User login

Unusual patch of skin

The physician diagnosed nevus comedonicus on the chest of this 15-year-old boy.

This is a congenital hamartoma with open comedones; it is not acne. Nevus comedonicus (comedonal nevus) is a rare congenital hamartoma characterized by an aggregation of comedones in one region of the skin. Comedonal nevi do not become melanoma because they lack melanocytes. Therefore, there is no reason to excise them other than for cosmetic reasons. However, comedonal nevi are large and the risks of excision outweigh the benefits.

In this case, the patient and his mother were reassured that no treatment was needed and they opted to leave it alone.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M, Usatine R. Benign nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:945-952.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The physician diagnosed nevus comedonicus on the chest of this 15-year-old boy.

This is a congenital hamartoma with open comedones; it is not acne. Nevus comedonicus (comedonal nevus) is a rare congenital hamartoma characterized by an aggregation of comedones in one region of the skin. Comedonal nevi do not become melanoma because they lack melanocytes. Therefore, there is no reason to excise them other than for cosmetic reasons. However, comedonal nevi are large and the risks of excision outweigh the benefits.

In this case, the patient and his mother were reassured that no treatment was needed and they opted to leave it alone.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M, Usatine R. Benign nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:945-952.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The physician diagnosed nevus comedonicus on the chest of this 15-year-old boy.

This is a congenital hamartoma with open comedones; it is not acne. Nevus comedonicus (comedonal nevus) is a rare congenital hamartoma characterized by an aggregation of comedones in one region of the skin. Comedonal nevi do not become melanoma because they lack melanocytes. Therefore, there is no reason to excise them other than for cosmetic reasons. However, comedonal nevi are large and the risks of excision outweigh the benefits.

In this case, the patient and his mother were reassured that no treatment was needed and they opted to leave it alone.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M, Usatine R. Benign nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:945-952.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Light skin on back of neck

The FP diagnosed nevus anemicus in this patient.

Nevus anemicus is a congenital hypopigmented macule or patch that is stable in relative size and distribution. It occurs as a result of localized hypersensitivity to catecholamines and not as a result of a decrease in melanocytes. The localized hypersensitivity to catecholamines causes the affected area to stay lighter than the surrounding skin. On diascopy (pressure with a glass slide), the skin is indistinguishable from the surrounding skin.

There is no treatment for this benign condition, and it is not associated with any underlying malignancy or other health problem.

Photo courtesy of the University of Texas Health, San Antonio and text courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M, Usatine R. Benign nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:945-952.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP diagnosed nevus anemicus in this patient.

Nevus anemicus is a congenital hypopigmented macule or patch that is stable in relative size and distribution. It occurs as a result of localized hypersensitivity to catecholamines and not as a result of a decrease in melanocytes. The localized hypersensitivity to catecholamines causes the affected area to stay lighter than the surrounding skin. On diascopy (pressure with a glass slide), the skin is indistinguishable from the surrounding skin.

There is no treatment for this benign condition, and it is not associated with any underlying malignancy or other health problem.

Photo courtesy of the University of Texas Health, San Antonio and text courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M, Usatine R. Benign nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:945-952.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP diagnosed nevus anemicus in this patient.

Nevus anemicus is a congenital hypopigmented macule or patch that is stable in relative size and distribution. It occurs as a result of localized hypersensitivity to catecholamines and not as a result of a decrease in melanocytes. The localized hypersensitivity to catecholamines causes the affected area to stay lighter than the surrounding skin. On diascopy (pressure with a glass slide), the skin is indistinguishable from the surrounding skin.

There is no treatment for this benign condition, and it is not associated with any underlying malignancy or other health problem.

Photo courtesy of the University of Texas Health, San Antonio and text courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M, Usatine R. Benign nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:945-952.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Lighter skin on left cheek

The FP made the diagnosis of nevus depigmentosus.

Nevus depigmentosus is usually present at birth or develops in early childhood. There is a decreased number of melanosomes within a normal number of melanocytes. The hypopigmented area typically has a serrated or jagged edge and has been compared to the appearance of a continent.

Nevus depigmentosus presents no danger or increased malignant potential. Excision, which is not an advisable option, is the only available treatment. Patients who want to camouflage the appearance of the hypopigmentation can use cover-up makeup.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M, Usatine R. Benign nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:945-952.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP made the diagnosis of nevus depigmentosus.

Nevus depigmentosus is usually present at birth or develops in early childhood. There is a decreased number of melanosomes within a normal number of melanocytes. The hypopigmented area typically has a serrated or jagged edge and has been compared to the appearance of a continent.

Nevus depigmentosus presents no danger or increased malignant potential. Excision, which is not an advisable option, is the only available treatment. Patients who want to camouflage the appearance of the hypopigmentation can use cover-up makeup.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M, Usatine R. Benign nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:945-952.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP made the diagnosis of nevus depigmentosus.

