User login

Growths and darkened skin

Based on the dark velvety skin on the patient’s neck, the FP diagnosed acanthosis nigricans accompanied by multiple skin tags (acrochordons). The patient told the physician that he wanted to have the skin tags removed and the darkened skin treated. Because both conditions are associated with obesity and diabetes, the FP recommended that the patient increase his weight loss efforts through improved diet and increased exercise.

The FP also explained that treatment options for the skin tags included cryotherapy, snip excisions, and electrosurgery. The patient did not want to wait for the skin tags to fall off after cryotherapy or electrosurgery, so he chose snip excisions for immediate results. The skin tags were pedunculated with narrow stalks, so the snip excisions were performed without anesthesia. Aluminum chloride was applied to stop the bleeding on some of the skin tags. The patient noted some stinging, but tolerated the treatment well.

For the acanthosis nigricans, the FP explained that there are no highly effective treatments. In addition to recommending weight loss, the FP prescribed topical tretinoin cream 0.025% to be applied to the darkened skin before bed (only after the cuts from the skin tag removals had healed). The FP told the patient that the treatment might be only partially beneficial (or might not work at all). Other treatment options for acanthosis nigricans (with limited effectiveness) include keratolytic agents (eg, salicylic acid, ammonium lactate) and topical vitamin D analogs. At follow-up one month later, the patient had not yet noticed any changes to the acanthosis nigricans, but he was satisfied with the results of the skin tag removal.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith AM. Skin tags. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 922-925.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Based on the dark velvety skin on the patient’s neck, the FP diagnosed acanthosis nigricans accompanied by multiple skin tags (acrochordons). The patient told the physician that he wanted to have the skin tags removed and the darkened skin treated. Because both conditions are associated with obesity and diabetes, the FP recommended that the patient increase his weight loss efforts through improved diet and increased exercise.

The FP also explained that treatment options for the skin tags included cryotherapy, snip excisions, and electrosurgery. The patient did not want to wait for the skin tags to fall off after cryotherapy or electrosurgery, so he chose snip excisions for immediate results. The skin tags were pedunculated with narrow stalks, so the snip excisions were performed without anesthesia. Aluminum chloride was applied to stop the bleeding on some of the skin tags. The patient noted some stinging, but tolerated the treatment well.

For the acanthosis nigricans, the FP explained that there are no highly effective treatments. In addition to recommending weight loss, the FP prescribed topical tretinoin cream 0.025% to be applied to the darkened skin before bed (only after the cuts from the skin tag removals had healed). The FP told the patient that the treatment might be only partially beneficial (or might not work at all). Other treatment options for acanthosis nigricans (with limited effectiveness) include keratolytic agents (eg, salicylic acid, ammonium lactate) and topical vitamin D analogs. At follow-up one month later, the patient had not yet noticed any changes to the acanthosis nigricans, but he was satisfied with the results of the skin tag removal.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith AM. Skin tags. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 922-925.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Based on the dark velvety skin on the patient’s neck, the FP diagnosed acanthosis nigricans accompanied by multiple skin tags (acrochordons). The patient told the physician that he wanted to have the skin tags removed and the darkened skin treated. Because both conditions are associated with obesity and diabetes, the FP recommended that the patient increase his weight loss efforts through improved diet and increased exercise.

The FP also explained that treatment options for the skin tags included cryotherapy, snip excisions, and electrosurgery. The patient did not want to wait for the skin tags to fall off after cryotherapy or electrosurgery, so he chose snip excisions for immediate results. The skin tags were pedunculated with narrow stalks, so the snip excisions were performed without anesthesia. Aluminum chloride was applied to stop the bleeding on some of the skin tags. The patient noted some stinging, but tolerated the treatment well.

For the acanthosis nigricans, the FP explained that there are no highly effective treatments. In addition to recommending weight loss, the FP prescribed topical tretinoin cream 0.025% to be applied to the darkened skin before bed (only after the cuts from the skin tag removals had healed). The FP told the patient that the treatment might be only partially beneficial (or might not work at all). Other treatment options for acanthosis nigricans (with limited effectiveness) include keratolytic agents (eg, salicylic acid, ammonium lactate) and topical vitamin D analogs. At follow-up one month later, the patient had not yet noticed any changes to the acanthosis nigricans, but he was satisfied with the results of the skin tag removal.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith AM. Skin tags. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 922-925.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Segmental distribution of nodules on trunk

