User login

European Commission approves rituximab biosimilar

The European Commission has approved a biosimilar rituximab product, Truxima™, for all the same indications as the reference product, MabThera.

This means Truxima (formerly called CT-P10) is approved for use in the European Union to treat patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), and microscopic polyangiitis (MPA).

Truxima, a product of Celltrion Healthcare Hungary Kft, is the first biosimilar monoclonal antibody approved in an oncology indication worldwide.

The approval is based on data submitted to the European Medicines Agency.

The agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) said the evidence suggests Truxima and MabThera are similar in terms of efficacy, safety, immunogenicity, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics in patients with RA and advanced follicular lymphoma (FL).

Therefore, the European Commission approved Truxima for the following indications.

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

Truxima is indicated for use in combination with chemotherapy to treat previously untreated patients with stage III-IV FL.

Truxima maintenance therapy is indicated for the treatment of FL patients responding to induction therapy.

Truxima monotherapy is indicated for the treatment of patients with stage III-IV FL who are chemo-resistant or are in their second or subsequent relapse after chemotherapy.

Truxima is indicated for use in combination with CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone) for the treatment of patients with CD20-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia

Truxima in combination with chemotherapy is indicated for the treatment of patients with previously untreated and relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

The CHMP noted that limited efficacy and safety data are available for patients previously treated with monoclonal antibodies, including rituximab, or patients who are refractory to previous rituximab plus chemotherapy.

RA, GPA, and MPA

Truxima in combination with methotrexate is indicated for the treatment of adults with severe, active RA who have had an inadequate response to or cannot tolerate other disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, including one or more tumor necrosis factor inhibitor therapies.

Truxima in combination with glucocorticoids is indicated for the induction of remission in adults with severe, active GPA or MPA.

Truxima studies

There are 3 ongoing, phase 3 trials of Truxima in patients with RA (NCT02149121), advanced FL (NCT02162771), and low-tumor-burden FL (NCT02260804).

Results from the phase 1/3 trial in patients with newly diagnosed, advanced FL suggest that Truxima and the reference rituximab are similar with regard to pharmacokinetics, immunogenicity, and safety (B Coiffier et al. ASH 2016, abstract 1807).

Results from the phase 3 study of RA patients indicate that Truxima is similar to reference products (EU and US-sourced rituximab) with regard to pharmacodynamics, safety, and efficacy for up to 24 weeks (DH Yoo et al. 2016 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting, abstract 1635). ![]()

The European Commission has approved a biosimilar rituximab product, Truxima™, for all the same indications as the reference product, MabThera.

This means Truxima (formerly called CT-P10) is approved for use in the European Union to treat patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), and microscopic polyangiitis (MPA).

Truxima, a product of Celltrion Healthcare Hungary Kft, is the first biosimilar monoclonal antibody approved in an oncology indication worldwide.

The approval is based on data submitted to the European Medicines Agency.

The agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) said the evidence suggests Truxima and MabThera are similar in terms of efficacy, safety, immunogenicity, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics in patients with RA and advanced follicular lymphoma (FL).

Therefore, the European Commission approved Truxima for the following indications.

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

Truxima is indicated for use in combination with chemotherapy to treat previously untreated patients with stage III-IV FL.

Truxima maintenance therapy is indicated for the treatment of FL patients responding to induction therapy.

Truxima monotherapy is indicated for the treatment of patients with stage III-IV FL who are chemo-resistant or are in their second or subsequent relapse after chemotherapy.

Truxima is indicated for use in combination with CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone) for the treatment of patients with CD20-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia

Truxima in combination with chemotherapy is indicated for the treatment of patients with previously untreated and relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

The CHMP noted that limited efficacy and safety data are available for patients previously treated with monoclonal antibodies, including rituximab, or patients who are refractory to previous rituximab plus chemotherapy.

RA, GPA, and MPA

Truxima in combination with methotrexate is indicated for the treatment of adults with severe, active RA who have had an inadequate response to or cannot tolerate other disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, including one or more tumor necrosis factor inhibitor therapies.

Truxima in combination with glucocorticoids is indicated for the induction of remission in adults with severe, active GPA or MPA.

Truxima studies

There are 3 ongoing, phase 3 trials of Truxima in patients with RA (NCT02149121), advanced FL (NCT02162771), and low-tumor-burden FL (NCT02260804).

Results from the phase 1/3 trial in patients with newly diagnosed, advanced FL suggest that Truxima and the reference rituximab are similar with regard to pharmacokinetics, immunogenicity, and safety (B Coiffier et al. ASH 2016, abstract 1807).

Results from the phase 3 study of RA patients indicate that Truxima is similar to reference products (EU and US-sourced rituximab) with regard to pharmacodynamics, safety, and efficacy for up to 24 weeks (DH Yoo et al. 2016 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting, abstract 1635). ![]()

The European Commission has approved a biosimilar rituximab product, Truxima™, for all the same indications as the reference product, MabThera.

This means Truxima (formerly called CT-P10) is approved for use in the European Union to treat patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), and microscopic polyangiitis (MPA).

Truxima, a product of Celltrion Healthcare Hungary Kft, is the first biosimilar monoclonal antibody approved in an oncology indication worldwide.

The approval is based on data submitted to the European Medicines Agency.

The agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) said the evidence suggests Truxima and MabThera are similar in terms of efficacy, safety, immunogenicity, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics in patients with RA and advanced follicular lymphoma (FL).

Therefore, the European Commission approved Truxima for the following indications.

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

Truxima is indicated for use in combination with chemotherapy to treat previously untreated patients with stage III-IV FL.

Truxima maintenance therapy is indicated for the treatment of FL patients responding to induction therapy.

Truxima monotherapy is indicated for the treatment of patients with stage III-IV FL who are chemo-resistant or are in their second or subsequent relapse after chemotherapy.

Truxima is indicated for use in combination with CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone) for the treatment of patients with CD20-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia

Truxima in combination with chemotherapy is indicated for the treatment of patients with previously untreated and relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

The CHMP noted that limited efficacy and safety data are available for patients previously treated with monoclonal antibodies, including rituximab, or patients who are refractory to previous rituximab plus chemotherapy.

RA, GPA, and MPA

Truxima in combination with methotrexate is indicated for the treatment of adults with severe, active RA who have had an inadequate response to or cannot tolerate other disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, including one or more tumor necrosis factor inhibitor therapies.

Truxima in combination with glucocorticoids is indicated for the induction of remission in adults with severe, active GPA or MPA.

Truxima studies

There are 3 ongoing, phase 3 trials of Truxima in patients with RA (NCT02149121), advanced FL (NCT02162771), and low-tumor-burden FL (NCT02260804).

Results from the phase 1/3 trial in patients with newly diagnosed, advanced FL suggest that Truxima and the reference rituximab are similar with regard to pharmacokinetics, immunogenicity, and safety (B Coiffier et al. ASH 2016, abstract 1807).

Results from the phase 3 study of RA patients indicate that Truxima is similar to reference products (EU and US-sourced rituximab) with regard to pharmacodynamics, safety, and efficacy for up to 24 weeks (DH Yoo et al. 2016 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting, abstract 1635). ![]()

Immunotherapy receives fast track designation

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted fast track designation to CMD-003 (baltaleucel-T) for patients with relapsed/refractory lymphoma and post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).

CMD-003 consists of patient-derived T cells that have been activated to kill malignant cells expressing antigens associated with EBV.

The T cells specifically target 4 EBV epitopes—LMP1, LMP2, EBNA, and BARF1.

CMD-003 is being developed by Cell Medica and the Baylor College of Medicine with funding provided, in part, by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas.

About fast track designation

The FDA’s fast track program is designed to facilitate the development and expedite the review of products intended to treat or prevent serious or life-threatening conditions and address unmet medical need.

Through the FDA’s fast track program, a product may be eligible for priority review. In addition, the company developing the product may be allowed to submit sections of the biologic license application or new drug application on a rolling basis as data become available.

Fast track designation also provides the company with opportunities for more frequent meetings and written communications with the FDA.

