User login

Shoulder Arthroplasty in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Population-Based Study Examining Utilization, Adverse Events, Length of Stay, and Cost

ABSTRACT

It has been suggested that the utilization of joint arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is decreasing; however, this observation is largely based upon evidence pertaining to lower-extremity joint arthroplasty. It remains unknown if these observed trends also hold true for shoulder arthroplasty. The purpose of this study is to utilize a nationally representative population database in the US to identify trends in the utilization of shoulder arthroplasty among patients with RA. Secondarily, we sought to determine the rate of early adverse events, length of stay, and hospitalization costs associated with RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty and to compare these outcomes to those of patients without a diagnosis of RA undergoing shoulder arthroplasty. Using a large population database in the US, we determined the annual rates of shoulder arthroplasty (overall and individual) in RA patients between 2002 and 2011. Early adverse events, length of stay, and hospitalization costs were determined and compared with those of non-RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty. Overall, we identified 332,593 patients who underwent shoulder arthroplasty between 2002 and 2011, of whom 17,883 patients (5.4%) had a diagnosis of RA. Over the study period, there was a significant increase in the utilization of shoulder arthroplasty in RA patients, particularly total shoulder arthroplasty. Over the same period, there was a significant increase in the number of RA patients who underwent shoulder arthroplasty with a diagnosis of rotator cuff disease. There were no significant differences in adverse events or mean hospitalization costs between RA and non-RA patients. Non-RA patients had a significantly shorter length of stay; however, the difference did not appear to be clinically significant. In conclusion, the utilization of shoulder arthroplasty in patients with RA significantly increased from 2002 to 2011, which may partly reflect a trend toward management of rotator cuff disease with arthroplasty rather than repair.

Continue to: It has been suggested...

It has been suggested that the utilization of total joint arthroplasty (TJA) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is decreasing over time;1 however, this observation is largely based upon evidence pertaining to lower extremity TJA.2 It remains unknown if these observed trends also hold true for shoulder arthroplasty, whereby the utilization of shoulder arthroplasty in RA patients is not limited to the management of end-stage inflammatory arthropathy. In this study, we used a nationally representative population database in the US to identify trends in the utilization of shoulder arthroplasty among patients with RA. As a secondary objective, we sought to determine the rate of early adverse events, length of stay, and hospitalization costs associated with RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty and compare these outcomes to those of patients without a diagnosis of RA undergoing shoulder arthroplasty. We hypothesize that the utilization of shoulder arthroplasty in RA patients would be decreasing, but adverse events, length of stay, and hospitalization costs would not differ between patients with and without RA undergoing shoulder arthroplasty.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) from 2002 to 2011.3 The NIS comprises a 20% stratified sample of all hospital discharges in the US. The NIS includes information about patient characteristics (age, sex, insurance status, and medical comorbidities) and hospitalization outcomes (adverse events, costs, and length of stay). The NIS allows identification of hospitalizations according to procedures and diagnoses using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes. Given the anonymity of this study, it was exempt from Institutional Review Board ethics approval.

Hospitalizations were selected for the study based on ICD-9-CM procedural codes for hemiarthroplasty (81.81), anatomic total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) (81.80), and reverse TSA (81.88). These patients were then stratified by an ICD-9-CM diagnosis of RA (714.X). We also utilized ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes to determine the presence of rotator cuff pathology at the time of shoulder arthroplasty (726.13, 727.61, 840.4) and to exclude patients with a history of trauma (812.X, 716.11, 733.8X). In a separate analysis, all patients in the NIS database with an ICD-9-CM diagnosis of RA were identified for each calendar year of the study, and a national estimate of RA patients was generated annually to assess overall and individual utilization rates of shoulder arthroplasty in this population (the national estimate served as the denominator).

Preoperative patient data withdrawn from the NIS included age, sex, insurance status, and medical comorbidities. An Elixhauser Comorbidity Index (ECI) was generated for each patient based on the presence of 29 comorbid conditions. The ECI was chosen because of its capacity to accurately predict mortality and represent the patient burden of comorbidities in similar administrative database studies.4-6

Early adverse events were also chosen based on ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes (Appendix A), and included the following: death, acute kidney injury, cardiac arrest, thromboembolic event, myocardial infarction, peripheral nerve injury, pneumonia, sepsis, stroke, surgical site infection, urinary tract infection, and wound dehiscence. The overall adverse event rate was defined as the occurrence of ≥1 of the above adverse events in a patient.

Appendix A. ICD-9-CM Codes Corresponding to Postoperative Adverse Events

Event | ICD-9-CM |

Acute kidney injury | 584.5-584.9 |

Cardiac arrest | 427.41, 427.5 |

Thromboembolic event | 453.2-453.4, 453.82-453.86, 415.1 |

Myocardial Infarction | 410.00-410.92 |

Peripheral nerve injury | 953.0-953.9 954.0-954.9, 955.0-955.9, 956.0-956.9 |

Pneumonia | 480.0-480.9, 481, 482.0-482.9, 483.0-483.8, 484.1-484.8, 485, 486 |

Sepsis | 038.0-038.9, 112.5, 785.52, 995.91, 995.92 |

Stroke | 430, 432, 433.01-434.91, 997.02 |

Surgical site infection | 998.51, 998.59, 996.67 |

Urinary tract infection | 599 |

Wound dehiscence | 998.30-998.33 |

Abbreviation: ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification

Length of stay and total hospital charges were available for each patient. Length of stay represents the number of calendar days a patient stayed in the hospital. All hospital charges were converted to hospitalization costs using the HCUP Cost-to-Charge Ratio Files. All hospitalization costs were adjusted for inflation using the US Bureau of Labor statistics yearly inflation calculator to represent charges in the year 2011, which was the final and most recent year in this study.

Continue to: Statistical analysis...

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata version 13.1 (StataCorp, LP). All analyses took into account the complex survey design of the NIS. Discharge weights, strata, and cluster variables were included to correctly estimate variance and to produce national estimates from the stratified sample. Pearson’s chi-squared test was used to compare age, sex, ECI, and insurance status between RA and non-RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty.

Bivariate and multivariate logistic regressions were subsequently used to compare the rates of adverse events between RA and non-RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty (non-RA cases were used as the reference). Multivariate linear regressions were used to compare hospital length of stay and hospitalization costs between RA and non-RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty. The multivariate regressions were adjusted for baseline differences in age, sex, ECI, and insurance status. Cochran-Armitage tests for trend were used to assess trends over time. All tests were 2-tailed, and the statistical difference was established at a 2-sided α level of 0.05 (P < .05).

