User login

Papules on trunk

Dermatopathologic evaluation of the tissue sample indicated that the lesion was a neurofibroma, and clinical correlation fine-tuned the diagnosis to segmental neurofibromatosis (NF). The diagnosis of segmental NF is clinical, with biopsy to confirm that the lesions are neurofibromas. Segmental NF is a mosaic form of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) that results from a postzygotic mutation of the NF1 gene. While NF1 is a relatively common neurocutaneous disorder that occurs with a frequency of 1 in 3000, segmental NF is uncommon, with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 40,000.

NF1 often follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, although up to 50% of patients with NF1 arise de novo from spontaneous mutations. NF1 is characterized by multiple café-au-lait macules, axillary freckling, neurofibromas, and Lisch nodules (pigmented iris hamartomas). Systemic findings associated with NF1 include malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, optic gliomas, and vasculopathy. While patients with segmental NF may exhibit some of these same findings, the distribution of the neurofibromas is often limited to a single dermatome. Additionally, patients with segmental NF typically do not exhibit extracutaneous lesions, systemic involvement, or a family history of NF. Segmental NF treatment typically focuses on symptomatic management or cosmetic concerns.

This patient did not have any of the systemic complications that occasionally occur with segmental NF, so no medical treatment was required. The patient was advised that cutaneous and subcutaneous neurofibromas do not require removal unless there is pain, bleeding, disfigurement, or signs of malignant transformation. The patient was not interested in removal of the nodules for cosmetic reasons, so he was encouraged to seek follow-up care, as needed.

This case was adapted from: Laurent KJ, Beachkofsky TM, Loyd A, et al. Segmental distribution of nodules on trunk. J Fam Pract. 2017;66: 765-767.

Dermatopathologic evaluation of the tissue sample indicated that the lesion was a neurofibroma, and clinical correlation fine-tuned the diagnosis to segmental neurofibromatosis (NF). The diagnosis of segmental NF is clinical, with biopsy to confirm that the lesions are neurofibromas. Segmental NF is a mosaic form of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) that results from a postzygotic mutation of the NF1 gene. While NF1 is a relatively common neurocutaneous disorder that occurs with a frequency of 1 in 3000, segmental NF is uncommon, with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 40,000.

NF1 often follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, although up to 50% of patients with NF1 arise de novo from spontaneous mutations. NF1 is characterized by multiple café-au-lait macules, axillary freckling, neurofibromas, and Lisch nodules (pigmented iris hamartomas). Systemic findings associated with NF1 include malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, optic gliomas, and vasculopathy. While patients with segmental NF may exhibit some of these same findings, the distribution of the neurofibromas is often limited to a single dermatome. Additionally, patients with segmental NF typically do not exhibit extracutaneous lesions, systemic involvement, or a family history of NF. Segmental NF treatment typically focuses on symptomatic management or cosmetic concerns.

This patient did not have any of the systemic complications that occasionally occur with segmental NF, so no medical treatment was required. The patient was advised that cutaneous and subcutaneous neurofibromas do not require removal unless there is pain, bleeding, disfigurement, or signs of malignant transformation. The patient was not interested in removal of the nodules for cosmetic reasons, so he was encouraged to seek follow-up care, as needed.

This case was adapted from: Laurent KJ, Beachkofsky TM, Loyd A, et al. Segmental distribution of nodules on trunk. J Fam Pract. 2017;66: 765-767.

Dermatopathologic evaluation of the tissue sample indicated that the lesion was a neurofibroma, and clinical correlation fine-tuned the diagnosis to segmental neurofibromatosis (NF). The diagnosis of segmental NF is clinical, with biopsy to confirm that the lesions are neurofibromas. Segmental NF is a mosaic form of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) that results from a postzygotic mutation of the NF1 gene. While NF1 is a relatively common neurocutaneous disorder that occurs with a frequency of 1 in 3000, segmental NF is uncommon, with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 40,000.

NF1 often follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, although up to 50% of patients with NF1 arise de novo from spontaneous mutations. NF1 is characterized by multiple café-au-lait macules, axillary freckling, neurofibromas, and Lisch nodules (pigmented iris hamartomas). Systemic findings associated with NF1 include malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, optic gliomas, and vasculopathy. While patients with segmental NF may exhibit some of these same findings, the distribution of the neurofibromas is often limited to a single dermatome. Additionally, patients with segmental NF typically do not exhibit extracutaneous lesions, systemic involvement, or a family history of NF. Segmental NF treatment typically focuses on symptomatic management or cosmetic concerns.

This patient did not have any of the systemic complications that occasionally occur with segmental NF, so no medical treatment was required. The patient was advised that cutaneous and subcutaneous neurofibromas do not require removal unless there is pain, bleeding, disfigurement, or signs of malignant transformation. The patient was not interested in removal of the nodules for cosmetic reasons, so he was encouraged to seek follow-up care, as needed.

This case was adapted from: Laurent KJ, Beachkofsky TM, Loyd A, et al. Segmental distribution of nodules on trunk. J Fam Pract. 2017;66: 765-767.

Fingernail deformity

The groove in the patient’s nail, and associated splitting, was due to a digital mucous cyst seen in the photo proximal to the cuticle.

In spite of the name, these cysts do not contain mucus. Instead, they contain synovial fluid and represent an outpouching of the distal interphalangeal joint of the index finger. This same process is called a ganglion cyst when it is seen at the wrist and a Baker’s cyst when it is behind the knee. These cysts typically form from an increase in synovial fluid, often due to underlying osteoarthritis, injury, or degenerative changes of the joint capsule. If the patient is asymptomatic, no treatment is required. Half of the lesions spontaneously resolve. If the patient is symptomatic, treatment options include a steroid injection; aspirating the cyst and then using a compressive cryosurgery tip to freeze the superficial and deep aspects of the cyst to scar it down; and surgical resection of the cyst.

In this case, the patient was in pain because the abnormally shaped nail was breaking. She elected to have a steroid injection into the cyst—0.25 ml of triamcinolone 20 mg/ml. The family physician (FP) advised her that this would reduce the inflammation in the distal interphalangeal joint, hopefully reducing the size of the digital mucous cyst. The FP also indicated that she might require several injections to achieve a positive outcome and that it would take 6 months for her fingernail to return to normal.

Images and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

The groove in the patient’s nail, and associated splitting, was due to a digital mucous cyst seen in the photo proximal to the cuticle.

In spite of the name, these cysts do not contain mucus. Instead, they contain synovial fluid and represent an outpouching of the distal interphalangeal joint of the index finger. This same process is called a ganglion cyst when it is seen at the wrist and a Baker’s cyst when it is behind the knee. These cysts typically form from an increase in synovial fluid, often due to underlying osteoarthritis, injury, or degenerative changes of the joint capsule. If the patient is asymptomatic, no treatment is required. Half of the lesions spontaneously resolve. If the patient is symptomatic, treatment options include a steroid injection; aspirating the cyst and then using a compressive cryosurgery tip to freeze the superficial and deep aspects of the cyst to scar it down; and surgical resection of the cyst.

In this case, the patient was in pain because the abnormally shaped nail was breaking. She elected to have a steroid injection into the cyst—0.25 ml of triamcinolone 20 mg/ml. The family physician (FP) advised her that this would reduce the inflammation in the distal interphalangeal joint, hopefully reducing the size of the digital mucous cyst. The FP also indicated that she might require several injections to achieve a positive outcome and that it would take 6 months for her fingernail to return to normal.

Images and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

The groove in the patient’s nail, and associated splitting, was due to a digital mucous cyst seen in the photo proximal to the cuticle.

In spite of the name, these cysts do not contain mucus. Instead, they contain synovial fluid and represent an outpouching of the distal interphalangeal joint of the index finger. This same process is called a ganglion cyst when it is seen at the wrist and a Baker’s cyst when it is behind the knee. These cysts typically form from an increase in synovial fluid, often due to underlying osteoarthritis, injury, or degenerative changes of the joint capsule. If the patient is asymptomatic, no treatment is required. Half of the lesions spontaneously resolve. If the patient is symptomatic, treatment options include a steroid injection; aspirating the cyst and then using a compressive cryosurgery tip to freeze the superficial and deep aspects of the cyst to scar it down; and surgical resection of the cyst.

In this case, the patient was in pain because the abnormally shaped nail was breaking. She elected to have a steroid injection into the cyst—0.25 ml of triamcinolone 20 mg/ml. The family physician (FP) advised her that this would reduce the inflammation in the distal interphalangeal joint, hopefully reducing the size of the digital mucous cyst. The FP also indicated that she might require several injections to achieve a positive outcome and that it would take 6 months for her fingernail to return to normal.

