User login

Patient-Specific Guides/Instrumentation in Shoulder Arthroplasty

ABSTRACT

Optimal outcomes following total shoulder arthroplasty TSA and reverse shoulder arthroplasty RSA are dependent on proper implant position. Multiple cadaver studies have demonstrated improved accuracy of implant positioning with use of patient-specific guides/instrumentation compared to traditional methods. At this time, there are 3 commercially available single use patient-specific instrumentation systems and 1 commercially available reusable patient-specific instrumentation system. Currently though, there are no studies comparing the clinical outcomes of patient-specific guides to those of traditional methods of glenoid placement, and limited research has been done comparing the accuracy of each system’s 3-dimensional planning software. Future work is necessary to elucidate the ideal indications for the use of patient-specific guides and instrumentation, but it is likely, particularly in the setting of advanced glenoid deformity, that these systems will improve a surgeon's ability to put the implant in the best position possible.

Continue to: Optimal functional recovery...

Optimal functional recovery and implant longevity following both total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) and reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) depend, in large part, on proper placement of the glenoid component. Glenoid component malpositioning has an adverse effect on shoulder stability, range of motion (ROM), impingement, and glenoid implant longevity.

Traditionally, glenoid component positioning has been done manually by the surgeons based on their review of preoperative films and knowledge of glenoid anatomy. Anatomic studies have demonstrated high individual variability in the version of the native glenoid, thus making ideal placement of the initial glenoid guide pin difficult using standard guide pin guides.1

The following 2 methods have been described for improving the accuracy of glenoid guide pin insertion and subsequent glenoid implant placement: (1) computerized navigation and (2) patient-specific guides/instrumentation. Although navigated shoulder systems have demonstrated improved accuracy in glenoid placement compared with traditional methods, navigated systems require often large and expensive systems for implementation. The majority of them also require placement of guide pins or arrays on scapular bony landmarks, likely leading to an increase in operative time and possible iatrogenic complications, including fracture and pin site infections.

This review focuses on the use of patient-specific guides/instrumentation in shoulder arthroplasty. This includes the topic of proper glenoid and glenosphere placement as well as patient-specific guides/instrumentation and their accuracy.

GLENOID PLACEMENT

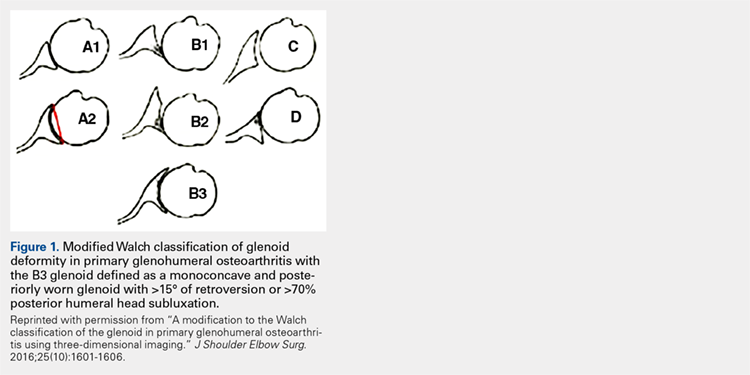

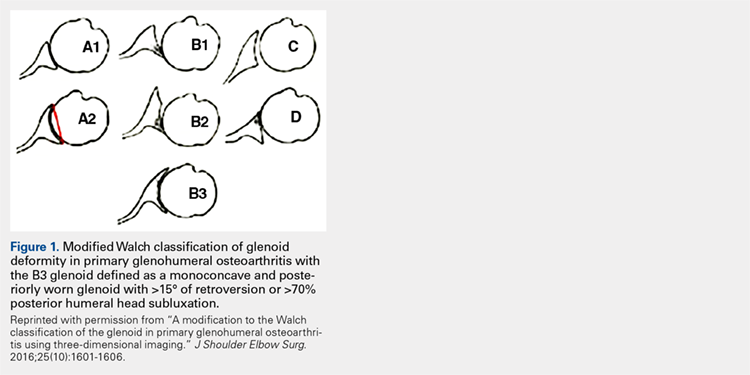

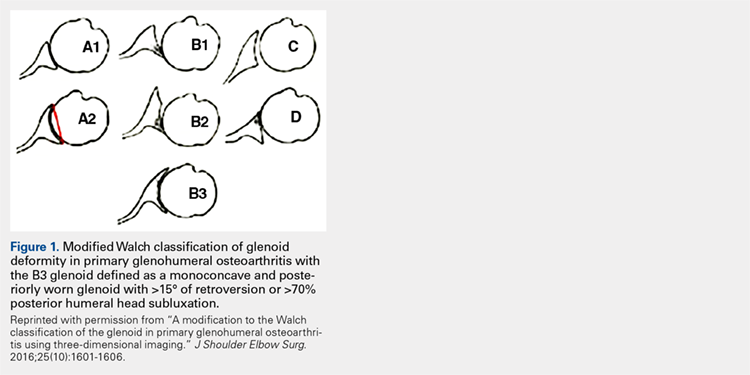

Glenohumeral osteoarthritis is the most common indication for TSA2 and commonly results in glenoid deformity. Using computed tomography (CT) scans of 45 arthritic shoulders and 19 normal shoulders, Mullaji and colleagues3 reported that the anteroposterior dimensions of the glenoid were increased by an average of 5 mm to 8 mm in osteoarthritic shoulders and by an average of 6 mm in rheumatoid arthritic shoulders compared to those in normal shoulders. A retrospective review of serial CT scans performed preoperatively on 113 osteoarthritic shoulders by Walch and colleagues4 demonstrated an average retroversion of 16°, and it has been the basis for the commonly used Walch classification of glenoid wear in osteoarthritis. Increased glenoid wear and increased glenoid retroversion make the proper restoration of glenoid version, inclination, and offset during shoulder arthroplasty more difficult and lead to increased glenoid component malpositioning.

Continue to: The ideal placement of the glenoid...

The ideal placement of the glenoid to maximize function, ROM, and implant longevity is in a mechanically neutral alignment with no superoinferior inclination1 and neutral version with respect to the transverse axis of the scapula.5

Improper glenoid positioning has an adverse effect on the functional results of shoulder arthroplasty. Yian and colleagues6 evaluated 47 cemented, pegged glenoids using standard radiography and CT scans at a mean follow-up of 40 months. They observed a significant correlation between increased glenoid component retroversion and lower Constant scores. Hasan and colleagues7 evaluated 139 consecutive patients who were dissatisfied with the result of their primary arthroplasty and found that 28% of them had at least 1 substantially malpositioned component identified either on radiography or during a revision surgery. They also found a significant correlation between stiffness, instability, and component malposition in their cohort.

Glenoid longevity is also dependent on proper component positioning, with the worst outcomes coming if the glenoid is malaligned with either superior or inferior inclination. Hasan and colleagues7 found that of their 74 patients with failed TSAs, 44 patients (59%) demonstrated mechanical loosening of their glenoid components either radiographically or during revision surgery, and 10 of their 44 patients with loose glenoids (23%) also had a malpositioned component. Using finite element analysis, Hopkins and colleagues8 analyzed the stresses through the cement mantle in glenoid prostheses that were centrally aligned, superiorly inclined, inferiorly inclined, anteverted, and retroverted. They found that malalignment of the glenoid increases the stresses through the cement mantle, leading to increased likelihood of mantle failure compared to that of centrally aligned glenoids, especially if there is malalignment with superior or inferior inclination or retroversion.

The accuracy of traditional methods of glenoid placement using an initial guide pin is limited and decreases with increasing amounts of glenoid deformity and retroversion. Iannotti and colleagues 9 investigated 13 patients undergoing TSA with an average preoperative retroversion of 13° and evaluated them using a 3-dimensional (3-D) surgical simulator. They found that the postoperative glenoid version was within 5° of ideal version in only 7 of their 13 patients (54%) and within 10° of ideal version in only 10 of their 13 patients (77%). In their study, the ideal version was considered to be the version as close to perpendicular to the plane of the scapula as possible with complete contact of the back side of the component on glenoid bone and maintenance of the center peg of the component within bone. In addition, they found that of their 7 patients with preoperative retroversion >10°, only 1 patient (14%) had a postoperative glenoid with <10° of retroversion with regard to the plane of the scapula and that all 6 of their patients with preoperative glenoid retroversion of <10° had a postoperative glenoid version of <10°.

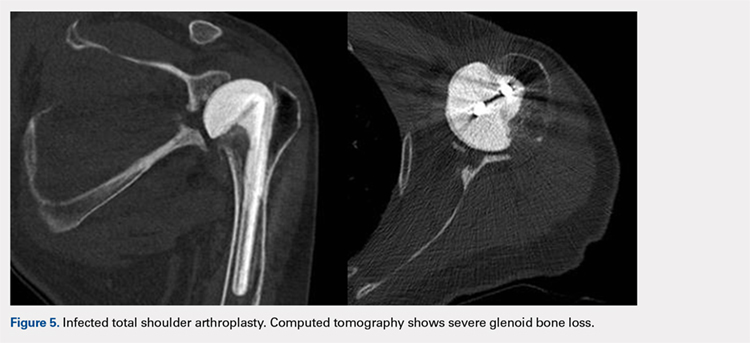

Preoperative CT scans are much more accurate at determining glenoid version and thus how much glenoid correction is required to reestablish neutral version than plain radiography. Nyffeler and colleagues10 compared CT scans with axillary views for comparing glenoid version in 25 patients with no shoulder prosthesis present and 25 patients with a TSA in place. They found that glenoid retroversion was overestimated on plain radiographs in 86% of their patients with an average difference between CT and plain radiography of 6.4° and a maximum difference of 21°. They also found poor interobserver reliability in the plain radiography group and good interobserver reliability in the CT group, with coefficients of correlation of 0.77 for the plain radiography group and 0.93 for the CT group. Thus, they concluded that glenoid version cannot be accurately measured by plain radiography and that CT should be used. Hoenecke and colleagues11 subsequently evaluated 33 patients scheduled for TSA and found that CT version measurements made on 2-dimensional (2-D) CT slices compared with 3-D-reconstructed models of the same CT slices differed by an average of 5.1° because the axial CT slices were most often made perpendicular to the axis of the patient’s torso and not perpendicular to the body of the scapula. Accurate version assessment is critically important in planning for the degree of correction required to restore neutral glenoid version, and differences of 6.4° between CT assessment and plain radiography, and 5.1° between 2-D and 3-D CT scan assessments may lead to inadequate version correction intraoperatively and inferior postoperative results.

Continue to: GLENOSPHERE PLACEMENT

GLENOSPHERE PLACEMENT

The most common indication for reverse TSA is rotator cuff arthropathy characterized by rotator cuff dysfunction and end-stage glenohumeral arthritis.12 These patients require accurate and reproducible glenoid placement to optimize their postoperative range of motion and stability and minimize scapular notching.

Ideal glenosphere placement is the location and orientation that maximizes impingement-free ROM and stability while avoiding notching. Individual patient anatomy determines ideal placement; however, several guidelines for placement include inferior translation on the glenoid with neutral to inferior inclination. Gutiérrez and colleagues13 developed a computer model to assess the hierarchy of surgical factors affecting the ROM after a reverse TSA. They found that lateralizing the center of rotation gave the largest increase in impingement-free abduction, followed closely by inferior translation of the glenosphere on the glenoid.

Avoiding scapular notching is also a very important factor in ideal glenosphere placement. Scapular notching can be described as impingement of the humeral cup against the scapular neck during arm adduction and/or humeral rotation. Gutiérrez and colleagues13 also found that decreasing the neck shaft angle to create a more varus proximal humerus was the most important factor in increasing the impingement-free adduction. Roche and colleagues14 reviewed the radiographs of 151 patients who underwent primary reverse TSA at a mean follow-up of 28.3 months postoperatively; they found that 13.2% of their patients had a notch and that, on average, their patients who had no scapular notch had significantly more inferior glenosphere overhang than those who had a scapular notch. Poon and colleagues15 found that a glenosphere overhang of >3.5 mm prevented notching in their randomized control trial comparing concentrically and eccentrically placed glenospheres. Multiple other studies have demonstrated similar results and recommended inferior glenoid translation and inferior glenoid inclination to avoid scapular notching.16,17 Lévigne and colleagues18 retrospectively reviewed 337 reverse TSAs and observed a correlation between scapular notching and radiolucencies around the glenosphere component, with 14% of patients with scapular notching displaying radiolucencies vs 4% of patients without scapula notching displaying radiolucencies.

Several studies have also focused on the ideal amount of inferior glenoid inclination to maximize impingement-free ROM. Li and colleagues17 performed a computer simulation study on the Comprehensive Reverse Shoulder System (Zimmer Biomet) to determine impingement-free internal and external ROM with varying amounts of glenosphere offset, translation, and inclination. They found that progressive glenosphere inferior inclination up to 30° improved impingement-free rotational ROM at all degrees of scaption. Gutiérrez and colleagues19 used computer modeling to compare concentrically placed glenospheres in neutral inclination with eccentrically placed glenospheres in varying degrees of inclination. They found that the lowest forces across the baseplate occurred in the lateralized and inferiorly inclined glenospheres, and the highest forces occurred in the lateralized and superiorly inclined glenospheres. Together, these studies show that inferior glenoid inclination increases impingement-free ROM and, combined with lateralization, may result in improved glenosphere longevity due to significantly decreased forces at the RSA glenoid baseplate when compared to that at superiorly inclined glenoids.

