-van Gieson stain.1 Over time, the atrophic patches have the potential to evolve into herniated forms of anetoderma. Self-healing or improvement of the lesions often does not occur. Although the lesion is benign, it often requires surgical correction later in life for cosmesis.

Infants in the NICU are at risk for iatrogenic cutaneous injuries, which rarely may include anetoderma. Anetoderma of prematurity has been linked to the use of monitoring leads, adhesive tape, and other medical devices placed on the skin. Prizant et al4 postulated that the cause of anetoderma in these infants was irritants such as skin cleansers, urine, or sweat that may be trapped under the electrodes. Other hypotheses include local hypoxemia due to prolonged pressure from the electrodes on immature skin or excessive traction used when removing adhesive tape from the skin.7,8 Premature infants may be more susceptible to these lesions because of the reduced epidermal thickness of premature skin; immaturity of skin structure; or functional immaturity of elastin deposition regulators, such as elastase, lysyl oxidase, the complement system, and decay-accelerating factor.3 The diagnosis should be differentiated from congenital anetoderma, which also has been described in premature neonates but is characterized by lesions that are present at birth. Its origins are still unclear, despite having histopathologic features similar to iatrogenic anetoderma.9

Focal dermal hypoplasia (FDH) is the hallmark cutaneous finding in Goltz syndrome, a rare set of congenital abnormalities of the skin, oral structures, musculoskeletal system, and central nervous system. Similar to congenital anetoderma, FDH also is characterized by atrophic cutaneous lesions; however, the cutaneous lesions in FDH appear as linear, streaky atrophic lesions often with telangiectasias that follow Blaschko lines.10 The cutaneous lesions in FDH often are associated with other noncutaneous signs such as polydactyly or asymmetric limbs.10 Cutis laxa is caused by an abnormality in the elastic tissue resulting in a loose sagging appearance of the skin and frequently results in an aged facial appearance. There are both acquired and inherited forms that can be either solely cutaneous or present with extracutaneous features, such as cardiac abnormalities or emphysema.11

In contrast to the atrophic appearance of anetodermas, connective tissue nevi and nevus lipomatosus superficialis present as hamartomas that either can be present at birth or arise in infancy. Connective tissue nevi are hamartomas of dermal connective tissue that consist of excessive production of collagen, elastin, or glycosaminoglycans and appear as slightly elevated, flesh-colored to yellow nodules or plaques.12 Connective tissue nevi often are described in association with other diseases, most commonly tuberous sclerosis (shagreen patches) or familial cutaneous collagenoma. Nevus lipomatosus superficialis is an asymptomatic connective tissue hamartoma composed of mature adipocytes in the dermis. The lesions consist of clusters of flesh-colored to yellow, soft, rubbery papules or nodules with a smooth or verrucoid surface that do not cross the midline and may follow Blaschko lines.11

With advances in neonatal infant medical care, survival of extremely premature infants is increasing, and it is possible that this rare cutaneous disorder may become more prevalent. Care should be taken to avoid unnecessary pressure on surfaces where electrodes are placed and tightly applied adhesive tape. When electrodes are placed on the ventral side, the child should be placed supine; similarly, place electrodes on the dorsal side when the child is lying prone.5 A diagnosis of anetoderma of prematurity later in childhood may be difficult, so knowledge and awareness can help guide pediatricians and dermatologists to a correct diagnosis and prevent unnecessary evaluations and/or concerns.

The Diagnosis: Anetoderma of Prematurity

Anetoderma is a rare benign cutaneous disorder characterized by atrophic patches of skin due to dermal thinning. The term anetoderma is derived from the Greek words anetos (relaxed) and derma (skin).1 The physical appearance of the skin is associated with a reduction or loss of elastic tissue in the dermal layer, as seen on histolopathology.2

Two forms of anetoderma have been described. Primary anetoderma is an idiopathic form with no preceding inflammatory lesions. Secondary anetoderma is a reactive process linked to a known preceding inflammatory, infectious, autoimmune, or drug-induced condition.3 On histopathology, both primary and secondary anetoderma are characterized by a loss of elastic tissue or elastin fibers in the superficial to mid dermis.2

Anetoderma of prematurity was first described in 1996 by Prizant et al4 in 9 extremely premature (24-29 weeks' gestation) infants in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs). Although the exact mechanism behind anetoderma of prematurity is still unknown, Prizant et al4 and other investigators5 postulated that application of adhesive monitoring leads in the NICU played a role in the development of the lesions.

Iatrogenic anetoderma of prematurity is clinically characterized by circumscribed areas of either wrinkled macular depression or pouchlike herniations, ranging from flesh-colored to violaceous hues. Lesion size varies from a few millimeters to several centimeters in diameter, and they often are oval or round in shape.2 Although not common, it is possible for the atrophic patches to be preceded by an area of ecchymosis without necrosis or atrophy and, if present, they usually evolve within a few days to the characteristic appearance of anetoderma.3 They are found at discrete sites where monitoring leads or other medical devices are commonly placed, such as the forehead, abdomen, chest, and proximal limbs.

Lesions of anetoderma of prematurity are not present at birth, which distinguishes them from congenital anetoderma.6 It is unclear if the lesions are associated with the degree of prematurity, extremely low birth weight, or other associated factors of preterm birth. Although often clinically diagnosed, the diagnosis can be confirmed by a loss of elastic fibers on histopathology when stained with Verhoeff-van Gieson stain.1 Over time, the atrophic patches have the potential to evolve into herniated forms of anetoderma. Self-healing or improvement of the lesions often does not occur. Although the lesion is benign, it often requires surgical correction later in life for cosmesis.

Infants in the NICU are at risk for iatrogenic cutaneous injuries, which rarely may include anetoderma. Anetoderma of prematurity has been linked to the use of monitoring leads, adhesive tape, and other medical devices placed on the skin. Prizant et al4 postulated that the cause of anetoderma in these infants was irritants such as skin cleansers, urine, or sweat that may be trapped under the electrodes. Other hypotheses include local hypoxemia due to prolonged pressure from the electrodes on immature skin or excessive traction used when removing adhesive tape from the skin.7,8 Premature infants may be more susceptible to these lesions because of the reduced epidermal thickness of premature skin; immaturity of skin structure; or functional immaturity of elastin deposition regulators, such as elastase, lysyl oxidase, the complement system, and decay-accelerating factor.3 The diagnosis should be differentiated from congenital anetoderma, which also has been described in premature neonates but is characterized by lesions that are present at birth. Its origins are still unclear, despite having histopathologic features similar to iatrogenic anetoderma.9

