User login

Nomogram may direct diabetes patients to best operation

PHILADELPHIA – A nomogram that assigns a disease severity score to individuals with type 2 diabetes may provide a tool that helps surgeons, endocrinologists, and primary care physicians determine which weight-loss surgical procedure would be most effective, according to an analysis of 900 patients from Cleveland Clinic and University Hospital Clinic, Barcelona, reported at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

“This is the largest reported cohort with long-term glycemic follow-up data that categorizes diabetes into three validated stages of severity to guide procedure selection,” said Ali Aminian, MD, of Cleveland Clinic. The study also highlighted the importance of surgery in early diabetes. The study involved a modeling cohort of 659 patients who had bariatric procedures at Cleveland Clinic from 2005 to 2011 and a separate data set of 241 patients from Barcelona to validate the findings. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) was performed in 78% of the Cleveland Clinic group and 49% of the Barcelona group, with the remainder having sleeve gastrectomy (SG).

RYGB and SG account for more than 95% of all bariatric procedures in people with type 2 diabetes, Dr. Aminian said, but outcomes of clinical trials have been variable, some reporting up to half of patients having long-term relapses. The Cleveland Clinic study involved all patients with type 2 diabetes who had RYGB or SG from 2005 to 2011 with 5 years or more of glycemic data, with a median follow-up of 7 years. The study used American Diabetes Association targets to define remission and glycemic control.

“Long-term response after bariatric surgery in patients with diabetes significantly differs according to diabetes severity,” Dr. Aminian said. “For example, the outcome of surgery in a patient who has diabetes for 2 years is significantly different than a patient who has diabetes for 15 years taking three medications, including insulin.”

The researchers generated the nomogram based on these four independent preoperative factors:

- Number of preoperative diabetes medications (P less than .0001).

- Insulin use (P = .002).

- Duration of diabetes (P less than .0001).

- Glycemic control (P = .002).

“These factors are readily available in clinical practice and are considered a proxy of functional pancreatic beta-cell reserve,” Dr. Aminian said. The nomogram scores the severity of each factor on a scale of 0 to 100. For example, one preoperative medication scores 12, but five scores 63; duration of diabetes of 1 year scores five points, but 16 years scores 60. The patient’s total points represent the Individualized Metabolic Surgery score.

The researchers assigned three categories: A score of 25 or less represents mild disease, a score of 25-95 represents moderate, and 95 to the maximum 180 is severe disease.

Based on the Cleveland Clinic and Barcelona cohorts, the researchers next developed recommendations for average risk patients in each category.

RYGB is “suggested” in mild disease based on remission rates of 92% in the Cleveland subgroup and 91% in the Barcelona subgroup vs. SG remission rates of 74% and 91%, respectively. On the other end of the spectrum, in patients with severe diabetes, both procedures were less effective in achieving long-term diabetes remission. The disparities were more pronounced for the moderate group: 60% and 70% for RYGB and 25% and 56% for SG in the Cleveland Clinic and Barcelona subgroups, respectively. Hence the nomogram highly “recommends” RYGB. An online calculator to determine Individualized Metabolic Surgery score is available at http://riskcalc.org/Metabolic_Surgery_Score/.

“Obviously, this is the first attempt toward individualized procedure selection and more work needs to be done,” Dr. Aminian said. “Our findings also highlight the importance of surgical intervention in early stages of diabetes in order to achieve sustainable remission.”

In his discussion, Matthew M. Hutter, MD, FACS, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, offered to “quibble” with Dr. Aminian’s conclusions. “I challenge you on your conclusion for the mild and severe categories,” Dr. Hutter said. “My rate-of-cure data makes me want to recommend bypass for any patient with diabetes – mild, moderate or severe.”

Dr. Aminian acknowledged that the number of SG cases in the severe subgroup – 51 – was not great, and long-term diabetes remission was comparable between the two procedures. The key distinguishing measure in the severe category was a net 8% difference between two procedures in glycemic control at last follow-up. “This is the difference that we must decide whether it’s clinically important or not – whether we’re willing to recommend a riskier procedure for an extra 8% achieving glycemic control,” Dr. Aminian said. “If someone thinks it’s worth the risk, then they may suggest gastric bypass. If someone thinks it’s not worth the risk, then they may suggest a sleeve gastrectomy. But, we should remember that patients in the severe group are very high-risk patients.”

Dr. Aminian reported no financial disclosures. Dr. Hutter disclosed receiving conference reimbursement from Olympus.

The complete manuscript of this study and its presentation at the American Surgical Association’s 137th Annual Meeting, April 2017, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, is to be published in Annals of Surgery pending editorial review.

PHILADELPHIA – A nomogram that assigns a disease severity score to individuals with type 2 diabetes may provide a tool that helps surgeons, endocrinologists, and primary care physicians determine which weight-loss surgical procedure would be most effective, according to an analysis of 900 patients from Cleveland Clinic and University Hospital Clinic, Barcelona, reported at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

“This is the largest reported cohort with long-term glycemic follow-up data that categorizes diabetes into three validated stages of severity to guide procedure selection,” said Ali Aminian, MD, of Cleveland Clinic. The study also highlighted the importance of surgery in early diabetes. The study involved a modeling cohort of 659 patients who had bariatric procedures at Cleveland Clinic from 2005 to 2011 and a separate data set of 241 patients from Barcelona to validate the findings. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) was performed in 78% of the Cleveland Clinic group and 49% of the Barcelona group, with the remainder having sleeve gastrectomy (SG).

RYGB and SG account for more than 95% of all bariatric procedures in people with type 2 diabetes, Dr. Aminian said, but outcomes of clinical trials have been variable, some reporting up to half of patients having long-term relapses. The Cleveland Clinic study involved all patients with type 2 diabetes who had RYGB or SG from 2005 to 2011 with 5 years or more of glycemic data, with a median follow-up of 7 years. The study used American Diabetes Association targets to define remission and glycemic control.

“Long-term response after bariatric surgery in patients with diabetes significantly differs according to diabetes severity,” Dr. Aminian said. “For example, the outcome of surgery in a patient who has diabetes for 2 years is significantly different than a patient who has diabetes for 15 years taking three medications, including insulin.”

The researchers generated the nomogram based on these four independent preoperative factors:

- Number of preoperative diabetes medications (P less than .0001).

- Insulin use (P = .002).

- Duration of diabetes (P less than .0001).

- Glycemic control (P = .002).

“These factors are readily available in clinical practice and are considered a proxy of functional pancreatic beta-cell reserve,” Dr. Aminian said. The nomogram scores the severity of each factor on a scale of 0 to 100. For example, one preoperative medication scores 12, but five scores 63; duration of diabetes of 1 year scores five points, but 16 years scores 60. The patient’s total points represent the Individualized Metabolic Surgery score.

The researchers assigned three categories: A score of 25 or less represents mild disease, a score of 25-95 represents moderate, and 95 to the maximum 180 is severe disease.

Based on the Cleveland Clinic and Barcelona cohorts, the researchers next developed recommendations for average risk patients in each category.

RYGB is “suggested” in mild disease based on remission rates of 92% in the Cleveland subgroup and 91% in the Barcelona subgroup vs. SG remission rates of 74% and 91%, respectively. On the other end of the spectrum, in patients with severe diabetes, both procedures were less effective in achieving long-term diabetes remission. The disparities were more pronounced for the moderate group: 60% and 70% for RYGB and 25% and 56% for SG in the Cleveland Clinic and Barcelona subgroups, respectively. Hence the nomogram highly “recommends” RYGB. An online calculator to determine Individualized Metabolic Surgery score is available at http://riskcalc.org/Metabolic_Surgery_Score/.

“Obviously, this is the first attempt toward individualized procedure selection and more work needs to be done,” Dr. Aminian said. “Our findings also highlight the importance of surgical intervention in early stages of diabetes in order to achieve sustainable remission.”

