User login

Study finds quality of topical steroid withdrawal videos on YouTube subpar

NEW ORLEANS –

“Video-sharing platforms such as YouTube are a great place for patients to connect and find community with others dealing with the same conditions,” senior author Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, where the study was presented during an e-poster session. “There is no doubt tremendous value in viewing the shared experience; however, it is important that medical advice be evidence based and validated. Seeking said advice from a medical professional such as a board-certified dermatologist will no doubt increase the likelihood that said guidance is supported by the literature and most importantly, will do no harm.”

Noting a trend of increased user-created content on social media and Internet sites about topical steroid withdrawal in recent years, Dr. Friedman, first author Erika McCormick, a fourth-year medical student at George Washington University, and colleagues used the keywords “topical steroid withdrawal” on YouTube to search for and analyze the top 10 most viewed videos on the subject.

Two independent reviewers used the modified DISCERN (mDISCERN) tool and the Global Quality Scale (GQS) to assess reliability and quality/scientific accuracy of videos, respectively. Average scores were generated for each video and the researchers used one way ANOVA, unpaired t-tests, and linear regression to analyze the ratings. For mDISCERN criteria, a point is given per each of five criteria for a possible score between 0 and 5. Examples of criteria included “Are the aims clear and achieved?” and “Is the information presented both balanced and unbiased”? For GQS, a score from 1 to 5 is designated based on criteria ranging from “poor quality, poor flow, most information missing” to “excellent quality and flow, very useful for patients.”

The researchers found that the mean combined mDISCERN score of the 10 videos was a 2, which indicates poor reliability and shortcomings. Similarly, the combined mean GQS score was 2.5, which suggests poor to moderate quality of videos, missing discussion of important topics, and limited use to patients. The researchers found no correlation between mDISCERN or GQS scores and length of video, duration on YouTube, or number of views, subscribers, or likes.

“We were disheartened that patient testimonial videos had the poorest quality and reliability of the information sources,” Ms. McCormick said in an interview. “Videos that included medical research and information from dermatologists had significantly higher quality and reliability scores than the remainder of videos.” Accurate information online is essential to help patients recognize topical steroid withdrawal and seek medical care, she continued.

Conversely, wide viewership of unreliable information “may contribute to fear of topical corticosteroids and dissuade use in patients with primary skin diseases that may benefit from this common treatment,” Dr. Friedman said. “Dermatologists must be aware of the content patients are consuming online, should guide patients in appraising quality and reliability of online resources, and must provide valid sources of additional information for their patients.” One such resource he recommended is the National Eczema Association, which has created online content for patients about topical steroid withdrawal.

Doris Day, MD, a New York–based dermatologist who was asked to comment on the study, said that many patients rely on YouTube as a go-to resource, with videos that can be watched at times of their choosing. “Oftentimes, the person on the video is relatable and has some general knowledge but is lacking the information that would be relevant and important for the individual patient,” said Dr. Day, who was not involved with the study. “The downside of this is that the person who takes that advice may not use the prescription properly or for the correct amount of time, which can lead to either undertreating or, even worse, overtreatment, which can have permanent consequences.”

One possible solution is for more doctors to create videos for YouTube, she added, “but that doesn’t guarantee that those would be the ones patients would choose to watch.” Another solution “is to have YouTube add qualifiers indicating that the information being discussed is not medical,” she suggested. “Ideally, patients will get all the information they need while they are in the office and also have clear written instructions and even a video they can review at a later time, made by the office, to help them feel they are getting personalized care and the attention they need.”

Ms. McCormick’s research is funded by a grant from Galderma. Dr. Friedman and Dr. Day had no relevant disclosures to report.

NEW ORLEANS –

“Video-sharing platforms such as YouTube are a great place for patients to connect and find community with others dealing with the same conditions,” senior author Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, where the study was presented during an e-poster session. “There is no doubt tremendous value in viewing the shared experience; however, it is important that medical advice be evidence based and validated. Seeking said advice from a medical professional such as a board-certified dermatologist will no doubt increase the likelihood that said guidance is supported by the literature and most importantly, will do no harm.”

Noting a trend of increased user-created content on social media and Internet sites about topical steroid withdrawal in recent years, Dr. Friedman, first author Erika McCormick, a fourth-year medical student at George Washington University, and colleagues used the keywords “topical steroid withdrawal” on YouTube to search for and analyze the top 10 most viewed videos on the subject.

Two independent reviewers used the modified DISCERN (mDISCERN) tool and the Global Quality Scale (GQS) to assess reliability and quality/scientific accuracy of videos, respectively. Average scores were generated for each video and the researchers used one way ANOVA, unpaired t-tests, and linear regression to analyze the ratings. For mDISCERN criteria, a point is given per each of five criteria for a possible score between 0 and 5. Examples of criteria included “Are the aims clear and achieved?” and “Is the information presented both balanced and unbiased”? For GQS, a score from 1 to 5 is designated based on criteria ranging from “poor quality, poor flow, most information missing” to “excellent quality and flow, very useful for patients.”

The researchers found that the mean combined mDISCERN score of the 10 videos was a 2, which indicates poor reliability and shortcomings. Similarly, the combined mean GQS score was 2.5, which suggests poor to moderate quality of videos, missing discussion of important topics, and limited use to patients. The researchers found no correlation between mDISCERN or GQS scores and length of video, duration on YouTube, or number of views, subscribers, or likes.

“We were disheartened that patient testimonial videos had the poorest quality and reliability of the information sources,” Ms. McCormick said in an interview. “Videos that included medical research and information from dermatologists had significantly higher quality and reliability scores than the remainder of videos.” Accurate information online is essential to help patients recognize topical steroid withdrawal and seek medical care, she continued.

Conversely, wide viewership of unreliable information “may contribute to fear of topical corticosteroids and dissuade use in patients with primary skin diseases that may benefit from this common treatment,” Dr. Friedman said. “Dermatologists must be aware of the content patients are consuming online, should guide patients in appraising quality and reliability of online resources, and must provide valid sources of additional information for their patients.” One such resource he recommended is the National Eczema Association, which has created online content for patients about topical steroid withdrawal.

Doris Day, MD, a New York–based dermatologist who was asked to comment on the study, said that many patients rely on YouTube as a go-to resource, with videos that can be watched at times of their choosing. “Oftentimes, the person on the video is relatable and has some general knowledge but is lacking the information that would be relevant and important for the individual patient,” said Dr. Day, who was not involved with the study. “The downside of this is that the person who takes that advice may not use the prescription properly or for the correct amount of time, which can lead to either undertreating or, even worse, overtreatment, which can have permanent consequences.”

One possible solution is for more doctors to create videos for YouTube, she added, “but that doesn’t guarantee that those would be the ones patients would choose to watch.” Another solution “is to have YouTube add qualifiers indicating that the information being discussed is not medical,” she suggested. “Ideally, patients will get all the information they need while they are in the office and also have clear written instructions and even a video they can review at a later time, made by the office, to help them feel they are getting personalized care and the attention they need.”

Ms. McCormick’s research is funded by a grant from Galderma. Dr. Friedman and Dr. Day had no relevant disclosures to report.

NEW ORLEANS –

“Video-sharing platforms such as YouTube are a great place for patients to connect and find community with others dealing with the same conditions,” senior author Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, where the study was presented during an e-poster session. “There is no doubt tremendous value in viewing the shared experience; however, it is important that medical advice be evidence based and validated. Seeking said advice from a medical professional such as a board-certified dermatologist will no doubt increase the likelihood that said guidance is supported by the literature and most importantly, will do no harm.”

Noting a trend of increased user-created content on social media and Internet sites about topical steroid withdrawal in recent years, Dr. Friedman, first author Erika McCormick, a fourth-year medical student at George Washington University, and colleagues used the keywords “topical steroid withdrawal” on YouTube to search for and analyze the top 10 most viewed videos on the subject.

Two independent reviewers used the modified DISCERN (mDISCERN) tool and the Global Quality Scale (GQS) to assess reliability and quality/scientific accuracy of videos, respectively. Average scores were generated for each video and the researchers used one way ANOVA, unpaired t-tests, and linear regression to analyze the ratings. For mDISCERN criteria, a point is given per each of five criteria for a possible score between 0 and 5. Examples of criteria included “Are the aims clear and achieved?” and “Is the information presented both balanced and unbiased”? For GQS, a score from 1 to 5 is designated based on criteria ranging from “poor quality, poor flow, most information missing” to “excellent quality and flow, very useful for patients.”

The researchers found that the mean combined mDISCERN score of the 10 videos was a 2, which indicates poor reliability and shortcomings. Similarly, the combined mean GQS score was 2.5, which suggests poor to moderate quality of videos, missing discussion of important topics, and limited use to patients. The researchers found no correlation between mDISCERN or GQS scores and length of video, duration on YouTube, or number of views, subscribers, or likes.

“We were disheartened that patient testimonial videos had the poorest quality and reliability of the information sources,” Ms. McCormick said in an interview. “Videos that included medical research and information from dermatologists had significantly higher quality and reliability scores than the remainder of videos.” Accurate information online is essential to help patients recognize topical steroid withdrawal and seek medical care, she continued.