RESULTS

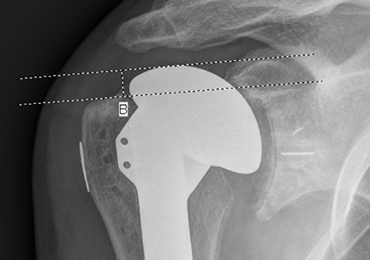

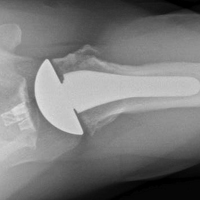

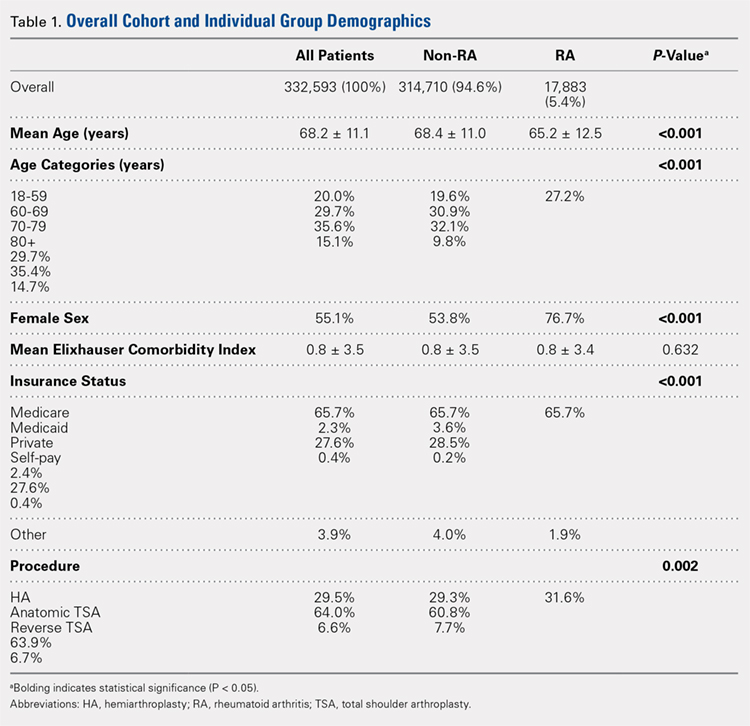

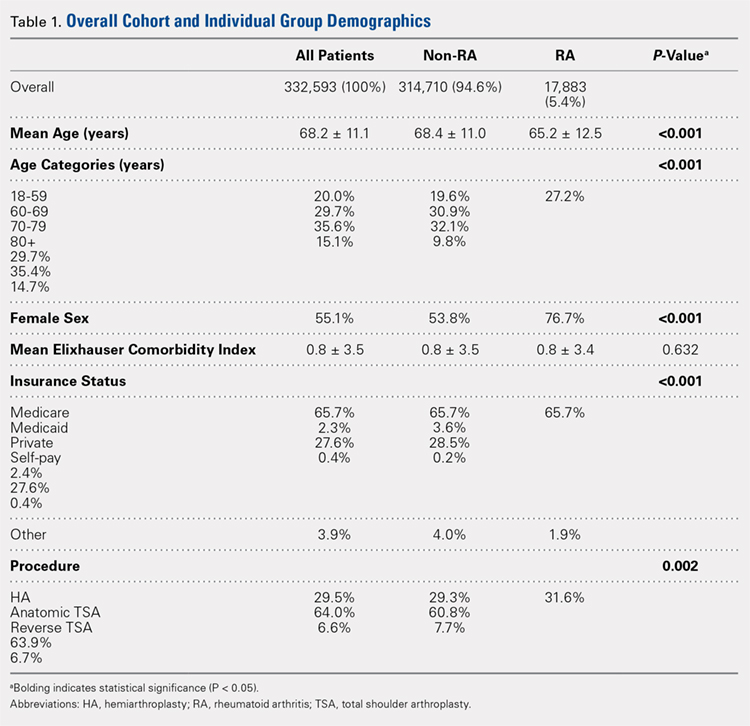

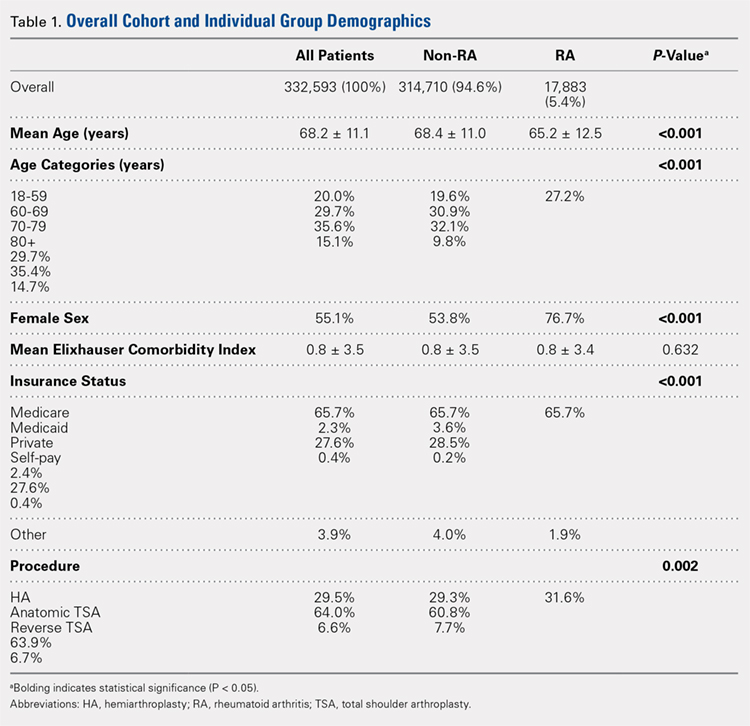

Overall, we identified 332,593 patients who underwent shoulder arthroplasty in the US between 2002 and 2011, of which 17,883 patients (5.4%) had a diagnosis of RA. In comparison with non-RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty, patients with RA at the time of shoulder arthroplasty were significantly younger (65.2 ± 12.5 years vs 68.4 ± 11.0 years, P < .001), included a significantly greater proportion of female patients (76.7% vs 53.8%, P < .001), and included a significantly higher proportion of patients with Medicaid insurance (3.6% vs 2.3%, P < .001). There were no significant differences in the mean ECI between patients with and without a diagnosis of RA (Table 1). As depicted in Table 1, there were significant differences in the utilization of specific shoulder arthroplasty types between patients with and without RA, whereby a significantly greater proportion of RA patients underwent hemiarthroplasty (HA) (31.6% vs 29.3%, P = .002) and reverse TSA (7.7% vs 6.6%, P = .002), whereas a significantly greater proportion of non-RA patients underwent anatomic SA (64.0% vs 60.8%, P = .002).

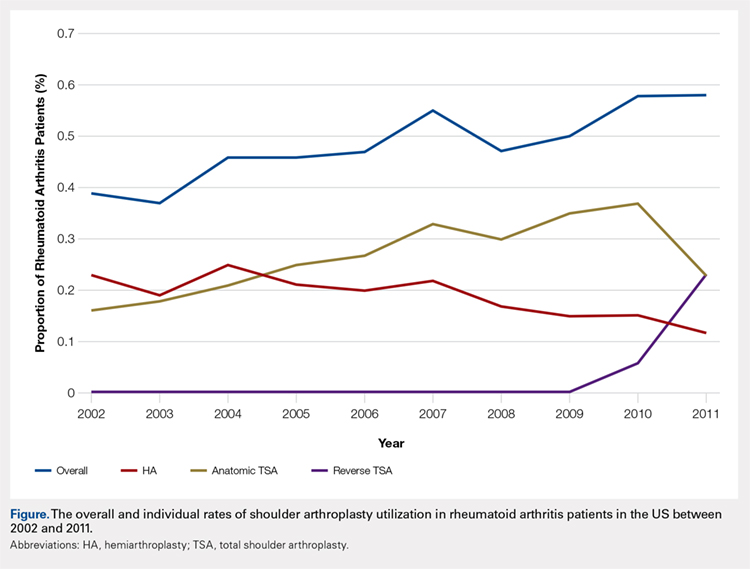

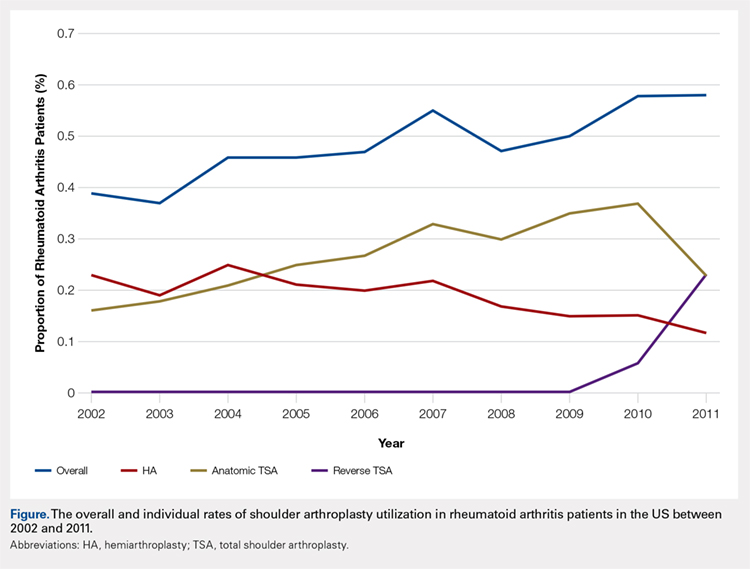

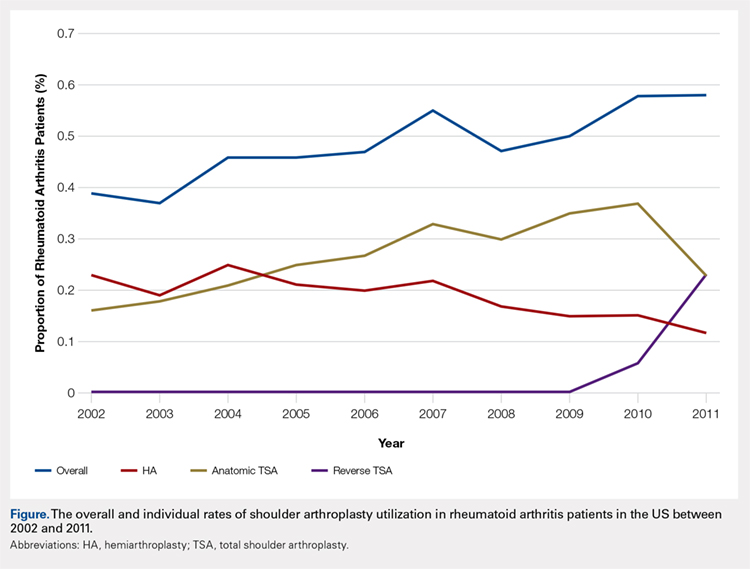

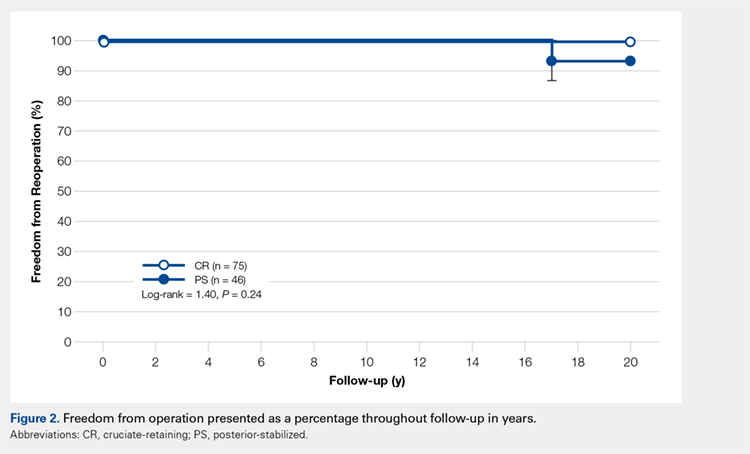

Over the study period from 2002 to 2011, there was a significant increase in the overall utilization of shoulder arthroplasty in RA patients, as indicated by both the absolute number and the proportion of patients with a diagnosis of RA (P < .001) (Table 2, Figure). More specifically, 0.39% of RA patients underwent shoulder arthroplasty in 2002, as compared with 0.58% of RA patients in 2011 (P < .001) (Table 2). With respect to specific arthroplasty types, there was an exponential rise in the utilization of reverse TSA beginning in 2010 and a corresponding decrease in the rates of both HA and anatomic TSA (Table 2, Figure). In addition to changes in shoulder arthroplasty utilization over time among RA patients, we also observed a significant increase in the number of RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty with a corresponding diagnosis of rotator cuff disease (9.7% in 2002 to 15.2% in 2011, P < .001).