Images and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

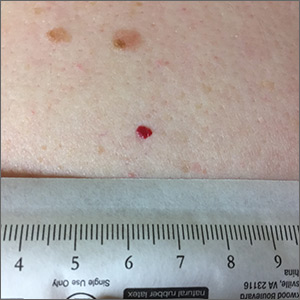

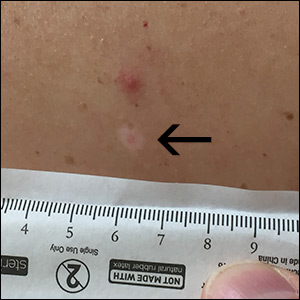

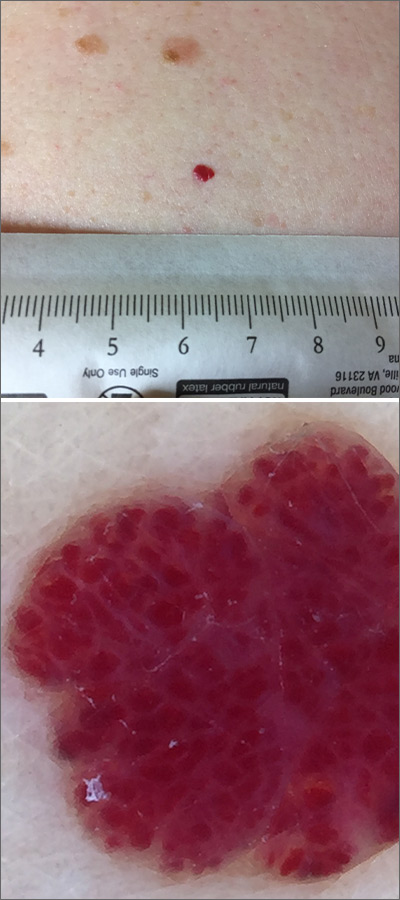

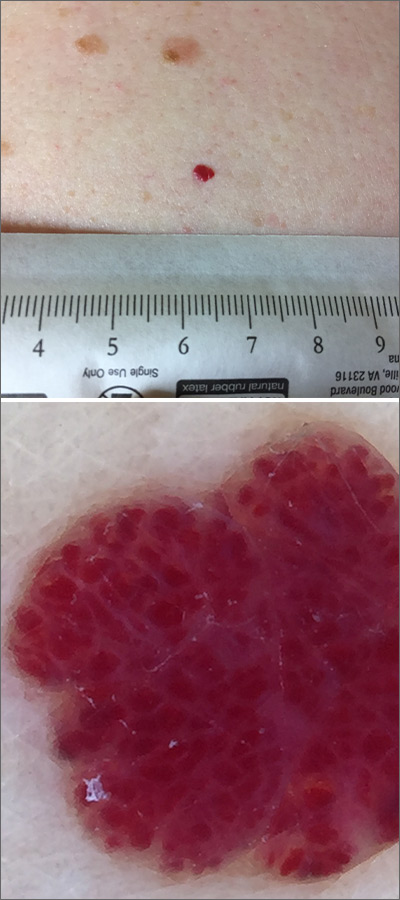

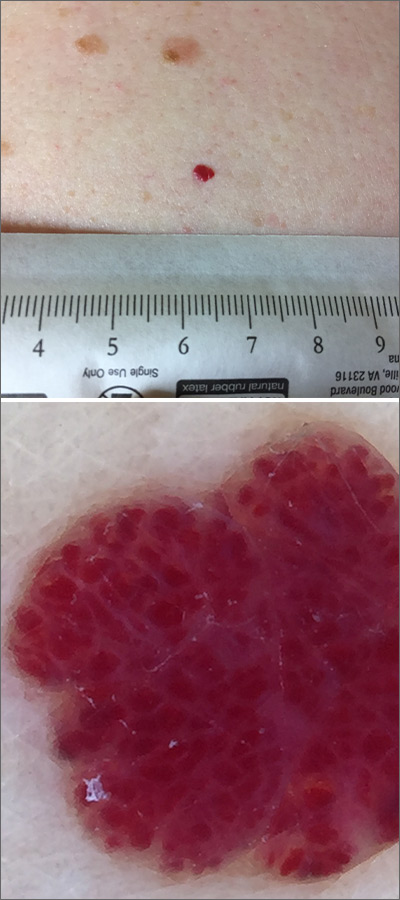

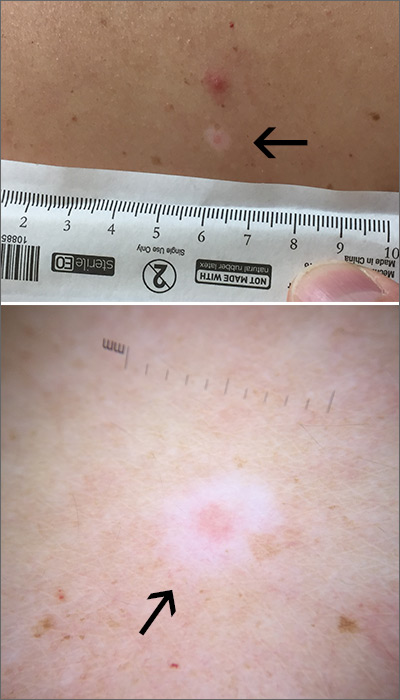

Red lesion on back

Dermoscopy was performed, which confirmed that this was a cherry angioma, also called a cherry hemangioma or Campbell de Morgan spot.

Cherry angiomas are benign proliferations that typically appear after age 30 as tiny bright erythematous macules that, over time, enlarge into papules. In their early, and smaller, stages they are typically maraschino cherry red, hence the name cherry angiomas. As they enlarge or become thrombosed, some lesions become darker red or even black in color. (The dermoscopy image shown here demonstrates the bright red globular red pattern that is classically seen with cherry angiomas.)

Cherry angiomas do not require treatment. If treatment is desired for cosmetic purposes, they can be treated with electrocautery, cryosurgery, or laser. The patient in this case was not worried about the appearance of the lesion and opted to leave it alone unless he developed symptoms.

Images and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Dermoscopy was performed, which confirmed that this was a cherry angioma, also called a cherry hemangioma or Campbell de Morgan spot.

Cherry angiomas are benign proliferations that typically appear after age 30 as tiny bright erythematous macules that, over time, enlarge into papules. In their early, and smaller, stages they are typically maraschino cherry red, hence the name cherry angiomas. As they enlarge or become thrombosed, some lesions become darker red or even black in color. (The dermoscopy image shown here demonstrates the bright red globular red pattern that is classically seen with cherry angiomas.)

Cherry angiomas do not require treatment. If treatment is desired for cosmetic purposes, they can be treated with electrocautery, cryosurgery, or laser. The patient in this case was not worried about the appearance of the lesion and opted to leave it alone unless he developed symptoms.

Images and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Dermoscopy was performed, which confirmed that this was a cherry angioma, also called a cherry hemangioma or Campbell de Morgan spot.

Cherry angiomas are benign proliferations that typically appear after age 30 as tiny bright erythematous macules that, over time, enlarge into papules. In their early, and smaller, stages they are typically maraschino cherry red, hence the name cherry angiomas. As they enlarge or become thrombosed, some lesions become darker red or even black in color. (The dermoscopy image shown here demonstrates the bright red globular red pattern that is classically seen with cherry angiomas.)

Cherry angiomas do not require treatment. If treatment is desired for cosmetic purposes, they can be treated with electrocautery, cryosurgery, or laser. The patient in this case was not worried about the appearance of the lesion and opted to leave it alone unless he developed symptoms.

Images and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

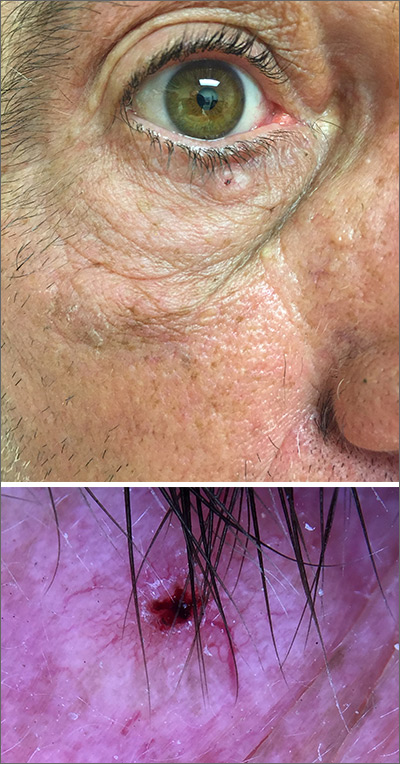

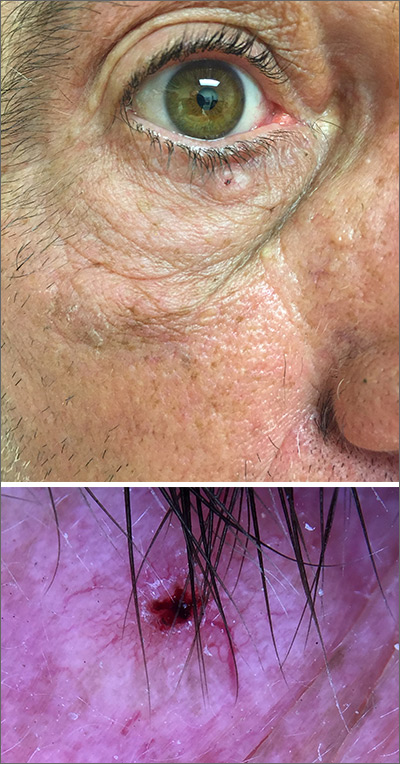

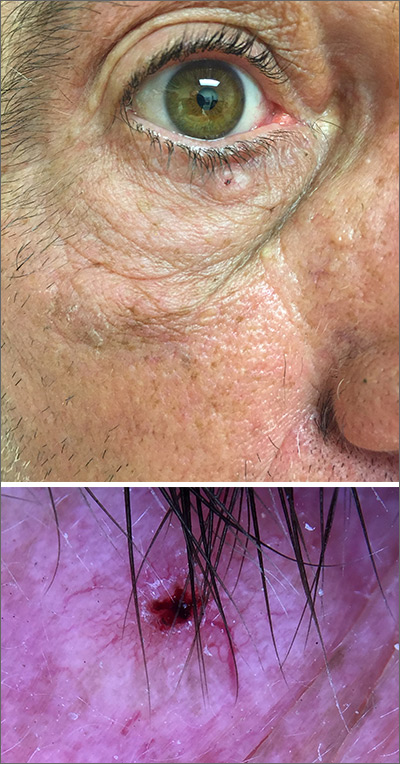

Pigmented lesion on face

While the lesion’s proximity to the eyelashes and lid margin made dermoscopy difficult, the physician was able to use a dermatoscope to view the lesion and recognize it as nodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC). (If dermoscopy had not been an option, a hand magnifier or otoscope could have been used to help with magnification and diagnosis.)

Nodular BCCs usually present with a raised pearly border, a central ulceration, and telangiectasias. In this case, the central erosion was much more obvious with dermoscopy. Also visible were abnormal telangiectasias around the central erosion; they were especially dilated and tortuous (referred to as an arborizing pattern) at the 4:00 position. The diagnosis was confirmed by a small tangential shave biopsy of the inferior aspect of the lesion.

BCCs are referred for Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) when they are any of the following: in high-risk locations such as the T-zone of the face (eyes, nose, and mouth); > 2 cm in diameter; a recurrence of a previous BCC; or a high-risk type including infiltrating, morpheaform, or basosquamous (based on pathology). Lower risk nodular BCCs are usually treated with excision or electrodesiccation and curettage.

In this case, the BCC was in a high-risk location and required MMS. The challenge was that the lesion was so close to the lid margin that resection of the cancer and subsequent repair could lead to ectropion/poor lid closure. The Mohs surgeon resected the lesion in 3 stages. The oculoplastic surgeon then closed the defect via a multilayered repair.

Images and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

While the lesion’s proximity to the eyelashes and lid margin made dermoscopy difficult, the physician was able to use a dermatoscope to view the lesion and recognize it as nodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC). (If dermoscopy had not been an option, a hand magnifier or otoscope could have been used to help with magnification and diagnosis.)

Nodular BCCs usually present with a raised pearly border, a central ulceration, and telangiectasias. In this case, the central erosion was much more obvious with dermoscopy. Also visible were abnormal telangiectasias around the central erosion; they were especially dilated and tortuous (referred to as an arborizing pattern) at the 4:00 position. The diagnosis was confirmed by a small tangential shave biopsy of the inferior aspect of the lesion.

BCCs are referred for Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) when they are any of the following: in high-risk locations such as the T-zone of the face (eyes, nose, and mouth); > 2 cm in diameter; a recurrence of a previous BCC; or a high-risk type including infiltrating, morpheaform, or basosquamous (based on pathology). Lower risk nodular BCCs are usually treated with excision or electrodesiccation and curettage.

In this case, the BCC was in a high-risk location and required MMS. The challenge was that the lesion was so close to the lid margin that resection of the cancer and subsequent repair could lead to ectropion/poor lid closure. The Mohs surgeon resected the lesion in 3 stages. The oculoplastic surgeon then closed the defect via a multilayered repair.

Images and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

While the lesion’s proximity to the eyelashes and lid margin made dermoscopy difficult, the physician was able to use a dermatoscope to view the lesion and recognize it as nodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC). (If dermoscopy had not been an option, a hand magnifier or otoscope could have been used to help with magnification and diagnosis.)

Nodular BCCs usually present with a raised pearly border, a central ulceration, and telangiectasias. In this case, the central erosion was much more obvious with dermoscopy. Also visible were abnormal telangiectasias around the central erosion; they were especially dilated and tortuous (referred to as an arborizing pattern) at the 4:00 position. The diagnosis was confirmed by a small tangential shave biopsy of the inferior aspect of the lesion.

BCCs are referred for Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) when they are any of the following: in high-risk locations such as the T-zone of the face (eyes, nose, and mouth); > 2 cm in diameter; a recurrence of a previous BCC; or a high-risk type including infiltrating, morpheaform, or basosquamous (based on pathology). Lower risk nodular BCCs are usually treated with excision or electrodesiccation and curettage.

In this case, the BCC was in a high-risk location and required MMS. The challenge was that the lesion was so close to the lid margin that resection of the cancer and subsequent repair could lead to ectropion/poor lid closure. The Mohs surgeon resected the lesion in 3 stages. The oculoplastic surgeon then closed the defect via a multilayered repair.