The ideal amount of mediolateral glenosphere offset has not been well defined. Grammont design systems place the center of rotation of the glenosphere medial to the glenoid baseplate together with valgus humeral component neck shaft angles of around 155°. These design elements are believed to decrease shear stresses through the glenoid baseplate to the glenoid interface and improve shoulder stability, but they are also associated with reduced impingement-free ROM and increased rates of scapular notching.13 This effect is accentuated in patients with preexisting glenoid bone loss and/or congenitally short scapular necks that further medialize the glenosphere. Medialization of the glenosphere may also shorten the remaining rotator cuff muscles and result in decreased implant stability and external rotation strength. Several implant systems have options to vary the amount of lateral offset. The correct amount of lateral offset for each patient requires the understanding that improving patients’ impingement-free ROM by increasing the amount of lateral offset comes at the price of increasing the shear forces experienced by the interface between the glenoid baseplate and the glenoid. As glenoid fixation technology improves increased lateralization of glenospheres without increased rates of glenoid baseplate, loosening should improve the ROM after reverse TSA.

Continue to: Regardless of the intraoperative goals...

Regardless of the intraoperative goals for placement and orientation of the glenosphere components, it is vitally important to accurately and consistently meet those goals for achieving optimal patient outcomes. Verborgt and colleagues20 implanted 7 glenospheres in cadaveric specimens without any glenohumeral arthritis using standard techniques to evaluate the accuracy of glenosphere version and inclination. Their goal was to place components in neutral version and with 10° of inferior inclination. Their average glenoid version postoperatively was 8.7° of anteversion, and their average inclination was 0.9° of superior inclination. Throckmorton and colleagues21 randomized 35 cadaveric shoulders to receive either an anatomic or a reverse total shoulder prosthesis from high-, mid-, and low-volume surgeons. They found that components placed using traditional guides averaged 6° of deviation in version and 5° of deviation in inclination from their target values, with no significant differences between surgeons of different volumes.

PATIENT-SPECIFIC GUIDES/INSTRUMENTATION

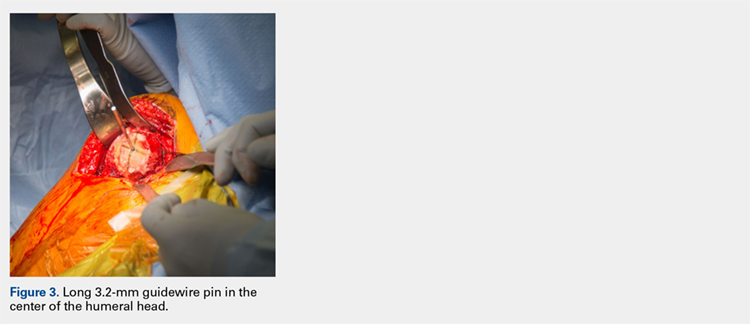

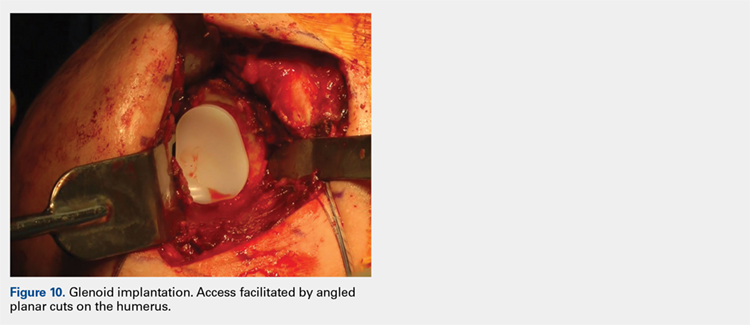

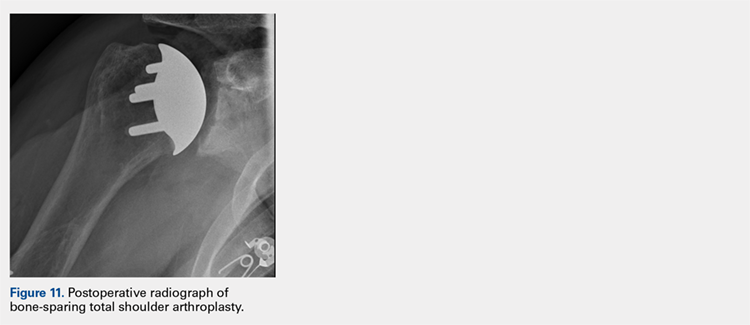

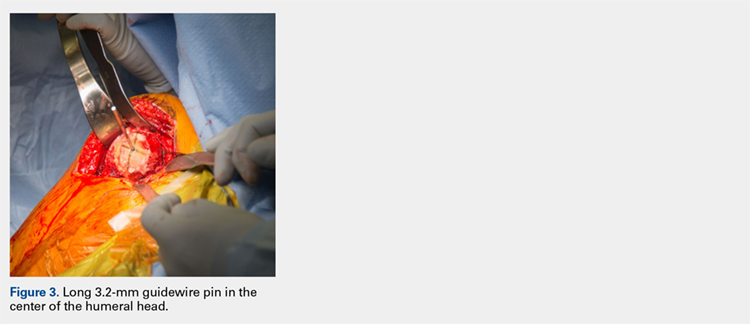

Patient-specific guides/instrumentation and intraoperative navigation are the 2 techniques that have been used to improve the accuracy of glenoid and glenosphere placement. Both techniques require the use of high-resolution CT scans and computer software to determine the proper position for glenoid or glenosphere placement based on the patient’s individual anatomy. Patient-specific guides and instrumentation use the data acquired from a CT scan to generate a preoperative plan for the location and orientation of the glenoid baseplate. Once the surgeon approves the preoperative plan, a patient-specific guide is created using the patient’s glenoid as a reference for the location and orientation of the central guide pin. The location of the central guide pin on the glenoid determines the center of the glenoid baseplate, and the guide pin’s orientation determines the version and inclination of the glenoid or the glenosphere. Once the guide pin is placed in the glenoid, the remainder of the glenoid implantation uses the guide pin as a reference, and, in that way, patient-specific guides control the orientation of the glenoid at the time of surgery.

Intraoperative navigation uses an optical tracking system to determine the location and orientation of the central guide pin. Navigation systems require intraoperative calibration of the optical tracking system before they can track the location of implantation relative to bony landmarks on the patient’s scapula. Their advantage over patient-specific instrumentation (PSI) is that they do not require the manufacture of a custom guide; however, they may add significantly increased cost and surgical time due to the need for calibration prior to use and the cost of the navigation system along with any disposable components associated with it. Kircher and colleagues22 performed a prospective randomized clinical study of navigation-aided TSA compared with conventional TSA and found that operating time was significantly increased for the navigated group with an average operating room time of 169.5 minutes compared to 138 minutes for the conventional group. They also found that navigation had to be abandoned in 37.5% of their navigated patients due to technical errors during glenoid referencing.

COMMERCIAL PATIENT-SPECIFIC INSTRUMENTATION SYSTEMS

The 2 types of PSI that are currently available are single-use PSI and reusable PSI. The single-use PSI involves the fabrication of unique guides based on surgeon-approved preoperative plans generated by computer-software-processed preoperative CT scans. The guides are fabricated to rest on the glenoid articular surface and direct the guide pin to the correct location and in the correct direction to place the glenoid baseplate in the desired position with the desired version and inclination. Most of these systems also provide a 3-D model of the patient’s glenoid so that surgeons can visualize glenoid deformities and the correct guide placement on the glenoid. Single-use PSI systems are available from DJO Global, Wright Medical Group, and Zimmer Biomet. The second category of PSI is reusable and is available from Arthrex. The guide pin for this system is adjusted to fit individual patient anatomy and guide the guide pin into the glenoid in a location and orientation preplanned on the CT-scan-based computer software or using a 3-D model of the patient’s glenoid (Table).

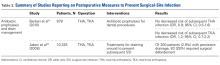

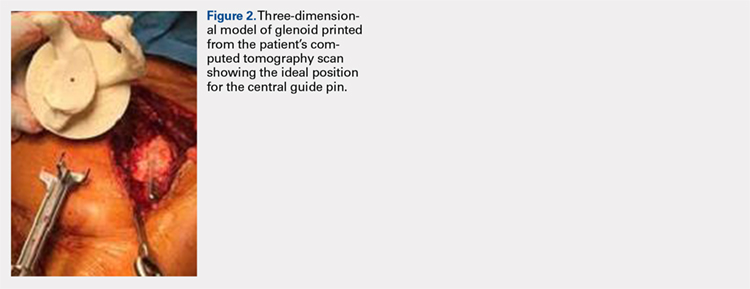

Table. Details of Available Patient-Specific Instrumentation Systems

| System | Manufacturer | Single-Use/Reusable | Guides |

| MatchPoint System | DJO Global | Single-use | Central guide pin |

| Blueprint 3D Planning + PSI | Wright Medical Group | Single-use | Central guide pin |

| Zimmer Patient Specific Instruments Shoulder | Zimmer Biomet | Single-use | Central guide pin, reaming guide, roll guide, screw drill guide |

| Virtual Implant Positioning System | Arthrex | Reusable | Central guide pin |

The DJO Global patient-specific guide is termed as the MatchPoint System. This system creates 3-D renderings of the scapula and allows the surgeon to manipulate the glenoid baseplate on the scapula. The surgeon chooses the glenoid baseplate, location, version, and inclination on the computerized 3-D model. The system then fabricates a guide pin matching the computerized template that references the patient’s glenoid surface with a hook to orient it against the coracoid. A 3-D model of the glenoid is also provided along with the customized guide pin.

Continue to: Blueprint 3D Planning + PSI...

Blueprint 3D Planning + PSI (Wright Medical Group) allows custom placement of the glenoid version, inclination, and position on computerized 3-D models of the patient’s scapula. This PSI references the glenoid with 4 feet that captures the edge of the patient’s glenoid at specific locations and is unique because it allows the surgeon to control where on the glenoid edge to 4 feet contact as long as 1 foot is placed on the posterior edge of the glenoid and the remaining 3 feet are placed on the anterior edge of the glenoid. A 3-D model of the glenoid is also provided with this guide.

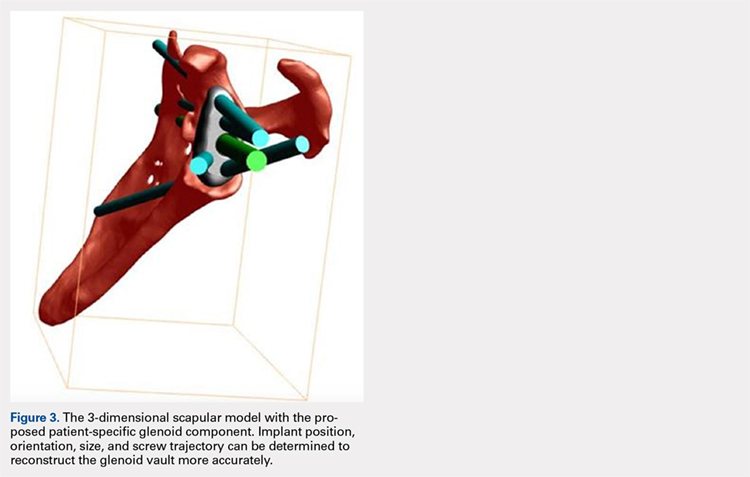

The Zimmer Biomet patient-specific guide is termed as the Zimmer Patient Specific Instruments Shoulder. Its computer software allows custom placement of the glenoid as well, but it also includes computerized customization of the reaming depth, screw angles, and screw lengths to optimize fixation. Their system includes a central guide pin to set the glenoid baseplate’s location and orientation, a reaming guide to control reaming depth and direction, a roll guide to control the glenoid baseplate’s rotation, and a drill guide to control the screw direction. They also provide a 3-D model of the glenoid.