Table 2. The Annual Utilization of Shoulder Arthroplasty Among Patients with a Diagnosis of Rheumatoid Arthritis.

Proportion of RA patients |

| ||||

Year | Overall Rate of Shoulder Arthroplastya | HA | Anatomic TSA | Reverse TSA | |

2002 | 0.39 | 0.23 | 0.16 | 0 | |

2003 | 0.37 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0 | |

2004 | 0.46 | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0 | |

2005 | 0.46 | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0 | |

2006 | 0.47 | 0.20 | 0.27 | 0 | |

2007 | 0.55 | 0.22 | 0.33 | 0 | |

2008 | 0.47 | 0.17 | 0.30 | 0 | |

2009 | 0.50 | 0.15 | 0.35 | 0 | |

2010 | 0.58 | 0.15 | 0.37 | 0.06 | |

2011 | 0.58 | 0.12 | 0.23 | 0.23 | |

Absolute number of RA patients |

| ||||

2002 | 1295 | 768 | 527 | 0 | |

2003 | 1247 | 650 | 597 | 0 | |

2004 | 1667 | 906 | 761 | 0 | |

2005 | 1722 | 776 | 946 | 0 | |

2006 | 1847 | 794 | 1053 | 0 | |

2007 | 2249 | 910 | 1339 | 0 | |

2008 | 2194 | 799 | 1395 | 0 | |

2009 | 2407 | 724 | 1683 | 0 | |

2010 | 2869 | 722 | 1857 | 290 | |

2011 | 3193 | 649 | 1261 | 1283 | |

aRate determined as number of RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty compared to the number of patients with an RA diagnosis in the stated calendar year.

Abbreviations: HA, hemiarthroplasty; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; TSA, total shoulder arthroplasty.

Continue to: Among patients with RA...

Among patients with RA undergoing shoulder arthroplasty, the overall rate of early adverse events was 3.12%, of which the most common early adverse events were urinary tract infections (1.8%), acute kidney injury (0.66%), and pneumonia (0.38%) (Table 3). As compared with patients without a diagnosis of RA undergoing shoulder arthroplasty, there were no significant differences in the overall and individual rates of early adverse events (Table 3).

Table 3. A Comparison of Early Adverse Events, Length of Stay, and Cost Between Patients With and Without Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) Undergoing Shoulder Arthroplasty

Comparison of Early Adverse Event Rates |

| ||||

| Non-RA Patients | RA Patients | Multivariate Logistic Regression | ||

Odds Ratio | P-Value | ||||

Overall adverse event rate | 3.02% | 3.12% | 1.0 | 0.83 | |

Specific adverse event rate |

|

|

|

| |

Death | 0.08% | 0.05% | 0.9 | 0.91 | |

Acute kidney injury | 0.85% | 0.66% | 0.9 | 0.59 | |

Cardiac arrest | 0.05% | 0.05% | 1.3 | 0.70 | |

Thromboembolic event | 0.01% | 0.00% | - | - | |

Myocardial Infarction | 0.22% | 0.06% | 0.4 | 0.17 | |

Peripheral nerve injury | 0.08% | 0.11% | 1.5 | 0.45 | |

Pneumonia | 0.47% | 0.38% | 0.9 | 0.70 | |

Sepsis | 0.08% | 0.08% | 1.3 | 0.62 | |

Stroke | 0.07% | 0.05% | 0.9 | 0.93 | |

Surgical site infection | 0.09% | 0.13% | 1.4 | 0.52 | |

Urinary tract infection | 1.44% | 1.80% | 1.1 | 0.46 | |

Wound dehiscence | 0.01% | 0.05% | 3.6 | 0.09 | |

Comparison of Length of Stay and Hospital Charges | |||||

| Non-RA Patients (percent) | RA Patients (percent) | Multivariate Linear Regression | ||

Beta | P-Value | ||||

Length of staya | 2.3±2.0 | 2.4±1.6 | +0.1 | 0.002 | |

Hospitalization costb | 14,826±8,336 | 14,787±7,625 | +93 | 0.59 | |

aReported in days. bReported in 2011 US dollars, adjusted for inflation.

The mean length of stay following shoulder arthroplasty in RA patients was 2.4 ± 1.6 days, and the mean hospitalization cost was $14,787 ± $7625 (Table 3). As compared with non-RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty, there were no significant differences in the mean hospitalization costs; however, non-RA patients had a significantly shorter length of stay by 0.1 days (P = .002) (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we observed that the utilization of shoulder arthroplasty in patients with RA increased significantly in the decade from 2002 to 2011, largely related to a rise in TSA. Interestingly, we also observed a corresponding rise in the proportion of RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty with a diagnosis of rotator cuff disease, and we believe that this may partly account for the recent increase in the use of the reverse TSA in this patient population. Additionally, we found shoulder arthroplasty in RA patients to be safe in the early postoperative period, with no significant increase in cost as compared with patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty without a diagnosis of RA. Although we did observe a significant increase in length of stay among RA patients as compared with non-RA patients, the absolute difference was only 0.1 days, and given the aforementioned similarities in cost between RA and non-RA patients, we do not believe this difference to be clinically significant.

It has been theorized that the utilization of TJA in RA patients has been decreasing with improvements in medical management; however, this is largely based upon literature pertaining to lower extremity TJA.2 On the contrary, past research pertaining to the utilization of shoulder arthroplasty in RA patients has been highly variable. For instance, a Swedish study demonstrated a statistically significant decrease in admissions associated with RA-related upper limb surgery and a stable rate of shoulder arthroplasty between 1998 and 2004.7 Similarly, a Finnish study demonstrated that the annual incidence of primary joint arthroplasty in RA patients had declined from 1995 to 2010, with a greater decline for upper-limb arthroplasty as compared with lower-limb arthroplasty.8 Despite these European observations, Jain and colleagues9 reported an increasing rate of TSA among RA patients in the US between the years 1992 and 2005. In this study, we demonstrate a clear increase in the utilization of shoulder arthroplasty among RA patients between 2002 and 2011. What was most striking about our observation was that the rise in utilization appeared to be driven by an increase in TSA, whereas the utilization of HA decreased over time. This change in practice likely reflects several factors, including the multitude of studies that have demonstrated improved outcomes with anatomic TSA as compared with HA in RA patients.10-14

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of our data was the recent exponential rise in the utilization of the reverse TSA. Despite improved outcomes following TSA as compared with HA in RA patients, these outcomes all appear to be highly dependent upon the integrity of the rotator cuff.10 In fact, there is evidence that failure of the rotator cuff could be as high as 75% within 10 years of TSA in patients with RA,15 which ultimately could jeopardize the long-term durability of the TSA implant in this patient population.11 For this reason, interest in the reverse TSA for the RA patient population has increased since its introduction in the US in 2004;16 in fact, in RA patients with end-stage inflammatory arthropathy and a damaged rotator cuff, the reverse TSA has demonstrated excellent results.17-20 Based upon this evidence, it is not surprising that we found an exponential rise in the use of the reverse TSA since 2010, which corresponds to the introduction of an ICD-9 code for this implant.21 Prior to 2010, it is likely that many implanted reverse TSAs were coded as TSA, and for this reason, we believe that the observed rise in the utilization of TSA in RA patients prior to 2010 may have been partly fueled by an increase in the use of the reverse TSA. To further support this theory, there was a dramatic decrease in the use of anatomic TSA following 2010, and we believe this was related to increased awareness of the newly introduced reverse TSA code among surgeons.

Another consideration when examining the utilization of shoulder arthroplasty in RA patients is its versatility in managing different disease states, including rotator cuff disease. As has been documented in the literature, outcomes of rotator cuff repair in RA patients are discouraging.22 For this reason, it is reasonable for surgeons and patients with RA to consider alternatives to rotator cuff repair when nonoperative management has failed to provide adequate improvement in symptoms. One alternative may be shoulder arthroplasty, namely the reverse TSA. In this study, we observed a significant increase in the rate of diagnosis of rotator cuff disease among RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty from 2002 to 2011 (9.7% in 2002 to 15.2% in 2011, P < .001), and it is our belief that the simultaneous increase in the diagnosis of rotator cuff disease and use of TSA is not coincidental. More specifically, there is likely an emerging trend among surgeons toward using the reverse TSA to manage rotator cuff tears in the RA population, rather than undertaking a rotator cuff repair that carries a high rate of failure. Going forward, there is a need to not only identify this trend more clearly but to also compare the outcomes between reverse TSA and rotator cuff repair in the management of rotator cuff tears in RA patients.

Continue to: In this study, we observed...

In this study, we observed that RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty were significantly younger than non-RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty. At first, this observation seems to counter recent literature suggesting that the age of patients with inflammatory arthropathy undergoing TJA is increasing over time;1 however, looking more closely at the data, it becomes clearer that the mean age we report is actually a relative increase as compared with past clinical studies pertaining to RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty (mean ages of 47 years,23 55 years,24 60 years,10 and 62 years25). On the other hand, the continued existence of an age gap between RA and non-RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty may be the result of several possible phenomena. First, this may reflect issues with patient access to and coverage of expensive biologic antirheumatic medication that would otherwise mitigate disease progression. For instance, the out-of-pocket expense for biologic medication through Medicaid and Medicare is substantial,26 which has direct implications on over two-thirds of our RA cohort. Second, it may be skewed by the proportion of RA patients who have previously been or continue to be poorly managed, enabling disease progression to end-stage arthropathy at a younger age. Ultimately, further investigation is needed to determine the reasons for this continued age disparity.

