User login

Hyperpigmented growth on nose

At follow-up 2 weeks later, pathology revealed a diagnosis of sebaceous hyperplasia (SH). On close examination of the face and nose, the FP noted other nonpigmented SHs and telangiectasias, which confirmed an overall diagnosis of rosacea.

The FP explained to the patient that SH is benign and that there are treatments for rosacea. In this case, the FP prescribed 1% metronidazole gel for the rosacea. At follow-up one month later, the shave biopsy had effectively removed the SH and the site had healed well. The metronidazole gel was also improving the appearance of the patient’s face. The patient indicated that he’d been avoiding the sun and drinking less alcohol, which was helping the rosacea and was, of course, good for his overall health.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Sebaceous hyperplasia. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 931-934.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

At follow-up 2 weeks later, pathology revealed a diagnosis of sebaceous hyperplasia (SH). On close examination of the face and nose, the FP noted other nonpigmented SHs and telangiectasias, which confirmed an overall diagnosis of rosacea.

The FP explained to the patient that SH is benign and that there are treatments for rosacea. In this case, the FP prescribed 1% metronidazole gel for the rosacea. At follow-up one month later, the shave biopsy had effectively removed the SH and the site had healed well. The metronidazole gel was also improving the appearance of the patient’s face. The patient indicated that he’d been avoiding the sun and drinking less alcohol, which was helping the rosacea and was, of course, good for his overall health.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Sebaceous hyperplasia. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 931-934.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

At follow-up 2 weeks later, pathology revealed a diagnosis of sebaceous hyperplasia (SH). On close examination of the face and nose, the FP noted other nonpigmented SHs and telangiectasias, which confirmed an overall diagnosis of rosacea.

The FP explained to the patient that SH is benign and that there are treatments for rosacea. In this case, the FP prescribed 1% metronidazole gel for the rosacea. At follow-up one month later, the shave biopsy had effectively removed the SH and the site had healed well. The metronidazole gel was also improving the appearance of the patient’s face. The patient indicated that he’d been avoiding the sun and drinking less alcohol, which was helping the rosacea and was, of course, good for his overall health.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Sebaceous hyperplasia. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 931-934.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Papules below eyes

The FP looked at the small papules closely and recognized them as white milia cysts and flesh-colored syringomas. He explained to the patient that both conditions were benign and discussed treatment options.

Milia cysts, which appear as shiny white papules, can be extracted. This procedure is performed without local anesthesia, and the most uncomfortable part is when pressure is applied with the comedone extractor against the infraorbital bone. (The billing code for this procedure is the same as the one used for acne surgery.)

Syringomas, however, are not easily treated. New lesions can form even if some resolve. Treatment options for syringomas include topical trichloroacetic acid, cryosurgery, and electrosurgery. Because this patient’s lesions were on the eyelids, as they often are, there are risks involved.

The patient agreed to extraction of the milia cysts, so the FP removed a number of them using the tip of a Number 11 scalpel blade and a comedone extractor. The patient was happy to have them removed and said that he would think about the options for syringoma treatment at a future date.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Sebaceous hyperplasia. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 931-934.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP looked at the small papules closely and recognized them as white milia cysts and flesh-colored syringomas. He explained to the patient that both conditions were benign and discussed treatment options.

Milia cysts, which appear as shiny white papules, can be extracted. This procedure is performed without local anesthesia, and the most uncomfortable part is when pressure is applied with the comedone extractor against the infraorbital bone. (The billing code for this procedure is the same as the one used for acne surgery.)

Syringomas, however, are not easily treated. New lesions can form even if some resolve. Treatment options for syringomas include topical trichloroacetic acid, cryosurgery, and electrosurgery. Because this patient’s lesions were on the eyelids, as they often are, there are risks involved.

The patient agreed to extraction of the milia cysts, so the FP removed a number of them using the tip of a Number 11 scalpel blade and a comedone extractor. The patient was happy to have them removed and said that he would think about the options for syringoma treatment at a future date.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Sebaceous hyperplasia. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 931-934.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP looked at the small papules closely and recognized them as white milia cysts and flesh-colored syringomas. He explained to the patient that both conditions were benign and discussed treatment options.

Milia cysts, which appear as shiny white papules, can be extracted. This procedure is performed without local anesthesia, and the most uncomfortable part is when pressure is applied with the comedone extractor against the infraorbital bone. (The billing code for this procedure is the same as the one used for acne surgery.)

Syringomas, however, are not easily treated. New lesions can form even if some resolve. Treatment options for syringomas include topical trichloroacetic acid, cryosurgery, and electrosurgery. Because this patient’s lesions were on the eyelids, as they often are, there are risks involved.

The patient agreed to extraction of the milia cysts, so the FP removed a number of them using the tip of a Number 11 scalpel blade and a comedone extractor. The patient was happy to have them removed and said that he would think about the options for syringoma treatment at a future date.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Sebaceous hyperplasia. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 931-934.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Lesion with vessels

The FP performed a shave biopsy with a sharp razor blade after using local anesthesia (lidocaine and epinephrine), and pathology confirmed the suspected diagnosis of a nodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC). While this case of BCC was diagnosed with naked eye examination, dermoscopic examination would have revealed shiny white structures and branching vessels. This would increase the FP’s confidence in a diagnosis of BCC before a biopsy was even performed.

The FP was experienced with skin surgery and performed an elliptical excision with 4 mm margins. The ellipse was oriented horizontally across the patient’s forehead, so that the healing incision would be hidden among her wrinkle lines. A 2-layer closure was employed using absorbable 4-0 Vicryl for the deep sutures and running 5-0 Prolene for the epidermal layer.

At follow-up 6 days later, the incision was healing well without signs of infection and the external sutures were removed. Pathology showed that the margins were clear of tumor. The FP suggested a total body skin exam to make sure there were no other skin cancers in hiding. The patient agreed, and the remainder of the skin exam was clear. The FP also talked to the patient about sun avoidance and protection. A follow-up was scheduled for 6 months later to recheck the skin, since the diagnosis of one BCC increases the risk for additional skin cancers.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Sebaceous hyperplasia. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 931-934.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP performed a shave biopsy with a sharp razor blade after using local anesthesia (lidocaine and epinephrine), and pathology confirmed the suspected diagnosis of a nodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC). While this case of BCC was diagnosed with naked eye examination, dermoscopic examination would have revealed shiny white structures and branching vessels. This would increase the FP’s confidence in a diagnosis of BCC before a biopsy was even performed.

The FP was experienced with skin surgery and performed an elliptical excision with 4 mm margins. The ellipse was oriented horizontally across the patient’s forehead, so that the healing incision would be hidden among her wrinkle lines. A 2-layer closure was employed using absorbable 4-0 Vicryl for the deep sutures and running 5-0 Prolene for the epidermal layer.

At follow-up 6 days later, the incision was healing well without signs of infection and the external sutures were removed. Pathology showed that the margins were clear of tumor. The FP suggested a total body skin exam to make sure there were no other skin cancers in hiding. The patient agreed, and the remainder of the skin exam was clear. The FP also talked to the patient about sun avoidance and protection. A follow-up was scheduled for 6 months later to recheck the skin, since the diagnosis of one BCC increases the risk for additional skin cancers.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Sebaceous hyperplasia. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 931-934.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP performed a shave biopsy with a sharp razor blade after using local anesthesia (lidocaine and epinephrine), and pathology confirmed the suspected diagnosis of a nodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC). While this case of BCC was diagnosed with naked eye examination, dermoscopic examination would have revealed shiny white structures and branching vessels. This would increase the FP’s confidence in a diagnosis of BCC before a biopsy was even performed.

The FP was experienced with skin surgery and performed an elliptical excision with 4 mm margins. The ellipse was oriented horizontally across the patient’s forehead, so that the healing incision would be hidden among her wrinkle lines. A 2-layer closure was employed using absorbable 4-0 Vicryl for the deep sutures and running 5-0 Prolene for the epidermal layer.

At follow-up 6 days later, the incision was healing well without signs of infection and the external sutures were removed. Pathology showed that the margins were clear of tumor. The FP suggested a total body skin exam to make sure there were no other skin cancers in hiding. The patient agreed, and the remainder of the skin exam was clear. The FP also talked to the patient about sun avoidance and protection. A follow-up was scheduled for 6 months later to recheck the skin, since the diagnosis of one BCC increases the risk for additional skin cancers.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Sebaceous hyperplasia. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 931-934.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Forehead growth

Based on the doughnut shape of the growth, and other similar-looking lesions on the patient’s face, the FP diagnosed sebaceous hyperplasia (SH).

SH is a common, benign condition of the sebaceous glands. It becomes more common on the face starting in middle age. The cells that form the sebaceous gland (sebocytes) accumulate lipid material as they migrate from the basal layer of the gland to the central duct, where they release the lipid content as sebum. In younger individuals, turnover of sebocytes occurs approximately every month. With aging, the sebocyte turnover slows down. This results in crowding of primitive sebocytes within the sebaceous gland, causing the benign hamartomatous enlargement known as SH. Fortunately, there is no known potential for malignant transformation.

SH is located on the face, particularly the cheeks, forehead and nose. (There are other variations of sebaceous hyperplasia found on the lips, areolas, and genitalia.) Single—or groups—of lesions appear as yellowish, soft, small papules ranging in size from 2 to 9 mm. Aging and genetics are the most common risk factors. A small amount of sebum can sometimes be expressed with gentle pressure.

Dermoscopy aids in distinguishing between SH and nodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC). SH has a pattern of crown vessels that extend toward the center of the lesion and do not cross the midline, whereas BCC has branching vessels that can be found randomly distributed throughout the lesion. A biopsy isn’t usually necessary, unless there are features suspicious for BCC. Options for removal include electrodesiccation, cryotherapy, laser treatment, photodynamic therapy, and shave excision. Electrodessication can be performed without anesthesia using a very low setting of an electrosurgical instrument.

The patient in this case wanted the SH removed, so a shave biopsy was performed to make sure this was not a BCC. Pathology confirmed SH and the cosmetic result was excellent.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Sebaceous hyperplasia. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 931-934.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Based on the doughnut shape of the growth, and other similar-looking lesions on the patient’s face, the FP diagnosed sebaceous hyperplasia (SH).

SH is a common, benign condition of the sebaceous glands. It becomes more common on the face starting in middle age. The cells that form the sebaceous gland (sebocytes) accumulate lipid material as they migrate from the basal layer of the gland to the central duct, where they release the lipid content as sebum. In younger individuals, turnover of sebocytes occurs approximately every month. With aging, the sebocyte turnover slows down. This results in crowding of primitive sebocytes within the sebaceous gland, causing the benign hamartomatous enlargement known as SH. Fortunately, there is no known potential for malignant transformation.

SH is located on the face, particularly the cheeks, forehead and nose. (There are other variations of sebaceous hyperplasia found on the lips, areolas, and genitalia.) Single—or groups—of lesions appear as yellowish, soft, small papules ranging in size from 2 to 9 mm. Aging and genetics are the most common risk factors. A small amount of sebum can sometimes be expressed with gentle pressure.

Dermoscopy aids in distinguishing between SH and nodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC). SH has a pattern of crown vessels that extend toward the center of the lesion and do not cross the midline, whereas BCC has branching vessels that can be found randomly distributed throughout the lesion. A biopsy isn’t usually necessary, unless there are features suspicious for BCC. Options for removal include electrodesiccation, cryotherapy, laser treatment, photodynamic therapy, and shave excision. Electrodessication can be performed without anesthesia using a very low setting of an electrosurgical instrument.

