User login

CDC: Older kids should get annual flu vaccine, too

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has made 2 significant changes to its annual recommendations for the prevention of influenza during the 2008-2009 flu season:1

- Annual vaccination is now recommended for all children ages 6 months through 18 years. (Last year, universal influenza vaccination was recommended only for children ages 6 months through 4 years.)

- The live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) can now be used starting at 2 years of age.

Vaccinate older children

The CDC now recommends that 5- to 18-year-olds receive the influenza vaccine annually, and that this routine vaccination start as soon as possible, but no later than the 2009-2010 flu season. In other words, if routine vaccination can be achieved this year it is encouraged, but the CDC recognizes that it may not be possible to achieve in some settings until next year.

If family physicians do not incorporate routine vaccination for those ages 5 to 18 this year, they should still provide it for those in this age group who are at high risk for influenza complications, including those who:

- are on long-term aspirin therapy;

- have chronic pulmonary (including asthma), cardiovascular, renal, hepatic, hematological, or metabolic disorders;

- are immunosuppressed; or

- have disorders that alter respiratory functions or the handling of respiratory secretions.

Children who live in households with others who are at higher risk (children who are <5 years old, adults >50 years, and anyone with a medical condition that places him or her at high risk for severe influenza complications) should also be vaccinated.

LAIV is an option for even younger kids

Last year, the LAIV vaccine was licensed for children starting at age 5. Now, the LAIV can be given to healthy children starting at age 2, as well as to adolescents and adults through age 49. TABLE 1 compares the LAIV with the trivalent influenza vaccine (TIV).

Because LAIV is an attenuated live virus vaccine, some children should not receive it, including those younger than 5 years of age with reactive airway disease (recurrent wheezing or recent wheezing); those with a medical condition that places them at high risk of influenza complications; and those younger than 2 years of age. The TIV can be used in these children, starting at 6 months of age.

Regardless of whether a child receives LAIV or TIV, those younger than 9 years of age who are receiving influenza vaccine for the first time should receive 2 doses 4 weeks apart. If a child received only 1 dose in the first year, the following year he or she should receive 2 doses 4 weeks apart.

TABLE 1

LAIV vs TIV: How the 2 compare

| LAIV | TIV | |

|---|---|---|

| Route of administration | Intranasal spray | Intramuscular injection |

| Type of vaccine | Live attenuated virus | Killed virus |

| Approved age | 2-49 years | ≥6 months |

| Interval between 2 doses recommended for children 6 months to 8 years who are receiving influenza vaccine for the first time | 4 weeks | 4 weeks |

| Use with other live virus vaccines | Simultaneously or separated by 4 weeks | No restrictions |

| Use with influenza antiviral medication | Wait 48 hours after last antiviral dose to administer LAIV; wait 2 weeks after LAIV to administer antivirals | No restrictions |

| Contraindications and precautions | Chronic illness | Anaphylactic hypersensitivity to eggs |

| Chronic aspirin therapy | Moderate-to-severe illness (precaution) | |

| History of Guillain-Barre syndrome | ||

| Pregnancy | ||

| Caregiver to severely immune-suppressed individual | ||

| LAIV, live attenuated influenza vaccine; TIV, trivalent influenza vaccine. | ||

Coverage rates still need to improve

Influenza vaccine and antiviral agents continue to be underutilized. TABLE 2 lists estimated coverage with influenza vaccine for specific groups for whom immunization is recommended. It is particularly important that coverage rates for health care workers—which remain below 50%—be improved. Health care workers are at high risk of exposure to influenza and pose a risk of disease transmission to their families, other staff members, and patients. Family physicians should ensure that they and their staff are vaccinated each year.

Missed opportunities. Many patients for whom influenza vaccine is recommended fail to receive the vaccine because of missed opportunities. Physicians should offer the vaccine starting in October (or as soon as the vaccine supply allows) and continue to offer and encourage it through the entire flu season. Peak influenza activity can occur as late as April and May and occurs after February on average of 1 in every 5 years.

TABLE 2

Immunization is recommended, but what were the coverage rates?*

| POPULATION GROUP | COVERAGE |

|---|---|

| Age 6-23 months | 32.2% |

| Age 2-4 years | 37.9% |

| Age ≥65 years | 65.6% |

| Pregnant women | 13.4% |

| Health care workers | 41.8% |

| Ages 18-64 years with high-risk conditions | 35.3% |

| * Influenza vaccination coverage is for the most recent year surveyed (2005-06 or 2006-07). | |

Autism concerns persist among parents

Despite clear scientific evidence that neither vaccines nor thimerosal preservative cause autism, some parents remain concerned. Some states have passed laws prohibiting the use of any thimerosal-containing vaccines and some parents may request thimerosal-free vaccines. TABLE 3 lists all the influenza vaccines and their thimerosal content.

TABLE 3

Which vaccines contain thimerosal—and how much?

| VACCINE | TRADE NAME | MANUFACTURER | HOW SUPPLIED | MERCURY CONTENT (MCG HG/0.5 ML DOSE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIV | Fluzone | Sanofi Pasteur | 0.25-mL prefilled syringe | 0 |

| 0.5-mL prefilled syringe | 0 | |||

| 0.5-mL vial | 0 | |||

| 5-mL multidose vial | 25 | |||

| TIV | Fluvirin | Novartis Vaccines | 5-mL multidose vial | 25 |

| 0.5-mL prefilled syringe | ≤1 | |||

| TIV | Fluarix | GlaxoSmithKline | 0.5-mL prefilled syringe | ≤1 |

| TIV | FluLaval | GlaxoSmithKline | 5-mL multidose vial | 25 |

| TIV | Afluria | CSL Biotherapies | 0.5-mL prefilled syringe | 0 |

| 5-mL multidose vial | 24.5 | |||

| LAIV | FluMist | MedImmune | 0.2-mL sprayer | 0 |

Make use of antivirals

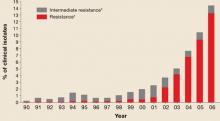

Two antiviral medications are licensed and approved for the treatment and prevention of influenza: oseltamivir (Tamiflu) and zanamivir (Relenza). Two others (amantadine and rimantadine) are licensed but not currently recommended due to the high rates of resistance that influenza has developed against them.

Oseltamivir is approved for the treatment and prophylaxis of influenza starting at 1 year of age.

Zanamivir is approved for the treatment of influenza starting at 7 years of age and for prophylaxis starting at 5 years of age.

Treatment, if started within 48 hours of symptom onset, reduces the severity and length of infection and the length of infectiousness. Antiviral prophylaxis should be considered when there is increased influenza activity for those listed in TABLE 4.

TABLE 4

Increased flu activity in the community? Consider antiviral prophylaxis

|

| Note: Recommended antiviral medications (neuraminidase inhibitors) are not licensed for prophylaxis of children <1 year of age (oseltamivir) or <5 years of age (zanamivir). |

Every bit helps

Each year, influenza kills, on average, 36,000 Americans and hospitalizes another 200,000. Much of this morbidity and mortality could be avoided with full utilization of influenza vaccines and antiviral medications. You can contribute to improved public health by assuring that your patients and staff are fully immunized, that office infection control practices are adhered to, and that antiviral prophylaxis is used when indicated.

Reference

1. Prevention and control of influenza. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2008. MMWR;57(Early Release: July 17, 2008). Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr57e717a1.htm. Accessed August 25, 2008.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has made 2 significant changes to its annual recommendations for the prevention of influenza during the 2008-2009 flu season:1

- Annual vaccination is now recommended for all children ages 6 months through 18 years. (Last year, universal influenza vaccination was recommended only for children ages 6 months through 4 years.)

- The live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) can now be used starting at 2 years of age.

Vaccinate older children

The CDC now recommends that 5- to 18-year-olds receive the influenza vaccine annually, and that this routine vaccination start as soon as possible, but no later than the 2009-2010 flu season. In other words, if routine vaccination can be achieved this year it is encouraged, but the CDC recognizes that it may not be possible to achieve in some settings until next year.

