User login

Swelling of big toe

|

|

|

| FIGURE 1 | FIGURE 2 | FIGURE 3 |

The family physician (FP) easily diagnosed a bunion deformity (FIGURE 1); an x-ray showed medial angulation of the first metatarsal and lateral deviation of the hallux (FIGURE 2).

Commonly associated signs that accompany a bunion include: hypermobility, flatfoot deformity, second MTP joint pain, pain under the second metatarsal head, overlapped second digit, decreased ankle dorsiflexion, concurrent gout, decreased first MTP joint range of motion, sesamoiditis, hyperkeratosis, and hammertoe deformity. A unilateral bunion deformity is often a result of limb length discrepancy.

Conservative treatment measures include:

- change in shoes

- placing a toe spacer in the first interdigital space to straighten the hallux and decreases the irritation caused by rubbing of the first and second digits

- padding to limit shearing force from shoes

- water-soluble cortisone injection into the first MTP joint for patients who complain of joint pain secondary to early-stage osteoarthritis

- custom-made orthotics to help slow the progression of the deformity caused by biomechanical factors

- resting, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and ice to help an inflamed joint and/or shoe irritation

- physical therapy to help improve joint range of motion, reduce edema, or decrease nerve pain.

In this case, the patient required surgical correction. First metatarsal–cuneiform joint fusion was chosen to correct the medial angulation; dorsal elevation of the first metatarsal and lateral soft tissue release at the first MTP joint was done to correct the lateral deviation of the hallux. The medial aspect of the first metatarsal head was also resected (FIGURE 3).

The patient was placed in a short-leg cast for 6 weeks and slowly progressed to a regular shoe over the next month. The patient was encouraged to use the custom-made orthotics for her flatfoot to prevent a recurrence of the bunion.

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. Images courtesy of Naohiro Shibuya, DPM. This case was adapted from: Shibuya N, Fontaine J. Bunion deformity. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:896-899.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

|

|

|

| FIGURE 1 | FIGURE 2 | FIGURE 3 |

The family physician (FP) easily diagnosed a bunion deformity (FIGURE 1); an x-ray showed medial angulation of the first metatarsal and lateral deviation of the hallux (FIGURE 2).

Commonly associated signs that accompany a bunion include: hypermobility, flatfoot deformity, second MTP joint pain, pain under the second metatarsal head, overlapped second digit, decreased ankle dorsiflexion, concurrent gout, decreased first MTP joint range of motion, sesamoiditis, hyperkeratosis, and hammertoe deformity. A unilateral bunion deformity is often a result of limb length discrepancy.

Conservative treatment measures include:

- change in shoes

- placing a toe spacer in the first interdigital space to straighten the hallux and decreases the irritation caused by rubbing of the first and second digits

- padding to limit shearing force from shoes

- water-soluble cortisone injection into the first MTP joint for patients who complain of joint pain secondary to early-stage osteoarthritis

- custom-made orthotics to help slow the progression of the deformity caused by biomechanical factors

- resting, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and ice to help an inflamed joint and/or shoe irritation

- physical therapy to help improve joint range of motion, reduce edema, or decrease nerve pain.

In this case, the patient required surgical correction. First metatarsal–cuneiform joint fusion was chosen to correct the medial angulation; dorsal elevation of the first metatarsal and lateral soft tissue release at the first MTP joint was done to correct the lateral deviation of the hallux. The medial aspect of the first metatarsal head was also resected (FIGURE 3).

The patient was placed in a short-leg cast for 6 weeks and slowly progressed to a regular shoe over the next month. The patient was encouraged to use the custom-made orthotics for her flatfoot to prevent a recurrence of the bunion.

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. Images courtesy of Naohiro Shibuya, DPM. This case was adapted from: Shibuya N, Fontaine J. Bunion deformity. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:896-899.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

|

|

|

| FIGURE 1 | FIGURE 2 | FIGURE 3 |

The family physician (FP) easily diagnosed a bunion deformity (FIGURE 1); an x-ray showed medial angulation of the first metatarsal and lateral deviation of the hallux (FIGURE 2).

Commonly associated signs that accompany a bunion include: hypermobility, flatfoot deformity, second MTP joint pain, pain under the second metatarsal head, overlapped second digit, decreased ankle dorsiflexion, concurrent gout, decreased first MTP joint range of motion, sesamoiditis, hyperkeratosis, and hammertoe deformity. A unilateral bunion deformity is often a result of limb length discrepancy.

Conservative treatment measures include:

- change in shoes

- placing a toe spacer in the first interdigital space to straighten the hallux and decreases the irritation caused by rubbing of the first and second digits

- padding to limit shearing force from shoes

- water-soluble cortisone injection into the first MTP joint for patients who complain of joint pain secondary to early-stage osteoarthritis

- custom-made orthotics to help slow the progression of the deformity caused by biomechanical factors

- resting, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and ice to help an inflamed joint and/or shoe irritation

- physical therapy to help improve joint range of motion, reduce edema, or decrease nerve pain.

In this case, the patient required surgical correction. First metatarsal–cuneiform joint fusion was chosen to correct the medial angulation; dorsal elevation of the first metatarsal and lateral soft tissue release at the first MTP joint was done to correct the lateral deviation of the hallux. The medial aspect of the first metatarsal head was also resected (FIGURE 3).

The patient was placed in a short-leg cast for 6 weeks and slowly progressed to a regular shoe over the next month. The patient was encouraged to use the custom-made orthotics for her flatfoot to prevent a recurrence of the bunion.

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. Images courtesy of Naohiro Shibuya, DPM. This case was adapted from: Shibuya N, Fontaine J. Bunion deformity. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:896-899.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

Obstipation unresponsive to usual therapeutic maneuvers

A 64-year-old woman came into our emergency department (ED) complaining of constipation and worsening rectal pain. In an attempt to promote her overall health, the patient had recently begun experimenting with healthy alternatives to her regular diet. Three days before her visit, she had ceased having stools and was experiencing intermittent abdominal cramping. She self-administered 2 bisacodyl suppositories, 2 sodium biphosphate enemas, one 10-ounce bottle of magnesium citrate, and 15 senna-containing laxative tablets without improvement.

She sought care at an urgent care clinic where she received 2 additional enemas and a trial of manual disimpaction—without results. She was sent home to rest and asked to return the next morning for another trial of disimpaction. When the patient’s efforts to manually disimpact herself at home were unsuccessful, she contacted her primary care physician, who arranged a house call. When his own protracted disimpaction procedure was unsuccessful, he referred her to our ED.

On presentation, the patient had lower abdominal and rectal discomfort. Her vital signs were normal except for a temperature of 38.8° C. Her abdomen was soft and nontender. Inspection of her perianal area revealed erythema and excoriations. On digital rectal exam (which was poorly tolerated because of pain), we noted a moderate amount of soft, clay-like feces in the rectal vault, with overflow liquid stool expulsion.

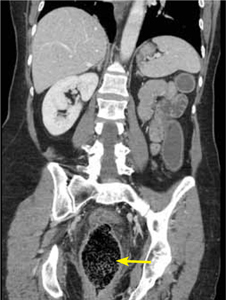

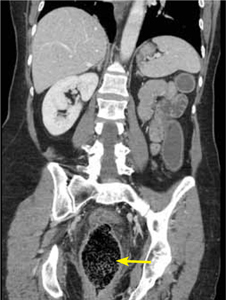

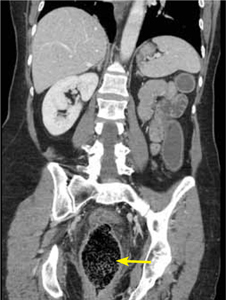

Computed tomography (CT) imaging of the abdomen was obtained to rule out rectal injury or colonic perforation (FIGURE 1).

FIGURE 1

CT scan reveals a speckled intraluminal mass

The patient had a markedly distended rectum and distal sigmoid colon caused by an intraluminal mass. Also present: circumferential wall thickening, perirectal edema without extraluminal gas, and generalized proximal colonic wall edema without a drainable collection.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Fecal impaction caused by a proctophytobezoar

CT imaging revealed a proctophytobezoar. On follow-up questioning, the patient recalled consuming approximately 10 ounces of cooked quinoa, a nutritious, gluten-free, high-protein seed, just prior to the onset of her constipation.

