User login

Index finger plaque

The characteristic finding of small, scattered vesicular lesions on the hands that sometimes coalesce, and often are itchy or irritated led to the diagnosis of vesicular hand dermatitis, a form of eczema. It also is referred to as dyshidrotic eczema or pompholyx. (Worth noting is the fact that common warts and flat warts usually present as raised papular—not vesicular—lesions on the hands.)

The exact etiology of vesicular hand dermatitis is unknown. It is more common in women than men and often occurs in patients 20 to 40 years of age who tend to have a positive family history of eczema. It usually develops acutely and often is triggered by topical irritants or frequent hand washing. Treatment during the acute phase includes topical steroids. Avoidance of topical irritants, use of mild cleansers instead of harsh soaps, reduction of hand washing frequency (if possible), and frequent application of emollients can reduce recurrence.

This patient’s eczema had been successfully treated with betamethasone dipropionate ointment 0.05% in the past. Since she still had some at home, she was instructed to use it twice daily along with topical emmolients. She reported great improvement within 1 week.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Sobering G, Dika C. Vesicular hand dermatitis. Nurse Pract. 2018;43:33-37.

The characteristic finding of small, scattered vesicular lesions on the hands that sometimes coalesce, and often are itchy or irritated led to the diagnosis of vesicular hand dermatitis, a form of eczema. It also is referred to as dyshidrotic eczema or pompholyx. (Worth noting is the fact that common warts and flat warts usually present as raised papular—not vesicular—lesions on the hands.)

The exact etiology of vesicular hand dermatitis is unknown. It is more common in women than men and often occurs in patients 20 to 40 years of age who tend to have a positive family history of eczema. It usually develops acutely and often is triggered by topical irritants or frequent hand washing. Treatment during the acute phase includes topical steroids. Avoidance of topical irritants, use of mild cleansers instead of harsh soaps, reduction of hand washing frequency (if possible), and frequent application of emollients can reduce recurrence.

This patient’s eczema had been successfully treated with betamethasone dipropionate ointment 0.05% in the past. Since she still had some at home, she was instructed to use it twice daily along with topical emmolients. She reported great improvement within 1 week.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

The characteristic finding of small, scattered vesicular lesions on the hands that sometimes coalesce, and often are itchy or irritated led to the diagnosis of vesicular hand dermatitis, a form of eczema. It also is referred to as dyshidrotic eczema or pompholyx. (Worth noting is the fact that common warts and flat warts usually present as raised papular—not vesicular—lesions on the hands.)

The exact etiology of vesicular hand dermatitis is unknown. It is more common in women than men and often occurs in patients 20 to 40 years of age who tend to have a positive family history of eczema. It usually develops acutely and often is triggered by topical irritants or frequent hand washing. Treatment during the acute phase includes topical steroids. Avoidance of topical irritants, use of mild cleansers instead of harsh soaps, reduction of hand washing frequency (if possible), and frequent application of emollients can reduce recurrence.

This patient’s eczema had been successfully treated with betamethasone dipropionate ointment 0.05% in the past. Since she still had some at home, she was instructed to use it twice daily along with topical emmolients. She reported great improvement within 1 week.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Sobering G, Dika C. Vesicular hand dermatitis. Nurse Pract. 2018;43:33-37.

Sobering G, Dika C. Vesicular hand dermatitis. Nurse Pract. 2018;43:33-37.

Chronic, nonhealing leg ulcer

An 80-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, psoriasis vulgaris with associated pruritus, and well-controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus presented with a slowly enlarging ulceration on her left leg of 1 year’s duration. She noted that this lesion healed less rapidly than previous stasis leg ulcerations, despite using the same treatment approach that included dressings, elevation, and diuretics to decrease pedal edema.

Physical examination revealed plaques with white micaceous scaling over her extensor surfaces and scalp, as well as guttate lesions on the trunk, typical of psoriasis vulgaris. A 5.8 × 7.2-cm malodorous ulceration was superimposed on a large psoriatic plaque on her left anterior lower leg (FIGURE 1). A 4-mm punch biopsy was obtained from the peripheral margin.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Basal cell carcinoma