Focal dermal hypoplasia (FDH) is the hallmark cutaneous finding in Goltz syndrome, a rare set of congenital abnormalities of the skin, oral structures, musculoskeletal system, and central nervous system. Similar to congenital anetoderma, FDH also is characterized by atrophic cutaneous lesions; however, the cutaneous lesions in FDH appear as linear, streaky atrophic lesions often with telangiectasias that follow Blaschko lines.10 The cutaneous lesions in FDH often are associated with other noncutaneous signs such as polydactyly or asymmetric limbs.10 Cutis laxa is caused by an abnormality in the elastic tissue resulting in a loose sagging appearance of the skin and frequently results in an aged facial appearance. There are both acquired and inherited forms that can be either solely cutaneous or present with extracutaneous features, such as cardiac abnormalities or emphysema.11

In contrast to the atrophic appearance of anetodermas, connective tissue nevi and nevus lipomatosus superficialis present as hamartomas that either can be present at birth or arise in infancy. Connective tissue nevi are hamartomas of dermal connective tissue that consist of excessive production of collagen, elastin, or glycosaminoglycans and appear as slightly elevated, flesh-colored to yellow nodules or plaques.12 Connective tissue nevi often are described in association with other diseases, most commonly tuberous sclerosis (shagreen patches) or familial cutaneous collagenoma. Nevus lipomatosus superficialis is an asymptomatic connective tissue hamartoma composed of mature adipocytes in the dermis. The lesions consist of clusters of flesh-colored to yellow, soft, rubbery papules or nodules with a smooth or verrucoid surface that do not cross the midline and may follow Blaschko lines.11

With advances in neonatal infant medical care, survival of extremely premature infants is increasing, and it is possible that this rare cutaneous disorder may become more prevalent. Care should be taken to avoid unnecessary pressure on surfaces where electrodes are placed and tightly applied adhesive tape. When electrodes are placed on the ventral side, the child should be placed supine; similarly, place electrodes on the dorsal side when the child is lying prone.5 A diagnosis of anetoderma of prematurity later in childhood may be difficult, so knowledge and awareness can help guide pediatricians and dermatologists to a correct diagnosis and prevent unnecessary evaluations and/or concerns.

- Misch KJ, Rhodes EL, Allen J, et al. Anetoderma of Jadassohn. J R Soc Med.1988;81:734-736.

- Venencie PY, Winkelmann RK. Histopathologic findings in anetoderma. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1040-1044.

- Maffeis L, Pugni L, Pietrasanta C, et al. Case report iatrogenic anetoderma of prematurity: a case report and review of the literature. 2014;2014:781493.

- Prizant TL, Lucky AW, Frieden IJ, et al. Spontaneous atrophic patches in extremely premature infants: anetoderma of prematurity. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:671-674.

- Goujon E, Beer F, Gay S, et al. Anetoderma of prematurity: an iatrogenic consequence of neonatal intensive care anetoderma of prematurity from NICU. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:565-567.

- Wain EM, Mellerio JE, Robson A, et al. Congenital anetoderma in a preterm infant. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:626-629.

- Colditz PB, Dunster KR, Joy GJ, et al. Anetoderma of prematurity in association with electrocardiographic electrodes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:479-481.

- Goujan E, Beer F, Gay S, et al. Study supervision. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:565-567.

- Aberer E, Weissenbacher G. Congenital anetoderma induced by intrauterine infection? Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:526-527.

- Mallory SB, Krafchik BR, Moore DJ, et al. Goltz syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 1989;6:251-253.

- Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L. Dermatology. Elsevier Saunders; 2017.

- Uitto J, Santa Cruz DJ, Eisen AZ. Connective tissue nevi of the skin. clinical, genetic, and histopathologic classification of hamartomas of the collagen, elastin, and proteoglycan type. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:441-461.

- Misch KJ, Rhodes EL, Allen J, et al. Anetoderma of Jadassohn. J R Soc Med.1988;81:734-736.

- Venencie PY, Winkelmann RK. Histopathologic findings in anetoderma. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1040-1044.

- Maffeis L, Pugni L, Pietrasanta C, et al. Case report iatrogenic anetoderma of prematurity: a case report and review of the literature. 2014;2014:781493.

- Prizant TL, Lucky AW, Frieden IJ, et al. Spontaneous atrophic patches in extremely premature infants: anetoderma of prematurity. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:671-674.

- Goujon E, Beer F, Gay S, et al. Anetoderma of prematurity: an iatrogenic consequence of neonatal intensive care anetoderma of prematurity from NICU. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:565-567.

- Wain EM, Mellerio JE, Robson A, et al. Congenital anetoderma in a preterm infant. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:626-629.

- Colditz PB, Dunster KR, Joy GJ, et al. Anetoderma of prematurity in association with electrocardiographic electrodes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:479-481.

- Goujan E, Beer F, Gay S, et al. Study supervision. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:565-567.

- Aberer E, Weissenbacher G. Congenital anetoderma induced by intrauterine infection? Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:526-527.

- Mallory SB, Krafchik BR, Moore DJ, et al. Goltz syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 1989;6:251-253.

- Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L. Dermatology. Elsevier Saunders; 2017.

- Uitto J, Santa Cruz DJ, Eisen AZ. Connective tissue nevi of the skin. clinical, genetic, and histopathologic classification of hamartomas of the collagen, elastin, and proteoglycan type. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:441-461.

An 18-month-old child presented with a 4-cm, atrophic, flesh-colored plaque on the left lateral aspect of the abdomen with overlying wrinkling of the skin. There was no outpouching of the skin or pain associated with the lesion. No other skin abnormalities were noted. The child was born premature at 30 weeks’ gestation (birth weight, 1400 g). The postnatal course was complicated by respiratory distress syndrome requiring prolonged ventilator support. The infant was in the neonatal intensive care unit for 5 months. The atrophic lesion first developed at 5 months of life and remained stable. Although the lesion was not present at birth, the parents noted that it was preceded by an ecchymotic lesion without necrosis that was first noticed at 2 months of life while the patient was in the neonatal intensive care unit.

