User login

State of Hospital Medicine Report an Evaluation Tool for Hospital Medicine Groups

I think my team of hospitalists is probably tired of hearing my sports analogies. But as I look at the State of Hospital Medicine 2014 report (SOHM), I cannot help but see relationships to athletics.

When you think about football, you automatically contemplate the scope of a particular team and the context of the upcoming season. What are the strengths of the team—do we emphasize offense or defense or special teams? How about the variety of formations or the scheduling and strength of opponents? How about the depth of our roster—what is the talent level available? How do we compare to other teams?

How in the world does this relate to the SOHM? It gives us a chance to evaluate our own hospital medicine groups (HMGs) in the context of the other HMGs across the country. When I look at scope of services and, particularly, the data from Figure 3.1, I am struck with the breadth of the range of services in which HMGs engage. Certainly, our core identity as hospitalists includes admitting referral patients and unassigned patients, but, as of 2014, nearly 90% of hospitalist groups are also managing and co-managing surgical and medical subspecialty patients. To my eyes, the big change since 2012 is the 20% increase in the number of HMGs medically co-managing medical subspecialty patients.

There are some newcomers to our roster, as well—the palliative care and post-acute care work being done by 15% and 25% of our groups, respectively. Particularly striking is the fact that one quarter of HMGs are involved in post-acute care, follow-up clinics, nursing homes, and the like.

My take on this is that factors such as increased complexity of hospitalized patients with lean length of stay and higher acuity needs at discharge transition are driving the need for a measure of continuity and expertise post discharge that may best be provided by HMGs. The trending of the post-acute care challenges/opportunities will certainly be worth watching—sort of like a rookie player who is having a big impact.

As hospitalists may become focused on throughput (admissions discharges and transfers), the interruption to perform procedures may decrease the net value of the hospitalist to the institution.

—William A. Landis, MD, FHM

Not surprisingly, nighttime admissions work continues to gain traction. Nearly 60% of HMGs are performing nighttime admissions.

In my regional chapter, we recently heard a presentation on “nocturnists.” An interesting contention that caught my attention was that the nocturnist viewed herself as providing expert clinical care during off-hours—particularly at night—and that she was looking to increase the value and not just “put her finger in the dike,” so to speak, until the cavalry arrived at daybreak. As HMG responsibilities increase during the off-hours, I am thinking that my colleague is right: We are going to have to increase our depth and strength at this particular position so that we might actually become known as the “nighttime experts.” I look for this trend to continue.

Finally, I am drawn to the data on care of patients in the ICU, a number that continues to rise—almost 70% of HMGs now. Meanwhile, procedures have dipped to 33% from 53% in the last report. At first, it seemed a little bit puzzling to me that as involvement in the ICUs seemed to increase, procedures diminished. My anecdotal experience is that most of my procedures occurred on patients who had intensive care requirements. Nonetheless, many hospitalists I have talked to seem to believe that the requirement/expectation of imaging in the performance of more and more invasive procedures—now a standard of care— has increasingly driven procedures to specialized areas of the hospital such as imaging/radiology departments. There may also be a net decrease in the number of procedures performed as more noninvasive diagnostic modalities provide satisfactory information.

As hospitalists may become focused on throughput (admissions discharges and transfers), the interruption to perform procedures may decrease the net value of the hospitalist to the institution. It may make sense for others to be doing procedures. Whatever the cause, my guess is these two trends may continue.

Diving deeper into the granularity of the report will lead the reader to discover subtle differences and trends. Academics, pediatric hospitalists, and independent HMGs all have some nuances, not to mention regional variation. You will have to dig into the report yourself to explore.

Just as there is a freshness to every new sports season, there is a freshness to reviewing the information from the SOHM reports, and evaluating the scope of service is always an exciting moment.

Dr. Landis is medical director of Wellspan Hospitalists in York, Pa., and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

I think my team of hospitalists is probably tired of hearing my sports analogies. But as I look at the State of Hospital Medicine 2014 report (SOHM), I cannot help but see relationships to athletics.

When you think about football, you automatically contemplate the scope of a particular team and the context of the upcoming season. What are the strengths of the team—do we emphasize offense or defense or special teams? How about the variety of formations or the scheduling and strength of opponents? How about the depth of our roster—what is the talent level available? How do we compare to other teams?

How in the world does this relate to the SOHM? It gives us a chance to evaluate our own hospital medicine groups (HMGs) in the context of the other HMGs across the country. When I look at scope of services and, particularly, the data from Figure 3.1, I am struck with the breadth of the range of services in which HMGs engage. Certainly, our core identity as hospitalists includes admitting referral patients and unassigned patients, but, as of 2014, nearly 90% of hospitalist groups are also managing and co-managing surgical and medical subspecialty patients. To my eyes, the big change since 2012 is the 20% increase in the number of HMGs medically co-managing medical subspecialty patients.

There are some newcomers to our roster, as well—the palliative care and post-acute care work being done by 15% and 25% of our groups, respectively. Particularly striking is the fact that one quarter of HMGs are involved in post-acute care, follow-up clinics, nursing homes, and the like.

My take on this is that factors such as increased complexity of hospitalized patients with lean length of stay and higher acuity needs at discharge transition are driving the need for a measure of continuity and expertise post discharge that may best be provided by HMGs. The trending of the post-acute care challenges/opportunities will certainly be worth watching—sort of like a rookie player who is having a big impact.

As hospitalists may become focused on throughput (admissions discharges and transfers), the interruption to perform procedures may decrease the net value of the hospitalist to the institution.

—William A. Landis, MD, FHM

Not surprisingly, nighttime admissions work continues to gain traction. Nearly 60% of HMGs are performing nighttime admissions.

In my regional chapter, we recently heard a presentation on “nocturnists.” An interesting contention that caught my attention was that the nocturnist viewed herself as providing expert clinical care during off-hours—particularly at night—and that she was looking to increase the value and not just “put her finger in the dike,” so to speak, until the cavalry arrived at daybreak. As HMG responsibilities increase during the off-hours, I am thinking that my colleague is right: We are going to have to increase our depth and strength at this particular position so that we might actually become known as the “nighttime experts.” I look for this trend to continue.

Finally, I am drawn to the data on care of patients in the ICU, a number that continues to rise—almost 70% of HMGs now. Meanwhile, procedures have dipped to 33% from 53% in the last report. At first, it seemed a little bit puzzling to me that as involvement in the ICUs seemed to increase, procedures diminished. My anecdotal experience is that most of my procedures occurred on patients who had intensive care requirements. Nonetheless, many hospitalists I have talked to seem to believe that the requirement/expectation of imaging in the performance of more and more invasive procedures—now a standard of care— has increasingly driven procedures to specialized areas of the hospital such as imaging/radiology departments. There may also be a net decrease in the number of procedures performed as more noninvasive diagnostic modalities provide satisfactory information.

As hospitalists may become focused on throughput (admissions discharges and transfers), the interruption to perform procedures may decrease the net value of the hospitalist to the institution. It may make sense for others to be doing procedures. Whatever the cause, my guess is these two trends may continue.

Diving deeper into the granularity of the report will lead the reader to discover subtle differences and trends. Academics, pediatric hospitalists, and independent HMGs all have some nuances, not to mention regional variation. You will have to dig into the report yourself to explore.

Just as there is a freshness to every new sports season, there is a freshness to reviewing the information from the SOHM reports, and evaluating the scope of service is always an exciting moment.

Dr. Landis is medical director of Wellspan Hospitalists in York, Pa., and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

I think my team of hospitalists is probably tired of hearing my sports analogies. But as I look at the State of Hospital Medicine 2014 report (SOHM), I cannot help but see relationships to athletics.

