User login

Painful bumps

|

|

The FP suspected xanthomas secondary to hyperlipidemia. Blood work revealed a random blood sugar of 203 mg/dL, a fasting triglyceride level >7000 mg/dL, and total cholesterol >700 mg/dL. High-density lipoproteins were 32 mg/dL, and there were no chylomicrons present. The FP diagnosed xanthomas, poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia.

Xanthomas are usually a consequence of primary or secondary hyperlipidemia. There are 5 basic types:

- Eruptive xanthomas—the source of this patient’s discomfort—are the most common. They appear as crops of yellow or hyperpigmented papules with erythematous halos in Caucasian patients.

- Tendon xanthomas are frequently seen on the Achilles and extensor finger tendons.

- Plane xanthomas are flat and commonly found on the palmar creases, face, upper trunk, and on scars.

- Tuberous xanthomas are found most frequently on the hands or over large joints.

- Xanthelasma are yellow papules located on the eyelids.

Initial treatment should target the underlying hyperlipidemia (when present) because hypolipidemic drug treatment often results in regression of the lesions. When standard therapy fails, low-density lipoprotein apheresis can be effective for tendon xanthomas.

Recognizing the importance of treating the patient’s diabetes, as well as hyperlipidemia, the FP in this case started the patient on metformin, gemfibrozil, and an HMG-CoA-reductase inhibitor.

The patient was lost to follow-up.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Xanthomas. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:951-953.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

|

|

The FP suspected xanthomas secondary to hyperlipidemia. Blood work revealed a random blood sugar of 203 mg/dL, a fasting triglyceride level >7000 mg/dL, and total cholesterol >700 mg/dL. High-density lipoproteins were 32 mg/dL, and there were no chylomicrons present. The FP diagnosed xanthomas, poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia.

Xanthomas are usually a consequence of primary or secondary hyperlipidemia. There are 5 basic types:

- Eruptive xanthomas—the source of this patient’s discomfort—are the most common. They appear as crops of yellow or hyperpigmented papules with erythematous halos in Caucasian patients.

- Tendon xanthomas are frequently seen on the Achilles and extensor finger tendons.

- Plane xanthomas are flat and commonly found on the palmar creases, face, upper trunk, and on scars.

- Tuberous xanthomas are found most frequently on the hands or over large joints.

- Xanthelasma are yellow papules located on the eyelids.

Initial treatment should target the underlying hyperlipidemia (when present) because hypolipidemic drug treatment often results in regression of the lesions. When standard therapy fails, low-density lipoprotein apheresis can be effective for tendon xanthomas.

Recognizing the importance of treating the patient’s diabetes, as well as hyperlipidemia, the FP in this case started the patient on metformin, gemfibrozil, and an HMG-CoA-reductase inhibitor.

The patient was lost to follow-up.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Xanthomas. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:951-953.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

|

|

The FP suspected xanthomas secondary to hyperlipidemia. Blood work revealed a random blood sugar of 203 mg/dL, a fasting triglyceride level >7000 mg/dL, and total cholesterol >700 mg/dL. High-density lipoproteins were 32 mg/dL, and there were no chylomicrons present. The FP diagnosed xanthomas, poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia.

Xanthomas are usually a consequence of primary or secondary hyperlipidemia. There are 5 basic types:

- Eruptive xanthomas—the source of this patient’s discomfort—are the most common. They appear as crops of yellow or hyperpigmented papules with erythematous halos in Caucasian patients.

- Tendon xanthomas are frequently seen on the Achilles and extensor finger tendons.

- Plane xanthomas are flat and commonly found on the palmar creases, face, upper trunk, and on scars.

- Tuberous xanthomas are found most frequently on the hands or over large joints.

- Xanthelasma are yellow papules located on the eyelids.

Initial treatment should target the underlying hyperlipidemia (when present) because hypolipidemic drug treatment often results in regression of the lesions. When standard therapy fails, low-density lipoprotein apheresis can be effective for tendon xanthomas.

Recognizing the importance of treating the patient’s diabetes, as well as hyperlipidemia, the FP in this case started the patient on metformin, gemfibrozil, and an HMG-CoA-reductase inhibitor.

The patient was lost to follow-up.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Xanthomas. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:951-953.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

Erythematous penile lesion

A 63-YEAR-OLD MAN came to our clinic complaining of a rash on his penis. He indicated that the rash had been there for almost 2 years and that he’d seen 2 other doctors about it, but they’d been unable to make a diagnosis.

The patient said the rash was mildly painful and tender. He denied pain on urination, discharge, fever, malaise, or arthralgias. He also denied any sexual contact outside of his marriage and indicated that he had not been able to have intimate contact with his wife because of the problem.

The patient was uncircumcised and when the foreskin was retracted, a bright red erythematous nonscaly circumferential plaque was visible on the glans penis, spreading to the foreskin (FIGURE 1).

FIGURE 1

A nonscaly, circumferential plaque on the glans penis

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Zoon’s balanitis

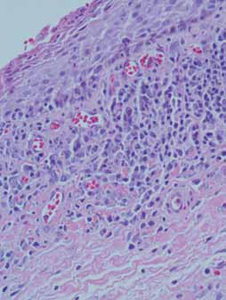

We ordered a biopsy because we suspected that the cause of the rash was either erythroplasia of Queyrat (a premalignant condition also known as Bowen’s disease of the glans penis) or Zoon’s balanitis (plasma cell balanitis or balanitis circumscripta plasmacellularis). The biopsy report confirmed the diagnosis of Zoon’s balanitis and showed no signs of malignancy. The features of Zoon’s balanitis include epidermal atrophy, loss of rete ridges, spongiosis, and subepidermal plasma cell infiltrate without evidence of malignancy (FIGURE 2).

FIGURE 2

Dense plasmacytic infiltration underlying the mucosal epidermis

Condition affects older, uncircumcised men

Zoon’s balanitis is thought to be a benign condition that typically affects uncircumcised middle-aged to elderly men.1,2 Worldwide prevalence among uncircumcised men is approximately 3%.2 The etiology is unknown; it’s thought that this condition may be caused by friction, trauma, heat, lack of hygiene, exogenous or infectious agents, an IgE hypersensitivity, or a chronic infection with Mycobacterium smegmatis.1,2

Typically, the appearance of the lesion precedes diagnosis by about one to 2 years.1 The patient usually complains of mild pruritus and tenderness. Undergarments may be bloodstained.

The differential for penile lesions is extensive, and includes psoriasis, nummular eczema, candidiasis, herpes simplex, scabies, lichen sclerosus et atrophicus or lichen planus, syphilis, balanitis, and erythroplasia of Queyrat.

The lesion associated with Zoon’s balanitis is a solitary, glistening, shiny, red-to-orange plaque of the glans penis or prepuce of an uncircumcised male. Pinpoint erythematous spots or “cayenne pepper spots” may also be associated with this condition.

Patients with erythroplasia of Queyrat have either a solitary or multiple nonhealing erythematous plaques on the glans penis. These lesions may also affect the adjacent mucosal epithelium. As is true with Zoon’s balanitis, the typical patient is uncircumcised and middle-aged to elderly.1,2

Presentations may be similar, but treatment differs

Because the treatments for Zoon’s balanitis and erythroplasia of Queyrat are different, a biopsy is imperative. Erythroplasia of Queyrat is a premalignant condition that is treated with topical fluorouracil or surgical excision.3 Treatment for Zoon’s balanitis consists of a topical corticosteroid with or without topical anticandidal agents and circumcision after the acute inflammation resolves.1,2 (If a skin biopsy cannot be obtained in the clinic, the foreskin [if affected] can be sent for biopsy after the circumcision.)

If resolution is not seen with topical steroid treatment, other treatments have demonstrated efficacy. These include topical tacrolimus, as well as YAG and carbon dioxide laser treatments.4-6

Although information is limited on rates of recurrence, circumcision is considered the treatment of choice and is usually curative.1

Ointment does the trick for our patient

Our patient was treated with a single combined topical ointment consisting of nystatin and triamcinolone cream with zinc oxide. The lesion resolved completely after 10 days. We requested a urology consult so that a circumcision could be performed.

CORRESPONDENCE Matthew R. Noss, DO, MSEd, Fort Belvoir Community Hospital Family Medicine Clinic, 1st Floor, Eagle Pavilion, 9300 Dewitt Loop, Ft. Belvoir, VA 22060; [email protected]

1. Scheinfeld NS, Keough GC, Lehman DS. Balanitis circumscripta plasmacellularis. Medscape. June 8, 2012. Available at: emedicine.medscape.com/article/1122283. Accessed October 26, 2012.

2. Barrisford GW. Balanitis and balanoposthitis in adults. UpToDate. December 19, 2011. Available at: www.uptodate.com/contents/balanitis-and-balanoposthitis-in-adults. Accessed October 26, 2012.

3. Egan KM, Maino KL. Erythroplasia of Queyrat (Bowen disease of the glans penis). Medscape. May 31, 2012. Available at: emedicine.medscape.com/article/1100317. Accessed October 26, 2012.

4. Santos-Juanes J, Sanchez del Rio J, Galache C, et al. Topical tacrolimus: an effective therapy for Zoon balanitis. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1538-1539.

5. Wollina U. Ablative erbium: YAG laser treatment of idiopathic chronic inflammatory non-cicatricial balanoposthitis (Zoon’s disease)—a series of 20 patients with long-term outcome. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2010;12:120-123.

