User login

Bronchitis the leader at putting children in the hospital

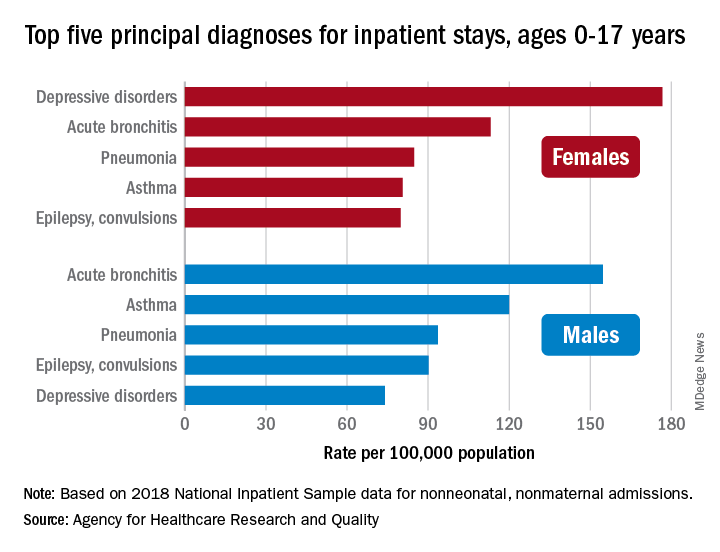

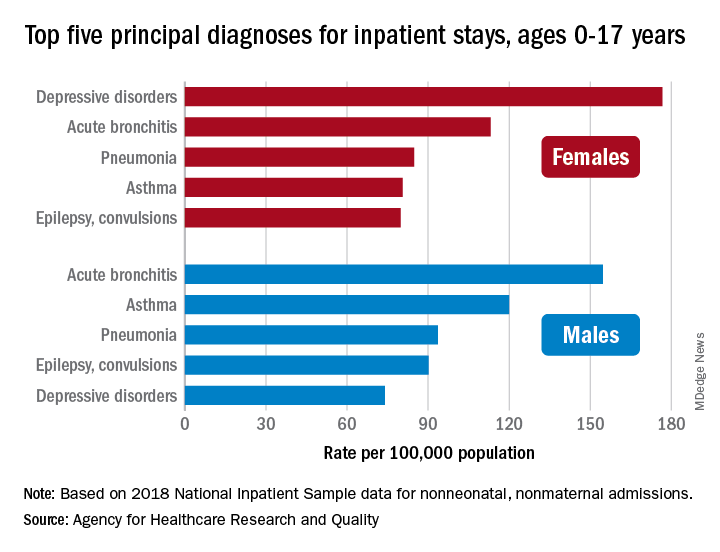

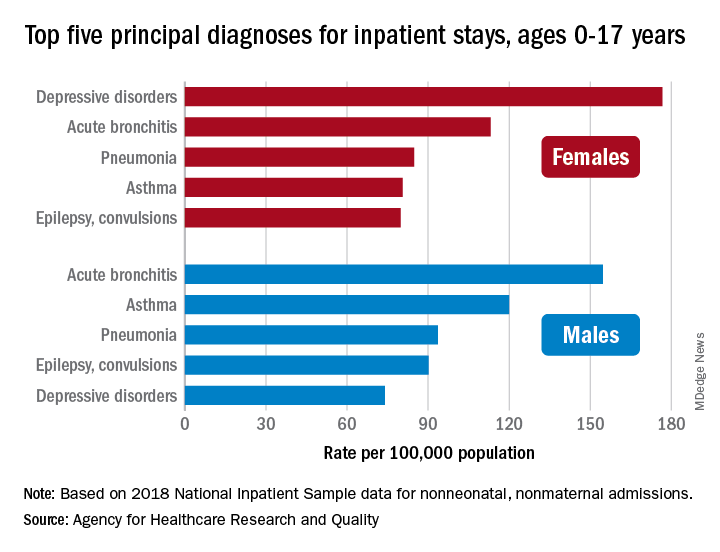

About 7% (99,000) of the 1.47 million nonmaternal, nonneonatal hospital stays in children aged 0-17 years involved a primary diagnosis of acute bronchitis in 2018, representing the leading cause of admissions in boys (154.7 stays per 100,000 population) and the second-leading diagnosis in girls (113.1 stays per 100,000), Kimberly W. McDermott, PhD, and Marc Roemer, MS, said in a statistical brief.

Depressive disorders were the most common primary diagnosis in girls, with a rate of 176.7 stays per 100,000, and the second-leading diagnosis overall, although the rate was less than half that (74.0 per 100,000) in boys. Two other respiratory conditions, asthma and pneumonia, were among the top five for both girls and boys, as was epilepsy, they reported.

The combined rate for all diagnoses was slightly higher for boys, 2,051 per 100,000, compared with 1,922 for girls, they said based on data from the National Inpatient Sample.

“Identifying the most frequent primary conditions for which patients are admitted to the hospital is important to the implementation and improvement of health care delivery, quality initiatives, and health policy,” said Dr. McDermott of IBM Watson Health and Mr. Roemer of the AHRQ.

About 7% (99,000) of the 1.47 million nonmaternal, nonneonatal hospital stays in children aged 0-17 years involved a primary diagnosis of acute bronchitis in 2018, representing the leading cause of admissions in boys (154.7 stays per 100,000 population) and the second-leading diagnosis in girls (113.1 stays per 100,000), Kimberly W. McDermott, PhD, and Marc Roemer, MS, said in a statistical brief.

Depressive disorders were the most common primary diagnosis in girls, with a rate of 176.7 stays per 100,000, and the second-leading diagnosis overall, although the rate was less than half that (74.0 per 100,000) in boys. Two other respiratory conditions, asthma and pneumonia, were among the top five for both girls and boys, as was epilepsy, they reported.

The combined rate for all diagnoses was slightly higher for boys, 2,051 per 100,000, compared with 1,922 for girls, they said based on data from the National Inpatient Sample.

“Identifying the most frequent primary conditions for which patients are admitted to the hospital is important to the implementation and improvement of health care delivery, quality initiatives, and health policy,” said Dr. McDermott of IBM Watson Health and Mr. Roemer of the AHRQ.

About 7% (99,000) of the 1.47 million nonmaternal, nonneonatal hospital stays in children aged 0-17 years involved a primary diagnosis of acute bronchitis in 2018, representing the leading cause of admissions in boys (154.7 stays per 100,000 population) and the second-leading diagnosis in girls (113.1 stays per 100,000), Kimberly W. McDermott, PhD, and Marc Roemer, MS, said in a statistical brief.

Depressive disorders were the most common primary diagnosis in girls, with a rate of 176.7 stays per 100,000, and the second-leading diagnosis overall, although the rate was less than half that (74.0 per 100,000) in boys. Two other respiratory conditions, asthma and pneumonia, were among the top five for both girls and boys, as was epilepsy, they reported.

The combined rate for all diagnoses was slightly higher for boys, 2,051 per 100,000, compared with 1,922 for girls, they said based on data from the National Inpatient Sample.

“Identifying the most frequent primary conditions for which patients are admitted to the hospital is important to the implementation and improvement of health care delivery, quality initiatives, and health policy,” said Dr. McDermott of IBM Watson Health and Mr. Roemer of the AHRQ.

No link between childhood vaccinations and allergies or asthma

A meta-analysis by Australian researchers found no link between childhood vaccinations and an increase in allergies and asthma. In fact, children who received the BCG vaccine actually had a lesser incidence of eczema than other children, but there was no difference shown in any of the allergies or asthma.

The researchers, in a report published in the journal Allergy, write, “We found no evidence that childhood vaccination with commonly administered vaccines was associated with increased risk of later allergic disease.”

“Allergies have increased worldwide in the last 50 years, and in developed countries, earlier,” said study author Caroline J. Lodge, PhD, principal research fellow at the University of Melbourne, in an interview. “In developing countries, it is still a crisis.” No one knows why, she said. That was the reason for the recent study.

Allergic diseases such as allergic rhinitis (hay fever) and food allergies have a serious influence on quality of life, and the incidence is growing. According to the Global Asthma Network, there are 334 million people living with asthma. Between 2%-10% of adults have atopic eczema, and more than a 250,000 people have food allergies. This coincides temporally with an increase in mass vaccination of children.

Unlike the controversy surrounding vaccinations and autism, which has long been debunked as baseless, a hygiene hypothesis postulates that when children acquire immunity from many diseases, they become vulnerable to allergic reactions. Thanks to vaccinations, children in the developed world now are routinely immune to dozens of diseases.

That immunity leads to suppression of a major antibody response, increasing sensitivity to allergens and allergic disease. Suspicion of a link with childhood vaccinations has been used by opponents of vaccines in lobbying campaigns jeopardizing the sustainability of vaccine programs. In recent days, for example, the state of Tennessee has halted a program to encourage vaccination for COVID-19 as well as all other vaccinations, the result of pressure on the state by anti-vaccination lobbying.

