User login

Midterm ballot initiatives mostly favor physicians

California voters rejected a ballot initiative that would have required doctors to submit to random drug and alcohol testing within 12 hours of when an adverse event has been identified, while voters in South Dakota approved a measure to loosen insurance companies’ provider panels.

With all precincts reporting, more than 67% of California voters (nearly 3.42 million) voted no on Proposition 46, a measure that doctors in the state said would unreasonably penalize doctors unable to meet testing rules and lead to excessive suspensions. The initiative applied only to doctors who practice in hospitals or have hospital privileges.

The ballot initiative also contained two other components – a requirement that doctors consult a statewide database before prescribing schedule II and schedule III drugs and a raising of the medical malpractice cap on noneconomic damages from $250,000 to $1.1 million. Doctors argued that the database lacked the funding and staff to be effective in identifying patients engaged in doctor-shopping or otherwise abusing prescription controlled substances.

In South Dakota, 61.8% of the voters (166,351, with all precincts reporting) approved Measure 17, which allows providers who are willing to meet a health insurer’s coverage terms to provide health care services to insured patients without having to join that patient’s insurance plan network, and protects patients from out-of-network costs if they use that physician.

Voters in Arizona approved Proposition 303, which allows eligible patients with a terminal illness that has no Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment option to have access to an investigational drug, provided the drug has successfully completed phase I testing and remains under clinical investigation. The pharmaceutical manufacturer would decide whether to provide access, and insurance companies are not required under the measure to provide coverage for it. The measure also offered some liability protection for physicians who recommend the investigational treatment. More than 78% of the votes (849,350, with 97% of the precincts reporting) supported the measure.

In Illinois, voters supported a ballot initiative that would require insurance plans in the state that have prescription drug coverage to “include prescription birth control as part of that coverage.” No details were included in the text of the initiative on the scope of what needs to be included, but its passage means the state legislature must enact a law to implement the will of the voters. Sixty-six percent of the votes (2.2 million, with 99 percent of precincts reporting) were in favor of this initiative.

Residents in three states acted on abortion-related measures. In North Dakota, a ballot initiative would have amended the state constitution to provide for the “inalienable right to life” beginning at conception. With all precincts reporting, the amendment failed, with more than 64% of votes against. In Colorado, a constitutional amendment to include the unborn in the definition of “person” and “child” in the state criminal code failed, with more than 64% of the votes (nearly 1.2 million, with 94% of precincts reporting) going against the amendment.

And in Tennessee, voters approved a constitutional amendment that empowers the state legislature “to enact, amend, or repeal statutes regarding abortion, including but not limited to, circumstances of pregnancy resulting from rape or incest, or when necessary to save the life of the mother.” It passed with more than 52% of the votes (728,751 with 99 percent of the precincts reporting). The amendment was in reaction to a 2000 state supreme court ruling that struck down a number of state laws that placed limits around abortions.

California voters rejected a ballot initiative that would have required doctors to submit to random drug and alcohol testing within 12 hours of when an adverse event has been identified, while voters in South Dakota approved a measure to loosen insurance companies’ provider panels.

With all precincts reporting, more than 67% of California voters (nearly 3.42 million) voted no on Proposition 46, a measure that doctors in the state said would unreasonably penalize doctors unable to meet testing rules and lead to excessive suspensions. The initiative applied only to doctors who practice in hospitals or have hospital privileges.

The ballot initiative also contained two other components – a requirement that doctors consult a statewide database before prescribing schedule II and schedule III drugs and a raising of the medical malpractice cap on noneconomic damages from $250,000 to $1.1 million. Doctors argued that the database lacked the funding and staff to be effective in identifying patients engaged in doctor-shopping or otherwise abusing prescription controlled substances.

In South Dakota, 61.8% of the voters (166,351, with all precincts reporting) approved Measure 17, which allows providers who are willing to meet a health insurer’s coverage terms to provide health care services to insured patients without having to join that patient’s insurance plan network, and protects patients from out-of-network costs if they use that physician.

Voters in Arizona approved Proposition 303, which allows eligible patients with a terminal illness that has no Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment option to have access to an investigational drug, provided the drug has successfully completed phase I testing and remains under clinical investigation. The pharmaceutical manufacturer would decide whether to provide access, and insurance companies are not required under the measure to provide coverage for it. The measure also offered some liability protection for physicians who recommend the investigational treatment. More than 78% of the votes (849,350, with 97% of the precincts reporting) supported the measure.

In Illinois, voters supported a ballot initiative that would require insurance plans in the state that have prescription drug coverage to “include prescription birth control as part of that coverage.” No details were included in the text of the initiative on the scope of what needs to be included, but its passage means the state legislature must enact a law to implement the will of the voters. Sixty-six percent of the votes (2.2 million, with 99 percent of precincts reporting) were in favor of this initiative.

Residents in three states acted on abortion-related measures. In North Dakota, a ballot initiative would have amended the state constitution to provide for the “inalienable right to life” beginning at conception. With all precincts reporting, the amendment failed, with more than 64% of votes against. In Colorado, a constitutional amendment to include the unborn in the definition of “person” and “child” in the state criminal code failed, with more than 64% of the votes (nearly 1.2 million, with 94% of precincts reporting) going against the amendment.

And in Tennessee, voters approved a constitutional amendment that empowers the state legislature “to enact, amend, or repeal statutes regarding abortion, including but not limited to, circumstances of pregnancy resulting from rape or incest, or when necessary to save the life of the mother.” It passed with more than 52% of the votes (728,751 with 99 percent of the precincts reporting). The amendment was in reaction to a 2000 state supreme court ruling that struck down a number of state laws that placed limits around abortions.

California voters rejected a ballot initiative that would have required doctors to submit to random drug and alcohol testing within 12 hours of when an adverse event has been identified, while voters in South Dakota approved a measure to loosen insurance companies’ provider panels.

With all precincts reporting, more than 67% of California voters (nearly 3.42 million) voted no on Proposition 46, a measure that doctors in the state said would unreasonably penalize doctors unable to meet testing rules and lead to excessive suspensions. The initiative applied only to doctors who practice in hospitals or have hospital privileges.

The ballot initiative also contained two other components – a requirement that doctors consult a statewide database before prescribing schedule II and schedule III drugs and a raising of the medical malpractice cap on noneconomic damages from $250,000 to $1.1 million. Doctors argued that the database lacked the funding and staff to be effective in identifying patients engaged in doctor-shopping or otherwise abusing prescription controlled substances.

In South Dakota, 61.8% of the voters (166,351, with all precincts reporting) approved Measure 17, which allows providers who are willing to meet a health insurer’s coverage terms to provide health care services to insured patients without having to join that patient’s insurance plan network, and protects patients from out-of-network costs if they use that physician.

Voters in Arizona approved Proposition 303, which allows eligible patients with a terminal illness that has no Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment option to have access to an investigational drug, provided the drug has successfully completed phase I testing and remains under clinical investigation. The pharmaceutical manufacturer would decide whether to provide access, and insurance companies are not required under the measure to provide coverage for it. The measure also offered some liability protection for physicians who recommend the investigational treatment. More than 78% of the votes (849,350, with 97% of the precincts reporting) supported the measure.

In Illinois, voters supported a ballot initiative that would require insurance plans in the state that have prescription drug coverage to “include prescription birth control as part of that coverage.” No details were included in the text of the initiative on the scope of what needs to be included, but its passage means the state legislature must enact a law to implement the will of the voters. Sixty-six percent of the votes (2.2 million, with 99 percent of precincts reporting) were in favor of this initiative.

Residents in three states acted on abortion-related measures. In North Dakota, a ballot initiative would have amended the state constitution to provide for the “inalienable right to life” beginning at conception. With all precincts reporting, the amendment failed, with more than 64% of votes against. In Colorado, a constitutional amendment to include the unborn in the definition of “person” and “child” in the state criminal code failed, with more than 64% of the votes (nearly 1.2 million, with 94% of precincts reporting) going against the amendment.