CMD-003-related research

CMD-003 is currently under investigation in the phase 2 CITADEL trial for patients with extranodal natural killer T-cell lymphoma and the phase 2 CIVIC trial for patients with EBV-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, and post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease.

Researchers have not published results from any trials of CMD-003, but they have published results with EBV-specific T-cell products related to CMD-003.

In one study, published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in 2014, researchers administered cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) in 50 patients with EBV-associated Hodgkin or non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Twenty-nine of the patients were in remission when they received CTL infusions, but they were at a high risk of relapse. The remaining 21 patients had relapsed or refractory disease at the time of CTL infusion.

Twenty-seven of the patients who received CTLs as an adjuvant treatment remained in remission at 3.1 years after treatment.

Their 2-year event-free survival rate was 82%. None of the patients died of lymphoma, but 9 died from complications associated with the chemotherapy and radiation they had received.

Of the 21 patients with relapsed or refractory disease, 13 responded to CTL infusions, and 11 patients achieved a complete response. In this group, the 2-year event-free survival rate was about 50%.

The researchers said there were no toxicities that were definitively related to CTL infusion.

One patient had central nervous system deterioration 2 weeks after infusion. This was attributed to disease progression but could possibly have been treatment-related.

Another patient developed respiratory complications about 4 weeks after a second CTL infusion that may have been treatment-related. However, the researchers attributed it to an intercurrent infection, and the patient made a complete recovery.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted fast track designation to CMD-003 (baltaleucel-T) for patients with relapsed/refractory lymphoma and post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).

CMD-003 consists of patient-derived T cells that have been activated to kill malignant cells expressing antigens associated with EBV.

The T cells specifically target 4 EBV epitopes—LMP1, LMP2, EBNA, and BARF1.

CMD-003 is being developed by Cell Medica and the Baylor College of Medicine with funding provided, in part, by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas.

About fast track designation

The FDA’s fast track program is designed to facilitate the development and expedite the review of products intended to treat or prevent serious or life-threatening conditions and address unmet medical need.

Through the FDA’s fast track program, a product may be eligible for priority review. In addition, the company developing the product may be allowed to submit sections of the biologic license application or new drug application on a rolling basis as data become available.

Fast track designation also provides the company with opportunities for more frequent meetings and written communications with the FDA.

CMD-003-related research

CMD-003 is currently under investigation in the phase 2 CITADEL trial for patients with extranodal natural killer T-cell lymphoma and the phase 2 CIVIC trial for patients with EBV-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, and post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease.

Researchers have not published results from any trials of CMD-003, but they have published results with EBV-specific T-cell products related to CMD-003.

In one study, published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in 2014, researchers administered cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) in 50 patients with EBV-associated Hodgkin or non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Twenty-nine of the patients were in remission when they received CTL infusions, but they were at a high risk of relapse. The remaining 21 patients had relapsed or refractory disease at the time of CTL infusion.

Twenty-seven of the patients who received CTLs as an adjuvant treatment remained in remission at 3.1 years after treatment.

Their 2-year event-free survival rate was 82%. None of the patients died of lymphoma, but 9 died from complications associated with the chemotherapy and radiation they had received.

Of the 21 patients with relapsed or refractory disease, 13 responded to CTL infusions, and 11 patients achieved a complete response. In this group, the 2-year event-free survival rate was about 50%.

The researchers said there were no toxicities that were definitively related to CTL infusion.

One patient had central nervous system deterioration 2 weeks after infusion. This was attributed to disease progression but could possibly have been treatment-related.

Another patient developed respiratory complications about 4 weeks after a second CTL infusion that may have been treatment-related. However, the researchers attributed it to an intercurrent infection, and the patient made a complete recovery.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted fast track designation to CMD-003 (baltaleucel-T) for patients with relapsed/refractory lymphoma and post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).

CMD-003 consists of patient-derived T cells that have been activated to kill malignant cells expressing antigens associated with EBV.

The T cells specifically target 4 EBV epitopes—LMP1, LMP2, EBNA, and BARF1.

CMD-003 is being developed by Cell Medica and the Baylor College of Medicine with funding provided, in part, by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas.

About fast track designation

The FDA’s fast track program is designed to facilitate the development and expedite the review of products intended to treat or prevent serious or life-threatening conditions and address unmet medical need.

Through the FDA’s fast track program, a product may be eligible for priority review. In addition, the company developing the product may be allowed to submit sections of the biologic license application or new drug application on a rolling basis as data become available.

Fast track designation also provides the company with opportunities for more frequent meetings and written communications with the FDA.

CMD-003-related research

CMD-003 is currently under investigation in the phase 2 CITADEL trial for patients with extranodal natural killer T-cell lymphoma and the phase 2 CIVIC trial for patients with EBV-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, and post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease.

Researchers have not published results from any trials of CMD-003, but they have published results with EBV-specific T-cell products related to CMD-003.

In one study, published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in 2014, researchers administered cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) in 50 patients with EBV-associated Hodgkin or non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Twenty-nine of the patients were in remission when they received CTL infusions, but they were at a high risk of relapse. The remaining 21 patients had relapsed or refractory disease at the time of CTL infusion.

Twenty-seven of the patients who received CTLs as an adjuvant treatment remained in remission at 3.1 years after treatment.

Their 2-year event-free survival rate was 82%. None of the patients died of lymphoma, but 9 died from complications associated with the chemotherapy and radiation they had received.

Of the 21 patients with relapsed or refractory disease, 13 responded to CTL infusions, and 11 patients achieved a complete response. In this group, the 2-year event-free survival rate was about 50%.

The researchers said there were no toxicities that were definitively related to CTL infusion.

One patient had central nervous system deterioration 2 weeks after infusion. This was attributed to disease progression but could possibly have been treatment-related.

Another patient developed respiratory complications about 4 weeks after a second CTL infusion that may have been treatment-related. However, the researchers attributed it to an intercurrent infection, and the patient made a complete recovery.

Styrene exposure linked to myeloid leukemia, HL

A new study links styrene—a chemical used in the manufacture of plastics, rubber, and resins—to certain cancers.

The research showed that, contrary to previous suggestions, employees who have worked with styrene do not have an increased incidence of esophageal, pancreatic, lung, kidney, or bladder cancer.

On the other hand, they may have an increased risk of nasal and paranasal cancer, as well as myeloid leukemia and Hodgkin lymphoma (HL).

The research was published in Epidemiology.

“It is important to know for present and former workers exposed to styrene that they are unlikely to have become ill by doing their job if they have developed cancer of the esophagus, pancreas, lungs, kidneys, bladder, or a wide range of other types of cancer,” said study author Henrik A. Kolstad, MD, PhD, of Aarhus University in Denmark.

“This is also new and important knowledge in the USA, where styrene was added to the list of carcinogenic substances in 2011.”

In relation to the cancers for which the study shows a possible increased risk, Dr Kolstad emphasized that additional research is needed to determine if styrene is the actual cause of the employees’ disease.

For the current study, Dr Kolstad and his colleagues analyzed data on 72,292 employees who worked for 1 of 443 small and medium-sized companies in Denmark that used styrene for the production of wind turbines, pleasure boats, and other products from 1964 to 2007.

There were 8961 incident cases of cancer in this cohort from 1968 to 2012. The standardized incidence rate ratio (SIR) for all cancers was 1.04. When the researchers included a 10-year lag period, the SIR for all cancers was still 1.04.

As for hematologic malignancies, the researchers said they observed increased rate ratios associated with increased duration of employment for HL and myeloid leukemia.

For HL, the SIRs were 1.21 with no lag and 1.22 with a 10-year lag. For myeloid leukemia, the SIRs were 1.06 and 1.13, respectively.

The SIRs for non-Hodgkin lymphoma were 0.97 with no lag and 0.94 with a 10-year lag. The SIRs for multiple myeloma were 0.79 and 0.77, respectively.

For cancers of lymphatic and hematopoietic tissue, the SIRs were 0.97 with no lag and 0.96 with a 10-year lag. For lymphatic leukemia, the SIR was 0.96 for both time points.