Nevus depigmentosus is usually present at birth or develops in early childhood. There is a decreased number of melanosomes within a normal number of melanocytes. The hypopigmented area typically has a serrated or jagged edge and has been compared to the appearance of a continent.

Nevus depigmentosus presents no danger or increased malignant potential. Excision, which is not an advisable option, is the only available treatment. Patients who want to camouflage the appearance of the hypopigmentation can use cover-up makeup.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M, Usatine R. Benign nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:945-952.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Enlarging dark patch on back

The FP recognized this to be a Becker's nevus, also known as a Becker nevus.

This nevus, which tends to occur in adolescent males, presents as a brown patch (often with hair) that is located on the shoulder, back, or submammary area. The lesion may enlarge to cover an entire shoulder or upper arm. While the nevus in this case did not have hair, it did have increased acne within the area—another feature of Becker nevus.

Although it is called a nevus, it does not actually have nevus cells and has no malignant potential. It is a type of hamartoma—an abnormal mixture of cells and tissues normally found in the area of the body where the growth occurs. Becker nevi do not become melanoma because they lack melanocytes. Therefore, there is no reason to excise them. Generally, these lesions are large and the risks of excision for cosmetic reasons outweigh the benefits.

In this case, the patient and his mother were reassured that no treatment was needed and they opted to leave it alone.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M, Usatine R. Benign nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:945-952.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP recognized this to be a Becker's nevus, also known as a Becker nevus.

This nevus, which tends to occur in adolescent males, presents as a brown patch (often with hair) that is located on the shoulder, back, or submammary area. The lesion may enlarge to cover an entire shoulder or upper arm. While the nevus in this case did not have hair, it did have increased acne within the area—another feature of Becker nevus.

Although it is called a nevus, it does not actually have nevus cells and has no malignant potential. It is a type of hamartoma—an abnormal mixture of cells and tissues normally found in the area of the body where the growth occurs. Becker nevi do not become melanoma because they lack melanocytes. Therefore, there is no reason to excise them. Generally, these lesions are large and the risks of excision for cosmetic reasons outweigh the benefits.

In this case, the patient and his mother were reassured that no treatment was needed and they opted to leave it alone.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M, Usatine R. Benign nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:945-952.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP recognized this to be a Becker's nevus, also known as a Becker nevus.

This nevus, which tends to occur in adolescent males, presents as a brown patch (often with hair) that is located on the shoulder, back, or submammary area. The lesion may enlarge to cover an entire shoulder or upper arm. While the nevus in this case did not have hair, it did have increased acne within the area—another feature of Becker nevus.

Although it is called a nevus, it does not actually have nevus cells and has no malignant potential. It is a type of hamartoma—an abnormal mixture of cells and tissues normally found in the area of the body where the growth occurs. Becker nevi do not become melanoma because they lack melanocytes. Therefore, there is no reason to excise them. Generally, these lesions are large and the risks of excision for cosmetic reasons outweigh the benefits.

In this case, the patient and his mother were reassured that no treatment was needed and they opted to leave it alone.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M, Usatine R. Benign nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:945-952.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

