User login

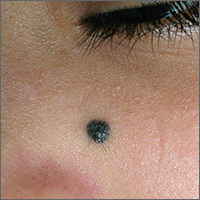

Dark mole on face

The physician suspected that this was a benign blue nevus because it had a regular border and was uniformly dark in color. He also recognized that melanoma is very rare at age 19. That said, it is hard to ignore a changing mole that is so black in color.

The patient wanted it removed, so a 5-mm punch biopsy was performed. (See the Watch and Learn video on punch biopsy.)

When the punch core was removed, the physician noted that the pigment was visible in the deep dermis (as expected with a blue nevus). A single suture was placed, and the patient was scheduled for follow-up in one week. The pathology report came back as a blue nevus, which is completely benign.

While many blue nevi actually appear blue because of the Tyndall effect causing the dark melanin in the deep dermis to create a blue coloration, some will appear black (as was seen in this case). On the follow-up visit, the suture was removed and the incision was healing well. The patient was reassured that this was a benign mole and was happy with the cosmetic result.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M, Usatine R. Benign nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:945-952.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The physician suspected that this was a benign blue nevus because it had a regular border and was uniformly dark in color. He also recognized that melanoma is very rare at age 19. That said, it is hard to ignore a changing mole that is so black in color.

The patient wanted it removed, so a 5-mm punch biopsy was performed. (See the Watch and Learn video on punch biopsy.)

When the punch core was removed, the physician noted that the pigment was visible in the deep dermis (as expected with a blue nevus). A single suture was placed, and the patient was scheduled for follow-up in one week. The pathology report came back as a blue nevus, which is completely benign.

While many blue nevi actually appear blue because of the Tyndall effect causing the dark melanin in the deep dermis to create a blue coloration, some will appear black (as was seen in this case). On the follow-up visit, the suture was removed and the incision was healing well. The patient was reassured that this was a benign mole and was happy with the cosmetic result.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M, Usatine R. Benign nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:945-952.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The physician suspected that this was a benign blue nevus because it had a regular border and was uniformly dark in color. He also recognized that melanoma is very rare at age 19. That said, it is hard to ignore a changing mole that is so black in color.

The patient wanted it removed, so a 5-mm punch biopsy was performed. (See the Watch and Learn video on punch biopsy.)

When the punch core was removed, the physician noted that the pigment was visible in the deep dermis (as expected with a blue nevus). A single suture was placed, and the patient was scheduled for follow-up in one week. The pathology report came back as a blue nevus, which is completely benign.

While many blue nevi actually appear blue because of the Tyndall effect causing the dark melanin in the deep dermis to create a blue coloration, some will appear black (as was seen in this case). On the follow-up visit, the suture was removed and the incision was healing well. The patient was reassured that this was a benign mole and was happy with the cosmetic result.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M, Usatine R. Benign nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:945-952.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Diffuse erythematous rash resistant to treatment

A 39-year-old woman presented to the emergency department for evaluation of diffuse redness, itching, and tenderness of her skin. The patient said the eruption began 4 months earlier as localized plaques on her scalp, elbows, and beneath both breasts. Over the course of a few days, the redness became more diffuse, affecting most of her body. She also noticed swelling and skin desquamation on her lower extremities.

The patient had visited multiple urgent care clinics and underwent several courses of prednisone with initial improvement of symptoms, but experienced recurrence shortly after finishing the tapers.

On physical examination, more than 95% of the patient’s skin was bright red and tender to the touch, with associated exfoliation (FIGURES 1A-1B). Her lower extremities had pitting edema with superficial erosions that were weeping serous fluid. She was afebrile and normotensive, but had shaking chills and was tachycardic, with a heart rate of 115 bpm. There was no nail pitting, pustules, or lymphadenopathy. Lab tests revealed a low albumin level of 2.2 g/dL (normal: 3.5-5.5 g/dL), an elevated white blood cell count of 14,700 cells/mcL (normal: 4500-11,000 cells/mcL), and normocytic anemia (low hemoglobin of 8.7 g/dL; normal: 12-15.5 g/dL). The patient was admitted.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythroderma

Based on the patient’s clinical presentation, we diagnosed severe erythroderma secondary to psoriasis. A punch biopsy was performed, and pathology demonstrated subacute spongiotic dermatitis with superficial neutrophilic infiltrates, consistent with psoriasis.

Erythroderma is widespread reddening of the skin associated with desquamation, typically involving more than 90% of the body’s surface area.1 In most instances, erythroderma is a clinical presentation of an existing dermatosis. The most common causative conditions include primary skin disorders (such as psoriasis or atopic dermatitis), idiopathic erythroderma, and drug eruptions. Less common causes include cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, pityriasis rubra pilaris, and contact dermatitis.1

It’s unclear why some skin diseases progress to erythroderma; the pathogenesis is complicated and involves keratinocytes and lymphocytes interacting with adhesion molecules and cytokines. Erythroderma can arise at any age and occurs in all races, but is more common in males and older adults, with a mean age of 42 to 61 years.2 The annual incidence of erythroderma is estimated to be one per 100,000 adults.3

A complete picture of the patient is essential to making the diagnosis

Diagnosis can be difficult and hinges on historical and physical exam findings, as well as lab evaluations and skin biopsies. The history should focus on current and former medications, while the physical exam should hone in on clinical manifestations of existing dermatoses. The most common extracutaneous finding is generalized lymphadenopathy, which if prominent, may warrant lymph node biopsy, with studies for evaluation of underlying lymphoma.

Tachycardia develops in 40% of patients, secondary to increased blood flow to the skin and fluid loss, with risk of high-output cardiac failure.2 Patients often have chills because their skin is not able to regulate their body temperature normally.4

The lab evaluation should include a complete blood count with differential and a comprehensive metabolic panel, as well as blood, skin, and urine cultures if infection is suspected as an inciting factor. Typical findings include mild anemia, leukocytosis, eosinophilia, and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate.5 In addition, patients with chronic erythroderma commonly have low albumin.6 Unfortunately, lab studies don’t always reveal the underlying cause of the erythroderma.

Biopsies are commonly performed. However, the underlying etiology is often not clearly reflected in the result. Histology is typically nonspecific; findings frequently include hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, spongiosis, and perivascular inflammatory infiltrate. Additionally, the prominence of histologic features may vary depending on the stage of disease and the severity of inflammation. More specific findings may become evident later in the disease as the erythroderma clears, so repeated skin biopsies over time may be needed for diagnosis.7

Consider these conditions, which can lead to erythroderma

First and foremost, it is important to get a thorough history, particularly about prior skin conditions and symptoms that may indicate the presence of undiagnosed skin conditions.

Psoriasis is one of the most common causes of erythroderma. A history of pre-existing psoriasis is very helpful, but when this is not present, a biopsy can help confirm a clinical suspicion for psoriasis. It also helps to look for clues of psoriasis like nail changes or a history of plaques over the elbows and knees.

Atopic dermatitis is another common cause of erythroderma, and the history might include scaling and erythematous patches or plaques involving flexural surfaces before erythroderma occurs. Patients may have a history of atopic dermatitis from childhood and/or a history of other atopic conditions such as asthma and allergic rhinitis.

Drug eruptions occur following the administration of a new medication and can mimic a myriad of dermatoses.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma can lead to erythroderma and be differentiated with skin biopsy; pathology may show atypical lymphocytes, and Pautrier’s microabscesses may be seen.8

Pityriasis rubra pilaris is a relatively rare condition that presents with red-orange scaling patches and thickened yellowish palms and soles.9

Tx targets underlying etiology and associated complications

When treating a patient with erythroderma, it’s important to prevent hypothermia and secondary infections. If symptoms are severe, hospitalization should be considered. Nutrition should be assessed, and any fluid or electrolyte imbalances should be corrected.

Oral antihistamines are commonly administered to suppress associated pruritus. Topical treatment usually consists of corticosteroids under occlusion with bland emollients. Depending upon the underlying disease, the following systemic medications may be started: methotrexate 7.5 to 15 mg once/week; acitretin 10 to 25 mg/d; or cyclosporine 2.5 to 5 mg/kg/d; in addition to topical treatment.4

Our patient. Pathology for our patient was indicative of psoriasis. She was started on a regimen of cyclosporine 4 to 5 mg/kg/d, diphenhydramine 25 to 50 mg as needed for itching, triamcinolone 0.1% ointment under wet wraps to her trunk and extremities, and hydrocortisone 2.5% ointment to be applied to her face daily. She was released after 5 days in the hospital. At outpatient follow-up one week later, her erythroderma was resolving. One month later, her erythroderma was resolved (FIGURE 2), although she did have psoriatic plaques on her lower legs.

CORRESPONDENCE

Richard P. Usatine, MD, University of Texas Health San Antonio, 7703 Floyd Curl Dr., San Antonio, TX 78229; [email protected].

1. Keisham C, Sahoo B, Khurana N, et al. Clinicopathologic study of erythroderma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:AB85.

2. Li J, Zheng H-Y. Erythroderma: a clinical and prognostic study. Dermatology. 2012;225:154-162.

3. Sigurdsson V, Steegmans PH, van Vioten WA. The incidence of erythroderma: a survey among all dermatologists in The Netherlands. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:675-678.

4. Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Duncan K, et al. Dermatology essentials. 1st ed. Oxford, England: Elsevier Saunders; 2014.

5. Karakayli G, Beckham G, Orengo I, et al. Exfoliative dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 1999;59:625-630.

6. Rothe MJ, Bialy TL, Grant-Kels JM. Erythroderma. Dermatol Clin. 2000;18:405-415.

7. Walsh NM, Prokopetz R, Tron VA, et al. Histopathology in erythroderma: review of a series of cases by multiple observers. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:419-423.

8. Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part I. Diagnosis: clinical and histopathologic features and new molecular and biologic markers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:205.e1-e16.

9. Abdel-Azim NE, Ismail SA, Fathy E. Differentiation of pityriasis rubra pilaris from plaque psoriasis by dermoscopy. Arch Dermatol Res. 2017;309:311-314.

A 39-year-old woman presented to the emergency department for evaluation of diffuse redness, itching, and tenderness of her skin. The patient said the eruption began 4 months earlier as localized plaques on her scalp, elbows, and beneath both breasts. Over the course of a few days, the redness became more diffuse, affecting most of her body. She also noticed swelling and skin desquamation on her lower extremities.

The patient had visited multiple urgent care clinics and underwent several courses of prednisone with initial improvement of symptoms, but experienced recurrence shortly after finishing the tapers.

On physical examination, more than 95% of the patient’s skin was bright red and tender to the touch, with associated exfoliation (FIGURES 1A-1B). Her lower extremities had pitting edema with superficial erosions that were weeping serous fluid. She was afebrile and normotensive, but had shaking chills and was tachycardic, with a heart rate of 115 bpm. There was no nail pitting, pustules, or lymphadenopathy. Lab tests revealed a low albumin level of 2.2 g/dL (normal: 3.5-5.5 g/dL), an elevated white blood cell count of 14,700 cells/mcL (normal: 4500-11,000 cells/mcL), and normocytic anemia (low hemoglobin of 8.7 g/dL; normal: 12-15.5 g/dL). The patient was admitted.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythroderma

Based on the patient’s clinical presentation, we diagnosed severe erythroderma secondary to psoriasis. A punch biopsy was performed, and pathology demonstrated subacute spongiotic dermatitis with superficial neutrophilic infiltrates, consistent with psoriasis.

Erythroderma is widespread reddening of the skin associated with desquamation, typically involving more than 90% of the body’s surface area.1 In most instances, erythroderma is a clinical presentation of an existing dermatosis. The most common causative conditions include primary skin disorders (such as psoriasis or atopic dermatitis), idiopathic erythroderma, and drug eruptions. Less common causes include cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, pityriasis rubra pilaris, and contact dermatitis.1

It’s unclear why some skin diseases progress to erythroderma; the pathogenesis is complicated and involves keratinocytes and lymphocytes interacting with adhesion molecules and cytokines. Erythroderma can arise at any age and occurs in all races, but is more common in males and older adults, with a mean age of 42 to 61 years.2 The annual incidence of erythroderma is estimated to be one per 100,000 adults.3

A complete picture of the patient is essential to making the diagnosis

Diagnosis can be difficult and hinges on historical and physical exam findings, as well as lab evaluations and skin biopsies. The history should focus on current and former medications, while the physical exam should hone in on clinical manifestations of existing dermatoses. The most common extracutaneous finding is generalized lymphadenopathy, which if prominent, may warrant lymph node biopsy, with studies for evaluation of underlying lymphoma.

Tachycardia develops in 40% of patients, secondary to increased blood flow to the skin and fluid loss, with risk of high-output cardiac failure.2 Patients often have chills because their skin is not able to regulate their body temperature normally.4

The lab evaluation should include a complete blood count with differential and a comprehensive metabolic panel, as well as blood, skin, and urine cultures if infection is suspected as an inciting factor. Typical findings include mild anemia, leukocytosis, eosinophilia, and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate.5 In addition, patients with chronic erythroderma commonly have low albumin.6 Unfortunately, lab studies don’t always reveal the underlying cause of the erythroderma.

Biopsies are commonly performed. However, the underlying etiology is often not clearly reflected in the result. Histology is typically nonspecific; findings frequently include hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, spongiosis, and perivascular inflammatory infiltrate. Additionally, the prominence of histologic features may vary depending on the stage of disease and the severity of inflammation. More specific findings may become evident later in the disease as the erythroderma clears, so repeated skin biopsies over time may be needed for diagnosis.7

Consider these conditions, which can lead to erythroderma

First and foremost, it is important to get a thorough history, particularly about prior skin conditions and symptoms that may indicate the presence of undiagnosed skin conditions.

Psoriasis is one of the most common causes of erythroderma. A history of pre-existing psoriasis is very helpful, but when this is not present, a biopsy can help confirm a clinical suspicion for psoriasis. It also helps to look for clues of psoriasis like nail changes or a history of plaques over the elbows and knees.

Atopic dermatitis is another common cause of erythroderma, and the history might include scaling and erythematous patches or plaques involving flexural surfaces before erythroderma occurs. Patients may have a history of atopic dermatitis from childhood and/or a history of other atopic conditions such as asthma and allergic rhinitis.

Drug eruptions occur following the administration of a new medication and can mimic a myriad of dermatoses.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma can lead to erythroderma and be differentiated with skin biopsy; pathology may show atypical lymphocytes, and Pautrier’s microabscesses may be seen.8

Pityriasis rubra pilaris is a relatively rare condition that presents with red-orange scaling patches and thickened yellowish palms and soles.9

Tx targets underlying etiology and associated complications

When treating a patient with erythroderma, it’s important to prevent hypothermia and secondary infections. If symptoms are severe, hospitalization should be considered. Nutrition should be assessed, and any fluid or electrolyte imbalances should be corrected.

Oral antihistamines are commonly administered to suppress associated pruritus. Topical treatment usually consists of corticosteroids under occlusion with bland emollients. Depending upon the underlying disease, the following systemic medications may be started: methotrexate 7.5 to 15 mg once/week; acitretin 10 to 25 mg/d; or cyclosporine 2.5 to 5 mg/kg/d; in addition to topical treatment.4

Our patient. Pathology for our patient was indicative of psoriasis. She was started on a regimen of cyclosporine 4 to 5 mg/kg/d, diphenhydramine 25 to 50 mg as needed for itching, triamcinolone 0.1% ointment under wet wraps to her trunk and extremities, and hydrocortisone 2.5% ointment to be applied to her face daily. She was released after 5 days in the hospital. At outpatient follow-up one week later, her erythroderma was resolving. One month later, her erythroderma was resolved (FIGURE 2), although she did have psoriatic plaques on her lower legs.

CORRESPONDENCE

Richard P. Usatine, MD, University of Texas Health San Antonio, 7703 Floyd Curl Dr., San Antonio, TX 78229; [email protected].

A 39-year-old woman presented to the emergency department for evaluation of diffuse redness, itching, and tenderness of her skin. The patient said the eruption began 4 months earlier as localized plaques on her scalp, elbows, and beneath both breasts. Over the course of a few days, the redness became more diffuse, affecting most of her body. She also noticed swelling and skin desquamation on her lower extremities.

The patient had visited multiple urgent care clinics and underwent several courses of prednisone with initial improvement of symptoms, but experienced recurrence shortly after finishing the tapers.

On physical examination, more than 95% of the patient’s skin was bright red and tender to the touch, with associated exfoliation (FIGURES 1A-1B). Her lower extremities had pitting edema with superficial erosions that were weeping serous fluid. She was afebrile and normotensive, but had shaking chills and was tachycardic, with a heart rate of 115 bpm. There was no nail pitting, pustules, or lymphadenopathy. Lab tests revealed a low albumin level of 2.2 g/dL (normal: 3.5-5.5 g/dL), an elevated white blood cell count of 14,700 cells/mcL (normal: 4500-11,000 cells/mcL), and normocytic anemia (low hemoglobin of 8.7 g/dL; normal: 12-15.5 g/dL). The patient was admitted.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythroderma

Based on the patient’s clinical presentation, we diagnosed severe erythroderma secondary to psoriasis. A punch biopsy was performed, and pathology demonstrated subacute spongiotic dermatitis with superficial neutrophilic infiltrates, consistent with psoriasis.

Erythroderma is widespread reddening of the skin associated with desquamation, typically involving more than 90% of the body’s surface area.1 In most instances, erythroderma is a clinical presentation of an existing dermatosis. The most common causative conditions include primary skin disorders (such as psoriasis or atopic dermatitis), idiopathic erythroderma, and drug eruptions. Less common causes include cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, pityriasis rubra pilaris, and contact dermatitis.1

It’s unclear why some skin diseases progress to erythroderma; the pathogenesis is complicated and involves keratinocytes and lymphocytes interacting with adhesion molecules and cytokines. Erythroderma can arise at any age and occurs in all races, but is more common in males and older adults, with a mean age of 42 to 61 years.2 The annual incidence of erythroderma is estimated to be one per 100,000 adults.3

A complete picture of the patient is essential to making the diagnosis

Diagnosis can be difficult and hinges on historical and physical exam findings, as well as lab evaluations and skin biopsies. The history should focus on current and former medications, while the physical exam should hone in on clinical manifestations of existing dermatoses. The most common extracutaneous finding is generalized lymphadenopathy, which if prominent, may warrant lymph node biopsy, with studies for evaluation of underlying lymphoma.