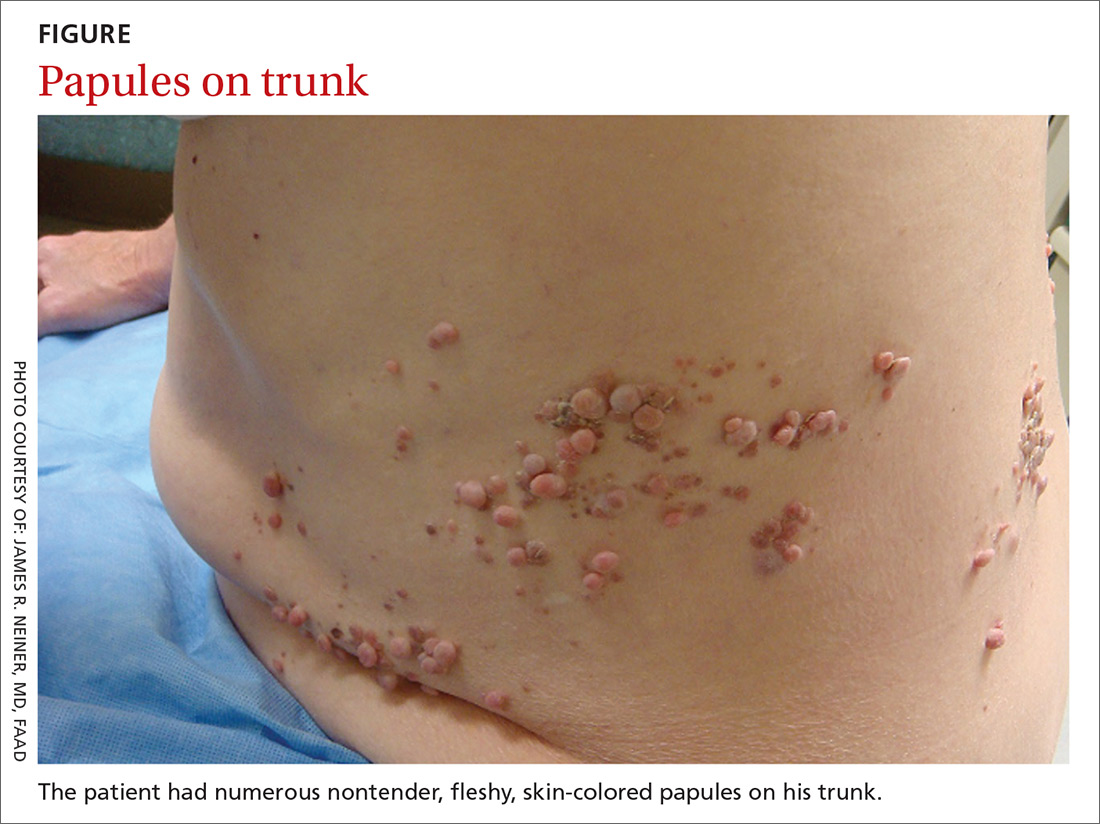

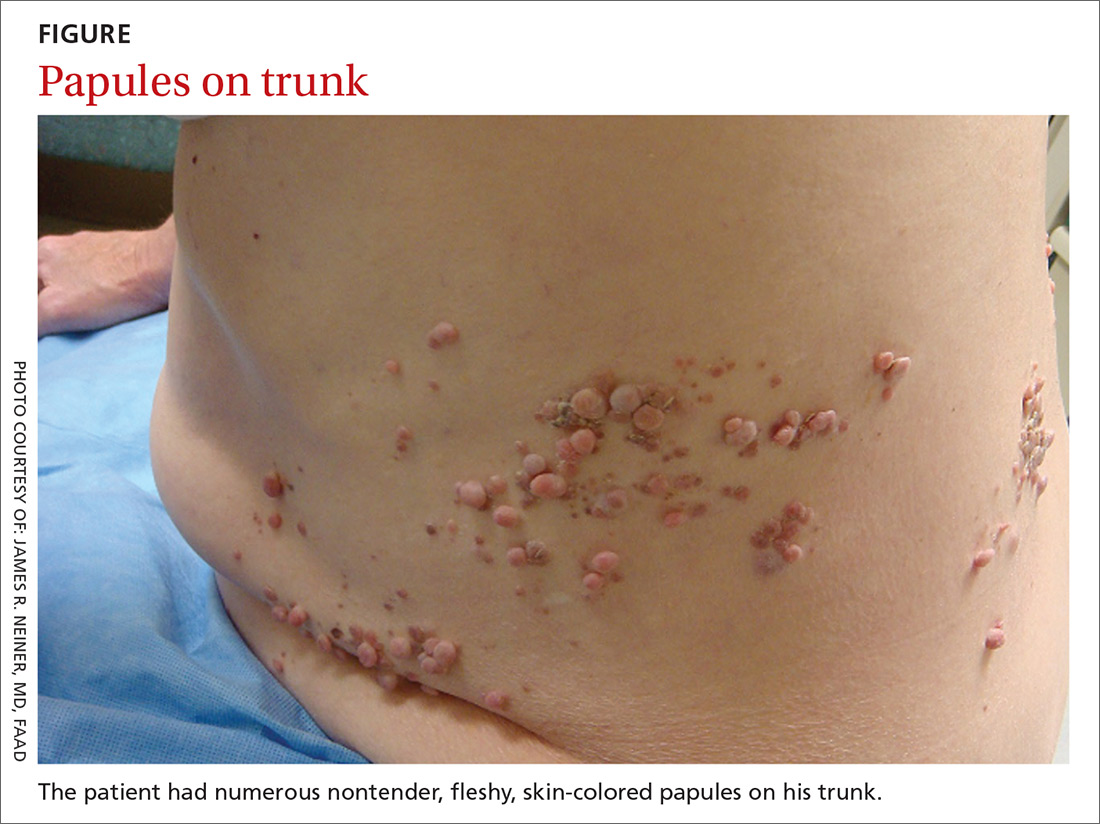

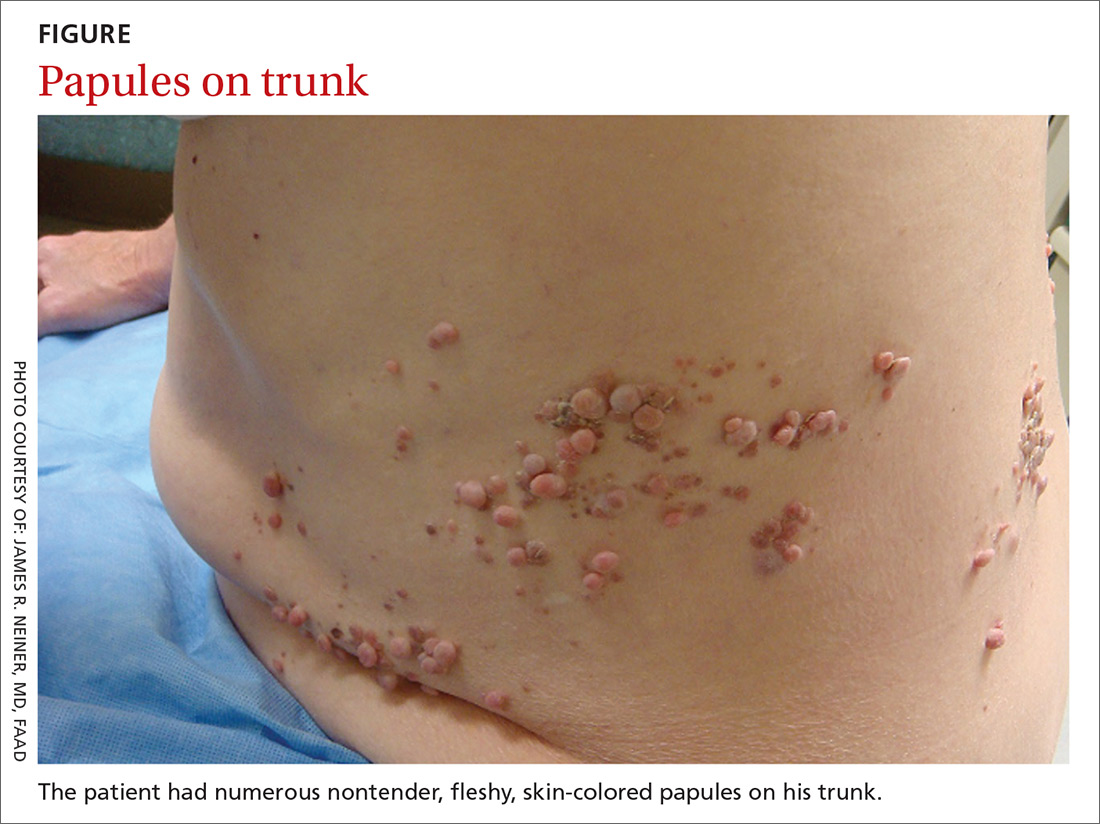

A 70-year-old Caucasian man presented with a longstanding history of numerous nontender, fleshy, skin-colored papules on his trunk, ranging from 3 to 8 mm in size (FIGURE). They were noted incidentally during an examination of unrelated nonhealing lesions on the patient’s left cheek. He said the lesions on his trunk first appeared when he was 28 years old and had continued to grow in size and number. The patient said his son had at least one similar lesion on his upper back, but otherwise there was no family history of these lesions.

A biopsy was performed on one of the nodules.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Segmental neurofibromatosis

Dermatopathologic evaluation of the tissue sample indicated that the lesion was a neurofibroma, and clinical correlation fine-tuned the diagnosis to segmental neurofibromatosis (NF). The diagnosis of segmental NF is clinical with biopsy to confirm the lesions are neurofibromas. Segmental NF is a mosaic form of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) that results from a postzygotic mutation of the NF1 gene. While NF1 is a relatively common neurocutaneous disorder that occurs with a frequency of one in 3000,1 segmental NF is more rare, with an estimated prevalence of one in 40,000.2

NF1 often follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, although up to 50% of patients with NF1 arise de novo from spontaneous mutations.3 NF1 is characterized by multiple café-au-lait macules, axillary freckling, neurofibromas, and Lisch nodules (pigmented iris hamartomas).

Systemic findings that are associated with NF1 include malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, optic gliomas, and vasculopathy.3 While patients with segmental NF may exhibit some of these same findings, the distribution of neurofibromas is often limited to one dermatome. Additionally, patients with segmental NF typically do not exhibit extracutaneous lesions, systemic involvement, or a family history of NF.

Rule out these dermatomal lesions

This case highlights a unique pattern of neoplasm development along a dermatome, an area of skin where innervation derives from a single spinal nerve. Symptoms that follow a dermatome often point to a pathology involving the related nerve root.

This differs from Blaschko lines, which form a specific surface pattern that is believed to reflect the migration of embryonic skin cells. Blaschko lines do not follow any known vascular, nervous, or lymphatic structures of the skin. Interestingly, when patients with segmental NF have associated pigmentary lesions, such as café-au-lait macules, these lesions may border Blaschko lines.

Herpes zoster, also known as shingles, is the most common infectious process that presents in a dermatomal pattern. Herpes zoster is caused by reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus, which lies within the dorsal root ganglion of a spinal nerve. This condition commonly results in a dermatomal distribution of vesicles/bullae on an erythematous base.