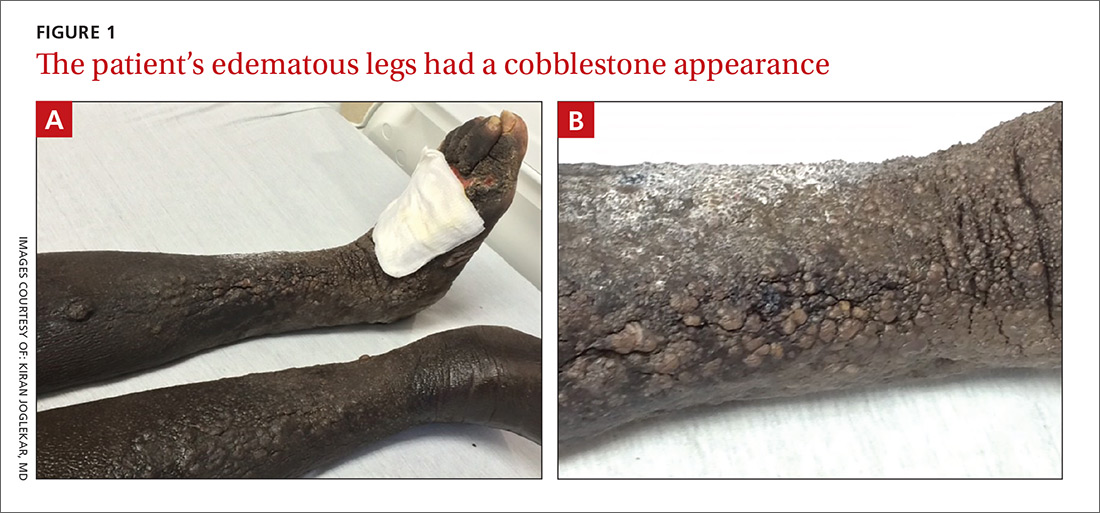

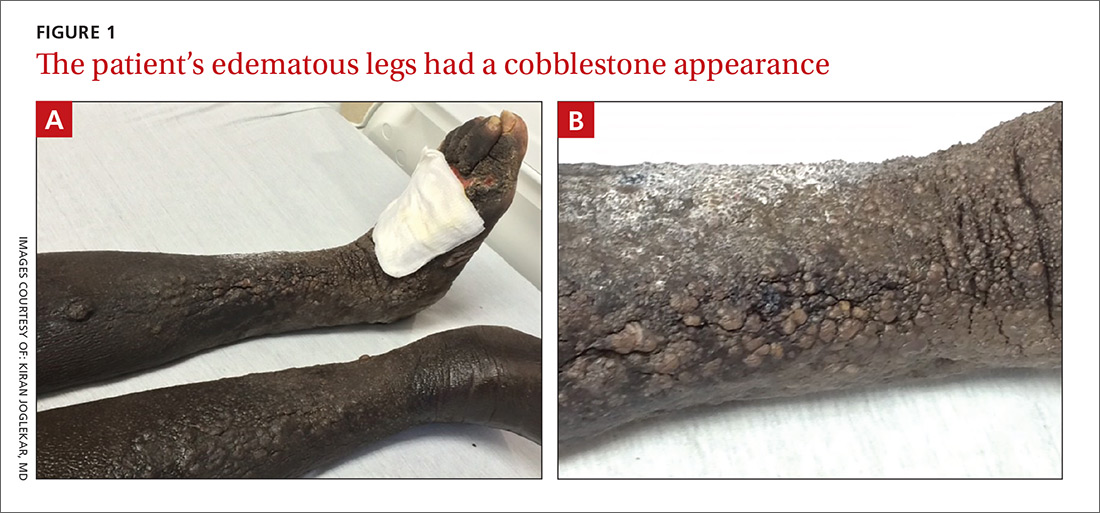

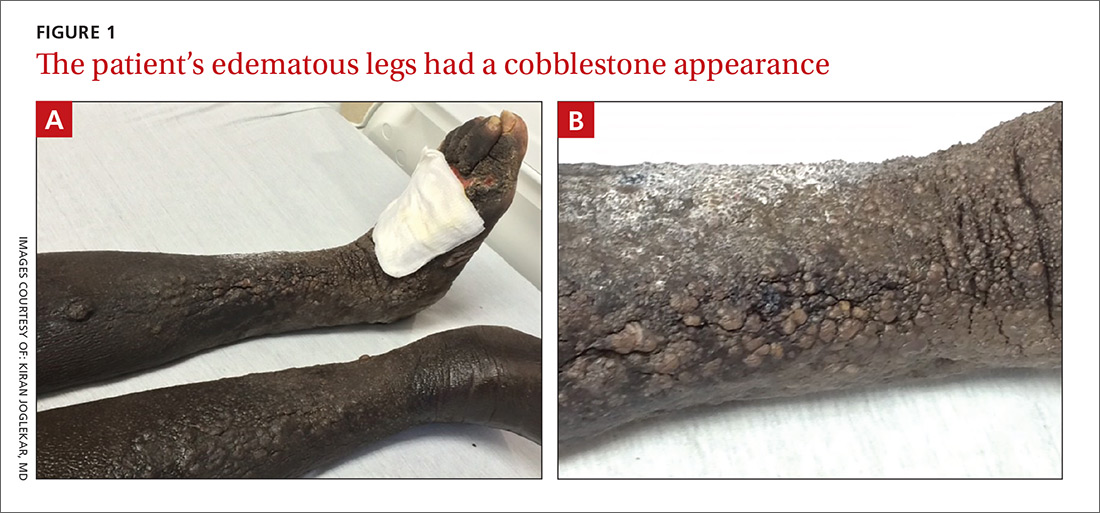

Bilateral nonpitting edema and xerotic skin

A 60-year-old African American woman who had congestive heart failure (CHF) with reduced ejection fraction, untreated hepatitis C virus infection, and chronic kidney disease presented to the emergency department (ED) with a 6-month history of bilateral lower extremity edema. Use of diuretics and antibiotic therapy for suspected CHF exacerbation and cellulitis, directed by her primary care physician, had no effect. In the month prior to presenting to the ED, the patient took 2 different antibiotics, each for 10 days: clindamycin 300 mg every 6 hours and doxycycline 100 mg every 12 hours. Additionally, she was taking furosemide 40 mg/d with good urine output, but no appreciable improvement in lower extremity edema.

The physical examination revealed bilateral nonpitting edema. Weeping pearly papules, xerotic skin, and a cobblestone appearance extended from the dorsa of the patient’s feet to her knees (FIGURES 1A and 1B). The patient underwent Doppler ultrasound of the lower extremities and a skin biopsy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa

The Doppler ultrasound was negative, and the biopsy ruled out malignancy and infection; however, the pathology report was histologically consistent with a diagnosis of elephantiasis nostras verrucosa (ENV).