The SIRs for monocytic leukemia were 0.77 with no lag and 0.56 with a 10-year lag. The SIRs for other and unspecified leukemias were 1.05 and 1.26, respectively.

The researchers noted that workers first employed in the 1960s had a higher risk of HL than workers first employed in subsequent years.

The SIRs were 2.12 for those first employed in 1964-1969, 0.82 for 1970-1979, 1.07 for 1980-1989, 1.52 for 1990-1999, and 1.10 for those first employed in 2000-2007.

There were no such associations for other cancer sites. ![]()

A new study links styrene—a chemical used in the manufacture of plastics, rubber, and resins—to certain cancers.

The research showed that, contrary to previous suggestions, employees who have worked with styrene do not have an increased incidence of esophageal, pancreatic, lung, kidney, or bladder cancer.

On the other hand, they may have an increased risk of nasal and paranasal cancer, as well as myeloid leukemia and Hodgkin lymphoma (HL).

The research was published in Epidemiology.

“It is important to know for present and former workers exposed to styrene that they are unlikely to have become ill by doing their job if they have developed cancer of the esophagus, pancreas, lungs, kidneys, bladder, or a wide range of other types of cancer,” said study author Henrik A. Kolstad, MD, PhD, of Aarhus University in Denmark.

“This is also new and important knowledge in the USA, where styrene was added to the list of carcinogenic substances in 2011.”

In relation to the cancers for which the study shows a possible increased risk, Dr Kolstad emphasized that additional research is needed to determine if styrene is the actual cause of the employees’ disease.

For the current study, Dr Kolstad and his colleagues analyzed data on 72,292 employees who worked for 1 of 443 small and medium-sized companies in Denmark that used styrene for the production of wind turbines, pleasure boats, and other products from 1964 to 2007.

There were 8961 incident cases of cancer in this cohort from 1968 to 2012. The standardized incidence rate ratio (SIR) for all cancers was 1.04. When the researchers included a 10-year lag period, the SIR for all cancers was still 1.04.

As for hematologic malignancies, the researchers said they observed increased rate ratios associated with increased duration of employment for HL and myeloid leukemia.

For HL, the SIRs were 1.21 with no lag and 1.22 with a 10-year lag. For myeloid leukemia, the SIRs were 1.06 and 1.13, respectively.

The SIRs for non-Hodgkin lymphoma were 0.97 with no lag and 0.94 with a 10-year lag. The SIRs for multiple myeloma were 0.79 and 0.77, respectively.

For cancers of lymphatic and hematopoietic tissue, the SIRs were 0.97 with no lag and 0.96 with a 10-year lag. For lymphatic leukemia, the SIR was 0.96 for both time points.

The SIRs for monocytic leukemia were 0.77 with no lag and 0.56 with a 10-year lag. The SIRs for other and unspecified leukemias were 1.05 and 1.26, respectively.

The researchers noted that workers first employed in the 1960s had a higher risk of HL than workers first employed in subsequent years.

The SIRs were 2.12 for those first employed in 1964-1969, 0.82 for 1970-1979, 1.07 for 1980-1989, 1.52 for 1990-1999, and 1.10 for those first employed in 2000-2007.

There were no such associations for other cancer sites. ![]()

A new study links styrene—a chemical used in the manufacture of plastics, rubber, and resins—to certain cancers.

The research showed that, contrary to previous suggestions, employees who have worked with styrene do not have an increased incidence of esophageal, pancreatic, lung, kidney, or bladder cancer.

On the other hand, they may have an increased risk of nasal and paranasal cancer, as well as myeloid leukemia and Hodgkin lymphoma (HL).

The research was published in Epidemiology.

“It is important to know for present and former workers exposed to styrene that they are unlikely to have become ill by doing their job if they have developed cancer of the esophagus, pancreas, lungs, kidneys, bladder, or a wide range of other types of cancer,” said study author Henrik A. Kolstad, MD, PhD, of Aarhus University in Denmark.

“This is also new and important knowledge in the USA, where styrene was added to the list of carcinogenic substances in 2011.”

In relation to the cancers for which the study shows a possible increased risk, Dr Kolstad emphasized that additional research is needed to determine if styrene is the actual cause of the employees’ disease.

For the current study, Dr Kolstad and his colleagues analyzed data on 72,292 employees who worked for 1 of 443 small and medium-sized companies in Denmark that used styrene for the production of wind turbines, pleasure boats, and other products from 1964 to 2007.

There were 8961 incident cases of cancer in this cohort from 1968 to 2012. The standardized incidence rate ratio (SIR) for all cancers was 1.04. When the researchers included a 10-year lag period, the SIR for all cancers was still 1.04.

As for hematologic malignancies, the researchers said they observed increased rate ratios associated with increased duration of employment for HL and myeloid leukemia.

For HL, the SIRs were 1.21 with no lag and 1.22 with a 10-year lag. For myeloid leukemia, the SIRs were 1.06 and 1.13, respectively.

The SIRs for non-Hodgkin lymphoma were 0.97 with no lag and 0.94 with a 10-year lag. The SIRs for multiple myeloma were 0.79 and 0.77, respectively.

For cancers of lymphatic and hematopoietic tissue, the SIRs were 0.97 with no lag and 0.96 with a 10-year lag. For lymphatic leukemia, the SIR was 0.96 for both time points.

The SIRs for monocytic leukemia were 0.77 with no lag and 0.56 with a 10-year lag. The SIRs for other and unspecified leukemias were 1.05 and 1.26, respectively.

The researchers noted that workers first employed in the 1960s had a higher risk of HL than workers first employed in subsequent years.

The SIRs were 2.12 for those first employed in 1964-1969, 0.82 for 1970-1979, 1.07 for 1980-1989, 1.52 for 1990-1999, and 1.10 for those first employed in 2000-2007.

There were no such associations for other cancer sites. ![]()

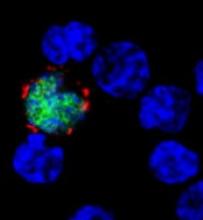

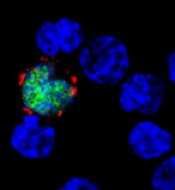

How EBV causes lymphoma, other cancers

among uninfected cells (blue)

Image courtesy of

Benjamin Chaigne-Delalande

New research published in Nature Communications appears to explain how Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) reprograms cells into cancer cells.

Investigators said they discovered a mechanism by which EBV particles induce chromosomal instability without establishing a chronic infection, thereby conferring a risk for the development of tumors that do not necessarily carry the viral genome.

“The contribution of the viral infection to cancer development in patients with a weakened immune system is well understood,” said study author Henri-Jacques Delecluse, MD, PhD, of the German Cancer Research Center (Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, DKFZ) in Heidelberg.

“But in the majority of cases, it remains unclear how an EBV infection leads to cancer development.”

With their research, Dr Delecluse and his colleagues found that BNRF1, a protein component of EBV, promotes the development of cancer. They said BNRF1 induces centrosome amplification, which is associated with chromosomal instability.

When a dividing cell comes in contact with EBV, BNRF1 frequently prompts the formation of an excessive number of centrosomes. As a result, chromosomes are no longer divided equally and accurately between daughter cells—a known cancer risk factor.

In contrast, when the investigators studied EBV deficient of BNRF1, they found the virus did not interfere with chromosome distribution to daughter cells.

The team noted that EBV normally remains silent in a few infected cells, but, occasionally, it reactivates to produce viral offspring that infects nearby cells. As a consequence, these cells come in close contact with BNRF1, thus increasing their risk of transforming into cancer cells.

“The novelty of our work is that we have uncovered a component of the viral particle as a cancer driver,” Dr Delecluse said. “All human-tumors viruses that have been studied so far cause cancer in a completely different manner.”

“Usually, the genetic material of the viruses needs to be permanently present in the infected cell, thus causing the activation of one or several viral genes that cause cancer development. However, these gene products are not present in the infectious particle itself.”