But the Melbourne researchers reported that the meta-analysis of 42 published research studies doesn’t support the vaccine–allergy hypothesis. Using PubMed and EMBASE records between January 1946 and January 2018, researchers selected studies to be included in the analysis, looking for allergic outcomes in children given BCG or vaccines for measles or pertussis. Thirty-five publications reported cohort studies, and seven were based on randomized controlled trials.

The Australian study is not the only one showing the same lack of linkage between vaccination and allergy. The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) found no association between mass vaccination and atopic disease. A 1998 Swedish study of 669 children found no differences in the incidence of allergic diseases between those who received pertussis vaccine and those who did not.

“The bottom line is that vaccines prevent infectious diseases,” said Matthew B. Laurens, associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, in an interview. Dr. Laurens was not part of the Australian study.

“Large-scale epidemiological studies do not support the theory that vaccines are associated with an increased risk of allergy or asthma,” he stressed. “Parents should not be deterred from vaccinating their children because of fears that this would increase risks of allergy and/or asthma.”

Dr. Lodge and Dr. Laurens have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A meta-analysis by Australian researchers found no link between childhood vaccinations and an increase in allergies and asthma. In fact, children who received the BCG vaccine actually had a lesser incidence of eczema than other children, but there was no difference shown in any of the allergies or asthma.

The researchers, in a report published in the journal Allergy, write, “We found no evidence that childhood vaccination with commonly administered vaccines was associated with increased risk of later allergic disease.”

“Allergies have increased worldwide in the last 50 years, and in developed countries, earlier,” said study author Caroline J. Lodge, PhD, principal research fellow at the University of Melbourne, in an interview. “In developing countries, it is still a crisis.” No one knows why, she said. That was the reason for the recent study.

Allergic diseases such as allergic rhinitis (hay fever) and food allergies have a serious influence on quality of life, and the incidence is growing. According to the Global Asthma Network, there are 334 million people living with asthma. Between 2%-10% of adults have atopic eczema, and more than a 250,000 people have food allergies. This coincides temporally with an increase in mass vaccination of children.

Unlike the controversy surrounding vaccinations and autism, which has long been debunked as baseless, a hygiene hypothesis postulates that when children acquire immunity from many diseases, they become vulnerable to allergic reactions. Thanks to vaccinations, children in the developed world now are routinely immune to dozens of diseases.

That immunity leads to suppression of a major antibody response, increasing sensitivity to allergens and allergic disease. Suspicion of a link with childhood vaccinations has been used by opponents of vaccines in lobbying campaigns jeopardizing the sustainability of vaccine programs. In recent days, for example, the state of Tennessee has halted a program to encourage vaccination for COVID-19 as well as all other vaccinations, the result of pressure on the state by anti-vaccination lobbying.

But the Melbourne researchers reported that the meta-analysis of 42 published research studies doesn’t support the vaccine–allergy hypothesis. Using PubMed and EMBASE records between January 1946 and January 2018, researchers selected studies to be included in the analysis, looking for allergic outcomes in children given BCG or vaccines for measles or pertussis. Thirty-five publications reported cohort studies, and seven were based on randomized controlled trials.

The Australian study is not the only one showing the same lack of linkage between vaccination and allergy. The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) found no association between mass vaccination and atopic disease. A 1998 Swedish study of 669 children found no differences in the incidence of allergic diseases between those who received pertussis vaccine and those who did not.

“The bottom line is that vaccines prevent infectious diseases,” said Matthew B. Laurens, associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, in an interview. Dr. Laurens was not part of the Australian study.

“Large-scale epidemiological studies do not support the theory that vaccines are associated with an increased risk of allergy or asthma,” he stressed. “Parents should not be deterred from vaccinating their children because of fears that this would increase risks of allergy and/or asthma.”

Dr. Lodge and Dr. Laurens have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A meta-analysis by Australian researchers found no link between childhood vaccinations and an increase in allergies and asthma. In fact, children who received the BCG vaccine actually had a lesser incidence of eczema than other children, but there was no difference shown in any of the allergies or asthma.

The researchers, in a report published in the journal Allergy, write, “We found no evidence that childhood vaccination with commonly administered vaccines was associated with increased risk of later allergic disease.”

“Allergies have increased worldwide in the last 50 years, and in developed countries, earlier,” said study author Caroline J. Lodge, PhD, principal research fellow at the University of Melbourne, in an interview. “In developing countries, it is still a crisis.” No one knows why, she said. That was the reason for the recent study.

Allergic diseases such as allergic rhinitis (hay fever) and food allergies have a serious influence on quality of life, and the incidence is growing. According to the Global Asthma Network, there are 334 million people living with asthma. Between 2%-10% of adults have atopic eczema, and more than a 250,000 people have food allergies. This coincides temporally with an increase in mass vaccination of children.

Unlike the controversy surrounding vaccinations and autism, which has long been debunked as baseless, a hygiene hypothesis postulates that when children acquire immunity from many diseases, they become vulnerable to allergic reactions. Thanks to vaccinations, children in the developed world now are routinely immune to dozens of diseases.

That immunity leads to suppression of a major antibody response, increasing sensitivity to allergens and allergic disease. Suspicion of a link with childhood vaccinations has been used by opponents of vaccines in lobbying campaigns jeopardizing the sustainability of vaccine programs. In recent days, for example, the state of Tennessee has halted a program to encourage vaccination for COVID-19 as well as all other vaccinations, the result of pressure on the state by anti-vaccination lobbying.

But the Melbourne researchers reported that the meta-analysis of 42 published research studies doesn’t support the vaccine–allergy hypothesis. Using PubMed and EMBASE records between January 1946 and January 2018, researchers selected studies to be included in the analysis, looking for allergic outcomes in children given BCG or vaccines for measles or pertussis. Thirty-five publications reported cohort studies, and seven were based on randomized controlled trials.

The Australian study is not the only one showing the same lack of linkage between vaccination and allergy. The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) found no association between mass vaccination and atopic disease. A 1998 Swedish study of 669 children found no differences in the incidence of allergic diseases between those who received pertussis vaccine and those who did not.

“The bottom line is that vaccines prevent infectious diseases,” said Matthew B. Laurens, associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, in an interview. Dr. Laurens was not part of the Australian study.

“Large-scale epidemiological studies do not support the theory that vaccines are associated with an increased risk of allergy or asthma,” he stressed. “Parents should not be deterred from vaccinating their children because of fears that this would increase risks of allergy and/or asthma.”

Dr. Lodge and Dr. Laurens have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Dupilumab safe, effective in kids 6-11 with moderate-to-severe asthma

Dupilumab (Dupixent, Sanofi and Regeneron) significantly reduced exacerbations compared with placebo in children ages 6-11 years who had moderate-to-severe asthma in a phase 3 trial.

A fully human monoclonal antibody, dupilumab also improved lung function versus placebo by week 12, an improvement that lasted the length of the 52-week trial.

Dupilumab previously had been shown to be safe and effective in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe asthma, patients 6 years and older with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis, and adults with chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis, but its safety and effectiveness for moderate-to-severe asthma in the 6-11 years age group was not known.

Results from the randomized, double-blind VOYAGE study conducted across several countries were presented Saturday, July 10, at the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) Hybrid Congress 2021.

Leonard B. Bacharier, MD, professor of pediatrics, allergy/immunology/pulmonary medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee, presented the results from the trial, which was funded by Sanofi/Regeneron.

Researchers enrolled 408 children ages 6-11 years with uncontrolled moderate-to-severe asthma. Children on high-dose inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) alone or medium-to-high–dose ICS with a second controller were randomly assigned either to add-on subcutaneous dupilumab 100 mg or 200 mg, based on body weight at study start, or to placebo every 2 weeks for 52 weeks.

Analyses were done in two populations: 350 patients with markers of type 2 inflammation (baseline blood eosinophils ≥150 cells/μl or fractional exhaled nitric oxide [FeNO] ≥20 ppb) and 259 patients with baseline blood eosinophils ≥300 cells/µl.

“The primary endpoint was the annualized rate of severe asthma exacerbations,” Dr. Bacharier said. “The key secondary endpoint was change in percent predicted prebronchodilator FEV1 [forced expiratory volume at 1 second] from baseline to week 12.”

At week 12, the annualized severe asthma exacerbation rate was reduced by 59% (P < .0001) in children with blood eosinophils ≥300 cells/µL and results were similar in those with the type 2 inflammatory phenotype compared with placebo.

Results also indicate a favorable safety profile for dupilumab.

James M. Tracy, DO, an expert with the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, told this news organization that adding the dupilumab option for children in the 6-11 age group is “huge.”

Dr. Tracy, who was not involved with the study, said although omalizumab (Xolair, Genentech) is also available for these children, dupilumab stands out because of the range of comorbidities it can treat.