Constipation disproportionately affects the elderly and the young.1 Fecal impaction is a sequelae of constipation. Most commonly defined as hard, compacted feces in the rectum, fecal impaction can also include more proximal impactions due to fecal loading or retention.2

Causes of constipation and fecal impaction are similar and include low intake of dietary fiber, dehydration, immobility, alcohol ingestion, laxative abuse, medication adverse effects, depression, dementia, spinal cord dysfunction, diabetes, metabolic imbalances, and hypothyroidism.2,3 Insufficient hydration with consumption of a high-fiber food, as in this case, or with a bulk-forming laxative such as psyllium seed can result in fecal impaction.3

The many causes of a bezoar

A bezoar is a mass of poorly digested material that forms within the gastrointestinal tract—usually in the stomach—and less commonly in the small or large intestine.4 Trichobezoars (hair), lactobezoars (milk curd), phytobezoars (plant fiber), medication bezoars, and lithobezoars (small stones, pebbles, or gravel) are named after their contents. In keeping with this naming tradition, a gummi bear bezoar5 has also been described. Fecal impaction due to phytobezoars primarily composed of seeds has been associated with prickly pears, watermelons, sunflowers, pumpkins, pomegranates,6,7 and sesame seeds.4 Our patient’s experience adds quinoa seeds to this list.

Patients will complain of nausea and rectal urgency

Patients with fecal impaction may complain of nausea, rectal urgency, and rectalgia. A ball-valve effect of the fecal mass may allow paradoxical fecal incontinence and diarrhea.3 Digital rectal exam may demonstrate stool of any consistency, from rock hard pellets to soft clay-like stool.3 Absence of stool in the rectal vault does not rule out fecal impaction, and more proximal impactions may be revealed on plain abdominal radiography as bubbly, speckled masses of stool with associated signs of obstruction, such as colonic dilatation.

Fever, increased leukocyte count, and abdominal tenderness may indicate colonic perforation or ulceration. Signs of generalized peritonitis and free air on abdominal radiography warrant an immediate surgical consult.3

Complications from fecal impaction include bowel obstruction, sigmoid volvulus, and rectal prolapse.2 Stercoral ulceration and perforation due to pressure necrosis from a hard, inspissated fecal mass is an uncommon but life-threatening complication requiring resection of the affected colonic segment.8

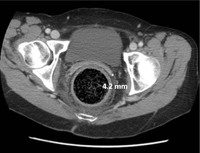

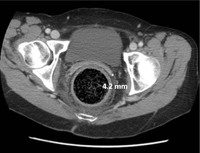

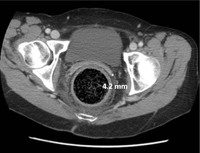

What to look for on the CT. When the diagnosis is unclear or signs of complications are present, an abdominal CT is indicated. Concerning CT findings include ulceration, bowel wall enhancement and thickening (FIGURE 2), discontinuity of the bowel wall, presence of fecal material either protruding through the colonic wall or lying free within the intra-abdominal cavity, and extraluminal air.8

FIGURE 2

CT scan shows bowel wall thickening

Treatment begins with a pharmacologic approach

By the time a patient with a fecal impaction gets to your office, it’s likely that he or she will have already tried over-the-counter laxatives, stool softeners, and perhaps an enema.

When such pharmacologic management has failed, you’ll need to perform a manual fragmentation and extraction of the fecal mass. Apply topical 2% lidocaine jelly for analgesia and lubrication, and then gently and progressively dilate the anal sphincter with one and then 2 fingers. A scissoring action will fragment the impaction.3

Once fragmentation and partial expulsion has been achieved, you may want to try a lubricating mineral oil enema, bisacodyl suppository, or rectal lavage. If the impaction extends beyond the reach of the fingers, sigmoidoscopic visualization and lavage are indicated.

Adding water-soluble contrast material (Gastrografin) in 20% to 50% solutions directed by fluoroscopy draws water into the lumen, thus lubricating the fecal mass3,9 and helping it to pass spontaneously.

Our patient’s case resolved with a trip to the OR

Since conservative and comprehensive management to improve our patient’s condition failed, she was taken to the operating room for a proctosigmoidoscopic disimpaction. A beveled metal proctoscope was used to disimpact the distal-most 10 cm and then a rigid sigmoidoscope was used to clear the colon of quinoa-laden fecal material to a total distance of 18 cm. Bowel walls were ecchymotic, yet viable and without laceration. She made an uneventful recovery and was discharged on hospital Day 3.

CORRESPONDENCE George L. Higgins, III, MD, Maine Medical Center, Department of Emergency Medicine, 47 Bramhall Street, Portland, ME 04102; [email protected]

1. Rao SS, Go JT. Update on the management of constipation in the elderly: new treatment options. Clin Interv Aging. 2010;5:163-171.

2. Creason N, Sparks D. Fecal impaction: a review. Nurs Diagn. 2000;11:15-23.

3. Wrenn K. Fecal impaction. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:658-662.

4. Shaw AG, Peacock O, Lund JN, et al. Large bowel obstruction due to sesame seed bezoar: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2007;1:159.-

5. Barron MM, Steerman P. Gummi bear bezoar: a case report. J Emerg Med. 1989;7:143-144.

6. Eitan A, Bickel A, Katz IM. Fecal impaction in adults: report of 30 cases of seed bezoars in the rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1768-1771.

7. Eitan A, Katz IM, Sweed Y, et al. Fecal impaction in children: report of 53 cases of rectal seed bezoars. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:1114-1117.

8. Kumar P, Pearce O, Higginson A. Imaging manifestations of faecal impaction and stercoral perforation. Clin Radiol. 2011;66:83-88.

9. Brenner BE, Simon RR. Anorectal emergencies. Ann Emerg Med. 1983;12:367-376.

A 64-year-old woman came into our emergency department (ED) complaining of constipation and worsening rectal pain. In an attempt to promote her overall health, the patient had recently begun experimenting with healthy alternatives to her regular diet. Three days before her visit, she had ceased having stools and was experiencing intermittent abdominal cramping. She self-administered 2 bisacodyl suppositories, 2 sodium biphosphate enemas, one 10-ounce bottle of magnesium citrate, and 15 senna-containing laxative tablets without improvement.

She sought care at an urgent care clinic where she received 2 additional enemas and a trial of manual disimpaction—without results. She was sent home to rest and asked to return the next morning for another trial of disimpaction. When the patient’s efforts to manually disimpact herself at home were unsuccessful, she contacted her primary care physician, who arranged a house call. When his own protracted disimpaction procedure was unsuccessful, he referred her to our ED.

On presentation, the patient had lower abdominal and rectal discomfort. Her vital signs were normal except for a temperature of 38.8° C. Her abdomen was soft and nontender. Inspection of her perianal area revealed erythema and excoriations. On digital rectal exam (which was poorly tolerated because of pain), we noted a moderate amount of soft, clay-like feces in the rectal vault, with overflow liquid stool expulsion.

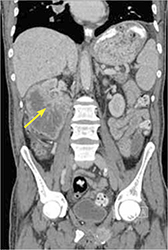

Computed tomography (CT) imaging of the abdomen was obtained to rule out rectal injury or colonic perforation (FIGURE 1).

FIGURE 1

CT scan reveals a speckled intraluminal mass

The patient had a markedly distended rectum and distal sigmoid colon caused by an intraluminal mass. Also present: circumferential wall thickening, perirectal edema without extraluminal gas, and generalized proximal colonic wall edema without a drainable collection.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Fecal impaction caused by a proctophytobezoar

CT imaging revealed a proctophytobezoar. On follow-up questioning, the patient recalled consuming approximately 10 ounces of cooked quinoa, a nutritious, gluten-free, high-protein seed, just prior to the onset of her constipation.