When you think about football, you automatically contemplate the scope of a particular team and the context of the upcoming season. What are the strengths of the team—do we emphasize offense or defense or special teams? How about the variety of formations or the scheduling and strength of opponents? How about the depth of our roster—what is the talent level available? How do we compare to other teams?

How in the world does this relate to the SOHM? It gives us a chance to evaluate our own hospital medicine groups (HMGs) in the context of the other HMGs across the country. When I look at scope of services and, particularly, the data from Figure 3.1, I am struck with the breadth of the range of services in which HMGs engage. Certainly, our core identity as hospitalists includes admitting referral patients and unassigned patients, but, as of 2014, nearly 90% of hospitalist groups are also managing and co-managing surgical and medical subspecialty patients. To my eyes, the big change since 2012 is the 20% increase in the number of HMGs medically co-managing medical subspecialty patients.

There are some newcomers to our roster, as well—the palliative care and post-acute care work being done by 15% and 25% of our groups, respectively. Particularly striking is the fact that one quarter of HMGs are involved in post-acute care, follow-up clinics, nursing homes, and the like.

My take on this is that factors such as increased complexity of hospitalized patients with lean length of stay and higher acuity needs at discharge transition are driving the need for a measure of continuity and expertise post discharge that may best be provided by HMGs. The trending of the post-acute care challenges/opportunities will certainly be worth watching—sort of like a rookie player who is having a big impact.

As hospitalists may become focused on throughput (admissions discharges and transfers), the interruption to perform procedures may decrease the net value of the hospitalist to the institution.

—William A. Landis, MD, FHM

Not surprisingly, nighttime admissions work continues to gain traction. Nearly 60% of HMGs are performing nighttime admissions.

In my regional chapter, we recently heard a presentation on “nocturnists.” An interesting contention that caught my attention was that the nocturnist viewed herself as providing expert clinical care during off-hours—particularly at night—and that she was looking to increase the value and not just “put her finger in the dike,” so to speak, until the cavalry arrived at daybreak. As HMG responsibilities increase during the off-hours, I am thinking that my colleague is right: We are going to have to increase our depth and strength at this particular position so that we might actually become known as the “nighttime experts.” I look for this trend to continue.

Finally, I am drawn to the data on care of patients in the ICU, a number that continues to rise—almost 70% of HMGs now. Meanwhile, procedures have dipped to 33% from 53% in the last report. At first, it seemed a little bit puzzling to me that as involvement in the ICUs seemed to increase, procedures diminished. My anecdotal experience is that most of my procedures occurred on patients who had intensive care requirements. Nonetheless, many hospitalists I have talked to seem to believe that the requirement/expectation of imaging in the performance of more and more invasive procedures—now a standard of care— has increasingly driven procedures to specialized areas of the hospital such as imaging/radiology departments. There may also be a net decrease in the number of procedures performed as more noninvasive diagnostic modalities provide satisfactory information.

As hospitalists may become focused on throughput (admissions discharges and transfers), the interruption to perform procedures may decrease the net value of the hospitalist to the institution. It may make sense for others to be doing procedures. Whatever the cause, my guess is these two trends may continue.

Diving deeper into the granularity of the report will lead the reader to discover subtle differences and trends. Academics, pediatric hospitalists, and independent HMGs all have some nuances, not to mention regional variation. You will have to dig into the report yourself to explore.

Just as there is a freshness to every new sports season, there is a freshness to reviewing the information from the SOHM reports, and evaluating the scope of service is always an exciting moment.

Dr. Landis is medical director of Wellspan Hospitalists in York, Pa., and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Medication Reconciliation Toolkit Updated, Available to Hospitalists

Adverse drug events and medication errors are unfortunately all too common within hospitals, but hospitalists can now take the lead in preventing them using SHM’s MARQUIS [Multi-Center Medication Reconciliation Quality Improvement Study] toolkit.

The authors of the new toolkit outline the hospitalist’s role in reducing medication errors as:

- Take responsibility for the accuracy of the medication reconciliation process for each patient under your care;

- Lead, coordinate, or participate in medication reconciliation quality improvement (QI) efforts with other key team members on the “front lines” to inform the hospital QI team on key interventions that would lead to improved patient outcomes;

- Become trained in taking the “best possible medication history” and in using effective discharge medication counseling; and

- Identify patients who are at high risk for a medication reconciliation error and would benefit from a more intensive medication reconciliation process.

“The MARQUIS study is important because it shows the potential of a mentored implementation effort, working with local hospitalist leaders and a QI toolkit, to improve medication safety related to the medication reconciliation process,” says MARQUIS principal investigator Jeff Schnipper, MD, MPH, FHM.

“It also shows the importance of institutional commitment to the success of these efforts. Lastly, hospitalists need to realize that medication reconciliation is not just some external regulatory requirement—it’s about the safety of the medications they order—and, therefore, that they need to ensure the quality of the process for the patients they care for and to lead efforts to improve the process across their hospitals.”

For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/marquis.

Adverse drug events and medication errors are unfortunately all too common within hospitals, but hospitalists can now take the lead in preventing them using SHM’s MARQUIS [Multi-Center Medication Reconciliation Quality Improvement Study] toolkit.

The authors of the new toolkit outline the hospitalist’s role in reducing medication errors as:

- Take responsibility for the accuracy of the medication reconciliation process for each patient under your care;

- Lead, coordinate, or participate in medication reconciliation quality improvement (QI) efforts with other key team members on the “front lines” to inform the hospital QI team on key interventions that would lead to improved patient outcomes;

- Become trained in taking the “best possible medication history” and in using effective discharge medication counseling; and

- Identify patients who are at high risk for a medication reconciliation error and would benefit from a more intensive medication reconciliation process.

“The MARQUIS study is important because it shows the potential of a mentored implementation effort, working with local hospitalist leaders and a QI toolkit, to improve medication safety related to the medication reconciliation process,” says MARQUIS principal investigator Jeff Schnipper, MD, MPH, FHM.

“It also shows the importance of institutional commitment to the success of these efforts. Lastly, hospitalists need to realize that medication reconciliation is not just some external regulatory requirement—it’s about the safety of the medications they order—and, therefore, that they need to ensure the quality of the process for the patients they care for and to lead efforts to improve the process across their hospitals.”

For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/marquis.

Adverse drug events and medication errors are unfortunately all too common within hospitals, but hospitalists can now take the lead in preventing them using SHM’s MARQUIS [Multi-Center Medication Reconciliation Quality Improvement Study] toolkit.

The authors of the new toolkit outline the hospitalist’s role in reducing medication errors as:

- Take responsibility for the accuracy of the medication reconciliation process for each patient under your care;

- Lead, coordinate, or participate in medication reconciliation quality improvement (QI) efforts with other key team members on the “front lines” to inform the hospital QI team on key interventions that would lead to improved patient outcomes;

- Become trained in taking the “best possible medication history” and in using effective discharge medication counseling; and

- Identify patients who are at high risk for a medication reconciliation error and would benefit from a more intensive medication reconciliation process.

“The MARQUIS study is important because it shows the potential of a mentored implementation effort, working with local hospitalist leaders and a QI toolkit, to improve medication safety related to the medication reconciliation process,” says MARQUIS principal investigator Jeff Schnipper, MD, MPH, FHM.

“It also shows the importance of institutional commitment to the success of these efforts. Lastly, hospitalists need to realize that medication reconciliation is not just some external regulatory requirement—it’s about the safety of the medications they order—and, therefore, that they need to ensure the quality of the process for the patients they care for and to lead efforts to improve the process across their hospitals.”

For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/marquis.

Post-Acute Care Transitions Toolkit Available to Hospitalists

Hospitalists know that many hospitalizations aren’t like those on TV. Instead of being discharged to their homes, many patients are discharged to post-acute care facilities for further care. And those transitions from hospital to post-acute care can be just as challenging as—if not more than—discharges to home care.