Tachycardia develops in 40% of patients, secondary to increased blood flow to the skin and fluid loss, with risk of high-output cardiac failure.2 Patients often have chills because their skin is not able to regulate their body temperature normally.4

The lab evaluation should include a complete blood count with differential and a comprehensive metabolic panel, as well as blood, skin, and urine cultures if infection is suspected as an inciting factor. Typical findings include mild anemia, leukocytosis, eosinophilia, and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate.5 In addition, patients with chronic erythroderma commonly have low albumin.6 Unfortunately, lab studies don’t always reveal the underlying cause of the erythroderma.

Biopsies are commonly performed. However, the underlying etiology is often not clearly reflected in the result. Histology is typically nonspecific; findings frequently include hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, spongiosis, and perivascular inflammatory infiltrate. Additionally, the prominence of histologic features may vary depending on the stage of disease and the severity of inflammation. More specific findings may become evident later in the disease as the erythroderma clears, so repeated skin biopsies over time may be needed for diagnosis.7

Consider these conditions, which can lead to erythroderma

First and foremost, it is important to get a thorough history, particularly about prior skin conditions and symptoms that may indicate the presence of undiagnosed skin conditions.

Psoriasis is one of the most common causes of erythroderma. A history of pre-existing psoriasis is very helpful, but when this is not present, a biopsy can help confirm a clinical suspicion for psoriasis. It also helps to look for clues of psoriasis like nail changes or a history of plaques over the elbows and knees.

Atopic dermatitis is another common cause of erythroderma, and the history might include scaling and erythematous patches or plaques involving flexural surfaces before erythroderma occurs. Patients may have a history of atopic dermatitis from childhood and/or a history of other atopic conditions such as asthma and allergic rhinitis.

Drug eruptions occur following the administration of a new medication and can mimic a myriad of dermatoses.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma can lead to erythroderma and be differentiated with skin biopsy; pathology may show atypical lymphocytes, and Pautrier’s microabscesses may be seen.8

Pityriasis rubra pilaris is a relatively rare condition that presents with red-orange scaling patches and thickened yellowish palms and soles.9

Tx targets underlying etiology and associated complications

When treating a patient with erythroderma, it’s important to prevent hypothermia and secondary infections. If symptoms are severe, hospitalization should be considered. Nutrition should be assessed, and any fluid or electrolyte imbalances should be corrected.

Oral antihistamines are commonly administered to suppress associated pruritus. Topical treatment usually consists of corticosteroids under occlusion with bland emollients. Depending upon the underlying disease, the following systemic medications may be started: methotrexate 7.5 to 15 mg once/week; acitretin 10 to 25 mg/d; or cyclosporine 2.5 to 5 mg/kg/d; in addition to topical treatment.4

Our patient. Pathology for our patient was indicative of psoriasis. She was started on a regimen of cyclosporine 4 to 5 mg/kg/d, diphenhydramine 25 to 50 mg as needed for itching, triamcinolone 0.1% ointment under wet wraps to her trunk and extremities, and hydrocortisone 2.5% ointment to be applied to her face daily. She was released after 5 days in the hospital. At outpatient follow-up one week later, her erythroderma was resolving. One month later, her erythroderma was resolved (FIGURE 2), although she did have psoriatic plaques on her lower legs.

CORRESPONDENCE

Richard P. Usatine, MD, University of Texas Health San Antonio, 7703 Floyd Curl Dr., San Antonio, TX 78229; [email protected].

1. Keisham C, Sahoo B, Khurana N, et al. Clinicopathologic study of erythroderma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:AB85.

2. Li J, Zheng H-Y. Erythroderma: a clinical and prognostic study. Dermatology. 2012;225:154-162.

3. Sigurdsson V, Steegmans PH, van Vioten WA. The incidence of erythroderma: a survey among all dermatologists in The Netherlands. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:675-678.

4. Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Duncan K, et al. Dermatology essentials. 1st ed. Oxford, England: Elsevier Saunders; 2014.

5. Karakayli G, Beckham G, Orengo I, et al. Exfoliative dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 1999;59:625-630.

6. Rothe MJ, Bialy TL, Grant-Kels JM. Erythroderma. Dermatol Clin. 2000;18:405-415.

7. Walsh NM, Prokopetz R, Tron VA, et al. Histopathology in erythroderma: review of a series of cases by multiple observers. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:419-423.

8. Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part I. Diagnosis: clinical and histopathologic features and new molecular and biologic markers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:205.e1-e16.

9. Abdel-Azim NE, Ismail SA, Fathy E. Differentiation of pityriasis rubra pilaris from plaque psoriasis by dermoscopy. Arch Dermatol Res. 2017;309:311-314.

1. Keisham C, Sahoo B, Khurana N, et al. Clinicopathologic study of erythroderma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:AB85.

2. Li J, Zheng H-Y. Erythroderma: a clinical and prognostic study. Dermatology. 2012;225:154-162.

3. Sigurdsson V, Steegmans PH, van Vioten WA. The incidence of erythroderma: a survey among all dermatologists in The Netherlands. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:675-678.

4. Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Duncan K, et al. Dermatology essentials. 1st ed. Oxford, England: Elsevier Saunders; 2014.

5. Karakayli G, Beckham G, Orengo I, et al. Exfoliative dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 1999;59:625-630.

6. Rothe MJ, Bialy TL, Grant-Kels JM. Erythroderma. Dermatol Clin. 2000;18:405-415.

7. Walsh NM, Prokopetz R, Tron VA, et al. Histopathology in erythroderma: review of a series of cases by multiple observers. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:419-423.

8. Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part I. Diagnosis: clinical and histopathologic features and new molecular and biologic markers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:205.e1-e16.

9. Abdel-Azim NE, Ismail SA, Fathy E. Differentiation of pityriasis rubra pilaris from plaque psoriasis by dermoscopy. Arch Dermatol Res. 2017;309:311-314.