Constipation disproportionately affects the elderly and the young.1 Fecal impaction is a sequelae of constipation. Most commonly defined as hard, compacted feces in the rectum, fecal impaction can also include more proximal impactions due to fecal loading or retention.2

Causes of constipation and fecal impaction are similar and include low intake of dietary fiber, dehydration, immobility, alcohol ingestion, laxative abuse, medication adverse effects, depression, dementia, spinal cord dysfunction, diabetes, metabolic imbalances, and hypothyroidism.2,3 Insufficient hydration with consumption of a high-fiber food, as in this case, or with a bulk-forming laxative such as psyllium seed can result in fecal impaction.3

The many causes of a bezoar

A bezoar is a mass of poorly digested material that forms within the gastrointestinal tract—usually in the stomach—and less commonly in the small or large intestine.4 Trichobezoars (hair), lactobezoars (milk curd), phytobezoars (plant fiber), medication bezoars, and lithobezoars (small stones, pebbles, or gravel) are named after their contents. In keeping with this naming tradition, a gummi bear bezoar5 has also been described. Fecal impaction due to phytobezoars primarily composed of seeds has been associated with prickly pears, watermelons, sunflowers, pumpkins, pomegranates,6,7 and sesame seeds.4 Our patient’s experience adds quinoa seeds to this list.

Patients will complain of nausea and rectal urgency

Patients with fecal impaction may complain of nausea, rectal urgency, and rectalgia. A ball-valve effect of the fecal mass may allow paradoxical fecal incontinence and diarrhea.3 Digital rectal exam may demonstrate stool of any consistency, from rock hard pellets to soft clay-like stool.3 Absence of stool in the rectal vault does not rule out fecal impaction, and more proximal impactions may be revealed on plain abdominal radiography as bubbly, speckled masses of stool with associated signs of obstruction, such as colonic dilatation.

Fever, increased leukocyte count, and abdominal tenderness may indicate colonic perforation or ulceration. Signs of generalized peritonitis and free air on abdominal radiography warrant an immediate surgical consult.3

Complications from fecal impaction include bowel obstruction, sigmoid volvulus, and rectal prolapse.2 Stercoral ulceration and perforation due to pressure necrosis from a hard, inspissated fecal mass is an uncommon but life-threatening complication requiring resection of the affected colonic segment.8

What to look for on the CT. When the diagnosis is unclear or signs of complications are present, an abdominal CT is indicated. Concerning CT findings include ulceration, bowel wall enhancement and thickening (FIGURE 2), discontinuity of the bowel wall, presence of fecal material either protruding through the colonic wall or lying free within the intra-abdominal cavity, and extraluminal air.8

FIGURE 2

CT scan shows bowel wall thickening

Treatment begins with a pharmacologic approach

By the time a patient with a fecal impaction gets to your office, it’s likely that he or she will have already tried over-the-counter laxatives, stool softeners, and perhaps an enema.

When such pharmacologic management has failed, you’ll need to perform a manual fragmentation and extraction of the fecal mass. Apply topical 2% lidocaine jelly for analgesia and lubrication, and then gently and progressively dilate the anal sphincter with one and then 2 fingers. A scissoring action will fragment the impaction.3

Once fragmentation and partial expulsion has been achieved, you may want to try a lubricating mineral oil enema, bisacodyl suppository, or rectal lavage. If the impaction extends beyond the reach of the fingers, sigmoidoscopic visualization and lavage are indicated.

Adding water-soluble contrast material (Gastrografin) in 20% to 50% solutions directed by fluoroscopy draws water into the lumen, thus lubricating the fecal mass3,9 and helping it to pass spontaneously.

Our patient’s case resolved with a trip to the OR

Since conservative and comprehensive management to improve our patient’s condition failed, she was taken to the operating room for a proctosigmoidoscopic disimpaction. A beveled metal proctoscope was used to disimpact the distal-most 10 cm and then a rigid sigmoidoscope was used to clear the colon of quinoa-laden fecal material to a total distance of 18 cm. Bowel walls were ecchymotic, yet viable and without laceration. She made an uneventful recovery and was discharged on hospital Day 3.

CORRESPONDENCE George L. Higgins, III, MD, Maine Medical Center, Department of Emergency Medicine, 47 Bramhall Street, Portland, ME 04102; [email protected]

A 64-year-old woman came into our emergency department (ED) complaining of constipation and worsening rectal pain. In an attempt to promote her overall health, the patient had recently begun experimenting with healthy alternatives to her regular diet. Three days before her visit, she had ceased having stools and was experiencing intermittent abdominal cramping. She self-administered 2 bisacodyl suppositories, 2 sodium biphosphate enemas, one 10-ounce bottle of magnesium citrate, and 15 senna-containing laxative tablets without improvement.

She sought care at an urgent care clinic where she received 2 additional enemas and a trial of manual disimpaction—without results. She was sent home to rest and asked to return the next morning for another trial of disimpaction. When the patient’s efforts to manually disimpact herself at home were unsuccessful, she contacted her primary care physician, who arranged a house call. When his own protracted disimpaction procedure was unsuccessful, he referred her to our ED.

On presentation, the patient had lower abdominal and rectal discomfort. Her vital signs were normal except for a temperature of 38.8° C. Her abdomen was soft and nontender. Inspection of her perianal area revealed erythema and excoriations. On digital rectal exam (which was poorly tolerated because of pain), we noted a moderate amount of soft, clay-like feces in the rectal vault, with overflow liquid stool expulsion.

Computed tomography (CT) imaging of the abdomen was obtained to rule out rectal injury or colonic perforation (FIGURE 1).

FIGURE 1

CT scan reveals a speckled intraluminal mass

The patient had a markedly distended rectum and distal sigmoid colon caused by an intraluminal mass. Also present: circumferential wall thickening, perirectal edema without extraluminal gas, and generalized proximal colonic wall edema without a drainable collection.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Fecal impaction caused by a proctophytobezoar

CT imaging revealed a proctophytobezoar. On follow-up questioning, the patient recalled consuming approximately 10 ounces of cooked quinoa, a nutritious, gluten-free, high-protein seed, just prior to the onset of her constipation.

Constipation disproportionately affects the elderly and the young.1 Fecal impaction is a sequelae of constipation. Most commonly defined as hard, compacted feces in the rectum, fecal impaction can also include more proximal impactions due to fecal loading or retention.2

Causes of constipation and fecal impaction are similar and include low intake of dietary fiber, dehydration, immobility, alcohol ingestion, laxative abuse, medication adverse effects, depression, dementia, spinal cord dysfunction, diabetes, metabolic imbalances, and hypothyroidism.2,3 Insufficient hydration with consumption of a high-fiber food, as in this case, or with a bulk-forming laxative such as psyllium seed can result in fecal impaction.3

The many causes of a bezoar

A bezoar is a mass of poorly digested material that forms within the gastrointestinal tract—usually in the stomach—and less commonly in the small or large intestine.4 Trichobezoars (hair), lactobezoars (milk curd), phytobezoars (plant fiber), medication bezoars, and lithobezoars (small stones, pebbles, or gravel) are named after their contents. In keeping with this naming tradition, a gummi bear bezoar5 has also been described. Fecal impaction due to phytobezoars primarily composed of seeds has been associated with prickly pears, watermelons, sunflowers, pumpkins, pomegranates,6,7 and sesame seeds.4 Our patient’s experience adds quinoa seeds to this list.

Patients will complain of nausea and rectal urgency

Patients with fecal impaction may complain of nausea, rectal urgency, and rectalgia. A ball-valve effect of the fecal mass may allow paradoxical fecal incontinence and diarrhea.3 Digital rectal exam may demonstrate stool of any consistency, from rock hard pellets to soft clay-like stool.3 Absence of stool in the rectal vault does not rule out fecal impaction, and more proximal impactions may be revealed on plain abdominal radiography as bubbly, speckled masses of stool with associated signs of obstruction, such as colonic dilatation.