Conversely, wide viewership of unreliable information “may contribute to fear of topical corticosteroids and dissuade use in patients with primary skin diseases that may benefit from this common treatment,” Dr. Friedman said. “Dermatologists must be aware of the content patients are consuming online, should guide patients in appraising quality and reliability of online resources, and must provide valid sources of additional information for their patients.” One such resource he recommended is the National Eczema Association, which has created online content for patients about topical steroid withdrawal.

Doris Day, MD, a New York–based dermatologist who was asked to comment on the study, said that many patients rely on YouTube as a go-to resource, with videos that can be watched at times of their choosing. “Oftentimes, the person on the video is relatable and has some general knowledge but is lacking the information that would be relevant and important for the individual patient,” said Dr. Day, who was not involved with the study. “The downside of this is that the person who takes that advice may not use the prescription properly or for the correct amount of time, which can lead to either undertreating or, even worse, overtreatment, which can have permanent consequences.”

One possible solution is for more doctors to create videos for YouTube, she added, “but that doesn’t guarantee that those would be the ones patients would choose to watch.” Another solution “is to have YouTube add qualifiers indicating that the information being discussed is not medical,” she suggested. “Ideally, patients will get all the information they need while they are in the office and also have clear written instructions and even a video they can review at a later time, made by the office, to help them feel they are getting personalized care and the attention they need.”

Ms. McCormick’s research is funded by a grant from Galderma. Dr. Friedman and Dr. Day had no relevant disclosures to report.

AT AAD 2023

Lebrikizumab monotherapy for AD found safe, effective during induction

, researchers reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The identically designed, 52-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials enrolled 851 adolescents and adults with moderate to severe AD and included a 16-week induction period followed by a 36-week maintenance period. At week 16, the results “show a rapid onset of action in multiple domains of the disease, such as skin clearance and itch,” wrote lead author Jonathan Silverberg, MD, PhD, director of clinical research and contact dermatitis, at George Washington University, Washington, and colleagues. “Although 16 weeks of treatment with lebrikizumab is not sufficient to assess its long-term safety, the results from the induction period of these two trials suggest a safety profile that is consistent with findings in previous trials,” they added.

Results presented at the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 2022 annual meeting, but not yet published, showed similar efficacy maintained through the end of the trial.

Eligible patients were randomly assigned to receive either lebrikizumab 250 mg (with a 500-mg loading dose given at baseline and at week 2) or placebo, administered subcutaneously every 2 weeks, with concomitant topical or systemic treatments prohibited through week 16 except when deemed appropriate as rescue therapy. In such cases, moderate-potency topical glucocorticoids were preferred as first-line rescue therapy, while the study drug was discontinued if systemic therapy was needed.

In both trials, the primary efficacy outcome – a score of 0 or 1 on the Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) – and a reduction of at least 2 points from baseline at week 16, was met by more patients treated with lebrikizumab than with placebo: 43.1% vs. 12.7% respectively in trial 1 (P < .001); and 33.2% vs. 10.8% in trial 2 (P < .001).

Similarly, in both trials, a higher percentage of the lebrikizumab than placebo patients had an EASI-75 response (75% improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index score): 58.8% vs. 16.2% (P < .001) in trial 1 and 52.1% vs. 18.1% (P < .001) in trial 2.

Improvement in itch was also significantly better in patients treated with lebrikizumab, compared with placebo. This was measured by a reduction of at least 4 points in the Pruritus NRS from baseline to week 16 and a reduction in the Sleep-Loss Scale score of at least 2 points from baseline to week 16 (P < .001 for both measures in both trials).

A higher percentage of placebo vs. lebrikizumab patients discontinued the trials during the induction phases (14.9% vs. 7.1% in trial 1 and 11.0% vs. 7.8% in trial 2), and the use of rescue medication was approximately three times and two times higher in both placebo groups respectively.

Conjunctivitis was the most common adverse event, occurring consistently more frequently in patients treated with lebrikizumab, compared with placebo (7.4% vs. 2.8% in trial 1 and 7.5% vs. 2.1% in trial 2).

“Although several theories have been proposed for the pathogenesis of conjunctivitis in patients with atopic dermatitis treated with this class of biologic agents, the mechanism remains unclear and warrants further study,” the investigators wrote.

Asked to comment on the new results, Zelma Chiesa Fuxench, MD, who was not involved in the research, said they “continue to demonstrate the superior efficacy and favorable safety profile” of lebrikizumab in adolescents and adults and support the results of earlier phase 2 studies. “The results of these studies thus far continue to offer more hope and the possibility of a better future for our patients with atopic dermatitis who are still struggling to achieve control of their disease.”

Dr. Chiesa Fuxench from the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said she looks forward to reviewing the full study results in which patients who achieved the primary outcomes of interest were then rerandomized to either placebo, or lebrikizumab every 2 weeks or every 4 weeks for the 36-week maintenance period “because we know that there is data for other biologics in atopic dermatitis (such as tralokinumab) that demonstrate that a decrease in the frequency of injections may be possible for patients who achieve disease control after an initial 16 weeks of therapy every 2 weeks.”

The research was supported by Dermira, a wholly owned subsidiary of Eli Lilly. Dr. Silverberg disclosed he is a consultant for Dermira and Eli Lilly, as are other coauthors on the paper who additionally disclosed grants from Dermira and other relationships with Eli Lilly such as advisory board membership and having received lecture fees. Three authors are Eli Lilly employees. Dr. Chiesa Fuxench disclosed that she is a consultant for the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America, National Eczema Association, Pfizer, Abbvie, and Incyte for which she has received honoraria for work related to AD. Dr. Chiesa Fuxench has also been a recipient of research grants from Regeneron, Sanofi, Tioga, Vanda, Menlo Therapeutics, Leo Pharma, and Eli Lilly for work related to AD as well as honoraria for continuing medical education work related to AD sponsored through educational grants from Regeneron/Sanofi and Pfizer.

, researchers reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The identically designed, 52-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials enrolled 851 adolescents and adults with moderate to severe AD and included a 16-week induction period followed by a 36-week maintenance period. At week 16, the results “show a rapid onset of action in multiple domains of the disease, such as skin clearance and itch,” wrote lead author Jonathan Silverberg, MD, PhD, director of clinical research and contact dermatitis, at George Washington University, Washington, and colleagues. “Although 16 weeks of treatment with lebrikizumab is not sufficient to assess its long-term safety, the results from the induction period of these two trials suggest a safety profile that is consistent with findings in previous trials,” they added.

Results presented at the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 2022 annual meeting, but not yet published, showed similar efficacy maintained through the end of the trial.

Eligible patients were randomly assigned to receive either lebrikizumab 250 mg (with a 500-mg loading dose given at baseline and at week 2) or placebo, administered subcutaneously every 2 weeks, with concomitant topical or systemic treatments prohibited through week 16 except when deemed appropriate as rescue therapy. In such cases, moderate-potency topical glucocorticoids were preferred as first-line rescue therapy, while the study drug was discontinued if systemic therapy was needed.

In both trials, the primary efficacy outcome – a score of 0 or 1 on the Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) – and a reduction of at least 2 points from baseline at week 16, was met by more patients treated with lebrikizumab than with placebo: 43.1% vs. 12.7% respectively in trial 1 (P < .001); and 33.2% vs. 10.8% in trial 2 (P < .001).

Similarly, in both trials, a higher percentage of the lebrikizumab than placebo patients had an EASI-75 response (75% improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index score): 58.8% vs. 16.2% (P < .001) in trial 1 and 52.1% vs. 18.1% (P < .001) in trial 2.

Improvement in itch was also significantly better in patients treated with lebrikizumab, compared with placebo. This was measured by a reduction of at least 4 points in the Pruritus NRS from baseline to week 16 and a reduction in the Sleep-Loss Scale score of at least 2 points from baseline to week 16 (P < .001 for both measures in both trials).

A higher percentage of placebo vs. lebrikizumab patients discontinued the trials during the induction phases (14.9% vs. 7.1% in trial 1 and 11.0% vs. 7.8% in trial 2), and the use of rescue medication was approximately three times and two times higher in both placebo groups respectively.

Conjunctivitis was the most common adverse event, occurring consistently more frequently in patients treated with lebrikizumab, compared with placebo (7.4% vs. 2.8% in trial 1 and 7.5% vs. 2.1% in trial 2).

“Although several theories have been proposed for the pathogenesis of conjunctivitis in patients with atopic dermatitis treated with this class of biologic agents, the mechanism remains unclear and warrants further study,” the investigators wrote.

Asked to comment on the new results, Zelma Chiesa Fuxench, MD, who was not involved in the research, said they “continue to demonstrate the superior efficacy and favorable safety profile” of lebrikizumab in adolescents and adults and support the results of earlier phase 2 studies. “The results of these studies thus far continue to offer more hope and the possibility of a better future for our patients with atopic dermatitis who are still struggling to achieve control of their disease.”

Dr. Chiesa Fuxench from the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said she looks forward to reviewing the full study results in which patients who achieved the primary outcomes of interest were then rerandomized to either placebo, or lebrikizumab every 2 weeks or every 4 weeks for the 36-week maintenance period “because we know that there is data for other biologics in atopic dermatitis (such as tralokinumab) that demonstrate that a decrease in the frequency of injections may be possible for patients who achieve disease control after an initial 16 weeks of therapy every 2 weeks.”

