User login

It’s Time to Use an Age-based Approach to D-dimer

PRACTICE CHANGER

Use an age-adjusted d-dimer cutoff (patient age in years × 10 μg/L) for patients older than 50 when evaluating for venous thromboembolism (VTE); it reduces false-positives without substantially increasing false-negatives.1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

A: Based on consistent and good-quality patient-centered evidence from a meta-analysis of cohort studies.1

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 78-year-old woman with no significant medical history or recent immobility comes to your clinic complaining of left lower extremity pain and swelling. Her d-dimer is 650 μg/L. What is your next step?

Although d-dimer is recognized as a reasonable screening tool for VTE, the specificity of d-dimer testing using a conventional cutoff value of 500 μg/L is particularly poor in patients older than 50. In low-risk patients older than 80, the specificity is 14.7%.2-5 As a result, conventional d-dimer testing is not very helpful for ruling out VTE in older patients.2-5

Improved testing is needed for a population at heightened risk

In the United States, there are more than 600,000 cases of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) each year.2 The incidence of PE increases from 1:1,000 in younger patients to 8:1,000 in older patients,4 and the mortality rate can reach 30%.6 The gold standards of venography and pulmonary angiography have been replaced by less burdensome tests, primarily lower extremity duplex ultrasound and CT pulmonary angiogram. However, even these tests are expensive and often present logistical challenges in elderly patients. For these reasons, it is helpful to have a simple, less-expensive tool to rule out VTE in older patients who have signs or symptoms.

Continued on next page >>

STUDY SUMMARY

Using age-adjusted d-dimer cutoffs significantly reduced false-positives

Schouten et al1 performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies of older patients with suspected VTE who had d-dimer testing using both conventional and age-adjusted cutoff values. The authors searched Medline and Embase for studies that were performed in outpatient, inpatient, or emergency department settings. They excluded studies of high-risk patients, specifically perioperative patients and those who’d had VTE, cancer, or a coagulation disorder.

Five high-quality studies of 13 cohorts were included in this analysis (N = 12,497; 6,969 patients older than 50). Each of these studies was a retrospective analysis of patients with a low clinical probability of VTE, as determined by Geneva or Wells scoring. The authors calculated the VTE prevalence and d-dimer sensitivity and specificity for patients ages ≤ 50, 51 to 60, 61 to 70, 71 to 80, and > 80.

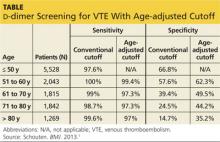

The specificity of the conventional d-dimer cutoff value for VTE decreased with age from 57.6% in those ages 51 to 60 to 14.7% in those older than 80. When age-adjusted cutoffs were used (age in years × 10 μg/L), specificities improved in all age categories, particularly for older patients. For example, using age-adjusted cutoff values improved specificity to 62.3% in patients ages 51 to 60 and to 35.2% in those older than 80 (see table). Using a hypothetical model, Schouten et al1 calculated that applying age-adjusted cutoff values would exclude VTE in 303/1,000 patients older than 80, compared with 124/1,000 when using the conventional cutoff.

The benefit of using an age-adjusted cutoff is the ability to exclude VTE in more patients (1 out of 3 in those older than 80) while not significantly increasing the number of missed VTE. In fact, the number of missed cases in the older population using the age-adjusted cutoff (approximately 1 to 4 per 1,000 patients) is comparable to the false-negative rate in those ages 50 and younger (3 per 1,000). The advantages are most notable with the use of enzyme linked fluorescent assays because these assays have a higher sensitivity and a trend toward lower specificity compared with other assays.

Continued on next page >>

WHAT’S NEW?

We can now use d-dimer in older patients

Up until now, it was acknowledged that the simple and less expensive d-dimer test was less useful for older patients. In fact, in their 2007 clinical practice guideline on the diagnosis of VTE in primary care, the American Academy of Family Physicians and the American College of Physicians commented on the poor performance of the test in older patients.2 A more recent guideline—released by the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement in January 2013—provided no specific guidance for patients older than 50.7 The meta-analysis reported on here, however, provides that guidance: Using an age-adjusted d-dimer cutoff improves the diagnostic accuracy of d-dimer screening in older adults.

CAVEATS

Results are not generalizable to patients at higher risk

These findings are not generalizable to all patients, particularly those at higher clinical risk who would undergo imaging regardless of d-dimer results. Not all patients included in this meta-analysis whose d-dimer was negative received imaging to confirm that they did not have VTE. As a result, the diagnostic accuracy of the age-adjusted cutoff could have been overestimated, although this is likely not clinically important because these cases would have remained symptomatic within the 45-day to 3-month follow-up period.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

You, not the lab, will need to do the calculation

One of the more valuable aspects of this study is its identification of a simple calculation that can directly improve patient care. Clinicians can easily apply an age-adjusted d-dimer cutoff as they interpret lab results by multiplying the patient’s age in years × 10 μg/L. While this does not require institutional changes by the lab, hospital, or clinic, it would be helpful if the age-adjusted d-dimer calculation was provided with the lab results.

REFERENCES

1. Schouten HJ, Geersing GJ, Koek HL, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of conventional or age adjusted D-dimer cut-off values in older patients with suspected venous thromboembolism: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346: f2492.

2. Qaseem A, Snow V, Barry P, et al; Joint American Academy of Family Physicians/American College of Physicians Panel on Deep Venous Thrombosis/Pulmonary Embolism. Current diagnosis of venous thromboembolism in primary care: a clinical practice guideline from the American Academy of Family Physicians and the American College of Physicians. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5:57-62.

3. Vossen JA, Albrektson J, Sensarma A, et al. Clinical usefulness of adjusted D-dimer cutoff values to exclude pulmonary embolism in a community hospital emergency department patient population. Acta Radiol. 2012;53:

765-768.

4. van Es J, Mos I, Douma R, et al. The combination of four different clinical decision rules and an age-adjusted D-dimer cut-off increases the number of patients in whom acute pulmonary embolism can safely be excluded. Thromb Haemost. 2012;107:167-171.

5. Deep vein thrombosis (DVT). DynaMed Web site. http://bit.ly/1gPkLoE. Accessed March 3, 2014.

6. Horlander KT, Mannino DM, Leeper KV. Pulmonary embolism mortality in the United States, 1979–1998: an analysis using multiple-cause mortality data. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1711-1717.

7. Dupras D, Bluhm J, Felty C, et al. Venous thromboembolism diagnosis and treatment. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement Web site. Available at: https://www.icsi.org/_asset/sw0pgp/VTE.pdf. Accessed March 3, 2014.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2014. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice. 2014;63(3):155-156, 158.

PRACTICE CHANGER

Use an age-adjusted d-dimer cutoff (patient age in years × 10 μg/L) for patients older than 50 when evaluating for venous thromboembolism (VTE); it reduces false-positives without substantially increasing false-negatives.1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

A: Based on consistent and good-quality patient-centered evidence from a meta-analysis of cohort studies.1

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 78-year-old woman with no significant medical history or recent immobility comes to your clinic complaining of left lower extremity pain and swelling. Her d-dimer is 650 μg/L. What is your next step?

Although d-dimer is recognized as a reasonable screening tool for VTE, the specificity of d-dimer testing using a conventional cutoff value of 500 μg/L is particularly poor in patients older than 50. In low-risk patients older than 80, the specificity is 14.7%.2-5 As a result, conventional d-dimer testing is not very helpful for ruling out VTE in older patients.2-5

Improved testing is needed for a population at heightened risk

In the United States, there are more than 600,000 cases of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) each year.2 The incidence of PE increases from 1:1,000 in younger patients to 8:1,000 in older patients,4 and the mortality rate can reach 30%.6 The gold standards of venography and pulmonary angiography have been replaced by less burdensome tests, primarily lower extremity duplex ultrasound and CT pulmonary angiogram. However, even these tests are expensive and often present logistical challenges in elderly patients. For these reasons, it is helpful to have a simple, less-expensive tool to rule out VTE in older patients who have signs or symptoms.