ENV is a disfiguring, nonfilarial lymphedema that affects the lower extremities and is characterized by progressive cobblestoning and verrucous distortion of gravity-dependent areas.1 The skin changes are caused by lymphatic damage and obstruction from an accumulation of protein-rich fluid in the dermis and subcutaneous tissues.1,2

The term ENV was first coined by Aldo Castellani in 1934 to differentiate the condition from elephantiasis tropica (filariasis), which is caused by parasitic Wuchereria worms.3 ENV is also known as lymphangitis recurrens elephantogenica, elephantiasis verrucosa, elephantiasis nostra, mossy leg, and elephantiasis of the temperate zone.1

ENV is notably uncommon; its exact incidence is unknown. The etiology is multifactorial but can include obesity, chronic lymphedema, CHF, and recurrent cellulitis (the latter 2 were noted in our patient’s history).1

Although the diagnosis can be made based on patient history and physical examination alone, skin biopsy is warranted to rule out underlying malignancy or fungal infection.1,4 Histologic findings suggestive of ENV include pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, lymph channel dilation, widened tissue spaces, and loss of dermal papillae.1 In our patient’s case, the pathology report revealed dermal fibrosis, dilated lymph channels, and a mixed inflammatory infiltrate. Her lab work, which included a complete blood count and basic metabolic panel, was significant for neutrophilic leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 30,000 cells/mcL), chronic kidney disease, and elevated inflammatory markers.

The differential includes other types of edema and infections

Several other diseases must be differentiated from ENV, including:

Venous stasis dermatitis. Unlike ENV, this condition involves pitting edema with erythema and does not have a verrucous appearance.2,4

Lipedema. Histologically, lipedema shows no changes. It typically spares the feet, has an early age of onset, and is associated with a positive family history.1,2,4

Lipodermatosclerosis. This condition is caused by venous stasis with swelling of the proximal lower extremity and fibrosis of the distal parts. The affected leg develops an “inverted wine bottle” appearance.2,4

Pretibial myxedema. Patients with pretibial myxedema will have thyroid function test abnormalities and exhibit other signs of hyperthyroidism. If suspected, the laboratory evaluation should include thyroid-stimulating hormone levels.2,4

Filariasis. Endemic to tropical regions, filariasis is a parasitic infection. A travel history helps to differentiate this from ENV. If suspected, include a Giemsa blood smear in the laboratory evaluation.2

Chromoblastomycosis. This chronic fungal infection is typically contracted in rural tropical or subtropical regions. The causative fungi, which are present in soil, enter the skin through minor wounds (eg, thorns or splinters). The wounds are typically forgotten by the time the patient seeks medical attention. Biopsy can effectively rule out this condition.1,2,5

Treatment centers on preserving function, preventing complications

Currently, no standard treatment exists for ENV.1,4 Therapies are aimed at treating the underlying cause, preserving function in the affected limb, and preventing complications. Conservative therapy includes elevation of the affected limb and use of compression devices for edema. Antibiotics can be administered for associated cellulitis. There have been few case reports of successful treatment with oral retinoids. If medical therapy fails, surgical debridement serves as a last resort.1,4,6

Our patient improved after a week with antibiotic therapy (IV piperacillin/tazobactam 3.375 g every 6 hours) and other conservative measures, such as leg elevation.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kavita Natrajan, MBBS, George Washington University/Medical Faculty Associates, Division of Hematology and Oncology, 2150 Pennsylvania Avenue NW, DC 20037; [email protected].

1. Sisto K, Khachemoune A. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:141-146.

2. Liaw FY, Huang CF, Wu YC, et al. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: swelling with verrucose appearance of lower limbs. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:e551-e553.

3. Castellani A. Researches on elephantiasis nostras and elephantiasis tropica with special regard to their initial stage of recurring lymphangitis (lymphangitis recurrens elephantogenica). J Trop Med Hyg. 1969;72:89-97.

4. Baird D, Bode D, Akers T, et al. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa (ENV): a complication of congestive heart failure and obesity. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23:413-417.

5. Queiroz-Telles F, Fahal AH, Falci R, et. al. Neglected endemic mycoses. Lancet Inf Dis. 2017;17:e367-e377.

6. Han HH, Lim SY, Oh DY. Successful surgical treatment for elephantiasis nostras verrucosa using a new designed column flap. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2015;14:299-302.

A 60-year-old African American woman who had congestive heart failure (CHF) with reduced ejection fraction, untreated hepatitis C virus infection, and chronic kidney disease presented to the emergency department (ED) with a 6-month history of bilateral lower extremity edema. Use of diuretics and antibiotic therapy for suspected CHF exacerbation and cellulitis, directed by her primary care physician, had no effect. In the month prior to presenting to the ED, the patient took 2 different antibiotics, each for 10 days: clindamycin 300 mg every 6 hours and doxycycline 100 mg every 12 hours. Additionally, she was taking furosemide 40 mg/d with good urine output, but no appreciable improvement in lower extremity edema.