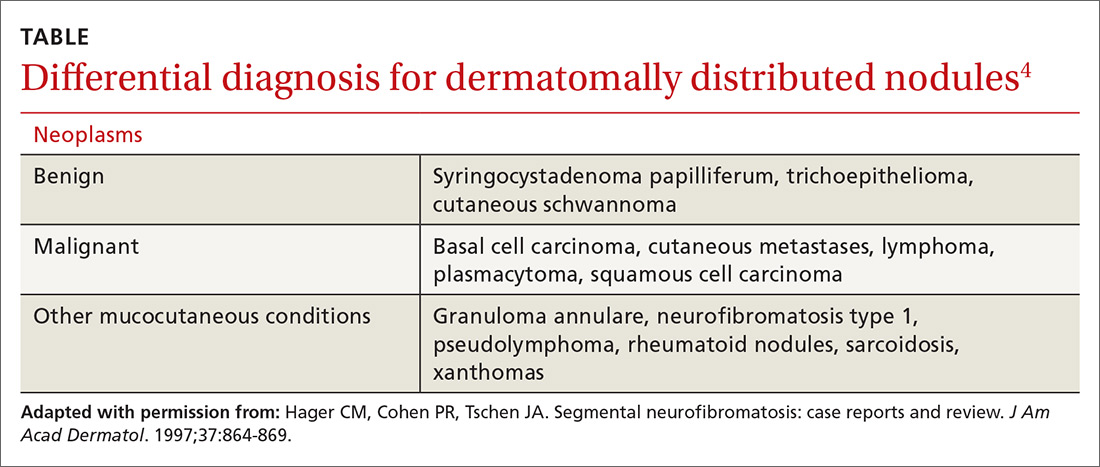

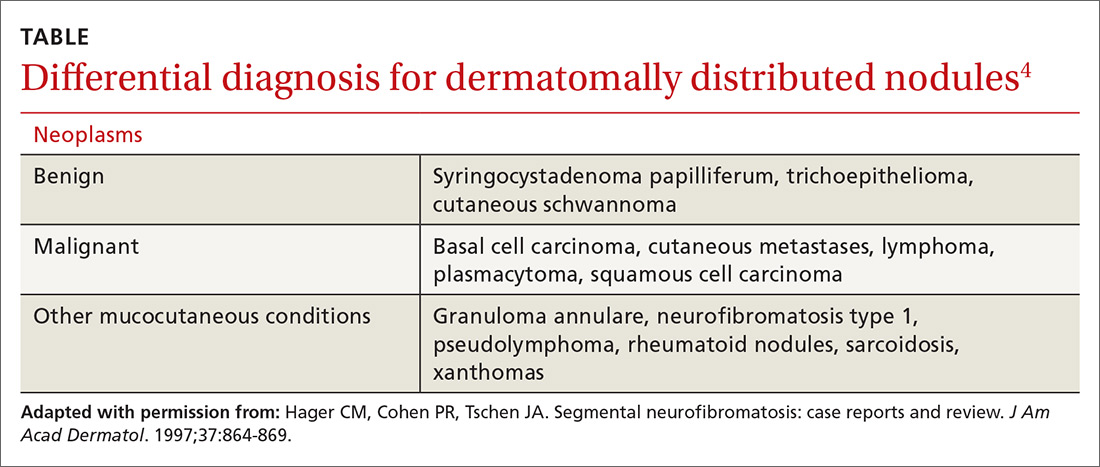

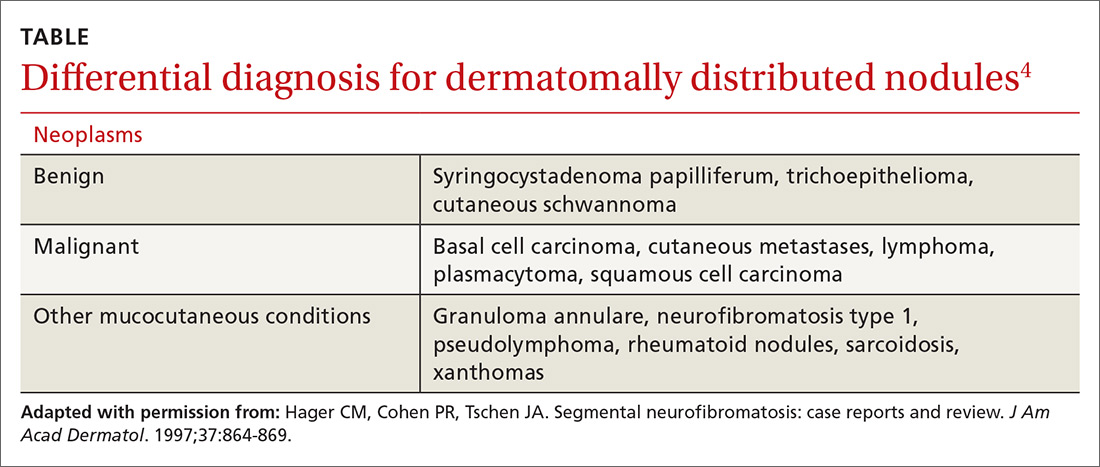

Neoplasms—including common cutaneous malignancies, such as basal cell carcinoma, as well as rare benign cutaneous conditions, such as cutaneous schwannoma, may have a distribution similar to that of segmental NF. A biopsy can help distinguish the diagnosis. See the TABLE4 for a complete differential diagnosis for dermatomally distributed nodules.

Classifying neurofibromatosis

It’s important to classify the type of NF in order to get a better handle on the patient’s prognosis and to facilitate genetic counseling. In particular, the much more common NF1 comes with an increased risk of systemic findings such as malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, optic gliomas, other gliomas, and leukemia. Few patients with segmental NF, on the other hand, will have these systemic findings.4 Segmental NF treatment typically focuses on symptomatic management or cosmetic concerns.

Our patient did not have any of the systemic complications that occasionally occur with segmental NF as discussed above, so no medical treatment was required. We informed him that the cutaneous and subcutaneous neurofibromas do not require removal unless there is pain, bleeding, disfigurement, or signs of malignant transformation. Our patient was not interested in removal of the nodules for cosmetic reasons, so we recommended follow-up as needed.

CORRESPONDENCE

Thomas M. Beachkofsky, MD, FAAD, San Antonio Uniformed Services Health Education Consortium, Brooke Army Medical Center, 3551 Roger Brooke Dr, Fort Sam Houston, TX 78234; [email protected].

1. Riccardi VM. Von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:1617-1627.

2. Ruggieri M, Huson SM. The clinical and diagnostic implications of mosaicism in the neurofibromatoses. Neurology. 2001;56:1433-1443.

3. Jett K, Friedman JM. Clinical and genetic aspects of neurofibromatosis 1. Genet Med. 2010;12:1-11.

4. Hager CM, Cohen PR, Tschen JA. Segmental neurofibromatosis: case reports and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:864-869.

A 70-year-old Caucasian man presented with a longstanding history of numerous nontender, fleshy, skin-colored papules on his trunk, ranging from 3 to 8 mm in size (FIGURE). They were noted incidentally during an examination of unrelated nonhealing lesions on the patient’s left cheek. He said the lesions on his trunk first appeared when he was 28 years old and had continued to grow in size and number. The patient said his son had at least one similar lesion on his upper back, but otherwise there was no family history of these lesions.

A biopsy was performed on one of the nodules.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Segmental neurofibromatosis

Dermatopathologic evaluation of the tissue sample indicated that the lesion was a neurofibroma, and clinical correlation fine-tuned the diagnosis to segmental neurofibromatosis (NF). The diagnosis of segmental NF is clinical with biopsy to confirm the lesions are neurofibromas. Segmental NF is a mosaic form of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) that results from a postzygotic mutation of the NF1 gene. While NF1 is a relatively common neurocutaneous disorder that occurs with a frequency of one in 3000,1 segmental NF is more rare, with an estimated prevalence of one in 40,000.2

NF1 often follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, although up to 50% of patients with NF1 arise de novo from spontaneous mutations.3 NF1 is characterized by multiple café-au-lait macules, axillary freckling, neurofibromas, and Lisch nodules (pigmented iris hamartomas).

Systemic findings that are associated with NF1 include malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, optic gliomas, and vasculopathy.3 While patients with segmental NF may exhibit some of these same findings, the distribution of neurofibromas is often limited to one dermatome. Additionally, patients with segmental NF typically do not exhibit extracutaneous lesions, systemic involvement, or a family history of NF.

Rule out these dermatomal lesions

This case highlights a unique pattern of neoplasm development along a dermatome, an area of skin where innervation derives from a single spinal nerve. Symptoms that follow a dermatome often point to a pathology involving the related nerve root.

This differs from Blaschko lines, which form a specific surface pattern that is believed to reflect the migration of embryonic skin cells. Blaschko lines do not follow any known vascular, nervous, or lymphatic structures of the skin. Interestingly, when patients with segmental NF have associated pigmentary lesions, such as café-au-lait macules, these lesions may border Blaschko lines.

Herpes zoster, also known as shingles, is the most common infectious process that presents in a dermatomal pattern. Herpes zoster is caused by reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus, which lies within the dorsal root ganglion of a spinal nerve. This condition commonly results in a dermatomal distribution of vesicles/bullae on an erythematous base.

Neoplasms—including common cutaneous malignancies, such as basal cell carcinoma, as well as rare benign cutaneous conditions, such as cutaneous schwannoma, may have a distribution similar to that of segmental NF. A biopsy can help distinguish the diagnosis. See the TABLE4 for a complete differential diagnosis for dermatomally distributed nodules.

Classifying neurofibromatosis

It’s important to classify the type of NF in order to get a better handle on the patient’s prognosis and to facilitate genetic counseling. In particular, the much more common NF1 comes with an increased risk of systemic findings such as malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, optic gliomas, other gliomas, and leukemia. Few patients with segmental NF, on the other hand, will have these systemic findings.4 Segmental NF treatment typically focuses on symptomatic management or cosmetic concerns.

Our patient did not have any of the systemic complications that occasionally occur with segmental NF as discussed above, so no medical treatment was required. We informed him that the cutaneous and subcutaneous neurofibromas do not require removal unless there is pain, bleeding, disfigurement, or signs of malignant transformation. Our patient was not interested in removal of the nodules for cosmetic reasons, so we recommended follow-up as needed.

CORRESPONDENCE

Thomas M. Beachkofsky, MD, FAAD, San Antonio Uniformed Services Health Education Consortium, Brooke Army Medical Center, 3551 Roger Brooke Dr, Fort Sam Houston, TX 78234; [email protected].

A 70-year-old Caucasian man presented with a longstanding history of numerous nontender, fleshy, skin-colored papules on his trunk, ranging from 3 to 8 mm in size (FIGURE). They were noted incidentally during an examination of unrelated nonhealing lesions on the patient’s left cheek. He said the lesions on his trunk first appeared when he was 28 years old and had continued to grow in size and number. The patient said his son had at least one similar lesion on his upper back, but otherwise there was no family history of these lesions.