Continued on next page >>

STUDY SUMMARY

Using age-adjusted d-dimer cutoffs significantly reduced false-positives

Schouten et al1 performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies of older patients with suspected VTE who had d-dimer testing using both conventional and age-adjusted cutoff values. The authors searched Medline and Embase for studies that were performed in outpatient, inpatient, or emergency department settings. They excluded studies of high-risk patients, specifically perioperative patients and those who’d had VTE, cancer, or a coagulation disorder.

Five high-quality studies of 13 cohorts were included in this analysis (N = 12,497; 6,969 patients older than 50). Each of these studies was a retrospective analysis of patients with a low clinical probability of VTE, as determined by Geneva or Wells scoring. The authors calculated the VTE prevalence and d-dimer sensitivity and specificity for patients ages ≤ 50, 51 to 60, 61 to 70, 71 to 80, and > 80.

The specificity of the conventional d-dimer cutoff value for VTE decreased with age from 57.6% in those ages 51 to 60 to 14.7% in those older than 80. When age-adjusted cutoffs were used (age in years × 10 μg/L), specificities improved in all age categories, particularly for older patients. For example, using age-adjusted cutoff values improved specificity to 62.3% in patients ages 51 to 60 and to 35.2% in those older than 80 (see table). Using a hypothetical model, Schouten et al1 calculated that applying age-adjusted cutoff values would exclude VTE in 303/1,000 patients older than 80, compared with 124/1,000 when using the conventional cutoff.

The benefit of using an age-adjusted cutoff is the ability to exclude VTE in more patients (1 out of 3 in those older than 80) while not significantly increasing the number of missed VTE. In fact, the number of missed cases in the older population using the age-adjusted cutoff (approximately 1 to 4 per 1,000 patients) is comparable to the false-negative rate in those ages 50 and younger (3 per 1,000). The advantages are most notable with the use of enzyme linked fluorescent assays because these assays have a higher sensitivity and a trend toward lower specificity compared with other assays.

Continued on next page >>

WHAT’S NEW?

We can now use d-dimer in older patients

Up until now, it was acknowledged that the simple and less expensive d-dimer test was less useful for older patients. In fact, in their 2007 clinical practice guideline on the diagnosis of VTE in primary care, the American Academy of Family Physicians and the American College of Physicians commented on the poor performance of the test in older patients.2 A more recent guideline—released by the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement in January 2013—provided no specific guidance for patients older than 50.7 The meta-analysis reported on here, however, provides that guidance: Using an age-adjusted d-dimer cutoff improves the diagnostic accuracy of d-dimer screening in older adults.

CAVEATS

Results are not generalizable to patients at higher risk

These findings are not generalizable to all patients, particularly those at higher clinical risk who would undergo imaging regardless of d-dimer results. Not all patients included in this meta-analysis whose d-dimer was negative received imaging to confirm that they did not have VTE. As a result, the diagnostic accuracy of the age-adjusted cutoff could have been overestimated, although this is likely not clinically important because these cases would have remained symptomatic within the 45-day to 3-month follow-up period.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

You, not the lab, will need to do the calculation

One of the more valuable aspects of this study is its identification of a simple calculation that can directly improve patient care. Clinicians can easily apply an age-adjusted d-dimer cutoff as they interpret lab results by multiplying the patient’s age in years × 10 μg/L. While this does not require institutional changes by the lab, hospital, or clinic, it would be helpful if the age-adjusted d-dimer calculation was provided with the lab results.

REFERENCES

1. Schouten HJ, Geersing GJ, Koek HL, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of conventional or age adjusted D-dimer cut-off values in older patients with suspected venous thromboembolism: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346: f2492.

2. Qaseem A, Snow V, Barry P, et al; Joint American Academy of Family Physicians/American College of Physicians Panel on Deep Venous Thrombosis/Pulmonary Embolism. Current diagnosis of venous thromboembolism in primary care: a clinical practice guideline from the American Academy of Family Physicians and the American College of Physicians. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5:57-62.

3. Vossen JA, Albrektson J, Sensarma A, et al. Clinical usefulness of adjusted D-dimer cutoff values to exclude pulmonary embolism in a community hospital emergency department patient population. Acta Radiol. 2012;53:

765-768.

4. van Es J, Mos I, Douma R, et al. The combination of four different clinical decision rules and an age-adjusted D-dimer cut-off increases the number of patients in whom acute pulmonary embolism can safely be excluded. Thromb Haemost. 2012;107:167-171.

5. Deep vein thrombosis (DVT). DynaMed Web site. http://bit.ly/1gPkLoE. Accessed March 3, 2014.

6. Horlander KT, Mannino DM, Leeper KV. Pulmonary embolism mortality in the United States, 1979–1998: an analysis using multiple-cause mortality data. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1711-1717.

7. Dupras D, Bluhm J, Felty C, et al. Venous thromboembolism diagnosis and treatment. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement Web site. Available at: https://www.icsi.org/_asset/sw0pgp/VTE.pdf. Accessed March 3, 2014.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2014. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice. 2014;63(3):155-156, 158.

PRACTICE CHANGER

Use an age-adjusted d-dimer cutoff (patient age in years × 10 μg/L) for patients older than 50 when evaluating for venous thromboembolism (VTE); it reduces false-positives without substantially increasing false-negatives.1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

A: Based on consistent and good-quality patient-centered evidence from a meta-analysis of cohort studies.1

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 78-year-old woman with no significant medical history or recent immobility comes to your clinic complaining of left lower extremity pain and swelling. Her d-dimer is 650 μg/L. What is your next step?

Although d-dimer is recognized as a reasonable screening tool for VTE, the specificity of d-dimer testing using a conventional cutoff value of 500 μg/L is particularly poor in patients older than 50. In low-risk patients older than 80, the specificity is 14.7%.2-5 As a result, conventional d-dimer testing is not very helpful for ruling out VTE in older patients.2-5

Improved testing is needed for a population at heightened risk

In the United States, there are more than 600,000 cases of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) each year.2 The incidence of PE increases from 1:1,000 in younger patients to 8:1,000 in older patients,4 and the mortality rate can reach 30%.6 The gold standards of venography and pulmonary angiography have been replaced by less burdensome tests, primarily lower extremity duplex ultrasound and CT pulmonary angiogram. However, even these tests are expensive and often present logistical challenges in elderly patients. For these reasons, it is helpful to have a simple, less-expensive tool to rule out VTE in older patients who have signs or symptoms.

Continued on next page >>

STUDY SUMMARY

Using age-adjusted d-dimer cutoffs significantly reduced false-positives

Schouten et al1 performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies of older patients with suspected VTE who had d-dimer testing using both conventional and age-adjusted cutoff values. The authors searched Medline and Embase for studies that were performed in outpatient, inpatient, or emergency department settings. They excluded studies of high-risk patients, specifically perioperative patients and those who’d had VTE, cancer, or a coagulation disorder.

Five high-quality studies of 13 cohorts were included in this analysis (N = 12,497; 6,969 patients older than 50). Each of these studies was a retrospective analysis of patients with a low clinical probability of VTE, as determined by Geneva or Wells scoring. The authors calculated the VTE prevalence and d-dimer sensitivity and specificity for patients ages ≤ 50, 51 to 60, 61 to 70, 71 to 80, and > 80.

The specificity of the conventional d-dimer cutoff value for VTE decreased with age from 57.6% in those ages 51 to 60 to 14.7% in those older than 80. When age-adjusted cutoffs were used (age in years × 10 μg/L), specificities improved in all age categories, particularly for older patients. For example, using age-adjusted cutoff values improved specificity to 62.3% in patients ages 51 to 60 and to 35.2% in those older than 80 (see table). Using a hypothetical model, Schouten et al1 calculated that applying age-adjusted cutoff values would exclude VTE in 303/1,000 patients older than 80, compared with 124/1,000 when using the conventional cutoff.