If family physicians do not incorporate routine vaccination for those ages 5 to 18 this year, they should still provide it for those in this age group who are at high risk for influenza complications, including those who:

- are on long-term aspirin therapy;

- have chronic pulmonary (including asthma), cardiovascular, renal, hepatic, hematological, or metabolic disorders;

- are immunosuppressed; or

- have disorders that alter respiratory functions or the handling of respiratory secretions.

Children who live in households with others who are at higher risk (children who are <5 years old, adults >50 years, and anyone with a medical condition that places him or her at high risk for severe influenza complications) should also be vaccinated.

LAIV is an option for even younger kids

Last year, the LAIV vaccine was licensed for children starting at age 5. Now, the LAIV can be given to healthy children starting at age 2, as well as to adolescents and adults through age 49. TABLE 1 compares the LAIV with the trivalent influenza vaccine (TIV).

Because LAIV is an attenuated live virus vaccine, some children should not receive it, including those younger than 5 years of age with reactive airway disease (recurrent wheezing or recent wheezing); those with a medical condition that places them at high risk of influenza complications; and those younger than 2 years of age. The TIV can be used in these children, starting at 6 months of age.

Regardless of whether a child receives LAIV or TIV, those younger than 9 years of age who are receiving influenza vaccine for the first time should receive 2 doses 4 weeks apart. If a child received only 1 dose in the first year, the following year he or she should receive 2 doses 4 weeks apart.

TABLE 1

LAIV vs TIV: How the 2 compare

| LAIV | TIV | |

|---|---|---|

| Route of administration | Intranasal spray | Intramuscular injection |

| Type of vaccine | Live attenuated virus | Killed virus |

| Approved age | 2-49 years | ≥6 months |

| Interval between 2 doses recommended for children 6 months to 8 years who are receiving influenza vaccine for the first time | 4 weeks | 4 weeks |

| Use with other live virus vaccines | Simultaneously or separated by 4 weeks | No restrictions |

| Use with influenza antiviral medication | Wait 48 hours after last antiviral dose to administer LAIV; wait 2 weeks after LAIV to administer antivirals | No restrictions |

| Contraindications and precautions | Chronic illness | Anaphylactic hypersensitivity to eggs |

| Chronic aspirin therapy | Moderate-to-severe illness (precaution) | |

| History of Guillain-Barre syndrome | ||

| Pregnancy | ||

| Caregiver to severely immune-suppressed individual | ||

| LAIV, live attenuated influenza vaccine; TIV, trivalent influenza vaccine. | ||

Coverage rates still need to improve

Influenza vaccine and antiviral agents continue to be underutilized. TABLE 2 lists estimated coverage with influenza vaccine for specific groups for whom immunization is recommended. It is particularly important that coverage rates for health care workers—which remain below 50%—be improved. Health care workers are at high risk of exposure to influenza and pose a risk of disease transmission to their families, other staff members, and patients. Family physicians should ensure that they and their staff are vaccinated each year.

Missed opportunities. Many patients for whom influenza vaccine is recommended fail to receive the vaccine because of missed opportunities. Physicians should offer the vaccine starting in October (or as soon as the vaccine supply allows) and continue to offer and encourage it through the entire flu season. Peak influenza activity can occur as late as April and May and occurs after February on average of 1 in every 5 years.

TABLE 2

Immunization is recommended, but what were the coverage rates?*

| POPULATION GROUP | COVERAGE |

|---|---|

| Age 6-23 months | 32.2% |

| Age 2-4 years | 37.9% |

| Age ≥65 years | 65.6% |

| Pregnant women | 13.4% |

| Health care workers | 41.8% |

| Ages 18-64 years with high-risk conditions | 35.3% |

| * Influenza vaccination coverage is for the most recent year surveyed (2005-06 or 2006-07). | |

Autism concerns persist among parents

Despite clear scientific evidence that neither vaccines nor thimerosal preservative cause autism, some parents remain concerned. Some states have passed laws prohibiting the use of any thimerosal-containing vaccines and some parents may request thimerosal-free vaccines. TABLE 3 lists all the influenza vaccines and their thimerosal content.

TABLE 3

Which vaccines contain thimerosal—and how much?

| VACCINE | TRADE NAME | MANUFACTURER | HOW SUPPLIED | MERCURY CONTENT (MCG HG/0.5 ML DOSE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIV | Fluzone | Sanofi Pasteur | 0.25-mL prefilled syringe | 0 |

| 0.5-mL prefilled syringe | 0 | |||

| 0.5-mL vial | 0 | |||

| 5-mL multidose vial | 25 | |||

| TIV | Fluvirin | Novartis Vaccines | 5-mL multidose vial | 25 |

| 0.5-mL prefilled syringe | ≤1 | |||

| TIV | Fluarix | GlaxoSmithKline | 0.5-mL prefilled syringe | ≤1 |

| TIV | FluLaval | GlaxoSmithKline | 5-mL multidose vial | 25 |

| TIV | Afluria | CSL Biotherapies | 0.5-mL prefilled syringe | 0 |

| 5-mL multidose vial | 24.5 | |||

| LAIV | FluMist | MedImmune | 0.2-mL sprayer | 0 |

Make use of antivirals

Two antiviral medications are licensed and approved for the treatment and prevention of influenza: oseltamivir (Tamiflu) and zanamivir (Relenza). Two others (amantadine and rimantadine) are licensed but not currently recommended due to the high rates of resistance that influenza has developed against them.

Oseltamivir is approved for the treatment and prophylaxis of influenza starting at 1 year of age.

Zanamivir is approved for the treatment of influenza starting at 7 years of age and for prophylaxis starting at 5 years of age.

Treatment, if started within 48 hours of symptom onset, reduces the severity and length of infection and the length of infectiousness. Antiviral prophylaxis should be considered when there is increased influenza activity for those listed in TABLE 4.

TABLE 4

Increased flu activity in the community? Consider antiviral prophylaxis

|

| Note: Recommended antiviral medications (neuraminidase inhibitors) are not licensed for prophylaxis of children <1 year of age (oseltamivir) or <5 years of age (zanamivir). |

Every bit helps

Each year, influenza kills, on average, 36,000 Americans and hospitalizes another 200,000. Much of this morbidity and mortality could be avoided with full utilization of influenza vaccines and antiviral medications. You can contribute to improved public health by assuring that your patients and staff are fully immunized, that office infection control practices are adhered to, and that antiviral prophylaxis is used when indicated.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has made 2 significant changes to its annual recommendations for the prevention of influenza during the 2008-2009 flu season:1

- Annual vaccination is now recommended for all children ages 6 months through 18 years. (Last year, universal influenza vaccination was recommended only for children ages 6 months through 4 years.)

- The live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) can now be used starting at 2 years of age.

Vaccinate older children

The CDC now recommends that 5- to 18-year-olds receive the influenza vaccine annually, and that this routine vaccination start as soon as possible, but no later than the 2009-2010 flu season. In other words, if routine vaccination can be achieved this year it is encouraged, but the CDC recognizes that it may not be possible to achieve in some settings until next year.

If family physicians do not incorporate routine vaccination for those ages 5 to 18 this year, they should still provide it for those in this age group who are at high risk for influenza complications, including those who:

- are on long-term aspirin therapy;

- have chronic pulmonary (including asthma), cardiovascular, renal, hepatic, hematological, or metabolic disorders;

- are immunosuppressed; or

- have disorders that alter respiratory functions or the handling of respiratory secretions.

Children who live in households with others who are at higher risk (children who are <5 years old, adults >50 years, and anyone with a medical condition that places him or her at high risk for severe influenza complications) should also be vaccinated.

LAIV is an option for even younger kids

Last year, the LAIV vaccine was licensed for children starting at age 5. Now, the LAIV can be given to healthy children starting at age 2, as well as to adolescents and adults through age 49. TABLE 1 compares the LAIV with the trivalent influenza vaccine (TIV).

Because LAIV is an attenuated live virus vaccine, some children should not receive it, including those younger than 5 years of age with reactive airway disease (recurrent wheezing or recent wheezing); those with a medical condition that places them at high risk of influenza complications; and those younger than 2 years of age. The TIV can be used in these children, starting at 6 months of age.