Expanding Verrucous Plaque on the Face

The Diagnosis: Blastomycosis

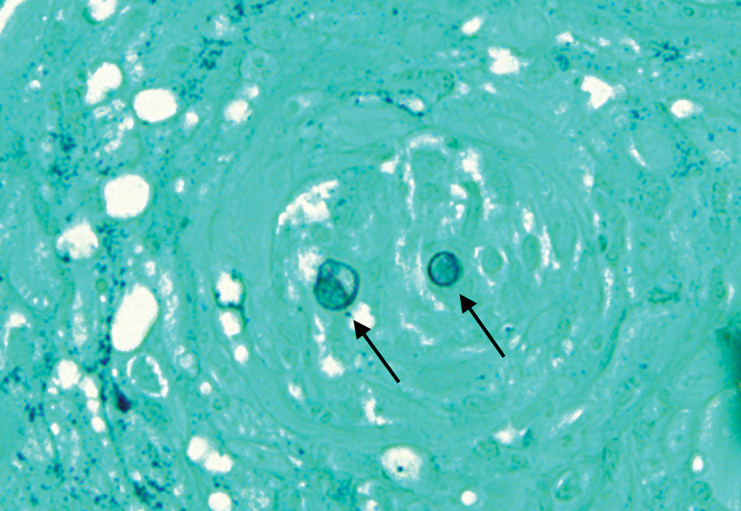

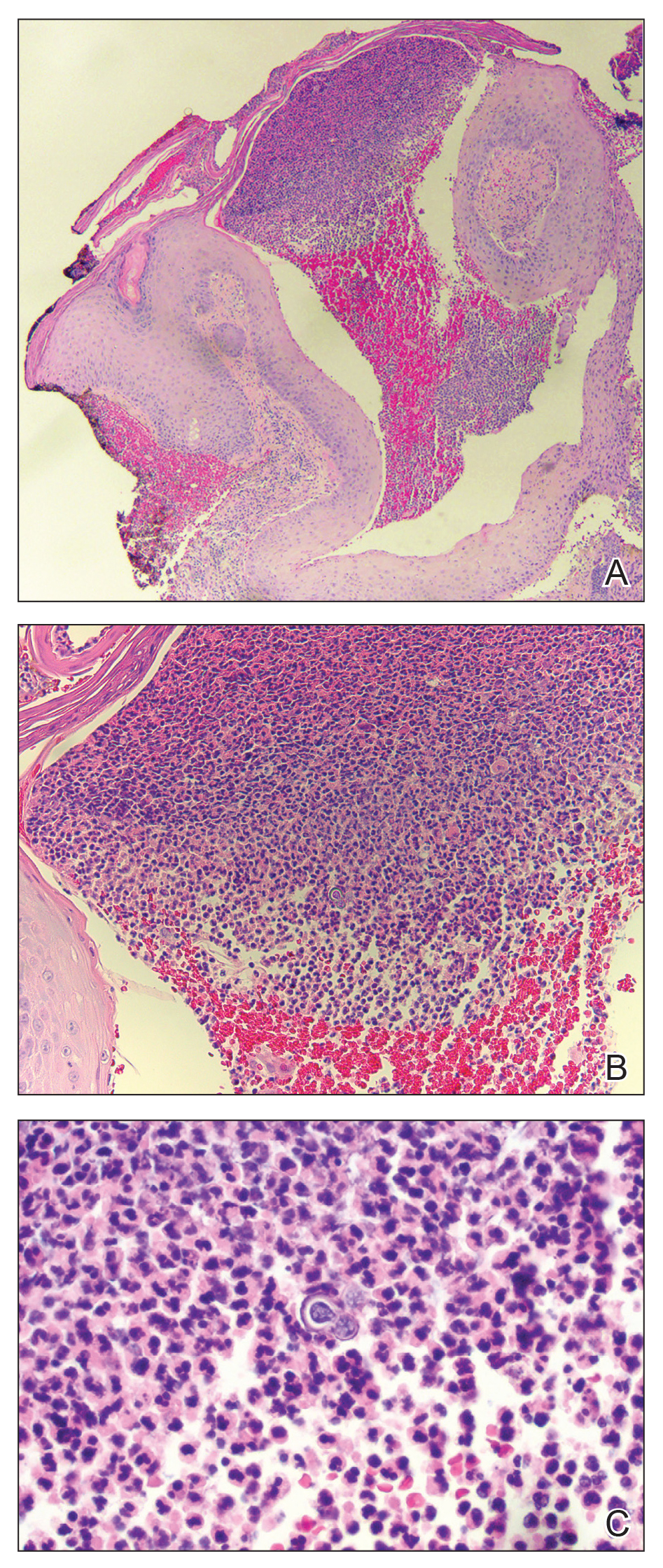

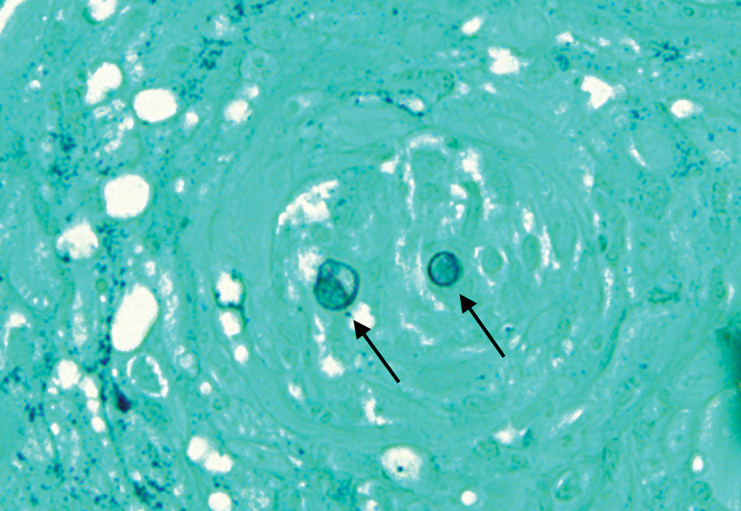

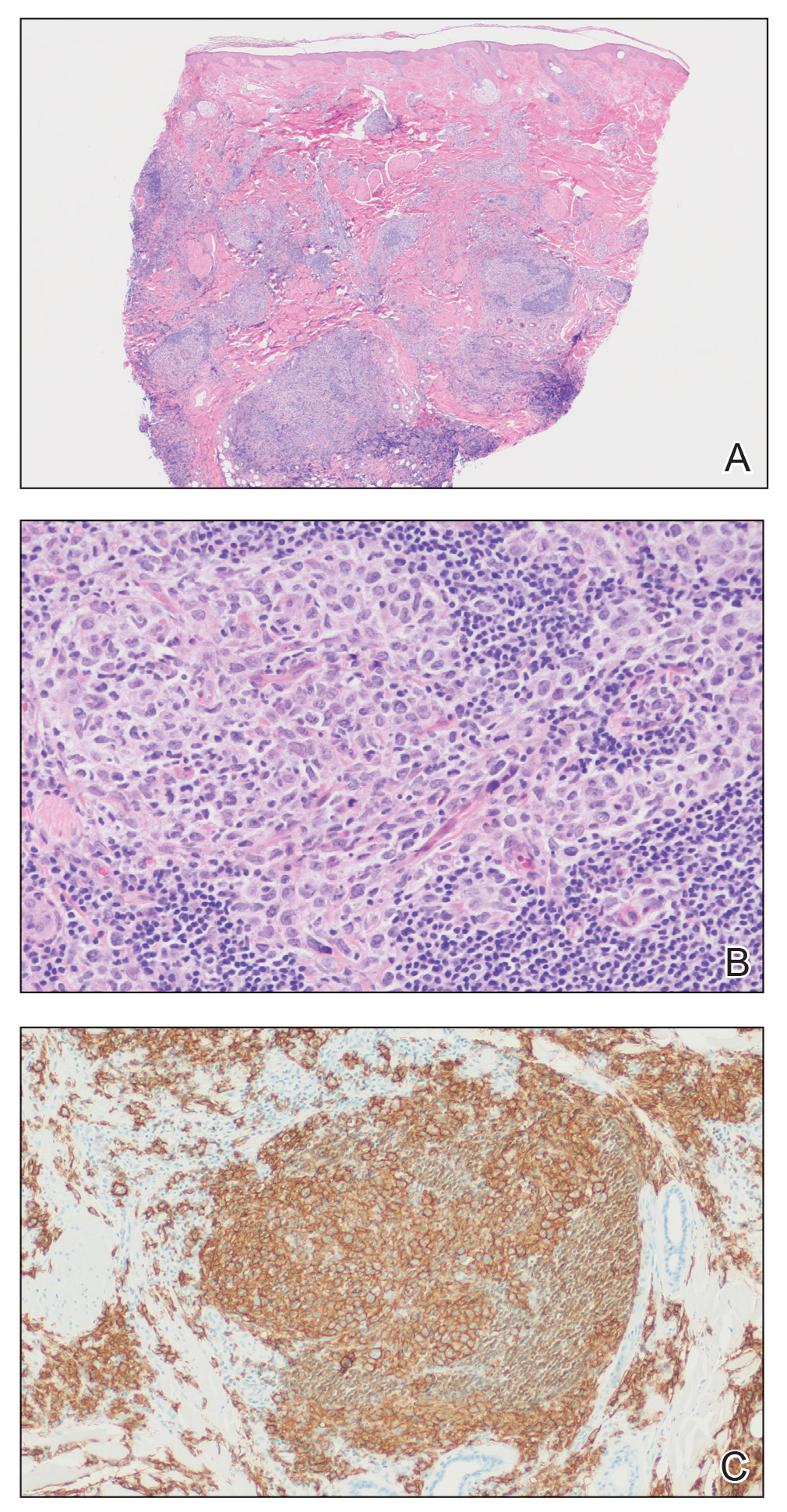

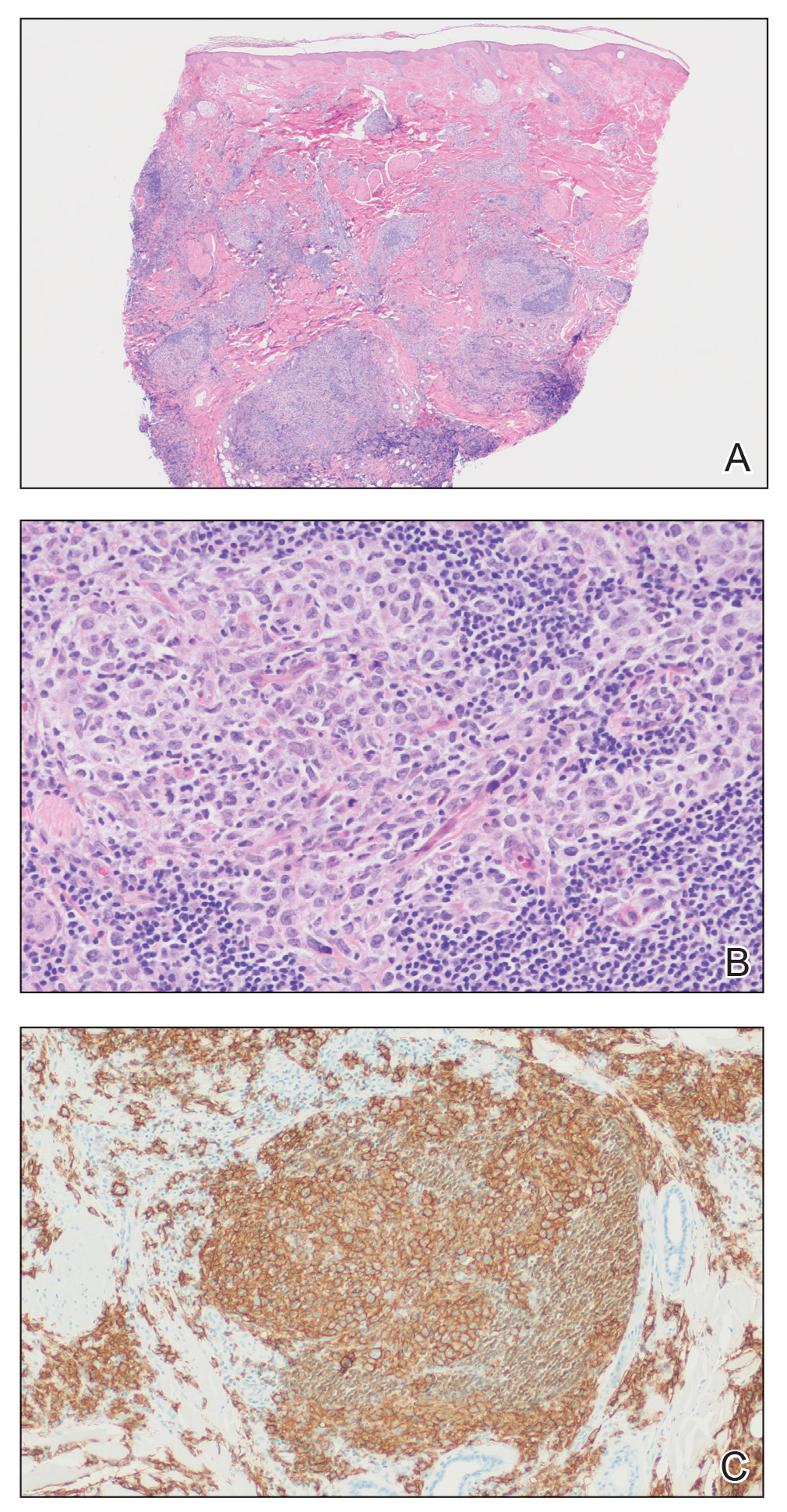

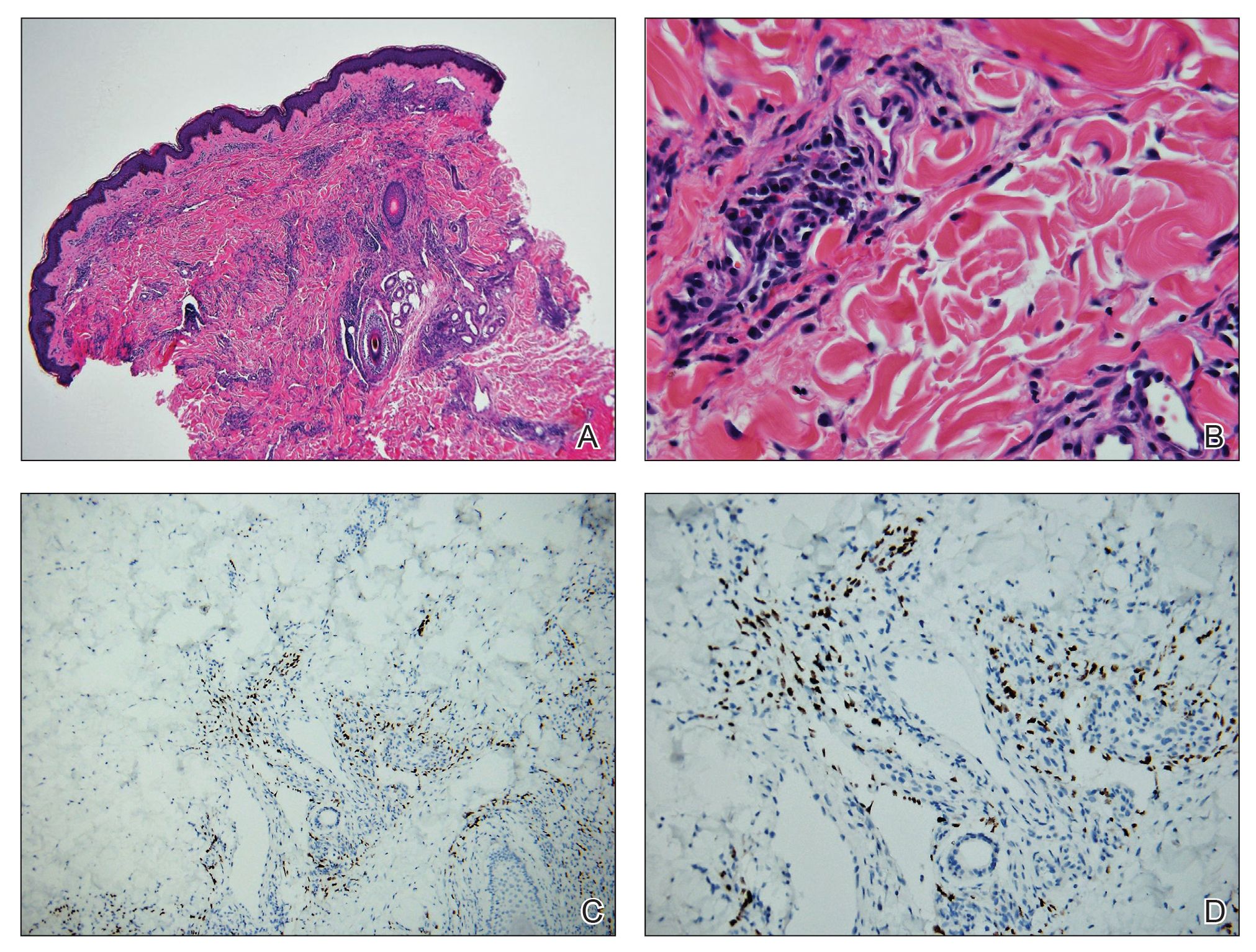

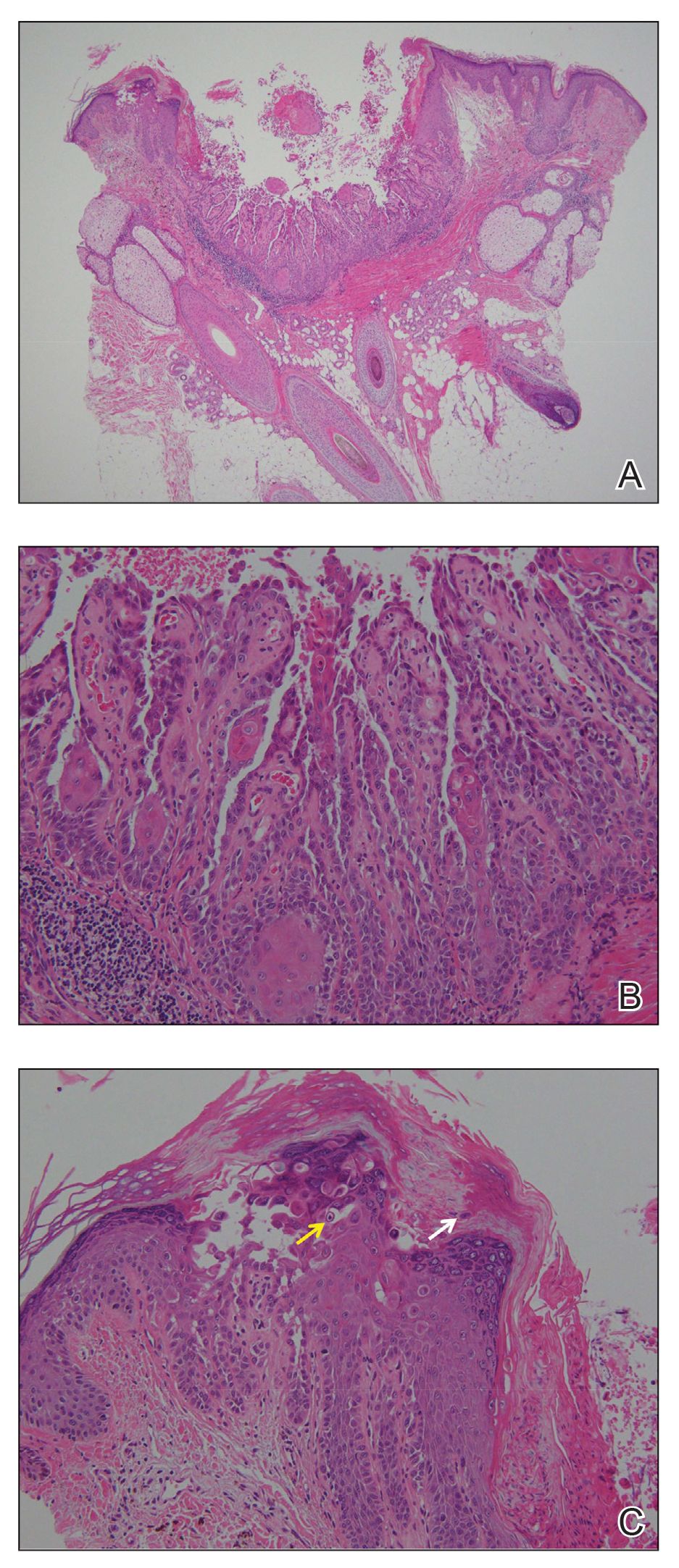