The benefit of using an age-adjusted cutoff is the ability to exclude VTE in more patients (1 out of 3 in those older than 80) while not significantly increasing the number of missed VTE. In fact, the number of missed cases in the older population using the age-adjusted cutoff (approximately 1 to 4 per 1,000 patients) is comparable to the false-negative rate in those ages 50 and younger (3 per 1,000). The advantages are most notable with the use of enzyme linked fluorescent assays because these assays have a higher sensitivity and a trend toward lower specificity compared with other assays.

Continued on next page >>

WHAT’S NEW?

We can now use d-dimer in older patients

Up until now, it was acknowledged that the simple and less expensive d-dimer test was less useful for older patients. In fact, in their 2007 clinical practice guideline on the diagnosis of VTE in primary care, the American Academy of Family Physicians and the American College of Physicians commented on the poor performance of the test in older patients.2 A more recent guideline—released by the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement in January 2013—provided no specific guidance for patients older than 50.7 The meta-analysis reported on here, however, provides that guidance: Using an age-adjusted d-dimer cutoff improves the diagnostic accuracy of d-dimer screening in older adults.

CAVEATS

Results are not generalizable to patients at higher risk

These findings are not generalizable to all patients, particularly those at higher clinical risk who would undergo imaging regardless of d-dimer results. Not all patients included in this meta-analysis whose d-dimer was negative received imaging to confirm that they did not have VTE. As a result, the diagnostic accuracy of the age-adjusted cutoff could have been overestimated, although this is likely not clinically important because these cases would have remained symptomatic within the 45-day to 3-month follow-up period.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

You, not the lab, will need to do the calculation

One of the more valuable aspects of this study is its identification of a simple calculation that can directly improve patient care. Clinicians can easily apply an age-adjusted d-dimer cutoff as they interpret lab results by multiplying the patient’s age in years × 10 μg/L. While this does not require institutional changes by the lab, hospital, or clinic, it would be helpful if the age-adjusted d-dimer calculation was provided with the lab results.

REFERENCES

1. Schouten HJ, Geersing GJ, Koek HL, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of conventional or age adjusted D-dimer cut-off values in older patients with suspected venous thromboembolism: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346: f2492.

2. Qaseem A, Snow V, Barry P, et al; Joint American Academy of Family Physicians/American College of Physicians Panel on Deep Venous Thrombosis/Pulmonary Embolism. Current diagnosis of venous thromboembolism in primary care: a clinical practice guideline from the American Academy of Family Physicians and the American College of Physicians. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5:57-62.

3. Vossen JA, Albrektson J, Sensarma A, et al. Clinical usefulness of adjusted D-dimer cutoff values to exclude pulmonary embolism in a community hospital emergency department patient population. Acta Radiol. 2012;53:

765-768.

4. van Es J, Mos I, Douma R, et al. The combination of four different clinical decision rules and an age-adjusted D-dimer cut-off increases the number of patients in whom acute pulmonary embolism can safely be excluded. Thromb Haemost. 2012;107:167-171.

5. Deep vein thrombosis (DVT). DynaMed Web site. http://bit.ly/1gPkLoE. Accessed March 3, 2014.

6. Horlander KT, Mannino DM, Leeper KV. Pulmonary embolism mortality in the United States, 1979–1998: an analysis using multiple-cause mortality data. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1711-1717.

7. Dupras D, Bluhm J, Felty C, et al. Venous thromboembolism diagnosis and treatment. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement Web site. Available at: https://www.icsi.org/_asset/sw0pgp/VTE.pdf. Accessed March 3, 2014.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2014. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice. 2014;63(3):155-156, 158.

Prolotherapy: A nontraditional approach to knee osteoarthritis

Recommend prolotherapy for patients with knee osteoarthritis (OA) that does not respond to conventional therapies.1

Strength of recommendation

B: Based on a 3-arm, blinded, randomized controlled trial (RCT).

Rabago D, Patterson JJ, Mundt M, et al. Dextrose prolotherapy for knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:229-237.

Illustrative case

A 59-year-old woman with OA comes to your office with chronic knee pain. She has tried acetaminophen, ibuprofen, intra-articular corticosteroid injections, and physical therapy without significant improvement in pain or functioning. She wants to avoid daily medications or surgery and wonders if there are any interventions that will not lead to prolonged time away from work. What would you consider?

Additional options needed for knee OA

More than 25% of adults ages 55 years and older suffer from knee pain, and OA is an increasingly common cause.2 Knee pain is a major source of morbidity in the United States; it limits patients’ activities and increases comorbidities such as depression and obesity.

Conventional outpatient treatments for knee pain range from acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, glucosamine, chondroitin, and opiates to topical capsaicin therapy, intra-articular hyaluronic acid, and corticosteroid injections. Cost, efficacy, and safety limit these therapies.3

Prolotherapy is another option used to treat musculoskeletal pain. It involves repeatedly injecting a sclerosing solution (usually dextrose) into the sites of chronic musculoskeletal pain.4 The mechanism of action is thought to be the result of local tissue irritation stimulating inflammatory pathways, which leads to the release of growth factors and subsequent healing.4,5 Previous studies evaluating the usefulness of prolotherapy have lacked methodological rigor, have not been randomized adequately, or have lacked a placebo comparison.6-9

STUDY SUMMARY: Prolotherapy reduces pain more than exercise or placebo

Rabago et al1 randomized 90 participants to dextrose prolotherapy, placebo saline injections, or at-home exercise. Participants had a ≥3 month history of painful knee OA based on a self-reported pain scale, radiographic evidence of knee OA within the past 5 years, and tenderness of ≥1 or more anterior knee structures on exam.

Sixty-six percent of participants were female. The mean age was 56.7 years and 74% were overweight (body mass index [BMI], 25-29.9) or obese (BMI ≥30). Participants chose to have one or both knees treated; 43 knees were injected in the dextrose group, 41 received saline injections, and 47 were assessed in the exercise group. There were no significant differences among groups at baseline.

Participants in the prolotherapy and saline groups received injections at 1, 5, and 9 weeks, plus optional injections at 13 and 17 weeks per physician and participant preference. Injections were administered both extra- and intra-articularly. Intra-articular injections were delivered using a 25-gauge needle with a mixture of 25% dextrose, 1% saline, and 1% lidocaine for a total volume of 6 mL. Extra-articular injections were delivered with a peppering technique with a maximum of 15 punctures over painful ligaments and tendons around the knee. The extra-articular solution was similar to the intra-articular except 15% dextrose was used, with a total maximum volume of 22.5 mL.

The placebo injection group received injections in the same pattern and technique, but the solution was the same quantity of 1% lidocaine plus 1% saline to achieve the same volume. The injector, outcome assessor, primary investigator, and participants were blinded to injection group.

In the exercise group, a study coordinator taught participants knee exercises and gave them a pamphlet with 10 exercises to perform at home. Adherence to at-home exercises was assessed with monthly logs that participants mailed in for the first 20 weeks of the study. Seventy-seven percent of participants reported doing their at-home exercises.

The primary outcome measure was change in composite score on the Western Ontario McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC), a validated questionnaire used to evaluate knee-related quality of life that features subscales for pain, stiffness, and function.10 The minimal clinically important difference in change in score on this 100-point instrument is 12 points; higher scores indicate better quality of life.11 The secondary outcome was change in score on the Knee Pain Scale (KPS), a validated questionnaire that uses a 4-point scale to measure pain frequency and a 5-point scale to measure pain severity; higher scores indicate worse symptoms.12

Improvements seen in both scores

Using an intention-to-treat analysis for all groups, WOMAC composite scores improved at 9 weeks and remained improved through 52 weeks. At 9 weeks, the dextrose group increased 13.91 points, compared with 6.75 (P=.020) in the saline group and 2.51 (P=.001) points in the exercise group.