6. Retamar RA, Kien MC, Couela EN. Zoon’s balanitis: presentation of 15 patients, five treated with a carbon dioxide laser. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:305-307.

A 63-YEAR-OLD MAN came to our clinic complaining of a rash on his penis. He indicated that the rash had been there for almost 2 years and that he’d seen 2 other doctors about it, but they’d been unable to make a diagnosis.

The patient said the rash was mildly painful and tender. He denied pain on urination, discharge, fever, malaise, or arthralgias. He also denied any sexual contact outside of his marriage and indicated that he had not been able to have intimate contact with his wife because of the problem.

The patient was uncircumcised and when the foreskin was retracted, a bright red erythematous nonscaly circumferential plaque was visible on the glans penis, spreading to the foreskin (FIGURE 1).

FIGURE 1

A nonscaly, circumferential plaque on the glans penis

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Zoon’s balanitis

We ordered a biopsy because we suspected that the cause of the rash was either erythroplasia of Queyrat (a premalignant condition also known as Bowen’s disease of the glans penis) or Zoon’s balanitis (plasma cell balanitis or balanitis circumscripta plasmacellularis). The biopsy report confirmed the diagnosis of Zoon’s balanitis and showed no signs of malignancy. The features of Zoon’s balanitis include epidermal atrophy, loss of rete ridges, spongiosis, and subepidermal plasma cell infiltrate without evidence of malignancy (FIGURE 2).

FIGURE 2

Dense plasmacytic infiltration underlying the mucosal epidermis

Condition affects older, uncircumcised men

Zoon’s balanitis is thought to be a benign condition that typically affects uncircumcised middle-aged to elderly men.1,2 Worldwide prevalence among uncircumcised men is approximately 3%.2 The etiology is unknown; it’s thought that this condition may be caused by friction, trauma, heat, lack of hygiene, exogenous or infectious agents, an IgE hypersensitivity, or a chronic infection with Mycobacterium smegmatis.1,2

Typically, the appearance of the lesion precedes diagnosis by about one to 2 years.1 The patient usually complains of mild pruritus and tenderness. Undergarments may be bloodstained.

The differential for penile lesions is extensive, and includes psoriasis, nummular eczema, candidiasis, herpes simplex, scabies, lichen sclerosus et atrophicus or lichen planus, syphilis, balanitis, and erythroplasia of Queyrat.

The lesion associated with Zoon’s balanitis is a solitary, glistening, shiny, red-to-orange plaque of the glans penis or prepuce of an uncircumcised male. Pinpoint erythematous spots or “cayenne pepper spots” may also be associated with this condition.

Patients with erythroplasia of Queyrat have either a solitary or multiple nonhealing erythematous plaques on the glans penis. These lesions may also affect the adjacent mucosal epithelium. As is true with Zoon’s balanitis, the typical patient is uncircumcised and middle-aged to elderly.1,2

Presentations may be similar, but treatment differs

Because the treatments for Zoon’s balanitis and erythroplasia of Queyrat are different, a biopsy is imperative. Erythroplasia of Queyrat is a premalignant condition that is treated with topical fluorouracil or surgical excision.3 Treatment for Zoon’s balanitis consists of a topical corticosteroid with or without topical anticandidal agents and circumcision after the acute inflammation resolves.1,2 (If a skin biopsy cannot be obtained in the clinic, the foreskin [if affected] can be sent for biopsy after the circumcision.)

If resolution is not seen with topical steroid treatment, other treatments have demonstrated efficacy. These include topical tacrolimus, as well as YAG and carbon dioxide laser treatments.4-6

Although information is limited on rates of recurrence, circumcision is considered the treatment of choice and is usually curative.1

Ointment does the trick for our patient

Our patient was treated with a single combined topical ointment consisting of nystatin and triamcinolone cream with zinc oxide. The lesion resolved completely after 10 days. We requested a urology consult so that a circumcision could be performed.

CORRESPONDENCE Matthew R. Noss, DO, MSEd, Fort Belvoir Community Hospital Family Medicine Clinic, 1st Floor, Eagle Pavilion, 9300 Dewitt Loop, Ft. Belvoir, VA 22060; [email protected]

A 63-YEAR-OLD MAN came to our clinic complaining of a rash on his penis. He indicated that the rash had been there for almost 2 years and that he’d seen 2 other doctors about it, but they’d been unable to make a diagnosis.

The patient said the rash was mildly painful and tender. He denied pain on urination, discharge, fever, malaise, or arthralgias. He also denied any sexual contact outside of his marriage and indicated that he had not been able to have intimate contact with his wife because of the problem.

The patient was uncircumcised and when the foreskin was retracted, a bright red erythematous nonscaly circumferential plaque was visible on the glans penis, spreading to the foreskin (FIGURE 1).

FIGURE 1

A nonscaly, circumferential plaque on the glans penis

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Zoon’s balanitis

We ordered a biopsy because we suspected that the cause of the rash was either erythroplasia of Queyrat (a premalignant condition also known as Bowen’s disease of the glans penis) or Zoon’s balanitis (plasma cell balanitis or balanitis circumscripta plasmacellularis). The biopsy report confirmed the diagnosis of Zoon’s balanitis and showed no signs of malignancy. The features of Zoon’s balanitis include epidermal atrophy, loss of rete ridges, spongiosis, and subepidermal plasma cell infiltrate without evidence of malignancy (FIGURE 2).

FIGURE 2

Dense plasmacytic infiltration underlying the mucosal epidermis

Condition affects older, uncircumcised men

Zoon’s balanitis is thought to be a benign condition that typically affects uncircumcised middle-aged to elderly men.1,2 Worldwide prevalence among uncircumcised men is approximately 3%.2 The etiology is unknown; it’s thought that this condition may be caused by friction, trauma, heat, lack of hygiene, exogenous or infectious agents, an IgE hypersensitivity, or a chronic infection with Mycobacterium smegmatis.1,2

Typically, the appearance of the lesion precedes diagnosis by about one to 2 years.1 The patient usually complains of mild pruritus and tenderness. Undergarments may be bloodstained.

The differential for penile lesions is extensive, and includes psoriasis, nummular eczema, candidiasis, herpes simplex, scabies, lichen sclerosus et atrophicus or lichen planus, syphilis, balanitis, and erythroplasia of Queyrat.

The lesion associated with Zoon’s balanitis is a solitary, glistening, shiny, red-to-orange plaque of the glans penis or prepuce of an uncircumcised male. Pinpoint erythematous spots or “cayenne pepper spots” may also be associated with this condition.

Patients with erythroplasia of Queyrat have either a solitary or multiple nonhealing erythematous plaques on the glans penis. These lesions may also affect the adjacent mucosal epithelium. As is true with Zoon’s balanitis, the typical patient is uncircumcised and middle-aged to elderly.1,2

Presentations may be similar, but treatment differs

Because the treatments for Zoon’s balanitis and erythroplasia of Queyrat are different, a biopsy is imperative. Erythroplasia of Queyrat is a premalignant condition that is treated with topical fluorouracil or surgical excision.3 Treatment for Zoon’s balanitis consists of a topical corticosteroid with or without topical anticandidal agents and circumcision after the acute inflammation resolves.1,2 (If a skin biopsy cannot be obtained in the clinic, the foreskin [if affected] can be sent for biopsy after the circumcision.)

If resolution is not seen with topical steroid treatment, other treatments have demonstrated efficacy. These include topical tacrolimus, as well as YAG and carbon dioxide laser treatments.4-6

Although information is limited on rates of recurrence, circumcision is considered the treatment of choice and is usually curative.1

Ointment does the trick for our patient

Our patient was treated with a single combined topical ointment consisting of nystatin and triamcinolone cream with zinc oxide. The lesion resolved completely after 10 days. We requested a urology consult so that a circumcision could be performed.

CORRESPONDENCE Matthew R. Noss, DO, MSEd, Fort Belvoir Community Hospital Family Medicine Clinic, 1st Floor, Eagle Pavilion, 9300 Dewitt Loop, Ft. Belvoir, VA 22060; [email protected]

1. Scheinfeld NS, Keough GC, Lehman DS. Balanitis circumscripta plasmacellularis. Medscape. June 8, 2012. Available at: emedicine.medscape.com/article/1122283. Accessed October 26, 2012.

2. Barrisford GW. Balanitis and balanoposthitis in adults. UpToDate. December 19, 2011. Available at: www.uptodate.com/contents/balanitis-and-balanoposthitis-in-adults. Accessed October 26, 2012.

3. Egan KM, Maino KL. Erythroplasia of Queyrat (Bowen disease of the glans penis). Medscape. May 31, 2012. Available at: emedicine.medscape.com/article/1100317. Accessed October 26, 2012.

4. Santos-Juanes J, Sanchez del Rio J, Galache C, et al. Topical tacrolimus: an effective therapy for Zoon balanitis. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1538-1539.

5. Wollina U. Ablative erbium: YAG laser treatment of idiopathic chronic inflammatory non-cicatricial balanoposthitis (Zoon’s disease)—a series of 20 patients with long-term outcome. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2010;12:120-123.

6. Retamar RA, Kien MC, Couela EN. Zoon’s balanitis: presentation of 15 patients, five treated with a carbon dioxide laser. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:305-307.