The research was supported by Dermira, a wholly owned subsidiary of Eli Lilly. Dr. Silverberg disclosed he is a consultant for Dermira and Eli Lilly, as are other coauthors on the paper who additionally disclosed grants from Dermira and other relationships with Eli Lilly such as advisory board membership and having received lecture fees. Three authors are Eli Lilly employees. Dr. Chiesa Fuxench disclosed that she is a consultant for the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America, National Eczema Association, Pfizer, Abbvie, and Incyte for which she has received honoraria for work related to AD. Dr. Chiesa Fuxench has also been a recipient of research grants from Regeneron, Sanofi, Tioga, Vanda, Menlo Therapeutics, Leo Pharma, and Eli Lilly for work related to AD as well as honoraria for continuing medical education work related to AD sponsored through educational grants from Regeneron/Sanofi and Pfizer.

, researchers reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The identically designed, 52-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials enrolled 851 adolescents and adults with moderate to severe AD and included a 16-week induction period followed by a 36-week maintenance period. At week 16, the results “show a rapid onset of action in multiple domains of the disease, such as skin clearance and itch,” wrote lead author Jonathan Silverberg, MD, PhD, director of clinical research and contact dermatitis, at George Washington University, Washington, and colleagues. “Although 16 weeks of treatment with lebrikizumab is not sufficient to assess its long-term safety, the results from the induction period of these two trials suggest a safety profile that is consistent with findings in previous trials,” they added.

Results presented at the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 2022 annual meeting, but not yet published, showed similar efficacy maintained through the end of the trial.

Eligible patients were randomly assigned to receive either lebrikizumab 250 mg (with a 500-mg loading dose given at baseline and at week 2) or placebo, administered subcutaneously every 2 weeks, with concomitant topical or systemic treatments prohibited through week 16 except when deemed appropriate as rescue therapy. In such cases, moderate-potency topical glucocorticoids were preferred as first-line rescue therapy, while the study drug was discontinued if systemic therapy was needed.

In both trials, the primary efficacy outcome – a score of 0 or 1 on the Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) – and a reduction of at least 2 points from baseline at week 16, was met by more patients treated with lebrikizumab than with placebo: 43.1% vs. 12.7% respectively in trial 1 (P < .001); and 33.2% vs. 10.8% in trial 2 (P < .001).

Similarly, in both trials, a higher percentage of the lebrikizumab than placebo patients had an EASI-75 response (75% improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index score): 58.8% vs. 16.2% (P < .001) in trial 1 and 52.1% vs. 18.1% (P < .001) in trial 2.

Improvement in itch was also significantly better in patients treated with lebrikizumab, compared with placebo. This was measured by a reduction of at least 4 points in the Pruritus NRS from baseline to week 16 and a reduction in the Sleep-Loss Scale score of at least 2 points from baseline to week 16 (P < .001 for both measures in both trials).

A higher percentage of placebo vs. lebrikizumab patients discontinued the trials during the induction phases (14.9% vs. 7.1% in trial 1 and 11.0% vs. 7.8% in trial 2), and the use of rescue medication was approximately three times and two times higher in both placebo groups respectively.

Conjunctivitis was the most common adverse event, occurring consistently more frequently in patients treated with lebrikizumab, compared with placebo (7.4% vs. 2.8% in trial 1 and 7.5% vs. 2.1% in trial 2).

“Although several theories have been proposed for the pathogenesis of conjunctivitis in patients with atopic dermatitis treated with this class of biologic agents, the mechanism remains unclear and warrants further study,” the investigators wrote.

Asked to comment on the new results, Zelma Chiesa Fuxench, MD, who was not involved in the research, said they “continue to demonstrate the superior efficacy and favorable safety profile” of lebrikizumab in adolescents and adults and support the results of earlier phase 2 studies. “The results of these studies thus far continue to offer more hope and the possibility of a better future for our patients with atopic dermatitis who are still struggling to achieve control of their disease.”

Dr. Chiesa Fuxench from the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said she looks forward to reviewing the full study results in which patients who achieved the primary outcomes of interest were then rerandomized to either placebo, or lebrikizumab every 2 weeks or every 4 weeks for the 36-week maintenance period “because we know that there is data for other biologics in atopic dermatitis (such as tralokinumab) that demonstrate that a decrease in the frequency of injections may be possible for patients who achieve disease control after an initial 16 weeks of therapy every 2 weeks.”

The research was supported by Dermira, a wholly owned subsidiary of Eli Lilly. Dr. Silverberg disclosed he is a consultant for Dermira and Eli Lilly, as are other coauthors on the paper who additionally disclosed grants from Dermira and other relationships with Eli Lilly such as advisory board membership and having received lecture fees. Three authors are Eli Lilly employees. Dr. Chiesa Fuxench disclosed that she is a consultant for the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America, National Eczema Association, Pfizer, Abbvie, and Incyte for which she has received honoraria for work related to AD. Dr. Chiesa Fuxench has also been a recipient of research grants from Regeneron, Sanofi, Tioga, Vanda, Menlo Therapeutics, Leo Pharma, and Eli Lilly for work related to AD as well as honoraria for continuing medical education work related to AD sponsored through educational grants from Regeneron/Sanofi and Pfizer.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Cyclosporine-Induced Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome: An Adverse Effect in a Patient With Atopic Dermatitis

To the Editor:

Cyclosporine is an immunomodulatory medication that impacts T-lymphocyte function through calcineurin inhibition and suppression of IL-2 expression. Oral cyclosporine at low doses (1–3 mg/kg/d) is one of the more common systemic treatment options for moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. At these doses it has been shown to have therapeutic benefit in several skin conditions, including chronic spontaneous urticaria,1 psoriasis,2 and atopic dermatitis.3 When used at higher doses for conditions such as glomerulonephritis or transplantation, adverse effects may be notable, and close monitoring of drug metabolism as well as end-organ function is required. In contrast, severe adverse effects are uncommon with the lower doses of cyclosporine used for cutaneous conditions, and monitoring serum drug levels is not routinely practiced.4