The patient in this case wanted the SH removed, so a shave biopsy was performed to make sure this was not a BCC. Pathology confirmed SH and the cosmetic result was excellent.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Sebaceous hyperplasia. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 931-934.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Based on the doughnut shape of the growth, and other similar-looking lesions on the patient’s face, the FP diagnosed sebaceous hyperplasia (SH).

SH is a common, benign condition of the sebaceous glands. It becomes more common on the face starting in middle age. The cells that form the sebaceous gland (sebocytes) accumulate lipid material as they migrate from the basal layer of the gland to the central duct, where they release the lipid content as sebum. In younger individuals, turnover of sebocytes occurs approximately every month. With aging, the sebocyte turnover slows down. This results in crowding of primitive sebocytes within the sebaceous gland, causing the benign hamartomatous enlargement known as SH. Fortunately, there is no known potential for malignant transformation.

SH is located on the face, particularly the cheeks, forehead and nose. (There are other variations of sebaceous hyperplasia found on the lips, areolas, and genitalia.) Single—or groups—of lesions appear as yellowish, soft, small papules ranging in size from 2 to 9 mm. Aging and genetics are the most common risk factors. A small amount of sebum can sometimes be expressed with gentle pressure.

Dermoscopy aids in distinguishing between SH and nodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC). SH has a pattern of crown vessels that extend toward the center of the lesion and do not cross the midline, whereas BCC has branching vessels that can be found randomly distributed throughout the lesion. A biopsy isn’t usually necessary, unless there are features suspicious for BCC. Options for removal include electrodesiccation, cryotherapy, laser treatment, photodynamic therapy, and shave excision. Electrodessication can be performed without anesthesia using a very low setting of an electrosurgical instrument.

The patient in this case wanted the SH removed, so a shave biopsy was performed to make sure this was not a BCC. Pathology confirmed SH and the cosmetic result was excellent.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Sebaceous hyperplasia. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 931-934.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Painful jaw lesion

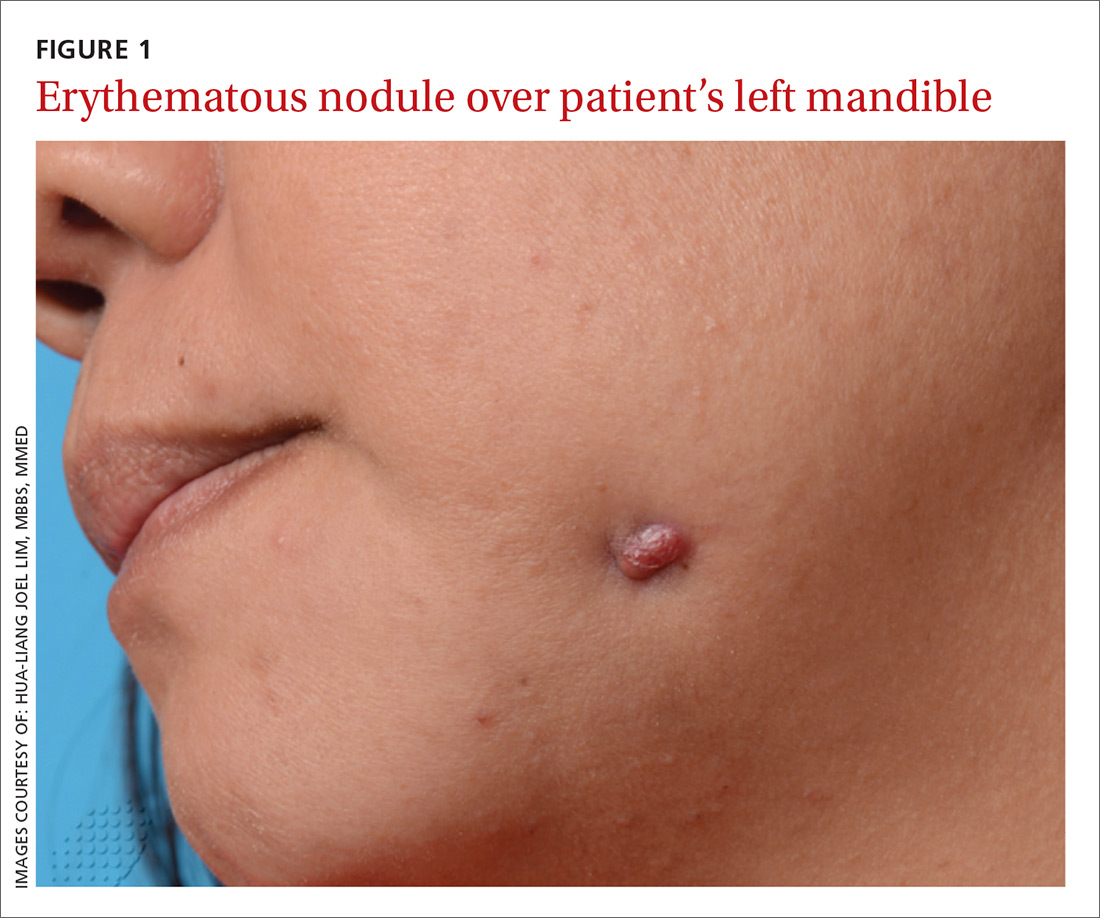

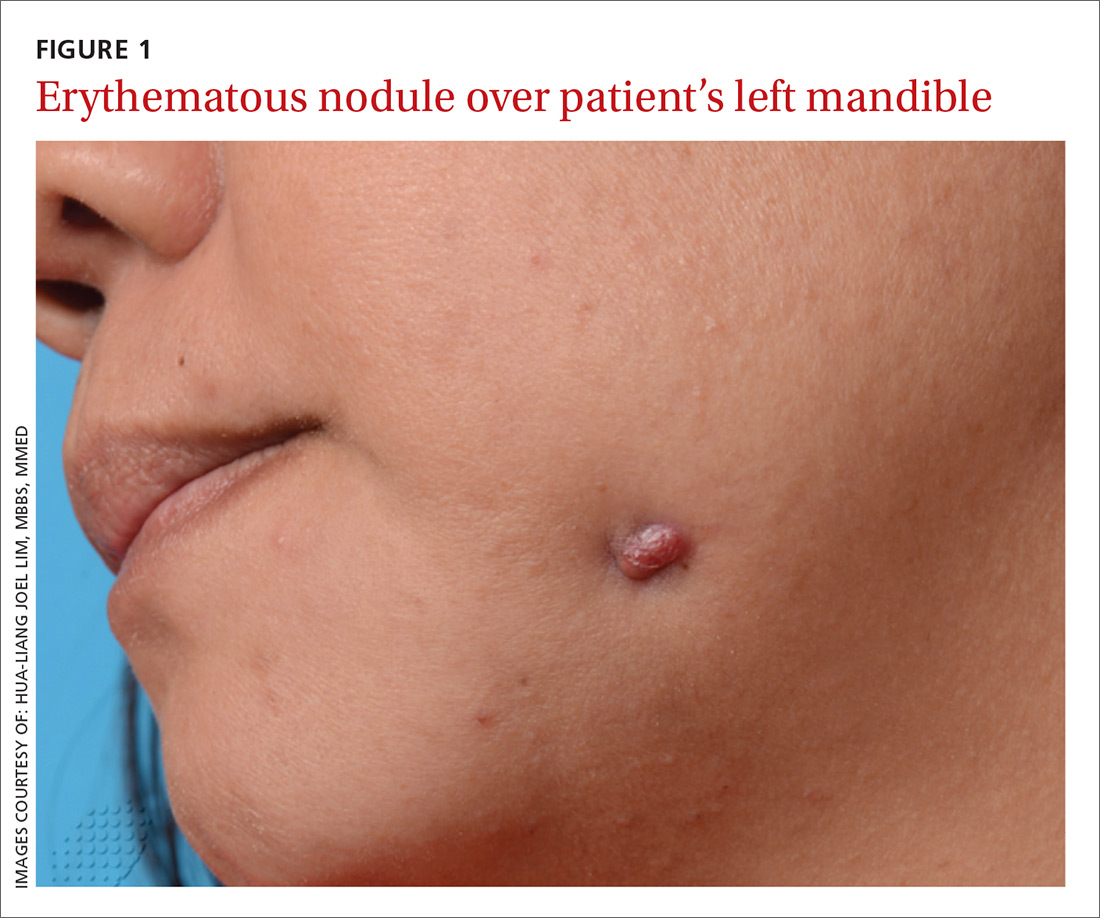

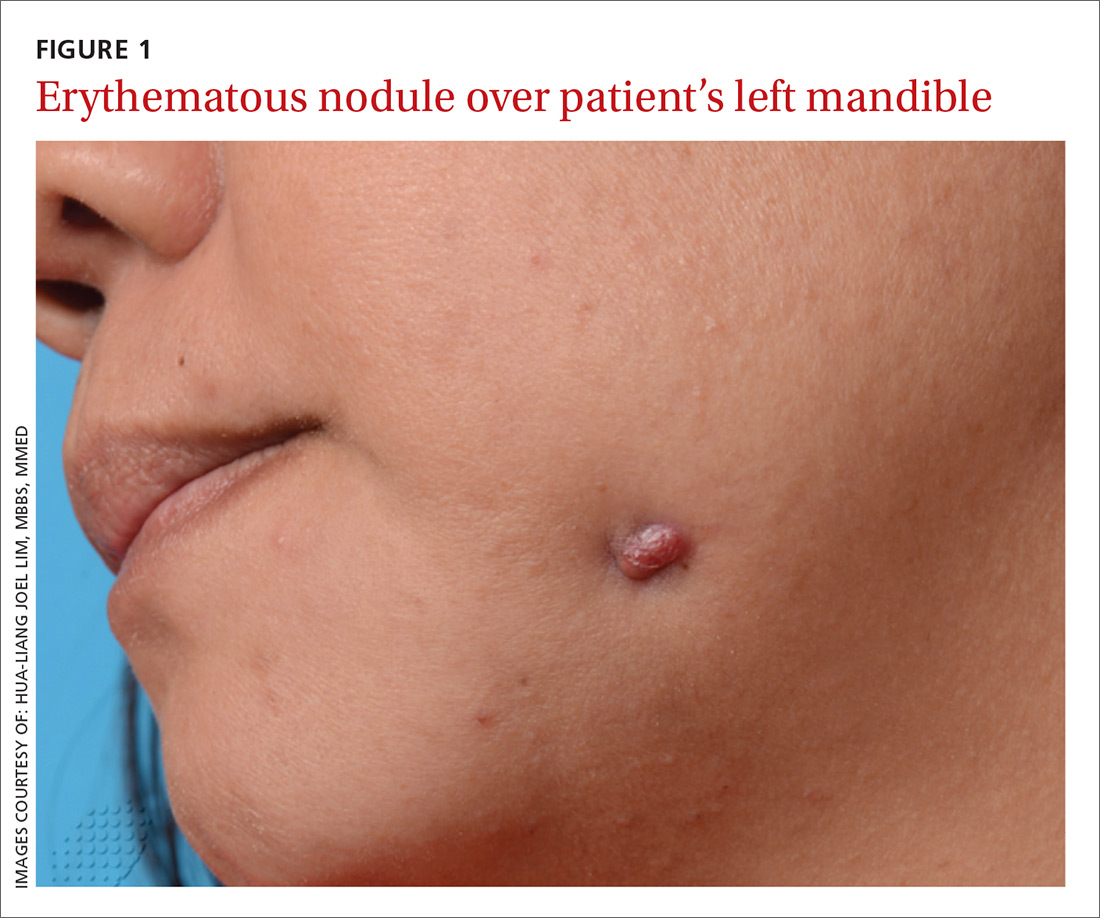

A 48-year-old Chinese woman was referred to our center with a 7-month history of a painful lesion on her left jaw that had been gradually increasing in size. The patient noted occasional purulent and bloody discharge from the lesion. She denied having a toothache.