Regardless of whether a child receives LAIV or TIV, those younger than 9 years of age who are receiving influenza vaccine for the first time should receive 2 doses 4 weeks apart. If a child received only 1 dose in the first year, the following year he or she should receive 2 doses 4 weeks apart.

TABLE 1

LAIV vs TIV: How the 2 compare

| LAIV | TIV | |

|---|---|---|

| Route of administration | Intranasal spray | Intramuscular injection |

| Type of vaccine | Live attenuated virus | Killed virus |

| Approved age | 2-49 years | ≥6 months |

| Interval between 2 doses recommended for children 6 months to 8 years who are receiving influenza vaccine for the first time | 4 weeks | 4 weeks |

| Use with other live virus vaccines | Simultaneously or separated by 4 weeks | No restrictions |

| Use with influenza antiviral medication | Wait 48 hours after last antiviral dose to administer LAIV; wait 2 weeks after LAIV to administer antivirals | No restrictions |

| Contraindications and precautions | Chronic illness | Anaphylactic hypersensitivity to eggs |

| Chronic aspirin therapy | Moderate-to-severe illness (precaution) | |

| History of Guillain-Barre syndrome | ||

| Pregnancy | ||

| Caregiver to severely immune-suppressed individual | ||

| LAIV, live attenuated influenza vaccine; TIV, trivalent influenza vaccine. | ||

Coverage rates still need to improve

Influenza vaccine and antiviral agents continue to be underutilized. TABLE 2 lists estimated coverage with influenza vaccine for specific groups for whom immunization is recommended. It is particularly important that coverage rates for health care workers—which remain below 50%—be improved. Health care workers are at high risk of exposure to influenza and pose a risk of disease transmission to their families, other staff members, and patients. Family physicians should ensure that they and their staff are vaccinated each year.

Missed opportunities. Many patients for whom influenza vaccine is recommended fail to receive the vaccine because of missed opportunities. Physicians should offer the vaccine starting in October (or as soon as the vaccine supply allows) and continue to offer and encourage it through the entire flu season. Peak influenza activity can occur as late as April and May and occurs after February on average of 1 in every 5 years.

TABLE 2

Immunization is recommended, but what were the coverage rates?*

| POPULATION GROUP | COVERAGE |

|---|---|

| Age 6-23 months | 32.2% |

| Age 2-4 years | 37.9% |

| Age ≥65 years | 65.6% |

| Pregnant women | 13.4% |

| Health care workers | 41.8% |

| Ages 18-64 years with high-risk conditions | 35.3% |

| * Influenza vaccination coverage is for the most recent year surveyed (2005-06 or 2006-07). | |

Autism concerns persist among parents

Despite clear scientific evidence that neither vaccines nor thimerosal preservative cause autism, some parents remain concerned. Some states have passed laws prohibiting the use of any thimerosal-containing vaccines and some parents may request thimerosal-free vaccines. TABLE 3 lists all the influenza vaccines and their thimerosal content.

TABLE 3

Which vaccines contain thimerosal—and how much?

| VACCINE | TRADE NAME | MANUFACTURER | HOW SUPPLIED | MERCURY CONTENT (MCG HG/0.5 ML DOSE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIV | Fluzone | Sanofi Pasteur | 0.25-mL prefilled syringe | 0 |

| 0.5-mL prefilled syringe | 0 | |||

| 0.5-mL vial | 0 | |||

| 5-mL multidose vial | 25 | |||

| TIV | Fluvirin | Novartis Vaccines | 5-mL multidose vial | 25 |

| 0.5-mL prefilled syringe | ≤1 | |||

| TIV | Fluarix | GlaxoSmithKline | 0.5-mL prefilled syringe | ≤1 |

| TIV | FluLaval | GlaxoSmithKline | 5-mL multidose vial | 25 |

| TIV | Afluria | CSL Biotherapies | 0.5-mL prefilled syringe | 0 |

| 5-mL multidose vial | 24.5 | |||

| LAIV | FluMist | MedImmune | 0.2-mL sprayer | 0 |

Make use of antivirals

Two antiviral medications are licensed and approved for the treatment and prevention of influenza: oseltamivir (Tamiflu) and zanamivir (Relenza). Two others (amantadine and rimantadine) are licensed but not currently recommended due to the high rates of resistance that influenza has developed against them.

Oseltamivir is approved for the treatment and prophylaxis of influenza starting at 1 year of age.

Zanamivir is approved for the treatment of influenza starting at 7 years of age and for prophylaxis starting at 5 years of age.

Treatment, if started within 48 hours of symptom onset, reduces the severity and length of infection and the length of infectiousness. Antiviral prophylaxis should be considered when there is increased influenza activity for those listed in TABLE 4.

TABLE 4

Increased flu activity in the community? Consider antiviral prophylaxis

|

| Note: Recommended antiviral medications (neuraminidase inhibitors) are not licensed for prophylaxis of children <1 year of age (oseltamivir) or <5 years of age (zanamivir). |

Every bit helps

Each year, influenza kills, on average, 36,000 Americans and hospitalizes another 200,000. Much of this morbidity and mortality could be avoided with full utilization of influenza vaccines and antiviral medications. You can contribute to improved public health by assuring that your patients and staff are fully immunized, that office infection control practices are adhered to, and that antiviral prophylaxis is used when indicated.

Reference

1. Prevention and control of influenza. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2008. MMWR;57(Early Release: July 17, 2008). Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr57e717a1.htm. Accessed August 25, 2008.

Reference

1. Prevention and control of influenza. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2008. MMWR;57(Early Release: July 17, 2008). Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr57e717a1.htm. Accessed August 25, 2008.

Should you screen—or not? The latest recommendations

Not enough time and too many potential tests to do. This is the problem faced daily by family physicians. We want to practice up-to-date preventive medicine, but there’s little time to analyze the latest studies. Thankfully, we can rely on the United States Preventive Services Task Force, the organization with the most rigorous evidence-based approach, to do the legwork for us.1

Last year, and in the early part of this year, the Task Force issued a number of recommendations on topics ranging from hypertension screening to screening for illicit drug use. (See TABLE 1 for a breakdown of the 5 categories of recommendations.)

While some of these recommendations (TABLE 2) were reaffirmations of past recommendations, others included some changes.

The Task Force has:

- dropped the age for routine screening for Chlamydia in sexually active women from 25 years and younger to 24 and younger.

- added a recommendation against the use of aspirin or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to prevent colorectal cancer (CRC).

- changed its recommendation on screening for carotid artery stenosis. In 1996, the Task Force noted that the evidence was insufficient to make a recommendation; in 2007 it recommended against such routine screening.

- added recommendations on counseling patients about drinking and driving, as well as on screening for illicit drug use. In both cases, the Task Force says the evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against.

TABLE 1

USPSTF recommendation categories

| A Recommendation: The Task Force recommends the service. There is a high certainty that the net benefit is substantial. |

| B Recommendation: The Task Force recommends the service. There is high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial. |

| C Recommendation: The Task Force recommends against routinely providing the service. There may be considerations that support providing the service in an individual patient. There is at least moderate certainty that the net benefit is small. |

| D Recommendation: The Task Force recommends against the service. There is moderate or high certainty that the service has no net benefit or that the harms outweigh the benefits. |

| I Recommendation: The Task Force concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of the service. Evidence is lacking, of poor quality, or conflicting, and the balance of benefits and harms cannot be determined. |

TABLE 2

Summary of new USPSTF recommendations

| A RECOMMENDATIONS |

The USPSTF recommends routinely:

|

| B RECOMMENDATIONS |

The USPSTF recommends routinely:

|

| C RECOMMENDATIONS |

The USPSTF recommends against routine:

|

| D RECOMMENDATIONS |

The USPSTF recommends against routine:

|

| I RECOMMENDATIONS |

The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against routine:

|

Continue to screen for HTN, sickle cell, Chlamydia

The latest A and B recommendations from the Task Force largely reaffirm previous recommendations. These recommendations cover hypertension, sickle cell disease, and Chlamydia.