In his discussion, Matthew M. Hutter, MD, FACS, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, offered to “quibble” with Dr. Aminian’s conclusions. “I challenge you on your conclusion for the mild and severe categories,” Dr. Hutter said. “My rate-of-cure data makes me want to recommend bypass for any patient with diabetes – mild, moderate or severe.”

Dr. Aminian acknowledged that the number of SG cases in the severe subgroup – 51 – was not great, and long-term diabetes remission was comparable between the two procedures. The key distinguishing measure in the severe category was a net 8% difference between two procedures in glycemic control at last follow-up. “This is the difference that we must decide whether it’s clinically important or not – whether we’re willing to recommend a riskier procedure for an extra 8% achieving glycemic control,” Dr. Aminian said. “If someone thinks it’s worth the risk, then they may suggest gastric bypass. If someone thinks it’s not worth the risk, then they may suggest a sleeve gastrectomy. But, we should remember that patients in the severe group are very high-risk patients.”

Dr. Aminian reported no financial disclosures. Dr. Hutter disclosed receiving conference reimbursement from Olympus.

The complete manuscript of this study and its presentation at the American Surgical Association’s 137th Annual Meeting, April 2017, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, is to be published in Annals of Surgery pending editorial review.

PHILADELPHIA – A nomogram that assigns a disease severity score to individuals with type 2 diabetes may provide a tool that helps surgeons, endocrinologists, and primary care physicians determine which weight-loss surgical procedure would be most effective, according to an analysis of 900 patients from Cleveland Clinic and University Hospital Clinic, Barcelona, reported at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

“This is the largest reported cohort with long-term glycemic follow-up data that categorizes diabetes into three validated stages of severity to guide procedure selection,” said Ali Aminian, MD, of Cleveland Clinic. The study also highlighted the importance of surgery in early diabetes. The study involved a modeling cohort of 659 patients who had bariatric procedures at Cleveland Clinic from 2005 to 2011 and a separate data set of 241 patients from Barcelona to validate the findings. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) was performed in 78% of the Cleveland Clinic group and 49% of the Barcelona group, with the remainder having sleeve gastrectomy (SG).

RYGB and SG account for more than 95% of all bariatric procedures in people with type 2 diabetes, Dr. Aminian said, but outcomes of clinical trials have been variable, some reporting up to half of patients having long-term relapses. The Cleveland Clinic study involved all patients with type 2 diabetes who had RYGB or SG from 2005 to 2011 with 5 years or more of glycemic data, with a median follow-up of 7 years. The study used American Diabetes Association targets to define remission and glycemic control.

“Long-term response after bariatric surgery in patients with diabetes significantly differs according to diabetes severity,” Dr. Aminian said. “For example, the outcome of surgery in a patient who has diabetes for 2 years is significantly different than a patient who has diabetes for 15 years taking three medications, including insulin.”

The researchers generated the nomogram based on these four independent preoperative factors:

- Number of preoperative diabetes medications (P less than .0001).

- Insulin use (P = .002).

- Duration of diabetes (P less than .0001).

- Glycemic control (P = .002).

“These factors are readily available in clinical practice and are considered a proxy of functional pancreatic beta-cell reserve,” Dr. Aminian said. The nomogram scores the severity of each factor on a scale of 0 to 100. For example, one preoperative medication scores 12, but five scores 63; duration of diabetes of 1 year scores five points, but 16 years scores 60. The patient’s total points represent the Individualized Metabolic Surgery score.

The researchers assigned three categories: A score of 25 or less represents mild disease, a score of 25-95 represents moderate, and 95 to the maximum 180 is severe disease.

Based on the Cleveland Clinic and Barcelona cohorts, the researchers next developed recommendations for average risk patients in each category.

RYGB is “suggested” in mild disease based on remission rates of 92% in the Cleveland subgroup and 91% in the Barcelona subgroup vs. SG remission rates of 74% and 91%, respectively. On the other end of the spectrum, in patients with severe diabetes, both procedures were less effective in achieving long-term diabetes remission. The disparities were more pronounced for the moderate group: 60% and 70% for RYGB and 25% and 56% for SG in the Cleveland Clinic and Barcelona subgroups, respectively. Hence the nomogram highly “recommends” RYGB. An online calculator to determine Individualized Metabolic Surgery score is available at http://riskcalc.org/Metabolic_Surgery_Score/.

“Obviously, this is the first attempt toward individualized procedure selection and more work needs to be done,” Dr. Aminian said. “Our findings also highlight the importance of surgical intervention in early stages of diabetes in order to achieve sustainable remission.”

In his discussion, Matthew M. Hutter, MD, FACS, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, offered to “quibble” with Dr. Aminian’s conclusions. “I challenge you on your conclusion for the mild and severe categories,” Dr. Hutter said. “My rate-of-cure data makes me want to recommend bypass for any patient with diabetes – mild, moderate or severe.”

Dr. Aminian acknowledged that the number of SG cases in the severe subgroup – 51 – was not great, and long-term diabetes remission was comparable between the two procedures. The key distinguishing measure in the severe category was a net 8% difference between two procedures in glycemic control at last follow-up. “This is the difference that we must decide whether it’s clinically important or not – whether we’re willing to recommend a riskier procedure for an extra 8% achieving glycemic control,” Dr. Aminian said. “If someone thinks it’s worth the risk, then they may suggest gastric bypass. If someone thinks it’s not worth the risk, then they may suggest a sleeve gastrectomy. But, we should remember that patients in the severe group are very high-risk patients.”

Dr. Aminian reported no financial disclosures. Dr. Hutter disclosed receiving conference reimbursement from Olympus.

The complete manuscript of this study and its presentation at the American Surgical Association’s 137th Annual Meeting, April 2017, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, is to be published in Annals of Surgery pending editorial review.

AT THE ASA ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: A nomogram has been developed that assigns an Individualized Metabolic Surgery score to individuals with type 2 diabetes to help determine which type of bariatric procedure would provide best outcomes.

Major finding: In mild diabetes (Individualized Metabolic Surgery score less than or equal to 25), Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy significantly improve diabetes. For patients with severe diabetes (IMS Score greater than 95), both procedures have similarly low efficacy for diabetes remission.

Data source: Analysis of 900 patients with type 2 diabetes who had either Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy with a minimum 5-year follow-up.

Disclosure: Dr. Aminian reported no financial disclosures. Dr. Hutter disclosed receiving conference reimbursement from Olympus.

How bariatric surgery improves knee osteoarthritis

LAS VEGAS – Most of the improvement in knee pain that occurs following bariatric surgery in obese patients with knee osteoarthritis happens in the first month after surgery, well before the bulk of the weight loss takes place, Jonathan Samuels, MD, reported at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis.

This observation suggests that bariatric surgery’s mechanism of benefit in patients with knee osteoarthritis (OA) isn’t simply a matter of reduced mechanical load on the joints caused by a lessened weight burden, Dr. Samuels observed at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis, sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

Indeed, his prospective study of 150 obese patients with comorbid knee OA points to metabolic factors as likely playing a key role.

His study, featuring 2 years of follow-up to date, showed that bariatric surgery improved knee OA proportionate to the percentage of excess weight loss achieved. The greatest reduction in knee pain as well as the most profound weight loss occurred in the 35 patients who underwent gastric bypass and the 97 who opted for sleeve gastrectomy; patients who underwent laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding had more modest outcomes on both scores.

The disparate timing of the reductions in excess weight and knee pain was particularly eye catching. With all three forms of bariatric surgery, weight loss continued steadily for roughly the first 12 months. It then plateaued and was generally maintained at the new body mass index for the second 12 months.

In contrast, improvement in knee pain according to the validated Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) leveled out after just 1 month post surgery and was then sustained through 23 months. Levels of the inflammatory cytokines and adipokines interleukin-6, interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, and lipopolysaccharides were elevated at baseline but dropped steadily in concert with the reduction in excess body weight during the first 12 months after surgery. In contrast, levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokine sRAGE (soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products) were abnormally low prior to surgery but increased sharply for the first 3 months afterward before leveling off. And levels of serum leptin, which were roughly sevenfold greater than in normal controls at baseline, fell precipitously during the first month after bariatric surgery before plateauing, following the same pattern as the improvement in knee pain.

