User login

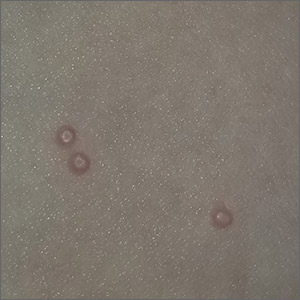

Papules on a child’s chest

Potassium hydroxide preparation of expressed contents revealed no molluscum bodies, but rather, small-caliber, trapped, and coiled hairs consistent with eruptive vellus hair cysts (EVHCs).

Vellus hairs are fine, light-colored (nonterminal) hairs that normally are found on the face, trunk, and limbs. EVHCs are typically asymptomatic papules containing an entrapped vellus hair. They form from entrapment of the hair follicle just proximal to the infundibulum, leading to hair bulb atrophy and dilation of the follicle. EVHCs typically are dome-shaped, flesh-colored soft papules that are 2 to 3 mm in size.

Diagnostic confusion can arise with molluscum contagiosum because those lesions also tend to be umbilicated and flesh colored. EVHCs can appear at any age but are more common in the first 3 decades of life. Familial types exist, presenting earlier in life than sporadic types. The differential diagnosis includes molluscum contagiosum, folliculitis, and steatocystoma multiplex. Rare genodermatoses have been associated with EVHCs, including autosomal dominant familial keratin gene mutation, anhidrotic and hidrotic ectodermal dysplasia, and pachyonychia congenita.

Up to 25% of cases spontaneously resolve, so patients can be counseled to observe the lesions. Alternative options including topical emollients or various topical keratolytics, including ammonium lactate 20% once to twice daily, topical urea, or topical salicylic acid until the lesions are flat and smooth. Topical and systemic retinoids have been reported to have limited success. Individual lesions of concern may be removed surgically by excision, curettage, cryotherapy, or laser but will likely leave a minor scar.

The patient and his family were reassured of the benign nature of the lesions and instructed to treat the papules with topical ammonium lactate 20% twice daily until the next appointment in 12 weeks. At follow-up, many, but not all, of the lesions had resolved.

Text courtesy of Tristan Reynolds, DO, Maine Dartmouth Family Medicine Residency, and Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

Torchia D, Vega J, Schachner LA. Eruptive vellus hair cysts: a systematic review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:19-28.

Potassium hydroxide preparation of expressed contents revealed no molluscum bodies, but rather, small-caliber, trapped, and coiled hairs consistent with eruptive vellus hair cysts (EVHCs).

Vellus hairs are fine, light-colored (nonterminal) hairs that normally are found on the face, trunk, and limbs. EVHCs are typically asymptomatic papules containing an entrapped vellus hair. They form from entrapment of the hair follicle just proximal to the infundibulum, leading to hair bulb atrophy and dilation of the follicle. EVHCs typically are dome-shaped, flesh-colored soft papules that are 2 to 3 mm in size.

Diagnostic confusion can arise with molluscum contagiosum because those lesions also tend to be umbilicated and flesh colored. EVHCs can appear at any age but are more common in the first 3 decades of life. Familial types exist, presenting earlier in life than sporadic types. The differential diagnosis includes molluscum contagiosum, folliculitis, and steatocystoma multiplex. Rare genodermatoses have been associated with EVHCs, including autosomal dominant familial keratin gene mutation, anhidrotic and hidrotic ectodermal dysplasia, and pachyonychia congenita.

Up to 25% of cases spontaneously resolve, so patients can be counseled to observe the lesions. Alternative options including topical emollients or various topical keratolytics, including ammonium lactate 20% once to twice daily, topical urea, or topical salicylic acid until the lesions are flat and smooth. Topical and systemic retinoids have been reported to have limited success. Individual lesions of concern may be removed surgically by excision, curettage, cryotherapy, or laser but will likely leave a minor scar.

The patient and his family were reassured of the benign nature of the lesions and instructed to treat the papules with topical ammonium lactate 20% twice daily until the next appointment in 12 weeks. At follow-up, many, but not all, of the lesions had resolved.

Text courtesy of Tristan Reynolds, DO, Maine Dartmouth Family Medicine Residency, and Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

Potassium hydroxide preparation of expressed contents revealed no molluscum bodies, but rather, small-caliber, trapped, and coiled hairs consistent with eruptive vellus hair cysts (EVHCs).

Vellus hairs are fine, light-colored (nonterminal) hairs that normally are found on the face, trunk, and limbs. EVHCs are typically asymptomatic papules containing an entrapped vellus hair. They form from entrapment of the hair follicle just proximal to the infundibulum, leading to hair bulb atrophy and dilation of the follicle. EVHCs typically are dome-shaped, flesh-colored soft papules that are 2 to 3 mm in size.

Diagnostic confusion can arise with molluscum contagiosum because those lesions also tend to be umbilicated and flesh colored. EVHCs can appear at any age but are more common in the first 3 decades of life. Familial types exist, presenting earlier in life than sporadic types. The differential diagnosis includes molluscum contagiosum, folliculitis, and steatocystoma multiplex. Rare genodermatoses have been associated with EVHCs, including autosomal dominant familial keratin gene mutation, anhidrotic and hidrotic ectodermal dysplasia, and pachyonychia congenita.

Up to 25% of cases spontaneously resolve, so patients can be counseled to observe the lesions. Alternative options including topical emollients or various topical keratolytics, including ammonium lactate 20% once to twice daily, topical urea, or topical salicylic acid until the lesions are flat and smooth. Topical and systemic retinoids have been reported to have limited success. Individual lesions of concern may be removed surgically by excision, curettage, cryotherapy, or laser but will likely leave a minor scar.

The patient and his family were reassured of the benign nature of the lesions and instructed to treat the papules with topical ammonium lactate 20% twice daily until the next appointment in 12 weeks. At follow-up, many, but not all, of the lesions had resolved.

Text courtesy of Tristan Reynolds, DO, Maine Dartmouth Family Medicine Residency, and Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

Torchia D, Vega J, Schachner LA. Eruptive vellus hair cysts: a systematic review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:19-28.

Torchia D, Vega J, Schachner LA. Eruptive vellus hair cysts: a systematic review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:19-28.

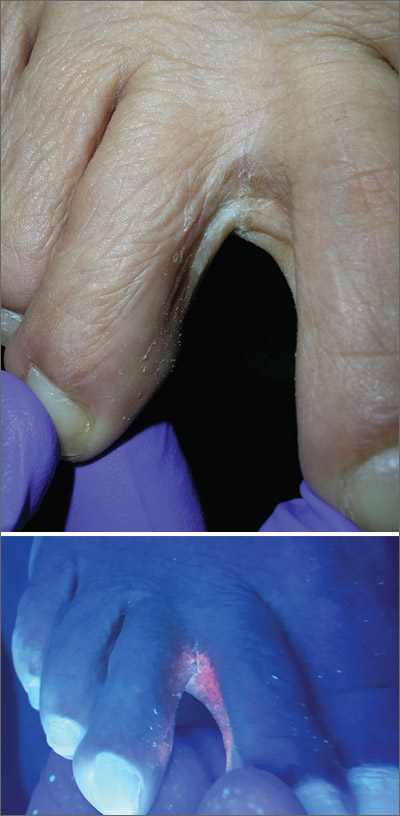

Bumps on the thighs

The photograph submitted for the telemedicine visit showed 2 classic umbilicated lesions and 1 dome-shaped papule consistent with molluscum contagiosum. Not all skin conditions can be diagnosed or treated via telehealth, but with a careful history, cooperative patients (and parents in this case), and photos taken on newer cell phones or digital cameras, many conditions can be diagnosed and managed appropriately.

Molluscum contagiosum is caused by the Molluscipox genus poxvirus and Is commonly seen in preschool and school-aged children. It can be passed through direct contact with infected individuals or spread by fomites. (In this case, the child may have picked up the virus by sharing a towel with an infected individual.)

The flesh-colored lesions are umbilicated or popular, and occur in clusters on the trunk, face, and extremities. Typically, the lesions will resolve spontaneously, but it may take several weeks to many months for resolution.

Given this lengthy time for spontaneous resolution, the risk of spreading to family members or other contacts, and the skin’s appearance, many patients choose to treat the lesions. Treatment options include curettage, cryosurgery, and laser. Available topical destructive agents include podophyllotoxin, trichloroacetic acid, benzoyl peroxide, potassium hydroxide, and cantharidin (which is from the blister beetle and often difficult to obtain). There also are naturopathic topical products and immune system modulators, including topical imiquimod. These treatments are commonly used, but are off-label for the treatment of molluscum contagiosum.

