User login

Infectious disease physicians: Antibiotic shortages are the new norm

NEW ORLEANS – Antibiotic shortages reported by the Emerging Infections Network (EIN) in 2011 persist in 2016, according to a web-based follow-up survey of infectious disease physicians.

Of 701 network members who responded to the EIN survey in early 2016, 70% reported needing to modify their antimicrobial choice because of a shortage in the past 2 years. They did so by using broader-spectrum agents (75% of respondents), more costly agents (58%), less effective second-line agents (45%), and more toxic agents (37%), Adi Gundlapalli, MD, PhD, reported at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

In addition, 73% of respondents reported that the shortages affected patient care or outcomes, reported Dr. Gundlapalli of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

The percentage of respondents reporting adverse patient outcomes related to shortages increased from 2011 to 2016 (51% vs.73%), he noted at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society of Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

The top 10 antimicrobials they reported as being in short supply were piperacillin-tazobactam, ampicillin-sulbactam, meropenem, cefotaxime, cefepime, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX), doxycycline, imipenem, acyclovir, and amikacin. TMP-SMX and acyclovir were in short supply at both time points.

The most common ways respondents reported learning about drug shortages were from hospital notification (76%), from a colleague (56%), from a pharmacy that contacted them regarding a prescription for the agent (53%), or from the Food and Drug Administration website or another website on shortages (23%). The most common ways of learning about a shortage changed – from notification after trying to prescribe a drug in 2011, to proactive hospital/system (local) notification in 2016; 71% of respondents said that communications in 2016 were sufficient.

Most respondents (83%) reported that guidelines for dealing with shortages had been developed by an antimicrobial stewardship program (ASP) at their institution.

“This, I think, is one of the highlight results,” said Dr. Gundlapalli, who is also a staff physician at the VA Salt Lake City Health System. “In 2011, we had no specific question or comments received about [ASPs], and here in 2016, 83% of respondents’ institutions had developed guidelines related to drug shortages.”

Respondents also had the opportunity to submit free-text responses, and among the themes that emerged was concern regarding toxicity and adverse outcomes associated with increased use of aminoglycosides because of the shortage of piperacillin-tazobactam. Another – described as a blessing in disguise – was the shortage of meropenem, which led one ASP to “institute restrictions on its use, which have continued,” he said.

“Another theme was ‘simpler agents seem more likely to be in shortage,’ ” Dr. Gundlapalli said, noting ampicillin-sulbactam in 2016 and Pen-G as examples.

“And then, of course, the other theme across the board ... was our new asset,” he said, explaining that some respondents commented on the value of ASP pharmacists and programs to help with drug shortage issues.

The overall theme of this follow-up survey, in the context of prior surveys in 2001 and 2011, is that antibiotic shortages are the “new normal – a way of life,” Dr. Gundlapalli said.

“The concerns do persist, and we feel there is further work to be done here,” he said. He specifically noted that there is a need to inform and educate fellows and colleagues in hospitals, increase awareness generally, improve communication strategies, and conduct detailed studies on adverse effects and outcomes.

“And now, since ASPs are very pervasive ... maybe it’s time to formalize and delineate the role of ASPs in antimicrobial shortages,” he said.

The problem of antibiotic shortages “harkens back to the day when penicillin was recycled in the urine [of soldiers in World War II] to save this very scarce resource ... but that’s a very extreme measure to take,” noted Donald Graham, MD, of the Springfield (Ill.) Clinic, one of the study’s coauthors. “It seems like it’s time for the other federal arm – namely, the Food and Drug Administration – to do something about this.”

Dr. Graham said he believes the problem is in part because of economics, and in part because of “the higher standards that the FDA imposes upon these manufacturing concerns.” These drugs often are low-profit items, and it isn’t always in the financial best interest of a pharmaceutical company to upgrade their facilities.

“But they really have to recognize the importance of having availability of these simple agents,” he said, pleading with any FDA representatives in the audience to “maybe think about some of these very high standards.”

Dr. Gundlapalli reported having no disclosures. Dr. Graham disclosed relationships with Astellas and Theravance Biopharma.

NEW ORLEANS – Antibiotic shortages reported by the Emerging Infections Network (EIN) in 2011 persist in 2016, according to a web-based follow-up survey of infectious disease physicians.

Of 701 network members who responded to the EIN survey in early 2016, 70% reported needing to modify their antimicrobial choice because of a shortage in the past 2 years. They did so by using broader-spectrum agents (75% of respondents), more costly agents (58%), less effective second-line agents (45%), and more toxic agents (37%), Adi Gundlapalli, MD, PhD, reported at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

In addition, 73% of respondents reported that the shortages affected patient care or outcomes, reported Dr. Gundlapalli of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

The percentage of respondents reporting adverse patient outcomes related to shortages increased from 2011 to 2016 (51% vs.73%), he noted at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society of Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

The top 10 antimicrobials they reported as being in short supply were piperacillin-tazobactam, ampicillin-sulbactam, meropenem, cefotaxime, cefepime, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX), doxycycline, imipenem, acyclovir, and amikacin. TMP-SMX and acyclovir were in short supply at both time points.

The most common ways respondents reported learning about drug shortages were from hospital notification (76%), from a colleague (56%), from a pharmacy that contacted them regarding a prescription for the agent (53%), or from the Food and Drug Administration website or another website on shortages (23%). The most common ways of learning about a shortage changed – from notification after trying to prescribe a drug in 2011, to proactive hospital/system (local) notification in 2016; 71% of respondents said that communications in 2016 were sufficient.

Most respondents (83%) reported that guidelines for dealing with shortages had been developed by an antimicrobial stewardship program (ASP) at their institution.

“This, I think, is one of the highlight results,” said Dr. Gundlapalli, who is also a staff physician at the VA Salt Lake City Health System. “In 2011, we had no specific question or comments received about [ASPs], and here in 2016, 83% of respondents’ institutions had developed guidelines related to drug shortages.”

Respondents also had the opportunity to submit free-text responses, and among the themes that emerged was concern regarding toxicity and adverse outcomes associated with increased use of aminoglycosides because of the shortage of piperacillin-tazobactam. Another – described as a blessing in disguise – was the shortage of meropenem, which led one ASP to “institute restrictions on its use, which have continued,” he said.

“Another theme was ‘simpler agents seem more likely to be in shortage,’ ” Dr. Gundlapalli said, noting ampicillin-sulbactam in 2016 and Pen-G as examples.

“And then, of course, the other theme across the board ... was our new asset,” he said, explaining that some respondents commented on the value of ASP pharmacists and programs to help with drug shortage issues.

The overall theme of this follow-up survey, in the context of prior surveys in 2001 and 2011, is that antibiotic shortages are the “new normal – a way of life,” Dr. Gundlapalli said.

“The concerns do persist, and we feel there is further work to be done here,” he said. He specifically noted that there is a need to inform and educate fellows and colleagues in hospitals, increase awareness generally, improve communication strategies, and conduct detailed studies on adverse effects and outcomes.

“And now, since ASPs are very pervasive ... maybe it’s time to formalize and delineate the role of ASPs in antimicrobial shortages,” he said.

The problem of antibiotic shortages “harkens back to the day when penicillin was recycled in the urine [of soldiers in World War II] to save this very scarce resource ... but that’s a very extreme measure to take,” noted Donald Graham, MD, of the Springfield (Ill.) Clinic, one of the study’s coauthors. “It seems like it’s time for the other federal arm – namely, the Food and Drug Administration – to do something about this.”

Dr. Graham said he believes the problem is in part because of economics, and in part because of “the higher standards that the FDA imposes upon these manufacturing concerns.” These drugs often are low-profit items, and it isn’t always in the financial best interest of a pharmaceutical company to upgrade their facilities.

“But they really have to recognize the importance of having availability of these simple agents,” he said, pleading with any FDA representatives in the audience to “maybe think about some of these very high standards.”

Dr. Gundlapalli reported having no disclosures. Dr. Graham disclosed relationships with Astellas and Theravance Biopharma.

NEW ORLEANS – Antibiotic shortages reported by the Emerging Infections Network (EIN) in 2011 persist in 2016, according to a web-based follow-up survey of infectious disease physicians.