A biopsy was performed on one of the nodules.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Segmental neurofibromatosis

Dermatopathologic evaluation of the tissue sample indicated that the lesion was a neurofibroma, and clinical correlation fine-tuned the diagnosis to segmental neurofibromatosis (NF). The diagnosis of segmental NF is clinical with biopsy to confirm the lesions are neurofibromas. Segmental NF is a mosaic form of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) that results from a postzygotic mutation of the NF1 gene. While NF1 is a relatively common neurocutaneous disorder that occurs with a frequency of one in 3000,1 segmental NF is more rare, with an estimated prevalence of one in 40,000.2

NF1 often follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, although up to 50% of patients with NF1 arise de novo from spontaneous mutations.3 NF1 is characterized by multiple café-au-lait macules, axillary freckling, neurofibromas, and Lisch nodules (pigmented iris hamartomas).

Systemic findings that are associated with NF1 include malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, optic gliomas, and vasculopathy.3 While patients with segmental NF may exhibit some of these same findings, the distribution of neurofibromas is often limited to one dermatome. Additionally, patients with segmental NF typically do not exhibit extracutaneous lesions, systemic involvement, or a family history of NF.

Rule out these dermatomal lesions

This case highlights a unique pattern of neoplasm development along a dermatome, an area of skin where innervation derives from a single spinal nerve. Symptoms that follow a dermatome often point to a pathology involving the related nerve root.

This differs from Blaschko lines, which form a specific surface pattern that is believed to reflect the migration of embryonic skin cells. Blaschko lines do not follow any known vascular, nervous, or lymphatic structures of the skin. Interestingly, when patients with segmental NF have associated pigmentary lesions, such as café-au-lait macules, these lesions may border Blaschko lines.

Herpes zoster, also known as shingles, is the most common infectious process that presents in a dermatomal pattern. Herpes zoster is caused by reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus, which lies within the dorsal root ganglion of a spinal nerve. This condition commonly results in a dermatomal distribution of vesicles/bullae on an erythematous base.

Neoplasms—including common cutaneous malignancies, such as basal cell carcinoma, as well as rare benign cutaneous conditions, such as cutaneous schwannoma, may have a distribution similar to that of segmental NF. A biopsy can help distinguish the diagnosis. See the TABLE4 for a complete differential diagnosis for dermatomally distributed nodules.

Classifying neurofibromatosis

It’s important to classify the type of NF in order to get a better handle on the patient’s prognosis and to facilitate genetic counseling. In particular, the much more common NF1 comes with an increased risk of systemic findings such as malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, optic gliomas, other gliomas, and leukemia. Few patients with segmental NF, on the other hand, will have these systemic findings.4 Segmental NF treatment typically focuses on symptomatic management or cosmetic concerns.

Our patient did not have any of the systemic complications that occasionally occur with segmental NF as discussed above, so no medical treatment was required. We informed him that the cutaneous and subcutaneous neurofibromas do not require removal unless there is pain, bleeding, disfigurement, or signs of malignant transformation. Our patient was not interested in removal of the nodules for cosmetic reasons, so we recommended follow-up as needed.

CORRESPONDENCE

Thomas M. Beachkofsky, MD, FAAD, San Antonio Uniformed Services Health Education Consortium, Brooke Army Medical Center, 3551 Roger Brooke Dr, Fort Sam Houston, TX 78234; [email protected].

1. Riccardi VM. Von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:1617-1627.

2. Ruggieri M, Huson SM. The clinical and diagnostic implications of mosaicism in the neurofibromatoses. Neurology. 2001;56:1433-1443.

3. Jett K, Friedman JM. Clinical and genetic aspects of neurofibromatosis 1. Genet Med. 2010;12:1-11.

4. Hager CM, Cohen PR, Tschen JA. Segmental neurofibromatosis: case reports and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:864-869.

1. Riccardi VM. Von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:1617-1627.

2. Ruggieri M, Huson SM. The clinical and diagnostic implications of mosaicism in the neurofibromatoses. Neurology. 2001;56:1433-1443.

3. Jett K, Friedman JM. Clinical and genetic aspects of neurofibromatosis 1. Genet Med. 2010;12:1-11.

4. Hager CM, Cohen PR, Tschen JA. Segmental neurofibromatosis: case reports and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:864-869.

Longstanding neck growths

After palpating the soft growths and noting more than 5 café au lait macules and axillary freckling, the FP made a diagnosis of neurofibromatosis type 1. Neurofibromatosis type 1 is an autosomal dominant genetic condition that leads to the development of tumors along the nerves in the skin, brain, and other parts of the body. The FP explained to the patient that these were neurofibromas—not skin tags—and that there can be serious health issues associated with neurofibromatosis, including tumors of the eye (optic gliomas) and nervous system. The patient was willing to see an ophthalmologist, but still wanted some of the growths removed.

The FP scheduled an appointment to remove some of the neurofibromas. He explained to the patient that he would not have time to remove them all but could take care of the ones that bothered her the most. At the patient’s next scheduled appointment, the FP removed the largest neurofibroma on the anterior neck using an elliptical excision at the base of the neurofibroma and sutured it closed using 4-0 nylon as a running suture. The FP sent the first excision to Pathology. (See a video on how to perform an elliptical excision here.)

One week later, the patient returned to have the sutures removed. The pathology report had come back and it confirmed the diagnosis of neurofibromas. The FP planned to remove some of the small neurofibromas using punch excision in the future. At follow-up one month later, the patient was happy with how her skin had healed. Her ophthalmology evaluation did not show any serious tumors.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith AM. Skin tags. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 922-925.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

After palpating the soft growths and noting more than 5 café au lait macules and axillary freckling, the FP made a diagnosis of neurofibromatosis type 1. Neurofibromatosis type 1 is an autosomal dominant genetic condition that leads to the development of tumors along the nerves in the skin, brain, and other parts of the body. The FP explained to the patient that these were neurofibromas—not skin tags—and that there can be serious health issues associated with neurofibromatosis, including tumors of the eye (optic gliomas) and nervous system. The patient was willing to see an ophthalmologist, but still wanted some of the growths removed.

The FP scheduled an appointment to remove some of the neurofibromas. He explained to the patient that he would not have time to remove them all but could take care of the ones that bothered her the most. At the patient’s next scheduled appointment, the FP removed the largest neurofibroma on the anterior neck using an elliptical excision at the base of the neurofibroma and sutured it closed using 4-0 nylon as a running suture. The FP sent the first excision to Pathology. (See a video on how to perform an elliptical excision here.)

One week later, the patient returned to have the sutures removed. The pathology report had come back and it confirmed the diagnosis of neurofibromas. The FP planned to remove some of the small neurofibromas using punch excision in the future. At follow-up one month later, the patient was happy with how her skin had healed. Her ophthalmology evaluation did not show any serious tumors.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith AM. Skin tags. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 922-925.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

After palpating the soft growths and noting more than 5 café au lait macules and axillary freckling, the FP made a diagnosis of neurofibromatosis type 1. Neurofibromatosis type 1 is an autosomal dominant genetic condition that leads to the development of tumors along the nerves in the skin, brain, and other parts of the body. The FP explained to the patient that these were neurofibromas—not skin tags—and that there can be serious health issues associated with neurofibromatosis, including tumors of the eye (optic gliomas) and nervous system. The patient was willing to see an ophthalmologist, but still wanted some of the growths removed.

The FP scheduled an appointment to remove some of the neurofibromas. He explained to the patient that he would not have time to remove them all but could take care of the ones that bothered her the most. At the patient’s next scheduled appointment, the FP removed the largest neurofibroma on the anterior neck using an elliptical excision at the base of the neurofibroma and sutured it closed using 4-0 nylon as a running suture. The FP sent the first excision to Pathology. (See a video on how to perform an elliptical excision here.)

One week later, the patient returned to have the sutures removed. The pathology report had come back and it confirmed the diagnosis of neurofibromas. The FP planned to remove some of the small neurofibromas using punch excision in the future. At follow-up one month later, the patient was happy with how her skin had healed. Her ophthalmology evaluation did not show any serious tumors.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith AM. Skin tags. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 922-925.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Growths on eyelids

The FP diagnosed skin tags (acrochordons) on her eyelids and explained that they were not dangerous. Removal options include cryotherapy, snip excisions, and electrosurgery.

The safest method of cryotherapy in a case like this is to use Cryo Tweezers. (See a video on how to perform cryosurgery here.) Using a cryo-spray in this area could result in the treatment getting into the eye.

Cryo Tweezers can apply cold to the skin tags without risking damage to the eye. The Cryo Tweezers are made cold by dipping them into liquid nitrogen. Then, each skin tag is grasped while gently pulling it away from the orbit. The skin tag is held between the 2 ends of the tweezer until it turns white. This method is very safe and causes very little discomfort to the patient.

Snip excisions on the eyelid are challenging for a number of reasons, including the fact that aluminum chloride or other chemical hemostatic agents are not safe for the eye. Electrosurgery can be performed with a loop electrode but only after the skin tags are numbed by injecting a local anesthetic into the eyelids. While it is possible for this to be performed safely, it is more challenging than using the Cryo Tweezers, which do not require a local anesthetic.