An examination revealed an erythematous nodule with perilesional puckering superior to the left body of the mandible, measuring 7 × 8 mm, with no discharge or surrounding inflammation (FIGURE 1). There was no cervical lymphadenopathy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Odontogenic sinus tract

Further examination on the inside of the patient’s mouth revealed root stumps of the left inferior molars (FIGURE 2). Based on the appearance of the lesion and molar involvement, we diagnosed odontogenic sinus tract (OST). OST, also known as odontogenic fistula or dental sinus, is a clinical diagnosis.

Symptoms such as odontalgia may be present in only 50% of patients with OST; thus, patients often initially consult their physician, rather than their dentist.1 If OST is suspected, evaluation should begin with a thorough history focusing on any recent facial trauma or past dental diseases. Dental panoramic or periapical radiography can be performed to confirm the extent of dental disease, and pulp vitality testing can determine if a diseased tooth is restorable.

A biopsy of the sinus tract is not required, as it would only reveal granulation tissue. Bimanual palpation of the oral cavity may reveal a cord-like structure from the cutaneous sinus to the underlying alveolar bone. (This structure was palpated in our patient.)

The pathogenesis of OST begins with dental caries, which progress to degeneration of the pulp and formation of periapical abscesses and root stumps. Progressive suppuration causes local destruction and subsequent tract formation through the alveolar bone and mandible. The build-up in pressure within this tract results in an eruption through the skin, manifesting as a sinus with extrusion of pus. The most common site of OST is at the angle of the mandible.2

The differential Dx is limited

There are a small number of other cutaneous conditions that may arise in the region of the mandible, but they have clinical features that distinguish them from OST.

Pyogenic granuloma presents as an erythematous papule that bleeds on contact. It usually develops rapidly following antecedent trauma.

Actinomycosis usually appears as an indolent plaque, with draining sinuses that extrude yellow grains on pressure. It may result from an underlying dental infection.

Squamous cell carcinoma of the skin often presents as a scaly plaque or non-healing ulcer with irregular margins and everted edges.

A furuncle is a tender, erythematous papule or nodule centered on a hair follicle. It is commonly associated with Staphylococcus aureus infection.

Treating OST

Treatment requires endodontic referral for root canal therapy, after which most cases resolve within a few weeks. OST can heal with post-inflammatory hyper- or hypopigmentation as a result of melanocyte damage. Systemic antibiotic administration is not necessary.3

We referred our patient to a dentist, who removed the root stumps and provided root canal treatment. The OST healed within several weeks. The patient had residual hypopigmentation after the OST healed, but was satisfied with the outcome.

CORRESPONDENCE

Hua-Liang Joel Lim, MBBS, MMed, National Skin Centre, 1 Mandalay Rd, Singapore 308205; [email protected].

1. Cioffi GA, Terezhalmy GT, Parlette HL. Cutaneous draining sinus tract: an odontogenic etiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14:94-100.

2. Brown RS, Jones R, Feimster T, et al. Cutaneous sinus tracts (or emerging sinus tracts) of odontogenic origin: a report of 3 cases. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent. 2010;2:63-67.

3. Susic M, Krakar N, Borcic J, et al. Odontogenic sinus tract to the neck skin: a case report. J Dermatol. 2004;31:920-922.

A 48-year-old Chinese woman was referred to our center with a 7-month history of a painful lesion on her left jaw that had been gradually increasing in size. The patient noted occasional purulent and bloody discharge from the lesion. She denied having a toothache.

An examination revealed an erythematous nodule with perilesional puckering superior to the left body of the mandible, measuring 7 × 8 mm, with no discharge or surrounding inflammation (FIGURE 1). There was no cervical lymphadenopathy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Odontogenic sinus tract

Further examination on the inside of the patient’s mouth revealed root stumps of the left inferior molars (FIGURE 2). Based on the appearance of the lesion and molar involvement, we diagnosed odontogenic sinus tract (OST). OST, also known as odontogenic fistula or dental sinus, is a clinical diagnosis.

Symptoms such as odontalgia may be present in only 50% of patients with OST; thus, patients often initially consult their physician, rather than their dentist.1 If OST is suspected, evaluation should begin with a thorough history focusing on any recent facial trauma or past dental diseases. Dental panoramic or periapical radiography can be performed to confirm the extent of dental disease, and pulp vitality testing can determine if a diseased tooth is restorable.

A biopsy of the sinus tract is not required, as it would only reveal granulation tissue. Bimanual palpation of the oral cavity may reveal a cord-like structure from the cutaneous sinus to the underlying alveolar bone. (This structure was palpated in our patient.)

The pathogenesis of OST begins with dental caries, which progress to degeneration of the pulp and formation of periapical abscesses and root stumps. Progressive suppuration causes local destruction and subsequent tract formation through the alveolar bone and mandible. The build-up in pressure within this tract results in an eruption through the skin, manifesting as a sinus with extrusion of pus. The most common site of OST is at the angle of the mandible.2

The differential Dx is limited

There are a small number of other cutaneous conditions that may arise in the region of the mandible, but they have clinical features that distinguish them from OST.

Pyogenic granuloma presents as an erythematous papule that bleeds on contact. It usually develops rapidly following antecedent trauma.

Actinomycosis usually appears as an indolent plaque, with draining sinuses that extrude yellow grains on pressure. It may result from an underlying dental infection.

Squamous cell carcinoma of the skin often presents as a scaly plaque or non-healing ulcer with irregular margins and everted edges.

A furuncle is a tender, erythematous papule or nodule centered on a hair follicle. It is commonly associated with Staphylococcus aureus infection.

Treating OST

Treatment requires endodontic referral for root canal therapy, after which most cases resolve within a few weeks. OST can heal with post-inflammatory hyper- or hypopigmentation as a result of melanocyte damage. Systemic antibiotic administration is not necessary.3

We referred our patient to a dentist, who removed the root stumps and provided root canal treatment. The OST healed within several weeks. The patient had residual hypopigmentation after the OST healed, but was satisfied with the outcome.

CORRESPONDENCE

Hua-Liang Joel Lim, MBBS, MMed, National Skin Centre, 1 Mandalay Rd, Singapore 308205; [email protected].

A 48-year-old Chinese woman was referred to our center with a 7-month history of a painful lesion on her left jaw that had been gradually increasing in size. The patient noted occasional purulent and bloody discharge from the lesion. She denied having a toothache.

An examination revealed an erythematous nodule with perilesional puckering superior to the left body of the mandible, measuring 7 × 8 mm, with no discharge or surrounding inflammation (FIGURE 1). There was no cervical lymphadenopathy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Odontogenic sinus tract

Further examination on the inside of the patient’s mouth revealed root stumps of the left inferior molars (FIGURE 2). Based on the appearance of the lesion and molar involvement, we diagnosed odontogenic sinus tract (OST). OST, also known as odontogenic fistula or dental sinus, is a clinical diagnosis.

Symptoms such as odontalgia may be present in only 50% of patients with OST; thus, patients often initially consult their physician, rather than their dentist.1 If OST is suspected, evaluation should begin with a thorough history focusing on any recent facial trauma or past dental diseases. Dental panoramic or periapical radiography can be performed to confirm the extent of dental disease, and pulp vitality testing can determine if a diseased tooth is restorable.

A biopsy of the sinus tract is not required, as it would only reveal granulation tissue. Bimanual palpation of the oral cavity may reveal a cord-like structure from the cutaneous sinus to the underlying alveolar bone. (This structure was palpated in our patient.)

The pathogenesis of OST begins with dental caries, which progress to degeneration of the pulp and formation of periapical abscesses and root stumps. Progressive suppuration causes local destruction and subsequent tract formation through the alveolar bone and mandible. The build-up in pressure within this tract results in an eruption through the skin, manifesting as a sinus with extrusion of pus. The most common site of OST is at the angle of the mandible.2

The differential Dx is limited

There are a small number of other cutaneous conditions that may arise in the region of the mandible, but they have clinical features that distinguish them from OST.

Pyogenic granuloma presents as an erythematous papule that bleeds on contact. It usually develops rapidly following antecedent trauma.

Actinomycosis usually appears as an indolent plaque, with draining sinuses that extrude yellow grains on pressure. It may result from an underlying dental infection.

Squamous cell carcinoma of the skin often presents as a scaly plaque or non-healing ulcer with irregular margins and everted edges.

A furuncle is a tender, erythematous papule or nodule centered on a hair follicle. It is commonly associated with Staphylococcus aureus infection.

Treating OST

Treatment requires endodontic referral for root canal therapy, after which most cases resolve within a few weeks. OST can heal with post-inflammatory hyper- or hypopigmentation as a result of melanocyte damage. Systemic antibiotic administration is not necessary.3

We referred our patient to a dentist, who removed the root stumps and provided root canal treatment. The OST healed within several weeks. The patient had residual hypopigmentation after the OST healed, but was satisfied with the outcome.

CORRESPONDENCE

Hua-Liang Joel Lim, MBBS, MMed, National Skin Centre, 1 Mandalay Rd, Singapore 308205; [email protected].

1. Cioffi GA, Terezhalmy GT, Parlette HL. Cutaneous draining sinus tract: an odontogenic etiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14:94-100.

2. Brown RS, Jones R, Feimster T, et al. Cutaneous sinus tracts (or emerging sinus tracts) of odontogenic origin: a report of 3 cases. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent. 2010;2:63-67.

3. Susic M, Krakar N, Borcic J, et al. Odontogenic sinus tract to the neck skin: a case report. J Dermatol. 2004;31:920-922.

1. Cioffi GA, Terezhalmy GT, Parlette HL. Cutaneous draining sinus tract: an odontogenic etiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14:94-100.

2. Brown RS, Jones R, Feimster T, et al. Cutaneous sinus tracts (or emerging sinus tracts) of odontogenic origin: a report of 3 cases. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent. 2010;2:63-67.

3. Susic M, Krakar N, Borcic J, et al. Odontogenic sinus tract to the neck skin: a case report. J Dermatol. 2004;31:920-922.

Worsening dyspnea

A 62-year-old woman presented with a 2- to 3-week history of fatigue, nonproductive cough, dyspnea on exertion, and intermittent fever/chills. Her past medical history was significant for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) that had been treated with methotrexate and prednisone for the past 6 years. The patient was currently smoking half a pack a day with a 40-pack year history. The patient was a lifelong resident of Arizona and had previously worked in a stone mine.