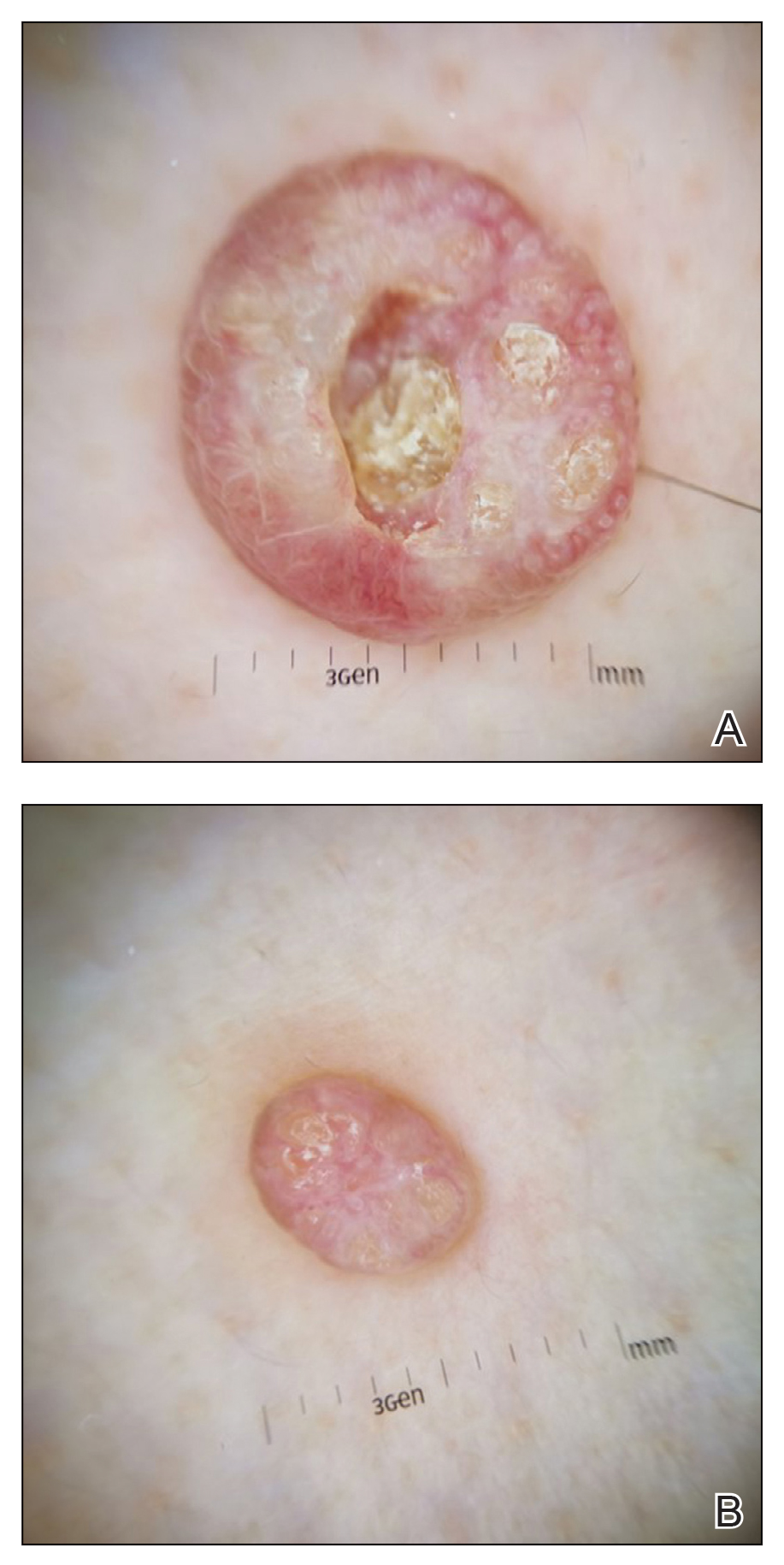

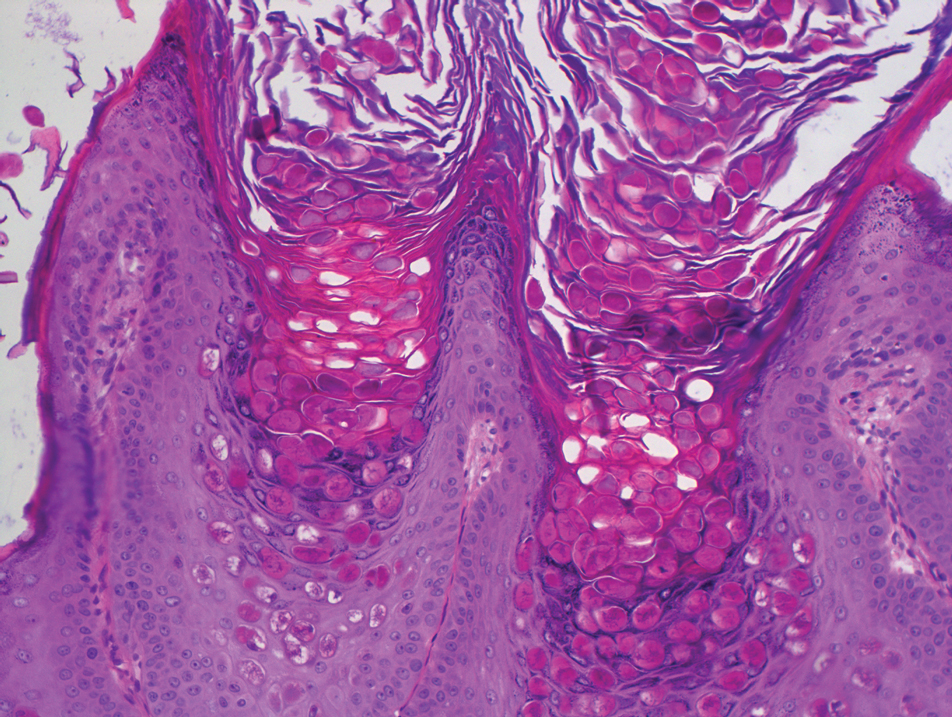

Histopathologic examination of 3 punch biopsies from the left side of the upper lip showed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal microabscesses and dermal suppurative granulomatous inflammation (Figure 1A). Stains were negative for periodic acid-Schiff, herpes simplex virus, and varicella-zoster virus. Direct and indirect immunofluorescence for skin autoantibodies were negative. Two separate tissue culture specimens showed no bacterial, fungal, or mycobacterial growth. Leishmania polymerase chain reaction and DNA sequencing were negative. An additional punch biopsy revealed yeast forms with broad-based budding and refractile walls (Figures 1B and 1C) that were highlighted with Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain of the tissue (Figure 2). Chest radiography demonstrated no pulmonary involvement. In collaboration with an infectious disease specialist, the patient was started on itraconazole 200 mg twice daily for a total of 6 months.