And in Tennessee, voters approved a constitutional amendment that empowers the state legislature “to enact, amend, or repeal statutes regarding abortion, including but not limited to, circumstances of pregnancy resulting from rape or incest, or when necessary to save the life of the mother.” It passed with more than 52% of the votes (728,751 with 99 percent of the precincts reporting). The amendment was in reaction to a 2000 state supreme court ruling that struck down a number of state laws that placed limits around abortions.

Hospitalist Pioneer Bob Wachter Warns Waste Reduction Is New Quality Focus

Dr. Wachter closed SHM's 2013 annual meeting in National Harbor, MD, with a keynote address that identified cost and waste reduction as new planks of hospitalist's value proposition.

Dr. Wachter closed SHM's 2013 annual meeting in National Harbor, MD, with a keynote address that identified cost and waste reduction as new planks of hospitalist's value proposition.

Dr. Wachter closed SHM's 2013 annual meeting in National Harbor, MD, with a keynote address that identified cost and waste reduction as new planks of hospitalist's value proposition.

Medicaid expansion predicted to further crowd EDs

CHICAGO – Emergency department visits are projected to increase annually by more than 2 million visits with expansion of Medicaid eligibility under the Affordable Care Act, Christina M. Cutter reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Emergency Physicians.

Similarly, primary care–treatable ED visits – visits that require immediate care but could be treated in an outpatient setting – are projected to increase by nearly 1 million visits nationally among new adult Medicaid beneficiaries.

The projections, based on results from the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment (OHIE), amplify concerns that the nation’s already strained ED system will be further challenged by Medicaid expansion under the ACA, said Ms. Cutter, a medical student at the University of Colorado, Aurora.

To estimate ED utilization by Medicaid beneficiaries following the expansion of Medicaid eligibility under the Affordable Care Act, Ms. Cutter and her colleague Dr. Arjun K. Venkatesh, of Yale University in New Haven, Conn., conducted a cross-sectional analysis of population-level data derived from the American Community Survey, National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, and Kaiser Family Foundation.

Initially, they approximated baseline ED visits at the state-level by adults aged 18-64 years with Medicaid. To estimate state and national changes in ED visitation and state-level increases in primary care–treatable conditions, the researchers assumed that all states expanding Medicaid would have increases in ED visits that were proportionate to those observed in the OHIE.

Primary care–treatable ED visits were defined using the N.Y.U. Billings Algorithm. State-level data on measures of emergency care access were obtained from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Hospital Compare file, AMA Physician Professional file, Health Resources and Sservices Administration Geospatial Data Warehouse, and the American College of Emergency Physicians Emergency Care Environment Report Card. States expanding Medicaid coverage were compared with those not expanding Medicaid.

Based on these measures, the researchers estimated a total of 80,819,573 ED visits in 2012 for the U.S. adult population, of which 25,054,068 were adults with Medicaid. They estimated 8,749,000 additional adult enrollees in the 28 states expanding Medicaid eligibility.

Based on projections using the OHIE, ED visits will increase by 2,143,260 visits in states expanding eligibility and primary care–treatable ED visits will increase by 943,034 nationally among new adult Medicaid beneficiaries, according to the researchers.

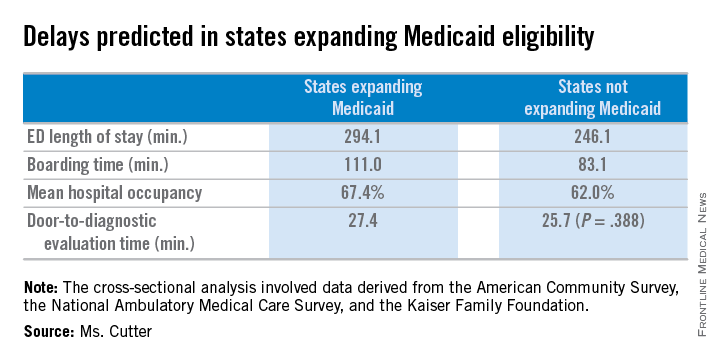

States expanding Medicaid eligibility have longer ED length of stay (294.1 vs. 246.1 minutes, P = .007), longer boarding time (111.0 vs. 83.1 minutes, P = .007), and higher mean hospital occupancy (67.4 vs. 62.0 per 100 staffed beds, P = .012), but no difference in door-to-diagnostic evaluation time (27.4 vs. 25.7 minutes, P = .388).

States expanding eligibility also have fewer EDs (14.8 vs. 24.0/1,000,000 population, P = .004), but are less likely to have shortages of mental health provider shortages (0.6 vs. 1.0 needed full-time equivalents, P = .021) and have no difference in psychiatric beds (24.4 vs. 28.2/100,000 population, P = .557). States expanding Medicaid also have a greater supply of emergency physicians (15 vs. 11.7/100,000 population, P = .004), Ms. Cutter reported.

CHICAGO – Emergency department visits are projected to increase annually by more than 2 million visits with expansion of Medicaid eligibility under the Affordable Care Act, Christina M. Cutter reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Emergency Physicians.

Similarly, primary care–treatable ED visits – visits that require immediate care but could be treated in an outpatient setting – are projected to increase by nearly 1 million visits nationally among new adult Medicaid beneficiaries.

The projections, based on results from the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment (OHIE), amplify concerns that the nation’s already strained ED system will be further challenged by Medicaid expansion under the ACA, said Ms. Cutter, a medical student at the University of Colorado, Aurora.

To estimate ED utilization by Medicaid beneficiaries following the expansion of Medicaid eligibility under the Affordable Care Act, Ms. Cutter and her colleague Dr. Arjun K. Venkatesh, of Yale University in New Haven, Conn., conducted a cross-sectional analysis of population-level data derived from the American Community Survey, National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, and Kaiser Family Foundation.

Initially, they approximated baseline ED visits at the state-level by adults aged 18-64 years with Medicaid. To estimate state and national changes in ED visitation and state-level increases in primary care–treatable conditions, the researchers assumed that all states expanding Medicaid would have increases in ED visits that were proportionate to those observed in the OHIE.

Primary care–treatable ED visits were defined using the N.Y.U. Billings Algorithm. State-level data on measures of emergency care access were obtained from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Hospital Compare file, AMA Physician Professional file, Health Resources and Sservices Administration Geospatial Data Warehouse, and the American College of Emergency Physicians Emergency Care Environment Report Card. States expanding Medicaid coverage were compared with those not expanding Medicaid.

Based on these measures, the researchers estimated a total of 80,819,573 ED visits in 2012 for the U.S. adult population, of which 25,054,068 were adults with Medicaid. They estimated 8,749,000 additional adult enrollees in the 28 states expanding Medicaid eligibility.

Based on projections using the OHIE, ED visits will increase by 2,143,260 visits in states expanding eligibility and primary care–treatable ED visits will increase by 943,034 nationally among new adult Medicaid beneficiaries, according to the researchers.

States expanding Medicaid eligibility have longer ED length of stay (294.1 vs. 246.1 minutes, P = .007), longer boarding time (111.0 vs. 83.1 minutes, P = .007), and higher mean hospital occupancy (67.4 vs. 62.0 per 100 staffed beds, P = .012), but no difference in door-to-diagnostic evaluation time (27.4 vs. 25.7 minutes, P = .388).

States expanding eligibility also have fewer EDs (14.8 vs. 24.0/1,000,000 population, P = .004), but are less likely to have shortages of mental health provider shortages (0.6 vs. 1.0 needed full-time equivalents, P = .021) and have no difference in psychiatric beds (24.4 vs. 28.2/100,000 population, P = .557). States expanding Medicaid also have a greater supply of emergency physicians (15 vs. 11.7/100,000 population, P = .004), Ms. Cutter reported.