In comparing RA and non-RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty, we did not find a significant difference in the overall nor the individual rates of early adverse events. This finding appears to be unique, as similar studies pertaining to total knee arthroplasty (TKA) demonstrated a significantly higher incidence of postoperative pneumonia and bleeding requiring transfusion among RA patients as compared with non-RA patients.27 In patients with RA being treated with biologic medication and undergoing shoulder arthroplasty, the frequent concern in the postoperative period is the integrity of the wound and the potential for infection.28 In this study, we did not find a significant difference in the rate of early infection, and although the difference in the rate of early wound dehiscence approached significance, it did not meet the threshold of 0.05 (P = .09). This finding is in keeping with the aforementioned NIS study pertaining to TKA, and we believe that it likely reflects the short duration of follow-up for patients in both studies. Given the nature of the database we utilized, we were only privy to complications that arose during the inpatient hospital stay, and it is likely that the clear majority of patients who develop a postoperative infection or wound dehiscence do so in the postoperative setting following discharge. A second concern regarding postoperative wound complications is the management of biologic medication in the perioperative period, which we cannot determine using this database. Despite all these limitations specific to this database, a past systematic review of reverse TSA in RA patients found a low rate of deep infection after reverse TSA in RA patients (3.3%),17 which was not higher than that after shoulder arthroplasty performed in non-RA patients.

A final demonstration from this study is that the hospital length of stay was significantly longer for RA patients than non-RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty; however, given that the difference was only 0.1 days, and there was no significant difference in hospitalization cost, we are inclined to believe that statistical significance may not translate into clinical significance in this scenario. Ultimately, we do believe that length of stay is an important consideration in the current healthcare system, and given our finding that shoulder arthroplasty in the RA patient is safe in the early postoperative period, that a prolonged postoperative hospitalization is not warranted on the sole basis of a patient’s history of RA.

As with all studies using data from a search of an administrative database, such as the NIS database, this study has limitations. First, this type of research is limited by the reliability of both diagnosis and procedural coding. Although the NIS database has demonstrated high reliability,3 it is still possible that events may have been miscoded. Second, the tracking period for adverse events is limited to the inpatient hospital stay, which may be too short to detect certain postoperative complications. As such, the rates we report are likely underestimates of the true incidence of these complications, but this is true for both the RA and non-RA populations. Third, the comparisons we draw between RA and non-RA patients are limited to the scope of the NIS database and the available data; as such, we could not draw comparisons between preoperative disease stage, intraoperative findings, and postoperative course following hospital discharge. Lastly, our data are limited to a distinct period between 2002 and 2011 and may not reflect current practice. Ultimately, our findings may underestimate current trends in shoulder arthroplasty utilization among RA patients, particularly for the reverse TSA.

CONCLUSION

In this study, we found that the utilization of shoulder arthroplasty in patients with RA increased significantly from 2002 to 2011, largely related to a rise in the utilization of TSA. Similarly, we observed a rise in the proportion of RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty with a corresponding diagnosis of rotator cuff disease, and we believe the increased utilization of shoulder arthroplasty among RA patients resulted from management of both end-stage inflammatory arthropathy and rotator cuff disease. Although we did not find a significant difference between RA and non-RA patients in the rates of early adverse events and overall hospitalization costs following shoulder arthroplasty, length of stay was significantly longer among RA patients; however, the absolute difference does not appear to be clinically significant.

- Mertelsmann-Voss C, Lyman S, Pan TJ, Goodman SM, Figgie MP, Mandl LA. US trends in rates of arthroplasty for inflammatory arthritis including rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(6):1432-1439. doi:10.1002/art.38384.

- Louie GH, Ward MM. Changes in the rates of joint surgery among patients with rheumatoid arthritis in California, 1983-2007. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(5):868-871. doi:10.1136/ard.2009.112474.

- HCUP Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2002-2011.

- Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8-27. doi:10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004.

- Sharabiani MT, Aylin P, Bottle A. Systematic review of comorbidity indices for administrative data. Med Care. 2012;50(12):1109-1118. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e31825f64d0.

- van Walraven C, Austin PC, Jennings A, Quan H, Forster AJ. A modification of the Elixhauser comorbidity measures into a point system for hospital death using administrative data. Med Care. 2009;47(6):626-633. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819432e5.

- Weiss RJ, Ehlin A, Montgomery SM, Wick MC, Stark A, Wretenberg P. Decrease of RA-related orthopaedic surgery of the upper limbs between 1998 and 2004: data from 54,579 Swedish RA inpatients. Rheumatol Oxf. 2008 ;47(4):491-494. doi. 10.1093/rheumatology/ken009.

- Jämsen E, Virta LJ, Hakala M, Kauppi MJ, Malmivaara A, Lehto MU. The decline in joint replacement surgery in rheumatoid arthritis is associated with a concomitant increase in the intensity of anti-rheumatic therapy: a nationwide register-based study from 1995 through 2010. Acta Orthop. 2013;84(4):331-337. doi:10.3109/17453674.2013.810519.

- Jain A, Stein BE, Skolasky RL, Jones LC, Hungerford MW. Total joint arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a United States experience from 1992 through 2005. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(6):881-888. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2011.12.027.

- Barlow JD, Yuan BJ, Schleck CD, Harmsen WS, Cofield RH, Sperling JW. Shoulder arthroplasty for rheumatoid arthritis: 303 consecutive cases with minimum 5-year follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(6):791-799. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2013.09.016.

- Collins DN, Harryman DT, Wirth MA. Shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of inflammatory arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86–A(11):2489-2496. doi:10.2106/00004623-200411000-00020.

- Rahme H, Mattsson P, Wikblad L, Larsson S. Cement and press-fit humeral stem fixation provides similar results in rheumatoid patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;448:28-32. doi:10.1097/01.blo.0000224007.25636.85.

- Rozing PM, Nagels J, Rozing MP. Prognostic factors in arthroplasty in the rheumatoid shoulder. HSS J. 2011;7(1):29-36. doi:10.1007/s11420-010-9172-1.

- Sperling JW, Cofield RH, Schleck CD, Harmsen WS. Total shoulder arthroplasty versus hemiarthroplasty for rheumatoid arthritis of the shoulder: results of 303 consecutive cases. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(6):683-690. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2007.02.135.

- Khan A, Bunker TD, Kitson JB. Clinical and radiological follow-up of the Aequalis third-generation cemented total shoulder replacement: a minimum ten-year study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91(12):1594-1600. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.91B12.22139.

- Guery J, Favard L, Sirveaux F, Oudet D, Mole D, Walch G. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: survivorship analysis of eighty replacements followed for five to ten years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(8):1742-1747. doi:10.2106/JBJS.E.00851.

- Gee ECA, Hanson EK, Saithna A. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty in rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review. Open Orthop J. 2015;9:237-245. doi:10.2174/1874325001509010237.

- Holcomb JO, Hebert DJ, Mighell MA, et al. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(7):1076-1084. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2009.11.049.

- Postacchini R, Carbone S, Canero G, Ripani M, Postacchini F. Reverse shoulder prosthesis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Int Orthop. 2016;40(5):965-973. doi:10.1007/s00264-015-2916-2.

- Rittmeister M, Kerschbaumer F. Grammont reverse total shoulder arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and nonreconstructible rotator cuff lesions. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10(1):17-22. doi:10.1067/mse.2001.110515.

- American Medical Association. American Medical Association Web site. www.ama-assn.org/ama. Accessed January 15, 2016.

- Smith AM, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Rotator cuff repair in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg. 2005;87(8):1782-1787. doi:10.2106/JBJS.D.02452.

- Betts HM, Abu-Rajab R, Nunn T, Brooksbank AJ. Total shoulder replacement in rheumatoid disease: a 16- to 23-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91(9):1197-1200. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.91B9.22035.

- Geervliet PC, Somford MP, Winia P, van den Bekerom MP. Long-term results of shoulder hemiarthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Orthopedics. 2015;38(1):e38-e42. doi:10.3928/01477447-20150105-58.

- Hettrich CM, Weldon E III, Boorman RS, Parsons M IV, Matsen FA III. Preoperative factors associated with improvements in shoulder function after humeral hemiarthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg. 2004;86–A(7):1446-1451.

- Yazdany J, Dudley RA, Chen R, Lin GA, Tseng CW. Coverage for high-cost specialty drugs for rheumatoid arthritis in Medicare Part D. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(6):1474-1480. doi:10.1002/art.39079.

- Jauregui JJ, Kapadia BH, Dixit A, et al. Thirty-day complications in rheumatoid patients following total knee arthroplasty. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35(3):595-600. doi:10.1007/s10067-015-3037-4.

- Trail IA, Nuttall D. The results of shoulder arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84(8):1121-1125. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.84B8.0841121

ABSTRACT

It has been suggested that the utilization of joint arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is decreasing; however, this observation is largely based upon evidence pertaining to lower-extremity joint arthroplasty. It remains unknown if these observed trends also hold true for shoulder arthroplasty. The purpose of this study is to utilize a nationally representative population database in the US to identify trends in the utilization of shoulder arthroplasty among patients with RA. Secondarily, we sought to determine the rate of early adverse events, length of stay, and hospitalization costs associated with RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty and to compare these outcomes to those of patients without a diagnosis of RA undergoing shoulder arthroplasty. Using a large population database in the US, we determined the annual rates of shoulder arthroplasty (overall and individual) in RA patients between 2002 and 2011. Early adverse events, length of stay, and hospitalization costs were determined and compared with those of non-RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty. Overall, we identified 332,593 patients who underwent shoulder arthroplasty between 2002 and 2011, of whom 17,883 patients (5.4%) had a diagnosis of RA. Over the study period, there was a significant increase in the utilization of shoulder arthroplasty in RA patients, particularly total shoulder arthroplasty. Over the same period, there was a significant increase in the number of RA patients who underwent shoulder arthroplasty with a diagnosis of rotator cuff disease. There were no significant differences in adverse events or mean hospitalization costs between RA and non-RA patients. Non-RA patients had a significantly shorter length of stay; however, the difference did not appear to be clinically significant. In conclusion, the utilization of shoulder arthroplasty in patients with RA significantly increased from 2002 to 2011, which may partly reflect a trend toward management of rotator cuff disease with arthroplasty rather than repair.