“[Children] don’t have the same rhinosinusitis and polyposis that adults would have, but a lot of them have eczema, and this drug with multiple prongs is incredibly useful and addresses a broad array of allergic conditions,” Dr. Tracy said.

More than 90% of children in the study had at least one concurrent type 2 inflammatory condition, including atopic dermatitis and eosinophilic esophagitis. Dupilumab blocks the shared receptor for interleukin (IL)-4/IL-13, which are key drivers of type 2 inflammation in multiple diseases.

Dr. Tracy said that while dupilumab is not the only drug available to treat children 6-11 years with moderate-to-severe asthma, it is “a significant and unique addition to the armamentarium of the individual practitioner taking care of these very severe asthmatics in the 6-11 age group.”

Dupilumab also led to rapid and sustained improvement in lung function. At 12 weeks, children assigned dupilumab improved their lung function as measured by FEV1 by 5.21% (P = .0009), and that continued through the 52-week study period.

“What we know is the [improved lung function] effect is sustained. What we don’t know is how long you have to keep on the drug for a more permanent effect, which is an issue for all these biologics,” Tracy said.

Dr. Bacharier reported speaker fees and research support from Sanofi/Regeneron. Dr. Tracy has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Dupilumab (Dupixent, Sanofi and Regeneron) significantly reduced exacerbations compared with placebo in children ages 6-11 years who had moderate-to-severe asthma in a phase 3 trial.

A fully human monoclonal antibody, dupilumab also improved lung function versus placebo by week 12, an improvement that lasted the length of the 52-week trial.

Dupilumab previously had been shown to be safe and effective in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe asthma, patients 6 years and older with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis, and adults with chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis, but its safety and effectiveness for moderate-to-severe asthma in the 6-11 years age group was not known.

Results from the randomized, double-blind VOYAGE study conducted across several countries were presented Saturday, July 10, at the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) Hybrid Congress 2021.

Leonard B. Bacharier, MD, professor of pediatrics, allergy/immunology/pulmonary medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee, presented the results from the trial, which was funded by Sanofi/Regeneron.

Researchers enrolled 408 children ages 6-11 years with uncontrolled moderate-to-severe asthma. Children on high-dose inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) alone or medium-to-high–dose ICS with a second controller were randomly assigned either to add-on subcutaneous dupilumab 100 mg or 200 mg, based on body weight at study start, or to placebo every 2 weeks for 52 weeks.

Analyses were done in two populations: 350 patients with markers of type 2 inflammation (baseline blood eosinophils ≥150 cells/μl or fractional exhaled nitric oxide [FeNO] ≥20 ppb) and 259 patients with baseline blood eosinophils ≥300 cells/µl.

“The primary endpoint was the annualized rate of severe asthma exacerbations,” Dr. Bacharier said. “The key secondary endpoint was change in percent predicted prebronchodilator FEV1 [forced expiratory volume at 1 second] from baseline to week 12.”

At week 12, the annualized severe asthma exacerbation rate was reduced by 59% (P < .0001) in children with blood eosinophils ≥300 cells/µL and results were similar in those with the type 2 inflammatory phenotype compared with placebo.

Results also indicate a favorable safety profile for dupilumab.

James M. Tracy, DO, an expert with the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, told this news organization that adding the dupilumab option for children in the 6-11 age group is “huge.”

Dr. Tracy, who was not involved with the study, said although omalizumab (Xolair, Genentech) is also available for these children, dupilumab stands out because of the range of comorbidities it can treat.

“[Children] don’t have the same rhinosinusitis and polyposis that adults would have, but a lot of them have eczema, and this drug with multiple prongs is incredibly useful and addresses a broad array of allergic conditions,” Dr. Tracy said.

More than 90% of children in the study had at least one concurrent type 2 inflammatory condition, including atopic dermatitis and eosinophilic esophagitis. Dupilumab blocks the shared receptor for interleukin (IL)-4/IL-13, which are key drivers of type 2 inflammation in multiple diseases.

Dr. Tracy said that while dupilumab is not the only drug available to treat children 6-11 years with moderate-to-severe asthma, it is “a significant and unique addition to the armamentarium of the individual practitioner taking care of these very severe asthmatics in the 6-11 age group.”

Dupilumab also led to rapid and sustained improvement in lung function. At 12 weeks, children assigned dupilumab improved their lung function as measured by FEV1 by 5.21% (P = .0009), and that continued through the 52-week study period.

“What we know is the [improved lung function] effect is sustained. What we don’t know is how long you have to keep on the drug for a more permanent effect, which is an issue for all these biologics,” Tracy said.

Dr. Bacharier reported speaker fees and research support from Sanofi/Regeneron. Dr. Tracy has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Dupilumab (Dupixent, Sanofi and Regeneron) significantly reduced exacerbations compared with placebo in children ages 6-11 years who had moderate-to-severe asthma in a phase 3 trial.

A fully human monoclonal antibody, dupilumab also improved lung function versus placebo by week 12, an improvement that lasted the length of the 52-week trial.

Dupilumab previously had been shown to be safe and effective in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe asthma, patients 6 years and older with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis, and adults with chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis, but its safety and effectiveness for moderate-to-severe asthma in the 6-11 years age group was not known.

Results from the randomized, double-blind VOYAGE study conducted across several countries were presented Saturday, July 10, at the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) Hybrid Congress 2021.

Leonard B. Bacharier, MD, professor of pediatrics, allergy/immunology/pulmonary medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee, presented the results from the trial, which was funded by Sanofi/Regeneron.

Researchers enrolled 408 children ages 6-11 years with uncontrolled moderate-to-severe asthma. Children on high-dose inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) alone or medium-to-high–dose ICS with a second controller were randomly assigned either to add-on subcutaneous dupilumab 100 mg or 200 mg, based on body weight at study start, or to placebo every 2 weeks for 52 weeks.

Analyses were done in two populations: 350 patients with markers of type 2 inflammation (baseline blood eosinophils ≥150 cells/μl or fractional exhaled nitric oxide [FeNO] ≥20 ppb) and 259 patients with baseline blood eosinophils ≥300 cells/µl.

“The primary endpoint was the annualized rate of severe asthma exacerbations,” Dr. Bacharier said. “The key secondary endpoint was change in percent predicted prebronchodilator FEV1 [forced expiratory volume at 1 second] from baseline to week 12.”

At week 12, the annualized severe asthma exacerbation rate was reduced by 59% (P < .0001) in children with blood eosinophils ≥300 cells/µL and results were similar in those with the type 2 inflammatory phenotype compared with placebo.

Results also indicate a favorable safety profile for dupilumab.

James M. Tracy, DO, an expert with the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, told this news organization that adding the dupilumab option for children in the 6-11 age group is “huge.”

Dr. Tracy, who was not involved with the study, said although omalizumab (Xolair, Genentech) is also available for these children, dupilumab stands out because of the range of comorbidities it can treat.

“[Children] don’t have the same rhinosinusitis and polyposis that adults would have, but a lot of them have eczema, and this drug with multiple prongs is incredibly useful and addresses a broad array of allergic conditions,” Dr. Tracy said.

More than 90% of children in the study had at least one concurrent type 2 inflammatory condition, including atopic dermatitis and eosinophilic esophagitis. Dupilumab blocks the shared receptor for interleukin (IL)-4/IL-13, which are key drivers of type 2 inflammation in multiple diseases.

Dr. Tracy said that while dupilumab is not the only drug available to treat children 6-11 years with moderate-to-severe asthma, it is “a significant and unique addition to the armamentarium of the individual practitioner taking care of these very severe asthmatics in the 6-11 age group.”

Dupilumab also led to rapid and sustained improvement in lung function. At 12 weeks, children assigned dupilumab improved their lung function as measured by FEV1 by 5.21% (P = .0009), and that continued through the 52-week study period.

“What we know is the [improved lung function] effect is sustained. What we don’t know is how long you have to keep on the drug for a more permanent effect, which is an issue for all these biologics,” Tracy said.

Dr. Bacharier reported speaker fees and research support from Sanofi/Regeneron. Dr. Tracy has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Optimizing Severe Asthma Treatment: Challenges and Approaches to Care

Asthma is a complex, heterogeneous disease with unmet treatment needs. Patients with severe asthma generally continue to have severe disease despite being on controller therapies.

Uncontrolled asthma can result in unnecessary suffering and interfere with daily activities. It also increases the risk for exacerbations and places substantial burden on the healthcare system.

In this ReCAP, Drs Sandhya Khurana and Steve N. Georas, from the Mary H. Parkes Center for Asthma, Allergy, and Pulmonary Care in Rochester, New York, discuss current challenges in the management of severe asthma, and how advances in the understanding of phenotypes and therapeutic options guide their approaches to asthma management.

