User login

Lesions on elbow

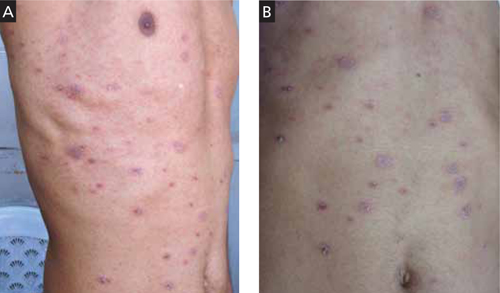

The family physician (FP) performed a shave biopsy, which revealed Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS). The patient subsequently tested positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and began treatment with antiretroviral combination therapy.

KS is the most common malignancy seen in acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients. KS is an angioproliferative disease, with abnormal proliferation of endothelial cells, myofibroblasts, and monocyte cells. Human herpes virus 8 produces a receptor that promotes endothelial cell proliferation. Lesions often begin as papules or patches and progress to plaques as proliferation continues.

Cutaneous lesions are usually multifocal, papular, and reddish-purple in color. Plaques or fungating lesions can be seen on the lower extremities, including the soles of the feet. Oral cavity lesions can be flat or nodular and are red to purple in color. Gastrointestinal lesions can be asymptomatic or cause abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, bleeding, or weight loss. Pulmonary lesions can cause shortness of breath or may appear as infiltrates, nodules, or pleural effusions on chest radiographs.

KS is not curable; treatments include antiretrovirals and chemotherapeutic agents to reduce disease burden and slow progression. Alitretinoin gel 0.1% can be applied to lesions 2 times a day, increasing to 3 to 4 times a day if tolerated, for 4 to 8 weeks. The response rate is 66%. Liposomal doxorubicin 20 mg/m2 every 3 weeks or liposomal daunorubicin 40 mg/m2 every 2 weeks has produced a 50% response rate. Intralesional vinblastine (70% response rate) or radiation therapy (80% response rate) are also effective for skin lesions.

The FP referred the patient to an oncologist who suggested the topical alitretinoin gel treatment, as described above. The KS lesions resolved within 6 weeks. Fortunately, the patient had no gastrointestinal or pulmonary involvement. Also, his HIV viral load dropped to undetectable levels with antiretroviral therapy.

Photo courtesy of Heather Goff, MD, and McGraw-Hill. Text for Photo Rounds Friday is courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H. Kaposi’s sarcoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:929-932.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

The family physician (FP) performed a shave biopsy, which revealed Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS). The patient subsequently tested positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and began treatment with antiretroviral combination therapy.

KS is the most common malignancy seen in acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients. KS is an angioproliferative disease, with abnormal proliferation of endothelial cells, myofibroblasts, and monocyte cells. Human herpes virus 8 produces a receptor that promotes endothelial cell proliferation. Lesions often begin as papules or patches and progress to plaques as proliferation continues.

Cutaneous lesions are usually multifocal, papular, and reddish-purple in color. Plaques or fungating lesions can be seen on the lower extremities, including the soles of the feet. Oral cavity lesions can be flat or nodular and are red to purple in color. Gastrointestinal lesions can be asymptomatic or cause abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, bleeding, or weight loss. Pulmonary lesions can cause shortness of breath or may appear as infiltrates, nodules, or pleural effusions on chest radiographs.

KS is not curable; treatments include antiretrovirals and chemotherapeutic agents to reduce disease burden and slow progression. Alitretinoin gel 0.1% can be applied to lesions 2 times a day, increasing to 3 to 4 times a day if tolerated, for 4 to 8 weeks. The response rate is 66%. Liposomal doxorubicin 20 mg/m2 every 3 weeks or liposomal daunorubicin 40 mg/m2 every 2 weeks has produced a 50% response rate. Intralesional vinblastine (70% response rate) or radiation therapy (80% response rate) are also effective for skin lesions.

The FP referred the patient to an oncologist who suggested the topical alitretinoin gel treatment, as described above. The KS lesions resolved within 6 weeks. Fortunately, the patient had no gastrointestinal or pulmonary involvement. Also, his HIV viral load dropped to undetectable levels with antiretroviral therapy.

Photo courtesy of Heather Goff, MD, and McGraw-Hill. Text for Photo Rounds Friday is courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H. Kaposi’s sarcoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:929-932.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

The family physician (FP) performed a shave biopsy, which revealed Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS). The patient subsequently tested positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and began treatment with antiretroviral combination therapy.

KS is the most common malignancy seen in acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients. KS is an angioproliferative disease, with abnormal proliferation of endothelial cells, myofibroblasts, and monocyte cells. Human herpes virus 8 produces a receptor that promotes endothelial cell proliferation. Lesions often begin as papules or patches and progress to plaques as proliferation continues.

Cutaneous lesions are usually multifocal, papular, and reddish-purple in color. Plaques or fungating lesions can be seen on the lower extremities, including the soles of the feet. Oral cavity lesions can be flat or nodular and are red to purple in color. Gastrointestinal lesions can be asymptomatic or cause abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, bleeding, or weight loss. Pulmonary lesions can cause shortness of breath or may appear as infiltrates, nodules, or pleural effusions on chest radiographs.

KS is not curable; treatments include antiretrovirals and chemotherapeutic agents to reduce disease burden and slow progression. Alitretinoin gel 0.1% can be applied to lesions 2 times a day, increasing to 3 to 4 times a day if tolerated, for 4 to 8 weeks. The response rate is 66%. Liposomal doxorubicin 20 mg/m2 every 3 weeks or liposomal daunorubicin 40 mg/m2 every 2 weeks has produced a 50% response rate. Intralesional vinblastine (70% response rate) or radiation therapy (80% response rate) are also effective for skin lesions.

The FP referred the patient to an oncologist who suggested the topical alitretinoin gel treatment, as described above. The KS lesions resolved within 6 weeks. Fortunately, the patient had no gastrointestinal or pulmonary involvement. Also, his HIV viral load dropped to undetectable levels with antiretroviral therapy.

Photo courtesy of Heather Goff, MD, and McGraw-Hill. Text for Photo Rounds Friday is courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H. Kaposi’s sarcoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:929-932.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

Hyperpigmentation and atrophy

A 35-year-old woman sought care at our clinic for a plaque on her upper left arm. She said that it had started 3 months earlier as a small indentation, but had recently became larger and hyperpigmented. The lesion was not pruritic or painful, and she had no associated weakness or systemic symptoms. The patient denied any insect bites, instrumentation, topical ointments, or trauma to the area.

Physical examination revealed a 3.5 × 2.5 cm area of hyperpigmentation on the posterior aspect of the left arm, overlying the musculotendinous junction of the lateral head of the triceps (FIGURE 1). The lesion had an irregular border and a central region approximately 1 cm in diameter associated with a nontender subcutaneous mass that felt tethered to the skin. There was significant thinning of the subcutaneous fat beneath the hyperpigmentation relative to the normal surrounding skin. The patient had normal triceps function and a normal distal neurovascular exam.

Concerned about malignancy, we ordered computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the left arm. Both demonstrated a nonspecific density in the subcutaneous tissue, and focal indentation and architectural distortion of the skin and subcutaneous tissue in the area in question. In addition, the MRI showed skin tethering extending to the superficial myofascial layer of the posterior triceps muscle and a small superficial blood vessel (FIGURE 2).

We referred the patient to Plastic Surgery for tissue diagnosis. A punch biopsy revealed dense dermal sclerosis that could be consistent with a morphea-like process. As malignancy could not be excluded, the patient was then referred to a dermatologist to determine the need for excision.

FIGURE 1

A 3.5 × 2.5 cm lesion on the left posterior arm

FIGURE 2

MRI reveals skin tethering to superficial myofascial layer

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Atrophy due to a steroid injection

During further discussion with the patient, she revealed that she had received a steroid injection 4 to 5 months before the lesion appeared. Although we felt reasonably certain that the steroid injection was the cause of the lesion, the patient had the lesion excised.