CHICAGO – Emergency department visits are projected to increase annually by more than 2 million visits with expansion of Medicaid eligibility under the Affordable Care Act, Christina M. Cutter reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Emergency Physicians.

Similarly, primary care–treatable ED visits – visits that require immediate care but could be treated in an outpatient setting – are projected to increase by nearly 1 million visits nationally among new adult Medicaid beneficiaries.

The projections, based on results from the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment (OHIE), amplify concerns that the nation’s already strained ED system will be further challenged by Medicaid expansion under the ACA, said Ms. Cutter, a medical student at the University of Colorado, Aurora.

To estimate ED utilization by Medicaid beneficiaries following the expansion of Medicaid eligibility under the Affordable Care Act, Ms. Cutter and her colleague Dr. Arjun K. Venkatesh, of Yale University in New Haven, Conn., conducted a cross-sectional analysis of population-level data derived from the American Community Survey, National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, and Kaiser Family Foundation.

Initially, they approximated baseline ED visits at the state-level by adults aged 18-64 years with Medicaid. To estimate state and national changes in ED visitation and state-level increases in primary care–treatable conditions, the researchers assumed that all states expanding Medicaid would have increases in ED visits that were proportionate to those observed in the OHIE.

Primary care–treatable ED visits were defined using the N.Y.U. Billings Algorithm. State-level data on measures of emergency care access were obtained from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Hospital Compare file, AMA Physician Professional file, Health Resources and Sservices Administration Geospatial Data Warehouse, and the American College of Emergency Physicians Emergency Care Environment Report Card. States expanding Medicaid coverage were compared with those not expanding Medicaid.

Based on these measures, the researchers estimated a total of 80,819,573 ED visits in 2012 for the U.S. adult population, of which 25,054,068 were adults with Medicaid. They estimated 8,749,000 additional adult enrollees in the 28 states expanding Medicaid eligibility.

Based on projections using the OHIE, ED visits will increase by 2,143,260 visits in states expanding eligibility and primary care–treatable ED visits will increase by 943,034 nationally among new adult Medicaid beneficiaries, according to the researchers.

States expanding Medicaid eligibility have longer ED length of stay (294.1 vs. 246.1 minutes, P = .007), longer boarding time (111.0 vs. 83.1 minutes, P = .007), and higher mean hospital occupancy (67.4 vs. 62.0 per 100 staffed beds, P = .012), but no difference in door-to-diagnostic evaluation time (27.4 vs. 25.7 minutes, P = .388).

States expanding eligibility also have fewer EDs (14.8 vs. 24.0/1,000,000 population, P = .004), but are less likely to have shortages of mental health provider shortages (0.6 vs. 1.0 needed full-time equivalents, P = .021) and have no difference in psychiatric beds (24.4 vs. 28.2/100,000 population, P = .557). States expanding Medicaid also have a greater supply of emergency physicians (15 vs. 11.7/100,000 population, P = .004), Ms. Cutter reported.

AT ACEP 2014

Key clinical point: ED lengths of stay are predicted to become longer as more states expand Medicaid coverage.

Major finding: States expanding Medicaid eligibility have longer mean ED lengths of stay (294.1 vs. 246.1 minutes, P = .007), longer mean boarding time (111.0 vs. 83.1 minutes, P = .007), and higher mean hospital occupancy (67.4 vs. 62.0 per 100 staffed beds, P = .012).

Data source: Historical data from the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment.

Disclosures: Ms. Cutter had no relevant financial disclosures.

Malpractice climate: ‘Stable, but still dysfunctional’

Fewer malpractice suits are resulting in paid claims against physicians while malpractice insurance premiums have remained stable or declined over the last 12 years, according to an analysis published Oct. 30 in JAMA.

Since 2002, the rate of paid malpractice claims against doctors of medicine has decreased by an estimated 6% annually; for doctors of osteopathy, the rate has declined about 5% annually, Michelle M. Mello of Stanford (Calif.) University and her colleagues reported (JAMA 2014 Oct. 30 [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.10705]).

Dr. Mello and her colleagues analyzed paid legal claims against MDs and DOs between 1994 and 2013 from the National Practitioner Data Bank and the American Medical Association’s Physician Masterfile. They also evaluated premium data from the Medical Liability Monitor’s Annual Rate Survey.

The rate of paid malpractice claims against MDs fell from 18.6 to 9.9 paid claims per 1,000 physicians between 2002 and 2013, they found. For DOs, rates dropped from about 19 in 2002 to about 12.2 paid claims per 1,000 physicians in 2013.

The median compensation paid to plaintiffs rose by 63% between 1994 and 2007, from $133,799 to $218,400, in adjusted 2013 dollars. However, since 2007, that number has declined, reaching $195,000 in 2013. Only 3.4% of payments made during the 20-year period resulted from jury verdicts; the others stemmed from settlements.

For the premiums review, Dr. Mello and colleagues analyzed insurance data from 2004 to 2013 from five geographical areas: Los Angeles, Orange, Kern, and Ventura counties in California; Nassau and Suffolk counties in New York; Cook, Madison, St. Clair, and Will counties in Illinois; and the states of Tennessee and Colorado. The locations were selected based on geographic diversity and because each had an insurer with a dominant market share.

In California, Illinois, and Tennessee, internists and ob.gyns. saw a 36% decrease in premiums charged by each state’s largest medical malpractice insurer from 2004 to 2013. Premiums charged to general surgeons fell by 30% in these states. In Colorado, internists saw a 20% decrease in premiums over the same time period, but general surgeons saw an increase of 13% and ob.gyns. experienced an 11% rise. In New York, rates charged by the largest insurer rose by 12% for ob.gyns, 16% for internists, and 35% for general surgeons.

It remains unclear why the rate of paid claims has decreased and why premiums have remained fairly stable, Dr. Mello and colleagues said. While medical organizations like to point to tort reform, traditional reforms such as award caps do not address problems within the malpractice system’s core functions – compensating negligently injured patients and deterring substandard care, they added.

“The weight of evidence suggests that the system’s effectiveness as both a compensation and a deterrence mechanism is mediocre at best, and there is little to suggest it has improved over the past decade,” they wrote. “Thus, ‘stable but still dysfunctional’ might describe today’s liability environment.”

The authors offered alternatives to traditional tort reform, such as communication and resolution programs, mandatory presuit notification laws, and judge-directed negotiation.

In communication and resolution programs, clinicians and institutions openly discuss adverse outcomes with patients and proactively seek resolution, including offering an apology, and, if the standard of care was not met, compensation. Mandatory presuit notification refers to requiring plaintiffs to give defendants advance notice that they intend to sue. Judge-directed negotiation centers on court policies in which malpractice litigants meet early and often with judges to discuss settlement. In such negotiations, the court employs an attorney with clinical training to help judges understand clinical issues.

The authors conclude that action to improve the medical liability system is necessary while the legal climate is stable, and not after a crisis.

“During malpractice crises, interest in liability reform intensifies, but one lesson of the last 40 years is that an atmosphere of crisis is not conducive to thoughtful and enduring solutions,” study authors said. “Action now to reduce the amplitude of the next medical liability cycle is both prudent and feasible. Further testing of nontraditional reforms, followed by wider implementation of those that work, holds the most promise.”

On Twitter @legal_med

Fewer malpractice suits are resulting in paid claims against physicians while malpractice insurance premiums have remained stable or declined over the last 12 years, according to an analysis published Oct. 30 in JAMA.

Since 2002, the rate of paid malpractice claims against doctors of medicine has decreased by an estimated 6% annually; for doctors of osteopathy, the rate has declined about 5% annually, Michelle M. Mello of Stanford (Calif.) University and her colleagues reported (JAMA 2014 Oct. 30 [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.10705]).

Dr. Mello and her colleagues analyzed paid legal claims against MDs and DOs between 1994 and 2013 from the National Practitioner Data Bank and the American Medical Association’s Physician Masterfile. They also evaluated premium data from the Medical Liability Monitor’s Annual Rate Survey.