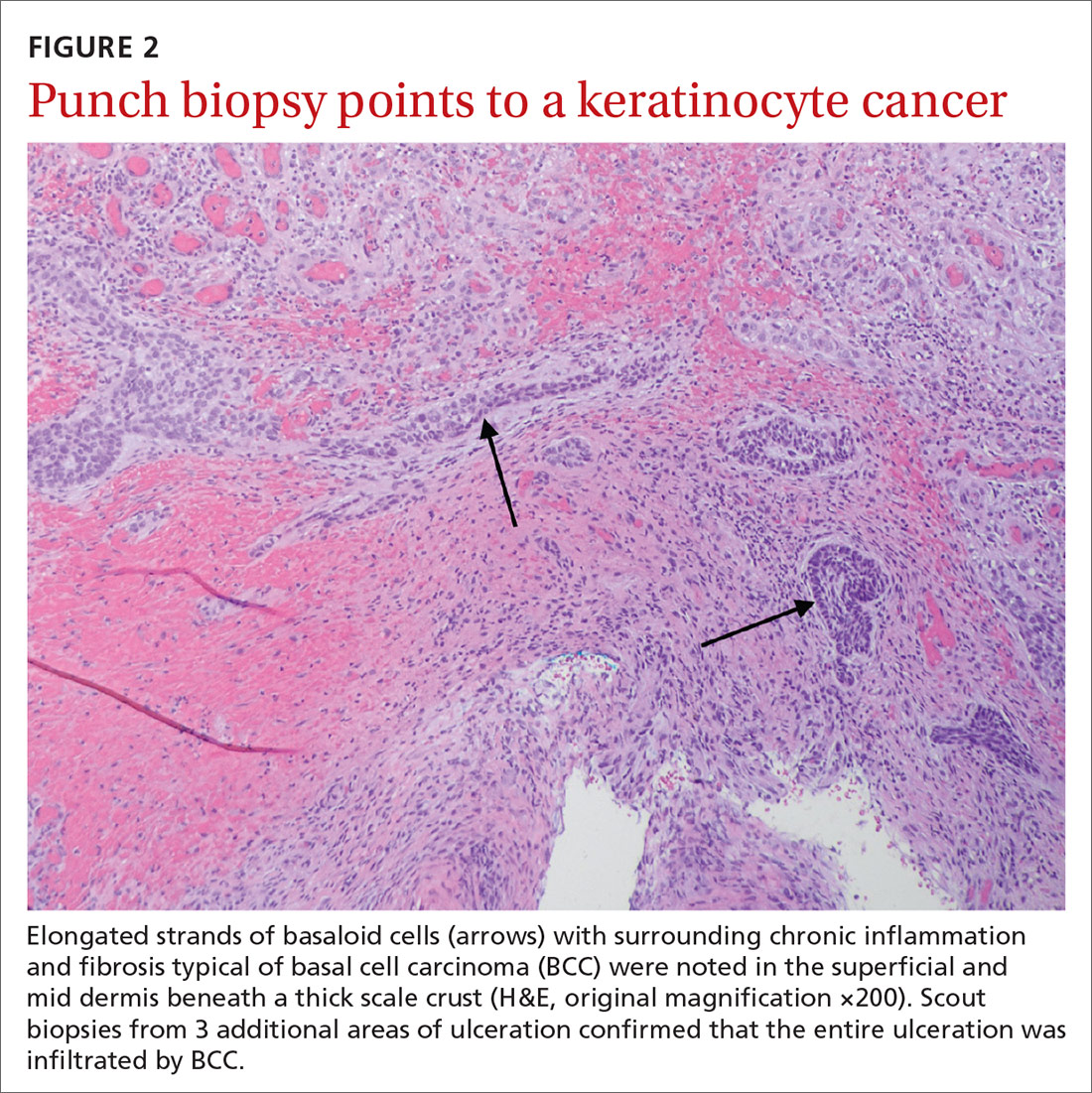

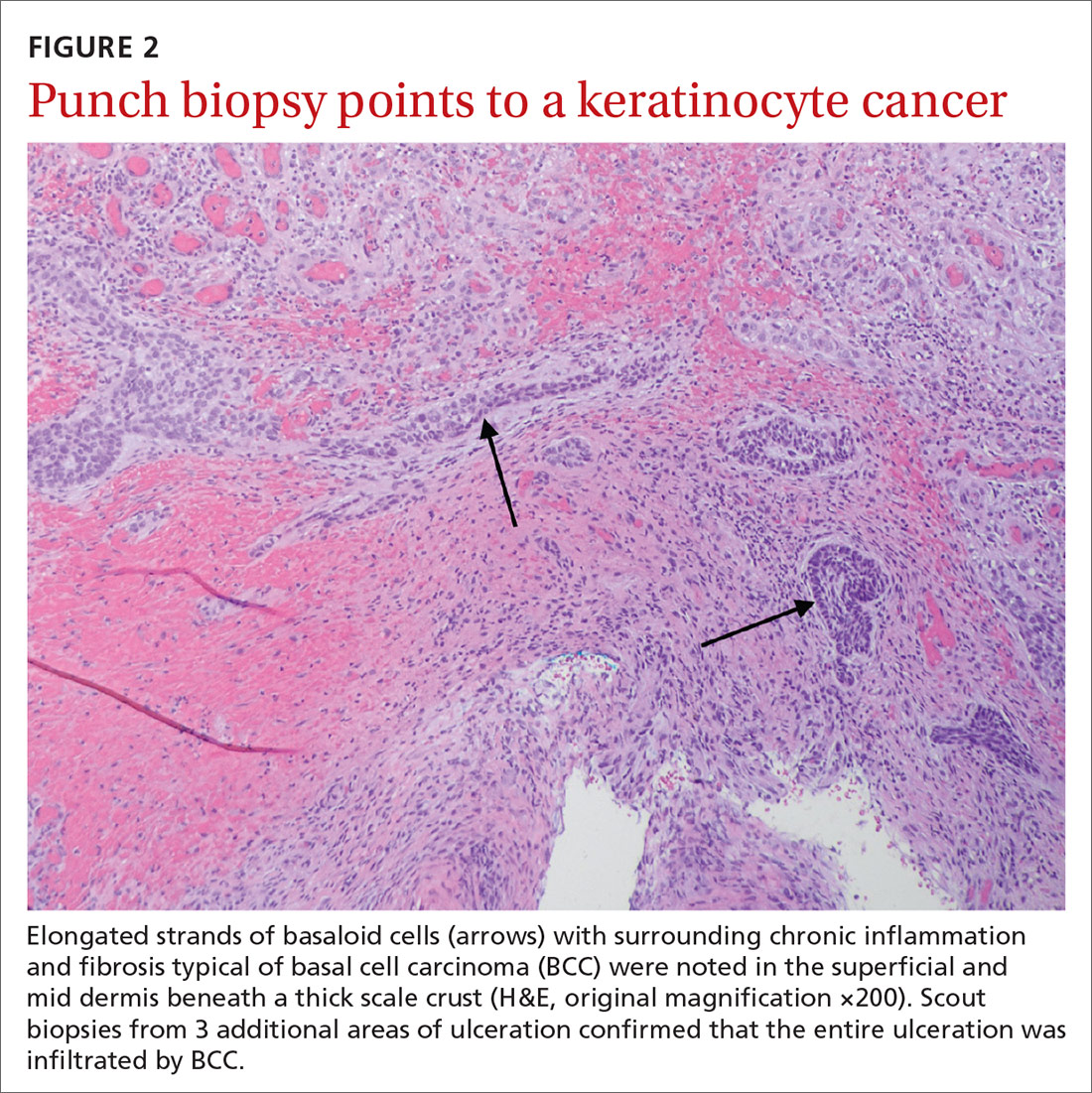

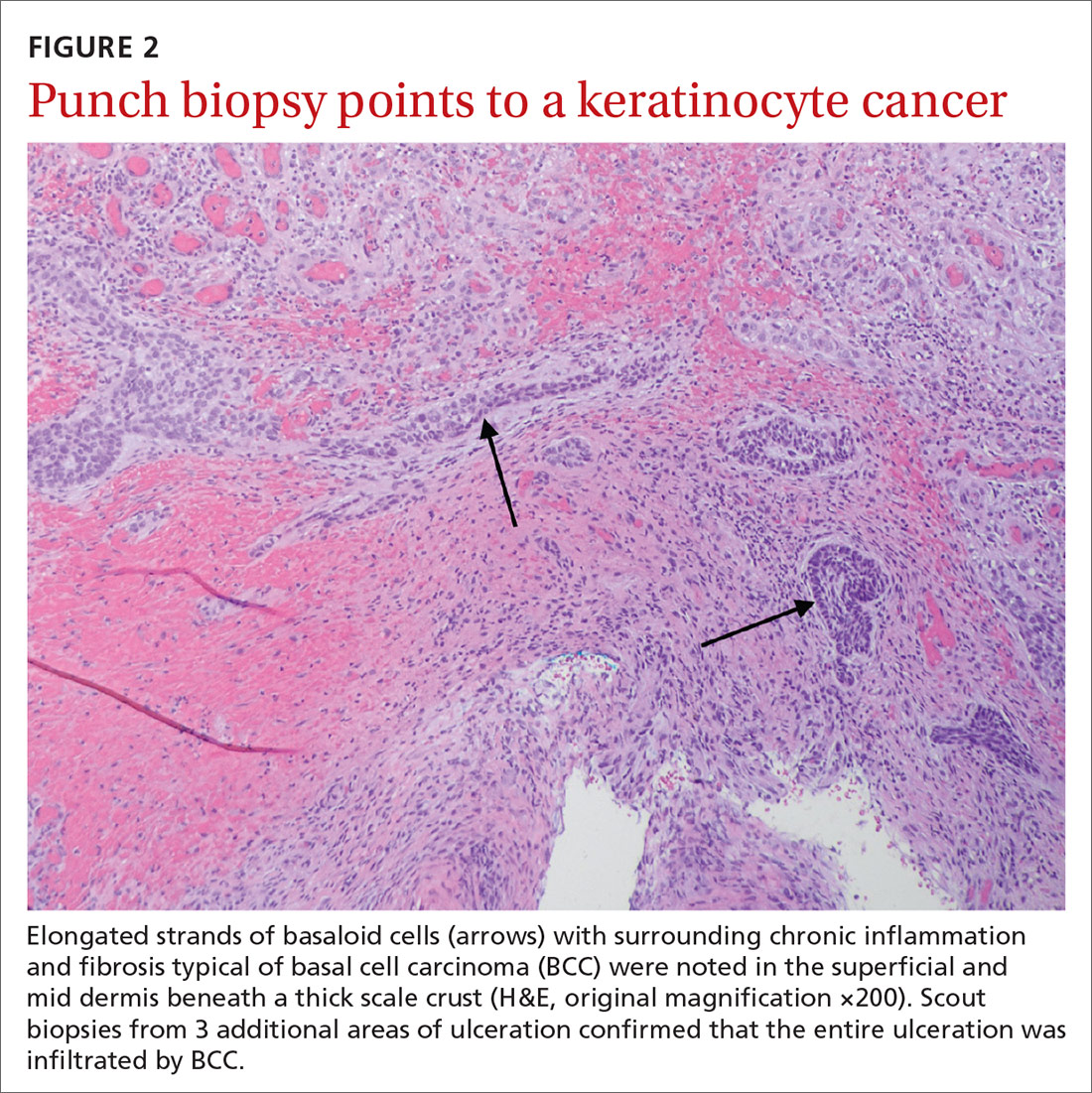

Histopathological examination revealed elongated strands of closely packed basaloid cells embedded in a dense fibrous stroma with overlying ulceration and crusting (FIGURE 2). Immunohistochemical staining with cytokeratin (CK) 5/6 decorated the cytoplasm of the tumor cells, which confirmed that the tumor was a keratinocyte cancer. CK 20 was negative, excluding the possibility of a Merkel cell carcinoma. Scout biopsies from 3 additional areas of ulceration confirmed that the entire ulceration was infiltrated by basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

A surprise hidden in a chronic ulcer

More than 6 million Americans have chronic ulcers and most occur on the legs.1 The majority of these chronic ulcerations are etiologically related to venous stasis, arterial insufficiency, or neuropathy.2

Bacterial pyoderma, chronic infection caused by atypical acid-fast bacilli or deep fungal infection, pyoderma gangrenosum, cutaneous vasculitis, calciphylaxis, and venous ulceration were all considered to explain this patient’s nonhealing wound. A biopsy was required to fully assess these possibilities.

Don’t overlook the possibility of malignancy. In a cross-sectional, multicenter study by Senet et al,3 144 patients with 154 total chronic leg ulcers were evaluated in tertiary care centers for malignancy, which was found to occur at a rate of 10.4%. Similarly, Ghasemi et al4 demonstrated a malignancy rate of 16.1% in 124 patients who underwent biopsy; the anterior shin was determined to be the most frequent location for malignancy. The most common skin cancer identified within the setting of chronic ulcers is squamous cell carcinoma.3 Although rare, there are reports of BCC identified in chronic wounds.3-7

Morphological signs suggestive of malignancy in chronic ulcerations include hyperkeratosis, granulation tissue surrounded by a raised border, unusual pain or bleeding, and increased tissue friability. Our patient had none of these signs and symptoms. However, it is possible that she had a tumor that ulcerated and would not heal.

Continue to: Which came first?

Which came first? It’s difficult to know in this case whether a persistent BCC ulcerated, forming this lesion, or if scarring associated with a chronic ulceration led to the development of the BCC.6 Based on biopsies taken at an earlier date, Schnirring-Judge and Belpedio7 concluded that a chronic leg ulcer could, indeed, transform into a BCC; however, pre-existing BCC more commonly ulcerates and then does not heal.

Treatment options

While smaller, superficial BCCs can be treated with topical imiquimod, photodynamic therapy, or electrodesiccation and curettage, larger lesions should be treated with Mohs micrographic surgery and excisional surgery with grafting. Inoperable tumors may be treated with radiation therapy and vismodegib.

Our patient. Once the diagnosis of BCC was established, treatment options were discussed, including excision, local radiation therapy, and oral hedgehog inhibitor drug therapy.8 Our patient opted to undergo a wide local excision of the lesion followed by negative-pressure wound therapy, which led to complete healing.

CORRESPONDENCE

David Crasto, DO, William Carey University College of Osteopathic Medicine, 498 Tuscan Avenue, Hattiesburg, MS 39401; [email protected]

1. Sen CK, Gordillo GM, Roy S, et al. Human skin wounds: a major and snowballing threat to public health and the economy. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17:763-771.

2. Fox JD, Baquerizo Nole KL, Berriman SJ, et al. Chronic wounds: the need for greater emphasis in medical schools, post-graduate training and public health discussions. Ann Surg. 2016;264:241-243.

3. Senet P, Combemale P, Debure C, et al. Malignancy and chronic leg ulcers. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:704-708.

4. Ghasemi F, Anooshirvani N, Sibbald RG, et al. The point prevalence of malignancy in a wound clinic. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2016;15:58-62.

5. Labropoulos N, Manalo D, Patel N, et al. Uncommon leg ulcers in the lower extremity. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:568-573.

6. Tchanque-Fossuo CN, Millsop J, Johnson MA, et al. Ulcerated basal cell carcinomas masquerading as venous leg ulcers. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2018;31:130-134.

7. Schnirring-Judge M, Belpedio D. Malignant transformation of a chronic venous stasis ulcer to basal cell carcinoma in a diabetic patient: case and review of the pathophysiology. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2010;49:75-79.