Dr Delecluse and his colleagues therefore suspect that EBV could cause cancers other than those that have already been linked to EBV. Certain cancers might not have been linked to the virus because they do not carry the viral genetic material.

“We must push forward with the development of a vaccine against EBV infection,” Dr Delecluse said. “This would be the most direct strategy to prevent an infection with the virus.”

“Our latest results show that the first infection could already be a cancer risk, and this fits with earlier work that showed an increase in the incidence of Hodgkin’s lymphoma in people who underwent an episode of infectious mononucleosis.” ![]()

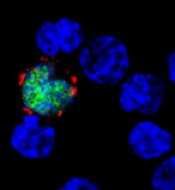

among uninfected cells (blue)

Image courtesy of

Benjamin Chaigne-Delalande

New research published in Nature Communications appears to explain how Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) reprograms cells into cancer cells.

Investigators said they discovered a mechanism by which EBV particles induce chromosomal instability without establishing a chronic infection, thereby conferring a risk for the development of tumors that do not necessarily carry the viral genome.

“The contribution of the viral infection to cancer development in patients with a weakened immune system is well understood,” said study author Henri-Jacques Delecluse, MD, PhD, of the German Cancer Research Center (Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, DKFZ) in Heidelberg.

“But in the majority of cases, it remains unclear how an EBV infection leads to cancer development.”

With their research, Dr Delecluse and his colleagues found that BNRF1, a protein component of EBV, promotes the development of cancer. They said BNRF1 induces centrosome amplification, which is associated with chromosomal instability.

When a dividing cell comes in contact with EBV, BNRF1 frequently prompts the formation of an excessive number of centrosomes. As a result, chromosomes are no longer divided equally and accurately between daughter cells—a known cancer risk factor.

In contrast, when the investigators studied EBV deficient of BNRF1, they found the virus did not interfere with chromosome distribution to daughter cells.

The team noted that EBV normally remains silent in a few infected cells, but, occasionally, it reactivates to produce viral offspring that infects nearby cells. As a consequence, these cells come in close contact with BNRF1, thus increasing their risk of transforming into cancer cells.

“The novelty of our work is that we have uncovered a component of the viral particle as a cancer driver,” Dr Delecluse said. “All human-tumors viruses that have been studied so far cause cancer in a completely different manner.”

“Usually, the genetic material of the viruses needs to be permanently present in the infected cell, thus causing the activation of one or several viral genes that cause cancer development. However, these gene products are not present in the infectious particle itself.”

Dr Delecluse and his colleagues therefore suspect that EBV could cause cancers other than those that have already been linked to EBV. Certain cancers might not have been linked to the virus because they do not carry the viral genetic material.

“We must push forward with the development of a vaccine against EBV infection,” Dr Delecluse said. “This would be the most direct strategy to prevent an infection with the virus.”

“Our latest results show that the first infection could already be a cancer risk, and this fits with earlier work that showed an increase in the incidence of Hodgkin’s lymphoma in people who underwent an episode of infectious mononucleosis.” ![]()

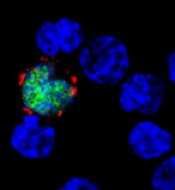

among uninfected cells (blue)

Image courtesy of

Benjamin Chaigne-Delalande

New research published in Nature Communications appears to explain how Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) reprograms cells into cancer cells.

Investigators said they discovered a mechanism by which EBV particles induce chromosomal instability without establishing a chronic infection, thereby conferring a risk for the development of tumors that do not necessarily carry the viral genome.

“The contribution of the viral infection to cancer development in patients with a weakened immune system is well understood,” said study author Henri-Jacques Delecluse, MD, PhD, of the German Cancer Research Center (Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, DKFZ) in Heidelberg.

“But in the majority of cases, it remains unclear how an EBV infection leads to cancer development.”

With their research, Dr Delecluse and his colleagues found that BNRF1, a protein component of EBV, promotes the development of cancer. They said BNRF1 induces centrosome amplification, which is associated with chromosomal instability.

When a dividing cell comes in contact with EBV, BNRF1 frequently prompts the formation of an excessive number of centrosomes. As a result, chromosomes are no longer divided equally and accurately between daughter cells—a known cancer risk factor.

In contrast, when the investigators studied EBV deficient of BNRF1, they found the virus did not interfere with chromosome distribution to daughter cells.

The team noted that EBV normally remains silent in a few infected cells, but, occasionally, it reactivates to produce viral offspring that infects nearby cells. As a consequence, these cells come in close contact with BNRF1, thus increasing their risk of transforming into cancer cells.

“The novelty of our work is that we have uncovered a component of the viral particle as a cancer driver,” Dr Delecluse said. “All human-tumors viruses that have been studied so far cause cancer in a completely different manner.”

“Usually, the genetic material of the viruses needs to be permanently present in the infected cell, thus causing the activation of one or several viral genes that cause cancer development. However, these gene products are not present in the infectious particle itself.”

Dr Delecluse and his colleagues therefore suspect that EBV could cause cancers other than those that have already been linked to EBV. Certain cancers might not have been linked to the virus because they do not carry the viral genetic material.

“We must push forward with the development of a vaccine against EBV infection,” Dr Delecluse said. “This would be the most direct strategy to prevent an infection with the virus.”

“Our latest results show that the first infection could already be a cancer risk, and this fits with earlier work that showed an increase in the incidence of Hodgkin’s lymphoma in people who underwent an episode of infectious mononucleosis.” ![]()

G-CSF could prevent infertility in cancer patients

Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) could prevent infertility in male cancer patients, according to preclinical research published in Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology.

Researchers said they found that G-CSF protects spermatogenesis after alkylating chemotherapy by stimulating the proliferation of surviving spermatogonia.

The team also found evidence to suggest that G-CSF may be useful as a fertility-restoring treatment.

The researchers have been pursuing initiatives to restore fertility in men who have lost their ability to have children as a result of cancer treatments they received as children.

While working on methods to restart sperm production, the team discovered a link between G-CSF and the absence of normal damage to reproductive ability.

“We were using G-CSF to prevent infections in our research experiments,” said study author Brian Hermann, PhD, of The University of Texas at San Antonio.

“It turned out that the drug also had the unexpected impact of guarding against male infertility.”

To test the fertility-related impact of G-CSF, the researchers treated male mice with G-CSF before and/or after treatment with busulfan.

The team then evaluated effects on spermatogenesis in these mice and control mice that only received busulfan.

G-CSF had a protective effect on spermatogenesis that was stable for at least 19 weeks after chemotherapy.

And mice treated with G-CSF for 4 days after busulfan showed modestly enhanced spermatogenic recovery compared to controls.

The researchers said these results suggest G-CSF promotes spermatogonial proliferation, leading to enhanced spermatogenic regeneration from surviving spermatogonial stem cells. ![]()

Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) could prevent infertility in male cancer patients, according to preclinical research published in Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology.

Researchers said they found that G-CSF protects spermatogenesis after alkylating chemotherapy by stimulating the proliferation of surviving spermatogonia.

The team also found evidence to suggest that G-CSF may be useful as a fertility-restoring treatment.

The researchers have been pursuing initiatives to restore fertility in men who have lost their ability to have children as a result of cancer treatments they received as children.

While working on methods to restart sperm production, the team discovered a link between G-CSF and the absence of normal damage to reproductive ability.

“We were using G-CSF to prevent infections in our research experiments,” said study author Brian Hermann, PhD, of The University of Texas at San Antonio.

“It turned out that the drug also had the unexpected impact of guarding against male infertility.”

To test the fertility-related impact of G-CSF, the researchers treated male mice with G-CSF before and/or after treatment with busulfan.

The team then evaluated effects on spermatogenesis in these mice and control mice that only received busulfan.

G-CSF had a protective effect on spermatogenesis that was stable for at least 19 weeks after chemotherapy.

And mice treated with G-CSF for 4 days after busulfan showed modestly enhanced spermatogenic recovery compared to controls.

The researchers said these results suggest G-CSF promotes spermatogonial proliferation, leading to enhanced spermatogenic regeneration from surviving spermatogonial stem cells. ![]()

Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) could prevent infertility in male cancer patients, according to preclinical research published in Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology.