At 52 weeks, the dextrose group showed an improvement of 15.32 points compared with 7.59 (P=.022) in the saline group and 8.24 (P=.034) in the exercise group. Fifty percent (15/30) of participants in the dextrose group had clinically meaningful improvement as measured by an increase of ≥12 points on the WOMAC, compared with 34% (10/29) and 26% (8/31) in the saline and exercise groups, respectively. At 52 weeks, the dextrose group had significantly decreased KPS knee pain frequency scores compared with the saline group (mean difference [MD], -1.20 vs. -0.60; P<.05) and exercise group (MD, -1.20 vs. -0.40; P<.05). Knee pain severity scores also decreased in the dextrose group compared to the saline (MD, -0.92 vs. -0.32, P<.05) and exercise groups (MD, -0.92 vs. -0.11; P<.05). There were no significant differences in KPS score decreases between the saline and exercise groups.

What about patient satisfaction?

At week 52, all participants were asked, “Would you recommend the therapy you received in this study to others with knee OA like yours?” Ninety-one percent of the dextrose group, 82% of the saline group, and 89% of the exercise group answered “Yes.”

All participants who received injections reported mild to moderate post-injection pain. Five participants in the saline group and 3 in the dextrose group experienced bruising. No other side effects or adverse events were documented. According to daily logs of medication use in the 7 days after injection, 74% of patients in the dextrose group used acetaminophen and 47% used oxycodone, compared with 63% and 43%, respectively, in the saline group. The study authors did not comment on the significance of these differences.

WHAT'S NEW: A randomized study provides support for prolotherapy

This study is the first to adequately demonstrate improvement in knee-related quality of life with prolotherapy compared with placebo (saline) or exercise. Family physicians can now add this therapy to their “toolbox” for patient complaints of OA pain.

CAVEATS: Efficacy is unknown in patients with certain comorbidities

Efficacy is unknown in patients with certain comorbidities Of 894 people screened, only 118 met initial eligibility criteria. This study did not include patients who were taking daily opioids, had diabetes, or had a BMI >40, so its results may not be generalizable to such patients.

Also, while the study demonstrated no side effects or adverse events other than bruising in 8 patients, the sample size may have been too small to detect less common adverse events. However, prior studies of prolotherapy have not revealed any substantial adverse effects.7

Strong evidence for some conditions… not for others. The strongest data support the efficacy of prolotherapy for focal tendinopathy (lateral epicondylosis) and knee OA. Evidence supporting prolotherapy for multimodal conditions, such as chronic low back pain, is less robust.4

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: Finding a prolotherapist near you may not be easy

The main challenge to implementation is finding a certified prolotherapist, or obtaining training in the technique. The prolotherapy knee protocol can be performed in an outpatient setting in less than 15 minutes, but the technique requires training. Prolotherapy training is available from multiple organizations, including the American Association of Orthopaedic Medicine, which requires 100 course hours for prolotherapy certification.4 No formal survey on the number of prolotherapists in the United States has been conducted since 1993,13 but Rabago et al1 estimated that the number is in the hundreds.

Insurance coverage frequently is a challenge. Most third-party payers do not cover prolotherapy, and currently most patients pay out-of-pocket. Rabago et al1 indicated that at their institution, the cost is $218 per injection session. Another study published in 2010 put the average total cost of 4 to 6 prolotherapy sessions at $1800.14

And from the patient’s perspective … The multiple needle sticks involved in prolotherapy can be painful.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center of Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Rabago D, Patterson JJ, Mundt M, et al. Dextrose prolotherapy for knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:229-237.

2. Peat G, McCarney R, Croft P. Knee pain and osteoarthritis in older adults: a review of community burden and current use of primary health care. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:91-97.

3. Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, et al; National Arthritis Data Workgroup. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:26-35.

4. Rabago D, Slattengren A, Zgierska A. Prolotherapy in primary care practice. Prim Care. 2010;37:65-80.

5. Hackett GS, Hemwall GA, Montgomery GA. Ligament and Tendon Relaxation Treated by Prolotherapy. 5th ed. Oak Park, IL: Institute in Basic Life Principles; 1991.

6. Schultz LW. A treatment for subluxation of the temporomandibular joint. JAMA. 1937;109:1032-1035.

7. Rabago D, Best TM, Beamsley M, et al. A systematic review of prolotherapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain. Clin J Sport Med. 2005;15:376-380.

8. Reeves KD, Hassanein KM. Long-term effects of dextrose prolotherapy for anterior cruciate ligament laxity. Altern Ther Health Med. 2003;9:58-62.

9. Reeves KD, Hassanein K. Randomized prospective double-blind placebo-controlled study of dextrose prolotherapy for knee osteoarthritis with or without ACL laxity. Altern Ther Health Med. 2000;6:68-74,77-80.

10. Roos EM, Klässbo M, Lohmander LS. WOMAC osteoarthritis index. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness in patients with arthroscopically assessed osteoarthritis. Western Ontario and MacMaster Universities. Scand J Rheumatol. 1999;28:210-215.

11. Ehrich EW, Davies GM, Watson DJ, et al. Minimal perceptible clinical improvement with the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities osteoarthritis index questionnaire and global assessments in patients with osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:2635-2641.

12. Rejeski WJ, Ettinger WH Jr, Shumaker S, et al. The evaluation of pain in patients with knee osteoarthritis: the knee pain scale. J Rheumatol. 1995;22:1124-1129.

13. Dorman TA. Prolotherapy: A survey. J Orthop Med. 1993;15:28-32.

14. Hauser RA, Hauser MA, Baird NM, et al. Prolotherapy as an alternative to surgery: A prospective pilot study of 34 patients from a private medical practice. J Prolotherapy. 2010;2:272-281.

Recommend prolotherapy for patients with knee osteoarthritis (OA) that does not respond to conventional therapies.1

Strength of recommendation

B: Based on a 3-arm, blinded, randomized controlled trial (RCT).

Rabago D, Patterson JJ, Mundt M, et al. Dextrose prolotherapy for knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:229-237.

Illustrative case

A 59-year-old woman with OA comes to your office with chronic knee pain. She has tried acetaminophen, ibuprofen, intra-articular corticosteroid injections, and physical therapy without significant improvement in pain or functioning. She wants to avoid daily medications or surgery and wonders if there are any interventions that will not lead to prolonged time away from work. What would you consider?

Additional options needed for knee OA

More than 25% of adults ages 55 years and older suffer from knee pain, and OA is an increasingly common cause.2 Knee pain is a major source of morbidity in the United States; it limits patients’ activities and increases comorbidities such as depression and obesity.

Conventional outpatient treatments for knee pain range from acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, glucosamine, chondroitin, and opiates to topical capsaicin therapy, intra-articular hyaluronic acid, and corticosteroid injections. Cost, efficacy, and safety limit these therapies.3

Prolotherapy is another option used to treat musculoskeletal pain. It involves repeatedly injecting a sclerosing solution (usually dextrose) into the sites of chronic musculoskeletal pain.4 The mechanism of action is thought to be the result of local tissue irritation stimulating inflammatory pathways, which leads to the release of growth factors and subsequent healing.4,5 Previous studies evaluating the usefulness of prolotherapy have lacked methodological rigor, have not been randomized adequately, or have lacked a placebo comparison.6-9

STUDY SUMMARY: Prolotherapy reduces pain more than exercise or placebo

Rabago et al1 randomized 90 participants to dextrose prolotherapy, placebo saline injections, or at-home exercise. Participants had a ≥3 month history of painful knee OA based on a self-reported pain scale, radiographic evidence of knee OA within the past 5 years, and tenderness of ≥1 or more anterior knee structures on exam.

Sixty-six percent of participants were female. The mean age was 56.7 years and 74% were overweight (body mass index [BMI], 25-29.9) or obese (BMI ≥30). Participants chose to have one or both knees treated; 43 knees were injected in the dextrose group, 41 received saline injections, and 47 were assessed in the exercise group. There were no significant differences among groups at baseline.