Of 701 network members who responded to the EIN survey in early 2016, 70% reported needing to modify their antimicrobial choice because of a shortage in the past 2 years. They did so by using broader-spectrum agents (75% of respondents), more costly agents (58%), less effective second-line agents (45%), and more toxic agents (37%), Adi Gundlapalli, MD, PhD, reported at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

In addition, 73% of respondents reported that the shortages affected patient care or outcomes, reported Dr. Gundlapalli of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

The percentage of respondents reporting adverse patient outcomes related to shortages increased from 2011 to 2016 (51% vs.73%), he noted at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society of Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

The top 10 antimicrobials they reported as being in short supply were piperacillin-tazobactam, ampicillin-sulbactam, meropenem, cefotaxime, cefepime, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX), doxycycline, imipenem, acyclovir, and amikacin. TMP-SMX and acyclovir were in short supply at both time points.

The most common ways respondents reported learning about drug shortages were from hospital notification (76%), from a colleague (56%), from a pharmacy that contacted them regarding a prescription for the agent (53%), or from the Food and Drug Administration website or another website on shortages (23%). The most common ways of learning about a shortage changed – from notification after trying to prescribe a drug in 2011, to proactive hospital/system (local) notification in 2016; 71% of respondents said that communications in 2016 were sufficient.

Most respondents (83%) reported that guidelines for dealing with shortages had been developed by an antimicrobial stewardship program (ASP) at their institution.

“This, I think, is one of the highlight results,” said Dr. Gundlapalli, who is also a staff physician at the VA Salt Lake City Health System. “In 2011, we had no specific question or comments received about [ASPs], and here in 2016, 83% of respondents’ institutions had developed guidelines related to drug shortages.”

Respondents also had the opportunity to submit free-text responses, and among the themes that emerged was concern regarding toxicity and adverse outcomes associated with increased use of aminoglycosides because of the shortage of piperacillin-tazobactam. Another – described as a blessing in disguise – was the shortage of meropenem, which led one ASP to “institute restrictions on its use, which have continued,” he said.

“Another theme was ‘simpler agents seem more likely to be in shortage,’ ” Dr. Gundlapalli said, noting ampicillin-sulbactam in 2016 and Pen-G as examples.

“And then, of course, the other theme across the board ... was our new asset,” he said, explaining that some respondents commented on the value of ASP pharmacists and programs to help with drug shortage issues.

The overall theme of this follow-up survey, in the context of prior surveys in 2001 and 2011, is that antibiotic shortages are the “new normal – a way of life,” Dr. Gundlapalli said.

“The concerns do persist, and we feel there is further work to be done here,” he said. He specifically noted that there is a need to inform and educate fellows and colleagues in hospitals, increase awareness generally, improve communication strategies, and conduct detailed studies on adverse effects and outcomes.

“And now, since ASPs are very pervasive ... maybe it’s time to formalize and delineate the role of ASPs in antimicrobial shortages,” he said.

The problem of antibiotic shortages “harkens back to the day when penicillin was recycled in the urine [of soldiers in World War II] to save this very scarce resource ... but that’s a very extreme measure to take,” noted Donald Graham, MD, of the Springfield (Ill.) Clinic, one of the study’s coauthors. “It seems like it’s time for the other federal arm – namely, the Food and Drug Administration – to do something about this.”

Dr. Graham said he believes the problem is in part because of economics, and in part because of “the higher standards that the FDA imposes upon these manufacturing concerns.” These drugs often are low-profit items, and it isn’t always in the financial best interest of a pharmaceutical company to upgrade their facilities.

“But they really have to recognize the importance of having availability of these simple agents,” he said, pleading with any FDA representatives in the audience to “maybe think about some of these very high standards.”

Dr. Gundlapalli reported having no disclosures. Dr. Graham disclosed relationships with Astellas and Theravance Biopharma.

AT IDWEEK 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: 70% of respondents reported needing to modify their antimicrobial choice because of a shortage in the past 2 years, and 73% said shortages affected patient care or outcomes.

Data source: A follow-up survey of 701 physicians.

Disclosures: Dr. Gundlapalli reported having no disclosures. Dr. Graham disclosed relationships with Astellas and Theravance Biopharma.

Behavioral interventions durably reduced inappropriate antibiotic prescribing

NEW ORLEANS – The benefits of an 18-month behavioral intervention to reduce inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in the primary care setting were maintained 18 months after the intervention ended, according to follow-up data from a cluster randomized clinical trial.

During the 18-month intervention period, physicians at 47 adult and pediatric practices that participated in the trial, which compared three behavioral interventions and intervention combinations, significantly reduced their inappropriate prescribing.

After 18 months, the results were durable – and particularly so in the groups that received interventions that used “social motivation,” Jeffrey Linder, MD, of Brigham & Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, reported at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

A total of 16,959 antibiotic-inappropriate visits (visits for nonspecific upper respiratory tract infections, acute bronchitis, and influenza) were made to 248 clinicians during the 18-month intervention period, and 3,192 such visits were made to 224 clinicians during the postintervention period (JAMA. 2016 Feb 9;315[6]:562-70).

The interventions included “suggested alternatives,” which was an electronic health record-based approach that prompted the prescriber to answer whether a prescription was for an acute respiratory infection. A “yes” answer resulted in the prescriber receiving information about appropriate prescribing, along with a list of “easy nonantibiotic alternatives,” Dr. Linder explained, noting that the interventions involved “trying to make it easy to do the right thing.”

An “accountable justification” intervention used a similar process, but rather than suggesting alternative options, the program asked the prescriber to input a “tweet-length justification” of the prescription. The justification was then entered into the patient’s chart.

The third intervention involved “peer comparison.” Prescribers received monthly e-mail feedback regarding how their prescribing stacked up to that of their peers – specifically noting whether they were or were not “top performers.”

Some of the groups in the trial received combinations of these interventions, but the follow-up analysis showed that the latter two approaches, which involved “social motivation,” had the most durable effects.

For example, the inappropriate antibiotic prescribing rate for those in the “accountable justification” group decreased from 23.2% to 5.2% at the end of the 18-month intervention period (absolute difference, -18.1%) and increased to 9% at the end of follow-up.

The inappropriate prescribing rate decreased from about 20% to about 4% in the “peer comparison” group at the end of the intervention period (absolute difference of -16.3%), then increased to 5% at the end of follow-up, Dr. Linder said at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

“The statistically best player here – the peer comparison group – went from 20% to 4% to 5%, so it only went back up 1% even after we turned the intervention off for 18 months,” he said.

Antibiotics often are inappropriately prescribed for acute respiratory infections in primary care. Such infections – including colds, sinusitis, strep throat, nonstrep pharyngitis, acute bronchitis, and influenza – make up only 10% of all ambulatory visits in the United States, but they account for 44% of all antibiotic prescribing, Dr. Linder said.

An estimated 50% of antibiotic prescriptions for acute respiratory infections are inappropriate, he added, noting that little success has been achieved with prior antibiotic stewardship efforts that focused largely on clinician education.

“So, we tried to tackle it a bit differently,” he said. “We saw a persistent significant change in antibiotic prescribing in the peer comparison intervention group. ... I would say that interventions that take advantage of social motivation appear to be effective or persistent.”

Dr. Linder reported having no relevant disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – The benefits of an 18-month behavioral intervention to reduce inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in the primary care setting were maintained 18 months after the intervention ended, according to follow-up data from a cluster randomized clinical trial.

During the 18-month intervention period, physicians at 47 adult and pediatric practices that participated in the trial, which compared three behavioral interventions and intervention combinations, significantly reduced their inappropriate prescribing.

After 18 months, the results were durable – and particularly so in the groups that received interventions that used “social motivation,” Jeffrey Linder, MD, of Brigham & Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, reported at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

A total of 16,959 antibiotic-inappropriate visits (visits for nonspecific upper respiratory tract infections, acute bronchitis, and influenza) were made to 248 clinicians during the 18-month intervention period, and 3,192 such visits were made to 224 clinicians during the postintervention period (JAMA. 2016 Feb 9;315[6]:562-70).