Researchers said they found that G-CSF protects spermatogenesis after alkylating chemotherapy by stimulating the proliferation of surviving spermatogonia.

The team also found evidence to suggest that G-CSF may be useful as a fertility-restoring treatment.

The researchers have been pursuing initiatives to restore fertility in men who have lost their ability to have children as a result of cancer treatments they received as children.

While working on methods to restart sperm production, the team discovered a link between G-CSF and the absence of normal damage to reproductive ability.

“We were using G-CSF to prevent infections in our research experiments,” said study author Brian Hermann, PhD, of The University of Texas at San Antonio.

“It turned out that the drug also had the unexpected impact of guarding against male infertility.”

To test the fertility-related impact of G-CSF, the researchers treated male mice with G-CSF before and/or after treatment with busulfan.

The team then evaluated effects on spermatogenesis in these mice and control mice that only received busulfan.

G-CSF had a protective effect on spermatogenesis that was stable for at least 19 weeks after chemotherapy.

And mice treated with G-CSF for 4 days after busulfan showed modestly enhanced spermatogenic recovery compared to controls.

The researchers said these results suggest G-CSF promotes spermatogonial proliferation, leading to enhanced spermatogenic regeneration from surviving spermatogonial stem cells. ![]()

Team creates online database of cancer mutations

Image by Spencer Phillips

Researchers have developed an online “knowledgebase” called CIViC, an open access resource for collecting and interpreting information from scientific publications on cancer genetics.

“CIViC” stands for Clinical Interpretations of Variants in Cancer, and the researchers liken it to a Wikipedia of cancer genetics.

Anyone can create an account and contribute information. That information is then curated by editors and moderators who are considered experts in the field.

The researchers described the resource in Nature Genetics.

“It’s relatively easy now to sequence the DNA of tumors—to gather the raw information—but there’s a big interpretation problem,” said study author Obi L. Griffith, PhD, of Washington University School of Medicine in St Louis, Missouri.

“What do these hundreds or thousands of mutations mean for this patient? There are a lot of studies being done to answer these questions. But oncologists trying to interpret the raw data are faced with an overwhelming task of plumbing the literature, reading papers, trying to understand what the latest studies tell them about these mutations and how they may or may not be important.”

The CIViC knowledgebase is an attempt to solve this problem. The researchers said this is one of many efforts to collect and interpret such information, but, to their knowledge, CIViC is the only one that is entirely open access. Anyone is free to contribute and use the content as well as the source code.

“We are committed to keeping this resource open and available to anyone who wants to contribute or make use of the information,” said Malachi Griffith, PhD, of Washington University School of Medicine.

“We would like it to be a community exercise and public resource. The information is in the public domain. There are no restrictions on its use, academic or commercial.”

Though anyone can submit a new piece of information or suggest edits to existing data, at least 2 independent contributors must agree that the new information should be incorporated, and 1 of those users must be an “expert editor.”

Expert editors are not permitted to approve their own submissions. Information on the CIViC website provides details about how new users may be promoted to expert editors and administrators.

To date, the site has seen over 17,500 users from academic institutions, governmental organizations, and commercial entities around the world.

Since CIViC’s launch, 59 users have volunteered their time to contribute their knowledge to CIViC, including descriptions of the clinical relevance of 732 mutations from 285 genes for 203 types of cancer, all gleaned from reviewing 1090 scientific and medical publications.

Despite the fact that there are many groups attempting to collect and interpret genomic variants in cancer, the researchers said the sheer volume of information has resulted in relatively little overlap in data gathered so far.

“While we believe this is the only such open access knowledgebase, there are other large research centers with similar resources,” Malachi Griffith said. “We did an analysis to compare the big ones.”

“Even though we all have access to the same published literature, if you look at the overlap of the information mined by each of these resources, it’s remarkably small. We’re all approaching the same problem, and, just by chance—and probably because of the amount of information out there—we haven’t duplicated our efforts very much yet.”

Obi and Malachi Griffith said finding a way to combine these resources is the primary goal of an international group they are helping lead called the Variant Interpretation for Cancer Consortium, which is a part of the Global Alliance for Genomics and Health (GA4GH).

“We’re just scratching the surface of the potential this holds for precision medicine,” Obi Griffith said. “There’s a lot of work to do.” ![]()

Image by Spencer Phillips

Researchers have developed an online “knowledgebase” called CIViC, an open access resource for collecting and interpreting information from scientific publications on cancer genetics.

“CIViC” stands for Clinical Interpretations of Variants in Cancer, and the researchers liken it to a Wikipedia of cancer genetics.

Anyone can create an account and contribute information. That information is then curated by editors and moderators who are considered experts in the field.

The researchers described the resource in Nature Genetics.

“It’s relatively easy now to sequence the DNA of tumors—to gather the raw information—but there’s a big interpretation problem,” said study author Obi L. Griffith, PhD, of Washington University School of Medicine in St Louis, Missouri.

“What do these hundreds or thousands of mutations mean for this patient? There are a lot of studies being done to answer these questions. But oncologists trying to interpret the raw data are faced with an overwhelming task of plumbing the literature, reading papers, trying to understand what the latest studies tell them about these mutations and how they may or may not be important.”

The CIViC knowledgebase is an attempt to solve this problem. The researchers said this is one of many efforts to collect and interpret such information, but, to their knowledge, CIViC is the only one that is entirely open access. Anyone is free to contribute and use the content as well as the source code.

“We are committed to keeping this resource open and available to anyone who wants to contribute or make use of the information,” said Malachi Griffith, PhD, of Washington University School of Medicine.

“We would like it to be a community exercise and public resource. The information is in the public domain. There are no restrictions on its use, academic or commercial.”

Though anyone can submit a new piece of information or suggest edits to existing data, at least 2 independent contributors must agree that the new information should be incorporated, and 1 of those users must be an “expert editor.”

Expert editors are not permitted to approve their own submissions. Information on the CIViC website provides details about how new users may be promoted to expert editors and administrators.

To date, the site has seen over 17,500 users from academic institutions, governmental organizations, and commercial entities around the world.

Since CIViC’s launch, 59 users have volunteered their time to contribute their knowledge to CIViC, including descriptions of the clinical relevance of 732 mutations from 285 genes for 203 types of cancer, all gleaned from reviewing 1090 scientific and medical publications.

Despite the fact that there are many groups attempting to collect and interpret genomic variants in cancer, the researchers said the sheer volume of information has resulted in relatively little overlap in data gathered so far.

“While we believe this is the only such open access knowledgebase, there are other large research centers with similar resources,” Malachi Griffith said. “We did an analysis to compare the big ones.”

“Even though we all have access to the same published literature, if you look at the overlap of the information mined by each of these resources, it’s remarkably small. We’re all approaching the same problem, and, just by chance—and probably because of the amount of information out there—we haven’t duplicated our efforts very much yet.”

Obi and Malachi Griffith said finding a way to combine these resources is the primary goal of an international group they are helping lead called the Variant Interpretation for Cancer Consortium, which is a part of the Global Alliance for Genomics and Health (GA4GH).

“We’re just scratching the surface of the potential this holds for precision medicine,” Obi Griffith said. “There’s a lot of work to do.” ![]()

Image by Spencer Phillips

Researchers have developed an online “knowledgebase” called CIViC, an open access resource for collecting and interpreting information from scientific publications on cancer genetics.

“CIViC” stands for Clinical Interpretations of Variants in Cancer, and the researchers liken it to a Wikipedia of cancer genetics.

Anyone can create an account and contribute information. That information is then curated by editors and moderators who are considered experts in the field.

The researchers described the resource in Nature Genetics.

“It’s relatively easy now to sequence the DNA of tumors—to gather the raw information—but there’s a big interpretation problem,” said study author Obi L. Griffith, PhD, of Washington University School of Medicine in St Louis, Missouri.

“What do these hundreds or thousands of mutations mean for this patient? There are a lot of studies being done to answer these questions. But oncologists trying to interpret the raw data are faced with an overwhelming task of plumbing the literature, reading papers, trying to understand what the latest studies tell them about these mutations and how they may or may not be important.”