1. Scheinfeld NS, Keough GC, Lehman DS. Balanitis circumscripta plasmacellularis. Medscape. June 8, 2012. Available at: emedicine.medscape.com/article/1122283. Accessed October 26, 2012.

2. Barrisford GW. Balanitis and balanoposthitis in adults. UpToDate. December 19, 2011. Available at: www.uptodate.com/contents/balanitis-and-balanoposthitis-in-adults. Accessed October 26, 2012.

3. Egan KM, Maino KL. Erythroplasia of Queyrat (Bowen disease of the glans penis). Medscape. May 31, 2012. Available at: emedicine.medscape.com/article/1100317. Accessed October 26, 2012.

4. Santos-Juanes J, Sanchez del Rio J, Galache C, et al. Topical tacrolimus: an effective therapy for Zoon balanitis. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1538-1539.

5. Wollina U. Ablative erbium: YAG laser treatment of idiopathic chronic inflammatory non-cicatricial balanoposthitis (Zoon’s disease)—a series of 20 patients with long-term outcome. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2010;12:120-123.

6. Retamar RA, Kien MC, Couela EN. Zoon’s balanitis: presentation of 15 patients, five treated with a carbon dioxide laser. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:305-307.

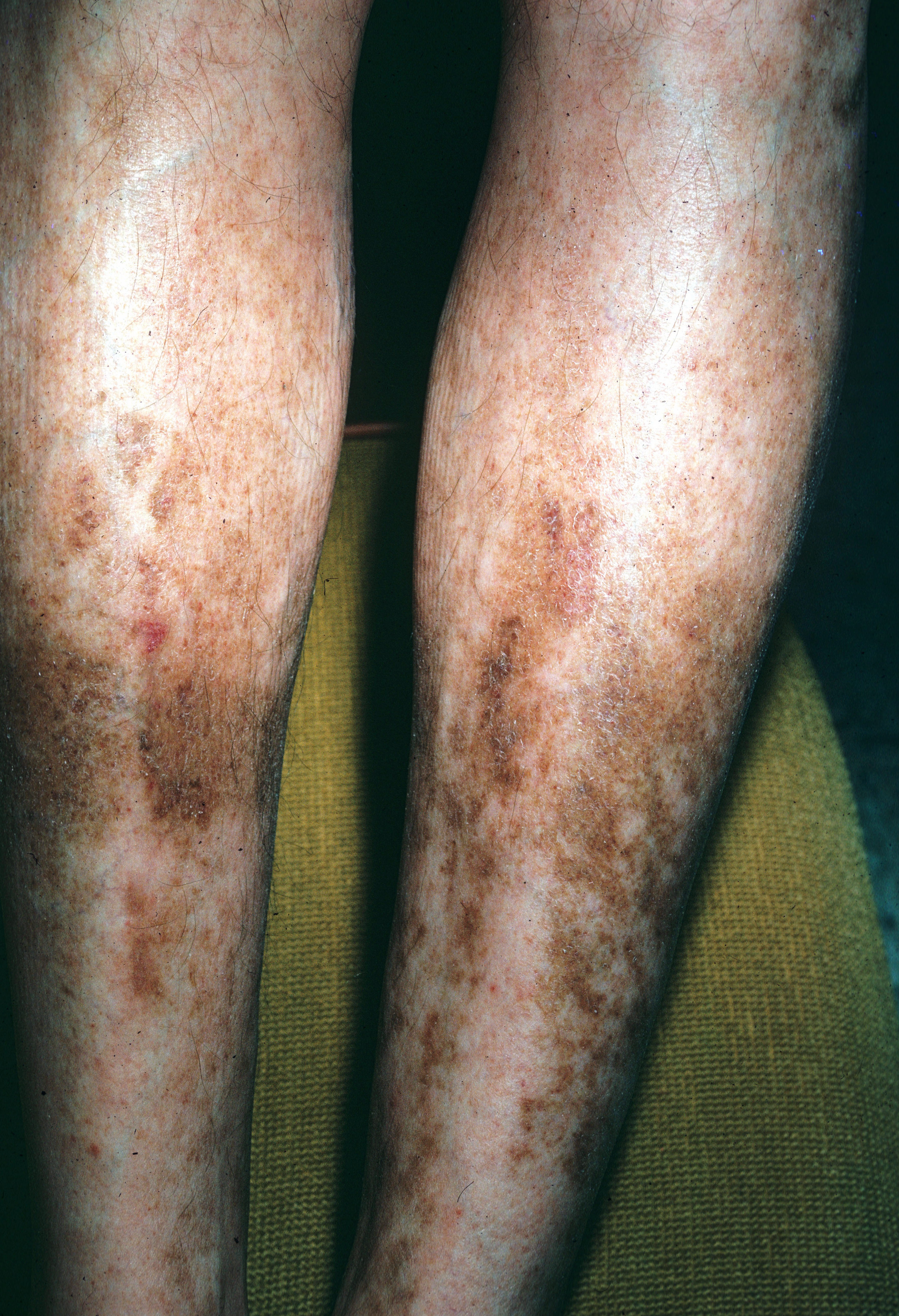

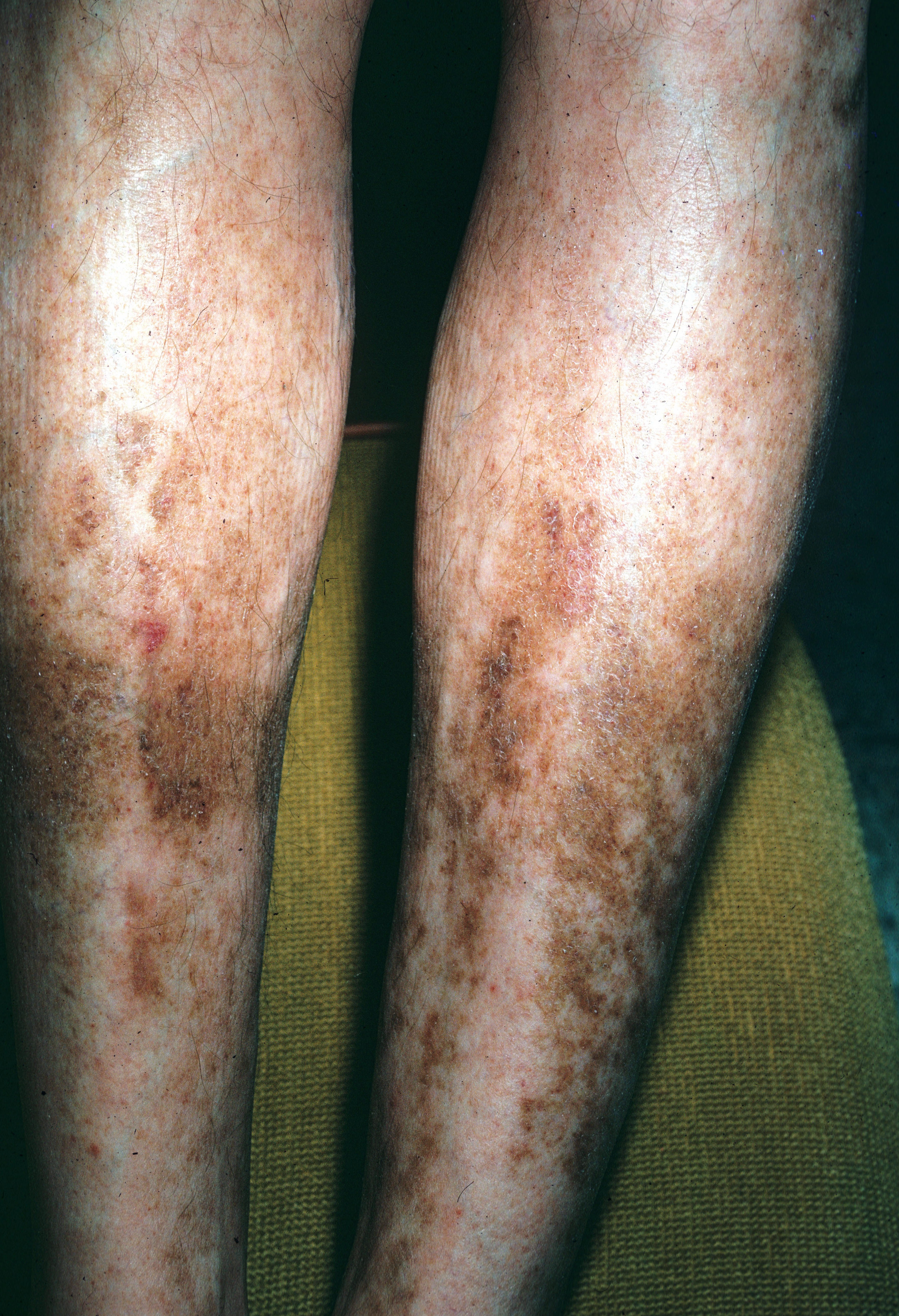

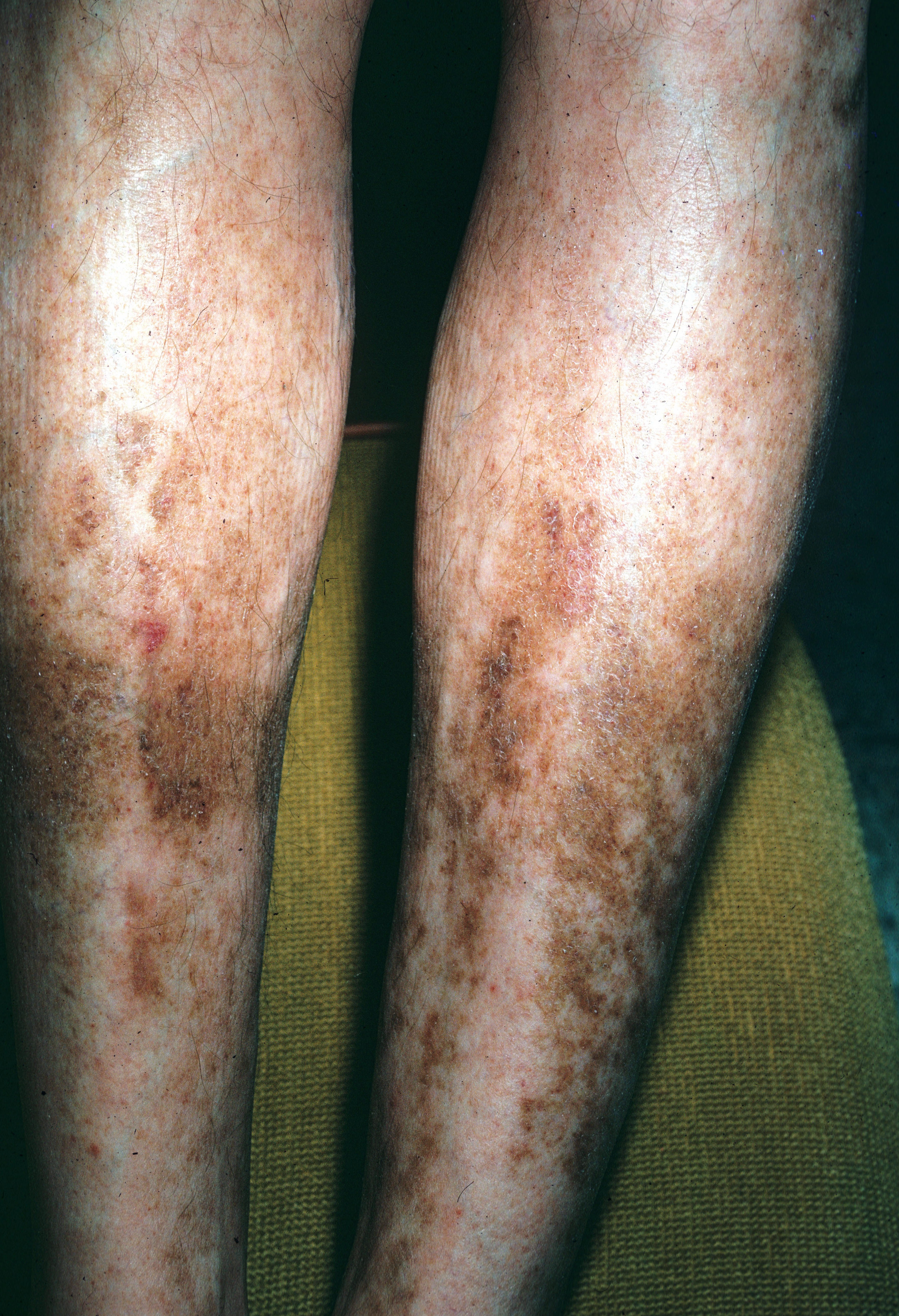

Discolored lower legs

The FP recognized the lesions as necrobiosis lipoidica (NL) and ordered some lab work. The following day, the patient’s fasting blood sugar was 121 mg/dL, with a glycosylated hemoglobin value of 6.1%.

NL was previously called necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum because it was thought to be seen almost exclusively in patients with diabetes. A significant minority of patients with NL do not have diabetes, however, so the newer name is NL. The condition is rare, and occurs in 0.3% of patients with diabetes. NL primarily affects women—particularly those with type 1 diabetes—but it can occur with type 2. Average age of onset is 34 years.

The cause of NL remains unknown. The lesions are usually located on the shins. They begin as erythematous papules or plaques in the pretibial area and become larger and darker, with irregular margins and raised erythematous borders. The lesion’s center atrophies and turns yellow in color. There is often a prominent brown color or hyperpigmentation. The lesions may ulcerate and become painful. Telangiectasias and prominent blood vessels may be seen within the lesions. The yellow color may result from lipid deposits or beta-carotene—hence the term “lipoidica.”

Treatment options include topical steroids or intralesional injections (2.5 mg/mL triamcinolone). Treatment risks include increasing the existing atrophy, so patients should be informed of risks and benefits before initiating steroid treatments. Another treatment option (off-label) is pentoxifylline (400 mg, 2-3 times daily). Pentoxifylline improves blood flow and decreases red cell and platelet aggregation; however, it’s use is only supported by case reports.

In this case, the FP recommended diet and exercise for the patient’s borderline diabetes and prescribed a moderate-strength topical corticosteroid.

Photo courtesy of Suraj Reddy, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Necrobiosis lipoidica. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:948-950.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone, iPad, and all Android devices by clicking this link

The FP recognized the lesions as necrobiosis lipoidica (NL) and ordered some lab work. The following day, the patient’s fasting blood sugar was 121 mg/dL, with a glycosylated hemoglobin value of 6.1%.

NL was previously called necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum because it was thought to be seen almost exclusively in patients with diabetes. A significant minority of patients with NL do not have diabetes, however, so the newer name is NL. The condition is rare, and occurs in 0.3% of patients with diabetes. NL primarily affects women—particularly those with type 1 diabetes—but it can occur with type 2. Average age of onset is 34 years.

The cause of NL remains unknown. The lesions are usually located on the shins. They begin as erythematous papules or plaques in the pretibial area and become larger and darker, with irregular margins and raised erythematous borders. The lesion’s center atrophies and turns yellow in color. There is often a prominent brown color or hyperpigmentation. The lesions may ulcerate and become painful. Telangiectasias and prominent blood vessels may be seen within the lesions. The yellow color may result from lipid deposits or beta-carotene—hence the term “lipoidica.”