On physical examination she appeared comfortable without any increased work of breathing. Her vital signs included a temperature of 36.6° C, a blood pressure of 110/54 mm Hg, a pulse of 90 beats/min, respirations of 16/min, and room-air oxygen saturation of 87%. Pulmonary examination revealed scattered wheezes with fine bibasilar crackles. The remainder of her physical exam was normal. Because she was hypoxic, she was admitted to the hospital.

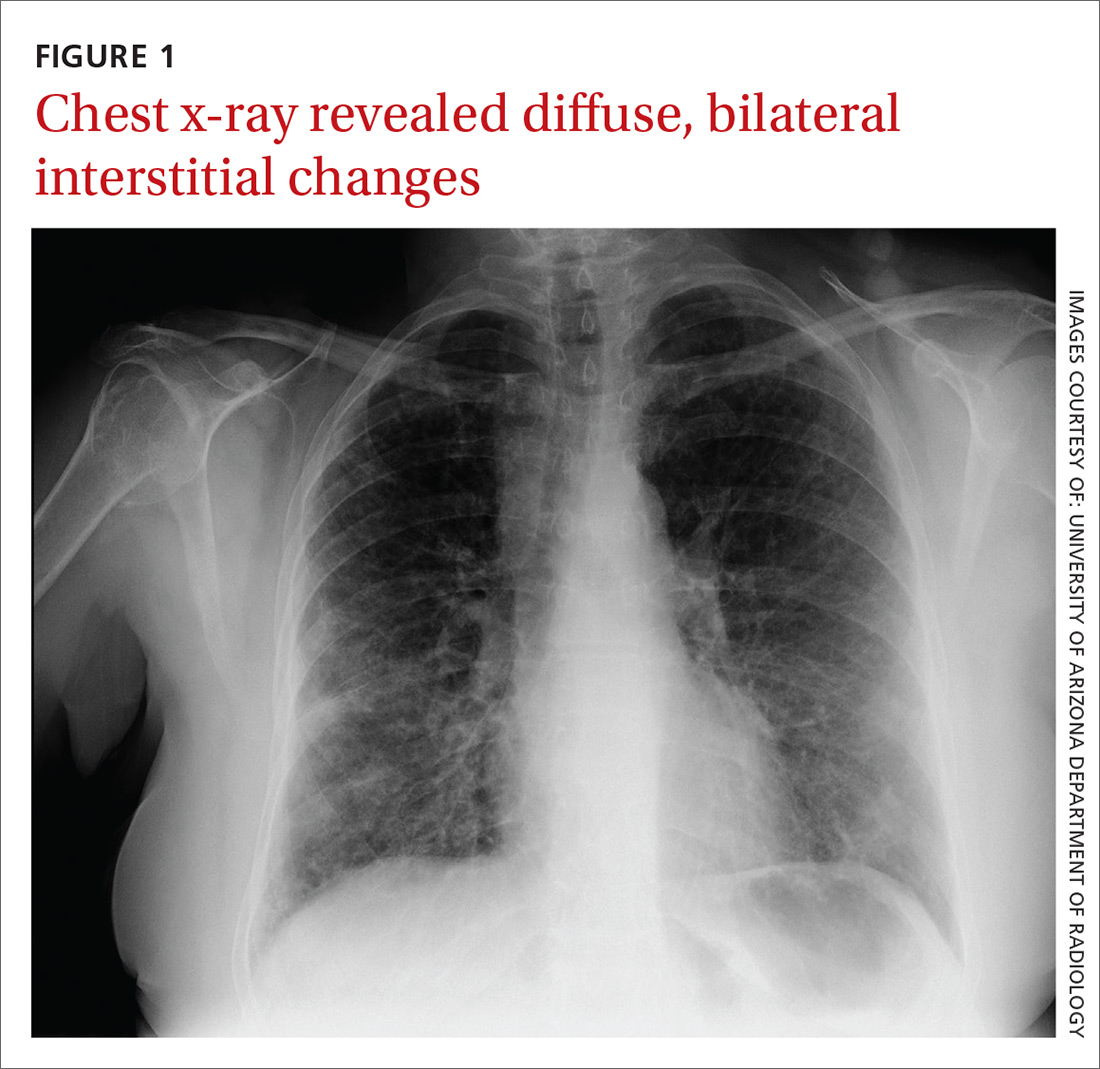

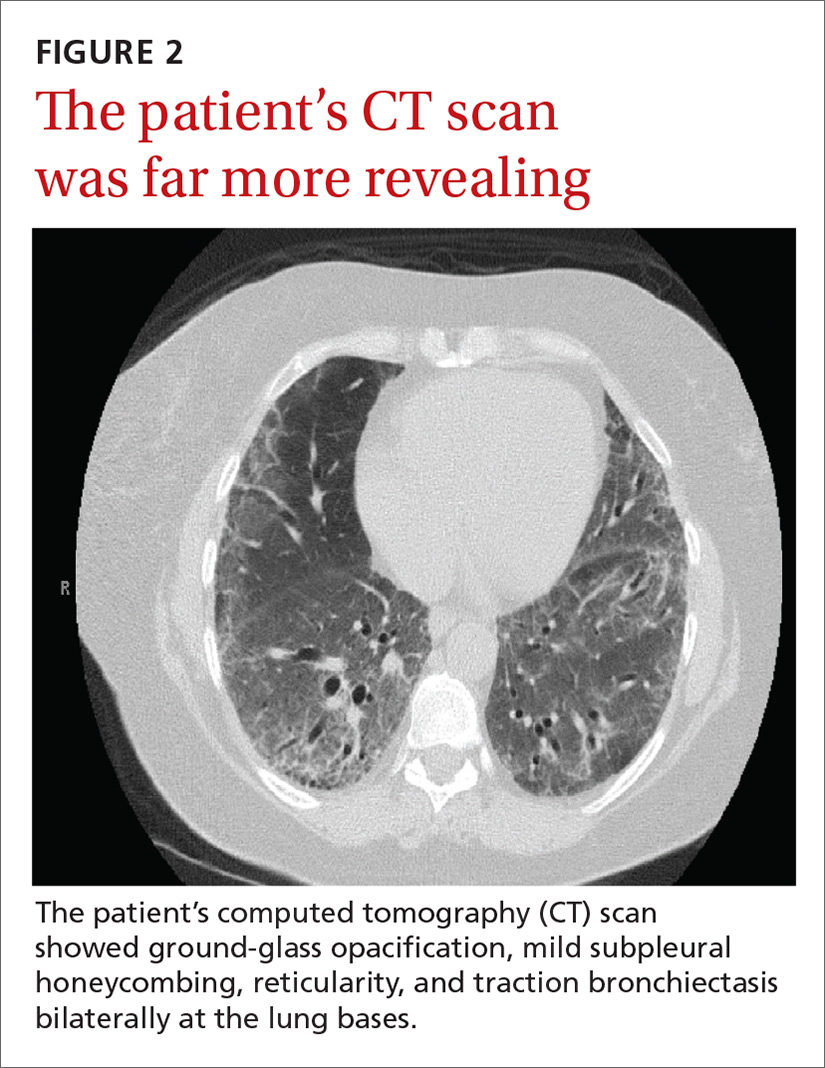

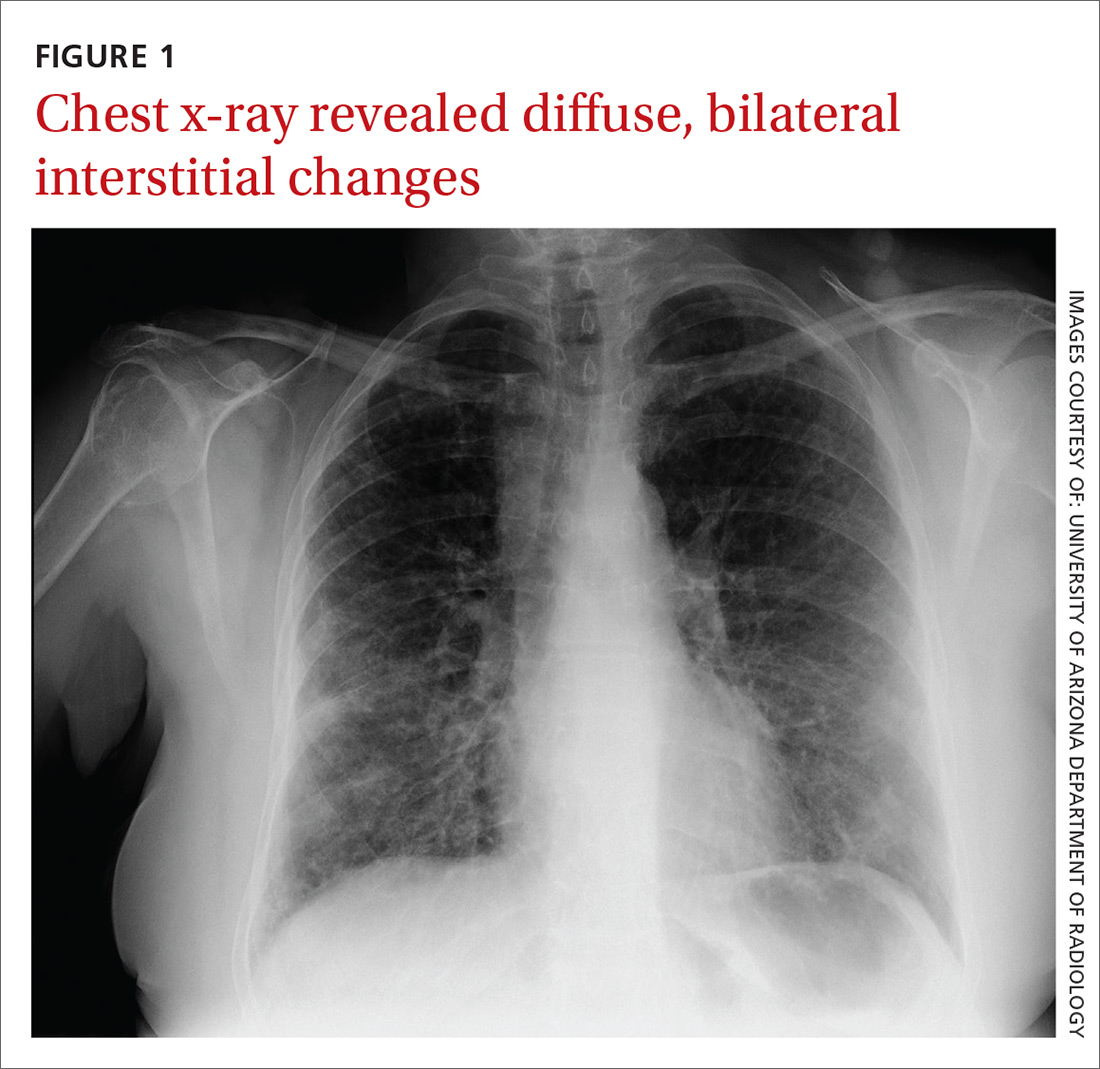

At the hospital, a chest x-ray showed diffuse, bilateral interstitial changes (FIGURE 1). Laboratory tests revealed a white blood cell count of 13,800/mcL (normal: 4500-10,500/mcL) with 73% neutrophils (normal: 40%-60%), 3% bands (normal: 0-3%), 14% monocytes (normal: 2%-8%), 6% eosinophils (normal: 1%-4%), and 3% lymphocytes (normal: 20%-30%). Community-acquired pneumonia was suspected, and the patient was started on levofloxacin. Over the next 2 days, her dyspnea worsened. She became tachycardic, and her oxygen requirement increased to 15 L/min via a non-rebreather mask. She was transferred to the intensive care unit.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Interstitial lung disease