Participants in the prolotherapy and saline groups received injections at 1, 5, and 9 weeks, plus optional injections at 13 and 17 weeks per physician and participant preference. Injections were administered both extra- and intra-articularly. Intra-articular injections were delivered using a 25-gauge needle with a mixture of 25% dextrose, 1% saline, and 1% lidocaine for a total volume of 6 mL. Extra-articular injections were delivered with a peppering technique with a maximum of 15 punctures over painful ligaments and tendons around the knee. The extra-articular solution was similar to the intra-articular except 15% dextrose was used, with a total maximum volume of 22.5 mL.

The placebo injection group received injections in the same pattern and technique, but the solution was the same quantity of 1% lidocaine plus 1% saline to achieve the same volume. The injector, outcome assessor, primary investigator, and participants were blinded to injection group.

In the exercise group, a study coordinator taught participants knee exercises and gave them a pamphlet with 10 exercises to perform at home. Adherence to at-home exercises was assessed with monthly logs that participants mailed in for the first 20 weeks of the study. Seventy-seven percent of participants reported doing their at-home exercises.

The primary outcome measure was change in composite score on the Western Ontario McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC), a validated questionnaire used to evaluate knee-related quality of life that features subscales for pain, stiffness, and function.10 The minimal clinically important difference in change in score on this 100-point instrument is 12 points; higher scores indicate better quality of life.11 The secondary outcome was change in score on the Knee Pain Scale (KPS), a validated questionnaire that uses a 4-point scale to measure pain frequency and a 5-point scale to measure pain severity; higher scores indicate worse symptoms.12

Improvements seen in both scores

Using an intention-to-treat analysis for all groups, WOMAC composite scores improved at 9 weeks and remained improved through 52 weeks. At 9 weeks, the dextrose group increased 13.91 points, compared with 6.75 (P=.020) in the saline group and 2.51 (P=.001) points in the exercise group.

At 52 weeks, the dextrose group showed an improvement of 15.32 points compared with 7.59 (P=.022) in the saline group and 8.24 (P=.034) in the exercise group. Fifty percent (15/30) of participants in the dextrose group had clinically meaningful improvement as measured by an increase of ≥12 points on the WOMAC, compared with 34% (10/29) and 26% (8/31) in the saline and exercise groups, respectively. At 52 weeks, the dextrose group had significantly decreased KPS knee pain frequency scores compared with the saline group (mean difference [MD], -1.20 vs. -0.60; P<.05) and exercise group (MD, -1.20 vs. -0.40; P<.05). Knee pain severity scores also decreased in the dextrose group compared to the saline (MD, -0.92 vs. -0.32, P<.05) and exercise groups (MD, -0.92 vs. -0.11; P<.05). There were no significant differences in KPS score decreases between the saline and exercise groups.

What about patient satisfaction?

At week 52, all participants were asked, “Would you recommend the therapy you received in this study to others with knee OA like yours?” Ninety-one percent of the dextrose group, 82% of the saline group, and 89% of the exercise group answered “Yes.”

All participants who received injections reported mild to moderate post-injection pain. Five participants in the saline group and 3 in the dextrose group experienced bruising. No other side effects or adverse events were documented. According to daily logs of medication use in the 7 days after injection, 74% of patients in the dextrose group used acetaminophen and 47% used oxycodone, compared with 63% and 43%, respectively, in the saline group. The study authors did not comment on the significance of these differences.

WHAT'S NEW: A randomized study provides support for prolotherapy

This study is the first to adequately demonstrate improvement in knee-related quality of life with prolotherapy compared with placebo (saline) or exercise. Family physicians can now add this therapy to their “toolbox” for patient complaints of OA pain.

CAVEATS: Efficacy is unknown in patients with certain comorbidities

Efficacy is unknown in patients with certain comorbidities Of 894 people screened, only 118 met initial eligibility criteria. This study did not include patients who were taking daily opioids, had diabetes, or had a BMI >40, so its results may not be generalizable to such patients.

Also, while the study demonstrated no side effects or adverse events other than bruising in 8 patients, the sample size may have been too small to detect less common adverse events. However, prior studies of prolotherapy have not revealed any substantial adverse effects.7

Strong evidence for some conditions… not for others. The strongest data support the efficacy of prolotherapy for focal tendinopathy (lateral epicondylosis) and knee OA. Evidence supporting prolotherapy for multimodal conditions, such as chronic low back pain, is less robust.4

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: Finding a prolotherapist near you may not be easy

The main challenge to implementation is finding a certified prolotherapist, or obtaining training in the technique. The prolotherapy knee protocol can be performed in an outpatient setting in less than 15 minutes, but the technique requires training. Prolotherapy training is available from multiple organizations, including the American Association of Orthopaedic Medicine, which requires 100 course hours for prolotherapy certification.4 No formal survey on the number of prolotherapists in the United States has been conducted since 1993,13 but Rabago et al1 estimated that the number is in the hundreds.

Insurance coverage frequently is a challenge. Most third-party payers do not cover prolotherapy, and currently most patients pay out-of-pocket. Rabago et al1 indicated that at their institution, the cost is $218 per injection session. Another study published in 2010 put the average total cost of 4 to 6 prolotherapy sessions at $1800.14

And from the patient’s perspective … The multiple needle sticks involved in prolotherapy can be painful.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center of Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Recommend prolotherapy for patients with knee osteoarthritis (OA) that does not respond to conventional therapies.1

Strength of recommendation

B: Based on a 3-arm, blinded, randomized controlled trial (RCT).

Rabago D, Patterson JJ, Mundt M, et al. Dextrose prolotherapy for knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:229-237.

Illustrative case

A 59-year-old woman with OA comes to your office with chronic knee pain. She has tried acetaminophen, ibuprofen, intra-articular corticosteroid injections, and physical therapy without significant improvement in pain or functioning. She wants to avoid daily medications or surgery and wonders if there are any interventions that will not lead to prolonged time away from work. What would you consider?

Additional options needed for knee OA

More than 25% of adults ages 55 years and older suffer from knee pain, and OA is an increasingly common cause.2 Knee pain is a major source of morbidity in the United States; it limits patients’ activities and increases comorbidities such as depression and obesity.

Conventional outpatient treatments for knee pain range from acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, glucosamine, chondroitin, and opiates to topical capsaicin therapy, intra-articular hyaluronic acid, and corticosteroid injections. Cost, efficacy, and safety limit these therapies.3

Prolotherapy is another option used to treat musculoskeletal pain. It involves repeatedly injecting a sclerosing solution (usually dextrose) into the sites of chronic musculoskeletal pain.4 The mechanism of action is thought to be the result of local tissue irritation stimulating inflammatory pathways, which leads to the release of growth factors and subsequent healing.4,5 Previous studies evaluating the usefulness of prolotherapy have lacked methodological rigor, have not been randomized adequately, or have lacked a placebo comparison.6-9

STUDY SUMMARY: Prolotherapy reduces pain more than exercise or placebo

Rabago et al1 randomized 90 participants to dextrose prolotherapy, placebo saline injections, or at-home exercise. Participants had a ≥3 month history of painful knee OA based on a self-reported pain scale, radiographic evidence of knee OA within the past 5 years, and tenderness of ≥1 or more anterior knee structures on exam.

Sixty-six percent of participants were female. The mean age was 56.7 years and 74% were overweight (body mass index [BMI], 25-29.9) or obese (BMI ≥30). Participants chose to have one or both knees treated; 43 knees were injected in the dextrose group, 41 received saline injections, and 47 were assessed in the exercise group. There were no significant differences among groups at baseline.

Participants in the prolotherapy and saline groups received injections at 1, 5, and 9 weeks, plus optional injections at 13 and 17 weeks per physician and participant preference. Injections were administered both extra- and intra-articularly. Intra-articular injections were delivered using a 25-gauge needle with a mixture of 25% dextrose, 1% saline, and 1% lidocaine for a total volume of 6 mL. Extra-articular injections were delivered with a peppering technique with a maximum of 15 punctures over painful ligaments and tendons around the knee. The extra-articular solution was similar to the intra-articular except 15% dextrose was used, with a total maximum volume of 22.5 mL.