The rate of paid malpractice claims against MDs fell from 18.6 to 9.9 paid claims per 1,000 physicians between 2002 and 2013, they found. For DOs, rates dropped from about 19 in 2002 to about 12.2 paid claims per 1,000 physicians in 2013.

The median compensation paid to plaintiffs rose by 63% between 1994 and 2007, from $133,799 to $218,400, in adjusted 2013 dollars. However, since 2007, that number has declined, reaching $195,000 in 2013. Only 3.4% of payments made during the 20-year period resulted from jury verdicts; the others stemmed from settlements.

For the premiums review, Dr. Mello and colleagues analyzed insurance data from 2004 to 2013 from five geographical areas: Los Angeles, Orange, Kern, and Ventura counties in California; Nassau and Suffolk counties in New York; Cook, Madison, St. Clair, and Will counties in Illinois; and the states of Tennessee and Colorado. The locations were selected based on geographic diversity and because each had an insurer with a dominant market share.

In California, Illinois, and Tennessee, internists and ob.gyns. saw a 36% decrease in premiums charged by each state’s largest medical malpractice insurer from 2004 to 2013. Premiums charged to general surgeons fell by 30% in these states. In Colorado, internists saw a 20% decrease in premiums over the same time period, but general surgeons saw an increase of 13% and ob.gyns. experienced an 11% rise. In New York, rates charged by the largest insurer rose by 12% for ob.gyns, 16% for internists, and 35% for general surgeons.

It remains unclear why the rate of paid claims has decreased and why premiums have remained fairly stable, Dr. Mello and colleagues said. While medical organizations like to point to tort reform, traditional reforms such as award caps do not address problems within the malpractice system’s core functions – compensating negligently injured patients and deterring substandard care, they added.

“The weight of evidence suggests that the system’s effectiveness as both a compensation and a deterrence mechanism is mediocre at best, and there is little to suggest it has improved over the past decade,” they wrote. “Thus, ‘stable but still dysfunctional’ might describe today’s liability environment.”

The authors offered alternatives to traditional tort reform, such as communication and resolution programs, mandatory presuit notification laws, and judge-directed negotiation.

In communication and resolution programs, clinicians and institutions openly discuss adverse outcomes with patients and proactively seek resolution, including offering an apology, and, if the standard of care was not met, compensation. Mandatory presuit notification refers to requiring plaintiffs to give defendants advance notice that they intend to sue. Judge-directed negotiation centers on court policies in which malpractice litigants meet early and often with judges to discuss settlement. In such negotiations, the court employs an attorney with clinical training to help judges understand clinical issues.

The authors conclude that action to improve the medical liability system is necessary while the legal climate is stable, and not after a crisis.

“During malpractice crises, interest in liability reform intensifies, but one lesson of the last 40 years is that an atmosphere of crisis is not conducive to thoughtful and enduring solutions,” study authors said. “Action now to reduce the amplitude of the next medical liability cycle is both prudent and feasible. Further testing of nontraditional reforms, followed by wider implementation of those that work, holds the most promise.”

On Twitter @legal_med

Fewer malpractice suits are resulting in paid claims against physicians while malpractice insurance premiums have remained stable or declined over the last 12 years, according to an analysis published Oct. 30 in JAMA.

Since 2002, the rate of paid malpractice claims against doctors of medicine has decreased by an estimated 6% annually; for doctors of osteopathy, the rate has declined about 5% annually, Michelle M. Mello of Stanford (Calif.) University and her colleagues reported (JAMA 2014 Oct. 30 [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.10705]).

Dr. Mello and her colleagues analyzed paid legal claims against MDs and DOs between 1994 and 2013 from the National Practitioner Data Bank and the American Medical Association’s Physician Masterfile. They also evaluated premium data from the Medical Liability Monitor’s Annual Rate Survey.

The rate of paid malpractice claims against MDs fell from 18.6 to 9.9 paid claims per 1,000 physicians between 2002 and 2013, they found. For DOs, rates dropped from about 19 in 2002 to about 12.2 paid claims per 1,000 physicians in 2013.

The median compensation paid to plaintiffs rose by 63% between 1994 and 2007, from $133,799 to $218,400, in adjusted 2013 dollars. However, since 2007, that number has declined, reaching $195,000 in 2013. Only 3.4% of payments made during the 20-year period resulted from jury verdicts; the others stemmed from settlements.

For the premiums review, Dr. Mello and colleagues analyzed insurance data from 2004 to 2013 from five geographical areas: Los Angeles, Orange, Kern, and Ventura counties in California; Nassau and Suffolk counties in New York; Cook, Madison, St. Clair, and Will counties in Illinois; and the states of Tennessee and Colorado. The locations were selected based on geographic diversity and because each had an insurer with a dominant market share.

In California, Illinois, and Tennessee, internists and ob.gyns. saw a 36% decrease in premiums charged by each state’s largest medical malpractice insurer from 2004 to 2013. Premiums charged to general surgeons fell by 30% in these states. In Colorado, internists saw a 20% decrease in premiums over the same time period, but general surgeons saw an increase of 13% and ob.gyns. experienced an 11% rise. In New York, rates charged by the largest insurer rose by 12% for ob.gyns, 16% for internists, and 35% for general surgeons.

It remains unclear why the rate of paid claims has decreased and why premiums have remained fairly stable, Dr. Mello and colleagues said. While medical organizations like to point to tort reform, traditional reforms such as award caps do not address problems within the malpractice system’s core functions – compensating negligently injured patients and deterring substandard care, they added.

“The weight of evidence suggests that the system’s effectiveness as both a compensation and a deterrence mechanism is mediocre at best, and there is little to suggest it has improved over the past decade,” they wrote. “Thus, ‘stable but still dysfunctional’ might describe today’s liability environment.”

The authors offered alternatives to traditional tort reform, such as communication and resolution programs, mandatory presuit notification laws, and judge-directed negotiation.

In communication and resolution programs, clinicians and institutions openly discuss adverse outcomes with patients and proactively seek resolution, including offering an apology, and, if the standard of care was not met, compensation. Mandatory presuit notification refers to requiring plaintiffs to give defendants advance notice that they intend to sue. Judge-directed negotiation centers on court policies in which malpractice litigants meet early and often with judges to discuss settlement. In such negotiations, the court employs an attorney with clinical training to help judges understand clinical issues.

The authors conclude that action to improve the medical liability system is necessary while the legal climate is stable, and not after a crisis.

“During malpractice crises, interest in liability reform intensifies, but one lesson of the last 40 years is that an atmosphere of crisis is not conducive to thoughtful and enduring solutions,” study authors said. “Action now to reduce the amplitude of the next medical liability cycle is both prudent and feasible. Further testing of nontraditional reforms, followed by wider implementation of those that work, holds the most promise.”

On Twitter @legal_med

Key clinical point: Doctors have experienced a steady decrease in paid malpractice claims since 2002.

Major finding: The rate of paid malpractice claims against MDs fell from 18.6 to 9.9 paid claims per 1,000 physicians between 2002 and 2013.

Data source: Data analysis of paid claims and insurance premiums

Disclosures: Michelle M. Mello, Ph.D., and Dr. Allen Kachalia report that they served as investigators on several of the demonstration projects described in the JAMA article. Dr Mello also reports that she is an investigator on the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s toolkit project. Dr. Mello and Dr. Kachalia report that they have served as consultants to the state of Oregon on liability issues.

Medicare begins bundled hospital outpatient payments in 2015

After a year-long delay, Medicare officials are implementing bundled payments for a number of services performed in hospital outpatient departments.

The new payments, which were finalized in the 2015 Medicare Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System rule, take effect on Jan. 1, 2015.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services selected 25 primary services and their adjunctive services and supplies as comprehensive ambulatory payment classifications (C-APCs) and will provide a single payment under Medicare Part B. Medicare beneficiaries will pay a single copayment for the C-APC services.