Blastomycosis is a fungal infection caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, a thermally dimorphic fungus endemic in the soils of the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys and southeastern United States.1 It most commonly manifests as a pulmonary infection following inhalation of spores that are transformed into thick-walled yeasts capable of evading the host's immune system. Unlike other deep fungal infections, blastomycosis occurs in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts. Extrapulmonary disease after hematogenous dissemination from the lungs occurs in approximately 25% to 30% of patients, with the skin as the most common site of dissemination.2 Clinically, cutaneous blastomycosis typically starts as papules that evolve into crusted vegetative plaques, often with central clearing or ulceration. Primary cutaneous blastomycosis is rare and occurs due to direct inoculation after trauma to the skin via an infected animal bite, direct inoculation in laboratory settings, or due to injury during outdoor activities involving contact with soil.3 Given our patient's horticultural hobbies, lack of pulmonary symptoms, and negative radiologic examination, primary cutaneous blastomycosis infection due to direct inoculation from contaminated soil was a possibility; however, definite confirmation was difficult, as the primary pulmonary infection of blastomycosis can be asymptomatic and therefore often goes undetected.

Cutaneous blastomycosis can be mistaken for pemphigus vegetans, leishmaniasis, herpes vegetans, bacterial pyoderma, and other deep fungal infections that also display pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with pyogranulomatous inflammation on histopathology. Direct visualization of the characteristic yeast forms in a histologic specimen or the growth of fungus in culture is essential for a definitive diagnosis. The yeasts are 8 to 15 µm in diameter with thick, double-contoured walls and characteristically display broad-based budding.4 This budding pattern aids in differentiating blastomycosis from other entities with a similar histopathologic appearance. Chromoblastomycosis would show brown, thick-walled fungal cells inside giant cells, while coccidioidomycosis displays large spherules containing endospores, and leishmaniasis demonstrates amastigotes (small oval organisms with a bar-shaped kinetoplast) highlighted with Giemsa staining. Pemphigus vegetans would show intercellular deposition of IgG on direct immunofluorescence. Blastomyces dermatitidis can be difficult to visualize with routine hematoxylin and eosin stains, and it is important to note that a negative result does not exclude the possibility of blastomycosis, as demonstrated in our case.4 Special stains including Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid-Schiff can aid in examining tissue for the presence of fungal elements, which typically can be found within histiocytes or abscesses in the dermis. Culture is the most sensitive method for detecting and diagnosing blastomycosis. Growth typically is detected in 5 to 10 days but can take up to 30 days if few organisms are present in the specimen.1

Although spontaneous remission can occur, it is recommended that all patients with cutaneous blastomycosis be treated to avoid dissemination and recurrence. Itraconazole currently is the treatment of choice.5 Doses typically are 200 to 400 mg/d for 8 to 12 months.6 Itraconazole-related side effects experienced by our patient during his 6-month treatment course included leg edema, 20-lb weight gain, gastrointestinal upset, blurred vision, and a transient increase in blood pressure, all resolving once the medication was discontinued. Complete resolution of the lesion was noted at the completion of the treatment course. At a 6-month posttreatment follow-up, residual scarring and alopecia were noted in parts of the previously affected areas of the upper cutaneous lip and nasolabial fold.

- Saccente M, Woods GL. Clinical and laboratory update on blastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:367-831.

- Chapman SW, Lin AC, Hendricks KA, et al. Endemic blastomycosis in Mississippi: epidemiological and clinical studies. Semin Respir Infect. 1997;12:219-228.

- Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:E44-E49.

- Patel AJ, Gattuso P, Reddy VB. Diagnosis of blastomycosis in surgical pathology and cytopathology: correlation with microbiologic culture. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:256-261.

- Chapman SW, Dismukes WE, Proia LA, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of blastomycosis: 2008 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1801-1812.

- Lomaestro, BM, Piatek MA. Update on drug interactions with azole antifungal agents. Ann Pharmacother. 1998;32:915-928.

The Diagnosis: Blastomycosis

Histopathologic examination of 3 punch biopsies from the left side of the upper lip showed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal microabscesses and dermal suppurative granulomatous inflammation (Figure 1A). Stains were negative for periodic acid-Schiff, herpes simplex virus, and varicella-zoster virus. Direct and indirect immunofluorescence for skin autoantibodies were negative. Two separate tissue culture specimens showed no bacterial, fungal, or mycobacterial growth. Leishmania polymerase chain reaction and DNA sequencing were negative. An additional punch biopsy revealed yeast forms with broad-based budding and refractile walls (Figures 1B and 1C) that were highlighted with Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain of the tissue (Figure 2). Chest radiography demonstrated no pulmonary involvement. In collaboration with an infectious disease specialist, the patient was started on itraconazole 200 mg twice daily for a total of 6 months.

Blastomycosis is a fungal infection caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, a thermally dimorphic fungus endemic in the soils of the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys and southeastern United States.1 It most commonly manifests as a pulmonary infection following inhalation of spores that are transformed into thick-walled yeasts capable of evading the host's immune system. Unlike other deep fungal infections, blastomycosis occurs in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts. Extrapulmonary disease after hematogenous dissemination from the lungs occurs in approximately 25% to 30% of patients, with the skin as the most common site of dissemination.2 Clinically, cutaneous blastomycosis typically starts as papules that evolve into crusted vegetative plaques, often with central clearing or ulceration. Primary cutaneous blastomycosis is rare and occurs due to direct inoculation after trauma to the skin via an infected animal bite, direct inoculation in laboratory settings, or due to injury during outdoor activities involving contact with soil.3 Given our patient's horticultural hobbies, lack of pulmonary symptoms, and negative radiologic examination, primary cutaneous blastomycosis infection due to direct inoculation from contaminated soil was a possibility; however, definite confirmation was difficult, as the primary pulmonary infection of blastomycosis can be asymptomatic and therefore often goes undetected.