The CIViC knowledgebase is an attempt to solve this problem. The researchers said this is one of many efforts to collect and interpret such information, but, to their knowledge, CIViC is the only one that is entirely open access. Anyone is free to contribute and use the content as well as the source code.

“We are committed to keeping this resource open and available to anyone who wants to contribute or make use of the information,” said Malachi Griffith, PhD, of Washington University School of Medicine.

“We would like it to be a community exercise and public resource. The information is in the public domain. There are no restrictions on its use, academic or commercial.”

Though anyone can submit a new piece of information or suggest edits to existing data, at least 2 independent contributors must agree that the new information should be incorporated, and 1 of those users must be an “expert editor.”

Expert editors are not permitted to approve their own submissions. Information on the CIViC website provides details about how new users may be promoted to expert editors and administrators.

To date, the site has seen over 17,500 users from academic institutions, governmental organizations, and commercial entities around the world.

Since CIViC’s launch, 59 users have volunteered their time to contribute their knowledge to CIViC, including descriptions of the clinical relevance of 732 mutations from 285 genes for 203 types of cancer, all gleaned from reviewing 1090 scientific and medical publications.

Despite the fact that there are many groups attempting to collect and interpret genomic variants in cancer, the researchers said the sheer volume of information has resulted in relatively little overlap in data gathered so far.

“While we believe this is the only such open access knowledgebase, there are other large research centers with similar resources,” Malachi Griffith said. “We did an analysis to compare the big ones.”

“Even though we all have access to the same published literature, if you look at the overlap of the information mined by each of these resources, it’s remarkably small. We’re all approaching the same problem, and, just by chance—and probably because of the amount of information out there—we haven’t duplicated our efforts very much yet.”

Obi and Malachi Griffith said finding a way to combine these resources is the primary goal of an international group they are helping lead called the Variant Interpretation for Cancer Consortium, which is a part of the Global Alliance for Genomics and Health (GA4GH).

“We’re just scratching the surface of the potential this holds for precision medicine,” Obi Griffith said. “There’s a lot of work to do.” ![]()

Investigators report new risk loci for CLL

Investigators say they have identified 9 new risk loci for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

The team says the research, published in Nature Communications, provides additional evidence for genetic susceptibility to CLL and sheds new light on the biological basis of CLL development.

They also believe their findings could aid the development of new drugs for CLL or help in selecting existing therapies for CLL

patients.

“We knew people were more likely to develop chronic lymphocytic leukemia if someone in their family had suffered from the disease, but our new research takes a big step towards explaining the underlying genetics,” said study author Richard Houlston, MD, PhD, of The Institute of Cancer Research in London, UK.

“CLL is essentially a disease of the immune system, and it’s fascinating that so many of the new genetic variants we have uncovered seem to directly affect the behavior of white blood cells and their ability to fight disease. Understanding the genetics of CLL can point us towards new treatments for the disease and help us to use existing targeted drugs more effectively.”

For this study, Dr Houlston and his colleagues analyzed data from 8 studies involving a total of 6200 CLL patients and 17,598 controls.

From this, the team identified 9 CLL risk loci:

- 1p36.11 (rs34676223, P=5.04 × 10−13)

- 1q42.13 (rs41271473, P=1.06 × 10−10)

- 4q24 (rs71597109, P=1.37 × 10−10)

- 4q35.1 (rs57214277, P=3.69 × 10−8)

- 6p21.31 (rs3800461, P=1.97 × 10−8)

- 11q23.2 (rs61904987, P=2.64 × 10−11)

- 18q21.1 (rs1036935, P=3.27 × 10−8)

- 19p13.3 (rs7254272, P=4.67 × 10−8)

- 22q13.33 (rs140522, P=2.70 × 10−9).

The investigators noted that the 4q24 association marked by rs71597109 maps to intron 1 of the gene encoding BANK1 (B-cell scaffold protein with ankyrin repeats 1). BANK1 is only ever activated in B cells and is linked to the autoimmune disease lupus.

The team also pointed out that the 19p13.3 association marked by rs7254272 maps 2.5 kb 5′ to ZBTB7A (zinc finger and BTB domain-containing protein 7a), which is a master regulator of B versus T lymphoid fate. So errors in ZBTB7A could lead to too many B cells in the bloodstream and bone marrow.

And rs140522 maps to 22q13.33, which has been linked to the development of multiple sclerosis. The investigators noted that this region of linkage disequilibrium contains 4 genes. One of them, NCAPH2 (non-SMC condensin II complex subunit H2), is differentially expressed in CLL and normal B cells.

“This fascinating study makes a link between genetic variants in the immune system and the development of leukemia and implicates regions of DNA which are also involved in autoimmune diseases,” said Paul Workman, PhD, chief executive and president of The Institute of Cancer Research, who was not involved in this research.

“The findings could point us towards new ways of treating leukemia or better ways of using existing treatments—potentially including immunotherapies.” ![]()

Investigators say they have identified 9 new risk loci for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

The team says the research, published in Nature Communications, provides additional evidence for genetic susceptibility to CLL and sheds new light on the biological basis of CLL development.

They also believe their findings could aid the development of new drugs for CLL or help in selecting existing therapies for CLL

patients.

“We knew people were more likely to develop chronic lymphocytic leukemia if someone in their family had suffered from the disease, but our new research takes a big step towards explaining the underlying genetics,” said study author Richard Houlston, MD, PhD, of The Institute of Cancer Research in London, UK.

“CLL is essentially a disease of the immune system, and it’s fascinating that so many of the new genetic variants we have uncovered seem to directly affect the behavior of white blood cells and their ability to fight disease. Understanding the genetics of CLL can point us towards new treatments for the disease and help us to use existing targeted drugs more effectively.”

For this study, Dr Houlston and his colleagues analyzed data from 8 studies involving a total of 6200 CLL patients and 17,598 controls.

From this, the team identified 9 CLL risk loci:

- 1p36.11 (rs34676223, P=5.04 × 10−13)

- 1q42.13 (rs41271473, P=1.06 × 10−10)

- 4q24 (rs71597109, P=1.37 × 10−10)

- 4q35.1 (rs57214277, P=3.69 × 10−8)

- 6p21.31 (rs3800461, P=1.97 × 10−8)

- 11q23.2 (rs61904987, P=2.64 × 10−11)

- 18q21.1 (rs1036935, P=3.27 × 10−8)

- 19p13.3 (rs7254272, P=4.67 × 10−8)

- 22q13.33 (rs140522, P=2.70 × 10−9).

The investigators noted that the 4q24 association marked by rs71597109 maps to intron 1 of the gene encoding BANK1 (B-cell scaffold protein with ankyrin repeats 1). BANK1 is only ever activated in B cells and is linked to the autoimmune disease lupus.

The team also pointed out that the 19p13.3 association marked by rs7254272 maps 2.5 kb 5′ to ZBTB7A (zinc finger and BTB domain-containing protein 7a), which is a master regulator of B versus T lymphoid fate. So errors in ZBTB7A could lead to too many B cells in the bloodstream and bone marrow.

And rs140522 maps to 22q13.33, which has been linked to the development of multiple sclerosis. The investigators noted that this region of linkage disequilibrium contains 4 genes. One of them, NCAPH2 (non-SMC condensin II complex subunit H2), is differentially expressed in CLL and normal B cells.

“This fascinating study makes a link between genetic variants in the immune system and the development of leukemia and implicates regions of DNA which are also involved in autoimmune diseases,” said Paul Workman, PhD, chief executive and president of The Institute of Cancer Research, who was not involved in this research.

“The findings could point us towards new ways of treating leukemia or better ways of using existing treatments—potentially including immunotherapies.” ![]()

Investigators say they have identified 9 new risk loci for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

The team says the research, published in Nature Communications, provides additional evidence for genetic susceptibility to CLL and sheds new light on the biological basis of CLL development.

They also believe their findings could aid the development of new drugs for CLL or help in selecting existing therapies for CLL

patients.