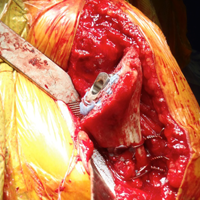

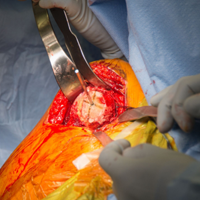

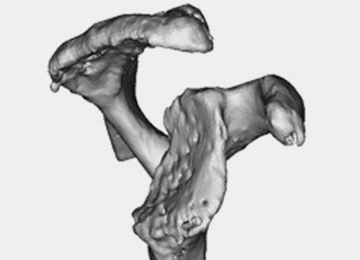

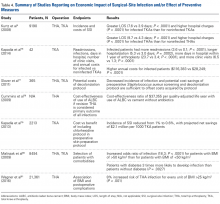

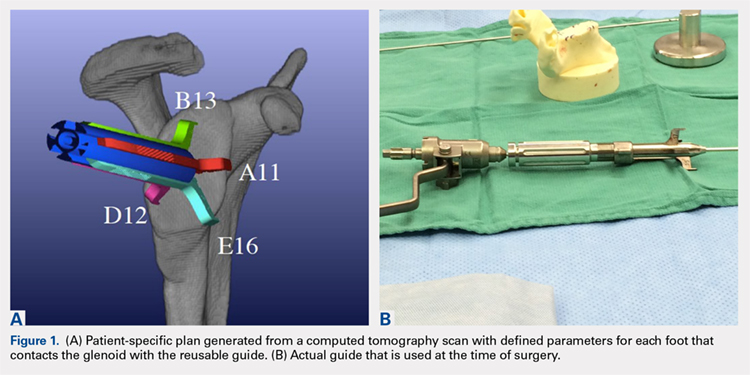

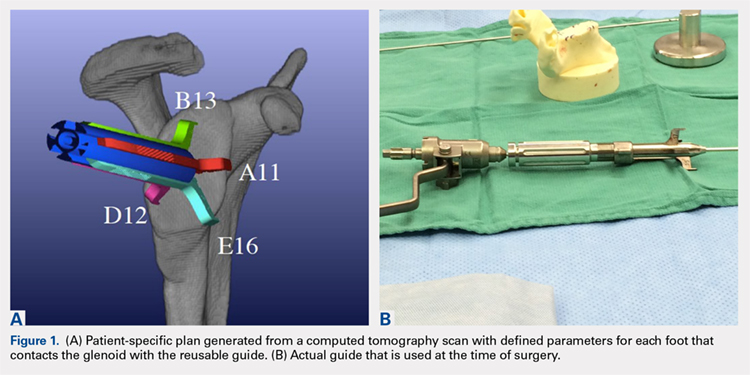

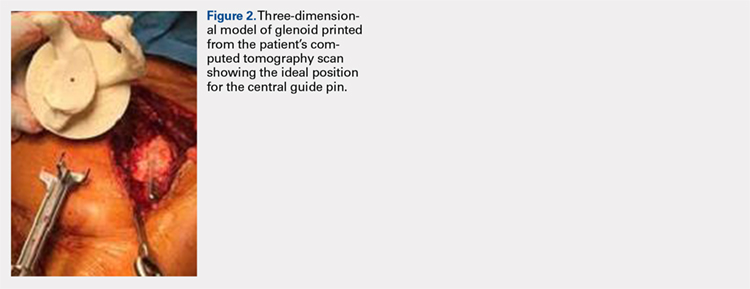

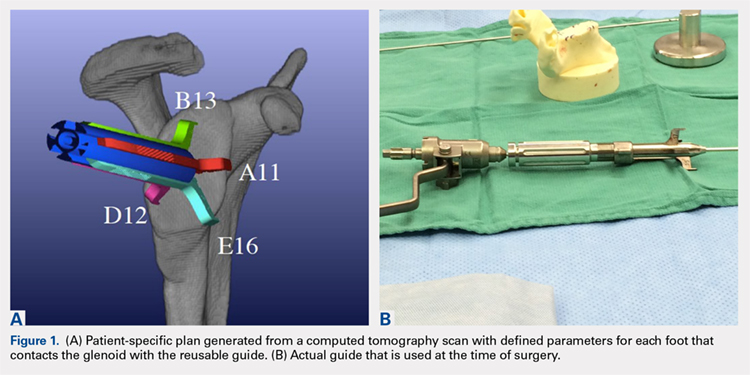

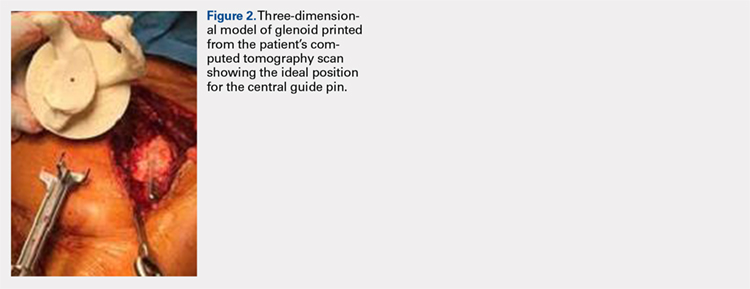

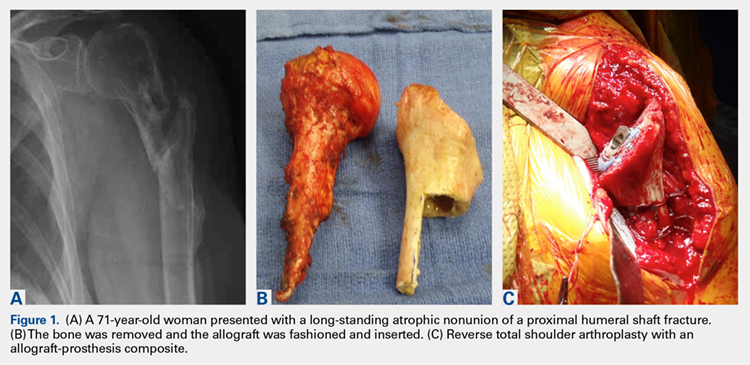

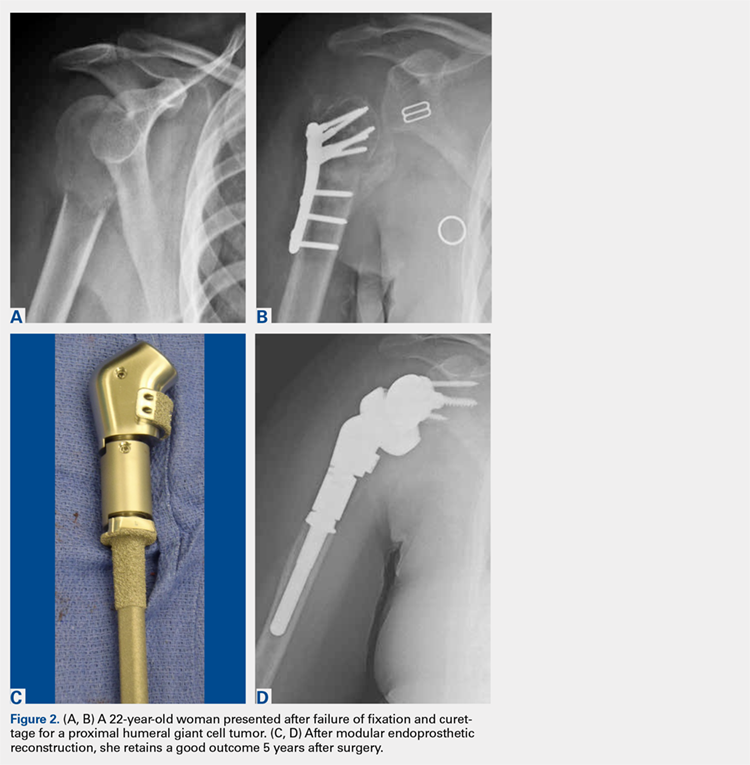

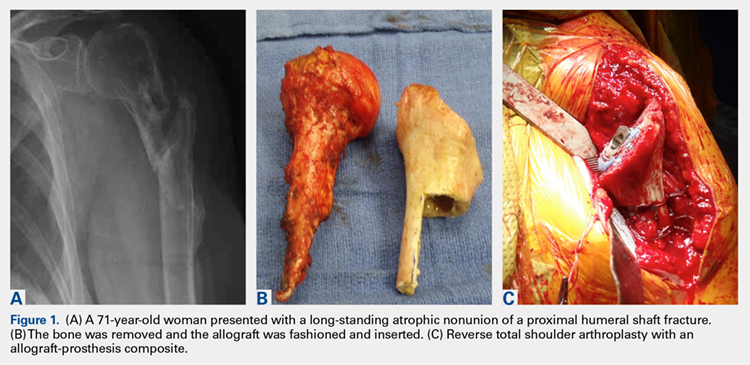

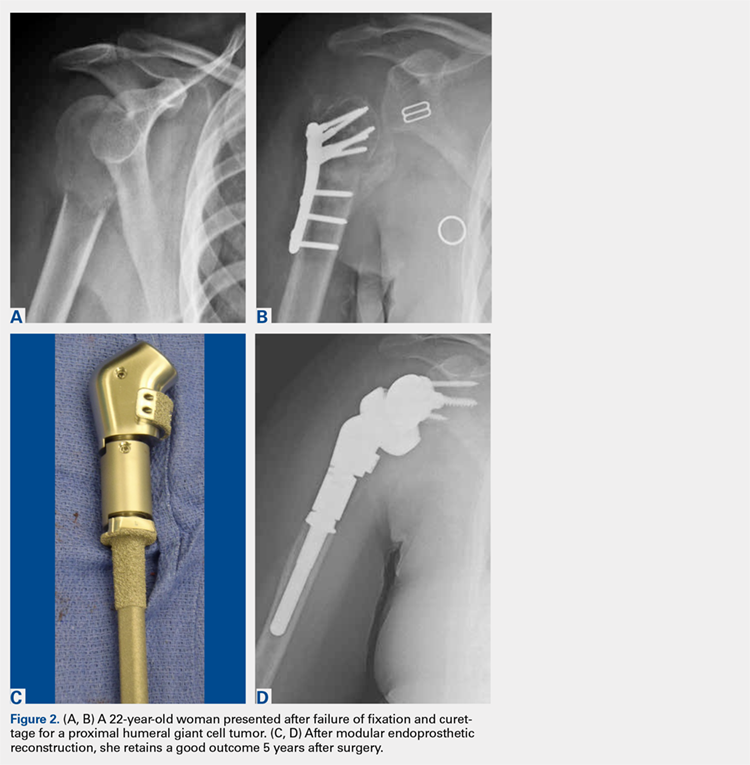

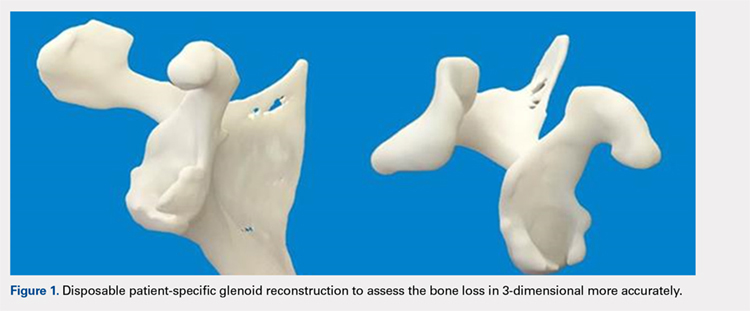

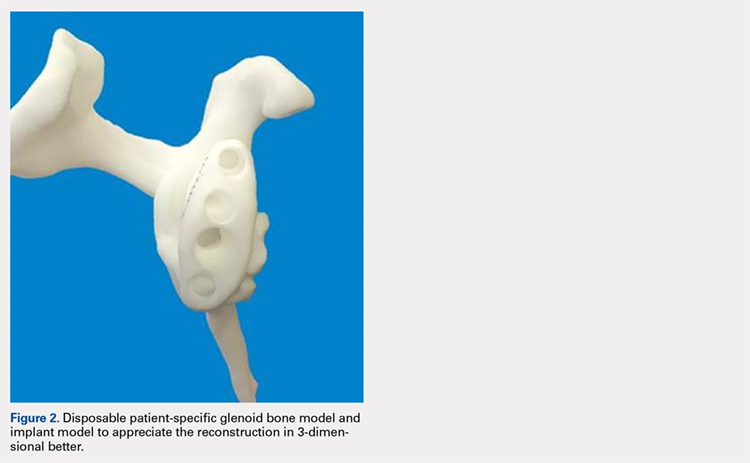

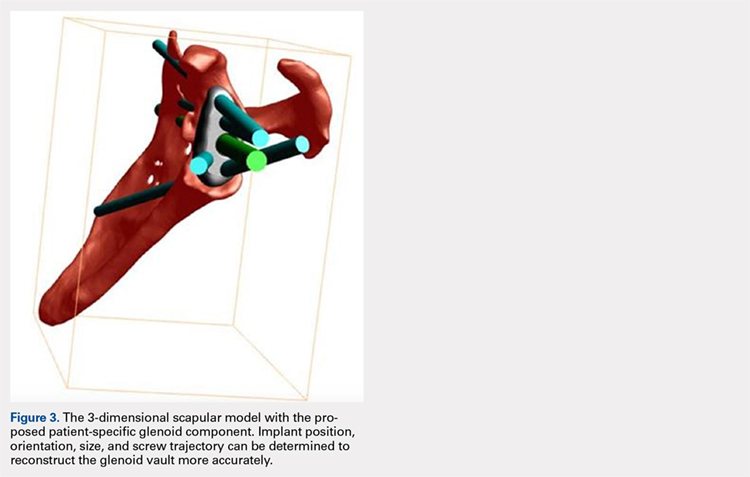

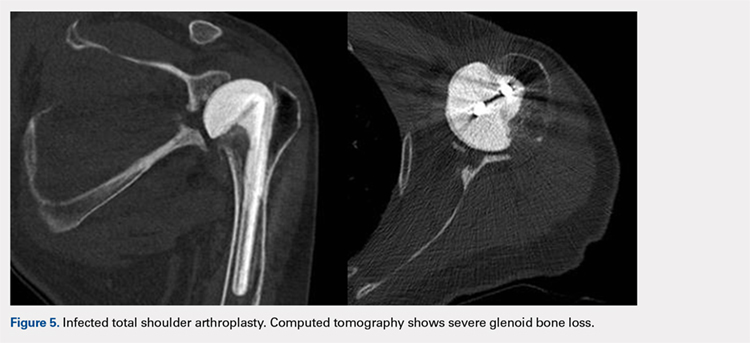

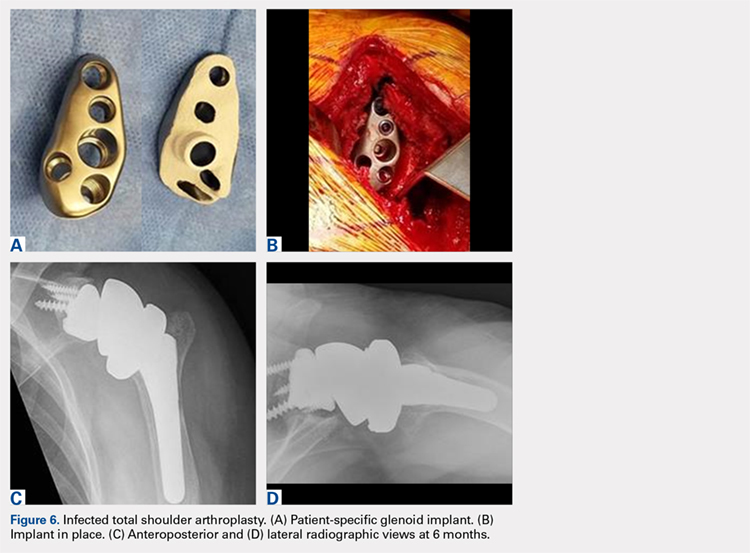

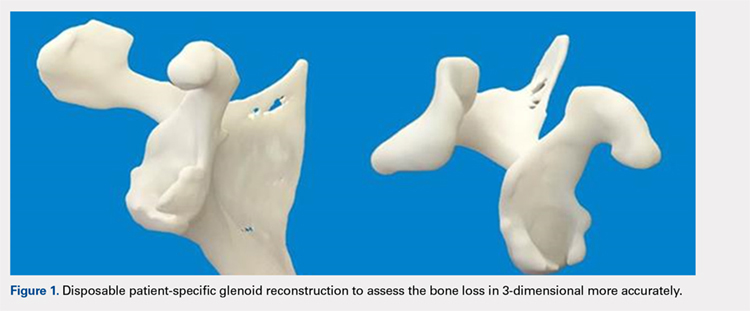

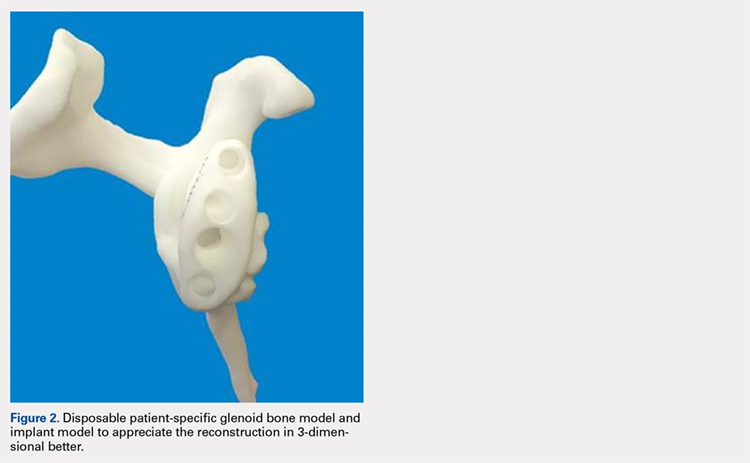

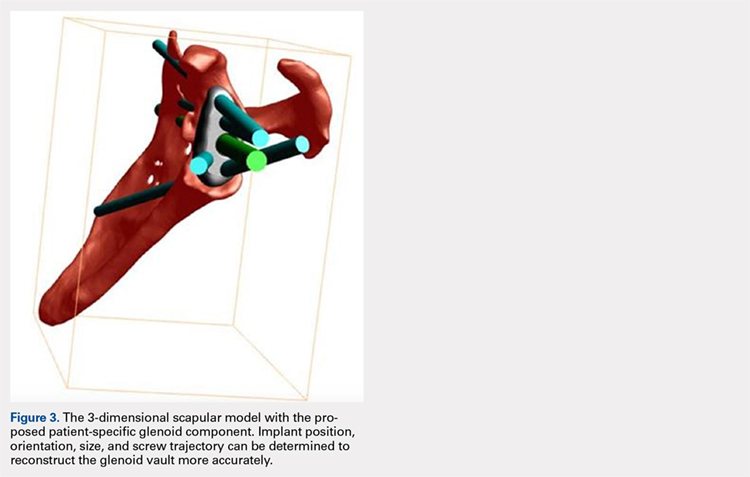

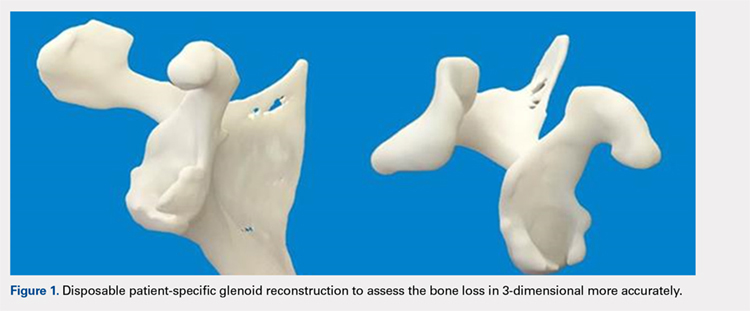

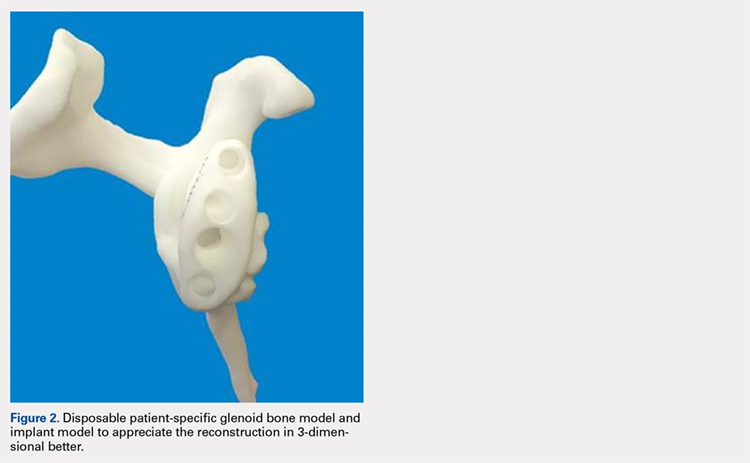

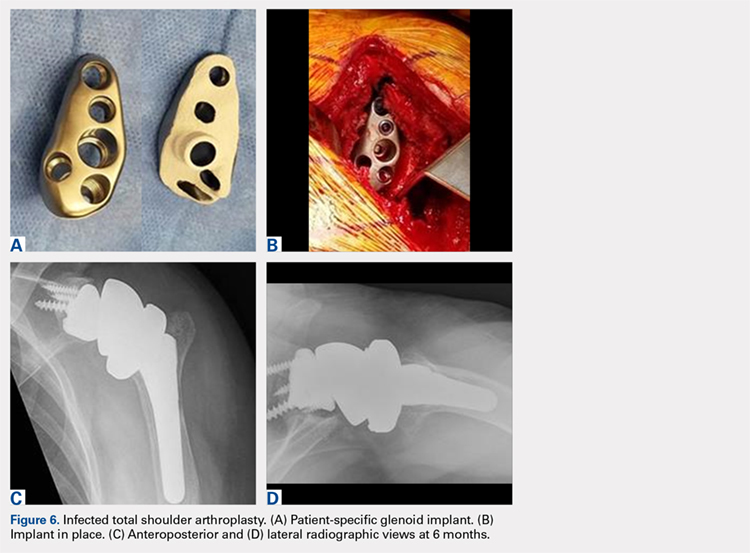

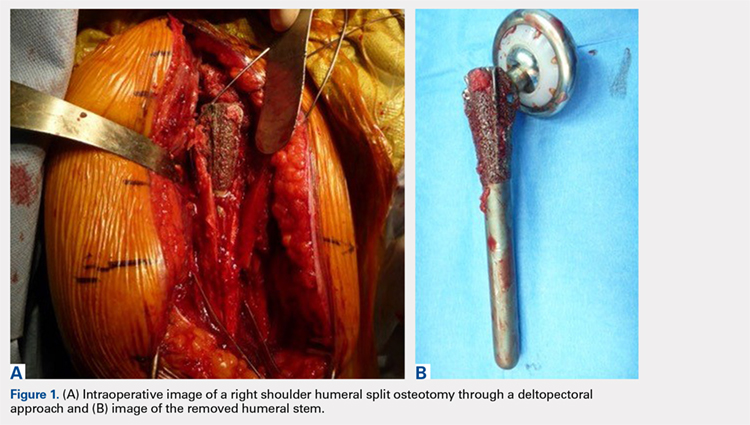

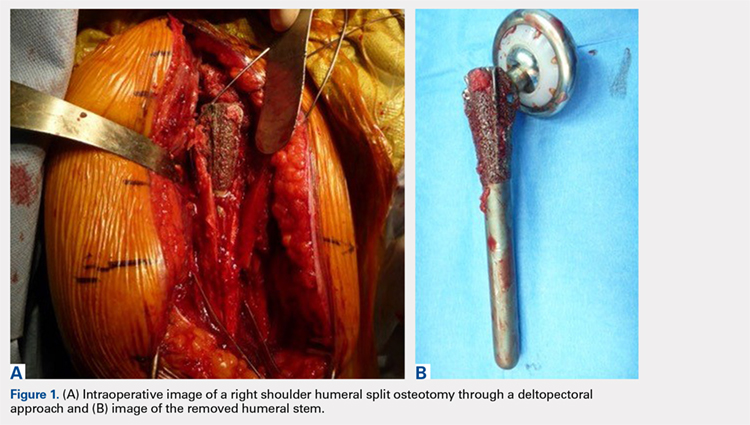

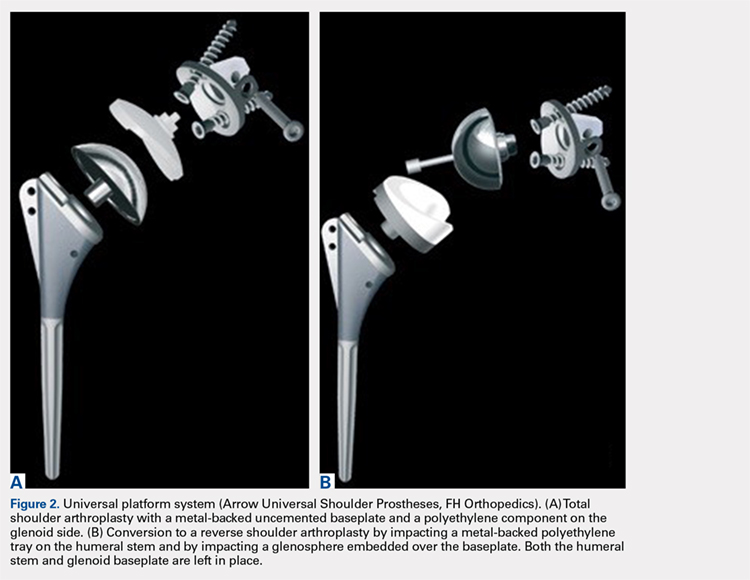

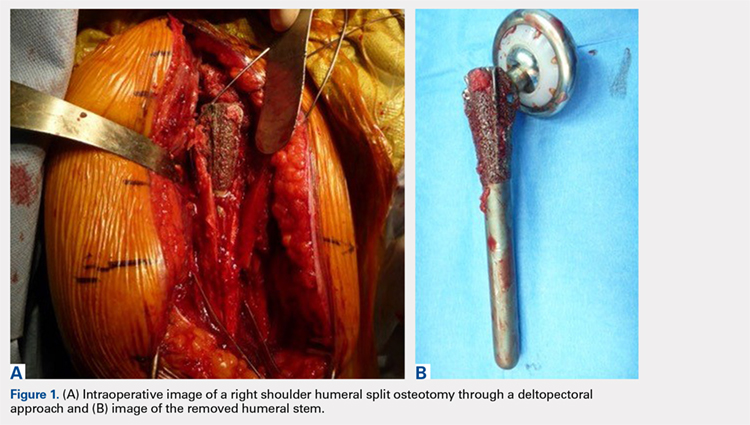

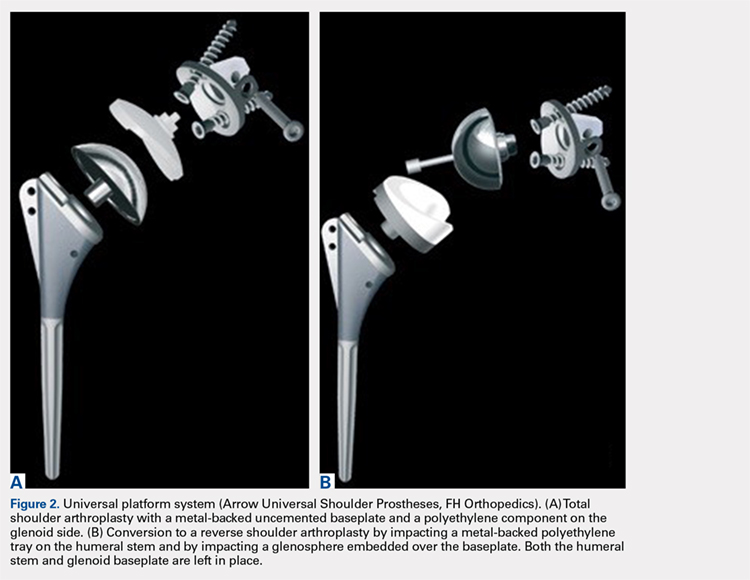

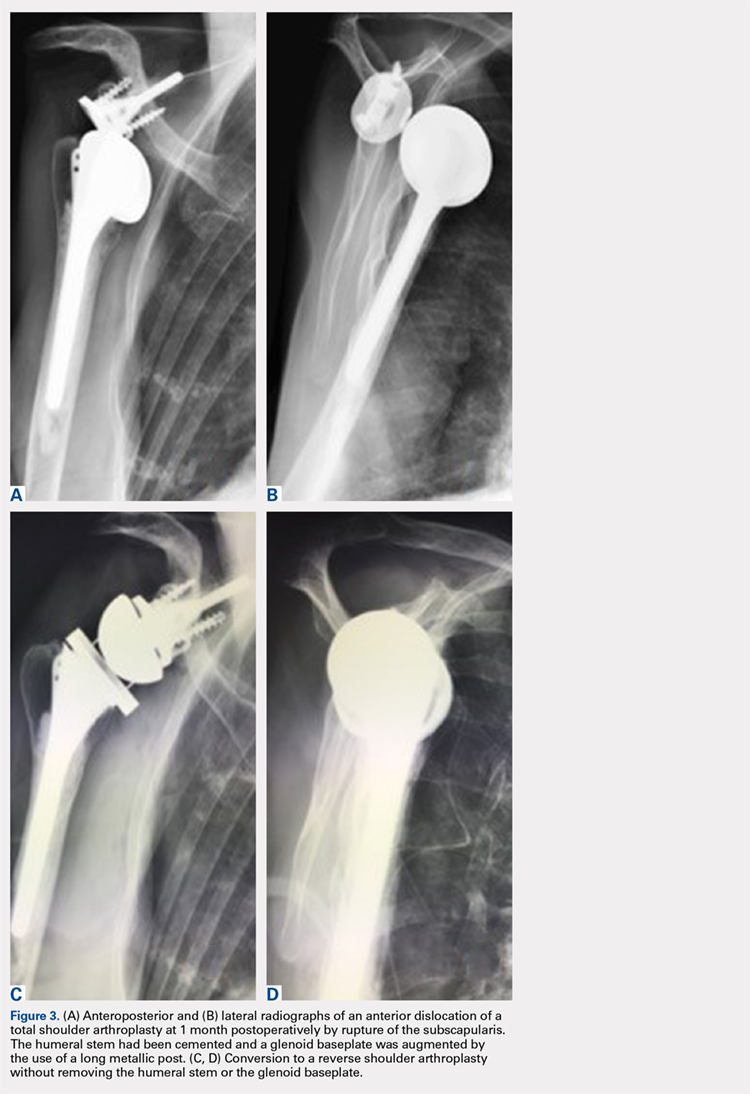

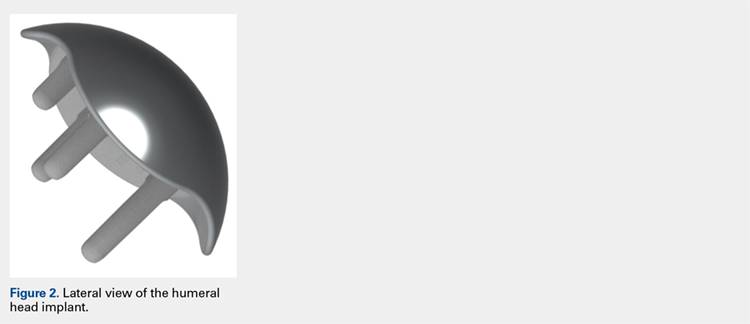

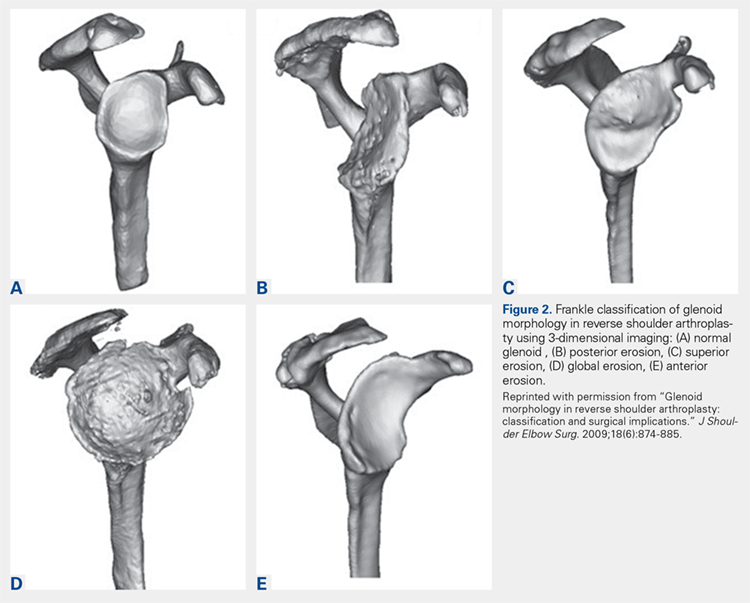

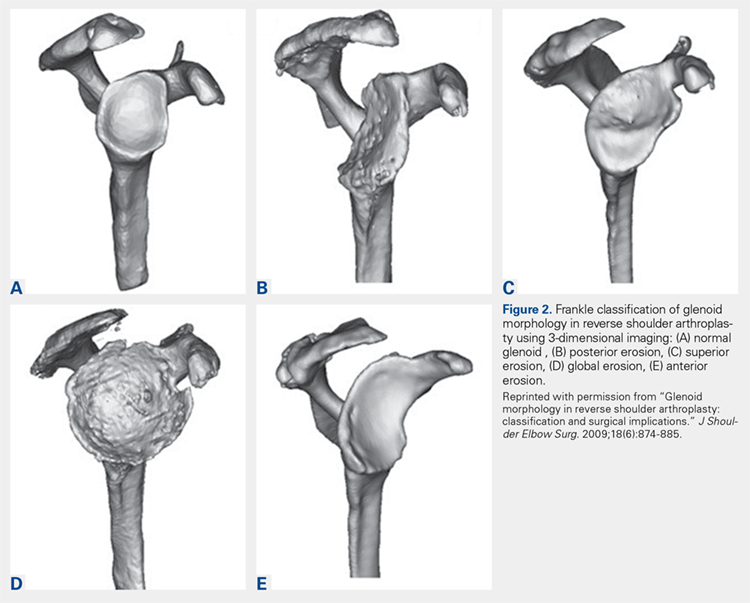

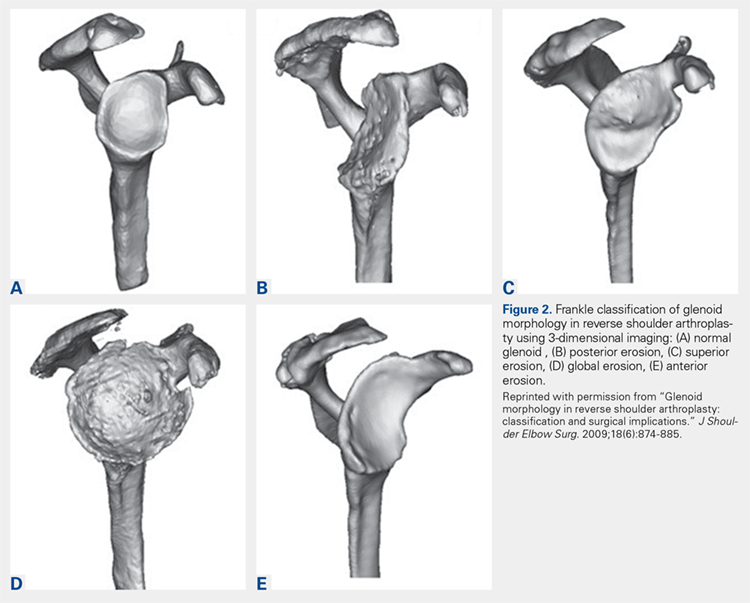

The Arthrex Virtual Implant Positioning (VIP) System is similar to other systems in that its 3-D planning software is based on CT images uploaded by the surgeon. The unique aspect of this system is that the guide pin is adjusted by the surgeon for each individual patient based on instructions generated by the planning software; however, after use, the instruments are resterilized and reused on subsequent patients (Figures 1A, 1B). In this manner, their instruments are reusable and allow custom adjustment for each patient with the ability to set the pin location and glenoid version in a patient-specific manner. This has the potential benefit of keeping costs down. For more complex deformity cases, the Arthrex VIP System can also 3-D-print a sterile model of the glenoid to help surgeons appreciate the deformity better (Figure 2).

DATA ON PATIENT-SPECIFIC INSTRUMENTS

Several studies have measured the accuracy of patient-specific guides and have compared the accuracy of patient-specific guides to that of traditional methods. Levy and colleagues23 investigated the accuracy of single-use patient-specific guides compared to that of preoperative plans. They used patient-specific guides on 14 cadaveric shoulders based on plans developed by virtual preoperative 3-D planning system using CT images. Once the guide pin was drilled using the patient-specific guide, they obtained a second CT scan to compare the accuracy of the patient-specific guide to the surgical plan generated preoperatively. They found that the translational accuracy of the starting point for the guide pin averaged 1.2 mm ± 0.7 mm, the accuracy of the inferior inclination was 1.2° ± 1.2°, and the accuracy of the glenoid version was 2.6° ± 1.7°. They concluded that patient-specific guides were highly accurate in reproducing the starting point, inclination, and version set on preoperative guides.