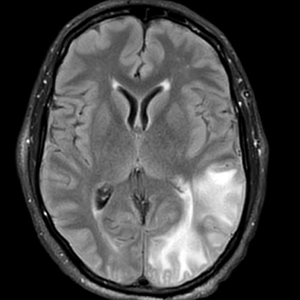

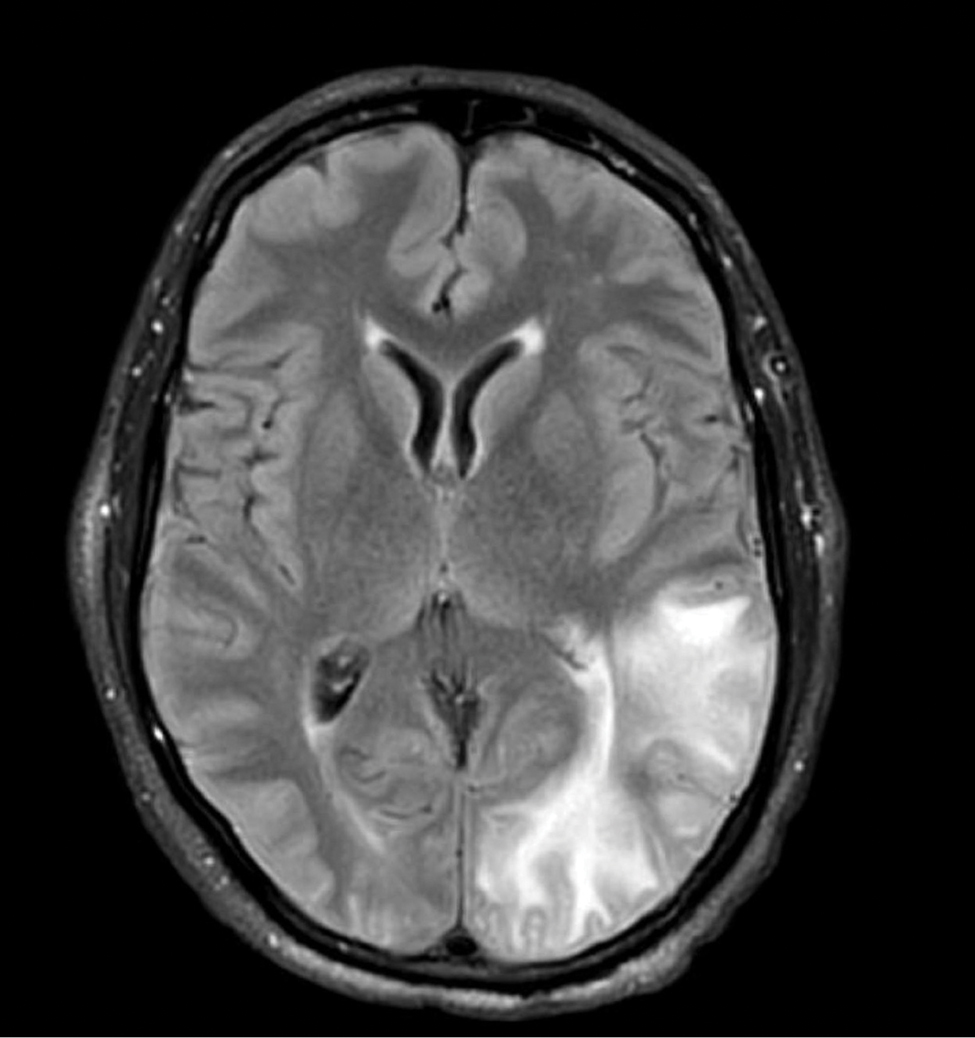

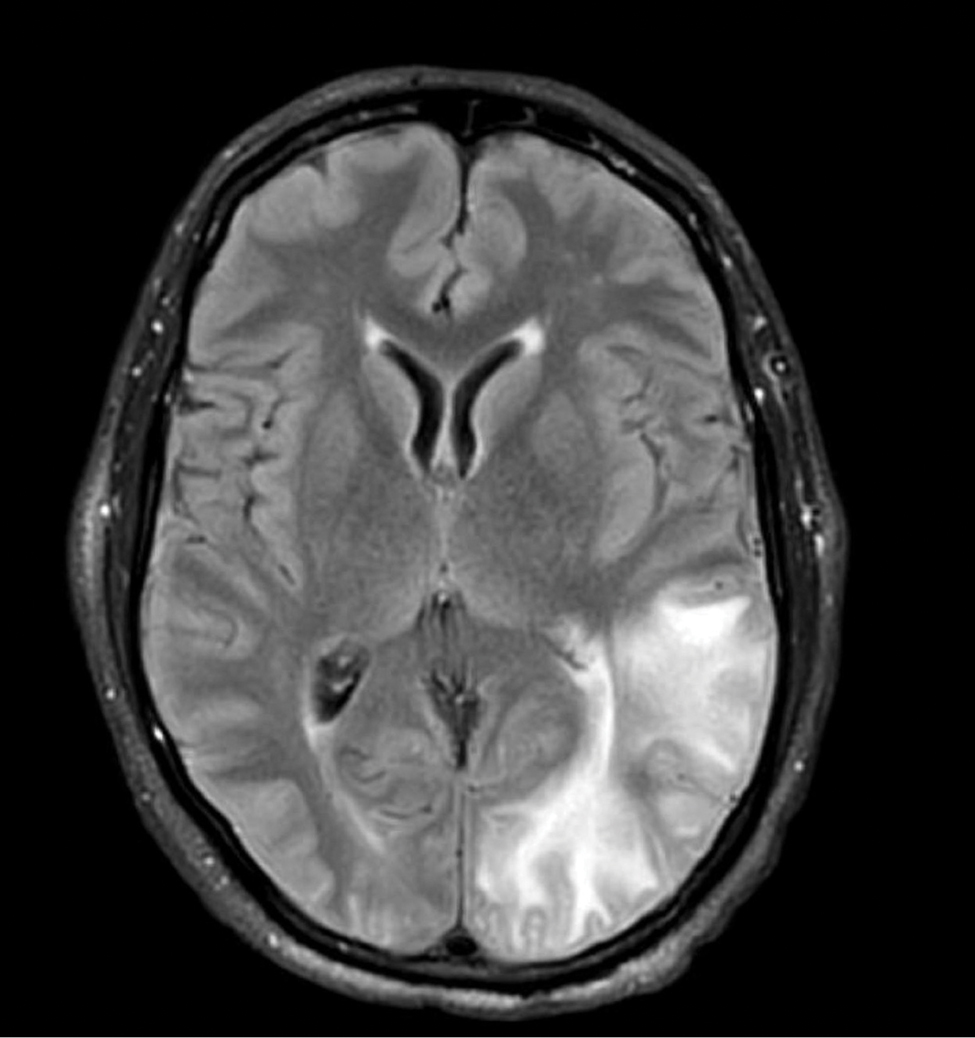

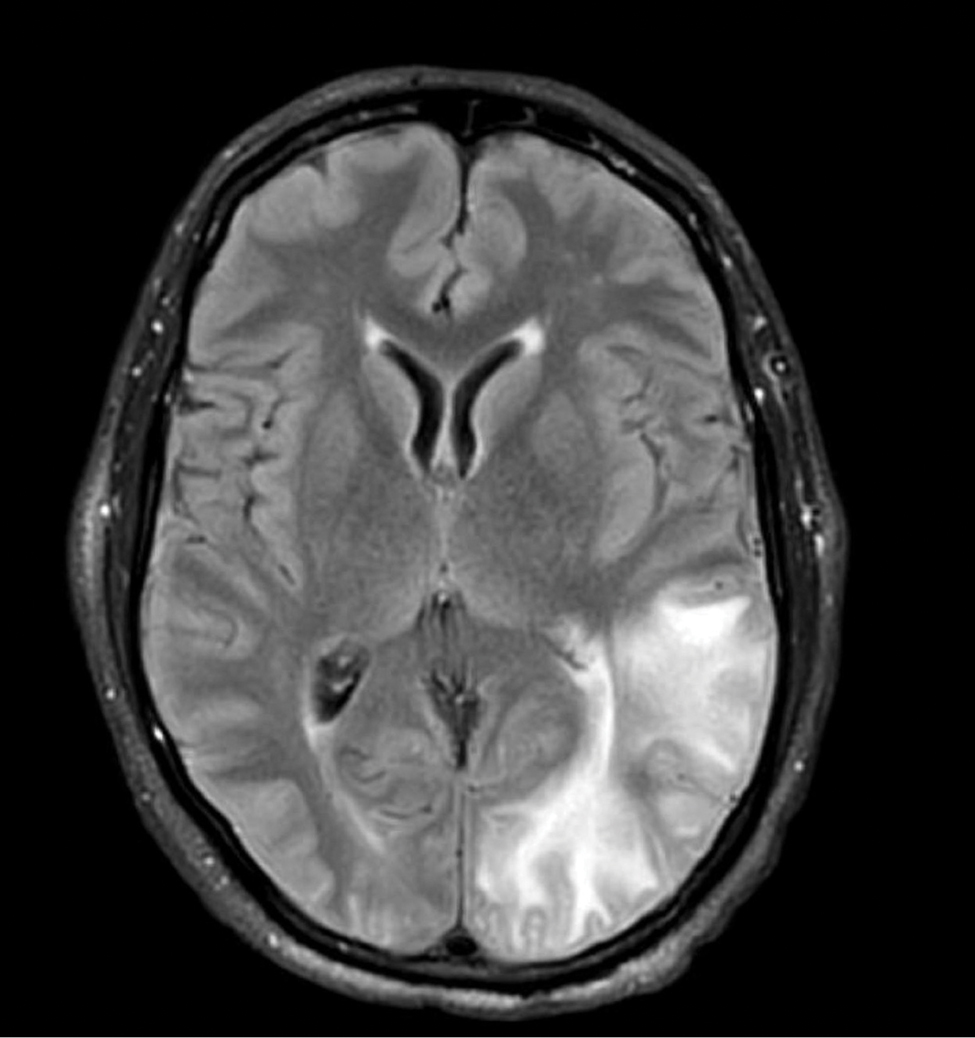

A 58-year-old man was referred to clinic with severe atopic dermatitis refractory to maximal topical therapy prescribed by an outside physician. He was started on cyclosporine as an anticipated bridge to dupilumab biologic therapy. He had no history of hypertension, renal disease, or hepatic insufficiency prior to starting therapy. He demonstrated notable clinical improvement at a cyclosporine dosage of 300 mg/d (equating to 3.7 mg/kg/d). Three months after initiation of therapy, the patient presented to a local emergency department with new-onset seizurelike activity, confusion, and agitation. He was normotensive with clinical concern for status epilepticus. An initial laboratory assessment included a complete blood cell count, serum electrolyte panel, and urine toxicology screen, which were unremarkable. Computed tomography of the head showed confluent white-matter hypodensities in the left parietal-temporal-occipital lobes. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed innumerable peripherally distributed foci of microhemorrhage and vasogenic edema within the left parietal-temporal-occipital lobes (Figure).

He was intubated and sedated with admission to the medical intensive care unit, where a random cyclosporine level drawn approximately 9 hours after the prior dose was noted to be 263 ng/mL. Although target therapeutic levels for cyclosporine vary based on indication, toxic supratherapeutic levels generally are considered to be greater than 400 ng/mL.5 He had no evidence of acute kidney injury, uremia, or hypertension throughout hospitalization. An electroencephalogram showed left parieto-occipital periodic epileptiform discharges with generalized slowing. Cyclosporine was discontinued, and he was started on levetiracetam. His clinical and neuroimaging findings improved over the course of the 1-week hospitalization without any further intervention. Four weeks after hospitalization, he had full neurologic, electroencephalogram, and imaging recovery. Based on the presenting symptoms, transient neuroimaging findings, and full recovery with discontinuation of cyclosporine, the patient was diagnosed with cyclosporine-induced posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES).