8. Puig S, Berrocal A. Management of high-risk and advanced basal cell carcinoma. Clin Transl Oncol. 2015;17:497-503.

An 80-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, psoriasis vulgaris with associated pruritus, and well-controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus presented with a slowly enlarging ulceration on her left leg of 1 year’s duration. She noted that this lesion healed less rapidly than previous stasis leg ulcerations, despite using the same treatment approach that included dressings, elevation, and diuretics to decrease pedal edema.

Physical examination revealed plaques with white micaceous scaling over her extensor surfaces and scalp, as well as guttate lesions on the trunk, typical of psoriasis vulgaris. A 5.8 × 7.2-cm malodorous ulceration was superimposed on a large psoriatic plaque on her left anterior lower leg (FIGURE 1). A 4-mm punch biopsy was obtained from the peripheral margin.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Basal cell carcinoma

Histopathological examination revealed elongated strands of closely packed basaloid cells embedded in a dense fibrous stroma with overlying ulceration and crusting (FIGURE 2). Immunohistochemical staining with cytokeratin (CK) 5/6 decorated the cytoplasm of the tumor cells, which confirmed that the tumor was a keratinocyte cancer. CK 20 was negative, excluding the possibility of a Merkel cell carcinoma. Scout biopsies from 3 additional areas of ulceration confirmed that the entire ulceration was infiltrated by basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

A surprise hidden in a chronic ulcer

More than 6 million Americans have chronic ulcers and most occur on the legs.1 The majority of these chronic ulcerations are etiologically related to venous stasis, arterial insufficiency, or neuropathy.2

Bacterial pyoderma, chronic infection caused by atypical acid-fast bacilli or deep fungal infection, pyoderma gangrenosum, cutaneous vasculitis, calciphylaxis, and venous ulceration were all considered to explain this patient’s nonhealing wound. A biopsy was required to fully assess these possibilities.

Don’t overlook the possibility of malignancy. In a cross-sectional, multicenter study by Senet et al,3 144 patients with 154 total chronic leg ulcers were evaluated in tertiary care centers for malignancy, which was found to occur at a rate of 10.4%. Similarly, Ghasemi et al4 demonstrated a malignancy rate of 16.1% in 124 patients who underwent biopsy; the anterior shin was determined to be the most frequent location for malignancy. The most common skin cancer identified within the setting of chronic ulcers is squamous cell carcinoma.3 Although rare, there are reports of BCC identified in chronic wounds.3-7

Morphological signs suggestive of malignancy in chronic ulcerations include hyperkeratosis, granulation tissue surrounded by a raised border, unusual pain or bleeding, and increased tissue friability. Our patient had none of these signs and symptoms. However, it is possible that she had a tumor that ulcerated and would not heal.

Continue to: Which came first?

Which came first? It’s difficult to know in this case whether a persistent BCC ulcerated, forming this lesion, or if scarring associated with a chronic ulceration led to the development of the BCC.6 Based on biopsies taken at an earlier date, Schnirring-Judge and Belpedio7 concluded that a chronic leg ulcer could, indeed, transform into a BCC; however, pre-existing BCC more commonly ulcerates and then does not heal.

Treatment options

While smaller, superficial BCCs can be treated with topical imiquimod, photodynamic therapy, or electrodesiccation and curettage, larger lesions should be treated with Mohs micrographic surgery and excisional surgery with grafting. Inoperable tumors may be treated with radiation therapy and vismodegib.

Our patient. Once the diagnosis of BCC was established, treatment options were discussed, including excision, local radiation therapy, and oral hedgehog inhibitor drug therapy.8 Our patient opted to undergo a wide local excision of the lesion followed by negative-pressure wound therapy, which led to complete healing.

CORRESPONDENCE

David Crasto, DO, William Carey University College of Osteopathic Medicine, 498 Tuscan Avenue, Hattiesburg, MS 39401; [email protected]

An 80-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, psoriasis vulgaris with associated pruritus, and well-controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus presented with a slowly enlarging ulceration on her left leg of 1 year’s duration. She noted that this lesion healed less rapidly than previous stasis leg ulcerations, despite using the same treatment approach that included dressings, elevation, and diuretics to decrease pedal edema.

Physical examination revealed plaques with white micaceous scaling over her extensor surfaces and scalp, as well as guttate lesions on the trunk, typical of psoriasis vulgaris. A 5.8 × 7.2-cm malodorous ulceration was superimposed on a large psoriatic plaque on her left anterior lower leg (FIGURE 1). A 4-mm punch biopsy was obtained from the peripheral margin.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Basal cell carcinoma

Histopathological examination revealed elongated strands of closely packed basaloid cells embedded in a dense fibrous stroma with overlying ulceration and crusting (FIGURE 2). Immunohistochemical staining with cytokeratin (CK) 5/6 decorated the cytoplasm of the tumor cells, which confirmed that the tumor was a keratinocyte cancer. CK 20 was negative, excluding the possibility of a Merkel cell carcinoma. Scout biopsies from 3 additional areas of ulceration confirmed that the entire ulceration was infiltrated by basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

A surprise hidden in a chronic ulcer

More than 6 million Americans have chronic ulcers and most occur on the legs.1 The majority of these chronic ulcerations are etiologically related to venous stasis, arterial insufficiency, or neuropathy.2

Bacterial pyoderma, chronic infection caused by atypical acid-fast bacilli or deep fungal infection, pyoderma gangrenosum, cutaneous vasculitis, calciphylaxis, and venous ulceration were all considered to explain this patient’s nonhealing wound. A biopsy was required to fully assess these possibilities.

Don’t overlook the possibility of malignancy. In a cross-sectional, multicenter study by Senet et al,3 144 patients with 154 total chronic leg ulcers were evaluated in tertiary care centers for malignancy, which was found to occur at a rate of 10.4%. Similarly, Ghasemi et al4 demonstrated a malignancy rate of 16.1% in 124 patients who underwent biopsy; the anterior shin was determined to be the most frequent location for malignancy. The most common skin cancer identified within the setting of chronic ulcers is squamous cell carcinoma.3 Although rare, there are reports of BCC identified in chronic wounds.3-7

Morphological signs suggestive of malignancy in chronic ulcerations include hyperkeratosis, granulation tissue surrounded by a raised border, unusual pain or bleeding, and increased tissue friability. Our patient had none of these signs and symptoms. However, it is possible that she had a tumor that ulcerated and would not heal.

Continue to: Which came first?

Which came first? It’s difficult to know in this case whether a persistent BCC ulcerated, forming this lesion, or if scarring associated with a chronic ulceration led to the development of the BCC.6 Based on biopsies taken at an earlier date, Schnirring-Judge and Belpedio7 concluded that a chronic leg ulcer could, indeed, transform into a BCC; however, pre-existing BCC more commonly ulcerates and then does not heal.

Treatment options

While smaller, superficial BCCs can be treated with topical imiquimod, photodynamic therapy, or electrodesiccation and curettage, larger lesions should be treated with Mohs micrographic surgery and excisional surgery with grafting. Inoperable tumors may be treated with radiation therapy and vismodegib.

Our patient. Once the diagnosis of BCC was established, treatment options were discussed, including excision, local radiation therapy, and oral hedgehog inhibitor drug therapy.8 Our patient opted to undergo a wide local excision of the lesion followed by negative-pressure wound therapy, which led to complete healing.

CORRESPONDENCE

David Crasto, DO, William Carey University College of Osteopathic Medicine, 498 Tuscan Avenue, Hattiesburg, MS 39401; [email protected]

1. Sen CK, Gordillo GM, Roy S, et al. Human skin wounds: a major and snowballing threat to public health and the economy. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17:763-771.

2. Fox JD, Baquerizo Nole KL, Berriman SJ, et al. Chronic wounds: the need for greater emphasis in medical schools, post-graduate training and public health discussions. Ann Surg. 2016;264:241-243.

3. Senet P, Combemale P, Debure C, et al. Malignancy and chronic leg ulcers. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:704-708.

4. Ghasemi F, Anooshirvani N, Sibbald RG, et al. The point prevalence of malignancy in a wound clinic. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2016;15:58-62.

5. Labropoulos N, Manalo D, Patel N, et al. Uncommon leg ulcers in the lower extremity. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:568-573.

6. Tchanque-Fossuo CN, Millsop J, Johnson MA, et al. Ulcerated basal cell carcinomas masquerading as venous leg ulcers. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2018;31:130-134.

7. Schnirring-Judge M, Belpedio D. Malignant transformation of a chronic venous stasis ulcer to basal cell carcinoma in a diabetic patient: case and review of the pathophysiology. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2010;49:75-79.

8. Puig S, Berrocal A. Management of high-risk and advanced basal cell carcinoma. Clin Transl Oncol. 2015;17:497-503.

1. Sen CK, Gordillo GM, Roy S, et al. Human skin wounds: a major and snowballing threat to public health and the economy. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17:763-771.

2. Fox JD, Baquerizo Nole KL, Berriman SJ, et al. Chronic wounds: the need for greater emphasis in medical schools, post-graduate training and public health discussions. Ann Surg. 2016;264:241-243.

3. Senet P, Combemale P, Debure C, et al. Malignancy and chronic leg ulcers. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:704-708.

4. Ghasemi F, Anooshirvani N, Sibbald RG, et al. The point prevalence of malignancy in a wound clinic. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2016;15:58-62.

5. Labropoulos N, Manalo D, Patel N, et al. Uncommon leg ulcers in the lower extremity. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:568-573.

6. Tchanque-Fossuo CN, Millsop J, Johnson MA, et al. Ulcerated basal cell carcinomas masquerading as venous leg ulcers. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2018;31:130-134.