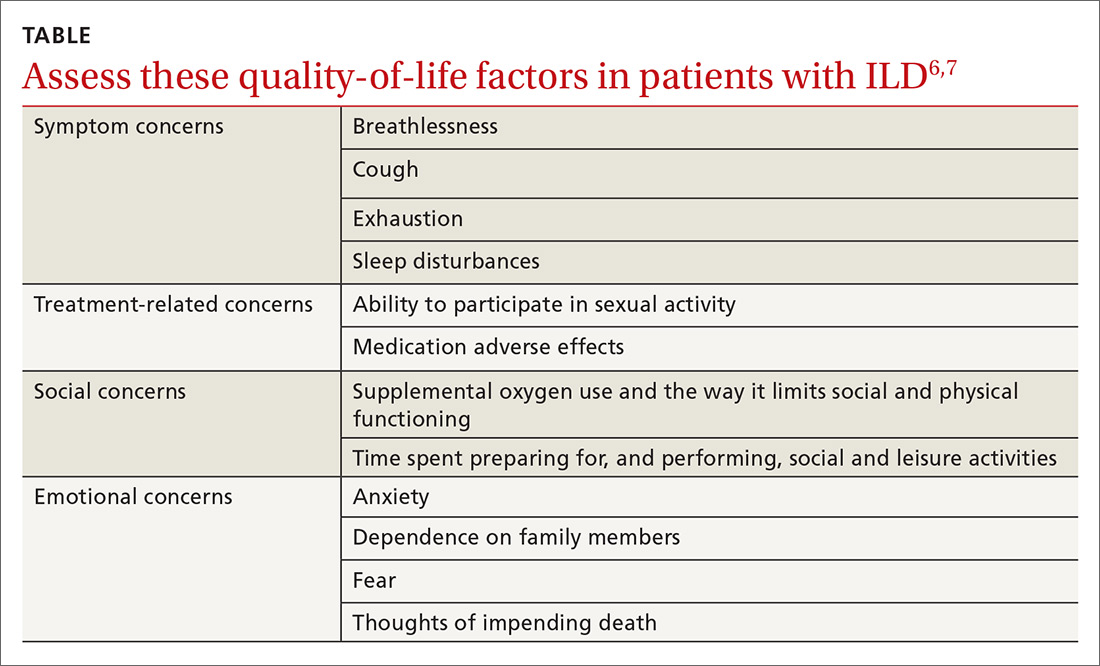

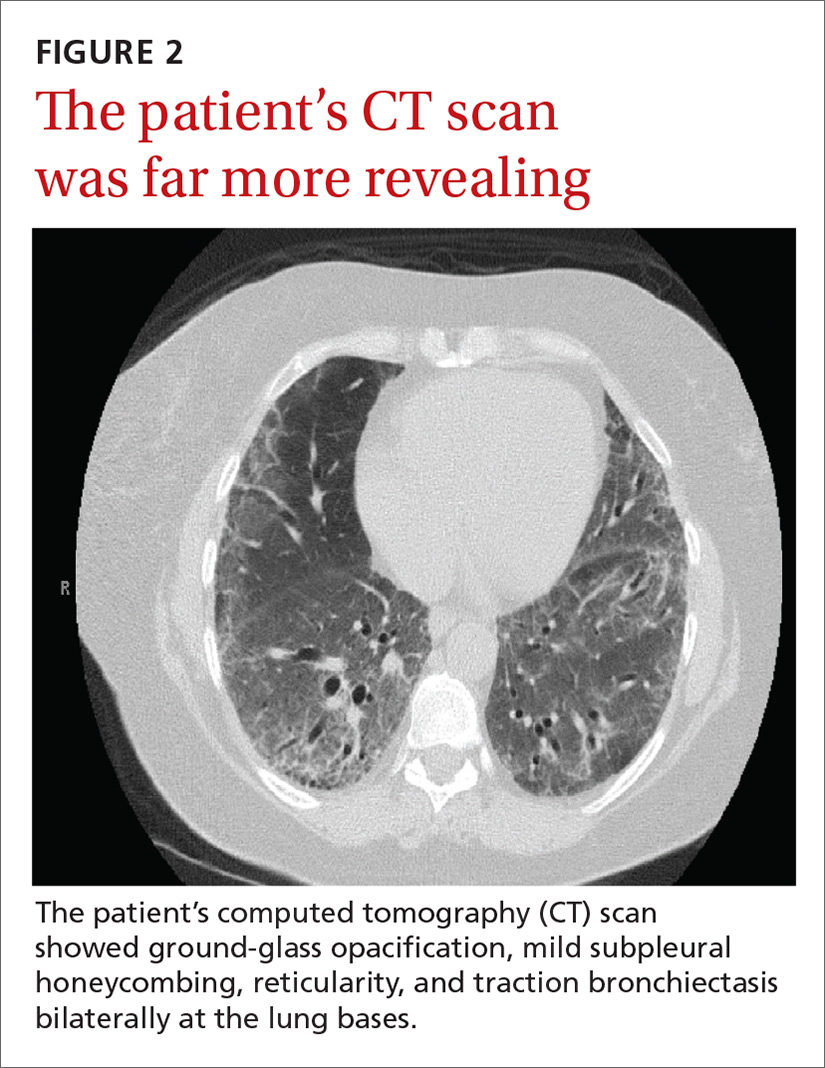

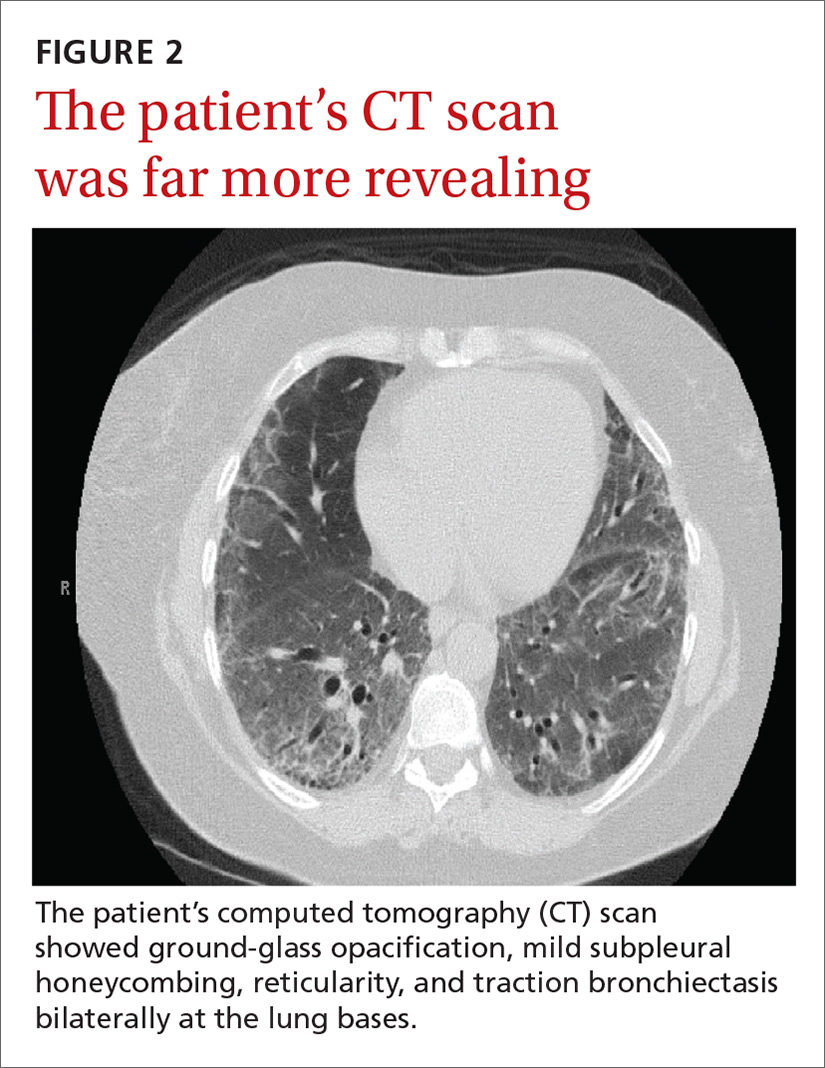

Given the patient’s worsening respiratory status, a computed tomography (CT) scan was ordered (FIGURE 2). Review of the CT scan showed ground-glass opacification, mild subpleural honeycombing, reticularity, and traction bronchiectasis bilaterally at the lung bases. Bronchoscopy with lavage was performed to rule out infectious etiologies and was negative. These findings, along with the patient’s medical history of RA and use of methotrexate, led us to diagnose interstitial lung disease (ILD) in this patient.

ILD refers to a group of disorders that primarily affects the pulmonary interstitium, rather than the alveolar spaces or pleura.1 The most common causes of ILD seen in primary care are idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, connective tissue disease, and hypersensitivity pneumonitis secondary to drugs (such as methotrexate, citalopram, fluoxetine, nitrofurantoin, and cephalosporins), radiation, or occupational exposures. (Textile, metal, and plastic workers are at a heightened risk, as are painters and individuals who work with animals.)1 In 2010, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis had a prevalence of 18.2 cases per 100,000 people.2 Determining the underlying cause of ILD is important, as it may influence prognosis and treatment decisions.

The most common presenting symptoms of ILD are exertional dyspnea, cough with insidious onset, fatigue, and weakness.1,3 Bear in mind, however, that patients with ILD associated with a connective tissue disease may have more subtle manifestations of exertional dyspnea, such as a change in activity level or low resting oxygen saturations. The pulmonary exam can be normal or can reveal fine end-inspiratory crackles, and may include high-pitched, inspiratory rhonchi, or “squeaks.”1

When a diagnosis of ILD is suspected, investigation should begin with high-resolution CT (HRCT).1.3-5 In patients for whom a potential cause of ILD is not identified or who have more than one potential cause, specific patterns seen on the HRCT can help determine the most likely etiology.5 Chest x-ray has low sensitivity and specificity for ILD and can frequently be misinterpreted, as occurred with our patient.1

Rule out other causes of dyspnea

The differential diagnosis for dyspnea includes:

Heart failure. Congestive heart failure can present with acutely worsening dyspnea and cough, but is also commonly associated with orthopnea and/or paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea. On physical examination, findings of volume overload such as pulmonary crackles, lower extremity edema, and elevated jugular venous pressure are additional signs that heart failure is present.

Pulmonary embolism (PE). Patients with PE commonly present with acute dyspnea, chest pain, and may also have a cough. Additional risk factors for PE (prolonged immobility, fracture, recent hospitalization) may also be present. A Wells score and a D-dimer test can be used to determine the probability of a patient having PE.

Asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD exacerbations commonly present with a productive cough and worsening dyspnea. Pulmonary exam findings include wheezing, tachypnea, increased respiratory effort, and poor air movement.

Infection (including coccidioidomycosis in the desert southwest, where this patient lived). Our patient was initially treated for pneumonia because she had reported fevers associated with dyspnea and cough along with an elevated white blood cell count. Chest x-ray findings in patients with pneumonia can reveal either lobar consolidation or interstitial infiltrates.