Continue to: It has been suggested...

It has been suggested that the utilization of total joint arthroplasty (TJA) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is decreasing over time;1 however, this observation is largely based upon evidence pertaining to lower extremity TJA.2 It remains unknown if these observed trends also hold true for shoulder arthroplasty, whereby the utilization of shoulder arthroplasty in RA patients is not limited to the management of end-stage inflammatory arthropathy. In this study, we used a nationally representative population database in the US to identify trends in the utilization of shoulder arthroplasty among patients with RA. As a secondary objective, we sought to determine the rate of early adverse events, length of stay, and hospitalization costs associated with RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty and compare these outcomes to those of patients without a diagnosis of RA undergoing shoulder arthroplasty. We hypothesize that the utilization of shoulder arthroplasty in RA patients would be decreasing, but adverse events, length of stay, and hospitalization costs would not differ between patients with and without RA undergoing shoulder arthroplasty.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) from 2002 to 2011.3 The NIS comprises a 20% stratified sample of all hospital discharges in the US. The NIS includes information about patient characteristics (age, sex, insurance status, and medical comorbidities) and hospitalization outcomes (adverse events, costs, and length of stay). The NIS allows identification of hospitalizations according to procedures and diagnoses using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes. Given the anonymity of this study, it was exempt from Institutional Review Board ethics approval.

Hospitalizations were selected for the study based on ICD-9-CM procedural codes for hemiarthroplasty (81.81), anatomic total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) (81.80), and reverse TSA (81.88). These patients were then stratified by an ICD-9-CM diagnosis of RA (714.X). We also utilized ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes to determine the presence of rotator cuff pathology at the time of shoulder arthroplasty (726.13, 727.61, 840.4) and to exclude patients with a history of trauma (812.X, 716.11, 733.8X). In a separate analysis, all patients in the NIS database with an ICD-9-CM diagnosis of RA were identified for each calendar year of the study, and a national estimate of RA patients was generated annually to assess overall and individual utilization rates of shoulder arthroplasty in this population (the national estimate served as the denominator).

Preoperative patient data withdrawn from the NIS included age, sex, insurance status, and medical comorbidities. An Elixhauser Comorbidity Index (ECI) was generated for each patient based on the presence of 29 comorbid conditions. The ECI was chosen because of its capacity to accurately predict mortality and represent the patient burden of comorbidities in similar administrative database studies.4-6

Early adverse events were also chosen based on ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes (Appendix A), and included the following: death, acute kidney injury, cardiac arrest, thromboembolic event, myocardial infarction, peripheral nerve injury, pneumonia, sepsis, stroke, surgical site infection, urinary tract infection, and wound dehiscence. The overall adverse event rate was defined as the occurrence of ≥1 of the above adverse events in a patient.

Appendix A. ICD-9-CM Codes Corresponding to Postoperative Adverse Events

Event | ICD-9-CM |

Acute kidney injury | 584.5-584.9 |

Cardiac arrest | 427.41, 427.5 |

Thromboembolic event | 453.2-453.4, 453.82-453.86, 415.1 |

Myocardial Infarction | 410.00-410.92 |

Peripheral nerve injury | 953.0-953.9 954.0-954.9, 955.0-955.9, 956.0-956.9 |

Pneumonia | 480.0-480.9, 481, 482.0-482.9, 483.0-483.8, 484.1-484.8, 485, 486 |

Sepsis | 038.0-038.9, 112.5, 785.52, 995.91, 995.92 |

Stroke | 430, 432, 433.01-434.91, 997.02 |

Surgical site infection | 998.51, 998.59, 996.67 |

Urinary tract infection | 599 |

Wound dehiscence | 998.30-998.33 |

Abbreviation: ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification

Length of stay and total hospital charges were available for each patient. Length of stay represents the number of calendar days a patient stayed in the hospital. All hospital charges were converted to hospitalization costs using the HCUP Cost-to-Charge Ratio Files. All hospitalization costs were adjusted for inflation using the US Bureau of Labor statistics yearly inflation calculator to represent charges in the year 2011, which was the final and most recent year in this study.

Continue to: Statistical analysis...

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata version 13.1 (StataCorp, LP). All analyses took into account the complex survey design of the NIS. Discharge weights, strata, and cluster variables were included to correctly estimate variance and to produce national estimates from the stratified sample. Pearson’s chi-squared test was used to compare age, sex, ECI, and insurance status between RA and non-RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty.

Bivariate and multivariate logistic regressions were subsequently used to compare the rates of adverse events between RA and non-RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty (non-RA cases were used as the reference). Multivariate linear regressions were used to compare hospital length of stay and hospitalization costs between RA and non-RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty. The multivariate regressions were adjusted for baseline differences in age, sex, ECI, and insurance status. Cochran-Armitage tests for trend were used to assess trends over time. All tests were 2-tailed, and the statistical difference was established at a 2-sided α level of 0.05 (P < .05).

RESULTS

Overall, we identified 332,593 patients who underwent shoulder arthroplasty in the US between 2002 and 2011, of which 17,883 patients (5.4%) had a diagnosis of RA. In comparison with non-RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty, patients with RA at the time of shoulder arthroplasty were significantly younger (65.2 ± 12.5 years vs 68.4 ± 11.0 years, P < .001), included a significantly greater proportion of female patients (76.7% vs 53.8%, P < .001), and included a significantly higher proportion of patients with Medicaid insurance (3.6% vs 2.3%, P < .001). There were no significant differences in the mean ECI between patients with and without a diagnosis of RA (Table 1). As depicted in Table 1, there were significant differences in the utilization of specific shoulder arthroplasty types between patients with and without RA, whereby a significantly greater proportion of RA patients underwent hemiarthroplasty (HA) (31.6% vs 29.3%, P = .002) and reverse TSA (7.7% vs 6.6%, P = .002), whereas a significantly greater proportion of non-RA patients underwent anatomic SA (64.0% vs 60.8%, P = .002).

Over the study period from 2002 to 2011, there was a significant increase in the overall utilization of shoulder arthroplasty in RA patients, as indicated by both the absolute number and the proportion of patients with a diagnosis of RA (P < .001) (Table 2, Figure). More specifically, 0.39% of RA patients underwent shoulder arthroplasty in 2002, as compared with 0.58% of RA patients in 2011 (P < .001) (Table 2). With respect to specific arthroplasty types, there was an exponential rise in the utilization of reverse TSA beginning in 2010 and a corresponding decrease in the rates of both HA and anatomic TSA (Table 2, Figure). In addition to changes in shoulder arthroplasty utilization over time among RA patients, we also observed a significant increase in the number of RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty with a corresponding diagnosis of rotator cuff disease (9.7% in 2002 to 15.2% in 2011, P < .001).

Table 2. The Annual Utilization of Shoulder Arthroplasty Among Patients with a Diagnosis of Rheumatoid Arthritis.

Proportion of RA patients |

| ||||

Year | Overall Rate of Shoulder Arthroplastya | HA | Anatomic TSA | Reverse TSA | |

2002 | 0.39 | 0.23 | 0.16 | 0 | |

2003 | 0.37 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0 | |

2004 | 0.46 | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0 | |

2005 | 0.46 | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0 | |

2006 | 0.47 | 0.20 | 0.27 | 0 | |

2007 | 0.55 | 0.22 | 0.33 | 0 | |

2008 | 0.47 | 0.17 | 0.30 | 0 | |

2009 | 0.50 | 0.15 | 0.35 | 0 | |

2010 | 0.58 | 0.15 | 0.37 | 0.06 | |

2011 | 0.58 | 0.12 | 0.23 | 0.23 | |

Absolute number of RA patients |

| ||||

2002 | 1295 | 768 | 527 | 0 | |

2003 | 1247 | 650 | 597 | 0 | |

2004 | 1667 | 906 | 761 | 0 | |

2005 | 1722 | 776 | 946 | 0 | |

2006 | 1847 | 794 | 1053 | 0 | |

2007 | 2249 | 910 | 1339 | 0 | |

2008 | 2194 | 799 | 1395 | 0 | |

2009 | 2407 | 724 | 1683 | 0 | |

2010 | 2869 | 722 | 1857 | 290 | |

2011 | 3193 | 649 | 1261 | 1283 | |

aRate determined as number of RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty compared to the number of patients with an RA diagnosis in the stated calendar year.

Abbreviations: HA, hemiarthroplasty; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; TSA, total shoulder arthroplasty.

Continue to: Among patients with RA...

Among patients with RA undergoing shoulder arthroplasty, the overall rate of early adverse events was 3.12%, of which the most common early adverse events were urinary tract infections (1.8%), acute kidney injury (0.66%), and pneumonia (0.38%) (Table 3). As compared with patients without a diagnosis of RA undergoing shoulder arthroplasty, there were no significant differences in the overall and individual rates of early adverse events (Table 3).