Images and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

An erythematous facial rash

A 59-year-old woman presented to our clinic with a large asymptomatic facial rash that had developed several months earlier. The rash had been slowly growing but did not change day to day. Her past medical history was significant for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and cutaneous lymphoma, which was localized to her arms. She denied the use of any new products, including hair or facial products, nail polish, or any new medications.

Initially, she was presumed (by an outside provider) to have rosacea, and she received treatment with doxycycline 100 mg/d for 2 months. However, the rash did not improve.

Physical examination revealed a large erythematous rash involving her cheeks, nose, and periocular area with no other significant findings (FIGURE).

A biopsy of her right cheek was performed.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Mycosis fungoides

Following the biopsy of her right cheek, a histopathologic analysis demonstrated an atypical lymphocytic infiltrate positive for CD3 and CD4. These histopathologic features led to a diagnosis of recurrent mycosis fungoides (MF), a type of cutaneous lymphoma. (Our patient’s cutaneous lymphoma had been in remission for a year following local radiotherapy.)

MF is the most common type of cutaneous lymphoma, with an incidence of 6.4 to 9.6 cases per million people in the United States.1 There are also 2 rare subtypes of MF: the psoriasiform and palmoplantar forms. Psoriasiform MF presents with psoriasis-like plaques, while palmoplantar MF initially presents on the palms and soles.

Patients with classic MF typically present with patches and plaques—with the late evolution of tumors—on non–sun-exposed areas.1 Our patient’s clinical presentation was atypical because the rash manifested on a sun-exposed area of her body.

MF and other cutaneous lymphomas should always be part of the differential diagnosis for an unexplained persistent rash, especially in a patient with a history of MF. The development of lymphomas is thought to be a stepwise process through which chronic antigenic stimulation results in an accumulation of genetic mutations that then cause cells to undergo clonal expansion and, ultimately, malignant transformation. Genetic, environmental, and immunologic factors that contribute to the disease pathogenesis have been identified.2

Once clinical features point toward MF, the diagnosis can be further differentiated from other benign inflammatory mimics with a biopsy demonstrating cerebriform lymphocytes homing toward the epidermis, monoclonal expansion of T cells, and defective apoptosis.3

Continue to: Differential includes rosacea and seborrheic dermatitis

Differential includes rosacea and seborrheic dermatitis

The diagnosis of MF can be difficult as it often imitates other benign inflammatory conditions.

Rosacea manifests as an erythematous facial rash but usually spares the nasolabial folds and eyelids. There are several forms, including ocular (featuring swollen and irritated conjunctiva), erythematotelangiectatic (with visible blood vessels), and papulopustular (with acneic lesions). Over time, the skin may develop a thickened, bumpy texture, referred to as phymatous rosacea.4 A history of acute worsening with exposure to certain hot or spicy foods, alcohol, or ultraviolet light suggests a diagnosis of rosacea.

Seborrheic dermatitis classically presents as yellow scaling on a mildly erythematous base and often involves nasolabial folds and eyebrows. Seborrheic dermatitis can be associated with human immunodeficiency virus, Parkinson’s disease, and other chronic medical conditions.

Allergic contact dermatitis can look identical to MF, but in our case, there was no new allergen in the history. A thorough history regarding new medications, creams, and household supplies is integral to differentiating this diagnosis.

Misdiagnosis can lead to advanced-stage disease

This case of persistent facial erythema, originally treated as rosacea, highlights the importance of having a low threshold of suspicion of MF, especially in a patient with a prior history of MF. A recent study by Kelati et al3 indicated that certain subtypes of MF are easily misdiagnosed and treated as psoriasis or eczema respectively for an average of 10.5 years.3 These years of misdiagnosis are significantly correlated with the development of advanced-stage MF, which is more difficult to treat.3

Continue to: Treatment with topical desonide and mechlorethamine

Treatment with topical desonide and mechlorethamine

There are multiple treatment options for MF, depending on the stage, starting with topical therapies and advancing to systemic therapies in more advanced stages. Topical treatments include steroids, nitrogen mustard, and retinoids.5 Our patient was referred to a multidisciplinary lymphoma clinic, where topical treatment was initiated with desonide cream .05% and mechlorethamine gel .016%. Our patient experienced a 50% improvement in skin involvement at 3 months.

As MF progresses to more advanced stages, treatment often combines skin-directed therapies with systemic immunomodulators, biologics, radiation, and total skin electron beam therapy.6 TSEBT is a low-dose full-body radiation treatment that targets the skin surface and therefore effectively treats cutaneous lymphoma. Although TSEBT is usually well tolerated, there have been documented acute and chronic adverse effects, including dermatitis, alopecia, peripheral edema, cutaneous malignancies, and infertility in men.7

While the use of topical desonide and mechlorethamine was initially favored over radiation due to eyelid involvement, our patient developed new patches on her legs 11 months after her initial visit. When biopsies indicated MF with large cell transformation, she received 1 course of low-dose TSEBT (12 Gy), with complete response noted at the 2 month follow-up.

CORRESPONDENCE

Lucia Seminario-Vidal, MD, PhD, Department of Dermatology and Cutaneous Surgery, 13330 USF Laurel Drive, Tampa, FL 33612; [email protected]

1. Jawed S, Myskowski P, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome). Part I. Diagnosis: clinical and histopathologic features and new molecular and biologic markers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:205.e1-e16.

2. Wohl Y, Tur E. Environmental risk factors for mycosis fungoides. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2007;35:52-64.

3. Kelati A, Gallouj S, Tahiri L, et al. Defining the mimics and clinico-histological diagnosis criteria for mycosis fungoides to minimize misdiagnosis. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3:100-106.

4. Two AM, Wu W, Gallo RL, et al. Rosacea. part I. Introduction, categorization, histology, pathogenesis, and risk factors. J AM Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:749-758.

5. Lessin SR, Duvic M, Guitart J, et al. Topical chemotherapy in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma positive results of a randomized, controlled, multicenter trial testing the efficacy and safety of a novel mechlorethamine, 0.02%, gel in mycosis fungoides. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:25-32.

6. Jawed S, Myskowski P, Horwitz S, et al. Continuing medical education: Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part II. Prognosis, management, and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:223.e1-e17.

7. De Moraes FY, Carvalho Hde A, Hanna SA, et al. Literature review of clinical results of total skin electron irradiation (TSEBT) of mycosis fungoides in adults. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2014;19:92-98.

A 59-year-old woman presented to our clinic with a large asymptomatic facial rash that had developed several months earlier. The rash had been slowly growing but did not change day to day. Her past medical history was significant for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and cutaneous lymphoma, which was localized to her arms. She denied the use of any new products, including hair or facial products, nail polish, or any new medications.

Initially, she was presumed (by an outside provider) to have rosacea, and she received treatment with doxycycline 100 mg/d for 2 months. However, the rash did not improve.

Physical examination revealed a large erythematous rash involving her cheeks, nose, and periocular area with no other significant findings (FIGURE).

A biopsy of her right cheek was performed.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Mycosis fungoides

Following the biopsy of her right cheek, a histopathologic analysis demonstrated an atypical lymphocytic infiltrate positive for CD3 and CD4. These histopathologic features led to a diagnosis of recurrent mycosis fungoides (MF), a type of cutaneous lymphoma. (Our patient’s cutaneous lymphoma had been in remission for a year following local radiotherapy.)

MF is the most common type of cutaneous lymphoma, with an incidence of 6.4 to 9.6 cases per million people in the United States.1 There are also 2 rare subtypes of MF: the psoriasiform and palmoplantar forms. Psoriasiform MF presents with psoriasis-like plaques, while palmoplantar MF initially presents on the palms and soles.

Patients with classic MF typically present with patches and plaques—with the late evolution of tumors—on non–sun-exposed areas.1 Our patient’s clinical presentation was atypical because the rash manifested on a sun-exposed area of her body.

MF and other cutaneous lymphomas should always be part of the differential diagnosis for an unexplained persistent rash, especially in a patient with a history of MF. The development of lymphomas is thought to be a stepwise process through which chronic antigenic stimulation results in an accumulation of genetic mutations that then cause cells to undergo clonal expansion and, ultimately, malignant transformation. Genetic, environmental, and immunologic factors that contribute to the disease pathogenesis have been identified.2

Once clinical features point toward MF, the diagnosis can be further differentiated from other benign inflammatory mimics with a biopsy demonstrating cerebriform lymphocytes homing toward the epidermis, monoclonal expansion of T cells, and defective apoptosis.3

Continue to: Differential includes rosacea and seborrheic dermatitis

Differential includes rosacea and seborrheic dermatitis

The diagnosis of MF can be difficult as it often imitates other benign inflammatory conditions.

Rosacea manifests as an erythematous facial rash but usually spares the nasolabial folds and eyelids. There are several forms, including ocular (featuring swollen and irritated conjunctiva), erythematotelangiectatic (with visible blood vessels), and papulopustular (with acneic lesions). Over time, the skin may develop a thickened, bumpy texture, referred to as phymatous rosacea.4 A history of acute worsening with exposure to certain hot or spicy foods, alcohol, or ultraviolet light suggests a diagnosis of rosacea.

Seborrheic dermatitis classically presents as yellow scaling on a mildly erythematous base and often involves nasolabial folds and eyebrows. Seborrheic dermatitis can be associated with human immunodeficiency virus, Parkinson’s disease, and other chronic medical conditions.

Allergic contact dermatitis can look identical to MF, but in our case, there was no new allergen in the history. A thorough history regarding new medications, creams, and household supplies is integral to differentiating this diagnosis.

Misdiagnosis can lead to advanced-stage disease

This case of persistent facial erythema, originally treated as rosacea, highlights the importance of having a low threshold of suspicion of MF, especially in a patient with a prior history of MF. A recent study by Kelati et al3 indicated that certain subtypes of MF are easily misdiagnosed and treated as psoriasis or eczema respectively for an average of 10.5 years.3 These years of misdiagnosis are significantly correlated with the development of advanced-stage MF, which is more difficult to treat.3

Continue to: Treatment with topical desonide and mechlorethamine

Treatment with topical desonide and mechlorethamine

There are multiple treatment options for MF, depending on the stage, starting with topical therapies and advancing to systemic therapies in more advanced stages. Topical treatments include steroids, nitrogen mustard, and retinoids.5 Our patient was referred to a multidisciplinary lymphoma clinic, where topical treatment was initiated with desonide cream .05% and mechlorethamine gel .016%. Our patient experienced a 50% improvement in skin involvement at 3 months.

As MF progresses to more advanced stages, treatment often combines skin-directed therapies with systemic immunomodulators, biologics, radiation, and total skin electron beam therapy.6 TSEBT is a low-dose full-body radiation treatment that targets the skin surface and therefore effectively treats cutaneous lymphoma. Although TSEBT is usually well tolerated, there have been documented acute and chronic adverse effects, including dermatitis, alopecia, peripheral edema, cutaneous malignancies, and infertility in men.7

While the use of topical desonide and mechlorethamine was initially favored over radiation due to eyelid involvement, our patient developed new patches on her legs 11 months after her initial visit. When biopsies indicated MF with large cell transformation, she received 1 course of low-dose TSEBT (12 Gy), with complete response noted at the 2 month follow-up.

CORRESPONDENCE

Lucia Seminario-Vidal, MD, PhD, Department of Dermatology and Cutaneous Surgery, 13330 USF Laurel Drive, Tampa, FL 33612; [email protected]

A 59-year-old woman presented to our clinic with a large asymptomatic facial rash that had developed several months earlier. The rash had been slowly growing but did not change day to day. Her past medical history was significant for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and cutaneous lymphoma, which was localized to her arms. She denied the use of any new products, including hair or facial products, nail polish, or any new medications.