Fever, increased leukocyte count, and abdominal tenderness may indicate colonic perforation or ulceration. Signs of generalized peritonitis and free air on abdominal radiography warrant an immediate surgical consult.3

Complications from fecal impaction include bowel obstruction, sigmoid volvulus, and rectal prolapse.2 Stercoral ulceration and perforation due to pressure necrosis from a hard, inspissated fecal mass is an uncommon but life-threatening complication requiring resection of the affected colonic segment.8

What to look for on the CT. When the diagnosis is unclear or signs of complications are present, an abdominal CT is indicated. Concerning CT findings include ulceration, bowel wall enhancement and thickening (FIGURE 2), discontinuity of the bowel wall, presence of fecal material either protruding through the colonic wall or lying free within the intra-abdominal cavity, and extraluminal air.8

FIGURE 2

CT scan shows bowel wall thickening

Treatment begins with a pharmacologic approach

By the time a patient with a fecal impaction gets to your office, it’s likely that he or she will have already tried over-the-counter laxatives, stool softeners, and perhaps an enema.

When such pharmacologic management has failed, you’ll need to perform a manual fragmentation and extraction of the fecal mass. Apply topical 2% lidocaine jelly for analgesia and lubrication, and then gently and progressively dilate the anal sphincter with one and then 2 fingers. A scissoring action will fragment the impaction.3

Once fragmentation and partial expulsion has been achieved, you may want to try a lubricating mineral oil enema, bisacodyl suppository, or rectal lavage. If the impaction extends beyond the reach of the fingers, sigmoidoscopic visualization and lavage are indicated.

Adding water-soluble contrast material (Gastrografin) in 20% to 50% solutions directed by fluoroscopy draws water into the lumen, thus lubricating the fecal mass3,9 and helping it to pass spontaneously.

Our patient’s case resolved with a trip to the OR

Since conservative and comprehensive management to improve our patient’s condition failed, she was taken to the operating room for a proctosigmoidoscopic disimpaction. A beveled metal proctoscope was used to disimpact the distal-most 10 cm and then a rigid sigmoidoscope was used to clear the colon of quinoa-laden fecal material to a total distance of 18 cm. Bowel walls were ecchymotic, yet viable and without laceration. She made an uneventful recovery and was discharged on hospital Day 3.

CORRESPONDENCE George L. Higgins, III, MD, Maine Medical Center, Department of Emergency Medicine, 47 Bramhall Street, Portland, ME 04102; [email protected]

1. Rao SS, Go JT. Update on the management of constipation in the elderly: new treatment options. Clin Interv Aging. 2010;5:163-171.

2. Creason N, Sparks D. Fecal impaction: a review. Nurs Diagn. 2000;11:15-23.

3. Wrenn K. Fecal impaction. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:658-662.

4. Shaw AG, Peacock O, Lund JN, et al. Large bowel obstruction due to sesame seed bezoar: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2007;1:159.-

5. Barron MM, Steerman P. Gummi bear bezoar: a case report. J Emerg Med. 1989;7:143-144.

6. Eitan A, Bickel A, Katz IM. Fecal impaction in adults: report of 30 cases of seed bezoars in the rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1768-1771.

7. Eitan A, Katz IM, Sweed Y, et al. Fecal impaction in children: report of 53 cases of rectal seed bezoars. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:1114-1117.

8. Kumar P, Pearce O, Higginson A. Imaging manifestations of faecal impaction and stercoral perforation. Clin Radiol. 2011;66:83-88.

9. Brenner BE, Simon RR. Anorectal emergencies. Ann Emerg Med. 1983;12:367-376.

1. Rao SS, Go JT. Update on the management of constipation in the elderly: new treatment options. Clin Interv Aging. 2010;5:163-171.

2. Creason N, Sparks D. Fecal impaction: a review. Nurs Diagn. 2000;11:15-23.

3. Wrenn K. Fecal impaction. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:658-662.

4. Shaw AG, Peacock O, Lund JN, et al. Large bowel obstruction due to sesame seed bezoar: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2007;1:159.-

5. Barron MM, Steerman P. Gummi bear bezoar: a case report. J Emerg Med. 1989;7:143-144.

6. Eitan A, Bickel A, Katz IM. Fecal impaction in adults: report of 30 cases of seed bezoars in the rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1768-1771.

7. Eitan A, Katz IM, Sweed Y, et al. Fecal impaction in children: report of 53 cases of rectal seed bezoars. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:1114-1117.

8. Kumar P, Pearce O, Higginson A. Imaging manifestations of faecal impaction and stercoral perforation. Clin Radiol. 2011;66:83-88.

9. Brenner BE, Simon RR. Anorectal emergencies. Ann Emerg Med. 1983;12:367-376.

Itchy red rings

|

|

| FIGURE 1 | FIGURE 2 |

The physician diagnosed erythema annular centrifugum (EAC) in this patient. EAC has large, scaly, erythematous plaques (FIGURE 1), which begin as papules and spread peripherally with a central clearing forming a “trailing” scale (FIGURE 2). Pruritus is common, but not always present. A skin biopsy is not always needed, but can confirm clinical suspicion. Lesions are typically found in the lower extremities—particularly the thighs—but can be found on the trunk and face, as well.

EAC may begin at any age. The mean age of onset is 40 years, with no predilection for either sex. The mean duration of this skin condition is 2.8 years, but it may last between 4 weeks and more than 30 years.

While the etiology and pathogenesis of EAC are unknown, it has been associated with other conditions such as fungal infections, malignancy, and other systemic illnesses. A few case reports have noted a diagnosis of cancer 2 years after presentation of EAC.

Bacterial infections that have been identified as triggers include cystitis, appendicitis, and tuberculosis. Viral triggers include Epstein-Barr virus, molluscum contagiosum, and herpes zoster. Parasites such as ascaris have also been linked with EAC. Certain drugs such as chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, estrogen, cimetidine, penicillin, salicylates, piroxicam, hydrochlorothiazide, and amitriptyline can also trigger EAC.

There is no proven treatment for EAC. Identifying and treating underlying medical conditions may help resolve the skin condition. Since EAC is seen in association with certain drugs, discontinuing the offending medication may resolve the problem. Topical corticosteroids have traditionally been used, but there is little evidence to support their use. Case reports have documented the benefits of using calcipotriol (Dovonex) daily for EAC.

In this case, the family physician (FP) explained that EAC is not contagious. Since topical steroids did not provide any relief for this patient in the past, the FP prescribed calcipotriol ointment.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Zaman S, Usatine R. Erythema annular centrifugum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds.The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:886-889.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

|

|

| FIGURE 1 | FIGURE 2 |

The physician diagnosed erythema annular centrifugum (EAC) in this patient. EAC has large, scaly, erythematous plaques (FIGURE 1), which begin as papules and spread peripherally with a central clearing forming a “trailing” scale (FIGURE 2). Pruritus is common, but not always present. A skin biopsy is not always needed, but can confirm clinical suspicion. Lesions are typically found in the lower extremities—particularly the thighs—but can be found on the trunk and face, as well.

EAC may begin at any age. The mean age of onset is 40 years, with no predilection for either sex. The mean duration of this skin condition is 2.8 years, but it may last between 4 weeks and more than 30 years.

While the etiology and pathogenesis of EAC are unknown, it has been associated with other conditions such as fungal infections, malignancy, and other systemic illnesses. A few case reports have noted a diagnosis of cancer 2 years after presentation of EAC.

Bacterial infections that have been identified as triggers include cystitis, appendicitis, and tuberculosis. Viral triggers include Epstein-Barr virus, molluscum contagiosum, and herpes zoster. Parasites such as ascaris have also been linked with EAC. Certain drugs such as chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, estrogen, cimetidine, penicillin, salicylates, piroxicam, hydrochlorothiazide, and amitriptyline can also trigger EAC.

There is no proven treatment for EAC. Identifying and treating underlying medical conditions may help resolve the skin condition. Since EAC is seen in association with certain drugs, discontinuing the offending medication may resolve the problem. Topical corticosteroids have traditionally been used, but there is little evidence to support their use. Case reports have documented the benefits of using calcipotriol (Dovonex) daily for EAC.