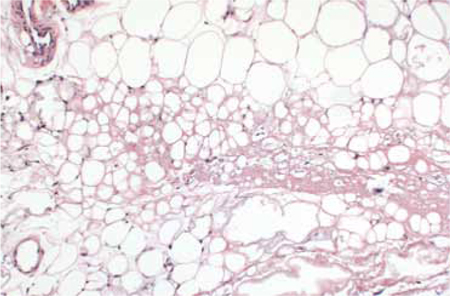

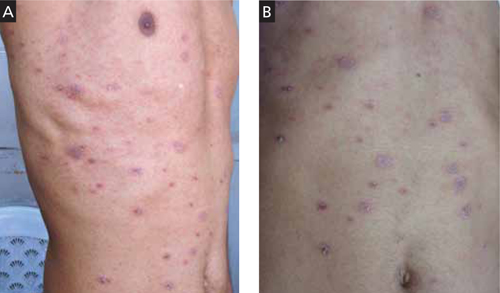

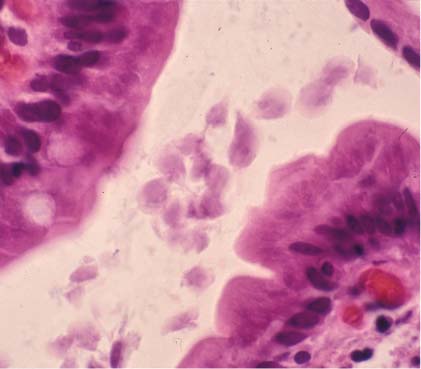

The most striking pathologic findings in the excised specimen were seen in the subcutaneous tissue; there was extensive fat necrosis, with abundant amorphous eosinophilic and amphophilic debris replacing, and interspersed between, adipocytes (FIGURE 3). Extensive lipomembranous changes were also seen. The constellation of pathologic findings was nonspecific.

FIGURE 3

Variation in adipocyte size

Low magnification of the excised specimen shows variation of adipocyte size, with some fat cells being replaced by amorphous eosinophilic and amphophilic material.

When treatment does harm

Steroid injections are commonly used to treat dermatologic and musculoskeletal conditions such as keloids, alopecia areata, neuromas, and inflamed bursas. However, these injections can have long-lasting dermatologic consequences such as altered pigmentation, dermal and fat atrophy, hypo- and hyperpigmentation, and telangiectasias.1-13 Localized lipodystrophy, the loss of subcutaneous fat in a localized area, can also be a result of steroid injection, as well as the injection of other drugs such as insulin or antibiotics.14

Morphea-like change, which we saw in our patient, is less common, but has also been described in the literature.1,2 Morphea presents with a single or several circumscribed indurated patches or plaques, usually with hypo- or hyperpigmentation.15

The timing of cutaneous changes due to steroid injection is variable. Case reports describe changes in pigmentation and atrophy beginning several weeks to several months after injection.9,10,12,13 This delay may occur because depot steroid preparations can remain in the skin for prolonged periods; one study demonstrated that small amounts persisted for more than a year after injection.2

Lesion with unclear etiology? Focus on the history

Because the cutaneous changes that steroids can induce are varied and nonspecific, it is important to carefully elicit any history of steroid injections when working up a patient for a cutaneous lesion of unclear etiology. Additional workup of neoplastic, infiltrative, vascular, and less commonly, infectious causes should be conducted if the etiology of such a lesion cannot be explained.

Although lesions from steroid injections are not usually evaluated with CT or MRI imaging, one study involving 2 volunteers suggested that pulsed ultrasound may be helpful in determining the long-term changes in skin thickness from steroid injection.16 Thus, it appears that radiological studies have little role in the diagnosis of steroid-induced skin changes, but may be used to raise or lower suspicion for other etiologies of cutaneous change when the diagnosis is unclear.

Healing comes in time, and sometimes, with saline

Cutaneous atrophy caused by steroid injections may resolve spontaneously within one to 2 years, or may persist.7,10,13,16,17 Treatment of persistent atrophy with normal saline infiltration has been used, and appears to be safe, tolerable, and relatively effective.17

Preventive steps to keep in mind

Attention to risk may reduce the likelihood and severity of cutaneous damage. Insoluble preparations should be used only for deep injections into joints, bursae, or muscles, and care should be taken not to track the steroid into the more superficial tissues.

More soluble preparations should be used for superficial structures.10,12 In addition, the lowest effective concentration of steroid preparation should be used, and it should not be mixed with vasoconstrictors like epinephrine.10 The anatomical location of the injection also plays a role in the extent and duration of change.10 For instance, injections into more superficial structures (eg, skin, tendons) could produce cutaneous changes that are more obvious than injections into deeper structures (eg, joints, bursae).10

Our patient

As noted earlier, our patient had the lesion excised. At follow-up one week later, she continued to progress well clinically.

CORRESPONDENCE Tia Kostas, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 75 Francis Street, Boston, MA 02115; [email protected]

1. Holt PJ, Marks R, Waddington E. ‘Pseudomorphoea’: a side effect of subcutaneous corticosteroid injection. Br J Dermatol. 1975;92:689-691.

2. Joshi R. Incidental finding of skin deposits of corticosteroids without associated granulomatous inflammation: report of three cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:44-46.

3. Reddy PD, Zelicof SB, Ruotolo C, et al. Interdigital neuroma. Local cutaneous changes after corticosteroid injection. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995;(317):185-187.

4. Stapczynski JS. Localized depigmentation after steroid injection of a ganglion cyst on the hand. Ann Emerg Med. 1991;20:807-809.

5. Okere K, Jones MC. A case of skin hypopigmentation secondary to a corticosteroid injection. South Med J. 2006;99:1393-1394.

6. Basadonna PT, Rucco V, Gasparini D, et al. Plantar fat pad atrophy after corticosteroid injection for an interdigital neuroma: a case report. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;78:283-285.

7. DiStefano V, Nixon JE. Steroid-induced skin changes following local injection. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1972;87:254-256.

8. Friedman SJ, Butler DF, Pittelkow MR. Perilesional linear atrophy and hypopigmentation after intralesional corticosteroid therapy. Report of two cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;19:537-541.

9. Gallardo MJ, Johnson DA. Cutaneous hypopigmentation following a posterior sub-tenon triamcinolone injection. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137:779-780.

10. Jacobs MB. Local subcutaneous atrophy after corticosteroid injection. Postgrad Med. 1986;80:159-160.

11. Louis DS, Hankin FM, Eckenrode JF. Cutaneous atrophy after corticosteroid injection. Am Fam Physician. 1986;33:183-186.

12. Lund IM, Donde R, Knudsen EA. Persistent local cutaneous atrophy following corticosteroid injection for tendinitis. Rheumatol Rehabil. 1979;18:91-93.

13. Schetman D, Hambrick GW, Jr, Wilson CE. Cutaneous changes following local injection of triamcinolone. Arch Dermatol. 1963;88:820-828.

14. Myers SA, Sheedy MP. Lipodystrophy. In: Wolf KG, Lowell A, Katz SI, et al (eds). Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc; 2003:586–590.

15. Falanga V, Killoran CE. Morphea. In: Wolf KG, Lowell A, Katz SI, et al (eds). Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc; 2003:543–546.

16. Gomez EC, Berman B, Miller DL. Ultrasonic assessment of cutaneous atrophy caused by intradermal corticosteroids. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1982;8:1071-1074.

17. Shumaker PR, Rao J, Goldman MP. Treatment of local, persistent cutaneous atrophy following corticosteroid injection with normal saline infiltration. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:1340-1343.

A 35-year-old woman sought care at our clinic for a plaque on her upper left arm. She said that it had started 3 months earlier as a small indentation, but had recently became larger and hyperpigmented. The lesion was not pruritic or painful, and she had no associated weakness or systemic symptoms. The patient denied any insect bites, instrumentation, topical ointments, or trauma to the area.

Physical examination revealed a 3.5 × 2.5 cm area of hyperpigmentation on the posterior aspect of the left arm, overlying the musculotendinous junction of the lateral head of the triceps (FIGURE 1). The lesion had an irregular border and a central region approximately 1 cm in diameter associated with a nontender subcutaneous mass that felt tethered to the skin. There was significant thinning of the subcutaneous fat beneath the hyperpigmentation relative to the normal surrounding skin. The patient had normal triceps function and a normal distal neurovascular exam.