They review key indicators of severe asthma, tools to assess asthma control, approaches to phenotyping patients, treatment options for type 2 and non–type 2 asthma, and emerging agents.

--

Sandhya Khurana, MD is a Professor, Department of Medicine, University of Rochester, Director, Mary H. Parkes Center for Asthma, Allergy, and Pulmonary Care, Rochester, New York.

Sandhya Khurana, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Received research grant from: GlaxoSmithKline.

Steve N. Georas, MD is a Professor, Department of Medicine, University of Rochester; Walter & Carmina Mary Parkes Family Endowed Professor; Director, Pulmonary Function Labs, Mary H. Parkes Center for Asthma, Allergy, and Pulmonary Care, Rochester, New York.

Steve N. Georas, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Asthma is a complex, heterogeneous disease with unmet treatment needs. Patients with severe asthma generally continue to have severe disease despite being on controller therapies.

Uncontrolled asthma can result in unnecessary suffering and interfere with daily activities. It also increases the risk for exacerbations and places substantial burden on the healthcare system.

In this ReCAP, Drs Sandhya Khurana and Steve N. Georas, from the Mary H. Parkes Center for Asthma, Allergy, and Pulmonary Care in Rochester, New York, discuss current challenges in the management of severe asthma, and how advances in the understanding of phenotypes and therapeutic options guide their approaches to asthma management.

They review key indicators of severe asthma, tools to assess asthma control, approaches to phenotyping patients, treatment options for type 2 and non–type 2 asthma, and emerging agents.

--

Sandhya Khurana, MD is a Professor, Department of Medicine, University of Rochester, Director, Mary H. Parkes Center for Asthma, Allergy, and Pulmonary Care, Rochester, New York.

Sandhya Khurana, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Received research grant from: GlaxoSmithKline.

Steve N. Georas, MD is a Professor, Department of Medicine, University of Rochester; Walter & Carmina Mary Parkes Family Endowed Professor; Director, Pulmonary Function Labs, Mary H. Parkes Center for Asthma, Allergy, and Pulmonary Care, Rochester, New York.

Steve N. Georas, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Asthma is a complex, heterogeneous disease with unmet treatment needs. Patients with severe asthma generally continue to have severe disease despite being on controller therapies.

Uncontrolled asthma can result in unnecessary suffering and interfere with daily activities. It also increases the risk for exacerbations and places substantial burden on the healthcare system.

In this ReCAP, Drs Sandhya Khurana and Steve N. Georas, from the Mary H. Parkes Center for Asthma, Allergy, and Pulmonary Care in Rochester, New York, discuss current challenges in the management of severe asthma, and how advances in the understanding of phenotypes and therapeutic options guide their approaches to asthma management.

They review key indicators of severe asthma, tools to assess asthma control, approaches to phenotyping patients, treatment options for type 2 and non–type 2 asthma, and emerging agents.

--

Sandhya Khurana, MD is a Professor, Department of Medicine, University of Rochester, Director, Mary H. Parkes Center for Asthma, Allergy, and Pulmonary Care, Rochester, New York.

Sandhya Khurana, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Received research grant from: GlaxoSmithKline.

Steve N. Georas, MD is a Professor, Department of Medicine, University of Rochester; Walter & Carmina Mary Parkes Family Endowed Professor; Director, Pulmonary Function Labs, Mary H. Parkes Center for Asthma, Allergy, and Pulmonary Care, Rochester, New York.

Steve N. Georas, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Respiratory infection– and asthma-prone children

Some children are more susceptible to viral and bacterial respiratory infections in the first few years of life than others. However, the factors contributing to this susceptibility are incompletely understood. The pathogenesis, development, severity, and clinical outcomes of respiratory infections are largely dependent on the resident composition of the nasopharyngeal microbiome and immune defense.1

Respiratory infections caused by bacteria and/or viruses are a leading cause of death in children in the United States and worldwide. The well-recognized, predominant causative bacteria are Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus), nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (Hflu), and Moraxella catarrhalis (Mcat). Respiratory infections caused by these pathogens result in considerable morbidity, mortality, and account for high health care costs. The clinical and laboratory group that I lead in Rochester, N.Y., has been studying acute otitis media (AOM) etiology, epidemiology, pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment for over 3 decades. Our research findings are likely applicable and generalizable to understanding the pathogenesis and immune response to other infectious diseases induced by pneumococcus, Hflu, and Mcat since they are also key pathogens causing sinusitis and lung infections.

Previous immunologic analysis of children with AOM by our group provided clarity in differences between infection-prone children manifest as otitis prone (OP; often referred to in our publications as stringently defined OP because of the stringent diagnostic requirement of tympanocentesis-proven etiology of infection) and non-OP children. We showed that about 90% of OP children have deficient immune responses following nasopharyngeal colonization and AOM, demonstrated by inadequate innate responses and adaptive immune responses.2 Many of these children also showed an increased propensity to viral upper respiratory infection and 30% fail to produce protective antibody responses after injection of routine pediatric vaccines.3,4

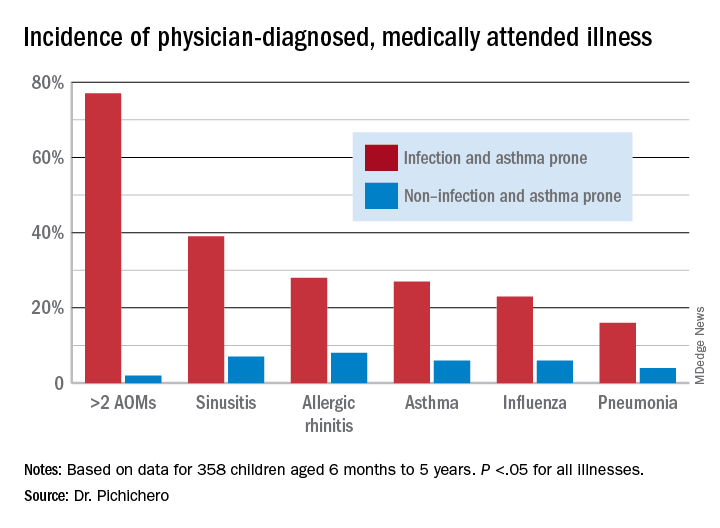

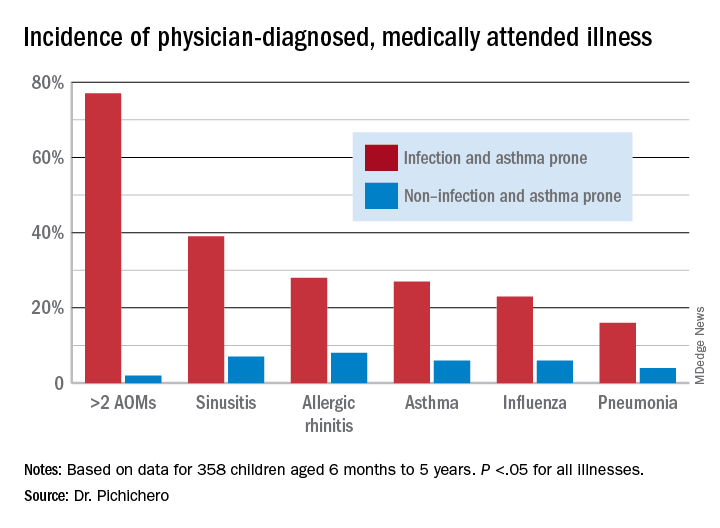

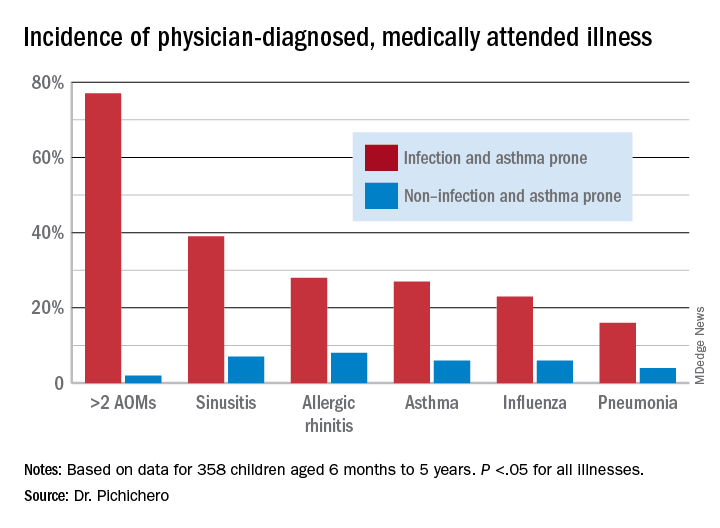

In this column, I want to share new information regarding differences in the nasopharyngeal microbiome of children who are respiratory infection prone versus those who are non–respiratory infection prone and children with asthma versus those who do not exhibit that clinical phenotype. We performed a retrospective analysis of clinical samples collected from 358 children, aged 6 months to 5 years, from our prospectively enrolled cohort in Rochester, N.Y., to determine associations between AOM and other childhood respiratory illnesses and nasopharyngeal microbiota. In order to define subgroups of children within the cohort, we used a statistical method called unsupervised clustering analysis to see if relatively unique groups of children could be discerned. The overall cohort successfully clustered into two groups, showing marked differences in the prevalence of respiratory infections and asthma.5 We termed the two clinical phenotypes infection and asthma prone (n = 99, 28% of the children) and non–infection and asthma prone (n = 259, 72% of the children). Infection- and asthma-prone children were significantly more likely to experience recurrent AOM, influenza, sinusitis, pneumonia, asthma, and allergic rhinitis, compared with non–infection- and asthma-prone children (Figure).