“This suggests that perhaps leptin is the key mediator in this OA population,” said Dr. Samuels.

Obese patients with knee OA are in a catch-22 situation. Obese individuals are at greatly increased lifetime risk of developing knee OA, and patients with chronic knee pain have a tough time losing weight.

“The treatments that might work with either obesity or knee pain alone often fail when both of these are present,” he observed.

That’s why bariatric surgery is becoming an increasingly popular treatment strategy in these patients. Sleeve gastrectomy, gastric bypass, and laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding are all Food and Drug Administration approved treatments for obesity in the presence of at least one qualifying comorbid condition, and knee OA qualifies.

Dr. Samuels reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study.

LAS VEGAS – Most of the improvement in knee pain that occurs following bariatric surgery in obese patients with knee osteoarthritis happens in the first month after surgery, well before the bulk of the weight loss takes place, Jonathan Samuels, MD, reported at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis.

This observation suggests that bariatric surgery’s mechanism of benefit in patients with knee osteoarthritis (OA) isn’t simply a matter of reduced mechanical load on the joints caused by a lessened weight burden, Dr. Samuels observed at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis, sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

Indeed, his prospective study of 150 obese patients with comorbid knee OA points to metabolic factors as likely playing a key role.

His study, featuring 2 years of follow-up to date, showed that bariatric surgery improved knee OA proportionate to the percentage of excess weight loss achieved. The greatest reduction in knee pain as well as the most profound weight loss occurred in the 35 patients who underwent gastric bypass and the 97 who opted for sleeve gastrectomy; patients who underwent laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding had more modest outcomes on both scores.

The disparate timing of the reductions in excess weight and knee pain was particularly eye catching. With all three forms of bariatric surgery, weight loss continued steadily for roughly the first 12 months. It then plateaued and was generally maintained at the new body mass index for the second 12 months.

In contrast, improvement in knee pain according to the validated Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) leveled out after just 1 month post surgery and was then sustained through 23 months. Levels of the inflammatory cytokines and adipokines interleukin-6, interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, and lipopolysaccharides were elevated at baseline but dropped steadily in concert with the reduction in excess body weight during the first 12 months after surgery. In contrast, levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokine sRAGE (soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products) were abnormally low prior to surgery but increased sharply for the first 3 months afterward before leveling off. And levels of serum leptin, which were roughly sevenfold greater than in normal controls at baseline, fell precipitously during the first month after bariatric surgery before plateauing, following the same pattern as the improvement in knee pain.

“This suggests that perhaps leptin is the key mediator in this OA population,” said Dr. Samuels.

Obese patients with knee OA are in a catch-22 situation. Obese individuals are at greatly increased lifetime risk of developing knee OA, and patients with chronic knee pain have a tough time losing weight.

“The treatments that might work with either obesity or knee pain alone often fail when both of these are present,” he observed.

That’s why bariatric surgery is becoming an increasingly popular treatment strategy in these patients. Sleeve gastrectomy, gastric bypass, and laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding are all Food and Drug Administration approved treatments for obesity in the presence of at least one qualifying comorbid condition, and knee OA qualifies.

Dr. Samuels reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study.

LAS VEGAS – Most of the improvement in knee pain that occurs following bariatric surgery in obese patients with knee osteoarthritis happens in the first month after surgery, well before the bulk of the weight loss takes place, Jonathan Samuels, MD, reported at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis.

This observation suggests that bariatric surgery’s mechanism of benefit in patients with knee osteoarthritis (OA) isn’t simply a matter of reduced mechanical load on the joints caused by a lessened weight burden, Dr. Samuels observed at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis, sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

Indeed, his prospective study of 150 obese patients with comorbid knee OA points to metabolic factors as likely playing a key role.

His study, featuring 2 years of follow-up to date, showed that bariatric surgery improved knee OA proportionate to the percentage of excess weight loss achieved. The greatest reduction in knee pain as well as the most profound weight loss occurred in the 35 patients who underwent gastric bypass and the 97 who opted for sleeve gastrectomy; patients who underwent laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding had more modest outcomes on both scores.

The disparate timing of the reductions in excess weight and knee pain was particularly eye catching. With all three forms of bariatric surgery, weight loss continued steadily for roughly the first 12 months. It then plateaued and was generally maintained at the new body mass index for the second 12 months.

In contrast, improvement in knee pain according to the validated Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) leveled out after just 1 month post surgery and was then sustained through 23 months. Levels of the inflammatory cytokines and adipokines interleukin-6, interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, and lipopolysaccharides were elevated at baseline but dropped steadily in concert with the reduction in excess body weight during the first 12 months after surgery. In contrast, levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokine sRAGE (soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products) were abnormally low prior to surgery but increased sharply for the first 3 months afterward before leveling off. And levels of serum leptin, which were roughly sevenfold greater than in normal controls at baseline, fell precipitously during the first month after bariatric surgery before plateauing, following the same pattern as the improvement in knee pain.

“This suggests that perhaps leptin is the key mediator in this OA population,” said Dr. Samuels.

Obese patients with knee OA are in a catch-22 situation. Obese individuals are at greatly increased lifetime risk of developing knee OA, and patients with chronic knee pain have a tough time losing weight.

“The treatments that might work with either obesity or knee pain alone often fail when both of these are present,” he observed.

That’s why bariatric surgery is becoming an increasingly popular treatment strategy in these patients. Sleeve gastrectomy, gastric bypass, and laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding are all Food and Drug Administration approved treatments for obesity in the presence of at least one qualifying comorbid condition, and knee OA qualifies.

Dr. Samuels reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study.

AT OARSI 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Most of the improvement in knee pain – and most of the accompanying drop in serum leptin – happens in the first month following bariatric surgery, well before most weight loss has occurred.

Data source: A prospective observational study of 150 obese patients with knee osteoarthritis who underwent bariatric surgery.

Disclosures: The study presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

Endoscopic weight loss surgery cuts costs, side effects

Obese patients who underwent endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty had significantly fewer complications and shorter hospital stays than did those who had laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy or laparoscopic band placement, according to results from a study of 278 adults. The data were presented at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

Overall, 1% of patients who underwent endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty (ESG) experienced adverse events, compared with 8% of those who underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) and 9% of those who underwent laparoscopic band placement (LAGB).

ESG, which reduces gastric volume by use of an endoscopic suturing system of full-thickness sutures through the greater curvature of the stomach, is becoming a popular weight-loss procedure for patients with a body mass index greater than 30 kg/m2 who are poor candidates for laparoscopic surgery or who would prefer a less invasive procedure, according to Reem Z. Sharaiha, MD, of Cornell University, New York.

Dr. Sharaiha and her colleagues randomized 91 patients to ESG, 120 to LSG, and 67 to LAGB. Patient demographic characteristics, including age, gender, and diabetes, were similar among the three groups. However, patients in the LSG group had a higher average BMI than did the LAGB and ESG groups (47.3 kg/m2, 45.7 kg/m2, and 38.8 kg/m2, respectively). In addition, the incidence of hypertension, and hyperlipidemia was significantly higher in each of the surgical groups compared to the ESG group (P less than .01).

The average postprocedure hospital stay was 0.13 days for ESG patients compared with 3.09 days for LSG patients and 1.68 days for LAGB patients. ESG also had the lowest cost of the three procedures, averaging $12,000 for the procedure compared to $22,000 for LSG and $15,000 for LAGB.

After 1 year, patients in the LSG group had the greatest percentage of total body weight loss (29.3%), followed by ESG patients (17.6%), and LAGB patients (14.5%). Rates of leaks, pulmonary embolism events, and 90-day readmission were not significantly different among the groups.