The physical examination revealed bilateral nonpitting edema. Weeping pearly papules, xerotic skin, and a cobblestone appearance extended from the dorsa of the patient’s feet to her knees (FIGURES 1A and 1B). The patient underwent Doppler ultrasound of the lower extremities and a skin biopsy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa

The Doppler ultrasound was negative, and the biopsy ruled out malignancy and infection; however, the pathology report was histologically consistent with a diagnosis of elephantiasis nostras verrucosa (ENV).

ENV is a disfiguring, nonfilarial lymphedema that affects the lower extremities and is characterized by progressive cobblestoning and verrucous distortion of gravity-dependent areas.1 The skin changes are caused by lymphatic damage and obstruction from an accumulation of protein-rich fluid in the dermis and subcutaneous tissues.1,2

The term ENV was first coined by Aldo Castellani in 1934 to differentiate the condition from elephantiasis tropica (filariasis), which is caused by parasitic Wuchereria worms.3 ENV is also known as lymphangitis recurrens elephantogenica, elephantiasis verrucosa, elephantiasis nostra, mossy leg, and elephantiasis of the temperate zone.1

ENV is notably uncommon; its exact incidence is unknown. The etiology is multifactorial but can include obesity, chronic lymphedema, CHF, and recurrent cellulitis (the latter 2 were noted in our patient’s history).1

Although the diagnosis can be made based on patient history and physical examination alone, skin biopsy is warranted to rule out underlying malignancy or fungal infection.1,4 Histologic findings suggestive of ENV include pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, lymph channel dilation, widened tissue spaces, and loss of dermal papillae.1 In our patient’s case, the pathology report revealed dermal fibrosis, dilated lymph channels, and a mixed inflammatory infiltrate. Her lab work, which included a complete blood count and basic metabolic panel, was significant for neutrophilic leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 30,000 cells/mcL), chronic kidney disease, and elevated inflammatory markers.

The differential includes other types of edema and infections

Several other diseases must be differentiated from ENV, including:

Venous stasis dermatitis. Unlike ENV, this condition involves pitting edema with erythema and does not have a verrucous appearance.2,4

Lipedema. Histologically, lipedema shows no changes. It typically spares the feet, has an early age of onset, and is associated with a positive family history.1,2,4

Lipodermatosclerosis. This condition is caused by venous stasis with swelling of the proximal lower extremity and fibrosis of the distal parts. The affected leg develops an “inverted wine bottle” appearance.2,4

Pretibial myxedema. Patients with pretibial myxedema will have thyroid function test abnormalities and exhibit other signs of hyperthyroidism. If suspected, the laboratory evaluation should include thyroid-stimulating hormone levels.2,4

Filariasis. Endemic to tropical regions, filariasis is a parasitic infection. A travel history helps to differentiate this from ENV. If suspected, include a Giemsa blood smear in the laboratory evaluation.2

Chromoblastomycosis. This chronic fungal infection is typically contracted in rural tropical or subtropical regions. The causative fungi, which are present in soil, enter the skin through minor wounds (eg, thorns or splinters). The wounds are typically forgotten by the time the patient seeks medical attention. Biopsy can effectively rule out this condition.1,2,5

Treatment centers on preserving function, preventing complications

Currently, no standard treatment exists for ENV.1,4 Therapies are aimed at treating the underlying cause, preserving function in the affected limb, and preventing complications. Conservative therapy includes elevation of the affected limb and use of compression devices for edema. Antibiotics can be administered for associated cellulitis. There have been few case reports of successful treatment with oral retinoids. If medical therapy fails, surgical debridement serves as a last resort.1,4,6

Our patient improved after a week with antibiotic therapy (IV piperacillin/tazobactam 3.375 g every 6 hours) and other conservative measures, such as leg elevation.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kavita Natrajan, MBBS, George Washington University/Medical Faculty Associates, Division of Hematology and Oncology, 2150 Pennsylvania Avenue NW, DC 20037; [email protected].

A 60-year-old African American woman who had congestive heart failure (CHF) with reduced ejection fraction, untreated hepatitis C virus infection, and chronic kidney disease presented to the emergency department (ED) with a 6-month history of bilateral lower extremity edema. Use of diuretics and antibiotic therapy for suspected CHF exacerbation and cellulitis, directed by her primary care physician, had no effect. In the month prior to presenting to the ED, the patient took 2 different antibiotics, each for 10 days: clindamycin 300 mg every 6 hours and doxycycline 100 mg every 12 hours. Additionally, she was taking furosemide 40 mg/d with good urine output, but no appreciable improvement in lower extremity edema.