Table 3. A Comparison of Early Adverse Events, Length of Stay, and Cost Between Patients With and Without Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) Undergoing Shoulder Arthroplasty

Comparison of Early Adverse Event Rates |

| ||||

| Non-RA Patients | RA Patients | Multivariate Logistic Regression | ||

Odds Ratio | P-Value | ||||

Overall adverse event rate | 3.02% | 3.12% | 1.0 | 0.83 | |

Specific adverse event rate |

|

|

|

| |

Death | 0.08% | 0.05% | 0.9 | 0.91 | |

Acute kidney injury | 0.85% | 0.66% | 0.9 | 0.59 | |

Cardiac arrest | 0.05% | 0.05% | 1.3 | 0.70 | |

Thromboembolic event | 0.01% | 0.00% | - | - | |

Myocardial Infarction | 0.22% | 0.06% | 0.4 | 0.17 | |

Peripheral nerve injury | 0.08% | 0.11% | 1.5 | 0.45 | |

Pneumonia | 0.47% | 0.38% | 0.9 | 0.70 | |

Sepsis | 0.08% | 0.08% | 1.3 | 0.62 | |

Stroke | 0.07% | 0.05% | 0.9 | 0.93 | |

Surgical site infection | 0.09% | 0.13% | 1.4 | 0.52 | |

Urinary tract infection | 1.44% | 1.80% | 1.1 | 0.46 | |

Wound dehiscence | 0.01% | 0.05% | 3.6 | 0.09 | |

Comparison of Length of Stay and Hospital Charges | |||||

| Non-RA Patients (percent) | RA Patients (percent) | Multivariate Linear Regression | ||

Beta | P-Value | ||||

Length of staya | 2.3±2.0 | 2.4±1.6 | +0.1 | 0.002 | |

Hospitalization costb | 14,826±8,336 | 14,787±7,625 | +93 | 0.59 | |

aReported in days. bReported in 2011 US dollars, adjusted for inflation.

The mean length of stay following shoulder arthroplasty in RA patients was 2.4 ± 1.6 days, and the mean hospitalization cost was $14,787 ± $7625 (Table 3). As compared with non-RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty, there were no significant differences in the mean hospitalization costs; however, non-RA patients had a significantly shorter length of stay by 0.1 days (P = .002) (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we observed that the utilization of shoulder arthroplasty in patients with RA increased significantly in the decade from 2002 to 2011, largely related to a rise in TSA. Interestingly, we also observed a corresponding rise in the proportion of RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty with a diagnosis of rotator cuff disease, and we believe that this may partly account for the recent increase in the use of the reverse TSA in this patient population. Additionally, we found shoulder arthroplasty in RA patients to be safe in the early postoperative period, with no significant increase in cost as compared with patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty without a diagnosis of RA. Although we did observe a significant increase in length of stay among RA patients as compared with non-RA patients, the absolute difference was only 0.1 days, and given the aforementioned similarities in cost between RA and non-RA patients, we do not believe this difference to be clinically significant.

It has been theorized that the utilization of TJA in RA patients has been decreasing with improvements in medical management; however, this is largely based upon literature pertaining to lower extremity TJA.2 On the contrary, past research pertaining to the utilization of shoulder arthroplasty in RA patients has been highly variable. For instance, a Swedish study demonstrated a statistically significant decrease in admissions associated with RA-related upper limb surgery and a stable rate of shoulder arthroplasty between 1998 and 2004.7 Similarly, a Finnish study demonstrated that the annual incidence of primary joint arthroplasty in RA patients had declined from 1995 to 2010, with a greater decline for upper-limb arthroplasty as compared with lower-limb arthroplasty.8 Despite these European observations, Jain and colleagues9 reported an increasing rate of TSA among RA patients in the US between the years 1992 and 2005. In this study, we demonstrate a clear increase in the utilization of shoulder arthroplasty among RA patients between 2002 and 2011. What was most striking about our observation was that the rise in utilization appeared to be driven by an increase in TSA, whereas the utilization of HA decreased over time. This change in practice likely reflects several factors, including the multitude of studies that have demonstrated improved outcomes with anatomic TSA as compared with HA in RA patients.10-14

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of our data was the recent exponential rise in the utilization of the reverse TSA. Despite improved outcomes following TSA as compared with HA in RA patients, these outcomes all appear to be highly dependent upon the integrity of the rotator cuff.10 In fact, there is evidence that failure of the rotator cuff could be as high as 75% within 10 years of TSA in patients with RA,15 which ultimately could jeopardize the long-term durability of the TSA implant in this patient population.11 For this reason, interest in the reverse TSA for the RA patient population has increased since its introduction in the US in 2004;16 in fact, in RA patients with end-stage inflammatory arthropathy and a damaged rotator cuff, the reverse TSA has demonstrated excellent results.17-20 Based upon this evidence, it is not surprising that we found an exponential rise in the use of the reverse TSA since 2010, which corresponds to the introduction of an ICD-9 code for this implant.21 Prior to 2010, it is likely that many implanted reverse TSAs were coded as TSA, and for this reason, we believe that the observed rise in the utilization of TSA in RA patients prior to 2010 may have been partly fueled by an increase in the use of the reverse TSA. To further support this theory, there was a dramatic decrease in the use of anatomic TSA following 2010, and we believe this was related to increased awareness of the newly introduced reverse TSA code among surgeons.

Another consideration when examining the utilization of shoulder arthroplasty in RA patients is its versatility in managing different disease states, including rotator cuff disease. As has been documented in the literature, outcomes of rotator cuff repair in RA patients are discouraging.22 For this reason, it is reasonable for surgeons and patients with RA to consider alternatives to rotator cuff repair when nonoperative management has failed to provide adequate improvement in symptoms. One alternative may be shoulder arthroplasty, namely the reverse TSA. In this study, we observed a significant increase in the rate of diagnosis of rotator cuff disease among RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty from 2002 to 2011 (9.7% in 2002 to 15.2% in 2011, P < .001), and it is our belief that the simultaneous increase in the diagnosis of rotator cuff disease and use of TSA is not coincidental. More specifically, there is likely an emerging trend among surgeons toward using the reverse TSA to manage rotator cuff tears in the RA population, rather than undertaking a rotator cuff repair that carries a high rate of failure. Going forward, there is a need to not only identify this trend more clearly but to also compare the outcomes between reverse TSA and rotator cuff repair in the management of rotator cuff tears in RA patients.

Continue to: In this study, we observed...

In this study, we observed that RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty were significantly younger than non-RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty. At first, this observation seems to counter recent literature suggesting that the age of patients with inflammatory arthropathy undergoing TJA is increasing over time;1 however, looking more closely at the data, it becomes clearer that the mean age we report is actually a relative increase as compared with past clinical studies pertaining to RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty (mean ages of 47 years,23 55 years,24 60 years,10 and 62 years25). On the other hand, the continued existence of an age gap between RA and non-RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty may be the result of several possible phenomena. First, this may reflect issues with patient access to and coverage of expensive biologic antirheumatic medication that would otherwise mitigate disease progression. For instance, the out-of-pocket expense for biologic medication through Medicaid and Medicare is substantial,26 which has direct implications on over two-thirds of our RA cohort. Second, it may be skewed by the proportion of RA patients who have previously been or continue to be poorly managed, enabling disease progression to end-stage arthropathy at a younger age. Ultimately, further investigation is needed to determine the reasons for this continued age disparity.

In comparing RA and non-RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty, we did not find a significant difference in the overall nor the individual rates of early adverse events. This finding appears to be unique, as similar studies pertaining to total knee arthroplasty (TKA) demonstrated a significantly higher incidence of postoperative pneumonia and bleeding requiring transfusion among RA patients as compared with non-RA patients.27 In patients with RA being treated with biologic medication and undergoing shoulder arthroplasty, the frequent concern in the postoperative period is the integrity of the wound and the potential for infection.28 In this study, we did not find a significant difference in the rate of early infection, and although the difference in the rate of early wound dehiscence approached significance, it did not meet the threshold of 0.05 (P = .09). This finding is in keeping with the aforementioned NIS study pertaining to TKA, and we believe that it likely reflects the short duration of follow-up for patients in both studies. Given the nature of the database we utilized, we were only privy to complications that arose during the inpatient hospital stay, and it is likely that the clear majority of patients who develop a postoperative infection or wound dehiscence do so in the postoperative setting following discharge. A second concern regarding postoperative wound complications is the management of biologic medication in the perioperative period, which we cannot determine using this database. Despite all these limitations specific to this database, a past systematic review of reverse TSA in RA patients found a low rate of deep infection after reverse TSA in RA patients (3.3%),17 which was not higher than that after shoulder arthroplasty performed in non-RA patients.

A final demonstration from this study is that the hospital length of stay was significantly longer for RA patients than non-RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty; however, given that the difference was only 0.1 days, and there was no significant difference in hospitalization cost, we are inclined to believe that statistical significance may not translate into clinical significance in this scenario. Ultimately, we do believe that length of stay is an important consideration in the current healthcare system, and given our finding that shoulder arthroplasty in the RA patient is safe in the early postoperative period, that a prolonged postoperative hospitalization is not warranted on the sole basis of a patient’s history of RA.

As with all studies using data from a search of an administrative database, such as the NIS database, this study has limitations. First, this type of research is limited by the reliability of both diagnosis and procedural coding. Although the NIS database has demonstrated high reliability,3 it is still possible that events may have been miscoded. Second, the tracking period for adverse events is limited to the inpatient hospital stay, which may be too short to detect certain postoperative complications. As such, the rates we report are likely underestimates of the true incidence of these complications, but this is true for both the RA and non-RA populations. Third, the comparisons we draw between RA and non-RA patients are limited to the scope of the NIS database and the available data; as such, we could not draw comparisons between preoperative disease stage, intraoperative findings, and postoperative course following hospital discharge. Lastly, our data are limited to a distinct period between 2002 and 2011 and may not reflect current practice. Ultimately, our findings may underestimate current trends in shoulder arthroplasty utilization among RA patients, particularly for the reverse TSA.