The placebo injection group received injections in the same pattern and technique, but the solution was the same quantity of 1% lidocaine plus 1% saline to achieve the same volume. The injector, outcome assessor, primary investigator, and participants were blinded to injection group.

In the exercise group, a study coordinator taught participants knee exercises and gave them a pamphlet with 10 exercises to perform at home. Adherence to at-home exercises was assessed with monthly logs that participants mailed in for the first 20 weeks of the study. Seventy-seven percent of participants reported doing their at-home exercises.

The primary outcome measure was change in composite score on the Western Ontario McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC), a validated questionnaire used to evaluate knee-related quality of life that features subscales for pain, stiffness, and function.10 The minimal clinically important difference in change in score on this 100-point instrument is 12 points; higher scores indicate better quality of life.11 The secondary outcome was change in score on the Knee Pain Scale (KPS), a validated questionnaire that uses a 4-point scale to measure pain frequency and a 5-point scale to measure pain severity; higher scores indicate worse symptoms.12

Improvements seen in both scores

Using an intention-to-treat analysis for all groups, WOMAC composite scores improved at 9 weeks and remained improved through 52 weeks. At 9 weeks, the dextrose group increased 13.91 points, compared with 6.75 (P=.020) in the saline group and 2.51 (P=.001) points in the exercise group.

At 52 weeks, the dextrose group showed an improvement of 15.32 points compared with 7.59 (P=.022) in the saline group and 8.24 (P=.034) in the exercise group. Fifty percent (15/30) of participants in the dextrose group had clinically meaningful improvement as measured by an increase of ≥12 points on the WOMAC, compared with 34% (10/29) and 26% (8/31) in the saline and exercise groups, respectively. At 52 weeks, the dextrose group had significantly decreased KPS knee pain frequency scores compared with the saline group (mean difference [MD], -1.20 vs. -0.60; P<.05) and exercise group (MD, -1.20 vs. -0.40; P<.05). Knee pain severity scores also decreased in the dextrose group compared to the saline (MD, -0.92 vs. -0.32, P<.05) and exercise groups (MD, -0.92 vs. -0.11; P<.05). There were no significant differences in KPS score decreases between the saline and exercise groups.

What about patient satisfaction?

At week 52, all participants were asked, “Would you recommend the therapy you received in this study to others with knee OA like yours?” Ninety-one percent of the dextrose group, 82% of the saline group, and 89% of the exercise group answered “Yes.”

All participants who received injections reported mild to moderate post-injection pain. Five participants in the saline group and 3 in the dextrose group experienced bruising. No other side effects or adverse events were documented. According to daily logs of medication use in the 7 days after injection, 74% of patients in the dextrose group used acetaminophen and 47% used oxycodone, compared with 63% and 43%, respectively, in the saline group. The study authors did not comment on the significance of these differences.

WHAT'S NEW: A randomized study provides support for prolotherapy

This study is the first to adequately demonstrate improvement in knee-related quality of life with prolotherapy compared with placebo (saline) or exercise. Family physicians can now add this therapy to their “toolbox” for patient complaints of OA pain.

CAVEATS: Efficacy is unknown in patients with certain comorbidities

Efficacy is unknown in patients with certain comorbidities Of 894 people screened, only 118 met initial eligibility criteria. This study did not include patients who were taking daily opioids, had diabetes, or had a BMI >40, so its results may not be generalizable to such patients.

Also, while the study demonstrated no side effects or adverse events other than bruising in 8 patients, the sample size may have been too small to detect less common adverse events. However, prior studies of prolotherapy have not revealed any substantial adverse effects.7

Strong evidence for some conditions… not for others. The strongest data support the efficacy of prolotherapy for focal tendinopathy (lateral epicondylosis) and knee OA. Evidence supporting prolotherapy for multimodal conditions, such as chronic low back pain, is less robust.4

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: Finding a prolotherapist near you may not be easy

The main challenge to implementation is finding a certified prolotherapist, or obtaining training in the technique. The prolotherapy knee protocol can be performed in an outpatient setting in less than 15 minutes, but the technique requires training. Prolotherapy training is available from multiple organizations, including the American Association of Orthopaedic Medicine, which requires 100 course hours for prolotherapy certification.4 No formal survey on the number of prolotherapists in the United States has been conducted since 1993,13 but Rabago et al1 estimated that the number is in the hundreds.

Insurance coverage frequently is a challenge. Most third-party payers do not cover prolotherapy, and currently most patients pay out-of-pocket. Rabago et al1 indicated that at their institution, the cost is $218 per injection session. Another study published in 2010 put the average total cost of 4 to 6 prolotherapy sessions at $1800.14

And from the patient’s perspective … The multiple needle sticks involved in prolotherapy can be painful.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center of Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Rabago D, Patterson JJ, Mundt M, et al. Dextrose prolotherapy for knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:229-237.

2. Peat G, McCarney R, Croft P. Knee pain and osteoarthritis in older adults: a review of community burden and current use of primary health care. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:91-97.

3. Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, et al; National Arthritis Data Workgroup. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:26-35.

4. Rabago D, Slattengren A, Zgierska A. Prolotherapy in primary care practice. Prim Care. 2010;37:65-80.

5. Hackett GS, Hemwall GA, Montgomery GA. Ligament and Tendon Relaxation Treated by Prolotherapy. 5th ed. Oak Park, IL: Institute in Basic Life Principles; 1991.

6. Schultz LW. A treatment for subluxation of the temporomandibular joint. JAMA. 1937;109:1032-1035.

7. Rabago D, Best TM, Beamsley M, et al. A systematic review of prolotherapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain. Clin J Sport Med. 2005;15:376-380.

8. Reeves KD, Hassanein KM. Long-term effects of dextrose prolotherapy for anterior cruciate ligament laxity. Altern Ther Health Med. 2003;9:58-62.

9. Reeves KD, Hassanein K. Randomized prospective double-blind placebo-controlled study of dextrose prolotherapy for knee osteoarthritis with or without ACL laxity. Altern Ther Health Med. 2000;6:68-74,77-80.

10. Roos EM, Klässbo M, Lohmander LS. WOMAC osteoarthritis index. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness in patients with arthroscopically assessed osteoarthritis. Western Ontario and MacMaster Universities. Scand J Rheumatol. 1999;28:210-215.

11. Ehrich EW, Davies GM, Watson DJ, et al. Minimal perceptible clinical improvement with the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities osteoarthritis index questionnaire and global assessments in patients with osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:2635-2641.

12. Rejeski WJ, Ettinger WH Jr, Shumaker S, et al. The evaluation of pain in patients with knee osteoarthritis: the knee pain scale. J Rheumatol. 1995;22:1124-1129.

13. Dorman TA. Prolotherapy: A survey. J Orthop Med. 1993;15:28-32.

14. Hauser RA, Hauser MA, Baird NM, et al. Prolotherapy as an alternative to surgery: A prospective pilot study of 34 patients from a private medical practice. J Prolotherapy. 2010;2:272-281.

1. Rabago D, Patterson JJ, Mundt M, et al. Dextrose prolotherapy for knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:229-237.

2. Peat G, McCarney R, Croft P. Knee pain and osteoarthritis in older adults: a review of community burden and current use of primary health care. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:91-97.

3. Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, et al; National Arthritis Data Workgroup. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:26-35.

4. Rabago D, Slattengren A, Zgierska A. Prolotherapy in primary care practice. Prim Care. 2010;37:65-80.

5. Hackett GS, Hemwall GA, Montgomery GA. Ligament and Tendon Relaxation Treated by Prolotherapy. 5th ed. Oak Park, IL: Institute in Basic Life Principles; 1991.

6. Schultz LW. A treatment for subluxation of the temporomandibular joint. JAMA. 1937;109:1032-1035.

7. Rabago D, Best TM, Beamsley M, et al. A systematic review of prolotherapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain. Clin J Sport Med. 2005;15:376-380.