The two groups did not experience significantly different rates of eczema, food allergy, skin infections, urinary tract infections, or acute gastroenteritis, suggesting a common thread involving the respiratory tract that did not cross over to the gastrointestinal, skin, or urinary tract. We found that age at first nasopharyngeal colonization with any of the three bacterial respiratory pathogens (pneumococcus, Hflu, or Mcat) was significantly associated with the respiratory infection– and asthma-prone clinical phenotype. Specifically, respiratory infection– and asthma-prone children experienced colonization at a significantly earlier age than nonprone children did for all three bacteria. In an analysis of individual conditions, early Mcat colonization significantly associated with pneumonia, sinusitis, and asthma susceptibility; Hflu with pneumonia, sinusitis, influenza, and allergic rhinitis; and pneumococcus with sinusitis.

Since early colonization with the three bacterial respiratory pathogens was strongly associated with respiratory illnesses and asthma, nasopharyngeal microbiome analysis was performed on an available subset of samples. Bacterial diversity trended lower in infection- and asthma-prone children, consistent with dysbiosis in the respiratory infection– and asthma-prone clinical phenotype. Nine different bacteria genera were found to be differentially abundant when comparing respiratory infection– and asthma-prone and nonprone children, pointing the way to possible interventions to make the respiratory infection– and asthma-prone child nasopharyngeal microbiome more like the nonprone child.

As I have written previously in this column, recent accumulating data have shed light on the importance of the human microbiome in modulating immune homeostasis and disease susceptibility.6 My group is working toward generating new knowledge for the long-term goal of identifying new therapeutic strategies to facilitate a protective, diverse nasopharyngeal microbiome (with appropriately tuned intranasal probiotics) to prevent respiratory pathogen colonization and/or subsequent progression to respiratory infection and asthma. Also, vaccines directed against colonization-enhancing members of the microbiome may provide a means to indirectly control respiratory pathogen nasopharyngeal colonization.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He has no conflicts to declare. Contact him at [email protected]

References

1. Man WH et al. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2017;15(5):259-70.

2. Pichichero ME. J Infect. 2020;80(6):614-22.

3. Ren D et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(9):1566-74.

4. Pichichero ME et al. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32(11):1163-8.

5. Chapman T et al. PLoS One. 2020 Dec 11;15(12).

6. Blaser MJ. The microbiome revolution. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:4162-5.

Some children are more susceptible to viral and bacterial respiratory infections in the first few years of life than others. However, the factors contributing to this susceptibility are incompletely understood. The pathogenesis, development, severity, and clinical outcomes of respiratory infections are largely dependent on the resident composition of the nasopharyngeal microbiome and immune defense.1

Respiratory infections caused by bacteria and/or viruses are a leading cause of death in children in the United States and worldwide. The well-recognized, predominant causative bacteria are Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus), nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (Hflu), and Moraxella catarrhalis (Mcat). Respiratory infections caused by these pathogens result in considerable morbidity, mortality, and account for high health care costs. The clinical and laboratory group that I lead in Rochester, N.Y., has been studying acute otitis media (AOM) etiology, epidemiology, pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment for over 3 decades. Our research findings are likely applicable and generalizable to understanding the pathogenesis and immune response to other infectious diseases induced by pneumococcus, Hflu, and Mcat since they are also key pathogens causing sinusitis and lung infections.

Previous immunologic analysis of children with AOM by our group provided clarity in differences between infection-prone children manifest as otitis prone (OP; often referred to in our publications as stringently defined OP because of the stringent diagnostic requirement of tympanocentesis-proven etiology of infection) and non-OP children. We showed that about 90% of OP children have deficient immune responses following nasopharyngeal colonization and AOM, demonstrated by inadequate innate responses and adaptive immune responses.2 Many of these children also showed an increased propensity to viral upper respiratory infection and 30% fail to produce protective antibody responses after injection of routine pediatric vaccines.3,4

In this column, I want to share new information regarding differences in the nasopharyngeal microbiome of children who are respiratory infection prone versus those who are non–respiratory infection prone and children with asthma versus those who do not exhibit that clinical phenotype. We performed a retrospective analysis of clinical samples collected from 358 children, aged 6 months to 5 years, from our prospectively enrolled cohort in Rochester, N.Y., to determine associations between AOM and other childhood respiratory illnesses and nasopharyngeal microbiota. In order to define subgroups of children within the cohort, we used a statistical method called unsupervised clustering analysis to see if relatively unique groups of children could be discerned. The overall cohort successfully clustered into two groups, showing marked differences in the prevalence of respiratory infections and asthma.5 We termed the two clinical phenotypes infection and asthma prone (n = 99, 28% of the children) and non–infection and asthma prone (n = 259, 72% of the children). Infection- and asthma-prone children were significantly more likely to experience recurrent AOM, influenza, sinusitis, pneumonia, asthma, and allergic rhinitis, compared with non–infection- and asthma-prone children (Figure).

The two groups did not experience significantly different rates of eczema, food allergy, skin infections, urinary tract infections, or acute gastroenteritis, suggesting a common thread involving the respiratory tract that did not cross over to the gastrointestinal, skin, or urinary tract. We found that age at first nasopharyngeal colonization with any of the three bacterial respiratory pathogens (pneumococcus, Hflu, or Mcat) was significantly associated with the respiratory infection– and asthma-prone clinical phenotype. Specifically, respiratory infection– and asthma-prone children experienced colonization at a significantly earlier age than nonprone children did for all three bacteria. In an analysis of individual conditions, early Mcat colonization significantly associated with pneumonia, sinusitis, and asthma susceptibility; Hflu with pneumonia, sinusitis, influenza, and allergic rhinitis; and pneumococcus with sinusitis.

Since early colonization with the three bacterial respiratory pathogens was strongly associated with respiratory illnesses and asthma, nasopharyngeal microbiome analysis was performed on an available subset of samples. Bacterial diversity trended lower in infection- and asthma-prone children, consistent with dysbiosis in the respiratory infection– and asthma-prone clinical phenotype. Nine different bacteria genera were found to be differentially abundant when comparing respiratory infection– and asthma-prone and nonprone children, pointing the way to possible interventions to make the respiratory infection– and asthma-prone child nasopharyngeal microbiome more like the nonprone child.

As I have written previously in this column, recent accumulating data have shed light on the importance of the human microbiome in modulating immune homeostasis and disease susceptibility.6 My group is working toward generating new knowledge for the long-term goal of identifying new therapeutic strategies to facilitate a protective, diverse nasopharyngeal microbiome (with appropriately tuned intranasal probiotics) to prevent respiratory pathogen colonization and/or subsequent progression to respiratory infection and asthma. Also, vaccines directed against colonization-enhancing members of the microbiome may provide a means to indirectly control respiratory pathogen nasopharyngeal colonization.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He has no conflicts to declare. Contact him at [email protected]

References

1. Man WH et al. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2017;15(5):259-70.

2. Pichichero ME. J Infect. 2020;80(6):614-22.

3. Ren D et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(9):1566-74.

4. Pichichero ME et al. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32(11):1163-8.

5. Chapman T et al. PLoS One. 2020 Dec 11;15(12).

6. Blaser MJ. The microbiome revolution. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:4162-5.

Some children are more susceptible to viral and bacterial respiratory infections in the first few years of life than others. However, the factors contributing to this susceptibility are incompletely understood. The pathogenesis, development, severity, and clinical outcomes of respiratory infections are largely dependent on the resident composition of the nasopharyngeal microbiome and immune defense.1

Respiratory infections caused by bacteria and/or viruses are a leading cause of death in children in the United States and worldwide. The well-recognized, predominant causative bacteria are Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus), nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (Hflu), and Moraxella catarrhalis (Mcat). Respiratory infections caused by these pathogens result in considerable morbidity, mortality, and account for high health care costs. The clinical and laboratory group that I lead in Rochester, N.Y., has been studying acute otitis media (AOM) etiology, epidemiology, pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment for over 3 decades. Our research findings are likely applicable and generalizable to understanding the pathogenesis and immune response to other infectious diseases induced by pneumococcus, Hflu, and Mcat since they are also key pathogens causing sinusitis and lung infections.