The interventions included “suggested alternatives,” which was an electronic health record-based approach that prompted the prescriber to answer whether a prescription was for an acute respiratory infection. A “yes” answer resulted in the prescriber receiving information about appropriate prescribing, along with a list of “easy nonantibiotic alternatives,” Dr. Linder explained, noting that the interventions involved “trying to make it easy to do the right thing.”

An “accountable justification” intervention used a similar process, but rather than suggesting alternative options, the program asked the prescriber to input a “tweet-length justification” of the prescription. The justification was then entered into the patient’s chart.

The third intervention involved “peer comparison.” Prescribers received monthly e-mail feedback regarding how their prescribing stacked up to that of their peers – specifically noting whether they were or were not “top performers.”

Some of the groups in the trial received combinations of these interventions, but the follow-up analysis showed that the latter two approaches, which involved “social motivation,” had the most durable effects.

For example, the inappropriate antibiotic prescribing rate for those in the “accountable justification” group decreased from 23.2% to 5.2% at the end of the 18-month intervention period (absolute difference, -18.1%) and increased to 9% at the end of follow-up.

The inappropriate prescribing rate decreased from about 20% to about 4% in the “peer comparison” group at the end of the intervention period (absolute difference of -16.3%), then increased to 5% at the end of follow-up, Dr. Linder said at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

“The statistically best player here – the peer comparison group – went from 20% to 4% to 5%, so it only went back up 1% even after we turned the intervention off for 18 months,” he said.

Antibiotics often are inappropriately prescribed for acute respiratory infections in primary care. Such infections – including colds, sinusitis, strep throat, nonstrep pharyngitis, acute bronchitis, and influenza – make up only 10% of all ambulatory visits in the United States, but they account for 44% of all antibiotic prescribing, Dr. Linder said.

An estimated 50% of antibiotic prescriptions for acute respiratory infections are inappropriate, he added, noting that little success has been achieved with prior antibiotic stewardship efforts that focused largely on clinician education.

“So, we tried to tackle it a bit differently,” he said. “We saw a persistent significant change in antibiotic prescribing in the peer comparison intervention group. ... I would say that interventions that take advantage of social motivation appear to be effective or persistent.”

Dr. Linder reported having no relevant disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – The benefits of an 18-month behavioral intervention to reduce inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in the primary care setting were maintained 18 months after the intervention ended, according to follow-up data from a cluster randomized clinical trial.

During the 18-month intervention period, physicians at 47 adult and pediatric practices that participated in the trial, which compared three behavioral interventions and intervention combinations, significantly reduced their inappropriate prescribing.

After 18 months, the results were durable – and particularly so in the groups that received interventions that used “social motivation,” Jeffrey Linder, MD, of Brigham & Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, reported at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

A total of 16,959 antibiotic-inappropriate visits (visits for nonspecific upper respiratory tract infections, acute bronchitis, and influenza) were made to 248 clinicians during the 18-month intervention period, and 3,192 such visits were made to 224 clinicians during the postintervention period (JAMA. 2016 Feb 9;315[6]:562-70).

The interventions included “suggested alternatives,” which was an electronic health record-based approach that prompted the prescriber to answer whether a prescription was for an acute respiratory infection. A “yes” answer resulted in the prescriber receiving information about appropriate prescribing, along with a list of “easy nonantibiotic alternatives,” Dr. Linder explained, noting that the interventions involved “trying to make it easy to do the right thing.”

An “accountable justification” intervention used a similar process, but rather than suggesting alternative options, the program asked the prescriber to input a “tweet-length justification” of the prescription. The justification was then entered into the patient’s chart.

The third intervention involved “peer comparison.” Prescribers received monthly e-mail feedback regarding how their prescribing stacked up to that of their peers – specifically noting whether they were or were not “top performers.”

Some of the groups in the trial received combinations of these interventions, but the follow-up analysis showed that the latter two approaches, which involved “social motivation,” had the most durable effects.

For example, the inappropriate antibiotic prescribing rate for those in the “accountable justification” group decreased from 23.2% to 5.2% at the end of the 18-month intervention period (absolute difference, -18.1%) and increased to 9% at the end of follow-up.

The inappropriate prescribing rate decreased from about 20% to about 4% in the “peer comparison” group at the end of the intervention period (absolute difference of -16.3%), then increased to 5% at the end of follow-up, Dr. Linder said at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

“The statistically best player here – the peer comparison group – went from 20% to 4% to 5%, so it only went back up 1% even after we turned the intervention off for 18 months,” he said.

Antibiotics often are inappropriately prescribed for acute respiratory infections in primary care. Such infections – including colds, sinusitis, strep throat, nonstrep pharyngitis, acute bronchitis, and influenza – make up only 10% of all ambulatory visits in the United States, but they account for 44% of all antibiotic prescribing, Dr. Linder said.

An estimated 50% of antibiotic prescriptions for acute respiratory infections are inappropriate, he added, noting that little success has been achieved with prior antibiotic stewardship efforts that focused largely on clinician education.

“So, we tried to tackle it a bit differently,” he said. “We saw a persistent significant change in antibiotic prescribing in the peer comparison intervention group. ... I would say that interventions that take advantage of social motivation appear to be effective or persistent.”

Dr. Linder reported having no relevant disclosures.

Key clinical point: The benefits of an 18-month behavioral intervention to reduce inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in the primary care setting were maintained 18 months after the intervention ended, according to follow-up data from a cluster randomized clinical trial.

Major finding: Inappropriate antibiotic prescribing increased only slightly, from 4% to 5%, during 18 months of follow-up in the “peer comparison” group.

Data source: Follow-up of a cluster randomized, controlled clinical trial involving nearly 3,200 patient visits with 224 clinicians.

Disclosures: Dr. Linder reported having no disclosures.

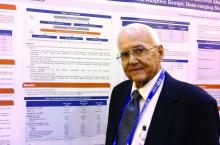

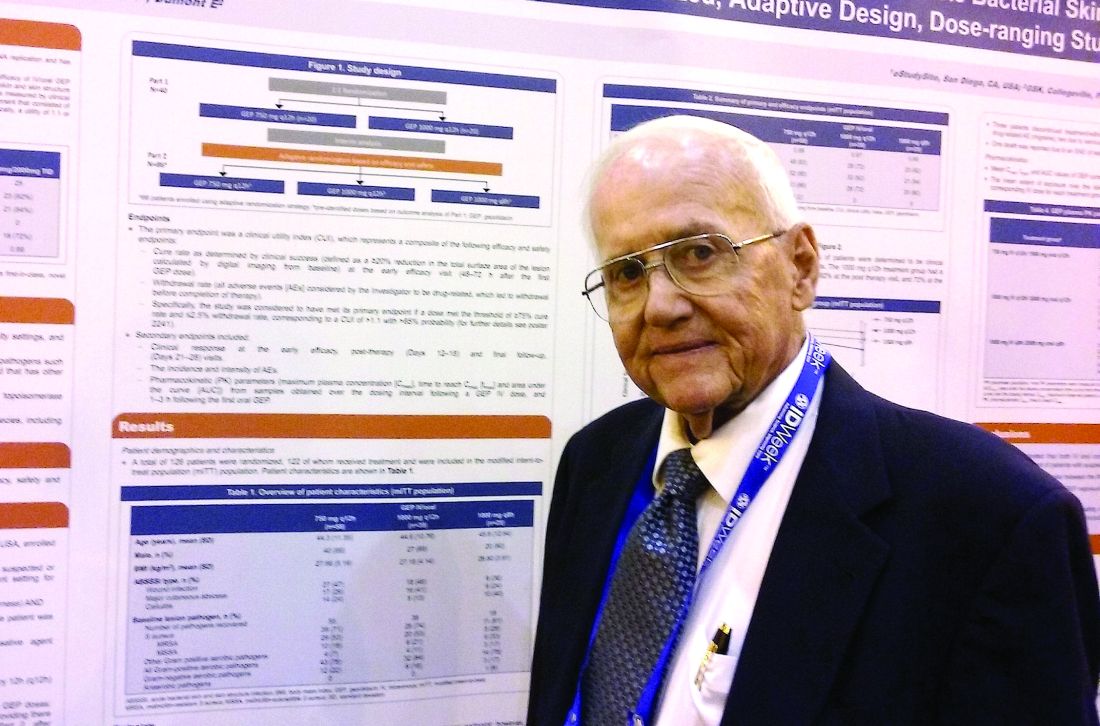

Novel antibiotic hits skin and soft tissue infections with one-two punch

NEW ORLEANS – A novel antibiotic in development fared well in terms of efficacy and safety for patients hospitalized for suspected or confirmed Gram-positive acute skin and soft tissue infections, reveals the first reported findings of a phase II, randomized study.