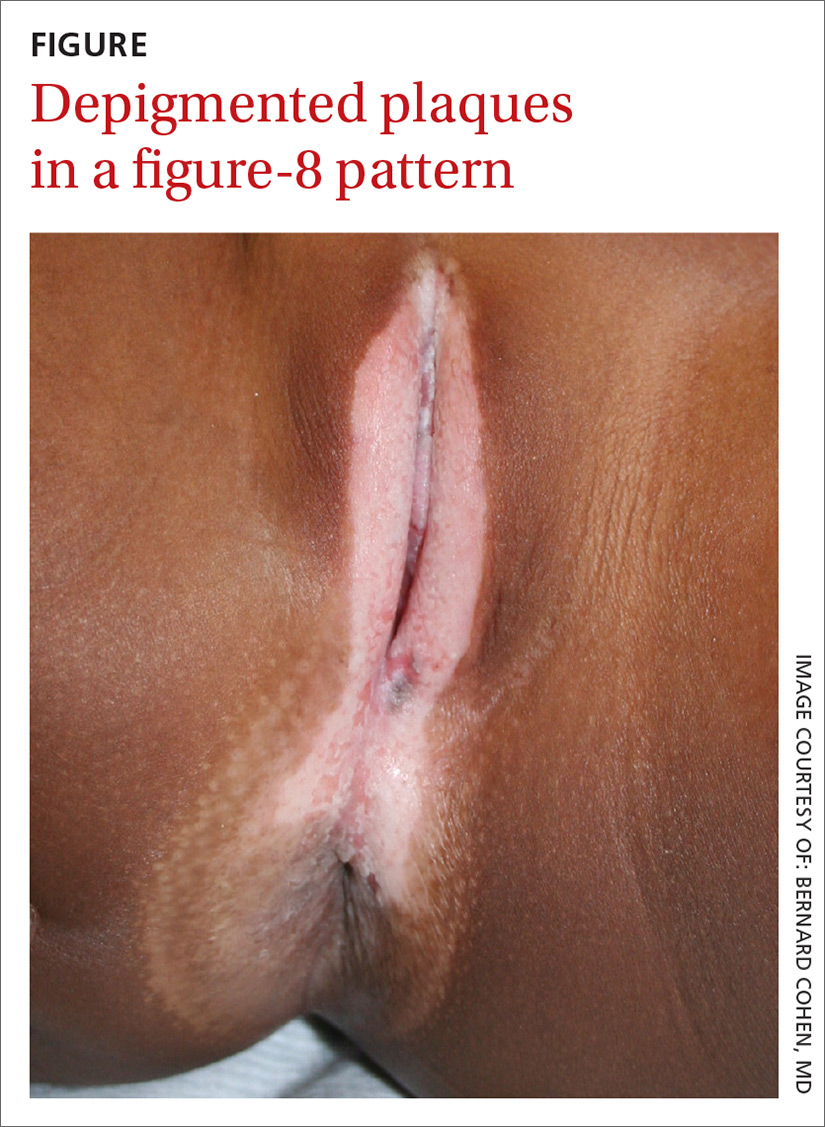

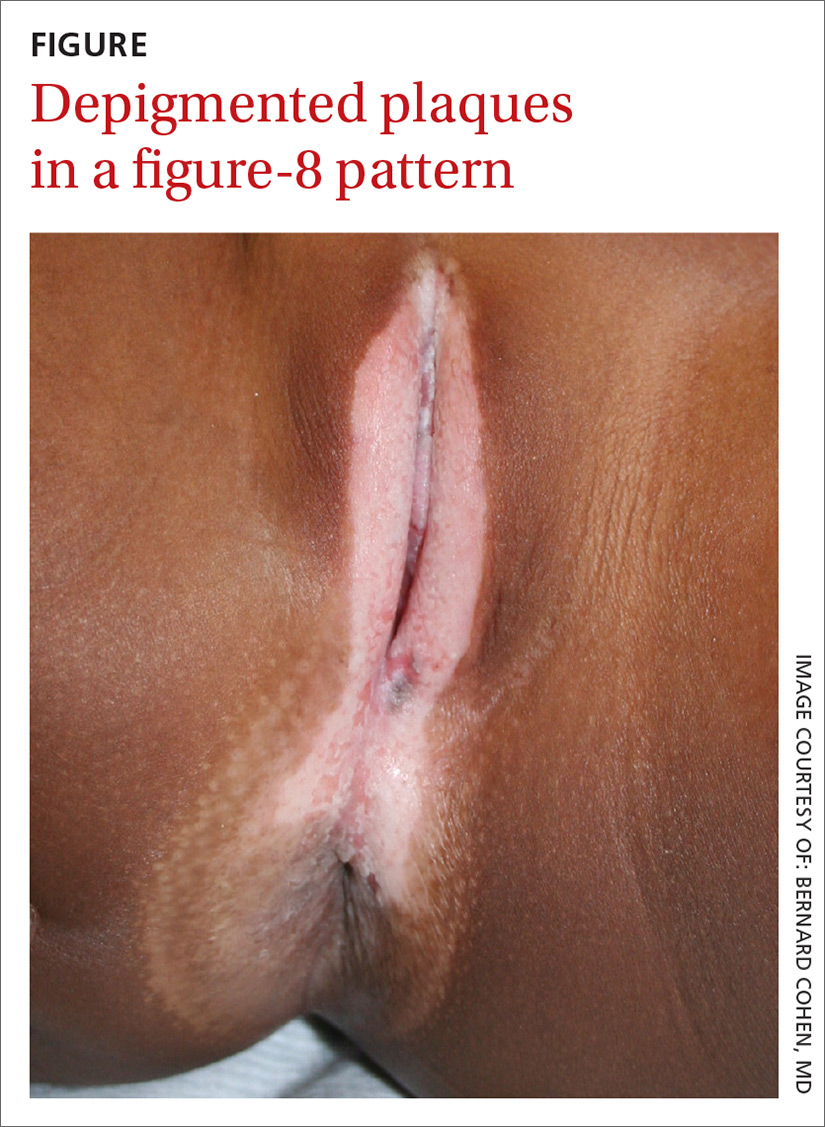

Depigmented plaques on vulva

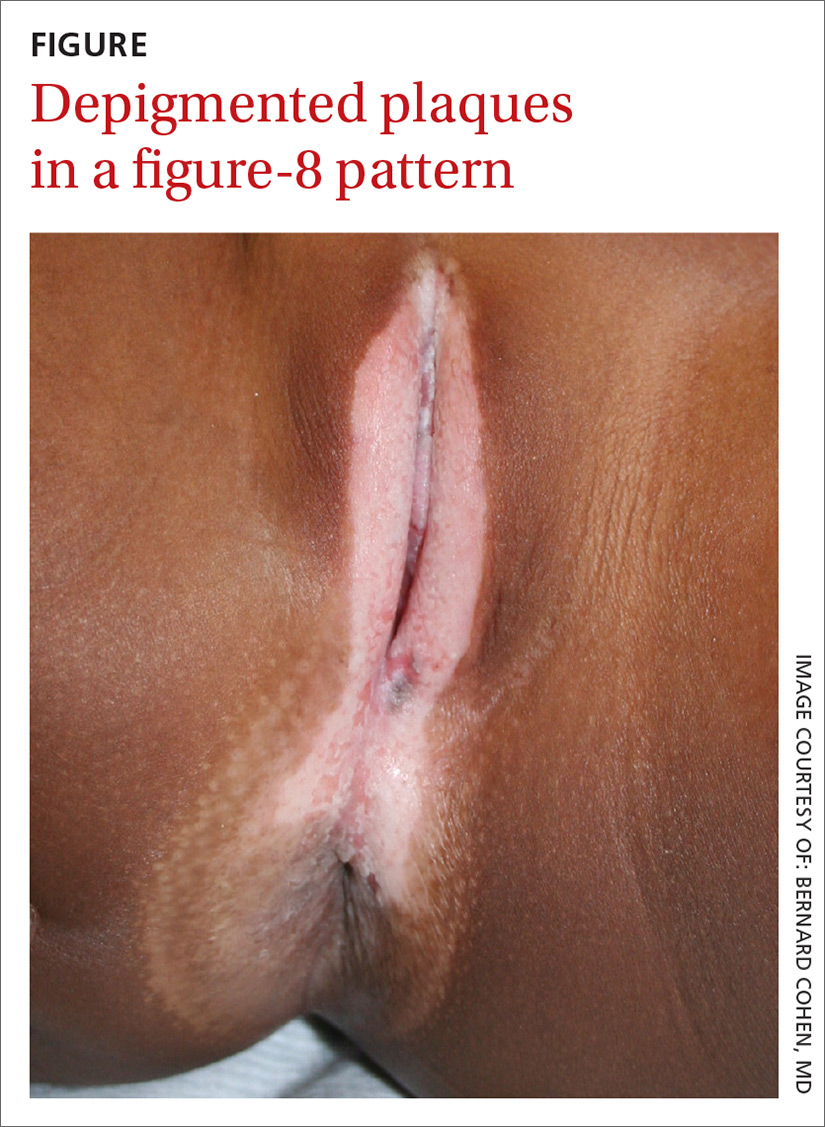

A mother brought her 8-year-old daughter to our office for evaluation of vitiligo “down there” (FIGURE). The skin eruption first appeared on her vulva a year earlier and was intermittently pruritic. The lesions were initially smaller and red, but had since lightened in color, coalesced, and had begun to spread to the perianal area. The patient’s mother had received a call from her daughter’s teacher who observed that her daughter was scratching the area and might be masturbating in class.

The mother reported that 6 months earlier, her daughter had experienced bloody spots in her underwear accompanied by dysuria. The mother brought her to the emergency department, where she was treated with antibiotics for a urinary tract infection.

Our physical examination revealed well-circumscribed, symmetric, depigmented, confluent, crinkled, parchment-like plaques with small hemorrhagic erosions on the medial labia majora and minora. The lesions had spread to the perianal area with depigmentation superiorly and hypopigmentation inferiorly, creating a figure-8 pattern.

A review of systems was negative for pruritus, pain, dysuria, dyschezia, constipation, and vaginal discharge. The patient denied sexual activity, depression, or anxiety. Her mother denied behavioral changes in her daughter and said that her daughter hadn’t had any one-on-one time alone with any adults besides herself. Her mother was concerned that the white spots might spread to the rest of her daughter’s body, which could affect her socially.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Lichen sclerosus

Based on the history and clinical findings, including the classic figure-8 pattern, we diagnosed childhood lichen sclerosus (LS) in this patient. LS is a chronic inflammatory skin disorder that primarily affects the genital mucosa. The disorder can present at any age, but is most common among postmenopausal women, with a prevalence estimated to be as high as one in 30.1-3 A second incidence peak is observed in prepubescent girls, with a prevalence of one in 900.3,4 LS is less common in men and boys, with a female-to-male ratio that can reach 10:1.5 The classic symptoms of LS are pruritus and pain, which may be intermittent or persistent.

In girls, initial manifestations may be constipation, dysuria, or even behavioral symptoms such as night fears, which can occur because children are less active at night and become more aware of urinary discomfort.1,2,6 Typical signs of LS are thin atrophic plaques that spare the vagina and cervix. The plaques can be ivory-white, erythematous, or violaceous. Some patients have perianal lesions as well, and can display the pathognomonic figure-8 pattern of porcelain plaques around the vulva and anus.5

With more advanced disease, erosions, lichenification, and even distortion of vulvar architecture may occur.2,4,7 In severe cases, labia resorption and clitoral phimosis may develop.5 Complications include secondary infection, dyspareunia, and psychosexual distress. The most worrisome sequela of LS is squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva (SCCV), which occurs in 5% of female patients with LS.4

In men and boys, LS typically involves the foreskin and the glans, while sparing the perianal region.5 Scarring of the foreskin can lead to phimosis, and patients may complain of painful erections and difficulty urinating. LS can also occur away from the genitalia in both males and females.