The family was counseled that there is debate about the effectiveness of imiquimod for molluscum contagiosum, but that some studies find it to be useful. In this case, the mother chose a prescription for imiquimod cream 5%, to be applied 3 times weekly at bedtime until the lesions resolved. (The cream can be used for up to 16 weeks.) The family was advised that erythema and irritation are expected adverse effects at the application site.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Badavanis G, Pasmatzi E, Monastirli A, et al. Topical imiquimod is an effective and safe drug for molluscum contagiosum in children. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2017;25:164-166.

The photograph submitted for the telemedicine visit showed 2 classic umbilicated lesions and 1 dome-shaped papule consistent with molluscum contagiosum. Not all skin conditions can be diagnosed or treated via telehealth, but with a careful history, cooperative patients (and parents in this case), and photos taken on newer cell phones or digital cameras, many conditions can be diagnosed and managed appropriately.

Molluscum contagiosum is caused by the Molluscipox genus poxvirus and Is commonly seen in preschool and school-aged children. It can be passed through direct contact with infected individuals or spread by fomites. (In this case, the child may have picked up the virus by sharing a towel with an infected individual.)

The flesh-colored lesions are umbilicated or popular, and occur in clusters on the trunk, face, and extremities. Typically, the lesions will resolve spontaneously, but it may take several weeks to many months for resolution.

Given this lengthy time for spontaneous resolution, the risk of spreading to family members or other contacts, and the skin’s appearance, many patients choose to treat the lesions. Treatment options include curettage, cryosurgery, and laser. Available topical destructive agents include podophyllotoxin, trichloroacetic acid, benzoyl peroxide, potassium hydroxide, and cantharidin (which is from the blister beetle and often difficult to obtain). There also are naturopathic topical products and immune system modulators, including topical imiquimod. These treatments are commonly used, but are off-label for the treatment of molluscum contagiosum.

The family was counseled that there is debate about the effectiveness of imiquimod for molluscum contagiosum, but that some studies find it to be useful. In this case, the mother chose a prescription for imiquimod cream 5%, to be applied 3 times weekly at bedtime until the lesions resolved. (The cream can be used for up to 16 weeks.) The family was advised that erythema and irritation are expected adverse effects at the application site.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

The photograph submitted for the telemedicine visit showed 2 classic umbilicated lesions and 1 dome-shaped papule consistent with molluscum contagiosum. Not all skin conditions can be diagnosed or treated via telehealth, but with a careful history, cooperative patients (and parents in this case), and photos taken on newer cell phones or digital cameras, many conditions can be diagnosed and managed appropriately.

Molluscum contagiosum is caused by the Molluscipox genus poxvirus and Is commonly seen in preschool and school-aged children. It can be passed through direct contact with infected individuals or spread by fomites. (In this case, the child may have picked up the virus by sharing a towel with an infected individual.)

The flesh-colored lesions are umbilicated or popular, and occur in clusters on the trunk, face, and extremities. Typically, the lesions will resolve spontaneously, but it may take several weeks to many months for resolution.

Given this lengthy time for spontaneous resolution, the risk of spreading to family members or other contacts, and the skin’s appearance, many patients choose to treat the lesions. Treatment options include curettage, cryosurgery, and laser. Available topical destructive agents include podophyllotoxin, trichloroacetic acid, benzoyl peroxide, potassium hydroxide, and cantharidin (which is from the blister beetle and often difficult to obtain). There also are naturopathic topical products and immune system modulators, including topical imiquimod. These treatments are commonly used, but are off-label for the treatment of molluscum contagiosum.

The family was counseled that there is debate about the effectiveness of imiquimod for molluscum contagiosum, but that some studies find it to be useful. In this case, the mother chose a prescription for imiquimod cream 5%, to be applied 3 times weekly at bedtime until the lesions resolved. (The cream can be used for up to 16 weeks.) The family was advised that erythema and irritation are expected adverse effects at the application site.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Badavanis G, Pasmatzi E, Monastirli A, et al. Topical imiquimod is an effective and safe drug for molluscum contagiosum in children. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2017;25:164-166.

Badavanis G, Pasmatzi E, Monastirli A, et al. Topical imiquimod is an effective and safe drug for molluscum contagiosum in children. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2017;25:164-166.

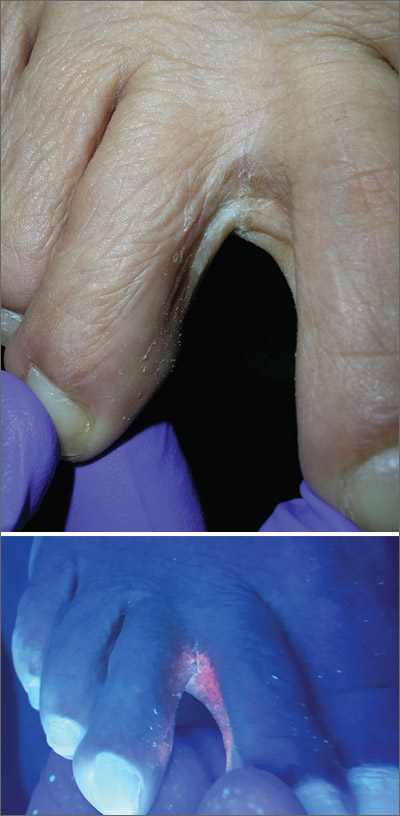

Ulcerated hand lesion

While the eroded scabbed area in a raised lesion with pearly borders raised the suspicion of basal cell carcinoma (BCC), a superficial shave biopsy revealed that this was sclerosing basosquamous carcinoma.

Basosquamous carcinoma is an uncommon form of BCC. It features nests/clusters of basaloid cells arising from the basal layer of the epidermis (a hallmark of BCC), as well as keratinization, which is seen in squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Basosquamous carcinoma occurs in the same areas as more common types of nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs)—that is, sun-exposed areas. Not surprisingly, then, the highest risk areas for basosquamous carcinoma are the face, hands, arms, scalp (in those without hair), and back. People with occupational or intentional sun exposure through tanning have even higher rates of NMSC than the average population; patients using tanning booths exposing their entire bodies warrant more extensive physical exams.

Basosquamous carcinoma is one of the subtypes of BCC that is associated with a higher risk of local invasion, recurrence, and metastasis. Treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) reduces the risk of recurrence to 4% (from 12% to 51%). Even with MMS, basosquamous carcinoma can be particularly challenging. It may require additional excision stages, as well as a larger than anticipated excision size at the time of surgery.

In this case, the patient was referred for MMS due to the high-risk nature of this lesion.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Garcia C, Poletti E, Crowson AN. Basosquamous carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:137-143.

While the eroded scabbed area in a raised lesion with pearly borders raised the suspicion of basal cell carcinoma (BCC), a superficial shave biopsy revealed that this was sclerosing basosquamous carcinoma.

Basosquamous carcinoma is an uncommon form of BCC. It features nests/clusters of basaloid cells arising from the basal layer of the epidermis (a hallmark of BCC), as well as keratinization, which is seen in squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Basosquamous carcinoma occurs in the same areas as more common types of nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs)—that is, sun-exposed areas. Not surprisingly, then, the highest risk areas for basosquamous carcinoma are the face, hands, arms, scalp (in those without hair), and back. People with occupational or intentional sun exposure through tanning have even higher rates of NMSC than the average population; patients using tanning booths exposing their entire bodies warrant more extensive physical exams.

Basosquamous carcinoma is one of the subtypes of BCC that is associated with a higher risk of local invasion, recurrence, and metastasis. Treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) reduces the risk of recurrence to 4% (from 12% to 51%). Even with MMS, basosquamous carcinoma can be particularly challenging. It may require additional excision stages, as well as a larger than anticipated excision size at the time of surgery.

In this case, the patient was referred for MMS due to the high-risk nature of this lesion.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

While the eroded scabbed area in a raised lesion with pearly borders raised the suspicion of basal cell carcinoma (BCC), a superficial shave biopsy revealed that this was sclerosing basosquamous carcinoma.

Basosquamous carcinoma is an uncommon form of BCC. It features nests/clusters of basaloid cells arising from the basal layer of the epidermis (a hallmark of BCC), as well as keratinization, which is seen in squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Basosquamous carcinoma occurs in the same areas as more common types of nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs)—that is, sun-exposed areas. Not surprisingly, then, the highest risk areas for basosquamous carcinoma are the face, hands, arms, scalp (in those without hair), and back. People with occupational or intentional sun exposure through tanning have even higher rates of NMSC than the average population; patients using tanning booths exposing their entire bodies warrant more extensive physical exams.

Basosquamous carcinoma is one of the subtypes of BCC that is associated with a higher risk of local invasion, recurrence, and metastasis. Treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) reduces the risk of recurrence to 4% (from 12% to 51%). Even with MMS, basosquamous carcinoma can be particularly challenging. It may require additional excision stages, as well as a larger than anticipated excision size at the time of surgery.