Investigators randomized 122 patients over 18 years of age with wound infections, major cutaneous abscesses, or cellulitis to three different dosing intravenous/oral regimens of gepotidacin (GlaxoSmithKline). Patients in the 750-mg/1,500-mg q12h and 1,000-mg/2,000-mg q8h groups met the primary efficacy endpoint of an 80% or greater clinical success (83% and 92%, respectively) within 2-3 days. A third group, randomized to 1,000-mg/2,000-mg q12h, had a 72% early success rate.

All three groups of patients achieved the primary safety outcome, defined as less than a 2.5% withdrawal rate due to drug-related adverse events during gepotidacin treatment. One patient in the 750-mg q12h group withdrew because of a migraine related to the study drug.

Gepotidacin cleaves bacterial DNA in two places to block replication. “Because of its dual mechanism, there are a lot of potential applications,” Dr. O’Riordan said at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. Gepotidacin is also being assessed in ongoing gonorrhea, complicated intra-abdominal infections, and urinary tract infection studies.

The researchers in the current study also measured clinical success at post therapy days 12-18. They found 90% of the 750-mg/1,500-mg q12h group, 82% of the 1,000-mg/2,000-mg q8h, and 84% of the 1,000-mg/2,000-mg q12h group achieved the composite efficacy endpoint.

Overall, 84 or 69% of study participants experienced an adverse event. Nausea, diarrhea, and vomiting were the most common mild-to-moderate adverse events associated with the 10 days of gepotidacin treatment. Two serious adverse events not related to treatment also occurred during the study.

The “low adverse events and reproducible resolution of skin infections” in this phase II study support further development of gepotidacin, Dr. O’Riordan said.

Dr. O’Riordan had no relevant disclosures. Some study coauthors are GlaxoSmithKline employees.

NEW ORLEANS – A novel antibiotic in development fared well in terms of efficacy and safety for patients hospitalized for suspected or confirmed Gram-positive acute skin and soft tissue infections, reveals the first reported findings of a phase II, randomized study.

Investigators randomized 122 patients over 18 years of age with wound infections, major cutaneous abscesses, or cellulitis to three different dosing intravenous/oral regimens of gepotidacin (GlaxoSmithKline). Patients in the 750-mg/1,500-mg q12h and 1,000-mg/2,000-mg q8h groups met the primary efficacy endpoint of an 80% or greater clinical success (83% and 92%, respectively) within 2-3 days. A third group, randomized to 1,000-mg/2,000-mg q12h, had a 72% early success rate.

All three groups of patients achieved the primary safety outcome, defined as less than a 2.5% withdrawal rate due to drug-related adverse events during gepotidacin treatment. One patient in the 750-mg q12h group withdrew because of a migraine related to the study drug.

Gepotidacin cleaves bacterial DNA in two places to block replication. “Because of its dual mechanism, there are a lot of potential applications,” Dr. O’Riordan said at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. Gepotidacin is also being assessed in ongoing gonorrhea, complicated intra-abdominal infections, and urinary tract infection studies.

The researchers in the current study also measured clinical success at post therapy days 12-18. They found 90% of the 750-mg/1,500-mg q12h group, 82% of the 1,000-mg/2,000-mg q8h, and 84% of the 1,000-mg/2,000-mg q12h group achieved the composite efficacy endpoint.

Overall, 84 or 69% of study participants experienced an adverse event. Nausea, diarrhea, and vomiting were the most common mild-to-moderate adverse events associated with the 10 days of gepotidacin treatment. Two serious adverse events not related to treatment also occurred during the study.

The “low adverse events and reproducible resolution of skin infections” in this phase II study support further development of gepotidacin, Dr. O’Riordan said.

Dr. O’Riordan had no relevant disclosures. Some study coauthors are GlaxoSmithKline employees.

NEW ORLEANS – A novel antibiotic in development fared well in terms of efficacy and safety for patients hospitalized for suspected or confirmed Gram-positive acute skin and soft tissue infections, reveals the first reported findings of a phase II, randomized study.

Investigators randomized 122 patients over 18 years of age with wound infections, major cutaneous abscesses, or cellulitis to three different dosing intravenous/oral regimens of gepotidacin (GlaxoSmithKline). Patients in the 750-mg/1,500-mg q12h and 1,000-mg/2,000-mg q8h groups met the primary efficacy endpoint of an 80% or greater clinical success (83% and 92%, respectively) within 2-3 days. A third group, randomized to 1,000-mg/2,000-mg q12h, had a 72% early success rate.

All three groups of patients achieved the primary safety outcome, defined as less than a 2.5% withdrawal rate due to drug-related adverse events during gepotidacin treatment. One patient in the 750-mg q12h group withdrew because of a migraine related to the study drug.

Gepotidacin cleaves bacterial DNA in two places to block replication. “Because of its dual mechanism, there are a lot of potential applications,” Dr. O’Riordan said at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. Gepotidacin is also being assessed in ongoing gonorrhea, complicated intra-abdominal infections, and urinary tract infection studies.

The researchers in the current study also measured clinical success at post therapy days 12-18. They found 90% of the 750-mg/1,500-mg q12h group, 82% of the 1,000-mg/2,000-mg q8h, and 84% of the 1,000-mg/2,000-mg q12h group achieved the composite efficacy endpoint.

Overall, 84 or 69% of study participants experienced an adverse event. Nausea, diarrhea, and vomiting were the most common mild-to-moderate adverse events associated with the 10 days of gepotidacin treatment. Two serious adverse events not related to treatment also occurred during the study.

The “low adverse events and reproducible resolution of skin infections” in this phase II study support further development of gepotidacin, Dr. O’Riordan said.

Dr. O’Riordan had no relevant disclosures. Some study coauthors are GlaxoSmithKline employees.

AT IDWEEK 2016

Key clinical point: A dual-mechanism-of-action antibiotic in development shows good efficacy and a low adverse event rate in a phase II study.

Major finding: A total 71 of 122 adult patients achieved clinical success within 48 to 72 hours with gepotidacin treatment.

Data source: 122 patients over 18 years of age with wound infections, major cutaneous abscesses, or cellulitis.

Disclosures: Dr. O’Riordan had no relevant disclosures. Some study coauthors are GlaxoSmithKline employees.

CDC: Seven cases of multidrug resistant C. auris have occurred in United States

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have reported the first cases of the multidrug-resistant fungal infection Candida auris in the United States, with evidence suggesting transmission may have occurred within U.S. health care facilities.

The report, published in the Nov. 4 edition of Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, described seven cases of patients infected with C. auris, which was isolated from blood in five cases, urine in one, and the ear in one. All the patients with bloodstream infections had central venous catheters at the time of diagnosis, and four of these patients died in the weeks and months after diagnosis of the infection.

Patients’ underlying conditions usually involved immune system suppression resulting from corticisteroid therapy, malignancty, short gut syndrome, or parapleglia with a long-term, indwelling Foley catheter.

C. auris was first isolated in 2009 in Japan, but has since been reported in countries including Colombia, India, South Africa, Israel, and the United Kingdom. Snigdha Vallabhaneni, MD, of the mycotic diseases branch of CDC’s division of food water and environmental diseases, and her coauthors, said its appearance in the United States is a cause for serious concern (MMWR. 2016 Nov 4. doi: 0.15585/mmwr.mm6544e1).

“First, many isolates are multidrug resistant, with some strains having elevated minimum inhibitory concentrations to drugs in all three major classes of antifungal medications, a feature not found in other clinically relevant Candida species,” the authors wrote. All the patients with bloodstream infections were treated with antifungal echinocandins, and one also received liposomal amphotericin B.

“Second, C. auris is challenging to identify, requiring specialized methods such as matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight or molecular identification based on sequencing the D1-D2 region of the 28s ribosomal DNA.”