Initially, she was presumed (by an outside provider) to have rosacea, and she received treatment with doxycycline 100 mg/d for 2 months. However, the rash did not improve.

Physical examination revealed a large erythematous rash involving her cheeks, nose, and periocular area with no other significant findings (FIGURE).

A biopsy of her right cheek was performed.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Mycosis fungoides

Following the biopsy of her right cheek, a histopathologic analysis demonstrated an atypical lymphocytic infiltrate positive for CD3 and CD4. These histopathologic features led to a diagnosis of recurrent mycosis fungoides (MF), a type of cutaneous lymphoma. (Our patient’s cutaneous lymphoma had been in remission for a year following local radiotherapy.)

MF is the most common type of cutaneous lymphoma, with an incidence of 6.4 to 9.6 cases per million people in the United States.1 There are also 2 rare subtypes of MF: the psoriasiform and palmoplantar forms. Psoriasiform MF presents with psoriasis-like plaques, while palmoplantar MF initially presents on the palms and soles.

Patients with classic MF typically present with patches and plaques—with the late evolution of tumors—on non–sun-exposed areas.1 Our patient’s clinical presentation was atypical because the rash manifested on a sun-exposed area of her body.

MF and other cutaneous lymphomas should always be part of the differential diagnosis for an unexplained persistent rash, especially in a patient with a history of MF. The development of lymphomas is thought to be a stepwise process through which chronic antigenic stimulation results in an accumulation of genetic mutations that then cause cells to undergo clonal expansion and, ultimately, malignant transformation. Genetic, environmental, and immunologic factors that contribute to the disease pathogenesis have been identified.2

Once clinical features point toward MF, the diagnosis can be further differentiated from other benign inflammatory mimics with a biopsy demonstrating cerebriform lymphocytes homing toward the epidermis, monoclonal expansion of T cells, and defective apoptosis.3

Continue to: Differential includes rosacea and seborrheic dermatitis

Differential includes rosacea and seborrheic dermatitis

The diagnosis of MF can be difficult as it often imitates other benign inflammatory conditions.

Rosacea manifests as an erythematous facial rash but usually spares the nasolabial folds and eyelids. There are several forms, including ocular (featuring swollen and irritated conjunctiva), erythematotelangiectatic (with visible blood vessels), and papulopustular (with acneic lesions). Over time, the skin may develop a thickened, bumpy texture, referred to as phymatous rosacea.4 A history of acute worsening with exposure to certain hot or spicy foods, alcohol, or ultraviolet light suggests a diagnosis of rosacea.

Seborrheic dermatitis classically presents as yellow scaling on a mildly erythematous base and often involves nasolabial folds and eyebrows. Seborrheic dermatitis can be associated with human immunodeficiency virus, Parkinson’s disease, and other chronic medical conditions.

Allergic contact dermatitis can look identical to MF, but in our case, there was no new allergen in the history. A thorough history regarding new medications, creams, and household supplies is integral to differentiating this diagnosis.

Misdiagnosis can lead to advanced-stage disease

This case of persistent facial erythema, originally treated as rosacea, highlights the importance of having a low threshold of suspicion of MF, especially in a patient with a prior history of MF. A recent study by Kelati et al3 indicated that certain subtypes of MF are easily misdiagnosed and treated as psoriasis or eczema respectively for an average of 10.5 years.3 These years of misdiagnosis are significantly correlated with the development of advanced-stage MF, which is more difficult to treat.3

Continue to: Treatment with topical desonide and mechlorethamine

Treatment with topical desonide and mechlorethamine

There are multiple treatment options for MF, depending on the stage, starting with topical therapies and advancing to systemic therapies in more advanced stages. Topical treatments include steroids, nitrogen mustard, and retinoids.5 Our patient was referred to a multidisciplinary lymphoma clinic, where topical treatment was initiated with desonide cream .05% and mechlorethamine gel .016%. Our patient experienced a 50% improvement in skin involvement at 3 months.

As MF progresses to more advanced stages, treatment often combines skin-directed therapies with systemic immunomodulators, biologics, radiation, and total skin electron beam therapy.6 TSEBT is a low-dose full-body radiation treatment that targets the skin surface and therefore effectively treats cutaneous lymphoma. Although TSEBT is usually well tolerated, there have been documented acute and chronic adverse effects, including dermatitis, alopecia, peripheral edema, cutaneous malignancies, and infertility in men.7

While the use of topical desonide and mechlorethamine was initially favored over radiation due to eyelid involvement, our patient developed new patches on her legs 11 months after her initial visit. When biopsies indicated MF with large cell transformation, she received 1 course of low-dose TSEBT (12 Gy), with complete response noted at the 2 month follow-up.

CORRESPONDENCE

Lucia Seminario-Vidal, MD, PhD, Department of Dermatology and Cutaneous Surgery, 13330 USF Laurel Drive, Tampa, FL 33612; [email protected]

1. Jawed S, Myskowski P, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome). Part I. Diagnosis: clinical and histopathologic features and new molecular and biologic markers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:205.e1-e16.

2. Wohl Y, Tur E. Environmental risk factors for mycosis fungoides. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2007;35:52-64.

3. Kelati A, Gallouj S, Tahiri L, et al. Defining the mimics and clinico-histological diagnosis criteria for mycosis fungoides to minimize misdiagnosis. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3:100-106.

4. Two AM, Wu W, Gallo RL, et al. Rosacea. part I. Introduction, categorization, histology, pathogenesis, and risk factors. J AM Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:749-758.

5. Lessin SR, Duvic M, Guitart J, et al. Topical chemotherapy in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma positive results of a randomized, controlled, multicenter trial testing the efficacy and safety of a novel mechlorethamine, 0.02%, gel in mycosis fungoides. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:25-32.

6. Jawed S, Myskowski P, Horwitz S, et al. Continuing medical education: Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part II. Prognosis, management, and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:223.e1-e17.

7. De Moraes FY, Carvalho Hde A, Hanna SA, et al. Literature review of clinical results of total skin electron irradiation (TSEBT) of mycosis fungoides in adults. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2014;19:92-98.

1. Jawed S, Myskowski P, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome). Part I. Diagnosis: clinical and histopathologic features and new molecular and biologic markers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:205.e1-e16.

2. Wohl Y, Tur E. Environmental risk factors for mycosis fungoides. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2007;35:52-64.

3. Kelati A, Gallouj S, Tahiri L, et al. Defining the mimics and clinico-histological diagnosis criteria for mycosis fungoides to minimize misdiagnosis. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3:100-106.

4. Two AM, Wu W, Gallo RL, et al. Rosacea. part I. Introduction, categorization, histology, pathogenesis, and risk factors. J AM Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:749-758.

5. Lessin SR, Duvic M, Guitart J, et al. Topical chemotherapy in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma positive results of a randomized, controlled, multicenter trial testing the efficacy and safety of a novel mechlorethamine, 0.02%, gel in mycosis fungoides. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:25-32.

6. Jawed S, Myskowski P, Horwitz S, et al. Continuing medical education: Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part II. Prognosis, management, and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:223.e1-e17.

7. De Moraes FY, Carvalho Hde A, Hanna SA, et al. Literature review of clinical results of total skin electron irradiation (TSEBT) of mycosis fungoides in adults. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2014;19:92-98.

Infant with bilious emesis

A 4-week-old term boy presented to the emergency department (ED) with recurrent bilious emesis. He had a history of neonatal abstinence syndrome, related to his mother’s use of Subutex (a form of suboxone that is considered safer during pregnancy) for her opioid addiction, and a Ladd procedure at Day 7 of life for intestinal malrotation with volvulus. He had been discharged from the hospital 4 days earlier, after recovery from surgery.

He had been doing well until the prior evening, when he developed “yellow-green” emesis and appeared to have intermittent abdominal pain. His parents said that he was refusing to take formula and he’d had frequent bilious emesis. They also noted he’d had 1 wet diaper in the past 12 hours and appeared “sleepier” than usual.

In the ED, the patient was listless, with thin and tremulous extremities. His fontanelle was flat, and his pupils were equal, round, and reactive. His mucous membranes were dry, skin was mottled, and capillary refill was delayed. His cardiopulmonary exam was normal. His abdomen was soft, mildly distended, and diffusely tender to palpation, with well-healing laparotomy scars. His reflexes were normal, with slightly increased tone. No bruising was noted.