Treatment options include topical steroids or intralesional injections (2.5 mg/mL triamcinolone). Treatment risks include increasing the existing atrophy, so patients should be informed of risks and benefits before initiating steroid treatments. Another treatment option (off-label) is pentoxifylline (400 mg, 2-3 times daily). Pentoxifylline improves blood flow and decreases red cell and platelet aggregation; however, it’s use is only supported by case reports.

In this case, the FP recommended diet and exercise for the patient’s borderline diabetes and prescribed a moderate-strength topical corticosteroid.

Photo courtesy of Suraj Reddy, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Necrobiosis lipoidica. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:948-950.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone, iPad, and all Android devices by clicking this link

The FP recognized the lesions as necrobiosis lipoidica (NL) and ordered some lab work. The following day, the patient’s fasting blood sugar was 121 mg/dL, with a glycosylated hemoglobin value of 6.1%.

NL was previously called necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum because it was thought to be seen almost exclusively in patients with diabetes. A significant minority of patients with NL do not have diabetes, however, so the newer name is NL. The condition is rare, and occurs in 0.3% of patients with diabetes. NL primarily affects women—particularly those with type 1 diabetes—but it can occur with type 2. Average age of onset is 34 years.

The cause of NL remains unknown. The lesions are usually located on the shins. They begin as erythematous papules or plaques in the pretibial area and become larger and darker, with irregular margins and raised erythematous borders. The lesion’s center atrophies and turns yellow in color. There is often a prominent brown color or hyperpigmentation. The lesions may ulcerate and become painful. Telangiectasias and prominent blood vessels may be seen within the lesions. The yellow color may result from lipid deposits or beta-carotene—hence the term “lipoidica.”

Treatment options include topical steroids or intralesional injections (2.5 mg/mL triamcinolone). Treatment risks include increasing the existing atrophy, so patients should be informed of risks and benefits before initiating steroid treatments. Another treatment option (off-label) is pentoxifylline (400 mg, 2-3 times daily). Pentoxifylline improves blood flow and decreases red cell and platelet aggregation; however, it’s use is only supported by case reports.

In this case, the FP recommended diet and exercise for the patient’s borderline diabetes and prescribed a moderate-strength topical corticosteroid.

Photo courtesy of Suraj Reddy, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Necrobiosis lipoidica. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:948-950.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone, iPad, and all Android devices by clicking this link

Darkened skin on neck

The FP recognized the dark velvety skin as acanthosis nigricans. He also noted multiple skin tags (acrochordons) on the patient’s neck. The patient requested that the skin tags be removed and wanted to know what could be done about the dark color on her neck. She was worried that it looked dirty.

The FP suggested that the patient increase her efforts at weight loss through improved diet and increased exercise. The patient was willing to work on weight loss, but still wanted something to decrease the skin hyperpigmentation. The FP prescribed topical tretinoin cream 0.025% to be applied before bed. Other treatment options for the acanthosis nigricans include keratolytic agents (eg, salicylic acid, ammonium lactate) and topical vitamin D analogs.

Before the visit was over, the FP snipped off the skin tags with a sharp iris scissor and stopped the bleeding with topical aluminum chloride.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Acanthosis nigricans. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:942-944

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone, iPad, and all Android devices by clicking this link

The FP recognized the dark velvety skin as acanthosis nigricans. He also noted multiple skin tags (acrochordons) on the patient’s neck. The patient requested that the skin tags be removed and wanted to know what could be done about the dark color on her neck. She was worried that it looked dirty.