Failure to respond to treatment of the more common causes of dyspnea, as occurred with our patient, should prompt consideration of ILD, particularly in those who have a history of connective tissue disease. Once a diagnosis of ILD is made, referral to a pulmonary specialist is advised.1,3

A poor prognosis and a focus on quality of life

Immunosuppressive therapy is currently the standard treatment for ILD, although there is little evidence to support this practice.1,3,4 Therapy usually includes corticosteroids with or without the addition of a second immunosuppressive agent such as azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, or cyclophosphamide.1,4

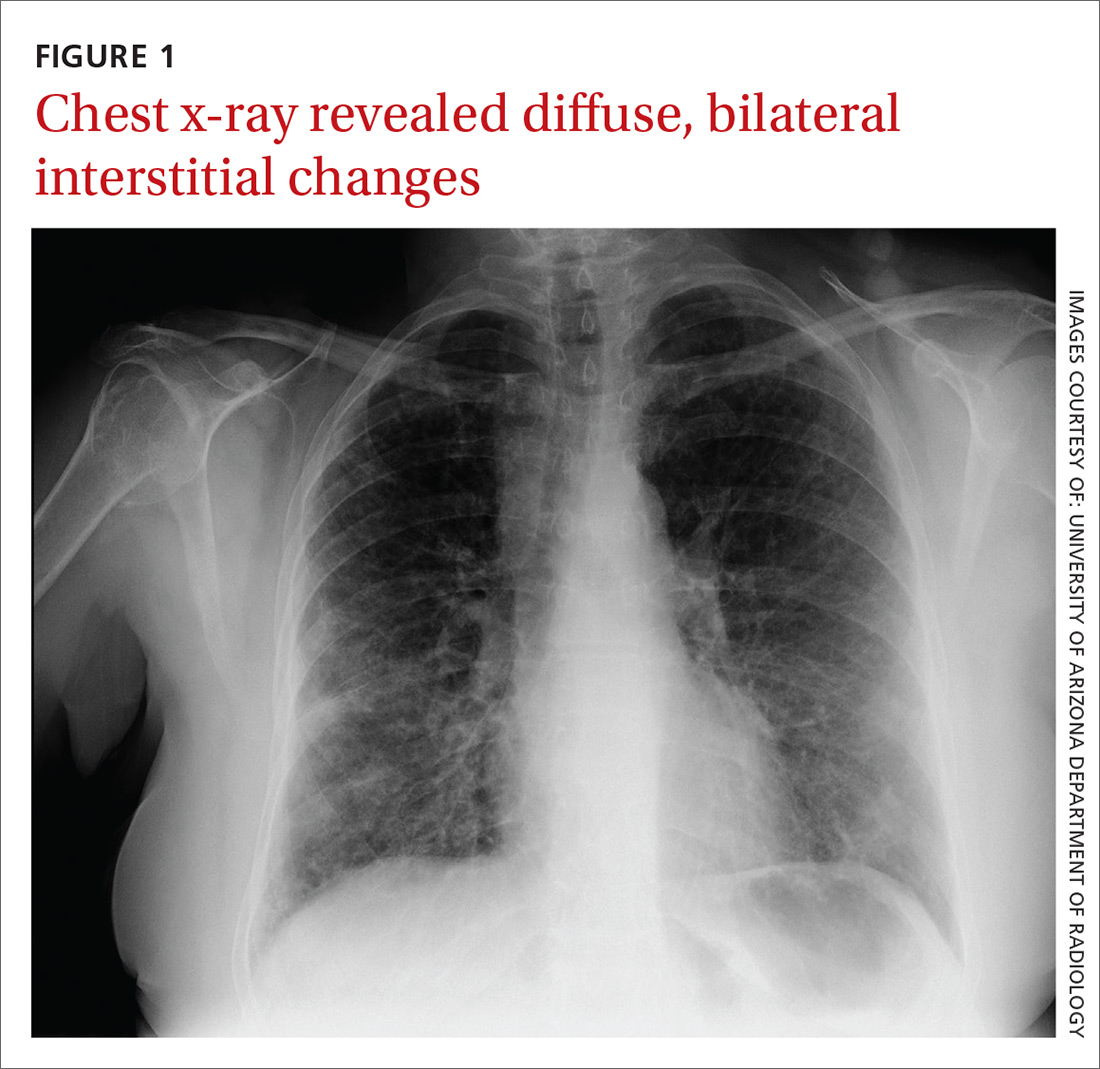

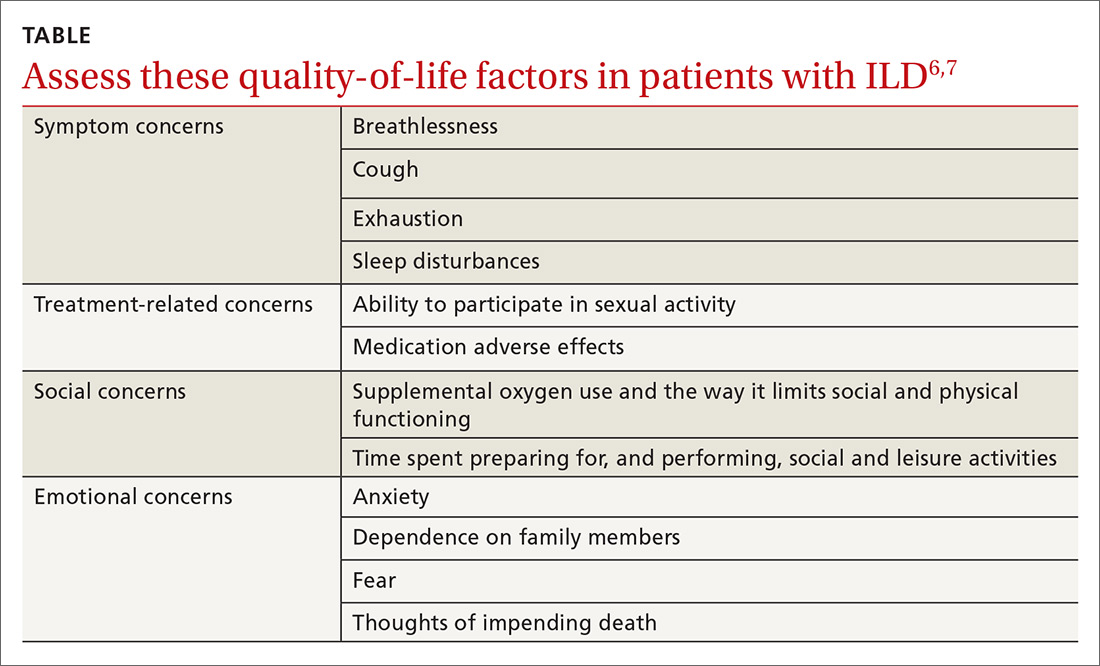

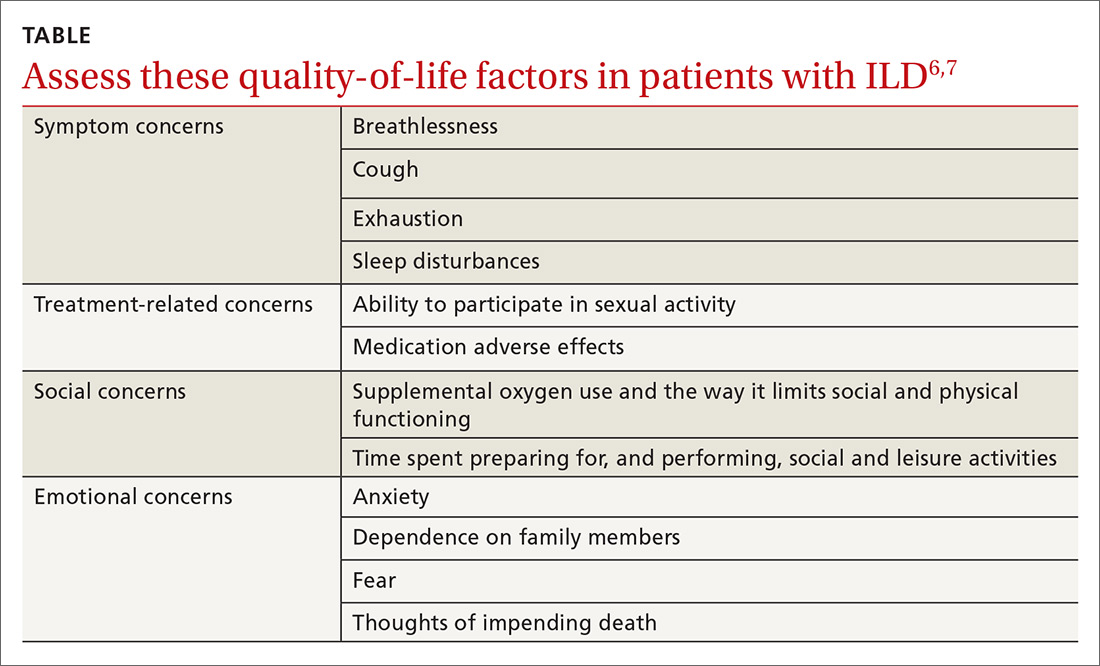

In addition to drug therapy, the American College of Chest Physicians recommends routine assessment of quality-of-life (QOL) concerns in patients with ILD (TABLE).6,7 Additional QOL tools available to physicians include the Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form 36-Item Instrument8 and the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire.9

The prognosis is poor, even with treatment. Patients with ILD have a life expectancy that averages 2 to 4 years from diagnosis.6 Patients with ILD are frequently distressed about worsening control of dyspnea and becoming a burden to family members; they also have anxiety about dying.6 It’s important to allocate sufficient time for end-of-life discussions, as studies have shown that patients would like their physicians to address the issue more thoroughly.10

Our patient was started on high-flow oxygen and high-dose steroids. Azathioprine was later added. The patient’s methotrexate was stopped, in light of its association with ILD. Unfortunately, the treatments were not successful and the patient’s respiratory status continued to deteriorate. A family meeting was held with the patient to discuss end-of-life wishes, and the patient expressed a preference for hospice care. She died a few days after hospice enrollment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Karyn B. Kolman, MD, University of Arizona College of Medicine at South Campus Family Medicine Residency, 2800 E Ajo Way, Room 3006, Tucson, AZ 85713; [email protected].

1. Wallis A, Spinks K. The diagnosis and management of interstial lung disease. BMJ. 2015;350:h2072.

2. Raghu G, Chen SY, Hou Q, et al. Incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in US adults 18-64 years old. Eur Respir J. 2016;48:179-186.

3. Yunt ZX, Solomon JJ. Lung disease in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2015;41:225-236.

4. Vij R, Strek ME. Diagnosis and treatment of connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease. Chest. 2013;143:814-824.

5. Nair A, Walsh SL, Desai SR. Imaging of pulmonary involvement in rheumatic disease. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2015;41:167-196.

6. Gilbert CR, Smith CM. Advanced parenchymal lung disease: quality of life and palliative care. Mt Sinai J Med. 2009;76:63-70.

7. Swigris JJ, Stewart AL, Gould MK, et al. Patients’ perspectives on how idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis affects the quality of their lives. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;3:61.

8. RAND. Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36). Available at: http://www.rand.org/health/surveys_tools/mos/mos_core_36item.html. Accessed May 27, 2016.

9. St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire. Available at: http://www.healthstatus.sgul.ac.uk/. Accessed May 27, 2016.