“We knew people were more likely to develop chronic lymphocytic leukemia if someone in their family had suffered from the disease, but our new research takes a big step towards explaining the underlying genetics,” said study author Richard Houlston, MD, PhD, of The Institute of Cancer Research in London, UK.

“CLL is essentially a disease of the immune system, and it’s fascinating that so many of the new genetic variants we have uncovered seem to directly affect the behavior of white blood cells and their ability to fight disease. Understanding the genetics of CLL can point us towards new treatments for the disease and help us to use existing targeted drugs more effectively.”

For this study, Dr Houlston and his colleagues analyzed data from 8 studies involving a total of 6200 CLL patients and 17,598 controls.

From this, the team identified 9 CLL risk loci:

- 1p36.11 (rs34676223, P=5.04 × 10−13)

- 1q42.13 (rs41271473, P=1.06 × 10−10)

- 4q24 (rs71597109, P=1.37 × 10−10)

- 4q35.1 (rs57214277, P=3.69 × 10−8)

- 6p21.31 (rs3800461, P=1.97 × 10−8)

- 11q23.2 (rs61904987, P=2.64 × 10−11)

- 18q21.1 (rs1036935, P=3.27 × 10−8)

- 19p13.3 (rs7254272, P=4.67 × 10−8)

- 22q13.33 (rs140522, P=2.70 × 10−9).

The investigators noted that the 4q24 association marked by rs71597109 maps to intron 1 of the gene encoding BANK1 (B-cell scaffold protein with ankyrin repeats 1). BANK1 is only ever activated in B cells and is linked to the autoimmune disease lupus.

The team also pointed out that the 19p13.3 association marked by rs7254272 maps 2.5 kb 5′ to ZBTB7A (zinc finger and BTB domain-containing protein 7a), which is a master regulator of B versus T lymphoid fate. So errors in ZBTB7A could lead to too many B cells in the bloodstream and bone marrow.

And rs140522 maps to 22q13.33, which has been linked to the development of multiple sclerosis. The investigators noted that this region of linkage disequilibrium contains 4 genes. One of them, NCAPH2 (non-SMC condensin II complex subunit H2), is differentially expressed in CLL and normal B cells.

“This fascinating study makes a link between genetic variants in the immune system and the development of leukemia and implicates regions of DNA which are also involved in autoimmune diseases,” said Paul Workman, PhD, chief executive and president of The Institute of Cancer Research, who was not involved in this research.

“The findings could point us towards new ways of treating leukemia or better ways of using existing treatments—potentially including immunotherapies.” ![]()

Obinutuzumab approved to treat FL in Canada

Health Canada has approved the use of obinutuzumab (Gazyva®), an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, in patients with follicular lymphoma (FL).

The approval means obinutuzumab can be given, first in combination with bendamustine and then alone as maintenance therapy, to FL patients who relapsed after, or are refractory to, a rituximab-containing regimen.

Obinutuzumab is also approved in Canada for use in combination with chlorambucil to treat patients with previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Obinutuzumab is a product of Roche.

Health Canada’s approval of obinutuzumab in FL is based on results from the phase 3 GADOLIN trial.

The study included 413 patients with rituximab-refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma, including 321 patients with FL, 46 with marginal zone lymphoma, and 28 with small lymphocytic lymphoma.

The patients were randomized to receive bendamustine alone (control arm) or a combination of bendamustine and obinutuzumab followed by obinutuzumab maintenance (every 2 months for 2 years or until progression).

The primary endpoint of the study was progression-free survival (PFS), as assessed by an independent review committee (IRC). The secondary endpoints were PFS assessed by investigator review, best overall response, complete response (CR), partial response (PR), duration of response, overall survival, and safety profile.

Among patients with FL, the obinutuzumab regimen improved PFS compared to bendamustine alone, as assessed by the IRC (hazard ratio [HR]=0.48, P<0.0001). The median PFS was not reached in patients receiving the obinutuzumab regimen but was 13.8 months in those receiving bendamustine alone.

Investigator-assessed PFS was consistent with IRC-assessed PFS. Investigators said the median PFS with the obinutuzumab regimen was more than double that with bendamustine alone—29.2 months vs 13.7 months (HR=0.48, P<0.0001).

The best overall response for patients receiving the obinutuzumab regimen was 78.7% (15.5% CR, 63.2% PR), compared to 74.7% (18.7% CR, 56% PR) for those receiving bendamustine alone, as assessed by the IRC.

The median duration of response was not reached for patients receiving the obinutuzumab regimen and was 11.6 months for those receiving bendamustine alone.

At last follow-up, the median overall survival had not been reached in either study arm.

The most common grade 3/4 adverse events observed in patients receiving the obinutuzumab regimen were neutropenia (33%), infusion reactions (11%), and thrombocytopenia (10%).

The most common adverse events of any grade were infusion reactions (69%), neutropenia (35%), nausea (54%), fatigue (39%), cough (26%), diarrhea (27%), constipation (19%), fever (18%), thrombocytopenia (15%), vomiting (22%), upper respiratory tract infection (13%), decreased appetite (18%), joint or muscle pain (12%), sinusitis (12%), anemia (12%), general weakness (11%), and urinary tract infection (10%). ![]()

Health Canada has approved the use of obinutuzumab (Gazyva®), an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, in patients with follicular lymphoma (FL).

The approval means obinutuzumab can be given, first in combination with bendamustine and then alone as maintenance therapy, to FL patients who relapsed after, or are refractory to, a rituximab-containing regimen.

Obinutuzumab is also approved in Canada for use in combination with chlorambucil to treat patients with previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Obinutuzumab is a product of Roche.

Health Canada’s approval of obinutuzumab in FL is based on results from the phase 3 GADOLIN trial.

The study included 413 patients with rituximab-refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma, including 321 patients with FL, 46 with marginal zone lymphoma, and 28 with small lymphocytic lymphoma.

The patients were randomized to receive bendamustine alone (control arm) or a combination of bendamustine and obinutuzumab followed by obinutuzumab maintenance (every 2 months for 2 years or until progression).

The primary endpoint of the study was progression-free survival (PFS), as assessed by an independent review committee (IRC). The secondary endpoints were PFS assessed by investigator review, best overall response, complete response (CR), partial response (PR), duration of response, overall survival, and safety profile.

Among patients with FL, the obinutuzumab regimen improved PFS compared to bendamustine alone, as assessed by the IRC (hazard ratio [HR]=0.48, P<0.0001). The median PFS was not reached in patients receiving the obinutuzumab regimen but was 13.8 months in those receiving bendamustine alone.

Investigator-assessed PFS was consistent with IRC-assessed PFS. Investigators said the median PFS with the obinutuzumab regimen was more than double that with bendamustine alone—29.2 months vs 13.7 months (HR=0.48, P<0.0001).

The best overall response for patients receiving the obinutuzumab regimen was 78.7% (15.5% CR, 63.2% PR), compared to 74.7% (18.7% CR, 56% PR) for those receiving bendamustine alone, as assessed by the IRC.

The median duration of response was not reached for patients receiving the obinutuzumab regimen and was 11.6 months for those receiving bendamustine alone.

At last follow-up, the median overall survival had not been reached in either study arm.

The most common grade 3/4 adverse events observed in patients receiving the obinutuzumab regimen were neutropenia (33%), infusion reactions (11%), and thrombocytopenia (10%).

The most common adverse events of any grade were infusion reactions (69%), neutropenia (35%), nausea (54%), fatigue (39%), cough (26%), diarrhea (27%), constipation (19%), fever (18%), thrombocytopenia (15%), vomiting (22%), upper respiratory tract infection (13%), decreased appetite (18%), joint or muscle pain (12%), sinusitis (12%), anemia (12%), general weakness (11%), and urinary tract infection (10%). ![]()

Health Canada has approved the use of obinutuzumab (Gazyva®), an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, in patients with follicular lymphoma (FL).

The approval means obinutuzumab can be given, first in combination with bendamustine and then alone as maintenance therapy, to FL patients who relapsed after, or are refractory to, a rituximab-containing regimen.