Making those transitions safer, smoother, and more effective can not only help an individual patient, but it can have a broader impact, according to the lead author of SHM’s new Post-Acute Care Transitions Toolkit, now available at www.hospitalmedicine.org/pact.

“Post-acute care transitions is an important area where hospitalists can contribute to improving the population health of their community,” says hospitalist Robert Young, MD, of Northwestern University in Chicago.

Both Dr. Young and the new toolkit recommend that hospitalists partner with the post-acute providers to make sure that communication between settings is complete during transitioning and open for ongoing questions as they arise. “Developing a relationship with your post-acute providers to work on these transitions issues provides the opportunity for ongoing quality and process improvement vital to our patients’ care,” Dr. Young says.

Hospitalists know that many hospitalizations aren’t like those on TV. Instead of being discharged to their homes, many patients are discharged to post-acute care facilities for further care. And those transitions from hospital to post-acute care can be just as challenging as—if not more than—discharges to home care.

Making those transitions safer, smoother, and more effective can not only help an individual patient, but it can have a broader impact, according to the lead author of SHM’s new Post-Acute Care Transitions Toolkit, now available at www.hospitalmedicine.org/pact.

“Post-acute care transitions is an important area where hospitalists can contribute to improving the population health of their community,” says hospitalist Robert Young, MD, of Northwestern University in Chicago.

Both Dr. Young and the new toolkit recommend that hospitalists partner with the post-acute providers to make sure that communication between settings is complete during transitioning and open for ongoing questions as they arise. “Developing a relationship with your post-acute providers to work on these transitions issues provides the opportunity for ongoing quality and process improvement vital to our patients’ care,” Dr. Young says.

Hospitalists know that many hospitalizations aren’t like those on TV. Instead of being discharged to their homes, many patients are discharged to post-acute care facilities for further care. And those transitions from hospital to post-acute care can be just as challenging as—if not more than—discharges to home care.

Making those transitions safer, smoother, and more effective can not only help an individual patient, but it can have a broader impact, according to the lead author of SHM’s new Post-Acute Care Transitions Toolkit, now available at www.hospitalmedicine.org/pact.

“Post-acute care transitions is an important area where hospitalists can contribute to improving the population health of their community,” says hospitalist Robert Young, MD, of Northwestern University in Chicago.

Both Dr. Young and the new toolkit recommend that hospitalists partner with the post-acute providers to make sure that communication between settings is complete during transitioning and open for ongoing questions as they arise. “Developing a relationship with your post-acute providers to work on these transitions issues provides the opportunity for ongoing quality and process improvement vital to our patients’ care,” Dr. Young says.

Tips, Tools to Control Diabetes, Hyperglycemia in Hospitalized Patients

Controlling diabetes in the hospital is one of the most predominant challenges hospitalists face. In addition to the condition’s increased prevalence among the general population, patients with diabetes are commonly admitted to the hospital multiple times. And the treatment of diabetes can make the treatment of other conditions more difficult.

In fact, a 2014 study conducted in California by the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research and the California Center for Public Health Advocacy revealed that one-third of hospitalized patients older than 34 in California have diabetes.

For hospitalists ready to tackle a condition like diabetes—increasingly common and challenging to treat—SHM now has more resources than ever. And hospitalists can start to take advantage of them today.

Glycemic Control Implementation Toolkit

SHM’s Glycemic Control Implementation Toolkit gives hospitalists the first advantages in treating hyperglycemia in the hospital. Using SHM’s proven approach to quality improvement, including personal experience and evidence-based medicine, the toolkit enables hospitalists to implement effective regimens and protocols that optimize glycemic control and minimize hypoglycemia.

The toolkit (www.hospitalmedicine.org/gcmi) is easy to use and includes step-by-step instructions, from first steps to performance tracking to continuing improvement.

Hospital Medicine 2015

Ready to learn directly from the experts in inpatient glycemic control and share experiences with thousands of other hospitalists? HM15 will feature the most current information and research from the leading authorities on glycemic control.

For more information and to register online, visit www.hospitalmedicine2015.org.

Glycemic Control Mentored Implementation

SHM’s signature mentored implementation model helps hospitals create and implement programs that make a difference. The Glycemic Control Mentored Implementation (GCMI) Program links hospitals with national leaders in the field for a mentored relationship, critical data benchmarking, and collaboration with peers.

GCMI has now moved to a rolling acceptance model, so hospitals can now apply any time to start preventing hypoglycemia and better managing their inpatients with hyperglycemia and diabetes. For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/gcmi.

Brendon Shank is SHM’s associate vice president of communications.

Controlling diabetes in the hospital is one of the most predominant challenges hospitalists face. In addition to the condition’s increased prevalence among the general population, patients with diabetes are commonly admitted to the hospital multiple times. And the treatment of diabetes can make the treatment of other conditions more difficult.

In fact, a 2014 study conducted in California by the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research and the California Center for Public Health Advocacy revealed that one-third of hospitalized patients older than 34 in California have diabetes.

For hospitalists ready to tackle a condition like diabetes—increasingly common and challenging to treat—SHM now has more resources than ever. And hospitalists can start to take advantage of them today.

Glycemic Control Implementation Toolkit

SHM’s Glycemic Control Implementation Toolkit gives hospitalists the first advantages in treating hyperglycemia in the hospital. Using SHM’s proven approach to quality improvement, including personal experience and evidence-based medicine, the toolkit enables hospitalists to implement effective regimens and protocols that optimize glycemic control and minimize hypoglycemia.

The toolkit (www.hospitalmedicine.org/gcmi) is easy to use and includes step-by-step instructions, from first steps to performance tracking to continuing improvement.

Hospital Medicine 2015

Ready to learn directly from the experts in inpatient glycemic control and share experiences with thousands of other hospitalists? HM15 will feature the most current information and research from the leading authorities on glycemic control.

For more information and to register online, visit www.hospitalmedicine2015.org.

Glycemic Control Mentored Implementation

SHM’s signature mentored implementation model helps hospitals create and implement programs that make a difference. The Glycemic Control Mentored Implementation (GCMI) Program links hospitals with national leaders in the field for a mentored relationship, critical data benchmarking, and collaboration with peers.

GCMI has now moved to a rolling acceptance model, so hospitals can now apply any time to start preventing hypoglycemia and better managing their inpatients with hyperglycemia and diabetes. For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/gcmi.

Brendon Shank is SHM’s associate vice president of communications.

Controlling diabetes in the hospital is one of the most predominant challenges hospitalists face. In addition to the condition’s increased prevalence among the general population, patients with diabetes are commonly admitted to the hospital multiple times. And the treatment of diabetes can make the treatment of other conditions more difficult.

In fact, a 2014 study conducted in California by the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research and the California Center for Public Health Advocacy revealed that one-third of hospitalized patients older than 34 in California have diabetes.

For hospitalists ready to tackle a condition like diabetes—increasingly common and challenging to treat—SHM now has more resources than ever. And hospitalists can start to take advantage of them today.

Glycemic Control Implementation Toolkit

SHM’s Glycemic Control Implementation Toolkit gives hospitalists the first advantages in treating hyperglycemia in the hospital. Using SHM’s proven approach to quality improvement, including personal experience and evidence-based medicine, the toolkit enables hospitalists to implement effective regimens and protocols that optimize glycemic control and minimize hypoglycemia.

The toolkit (www.hospitalmedicine.org/gcmi) is easy to use and includes step-by-step instructions, from first steps to performance tracking to continuing improvement.

Hospital Medicine 2015

Ready to learn directly from the experts in inpatient glycemic control and share experiences with thousands of other hospitalists? HM15 will feature the most current information and research from the leading authorities on glycemic control.

For more information and to register online, visit www.hospitalmedicine2015.org.