In this case, the patient was referred for MMS due to the high-risk nature of this lesion.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Garcia C, Poletti E, Crowson AN. Basosquamous carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:137-143.

Garcia C, Poletti E, Crowson AN. Basosquamous carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:137-143.

Scaly hand papule

This pink raised nodule underlying a scaly surface was suspicious for squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Since this was a virtual visit, and the lesion required pathology due to the likelihood of cancer, the patient was brought into the clinic for additional evaluation. A broad-based deep shave biopsy was performed to remove the visible lesion. Pathology showed SCC in situ, with borders uninvolved.

Patients who have had AKs are extremely likely to develop additional AKs. A notable percentage of AKs will, over time, develop into SCC in situ and then invasive SCC if not treated. While cryosurgery of an SK should not result in SCC, it’s most likely that in this case, an AK adjacent to the SK progressed to the SCC in situ.

There are multiple treatments available for SCC in situ. Topical imiquimod has been shown to be somewhat effective in stimulating the immune system, thus leading to resolution of SCC in situ. But there is a significant risk of recurrence. Topical 5-FU can be utilized on a daily or twice daily basis for 2 weeks (or up to several months). The risk of recurrence ranges from 7% to 33%. Electrodesiccation and curettage is often used for SCC in situ, with recurrence rates of 2% to 19%. Cryosurgery for SCC in situ requires an aggressive freeze, with freeze times of up to 30 seconds. Photodynamic therapy also is an option; however, it requires multiple sessions and is more costly than other treatment options.

This patient’s borders were uninvolved on pathology, but it was possible that there was some residual SCC in situ due to the standard “bread loaf slicing” used for routine pathology. To treat possible residual SCC in situ at the wound site and surrounding tissue, the patient was given a prescription for topical 5-FU to apply twice daily for 6 weeks. The patient was instructed to return for follow-up in 6 months, or sooner, if any problems arose.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Shimizu I, Cruz A, Chang KH, et al. Treatment of squamous cell carcinoma in situ: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:1394-1411.

This pink raised nodule underlying a scaly surface was suspicious for squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Since this was a virtual visit, and the lesion required pathology due to the likelihood of cancer, the patient was brought into the clinic for additional evaluation. A broad-based deep shave biopsy was performed to remove the visible lesion. Pathology showed SCC in situ, with borders uninvolved.

Patients who have had AKs are extremely likely to develop additional AKs. A notable percentage of AKs will, over time, develop into SCC in situ and then invasive SCC if not treated. While cryosurgery of an SK should not result in SCC, it’s most likely that in this case, an AK adjacent to the SK progressed to the SCC in situ.

There are multiple treatments available for SCC in situ. Topical imiquimod has been shown to be somewhat effective in stimulating the immune system, thus leading to resolution of SCC in situ. But there is a significant risk of recurrence. Topical 5-FU can be utilized on a daily or twice daily basis for 2 weeks (or up to several months). The risk of recurrence ranges from 7% to 33%. Electrodesiccation and curettage is often used for SCC in situ, with recurrence rates of 2% to 19%. Cryosurgery for SCC in situ requires an aggressive freeze, with freeze times of up to 30 seconds. Photodynamic therapy also is an option; however, it requires multiple sessions and is more costly than other treatment options.

This patient’s borders were uninvolved on pathology, but it was possible that there was some residual SCC in situ due to the standard “bread loaf slicing” used for routine pathology. To treat possible residual SCC in situ at the wound site and surrounding tissue, the patient was given a prescription for topical 5-FU to apply twice daily for 6 weeks. The patient was instructed to return for follow-up in 6 months, or sooner, if any problems arose.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

This pink raised nodule underlying a scaly surface was suspicious for squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Since this was a virtual visit, and the lesion required pathology due to the likelihood of cancer, the patient was brought into the clinic for additional evaluation. A broad-based deep shave biopsy was performed to remove the visible lesion. Pathology showed SCC in situ, with borders uninvolved.

Patients who have had AKs are extremely likely to develop additional AKs. A notable percentage of AKs will, over time, develop into SCC in situ and then invasive SCC if not treated. While cryosurgery of an SK should not result in SCC, it’s most likely that in this case, an AK adjacent to the SK progressed to the SCC in situ.

There are multiple treatments available for SCC in situ. Topical imiquimod has been shown to be somewhat effective in stimulating the immune system, thus leading to resolution of SCC in situ. But there is a significant risk of recurrence. Topical 5-FU can be utilized on a daily or twice daily basis for 2 weeks (or up to several months). The risk of recurrence ranges from 7% to 33%. Electrodesiccation and curettage is often used for SCC in situ, with recurrence rates of 2% to 19%. Cryosurgery for SCC in situ requires an aggressive freeze, with freeze times of up to 30 seconds. Photodynamic therapy also is an option; however, it requires multiple sessions and is more costly than other treatment options.

This patient’s borders were uninvolved on pathology, but it was possible that there was some residual SCC in situ due to the standard “bread loaf slicing” used for routine pathology. To treat possible residual SCC in situ at the wound site and surrounding tissue, the patient was given a prescription for topical 5-FU to apply twice daily for 6 weeks. The patient was instructed to return for follow-up in 6 months, or sooner, if any problems arose.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Shimizu I, Cruz A, Chang KH, et al. Treatment of squamous cell carcinoma in situ: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:1394-1411.

Shimizu I, Cruz A, Chang KH, et al. Treatment of squamous cell carcinoma in situ: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:1394-1411.

Large, painful facial cysts

The abrupt onset of painful, violaceous coalescing papules, pustules, cysts, and nodules exclusively involving the centrofacial area with an overlying red-cyanotic erythema are the hallmarks of pyoderma faciale.

Pyoderma faciale is a rare disease that affects females in the second and third decades of life; 50% of these patients have a history of acne. The etiology of the condition remains unclear. Hormonal imbalance, inflammatory bowel disease, liver disease, and thyroid disease have been associated with the disorder. Ribavirin and interferon therapies for the treatment of hepatitis C along with high levels of vitamins (B6 and B12) have been identified as triggers. Culture of purulent drainage typically is sterile or may reveal commensal organisms.

The differential diagnosis includes acne fulminans and acne conglobata. Acne fulminans is not restricted to the face, as is pyoderma faciale, and it involves constitutional symptoms. Acne conglobata is a chronic process that affects males and females. It also involves purulent sinus tracts.

Prompt treatment of pyoderma faciale is essential to prevent widespread eruption, minimize the distress associated with the disfiguring nature of the disorder, and ultimately reduce scarring. Standard therapy consists of oral steroids (prednisone 1 mg/kg/d) for 1 week followed by a slow taper in combination with oral isotretinoin at a low dosage (0.2–0.5 mg/kg). The systemic retinoid is continued until all inflammatory lesions are healed.

In this case, a culture swab taken from the patient’s left cheek did not reveal any unexpected pathogens. The patient was started on oral doxycycline 100 mg bid and prednisone 50 mg/d tapered to 10 mg/d. She was counseled about the risks and benefits of isotretinoin and registered in the iPLEDGE system in anticipation of starting oral isotretinoin at 20 mg/d after negative pregnancy tests, 2 forms of contraception, and the 1-month qualification period.

Photo courtesy of Catherine N. Tchanque-Fossuo, MD, MS, and text courtesy of Catherine N. Tchanque-Fossuo, MD, MS, Department of Dermatology, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Sharma RK, Pulimood S, Peter D, et al. A case report with review of literature on pyoderma faciale in pregnancy–a therapeutic dilemma. JDA Indian J Clin Dermatol. 2018;1:96-99.

The abrupt onset of painful, violaceous coalescing papules, pustules, cysts, and nodules exclusively involving the centrofacial area with an overlying red-cyanotic erythema are the hallmarks of pyoderma faciale.

Pyoderma faciale is a rare disease that affects females in the second and third decades of life; 50% of these patients have a history of acne. The etiology of the condition remains unclear. Hormonal imbalance, inflammatory bowel disease, liver disease, and thyroid disease have been associated with the disorder. Ribavirin and interferon therapies for the treatment of hepatitis C along with high levels of vitamins (B6 and B12) have been identified as triggers. Culture of purulent drainage typically is sterile or may reveal commensal organisms.

The differential diagnosis includes acne fulminans and acne conglobata. Acne fulminans is not restricted to the face, as is pyoderma faciale, and it involves constitutional symptoms. Acne conglobata is a chronic process that affects males and females. It also involves purulent sinus tracts.