The 25 C-APCs fall within 12 clinical families:

• automatic implantable cardiac defibrillators, pacemakers, and related devices.

• breast surgery.

• ENT procedures.

• cardiac electrophysiology.

• ophthalmic surgery.

• gastrointestinal procedures.

• neurostimulators.

• orthopedic surgery.

• implantable drug delivery systems.

• radiation oncology.

• urogenital procedures.

• vascular procedures.

For instance, Medicare has designated implantation of a drug infusion device as a C-APC (0227) with a bundled Part B Medicare payment of $15,566.

The final rule, which was released by CMS on Oct. 31, also reversed the CMS policy of requiring physician certification for all Medicare Part A hospital admissions.

Starting Jan. 1, a formal physician certification is required only for long-stay cases of 20 days or more, or in costly outlier cases. For most patients, the admission order, medical record, and progress notes will contain “sufficient information to support the medical necessity of an inpatient admission without a separate requirement of an additional, formal, physician certification,” according to the final rule.

The revision of the physician certification policy does not remove any of the requirements associated with Medicare’s controversial 2-midnight policy, which governs short-stay hospitalizations.

The final rule will be published in the Federal Register on Nov. 10.

On Twitter @maryellenny

After a year-long delay, Medicare officials are implementing bundled payments for a number of services performed in hospital outpatient departments.

The new payments, which were finalized in the 2015 Medicare Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System rule, take effect on Jan. 1, 2015.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services selected 25 primary services and their adjunctive services and supplies as comprehensive ambulatory payment classifications (C-APCs) and will provide a single payment under Medicare Part B. Medicare beneficiaries will pay a single copayment for the C-APC services.

The 25 C-APCs fall within 12 clinical families:

• automatic implantable cardiac defibrillators, pacemakers, and related devices.

• breast surgery.

• ENT procedures.

• cardiac electrophysiology.

• ophthalmic surgery.

• gastrointestinal procedures.

• neurostimulators.

• orthopedic surgery.

• implantable drug delivery systems.

• radiation oncology.

• urogenital procedures.

• vascular procedures.

For instance, Medicare has designated implantation of a drug infusion device as a C-APC (0227) with a bundled Part B Medicare payment of $15,566.

The final rule, which was released by CMS on Oct. 31, also reversed the CMS policy of requiring physician certification for all Medicare Part A hospital admissions.

Starting Jan. 1, a formal physician certification is required only for long-stay cases of 20 days or more, or in costly outlier cases. For most patients, the admission order, medical record, and progress notes will contain “sufficient information to support the medical necessity of an inpatient admission without a separate requirement of an additional, formal, physician certification,” according to the final rule.

The revision of the physician certification policy does not remove any of the requirements associated with Medicare’s controversial 2-midnight policy, which governs short-stay hospitalizations.

The final rule will be published in the Federal Register on Nov. 10.

On Twitter @maryellenny

After a year-long delay, Medicare officials are implementing bundled payments for a number of services performed in hospital outpatient departments.

The new payments, which were finalized in the 2015 Medicare Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System rule, take effect on Jan. 1, 2015.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services selected 25 primary services and their adjunctive services and supplies as comprehensive ambulatory payment classifications (C-APCs) and will provide a single payment under Medicare Part B. Medicare beneficiaries will pay a single copayment for the C-APC services.

The 25 C-APCs fall within 12 clinical families:

• automatic implantable cardiac defibrillators, pacemakers, and related devices.

• breast surgery.

• ENT procedures.

• cardiac electrophysiology.

• ophthalmic surgery.

• gastrointestinal procedures.

• neurostimulators.

• orthopedic surgery.

• implantable drug delivery systems.

• radiation oncology.

• urogenital procedures.

• vascular procedures.

For instance, Medicare has designated implantation of a drug infusion device as a C-APC (0227) with a bundled Part B Medicare payment of $15,566.

The final rule, which was released by CMS on Oct. 31, also reversed the CMS policy of requiring physician certification for all Medicare Part A hospital admissions.

Starting Jan. 1, a formal physician certification is required only for long-stay cases of 20 days or more, or in costly outlier cases. For most patients, the admission order, medical record, and progress notes will contain “sufficient information to support the medical necessity of an inpatient admission without a separate requirement of an additional, formal, physician certification,” according to the final rule.

The revision of the physician certification policy does not remove any of the requirements associated with Medicare’s controversial 2-midnight policy, which governs short-stay hospitalizations.

The final rule will be published in the Federal Register on Nov. 10.

On Twitter @maryellenny

Emergency Departments Monitored, Investigated by Hospital Committees, Governmental Agencies

Why is it that there are no focused looks into the ED? We all know, as hospitalists, that the ED locks us into many admissions. Yet I see no initiatives through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) going after the ED for wanting patients admitted rather than trying to get these patients sent home for outpatient therapy.

–Ray Nowaczyk, DO

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Au contraire, my fellow hospitalist! The ED is monitored and investigated by many hospital committees and governmental agencies. Although we physicians, and I’m sure most hospitals, have always acknowledged our responsibilities to take care of patients during an emergency, this responsibility was enshrined in legalese in 1986 with the passage of the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA), also known as the “antidumping law.” Since its passage, any hospital that receives Medicare or Medicaid funding, which includes almost all of them, is at risk of being fined or losing this vital source of funding if this law is violated.

EMTALA essentially states that any patient who presents to the ED must be provided a screening exam and treatment for any “emergent medical condition” (including labor), regardless of the individual’s ability to pay. The hospital is then required to provide “stabilizing” treatment for these patients or transfer them to another facility where this treatment can be provided. Furthermore, hospitals that refuse to accept these patients in transfer without valid reasons (e.g. no open beds) can be charged with an EMTALA violation.

As you well know, what is considered stabilized or at baseline by one clinician can be seen as unstable or requiring urgent care by another. The real day-to-day practice of medicine often defies evidence-based logic and forces us to make decisions based on many clinical and nonclinical variables.

These situations are further compounded by recent CMS attempts to hold hospitals publicly accountable for ED throughput by posting these measures on its website. Along with other metrics, the citizenry can now see how long it takes an ED patient to be seen by a health professional, receive pain medication if they have a broken bone, receive appropriate treatment and be sent home, or, if admitted, how long it takes to get into a bed.

This information makes it clearer that in situations of clinical uncertainty, it may be easier for many ED physicians to admit than to discharge. The “treat-‘em or street-‘em” mentality of triaging patients, of course, varies from doc to doc and can definitely create antipathy towards physicians in the ED. As much as I may disagree with some of our ED doc’s admissions, I always—OK, maybe not always—try to assume they have the patient’s best interest at heart.

Once admitted, the onus is placed on us, as hospitalists, to determine whether the patient requires ongoing inpatient care, can be cared for in an “observation” capacity, or should be discharged. We all have received calls from a nurse informing us that the patient “does not meet inpatient criteria”—even if the patient is hypotensive with systemic inflammatory response syndrome and lactic acidosis. Oh, if we could only send them back to the ED!

Do you have a problem or concern that you’d like Dr. Hospitalist to address? Email your questions to [email protected].

Why is it that there are no focused looks into the ED? We all know, as hospitalists, that the ED locks us into many admissions. Yet I see no initiatives through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) going after the ED for wanting patients admitted rather than trying to get these patients sent home for outpatient therapy.

–Ray Nowaczyk, DO

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Au contraire, my fellow hospitalist! The ED is monitored and investigated by many hospital committees and governmental agencies. Although we physicians, and I’m sure most hospitals, have always acknowledged our responsibilities to take care of patients during an emergency, this responsibility was enshrined in legalese in 1986 with the passage of the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA), also known as the “antidumping law.” Since its passage, any hospital that receives Medicare or Medicaid funding, which includes almost all of them, is at risk of being fined or losing this vital source of funding if this law is violated.