Concerned about malignancy, we ordered computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the left arm. Both demonstrated a nonspecific density in the subcutaneous tissue, and focal indentation and architectural distortion of the skin and subcutaneous tissue in the area in question. In addition, the MRI showed skin tethering extending to the superficial myofascial layer of the posterior triceps muscle and a small superficial blood vessel (FIGURE 2).

We referred the patient to Plastic Surgery for tissue diagnosis. A punch biopsy revealed dense dermal sclerosis that could be consistent with a morphea-like process. As malignancy could not be excluded, the patient was then referred to a dermatologist to determine the need for excision.

FIGURE 1

A 3.5 × 2.5 cm lesion on the left posterior arm

FIGURE 2

MRI reveals skin tethering to superficial myofascial layer

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Atrophy due to a steroid injection

During further discussion with the patient, she revealed that she had received a steroid injection 4 to 5 months before the lesion appeared. Although we felt reasonably certain that the steroid injection was the cause of the lesion, the patient had the lesion excised.

The most striking pathologic findings in the excised specimen were seen in the subcutaneous tissue; there was extensive fat necrosis, with abundant amorphous eosinophilic and amphophilic debris replacing, and interspersed between, adipocytes (FIGURE 3). Extensive lipomembranous changes were also seen. The constellation of pathologic findings was nonspecific.

FIGURE 3

Variation in adipocyte size

Low magnification of the excised specimen shows variation of adipocyte size, with some fat cells being replaced by amorphous eosinophilic and amphophilic material.

When treatment does harm

Steroid injections are commonly used to treat dermatologic and musculoskeletal conditions such as keloids, alopecia areata, neuromas, and inflamed bursas. However, these injections can have long-lasting dermatologic consequences such as altered pigmentation, dermal and fat atrophy, hypo- and hyperpigmentation, and telangiectasias.1-13 Localized lipodystrophy, the loss of subcutaneous fat in a localized area, can also be a result of steroid injection, as well as the injection of other drugs such as insulin or antibiotics.14

Morphea-like change, which we saw in our patient, is less common, but has also been described in the literature.1,2 Morphea presents with a single or several circumscribed indurated patches or plaques, usually with hypo- or hyperpigmentation.15

The timing of cutaneous changes due to steroid injection is variable. Case reports describe changes in pigmentation and atrophy beginning several weeks to several months after injection.9,10,12,13 This delay may occur because depot steroid preparations can remain in the skin for prolonged periods; one study demonstrated that small amounts persisted for more than a year after injection.2

Lesion with unclear etiology? Focus on the history

Because the cutaneous changes that steroids can induce are varied and nonspecific, it is important to carefully elicit any history of steroid injections when working up a patient for a cutaneous lesion of unclear etiology. Additional workup of neoplastic, infiltrative, vascular, and less commonly, infectious causes should be conducted if the etiology of such a lesion cannot be explained.

Although lesions from steroid injections are not usually evaluated with CT or MRI imaging, one study involving 2 volunteers suggested that pulsed ultrasound may be helpful in determining the long-term changes in skin thickness from steroid injection.16 Thus, it appears that radiological studies have little role in the diagnosis of steroid-induced skin changes, but may be used to raise or lower suspicion for other etiologies of cutaneous change when the diagnosis is unclear.

Healing comes in time, and sometimes, with saline

Cutaneous atrophy caused by steroid injections may resolve spontaneously within one to 2 years, or may persist.7,10,13,16,17 Treatment of persistent atrophy with normal saline infiltration has been used, and appears to be safe, tolerable, and relatively effective.17

Preventive steps to keep in mind

Attention to risk may reduce the likelihood and severity of cutaneous damage. Insoluble preparations should be used only for deep injections into joints, bursae, or muscles, and care should be taken not to track the steroid into the more superficial tissues.

More soluble preparations should be used for superficial structures.10,12 In addition, the lowest effective concentration of steroid preparation should be used, and it should not be mixed with vasoconstrictors like epinephrine.10 The anatomical location of the injection also plays a role in the extent and duration of change.10 For instance, injections into more superficial structures (eg, skin, tendons) could produce cutaneous changes that are more obvious than injections into deeper structures (eg, joints, bursae).10

Our patient

As noted earlier, our patient had the lesion excised. At follow-up one week later, she continued to progress well clinically.

CORRESPONDENCE Tia Kostas, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 75 Francis Street, Boston, MA 02115; [email protected]

A 35-year-old woman sought care at our clinic for a plaque on her upper left arm. She said that it had started 3 months earlier as a small indentation, but had recently became larger and hyperpigmented. The lesion was not pruritic or painful, and she had no associated weakness or systemic symptoms. The patient denied any insect bites, instrumentation, topical ointments, or trauma to the area.

Physical examination revealed a 3.5 × 2.5 cm area of hyperpigmentation on the posterior aspect of the left arm, overlying the musculotendinous junction of the lateral head of the triceps (FIGURE 1). The lesion had an irregular border and a central region approximately 1 cm in diameter associated with a nontender subcutaneous mass that felt tethered to the skin. There was significant thinning of the subcutaneous fat beneath the hyperpigmentation relative to the normal surrounding skin. The patient had normal triceps function and a normal distal neurovascular exam.

Concerned about malignancy, we ordered computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the left arm. Both demonstrated a nonspecific density in the subcutaneous tissue, and focal indentation and architectural distortion of the skin and subcutaneous tissue in the area in question. In addition, the MRI showed skin tethering extending to the superficial myofascial layer of the posterior triceps muscle and a small superficial blood vessel (FIGURE 2).

We referred the patient to Plastic Surgery for tissue diagnosis. A punch biopsy revealed dense dermal sclerosis that could be consistent with a morphea-like process. As malignancy could not be excluded, the patient was then referred to a dermatologist to determine the need for excision.

FIGURE 1

A 3.5 × 2.5 cm lesion on the left posterior arm

FIGURE 2

MRI reveals skin tethering to superficial myofascial layer

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Atrophy due to a steroid injection

During further discussion with the patient, she revealed that she had received a steroid injection 4 to 5 months before the lesion appeared. Although we felt reasonably certain that the steroid injection was the cause of the lesion, the patient had the lesion excised.

The most striking pathologic findings in the excised specimen were seen in the subcutaneous tissue; there was extensive fat necrosis, with abundant amorphous eosinophilic and amphophilic debris replacing, and interspersed between, adipocytes (FIGURE 3). Extensive lipomembranous changes were also seen. The constellation of pathologic findings was nonspecific.

FIGURE 3

Variation in adipocyte size

Low magnification of the excised specimen shows variation of adipocyte size, with some fat cells being replaced by amorphous eosinophilic and amphophilic material.

When treatment does harm

Steroid injections are commonly used to treat dermatologic and musculoskeletal conditions such as keloids, alopecia areata, neuromas, and inflamed bursas. However, these injections can have long-lasting dermatologic consequences such as altered pigmentation, dermal and fat atrophy, hypo- and hyperpigmentation, and telangiectasias.1-13 Localized lipodystrophy, the loss of subcutaneous fat in a localized area, can also be a result of steroid injection, as well as the injection of other drugs such as insulin or antibiotics.14

Morphea-like change, which we saw in our patient, is less common, but has also been described in the literature.1,2 Morphea presents with a single or several circumscribed indurated patches or plaques, usually with hypo- or hyperpigmentation.15

The timing of cutaneous changes due to steroid injection is variable. Case reports describe changes in pigmentation and atrophy beginning several weeks to several months after injection.9,10,12,13 This delay may occur because depot steroid preparations can remain in the skin for prolonged periods; one study demonstrated that small amounts persisted for more than a year after injection.2

Lesion with unclear etiology? Focus on the history

Because the cutaneous changes that steroids can induce are varied and nonspecific, it is important to carefully elicit any history of steroid injections when working up a patient for a cutaneous lesion of unclear etiology. Additional workup of neoplastic, infiltrative, vascular, and less commonly, infectious causes should be conducted if the etiology of such a lesion cannot be explained.