Hypertension. Screening and treatment of hypertension in adults leads to lower morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular disease and is still recommended.2

Sickle cell disease. Screening newborns for sickle cell disease and treating those affected with oral prophylactic penicillin prevents serious bacterial infections. It also remains a recommended service.3

Chlamydia. Following a review of the evidence, the Task Force reconfirms the benefits of screening for Chlamydia in sexually active young women, but it has changed the age cutoff. In 2001, the Task Force indicated that sexually active women who were 25 years of age and younger should be screened. In 2007, the Task Force dropped the age to 24 and younger.

The latest recommendation reaffirms the need to screen women (above the cutoff) who are at risk—that is, women who have previously had a sexually transmitted infection (STI), those who have a new or multiple sex partners, and those who exchange sex for money or drugs.4 Screening is recommended annually; nucleic acid amplification tests are acceptable, allowing testing of urine or vaginal swabs.

Screening during pregnancy is recommended for the same groups—women who are 24 and younger and older women at risk—at the first prenatal visit and again in the third trimester if risk continues. Chlamydia is the most common bacterial STI, and screening and treatment prevents pelvic inflammatory disease in women and leads to improved pregnancy outcomes.

Interventions that are not recommended

Chemopreventon of colorectal cancer. For the first time, the Task Force issued a recommendation on the use of aspirin or other NSAIDs to prevent CRC. The Task Force does not recommend the routine use of these agents.5 The dosage needed to prevent CRC is higher than that which prevents cardiovascular disease and can cause significant harm.

Aspirin use is associated with gastrointestinal bleeding and hemorrhagic stroke; NSAID use is associated with gastrointestinal bleeding and renal impairment. The Task Force concludes that in the general adult population, potential harms exceed potential benefits.

Screening for carotid artery stenosis. In 1996, the Task Force found insufficient evidence to recommend for or against routine screening for carotid artery stenosis. In 2007, the Task Force made a recommendation against routine screening for carotid artery stenosis.6 Screening with duplex ultrasonography results in frequent false positives. Confirmatory testing with angiography is associated with a 1% rate of stroke. Endarterectomy itself has a death or stroke rate of about 3%.

In the general population, close to 8700 adults would need to be screened to prevent 1 disabling stroke. The Task Force indicates that primary care physicians would have better outcomes by concentrating on optimal management of risk factors for cerebral artery disease.

Screening for bacterial vaginosis among low-risk pregnant women. The final D recommendation pertains to screening for bacterial vaginosis during pregnancy to prevent preterm delivery.7 Pregnant women who have not had a previous preterm delivery are considered at low risk for preterm delivery and there is good evidence that this group does not benefit from screening for, or treatment of, asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis. (A similar recommendation was made in 2001, but it referred to women of “average” risk.)

Insufficient evidence to make a recommendation

Routinely screening men for Chlamydia. While it makes clinical sense to test and treat male partners of women with Chlamydia infection, the Task Force could not find evidence of the effectiveness of routinely screening men as a way to prevent infection in women.4 That said, the Task Force points out that screening men is relatively inexpensive and has negligible harms.

Screening for hyperlipidemia in children. While 50% of children with hyperlipidemia continue to have this disorder as adults, the long-term benefits and harms of early detection and treatment with medications and lipid-lowering diets have not been studied.8 This echoes the position the Task Force took in 1996, when it commented on children as part of an adult hyperlipidemia recommendation.

Physician counseling on drinking and driving. Motor vehicle crashes result in significant morbidity and mortality—especially among adolescents and young adults. Improved car and road design, as well as public health safety efforts, have led to significant improvements in motor vehicle safety. While avoidance of driving under the influence and proper use of occupant restraints are important public health goals, the Task Force, in this first recommendation on the subject, could find no evidence that physician counseling added benefit above those provided by community-wide efforts.9

Screening for bacterial vaginosis in pregnant women at high risk for preterm birth. As mentioned previously, screening low-risk pregnant women for bacterial vaginosis results in no benefit. The issue is less clear cut among women at high risk for a preterm delivery—that is, those who have had one previously.

The evidence regarding screening and treating asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis as a means of preventing preterm delivery in these women is mixed and the Task Force was unable to recommend for or against this practice.7 This reaffirms the Task Force’s 2001 recommendation.

Screening for illicit drug use. The Task Force recognizes that illicit drug use is a major cause of illness and social problems. It would appear to have great potential for early detection and intervention. However, the Task Force, in this first-time recommendation, found that screening tools have not been well studied, nor have the long-term effects of different treatment strategies.10 These are high priority areas for future research.

Correspondence

Doug Campos-Outcalt, MD, MPA, 550 E. Van Buren, Phoenix, AZ 85004; [email protected]

1. Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research. USPSTF. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstfix.htm. Accessed May 5, 2008.

2. USPSTF. Screening for High Blood Pressure. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspshype.htm. Accessed May 5, 2008.

3. USPSTF. Screening for Sickle Cell Disease in Newborns. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspshemo.htm. Accessed May 5, 2008.

4. USPSTF. Screening for Chlamydia Infection. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspschlm.htm. Accessed May 5, 2008.

5. USPSTF. Aspirin or Nonsteroidal Anti-inflamatory Drugs for the Primary Prevention of Colorectal Cancer. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspsasco.htm. Accessed May 5, 2008.

6. USPSTF. Screening for Carotid Artery Stenosis. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspsacas.htm. Accessed May 5, 2008.

7. USPSTF. Screening for Bacterial Vaginosis in Pregnancy. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspsbvag.htm. Accessed May 5, 2008.

8. USPSTF. Screening for Lipid Disorders in Children. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspschlip.htm. Accessed May 5, 2008.

9. USPSTF. Counseling About Proper Use of Motor Vehicle Occupant Restraints and Avoidance of Alcohol Use While Driving. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspsmvin.htm. Accessed May 5, 2008.

10. USPSTF. Screening for Illicit Drug Use. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspsdrug.htm. Accessed May 5, 2008.

Not enough time and too many potential tests to do. This is the problem faced daily by family physicians. We want to practice up-to-date preventive medicine, but there’s little time to analyze the latest studies. Thankfully, we can rely on the United States Preventive Services Task Force, the organization with the most rigorous evidence-based approach, to do the legwork for us.1

Last year, and in the early part of this year, the Task Force issued a number of recommendations on topics ranging from hypertension screening to screening for illicit drug use. (See TABLE 1 for a breakdown of the 5 categories of recommendations.)

While some of these recommendations (TABLE 2) were reaffirmations of past recommendations, others included some changes.

The Task Force has:

- dropped the age for routine screening for Chlamydia in sexually active women from 25 years and younger to 24 and younger.

- added a recommendation against the use of aspirin or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to prevent colorectal cancer (CRC).

- changed its recommendation on screening for carotid artery stenosis. In 1996, the Task Force noted that the evidence was insufficient to make a recommendation; in 2007 it recommended against such routine screening.

- added recommendations on counseling patients about drinking and driving, as well as on screening for illicit drug use. In both cases, the Task Force says the evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against.

TABLE 1

USPSTF recommendation categories

| A Recommendation: The Task Force recommends the service. There is a high certainty that the net benefit is substantial. |

| B Recommendation: The Task Force recommends the service. There is high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial. |

| C Recommendation: The Task Force recommends against routinely providing the service. There may be considerations that support providing the service in an individual patient. There is at least moderate certainty that the net benefit is small. |

| D Recommendation: The Task Force recommends against the service. There is moderate or high certainty that the service has no net benefit or that the harms outweigh the benefits. |

| I Recommendation: The Task Force concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of the service. Evidence is lacking, of poor quality, or conflicting, and the balance of benefits and harms cannot be determined. |

TABLE 2

Summary of new USPSTF recommendations

| A RECOMMENDATIONS |

The USPSTF recommends routinely:

|

| B RECOMMENDATIONS |

The USPSTF recommends routinely:

|

| C RECOMMENDATIONS |

The USPSTF recommends against routine:

|

| D RECOMMENDATIONS |

The USPSTF recommends against routine:

|

| I RECOMMENDATIONS |

The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against routine:

|

Continue to screen for HTN, sickle cell, Chlamydia

The latest A and B recommendations from the Task Force largely reaffirm previous recommendations. These recommendations cover hypertension, sickle cell disease, and Chlamydia.