10. Bajwah S, Koffman J, Higginson IJ, et. al. ‘I wish I knew more…’ the end-of-life planning and information needs for end-stage fibrotic interstitial lung disease: views of patients, carers, and health professionals. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2013;3;84-90.

A 62-year-old woman presented with a 2- to 3-week history of fatigue, nonproductive cough, dyspnea on exertion, and intermittent fever/chills. Her past medical history was significant for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) that had been treated with methotrexate and prednisone for the past 6 years. The patient was currently smoking half a pack a day with a 40-pack year history. The patient was a lifelong resident of Arizona and had previously worked in a stone mine.

On physical examination she appeared comfortable without any increased work of breathing. Her vital signs included a temperature of 36.6° C, a blood pressure of 110/54 mm Hg, a pulse of 90 beats/min, respirations of 16/min, and room-air oxygen saturation of 87%. Pulmonary examination revealed scattered wheezes with fine bibasilar crackles. The remainder of her physical exam was normal. Because she was hypoxic, she was admitted to the hospital.

At the hospital, a chest x-ray showed diffuse, bilateral interstitial changes (FIGURE 1). Laboratory tests revealed a white blood cell count of 13,800/mcL (normal: 4500-10,500/mcL) with 73% neutrophils (normal: 40%-60%), 3% bands (normal: 0-3%), 14% monocytes (normal: 2%-8%), 6% eosinophils (normal: 1%-4%), and 3% lymphocytes (normal: 20%-30%). Community-acquired pneumonia was suspected, and the patient was started on levofloxacin. Over the next 2 days, her dyspnea worsened. She became tachycardic, and her oxygen requirement increased to 15 L/min via a non-rebreather mask. She was transferred to the intensive care unit.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Interstitial lung disease

Given the patient’s worsening respiratory status, a computed tomography (CT) scan was ordered (FIGURE 2). Review of the CT scan showed ground-glass opacification, mild subpleural honeycombing, reticularity, and traction bronchiectasis bilaterally at the lung bases. Bronchoscopy with lavage was performed to rule out infectious etiologies and was negative. These findings, along with the patient’s medical history of RA and use of methotrexate, led us to diagnose interstitial lung disease (ILD) in this patient.

ILD refers to a group of disorders that primarily affects the pulmonary interstitium, rather than the alveolar spaces or pleura.1 The most common causes of ILD seen in primary care are idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, connective tissue disease, and hypersensitivity pneumonitis secondary to drugs (such as methotrexate, citalopram, fluoxetine, nitrofurantoin, and cephalosporins), radiation, or occupational exposures. (Textile, metal, and plastic workers are at a heightened risk, as are painters and individuals who work with animals.)1 In 2010, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis had a prevalence of 18.2 cases per 100,000 people.2 Determining the underlying cause of ILD is important, as it may influence prognosis and treatment decisions.

The most common presenting symptoms of ILD are exertional dyspnea, cough with insidious onset, fatigue, and weakness.1,3 Bear in mind, however, that patients with ILD associated with a connective tissue disease may have more subtle manifestations of exertional dyspnea, such as a change in activity level or low resting oxygen saturations. The pulmonary exam can be normal or can reveal fine end-inspiratory crackles, and may include high-pitched, inspiratory rhonchi, or “squeaks.”1

When a diagnosis of ILD is suspected, investigation should begin with high-resolution CT (HRCT).1.3-5 In patients for whom a potential cause of ILD is not identified or who have more than one potential cause, specific patterns seen on the HRCT can help determine the most likely etiology.5 Chest x-ray has low sensitivity and specificity for ILD and can frequently be misinterpreted, as occurred with our patient.1

Rule out other causes of dyspnea

The differential diagnosis for dyspnea includes:

Heart failure. Congestive heart failure can present with acutely worsening dyspnea and cough, but is also commonly associated with orthopnea and/or paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea. On physical examination, findings of volume overload such as pulmonary crackles, lower extremity edema, and elevated jugular venous pressure are additional signs that heart failure is present.

Pulmonary embolism (PE). Patients with PE commonly present with acute dyspnea, chest pain, and may also have a cough. Additional risk factors for PE (prolonged immobility, fracture, recent hospitalization) may also be present. A Wells score and a D-dimer test can be used to determine the probability of a patient having PE.

Asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD exacerbations commonly present with a productive cough and worsening dyspnea. Pulmonary exam findings include wheezing, tachypnea, increased respiratory effort, and poor air movement.

Infection (including coccidioidomycosis in the desert southwest, where this patient lived). Our patient was initially treated for pneumonia because she had reported fevers associated with dyspnea and cough along with an elevated white blood cell count. Chest x-ray findings in patients with pneumonia can reveal either lobar consolidation or interstitial infiltrates.

Failure to respond to treatment of the more common causes of dyspnea, as occurred with our patient, should prompt consideration of ILD, particularly in those who have a history of connective tissue disease. Once a diagnosis of ILD is made, referral to a pulmonary specialist is advised.1,3

A poor prognosis and a focus on quality of life

Immunosuppressive therapy is currently the standard treatment for ILD, although there is little evidence to support this practice.1,3,4 Therapy usually includes corticosteroids with or without the addition of a second immunosuppressive agent such as azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, or cyclophosphamide.1,4

In addition to drug therapy, the American College of Chest Physicians recommends routine assessment of quality-of-life (QOL) concerns in patients with ILD (TABLE).6,7 Additional QOL tools available to physicians include the Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form 36-Item Instrument8 and the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire.9

The prognosis is poor, even with treatment. Patients with ILD have a life expectancy that averages 2 to 4 years from diagnosis.6 Patients with ILD are frequently distressed about worsening control of dyspnea and becoming a burden to family members; they also have anxiety about dying.6 It’s important to allocate sufficient time for end-of-life discussions, as studies have shown that patients would like their physicians to address the issue more thoroughly.10

Our patient was started on high-flow oxygen and high-dose steroids. Azathioprine was later added. The patient’s methotrexate was stopped, in light of its association with ILD. Unfortunately, the treatments were not successful and the patient’s respiratory status continued to deteriorate. A family meeting was held with the patient to discuss end-of-life wishes, and the patient expressed a preference for hospice care. She died a few days after hospice enrollment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Karyn B. Kolman, MD, University of Arizona College of Medicine at South Campus Family Medicine Residency, 2800 E Ajo Way, Room 3006, Tucson, AZ 85713; [email protected].

A 62-year-old woman presented with a 2- to 3-week history of fatigue, nonproductive cough, dyspnea on exertion, and intermittent fever/chills. Her past medical history was significant for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) that had been treated with methotrexate and prednisone for the past 6 years. The patient was currently smoking half a pack a day with a 40-pack year history. The patient was a lifelong resident of Arizona and had previously worked in a stone mine.

On physical examination she appeared comfortable without any increased work of breathing. Her vital signs included a temperature of 36.6° C, a blood pressure of 110/54 mm Hg, a pulse of 90 beats/min, respirations of 16/min, and room-air oxygen saturation of 87%. Pulmonary examination revealed scattered wheezes with fine bibasilar crackles. The remainder of her physical exam was normal. Because she was hypoxic, she was admitted to the hospital.

At the hospital, a chest x-ray showed diffuse, bilateral interstitial changes (FIGURE 1). Laboratory tests revealed a white blood cell count of 13,800/mcL (normal: 4500-10,500/mcL) with 73% neutrophils (normal: 40%-60%), 3% bands (normal: 0-3%), 14% monocytes (normal: 2%-8%), 6% eosinophils (normal: 1%-4%), and 3% lymphocytes (normal: 20%-30%). Community-acquired pneumonia was suspected, and the patient was started on levofloxacin. Over the next 2 days, her dyspnea worsened. She became tachycardic, and her oxygen requirement increased to 15 L/min via a non-rebreather mask. She was transferred to the intensive care unit.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Interstitial lung disease

Given the patient’s worsening respiratory status, a computed tomography (CT) scan was ordered (FIGURE 2). Review of the CT scan showed ground-glass opacification, mild subpleural honeycombing, reticularity, and traction bronchiectasis bilaterally at the lung bases. Bronchoscopy with lavage was performed to rule out infectious etiologies and was negative. These findings, along with the patient’s medical history of RA and use of methotrexate, led us to diagnose interstitial lung disease (ILD) in this patient.

ILD refers to a group of disorders that primarily affects the pulmonary interstitium, rather than the alveolar spaces or pleura.1 The most common causes of ILD seen in primary care are idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, connective tissue disease, and hypersensitivity pneumonitis secondary to drugs (such as methotrexate, citalopram, fluoxetine, nitrofurantoin, and cephalosporins), radiation, or occupational exposures. (Textile, metal, and plastic workers are at a heightened risk, as are painters and individuals who work with animals.)1 In 2010, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis had a prevalence of 18.2 cases per 100,000 people.2 Determining the underlying cause of ILD is important, as it may influence prognosis and treatment decisions.

The most common presenting symptoms of ILD are exertional dyspnea, cough with insidious onset, fatigue, and weakness.1,3 Bear in mind, however, that patients with ILD associated with a connective tissue disease may have more subtle manifestations of exertional dyspnea, such as a change in activity level or low resting oxygen saturations. The pulmonary exam can be normal or can reveal fine end-inspiratory crackles, and may include high-pitched, inspiratory rhonchi, or “squeaks.”1

When a diagnosis of ILD is suspected, investigation should begin with high-resolution CT (HRCT).1.3-5 In patients for whom a potential cause of ILD is not identified or who have more than one potential cause, specific patterns seen on the HRCT can help determine the most likely etiology.5 Chest x-ray has low sensitivity and specificity for ILD and can frequently be misinterpreted, as occurred with our patient.1

Rule out other causes of dyspnea

The differential diagnosis for dyspnea includes:

Heart failure. Congestive heart failure can present with acutely worsening dyspnea and cough, but is also commonly associated with orthopnea and/or paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea. On physical examination, findings of volume overload such as pulmonary crackles, lower extremity edema, and elevated jugular venous pressure are additional signs that heart failure is present.

Pulmonary embolism (PE). Patients with PE commonly present with acute dyspnea, chest pain, and may also have a cough. Additional risk factors for PE (prolonged immobility, fracture, recent hospitalization) may also be present. A Wells score and a D-dimer test can be used to determine the probability of a patient having PE.

Asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD exacerbations commonly present with a productive cough and worsening dyspnea. Pulmonary exam findings include wheezing, tachypnea, increased respiratory effort, and poor air movement.

Infection (including coccidioidomycosis in the desert southwest, where this patient lived). Our patient was initially treated for pneumonia because she had reported fevers associated with dyspnea and cough along with an elevated white blood cell count. Chest x-ray findings in patients with pneumonia can reveal either lobar consolidation or interstitial infiltrates.