Glycemic Control Mentored Implementation

SHM’s signature mentored implementation model helps hospitals create and implement programs that make a difference. The Glycemic Control Mentored Implementation (GCMI) Program links hospitals with national leaders in the field for a mentored relationship, critical data benchmarking, and collaboration with peers.

GCMI has now moved to a rolling acceptance model, so hospitals can now apply any time to start preventing hypoglycemia and better managing their inpatients with hyperglycemia and diabetes. For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/gcmi.

Brendon Shank is SHM’s associate vice president of communications.

10 Things Obstetricians Want Hospitalists to Know

Many hospitalists feel an understandable wave of trepidation when confronted with treating a pregnant woman. They are unfamiliar with the special concerns of pregnancy and unacquainted with how pregnancy can affect preexisting conditions. Historically, most pregnant women have been young and have not yet experienced the typical health challenges that emerge as people age; however, expectant mothers still appear as patients in hospitals.1

With more women putting off pregnancy until their late 30s or early 40s, advances in reproductive medicine that allow pregnancies at more advanced ages, and a rise in obesity and related conditions, more and more pregnant women find themselves in the ED or admitted to the hospital.2

To increase the comfort level of practitioners nationwide, The Hospitalist spoke with several obstetricians (OBs) and hospitalists about what they thought were the most important things you should know when treating a mother-to-be. Here are their answers.

1 Involve an OB in the decision-making process as early as possible.

The most efficient and most comfortable way to proceed is to get input from an OB early in the process of treating a pregnant woman. The specialist can give expert opinions on what tests should be ordered and any special precautions to take to protect the fetus.3 Determining which medications can be prescribed safely is an area of particular discomfort for internal medicine hospitalists.

Edward Ma, MD, a hospitalist at the Coatesville VA Medical Center in Coatesville, Pa., explains the dilemma: “I am comfortable using Category A drugs and usually Category B medications, but because I do not [treat pregnant women] very often, I feel very uncomfortable giving a Category C medication unless I’ve spoken with an OB. This is where I really want guidance.”

In cases where the usual medication for a condition may not be indicated for pregnancy, an OB can help you balance the interests of the mother and child. Making these decisions is made much more comfortable when a physician who treats pregnancy on a daily basis can help.

2 Perform the tests you would perform if the patient were not pregnant.

An important axiom to remember when assessing a pregnant woman is that unless the mother is healthy, the baby cannot be healthy. Therefore, you must do what needs to be done to properly diagnose and treat the mother, and this includes the studies that would be performed if she were not pregnant.

Robert Olson, MD, an OB/GYN hospitalist at PeaceHealth St. Joseph Medical Center in Bellingham, Wash., and founding president of the Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists, cautions hospitalists to proceed as normal with testing. “Whether she’s pregnant or not,” he says, “she needs all the studies a nonpregnant woman would get. If an asthma patient needs a chest X-ray to rule out pneumonia, then do it, because if the mother is not getting enough oxygen, the baby is not getting enough oxygen.”

The tests should be performed as responsibly as possible, Dr. Olson adds. During that chest X-ray, for example, shield the abdomen with a lead apron.4

3 When analyzing test results, make sure you are familiar with what is “normal” for a pregnant woman.

The physiological changes in the body during pregnancy can be extreme, and as a result, the parameters of what is considered acceptable in test results may be dramatically different from those seen in nonpregnant patients. For example, early in pregnancy, progesterone causes respiratory alkalosis, so maternal carbon dioxide parameters that range between 28 and 30 are much lower than the nonpregnant normal of 40. A result of 40 from a blood gases test in pregnancy indicates that the woman is on the verge of respiratory failure.

A hospitalist unfamiliar with the correct parameters in pregnancy could make a significant and life-threatening misjudgment.5

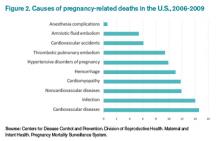

4 Thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism are some of the most common causes of maternal death.6

According to Carolyn M. Zelop, MD, board certified maternal-fetal medicine specialist and director of perinatal ultrasound and research at Valley Hospital in Ridgewood, N.J., “Thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism should always remain part of your differential, even if they are not at the top of the list of possible diagnoses.

“Tests required to exclude these diagnoses, even though they involve very small amounts of radiation, are important to perform,” says Dr. Zelop, a clinical professor at NYU School of Medicine in New York City.

Approaching these diagnostic tests with caution is justified, but it is trumped by the necessity of excluding a life-threatening condition.

5 Prior to 20 weeks, admit the patient to the physician treating her chief complaint.

“Whatever medical condition brings a patient to the hospital prior to 20 weeks, that is the physician that should do the admission,” Dr. Olson says. “If she is suffering from asthma, the internal medicine hospitalist or pulmonologist should admit. If it is appendicitis, the surgeon should do the admission.

“We need to take care of pregnant patients just as well as if they weren’t pregnant.”

During the first half of the pregnancy, care should be directed to the mother. Up until 20 weeks, what is best for the mother is what is best for the baby because the fetus is not viable. It cannot survive outside the mother, so the mother must be saved in order to save the fetus. That means you must give the mother all necessary care to return her to health.

6 After 20 weeks, make sure a pregnant woman is always tilted toward her left side—never supine.

Once an expectant mother reaches 20 weeks, the weight of her expanding uterus can compress the aorta and inferior vena cava, resulting in inadequate blood flow to the baby and to the mother’s brain. A supine position is detrimental not only because it can cause a pregnant woman to feel faint, but also because the interruption in normal blood flow can throw off test results during assessment. Shifting a woman to her left, even with a small tilt from an IV bag under her right hip, can return hemodynamics to homeostasis.

“Left lateral uterine displacement is particularly critical during surgery and while trying to resuscitate a pregnant woman who has coded,” Dr. Zelop says. “The supine position dramatically alters cardiac output. It is nearly impossible to revive someone when the blood flow is compromised by the compression of the uterus in the latter half of pregnancy.”

Click here to listen to Dr. Carolyn Zelop discuss cardiovascular emergencies in pregnant patients.

Remember, however, that the 20-week rule applies to single pregnancies—multiples create a heavier uterus earlier in the pregnancy, so base the timing of lateral uterine displacement on size, not gestational age.

7 Almost all medications can be used in pregnancy.

Despite the stated pregnancy category you read on Hippocrates and warnings pharmaceutical companies place on drug labels, almost all medications can be used in an acute crisis, and even in a subacute situation. As with the choice to perform the necessary tests to correctly diagnose a pregnant woman, the correct drugs to treat the mother must be used. Although there are medications to which you would not chronically expose a fetus, in an emergency situation, they may be acceptable.

This is an area where an OB consult can be especially helpful to balance the needs of mother and baby. If a particular drug is not the best choice for a fetus, an OB can help find the next best option. The specialist’s familiarity with the use of medications in pregnancy may also shed light on a drug labeled “unsafe”: it may be problematic only during certain gestational ages or in concert with a particular drug.

“Sometimes right medication use is not obvious,” says Brigid McCue, MD, chief of the department of OB/GYN at Jordan Hospital in Plymouth, Mass. “Most people would not assume a pregnant woman could undergo chemotherapy for breast cancer or leukemia, but there are options out there. Many patients have been treated for cancer during their pregnancy and have perfectly healthy babies.

“It is a challenge, and every decision is weighed carefully. There is usually some consequence to the baby—maybe it is delivered early or is smaller. But it’s so much nicer for the mom to survive her cancer and be there for the baby.”

8 You can determine gestational age by the position of the uterus relative to the umbilicus.

To make a correct judgment about which medications to use, as well as other treatment decisions, it is vital to ascertain the gestational age of the fetus, but in an acute emergency, there may not be time to do an ultrasound to determine gestational age.