Hypertension. Screening and treatment of hypertension in adults leads to lower morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular disease and is still recommended.2

Sickle cell disease. Screening newborns for sickle cell disease and treating those affected with oral prophylactic penicillin prevents serious bacterial infections. It also remains a recommended service.3

Chlamydia. Following a review of the evidence, the Task Force reconfirms the benefits of screening for Chlamydia in sexually active young women, but it has changed the age cutoff. In 2001, the Task Force indicated that sexually active women who were 25 years of age and younger should be screened. In 2007, the Task Force dropped the age to 24 and younger.

The latest recommendation reaffirms the need to screen women (above the cutoff) who are at risk—that is, women who have previously had a sexually transmitted infection (STI), those who have a new or multiple sex partners, and those who exchange sex for money or drugs.4 Screening is recommended annually; nucleic acid amplification tests are acceptable, allowing testing of urine or vaginal swabs.

Screening during pregnancy is recommended for the same groups—women who are 24 and younger and older women at risk—at the first prenatal visit and again in the third trimester if risk continues. Chlamydia is the most common bacterial STI, and screening and treatment prevents pelvic inflammatory disease in women and leads to improved pregnancy outcomes.

Interventions that are not recommended

Chemopreventon of colorectal cancer. For the first time, the Task Force issued a recommendation on the use of aspirin or other NSAIDs to prevent CRC. The Task Force does not recommend the routine use of these agents.5 The dosage needed to prevent CRC is higher than that which prevents cardiovascular disease and can cause significant harm.

Aspirin use is associated with gastrointestinal bleeding and hemorrhagic stroke; NSAID use is associated with gastrointestinal bleeding and renal impairment. The Task Force concludes that in the general adult population, potential harms exceed potential benefits.

Screening for carotid artery stenosis. In 1996, the Task Force found insufficient evidence to recommend for or against routine screening for carotid artery stenosis. In 2007, the Task Force made a recommendation against routine screening for carotid artery stenosis.6 Screening with duplex ultrasonography results in frequent false positives. Confirmatory testing with angiography is associated with a 1% rate of stroke. Endarterectomy itself has a death or stroke rate of about 3%.

In the general population, close to 8700 adults would need to be screened to prevent 1 disabling stroke. The Task Force indicates that primary care physicians would have better outcomes by concentrating on optimal management of risk factors for cerebral artery disease.

Screening for bacterial vaginosis among low-risk pregnant women. The final D recommendation pertains to screening for bacterial vaginosis during pregnancy to prevent preterm delivery.7 Pregnant women who have not had a previous preterm delivery are considered at low risk for preterm delivery and there is good evidence that this group does not benefit from screening for, or treatment of, asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis. (A similar recommendation was made in 2001, but it referred to women of “average” risk.)

Insufficient evidence to make a recommendation

Routinely screening men for Chlamydia. While it makes clinical sense to test and treat male partners of women with Chlamydia infection, the Task Force could not find evidence of the effectiveness of routinely screening men as a way to prevent infection in women.4 That said, the Task Force points out that screening men is relatively inexpensive and has negligible harms.

Screening for hyperlipidemia in children. While 50% of children with hyperlipidemia continue to have this disorder as adults, the long-term benefits and harms of early detection and treatment with medications and lipid-lowering diets have not been studied.8 This echoes the position the Task Force took in 1996, when it commented on children as part of an adult hyperlipidemia recommendation.

Physician counseling on drinking and driving. Motor vehicle crashes result in significant morbidity and mortality—especially among adolescents and young adults. Improved car and road design, as well as public health safety efforts, have led to significant improvements in motor vehicle safety. While avoidance of driving under the influence and proper use of occupant restraints are important public health goals, the Task Force, in this first recommendation on the subject, could find no evidence that physician counseling added benefit above those provided by community-wide efforts.9

Screening for bacterial vaginosis in pregnant women at high risk for preterm birth. As mentioned previously, screening low-risk pregnant women for bacterial vaginosis results in no benefit. The issue is less clear cut among women at high risk for a preterm delivery—that is, those who have had one previously.

The evidence regarding screening and treating asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis as a means of preventing preterm delivery in these women is mixed and the Task Force was unable to recommend for or against this practice.7 This reaffirms the Task Force’s 2001 recommendation.

Screening for illicit drug use. The Task Force recognizes that illicit drug use is a major cause of illness and social problems. It would appear to have great potential for early detection and intervention. However, the Task Force, in this first-time recommendation, found that screening tools have not been well studied, nor have the long-term effects of different treatment strategies.10 These are high priority areas for future research.

Correspondence

Doug Campos-Outcalt, MD, MPA, 550 E. Van Buren, Phoenix, AZ 85004; [email protected]

Not enough time and too many potential tests to do. This is the problem faced daily by family physicians. We want to practice up-to-date preventive medicine, but there’s little time to analyze the latest studies. Thankfully, we can rely on the United States Preventive Services Task Force, the organization with the most rigorous evidence-based approach, to do the legwork for us.1

Last year, and in the early part of this year, the Task Force issued a number of recommendations on topics ranging from hypertension screening to screening for illicit drug use. (See TABLE 1 for a breakdown of the 5 categories of recommendations.)

While some of these recommendations (TABLE 2) were reaffirmations of past recommendations, others included some changes.

The Task Force has:

- dropped the age for routine screening for Chlamydia in sexually active women from 25 years and younger to 24 and younger.

- added a recommendation against the use of aspirin or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to prevent colorectal cancer (CRC).

- changed its recommendation on screening for carotid artery stenosis. In 1996, the Task Force noted that the evidence was insufficient to make a recommendation; in 2007 it recommended against such routine screening.

- added recommendations on counseling patients about drinking and driving, as well as on screening for illicit drug use. In both cases, the Task Force says the evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against.

TABLE 1

USPSTF recommendation categories

| A Recommendation: The Task Force recommends the service. There is a high certainty that the net benefit is substantial. |

| B Recommendation: The Task Force recommends the service. There is high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial. |

| C Recommendation: The Task Force recommends against routinely providing the service. There may be considerations that support providing the service in an individual patient. There is at least moderate certainty that the net benefit is small. |

| D Recommendation: The Task Force recommends against the service. There is moderate or high certainty that the service has no net benefit or that the harms outweigh the benefits. |

| I Recommendation: The Task Force concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of the service. Evidence is lacking, of poor quality, or conflicting, and the balance of benefits and harms cannot be determined. |

TABLE 2

Summary of new USPSTF recommendations

| A RECOMMENDATIONS |

The USPSTF recommends routinely:

|

| B RECOMMENDATIONS |

The USPSTF recommends routinely:

|

| C RECOMMENDATIONS |

The USPSTF recommends against routine:

|

| D RECOMMENDATIONS |

The USPSTF recommends against routine:

|

| I RECOMMENDATIONS |

The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against routine:

|

Continue to screen for HTN, sickle cell, Chlamydia

The latest A and B recommendations from the Task Force largely reaffirm previous recommendations. These recommendations cover hypertension, sickle cell disease, and Chlamydia.

Hypertension. Screening and treatment of hypertension in adults leads to lower morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular disease and is still recommended.2

Sickle cell disease. Screening newborns for sickle cell disease and treating those affected with oral prophylactic penicillin prevents serious bacterial infections. It also remains a recommended service.3

Chlamydia. Following a review of the evidence, the Task Force reconfirms the benefits of screening for Chlamydia in sexually active young women, but it has changed the age cutoff. In 2001, the Task Force indicated that sexually active women who were 25 years of age and younger should be screened. In 2007, the Task Force dropped the age to 24 and younger.