The diagnosis of PRES requires evidence of acute neurologic symptoms and radiographic findings of cortical/subcortical white-matter changes on computed tomography or MRI consistent with edema. The pathophysiology is not fully understood but appears to be related to vasogenic edema, primarily impacting the posterior aspect of the brain. There have been many reported offending agents, and symptoms typically resolve following cessation of these medications. Cases of cyclosporine-induced PRES have been reported, but most occurred at higher doses within weeks of medication initiation. Two cases of cyclosporine-induced PRES treated with cutaneous dosing have been reported; neither patient was taking it for atopic dermatitis.6

Cyclosporine-induced PRES remains a pathophysiologic conundrum. However, there is evidence to support direct endothelial damage causing cellular apoptosis in the brain of mouse models that is medication specific and not necessarily related to the dosages used.7 Our case highlights a rare but important adverse event associated with even low-dose cyclosporine use that should be considered in patients currently taking cyclosporine who present with acute neurologic changes.

- Kulthanan K, Chaweekulrat P, Komoltri C, et al. Cyclosporine for chronic spontaneous urticaria: a meta-analysis and systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6:586-599. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2017.07.017

- Armstrong AW, Read C. Pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and treatment of psoriasis: a review. JAMA. 2020;323:1945-1960. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.4006

- Seger EW, Wechter T, Strowd L, et al. Relative efficacy of systemic treatments for atopic dermatitis [published online October 6, 2018]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:411-416.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.053

- Blake SC, Murrell DF. Monitoring trough levels in cyclosporine for atopic dermatitis: a systematic review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:843-853. doi:10.1111/pde.13999

- Tapia C, Nessel TA, Zito PM. Cyclosporine. StatPearls Publishing: 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482450/

- Cosottini M, Lazzarotti G, Ceravolo R, et al. Cyclosporine‐related posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) in non‐transplant patient: a case report and literature review. Eur J Neurol. 2003;10:461-462. doi:10.1046/j.1468-1331.2003.00608_1.x

- Kochi S, Takanaga H, Matsuo H, et al. Induction of apoptosis in mouse brain capillary endothelial cells by cyclosporin A and tacrolimus. Life Sci. 2000;66:2255-2260. doi:10.1016/s0024-3205(00)00554-3

To the Editor:

Cyclosporine is an immunomodulatory medication that impacts T-lymphocyte function through calcineurin inhibition and suppression of IL-2 expression. Oral cyclosporine at low doses (1–3 mg/kg/d) is one of the more common systemic treatment options for moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. At these doses it has been shown to have therapeutic benefit in several skin conditions, including chronic spontaneous urticaria,1 psoriasis,2 and atopic dermatitis.3 When used at higher doses for conditions such as glomerulonephritis or transplantation, adverse effects may be notable, and close monitoring of drug metabolism as well as end-organ function is required. In contrast, severe adverse effects are uncommon with the lower doses of cyclosporine used for cutaneous conditions, and monitoring serum drug levels is not routinely practiced.4

A 58-year-old man was referred to clinic with severe atopic dermatitis refractory to maximal topical therapy prescribed by an outside physician. He was started on cyclosporine as an anticipated bridge to dupilumab biologic therapy. He had no history of hypertension, renal disease, or hepatic insufficiency prior to starting therapy. He demonstrated notable clinical improvement at a cyclosporine dosage of 300 mg/d (equating to 3.7 mg/kg/d). Three months after initiation of therapy, the patient presented to a local emergency department with new-onset seizurelike activity, confusion, and agitation. He was normotensive with clinical concern for status epilepticus. An initial laboratory assessment included a complete blood cell count, serum electrolyte panel, and urine toxicology screen, which were unremarkable. Computed tomography of the head showed confluent white-matter hypodensities in the left parietal-temporal-occipital lobes. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed innumerable peripherally distributed foci of microhemorrhage and vasogenic edema within the left parietal-temporal-occipital lobes (Figure).

He was intubated and sedated with admission to the medical intensive care unit, where a random cyclosporine level drawn approximately 9 hours after the prior dose was noted to be 263 ng/mL. Although target therapeutic levels for cyclosporine vary based on indication, toxic supratherapeutic levels generally are considered to be greater than 400 ng/mL.5 He had no evidence of acute kidney injury, uremia, or hypertension throughout hospitalization. An electroencephalogram showed left parieto-occipital periodic epileptiform discharges with generalized slowing. Cyclosporine was discontinued, and he was started on levetiracetam. His clinical and neuroimaging findings improved over the course of the 1-week hospitalization without any further intervention. Four weeks after hospitalization, he had full neurologic, electroencephalogram, and imaging recovery. Based on the presenting symptoms, transient neuroimaging findings, and full recovery with discontinuation of cyclosporine, the patient was diagnosed with cyclosporine-induced posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES).

The diagnosis of PRES requires evidence of acute neurologic symptoms and radiographic findings of cortical/subcortical white-matter changes on computed tomography or MRI consistent with edema. The pathophysiology is not fully understood but appears to be related to vasogenic edema, primarily impacting the posterior aspect of the brain. There have been many reported offending agents, and symptoms typically resolve following cessation of these medications. Cases of cyclosporine-induced PRES have been reported, but most occurred at higher doses within weeks of medication initiation. Two cases of cyclosporine-induced PRES treated with cutaneous dosing have been reported; neither patient was taking it for atopic dermatitis.6

Cyclosporine-induced PRES remains a pathophysiologic conundrum. However, there is evidence to support direct endothelial damage causing cellular apoptosis in the brain of mouse models that is medication specific and not necessarily related to the dosages used.7 Our case highlights a rare but important adverse event associated with even low-dose cyclosporine use that should be considered in patients currently taking cyclosporine who present with acute neurologic changes.

To the Editor:

Cyclosporine is an immunomodulatory medication that impacts T-lymphocyte function through calcineurin inhibition and suppression of IL-2 expression. Oral cyclosporine at low doses (1–3 mg/kg/d) is one of the more common systemic treatment options for moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. At these doses it has been shown to have therapeutic benefit in several skin conditions, including chronic spontaneous urticaria,1 psoriasis,2 and atopic dermatitis.3 When used at higher doses for conditions such as glomerulonephritis or transplantation, adverse effects may be notable, and close monitoring of drug metabolism as well as end-organ function is required. In contrast, severe adverse effects are uncommon with the lower doses of cyclosporine used for cutaneous conditions, and monitoring serum drug levels is not routinely practiced.4

A 58-year-old man was referred to clinic with severe atopic dermatitis refractory to maximal topical therapy prescribed by an outside physician. He was started on cyclosporine as an anticipated bridge to dupilumab biologic therapy. He had no history of hypertension, renal disease, or hepatic insufficiency prior to starting therapy. He demonstrated notable clinical improvement at a cyclosporine dosage of 300 mg/d (equating to 3.7 mg/kg/d). Three months after initiation of therapy, the patient presented to a local emergency department with new-onset seizurelike activity, confusion, and agitation. He was normotensive with clinical concern for status epilepticus. An initial laboratory assessment included a complete blood cell count, serum electrolyte panel, and urine toxicology screen, which were unremarkable. Computed tomography of the head showed confluent white-matter hypodensities in the left parietal-temporal-occipital lobes. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed innumerable peripherally distributed foci of microhemorrhage and vasogenic edema within the left parietal-temporal-occipital lobes (Figure).

He was intubated and sedated with admission to the medical intensive care unit, where a random cyclosporine level drawn approximately 9 hours after the prior dose was noted to be 263 ng/mL. Although target therapeutic levels for cyclosporine vary based on indication, toxic supratherapeutic levels generally are considered to be greater than 400 ng/mL.5 He had no evidence of acute kidney injury, uremia, or hypertension throughout hospitalization. An electroencephalogram showed left parieto-occipital periodic epileptiform discharges with generalized slowing. Cyclosporine was discontinued, and he was started on levetiracetam. His clinical and neuroimaging findings improved over the course of the 1-week hospitalization without any further intervention. Four weeks after hospitalization, he had full neurologic, electroencephalogram, and imaging recovery. Based on the presenting symptoms, transient neuroimaging findings, and full recovery with discontinuation of cyclosporine, the patient was diagnosed with cyclosporine-induced posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES).

The diagnosis of PRES requires evidence of acute neurologic symptoms and radiographic findings of cortical/subcortical white-matter changes on computed tomography or MRI consistent with edema. The pathophysiology is not fully understood but appears to be related to vasogenic edema, primarily impacting the posterior aspect of the brain. There have been many reported offending agents, and symptoms typically resolve following cessation of these medications. Cases of cyclosporine-induced PRES have been reported, but most occurred at higher doses within weeks of medication initiation. Two cases of cyclosporine-induced PRES treated with cutaneous dosing have been reported; neither patient was taking it for atopic dermatitis.6

Cyclosporine-induced PRES remains a pathophysiologic conundrum. However, there is evidence to support direct endothelial damage causing cellular apoptosis in the brain of mouse models that is medication specific and not necessarily related to the dosages used.7 Our case highlights a rare but important adverse event associated with even low-dose cyclosporine use that should be considered in patients currently taking cyclosporine who present with acute neurologic changes.