The study results do not imply that ESG will replace either LAGB or LSG for weight loss, Dr. Sharaiha noted, but the results suggest that ESG is a viable option for some patients.

Dr. Sharaiha had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

Digestive Disease Week® is jointly sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

Obese patients who underwent endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty had significantly fewer complications and shorter hospital stays than did those who had laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy or laparoscopic band placement, according to results from a study of 278 adults. The data were presented at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

Overall, 1% of patients who underwent endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty (ESG) experienced adverse events, compared with 8% of those who underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) and 9% of those who underwent laparoscopic band placement (LAGB).

ESG, which reduces gastric volume by use of an endoscopic suturing system of full-thickness sutures through the greater curvature of the stomach, is becoming a popular weight-loss procedure for patients with a body mass index greater than 30 kg/m2 who are poor candidates for laparoscopic surgery or who would prefer a less invasive procedure, according to Reem Z. Sharaiha, MD, of Cornell University, New York.

Dr. Sharaiha and her colleagues randomized 91 patients to ESG, 120 to LSG, and 67 to LAGB. Patient demographic characteristics, including age, gender, and diabetes, were similar among the three groups. However, patients in the LSG group had a higher average BMI than did the LAGB and ESG groups (47.3 kg/m2, 45.7 kg/m2, and 38.8 kg/m2, respectively). In addition, the incidence of hypertension, and hyperlipidemia was significantly higher in each of the surgical groups compared to the ESG group (P less than .01).

The average postprocedure hospital stay was 0.13 days for ESG patients compared with 3.09 days for LSG patients and 1.68 days for LAGB patients. ESG also had the lowest cost of the three procedures, averaging $12,000 for the procedure compared to $22,000 for LSG and $15,000 for LAGB.

After 1 year, patients in the LSG group had the greatest percentage of total body weight loss (29.3%), followed by ESG patients (17.6%), and LAGB patients (14.5%). Rates of leaks, pulmonary embolism events, and 90-day readmission were not significantly different among the groups.

The study results do not imply that ESG will replace either LAGB or LSG for weight loss, Dr. Sharaiha noted, but the results suggest that ESG is a viable option for some patients.

Dr. Sharaiha had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

Digestive Disease Week® is jointly sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

Obese patients who underwent endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty had significantly fewer complications and shorter hospital stays than did those who had laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy or laparoscopic band placement, according to results from a study of 278 adults. The data were presented at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

Overall, 1% of patients who underwent endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty (ESG) experienced adverse events, compared with 8% of those who underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) and 9% of those who underwent laparoscopic band placement (LAGB).

ESG, which reduces gastric volume by use of an endoscopic suturing system of full-thickness sutures through the greater curvature of the stomach, is becoming a popular weight-loss procedure for patients with a body mass index greater than 30 kg/m2 who are poor candidates for laparoscopic surgery or who would prefer a less invasive procedure, according to Reem Z. Sharaiha, MD, of Cornell University, New York.

Dr. Sharaiha and her colleagues randomized 91 patients to ESG, 120 to LSG, and 67 to LAGB. Patient demographic characteristics, including age, gender, and diabetes, were similar among the three groups. However, patients in the LSG group had a higher average BMI than did the LAGB and ESG groups (47.3 kg/m2, 45.7 kg/m2, and 38.8 kg/m2, respectively). In addition, the incidence of hypertension, and hyperlipidemia was significantly higher in each of the surgical groups compared to the ESG group (P less than .01).

The average postprocedure hospital stay was 0.13 days for ESG patients compared with 3.09 days for LSG patients and 1.68 days for LAGB patients. ESG also had the lowest cost of the three procedures, averaging $12,000 for the procedure compared to $22,000 for LSG and $15,000 for LAGB.

After 1 year, patients in the LSG group had the greatest percentage of total body weight loss (29.3%), followed by ESG patients (17.6%), and LAGB patients (14.5%). Rates of leaks, pulmonary embolism events, and 90-day readmission were not significantly different among the groups.

The study results do not imply that ESG will replace either LAGB or LSG for weight loss, Dr. Sharaiha noted, but the results suggest that ESG is a viable option for some patients.

Dr. Sharaiha had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

Digestive Disease Week® is jointly sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

FROM DDW

Key clinical point: Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty is a viable option for patients seeking weight loss but wishing to avoid major surgery.

Major finding: After 1 year, 1% of patients who underwent endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty experienced adverse events, compared with 8% of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy patients, and 9% of laparoscopic band placement patients.

Data source: A randomized trial of 278 obese adults who underwent one of three weight loss procedures.

Disclosures: Dr. Sharaiha had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

Series supports viability of ambulatory laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy

HOUSTON – An ambulatory approach to laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy is a safe and viable option to improve patient satisfaction and soften the economic blow of these procedures on patients, based on a large series at one surgery center in Cincinnati.

“With proper patient selection, utilization of enhanced recovery pathways with an overall low readmission rate and the complication profile point to the feasibility of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy [LSG] as a safe outpatient procedure,” said Sepehr Lalezari, MD, now a surgical fellow at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

About 105,000 LSG operations were performed in the United States in 2015, representing 54% of all bariatric operations, according to the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

Patient selection and strict adherence to protocols are keys to success for ambulatory LSG, Dr. Lalezari said. Suitable patients were found to be ambulatory, between ages 18 and 65 years; had a body mass index (BMI) less than 55 kg/m2 for males and less than 60 kg/m2 for females; weighed less than 500 lb; had an American Society of Anesthesiologists’ classification score less than 4; and had no significant cardiopulmonary impairment, had no history of renal failure or organ transplant, and were not on a transplant wait list.

In this series, 71% of patients (579) were female, and the average BMI was 43. The total complication rate was 2.3% (19); 17 of these patients required hospital admission.

Postoperative complications included gastric leaks (seven, 0.9%); intra-abdominal abscess requiring percutaneous drainage (four, 0.5%); dehydration, nausea, and/or vomiting (four, 0.5%); and one of each of the following: acute cholecystitis, postoperative bleeding, surgical site infection (SSI), and portal vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism.

The two complications managed on an outpatient basis were the SSI and one intra-abdominal abscess, Dr. Lalezari said.

“The only readmissions in our series that could have been possibly prevented with an overnight stay in the hospital were the four cases of nausea, vomiting, and/or dehydration,” he said. “These only accounted for 0.5% of the total cases performed.”

The readmission rates for ambulatory LSG in this series compared favorably with large trials that did not distinguish between ambulatory and inpatient LSG procedures, Dr. Lalezari noted. A 2016 analysis of 35,655 patients in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database reported a readmission rate of 3.7% for LSG (Surg Endosc. 2016 Jun;30[6]:2342-50).

A larger study of 130,000 patients who had bariatric surgery reported an LSG readmission rate of 2.8% (Ann Surg. 2016 Nov 15. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002079). The most common cause for readmissions these trials reported were nausea, vomiting, and/or dehydration.

Bariatric surgeons have embraced enhanced recovery pathways and fast-track surgery, with good results, Dr. Lalezari said, citing work by Zhamak Khorgami, MD, and colleagues at the Cleveland Clinic (Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017 Feb;13[2]:273-80).

“Looking at fast-track surgery, they found that patients discharged on postoperative day 1 vs. day 2 or 3 did not change outcomes”; those discharged later than postoperative day 1 trended toward a higher readmission rate of 2.8% vs. 3.6%, Dr. Lalezari said.

The enhanced recovery/fast track protocol Dr. Lalezari and his coauthors used involves placing intravenous lines and infusing 1 L crystalloid before starting the procedure, and administration of famotidine and metoclopramide prior to anesthesia. The protocol utilizes sequential compression devices and avoids Foley catheters and intra-abdominal drains. Patients receive dexamethasone and ondansetron during the operation. The protocol emphasizes early ambulation and resumption of oral intake.

The operation uses a 36-French bougie starting about 5 cm from the pylorus, and all staple lines are reinforced with buttress material. At the end of the surgery, all incisions are infiltrated with 30 cc of 0.5% bupivacaine with epinephrine.