The physical examination revealed bilateral nonpitting edema. Weeping pearly papules, xerotic skin, and a cobblestone appearance extended from the dorsa of the patient’s feet to her knees (FIGURES 1A and 1B). The patient underwent Doppler ultrasound of the lower extremities and a skin biopsy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa

The Doppler ultrasound was negative, and the biopsy ruled out malignancy and infection; however, the pathology report was histologically consistent with a diagnosis of elephantiasis nostras verrucosa (ENV).

ENV is a disfiguring, nonfilarial lymphedema that affects the lower extremities and is characterized by progressive cobblestoning and verrucous distortion of gravity-dependent areas.1 The skin changes are caused by lymphatic damage and obstruction from an accumulation of protein-rich fluid in the dermis and subcutaneous tissues.1,2

The term ENV was first coined by Aldo Castellani in 1934 to differentiate the condition from elephantiasis tropica (filariasis), which is caused by parasitic Wuchereria worms.3 ENV is also known as lymphangitis recurrens elephantogenica, elephantiasis verrucosa, elephantiasis nostra, mossy leg, and elephantiasis of the temperate zone.1

ENV is notably uncommon; its exact incidence is unknown. The etiology is multifactorial but can include obesity, chronic lymphedema, CHF, and recurrent cellulitis (the latter 2 were noted in our patient’s history).1

Although the diagnosis can be made based on patient history and physical examination alone, skin biopsy is warranted to rule out underlying malignancy or fungal infection.1,4 Histologic findings suggestive of ENV include pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, lymph channel dilation, widened tissue spaces, and loss of dermal papillae.1 In our patient’s case, the pathology report revealed dermal fibrosis, dilated lymph channels, and a mixed inflammatory infiltrate. Her lab work, which included a complete blood count and basic metabolic panel, was significant for neutrophilic leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 30,000 cells/mcL), chronic kidney disease, and elevated inflammatory markers.

The differential includes other types of edema and infections

Several other diseases must be differentiated from ENV, including:

Venous stasis dermatitis. Unlike ENV, this condition involves pitting edema with erythema and does not have a verrucous appearance.2,4

Lipedema. Histologically, lipedema shows no changes. It typically spares the feet, has an early age of onset, and is associated with a positive family history.1,2,4

Lipodermatosclerosis. This condition is caused by venous stasis with swelling of the proximal lower extremity and fibrosis of the distal parts. The affected leg develops an “inverted wine bottle” appearance.2,4

Pretibial myxedema. Patients with pretibial myxedema will have thyroid function test abnormalities and exhibit other signs of hyperthyroidism. If suspected, the laboratory evaluation should include thyroid-stimulating hormone levels.2,4

Filariasis. Endemic to tropical regions, filariasis is a parasitic infection. A travel history helps to differentiate this from ENV. If suspected, include a Giemsa blood smear in the laboratory evaluation.2

Chromoblastomycosis. This chronic fungal infection is typically contracted in rural tropical or subtropical regions. The causative fungi, which are present in soil, enter the skin through minor wounds (eg, thorns or splinters). The wounds are typically forgotten by the time the patient seeks medical attention. Biopsy can effectively rule out this condition.1,2,5

Treatment centers on preserving function, preventing complications

Currently, no standard treatment exists for ENV.1,4 Therapies are aimed at treating the underlying cause, preserving function in the affected limb, and preventing complications. Conservative therapy includes elevation of the affected limb and use of compression devices for edema. Antibiotics can be administered for associated cellulitis. There have been few case reports of successful treatment with oral retinoids. If medical therapy fails, surgical debridement serves as a last resort.1,4,6

Our patient improved after a week with antibiotic therapy (IV piperacillin/tazobactam 3.375 g every 6 hours) and other conservative measures, such as leg elevation.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kavita Natrajan, MBBS, George Washington University/Medical Faculty Associates, Division of Hematology and Oncology, 2150 Pennsylvania Avenue NW, DC 20037; [email protected].

1. Sisto K, Khachemoune A. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:141-146.

2. Liaw FY, Huang CF, Wu YC, et al. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: swelling with verrucose appearance of lower limbs. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:e551-e553.

3. Castellani A. Researches on elephantiasis nostras and elephantiasis tropica with special regard to their initial stage of recurring lymphangitis (lymphangitis recurrens elephantogenica). J Trop Med Hyg. 1969;72:89-97.

4. Baird D, Bode D, Akers T, et al. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa (ENV): a complication of congestive heart failure and obesity. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23:413-417.

5. Queiroz-Telles F, Fahal AH, Falci R, et. al. Neglected endemic mycoses. Lancet Inf Dis. 2017;17:e367-e377.

6. Han HH, Lim SY, Oh DY. Successful surgical treatment for elephantiasis nostras verrucosa using a new designed column flap. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2015;14:299-302.

1. Sisto K, Khachemoune A. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:141-146.

2. Liaw FY, Huang CF, Wu YC, et al. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: swelling with verrucose appearance of lower limbs. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:e551-e553.