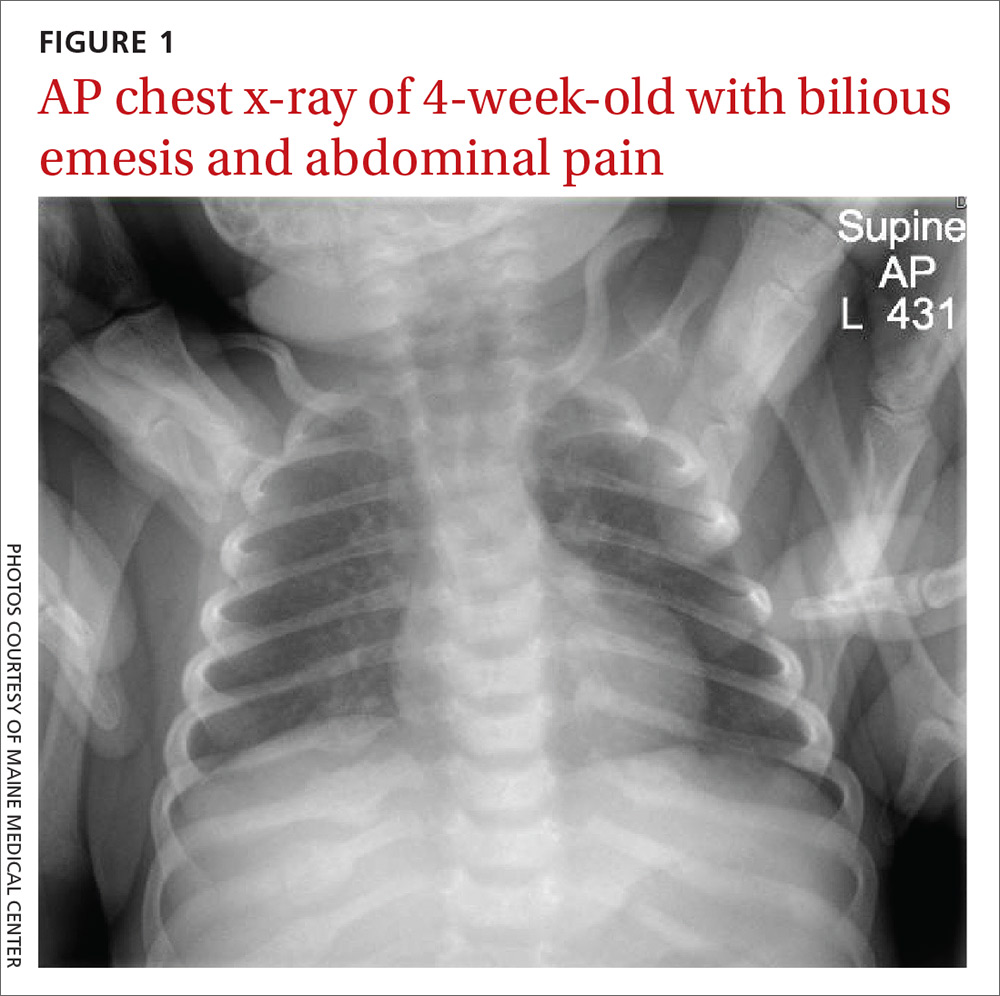

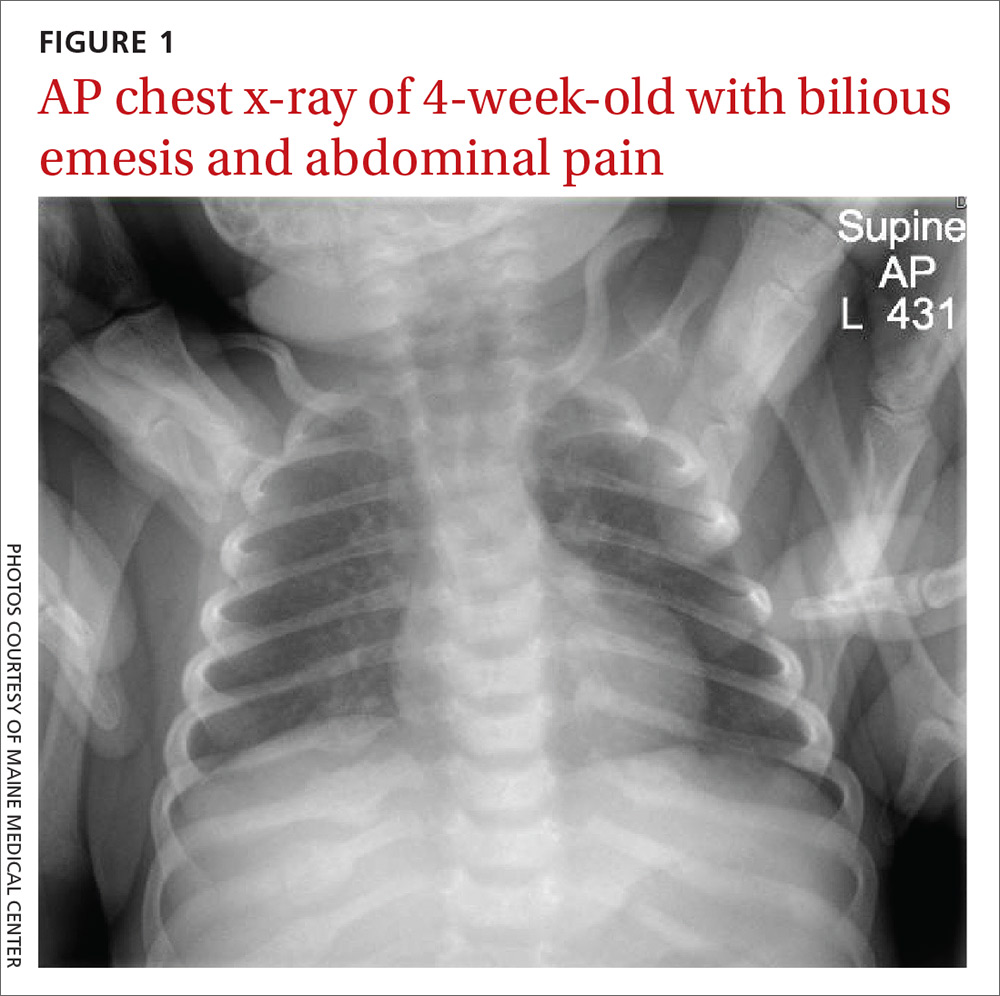

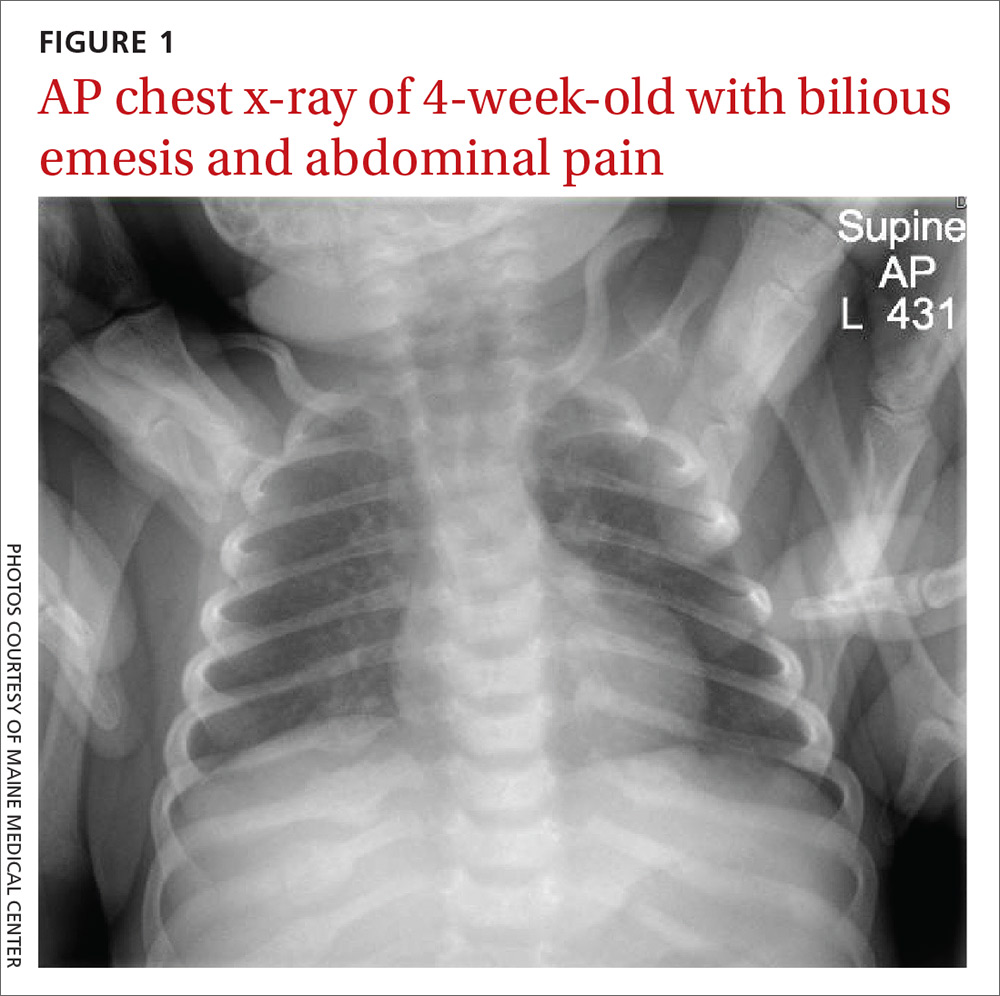

An acute abdominal series, including an AP view chest x-ray (FIGURE 1), was obtained to rule out recurrent volvulus, free air, or small bowel obstruction.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Nonaccidental trauma