Patients are ambulating about 90 minutes after surgery and are monitored for 3-4 hours. They receive a total volume of 3-4 L crystalloids. When they’re tolerating clear liquids, voiding spontaneously, and walking independently, and their pain is well controlled (pain score less than 5/10) and vital signs are within normal limits, they’re discharged.

Postoperative follow-up involves a call at 48 hours and in-clinic follow-up at weeks 1 and 4. Additional follow-up is scheduled at 3-month intervals for 1 year, then at 6 months for up to 2 years, and then yearly afterward.

“With proper patient selection and utilization of enhanced recovery pathways, the low overall readmission rate (2.1%) and complication profile (2.3%) in our series point to the feasibility of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy as a safe outpatient procedure,” Dr. Lalezari said.

He reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – An ambulatory approach to laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy is a safe and viable option to improve patient satisfaction and soften the economic blow of these procedures on patients, based on a large series at one surgery center in Cincinnati.

“With proper patient selection, utilization of enhanced recovery pathways with an overall low readmission rate and the complication profile point to the feasibility of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy [LSG] as a safe outpatient procedure,” said Sepehr Lalezari, MD, now a surgical fellow at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

About 105,000 LSG operations were performed in the United States in 2015, representing 54% of all bariatric operations, according to the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

Patient selection and strict adherence to protocols are keys to success for ambulatory LSG, Dr. Lalezari said. Suitable patients were found to be ambulatory, between ages 18 and 65 years; had a body mass index (BMI) less than 55 kg/m2 for males and less than 60 kg/m2 for females; weighed less than 500 lb; had an American Society of Anesthesiologists’ classification score less than 4; and had no significant cardiopulmonary impairment, had no history of renal failure or organ transplant, and were not on a transplant wait list.

In this series, 71% of patients (579) were female, and the average BMI was 43. The total complication rate was 2.3% (19); 17 of these patients required hospital admission.

Postoperative complications included gastric leaks (seven, 0.9%); intra-abdominal abscess requiring percutaneous drainage (four, 0.5%); dehydration, nausea, and/or vomiting (four, 0.5%); and one of each of the following: acute cholecystitis, postoperative bleeding, surgical site infection (SSI), and portal vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism.

The two complications managed on an outpatient basis were the SSI and one intra-abdominal abscess, Dr. Lalezari said.

“The only readmissions in our series that could have been possibly prevented with an overnight stay in the hospital were the four cases of nausea, vomiting, and/or dehydration,” he said. “These only accounted for 0.5% of the total cases performed.”

The readmission rates for ambulatory LSG in this series compared favorably with large trials that did not distinguish between ambulatory and inpatient LSG procedures, Dr. Lalezari noted. A 2016 analysis of 35,655 patients in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database reported a readmission rate of 3.7% for LSG (Surg Endosc. 2016 Jun;30[6]:2342-50).

A larger study of 130,000 patients who had bariatric surgery reported an LSG readmission rate of 2.8% (Ann Surg. 2016 Nov 15. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002079). The most common cause for readmissions these trials reported were nausea, vomiting, and/or dehydration.

Bariatric surgeons have embraced enhanced recovery pathways and fast-track surgery, with good results, Dr. Lalezari said, citing work by Zhamak Khorgami, MD, and colleagues at the Cleveland Clinic (Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017 Feb;13[2]:273-80).

“Looking at fast-track surgery, they found that patients discharged on postoperative day 1 vs. day 2 or 3 did not change outcomes”; those discharged later than postoperative day 1 trended toward a higher readmission rate of 2.8% vs. 3.6%, Dr. Lalezari said.

The enhanced recovery/fast track protocol Dr. Lalezari and his coauthors used involves placing intravenous lines and infusing 1 L crystalloid before starting the procedure, and administration of famotidine and metoclopramide prior to anesthesia. The protocol utilizes sequential compression devices and avoids Foley catheters and intra-abdominal drains. Patients receive dexamethasone and ondansetron during the operation. The protocol emphasizes early ambulation and resumption of oral intake.

The operation uses a 36-French bougie starting about 5 cm from the pylorus, and all staple lines are reinforced with buttress material. At the end of the surgery, all incisions are infiltrated with 30 cc of 0.5% bupivacaine with epinephrine.

Patients are ambulating about 90 minutes after surgery and are monitored for 3-4 hours. They receive a total volume of 3-4 L crystalloids. When they’re tolerating clear liquids, voiding spontaneously, and walking independently, and their pain is well controlled (pain score less than 5/10) and vital signs are within normal limits, they’re discharged.

Postoperative follow-up involves a call at 48 hours and in-clinic follow-up at weeks 1 and 4. Additional follow-up is scheduled at 3-month intervals for 1 year, then at 6 months for up to 2 years, and then yearly afterward.

“With proper patient selection and utilization of enhanced recovery pathways, the low overall readmission rate (2.1%) and complication profile (2.3%) in our series point to the feasibility of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy as a safe outpatient procedure,” Dr. Lalezari said.

He reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – An ambulatory approach to laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy is a safe and viable option to improve patient satisfaction and soften the economic blow of these procedures on patients, based on a large series at one surgery center in Cincinnati.

“With proper patient selection, utilization of enhanced recovery pathways with an overall low readmission rate and the complication profile point to the feasibility of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy [LSG] as a safe outpatient procedure,” said Sepehr Lalezari, MD, now a surgical fellow at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

About 105,000 LSG operations were performed in the United States in 2015, representing 54% of all bariatric operations, according to the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

Patient selection and strict adherence to protocols are keys to success for ambulatory LSG, Dr. Lalezari said. Suitable patients were found to be ambulatory, between ages 18 and 65 years; had a body mass index (BMI) less than 55 kg/m2 for males and less than 60 kg/m2 for females; weighed less than 500 lb; had an American Society of Anesthesiologists’ classification score less than 4; and had no significant cardiopulmonary impairment, had no history of renal failure or organ transplant, and were not on a transplant wait list.

In this series, 71% of patients (579) were female, and the average BMI was 43. The total complication rate was 2.3% (19); 17 of these patients required hospital admission.

Postoperative complications included gastric leaks (seven, 0.9%); intra-abdominal abscess requiring percutaneous drainage (four, 0.5%); dehydration, nausea, and/or vomiting (four, 0.5%); and one of each of the following: acute cholecystitis, postoperative bleeding, surgical site infection (SSI), and portal vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism.

The two complications managed on an outpatient basis were the SSI and one intra-abdominal abscess, Dr. Lalezari said.

“The only readmissions in our series that could have been possibly prevented with an overnight stay in the hospital were the four cases of nausea, vomiting, and/or dehydration,” he said. “These only accounted for 0.5% of the total cases performed.”

The readmission rates for ambulatory LSG in this series compared favorably with large trials that did not distinguish between ambulatory and inpatient LSG procedures, Dr. Lalezari noted. A 2016 analysis of 35,655 patients in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database reported a readmission rate of 3.7% for LSG (Surg Endosc. 2016 Jun;30[6]:2342-50).

A larger study of 130,000 patients who had bariatric surgery reported an LSG readmission rate of 2.8% (Ann Surg. 2016 Nov 15. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002079). The most common cause for readmissions these trials reported were nausea, vomiting, and/or dehydration.

Bariatric surgeons have embraced enhanced recovery pathways and fast-track surgery, with good results, Dr. Lalezari said, citing work by Zhamak Khorgami, MD, and colleagues at the Cleveland Clinic (Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017 Feb;13[2]:273-80).

“Looking at fast-track surgery, they found that patients discharged on postoperative day 1 vs. day 2 or 3 did not change outcomes”; those discharged later than postoperative day 1 trended toward a higher readmission rate of 2.8% vs. 3.6%, Dr. Lalezari said.