A good way to determine gestational age is to use the umbilicus as a landmark during the physical exam. The rule of thumb is that the uterus touches the umbilicus at 20 weeks and travels one centimeter above it every week thereafter until week 36 or so. As with left lateral uterine displacement after 20 weeks, this rule applies to singleton pregnancies. Multiple fetuses cause a larger uterus earlier in the pregnancy.

9 Do not use lower extremities for vascular access in a pregnant woman.

Dr. Zelop points out that the weight of a pregnant uterus can “significantly compromise intravascular blood flow in the lower extremities.”

“Going below the waist for access can be problematic,” she adds. “Although there may be cases of trauma that make access in the upper limbs difficult or impossible, the lower extremities are not a viable choice.”

Some resuscitation protocols recommend intraosseous access; however, the lower extremities are still not recommended for access in a pregnant woman.

10 The pregnant airway must be treated with respect.

The pregnant airway differs from that of a nonpregnant woman in many important ways, so if intubation becomes necessary, make sure you are familiar with what you are facing. The airway is edematous, which varies the usual landmarks. Increased progesterone causes relaxation of the sphincters between the esophagus and the stomach, and this change predisposes pregnant women to aspiration and loss of consciousness.

In some studies, a failure rate as high as one in 250 is reported. If the patient’s airway needs to be secured, find the most experienced person available to do the intubation. Also, use a smaller tube than would be used for a nonpregnant intubation, usually one size down.

Always ask a woman in labor if she has had any complications during her pregnancy before doing a vaginal exam.

In most cases, deliveries go well for mother and baby; however, certain conditions not immediately apparent upon observation can cause severe problems. For example, a vaginal exam in a pregnant woman with placenta previa can result in a massive hemorrhage.

“In the third trimester, 500 cc of blood per minute flows to the uterus, so a tremendous amount of blood can be lost very quickly,” Dr. Zelop cautions. “Even in cases of women who appear healthy and normal, your radar must be up because an unknown complication can result in major bleeding.”

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Ma, Edward. Coatesville VA Medical Center, Coatesville, Pa. Telephone interview. October 31, 2013.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, et al. National Vital Statistics Reports: Volume 62, Number 1. June 28, 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr62/nvsr62_01.pdf. Accessed October 6, 2014.

- McCue, Brigid. Chief, department of OB/GYN, Jordan Hospital, Plymouth, Mass. Telephone interview. October 28, 2013.

- Olson, Robert. Founding president, Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists; OB/GYN hospitalist at PeaceHealth St. Joseph Medical Center, Bellingham, Wash. Telephone interview. October 31, 2013.

- Zelop, Carolyn M. Director, perinatal ultrasound and research, Valley Hospital, Ridgewood, N.J. Telephone interview. October 30, 2013.

- Callahan, William. Chief, Maternal and Infant Health Branch, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. E-mail interview. November 12, 2013.

Many hospitalists feel an understandable wave of trepidation when confronted with treating a pregnant woman. They are unfamiliar with the special concerns of pregnancy and unacquainted with how pregnancy can affect preexisting conditions. Historically, most pregnant women have been young and have not yet experienced the typical health challenges that emerge as people age; however, expectant mothers still appear as patients in hospitals.1

With more women putting off pregnancy until their late 30s or early 40s, advances in reproductive medicine that allow pregnancies at more advanced ages, and a rise in obesity and related conditions, more and more pregnant women find themselves in the ED or admitted to the hospital.2

To increase the comfort level of practitioners nationwide, The Hospitalist spoke with several obstetricians (OBs) and hospitalists about what they thought were the most important things you should know when treating a mother-to-be. Here are their answers.

1 Involve an OB in the decision-making process as early as possible.

The most efficient and most comfortable way to proceed is to get input from an OB early in the process of treating a pregnant woman. The specialist can give expert opinions on what tests should be ordered and any special precautions to take to protect the fetus.3 Determining which medications can be prescribed safely is an area of particular discomfort for internal medicine hospitalists.

Edward Ma, MD, a hospitalist at the Coatesville VA Medical Center in Coatesville, Pa., explains the dilemma: “I am comfortable using Category A drugs and usually Category B medications, but because I do not [treat pregnant women] very often, I feel very uncomfortable giving a Category C medication unless I’ve spoken with an OB. This is where I really want guidance.”

In cases where the usual medication for a condition may not be indicated for pregnancy, an OB can help you balance the interests of the mother and child. Making these decisions is made much more comfortable when a physician who treats pregnancy on a daily basis can help.

2 Perform the tests you would perform if the patient were not pregnant.

An important axiom to remember when assessing a pregnant woman is that unless the mother is healthy, the baby cannot be healthy. Therefore, you must do what needs to be done to properly diagnose and treat the mother, and this includes the studies that would be performed if she were not pregnant.

Robert Olson, MD, an OB/GYN hospitalist at PeaceHealth St. Joseph Medical Center in Bellingham, Wash., and founding president of the Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists, cautions hospitalists to proceed as normal with testing. “Whether she’s pregnant or not,” he says, “she needs all the studies a nonpregnant woman would get. If an asthma patient needs a chest X-ray to rule out pneumonia, then do it, because if the mother is not getting enough oxygen, the baby is not getting enough oxygen.”

The tests should be performed as responsibly as possible, Dr. Olson adds. During that chest X-ray, for example, shield the abdomen with a lead apron.4

3 When analyzing test results, make sure you are familiar with what is “normal” for a pregnant woman.

The physiological changes in the body during pregnancy can be extreme, and as a result, the parameters of what is considered acceptable in test results may be dramatically different from those seen in nonpregnant patients. For example, early in pregnancy, progesterone causes respiratory alkalosis, so maternal carbon dioxide parameters that range between 28 and 30 are much lower than the nonpregnant normal of 40. A result of 40 from a blood gases test in pregnancy indicates that the woman is on the verge of respiratory failure.

A hospitalist unfamiliar with the correct parameters in pregnancy could make a significant and life-threatening misjudgment.5

4 Thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism are some of the most common causes of maternal death.6

According to Carolyn M. Zelop, MD, board certified maternal-fetal medicine specialist and director of perinatal ultrasound and research at Valley Hospital in Ridgewood, N.J., “Thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism should always remain part of your differential, even if they are not at the top of the list of possible diagnoses.

“Tests required to exclude these diagnoses, even though they involve very small amounts of radiation, are important to perform,” says Dr. Zelop, a clinical professor at NYU School of Medicine in New York City.

Approaching these diagnostic tests with caution is justified, but it is trumped by the necessity of excluding a life-threatening condition.

5 Prior to 20 weeks, admit the patient to the physician treating her chief complaint.

“Whatever medical condition brings a patient to the hospital prior to 20 weeks, that is the physician that should do the admission,” Dr. Olson says. “If she is suffering from asthma, the internal medicine hospitalist or pulmonologist should admit. If it is appendicitis, the surgeon should do the admission.

“We need to take care of pregnant patients just as well as if they weren’t pregnant.”

During the first half of the pregnancy, care should be directed to the mother. Up until 20 weeks, what is best for the mother is what is best for the baby because the fetus is not viable. It cannot survive outside the mother, so the mother must be saved in order to save the fetus. That means you must give the mother all necessary care to return her to health.

6 After 20 weeks, make sure a pregnant woman is always tilted toward her left side—never supine.

Once an expectant mother reaches 20 weeks, the weight of her expanding uterus can compress the aorta and inferior vena cava, resulting in inadequate blood flow to the baby and to the mother’s brain. A supine position is detrimental not only because it can cause a pregnant woman to feel faint, but also because the interruption in normal blood flow can throw off test results during assessment. Shifting a woman to her left, even with a small tilt from an IV bag under her right hip, can return hemodynamics to homeostasis.

“Left lateral uterine displacement is particularly critical during surgery and while trying to resuscitate a pregnant woman who has coded,” Dr. Zelop says. “The supine position dramatically alters cardiac output. It is nearly impossible to revive someone when the blood flow is compromised by the compression of the uterus in the latter half of pregnancy.”