The latest recommendation reaffirms the need to screen women (above the cutoff) who are at risk—that is, women who have previously had a sexually transmitted infection (STI), those who have a new or multiple sex partners, and those who exchange sex for money or drugs.4 Screening is recommended annually; nucleic acid amplification tests are acceptable, allowing testing of urine or vaginal swabs.

Screening during pregnancy is recommended for the same groups—women who are 24 and younger and older women at risk—at the first prenatal visit and again in the third trimester if risk continues. Chlamydia is the most common bacterial STI, and screening and treatment prevents pelvic inflammatory disease in women and leads to improved pregnancy outcomes.

Interventions that are not recommended

Chemopreventon of colorectal cancer. For the first time, the Task Force issued a recommendation on the use of aspirin or other NSAIDs to prevent CRC. The Task Force does not recommend the routine use of these agents.5 The dosage needed to prevent CRC is higher than that which prevents cardiovascular disease and can cause significant harm.

Aspirin use is associated with gastrointestinal bleeding and hemorrhagic stroke; NSAID use is associated with gastrointestinal bleeding and renal impairment. The Task Force concludes that in the general adult population, potential harms exceed potential benefits.

Screening for carotid artery stenosis. In 1996, the Task Force found insufficient evidence to recommend for or against routine screening for carotid artery stenosis. In 2007, the Task Force made a recommendation against routine screening for carotid artery stenosis.6 Screening with duplex ultrasonography results in frequent false positives. Confirmatory testing with angiography is associated with a 1% rate of stroke. Endarterectomy itself has a death or stroke rate of about 3%.

In the general population, close to 8700 adults would need to be screened to prevent 1 disabling stroke. The Task Force indicates that primary care physicians would have better outcomes by concentrating on optimal management of risk factors for cerebral artery disease.

Screening for bacterial vaginosis among low-risk pregnant women. The final D recommendation pertains to screening for bacterial vaginosis during pregnancy to prevent preterm delivery.7 Pregnant women who have not had a previous preterm delivery are considered at low risk for preterm delivery and there is good evidence that this group does not benefit from screening for, or treatment of, asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis. (A similar recommendation was made in 2001, but it referred to women of “average” risk.)

Insufficient evidence to make a recommendation

Routinely screening men for Chlamydia. While it makes clinical sense to test and treat male partners of women with Chlamydia infection, the Task Force could not find evidence of the effectiveness of routinely screening men as a way to prevent infection in women.4 That said, the Task Force points out that screening men is relatively inexpensive and has negligible harms.

Screening for hyperlipidemia in children. While 50% of children with hyperlipidemia continue to have this disorder as adults, the long-term benefits and harms of early detection and treatment with medications and lipid-lowering diets have not been studied.8 This echoes the position the Task Force took in 1996, when it commented on children as part of an adult hyperlipidemia recommendation.

Physician counseling on drinking and driving. Motor vehicle crashes result in significant morbidity and mortality—especially among adolescents and young adults. Improved car and road design, as well as public health safety efforts, have led to significant improvements in motor vehicle safety. While avoidance of driving under the influence and proper use of occupant restraints are important public health goals, the Task Force, in this first recommendation on the subject, could find no evidence that physician counseling added benefit above those provided by community-wide efforts.9

Screening for bacterial vaginosis in pregnant women at high risk for preterm birth. As mentioned previously, screening low-risk pregnant women for bacterial vaginosis results in no benefit. The issue is less clear cut among women at high risk for a preterm delivery—that is, those who have had one previously.

The evidence regarding screening and treating asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis as a means of preventing preterm delivery in these women is mixed and the Task Force was unable to recommend for or against this practice.7 This reaffirms the Task Force’s 2001 recommendation.

Screening for illicit drug use. The Task Force recognizes that illicit drug use is a major cause of illness and social problems. It would appear to have great potential for early detection and intervention. However, the Task Force, in this first-time recommendation, found that screening tools have not been well studied, nor have the long-term effects of different treatment strategies.10 These are high priority areas for future research.

Correspondence

Doug Campos-Outcalt, MD, MPA, 550 E. Van Buren, Phoenix, AZ 85004; [email protected]

1. Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research. USPSTF. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstfix.htm. Accessed May 5, 2008.

2. USPSTF. Screening for High Blood Pressure. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspshype.htm. Accessed May 5, 2008.

3. USPSTF. Screening for Sickle Cell Disease in Newborns. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspshemo.htm. Accessed May 5, 2008.

4. USPSTF. Screening for Chlamydia Infection. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspschlm.htm. Accessed May 5, 2008.

5. USPSTF. Aspirin or Nonsteroidal Anti-inflamatory Drugs for the Primary Prevention of Colorectal Cancer. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspsasco.htm. Accessed May 5, 2008.

6. USPSTF. Screening for Carotid Artery Stenosis. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspsacas.htm. Accessed May 5, 2008.

7. USPSTF. Screening for Bacterial Vaginosis in Pregnancy. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspsbvag.htm. Accessed May 5, 2008.

8. USPSTF. Screening for Lipid Disorders in Children. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspschlip.htm. Accessed May 5, 2008.

9. USPSTF. Counseling About Proper Use of Motor Vehicle Occupant Restraints and Avoidance of Alcohol Use While Driving. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspsmvin.htm. Accessed May 5, 2008.

10. USPSTF. Screening for Illicit Drug Use. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspsdrug.htm. Accessed May 5, 2008.

1. Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research. USPSTF. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstfix.htm. Accessed May 5, 2008.

2. USPSTF. Screening for High Blood Pressure. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspshype.htm. Accessed May 5, 2008.

3. USPSTF. Screening for Sickle Cell Disease in Newborns. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspshemo.htm. Accessed May 5, 2008.

4. USPSTF. Screening for Chlamydia Infection. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspschlm.htm. Accessed May 5, 2008.

5. USPSTF. Aspirin or Nonsteroidal Anti-inflamatory Drugs for the Primary Prevention of Colorectal Cancer. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspsasco.htm. Accessed May 5, 2008.

6. USPSTF. Screening for Carotid Artery Stenosis. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspsacas.htm. Accessed May 5, 2008.

7. USPSTF. Screening for Bacterial Vaginosis in Pregnancy. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspsbvag.htm. Accessed May 5, 2008.

8. USPSTF. Screening for Lipid Disorders in Children. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspschlip.htm. Accessed May 5, 2008.

9. USPSTF. Counseling About Proper Use of Motor Vehicle Occupant Restraints and Avoidance of Alcohol Use While Driving. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspsmvin.htm. Accessed May 5, 2008.

10. USPSTF. Screening for Illicit Drug Use. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspsdrug.htm. Accessed May 5, 2008.

MEASLES HITS HOME: Sobering lessons from 2 travel-related outbreaks

Inform concerned parents about the safety and effectiveness of vaccines.

2 doses of measles-containing vaccine are 99% effective.

Those exposed who are not immune should be vaccinated or offered immune globulin if the vaccine is contraindicated.

Contraindications

- Primary immune deficiency diseases of T-cell functions

- Acquired immune deficiency from leukemia, lymphoma, or generalized malignancy

- Therapy with corticosteroids: 2 mg/kg prednisone >2 weeks

- Previous anaphylactic reaction to measles vaccine, gelatin, or neomycins

- Pregnancy

Measles is still a threat. Endemic transmission of measles no longer occurs in the United States (or any of the Americas), yet this highly infectious disease is still a threat from importation by visitors from other countries and from US residents who have traveled abroad. Two recent outbreaks (described at left) illustrate these risks.

3 infants too young to be vaccinated contracted measles in their doctor’s office in San Diego, in January 2008. (An infant with measles rash [above] is for illustration only, and does not depict any of the 3.)

What the CDC discovered

The 2 outbreaks of import-linked measles brought home—literally—the sobering facts about vulnerability among US residents. The CDC report 1,2 of its investigation observed:

US travelers can be exposed almost anywhere, developed countries included. The California outbreak started with a visit to Switzerland.