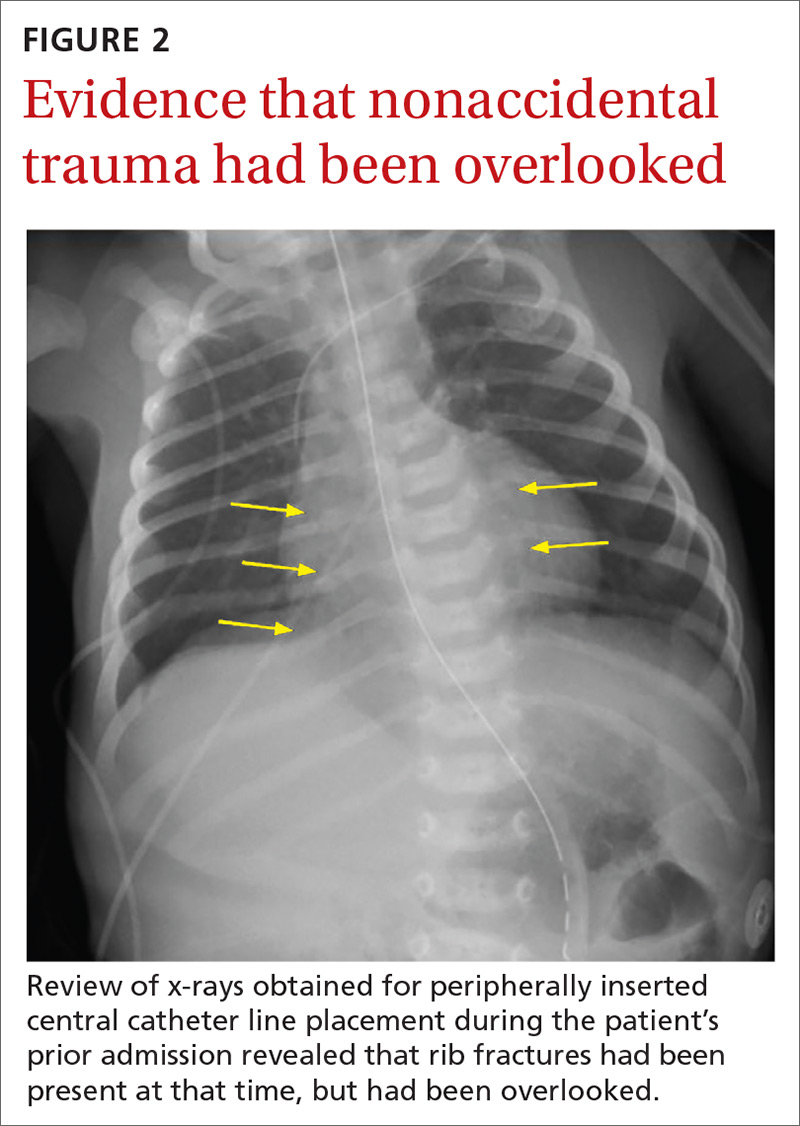

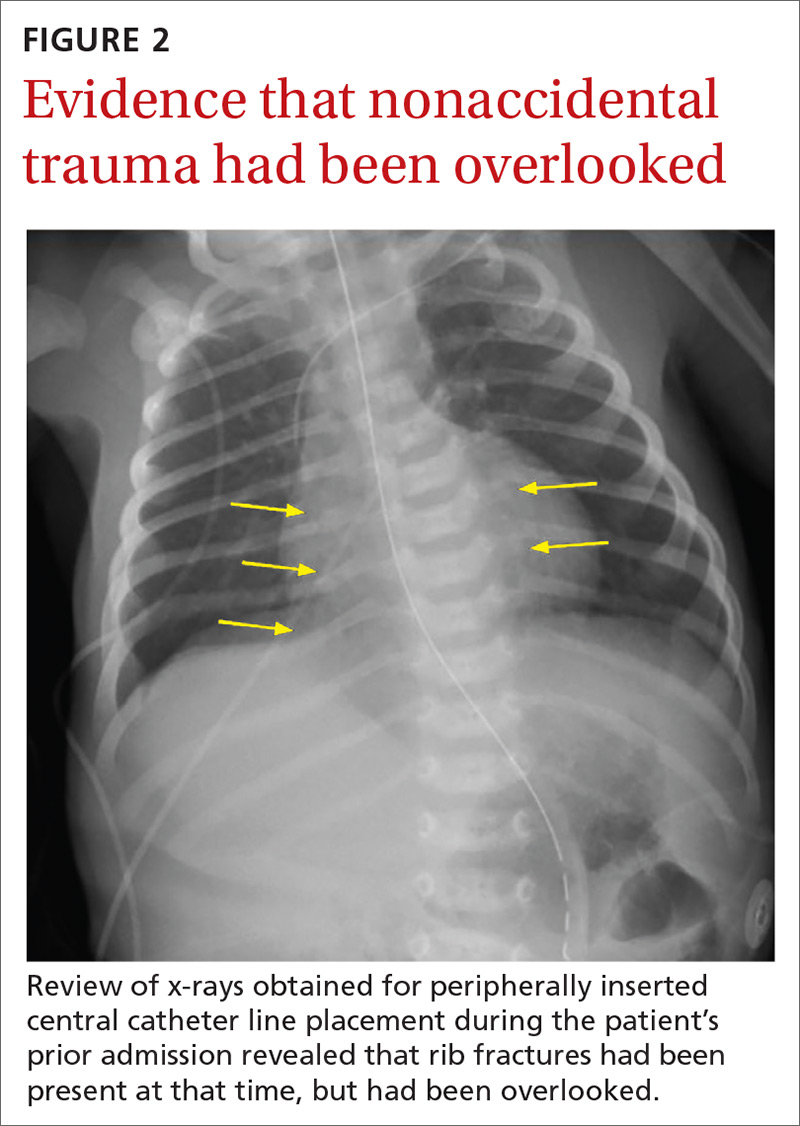

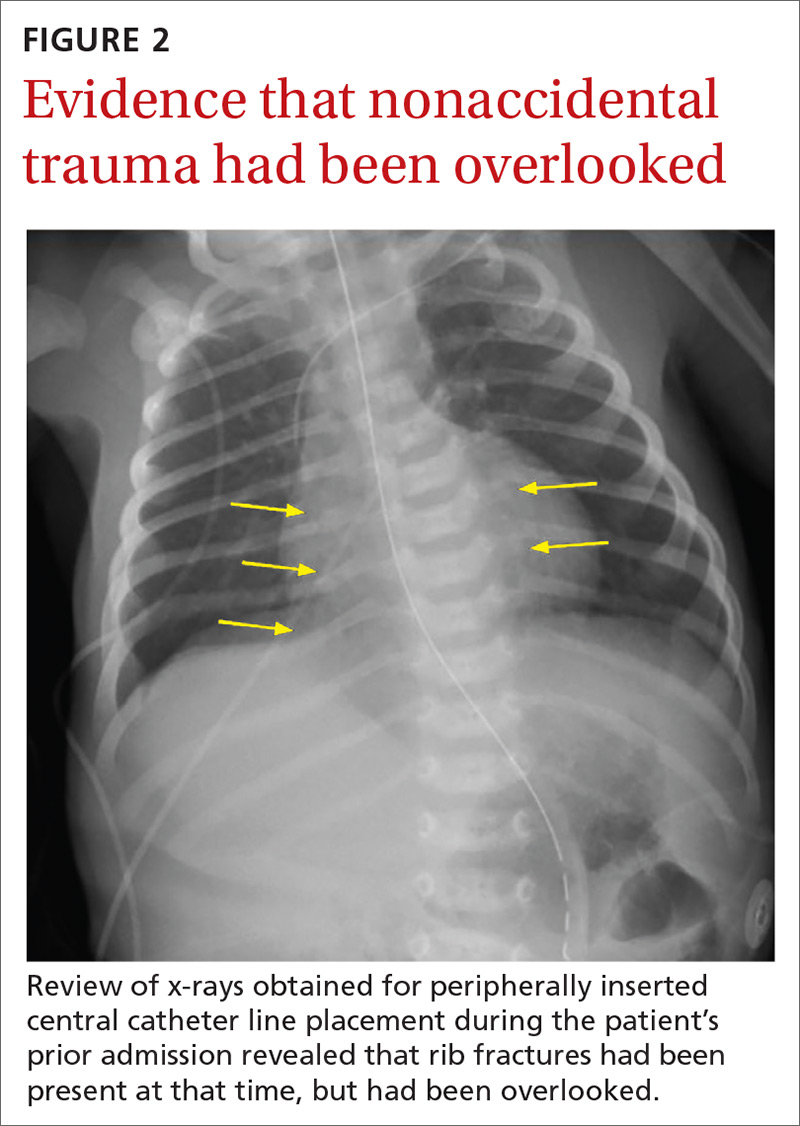

The chest x-ray (FIGURE 1) showed multiple bilateral posterior rib fractures concerning for nonaccidental trauma (NAT). The remaining acute abdominal series films (not shown) revealed the reason for his bilious emesis: a partial bowel obstruction related to his surgical procedure. Review of x-rays obtained for peripherally inserted central catheter line confirmation during his previous admission (FIGURE 2) revealed that the rib fractures had been present at that time but had been overlooked.

This case illustrates the importance of considering NAT in the differential diagnosis of any sick infant. There are an estimated 700,000 cases of child abuse and neglect and 600 fatalities per year in the United States.1,2 The differential diagnosis for fracture or bruising in infants includes accidental trauma, bony abnormalities (eg, osteogenesis imperfecta), bleeding disorders, and trauma from medical procedures such as CPR or surgery.1

Ask these questions, look beyond that single bruise

When evaluating for NAT, the history and physical exam are crucial. It is essential to ask if there were any witnesses, establish who was caring for the child, and investigate any delays in seeking medical evaluation.1 During the exam, undress the child and examine every inch of skin, looking for bruising or abrasions, especially on the face, ear, neck, and oral cavity.

Any bruising in a nonambulatory infant should raise suspicion for NAT. One study showed that more than half of infants with a single bruise had additional injuries identified upon further work-up.3 Fundoscopic exam with photographs should be completed to evaluate for retinal hemorrhage.

Additional work-up should include a skeletal survey for all children younger than 24 months2 in addition to computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging of the head, complete blood count, and a coagulation panel. If there is concern for abdominal trauma, a complete metabolic panel and lipase test may be useful.4 If liver function tests show elevated liver enzymes (> 80 IU/L), abdominal CT with contrast is indicated.4

Continue to: Research has underscored...

Research has underscored the importance of screening siblings and other contacts of abused children. In particular, the twin of an abused child has a much higher risk for abuse.5 A skeletal survey should be obtained in contacts (< 24 months) of abused children—regardless of their physical exam findings.5

Management depends on injury type

The management of children with NAT depends on the injuries. Once these injuries are addressed, the next step is to determine the safest place for the infant/child to be discharged. The involvement of local social workers and Child Protective Services (CPS) is pivotal for this determination.2

Our patient. To treat the partial small bowel obstruction noted on an abdominal CT, the patient received intravenous fluids and nasogastric tube decompression. However, due to ongoing distension and high nasogastric tube output, the patient was taken to the operating room for an exploratory laparotomy. An adhesive band in the right lower quadrant was found to be causing the obstruction and was lysed.

We consulted CPS and social workers about the rib fractures identified on x-ray. We considered osteogenesis imperfecta as a possible cause, but genetic testing was negative. The ophthalmology exam was negative for retinal hemorrhages. A bone scan confirmed posterior rib fractures with no other injuries. CPS was unable to confirm that the fractures had not been sustained while the child was an inpatient, so it was ultimately determined that the patient should be discharged home with his parents with supervision.

CORRESPONDENCE

Anne Huyler, MD, Maine Medical Center, 22 Bramhall Street, Portland, ME 04102; [email protected]

1. Berkowitz CD. Physical abuse of children. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1659-1666.

2. Lindberg DM, Berger RP, Reynolds MS, et al. Yield of skeletal survey by age in children referred to abuse specialists. J Pediatr. 2014;164:1268-1273.e1.

3. Harper NS, Feldman KW, Sugar NF, et al. Additional injuries in young infants with concern for abuse and apparently isolated bruises. J Pediatr. 2014;165:383-388.e1.

4. Lindberg DM, Shapiro RA, Blood EA, et al. Utility of hepatic transaminases in children with concern for abuse. Pediatrics. 2013;131:268-275.

5. Lindberg DM, Shapiro RA, Laskey AL, et al. Prevalence of abusive injuries in siblings and household contacts of physically abused children. Pediatrics. 2012;130:193-201.

A 4-week-old term boy presented to the emergency department (ED) with recurrent bilious emesis. He had a history of neonatal abstinence syndrome, related to his mother’s use of Subutex (a form of suboxone that is considered safer during pregnancy) for her opioid addiction, and a Ladd procedure at Day 7 of life for intestinal malrotation with volvulus. He had been discharged from the hospital 4 days earlier, after recovery from surgery.

He had been doing well until the prior evening, when he developed “yellow-green” emesis and appeared to have intermittent abdominal pain. His parents said that he was refusing to take formula and he’d had frequent bilious emesis. They also noted he’d had 1 wet diaper in the past 12 hours and appeared “sleepier” than usual.

In the ED, the patient was listless, with thin and tremulous extremities. His fontanelle was flat, and his pupils were equal, round, and reactive. His mucous membranes were dry, skin was mottled, and capillary refill was delayed. His cardiopulmonary exam was normal. His abdomen was soft, mildly distended, and diffusely tender to palpation, with well-healing laparotomy scars. His reflexes were normal, with slightly increased tone. No bruising was noted.

An acute abdominal series, including an AP view chest x-ray (FIGURE 1), was obtained to rule out recurrent volvulus, free air, or small bowel obstruction.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Nonaccidental trauma

The chest x-ray (FIGURE 1) showed multiple bilateral posterior rib fractures concerning for nonaccidental trauma (NAT). The remaining acute abdominal series films (not shown) revealed the reason for his bilious emesis: a partial bowel obstruction related to his surgical procedure. Review of x-rays obtained for peripherally inserted central catheter line confirmation during his previous admission (FIGURE 2) revealed that the rib fractures had been present at that time but had been overlooked.

This case illustrates the importance of considering NAT in the differential diagnosis of any sick infant. There are an estimated 700,000 cases of child abuse and neglect and 600 fatalities per year in the United States.1,2 The differential diagnosis for fracture or bruising in infants includes accidental trauma, bony abnormalities (eg, osteogenesis imperfecta), bleeding disorders, and trauma from medical procedures such as CPR or surgery.1

Ask these questions, look beyond that single bruise

When evaluating for NAT, the history and physical exam are crucial. It is essential to ask if there were any witnesses, establish who was caring for the child, and investigate any delays in seeking medical evaluation.1 During the exam, undress the child and examine every inch of skin, looking for bruising or abrasions, especially on the face, ear, neck, and oral cavity.

Any bruising in a nonambulatory infant should raise suspicion for NAT. One study showed that more than half of infants with a single bruise had additional injuries identified upon further work-up.3 Fundoscopic exam with photographs should be completed to evaluate for retinal hemorrhage.

Additional work-up should include a skeletal survey for all children younger than 24 months2 in addition to computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging of the head, complete blood count, and a coagulation panel. If there is concern for abdominal trauma, a complete metabolic panel and lipase test may be useful.4 If liver function tests show elevated liver enzymes (> 80 IU/L), abdominal CT with contrast is indicated.4

Continue to: Research has underscored...

Research has underscored the importance of screening siblings and other contacts of abused children. In particular, the twin of an abused child has a much higher risk for abuse.5 A skeletal survey should be obtained in contacts (< 24 months) of abused children—regardless of their physical exam findings.5

Management depends on injury type

The management of children with NAT depends on the injuries. Once these injuries are addressed, the next step is to determine the safest place for the infant/child to be discharged. The involvement of local social workers and Child Protective Services (CPS) is pivotal for this determination.2

Our patient. To treat the partial small bowel obstruction noted on an abdominal CT, the patient received intravenous fluids and nasogastric tube decompression. However, due to ongoing distension and high nasogastric tube output, the patient was taken to the operating room for an exploratory laparotomy. An adhesive band in the right lower quadrant was found to be causing the obstruction and was lysed.

We consulted CPS and social workers about the rib fractures identified on x-ray. We considered osteogenesis imperfecta as a possible cause, but genetic testing was negative. The ophthalmology exam was negative for retinal hemorrhages. A bone scan confirmed posterior rib fractures with no other injuries. CPS was unable to confirm that the fractures had not been sustained while the child was an inpatient, so it was ultimately determined that the patient should be discharged home with his parents with supervision.