EMTALA essentially states that any patient who presents to the ED must be provided a screening exam and treatment for any “emergent medical condition” (including labor), regardless of the individual’s ability to pay. The hospital is then required to provide “stabilizing” treatment for these patients or transfer them to another facility where this treatment can be provided. Furthermore, hospitals that refuse to accept these patients in transfer without valid reasons (e.g. no open beds) can be charged with an EMTALA violation.

As you well know, what is considered stabilized or at baseline by one clinician can be seen as unstable or requiring urgent care by another. The real day-to-day practice of medicine often defies evidence-based logic and forces us to make decisions based on many clinical and nonclinical variables.

These situations are further compounded by recent CMS attempts to hold hospitals publicly accountable for ED throughput by posting these measures on its website. Along with other metrics, the citizenry can now see how long it takes an ED patient to be seen by a health professional, receive pain medication if they have a broken bone, receive appropriate treatment and be sent home, or, if admitted, how long it takes to get into a bed.

This information makes it clearer that in situations of clinical uncertainty, it may be easier for many ED physicians to admit than to discharge. The “treat-‘em or street-‘em” mentality of triaging patients, of course, varies from doc to doc and can definitely create antipathy towards physicians in the ED. As much as I may disagree with some of our ED doc’s admissions, I always—OK, maybe not always—try to assume they have the patient’s best interest at heart.

Once admitted, the onus is placed on us, as hospitalists, to determine whether the patient requires ongoing inpatient care, can be cared for in an “observation” capacity, or should be discharged. We all have received calls from a nurse informing us that the patient “does not meet inpatient criteria”—even if the patient is hypotensive with systemic inflammatory response syndrome and lactic acidosis. Oh, if we could only send them back to the ED!

Do you have a problem or concern that you’d like Dr. Hospitalist to address? Email your questions to [email protected].

Why is it that there are no focused looks into the ED? We all know, as hospitalists, that the ED locks us into many admissions. Yet I see no initiatives through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) going after the ED for wanting patients admitted rather than trying to get these patients sent home for outpatient therapy.

–Ray Nowaczyk, DO

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Au contraire, my fellow hospitalist! The ED is monitored and investigated by many hospital committees and governmental agencies. Although we physicians, and I’m sure most hospitals, have always acknowledged our responsibilities to take care of patients during an emergency, this responsibility was enshrined in legalese in 1986 with the passage of the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA), also known as the “antidumping law.” Since its passage, any hospital that receives Medicare or Medicaid funding, which includes almost all of them, is at risk of being fined or losing this vital source of funding if this law is violated.

EMTALA essentially states that any patient who presents to the ED must be provided a screening exam and treatment for any “emergent medical condition” (including labor), regardless of the individual’s ability to pay. The hospital is then required to provide “stabilizing” treatment for these patients or transfer them to another facility where this treatment can be provided. Furthermore, hospitals that refuse to accept these patients in transfer without valid reasons (e.g. no open beds) can be charged with an EMTALA violation.

As you well know, what is considered stabilized or at baseline by one clinician can be seen as unstable or requiring urgent care by another. The real day-to-day practice of medicine often defies evidence-based logic and forces us to make decisions based on many clinical and nonclinical variables.

These situations are further compounded by recent CMS attempts to hold hospitals publicly accountable for ED throughput by posting these measures on its website. Along with other metrics, the citizenry can now see how long it takes an ED patient to be seen by a health professional, receive pain medication if they have a broken bone, receive appropriate treatment and be sent home, or, if admitted, how long it takes to get into a bed.

This information makes it clearer that in situations of clinical uncertainty, it may be easier for many ED physicians to admit than to discharge. The “treat-‘em or street-‘em” mentality of triaging patients, of course, varies from doc to doc and can definitely create antipathy towards physicians in the ED. As much as I may disagree with some of our ED doc’s admissions, I always—OK, maybe not always—try to assume they have the patient’s best interest at heart.

Once admitted, the onus is placed on us, as hospitalists, to determine whether the patient requires ongoing inpatient care, can be cared for in an “observation” capacity, or should be discharged. We all have received calls from a nurse informing us that the patient “does not meet inpatient criteria”—even if the patient is hypotensive with systemic inflammatory response syndrome and lactic acidosis. Oh, if we could only send them back to the ED!

Do you have a problem or concern that you’d like Dr. Hospitalist to address? Email your questions to [email protected].

Hospitals' Observation Status Designation May Trigger Malpractice Claims

I’m convinced that observation status is rapidly becoming a meaningful factor in patients’ decision to file a malpractice lawsuit.

First, let me concede that I don’t know of any hard data to support my claim. I even asked the nation’s largest malpractice insurer about this, and they didn’t have any data on it. I think that is because observation status has only become a really big issue in the last couple of years, and since it typically takes several years for a malpractice suit to conclude, it just hasn’t found its way onto their radar yet.

But I’m pretty sure that will change within the next few years.

Implications

As any seasoned practitioner in our field knows, all outpatient and inpatient physician charges for Medicare patients, along with those of other licensed practitioners, are billed through Medicare Part B. After meeting a deductible, patients with traditional fee-for-service Medicare are generally responsible for 20% of all approved Part B charges, with no upper limit. For patients seen by a large number of providers while hospitalized, this 20% can really add up. Some patients have a secondary insurance that pays for this.

Hospital charges for patients on inpatient status are billed through Medicare Part A. Patients have an annual Part A deductible, and only in the case of very long inpatient stays will they have to pay more than that for inpatient care each year.

But hospital charges for patients on observation status are billed through Part B. And because hospital charges add up so quickly, the 20% of this that the patient is responsible for can be a lot of money—thousands of dollars, even for stays of less than 24 hours. Understandably, patients are not at all happy about this.

Let’s say you’re admitted overnight on observation status and your doctor orders your usual Advair inhaler. You use it once. Most hospitals aren’t able to ensure compliance with regulations around dispensing medications for home use like a pharmacy, so they won’t let you take the inhaler home. A few weeks later you’re stunned to learn that the hospital charged $10,000 for all services provided, and you’re responsible for 20% of the allowable amount PLUS the cost of all “self administered” drugs, like inhalers, eye drops, and calcitonin nasal spray. You look over your bill to see that you’re asked to pay $350 for the inhaler you used once and couldn’t even take home with you! Many self-administered medications, including eye drops and calcitonin nasal spray, result in similarly alarming charges to patients.

On top of the unpleasant surprise of a large hospital bill, Medicare won’t pay for skilled nursing facility (SNF) care for patients who are on observation status. That is, observation is not a “qualifying” stay for beneficiaries to access their SNF benefit.

It is easy to see why patients are unhappy about observation status.

The Media Message

News media are making the public aware of the potentially high financial costs they face if placed on observation status. But, too often, they oversimplify the issue, making it seem as though the choice of observation vs. inpatient status is entirely up to the treating doctor.

Saying that this decision is entirely up to the doctor is a lot like saying it is entirely up to you to determine how fast you drive on a freeway. In a sense that is correct, because no one else is in your car to control how fast you go and, in theory, you could choose to go 100 mph or 30 mph. The only problem is that it wouldn’t be long before you’d be in trouble with the law. So you don’t have complete autonomy to choose your speed; you have to comply with the laws. The same is true for doctors choosing observation status. We must comply with regulations in choosing the status or face legal consequences like fines or accusations of fraud.

Most news stories, like this one from NBC news (www.nbcnews.com/video/nightly-news/54511352#54511352) in February, are generally accurate but leave out the important fact that hospitals and doctors have little autonomy to choose the status the patient prefers. Instead, media often simply encourage patients on observation status to argue for a change to inpatient status and “be persistent.” More and more often, patients and families are arguing with the treating doctor; in many cases, that is a hospitalist.