They also highlighted that C. auris is known to cause outbreaks in health care settings. Samples taken from the mattress, bedside table, bed rail, chair, and windowsill in the room of one patient all tested positive for C. auris.

The authors also sequenced the genome of the isolates and found that isolates taken from patients admitted to the same hospital in New Jersey or the same Illinois hospital were nearly identical.

“Facilities should ensure thorough daily and terminal cleaning of rooms of patients with C. auris infections, including use of an [Environmental Protection Agency]–registered disinfectant with a fungal claim,” the authors wrote, stressing that facilities and laboratories should continue to report cases and forward suspicious unidentified Candida isolates to state or local health authorities and the CDC.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have reported the first cases of the multidrug-resistant fungal infection Candida auris in the United States, with evidence suggesting transmission may have occurred within U.S. health care facilities.

The report, published in the Nov. 4 edition of Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, described seven cases of patients infected with C. auris, which was isolated from blood in five cases, urine in one, and the ear in one. All the patients with bloodstream infections had central venous catheters at the time of diagnosis, and four of these patients died in the weeks and months after diagnosis of the infection.

Patients’ underlying conditions usually involved immune system suppression resulting from corticisteroid therapy, malignancty, short gut syndrome, or parapleglia with a long-term, indwelling Foley catheter.

C. auris was first isolated in 2009 in Japan, but has since been reported in countries including Colombia, India, South Africa, Israel, and the United Kingdom. Snigdha Vallabhaneni, MD, of the mycotic diseases branch of CDC’s division of food water and environmental diseases, and her coauthors, said its appearance in the United States is a cause for serious concern (MMWR. 2016 Nov 4. doi: 0.15585/mmwr.mm6544e1).

“First, many isolates are multidrug resistant, with some strains having elevated minimum inhibitory concentrations to drugs in all three major classes of antifungal medications, a feature not found in other clinically relevant Candida species,” the authors wrote. All the patients with bloodstream infections were treated with antifungal echinocandins, and one also received liposomal amphotericin B.

“Second, C. auris is challenging to identify, requiring specialized methods such as matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight or molecular identification based on sequencing the D1-D2 region of the 28s ribosomal DNA.”

They also highlighted that C. auris is known to cause outbreaks in health care settings. Samples taken from the mattress, bedside table, bed rail, chair, and windowsill in the room of one patient all tested positive for C. auris.

The authors also sequenced the genome of the isolates and found that isolates taken from patients admitted to the same hospital in New Jersey or the same Illinois hospital were nearly identical.

“Facilities should ensure thorough daily and terminal cleaning of rooms of patients with C. auris infections, including use of an [Environmental Protection Agency]–registered disinfectant with a fungal claim,” the authors wrote, stressing that facilities and laboratories should continue to report cases and forward suspicious unidentified Candida isolates to state or local health authorities and the CDC.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have reported the first cases of the multidrug-resistant fungal infection Candida auris in the United States, with evidence suggesting transmission may have occurred within U.S. health care facilities.

The report, published in the Nov. 4 edition of Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, described seven cases of patients infected with C. auris, which was isolated from blood in five cases, urine in one, and the ear in one. All the patients with bloodstream infections had central venous catheters at the time of diagnosis, and four of these patients died in the weeks and months after diagnosis of the infection.

Patients’ underlying conditions usually involved immune system suppression resulting from corticisteroid therapy, malignancty, short gut syndrome, or parapleglia with a long-term, indwelling Foley catheter.

C. auris was first isolated in 2009 in Japan, but has since been reported in countries including Colombia, India, South Africa, Israel, and the United Kingdom. Snigdha Vallabhaneni, MD, of the mycotic diseases branch of CDC’s division of food water and environmental diseases, and her coauthors, said its appearance in the United States is a cause for serious concern (MMWR. 2016 Nov 4. doi: 0.15585/mmwr.mm6544e1).

“First, many isolates are multidrug resistant, with some strains having elevated minimum inhibitory concentrations to drugs in all three major classes of antifungal medications, a feature not found in other clinically relevant Candida species,” the authors wrote. All the patients with bloodstream infections were treated with antifungal echinocandins, and one also received liposomal amphotericin B.

“Second, C. auris is challenging to identify, requiring specialized methods such as matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight or molecular identification based on sequencing the D1-D2 region of the 28s ribosomal DNA.”

They also highlighted that C. auris is known to cause outbreaks in health care settings. Samples taken from the mattress, bedside table, bed rail, chair, and windowsill in the room of one patient all tested positive for C. auris.

The authors also sequenced the genome of the isolates and found that isolates taken from patients admitted to the same hospital in New Jersey or the same Illinois hospital were nearly identical.

“Facilities should ensure thorough daily and terminal cleaning of rooms of patients with C. auris infections, including use of an [Environmental Protection Agency]–registered disinfectant with a fungal claim,” the authors wrote, stressing that facilities and laboratories should continue to report cases and forward suspicious unidentified Candida isolates to state or local health authorities and the CDC.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

Key clinical point: The first cases of the multidrug-resistant fungal infection C. auris have been reported in the United States.

Major finding: Seven cases of infection with the multidrug-resistant emerging fungal infection C. auris have been reported in the United States, five of which were bloodstream infections.

Data source: Case series.

Disclosures: No conflicts of interest were declared.

Treated bacteremia that clears, then recurs, termed ‘skip phenomenon’

NEW ORLEANS – When Mayo Clinic physicians noticed some patients on appropriate antibiotic treatment for Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia cleared the infection, only to see it recur a few days later, Justin A. Fiala, MD and his colleagues grew curious.

Dr. Fiala, an infectious diseases internist at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., was intrigued by the possibility of fluctuating blood culture positivity in this subset of bacteremia patients.

“We wanted first to see whether or not this is a real entity and determine the prevalence of this ‘skip pattern,’” Dr. Fiala said at IDWeek 2016, the annual combined meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. He said identifying predictors and finding any differences in clinical outcomes compared to control S. aureus bacteremia (SAB) patients were additional aims.

Dr. Fiala and his colleagues assessed a hospitalized cohort of 726 adults with SAB at Mayo Clinic between July 2006 and June 2011. Patients with one or more negative blood cultures followed by a positive culture were identified within this group, and compared with 2 to 4 patients matched for age, sex and duration of bacteremia who served as controls.

The investigators found 29 patients – or 4% – of the 726 had this ‘skip pattern’ of infection, clearance, and reinfection. Those with the phenomenon were 90% male and tended to be older, with a mean age of 69 years, compared to the controls. They had index bacteremia about two days longer than controls. The study also revealed a significant difference in mean number of central venous catheters: 2.7 in the skip phenomenon group versus 1.7 in controls.

Given the predominance of the skip phenomenon in older, immunosuppressed males, “the takeaway … is that serial negative blood cultures may be warranted in these patient groups,” Dr. Fiala said.

The groups did not differ significantly by presence of implants or foreign bodies or by whether SAB was nosocomial or acquired in the community. “We thought it was interesting that 90% had immune suppression, although it was not statistically significant,” Dr. Fiala said.

With no prior reports in the medical literature, the researchers named this clinical entity “skip phenomenon.” Dr. Fiala noted that published studies have assessed recurrence of SAB after completion of antibiotics, but not specifically during treatment.

“We think this is a topic that is quite clinically prevalent and applicable,” Dr. Fiala said. He pointed out that SAB is common, accounting for about 20% of all nosocomial bacteremia cases. SAB also highly virulent with a mortality rate estimated between 20% and 35%. Although the study did not reveal significant mortality differences in the subgroup with skip phenomenon, “we can say there is increased morbidity.”

The most recent IDSA guidelines state that a single set of negative blood cultures is sufficient to demonstrate clearance of SAB, Dr. Fiala said. “Could this be falsely reassuring if Staphylococcus aureus does have a tendency to exhibit this fluctuating pattern?”

The retrospective design of the study and the relatively small number of patients with the skip phenomenon were limitations, the investigators acknowledged. Dr. Fiala had no relevant disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – When Mayo Clinic physicians noticed some patients on appropriate antibiotic treatment for Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia cleared the infection, only to see it recur a few days later, Justin A. Fiala, MD and his colleagues grew curious.