CORRESPONDENCE

Anne Huyler, MD, Maine Medical Center, 22 Bramhall Street, Portland, ME 04102; [email protected]

A 4-week-old term boy presented to the emergency department (ED) with recurrent bilious emesis. He had a history of neonatal abstinence syndrome, related to his mother’s use of Subutex (a form of suboxone that is considered safer during pregnancy) for her opioid addiction, and a Ladd procedure at Day 7 of life for intestinal malrotation with volvulus. He had been discharged from the hospital 4 days earlier, after recovery from surgery.

He had been doing well until the prior evening, when he developed “yellow-green” emesis and appeared to have intermittent abdominal pain. His parents said that he was refusing to take formula and he’d had frequent bilious emesis. They also noted he’d had 1 wet diaper in the past 12 hours and appeared “sleepier” than usual.

In the ED, the patient was listless, with thin and tremulous extremities. His fontanelle was flat, and his pupils were equal, round, and reactive. His mucous membranes were dry, skin was mottled, and capillary refill was delayed. His cardiopulmonary exam was normal. His abdomen was soft, mildly distended, and diffusely tender to palpation, with well-healing laparotomy scars. His reflexes were normal, with slightly increased tone. No bruising was noted.

An acute abdominal series, including an AP view chest x-ray (FIGURE 1), was obtained to rule out recurrent volvulus, free air, or small bowel obstruction.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Nonaccidental trauma

The chest x-ray (FIGURE 1) showed multiple bilateral posterior rib fractures concerning for nonaccidental trauma (NAT). The remaining acute abdominal series films (not shown) revealed the reason for his bilious emesis: a partial bowel obstruction related to his surgical procedure. Review of x-rays obtained for peripherally inserted central catheter line confirmation during his previous admission (FIGURE 2) revealed that the rib fractures had been present at that time but had been overlooked.

This case illustrates the importance of considering NAT in the differential diagnosis of any sick infant. There are an estimated 700,000 cases of child abuse and neglect and 600 fatalities per year in the United States.1,2 The differential diagnosis for fracture or bruising in infants includes accidental trauma, bony abnormalities (eg, osteogenesis imperfecta), bleeding disorders, and trauma from medical procedures such as CPR or surgery.1

Ask these questions, look beyond that single bruise

When evaluating for NAT, the history and physical exam are crucial. It is essential to ask if there were any witnesses, establish who was caring for the child, and investigate any delays in seeking medical evaluation.1 During the exam, undress the child and examine every inch of skin, looking for bruising or abrasions, especially on the face, ear, neck, and oral cavity.

Any bruising in a nonambulatory infant should raise suspicion for NAT. One study showed that more than half of infants with a single bruise had additional injuries identified upon further work-up.3 Fundoscopic exam with photographs should be completed to evaluate for retinal hemorrhage.

Additional work-up should include a skeletal survey for all children younger than 24 months2 in addition to computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging of the head, complete blood count, and a coagulation panel. If there is concern for abdominal trauma, a complete metabolic panel and lipase test may be useful.4 If liver function tests show elevated liver enzymes (> 80 IU/L), abdominal CT with contrast is indicated.4

Continue to: Research has underscored...

Research has underscored the importance of screening siblings and other contacts of abused children. In particular, the twin of an abused child has a much higher risk for abuse.5 A skeletal survey should be obtained in contacts (< 24 months) of abused children—regardless of their physical exam findings.5

Management depends on injury type

The management of children with NAT depends on the injuries. Once these injuries are addressed, the next step is to determine the safest place for the infant/child to be discharged. The involvement of local social workers and Child Protective Services (CPS) is pivotal for this determination.2

Our patient. To treat the partial small bowel obstruction noted on an abdominal CT, the patient received intravenous fluids and nasogastric tube decompression. However, due to ongoing distension and high nasogastric tube output, the patient was taken to the operating room for an exploratory laparotomy. An adhesive band in the right lower quadrant was found to be causing the obstruction and was lysed.

We consulted CPS and social workers about the rib fractures identified on x-ray. We considered osteogenesis imperfecta as a possible cause, but genetic testing was negative. The ophthalmology exam was negative for retinal hemorrhages. A bone scan confirmed posterior rib fractures with no other injuries. CPS was unable to confirm that the fractures had not been sustained while the child was an inpatient, so it was ultimately determined that the patient should be discharged home with his parents with supervision.

CORRESPONDENCE

Anne Huyler, MD, Maine Medical Center, 22 Bramhall Street, Portland, ME 04102; [email protected]

1. Berkowitz CD. Physical abuse of children. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1659-1666.

2. Lindberg DM, Berger RP, Reynolds MS, et al. Yield of skeletal survey by age in children referred to abuse specialists. J Pediatr. 2014;164:1268-1273.e1.

3. Harper NS, Feldman KW, Sugar NF, et al. Additional injuries in young infants with concern for abuse and apparently isolated bruises. J Pediatr. 2014;165:383-388.e1.

4. Lindberg DM, Shapiro RA, Blood EA, et al. Utility of hepatic transaminases in children with concern for abuse. Pediatrics. 2013;131:268-275.

5. Lindberg DM, Shapiro RA, Laskey AL, et al. Prevalence of abusive injuries in siblings and household contacts of physically abused children. Pediatrics. 2012;130:193-201.

1. Berkowitz CD. Physical abuse of children. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1659-1666.

2. Lindberg DM, Berger RP, Reynolds MS, et al. Yield of skeletal survey by age in children referred to abuse specialists. J Pediatr. 2014;164:1268-1273.e1.

3. Harper NS, Feldman KW, Sugar NF, et al. Additional injuries in young infants with concern for abuse and apparently isolated bruises. J Pediatr. 2014;165:383-388.e1.

4. Lindberg DM, Shapiro RA, Blood EA, et al. Utility of hepatic transaminases in children with concern for abuse. Pediatrics. 2013;131:268-275.

5. Lindberg DM, Shapiro RA, Laskey AL, et al. Prevalence of abusive injuries in siblings and household contacts of physically abused children. Pediatrics. 2012;130:193-201.

Mole on back

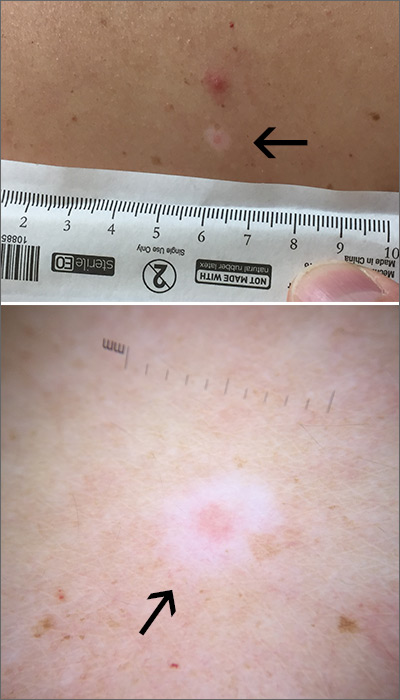

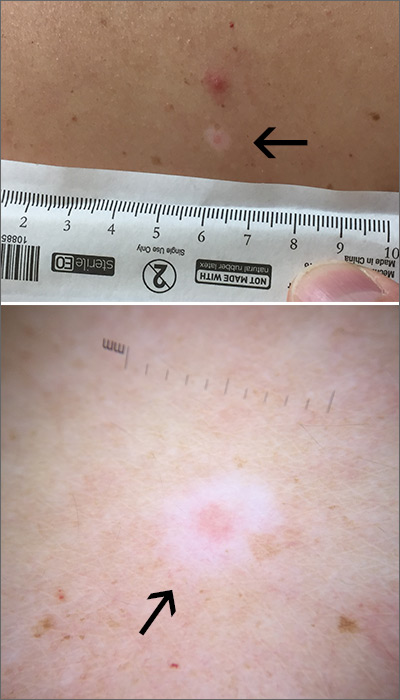

The FP used a dermatoscope to get a better look at the lesion and recognized this as a halo nevus, which is characterized by a central nevus with a halo of depigmentation around it (arrow) and sometimes depigmentation within the nevus itself.

The halo is caused when, occasionally, the body develops an immune reaction to a nevus and its melanocytes. As cytotoxic T cells target those melanocytes, there is loss of pigment to the tissue surrounding the nevus.1

The appearance of the central nevus, rather than the hypopigmentation, determines management strategies. A globular or homogeneous pattern seen on dermoscopy is typically indicative of a benign lesion.2 An atypical pigment network or other melanoma specific structures should raise your suspicions for melanoma or atypical nevus and prompt a deep shave excision sent for pathology to rule out melanoma. A nevus without suspicious features, other than the surrounding hypopigmentation, can be managed conservatively with self-monitoring and re-evaluation.

In this case, the lesion displayed a homogeneous pattern, and the FP advised the patient to self-monitor.

Images and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque, NM.

1. Bayer-Garner IB, Ivan D, Schwartz MR, et al. The immunopathology of regression in benign lichenoid keratosis, keratoacanthoma and halo nevus. Clin Med Res. 2004;2:89-97.

2. Porto AC, Blumetti TP, de Paula Ramos Castro R, et al. Recurrent halo nevus: dermoscopy and confocal microscopy features. JAAD Case Rep. 2017;3:256-258.

The FP used a dermatoscope to get a better look at the lesion and recognized this as a halo nevus, which is characterized by a central nevus with a halo of depigmentation around it (arrow) and sometimes depigmentation within the nevus itself.

The halo is caused when, occasionally, the body develops an immune reaction to a nevus and its melanocytes. As cytotoxic T cells target those melanocytes, there is loss of pigment to the tissue surrounding the nevus.1

The appearance of the central nevus, rather than the hypopigmentation, determines management strategies. A globular or homogeneous pattern seen on dermoscopy is typically indicative of a benign lesion.2 An atypical pigment network or other melanoma specific structures should raise your suspicions for melanoma or atypical nevus and prompt a deep shave excision sent for pathology to rule out melanoma. A nevus without suspicious features, other than the surrounding hypopigmentation, can be managed conservatively with self-monitoring and re-evaluation.

In this case, the lesion displayed a homogeneous pattern, and the FP advised the patient to self-monitor.

Images and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque, NM.

The FP used a dermatoscope to get a better look at the lesion and recognized this as a halo nevus, which is characterized by a central nevus with a halo of depigmentation around it (arrow) and sometimes depigmentation within the nevus itself.

The halo is caused when, occasionally, the body develops an immune reaction to a nevus and its melanocytes. As cytotoxic T cells target those melanocytes, there is loss of pigment to the tissue surrounding the nevus.1

The appearance of the central nevus, rather than the hypopigmentation, determines management strategies. A globular or homogeneous pattern seen on dermoscopy is typically indicative of a benign lesion.2 An atypical pigment network or other melanoma specific structures should raise your suspicions for melanoma or atypical nevus and prompt a deep shave excision sent for pathology to rule out melanoma. A nevus without suspicious features, other than the surrounding hypopigmentation, can be managed conservatively with self-monitoring and re-evaluation.

In this case, the lesion displayed a homogeneous pattern, and the FP advised the patient to self-monitor.

Images and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque, NM.

1. Bayer-Garner IB, Ivan D, Schwartz MR, et al. The immunopathology of regression in benign lichenoid keratosis, keratoacanthoma and halo nevus. Clin Med Res. 2004;2:89-97.

2. Porto AC, Blumetti TP, de Paula Ramos Castro R, et al. Recurrent halo nevus: dermoscopy and confocal microscopy features. JAAD Case Rep. 2017;3:256-258.

1. Bayer-Garner IB, Ivan D, Schwartz MR, et al. The immunopathology of regression in benign lichenoid keratosis, keratoacanthoma and halo nevus. Clin Med Res. 2004;2:89-97.