Cutaneous blastomycosis can be mistaken for pemphigus vegetans, leishmaniasis, herpes vegetans, bacterial pyoderma, and other deep fungal infections that also display pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with pyogranulomatous inflammation on histopathology. Direct visualization of the characteristic yeast forms in a histologic specimen or the growth of fungus in culture is essential for a definitive diagnosis. The yeasts are 8 to 15 µm in diameter with thick, double-contoured walls and characteristically display broad-based budding.4 This budding pattern aids in differentiating blastomycosis from other entities with a similar histopathologic appearance. Chromoblastomycosis would show brown, thick-walled fungal cells inside giant cells, while coccidioidomycosis displays large spherules containing endospores, and leishmaniasis demonstrates amastigotes (small oval organisms with a bar-shaped kinetoplast) highlighted with Giemsa staining. Pemphigus vegetans would show intercellular deposition of IgG on direct immunofluorescence. Blastomyces dermatitidis can be difficult to visualize with routine hematoxylin and eosin stains, and it is important to note that a negative result does not exclude the possibility of blastomycosis, as demonstrated in our case.4 Special stains including Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid-Schiff can aid in examining tissue for the presence of fungal elements, which typically can be found within histiocytes or abscesses in the dermis. Culture is the most sensitive method for detecting and diagnosing blastomycosis. Growth typically is detected in 5 to 10 days but can take up to 30 days if few organisms are present in the specimen.1

Although spontaneous remission can occur, it is recommended that all patients with cutaneous blastomycosis be treated to avoid dissemination and recurrence. Itraconazole currently is the treatment of choice.5 Doses typically are 200 to 400 mg/d for 8 to 12 months.6 Itraconazole-related side effects experienced by our patient during his 6-month treatment course included leg edema, 20-lb weight gain, gastrointestinal upset, blurred vision, and a transient increase in blood pressure, all resolving once the medication was discontinued. Complete resolution of the lesion was noted at the completion of the treatment course. At a 6-month posttreatment follow-up, residual scarring and alopecia were noted in parts of the previously affected areas of the upper cutaneous lip and nasolabial fold.

The Diagnosis: Blastomycosis

Histopathologic examination of 3 punch biopsies from the left side of the upper lip showed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal microabscesses and dermal suppurative granulomatous inflammation (Figure 1A). Stains were negative for periodic acid-Schiff, herpes simplex virus, and varicella-zoster virus. Direct and indirect immunofluorescence for skin autoantibodies were negative. Two separate tissue culture specimens showed no bacterial, fungal, or mycobacterial growth. Leishmania polymerase chain reaction and DNA sequencing were negative. An additional punch biopsy revealed yeast forms with broad-based budding and refractile walls (Figures 1B and 1C) that were highlighted with Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain of the tissue (Figure 2). Chest radiography demonstrated no pulmonary involvement. In collaboration with an infectious disease specialist, the patient was started on itraconazole 200 mg twice daily for a total of 6 months.

Blastomycosis is a fungal infection caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, a thermally dimorphic fungus endemic in the soils of the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys and southeastern United States.1 It most commonly manifests as a pulmonary infection following inhalation of spores that are transformed into thick-walled yeasts capable of evading the host's immune system. Unlike other deep fungal infections, blastomycosis occurs in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts. Extrapulmonary disease after hematogenous dissemination from the lungs occurs in approximately 25% to 30% of patients, with the skin as the most common site of dissemination.2 Clinically, cutaneous blastomycosis typically starts as papules that evolve into crusted vegetative plaques, often with central clearing or ulceration. Primary cutaneous blastomycosis is rare and occurs due to direct inoculation after trauma to the skin via an infected animal bite, direct inoculation in laboratory settings, or due to injury during outdoor activities involving contact with soil.3 Given our patient's horticultural hobbies, lack of pulmonary symptoms, and negative radiologic examination, primary cutaneous blastomycosis infection due to direct inoculation from contaminated soil was a possibility; however, definite confirmation was difficult, as the primary pulmonary infection of blastomycosis can be asymptomatic and therefore often goes undetected.

Cutaneous blastomycosis can be mistaken for pemphigus vegetans, leishmaniasis, herpes vegetans, bacterial pyoderma, and other deep fungal infections that also display pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with pyogranulomatous inflammation on histopathology. Direct visualization of the characteristic yeast forms in a histologic specimen or the growth of fungus in culture is essential for a definitive diagnosis. The yeasts are 8 to 15 µm in diameter with thick, double-contoured walls and characteristically display broad-based budding.4 This budding pattern aids in differentiating blastomycosis from other entities with a similar histopathologic appearance. Chromoblastomycosis would show brown, thick-walled fungal cells inside giant cells, while coccidioidomycosis displays large spherules containing endospores, and leishmaniasis demonstrates amastigotes (small oval organisms with a bar-shaped kinetoplast) highlighted with Giemsa staining. Pemphigus vegetans would show intercellular deposition of IgG on direct immunofluorescence. Blastomyces dermatitidis can be difficult to visualize with routine hematoxylin and eosin stains, and it is important to note that a negative result does not exclude the possibility of blastomycosis, as demonstrated in our case.4 Special stains including Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid-Schiff can aid in examining tissue for the presence of fungal elements, which typically can be found within histiocytes or abscesses in the dermis. Culture is the most sensitive method for detecting and diagnosing blastomycosis. Growth typically is detected in 5 to 10 days but can take up to 30 days if few organisms are present in the specimen.1

Although spontaneous remission can occur, it is recommended that all patients with cutaneous blastomycosis be treated to avoid dissemination and recurrence. Itraconazole currently is the treatment of choice.5 Doses typically are 200 to 400 mg/d for 8 to 12 months.6 Itraconazole-related side effects experienced by our patient during his 6-month treatment course included leg edema, 20-lb weight gain, gastrointestinal upset, blurred vision, and a transient increase in blood pressure, all resolving once the medication was discontinued. Complete resolution of the lesion was noted at the completion of the treatment course. At a 6-month posttreatment follow-up, residual scarring and alopecia were noted in parts of the previously affected areas of the upper cutaneous lip and nasolabial fold.

- Saccente M, Woods GL. Clinical and laboratory update on blastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:367-831.

- Chapman SW, Lin AC, Hendricks KA, et al. Endemic blastomycosis in Mississippi: epidemiological and clinical studies. Semin Respir Infect. 1997;12:219-228.

- Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:E44-E49.

- Patel AJ, Gattuso P, Reddy VB. Diagnosis of blastomycosis in surgical pathology and cytopathology: correlation with microbiologic culture. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:256-261.

- Chapman SW, Dismukes WE, Proia LA, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of blastomycosis: 2008 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1801-1812.

- Lomaestro, BM, Piatek MA. Update on drug interactions with azole antifungal agents. Ann Pharmacother. 1998;32:915-928.

- Saccente M, Woods GL. Clinical and laboratory update on blastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:367-831.

- Chapman SW, Lin AC, Hendricks KA, et al. Endemic blastomycosis in Mississippi: epidemiological and clinical studies. Semin Respir Infect. 1997;12:219-228.

- Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:E44-E49.

- Patel AJ, Gattuso P, Reddy VB. Diagnosis of blastomycosis in surgical pathology and cytopathology: correlation with microbiologic culture. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:256-261.

- Chapman SW, Dismukes WE, Proia LA, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of blastomycosis: 2008 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1801-1812.