7. Schnirring-Judge M, Belpedio D. Malignant transformation of a chronic venous stasis ulcer to basal cell carcinoma in a diabetic patient: case and review of the pathophysiology. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2010;49:75-79.

8. Puig S, Berrocal A. Management of high-risk and advanced basal cell carcinoma. Clin Transl Oncol. 2015;17:497-503.

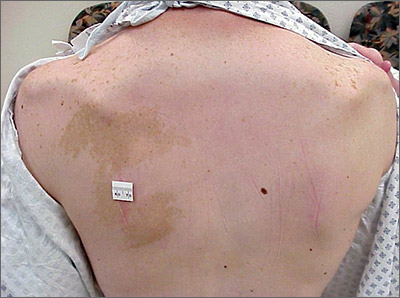

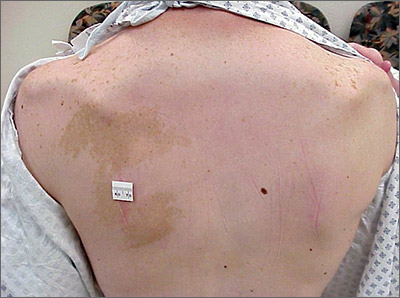

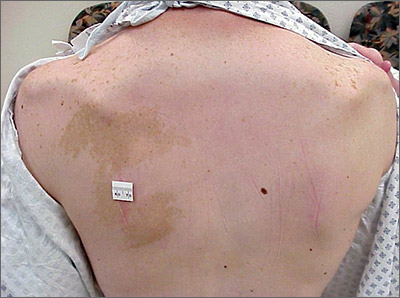

Hyperpigmented patch on the back

Large unilateral hyperpigmented patches on the trunk with onset around puberty are the hallmark of a Becker nevus, also more descriptively called pigmented hairy epidermal nevus.

Becker nevi are a form of epidermal nevus that usually occur on the upper back or chest. They most commonly develop during puberty when there are increasing circulating levels of androgens. (Becker nevus cells are androgen sensitive.) This is consistent with this patient’s history of the lesion developing in her teens when the lesions become hyperpigmented and noticeable. The localized androgen sensitivity also can lead to unilateral hypoplastic breast growth when it occurs on the chest in young women.

The lesions are more common in males than females and often have associated hypertrichosis. The etiology is not certain but is thought to be due to regional loss of heterozygosity during embryogenesis leading to the abnormally elevated levels of androgen receptors and increased androgen sensitivity in the basal keratinocytes and dermal fibroblasts.

Laser is the most effective therapy for the hyperpigmentation and for hypertrichosis when present. If a young woman with a Becker nevus has breast hypoplasia, spironolactone (an antiandrogen) has been helpful in restoring breast growth. For this patient, the hyperpigmented patch was asymptomatic and not troublesome, so she opted not to treat it.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Patel P, Malik K, Khachemoune A. Sebaceus and Becker’s nevus: overview of their presentation, pathogenesis, associations, and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:197-204.

Large unilateral hyperpigmented patches on the trunk with onset around puberty are the hallmark of a Becker nevus, also more descriptively called pigmented hairy epidermal nevus.

Becker nevi are a form of epidermal nevus that usually occur on the upper back or chest. They most commonly develop during puberty when there are increasing circulating levels of androgens. (Becker nevus cells are androgen sensitive.) This is consistent with this patient’s history of the lesion developing in her teens when the lesions become hyperpigmented and noticeable. The localized androgen sensitivity also can lead to unilateral hypoplastic breast growth when it occurs on the chest in young women.

The lesions are more common in males than females and often have associated hypertrichosis. The etiology is not certain but is thought to be due to regional loss of heterozygosity during embryogenesis leading to the abnormally elevated levels of androgen receptors and increased androgen sensitivity in the basal keratinocytes and dermal fibroblasts.

Laser is the most effective therapy for the hyperpigmentation and for hypertrichosis when present. If a young woman with a Becker nevus has breast hypoplasia, spironolactone (an antiandrogen) has been helpful in restoring breast growth. For this patient, the hyperpigmented patch was asymptomatic and not troublesome, so she opted not to treat it.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Large unilateral hyperpigmented patches on the trunk with onset around puberty are the hallmark of a Becker nevus, also more descriptively called pigmented hairy epidermal nevus.

Becker nevi are a form of epidermal nevus that usually occur on the upper back or chest. They most commonly develop during puberty when there are increasing circulating levels of androgens. (Becker nevus cells are androgen sensitive.) This is consistent with this patient’s history of the lesion developing in her teens when the lesions become hyperpigmented and noticeable. The localized androgen sensitivity also can lead to unilateral hypoplastic breast growth when it occurs on the chest in young women.

The lesions are more common in males than females and often have associated hypertrichosis. The etiology is not certain but is thought to be due to regional loss of heterozygosity during embryogenesis leading to the abnormally elevated levels of androgen receptors and increased androgen sensitivity in the basal keratinocytes and dermal fibroblasts.

Laser is the most effective therapy for the hyperpigmentation and for hypertrichosis when present. If a young woman with a Becker nevus has breast hypoplasia, spironolactone (an antiandrogen) has been helpful in restoring breast growth. For this patient, the hyperpigmented patch was asymptomatic and not troublesome, so she opted not to treat it.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Patel P, Malik K, Khachemoune A. Sebaceus and Becker’s nevus: overview of their presentation, pathogenesis, associations, and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:197-204.

Patel P, Malik K, Khachemoune A. Sebaceus and Becker’s nevus: overview of their presentation, pathogenesis, associations, and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:197-204.

Recurrent leg lesions

Tender erythematous nodules or plaques on the extensor surfaces—usually on the legs and occasionally on the arms—are the hallmarks for erythema nodosum, which was diagnosed in this case. It typically occurs in young women, ages 15 to 30, and the nodules or plaques are often accompanied by prodromal fever and malaise. The lesions often are painful and tender to pressure or palpation; they are thought to be caused by a reaction to a stimulus, leading to inflammation of the septa in the subcutaneous fat. While the trigger is often unknown, in some cases, an underlying infection, particularly Streptococcus or tuberculosis (TB), is identified. Sarcoidosis, malignancy, or an increase in estrogen (exogenous or endogenous) also can provoke the disorder.

Due to the risk of underlying disease or triggers, it is prudent to perform radiography of the chest, as well as obtain a complete blood count, sedimentation rate or C reactive protein, and an antistreptolysin O titer when you suspect erythema nodosum. TB testing is also advised. Biopsy typically is not performed because the diagnosis usually is made clinically. If the diagnosis is in doubt, a biopsy can offer confirmation or lead to a different diagnosis such as vasculitis—especially if the lesions are eroded. Since erythema nodosum is an inflammation of the subcutaneous fat, it is important to sample skin lesions deeper than the usual punch biopsy; an incisional biopsy may be required to get an adequate sample.

Erythema nodosum typically resolves spontaneously over a period of weeks, even if there is underlying disease. Therefore, it may be possible to defer treatment if minimal symptoms are present. Otherwise, first-line treatment for the pain and malaise is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID). Oral potassium iodide (360-900 mg/d) is considered second-line treatment and systemic corticosteroids are a third-line option.

For this patient, biopsy was deferred and diagnostic tests were all negative. She had notable pain and a history of good resolution of symptoms with prednisone (5 mg/d), so this drug was prescribed for a 7-day course. She was counseled to avoid taking the NSAIDs and prednisone together due to increased risk of gastritis and ulceration. Recurrent disease can be treated with dapsone (100 mg/d) or hydroxychloroquine (200 mg bid).

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Blake T, Manahan M, Rodins K. Erythema nodosum - a review of an uncommon panniculitis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:22376.

Tender erythematous nodules or plaques on the extensor surfaces—usually on the legs and occasionally on the arms—are the hallmarks for erythema nodosum, which was diagnosed in this case. It typically occurs in young women, ages 15 to 30, and the nodules or plaques are often accompanied by prodromal fever and malaise. The lesions often are painful and tender to pressure or palpation; they are thought to be caused by a reaction to a stimulus, leading to inflammation of the septa in the subcutaneous fat. While the trigger is often unknown, in some cases, an underlying infection, particularly Streptococcus or tuberculosis (TB), is identified. Sarcoidosis, malignancy, or an increase in estrogen (exogenous or endogenous) also can provoke the disorder.

Due to the risk of underlying disease or triggers, it is prudent to perform radiography of the chest, as well as obtain a complete blood count, sedimentation rate or C reactive protein, and an antistreptolysin O titer when you suspect erythema nodosum. TB testing is also advised. Biopsy typically is not performed because the diagnosis usually is made clinically. If the diagnosis is in doubt, a biopsy can offer confirmation or lead to a different diagnosis such as vasculitis—especially if the lesions are eroded. Since erythema nodosum is an inflammation of the subcutaneous fat, it is important to sample skin lesions deeper than the usual punch biopsy; an incisional biopsy may be required to get an adequate sample.

Erythema nodosum typically resolves spontaneously over a period of weeks, even if there is underlying disease. Therefore, it may be possible to defer treatment if minimal symptoms are present. Otherwise, first-line treatment for the pain and malaise is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID). Oral potassium iodide (360-900 mg/d) is considered second-line treatment and systemic corticosteroids are a third-line option.

For this patient, biopsy was deferred and diagnostic tests were all negative. She had notable pain and a history of good resolution of symptoms with prednisone (5 mg/d), so this drug was prescribed for a 7-day course. She was counseled to avoid taking the NSAIDs and prednisone together due to increased risk of gastritis and ulceration. Recurrent disease can be treated with dapsone (100 mg/d) or hydroxychloroquine (200 mg bid).