The patient in this case chose Cryo Tweezers for treatment and tolerated it well. The FP also documented that the patient believed the skin tags were affecting her vision in an effort to increase the likelihood that her insurance would cover the procedure. At a follow-up appointment 2 months later for the patient’s diabetes, the skin tags on her eyelids had resolved.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith AM. Skin tags. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 922-925.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed skin tags (acrochordons) on her eyelids and explained that they were not dangerous. Removal options include cryotherapy, snip excisions, and electrosurgery.

The safest method of cryotherapy in a case like this is to use Cryo Tweezers. (See a video on how to perform cryosurgery here.) Using a cryo-spray in this area could result in the treatment getting into the eye.

Cryo Tweezers can apply cold to the skin tags without risking damage to the eye. The Cryo Tweezers are made cold by dipping them into liquid nitrogen. Then, each skin tag is grasped while gently pulling it away from the orbit. The skin tag is held between the 2 ends of the tweezer until it turns white. This method is very safe and causes very little discomfort to the patient.

Snip excisions on the eyelid are challenging for a number of reasons, including the fact that aluminum chloride or other chemical hemostatic agents are not safe for the eye. Electrosurgery can be performed with a loop electrode but only after the skin tags are numbed by injecting a local anesthetic into the eyelids. While it is possible for this to be performed safely, it is more challenging than using the Cryo Tweezers, which do not require a local anesthetic.

The patient in this case chose Cryo Tweezers for treatment and tolerated it well. The FP also documented that the patient believed the skin tags were affecting her vision in an effort to increase the likelihood that her insurance would cover the procedure. At a follow-up appointment 2 months later for the patient’s diabetes, the skin tags on her eyelids had resolved.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith AM. Skin tags. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 922-925.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed skin tags (acrochordons) on her eyelids and explained that they were not dangerous. Removal options include cryotherapy, snip excisions, and electrosurgery.

The safest method of cryotherapy in a case like this is to use Cryo Tweezers. (See a video on how to perform cryosurgery here.) Using a cryo-spray in this area could result in the treatment getting into the eye.

Cryo Tweezers can apply cold to the skin tags without risking damage to the eye. The Cryo Tweezers are made cold by dipping them into liquid nitrogen. Then, each skin tag is grasped while gently pulling it away from the orbit. The skin tag is held between the 2 ends of the tweezer until it turns white. This method is very safe and causes very little discomfort to the patient.

Snip excisions on the eyelid are challenging for a number of reasons, including the fact that aluminum chloride or other chemical hemostatic agents are not safe for the eye. Electrosurgery can be performed with a loop electrode but only after the skin tags are numbed by injecting a local anesthetic into the eyelids. While it is possible for this to be performed safely, it is more challenging than using the Cryo Tweezers, which do not require a local anesthetic.

The patient in this case chose Cryo Tweezers for treatment and tolerated it well. The FP also documented that the patient believed the skin tags were affecting her vision in an effort to increase the likelihood that her insurance would cover the procedure. At a follow-up appointment 2 months later for the patient’s diabetes, the skin tags on her eyelids had resolved.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith AM. Skin tags. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 922-925.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Conjunctivitis and oral inflammation

This patient was diagnosed with reactive arthritis, based on her clinical syndrome of conjunctivitis, arthralgias, mucositis, and cervicitis. The widespread distribution of symptoms in this syndrome may be due to activation of the immune system by a viral or bacterial agent. In this case, a complete blood count revealed a white blood cell count of 17,000/mcL (with a left shift of 6% bands). An endocervical DNA probe was positive for Chlamydia trachomatis.

Interestingly, a test for the human leukocyte antigen HLA-B27 came back negative. This did not, however, change the diagnosis. Only 85% of patients with reactive arthritis are positive for HLA-B27, and the test results are frequently negative in African Americans.

Because many sexually transmitted diseases occur concurrently—or are transmitted together—the patient was also tested for human immunodeficiency virus, syphilis, and hepatitis B and C. All of these tests were negative.

The patient was hospitalized and given an injection of ceftriaxone 250 mg, as well as oral azithromycin 1 g for chlamydia (and possible gonorrhea). She also received nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for pain control. She responded rapidly to therapy as evidenced by decreased arthralgias, normalization of temperature and white blood cell count, and decreased abdominal pain. The patient was discharged after her third day in the hospital with instructions to take doxycycline twice daily, and to finish the 14-day course.

Historical note: “Reiter’s syndrome” is no longer the preferred term for reactive arthritis, as Dr. Reiter was affiliated with the Nazi Party and performed unethical experimentation on human subjects.

Photo courtesy of Joseph Mazziotta, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H, Shedd A, Reddy S, et al. Reactive arthritis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 910-914; Mazziotta JM, Ahmed N. Conjunctivitis and cervicitis. J Fam Pract. 2004;53:121-123.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

This patient was diagnosed with reactive arthritis, based on her clinical syndrome of conjunctivitis, arthralgias, mucositis, and cervicitis. The widespread distribution of symptoms in this syndrome may be due to activation of the immune system by a viral or bacterial agent. In this case, a complete blood count revealed a white blood cell count of 17,000/mcL (with a left shift of 6% bands). An endocervical DNA probe was positive for Chlamydia trachomatis.

Interestingly, a test for the human leukocyte antigen HLA-B27 came back negative. This did not, however, change the diagnosis. Only 85% of patients with reactive arthritis are positive for HLA-B27, and the test results are frequently negative in African Americans.

Because many sexually transmitted diseases occur concurrently—or are transmitted together—the patient was also tested for human immunodeficiency virus, syphilis, and hepatitis B and C. All of these tests were negative.

The patient was hospitalized and given an injection of ceftriaxone 250 mg, as well as oral azithromycin 1 g for chlamydia (and possible gonorrhea). She also received nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for pain control. She responded rapidly to therapy as evidenced by decreased arthralgias, normalization of temperature and white blood cell count, and decreased abdominal pain. The patient was discharged after her third day in the hospital with instructions to take doxycycline twice daily, and to finish the 14-day course.

Historical note: “Reiter’s syndrome” is no longer the preferred term for reactive arthritis, as Dr. Reiter was affiliated with the Nazi Party and performed unethical experimentation on human subjects.

Photo courtesy of Joseph Mazziotta, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H, Shedd A, Reddy S, et al. Reactive arthritis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 910-914; Mazziotta JM, Ahmed N. Conjunctivitis and cervicitis. J Fam Pract. 2004;53:121-123.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

This patient was diagnosed with reactive arthritis, based on her clinical syndrome of conjunctivitis, arthralgias, mucositis, and cervicitis. The widespread distribution of symptoms in this syndrome may be due to activation of the immune system by a viral or bacterial agent. In this case, a complete blood count revealed a white blood cell count of 17,000/mcL (with a left shift of 6% bands). An endocervical DNA probe was positive for Chlamydia trachomatis.

Interestingly, a test for the human leukocyte antigen HLA-B27 came back negative. This did not, however, change the diagnosis. Only 85% of patients with reactive arthritis are positive for HLA-B27, and the test results are frequently negative in African Americans.

Because many sexually transmitted diseases occur concurrently—or are transmitted together—the patient was also tested for human immunodeficiency virus, syphilis, and hepatitis B and C. All of these tests were negative.

The patient was hospitalized and given an injection of ceftriaxone 250 mg, as well as oral azithromycin 1 g for chlamydia (and possible gonorrhea). She also received nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for pain control. She responded rapidly to therapy as evidenced by decreased arthralgias, normalization of temperature and white blood cell count, and decreased abdominal pain. The patient was discharged after her third day in the hospital with instructions to take doxycycline twice daily, and to finish the 14-day course.

Historical note: “Reiter’s syndrome” is no longer the preferred term for reactive arthritis, as Dr. Reiter was affiliated with the Nazi Party and performed unethical experimentation on human subjects.

Photo courtesy of Joseph Mazziotta, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H, Shedd A, Reddy S, et al. Reactive arthritis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 910-914; Mazziotta JM, Ahmed N. Conjunctivitis and cervicitis. J Fam Pract. 2004;53:121-123.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Extensive rash and joint pain

Based on the patient’s tender finger and wrist joints and exfoliation of skin, the FP diagnosed erythrodermic psoriasis, although the patient’s dark skin made the erythema less visible. The patient was not systemically ill; however, the FP recognized that he would need systemic therapy for the arthritis and severe skin manifestations and referred the patient to a dermatology specialist.

The dermatology specialist agreed to see the patient the next day. She ordered the following lab tests: complete blood count (CBC), chemistry panel, QuantiFERON TB gold, hepatitis C antibody, and hepatitis B surface antigen, surface antibody, and core antibody. She also ordered bilateral hand films, which showed early juxta-articular erosions (consistent with psoriatic arthritis). Because of the strong skin, nail, and joint evidence, the dermatology specialist determined a biopsy was not necessary.