CONCLUSION

In this study, we found that the utilization of shoulder arthroplasty in patients with RA increased significantly from 2002 to 2011, largely related to a rise in the utilization of TSA. Similarly, we observed a rise in the proportion of RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty with a corresponding diagnosis of rotator cuff disease, and we believe the increased utilization of shoulder arthroplasty among RA patients resulted from management of both end-stage inflammatory arthropathy and rotator cuff disease. Although we did not find a significant difference between RA and non-RA patients in the rates of early adverse events and overall hospitalization costs following shoulder arthroplasty, length of stay was significantly longer among RA patients; however, the absolute difference does not appear to be clinically significant.

ABSTRACT

It has been suggested that the utilization of joint arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is decreasing; however, this observation is largely based upon evidence pertaining to lower-extremity joint arthroplasty. It remains unknown if these observed trends also hold true for shoulder arthroplasty. The purpose of this study is to utilize a nationally representative population database in the US to identify trends in the utilization of shoulder arthroplasty among patients with RA. Secondarily, we sought to determine the rate of early adverse events, length of stay, and hospitalization costs associated with RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty and to compare these outcomes to those of patients without a diagnosis of RA undergoing shoulder arthroplasty. Using a large population database in the US, we determined the annual rates of shoulder arthroplasty (overall and individual) in RA patients between 2002 and 2011. Early adverse events, length of stay, and hospitalization costs were determined and compared with those of non-RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty. Overall, we identified 332,593 patients who underwent shoulder arthroplasty between 2002 and 2011, of whom 17,883 patients (5.4%) had a diagnosis of RA. Over the study period, there was a significant increase in the utilization of shoulder arthroplasty in RA patients, particularly total shoulder arthroplasty. Over the same period, there was a significant increase in the number of RA patients who underwent shoulder arthroplasty with a diagnosis of rotator cuff disease. There were no significant differences in adverse events or mean hospitalization costs between RA and non-RA patients. Non-RA patients had a significantly shorter length of stay; however, the difference did not appear to be clinically significant. In conclusion, the utilization of shoulder arthroplasty in patients with RA significantly increased from 2002 to 2011, which may partly reflect a trend toward management of rotator cuff disease with arthroplasty rather than repair.

Continue to: It has been suggested...

It has been suggested that the utilization of total joint arthroplasty (TJA) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is decreasing over time;1 however, this observation is largely based upon evidence pertaining to lower extremity TJA.2 It remains unknown if these observed trends also hold true for shoulder arthroplasty, whereby the utilization of shoulder arthroplasty in RA patients is not limited to the management of end-stage inflammatory arthropathy. In this study, we used a nationally representative population database in the US to identify trends in the utilization of shoulder arthroplasty among patients with RA. As a secondary objective, we sought to determine the rate of early adverse events, length of stay, and hospitalization costs associated with RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty and compare these outcomes to those of patients without a diagnosis of RA undergoing shoulder arthroplasty. We hypothesize that the utilization of shoulder arthroplasty in RA patients would be decreasing, but adverse events, length of stay, and hospitalization costs would not differ between patients with and without RA undergoing shoulder arthroplasty.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) from 2002 to 2011.3 The NIS comprises a 20% stratified sample of all hospital discharges in the US. The NIS includes information about patient characteristics (age, sex, insurance status, and medical comorbidities) and hospitalization outcomes (adverse events, costs, and length of stay). The NIS allows identification of hospitalizations according to procedures and diagnoses using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes. Given the anonymity of this study, it was exempt from Institutional Review Board ethics approval.

Hospitalizations were selected for the study based on ICD-9-CM procedural codes for hemiarthroplasty (81.81), anatomic total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) (81.80), and reverse TSA (81.88). These patients were then stratified by an ICD-9-CM diagnosis of RA (714.X). We also utilized ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes to determine the presence of rotator cuff pathology at the time of shoulder arthroplasty (726.13, 727.61, 840.4) and to exclude patients with a history of trauma (812.X, 716.11, 733.8X). In a separate analysis, all patients in the NIS database with an ICD-9-CM diagnosis of RA were identified for each calendar year of the study, and a national estimate of RA patients was generated annually to assess overall and individual utilization rates of shoulder arthroplasty in this population (the national estimate served as the denominator).

Preoperative patient data withdrawn from the NIS included age, sex, insurance status, and medical comorbidities. An Elixhauser Comorbidity Index (ECI) was generated for each patient based on the presence of 29 comorbid conditions. The ECI was chosen because of its capacity to accurately predict mortality and represent the patient burden of comorbidities in similar administrative database studies.4-6

Early adverse events were also chosen based on ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes (Appendix A), and included the following: death, acute kidney injury, cardiac arrest, thromboembolic event, myocardial infarction, peripheral nerve injury, pneumonia, sepsis, stroke, surgical site infection, urinary tract infection, and wound dehiscence. The overall adverse event rate was defined as the occurrence of ≥1 of the above adverse events in a patient.

Appendix A. ICD-9-CM Codes Corresponding to Postoperative Adverse Events

Event | ICD-9-CM |

Acute kidney injury | 584.5-584.9 |

Cardiac arrest | 427.41, 427.5 |

Thromboembolic event | 453.2-453.4, 453.82-453.86, 415.1 |

Myocardial Infarction | 410.00-410.92 |

Peripheral nerve injury | 953.0-953.9 954.0-954.9, 955.0-955.9, 956.0-956.9 |

Pneumonia | 480.0-480.9, 481, 482.0-482.9, 483.0-483.8, 484.1-484.8, 485, 486 |

Sepsis | 038.0-038.9, 112.5, 785.52, 995.91, 995.92 |

Stroke | 430, 432, 433.01-434.91, 997.02 |

Surgical site infection | 998.51, 998.59, 996.67 |

Urinary tract infection | 599 |

Wound dehiscence | 998.30-998.33 |

Abbreviation: ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification

Length of stay and total hospital charges were available for each patient. Length of stay represents the number of calendar days a patient stayed in the hospital. All hospital charges were converted to hospitalization costs using the HCUP Cost-to-Charge Ratio Files. All hospitalization costs were adjusted for inflation using the US Bureau of Labor statistics yearly inflation calculator to represent charges in the year 2011, which was the final and most recent year in this study.

Continue to: Statistical analysis...

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata version 13.1 (StataCorp, LP). All analyses took into account the complex survey design of the NIS. Discharge weights, strata, and cluster variables were included to correctly estimate variance and to produce national estimates from the stratified sample. Pearson’s chi-squared test was used to compare age, sex, ECI, and insurance status between RA and non-RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty.

Bivariate and multivariate logistic regressions were subsequently used to compare the rates of adverse events between RA and non-RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty (non-RA cases were used as the reference). Multivariate linear regressions were used to compare hospital length of stay and hospitalization costs between RA and non-RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty. The multivariate regressions were adjusted for baseline differences in age, sex, ECI, and insurance status. Cochran-Armitage tests for trend were used to assess trends over time. All tests were 2-tailed, and the statistical difference was established at a 2-sided α level of 0.05 (P < .05).

RESULTS

Overall, we identified 332,593 patients who underwent shoulder arthroplasty in the US between 2002 and 2011, of which 17,883 patients (5.4%) had a diagnosis of RA. In comparison with non-RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty, patients with RA at the time of shoulder arthroplasty were significantly younger (65.2 ± 12.5 years vs 68.4 ± 11.0 years, P < .001), included a significantly greater proportion of female patients (76.7% vs 53.8%, P < .001), and included a significantly higher proportion of patients with Medicaid insurance (3.6% vs 2.3%, P < .001). There were no significant differences in the mean ECI between patients with and without a diagnosis of RA (Table 1). As depicted in Table 1, there were significant differences in the utilization of specific shoulder arthroplasty types between patients with and without RA, whereby a significantly greater proportion of RA patients underwent hemiarthroplasty (HA) (31.6% vs 29.3%, P = .002) and reverse TSA (7.7% vs 6.6%, P = .002), whereas a significantly greater proportion of non-RA patients underwent anatomic SA (64.0% vs 60.8%, P = .002).

Over the study period from 2002 to 2011, there was a significant increase in the overall utilization of shoulder arthroplasty in RA patients, as indicated by both the absolute number and the proportion of patients with a diagnosis of RA (P < .001) (Table 2, Figure). More specifically, 0.39% of RA patients underwent shoulder arthroplasty in 2002, as compared with 0.58% of RA patients in 2011 (P < .001) (Table 2). With respect to specific arthroplasty types, there was an exponential rise in the utilization of reverse TSA beginning in 2010 and a corresponding decrease in the rates of both HA and anatomic TSA (Table 2, Figure). In addition to changes in shoulder arthroplasty utilization over time among RA patients, we also observed a significant increase in the number of RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty with a corresponding diagnosis of rotator cuff disease (9.7% in 2002 to 15.2% in 2011, P < .001).

Table 2. The Annual Utilization of Shoulder Arthroplasty Among Patients with a Diagnosis of Rheumatoid Arthritis.

Proportion of RA patients |

| ||||

Year | Overall Rate of Shoulder Arthroplastya | HA | Anatomic TSA | Reverse TSA | |

2002 | 0.39 | 0.23 | 0.16 | 0 | |

2003 | 0.37 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0 | |

2004 | 0.46 | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0 | |

2005 | 0.46 | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0 | |

2006 | 0.47 | 0.20 | 0.27 | 0 | |

2007 | 0.55 | 0.22 | 0.33 | 0 | |

2008 | 0.47 | 0.17 | 0.30 | 0 | |

2009 | 0.50 | 0.15 | 0.35 | 0 | |

2010 | 0.58 | 0.15 | 0.37 | 0.06 | |

2011 | 0.58 | 0.12 | 0.23 | 0.23 | |

Absolute number of RA patients |

| ||||

2002 | 1295 | 768 | 527 | 0 | |

2003 | 1247 | 650 | 597 | 0 | |

2004 | 1667 | 906 | 761 | 0 | |

2005 | 1722 | 776 | 946 | 0 | |

2006 | 1847 | 794 | 1053 | 0 | |

2007 | 2249 | 910 | 1339 | 0 | |

2008 | 2194 | 799 | 1395 | 0 | |

2009 | 2407 | 724 | 1683 | 0 | |

2010 | 2869 | 722 | 1857 | 290 | |

2011 | 3193 | 649 | 1261 | 1283 | |

aRate determined as number of RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty compared to the number of patients with an RA diagnosis in the stated calendar year.