Autoimmune mechanisms, genetics, and hormones play a role

The exact pathogenesis of LS remains unknown, but multiple factors are likely at work.

Autoimmune mechanisms. Up to 60% of women with LS have an autoimmune disorder, which is most commonly vitiligo, alopecia areata, or thyroid disease.5 In addition, 67% of patients have autoantibodies against extracellular matrix protein 1, and 30% have them against bullous pemphigoid antigen 180.1,8

Genetics. LS is associated with certain human leukocyte antigen class II haplotypes (especially DQ7) and with polymorphisms at the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist gene locus.5,6,9

Hormones. The clear peaks of incidence during times of low estrogen, and a higher incidence in patients with Turner syndrome or kidney disease, suggest that low estrogen may play a role in the development of LS, as well.1,5,6

While it is generally accepted that trauma may trigger LS via the Koebner phenomenon (the appearance of lesions at the site of injury), there is debate as to whether microbes—especially Borrelia burgdorferi and human papillomavirus (HPV)—might play a role.1,5

Diagnosis is often delayed, misdiagnosis is common

The average delay from symptom onset to diagnosis of LS is 1.3 years, and up to 84% of childhood LS is misdiagnosed before referral.2,9 The differential diagnosis includes:

Sexual abuse. In prepubertal girls presenting with genital redness, the can’t-miss diagnosis is sexual abuse, which occurs in more than 25% of children in the United States.10 Initial manifestations may be regression in developmental milestones, such as new-onset bedwetting, or behavioral changes such as social withdrawal or declining academic performance.11

However, physicians must be conscientious about ruling out medical etiologies before prematurely diagnosing abuse. Fourteen percent of girls with LS are incorrectly diagnosed as having been sexually abused.2 A clinical pearl is that while LS may resemble abuse on exam, it rarely affects the hymenal structure.12 It is also important to keep in mind that the 2 entities are not incompatible, as sexual abuse leading to LS via Koebnerization is a well-described phenomenon.12

Lichen planus. LP, which is also an immune-mediated inflammatory disorder affecting the vulva, classically presents with the 6 Ps: pruritic, polygonal, planar, purple papules and plaques.4 LP is distinguished from LS by being rare in childhood, having a predilection for the flexor wrists, and involving the oral and vaginal mucosa.4

Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) is a chronic, circumscribed, pruritic, eczematous condition that becomes lichenified with thickened skin secondary to repeated scratching.13 Children with atopic dermatitis can develop LSC, but other children can also develop the scratch-itch cycle that results in the thickened plaques of LSC. Like LS, LSC can occur in areas other than the genitalia, including the neck and feet.14

Allergic contact dermatitis can occur in the genital area from diaper creams, soaps, and perfumes. Irritant contact dermatitis can occur from exposure to diarrhea, bedwetting, and other irritants. Contact dermatitis is less likely to have the classic figure-8 pattern seen in LS.

Psoriasis in the genital area can be confused with LS. However, psoriasis favors the groin creases in what is called inverse psoriasis. In addition, psoriasis tends to involve multiple areas, including the extensor surfaces of the elbows and knees, the nails, and the scalp.

Vitiligo can present on the genitals as circumscribed hypopigmented and depigmented patches that are flat. Vitiligo is asymptomatic, and the only pathology is the change in skin color. With LS, there is lichenification, atrophy, and sclerosis.4 Vitiligo often occurs with bilateral symmetric involvement in areas of trauma including the face, neck, scalp, elbows, wrists, hands, knees, ankles, and feet.

Treatment aims to improve symptoms

LS is usually diagnosed clinically (especially in children, as a biopsy is a great challenge to perform). However, when the clinical presentation is unclear, a skin biopsy will demonstrate the diagnostic findings of thinning of the epidermis, loss of rete pegs, hyperkeratosis, and dermal fibrosis with a T-lymphocyte-dominant inflammatory infiltrate.1,2,4,5

LS is a remitting and relapsing condition with no cure. The goals of treatment are to provide symptom relief and minimize scarring and atrophy,2 but it is unknown whether treatment reduces the risk of malignancy.9

First-line treatment for both genders and all ages is ultrapotent topical corticosteroids; clobetasol propionate 0.05% is most commonly used.1,6 Regimens vary, but the vast majority of patients improve within 3 months of once-daily treatment.4

For refractory LS, calcineurin inhibitors such as tacrolimus may be used. Although it has a black box warning regarding a potential cancer risk, long-term studies of children using tacrolimus for atopic dermatitis have not demonstrated an increased risk of malignancy.6,9 Because of a considerable adverse effect profile, oral retinoids are limited to refractory cases in adults.6 Surgery is reserved for scarring and adhesions.4

Follow-up plays an important role in management

Historically, it was believed that pediatric LS had an excellent prognosis, with patients achieving complete resolution after puberty.1,4 Recent findings have shown mixed results, with LS persisting in many patients beyond puberty.2,4 Therefore, regular follow-up is recommended every 6 to 12 months.

For uncomplicated LS, specialist follow-up is not indicated. Female patients should regularly conduct self-examinations and, at a minimum, undergo annual examinations by their primary care physician. Those who require specialist follow-up include patients with difficult-to-control symptoms, hypertrophic lesions, a history of SCCV or differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (dVIN), or pathology showing possible dVIN.15

Our patient. We prescribed clobetasol propionate 0.05% ointment to be used once daily for 8 weeks. We stressed the importance of genital self-examinations using a mirror to monitor for any concerning changes such as skin thickening. We showed the patient and her mother photos of normal female genitalia to help normalize the genital exam, and taught the patient how to find her plaques in the mirror. We set expectations by emphasizing the chronic nature of LS and the likelihood of recurrence. We also encouraged HPV vaccination in the upcoming years to prevent both cervical cancer and HPV-related SCCV.

CORRESPONDENCE

Somya Abubucker, MD, University of Hawaii, 1356 Lusitana Street, 7th floor, Honolulu, HI 96813; [email protected].

1. Murphy R. Lichen sclerosus. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:707-715.

2. Dendrinos ML, Quint EH. Lichen sclerosus in children and adolescents. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2013;25:370-374.

3. Eva LJ. Screening and follow up of vulval skin disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;26:175-188.

4. Focseneanu MA, Gupta M, Squires KC, et al. The course of lichen sclerosus diagnosed prior to puberty. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2013;26:153-155.

5. Funaro D. Lichen sclerosus: a review and practical approach. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:28-37.

6. Heymann WR. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:683-684.

7. Tong LX, Sun GS, Teng JM. Pediatric lichen sclerosus: a review of the epidemiology and treatment options. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:593-599.

8. Lagerstedt M, Karvinen K, Joki-Erkkilä M, et al. Childhood lichen sclerosus—a challenge for clinicians. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:444-450.

9. Keith PJ, Wolz MM, Peters MS. Eosinophils in lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:693-698.

10. National Sexual Violence Resource Center. Child sexual abuse prevention. 2011. Available at: https://www.nsvrc.org/sites/default/files/Publications_NSVRC_Overview_Child-sexual-abuse-prevention_0.pdf. Accessed February 8, 2018.

11. Dubowitz H, Lane WG. Abused and neglected children. In: Kliegman RM, Stanton BF, St. Geme JW, et al, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 20th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:236-249.

12. Powell J, Wojnarowska F. Childhood vulvar lichen sclerosus: an increasingly common problem. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:803-806.

13. Reamy BV, Bunt CW, Fletcher S. A diagnostic approach to pruritus. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:195-202.

14. Warshaw E, Hook K. Dermatitis. In: Soutor C, Hordinsky MK, eds. Clinical Dermatology. 1st ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

15. Jones RW, Scurry J, Neill S, et al. Guidelines for the follow-up of women with vulvar lichen sclerosus in specialist clinics. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:496.e1-e3.

A mother brought her 8-year-old daughter to our office for evaluation of vitiligo “down there” (FIGURE). The skin eruption first appeared on her vulva a year earlier and was intermittently pruritic. The lesions were initially smaller and red, but had since lightened in color, coalesced, and had begun to spread to the perianal area. The patient’s mother had received a call from her daughter’s teacher who observed that her daughter was scratching the area and might be masturbating in class.

The mother reported that 6 months earlier, her daughter had experienced bloody spots in her underwear accompanied by dysuria. The mother brought her to the emergency department, where she was treated with antibiotics for a urinary tract infection.

Our physical examination revealed well-circumscribed, symmetric, depigmented, confluent, crinkled, parchment-like plaques with small hemorrhagic erosions on the medial labia majora and minora. The lesions had spread to the perianal area with depigmentation superiorly and hypopigmentation inferiorly, creating a figure-8 pattern.