The patient was instructed to apply 0.1% triamcinolone ointment to his entire body using the wet pajama technique overnight. At follow-up, he said his skin felt better, but his joints did not. The dermatology specialist reviewed the lab results and explained to the patient that the 2 best options were oral methotrexate weekly or an expensive injectable biologic agent. Because most health insurance companies now require that the patient fail a less expensive agent such as methotrexate before trying the biologic, the decision was made to start with methotrexate. Within a month, the patient's skin was remarkably better and his joint pain and stiffness had improved significantly.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Henderson D. Erythroderma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 915-921.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Based on the patient’s tender finger and wrist joints and exfoliation of skin, the FP diagnosed erythrodermic psoriasis, although the patient’s dark skin made the erythema less visible. The patient was not systemically ill; however, the FP recognized that he would need systemic therapy for the arthritis and severe skin manifestations and referred the patient to a dermatology specialist.

The dermatology specialist agreed to see the patient the next day. She ordered the following lab tests: complete blood count (CBC), chemistry panel, QuantiFERON TB gold, hepatitis C antibody, and hepatitis B surface antigen, surface antibody, and core antibody. She also ordered bilateral hand films, which showed early juxta-articular erosions (consistent with psoriatic arthritis). Because of the strong skin, nail, and joint evidence, the dermatology specialist determined a biopsy was not necessary.

The patient was instructed to apply 0.1% triamcinolone ointment to his entire body using the wet pajama technique overnight. At follow-up, he said his skin felt better, but his joints did not. The dermatology specialist reviewed the lab results and explained to the patient that the 2 best options were oral methotrexate weekly or an expensive injectable biologic agent. Because most health insurance companies now require that the patient fail a less expensive agent such as methotrexate before trying the biologic, the decision was made to start with methotrexate. Within a month, the patient's skin was remarkably better and his joint pain and stiffness had improved significantly.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Henderson D. Erythroderma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 915-921.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Based on the patient’s tender finger and wrist joints and exfoliation of skin, the FP diagnosed erythrodermic psoriasis, although the patient’s dark skin made the erythema less visible. The patient was not systemically ill; however, the FP recognized that he would need systemic therapy for the arthritis and severe skin manifestations and referred the patient to a dermatology specialist.

The dermatology specialist agreed to see the patient the next day. She ordered the following lab tests: complete blood count (CBC), chemistry panel, QuantiFERON TB gold, hepatitis C antibody, and hepatitis B surface antigen, surface antibody, and core antibody. She also ordered bilateral hand films, which showed early juxta-articular erosions (consistent with psoriatic arthritis). Because of the strong skin, nail, and joint evidence, the dermatology specialist determined a biopsy was not necessary.

The patient was instructed to apply 0.1% triamcinolone ointment to his entire body using the wet pajama technique overnight. At follow-up, he said his skin felt better, but his joints did not. The dermatology specialist reviewed the lab results and explained to the patient that the 2 best options were oral methotrexate weekly or an expensive injectable biologic agent. Because most health insurance companies now require that the patient fail a less expensive agent such as methotrexate before trying the biologic, the decision was made to start with methotrexate. Within a month, the patient's skin was remarkably better and his joint pain and stiffness had improved significantly.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Henderson D. Erythroderma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 915-921.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Shedding skin

The physician made a diagnosis of erythroderma. The FP considered psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, or another, more rare disease as causes. Psoriasis was the most likely etiology due to the nail pitting and the fact that atopic dermatitis starts in childhood. A 4-mm punch biopsy (rush requested) was performed to confirm this.

Erythroderma is an uncommon condition that affects all age groups and is characterized by a generalized erythematous rash with associated scaling. It is generally a manifestation of another underlying dermatosis or systemic disorder. Erythroderma is associated with a range of morbidity, and can have life-threatening metabolic and cardiovascular complications. Therapy is usually focused on treating the underlying disease, as well as addressing the systemic complications.

In this patient’s case, the FP consulted a dermatology colleague (an FP with dermatology fellowship training). She recommended ordering the following labs in anticipation of oral cyclosporine therapy: complete blood count, chemistry panel, uric acid, magnesium level, QuantiFERON TB gold, hepatitis C antibody, and hepatitis B surface antigen, surface antibody, and core antibody.

The FP prescribed a one-pound jar of 0.1% triamcinolone ointment to be applied twice daily. He instructed the patient to apply the ointment to the red areas, cover the involved skin with wet pajamas or soft clothing, then apply a dry blanket over the wet layer. (The pajamas should be made wet with lukewarm water and wrung out so that they are not dripping.) The FP instructed the patient to sleep in this overnight and only remove it if he became chilled or was unable to sleep. The patient was also counseled to quit smoking and drinking.

The dermatology specialist agreed to see the patient in 2 days. At that time, the patient’s lab results were normal and he was feeling a bit better from the topical triamcinolone. The dermatology specialist started the patient on cyclosporine and he improved rapidly. At follow-up, the dermatology specialist discussed other systemic treatments and the need to taper off the cyclosporine. Fortunately, the patient had stopped smoking and drinking, and his blood pressure and labs remained normal.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Henderson D. Erythroderma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 915-921.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The physician made a diagnosis of erythroderma. The FP considered psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, or another, more rare disease as causes. Psoriasis was the most likely etiology due to the nail pitting and the fact that atopic dermatitis starts in childhood. A 4-mm punch biopsy (rush requested) was performed to confirm this.

Erythroderma is an uncommon condition that affects all age groups and is characterized by a generalized erythematous rash with associated scaling. It is generally a manifestation of another underlying dermatosis or systemic disorder. Erythroderma is associated with a range of morbidity, and can have life-threatening metabolic and cardiovascular complications. Therapy is usually focused on treating the underlying disease, as well as addressing the systemic complications.

In this patient’s case, the FP consulted a dermatology colleague (an FP with dermatology fellowship training). She recommended ordering the following labs in anticipation of oral cyclosporine therapy: complete blood count, chemistry panel, uric acid, magnesium level, QuantiFERON TB gold, hepatitis C antibody, and hepatitis B surface antigen, surface antibody, and core antibody.

The FP prescribed a one-pound jar of 0.1% triamcinolone ointment to be applied twice daily. He instructed the patient to apply the ointment to the red areas, cover the involved skin with wet pajamas or soft clothing, then apply a dry blanket over the wet layer. (The pajamas should be made wet with lukewarm water and wrung out so that they are not dripping.) The FP instructed the patient to sleep in this overnight and only remove it if he became chilled or was unable to sleep. The patient was also counseled to quit smoking and drinking.

The dermatology specialist agreed to see the patient in 2 days. At that time, the patient’s lab results were normal and he was feeling a bit better from the topical triamcinolone. The dermatology specialist started the patient on cyclosporine and he improved rapidly. At follow-up, the dermatology specialist discussed other systemic treatments and the need to taper off the cyclosporine. Fortunately, the patient had stopped smoking and drinking, and his blood pressure and labs remained normal.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Henderson D. Erythroderma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 915-921.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The physician made a diagnosis of erythroderma. The FP considered psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, or another, more rare disease as causes. Psoriasis was the most likely etiology due to the nail pitting and the fact that atopic dermatitis starts in childhood. A 4-mm punch biopsy (rush requested) was performed to confirm this.

Erythroderma is an uncommon condition that affects all age groups and is characterized by a generalized erythematous rash with associated scaling. It is generally a manifestation of another underlying dermatosis or systemic disorder. Erythroderma is associated with a range of morbidity, and can have life-threatening metabolic and cardiovascular complications. Therapy is usually focused on treating the underlying disease, as well as addressing the systemic complications.

In this patient’s case, the FP consulted a dermatology colleague (an FP with dermatology fellowship training). She recommended ordering the following labs in anticipation of oral cyclosporine therapy: complete blood count, chemistry panel, uric acid, magnesium level, QuantiFERON TB gold, hepatitis C antibody, and hepatitis B surface antigen, surface antibody, and core antibody.

The FP prescribed a one-pound jar of 0.1% triamcinolone ointment to be applied twice daily. He instructed the patient to apply the ointment to the red areas, cover the involved skin with wet pajamas or soft clothing, then apply a dry blanket over the wet layer. (The pajamas should be made wet with lukewarm water and wrung out so that they are not dripping.) The FP instructed the patient to sleep in this overnight and only remove it if he became chilled or was unable to sleep. The patient was also counseled to quit smoking and drinking.

The dermatology specialist agreed to see the patient in 2 days. At that time, the patient’s lab results were normal and he was feeling a bit better from the topical triamcinolone. The dermatology specialist started the patient on cyclosporine and he improved rapidly. At follow-up, the dermatology specialist discussed other systemic treatments and the need to taper off the cyclosporine. Fortunately, the patient had stopped smoking and drinking, and his blood pressure and labs remained normal.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Henderson D. Erythroderma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 915-921.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Red, peeling skin

The FP diagnosed erythroderma, which can be life-threatening because of dehydration. The severe exfoliation (sheets of skin peeling off) impairs the skin’s barrier function, which leads to dehydration and makes the patient susceptible to infection. (This is similar to a patient with second-degree burns.)