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Tender erythematous nodules or plaques on the extensor surfaces—usually on the legs and occasionally on the arms—are the hallmarks for erythema nodosum, which was diagnosed in this case. It typically occurs in young women, ages 15 to 30, and the nodules or plaques are often accompanied by prodromal fever and malaise. The lesions often are painful and tender to pressure or palpation; they are thought to be caused by a reaction to a stimulus, leading to inflammation of the septa in the subcutaneous fat. While the trigger is often unknown, in some cases, an underlying infection, particularly Streptococcus or tuberculosis (TB), is identified. Sarcoidosis, malignancy, or an increase in estrogen (exogenous or endogenous) also can provoke the disorder.

Due to the risk of underlying disease or triggers, it is prudent to perform radiography of the chest, as well as obtain a complete blood count, sedimentation rate or C reactive protein, and an antistreptolysin O titer when you suspect erythema nodosum. TB testing is also advised. Biopsy typically is not performed because the diagnosis usually is made clinically. If the diagnosis is in doubt, a biopsy can offer confirmation or lead to a different diagnosis such as vasculitis—especially if the lesions are eroded. Since erythema nodosum is an inflammation of the subcutaneous fat, it is important to sample skin lesions deeper than the usual punch biopsy; an incisional biopsy may be required to get an adequate sample.

Erythema nodosum typically resolves spontaneously over a period of weeks, even if there is underlying disease. Therefore, it may be possible to defer treatment if minimal symptoms are present. Otherwise, first-line treatment for the pain and malaise is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID). Oral potassium iodide (360-900 mg/d) is considered second-line treatment and systemic corticosteroids are a third-line option.

For this patient, biopsy was deferred and diagnostic tests were all negative. She had notable pain and a history of good resolution of symptoms with prednisone (5 mg/d), so this drug was prescribed for a 7-day course. She was counseled to avoid taking the NSAIDs and prednisone together due to increased risk of gastritis and ulceration. Recurrent disease can be treated with dapsone (100 mg/d) or hydroxychloroquine (200 mg bid).

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Blake T, Manahan M, Rodins K. Erythema nodosum - a review of an uncommon panniculitis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:22376.

Blake T, Manahan M, Rodins K. Erythema nodosum - a review of an uncommon panniculitis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:22376.

Hair loss and scalp papules

The punch biopsies were consistent with lichen planopilaris, an idiopathic, immune-mediated scarring alopecia that largely affects women between the ages of 40 and 70 years. In this variant of lichen planus, T cells target hair bulbs and cause destruction with scarring and permanent hair loss. Distribution may be patchy or may be more concentrated on the crown or involve the frontal scalp—a subtype called frontal fibrosing alopecia. Early recognition and intervention may save hair follicles and minimize disease severity.

The differential diagnosis includes traction alopecia, discoid lupus erythematosus, alopecia areata, centrifugal cicatricial alopecia, and folliculitis decalvans. The diagnosis may be confirmed with a scalp biopsy of actively inflamed follicles. Biopsy of scarred areas is likely to be nonspecific and unhelpful.

Treatment is targeted at slowing progression and symptom management. First-line therapy often includes potent corticosteroids (intralesional, topical, or systemic). Longer courses of steroid-sparing agents may be considered, including hydroxychloroquine, tacrolimus, ciclosporin, methotrexate, or acitretin. Hair styling and coloring, as well as hairpieces, often are used to conceal patches of hair loss. Hair transplantation is expensive but can be used to increase hair density in scarred areas once disease is controlled.

In this case, the patient was started on clobetasol solution 0.05% to be applied nightly to affected areas of the scalp. This treatment helped with the itching, but the inflammation and hair loss continued to worsen after 2 months. At that point, hydroxychloroquine 200 mg bid was added to the regimen, and hair loss and associated symptoms stopped. The patient remained on this therapy for 16 months. The hydroxychloroquine was then stopped, and the patient was advised to use the topical clobetasol, as needed.

Text courtesy of Tristan Reynolds, DO, Maine Dartmouth Family Medicine Residency, and Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

Errichetti E, Figini M, Croatto M, et al. Therapeutic management of classic lichen planopilaris: a systematic review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2018;11:91-102.

The punch biopsies were consistent with lichen planopilaris, an idiopathic, immune-mediated scarring alopecia that largely affects women between the ages of 40 and 70 years. In this variant of lichen planus, T cells target hair bulbs and cause destruction with scarring and permanent hair loss. Distribution may be patchy or may be more concentrated on the crown or involve the frontal scalp—a subtype called frontal fibrosing alopecia. Early recognition and intervention may save hair follicles and minimize disease severity.

The differential diagnosis includes traction alopecia, discoid lupus erythematosus, alopecia areata, centrifugal cicatricial alopecia, and folliculitis decalvans. The diagnosis may be confirmed with a scalp biopsy of actively inflamed follicles. Biopsy of scarred areas is likely to be nonspecific and unhelpful.

Treatment is targeted at slowing progression and symptom management. First-line therapy often includes potent corticosteroids (intralesional, topical, or systemic). Longer courses of steroid-sparing agents may be considered, including hydroxychloroquine, tacrolimus, ciclosporin, methotrexate, or acitretin. Hair styling and coloring, as well as hairpieces, often are used to conceal patches of hair loss. Hair transplantation is expensive but can be used to increase hair density in scarred areas once disease is controlled.

In this case, the patient was started on clobetasol solution 0.05% to be applied nightly to affected areas of the scalp. This treatment helped with the itching, but the inflammation and hair loss continued to worsen after 2 months. At that point, hydroxychloroquine 200 mg bid was added to the regimen, and hair loss and associated symptoms stopped. The patient remained on this therapy for 16 months. The hydroxychloroquine was then stopped, and the patient was advised to use the topical clobetasol, as needed.

Text courtesy of Tristan Reynolds, DO, Maine Dartmouth Family Medicine Residency, and Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

The punch biopsies were consistent with lichen planopilaris, an idiopathic, immune-mediated scarring alopecia that largely affects women between the ages of 40 and 70 years. In this variant of lichen planus, T cells target hair bulbs and cause destruction with scarring and permanent hair loss. Distribution may be patchy or may be more concentrated on the crown or involve the frontal scalp—a subtype called frontal fibrosing alopecia. Early recognition and intervention may save hair follicles and minimize disease severity.

The differential diagnosis includes traction alopecia, discoid lupus erythematosus, alopecia areata, centrifugal cicatricial alopecia, and folliculitis decalvans. The diagnosis may be confirmed with a scalp biopsy of actively inflamed follicles. Biopsy of scarred areas is likely to be nonspecific and unhelpful.

Treatment is targeted at slowing progression and symptom management. First-line therapy often includes potent corticosteroids (intralesional, topical, or systemic). Longer courses of steroid-sparing agents may be considered, including hydroxychloroquine, tacrolimus, ciclosporin, methotrexate, or acitretin. Hair styling and coloring, as well as hairpieces, often are used to conceal patches of hair loss. Hair transplantation is expensive but can be used to increase hair density in scarred areas once disease is controlled.

In this case, the patient was started on clobetasol solution 0.05% to be applied nightly to affected areas of the scalp. This treatment helped with the itching, but the inflammation and hair loss continued to worsen after 2 months. At that point, hydroxychloroquine 200 mg bid was added to the regimen, and hair loss and associated symptoms stopped. The patient remained on this therapy for 16 months. The hydroxychloroquine was then stopped, and the patient was advised to use the topical clobetasol, as needed.

Text courtesy of Tristan Reynolds, DO, Maine Dartmouth Family Medicine Residency, and Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

Errichetti E, Figini M, Croatto M, et al. Therapeutic management of classic lichen planopilaris: a systematic review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2018;11:91-102.

Errichetti E, Figini M, Croatto M, et al. Therapeutic management of classic lichen planopilaris: a systematic review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2018;11:91-102.

Painful periocular rash

This patient was given a diagnosis of primary herpes simplex virus (HSV) based on the appearance of her eyelid. Swabs were performed for bacterial culture, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing was done for HSV and varicella, but results were pending prior to her transfer to the Emergency Department (ED).

The patient was given a single dose of 800 mg oral acyclovir (200 mg/5mL) and 500 mg of oral cephalexin (250 mg/5mL) and referred to the ED for a more detailed eye exam and to exclude orbital erosions.

HSV classically causes clustered vesicles on an erythematous base. Superinfection with skin flora can cause pustules instead of vesicles. Severe complications of HSV can include widespread skin involvement, eczema herpeticum, local destruction, central nervous system involvement, throat infections (affecting airway and oral intake), and dissemination in immunocompromised hosts. Ocular or periorbital infections increase the risk of keratitis, corneal ulcers, and loss of sight. Viral involvement of the cornea is best seen with fluorescein staining.

In cases like this one, PCR is the preferred method of testing over viral cultures or serology, given its speed, accuracy, and temporal relevance. Ophthalmology referral is warranted, although it should not delay treatment. Topical and oral antivirals are both effective when treating corneal disease; patient preference should be considered.

Most cases of HSV may resolve without treatment; however, treatment started while vesicles are present and within 72 hours of infection may shorten the time of viral replication and prevent progression to stromal involvement.

After a 12-hour wait in the ED, this patient was seen by an ophthalmology resident who did not observe orbital erosions but did note umbilication and misdiagnosed molluscum contagiosum. Umbilication is not pathognomonic for molluscum; few experienced in diagnosing molluscum contagiosum would make this error.

The patient was instructed to stop the acyclovir. Two days later when the PCR came back positive for HSV-1 and the bacterial culture confirmed growth of superimposed Staphylococcus aureus, the patient had been lost to follow-up. A better approach would have been for the ophthalmology resident to continue the acyclovir until PCR excluded herpetic disease.

Text courtesy of Tristan Reynolds, DO, Maine Dartmouth Family Medicine Residency, and Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

Barker NH. Ocular herpes simplex. BMJ Clin Evid. 2008;2008:0707.