Obinutuzumab is also approved in Canada for use in combination with chlorambucil to treat patients with previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Obinutuzumab is a product of Roche.

Health Canada’s approval of obinutuzumab in FL is based on results from the phase 3 GADOLIN trial.

The study included 413 patients with rituximab-refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma, including 321 patients with FL, 46 with marginal zone lymphoma, and 28 with small lymphocytic lymphoma.

The patients were randomized to receive bendamustine alone (control arm) or a combination of bendamustine and obinutuzumab followed by obinutuzumab maintenance (every 2 months for 2 years or until progression).

The primary endpoint of the study was progression-free survival (PFS), as assessed by an independent review committee (IRC). The secondary endpoints were PFS assessed by investigator review, best overall response, complete response (CR), partial response (PR), duration of response, overall survival, and safety profile.

Among patients with FL, the obinutuzumab regimen improved PFS compared to bendamustine alone, as assessed by the IRC (hazard ratio [HR]=0.48, P<0.0001). The median PFS was not reached in patients receiving the obinutuzumab regimen but was 13.8 months in those receiving bendamustine alone.

Investigator-assessed PFS was consistent with IRC-assessed PFS. Investigators said the median PFS with the obinutuzumab regimen was more than double that with bendamustine alone—29.2 months vs 13.7 months (HR=0.48, P<0.0001).

The best overall response for patients receiving the obinutuzumab regimen was 78.7% (15.5% CR, 63.2% PR), compared to 74.7% (18.7% CR, 56% PR) for those receiving bendamustine alone, as assessed by the IRC.

The median duration of response was not reached for patients receiving the obinutuzumab regimen and was 11.6 months for those receiving bendamustine alone.

At last follow-up, the median overall survival had not been reached in either study arm.

The most common grade 3/4 adverse events observed in patients receiving the obinutuzumab regimen were neutropenia (33%), infusion reactions (11%), and thrombocytopenia (10%).

The most common adverse events of any grade were infusion reactions (69%), neutropenia (35%), nausea (54%), fatigue (39%), cough (26%), diarrhea (27%), constipation (19%), fever (18%), thrombocytopenia (15%), vomiting (22%), upper respiratory tract infection (13%), decreased appetite (18%), joint or muscle pain (12%), sinusitis (12%), anemia (12%), general weakness (11%), and urinary tract infection (10%). ![]()

Neuropathic pain puts cancer survivors out of work

AMSTERDAM – Five years after a cancer diagnosis, patients who report having chronic neuropathic pain are twice as likely to be out of work as patients who report having no neuropathic pain, authors of a large longitudinal study said.

“For middle-term cancer survivors, suffering from chronic neuropathic pain unfortunately predicts labor-market exit,” said Marc-Karim Bendiane, from Aix-Marseille University in Marseille, France.

Pain is still frequently underdiagnosed, poorly managed, and undertreated among cancer survivors, and there is a need for alternatives to analgesics for control of chronic neuropathic pain (CNP), Mr. Bendiane said at an annual congress sponsored by the European Cancer Organisation.

Mr. Bendiane and colleagues used data from VICAN, a longitudinal survey of issues of concern to cancer survivors 2 years and 5 years after a diagnosis. The cohort consists of patients diagnosed with cancers who comprise 88% of all cancer diagnoses in France, including cancers of the breast; colon and rectum; lip, oral cavity, and pharynx; kidney; cervix; endometrium; non-Hodgkin lymphoma; melanoma; thyroid; bladder; and prostate.

To assess CNP, the researchers used data from a seven-item questionnaire designed to identify neuropathic characteristics of pain experienced by patients in the 2 weeks prior to a comprehensive patient interview.

Of the 982 patients who were working at the time of diagnosis, 36% reported pain within the previous 2 weeks, and of this group, 79% had chronic pain of neuropathic origin. CNP was more common in women than in men (P less than .01); in college-educated people, compared with less-educated people (P less than .001); those who had undergone chemotherapy, compared with no chemotherapy (P less than .001); and those who had radiotherapy vs. no radiotherapy (P less than .001).

For each cancer site, the prevalence of CNP among 5-year cancer survivors was substantially higher than the overall prevalence in France of 7%. For example, 34% of patients with cancers of the cervix and endometrium reported CNP, as did 29.9% of patients who survived cancers of the lip, oral cavity, and pharynx, 32.1% of lung cancer survivors, and 32.7% of breast cancer survivors.

Five years after diagnosis, 22.6% of patients who had been employed in 2010 were out of work in 2015.

The presence of CNP was associated with a nearly twofold greater risk of unemployment (adjusted odds ratio, 1.96; P less than .001) in a multivariate logistic regression analysis comparing employed and unemployed patients and controlling for social and demographic characteristics, job characteristics at diagnosis, and medical factors such as tumor site, prognosis, and treatment type.

The French National Cancer Institute and INSERM, the National Institute for Research in Health and Medicine, supported the study. The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

AMSTERDAM – Five years after a cancer diagnosis, patients who report having chronic neuropathic pain are twice as likely to be out of work as patients who report having no neuropathic pain, authors of a large longitudinal study said.

“For middle-term cancer survivors, suffering from chronic neuropathic pain unfortunately predicts labor-market exit,” said Marc-Karim Bendiane, from Aix-Marseille University in Marseille, France.

Pain is still frequently underdiagnosed, poorly managed, and undertreated among cancer survivors, and there is a need for alternatives to analgesics for control of chronic neuropathic pain (CNP), Mr. Bendiane said at an annual congress sponsored by the European Cancer Organisation.

Mr. Bendiane and colleagues used data from VICAN, a longitudinal survey of issues of concern to cancer survivors 2 years and 5 years after a diagnosis. The cohort consists of patients diagnosed with cancers who comprise 88% of all cancer diagnoses in France, including cancers of the breast; colon and rectum; lip, oral cavity, and pharynx; kidney; cervix; endometrium; non-Hodgkin lymphoma; melanoma; thyroid; bladder; and prostate.

To assess CNP, the researchers used data from a seven-item questionnaire designed to identify neuropathic characteristics of pain experienced by patients in the 2 weeks prior to a comprehensive patient interview.

Of the 982 patients who were working at the time of diagnosis, 36% reported pain within the previous 2 weeks, and of this group, 79% had chronic pain of neuropathic origin. CNP was more common in women than in men (P less than .01); in college-educated people, compared with less-educated people (P less than .001); those who had undergone chemotherapy, compared with no chemotherapy (P less than .001); and those who had radiotherapy vs. no radiotherapy (P less than .001).

For each cancer site, the prevalence of CNP among 5-year cancer survivors was substantially higher than the overall prevalence in France of 7%. For example, 34% of patients with cancers of the cervix and endometrium reported CNP, as did 29.9% of patients who survived cancers of the lip, oral cavity, and pharynx, 32.1% of lung cancer survivors, and 32.7% of breast cancer survivors.

Five years after diagnosis, 22.6% of patients who had been employed in 2010 were out of work in 2015.

The presence of CNP was associated with a nearly twofold greater risk of unemployment (adjusted odds ratio, 1.96; P less than .001) in a multivariate logistic regression analysis comparing employed and unemployed patients and controlling for social and demographic characteristics, job characteristics at diagnosis, and medical factors such as tumor site, prognosis, and treatment type.

The French National Cancer Institute and INSERM, the National Institute for Research in Health and Medicine, supported the study. The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

AMSTERDAM – Five years after a cancer diagnosis, patients who report having chronic neuropathic pain are twice as likely to be out of work as patients who report having no neuropathic pain, authors of a large longitudinal study said.

“For middle-term cancer survivors, suffering from chronic neuropathic pain unfortunately predicts labor-market exit,” said Marc-Karim Bendiane, from Aix-Marseille University in Marseille, France.

Pain is still frequently underdiagnosed, poorly managed, and undertreated among cancer survivors, and there is a need for alternatives to analgesics for control of chronic neuropathic pain (CNP), Mr. Bendiane said at an annual congress sponsored by the European Cancer Organisation.