3. Castellani A. Researches on elephantiasis nostras and elephantiasis tropica with special regard to their initial stage of recurring lymphangitis (lymphangitis recurrens elephantogenica). J Trop Med Hyg. 1969;72:89-97.

4. Baird D, Bode D, Akers T, et al. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa (ENV): a complication of congestive heart failure and obesity. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23:413-417.

5. Queiroz-Telles F, Fahal AH, Falci R, et. al. Neglected endemic mycoses. Lancet Inf Dis. 2017;17:e367-e377.

6. Han HH, Lim SY, Oh DY. Successful surgical treatment for elephantiasis nostras verrucosa using a new designed column flap. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2015;14:299-302.

Newborn with multiple plaques

Giant congenital nevus was diagnosed in this patient. Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMN) are pigmented lesions that are present at birth and created by the abnormal migration of neural crest cells during embryogenesis. Nevi are categorized by size as small (<1.5 cm), medium (1.5-20 cm), large (>20 cm), or giant (>40 cm).

Congenital nevi tend to start out flat, with uniform pigmentation, but can become more variegated in texture and color as normal growth and development continue. Giant congenital nevi, which are rare, are likely to thicken, darken, and enlarge as the patient grows. Some nevi may develop very coarse or dark hair. CMN can cover any part of the body and occur independent of skin color and other ethnic factors.

CMN may present in almost any location and may be brown, black, pink, or purple in color. Café au lait macules, blue-gray spots, nevus of Ota, nevus spilus, and vascular malformations are part of the differential diagnosis for CMN and have individual location and color characteristics that set them apart clinically.

Patients with CMN are at increased risk for neurocutaneous melanosis (NCM; a melanocyte proliferation in the central nervous system) and melanoma. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is helpful to exclude NCM. Treatment options for patients with large and giant CMN include early curettage, local excision, dermabrasion, and laser therapy. (There is, however, considerable debate about the value of surgery.) The newborn in the case underwent an MRI and the results were normal. At 4 months of age, he hadn’t developed any neurologic symptoms. The child’s nevi continue to grow and he sees his family physician for routine well-child visits and a dermatologist annually to monitor the nevi.

Adapted from: Karnes J, Griffin C. Large plaques on a baby boy. J Fam Pract. 2016;65:407-409.

Giant congenital nevus was diagnosed in this patient. Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMN) are pigmented lesions that are present at birth and created by the abnormal migration of neural crest cells during embryogenesis. Nevi are categorized by size as small (<1.5 cm), medium (1.5-20 cm), large (>20 cm), or giant (>40 cm).

Congenital nevi tend to start out flat, with uniform pigmentation, but can become more variegated in texture and color as normal growth and development continue. Giant congenital nevi, which are rare, are likely to thicken, darken, and enlarge as the patient grows. Some nevi may develop very coarse or dark hair. CMN can cover any part of the body and occur independent of skin color and other ethnic factors.

CMN may present in almost any location and may be brown, black, pink, or purple in color. Café au lait macules, blue-gray spots, nevus of Ota, nevus spilus, and vascular malformations are part of the differential diagnosis for CMN and have individual location and color characteristics that set them apart clinically.

Patients with CMN are at increased risk for neurocutaneous melanosis (NCM; a melanocyte proliferation in the central nervous system) and melanoma. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is helpful to exclude NCM. Treatment options for patients with large and giant CMN include early curettage, local excision, dermabrasion, and laser therapy. (There is, however, considerable debate about the value of surgery.) The newborn in the case underwent an MRI and the results were normal. At 4 months of age, he hadn’t developed any neurologic symptoms. The child’s nevi continue to grow and he sees his family physician for routine well-child visits and a dermatologist annually to monitor the nevi.

Adapted from: Karnes J, Griffin C. Large plaques on a baby boy. J Fam Pract. 2016;65:407-409.

Giant congenital nevus was diagnosed in this patient. Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMN) are pigmented lesions that are present at birth and created by the abnormal migration of neural crest cells during embryogenesis. Nevi are categorized by size as small (<1.5 cm), medium (1.5-20 cm), large (>20 cm), or giant (>40 cm).

Congenital nevi tend to start out flat, with uniform pigmentation, but can become more variegated in texture and color as normal growth and development continue. Giant congenital nevi, which are rare, are likely to thicken, darken, and enlarge as the patient grows. Some nevi may develop very coarse or dark hair. CMN can cover any part of the body and occur independent of skin color and other ethnic factors.

CMN may present in almost any location and may be brown, black, pink, or purple in color. Café au lait macules, blue-gray spots, nevus of Ota, nevus spilus, and vascular malformations are part of the differential diagnosis for CMN and have individual location and color characteristics that set them apart clinically.

Patients with CMN are at increased risk for neurocutaneous melanosis (NCM; a melanocyte proliferation in the central nervous system) and melanoma. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is helpful to exclude NCM. Treatment options for patients with large and giant CMN include early curettage, local excision, dermabrasion, and laser therapy. (There is, however, considerable debate about the value of surgery.) The newborn in the case underwent an MRI and the results were normal. At 4 months of age, he hadn’t developed any neurologic symptoms. The child’s nevi continue to grow and he sees his family physician for routine well-child visits and a dermatologist annually to monitor the nevi.