8. Reeves KD, Hassanein KM. Long-term effects of dextrose prolotherapy for anterior cruciate ligament laxity. Altern Ther Health Med. 2003;9:58-62.

9. Reeves KD, Hassanein K. Randomized prospective double-blind placebo-controlled study of dextrose prolotherapy for knee osteoarthritis with or without ACL laxity. Altern Ther Health Med. 2000;6:68-74,77-80.

10. Roos EM, Klässbo M, Lohmander LS. WOMAC osteoarthritis index. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness in patients with arthroscopically assessed osteoarthritis. Western Ontario and MacMaster Universities. Scand J Rheumatol. 1999;28:210-215.

11. Ehrich EW, Davies GM, Watson DJ, et al. Minimal perceptible clinical improvement with the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities osteoarthritis index questionnaire and global assessments in patients with osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:2635-2641.

12. Rejeski WJ, Ettinger WH Jr, Shumaker S, et al. The evaluation of pain in patients with knee osteoarthritis: the knee pain scale. J Rheumatol. 1995;22:1124-1129.

13. Dorman TA. Prolotherapy: A survey. J Orthop Med. 1993;15:28-32.

14. Hauser RA, Hauser MA, Baird NM, et al. Prolotherapy as an alternative to surgery: A prospective pilot study of 34 patients from a private medical practice. J Prolotherapy. 2010;2:272-281.

Copyright © 2014 Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

It’s time to use an age-based approach to D-dimer

Use an age-adjusted D-dimer cutoff (patient’s age in years × 10 mcg/L) for patients over age 50 years when evaluating for venous thromboembolism (VTE); it reduces false positives without substantially increasing false negatives.1

Strength of recommendation

A: Based on consistent and good quality patient-centered evidence from a meta-analysis of cohort studies.

Schouten HJ, Geersing GJ, Koek HL, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of conventional or age adjusted D-dimer cut-off values in older patients with suspected venous thromboembolism: systematic review and metaanalysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f2492.

Illustrative case

A 78-year-old woman with no significant past medical history or recent immobility comes into your clinic complaining of left lower extremity pain and swelling. Her D-dimer is 650 mcg/L. What is your next step?

Although D-dimer is recognized as a reasonable screening tool for VTE, the specificity of D-dimer testing using a conventional cutoff value of 500 mcg/L is particularly poor in patients over 50 years. In low-risk patients over 80 years old, the specificity is 14.7% (95% confidence interval, 11.3%-18.6%).2-5 As a result, conventional D-dimer testing is not very helpful for ruling out VTE in older patients.2-5

Improved testing is needed for a population at heightened risk

In the United States, there are more than 600,000 cases of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) each year.2 The incidence of PE increases from 1:1000 in younger patients to 8:1000 in older patients4 and the mortality rate can reach 30%.6 The gold standards of venography and pulmonary angiography have been replaced by less burdensome tests, primarily lower extremity duplex ultrasound and computed tomography pulmonary angiogram. However, even these tests are expensive and often present logistical challenges in elderly patients. For these reasons, it is helpful to have a simple, less-expensive tool to rule out VTE in older patients who have signs or symptoms.

STUDY SUMMARY: Using age-adjusted D-dimer cutoffs significantly reduced false positives

Schouten et al1 performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies of older patients with suspected VTE who had D-dimer testing using both conventional and age-adjusted cutoff values. The authors searched Medline and Embase for studies published before June 21, 2012 that were performed in outpatient, inpatient, or emergency department settings. They excluded studies of high-risk patients, specifically perioperative patients and those who’d had VTE, cancer, or a coagulation disorder.

Five high-quality studies of 13 cohorts were included in this analysis (N=12,497; 6969 patients >50 years). Each of these studies was a retrospective analysis of patients with a low clinical probability of VTE, as determined by Geneva or Wells scoring. The authors calculated the VTE prevalence and D-dimer sensitivity and specificity for patients ages ≤50, 51 to 60, 61 to 70, 71 to 80, and >80 years.

The specificity of using the conventional D-dimer cutoff value for VTE (500 mcg/L) decreased with age from 57.6% in those ages 51 to 60 to 14.7% in those older than 80. When age-adjusted cutoffs were used (age in years × 10 mcg/L), specificities improved in all age categories, particularly for older patients. For example, using age-adjusted cutoff values improved specificity to 62.3% in patients ages 51 to 60 and to 35.2% in those older than 80 (TABLE). Using a hypothetical model, Schouten et al1 calculated that applying age-adjusted cutoff values would exclude VTE in 303/1000 patients >80 years, compared with 124/1000 when using the conventional cutoff.

The benefit of using an age-adjusted cutoff is the ability to exclude VTE in more patients (1 out of 3 in those older than age 80) while not significantly increasing the number of missed VTE. In fact, the number of missed cases in the older population using the age-adjusted cutoff (approximately 1 to 4 per 1000 patients) is comparable to the false negative rate in those age, ≤50 (3 per 1000). The advantages of an age-adjusted cutoff are most notable with the use of enzyme linked fluorescent assays because these assays have a higher sensitivity and a trend toward lower specificity compared with other assays.

WHAT'S NEW?: We can now make use of the D-dimer in older patients

Up until now, it was acknowledged that the simple and less expensive D-dimer test was less useful for our older patients. In fact, in their 2007 clinical practice guideline on the diagnosis of VTE in primary care, the American Academy of Family Physicians and the American College of Physicians commented on the poor performance of the test in older patients.2 A more recent guideline—released by the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement in January 2013—provided no specific guidance for patients over age 50.7 The meta-analysis reported on here, however, provides that guidance: Using an age-adjusted D-dimer cutoff improves the diagnostic accuracy of D-dimer screening in older adults.

CAVEATS: Results are not generalizable to patients at higher risk

These findings are not generalizable to all patients, particularly those at higher clinical risk who would undergo imaging regardless of D-dimer results. Not all patients included in this meta-analysis whose D-dimer was negative received imaging to confirm that they did not have VTE. As a result, the diagnostic accuracy of using an age-adjusted cutoff could have been overestimated, although this is likely not clinically important because these cases would have remained symptomatic within the 45-day to 3-month follow-up period.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: You, not the lab, will need to do the calculation

One of the more valuable aspects of this study is it identifies a simple calculation that can directly improve patient care. Physicians can easily apply an age-adjusted D-dimer cutoff as they interpret lab results by multiplying the patient’s age in years × 10 mcg/L. While this does not require institutional changes by the lab, hospital, or clinic, it would be helpful if the age-adjusted D-dimer calculation was provided with the lab results.

Acknowledgement

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Schouten HJ, Geersing GJ, Koek HL, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of conventional or age adjusted D-dimer cut-off values in older patients with suspected venous thromboembolism: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013; 346:f2492.

2. Qaseem A, Snow V, Barry P, et al; Joint American Academy of Family Physicians/American College of Physicians Panel on Deep Venous Thrombosis/Pulmonary Embolism. Current diagnosis of venous thromboembolism in primary care: a clinical practice guideline from the American Academy of Family Physicians and the American College of Physicians. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5:57-62.

3. Vossen JA, Albrektson J, Sensarma A, et al. Clinical usefulness of adjusted D-dimer cutoff values to exclude pulmonary embolism in a community hospital emergency department patient population. Acta Radiol. 2012;53:765-768.

4. van Es J, Mos I, Douma R, et al. The combination of four different clinical decision rules and an age-adjusted D-dimer cut-off increases the number of patients in whom acute pulmonary embolism can safely be excluded. Thromb Haemost. 2012;107:167-171.

5. Deep vein thrombosis (DVT). DynaMed Web site. Available at: http://bit.ly/1vStJtm. Updated January 30, 2014. Accessed February 13, 2014.

6. Horlander KT, Mannino DM, Leeper KV. Pulmonary embolism mortality in the United States, 1979–1998: an analysis using multiple-cause mortality data. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1711–1717.