This patient was given a diagnosis of primary herpes simplex virus (HSV) based on the appearance of her eyelid. Swabs were performed for bacterial culture, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing was done for HSV and varicella, but results were pending prior to her transfer to the Emergency Department (ED).

The patient was given a single dose of 800 mg oral acyclovir (200 mg/5mL) and 500 mg of oral cephalexin (250 mg/5mL) and referred to the ED for a more detailed eye exam and to exclude orbital erosions.

HSV classically causes clustered vesicles on an erythematous base. Superinfection with skin flora can cause pustules instead of vesicles. Severe complications of HSV can include widespread skin involvement, eczema herpeticum, local destruction, central nervous system involvement, throat infections (affecting airway and oral intake), and dissemination in immunocompromised hosts. Ocular or periorbital infections increase the risk of keratitis, corneal ulcers, and loss of sight. Viral involvement of the cornea is best seen with fluorescein staining.

In cases like this one, PCR is the preferred method of testing over viral cultures or serology, given its speed, accuracy, and temporal relevance. Ophthalmology referral is warranted, although it should not delay treatment. Topical and oral antivirals are both effective when treating corneal disease; patient preference should be considered.

Most cases of HSV may resolve without treatment; however, treatment started while vesicles are present and within 72 hours of infection may shorten the time of viral replication and prevent progression to stromal involvement.

After a 12-hour wait in the ED, this patient was seen by an ophthalmology resident who did not observe orbital erosions but did note umbilication and misdiagnosed molluscum contagiosum. Umbilication is not pathognomonic for molluscum; few experienced in diagnosing molluscum contagiosum would make this error.

The patient was instructed to stop the acyclovir. Two days later when the PCR came back positive for HSV-1 and the bacterial culture confirmed growth of superimposed Staphylococcus aureus, the patient had been lost to follow-up. A better approach would have been for the ophthalmology resident to continue the acyclovir until PCR excluded herpetic disease.

Text courtesy of Tristan Reynolds, DO, Maine Dartmouth Family Medicine Residency, and Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

This patient was given a diagnosis of primary herpes simplex virus (HSV) based on the appearance of her eyelid. Swabs were performed for bacterial culture, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing was done for HSV and varicella, but results were pending prior to her transfer to the Emergency Department (ED).

The patient was given a single dose of 800 mg oral acyclovir (200 mg/5mL) and 500 mg of oral cephalexin (250 mg/5mL) and referred to the ED for a more detailed eye exam and to exclude orbital erosions.

HSV classically causes clustered vesicles on an erythematous base. Superinfection with skin flora can cause pustules instead of vesicles. Severe complications of HSV can include widespread skin involvement, eczema herpeticum, local destruction, central nervous system involvement, throat infections (affecting airway and oral intake), and dissemination in immunocompromised hosts. Ocular or periorbital infections increase the risk of keratitis, corneal ulcers, and loss of sight. Viral involvement of the cornea is best seen with fluorescein staining.

In cases like this one, PCR is the preferred method of testing over viral cultures or serology, given its speed, accuracy, and temporal relevance. Ophthalmology referral is warranted, although it should not delay treatment. Topical and oral antivirals are both effective when treating corneal disease; patient preference should be considered.

Most cases of HSV may resolve without treatment; however, treatment started while vesicles are present and within 72 hours of infection may shorten the time of viral replication and prevent progression to stromal involvement.

After a 12-hour wait in the ED, this patient was seen by an ophthalmology resident who did not observe orbital erosions but did note umbilication and misdiagnosed molluscum contagiosum. Umbilication is not pathognomonic for molluscum; few experienced in diagnosing molluscum contagiosum would make this error.

The patient was instructed to stop the acyclovir. Two days later when the PCR came back positive for HSV-1 and the bacterial culture confirmed growth of superimposed Staphylococcus aureus, the patient had been lost to follow-up. A better approach would have been for the ophthalmology resident to continue the acyclovir until PCR excluded herpetic disease.

Text courtesy of Tristan Reynolds, DO, Maine Dartmouth Family Medicine Residency, and Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

Barker NH. Ocular herpes simplex. BMJ Clin Evid. 2008;2008:0707.

Barker NH. Ocular herpes simplex. BMJ Clin Evid. 2008;2008:0707.

Rash, muscle weakness, and confusion

The constellation of symptoms was suggestive of Lyme disease, although connective tissue disease and syphilis were also considered. Two punch biopsies were performed in the office, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), complete blood cell count (CBC), international normalized ratio (INR), comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), Lyme enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) antibody panel, and rapid plasma reagin (RPR) laboratory tests were ordered.

Immediately available laboratory results included ESR, CBC, INR, and CMP. Findings were notable for elevated INR, as well as elevated alanine aminotransferase and aspartate transaminase. The transaminitis suggested myopathy and was consistent with clinical muscle weakness. RPR testing was negative.

Because of the confusion, severity of muscle weakness, and plausibility of early encephalopathy with Lyme disease, the patient was admitted to the hospital for further work-up. Lumbar puncture was delayed until his INR was reduced, but subsequently was found to be normal. He received intravenous (IV) ceftriaxone (2 g/d) empirically for possible early disseminated disease with neurologic complications. His confusion, muscle weakness, and transaminitis rapidly improved.

His Lyme antibody panel was positive for IgM after his third day of hospitalization. A reflexive confirmatory western blot for IgG was not positive on the initial set of labs but was positive when redrawn 4 weeks after this hospitalization, confirming Lyme disease.

Lyme disease is a vector-borne disease caused by the Borrelia genus of spirochete bacteria, most commonly Borrelia burgdorferi in North America. Transmission occurs through prolonged (typically 36-48 hours) attachment of a blacklegged tick.

The disease can be divided into 3 stages:

- localized (3-30 days): erythema migrans rash and flulike illness

- early disseminated (days to weeks; seen in this patient): multiple erythema migrans rashes, early neuroborreliosis, arthritis, carditis, and rarely hepatitis and uveitis

- late disseminated (months to years): chronic Lyme arthritis, chronic neurological disorders (eg, encephalopathy, radicular pain, and chronic neuropathy).

The initial erythema migrans rash is classically red and targetoid; it expands from the site of attachment. Early disseminated patches tend to be smaller and can occur on any body part. The rash is rarely itchy or painful but may be warm to the touch or sensitive. The rash resolves spontaneously within 3 to 4 weeks of onset.

Treatment of all early and early disseminated Lyme disease typically involves a 14- to 28-day course of doxycycline (100 mg bid for adults, 2.2 mg/kg bid [maximum 100 mg bid] for children). Patients with acute neurologic disease often can be treated with doxycycline, but patients who cannot tolerate doxycycline and those with parenchymal disease such as encephalitis should receive IV therapy with ceftriaxone 2 g/d.

In this case, the patient was discharged home on a 3-week course of doxycycline 100 mg bid and cleared without further symptoms.

Text courtesy of Tristan Reynolds, DO, Maine Dartmouth Family Medicine Residency, and Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

Lyme disease. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/healthcare/index.html. Accessed September 1, 2020.

The constellation of symptoms was suggestive of Lyme disease, although connective tissue disease and syphilis were also considered. Two punch biopsies were performed in the office, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), complete blood cell count (CBC), international normalized ratio (INR), comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), Lyme enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) antibody panel, and rapid plasma reagin (RPR) laboratory tests were ordered.

Immediately available laboratory results included ESR, CBC, INR, and CMP. Findings were notable for elevated INR, as well as elevated alanine aminotransferase and aspartate transaminase. The transaminitis suggested myopathy and was consistent with clinical muscle weakness. RPR testing was negative.

Because of the confusion, severity of muscle weakness, and plausibility of early encephalopathy with Lyme disease, the patient was admitted to the hospital for further work-up. Lumbar puncture was delayed until his INR was reduced, but subsequently was found to be normal. He received intravenous (IV) ceftriaxone (2 g/d) empirically for possible early disseminated disease with neurologic complications. His confusion, muscle weakness, and transaminitis rapidly improved.

His Lyme antibody panel was positive for IgM after his third day of hospitalization. A reflexive confirmatory western blot for IgG was not positive on the initial set of labs but was positive when redrawn 4 weeks after this hospitalization, confirming Lyme disease.

Lyme disease is a vector-borne disease caused by the Borrelia genus of spirochete bacteria, most commonly Borrelia burgdorferi in North America. Transmission occurs through prolonged (typically 36-48 hours) attachment of a blacklegged tick.

The disease can be divided into 3 stages:

- localized (3-30 days): erythema migrans rash and flulike illness

- early disseminated (days to weeks; seen in this patient): multiple erythema migrans rashes, early neuroborreliosis, arthritis, carditis, and rarely hepatitis and uveitis

- late disseminated (months to years): chronic Lyme arthritis, chronic neurological disorders (eg, encephalopathy, radicular pain, and chronic neuropathy).

The initial erythema migrans rash is classically red and targetoid; it expands from the site of attachment. Early disseminated patches tend to be smaller and can occur on any body part. The rash is rarely itchy or painful but may be warm to the touch or sensitive. The rash resolves spontaneously within 3 to 4 weeks of onset.

Treatment of all early and early disseminated Lyme disease typically involves a 14- to 28-day course of doxycycline (100 mg bid for adults, 2.2 mg/kg bid [maximum 100 mg bid] for children). Patients with acute neurologic disease often can be treated with doxycycline, but patients who cannot tolerate doxycycline and those with parenchymal disease such as encephalitis should receive IV therapy with ceftriaxone 2 g/d.

In this case, the patient was discharged home on a 3-week course of doxycycline 100 mg bid and cleared without further symptoms.

Text courtesy of Tristan Reynolds, DO, Maine Dartmouth Family Medicine Residency, and Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

The constellation of symptoms was suggestive of Lyme disease, although connective tissue disease and syphilis were also considered. Two punch biopsies were performed in the office, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), complete blood cell count (CBC), international normalized ratio (INR), comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), Lyme enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) antibody panel, and rapid plasma reagin (RPR) laboratory tests were ordered.