The FP suggested that the patient increase her efforts at weight loss through improved diet and increased exercise. The patient was willing to work on weight loss, but still wanted something to decrease the skin hyperpigmentation. The FP prescribed topical tretinoin cream 0.025% to be applied before bed. Other treatment options for the acanthosis nigricans include keratolytic agents (eg, salicylic acid, ammonium lactate) and topical vitamin D analogs.

Before the visit was over, the FP snipped off the skin tags with a sharp iris scissor and stopped the bleeding with topical aluminum chloride.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Acanthosis nigricans. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:942-944

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone, iPad, and all Android devices by clicking this link

The FP recognized the dark velvety skin as acanthosis nigricans. He also noted multiple skin tags (acrochordons) on the patient’s neck. The patient requested that the skin tags be removed and wanted to know what could be done about the dark color on her neck. She was worried that it looked dirty.

The FP suggested that the patient increase her efforts at weight loss through improved diet and increased exercise. The patient was willing to work on weight loss, but still wanted something to decrease the skin hyperpigmentation. The FP prescribed topical tretinoin cream 0.025% to be applied before bed. Other treatment options for the acanthosis nigricans include keratolytic agents (eg, salicylic acid, ammonium lactate) and topical vitamin D analogs.

Before the visit was over, the FP snipped off the skin tags with a sharp iris scissor and stopped the bleeding with topical aluminum chloride.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Acanthosis nigricans. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:942-944

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone, iPad, and all Android devices by clicking this link

Red lesion on shins

The patient was given a diagnosis of diabetic dermopathy. This condition is the most common cutaneous marker of diabetes mellitus and is found in 12% to 40% of patients—typically the elderly. The cause of diabetic dermopathy is unknown, thought the condition may be related to mechanical or thermal trauma, especially in patients with neuropathy.

Lesions have been classified as vascular because the histology demonstrates red blood cell extravasation and capillary basement membrane thickening. There is an association between diabetic dermopathy and retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy.

Lesions often begin as pink patches (0.5–1 cm), which become hyperpigmented, with surface atrophy and fine scale. Pretibial and lateral areas of the calf are involved. Histology shows epidermal atrophy, thickened small superficial dermal blood vessels, and hemorrhage with hemosiderin deposits. There is no effective treatment, and the lesions may resolve spontaneously. It’s not known whether the lesions improve with better diabetes control.

In this case, the patient promised to work harder with her physician to achieve better control of her diabetes.

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. Photo courtesy of University of Texas Health Sciences Center, Division of Dermatology. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Diabetic dermopathy. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:945-947.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone, iPad, and all Android devices by clicking this link

The patient was given a diagnosis of diabetic dermopathy. This condition is the most common cutaneous marker of diabetes mellitus and is found in 12% to 40% of patients—typically the elderly. The cause of diabetic dermopathy is unknown, thought the condition may be related to mechanical or thermal trauma, especially in patients with neuropathy.

Lesions have been classified as vascular because the histology demonstrates red blood cell extravasation and capillary basement membrane thickening. There is an association between diabetic dermopathy and retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy.

Lesions often begin as pink patches (0.5–1 cm), which become hyperpigmented, with surface atrophy and fine scale. Pretibial and lateral areas of the calf are involved. Histology shows epidermal atrophy, thickened small superficial dermal blood vessels, and hemorrhage with hemosiderin deposits. There is no effective treatment, and the lesions may resolve spontaneously. It’s not known whether the lesions improve with better diabetes control.

In this case, the patient promised to work harder with her physician to achieve better control of her diabetes.

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. Photo courtesy of University of Texas Health Sciences Center, Division of Dermatology. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Diabetic dermopathy. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:945-947.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone, iPad, and all Android devices by clicking this link

The patient was given a diagnosis of diabetic dermopathy. This condition is the most common cutaneous marker of diabetes mellitus and is found in 12% to 40% of patients—typically the elderly. The cause of diabetic dermopathy is unknown, thought the condition may be related to mechanical or thermal trauma, especially in patients with neuropathy.

Lesions have been classified as vascular because the histology demonstrates red blood cell extravasation and capillary basement membrane thickening. There is an association between diabetic dermopathy and retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy.

Lesions often begin as pink patches (0.5–1 cm), which become hyperpigmented, with surface atrophy and fine scale. Pretibial and lateral areas of the calf are involved. Histology shows epidermal atrophy, thickened small superficial dermal blood vessels, and hemorrhage with hemosiderin deposits. There is no effective treatment, and the lesions may resolve spontaneously. It’s not known whether the lesions improve with better diabetes control.

In this case, the patient promised to work harder with her physician to achieve better control of her diabetes.

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. Photo courtesy of University of Texas Health Sciences Center, Division of Dermatology. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Diabetic dermopathy. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:945-947.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone, iPad, and all Android devices by clicking this link

Discoloration under arm

The FP diagnosed acanthosis nigricans (AN) in this patient and continued to work with the girl and her family on the issues of diet, exercise, and weight loss. AN is a skin condition usually associated with insulin resistance (IR) and is seen in patients with type 2 diabetes, obesity, and polycystic ovary syndrome. AN is sometimes associated with malignancy, primarily adenocarcinoma of the stomach, colon, ovary, pancreas, rectum, and uterus.

AN results from long-term exposure of keratinocytes to insulin. Keratinocytes have insulin and insulin-like growth receptors on their surfaces, and the pathogenesis of this condition may be linked to insulin binding to insulin-like growth receptors in the epidermis.

AN ranges in appearance from diffuse streaky thickened brown velvety lesions to leathery verrucous papillomatous lesions. It is commonly located on the neck or skin folds (eg, axillae, inframammary folds, groin, and perineum). Weight loss through diet and exercise helps reverse the process, probably by reducing both IR and compensatory hyperinsulinemia. The use of keratolytic agents (eg, salicylic acid) may improve the appearance of the lesions. Other drugs such as metformin, topical retinoids, and topical vitamin D analogs have also been used to treat AN.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Acanthosis nigricans. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:942-944.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone, iPad, and all Android devices by clicking this link

The FP diagnosed acanthosis nigricans (AN) in this patient and continued to work with the girl and her family on the issues of diet, exercise, and weight loss. AN is a skin condition usually associated with insulin resistance (IR) and is seen in patients with type 2 diabetes, obesity, and polycystic ovary syndrome. AN is sometimes associated with malignancy, primarily adenocarcinoma of the stomach, colon, ovary, pancreas, rectum, and uterus.

AN results from long-term exposure of keratinocytes to insulin. Keratinocytes have insulin and insulin-like growth receptors on their surfaces, and the pathogenesis of this condition may be linked to insulin binding to insulin-like growth receptors in the epidermis.

AN ranges in appearance from diffuse streaky thickened brown velvety lesions to leathery verrucous papillomatous lesions. It is commonly located on the neck or skin folds (eg, axillae, inframammary folds, groin, and perineum). Weight loss through diet and exercise helps reverse the process, probably by reducing both IR and compensatory hyperinsulinemia. The use of keratolytic agents (eg, salicylic acid) may improve the appearance of the lesions. Other drugs such as metformin, topical retinoids, and topical vitamin D analogs have also been used to treat AN.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Acanthosis nigricans. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:942-944.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone, iPad, and all Android devices by clicking this link

The FP diagnosed acanthosis nigricans (AN) in this patient and continued to work with the girl and her family on the issues of diet, exercise, and weight loss. AN is a skin condition usually associated with insulin resistance (IR) and is seen in patients with type 2 diabetes, obesity, and polycystic ovary syndrome. AN is sometimes associated with malignancy, primarily adenocarcinoma of the stomach, colon, ovary, pancreas, rectum, and uterus.

AN results from long-term exposure of keratinocytes to insulin. Keratinocytes have insulin and insulin-like growth receptors on their surfaces, and the pathogenesis of this condition may be linked to insulin binding to insulin-like growth receptors in the epidermis.

AN ranges in appearance from diffuse streaky thickened brown velvety lesions to leathery verrucous papillomatous lesions. It is commonly located on the neck or skin folds (eg, axillae, inframammary folds, groin, and perineum). Weight loss through diet and exercise helps reverse the process, probably by reducing both IR and compensatory hyperinsulinemia. The use of keratolytic agents (eg, salicylic acid) may improve the appearance of the lesions. Other drugs such as metformin, topical retinoids, and topical vitamin D analogs have also been used to treat AN.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Acanthosis nigricans. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:942-944.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone, iPad, and all Android devices by clicking this link

Crying infant with painful toes

A WELL-DEVELOPED AND PREVIOUSLY HEALTHY INFANT was brought to our emergency department (ED) by her parents, who said that their child was experiencing significant toe pain. Two reddened, swollen toes (FIGURE) were immediately identifiable on the left foot. The patient’s parents denied any trauma or unusual activity involving the infant.

FIGURE

Two reddened and swollen toes

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Hair tourniquet

Upon close inspection, we discovered hair thread tourniquets constricting the fourth and fifth toes on the baby’s left foot.

Hair tourniquet syndrome primarily affects infants in the first few months of life. The average age of occurrence is 4 months, a time when maternal postpartum hair loss (telogen effluvium) is at its maximum.1,2 It is worth noting, however, that this syndrome has also been observed in toddlers and adolescents.3

Toes are most frequently involved, although cases of hair tourniquets affecting the fingers, penis, labia, clitoris and uvula have been reported.2-7 Infants may be brought to the office or ED with irritability or crying, or with an erythematous extremity.