A review of systems was negative for pruritus, pain, dysuria, dyschezia, constipation, and vaginal discharge. The patient denied sexual activity, depression, or anxiety. Her mother denied behavioral changes in her daughter and said that her daughter hadn’t had any one-on-one time alone with any adults besides herself. Her mother was concerned that the white spots might spread to the rest of her daughter’s body, which could affect her socially.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Lichen sclerosus

Based on the history and clinical findings, including the classic figure-8 pattern, we diagnosed childhood lichen sclerosus (LS) in this patient. LS is a chronic inflammatory skin disorder that primarily affects the genital mucosa. The disorder can present at any age, but is most common among postmenopausal women, with a prevalence estimated to be as high as one in 30.1-3 A second incidence peak is observed in prepubescent girls, with a prevalence of one in 900.3,4 LS is less common in men and boys, with a female-to-male ratio that can reach 10:1.5 The classic symptoms of LS are pruritus and pain, which may be intermittent or persistent.

In girls, initial manifestations may be constipation, dysuria, or even behavioral symptoms such as night fears, which can occur because children are less active at night and become more aware of urinary discomfort.1,2,6 Typical signs of LS are thin atrophic plaques that spare the vagina and cervix. The plaques can be ivory-white, erythematous, or violaceous. Some patients have perianal lesions as well, and can display the pathognomonic figure-8 pattern of porcelain plaques around the vulva and anus.5

With more advanced disease, erosions, lichenification, and even distortion of vulvar architecture may occur.2,4,7 In severe cases, labia resorption and clitoral phimosis may develop.5 Complications include secondary infection, dyspareunia, and psychosexual distress. The most worrisome sequela of LS is squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva (SCCV), which occurs in 5% of female patients with LS.4

In men and boys, LS typically involves the foreskin and the glans, while sparing the perianal region.5 Scarring of the foreskin can lead to phimosis, and patients may complain of painful erections and difficulty urinating. LS can also occur away from the genitalia in both males and females.

Autoimmune mechanisms, genetics, and hormones play a role

The exact pathogenesis of LS remains unknown, but multiple factors are likely at work.

Autoimmune mechanisms. Up to 60% of women with LS have an autoimmune disorder, which is most commonly vitiligo, alopecia areata, or thyroid disease.5 In addition, 67% of patients have autoantibodies against extracellular matrix protein 1, and 30% have them against bullous pemphigoid antigen 180.1,8

Genetics. LS is associated with certain human leukocyte antigen class II haplotypes (especially DQ7) and with polymorphisms at the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist gene locus.5,6,9

Hormones. The clear peaks of incidence during times of low estrogen, and a higher incidence in patients with Turner syndrome or kidney disease, suggest that low estrogen may play a role in the development of LS, as well.1,5,6

While it is generally accepted that trauma may trigger LS via the Koebner phenomenon (the appearance of lesions at the site of injury), there is debate as to whether microbes—especially Borrelia burgdorferi and human papillomavirus (HPV)—might play a role.1,5

Diagnosis is often delayed, misdiagnosis is common

The average delay from symptom onset to diagnosis of LS is 1.3 years, and up to 84% of childhood LS is misdiagnosed before referral.2,9 The differential diagnosis includes:

Sexual abuse. In prepubertal girls presenting with genital redness, the can’t-miss diagnosis is sexual abuse, which occurs in more than 25% of children in the United States.10 Initial manifestations may be regression in developmental milestones, such as new-onset bedwetting, or behavioral changes such as social withdrawal or declining academic performance.11

However, physicians must be conscientious about ruling out medical etiologies before prematurely diagnosing abuse. Fourteen percent of girls with LS are incorrectly diagnosed as having been sexually abused.2 A clinical pearl is that while LS may resemble abuse on exam, it rarely affects the hymenal structure.12 It is also important to keep in mind that the 2 entities are not incompatible, as sexual abuse leading to LS via Koebnerization is a well-described phenomenon.12

Lichen planus. LP, which is also an immune-mediated inflammatory disorder affecting the vulva, classically presents with the 6 Ps: pruritic, polygonal, planar, purple papules and plaques.4 LP is distinguished from LS by being rare in childhood, having a predilection for the flexor wrists, and involving the oral and vaginal mucosa.4

Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) is a chronic, circumscribed, pruritic, eczematous condition that becomes lichenified with thickened skin secondary to repeated scratching.13 Children with atopic dermatitis can develop LSC, but other children can also develop the scratch-itch cycle that results in the thickened plaques of LSC. Like LS, LSC can occur in areas other than the genitalia, including the neck and feet.14

Allergic contact dermatitis can occur in the genital area from diaper creams, soaps, and perfumes. Irritant contact dermatitis can occur from exposure to diarrhea, bedwetting, and other irritants. Contact dermatitis is less likely to have the classic figure-8 pattern seen in LS.

Psoriasis in the genital area can be confused with LS. However, psoriasis favors the groin creases in what is called inverse psoriasis. In addition, psoriasis tends to involve multiple areas, including the extensor surfaces of the elbows and knees, the nails, and the scalp.

Vitiligo can present on the genitals as circumscribed hypopigmented and depigmented patches that are flat. Vitiligo is asymptomatic, and the only pathology is the change in skin color. With LS, there is lichenification, atrophy, and sclerosis.4 Vitiligo often occurs with bilateral symmetric involvement in areas of trauma including the face, neck, scalp, elbows, wrists, hands, knees, ankles, and feet.

Treatment aims to improve symptoms

LS is usually diagnosed clinically (especially in children, as a biopsy is a great challenge to perform). However, when the clinical presentation is unclear, a skin biopsy will demonstrate the diagnostic findings of thinning of the epidermis, loss of rete pegs, hyperkeratosis, and dermal fibrosis with a T-lymphocyte-dominant inflammatory infiltrate.1,2,4,5

LS is a remitting and relapsing condition with no cure. The goals of treatment are to provide symptom relief and minimize scarring and atrophy,2 but it is unknown whether treatment reduces the risk of malignancy.9

First-line treatment for both genders and all ages is ultrapotent topical corticosteroids; clobetasol propionate 0.05% is most commonly used.1,6 Regimens vary, but the vast majority of patients improve within 3 months of once-daily treatment.4

For refractory LS, calcineurin inhibitors such as tacrolimus may be used. Although it has a black box warning regarding a potential cancer risk, long-term studies of children using tacrolimus for atopic dermatitis have not demonstrated an increased risk of malignancy.6,9 Because of a considerable adverse effect profile, oral retinoids are limited to refractory cases in adults.6 Surgery is reserved for scarring and adhesions.4

Follow-up plays an important role in management

Historically, it was believed that pediatric LS had an excellent prognosis, with patients achieving complete resolution after puberty.1,4 Recent findings have shown mixed results, with LS persisting in many patients beyond puberty.2,4 Therefore, regular follow-up is recommended every 6 to 12 months.

For uncomplicated LS, specialist follow-up is not indicated. Female patients should regularly conduct self-examinations and, at a minimum, undergo annual examinations by their primary care physician. Those who require specialist follow-up include patients with difficult-to-control symptoms, hypertrophic lesions, a history of SCCV or differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (dVIN), or pathology showing possible dVIN.15

Our patient. We prescribed clobetasol propionate 0.05% ointment to be used once daily for 8 weeks. We stressed the importance of genital self-examinations using a mirror to monitor for any concerning changes such as skin thickening. We showed the patient and her mother photos of normal female genitalia to help normalize the genital exam, and taught the patient how to find her plaques in the mirror. We set expectations by emphasizing the chronic nature of LS and the likelihood of recurrence. We also encouraged HPV vaccination in the upcoming years to prevent both cervical cancer and HPV-related SCCV.

CORRESPONDENCE

Somya Abubucker, MD, University of Hawaii, 1356 Lusitana Street, 7th floor, Honolulu, HI 96813; [email protected].

A mother brought her 8-year-old daughter to our office for evaluation of vitiligo “down there” (FIGURE). The skin eruption first appeared on her vulva a year earlier and was intermittently pruritic. The lesions were initially smaller and red, but had since lightened in color, coalesced, and had begun to spread to the perianal area. The patient’s mother had received a call from her daughter’s teacher who observed that her daughter was scratching the area and might be masturbating in class.

The mother reported that 6 months earlier, her daughter had experienced bloody spots in her underwear accompanied by dysuria. The mother brought her to the emergency department, where she was treated with antibiotics for a urinary tract infection.

Our physical examination revealed well-circumscribed, symmetric, depigmented, confluent, crinkled, parchment-like plaques with small hemorrhagic erosions on the medial labia majora and minora. The lesions had spread to the perianal area with depigmentation superiorly and hypopigmentation inferiorly, creating a figure-8 pattern.

A review of systems was negative for pruritus, pain, dysuria, dyschezia, constipation, and vaginal discharge. The patient denied sexual activity, depression, or anxiety. Her mother denied behavioral changes in her daughter and said that her daughter hadn’t had any one-on-one time alone with any adults besides herself. Her mother was concerned that the white spots might spread to the rest of her daughter’s body, which could affect her socially.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Lichen sclerosus

Based on the history and clinical findings, including the classic figure-8 pattern, we diagnosed childhood lichen sclerosus (LS) in this patient. LS is a chronic inflammatory skin disorder that primarily affects the genital mucosa. The disorder can present at any age, but is most common among postmenopausal women, with a prevalence estimated to be as high as one in 30.1-3 A second incidence peak is observed in prepubescent girls, with a prevalence of one in 900.3,4 LS is less common in men and boys, with a female-to-male ratio that can reach 10:1.5 The classic symptoms of LS are pruritus and pain, which may be intermittent or persistent.