Prompt treatment of pyoderma faciale is essential to prevent widespread eruption, minimize the distress associated with the disfiguring nature of the disorder, and ultimately reduce scarring. Standard therapy consists of oral steroids (prednisone 1 mg/kg/d) for 1 week followed by a slow taper in combination with oral isotretinoin at a low dosage (0.2–0.5 mg/kg). The systemic retinoid is continued until all inflammatory lesions are healed.

In this case, a culture swab taken from the patient’s left cheek did not reveal any unexpected pathogens. The patient was started on oral doxycycline 100 mg bid and prednisone 50 mg/d tapered to 10 mg/d. She was counseled about the risks and benefits of isotretinoin and registered in the iPLEDGE system in anticipation of starting oral isotretinoin at 20 mg/d after negative pregnancy tests, 2 forms of contraception, and the 1-month qualification period.

Photo courtesy of Catherine N. Tchanque-Fossuo, MD, MS, and text courtesy of Catherine N. Tchanque-Fossuo, MD, MS, Department of Dermatology, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

The abrupt onset of painful, violaceous coalescing papules, pustules, cysts, and nodules exclusively involving the centrofacial area with an overlying red-cyanotic erythema are the hallmarks of pyoderma faciale.

Pyoderma faciale is a rare disease that affects females in the second and third decades of life; 50% of these patients have a history of acne. The etiology of the condition remains unclear. Hormonal imbalance, inflammatory bowel disease, liver disease, and thyroid disease have been associated with the disorder. Ribavirin and interferon therapies for the treatment of hepatitis C along with high levels of vitamins (B6 and B12) have been identified as triggers. Culture of purulent drainage typically is sterile or may reveal commensal organisms.

The differential diagnosis includes acne fulminans and acne conglobata. Acne fulminans is not restricted to the face, as is pyoderma faciale, and it involves constitutional symptoms. Acne conglobata is a chronic process that affects males and females. It also involves purulent sinus tracts.

Prompt treatment of pyoderma faciale is essential to prevent widespread eruption, minimize the distress associated with the disfiguring nature of the disorder, and ultimately reduce scarring. Standard therapy consists of oral steroids (prednisone 1 mg/kg/d) for 1 week followed by a slow taper in combination with oral isotretinoin at a low dosage (0.2–0.5 mg/kg). The systemic retinoid is continued until all inflammatory lesions are healed.

In this case, a culture swab taken from the patient’s left cheek did not reveal any unexpected pathogens. The patient was started on oral doxycycline 100 mg bid and prednisone 50 mg/d tapered to 10 mg/d. She was counseled about the risks and benefits of isotretinoin and registered in the iPLEDGE system in anticipation of starting oral isotretinoin at 20 mg/d after negative pregnancy tests, 2 forms of contraception, and the 1-month qualification period.

Photo courtesy of Catherine N. Tchanque-Fossuo, MD, MS, and text courtesy of Catherine N. Tchanque-Fossuo, MD, MS, Department of Dermatology, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Sharma RK, Pulimood S, Peter D, et al. A case report with review of literature on pyoderma faciale in pregnancy–a therapeutic dilemma. JDA Indian J Clin Dermatol. 2018;1:96-99.

Sharma RK, Pulimood S, Peter D, et al. A case report with review of literature on pyoderma faciale in pregnancy–a therapeutic dilemma. JDA Indian J Clin Dermatol. 2018;1:96-99.

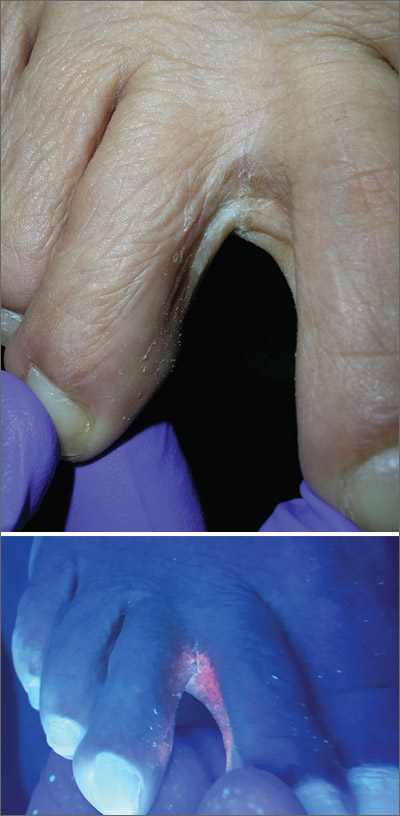

Scaly foot rash

The Wood’s lamp revealed a coral-red fluorescence in the interdigital spaces, which led to a diagnosis of erythrasma.

The coral-red fluorescence seen under the Wood’s lamp is due to porphyrins produced by Corynebacterium minutissimum. The organism invades the stratum corneum where it proliferates and causes erythrasma. Erythrasma typically appears as delineated, dry, red-brown patches in intertriginous areas, such as the axilla, groin, interdigital spaces, intergluteal cleft, perianal skin, and inframammary area.

Erythrasma affects 4% of the population; risk factors include poor hygiene, hyperhidrosis, obesity, warm climate, diabetes, and an immunocompromised state. The differential diagnosis for a pruritic rash between the toes includes tinea pedis and contact dermatitis.

First-line management of erythrasma includes both nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic modalities. Good hygiene and, depending on the area affected, loose-fitting cotton undergarments can help treat and prevent erythrasma.

Topical 2% miconazole bid for 2 weeks has resulted in clearance rates as high as 88%. Its affordable price, over-the-counter availability, and lack of adverse effects make miconazole a reasonable choice. It is also a smart treatment choice when erythrasma is coexisting with tinea because it can treat both conditions.

Topical 1% clindamycin or 2% erythromycin solution or gel bid for 2 weeks also can be used to treat the condition. However, given that topical antibiotics are more expensive than single-dose oral treatment and are no better than the oral formulations of these antibiotics, clarithromycin 1 g taken once orally may be preferred. Our patient was treated with a single dose of clarithromycin 1 g. At follow-up, her erythrasma was clear.

This case was adapted from: Vo T, Usatine RP. Persistent rash on feet. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:107-109

The Wood’s lamp revealed a coral-red fluorescence in the interdigital spaces, which led to a diagnosis of erythrasma.

The coral-red fluorescence seen under the Wood’s lamp is due to porphyrins produced by Corynebacterium minutissimum. The organism invades the stratum corneum where it proliferates and causes erythrasma. Erythrasma typically appears as delineated, dry, red-brown patches in intertriginous areas, such as the axilla, groin, interdigital spaces, intergluteal cleft, perianal skin, and inframammary area.

Erythrasma affects 4% of the population; risk factors include poor hygiene, hyperhidrosis, obesity, warm climate, diabetes, and an immunocompromised state. The differential diagnosis for a pruritic rash between the toes includes tinea pedis and contact dermatitis.

First-line management of erythrasma includes both nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic modalities. Good hygiene and, depending on the area affected, loose-fitting cotton undergarments can help treat and prevent erythrasma.

Topical 2% miconazole bid for 2 weeks has resulted in clearance rates as high as 88%. Its affordable price, over-the-counter availability, and lack of adverse effects make miconazole a reasonable choice. It is also a smart treatment choice when erythrasma is coexisting with tinea because it can treat both conditions.

Topical 1% clindamycin or 2% erythromycin solution or gel bid for 2 weeks also can be used to treat the condition. However, given that topical antibiotics are more expensive than single-dose oral treatment and are no better than the oral formulations of these antibiotics, clarithromycin 1 g taken once orally may be preferred. Our patient was treated with a single dose of clarithromycin 1 g. At follow-up, her erythrasma was clear.

This case was adapted from: Vo T, Usatine RP. Persistent rash on feet. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:107-109

The Wood’s lamp revealed a coral-red fluorescence in the interdigital spaces, which led to a diagnosis of erythrasma.

The coral-red fluorescence seen under the Wood’s lamp is due to porphyrins produced by Corynebacterium minutissimum. The organism invades the stratum corneum where it proliferates and causes erythrasma. Erythrasma typically appears as delineated, dry, red-brown patches in intertriginous areas, such as the axilla, groin, interdigital spaces, intergluteal cleft, perianal skin, and inframammary area.

Erythrasma affects 4% of the population; risk factors include poor hygiene, hyperhidrosis, obesity, warm climate, diabetes, and an immunocompromised state. The differential diagnosis for a pruritic rash between the toes includes tinea pedis and contact dermatitis.

First-line management of erythrasma includes both nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic modalities. Good hygiene and, depending on the area affected, loose-fitting cotton undergarments can help treat and prevent erythrasma.