In this case, the family physician (FP) explained that EAC is not contagious. Since topical steroids did not provide any relief for this patient in the past, the FP prescribed calcipotriol ointment.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Zaman S, Usatine R. Erythema annular centrifugum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds.The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:886-889.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

|

|

| FIGURE 1 | FIGURE 2 |

The physician diagnosed erythema annular centrifugum (EAC) in this patient. EAC has large, scaly, erythematous plaques (FIGURE 1), which begin as papules and spread peripherally with a central clearing forming a “trailing” scale (FIGURE 2). Pruritus is common, but not always present. A skin biopsy is not always needed, but can confirm clinical suspicion. Lesions are typically found in the lower extremities—particularly the thighs—but can be found on the trunk and face, as well.

EAC may begin at any age. The mean age of onset is 40 years, with no predilection for either sex. The mean duration of this skin condition is 2.8 years, but it may last between 4 weeks and more than 30 years.

While the etiology and pathogenesis of EAC are unknown, it has been associated with other conditions such as fungal infections, malignancy, and other systemic illnesses. A few case reports have noted a diagnosis of cancer 2 years after presentation of EAC.

Bacterial infections that have been identified as triggers include cystitis, appendicitis, and tuberculosis. Viral triggers include Epstein-Barr virus, molluscum contagiosum, and herpes zoster. Parasites such as ascaris have also been linked with EAC. Certain drugs such as chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, estrogen, cimetidine, penicillin, salicylates, piroxicam, hydrochlorothiazide, and amitriptyline can also trigger EAC.

There is no proven treatment for EAC. Identifying and treating underlying medical conditions may help resolve the skin condition. Since EAC is seen in association with certain drugs, discontinuing the offending medication may resolve the problem. Topical corticosteroids have traditionally been used, but there is little evidence to support their use. Case reports have documented the benefits of using calcipotriol (Dovonex) daily for EAC.

In this case, the family physician (FP) explained that EAC is not contagious. Since topical steroids did not provide any relief for this patient in the past, the FP prescribed calcipotriol ointment.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Zaman S, Usatine R. Erythema annular centrifugum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds.The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:886-889.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

Dry skin

The physician suspected that the patient had X-linked ichthyosis. This condition is inherited in an X-linked recessive manner, and thus is found almost exclusively in males. These males have an increased incidence of cryptorchidism and are at an increased risk of testicular cancer. Often, patients with this condition were delivered by cesarean section because a placental sulfatase deficiency results in a failure of labor to progress.

Most of the body is involved, except for the typical sparing of the flexures, face, palms, and soles. There is an accentuation noted on the neck, giving these patients a characteristic “dirty neck” appearance.

X-linked ichthyosis is rare and treatments are based on the clinical experience, rather than large studies. Frequent application of emollients, humectants, and keratinolytics are the mainstay of therapy. There are many effective over-the-counter and prescription products that contain propylene glycol, urea, or lactic acid. Salicylic acid products should be used only on a limited body surface area, as systemic absorption has led to salicylate toxicity in some patients. The physician in this case prescribed 12% ammonium lactate and educated the family about the genetics of this disorder.

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. Photo courtesy of the University of Texas Health Sciences Center, Division of Dermatology. This case was adapted from: Babcock M. Genodermatosis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:881-885.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

The physician suspected that the patient had X-linked ichthyosis. This condition is inherited in an X-linked recessive manner, and thus is found almost exclusively in males. These males have an increased incidence of cryptorchidism and are at an increased risk of testicular cancer. Often, patients with this condition were delivered by cesarean section because a placental sulfatase deficiency results in a failure of labor to progress.

Most of the body is involved, except for the typical sparing of the flexures, face, palms, and soles. There is an accentuation noted on the neck, giving these patients a characteristic “dirty neck” appearance.

X-linked ichthyosis is rare and treatments are based on the clinical experience, rather than large studies. Frequent application of emollients, humectants, and keratinolytics are the mainstay of therapy. There are many effective over-the-counter and prescription products that contain propylene glycol, urea, or lactic acid. Salicylic acid products should be used only on a limited body surface area, as systemic absorption has led to salicylate toxicity in some patients. The physician in this case prescribed 12% ammonium lactate and educated the family about the genetics of this disorder.

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. Photo courtesy of the University of Texas Health Sciences Center, Division of Dermatology. This case was adapted from: Babcock M. Genodermatosis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:881-885.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

The physician suspected that the patient had X-linked ichthyosis. This condition is inherited in an X-linked recessive manner, and thus is found almost exclusively in males. These males have an increased incidence of cryptorchidism and are at an increased risk of testicular cancer. Often, patients with this condition were delivered by cesarean section because a placental sulfatase deficiency results in a failure of labor to progress.

Most of the body is involved, except for the typical sparing of the flexures, face, palms, and soles. There is an accentuation noted on the neck, giving these patients a characteristic “dirty neck” appearance.

X-linked ichthyosis is rare and treatments are based on the clinical experience, rather than large studies. Frequent application of emollients, humectants, and keratinolytics are the mainstay of therapy. There are many effective over-the-counter and prescription products that contain propylene glycol, urea, or lactic acid. Salicylic acid products should be used only on a limited body surface area, as systemic absorption has led to salicylate toxicity in some patients. The physician in this case prescribed 12% ammonium lactate and educated the family about the genetics of this disorder.

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. Photo courtesy of the University of Texas Health Sciences Center, Division of Dermatology. This case was adapted from: Babcock M. Genodermatosis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:881-885.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

Scale on face

|

|

|

This patient was given a diagnosis of Darier’s disease, an autosomal dominant genodermatosis also known as keratosis follicularis. It starts with greasy, hyperkeratotic, yellowish-brown papules in a seborrheic distribution (FIGURE 1). (FIGURE 2 shows the papules on the patient’s scalp, which were visible after she removed her wig.) The feet may be covered with hyperkeratotic plaques, palms may have pits or keratotic papules, and the nails may have V-shaped nicking (FIGURE 3) and alternating longitudinal red and white bands. The keratotic papules can be intensely malodorous.

In early, mild, or partially treated disease, only the ears and postauricular areas may be affected. Skin biopsy reveals the characteristic histopathology. A test for the ATP2A2 gene mutation can be performed. The odor that accompanies the disease, as well as the facial involvement, often adversely affect the patient’s quality of life; thus, treatment is often warranted. Mild-to-moderate disease can be treated by avoiding exacerbating factors (sunlight, heat, and occlusion) and with topical medications; severe disease is best treated with oral retinoids.

Darier’s disease is so rare that there are no randomized controlled trials to guide treatment. Topical retinoids (adapalene, tretinoin, or tazarotene) are effective in some patients, but their main limitation is irritation. Topical corticosteroids may help. Lower-potency topical corticosteroids should be used on the face, groin, and axillae to minimize adverse effects in these areas. Systemic retinoids (acitretin or isotretinoin) are the most potent treatment. Patients on systemic retinoids require close monitoring and careful selection, as these agents are teratogenic (category X) and can cause hyperlipidemia, hypertriglyceridemia, mucous membrane dryness, alopecia, hepatotoxicity, and possibly mood disturbances. Cyclosporine can be used for acute flares. Laser, radiation, photodynamic therapy, and gene therapy are newer treatment modalities that are being investigated.

This patient was postmenopausal, so the physician was willing to treat her with acitretin. Acitretin is very expensive, and the patient’s health plan did not cover it. She was able to get it through a patient assistance program and benefitted from using it.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Babcock M. Genodermatosis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:881-885.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

|

|

|

This patient was given a diagnosis of Darier’s disease, an autosomal dominant genodermatosis also known as keratosis follicularis. It starts with greasy, hyperkeratotic, yellowish-brown papules in a seborrheic distribution (FIGURE 1). (FIGURE 2 shows the papules on the patient’s scalp, which were visible after she removed her wig.) The feet may be covered with hyperkeratotic plaques, palms may have pits or keratotic papules, and the nails may have V-shaped nicking (FIGURE 3) and alternating longitudinal red and white bands. The keratotic papules can be intensely malodorous.