Previous immunologic analysis of children with AOM by our group provided clarity in differences between infection-prone children manifest as otitis prone (OP; often referred to in our publications as stringently defined OP because of the stringent diagnostic requirement of tympanocentesis-proven etiology of infection) and non-OP children. We showed that about 90% of OP children have deficient immune responses following nasopharyngeal colonization and AOM, demonstrated by inadequate innate responses and adaptive immune responses.2 Many of these children also showed an increased propensity to viral upper respiratory infection and 30% fail to produce protective antibody responses after injection of routine pediatric vaccines.3,4

In this column, I want to share new information regarding differences in the nasopharyngeal microbiome of children who are respiratory infection prone versus those who are non–respiratory infection prone and children with asthma versus those who do not exhibit that clinical phenotype. We performed a retrospective analysis of clinical samples collected from 358 children, aged 6 months to 5 years, from our prospectively enrolled cohort in Rochester, N.Y., to determine associations between AOM and other childhood respiratory illnesses and nasopharyngeal microbiota. In order to define subgroups of children within the cohort, we used a statistical method called unsupervised clustering analysis to see if relatively unique groups of children could be discerned. The overall cohort successfully clustered into two groups, showing marked differences in the prevalence of respiratory infections and asthma.5 We termed the two clinical phenotypes infection and asthma prone (n = 99, 28% of the children) and non–infection and asthma prone (n = 259, 72% of the children). Infection- and asthma-prone children were significantly more likely to experience recurrent AOM, influenza, sinusitis, pneumonia, asthma, and allergic rhinitis, compared with non–infection- and asthma-prone children (Figure).

The two groups did not experience significantly different rates of eczema, food allergy, skin infections, urinary tract infections, or acute gastroenteritis, suggesting a common thread involving the respiratory tract that did not cross over to the gastrointestinal, skin, or urinary tract. We found that age at first nasopharyngeal colonization with any of the three bacterial respiratory pathogens (pneumococcus, Hflu, or Mcat) was significantly associated with the respiratory infection– and asthma-prone clinical phenotype. Specifically, respiratory infection– and asthma-prone children experienced colonization at a significantly earlier age than nonprone children did for all three bacteria. In an analysis of individual conditions, early Mcat colonization significantly associated with pneumonia, sinusitis, and asthma susceptibility; Hflu with pneumonia, sinusitis, influenza, and allergic rhinitis; and pneumococcus with sinusitis.

Since early colonization with the three bacterial respiratory pathogens was strongly associated with respiratory illnesses and asthma, nasopharyngeal microbiome analysis was performed on an available subset of samples. Bacterial diversity trended lower in infection- and asthma-prone children, consistent with dysbiosis in the respiratory infection– and asthma-prone clinical phenotype. Nine different bacteria genera were found to be differentially abundant when comparing respiratory infection– and asthma-prone and nonprone children, pointing the way to possible interventions to make the respiratory infection– and asthma-prone child nasopharyngeal microbiome more like the nonprone child.

As I have written previously in this column, recent accumulating data have shed light on the importance of the human microbiome in modulating immune homeostasis and disease susceptibility.6 My group is working toward generating new knowledge for the long-term goal of identifying new therapeutic strategies to facilitate a protective, diverse nasopharyngeal microbiome (with appropriately tuned intranasal probiotics) to prevent respiratory pathogen colonization and/or subsequent progression to respiratory infection and asthma. Also, vaccines directed against colonization-enhancing members of the microbiome may provide a means to indirectly control respiratory pathogen nasopharyngeal colonization.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He has no conflicts to declare. Contact him at [email protected]

References

1. Man WH et al. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2017;15(5):259-70.

2. Pichichero ME. J Infect. 2020;80(6):614-22.

3. Ren D et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(9):1566-74.

4. Pichichero ME et al. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32(11):1163-8.

5. Chapman T et al. PLoS One. 2020 Dec 11;15(12).

6. Blaser MJ. The microbiome revolution. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:4162-5.

Sublingual immunotherapy: Where does it stand?

Sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT) emerged over a century ago as a gentler alternative to allergy shots. It uses the same antigens found in allergy shots, delivering them through tablets or drops under the tongue rather than by injecting them into the skin.

Yet injection immunotherapy has been the mainstay of allergy treatment in the United States. Allergy shots are “the bread and butter, keeping the lights on at allergy practices,” said allergist Sakina Bajowala, MD, of Kaneland Allergy and Asthma Center, in the Chicago area. So even “when environmental SLIT showed quite clearly that it had efficacy, people were so slow to adapt.”

SLIT – a daily treatment that builds protection from allergens gradually over years with few side effects – is popular around the globe, particularly for environmental allergies. But only a handful of clinics offer food SLIT. Even though recent trials in peanut-allergic children show that SLIT is far safer than oral immunotherapy and about as effective as the Food and Drug Administration–approved peanut-allergy product and has lasting benefits for toddlers, many allergists lack experience with customized immunotherapies and hesitate to offer an unregulated treatment for which the evidence base is still emerging.

Why hasn’t food allergy SLIT caught on?

One issue is that there is scant evidence from randomized, controlled trials. The treatments that clinics offer often hinge on insurance coverage, and increasingly, insurers only cover FDA-approved products. FDA approval requires thousands of patients being enrolled in long, expensive studies to prove the treatment’s merit. In a similar vein, doctors are trained to question methods that lack a strong publication base, for good reason.

Yet SLIT caught the attention of pioneering physicians who were intrigued by this “low-and-slow” immune-modifying approach, despite limited published evidence, and they sought real-world experience.

The late physician David Morris, MD, came across SLIT in the 1960s while searching for alternative ways to help mold-allergic farmers who were suffering terrible side effects from allergy shots. Dr. Morris attended conferences, learned more about sublingual techniques, got board certified in allergy, and opened Allergy Associates of La Crosse (Wis.), in 1970 to offer SLIT as a treatment for food and environmental allergies.

Dr. Morris and colleagues developed a protocol to create custom SLIT drops tailored to individual patients’ clinical histories and allergy test results. The method has been used to treat more than 200,000 patients. It has been used by allergist Nikhila Schroeder, MD, MEng, who learned SLIT methods while treating nearly 1,000 patients at Allergy Associates. In 2018, she opened her own direct-care SLIT practice, Allergenuity Health, in the Charlotte metropolitan area of North Carolina (see part 2 of this series).

Dr. Bajowala’s clinic offers SLIT in addition to oral immunotherapy (OIT). She was encouraged by the recent toddler SLIT data but wondered whether it would translate to a real-world setting. According to her calculations, the published protocol – according to which participants receive up to 4 mg/d over 6 months and continue receiving a daily maintenance dose of 4 mg for 3 years – would cost $10,000 per patient.

With this dosing regimen, the intervention is unaffordable, Dr. Bajowala said. And “there’s no way to make it cheaper because that’s the raw materials cost. It does not include labor or bottles or profit at all. That’s just $10,000 in peanut extract.”

Owing to cost, Dr. Bajowala’s clinic generally uses SLIT as a bridge to OIT. Her food allergy patients receive up to 1 mg/d and remain at that dose for a month or so before transitioning to OIT, “for which the supplies are orders of magnitude cheaper,” she said.

Dr. Schroeder said there is evidence for efficacy at microgram and even nanogram dosing – much lower than used in the recent food SLIT trials. Maintenance doses range from 50 ng/d to 25 mcg/d for environmental SLIT and 4-37 mcg/d for food SLIT, she said. The La Crosse method uses even lower dose ranges.

However, dosing information is not readily available, Dr. Schroeder noted. She has spent years scrutinizing articles and compiling information from allergen extract suppliers – all the while treating hundreds of SLIT patients. “I have had to expend a lot of time and effort,” said Dr. Schroeder. “It’s really hard to explain quickly.”

In the published literature, SLIT dosing recommendations vary widely. According to a 2007 analysis, environmental allergy symptoms improved with doses over a 1,000-fold range. What’s more, success did not scale with increased dosing and seemed to depend more on frequency and duration of treatment.

There are fewer studies regarding food SLIT. The most promising data come from recent trials of peanut-allergic children led by Edwin Kim, MD, director of the UNC Food Allergy Initiative, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Still, “I am nervous to tell people to go do this based on 150 kids at one site,” Dr. Kim said. “We need to have a gigantic study across multiple sites that actually confirms what we have found in our single center.”

Because there are few published trials of food SLIT, confusion about which doses are optimal, how early to start, and how long the benefits last will be a barrier for many clinicians, said Douglas Mack, MD, FRCPC, assistant clinical professor in pediatrics at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

Much could be learned from Allergy Associates of La Crosse, Allergenuity Health, and other clinics with SLIT experience involving thousands of patients. But that real-world data are messy and difficult to publish. Plus, it is hard for private allergists to find time to review charts, analyze data, and draft papers alongside seeing patients and running a clinic – especially without students and interns, who typically assist with academic research, Dr. Schroeder said.