Click here to listen to Dr. Carolyn Zelop discuss cardiovascular emergencies in pregnant patients.

Remember, however, that the 20-week rule applies to single pregnancies—multiples create a heavier uterus earlier in the pregnancy, so base the timing of lateral uterine displacement on size, not gestational age.

7 Almost all medications can be used in pregnancy.

Despite the stated pregnancy category you read on Hippocrates and warnings pharmaceutical companies place on drug labels, almost all medications can be used in an acute crisis, and even in a subacute situation. As with the choice to perform the necessary tests to correctly diagnose a pregnant woman, the correct drugs to treat the mother must be used. Although there are medications to which you would not chronically expose a fetus, in an emergency situation, they may be acceptable.

This is an area where an OB consult can be especially helpful to balance the needs of mother and baby. If a particular drug is not the best choice for a fetus, an OB can help find the next best option. The specialist’s familiarity with the use of medications in pregnancy may also shed light on a drug labeled “unsafe”: it may be problematic only during certain gestational ages or in concert with a particular drug.

“Sometimes right medication use is not obvious,” says Brigid McCue, MD, chief of the department of OB/GYN at Jordan Hospital in Plymouth, Mass. “Most people would not assume a pregnant woman could undergo chemotherapy for breast cancer or leukemia, but there are options out there. Many patients have been treated for cancer during their pregnancy and have perfectly healthy babies.

“It is a challenge, and every decision is weighed carefully. There is usually some consequence to the baby—maybe it is delivered early or is smaller. But it’s so much nicer for the mom to survive her cancer and be there for the baby.”

8 You can determine gestational age by the position of the uterus relative to the umbilicus.

To make a correct judgment about which medications to use, as well as other treatment decisions, it is vital to ascertain the gestational age of the fetus, but in an acute emergency, there may not be time to do an ultrasound to determine gestational age.

A good way to determine gestational age is to use the umbilicus as a landmark during the physical exam. The rule of thumb is that the uterus touches the umbilicus at 20 weeks and travels one centimeter above it every week thereafter until week 36 or so. As with left lateral uterine displacement after 20 weeks, this rule applies to singleton pregnancies. Multiple fetuses cause a larger uterus earlier in the pregnancy.

9 Do not use lower extremities for vascular access in a pregnant woman.

Dr. Zelop points out that the weight of a pregnant uterus can “significantly compromise intravascular blood flow in the lower extremities.”

“Going below the waist for access can be problematic,” she adds. “Although there may be cases of trauma that make access in the upper limbs difficult or impossible, the lower extremities are not a viable choice.”

Some resuscitation protocols recommend intraosseous access; however, the lower extremities are still not recommended for access in a pregnant woman.

10 The pregnant airway must be treated with respect.

The pregnant airway differs from that of a nonpregnant woman in many important ways, so if intubation becomes necessary, make sure you are familiar with what you are facing. The airway is edematous, which varies the usual landmarks. Increased progesterone causes relaxation of the sphincters between the esophagus and the stomach, and this change predisposes pregnant women to aspiration and loss of consciousness.

In some studies, a failure rate as high as one in 250 is reported. If the patient’s airway needs to be secured, find the most experienced person available to do the intubation. Also, use a smaller tube than would be used for a nonpregnant intubation, usually one size down.

Always ask a woman in labor if she has had any complications during her pregnancy before doing a vaginal exam.

In most cases, deliveries go well for mother and baby; however, certain conditions not immediately apparent upon observation can cause severe problems. For example, a vaginal exam in a pregnant woman with placenta previa can result in a massive hemorrhage.

“In the third trimester, 500 cc of blood per minute flows to the uterus, so a tremendous amount of blood can be lost very quickly,” Dr. Zelop cautions. “Even in cases of women who appear healthy and normal, your radar must be up because an unknown complication can result in major bleeding.”

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Ma, Edward. Coatesville VA Medical Center, Coatesville, Pa. Telephone interview. October 31, 2013.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, et al. National Vital Statistics Reports: Volume 62, Number 1. June 28, 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr62/nvsr62_01.pdf. Accessed October 6, 2014.

- McCue, Brigid. Chief, department of OB/GYN, Jordan Hospital, Plymouth, Mass. Telephone interview. October 28, 2013.

- Olson, Robert. Founding president, Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists; OB/GYN hospitalist at PeaceHealth St. Joseph Medical Center, Bellingham, Wash. Telephone interview. October 31, 2013.

- Zelop, Carolyn M. Director, perinatal ultrasound and research, Valley Hospital, Ridgewood, N.J. Telephone interview. October 30, 2013.

- Callahan, William. Chief, Maternal and Infant Health Branch, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. E-mail interview. November 12, 2013.

Many hospitalists feel an understandable wave of trepidation when confronted with treating a pregnant woman. They are unfamiliar with the special concerns of pregnancy and unacquainted with how pregnancy can affect preexisting conditions. Historically, most pregnant women have been young and have not yet experienced the typical health challenges that emerge as people age; however, expectant mothers still appear as patients in hospitals.1

With more women putting off pregnancy until their late 30s or early 40s, advances in reproductive medicine that allow pregnancies at more advanced ages, and a rise in obesity and related conditions, more and more pregnant women find themselves in the ED or admitted to the hospital.2

To increase the comfort level of practitioners nationwide, The Hospitalist spoke with several obstetricians (OBs) and hospitalists about what they thought were the most important things you should know when treating a mother-to-be. Here are their answers.

1 Involve an OB in the decision-making process as early as possible.

The most efficient and most comfortable way to proceed is to get input from an OB early in the process of treating a pregnant woman. The specialist can give expert opinions on what tests should be ordered and any special precautions to take to protect the fetus.3 Determining which medications can be prescribed safely is an area of particular discomfort for internal medicine hospitalists.

Edward Ma, MD, a hospitalist at the Coatesville VA Medical Center in Coatesville, Pa., explains the dilemma: “I am comfortable using Category A drugs and usually Category B medications, but because I do not [treat pregnant women] very often, I feel very uncomfortable giving a Category C medication unless I’ve spoken with an OB. This is where I really want guidance.”

In cases where the usual medication for a condition may not be indicated for pregnancy, an OB can help you balance the interests of the mother and child. Making these decisions is made much more comfortable when a physician who treats pregnancy on a daily basis can help.

2 Perform the tests you would perform if the patient were not pregnant.

An important axiom to remember when assessing a pregnant woman is that unless the mother is healthy, the baby cannot be healthy. Therefore, you must do what needs to be done to properly diagnose and treat the mother, and this includes the studies that would be performed if she were not pregnant.

Robert Olson, MD, an OB/GYN hospitalist at PeaceHealth St. Joseph Medical Center in Bellingham, Wash., and founding president of the Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists, cautions hospitalists to proceed as normal with testing. “Whether she’s pregnant or not,” he says, “she needs all the studies a nonpregnant woman would get. If an asthma patient needs a chest X-ray to rule out pneumonia, then do it, because if the mother is not getting enough oxygen, the baby is not getting enough oxygen.”

The tests should be performed as responsibly as possible, Dr. Olson adds. During that chest X-ray, for example, shield the abdomen with a lead apron.4

3 When analyzing test results, make sure you are familiar with what is “normal” for a pregnant woman.

The physiological changes in the body during pregnancy can be extreme, and as a result, the parameters of what is considered acceptable in test results may be dramatically different from those seen in nonpregnant patients. For example, early in pregnancy, progesterone causes respiratory alkalosis, so maternal carbon dioxide parameters that range between 28 and 30 are much lower than the nonpregnant normal of 40. A result of 40 from a blood gases test in pregnancy indicates that the woman is on the verge of respiratory failure.