Immediately available laboratory results included ESR, CBC, INR, and CMP. Findings were notable for elevated INR, as well as elevated alanine aminotransferase and aspartate transaminase. The transaminitis suggested myopathy and was consistent with clinical muscle weakness. RPR testing was negative.

Because of the confusion, severity of muscle weakness, and plausibility of early encephalopathy with Lyme disease, the patient was admitted to the hospital for further work-up. Lumbar puncture was delayed until his INR was reduced, but subsequently was found to be normal. He received intravenous (IV) ceftriaxone (2 g/d) empirically for possible early disseminated disease with neurologic complications. His confusion, muscle weakness, and transaminitis rapidly improved.

His Lyme antibody panel was positive for IgM after his third day of hospitalization. A reflexive confirmatory western blot for IgG was not positive on the initial set of labs but was positive when redrawn 4 weeks after this hospitalization, confirming Lyme disease.

Lyme disease is a vector-borne disease caused by the Borrelia genus of spirochete bacteria, most commonly Borrelia burgdorferi in North America. Transmission occurs through prolonged (typically 36-48 hours) attachment of a blacklegged tick.

The disease can be divided into 3 stages:

- localized (3-30 days): erythema migrans rash and flulike illness

- early disseminated (days to weeks; seen in this patient): multiple erythema migrans rashes, early neuroborreliosis, arthritis, carditis, and rarely hepatitis and uveitis

- late disseminated (months to years): chronic Lyme arthritis, chronic neurological disorders (eg, encephalopathy, radicular pain, and chronic neuropathy).

The initial erythema migrans rash is classically red and targetoid; it expands from the site of attachment. Early disseminated patches tend to be smaller and can occur on any body part. The rash is rarely itchy or painful but may be warm to the touch or sensitive. The rash resolves spontaneously within 3 to 4 weeks of onset.

Treatment of all early and early disseminated Lyme disease typically involves a 14- to 28-day course of doxycycline (100 mg bid for adults, 2.2 mg/kg bid [maximum 100 mg bid] for children). Patients with acute neurologic disease often can be treated with doxycycline, but patients who cannot tolerate doxycycline and those with parenchymal disease such as encephalitis should receive IV therapy with ceftriaxone 2 g/d.

In this case, the patient was discharged home on a 3-week course of doxycycline 100 mg bid and cleared without further symptoms.

Text courtesy of Tristan Reynolds, DO, Maine Dartmouth Family Medicine Residency, and Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

Lyme disease. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/healthcare/index.html. Accessed September 1, 2020.

Lyme disease. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/healthcare/index.html. Accessed September 1, 2020.

Chronic abdominal pain and diarrhea

A 15-year-old girl was brought to the Family Medicine Clinic in Somaliland, Africa, for evaluation of intermittent abdominal pain and watery diarrhea of 12 years’ duration. Over the previous 2 months, her symptoms had worsened and included vomiting and weight loss. She denied fever, melena, or hematemesis.

Physical examination revealed a thin female with a normal abdominal exam and numerous hyperpigmented macules on the lips, buccal mucosa, fingers, and toes (FIGURE 1). Her family reported that the black spots on her lips had been there since birth. There was no known family history of similar symptoms or black spots.

Her hemoglobin was 10 g/dL (reference range, 12–15 g/dL). A probable diagnosis was discussed with the family, and they elected to travel to India for further evaluation due to limited diagnostic resources in their location. In India, computed tomography (CT) and ultrasonography showed duodenojejunal intussusception. Upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy revealed multiple polyps from the lower stomach to the jejunum of the small bowel; colonoscopy was normal.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Peutz-Jeghers syndrome

Our patient was given a diagnosis of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS) based on the characteristic pigmented mucocutaneous macules and numerous polyps in the stomach and small bowel. PJS is an autosomal dominant syndrome characterized by mucocutaneous pigmentation, polyposis of the GI tract, and increased cancer risk. The prevalence is approximately 1 in 100,000.1 Genetic testing for the STK11 gene mutation, which is found in 70% of familial cases and 30% to 67% of sporadic cases, is not required for diagnosis.1

What you’ll see. The bluish brown to black spots of PJS often are apparent at birth or in early infancy. They are most common on the lips, buccal mucosa, perioral region, palms, and soles.

The polyps may cause bleeding, anemia, and abdominal pain due to intussusception, obstruction, or infarction.2 Intussusception is the most frequent cause of morbidity in childhood for PJS patients.3,4 Recurrent attacks of abdominal pain likely result from recurring transient episodes of incomplete intussusception. The polyps usually are benign, but patients are at increased risk of GI and non-GI malignancies such as breast, pancreas, lung, and reproductive tract cancers.1 Most cancers associated with PJS occur during adulthood.2

Other possible causes of hyperpigmentation

PJS can be differentiated from other causes of hyperpigmentation by clinical presentation and/or genetic testing.

Laugier-Hunziker syndrome manifests with macular hyperpigmentation of the lips and buccal mucosa and pigmented bands on the nails in young or middle-aged adults. It is not associated with intestinal polyps.

Continue to: Cronkhite-Canada syndrome

Cronkhite-Canada syndrome consists of acral and oral pigmented macules and GI polyps as well as generalized darkening of the skin, extensive alopecia, loss of taste, and nail dystrophy.

Familial lentiginosis syndromes such as Noonan syndrome and NAME syndrome (nevi, atrial myxoma, myxoid neurofibroma, ephelides) have other systemic signs such as cardiac abnormalities, and the pigmentation is not as clearly perioral.

Albright syndrome manifests with oral pigmented macules but also is associated with precocious puberty and polyostotic fibrous dysplasia.

Addison disease may cause multiple hyperpigmented macules but has other systemic involvement; adrenocorticotropic hormone levels are elevated.

Juvenile polyposis syndrome manifests with GI polyps but is not associated with mucosal pigmentation.

Continue to: Use these 4 criteria to make the diagnosis

Use these 4 criteria to make the diagnosis

The diagnosis of PJS is made using the following criteria: (1) two or more histologically confirmed PJS polyps, (2) any number of PJS polyps and a family history of PJS, (3) characteristic mucocutaneous pigmentation and a family history of PJS, or (4) any number of PJS polyps and characteristic mucocutaneous pigmentation.2

When PJS is suspected, the entire GI tract should be investigated. The hamartomatous polyps may be found from the stomach to the anal canal, but the small bowel most commonly is involved. The polyps may occur in early childhood, with one study of 14 children reporting a median age of 4.5 years.5 Polyp biopsy will show smooth muscle arborization. When possible, those who meet clinical criteria for PJS should undergo genetic testing for a STK11 gene mutation. PJS may occur due to de novo mutations in patients with no family history.6

Long-term management involves surveillance for polyps and cancer

Screening guidelines for polyps vary. Some suggest starting screening at age 8 to 10 years with esophagogastroduodenoscopy or capsule endoscopy and if negative, colonoscopy at age 18. Others suggest starting screening at 4 to 5 years of age.5 The recommendation is to remove polyps if technically feasible.3 Surveillance for Sertoli cell tumors (sex cord stromal tumors) should be done before puberty, and evaluation of other organs at risk of malignancy should begin by the end of adolescence.

The pigmented macules do not require treatment. Macules on the lips may disappear with time, while those on the buccal mucosa persist. The lip lesions can be lightened with chemical peels or laser.

Our patient underwent laparotomy, which revealed a grossly dilated and gangrenous small bowel segment. Intussusception was not present and was thought to have spontaneously reduced. Resection and anastomosis of the affected small bowel was performed. The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful, and her diarrhea and abdominal pain resolved. We recommended follow-up in her home city with primary care and a GI specialist and explained the need for surveillance of her condition.

CORRESPONDENCE

Josette R. McMichael, MD, Department of Dermatology, Emory University, 1525 Clifton Road NE, 1st Floor, Atlanta, GA 30322; [email protected]

1. Kopacova M, Tacheci I, Rejchrt S, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: diagnostic and therapeutic approach. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5397-5408.

2. Beggs AD, Latchford AR, Vasen HF, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: a systematic review and recommendations for management. Gut. 2010;59:975-986.

3. van Lier MG, Mathus-Vliegen EM, Wagner A, et al. High cumulative risk of intussusception in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: time to update surveillance guidelines? Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:940-945.

4. Vidal I, Podevin G, Piloquet H, et al. Follow-up and surgical management of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48:419-425.

5. Goldstein SA, Hoffenberg EJ. Peutz-Jegher syndrome in childhood: need for updated recommendations? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;56:191-195.

6. Hernan I, Roig I, Martin B, et al. De novo germline mutation in the serine-threonine kinase STK11/LKB1 gene associated with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Clin Genet. 2004;66:58-62.

A 15-year-old girl was brought to the Family Medicine Clinic in Somaliland, Africa, for evaluation of intermittent abdominal pain and watery diarrhea of 12 years’ duration. Over the previous 2 months, her symptoms had worsened and included vomiting and weight loss. She denied fever, melena, or hematemesis.

Physical examination revealed a thin female with a normal abdominal exam and numerous hyperpigmented macules on the lips, buccal mucosa, fingers, and toes (FIGURE 1). Her family reported that the black spots on her lips had been there since birth. There was no known family history of similar symptoms or black spots.