Measles spreads rapidly in susceptible subgroups, unless effective control strategies are used. In California, on 2 consecutive days, 5 school children and 4 children in a doctor’s office were infected; all were unvaccinated.

People not considered at risk can contract measles. Although 2 doses of vaccine are 99% effective, vaccinated individuals, such as the college students, can contract measles. Likewise, people born before 1957 may not be immune, in contrast to the general definition of immunity (see Measles Basics. Case in point: the airline passenger, born in 1954.

Disease can be severe. The 40-year-old salesperson (no documented vaccination) was hospitalized with seizure, 105ºF fever, and pneumonia. One of the infants was hospitalized due to dehydration.

People in routine contact with travelers entering the United States can be exposed to measles—like the airline worker.

CALIFORNIA - A February 22 early-release CDC report1 linked 12 measles cases in California to an unvaccinated 7-year-old boy infected while traveling in Europe with his family in January. He was taken to his pediatrician after onset of rash, and to the emergency department the next day, because of high fever and generalized rash. No isolation precautions were used in the office or hospital.

The boy’s 2 siblings, 5 children at his school, and 4 children at the doctor’s office while he was there contracted measles (3 of whom were infants <12 months of age).

Nearly 10% of the children at the index case’s school were unvaccinated because of personal belief exemptions.

PENNSYLVANIA, MICHIGAN, TEXAS - A young boy from Japan participated in an international sporting event and attended a related sales event in Pennsylvania last August. He was infectious when he left Japan and as he traveled in the United States.

The CDC2 linked a total of 6 additional cases of measles in US-born residents to the index case: another young person from Japan who watched the sporting event; a 53-year-old airline passenger and a 25-year-old airline worker in Michigan; and a corporate sales representative who had met the index patient at the sales event and subsequently made sales visits to Houston-area colleges, where 2 college roommates became infected.

Viral genotyping supported a single chain of transmission, and genetic sequencing linked 6 of the 7 cases.

Take-home lessons for family physicians

Include measles in the differential diagnosis of patients who have fever and rash, especially if they have traveled to another country within the past 3 to 4 weeks. Any patient who meets the definition of measles (fever 101ºF or higher; rash; and at least 1 of the 3 Cs—cough, coryza, conjunctivitis) should be immediately reported to the local health department. The health department will provide instructions for collecting laboratory samples for confirmation; instructions on patient isolation; and assistance with notification and disease control measures for exposed individuals.

Immunize patients and staff. These recurring cases of imported measles underscore the importance of maintaining a high level of immunity. Outbreaks can happen even where immunity is 90% to 95%. When vaccination rates dip below 90%, sustained outbreaks can occur.6

Ensure that staff and patients are all immunized against vaccine-preventable diseases, and inform concerned parents about the safety and effectiveness of vaccines. Parents who refuse to have their children vaccinated place their children at risk and contribute to higher community risk. Communities that have higher rates of non-adherence to vaccine recommendations are more likely to have outbreaks.7,8

Use strict infection control in the office. The recent outbreak in California where 4 children were infected in their physician’s office reinforces the need for strict infection-control practices. Do not allow patients with rash and fever to remain in a common waiting area. Move them to an examination room, preferably an airborne infection isolation room. Keep the door to the examination room closed, and be sure that all health care personnel who come in contact with such patients are immune. Do not use triage rooms for 2 hours after the patient suspected of having measles leaves. Do not send these patients to other health care facilities, such as laboratories, unless infection control measures can be adhered to at those locations. Guidelines on infection control practices in health care settings are available.9,10

Quick response

Quick control of these outbreaks shows the value of the public health infrastructure. Disease surveillance and outbreak response is vital to the public health system, and its value is frequently under-appreciated by physicians and the public.

Fewer than 100 cases of measles occur in the United States each year, and virtually all are linked to imported cases.3 Before vaccine was introduced in 1963, 3 to 4 million cases per year occurred, and caused, on average, 450 deaths, 1000 chronic disabilities, and 28,000 hospitalizations.1 Success in controlling measles is due largely to high levels of coverage with 2 doses of measles-containing vaccine and public health surveillance and disease control.

Measles virus is highly infectious and is spread by airborne droplets and direct contact with nose and throat secretions. The incubation is 7 to 18 days.

Measles begins with fever, cough, coryza, conjunctivitis, and whitish spots on the buccal mucosa (Koplick spots).4 Rash appears on the 3rd to 7th day and lasts 4 to 7 days. It begins on the face but soon becomes generalized. An infected person is contagious from 5 days before the rash until 4 days after the rash appears. The diagnosis of measles can be confirrmed by serum measles IGM, which occurs within 3 days of rash, or a rise in measles IGG between acute and 2-week convalescent serum titers.

Complications: pneumonia (5%), otitis media (10%), and encephalitis 1/1000). Death rates: 1 to 2/1000, varying greatly based on age and nutrition; more severe in the very young and the malnourished. Worldwide, about 500,000 children die from measles each year.5

Immunity is defined as:

- 2 vaccine doses at least 1 month apart, both given after the 1st birthday,

- born before 1957,

- serological evidence, or

- history of physician-diagnosed measles.

1. CDC. Outbreak of measles—San Diego, California, January-February 2008. MMWR. 2008;57:Early Release February 22, 2008.-

2. CDC. Multistate measles outbreak associated with an international youth sporting event—Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Texas, August-September 2007. MMWR. 2008;57:169-173.

3. CDC. Measles—United States, 2005. MMWR. 2006;55:1348-1351.

4. Measles. In: Heyman DL. Control of Communicable Diseases Manual. 18th ed. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association.

5. CDC. Parents’ guide to childhood immunizations. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd-vac/measles/downloads/pg_why_vacc_measles.pdf. Accessed March 17, 2008.

6. Richard JL, Masserey-Spicher V, Santibanez S, Mankertz A. Measles outbreak in Switzerland. Available at: http://www.eurosurveillance.org/edition/v13n08/080221_1.asp. Accessed March 17. 2008.

7. Salmon DA, Haber M, Gangarosa EJ, et al. Health consequences of religious and philosophical exemptions from immunization laws; individual and societal risk of measles. JAMA. 1999;282:47-53

8. Feikin DR, Lezotte DC, Hamman RF, et al. Individual and community risks of measles and pertussis associated with personal exemptions to immunization. JAMA. 2008;284:3145-3150.

9. Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, Chiarello L. Health care infection control practices advisory committee, 2007.Guideline for isolation precautions: preventing transmission of infectious agents in health care settings. Am J Infect Control. 2007;35(suppl 2):S65-164.

10. Campos-Outcalt D. Infection control in outpatient settings. J Fam Pract. 2004;53:485-488.

Inform concerned parents about the safety and effectiveness of vaccines.

2 doses of measles-containing vaccine are 99% effective.

Those exposed who are not immune should be vaccinated or offered immune globulin if the vaccine is contraindicated.

Contraindications

- Primary immune deficiency diseases of T-cell functions

- Acquired immune deficiency from leukemia, lymphoma, or generalized malignancy

- Therapy with corticosteroids: 2 mg/kg prednisone >2 weeks

- Previous anaphylactic reaction to measles vaccine, gelatin, or neomycins

- Pregnancy

Measles is still a threat. Endemic transmission of measles no longer occurs in the United States (or any of the Americas), yet this highly infectious disease is still a threat from importation by visitors from other countries and from US residents who have traveled abroad. Two recent outbreaks (described at left) illustrate these risks.

3 infants too young to be vaccinated contracted measles in their doctor’s office in San Diego, in January 2008. (An infant with measles rash [above] is for illustration only, and does not depict any of the 3.)

What the CDC discovered

The 2 outbreaks of import-linked measles brought home—literally—the sobering facts about vulnerability among US residents. The CDC report 1,2 of its investigation observed:

US travelers can be exposed almost anywhere, developed countries included. The California outbreak started with a visit to Switzerland.

Measles spreads rapidly in susceptible subgroups, unless effective control strategies are used. In California, on 2 consecutive days, 5 school children and 4 children in a doctor’s office were infected; all were unvaccinated.