A hospitalist unfamiliar with the correct parameters in pregnancy could make a significant and life-threatening misjudgment.5

4 Thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism are some of the most common causes of maternal death.6

According to Carolyn M. Zelop, MD, board certified maternal-fetal medicine specialist and director of perinatal ultrasound and research at Valley Hospital in Ridgewood, N.J., “Thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism should always remain part of your differential, even if they are not at the top of the list of possible diagnoses.

“Tests required to exclude these diagnoses, even though they involve very small amounts of radiation, are important to perform,” says Dr. Zelop, a clinical professor at NYU School of Medicine in New York City.

Approaching these diagnostic tests with caution is justified, but it is trumped by the necessity of excluding a life-threatening condition.

5 Prior to 20 weeks, admit the patient to the physician treating her chief complaint.

“Whatever medical condition brings a patient to the hospital prior to 20 weeks, that is the physician that should do the admission,” Dr. Olson says. “If she is suffering from asthma, the internal medicine hospitalist or pulmonologist should admit. If it is appendicitis, the surgeon should do the admission.

“We need to take care of pregnant patients just as well as if they weren’t pregnant.”

During the first half of the pregnancy, care should be directed to the mother. Up until 20 weeks, what is best for the mother is what is best for the baby because the fetus is not viable. It cannot survive outside the mother, so the mother must be saved in order to save the fetus. That means you must give the mother all necessary care to return her to health.

6 After 20 weeks, make sure a pregnant woman is always tilted toward her left side—never supine.

Once an expectant mother reaches 20 weeks, the weight of her expanding uterus can compress the aorta and inferior vena cava, resulting in inadequate blood flow to the baby and to the mother’s brain. A supine position is detrimental not only because it can cause a pregnant woman to feel faint, but also because the interruption in normal blood flow can throw off test results during assessment. Shifting a woman to her left, even with a small tilt from an IV bag under her right hip, can return hemodynamics to homeostasis.

“Left lateral uterine displacement is particularly critical during surgery and while trying to resuscitate a pregnant woman who has coded,” Dr. Zelop says. “The supine position dramatically alters cardiac output. It is nearly impossible to revive someone when the blood flow is compromised by the compression of the uterus in the latter half of pregnancy.”

Click here to listen to Dr. Carolyn Zelop discuss cardiovascular emergencies in pregnant patients.

Remember, however, that the 20-week rule applies to single pregnancies—multiples create a heavier uterus earlier in the pregnancy, so base the timing of lateral uterine displacement on size, not gestational age.

7 Almost all medications can be used in pregnancy.

Despite the stated pregnancy category you read on Hippocrates and warnings pharmaceutical companies place on drug labels, almost all medications can be used in an acute crisis, and even in a subacute situation. As with the choice to perform the necessary tests to correctly diagnose a pregnant woman, the correct drugs to treat the mother must be used. Although there are medications to which you would not chronically expose a fetus, in an emergency situation, they may be acceptable.

This is an area where an OB consult can be especially helpful to balance the needs of mother and baby. If a particular drug is not the best choice for a fetus, an OB can help find the next best option. The specialist’s familiarity with the use of medications in pregnancy may also shed light on a drug labeled “unsafe”: it may be problematic only during certain gestational ages or in concert with a particular drug.

“Sometimes right medication use is not obvious,” says Brigid McCue, MD, chief of the department of OB/GYN at Jordan Hospital in Plymouth, Mass. “Most people would not assume a pregnant woman could undergo chemotherapy for breast cancer or leukemia, but there are options out there. Many patients have been treated for cancer during their pregnancy and have perfectly healthy babies.

“It is a challenge, and every decision is weighed carefully. There is usually some consequence to the baby—maybe it is delivered early or is smaller. But it’s so much nicer for the mom to survive her cancer and be there for the baby.”

8 You can determine gestational age by the position of the uterus relative to the umbilicus.

To make a correct judgment about which medications to use, as well as other treatment decisions, it is vital to ascertain the gestational age of the fetus, but in an acute emergency, there may not be time to do an ultrasound to determine gestational age.

A good way to determine gestational age is to use the umbilicus as a landmark during the physical exam. The rule of thumb is that the uterus touches the umbilicus at 20 weeks and travels one centimeter above it every week thereafter until week 36 or so. As with left lateral uterine displacement after 20 weeks, this rule applies to singleton pregnancies. Multiple fetuses cause a larger uterus earlier in the pregnancy.

9 Do not use lower extremities for vascular access in a pregnant woman.

Dr. Zelop points out that the weight of a pregnant uterus can “significantly compromise intravascular blood flow in the lower extremities.”

“Going below the waist for access can be problematic,” she adds. “Although there may be cases of trauma that make access in the upper limbs difficult or impossible, the lower extremities are not a viable choice.”

Some resuscitation protocols recommend intraosseous access; however, the lower extremities are still not recommended for access in a pregnant woman.

10 The pregnant airway must be treated with respect.

The pregnant airway differs from that of a nonpregnant woman in many important ways, so if intubation becomes necessary, make sure you are familiar with what you are facing. The airway is edematous, which varies the usual landmarks. Increased progesterone causes relaxation of the sphincters between the esophagus and the stomach, and this change predisposes pregnant women to aspiration and loss of consciousness.

In some studies, a failure rate as high as one in 250 is reported. If the patient’s airway needs to be secured, find the most experienced person available to do the intubation. Also, use a smaller tube than would be used for a nonpregnant intubation, usually one size down.

Always ask a woman in labor if she has had any complications during her pregnancy before doing a vaginal exam.

In most cases, deliveries go well for mother and baby; however, certain conditions not immediately apparent upon observation can cause severe problems. For example, a vaginal exam in a pregnant woman with placenta previa can result in a massive hemorrhage.

“In the third trimester, 500 cc of blood per minute flows to the uterus, so a tremendous amount of blood can be lost very quickly,” Dr. Zelop cautions. “Even in cases of women who appear healthy and normal, your radar must be up because an unknown complication can result in major bleeding.”

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Ma, Edward. Coatesville VA Medical Center, Coatesville, Pa. Telephone interview. October 31, 2013.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, et al. National Vital Statistics Reports: Volume 62, Number 1. June 28, 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr62/nvsr62_01.pdf. Accessed October 6, 2014.

- McCue, Brigid. Chief, department of OB/GYN, Jordan Hospital, Plymouth, Mass. Telephone interview. October 28, 2013.

- Olson, Robert. Founding president, Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists; OB/GYN hospitalist at PeaceHealth St. Joseph Medical Center, Bellingham, Wash. Telephone interview. October 31, 2013.

- Zelop, Carolyn M. Director, perinatal ultrasound and research, Valley Hospital, Ridgewood, N.J. Telephone interview. October 30, 2013.

- Callahan, William. Chief, Maternal and Infant Health Branch, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. E-mail interview. November 12, 2013.

Hospitalists Should Play Vital Role in Managing Diabetic Inpatients

Inpatient hyperglycemia, defined as a blood glucose greater than 140, is present in more than half of patients in intensive care units (ICUs) and approximately 30%-40% of patients in the non-ICU setting, according to the American Diabetes Association (ADA).

Joshua D. Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM, a hospitalist and associate professor of clinical medicine and anesthesiology at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, can attest to the growing problem. “Patients with diabetes are ubiquitous in our hospital,” he says. “Because I work in an urban, tertiary care, safety net teaching hospital, most of our cases are on the severe end of the acuity scale. Some arrive in full-blown diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) or hyperosmolar nonketotic hyperglycemia; others are admitted with profound fluid and electrolyte abnormalities from chronically uncontrolled diabetes.”

Caitlin Foxley, MD, FHM, an assistant professor of medicine and the lead hospitalist at Private Hospitalist Service at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha, says most inpatients have at least one complication of diabetes—usually chronic kidney disease and/or circulatory complications.