2. Porto AC, Blumetti TP, de Paula Ramos Castro R, et al. Recurrent halo nevus: dermoscopy and confocal microscopy features. JAAD Case Rep. 2017;3:256-258.

Symmetric hair loss across frontal and temporal scalp

The FP referred the patient to a dermatology clinic that specialized in hair loss. Based on the clinical findings, physicians at the clinic suspected that this was a case of frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA), a primary lymphocytic cicatricial (scarring) alopecia. A dermatopathologist confirmed the diagnosis via histologic review.

FFA is characterized by symmetric band-like hair loss with evidence of scarring in the frontal and temporal regions of the scalp. (The extent of hair loss can be assessed by retracting the patient’s hair and having the patient raise his or her eyebrows and wrinkle the forehead in a surprised look.) FFA is accompanied by eyebrow loss in 73% to 95% of patients. Mild to severe perifollicular (and possibly more generalized) erythema and scale are usually present. In addition, erythematous or skin-colored papules may appear on the face, and marked exaggeration of the temporal veins is a common finding.

Most patients with FFA (83%) are postmenopausal women and nearly all (98.6%) have Fitzpatrick skin type 1 or 2 (white skin that burns easily and doesn’t readily tan). Other pertinent findings include the absence of oral lesions, nail changes, or other skin diseases.

A punch biopsy taken from the leading edge of the hair loss confirms the diagnosis of FFA and, ideally, should be reviewed by a dermatopathologist. Histologic examination will reveal a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate (predominantly around the hair follicle where the follicular stem cells reside), resulting in fibrosis and scarring. In addition to confirming the diagnosis with histologic examination, the following conditions must be ruled out in the differential: alopecia areata, female pattern hair loss, discoid lupus erythematosus, central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia, and traction alopecia.

Early detection is key. In general, physicians should initiate treatment as soon as possible to prevent disease progression and reduce permanent scarring and hair loss. Intralesional steroids such as triamcinolone acetonide (5-10 mg/cc), as well as high-potency topical steroids, are generally helpful to stabilize the disease. There is also some evidence of benefit from oral dutasteride or finasteride at variable doses. Immunosuppressants such as hydroxychloroquine also may be used as second-line treatments, although the benefit-to-risk ratio needs to be taken into consideration.

This patient was started on a regimen of topical high-potency steroids (clobetasol foam, 0.05%), with targeted, intralesional injection of steroids (10 mg/cc of triamcinolone acetonide) to areas with the most inflammation. She also was advised to use ketoconazole 2% shampoo while showering. These interventions decreased the patient’s symptoms dramatically. Her scalp erythema and scale improved, but the hair did not regrow. One year later, her hairline was clinically stable with no evidence of disease progression. She continued to see a dermatologist annually.

This case was adapted from: Power DV, Disse M, Hordinsky M. Progressive hair loss. J Fam Pract. 2017;66:521-523.

The FP referred the patient to a dermatology clinic that specialized in hair loss. Based on the clinical findings, physicians at the clinic suspected that this was a case of frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA), a primary lymphocytic cicatricial (scarring) alopecia. A dermatopathologist confirmed the diagnosis via histologic review.

FFA is characterized by symmetric band-like hair loss with evidence of scarring in the frontal and temporal regions of the scalp. (The extent of hair loss can be assessed by retracting the patient’s hair and having the patient raise his or her eyebrows and wrinkle the forehead in a surprised look.) FFA is accompanied by eyebrow loss in 73% to 95% of patients. Mild to severe perifollicular (and possibly more generalized) erythema and scale are usually present. In addition, erythematous or skin-colored papules may appear on the face, and marked exaggeration of the temporal veins is a common finding.

Most patients with FFA (83%) are postmenopausal women and nearly all (98.6%) have Fitzpatrick skin type 1 or 2 (white skin that burns easily and doesn’t readily tan). Other pertinent findings include the absence of oral lesions, nail changes, or other skin diseases.

A punch biopsy taken from the leading edge of the hair loss confirms the diagnosis of FFA and, ideally, should be reviewed by a dermatopathologist. Histologic examination will reveal a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate (predominantly around the hair follicle where the follicular stem cells reside), resulting in fibrosis and scarring. In addition to confirming the diagnosis with histologic examination, the following conditions must be ruled out in the differential: alopecia areata, female pattern hair loss, discoid lupus erythematosus, central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia, and traction alopecia.

Early detection is key. In general, physicians should initiate treatment as soon as possible to prevent disease progression and reduce permanent scarring and hair loss. Intralesional steroids such as triamcinolone acetonide (5-10 mg/cc), as well as high-potency topical steroids, are generally helpful to stabilize the disease. There is also some evidence of benefit from oral dutasteride or finasteride at variable doses. Immunosuppressants such as hydroxychloroquine also may be used as second-line treatments, although the benefit-to-risk ratio needs to be taken into consideration.

This patient was started on a regimen of topical high-potency steroids (clobetasol foam, 0.05%), with targeted, intralesional injection of steroids (10 mg/cc of triamcinolone acetonide) to areas with the most inflammation. She also was advised to use ketoconazole 2% shampoo while showering. These interventions decreased the patient’s symptoms dramatically. Her scalp erythema and scale improved, but the hair did not regrow. One year later, her hairline was clinically stable with no evidence of disease progression. She continued to see a dermatologist annually.

This case was adapted from: Power DV, Disse M, Hordinsky M. Progressive hair loss. J Fam Pract. 2017;66:521-523.

The FP referred the patient to a dermatology clinic that specialized in hair loss. Based on the clinical findings, physicians at the clinic suspected that this was a case of frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA), a primary lymphocytic cicatricial (scarring) alopecia. A dermatopathologist confirmed the diagnosis via histologic review.

FFA is characterized by symmetric band-like hair loss with evidence of scarring in the frontal and temporal regions of the scalp. (The extent of hair loss can be assessed by retracting the patient’s hair and having the patient raise his or her eyebrows and wrinkle the forehead in a surprised look.) FFA is accompanied by eyebrow loss in 73% to 95% of patients. Mild to severe perifollicular (and possibly more generalized) erythema and scale are usually present. In addition, erythematous or skin-colored papules may appear on the face, and marked exaggeration of the temporal veins is a common finding.

Most patients with FFA (83%) are postmenopausal women and nearly all (98.6%) have Fitzpatrick skin type 1 or 2 (white skin that burns easily and doesn’t readily tan). Other pertinent findings include the absence of oral lesions, nail changes, or other skin diseases.

A punch biopsy taken from the leading edge of the hair loss confirms the diagnosis of FFA and, ideally, should be reviewed by a dermatopathologist. Histologic examination will reveal a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate (predominantly around the hair follicle where the follicular stem cells reside), resulting in fibrosis and scarring. In addition to confirming the diagnosis with histologic examination, the following conditions must be ruled out in the differential: alopecia areata, female pattern hair loss, discoid lupus erythematosus, central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia, and traction alopecia.

Early detection is key. In general, physicians should initiate treatment as soon as possible to prevent disease progression and reduce permanent scarring and hair loss. Intralesional steroids such as triamcinolone acetonide (5-10 mg/cc), as well as high-potency topical steroids, are generally helpful to stabilize the disease. There is also some evidence of benefit from oral dutasteride or finasteride at variable doses. Immunosuppressants such as hydroxychloroquine also may be used as second-line treatments, although the benefit-to-risk ratio needs to be taken into consideration.

This patient was started on a regimen of topical high-potency steroids (clobetasol foam, 0.05%), with targeted, intralesional injection of steroids (10 mg/cc of triamcinolone acetonide) to areas with the most inflammation. She also was advised to use ketoconazole 2% shampoo while showering. These interventions decreased the patient’s symptoms dramatically. Her scalp erythema and scale improved, but the hair did not regrow. One year later, her hairline was clinically stable with no evidence of disease progression. She continued to see a dermatologist annually.

This case was adapted from: Power DV, Disse M, Hordinsky M. Progressive hair loss. J Fam Pract. 2017;66:521-523.

Firm and tender growth in right nostril

The clinical features were consistent with a filiform wart, which is caused by human papillomavirus and common on the face. Filiform warts may occur on mucosal surfaces, including the nasal mucosa, lips, or eyelids. Most are benign and resolve within 2 years without treatment, but others can be symptomatic. Larger filiform warts may develop the clinical features of a cutaneous horn and mimic a squamous cell carcinoma.

Patients often want the wart removed for functional or cosmetic reasons. Although, there are many treatments available for warts, none have success rates that exceed about 70%. The most common options for treatment include topical salicylic acid in a liquid or plaster, cryotherapy, intralesional immunotherapy with candida antigen, excision, and topical acid.

The location of this patient’s wart limited the treatment options to cryotherapy or snip excision and cautery. The patient opted for cryotherapy. In this process, a hemostat or heavy gauge tweezer is dipped in liquid nitrogen and allowed to cool. Then, without anesthesia, the clinician pinches the lesion gently with the instrument and holds it until the freeze horizon extends to the base. This is then repeated. Each cycle may take 10 and 15 seconds. A benefit of this technique (which is also useful for skin tags and lesions close to the eye) is the ability to avoid overspray of liquid nitrogen and thus, minimize collateral tissue damage. It is also quick and bloodless.

The FP performed cryotherapy on the wart and advised the patient to expect the lesion to become more inflamed over the next 2 to 3 days and then peel off within 1 to 2 weeks. The FP also instructed the patient to return in a week or 2 so that the FP could evaluate whether additional treatment would be necessary. In general, non-genital warts require 2 to 3 individual treatments to clear, but a smaller and pedunculated wart like the one seen in this case tend to clear more easily.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

The clinical features were consistent with a filiform wart, which is caused by human papillomavirus and common on the face. Filiform warts may occur on mucosal surfaces, including the nasal mucosa, lips, or eyelids. Most are benign and resolve within 2 years without treatment, but others can be symptomatic. Larger filiform warts may develop the clinical features of a cutaneous horn and mimic a squamous cell carcinoma.

Patients often want the wart removed for functional or cosmetic reasons. Although, there are many treatments available for warts, none have success rates that exceed about 70%. The most common options for treatment include topical salicylic acid in a liquid or plaster, cryotherapy, intralesional immunotherapy with candida antigen, excision, and topical acid.

The location of this patient’s wart limited the treatment options to cryotherapy or snip excision and cautery. The patient opted for cryotherapy. In this process, a hemostat or heavy gauge tweezer is dipped in liquid nitrogen and allowed to cool. Then, without anesthesia, the clinician pinches the lesion gently with the instrument and holds it until the freeze horizon extends to the base. This is then repeated. Each cycle may take 10 and 15 seconds. A benefit of this technique (which is also useful for skin tags and lesions close to the eye) is the ability to avoid overspray of liquid nitrogen and thus, minimize collateral tissue damage. It is also quick and bloodless.

The FP performed cryotherapy on the wart and advised the patient to expect the lesion to become more inflamed over the next 2 to 3 days and then peel off within 1 to 2 weeks. The FP also instructed the patient to return in a week or 2 so that the FP could evaluate whether additional treatment would be necessary. In general, non-genital warts require 2 to 3 individual treatments to clear, but a smaller and pedunculated wart like the one seen in this case tend to clear more easily.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

The clinical features were consistent with a filiform wart, which is caused by human papillomavirus and common on the face. Filiform warts may occur on mucosal surfaces, including the nasal mucosa, lips, or eyelids. Most are benign and resolve within 2 years without treatment, but others can be symptomatic. Larger filiform warts may develop the clinical features of a cutaneous horn and mimic a squamous cell carcinoma.