The enhanced recovery/fast track protocol Dr. Lalezari and his coauthors used involves placing intravenous lines and infusing 1 L crystalloid before starting the procedure, and administration of famotidine and metoclopramide prior to anesthesia. The protocol utilizes sequential compression devices and avoids Foley catheters and intra-abdominal drains. Patients receive dexamethasone and ondansetron during the operation. The protocol emphasizes early ambulation and resumption of oral intake.

The operation uses a 36-French bougie starting about 5 cm from the pylorus, and all staple lines are reinforced with buttress material. At the end of the surgery, all incisions are infiltrated with 30 cc of 0.5% bupivacaine with epinephrine.

Patients are ambulating about 90 minutes after surgery and are monitored for 3-4 hours. They receive a total volume of 3-4 L crystalloids. When they’re tolerating clear liquids, voiding spontaneously, and walking independently, and their pain is well controlled (pain score less than 5/10) and vital signs are within normal limits, they’re discharged.

Postoperative follow-up involves a call at 48 hours and in-clinic follow-up at weeks 1 and 4. Additional follow-up is scheduled at 3-month intervals for 1 year, then at 6 months for up to 2 years, and then yearly afterward.

“With proper patient selection and utilization of enhanced recovery pathways, the low overall readmission rate (2.1%) and complication profile (2.3%) in our series point to the feasibility of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy as a safe outpatient procedure,” Dr. Lalezari said.

He reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

AT SAGES 2017

Key clinical point: Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy is a safe outpatient procedure – with strict adherence to enhanced recovery pathways and fast-track protocols.

Major finding: This series reported an overall readmission rate of 2.1% and a complication rate of 2.3% in patients who had outpatient LSG.

Data source: A retrospective review of 821 patients who had ambulatory LSG by a single surgeon from 2011 to 2015.

Disclosures: Dr. Lalezari reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Study underscores antipsoriatic effect of gastric bypass surgery

Gastric bypass surgery was associated with more than a 50% drop in baseline rates of psoriasis, and with about a 70% decrease in the incidence of psoriatic arthritis, investigators reported.

In contrast, gastric banding did not appear to affect baselines rates of either of these autoimmune conditions, Alexander Egeberg, MD, of Herlev and Gentofte Hospital, Hellerup, Denmark, and associates reported in JAMA Surgery. “Although speculative, these findings may be the result of post-operative differences in weight loss and nutrient uptake, as well as differences in the postsurgical secretion of a number of gut hormones, including [glucagon-like peptide-1],” they wrote.

Psoriasis strongly correlates with obesity, and weight loss appears to mitigate psoriatic symptoms, the investigators noted. Previously, small studies and case series indicated that bariatric surgery might induce remission of psoriasis. To further investigate this possibility, Dr. Egeberg and his associates conducted a longitudinal cohort study of all 12,364 patients who underwent gastric bypass surgery and all 1,071 patients who underwent gastric banding in Denmark between 1997 and 2012 (JAMA Surg. 2017;152:344-349). No patient had psoriasis symptoms at the start of the study. A total of 272 (2%) gastric bypass patients developed psoriasis before their surgery, while only 0.5% did so afterward. In contrast, gastric banding was not tied to a significant change in the incidence of psoriasis – the preoperative rate was 0.5%, and the postoperative rate was 0.4%. Similarly, respective rates of psoriatic arthritis were 0.5% and 0.1% before and after gastric bypass, but were 0.3% and 0.6% before and after gastric banding. Additionally, respective rates of severe psoriasis were 0.8% and 0% before and after gastric bypass, but were about 0.2% and 0.5% before and after gastric banding.

After adjusting for age, sex, alcohol abuse, socioeconomic status, smoking, and diabetes status, gastric bypass was associated with about a 48% drop in the incidence of any type of psoriasis (P = .004), with about a 56% drop in the rate of severe psoriasis (P = .02), and with about a 71% drop in the rate of psoriatic arthritis (P = .01). In contrast, neither crude nor adjusted models linked gastric banding to a decrease in the incidence of psoriasis, severe psoriasis, or psoriatic arthritis, the researchers said.

Gastric banding is “a purely restrictive procedure,” while gastric bypass – especially Roux-en-Y bypass – diverts nutrients to the distal small intestine, where enteroendocrine cells secrete GLP-1, the researchers wrote.

“These postoperative hormonal changes may, in addition to the weight loss, be important for the antipsoriatic effect of gastric bypass,” they added. “Both gastric bypass and gastric banding have been shown to lead to sustained weight loss, suggesting that the observed differences in our study might be caused by factors other than weight loss.”

An unrestricted research grant from the Novo Nordisk Foundation funded the work. Dr. Egeberg disclosed ties to Pfizer and Eli Lilly. One coinvestigator disclosed ties to these and several other pharmaceutical companies.

Gastric bypass surgery was associated with more than a 50% drop in baseline rates of psoriasis, and with about a 70% decrease in the incidence of psoriatic arthritis, investigators reported.

In contrast, gastric banding did not appear to affect baselines rates of either of these autoimmune conditions, Alexander Egeberg, MD, of Herlev and Gentofte Hospital, Hellerup, Denmark, and associates reported in JAMA Surgery. “Although speculative, these findings may be the result of post-operative differences in weight loss and nutrient uptake, as well as differences in the postsurgical secretion of a number of gut hormones, including [glucagon-like peptide-1],” they wrote.

Psoriasis strongly correlates with obesity, and weight loss appears to mitigate psoriatic symptoms, the investigators noted. Previously, small studies and case series indicated that bariatric surgery might induce remission of psoriasis. To further investigate this possibility, Dr. Egeberg and his associates conducted a longitudinal cohort study of all 12,364 patients who underwent gastric bypass surgery and all 1,071 patients who underwent gastric banding in Denmark between 1997 and 2012 (JAMA Surg. 2017;152:344-349). No patient had psoriasis symptoms at the start of the study. A total of 272 (2%) gastric bypass patients developed psoriasis before their surgery, while only 0.5% did so afterward. In contrast, gastric banding was not tied to a significant change in the incidence of psoriasis – the preoperative rate was 0.5%, and the postoperative rate was 0.4%. Similarly, respective rates of psoriatic arthritis were 0.5% and 0.1% before and after gastric bypass, but were 0.3% and 0.6% before and after gastric banding. Additionally, respective rates of severe psoriasis were 0.8% and 0% before and after gastric bypass, but were about 0.2% and 0.5% before and after gastric banding.

After adjusting for age, sex, alcohol abuse, socioeconomic status, smoking, and diabetes status, gastric bypass was associated with about a 48% drop in the incidence of any type of psoriasis (P = .004), with about a 56% drop in the rate of severe psoriasis (P = .02), and with about a 71% drop in the rate of psoriatic arthritis (P = .01). In contrast, neither crude nor adjusted models linked gastric banding to a decrease in the incidence of psoriasis, severe psoriasis, or psoriatic arthritis, the researchers said.

Gastric banding is “a purely restrictive procedure,” while gastric bypass – especially Roux-en-Y bypass – diverts nutrients to the distal small intestine, where enteroendocrine cells secrete GLP-1, the researchers wrote.

“These postoperative hormonal changes may, in addition to the weight loss, be important for the antipsoriatic effect of gastric bypass,” they added. “Both gastric bypass and gastric banding have been shown to lead to sustained weight loss, suggesting that the observed differences in our study might be caused by factors other than weight loss.”

An unrestricted research grant from the Novo Nordisk Foundation funded the work. Dr. Egeberg disclosed ties to Pfizer and Eli Lilly. One coinvestigator disclosed ties to these and several other pharmaceutical companies.

Gastric bypass surgery was associated with more than a 50% drop in baseline rates of psoriasis, and with about a 70% decrease in the incidence of psoriatic arthritis, investigators reported.

In contrast, gastric banding did not appear to affect baselines rates of either of these autoimmune conditions, Alexander Egeberg, MD, of Herlev and Gentofte Hospital, Hellerup, Denmark, and associates reported in JAMA Surgery. “Although speculative, these findings may be the result of post-operative differences in weight loss and nutrient uptake, as well as differences in the postsurgical secretion of a number of gut hormones, including [glucagon-like peptide-1],” they wrote.