Why tourniquets are overlooked

Infantile tourniquets may be overlooked because of the fine nature of human hair, the swelling of the involved appendage (which can hide the tourniquet itself), and the presence of baby booties, footed pajamas, and mittens that may obscure injured digits from view.

These tourniquets can cause significant morbidity if they are not quickly identified and removed. The tensile strength of human hair is quite strong, allowing for strangulation and even amputation of appendages. The repetitive motion of hands and feet inside booties or mittens allows constriction to increase.

As this tightening occurs, the tourniquet may cause constrictive lymphatic obstruction, edema of the involved soft tissues, and secondary vascular obstruction of venous outflow and arterial perfusion.5,8,9 Tourniquets can also cut through skin, injuring deeper tissues.

In most instances, the damaged tissue will rapidly reperfuse once the offending tourniquet is unraveled or removed. However, some cases may result in epithelialization over the tourniquet, ischemia, necrosis, and gangrene leading to amputation. Quick recognition of the condition and immediate removal of the constricting tourniquet are key to saving the injured appendage.

How best to remove the tourniquet

Methods of tourniquet removal include unwrapping, cutting, or dissolving the hair with commercial hair removal agents such as Nair (Church & Dwight Co, Inc, Princeton, NJ).2,10-12

Unwrapping. In cases where the tourniquet is easily visualized and minimal edema is present, simply unwrapping the constricting hair may be successful. This can be accomplished by identifying a loose end of the hair, grasping the free end with a pinching instrument such as a hemostat or forceps, and carefully unwrapping the hair from the appendage1,11 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B).

Cutting. If cutting the hair is necessary due to the presence of mild to moderate edema or failure of the unwrapping technique, a blunt probe may be inserted between the hair and the appendage to protect soft tissues from the cutting implement. Once the probe has been inserted, the tourniquet may be cut using scissors or a #11 scalpel blade applied to the surface of the blunt instrument1,11 (SOR: C). Alternative instrumentation, including a #12 Bard Parker curved scalpel blade and a Littauer suture-removal scissor, may be useful when the tourniquet is too tightly wound to allow for insertion of a blunt probe instrument (SOR: C).

Dissolving. A commercially available depilatory agent, such as Nair, may be useful for mild cases, but would not be appropriate when a tourniquet has cut into the skin. Calcium thioglycolate, a common depilatory active ingredient, breaks down disulfide bonds in keratin, thereby weakening hair strands. Chemical agents containing calcium thioglycolate should be used with caution, as keratin is also present in the epidermis and use of these agents may cause irritation to the skin.

When an incisional approach is needed

At times, epithelialization over the tourniquet or severe swelling of a digit may necessitate an incisional approach. If there is any doubt about whether you can completely remove all of the strands of the tourniquet, an incision into the digit itself must be made to disrupt constriction. Historically, a digital nerve block has been the preferred mode of analgesia; however, recent evidence suggests that less invasive pain management strategies, such as a sucrose pacifier, EMLA cream, or ZAP topical analgesia gel may be effective13 (SOR: A).

If you must use this approach, you’ll need to consider the placement of the digital neurovascular bundles of the fingers and toes, located at approximately the 2, 4, 8, and 10 o’clock positions. Following sterile preparation and draping, a longitudinal incision should be made at either the 3 or 9 o’clock position, thus locating it between neurovascular bundles1,11 (SOR: B).

Alternatively, a longitudinal incision can be made directly over the extensor tendon, located dorsally at 12 o’clock. Any resulting tendon laceration would be parallel to the tendon fibers, and could be expected to heal with splinting and wound care1,11,14 (SOR: B).

Prior to initiating treatment, parents or caregivers should be warned about the potential for bleeding and pain during the procedure.

Extreme cases may require surgery

Surgical consultation may be required in extreme cases of edema, neurovascular compromise, necrosis, amputation, or failure to completely remove the tourniquet.2

Other factors to keep in mind. While classically described as consisting of a single hair, tourniquets may be comprised of multiple hairs. That’s why it’s important to carefully inspect the area to be sure that all strands have been removed. Thorough treatment should include consideration of child abuse, tetanus immunization, and the need for antibiotics1,2,11 (SOR: B).

Relief for our young patient

To remove our patient’s hair tourniquets, we carefully cut the fibers with hooked Littauer suture-removal scissors and unwrapped the hair. Damage to the plantar aspect of both toes was significant enough that we had to cut through the soft tissue and into the flexor tendon to completely remove the hair. No sutures were required as the wound edges were well approximated without closure.

We cleaned and dressed the injured toes and arranged for close follow-up. The patient’s recovery was uneventful.

To avoid hair tourniquet syndrome, counsel parents to turn mittens and booties inside out to check for loose hairs. Also, advise parents to make sure there aren’t any hairs wrapped around their baby’s fingers or toes. Vigilance on the part of health care providers can provide quick recognition and appropriate treatment of this condition.

CORRESPONDENCE

Tania D. Strout, PhD, RN, MS, Director of Research, Department of Emergency Medicine, Maine Medical Center, 47 Bramhall Street, Portland, ME 04102; [email protected]

1. Loiselle JM, Cronan KM. Hair tourniquet removal. In: King C, Henretig FM, eds. Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Procedures. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008:1065–1069.

2. Strahlman RS. Toe tourniquet syndrome in association with maternal hair loss. Pediatrics. 2003;111:685-687.

3. Bacon JL, Burgis JT. Hair thread tourniquet syndrome in adolescents: a presentation and review of the literature. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2005;18:155-156.

4. Badawy H, Soliman A, Ouf A, et al. Progressive hair coil penile tourniquet syndrome: multicenter experience with 25 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:1514-1518.

5. Kuo JH, Smith LM, Berkowitz CD. A hair tourniquet resulting in strangulation and amputation of the clitoris. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:939-941.

6. McNeal RM, Cruickshank JC. Strangulation of the uvula by hair wrapping. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1987;26:599-600.

7. Krishna S, Paul RI. Hair tourniquet of the uvula. J Emerg Med. 2003;24:325-326.

8. Rich MA, Keating MA. Hair tourniquet syndrome of the clitoris. J Urol. 1999;162:190-191.

9. Sylwestrzak MS, Fischer BF, Fischer H. Recurrent clitoral tourniquet syndrome. Pediatrics. 2000;105:866-867.

10. Douglass DD. Dissolving hair wrapped around an infant’s digit. J Pediatr. 1977;91:162.-

11. Cardriche D. Hair tourniquet removal. Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1348969-overview. Updated January 30, 2012. Accessed October 3, 2012.

12. Peckler B, Hsu CK. Tourniquet syndrome: a review of constricting band removal. J Emerg Med. 2001;20:253-262.

13. Stevens B, Yamada J, Ohlsson A. Sucrose for analgesia in newborn infants undergoing painful procedures. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD001069.-

14. Barton DJ, Sloan GM, Nichter LS, et al. Hair-thread tourniquet syndrome. Pediatrics. 1988;82:925-928.

A WELL-DEVELOPED AND PREVIOUSLY HEALTHY INFANT was brought to our emergency department (ED) by her parents, who said that their child was experiencing significant toe pain. Two reddened, swollen toes (FIGURE) were immediately identifiable on the left foot. The patient’s parents denied any trauma or unusual activity involving the infant.

FIGURE

Two reddened and swollen toes

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Hair tourniquet

Upon close inspection, we discovered hair thread tourniquets constricting the fourth and fifth toes on the baby’s left foot.

Hair tourniquet syndrome primarily affects infants in the first few months of life. The average age of occurrence is 4 months, a time when maternal postpartum hair loss (telogen effluvium) is at its maximum.1,2 It is worth noting, however, that this syndrome has also been observed in toddlers and adolescents.3

Toes are most frequently involved, although cases of hair tourniquets affecting the fingers, penis, labia, clitoris and uvula have been reported.2-7 Infants may be brought to the office or ED with irritability or crying, or with an erythematous extremity.

Why tourniquets are overlooked

Infantile tourniquets may be overlooked because of the fine nature of human hair, the swelling of the involved appendage (which can hide the tourniquet itself), and the presence of baby booties, footed pajamas, and mittens that may obscure injured digits from view.

These tourniquets can cause significant morbidity if they are not quickly identified and removed. The tensile strength of human hair is quite strong, allowing for strangulation and even amputation of appendages. The repetitive motion of hands and feet inside booties or mittens allows constriction to increase.

As this tightening occurs, the tourniquet may cause constrictive lymphatic obstruction, edema of the involved soft tissues, and secondary vascular obstruction of venous outflow and arterial perfusion.5,8,9 Tourniquets can also cut through skin, injuring deeper tissues.

In most instances, the damaged tissue will rapidly reperfuse once the offending tourniquet is unraveled or removed. However, some cases may result in epithelialization over the tourniquet, ischemia, necrosis, and gangrene leading to amputation. Quick recognition of the condition and immediate removal of the constricting tourniquet are key to saving the injured appendage.