Although lesions from steroid injections are not usually evaluated with CT or MRI imaging, one study involving 2 volunteers suggested that pulsed ultrasound may be helpful in determining the long-term changes in skin thickness from steroid injection.16 Thus, it appears that radiological studies have little role in the diagnosis of steroid-induced skin changes, but may be used to raise or lower suspicion for other etiologies of cutaneous change when the diagnosis is unclear.

Healing comes in time, and sometimes, with saline

Cutaneous atrophy caused by steroid injections may resolve spontaneously within one to 2 years, or may persist.7,10,13,16,17 Treatment of persistent atrophy with normal saline infiltration has been used, and appears to be safe, tolerable, and relatively effective.17

Preventive steps to keep in mind

Attention to risk may reduce the likelihood and severity of cutaneous damage. Insoluble preparations should be used only for deep injections into joints, bursae, or muscles, and care should be taken not to track the steroid into the more superficial tissues.

More soluble preparations should be used for superficial structures.10,12 In addition, the lowest effective concentration of steroid preparation should be used, and it should not be mixed with vasoconstrictors like epinephrine.10 The anatomical location of the injection also plays a role in the extent and duration of change.10 For instance, injections into more superficial structures (eg, skin, tendons) could produce cutaneous changes that are more obvious than injections into deeper structures (eg, joints, bursae).10

Our patient

As noted earlier, our patient had the lesion excised. At follow-up one week later, she continued to progress well clinically.

CORRESPONDENCE Tia Kostas, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 75 Francis Street, Boston, MA 02115; [email protected]

1. Holt PJ, Marks R, Waddington E. ‘Pseudomorphoea’: a side effect of subcutaneous corticosteroid injection. Br J Dermatol. 1975;92:689-691.

2. Joshi R. Incidental finding of skin deposits of corticosteroids without associated granulomatous inflammation: report of three cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:44-46.

3. Reddy PD, Zelicof SB, Ruotolo C, et al. Interdigital neuroma. Local cutaneous changes after corticosteroid injection. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995;(317):185-187.

4. Stapczynski JS. Localized depigmentation after steroid injection of a ganglion cyst on the hand. Ann Emerg Med. 1991;20:807-809.

5. Okere K, Jones MC. A case of skin hypopigmentation secondary to a corticosteroid injection. South Med J. 2006;99:1393-1394.

6. Basadonna PT, Rucco V, Gasparini D, et al. Plantar fat pad atrophy after corticosteroid injection for an interdigital neuroma: a case report. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;78:283-285.

7. DiStefano V, Nixon JE. Steroid-induced skin changes following local injection. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1972;87:254-256.

8. Friedman SJ, Butler DF, Pittelkow MR. Perilesional linear atrophy and hypopigmentation after intralesional corticosteroid therapy. Report of two cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;19:537-541.

9. Gallardo MJ, Johnson DA. Cutaneous hypopigmentation following a posterior sub-tenon triamcinolone injection. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137:779-780.

10. Jacobs MB. Local subcutaneous atrophy after corticosteroid injection. Postgrad Med. 1986;80:159-160.

11. Louis DS, Hankin FM, Eckenrode JF. Cutaneous atrophy after corticosteroid injection. Am Fam Physician. 1986;33:183-186.

12. Lund IM, Donde R, Knudsen EA. Persistent local cutaneous atrophy following corticosteroid injection for tendinitis. Rheumatol Rehabil. 1979;18:91-93.

13. Schetman D, Hambrick GW, Jr, Wilson CE. Cutaneous changes following local injection of triamcinolone. Arch Dermatol. 1963;88:820-828.

14. Myers SA, Sheedy MP. Lipodystrophy. In: Wolf KG, Lowell A, Katz SI, et al (eds). Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc; 2003:586–590.

15. Falanga V, Killoran CE. Morphea. In: Wolf KG, Lowell A, Katz SI, et al (eds). Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc; 2003:543–546.

16. Gomez EC, Berman B, Miller DL. Ultrasonic assessment of cutaneous atrophy caused by intradermal corticosteroids. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1982;8:1071-1074.

17. Shumaker PR, Rao J, Goldman MP. Treatment of local, persistent cutaneous atrophy following corticosteroid injection with normal saline infiltration. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:1340-1343.

1. Holt PJ, Marks R, Waddington E. ‘Pseudomorphoea’: a side effect of subcutaneous corticosteroid injection. Br J Dermatol. 1975;92:689-691.

2. Joshi R. Incidental finding of skin deposits of corticosteroids without associated granulomatous inflammation: report of three cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:44-46.

3. Reddy PD, Zelicof SB, Ruotolo C, et al. Interdigital neuroma. Local cutaneous changes after corticosteroid injection. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995;(317):185-187.

4. Stapczynski JS. Localized depigmentation after steroid injection of a ganglion cyst on the hand. Ann Emerg Med. 1991;20:807-809.

5. Okere K, Jones MC. A case of skin hypopigmentation secondary to a corticosteroid injection. South Med J. 2006;99:1393-1394.

6. Basadonna PT, Rucco V, Gasparini D, et al. Plantar fat pad atrophy after corticosteroid injection for an interdigital neuroma: a case report. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;78:283-285.

7. DiStefano V, Nixon JE. Steroid-induced skin changes following local injection. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1972;87:254-256.

8. Friedman SJ, Butler DF, Pittelkow MR. Perilesional linear atrophy and hypopigmentation after intralesional corticosteroid therapy. Report of two cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;19:537-541.

9. Gallardo MJ, Johnson DA. Cutaneous hypopigmentation following a posterior sub-tenon triamcinolone injection. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137:779-780.

10. Jacobs MB. Local subcutaneous atrophy after corticosteroid injection. Postgrad Med. 1986;80:159-160.

11. Louis DS, Hankin FM, Eckenrode JF. Cutaneous atrophy after corticosteroid injection. Am Fam Physician. 1986;33:183-186.

12. Lund IM, Donde R, Knudsen EA. Persistent local cutaneous atrophy following corticosteroid injection for tendinitis. Rheumatol Rehabil. 1979;18:91-93.

13. Schetman D, Hambrick GW, Jr, Wilson CE. Cutaneous changes following local injection of triamcinolone. Arch Dermatol. 1963;88:820-828.

14. Myers SA, Sheedy MP. Lipodystrophy. In: Wolf KG, Lowell A, Katz SI, et al (eds). Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc; 2003:586–590.

15. Falanga V, Killoran CE. Morphea. In: Wolf KG, Lowell A, Katz SI, et al (eds). Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc; 2003:543–546.

16. Gomez EC, Berman B, Miller DL. Ultrasonic assessment of cutaneous atrophy caused by intradermal corticosteroids. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1982;8:1071-1074.

17. Shumaker PR, Rao J, Goldman MP. Treatment of local, persistent cutaneous atrophy following corticosteroid injection with normal saline infiltration. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:1340-1343.

Sores on penis

The FP suspected that the patient had syphilis, herpes, or both. The FP performed a herpes culture and sent the patient for serologic testing for syphilis and HIV. The rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test came back positive at 1:16 and the confirmatory treponemal test was positive, as well. The herpes culture and HIV tests were negative. The final diagnosis was primary syphilis and the patient was treated with 2.4 million units of benzathine penicillin IM.

It was fortunate that in this case, the presence of multiple ulcers did not dissuade the clinician from considering syphilis in the differential diagnosis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Syphilis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:924-928.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

The FP suspected that the patient had syphilis, herpes, or both. The FP performed a herpes culture and sent the patient for serologic testing for syphilis and HIV. The rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test came back positive at 1:16 and the confirmatory treponemal test was positive, as well. The herpes culture and HIV tests were negative. The final diagnosis was primary syphilis and the patient was treated with 2.4 million units of benzathine penicillin IM.

It was fortunate that in this case, the presence of multiple ulcers did not dissuade the clinician from considering syphilis in the differential diagnosis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Syphilis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:924-928.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

The FP suspected that the patient had syphilis, herpes, or both. The FP performed a herpes culture and sent the patient for serologic testing for syphilis and HIV. The rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test came back positive at 1:16 and the confirmatory treponemal test was positive, as well. The herpes culture and HIV tests were negative. The final diagnosis was primary syphilis and the patient was treated with 2.4 million units of benzathine penicillin IM.