In early, mild, or partially treated disease, only the ears and postauricular areas may be affected. Skin biopsy reveals the characteristic histopathology. A test for the ATP2A2 gene mutation can be performed. The odor that accompanies the disease, as well as the facial involvement, often adversely affect the patient’s quality of life; thus, treatment is often warranted. Mild-to-moderate disease can be treated by avoiding exacerbating factors (sunlight, heat, and occlusion) and with topical medications; severe disease is best treated with oral retinoids.

Darier’s disease is so rare that there are no randomized controlled trials to guide treatment. Topical retinoids (adapalene, tretinoin, or tazarotene) are effective in some patients, but their main limitation is irritation. Topical corticosteroids may help. Lower-potency topical corticosteroids should be used on the face, groin, and axillae to minimize adverse effects in these areas. Systemic retinoids (acitretin or isotretinoin) are the most potent treatment. Patients on systemic retinoids require close monitoring and careful selection, as these agents are teratogenic (category X) and can cause hyperlipidemia, hypertriglyceridemia, mucous membrane dryness, alopecia, hepatotoxicity, and possibly mood disturbances. Cyclosporine can be used for acute flares. Laser, radiation, photodynamic therapy, and gene therapy are newer treatment modalities that are being investigated.

This patient was postmenopausal, so the physician was willing to treat her with acitretin. Acitretin is very expensive, and the patient’s health plan did not cover it. She was able to get it through a patient assistance program and benefitted from using it.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Babcock M. Genodermatosis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:881-885.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

|

|

|

This patient was given a diagnosis of Darier’s disease, an autosomal dominant genodermatosis also known as keratosis follicularis. It starts with greasy, hyperkeratotic, yellowish-brown papules in a seborrheic distribution (FIGURE 1). (FIGURE 2 shows the papules on the patient’s scalp, which were visible after she removed her wig.) The feet may be covered with hyperkeratotic plaques, palms may have pits or keratotic papules, and the nails may have V-shaped nicking (FIGURE 3) and alternating longitudinal red and white bands. The keratotic papules can be intensely malodorous.

In early, mild, or partially treated disease, only the ears and postauricular areas may be affected. Skin biopsy reveals the characteristic histopathology. A test for the ATP2A2 gene mutation can be performed. The odor that accompanies the disease, as well as the facial involvement, often adversely affect the patient’s quality of life; thus, treatment is often warranted. Mild-to-moderate disease can be treated by avoiding exacerbating factors (sunlight, heat, and occlusion) and with topical medications; severe disease is best treated with oral retinoids.

Darier’s disease is so rare that there are no randomized controlled trials to guide treatment. Topical retinoids (adapalene, tretinoin, or tazarotene) are effective in some patients, but their main limitation is irritation. Topical corticosteroids may help. Lower-potency topical corticosteroids should be used on the face, groin, and axillae to minimize adverse effects in these areas. Systemic retinoids (acitretin or isotretinoin) are the most potent treatment. Patients on systemic retinoids require close monitoring and careful selection, as these agents are teratogenic (category X) and can cause hyperlipidemia, hypertriglyceridemia, mucous membrane dryness, alopecia, hepatotoxicity, and possibly mood disturbances. Cyclosporine can be used for acute flares. Laser, radiation, photodynamic therapy, and gene therapy are newer treatment modalities that are being investigated.

This patient was postmenopausal, so the physician was willing to treat her with acitretin. Acitretin is very expensive, and the patient’s health plan did not cover it. She was able to get it through a patient assistance program and benefitted from using it.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Babcock M. Genodermatosis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:881-885.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

Nodules on trunk

|

|

This patient had keloids—dermal fibrotic lesions (FIGURE 1) that are a variation of the normal wound healing process in the spectrum of fibroproliferative disorders. Keloids can occur up to a year after an injury and enlarge beyond the scar margin. Keloids are more common in individuals with darker pigmentation.

Patients frequently want keloids treated because of symptoms (pain and pruritus) and concerns about appearance. Cryosurgery and intralesional triamcinolone have been used to treat keloids with some success. Intralesional steroid injections of triamcinolone acetonide (10–40 mg/mL) may decrease pruritus, as well as keloid size. These injections may be repeated monthly, as needed. Silicone gel sheeting as a treatment for hypertrophic and keloid scarring is supported by poor-quality trials only.

This patient opted for intralesional steroids (FIGURE 2) to the most symptomatic keloids. The patient understood that the injection would not remove the keloid, but it did eliminate the pruritus and pain at the site.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Varela A, Usatine R. Keloids. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:878-880.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

|

|

This patient had keloids—dermal fibrotic lesions (FIGURE 1) that are a variation of the normal wound healing process in the spectrum of fibroproliferative disorders. Keloids can occur up to a year after an injury and enlarge beyond the scar margin. Keloids are more common in individuals with darker pigmentation.

Patients frequently want keloids treated because of symptoms (pain and pruritus) and concerns about appearance. Cryosurgery and intralesional triamcinolone have been used to treat keloids with some success. Intralesional steroid injections of triamcinolone acetonide (10–40 mg/mL) may decrease pruritus, as well as keloid size. These injections may be repeated monthly, as needed. Silicone gel sheeting as a treatment for hypertrophic and keloid scarring is supported by poor-quality trials only.

This patient opted for intralesional steroids (FIGURE 2) to the most symptomatic keloids. The patient understood that the injection would not remove the keloid, but it did eliminate the pruritus and pain at the site.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Varela A, Usatine R. Keloids. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:878-880.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

|

|

This patient had keloids—dermal fibrotic lesions (FIGURE 1) that are a variation of the normal wound healing process in the spectrum of fibroproliferative disorders. Keloids can occur up to a year after an injury and enlarge beyond the scar margin. Keloids are more common in individuals with darker pigmentation.

Patients frequently want keloids treated because of symptoms (pain and pruritus) and concerns about appearance. Cryosurgery and intralesional triamcinolone have been used to treat keloids with some success. Intralesional steroid injections of triamcinolone acetonide (10–40 mg/mL) may decrease pruritus, as well as keloid size. These injections may be repeated monthly, as needed. Silicone gel sheeting as a treatment for hypertrophic and keloid scarring is supported by poor-quality trials only.

This patient opted for intralesional steroids (FIGURE 2) to the most symptomatic keloids. The patient understood that the injection would not remove the keloid, but it did eliminate the pruritus and pain at the site.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Varela A, Usatine R. Keloids. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:878-880.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

You can now get The Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app for mobile devices including the iPhone and iPad by clicking this link:

Painful leg mass

A 61-year-old Caucasian man sought care at our emergency department for a painful mass on his right leg that had appeared and progressively enlarged over the past 3 weeks. The patient denied trauma prior to the appearance of the mass, but did note extensive varicosities spanning from the right groin to the right foot a few weeks before the lesion appeared.

He also indicated that he’d had progressive dyspnea and intermittent chest pain for the past 4 months, a 30-lb weight loss in the past 6 months without change in appetite or diet, a depressed mood, and generalized weakness.

The patient’s past medical history was notable for hypertension and coronary artery disease. He reported a 30 pack-year smoking history, but had quit 12 years earlier. He denied alcohol use, although there was a family history of alcoholism and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Physical examination revealed a frail, pale, unkempt man. His vital signs were normal except for mild tachycardia. Additional findings included:

- nonicteric, pale palpebral conjunctivae

- a 3/6 nonradiating holosystolic murmur heard along the left upper sternal border

- a large friable 3.5-cm pedunculated mass on a 2-cm stalk located on right lower leg (FIGURE 1); the lesion was moist, purple, and exophytic

- bilateral enlargement of the inguinal lymph nodes.

Lab work revealed microcytic anemia with a hemoglobin count of 5.8 g/dL and mild hyponatremia. The patient’s liver and renal function were normal. Urinalysis showed 3 red blood cells (RBCs) and a chest x-ray revealed bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy.

FIGURE 1

Exophytic mass on right lower leg

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Renal cell carcinoma

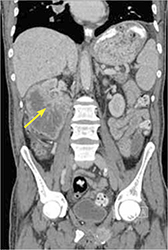

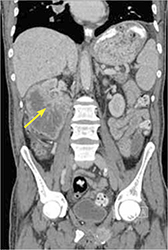

The patient was admitted and stabilized with packed RBCs for symptomatic anemia. He underwent biopsy of the right leg lesion and computed tomography (CT) imaging of his chest, abdomen, and pelvis.