Ruchi Gupta, MD, MPH, professor of pediatrics and medicine at Northwestern University, Chicago, and colleagues worked with a La Crosse team 6 or 7 years ago to try to analyze and publish SLIT outcomes for 121 peanut-allergic children who were treated for food and environmental allergies at the Wisconsin clinic. The researchers had hoped to publish an article describing caregiver-reported and clinical outcomes.

Among 73 caregivers who responded to a survey, more than half reported improved eczema, asthma, and environmental allergy symptoms, and virtually all families said SLIT calmed anxieties and minimized fear of allergic reactions. However, the clinical outcomes – skinprick test results, immune changes, and oral food challenges – were not as robust. And the data were incomplete. Some patients had traveled to La Crosse for SLIT drops but underwent skin and blood testing with their local allergist. Compiling records is “so much harder when you’re not doing a prospective clinical trial,” Dr. Gupta said.

The caregiver-reported outcomes were presented as a poster at the 2015 annual meeting of the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology and the 2016 annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Society, said Jeff Kessler, MBA, FACHE, who is practice executive at La Crosse. However, with only self-reported data and no convincing lab metrics, the findings were never submitted for publication.

Others are eager to see clearer proof that SLIT works at doses lower than those published in the most recent trials. “If we can get efficacy with lower doses, that means we can increase accessibility, because we can lower the cost,” Dr. Bajowala said.

Robert Wood, MD, professor of pediatrics and director of pediatric allergy and immunology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, has a pending grant proposal for a multifood trial of SLIT. “It’s a big missing piece,” he said.

Dr. Mack said that in Canada there was “almost an instant change in group think” when the Canadian Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology published guidelines in support of OIT. With the new guidelines, “people are less concerned about liability. Once they start getting into OIT, I think you’re going to see SLIT coming right along for the ride.”

The shift will be slower in the United States, which has 20 times as many practicing allergists as Canada. Nevertheless, “I totally think SLIT has a place at the table,” Dr. Mack said. “I hope we start to see more high-quality data and people start to use it and experiment with it a bit and see how it works.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com. This is part three of a three-part series. Part one is here. Part two is here.

Sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT) emerged over a century ago as a gentler alternative to allergy shots. It uses the same antigens found in allergy shots, delivering them through tablets or drops under the tongue rather than by injecting them into the skin.

Yet injection immunotherapy has been the mainstay of allergy treatment in the United States. Allergy shots are “the bread and butter, keeping the lights on at allergy practices,” said allergist Sakina Bajowala, MD, of Kaneland Allergy and Asthma Center, in the Chicago area. So even “when environmental SLIT showed quite clearly that it had efficacy, people were so slow to adapt.”

SLIT – a daily treatment that builds protection from allergens gradually over years with few side effects – is popular around the globe, particularly for environmental allergies. But only a handful of clinics offer food SLIT. Even though recent trials in peanut-allergic children show that SLIT is far safer than oral immunotherapy and about as effective as the Food and Drug Administration–approved peanut-allergy product and has lasting benefits for toddlers, many allergists lack experience with customized immunotherapies and hesitate to offer an unregulated treatment for which the evidence base is still emerging.

Why hasn’t food allergy SLIT caught on?

One issue is that there is scant evidence from randomized, controlled trials. The treatments that clinics offer often hinge on insurance coverage, and increasingly, insurers only cover FDA-approved products. FDA approval requires thousands of patients being enrolled in long, expensive studies to prove the treatment’s merit. In a similar vein, doctors are trained to question methods that lack a strong publication base, for good reason.

Yet SLIT caught the attention of pioneering physicians who were intrigued by this “low-and-slow” immune-modifying approach, despite limited published evidence, and they sought real-world experience.

The late physician David Morris, MD, came across SLIT in the 1960s while searching for alternative ways to help mold-allergic farmers who were suffering terrible side effects from allergy shots. Dr. Morris attended conferences, learned more about sublingual techniques, got board certified in allergy, and opened Allergy Associates of La Crosse (Wis.), in 1970 to offer SLIT as a treatment for food and environmental allergies.

Dr. Morris and colleagues developed a protocol to create custom SLIT drops tailored to individual patients’ clinical histories and allergy test results. The method has been used to treat more than 200,000 patients. It has been used by allergist Nikhila Schroeder, MD, MEng, who learned SLIT methods while treating nearly 1,000 patients at Allergy Associates. In 2018, she opened her own direct-care SLIT practice, Allergenuity Health, in the Charlotte metropolitan area of North Carolina (see part 2 of this series).

Dr. Bajowala’s clinic offers SLIT in addition to oral immunotherapy (OIT). She was encouraged by the recent toddler SLIT data but wondered whether it would translate to a real-world setting. According to her calculations, the published protocol – according to which participants receive up to 4 mg/d over 6 months and continue receiving a daily maintenance dose of 4 mg for 3 years – would cost $10,000 per patient.

With this dosing regimen, the intervention is unaffordable, Dr. Bajowala said. And “there’s no way to make it cheaper because that’s the raw materials cost. It does not include labor or bottles or profit at all. That’s just $10,000 in peanut extract.”

Owing to cost, Dr. Bajowala’s clinic generally uses SLIT as a bridge to OIT. Her food allergy patients receive up to 1 mg/d and remain at that dose for a month or so before transitioning to OIT, “for which the supplies are orders of magnitude cheaper,” she said.

Dr. Schroeder said there is evidence for efficacy at microgram and even nanogram dosing – much lower than used in the recent food SLIT trials. Maintenance doses range from 50 ng/d to 25 mcg/d for environmental SLIT and 4-37 mcg/d for food SLIT, she said. The La Crosse method uses even lower dose ranges.

However, dosing information is not readily available, Dr. Schroeder noted. She has spent years scrutinizing articles and compiling information from allergen extract suppliers – all the while treating hundreds of SLIT patients. “I have had to expend a lot of time and effort,” said Dr. Schroeder. “It’s really hard to explain quickly.”

In the published literature, SLIT dosing recommendations vary widely. According to a 2007 analysis, environmental allergy symptoms improved with doses over a 1,000-fold range. What’s more, success did not scale with increased dosing and seemed to depend more on frequency and duration of treatment.

There are fewer studies regarding food SLIT. The most promising data come from recent trials of peanut-allergic children led by Edwin Kim, MD, director of the UNC Food Allergy Initiative, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Still, “I am nervous to tell people to go do this based on 150 kids at one site,” Dr. Kim said. “We need to have a gigantic study across multiple sites that actually confirms what we have found in our single center.”

Because there are few published trials of food SLIT, confusion about which doses are optimal, how early to start, and how long the benefits last will be a barrier for many clinicians, said Douglas Mack, MD, FRCPC, assistant clinical professor in pediatrics at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

Much could be learned from Allergy Associates of La Crosse, Allergenuity Health, and other clinics with SLIT experience involving thousands of patients. But that real-world data are messy and difficult to publish. Plus, it is hard for private allergists to find time to review charts, analyze data, and draft papers alongside seeing patients and running a clinic – especially without students and interns, who typically assist with academic research, Dr. Schroeder said.

Ruchi Gupta, MD, MPH, professor of pediatrics and medicine at Northwestern University, Chicago, and colleagues worked with a La Crosse team 6 or 7 years ago to try to analyze and publish SLIT outcomes for 121 peanut-allergic children who were treated for food and environmental allergies at the Wisconsin clinic. The researchers had hoped to publish an article describing caregiver-reported and clinical outcomes.

Among 73 caregivers who responded to a survey, more than half reported improved eczema, asthma, and environmental allergy symptoms, and virtually all families said SLIT calmed anxieties and minimized fear of allergic reactions. However, the clinical outcomes – skinprick test results, immune changes, and oral food challenges – were not as robust. And the data were incomplete. Some patients had traveled to La Crosse for SLIT drops but underwent skin and blood testing with their local allergist. Compiling records is “so much harder when you’re not doing a prospective clinical trial,” Dr. Gupta said.

The caregiver-reported outcomes were presented as a poster at the 2015 annual meeting of the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology and the 2016 annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Society, said Jeff Kessler, MBA, FACHE, who is practice executive at La Crosse. However, with only self-reported data and no convincing lab metrics, the findings were never submitted for publication.

Others are eager to see clearer proof that SLIT works at doses lower than those published in the most recent trials. “If we can get efficacy with lower doses, that means we can increase accessibility, because we can lower the cost,” Dr. Bajowala said.

Robert Wood, MD, professor of pediatrics and director of pediatric allergy and immunology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, has a pending grant proposal for a multifood trial of SLIT. “It’s a big missing piece,” he said.

Dr. Mack said that in Canada there was “almost an instant change in group think” when the Canadian Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology published guidelines in support of OIT. With the new guidelines, “people are less concerned about liability. Once they start getting into OIT, I think you’re going to see SLIT coming right along for the ride.”