- Kulthanan K, Chaweekulrat P, Komoltri C, et al. Cyclosporine for chronic spontaneous urticaria: a meta-analysis and systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6:586-599. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2017.07.017

- Armstrong AW, Read C. Pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and treatment of psoriasis: a review. JAMA. 2020;323:1945-1960. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.4006

- Seger EW, Wechter T, Strowd L, et al. Relative efficacy of systemic treatments for atopic dermatitis [published online October 6, 2018]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:411-416.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.053

- Blake SC, Murrell DF. Monitoring trough levels in cyclosporine for atopic dermatitis: a systematic review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:843-853. doi:10.1111/pde.13999

- Tapia C, Nessel TA, Zito PM. Cyclosporine. StatPearls Publishing: 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482450/

- Cosottini M, Lazzarotti G, Ceravolo R, et al. Cyclosporine‐related posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) in non‐transplant patient: a case report and literature review. Eur J Neurol. 2003;10:461-462. doi:10.1046/j.1468-1331.2003.00608_1.x

- Kochi S, Takanaga H, Matsuo H, et al. Induction of apoptosis in mouse brain capillary endothelial cells by cyclosporin A and tacrolimus. Life Sci. 2000;66:2255-2260. doi:10.1016/s0024-3205(00)00554-3

- Kulthanan K, Chaweekulrat P, Komoltri C, et al. Cyclosporine for chronic spontaneous urticaria: a meta-analysis and systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6:586-599. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2017.07.017

- Armstrong AW, Read C. Pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and treatment of psoriasis: a review. JAMA. 2020;323:1945-1960. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.4006

- Seger EW, Wechter T, Strowd L, et al. Relative efficacy of systemic treatments for atopic dermatitis [published online October 6, 2018]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:411-416.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.053

- Blake SC, Murrell DF. Monitoring trough levels in cyclosporine for atopic dermatitis: a systematic review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:843-853. doi:10.1111/pde.13999

- Tapia C, Nessel TA, Zito PM. Cyclosporine. StatPearls Publishing: 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482450/

- Cosottini M, Lazzarotti G, Ceravolo R, et al. Cyclosporine‐related posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) in non‐transplant patient: a case report and literature review. Eur J Neurol. 2003;10:461-462. doi:10.1046/j.1468-1331.2003.00608_1.x

- Kochi S, Takanaga H, Matsuo H, et al. Induction of apoptosis in mouse brain capillary endothelial cells by cyclosporin A and tacrolimus. Life Sci. 2000;66:2255-2260. doi:10.1016/s0024-3205(00)00554-3

Practice Points

- Cyclosporine is an immunomodulatory therapeutic utilized for several indications in dermatology practice, most commonly in low doses.

- Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) is a known but rare adverse effect of cyclosporine presenting with acute encephalopathic changes and radiographic findings on central imaging.

- Knowledge of this association is critical, as symptoms are reversible with prompt recognition, appropriate inpatient supportive care, and discontinuation of offending medications.

Dermatologic Implications of Sleep Deprivation in the US Military

Sleep deprivation can increase emotional distress and mood disorders; reduce quality of life; and lead to cognitive, memory, and performance deficits.1 Military service predisposes members to disordered sleep due to the rigors of deployments and field training, such as long shifts, shift changes, stressful work environments, and time zone changes. Evidence shows that sleep deprivation is associated with cardiovascular disease, gastrointestinal disease, and some cancers.2 We explore multiple mechanisms by which sleep deprivation may affect the skin. We also review the potential impacts of sleep deprivation on specific topics in dermatology, including atopic dermatitis (AD), psoriasis, alopecia areata, physical attractiveness, wound healing, and skin cancer.

Sleep and Military Service

Approximately 35.2% of Americans experience short sleep duration, which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines as sleeping fewer than 7 hours per 24-hour period.3 Short sleep duration is even more common among individuals working in protective services and the military (50.4%).4 United States military service members experience multiple contributors to disordered sleep, including combat operations, shift work, psychiatric disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder, and traumatic brain injury.5 Bramoweth and Germain6 described the case of a 27-year-old man who served 2 combat tours as an infantryman in Afghanistan, during which time he routinely remained awake for more than 24 hours at a time due to night missions and extended operations. Even when he was not directly involved in combat operations, he was rarely able to keep a regular sleep schedule.6 Service members returning from deployment also report decreased sleep. In one study (N=2717), 43% of respondents reported short sleep duration (<7 hours of sleep per night) and 29% reported very short sleep duration (<6 hours of sleep per night).7 Even stateside, service members experience acute sleep deprivation during training.8

Sleep and Skin

The idea that skin conditions can affect quality of sleep is not controversial. Pruritus, pain, and emotional distress associated with different dermatologic conditions have all been implicated in adversely affecting sleep.9 Given the effects of sleep deprivation on other organ systems, it also can affect the skin. Possible mechanisms of action include negative effects of sleep deprivation on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, cutaneous barrier function, and immune function. First, the HPA axis activity follows a circadian rhythm.10 Activation outside of the bounds of this normal rhythm can have adverse effects on sleep. Alternatively, sleep deprivation and decreased sleep quality can negatively affect the HPA axis.10 These changes can adversely affect cutaneous barrier and immune function.11 Cutaneous barrier function is vitally important in the context of inflammatory dermatologic conditions. Transepidermal water loss, a measurement used to estimate cutaneous barrier function, is increased by sleep deprivation.12 Finally, the cutaneous immune system is an important component of inflammatory dermatologic conditions, cancer immune surveillance, and wound healing, and it also is negatively impacted by sleep deprivation.13 This framework of sleep deprivation affecting the HPA axis, cutaneous barrier function, and cutaneous immune function will help to guide the following discussion on the effects of decreased sleep on specific dermatologic conditions.

Atopic Dermatitis—Individuals with AD are at higher odds of having insomnia, fatigue, and overall poorer health status, including more sick days and increased visits to a physician.14 Additionally, it is possible that the relationship between AD and sleep is not unidirectional. Chang and Chiang15 discussed the possibility of sleep disturbances contributing to AD flares and listed 3 possible mechanisms by which sleep disturbance could potentially flare AD: exacerbation of the itch-scratch cycle; changes in the immune system, including a possible shift to helper T cell (TH2) dominance; and worsening of chronic stress in patients with AD. These changes may lead to a vicious cycle of impaired sleep and AD exacerbations. It may be helpful to view sleep impairment and AD as comorbid conditions requiring co-management for optimal outcomes. This perspective has military relevance because even without considering sleep deprivation, deployment and field conditions are known to increase the risk for AD flares.16

Psoriasis—Psoriasis also may have a bidirectional relationship with sleep. A study utilizing data from the Nurses’ Health Study showed that working a night shift increased the risk for psoriasis.17 Importantly, this connection is associative and not causative. It is possible that other factors in those who worked night shifts such as probable decreased UV exposure or reported increased body mass index played a role. Studies using psoriasis mice models have shown increased inflammation with sleep deprivation.18 Another possible connection is the effect of sleep deprivation on the gut microbiome. Sleep dysfunction is associated with altered gut bacteria ratios, and similar gut bacteria ratios were found in patients with psoriasis, which may indicate an association between sleep deprivation and psoriasis disease progression.19 There also is an increased association of obstructive sleep apnea in patients with psoriasis compared to the general population.20 Fortunately, the rate of consultations for psoriasis in deployed soldiers in the last several conflicts has been quite low, making up only 2.1% of diagnosed dermatologic conditions,21 which is because service members with moderate to severe psoriasis likely will not be deployed.

Alopecia Areata—Alopecia areata also may be associated with sleep deprivation. A large retrospective cohort study looking at the risk for alopecia in patients with sleep disorders showed that a sleep disorder was an independent risk factor for alopecia areata.22 The impact of sleep on the HPA axis portrays a possible mechanism for the negative effects of sleep deprivation on the immune system. Interestingly, in this study, the association was strongest for the 0- to 24-year-old age group. According to the 2020 demographics profile of the military community, 45% of active-duty personnel are 25 years or younger.23 Fortunately, although alopecia areata can be a distressing condition, it should not have much effect on military readiness, as most individuals with this diagnosis are still deployable.

Physical Appearance—

Wound Healing—Wound healing is of particular importance to the health of military members. Research is suggestive but not definitive of the relationship between sleep and wound healing. One intriguing study looked at the healing of blisters induced via suction in well-rested and sleep-deprived individuals. The results showed a difference, with the sleep-deprived individuals taking approximately 1 day longer to heal.13 This has some specific relevance to the military, as friction blisters can be common.30 A cross-sectional survey looking at a group of service members deployed in Iraq showed a prevalence of foot friction blisters of 33%, with 11% of individuals requiring medical care.31 Although this is an interesting example, it is not necessarily applicable to full-thickness wounds. A study utilizing rat models did not identify any differences between sleep-deprived and well-rested models in the healing of punch biopsy sites.32

Skin Cancer—Altered circadian rhythms resulting in changes in melatonin levels, changes in circadian rhythm–related gene pathways, and immunologic changes have been proposed as possible contributing mechanisms for the observed increased risk for skin cancers in military and civilian pilots.33,34 One study showed that UV-related erythema resolved quicker in well-rested individuals compared with those with short sleep duration, which could represent more efficient DNA repair given the relationship between UV-associated erythema and DNA damage and repair.35 Another study looking at circadian changes in the repair of UV-related DNA damage showed that mice exposed to UV radiation in the early morning had higher rates of squamous cell carcinoma than those exposed in the afternoon.36 However, a large cohort study using data from the Nurses’ Health Study II did not support a positive connection between short sleep duration and skin cancer; rather, it showed that a short sleep duration was associated with a decreased risk for melanoma and basal cell carcinoma, with no effect noted for squamous cell carcinoma.37 This does not support a positive association between short sleep duration and skin cancer and in some cases actually suggests a negative association.