Adapted from: Karnes J, Griffin C. Large plaques on a baby boy. J Fam Pract. 2016;65:407-409.

Growth on nose

The FP considered several possibilities as part of the differential diagnosis: compound nevus, Spitz nevus, dysplastic nevus, fibrous papule, angiokeratoma, and amelanotic melanoma. A shave biopsy identified the lesion as a Spitz nevus.

Spitz nevi are uncommon solitary pink to black colored dome-shaped papules that usually appear in the first 2 decades of life. They have features that are histologically similar to melanoma and some may, in fact, be Spitzoid melanomas. When a Spitz nevus is suspected, the lesion should be biopsied for histopathologic diagnosis. If the diagnosis is confirmed, the typical treatment is to perform a complete excision with clear margins.

In this case, the pathologist noted that the deep margin was positive and recommended a conservative re-excision. The patient was sent to a dermatologist who fully excised the lesion with no complications.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M, Usatine R. Benign nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:945-952.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP considered several possibilities as part of the differential diagnosis: compound nevus, Spitz nevus, dysplastic nevus, fibrous papule, angiokeratoma, and amelanotic melanoma. A shave biopsy identified the lesion as a Spitz nevus.

Spitz nevi are uncommon solitary pink to black colored dome-shaped papules that usually appear in the first 2 decades of life. They have features that are histologically similar to melanoma and some may, in fact, be Spitzoid melanomas. When a Spitz nevus is suspected, the lesion should be biopsied for histopathologic diagnosis. If the diagnosis is confirmed, the typical treatment is to perform a complete excision with clear margins.

In this case, the pathologist noted that the deep margin was positive and recommended a conservative re-excision. The patient was sent to a dermatologist who fully excised the lesion with no complications.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M, Usatine R. Benign nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:945-952.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP considered several possibilities as part of the differential diagnosis: compound nevus, Spitz nevus, dysplastic nevus, fibrous papule, angiokeratoma, and amelanotic melanoma. A shave biopsy identified the lesion as a Spitz nevus.

Spitz nevi are uncommon solitary pink to black colored dome-shaped papules that usually appear in the first 2 decades of life. They have features that are histologically similar to melanoma and some may, in fact, be Spitzoid melanomas. When a Spitz nevus is suspected, the lesion should be biopsied for histopathologic diagnosis. If the diagnosis is confirmed, the typical treatment is to perform a complete excision with clear margins.

In this case, the pathologist noted that the deep margin was positive and recommended a conservative re-excision. The patient was sent to a dermatologist who fully excised the lesion with no complications.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M, Usatine R. Benign nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:945-952.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Dark patch on leg

The FP recognized this to be a nevus spilus (speckled nevus).

He explained that this was a benign nevus and that no treatment was indicated—especially because the only effective treatment would be deep excision down to the subcutaneous fat layer (requiring a graft for closure). The patient probably wouldn’t like the cosmetic result and the risks of this surgery (pain, infection, graft not taking) are not acceptable for this condition. Also, the procedure would not be covered by insurance, as this would be considered cosmetic surgery.

The physician explained that in the unlikely event of significant changes in the nevus, she should seek further evaluation. The patient understood the reality of the situation and thanked the doctor for explaining the diagnosis to her. She was reassured that this was benign.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M, Usatine R. Benign nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:945-952.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP recognized this to be a nevus spilus (speckled nevus).

He explained that this was a benign nevus and that no treatment was indicated—especially because the only effective treatment would be deep excision down to the subcutaneous fat layer (requiring a graft for closure). The patient probably wouldn’t like the cosmetic result and the risks of this surgery (pain, infection, graft not taking) are not acceptable for this condition. Also, the procedure would not be covered by insurance, as this would be considered cosmetic surgery.

The physician explained that in the unlikely event of significant changes in the nevus, she should seek further evaluation. The patient understood the reality of the situation and thanked the doctor for explaining the diagnosis to her. She was reassured that this was benign.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M, Usatine R. Benign nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:945-952.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP recognized this to be a nevus spilus (speckled nevus).

He explained that this was a benign nevus and that no treatment was indicated—especially because the only effective treatment would be deep excision down to the subcutaneous fat layer (requiring a graft for closure). The patient probably wouldn’t like the cosmetic result and the risks of this surgery (pain, infection, graft not taking) are not acceptable for this condition. Also, the procedure would not be covered by insurance, as this would be considered cosmetic surgery.

The physician explained that in the unlikely event of significant changes in the nevus, she should seek further evaluation. The patient understood the reality of the situation and thanked the doctor for explaining the diagnosis to her. She was reassured that this was benign.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M, Usatine R. Benign nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:945-952.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.