It was fortunate that in this case, the presence of multiple ulcers did not dissuade the clinician from considering syphilis in the differential diagnosis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Syphilis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:924-928.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

Ulcer on lip

|

|

| FIGURE 1 | FIGURE 2 |

The family physician (FP) recognized the nonpainful ulcer (FIGURE 1) and rash (FIGURE 2) as a combination of primary and secondary syphilis. Rapid plasma reagin (RPR) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) tests were drawn; the patient was treated immediately with IM benzathine penicillin.

The RPR came back as 1:128 and the ulcer was healed within 1 week. Her HIV test was negative and the physician recommended that she also have a Pap smear with screening for gonorrhea and chlamydia. The patient was told that she should inform her boyfriend of the diagnosis and encourage him to get evaluated and treated as soon as possible. The result was also reported to the Health Department.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) recommended treatment for primary, secondary, and early latent syphilis is benzathine penicillin G, 2.4 million units IM. For patients who have a penicillin allergy, doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 days is recommended.

Patients should be evaluated clinically and serologically at 6 and 12 months after therapy. Failure of nontreponemal test titers to decline 4-fold within 6 to 12 months of therapy may be indicative of treatment failure. Further evaluation should be performed, including a repeat HIV test. For further information on the management of syphilis, see the CDC’s Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2010 at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2010/genital-ulcers.htm#syphilis

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Syphilis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:924-928

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

|

|

| FIGURE 1 | FIGURE 2 |

The family physician (FP) recognized the nonpainful ulcer (FIGURE 1) and rash (FIGURE 2) as a combination of primary and secondary syphilis. Rapid plasma reagin (RPR) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) tests were drawn; the patient was treated immediately with IM benzathine penicillin.

The RPR came back as 1:128 and the ulcer was healed within 1 week. Her HIV test was negative and the physician recommended that she also have a Pap smear with screening for gonorrhea and chlamydia. The patient was told that she should inform her boyfriend of the diagnosis and encourage him to get evaluated and treated as soon as possible. The result was also reported to the Health Department.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) recommended treatment for primary, secondary, and early latent syphilis is benzathine penicillin G, 2.4 million units IM. For patients who have a penicillin allergy, doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 days is recommended.

Patients should be evaluated clinically and serologically at 6 and 12 months after therapy. Failure of nontreponemal test titers to decline 4-fold within 6 to 12 months of therapy may be indicative of treatment failure. Further evaluation should be performed, including a repeat HIV test. For further information on the management of syphilis, see the CDC’s Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2010 at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2010/genital-ulcers.htm#syphilis

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Syphilis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:924-928

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

|

|

| FIGURE 1 | FIGURE 2 |

The family physician (FP) recognized the nonpainful ulcer (FIGURE 1) and rash (FIGURE 2) as a combination of primary and secondary syphilis. Rapid plasma reagin (RPR) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) tests were drawn; the patient was treated immediately with IM benzathine penicillin.

The RPR came back as 1:128 and the ulcer was healed within 1 week. Her HIV test was negative and the physician recommended that she also have a Pap smear with screening for gonorrhea and chlamydia. The patient was told that she should inform her boyfriend of the diagnosis and encourage him to get evaluated and treated as soon as possible. The result was also reported to the Health Department.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) recommended treatment for primary, secondary, and early latent syphilis is benzathine penicillin G, 2.4 million units IM. For patients who have a penicillin allergy, doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 days is recommended.

Patients should be evaluated clinically and serologically at 6 and 12 months after therapy. Failure of nontreponemal test titers to decline 4-fold within 6 to 12 months of therapy may be indicative of treatment failure. Further evaluation should be performed, including a repeat HIV test. For further information on the management of syphilis, see the CDC’s Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2010 at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2010/genital-ulcers.htm#syphilis

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Syphilis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:924-928

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

Burning on urination

The FP told the patient that it was likely that he had nongonococcal urethritis caused by chlamydia. The urine test was sent for nucleic acid amplification testing to detect chlamydia and gonorrhea. (Note: The discharge is clearer and less purulent with chlamydia than it is with gonorrhea.)

The FP prescribed azithromycin 1 g orally for presumed chlamydia. As an alternative, the FP could have prescribed doxycycline 100 mg orally twice a day for 7 days. Other less commonly used alternate regimens include:

- erythromycin base 500 mg 4 times a day for 7 days

- erythromycin ethylsuccinate 800 mg 4 times a day for 7 days

- ofloxacin 300 mg orally twice a day for 7 days

- levofloxacin 500 mg orally once daily for 7 days.

The patient was also given a prescription for 1 g azithromycin to give to his girlfriend if the urine testing came back positive. When it did come back positive, the FP called the patient and asked him to discuss the situation with his girlfriend and to offer her the prescription.

The patient was counseled to make sure his girlfriend wasn’t allergic to azithromycin and to give her the option of going to her own physician, rather than just taking the prescription as is. This process is called expedited partner therapy. Legal status by state is available at http://www.cdc.gov/std/ept/legal/default.htm. Currently EPT is prohibited in 7 states.

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. Photograph courtesy of University of Washington STD/HIV Prevention Training Center. This case was adapted from: Chumley H. Gonococcal urethritis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:921-923.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

The FP told the patient that it was likely that he had nongonococcal urethritis caused by chlamydia. The urine test was sent for nucleic acid amplification testing to detect chlamydia and gonorrhea. (Note: The discharge is clearer and less purulent with chlamydia than it is with gonorrhea.)

The FP prescribed azithromycin 1 g orally for presumed chlamydia. As an alternative, the FP could have prescribed doxycycline 100 mg orally twice a day for 7 days. Other less commonly used alternate regimens include:

- erythromycin base 500 mg 4 times a day for 7 days

- erythromycin ethylsuccinate 800 mg 4 times a day for 7 days

- ofloxacin 300 mg orally twice a day for 7 days

- levofloxacin 500 mg orally once daily for 7 days.

The patient was also given a prescription for 1 g azithromycin to give to his girlfriend if the urine testing came back positive. When it did come back positive, the FP called the patient and asked him to discuss the situation with his girlfriend and to offer her the prescription.

The patient was counseled to make sure his girlfriend wasn’t allergic to azithromycin and to give her the option of going to her own physician, rather than just taking the prescription as is. This process is called expedited partner therapy. Legal status by state is available at http://www.cdc.gov/std/ept/legal/default.htm. Currently EPT is prohibited in 7 states.

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. Photograph courtesy of University of Washington STD/HIV Prevention Training Center. This case was adapted from: Chumley H. Gonococcal urethritis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:921-923.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

The FP told the patient that it was likely that he had nongonococcal urethritis caused by chlamydia. The urine test was sent for nucleic acid amplification testing to detect chlamydia and gonorrhea. (Note: The discharge is clearer and less purulent with chlamydia than it is with gonorrhea.)

The FP prescribed azithromycin 1 g orally for presumed chlamydia. As an alternative, the FP could have prescribed doxycycline 100 mg orally twice a day for 7 days. Other less commonly used alternate regimens include:

- erythromycin base 500 mg 4 times a day for 7 days

- erythromycin ethylsuccinate 800 mg 4 times a day for 7 days

- ofloxacin 300 mg orally twice a day for 7 days

- levofloxacin 500 mg orally once daily for 7 days.

The patient was also given a prescription for 1 g azithromycin to give to his girlfriend if the urine testing came back positive. When it did come back positive, the FP called the patient and asked him to discuss the situation with his girlfriend and to offer her the prescription.

The patient was counseled to make sure his girlfriend wasn’t allergic to azithromycin and to give her the option of going to her own physician, rather than just taking the prescription as is. This process is called expedited partner therapy. Legal status by state is available at http://www.cdc.gov/std/ept/legal/default.htm. Currently EPT is prohibited in 7 states.

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. Photograph courtesy of University of Washington STD/HIV Prevention Training Center. This case was adapted from: Chumley H. Gonococcal urethritis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:921-923.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

Penile discharge

Based on clinical appearance, the family physician (FP) diagnosed gonococcal urethritis in this patient; a urine specimen was sent for testing to confirm the gonorrhea and to test for chlamydia.

Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis are the most common infectious causes of urethritis. Other infectious agents include Mycoplasma genitalium, Ureaplasma urealyticum, Trichomonas vaginalis, herpes simplex virus 1 and 2, adenovirus, and enteric bacteria. Noninfectious causes include trauma, foreign bodies, granulomas or unusual tumors, allergic reactions, or voiding dysfunction.

A nucleic acid amplification test is used to screen asymptomatic at-risk men and symptomatic men. Urine is a better specimen than urethral swab and does not hurt.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations (August 2012) call for uncomplicated gonococcal urethritis to be treated with combination therapy using ceftriaxone 250 mg IM plus either azithromycin 1 g orally or doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily for 7 days. For patients with a severe allergy to cephalosporins, the CDC recommends a single 2-g dose of azithromycin orally. Avoid fluoroquinolones and cefixime, as drug resistance is high.

In this case, the clinical picture was so probable for gonorrhea that the FP initiated treatment with ceftriaxone 250 mg IM and 1 g oral azithromycin (which would also treat possible coexisting chlamydia). The patient was offered (and agreed to) testing for other sexually transmitted diseases. He was told to inform his partners of the diagnosis. He was also counseled about safe sex; drug rehabilitation was recommended.

On his one-week follow-up visit, his symptoms were gone and he had no further discharge. His gonorrhea nucleic acid amplification test was positive; his chlamydia, rapid plasma reagin, and human immunodeficiency virus tests were negative. His FP reported the case to the Health Department for contact tracing.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H. Gonococcal urethritis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:921-923.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

Based on clinical appearance, the family physician (FP) diagnosed gonococcal urethritis in this patient; a urine specimen was sent for testing to confirm the gonorrhea and to test for chlamydia.

Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis are the most common infectious causes of urethritis. Other infectious agents include Mycoplasma genitalium, Ureaplasma urealyticum, Trichomonas vaginalis, herpes simplex virus 1 and 2, adenovirus, and enteric bacteria. Noninfectious causes include trauma, foreign bodies, granulomas or unusual tumors, allergic reactions, or voiding dysfunction.

A nucleic acid amplification test is used to screen asymptomatic at-risk men and symptomatic men. Urine is a better specimen than urethral swab and does not hurt.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations (August 2012) call for uncomplicated gonococcal urethritis to be treated with combination therapy using ceftriaxone 250 mg IM plus either azithromycin 1 g orally or doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily for 7 days. For patients with a severe allergy to cephalosporins, the CDC recommends a single 2-g dose of azithromycin orally. Avoid fluoroquinolones and cefixime, as drug resistance is high.

In this case, the clinical picture was so probable for gonorrhea that the FP initiated treatment with ceftriaxone 250 mg IM and 1 g oral azithromycin (which would also treat possible coexisting chlamydia). The patient was offered (and agreed to) testing for other sexually transmitted diseases. He was told to inform his partners of the diagnosis. He was also counseled about safe sex; drug rehabilitation was recommended.

On his one-week follow-up visit, his symptoms were gone and he had no further discharge. His gonorrhea nucleic acid amplification test was positive; his chlamydia, rapid plasma reagin, and human immunodeficiency virus tests were negative. His FP reported the case to the Health Department for contact tracing.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H. Gonococcal urethritis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:921-923.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

Based on clinical appearance, the family physician (FP) diagnosed gonococcal urethritis in this patient; a urine specimen was sent for testing to confirm the gonorrhea and to test for chlamydia.

Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis are the most common infectious causes of urethritis. Other infectious agents include Mycoplasma genitalium, Ureaplasma urealyticum, Trichomonas vaginalis, herpes simplex virus 1 and 2, adenovirus, and enteric bacteria. Noninfectious causes include trauma, foreign bodies, granulomas or unusual tumors, allergic reactions, or voiding dysfunction.

A nucleic acid amplification test is used to screen asymptomatic at-risk men and symptomatic men. Urine is a better specimen than urethral swab and does not hurt.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations (August 2012) call for uncomplicated gonococcal urethritis to be treated with combination therapy using ceftriaxone 250 mg IM plus either azithromycin 1 g orally or doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily for 7 days. For patients with a severe allergy to cephalosporins, the CDC recommends a single 2-g dose of azithromycin orally. Avoid fluoroquinolones and cefixime, as drug resistance is high.

In this case, the clinical picture was so probable for gonorrhea that the FP initiated treatment with ceftriaxone 250 mg IM and 1 g oral azithromycin (which would also treat possible coexisting chlamydia). The patient was offered (and agreed to) testing for other sexually transmitted diseases. He was told to inform his partners of the diagnosis. He was also counseled about safe sex; drug rehabilitation was recommended.

On his one-week follow-up visit, his symptoms were gone and he had no further discharge. His gonorrhea nucleic acid amplification test was positive; his chlamydia, rapid plasma reagin, and human immunodeficiency virus tests were negative. His FP reported the case to the Health Department for contact tracing.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chumley H. Gonococcal urethritis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:921-923.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

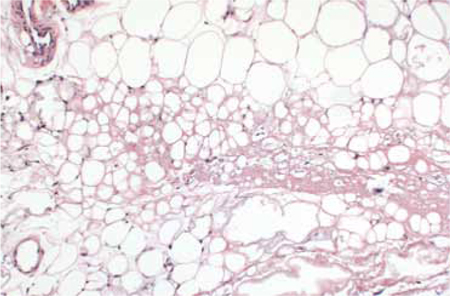

Pruritic rash

The patient’s punch biopsy showed an unremarkable epidermis but a superficial perivascular infiltrate (predominantly plasma cells). However, further investigation prompted the physician to suspect syphilis.(The patient had revealed a history of unprotected sex with multiple women.)

A subsequent rapid plasma reagin (RPR) was elevated with a titer of 1:256. Specific treponemal antibody tests confirmed the diagnosis of syphilis. The patient’s human immunodeficiency virus test was negative.

Syphilis, a systemic disease with varied dermatological findings, has been described as "the great imitator." Although it is on the list of differential diagnoses for multiple conditions, it is rarely the culprit—especially given how uncommon it has become in 20th century medicine. However, beginning in 2002, its incidence started to rise, reaching 4.6/100,000 in 2009.

Treatment for syphilis depends upon the stage of infection, which can range from the primary stage (10-90 days following exposure) to the late latent (>1 year of no symptoms) and tertiary stages (months to years after infection).

Given the nebulous history of the patient’s exposure, the physician treated the patient as having late latent syphilis and administered 2.4 million units benzathine penicillin G IM weekly for 3 weeks. After this treatment course, the pruritic lesions resolved and the patient’s RPR titer dropped to 1:8 in 3 months.

Adapted from: Mattei PL, Johnson RP, Beachkofsky TM, et al. Photo Rounds: Pruritic rash on trunk. J Fam Pract. 2011;60:539-542.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

The patient’s punch biopsy showed an unremarkable epidermis but a superficial perivascular infiltrate (predominantly plasma cells). However, further investigation prompted the physician to suspect syphilis.(The patient had revealed a history of unprotected sex with multiple women.)

A subsequent rapid plasma reagin (RPR) was elevated with a titer of 1:256. Specific treponemal antibody tests confirmed the diagnosis of syphilis. The patient’s human immunodeficiency virus test was negative.

Syphilis, a systemic disease with varied dermatological findings, has been described as "the great imitator." Although it is on the list of differential diagnoses for multiple conditions, it is rarely the culprit—especially given how uncommon it has become in 20th century medicine. However, beginning in 2002, its incidence started to rise, reaching 4.6/100,000 in 2009.

Treatment for syphilis depends upon the stage of infection, which can range from the primary stage (10-90 days following exposure) to the late latent (>1 year of no symptoms) and tertiary stages (months to years after infection).

Given the nebulous history of the patient’s exposure, the physician treated the patient as having late latent syphilis and administered 2.4 million units benzathine penicillin G IM weekly for 3 weeks. After this treatment course, the pruritic lesions resolved and the patient’s RPR titer dropped to 1:8 in 3 months.