People not considered at risk can contract measles. Although 2 doses of vaccine are 99% effective, vaccinated individuals, such as the college students, can contract measles. Likewise, people born before 1957 may not be immune, in contrast to the general definition of immunity (see Measles Basics. Case in point: the airline passenger, born in 1954.

Disease can be severe. The 40-year-old salesperson (no documented vaccination) was hospitalized with seizure, 105ºF fever, and pneumonia. One of the infants was hospitalized due to dehydration.

People in routine contact with travelers entering the United States can be exposed to measles—like the airline worker.

CALIFORNIA - A February 22 early-release CDC report1 linked 12 measles cases in California to an unvaccinated 7-year-old boy infected while traveling in Europe with his family in January. He was taken to his pediatrician after onset of rash, and to the emergency department the next day, because of high fever and generalized rash. No isolation precautions were used in the office or hospital.

The boy’s 2 siblings, 5 children at his school, and 4 children at the doctor’s office while he was there contracted measles (3 of whom were infants <12 months of age).

Nearly 10% of the children at the index case’s school were unvaccinated because of personal belief exemptions.

PENNSYLVANIA, MICHIGAN, TEXAS - A young boy from Japan participated in an international sporting event and attended a related sales event in Pennsylvania last August. He was infectious when he left Japan and as he traveled in the United States.

The CDC2 linked a total of 6 additional cases of measles in US-born residents to the index case: another young person from Japan who watched the sporting event; a 53-year-old airline passenger and a 25-year-old airline worker in Michigan; and a corporate sales representative who had met the index patient at the sales event and subsequently made sales visits to Houston-area colleges, where 2 college roommates became infected.

Viral genotyping supported a single chain of transmission, and genetic sequencing linked 6 of the 7 cases.

Take-home lessons for family physicians

Include measles in the differential diagnosis of patients who have fever and rash, especially if they have traveled to another country within the past 3 to 4 weeks. Any patient who meets the definition of measles (fever 101ºF or higher; rash; and at least 1 of the 3 Cs—cough, coryza, conjunctivitis) should be immediately reported to the local health department. The health department will provide instructions for collecting laboratory samples for confirmation; instructions on patient isolation; and assistance with notification and disease control measures for exposed individuals.

Immunize patients and staff. These recurring cases of imported measles underscore the importance of maintaining a high level of immunity. Outbreaks can happen even where immunity is 90% to 95%. When vaccination rates dip below 90%, sustained outbreaks can occur.6

Ensure that staff and patients are all immunized against vaccine-preventable diseases, and inform concerned parents about the safety and effectiveness of vaccines. Parents who refuse to have their children vaccinated place their children at risk and contribute to higher community risk. Communities that have higher rates of non-adherence to vaccine recommendations are more likely to have outbreaks.7,8

Use strict infection control in the office. The recent outbreak in California where 4 children were infected in their physician’s office reinforces the need for strict infection-control practices. Do not allow patients with rash and fever to remain in a common waiting area. Move them to an examination room, preferably an airborne infection isolation room. Keep the door to the examination room closed, and be sure that all health care personnel who come in contact with such patients are immune. Do not use triage rooms for 2 hours after the patient suspected of having measles leaves. Do not send these patients to other health care facilities, such as laboratories, unless infection control measures can be adhered to at those locations. Guidelines on infection control practices in health care settings are available.9,10

Quick response

Quick control of these outbreaks shows the value of the public health infrastructure. Disease surveillance and outbreak response is vital to the public health system, and its value is frequently under-appreciated by physicians and the public.

Fewer than 100 cases of measles occur in the United States each year, and virtually all are linked to imported cases.3 Before vaccine was introduced in 1963, 3 to 4 million cases per year occurred, and caused, on average, 450 deaths, 1000 chronic disabilities, and 28,000 hospitalizations.1 Success in controlling measles is due largely to high levels of coverage with 2 doses of measles-containing vaccine and public health surveillance and disease control.

Measles virus is highly infectious and is spread by airborne droplets and direct contact with nose and throat secretions. The incubation is 7 to 18 days.

Measles begins with fever, cough, coryza, conjunctivitis, and whitish spots on the buccal mucosa (Koplick spots).4 Rash appears on the 3rd to 7th day and lasts 4 to 7 days. It begins on the face but soon becomes generalized. An infected person is contagious from 5 days before the rash until 4 days after the rash appears. The diagnosis of measles can be confirrmed by serum measles IGM, which occurs within 3 days of rash, or a rise in measles IGG between acute and 2-week convalescent serum titers.

Complications: pneumonia (5%), otitis media (10%), and encephalitis 1/1000). Death rates: 1 to 2/1000, varying greatly based on age and nutrition; more severe in the very young and the malnourished. Worldwide, about 500,000 children die from measles each year.5

Immunity is defined as:

- 2 vaccine doses at least 1 month apart, both given after the 1st birthday,

- born before 1957,

- serological evidence, or

- history of physician-diagnosed measles.

Inform concerned parents about the safety and effectiveness of vaccines.

2 doses of measles-containing vaccine are 99% effective.

Those exposed who are not immune should be vaccinated or offered immune globulin if the vaccine is contraindicated.

Contraindications

- Primary immune deficiency diseases of T-cell functions

- Acquired immune deficiency from leukemia, lymphoma, or generalized malignancy

- Therapy with corticosteroids: 2 mg/kg prednisone >2 weeks

- Previous anaphylactic reaction to measles vaccine, gelatin, or neomycins

- Pregnancy

Measles is still a threat. Endemic transmission of measles no longer occurs in the United States (or any of the Americas), yet this highly infectious disease is still a threat from importation by visitors from other countries and from US residents who have traveled abroad. Two recent outbreaks (described at left) illustrate these risks.

3 infants too young to be vaccinated contracted measles in their doctor’s office in San Diego, in January 2008. (An infant with measles rash [above] is for illustration only, and does not depict any of the 3.)

What the CDC discovered

The 2 outbreaks of import-linked measles brought home—literally—the sobering facts about vulnerability among US residents. The CDC report 1,2 of its investigation observed:

US travelers can be exposed almost anywhere, developed countries included. The California outbreak started with a visit to Switzerland.

Measles spreads rapidly in susceptible subgroups, unless effective control strategies are used. In California, on 2 consecutive days, 5 school children and 4 children in a doctor’s office were infected; all were unvaccinated.

People not considered at risk can contract measles. Although 2 doses of vaccine are 99% effective, vaccinated individuals, such as the college students, can contract measles. Likewise, people born before 1957 may not be immune, in contrast to the general definition of immunity (see Measles Basics. Case in point: the airline passenger, born in 1954.

Disease can be severe. The 40-year-old salesperson (no documented vaccination) was hospitalized with seizure, 105ºF fever, and pneumonia. One of the infants was hospitalized due to dehydration.

People in routine contact with travelers entering the United States can be exposed to measles—like the airline worker.

CALIFORNIA - A February 22 early-release CDC report1 linked 12 measles cases in California to an unvaccinated 7-year-old boy infected while traveling in Europe with his family in January. He was taken to his pediatrician after onset of rash, and to the emergency department the next day, because of high fever and generalized rash. No isolation precautions were used in the office or hospital.

The boy’s 2 siblings, 5 children at his school, and 4 children at the doctor’s office while he was there contracted measles (3 of whom were infants <12 months of age).

Nearly 10% of the children at the index case’s school were unvaccinated because of personal belief exemptions.

PENNSYLVANIA, MICHIGAN, TEXAS - A young boy from Japan participated in an international sporting event and attended a related sales event in Pennsylvania last August. He was infectious when he left Japan and as he traveled in the United States.

The CDC2 linked a total of 6 additional cases of measles in US-born residents to the index case: another young person from Japan who watched the sporting event; a 53-year-old airline passenger and a 25-year-old airline worker in Michigan; and a corporate sales representative who had met the index patient at the sales event and subsequently made sales visits to Houston-area colleges, where 2 college roommates became infected.

Viral genotyping supported a single chain of transmission, and genetic sequencing linked 6 of the 7 cases.

Take-home lessons for family physicians