Complaints Surge

At the 2014 SHM annual meeting last spring in Las Vegas, I spoke with many hospitalists who said that, increasingly, they are targets of observation-status complaints. One hospitalist group recently had each doctor list his or her top three frustrations with work; difficult and stressful conversations about observation status topped the list.

Patient anger regarding observation status can turn a satisfied patient into an angry one. We all know that unhappy patients are the ones most likely to pursue malpractice lawsuits. While anger over observation status doesn’t equal medical malpractice, it can change a patient’s opinion of our care, which may in some cases result in a malpractice claim.

Solutions

Medicare is unlikely to do away with observation status, so the best way to prevent complaints is to ensure that all its implications are explained to patients and families, ideally before they’re put into the hospital (e.g., while still in the ED). I think it is best if this message is delivered by someone other than the treating doctor(s): For example, a case manager might handle the discussion. Of course, patients and families are often too overwhelmed in the ED to absorb this information, so the message may need to be repeated later.

Maybe everyone should tell observation patients, “We’re going to observe you” without using any form of the word “admission.” And having these patients stay in distinct observation units probably reduces misunderstandings and complaints compared to the common practice of mixing these patients in “regular” hospital floors housing those on inpatient status.

Unfortunately, I couldn’t find research data to support this idea.

I bet some hospitals have even more elegant and effective ways to reduce misunderstandings and complaints around observation status. I’d love to hear from you if you know of any. E-mail me at [email protected].

I’m convinced that observation status is rapidly becoming a meaningful factor in patients’ decision to file a malpractice lawsuit.

First, let me concede that I don’t know of any hard data to support my claim. I even asked the nation’s largest malpractice insurer about this, and they didn’t have any data on it. I think that is because observation status has only become a really big issue in the last couple of years, and since it typically takes several years for a malpractice suit to conclude, it just hasn’t found its way onto their radar yet.

But I’m pretty sure that will change within the next few years.

Implications

As any seasoned practitioner in our field knows, all outpatient and inpatient physician charges for Medicare patients, along with those of other licensed practitioners, are billed through Medicare Part B. After meeting a deductible, patients with traditional fee-for-service Medicare are generally responsible for 20% of all approved Part B charges, with no upper limit. For patients seen by a large number of providers while hospitalized, this 20% can really add up. Some patients have a secondary insurance that pays for this.

Hospital charges for patients on inpatient status are billed through Medicare Part A. Patients have an annual Part A deductible, and only in the case of very long inpatient stays will they have to pay more than that for inpatient care each year.

But hospital charges for patients on observation status are billed through Part B. And because hospital charges add up so quickly, the 20% of this that the patient is responsible for can be a lot of money—thousands of dollars, even for stays of less than 24 hours. Understandably, patients are not at all happy about this.

Let’s say you’re admitted overnight on observation status and your doctor orders your usual Advair inhaler. You use it once. Most hospitals aren’t able to ensure compliance with regulations around dispensing medications for home use like a pharmacy, so they won’t let you take the inhaler home. A few weeks later you’re stunned to learn that the hospital charged $10,000 for all services provided, and you’re responsible for 20% of the allowable amount PLUS the cost of all “self administered” drugs, like inhalers, eye drops, and calcitonin nasal spray. You look over your bill to see that you’re asked to pay $350 for the inhaler you used once and couldn’t even take home with you! Many self-administered medications, including eye drops and calcitonin nasal spray, result in similarly alarming charges to patients.

On top of the unpleasant surprise of a large hospital bill, Medicare won’t pay for skilled nursing facility (SNF) care for patients who are on observation status. That is, observation is not a “qualifying” stay for beneficiaries to access their SNF benefit.

It is easy to see why patients are unhappy about observation status.

The Media Message

News media are making the public aware of the potentially high financial costs they face if placed on observation status. But, too often, they oversimplify the issue, making it seem as though the choice of observation vs. inpatient status is entirely up to the treating doctor.

Saying that this decision is entirely up to the doctor is a lot like saying it is entirely up to you to determine how fast you drive on a freeway. In a sense that is correct, because no one else is in your car to control how fast you go and, in theory, you could choose to go 100 mph or 30 mph. The only problem is that it wouldn’t be long before you’d be in trouble with the law. So you don’t have complete autonomy to choose your speed; you have to comply with the laws. The same is true for doctors choosing observation status. We must comply with regulations in choosing the status or face legal consequences like fines or accusations of fraud.

Most news stories, like this one from NBC news (www.nbcnews.com/video/nightly-news/54511352#54511352) in February, are generally accurate but leave out the important fact that hospitals and doctors have little autonomy to choose the status the patient prefers. Instead, media often simply encourage patients on observation status to argue for a change to inpatient status and “be persistent.” More and more often, patients and families are arguing with the treating doctor; in many cases, that is a hospitalist.

Complaints Surge

At the 2014 SHM annual meeting last spring in Las Vegas, I spoke with many hospitalists who said that, increasingly, they are targets of observation-status complaints. One hospitalist group recently had each doctor list his or her top three frustrations with work; difficult and stressful conversations about observation status topped the list.

Patient anger regarding observation status can turn a satisfied patient into an angry one. We all know that unhappy patients are the ones most likely to pursue malpractice lawsuits. While anger over observation status doesn’t equal medical malpractice, it can change a patient’s opinion of our care, which may in some cases result in a malpractice claim.

Solutions

Medicare is unlikely to do away with observation status, so the best way to prevent complaints is to ensure that all its implications are explained to patients and families, ideally before they’re put into the hospital (e.g., while still in the ED). I think it is best if this message is delivered by someone other than the treating doctor(s): For example, a case manager might handle the discussion. Of course, patients and families are often too overwhelmed in the ED to absorb this information, so the message may need to be repeated later.

Maybe everyone should tell observation patients, “We’re going to observe you” without using any form of the word “admission.” And having these patients stay in distinct observation units probably reduces misunderstandings and complaints compared to the common practice of mixing these patients in “regular” hospital floors housing those on inpatient status.

Unfortunately, I couldn’t find research data to support this idea.

I bet some hospitals have even more elegant and effective ways to reduce misunderstandings and complaints around observation status. I’d love to hear from you if you know of any. E-mail me at [email protected].

I’m convinced that observation status is rapidly becoming a meaningful factor in patients’ decision to file a malpractice lawsuit.

First, let me concede that I don’t know of any hard data to support my claim. I even asked the nation’s largest malpractice insurer about this, and they didn’t have any data on it. I think that is because observation status has only become a really big issue in the last couple of years, and since it typically takes several years for a malpractice suit to conclude, it just hasn’t found its way onto their radar yet.

But I’m pretty sure that will change within the next few years.

Implications

As any seasoned practitioner in our field knows, all outpatient and inpatient physician charges for Medicare patients, along with those of other licensed practitioners, are billed through Medicare Part B. After meeting a deductible, patients with traditional fee-for-service Medicare are generally responsible for 20% of all approved Part B charges, with no upper limit. For patients seen by a large number of providers while hospitalized, this 20% can really add up. Some patients have a secondary insurance that pays for this.

Hospital charges for patients on inpatient status are billed through Medicare Part A. Patients have an annual Part A deductible, and only in the case of very long inpatient stays will they have to pay more than that for inpatient care each year.

But hospital charges for patients on observation status are billed through Part B. And because hospital charges add up so quickly, the 20% of this that the patient is responsible for can be a lot of money—thousands of dollars, even for stays of less than 24 hours. Understandably, patients are not at all happy about this.

Let’s say you’re admitted overnight on observation status and your doctor orders your usual Advair inhaler. You use it once. Most hospitals aren’t able to ensure compliance with regulations around dispensing medications for home use like a pharmacy, so they won’t let you take the inhaler home. A few weeks later you’re stunned to learn that the hospital charged $10,000 for all services provided, and you’re responsible for 20% of the allowable amount PLUS the cost of all “self administered” drugs, like inhalers, eye drops, and calcitonin nasal spray. You look over your bill to see that you’re asked to pay $350 for the inhaler you used once and couldn’t even take home with you! Many self-administered medications, including eye drops and calcitonin nasal spray, result in similarly alarming charges to patients.