Walch and colleagues24 subsequently performed a similar study using 15 cadaveric scapulae without any other shoulder soft tissue or bone attached. They also used CT-scan-based 3-D planning software to plan their glenoid placement with a subsequently fabricated single-use patient-specific guide used to place a guide pin. They obtained a second CT scan after guide pin implantation and compared the preoperative plan with the subsequent guide pin. They found a mean entry point position error of 1.05 mm ± 0.31 mm, a mean inclination error of 1.42° ± 1.37°, and a mean version error of 1.64° ± 1.01°.

Continue to: Throckmorton and colleagues...

Throckmorton and colleagues21 used 70 cadaveric shoulders with radiographically confirmed arthritis and randomized them to undergo either anatomic or reverse TSA using either a patient-specific guide or standard instrumentation. Postoperative CT scans were used to evaluate the glenoid inclination, version, and starting point. They found that glenoid components implanted using patient-specific guides were more accurate than those placed using traditional instrumentation. The average deviation from intended inclination was 3° for patient-specific guides and 7° for traditional instrumentation, the average deviation from intended version was 5° for patient-specific guides and 8° for traditional instrumentation, and the average deviation in intended starting point was 2 mm for patient-specific guides and 3 mm for traditional instrumentation. They also analyzed significantly malpositioned components as defined by a variation in version or inclination of >10° or >4 mm in starting point. They found that 6 of their 35 glenoids using patient-specific guides were significantly malpositioned compared to 23 of 35 glenoids using traditional instrumentation. They concluded that patient-specific guides were more accurate and reduced the number of significantly malpositioned implants when compared with traditional instrumentation.

Early and colleagues25 analyzed the effect of severe glenoid bone defects on the accuracy of patient-specific guides compared with traditional guides. Using 10 cadaveric shoulders, they created anterior, central, or posterior glenoid defects using a reamer and chisel to erode the bone past the coracoid base. Subsequent CT scans were performed on the specimens, and patient-specific guides were fabricated and used for reverse TSA in 5 of the 10 specimens. A reverse TSA was performed using traditional instrumentation in the remaining 5 specimens. They found that the average deviation in inclination and version from preoperative plan was more accurate in the patient-specific guide cohort than that in the traditional instrument cohort, with an average deviation in inclination and version of 1.2° ± 1.2° and 1.8° ± 1.2° respectively for the cohort using patient-specific instruments vs 2.8° ± 1.8° and 3.5° ± 3° for the cohort using traditional instruments. They also found that their total bone screw lengths were longer in the patient-specific guide group than those in the traditional group, with screws averaging 52% of preoperatively planned length in the traditional instrument cohort vs 89% of preoperatively planned length in the patient-specific instrument cohort.

Gauci and colleagues26 measured the accuracy of patient-specific guides in vivo in 17 patients receiving TSA. Preoperative CT scans were used to fabricate patient-specific guides, and postoperative CT scans were used to measure version, inclination, and error of entry in comparison with the templated goals used to create patient-specific guides. They found a mean error in version and inclination of 3.4° and 1.8°, respectively, and a mean error in entry of 0.9 mm of translation on the glenoid. Dallalana and colleagues27 performed a very similar study on 20 patients and found a mean deviation in glenoid version of 1.8° ± 1.9°, a mean deviation in glenoid inclination of 1.3° ± 1.0°, a mean translation in anterior-posterior plane of 0.5 mm ± 0.3 mm, and a mean translation in the superior-inferior plane of 0.8 mm ± 0.5 mm.