Abbreviations: HA, hemiarthroplasty; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; TSA, total shoulder arthroplasty.

Continue to: Among patients with RA...

Among patients with RA undergoing shoulder arthroplasty, the overall rate of early adverse events was 3.12%, of which the most common early adverse events were urinary tract infections (1.8%), acute kidney injury (0.66%), and pneumonia (0.38%) (Table 3). As compared with patients without a diagnosis of RA undergoing shoulder arthroplasty, there were no significant differences in the overall and individual rates of early adverse events (Table 3).

Table 3. A Comparison of Early Adverse Events, Length of Stay, and Cost Between Patients With and Without Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) Undergoing Shoulder Arthroplasty

Comparison of Early Adverse Event Rates |

| ||||

| Non-RA Patients | RA Patients | Multivariate Logistic Regression | ||

Odds Ratio | P-Value | ||||

Overall adverse event rate | 3.02% | 3.12% | 1.0 | 0.83 | |

Specific adverse event rate |

|

|

|

| |

Death | 0.08% | 0.05% | 0.9 | 0.91 | |

Acute kidney injury | 0.85% | 0.66% | 0.9 | 0.59 | |

Cardiac arrest | 0.05% | 0.05% | 1.3 | 0.70 | |

Thromboembolic event | 0.01% | 0.00% | - | - | |

Myocardial Infarction | 0.22% | 0.06% | 0.4 | 0.17 | |

Peripheral nerve injury | 0.08% | 0.11% | 1.5 | 0.45 | |

Pneumonia | 0.47% | 0.38% | 0.9 | 0.70 | |

Sepsis | 0.08% | 0.08% | 1.3 | 0.62 | |

Stroke | 0.07% | 0.05% | 0.9 | 0.93 | |

Surgical site infection | 0.09% | 0.13% | 1.4 | 0.52 | |

Urinary tract infection | 1.44% | 1.80% | 1.1 | 0.46 | |

Wound dehiscence | 0.01% | 0.05% | 3.6 | 0.09 | |

Comparison of Length of Stay and Hospital Charges | |||||

| Non-RA Patients (percent) | RA Patients (percent) | Multivariate Linear Regression | ||

Beta | P-Value | ||||

Length of staya | 2.3±2.0 | 2.4±1.6 | +0.1 | 0.002 | |

Hospitalization costb | 14,826±8,336 | 14,787±7,625 | +93 | 0.59 | |

aReported in days. bReported in 2011 US dollars, adjusted for inflation.

The mean length of stay following shoulder arthroplasty in RA patients was 2.4 ± 1.6 days, and the mean hospitalization cost was $14,787 ± $7625 (Table 3). As compared with non-RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty, there were no significant differences in the mean hospitalization costs; however, non-RA patients had a significantly shorter length of stay by 0.1 days (P = .002) (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we observed that the utilization of shoulder arthroplasty in patients with RA increased significantly in the decade from 2002 to 2011, largely related to a rise in TSA. Interestingly, we also observed a corresponding rise in the proportion of RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty with a diagnosis of rotator cuff disease, and we believe that this may partly account for the recent increase in the use of the reverse TSA in this patient population. Additionally, we found shoulder arthroplasty in RA patients to be safe in the early postoperative period, with no significant increase in cost as compared with patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty without a diagnosis of RA. Although we did observe a significant increase in length of stay among RA patients as compared with non-RA patients, the absolute difference was only 0.1 days, and given the aforementioned similarities in cost between RA and non-RA patients, we do not believe this difference to be clinically significant.

It has been theorized that the utilization of TJA in RA patients has been decreasing with improvements in medical management; however, this is largely based upon literature pertaining to lower extremity TJA.2 On the contrary, past research pertaining to the utilization of shoulder arthroplasty in RA patients has been highly variable. For instance, a Swedish study demonstrated a statistically significant decrease in admissions associated with RA-related upper limb surgery and a stable rate of shoulder arthroplasty between 1998 and 2004.7 Similarly, a Finnish study demonstrated that the annual incidence of primary joint arthroplasty in RA patients had declined from 1995 to 2010, with a greater decline for upper-limb arthroplasty as compared with lower-limb arthroplasty.8 Despite these European observations, Jain and colleagues9 reported an increasing rate of TSA among RA patients in the US between the years 1992 and 2005. In this study, we demonstrate a clear increase in the utilization of shoulder arthroplasty among RA patients between 2002 and 2011. What was most striking about our observation was that the rise in utilization appeared to be driven by an increase in TSA, whereas the utilization of HA decreased over time. This change in practice likely reflects several factors, including the multitude of studies that have demonstrated improved outcomes with anatomic TSA as compared with HA in RA patients.10-14

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of our data was the recent exponential rise in the utilization of the reverse TSA. Despite improved outcomes following TSA as compared with HA in RA patients, these outcomes all appear to be highly dependent upon the integrity of the rotator cuff.10 In fact, there is evidence that failure of the rotator cuff could be as high as 75% within 10 years of TSA in patients with RA,15 which ultimately could jeopardize the long-term durability of the TSA implant in this patient population.11 For this reason, interest in the reverse TSA for the RA patient population has increased since its introduction in the US in 2004;16 in fact, in RA patients with end-stage inflammatory arthropathy and a damaged rotator cuff, the reverse TSA has demonstrated excellent results.17-20 Based upon this evidence, it is not surprising that we found an exponential rise in the use of the reverse TSA since 2010, which corresponds to the introduction of an ICD-9 code for this implant.21 Prior to 2010, it is likely that many implanted reverse TSAs were coded as TSA, and for this reason, we believe that the observed rise in the utilization of TSA in RA patients prior to 2010 may have been partly fueled by an increase in the use of the reverse TSA. To further support this theory, there was a dramatic decrease in the use of anatomic TSA following 2010, and we believe this was related to increased awareness of the newly introduced reverse TSA code among surgeons.

Another consideration when examining the utilization of shoulder arthroplasty in RA patients is its versatility in managing different disease states, including rotator cuff disease. As has been documented in the literature, outcomes of rotator cuff repair in RA patients are discouraging.22 For this reason, it is reasonable for surgeons and patients with RA to consider alternatives to rotator cuff repair when nonoperative management has failed to provide adequate improvement in symptoms. One alternative may be shoulder arthroplasty, namely the reverse TSA. In this study, we observed a significant increase in the rate of diagnosis of rotator cuff disease among RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty from 2002 to 2011 (9.7% in 2002 to 15.2% in 2011, P < .001), and it is our belief that the simultaneous increase in the diagnosis of rotator cuff disease and use of TSA is not coincidental. More specifically, there is likely an emerging trend among surgeons toward using the reverse TSA to manage rotator cuff tears in the RA population, rather than undertaking a rotator cuff repair that carries a high rate of failure. Going forward, there is a need to not only identify this trend more clearly but to also compare the outcomes between reverse TSA and rotator cuff repair in the management of rotator cuff tears in RA patients.

Continue to: In this study, we observed...

In this study, we observed that RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty were significantly younger than non-RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty. At first, this observation seems to counter recent literature suggesting that the age of patients with inflammatory arthropathy undergoing TJA is increasing over time;1 however, looking more closely at the data, it becomes clearer that the mean age we report is actually a relative increase as compared with past clinical studies pertaining to RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty (mean ages of 47 years,23 55 years,24 60 years,10 and 62 years25). On the other hand, the continued existence of an age gap between RA and non-RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty may be the result of several possible phenomena. First, this may reflect issues with patient access to and coverage of expensive biologic antirheumatic medication that would otherwise mitigate disease progression. For instance, the out-of-pocket expense for biologic medication through Medicaid and Medicare is substantial,26 which has direct implications on over two-thirds of our RA cohort. Second, it may be skewed by the proportion of RA patients who have previously been or continue to be poorly managed, enabling disease progression to end-stage arthropathy at a younger age. Ultimately, further investigation is needed to determine the reasons for this continued age disparity.

In comparing RA and non-RA patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty, we did not find a significant difference in the overall nor the individual rates of early adverse events. This finding appears to be unique, as similar studies pertaining to total knee arthroplasty (TKA) demonstrated a significantly higher incidence of postoperative pneumonia and bleeding requiring transfusion among RA patients as compared with non-RA patients.27 In patients with RA being treated with biologic medication and undergoing shoulder arthroplasty, the frequent concern in the postoperative period is the integrity of the wound and the potential for infection.28 In this study, we did not find a significant difference in the rate of early infection, and although the difference in the rate of early wound dehiscence approached significance, it did not meet the threshold of 0.05 (P = .09). This finding is in keeping with the aforementioned NIS study pertaining to TKA, and we believe that it likely reflects the short duration of follow-up for patients in both studies. Given the nature of the database we utilized, we were only privy to complications that arose during the inpatient hospital stay, and it is likely that the clear majority of patients who develop a postoperative infection or wound dehiscence do so in the postoperative setting following discharge. A second concern regarding postoperative wound complications is the management of biologic medication in the perioperative period, which we cannot determine using this database. Despite all these limitations specific to this database, a past systematic review of reverse TSA in RA patients found a low rate of deep infection after reverse TSA in RA patients (3.3%),17 which was not higher than that after shoulder arthroplasty performed in non-RA patients.