Topical 2% miconazole bid for 2 weeks has resulted in clearance rates as high as 88%. Its affordable price, over-the-counter availability, and lack of adverse effects make miconazole a reasonable choice. It is also a smart treatment choice when erythrasma is coexisting with tinea because it can treat both conditions.

Topical 1% clindamycin or 2% erythromycin solution or gel bid for 2 weeks also can be used to treat the condition. However, given that topical antibiotics are more expensive than single-dose oral treatment and are no better than the oral formulations of these antibiotics, clarithromycin 1 g taken once orally may be preferred. Our patient was treated with a single dose of clarithromycin 1 g. At follow-up, her erythrasma was clear.

This case was adapted from: Vo T, Usatine RP. Persistent rash on feet. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:107-109

Fixed scaly lesion

The patient’s history of a recurrent wheal was consistent with a diagnosis of mastocytoma, the most common and least concerning form of cutaneous mastocytosis. Mastocytomas commonly appear in infants as 1 to 3 firm 1- to 5-cm papules (or a plaque) caused by a histamine release from a group of mast cells with abnormal growth receptors. When flaring, the surface may have a prominent orange peel texture because of tethered adnexal structures. When uninflamed, the skin surface may be slightly raised and flesh-colored to pink.

When first noticed, mastocytomas are easily mistaken for insect bites or congenital nevi. However, mastocytomas don’t resolve completely, as would an insect bite, and they become recurrently inflamed (spontaneously or with trauma). Inflammation that can be elicited with pressure or scratching is called Darrier sign and is helpful in making the diagnosis and distinguishing these lesions from congenital nevi.

Dermoscopy of a mastocytoma lacks signs of a melanocytic nevi, which further adds to the clinical diagnosis. Blood tests and biopsy are unnecessary, but if a biopsy is performed, it is important to mention the possibility of mast cell disease to the lab so that appropriate immunostaining for mast cells can be carried out.

Mastocytomas that appear in infancy usually resolve spontaneously in early childhood or by puberty, at the latest. If there is any notable itching or discomfort, oral antihistamines are helpful, as are topical steroids and topical tacrolimus. In this case, the diagnosis was made clinically and the patient’s parents were content to observe the area.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Leung AKC, Lam JM, Leong KF. Childhood solitary cutaneous mastocytoma: clinical manifestations, diagnosis, evaluation, and management. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2019;15:42-46.

The patient’s history of a recurrent wheal was consistent with a diagnosis of mastocytoma, the most common and least concerning form of cutaneous mastocytosis. Mastocytomas commonly appear in infants as 1 to 3 firm 1- to 5-cm papules (or a plaque) caused by a histamine release from a group of mast cells with abnormal growth receptors. When flaring, the surface may have a prominent orange peel texture because of tethered adnexal structures. When uninflamed, the skin surface may be slightly raised and flesh-colored to pink.

When first noticed, mastocytomas are easily mistaken for insect bites or congenital nevi. However, mastocytomas don’t resolve completely, as would an insect bite, and they become recurrently inflamed (spontaneously or with trauma). Inflammation that can be elicited with pressure or scratching is called Darrier sign and is helpful in making the diagnosis and distinguishing these lesions from congenital nevi.

Dermoscopy of a mastocytoma lacks signs of a melanocytic nevi, which further adds to the clinical diagnosis. Blood tests and biopsy are unnecessary, but if a biopsy is performed, it is important to mention the possibility of mast cell disease to the lab so that appropriate immunostaining for mast cells can be carried out.

Mastocytomas that appear in infancy usually resolve spontaneously in early childhood or by puberty, at the latest. If there is any notable itching or discomfort, oral antihistamines are helpful, as are topical steroids and topical tacrolimus. In this case, the diagnosis was made clinically and the patient’s parents were content to observe the area.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

The patient’s history of a recurrent wheal was consistent with a diagnosis of mastocytoma, the most common and least concerning form of cutaneous mastocytosis. Mastocytomas commonly appear in infants as 1 to 3 firm 1- to 5-cm papules (or a plaque) caused by a histamine release from a group of mast cells with abnormal growth receptors. When flaring, the surface may have a prominent orange peel texture because of tethered adnexal structures. When uninflamed, the skin surface may be slightly raised and flesh-colored to pink.

When first noticed, mastocytomas are easily mistaken for insect bites or congenital nevi. However, mastocytomas don’t resolve completely, as would an insect bite, and they become recurrently inflamed (spontaneously or with trauma). Inflammation that can be elicited with pressure or scratching is called Darrier sign and is helpful in making the diagnosis and distinguishing these lesions from congenital nevi.

Dermoscopy of a mastocytoma lacks signs of a melanocytic nevi, which further adds to the clinical diagnosis. Blood tests and biopsy are unnecessary, but if a biopsy is performed, it is important to mention the possibility of mast cell disease to the lab so that appropriate immunostaining for mast cells can be carried out.

Mastocytomas that appear in infancy usually resolve spontaneously in early childhood or by puberty, at the latest. If there is any notable itching or discomfort, oral antihistamines are helpful, as are topical steroids and topical tacrolimus. In this case, the diagnosis was made clinically and the patient’s parents were content to observe the area.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Leung AKC, Lam JM, Leong KF. Childhood solitary cutaneous mastocytoma: clinical manifestations, diagnosis, evaluation, and management. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2019;15:42-46.

Leung AKC, Lam JM, Leong KF. Childhood solitary cutaneous mastocytoma: clinical manifestations, diagnosis, evaluation, and management. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2019;15:42-46.

Hyperpigmentation of the legs

A 90-year-old man was admitted from the Emergency Department (ED) to our inpatient service for difficulty urinating and hematuria. In the ED, a complete blood count (CBC) with differential and a urinalysis were performed. CBC showed a mild normocytic anemia, consistent with the patient’s known chronic kidney disease. The urinalysis revealed moderate blood, trace ketones, proteinuria, small leukocyte esterases, positive nitrites, and more than 182 red blood cells—findings suspicious for a urinary tract infection. Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis was notable for a soft-tissue mass in the bladder.

He had a history of coronary artery disease (treated with stent placement), atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure, hypothyroidism, gastroesophageal reflux disease, gastrointestinal bleeding, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, a 60-pack-per-year history of tobacco dependence, chronic kidney disease, prostate cancer, benign prostatic hypertrophy, peripheral vascular disease, and gout. Medications included digoxin, metoprolol, torsemide, aspirin, levothyroxine, fluticasone, albuterol, omeprazole, diclofenac, escitalopram, and minocycline.

About 5 years earlier, doctors had discovered a popliteal thrombosis that required emergent thrombectomy of the infragenicular popliteal artery, thromboembolectomy of the right posterior tibial artery, graft angioplasty of the right posterior tibial artery, and right anterior fasciotomy for compartment syndrome.

Ten months later, an abscess formed at the incision site. His physician irrigated the popliteal wound and prescribed intravenous (IV) vancomycin. However, the patient developed an allergy and IV daptomycin was initiated and followed by chronic antibiotic suppression with oral minocycline 100 mg bid for about 3.5 years. Skin discoloration appeared within a year of starting the minocycline.

During his hospitalization on our service, we noted black pigmentation of both legs (FIGURE). He had intact strength and sensation in his legs, 1+ pitting edema, no pain upon palpation, and 2+ distal pulses. The patient was well appearing and in no acute distress.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation

The patient’s clinical presentation of chronic blue-black hyperpigmentation on the anterior shins of both legs after a prolonged antibiotic course led us to conclude that this was an adverse effect of minocycline. Commonly, doctors use minocycline to treat acne, rosacea, and rheumatoid arthritis. In this case, it was used to provide chronic antimicrobial suppression.

Not an uncommon reaction for a patient like ours. One small study conducted in an orthopedic patient population found that 54% of patients receiving long-term minocycline suppression developed hyperpigmentation after a mean follow-up of nearly 5 years.1 The hyperpigmentation is solely cosmetic and without known clinical complications, but it can be distressing for patients.

There are 3 types of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation:

- Type I is a circumscribed blue-black pigmentation that manifests in skin that previously was inflamed or scarred, such as facial acne scars.2 Histopathologic findings include black pigment granules in macrophages and throughout the dermis that stain with Perls Prussian blue iron.3

- Type II (which our patient had) is circumscribed blue-black pigmentation that appears in previously normal skin of the forearms or lower legs—especially the shins.3 On histopathology, black pigment granules are found in the dermis with macrophages that stain with Perls Prussian blue iron and Fontana-Masson.3

- Type III is a diffuse muddy brown hyperpigmentation in previously normal, sun-exposed skin.2 Histopathologic findings include increased melanin in basal keratinocytes and dermal melanophages that stain with Fontana-Masson.3

Types II and III may be related to cumulative dosing, whereas type I can occur at any point during treatment.2

Differential includes pigmentation disorders

The differential diagnosis includes Addison disease, argyria, hemochromatosis, and polycythemia vera, which all can cause diffuse blue-gray patches.4 Brown-violet pigmentation on sun-exposed areas, redness, and itching are more typical of Riehl melanosis.4

Continue to: Diltiazem

Diltiazem can produce slate-gray to blue-gray reticulated hyperpigmentation.5 Other drugs that can induce slate-gray macules or patches include amiodarone, chlorpromazine, imipramine, and desipramine.5

Treatment is simple, resolution takes time

The treatment for this condition is cessation of minocycline use. Pigmentation fades slowly and may persist for years. There has been successful treatment of type I and III minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation with the alexandrite 755 nm Q-switched laser combined with fractional photothermolysis.3,6 Unfortunately, insurance coverage is limited because these treatments are cosmetic in nature.