Hendel and colleagues28 performed a randomized prospective clinical trial comparing patient-specific guides with traditional methods for glenoid insertion. They randomized 31 patients to receive a glenoid implant using either a patient-specific guide or traditional methods and compared glenoid retroversion and inclination with their preoperative plan. They found an average version deviation of 6.9° in the traditional method cohort and 4.3° in the patient-specific guide cohort. Their average deviation in inclination was 11.6° in the traditional method cohort and 2.9° in the patient-specific guide cohort. For patients with preoperative retroversion >16°, the average deviation was 10° in the standard surgical cohort and 1.2° in the patient-specific instrument cohort. Their data suggest that increasing preoperative retroversion leads to an increased version variation from preoperative plan.

Iannotti and colleagues29 randomly assigned 46 patients to preoperatively undergo either CT scan with 3-D templating of glenoid component without patient-specific guide fabrication or CT scan with 3-D templating and patient-specific guide fabrication prior to receiving a TSA. They recorded the postoperative inclination and version for each patient and compared them to those of a nonrandomized control group of 17 patients who underwent TSA using standard instrumentation. They found no difference between the cohorts with or without patient-specific guide use with regard to implant location, inclination, or version; however, they did find a difference between the combined 3-D templating cohort compared with their standard instrumentation cohort. They concluded that 3-D templating significantly improved the surgeons’ ability to correctly position the glenoid component with or without the fabrication and the use of a patient-specific guide.

Continue to: Denard and colleagues...

Denard and colleagues30 compared the preoperative glenoid version and inclination measurements obtained using the Blueprint 3D Planning + PSI software and the VIP System 3D planning software. They analyzed the preoperative CT scans of 63 consecutive patients undergoing either TSA or reverse TSA using both the Blueprint and the VIP System 3D planning software and compared the resulting native glenoid version and inclination measured by the software. They found a statistically significant difference (P = 0.04) in the version measurements provided by the different planning software; however, the differences found in inclination did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.463). In 19 of the 63 patients (30%), the version measurements between the systems were >5°, and in 29 of the 63 patients (46%), the inclination measurements between the systems were 5° or greater. In addition, 12 of the 63 patients (19%) had both version and inclination measurement differences of >5° between the systems. In total, they found that 35 of the 63 patients had at least 1 measurement that varied by >5° between the systems, and that in 15 patients (24%), 1 measurement varied by >10°. Their data demonstrate considerable variability in the preoperative measurements provided by different 3-D planning software systems, and that further study of each commercially available 3-D planning software system is needed to evaluate their accuracy.