Psoriasis strongly correlates with obesity, and weight loss appears to mitigate psoriatic symptoms, the investigators noted. Previously, small studies and case series indicated that bariatric surgery might induce remission of psoriasis. To further investigate this possibility, Dr. Egeberg and his associates conducted a longitudinal cohort study of all 12,364 patients who underwent gastric bypass surgery and all 1,071 patients who underwent gastric banding in Denmark between 1997 and 2012 (JAMA Surg. 2017;152:344-349). No patient had psoriasis symptoms at the start of the study. A total of 272 (2%) gastric bypass patients developed psoriasis before their surgery, while only 0.5% did so afterward. In contrast, gastric banding was not tied to a significant change in the incidence of psoriasis – the preoperative rate was 0.5%, and the postoperative rate was 0.4%. Similarly, respective rates of psoriatic arthritis were 0.5% and 0.1% before and after gastric bypass, but were 0.3% and 0.6% before and after gastric banding. Additionally, respective rates of severe psoriasis were 0.8% and 0% before and after gastric bypass, but were about 0.2% and 0.5% before and after gastric banding.

After adjusting for age, sex, alcohol abuse, socioeconomic status, smoking, and diabetes status, gastric bypass was associated with about a 48% drop in the incidence of any type of psoriasis (P = .004), with about a 56% drop in the rate of severe psoriasis (P = .02), and with about a 71% drop in the rate of psoriatic arthritis (P = .01). In contrast, neither crude nor adjusted models linked gastric banding to a decrease in the incidence of psoriasis, severe psoriasis, or psoriatic arthritis, the researchers said.

Gastric banding is “a purely restrictive procedure,” while gastric bypass – especially Roux-en-Y bypass – diverts nutrients to the distal small intestine, where enteroendocrine cells secrete GLP-1, the researchers wrote.

“These postoperative hormonal changes may, in addition to the weight loss, be important for the antipsoriatic effect of gastric bypass,” they added. “Both gastric bypass and gastric banding have been shown to lead to sustained weight loss, suggesting that the observed differences in our study might be caused by factors other than weight loss.”

An unrestricted research grant from the Novo Nordisk Foundation funded the work. Dr. Egeberg disclosed ties to Pfizer and Eli Lilly. One coinvestigator disclosed ties to these and several other pharmaceutical companies.

Key clinical point: Gastric bypass, but not gastric banding, was associated with significant drops in rates of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis.

Major finding: In an adjusted model, gastric bypass was associated with about a 48% drop in the incidence of any type of psoriasis, with a 56% drop in the rate of severe psoriasis, and with a 71% drop in the rate of psoriatic arthritis.

Data source: A population-based cohort study of 12,364 gastric bypass patients and 1,071 gastric banding patients.

Disclosures: An unrestricted research grant from the Novo Nordisk Foundation funded the work. Dr. Egeberg disclosed ties to Pfizer and Eli Lilly. One coinvestigator disclosed ties to these and several other pharmaceutical companies. The other coinvestigators reported having no ties to industry.

Liver disease likely to become increasing indication for bariatric surgery

PHILADELPHIA – There is a long list of benefits from bariatric surgery in the morbidly obese, but prevention of end-stage liver disease and the need for a first or second liver transplant is likely to grow as an indication, according to an overview of weight loss surgery at Digestive Diseases: New Advances, held by Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, and Global Academy for Medical Education.

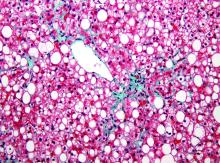

“Bariatric surgery is associated with significant improvement not just in diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and other complications of metabolic disorders but for me more interestingly, it is effective for treating fatty liver disease where you can see a 90% improvement in steatosis,” reported Subhashini Ayloo, MD, chief of minimally invasive robotic hepato-pancreato-biliary surgery and liver transplantation at New Jersey Medical School, Newark.

Trained in both bariatric surgery and liver transplant, Dr. Ayloo predicts that these fields will become increasingly connected because of the obesity epidemic and the related rise in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Dr. Ayloo reported that bariatric surgery is already being used in her center to avoid a second liver transplant in obese patients who are unable to lose sufficient weight to prevent progressive NAFLD after a first transplant.

The emphasis Dr. Ayloo placed on the role of bariatric surgery in preventing progression of NAFLD to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and the inflammatory process that leads to fibrosis, cirrhosis, and liver decompensation, was drawn from her interest in these two fields. However, she did not ignore the potential of protection from obesity control for other diseases.

“Obesity adversely affects every organ in the body,” Dr. Ayloo pointed out. As a result of weight loss achieved with bariatric surgery, there is now a large body of evidence supporting broad benefits, not just those related to fat deposited in hepatocytes.

“We have a couple of decades of experience that has been published [with bariatric surgery], and this has shown that it maintains weight loss long term, it improves all the obesity-associated comorbidities, and it is cost effective,” Dr. Ayloo said. Now with long-term follow-up, “all of the studies are showing that bariatric surgery improves survival.”

Although most of the survival data have been generated by retrospective cohort studies, Dr. Ayloo cited nine sets of data showing odds ratios associating bariatric surgery with up to a 90% reduction in death over periods of up to 10 years of follow-up. In a summary slide presented by Dr. Ayloo, the estimated mortality benefit over 5 years was listed as 85%. The same summary slide listed large improvements in relevant measures of morbidity for more than 10 organ systems, such as improvement or resolution of dyslipidemia and hypertension in the circulatory system, improvement or resolution of asthma and other diseases affecting the respiratory system, and resolution or improvement of gastroesophageal reflux disease and other diseases affecting the gastrointestinal system.

Specific to the liver, these benefits included a nearly 40% reduction in liver inflammation and 20% reduction in fibrosis. According to Dr. Ayloo, who noted that NAFLD is expected to overtake hepatitis C virus as the No. 1 cause of liver transplant within the next 5 years, these data are important for drawing attention to bariatric surgery as a strategy to control liver disease. She suggested that there is a need to create a tighter link between efforts to treat morbid obesity and advanced liver disease.

“There is an established literature showing that if somebody is morbidly obese, the rate of liver transplant is lower than when compared to patients with normal weight,” Dr. Ayloo said. “There is a call out in the transplant community that we need to address this and we cannot just be throwing this under the table.”

Because of the strong relationship between obesity and NAFLD, a systematic approach is needed to consider liver disease in obese patients and obesity in patients with liver disease, she said. The close relationship is relevant when planning interventions for either. Liver disease should be assessed prior to bariatric surgery regardless of the indication and then monitored closely as part of postoperative care, she said.

Dr. Ayloo identified weight control as an essential part of posttransplant care to prevent hepatic fat deposition that threatens transplant-free survival.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company. Dr. Ayloo reports no relevant financial relationships.

PHILADELPHIA – There is a long list of benefits from bariatric surgery in the morbidly obese, but prevention of end-stage liver disease and the need for a first or second liver transplant is likely to grow as an indication, according to an overview of weight loss surgery at Digestive Diseases: New Advances, held by Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, and Global Academy for Medical Education.

“Bariatric surgery is associated with significant improvement not just in diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and other complications of metabolic disorders but for me more interestingly, it is effective for treating fatty liver disease where you can see a 90% improvement in steatosis,” reported Subhashini Ayloo, MD, chief of minimally invasive robotic hepato-pancreato-biliary surgery and liver transplantation at New Jersey Medical School, Newark.

Trained in both bariatric surgery and liver transplant, Dr. Ayloo predicts that these fields will become increasingly connected because of the obesity epidemic and the related rise in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Dr. Ayloo reported that bariatric surgery is already being used in her center to avoid a second liver transplant in obese patients who are unable to lose sufficient weight to prevent progressive NAFLD after a first transplant.