The biopsy report from the resected right leg mass revealed metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma (RCC). The CT scan showed a large exophytic mass involving the right kidney measuring 12 × 11 × 9 cm. Additionally, the scan revealed multiple noncalcified nodules of both lungs with enlarged bilateral hilar and paratracheal lymph nodes, lytic bone lesions, and multiple enhancing round lesions throughout the liver, suggesting metastatic involvement (FIGURE 2).

FIGURE 2

Abdominal CT scan reveals a 12-cm mass on right kidney

Metastases on initial presentation? It’s not uncommon

More than 64,000 new cases of renal cancer are expected to be diagnosed in 2012 and 92% of them are expected to be cases of RCC.1 Interestingly, the incidence and mortality rates of RCC have been on the rise.2 Part of this increased incidence is likely secondary to increased detection of asymptomatic renal masses noted on imaging studies done for other reasons; however, the increased overall mortality from renal cancer is not fully understood.

Renal cancer risk factors include tobacco use, obesity, renal cystic disease, and toxic occupational exposures (eg, cadmium). A genetic predisposition also appears to play a role.2 The classic presenting symptoms of renal malignancy include hematuria, a flank mass, and abdominal pain. Patients may experience a single symptom but rarely all 3, and many patients come in with nonspecific complaints of fever, sweats, weight loss, and fatigue.2

RCC also has a propensity for paraneoplastic syndromes that may present with anemia, hypercalcemia, or hepatic dysfunction.2 Unfortunately, many smaller renal lesions are asymptomatic, so as many as 55% of patients may present with metastatic disease at the time of initial presentation.3

The most common sites for renal metastatic disease are the lungs, bone, lymph nodes, brain, and contralateral kidney.2 Skin metastases, occurring in 2% to 10% of RCC cases, are less common and are often a sign of poorer prognosis.4 Men who have RCC are more likely to have skin metastases than women; the typical locations are the head, neck, and trunk.4

Is it RCC, or something else?

Signs and symptoms suggestive of possible renal malignancy (eg, hematuria, flank pain, weight loss, flank mass on exam) should prompt a work-up that includes abdominal imaging. The preferred imaging modality is a CT scan. Final tissue diagnosis is made on review of biopsy specimens obtained from the renal mass.

Skin metastases in RCC may be mistaken for other skin lesions, such as pyogenic granulomas, melanomas, or dermatofibromas.5 Histopathological analysis (and sometimes even special immunohistochemical staining and cytogenic analysis) can be used to make a definitive diagnosis.

Management options include radical nephrectomy

Treatment options and the prognosis for RCC are dependent on the extent of disease involvement at diagnosis. Radical nephrectomy is the gold standard therapy for patients with local, locally advanced, and even minimally metastatic disease.6

Other therapies include immunotherapy, interferons, interleukins, and gene therapy.6 Chemotherapy and radiation therapy have a limited role, as RCC is generally resistant to them. However, with more advanced metastatic disease, most treatment is palliative. The median survival time after diagnosis of metastatic RCC is about 20 months.6

Patient opts for treatment, then discontinues it

My patient was transferred to a local hospital with oncology support for further evaluation and management. He was ultimately diagnosed with metastatic renal carcinoma with bony, cutaneous, liver, and lung metastases. His hospital course was complicated by the development of hematuria and anemia, which required additional blood transfusions.

The patient was initially started on immunotherapy with sorafenib but upon acceptance of his metastatic disease and poor prognosis, he opted to discontinue therapy and enter an inpatient hospice facility.

CORRESPONDENCE Lesli M. Lucas, MD, Naval Branch Health Clinic Dahlgren, 17457 Caffee Road, Dahlgren, VA 22448; [email protected]

1. American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures 2012. Available at: http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-031941.pdf. Accessed April 6, 2012.

2. Gillenwater JY. Renal tumors. In: Gillenwater JY, Grayhack JT, Howards SS, Mitchell ME, eds. Adult and Pediatric Urology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002: 612-641.

3. Cuckow P, Doyle P. Renal cell carcinoma presenting in the skin. J R Soc Med. 1991;84:497-498.

4. Preetha R. Cutaneous metastasis from silent renal cell carcinoma. J Postgrad Med. 2004;50:287-288.

5. Garcia TM. Skin metastases from a renal cell carcinoma [in Spanish]. Actas Urol Esp. 2007;31:556-558.

6. Vogelzang NJ, Stadler WM. Kidney cancer. Lancet. 1998;352:1691-1696.

A 61-year-old Caucasian man sought care at our emergency department for a painful mass on his right leg that had appeared and progressively enlarged over the past 3 weeks. The patient denied trauma prior to the appearance of the mass, but did note extensive varicosities spanning from the right groin to the right foot a few weeks before the lesion appeared.

He also indicated that he’d had progressive dyspnea and intermittent chest pain for the past 4 months, a 30-lb weight loss in the past 6 months without change in appetite or diet, a depressed mood, and generalized weakness.

The patient’s past medical history was notable for hypertension and coronary artery disease. He reported a 30 pack-year smoking history, but had quit 12 years earlier. He denied alcohol use, although there was a family history of alcoholism and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Physical examination revealed a frail, pale, unkempt man. His vital signs were normal except for mild tachycardia. Additional findings included:

- nonicteric, pale palpebral conjunctivae

- a 3/6 nonradiating holosystolic murmur heard along the left upper sternal border

- a large friable 3.5-cm pedunculated mass on a 2-cm stalk located on right lower leg (FIGURE 1); the lesion was moist, purple, and exophytic

- bilateral enlargement of the inguinal lymph nodes.

Lab work revealed microcytic anemia with a hemoglobin count of 5.8 g/dL and mild hyponatremia. The patient’s liver and renal function were normal. Urinalysis showed 3 red blood cells (RBCs) and a chest x-ray revealed bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy.

FIGURE 1

Exophytic mass on right lower leg

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Renal cell carcinoma

The patient was admitted and stabilized with packed RBCs for symptomatic anemia. He underwent biopsy of the right leg lesion and computed tomography (CT) imaging of his chest, abdomen, and pelvis.

The biopsy report from the resected right leg mass revealed metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma (RCC). The CT scan showed a large exophytic mass involving the right kidney measuring 12 × 11 × 9 cm. Additionally, the scan revealed multiple noncalcified nodules of both lungs with enlarged bilateral hilar and paratracheal lymph nodes, lytic bone lesions, and multiple enhancing round lesions throughout the liver, suggesting metastatic involvement (FIGURE 2).

FIGURE 2

Abdominal CT scan reveals a 12-cm mass on right kidney

Metastases on initial presentation? It’s not uncommon

More than 64,000 new cases of renal cancer are expected to be diagnosed in 2012 and 92% of them are expected to be cases of RCC.1 Interestingly, the incidence and mortality rates of RCC have been on the rise.2 Part of this increased incidence is likely secondary to increased detection of asymptomatic renal masses noted on imaging studies done for other reasons; however, the increased overall mortality from renal cancer is not fully understood.

Renal cancer risk factors include tobacco use, obesity, renal cystic disease, and toxic occupational exposures (eg, cadmium). A genetic predisposition also appears to play a role.2 The classic presenting symptoms of renal malignancy include hematuria, a flank mass, and abdominal pain. Patients may experience a single symptom but rarely all 3, and many patients come in with nonspecific complaints of fever, sweats, weight loss, and fatigue.2

RCC also has a propensity for paraneoplastic syndromes that may present with anemia, hypercalcemia, or hepatic dysfunction.2 Unfortunately, many smaller renal lesions are asymptomatic, so as many as 55% of patients may present with metastatic disease at the time of initial presentation.3

The most common sites for renal metastatic disease are the lungs, bone, lymph nodes, brain, and contralateral kidney.2 Skin metastases, occurring in 2% to 10% of RCC cases, are less common and are often a sign of poorer prognosis.4 Men who have RCC are more likely to have skin metastases than women; the typical locations are the head, neck, and trunk.4

Is it RCC, or something else?