Final Thoughts

Although more research is needed, there is evidence that sleep deprivation can negatively affect the skin. Randomized controlled trials looking at groups of individuals with specific dermatologic conditions with a very short sleep duration group (<6 hours of sleep per night), short sleep duration group (<7 hours of sleep per night), and a well-rested group (>7 hours of sleep per night) could be very helpful in this endeavor. Possible mechanisms include the HPA axis, immune system, and skin barrier function that are associated with sleep deprivation. Specific dermatologic conditions that may be affected by sleep deprivation include AD, psoriasis, alopecia areata, physical appearance, wound healing, and skin cancer. The impact of sleep deprivation on dermatologic conditions is particularly relevant to the military, as service members are at an increased risk for short sleep duration. It is possible that improving sleep may lead to better disease control for many dermatologic conditions.

- Carskadon M, Dement WC. Cumulative effects of sleep restriction on daytime sleepiness. Psychophysiology. 1981;18:107-113.

- Medic G, Wille M, Hemels ME. Short- and long-term health consequences of sleep disruption. Nat Sci Sleep. 2017;19;9:151-161.

- Sleep and sleep disorders. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Reviewed September 12, 2022. Accessed February 17, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/sleep/data_statistics.html

- Khubchandani J, Price JH. Short sleep duration in working American adults, 2010-2018. J Community Health. 2020;45:219-227.

- Good CH, Brager AJ, Capaldi VF, et al. Sleep in the United States military. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2020;45:176-191.

- Bramoweth AD, Germain A. Deployment-related insomnia in military personnel and veterans. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2013;15:401.

- Luxton DD, Greenburg D, Ryan J, et al. Prevalence and impact of short sleep duration in redeployed OIF soldiers. Sleep. 2011;34:1189-1195.

- Crowley SK, Wilkinson LL, Burroughs EL, et al. Sleep during basic combat training: a qualitative study. Mil Med. 2012;177:823-828.

- Spindler M, Przybyłowicz K, Hawro M, et al. Sleep disturbance in adult dermatologic patients: a cross-sectional study on prevalence, burden, and associated factors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:910-922.

- Guyon A, Balbo M, Morselli LL, et al. Adverse effects of two nights of sleep restriction on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in healthy men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:2861-2868.

- Lin TK, Zhong L, Santiago JL. Association between stress and the HPA axis in the atopic dermatitis. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:2131.

- Pinnagoda J, Tupker RA, Agner T, et al. Guidelines for transepidermal water loss (TEWL) measurement. a report from theStandardization Group of the European Society of Contact Dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 1990;22:164-178.

- Smith TJ, Wilson MA, Karl JP, et al. Impact of sleep restriction on local immune response and skin barrier restoration with and without “multinutrient” nutrition intervention. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2018;124:190-200.

- Silverberg JI, Garg NK, Paller AS, et al. Sleep disturbances in adults with eczema are associated with impaired overall health: a US population-based study. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:56-66.

- Chang YS, Chiang BL. Sleep disorders and atopic dermatitis: a 2-way street? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;142:1033-1040.

- Riegleman KL, Farnsworth GS, Wong EB. Atopic dermatitis in the US military. Cutis. 2019;104:144-147.

- Li WQ, Qureshi AA, Schernhammer ES, et al. Rotating night-shift work and risk of psoriasis in US women. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:565-567.

- Hirotsu C, Rydlewski M, Araújo MS, et al. Sleep loss and cytokines levels in an experimental model of psoriasis. PLoS One. 2012;7:E51183.

- Myers B, Vidhatha R, Nicholas B, et al. Sleep and the gut microbiome in psoriasis: clinical implications for disease progression and the development of cardiometabolic comorbidities. J Psoriasis Psoriatic Arthritis. 2021;6:27-37.

- Gupta MA, Simpson FC, Gupta AK. Psoriasis and sleep disorders: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2016;29:63-75.

- Gelman AB, Norton SA, Valdes-Rodriguez R, et al. A review of skin conditions in modern warfare and peacekeeping operations. Mil Med. 2015;180:32-37.

- Seo HM, Kim TL, Kim JS. The risk of alopecia areata and other related autoimmune diseases in patients with sleep disorders: a Korean population-based retrospective cohort study. Sleep. 2018;41:10.1093/sleep/zsy111.

- Department of Defense. 2020 Demographics: Profile of the Military Community. Military One Source website. Accessed February 17, 2023. https://download.militaryonesource.mil/12038/MOS/Reports/2020-demographics-report.pdf

- Sundelin T, Lekander M, Kecklund G, et al. Cues of fatigue: effects of sleep deprivation on facial appearance. Sleep. 2013;36:1355-1360.

- Sundelin T, Lekander M, Sorjonen K, et a. Negative effects of restricted sleep on facial appearance and social appeal. R Soc Open Sci. 2017;4:160918.

- Holding BC, Sundelin T, Cairns P, et al. The effect of sleep deprivation on objective and subjective measures of facial appearance. J Sleep Res. 2019;28:E12860.

- Léger D, Gauriau C, Etzi C, et al. “You look sleepy…” the impact of sleep restriction on skin parameters and facial appearance of 24 women. Sleep Med. 2022;89:97-103.

- Talamas SN, Mavor KI, Perrett DI. Blinded by beauty: attractiveness bias and accurate perceptions of academic performance. PLoS One. 2016;11:E0148284.

- Department of the Army. Enlisted Promotions and Reductions. Army Publishing Directorate website. Published May 16, 2019. Accessed February 17, 2023. https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/pdf/web/ARN17424_R600_8_19_Admin_FINAL.pdf

- Levy PD, Hile DC, Hile LM, et al. A prospective analysis of the treatment of friction blisters with 2-octylcyanoacrylate. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2006;96:232-237.

- Brennan FH Jr, Jackson CR, Olsen C, et al. Blisters on the battlefield: the prevalence of and factors associated with foot friction blisters during Operation Iraqi Freedom I. Mil Med. 2012;177:157-162.

- Mostaghimi L, Obermeyer WH, Ballamudi B, et al. Effects of sleep deprivation on wound healing. J Sleep Res. 2005;14:213-219.

- Wilkison BD, Wong EB. Skin cancer in military pilots: a special population with special risk factors. Cutis. 2017;100:218-220.

- IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans: Painting, Firefighting, and Shiftwork. World Health Organization International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2010. Accessed February 20, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK326814/

- Oyetakin-White P, Suggs A, Koo B, et al. Does poor sleep quality affect skin ageing? Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:17-22.

- Gaddameedhi S, Selby CP, Kaufmann WK, et al. Control of skin cancer by the circadian rhythm. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:18790-18795.

- Heckman CJ, Kloss JD, Feskanich D, et al. Associations among rotating night shift work, sleep and skin cancer in Nurses’ Health Study II participants. Occup Environ Med. 2017;74:169-175.

Sleep deprivation can increase emotional distress and mood disorders; reduce quality of life; and lead to cognitive, memory, and performance deficits.1 Military service predisposes members to disordered sleep due to the rigors of deployments and field training, such as long shifts, shift changes, stressful work environments, and time zone changes. Evidence shows that sleep deprivation is associated with cardiovascular disease, gastrointestinal disease, and some cancers.2 We explore multiple mechanisms by which sleep deprivation may affect the skin. We also review the potential impacts of sleep deprivation on specific topics in dermatology, including atopic dermatitis (AD), psoriasis, alopecia areata, physical attractiveness, wound healing, and skin cancer.

Sleep and Military Service

Approximately 35.2% of Americans experience short sleep duration, which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines as sleeping fewer than 7 hours per 24-hour period.3 Short sleep duration is even more common among individuals working in protective services and the military (50.4%).4 United States military service members experience multiple contributors to disordered sleep, including combat operations, shift work, psychiatric disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder, and traumatic brain injury.5 Bramoweth and Germain6 described the case of a 27-year-old man who served 2 combat tours as an infantryman in Afghanistan, during which time he routinely remained awake for more than 24 hours at a time due to night missions and extended operations. Even when he was not directly involved in combat operations, he was rarely able to keep a regular sleep schedule.6 Service members returning from deployment also report decreased sleep. In one study (N=2717), 43% of respondents reported short sleep duration (<7 hours of sleep per night) and 29% reported very short sleep duration (<6 hours of sleep per night).7 Even stateside, service members experience acute sleep deprivation during training.8

Sleep and Skin

The idea that skin conditions can affect quality of sleep is not controversial. Pruritus, pain, and emotional distress associated with different dermatologic conditions have all been implicated in adversely affecting sleep.9 Given the effects of sleep deprivation on other organ systems, it also can affect the skin. Possible mechanisms of action include negative effects of sleep deprivation on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, cutaneous barrier function, and immune function. First, the HPA axis activity follows a circadian rhythm.10 Activation outside of the bounds of this normal rhythm can have adverse effects on sleep. Alternatively, sleep deprivation and decreased sleep quality can negatively affect the HPA axis.10 These changes can adversely affect cutaneous barrier and immune function.11 Cutaneous barrier function is vitally important in the context of inflammatory dermatologic conditions. Transepidermal water loss, a measurement used to estimate cutaneous barrier function, is increased by sleep deprivation.12 Finally, the cutaneous immune system is an important component of inflammatory dermatologic conditions, cancer immune surveillance, and wound healing, and it also is negatively impacted by sleep deprivation.13 This framework of sleep deprivation affecting the HPA axis, cutaneous barrier function, and cutaneous immune function will help to guide the following discussion on the effects of decreased sleep on specific dermatologic conditions.