CONCLUSION

Optimal outcomes following TSA and reverse TSA are dependent on proper implant position. Multiple studies have demonstrated improved accuracy in implant positioning with the use of patient-specific guides compared to that with traditional methods. Currently, there are no studies comparing the clinical outcomes of patient-specific guides to those of traditional methods of glenoid placement, and limited research had been done comparing the accuracy of each system’s 3-D planning software with each other and with standardized measurements of glenoid version and inclination. Further research is required to determine the accuracy of each commercially available 3-D planning software system as well as the clinical benefit of patient-specific guides in shoulder arthroplasty.

1. Churchill RS, Brems JJ, Kotschi H. Glenoid size, inclination, and version: an anatomic study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10(4):327-332. doi:10.1067/mse.2001.115269.

2. Norris TR, Iannotti JP. Functional outcome after shoulder arthroplasty for primary osteoarthritis: a multicenter study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11(2):130-135. doi:10.1067/mse.2002.121146.

3. Mullaji AB, Beddow FH, Lamb GH. CT measurement of glenoid erosion in arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76(3):384-388.

4. Walch G, Badet R, Boulahia A, Khoury A. Morphologic study of the glenoid in primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Arthroplasty. 1999;14(6):756-760.

5. RJ Friedman, KB Hawthorne, BM Genez. The use of computerized tomography in the measurement of glenoid version. J Bone Joint Surg. 1992;74(7):1032-1037. doi:10.2106/00004623-199274070-00009.

6. Yian EH, Werner CM, Nyffeler RW, et al. Radiographic and computed tomography analysis of cemented pegged polyethylene glenoid components in total shoulder replacement. J Bone Joint Surg. 2005;87(9):1928-1936. doi:10.2106/00004623-200509000-00004.

7. Hasan SS, Leith JM, Campbell B, Kapil R, Smith KL, Matsen FA. Characteristics of unsatisfactory shoulder arthroplasties. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11(5):431-441.

8. Hopkins AR, Hansen UN, Amis AA, Emery R. The effects of glenoid component alignment variations on cement mantle stresses in total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;13(6):668-675. doi:10.1016/S1058274604001399.

9. Iannotti JP, Greeson C, Downing D, Sabesan V, Bryan JA. Effect of glenoid deformity on glenoid component placement in primary shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(1):48-55. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2011.02.011.

10. Nyffeler RW, Jost B, Pfirrmann CWA, Gerber C. Measurement of glenoid version: conventional radiographs versus computed tomography scans. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12(5):493-496. doi:10.1016/S1058274603001812.

11. Hoenecke HR, Hermida JC, Flores-Hernandez C, D'Lima DD. Accuracy of CT-based measurements of glenoid version for total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(2):166-171. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2009.08.009.

12. Wall B, Nové-Josserand L, O'Connor DP, Edwards TB, Walch G. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: a review of results according to etiology. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(7):1476-1485. doi:10.2106/JBJS.F.00666.

13. Gutiérrez S, Comiskey 4, Charles A, Luo Z, Pupello DR, Frankle MA. Range of impingement-free abduction and adduction deficit after reverse shoulder arthroplasty. hierarchy of surgical and implant-design-related factors. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(12):2606-2615. doi:10.2106/JBJS.H.00012.

14. Roche CP, Marczuk Y, Wright TW, et al. Scapular notching and osteophyte formation after reverse shoulder replacement: Radiological analysis of implant position in male and female patients. Bone Joint J. 2013;95-B(4):530-535. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.95B4.30442.

15. Poon PC, Chou J, Young SW, Astley T. A comparison of concentric and eccentric glenospheres in reverse shoulder arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(16):e138. doi:10.2106/JBJS.M.00941.

16. Nyffeler RW, Werner CML, Gerber C. Biomechanical relevance of glenoid component positioning in the reverse delta III total shoulder prosthesis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(5):524-528. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2004.09.010.

17. Li X, Knutson Z, Choi D, et al. Effects of glenosphere positioning on impingement-free internal and external rotation after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(6):807-813. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2012.07.013.

18. Lévigne C, Boileau P, Favard L, et al. Scapular notching in reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(6):925-935. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2008.02.010.

19. Gutiérrez S, Walker M, Willis M, Pupello DR, Frankle MA. Effects of tilt and glenosphere eccentricity on baseplate/bone interface forces in a computational model, validated by a mechanical model, of reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(5):732-739. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2010.10.035.

20. Verborgt O, De Smedt T, Vanhees M, Clockaerts S, Parizel PM, Van Glabbeek F. Accuracy of placement of the glenoid component in reversed shoulder arthroplasty with and without navigation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(1):21-26. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2010.07.014.

21. Throckmorton TW, Gulotta LV, Bonnarens FO, et al. Patient-specific targeting guides compared with traditional instrumentation for glenoid component placement in shoulder arthroplasty: A multi-surgeon study in 70 arthritic cadaver specimens. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(6):965-971. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2014.10.013.

22. Kircher J, Wiedemann M, Magosch P, Lichtenberg S, Habermeyer P. Improved accuracy of glenoid positioning in total shoulder arthroplasty with intraoperative navigation: a prospective-randomized clinical study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(4):515-520. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2009.03.014.

23. Levy JC, Everding NG, Frankle MA, Keppler LJ. Accuracy of patient-specific guided glenoid baseplate positioning for reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(10):1563-1567. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2014.01.051.

24. Walch G, Vezeridis PS, Boileau P, Deransart P, Chaoui J. Three-dimensional planning and use of patient-specific guides improve glenoid component position: an in vitro study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(2):302-309. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2014.05.029.

25. Eraly K, Stoffelen D, Vander Sloten J, Jonkers I, Debeer P. A patient-specific guide for optimizing custom-made glenoid implantation in cases of severe glenoid defects: an in vitro study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25(5):837-845. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2015.09.034.

26. Gauci MO, Boileau P, Baba M, Chaoui J, Walch G. Patient-specific glenoid guides provide accuracy and reproducibility in total shoulder arthroplasty. Bone Joint J. 2016;98-B(8):1080-1085. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.98B8.37257.

27. Dallalana RJ, McMahon RA, East B, Geraghty L. Accuracy of patient-specific instrumentation in anatomic and reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. Int J Shoulder Surg. 2016;10(2):59-66. doi:10.4103/09736042.180717.

28. Hendel MD, Bryan JA, Barsoum WK, et al. Comparison of patient-specific instruments with standard surgical instruments in determining glenoid component position: a randomized prospective clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg. 2012;94(23):2167-2175. doi:10.2106/JBJS.K.01209.

29. Iannotti JP, Weiner S, Rodriguez E, et al. Three-dimensional imaging and templating improve glenoid implant positioning. J Bone Joint Surg. 2015;97(8):651-658. doi:10.2106/JBJS.N.00493.

30. Denard PJ, Provencher MT, Lädermann A, Romeo AA, Dines JS. Version and inclination obtained with 3D planning in total shoulder arthroplasty: do different programs produce the same results? SECEC-ESSSE Congress, Berlin 2017. 2017.

ABSTRACT

Optimal outcomes following total shoulder arthroplasty TSA and reverse shoulder arthroplasty RSA are dependent on proper implant position. Multiple cadaver studies have demonstrated improved accuracy of implant positioning with use of patient-specific guides/instrumentation compared to traditional methods. At this time, there are 3 commercially available single use patient-specific instrumentation systems and 1 commercially available reusable patient-specific instrumentation system. Currently though, there are no studies comparing the clinical outcomes of patient-specific guides to those of traditional methods of glenoid placement, and limited research has been done comparing the accuracy of each system’s 3-dimensional planning software. Future work is necessary to elucidate the ideal indications for the use of patient-specific guides and instrumentation, but it is likely, particularly in the setting of advanced glenoid deformity, that these systems will improve a surgeon's ability to put the implant in the best position possible.

Continue to: Optimal functional recovery...

Optimal functional recovery and implant longevity following both total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) and reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) depend, in large part, on proper placement of the glenoid component. Glenoid component malpositioning has an adverse effect on shoulder stability, range of motion (ROM), impingement, and glenoid implant longevity.

Traditionally, glenoid component positioning has been done manually by the surgeons based on their review of preoperative films and knowledge of glenoid anatomy. Anatomic studies have demonstrated high individual variability in the version of the native glenoid, thus making ideal placement of the initial glenoid guide pin difficult using standard guide pin guides.1

The following 2 methods have been described for improving the accuracy of glenoid guide pin insertion and subsequent glenoid implant placement: (1) computerized navigation and (2) patient-specific guides/instrumentation. Although navigated shoulder systems have demonstrated improved accuracy in glenoid placement compared with traditional methods, navigated systems require often large and expensive systems for implementation. The majority of them also require placement of guide pins or arrays on scapular bony landmarks, likely leading to an increase in operative time and possible iatrogenic complications, including fracture and pin site infections.

This review focuses on the use of patient-specific guides/instrumentation in shoulder arthroplasty. This includes the topic of proper glenoid and glenosphere placement as well as patient-specific guides/instrumentation and their accuracy.

GLENOID PLACEMENT

Glenohumeral osteoarthritis is the most common indication for TSA2 and commonly results in glenoid deformity. Using computed tomography (CT) scans of 45 arthritic shoulders and 19 normal shoulders, Mullaji and colleagues3 reported that the anteroposterior dimensions of the glenoid were increased by an average of 5 mm to 8 mm in osteoarthritic shoulders and by an average of 6 mm in rheumatoid arthritic shoulders compared to those in normal shoulders. A retrospective review of serial CT scans performed preoperatively on 113 osteoarthritic shoulders by Walch and colleagues4 demonstrated an average retroversion of 16°, and it has been the basis for the commonly used Walch classification of glenoid wear in osteoarthritis. Increased glenoid wear and increased glenoid retroversion make the proper restoration of glenoid version, inclination, and offset during shoulder arthroplasty more difficult and lead to increased glenoid component malpositioning.

Continue to: The ideal placement of the glenoid...

The ideal placement of the glenoid to maximize function, ROM, and implant longevity is in a mechanically neutral alignment with no superoinferior inclination1 and neutral version with respect to the transverse axis of the scapula.5

Improper glenoid positioning has an adverse effect on the functional results of shoulder arthroplasty. Yian and colleagues6 evaluated 47 cemented, pegged glenoids using standard radiography and CT scans at a mean follow-up of 40 months. They observed a significant correlation between increased glenoid component retroversion and lower Constant scores. Hasan and colleagues7 evaluated 139 consecutive patients who were dissatisfied with the result of their primary arthroplasty and found that 28% of them had at least 1 substantially malpositioned component identified either on radiography or during a revision surgery. They also found a significant correlation between stiffness, instability, and component malposition in their cohort.

Glenoid longevity is also dependent on proper component positioning, with the worst outcomes coming if the glenoid is malaligned with either superior or inferior inclination. Hasan and colleagues7 found that of their 74 patients with failed TSAs, 44 patients (59%) demonstrated mechanical loosening of their glenoid components either radiographically or during revision surgery, and 10 of their 44 patients with loose glenoids (23%) also had a malpositioned component. Using finite element analysis, Hopkins and colleagues8 analyzed the stresses through the cement mantle in glenoid prostheses that were centrally aligned, superiorly inclined, inferiorly inclined, anteverted, and retroverted. They found that malalignment of the glenoid increases the stresses through the cement mantle, leading to increased likelihood of mantle failure compared to that of centrally aligned glenoids, especially if there is malalignment with superior or inferior inclination or retroversion.

The accuracy of traditional methods of glenoid placement using an initial guide pin is limited and decreases with increasing amounts of glenoid deformity and retroversion. Iannotti and colleagues 9 investigated 13 patients undergoing TSA with an average preoperative retroversion of 13° and evaluated them using a 3-dimensional (3-D) surgical simulator. They found that the postoperative glenoid version was within 5° of ideal version in only 7 of their 13 patients (54%) and within 10° of ideal version in only 10 of their 13 patients (77%). In their study, the ideal version was considered to be the version as close to perpendicular to the plane of the scapula as possible with complete contact of the back side of the component on glenoid bone and maintenance of the center peg of the component within bone. In addition, they found that of their 7 patients with preoperative retroversion >10°, only 1 patient (14%) had a postoperative glenoid with <10° of retroversion with regard to the plane of the scapula and that all 6 of their patients with preoperative glenoid retroversion of <10° had a postoperative glenoid version of <10°.

Preoperative CT scans are much more accurate at determining glenoid version and thus how much glenoid correction is required to reestablish neutral version than plain radiography. Nyffeler and colleagues10 compared CT scans with axillary views for comparing glenoid version in 25 patients with no shoulder prosthesis present and 25 patients with a TSA in place. They found that glenoid retroversion was overestimated on plain radiographs in 86% of their patients with an average difference between CT and plain radiography of 6.4° and a maximum difference of 21°. They also found poor interobserver reliability in the plain radiography group and good interobserver reliability in the CT group, with coefficients of correlation of 0.77 for the plain radiography group and 0.93 for the CT group. Thus, they concluded that glenoid version cannot be accurately measured by plain radiography and that CT should be used. Hoenecke and colleagues11 subsequently evaluated 33 patients scheduled for TSA and found that CT version measurements made on 2-dimensional (2-D) CT slices compared with 3-D-reconstructed models of the same CT slices differed by an average of 5.1° because the axial CT slices were most often made perpendicular to the axis of the patient’s torso and not perpendicular to the body of the scapula. Accurate version assessment is critically important in planning for the degree of correction required to restore neutral glenoid version, and differences of 6.4° between CT assessment and plain radiography, and 5.1° between 2-D and 3-D CT scan assessments may lead to inadequate version correction intraoperatively and inferior postoperative results.