The shift will be slower in the United States, which has 20 times as many practicing allergists as Canada. Nevertheless, “I totally think SLIT has a place at the table,” Dr. Mack said. “I hope we start to see more high-quality data and people start to use it and experiment with it a bit and see how it works.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com. This is part three of a three-part series. Part one is here. Part two is here.

Sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT) emerged over a century ago as a gentler alternative to allergy shots. It uses the same antigens found in allergy shots, delivering them through tablets or drops under the tongue rather than by injecting them into the skin.

Yet injection immunotherapy has been the mainstay of allergy treatment in the United States. Allergy shots are “the bread and butter, keeping the lights on at allergy practices,” said allergist Sakina Bajowala, MD, of Kaneland Allergy and Asthma Center, in the Chicago area. So even “when environmental SLIT showed quite clearly that it had efficacy, people were so slow to adapt.”

SLIT – a daily treatment that builds protection from allergens gradually over years with few side effects – is popular around the globe, particularly for environmental allergies. But only a handful of clinics offer food SLIT. Even though recent trials in peanut-allergic children show that SLIT is far safer than oral immunotherapy and about as effective as the Food and Drug Administration–approved peanut-allergy product and has lasting benefits for toddlers, many allergists lack experience with customized immunotherapies and hesitate to offer an unregulated treatment for which the evidence base is still emerging.

Why hasn’t food allergy SLIT caught on?

One issue is that there is scant evidence from randomized, controlled trials. The treatments that clinics offer often hinge on insurance coverage, and increasingly, insurers only cover FDA-approved products. FDA approval requires thousands of patients being enrolled in long, expensive studies to prove the treatment’s merit. In a similar vein, doctors are trained to question methods that lack a strong publication base, for good reason.

Yet SLIT caught the attention of pioneering physicians who were intrigued by this “low-and-slow” immune-modifying approach, despite limited published evidence, and they sought real-world experience.

The late physician David Morris, MD, came across SLIT in the 1960s while searching for alternative ways to help mold-allergic farmers who were suffering terrible side effects from allergy shots. Dr. Morris attended conferences, learned more about sublingual techniques, got board certified in allergy, and opened Allergy Associates of La Crosse (Wis.), in 1970 to offer SLIT as a treatment for food and environmental allergies.

Dr. Morris and colleagues developed a protocol to create custom SLIT drops tailored to individual patients’ clinical histories and allergy test results. The method has been used to treat more than 200,000 patients. It has been used by allergist Nikhila Schroeder, MD, MEng, who learned SLIT methods while treating nearly 1,000 patients at Allergy Associates. In 2018, she opened her own direct-care SLIT practice, Allergenuity Health, in the Charlotte metropolitan area of North Carolina (see part 2 of this series).

Dr. Bajowala’s clinic offers SLIT in addition to oral immunotherapy (OIT). She was encouraged by the recent toddler SLIT data but wondered whether it would translate to a real-world setting. According to her calculations, the published protocol – according to which participants receive up to 4 mg/d over 6 months and continue receiving a daily maintenance dose of 4 mg for 3 years – would cost $10,000 per patient.

With this dosing regimen, the intervention is unaffordable, Dr. Bajowala said. And “there’s no way to make it cheaper because that’s the raw materials cost. It does not include labor or bottles or profit at all. That’s just $10,000 in peanut extract.”

Owing to cost, Dr. Bajowala’s clinic generally uses SLIT as a bridge to OIT. Her food allergy patients receive up to 1 mg/d and remain at that dose for a month or so before transitioning to OIT, “for which the supplies are orders of magnitude cheaper,” she said.

Dr. Schroeder said there is evidence for efficacy at microgram and even nanogram dosing – much lower than used in the recent food SLIT trials. Maintenance doses range from 50 ng/d to 25 mcg/d for environmental SLIT and 4-37 mcg/d for food SLIT, she said. The La Crosse method uses even lower dose ranges.

However, dosing information is not readily available, Dr. Schroeder noted. She has spent years scrutinizing articles and compiling information from allergen extract suppliers – all the while treating hundreds of SLIT patients. “I have had to expend a lot of time and effort,” said Dr. Schroeder. “It’s really hard to explain quickly.”

In the published literature, SLIT dosing recommendations vary widely. According to a 2007 analysis, environmental allergy symptoms improved with doses over a 1,000-fold range. What’s more, success did not scale with increased dosing and seemed to depend more on frequency and duration of treatment.

There are fewer studies regarding food SLIT. The most promising data come from recent trials of peanut-allergic children led by Edwin Kim, MD, director of the UNC Food Allergy Initiative, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Still, “I am nervous to tell people to go do this based on 150 kids at one site,” Dr. Kim said. “We need to have a gigantic study across multiple sites that actually confirms what we have found in our single center.”

Because there are few published trials of food SLIT, confusion about which doses are optimal, how early to start, and how long the benefits last will be a barrier for many clinicians, said Douglas Mack, MD, FRCPC, assistant clinical professor in pediatrics at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

Much could be learned from Allergy Associates of La Crosse, Allergenuity Health, and other clinics with SLIT experience involving thousands of patients. But that real-world data are messy and difficult to publish. Plus, it is hard for private allergists to find time to review charts, analyze data, and draft papers alongside seeing patients and running a clinic – especially without students and interns, who typically assist with academic research, Dr. Schroeder said.

Ruchi Gupta, MD, MPH, professor of pediatrics and medicine at Northwestern University, Chicago, and colleagues worked with a La Crosse team 6 or 7 years ago to try to analyze and publish SLIT outcomes for 121 peanut-allergic children who were treated for food and environmental allergies at the Wisconsin clinic. The researchers had hoped to publish an article describing caregiver-reported and clinical outcomes.

Among 73 caregivers who responded to a survey, more than half reported improved eczema, asthma, and environmental allergy symptoms, and virtually all families said SLIT calmed anxieties and minimized fear of allergic reactions. However, the clinical outcomes – skinprick test results, immune changes, and oral food challenges – were not as robust. And the data were incomplete. Some patients had traveled to La Crosse for SLIT drops but underwent skin and blood testing with their local allergist. Compiling records is “so much harder when you’re not doing a prospective clinical trial,” Dr. Gupta said.

The caregiver-reported outcomes were presented as a poster at the 2015 annual meeting of the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology and the 2016 annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Society, said Jeff Kessler, MBA, FACHE, who is practice executive at La Crosse. However, with only self-reported data and no convincing lab metrics, the findings were never submitted for publication.

Others are eager to see clearer proof that SLIT works at doses lower than those published in the most recent trials. “If we can get efficacy with lower doses, that means we can increase accessibility, because we can lower the cost,” Dr. Bajowala said.

Robert Wood, MD, professor of pediatrics and director of pediatric allergy and immunology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, has a pending grant proposal for a multifood trial of SLIT. “It’s a big missing piece,” he said.

Dr. Mack said that in Canada there was “almost an instant change in group think” when the Canadian Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology published guidelines in support of OIT. With the new guidelines, “people are less concerned about liability. Once they start getting into OIT, I think you’re going to see SLIT coming right along for the ride.”

The shift will be slower in the United States, which has 20 times as many practicing allergists as Canada. Nevertheless, “I totally think SLIT has a place at the table,” Dr. Mack said. “I hope we start to see more high-quality data and people start to use it and experiment with it a bit and see how it works.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com. This is part three of a three-part series. Part one is here. Part two is here.

Direct-care allergy clinic specializes in sublingual immunotherapy

With degrees in electrical engineering and computer science from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Nikhila Schroeder, MD, MEng, brings a problem-solving mindset to medicine.

Being a doctor means having to “figure out all aspects of [a patient’s] situation and do my best to come up with an answer,” said Dr. Schroeder, who founded Allergenuity Health, a solo allergy practice in Huntersville, N.C., with her husband James, who serves as practice executive. It’s “being a medical detective for your patient.”

Yet, during her training, Dr. Schroeder found that market-driven health care makes it hard to practice medicine with a patient’s best interest foremost. Procedures for diagnosing and treating disease cater to insurance companies’ reimbursement policies. “You wind up having to tailor your care to whatever insurance will cover,” she said.

Insurers, in turn, look for evidence from large, peer-reviewed studies to prove that a treatment works. Many physicians hesitate to offer therapies that aren’t covered by insurance, for both liability and financial reasons. So treatment tends to be limited to those options that were rigorously vetted in long, costly, multisite trials that are difficult to conduct without a corporate sponsor.

This is why there is still only one licensed treatment for people with food allergies – a set of standardized peanut powder capsules (Palforzia) that was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in early 2020 for peanut-allergic children aged 4-17 years. A small but growing number of allergists offer unapproved oral immunotherapy (OIT) using commercial food products to treat allergies to peanuts and other foods.