Signs and symptoms suggestive of possible renal malignancy (eg, hematuria, flank pain, weight loss, flank mass on exam) should prompt a work-up that includes abdominal imaging. The preferred imaging modality is a CT scan. Final tissue diagnosis is made on review of biopsy specimens obtained from the renal mass.

Skin metastases in RCC may be mistaken for other skin lesions, such as pyogenic granulomas, melanomas, or dermatofibromas.5 Histopathological analysis (and sometimes even special immunohistochemical staining and cytogenic analysis) can be used to make a definitive diagnosis.

Management options include radical nephrectomy

Treatment options and the prognosis for RCC are dependent on the extent of disease involvement at diagnosis. Radical nephrectomy is the gold standard therapy for patients with local, locally advanced, and even minimally metastatic disease.6

Other therapies include immunotherapy, interferons, interleukins, and gene therapy.6 Chemotherapy and radiation therapy have a limited role, as RCC is generally resistant to them. However, with more advanced metastatic disease, most treatment is palliative. The median survival time after diagnosis of metastatic RCC is about 20 months.6

Patient opts for treatment, then discontinues it

My patient was transferred to a local hospital with oncology support for further evaluation and management. He was ultimately diagnosed with metastatic renal carcinoma with bony, cutaneous, liver, and lung metastases. His hospital course was complicated by the development of hematuria and anemia, which required additional blood transfusions.

The patient was initially started on immunotherapy with sorafenib but upon acceptance of his metastatic disease and poor prognosis, he opted to discontinue therapy and enter an inpatient hospice facility.

CORRESPONDENCE Lesli M. Lucas, MD, Naval Branch Health Clinic Dahlgren, 17457 Caffee Road, Dahlgren, VA 22448; [email protected]

A 61-year-old Caucasian man sought care at our emergency department for a painful mass on his right leg that had appeared and progressively enlarged over the past 3 weeks. The patient denied trauma prior to the appearance of the mass, but did note extensive varicosities spanning from the right groin to the right foot a few weeks before the lesion appeared.

He also indicated that he’d had progressive dyspnea and intermittent chest pain for the past 4 months, a 30-lb weight loss in the past 6 months without change in appetite or diet, a depressed mood, and generalized weakness.

The patient’s past medical history was notable for hypertension and coronary artery disease. He reported a 30 pack-year smoking history, but had quit 12 years earlier. He denied alcohol use, although there was a family history of alcoholism and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Physical examination revealed a frail, pale, unkempt man. His vital signs were normal except for mild tachycardia. Additional findings included:

- nonicteric, pale palpebral conjunctivae

- a 3/6 nonradiating holosystolic murmur heard along the left upper sternal border

- a large friable 3.5-cm pedunculated mass on a 2-cm stalk located on right lower leg (FIGURE 1); the lesion was moist, purple, and exophytic

- bilateral enlargement of the inguinal lymph nodes.

Lab work revealed microcytic anemia with a hemoglobin count of 5.8 g/dL and mild hyponatremia. The patient’s liver and renal function were normal. Urinalysis showed 3 red blood cells (RBCs) and a chest x-ray revealed bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy.

FIGURE 1

Exophytic mass on right lower leg

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Renal cell carcinoma

The patient was admitted and stabilized with packed RBCs for symptomatic anemia. He underwent biopsy of the right leg lesion and computed tomography (CT) imaging of his chest, abdomen, and pelvis.

The biopsy report from the resected right leg mass revealed metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma (RCC). The CT scan showed a large exophytic mass involving the right kidney measuring 12 × 11 × 9 cm. Additionally, the scan revealed multiple noncalcified nodules of both lungs with enlarged bilateral hilar and paratracheal lymph nodes, lytic bone lesions, and multiple enhancing round lesions throughout the liver, suggesting metastatic involvement (FIGURE 2).

FIGURE 2

Abdominal CT scan reveals a 12-cm mass on right kidney

Metastases on initial presentation? It’s not uncommon

More than 64,000 new cases of renal cancer are expected to be diagnosed in 2012 and 92% of them are expected to be cases of RCC.1 Interestingly, the incidence and mortality rates of RCC have been on the rise.2 Part of this increased incidence is likely secondary to increased detection of asymptomatic renal masses noted on imaging studies done for other reasons; however, the increased overall mortality from renal cancer is not fully understood.

Renal cancer risk factors include tobacco use, obesity, renal cystic disease, and toxic occupational exposures (eg, cadmium). A genetic predisposition also appears to play a role.2 The classic presenting symptoms of renal malignancy include hematuria, a flank mass, and abdominal pain. Patients may experience a single symptom but rarely all 3, and many patients come in with nonspecific complaints of fever, sweats, weight loss, and fatigue.2

RCC also has a propensity for paraneoplastic syndromes that may present with anemia, hypercalcemia, or hepatic dysfunction.2 Unfortunately, many smaller renal lesions are asymptomatic, so as many as 55% of patients may present with metastatic disease at the time of initial presentation.3

The most common sites for renal metastatic disease are the lungs, bone, lymph nodes, brain, and contralateral kidney.2 Skin metastases, occurring in 2% to 10% of RCC cases, are less common and are often a sign of poorer prognosis.4 Men who have RCC are more likely to have skin metastases than women; the typical locations are the head, neck, and trunk.4

Is it RCC, or something else?

Signs and symptoms suggestive of possible renal malignancy (eg, hematuria, flank pain, weight loss, flank mass on exam) should prompt a work-up that includes abdominal imaging. The preferred imaging modality is a CT scan. Final tissue diagnosis is made on review of biopsy specimens obtained from the renal mass.

Skin metastases in RCC may be mistaken for other skin lesions, such as pyogenic granulomas, melanomas, or dermatofibromas.5 Histopathological analysis (and sometimes even special immunohistochemical staining and cytogenic analysis) can be used to make a definitive diagnosis.

Management options include radical nephrectomy

Treatment options and the prognosis for RCC are dependent on the extent of disease involvement at diagnosis. Radical nephrectomy is the gold standard therapy for patients with local, locally advanced, and even minimally metastatic disease.6

Other therapies include immunotherapy, interferons, interleukins, and gene therapy.6 Chemotherapy and radiation therapy have a limited role, as RCC is generally resistant to them. However, with more advanced metastatic disease, most treatment is palliative. The median survival time after diagnosis of metastatic RCC is about 20 months.6

Patient opts for treatment, then discontinues it

My patient was transferred to a local hospital with oncology support for further evaluation and management. He was ultimately diagnosed with metastatic renal carcinoma with bony, cutaneous, liver, and lung metastases. His hospital course was complicated by the development of hematuria and anemia, which required additional blood transfusions.

The patient was initially started on immunotherapy with sorafenib but upon acceptance of his metastatic disease and poor prognosis, he opted to discontinue therapy and enter an inpatient hospice facility.

CORRESPONDENCE Lesli M. Lucas, MD, Naval Branch Health Clinic Dahlgren, 17457 Caffee Road, Dahlgren, VA 22448; [email protected]

1. American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures 2012. Available at: http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-031941.pdf. Accessed April 6, 2012.

2. Gillenwater JY. Renal tumors. In: Gillenwater JY, Grayhack JT, Howards SS, Mitchell ME, eds. Adult and Pediatric Urology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002: 612-641.

3. Cuckow P, Doyle P. Renal cell carcinoma presenting in the skin. J R Soc Med. 1991;84:497-498.

4. Preetha R. Cutaneous metastasis from silent renal cell carcinoma. J Postgrad Med. 2004;50:287-288.

5. Garcia TM. Skin metastases from a renal cell carcinoma [in Spanish]. Actas Urol Esp. 2007;31:556-558.

6. Vogelzang NJ, Stadler WM. Kidney cancer. Lancet. 1998;352:1691-1696.

1. American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures 2012. Available at: http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-031941.pdf. Accessed April 6, 2012.