In girls, initial manifestations may be constipation, dysuria, or even behavioral symptoms such as night fears, which can occur because children are less active at night and become more aware of urinary discomfort.1,2,6 Typical signs of LS are thin atrophic plaques that spare the vagina and cervix. The plaques can be ivory-white, erythematous, or violaceous. Some patients have perianal lesions as well, and can display the pathognomonic figure-8 pattern of porcelain plaques around the vulva and anus.5

With more advanced disease, erosions, lichenification, and even distortion of vulvar architecture may occur.2,4,7 In severe cases, labia resorption and clitoral phimosis may develop.5 Complications include secondary infection, dyspareunia, and psychosexual distress. The most worrisome sequela of LS is squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva (SCCV), which occurs in 5% of female patients with LS.4

In men and boys, LS typically involves the foreskin and the glans, while sparing the perianal region.5 Scarring of the foreskin can lead to phimosis, and patients may complain of painful erections and difficulty urinating. LS can also occur away from the genitalia in both males and females.

Autoimmune mechanisms, genetics, and hormones play a role

The exact pathogenesis of LS remains unknown, but multiple factors are likely at work.

Autoimmune mechanisms. Up to 60% of women with LS have an autoimmune disorder, which is most commonly vitiligo, alopecia areata, or thyroid disease.5 In addition, 67% of patients have autoantibodies against extracellular matrix protein 1, and 30% have them against bullous pemphigoid antigen 180.1,8

Genetics. LS is associated with certain human leukocyte antigen class II haplotypes (especially DQ7) and with polymorphisms at the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist gene locus.5,6,9

Hormones. The clear peaks of incidence during times of low estrogen, and a higher incidence in patients with Turner syndrome or kidney disease, suggest that low estrogen may play a role in the development of LS, as well.1,5,6

While it is generally accepted that trauma may trigger LS via the Koebner phenomenon (the appearance of lesions at the site of injury), there is debate as to whether microbes—especially Borrelia burgdorferi and human papillomavirus (HPV)—might play a role.1,5

Diagnosis is often delayed, misdiagnosis is common

The average delay from symptom onset to diagnosis of LS is 1.3 years, and up to 84% of childhood LS is misdiagnosed before referral.2,9 The differential diagnosis includes:

Sexual abuse. In prepubertal girls presenting with genital redness, the can’t-miss diagnosis is sexual abuse, which occurs in more than 25% of children in the United States.10 Initial manifestations may be regression in developmental milestones, such as new-onset bedwetting, or behavioral changes such as social withdrawal or declining academic performance.11

However, physicians must be conscientious about ruling out medical etiologies before prematurely diagnosing abuse. Fourteen percent of girls with LS are incorrectly diagnosed as having been sexually abused.2 A clinical pearl is that while LS may resemble abuse on exam, it rarely affects the hymenal structure.12 It is also important to keep in mind that the 2 entities are not incompatible, as sexual abuse leading to LS via Koebnerization is a well-described phenomenon.12

Lichen planus. LP, which is also an immune-mediated inflammatory disorder affecting the vulva, classically presents with the 6 Ps: pruritic, polygonal, planar, purple papules and plaques.4 LP is distinguished from LS by being rare in childhood, having a predilection for the flexor wrists, and involving the oral and vaginal mucosa.4

Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) is a chronic, circumscribed, pruritic, eczematous condition that becomes lichenified with thickened skin secondary to repeated scratching.13 Children with atopic dermatitis can develop LSC, but other children can also develop the scratch-itch cycle that results in the thickened plaques of LSC. Like LS, LSC can occur in areas other than the genitalia, including the neck and feet.14

Allergic contact dermatitis can occur in the genital area from diaper creams, soaps, and perfumes. Irritant contact dermatitis can occur from exposure to diarrhea, bedwetting, and other irritants. Contact dermatitis is less likely to have the classic figure-8 pattern seen in LS.

Psoriasis in the genital area can be confused with LS. However, psoriasis favors the groin creases in what is called inverse psoriasis. In addition, psoriasis tends to involve multiple areas, including the extensor surfaces of the elbows and knees, the nails, and the scalp.

Vitiligo can present on the genitals as circumscribed hypopigmented and depigmented patches that are flat. Vitiligo is asymptomatic, and the only pathology is the change in skin color. With LS, there is lichenification, atrophy, and sclerosis.4 Vitiligo often occurs with bilateral symmetric involvement in areas of trauma including the face, neck, scalp, elbows, wrists, hands, knees, ankles, and feet.

Treatment aims to improve symptoms

LS is usually diagnosed clinically (especially in children, as a biopsy is a great challenge to perform). However, when the clinical presentation is unclear, a skin biopsy will demonstrate the diagnostic findings of thinning of the epidermis, loss of rete pegs, hyperkeratosis, and dermal fibrosis with a T-lymphocyte-dominant inflammatory infiltrate.1,2,4,5

LS is a remitting and relapsing condition with no cure. The goals of treatment are to provide symptom relief and minimize scarring and atrophy,2 but it is unknown whether treatment reduces the risk of malignancy.9

First-line treatment for both genders and all ages is ultrapotent topical corticosteroids; clobetasol propionate 0.05% is most commonly used.1,6 Regimens vary, but the vast majority of patients improve within 3 months of once-daily treatment.4

For refractory LS, calcineurin inhibitors such as tacrolimus may be used. Although it has a black box warning regarding a potential cancer risk, long-term studies of children using tacrolimus for atopic dermatitis have not demonstrated an increased risk of malignancy.6,9 Because of a considerable adverse effect profile, oral retinoids are limited to refractory cases in adults.6 Surgery is reserved for scarring and adhesions.4

Follow-up plays an important role in management

Historically, it was believed that pediatric LS had an excellent prognosis, with patients achieving complete resolution after puberty.1,4 Recent findings have shown mixed results, with LS persisting in many patients beyond puberty.2,4 Therefore, regular follow-up is recommended every 6 to 12 months.

For uncomplicated LS, specialist follow-up is not indicated. Female patients should regularly conduct self-examinations and, at a minimum, undergo annual examinations by their primary care physician. Those who require specialist follow-up include patients with difficult-to-control symptoms, hypertrophic lesions, a history of SCCV or differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (dVIN), or pathology showing possible dVIN.15

Our patient. We prescribed clobetasol propionate 0.05% ointment to be used once daily for 8 weeks. We stressed the importance of genital self-examinations using a mirror to monitor for any concerning changes such as skin thickening. We showed the patient and her mother photos of normal female genitalia to help normalize the genital exam, and taught the patient how to find her plaques in the mirror. We set expectations by emphasizing the chronic nature of LS and the likelihood of recurrence. We also encouraged HPV vaccination in the upcoming years to prevent both cervical cancer and HPV-related SCCV.

CORRESPONDENCE

Somya Abubucker, MD, University of Hawaii, 1356 Lusitana Street, 7th floor, Honolulu, HI 96813; [email protected].

1. Murphy R. Lichen sclerosus. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:707-715.

2. Dendrinos ML, Quint EH. Lichen sclerosus in children and adolescents. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2013;25:370-374.

3. Eva LJ. Screening and follow up of vulval skin disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;26:175-188.

4. Focseneanu MA, Gupta M, Squires KC, et al. The course of lichen sclerosus diagnosed prior to puberty. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2013;26:153-155.

5. Funaro D. Lichen sclerosus: a review and practical approach. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:28-37.

6. Heymann WR. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:683-684.

7. Tong LX, Sun GS, Teng JM. Pediatric lichen sclerosus: a review of the epidemiology and treatment options. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:593-599.

8. Lagerstedt M, Karvinen K, Joki-Erkkilä M, et al. Childhood lichen sclerosus—a challenge for clinicians. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:444-450.

9. Keith PJ, Wolz MM, Peters MS. Eosinophils in lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:693-698.

10. National Sexual Violence Resource Center. Child sexual abuse prevention. 2011. Available at: https://www.nsvrc.org/sites/default/files/Publications_NSVRC_Overview_Child-sexual-abuse-prevention_0.pdf. Accessed February 8, 2018.

11. Dubowitz H, Lane WG. Abused and neglected children. In: Kliegman RM, Stanton BF, St. Geme JW, et al, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 20th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:236-249.

12. Powell J, Wojnarowska F. Childhood vulvar lichen sclerosus: an increasingly common problem. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:803-806.

13. Reamy BV, Bunt CW, Fletcher S. A diagnostic approach to pruritus. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:195-202.

14. Warshaw E, Hook K. Dermatitis. In: Soutor C, Hordinsky MK, eds. Clinical Dermatology. 1st ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

15. Jones RW, Scurry J, Neill S, et al. Guidelines for the follow-up of women with vulvar lichen sclerosus in specialist clinics. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:496.e1-e3.

1. Murphy R. Lichen sclerosus. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:707-715.

2. Dendrinos ML, Quint EH. Lichen sclerosus in children and adolescents. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2013;25:370-374.