On top of the unpleasant surprise of a large hospital bill, Medicare won’t pay for skilled nursing facility (SNF) care for patients who are on observation status. That is, observation is not a “qualifying” stay for beneficiaries to access their SNF benefit.

It is easy to see why patients are unhappy about observation status.

The Media Message

News media are making the public aware of the potentially high financial costs they face if placed on observation status. But, too often, they oversimplify the issue, making it seem as though the choice of observation vs. inpatient status is entirely up to the treating doctor.

Saying that this decision is entirely up to the doctor is a lot like saying it is entirely up to you to determine how fast you drive on a freeway. In a sense that is correct, because no one else is in your car to control how fast you go and, in theory, you could choose to go 100 mph or 30 mph. The only problem is that it wouldn’t be long before you’d be in trouble with the law. So you don’t have complete autonomy to choose your speed; you have to comply with the laws. The same is true for doctors choosing observation status. We must comply with regulations in choosing the status or face legal consequences like fines or accusations of fraud.

Most news stories, like this one from NBC news (www.nbcnews.com/video/nightly-news/54511352#54511352) in February, are generally accurate but leave out the important fact that hospitals and doctors have little autonomy to choose the status the patient prefers. Instead, media often simply encourage patients on observation status to argue for a change to inpatient status and “be persistent.” More and more often, patients and families are arguing with the treating doctor; in many cases, that is a hospitalist.

Complaints Surge

At the 2014 SHM annual meeting last spring in Las Vegas, I spoke with many hospitalists who said that, increasingly, they are targets of observation-status complaints. One hospitalist group recently had each doctor list his or her top three frustrations with work; difficult and stressful conversations about observation status topped the list.

Patient anger regarding observation status can turn a satisfied patient into an angry one. We all know that unhappy patients are the ones most likely to pursue malpractice lawsuits. While anger over observation status doesn’t equal medical malpractice, it can change a patient’s opinion of our care, which may in some cases result in a malpractice claim.

Solutions

Medicare is unlikely to do away with observation status, so the best way to prevent complaints is to ensure that all its implications are explained to patients and families, ideally before they’re put into the hospital (e.g., while still in the ED). I think it is best if this message is delivered by someone other than the treating doctor(s): For example, a case manager might handle the discussion. Of course, patients and families are often too overwhelmed in the ED to absorb this information, so the message may need to be repeated later.

Maybe everyone should tell observation patients, “We’re going to observe you” without using any form of the word “admission.” And having these patients stay in distinct observation units probably reduces misunderstandings and complaints compared to the common practice of mixing these patients in “regular” hospital floors housing those on inpatient status.

Unfortunately, I couldn’t find research data to support this idea.

I bet some hospitals have even more elegant and effective ways to reduce misunderstandings and complaints around observation status. I’d love to hear from you if you know of any. E-mail me at [email protected].

Physician Tips Help Hone Clinicians' Practice Management, Decision-Making Skills

EDITOR’S NOTE: Second in an occasional series of reviews of the Hospital Medicine: Current Concepts series by members of Team Hospitalist.

Summary

The third installment in the Hospital Medicine: Current Concepts series, Becoming a Consummate Clinician is written in two parts. Part 1, “Medical Musts and Must-Nots,” is focused on the basics of being a clinician: gathering an appropriate history, performing an effective physical examination, and formulating differential diagnoses. This section in particular is geared toward house officers and attending physicians on teaching teams. While the audience here is primarily clinicians on a teaching service, there is good advice for those in any practice setting about avoiding common mistakes and developing clinical sagacity.

In this first section, we are given advisement on treatment of and with medications. Regardless of a clinician’s level of experience, it is worth reading this text to review and internalize these authors’ advice regarding medication pitfalls. Simply putting this advice into one’s daily practice of medicine will take any practitioner a long way toward becoming a “consummate clinician.”

Part 2, “Medical Masteries,” logically builds upon material presented in Part 1. The final section of the book addresses aspects of critical analysis of medical data and encourages engagement of critical thinking skills in all aspects of clinical decision-making. Specific topics addressed include reducing medical errors, reevaluating evidence-based medicine, deconstructing several widely cited medical aphorisms, identifying sources of cognitive errors, and transforming information into understanding.

The authors devoted the final chapter to the discussion of “What is disease?” and “What is health?” which, quite frankly, adds little value to the book.

Drs. Goldberger and Goldberger discuss what they term the “interstitial curriculum”—what is not explicitly taught but should be. Included in the “interstitial curriculum” is examination of cognitive errors and how we are more apt to make these in the era of “high-throughput” patient care. Another topic included in their “interstitial curriculum” is the paucity of attention paid to addressing uncertainty in all aspects of medicine. These topics are worth the cost of this book, even if it only helps promote awareness of these important ideas and bring the discussion to a larger audience.

The complementary processes of constantly rethinking assumptions, researching information, and reformulating basic mechanisms are fundamental to practicing all types of medicine successfully. Such processes also help to avoid potentially lethal errors and help to rigorously and compassionately advance the inseparable sciences of prevention and healing. The deep and multidimensional challenges are central to the ongoing pursuit of becoming the consummate clinician.”

Analysis

There are times in this book, particularly in the beginning, when the reader feels this text was written for the benefit of the house officer and those practitioners serving on inpatient teaching services. Continued reading, however, finds brilliant advice for clinicians in all practice settings and in all stages of their careers.

The encouragement of all readers to rethink everything we assume to be true and to seek a deeper understanding of what we “know” is priceless.

The quotes included throughout the book were both valuable and enjoyable. The authors included quotes from Plutarch to Hector Barbosa from Pirates of the Caribbean. One quote that is particularly germane to the practice of hospital medicine in this age of the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems comes from Sir William Osler:

“Remember…that every patient upon whom you wait will examine you critically and form an estimate of you by the way in which you conduct yourself at the bedside. Skill and nicety in manipulation, in the simple act of feeling the pulse or in the performance of any minor operation, will do more towards establishing confidence in you than a string of diplomas, or the reputation of extensive hospital experience.”

Conversely, the computer-generated graphics added no value and were, in fact, a detractor. Hopefully, the next edition will not feature the sophomorically rendered bridge advising us to “bridge the classroom-to-clinic gap,” the flamingo, or the zigzagging line, among others.

Dr. Lindsey is chief operations officer and strategist of Synergy Surgicalists, and a member of Team Hospitalist.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Second in an occasional series of reviews of the Hospital Medicine: Current Concepts series by members of Team Hospitalist.

Summary

The third installment in the Hospital Medicine: Current Concepts series, Becoming a Consummate Clinician is written in two parts. Part 1, “Medical Musts and Must-Nots,” is focused on the basics of being a clinician: gathering an appropriate history, performing an effective physical examination, and formulating differential diagnoses. This section in particular is geared toward house officers and attending physicians on teaching teams. While the audience here is primarily clinicians on a teaching service, there is good advice for those in any practice setting about avoiding common mistakes and developing clinical sagacity.

In this first section, we are given advisement on treatment of and with medications. Regardless of a clinician’s level of experience, it is worth reading this text to review and internalize these authors’ advice regarding medication pitfalls. Simply putting this advice into one’s daily practice of medicine will take any practitioner a long way toward becoming a “consummate clinician.”

Part 2, “Medical Masteries,” logically builds upon material presented in Part 1. The final section of the book addresses aspects of critical analysis of medical data and encourages engagement of critical thinking skills in all aspects of clinical decision-making. Specific topics addressed include reducing medical errors, reevaluating evidence-based medicine, deconstructing several widely cited medical aphorisms, identifying sources of cognitive errors, and transforming information into understanding.

The authors devoted the final chapter to the discussion of “What is disease?” and “What is health?” which, quite frankly, adds little value to the book.