Given that hyperpigmentation is a known adverse effect of minocycline use, it’s important to counsel patients about the possibility prior to initiating treatment. It’s also important to monitor for signs of changing pigmentation to prevent psychological distress.

In this case, a biopsy was deemed unnecessary, as the antibiotic was the most likely cause of the pigmentation. The patient’s outpatient dermatologist recommended changing therapy if a medically appropriate alternative was available. Doxycycline would have been a reasonable alternative; however, the patient died shortly after his presentation to our hospital due to his multiple comorbidities.

CORRESPONDENCE

Bich-May Nguyen, MD, MPH, 14023 Southwest Freeway, Sugar Land, TX 77478; [email protected]

1. Hanada Y, Berbari EF, Steckelberg JM. Minocycline-induced cutaneous hyperpigmentation in an orthopedic patient population. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016;3:ofv107.

2. Mouton RW, Jordaan HF, Schneider JW. A new type of minocycline-induced cutaneous hyperpigmentation. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:8-14.

3. D’Agostino ML, Risser J, Robinson-Bostom L. Imipramine-induced hyperpigmentation: a case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:799-803.

4. Nisar MS, Iyer K, Brodell RT, et al. Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation: comparison of 3 Q-switched lasers to reverse its effects. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2013;6:159-162.

5. Scherschun L, Lee MW, Lim HW. Diltiazem-associated photodistributed hyperpigmentation. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:179-182.

6. Vangipuram RK, DeLozier WL, Geddes E, et al. Complete resolution of minocycline pigmentation following a single treatment with non-ablative 1550-nm fractional resurfacing in combination with the 755-nm Q-switched alexandrite laser. Lasers Surg Med. 2016;48:234-237.

A 90-year-old man was admitted from the Emergency Department (ED) to our inpatient service for difficulty urinating and hematuria. In the ED, a complete blood count (CBC) with differential and a urinalysis were performed. CBC showed a mild normocytic anemia, consistent with the patient’s known chronic kidney disease. The urinalysis revealed moderate blood, trace ketones, proteinuria, small leukocyte esterases, positive nitrites, and more than 182 red blood cells—findings suspicious for a urinary tract infection. Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis was notable for a soft-tissue mass in the bladder.

He had a history of coronary artery disease (treated with stent placement), atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure, hypothyroidism, gastroesophageal reflux disease, gastrointestinal bleeding, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, a 60-pack-per-year history of tobacco dependence, chronic kidney disease, prostate cancer, benign prostatic hypertrophy, peripheral vascular disease, and gout. Medications included digoxin, metoprolol, torsemide, aspirin, levothyroxine, fluticasone, albuterol, omeprazole, diclofenac, escitalopram, and minocycline.

About 5 years earlier, doctors had discovered a popliteal thrombosis that required emergent thrombectomy of the infragenicular popliteal artery, thromboembolectomy of the right posterior tibial artery, graft angioplasty of the right posterior tibial artery, and right anterior fasciotomy for compartment syndrome.

Ten months later, an abscess formed at the incision site. His physician irrigated the popliteal wound and prescribed intravenous (IV) vancomycin. However, the patient developed an allergy and IV daptomycin was initiated and followed by chronic antibiotic suppression with oral minocycline 100 mg bid for about 3.5 years. Skin discoloration appeared within a year of starting the minocycline.

During his hospitalization on our service, we noted black pigmentation of both legs (FIGURE). He had intact strength and sensation in his legs, 1+ pitting edema, no pain upon palpation, and 2+ distal pulses. The patient was well appearing and in no acute distress.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation

The patient’s clinical presentation of chronic blue-black hyperpigmentation on the anterior shins of both legs after a prolonged antibiotic course led us to conclude that this was an adverse effect of minocycline. Commonly, doctors use minocycline to treat acne, rosacea, and rheumatoid arthritis. In this case, it was used to provide chronic antimicrobial suppression.

Not an uncommon reaction for a patient like ours. One small study conducted in an orthopedic patient population found that 54% of patients receiving long-term minocycline suppression developed hyperpigmentation after a mean follow-up of nearly 5 years.1 The hyperpigmentation is solely cosmetic and without known clinical complications, but it can be distressing for patients.

There are 3 types of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation:

- Type I is a circumscribed blue-black pigmentation that manifests in skin that previously was inflamed or scarred, such as facial acne scars.2 Histopathologic findings include black pigment granules in macrophages and throughout the dermis that stain with Perls Prussian blue iron.3

- Type II (which our patient had) is circumscribed blue-black pigmentation that appears in previously normal skin of the forearms or lower legs—especially the shins.3 On histopathology, black pigment granules are found in the dermis with macrophages that stain with Perls Prussian blue iron and Fontana-Masson.3

- Type III is a diffuse muddy brown hyperpigmentation in previously normal, sun-exposed skin.2 Histopathologic findings include increased melanin in basal keratinocytes and dermal melanophages that stain with Fontana-Masson.3

Types II and III may be related to cumulative dosing, whereas type I can occur at any point during treatment.2

Differential includes pigmentation disorders

The differential diagnosis includes Addison disease, argyria, hemochromatosis, and polycythemia vera, which all can cause diffuse blue-gray patches.4 Brown-violet pigmentation on sun-exposed areas, redness, and itching are more typical of Riehl melanosis.4

Continue to: Diltiazem

Diltiazem can produce slate-gray to blue-gray reticulated hyperpigmentation.5 Other drugs that can induce slate-gray macules or patches include amiodarone, chlorpromazine, imipramine, and desipramine.5

Treatment is simple, resolution takes time

The treatment for this condition is cessation of minocycline use. Pigmentation fades slowly and may persist for years. There has been successful treatment of type I and III minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation with the alexandrite 755 nm Q-switched laser combined with fractional photothermolysis.3,6 Unfortunately, insurance coverage is limited because these treatments are cosmetic in nature.

Given that hyperpigmentation is a known adverse effect of minocycline use, it’s important to counsel patients about the possibility prior to initiating treatment. It’s also important to monitor for signs of changing pigmentation to prevent psychological distress.

In this case, a biopsy was deemed unnecessary, as the antibiotic was the most likely cause of the pigmentation. The patient’s outpatient dermatologist recommended changing therapy if a medically appropriate alternative was available. Doxycycline would have been a reasonable alternative; however, the patient died shortly after his presentation to our hospital due to his multiple comorbidities.

CORRESPONDENCE

Bich-May Nguyen, MD, MPH, 14023 Southwest Freeway, Sugar Land, TX 77478; [email protected]

A 90-year-old man was admitted from the Emergency Department (ED) to our inpatient service for difficulty urinating and hematuria. In the ED, a complete blood count (CBC) with differential and a urinalysis were performed. CBC showed a mild normocytic anemia, consistent with the patient’s known chronic kidney disease. The urinalysis revealed moderate blood, trace ketones, proteinuria, small leukocyte esterases, positive nitrites, and more than 182 red blood cells—findings suspicious for a urinary tract infection. Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis was notable for a soft-tissue mass in the bladder.

He had a history of coronary artery disease (treated with stent placement), atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure, hypothyroidism, gastroesophageal reflux disease, gastrointestinal bleeding, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, a 60-pack-per-year history of tobacco dependence, chronic kidney disease, prostate cancer, benign prostatic hypertrophy, peripheral vascular disease, and gout. Medications included digoxin, metoprolol, torsemide, aspirin, levothyroxine, fluticasone, albuterol, omeprazole, diclofenac, escitalopram, and minocycline.

About 5 years earlier, doctors had discovered a popliteal thrombosis that required emergent thrombectomy of the infragenicular popliteal artery, thromboembolectomy of the right posterior tibial artery, graft angioplasty of the right posterior tibial artery, and right anterior fasciotomy for compartment syndrome.