How best to remove the tourniquet

Methods of tourniquet removal include unwrapping, cutting, or dissolving the hair with commercial hair removal agents such as Nair (Church & Dwight Co, Inc, Princeton, NJ).2,10-12

Unwrapping. In cases where the tourniquet is easily visualized and minimal edema is present, simply unwrapping the constricting hair may be successful. This can be accomplished by identifying a loose end of the hair, grasping the free end with a pinching instrument such as a hemostat or forceps, and carefully unwrapping the hair from the appendage1,11 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B).

Cutting. If cutting the hair is necessary due to the presence of mild to moderate edema or failure of the unwrapping technique, a blunt probe may be inserted between the hair and the appendage to protect soft tissues from the cutting implement. Once the probe has been inserted, the tourniquet may be cut using scissors or a #11 scalpel blade applied to the surface of the blunt instrument1,11 (SOR: C). Alternative instrumentation, including a #12 Bard Parker curved scalpel blade and a Littauer suture-removal scissor, may be useful when the tourniquet is too tightly wound to allow for insertion of a blunt probe instrument (SOR: C).

Dissolving. A commercially available depilatory agent, such as Nair, may be useful for mild cases, but would not be appropriate when a tourniquet has cut into the skin. Calcium thioglycolate, a common depilatory active ingredient, breaks down disulfide bonds in keratin, thereby weakening hair strands. Chemical agents containing calcium thioglycolate should be used with caution, as keratin is also present in the epidermis and use of these agents may cause irritation to the skin.

When an incisional approach is needed

At times, epithelialization over the tourniquet or severe swelling of a digit may necessitate an incisional approach. If there is any doubt about whether you can completely remove all of the strands of the tourniquet, an incision into the digit itself must be made to disrupt constriction. Historically, a digital nerve block has been the preferred mode of analgesia; however, recent evidence suggests that less invasive pain management strategies, such as a sucrose pacifier, EMLA cream, or ZAP topical analgesia gel may be effective13 (SOR: A).

If you must use this approach, you’ll need to consider the placement of the digital neurovascular bundles of the fingers and toes, located at approximately the 2, 4, 8, and 10 o’clock positions. Following sterile preparation and draping, a longitudinal incision should be made at either the 3 or 9 o’clock position, thus locating it between neurovascular bundles1,11 (SOR: B).

Alternatively, a longitudinal incision can be made directly over the extensor tendon, located dorsally at 12 o’clock. Any resulting tendon laceration would be parallel to the tendon fibers, and could be expected to heal with splinting and wound care1,11,14 (SOR: B).

Prior to initiating treatment, parents or caregivers should be warned about the potential for bleeding and pain during the procedure.

Extreme cases may require surgery

Surgical consultation may be required in extreme cases of edema, neurovascular compromise, necrosis, amputation, or failure to completely remove the tourniquet.2

Other factors to keep in mind. While classically described as consisting of a single hair, tourniquets may be comprised of multiple hairs. That’s why it’s important to carefully inspect the area to be sure that all strands have been removed. Thorough treatment should include consideration of child abuse, tetanus immunization, and the need for antibiotics1,2,11 (SOR: B).

Relief for our young patient

To remove our patient’s hair tourniquets, we carefully cut the fibers with hooked Littauer suture-removal scissors and unwrapped the hair. Damage to the plantar aspect of both toes was significant enough that we had to cut through the soft tissue and into the flexor tendon to completely remove the hair. No sutures were required as the wound edges were well approximated without closure.

We cleaned and dressed the injured toes and arranged for close follow-up. The patient’s recovery was uneventful.

To avoid hair tourniquet syndrome, counsel parents to turn mittens and booties inside out to check for loose hairs. Also, advise parents to make sure there aren’t any hairs wrapped around their baby’s fingers or toes. Vigilance on the part of health care providers can provide quick recognition and appropriate treatment of this condition.

CORRESPONDENCE

Tania D. Strout, PhD, RN, MS, Director of Research, Department of Emergency Medicine, Maine Medical Center, 47 Bramhall Street, Portland, ME 04102; [email protected]

A WELL-DEVELOPED AND PREVIOUSLY HEALTHY INFANT was brought to our emergency department (ED) by her parents, who said that their child was experiencing significant toe pain. Two reddened, swollen toes (FIGURE) were immediately identifiable on the left foot. The patient’s parents denied any trauma or unusual activity involving the infant.

FIGURE

Two reddened and swollen toes

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Hair tourniquet

Upon close inspection, we discovered hair thread tourniquets constricting the fourth and fifth toes on the baby’s left foot.

Hair tourniquet syndrome primarily affects infants in the first few months of life. The average age of occurrence is 4 months, a time when maternal postpartum hair loss (telogen effluvium) is at its maximum.1,2 It is worth noting, however, that this syndrome has also been observed in toddlers and adolescents.3

Toes are most frequently involved, although cases of hair tourniquets affecting the fingers, penis, labia, clitoris and uvula have been reported.2-7 Infants may be brought to the office or ED with irritability or crying, or with an erythematous extremity.

Why tourniquets are overlooked

Infantile tourniquets may be overlooked because of the fine nature of human hair, the swelling of the involved appendage (which can hide the tourniquet itself), and the presence of baby booties, footed pajamas, and mittens that may obscure injured digits from view.

These tourniquets can cause significant morbidity if they are not quickly identified and removed. The tensile strength of human hair is quite strong, allowing for strangulation and even amputation of appendages. The repetitive motion of hands and feet inside booties or mittens allows constriction to increase.

As this tightening occurs, the tourniquet may cause constrictive lymphatic obstruction, edema of the involved soft tissues, and secondary vascular obstruction of venous outflow and arterial perfusion.5,8,9 Tourniquets can also cut through skin, injuring deeper tissues.

In most instances, the damaged tissue will rapidly reperfuse once the offending tourniquet is unraveled or removed. However, some cases may result in epithelialization over the tourniquet, ischemia, necrosis, and gangrene leading to amputation. Quick recognition of the condition and immediate removal of the constricting tourniquet are key to saving the injured appendage.

How best to remove the tourniquet

Methods of tourniquet removal include unwrapping, cutting, or dissolving the hair with commercial hair removal agents such as Nair (Church & Dwight Co, Inc, Princeton, NJ).2,10-12

Unwrapping. In cases where the tourniquet is easily visualized and minimal edema is present, simply unwrapping the constricting hair may be successful. This can be accomplished by identifying a loose end of the hair, grasping the free end with a pinching instrument such as a hemostat or forceps, and carefully unwrapping the hair from the appendage1,11 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B).

Cutting. If cutting the hair is necessary due to the presence of mild to moderate edema or failure of the unwrapping technique, a blunt probe may be inserted between the hair and the appendage to protect soft tissues from the cutting implement. Once the probe has been inserted, the tourniquet may be cut using scissors or a #11 scalpel blade applied to the surface of the blunt instrument1,11 (SOR: C). Alternative instrumentation, including a #12 Bard Parker curved scalpel blade and a Littauer suture-removal scissor, may be useful when the tourniquet is too tightly wound to allow for insertion of a blunt probe instrument (SOR: C).

Dissolving. A commercially available depilatory agent, such as Nair, may be useful for mild cases, but would not be appropriate when a tourniquet has cut into the skin. Calcium thioglycolate, a common depilatory active ingredient, breaks down disulfide bonds in keratin, thereby weakening hair strands. Chemical agents containing calcium thioglycolate should be used with caution, as keratin is also present in the epidermis and use of these agents may cause irritation to the skin.

When an incisional approach is needed

At times, epithelialization over the tourniquet or severe swelling of a digit may necessitate an incisional approach. If there is any doubt about whether you can completely remove all of the strands of the tourniquet, an incision into the digit itself must be made to disrupt constriction. Historically, a digital nerve block has been the preferred mode of analgesia; however, recent evidence suggests that less invasive pain management strategies, such as a sucrose pacifier, EMLA cream, or ZAP topical analgesia gel may be effective13 (SOR: A).

If you must use this approach, you’ll need to consider the placement of the digital neurovascular bundles of the fingers and toes, located at approximately the 2, 4, 8, and 10 o’clock positions. Following sterile preparation and draping, a longitudinal incision should be made at either the 3 or 9 o’clock position, thus locating it between neurovascular bundles1,11 (SOR: B).

Alternatively, a longitudinal incision can be made directly over the extensor tendon, located dorsally at 12 o’clock. Any resulting tendon laceration would be parallel to the tendon fibers, and could be expected to heal with splinting and wound care1,11,14 (SOR: B).

Prior to initiating treatment, parents or caregivers should be warned about the potential for bleeding and pain during the procedure.

Extreme cases may require surgery

Surgical consultation may be required in extreme cases of edema, neurovascular compromise, necrosis, amputation, or failure to completely remove the tourniquet.2

Other factors to keep in mind. While classically described as consisting of a single hair, tourniquets may be comprised of multiple hairs. That’s why it’s important to carefully inspect the area to be sure that all strands have been removed. Thorough treatment should include consideration of child abuse, tetanus immunization, and the need for antibiotics1,2,11 (SOR: B).

Relief for our young patient

To remove our patient’s hair tourniquets, we carefully cut the fibers with hooked Littauer suture-removal scissors and unwrapped the hair. Damage to the plantar aspect of both toes was significant enough that we had to cut through the soft tissue and into the flexor tendon to completely remove the hair. No sutures were required as the wound edges were well approximated without closure.

We cleaned and dressed the injured toes and arranged for close follow-up. The patient’s recovery was uneventful.