The emphasis Dr. Ayloo placed on the role of bariatric surgery in preventing progression of NAFLD to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and the inflammatory process that leads to fibrosis, cirrhosis, and liver decompensation, was drawn from her interest in these two fields. However, she did not ignore the potential of protection from obesity control for other diseases.

“Obesity adversely affects every organ in the body,” Dr. Ayloo pointed out. As a result of weight loss achieved with bariatric surgery, there is now a large body of evidence supporting broad benefits, not just those related to fat deposited in hepatocytes.

“We have a couple of decades of experience that has been published [with bariatric surgery], and this has shown that it maintains weight loss long term, it improves all the obesity-associated comorbidities, and it is cost effective,” Dr. Ayloo said. Now with long-term follow-up, “all of the studies are showing that bariatric surgery improves survival.”

Although most of the survival data have been generated by retrospective cohort studies, Dr. Ayloo cited nine sets of data showing odds ratios associating bariatric surgery with up to a 90% reduction in death over periods of up to 10 years of follow-up. In a summary slide presented by Dr. Ayloo, the estimated mortality benefit over 5 years was listed as 85%. The same summary slide listed large improvements in relevant measures of morbidity for more than 10 organ systems, such as improvement or resolution of dyslipidemia and hypertension in the circulatory system, improvement or resolution of asthma and other diseases affecting the respiratory system, and resolution or improvement of gastroesophageal reflux disease and other diseases affecting the gastrointestinal system.

Specific to the liver, these benefits included a nearly 40% reduction in liver inflammation and 20% reduction in fibrosis. According to Dr. Ayloo, who noted that NAFLD is expected to overtake hepatitis C virus as the No. 1 cause of liver transplant within the next 5 years, these data are important for drawing attention to bariatric surgery as a strategy to control liver disease. She suggested that there is a need to create a tighter link between efforts to treat morbid obesity and advanced liver disease.

“There is an established literature showing that if somebody is morbidly obese, the rate of liver transplant is lower than when compared to patients with normal weight,” Dr. Ayloo said. “There is a call out in the transplant community that we need to address this and we cannot just be throwing this under the table.”

Because of the strong relationship between obesity and NAFLD, a systematic approach is needed to consider liver disease in obese patients and obesity in patients with liver disease, she said. The close relationship is relevant when planning interventions for either. Liver disease should be assessed prior to bariatric surgery regardless of the indication and then monitored closely as part of postoperative care, she said.

Dr. Ayloo identified weight control as an essential part of posttransplant care to prevent hepatic fat deposition that threatens transplant-free survival.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company. Dr. Ayloo reports no relevant financial relationships.

PHILADELPHIA – There is a long list of benefits from bariatric surgery in the morbidly obese, but prevention of end-stage liver disease and the need for a first or second liver transplant is likely to grow as an indication, according to an overview of weight loss surgery at Digestive Diseases: New Advances, held by Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, and Global Academy for Medical Education.

“Bariatric surgery is associated with significant improvement not just in diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and other complications of metabolic disorders but for me more interestingly, it is effective for treating fatty liver disease where you can see a 90% improvement in steatosis,” reported Subhashini Ayloo, MD, chief of minimally invasive robotic hepato-pancreato-biliary surgery and liver transplantation at New Jersey Medical School, Newark.

Trained in both bariatric surgery and liver transplant, Dr. Ayloo predicts that these fields will become increasingly connected because of the obesity epidemic and the related rise in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Dr. Ayloo reported that bariatric surgery is already being used in her center to avoid a second liver transplant in obese patients who are unable to lose sufficient weight to prevent progressive NAFLD after a first transplant.

The emphasis Dr. Ayloo placed on the role of bariatric surgery in preventing progression of NAFLD to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and the inflammatory process that leads to fibrosis, cirrhosis, and liver decompensation, was drawn from her interest in these two fields. However, she did not ignore the potential of protection from obesity control for other diseases.

“Obesity adversely affects every organ in the body,” Dr. Ayloo pointed out. As a result of weight loss achieved with bariatric surgery, there is now a large body of evidence supporting broad benefits, not just those related to fat deposited in hepatocytes.

“We have a couple of decades of experience that has been published [with bariatric surgery], and this has shown that it maintains weight loss long term, it improves all the obesity-associated comorbidities, and it is cost effective,” Dr. Ayloo said. Now with long-term follow-up, “all of the studies are showing that bariatric surgery improves survival.”

Although most of the survival data have been generated by retrospective cohort studies, Dr. Ayloo cited nine sets of data showing odds ratios associating bariatric surgery with up to a 90% reduction in death over periods of up to 10 years of follow-up. In a summary slide presented by Dr. Ayloo, the estimated mortality benefit over 5 years was listed as 85%. The same summary slide listed large improvements in relevant measures of morbidity for more than 10 organ systems, such as improvement or resolution of dyslipidemia and hypertension in the circulatory system, improvement or resolution of asthma and other diseases affecting the respiratory system, and resolution or improvement of gastroesophageal reflux disease and other diseases affecting the gastrointestinal system.

Specific to the liver, these benefits included a nearly 40% reduction in liver inflammation and 20% reduction in fibrosis. According to Dr. Ayloo, who noted that NAFLD is expected to overtake hepatitis C virus as the No. 1 cause of liver transplant within the next 5 years, these data are important for drawing attention to bariatric surgery as a strategy to control liver disease. She suggested that there is a need to create a tighter link between efforts to treat morbid obesity and advanced liver disease.

“There is an established literature showing that if somebody is morbidly obese, the rate of liver transplant is lower than when compared to patients with normal weight,” Dr. Ayloo said. “There is a call out in the transplant community that we need to address this and we cannot just be throwing this under the table.”

Because of the strong relationship between obesity and NAFLD, a systematic approach is needed to consider liver disease in obese patients and obesity in patients with liver disease, she said. The close relationship is relevant when planning interventions for either. Liver disease should be assessed prior to bariatric surgery regardless of the indication and then monitored closely as part of postoperative care, she said.

Dr. Ayloo identified weight control as an essential part of posttransplant care to prevent hepatic fat deposition that threatens transplant-free survival.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company. Dr. Ayloo reports no relevant financial relationships.

Open-capsule PPIs linked to faster ulcer healing after Roux-en-Y

The use of proton pump inhibitors in opened instead of closed capsules was associated with a nearly fourfold shorter median healing time among patients who developed marginal ulcers after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, in a single-center retrospective cohort study.

In contrast, the specific class of proton pump inhibitor (PPI) did not affect healing times, wrote Allison R. Schulman, MD, and her associates at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. The report is in the April issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.10.015). “Given these results and the high prevalence of marginal ulceration in this patient population, further study in a randomized controlled setting is warranted, and use of open-capsule PPIs should be considered as a low-risk, low-cost alternative,” they added.

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass is one of the most common types of gastric bypass surgeries in the world, and up to 16% of patients develop postsurgical ulcers at the gastrojejunal anastomosis, the investigators noted. Acidity is a prime suspect in these “marginal ulcerations” because bypassing the acid-buffering duodenum exposes the jejunum to acid from the stomach, they added. High-dose PPIs are the main treatment, but there is no consensus on the formulation or dose of therapy. Because Roux-en-Y creates a small gastric pouch and hastens small-bowel transit, closed capsules designed to break down in the stomach “even may make their way to the colon before breakdown occurs,” they wrote.

They reviewed medical charts from patients who developed marginal ulcerations after undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass at their hospital from 2000 through 2015. A total of 115 patients received open-capsule PPIs and 49 received intact capsules. All were followed until their ulcers healed.

For the open-capsule group, median time to healing was 91 days, compared with 342 days for the closed-capsule group (P less than .001). Importantly, capsule type was the only independent predictor of healing time (hazard ratio, 6.0; 95% confidence interval, 3.7 to 9.8; P less than .001) in a Cox regression model that included other known correlates of ulcer healing, including age, smoking status, the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, Helicobacter pylori infection, the length of the gastric pouch, and the presence of fistulae or foreign bodies such as sutures or staples.