Atopic Dermatitis—Individuals with AD are at higher odds of having insomnia, fatigue, and overall poorer health status, including more sick days and increased visits to a physician.14 Additionally, it is possible that the relationship between AD and sleep is not unidirectional. Chang and Chiang15 discussed the possibility of sleep disturbances contributing to AD flares and listed 3 possible mechanisms by which sleep disturbance could potentially flare AD: exacerbation of the itch-scratch cycle; changes in the immune system, including a possible shift to helper T cell (TH2) dominance; and worsening of chronic stress in patients with AD. These changes may lead to a vicious cycle of impaired sleep and AD exacerbations. It may be helpful to view sleep impairment and AD as comorbid conditions requiring co-management for optimal outcomes. This perspective has military relevance because even without considering sleep deprivation, deployment and field conditions are known to increase the risk for AD flares.16

Psoriasis—Psoriasis also may have a bidirectional relationship with sleep. A study utilizing data from the Nurses’ Health Study showed that working a night shift increased the risk for psoriasis.17 Importantly, this connection is associative and not causative. It is possible that other factors in those who worked night shifts such as probable decreased UV exposure or reported increased body mass index played a role. Studies using psoriasis mice models have shown increased inflammation with sleep deprivation.18 Another possible connection is the effect of sleep deprivation on the gut microbiome. Sleep dysfunction is associated with altered gut bacteria ratios, and similar gut bacteria ratios were found in patients with psoriasis, which may indicate an association between sleep deprivation and psoriasis disease progression.19 There also is an increased association of obstructive sleep apnea in patients with psoriasis compared to the general population.20 Fortunately, the rate of consultations for psoriasis in deployed soldiers in the last several conflicts has been quite low, making up only 2.1% of diagnosed dermatologic conditions,21 which is because service members with moderate to severe psoriasis likely will not be deployed.

Alopecia Areata—Alopecia areata also may be associated with sleep deprivation. A large retrospective cohort study looking at the risk for alopecia in patients with sleep disorders showed that a sleep disorder was an independent risk factor for alopecia areata.22 The impact of sleep on the HPA axis portrays a possible mechanism for the negative effects of sleep deprivation on the immune system. Interestingly, in this study, the association was strongest for the 0- to 24-year-old age group. According to the 2020 demographics profile of the military community, 45% of active-duty personnel are 25 years or younger.23 Fortunately, although alopecia areata can be a distressing condition, it should not have much effect on military readiness, as most individuals with this diagnosis are still deployable.

Physical Appearance—

Wound Healing—Wound healing is of particular importance to the health of military members. Research is suggestive but not definitive of the relationship between sleep and wound healing. One intriguing study looked at the healing of blisters induced via suction in well-rested and sleep-deprived individuals. The results showed a difference, with the sleep-deprived individuals taking approximately 1 day longer to heal.13 This has some specific relevance to the military, as friction blisters can be common.30 A cross-sectional survey looking at a group of service members deployed in Iraq showed a prevalence of foot friction blisters of 33%, with 11% of individuals requiring medical care.31 Although this is an interesting example, it is not necessarily applicable to full-thickness wounds. A study utilizing rat models did not identify any differences between sleep-deprived and well-rested models in the healing of punch biopsy sites.32

Skin Cancer—Altered circadian rhythms resulting in changes in melatonin levels, changes in circadian rhythm–related gene pathways, and immunologic changes have been proposed as possible contributing mechanisms for the observed increased risk for skin cancers in military and civilian pilots.33,34 One study showed that UV-related erythema resolved quicker in well-rested individuals compared with those with short sleep duration, which could represent more efficient DNA repair given the relationship between UV-associated erythema and DNA damage and repair.35 Another study looking at circadian changes in the repair of UV-related DNA damage showed that mice exposed to UV radiation in the early morning had higher rates of squamous cell carcinoma than those exposed in the afternoon.36 However, a large cohort study using data from the Nurses’ Health Study II did not support a positive connection between short sleep duration and skin cancer; rather, it showed that a short sleep duration was associated with a decreased risk for melanoma and basal cell carcinoma, with no effect noted for squamous cell carcinoma.37 This does not support a positive association between short sleep duration and skin cancer and in some cases actually suggests a negative association.

Final Thoughts

Although more research is needed, there is evidence that sleep deprivation can negatively affect the skin. Randomized controlled trials looking at groups of individuals with specific dermatologic conditions with a very short sleep duration group (<6 hours of sleep per night), short sleep duration group (<7 hours of sleep per night), and a well-rested group (>7 hours of sleep per night) could be very helpful in this endeavor. Possible mechanisms include the HPA axis, immune system, and skin barrier function that are associated with sleep deprivation. Specific dermatologic conditions that may be affected by sleep deprivation include AD, psoriasis, alopecia areata, physical appearance, wound healing, and skin cancer. The impact of sleep deprivation on dermatologic conditions is particularly relevant to the military, as service members are at an increased risk for short sleep duration. It is possible that improving sleep may lead to better disease control for many dermatologic conditions.

Sleep deprivation can increase emotional distress and mood disorders; reduce quality of life; and lead to cognitive, memory, and performance deficits.1 Military service predisposes members to disordered sleep due to the rigors of deployments and field training, such as long shifts, shift changes, stressful work environments, and time zone changes. Evidence shows that sleep deprivation is associated with cardiovascular disease, gastrointestinal disease, and some cancers.2 We explore multiple mechanisms by which sleep deprivation may affect the skin. We also review the potential impacts of sleep deprivation on specific topics in dermatology, including atopic dermatitis (AD), psoriasis, alopecia areata, physical attractiveness, wound healing, and skin cancer.

Sleep and Military Service

Approximately 35.2% of Americans experience short sleep duration, which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines as sleeping fewer than 7 hours per 24-hour period.3 Short sleep duration is even more common among individuals working in protective services and the military (50.4%).4 United States military service members experience multiple contributors to disordered sleep, including combat operations, shift work, psychiatric disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder, and traumatic brain injury.5 Bramoweth and Germain6 described the case of a 27-year-old man who served 2 combat tours as an infantryman in Afghanistan, during which time he routinely remained awake for more than 24 hours at a time due to night missions and extended operations. Even when he was not directly involved in combat operations, he was rarely able to keep a regular sleep schedule.6 Service members returning from deployment also report decreased sleep. In one study (N=2717), 43% of respondents reported short sleep duration (<7 hours of sleep per night) and 29% reported very short sleep duration (<6 hours of sleep per night).7 Even stateside, service members experience acute sleep deprivation during training.8

Sleep and Skin

The idea that skin conditions can affect quality of sleep is not controversial. Pruritus, pain, and emotional distress associated with different dermatologic conditions have all been implicated in adversely affecting sleep.9 Given the effects of sleep deprivation on other organ systems, it also can affect the skin. Possible mechanisms of action include negative effects of sleep deprivation on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, cutaneous barrier function, and immune function. First, the HPA axis activity follows a circadian rhythm.10 Activation outside of the bounds of this normal rhythm can have adverse effects on sleep. Alternatively, sleep deprivation and decreased sleep quality can negatively affect the HPA axis.10 These changes can adversely affect cutaneous barrier and immune function.11 Cutaneous barrier function is vitally important in the context of inflammatory dermatologic conditions. Transepidermal water loss, a measurement used to estimate cutaneous barrier function, is increased by sleep deprivation.12 Finally, the cutaneous immune system is an important component of inflammatory dermatologic conditions, cancer immune surveillance, and wound healing, and it also is negatively impacted by sleep deprivation.13 This framework of sleep deprivation affecting the HPA axis, cutaneous barrier function, and cutaneous immune function will help to guide the following discussion on the effects of decreased sleep on specific dermatologic conditions.

Atopic Dermatitis—Individuals with AD are at higher odds of having insomnia, fatigue, and overall poorer health status, including more sick days and increased visits to a physician.14 Additionally, it is possible that the relationship between AD and sleep is not unidirectional. Chang and Chiang15 discussed the possibility of sleep disturbances contributing to AD flares and listed 3 possible mechanisms by which sleep disturbance could potentially flare AD: exacerbation of the itch-scratch cycle; changes in the immune system, including a possible shift to helper T cell (TH2) dominance; and worsening of chronic stress in patients with AD. These changes may lead to a vicious cycle of impaired sleep and AD exacerbations. It may be helpful to view sleep impairment and AD as comorbid conditions requiring co-management for optimal outcomes. This perspective has military relevance because even without considering sleep deprivation, deployment and field conditions are known to increase the risk for AD flares.16