To avoid hair tourniquet syndrome, counsel parents to turn mittens and booties inside out to check for loose hairs. Also, advise parents to make sure there aren’t any hairs wrapped around their baby’s fingers or toes. Vigilance on the part of health care providers can provide quick recognition and appropriate treatment of this condition.

CORRESPONDENCE

Tania D. Strout, PhD, RN, MS, Director of Research, Department of Emergency Medicine, Maine Medical Center, 47 Bramhall Street, Portland, ME 04102; [email protected]

1. Loiselle JM, Cronan KM. Hair tourniquet removal. In: King C, Henretig FM, eds. Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Procedures. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008:1065–1069.

2. Strahlman RS. Toe tourniquet syndrome in association with maternal hair loss. Pediatrics. 2003;111:685-687.

3. Bacon JL, Burgis JT. Hair thread tourniquet syndrome in adolescents: a presentation and review of the literature. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2005;18:155-156.

4. Badawy H, Soliman A, Ouf A, et al. Progressive hair coil penile tourniquet syndrome: multicenter experience with 25 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:1514-1518.

5. Kuo JH, Smith LM, Berkowitz CD. A hair tourniquet resulting in strangulation and amputation of the clitoris. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:939-941.

6. McNeal RM, Cruickshank JC. Strangulation of the uvula by hair wrapping. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1987;26:599-600.

7. Krishna S, Paul RI. Hair tourniquet of the uvula. J Emerg Med. 2003;24:325-326.

8. Rich MA, Keating MA. Hair tourniquet syndrome of the clitoris. J Urol. 1999;162:190-191.

9. Sylwestrzak MS, Fischer BF, Fischer H. Recurrent clitoral tourniquet syndrome. Pediatrics. 2000;105:866-867.

10. Douglass DD. Dissolving hair wrapped around an infant’s digit. J Pediatr. 1977;91:162.-

11. Cardriche D. Hair tourniquet removal. Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1348969-overview. Updated January 30, 2012. Accessed October 3, 2012.

12. Peckler B, Hsu CK. Tourniquet syndrome: a review of constricting band removal. J Emerg Med. 2001;20:253-262.

13. Stevens B, Yamada J, Ohlsson A. Sucrose for analgesia in newborn infants undergoing painful procedures. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD001069.-

14. Barton DJ, Sloan GM, Nichter LS, et al. Hair-thread tourniquet syndrome. Pediatrics. 1988;82:925-928.

1. Loiselle JM, Cronan KM. Hair tourniquet removal. In: King C, Henretig FM, eds. Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Procedures. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008:1065–1069.

2. Strahlman RS. Toe tourniquet syndrome in association with maternal hair loss. Pediatrics. 2003;111:685-687.

3. Bacon JL, Burgis JT. Hair thread tourniquet syndrome in adolescents: a presentation and review of the literature. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2005;18:155-156.

4. Badawy H, Soliman A, Ouf A, et al. Progressive hair coil penile tourniquet syndrome: multicenter experience with 25 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:1514-1518.

5. Kuo JH, Smith LM, Berkowitz CD. A hair tourniquet resulting in strangulation and amputation of the clitoris. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:939-941.

6. McNeal RM, Cruickshank JC. Strangulation of the uvula by hair wrapping. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1987;26:599-600.

7. Krishna S, Paul RI. Hair tourniquet of the uvula. J Emerg Med. 2003;24:325-326.

8. Rich MA, Keating MA. Hair tourniquet syndrome of the clitoris. J Urol. 1999;162:190-191.

9. Sylwestrzak MS, Fischer BF, Fischer H. Recurrent clitoral tourniquet syndrome. Pediatrics. 2000;105:866-867.

10. Douglass DD. Dissolving hair wrapped around an infant’s digit. J Pediatr. 1977;91:162.-

11. Cardriche D. Hair tourniquet removal. Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1348969-overview. Updated January 30, 2012. Accessed October 3, 2012.

12. Peckler B, Hsu CK. Tourniquet syndrome: a review of constricting band removal. J Emerg Med. 2001;20:253-262.

13. Stevens B, Yamada J, Ohlsson A. Sucrose for analgesia in newborn infants undergoing painful procedures. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD001069.-

14. Barton DJ, Sloan GM, Nichter LS, et al. Hair-thread tourniquet syndrome. Pediatrics. 1988;82:925-928.

Fever and rash

|

|

| FIGURE 1 | FIGURE 2 |

The FP recognized the annular eruptions on her shoulders and legs as erythema migrans (EM). He was also cognizant of the fact that the girl lived in an endemic area for Lyme disease. Lyme disease is caused by an infection with Borrelia burgdorferi. This organism lives in the deer tick and its common hosts include field mice, white-tailed deer, and household pets. The ticks must feed on infested hosts in order to infect humans. Thirty percent of infected patients do not recall being bitten. Once a human is infected, disease progression is categorized into 3 stages:

1. Localized (days to weeks): erythema migrans and flu-like symptoms.

2. Disseminated (days to months):

- inflammatory arthritis

- cranial nerve palsy (usually a Bell’s palsy)

- atrioventricular blockade, which is present in only 1% of patients with Lyme disease. Syncope, lightheadedness, and dyspnea are classic symptoms consistent with atrioventricular dysfunction

- aseptic meningitis. Patients may present with complaints similar to bacterial meningitis (photophobia, nuchal rigidity, and headache)

- fatigue.

3. Persistent (>1 year):

- chronic arthritis generally occurs in the knee, although other sites such as the shoulder, ankle, elbow, or wrist are not uncommon

- chronic fatigue

- meningoencephalitis, Symptoms vary from mild (memory loss, mood lability, irritability, or panic attacks) to severe (manic or psychotic episodes, paranoia, and obsessive/compulsive symptoms).

The patient described in this case had localized disease. Given that she was 11-years-old and had her adult teeth, her physician felt that he could safely prescribe doxycycline 100 mg BID for 14 days. He also recommended that she take over-the-counter acetaminophen or ibuprofen to treat the fever and myalgias. She responded quickly to the doxycycline.

Photos courtesy of Jeremy Golding, MD, and McGraw-Hill. The text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Corson T, Usatine, R. Lyme disease. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:933-939.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

|

|

| FIGURE 1 | FIGURE 2 |

The FP recognized the annular eruptions on her shoulders and legs as erythema migrans (EM). He was also cognizant of the fact that the girl lived in an endemic area for Lyme disease. Lyme disease is caused by an infection with Borrelia burgdorferi. This organism lives in the deer tick and its common hosts include field mice, white-tailed deer, and household pets. The ticks must feed on infested hosts in order to infect humans. Thirty percent of infected patients do not recall being bitten. Once a human is infected, disease progression is categorized into 3 stages:

1. Localized (days to weeks): erythema migrans and flu-like symptoms.

2. Disseminated (days to months):

- inflammatory arthritis

- cranial nerve palsy (usually a Bell’s palsy)

- atrioventricular blockade, which is present in only 1% of patients with Lyme disease. Syncope, lightheadedness, and dyspnea are classic symptoms consistent with atrioventricular dysfunction

- aseptic meningitis. Patients may present with complaints similar to bacterial meningitis (photophobia, nuchal rigidity, and headache)

- fatigue.

3. Persistent (>1 year):

- chronic arthritis generally occurs in the knee, although other sites such as the shoulder, ankle, elbow, or wrist are not uncommon

- chronic fatigue

- meningoencephalitis, Symptoms vary from mild (memory loss, mood lability, irritability, or panic attacks) to severe (manic or psychotic episodes, paranoia, and obsessive/compulsive symptoms).

The patient described in this case had localized disease. Given that she was 11-years-old and had her adult teeth, her physician felt that he could safely prescribe doxycycline 100 mg BID for 14 days. He also recommended that she take over-the-counter acetaminophen or ibuprofen to treat the fever and myalgias. She responded quickly to the doxycycline.

Photos courtesy of Jeremy Golding, MD, and McGraw-Hill. The text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Corson T, Usatine, R. Lyme disease. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:933-939.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

|

|

| FIGURE 1 | FIGURE 2 |

The FP recognized the annular eruptions on her shoulders and legs as erythema migrans (EM). He was also cognizant of the fact that the girl lived in an endemic area for Lyme disease. Lyme disease is caused by an infection with Borrelia burgdorferi. This organism lives in the deer tick and its common hosts include field mice, white-tailed deer, and household pets. The ticks must feed on infested hosts in order to infect humans. Thirty percent of infected patients do not recall being bitten. Once a human is infected, disease progression is categorized into 3 stages:

1. Localized (days to weeks): erythema migrans and flu-like symptoms.

2. Disseminated (days to months):

- inflammatory arthritis

- cranial nerve palsy (usually a Bell’s palsy)

- atrioventricular blockade, which is present in only 1% of patients with Lyme disease. Syncope, lightheadedness, and dyspnea are classic symptoms consistent with atrioventricular dysfunction

- aseptic meningitis. Patients may present with complaints similar to bacterial meningitis (photophobia, nuchal rigidity, and headache)

- fatigue.

3. Persistent (>1 year):

- chronic arthritis generally occurs in the knee, although other sites such as the shoulder, ankle, elbow, or wrist are not uncommon

- chronic fatigue

- meningoencephalitis, Symptoms vary from mild (memory loss, mood lability, irritability, or panic attacks) to severe (manic or psychotic episodes, paranoia, and obsessive/compulsive symptoms).