Adapted from: Mattei PL, Johnson RP, Beachkofsky TM, et al. Photo Rounds: Pruritic rash on trunk. J Fam Pract. 2011;60:539-542.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

The patient’s punch biopsy showed an unremarkable epidermis but a superficial perivascular infiltrate (predominantly plasma cells). However, further investigation prompted the physician to suspect syphilis.(The patient had revealed a history of unprotected sex with multiple women.)

A subsequent rapid plasma reagin (RPR) was elevated with a titer of 1:256. Specific treponemal antibody tests confirmed the diagnosis of syphilis. The patient’s human immunodeficiency virus test was negative.

Syphilis, a systemic disease with varied dermatological findings, has been described as "the great imitator." Although it is on the list of differential diagnoses for multiple conditions, it is rarely the culprit—especially given how uncommon it has become in 20th century medicine. However, beginning in 2002, its incidence started to rise, reaching 4.6/100,000 in 2009.

Treatment for syphilis depends upon the stage of infection, which can range from the primary stage (10-90 days following exposure) to the late latent (>1 year of no symptoms) and tertiary stages (months to years after infection).

Given the nebulous history of the patient’s exposure, the physician treated the patient as having late latent syphilis and administered 2.4 million units benzathine penicillin G IM weekly for 3 weeks. After this treatment course, the pruritic lesions resolved and the patient’s RPR titer dropped to 1:8 in 3 months.

Adapted from: Mattei PL, Johnson RP, Beachkofsky TM, et al. Photo Rounds: Pruritic rash on trunk. J Fam Pract. 2011;60:539-542.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

Sudden onset of generalized scaly eruptions

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

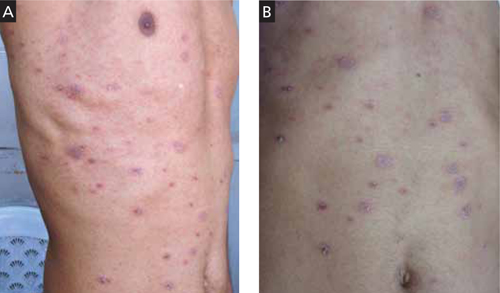

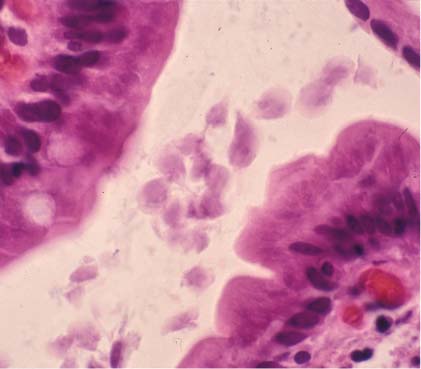

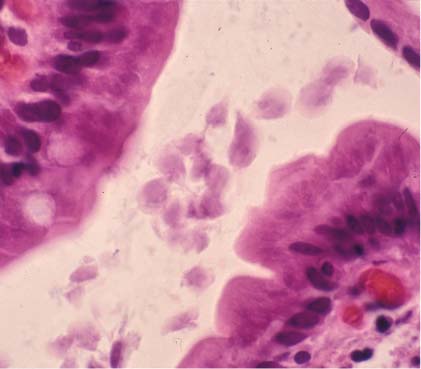

A 35-YEAR-OLD MAN came to our clinic for treatment of a slightly pruritic rash that had begun as a singular, annular erythematous plaque at the sixth intercostal space. The initial plaque erupted around the time he’d had a cold, with fever.

The present rash involved several similar, but smaller, eruptions on the anterior trunk and flank region (FIGURE 1A). Each lesion was surrounded by erythema and collarette scaling. The pattern of the secondary lesions ran parallel to the lines of cleavage. When looking at the patient head on, the pattern resembled a Christmas tree (FIGURE 1B).

The posterior trunk showed similar, but fewer, eruptions. The patient’s palms, soles, and mucous membranes were spared.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

FIGURE 1

Scaly plaques and papules

This 35-year-old patient had plaques and papules with collarette scales that followed the lines of cleavage (A) and formed a Christmas tree pattern (B).

Diagnosis: Pityriasis rosea

This patient was given a diagnosis of pityriasis rosea based on the clinical presentation.

Pityriasis rosea is a common erythematous and scaly disease that typically starts as a “herald patch” and later spreads as generalized eruptions on the trunk and extremities (secondary eruptions). The herald patch is a large lesion with an oval or round shape. Secondary lesions always occupy lines of cleavage (Langer’s lines), giving the eruptions a characteristic Christmas tree appearance. Some patients may exhibit significant pruritus. Both the herald patch and secondary eruptions show collarette scales, a hallmark of pityriasis rosea.1-3

A viral cause

The etiology of pityriasis rosea is uncertain and is most likely viral, possibly caused by human herpesvirus (HHV-6, -7, or -8).2,3 However, other viruses may also play a role. Also, the incidence of pityriasis rosea rises during the cold weather months.4,5

Immune dysregulation? Pityriasis rosea may be a presenting feature of immune dysregulation in patients with HIV infection or systemic malignancy. It may also occur with increasing frequency in those receiving chemotherapy or immunosuppressive drugs, pregnant women, and patients with diabetes.2,3

Resolves on its own. Pityriasis rosea is generally self-limiting—without any systemic complications—and resolves within 2 to 8 weeks of the appearance of the initial lesion.

Differential includes dermatophytosis and psoriasis

Pityriasis rosea must be differentiated from dermatophytosis, secondary syphilis, psoriasis, pityriasis lichenoides chronica, erythema annulare centrifugum, and pityriasis rosea-like drug eruptions.1-3,6

Dermatophytosis presents as an annular lesion with central clearing and a peripheral papulovesicular border. Patients will complain that the lesions are itchy. Skin scrapings for potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation reveal fungus under light microscope. (Lab tests do not aid in the diagnosis of pityriasis rosea.)

Secondary syphilis should be suspected in patients with a history of genital ulcers. Patients will have generalized lymphadenopathy and a dusky erythematous papulosquamous rash that involves the palms, soles, and mucosa. A venereal disease research laboratory test will be positive.

Psoriasis involves scaly plaques, typically on the knees, elbows, and scalp. The scales are silvery white and leave minute bleeding points on gentle scraping (Auspitz’s sign). Unlike pityriasis rosea, nail changes are often seen in psoriasis. These changes include pitting on the nail plate, onycholysis, oil drop sign, and subungual hyperkeratosis.

Pityriasis lichenoides chronica may mimic pityriasis rosea in distribution, but there are no collarette scales. Also, pityriasis lichenoides chronica does not self-resolve; it requires treatment.

Erythema annulare centrifugum is usually a single large erythematous plaque that slowly expands. There is often a history of a tick bite, and no Christmas tree distribution.

Provide symptomatic Tx

Symptomatic treatment of pityriasis rosea is generally adequate, and includes topical emollients, such as white petrolatum or mid-potency steroid creams and antihistamines for pruritus6 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A).

Erythromycin. In one study, erythromycin 250 mg QID for 2 weeks hastened the resolution of pityriasis rosea6 (SOR: B). It was suggested that the anti-inflammatory properties and immune modulation of the drug, rather than its antibiotic effect, may have aided the clinical resolution. However, such efficacy was not substantiated in subsequent trials with erythromycin or another macrolide, azithromycin.7-10

High-dose acyclovir. Acyclovir 800 mg 5 times a day has been shown to reduce disease severity and duration in some patients with pityriasis rosea.11 However, it is not recommended as first-line therapy2 (SOR: C).

Systemic steroids should be avoided in pityriasis rosea, as they may worsen the disease.6

Is the patient of school age? If so, the evidence suggests that he or she should not be kept out of school.6

My patient

I treated this patient with a topical mid-potency steroid (betamethasone dipropionate) twice daily on the affected areas and an oral antihistamine once daily for 10 days. The patient’s symptoms and skin lesions resolved.