Ten months later, an abscess formed at the incision site. His physician irrigated the popliteal wound and prescribed intravenous (IV) vancomycin. However, the patient developed an allergy and IV daptomycin was initiated and followed by chronic antibiotic suppression with oral minocycline 100 mg bid for about 3.5 years. Skin discoloration appeared within a year of starting the minocycline.

During his hospitalization on our service, we noted black pigmentation of both legs (FIGURE). He had intact strength and sensation in his legs, 1+ pitting edema, no pain upon palpation, and 2+ distal pulses. The patient was well appearing and in no acute distress.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation

The patient’s clinical presentation of chronic blue-black hyperpigmentation on the anterior shins of both legs after a prolonged antibiotic course led us to conclude that this was an adverse effect of minocycline. Commonly, doctors use minocycline to treat acne, rosacea, and rheumatoid arthritis. In this case, it was used to provide chronic antimicrobial suppression.

Not an uncommon reaction for a patient like ours. One small study conducted in an orthopedic patient population found that 54% of patients receiving long-term minocycline suppression developed hyperpigmentation after a mean follow-up of nearly 5 years.1 The hyperpigmentation is solely cosmetic and without known clinical complications, but it can be distressing for patients.

There are 3 types of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation:

- Type I is a circumscribed blue-black pigmentation that manifests in skin that previously was inflamed or scarred, such as facial acne scars.2 Histopathologic findings include black pigment granules in macrophages and throughout the dermis that stain with Perls Prussian blue iron.3

- Type II (which our patient had) is circumscribed blue-black pigmentation that appears in previously normal skin of the forearms or lower legs—especially the shins.3 On histopathology, black pigment granules are found in the dermis with macrophages that stain with Perls Prussian blue iron and Fontana-Masson.3

- Type III is a diffuse muddy brown hyperpigmentation in previously normal, sun-exposed skin.2 Histopathologic findings include increased melanin in basal keratinocytes and dermal melanophages that stain with Fontana-Masson.3

Types II and III may be related to cumulative dosing, whereas type I can occur at any point during treatment.2

Differential includes pigmentation disorders

The differential diagnosis includes Addison disease, argyria, hemochromatosis, and polycythemia vera, which all can cause diffuse blue-gray patches.4 Brown-violet pigmentation on sun-exposed areas, redness, and itching are more typical of Riehl melanosis.4

Continue to: Diltiazem

Diltiazem can produce slate-gray to blue-gray reticulated hyperpigmentation.5 Other drugs that can induce slate-gray macules or patches include amiodarone, chlorpromazine, imipramine, and desipramine.5

Treatment is simple, resolution takes time

The treatment for this condition is cessation of minocycline use. Pigmentation fades slowly and may persist for years. There has been successful treatment of type I and III minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation with the alexandrite 755 nm Q-switched laser combined with fractional photothermolysis.3,6 Unfortunately, insurance coverage is limited because these treatments are cosmetic in nature.

Given that hyperpigmentation is a known adverse effect of minocycline use, it’s important to counsel patients about the possibility prior to initiating treatment. It’s also important to monitor for signs of changing pigmentation to prevent psychological distress.

In this case, a biopsy was deemed unnecessary, as the antibiotic was the most likely cause of the pigmentation. The patient’s outpatient dermatologist recommended changing therapy if a medically appropriate alternative was available. Doxycycline would have been a reasonable alternative; however, the patient died shortly after his presentation to our hospital due to his multiple comorbidities.

CORRESPONDENCE

Bich-May Nguyen, MD, MPH, 14023 Southwest Freeway, Sugar Land, TX 77478; [email protected]

1. Hanada Y, Berbari EF, Steckelberg JM. Minocycline-induced cutaneous hyperpigmentation in an orthopedic patient population. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016;3:ofv107.

2. Mouton RW, Jordaan HF, Schneider JW. A new type of minocycline-induced cutaneous hyperpigmentation. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:8-14.

3. D’Agostino ML, Risser J, Robinson-Bostom L. Imipramine-induced hyperpigmentation: a case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:799-803.

4. Nisar MS, Iyer K, Brodell RT, et al. Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation: comparison of 3 Q-switched lasers to reverse its effects. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2013;6:159-162.

5. Scherschun L, Lee MW, Lim HW. Diltiazem-associated photodistributed hyperpigmentation. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:179-182.

6. Vangipuram RK, DeLozier WL, Geddes E, et al. Complete resolution of minocycline pigmentation following a single treatment with non-ablative 1550-nm fractional resurfacing in combination with the 755-nm Q-switched alexandrite laser. Lasers Surg Med. 2016;48:234-237.

1. Hanada Y, Berbari EF, Steckelberg JM. Minocycline-induced cutaneous hyperpigmentation in an orthopedic patient population. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016;3:ofv107.

2. Mouton RW, Jordaan HF, Schneider JW. A new type of minocycline-induced cutaneous hyperpigmentation. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:8-14.

3. D’Agostino ML, Risser J, Robinson-Bostom L. Imipramine-induced hyperpigmentation: a case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:799-803.

4. Nisar MS, Iyer K, Brodell RT, et al. Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation: comparison of 3 Q-switched lasers to reverse its effects. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2013;6:159-162.

5. Scherschun L, Lee MW, Lim HW. Diltiazem-associated photodistributed hyperpigmentation. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:179-182.

6. Vangipuram RK, DeLozier WL, Geddes E, et al. Complete resolution of minocycline pigmentation following a single treatment with non-ablative 1550-nm fractional resurfacing in combination with the 755-nm Q-switched alexandrite laser. Lasers Surg Med. 2016;48:234-237.

Painful, swollen elbow

A 32-year-old woman presented to our clinic with left elbow swelling and pain of 6 days’ duration. She’d had a posterior interosseous nerve (PIN) injection (hydrodissection) at another facility 12 days earlier for refractory intersection syndrome.

During nerve hydrodissection, fluid is injected into the area surrounding the nerve in an effort to displace the muscles, tendons, and fascia and thus reduce friction on the nerve. This treatment, often completed with ultrasound guidance, is utilized by patients who want to obtain pain relief without undergoing surgery for nerve entrapment syndromes.

In this case, a combination of 1 mL (40 mg) of methylprednisolone acetate, 1 mL of lidocaine 2%, and 3 mL of normal saline was injected into the supinator muscle belly (proximal dorsal aspect of the forearm) under ultrasound guidance. Six days later, the patient began to experience elbow pain, redness, and swelling. The symptoms progressed within several hours and became so notable that she sought care at an urgent care facility the next morning. At this facility, she was told she had an infection and was prescribed oral levofloxacin 500 mg/d.

The patient presented to our clinic after 4 days of oral levofloxacin with no improvement of symptoms. She denied chills or fever and described her pain as moderate and radiating to her fingers. There was no history of trauma. The patient reported riding her bike more frequently, which had caused the original forearm pain that warranted the PIN injection. There were no other recent changes to activity. Her medical, social, and surgical histories were otherwise unremarkable.

Her vital signs were normal. Physical exam revealed an erythematous and warm left elbow (FIGURE 1). Her left elbow range of motion (extension and flexion) was mildly decreased due to the pain and swelling.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Iatrogenic septic olecranon bursitis

Aspiration of the patient’s olecranon bursa produced 3 mL of cloudy fluid (FIGURE 2). The patient’s painful, swollen, erythematous, warm elbow, cloudy aspirate, and history of preceding PIN hydrodissection were consistent with a diagnosis of septic olecranon bursitis.

Septic bursitis usually is caused by bacteria.1,2 Bursal infection can result from the spread of infection from nearby tissues or direct inoculation from skin trauma. It can also be iatrogenic and occur among healthy individuals.2,3 Injection anywhere close to the bursa can inoculate enough bacteria to progress to cellulitis first and then septic bursitis. Inflammatory conditions such as gout and rheumatoid arthritis also can cause acute and/or chronic superficial bursitis.1,2,4

Differentiating between septic and nonseptic bursitis can be challenging on history and physical exam alone, but specific signs and symptoms should warrant concern for infection.1,2,4,5 Fever is present in up to 75% of septic cases5; however, lack of fever does not rule out septic bursitis. Pain, erythema, warmth, and an overlying skin lesion also can indicate infection.4 Diagnostic imaging modalities may help distinguish different types of olecranon bursitis, but in most cases, they are not necessary.2

Other joint disorders factor into the differential

The differential diagnosis is broad and includes a variety of joint disorders in addition to septic (and nonseptic) bursitis.2,3

Septic arthritis is a deeper infection that involves the elbow joint and is considered an orthopedic emergency due to potential joint destruction.

Continue to: A simple joint effusion

A simple joint effusion also arises from the elbow joint, but this diagnosis becomes less likely when the joint aspirate appears cloudy. A simple joint effusion would not produce bacteria on gram stain and culture.