Dr. Fiala, an infectious diseases internist at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., was intrigued by the possibility of fluctuating blood culture positivity in this subset of bacteremia patients.

“We wanted first to see whether or not this is a real entity and determine the prevalence of this ‘skip pattern,’” Dr. Fiala said at IDWeek 2016, the annual combined meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. He said identifying predictors and finding any differences in clinical outcomes compared to control S. aureus bacteremia (SAB) patients were additional aims.

Dr. Fiala and his colleagues assessed a hospitalized cohort of 726 adults with SAB at Mayo Clinic between July 2006 and June 2011. Patients with one or more negative blood cultures followed by a positive culture were identified within this group, and compared with 2 to 4 patients matched for age, sex and duration of bacteremia who served as controls.

The investigators found 29 patients – or 4% – of the 726 had this ‘skip pattern’ of infection, clearance, and reinfection. Those with the phenomenon were 90% male and tended to be older, with a mean age of 69 years, compared to the controls. They had index bacteremia about two days longer than controls. The study also revealed a significant difference in mean number of central venous catheters: 2.7 in the skip phenomenon group versus 1.7 in controls.

Given the predominance of the skip phenomenon in older, immunosuppressed males, “the takeaway … is that serial negative blood cultures may be warranted in these patient groups,” Dr. Fiala said.

The groups did not differ significantly by presence of implants or foreign bodies or by whether SAB was nosocomial or acquired in the community. “We thought it was interesting that 90% had immune suppression, although it was not statistically significant,” Dr. Fiala said.

With no prior reports in the medical literature, the researchers named this clinical entity “skip phenomenon.” Dr. Fiala noted that published studies have assessed recurrence of SAB after completion of antibiotics, but not specifically during treatment.

“We think this is a topic that is quite clinically prevalent and applicable,” Dr. Fiala said. He pointed out that SAB is common, accounting for about 20% of all nosocomial bacteremia cases. SAB also highly virulent with a mortality rate estimated between 20% and 35%. Although the study did not reveal significant mortality differences in the subgroup with skip phenomenon, “we can say there is increased morbidity.”

The most recent IDSA guidelines state that a single set of negative blood cultures is sufficient to demonstrate clearance of SAB, Dr. Fiala said. “Could this be falsely reassuring if Staphylococcus aureus does have a tendency to exhibit this fluctuating pattern?”

The retrospective design of the study and the relatively small number of patients with the skip phenomenon were limitations, the investigators acknowledged. Dr. Fiala had no relevant disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – When Mayo Clinic physicians noticed some patients on appropriate antibiotic treatment for Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia cleared the infection, only to see it recur a few days later, Justin A. Fiala, MD and his colleagues grew curious.

Dr. Fiala, an infectious diseases internist at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., was intrigued by the possibility of fluctuating blood culture positivity in this subset of bacteremia patients.

“We wanted first to see whether or not this is a real entity and determine the prevalence of this ‘skip pattern,’” Dr. Fiala said at IDWeek 2016, the annual combined meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. He said identifying predictors and finding any differences in clinical outcomes compared to control S. aureus bacteremia (SAB) patients were additional aims.

Dr. Fiala and his colleagues assessed a hospitalized cohort of 726 adults with SAB at Mayo Clinic between July 2006 and June 2011. Patients with one or more negative blood cultures followed by a positive culture were identified within this group, and compared with 2 to 4 patients matched for age, sex and duration of bacteremia who served as controls.

The investigators found 29 patients – or 4% – of the 726 had this ‘skip pattern’ of infection, clearance, and reinfection. Those with the phenomenon were 90% male and tended to be older, with a mean age of 69 years, compared to the controls. They had index bacteremia about two days longer than controls. The study also revealed a significant difference in mean number of central venous catheters: 2.7 in the skip phenomenon group versus 1.7 in controls.

Given the predominance of the skip phenomenon in older, immunosuppressed males, “the takeaway … is that serial negative blood cultures may be warranted in these patient groups,” Dr. Fiala said.

The groups did not differ significantly by presence of implants or foreign bodies or by whether SAB was nosocomial or acquired in the community. “We thought it was interesting that 90% had immune suppression, although it was not statistically significant,” Dr. Fiala said.

With no prior reports in the medical literature, the researchers named this clinical entity “skip phenomenon.” Dr. Fiala noted that published studies have assessed recurrence of SAB after completion of antibiotics, but not specifically during treatment.

“We think this is a topic that is quite clinically prevalent and applicable,” Dr. Fiala said. He pointed out that SAB is common, accounting for about 20% of all nosocomial bacteremia cases. SAB also highly virulent with a mortality rate estimated between 20% and 35%. Although the study did not reveal significant mortality differences in the subgroup with skip phenomenon, “we can say there is increased morbidity.”

The most recent IDSA guidelines state that a single set of negative blood cultures is sufficient to demonstrate clearance of SAB, Dr. Fiala said. “Could this be falsely reassuring if Staphylococcus aureus does have a tendency to exhibit this fluctuating pattern?”

The retrospective design of the study and the relatively small number of patients with the skip phenomenon were limitations, the investigators acknowledged. Dr. Fiala had no relevant disclosures.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: About 4% of S. aureus bacteremia cases may not clear completely, as judged by one negative blood culture, contrary to recent IDSA guidelines.

Data source: Nested case-control study of 726 adult inpatients at Mayo Clinic between July 2006 and June 2011 with ≥3 days of S. aureus bacteremia.

Disclosures: Dr. Fiala had no relevant disclosures.

CDC study finds worrisome trends in hospital antibiotic use

U.S. hospitals have not cut overall antibiotic use and have significantly increased the use of several broad-spectrum agents, according to a first-in-kind analysis of national hospital administrative data.

“We identified significant changes in specific antibiotic classes and regional variation that may have important implications for reducing antibiotic-resistant infections,” James Baggs, PhD, and colleagues from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, reported in the study, published online on September 19 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

The retrospective study included approximately 300 acute care hospitals in the Truven Health MarketScan Hospital Drug Database, which covered 34 million pediatric and adult patient discharges equating to 166 million patient-daysIn all, 55% of patients received at least one antibiotic dose while in the hospital, and for every 1,000 patient-days, 755 days included antibiotic therapy, the investigators said. Overall antibiotic use rose during the study period by only 5.6 average days of therapy per 1,000 patient-days, which was not statistically significant.

However, the use of third and fourth-generation cephalosporins rose by a mean of 10.3 days of therapy per 1,000 patient-days (95% confidence interval, 3.1 to 17.5), and hospitals also used significantly more macrolides (mean rise, 4.8 days of therapy per 1,000 patient-days; 95% confidence interval, 2.0 to 7.6 days), glycopeptides, (22.4; 17.5 to 27.3); β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations (18.0; 13.3 to 22.6), carbapenems (7.4; 4.6 to 10.2), and tetracyclines (3.3; 2.0 to 4.7)

Inpatient antibiotic use also varied significantly by region, the investigators said. Hospitals in rural areas used about 16 more days of antibiotic therapy per 1,000 patient-days compared with those in urban areas. Hospitals in Mid-Atlantic states (New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania) and Pacific Coast states (Alaska, California, Hawaii, Oregon, and Washington) used the least antibiotics (649 and 665 days per 1,000 patient-days, respectively), while Southwest Central states (Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Texas) used the most (823 days).

The CDC provided funding for the study. The researchers had no disclosures.

The dramatic variation in antibiotic prescribing across individual clinicians, regions in the United States, and internationally indicates great potential for improvement. ... In the article by Baggs et al, inpatient antibiotic prescribing in some regions of the United States is roughly 20% lower than other regions. On a per capita basis, Swedes consume less than half the antibiotics per capita than Americans.

Growing patterns of antibiotic resistance have driven calls for more physician education and new diagnostics. While these efforts may help, it is important to recognize that many emotionally salient factors are driving physicians to inappropriately prescribe antibiotics. Future interventions need to counterbalance these factors using tools from behavioral science to reduce the use of inappropriate antibiotics.

Ateev Mehrotra, MD, MPH, and Jeffrey A. Linder, MD, MPH, are at Harvard University, Boston. They had no disclosures. These comments are from an editorial that accompanied the study ( JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Sept 19. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.6254).