7. Dupras D, Bluhm J, Felty C, et al. Venous thromboembolism diagnosis and treatment. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement Web site. Available at: https://www.icsi.org/_asset/sw0pgp/VTE.pdf. Updated January 2013. Accessed October 23, 2013.

Use an age-adjusted D-dimer cutoff (patient’s age in years × 10 mcg/L) for patients over age 50 years when evaluating for venous thromboembolism (VTE); it reduces false positives without substantially increasing false negatives.1

Strength of recommendation

A: Based on consistent and good quality patient-centered evidence from a meta-analysis of cohort studies.

Schouten HJ, Geersing GJ, Koek HL, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of conventional or age adjusted D-dimer cut-off values in older patients with suspected venous thromboembolism: systematic review and metaanalysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f2492.

Illustrative case

A 78-year-old woman with no significant past medical history or recent immobility comes into your clinic complaining of left lower extremity pain and swelling. Her D-dimer is 650 mcg/L. What is your next step?

Although D-dimer is recognized as a reasonable screening tool for VTE, the specificity of D-dimer testing using a conventional cutoff value of 500 mcg/L is particularly poor in patients over 50 years. In low-risk patients over 80 years old, the specificity is 14.7% (95% confidence interval, 11.3%-18.6%).2-5 As a result, conventional D-dimer testing is not very helpful for ruling out VTE in older patients.2-5

Improved testing is needed for a population at heightened risk

In the United States, there are more than 600,000 cases of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) each year.2 The incidence of PE increases from 1:1000 in younger patients to 8:1000 in older patients4 and the mortality rate can reach 30%.6 The gold standards of venography and pulmonary angiography have been replaced by less burdensome tests, primarily lower extremity duplex ultrasound and computed tomography pulmonary angiogram. However, even these tests are expensive and often present logistical challenges in elderly patients. For these reasons, it is helpful to have a simple, less-expensive tool to rule out VTE in older patients who have signs or symptoms.

STUDY SUMMARY: Using age-adjusted D-dimer cutoffs significantly reduced false positives

Schouten et al1 performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies of older patients with suspected VTE who had D-dimer testing using both conventional and age-adjusted cutoff values. The authors searched Medline and Embase for studies published before June 21, 2012 that were performed in outpatient, inpatient, or emergency department settings. They excluded studies of high-risk patients, specifically perioperative patients and those who’d had VTE, cancer, or a coagulation disorder.

Five high-quality studies of 13 cohorts were included in this analysis (N=12,497; 6969 patients >50 years). Each of these studies was a retrospective analysis of patients with a low clinical probability of VTE, as determined by Geneva or Wells scoring. The authors calculated the VTE prevalence and D-dimer sensitivity and specificity for patients ages ≤50, 51 to 60, 61 to 70, 71 to 80, and >80 years.

The specificity of using the conventional D-dimer cutoff value for VTE (500 mcg/L) decreased with age from 57.6% in those ages 51 to 60 to 14.7% in those older than 80. When age-adjusted cutoffs were used (age in years × 10 mcg/L), specificities improved in all age categories, particularly for older patients. For example, using age-adjusted cutoff values improved specificity to 62.3% in patients ages 51 to 60 and to 35.2% in those older than 80 (TABLE). Using a hypothetical model, Schouten et al1 calculated that applying age-adjusted cutoff values would exclude VTE in 303/1000 patients >80 years, compared with 124/1000 when using the conventional cutoff.

The benefit of using an age-adjusted cutoff is the ability to exclude VTE in more patients (1 out of 3 in those older than age 80) while not significantly increasing the number of missed VTE. In fact, the number of missed cases in the older population using the age-adjusted cutoff (approximately 1 to 4 per 1000 patients) is comparable to the false negative rate in those age, ≤50 (3 per 1000). The advantages of an age-adjusted cutoff are most notable with the use of enzyme linked fluorescent assays because these assays have a higher sensitivity and a trend toward lower specificity compared with other assays.

WHAT'S NEW?: We can now make use of the D-dimer in older patients

Up until now, it was acknowledged that the simple and less expensive D-dimer test was less useful for our older patients. In fact, in their 2007 clinical practice guideline on the diagnosis of VTE in primary care, the American Academy of Family Physicians and the American College of Physicians commented on the poor performance of the test in older patients.2 A more recent guideline—released by the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement in January 2013—provided no specific guidance for patients over age 50.7 The meta-analysis reported on here, however, provides that guidance: Using an age-adjusted D-dimer cutoff improves the diagnostic accuracy of D-dimer screening in older adults.

CAVEATS: Results are not generalizable to patients at higher risk

These findings are not generalizable to all patients, particularly those at higher clinical risk who would undergo imaging regardless of D-dimer results. Not all patients included in this meta-analysis whose D-dimer was negative received imaging to confirm that they did not have VTE. As a result, the diagnostic accuracy of using an age-adjusted cutoff could have been overestimated, although this is likely not clinically important because these cases would have remained symptomatic within the 45-day to 3-month follow-up period.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: You, not the lab, will need to do the calculation

One of the more valuable aspects of this study is it identifies a simple calculation that can directly improve patient care. Physicians can easily apply an age-adjusted D-dimer cutoff as they interpret lab results by multiplying the patient’s age in years × 10 mcg/L. While this does not require institutional changes by the lab, hospital, or clinic, it would be helpful if the age-adjusted D-dimer calculation was provided with the lab results.

Acknowledgement

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Use an age-adjusted D-dimer cutoff (patient’s age in years × 10 mcg/L) for patients over age 50 years when evaluating for venous thromboembolism (VTE); it reduces false positives without substantially increasing false negatives.1

Strength of recommendation

A: Based on consistent and good quality patient-centered evidence from a meta-analysis of cohort studies.

Schouten HJ, Geersing GJ, Koek HL, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of conventional or age adjusted D-dimer cut-off values in older patients with suspected venous thromboembolism: systematic review and metaanalysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f2492.

Illustrative case

A 78-year-old woman with no significant past medical history or recent immobility comes into your clinic complaining of left lower extremity pain and swelling. Her D-dimer is 650 mcg/L. What is your next step?

Although D-dimer is recognized as a reasonable screening tool for VTE, the specificity of D-dimer testing using a conventional cutoff value of 500 mcg/L is particularly poor in patients over 50 years. In low-risk patients over 80 years old, the specificity is 14.7% (95% confidence interval, 11.3%-18.6%).2-5 As a result, conventional D-dimer testing is not very helpful for ruling out VTE in older patients.2-5

Improved testing is needed for a population at heightened risk

In the United States, there are more than 600,000 cases of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) each year.2 The incidence of PE increases from 1:1000 in younger patients to 8:1000 in older patients4 and the mortality rate can reach 30%.6 The gold standards of venography and pulmonary angiography have been replaced by less burdensome tests, primarily lower extremity duplex ultrasound and computed tomography pulmonary angiogram. However, even these tests are expensive and often present logistical challenges in elderly patients. For these reasons, it is helpful to have a simple, less-expensive tool to rule out VTE in older patients who have signs or symptoms.

STUDY SUMMARY: Using age-adjusted D-dimer cutoffs significantly reduced false positives

Schouten et al1 performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies of older patients with suspected VTE who had D-dimer testing using both conventional and age-adjusted cutoff values. The authors searched Medline and Embase for studies published before June 21, 2012 that were performed in outpatient, inpatient, or emergency department settings. They excluded studies of high-risk patients, specifically perioperative patients and those who’d had VTE, cancer, or a coagulation disorder.

Five high-quality studies of 13 cohorts were included in this analysis (N=12,497; 6969 patients >50 years). Each of these studies was a retrospective analysis of patients with a low clinical probability of VTE, as determined by Geneva or Wells scoring. The authors calculated the VTE prevalence and D-dimer sensitivity and specificity for patients ages ≤50, 51 to 60, 61 to 70, 71 to 80, and >80 years.