CORRESPONDENCE Vijay Zawar, MD, DNB, DVD, FAAD, Skin Diseases Center, 21 Shreeram Sankul, Opp. Hotel Panchavati, Vakilwadi Nashik-422001, Maharashtra, India; [email protected]

1. Drago F, Broccolo F, Rebora A. Pityriasis rosea: an update with a critical appraisal of its possible herpesviral etiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:303-318.

2. Chuh A, Lee A, Zawar V, et al. Pityriasis rosea—an update. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:311-315.

3. González LM, Allen R, Janniger CK, et al. Pityriasis rosea: an important papulosquamous disorder. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:757-764.

4. Zawar V, Jerajani H, Pol R. Current trends in pityriasis rosea. Expert Rev Dermatol. 2010;5:325-333.

5. Sharma L, Shrivastava K. Clinico-epidemiological study of pityriasis rosea. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:647-649.

6. Chuh AA, Dofitas BL, Comisel GG, et al. Interventions for pityriasis rosea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):CD005068.-

7. Sharma PK, Yadav TP, Gautam RK, et al. Erythromycin in pityriasis rosea: a double-blind, placebo controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:241-244.

8. Rasi A, Tajziehchi L, Savabi-Nasab S. Oral erythromycin is ineffective in the treatment of pityriasis rosea. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:35-38.

9. Bukhari IA. Oral erythromycin is ineffective in the treatment of pityriasis rosea. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:625.-

10. Amer A, Fischer H. Azithromycin does not cure pityriasis rosea. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1702-1705.

11. Drago F, Vecchio F, Rebora A. Use of high-dose acyclovir in pityriasis rosea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:82-85.

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 35-YEAR-OLD MAN came to our clinic for treatment of a slightly pruritic rash that had begun as a singular, annular erythematous plaque at the sixth intercostal space. The initial plaque erupted around the time he’d had a cold, with fever.

The present rash involved several similar, but smaller, eruptions on the anterior trunk and flank region (FIGURE 1A). Each lesion was surrounded by erythema and collarette scaling. The pattern of the secondary lesions ran parallel to the lines of cleavage. When looking at the patient head on, the pattern resembled a Christmas tree (FIGURE 1B).

The posterior trunk showed similar, but fewer, eruptions. The patient’s palms, soles, and mucous membranes were spared.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

FIGURE 1

Scaly plaques and papules

This 35-year-old patient had plaques and papules with collarette scales that followed the lines of cleavage (A) and formed a Christmas tree pattern (B).

Diagnosis: Pityriasis rosea

This patient was given a diagnosis of pityriasis rosea based on the clinical presentation.

Pityriasis rosea is a common erythematous and scaly disease that typically starts as a “herald patch” and later spreads as generalized eruptions on the trunk and extremities (secondary eruptions). The herald patch is a large lesion with an oval or round shape. Secondary lesions always occupy lines of cleavage (Langer’s lines), giving the eruptions a characteristic Christmas tree appearance. Some patients may exhibit significant pruritus. Both the herald patch and secondary eruptions show collarette scales, a hallmark of pityriasis rosea.1-3

A viral cause

The etiology of pityriasis rosea is uncertain and is most likely viral, possibly caused by human herpesvirus (HHV-6, -7, or -8).2,3 However, other viruses may also play a role. Also, the incidence of pityriasis rosea rises during the cold weather months.4,5

Immune dysregulation? Pityriasis rosea may be a presenting feature of immune dysregulation in patients with HIV infection or systemic malignancy. It may also occur with increasing frequency in those receiving chemotherapy or immunosuppressive drugs, pregnant women, and patients with diabetes.2,3

Resolves on its own. Pityriasis rosea is generally self-limiting—without any systemic complications—and resolves within 2 to 8 weeks of the appearance of the initial lesion.

Differential includes dermatophytosis and psoriasis

Pityriasis rosea must be differentiated from dermatophytosis, secondary syphilis, psoriasis, pityriasis lichenoides chronica, erythema annulare centrifugum, and pityriasis rosea-like drug eruptions.1-3,6

Dermatophytosis presents as an annular lesion with central clearing and a peripheral papulovesicular border. Patients will complain that the lesions are itchy. Skin scrapings for potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation reveal fungus under light microscope. (Lab tests do not aid in the diagnosis of pityriasis rosea.)

Secondary syphilis should be suspected in patients with a history of genital ulcers. Patients will have generalized lymphadenopathy and a dusky erythematous papulosquamous rash that involves the palms, soles, and mucosa. A venereal disease research laboratory test will be positive.

Psoriasis involves scaly plaques, typically on the knees, elbows, and scalp. The scales are silvery white and leave minute bleeding points on gentle scraping (Auspitz’s sign). Unlike pityriasis rosea, nail changes are often seen in psoriasis. These changes include pitting on the nail plate, onycholysis, oil drop sign, and subungual hyperkeratosis.

Pityriasis lichenoides chronica may mimic pityriasis rosea in distribution, but there are no collarette scales. Also, pityriasis lichenoides chronica does not self-resolve; it requires treatment.

Erythema annulare centrifugum is usually a single large erythematous plaque that slowly expands. There is often a history of a tick bite, and no Christmas tree distribution.

Provide symptomatic Tx

Symptomatic treatment of pityriasis rosea is generally adequate, and includes topical emollients, such as white petrolatum or mid-potency steroid creams and antihistamines for pruritus6 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A).

Erythromycin. In one study, erythromycin 250 mg QID for 2 weeks hastened the resolution of pityriasis rosea6 (SOR: B). It was suggested that the anti-inflammatory properties and immune modulation of the drug, rather than its antibiotic effect, may have aided the clinical resolution. However, such efficacy was not substantiated in subsequent trials with erythromycin or another macrolide, azithromycin.7-10

High-dose acyclovir. Acyclovir 800 mg 5 times a day has been shown to reduce disease severity and duration in some patients with pityriasis rosea.11 However, it is not recommended as first-line therapy2 (SOR: C).

Systemic steroids should be avoided in pityriasis rosea, as they may worsen the disease.6

Is the patient of school age? If so, the evidence suggests that he or she should not be kept out of school.6

My patient

I treated this patient with a topical mid-potency steroid (betamethasone dipropionate) twice daily on the affected areas and an oral antihistamine once daily for 10 days. The patient’s symptoms and skin lesions resolved.

CORRESPONDENCE Vijay Zawar, MD, DNB, DVD, FAAD, Skin Diseases Center, 21 Shreeram Sankul, Opp. Hotel Panchavati, Vakilwadi Nashik-422001, Maharashtra, India; [email protected]

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 35-YEAR-OLD MAN came to our clinic for treatment of a slightly pruritic rash that had begun as a singular, annular erythematous plaque at the sixth intercostal space. The initial plaque erupted around the time he’d had a cold, with fever.

The present rash involved several similar, but smaller, eruptions on the anterior trunk and flank region (FIGURE 1A). Each lesion was surrounded by erythema and collarette scaling. The pattern of the secondary lesions ran parallel to the lines of cleavage. When looking at the patient head on, the pattern resembled a Christmas tree (FIGURE 1B).

The posterior trunk showed similar, but fewer, eruptions. The patient’s palms, soles, and mucous membranes were spared.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

FIGURE 1

Scaly plaques and papules

This 35-year-old patient had plaques and papules with collarette scales that followed the lines of cleavage (A) and formed a Christmas tree pattern (B).

Diagnosis: Pityriasis rosea

This patient was given a diagnosis of pityriasis rosea based on the clinical presentation.

Pityriasis rosea is a common erythematous and scaly disease that typically starts as a “herald patch” and later spreads as generalized eruptions on the trunk and extremities (secondary eruptions). The herald patch is a large lesion with an oval or round shape. Secondary lesions always occupy lines of cleavage (Langer’s lines), giving the eruptions a characteristic Christmas tree appearance. Some patients may exhibit significant pruritus. Both the herald patch and secondary eruptions show collarette scales, a hallmark of pityriasis rosea.1-3

A viral cause

The etiology of pityriasis rosea is uncertain and is most likely viral, possibly caused by human herpesvirus (HHV-6, -7, or -8).2,3 However, other viruses may also play a role. Also, the incidence of pityriasis rosea rises during the cold weather months.4,5