3. Eva LJ. Screening and follow up of vulval skin disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;26:175-188.

4. Focseneanu MA, Gupta M, Squires KC, et al. The course of lichen sclerosus diagnosed prior to puberty. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2013;26:153-155.

5. Funaro D. Lichen sclerosus: a review and practical approach. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:28-37.

6. Heymann WR. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:683-684.

7. Tong LX, Sun GS, Teng JM. Pediatric lichen sclerosus: a review of the epidemiology and treatment options. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:593-599.

8. Lagerstedt M, Karvinen K, Joki-Erkkilä M, et al. Childhood lichen sclerosus—a challenge for clinicians. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:444-450.

9. Keith PJ, Wolz MM, Peters MS. Eosinophils in lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:693-698.

10. National Sexual Violence Resource Center. Child sexual abuse prevention. 2011. Available at: https://www.nsvrc.org/sites/default/files/Publications_NSVRC_Overview_Child-sexual-abuse-prevention_0.pdf. Accessed February 8, 2018.

11. Dubowitz H, Lane WG. Abused and neglected children. In: Kliegman RM, Stanton BF, St. Geme JW, et al, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 20th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:236-249.

12. Powell J, Wojnarowska F. Childhood vulvar lichen sclerosus: an increasingly common problem. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:803-806.

13. Reamy BV, Bunt CW, Fletcher S. A diagnostic approach to pruritus. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:195-202.

14. Warshaw E, Hook K. Dermatitis. In: Soutor C, Hordinsky MK, eds. Clinical Dermatology. 1st ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

15. Jones RW, Scurry J, Neill S, et al. Guidelines for the follow-up of women with vulvar lichen sclerosus in specialist clinics. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:496.e1-e3.

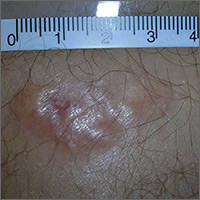

Mole on forehead

The FP recognized this as a probable intradermal nevus. (Even benign nevi can grow in early adulthood and not be malignant.)

The features that suggested that this was a benign intradermal nevus included that it was a raised symmetrical papule on the face without suspicious signs of melanoma. Intradermal nevi are frequently skin colored because the melanocytes are deep in the dermis. The nevi may show small amounts of color, but are not likely to be dark, as might be seen in a compound nevus or melanoma. The differential diagnosis for a slightly pearly lesion like this, with small visible blood vessels, includes a nodular basal cell carcinoma.

The patient wanted to have the nevus removed to ease her anxiety and because she didn’t like the way it looked. While many insurance companies would reject payment for a cosmetic procedure, they are unlikely to reject payment with a diagnosis of a changing nevus.

The FP reviewed the risks and benefits of a shave biopsy with the patient. A shave biopsy with a sterile razor blade was performed after anesthetizing the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine by injection. (See the Watch and Learn video on shave biopsy.) Hemostasis was easily achieved with aluminum chloride in water.

At the 2-week follow-up, the biopsy site was healing well and the patient was reassured that it was only a benign intradermal nevus.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M, Usatine R. Benign nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:945-952.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP recognized this as a probable intradermal nevus. (Even benign nevi can grow in early adulthood and not be malignant.)

The features that suggested that this was a benign intradermal nevus included that it was a raised symmetrical papule on the face without suspicious signs of melanoma. Intradermal nevi are frequently skin colored because the melanocytes are deep in the dermis. The nevi may show small amounts of color, but are not likely to be dark, as might be seen in a compound nevus or melanoma. The differential diagnosis for a slightly pearly lesion like this, with small visible blood vessels, includes a nodular basal cell carcinoma.

The patient wanted to have the nevus removed to ease her anxiety and because she didn’t like the way it looked. While many insurance companies would reject payment for a cosmetic procedure, they are unlikely to reject payment with a diagnosis of a changing nevus.

The FP reviewed the risks and benefits of a shave biopsy with the patient. A shave biopsy with a sterile razor blade was performed after anesthetizing the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine by injection. (See the Watch and Learn video on shave biopsy.) Hemostasis was easily achieved with aluminum chloride in water.

At the 2-week follow-up, the biopsy site was healing well and the patient was reassured that it was only a benign intradermal nevus.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M, Usatine R. Benign nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:945-952.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP recognized this as a probable intradermal nevus. (Even benign nevi can grow in early adulthood and not be malignant.)

The features that suggested that this was a benign intradermal nevus included that it was a raised symmetrical papule on the face without suspicious signs of melanoma. Intradermal nevi are frequently skin colored because the melanocytes are deep in the dermis. The nevi may show small amounts of color, but are not likely to be dark, as might be seen in a compound nevus or melanoma. The differential diagnosis for a slightly pearly lesion like this, with small visible blood vessels, includes a nodular basal cell carcinoma.

The patient wanted to have the nevus removed to ease her anxiety and because she didn’t like the way it looked. While many insurance companies would reject payment for a cosmetic procedure, they are unlikely to reject payment with a diagnosis of a changing nevus.

The FP reviewed the risks and benefits of a shave biopsy with the patient. A shave biopsy with a sterile razor blade was performed after anesthetizing the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine by injection. (See the Watch and Learn video on shave biopsy.) Hemostasis was easily achieved with aluminum chloride in water.

At the 2-week follow-up, the biopsy site was healing well and the patient was reassured that it was only a benign intradermal nevus.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M, Usatine R. Benign nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:945-952.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Bleeding lesion on nose

One week later, the pathologist reported that the growth was an amelanotic melanoma of 1.2 mm depth. The FP was relieved that he sent the tissue for pathology and did not assume this was a benign pyogenic granuloma. The patient was referred to a head and neck surgeon for complete excision with margins and a sentinel lymph node biopsy. She was fortunate to not have any nodal metastases. The FP performed a complete skin exam and found no other lesions suspicious for melanoma.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Usatine R. Pyogenic Granuloma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 940-944.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

One week later, the pathologist reported that the growth was an amelanotic melanoma of 1.2 mm depth. The FP was relieved that he sent the tissue for pathology and did not assume this was a benign pyogenic granuloma. The patient was referred to a head and neck surgeon for complete excision with margins and a sentinel lymph node biopsy. She was fortunate to not have any nodal metastases. The FP performed a complete skin exam and found no other lesions suspicious for melanoma.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Usatine R. Pyogenic Granuloma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 940-944.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

One week later, the pathologist reported that the growth was an amelanotic melanoma of 1.2 mm depth. The FP was relieved that he sent the tissue for pathology and did not assume this was a benign pyogenic granuloma. The patient was referred to a head and neck surgeon for complete excision with margins and a sentinel lymph node biopsy. She was fortunate to not have any nodal metastases. The FP performed a complete skin exam and found no other lesions suspicious for melanoma.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Usatine R. Pyogenic Granuloma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 940-944.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Growth on finger

The FP diagnosed pyogenic granuloma (PG), a common, benign, acquired vascular lesion of the skin and mucous membranes. PGs are erythematous, dome-shaped papules or nodules that bleed easily. They are prone to ulceration, erosion, and crusting, and rapid growth may occur over a period of weeks. The etiology for PG is unknown, but may be the result of trauma, infection, or preceding dermatoses. A more up-to-date and appropriate term for PG is lobular capillary hemangioma, because these lesions are neither pyogenic nor granulomas.

PGs are most often found on the fingers, lips, and hands. They may resemble a number of malignancies including basal cell carcinoma, Kaposi’s sarcoma, metastatic cutaneous lesions, squamous cell carcinoma, and amelanotic melanoma. For that reason, it’s especially important to send the excised lesion for pathology to ensure that malignancy isn’t missed.

The patient was eager to have the PG removed at this visit, as a number of previous visits to urgent care centers resulted in courses of antibiotics that didn’t help. After performing a digital block, the FP removed the PG with a shave excision, followed by electrodesiccation and curettage. The electrodesiccation and curettage are important to prevent recurrence. In this case, the pathology confirmed the diagnosis, and the PG did not recur.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Usatine R. Pyogenic Granuloma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 940-944.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed pyogenic granuloma (PG), a common, benign, acquired vascular lesion of the skin and mucous membranes. PGs are erythematous, dome-shaped papules or nodules that bleed easily. They are prone to ulceration, erosion, and crusting, and rapid growth may occur over a period of weeks. The etiology for PG is unknown, but may be the result of trauma, infection, or preceding dermatoses. A more up-to-date and appropriate term for PG is lobular capillary hemangioma, because these lesions are neither pyogenic nor granulomas.

PGs are most often found on the fingers, lips, and hands. They may resemble a number of malignancies including basal cell carcinoma, Kaposi’s sarcoma, metastatic cutaneous lesions, squamous cell carcinoma, and amelanotic melanoma. For that reason, it’s especially important to send the excised lesion for pathology to ensure that malignancy isn’t missed.

The patient was eager to have the PG removed at this visit, as a number of previous visits to urgent care centers resulted in courses of antibiotics that didn’t help. After performing a digital block, the FP removed the PG with a shave excision, followed by electrodesiccation and curettage. The electrodesiccation and curettage are important to prevent recurrence. In this case, the pathology confirmed the diagnosis, and the PG did not recur.