Continue to: GLENOSPHERE PLACEMENT

GLENOSPHERE PLACEMENT

The most common indication for reverse TSA is rotator cuff arthropathy characterized by rotator cuff dysfunction and end-stage glenohumeral arthritis.12 These patients require accurate and reproducible glenoid placement to optimize their postoperative range of motion and stability and minimize scapular notching.

Ideal glenosphere placement is the location and orientation that maximizes impingement-free ROM and stability while avoiding notching. Individual patient anatomy determines ideal placement; however, several guidelines for placement include inferior translation on the glenoid with neutral to inferior inclination. Gutiérrez and colleagues13 developed a computer model to assess the hierarchy of surgical factors affecting the ROM after a reverse TSA. They found that lateralizing the center of rotation gave the largest increase in impingement-free abduction, followed closely by inferior translation of the glenosphere on the glenoid.

Avoiding scapular notching is also a very important factor in ideal glenosphere placement. Scapular notching can be described as impingement of the humeral cup against the scapular neck during arm adduction and/or humeral rotation. Gutiérrez and colleagues13 also found that decreasing the neck shaft angle to create a more varus proximal humerus was the most important factor in increasing the impingement-free adduction. Roche and colleagues14 reviewed the radiographs of 151 patients who underwent primary reverse TSA at a mean follow-up of 28.3 months postoperatively; they found that 13.2% of their patients had a notch and that, on average, their patients who had no scapular notch had significantly more inferior glenosphere overhang than those who had a scapular notch. Poon and colleagues15 found that a glenosphere overhang of >3.5 mm prevented notching in their randomized control trial comparing concentrically and eccentrically placed glenospheres. Multiple other studies have demonstrated similar results and recommended inferior glenoid translation and inferior glenoid inclination to avoid scapular notching.16,17 Lévigne and colleagues18 retrospectively reviewed 337 reverse TSAs and observed a correlation between scapular notching and radiolucencies around the glenosphere component, with 14% of patients with scapular notching displaying radiolucencies vs 4% of patients without scapula notching displaying radiolucencies.

Several studies have also focused on the ideal amount of inferior glenoid inclination to maximize impingement-free ROM. Li and colleagues17 performed a computer simulation study on the Comprehensive Reverse Shoulder System (Zimmer Biomet) to determine impingement-free internal and external ROM with varying amounts of glenosphere offset, translation, and inclination. They found that progressive glenosphere inferior inclination up to 30° improved impingement-free rotational ROM at all degrees of scaption. Gutiérrez and colleagues19 used computer modeling to compare concentrically placed glenospheres in neutral inclination with eccentrically placed glenospheres in varying degrees of inclination. They found that the lowest forces across the baseplate occurred in the lateralized and inferiorly inclined glenospheres, and the highest forces occurred in the lateralized and superiorly inclined glenospheres. Together, these studies show that inferior glenoid inclination increases impingement-free ROM and, combined with lateralization, may result in improved glenosphere longevity due to significantly decreased forces at the RSA glenoid baseplate when compared to that at superiorly inclined glenoids.

The ideal amount of mediolateral glenosphere offset has not been well defined. Grammont design systems place the center of rotation of the glenosphere medial to the glenoid baseplate together with valgus humeral component neck shaft angles of around 155°. These design elements are believed to decrease shear stresses through the glenoid baseplate to the glenoid interface and improve shoulder stability, but they are also associated with reduced impingement-free ROM and increased rates of scapular notching.13 This effect is accentuated in patients with preexisting glenoid bone loss and/or congenitally short scapular necks that further medialize the glenosphere. Medialization of the glenosphere may also shorten the remaining rotator cuff muscles and result in decreased implant stability and external rotation strength. Several implant systems have options to vary the amount of lateral offset. The correct amount of lateral offset for each patient requires the understanding that improving patients’ impingement-free ROM by increasing the amount of lateral offset comes at the price of increasing the shear forces experienced by the interface between the glenoid baseplate and the glenoid. As glenoid fixation technology improves increased lateralization of glenospheres without increased rates of glenoid baseplate, loosening should improve the ROM after reverse TSA.

Continue to: Regardless of the intraoperative goals...

Regardless of the intraoperative goals for placement and orientation of the glenosphere components, it is vitally important to accurately and consistently meet those goals for achieving optimal patient outcomes. Verborgt and colleagues20 implanted 7 glenospheres in cadaveric specimens without any glenohumeral arthritis using standard techniques to evaluate the accuracy of glenosphere version and inclination. Their goal was to place components in neutral version and with 10° of inferior inclination. Their average glenoid version postoperatively was 8.7° of anteversion, and their average inclination was 0.9° of superior inclination. Throckmorton and colleagues21 randomized 35 cadaveric shoulders to receive either an anatomic or a reverse total shoulder prosthesis from high-, mid-, and low-volume surgeons. They found that components placed using traditional guides averaged 6° of deviation in version and 5° of deviation in inclination from their target values, with no significant differences between surgeons of different volumes.

PATIENT-SPECIFIC GUIDES/INSTRUMENTATION

Patient-specific guides/instrumentation and intraoperative navigation are the 2 techniques that have been used to improve the accuracy of glenoid and glenosphere placement. Both techniques require the use of high-resolution CT scans and computer software to determine the proper position for glenoid or glenosphere placement based on the patient’s individual anatomy. Patient-specific guides and instrumentation use the data acquired from a CT scan to generate a preoperative plan for the location and orientation of the glenoid baseplate. Once the surgeon approves the preoperative plan, a patient-specific guide is created using the patient’s glenoid as a reference for the location and orientation of the central guide pin. The location of the central guide pin on the glenoid determines the center of the glenoid baseplate, and the guide pin’s orientation determines the version and inclination of the glenoid or the glenosphere. Once the guide pin is placed in the glenoid, the remainder of the glenoid implantation uses the guide pin as a reference, and, in that way, patient-specific guides control the orientation of the glenoid at the time of surgery.

Intraoperative navigation uses an optical tracking system to determine the location and orientation of the central guide pin. Navigation systems require intraoperative calibration of the optical tracking system before they can track the location of implantation relative to bony landmarks on the patient’s scapula. Their advantage over patient-specific instrumentation (PSI) is that they do not require the manufacture of a custom guide; however, they may add significantly increased cost and surgical time due to the need for calibration prior to use and the cost of the navigation system along with any disposable components associated with it. Kircher and colleagues22 performed a prospective randomized clinical study of navigation-aided TSA compared with conventional TSA and found that operating time was significantly increased for the navigated group with an average operating room time of 169.5 minutes compared to 138 minutes for the conventional group. They also found that navigation had to be abandoned in 37.5% of their navigated patients due to technical errors during glenoid referencing.

COMMERCIAL PATIENT-SPECIFIC INSTRUMENTATION SYSTEMS

The 2 types of PSI that are currently available are single-use PSI and reusable PSI. The single-use PSI involves the fabrication of unique guides based on surgeon-approved preoperative plans generated by computer-software-processed preoperative CT scans. The guides are fabricated to rest on the glenoid articular surface and direct the guide pin to the correct location and in the correct direction to place the glenoid baseplate in the desired position with the desired version and inclination. Most of these systems also provide a 3-D model of the patient’s glenoid so that surgeons can visualize glenoid deformities and the correct guide placement on the glenoid. Single-use PSI systems are available from DJO Global, Wright Medical Group, and Zimmer Biomet. The second category of PSI is reusable and is available from Arthrex. The guide pin for this system is adjusted to fit individual patient anatomy and guide the guide pin into the glenoid in a location and orientation preplanned on the CT-scan-based computer software or using a 3-D model of the patient’s glenoid (Table).

Table. Details of Available Patient-Specific Instrumentation Systems

| System | Manufacturer | Single-Use/Reusable | Guides |

| MatchPoint System | DJO Global | Single-use | Central guide pin |

| Blueprint 3D Planning + PSI | Wright Medical Group | Single-use | Central guide pin |

| Zimmer Patient Specific Instruments Shoulder | Zimmer Biomet | Single-use | Central guide pin, reaming guide, roll guide, screw drill guide |

| Virtual Implant Positioning System | Arthrex | Reusable | Central guide pin |

The DJO Global patient-specific guide is termed as the MatchPoint System. This system creates 3-D renderings of the scapula and allows the surgeon to manipulate the glenoid baseplate on the scapula. The surgeon chooses the glenoid baseplate, location, version, and inclination on the computerized 3-D model. The system then fabricates a guide pin matching the computerized template that references the patient’s glenoid surface with a hook to orient it against the coracoid. A 3-D model of the glenoid is also provided along with the customized guide pin.

Continue to: Blueprint 3D Planning + PSI...

Blueprint 3D Planning + PSI (Wright Medical Group) allows custom placement of the glenoid version, inclination, and position on computerized 3-D models of the patient’s scapula. This PSI references the glenoid with 4 feet that captures the edge of the patient’s glenoid at specific locations and is unique because it allows the surgeon to control where on the glenoid edge to 4 feet contact as long as 1 foot is placed on the posterior edge of the glenoid and the remaining 3 feet are placed on the anterior edge of the glenoid. A 3-D model of the glenoid is also provided with this guide.

The Zimmer Biomet patient-specific guide is termed as the Zimmer Patient Specific Instruments Shoulder. Its computer software allows custom placement of the glenoid as well, but it also includes computerized customization of the reaming depth, screw angles, and screw lengths to optimize fixation. Their system includes a central guide pin to set the glenoid baseplate’s location and orientation, a reaming guide to control reaming depth and direction, a roll guide to control the glenoid baseplate’s rotation, and a drill guide to control the screw direction. They also provide a 3-D model of the glenoid.

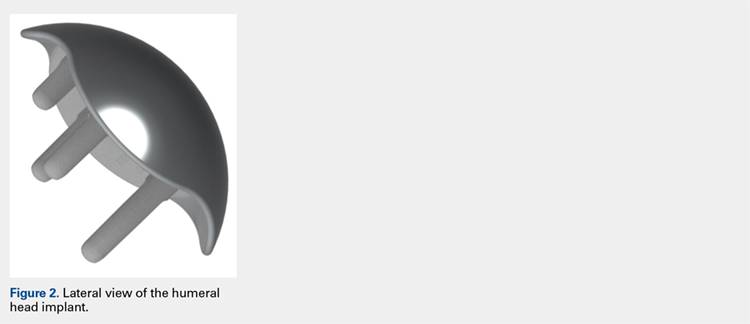

The Arthrex Virtual Implant Positioning (VIP) System is similar to other systems in that its 3-D planning software is based on CT images uploaded by the surgeon. The unique aspect of this system is that the guide pin is adjusted by the surgeon for each individual patient based on instructions generated by the planning software; however, after use, the instruments are resterilized and reused on subsequent patients (Figures 1A, 1B). In this manner, their instruments are reusable and allow custom adjustment for each patient with the ability to set the pin location and glenoid version in a patient-specific manner. This has the potential benefit of keeping costs down. For more complex deformity cases, the Arthrex VIP System can also 3-D-print a sterile model of the glenoid to help surgeons appreciate the deformity better (Figure 2).

DATA ON PATIENT-SPECIFIC INSTRUMENTS

Several studies have measured the accuracy of patient-specific guides and have compared the accuracy of patient-specific guides to that of traditional methods. Levy and colleagues23 investigated the accuracy of single-use patient-specific guides compared to that of preoperative plans. They used patient-specific guides on 14 cadaveric shoulders based on plans developed by virtual preoperative 3-D planning system using CT images. Once the guide pin was drilled using the patient-specific guide, they obtained a second CT scan to compare the accuracy of the patient-specific guide to the surgical plan generated preoperatively. They found that the translational accuracy of the starting point for the guide pin averaged 1.2 mm ± 0.7 mm, the accuracy of the inferior inclination was 1.2° ± 1.2°, and the accuracy of the glenoid version was 2.6° ± 1.7°. They concluded that patient-specific guides were highly accurate in reproducing the starting point, inclination, and version set on preoperative guides.

Walch and colleagues24 subsequently performed a similar study using 15 cadaveric scapulae without any other shoulder soft tissue or bone attached. They also used CT-scan-based 3-D planning software to plan their glenoid placement with a subsequently fabricated single-use patient-specific guide used to place a guide pin. They obtained a second CT scan after guide pin implantation and compared the preoperative plan with the subsequent guide pin. They found a mean entry point position error of 1.05 mm ± 0.31 mm, a mean inclination error of 1.42° ± 1.37°, and a mean version error of 1.64° ± 1.01°.

Continue to: Throckmorton and colleagues...

Throckmorton and colleagues21 used 70 cadaveric shoulders with radiographically confirmed arthritis and randomized them to undergo either anatomic or reverse TSA using either a patient-specific guide or standard instrumentation. Postoperative CT scans were used to evaluate the glenoid inclination, version, and starting point. They found that glenoid components implanted using patient-specific guides were more accurate than those placed using traditional instrumentation. The average deviation from intended inclination was 3° for patient-specific guides and 7° for traditional instrumentation, the average deviation from intended version was 5° for patient-specific guides and 8° for traditional instrumentation, and the average deviation in intended starting point was 2 mm for patient-specific guides and 3 mm for traditional instrumentation. They also analyzed significantly malpositioned components as defined by a variation in version or inclination of >10° or >4 mm in starting point. They found that 6 of their 35 glenoids using patient-specific guides were significantly malpositioned compared to 23 of 35 glenoids using traditional instrumentation. They concluded that patient-specific guides were more accurate and reduced the number of significantly malpositioned implants when compared with traditional instrumentation.