The dramatic variation in antibiotic prescribing across individual clinicians, regions in the United States, and internationally indicates great potential for improvement. ... In the article by Baggs et al, inpatient antibiotic prescribing in some regions of the United States is roughly 20% lower than other regions. On a per capita basis, Swedes consume less than half the antibiotics per capita than Americans.

Growing patterns of antibiotic resistance have driven calls for more physician education and new diagnostics. While these efforts may help, it is important to recognize that many emotionally salient factors are driving physicians to inappropriately prescribe antibiotics. Future interventions need to counterbalance these factors using tools from behavioral science to reduce the use of inappropriate antibiotics.

Ateev Mehrotra, MD, MPH, and Jeffrey A. Linder, MD, MPH, are at Harvard University, Boston. They had no disclosures. These comments are from an editorial that accompanied the study ( JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Sept 19. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.6254).

The dramatic variation in antibiotic prescribing across individual clinicians, regions in the United States, and internationally indicates great potential for improvement. ... In the article by Baggs et al, inpatient antibiotic prescribing in some regions of the United States is roughly 20% lower than other regions. On a per capita basis, Swedes consume less than half the antibiotics per capita than Americans.

Growing patterns of antibiotic resistance have driven calls for more physician education and new diagnostics. While these efforts may help, it is important to recognize that many emotionally salient factors are driving physicians to inappropriately prescribe antibiotics. Future interventions need to counterbalance these factors using tools from behavioral science to reduce the use of inappropriate antibiotics.

Ateev Mehrotra, MD, MPH, and Jeffrey A. Linder, MD, MPH, are at Harvard University, Boston. They had no disclosures. These comments are from an editorial that accompanied the study ( JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Sept 19. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.6254).

U.S. hospitals have not cut overall antibiotic use and have significantly increased the use of several broad-spectrum agents, according to a first-in-kind analysis of national hospital administrative data.

“We identified significant changes in specific antibiotic classes and regional variation that may have important implications for reducing antibiotic-resistant infections,” James Baggs, PhD, and colleagues from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, reported in the study, published online on September 19 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

The retrospective study included approximately 300 acute care hospitals in the Truven Health MarketScan Hospital Drug Database, which covered 34 million pediatric and adult patient discharges equating to 166 million patient-daysIn all, 55% of patients received at least one antibiotic dose while in the hospital, and for every 1,000 patient-days, 755 days included antibiotic therapy, the investigators said. Overall antibiotic use rose during the study period by only 5.6 average days of therapy per 1,000 patient-days, which was not statistically significant.

However, the use of third and fourth-generation cephalosporins rose by a mean of 10.3 days of therapy per 1,000 patient-days (95% confidence interval, 3.1 to 17.5), and hospitals also used significantly more macrolides (mean rise, 4.8 days of therapy per 1,000 patient-days; 95% confidence interval, 2.0 to 7.6 days), glycopeptides, (22.4; 17.5 to 27.3); β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations (18.0; 13.3 to 22.6), carbapenems (7.4; 4.6 to 10.2), and tetracyclines (3.3; 2.0 to 4.7)

Inpatient antibiotic use also varied significantly by region, the investigators said. Hospitals in rural areas used about 16 more days of antibiotic therapy per 1,000 patient-days compared with those in urban areas. Hospitals in Mid-Atlantic states (New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania) and Pacific Coast states (Alaska, California, Hawaii, Oregon, and Washington) used the least antibiotics (649 and 665 days per 1,000 patient-days, respectively), while Southwest Central states (Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Texas) used the most (823 days).

The CDC provided funding for the study. The researchers had no disclosures.

U.S. hospitals have not cut overall antibiotic use and have significantly increased the use of several broad-spectrum agents, according to a first-in-kind analysis of national hospital administrative data.

“We identified significant changes in specific antibiotic classes and regional variation that may have important implications for reducing antibiotic-resistant infections,” James Baggs, PhD, and colleagues from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, reported in the study, published online on September 19 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

The retrospective study included approximately 300 acute care hospitals in the Truven Health MarketScan Hospital Drug Database, which covered 34 million pediatric and adult patient discharges equating to 166 million patient-daysIn all, 55% of patients received at least one antibiotic dose while in the hospital, and for every 1,000 patient-days, 755 days included antibiotic therapy, the investigators said. Overall antibiotic use rose during the study period by only 5.6 average days of therapy per 1,000 patient-days, which was not statistically significant.

However, the use of third and fourth-generation cephalosporins rose by a mean of 10.3 days of therapy per 1,000 patient-days (95% confidence interval, 3.1 to 17.5), and hospitals also used significantly more macrolides (mean rise, 4.8 days of therapy per 1,000 patient-days; 95% confidence interval, 2.0 to 7.6 days), glycopeptides, (22.4; 17.5 to 27.3); β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations (18.0; 13.3 to 22.6), carbapenems (7.4; 4.6 to 10.2), and tetracyclines (3.3; 2.0 to 4.7)

Inpatient antibiotic use also varied significantly by region, the investigators said. Hospitals in rural areas used about 16 more days of antibiotic therapy per 1,000 patient-days compared with those in urban areas. Hospitals in Mid-Atlantic states (New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania) and Pacific Coast states (Alaska, California, Hawaii, Oregon, and Washington) used the least antibiotics (649 and 665 days per 1,000 patient-days, respectively), while Southwest Central states (Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Texas) used the most (823 days).

The CDC provided funding for the study. The researchers had no disclosures.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Inpatient antibiotic use did not decrease between 2006 and 2012, and the use of several broad-spectrum agents rose significantly.

Major finding: Hospitals significantly decreased their use of fluoroquinolones and first- and second-generation cephalosporins, but these trends were offset by significant rises in the use of vancomycin, carbapenem, third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins, and β-lactam/β- lactamase inhibitor combinations.

Data source: A retrospective study of administrative hospital discharge data for about 300 US hospitals from 2006 through 2012.

Disclosures: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provided funding. The researchers had no disclosures.

E. coli resistant to colistin and carbapenems found in U.S. patient

The first strain of Escherichia coli harboring the antibiotic-resistant genes mcr-1 and blaNDM-5 was isolated in the urine of a U.S. patient, according to a report in mBio.

A 76-year-old man was admitted to a tertiary-care hospital in New Jersey with a fever and flank pain in August 2014. The patient emigrated from India and resided in the United States for 1 year prior to this presentation. He had a history of prostate cancer treated with radiation therapy and subsequently developed recurrent urinary tract infections. He had also experienced bladder perforation requiring bilateral placement of nephrostomy tubes, which were clamped 5 days prior to presentation.

Using molecular analysis, the E. coli isolate from the study case (named MCR1_NJ) was shown to carry both mcr-1 and blaNDM-5 genes. In addition to mcr-1 and blaNDM-5, strain MCR1_NJ was found to harbor resistance genes for aminoglycosides, beta-lactams, chloramphenicol, fluoroquinolones, rifampin, sulfonamides, and tetracycline.

“This strain was isolated in August 2014, highlighting an earlier presence of mcr-1 within the region than previously known and raising the likelihood of ongoing undetected transmission,” wrote José R. Mediavilla, MBS, MPH of the New Jersey Medical School, Rutgers University, Newark, N.J., and his coauthors. “Active surveillance efforts involving all polymyxin- and carbapenem-resistant organisms are imperative in order to determine mcr-1 prevalence and prevent further dissemination.”

Find the full study in mBio (doi: 10.1128/mBio.01191-16).

The first strain of Escherichia coli harboring the antibiotic-resistant genes mcr-1 and blaNDM-5 was isolated in the urine of a U.S. patient, according to a report in mBio.

A 76-year-old man was admitted to a tertiary-care hospital in New Jersey with a fever and flank pain in August 2014. The patient emigrated from India and resided in the United States for 1 year prior to this presentation. He had a history of prostate cancer treated with radiation therapy and subsequently developed recurrent urinary tract infections. He had also experienced bladder perforation requiring bilateral placement of nephrostomy tubes, which were clamped 5 days prior to presentation.