Failure to respond to treatment of the more common causes of dyspnea, as occurred with our patient, should prompt consideration of ILD, particularly in those who have a history of connective tissue disease. Once a diagnosis of ILD is made, referral to a pulmonary specialist is advised.1,3

A poor prognosis and a focus on quality of life

Immunosuppressive therapy is currently the standard treatment for ILD, although there is little evidence to support this practice.1,3,4 Therapy usually includes corticosteroids with or without the addition of a second immunosuppressive agent such as azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, or cyclophosphamide.1,4

In addition to drug therapy, the American College of Chest Physicians recommends routine assessment of quality-of-life (QOL) concerns in patients with ILD (TABLE).6,7 Additional QOL tools available to physicians include the Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form 36-Item Instrument8 and the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire.9

The prognosis is poor, even with treatment. Patients with ILD have a life expectancy that averages 2 to 4 years from diagnosis.6 Patients with ILD are frequently distressed about worsening control of dyspnea and becoming a burden to family members; they also have anxiety about dying.6 It’s important to allocate sufficient time for end-of-life discussions, as studies have shown that patients would like their physicians to address the issue more thoroughly.10

Our patient was started on high-flow oxygen and high-dose steroids. Azathioprine was later added. The patient’s methotrexate was stopped, in light of its association with ILD. Unfortunately, the treatments were not successful and the patient’s respiratory status continued to deteriorate. A family meeting was held with the patient to discuss end-of-life wishes, and the patient expressed a preference for hospice care. She died a few days after hospice enrollment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Karyn B. Kolman, MD, University of Arizona College of Medicine at South Campus Family Medicine Residency, 2800 E Ajo Way, Room 3006, Tucson, AZ 85713; [email protected].

1. Wallis A, Spinks K. The diagnosis and management of interstial lung disease. BMJ. 2015;350:h2072.

2. Raghu G, Chen SY, Hou Q, et al. Incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in US adults 18-64 years old. Eur Respir J. 2016;48:179-186.

3. Yunt ZX, Solomon JJ. Lung disease in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2015;41:225-236.

4. Vij R, Strek ME. Diagnosis and treatment of connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease. Chest. 2013;143:814-824.

5. Nair A, Walsh SL, Desai SR. Imaging of pulmonary involvement in rheumatic disease. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2015;41:167-196.

6. Gilbert CR, Smith CM. Advanced parenchymal lung disease: quality of life and palliative care. Mt Sinai J Med. 2009;76:63-70.

7. Swigris JJ, Stewart AL, Gould MK, et al. Patients’ perspectives on how idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis affects the quality of their lives. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;3:61.

8. RAND. Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36). Available at: http://www.rand.org/health/surveys_tools/mos/mos_core_36item.html. Accessed May 27, 2016.

9. St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire. Available at: http://www.healthstatus.sgul.ac.uk/. Accessed May 27, 2016.

10. Bajwah S, Koffman J, Higginson IJ, et. al. ‘I wish I knew more…’ the end-of-life planning and information needs for end-stage fibrotic interstitial lung disease: views of patients, carers, and health professionals. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2013;3;84-90.

1. Wallis A, Spinks K. The diagnosis and management of interstial lung disease. BMJ. 2015;350:h2072.

2. Raghu G, Chen SY, Hou Q, et al. Incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in US adults 18-64 years old. Eur Respir J. 2016;48:179-186.

3. Yunt ZX, Solomon JJ. Lung disease in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2015;41:225-236.

4. Vij R, Strek ME. Diagnosis and treatment of connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease. Chest. 2013;143:814-824.

5. Nair A, Walsh SL, Desai SR. Imaging of pulmonary involvement in rheumatic disease. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2015;41:167-196.

6. Gilbert CR, Smith CM. Advanced parenchymal lung disease: quality of life and palliative care. Mt Sinai J Med. 2009;76:63-70.

7. Swigris JJ, Stewart AL, Gould MK, et al. Patients’ perspectives on how idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis affects the quality of their lives. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;3:61.

8. RAND. Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36). Available at: http://www.rand.org/health/surveys_tools/mos/mos_core_36item.html. Accessed May 27, 2016.

9. St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire. Available at: http://www.healthstatus.sgul.ac.uk/. Accessed May 27, 2016.

10. Bajwah S, Koffman J, Higginson IJ, et. al. ‘I wish I knew more…’ the end-of-life planning and information needs for end-stage fibrotic interstitial lung disease: views of patients, carers, and health professionals. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2013;3;84-90.

Recurrent rash

Based on the appearance and location of the lesions, a diagnosis of recurrent herpes simplex virus-2 (HSV-2) was made. HSV-2 is generally a genital eruption but can also occur on the buttocks, especially in women. (Our patient was not aware that she’d had a genital primary HSV-2 infection.) HSV-2 infects an estimated 5% to 25% of adults in western nations. In 2012, approximately 417 million people ages 15 to 49 were living with HSV-2 worldwide, including 19 million who were newly infected.

Following a genital primary infection, HSV-2 lies dormant in the sacral nerve root ganglia, which innervate both the genitals and sacrum. Reactivation can thus result in recurrences anywhere over the sacral dermatome. The sacral area is the most common nongenital site for recurrent HSV-2. Reactivation of HSV-2 is more common and more severe in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection.

The mainstay of treatment for HSV is antiviral therapy with acyclovir. Famciclovir and valacyclovir can be used, as well. These antivirals inhibit viral DNA replication, shorten duration of symptoms, increase lesion healing, and decrease viral shedding time. They are generally safe; the main adverse effects of oral therapy are nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

In general, nongenital recurrences of HSV are treated the same as genital recurrences. Dosing during prodromal symptoms or at the first sign of a recurrence is recommended for maximum efficacy. Suppressive therapy can be effective in patients who experience frequent recurrences and is generally recommended for 6 months to a year (or longer). Patients should also be warned that because of increased genital viral shedding during sacral recurrences, they should avoid sexual contact during outbreaks.

After a discussion about the benefits and risks of antiviral suppression, the patient decided she was ready to proceed with treatment. The physician prescribed oral valacyclovir 1 g daily for treatment and suppression. She had no recurrences over the next year.

Adapted from: Flowers H, Brodell RT. Recurrent vesicular rash over the sacrum. J Fam Pract. 2015;64:577-579.

Based on the appearance and location of the lesions, a diagnosis of recurrent herpes simplex virus-2 (HSV-2) was made. HSV-2 is generally a genital eruption but can also occur on the buttocks, especially in women. (Our patient was not aware that she’d had a genital primary HSV-2 infection.) HSV-2 infects an estimated 5% to 25% of adults in western nations. In 2012, approximately 417 million people ages 15 to 49 were living with HSV-2 worldwide, including 19 million who were newly infected.

Following a genital primary infection, HSV-2 lies dormant in the sacral nerve root ganglia, which innervate both the genitals and sacrum. Reactivation can thus result in recurrences anywhere over the sacral dermatome. The sacral area is the most common nongenital site for recurrent HSV-2. Reactivation of HSV-2 is more common and more severe in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection.

The mainstay of treatment for HSV is antiviral therapy with acyclovir. Famciclovir and valacyclovir can be used, as well. These antivirals inhibit viral DNA replication, shorten duration of symptoms, increase lesion healing, and decrease viral shedding time. They are generally safe; the main adverse effects of oral therapy are nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

In general, nongenital recurrences of HSV are treated the same as genital recurrences. Dosing during prodromal symptoms or at the first sign of a recurrence is recommended for maximum efficacy. Suppressive therapy can be effective in patients who experience frequent recurrences and is generally recommended for 6 months to a year (or longer). Patients should also be warned that because of increased genital viral shedding during sacral recurrences, they should avoid sexual contact during outbreaks.

After a discussion about the benefits and risks of antiviral suppression, the patient decided she was ready to proceed with treatment. The physician prescribed oral valacyclovir 1 g daily for treatment and suppression. She had no recurrences over the next year.

Adapted from: Flowers H, Brodell RT. Recurrent vesicular rash over the sacrum. J Fam Pract. 2015;64:577-579.

Based on the appearance and location of the lesions, a diagnosis of recurrent herpes simplex virus-2 (HSV-2) was made. HSV-2 is generally a genital eruption but can also occur on the buttocks, especially in women. (Our patient was not aware that she’d had a genital primary HSV-2 infection.) HSV-2 infects an estimated 5% to 25% of adults in western nations. In 2012, approximately 417 million people ages 15 to 49 were living with HSV-2 worldwide, including 19 million who were newly infected.

Following a genital primary infection, HSV-2 lies dormant in the sacral nerve root ganglia, which innervate both the genitals and sacrum. Reactivation can thus result in recurrences anywhere over the sacral dermatome. The sacral area is the most common nongenital site for recurrent HSV-2. Reactivation of HSV-2 is more common and more severe in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection.

The mainstay of treatment for HSV is antiviral therapy with acyclovir. Famciclovir and valacyclovir can be used, as well. These antivirals inhibit viral DNA replication, shorten duration of symptoms, increase lesion healing, and decrease viral shedding time. They are generally safe; the main adverse effects of oral therapy are nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

In general, nongenital recurrences of HSV are treated the same as genital recurrences. Dosing during prodromal symptoms or at the first sign of a recurrence is recommended for maximum efficacy. Suppressive therapy can be effective in patients who experience frequent recurrences and is generally recommended for 6 months to a year (or longer). Patients should also be warned that because of increased genital viral shedding during sacral recurrences, they should avoid sexual contact during outbreaks.

After a discussion about the benefits and risks of antiviral suppression, the patient decided she was ready to proceed with treatment. The physician prescribed oral valacyclovir 1 g daily for treatment and suppression. She had no recurrences over the next year.

Adapted from: Flowers H, Brodell RT. Recurrent vesicular rash over the sacrum. J Fam Pract. 2015;64:577-579.

Growing mass on trunk

The FP recognized that the patient had a large skin tag. He offered to excise it for the patient and explained that it could be removed with a deep elliptical excision and then repaired with sutures, or that it could be shaved off and allowed to heal by secondary intention. The patient opted for the shave excision because he preferred not to have sutures.

The FP numbed the area with an injection of 1% lidocaine and epinephrine, then shaved off the growth using a DermaBlade and sent it to pathology. (See a video on how to perform a shave biopsy here.) The FP used aluminum chloride to stop the bleeding. The Pathology report came back and indicated the lesion was a fibroepithelial polyp, which is essentially a large skin tag. At a 2-week follow-up, the biopsied area was healing well.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith AM. Skin tags. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 922-925.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP recognized that the patient had a large skin tag. He offered to excise it for the patient and explained that it could be removed with a deep elliptical excision and then repaired with sutures, or that it could be shaved off and allowed to heal by secondary intention. The patient opted for the shave excision because he preferred not to have sutures.

The FP numbed the area with an injection of 1% lidocaine and epinephrine, then shaved off the growth using a DermaBlade and sent it to pathology. (See a video on how to perform a shave biopsy here.) The FP used aluminum chloride to stop the bleeding. The Pathology report came back and indicated the lesion was a fibroepithelial polyp, which is essentially a large skin tag. At a 2-week follow-up, the biopsied area was healing well.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith AM. Skin tags. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 922-925.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP recognized that the patient had a large skin tag. He offered to excise it for the patient and explained that it could be removed with a deep elliptical excision and then repaired with sutures, or that it could be shaved off and allowed to heal by secondary intention. The patient opted for the shave excision because he preferred not to have sutures.

The FP numbed the area with an injection of 1% lidocaine and epinephrine, then shaved off the growth using a DermaBlade and sent it to pathology. (See a video on how to perform a shave biopsy here.) The FP used aluminum chloride to stop the bleeding. The Pathology report came back and indicated the lesion was a fibroepithelial polyp, which is essentially a large skin tag. At a 2-week follow-up, the biopsied area was healing well.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith AM. Skin tags. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 922-925.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com