Early and colleagues25 analyzed the effect of severe glenoid bone defects on the accuracy of patient-specific guides compared with traditional guides. Using 10 cadaveric shoulders, they created anterior, central, or posterior glenoid defects using a reamer and chisel to erode the bone past the coracoid base. Subsequent CT scans were performed on the specimens, and patient-specific guides were fabricated and used for reverse TSA in 5 of the 10 specimens. A reverse TSA was performed using traditional instrumentation in the remaining 5 specimens. They found that the average deviation in inclination and version from preoperative plan was more accurate in the patient-specific guide cohort than that in the traditional instrument cohort, with an average deviation in inclination and version of 1.2° ± 1.2° and 1.8° ± 1.2° respectively for the cohort using patient-specific instruments vs 2.8° ± 1.8° and 3.5° ± 3° for the cohort using traditional instruments. They also found that their total bone screw lengths were longer in the patient-specific guide group than those in the traditional group, with screws averaging 52% of preoperatively planned length in the traditional instrument cohort vs 89% of preoperatively planned length in the patient-specific instrument cohort.

Gauci and colleagues26 measured the accuracy of patient-specific guides in vivo in 17 patients receiving TSA. Preoperative CT scans were used to fabricate patient-specific guides, and postoperative CT scans were used to measure version, inclination, and error of entry in comparison with the templated goals used to create patient-specific guides. They found a mean error in version and inclination of 3.4° and 1.8°, respectively, and a mean error in entry of 0.9 mm of translation on the glenoid. Dallalana and colleagues27 performed a very similar study on 20 patients and found a mean deviation in glenoid version of 1.8° ± 1.9°, a mean deviation in glenoid inclination of 1.3° ± 1.0°, a mean translation in anterior-posterior plane of 0.5 mm ± 0.3 mm, and a mean translation in the superior-inferior plane of 0.8 mm ± 0.5 mm.

Hendel and colleagues28 performed a randomized prospective clinical trial comparing patient-specific guides with traditional methods for glenoid insertion. They randomized 31 patients to receive a glenoid implant using either a patient-specific guide or traditional methods and compared glenoid retroversion and inclination with their preoperative plan. They found an average version deviation of 6.9° in the traditional method cohort and 4.3° in the patient-specific guide cohort. Their average deviation in inclination was 11.6° in the traditional method cohort and 2.9° in the patient-specific guide cohort. For patients with preoperative retroversion >16°, the average deviation was 10° in the standard surgical cohort and 1.2° in the patient-specific instrument cohort. Their data suggest that increasing preoperative retroversion leads to an increased version variation from preoperative plan.

Iannotti and colleagues29 randomly assigned 46 patients to preoperatively undergo either CT scan with 3-D templating of glenoid component without patient-specific guide fabrication or CT scan with 3-D templating and patient-specific guide fabrication prior to receiving a TSA. They recorded the postoperative inclination and version for each patient and compared them to those of a nonrandomized control group of 17 patients who underwent TSA using standard instrumentation. They found no difference between the cohorts with or without patient-specific guide use with regard to implant location, inclination, or version; however, they did find a difference between the combined 3-D templating cohort compared with their standard instrumentation cohort. They concluded that 3-D templating significantly improved the surgeons’ ability to correctly position the glenoid component with or without the fabrication and the use of a patient-specific guide.

Continue to: Denard and colleagues...

Denard and colleagues30 compared the preoperative glenoid version and inclination measurements obtained using the Blueprint 3D Planning + PSI software and the VIP System 3D planning software. They analyzed the preoperative CT scans of 63 consecutive patients undergoing either TSA or reverse TSA using both the Blueprint and the VIP System 3D planning software and compared the resulting native glenoid version and inclination measured by the software. They found a statistically significant difference (P = 0.04) in the version measurements provided by the different planning software; however, the differences found in inclination did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.463). In 19 of the 63 patients (30%), the version measurements between the systems were >5°, and in 29 of the 63 patients (46%), the inclination measurements between the systems were 5° or greater. In addition, 12 of the 63 patients (19%) had both version and inclination measurement differences of >5° between the systems. In total, they found that 35 of the 63 patients had at least 1 measurement that varied by >5° between the systems, and that in 15 patients (24%), 1 measurement varied by >10°. Their data demonstrate considerable variability in the preoperative measurements provided by different 3-D planning software systems, and that further study of each commercially available 3-D planning software system is needed to evaluate their accuracy.

CONCLUSION

Optimal outcomes following TSA and reverse TSA are dependent on proper implant position. Multiple studies have demonstrated improved accuracy in implant positioning with the use of patient-specific guides compared to that with traditional methods. Currently, there are no studies comparing the clinical outcomes of patient-specific guides to those of traditional methods of glenoid placement, and limited research had been done comparing the accuracy of each system’s 3-D planning software with each other and with standardized measurements of glenoid version and inclination. Further research is required to determine the accuracy of each commercially available 3-D planning software system as well as the clinical benefit of patient-specific guides in shoulder arthroplasty.

ABSTRACT

Optimal outcomes following total shoulder arthroplasty TSA and reverse shoulder arthroplasty RSA are dependent on proper implant position. Multiple cadaver studies have demonstrated improved accuracy of implant positioning with use of patient-specific guides/instrumentation compared to traditional methods. At this time, there are 3 commercially available single use patient-specific instrumentation systems and 1 commercially available reusable patient-specific instrumentation system. Currently though, there are no studies comparing the clinical outcomes of patient-specific guides to those of traditional methods of glenoid placement, and limited research has been done comparing the accuracy of each system’s 3-dimensional planning software. Future work is necessary to elucidate the ideal indications for the use of patient-specific guides and instrumentation, but it is likely, particularly in the setting of advanced glenoid deformity, that these systems will improve a surgeon's ability to put the implant in the best position possible.

Continue to: Optimal functional recovery...

Optimal functional recovery and implant longevity following both total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) and reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) depend, in large part, on proper placement of the glenoid component. Glenoid component malpositioning has an adverse effect on shoulder stability, range of motion (ROM), impingement, and glenoid implant longevity.

Traditionally, glenoid component positioning has been done manually by the surgeons based on their review of preoperative films and knowledge of glenoid anatomy. Anatomic studies have demonstrated high individual variability in the version of the native glenoid, thus making ideal placement of the initial glenoid guide pin difficult using standard guide pin guides.1

The following 2 methods have been described for improving the accuracy of glenoid guide pin insertion and subsequent glenoid implant placement: (1) computerized navigation and (2) patient-specific guides/instrumentation. Although navigated shoulder systems have demonstrated improved accuracy in glenoid placement compared with traditional methods, navigated systems require often large and expensive systems for implementation. The majority of them also require placement of guide pins or arrays on scapular bony landmarks, likely leading to an increase in operative time and possible iatrogenic complications, including fracture and pin site infections.

This review focuses on the use of patient-specific guides/instrumentation in shoulder arthroplasty. This includes the topic of proper glenoid and glenosphere placement as well as patient-specific guides/instrumentation and their accuracy.

GLENOID PLACEMENT

Glenohumeral osteoarthritis is the most common indication for TSA2 and commonly results in glenoid deformity. Using computed tomography (CT) scans of 45 arthritic shoulders and 19 normal shoulders, Mullaji and colleagues3 reported that the anteroposterior dimensions of the glenoid were increased by an average of 5 mm to 8 mm in osteoarthritic shoulders and by an average of 6 mm in rheumatoid arthritic shoulders compared to those in normal shoulders. A retrospective review of serial CT scans performed preoperatively on 113 osteoarthritic shoulders by Walch and colleagues4 demonstrated an average retroversion of 16°, and it has been the basis for the commonly used Walch classification of glenoid wear in osteoarthritis. Increased glenoid wear and increased glenoid retroversion make the proper restoration of glenoid version, inclination, and offset during shoulder arthroplasty more difficult and lead to increased glenoid component malpositioning.

Continue to: The ideal placement of the glenoid...

The ideal placement of the glenoid to maximize function, ROM, and implant longevity is in a mechanically neutral alignment with no superoinferior inclination1 and neutral version with respect to the transverse axis of the scapula.5

Improper glenoid positioning has an adverse effect on the functional results of shoulder arthroplasty. Yian and colleagues6 evaluated 47 cemented, pegged glenoids using standard radiography and CT scans at a mean follow-up of 40 months. They observed a significant correlation between increased glenoid component retroversion and lower Constant scores. Hasan and colleagues7 evaluated 139 consecutive patients who were dissatisfied with the result of their primary arthroplasty and found that 28% of them had at least 1 substantially malpositioned component identified either on radiography or during a revision surgery. They also found a significant correlation between stiffness, instability, and component malposition in their cohort.

Glenoid longevity is also dependent on proper component positioning, with the worst outcomes coming if the glenoid is malaligned with either superior or inferior inclination. Hasan and colleagues7 found that of their 74 patients with failed TSAs, 44 patients (59%) demonstrated mechanical loosening of their glenoid components either radiographically or during revision surgery, and 10 of their 44 patients with loose glenoids (23%) also had a malpositioned component. Using finite element analysis, Hopkins and colleagues8 analyzed the stresses through the cement mantle in glenoid prostheses that were centrally aligned, superiorly inclined, inferiorly inclined, anteverted, and retroverted. They found that malalignment of the glenoid increases the stresses through the cement mantle, leading to increased likelihood of mantle failure compared to that of centrally aligned glenoids, especially if there is malalignment with superior or inferior inclination or retroversion.

The accuracy of traditional methods of glenoid placement using an initial guide pin is limited and decreases with increasing amounts of glenoid deformity and retroversion. Iannotti and colleagues 9 investigated 13 patients undergoing TSA with an average preoperative retroversion of 13° and evaluated them using a 3-dimensional (3-D) surgical simulator. They found that the postoperative glenoid version was within 5° of ideal version in only 7 of their 13 patients (54%) and within 10° of ideal version in only 10 of their 13 patients (77%). In their study, the ideal version was considered to be the version as close to perpendicular to the plane of the scapula as possible with complete contact of the back side of the component on glenoid bone and maintenance of the center peg of the component within bone. In addition, they found that of their 7 patients with preoperative retroversion >10°, only 1 patient (14%) had a postoperative glenoid with <10° of retroversion with regard to the plane of the scapula and that all 6 of their patients with preoperative glenoid retroversion of <10° had a postoperative glenoid version of <10°.

Preoperative CT scans are much more accurate at determining glenoid version and thus how much glenoid correction is required to reestablish neutral version than plain radiography. Nyffeler and colleagues10 compared CT scans with axillary views for comparing glenoid version in 25 patients with no shoulder prosthesis present and 25 patients with a TSA in place. They found that glenoid retroversion was overestimated on plain radiographs in 86% of their patients with an average difference between CT and plain radiography of 6.4° and a maximum difference of 21°. They also found poor interobserver reliability in the plain radiography group and good interobserver reliability in the CT group, with coefficients of correlation of 0.77 for the plain radiography group and 0.93 for the CT group. Thus, they concluded that glenoid version cannot be accurately measured by plain radiography and that CT should be used. Hoenecke and colleagues11 subsequently evaluated 33 patients scheduled for TSA and found that CT version measurements made on 2-dimensional (2-D) CT slices compared with 3-D-reconstructed models of the same CT slices differed by an average of 5.1° because the axial CT slices were most often made perpendicular to the axis of the patient’s torso and not perpendicular to the body of the scapula. Accurate version assessment is critically important in planning for the degree of correction required to restore neutral glenoid version, and differences of 6.4° between CT assessment and plain radiography, and 5.1° between 2-D and 3-D CT scan assessments may lead to inadequate version correction intraoperatively and inferior postoperative results.

Continue to: GLENOSPHERE PLACEMENT

GLENOSPHERE PLACEMENT

The most common indication for reverse TSA is rotator cuff arthropathy characterized by rotator cuff dysfunction and end-stage glenohumeral arthritis.12 These patients require accurate and reproducible glenoid placement to optimize their postoperative range of motion and stability and minimize scapular notching.

Ideal glenosphere placement is the location and orientation that maximizes impingement-free ROM and stability while avoiding notching. Individual patient anatomy determines ideal placement; however, several guidelines for placement include inferior translation on the glenoid with neutral to inferior inclination. Gutiérrez and colleagues13 developed a computer model to assess the hierarchy of surgical factors affecting the ROM after a reverse TSA. They found that lateralizing the center of rotation gave the largest increase in impingement-free abduction, followed closely by inferior translation of the glenosphere on the glenoid.

Avoiding scapular notching is also a very important factor in ideal glenosphere placement. Scapular notching can be described as impingement of the humeral cup against the scapular neck during arm adduction and/or humeral rotation. Gutiérrez and colleagues13 also found that decreasing the neck shaft angle to create a more varus proximal humerus was the most important factor in increasing the impingement-free adduction. Roche and colleagues14 reviewed the radiographs of 151 patients who underwent primary reverse TSA at a mean follow-up of 28.3 months postoperatively; they found that 13.2% of their patients had a notch and that, on average, their patients who had no scapular notch had significantly more inferior glenosphere overhang than those who had a scapular notch. Poon and colleagues15 found that a glenosphere overhang of >3.5 mm prevented notching in their randomized control trial comparing concentrically and eccentrically placed glenospheres. Multiple other studies have demonstrated similar results and recommended inferior glenoid translation and inferior glenoid inclination to avoid scapular notching.16,17 Lévigne and colleagues18 retrospectively reviewed 337 reverse TSAs and observed a correlation between scapular notching and radiolucencies around the glenosphere component, with 14% of patients with scapular notching displaying radiolucencies vs 4% of patients without scapula notching displaying radiolucencies.