Her hemoglobin was 10 g/dL (reference range, 12–15 g/dL). A probable diagnosis was discussed with the family, and they elected to travel to India for further evaluation due to limited diagnostic resources in their location. In India, computed tomography (CT) and ultrasonography showed duodenojejunal intussusception. Upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy revealed multiple polyps from the lower stomach to the jejunum of the small bowel; colonoscopy was normal.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Peutz-Jeghers syndrome

Our patient was given a diagnosis of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS) based on the characteristic pigmented mucocutaneous macules and numerous polyps in the stomach and small bowel. PJS is an autosomal dominant syndrome characterized by mucocutaneous pigmentation, polyposis of the GI tract, and increased cancer risk. The prevalence is approximately 1 in 100,000.1 Genetic testing for the STK11 gene mutation, which is found in 70% of familial cases and 30% to 67% of sporadic cases, is not required for diagnosis.1

What you’ll see. The bluish brown to black spots of PJS often are apparent at birth or in early infancy. They are most common on the lips, buccal mucosa, perioral region, palms, and soles.

The polyps may cause bleeding, anemia, and abdominal pain due to intussusception, obstruction, or infarction.2 Intussusception is the most frequent cause of morbidity in childhood for PJS patients.3,4 Recurrent attacks of abdominal pain likely result from recurring transient episodes of incomplete intussusception. The polyps usually are benign, but patients are at increased risk of GI and non-GI malignancies such as breast, pancreas, lung, and reproductive tract cancers.1 Most cancers associated with PJS occur during adulthood.2

Other possible causes of hyperpigmentation

PJS can be differentiated from other causes of hyperpigmentation by clinical presentation and/or genetic testing.

Laugier-Hunziker syndrome manifests with macular hyperpigmentation of the lips and buccal mucosa and pigmented bands on the nails in young or middle-aged adults. It is not associated with intestinal polyps.

Continue to: Cronkhite-Canada syndrome

Cronkhite-Canada syndrome consists of acral and oral pigmented macules and GI polyps as well as generalized darkening of the skin, extensive alopecia, loss of taste, and nail dystrophy.

Familial lentiginosis syndromes such as Noonan syndrome and NAME syndrome (nevi, atrial myxoma, myxoid neurofibroma, ephelides) have other systemic signs such as cardiac abnormalities, and the pigmentation is not as clearly perioral.

Albright syndrome manifests with oral pigmented macules but also is associated with precocious puberty and polyostotic fibrous dysplasia.

Addison disease may cause multiple hyperpigmented macules but has other systemic involvement; adrenocorticotropic hormone levels are elevated.

Juvenile polyposis syndrome manifests with GI polyps but is not associated with mucosal pigmentation.

Continue to: Use these 4 criteria to make the diagnosis

Use these 4 criteria to make the diagnosis

The diagnosis of PJS is made using the following criteria: (1) two or more histologically confirmed PJS polyps, (2) any number of PJS polyps and a family history of PJS, (3) characteristic mucocutaneous pigmentation and a family history of PJS, or (4) any number of PJS polyps and characteristic mucocutaneous pigmentation.2

When PJS is suspected, the entire GI tract should be investigated. The hamartomatous polyps may be found from the stomach to the anal canal, but the small bowel most commonly is involved. The polyps may occur in early childhood, with one study of 14 children reporting a median age of 4.5 years.5 Polyp biopsy will show smooth muscle arborization. When possible, those who meet clinical criteria for PJS should undergo genetic testing for a STK11 gene mutation. PJS may occur due to de novo mutations in patients with no family history.6

Long-term management involves surveillance for polyps and cancer

Screening guidelines for polyps vary. Some suggest starting screening at age 8 to 10 years with esophagogastroduodenoscopy or capsule endoscopy and if negative, colonoscopy at age 18. Others suggest starting screening at 4 to 5 years of age.5 The recommendation is to remove polyps if technically feasible.3 Surveillance for Sertoli cell tumors (sex cord stromal tumors) should be done before puberty, and evaluation of other organs at risk of malignancy should begin by the end of adolescence.

The pigmented macules do not require treatment. Macules on the lips may disappear with time, while those on the buccal mucosa persist. The lip lesions can be lightened with chemical peels or laser.

Our patient underwent laparotomy, which revealed a grossly dilated and gangrenous small bowel segment. Intussusception was not present and was thought to have spontaneously reduced. Resection and anastomosis of the affected small bowel was performed. The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful, and her diarrhea and abdominal pain resolved. We recommended follow-up in her home city with primary care and a GI specialist and explained the need for surveillance of her condition.

CORRESPONDENCE

Josette R. McMichael, MD, Department of Dermatology, Emory University, 1525 Clifton Road NE, 1st Floor, Atlanta, GA 30322; [email protected]

A 15-year-old girl was brought to the Family Medicine Clinic in Somaliland, Africa, for evaluation of intermittent abdominal pain and watery diarrhea of 12 years’ duration. Over the previous 2 months, her symptoms had worsened and included vomiting and weight loss. She denied fever, melena, or hematemesis.

Physical examination revealed a thin female with a normal abdominal exam and numerous hyperpigmented macules on the lips, buccal mucosa, fingers, and toes (FIGURE 1). Her family reported that the black spots on her lips had been there since birth. There was no known family history of similar symptoms or black spots.

Her hemoglobin was 10 g/dL (reference range, 12–15 g/dL). A probable diagnosis was discussed with the family, and they elected to travel to India for further evaluation due to limited diagnostic resources in their location. In India, computed tomography (CT) and ultrasonography showed duodenojejunal intussusception. Upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy revealed multiple polyps from the lower stomach to the jejunum of the small bowel; colonoscopy was normal.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Peutz-Jeghers syndrome

Our patient was given a diagnosis of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS) based on the characteristic pigmented mucocutaneous macules and numerous polyps in the stomach and small bowel. PJS is an autosomal dominant syndrome characterized by mucocutaneous pigmentation, polyposis of the GI tract, and increased cancer risk. The prevalence is approximately 1 in 100,000.1 Genetic testing for the STK11 gene mutation, which is found in 70% of familial cases and 30% to 67% of sporadic cases, is not required for diagnosis.1

What you’ll see. The bluish brown to black spots of PJS often are apparent at birth or in early infancy. They are most common on the lips, buccal mucosa, perioral region, palms, and soles.

The polyps may cause bleeding, anemia, and abdominal pain due to intussusception, obstruction, or infarction.2 Intussusception is the most frequent cause of morbidity in childhood for PJS patients.3,4 Recurrent attacks of abdominal pain likely result from recurring transient episodes of incomplete intussusception. The polyps usually are benign, but patients are at increased risk of GI and non-GI malignancies such as breast, pancreas, lung, and reproductive tract cancers.1 Most cancers associated with PJS occur during adulthood.2

Other possible causes of hyperpigmentation

PJS can be differentiated from other causes of hyperpigmentation by clinical presentation and/or genetic testing.

Laugier-Hunziker syndrome manifests with macular hyperpigmentation of the lips and buccal mucosa and pigmented bands on the nails in young or middle-aged adults. It is not associated with intestinal polyps.

Continue to: Cronkhite-Canada syndrome

Cronkhite-Canada syndrome consists of acral and oral pigmented macules and GI polyps as well as generalized darkening of the skin, extensive alopecia, loss of taste, and nail dystrophy.

Familial lentiginosis syndromes such as Noonan syndrome and NAME syndrome (nevi, atrial myxoma, myxoid neurofibroma, ephelides) have other systemic signs such as cardiac abnormalities, and the pigmentation is not as clearly perioral.

Albright syndrome manifests with oral pigmented macules but also is associated with precocious puberty and polyostotic fibrous dysplasia.

Addison disease may cause multiple hyperpigmented macules but has other systemic involvement; adrenocorticotropic hormone levels are elevated.

Juvenile polyposis syndrome manifests with GI polyps but is not associated with mucosal pigmentation.

Continue to: Use these 4 criteria to make the diagnosis

Use these 4 criteria to make the diagnosis

The diagnosis of PJS is made using the following criteria: (1) two or more histologically confirmed PJS polyps, (2) any number of PJS polyps and a family history of PJS, (3) characteristic mucocutaneous pigmentation and a family history of PJS, or (4) any number of PJS polyps and characteristic mucocutaneous pigmentation.2

When PJS is suspected, the entire GI tract should be investigated. The hamartomatous polyps may be found from the stomach to the anal canal, but the small bowel most commonly is involved. The polyps may occur in early childhood, with one study of 14 children reporting a median age of 4.5 years.5 Polyp biopsy will show smooth muscle arborization. When possible, those who meet clinical criteria for PJS should undergo genetic testing for a STK11 gene mutation. PJS may occur due to de novo mutations in patients with no family history.6

Long-term management involves surveillance for polyps and cancer

Screening guidelines for polyps vary. Some suggest starting screening at age 8 to 10 years with esophagogastroduodenoscopy or capsule endoscopy and if negative, colonoscopy at age 18. Others suggest starting screening at 4 to 5 years of age.5 The recommendation is to remove polyps if technically feasible.3 Surveillance for Sertoli cell tumors (sex cord stromal tumors) should be done before puberty, and evaluation of other organs at risk of malignancy should begin by the end of adolescence.

The pigmented macules do not require treatment. Macules on the lips may disappear with time, while those on the buccal mucosa persist. The lip lesions can be lightened with chemical peels or laser.

Our patient underwent laparotomy, which revealed a grossly dilated and gangrenous small bowel segment. Intussusception was not present and was thought to have spontaneously reduced. Resection and anastomosis of the affected small bowel was performed. The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful, and her diarrhea and abdominal pain resolved. We recommended follow-up in her home city with primary care and a GI specialist and explained the need for surveillance of her condition.

CORRESPONDENCE

Josette R. McMichael, MD, Department of Dermatology, Emory University, 1525 Clifton Road NE, 1st Floor, Atlanta, GA 30322; [email protected]

1. Kopacova M, Tacheci I, Rejchrt S, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: diagnostic and therapeutic approach. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5397-5408.

2. Beggs AD, Latchford AR, Vasen HF, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: a systematic review and recommendations for management. Gut. 2010;59:975-986.

3. van Lier MG, Mathus-Vliegen EM, Wagner A, et al. High cumulative risk of intussusception in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: time to update surveillance guidelines? Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:940-945.