At the hospital, the patient received supportive therapy with intravenous fluids and urine and blood cultures to check for infections. A Foley catheter was inserted to measure urine output. A dermatology colleague was available for consultation and performed a 4-mm punch biopsy to determine the etiology of the erythroderma, and a dermatopathologist was called.

The following labs were ordered in anticipation of cyclosporine therapy: complete blood count, chemistry panel, uric acid, magnesium level, QuantiFERON TB gold, hepatitis C antibody, and hepatitis B surface antigen, surface antibody, and core antibody.

The FP prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone ointment using the wet pajama technique: the ointment is applied over the red areas and then covered with wet hospital gowns overnight. The cloth is made wet with lukewarm water and wrung out so that it is not dripping with water. A dry blanket is applied over the wet layer of clothing. The patient then attempts to sleep in this and only removes it if she becomes chilled or is unable to sleep at all.

Results of the punch biopsy were consistent with erythrodermic psoriasis. The patient did not have a history of renal disease or hypertension, and lab tests returned sufficiently normal, so cyclosporine was not contraindicated. Oral cyclosporine was started while the patient was in the hospital. She recovered rapidly and was discharged with ongoing cyclosporine treatment and topical steroids. The patient followed up with the dermatologist for treatment.

Photo courtesy of Jack Resneck Sr, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Henderson D. Erythroderma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 915-921.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed erythroderma, which can be life-threatening because of dehydration. The severe exfoliation (sheets of skin peeling off) impairs the skin’s barrier function, which leads to dehydration and makes the patient susceptible to infection. (This is similar to a patient with second-degree burns.)

At the hospital, the patient received supportive therapy with intravenous fluids and urine and blood cultures to check for infections. A Foley catheter was inserted to measure urine output. A dermatology colleague was available for consultation and performed a 4-mm punch biopsy to determine the etiology of the erythroderma, and a dermatopathologist was called.

The following labs were ordered in anticipation of cyclosporine therapy: complete blood count, chemistry panel, uric acid, magnesium level, QuantiFERON TB gold, hepatitis C antibody, and hepatitis B surface antigen, surface antibody, and core antibody.

The FP prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone ointment using the wet pajama technique: the ointment is applied over the red areas and then covered with wet hospital gowns overnight. The cloth is made wet with lukewarm water and wrung out so that it is not dripping with water. A dry blanket is applied over the wet layer of clothing. The patient then attempts to sleep in this and only removes it if she becomes chilled or is unable to sleep at all.

Results of the punch biopsy were consistent with erythrodermic psoriasis. The patient did not have a history of renal disease or hypertension, and lab tests returned sufficiently normal, so cyclosporine was not contraindicated. Oral cyclosporine was started while the patient was in the hospital. She recovered rapidly and was discharged with ongoing cyclosporine treatment and topical steroids. The patient followed up with the dermatologist for treatment.

Photo courtesy of Jack Resneck Sr, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Henderson D. Erythroderma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 915-921.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP diagnosed erythroderma, which can be life-threatening because of dehydration. The severe exfoliation (sheets of skin peeling off) impairs the skin’s barrier function, which leads to dehydration and makes the patient susceptible to infection. (This is similar to a patient with second-degree burns.)

At the hospital, the patient received supportive therapy with intravenous fluids and urine and blood cultures to check for infections. A Foley catheter was inserted to measure urine output. A dermatology colleague was available for consultation and performed a 4-mm punch biopsy to determine the etiology of the erythroderma, and a dermatopathologist was called.

The following labs were ordered in anticipation of cyclosporine therapy: complete blood count, chemistry panel, uric acid, magnesium level, QuantiFERON TB gold, hepatitis C antibody, and hepatitis B surface antigen, surface antibody, and core antibody.

The FP prescribed 0.1% triamcinolone ointment using the wet pajama technique: the ointment is applied over the red areas and then covered with wet hospital gowns overnight. The cloth is made wet with lukewarm water and wrung out so that it is not dripping with water. A dry blanket is applied over the wet layer of clothing. The patient then attempts to sleep in this and only removes it if she becomes chilled or is unable to sleep at all.

Results of the punch biopsy were consistent with erythrodermic psoriasis. The patient did not have a history of renal disease or hypertension, and lab tests returned sufficiently normal, so cyclosporine was not contraindicated. Oral cyclosporine was started while the patient was in the hospital. She recovered rapidly and was discharged with ongoing cyclosporine treatment and topical steroids. The patient followed up with the dermatologist for treatment.

Photo courtesy of Jack Resneck Sr, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Henderson D. Erythroderma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 915-921.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Diffuse skin rash, altered mental status

A 74-year-old Caucasian man presented to the hospital with intractable back and chest pain, a diffuse skin rash, and altered mental status. He said that 2 days ago, he’d gone to a different local hospital for treatment of back pain and a headache that had begun 3 days earlier. He was treated with intravenous hydromorphone and sent home with a prescription for meperidine. He said that several hours after being treated with the hydromorphone, the rash developed on his head and then spread to his trunk and upper extremities.

On physical examination, the patient was afebrile. He had numerous erythematous papules and vesicles in various stages of development on his scalp, face, neck, chest (FIGURE), abdomen, back, upper extremities, and groin. The lesions continued to spread and eventually involved his posterior oropharynx. The patient also developed conjunctivitis.

Laboratory findings included a white blood cell count of 4000/mcL (normal: 4500-11,000/mcL) with 65.9% segmented neutrophils (normal: 40%-60%), and 16.7% lymphocytes (normal: 20%-40%). Lab tests also revealed an aspartate aminotransferase level of 263 U/L (normal: 10-40 U/L), alanine aminotransferase of 236 U/L (normal: 7-56 U/L), and lactate dehydrogenase of 628 U/L (normal: 140-280 U/L).

The patient’s medical history was significant for hypertension, osteoarthritis, and IgG-kappa multiple myeloma, which had been treated with multiple chemotherapy regimens that included lenalidomide. Five years earlier, he’d undergone an autologous bone marrow transplant (BMT). At the time of presentation, the patient was being treated with daratumumab; he received his most recent treatment approximately one month earlier. Other medications included amlodipine, esomeprazole, and escitalopram.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Disseminated varicella-zoster virus infection

Because of the patient’s immunocompromised state, his presentation with altered mental status and diffuse rash was concerning. On hospital Day 2, a sample was taken from one of his skin lesions. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) detected varicella-zoster virus (VZV), and we diagnosed disseminated VZV infection. On hospital Day 3, we performed a lumbar puncture because of worsening confusion and discovered that the cerebrospinal fluid was also positive for VZV.

Disseminated VZV is the most common cause of late infection in patients who have received an allogenic BMT; it is usually due to reactivation of the virus.1 In one study of 1186 patients who underwent BMT, 52% developed VZV infection within 5 years.2 Disseminated VZV may also involve visceral organs, causing pneumonitis, pancreatitis, hepatitis, or encephalitis. Mortality rates for disseminated VZV are as high as 50%.3 Because of this, physicians should be vigilant when patients who have received a BMT present with a rash and signs of systemic involvement.

Two reliable tests. Even when lesions are classic for VZV, the diagnosis must be confirmed by laboratory testing. Real-time PCR assay is a rapid and highly sensitive test for diagnosing VZV.4 Another rapid test that can be used to confirm the clinical diagnosis of VZV is a direct fluorescent antibody assay, which is becoming more widely available.

In contrast, the sensitivity of viral culture for VZV has been reported to be as low as 20%.5 Viral culture also takes much longer and has a significantly lower yield compared with newer methods.6 A biopsy of skin lesions will reveal multinucleated giant cells, but cannot differentiate between herpes simplex virus (HSV) and VZV.7

These lesions can be mimicked

When a rash develops following the use of intravenous hydromorphone, as occurred with our patient, a drug reaction must be ruled out. A drug reaction can cause almost any skin manifestation and may present as vesicles, a macular rash, a papular rash, or diffuse erythema. In this case, drug rash was ruled out by the positive VZV PCR.

Viral exanthems can also present in a variety of ways. They may cause a macular, papular, or vesicular rash.

Prompt management is crucial

Prompt treatment of VZV with acyclovir improves outcomes, but death may still occur, even with early diagnosis.3 Immunocompromised patients with VZV should be closely monitored for secondary infections, which may rapidly progress and become fatal.8 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends both airborne and contact precautions for patients with disseminated VZV until all lesions are dry and crusted.9

While the live zoster vaccine is approved for prevention of shingles in patients <60 years of age, it is contraindicated in patients with a history of primary or acquired immunodeficiency states including leukemia, lymphoma, or other malignant neoplasms affecting bone marrow.

Our patient. On admission, he was treated with intravenous (IV) acyclovir 10 mg/kg TID; IV vancomycin 15 mg/kg every 12 hours; and IV ceftriaxone 2 g/d. Slowly, his mental status returned to baseline, and his rash and conjunctivitis resolved. We discharged him on hospital Day 12. He was transitioned to oral valacyclovir 1000 mg TID. Including both inpatient and outpatient treatment, the patient received 3 weeks (total) of acyclovir/valacyclovir therapy.