“For us, patients of a lower socioeconomic status seem to be hospitalized more frequently with complications related to diabetes due to barriers to access of care,” she says. Barriers include difficulty obtaining supplies, particularly glucose strips and insulin, and finding transportation to appointments.

The University of New Mexico in Albuquerque is seeing more patients who are newly diagnosed with diabetes.

“Management wise, these inpatients are less complicated, but it’s alarming that we are seeing more of them,” says UNM hospitalist Kendall Rogers, MD, CPE, FACP, SFHM, a lead mentor in SHM’s glycemic control quality improvement program. “Overall inpatient management is becoming more complex: Inpatients are frequently on steroids, their nutritional intake varies, and kidney issues make glycemic control more challenging, while therapeutic options for outpatient therapies are escalating.”

Regardless of an inpatient diabetic’s status, hospitalists should play a vital role in their treatment. “Bread and butter diabetics—and even some pretty complex cases—should be owned by hospitalists,” says Dr. Rogers, who notes that more than 95% of diabetic patients at his 650-bed hospital are managed by hospitalists. “Every hospitalist should know how to treat simple to complex glycemic control in the inpatient setting.”

Kristen Kulasa, MD, assistant clinical professor of medicine and director of inpatient glycemic control in the division of endocrinology, diabetes, and metabolism at the University of California San Diego, agrees, especially if no one else is on hand to help treat diabetic patients.

“Many inpatient glycemic control efforts are spearheaded by hospitalists,” she says. “They are in the driver’s seat.”

Order Sets: What Works Best?

While there is consensus that hospitalists should play a primary role in treating inpatient diabetics, debate is ongoing regarding just how standardized order sets should be.

“Each patient is different and should be treated uniquely,” Dr. Lenchus says. “But standardized order sets are beneficial. They remind us of what should be ordered, reviewed, and addressed.”

For example, order sets that address an insulin correction factor should be designed to minimize the potential for hypoglycemic episodes by standardizing the amount of insulin a patient receives. Standard order sets for DKA could assist the physician and nursing staff in ensuring that the appropriate laboratory tests are accomplished within the prescribed time period.

At Jackson Memorial Hospital in Miami, most order sets are designed as a collaborative effort among endocrinologists, hospitalists, nurses, and pharmacists. Some organizations, including SHM, offer order set templates.

Guillermo Umpierrez, MD, CDE, FACE, FACP, professor of medicine at Emory University in Atlanta, Ga., and a member of the ADA board of directors, maintains that hospitalists should work with their information technology (IT) departments to set up appropriate insulin orders.

“Most hospitals have electronic medical records, so the IT department should be involved in having a set of orders to facilitate care,” he says.

Guideline Implementation

National guidelines regarding the management of hyperglycemia in inpatients set goals and explain how to achieve them. “But they are not granular enough to simply implement,” says Paul M. Szumita, PharmD, BCPS, clinical pharmacy practice manager director at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. “Goal glucose targets change slightly from organization to organization and from year to year, but how to achieve them hasn’t changed much in the past decade.”

To implement the recommendations from national guidelines, institutions must create guidelines and order sets to operationalize the guidelines on a local level.

“When general guidelines and order sets have been created, vetted, implemented, and assessed for efficacy and safety, then there is typically a need to create additional guidelines and order sets to capture practices not supported by the general guidelines [e.g. insulin pumps, patient self-management, peri-procedural, DKA],” Dr. Szumita says. “This approach typically requires a team of dedicated, multidisciplinary, physical champions to create, implement, assess, and refine.”

Hospitalists should be aware of recently revised guidelines for ICU and non-ICU settings. The ADA and American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists recommend using a target blood glucose between 140-180 mg/dl for most patients in the ICU and a lower range, between 110-140, for cardiovascular surgery patients. The Society of Critical Care Medicine, however, recommends a target blood glucose of less than 150 mg/dl for ICU patients.

“Both guidelines recommend careful monitoring to prevent hypoglycemia,” Dr. Umpierrez says.

In the non-ICU setting, the ADA and the Endocrine Society recommend maintaining a pre-meal blood glucose of less than 140 mg/dl and a random blood glucose of less than 180 mg/dl.1

“We provide a lot of education regarding timing and clinical assessment of the value. If a value seems like an outlier, nurses should question whether it’s an erroneous sample and if they should repeat the test or if there is a clinical scenario to explain the outlier, such as recent snack or interruption in tube feeds.”—Kristen Kulasa, MD, assistant clinical professor of medicine and director of inpatient glycemic control, division of endocrinology, diabetes, and metabolism, University of California San Diego

Resolving Issues

A variety of challenges can occur in the treatment of inpatient diabetics. Here’s a look at some of the more common ones, as well as some suggested solutions.

Coordinating tasks of the care team. Ensuring that glucose levels remain acceptable at all times is perhaps the biggest challenge that involves multiple staff. “You need to coordinate the food tray’s arrival time, obtain pre-meal fingersticks, assess how much the patient eats, and administer insulin accordingly,” Dr. Kulasa says.

To ensure a smooth process, she emphasizes the importance of communication and suggests as much standardization as possible.

“Standardization will help give nurses an idea of when to expect the meal tray and, therefore, when they should obtain their point of care blood glucose test and administer the nutritional and correctional insulin,” Dr. Kulasa says. “This way they can plan their workflow accordingly.”

Listen to Dr. Kulasa explain how hospitalists can work with nutritionists and dieticians to attain glycemic control.

The University of New Mexico has found success in having nurses control every step of the process. “A nurse takes a capillary blood glucose (CBG) reading, draws up the insulin, and then delivers the meal tray,” Dr. Rogers says.

Nurses only deliver diabetic trays, which are color coded. “But other facilities, and even floors within our own hospital, have found this to be controversial because nurses don’t feel that they should be responsible for checking CBGs or delivering trays.” Perhaps adding a second person to perform steps one and three would be more acceptable to other institutions.

NPO patients awaiting tests. When patients are NPO [nil per os, or nothing by mouth], they can be at an increased risk for hypoglycemia; however, if patients are properly dosed on basal/bolus regimens, only the bolus dose should be held when they go NPO.

“Nurses must be taught not to hold basal just because a patient is NPO,” Dr. Rogers says. “However, we sometimes see institutions with an overreliance on basal insulin compared to bolus doses, to the point that the basal dose is covering some nutritional needs. This could increase risk for hypoglycemia if continuing basal insulin at full dose when NPO.”

If there is a 50-50 split between basal and bolus insulin, then it should be safe for patients to continue their full basal insulin when they’re NPO, although some institutions choose to halve this dose for patients who are NPO. Basal insulin should not be routinely held, however. Each institution should standardize its practice in these instances and write them into insulin order sets.

“We try to explain that [those inpatients newly diagnosed] must tend to their disease every day. I think we lose a lot of folks at this crucial point, and those patients end up being readmitted. In addition, their ability to obtain medications and adhere to regimens is quite difficult.”—Joshua D. Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM, hospitalist, associate professor of medicine and anesthesiology, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine

Monitoring and adjusting blood sugar. Dr. Rogers finds that many physicians and nurses don’t recognize high as problematic. “Often physicians don’t even list hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia as an issue in their notes, and adjustments are not made to medications on a daily basis,” he says.

Nurses perform four CBG readings on eating patients throughout the day, and patients on a basal/bolus regimen receive four doses of insulin. “Each dose of insulin is evaluated by one of these blood glucose monitoring values,” he says. “This allows for customized tailoring of a patient’s needs.”

Dr. Rogers says some hospitals administer the same insulin order three times a day with every meal. “Patients may vary in their nutritional intake, and their insulin should be customized to match,” he maintains. “There should be separate insulin orders for each meal to allow for this.”