Crystalline inflammatory arthritis (gout, pseudogout) is due to intra-articular precipitation of crystals (uric acid crystals in gout, calcium pyrophosphate crystals in pseudogout).

Hematomas would produce gross blood or clot on joint aspiration.

Cellulitis is an infection of the superficial soft tissue (only) and thus, aspiration is not likely to yield fluid.

Diagnosis can be made with culture of fluid

Confirmation of septic olecranon bursitis is best attained by bursal needle aspiration and culture. Aspiration also can evaluate for other causes of elbow swelling. (If septic olecranon bursitis is suspected clinically, empiric antibiotics should be started while awaiting culture results.6) White blood cell counts from the aspirate also may be utilized but have a lower sensitivity and specificity for diagnosis.7

Continue to: In addition to aiding in diagnosis

In addition to aiding in diagnosis, bursal aspiration for a patient with septic bursitis can improve symptoms and reduce bacterial load.1-3,8 The use of a compressive bandage after aspiration may help reduce re-accumulation of the bursal fluid.1-3,8Staphylococcus aureus is responsible for the majority of septic olecranon bursitis cases.9-11

Tailoring the antibiotic regimen

There is wide variation in the treatment of septic olecranon bursitis due to the lack of strong evidence-based guidelines.1,2,8,11-13 When septic bursitis is strongly suspected (or confirmed) the patient should be started on an antibiotic regimen that covers S aureus.1,2 Once culture results and sensitivities return, the antibiotic regimen can be tailored appropriately.

In cases of mild-to-moderate septic olecranon bursitis in an immunocompetent host, the patient can be started on oral antibiotics and monitored closely as an outpatient.1-3,8 Patients with septic olecranon bursitis who meet the criteria for systemic inflammatory response syndrome or who are immunocompromised should be hospitalized and started on intravenous antibiotics.1-3 Recommended duration of antibiotic therapy varies but is usually about 10 to 14 days.1-3,8 In rare cases, surgical intervention with bursectomy may be necessary.1,2,14

Our patient was given a dose of ceftriaxone 250 mg intramuscularly and was started on oral sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim 800 mg/160 mg twice daily after aspiration of the bursa. Culture of the bursal fluid grew oxacillin-sensitive S aureus which was sensitive to a variety of antibiotics including levofloxacin and sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim. Her symptoms gradually improved (FIGURE 3) and resolved after a 14-day course of oral sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim.

CORRESPONDENCE

Morteza Khodaee, MD, MPH, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Department of Family Medicine & Orthopedics, AFW Clinic, 3055 Roslyn St, Denver, CO 80238; morteza. [email protected]

1. Baumbach SF, Lobo CM, Badyine I, et al. Prepatellar and olecranon bursitis: literature review and development of a treatment algorithm. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2014;134:359-370.

2. Khodaee M. Common superficial bursitis. Am Fam Physician. 2017;95:224-231.

3. Harris-Spinks C, Nabhan D, Khodaee M. Noniatrogenic septic olecranon bursitis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2016;15:33-37.

4. Reilly D, Kamineni S. Olecranon bursitis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25:158-167.

5. Blackwell JR, Hay BA, Bolt AM, et al. Olecranon bursitis: a systematic overview. Shoulder Elbow. 2014;6:182-190.

6. Del Buono A, Franceschi F, Palumbo A, et al. Diagnosis and management of olecranon bursitis. Surgeon. 2012;10:297-300.

7. Stell IM, Gransden WR. Simple tests for septic bursitis: comparative study. BMJ. 1998;316:1877.

8. Abzug JM, Chen NC, Jacoby SM. Septic olecranon bursitis. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:1252-1253.

9. Cea-Pereiro JC, Garcia-Meijide J, Mera-Varela A, et al. A comparison between septic bursitis caused by Staphylococcus aureus and those caused by other organisms. Clin Rheumatol. 2001;20:10-14.

10. Morrey BE. Bursitis. In: Morrey BE, Sanchez-Sotelo J, eds. The Elbow and its Disorders. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier 2009:1164-1173.

11. Wingert NC, DeMaio M, Shenenberger DW. Septic olecranon bursitis, contact dermatitis, and pneumonitis in a gas turbine engine mechanic. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21:E16-E20.

12. Baumbach SF, Michel M, Wyen H, et al. Current treatment concepts for olecranon and prepatellar bursitis in Austria. Z Orthop Unfall. 2013;151:149-155.

13. Sayegh ET, Strauch RJ. Treatment of olecranon bursitis: a systematic review. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2014;134:1517-1536.

14. Ogilvie-Harris DJ, Gilbart M. Endoscopic bursal resection: the olecranon bursa and prepatellar bursa. Arthroscopy. 2000;16:249-253.

A 32-year-old woman presented to our clinic with left elbow swelling and pain of 6 days’ duration. She’d had a posterior interosseous nerve (PIN) injection (hydrodissection) at another facility 12 days earlier for refractory intersection syndrome.

During nerve hydrodissection, fluid is injected into the area surrounding the nerve in an effort to displace the muscles, tendons, and fascia and thus reduce friction on the nerve. This treatment, often completed with ultrasound guidance, is utilized by patients who want to obtain pain relief without undergoing surgery for nerve entrapment syndromes.

In this case, a combination of 1 mL (40 mg) of methylprednisolone acetate, 1 mL of lidocaine 2%, and 3 mL of normal saline was injected into the supinator muscle belly (proximal dorsal aspect of the forearm) under ultrasound guidance. Six days later, the patient began to experience elbow pain, redness, and swelling. The symptoms progressed within several hours and became so notable that she sought care at an urgent care facility the next morning. At this facility, she was told she had an infection and was prescribed oral levofloxacin 500 mg/d.

The patient presented to our clinic after 4 days of oral levofloxacin with no improvement of symptoms. She denied chills or fever and described her pain as moderate and radiating to her fingers. There was no history of trauma. The patient reported riding her bike more frequently, which had caused the original forearm pain that warranted the PIN injection. There were no other recent changes to activity. Her medical, social, and surgical histories were otherwise unremarkable.

Her vital signs were normal. Physical exam revealed an erythematous and warm left elbow (FIGURE 1). Her left elbow range of motion (extension and flexion) was mildly decreased due to the pain and swelling.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Iatrogenic septic olecranon bursitis

Aspiration of the patient’s olecranon bursa produced 3 mL of cloudy fluid (FIGURE 2). The patient’s painful, swollen, erythematous, warm elbow, cloudy aspirate, and history of preceding PIN hydrodissection were consistent with a diagnosis of septic olecranon bursitis.

Septic bursitis usually is caused by bacteria.1,2 Bursal infection can result from the spread of infection from nearby tissues or direct inoculation from skin trauma. It can also be iatrogenic and occur among healthy individuals.2,3 Injection anywhere close to the bursa can inoculate enough bacteria to progress to cellulitis first and then septic bursitis. Inflammatory conditions such as gout and rheumatoid arthritis also can cause acute and/or chronic superficial bursitis.1,2,4

Differentiating between septic and nonseptic bursitis can be challenging on history and physical exam alone, but specific signs and symptoms should warrant concern for infection.1,2,4,5 Fever is present in up to 75% of septic cases5; however, lack of fever does not rule out septic bursitis. Pain, erythema, warmth, and an overlying skin lesion also can indicate infection.4 Diagnostic imaging modalities may help distinguish different types of olecranon bursitis, but in most cases, they are not necessary.2

Other joint disorders factor into the differential

The differential diagnosis is broad and includes a variety of joint disorders in addition to septic (and nonseptic) bursitis.2,3

Septic arthritis is a deeper infection that involves the elbow joint and is considered an orthopedic emergency due to potential joint destruction.

Continue to: A simple joint effusion

A simple joint effusion also arises from the elbow joint, but this diagnosis becomes less likely when the joint aspirate appears cloudy. A simple joint effusion would not produce bacteria on gram stain and culture.

Crystalline inflammatory arthritis (gout, pseudogout) is due to intra-articular precipitation of crystals (uric acid crystals in gout, calcium pyrophosphate crystals in pseudogout).

Hematomas would produce gross blood or clot on joint aspiration.

Cellulitis is an infection of the superficial soft tissue (only) and thus, aspiration is not likely to yield fluid.

Diagnosis can be made with culture of fluid

Confirmation of septic olecranon bursitis is best attained by bursal needle aspiration and culture. Aspiration also can evaluate for other causes of elbow swelling. (If septic olecranon bursitis is suspected clinically, empiric antibiotics should be started while awaiting culture results.6) White blood cell counts from the aspirate also may be utilized but have a lower sensitivity and specificity for diagnosis.7

Continue to: In addition to aiding in diagnosis