CORRESPONDENCE

Caitlyn T. Reed, MD, School of Medicine, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216; [email protected].

1. Locksley RM, Flournoy N, Sullivan KM, et al. Infection with varicella-zoster virus after marrow transplantation. J Infect Dis. 1985;152:1172-1181.

2. Han CS, Miller W, Haake R, et al. Varicella zoster infection after bone marrow transplantation: incidence, risk factors and complications. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1994;13:277-283.

3. David DS, Tegtmeier BR, O’Donnell MR, at el. Visceral varicella-zoster after bone marrow transplantation: report of a case series and review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:810-813.

4. Harbecke R, Oxman MN, Arnold BA, et al. A real-time PCR assay to identify and discriminate among wild-type and vaccine strains of varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex virus in clinical specimens, and comparison with the clinical diagnoses. J Med Virol. 2009;81:1310-1322.

5. Sauerbrei A, Eichhorn U, Schacke M, et al. Laboratory diagnosis of herpes zoster. J Clin Virol. 1999;14:31-36.

6. Gnann JW Jr, Whitley RJ. Clinical practice. Herpes zoster. N Engl J Med. 2002;347;340-346.

7. Mendoza N, Madkan V, Sra K, et al. Human herpesviruses. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd edition. China: Elsevier Limited; 2012:1321-1343.

8. Woznowski M, Quack I, Bölke E, et al. Fulminant staphylococcus lugdunensis septicaemia following a pelvic varicella-zoster virus infection in an immune-deficient patient: a case report. Eur J Med Res. 2010;15:410-414.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventing varicella in healthcare settings. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/chickenpox/hcp/healthcare-setting.html. Accessed October 6,2017.

A 74-year-old Caucasian man presented to the hospital with intractable back and chest pain, a diffuse skin rash, and altered mental status. He said that 2 days ago, he’d gone to a different local hospital for treatment of back pain and a headache that had begun 3 days earlier. He was treated with intravenous hydromorphone and sent home with a prescription for meperidine. He said that several hours after being treated with the hydromorphone, the rash developed on his head and then spread to his trunk and upper extremities.

On physical examination, the patient was afebrile. He had numerous erythematous papules and vesicles in various stages of development on his scalp, face, neck, chest (FIGURE), abdomen, back, upper extremities, and groin. The lesions continued to spread and eventually involved his posterior oropharynx. The patient also developed conjunctivitis.

Laboratory findings included a white blood cell count of 4000/mcL (normal: 4500-11,000/mcL) with 65.9% segmented neutrophils (normal: 40%-60%), and 16.7% lymphocytes (normal: 20%-40%). Lab tests also revealed an aspartate aminotransferase level of 263 U/L (normal: 10-40 U/L), alanine aminotransferase of 236 U/L (normal: 7-56 U/L), and lactate dehydrogenase of 628 U/L (normal: 140-280 U/L).

The patient’s medical history was significant for hypertension, osteoarthritis, and IgG-kappa multiple myeloma, which had been treated with multiple chemotherapy regimens that included lenalidomide. Five years earlier, he’d undergone an autologous bone marrow transplant (BMT). At the time of presentation, the patient was being treated with daratumumab; he received his most recent treatment approximately one month earlier. Other medications included amlodipine, esomeprazole, and escitalopram.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Disseminated varicella-zoster virus infection

Because of the patient’s immunocompromised state, his presentation with altered mental status and diffuse rash was concerning. On hospital Day 2, a sample was taken from one of his skin lesions. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) detected varicella-zoster virus (VZV), and we diagnosed disseminated VZV infection. On hospital Day 3, we performed a lumbar puncture because of worsening confusion and discovered that the cerebrospinal fluid was also positive for VZV.

Disseminated VZV is the most common cause of late infection in patients who have received an allogenic BMT; it is usually due to reactivation of the virus.1 In one study of 1186 patients who underwent BMT, 52% developed VZV infection within 5 years.2 Disseminated VZV may also involve visceral organs, causing pneumonitis, pancreatitis, hepatitis, or encephalitis. Mortality rates for disseminated VZV are as high as 50%.3 Because of this, physicians should be vigilant when patients who have received a BMT present with a rash and signs of systemic involvement.

Two reliable tests. Even when lesions are classic for VZV, the diagnosis must be confirmed by laboratory testing. Real-time PCR assay is a rapid and highly sensitive test for diagnosing VZV.4 Another rapid test that can be used to confirm the clinical diagnosis of VZV is a direct fluorescent antibody assay, which is becoming more widely available.

In contrast, the sensitivity of viral culture for VZV has been reported to be as low as 20%.5 Viral culture also takes much longer and has a significantly lower yield compared with newer methods.6 A biopsy of skin lesions will reveal multinucleated giant cells, but cannot differentiate between herpes simplex virus (HSV) and VZV.7

These lesions can be mimicked

When a rash develops following the use of intravenous hydromorphone, as occurred with our patient, a drug reaction must be ruled out. A drug reaction can cause almost any skin manifestation and may present as vesicles, a macular rash, a papular rash, or diffuse erythema. In this case, drug rash was ruled out by the positive VZV PCR.

Viral exanthems can also present in a variety of ways. They may cause a macular, papular, or vesicular rash.

Prompt management is crucial

Prompt treatment of VZV with acyclovir improves outcomes, but death may still occur, even with early diagnosis.3 Immunocompromised patients with VZV should be closely monitored for secondary infections, which may rapidly progress and become fatal.8 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends both airborne and contact precautions for patients with disseminated VZV until all lesions are dry and crusted.9

While the live zoster vaccine is approved for prevention of shingles in patients <60 years of age, it is contraindicated in patients with a history of primary or acquired immunodeficiency states including leukemia, lymphoma, or other malignant neoplasms affecting bone marrow.

Our patient. On admission, he was treated with intravenous (IV) acyclovir 10 mg/kg TID; IV vancomycin 15 mg/kg every 12 hours; and IV ceftriaxone 2 g/d. Slowly, his mental status returned to baseline, and his rash and conjunctivitis resolved. We discharged him on hospital Day 12. He was transitioned to oral valacyclovir 1000 mg TID. Including both inpatient and outpatient treatment, the patient received 3 weeks (total) of acyclovir/valacyclovir therapy.

CORRESPONDENCE

Caitlyn T. Reed, MD, School of Medicine, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216; [email protected].

A 74-year-old Caucasian man presented to the hospital with intractable back and chest pain, a diffuse skin rash, and altered mental status. He said that 2 days ago, he’d gone to a different local hospital for treatment of back pain and a headache that had begun 3 days earlier. He was treated with intravenous hydromorphone and sent home with a prescription for meperidine. He said that several hours after being treated with the hydromorphone, the rash developed on his head and then spread to his trunk and upper extremities.

On physical examination, the patient was afebrile. He had numerous erythematous papules and vesicles in various stages of development on his scalp, face, neck, chest (FIGURE), abdomen, back, upper extremities, and groin. The lesions continued to spread and eventually involved his posterior oropharynx. The patient also developed conjunctivitis.

Laboratory findings included a white blood cell count of 4000/mcL (normal: 4500-11,000/mcL) with 65.9% segmented neutrophils (normal: 40%-60%), and 16.7% lymphocytes (normal: 20%-40%). Lab tests also revealed an aspartate aminotransferase level of 263 U/L (normal: 10-40 U/L), alanine aminotransferase of 236 U/L (normal: 7-56 U/L), and lactate dehydrogenase of 628 U/L (normal: 140-280 U/L).

The patient’s medical history was significant for hypertension, osteoarthritis, and IgG-kappa multiple myeloma, which had been treated with multiple chemotherapy regimens that included lenalidomide. Five years earlier, he’d undergone an autologous bone marrow transplant (BMT). At the time of presentation, the patient was being treated with daratumumab; he received his most recent treatment approximately one month earlier. Other medications included amlodipine, esomeprazole, and escitalopram.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Disseminated varicella-zoster virus infection

Because of the patient’s immunocompromised state, his presentation with altered mental status and diffuse rash was concerning. On hospital Day 2, a sample was taken from one of his skin lesions. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) detected varicella-zoster virus (VZV), and we diagnosed disseminated VZV infection. On hospital Day 3, we performed a lumbar puncture because of worsening confusion and discovered that the cerebrospinal fluid was also positive for VZV.

Disseminated VZV is the most common cause of late infection in patients who have received an allogenic BMT; it is usually due to reactivation of the virus.1 In one study of 1186 patients who underwent BMT, 52% developed VZV infection within 5 years.2 Disseminated VZV may also involve visceral organs, causing pneumonitis, pancreatitis, hepatitis, or encephalitis. Mortality rates for disseminated VZV are as high as 50%.3 Because of this, physicians should be vigilant when patients who have received a BMT present with a rash and signs of systemic involvement.