Using molecular analysis, the E. coli isolate from the study case (named MCR1_NJ) was shown to carry both mcr-1 and blaNDM-5 genes. In addition to mcr-1 and blaNDM-5, strain MCR1_NJ was found to harbor resistance genes for aminoglycosides, beta-lactams, chloramphenicol, fluoroquinolones, rifampin, sulfonamides, and tetracycline.

“This strain was isolated in August 2014, highlighting an earlier presence of mcr-1 within the region than previously known and raising the likelihood of ongoing undetected transmission,” wrote José R. Mediavilla, MBS, MPH of the New Jersey Medical School, Rutgers University, Newark, N.J., and his coauthors. “Active surveillance efforts involving all polymyxin- and carbapenem-resistant organisms are imperative in order to determine mcr-1 prevalence and prevent further dissemination.”

Find the full study in mBio (doi: 10.1128/mBio.01191-16).

The first strain of Escherichia coli harboring the antibiotic-resistant genes mcr-1 and blaNDM-5 was isolated in the urine of a U.S. patient, according to a report in mBio.

A 76-year-old man was admitted to a tertiary-care hospital in New Jersey with a fever and flank pain in August 2014. The patient emigrated from India and resided in the United States for 1 year prior to this presentation. He had a history of prostate cancer treated with radiation therapy and subsequently developed recurrent urinary tract infections. He had also experienced bladder perforation requiring bilateral placement of nephrostomy tubes, which were clamped 5 days prior to presentation.

Using molecular analysis, the E. coli isolate from the study case (named MCR1_NJ) was shown to carry both mcr-1 and blaNDM-5 genes. In addition to mcr-1 and blaNDM-5, strain MCR1_NJ was found to harbor resistance genes for aminoglycosides, beta-lactams, chloramphenicol, fluoroquinolones, rifampin, sulfonamides, and tetracycline.

“This strain was isolated in August 2014, highlighting an earlier presence of mcr-1 within the region than previously known and raising the likelihood of ongoing undetected transmission,” wrote José R. Mediavilla, MBS, MPH of the New Jersey Medical School, Rutgers University, Newark, N.J., and his coauthors. “Active surveillance efforts involving all polymyxin- and carbapenem-resistant organisms are imperative in order to determine mcr-1 prevalence and prevent further dissemination.”

Find the full study in mBio (doi: 10.1128/mBio.01191-16).

Striking the balance: Who should be screened for CP-CRE acquisition?

Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) are extremely drug-resistant organisms. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Healthcare Safety Network, in 2014 in the United States, 3.6% of Enterobacteriaceae causing hospital-acquired infections were resistant to carbapenems.1 Antibiotic treatment options for CRE infections are severely limited, and mortality for invasive infections can be as high as 40%-50%.2

Resistance to carbapenems can be mediated by several mechanisms. From an epidemiologic standpoint, production of carbapenemases is the most-threatening mechanism because Enterobacteriaceae-harboring carbapenemases are highly transmissible.

Carbapenemase-producing CRE (CP-CRE) have caused large outbreaks throughout the world. Israel experienced a nationwide outbreak of CP-CRE, primarily Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase–producing Klebsiella pneumoniae, in the mid-2000s. At the peak of the outbreak in 2007, there were 185 new cases per month (55.5/100,000 patient-days). A successful intervention at the national level dramatically decreased the incidence to 4.8/100,000 patient days in 2012.3

One component of the intervention (which is still ongoing) is active surveillance of high-risk groups using rectal swabs. Upon admission to the hospital, we screen patients who were recently in other hospitals or long-term care facilities. In addition, when a patient is newly diagnosed with CP-CRE (either asymptomatic carriage or clinical infection), we screen patients who had contact with that index case before isolation measures were implemented.

We recently published a study in Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology that draws on our experience with CP-CRE screening of contacts at Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center.4 Both Israeli and International guidelines do not precisely define which contacts of a CP-CRE index case warrant screening. For example, should only roommates of index cases be screened or should we screen all patients on the same ward as the index case? Likewise, is there a minimum time of contact that should trigger screening?

Identifying which contacts are at high risk of acquiring CP-CRE is important for two reasons: We want to detect contacts who acquired CP-CRE so that they can be isolated before further transmission occurs, and we don’t want to waste resources and screen those at low risk. In our hospital, the criteria for being a contact are staying in the same ward and being treated by the same nursing staff as a newly identified CP-CRE patient.

This strategy appears to lead to overscreening, as we found that from October 2008 to June 2012, 3,158 screening tests were performed to detect 53 positive contacts (a yield of less than 2%). In order to screen more efficiently, our study aimed to determine risk factors for CP-CRE acquisition among patients exposed to a CP-CRE index patient.

We used a matched case-control design. The case group consisted of the 53 contacts who screened positive for CP-CRE. For each case we chose 2 controls: contacts who screened negative for CP-CRE. The basis for matching between the case and the 2 controls was that they were exposed to the same index patient. The benefit of matching this way was that it eliminated the question of whether a contact became positive because the index patient was more likely to transmit CP-CRE (e.g., because of diarrhea), and not because of characteristics of the contact patients themselves.

We found three factors that increased the risk that a contact would screen positive:

• Contact period of at least 3 days with the index case.

• Being on mechanical ventilation.

• Having a history of carriage or infection with another multidrug-resistant organism (such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus).

Unexpectedly, sharing a room with the index patient or being debilitated did not significantly increase the risk of acquiring CP-CRE.

Many studies have identified antibiotic use as a risk factor for acquiring CP-CRE. In our study, no class of antibiotic increased the risk of CP-CRE acquisition, probably because only a small number of patients received each class. We were surprised to find that contacts who had taken cephalosporins were less likely to acquire CP-CRE. On further examination, when we compared patients who received only cephalosporins with patients who received no antibiotic, this protective effect disappeared. Nevertheless, compared with other antibiotics, it appears that cephalosporins might pose less of a risk for CP-CRE acquisition. More studies are needed to confirm our findings.

Our findings have practical implications for infection control. Using the risk factors we identified could help us to avoid excessive screening. We calculated that selective screening, based on our three risk factors, would have decreased the number of contacts screened by 30%, but 2 out of 53 positive contacts would have been missed. Institutions need to decide whether that is a trade-off they are willing to make.

Another way to apply our findings could be to add an additional layer of infection control by preemptively implementing contact precautions for patients at highest risk, for example, those with more than one risk factor.

1. Weiner LM, Fridkin SK, Aponte-Torres Z, Avery L, Coffin N, Dudeck MA, Edwards JR, Jernigan JA, Konnor R, Soe MM, Peterson K, Clifford McDonald L. Vital signs: preventing antibiotic-resistant infections in hospitals - United States, 2014. Am J Transplant. 2016 Jul;16(7):2224-30.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Facility guidance for control of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE): November 2015 update – CRE Toolkit.

3. Schwaber MJ, Carmeli Y. An ongoing national intervention to contain the spread of carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae. Clin Infect Dis. 2014 Mar;58(5):697-703.

Schwartz-Neiderman A, Braun T, Fallach N, Schwartz D, Carmeli Y, Schechner V. Risk factors for carbapenemase-producing carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CP-CRE) acquisition among contacts of newly diagnosed CP-CRE patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016 Jul 25:1-7.

Vered Schechner, MD, MSc, is an infection control physician in the department of epidemiology at Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center.

Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) are extremely drug-resistant organisms. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Healthcare Safety Network, in 2014 in the United States, 3.6% of Enterobacteriaceae causing hospital-acquired infections were resistant to carbapenems.1 Antibiotic treatment options for CRE infections are severely limited, and mortality for invasive infections can be as high as 40%-50%.2

Resistance to carbapenems can be mediated by several mechanisms. From an epidemiologic standpoint, production of carbapenemases is the most-threatening mechanism because Enterobacteriaceae-harboring carbapenemases are highly transmissible.

Carbapenemase-producing CRE (CP-CRE) have caused large outbreaks throughout the world. Israel experienced a nationwide outbreak of CP-CRE, primarily Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase–producing Klebsiella pneumoniae, in the mid-2000s. At the peak of the outbreak in 2007, there were 185 new cases per month (55.5/100,000 patient-days). A successful intervention at the national level dramatically decreased the incidence to 4.8/100,000 patient days in 2012.3